User login

Formerly Skin & Allergy News

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')]

The leading independent newspaper covering dermatology news and commentary.

Match Day 2020: Online announcements replace celebrations, champagne

The third Friday in March usually marks a time when medical students across the United States participate in envelope-opening ceremonies with peers and family members. This year, the ruthless onslaught of coronavirus has forced residency programs to rethink their celebrations, leveraging social media platforms and other technologies to toast Match Day in cyberspace.

In the absence of ceremonies taking place due to restrictions on mass gatherings, “we anticipate that students may be more emotional than they expect,” Hannah R. Hughes, MD, president of the Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association (EMRA) said in an interview. To support these students on their journey to residency, EMRA has launched a social media campaign, asking medical students “to share with us their envelope-opening moments – either a selfie, photo, or video – that we can share with our online networks,” Dr. Hughes said.

EMRA is also asking program coordinators to forward photos and congratulatory messages to their new residents “so that we can share them with our networks at large,” she added.

Going virtual, it seems, has become the new norm.

At the University of California, San Francisco, the medical school decided to cancel its Match Day celebration for new interns, echoing many other programs across the United States. “We always send out a welcome email and make phone calls to all of our new interns,” said Rebecca Berman, MD, director of UCSF’s internal medicine residency program, which houses 63 medicine interns and 181 residents. Traditionally, the program has hosted the celebration for current residents. That, of course, had to change this year.

Current interns like to join in the fun, “since it means their internship is rapidly coming to a close,” said Dr. Berman, who at press time was considering a virtual toast via Zoom as a possible alternative. “These are difficult times for everyone, and we are doing our best to make our residents feel united and connected while they take care of patients in the era of social distancing.”

Melissa Held, MD, associate dean of medical student affairs at the University of Connecticut’s School of Medicine, Farmington, had been planning a celebration in the school’s academic rotunda with food and champagne. “Students typically come with their family members or significant others. The dean and I usually say a few words and then at noon, students get envelopes and can open them to find out where they matched for residency,” Dr. Held said. This year, the school will be uploading Match letters to its online system. Students can remotely find out where they matched at noon. “I plan to put together a slide show of pictures and congratulatory remarks from faculty and staff that will be sent to them around 11:30 a.m.,” Dr. Held said.

Mark Miceli, EdD, who oversees Match Day for the 130-plus medical students at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, is inviting faculty and staff to submit short videos of congratulations, which it will post on its student affairs Match Day Instagram account. Like other schools, it will share results with students in an email, said Dr. Miceli, assistant vice provost of student life. “This message will be more personalized to our school than the NRMP [National Resident Matching Program] message, and will also include links to our match stats, a map of our matched student locations, and a list of where folks matched,” he said.

Students can opt out of the list if they want to. The communications department has also provided templates for signs students can print out. “They can write in where they matched, and take pictures for social media. We are encouraging the use of various hashtags to help build a virtual community,” Dr. Miceli said.

In a state hit particularly hard by coronavirus, the University of Washington School of Medicine is spreading Match Day cheer through online meeting platforms and celebratory graphics. This five-state school, representing students from Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho, usually hosts several events across the different states and students have their pick of which to attend, according to Sarah Wood, associate director of student affairs.

In lieu of in-person events, some states are hosting a Zoom online celebration, others are using social media networking systems. “We’re inviting everyone to take part in an online event ... where we’ll do a slide show of photos that one of our students put together,” Ms. Wood said.

Students are disappointed in this change of plans, she said. To make things more festive, Ms. Wood is adding graphics such as fireworks and photos to the emails containing the Match results. “I want this to be more exciting for them than just a basic letter,” she said.

For now, Ms. Wood is trying to focus on the Match Day celebration, but admits that “my bigger fear is if we have to cancel graduation – and what that might look like.”

The third Friday in March usually marks a time when medical students across the United States participate in envelope-opening ceremonies with peers and family members. This year, the ruthless onslaught of coronavirus has forced residency programs to rethink their celebrations, leveraging social media platforms and other technologies to toast Match Day in cyberspace.

In the absence of ceremonies taking place due to restrictions on mass gatherings, “we anticipate that students may be more emotional than they expect,” Hannah R. Hughes, MD, president of the Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association (EMRA) said in an interview. To support these students on their journey to residency, EMRA has launched a social media campaign, asking medical students “to share with us their envelope-opening moments – either a selfie, photo, or video – that we can share with our online networks,” Dr. Hughes said.

EMRA is also asking program coordinators to forward photos and congratulatory messages to their new residents “so that we can share them with our networks at large,” she added.

Going virtual, it seems, has become the new norm.

At the University of California, San Francisco, the medical school decided to cancel its Match Day celebration for new interns, echoing many other programs across the United States. “We always send out a welcome email and make phone calls to all of our new interns,” said Rebecca Berman, MD, director of UCSF’s internal medicine residency program, which houses 63 medicine interns and 181 residents. Traditionally, the program has hosted the celebration for current residents. That, of course, had to change this year.

Current interns like to join in the fun, “since it means their internship is rapidly coming to a close,” said Dr. Berman, who at press time was considering a virtual toast via Zoom as a possible alternative. “These are difficult times for everyone, and we are doing our best to make our residents feel united and connected while they take care of patients in the era of social distancing.”

Melissa Held, MD, associate dean of medical student affairs at the University of Connecticut’s School of Medicine, Farmington, had been planning a celebration in the school’s academic rotunda with food and champagne. “Students typically come with their family members or significant others. The dean and I usually say a few words and then at noon, students get envelopes and can open them to find out where they matched for residency,” Dr. Held said. This year, the school will be uploading Match letters to its online system. Students can remotely find out where they matched at noon. “I plan to put together a slide show of pictures and congratulatory remarks from faculty and staff that will be sent to them around 11:30 a.m.,” Dr. Held said.

Mark Miceli, EdD, who oversees Match Day for the 130-plus medical students at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, is inviting faculty and staff to submit short videos of congratulations, which it will post on its student affairs Match Day Instagram account. Like other schools, it will share results with students in an email, said Dr. Miceli, assistant vice provost of student life. “This message will be more personalized to our school than the NRMP [National Resident Matching Program] message, and will also include links to our match stats, a map of our matched student locations, and a list of where folks matched,” he said.

Students can opt out of the list if they want to. The communications department has also provided templates for signs students can print out. “They can write in where they matched, and take pictures for social media. We are encouraging the use of various hashtags to help build a virtual community,” Dr. Miceli said.

In a state hit particularly hard by coronavirus, the University of Washington School of Medicine is spreading Match Day cheer through online meeting platforms and celebratory graphics. This five-state school, representing students from Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho, usually hosts several events across the different states and students have their pick of which to attend, according to Sarah Wood, associate director of student affairs.

In lieu of in-person events, some states are hosting a Zoom online celebration, others are using social media networking systems. “We’re inviting everyone to take part in an online event ... where we’ll do a slide show of photos that one of our students put together,” Ms. Wood said.

Students are disappointed in this change of plans, she said. To make things more festive, Ms. Wood is adding graphics such as fireworks and photos to the emails containing the Match results. “I want this to be more exciting for them than just a basic letter,” she said.

For now, Ms. Wood is trying to focus on the Match Day celebration, but admits that “my bigger fear is if we have to cancel graduation – and what that might look like.”

The third Friday in March usually marks a time when medical students across the United States participate in envelope-opening ceremonies with peers and family members. This year, the ruthless onslaught of coronavirus has forced residency programs to rethink their celebrations, leveraging social media platforms and other technologies to toast Match Day in cyberspace.

In the absence of ceremonies taking place due to restrictions on mass gatherings, “we anticipate that students may be more emotional than they expect,” Hannah R. Hughes, MD, president of the Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association (EMRA) said in an interview. To support these students on their journey to residency, EMRA has launched a social media campaign, asking medical students “to share with us their envelope-opening moments – either a selfie, photo, or video – that we can share with our online networks,” Dr. Hughes said.

