User login

News and Views that Matter to Physicians

Beta-blockers curb death risk in patients with primary prevention ICD

ROME – Beta-blocker therapy reduces the risks of all-cause mortality as well as cardiac death in patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction below 35% who get an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for primary prevention, Laurent Fauchier, MD, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Some physicians have recently urged reconsideration of current guidelines recommending routine use of beta-blockers for prevention of cardiovascular events in certain groups of patients with coronary artery disease, including those with chronic heart failure who have received an ICD for primary prevention of sudden death. And indeed it’s true that the now–relatively old randomized trials of ICDs for primary prevention in patients with chronic heart failure don’t provide any real evidence that beta-blockers reduce mortality in this setting. In fact, the guideline recommendation for beta-blockade has been based upon expert opinion. This was the impetus for Dr. Fauchier and coinvestigators to conduct a large retrospective observational study in a contemporary cohort of heart failure patients who received an ICD for primary prevention during a recent 10-year period at the 12 largest centers in France.

Fifteen percent of the 3,975 French ICD recipients did not receive a beta-blocker. They differed from those who did in that they were on average 2 years older, had an absolute 5% lower ejection fraction, and were more likely to also receive cardiac resynchronization therapy. Propensity score matching based on these and 19 other baseline characteristics enabled investigators to assemble a cohort of 541 closely matched patient pairs, explained Dr. Fauchier, professor of cardiology at Francois Rabelais University in Tours, France.

During a mean follow-up of 3.2 years, the risk of all-cause mortality in ICD recipients not on a beta-blocker was 34% higher than in those who were. Moreover, their risk of cardiac death was 50% greater.

In contrast, beta-blocker therapy had no effect on the risks of sudden death or of appropriate or inappropriate shocks.

The finding that beta-blocker therapy doesn’t prevent sudden death in patients with an ICD for primary prevention has not previously been reported. However, it makes sense. The device prevents such events so effectively that a beta-blocker adds nothing further in that regard, according to Dr. Fauchier.

“Beta-blockers should continue to be used widely, as currently recommended, for heart failure in the specific setting of patients with prophylactic ICD implantation. You do not have the benefit for prevention of sudden death, but you still have all the benefit from preventing cardiac death,” the electrophysiologist concluded.

This study was supported by French governmental research grants. Dr. Fauchier reported serving as a consultant to Bayer, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Medtronic, and Novartis.

ROME – Beta-blocker therapy reduces the risks of all-cause mortality as well as cardiac death in patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction below 35% who get an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for primary prevention, Laurent Fauchier, MD, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Some physicians have recently urged reconsideration of current guidelines recommending routine use of beta-blockers for prevention of cardiovascular events in certain groups of patients with coronary artery disease, including those with chronic heart failure who have received an ICD for primary prevention of sudden death. And indeed it’s true that the now–relatively old randomized trials of ICDs for primary prevention in patients with chronic heart failure don’t provide any real evidence that beta-blockers reduce mortality in this setting. In fact, the guideline recommendation for beta-blockade has been based upon expert opinion. This was the impetus for Dr. Fauchier and coinvestigators to conduct a large retrospective observational study in a contemporary cohort of heart failure patients who received an ICD for primary prevention during a recent 10-year period at the 12 largest centers in France.

Fifteen percent of the 3,975 French ICD recipients did not receive a beta-blocker. They differed from those who did in that they were on average 2 years older, had an absolute 5% lower ejection fraction, and were more likely to also receive cardiac resynchronization therapy. Propensity score matching based on these and 19 other baseline characteristics enabled investigators to assemble a cohort of 541 closely matched patient pairs, explained Dr. Fauchier, professor of cardiology at Francois Rabelais University in Tours, France.

During a mean follow-up of 3.2 years, the risk of all-cause mortality in ICD recipients not on a beta-blocker was 34% higher than in those who were. Moreover, their risk of cardiac death was 50% greater.

In contrast, beta-blocker therapy had no effect on the risks of sudden death or of appropriate or inappropriate shocks.

The finding that beta-blocker therapy doesn’t prevent sudden death in patients with an ICD for primary prevention has not previously been reported. However, it makes sense. The device prevents such events so effectively that a beta-blocker adds nothing further in that regard, according to Dr. Fauchier.

“Beta-blockers should continue to be used widely, as currently recommended, for heart failure in the specific setting of patients with prophylactic ICD implantation. You do not have the benefit for prevention of sudden death, but you still have all the benefit from preventing cardiac death,” the electrophysiologist concluded.

This study was supported by French governmental research grants. Dr. Fauchier reported serving as a consultant to Bayer, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Medtronic, and Novartis.

ROME – Beta-blocker therapy reduces the risks of all-cause mortality as well as cardiac death in patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction below 35% who get an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for primary prevention, Laurent Fauchier, MD, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Some physicians have recently urged reconsideration of current guidelines recommending routine use of beta-blockers for prevention of cardiovascular events in certain groups of patients with coronary artery disease, including those with chronic heart failure who have received an ICD for primary prevention of sudden death. And indeed it’s true that the now–relatively old randomized trials of ICDs for primary prevention in patients with chronic heart failure don’t provide any real evidence that beta-blockers reduce mortality in this setting. In fact, the guideline recommendation for beta-blockade has been based upon expert opinion. This was the impetus for Dr. Fauchier and coinvestigators to conduct a large retrospective observational study in a contemporary cohort of heart failure patients who received an ICD for primary prevention during a recent 10-year period at the 12 largest centers in France.

Fifteen percent of the 3,975 French ICD recipients did not receive a beta-blocker. They differed from those who did in that they were on average 2 years older, had an absolute 5% lower ejection fraction, and were more likely to also receive cardiac resynchronization therapy. Propensity score matching based on these and 19 other baseline characteristics enabled investigators to assemble a cohort of 541 closely matched patient pairs, explained Dr. Fauchier, professor of cardiology at Francois Rabelais University in Tours, France.

During a mean follow-up of 3.2 years, the risk of all-cause mortality in ICD recipients not on a beta-blocker was 34% higher than in those who were. Moreover, their risk of cardiac death was 50% greater.

In contrast, beta-blocker therapy had no effect on the risks of sudden death or of appropriate or inappropriate shocks.

The finding that beta-blocker therapy doesn’t prevent sudden death in patients with an ICD for primary prevention has not previously been reported. However, it makes sense. The device prevents such events so effectively that a beta-blocker adds nothing further in that regard, according to Dr. Fauchier.

“Beta-blockers should continue to be used widely, as currently recommended, for heart failure in the specific setting of patients with prophylactic ICD implantation. You do not have the benefit for prevention of sudden death, but you still have all the benefit from preventing cardiac death,” the electrophysiologist concluded.

This study was supported by French governmental research grants. Dr. Fauchier reported serving as a consultant to Bayer, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Medtronic, and Novartis.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction who received an ICD for primary prevention and were not on a beta-blocker were at an adjusted 50% increased risk for cardiac death and 34% increased risk for all-cause mortality during 3.2 years of follow-up, but they were at no increased risk for sudden death.

Data source: A retrospective observational study of all of the nearly 4,000 patients who received a primary prevention ICD at the 12 largest French centers during a recent 10-year period.

Disclosures: This study was supported by French governmental research funds. The presenter reported serving as a consultant to Bayer, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Medtronic, and Novartis.

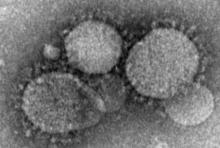

Health care workers at risk for mild MERS-CoV infections

Health care workers directly caring for patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) are more highly predisposed to contracting the virus, but in a milder form than that of their patients, thus making it difficult to diagnose and treat.

In a study published in Emerging Infectious Diseases, health care professionals (HCP) from the King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, were examined to determine their likelihood for getting MERS-CoV based on their proximity to patients who already had it.

“Healthcare settings are important amplifiers of transmission,” explained the investigators, led by Basem M. Alraddadi, MD. “Current MERS-CoV infection control recommendations are based on experience with other viruses rather than on a complete understanding of the epidemiology of MERS-CoV transmission.”

