User login

-

EMA Greenlights Four Drugs for Bladder and Other Cancers

Balversa

The CHMP endorsed the approval of Balversa (erdafitinib, Janssen-Cilag International N.V.), intended for the treatment of urothelial carcinoma, a type of cancer affecting the bladder and urinary system.

As a monotherapy, Balversa is indicated for the treatment of adult patients with unresectable or metastatic urothelial carcinoma harboring susceptible FGFR3 genetic alterations. These patients must have previously received at least one line of therapy containing a programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) or programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitor in the unresectable or metastatic treatment setting.

Urothelial carcinoma is the most common form of bladder cancer, the ninth most frequently diagnosed cancer worldwide. In 2022, there were approximately 614,000 new cases of bladder cancer and 220,000 deaths globally.

The highest incidence rates in both men and women are found in Southern Europe. Greece had 5800 new cases and 1537 deaths in 2018. Spain has the highest incidence rate in men globally. Since the 1990s, bladder cancer incidence trends have diverged by sex, with rates decreasing or stabilizing in men but increasing among women in certain European countries.

The CHMP recommendation is based on data from cohort 1 of the phase 3 THOR trial, which compared erdafitinib with standard-of-care chemotherapy (investigator’s choice of docetaxel or vinflunine). Cohort 1 included 266 adults with advanced urothelial cancer harboring selected FGFR3 alterations.

All patients had disease progression after one or two prior treatments, at least one of which included a PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitor. The major efficacy endpoints were overall survival, progression free survival, and objective response rate (ORR).

Treatment with erdafitinib reduced the risk for death by 36% compared with chemotherapy (hazard ratio [HR], 0.64; P = .005). Median overall survival was 12.1 months in the erdafitinib arm vs 7.8 months in the chemotherapy arm. Median progression-free survival was 5.6 months in the erdafitinib arm vs 2.7 months in the chemotherapy arm (HR, 0.58; P = .0002). ORR was 35.3% with erdafitinib compared with 8.5% with chemotherapy.

Balversa will be available as 3-mg, 4-mg, and 5-mg film-coated tablets. Erdafitinib, the active substance in Balversa, is an antineoplastic protein kinase inhibitor that suppresses fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) tyrosine kinases. Deregulation of FGFR3 signaling is implicated in the pathogenesis of urothelial cancer, and FGFR inhibition has demonstrated antitumor activity in FGFR-expressing cells.

Ordspono

The committee adopted a positive opinion for Ordspono (odronextamab, Regeneron Ireland Designated Activity Company), indicated as a monotherapy for the treatment of adult patients with:

- Relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma (rrFL), after two or more lines of systemic therapy.

- Relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (rrDLBCL), after two or more lines of systemic therapy.

The approval recommendation is based on phase 2 trials (NCT02290951, NCT03888105), which demonstrated high ORRs in patients with rrFL and rrDLBCL.

In the DLBCL cohort, a 49% ORR was achieved in heavily pretreated patients who had not received chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. A total of 31% achieved a complete response.

The FL cohort showed an 82% response rate in patients with grades I-IIIA disease, with 75% of the overall population achieving a complete response.

Ordspono will be available as a 2-mg, 80-mg, and 320-mg concentrate for solution for infusion. The active substance of Ordspono is odronextamab, a bispecific antibody that targets CD20-expressing B cells and CD3-expressing T cells. By binding to both, it induces T-cell activation and generates a polyclonal cytotoxic T-cell response, leading to the lysis of malignant B cells.

Generics

The panel also adopted positive opinions for two generic cancer medicines.

Enzalutamide Viatris (enzalutamide) is indicated for the treatment of adult men with prostate cancer in several scenarios:

- As monotherapy or with androgen-deprivation therapy for high-risk biochemical recurrent nonmetastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer in men unsuitable for salvage-radiotherapy.

- In combination with androgen-deprivation therapy for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer.

- For high-risk nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC).

- For metastatic CRPC in men who are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic after failure of androgen-deprivation therapy, where chemotherapy is not yet indicated.

- For metastatic CRPC in men whose disease has progressed on or after docetaxel therapy.

Enzalutamide Viatris is a generic version of Xtandi, authorized in the European Union since June 2013. Studies have confirmed the satisfactory quality and bioequivalence of Enzalutamide Viatris to Xtandi.

Enzalutamide Viatris will be available as 40-mg and 80-mg film-coated tablets. The active substance of Enzalutamide Viatris is enzalutamide, a hormone antagonist that blocks multiple steps in the androgen receptor–signaling pathway.

Nilotinib Accord (nilotinib) is indicated for the treatment of Philadelphia chromosome–positive chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML).

It is used in adult and pediatric patients with newly diagnosed CML in the chronic phase, adult patients with chronic phase and accelerated phase CML with resistance or intolerance to prior therapy including imatinib, and pediatric patients with CML with resistance or intolerance to prior therapy including imatinib.

Nilotinib Accord is a generic of Tasigna, authorized in the European Union since November 2007. Studies have demonstrated the satisfactory quality and bioequivalence of Nilotinib Accord to Tasigna.

Nilotinib Accord will be available as 50-mg, 150-mg, and 200-mg hard capsules. The active substance of Nilotinib Accord is nilotinib, an antineoplastic protein kinase inhibitor that targets BCR-ABL kinase and other oncogenic kinases.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Balversa

The CHMP endorsed the approval of Balversa (erdafitinib, Janssen-Cilag International N.V.), intended for the treatment of urothelial carcinoma, a type of cancer affecting the bladder and urinary system.

As a monotherapy, Balversa is indicated for the treatment of adult patients with unresectable or metastatic urothelial carcinoma harboring susceptible FGFR3 genetic alterations. These patients must have previously received at least one line of therapy containing a programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) or programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitor in the unresectable or metastatic treatment setting.

Urothelial carcinoma is the most common form of bladder cancer, the ninth most frequently diagnosed cancer worldwide. In 2022, there were approximately 614,000 new cases of bladder cancer and 220,000 deaths globally.

The highest incidence rates in both men and women are found in Southern Europe. Greece had 5800 new cases and 1537 deaths in 2018. Spain has the highest incidence rate in men globally. Since the 1990s, bladder cancer incidence trends have diverged by sex, with rates decreasing or stabilizing in men but increasing among women in certain European countries.

The CHMP recommendation is based on data from cohort 1 of the phase 3 THOR trial, which compared erdafitinib with standard-of-care chemotherapy (investigator’s choice of docetaxel or vinflunine). Cohort 1 included 266 adults with advanced urothelial cancer harboring selected FGFR3 alterations.

All patients had disease progression after one or two prior treatments, at least one of which included a PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitor. The major efficacy endpoints were overall survival, progression free survival, and objective response rate (ORR).

Treatment with erdafitinib reduced the risk for death by 36% compared with chemotherapy (hazard ratio [HR], 0.64; P = .005). Median overall survival was 12.1 months in the erdafitinib arm vs 7.8 months in the chemotherapy arm. Median progression-free survival was 5.6 months in the erdafitinib arm vs 2.7 months in the chemotherapy arm (HR, 0.58; P = .0002). ORR was 35.3% with erdafitinib compared with 8.5% with chemotherapy.

