User login

News and Views that Matter to Physicians

Prenatal exposure to TNF inhibitors does not increase infections in newborns

WASHINGTON – Prenatal exposure to tumor necrosis factor–inhibiting drugs does not significantly increase the risk of a serious antenatal infection in infants born to women taking the drugs for rheumatoid arthritis, according to a large database study.

Researchers from McGill University, Montreal, and the University of Alabama at Birmingham who conducted the study did find a higher rate of serious infections among infants born to users of a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi), especially among those exposed to infliximab, but after adjustment for maternal age and other antirheumatic drugs, the risk was not statistically significant.

Infliximab is unique among the TNFi drugs in that it concentrates in cord blood, reaching levels that can exceed 150% of the maternal blood level, Dr. Vinet noted. Adalimumab concentrates similarly, although the current study did not find any significantly increased infection risk associated with that medication.

Dr. Vinet and her colleagues analyzed drug exposure in 2,455 infants born to mothers with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), who were included in the PregnAncies in RA mothers and Outcomes in offspring in the United States cohort (PAROUS) registry. This cohort is drawn from data in the national MarketScan commercial database. The infants were age- and gender-matched with more than 11,000 matched controls born to women without RA, and with no prenatal TNFi exposure. Among these drugs, she looked for exposure to adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, and infliximab, as well as corticosteroids and other biologic and nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs).

Two exposures were considered: drugs taken during pregnancy and drugs taken before conception but not during pregnancy. These were compared with infants of mothers with RA who didn’t take TNFi drugs, and to the control infants. Serious infections were those that required a hospitalization during the first 12 months of life; only the index incident was counted.

Among the RA cohort, 290 (12%) were exposed to a TNFi during pregnancy and 109 (4%) were born to women who had taken a TNFi before conception. The remainder of the cohort was unexposed to those medications.

The mean maternal age was 32 years and similar in all RA categories and controls.

Corticosteroid use was common in women with RA, whether they took a TNFi during pregnancy (55%), before pregnancy (44%), or not at all (26%). Nonbiologic DMARDs were given to 19% of the TNFi cohort during pregnancy and 16% before pregnancy, as well as to 15% of those who didn’t take a TNFi.

The rate of serious neonatal infection was 2% among both infants born to RA mothers who didn’t take a TNFi and those born to RA mothers who took a TNFi before conception. Control infants born to women without RA had a serious infection rate of 0.2%.

Among infants exposed to a TNFi during pregnancy, the serious infection rate was 3%; it was also 3% among those exposed only in the third trimester.

A multivariate analysis that controlled for maternal age, prepregnancy diabetes, gestational diabetes, preterm birth, and exposure to the other drug categories determined that TNFi drugs did not significantly increase the risk of a serious infection in neonates with gestational exposure (odds ratio, 1.4) or whose mothers took the drugs before conception (OR, 0.9), compared with controls. The findings were similar when the analysis was restricted to TNFi exposure in the third trimester only.

When Dr. Vinet examined each drug independently, she found numerical differences in infection rates: golimumab and certolizumab pegol, 0%; adalimumab, 2.4%; etanercept 2.7%; and infliximab, 8.3%.

Because of the relatively small number of events, this portion of the regression analysis could not control for preterm birth and gestational diabetes. But after adjusting for maternal age and in utero corticosteroid exposure, Dr. Vinet found no significant associations with serious neonatal infection and any of the TNFi drugs, including infliximab (OR, 3.5; 95% CI, 0.8-15.0).

She and her colleagues had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

WASHINGTON – Prenatal exposure to tumor necrosis factor–inhibiting drugs does not significantly increase the risk of a serious antenatal infection in infants born to women taking the drugs for rheumatoid arthritis, according to a large database study.

Researchers from McGill University, Montreal, and the University of Alabama at Birmingham who conducted the study did find a higher rate of serious infections among infants born to users of a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi), especially among those exposed to infliximab, but after adjustment for maternal age and other antirheumatic drugs, the risk was not statistically significant.

Infliximab is unique among the TNFi drugs in that it concentrates in cord blood, reaching levels that can exceed 150% of the maternal blood level, Dr. Vinet noted. Adalimumab concentrates similarly, although the current study did not find any significantly increased infection risk associated with that medication.

Dr. Vinet and her colleagues analyzed drug exposure in 2,455 infants born to mothers with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), who were included in the PregnAncies in RA mothers and Outcomes in offspring in the United States cohort (PAROUS) registry. This cohort is drawn from data in the national MarketScan commercial database. The infants were age- and gender-matched with more than 11,000 matched controls born to women without RA, and with no prenatal TNFi exposure. Among these drugs, she looked for exposure to adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, and infliximab, as well as corticosteroids and other biologic and nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs).

Two exposures were considered: drugs taken during pregnancy and drugs taken before conception but not during pregnancy. These were compared with infants of mothers with RA who didn’t take TNFi drugs, and to the control infants. Serious infections were those that required a hospitalization during the first 12 months of life; only the index incident was counted.

Among the RA cohort, 290 (12%) were exposed to a TNFi during pregnancy and 109 (4%) were born to women who had taken a TNFi before conception. The remainder of the cohort was unexposed to those medications.

The mean maternal age was 32 years and similar in all RA categories and controls.

Corticosteroid use was common in women with RA, whether they took a TNFi during pregnancy (55%), before pregnancy (44%), or not at all (26%). Nonbiologic DMARDs were given to 19% of the TNFi cohort during pregnancy and 16% before pregnancy, as well as to 15% of those who didn’t take a TNFi.

The rate of serious neonatal infection was 2% among both infants born to RA mothers who didn’t take a TNFi and those born to RA mothers who took a TNFi before conception. Control infants born to women without RA had a serious infection rate of 0.2%.

Among infants exposed to a TNFi during pregnancy, the serious infection rate was 3%; it was also 3% among those exposed only in the third trimester.

A multivariate analysis that controlled for maternal age, prepregnancy diabetes, gestational diabetes, preterm birth, and exposure to the other drug categories determined that TNFi drugs did not significantly increase the risk of a serious infection in neonates with gestational exposure (odds ratio, 1.4) or whose mothers took the drugs before conception (OR, 0.9), compared with controls. The findings were similar when the analysis was restricted to TNFi exposure in the third trimester only.

When Dr. Vinet examined each drug independently, she found numerical differences in infection rates: golimumab and certolizumab pegol, 0%; adalimumab, 2.4%; etanercept 2.7%; and infliximab, 8.3%.

Because of the relatively small number of events, this portion of the regression analysis could not control for preterm birth and gestational diabetes. But after adjusting for maternal age and in utero corticosteroid exposure, Dr. Vinet found no significant associations with serious neonatal infection and any of the TNFi drugs, including infliximab (OR, 3.5; 95% CI, 0.8-15.0).

She and her colleagues had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

WASHINGTON – Prenatal exposure to tumor necrosis factor–inhibiting drugs does not significantly increase the risk of a serious antenatal infection in infants born to women taking the drugs for rheumatoid arthritis, according to a large database study.

Researchers from McGill University, Montreal, and the University of Alabama at Birmingham who conducted the study did find a higher rate of serious infections among infants born to users of a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi), especially among those exposed to infliximab, but after adjustment for maternal age and other antirheumatic drugs, the risk was not statistically significant.

Infliximab is unique among the TNFi drugs in that it concentrates in cord blood, reaching levels that can exceed 150% of the maternal blood level, Dr. Vinet noted. Adalimumab concentrates similarly, although the current study did not find any significantly increased infection risk associated with that medication.

Dr. Vinet and her colleagues analyzed drug exposure in 2,455 infants born to mothers with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), who were included in the PregnAncies in RA mothers and Outcomes in offspring in the United States cohort (PAROUS) registry. This cohort is drawn from data in the national MarketScan commercial database. The infants were age- and gender-matched with more than 11,000 matched controls born to women without RA, and with no prenatal TNFi exposure. Among these drugs, she looked for exposure to adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, and infliximab, as well as corticosteroids and other biologic and nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs).