Dr. Alraddadi and his coinvestigators identified 363 HCP, all of whom would be placed into one of three cohorts based on the department in which they worked most extensively: the Medical Intensive Care Unit (MICU), the emergency department (ED), and the neurology unit. A total of 292 HCP were ultimately enrolled in the study: 131 in MICU, 127 in ED, and 34 in neurology. After 9 subjects were excluded because of unavailability of serum specimens, 128 MICU, 122 ED, and 33 neurology unit workers remained.

While none of the neurology unit workers contracted the virus, 15 MICU workers (11.7%) and 5 ED workers (4.1%) did, for a total of 20 out of the 250 subjects in those two cohorts (8%). Radiology technicians were the most susceptible, as 5 of 17 (29.4%) got the virus, followed by 13 of 138 nurses (9.4%), 1 of 31 respiratory therapists (3.2%), and 1 of 41 physicians (2.4%).

“HCP who reported always covering their nose and mouth with either a medical mask or N95 respirator had lower risk for infection than did HCP reporting not always or never doing so, [while] those who reported always using N95 respirators for direct patient contact were less likely to be seropositive, a trend that approached statistical significance (P = .07),” the authors noted.

The most frequent symptoms reported by those surveyed were muscle pain, fevers, headaches, dry cough, and shortness of breath. In the 20-case HCP sample, however, 12 subjects (60%) only had mild illness while 3 (15%) were asymptomatic, making it very hard to diagnose and treat their infection. Three subjects (15%) had severe illness, while another two (10%) had moderate illness, meaning they were admitted to hospital but did not require any mechanical ventilation.

“Our study did not identify strong associations with underlying chronic illnesses, most likely because the prevalence of such conditions was low ([less than] 10%) in this population, [but] HCPs with a history of smoking had a risk for infection almost 3 times that of nonsmokers,” the authors wrote (Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 Nov. doi: 10.3201/eid2211.160920).

The Ministry of Health of Saudi Arabia and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the study. Dr. Alraddadi and his coauthors did not report any disclosures.

Health care workers directly caring for patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) are more highly predisposed to contracting the virus, but in a milder form than that of their patients, thus making it difficult to diagnose and treat.

In a study published in Emerging Infectious Diseases, health care professionals (HCP) from the King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, were examined to determine their likelihood for getting MERS-CoV based on their proximity to patients who already had it.

“Healthcare settings are important amplifiers of transmission,” explained the investigators, led by Basem M. Alraddadi, MD. “Current MERS-CoV infection control recommendations are based on experience with other viruses rather than on a complete understanding of the epidemiology of MERS-CoV transmission.”

Dr. Alraddadi and his coinvestigators identified 363 HCP, all of whom would be placed into one of three cohorts based on the department in which they worked most extensively: the Medical Intensive Care Unit (MICU), the emergency department (ED), and the neurology unit. A total of 292 HCP were ultimately enrolled in the study: 131 in MICU, 127 in ED, and 34 in neurology. After 9 subjects were excluded because of unavailability of serum specimens, 128 MICU, 122 ED, and 33 neurology unit workers remained.

While none of the neurology unit workers contracted the virus, 15 MICU workers (11.7%) and 5 ED workers (4.1%) did, for a total of 20 out of the 250 subjects in those two cohorts (8%). Radiology technicians were the most susceptible, as 5 of 17 (29.4%) got the virus, followed by 13 of 138 nurses (9.4%), 1 of 31 respiratory therapists (3.2%), and 1 of 41 physicians (2.4%).

“HCP who reported always covering their nose and mouth with either a medical mask or N95 respirator had lower risk for infection than did HCP reporting not always or never doing so, [while] those who reported always using N95 respirators for direct patient contact were less likely to be seropositive, a trend that approached statistical significance (P = .07),” the authors noted.

The most frequent symptoms reported by those surveyed were muscle pain, fevers, headaches, dry cough, and shortness of breath. In the 20-case HCP sample, however, 12 subjects (60%) only had mild illness while 3 (15%) were asymptomatic, making it very hard to diagnose and treat their infection. Three subjects (15%) had severe illness, while another two (10%) had moderate illness, meaning they were admitted to hospital but did not require any mechanical ventilation.

“Our study did not identify strong associations with underlying chronic illnesses, most likely because the prevalence of such conditions was low ([less than] 10%) in this population, [but] HCPs with a history of smoking had a risk for infection almost 3 times that of nonsmokers,” the authors wrote (Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 Nov. doi: 10.3201/eid2211.160920).

The Ministry of Health of Saudi Arabia and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the study. Dr. Alraddadi and his coauthors did not report any disclosures.

Health care workers directly caring for patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) are more highly predisposed to contracting the virus, but in a milder form than that of their patients, thus making it difficult to diagnose and treat.

In a study published in Emerging Infectious Diseases, health care professionals (HCP) from the King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, were examined to determine their likelihood for getting MERS-CoV based on their proximity to patients who already had it.

“Healthcare settings are important amplifiers of transmission,” explained the investigators, led by Basem M. Alraddadi, MD. “Current MERS-CoV infection control recommendations are based on experience with other viruses rather than on a complete understanding of the epidemiology of MERS-CoV transmission.”

Dr. Alraddadi and his coinvestigators identified 363 HCP, all of whom would be placed into one of three cohorts based on the department in which they worked most extensively: the Medical Intensive Care Unit (MICU), the emergency department (ED), and the neurology unit. A total of 292 HCP were ultimately enrolled in the study: 131 in MICU, 127 in ED, and 34 in neurology. After 9 subjects were excluded because of unavailability of serum specimens, 128 MICU, 122 ED, and 33 neurology unit workers remained.

While none of the neurology unit workers contracted the virus, 15 MICU workers (11.7%) and 5 ED workers (4.1%) did, for a total of 20 out of the 250 subjects in those two cohorts (8%). Radiology technicians were the most susceptible, as 5 of 17 (29.4%) got the virus, followed by 13 of 138 nurses (9.4%), 1 of 31 respiratory therapists (3.2%), and 1 of 41 physicians (2.4%).

“HCP who reported always covering their nose and mouth with either a medical mask or N95 respirator had lower risk for infection than did HCP reporting not always or never doing so, [while] those who reported always using N95 respirators for direct patient contact were less likely to be seropositive, a trend that approached statistical significance (P = .07),” the authors noted.

The most frequent symptoms reported by those surveyed were muscle pain, fevers, headaches, dry cough, and shortness of breath. In the 20-case HCP sample, however, 12 subjects (60%) only had mild illness while 3 (15%) were asymptomatic, making it very hard to diagnose and treat their infection. Three subjects (15%) had severe illness, while another two (10%) had moderate illness, meaning they were admitted to hospital but did not require any mechanical ventilation.

“Our study did not identify strong associations with underlying chronic illnesses, most likely because the prevalence of such conditions was low ([less than] 10%) in this population, [but] HCPs with a history of smoking had a risk for infection almost 3 times that of nonsmokers,” the authors wrote (Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 Nov. doi: 10.3201/eid2211.160920).

The Ministry of Health of Saudi Arabia and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the study. Dr. Alraddadi and his coauthors did not report any disclosures.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Among workers who actually treated MERS-CoV patients, 20 out of 250 (8%) contracted the virus, while none of the clerical staff or patient transporters did.

Data source: Retrospective, single-center study of 363 health care personnel during May-June 2014.

Disclosures: The Ministry of Health of Saudi Arabia and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the study. The authors reported no financial disclosures.

Earlier ischemic stroke presentation may sometimes mean delayed tPA

BALTIMORE – Going to the hospital soon after the development of symptoms of acute ischemic stroke may not guarantee quick treatment.

A study of 1,865 patients treated within the past decade at a large urban comprehensive stroke center has revealed delayed treatment with tissue plasminogen activator, compared with patients who came to the emergency room hours after symptom development, Dr. Kyle C. Rossi said at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

Treatment with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) within 3 hours after the first symptoms of acute ischemic stroke definitely improves long-term outcomes, but meeting this target time remains a challenge. Patients who present to the emergency room soon after symptom development would seemingly have an advantage, yet Dr. Rossi’s preliminary scrutiny of patient records at Mount Sinai raised doubts about this and prompted the present study.

The hypothesis was that cases with a shorter time between symptom development and diagnosis of stroke (last known well-to-stroke code time, or LKW-to-code) will have a longer time between diagnosis and tPA administration (code-to-tPA), “possibly due to the perception on the part of evaluating physicians of sufficient remaining time before the end of the tPA window.”