EMRA is also asking program coordinators to forward photos and congratulatory messages to their new residents “so that we can share them with our networks at large,” she added.

Going virtual, it seems, has become the new norm.

At the University of California, San Francisco, the medical school decided to cancel its Match Day celebration for new interns, echoing many other programs across the United States. “We always send out a welcome email and make phone calls to all of our new interns,” said Rebecca Berman, MD, director of UCSF’s internal medicine residency program, which houses 63 medicine interns and 181 residents. Traditionally, the program has hosted the celebration for current residents. That, of course, had to change this year.

Current interns like to join in the fun, “since it means their internship is rapidly coming to a close,” said Dr. Berman, who at press time was considering a virtual toast via Zoom as a possible alternative. “These are difficult times for everyone, and we are doing our best to make our residents feel united and connected while they take care of patients in the era of social distancing.”

Melissa Held, MD, associate dean of medical student affairs at the University of Connecticut’s School of Medicine, Farmington, had been planning a celebration in the school’s academic rotunda with food and champagne. “Students typically come with their family members or significant others. The dean and I usually say a few words and then at noon, students get envelopes and can open them to find out where they matched for residency,” Dr. Held said. This year, the school will be uploading Match letters to its online system. Students can remotely find out where they matched at noon. “I plan to put together a slide show of pictures and congratulatory remarks from faculty and staff that will be sent to them around 11:30 a.m.,” Dr. Held said.

Mark Miceli, EdD, who oversees Match Day for the 130-plus medical students at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, is inviting faculty and staff to submit short videos of congratulations, which it will post on its student affairs Match Day Instagram account. Like other schools, it will share results with students in an email, said Dr. Miceli, assistant vice provost of student life. “This message will be more personalized to our school than the NRMP [National Resident Matching Program] message, and will also include links to our match stats, a map of our matched student locations, and a list of where folks matched,” he said.

Students can opt out of the list if they want to. The communications department has also provided templates for signs students can print out. “They can write in where they matched, and take pictures for social media. We are encouraging the use of various hashtags to help build a virtual community,” Dr. Miceli said.

In a state hit particularly hard by coronavirus, the University of Washington School of Medicine is spreading Match Day cheer through online meeting platforms and celebratory graphics. This five-state school, representing students from Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho, usually hosts several events across the different states and students have their pick of which to attend, according to Sarah Wood, associate director of student affairs.

In lieu of in-person events, some states are hosting a Zoom online celebration, others are using social media networking systems. “We’re inviting everyone to take part in an online event ... where we’ll do a slide show of photos that one of our students put together,” Ms. Wood said.

Students are disappointed in this change of plans, she said. To make things more festive, Ms. Wood is adding graphics such as fireworks and photos to the emails containing the Match results. “I want this to be more exciting for them than just a basic letter,” she said.

For now, Ms. Wood is trying to focus on the Match Day celebration, but admits that “my bigger fear is if we have to cancel graduation – and what that might look like.”

Feds tout drug candidates to treat COVID-19

Therapeutics could be available in the near term to help treat COVID-19 patients, according to President Donald Trump.

During a March 19 press briefing, the president highlighted two drugs that could be put into play in the battle against the virus.

The first product is hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil), a drug used to treat malaria and severe arthritis, is showing promise as a possible treatment for COVID-19.

“The nice part is it’s been around for a long time, so we know that if things go as planned, it’s not going to kill anybody,” President Trump said. “When you go with a brand-new drug, you don’t know that that’s going to happen,” adding that it has shown “very, very encouraging” results as a potential treatment for COVID-19.

He said this drug will be made available “almost immediately.” During the press conference, Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Stephen M. Hahn, MD, suggested the drug would be made available in the context of a large pragmatic clinical trial, enabling the FDA to collect data on it and make a long-term decision on its viability to treat COVID-19.

Dr. Hahn also pointed to the Gilead drug remdesivir – a drug originally developed to fight Ebola and currently undergoing clinical trials – as another possible candidate for a near-term therapeutic to help treat patients while vaccine development occurs.

Dr. Hahn noted that, while the agency is striving to provide regulatory flexibility, safety is paramount. “Let me make one thing clear: FDA’s responsibility to the American people is to ensure that products are safe and effective and that we are continuing to do that.”

He noted that if these and other experimental drugs show promise, physicians can request them under “compassionate use” provisions.

“We have criteria for that, and very speedy approval for that,” Dr. Hahn said. “The important thing about compassionate use ... this is even beyond ‘right to try.’ [We] get to collect the information about that.”

He noted that the FDA is looking at other drugs that are approved for other indications. The examinations of existing therapies are meant to be a bridge as companies work to develop new therapeutics as well as vaccines.

Dr. Hahn also highlighted a cross-agency effort on convalescent plasma, which uses the plasma from a patient who has recovered from COVID-19 infection to help patients fight the virus. “This is a possible treatment; this is not a proven treatment, “ Dr. Hahn said.

Takeda is working on an immunoglobulin treatment based on its intravenous immunoglobulin product Gammagard Liquid.

Julie Kim, president of plasma-derived therapies at Takeda, said the company should be able to go straight into testing efficacy of this approach, given the known safety profile of the treatment. She made the comments during a March 18 press briefing hosted by Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA). Ms. Kim did caution that this would not be a mass market kind of treatment, as supply would depend on plasma donations from individuals who have fully recovered from a COVID-19 infection. She estimated that the treatment could be available to a targeted group of high-risk patients in 9-18 months.

PhRMA president and CEO Stephen Ubl said the industry is “literally working around the clock” on four key areas: development of new diagnostics, identification of potential existing treatments to make available through trials and compassionate use, development of novel therapies, and development of a vaccine.

There are more than 80 clinical trials underway on existing treatments that could have approval to treat COVID-19 in a matter of months, he said.

Mikael Dolsten, MD, PhD, chief scientific officer at Pfizer, said that the company is working with Germany-based BioNTech SE to develop an mRNA-based vaccine for COVID-19, with testing expected to begin in Germany, China, and the United States by the end of April. The company also is screening antiviral compounds that were previously in development against other coronavirus diseases.

Clement Lewin, PhD, associate vice president of R&D strategy for vaccines at Sanofi, said the company has partnered with Regeneron to launch a trial of sarilumab (Kevzara), a drug approved to treat moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis, to help treat COVID-19.

Meanwhile, Lilly Chief Scientific Officer Daniel Skovronsky, MD, PhD, noted that his company is collaborating with AbCellera to develop therapeutics using monoclonal antibodies isolated from one of the first U.S. patients who recovered from COVID-19. He said the goal is to begin testing within the next 4 months.

Separately, World Health Organization Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus announced during a March 18 press conference that it is spearheading a large international study examining a number of different treatments in what has been dubbed the SOLIDARITY trial. Argentina, Bahrain, Canada, France, Iran, Norway, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, and Thailand have signed on to be a part of the trial, with more countries expected to participate.

“I continue to be inspired by the many demonstrations of solidarity from all over the world,” he said. “These and other efforts give me hope that together, we can and will prevail. This virus is presenting us with an unprecedented threat. But it’s also an unprecedented opportunity to come together as one against a common enemy, an enemy against humanity.”

Therapeutics could be available in the near term to help treat COVID-19 patients, according to President Donald Trump.

During a March 19 press briefing, the president highlighted two drugs that could be put into play in the battle against the virus.

The first product is hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil), a drug used to treat malaria and severe arthritis, is showing promise as a possible treatment for COVID-19.

“The nice part is it’s been around for a long time, so we know that if things go as planned, it’s not going to kill anybody,” President Trump said. “When you go with a brand-new drug, you don’t know that that’s going to happen,” adding that it has shown “very, very encouraging” results as a potential treatment for COVID-19.

He said this drug will be made available “almost immediately.” During the press conference, Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Stephen M. Hahn, MD, suggested the drug would be made available in the context of a large pragmatic clinical trial, enabling the FDA to collect data on it and make a long-term decision on its viability to treat COVID-19.

