User login

News and Views that Matter to Physicians

Health sector claims 4 spots among top 10 lobbyers in 2016

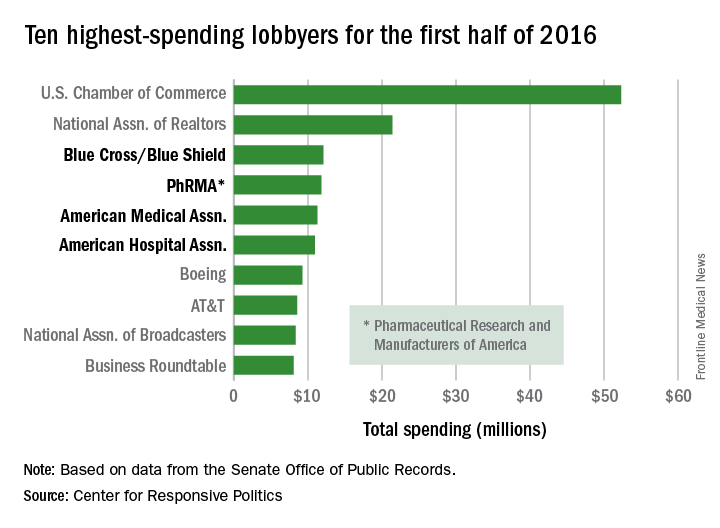

Four of the 10 highest-spending lobbyers for the first half of 2016 were in the health sector, with Blue Cross/Blue Shield occupying the sector’s top spot by a relatively small margin, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

The four health-sectors concerns filled spots 3-6 in the overall top 10. Blue Cross/Blue Shield spent almost $12.1 million on lobbying in the first half of the year, putting it just ahead of the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), which spent $11.8 million. The American Medical Association was next at $11.3 million, followed by the American Hospital Association at $10.9 million, the center reported on OpenSecrets.org.

After those four, the next-highest health-sector spender was Pfizer, which put up almost $6.2 million in lobbying – good for 18th place for the first half of 2016. The health sector itself was the highest spending of the 121 ranked, taking a $266 million bite out of the total $1.6 billion lobbying pie for the year so far, according to the center’s analysis of data downloaded from the Senate Office of Public Records on Aug. 9.

The perennial leading spender on lobbying, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, was well ahead of second place, with its $52.3 million more than doubling the $21.4 million spent by the National Association of Realtors. The two groups have finished 1-2 in lobbying spending every year since 2012, and the Chamber of Commerce has been the leading spender since 2001, data on OpenSecrets show.

Four of the 10 highest-spending lobbyers for the first half of 2016 were in the health sector, with Blue Cross/Blue Shield occupying the sector’s top spot by a relatively small margin, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

The four health-sectors concerns filled spots 3-6 in the overall top 10. Blue Cross/Blue Shield spent almost $12.1 million on lobbying in the first half of the year, putting it just ahead of the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), which spent $11.8 million. The American Medical Association was next at $11.3 million, followed by the American Hospital Association at $10.9 million, the center reported on OpenSecrets.org.

After those four, the next-highest health-sector spender was Pfizer, which put up almost $6.2 million in lobbying – good for 18th place for the first half of 2016. The health sector itself was the highest spending of the 121 ranked, taking a $266 million bite out of the total $1.6 billion lobbying pie for the year so far, according to the center’s analysis of data downloaded from the Senate Office of Public Records on Aug. 9.

The perennial leading spender on lobbying, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, was well ahead of second place, with its $52.3 million more than doubling the $21.4 million spent by the National Association of Realtors. The two groups have finished 1-2 in lobbying spending every year since 2012, and the Chamber of Commerce has been the leading spender since 2001, data on OpenSecrets show.

Four of the 10 highest-spending lobbyers for the first half of 2016 were in the health sector, with Blue Cross/Blue Shield occupying the sector’s top spot by a relatively small margin, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

The four health-sectors concerns filled spots 3-6 in the overall top 10. Blue Cross/Blue Shield spent almost $12.1 million on lobbying in the first half of the year, putting it just ahead of the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), which spent $11.8 million. The American Medical Association was next at $11.3 million, followed by the American Hospital Association at $10.9 million, the center reported on OpenSecrets.org.

After those four, the next-highest health-sector spender was Pfizer, which put up almost $6.2 million in lobbying – good for 18th place for the first half of 2016. The health sector itself was the highest spending of the 121 ranked, taking a $266 million bite out of the total $1.6 billion lobbying pie for the year so far, according to the center’s analysis of data downloaded from the Senate Office of Public Records on Aug. 9.

The perennial leading spender on lobbying, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, was well ahead of second place, with its $52.3 million more than doubling the $21.4 million spent by the National Association of Realtors. The two groups have finished 1-2 in lobbying spending every year since 2012, and the Chamber of Commerce has been the leading spender since 2001, data on OpenSecrets show.

The frequency of influenza and bacterial coinfection

Treatment of patients admitted to the hospital with an upper respiratory infection is often complicated by the lack of diagnostics. Even in cases where a patient has a confirmed case of influenza, there is still the possibility that they may have, or become infected by, a secondary bacterial infection. This leads clinicians to treat patients empirically with antibiotics, which can result in unnecessary antibiotic use among patients without a bacterial infection.

Though antibiotics can be a lifesaving drug, their use is not without risks. Estimates suggest that 20% of patients taking common antibiotics experience some side effect. While most side effects are not life-threatening gastrointestinal effects, other nonnegligible side effects include anaphylactic shock, drug‐induced liver injury, increases in the risk of retinal detachment, serious arrhythmias, and superinfection with resistant bacteria. Antibiotics can also lead to secondary infections, such as Clostridium difficile.

Yet, despite these risks, there has been limited research on the percentage of patients with influenza who actually have a bacterial coinfection. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by my colleagues at Johns Hopkins University and the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy examined the frequency of bacterial coinfection among hospitalized patients with influenza and identified the most common infecting bacterial species.

The findings, published in the journal Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses, found that in the majority of studies, between 11% and 35% of patients with confirmed influenza had a bacterial coinfection. The most common coinfecting bacteria were found to be Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus. Combined, S. pneumoniae and S. aureus accounted for more than 60% of the identified coinfecting bacteria; however, many other bacterial species were found to cause infections as well.

The results suggest that while bacterial infection is common in influenza patients, only about a quarter of patients are likely to be infected. However, the studies were widely heterogeneous, both in patient makeup and results. Analyses of age, setting, enrollment year, study type, study size, and bacterial collection methods did not reveal a source for the heterogeneity in results. Thus, additional factors, such as patient comorbidities or prior antibiotic use, which could not be systematically assessed, may affect the likelihood of coinfection.

Given that the symptoms of influenza and bacterial infection often overlap, correctly diagnosing bacterial coinfection without a laboratory culture can present a challenge. This diagnostic uncertainty leads to significant overuse of antibiotics in patients with influenza alone. Most influenza cases will never result in serious bacterial infections (particularly in nonhospitalized patients), and thus a lot of antibiotic use is unnecessary. As mentioned earlier, unnecessary antibiotic use poses a nonnegligible risk to patients, but it also contributes significantly to rising rates of antibiotic resistance, a major public health issue.

The results from this study highlight that the majority of patients hospitalized with influenza are unlikely to be coinfected with a bacterial pathogen. Thus, it is important for clinicians to appropriately treat patients with antiviral drugs, and ensure that bacterial testing is done when presumptively starting patients on antibiotics. Based on the microbiology results, antibiotics can be stopped if no pathogen is identified or altered to be more appropriate depending on the pathogen found.

Although the findings of this study suggest we need a more thorough analysis of the issue, the results should still aid clinicians by improving their understanding of the likelihood of bacterial coinfection in hospitalized patients with influenza, and thus help them balance the need to minimize patient risks as well as the individual and societal risks of nonessential antibiotic use.

Eili Klein, PhD, is assistant professor in the department of emergency medicine at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore.

Treatment of patients admitted to the hospital with an upper respiratory infection is often complicated by the lack of diagnostics. Even in cases where a patient has a confirmed case of influenza, there is still the possibility that they may have, or become infected by, a secondary bacterial infection. This leads clinicians to treat patients empirically with antibiotics, which can result in unnecessary antibiotic use among patients without a bacterial infection.