Balversa will be available as 3-mg, 4-mg, and 5-mg film-coated tablets. Erdafitinib, the active substance in Balversa, is an antineoplastic protein kinase inhibitor that suppresses fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) tyrosine kinases. Deregulation of FGFR3 signaling is implicated in the pathogenesis of urothelial cancer, and FGFR inhibition has demonstrated antitumor activity in FGFR-expressing cells.

Ordspono

The committee adopted a positive opinion for Ordspono (odronextamab, Regeneron Ireland Designated Activity Company), indicated as a monotherapy for the treatment of adult patients with:

- Relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma (rrFL), after two or more lines of systemic therapy.

- Relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (rrDLBCL), after two or more lines of systemic therapy.

The approval recommendation is based on phase 2 trials (NCT02290951, NCT03888105), which demonstrated high ORRs in patients with rrFL and rrDLBCL.

In the DLBCL cohort, a 49% ORR was achieved in heavily pretreated patients who had not received chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. A total of 31% achieved a complete response.

The FL cohort showed an 82% response rate in patients with grades I-IIIA disease, with 75% of the overall population achieving a complete response.

Ordspono will be available as a 2-mg, 80-mg, and 320-mg concentrate for solution for infusion. The active substance of Ordspono is odronextamab, a bispecific antibody that targets CD20-expressing B cells and CD3-expressing T cells. By binding to both, it induces T-cell activation and generates a polyclonal cytotoxic T-cell response, leading to the lysis of malignant B cells.

Generics

The panel also adopted positive opinions for two generic cancer medicines.

Enzalutamide Viatris (enzalutamide) is indicated for the treatment of adult men with prostate cancer in several scenarios:

- As monotherapy or with androgen-deprivation therapy for high-risk biochemical recurrent nonmetastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer in men unsuitable for salvage-radiotherapy.

- In combination with androgen-deprivation therapy for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer.

- For high-risk nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC).

- For metastatic CRPC in men who are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic after failure of androgen-deprivation therapy, where chemotherapy is not yet indicated.

- For metastatic CRPC in men whose disease has progressed on or after docetaxel therapy.

Enzalutamide Viatris is a generic version of Xtandi, authorized in the European Union since June 2013. Studies have confirmed the satisfactory quality and bioequivalence of Enzalutamide Viatris to Xtandi.

Enzalutamide Viatris will be available as 40-mg and 80-mg film-coated tablets. The active substance of Enzalutamide Viatris is enzalutamide, a hormone antagonist that blocks multiple steps in the androgen receptor–signaling pathway.

Nilotinib Accord (nilotinib) is indicated for the treatment of Philadelphia chromosome–positive chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML).

It is used in adult and pediatric patients with newly diagnosed CML in the chronic phase, adult patients with chronic phase and accelerated phase CML with resistance or intolerance to prior therapy including imatinib, and pediatric patients with CML with resistance or intolerance to prior therapy including imatinib.

Nilotinib Accord is a generic of Tasigna, authorized in the European Union since November 2007. Studies have demonstrated the satisfactory quality and bioequivalence of Nilotinib Accord to Tasigna.

Nilotinib Accord will be available as 50-mg, 150-mg, and 200-mg hard capsules. The active substance of Nilotinib Accord is nilotinib, an antineoplastic protein kinase inhibitor that targets BCR-ABL kinase and other oncogenic kinases.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Balversa

The CHMP endorsed the approval of Balversa (erdafitinib, Janssen-Cilag International N.V.), intended for the treatment of urothelial carcinoma, a type of cancer affecting the bladder and urinary system.

As a monotherapy, Balversa is indicated for the treatment of adult patients with unresectable or metastatic urothelial carcinoma harboring susceptible FGFR3 genetic alterations. These patients must have previously received at least one line of therapy containing a programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) or programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitor in the unresectable or metastatic treatment setting.

Urothelial carcinoma is the most common form of bladder cancer, the ninth most frequently diagnosed cancer worldwide. In 2022, there were approximately 614,000 new cases of bladder cancer and 220,000 deaths globally.

The highest incidence rates in both men and women are found in Southern Europe. Greece had 5800 new cases and 1537 deaths in 2018. Spain has the highest incidence rate in men globally. Since the 1990s, bladder cancer incidence trends have diverged by sex, with rates decreasing or stabilizing in men but increasing among women in certain European countries.

The CHMP recommendation is based on data from cohort 1 of the phase 3 THOR trial, which compared erdafitinib with standard-of-care chemotherapy (investigator’s choice of docetaxel or vinflunine). Cohort 1 included 266 adults with advanced urothelial cancer harboring selected FGFR3 alterations.

All patients had disease progression after one or two prior treatments, at least one of which included a PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitor. The major efficacy endpoints were overall survival, progression free survival, and objective response rate (ORR).

Treatment with erdafitinib reduced the risk for death by 36% compared with chemotherapy (hazard ratio [HR], 0.64; P = .005). Median overall survival was 12.1 months in the erdafitinib arm vs 7.8 months in the chemotherapy arm. Median progression-free survival was 5.6 months in the erdafitinib arm vs 2.7 months in the chemotherapy arm (HR, 0.58; P = .0002). ORR was 35.3% with erdafitinib compared with 8.5% with chemotherapy.

Balversa will be available as 3-mg, 4-mg, and 5-mg film-coated tablets. Erdafitinib, the active substance in Balversa, is an antineoplastic protein kinase inhibitor that suppresses fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) tyrosine kinases. Deregulation of FGFR3 signaling is implicated in the pathogenesis of urothelial cancer, and FGFR inhibition has demonstrated antitumor activity in FGFR-expressing cells.

Ordspono

The committee adopted a positive opinion for Ordspono (odronextamab, Regeneron Ireland Designated Activity Company), indicated as a monotherapy for the treatment of adult patients with:

- Relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma (rrFL), after two or more lines of systemic therapy.

- Relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (rrDLBCL), after two or more lines of systemic therapy.

The approval recommendation is based on phase 2 trials (NCT02290951, NCT03888105), which demonstrated high ORRs in patients with rrFL and rrDLBCL.

In the DLBCL cohort, a 49% ORR was achieved in heavily pretreated patients who had not received chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. A total of 31% achieved a complete response.

The FL cohort showed an 82% response rate in patients with grades I-IIIA disease, with 75% of the overall population achieving a complete response.

Ordspono will be available as a 2-mg, 80-mg, and 320-mg concentrate for solution for infusion. The active substance of Ordspono is odronextamab, a bispecific antibody that targets CD20-expressing B cells and CD3-expressing T cells. By binding to both, it induces T-cell activation and generates a polyclonal cytotoxic T-cell response, leading to the lysis of malignant B cells.

Generics

The panel also adopted positive opinions for two generic cancer medicines.

Enzalutamide Viatris (enzalutamide) is indicated for the treatment of adult men with prostate cancer in several scenarios:

- As monotherapy or with androgen-deprivation therapy for high-risk biochemical recurrent nonmetastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer in men unsuitable for salvage-radiotherapy.