Two exposures were considered: drugs taken during pregnancy and drugs taken before conception but not during pregnancy. These were compared with infants of mothers with RA who didn’t take TNFi drugs, and to the control infants. Serious infections were those that required a hospitalization during the first 12 months of life; only the index incident was counted.

Among the RA cohort, 290 (12%) were exposed to a TNFi during pregnancy and 109 (4%) were born to women who had taken a TNFi before conception. The remainder of the cohort was unexposed to those medications.

The mean maternal age was 32 years and similar in all RA categories and controls.

Corticosteroid use was common in women with RA, whether they took a TNFi during pregnancy (55%), before pregnancy (44%), or not at all (26%). Nonbiologic DMARDs were given to 19% of the TNFi cohort during pregnancy and 16% before pregnancy, as well as to 15% of those who didn’t take a TNFi.

The rate of serious neonatal infection was 2% among both infants born to RA mothers who didn’t take a TNFi and those born to RA mothers who took a TNFi before conception. Control infants born to women without RA had a serious infection rate of 0.2%.

Among infants exposed to a TNFi during pregnancy, the serious infection rate was 3%; it was also 3% among those exposed only in the third trimester.

A multivariate analysis that controlled for maternal age, prepregnancy diabetes, gestational diabetes, preterm birth, and exposure to the other drug categories determined that TNFi drugs did not significantly increase the risk of a serious infection in neonates with gestational exposure (odds ratio, 1.4) or whose mothers took the drugs before conception (OR, 0.9), compared with controls. The findings were similar when the analysis was restricted to TNFi exposure in the third trimester only.

When Dr. Vinet examined each drug independently, she found numerical differences in infection rates: golimumab and certolizumab pegol, 0%; adalimumab, 2.4%; etanercept 2.7%; and infliximab, 8.3%.

Because of the relatively small number of events, this portion of the regression analysis could not control for preterm birth and gestational diabetes. But after adjusting for maternal age and in utero corticosteroid exposure, Dr. Vinet found no significant associations with serious neonatal infection and any of the TNFi drugs, including infliximab (OR, 3.5; 95% CI, 0.8-15.0).

She and her colleagues had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The rates of serious neonatal infection were 2% among infants born to RA mothers without exposure to TNFi drugs and 3% among those exposed to the drugs during gestation.

Data source: The case-control study comprised 2,455 cases and more than 11,000 controls.

Disclosures: Dr. Vinet and her colleagues had no financial disclosures.

Diabetes treatment costs doubled in Sweden since 2006

MUNICH – Sweden has experienced a doubling in its national costs for treating type 2 diabetes from €608 million in 2006 to €1.27 billion in 2014.

The increase is directly related to a surge of more than 100,000 in the number of patients with the disease and has been driven by increased hospitalizations for cardiovascular complications of diabetes, Almina Kalkan, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Costs jumped on a per-patient level as well, but the increase wasn’t related to diabetes treatment – in fact, antidiabetic medication costs remained stable at 4% over the entire study period. The real driver was the cost of treating heart failure and stroke, which increased by 92% and 73%, respectively, over the study period.

“You can really see that preventing these diabetes complications is of major importance, not only for patient quality of life but for reducing health care expenditures,” said Dr. Kalkan.

She and her colleagues searched the Swedish Prescribed Drug Registry to identify patients treated for type 2 diabetes, and linked those patients with annual hospital admissions, discharges, and hospital outpatient visits in the National Patient Register. This database doesn’t contain information on primary care visits, so this was imputed from prior studies, as were data on lost work productivity due to the disease.

According to national records, 206,183 Swedish citizens were treated for type 2 diabetes in 2006; by 2014, that number was 366,492. The mean patient age was unchanged (67 years). There was a significant increase of 2% in the number of patients who had cardiovascular disease (33%-35%). That was driven by increases in heart failure and atrial fibrillation; the proportion with myocardial infarction and stroke was unchanged.

Significantly more patients also had kidney disease by 2014 (1.5%-3.2%), although macrovascular disease had decreased by 4%. Lower limb amputations increased as well.

In the overall analysis, inpatient hospital visits accounted for the bulk of the spending, rising from €355 million in 2006 to €783 million in 2014. This was followed by spending on outpatient hospital care (from €112 million to €303 million). Spending on diabetes medications went from €39 million to €84 million, but the increase stayed proportional at just over 6%.

The total annual cost per patient increased as well, from just under €3,000/year to €3,500/year – an 18% increase.

“We still see that the main driver was inpatient and outpatient hospital care,“ Dr. Kalkan said. “Total inpatient costs increased by 24% per patient, and total outpatient costs increased by 52%.”

The proportion spent on inpatient and outpatient hospital care for each patient increased from 77% to 85% of total expenditures. Again, there was no change in the cost of diabetes medications or in the proportion of costs spent on such drugs.

Dr. Kalkan and her colleagues then conducted a societal cost analysis, which included data on primary care visits and lost job productivity related to diabetes. There was an overall 22% increase in national cost during the study period, rising from €4,200 to €5,300/patient-year.

“Inpatient visits increased by 72%, although length of stay decreased, from 13 to 11 days,” Dr. Kalkan said. “Despite this, the costs proportionately increased. This was directly due to the cost of treating the most common cardiovascular comorbidities of diabetes: heart failure, chest pain, myocardial infarction, and stroke.”

In this analysis, the cost of antidiabetic drugs was also quite small and remained stable, at 4% over the entire study period.

The cost of lost productivity was drawn from a 2015 report issued by the Swedish Institute for Health Economics. This report found that type 2 diabetes was related to a net per patient loss of €206/year in 2006 and €317/year in 2014 – a significant change.

The cost analysis was a collaborative project of AstraZeneca, Uppsala University, and the Karolinksa Institute. Dr. Kalkan is an employee of AstraZeneca.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

MUNICH – Sweden has experienced a doubling in its national costs for treating type 2 diabetes from €608 million in 2006 to €1.27 billion in 2014.

The increase is directly related to a surge of more than 100,000 in the number of patients with the disease and has been driven by increased hospitalizations for cardiovascular complications of diabetes, Almina Kalkan, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Costs jumped on a per-patient level as well, but the increase wasn’t related to diabetes treatment – in fact, antidiabetic medication costs remained stable at 4% over the entire study period. The real driver was the cost of treating heart failure and stroke, which increased by 92% and 73%, respectively, over the study period.

“You can really see that preventing these diabetes complications is of major importance, not only for patient quality of life but for reducing health care expenditures,” said Dr. Kalkan.

She and her colleagues searched the Swedish Prescribed Drug Registry to identify patients treated for type 2 diabetes, and linked those patients with annual hospital admissions, discharges, and hospital outpatient visits in the National Patient Register. This database doesn’t contain information on primary care visits, so this was imputed from prior studies, as were data on lost work productivity due to the disease.

According to national records, 206,183 Swedish citizens were treated for type 2 diabetes in 2006; by 2014, that number was 366,492. The mean patient age was unchanged (67 years). There was a significant increase of 2% in the number of patients who had cardiovascular disease (33%-35%). That was driven by increases in heart failure and atrial fibrillation; the proportion with myocardial infarction and stroke was unchanged.

Significantly more patients also had kidney disease by 2014 (1.5%-3.2%), although macrovascular disease had decreased by 4%. Lower limb amputations increased as well.

In the overall analysis, inpatient hospital visits accounted for the bulk of the spending, rising from €355 million in 2006 to €783 million in 2014. This was followed by spending on outpatient hospital care (from €112 million to €303 million). Spending on diabetes medications went from €39 million to €84 million, but the increase stayed proportional at just over 6%.

The total annual cost per patient increased as well, from just under €3,000/year to €3,500/year – an 18% increase.

“We still see that the main driver was inpatient and outpatient hospital care,“ Dr. Kalkan said. “Total inpatient costs increased by 24% per patient, and total outpatient costs increased by 52%.”