Though antibiotics can be a lifesaving drug, their use is not without risks. Estimates suggest that 20% of patients taking common antibiotics experience some side effect. While most side effects are not life-threatening gastrointestinal effects, other nonnegligible side effects include anaphylactic shock, drug‐induced liver injury, increases in the risk of retinal detachment, serious arrhythmias, and superinfection with resistant bacteria. Antibiotics can also lead to secondary infections, such as Clostridium difficile.

Yet, despite these risks, there has been limited research on the percentage of patients with influenza who actually have a bacterial coinfection. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by my colleagues at Johns Hopkins University and the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy examined the frequency of bacterial coinfection among hospitalized patients with influenza and identified the most common infecting bacterial species.

The findings, published in the journal Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses, found that in the majority of studies, between 11% and 35% of patients with confirmed influenza had a bacterial coinfection. The most common coinfecting bacteria were found to be Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus. Combined, S. pneumoniae and S. aureus accounted for more than 60% of the identified coinfecting bacteria; however, many other bacterial species were found to cause infections as well.

The results suggest that while bacterial infection is common in influenza patients, only about a quarter of patients are likely to be infected. However, the studies were widely heterogeneous, both in patient makeup and results. Analyses of age, setting, enrollment year, study type, study size, and bacterial collection methods did not reveal a source for the heterogeneity in results. Thus, additional factors, such as patient comorbidities or prior antibiotic use, which could not be systematically assessed, may affect the likelihood of coinfection.

Given that the symptoms of influenza and bacterial infection often overlap, correctly diagnosing bacterial coinfection without a laboratory culture can present a challenge. This diagnostic uncertainty leads to significant overuse of antibiotics in patients with influenza alone. Most influenza cases will never result in serious bacterial infections (particularly in nonhospitalized patients), and thus a lot of antibiotic use is unnecessary. As mentioned earlier, unnecessary antibiotic use poses a nonnegligible risk to patients, but it also contributes significantly to rising rates of antibiotic resistance, a major public health issue.

The results from this study highlight that the majority of patients hospitalized with influenza are unlikely to be coinfected with a bacterial pathogen. Thus, it is important for clinicians to appropriately treat patients with antiviral drugs, and ensure that bacterial testing is done when presumptively starting patients on antibiotics. Based on the microbiology results, antibiotics can be stopped if no pathogen is identified or altered to be more appropriate depending on the pathogen found.

Although the findings of this study suggest we need a more thorough analysis of the issue, the results should still aid clinicians by improving their understanding of the likelihood of bacterial coinfection in hospitalized patients with influenza, and thus help them balance the need to minimize patient risks as well as the individual and societal risks of nonessential antibiotic use.

Eili Klein, PhD, is assistant professor in the department of emergency medicine at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore.

Treatment of patients admitted to the hospital with an upper respiratory infection is often complicated by the lack of diagnostics. Even in cases where a patient has a confirmed case of influenza, there is still the possibility that they may have, or become infected by, a secondary bacterial infection. This leads clinicians to treat patients empirically with antibiotics, which can result in unnecessary antibiotic use among patients without a bacterial infection.

Though antibiotics can be a lifesaving drug, their use is not without risks. Estimates suggest that 20% of patients taking common antibiotics experience some side effect. While most side effects are not life-threatening gastrointestinal effects, other nonnegligible side effects include anaphylactic shock, drug‐induced liver injury, increases in the risk of retinal detachment, serious arrhythmias, and superinfection with resistant bacteria. Antibiotics can also lead to secondary infections, such as Clostridium difficile.

Yet, despite these risks, there has been limited research on the percentage of patients with influenza who actually have a bacterial coinfection. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by my colleagues at Johns Hopkins University and the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy examined the frequency of bacterial coinfection among hospitalized patients with influenza and identified the most common infecting bacterial species.

The findings, published in the journal Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses, found that in the majority of studies, between 11% and 35% of patients with confirmed influenza had a bacterial coinfection. The most common coinfecting bacteria were found to be Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus. Combined, S. pneumoniae and S. aureus accounted for more than 60% of the identified coinfecting bacteria; however, many other bacterial species were found to cause infections as well.

The results suggest that while bacterial infection is common in influenza patients, only about a quarter of patients are likely to be infected. However, the studies were widely heterogeneous, both in patient makeup and results. Analyses of age, setting, enrollment year, study type, study size, and bacterial collection methods did not reveal a source for the heterogeneity in results. Thus, additional factors, such as patient comorbidities or prior antibiotic use, which could not be systematically assessed, may affect the likelihood of coinfection.

Given that the symptoms of influenza and bacterial infection often overlap, correctly diagnosing bacterial coinfection without a laboratory culture can present a challenge. This diagnostic uncertainty leads to significant overuse of antibiotics in patients with influenza alone. Most influenza cases will never result in serious bacterial infections (particularly in nonhospitalized patients), and thus a lot of antibiotic use is unnecessary. As mentioned earlier, unnecessary antibiotic use poses a nonnegligible risk to patients, but it also contributes significantly to rising rates of antibiotic resistance, a major public health issue.

The results from this study highlight that the majority of patients hospitalized with influenza are unlikely to be coinfected with a bacterial pathogen. Thus, it is important for clinicians to appropriately treat patients with antiviral drugs, and ensure that bacterial testing is done when presumptively starting patients on antibiotics. Based on the microbiology results, antibiotics can be stopped if no pathogen is identified or altered to be more appropriate depending on the pathogen found.

Although the findings of this study suggest we need a more thorough analysis of the issue, the results should still aid clinicians by improving their understanding of the likelihood of bacterial coinfection in hospitalized patients with influenza, and thus help them balance the need to minimize patient risks as well as the individual and societal risks of nonessential antibiotic use.

Eili Klein, PhD, is assistant professor in the department of emergency medicine at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore.

Many patients with diabetic foot infections get unnecessary MRSA treatment

Many patients with diabetic foot infections receive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus antibiotics unnecessarily, according to Kelly Reveles, PharmD, and her associates.

Among the 318 patients with diabetic foot infections (DFIs) in the study, S. aureus was the most common pathogen, accounting for 146 cases. MRSA accounted for 47 of S. aureus cases, and 15% of overall cases. Although MRSA accounted for a relatively small number of cases, MRSA antibiotics were administered to 86% of all patients, resulting in 71% of all patients receiving the treatment unnecessarily.

Independent risk factors for MRSA DFI were male sex and bone involvement. Other risk factors included previous MRSA infection, more severe infection, and a higher white cell count. The most common comorbidities of DFI were hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity.

“The improper use of antibiotics unnecessarily exposes the patient to potential complications of the therapy. Furthermore, the overuse of antibiotics drives antimicrobial resistance and is likely to increase the health care burden,” the investigators wrote.

Find the full study in PLoS One (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161658).

Many patients with diabetic foot infections receive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus antibiotics unnecessarily, according to Kelly Reveles, PharmD, and her associates.

Among the 318 patients with diabetic foot infections (DFIs) in the study, S. aureus was the most common pathogen, accounting for 146 cases. MRSA accounted for 47 of S. aureus cases, and 15% of overall cases. Although MRSA accounted for a relatively small number of cases, MRSA antibiotics were administered to 86% of all patients, resulting in 71% of all patients receiving the treatment unnecessarily.

Independent risk factors for MRSA DFI were male sex and bone involvement. Other risk factors included previous MRSA infection, more severe infection, and a higher white cell count. The most common comorbidities of DFI were hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity.

“The improper use of antibiotics unnecessarily exposes the patient to potential complications of the therapy. Furthermore, the overuse of antibiotics drives antimicrobial resistance and is likely to increase the health care burden,” the investigators wrote.

Find the full study in PLoS One (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161658).

Many patients with diabetic foot infections receive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus antibiotics unnecessarily, according to Kelly Reveles, PharmD, and her associates.

