User login

Formerly Skin & Allergy News

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')]

The leading independent newspaper covering dermatology news and commentary.

Proposed HIPAA overhaul to ease access to patient health info

The Department of Health & Human Services is proposing an overhaul of HIPAA that will make it easier to access patients’ personal health information, including the health records of patients with mental illness. The proposal would also do away with the requirement that all patients sign a notice of privacy practices.

The changes are contained in a 357-page proposed rule, which was unveiled by federal officials Dec. 10. Roger Severino, director of HHS’ Office for Civil Rights, said in a briefing that the sweeping proposal would empower patients, reduce the administrative burden for health care providers, and pave the way to better-coordinated care.

HHS estimated that the rule could save $3.2 billion over 5 years, but it’s not clear how much of that would accrue to clinical practices.

The most obvious cost-saving aspect for medical and dental practices is the proposal that practitioners would no longer have to provide and collect signed notifications of privacy practices.

“This has been a tremendous waste of time and effort and has caused massive confusion,” said Mr. Severino. He said some patients thought they were waiving privacy rights and that, in some cases, physicians refused to administer care unless patients signed the notices. “That was never the intent.”

Requiring that patients sign the form and that practices keep copies for 6 years is an “unnecessary burden,” said Mr. Severino. “We’ve lost whole forests from this regulation.”

Under the new proposal, health care providers would merely have to let patients know where to find their privacy policies.

Sharing mental health info

The rule would also ease the standard for sharing information about a patient who is in a mental health crisis, such as an exacerbation of a serious mental illness or a crisis related to a substance use disorder, including an overdose.

Currently, clinicians can choose to disclose protected health information – to a family member, a caregiver, a law enforcement official, a doctor, or an insurer – if they believe that doing so is advisable in their “professional judgment.” The rule proposes to ease that to a “good faith” belief that a disclosure would be in the best interest of the patient. In both instances, the patient can still object and block the disclosure.

As an example, HHS said that, in the case of a young adult who had experienced an overdose of opioids, a licensed health care professional could make the determination to “disclose relevant information to a parent who is involved in the patient’s treatment and who the young adult would expect, based on their relationship, to participate in or be involved with the patient’s recovery from the overdose.”

HHS is also proposing to let clinicians disclose information in cases in which an individual might be a threat to himself or others, provided the harm is “serious and reasonably foreseeable.”

Currently, information can only be disclosed if it appears there is a “serious and imminent” threat to health or safety. If an individual experienced suicidal ideation, for instance, a health care professional could notify family that the individual is at risk.

Fast, no-cost access

The rule also aims to make it easier for patients to get access to their own health care information quickly – within 15 days of a request – instead of the 30 days currently allowed, and sometimes at no cost.

The 30-day time frame is “a relic of a pre-Internet age that should be dispensed with,” said Mr. Severino.

Patients can also request that a treating physician get his or her records from a clinician who had previously treated the individual. The request would be fulfilled within 15 days, although extensions might be possible.

“That takes away the burden of coordination from the patient and puts it on those parties that are responsible for the actual provision of care and that are better positioned to do that coordination,” Mr. Severino said.

Health care professionals will also have to share with patients a fee schedule for records requests. However, if records are shared through a patient portal with view, download, and transmit capabilities, the provider can’t charge the patient for the time it took to upload the information into the system.

“We do not believe a patient’s personal medical record should be profit centers for providers,” Mr. Severino said.

Patients will be allowed to take photos with a smartphone of personal health information – such as an x-ray or sonogram – while receiving care.

The rule is open for public comment until mid-February. After that, it will become final in 180 days. The agency said it would not begin enforcement until 240 days after the final rule was published.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Department of Health & Human Services is proposing an overhaul of HIPAA that will make it easier to access patients’ personal health information, including the health records of patients with mental illness. The proposal would also do away with the requirement that all patients sign a notice of privacy practices.

The changes are contained in a 357-page proposed rule, which was unveiled by federal officials Dec. 10. Roger Severino, director of HHS’ Office for Civil Rights, said in a briefing that the sweeping proposal would empower patients, reduce the administrative burden for health care providers, and pave the way to better-coordinated care.

HHS estimated that the rule could save $3.2 billion over 5 years, but it’s not clear how much of that would accrue to clinical practices.

The most obvious cost-saving aspect for medical and dental practices is the proposal that practitioners would no longer have to provide and collect signed notifications of privacy practices.

“This has been a tremendous waste of time and effort and has caused massive confusion,” said Mr. Severino. He said some patients thought they were waiving privacy rights and that, in some cases, physicians refused to administer care unless patients signed the notices. “That was never the intent.”

Requiring that patients sign the form and that practices keep copies for 6 years is an “unnecessary burden,” said Mr. Severino. “We’ve lost whole forests from this regulation.”

Under the new proposal, health care providers would merely have to let patients know where to find their privacy policies.

Sharing mental health info

The rule would also ease the standard for sharing information about a patient who is in a mental health crisis, such as an exacerbation of a serious mental illness or a crisis related to a substance use disorder, including an overdose.

Currently, clinicians can choose to disclose protected health information – to a family member, a caregiver, a law enforcement official, a doctor, or an insurer – if they believe that doing so is advisable in their “professional judgment.” The rule proposes to ease that to a “good faith” belief that a disclosure would be in the best interest of the patient. In both instances, the patient can still object and block the disclosure.

As an example, HHS said that, in the case of a young adult who had experienced an overdose of opioids, a licensed health care professional could make the determination to “disclose relevant information to a parent who is involved in the patient’s treatment and who the young adult would expect, based on their relationship, to participate in or be involved with the patient’s recovery from the overdose.”

HHS is also proposing to let clinicians disclose information in cases in which an individual might be a threat to himself or others, provided the harm is “serious and reasonably foreseeable.”

Currently, information can only be disclosed if it appears there is a “serious and imminent” threat to health or safety. If an individual experienced suicidal ideation, for instance, a health care professional could notify family that the individual is at risk.

Fast, no-cost access

The rule also aims to make it easier for patients to get access to their own health care information quickly – within 15 days of a request – instead of the 30 days currently allowed, and sometimes at no cost.

The 30-day time frame is “a relic of a pre-Internet age that should be dispensed with,” said Mr. Severino.

Patients can also request that a treating physician get his or her records from a clinician who had previously treated the individual. The request would be fulfilled within 15 days, although extensions might be possible.

“That takes away the burden of coordination from the patient and puts it on those parties that are responsible for the actual provision of care and that are better positioned to do that coordination,” Mr. Severino said.

Health care professionals will also have to share with patients a fee schedule for records requests. However, if records are shared through a patient portal with view, download, and transmit capabilities, the provider can’t charge the patient for the time it took to upload the information into the system.

“We do not believe a patient’s personal medical record should be profit centers for providers,” Mr. Severino said.

Patients will be allowed to take photos with a smartphone of personal health information – such as an x-ray or sonogram – while receiving care.

The rule is open for public comment until mid-February. After that, it will become final in 180 days. The agency said it would not begin enforcement until 240 days after the final rule was published.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Department of Health & Human Services is proposing an overhaul of HIPAA that will make it easier to access patients’ personal health information, including the health records of patients with mental illness. The proposal would also do away with the requirement that all patients sign a notice of privacy practices.

The changes are contained in a 357-page proposed rule, which was unveiled by federal officials Dec. 10. Roger Severino, director of HHS’ Office for Civil Rights, said in a briefing that the sweeping proposal would empower patients, reduce the administrative burden for health care providers, and pave the way to better-coordinated care.

HHS estimated that the rule could save $3.2 billion over 5 years, but it’s not clear how much of that would accrue to clinical practices.

The most obvious cost-saving aspect for medical and dental practices is the proposal that practitioners would no longer have to provide and collect signed notifications of privacy practices.

“This has been a tremendous waste of time and effort and has caused massive confusion,” said Mr. Severino. He said some patients thought they were waiving privacy rights and that, in some cases, physicians refused to administer care unless patients signed the notices. “That was never the intent.”

Requiring that patients sign the form and that practices keep copies for 6 years is an “unnecessary burden,” said Mr. Severino. “We’ve lost whole forests from this regulation.”

Under the new proposal, health care providers would merely have to let patients know where to find their privacy policies.

Sharing mental health info

The rule would also ease the standard for sharing information about a patient who is in a mental health crisis, such as an exacerbation of a serious mental illness or a crisis related to a substance use disorder, including an overdose.

Currently, clinicians can choose to disclose protected health information – to a family member, a caregiver, a law enforcement official, a doctor, or an insurer – if they believe that doing so is advisable in their “professional judgment.” The rule proposes to ease that to a “good faith” belief that a disclosure would be in the best interest of the patient. In both instances, the patient can still object and block the disclosure.