- In combination with androgen-deprivation therapy for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer.

- For high-risk nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC).

- For metastatic CRPC in men who are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic after failure of androgen-deprivation therapy, where chemotherapy is not yet indicated.

- For metastatic CRPC in men whose disease has progressed on or after docetaxel therapy.

Enzalutamide Viatris is a generic version of Xtandi, authorized in the European Union since June 2013. Studies have confirmed the satisfactory quality and bioequivalence of Enzalutamide Viatris to Xtandi.

Enzalutamide Viatris will be available as 40-mg and 80-mg film-coated tablets. The active substance of Enzalutamide Viatris is enzalutamide, a hormone antagonist that blocks multiple steps in the androgen receptor–signaling pathway.

Nilotinib Accord (nilotinib) is indicated for the treatment of Philadelphia chromosome–positive chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML).

It is used in adult and pediatric patients with newly diagnosed CML in the chronic phase, adult patients with chronic phase and accelerated phase CML with resistance or intolerance to prior therapy including imatinib, and pediatric patients with CML with resistance or intolerance to prior therapy including imatinib.

Nilotinib Accord is a generic of Tasigna, authorized in the European Union since November 2007. Studies have demonstrated the satisfactory quality and bioequivalence of Nilotinib Accord to Tasigna.

Nilotinib Accord will be available as 50-mg, 150-mg, and 200-mg hard capsules. The active substance of Nilotinib Accord is nilotinib, an antineoplastic protein kinase inhibitor that targets BCR-ABL kinase and other oncogenic kinases.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

ASCO 2024: Treating Myeloma Just Got More Complicated

For brevity’s sake, I’ll focus on trials about newly diagnosed MM and myeloma at first relapse. Here’s my take on how to interpret those studies in light of broader evidence, what I view as their key limitations, and how what came out of ASCO 2024 changes my approach.

The Return of Belantamab

Belantamab, a BCMA targeting antibody-drug conjugate, previously had shown a response rate of 34% in a single-arm, heavily pretreated population, albeit with modest progression free survival (PFS), only to fail its confirmatory randomized study against pomalidomide/dexamethasone. Given the ocular toxicity associated with belantamab, many — including myself — had written off this drug (save in exceptional/unique circumstances), especially with the rise of novel immunotherapies targeting BCMA, such as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR T-cell) therapy and bispecific antibodies.

However, this year at ASCO, two key randomized trials were presented with concurrent publications, a trial of belantamab/bortezomib/dexamethasone versus daratumumab/bortezomib/dexamethasone (DVd) (DREAMM-7), and a trial of belantamab/pomalidomide/dexamethasone versus bortezomib/pomalidomide/dexamethasone (DREAMM-8). Both trials evaluated patients with myeloma who had relapsed disease and had received at least one prior line of therapy.

In both trials, the belantamab triplet beat the other triplets for the endpoint of PFS (median PFS 36.6 vs 13 months for DREAMM-7, and 12 months PFS 71% vs 51% for DREAMM-8). We must commend the bold three-versus-three design and a convincing result.

What are the caveats? Some censoring of information happened in DREAMM-7, which helped make the intervention arm look better than reality and the control arm look even worse than reality. To illustrate this point: the control arm of DVd (PFS 13 months) underperformed, compared to the CASTOR trial, where DVd led to a PFS of 16.7 months. The drug remains toxic, with high rates of keratopathy and vision problems in its current dosing schema. (Perhaps the future lies in less frequent dosing.) This toxicity is almost always reversible, but it is a huge problem to deal with, and our current quality-of-life instruments fail miserably at capturing this.

Furthermore, DVd is now emerging as perhaps the weakest daratumumab triplet that exists. Almost all patients in this trial had disease sensitivity to lenalidomide, and daratumumab/lenalidomide/dexamethasone (PFS of 45 months in the POLLUX trial) is unequivocally easier to use and handle (in my opinion) than this belantamab triplet--which is quite literally “an eyesore.” Would belantamab-based triplets beat dara/len/dex for patients with lenalidomide sensitive disease? Or, for that matter, would belantamab combos beat anti-CD38+carfilzomib+dex combinations, or cilta-cel (which is also now approved for first relapse)?