Among the 318 patients with diabetic foot infections (DFIs) in the study, S. aureus was the most common pathogen, accounting for 146 cases. MRSA accounted for 47 of S. aureus cases, and 15% of overall cases. Although MRSA accounted for a relatively small number of cases, MRSA antibiotics were administered to 86% of all patients, resulting in 71% of all patients receiving the treatment unnecessarily.

Independent risk factors for MRSA DFI were male sex and bone involvement. Other risk factors included previous MRSA infection, more severe infection, and a higher white cell count. The most common comorbidities of DFI were hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity.

“The improper use of antibiotics unnecessarily exposes the patient to potential complications of the therapy. Furthermore, the overuse of antibiotics drives antimicrobial resistance and is likely to increase the health care burden,” the investigators wrote.

Find the full study in PLoS One (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161658).

FROM PLOS ONE

WHO updates ranking of critically important antimicrobials

In light of increasing antibiotic resistance among pathogens, the World Health Organization has revised its global rankings of critically important antimicrobials used in human medicine, designating quinolones, third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, macrolides and ketolides, and glycopeptides as among the highest-priority drugs in the world.

Peter C. Collignon, MBBS, of Canberra (Australia) Hospital and his colleagues on the WHO Advisory Group on Integrated Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance, created the rankings for use in developing risk management strategies related to antimicrobial use in food production animals. According to Dr. Collignon and his coauthors, the rankings are intended to help regulators and other stakeholders know which types of antimicrobials used in animals present potentially higher risks to human populations and help inform how this use might be better managed (e.g. restriction to single-animal therapy or prohibition of mass treatment and extra-label use) to minimize the risk of transmission of resistance to the human population.

WHO studies previously suggested that antimicrobials which currently have no veterinary equivalent (for example, carbapenems) “as well as any new class of antimicrobial developed for human therapy should not be used in animals.” Dr. Collignon’s WHO Advisory Group followed two essential criteria to designate antimicrobials of utmost importance to human health in the new study: 1. antimicrobials that are the sole, or one of limited available therapies, to treat serious bacterial infections in people and 2. antimicrobials used to treat infections in people caused by either (a) bacteria that may be transmitted to humans from nonhuman sources or (b) bacteria that may acquire resistance genes from nonhuman sources.

The highest-priority and most critically important antimicrobials are those which meet the criteria listed above and that are used in greatest volume or highest frequency by humans. Another criteria for prioritization involves antimicrobial classes where evidence suggests that the “transmission of resistant bacteria or resistance genes from nonhuman sources is already occurring, or has occurred previously.” Quinolones, third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, macrolides and ketolides, and glycopeptides were the only antimicrobials that met all criteria for prioritization.

“Antimicrobial resistance remains a threat to human health and drivers of resistance act in all sectors; human, animal, and the environment,” the WHO Advisory Group concluded. “Prioritizing the antimicrobials that are critically important for humans is a valuable and strategic risk-management tool and will be improved with the evidence-based approach which is currently underway.”

Read the full study in Clinical Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw475).

In light of increasing antibiotic resistance among pathogens, the World Health Organization has revised its global rankings of critically important antimicrobials used in human medicine, designating quinolones, third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, macrolides and ketolides, and glycopeptides as among the highest-priority drugs in the world.

Peter C. Collignon, MBBS, of Canberra (Australia) Hospital and his colleagues on the WHO Advisory Group on Integrated Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance, created the rankings for use in developing risk management strategies related to antimicrobial use in food production animals. According to Dr. Collignon and his coauthors, the rankings are intended to help regulators and other stakeholders know which types of antimicrobials used in animals present potentially higher risks to human populations and help inform how this use might be better managed (e.g. restriction to single-animal therapy or prohibition of mass treatment and extra-label use) to minimize the risk of transmission of resistance to the human population.

WHO studies previously suggested that antimicrobials which currently have no veterinary equivalent (for example, carbapenems) “as well as any new class of antimicrobial developed for human therapy should not be used in animals.” Dr. Collignon’s WHO Advisory Group followed two essential criteria to designate antimicrobials of utmost importance to human health in the new study: 1. antimicrobials that are the sole, or one of limited available therapies, to treat serious bacterial infections in people and 2. antimicrobials used to treat infections in people caused by either (a) bacteria that may be transmitted to humans from nonhuman sources or (b) bacteria that may acquire resistance genes from nonhuman sources.

The highest-priority and most critically important antimicrobials are those which meet the criteria listed above and that are used in greatest volume or highest frequency by humans. Another criteria for prioritization involves antimicrobial classes where evidence suggests that the “transmission of resistant bacteria or resistance genes from nonhuman sources is already occurring, or has occurred previously.” Quinolones, third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, macrolides and ketolides, and glycopeptides were the only antimicrobials that met all criteria for prioritization.

“Antimicrobial resistance remains a threat to human health and drivers of resistance act in all sectors; human, animal, and the environment,” the WHO Advisory Group concluded. “Prioritizing the antimicrobials that are critically important for humans is a valuable and strategic risk-management tool and will be improved with the evidence-based approach which is currently underway.”

Read the full study in Clinical Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw475).

In light of increasing antibiotic resistance among pathogens, the World Health Organization has revised its global rankings of critically important antimicrobials used in human medicine, designating quinolones, third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, macrolides and ketolides, and glycopeptides as among the highest-priority drugs in the world.

Peter C. Collignon, MBBS, of Canberra (Australia) Hospital and his colleagues on the WHO Advisory Group on Integrated Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance, created the rankings for use in developing risk management strategies related to antimicrobial use in food production animals. According to Dr. Collignon and his coauthors, the rankings are intended to help regulators and other stakeholders know which types of antimicrobials used in animals present potentially higher risks to human populations and help inform how this use might be better managed (e.g. restriction to single-animal therapy or prohibition of mass treatment and extra-label use) to minimize the risk of transmission of resistance to the human population.

WHO studies previously suggested that antimicrobials which currently have no veterinary equivalent (for example, carbapenems) “as well as any new class of antimicrobial developed for human therapy should not be used in animals.” Dr. Collignon’s WHO Advisory Group followed two essential criteria to designate antimicrobials of utmost importance to human health in the new study: 1. antimicrobials that are the sole, or one of limited available therapies, to treat serious bacterial infections in people and 2. antimicrobials used to treat infections in people caused by either (a) bacteria that may be transmitted to humans from nonhuman sources or (b) bacteria that may acquire resistance genes from nonhuman sources.

The highest-priority and most critically important antimicrobials are those which meet the criteria listed above and that are used in greatest volume or highest frequency by humans. Another criteria for prioritization involves antimicrobial classes where evidence suggests that the “transmission of resistant bacteria or resistance genes from nonhuman sources is already occurring, or has occurred previously.” Quinolones, third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, macrolides and ketolides, and glycopeptides were the only antimicrobials that met all criteria for prioritization.

“Antimicrobial resistance remains a threat to human health and drivers of resistance act in all sectors; human, animal, and the environment,” the WHO Advisory Group concluded. “Prioritizing the antimicrobials that are critically important for humans is a valuable and strategic risk-management tool and will be improved with the evidence-based approach which is currently underway.”

Read the full study in Clinical Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw475).

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

ANTARCTIC results chill enthusiasm for platelet monitoring

ROME – Measuring platelet function in order to tailor antiplatelet therapy in elderly patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndromes did not improve their clinical outcomes in the randomized ANTARCTIC trial, Gilles Montalescot, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“We found absolutely no benefit for this strategy of adjustment of antiplatelet therapy based upon platelet function testing. The study was completely neutral on all types of endpoints, ischemic as well as bleeding,” said Dr. Montalescot, professor of cardiology at the University of Paris VI and director of the cardiac care unit at Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital.