As an example, HHS said that, in the case of a young adult who had experienced an overdose of opioids, a licensed health care professional could make the determination to “disclose relevant information to a parent who is involved in the patient’s treatment and who the young adult would expect, based on their relationship, to participate in or be involved with the patient’s recovery from the overdose.”

HHS is also proposing to let clinicians disclose information in cases in which an individual might be a threat to himself or others, provided the harm is “serious and reasonably foreseeable.”

Currently, information can only be disclosed if it appears there is a “serious and imminent” threat to health or safety. If an individual experienced suicidal ideation, for instance, a health care professional could notify family that the individual is at risk.

Fast, no-cost access

The rule also aims to make it easier for patients to get access to their own health care information quickly – within 15 days of a request – instead of the 30 days currently allowed, and sometimes at no cost.

The 30-day time frame is “a relic of a pre-Internet age that should be dispensed with,” said Mr. Severino.

Patients can also request that a treating physician get his or her records from a clinician who had previously treated the individual. The request would be fulfilled within 15 days, although extensions might be possible.

“That takes away the burden of coordination from the patient and puts it on those parties that are responsible for the actual provision of care and that are better positioned to do that coordination,” Mr. Severino said.

Health care professionals will also have to share with patients a fee schedule for records requests. However, if records are shared through a patient portal with view, download, and transmit capabilities, the provider can’t charge the patient for the time it took to upload the information into the system.

“We do not believe a patient’s personal medical record should be profit centers for providers,” Mr. Severino said.

Patients will be allowed to take photos with a smartphone of personal health information – such as an x-ray or sonogram – while receiving care.

The rule is open for public comment until mid-February. After that, it will become final in 180 days. The agency said it would not begin enforcement until 240 days after the final rule was published.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A girl presents with blotchy, slightly itchy spots on her chest, back

On close evaluation of the picture on her chest, she has pale macules and patches surrounded by erythematous ill-defined patches consistent with nevus anemicus. The findings of the picture raise the suspicion for neurofibromatosis, and it was recommended for her to be evaluated in person.

She comes several days later to the clinic. The caretaker, who is her aunt, reports she does not know much of the girl’s medical history as she recently moved from South America to live with her. The girl is a very nice and pleasant 8-year-old. She reports noticing the spots on her chest for about a year and that they seem to get a little itchier and more noticeable when she is hot or when she is running. She also reports increasing headaches for several months. She is being home schooled, and according to her aunt she is at par with her cousins who are about the same age. There is no history of seizures. She has had back surgery in the past. There is no history of hypertension. There is no family history of any genetic disorder or similar lesions.

On physical exam, her vital signs are normal, but her head circumference is over the 90th percentile. She is pleasant and interactive. On skin examination, she has slightly noticeable pale macules and patches on the chest and back that become more apparent after rubbing her skin. She has multiple light brown macules and oval patches on the chest, back, and neck. She has no axillary or inguinal freckling. She has scars on the back from her prior surgery.

As she was having worsening headaches, an MRI of the brain was ordered, which showed a left optic glioma. She was then referred to ophthalmology, neurology, and genetics.

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is a common genetic autosomal dominant disorder cause by mutations on the NF1 gene on chromosome 17, which encodes for the protein neurofibromin. This protein works in the Ras-mitogen–activated protein kinase pathway as a negative regulator. Based on the National Institute of Health criteria, children need two or more of the following to be diagnosed with NF1: more than six café au lait macules larger than 5 mm in prepubescent children and 2.5 cm after puberty; axillary or inguinal freckling; two or more Lisch nodules; optic gliomas; two or more neurofibromas or one plexiform neurofibroma; or a first degree relative with a diagnosis of NF1. With these criteria, about 70% of the children can be diagnosed before the age of 1 year.1

Nevus anemicus is an uncommon birthmark, sometimes overlooked, that is characterized by pale, hypopigmented, well-defined macules and patches that do not turn red after trauma or changes in temperature. Nevus anemicus is usually localized on the torso but can be seen on the face, neck, and extremities. These lesions are present in 1%-2% of the general population. They are thought to occur because of increased sensitivity of the affected blood vessels to catecholamines, which causes permanent vasoconstriction, which leads to hypopigmentation on the area.2 These lesions are usually present at birth and have been described in patients with tuberous sclerosis, neurofibromatosis, and phakomatosis pigmentovascularis.

Recent studies of patients with neurofibromatosis and other RASopathies have noticed that nevus anemicus is present in about 8.8%-51% of the patients studied with a diagnosis NF1, compared with only 2% of the controls.3,4 The studies failed to report any cases of nevus anemicus in patients with other RASopathies associated with café au lait macules. Bulteel and colleagues recently reported two cases of non-NF1 RASopathies also associated with nevus anemicus in a patient with Legius syndrome and a patient with Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines.5 The nevus anemicus was reported to occur most commonly on the anterior chest and be multiple, as seen in our patient.

The authors of the published studies advocate for the introduction of nevus anemicus as part of the diagnostic criteria for NF1, especially because it can be an early finding seen in babies, which can aid in early diagnosis of NF1.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Matiz at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatrics. 2000 Mar. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.3.608.

2. Nevus Anemicus. StatPearls [Internet] (Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan).

3. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.039.

4. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015 May-Jun. doi: 10.1111/pde.12525.

5. JAAD Case Rep. 2018 Apr 5. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.09.037.

On close evaluation of the picture on her chest, she has pale macules and patches surrounded by erythematous ill-defined patches consistent with nevus anemicus. The findings of the picture raise the suspicion for neurofibromatosis, and it was recommended for her to be evaluated in person.

She comes several days later to the clinic. The caretaker, who is her aunt, reports she does not know much of the girl’s medical history as she recently moved from South America to live with her. The girl is a very nice and pleasant 8-year-old. She reports noticing the spots on her chest for about a year and that they seem to get a little itchier and more noticeable when she is hot or when she is running. She also reports increasing headaches for several months. She is being home schooled, and according to her aunt she is at par with her cousins who are about the same age. There is no history of seizures. She has had back surgery in the past. There is no history of hypertension. There is no family history of any genetic disorder or similar lesions.

On physical exam, her vital signs are normal, but her head circumference is over the 90th percentile. She is pleasant and interactive. On skin examination, she has slightly noticeable pale macules and patches on the chest and back that become more apparent after rubbing her skin. She has multiple light brown macules and oval patches on the chest, back, and neck. She has no axillary or inguinal freckling. She has scars on the back from her prior surgery.

As she was having worsening headaches, an MRI of the brain was ordered, which showed a left optic glioma. She was then referred to ophthalmology, neurology, and genetics.

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is a common genetic autosomal dominant disorder cause by mutations on the NF1 gene on chromosome 17, which encodes for the protein neurofibromin. This protein works in the Ras-mitogen–activated protein kinase pathway as a negative regulator. Based on the National Institute of Health criteria, children need two or more of the following to be diagnosed with NF1: more than six café au lait macules larger than 5 mm in prepubescent children and 2.5 cm after puberty; axillary or inguinal freckling; two or more Lisch nodules; optic gliomas; two or more neurofibromas or one plexiform neurofibroma; or a first degree relative with a diagnosis of NF1. With these criteria, about 70% of the children can be diagnosed before the age of 1 year.1

Nevus anemicus is an uncommon birthmark, sometimes overlooked, that is characterized by pale, hypopigmented, well-defined macules and patches that do not turn red after trauma or changes in temperature. Nevus anemicus is usually localized on the torso but can be seen on the face, neck, and extremities. These lesions are present in 1%-2% of the general population. They are thought to occur because of increased sensitivity of the affected blood vessels to catecholamines, which causes permanent vasoconstriction, which leads to hypopigmentation on the area.2 These lesions are usually present at birth and have been described in patients with tuberous sclerosis, neurofibromatosis, and phakomatosis pigmentovascularis.

Recent studies of patients with neurofibromatosis and other RASopathies have noticed that nevus anemicus is present in about 8.8%-51% of the patients studied with a diagnosis NF1, compared with only 2% of the controls.3,4 The studies failed to report any cases of nevus anemicus in patients with other RASopathies associated with café au lait macules. Bulteel and colleagues recently reported two cases of non-NF1 RASopathies also associated with nevus anemicus in a patient with Legius syndrome and a patient with Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines.5 The nevus anemicus was reported to occur most commonly on the anterior chest and be multiple, as seen in our patient.

The authors of the published studies advocate for the introduction of nevus anemicus as part of the diagnostic criteria for NF1, especially because it can be an early finding seen in babies, which can aid in early diagnosis of NF1.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Matiz at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatrics. 2000 Mar. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.3.608.