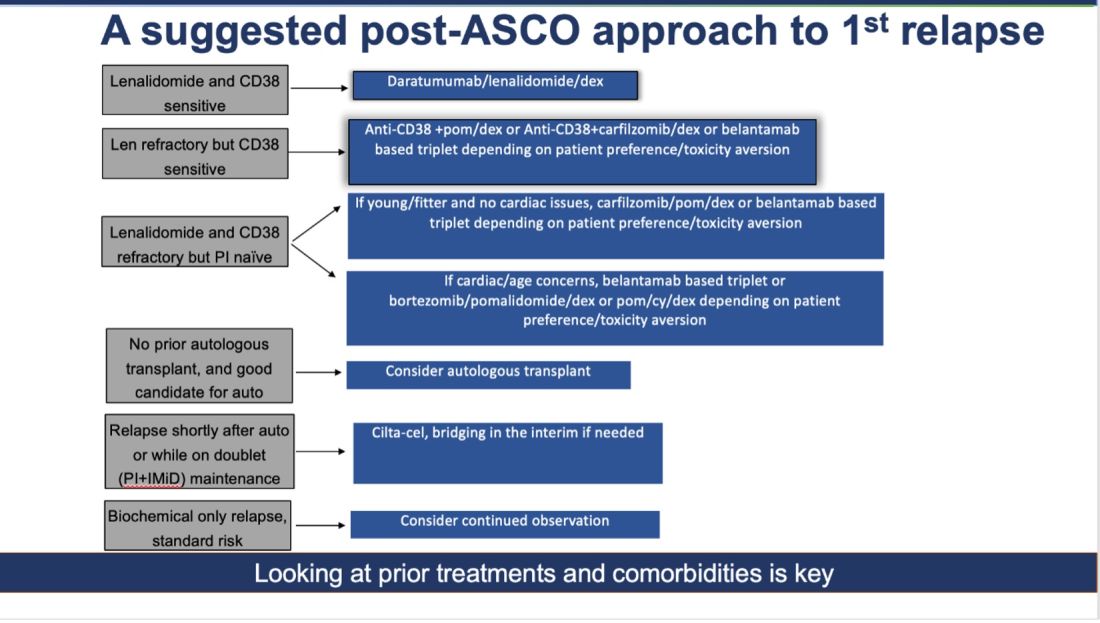

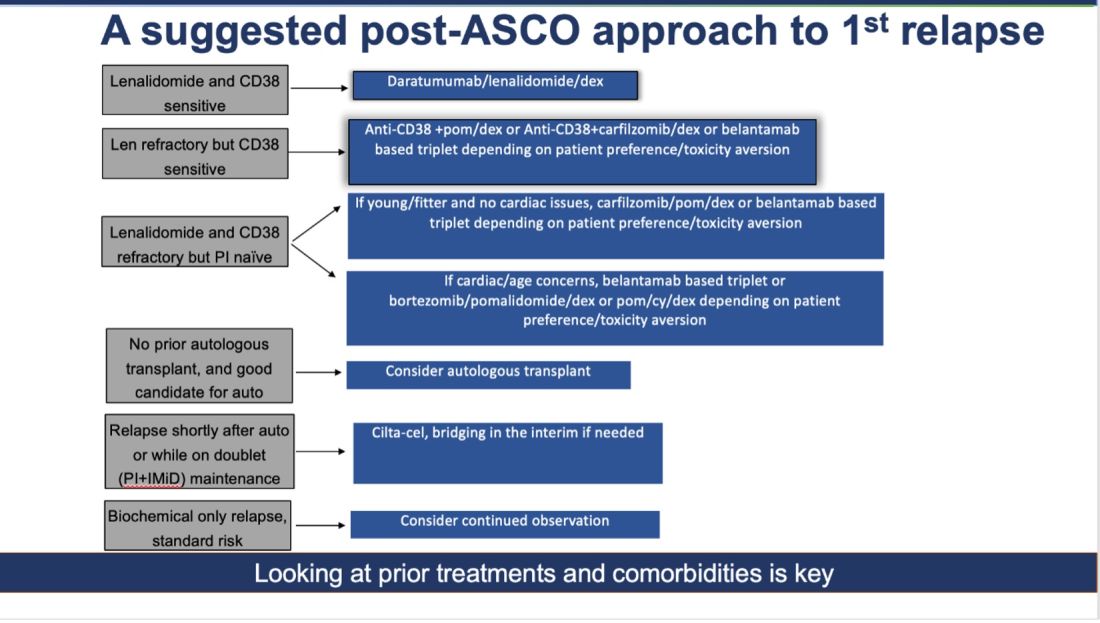

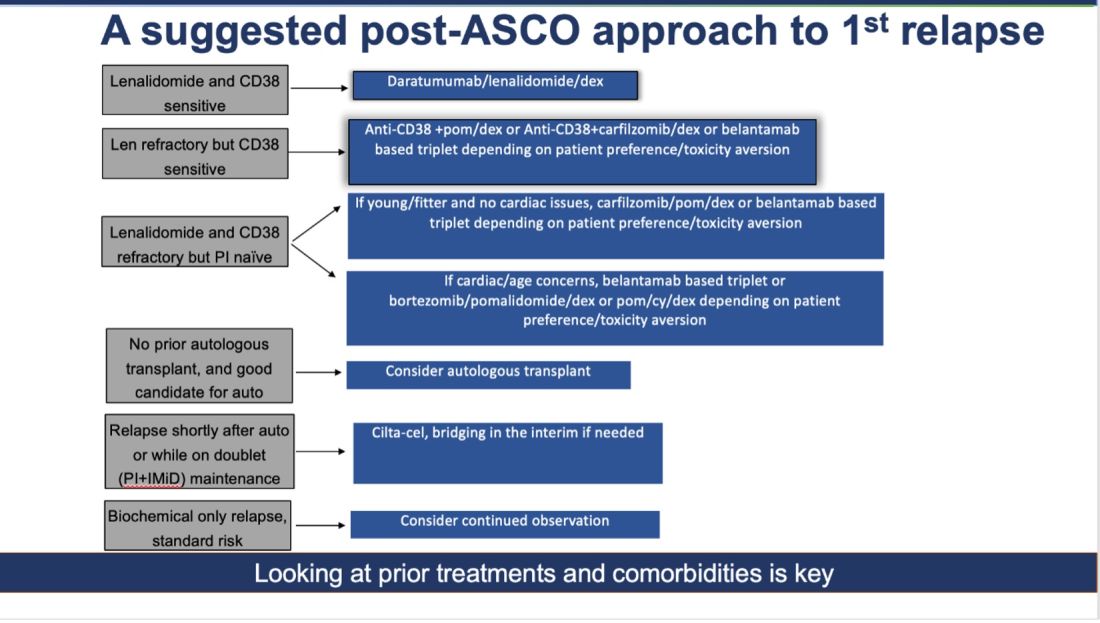

How do I foresee the future of belantamab? Despite these unequivocally positive results, I am not enthused about using it for most patients at first relapse. When trials for bispecifics at first relapse read out, my enthusiasm will likely wane even more. Still, it is useful to have belantamab in the armamentarium. For some patients perceived to be at very high risk of infection, belantamab-based triplets may indeed prove to be a better option than bispecifics. However, I suspect that with better dosing strategies for bispecifics, perhaps even that trend may be mitigated. Since we do not yet have bispecifics available in this line, my suggested algorithm for first relapse is as follows:

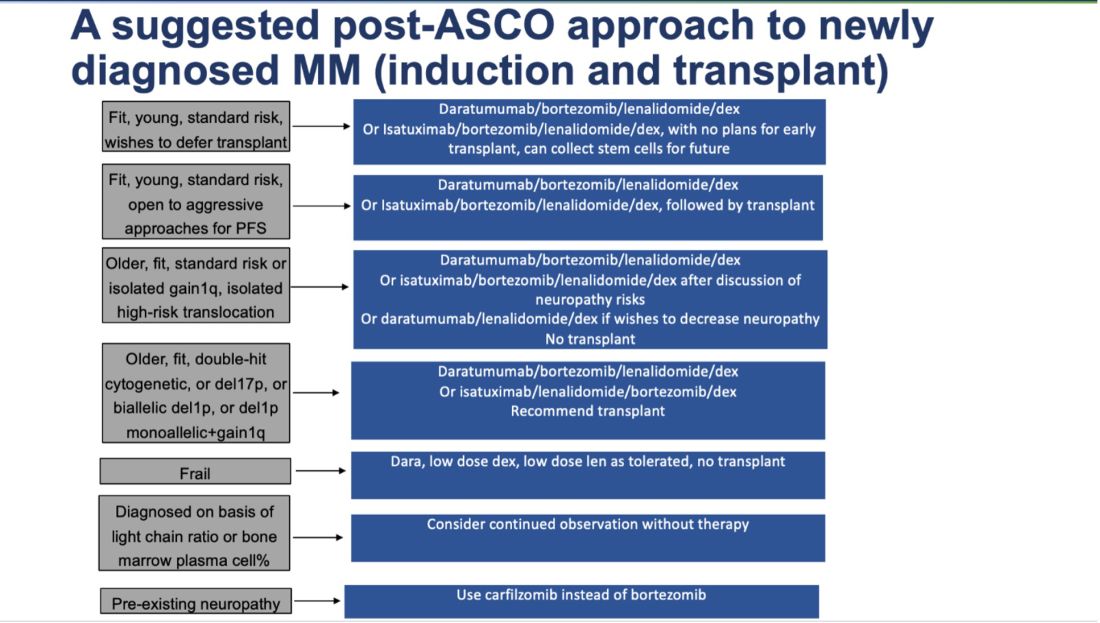

Newly Diagnosed MM: The Era of Quads Solidifies

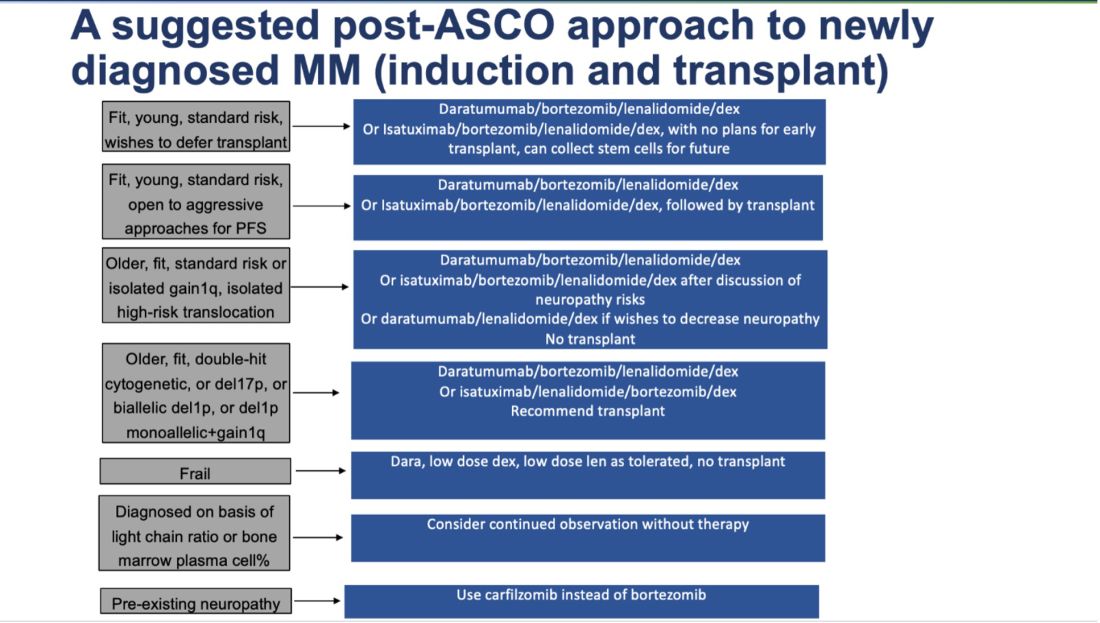

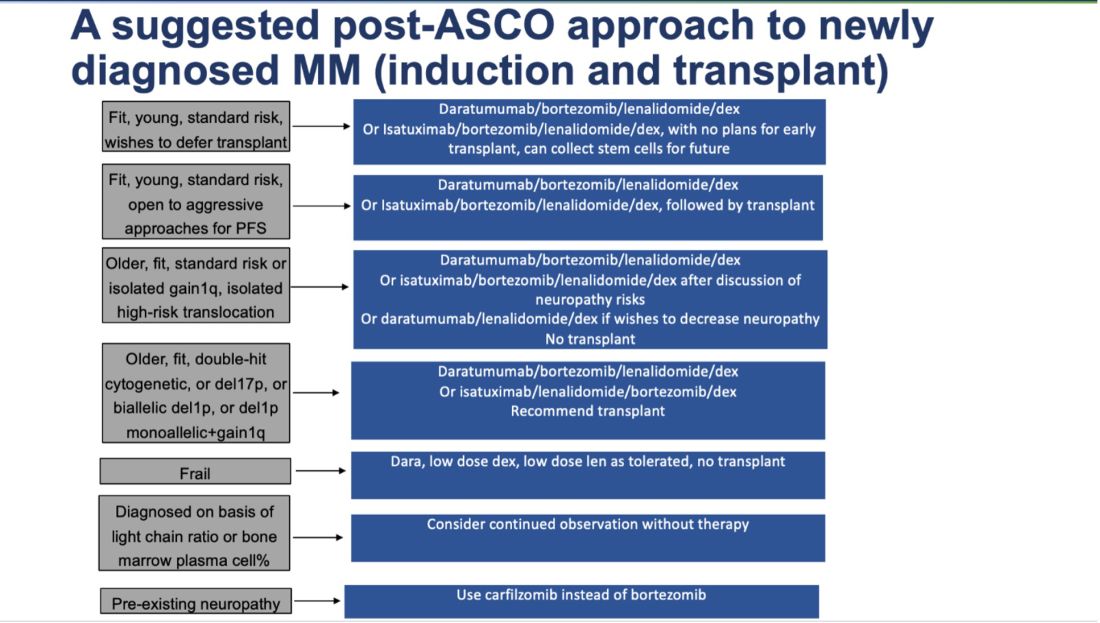

At ASCO 2024, two key trials with concurrent publications assessed the role of quadruplets (without the use of transplant): the IMROZ trial of a quadruplet of isatuximab/bortezomib/lenalidomide/dexamethasone versus bortezomib/lenalidomide/dexamethasone (VRd), and the BENEFIT trial (isatuximab/lenalidomide/bortezomib/dexamethasone versus isatuximab/lenalidomide/dexamethasone).

The IMROZ trial tested the addition of an anti-CD38 antibody to a triplet backbone, and the results are compelling. The PFS was not reached for the quad vs 54 months for VRd. Unlike in the belantamab trial (where the control arm underperformed), here the control arm really overperformed. In this case, we have never seen such a compelling PFS of 54 months for VRd before. (Based on other trials, VRd PFS has been more in the ballpark of 35-43 months.) This speaks to the fitness and biology of the patients enrolled in this trial, and perhaps to how we will not see such stellar results with this quad recreated in real life.

The addition of isatuximab did not seem to impair quality of life, and although there were more treatment-related deaths with isatuximab, those higher numbers seem to have been driven by longer treatment durations. For this study, the upper age limit was 80 years, and most patients enrolled had an excellent functional status--making it clear that frail patients were greatly underrepresented.

What can we conclude from this study? For fit, older patients (who would have been transplant-eligible in the United States), this study provides excellent proof of concept that very good outcomes can be obtained without the use of transplantation. In treating frail patients, we do not know if quads are safe (or even necessary, compared to gentler sequencing), so these data are not applicable.

High-risk cytogenetics were underrepresented, and although the subgroup analysis for such patients did not show a benefit, it is hard to draw conclusions either way. For me, this trial is further evidence that for many older patients with MM, even if you “can” do a transplant, you probably “shouldn’t, they will experience increasingly better outcomes.

The standard for newly diagnosed MM in older patients for whom transplant is not intended is currently dara/len/dex. Is isa/bort/len/dex better? I do not know. It may give a better PFS, but the addition of bortezomib will lead to more neuropathy: 60% of patients developed neuropathy here, with 7% developing Grade III/IV peripheral neuropathy.

To resolve this issue, highly individualized discussions with patients will be needed. The BENEFIT trial evaluated this question more directly, with a randomized comparison of Isa-VRd versus Isa-Rd (the role of bortezomib being the main variable assessed here) with a primary endpoint of MRD negativity at 10-5 at 18 months. Although MRD negativity allows for a quick read-out, having MRD as an endpoint is a foregone conclusion. Adding another drug will almost certainly lead to deeper responses. But is it worth it?

In the BENEFIT trial, the MRD negativity at 10-5 was 26% versus 53% with the quad. However, peripheral neuropathy rates were much higher with the quad (28% vs 52%). Without longer-term data such as PFS and OS, I do not know whether it is worth the extra risks of neuropathy for older patients. Their priority may not be eradication of cancer cells at all costs. Instead, it may be better quality of life and functioning while preserving survival.