The researchers examined patient records from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association’s “Get with the Guidelines” stroke program, a voluntary observational registry for patients with acute stroke. Of the 1,865 ischemic stroke patients treated during 2009-2015, 122 who received intravenous tPA were allocated to three LKW-to-code groups: within an hour (38 patients), within the next hour (49 patients), or 2 hours or more (35 patients).

The patients tended to be in their late 60s. Just over half were female, and about 40% were white.

Overall, the average LKW-to-code time was 91 ± 48 minutes and the average code-to-tPA time was 67 ± 26 minutes.

Average code-to-tPA times were 80, 67, and 52 minutes, respectively, for the three groups (P less than .0001). On average, it took 28 minutes longer to give tPA to patients who presented within an hour than to patients presenting 2 hours or longer after their first stroke symptom. There was an increase in code-to-tPA time of 1 minute for every decrease in LKW-to-code time of 4 minutes (P less than .0001).

The delay in the time to treat patients who arrive sooner after development of stroke symptoms may result from a decision made by the evaluating neurologist to conduct additional testing prior to administering tPA. Sometimes other staff may be unaware of the decision to delay treatment, according to Dr. Rossi and his colleagues.

“Absolutely, folks coming in soon after symptoms develop should be treated early. But treatment needs to balance rapid delivery with adequate testing. Sometimes, when there is some time to spare before the optimum treatment window closes we can do a more thorough examination and address lingering questions,” Dr. Rossi said.

The decision to get more information about the patient’s condition reflects the goal to give tPA as soon as safely possible to the right patients. While laudable, the study highlights that the timing of treatment can be improved.

Dr. Rossi reported having no financial disclosures.

BALTIMORE – Going to the hospital soon after the development of symptoms of acute ischemic stroke may not guarantee quick treatment.

A study of 1,865 patients treated within the past decade at a large urban comprehensive stroke center has revealed delayed treatment with tissue plasminogen activator, compared with patients who came to the emergency room hours after symptom development, Dr. Kyle C. Rossi said at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

Treatment with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) within 3 hours after the first symptoms of acute ischemic stroke definitely improves long-term outcomes, but meeting this target time remains a challenge. Patients who present to the emergency room soon after symptom development would seemingly have an advantage, yet Dr. Rossi’s preliminary scrutiny of patient records at Mount Sinai raised doubts about this and prompted the present study.

The hypothesis was that cases with a shorter time between symptom development and diagnosis of stroke (last known well-to-stroke code time, or LKW-to-code) will have a longer time between diagnosis and tPA administration (code-to-tPA), “possibly due to the perception on the part of evaluating physicians of sufficient remaining time before the end of the tPA window.”

The researchers examined patient records from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association’s “Get with the Guidelines” stroke program, a voluntary observational registry for patients with acute stroke. Of the 1,865 ischemic stroke patients treated during 2009-2015, 122 who received intravenous tPA were allocated to three LKW-to-code groups: within an hour (38 patients), within the next hour (49 patients), or 2 hours or more (35 patients).

The patients tended to be in their late 60s. Just over half were female, and about 40% were white.

Overall, the average LKW-to-code time was 91 ± 48 minutes and the average code-to-tPA time was 67 ± 26 minutes.

Average code-to-tPA times were 80, 67, and 52 minutes, respectively, for the three groups (P less than .0001). On average, it took 28 minutes longer to give tPA to patients who presented within an hour than to patients presenting 2 hours or longer after their first stroke symptom. There was an increase in code-to-tPA time of 1 minute for every decrease in LKW-to-code time of 4 minutes (P less than .0001).

The delay in the time to treat patients who arrive sooner after development of stroke symptoms may result from a decision made by the evaluating neurologist to conduct additional testing prior to administering tPA. Sometimes other staff may be unaware of the decision to delay treatment, according to Dr. Rossi and his colleagues.

“Absolutely, folks coming in soon after symptoms develop should be treated early. But treatment needs to balance rapid delivery with adequate testing. Sometimes, when there is some time to spare before the optimum treatment window closes we can do a more thorough examination and address lingering questions,” Dr. Rossi said.

The decision to get more information about the patient’s condition reflects the goal to give tPA as soon as safely possible to the right patients. While laudable, the study highlights that the timing of treatment can be improved.

Dr. Rossi reported having no financial disclosures.

BALTIMORE – Going to the hospital soon after the development of symptoms of acute ischemic stroke may not guarantee quick treatment.

A study of 1,865 patients treated within the past decade at a large urban comprehensive stroke center has revealed delayed treatment with tissue plasminogen activator, compared with patients who came to the emergency room hours after symptom development, Dr. Kyle C. Rossi said at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

Treatment with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) within 3 hours after the first symptoms of acute ischemic stroke definitely improves long-term outcomes, but meeting this target time remains a challenge. Patients who present to the emergency room soon after symptom development would seemingly have an advantage, yet Dr. Rossi’s preliminary scrutiny of patient records at Mount Sinai raised doubts about this and prompted the present study.

The hypothesis was that cases with a shorter time between symptom development and diagnosis of stroke (last known well-to-stroke code time, or LKW-to-code) will have a longer time between diagnosis and tPA administration (code-to-tPA), “possibly due to the perception on the part of evaluating physicians of sufficient remaining time before the end of the tPA window.”

The researchers examined patient records from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association’s “Get with the Guidelines” stroke program, a voluntary observational registry for patients with acute stroke. Of the 1,865 ischemic stroke patients treated during 2009-2015, 122 who received intravenous tPA were allocated to three LKW-to-code groups: within an hour (38 patients), within the next hour (49 patients), or 2 hours or more (35 patients).

The patients tended to be in their late 60s. Just over half were female, and about 40% were white.

Overall, the average LKW-to-code time was 91 ± 48 minutes and the average code-to-tPA time was 67 ± 26 minutes.

Average code-to-tPA times were 80, 67, and 52 minutes, respectively, for the three groups (P less than .0001). On average, it took 28 minutes longer to give tPA to patients who presented within an hour than to patients presenting 2 hours or longer after their first stroke symptom. There was an increase in code-to-tPA time of 1 minute for every decrease in LKW-to-code time of 4 minutes (P less than .0001).

The delay in the time to treat patients who arrive sooner after development of stroke symptoms may result from a decision made by the evaluating neurologist to conduct additional testing prior to administering tPA. Sometimes other staff may be unaware of the decision to delay treatment, according to Dr. Rossi and his colleagues.

“Absolutely, folks coming in soon after symptoms develop should be treated early. But treatment needs to balance rapid delivery with adequate testing. Sometimes, when there is some time to spare before the optimum treatment window closes we can do a more thorough examination and address lingering questions,” Dr. Rossi said.

The decision to get more information about the patient’s condition reflects the goal to give tPA as soon as safely possible to the right patients. While laudable, the study highlights that the timing of treatment can be improved.

Dr. Rossi reported having no financial disclosures.

AT ANA 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: TPA was delivered 28 minutes longer on average for patients presenting less than 1 hour after stroke symptoms, compared with patients presenting more than 2 hours after.

Data source: Analysis of 1,865 patients with acute ischemic stroke in the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association’s “Get with the Guidelines” stroke program who were diagnosed at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

Disclosures: Dr. Rossi reported having no financial disclosures.

Psychiatric patients face inordinately long wait times in emergency departments

Individuals with psychiatric conditions are facing increasingly longer wait times in emergency departments across the country, including children, according to a pair of studies presented by the American College of Emergency Physicians.

“I really started doing this research because of my clinical experience,” explained Suzanne Catherine Lippert, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and the lead author of both studies during an Oct. 17 conference call, saying that seeing patients sit in the ED for days prompted her to finally look into this issue.

Patients with bipolar disorder had the highest likelihood of waiting more than 24 hours in the ED, with an odds ratio of 3.7 (95% confidence interval, 1.5-9.4). This was followed by patients with a diagnosis of psychosis, a dual diagnosis of psychiatric disorders, multiple psychiatric diagnoses, or depression. The most common diagnoses were substance abuse, anxiety, and depression, which constituted 41%, 26%, and 23% of the diagnoses, respectively. Patients with psychosis were admitted 34% of the time and transferred 24% of the time; those who self-harmed were admitted 33% of the time and transferred 29% of the time; and patients with bipolar disorder were admitted 29% of the time and transferred 40% of the time. Patients who had either two or three diagnoses were admitted 9% and 10% of the time, respectively.