The proportion spent on inpatient and outpatient hospital care for each patient increased from 77% to 85% of total expenditures. Again, there was no change in the cost of diabetes medications or in the proportion of costs spent on such drugs.

Dr. Kalkan and her colleagues then conducted a societal cost analysis, which included data on primary care visits and lost job productivity related to diabetes. There was an overall 22% increase in national cost during the study period, rising from €4,200 to €5,300/patient-year.

“Inpatient visits increased by 72%, although length of stay decreased, from 13 to 11 days,” Dr. Kalkan said. “Despite this, the costs proportionately increased. This was directly due to the cost of treating the most common cardiovascular comorbidities of diabetes: heart failure, chest pain, myocardial infarction, and stroke.”

In this analysis, the cost of antidiabetic drugs was also quite small and remained stable, at 4% over the entire study period.

The cost of lost productivity was drawn from a 2015 report issued by the Swedish Institute for Health Economics. This report found that type 2 diabetes was related to a net per patient loss of €206/year in 2006 and €317/year in 2014 – a significant change.

The cost analysis was a collaborative project of AstraZeneca, Uppsala University, and the Karolinksa Institute. Dr. Kalkan is an employee of AstraZeneca.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

MUNICH – Sweden has experienced a doubling in its national costs for treating type 2 diabetes from €608 million in 2006 to €1.27 billion in 2014.

The increase is directly related to a surge of more than 100,000 in the number of patients with the disease and has been driven by increased hospitalizations for cardiovascular complications of diabetes, Almina Kalkan, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Costs jumped on a per-patient level as well, but the increase wasn’t related to diabetes treatment – in fact, antidiabetic medication costs remained stable at 4% over the entire study period. The real driver was the cost of treating heart failure and stroke, which increased by 92% and 73%, respectively, over the study period.

“You can really see that preventing these diabetes complications is of major importance, not only for patient quality of life but for reducing health care expenditures,” said Dr. Kalkan.

She and her colleagues searched the Swedish Prescribed Drug Registry to identify patients treated for type 2 diabetes, and linked those patients with annual hospital admissions, discharges, and hospital outpatient visits in the National Patient Register. This database doesn’t contain information on primary care visits, so this was imputed from prior studies, as were data on lost work productivity due to the disease.

According to national records, 206,183 Swedish citizens were treated for type 2 diabetes in 2006; by 2014, that number was 366,492. The mean patient age was unchanged (67 years). There was a significant increase of 2% in the number of patients who had cardiovascular disease (33%-35%). That was driven by increases in heart failure and atrial fibrillation; the proportion with myocardial infarction and stroke was unchanged.

Significantly more patients also had kidney disease by 2014 (1.5%-3.2%), although macrovascular disease had decreased by 4%. Lower limb amputations increased as well.

In the overall analysis, inpatient hospital visits accounted for the bulk of the spending, rising from €355 million in 2006 to €783 million in 2014. This was followed by spending on outpatient hospital care (from €112 million to €303 million). Spending on diabetes medications went from €39 million to €84 million, but the increase stayed proportional at just over 6%.

The total annual cost per patient increased as well, from just under €3,000/year to €3,500/year – an 18% increase.

“We still see that the main driver was inpatient and outpatient hospital care,“ Dr. Kalkan said. “Total inpatient costs increased by 24% per patient, and total outpatient costs increased by 52%.”

The proportion spent on inpatient and outpatient hospital care for each patient increased from 77% to 85% of total expenditures. Again, there was no change in the cost of diabetes medications or in the proportion of costs spent on such drugs.

Dr. Kalkan and her colleagues then conducted a societal cost analysis, which included data on primary care visits and lost job productivity related to diabetes. There was an overall 22% increase in national cost during the study period, rising from €4,200 to €5,300/patient-year.

“Inpatient visits increased by 72%, although length of stay decreased, from 13 to 11 days,” Dr. Kalkan said. “Despite this, the costs proportionately increased. This was directly due to the cost of treating the most common cardiovascular comorbidities of diabetes: heart failure, chest pain, myocardial infarction, and stroke.”

In this analysis, the cost of antidiabetic drugs was also quite small and remained stable, at 4% over the entire study period.

The cost of lost productivity was drawn from a 2015 report issued by the Swedish Institute for Health Economics. This report found that type 2 diabetes was related to a net per patient loss of €206/year in 2006 and €317/year in 2014 – a significant change.

The cost analysis was a collaborative project of AstraZeneca, Uppsala University, and the Karolinksa Institute. Dr. Kalkan is an employee of AstraZeneca.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

AT EASD 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Treatment costs jumped from €608 million in 2006 to €1.27 billion in 2014.

Data source: The 8-year study used national health care data.

Disclosures: The cost analysis was a collaborative project of AstraZeneca, Uppsala University, and the Karolinksa Institute. Dr. Kalkan is an employee of AstraZeneca.

AGA Guideline: Preventing Crohn’s recurrence after resection

Patients whose Crohn’s disease fully remits after resection should not wait for endoscopic recurrence to start tumor-necrosis-factor inhibitors or thiopurines, according to a new guideline from the American Gastroenterological Association.

Patients who are low risk or worried about side effects, however, “may reasonably select endoscopy-guided pharmacological treatment,” the guidelines state (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.038).

Early pharmacologic prophylaxis usually begins within 8 weeks of surgery, they noted. Whether this approach bests endoscopy-guided treatment is unclear: In one small trial (Gastroenterology. 2013;145[4]:766-74.e1), early azathioprine therapy failed to best endoscopy-guided therapy for preventing clinical or endoscopic recurrence.

Early prophylaxis, however, is usually reasonable because most Crohn’s patients who undergo surgery have at least one risk factor for recurrence, Dr. Nguyen and his associates emphasize. They suggest reserving endoscopy-guided therapy for patients who have real concerns about side effects and are at low risk, such as nonsmokers who were diagnosed within 10 years and have less than 10-20 cm of fibrostenotic disease.

For prophylaxis, a moderate amount of evidence supports anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents, thiopurines, or combined therapy over other agents, the guideline also states. In placebo-controlled clinical trials, anti-TNF therapy reduced the chances of clinical recurrence by 49% and endoscopic recurrence by 76%, while thiopurines cut these rates by 65% and 60%, respectively. Evidence favors anti-TNF agents over thiopurines for preventing recurrence, but it is of low quality, the guideline says. Furthermore, only indirect evidence supports combined therapy in patients at highest risk of recurrence.

Among the antibiotics, only nitroimidazoles such as metronidazole have been adequately studied, and they posted worse results than anti-TNF agents or thiopurines. Antibiotic therapy decreased the risk of endoscopic recurrence of Crohn’s disease by about 50%, but long-term use is associated with peripheral neuropathy and disease usually recurs within 2 years of stopping treatment. Accordingly, the guidelines suggest using a nitroimidazole for only 3-12 months, and only in lower-risk patients who are concerned about the adverse effects of anti-TNF agents and thiopurines.

The AGA made a conditional recommendation against the prophylactic use of budesonide, probiotics, and 5-aminosalicylates such as mesalamine. Only low-quality evidence supports their efficacy after resection, and by using these agents, clinicians may inadvertently boost the risk of recurrence by forgoing better therapies, the guideline states.

The initial endoscopy should be timed for 6-12 months after resection, regardless of whether patients are receiving pharmacologic prophylaxis, the guideline states. If there is endoscopic recurrence, then anti-TNF or thiopurine therapy should be started or optimized.

In the Postoperative Crohn’s Endoscopic Recurrence (POCER) trial, endoscopic monitoring and treatment escalation in the face of endoscopic recurrence cut the risk of subsequent clinical and endoscopic recurrence by about 18% and 27%, respectively, compared with continuing the original treatment regimen. Most patients received azathioprine or adalimumab with 3 months of metronidazole postoperatively, so “even [those] who were already on postoperative prophylaxis benefited from endoscopic monitoring with colonoscopy at 6-12 months,” the guideline notes. However, patients who elect early prophylaxis after resection can reasonably forego colonoscopy if endoscopic recurrence is unlikely to affect their treatment plan, the AGA states. The guideline strongly recommends ongoing surveillance endoscopies if patients decide against early postresection prophylaxis, but notes a lack of evidence on how far to space out these procedures.