To sum up: Post-ASCO 2024, the approach to newly diagnosed MM just got a lot more complicated. For fit, older patients willing to endure extra toxicities of neuropathy (and acknowledging that we do not know whether survival will be any better with this approach), a quad is a very reasonable option to offer while forgoing transplant, in resource-rich areas of the world, such as the United States. Omitting a transplant now seems very reasonable for most older adults. However, a nuanced and individualized approach remains paramount. And given the speed of new developments, even this suggested approach will be outdated soon!

Dr. Mohyuddin is assistant professor in the multiple myeloma program at the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

For brevity’s sake, I’ll focus on trials about newly diagnosed MM and myeloma at first relapse. Here’s my take on how to interpret those studies in light of broader evidence, what I view as their key limitations, and how what came out of ASCO 2024 changes my approach.

The Return of Belantamab

Belantamab, a BCMA targeting antibody-drug conjugate, previously had shown a response rate of 34% in a single-arm, heavily pretreated population, albeit with modest progression free survival (PFS), only to fail its confirmatory randomized study against pomalidomide/dexamethasone. Given the ocular toxicity associated with belantamab, many — including myself — had written off this drug (save in exceptional/unique circumstances), especially with the rise of novel immunotherapies targeting BCMA, such as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR T-cell) therapy and bispecific antibodies.

However, this year at ASCO, two key randomized trials were presented with concurrent publications, a trial of belantamab/bortezomib/dexamethasone versus daratumumab/bortezomib/dexamethasone (DVd) (DREAMM-7), and a trial of belantamab/pomalidomide/dexamethasone versus bortezomib/pomalidomide/dexamethasone (DREAMM-8). Both trials evaluated patients with myeloma who had relapsed disease and had received at least one prior line of therapy.

In both trials, the belantamab triplet beat the other triplets for the endpoint of PFS (median PFS 36.6 vs 13 months for DREAMM-7, and 12 months PFS 71% vs 51% for DREAMM-8). We must commend the bold three-versus-three design and a convincing result.

What are the caveats? Some censoring of information happened in DREAMM-7, which helped make the intervention arm look better than reality and the control arm look even worse than reality. To illustrate this point: the control arm of DVd (PFS 13 months) underperformed, compared to the CASTOR trial, where DVd led to a PFS of 16.7 months. The drug remains toxic, with high rates of keratopathy and vision problems in its current dosing schema. (Perhaps the future lies in less frequent dosing.) This toxicity is almost always reversible, but it is a huge problem to deal with, and our current quality-of-life instruments fail miserably at capturing this.

Furthermore, DVd is now emerging as perhaps the weakest daratumumab triplet that exists. Almost all patients in this trial had disease sensitivity to lenalidomide, and daratumumab/lenalidomide/dexamethasone (PFS of 45 months in the POLLUX trial) is unequivocally easier to use and handle (in my opinion) than this belantamab triplet--which is quite literally “an eyesore.” Would belantamab-based triplets beat dara/len/dex for patients with lenalidomide sensitive disease? Or, for that matter, would belantamab combos beat anti-CD38+carfilzomib+dex combinations, or cilta-cel (which is also now approved for first relapse)?

How do I foresee the future of belantamab? Despite these unequivocally positive results, I am not enthused about using it for most patients at first relapse. When trials for bispecifics at first relapse read out, my enthusiasm will likely wane even more. Still, it is useful to have belantamab in the armamentarium. For some patients perceived to be at very high risk of infection, belantamab-based triplets may indeed prove to be a better option than bispecifics. However, I suspect that with better dosing strategies for bispecifics, perhaps even that trend may be mitigated. Since we do not yet have bispecifics available in this line, my suggested algorithm for first relapse is as follows:

Newly Diagnosed MM: The Era of Quads Solidifies

At ASCO 2024, two key trials with concurrent publications assessed the role of quadruplets (without the use of transplant): the IMROZ trial of a quadruplet of isatuximab/bortezomib/lenalidomide/dexamethasone versus bortezomib/lenalidomide/dexamethasone (VRd), and the BENEFIT trial (isatuximab/lenalidomide/bortezomib/dexamethasone versus isatuximab/lenalidomide/dexamethasone).

The IMROZ trial tested the addition of an anti-CD38 antibody to a triplet backbone, and the results are compelling. The PFS was not reached for the quad vs 54 months for VRd. Unlike in the belantamab trial (where the control arm underperformed), here the control arm really overperformed. In this case, we have never seen such a compelling PFS of 54 months for VRd before. (Based on other trials, VRd PFS has been more in the ballpark of 35-43 months.) This speaks to the fitness and biology of the patients enrolled in this trial, and perhaps to how we will not see such stellar results with this quad recreated in real life.

The addition of isatuximab did not seem to impair quality of life, and although there were more treatment-related deaths with isatuximab, those higher numbers seem to have been driven by longer treatment durations. For this study, the upper age limit was 80 years, and most patients enrolled had an excellent functional status--making it clear that frail patients were greatly underrepresented.

What can we conclude from this study? For fit, older patients (who would have been transplant-eligible in the United States), this study provides excellent proof of concept that very good outcomes can be obtained without the use of transplantation. In treating frail patients, we do not know if quads are safe (or even necessary, compared to gentler sequencing), so these data are not applicable.

High-risk cytogenetics were underrepresented, and although the subgroup analysis for such patients did not show a benefit, it is hard to draw conclusions either way. For me, this trial is further evidence that for many older patients with MM, even if you “can” do a transplant, you probably “shouldn’t, they will experience increasingly better outcomes.

The standard for newly diagnosed MM in older patients for whom transplant is not intended is currently dara/len/dex. Is isa/bort/len/dex better? I do not know. It may give a better PFS, but the addition of bortezomib will lead to more neuropathy: 60% of patients developed neuropathy here, with 7% developing Grade III/IV peripheral neuropathy.

To resolve this issue, highly individualized discussions with patients will be needed. The BENEFIT trial evaluated this question more directly, with a randomized comparison of Isa-VRd versus Isa-Rd (the role of bortezomib being the main variable assessed here) with a primary endpoint of MRD negativity at 10-5 at 18 months. Although MRD negativity allows for a quick read-out, having MRD as an endpoint is a foregone conclusion. Adding another drug will almost certainly lead to deeper responses. But is it worth it?

In the BENEFIT trial, the MRD negativity at 10-5 was 26% versus 53% with the quad. However, peripheral neuropathy rates were much higher with the quad (28% vs 52%). Without longer-term data such as PFS and OS, I do not know whether it is worth the extra risks of neuropathy for older patients. Their priority may not be eradication of cancer cells at all costs. Instead, it may be better quality of life and functioning while preserving survival.

To sum up: Post-ASCO 2024, the approach to newly diagnosed MM just got a lot more complicated. For fit, older patients willing to endure extra toxicities of neuropathy (and acknowledging that we do not know whether survival will be any better with this approach), a quad is a very reasonable option to offer while forgoing transplant, in resource-rich areas of the world, such as the United States. Omitting a transplant now seems very reasonable for most older adults. However, a nuanced and individualized approach remains paramount. And given the speed of new developments, even this suggested approach will be outdated soon!