“Further investigation of the systems affecting these patients, including placement of involuntary holds, availability of ED psychiatric consultants, or outpatient resources would delineate potential intervention points for the care of these vulnerable patients,” Dr. Lippert and her coauthors wrote.

The second study looked at the differences in waiting for care at EDs between psychiatric patients and medical patients. Length of stay was defined the same way it was in the previous study, with disposition meaning either “discharge, admission to medical or psychiatric bed, [or] transfer to any acute facility.” Length of stay was divided into the same three categories as the previous study, too.

Psychiatric patients were more likely than were medical patients to wait more than 6 hours for disposition, regardless of what the disposition itself ended up being, by a rate of 23% vs. 10%. Similarly, 7% of psychiatric patients vs. just 2.3% of medical patients had to wait longer than 12 hours in the ED, while 1.3% of psychiatric had to wait longer than 24 hours, compared with only 0.5% of medical patients. The average length of stay was significantly longer for psychiatric patients: 194 minutes vs. 138 minutes for medical patients (P less than .01).

Additionally, psychiatric patients were more likely to be uninsured, with 22% not having insurance, compared with 15% of medical patients being uninsured. Furthermore, 4.6% of the psychiatric patients’ previous visit to the ED had been within the prior 72 hours, compared with 3.6% of medical patients. A total of 21% of psychiatric patients required admittance, compared with 13% of medical patients, while 11% of psychiatric patients were transferred, compared with just 1.4% of medical patients.

“These results compel us to further investigate the potential causes of prolonged length of stay in psychiatric patients and to further characterize the population of psychiatric patients most at risk of prolonged stays,” Dr. Lippert and her coinvestigators concluded.

ACEP President Rebecca B. Parker, MD, chimed in during the conference call, explaining that a survey of more than 1,700 emergency physicians revealed some “troubling” findings about the state of emergency departments over the last year.

The nation’s dwindling mental health resources are having a direct impact on patients having psychiatric emergencies, including children,” Dr. Parker explained. “These patients are waiting longer for care, especially those patients who require hospitalization.”

Findings of the survey indicate that 48% of ED physicians witness psychiatric patients being “boarded” in their EDs at least once a day while they wait for a bed. Additionally, less than 17% of respondents said their ED has a psychiatrist on call to respond to psychiatric emergencies, with 11.7% responding that they have no psychiatrist on call to deal with such emergencies. And 52% of respondents said the mental health system in their community has gotten noticeably worse in just the last year.

In a separate statement, Dr. Parker voiced outrage about the situation. “Psychiatric patients wait in the emergency department for hours and even days for a bed, which delays the psychiatric care they so desperately need,” she said. “It also leads to delays in care and diminished resources for other emergency patients. The emergency department has become the dumping ground for these vulnerable patients who have been abandoned by every other part of the health care system.”

ACEP presented the findings during its annual meeting in Las Vegas. No funding sources for these studies were disclosed; Dr. Lippert did not report any financial disclosures.

Individuals with psychiatric conditions are facing increasingly longer wait times in emergency departments across the country, including children, according to a pair of studies presented by the American College of Emergency Physicians.

“I really started doing this research because of my clinical experience,” explained Suzanne Catherine Lippert, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and the lead author of both studies during an Oct. 17 conference call, saying that seeing patients sit in the ED for days prompted her to finally look into this issue.

Patients with bipolar disorder had the highest likelihood of waiting more than 24 hours in the ED, with an odds ratio of 3.7 (95% confidence interval, 1.5-9.4). This was followed by patients with a diagnosis of psychosis, a dual diagnosis of psychiatric disorders, multiple psychiatric diagnoses, or depression. The most common diagnoses were substance abuse, anxiety, and depression, which constituted 41%, 26%, and 23% of the diagnoses, respectively. Patients with psychosis were admitted 34% of the time and transferred 24% of the time; those who self-harmed were admitted 33% of the time and transferred 29% of the time; and patients with bipolar disorder were admitted 29% of the time and transferred 40% of the time. Patients who had either two or three diagnoses were admitted 9% and 10% of the time, respectively.

“Further investigation of the systems affecting these patients, including placement of involuntary holds, availability of ED psychiatric consultants, or outpatient resources would delineate potential intervention points for the care of these vulnerable patients,” Dr. Lippert and her coauthors wrote.

The second study looked at the differences in waiting for care at EDs between psychiatric patients and medical patients. Length of stay was defined the same way it was in the previous study, with disposition meaning either “discharge, admission to medical or psychiatric bed, [or] transfer to any acute facility.” Length of stay was divided into the same three categories as the previous study, too.

Psychiatric patients were more likely than were medical patients to wait more than 6 hours for disposition, regardless of what the disposition itself ended up being, by a rate of 23% vs. 10%. Similarly, 7% of psychiatric patients vs. just 2.3% of medical patients had to wait longer than 12 hours in the ED, while 1.3% of psychiatric had to wait longer than 24 hours, compared with only 0.5% of medical patients. The average length of stay was significantly longer for psychiatric patients: 194 minutes vs. 138 minutes for medical patients (P less than .01).

Additionally, psychiatric patients were more likely to be uninsured, with 22% not having insurance, compared with 15% of medical patients being uninsured. Furthermore, 4.6% of the psychiatric patients’ previous visit to the ED had been within the prior 72 hours, compared with 3.6% of medical patients. A total of 21% of psychiatric patients required admittance, compared with 13% of medical patients, while 11% of psychiatric patients were transferred, compared with just 1.4% of medical patients.

“These results compel us to further investigate the potential causes of prolonged length of stay in psychiatric patients and to further characterize the population of psychiatric patients most at risk of prolonged stays,” Dr. Lippert and her coinvestigators concluded.

ACEP President Rebecca B. Parker, MD, chimed in during the conference call, explaining that a survey of more than 1,700 emergency physicians revealed some “troubling” findings about the state of emergency departments over the last year.

The nation’s dwindling mental health resources are having a direct impact on patients having psychiatric emergencies, including children,” Dr. Parker explained. “These patients are waiting longer for care, especially those patients who require hospitalization.”

Findings of the survey indicate that 48% of ED physicians witness psychiatric patients being “boarded” in their EDs at least once a day while they wait for a bed. Additionally, less than 17% of respondents said their ED has a psychiatrist on call to respond to psychiatric emergencies, with 11.7% responding that they have no psychiatrist on call to deal with such emergencies. And 52% of respondents said the mental health system in their community has gotten noticeably worse in just the last year.

In a separate statement, Dr. Parker voiced outrage about the situation. “Psychiatric patients wait in the emergency department for hours and even days for a bed, which delays the psychiatric care they so desperately need,” she said. “It also leads to delays in care and diminished resources for other emergency patients. The emergency department has become the dumping ground for these vulnerable patients who have been abandoned by every other part of the health care system.”

ACEP presented the findings during its annual meeting in Las Vegas. No funding sources for these studies were disclosed; Dr. Lippert did not report any financial disclosures.

Individuals with psychiatric conditions are facing increasingly longer wait times in emergency departments across the country, including children, according to a pair of studies presented by the American College of Emergency Physicians.

“I really started doing this research because of my clinical experience,” explained Suzanne Catherine Lippert, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and the lead author of both studies during an Oct. 17 conference call, saying that seeing patients sit in the ED for days prompted her to finally look into this issue.

Patients with bipolar disorder had the highest likelihood of waiting more than 24 hours in the ED, with an odds ratio of 3.7 (95% confidence interval, 1.5-9.4). This was followed by patients with a diagnosis of psychosis, a dual diagnosis of psychiatric disorders, multiple psychiatric diagnoses, or depression. The most common diagnoses were substance abuse, anxiety, and depression, which constituted 41%, 26%, and 23% of the diagnoses, respectively. Patients with psychosis were admitted 34% of the time and transferred 24% of the time; those who self-harmed were admitted 33% of the time and transferred 29% of the time; and patients with bipolar disorder were admitted 29% of the time and transferred 40% of the time. Patients who had either two or three diagnoses were admitted 9% and 10% of the time, respectively.