None of the authors had relevant financial disclosures.

Patients whose Crohn’s disease fully remits after resection should not wait for endoscopic recurrence to start tumor-necrosis-factor inhibitors or thiopurines, according to a new guideline from the American Gastroenterological Association.

Patients who are low risk or worried about side effects, however, “may reasonably select endoscopy-guided pharmacological treatment,” the guidelines state (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.038).

Early pharmacologic prophylaxis usually begins within 8 weeks of surgery, they noted. Whether this approach bests endoscopy-guided treatment is unclear: In one small trial (Gastroenterology. 2013;145[4]:766-74.e1), early azathioprine therapy failed to best endoscopy-guided therapy for preventing clinical or endoscopic recurrence.

Early prophylaxis, however, is usually reasonable because most Crohn’s patients who undergo surgery have at least one risk factor for recurrence, Dr. Nguyen and his associates emphasize. They suggest reserving endoscopy-guided therapy for patients who have real concerns about side effects and are at low risk, such as nonsmokers who were diagnosed within 10 years and have less than 10-20 cm of fibrostenotic disease.

For prophylaxis, a moderate amount of evidence supports anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents, thiopurines, or combined therapy over other agents, the guideline also states. In placebo-controlled clinical trials, anti-TNF therapy reduced the chances of clinical recurrence by 49% and endoscopic recurrence by 76%, while thiopurines cut these rates by 65% and 60%, respectively. Evidence favors anti-TNF agents over thiopurines for preventing recurrence, but it is of low quality, the guideline says. Furthermore, only indirect evidence supports combined therapy in patients at highest risk of recurrence.

Among the antibiotics, only nitroimidazoles such as metronidazole have been adequately studied, and they posted worse results than anti-TNF agents or thiopurines. Antibiotic therapy decreased the risk of endoscopic recurrence of Crohn’s disease by about 50%, but long-term use is associated with peripheral neuropathy and disease usually recurs within 2 years of stopping treatment. Accordingly, the guidelines suggest using a nitroimidazole for only 3-12 months, and only in lower-risk patients who are concerned about the adverse effects of anti-TNF agents and thiopurines.

The AGA made a conditional recommendation against the prophylactic use of budesonide, probiotics, and 5-aminosalicylates such as mesalamine. Only low-quality evidence supports their efficacy after resection, and by using these agents, clinicians may inadvertently boost the risk of recurrence by forgoing better therapies, the guideline states.

The initial endoscopy should be timed for 6-12 months after resection, regardless of whether patients are receiving pharmacologic prophylaxis, the guideline states. If there is endoscopic recurrence, then anti-TNF or thiopurine therapy should be started or optimized.

In the Postoperative Crohn’s Endoscopic Recurrence (POCER) trial, endoscopic monitoring and treatment escalation in the face of endoscopic recurrence cut the risk of subsequent clinical and endoscopic recurrence by about 18% and 27%, respectively, compared with continuing the original treatment regimen. Most patients received azathioprine or adalimumab with 3 months of metronidazole postoperatively, so “even [those] who were already on postoperative prophylaxis benefited from endoscopic monitoring with colonoscopy at 6-12 months,” the guideline notes. However, patients who elect early prophylaxis after resection can reasonably forego colonoscopy if endoscopic recurrence is unlikely to affect their treatment plan, the AGA states. The guideline strongly recommends ongoing surveillance endoscopies if patients decide against early postresection prophylaxis, but notes a lack of evidence on how far to space out these procedures.

None of the authors had relevant financial disclosures.

Patients whose Crohn’s disease fully remits after resection should not wait for endoscopic recurrence to start tumor-necrosis-factor inhibitors or thiopurines, according to a new guideline from the American Gastroenterological Association.

Patients who are low risk or worried about side effects, however, “may reasonably select endoscopy-guided pharmacological treatment,” the guidelines state (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.038).

Early pharmacologic prophylaxis usually begins within 8 weeks of surgery, they noted. Whether this approach bests endoscopy-guided treatment is unclear: In one small trial (Gastroenterology. 2013;145[4]:766-74.e1), early azathioprine therapy failed to best endoscopy-guided therapy for preventing clinical or endoscopic recurrence.

Early prophylaxis, however, is usually reasonable because most Crohn’s patients who undergo surgery have at least one risk factor for recurrence, Dr. Nguyen and his associates emphasize. They suggest reserving endoscopy-guided therapy for patients who have real concerns about side effects and are at low risk, such as nonsmokers who were diagnosed within 10 years and have less than 10-20 cm of fibrostenotic disease.

For prophylaxis, a moderate amount of evidence supports anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents, thiopurines, or combined therapy over other agents, the guideline also states. In placebo-controlled clinical trials, anti-TNF therapy reduced the chances of clinical recurrence by 49% and endoscopic recurrence by 76%, while thiopurines cut these rates by 65% and 60%, respectively. Evidence favors anti-TNF agents over thiopurines for preventing recurrence, but it is of low quality, the guideline says. Furthermore, only indirect evidence supports combined therapy in patients at highest risk of recurrence.

Among the antibiotics, only nitroimidazoles such as metronidazole have been adequately studied, and they posted worse results than anti-TNF agents or thiopurines. Antibiotic therapy decreased the risk of endoscopic recurrence of Crohn’s disease by about 50%, but long-term use is associated with peripheral neuropathy and disease usually recurs within 2 years of stopping treatment. Accordingly, the guidelines suggest using a nitroimidazole for only 3-12 months, and only in lower-risk patients who are concerned about the adverse effects of anti-TNF agents and thiopurines.

The AGA made a conditional recommendation against the prophylactic use of budesonide, probiotics, and 5-aminosalicylates such as mesalamine. Only low-quality evidence supports their efficacy after resection, and by using these agents, clinicians may inadvertently boost the risk of recurrence by forgoing better therapies, the guideline states.

The initial endoscopy should be timed for 6-12 months after resection, regardless of whether patients are receiving pharmacologic prophylaxis, the guideline states. If there is endoscopic recurrence, then anti-TNF or thiopurine therapy should be started or optimized.

In the Postoperative Crohn’s Endoscopic Recurrence (POCER) trial, endoscopic monitoring and treatment escalation in the face of endoscopic recurrence cut the risk of subsequent clinical and endoscopic recurrence by about 18% and 27%, respectively, compared with continuing the original treatment regimen. Most patients received azathioprine or adalimumab with 3 months of metronidazole postoperatively, so “even [those] who were already on postoperative prophylaxis benefited from endoscopic monitoring with colonoscopy at 6-12 months,” the guideline notes. However, patients who elect early prophylaxis after resection can reasonably forego colonoscopy if endoscopic recurrence is unlikely to affect their treatment plan, the AGA states. The guideline strongly recommends ongoing surveillance endoscopies if patients decide against early postresection prophylaxis, but notes a lack of evidence on how far to space out these procedures.

None of the authors had relevant financial disclosures.

One in three older adults with epilepsy has poor adherence to antiepileptics

HOUSTON – One in three older Americans with epilepsy had poor adherence to antiepileptic drugs, according to a large retrospective study, and the numbers were even worse for members of minority populations.

In an analysis of Medicare claims, patients who were African American had an odds ratio of 1.56 (95% confidence interval, 1.46-1.68) for being non-adherent to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). For Hispanic patients, the OR was 1.40 (95% CI, 1.28-1.54), while for Asians, the OR was 1.41 (95% CI, 1.25-1.54).