2. Nevus Anemicus. StatPearls [Internet] (Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan).

3. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.039.

4. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015 May-Jun. doi: 10.1111/pde.12525.

5. JAAD Case Rep. 2018 Apr 5. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.09.037.

On close evaluation of the picture on her chest, she has pale macules and patches surrounded by erythematous ill-defined patches consistent with nevus anemicus. The findings of the picture raise the suspicion for neurofibromatosis, and it was recommended for her to be evaluated in person.

She comes several days later to the clinic. The caretaker, who is her aunt, reports she does not know much of the girl’s medical history as she recently moved from South America to live with her. The girl is a very nice and pleasant 8-year-old. She reports noticing the spots on her chest for about a year and that they seem to get a little itchier and more noticeable when she is hot or when she is running. She also reports increasing headaches for several months. She is being home schooled, and according to her aunt she is at par with her cousins who are about the same age. There is no history of seizures. She has had back surgery in the past. There is no history of hypertension. There is no family history of any genetic disorder or similar lesions.

On physical exam, her vital signs are normal, but her head circumference is over the 90th percentile. She is pleasant and interactive. On skin examination, she has slightly noticeable pale macules and patches on the chest and back that become more apparent after rubbing her skin. She has multiple light brown macules and oval patches on the chest, back, and neck. She has no axillary or inguinal freckling. She has scars on the back from her prior surgery.

As she was having worsening headaches, an MRI of the brain was ordered, which showed a left optic glioma. She was then referred to ophthalmology, neurology, and genetics.

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is a common genetic autosomal dominant disorder cause by mutations on the NF1 gene on chromosome 17, which encodes for the protein neurofibromin. This protein works in the Ras-mitogen–activated protein kinase pathway as a negative regulator. Based on the National Institute of Health criteria, children need two or more of the following to be diagnosed with NF1: more than six café au lait macules larger than 5 mm in prepubescent children and 2.5 cm after puberty; axillary or inguinal freckling; two or more Lisch nodules; optic gliomas; two or more neurofibromas or one plexiform neurofibroma; or a first degree relative with a diagnosis of NF1. With these criteria, about 70% of the children can be diagnosed before the age of 1 year.1

Nevus anemicus is an uncommon birthmark, sometimes overlooked, that is characterized by pale, hypopigmented, well-defined macules and patches that do not turn red after trauma or changes in temperature. Nevus anemicus is usually localized on the torso but can be seen on the face, neck, and extremities. These lesions are present in 1%-2% of the general population. They are thought to occur because of increased sensitivity of the affected blood vessels to catecholamines, which causes permanent vasoconstriction, which leads to hypopigmentation on the area.2 These lesions are usually present at birth and have been described in patients with tuberous sclerosis, neurofibromatosis, and phakomatosis pigmentovascularis.

Recent studies of patients with neurofibromatosis and other RASopathies have noticed that nevus anemicus is present in about 8.8%-51% of the patients studied with a diagnosis NF1, compared with only 2% of the controls.3,4 The studies failed to report any cases of nevus anemicus in patients with other RASopathies associated with café au lait macules. Bulteel and colleagues recently reported two cases of non-NF1 RASopathies also associated with nevus anemicus in a patient with Legius syndrome and a patient with Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines.5 The nevus anemicus was reported to occur most commonly on the anterior chest and be multiple, as seen in our patient.

The authors of the published studies advocate for the introduction of nevus anemicus as part of the diagnostic criteria for NF1, especially because it can be an early finding seen in babies, which can aid in early diagnosis of NF1.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Matiz at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatrics. 2000 Mar. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.3.608.

2. Nevus Anemicus. StatPearls [Internet] (Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan).

3. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.039.

4. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015 May-Jun. doi: 10.1111/pde.12525.

5. JAAD Case Rep. 2018 Apr 5. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.09.037.

Medicare payments could get tougher for docs

More than 40 value-based payment models – from direct contracting to bundled payments – have been introduced into the Medicare program in the past 10 years, with the goal of improving care while lowering costs. Hopes were high that they would be successful.

Physicians could suffer a huge blow to their income.

Many of the value-based care models simply did not work as expected, said Seema Verma, head of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, at a recent HLTH Conference. “They are not producing the types of savings the taxpayers deserve,” Ms. Verma said.

The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPac) concluded that, while dozens of payment models were tested, most failed to generate net savings for Medicare. Even the most successful of the models produced only modest savings. MedPac elaborated: “The track record raises the question of whether changes to particular models or CMMI’s [Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation’s] broader strategies might be warranted.”

What will happen now, as government officials admit that their value-based programs haven’t worked? The value-based programs could become more stringent. Here’s what physicians will have to contend with.

More risk. Experts agree that risk – financial risk – will be a component of future programs. Two-sided risk is likely to be the norm. This means that both parties – the provider and the insurer – are at financial risk for the patients covered by the program.

For example, a plan with 50,000 beneficiary patients would estimate the cost of caring for those patients on the basis of multiple variables. If the actual cost is lower than anticipated, both parties share in the savings. However, both share in the loss if the cost of caring for their patient population exceeds expectations.

This may compel physicians to enhance efficiency and potentially limit the services provided to patients. Typically, however, the strategy is to make efforts to prevent services like ED visits and admissions by focusing on health maintenance.

In contrast to most current value-based models, which feature little to no downside risk for physicians, double-sided risk means physicians could lose money. The loss may incorporate a cap – 5%, for example – but programs may differ. Experts concur that double-sided risk will be a hallmark of future programs.

Better data. The majority of health care services are rendered via fee-for-service: Patients receive services and physicians are paid, yet little or no information about outcomes is exchanged between insurers and physicians.

Penny Noyes, president of Health Business Navigators and contract negotiator for physicians, is not a fan of the current crop of value-based programs and feels that data transparency is positive. Sound metrics can lead to improvement, she said, adding: “It’s not money that drives physicians to make decisions; it’s what’s in the best interest of their patients and their patients’ long-term care.”

Value-based programs can work but only if applicable data are developed and given to physicians so that they can better understand their current performance and how to improve.

Mandated participation. Participation in value-based programs has been voluntary, but that may have skewed the results, which were better than what typical practice would have shown. Acknowledging this may lead CMS to call for mandated participation as a component of future programs. Physicians may be brought into programs, if only to determine whether the models really work. To date, participation in the programs has been voluntary, but that may change in the future.

Innovation. The private insurance market may end up as a key player. Over the past 6 months, health insurers have either consolidated partnerships with telemedicine companies to provide no-cost care to beneficiaries or have launched their own initiatives.

Others are focused on bringing together patients and providers operating outside of the traditional health care system, such as Aetna’s merger with CVS which now offers retail-based acute care (MinuteClinic) and chronic care (HealthHUB). Still other payers are gambling with physician practice ownership, as in the case of United Healthcare’s OptumHealth, which now boasts around 50,000 physicians throughout the country.

New practice models are emerging in private practices as well. Physicians are embracing remote care, proactively managing care transitions, and seeking out more methods to keep patients healthy and at home.

Not much was expected from value-based plans

Many are not surprised that the value-based models did not produce impressive results. Ms. Noyes doubted that positive outcomes will be achieved for physicians in comparison with what could have been attained under fee-for-service arrangements with lower administrative costs.

While the Affordable Care Act attempted to encourage alternative reimbursement, it limits the maximum medical loss ratio (MLR) a payer could achieve. For many plans, that maximum was 85%. Simply put, at least $0.85 of each premium collected had to be paid in claims; the remaining $0.15 went to margin, claims, and other administrative costs. A payer with an 82% MLR then would have to rebate the 3% difference to enrollees.

But that’s not what occurred, according to Ms. Noyes. Because value-based payments to providers are considered a claims expense, an MLR ratio of 82% allowed the payer to distribute the 3% difference to providers as value-based payments. Ms. Noyes said: “That may sound good for the provider, but the result was essentially a freeze on the provider’s fee-for-service reimbursement with the prospect of getting value-based payments like ‘shared savings.’

“When the providers tried to increase their base fee-for-service rates just to match inflation, payers often advised that any future raises had to be earned through value-based programs,” Ms. Noyes added. The value-based formulas confuse providers because payments are often made for periods as far back as 18 months, and providers do not have data systems to reconcile their payer report cards retrospectively. The result is that providers tended to accept whatever amount the payer distributed.

Executives at Lumeris, a company that helps health systems participate successfully in value-based care, see potential in a newer approach to alternative payments, such as CMS’ Direct Contracting initiative. This voluntary payment model offers options tailored to several types of organizations that aim to reduce costs while preserving or enhancing the quality of care for Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries.