“Further investigation of the systems affecting these patients, including placement of involuntary holds, availability of ED psychiatric consultants, or outpatient resources would delineate potential intervention points for the care of these vulnerable patients,” Dr. Lippert and her coauthors wrote.

The second study looked at the differences in waiting for care at EDs between psychiatric patients and medical patients. Length of stay was defined the same way it was in the previous study, with disposition meaning either “discharge, admission to medical or psychiatric bed, [or] transfer to any acute facility.” Length of stay was divided into the same three categories as the previous study, too.

Psychiatric patients were more likely than were medical patients to wait more than 6 hours for disposition, regardless of what the disposition itself ended up being, by a rate of 23% vs. 10%. Similarly, 7% of psychiatric patients vs. just 2.3% of medical patients had to wait longer than 12 hours in the ED, while 1.3% of psychiatric had to wait longer than 24 hours, compared with only 0.5% of medical patients. The average length of stay was significantly longer for psychiatric patients: 194 minutes vs. 138 minutes for medical patients (P less than .01).

Additionally, psychiatric patients were more likely to be uninsured, with 22% not having insurance, compared with 15% of medical patients being uninsured. Furthermore, 4.6% of the psychiatric patients’ previous visit to the ED had been within the prior 72 hours, compared with 3.6% of medical patients. A total of 21% of psychiatric patients required admittance, compared with 13% of medical patients, while 11% of psychiatric patients were transferred, compared with just 1.4% of medical patients.

“These results compel us to further investigate the potential causes of prolonged length of stay in psychiatric patients and to further characterize the population of psychiatric patients most at risk of prolonged stays,” Dr. Lippert and her coinvestigators concluded.

ACEP President Rebecca B. Parker, MD, chimed in during the conference call, explaining that a survey of more than 1,700 emergency physicians revealed some “troubling” findings about the state of emergency departments over the last year.

The nation’s dwindling mental health resources are having a direct impact on patients having psychiatric emergencies, including children,” Dr. Parker explained. “These patients are waiting longer for care, especially those patients who require hospitalization.”

Findings of the survey indicate that 48% of ED physicians witness psychiatric patients being “boarded” in their EDs at least once a day while they wait for a bed. Additionally, less than 17% of respondents said their ED has a psychiatrist on call to respond to psychiatric emergencies, with 11.7% responding that they have no psychiatrist on call to deal with such emergencies. And 52% of respondents said the mental health system in their community has gotten noticeably worse in just the last year.

In a separate statement, Dr. Parker voiced outrage about the situation. “Psychiatric patients wait in the emergency department for hours and even days for a bed, which delays the psychiatric care they so desperately need,” she said. “It also leads to delays in care and diminished resources for other emergency patients. The emergency department has become the dumping ground for these vulnerable patients who have been abandoned by every other part of the health care system.”

ACEP presented the findings during its annual meeting in Las Vegas. No funding sources for these studies were disclosed; Dr. Lippert did not report any financial disclosures.

FROM AN ACEP TELECONFERENCE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Higher percentages of psychiatric patients have to wait more than a day before disposition, compared with medical patients.

Data source: Two retrospective reviews of more than 65 million ED visits in the NHAMCS database from 2001-2011.

Disclosures: No funding sources or disclosures were reported.

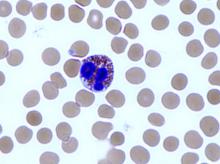

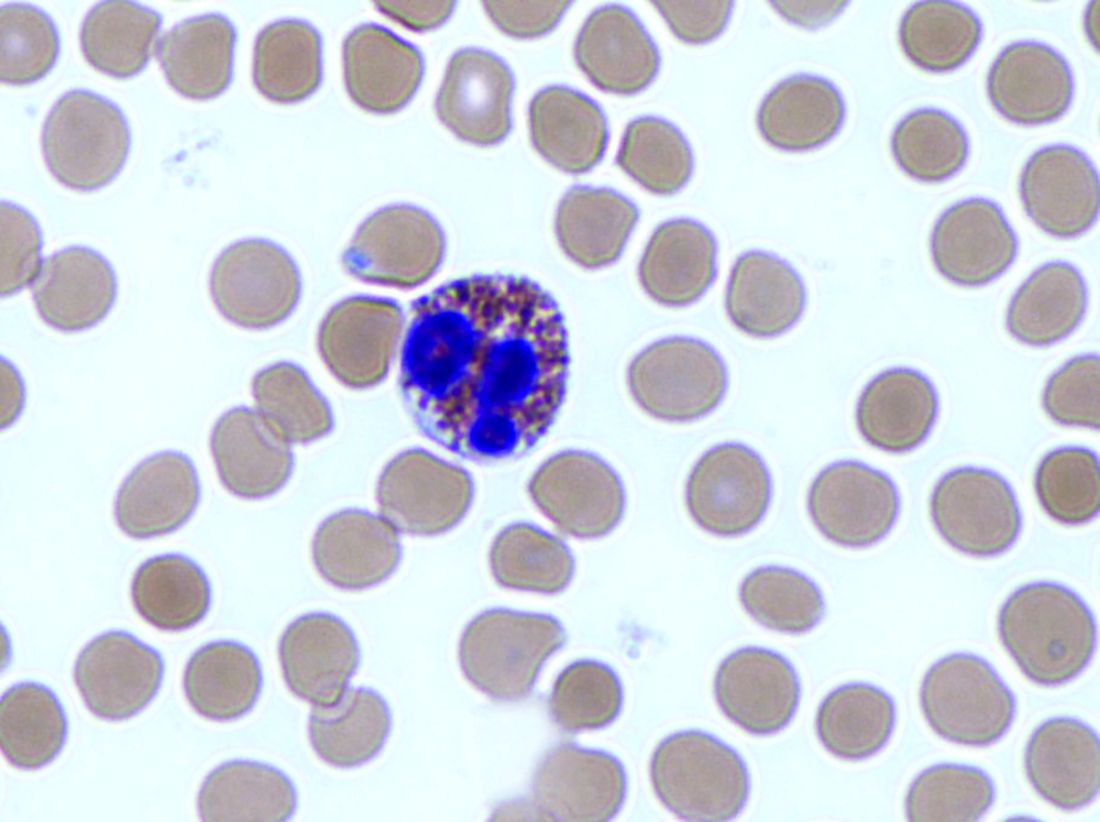

Reslizumab performance tied to eosinophil count

Reslizumab was most effective in patients with high baseline eosinophil counts, two randomized, placebo-controlled studies have determined. The companion studies were simultaneously published in the October issue of Chest.

The drug reslizumab, an anti–interleukin-5 monoclonal antibody, is made by Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D, who sponsored both studies.

The larger study, comprising 492 patients, found no significant benefit of reslizumab over placebo, Jonathan Corren, MD, and his colleagues wrote (Chest. 2016;150:799-810). But this study didn’t stratify patients by baseline eosinophil levels; a post-hoc subanalysis found a significant benefit in forced expiratory volume in 69 of the patients who had at least 400 eosinophils/microliter (mcL) when treatment began.

In these patients, the drug significantly improved not only lung function, but asthma symptoms and asthma-related quality of life scores.

“These efficacy findings are consistent with results from other reslizumab trials and combined with the favorable safety profile observed, support the use of reslizumab in patients with asthma and elevated blood eosinophils, uncontrolled by an inhaled corticosteroid-based regimen,” Dr. Bjermer and his coauthors wrote.

The unstratified trial was conducted at 66 sites in the U.S. All of the patients had poorly controlled asthma despite using at least a medium-dosed inhaled corticosteroid. They were randomized to infusions of reslizumab 3.0 mg/kg or placebo given once every 4 weeks for 16 weeks.*

The primary endpoint was the change in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1); secondary endpoints included quality of life scores; the need for rescue medication; forced vital capacity; and eosinophil count.

Patients in the placebo and reslizumab groups were an average age of 45.1 years and 44.9 years, respectively. The mean disease duration of patients in both groups was 26 years.

At week 16, the mean change in FEV1 from baseline was 255 ml in the active group and 187 ml in the placebo group – not a significant difference.

The team performed a post-hoc subgroup analysis that dichotomized the cohort based on baseline eosinophil levels. For the 343 with counts of less than 400 cells/mcL, there was no difference in FEV1 at 16 weeks, between the patients who received treatment and the patients who received a placebo. The FEV1s of these two groups were separated by just 33 mL.