“Overall, 31.8% were non-adherent to AEDs; range was from 24.1% for whites to 34.3% for African Americans,” wrote Maria Pisu, PhD, and her collaborators in an abstract accompanying the poster presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

The reasons for poor adherence are unknown, but warrant further investigation, said Dr. Pisu of the division of preventive medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The sample included 36,912 patients with epilepsy. In the enhanced sample, 19.2% of patients were white, 62.5% were African American, 11.3% were Hispanic, 5.0% were Asian, and 2.0% were American Indian or Alaskan Native. Of the sample, 61.6% were female; 41.5% of patients were aged 66-74 years; 36.1% were aged 75-84 years; and 22.4% were 85 years or older.

In order to determine whether patients with epilepsy or seizures were adherent, investigators looked at the ratio of days that at least one AED prescription was in the database for a given patient, divided by the total days of follow-up on record (“proportion of days covered”). The primary outcome measure of nonadherence was defined as a proportion of days covered of less than 0.80.

Most patients had one to several comorbidities: only 8.3% had no other comorbidities, while 46.0% had more than four. The remainder fell somewhere in the middle.

A majority of patients (59.2%) had some form of copay or coinsurance for prescriptions. About half of patients (50.2%) lived in the South.

Through multivariable analysis, the investigators explored the relationships between nonadherence and race or ethnicity, demographics, geographic area of residence, comorbidities, and whether the prescribed AEDs were enzyme-inducing. Additionally, socioeconomic status was estimated by factoring in eligibility for Medicare Part D low income subsidies and using zip code–level poverty data.

The differences between ethnic groups, wrote Dr. Pisu, were significant “after accounting for several factors that affect prescription-taking factors, e.g., economic constraints,” so it was not just low socioeconomic status that accounted for the discrepancy.

The retrospective claims-based study was limited by several factors, wrote Dr. Pisu and her colleagues. True adherence is difficult to quantify, and may be overestimated by measuring filled prescriptions; on the other hand, some patients may have had other insurance coverage, and obtained medication through a means not captured in the study. Finally, dose adjustments may mean patients can “stretch” medications, thereby remaining adherent without refilling prescriptions.

Still, the study shows that nonadherence is pervasive among older Americans with epilepsy, with worse adherence among members of minority populations. “Interventions to promote adherence are important. These should account for the impact of drug cost-sharing and socioeconomic status on epilepsy treatment,” wrote Dr. Pisu.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Pisu reported no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – One in three older Americans with epilepsy had poor adherence to antiepileptic drugs, according to a large retrospective study, and the numbers were even worse for members of minority populations.

In an analysis of Medicare claims, patients who were African American had an odds ratio of 1.56 (95% confidence interval, 1.46-1.68) for being non-adherent to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). For Hispanic patients, the OR was 1.40 (95% CI, 1.28-1.54), while for Asians, the OR was 1.41 (95% CI, 1.25-1.54).

“Overall, 31.8% were non-adherent to AEDs; range was from 24.1% for whites to 34.3% for African Americans,” wrote Maria Pisu, PhD, and her collaborators in an abstract accompanying the poster presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

The reasons for poor adherence are unknown, but warrant further investigation, said Dr. Pisu of the division of preventive medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The sample included 36,912 patients with epilepsy. In the enhanced sample, 19.2% of patients were white, 62.5% were African American, 11.3% were Hispanic, 5.0% were Asian, and 2.0% were American Indian or Alaskan Native. Of the sample, 61.6% were female; 41.5% of patients were aged 66-74 years; 36.1% were aged 75-84 years; and 22.4% were 85 years or older.

In order to determine whether patients with epilepsy or seizures were adherent, investigators looked at the ratio of days that at least one AED prescription was in the database for a given patient, divided by the total days of follow-up on record (“proportion of days covered”). The primary outcome measure of nonadherence was defined as a proportion of days covered of less than 0.80.

Most patients had one to several comorbidities: only 8.3% had no other comorbidities, while 46.0% had more than four. The remainder fell somewhere in the middle.

A majority of patients (59.2%) had some form of copay or coinsurance for prescriptions. About half of patients (50.2%) lived in the South.

Through multivariable analysis, the investigators explored the relationships between nonadherence and race or ethnicity, demographics, geographic area of residence, comorbidities, and whether the prescribed AEDs were enzyme-inducing. Additionally, socioeconomic status was estimated by factoring in eligibility for Medicare Part D low income subsidies and using zip code–level poverty data.

The differences between ethnic groups, wrote Dr. Pisu, were significant “after accounting for several factors that affect prescription-taking factors, e.g., economic constraints,” so it was not just low socioeconomic status that accounted for the discrepancy.

The retrospective claims-based study was limited by several factors, wrote Dr. Pisu and her colleagues. True adherence is difficult to quantify, and may be overestimated by measuring filled prescriptions; on the other hand, some patients may have had other insurance coverage, and obtained medication through a means not captured in the study. Finally, dose adjustments may mean patients can “stretch” medications, thereby remaining adherent without refilling prescriptions.

Still, the study shows that nonadherence is pervasive among older Americans with epilepsy, with worse adherence among members of minority populations. “Interventions to promote adherence are important. These should account for the impact of drug cost-sharing and socioeconomic status on epilepsy treatment,” wrote Dr. Pisu.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Pisu reported no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – One in three older Americans with epilepsy had poor adherence to antiepileptic drugs, according to a large retrospective study, and the numbers were even worse for members of minority populations.

In an analysis of Medicare claims, patients who were African American had an odds ratio of 1.56 (95% confidence interval, 1.46-1.68) for being non-adherent to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). For Hispanic patients, the OR was 1.40 (95% CI, 1.28-1.54), while for Asians, the OR was 1.41 (95% CI, 1.25-1.54).

“Overall, 31.8% were non-adherent to AEDs; range was from 24.1% for whites to 34.3% for African Americans,” wrote Maria Pisu, PhD, and her collaborators in an abstract accompanying the poster presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

The reasons for poor adherence are unknown, but warrant further investigation, said Dr. Pisu of the division of preventive medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The sample included 36,912 patients with epilepsy. In the enhanced sample, 19.2% of patients were white, 62.5% were African American, 11.3% were Hispanic, 5.0% were Asian, and 2.0% were American Indian or Alaskan Native. Of the sample, 61.6% were female; 41.5% of patients were aged 66-74 years; 36.1% were aged 75-84 years; and 22.4% were 85 years or older.

In order to determine whether patients with epilepsy or seizures were adherent, investigators looked at the ratio of days that at least one AED prescription was in the database for a given patient, divided by the total days of follow-up on record (“proportion of days covered”). The primary outcome measure of nonadherence was defined as a proportion of days covered of less than 0.80.

Most patients had one to several comorbidities: only 8.3% had no other comorbidities, while 46.0% had more than four. The remainder fell somewhere in the middle.

A majority of patients (59.2%) had some form of copay or coinsurance for prescriptions. About half of patients (50.2%) lived in the South.

Through multivariable analysis, the investigators explored the relationships between nonadherence and race or ethnicity, demographics, geographic area of residence, comorbidities, and whether the prescribed AEDs were enzyme-inducing. Additionally, socioeconomic status was estimated by factoring in eligibility for Medicare Part D low income subsidies and using zip code–level poverty data.

The differences between ethnic groups, wrote Dr. Pisu, were significant “after accounting for several factors that affect prescription-taking factors, e.g., economic constraints,” so it was not just low socioeconomic status that accounted for the discrepancy.

The retrospective claims-based study was limited by several factors, wrote Dr. Pisu and her colleagues. True adherence is difficult to quantify, and may be overestimated by measuring filled prescriptions; on the other hand, some patients may have had other insurance coverage, and obtained medication through a means not captured in the study. Finally, dose adjustments may mean patients can “stretch” medications, thereby remaining adherent without refilling prescriptions.

Still, the study shows that nonadherence is pervasive among older Americans with epilepsy, with worse adherence among members of minority populations. “Interventions to promote adherence are important. These should account for the impact of drug cost-sharing and socioeconomic status on epilepsy treatment,” wrote Dr. Pisu.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Pisu reported no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: For African-American patients, the odds ratio was 1.56 for being nonadherent (95% CI, 1.4-1.68).