This was a disappointing result in what was the largest-ever randomized clinical trial involving PCI in elderly patients, he said. This was a high-risk population, not only by virtue of everyone being over age 75 years, but because they all presented with ACS. Indeed, one-third of ANTARCTIC participants underwent primary PCI for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

ANTARCTIC (Assessment of a Normal Versus Tailored Dose of Prasugrel After Stenting in Patients Aged Over 75 Years to Reduce the Composite of Bleeding, Stent Thrombosis, and Ischemic Complications) was carried out as a follow-up to the earlier ARCTIC randomized trial, also conducted by Dr. Montalescot and his coinvestigators. Like ANTARCTIC, ARCTIC, too, showed no clinical benefit for platelet function testing in order to adjust antiplatelet therapy (N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2100-9). At the time, ARCTIC’s critics argued that this individualized strategy didn’t achieve the expected improved outcomes because the trial was conducted in low-risk, stable patients undergoing elective scheduled PCI. In contrast, if there was ever a high-risk population in which platelet function testing and tailored antiplatelet therapy should work, it was in the very high-risk ANTARCTIC population, he said.

ANTARCTIC included 877 elderly patients undergoing urgent PCI for ACS who were placed on low-dose aspirin and randomized to standard antiplatelet therapy with prasugrel (Effient) at 5 mg/day, the European approved dose for long-term maintenance therapy in elderly patients, or to tailored antiplatelet therapy.

Patients in the tailored therapy arm received prasugrel at 5 mg/day for the first 14 days, then underwent platelet function testing with the VerifyNow P2Y12 system. If they demonstrated high on-drug platelet activity, defined as at least 208 P2Y12 reaction units (PRU), their prasugrel was bumped up to 10 mg/day. If their PRU measurement was in what is considered the optimal range for quelling ischemia without promoting bleeding – that is, less than 208 but more than 85 PRU – they remained on prasugrel at 5 mg/day. And if they scored less than 85 PRU, exposing them to excess bleeding risk due to high suppression of platelets, they were switched to clopidogrel (Plavix) at 75 mg/day, a less potent antiplatelet regimen.

Two weeks after their first platelet function measurement, participants in the tailored therapy arm returned for a second round of platelet activity testing, with their antiplatelet regimen once again being adjusted on the basis of the results.

The primary study endpoint was net clinical benefit over a 12-month follow-up period. This was defined as the composite of cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, urgent revascularization, stent thrombosis, and Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) types 2, 3, or 5. This composite endpoint occurred in 27.6% of the platelet monitoring group and a near-identical 27.8% of conventionally managed patients.

Of note, 42% of patients in the actively monitored group were within the target platelet inhibition range when tested 14 days into the study. At study’s end, 55% of patients remained on prasugrel at 5 mg/day, 39% were on clopidogrel at 75 mg/day, and less than 4% were on prasugrel at 10 mg/day. Thus, most patients who underwent a dose adjustment on the basis of their VerifyNow results were downgraded to a less-potent antiplatelet regimen. Very few required enhanced platelet suppression in the form of 10 mg/day of prasugrel.

“Platelet function monitoring is difficult to use. Patients have to come back twice to be monitored. It’s costly. It’s time consuming. And platelet function monitoring clearly does not help,” the cardiologist said.

The ANTARCTIC results will likely lead to a revision of the American and European guidelines, which currently give a class IIb/level of evidence C recommendation for platelet function testing in high-risk situations.

“There is a huge literature showing that platelet reactivity affects clinical outcomes,” Dr. Montalescot continued. “One hypothesis now is that platelet reactivity may be only a marker of risk; you can modify it, but that has no impact on patient outcomes. We may be in the same situation here as with HDL cholesterol, for example.”

Discussant Steen Dalby Kristensen, MD, noted that ANTARCTIC is just the latest in a slew of negative randomized clinical trials of individualized antiplatelet therapy for coronary artery disease. In addition to ARCTIC, others include GRAVITAS, TRIGGER PCI, and ASCET. One study, the German/Austrian TROPICAL ACS trial, remains ongoing.

“It really is an intriguing concept that many of us have been fascinated by for years: to identify the sweet spot where, by measuring platelet aggregation and maybe changing the therapy, we can find just the right balance between bleeding and ischemia. The ANTARCTIC results are quite disappointing for platelet-monitoring enthusiasts. Is the whole concept wrong?” said Dr. Kristensen, professor of cardiology and head of the cardiovascular research center at Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital.

“I think even more disappointing for me than the lack of impact on ischemic events was the bleeding. I would have anticipated that maybe bleeding could be avoided by adjusting the dose, but this was not the case,” he added.

But Stephan Gielen, MD, saw a silver lining in the negative results for ANTARCTIC.

“From my perspective as a clinical interventionalist, I’m happy that you ended up in the way you did. Putting things positively, this study confirms the safety of dual-platelet inhibition with prasugrel at the reduced dose of 5 mg in an elderly population. There is no need to go to the trouble of monitoring platelet function even in this elderly population, which I think for clinical practice is a good message,” said Dr. Gielen of Detmold (Germany) Hospital, who cochaired a press conference where Dr. Montalescot presented the ANTARCTIC results.

Simultaneously with Dr. Montalescot’s presentation at ESC 2016 in Rome, the ANTARCTIC results were published online (Lancet. 2016 Aug 26. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31323-X).

ANTARCTIC was funded by Eli Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo, Stentys, Accriva Diagnostics, Medtronic, and the French Foundation for Heart Research. The presenter reported receiving research grants from and/or serving as a consultant to those organizations and numerous others.

ROME – Measuring platelet function in order to tailor antiplatelet therapy in elderly patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndromes did not improve their clinical outcomes in the randomized ANTARCTIC trial, Gilles Montalescot, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“We found absolutely no benefit for this strategy of adjustment of antiplatelet therapy based upon platelet function testing. The study was completely neutral on all types of endpoints, ischemic as well as bleeding,” said Dr. Montalescot, professor of cardiology at the University of Paris VI and director of the cardiac care unit at Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital.

This was a disappointing result in what was the largest-ever randomized clinical trial involving PCI in elderly patients, he said. This was a high-risk population, not only by virtue of everyone being over age 75 years, but because they all presented with ACS. Indeed, one-third of ANTARCTIC participants underwent primary PCI for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

ANTARCTIC (Assessment of a Normal Versus Tailored Dose of Prasugrel After Stenting in Patients Aged Over 75 Years to Reduce the Composite of Bleeding, Stent Thrombosis, and Ischemic Complications) was carried out as a follow-up to the earlier ARCTIC randomized trial, also conducted by Dr. Montalescot and his coinvestigators. Like ANTARCTIC, ARCTIC, too, showed no clinical benefit for platelet function testing in order to adjust antiplatelet therapy (N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2100-9). At the time, ARCTIC’s critics argued that this individualized strategy didn’t achieve the expected improved outcomes because the trial was conducted in low-risk, stable patients undergoing elective scheduled PCI. In contrast, if there was ever a high-risk population in which platelet function testing and tailored antiplatelet therapy should work, it was in the very high-risk ANTARCTIC population, he said.

ANTARCTIC included 877 elderly patients undergoing urgent PCI for ACS who were placed on low-dose aspirin and randomized to standard antiplatelet therapy with prasugrel (Effient) at 5 mg/day, the European approved dose for long-term maintenance therapy in elderly patients, or to tailored antiplatelet therapy.

Patients in the tailored therapy arm received prasugrel at 5 mg/day for the first 14 days, then underwent platelet function testing with the VerifyNow P2Y12 system. If they demonstrated high on-drug platelet activity, defined as at least 208 P2Y12 reaction units (PRU), their prasugrel was bumped up to 10 mg/day. If their PRU measurement was in what is considered the optimal range for quelling ischemia without promoting bleeding – that is, less than 208 but more than 85 PRU – they remained on prasugrel at 5 mg/day. And if they scored less than 85 PRU, exposing them to excess bleeding risk due to high suppression of platelets, they were switched to clopidogrel (Plavix) at 75 mg/day, a less potent antiplatelet regimen.

Two weeks after their first platelet function measurement, participants in the tailored therapy arm returned for a second round of platelet activity testing, with their antiplatelet regimen once again being adjusted on the basis of the results.

The primary study endpoint was net clinical benefit over a 12-month follow-up period. This was defined as the composite of cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, urgent revascularization, stent thrombosis, and Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) types 2, 3, or 5. This composite endpoint occurred in 27.6% of the platelet monitoring group and a near-identical 27.8% of conventionally managed patients.