The story was different for the 82 patients with at least 400 cells/mcL, with 69 of such patients receiving the drug and 13 of such patients receiving the placebo. At 16 weeks, the difference in FEV1 change was 270 mL, in favor of the active group. The strength of these findings may be weakened by the large difference in size between the treatment and placebo groups and the “near complete lack of response in the small number of placebo-treated patients.”

“Interpretation of the results in the [400 or more cells/mcL] subgroup is limited as the study was not designed or statistically powered to specifically test this group of patients,” the team wrote. Nevertheless, they concluded that reslizumab is a reasonable treatment option for this group. “These findings support an acceptable benefit-risk profile for reslizumab in asthma patients with a blood eosinophil threshold” of at least 400 cells/mcL.

The stratified study examined more endpoints: pre-bronchodilator spirometry (forced expiratory volume in one second FEV1, forced vital capacity, and forced expiratory flow), asthma symptoms, quality of life, rescue inhaler use, and blood eosinophil levels.

The 315 patients in this study all had a baseline eosinophil count of at least 400 cells/mcL. They were randomized to placebo or to 0.3 or 3.0 mg/kg reslizumab dose once every 4 weeks for 16 weeks. The mean ages for the patients taking the placebo, reslizumab 0.3 mg/kg, and reslizumab 3.0 mg/kg were 44.2, 44.5, and 43.0, respectively. The range of average disease durations for patients in the placebo group and two reslizumab groups was 20 to 20.7 years.

The final FEV1 was significantly improved over placebo in both active groups, although the change was much more pronounced in those taking 3.0 mg/kg, compared with those taking 0.3 mg/kg (160 mL and 115 mL, respectively, relative to placebo). Forced vital capacity also improved significantly in the 3.0 mg/kg dose group (130 mL relative to placebo).

Reslizumab was generally well tolerated in both studies. The most frequent adverse events in the stratified study were asthma worsening, headache, nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory infections, and sinusitis.

In the unstratified study, there were two anaphylactic reactions, but only one was related to the study drug. No deaths occurred in either treatment group of this study.

Both trials were sponsored by Teva. Dr. Bjermer has served on advisory boards or provided lectures for Aerocrine, Airsonett, ALK, Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Meda, Mundipharma, Nigaard, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi-Aventis, Takeda, and Teva. Dr. Corren has been involved in speaker bureau activities for Genentech and Merck; he has served on advisory boards for Genentech, Merck, Novartis, and Vectura.

*CORRECTION 12/9/16: An earlier version of this article misstated the infusion frequency.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

Persistent eosinophilic inflammation is present in about half of patients with severe asthma, and the studies by Corren and Bjermer represent important advances in learning how to target this inflammatory pathway, Richard Russell, MBBS, MRCP, and Christopher Brightling, PhD, FCCP, wrote in an accompanying editorial (Chest. 2016;150:766-8).

“The most advanced therapeutic target is IL-5, which is an attractive target because it is an obligate cytokine for eosinophil maturation and survival. Its inhibition is thus predicted to reduce bone marrow production of eosinophils and promote apoptosis,” wrote Dr. Russell, a clinical research fellow, and Dr. Brightling, a professor, both at the University of Leicester (England).

“These findings support the view that an elevated blood eosinophil count is associated with a good clinical response [to the antibody reslizumab] but [the studies] did not find a clear correlation between the intensity of the baseline eosinophil count and response,” the colleagues wrote. “Thus, the best cut-off for the blood eosinophil count to apply clinically remains uncertain.”

Clinicians and patients may find a different answer to this riddle than do payers.

“From a patient perspective there is an argument to select a low or no cut-off as there is some benefit even with low baseline eosinophil counts, whereas from a payer’s perspective the health economic benefit is better with a higher cut-off.”

As is often the case, more study will help clarify these new concerns.

“We are moving into a new era of Type-2 immunity-mediated therapies that will bring new opportunities for clinicians and our patients, but with this opportunity comes new challenges. Biomarkers will increase in importance to help drive precision medicine, but we need to understand how to use them, and, in particular, what cut-points to apply. For anti-IL-5 approaches, we probably need to look towards elevated blood eosinophil counts, as aiming for a high cut-off is most likely the best way we shall achieve success.”

Dr. Russell had no financial disclosures. Mr. Brightling reported financial relationships with several pharmaceutical companies, but not with Teva.

Persistent eosinophilic inflammation is present in about half of patients with severe asthma, and the studies by Corren and Bjermer represent important advances in learning how to target this inflammatory pathway, Richard Russell, MBBS, MRCP, and Christopher Brightling, PhD, FCCP, wrote in an accompanying editorial (Chest. 2016;150:766-8).

“The most advanced therapeutic target is IL-5, which is an attractive target because it is an obligate cytokine for eosinophil maturation and survival. Its inhibition is thus predicted to reduce bone marrow production of eosinophils and promote apoptosis,” wrote Dr. Russell, a clinical research fellow, and Dr. Brightling, a professor, both at the University of Leicester (England).

“These findings support the view that an elevated blood eosinophil count is associated with a good clinical response [to the antibody reslizumab] but [the studies] did not find a clear correlation between the intensity of the baseline eosinophil count and response,” the colleagues wrote. “Thus, the best cut-off for the blood eosinophil count to apply clinically remains uncertain.”

Clinicians and patients may find a different answer to this riddle than do payers.

“From a patient perspective there is an argument to select a low or no cut-off as there is some benefit even with low baseline eosinophil counts, whereas from a payer’s perspective the health economic benefit is better with a higher cut-off.”

As is often the case, more study will help clarify these new concerns.

“We are moving into a new era of Type-2 immunity-mediated therapies that will bring new opportunities for clinicians and our patients, but with this opportunity comes new challenges. Biomarkers will increase in importance to help drive precision medicine, but we need to understand how to use them, and, in particular, what cut-points to apply. For anti-IL-5 approaches, we probably need to look towards elevated blood eosinophil counts, as aiming for a high cut-off is most likely the best way we shall achieve success.”

Dr. Russell had no financial disclosures. Mr. Brightling reported financial relationships with several pharmaceutical companies, but not with Teva.

Persistent eosinophilic inflammation is present in about half of patients with severe asthma, and the studies by Corren and Bjermer represent important advances in learning how to target this inflammatory pathway, Richard Russell, MBBS, MRCP, and Christopher Brightling, PhD, FCCP, wrote in an accompanying editorial (Chest. 2016;150:766-8).

“The most advanced therapeutic target is IL-5, which is an attractive target because it is an obligate cytokine for eosinophil maturation and survival. Its inhibition is thus predicted to reduce bone marrow production of eosinophils and promote apoptosis,” wrote Dr. Russell, a clinical research fellow, and Dr. Brightling, a professor, both at the University of Leicester (England).

“These findings support the view that an elevated blood eosinophil count is associated with a good clinical response [to the antibody reslizumab] but [the studies] did not find a clear correlation between the intensity of the baseline eosinophil count and response,” the colleagues wrote. “Thus, the best cut-off for the blood eosinophil count to apply clinically remains uncertain.”

Clinicians and patients may find a different answer to this riddle than do payers.

“From a patient perspective there is an argument to select a low or no cut-off as there is some benefit even with low baseline eosinophil counts, whereas from a payer’s perspective the health economic benefit is better with a higher cut-off.”

As is often the case, more study will help clarify these new concerns.

“We are moving into a new era of Type-2 immunity-mediated therapies that will bring new opportunities for clinicians and our patients, but with this opportunity comes new challenges. Biomarkers will increase in importance to help drive precision medicine, but we need to understand how to use them, and, in particular, what cut-points to apply. For anti-IL-5 approaches, we probably need to look towards elevated blood eosinophil counts, as aiming for a high cut-off is most likely the best way we shall achieve success.”

Dr. Russell had no financial disclosures. Mr. Brightling reported financial relationships with several pharmaceutical companies, but not with Teva.

Reslizumab was most effective in patients with high baseline eosinophil counts, two randomized, placebo-controlled studies have determined. The companion studies were simultaneously published in the October issue of Chest.

The drug reslizumab, an anti–interleukin-5 monoclonal antibody, is made by Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D, who sponsored both studies.