Jeff Smith, chief commercial officer for population health at Lumeris, explained that the Direct Contracting initiative can provide physicians with a more attractive option than prior value-based models because it adjusts for the complexity and fragility of patients with complex and chronic conditions. By allowing providers to participate in the savings generated, the initiative stands in stark contrast to what Mr. Smith described as the “shared savings to nothingness” experienced by providers in earlier-stage alternative payment models.

Physicians engaged with value-based programs like Direct Contracting are investing in nurses to aid with initiatives regarding health promotion and transitions of care. When a patient is discharged, for example, the nurse contacts the patient to discuss medications, schedule follow-up appointments, and so forth – tasks typically left to the patient (or caregiver) to navigate in the traditional system.

The initiative recognizes the importance of managing high-risk patients, those whom physicians identify as having an extraordinary number of ED visits and admissions. These patients, as well as so-called “rising-risk” patients, are targeted by nurses who proactively communicate with patients (and caregivers) to address patient’s needs, including social determinants of health.

Physicians who have a large load of patients in value-based programs are hiring social workers, pharmacists, and behavioral health experts to help. Of course, these personnel are costly, but that’s what the value-based programs aim to reimburse.

Still, the road ahead to value based is rocky and may not gain momentum for some time. Johns Hopkins University’s Doug Hough, PhD, an economist, recounts a government research study that sought to assess the university’s health system participation in a value-based payment program. While there were positive impacts on the program’s target population, Hough and his team discovered that the returns achieved by the optional model didn’t justify the health system’s financial support for it. The increasingly indebted health system ultimately decided to drop the optional program.

Dr. Hough indicated that the health system – Johns Hopkins Medicine – likely would have continued its support for the program had the government at least allowed it to break even. Although the payment program under study was a 3-year project, the bigger challenge, declared Dr. Hough, is that “we can’t turn an aircraft carrier that quickly.”

“Three years won’t show whether value-based care is really working,” Dr. Hough said.

Robert Zipper, MD, a hospitalist and senior policy advisor for Sound Physicians, a company that works to improve outcomes in acute care, agreed with Dr. Hough that performance tends to improve with time. Yet, Dr. Zipper doesn’t see much change in the near term, because “after all, there is nothing to replace them [the programs].”

The problem gets even stickier for private payers because patients may be on an insurance panel for as little as a year or 2. Thanks to this rapid churn of beneficiaries, even the best-designed value-based program will have little time to prove its worth.

Dr. Zipper is among the many who don’t expect significant changes in the near term, asserting that “President Biden will want to get a few policy wins first, and health care is not the easiest place to start.”

But it’s likely that payers and others will want to see more emphasis on value-based programs despite these programs’ possible value to patients, physicians, and health systems alike.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

More than 40 value-based payment models – from direct contracting to bundled payments – have been introduced into the Medicare program in the past 10 years, with the goal of improving care while lowering costs. Hopes were high that they would be successful.

Physicians could suffer a huge blow to their income.

Many of the value-based care models simply did not work as expected, said Seema Verma, head of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, at a recent HLTH Conference. “They are not producing the types of savings the taxpayers deserve,” Ms. Verma said.

The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPac) concluded that, while dozens of payment models were tested, most failed to generate net savings for Medicare. Even the most successful of the models produced only modest savings. MedPac elaborated: “The track record raises the question of whether changes to particular models or CMMI’s [Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation’s] broader strategies might be warranted.”

What will happen now, as government officials admit that their value-based programs haven’t worked? The value-based programs could become more stringent. Here’s what physicians will have to contend with.

More risk. Experts agree that risk – financial risk – will be a component of future programs. Two-sided risk is likely to be the norm. This means that both parties – the provider and the insurer – are at financial risk for the patients covered by the program.

For example, a plan with 50,000 beneficiary patients would estimate the cost of caring for those patients on the basis of multiple variables. If the actual cost is lower than anticipated, both parties share in the savings. However, both share in the loss if the cost of caring for their patient population exceeds expectations.

This may compel physicians to enhance efficiency and potentially limit the services provided to patients. Typically, however, the strategy is to make efforts to prevent services like ED visits and admissions by focusing on health maintenance.

In contrast to most current value-based models, which feature little to no downside risk for physicians, double-sided risk means physicians could lose money. The loss may incorporate a cap – 5%, for example – but programs may differ. Experts concur that double-sided risk will be a hallmark of future programs.

Better data. The majority of health care services are rendered via fee-for-service: Patients receive services and physicians are paid, yet little or no information about outcomes is exchanged between insurers and physicians.

Penny Noyes, president of Health Business Navigators and contract negotiator for physicians, is not a fan of the current crop of value-based programs and feels that data transparency is positive. Sound metrics can lead to improvement, she said, adding: “It’s not money that drives physicians to make decisions; it’s what’s in the best interest of their patients and their patients’ long-term care.”

Value-based programs can work but only if applicable data are developed and given to physicians so that they can better understand their current performance and how to improve.

Mandated participation. Participation in value-based programs has been voluntary, but that may have skewed the results, which were better than what typical practice would have shown. Acknowledging this may lead CMS to call for mandated participation as a component of future programs. Physicians may be brought into programs, if only to determine whether the models really work. To date, participation in the programs has been voluntary, but that may change in the future.

Innovation. The private insurance market may end up as a key player. Over the past 6 months, health insurers have either consolidated partnerships with telemedicine companies to provide no-cost care to beneficiaries or have launched their own initiatives.

Others are focused on bringing together patients and providers operating outside of the traditional health care system, such as Aetna’s merger with CVS which now offers retail-based acute care (MinuteClinic) and chronic care (HealthHUB). Still other payers are gambling with physician practice ownership, as in the case of United Healthcare’s OptumHealth, which now boasts around 50,000 physicians throughout the country.

New practice models are emerging in private practices as well. Physicians are embracing remote care, proactively managing care transitions, and seeking out more methods to keep patients healthy and at home.

Not much was expected from value-based plans

Many are not surprised that the value-based models did not produce impressive results. Ms. Noyes doubted that positive outcomes will be achieved for physicians in comparison with what could have been attained under fee-for-service arrangements with lower administrative costs.

While the Affordable Care Act attempted to encourage alternative reimbursement, it limits the maximum medical loss ratio (MLR) a payer could achieve. For many plans, that maximum was 85%. Simply put, at least $0.85 of each premium collected had to be paid in claims; the remaining $0.15 went to margin, claims, and other administrative costs. A payer with an 82% MLR then would have to rebate the 3% difference to enrollees.

But that’s not what occurred, according to Ms. Noyes. Because value-based payments to providers are considered a claims expense, an MLR ratio of 82% allowed the payer to distribute the 3% difference to providers as value-based payments. Ms. Noyes said: “That may sound good for the provider, but the result was essentially a freeze on the provider’s fee-for-service reimbursement with the prospect of getting value-based payments like ‘shared savings.’

“When the providers tried to increase their base fee-for-service rates just to match inflation, payers often advised that any future raises had to be earned through value-based programs,” Ms. Noyes added. The value-based formulas confuse providers because payments are often made for periods as far back as 18 months, and providers do not have data systems to reconcile their payer report cards retrospectively. The result is that providers tended to accept whatever amount the payer distributed.

Executives at Lumeris, a company that helps health systems participate successfully in value-based care, see potential in a newer approach to alternative payments, such as CMS’ Direct Contracting initiative. This voluntary payment model offers options tailored to several types of organizations that aim to reduce costs while preserving or enhancing the quality of care for Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries.

Jeff Smith, chief commercial officer for population health at Lumeris, explained that the Direct Contracting initiative can provide physicians with a more attractive option than prior value-based models because it adjusts for the complexity and fragility of patients with complex and chronic conditions. By allowing providers to participate in the savings generated, the initiative stands in stark contrast to what Mr. Smith described as the “shared savings to nothingness” experienced by providers in earlier-stage alternative payment models.

Physicians engaged with value-based programs like Direct Contracting are investing in nurses to aid with initiatives regarding health promotion and transitions of care. When a patient is discharged, for example, the nurse contacts the patient to discuss medications, schedule follow-up appointments, and so forth – tasks typically left to the patient (or caregiver) to navigate in the traditional system.

The initiative recognizes the importance of managing high-risk patients, those whom physicians identify as having an extraordinary number of ED visits and admissions. These patients, as well as so-called “rising-risk” patients, are targeted by nurses who proactively communicate with patients (and caregivers) to address patient’s needs, including social determinants of health.

Physicians who have a large load of patients in value-based programs are hiring social workers, pharmacists, and behavioral health experts to help. Of course, these personnel are costly, but that’s what the value-based programs aim to reimburse.