Of note, 42% of patients in the actively monitored group were within the target platelet inhibition range when tested 14 days into the study. At study’s end, 55% of patients remained on prasugrel at 5 mg/day, 39% were on clopidogrel at 75 mg/day, and less than 4% were on prasugrel at 10 mg/day. Thus, most patients who underwent a dose adjustment on the basis of their VerifyNow results were downgraded to a less-potent antiplatelet regimen. Very few required enhanced platelet suppression in the form of 10 mg/day of prasugrel.

“Platelet function monitoring is difficult to use. Patients have to come back twice to be monitored. It’s costly. It’s time consuming. And platelet function monitoring clearly does not help,” the cardiologist said.

The ANTARCTIC results will likely lead to a revision of the American and European guidelines, which currently give a class IIb/level of evidence C recommendation for platelet function testing in high-risk situations.

“There is a huge literature showing that platelet reactivity affects clinical outcomes,” Dr. Montalescot continued. “One hypothesis now is that platelet reactivity may be only a marker of risk; you can modify it, but that has no impact on patient outcomes. We may be in the same situation here as with HDL cholesterol, for example.”

Discussant Steen Dalby Kristensen, MD, noted that ANTARCTIC is just the latest in a slew of negative randomized clinical trials of individualized antiplatelet therapy for coronary artery disease. In addition to ARCTIC, others include GRAVITAS, TRIGGER PCI, and ASCET. One study, the German/Austrian TROPICAL ACS trial, remains ongoing.

“It really is an intriguing concept that many of us have been fascinated by for years: to identify the sweet spot where, by measuring platelet aggregation and maybe changing the therapy, we can find just the right balance between bleeding and ischemia. The ANTARCTIC results are quite disappointing for platelet-monitoring enthusiasts. Is the whole concept wrong?” said Dr. Kristensen, professor of cardiology and head of the cardiovascular research center at Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital.

“I think even more disappointing for me than the lack of impact on ischemic events was the bleeding. I would have anticipated that maybe bleeding could be avoided by adjusting the dose, but this was not the case,” he added.

But Stephan Gielen, MD, saw a silver lining in the negative results for ANTARCTIC.

“From my perspective as a clinical interventionalist, I’m happy that you ended up in the way you did. Putting things positively, this study confirms the safety of dual-platelet inhibition with prasugrel at the reduced dose of 5 mg in an elderly population. There is no need to go to the trouble of monitoring platelet function even in this elderly population, which I think for clinical practice is a good message,” said Dr. Gielen of Detmold (Germany) Hospital, who cochaired a press conference where Dr. Montalescot presented the ANTARCTIC results.

Simultaneously with Dr. Montalescot’s presentation at ESC 2016 in Rome, the ANTARCTIC results were published online (Lancet. 2016 Aug 26. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31323-X).

ANTARCTIC was funded by Eli Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo, Stentys, Accriva Diagnostics, Medtronic, and the French Foundation for Heart Research. The presenter reported receiving research grants from and/or serving as a consultant to those organizations and numerous others.

ROME – Measuring platelet function in order to tailor antiplatelet therapy in elderly patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndromes did not improve their clinical outcomes in the randomized ANTARCTIC trial, Gilles Montalescot, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“We found absolutely no benefit for this strategy of adjustment of antiplatelet therapy based upon platelet function testing. The study was completely neutral on all types of endpoints, ischemic as well as bleeding,” said Dr. Montalescot, professor of cardiology at the University of Paris VI and director of the cardiac care unit at Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital.

This was a disappointing result in what was the largest-ever randomized clinical trial involving PCI in elderly patients, he said. This was a high-risk population, not only by virtue of everyone being over age 75 years, but because they all presented with ACS. Indeed, one-third of ANTARCTIC participants underwent primary PCI for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

ANTARCTIC (Assessment of a Normal Versus Tailored Dose of Prasugrel After Stenting in Patients Aged Over 75 Years to Reduce the Composite of Bleeding, Stent Thrombosis, and Ischemic Complications) was carried out as a follow-up to the earlier ARCTIC randomized trial, also conducted by Dr. Montalescot and his coinvestigators. Like ANTARCTIC, ARCTIC, too, showed no clinical benefit for platelet function testing in order to adjust antiplatelet therapy (N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2100-9). At the time, ARCTIC’s critics argued that this individualized strategy didn’t achieve the expected improved outcomes because the trial was conducted in low-risk, stable patients undergoing elective scheduled PCI. In contrast, if there was ever a high-risk population in which platelet function testing and tailored antiplatelet therapy should work, it was in the very high-risk ANTARCTIC population, he said.

ANTARCTIC included 877 elderly patients undergoing urgent PCI for ACS who were placed on low-dose aspirin and randomized to standard antiplatelet therapy with prasugrel (Effient) at 5 mg/day, the European approved dose for long-term maintenance therapy in elderly patients, or to tailored antiplatelet therapy.

Patients in the tailored therapy arm received prasugrel at 5 mg/day for the first 14 days, then underwent platelet function testing with the VerifyNow P2Y12 system. If they demonstrated high on-drug platelet activity, defined as at least 208 P2Y12 reaction units (PRU), their prasugrel was bumped up to 10 mg/day. If their PRU measurement was in what is considered the optimal range for quelling ischemia without promoting bleeding – that is, less than 208 but more than 85 PRU – they remained on prasugrel at 5 mg/day. And if they scored less than 85 PRU, exposing them to excess bleeding risk due to high suppression of platelets, they were switched to clopidogrel (Plavix) at 75 mg/day, a less potent antiplatelet regimen.

Two weeks after their first platelet function measurement, participants in the tailored therapy arm returned for a second round of platelet activity testing, with their antiplatelet regimen once again being adjusted on the basis of the results.

The primary study endpoint was net clinical benefit over a 12-month follow-up period. This was defined as the composite of cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, urgent revascularization, stent thrombosis, and Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) types 2, 3, or 5. This composite endpoint occurred in 27.6% of the platelet monitoring group and a near-identical 27.8% of conventionally managed patients.

Of note, 42% of patients in the actively monitored group were within the target platelet inhibition range when tested 14 days into the study. At study’s end, 55% of patients remained on prasugrel at 5 mg/day, 39% were on clopidogrel at 75 mg/day, and less than 4% were on prasugrel at 10 mg/day. Thus, most patients who underwent a dose adjustment on the basis of their VerifyNow results were downgraded to a less-potent antiplatelet regimen. Very few required enhanced platelet suppression in the form of 10 mg/day of prasugrel.

“Platelet function monitoring is difficult to use. Patients have to come back twice to be monitored. It’s costly. It’s time consuming. And platelet function monitoring clearly does not help,” the cardiologist said.

The ANTARCTIC results will likely lead to a revision of the American and European guidelines, which currently give a class IIb/level of evidence C recommendation for platelet function testing in high-risk situations.

“There is a huge literature showing that platelet reactivity affects clinical outcomes,” Dr. Montalescot continued. “One hypothesis now is that platelet reactivity may be only a marker of risk; you can modify it, but that has no impact on patient outcomes. We may be in the same situation here as with HDL cholesterol, for example.”

Discussant Steen Dalby Kristensen, MD, noted that ANTARCTIC is just the latest in a slew of negative randomized clinical trials of individualized antiplatelet therapy for coronary artery disease. In addition to ARCTIC, others include GRAVITAS, TRIGGER PCI, and ASCET. One study, the German/Austrian TROPICAL ACS trial, remains ongoing.

“It really is an intriguing concept that many of us have been fascinated by for years: to identify the sweet spot where, by measuring platelet aggregation and maybe changing the therapy, we can find just the right balance between bleeding and ischemia. The ANTARCTIC results are quite disappointing for platelet-monitoring enthusiasts. Is the whole concept wrong?” said Dr. Kristensen, professor of cardiology and head of the cardiovascular research center at Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital.

“I think even more disappointing for me than the lack of impact on ischemic events was the bleeding. I would have anticipated that maybe bleeding could be avoided by adjusting the dose, but this was not the case,” he added.

But Stephan Gielen, MD, saw a silver lining in the negative results for ANTARCTIC.