Data source: Retrospective analysis of Medicare administrative claims data from 2008 to 2010, examining a 5% sample of patients with epilepsy aged 66 and over, and including all members of racial/ethnic minority populations who had claims for diagnoses of seizures or epilepsy.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Pisu reported no relevant financial disclosures.

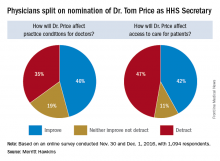

Trump HHS nominee could curb regulations, reshape health insurance

Opinions are mixed on what the nominations of Rep. Tom Price (R-Ga.) as Secretary of Health & Human Services will mean for medicine and health care.

An orthopedic surgeon and six-term congressman, Dr. Price is an outspoken critic of the Affordable Care Act and has sponsored or cosponsored numerous bills to replace it. President-elect Trump called Rep. Price “a renowned physician” who has “earned a reputation for being a tireless problem solver and the go-to expert on health care policy,” according to a statement.

Not everyone agrees.

But Adam Gaffney, MD, a pulmonologist at the Cambridge (Mass.) Health Alliance, said physicians’ ability to care for their patients would be compromised if Rep. Price succeeds with many of his proposals, such as the privatization of Medicare and block grants for Medicaid.

“If these reforms go through, we’re going to see the insurance protections of our patients get worse,” said Dr. Gaffney, a board member for Physicians for a National Health Program, which advocates for a single-payer health care system. “If [his] agenda is successful, I think it’s going to have a detrimental impact on our ability to provide the care that our patients need.”

ACA repeal, malpractice reform

In the House, Rep. Price has introduced the Empowering Patients First Act, legislation, which would allow doctors to opt out of Medicare and enter into private contracts with Medicare patients. The bill is seen by many as a potential blueprint for Trump administration health reform. Rep. Price is also a proponent of malpractice reform that would make it tougher for patients to sue doctors and would lower liability insurance premiums.

The Empowering Patients First Act would repeal the ACA and offer tax credits for the purchase of individual and family health insurance policies. It would also create incentives for patients to contribute to health savings accounts, offer state grants to subsidize coverage for high-risk patients, and authorize businesses to cover members through association health plans.

The American Medical Association praised Rep. Price’s nomination, expressing support for ability to lead HHS.

“Dr. Price has been a leader in the development of health policies to advance patient choice and market-based solutions as well as reduce excessive regulatory burdens that diminish time devoted to patient care and increase costs,” AMA Board of Trustees Chair Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in a statement.

The American College of Surgeons' Executive Director, David B. Hoyt, MD, FACS, issued a supportive statement about the nomination of Dr. Price. "“Dr. Price is a stalwart champion for patients and their surgeons, and the ACS looks forward to working with him on key issues, such as the implementation of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act,” said Dr. Hoyt in a statement. “The ACS encourages the Senate to swiftly confirm Dr. Price’s nomination as Secretary of HHS."

But thousands of physicians disagree. Rep. Price’s proposals on Medicaid and Medicare threaten to harm vulnerable patients and limit access to healthcare, according to an open letter to the AMA published on Medium and credited to Clinician Action Network, a nonpartisan group that supports evidence-based policies. The group was started in opposition to the nomination of Rep. Price.

“We cannot support the dismantling of Medicaid, which has helped 15 million Americans gain health coverage since 2014,” the letter states. “We oppose Dr. Price’s proposals to reduce funding for the Children’s Health Insurance Program, a critical mechanism by which poor children access preventative care.”

Value-based payment or fee for service?

Rep. Price’s experience as a physician fuels his efforts to reduce burdensome regulations for doctors and enhance care efficiency, according to one of his predecessors, Louis W. Sullivan, MD. If confirmed, Rep. Price will become the third physician to be HHS secretary; Dr. Sullivan served in the George H.W. Bush administration and Otis R. Bowen, MD, served in the Reagan administration.

“He is very much aware of the challenges that physicians face in trying to delivery care,” said Dr. Sullivan. “I know that he’ll be working to reduce regulation when feasible so that the cost and delays that some regulatory issues present will hopefully be relieved,”

Some of those regulatory modifications could affect value-based care programs, Dr. Rodriguez said. Rep. Price has been critical of the move from fee for service to quality-based care and has opposed some corresponding programs, such as bundled payment initiatives. Rep. Price and members of the GOP Doctors Caucus wrote to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in October to protest the regulations to implement the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) as too burdensome for smaller practices and calling for flexibility in quality reporting.

Rep. Price voted for passage of MACRA.

“He has been cautious about some of the changes that are being promoted in health care,” Dr. Rodriguez said. “He could slow that down – the processes being put in place. That might delay the impact those systems have in bringing about the improved quality that we want. [This would be] enormous, given the amount of work that we’ve been doing.”

A fair medical liability system also is a priority for Rep. Price, Dr. Sullivan said. His Empowering Patients First bill would require collaboration between HHS and physician associations to develop best practice guidelines that would provide a litigation safe harbor to physicians who practiced in accordance with the standards.

“I know that he will be working to develop strategies to reduce litigation in the health space,” Dr. Sullivan said in an interview. “That is one of the challenges that adds to health care costs, adds tension, and enhances an adversarial relationship between physicians and patients.”

But Dr. Gaffney said that he believes Rep. Price’s views on reproductive rights and gay marriage are regressive and that his agenda regarding health policy issues is bad for medicine.

“The overall [theme] of that agenda can be summed up as ‘take from the poor and sick and give to the rich,’ ” Dr. Gaffney said in an interview. “I think the financing of this [new health reform] system will be much more aggressive, and the result will be greater health care inequity.”

Rep. Price also has supported a ban on federal funding for Planned Parenthood, calling some of their practices barbaric. He has also voted to prohibit the importation of prescription drugs by nonsanctioned importers and has voted to repeal the medical device excise tax.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Opinions are mixed on what the nominations of Rep. Tom Price (R-Ga.) as Secretary of Health & Human Services will mean for medicine and health care.

An orthopedic surgeon and six-term congressman, Dr. Price is an outspoken critic of the Affordable Care Act and has sponsored or cosponsored numerous bills to replace it. President-elect Trump called Rep. Price “a renowned physician” who has “earned a reputation for being a tireless problem solver and the go-to expert on health care policy,” according to a statement.

Not everyone agrees.

But Adam Gaffney, MD, a pulmonologist at the Cambridge (Mass.) Health Alliance, said physicians’ ability to care for their patients would be compromised if Rep. Price succeeds with many of his proposals, such as the privatization of Medicare and block grants for Medicaid.

“If these reforms go through, we’re going to see the insurance protections of our patients get worse,” said Dr. Gaffney, a board member for Physicians for a National Health Program, which advocates for a single-payer health care system. “If [his] agenda is successful, I think it’s going to have a detrimental impact on our ability to provide the care that our patients need.”

ACA repeal, malpractice reform

In the House, Rep. Price has introduced the Empowering Patients First Act, legislation, which would allow doctors to opt out of Medicare and enter into private contracts with Medicare patients. The bill is seen by many as a potential blueprint for Trump administration health reform. Rep. Price is also a proponent of malpractice reform that would make it tougher for patients to sue doctors and would lower liability insurance premiums.

The Empowering Patients First Act would repeal the ACA and offer tax credits for the purchase of individual and family health insurance policies. It would also create incentives for patients to contribute to health savings accounts, offer state grants to subsidize coverage for high-risk patients, and authorize businesses to cover members through association health plans.

The American Medical Association praised Rep. Price’s nomination, expressing support for ability to lead HHS.

“Dr. Price has been a leader in the development of health policies to advance patient choice and market-based solutions as well as reduce excessive regulatory burdens that diminish time devoted to patient care and increase costs,” AMA Board of Trustees Chair Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in a statement.