Still, the road ahead to value based is rocky and may not gain momentum for some time. Johns Hopkins University’s Doug Hough, PhD, an economist, recounts a government research study that sought to assess the university’s health system participation in a value-based payment program. While there were positive impacts on the program’s target population, Hough and his team discovered that the returns achieved by the optional model didn’t justify the health system’s financial support for it. The increasingly indebted health system ultimately decided to drop the optional program.

Dr. Hough indicated that the health system – Johns Hopkins Medicine – likely would have continued its support for the program had the government at least allowed it to break even. Although the payment program under study was a 3-year project, the bigger challenge, declared Dr. Hough, is that “we can’t turn an aircraft carrier that quickly.”

“Three years won’t show whether value-based care is really working,” Dr. Hough said.

Robert Zipper, MD, a hospitalist and senior policy advisor for Sound Physicians, a company that works to improve outcomes in acute care, agreed with Dr. Hough that performance tends to improve with time. Yet, Dr. Zipper doesn’t see much change in the near term, because “after all, there is nothing to replace them [the programs].”

The problem gets even stickier for private payers because patients may be on an insurance panel for as little as a year or 2. Thanks to this rapid churn of beneficiaries, even the best-designed value-based program will have little time to prove its worth.

Dr. Zipper is among the many who don’t expect significant changes in the near term, asserting that “President Biden will want to get a few policy wins first, and health care is not the easiest place to start.”

But it’s likely that payers and others will want to see more emphasis on value-based programs despite these programs’ possible value to patients, physicians, and health systems alike.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

More than 40 value-based payment models – from direct contracting to bundled payments – have been introduced into the Medicare program in the past 10 years, with the goal of improving care while lowering costs. Hopes were high that they would be successful.

Physicians could suffer a huge blow to their income.

Many of the value-based care models simply did not work as expected, said Seema Verma, head of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, at a recent HLTH Conference. “They are not producing the types of savings the taxpayers deserve,” Ms. Verma said.

The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPac) concluded that, while dozens of payment models were tested, most failed to generate net savings for Medicare. Even the most successful of the models produced only modest savings. MedPac elaborated: “The track record raises the question of whether changes to particular models or CMMI’s [Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation’s] broader strategies might be warranted.”

What will happen now, as government officials admit that their value-based programs haven’t worked? The value-based programs could become more stringent. Here’s what physicians will have to contend with.

More risk. Experts agree that risk – financial risk – will be a component of future programs. Two-sided risk is likely to be the norm. This means that both parties – the provider and the insurer – are at financial risk for the patients covered by the program.

For example, a plan with 50,000 beneficiary patients would estimate the cost of caring for those patients on the basis of multiple variables. If the actual cost is lower than anticipated, both parties share in the savings. However, both share in the loss if the cost of caring for their patient population exceeds expectations.

This may compel physicians to enhance efficiency and potentially limit the services provided to patients. Typically, however, the strategy is to make efforts to prevent services like ED visits and admissions by focusing on health maintenance.

In contrast to most current value-based models, which feature little to no downside risk for physicians, double-sided risk means physicians could lose money. The loss may incorporate a cap – 5%, for example – but programs may differ. Experts concur that double-sided risk will be a hallmark of future programs.

Better data. The majority of health care services are rendered via fee-for-service: Patients receive services and physicians are paid, yet little or no information about outcomes is exchanged between insurers and physicians.

Penny Noyes, president of Health Business Navigators and contract negotiator for physicians, is not a fan of the current crop of value-based programs and feels that data transparency is positive. Sound metrics can lead to improvement, she said, adding: “It’s not money that drives physicians to make decisions; it’s what’s in the best interest of their patients and their patients’ long-term care.”

Value-based programs can work but only if applicable data are developed and given to physicians so that they can better understand their current performance and how to improve.

Mandated participation. Participation in value-based programs has been voluntary, but that may have skewed the results, which were better than what typical practice would have shown. Acknowledging this may lead CMS to call for mandated participation as a component of future programs. Physicians may be brought into programs, if only to determine whether the models really work. To date, participation in the programs has been voluntary, but that may change in the future.

Innovation. The private insurance market may end up as a key player. Over the past 6 months, health insurers have either consolidated partnerships with telemedicine companies to provide no-cost care to beneficiaries or have launched their own initiatives.

Others are focused on bringing together patients and providers operating outside of the traditional health care system, such as Aetna’s merger with CVS which now offers retail-based acute care (MinuteClinic) and chronic care (HealthHUB). Still other payers are gambling with physician practice ownership, as in the case of United Healthcare’s OptumHealth, which now boasts around 50,000 physicians throughout the country.

New practice models are emerging in private practices as well. Physicians are embracing remote care, proactively managing care transitions, and seeking out more methods to keep patients healthy and at home.

Not much was expected from value-based plans

Many are not surprised that the value-based models did not produce impressive results. Ms. Noyes doubted that positive outcomes will be achieved for physicians in comparison with what could have been attained under fee-for-service arrangements with lower administrative costs.

While the Affordable Care Act attempted to encourage alternative reimbursement, it limits the maximum medical loss ratio (MLR) a payer could achieve. For many plans, that maximum was 85%. Simply put, at least $0.85 of each premium collected had to be paid in claims; the remaining $0.15 went to margin, claims, and other administrative costs. A payer with an 82% MLR then would have to rebate the 3% difference to enrollees.

But that’s not what occurred, according to Ms. Noyes. Because value-based payments to providers are considered a claims expense, an MLR ratio of 82% allowed the payer to distribute the 3% difference to providers as value-based payments. Ms. Noyes said: “That may sound good for the provider, but the result was essentially a freeze on the provider’s fee-for-service reimbursement with the prospect of getting value-based payments like ‘shared savings.’

“When the providers tried to increase their base fee-for-service rates just to match inflation, payers often advised that any future raises had to be earned through value-based programs,” Ms. Noyes added. The value-based formulas confuse providers because payments are often made for periods as far back as 18 months, and providers do not have data systems to reconcile their payer report cards retrospectively. The result is that providers tended to accept whatever amount the payer distributed.

Executives at Lumeris, a company that helps health systems participate successfully in value-based care, see potential in a newer approach to alternative payments, such as CMS’ Direct Contracting initiative. This voluntary payment model offers options tailored to several types of organizations that aim to reduce costs while preserving or enhancing the quality of care for Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries.

Jeff Smith, chief commercial officer for population health at Lumeris, explained that the Direct Contracting initiative can provide physicians with a more attractive option than prior value-based models because it adjusts for the complexity and fragility of patients with complex and chronic conditions. By allowing providers to participate in the savings generated, the initiative stands in stark contrast to what Mr. Smith described as the “shared savings to nothingness” experienced by providers in earlier-stage alternative payment models.

Physicians engaged with value-based programs like Direct Contracting are investing in nurses to aid with initiatives regarding health promotion and transitions of care. When a patient is discharged, for example, the nurse contacts the patient to discuss medications, schedule follow-up appointments, and so forth – tasks typically left to the patient (or caregiver) to navigate in the traditional system.

The initiative recognizes the importance of managing high-risk patients, those whom physicians identify as having an extraordinary number of ED visits and admissions. These patients, as well as so-called “rising-risk” patients, are targeted by nurses who proactively communicate with patients (and caregivers) to address patient’s needs, including social determinants of health.

Physicians who have a large load of patients in value-based programs are hiring social workers, pharmacists, and behavioral health experts to help. Of course, these personnel are costly, but that’s what the value-based programs aim to reimburse.

Still, the road ahead to value based is rocky and may not gain momentum for some time. Johns Hopkins University’s Doug Hough, PhD, an economist, recounts a government research study that sought to assess the university’s health system participation in a value-based payment program. While there were positive impacts on the program’s target population, Hough and his team discovered that the returns achieved by the optional model didn’t justify the health system’s financial support for it. The increasingly indebted health system ultimately decided to drop the optional program.

Dr. Hough indicated that the health system – Johns Hopkins Medicine – likely would have continued its support for the program had the government at least allowed it to break even. Although the payment program under study was a 3-year project, the bigger challenge, declared Dr. Hough, is that “we can’t turn an aircraft carrier that quickly.”

“Three years won’t show whether value-based care is really working,” Dr. Hough said.

Robert Zipper, MD, a hospitalist and senior policy advisor for Sound Physicians, a company that works to improve outcomes in acute care, agreed with Dr. Hough that performance tends to improve with time. Yet, Dr. Zipper doesn’t see much change in the near term, because “after all, there is nothing to replace them [the programs].”

The problem gets even stickier for private payers because patients may be on an insurance panel for as little as a year or 2. Thanks to this rapid churn of beneficiaries, even the best-designed value-based program will have little time to prove its worth.

Dr. Zipper is among the many who don’t expect significant changes in the near term, asserting that “President Biden will want to get a few policy wins first, and health care is not the easiest place to start.”