“From my perspective as a clinical interventionalist, I’m happy that you ended up in the way you did. Putting things positively, this study confirms the safety of dual-platelet inhibition with prasugrel at the reduced dose of 5 mg in an elderly population. There is no need to go to the trouble of monitoring platelet function even in this elderly population, which I think for clinical practice is a good message,” said Dr. Gielen of Detmold (Germany) Hospital, who cochaired a press conference where Dr. Montalescot presented the ANTARCTIC results.

Simultaneously with Dr. Montalescot’s presentation at ESC 2016 in Rome, the ANTARCTIC results were published online (Lancet. 2016 Aug 26. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31323-X).

ANTARCTIC was funded by Eli Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo, Stentys, Accriva Diagnostics, Medtronic, and the French Foundation for Heart Research. The presenter reported receiving research grants from and/or serving as a consultant to those organizations and numerous others.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2016

Key clinical point: Researchers have just about given up on the notion that monitoring platelet function in order to individualize antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing PCI provides any clinical benefit.

Major finding: Individualized antiplatelet therapy based upon serial measurements of platelet function did not result in improved outcomes in elderly patients undergoing PCI for acute coronary syndrome (27.6% in the platelet monitoring group and 27.8% in conventionally managed patients).

Data source: ANTARCTIC was an open-label, blinded-endpoint randomized trial of tailored versus standard antiplatelet therapy in 877 elderly patients undergoing PCI for ACS.

Disclosures: ANTARCTIC was funded by Eli Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo, Stentys, Accriva Diagnostics, Medtronic, and the French Foundation for Heart Research. The presenter reported receiving research grants from and/or serving as a consultant to those organizations and numerous others.

Antibiotic stewardship lacking at many hospital nurseries

Nearly one-third of hospital newborn nurseries and neonatal ICUs do not have an antibiotic stewardship program, according to a survey of 146 hospital nursery centers across all 50 states.

Researchers randomly selected a level III NICU in each state using the 2014 American Hospital Association annual survey, then selected a level I and level II nursery in the same city. They collected data on the hospital, nursery, and antibiotic stewardship program characteristics and interviewed staff pharmacists and infectious diseases physicians (J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2016 Jul 15. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw040).

A total of 104 (71%) of responding hospitals had an antibiotic stewardship program in place for their nurseries. Hospitals with a nursery-based antibiotic stewardship programs tended to be larger, have more full-time equivalent staff dedicated to the antibiotic stewardship program, have higher level nurses, and be affiliated with a university, according to Joseph B. Cantey, MD, and his colleagues from the Texas A&M Health Science Center in Temple.

Geographic region and core stewardship strategies did not influence the likelihood of a nursery-based antibiotic stewardship program in place.

From the interviews, the researchers identified several barriers to implementation of antibiotic stewardship programs, and themes such as unwanted coverage, unnecessary coverage, and need for communication.

“Many [antibiotic stewardship program] and nursery representatives stated that nursery [antibiotic stewardship program] coverage was not important, either because antibiotic consumption was perceived as low (theme 1), narrow-spectrum (theme 2), or both,” the authors wrote.

Some nursery providers also argued that participating in stewardship programs was time consuming and not valuable, which the authors said was often related to a lack of pediatric expertise in the program providers. Some of those interviewed also spoke of issues relating to jurisdiction and responsibility for the programs, and there was also a common perception that antibiotic stewardship programs were more concerned with cost savings than patient care.

“Barriers to effective nursery stewardship are exacerbated by lack of communication between stewardship providers and their nursery counterparts,” the authors reported.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

Nearly one-third of hospital newborn nurseries and neonatal ICUs do not have an antibiotic stewardship program, according to a survey of 146 hospital nursery centers across all 50 states.

Researchers randomly selected a level III NICU in each state using the 2014 American Hospital Association annual survey, then selected a level I and level II nursery in the same city. They collected data on the hospital, nursery, and antibiotic stewardship program characteristics and interviewed staff pharmacists and infectious diseases physicians (J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2016 Jul 15. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw040).

A total of 104 (71%) of responding hospitals had an antibiotic stewardship program in place for their nurseries. Hospitals with a nursery-based antibiotic stewardship programs tended to be larger, have more full-time equivalent staff dedicated to the antibiotic stewardship program, have higher level nurses, and be affiliated with a university, according to Joseph B. Cantey, MD, and his colleagues from the Texas A&M Health Science Center in Temple.

Geographic region and core stewardship strategies did not influence the likelihood of a nursery-based antibiotic stewardship program in place.

From the interviews, the researchers identified several barriers to implementation of antibiotic stewardship programs, and themes such as unwanted coverage, unnecessary coverage, and need for communication.

“Many [antibiotic stewardship program] and nursery representatives stated that nursery [antibiotic stewardship program] coverage was not important, either because antibiotic consumption was perceived as low (theme 1), narrow-spectrum (theme 2), or both,” the authors wrote.

Some nursery providers also argued that participating in stewardship programs was time consuming and not valuable, which the authors said was often related to a lack of pediatric expertise in the program providers. Some of those interviewed also spoke of issues relating to jurisdiction and responsibility for the programs, and there was also a common perception that antibiotic stewardship programs were more concerned with cost savings than patient care.

“Barriers to effective nursery stewardship are exacerbated by lack of communication between stewardship providers and their nursery counterparts,” the authors reported.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

Nearly one-third of hospital newborn nurseries and neonatal ICUs do not have an antibiotic stewardship program, according to a survey of 146 hospital nursery centers across all 50 states.

Researchers randomly selected a level III NICU in each state using the 2014 American Hospital Association annual survey, then selected a level I and level II nursery in the same city. They collected data on the hospital, nursery, and antibiotic stewardship program characteristics and interviewed staff pharmacists and infectious diseases physicians (J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2016 Jul 15. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw040).

A total of 104 (71%) of responding hospitals had an antibiotic stewardship program in place for their nurseries. Hospitals with a nursery-based antibiotic stewardship programs tended to be larger, have more full-time equivalent staff dedicated to the antibiotic stewardship program, have higher level nurses, and be affiliated with a university, according to Joseph B. Cantey, MD, and his colleagues from the Texas A&M Health Science Center in Temple.

Geographic region and core stewardship strategies did not influence the likelihood of a nursery-based antibiotic stewardship program in place.

From the interviews, the researchers identified several barriers to implementation of antibiotic stewardship programs, and themes such as unwanted coverage, unnecessary coverage, and need for communication.

“Many [antibiotic stewardship program] and nursery representatives stated that nursery [antibiotic stewardship program] coverage was not important, either because antibiotic consumption was perceived as low (theme 1), narrow-spectrum (theme 2), or both,” the authors wrote.

Some nursery providers also argued that participating in stewardship programs was time consuming and not valuable, which the authors said was often related to a lack of pediatric expertise in the program providers. Some of those interviewed also spoke of issues relating to jurisdiction and responsibility for the programs, and there was also a common perception that antibiotic stewardship programs were more concerned with cost savings than patient care.

“Barriers to effective nursery stewardship are exacerbated by lack of communication between stewardship providers and their nursery counterparts,” the authors reported.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASES SOCIETY

Key clinical point: Many hospital newborn nurseries or neonatal ICUs do not have an antibiotic stewardship program in place.

Major finding: 29% of hospital nurseries surveyed did not have an antibiotic stewardship program.

Data source: Survey of 146 hospital nursery centers in 50 states.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were declared.

Zika’s not the only mosquito-borne virus to worry about

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – As the spread of Zika virus continues to garner attention in the national spotlight, two other mosquito-borne viral infections pose a potential threat to the United States: dengue fever and chikungunya.

At the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association, Iris Z. Ahronowitz, MD, shared tips on how to spot and diagnose patients with these viral infections.

“You really need to use all the data at your disposal, including a thorough symptom history, a thorough exposure history, and of course, our most important tool in all of this: our eyes,” said Dr. Ahronowitz, a dermatologist at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Reaching a diagnosis involves asking about epidemiologic exposure, symptoms, morphology, and performing confirmatory testing by PCR and/or ELISA. “Unfortunately we are not getting these results very quickly,” she said. “Sometimes the turn-around time can be 3 weeks or longer.”