Dr. Hahn also pointed to the Gilead drug remdesivir – a drug originally developed to fight Ebola and currently undergoing clinical trials – as another possible candidate for a near-term therapeutic to help treat patients while vaccine development occurs.

Dr. Hahn noted that, while the agency is striving to provide regulatory flexibility, safety is paramount. “Let me make one thing clear: FDA’s responsibility to the American people is to ensure that products are safe and effective and that we are continuing to do that.”

He noted that if these and other experimental drugs show promise, physicians can request them under “compassionate use” provisions.

“We have criteria for that, and very speedy approval for that,” Dr. Hahn said. “The important thing about compassionate use ... this is even beyond ‘right to try.’ [We] get to collect the information about that.”

He noted that the FDA is looking at other drugs that are approved for other indications. The examinations of existing therapies are meant to be a bridge as companies work to develop new therapeutics as well as vaccines.

Dr. Hahn also highlighted a cross-agency effort on convalescent plasma, which uses the plasma from a patient who has recovered from COVID-19 infection to help patients fight the virus. “This is a possible treatment; this is not a proven treatment, “ Dr. Hahn said.

Takeda is working on an immunoglobulin treatment based on its intravenous immunoglobulin product Gammagard Liquid.

Julie Kim, president of plasma-derived therapies at Takeda, said the company should be able to go straight into testing efficacy of this approach, given the known safety profile of the treatment. She made the comments during a March 18 press briefing hosted by Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA). Ms. Kim did caution that this would not be a mass market kind of treatment, as supply would depend on plasma donations from individuals who have fully recovered from a COVID-19 infection. She estimated that the treatment could be available to a targeted group of high-risk patients in 9-18 months.

PhRMA president and CEO Stephen Ubl said the industry is “literally working around the clock” on four key areas: development of new diagnostics, identification of potential existing treatments to make available through trials and compassionate use, development of novel therapies, and development of a vaccine.

There are more than 80 clinical trials underway on existing treatments that could have approval to treat COVID-19 in a matter of months, he said.

Mikael Dolsten, MD, PhD, chief scientific officer at Pfizer, said that the company is working with Germany-based BioNTech SE to develop an mRNA-based vaccine for COVID-19, with testing expected to begin in Germany, China, and the United States by the end of April. The company also is screening antiviral compounds that were previously in development against other coronavirus diseases.

Clement Lewin, PhD, associate vice president of R&D strategy for vaccines at Sanofi, said the company has partnered with Regeneron to launch a trial of sarilumab (Kevzara), a drug approved to treat moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis, to help treat COVID-19.

Meanwhile, Lilly Chief Scientific Officer Daniel Skovronsky, MD, PhD, noted that his company is collaborating with AbCellera to develop therapeutics using monoclonal antibodies isolated from one of the first U.S. patients who recovered from COVID-19. He said the goal is to begin testing within the next 4 months.

Separately, World Health Organization Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus announced during a March 18 press conference that it is spearheading a large international study examining a number of different treatments in what has been dubbed the SOLIDARITY trial. Argentina, Bahrain, Canada, France, Iran, Norway, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, and Thailand have signed on to be a part of the trial, with more countries expected to participate.

“I continue to be inspired by the many demonstrations of solidarity from all over the world,” he said. “These and other efforts give me hope that together, we can and will prevail. This virus is presenting us with an unprecedented threat. But it’s also an unprecedented opportunity to come together as one against a common enemy, an enemy against humanity.”

Therapeutics could be available in the near term to help treat COVID-19 patients, according to President Donald Trump.

During a March 19 press briefing, the president highlighted two drugs that could be put into play in the battle against the virus.

The first product is hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil), a drug used to treat malaria and severe arthritis, is showing promise as a possible treatment for COVID-19.

“The nice part is it’s been around for a long time, so we know that if things go as planned, it’s not going to kill anybody,” President Trump said. “When you go with a brand-new drug, you don’t know that that’s going to happen,” adding that it has shown “very, very encouraging” results as a potential treatment for COVID-19.

He said this drug will be made available “almost immediately.” During the press conference, Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Stephen M. Hahn, MD, suggested the drug would be made available in the context of a large pragmatic clinical trial, enabling the FDA to collect data on it and make a long-term decision on its viability to treat COVID-19.

Dr. Hahn also pointed to the Gilead drug remdesivir – a drug originally developed to fight Ebola and currently undergoing clinical trials – as another possible candidate for a near-term therapeutic to help treat patients while vaccine development occurs.

Dr. Hahn noted that, while the agency is striving to provide regulatory flexibility, safety is paramount. “Let me make one thing clear: FDA’s responsibility to the American people is to ensure that products are safe and effective and that we are continuing to do that.”

He noted that if these and other experimental drugs show promise, physicians can request them under “compassionate use” provisions.

“We have criteria for that, and very speedy approval for that,” Dr. Hahn said. “The important thing about compassionate use ... this is even beyond ‘right to try.’ [We] get to collect the information about that.”

He noted that the FDA is looking at other drugs that are approved for other indications. The examinations of existing therapies are meant to be a bridge as companies work to develop new therapeutics as well as vaccines.

Dr. Hahn also highlighted a cross-agency effort on convalescent plasma, which uses the plasma from a patient who has recovered from COVID-19 infection to help patients fight the virus. “This is a possible treatment; this is not a proven treatment, “ Dr. Hahn said.

Takeda is working on an immunoglobulin treatment based on its intravenous immunoglobulin product Gammagard Liquid.

Julie Kim, president of plasma-derived therapies at Takeda, said the company should be able to go straight into testing efficacy of this approach, given the known safety profile of the treatment. She made the comments during a March 18 press briefing hosted by Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA). Ms. Kim did caution that this would not be a mass market kind of treatment, as supply would depend on plasma donations from individuals who have fully recovered from a COVID-19 infection. She estimated that the treatment could be available to a targeted group of high-risk patients in 9-18 months.

PhRMA president and CEO Stephen Ubl said the industry is “literally working around the clock” on four key areas: development of new diagnostics, identification of potential existing treatments to make available through trials and compassionate use, development of novel therapies, and development of a vaccine.

There are more than 80 clinical trials underway on existing treatments that could have approval to treat COVID-19 in a matter of months, he said.

Mikael Dolsten, MD, PhD, chief scientific officer at Pfizer, said that the company is working with Germany-based BioNTech SE to develop an mRNA-based vaccine for COVID-19, with testing expected to begin in Germany, China, and the United States by the end of April. The company also is screening antiviral compounds that were previously in development against other coronavirus diseases.

Clement Lewin, PhD, associate vice president of R&D strategy for vaccines at Sanofi, said the company has partnered with Regeneron to launch a trial of sarilumab (Kevzara), a drug approved to treat moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis, to help treat COVID-19.

Meanwhile, Lilly Chief Scientific Officer Daniel Skovronsky, MD, PhD, noted that his company is collaborating with AbCellera to develop therapeutics using monoclonal antibodies isolated from one of the first U.S. patients who recovered from COVID-19. He said the goal is to begin testing within the next 4 months.

Separately, World Health Organization Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus announced during a March 18 press conference that it is spearheading a large international study examining a number of different treatments in what has been dubbed the SOLIDARITY trial. Argentina, Bahrain, Canada, France, Iran, Norway, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, and Thailand have signed on to be a part of the trial, with more countries expected to participate.

“I continue to be inspired by the many demonstrations of solidarity from all over the world,” he said. “These and other efforts give me hope that together, we can and will prevail. This virus is presenting us with an unprecedented threat. But it’s also an unprecedented opportunity to come together as one against a common enemy, an enemy against humanity.”

CD4 cells implicated in pathology of CCCA

in the lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate, according to a histopathological study of biopsy specimens.

“Evaluation of the T-cell infiltrate may be a useful way to distinguish CCCA from lichen planopilaris or frontal fibrosing alopecia in some cases when histopathological features alone cannot be used to definitely distinguish between them,” reported Alexandra Flamm, MD, Ata Moshiri, MD, and coauthors from the departments of dermatology and pathology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

The histopathological features of CCCA have been characterized previously, but the goal of this study was to go further in piecing together the pathophysiology, they noted.