The larger study, comprising 492 patients, found no significant benefit of reslizumab over placebo, Jonathan Corren, MD, and his colleagues wrote (Chest. 2016;150:799-810). But this study didn’t stratify patients by baseline eosinophil levels; a post-hoc subanalysis found a significant benefit in forced expiratory volume in 69 of the patients who had at least 400 eosinophils/microliter (mcL) when treatment began.

In these patients, the drug significantly improved not only lung function, but asthma symptoms and asthma-related quality of life scores.

“These efficacy findings are consistent with results from other reslizumab trials and combined with the favorable safety profile observed, support the use of reslizumab in patients with asthma and elevated blood eosinophils, uncontrolled by an inhaled corticosteroid-based regimen,” Dr. Bjermer and his coauthors wrote.

The unstratified trial was conducted at 66 sites in the U.S. All of the patients had poorly controlled asthma despite using at least a medium-dosed inhaled corticosteroid. They were randomized to infusions of reslizumab 3.0 mg/kg or placebo given once every 4 weeks for 16 weeks.*

The primary endpoint was the change in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1); secondary endpoints included quality of life scores; the need for rescue medication; forced vital capacity; and eosinophil count.

Patients in the placebo and reslizumab groups were an average age of 45.1 years and 44.9 years, respectively. The mean disease duration of patients in both groups was 26 years.

At week 16, the mean change in FEV1 from baseline was 255 ml in the active group and 187 ml in the placebo group – not a significant difference.

The team performed a post-hoc subgroup analysis that dichotomized the cohort based on baseline eosinophil levels. For the 343 with counts of less than 400 cells/mcL, there was no difference in FEV1 at 16 weeks, between the patients who received treatment and the patients who received a placebo. The FEV1s of these two groups were separated by just 33 mL.

The story was different for the 82 patients with at least 400 cells/mcL, with 69 of such patients receiving the drug and 13 of such patients receiving the placebo. At 16 weeks, the difference in FEV1 change was 270 mL, in favor of the active group. The strength of these findings may be weakened by the large difference in size between the treatment and placebo groups and the “near complete lack of response in the small number of placebo-treated patients.”

“Interpretation of the results in the [400 or more cells/mcL] subgroup is limited as the study was not designed or statistically powered to specifically test this group of patients,” the team wrote. Nevertheless, they concluded that reslizumab is a reasonable treatment option for this group. “These findings support an acceptable benefit-risk profile for reslizumab in asthma patients with a blood eosinophil threshold” of at least 400 cells/mcL.

The stratified study examined more endpoints: pre-bronchodilator spirometry (forced expiratory volume in one second FEV1, forced vital capacity, and forced expiratory flow), asthma symptoms, quality of life, rescue inhaler use, and blood eosinophil levels.

The 315 patients in this study all had a baseline eosinophil count of at least 400 cells/mcL. They were randomized to placebo or to 0.3 or 3.0 mg/kg reslizumab dose once every 4 weeks for 16 weeks. The mean ages for the patients taking the placebo, reslizumab 0.3 mg/kg, and reslizumab 3.0 mg/kg were 44.2, 44.5, and 43.0, respectively. The range of average disease durations for patients in the placebo group and two reslizumab groups was 20 to 20.7 years.

The final FEV1 was significantly improved over placebo in both active groups, although the change was much more pronounced in those taking 3.0 mg/kg, compared with those taking 0.3 mg/kg (160 mL and 115 mL, respectively, relative to placebo). Forced vital capacity also improved significantly in the 3.0 mg/kg dose group (130 mL relative to placebo).

Reslizumab was generally well tolerated in both studies. The most frequent adverse events in the stratified study were asthma worsening, headache, nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory infections, and sinusitis.

In the unstratified study, there were two anaphylactic reactions, but only one was related to the study drug. No deaths occurred in either treatment group of this study.

Both trials were sponsored by Teva. Dr. Bjermer has served on advisory boards or provided lectures for Aerocrine, Airsonett, ALK, Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Meda, Mundipharma, Nigaard, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi-Aventis, Takeda, and Teva. Dr. Corren has been involved in speaker bureau activities for Genentech and Merck; he has served on advisory boards for Genentech, Merck, Novartis, and Vectura.

*CORRECTION 12/9/16: An earlier version of this article misstated the infusion frequency.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

Reslizumab was most effective in patients with high baseline eosinophil counts, two randomized, placebo-controlled studies have determined. The companion studies were simultaneously published in the October issue of Chest.

The drug reslizumab, an anti–interleukin-5 monoclonal antibody, is made by Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D, who sponsored both studies.

The larger study, comprising 492 patients, found no significant benefit of reslizumab over placebo, Jonathan Corren, MD, and his colleagues wrote (Chest. 2016;150:799-810). But this study didn’t stratify patients by baseline eosinophil levels; a post-hoc subanalysis found a significant benefit in forced expiratory volume in 69 of the patients who had at least 400 eosinophils/microliter (mcL) when treatment began.

In these patients, the drug significantly improved not only lung function, but asthma symptoms and asthma-related quality of life scores.

“These efficacy findings are consistent with results from other reslizumab trials and combined with the favorable safety profile observed, support the use of reslizumab in patients with asthma and elevated blood eosinophils, uncontrolled by an inhaled corticosteroid-based regimen,” Dr. Bjermer and his coauthors wrote.

The unstratified trial was conducted at 66 sites in the U.S. All of the patients had poorly controlled asthma despite using at least a medium-dosed inhaled corticosteroid. They were randomized to infusions of reslizumab 3.0 mg/kg or placebo given once every 4 weeks for 16 weeks.*

The primary endpoint was the change in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1); secondary endpoints included quality of life scores; the need for rescue medication; forced vital capacity; and eosinophil count.

Patients in the placebo and reslizumab groups were an average age of 45.1 years and 44.9 years, respectively. The mean disease duration of patients in both groups was 26 years.

At week 16, the mean change in FEV1 from baseline was 255 ml in the active group and 187 ml in the placebo group – not a significant difference.

The team performed a post-hoc subgroup analysis that dichotomized the cohort based on baseline eosinophil levels. For the 343 with counts of less than 400 cells/mcL, there was no difference in FEV1 at 16 weeks, between the patients who received treatment and the patients who received a placebo. The FEV1s of these two groups were separated by just 33 mL.

The story was different for the 82 patients with at least 400 cells/mcL, with 69 of such patients receiving the drug and 13 of such patients receiving the placebo. At 16 weeks, the difference in FEV1 change was 270 mL, in favor of the active group. The strength of these findings may be weakened by the large difference in size between the treatment and placebo groups and the “near complete lack of response in the small number of placebo-treated patients.”

“Interpretation of the results in the [400 or more cells/mcL] subgroup is limited as the study was not designed or statistically powered to specifically test this group of patients,” the team wrote. Nevertheless, they concluded that reslizumab is a reasonable treatment option for this group. “These findings support an acceptable benefit-risk profile for reslizumab in asthma patients with a blood eosinophil threshold” of at least 400 cells/mcL.

The stratified study examined more endpoints: pre-bronchodilator spirometry (forced expiratory volume in one second FEV1, forced vital capacity, and forced expiratory flow), asthma symptoms, quality of life, rescue inhaler use, and blood eosinophil levels.

The 315 patients in this study all had a baseline eosinophil count of at least 400 cells/mcL. They were randomized to placebo or to 0.3 or 3.0 mg/kg reslizumab dose once every 4 weeks for 16 weeks. The mean ages for the patients taking the placebo, reslizumab 0.3 mg/kg, and reslizumab 3.0 mg/kg were 44.2, 44.5, and 43.0, respectively. The range of average disease durations for patients in the placebo group and two reslizumab groups was 20 to 20.7 years.

The final FEV1 was significantly improved over placebo in both active groups, although the change was much more pronounced in those taking 3.0 mg/kg, compared with those taking 0.3 mg/kg (160 mL and 115 mL, respectively, relative to placebo). Forced vital capacity also improved significantly in the 3.0 mg/kg dose group (130 mL relative to placebo).

Reslizumab was generally well tolerated in both studies. The most frequent adverse events in the stratified study were asthma worsening, headache, nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory infections, and sinusitis.