But it’s likely that payers and others will want to see more emphasis on value-based programs despite these programs’ possible value to patients, physicians, and health systems alike.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Should all skin cancer patients be taking nicotinamide?

In 2014, I began taking care of a patient (see photo) who had developed over 25 basal cell carcinomas on her lower legs, which were surgically removed. She has been clear of any skin cancers in the last 2 years since starting supplementation.

Nicotinamide, also known as niacinamide, is a water soluble form of vitamin B3 that has been shown to enhance the repair of UV-induced DNA damage. Nicotinamide is found naturally in meat, fish, nuts, grains, and legumes, and is a key component of the glycolysis pathway, by generating nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide for adenosine triphosphate production. Nicotinamide deficiency causes photosensitive dermatitis, diarrhea, and dementia. It has been studied for its anti-inflammatory benefits as an adjunct treatment for rosacea, bullous diseases, acne, and melasma.

Nonmelanoma skin cancers are known to be caused primarily by UV radiation. The supplementation of nicotinamide orally twice daily has been shown to reduce the rate of actinic keratoses and new nonmelanoma skin cancers compared with placebo after 1 year in patients who previously had skin cancer. In the phase 3 study published in 2015, a randomized, controlled trial of 386 patients who had at least two nonmelanoma skin cancers within the previous 5-year period, oral nicotinamide 500 mg given twice daily for a 12-month period significantly reduced the number of new nonmelanoma skin cancers by 23% versus those on placebo.

The recommended dose for nicotinamide, which is available over the counter as Vitamin B3, is 500 mg twice a day. Nicotinamide should not be confused with niacin (nicotinic acid), which has been used to treat high cholesterol and cardiovascular disease. There are no significant side effects from long-term use; however nicotinamide should not be used in patients with end-stage kidney disease or chronic kidney disease. (Niacin, however, can cause elevation of liver enzymes, headache, flushing, and increased blood pressure.) Nicotinamide crosses the placenta and should not be used in pregnancy as it has not been studied in pregnant populations.

We should counsel patients that this is not an oral sunscreen, and that sun avoidance, sunscreen, and yearly skin cancer checks are still the mainstay of skin cancer prevention. However, given the safety profile of nicotinamide and the protective effects, should all of our skin cancer patients be taking nicotinamide daily? In my practice they are, all of whom swear by it and have had significant reductions of both actinic keratoses and nonmelanoma skin cancers.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

In 2014, I began taking care of a patient (see photo) who had developed over 25 basal cell carcinomas on her lower legs, which were surgically removed. She has been clear of any skin cancers in the last 2 years since starting supplementation.

Nicotinamide, also known as niacinamide, is a water soluble form of vitamin B3 that has been shown to enhance the repair of UV-induced DNA damage. Nicotinamide is found naturally in meat, fish, nuts, grains, and legumes, and is a key component of the glycolysis pathway, by generating nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide for adenosine triphosphate production. Nicotinamide deficiency causes photosensitive dermatitis, diarrhea, and dementia. It has been studied for its anti-inflammatory benefits as an adjunct treatment for rosacea, bullous diseases, acne, and melasma.

Nonmelanoma skin cancers are known to be caused primarily by UV radiation. The supplementation of nicotinamide orally twice daily has been shown to reduce the rate of actinic keratoses and new nonmelanoma skin cancers compared with placebo after 1 year in patients who previously had skin cancer. In the phase 3 study published in 2015, a randomized, controlled trial of 386 patients who had at least two nonmelanoma skin cancers within the previous 5-year period, oral nicotinamide 500 mg given twice daily for a 12-month period significantly reduced the number of new nonmelanoma skin cancers by 23% versus those on placebo.

The recommended dose for nicotinamide, which is available over the counter as Vitamin B3, is 500 mg twice a day. Nicotinamide should not be confused with niacin (nicotinic acid), which has been used to treat high cholesterol and cardiovascular disease. There are no significant side effects from long-term use; however nicotinamide should not be used in patients with end-stage kidney disease or chronic kidney disease. (Niacin, however, can cause elevation of liver enzymes, headache, flushing, and increased blood pressure.) Nicotinamide crosses the placenta and should not be used in pregnancy as it has not been studied in pregnant populations.

We should counsel patients that this is not an oral sunscreen, and that sun avoidance, sunscreen, and yearly skin cancer checks are still the mainstay of skin cancer prevention. However, given the safety profile of nicotinamide and the protective effects, should all of our skin cancer patients be taking nicotinamide daily? In my practice they are, all of whom swear by it and have had significant reductions of both actinic keratoses and nonmelanoma skin cancers.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

In 2014, I began taking care of a patient (see photo) who had developed over 25 basal cell carcinomas on her lower legs, which were surgically removed. She has been clear of any skin cancers in the last 2 years since starting supplementation.

Nicotinamide, also known as niacinamide, is a water soluble form of vitamin B3 that has been shown to enhance the repair of UV-induced DNA damage. Nicotinamide is found naturally in meat, fish, nuts, grains, and legumes, and is a key component of the glycolysis pathway, by generating nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide for adenosine triphosphate production. Nicotinamide deficiency causes photosensitive dermatitis, diarrhea, and dementia. It has been studied for its anti-inflammatory benefits as an adjunct treatment for rosacea, bullous diseases, acne, and melasma.

Nonmelanoma skin cancers are known to be caused primarily by UV radiation. The supplementation of nicotinamide orally twice daily has been shown to reduce the rate of actinic keratoses and new nonmelanoma skin cancers compared with placebo after 1 year in patients who previously had skin cancer. In the phase 3 study published in 2015, a randomized, controlled trial of 386 patients who had at least two nonmelanoma skin cancers within the previous 5-year period, oral nicotinamide 500 mg given twice daily for a 12-month period significantly reduced the number of new nonmelanoma skin cancers by 23% versus those on placebo.

The recommended dose for nicotinamide, which is available over the counter as Vitamin B3, is 500 mg twice a day. Nicotinamide should not be confused with niacin (nicotinic acid), which has been used to treat high cholesterol and cardiovascular disease. There are no significant side effects from long-term use; however nicotinamide should not be used in patients with end-stage kidney disease or chronic kidney disease. (Niacin, however, can cause elevation of liver enzymes, headache, flushing, and increased blood pressure.) Nicotinamide crosses the placenta and should not be used in pregnancy as it has not been studied in pregnant populations.

We should counsel patients that this is not an oral sunscreen, and that sun avoidance, sunscreen, and yearly skin cancer checks are still the mainstay of skin cancer prevention. However, given the safety profile of nicotinamide and the protective effects, should all of our skin cancer patients be taking nicotinamide daily? In my practice they are, all of whom swear by it and have had significant reductions of both actinic keratoses and nonmelanoma skin cancers.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

Understanding messenger RNA and other SARS-CoV-2 vaccines

In mid-November, Pfizer/BioNTech were the first with surprising positive protection interim data for their coronavirus vaccine, BNT162b2. A week later, Moderna released interim efficacy results showing its coronavirus vaccine, mRNA-1273, also protected patients from developing SARS-CoV-2 infections. Both studies included mostly healthy adults. A diverse ethnic and racial vaccinated population was included. A reasonable number of persons aged over 65 years, and persons with stable compromising medical conditions were included. Adolescents aged 16 years and over were included. Younger adolescents have been vaccinated or such studies are in the planning or early implementation stage as 2020 came to a close.