Horizontal sections of 4-mm punch biopsy specimens were examined from 18 black women with a known diagnosis of CCCA. Both affected and unaffected follicles were evaluated with attention to the number and percentage of CD1a+ Langerhans cells, CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ lymphocytes.

In this series, the lymphocytic infiltrate in both the affected and unaffected follicles was predominantly composed of CD4+ cells. The perifollicular ratio for CD4+ to CD8+ cells in affected follicles was 5.3:1. It was only modestly lower in unaffected follicles (4.3:1) and in the intrafollicular space of affected follicles (2.5:1).

Affected follicles had a higher number of CD1a+ Langerhans cells than unaffected follicles. This finding suggests, as others have hypothesized, that the antigen-presenting Langerhans cells draw lymphocytes to the follicle, according to the investigators. Elevated numbers of Langerhans cells have also been reported in other forms of scarring alopecia, such as lichen planopilaris (LPP).

In the case of CCCA, CD1a+ Langerhans cells appear to localize to the hair follicle in response to stimulus such as an injury. The CD4+ cells that follow the Langerhans cells participate in an inflammatory reaction that drives follicle destruction. In addition to this damage and scarring, the inflammatory response is also likely to be disrupting the blood supply.

“Fibroplasia associated with follicular scarring displaces blood vessels away from the outer root sheath epithelium,” the authors explained. Ultimately, “the mucinous fibroplasia and perifollicular fibrosis may disrupt and fragment blood vessels in the fibrous sheath, leaving only small clusters of vessels more distant to the keratinocytes in the outer root sheath.”

Prior studies of scarring alopecia diseases, including LLP, frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA), and keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans (KFSD), have typically described a predominantly CD8+ lymphocytic infiltrate. The evidence from this study that the infiltrate is CD4+ predominant in CCCA supports the conclusion that the pathophysiologic features of this type of alopecia are unique, according to the authors.

Work by others has associated CCCA with mutations in the PAD13 gene, which suggests a defect in the formation of hair shaft structure, but this may speak to susceptibility but not the mechanism of hair follicle damage. Rather, this study suggests that it is the concentration of a CD4+ predominant lymphocytic infiltrate in the perifollicular space that induces the pathological events.

For determining the fundamental cause of CCCA, “it will be important to determine what recruits the Langerhans cells to affected follicles,” the investigators suggested. Meanwhile, they expressed hope that the progress being made into decoding the pathogenesis of CCCA will lead to novel therapeutic strategies.

The authors did not list any disclosures. The funding source was listed as the Center for Scientific Review (Grant/Award).

SOURCE: Flamm A et al. J Cutan Pathol. 2020 Feb 18.doi: 10.1111/cup.13666.

in the lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate, according to a histopathological study of biopsy specimens.

“Evaluation of the T-cell infiltrate may be a useful way to distinguish CCCA from lichen planopilaris or frontal fibrosing alopecia in some cases when histopathological features alone cannot be used to definitely distinguish between them,” reported Alexandra Flamm, MD, Ata Moshiri, MD, and coauthors from the departments of dermatology and pathology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

The histopathological features of CCCA have been characterized previously, but the goal of this study was to go further in piecing together the pathophysiology, they noted.

Horizontal sections of 4-mm punch biopsy specimens were examined from 18 black women with a known diagnosis of CCCA. Both affected and unaffected follicles were evaluated with attention to the number and percentage of CD1a+ Langerhans cells, CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ lymphocytes.

In this series, the lymphocytic infiltrate in both the affected and unaffected follicles was predominantly composed of CD4+ cells. The perifollicular ratio for CD4+ to CD8+ cells in affected follicles was 5.3:1. It was only modestly lower in unaffected follicles (4.3:1) and in the intrafollicular space of affected follicles (2.5:1).

Affected follicles had a higher number of CD1a+ Langerhans cells than unaffected follicles. This finding suggests, as others have hypothesized, that the antigen-presenting Langerhans cells draw lymphocytes to the follicle, according to the investigators. Elevated numbers of Langerhans cells have also been reported in other forms of scarring alopecia, such as lichen planopilaris (LPP).

In the case of CCCA, CD1a+ Langerhans cells appear to localize to the hair follicle in response to stimulus such as an injury. The CD4+ cells that follow the Langerhans cells participate in an inflammatory reaction that drives follicle destruction. In addition to this damage and scarring, the inflammatory response is also likely to be disrupting the blood supply.

“Fibroplasia associated with follicular scarring displaces blood vessels away from the outer root sheath epithelium,” the authors explained. Ultimately, “the mucinous fibroplasia and perifollicular fibrosis may disrupt and fragment blood vessels in the fibrous sheath, leaving only small clusters of vessels more distant to the keratinocytes in the outer root sheath.”

Prior studies of scarring alopecia diseases, including LLP, frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA), and keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans (KFSD), have typically described a predominantly CD8+ lymphocytic infiltrate. The evidence from this study that the infiltrate is CD4+ predominant in CCCA supports the conclusion that the pathophysiologic features of this type of alopecia are unique, according to the authors.

Work by others has associated CCCA with mutations in the PAD13 gene, which suggests a defect in the formation of hair shaft structure, but this may speak to susceptibility but not the mechanism of hair follicle damage. Rather, this study suggests that it is the concentration of a CD4+ predominant lymphocytic infiltrate in the perifollicular space that induces the pathological events.

For determining the fundamental cause of CCCA, “it will be important to determine what recruits the Langerhans cells to affected follicles,” the investigators suggested. Meanwhile, they expressed hope that the progress being made into decoding the pathogenesis of CCCA will lead to novel therapeutic strategies.

The authors did not list any disclosures. The funding source was listed as the Center for Scientific Review (Grant/Award).

SOURCE: Flamm A et al. J Cutan Pathol. 2020 Feb 18.doi: 10.1111/cup.13666.

in the lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate, according to a histopathological study of biopsy specimens.

“Evaluation of the T-cell infiltrate may be a useful way to distinguish CCCA from lichen planopilaris or frontal fibrosing alopecia in some cases when histopathological features alone cannot be used to definitely distinguish between them,” reported Alexandra Flamm, MD, Ata Moshiri, MD, and coauthors from the departments of dermatology and pathology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

The histopathological features of CCCA have been characterized previously, but the goal of this study was to go further in piecing together the pathophysiology, they noted.

Horizontal sections of 4-mm punch biopsy specimens were examined from 18 black women with a known diagnosis of CCCA. Both affected and unaffected follicles were evaluated with attention to the number and percentage of CD1a+ Langerhans cells, CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ lymphocytes.

In this series, the lymphocytic infiltrate in both the affected and unaffected follicles was predominantly composed of CD4+ cells. The perifollicular ratio for CD4+ to CD8+ cells in affected follicles was 5.3:1. It was only modestly lower in unaffected follicles (4.3:1) and in the intrafollicular space of affected follicles (2.5:1).

Affected follicles had a higher number of CD1a+ Langerhans cells than unaffected follicles. This finding suggests, as others have hypothesized, that the antigen-presenting Langerhans cells draw lymphocytes to the follicle, according to the investigators. Elevated numbers of Langerhans cells have also been reported in other forms of scarring alopecia, such as lichen planopilaris (LPP).

In the case of CCCA, CD1a+ Langerhans cells appear to localize to the hair follicle in response to stimulus such as an injury. The CD4+ cells that follow the Langerhans cells participate in an inflammatory reaction that drives follicle destruction. In addition to this damage and scarring, the inflammatory response is also likely to be disrupting the blood supply.

“Fibroplasia associated with follicular scarring displaces blood vessels away from the outer root sheath epithelium,” the authors explained. Ultimately, “the mucinous fibroplasia and perifollicular fibrosis may disrupt and fragment blood vessels in the fibrous sheath, leaving only small clusters of vessels more distant to the keratinocytes in the outer root sheath.”