The American College of Surgeons' Executive Director, David B. Hoyt, MD, FACS, issued a supportive statement about the nomination of Dr. Price. "“Dr. Price is a stalwart champion for patients and their surgeons, and the ACS looks forward to working with him on key issues, such as the implementation of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act,” said Dr. Hoyt in a statement. “The ACS encourages the Senate to swiftly confirm Dr. Price’s nomination as Secretary of HHS."

But thousands of physicians disagree. Rep. Price’s proposals on Medicaid and Medicare threaten to harm vulnerable patients and limit access to healthcare, according to an open letter to the AMA published on Medium and credited to Clinician Action Network, a nonpartisan group that supports evidence-based policies. The group was started in opposition to the nomination of Rep. Price.

“We cannot support the dismantling of Medicaid, which has helped 15 million Americans gain health coverage since 2014,” the letter states. “We oppose Dr. Price’s proposals to reduce funding for the Children’s Health Insurance Program, a critical mechanism by which poor children access preventative care.”

Value-based payment or fee for service?

Rep. Price’s experience as a physician fuels his efforts to reduce burdensome regulations for doctors and enhance care efficiency, according to one of his predecessors, Louis W. Sullivan, MD. If confirmed, Rep. Price will become the third physician to be HHS secretary; Dr. Sullivan served in the George H.W. Bush administration and Otis R. Bowen, MD, served in the Reagan administration.

“He is very much aware of the challenges that physicians face in trying to delivery care,” said Dr. Sullivan. “I know that he’ll be working to reduce regulation when feasible so that the cost and delays that some regulatory issues present will hopefully be relieved,”

Some of those regulatory modifications could affect value-based care programs, Dr. Rodriguez said. Rep. Price has been critical of the move from fee for service to quality-based care and has opposed some corresponding programs, such as bundled payment initiatives. Rep. Price and members of the GOP Doctors Caucus wrote to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in October to protest the regulations to implement the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) as too burdensome for smaller practices and calling for flexibility in quality reporting.

Rep. Price voted for passage of MACRA.

“He has been cautious about some of the changes that are being promoted in health care,” Dr. Rodriguez said. “He could slow that down – the processes being put in place. That might delay the impact those systems have in bringing about the improved quality that we want. [This would be] enormous, given the amount of work that we’ve been doing.”

A fair medical liability system also is a priority for Rep. Price, Dr. Sullivan said. His Empowering Patients First bill would require collaboration between HHS and physician associations to develop best practice guidelines that would provide a litigation safe harbor to physicians who practiced in accordance with the standards.

“I know that he will be working to develop strategies to reduce litigation in the health space,” Dr. Sullivan said in an interview. “That is one of the challenges that adds to health care costs, adds tension, and enhances an adversarial relationship between physicians and patients.”

But Dr. Gaffney said that he believes Rep. Price’s views on reproductive rights and gay marriage are regressive and that his agenda regarding health policy issues is bad for medicine.

“The overall [theme] of that agenda can be summed up as ‘take from the poor and sick and give to the rich,’ ” Dr. Gaffney said in an interview. “I think the financing of this [new health reform] system will be much more aggressive, and the result will be greater health care inequity.”

Rep. Price also has supported a ban on federal funding for Planned Parenthood, calling some of their practices barbaric. He has also voted to prohibit the importation of prescription drugs by nonsanctioned importers and has voted to repeal the medical device excise tax.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Opinions are mixed on what the nominations of Rep. Tom Price (R-Ga.) as Secretary of Health & Human Services will mean for medicine and health care.

An orthopedic surgeon and six-term congressman, Dr. Price is an outspoken critic of the Affordable Care Act and has sponsored or cosponsored numerous bills to replace it. President-elect Trump called Rep. Price “a renowned physician” who has “earned a reputation for being a tireless problem solver and the go-to expert on health care policy,” according to a statement.

Not everyone agrees.

But Adam Gaffney, MD, a pulmonologist at the Cambridge (Mass.) Health Alliance, said physicians’ ability to care for their patients would be compromised if Rep. Price succeeds with many of his proposals, such as the privatization of Medicare and block grants for Medicaid.

“If these reforms go through, we’re going to see the insurance protections of our patients get worse,” said Dr. Gaffney, a board member for Physicians for a National Health Program, which advocates for a single-payer health care system. “If [his] agenda is successful, I think it’s going to have a detrimental impact on our ability to provide the care that our patients need.”

ACA repeal, malpractice reform

In the House, Rep. Price has introduced the Empowering Patients First Act, legislation, which would allow doctors to opt out of Medicare and enter into private contracts with Medicare patients. The bill is seen by many as a potential blueprint for Trump administration health reform. Rep. Price is also a proponent of malpractice reform that would make it tougher for patients to sue doctors and would lower liability insurance premiums.

The Empowering Patients First Act would repeal the ACA and offer tax credits for the purchase of individual and family health insurance policies. It would also create incentives for patients to contribute to health savings accounts, offer state grants to subsidize coverage for high-risk patients, and authorize businesses to cover members through association health plans.

The American Medical Association praised Rep. Price’s nomination, expressing support for ability to lead HHS.

“Dr. Price has been a leader in the development of health policies to advance patient choice and market-based solutions as well as reduce excessive regulatory burdens that diminish time devoted to patient care and increase costs,” AMA Board of Trustees Chair Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in a statement.

The American College of Surgeons' Executive Director, David B. Hoyt, MD, FACS, issued a supportive statement about the nomination of Dr. Price. "“Dr. Price is a stalwart champion for patients and their surgeons, and the ACS looks forward to working with him on key issues, such as the implementation of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act,” said Dr. Hoyt in a statement. “The ACS encourages the Senate to swiftly confirm Dr. Price’s nomination as Secretary of HHS."

But thousands of physicians disagree. Rep. Price’s proposals on Medicaid and Medicare threaten to harm vulnerable patients and limit access to healthcare, according to an open letter to the AMA published on Medium and credited to Clinician Action Network, a nonpartisan group that supports evidence-based policies. The group was started in opposition to the nomination of Rep. Price.

“We cannot support the dismantling of Medicaid, which has helped 15 million Americans gain health coverage since 2014,” the letter states. “We oppose Dr. Price’s proposals to reduce funding for the Children’s Health Insurance Program, a critical mechanism by which poor children access preventative care.”

Value-based payment or fee for service?

Rep. Price’s experience as a physician fuels his efforts to reduce burdensome regulations for doctors and enhance care efficiency, according to one of his predecessors, Louis W. Sullivan, MD. If confirmed, Rep. Price will become the third physician to be HHS secretary; Dr. Sullivan served in the George H.W. Bush administration and Otis R. Bowen, MD, served in the Reagan administration.

“He is very much aware of the challenges that physicians face in trying to delivery care,” said Dr. Sullivan. “I know that he’ll be working to reduce regulation when feasible so that the cost and delays that some regulatory issues present will hopefully be relieved,”

Some of those regulatory modifications could affect value-based care programs, Dr. Rodriguez said. Rep. Price has been critical of the move from fee for service to quality-based care and has opposed some corresponding programs, such as bundled payment initiatives. Rep. Price and members of the GOP Doctors Caucus wrote to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in October to protest the regulations to implement the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) as too burdensome for smaller practices and calling for flexibility in quality reporting.

Rep. Price voted for passage of MACRA.

“He has been cautious about some of the changes that are being promoted in health care,” Dr. Rodriguez said. “He could slow that down – the processes being put in place. That might delay the impact those systems have in bringing about the improved quality that we want. [This would be] enormous, given the amount of work that we’ve been doing.”

A fair medical liability system also is a priority for Rep. Price, Dr. Sullivan said. His Empowering Patients First bill would require collaboration between HHS and physician associations to develop best practice guidelines that would provide a litigation safe harbor to physicians who practiced in accordance with the standards.

“I know that he will be working to develop strategies to reduce litigation in the health space,” Dr. Sullivan said in an interview. “That is one of the challenges that adds to health care costs, adds tension, and enhances an adversarial relationship between physicians and patients.”