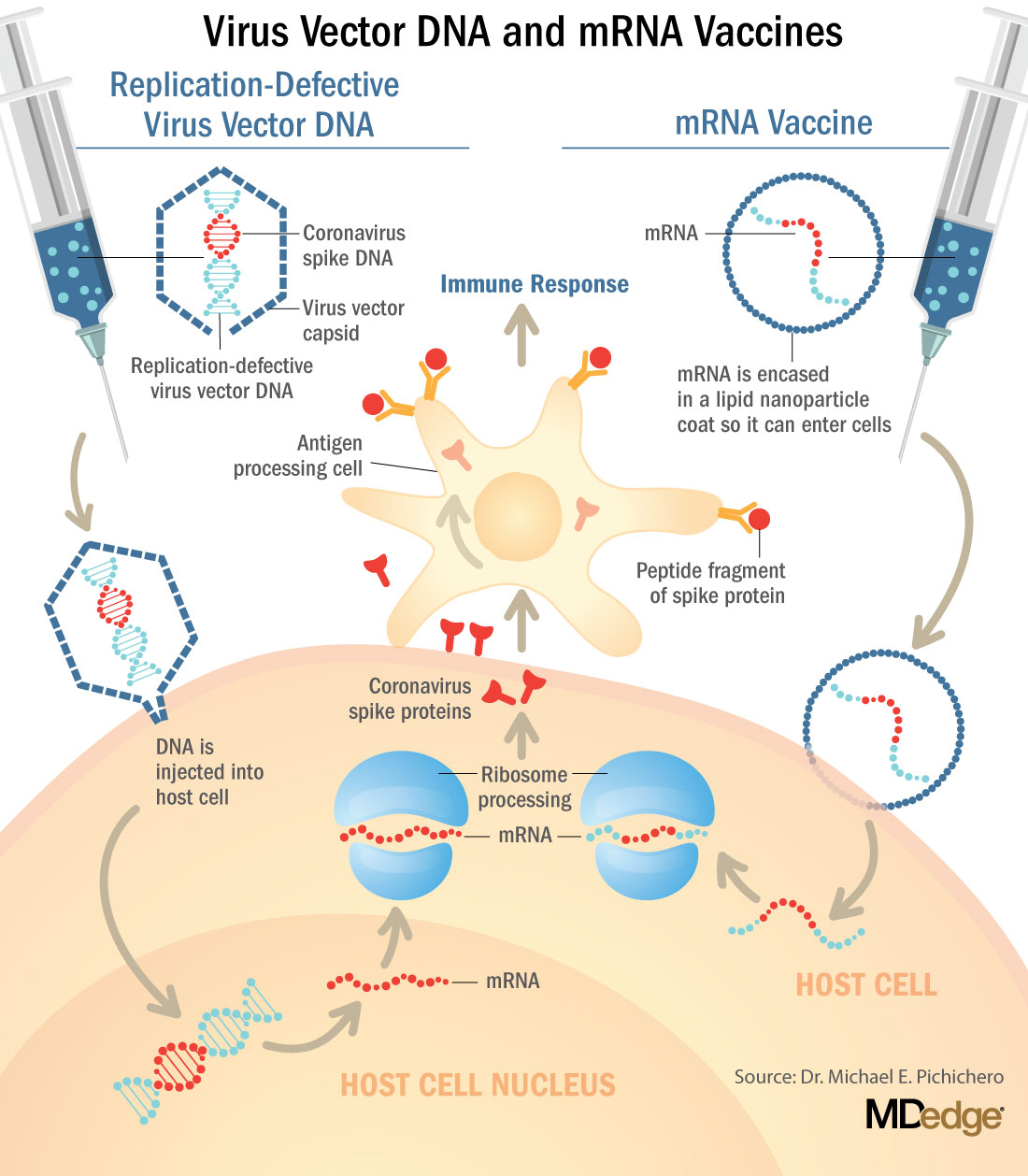

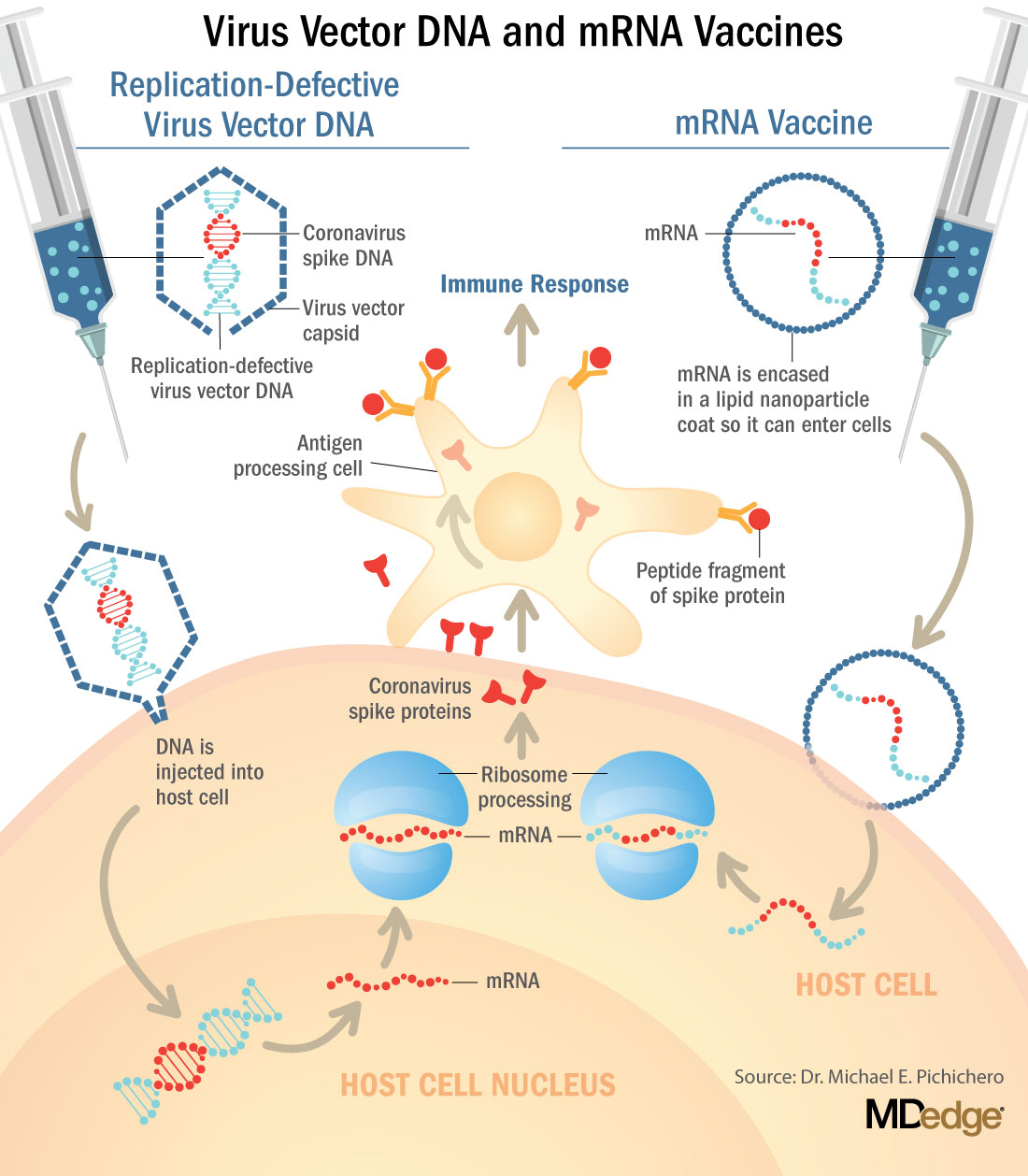

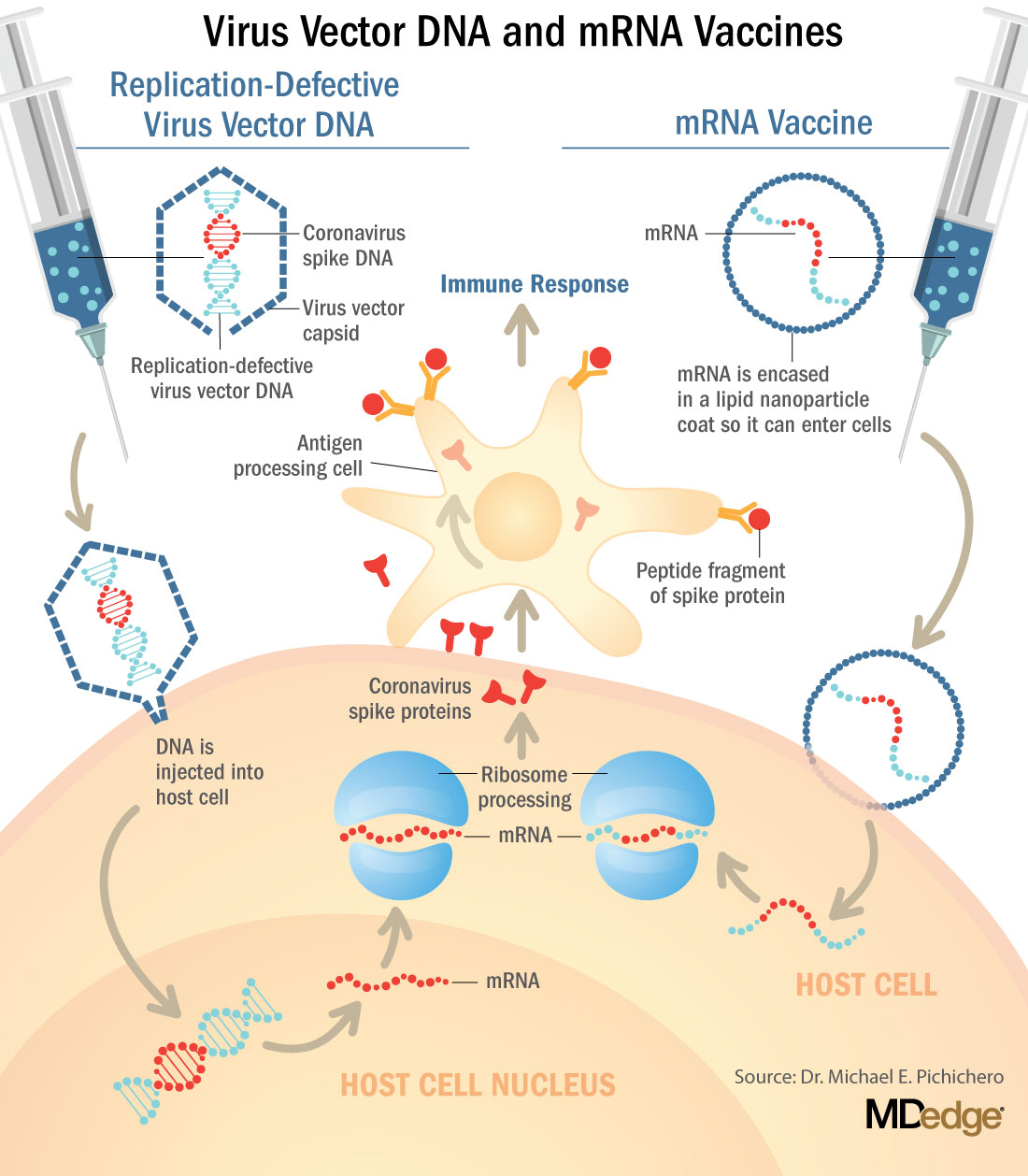

These are new and revolutionary vaccines, although the ability to inject mRNA into animals dates back to 1990, technological advances today make it a reality.1 Traditional vaccines typically involve injection with antigens such as purified proteins or polysaccharides or inactivated/attenuated viruses. In the case of Pfizer’s and Moderna’s vaccines, the mRNA provides the genetic information to synthesize the spike protein that the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to attach to and infect human cells. Each type of vaccine is packaged in proprietary lipid nanoparticles to protect the mRNA from rapid degradation, and the nanoparticles serve as an adjuvant to attract immune cells to the site of injection. (The properties of the respective lipid nanoparticle packaging may be the factor that impacts storage requirements discussed below.) When injected into muscle (myocyte), the lipid nanoparticles containing the mRNA inside are taken into muscle cells, where the cytoplasmic ribosomes detect and decode the mRNA resulting in the production of the spike protein antigen. It should be noted that the mRNA does not enter the nucleus, where the genetic information (DNA) of a cell is located, and can’t be reproduced or integrated into the DNA. The antigen is exported to the myocyte cell surface where the immune system’s antigen presenting cells detect the protein, ingest it, and take it to regional lymph nodes where interactions with T cells and B cells results in antibodies, T cell–mediated immunity, and generation of immune memory T cells and B cells. A particular subset of T cells – cytotoxic or killer T cells – destroy cells that have been infected by a pathogen. The SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine from Pfizer was reported to induce powerful cytotoxic T-cell responses. Results for Moderna’s vaccine had not been reported at the time this column was prepared, but I anticipate the same positive results.

The revolutionary aspect of mRNA vaccines is the speed at which they can be designed and produced. This is why they lead the pack among the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates and why the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases provided financial, technical, and/or clinical support. Indeed, once the amino acid sequence of a protein can be determined (a relatively easy task these days) it’s straightforward to synthesize mRNA in the lab – and it can be done incredibly fast. It is reported that the mRNA code for the vaccine by Moderna was made in 2 days and production development was completed in about 2 months.2

A 2007 World Health Organization report noted that infectious diseases are emerging at “the historically unprecedented rate of one per year.”3 Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Zika, Ebola, and avian and swine flu are recent examples. For most vaccines against emerging diseases, the challenge is about speed: developing and manufacturing a vaccine and getting it to persons who need it as quickly as possible. The current seasonal flu vaccine takes about 6 months to develop; it takes years for most of the traditional vaccines. That’s why once the infrastructure is in place, mRNA vaccines may prove to offer a big advantage as vaccines against emerging pathogens.

Early efficacy results have been surprising

Both vaccines were reported to produce about 95% efficacy in the final analysis. That was unexpectedly high because most vaccines for respiratory illness achieve efficacy of 60%-80%, e.g., flu vaccines. However, the efficacy rate may drop as time goes by because stimulation of short-term immunity would be in the earliest reported results.

Preventing SARS-CoV-2 cases is an important aspect of a coronavirus vaccine, but preventing severe illness is especially important considering that severe cases can result in prolonged intubation/artificial ventilation, prolonged disability and death. Pfizer/BioNTech had not released any data on the breakdown of severe cases as this column was finalized. In Moderna’s clinical trial, a secondary endpoint analyzed severe cases of COVID-19 and included 30 severe cases (as defined in the study protocol) in this analysis. All 30 cases occurred in the placebo group and none in the mRNA-1273–vaccinated group. In the Pfizer/BioNTech trial there were too few cases of severe illness to calculate efficacy.