Prior studies of scarring alopecia diseases, including LLP, frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA), and keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans (KFSD), have typically described a predominantly CD8+ lymphocytic infiltrate. The evidence from this study that the infiltrate is CD4+ predominant in CCCA supports the conclusion that the pathophysiologic features of this type of alopecia are unique, according to the authors.

Work by others has associated CCCA with mutations in the PAD13 gene, which suggests a defect in the formation of hair shaft structure, but this may speak to susceptibility but not the mechanism of hair follicle damage. Rather, this study suggests that it is the concentration of a CD4+ predominant lymphocytic infiltrate in the perifollicular space that induces the pathological events.

For determining the fundamental cause of CCCA, “it will be important to determine what recruits the Langerhans cells to affected follicles,” the investigators suggested. Meanwhile, they expressed hope that the progress being made into decoding the pathogenesis of CCCA will lead to novel therapeutic strategies.

The authors did not list any disclosures. The funding source was listed as the Center for Scientific Review (Grant/Award).

SOURCE: Flamm A et al. J Cutan Pathol. 2020 Feb 18.doi: 10.1111/cup.13666.

20% of U.S. COVID-19 deaths were aged 20-64 years

*Correction, 3/20/2020: An earlier version of this story misstated the age range for COVID-19 deaths. The headline of this story was corrected to read "20% of COVID-19 deaths were aged 20-64 years" and the text was adjusted to reflect the correct age range.

A review of more than 4,000 U.S. patients who were diagnosed with novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19) shows that an unexpected 20% of deaths occurred among adults aged 20-64 years, and 20% of those hospitalized were aged 20-44 years.

The expectation has been that people over 65 are most vulnerable to COVID-19 infection, but this study indicates that, at least in the United States, a significant number of patients under 45 can land in the hospital and can even die of the disease.

To assess rates of hospitalization, admission to an ICU, and death among patients with COVID-19 by age group, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention analyzed 4,226 COVID-19 cases in the United States that were reported between Feb. 12 and March 16.

Overall, older patients in this group were the most likely to be hospitalized, to be admitted to ICU, and to die of COVID-19. A total of 31% of the cases, 45% of hospitalizations, 53% of ICU admissions, and 80% of deaths occurred in patients aged 65 years and older. “Similar to reports from other countries, this finding suggests that the risk for serious disease and death from COVID-19 is higher in older age groups,” said the investigators. “In contrast, persons aged [19 years and younger] appear to have milder COVID-19 illness, with almost no hospitalizations or deaths reported to date in the United States in this age group.”

But compared with the under-19 group, patients aged 20-44 years appeared to be at higher risk for hospitalization and ICU admission, according to the data published March 18 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The researchers excluded from their analysis patients who repatriated to the United States from Wuhan, China, and from Japan, including patients repatriated from cruise ships. Data on serious underlying health conditions were not available, and many cases were missing key data, they noted.

Among 508 patients known to have been hospitalized, 9% were aged 85 years or older, 36% were aged 65-84 years, 17% were aged 55-64 years, 18% were 45-54 years, and 20% were aged 20-44 years.

Among 121 patients admitted to an ICU, 7% were aged 85 years or older, 46% were aged 65-84 years, 36% were aged 45-64 years, and 12% were aged 20-44 years. Between 11% and 31% of patients with COVID-19 aged 75-84 years were admitted to an ICU.

Of 44 deaths, more than a third occurred among adults aged 85 years and older, and 46% occurred among adults aged 65-84 years, and 20% occurred among adults aged 20-64 years.

More follow-up time is needed to determine outcomes among active cases, the researchers said. These results also might overestimate the prevalence of severe disease because the initial approach to testing for COVID-19 focused on people with more severe disease. “These preliminary data also demonstrate that severe illness leading to hospitalization, including ICU admission and death, can occur in adults of any age with COVID-19,” according to the CDC.

SOURCE: CDC COVID-19 Response Team. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Mar 18. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2.

*Correction, 3/20/2020: An earlier version of this story misstated the age range for COVID-19 deaths. The headline of this story was corrected to read "20% of COVID-19 deaths were aged 20-64 years" and the text was adjusted to reflect the correct age range.

A review of more than 4,000 U.S. patients who were diagnosed with novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19) shows that an unexpected 20% of deaths occurred among adults aged 20-64 years, and 20% of those hospitalized were aged 20-44 years.

The expectation has been that people over 65 are most vulnerable to COVID-19 infection, but this study indicates that, at least in the United States, a significant number of patients under 45 can land in the hospital and can even die of the disease.

To assess rates of hospitalization, admission to an ICU, and death among patients with COVID-19 by age group, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention analyzed 4,226 COVID-19 cases in the United States that were reported between Feb. 12 and March 16.

Overall, older patients in this group were the most likely to be hospitalized, to be admitted to ICU, and to die of COVID-19. A total of 31% of the cases, 45% of hospitalizations, 53% of ICU admissions, and 80% of deaths occurred in patients aged 65 years and older. “Similar to reports from other countries, this finding suggests that the risk for serious disease and death from COVID-19 is higher in older age groups,” said the investigators. “In contrast, persons aged [19 years and younger] appear to have milder COVID-19 illness, with almost no hospitalizations or deaths reported to date in the United States in this age group.”

But compared with the under-19 group, patients aged 20-44 years appeared to be at higher risk for hospitalization and ICU admission, according to the data published March 18 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The researchers excluded from their analysis patients who repatriated to the United States from Wuhan, China, and from Japan, including patients repatriated from cruise ships. Data on serious underlying health conditions were not available, and many cases were missing key data, they noted.

Among 508 patients known to have been hospitalized, 9% were aged 85 years or older, 36% were aged 65-84 years, 17% were aged 55-64 years, 18% were 45-54 years, and 20% were aged 20-44 years.

Among 121 patients admitted to an ICU, 7% were aged 85 years or older, 46% were aged 65-84 years, 36% were aged 45-64 years, and 12% were aged 20-44 years. Between 11% and 31% of patients with COVID-19 aged 75-84 years were admitted to an ICU.

Of 44 deaths, more than a third occurred among adults aged 85 years and older, and 46% occurred among adults aged 65-84 years, and 20% occurred among adults aged 20-64 years.

More follow-up time is needed to determine outcomes among active cases, the researchers said. These results also might overestimate the prevalence of severe disease because the initial approach to testing for COVID-19 focused on people with more severe disease. “These preliminary data also demonstrate that severe illness leading to hospitalization, including ICU admission and death, can occur in adults of any age with COVID-19,” according to the CDC.

SOURCE: CDC COVID-19 Response Team. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Mar 18. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2.

*Correction, 3/20/2020: An earlier version of this story misstated the age range for COVID-19 deaths. The headline of this story was corrected to read "20% of COVID-19 deaths were aged 20-64 years" and the text was adjusted to reflect the correct age range.

A review of more than 4,000 U.S. patients who were diagnosed with novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19) shows that an unexpected 20% of deaths occurred among adults aged 20-64 years, and 20% of those hospitalized were aged 20-44 years.

The expectation has been that people over 65 are most vulnerable to COVID-19 infection, but this study indicates that, at least in the United States, a significant number of patients under 45 can land in the hospital and can even die of the disease.

To assess rates of hospitalization, admission to an ICU, and death among patients with COVID-19 by age group, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention analyzed 4,226 COVID-19 cases in the United States that were reported between Feb. 12 and March 16.

Overall, older patients in this group were the most likely to be hospitalized, to be admitted to ICU, and to die of COVID-19. A total of 31% of the cases, 45% of hospitalizations, 53% of ICU admissions, and 80% of deaths occurred in patients aged 65 years and older. “Similar to reports from other countries, this finding suggests that the risk for serious disease and death from COVID-19 is higher in older age groups,” said the investigators. “In contrast, persons aged [19 years and younger] appear to have milder COVID-19 illness, with almost no hospitalizations or deaths reported to date in the United States in this age group.”