In the unstratified study, there were two anaphylactic reactions, but only one was related to the study drug. No deaths occurred in either treatment group of this study.

Both trials were sponsored by Teva. Dr. Bjermer has served on advisory boards or provided lectures for Aerocrine, Airsonett, ALK, Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Meda, Mundipharma, Nigaard, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi-Aventis, Takeda, and Teva. Dr. Corren has been involved in speaker bureau activities for Genentech and Merck; he has served on advisory boards for Genentech, Merck, Novartis, and Vectura.

*CORRECTION 12/9/16: An earlier version of this article misstated the infusion frequency.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

FROM CHEST

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) improved by 160 mL with reslizumab 3.0 mg/kg relative to placebo.

Data source: The two randomized, placebo-controlled studies comprised about 800 patients.

Disclosures: Both trials were sponsored by Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D. Dr. Bjermer has served on an advisory board or provided lectures for Teva. Dr. Corren has served on advisory boards and has been involved in speaker bureau activities for various pharmaceutical companies.

Longer hospitalization, greater care needed for depressed ischemic stroke patients

BALTIMORE – Patients admitted with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) with preexisting major depressive disorder (MDD) are less likely to die while in the hospital but are often hospitalized longer and are more likely to need specialty care when they are discharged, in comparison to similar patients without depression in the National Inpatient Sample.

“Our study displayed an increasing proportion of patients with MDD admitted due to AIS in the last decade with lower mortality but higher morbidity post stroke. In addition, there was less utilization of thrombolysis in this population,” study presenter Arpita Hazra, MD, Northwell Health, Jersey City, N.J., said at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

Thrombolysis was carried out in fewer depressed patients than in those without depression (3.8% vs. 4.8%; P less than .001). The odds of death during hospitalization were 36% less for patients with MDD. However, patients with MDD tended to be hospitalized longer than nondepressed patients (median 3.6 vs. 3.4 days; P less than .001) and were nearly 40% more likely to require specialty care following discharge.

“There is a need to explore the reasons behind this disparity in outcomes and thrombolysis utilization in order to improve poststroke outcome in this vulnerable population,” Dr. Hazra said.

At face value, the observation of decreased mortality in AIS patients with preexisting MDD was surprising, according to Dr. Hazra. She suggested that this may reflect prior hospital treatment for these patients, because of other comorbidities associated with depression.

Dr. Hazra reported having no financial disclosures.

BALTIMORE – Patients admitted with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) with preexisting major depressive disorder (MDD) are less likely to die while in the hospital but are often hospitalized longer and are more likely to need specialty care when they are discharged, in comparison to similar patients without depression in the National Inpatient Sample.

“Our study displayed an increasing proportion of patients with MDD admitted due to AIS in the last decade with lower mortality but higher morbidity post stroke. In addition, there was less utilization of thrombolysis in this population,” study presenter Arpita Hazra, MD, Northwell Health, Jersey City, N.J., said at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

Thrombolysis was carried out in fewer depressed patients than in those without depression (3.8% vs. 4.8%; P less than .001). The odds of death during hospitalization were 36% less for patients with MDD. However, patients with MDD tended to be hospitalized longer than nondepressed patients (median 3.6 vs. 3.4 days; P less than .001) and were nearly 40% more likely to require specialty care following discharge.

“There is a need to explore the reasons behind this disparity in outcomes and thrombolysis utilization in order to improve poststroke outcome in this vulnerable population,” Dr. Hazra said.

At face value, the observation of decreased mortality in AIS patients with preexisting MDD was surprising, according to Dr. Hazra. She suggested that this may reflect prior hospital treatment for these patients, because of other comorbidities associated with depression.

Dr. Hazra reported having no financial disclosures.

BALTIMORE – Patients admitted with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) with preexisting major depressive disorder (MDD) are less likely to die while in the hospital but are often hospitalized longer and are more likely to need specialty care when they are discharged, in comparison to similar patients without depression in the National Inpatient Sample.

“Our study displayed an increasing proportion of patients with MDD admitted due to AIS in the last decade with lower mortality but higher morbidity post stroke. In addition, there was less utilization of thrombolysis in this population,” study presenter Arpita Hazra, MD, Northwell Health, Jersey City, N.J., said at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

Thrombolysis was carried out in fewer depressed patients than in those without depression (3.8% vs. 4.8%; P less than .001). The odds of death during hospitalization were 36% less for patients with MDD. However, patients with MDD tended to be hospitalized longer than nondepressed patients (median 3.6 vs. 3.4 days; P less than .001) and were nearly 40% more likely to require specialty care following discharge.

“There is a need to explore the reasons behind this disparity in outcomes and thrombolysis utilization in order to improve poststroke outcome in this vulnerable population,” Dr. Hazra said.

At face value, the observation of decreased mortality in AIS patients with preexisting MDD was surprising, according to Dr. Hazra. She suggested that this may reflect prior hospital treatment for these patients, because of other comorbidities associated with depression.

Dr. Hazra reported having no financial disclosures.

AT ANA 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In-hospital mortality was significantly lower for depressed patients with acute ischemic stroke, compared with nondepressed patients, but depressed patients had a significantly longer length of hospitalization and higher rate of discharge to specialty care.

Data source: Study of 4.3 million hospital AIS-related admissions identified in the United States during 2002-2012 in the National Inpatient Sample.

Disclosures: Dr. Hazra reported having no financial disclosures.

Palliative care boosts heart failure patient outcomes

ORLANDO – Systematic introduction of palliative care interventions for patients with advanced heart failure improved patients’ quality of life and spurred their development of advanced-care preferences in a pair of independently performed, controlled, pilot studies.

But, despite demonstrating the ability of palliative-care interventions to help heart failure patients during their final months of life, the findings raised questions about the generalizability and reproducibility of palliative-care interventions that may depend on the skills and experience of the individual specialists who deliver the palliative care.

“Palliative care for patients with cardiovascular disease is in desperate need of good-quality evidence,” commented Larry A, Allen, MD, a heart failure cardiologist at the University of Colorado in Aurora and designated discussant for one of the two studies presented at the meeting. “We need large, randomized trials with clinical outcomes to look at patient outcomes from palliative-care interventions.”

The patients average 71 years old, about half were women, and about 40% were African Americans. They had been diagnosed with heart failure for an average of more than 5 years, all had advanced heart failure, about 60% spent at least half of their time awake immobilized in a bed or chair, and they had average NT-proBNP blood levels of greater than 10,000 pg/mL.

After 24 weeks of intervention, the palliative-care program produced both statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements in two different measures of health-related quality of life, the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) and the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Palliative Care (FACIT-PAL). The KCCQ showed the palliative care intervention linked with an average rise of more than 9 points compared with patients in the control arm after adjustment for age and sex, a statistically significant increase on a scale where a 5-point rise is considered clinically meaningful. The FACIT-PAL showed an average, adjusted 11-point rise linked with the intervention, a statistically significant increase on a scale where an increase of at least 10 is judged clinically meaningful, reported Dr. Rogers, a heart failure cardiologist and professor of medicine at Duke University.

The palliative-care intervention also led to significant improvements in measures of spirituality, depression, and anxiety, but intervention had no impact on mortality.

“I like these endpoints and the idea that we can make quality-of-life better. These are very sick patients, with a predicted 6-month mortality of 50%. Patients reach a time when they don’t want to live longer but want better life quality for the days they still have,” he said in an interview.

The second report came from a single-center pilot study of 50 patients enrolled when they were hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure and had at least one addition risk factor for poor prognosis such as age of at least 81 years, renal dysfunction, or a prior heart failure hospitalization within the past year. Patients randomized to the intervention arm underwent a structured evaluation based on the Serious Illness Conversation Guide and performed by a social worker experienced in palliative care and embedded in the heart failure clinical team. The primary endpoint of the SWAP-HF (Social Worker–Aided Palliative Care Intervention in High Risk Patients with Heart Failure) study was clinical-level documentation of advanced-care preferences by 6 months after the program began.

“Although more comprehensive, multidisciplinary palliative care interventions may also be effective, the focused approach [used in this study] may represent a cost-effective and scalable method for shepherding limited specialty resources to enhance the delivery of patient-centered care,” Dr. Desai said. In other words, a program with a social worker costs less than a two-person staff with a palliative-care physician and nurse practitioner.