Dr. Mohyuddin is assistant professor in the multiple myeloma program at the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

For brevity’s sake, I’ll focus on trials about newly diagnosed MM and myeloma at first relapse. Here’s my take on how to interpret those studies in light of broader evidence, what I view as their key limitations, and how what came out of ASCO 2024 changes my approach.

The Return of Belantamab

Belantamab, a BCMA targeting antibody-drug conjugate, previously had shown a response rate of 34% in a single-arm, heavily pretreated population, albeit with modest progression free survival (PFS), only to fail its confirmatory randomized study against pomalidomide/dexamethasone. Given the ocular toxicity associated with belantamab, many — including myself — had written off this drug (save in exceptional/unique circumstances), especially with the rise of novel immunotherapies targeting BCMA, such as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR T-cell) therapy and bispecific antibodies.

However, this year at ASCO, two key randomized trials were presented with concurrent publications, a trial of belantamab/bortezomib/dexamethasone versus daratumumab/bortezomib/dexamethasone (DVd) (DREAMM-7), and a trial of belantamab/pomalidomide/dexamethasone versus bortezomib/pomalidomide/dexamethasone (DREAMM-8). Both trials evaluated patients with myeloma who had relapsed disease and had received at least one prior line of therapy.

In both trials, the belantamab triplet beat the other triplets for the endpoint of PFS (median PFS 36.6 vs 13 months for DREAMM-7, and 12 months PFS 71% vs 51% for DREAMM-8). We must commend the bold three-versus-three design and a convincing result.

What are the caveats? Some censoring of information happened in DREAMM-7, which helped make the intervention arm look better than reality and the control arm look even worse than reality. To illustrate this point: the control arm of DVd (PFS 13 months) underperformed, compared to the CASTOR trial, where DVd led to a PFS of 16.7 months. The drug remains toxic, with high rates of keratopathy and vision problems in its current dosing schema. (Perhaps the future lies in less frequent dosing.) This toxicity is almost always reversible, but it is a huge problem to deal with, and our current quality-of-life instruments fail miserably at capturing this.

Furthermore, DVd is now emerging as perhaps the weakest daratumumab triplet that exists. Almost all patients in this trial had disease sensitivity to lenalidomide, and daratumumab/lenalidomide/dexamethasone (PFS of 45 months in the POLLUX trial) is unequivocally easier to use and handle (in my opinion) than this belantamab triplet--which is quite literally “an eyesore.” Would belantamab-based triplets beat dara/len/dex for patients with lenalidomide sensitive disease? Or, for that matter, would belantamab combos beat anti-CD38+carfilzomib+dex combinations, or cilta-cel (which is also now approved for first relapse)?

How do I foresee the future of belantamab? Despite these unequivocally positive results, I am not enthused about using it for most patients at first relapse. When trials for bispecifics at first relapse read out, my enthusiasm will likely wane even more. Still, it is useful to have belantamab in the armamentarium. For some patients perceived to be at very high risk of infection, belantamab-based triplets may indeed prove to be a better option than bispecifics. However, I suspect that with better dosing strategies for bispecifics, perhaps even that trend may be mitigated. Since we do not yet have bispecifics available in this line, my suggested algorithm for first relapse is as follows:

Newly Diagnosed MM: The Era of Quads Solidifies

At ASCO 2024, two key trials with concurrent publications assessed the role of quadruplets (without the use of transplant): the IMROZ trial of a quadruplet of isatuximab/bortezomib/lenalidomide/dexamethasone versus bortezomib/lenalidomide/dexamethasone (VRd), and the BENEFIT trial (isatuximab/lenalidomide/bortezomib/dexamethasone versus isatuximab/lenalidomide/dexamethasone).

The IMROZ trial tested the addition of an anti-CD38 antibody to a triplet backbone, and the results are compelling. The PFS was not reached for the quad vs 54 months for VRd. Unlike in the belantamab trial (where the control arm underperformed), here the control arm really overperformed. In this case, we have never seen such a compelling PFS of 54 months for VRd before. (Based on other trials, VRd PFS has been more in the ballpark of 35-43 months.) This speaks to the fitness and biology of the patients enrolled in this trial, and perhaps to how we will not see such stellar results with this quad recreated in real life.

The addition of isatuximab did not seem to impair quality of life, and although there were more treatment-related deaths with isatuximab, those higher numbers seem to have been driven by longer treatment durations. For this study, the upper age limit was 80 years, and most patients enrolled had an excellent functional status--making it clear that frail patients were greatly underrepresented.

What can we conclude from this study? For fit, older patients (who would have been transplant-eligible in the United States), this study provides excellent proof of concept that very good outcomes can be obtained without the use of transplantation. In treating frail patients, we do not know if quads are safe (or even necessary, compared to gentler sequencing), so these data are not applicable.

High-risk cytogenetics were underrepresented, and although the subgroup analysis for such patients did not show a benefit, it is hard to draw conclusions either way. For me, this trial is further evidence that for many older patients with MM, even if you “can” do a transplant, you probably “shouldn’t, they will experience increasingly better outcomes.

The standard for newly diagnosed MM in older patients for whom transplant is not intended is currently dara/len/dex. Is isa/bort/len/dex better? I do not know. It may give a better PFS, but the addition of bortezomib will lead to more neuropathy: 60% of patients developed neuropathy here, with 7% developing Grade III/IV peripheral neuropathy.

To resolve this issue, highly individualized discussions with patients will be needed. The BENEFIT trial evaluated this question more directly, with a randomized comparison of Isa-VRd versus Isa-Rd (the role of bortezomib being the main variable assessed here) with a primary endpoint of MRD negativity at 10-5 at 18 months. Although MRD negativity allows for a quick read-out, having MRD as an endpoint is a foregone conclusion. Adding another drug will almost certainly lead to deeper responses. But is it worth it?

In the BENEFIT trial, the MRD negativity at 10-5 was 26% versus 53% with the quad. However, peripheral neuropathy rates were much higher with the quad (28% vs 52%). Without longer-term data such as PFS and OS, I do not know whether it is worth the extra risks of neuropathy for older patients. Their priority may not be eradication of cancer cells at all costs. Instead, it may be better quality of life and functioning while preserving survival.

To sum up: Post-ASCO 2024, the approach to newly diagnosed MM just got a lot more complicated. For fit, older patients willing to endure extra toxicities of neuropathy (and acknowledging that we do not know whether survival will be any better with this approach), a quad is a very reasonable option to offer while forgoing transplant, in resource-rich areas of the world, such as the United States. Omitting a transplant now seems very reasonable for most older adults. However, a nuanced and individualized approach remains paramount. And given the speed of new developments, even this suggested approach will be outdated soon!

Dr. Mohyuddin is assistant professor in the multiple myeloma program at the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

AML: Shorter Venetoclax Course Shows Promise for Some

However, the azacitidine plus venetoclax therapy — the “7+7” regimen — was associated with lower platelet transfusion requirements and lower 8-week mortality, suggesting the regimen might be preferable in certain patient populations, Alexandre Bazinet, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, reported at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual meeting.