But compared with the under-19 group, patients aged 20-44 years appeared to be at higher risk for hospitalization and ICU admission, according to the data published March 18 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The researchers excluded from their analysis patients who repatriated to the United States from Wuhan, China, and from Japan, including patients repatriated from cruise ships. Data on serious underlying health conditions were not available, and many cases were missing key data, they noted.

Among 508 patients known to have been hospitalized, 9% were aged 85 years or older, 36% were aged 65-84 years, 17% were aged 55-64 years, 18% were 45-54 years, and 20% were aged 20-44 years.

Among 121 patients admitted to an ICU, 7% were aged 85 years or older, 46% were aged 65-84 years, 36% were aged 45-64 years, and 12% were aged 20-44 years. Between 11% and 31% of patients with COVID-19 aged 75-84 years were admitted to an ICU.

Of 44 deaths, more than a third occurred among adults aged 85 years and older, and 46% occurred among adults aged 65-84 years, and 20% occurred among adults aged 20-64 years.

More follow-up time is needed to determine outcomes among active cases, the researchers said. These results also might overestimate the prevalence of severe disease because the initial approach to testing for COVID-19 focused on people with more severe disease. “These preliminary data also demonstrate that severe illness leading to hospitalization, including ICU admission and death, can occur in adults of any age with COVID-19,” according to the CDC.

SOURCE: CDC COVID-19 Response Team. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Mar 18. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2.

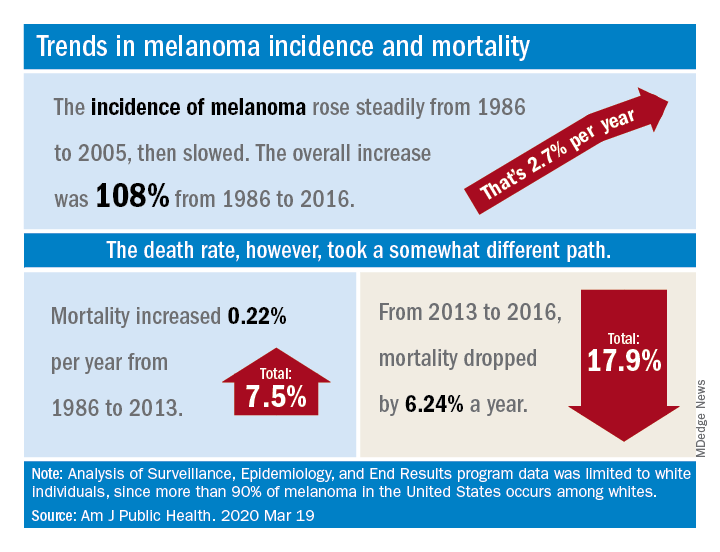

New melanoma treatments linked to mortality decline

Recent advances in treatment appear to have reversed the course of melanoma mortality since 2013, according to data published in the American Journal of Public Health.

The U.S. death rate for melanoma, which had been rising at a rate of 0.22% a year for more than 2 decades, dropped by 17.9%, or 6.24% per year, during 2013-2016. That decline “coincides with the introduction of multiple new and efficacious treatments for metastatic melanoma,” such as BRAF inhibitors and immune checkpoint inhibitors, study author Juliana Berk-Krauss, MD, of the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn and colleagues wrote.

The other possible explanation for the decline in deaths, “education and early detection resulting in migration toward earlier stage melanomas with a greater chance of surgical cure,” is unlikely, according to the investigators. That’s because the small decrease in median tumor thickness that occurred during 1989-2009 “is not associated with changes in prognosis.”

The investigators’ analysis encompassed data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry recorded during 1986-2016. Nine registry areas were included (Atlanta, Connecticut, Detroit, Hawaii, Iowa, New Mexico, San Francisco-Oakland, Seattle-Puget Sound, and Utah), which covered about 9.4% of the U.S. population. The analysis was limited to the white population, which accounts for more than 90% of melanoma cases in the United States.

The data showed a slight decline in annual percent change in melanoma incidence, from 3.24% for 1986-2005 to 1.72% for 2006-2016. However, over the whole period studied (1986-2016), melanoma incidence increased by 108%, or about 2.7% per year.

“Given the increased incidence of melanoma throughout this period and the lack of stage migration, these data strongly suggest that the mortality decline is due to the extended survival associated with these [newer] treatments,” the investigators wrote.

This study was funded by NYU Langone. Two investigators disclosed potential conflicts of interest, including relationships with Bio-Rad Laboratories, Novartis, Merck, and several other companies.

SOURCE: Berk-Krauss J et al. Am J Public Health. 2020 Mar 19. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305567.

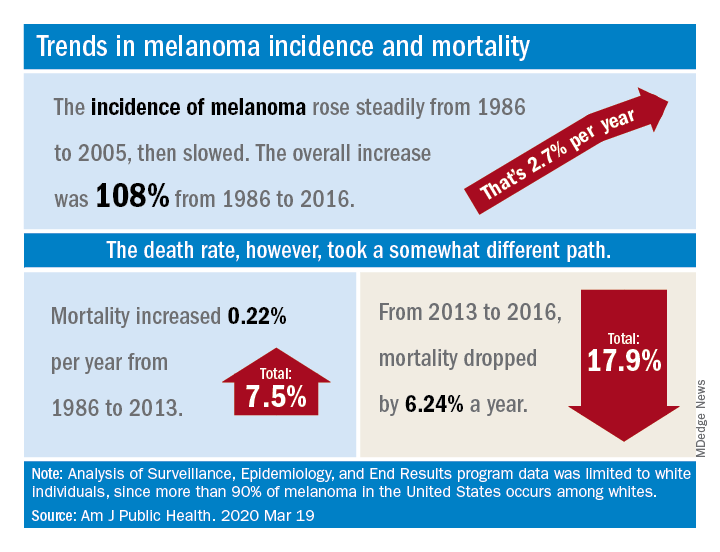

Recent advances in treatment appear to have reversed the course of melanoma mortality since 2013, according to data published in the American Journal of Public Health.

The U.S. death rate for melanoma, which had been rising at a rate of 0.22% a year for more than 2 decades, dropped by 17.9%, or 6.24% per year, during 2013-2016. That decline “coincides with the introduction of multiple new and efficacious treatments for metastatic melanoma,” such as BRAF inhibitors and immune checkpoint inhibitors, study author Juliana Berk-Krauss, MD, of the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn and colleagues wrote.

The other possible explanation for the decline in deaths, “education and early detection resulting in migration toward earlier stage melanomas with a greater chance of surgical cure,” is unlikely, according to the investigators. That’s because the small decrease in median tumor thickness that occurred during 1989-2009 “is not associated with changes in prognosis.”

The investigators’ analysis encompassed data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry recorded during 1986-2016. Nine registry areas were included (Atlanta, Connecticut, Detroit, Hawaii, Iowa, New Mexico, San Francisco-Oakland, Seattle-Puget Sound, and Utah), which covered about 9.4% of the U.S. population. The analysis was limited to the white population, which accounts for more than 90% of melanoma cases in the United States.

The data showed a slight decline in annual percent change in melanoma incidence, from 3.24% for 1986-2005 to 1.72% for 2006-2016. However, over the whole period studied (1986-2016), melanoma incidence increased by 108%, or about 2.7% per year.

“Given the increased incidence of melanoma throughout this period and the lack of stage migration, these data strongly suggest that the mortality decline is due to the extended survival associated with these [newer] treatments,” the investigators wrote.

This study was funded by NYU Langone. Two investigators disclosed potential conflicts of interest, including relationships with Bio-Rad Laboratories, Novartis, Merck, and several other companies.

SOURCE: Berk-Krauss J et al. Am J Public Health. 2020 Mar 19. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305567.