She discussed the case of a 32-year-old woman who had returned from travel to Central Mexico (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58[2]:308-16). Two days later, she developed fever, fatigue, and retro-orbital headache, as well as flushing macular erythema over the chest. Three days later, she developed a generalized morbilliform eruption. Her white blood cell count was 1.5, platelets were 37, aspartate aminotransferase was 124 and alanine aminotransferase was 87.

The differential diagnosis for morbilliform eruption plus fever in a returning traveler is extensive, Dr. Ahronowitz said, including measles, chikungunya, West Nile virus, O’nyong-nyong fever, Mayaro virus, Sindbis virus, Ross river disease, Ebola/Marburg, dengue, and Zika. Bacterial/rickettsial possibilities include typhoid fever, typhus, and leptospirosis.

The patient was ultimately diagnosed with dengue virus, a mosquito-borne flavivirus. Five serotypes have been identified, the most recent in 2013. According to Dr. Ahronowitz, dengue ranks as the most common febrile illness in travelers returning from the Caribbean, South American, and Southeast Asia. “There are up to 100 million cases every year, 40% of the world population is at risk, and an estimated 80% of people are asymptomatic carriers, which is facilitating the spread of this disease,” she said. The most common vector is Aedes aegypti, a daytime biting mosquito that is endemic to the tropics and subtropics. But a new vector is emerging, A. albopictus, which is common in temperate areas. “Both types of mosquitoes are in the United States, and they’re spreading rapidly,” she said. “This is probably due to a combination of climate change and international travel.”

Dengue classically presents with sudden onset of fevers, headaches, and particularly retro-orbital pain, severe myalgia; 50%-82% of cases develop a distinctive rash. “While most viruses have nonspecific lab abnormalities, one that can be very helpful to you with suspected dengue is thrombocytopenia,” she said. “The incubation period ranges from 3 to 14 days.”

Rashes associated with dengue are classically biphasic and sequential. The initial rash occurs within 24-48 hours of symptom onset and is often mistaken for sunburn, with a flushing erythema of the face, neck, and chest. Three to five days later, a subsequent rash develops that starts out as a generalized morbilliform eruption but becomes confluent with petechiae and islands of sparing. “It’s been described as white islands in a sea of red,” Dr. Ahronowitz said.

A more severe form of the disease, dengue hemorrhagic fever, is characterized by extensive purpura and bleeding from mucosa, GI tract, and injection sites. “The patients who get this have prior immunity to a different serotype,” she said. “This is thought to be due to a phenomenon called antibody-dependent enhancement whereby the presence of preexisting antibodies facilitates entry of the virus and produces a more robust inflammatory response. Most of these patients, even the ones with severe dengue, recover fully. The most common long-term sequela we’re seeing is chronic fatigue.”

The diagnosis is made with viral PCR from serum less than 7 days from onset of symptoms, or IgM ELISA more than 4 days from onset of symptoms. The treatment is supportive care with fluid resuscitation and analgesia; there’s no specific treatment. “Do not give NSAIDs, which can potentiate hemorrhage; give acetaminophen for pain and fevers,” she advised. “A tetravalent vaccine is now available for dengue. Prevention is so important because there is no treatment.”

Next, Dr. Ahronowitz discussed the case of a 38-year-old man who returned from travel to Bangladesh (Int J Dermatol. 2008;47[1]:1148-52). Two days after returning he developed fever to 104 degrees, headaches, and cervical lymphadenopathy. Three days after returning, he developed severe pain in the wrist, knees, and ankles, and a rash. “This rash was not specific, it was a morbilliform eruption primarily on the chest,” she said.

The patient was ultimately diagnosed with chikungunya, a single-strand RNA mosquito-borne virus with the same vectors as dengue. “This has been wreaking havoc across the Caribbean in the past few years,” Dr. Ahronowitz said. “Chikungunya was first identified in the Americas in 2013, and there have been hundreds of thousands of cases in the Caribbean.” The first case acquired in the United States occurred in Florida in the summer of 2014. As of January 2016 there were 679 imported cases of the infection in the United States. “Fortunately, this most recent epidemic is slowing down a bit, but it’s important to be aware of,” she said.

Clinical presentation of chikungunya includes an incubation period of 3-7 days, acute onset of high fevers, chills, and myalgia. Nonspecific exanthem around 3 days occurs in 40%-75% of cases, and symmetric polyarthralgias are common in the fingers, wrists, and ankles. Labs may reveal lymphopenia, AKI, and elevated AST/ALT. Acute symptoms resolve within 7-10 days.

Besides the rash, other cutaneous signs of the disease include aphthous-like ulcers and anogenital ulcers, particularly around the scrotum. Other patients may present with controfacial hyperpigmentation, also known as “brownie nose,” that appears with the rash. In babies, bullous lesions can occur. More than 20% of patients who acquire chikungunya still have severe joint pain 1 year after initial presentation. “This can be really debilitating,” she said. “A subset of patients will develop an inflammatory seronegative rheumatoid-like arthritis. It’s generally not a fatal condition except in the extremes of age and in people with a lot of comorbidities. Most people recover fully.”

As in dengue, clinicians can diagnose chikungunya by viral culture in the first 3 days of illness, and by RT-PCR in the first 8 days of illness. On serology, IgM is positive by 5 days of symptom onset.

“If testing is not available locally, contact the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention],” Dr. Ahronowitz said. “Treatment is supportive. Evaluate for and treat potential coinfections, including dengue, malaria, and bacterial infections. If dengue is in the differential diagnosis, avoid NSAIDs.” A new vaccine for chikungunya is currently in phase II trials.

Dr. Ahronowitz reported having no relevant disclosures.

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – As the spread of Zika virus continues to garner attention in the national spotlight, two other mosquito-borne viral infections pose a potential threat to the United States: dengue fever and chikungunya.

At the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association, Iris Z. Ahronowitz, MD, shared tips on how to spot and diagnose patients with these viral infections.

“You really need to use all the data at your disposal, including a thorough symptom history, a thorough exposure history, and of course, our most important tool in all of this: our eyes,” said Dr. Ahronowitz, a dermatologist at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Reaching a diagnosis involves asking about epidemiologic exposure, symptoms, morphology, and performing confirmatory testing by PCR and/or ELISA. “Unfortunately we are not getting these results very quickly,” she said. “Sometimes the turn-around time can be 3 weeks or longer.”

She discussed the case of a 32-year-old woman who had returned from travel to Central Mexico (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58[2]:308-16). Two days later, she developed fever, fatigue, and retro-orbital headache, as well as flushing macular erythema over the chest. Three days later, she developed a generalized morbilliform eruption. Her white blood cell count was 1.5, platelets were 37, aspartate aminotransferase was 124 and alanine aminotransferase was 87.

The differential diagnosis for morbilliform eruption plus fever in a returning traveler is extensive, Dr. Ahronowitz said, including measles, chikungunya, West Nile virus, O’nyong-nyong fever, Mayaro virus, Sindbis virus, Ross river disease, Ebola/Marburg, dengue, and Zika. Bacterial/rickettsial possibilities include typhoid fever, typhus, and leptospirosis.

The patient was ultimately diagnosed with dengue virus, a mosquito-borne flavivirus. Five serotypes have been identified, the most recent in 2013. According to Dr. Ahronowitz, dengue ranks as the most common febrile illness in travelers returning from the Caribbean, South American, and Southeast Asia. “There are up to 100 million cases every year, 40% of the world population is at risk, and an estimated 80% of people are asymptomatic carriers, which is facilitating the spread of this disease,” she said. The most common vector is Aedes aegypti, a daytime biting mosquito that is endemic to the tropics and subtropics. But a new vector is emerging, A. albopictus, which is common in temperate areas. “Both types of mosquitoes are in the United States, and they’re spreading rapidly,” she said. “This is probably due to a combination of climate change and international travel.”

Dengue classically presents with sudden onset of fevers, headaches, and particularly retro-orbital pain, severe myalgia; 50%-82% of cases develop a distinctive rash. “While most viruses have nonspecific lab abnormalities, one that can be very helpful to you with suspected dengue is thrombocytopenia,” she said. “The incubation period ranges from 3 to 14 days.”