But Dr. Gaffney said that he believes Rep. Price’s views on reproductive rights and gay marriage are regressive and that his agenda regarding health policy issues is bad for medicine.

“The overall [theme] of that agenda can be summed up as ‘take from the poor and sick and give to the rich,’ ” Dr. Gaffney said in an interview. “I think the financing of this [new health reform] system will be much more aggressive, and the result will be greater health care inequity.”

Rep. Price also has supported a ban on federal funding for Planned Parenthood, calling some of their practices barbaric. He has also voted to prohibit the importation of prescription drugs by nonsanctioned importers and has voted to repeal the medical device excise tax.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Aspirin use linked to increased ICH in trauma patients

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – Among a group of anticoagulated trauma patients, those on aspirin had the highest rate and risk of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), while those on novel oral anticoagulants were not at higher risk for ICH, ICH progression, or death, a multicenter study found.

“The number of patients on warfarin and antiplatelet agents has significantly increased over time,” Leslie Kobayashi, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. “These oral antithrombotic agents have been associated with poor outcomes following traumatic injury, including increased rates of intracranial hemorrhage, increased progression of intracranial hemorrhage, and increased mortality.”

In a prospective, multicenter observational study conducted by the AAST’s Multi-institutional Trials Committee, Dr. Kobayashi and her associates set out identify injury patterns and outcomes in trauma patients taking the NOAs, and to test their hypothesis that patients taking NOAs would have higher rates of ICH, ICH progression, and death, compared with patients taking traditional oral anticoagulant therapies (OATs). Patients were included if they were admitted to the trauma service on warfarin, aspirin, clopidogrel, dabigatran, apixaban, or rivaroxaban. Pregnant patients, prisoners, and minors were excluded from the study. Data collected included demographics, mechanism of injury, vitals on admission, injuries/injury severity scores, labs, interventions, and reversal agents used such as vitamin K, prothrombin complexes, dialysis, and transfusion of fresh frozen plasma (FFP). Outcomes studied included ICH, ICH progression, and death.

In all, 16 Level 1 trauma centers enrolled 1,847 patients over a 2-year period. Their average age was 75 years, 46% were female, 77% were white, their median Injury Severity Score (ISS) was 9, and 99% sustained a blunt mechanism of trauma. The top two causes of injury were falls (71%) and motor vehicle crashes (15%). One-third of patients (33%) were on warfarin, while the remainder were on aspirin (26%), clopidogrel (24%), NOAs (10%), and 7% took multiple or other agents.

The mechanism of injury pattern was similar between patients taking NOAs and those taking OATs, with the exception of patients on aspirin being significantly less likely to have sustained a fall. Patients on aspirin also had a significantly higher median ISS. “Patients on NOAs presented more frequently in shock as defined by a systolic blood pressure of less than 90 mmHg, but this was not associated with increased need for packed red blood cell transfusion, bleeding requiring an intervention, need for surgical procedure, hospital LOS, complications, or death,” Dr. Kobayashi said.

About 30% of all patients studied underwent an attempt at reversal. The types of agents used to reverse the patients differed depending on drug agent, with antiplatelet patients more frequently getting platelets, and patients on warfarin more frequently receiving FFP, vitamin K, and prothrombin complex. “Interestingly, patients on the anti-Xa inhibitors more frequently received prothrombin complex as well,” she said. “This likely reflects some of the recent literature which suggests that there may be a therapeutic benefit to using prothrombin complex in patients taking the oral anti-Xa inhibitors but not in patients on dabigatran.”

Overall, bleeding, need for surgical procedure, need for neurosurgical procedure, complications, length of stay, and death were similar between those on NOAs and those on OATs. However, the rate of ICH was significantly higher in patients on aspirin. “What is even more surprising is that 89% of the patients in the aspirin-only group were on an 81-mg baby aspirin rather than the larger 325-mg dose,” Dr. Kobayashi said. This difference was significant on univariate analysis and was retained after multivariate logistic regression adjusted for differences between populations, with an OR for aspirin of 1.7 and a P value of .024. “This is not to suggest that patients on aspirin are doing markedly worse, compared to their counterparts, but I think most of us would have assumed that aspirin patients would have done better,” she commented. “I think we’ve definitively shown that is not the case.” Other independent predictors of ICH were advanced age (OR, 1.02), Asian race (OR, 3.1), ISS of 10 or greater (OR, 2.2), and a Glasgow coma score (GCS) of 8 or less (OR, 5.6).

Despite their increased risk for ICH, patients on aspirin were significantly less likely to undergo an attempt at reversal with any type of agent, at 16% with a P value of less than .001, on univariate analysis. “This was significantly lower than all other medications and was retained after multivariate logistic regression, with an OR of 0.3 and a P value of less than .001,” she said.

Progression of ICH did not differ by medication group. Other independent predictors included intraparenchymal location of hemorrhage (OR, 2.2), need for a neurosurgical procedure (OR, 5.1), an attempt at reversal (OR, 2.3) and a GCS of 8 or lower at admission (OR, 4.3). Similarly, multivariate analysis of death showed no significant differences between the different medication groups. Independent predictors included advanced age (OR, 1.06), GCS of 8 or less (OR, 13), progression of head injury (OR, 10), bleeding (OR, 2.3), and complications (OR, 2.1).

Dr. Kobayashi acknowledged that the study’s observational design is a limitation, as well as the fact that it lacked a control group of age-matched patients who were not taking anticoagulants. “Additionally, we had a relatively low number of patients on NOAs, at only 10% of the study population,” she said. “Lastly, there is potential for enrollment bias as all sites involved in this study were level one trauma centers.” She reported having no financial disclosures.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – Among a group of anticoagulated trauma patients, those on aspirin had the highest rate and risk of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), while those on novel oral anticoagulants were not at higher risk for ICH, ICH progression, or death, a multicenter study found.

“The number of patients on warfarin and antiplatelet agents has significantly increased over time,” Leslie Kobayashi, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. “These oral antithrombotic agents have been associated with poor outcomes following traumatic injury, including increased rates of intracranial hemorrhage, increased progression of intracranial hemorrhage, and increased mortality.”

In a prospective, multicenter observational study conducted by the AAST’s Multi-institutional Trials Committee, Dr. Kobayashi and her associates set out identify injury patterns and outcomes in trauma patients taking the NOAs, and to test their hypothesis that patients taking NOAs would have higher rates of ICH, ICH progression, and death, compared with patients taking traditional oral anticoagulant therapies (OATs). Patients were included if they were admitted to the trauma service on warfarin, aspirin, clopidogrel, dabigatran, apixaban, or rivaroxaban. Pregnant patients, prisoners, and minors were excluded from the study. Data collected included demographics, mechanism of injury, vitals on admission, injuries/injury severity scores, labs, interventions, and reversal agents used such as vitamin K, prothrombin complexes, dialysis, and transfusion of fresh frozen plasma (FFP). Outcomes studied included ICH, ICH progression, and death.

In all, 16 Level 1 trauma centers enrolled 1,847 patients over a 2-year period. Their average age was 75 years, 46% were female, 77% were white, their median Injury Severity Score (ISS) was 9, and 99% sustained a blunt mechanism of trauma. The top two causes of injury were falls (71%) and motor vehicle crashes (15%). One-third of patients (33%) were on warfarin, while the remainder were on aspirin (26%), clopidogrel (24%), NOAs (10%), and 7% took multiple or other agents.

The mechanism of injury pattern was similar between patients taking NOAs and those taking OATs, with the exception of patients on aspirin being significantly less likely to have sustained a fall. Patients on aspirin also had a significantly higher median ISS. “Patients on NOAs presented more frequently in shock as defined by a systolic blood pressure of less than 90 mmHg, but this was not associated with increased need for packed red blood cell transfusion, bleeding requiring an intervention, need for surgical procedure, hospital LOS, complications, or death,” Dr. Kobayashi said.