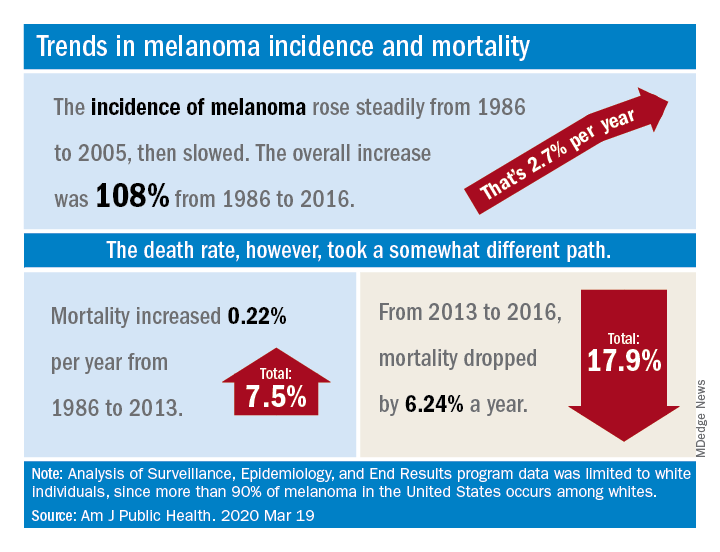

Recent advances in treatment appear to have reversed the course of melanoma mortality since 2013, according to data published in the American Journal of Public Health.

The U.S. death rate for melanoma, which had been rising at a rate of 0.22% a year for more than 2 decades, dropped by 17.9%, or 6.24% per year, during 2013-2016. That decline “coincides with the introduction of multiple new and efficacious treatments for metastatic melanoma,” such as BRAF inhibitors and immune checkpoint inhibitors, study author Juliana Berk-Krauss, MD, of the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn and colleagues wrote.

The other possible explanation for the decline in deaths, “education and early detection resulting in migration toward earlier stage melanomas with a greater chance of surgical cure,” is unlikely, according to the investigators. That’s because the small decrease in median tumor thickness that occurred during 1989-2009 “is not associated with changes in prognosis.”

The investigators’ analysis encompassed data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry recorded during 1986-2016. Nine registry areas were included (Atlanta, Connecticut, Detroit, Hawaii, Iowa, New Mexico, San Francisco-Oakland, Seattle-Puget Sound, and Utah), which covered about 9.4% of the U.S. population. The analysis was limited to the white population, which accounts for more than 90% of melanoma cases in the United States.

The data showed a slight decline in annual percent change in melanoma incidence, from 3.24% for 1986-2005 to 1.72% for 2006-2016. However, over the whole period studied (1986-2016), melanoma incidence increased by 108%, or about 2.7% per year.

“Given the increased incidence of melanoma throughout this period and the lack of stage migration, these data strongly suggest that the mortality decline is due to the extended survival associated with these [newer] treatments,” the investigators wrote.

This study was funded by NYU Langone. Two investigators disclosed potential conflicts of interest, including relationships with Bio-Rad Laboratories, Novartis, Merck, and several other companies.

SOURCE: Berk-Krauss J et al. Am J Public Health. 2020 Mar 19. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305567.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PUBLIC HEALTH

April 2020

Shiitake mushroom flagellate dermatitis

that resemble whiplash marks. The lesions may be extremely pruritic, and petechiae may be present in the streaks. The trunk is most commonly affected, although lesions can occur on the limbs. Mucosa is not affected. Sun exposure may exacerbate the condition. The dermatitis has been described in all ages and races, and males seem to be more affected than females.

Shiitake mushroom flagellate dermatitis typically occurs following the ingestion of raw or undercooked shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes). The mushrooms contain a polysaccharide called lentinan. Ingestion of lentinan activates interleukin-1 (IL-1), resulting in vasodilation and the subsequent dermatitis that can occur within a few hours and up to 5 days post ingestion. Associated gastrointestinal symptoms, fever, and localized swelling have been reported. The rash will resolve spontaneously over a few days to weeks.

Flagellate erythema has been described with bleomycin treatment. Other reported associations include peplomycin (a bleomycin derivative) and docetaxel. The rash may appear following administration of bleomycin by any route and has been shown to be dose independent. Onset occurs anywhere from 1 day to several months after exposure. Over time, the erythema will develop into postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Dermatomyositis may present with flagellate erythema. Other symptoms include muscle weakness and an inflammatory myopathy. A heliotrope rash on the eyelids, Gottron’s papules on the hands, ragged cuticles with prominent vessels on nail folds may be seen. Blood work may reveal elevated antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti–Mi-2 and anti–Jo-1. Adult-onset Still disease is characterized by fever, arthritis, and salmon-colored patches.

Our patient’s dermatitis resolved spontaneously without treatment.

This case and photo were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Shiitake mushroom flagellate dermatitis

that resemble whiplash marks. The lesions may be extremely pruritic, and petechiae may be present in the streaks. The trunk is most commonly affected, although lesions can occur on the limbs. Mucosa is not affected. Sun exposure may exacerbate the condition. The dermatitis has been described in all ages and races, and males seem to be more affected than females.

Shiitake mushroom flagellate dermatitis typically occurs following the ingestion of raw or undercooked shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes). The mushrooms contain a polysaccharide called lentinan. Ingestion of lentinan activates interleukin-1 (IL-1), resulting in vasodilation and the subsequent dermatitis that can occur within a few hours and up to 5 days post ingestion. Associated gastrointestinal symptoms, fever, and localized swelling have been reported. The rash will resolve spontaneously over a few days to weeks.

Flagellate erythema has been described with bleomycin treatment. Other reported associations include peplomycin (a bleomycin derivative) and docetaxel. The rash may appear following administration of bleomycin by any route and has been shown to be dose independent. Onset occurs anywhere from 1 day to several months after exposure. Over time, the erythema will develop into postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Dermatomyositis may present with flagellate erythema. Other symptoms include muscle weakness and an inflammatory myopathy. A heliotrope rash on the eyelids, Gottron’s papules on the hands, ragged cuticles with prominent vessels on nail folds may be seen. Blood work may reveal elevated antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti–Mi-2 and anti–Jo-1. Adult-onset Still disease is characterized by fever, arthritis, and salmon-colored patches.

Our patient’s dermatitis resolved spontaneously without treatment.

This case and photo were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Shiitake mushroom flagellate dermatitis

that resemble whiplash marks. The lesions may be extremely pruritic, and petechiae may be present in the streaks. The trunk is most commonly affected, although lesions can occur on the limbs. Mucosa is not affected. Sun exposure may exacerbate the condition. The dermatitis has been described in all ages and races, and males seem to be more affected than females.

Shiitake mushroom flagellate dermatitis typically occurs following the ingestion of raw or undercooked shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes). The mushrooms contain a polysaccharide called lentinan. Ingestion of lentinan activates interleukin-1 (IL-1), resulting in vasodilation and the subsequent dermatitis that can occur within a few hours and up to 5 days post ingestion. Associated gastrointestinal symptoms, fever, and localized swelling have been reported. The rash will resolve spontaneously over a few days to weeks.

Flagellate erythema has been described with bleomycin treatment. Other reported associations include peplomycin (a bleomycin derivative) and docetaxel. The rash may appear following administration of bleomycin by any route and has been shown to be dose independent. Onset occurs anywhere from 1 day to several months after exposure. Over time, the erythema will develop into postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Dermatomyositis may present with flagellate erythema. Other symptoms include muscle weakness and an inflammatory myopathy. A heliotrope rash on the eyelids, Gottron’s papules on the hands, ragged cuticles with prominent vessels on nail folds may be seen. Blood work may reveal elevated antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti–Mi-2 and anti–Jo-1. Adult-onset Still disease is characterized by fever, arthritis, and salmon-colored patches.

Our patient’s dermatitis resolved spontaneously without treatment.

This case and photo were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Rheumatologists to share knowledge in COVID-19 patient-centered registry

Rheumatologists the world over are joining forces to create a COVID-19 rheumatology registry designed to help both patients and providers learn from each other regarding management of rheumatologic diseases and risk of infection among patients who are commonly on chronic immunosuppressive medications.

The COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance, a consortium supported by more than 50 major clinical societies and foundations, quickly grew from messages on social media platforms to a multinational group focused on the common goal of helping to “guide rheumatology clinicians in assessing and treating patients with rheumatologic disease and in evaluating the risk of infection in patients on immunosuppression.”

As of this writing, the rheumatology registry is still being assembled, and organizers are currently seeking approvals from various authorities. As of March 17, 2020, the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of California, San Francisco, has determined that the registry is exempt from IRB approval requirements, a finding that should apply elsewhere in the United States, according to the registry website.

When it is fully up and running, clinicians will be able to report to the secure website on any and all cases of patients with rheumatologic disorders who present with COVID-19 of any severity, including patients with mild disease or asymptomatic patients who test positive.

“We are aiming for 5 to 10 minutes to input the data. We don’t want to drag them away from their clinical duties too much, but if clinicians are able to spare a few minutes to put in details about a patient, then that’s going to help build our knowledge and it’s going to help them with other patients,” said Philip Robinson, MBChB, associate professor of medicine at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, and the chief architect of the registry.

The data will be deindentified, with no protected health care information required or included, and made available to the global rheumatology community, but the registry will not offer clinical advice, Dr. Robinson said in an interview.

“This is observational data, it’s not randomized, but our approach is that some data is better than no data,” he said.

He also cautioned that the data will need careful interpretation, because information about patients with mild symptoms may offer false reassurances about the severity or extent of infection.

“For example, the patients with severe cases may be in the ICU, and can’t tell their doctors that they’re on methotrexate, so you can see how we need to be really careful about the messages from that data and not misinterpret it,” he said.

The COVID-19 rheumatology registry was inspired by a similar effort in the gastroenterology community, the Surveillance Epidemiology of Coronavirus Under Research Exclusion (SECURE-IBD) registry. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease are often treated with immunosuppressive biologic agents familiar to the rheumatology community, such as infliximab (Remicade and biosimilars) and adalimumab (Humira and biosimilars), and methotrexate.

Rheumatologists the world over are joining forces to create a COVID-19 rheumatology registry designed to help both patients and providers learn from each other regarding management of rheumatologic diseases and risk of infection among patients who are commonly on chronic immunosuppressive medications.

The COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance, a consortium supported by more than 50 major clinical societies and foundations, quickly grew from messages on social media platforms to a multinational group focused on the common goal of helping to “guide rheumatology clinicians in assessing and treating patients with rheumatologic disease and in evaluating the risk of infection in patients on immunosuppression.”

As of this writing, the rheumatology registry is still being assembled, and organizers are currently seeking approvals from various authorities. As of March 17, 2020, the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of California, San Francisco, has determined that the registry is exempt from IRB approval requirements, a finding that should apply elsewhere in the United States, according to the registry website.

When it is fully up and running, clinicians will be able to report to the secure website on any and all cases of patients with rheumatologic disorders who present with COVID-19 of any severity, including patients with mild disease or asymptomatic patients who test positive.

“We are aiming for 5 to 10 minutes to input the data. We don’t want to drag them away from their clinical duties too much, but if clinicians are able to spare a few minutes to put in details about a patient, then that’s going to help build our knowledge and it’s going to help them with other patients,” said Philip Robinson, MBChB, associate professor of medicine at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, and the chief architect of the registry.

The data will be deindentified, with no protected health care information required or included, and made available to the global rheumatology community, but the registry will not offer clinical advice, Dr. Robinson said in an interview.

“This is observational data, it’s not randomized, but our approach is that some data is better than no data,” he said.

He also cautioned that the data will need careful interpretation, because information about patients with mild symptoms may offer false reassurances about the severity or extent of infection.

“For example, the patients with severe cases may be in the ICU, and can’t tell their doctors that they’re on methotrexate, so you can see how we need to be really careful about the messages from that data and not misinterpret it,” he said.

The COVID-19 rheumatology registry was inspired by a similar effort in the gastroenterology community, the Surveillance Epidemiology of Coronavirus Under Research Exclusion (SECURE-IBD) registry. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease are often treated with immunosuppressive biologic agents familiar to the rheumatology community, such as infliximab (Remicade and biosimilars) and adalimumab (Humira and biosimilars), and methotrexate.

Rheumatologists the world over are joining forces to create a COVID-19 rheumatology registry designed to help both patients and providers learn from each other regarding management of rheumatologic diseases and risk of infection among patients who are commonly on chronic immunosuppressive medications.

The COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance, a consortium supported by more than 50 major clinical societies and foundations, quickly grew from messages on social media platforms to a multinational group focused on the common goal of helping to “guide rheumatology clinicians in assessing and treating patients with rheumatologic disease and in evaluating the risk of infection in patients on immunosuppression.”

As of this writing, the rheumatology registry is still being assembled, and organizers are currently seeking approvals from various authorities. As of March 17, 2020, the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of California, San Francisco, has determined that the registry is exempt from IRB approval requirements, a finding that should apply elsewhere in the United States, according to the registry website.

When it is fully up and running, clinicians will be able to report to the secure website on any and all cases of patients with rheumatologic disorders who present with COVID-19 of any severity, including patients with mild disease or asymptomatic patients who test positive.

“We are aiming for 5 to 10 minutes to input the data. We don’t want to drag them away from their clinical duties too much, but if clinicians are able to spare a few minutes to put in details about a patient, then that’s going to help build our knowledge and it’s going to help them with other patients,” said Philip Robinson, MBChB, associate professor of medicine at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, and the chief architect of the registry.

The data will be deindentified, with no protected health care information required or included, and made available to the global rheumatology community, but the registry will not offer clinical advice, Dr. Robinson said in an interview.

“This is observational data, it’s not randomized, but our approach is that some data is better than no data,” he said.

He also cautioned that the data will need careful interpretation, because information about patients with mild symptoms may offer false reassurances about the severity or extent of infection.

“For example, the patients with severe cases may be in the ICU, and can’t tell their doctors that they’re on methotrexate, so you can see how we need to be really careful about the messages from that data and not misinterpret it,” he said.

The COVID-19 rheumatology registry was inspired by a similar effort in the gastroenterology community, the Surveillance Epidemiology of Coronavirus Under Research Exclusion (SECURE-IBD) registry. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease are often treated with immunosuppressive biologic agents familiar to the rheumatology community, such as infliximab (Remicade and biosimilars) and adalimumab (Humira and biosimilars), and methotrexate.

Real-world shortages not addressed in new COVID-19 guidance

Newly updated guidance on treating patients with the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) has been published by the World Health Organization.

While it can’t replace clinical judgment or specialist consultation, the new guidance may help strengthen the clinical management of patients when COVID-19 is suspected, according to its authors.

The guidance, adapted from an earlier edition focused on the management of suspected Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), covers best practices for triage, infection prevention and control, and optimized supportive care for mild, severe, or critical coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

“This guidance should serve as a foundation for optimized supportive care to ensure the best possible chance for survival,” the authors wrote in the guidance.

While the WHO guidance does provide solid facts to support best practices for managing COVID-19, providers will also need to look beyond the document to tackle real-world issues, said David M. Ferraro, MD, FCCP, a pulmonary and critical care physician and associate professor of medicine at National Jewish Health in Denver.

For example, while the guidelines address the importance of screening and triage, limited COVID-19 testing may be a barrier to timely diagnoses that might compel more individuals to comply with social distancing recommendations, according to Dr. Ferraro, vice chair of the Fundamental Disaster Management Committee for the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM).

“If we’re not providing people with confirmation that they have the virus, they may potentially continue to be spreaders of the disease, because they don’t have that absolute proof,” Dr. Ferraro said in an interview. “I think that’s where we are limited right now, because often we’re not able to tell the mild symptomatic people – or even the asymptomatic people – that they really need to play a role in preventing further spread.”