Duration of immunity and need to revaccinate after initial primary vaccination are unknowns. Study of induction of B- and T-cell memory and levels of long-term protection have not been reported thus far.

Could mRNA COVID-19 vaccines be dangerous in the long term?

These will be the first-ever mRNA vaccines brought to market for humans. In order to receive Food and Drug Administration approval, the companies had to prove there were no immediate or short-term negative adverse effects from the vaccines. The companies reported that their independent data-monitoring committees hadn’t “reported any serious safety concerns.” However, fairly significant local reactions at the site of injection, fever, malaise, and fatigue occur with modest frequency following vaccinations with these products, reportedly in 10%-15% of vaccinees. Overall, the immediate reaction profile appears to be more severe than what occurs following seasonal influenza vaccination. When mass inoculations with these completely new and revolutionary vaccines begins, we will know virtually nothing about their long-term side effects. The possibility of systemic inflammatory responses that could lead to autoimmune conditions, persistence of the induced immunogen expression, development of autoreactive antibodies, and toxic effects of delivery components have been raised as theoretical concerns.4-6 None of these theoretical risks have been observed to date and postmarketing phase 4 safety monitoring studies are in place from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the companies that produce the vaccines. This is a risk public health authorities are willing to take because the risk to benefit calculation strongly favors taking theoretical risks, compared with clear benefits in preventing severe illnesses and death.

What about availability?

Pfizer/BioNTech expects to be able to produce up to 50 million vaccine doses in 2020 and up to 1.3 billion doses in 2021. Moderna expects to produce 20 million doses by the end of 2020, and 500 million to 1 billion doses in 2021. Storage requirements are inherent to the composition of the vaccines with their differing lipid nanoparticle delivery systems. Pfizer/BioNTech’s BNT162b2 has to be stored and transported at –80° C, which requires specialized freezers, which most doctors’ offices and pharmacies are unlikely to have on site, or dry ice containers. Once the vaccine is thawed, it can only remain in the refrigerator for 24 hours. Moderna’s mRNA-1273 will be much easier to distribute. The vaccine is stable in a standard freezer at –20° C for up to 6 months, in a refrigerator for up to 30 days within that 6-month shelf life, and at room temperature for up to 12 hours.

Timelines and testing other vaccines

Strong efficacy data from the two leading SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and emergency-use authorization Food and Drug Administration approval suggest the window for testing additional vaccine candidates in the United States could soon start to close. Of the more than 200 vaccines in development for SARS-CoV-2, at least 7 have a chance of gathering pivotal data before the front-runners become broadly available.

Testing diverse vaccine candidates, based on different technologies, is important for ensuring sufficient supply and could lead to products with tolerability and safety profiles that make them better suited, or more attractive, to subsets of the population. Different vaccine antigens and technologies also may yield different durations of protection, a question that will not be answered until long after the first products are on the market.

AstraZeneca enrolled about 23,000 subjects into its two phase 3 trials of AZD1222 (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19): a 40,000-subject U.S. trial and a 10,000-subject study in Brazil. AstraZeneca’s AZD1222, developed with the University of Oxford (England), uses a replication defective simian adenovirus vector called ChAdOx1.AZD1222 which encodes the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. After injection, the viral vector delivers recombinant DNA that is decoded to mRNA, followed by mRNA decoding to become a protein. A serendipitous manufacturing error for the first 3,000 doses resulted in a half dose for those subjects before the error was discovered. Full doses were given to those subjects on second injections and those subjects showed 90% efficacy. Subjects who received 2 full doses showed 62% efficacy. A vaccine cannot be licensed based on 3,000 subjects so AstraZeneca has started a new phase 3 trial involving many more subjects to receive the combination lower dose followed by the full dose.