Rashes associated with dengue are classically biphasic and sequential. The initial rash occurs within 24-48 hours of symptom onset and is often mistaken for sunburn, with a flushing erythema of the face, neck, and chest. Three to five days later, a subsequent rash develops that starts out as a generalized morbilliform eruption but becomes confluent with petechiae and islands of sparing. “It’s been described as white islands in a sea of red,” Dr. Ahronowitz said.

A more severe form of the disease, dengue hemorrhagic fever, is characterized by extensive purpura and bleeding from mucosa, GI tract, and injection sites. “The patients who get this have prior immunity to a different serotype,” she said. “This is thought to be due to a phenomenon called antibody-dependent enhancement whereby the presence of preexisting antibodies facilitates entry of the virus and produces a more robust inflammatory response. Most of these patients, even the ones with severe dengue, recover fully. The most common long-term sequela we’re seeing is chronic fatigue.”

The diagnosis is made with viral PCR from serum less than 7 days from onset of symptoms, or IgM ELISA more than 4 days from onset of symptoms. The treatment is supportive care with fluid resuscitation and analgesia; there’s no specific treatment. “Do not give NSAIDs, which can potentiate hemorrhage; give acetaminophen for pain and fevers,” she advised. “A tetravalent vaccine is now available for dengue. Prevention is so important because there is no treatment.”

Next, Dr. Ahronowitz discussed the case of a 38-year-old man who returned from travel to Bangladesh (Int J Dermatol. 2008;47[1]:1148-52). Two days after returning he developed fever to 104 degrees, headaches, and cervical lymphadenopathy. Three days after returning, he developed severe pain in the wrist, knees, and ankles, and a rash. “This rash was not specific, it was a morbilliform eruption primarily on the chest,” she said.

The patient was ultimately diagnosed with chikungunya, a single-strand RNA mosquito-borne virus with the same vectors as dengue. “This has been wreaking havoc across the Caribbean in the past few years,” Dr. Ahronowitz said. “Chikungunya was first identified in the Americas in 2013, and there have been hundreds of thousands of cases in the Caribbean.” The first case acquired in the United States occurred in Florida in the summer of 2014. As of January 2016 there were 679 imported cases of the infection in the United States. “Fortunately, this most recent epidemic is slowing down a bit, but it’s important to be aware of,” she said.

Clinical presentation of chikungunya includes an incubation period of 3-7 days, acute onset of high fevers, chills, and myalgia. Nonspecific exanthem around 3 days occurs in 40%-75% of cases, and symmetric polyarthralgias are common in the fingers, wrists, and ankles. Labs may reveal lymphopenia, AKI, and elevated AST/ALT. Acute symptoms resolve within 7-10 days.

Besides the rash, other cutaneous signs of the disease include aphthous-like ulcers and anogenital ulcers, particularly around the scrotum. Other patients may present with controfacial hyperpigmentation, also known as “brownie nose,” that appears with the rash. In babies, bullous lesions can occur. More than 20% of patients who acquire chikungunya still have severe joint pain 1 year after initial presentation. “This can be really debilitating,” she said. “A subset of patients will develop an inflammatory seronegative rheumatoid-like arthritis. It’s generally not a fatal condition except in the extremes of age and in people with a lot of comorbidities. Most people recover fully.”

As in dengue, clinicians can diagnose chikungunya by viral culture in the first 3 days of illness, and by RT-PCR in the first 8 days of illness. On serology, IgM is positive by 5 days of symptom onset.

“If testing is not available locally, contact the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention],” Dr. Ahronowitz said. “Treatment is supportive. Evaluate for and treat potential coinfections, including dengue, malaria, and bacterial infections. If dengue is in the differential diagnosis, avoid NSAIDs.” A new vaccine for chikungunya is currently in phase II trials.

Dr. Ahronowitz reported having no relevant disclosures.

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – As the spread of Zika virus continues to garner attention in the national spotlight, two other mosquito-borne viral infections pose a potential threat to the United States: dengue fever and chikungunya.

At the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association, Iris Z. Ahronowitz, MD, shared tips on how to spot and diagnose patients with these viral infections.

“You really need to use all the data at your disposal, including a thorough symptom history, a thorough exposure history, and of course, our most important tool in all of this: our eyes,” said Dr. Ahronowitz, a dermatologist at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Reaching a diagnosis involves asking about epidemiologic exposure, symptoms, morphology, and performing confirmatory testing by PCR and/or ELISA. “Unfortunately we are not getting these results very quickly,” she said. “Sometimes the turn-around time can be 3 weeks or longer.”

She discussed the case of a 32-year-old woman who had returned from travel to Central Mexico (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58[2]:308-16). Two days later, she developed fever, fatigue, and retro-orbital headache, as well as flushing macular erythema over the chest. Three days later, she developed a generalized morbilliform eruption. Her white blood cell count was 1.5, platelets were 37, aspartate aminotransferase was 124 and alanine aminotransferase was 87.

The differential diagnosis for morbilliform eruption plus fever in a returning traveler is extensive, Dr. Ahronowitz said, including measles, chikungunya, West Nile virus, O’nyong-nyong fever, Mayaro virus, Sindbis virus, Ross river disease, Ebola/Marburg, dengue, and Zika. Bacterial/rickettsial possibilities include typhoid fever, typhus, and leptospirosis.

The patient was ultimately diagnosed with dengue virus, a mosquito-borne flavivirus. Five serotypes have been identified, the most recent in 2013. According to Dr. Ahronowitz, dengue ranks as the most common febrile illness in travelers returning from the Caribbean, South American, and Southeast Asia. “There are up to 100 million cases every year, 40% of the world population is at risk, and an estimated 80% of people are asymptomatic carriers, which is facilitating the spread of this disease,” she said. The most common vector is Aedes aegypti, a daytime biting mosquito that is endemic to the tropics and subtropics. But a new vector is emerging, A. albopictus, which is common in temperate areas. “Both types of mosquitoes are in the United States, and they’re spreading rapidly,” she said. “This is probably due to a combination of climate change and international travel.”

Dengue classically presents with sudden onset of fevers, headaches, and particularly retro-orbital pain, severe myalgia; 50%-82% of cases develop a distinctive rash. “While most viruses have nonspecific lab abnormalities, one that can be very helpful to you with suspected dengue is thrombocytopenia,” she said. “The incubation period ranges from 3 to 14 days.”

Rashes associated with dengue are classically biphasic and sequential. The initial rash occurs within 24-48 hours of symptom onset and is often mistaken for sunburn, with a flushing erythema of the face, neck, and chest. Three to five days later, a subsequent rash develops that starts out as a generalized morbilliform eruption but becomes confluent with petechiae and islands of sparing. “It’s been described as white islands in a sea of red,” Dr. Ahronowitz said.

A more severe form of the disease, dengue hemorrhagic fever, is characterized by extensive purpura and bleeding from mucosa, GI tract, and injection sites. “The patients who get this have prior immunity to a different serotype,” she said. “This is thought to be due to a phenomenon called antibody-dependent enhancement whereby the presence of preexisting antibodies facilitates entry of the virus and produces a more robust inflammatory response. Most of these patients, even the ones with severe dengue, recover fully. The most common long-term sequela we’re seeing is chronic fatigue.”

The diagnosis is made with viral PCR from serum less than 7 days from onset of symptoms, or IgM ELISA more than 4 days from onset of symptoms. The treatment is supportive care with fluid resuscitation and analgesia; there’s no specific treatment. “Do not give NSAIDs, which can potentiate hemorrhage; give acetaminophen for pain and fevers,” she advised. “A tetravalent vaccine is now available for dengue. Prevention is so important because there is no treatment.”

Next, Dr. Ahronowitz discussed the case of a 38-year-old man who returned from travel to Bangladesh (Int J Dermatol. 2008;47[1]:1148-52). Two days after returning he developed fever to 104 degrees, headaches, and cervical lymphadenopathy. Three days after returning, he developed severe pain in the wrist, knees, and ankles, and a rash. “This rash was not specific, it was a morbilliform eruption primarily on the chest,” she said.