The composite complete remission (CRc) rate, including complete remission with or without complete count recovery, was identical at 72% among 82 patients treated with the 7+7 regimen and 166 treated with standard therapy, and the complete remission (CR) rate was 57% and 55%, respectively, Dr. Bazinet said.

The median number of cycles to first response was one in both groups, but 42% of responders in the 7+7 group required more than one cycle to achieve their first response, compared with just 1% of those in the standard therapy group, he noted, adding that the median number of cycles to achieve best response was two in the 7+7 group and one in the standard therapy group.

The mortality rate at 4 weeks was similar in the groups (2% vs 5% for 7+7 vs standard therapy), but at 8 weeks, the mortality rate was significantly higher in the standard therapy group (6% vs 16%, respectively). Median overall survival (OS) was 11.2 months versus 10.3 months, and median 2-year survival was 27.7% versus 33.6% in the groups, respectively.

Event-free survival was 6.5 versus 7.4 months, and 2-year event-free survival was 24.5% versus 27.0%, respectively.

Of note, fewer patients in the 7+7 group required platelet transfusions during cycle 1 (62% vs 77%) and the cycle 1 rates of neutropenic fever and red cell transfusion requirements were similar in the two treatment groups, Dr. Bazinet said.

Study participants were 82 adults from seven centers in France who received the 7+7 regimen, and 166 adults from MD Anderson who received standard therapy with a hypomethylating agent plus venetoclax doublets given for 21-28 days during induction. Preliminary data on the 7+7 regimen in patients from the French centers were reported previously and “suggested preserved efficacy with potentially less toxicity,” he noted.

“A hypomethylating agent plus venetoclax doublets are standard-of-care in patients with AML who are older or ineligible for chemotherapy due to comorbidities,” Dr. Bazinet explained, adding that although the venetoclax label calls for 28 days of drug per cycle, shorter courses of 14 to 21 days are commonly used.

These findings are limited by the retrospective study design and by small patient numbers in many subgroups, he said.

“In addition, the cohorts were heterogeneous, consisting of patients treated with a variety of different regimens and across multiple centers and countries. The distribution of FLT3-ITD and NRAS/KRAS mutations differed significantly between cohorts,” he explained, also noting that prophylactic azole use differed across the cohort. “Furthermore, analysis of the toxicity results was also limited by likely differing transfusion polices in different centers.”

Overall, however, the findings suggest that reducing the duration of venetoclax is safe and results in similar CRc rates, although responses may be faster with standard dosing, he said, adding that “7+7 is potentially less toxic and is attractive in patients who are more frail or at risk for complications.”

“Our data support further study of shorter venetoclax duration, within emerging triplet regimens in patients with intermediate or low predictive benefit to mitigate toxicity,” he concluded.

Dr. Bazinet reported having no disclosures.

However, the azacitidine plus venetoclax therapy — the “7+7” regimen — was associated with lower platelet transfusion requirements and lower 8-week mortality, suggesting the regimen might be preferable in certain patient populations, Alexandre Bazinet, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, reported at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual meeting.

The composite complete remission (CRc) rate, including complete remission with or without complete count recovery, was identical at 72% among 82 patients treated with the 7+7 regimen and 166 treated with standard therapy, and the complete remission (CR) rate was 57% and 55%, respectively, Dr. Bazinet said.

The median number of cycles to first response was one in both groups, but 42% of responders in the 7+7 group required more than one cycle to achieve their first response, compared with just 1% of those in the standard therapy group, he noted, adding that the median number of cycles to achieve best response was two in the 7+7 group and one in the standard therapy group.

The mortality rate at 4 weeks was similar in the groups (2% vs 5% for 7+7 vs standard therapy), but at 8 weeks, the mortality rate was significantly higher in the standard therapy group (6% vs 16%, respectively). Median overall survival (OS) was 11.2 months versus 10.3 months, and median 2-year survival was 27.7% versus 33.6% in the groups, respectively.

Event-free survival was 6.5 versus 7.4 months, and 2-year event-free survival was 24.5% versus 27.0%, respectively.

Of note, fewer patients in the 7+7 group required platelet transfusions during cycle 1 (62% vs 77%) and the cycle 1 rates of neutropenic fever and red cell transfusion requirements were similar in the two treatment groups, Dr. Bazinet said.

Study participants were 82 adults from seven centers in France who received the 7+7 regimen, and 166 adults from MD Anderson who received standard therapy with a hypomethylating agent plus venetoclax doublets given for 21-28 days during induction. Preliminary data on the 7+7 regimen in patients from the French centers were reported previously and “suggested preserved efficacy with potentially less toxicity,” he noted.

“A hypomethylating agent plus venetoclax doublets are standard-of-care in patients with AML who are older or ineligible for chemotherapy due to comorbidities,” Dr. Bazinet explained, adding that although the venetoclax label calls for 28 days of drug per cycle, shorter courses of 14 to 21 days are commonly used.

These findings are limited by the retrospective study design and by small patient numbers in many subgroups, he said.

“In addition, the cohorts were heterogeneous, consisting of patients treated with a variety of different regimens and across multiple centers and countries. The distribution of FLT3-ITD and NRAS/KRAS mutations differed significantly between cohorts,” he explained, also noting that prophylactic azole use differed across the cohort. “Furthermore, analysis of the toxicity results was also limited by likely differing transfusion polices in different centers.”

Overall, however, the findings suggest that reducing the duration of venetoclax is safe and results in similar CRc rates, although responses may be faster with standard dosing, he said, adding that “7+7 is potentially less toxic and is attractive in patients who are more frail or at risk for complications.”

“Our data support further study of shorter venetoclax duration, within emerging triplet regimens in patients with intermediate or low predictive benefit to mitigate toxicity,” he concluded.

Dr. Bazinet reported having no disclosures.

However, the azacitidine plus venetoclax therapy — the “7+7” regimen — was associated with lower platelet transfusion requirements and lower 8-week mortality, suggesting the regimen might be preferable in certain patient populations, Alexandre Bazinet, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, reported at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual meeting.

The composite complete remission (CRc) rate, including complete remission with or without complete count recovery, was identical at 72% among 82 patients treated with the 7+7 regimen and 166 treated with standard therapy, and the complete remission (CR) rate was 57% and 55%, respectively, Dr. Bazinet said.

The median number of cycles to first response was one in both groups, but 42% of responders in the 7+7 group required more than one cycle to achieve their first response, compared with just 1% of those in the standard therapy group, he noted, adding that the median number of cycles to achieve best response was two in the 7+7 group and one in the standard therapy group.

The mortality rate at 4 weeks was similar in the groups (2% vs 5% for 7+7 vs standard therapy), but at 8 weeks, the mortality rate was significantly higher in the standard therapy group (6% vs 16%, respectively). Median overall survival (OS) was 11.2 months versus 10.3 months, and median 2-year survival was 27.7% versus 33.6% in the groups, respectively.

Event-free survival was 6.5 versus 7.4 months, and 2-year event-free survival was 24.5% versus 27.0%, respectively.

Of note, fewer patients in the 7+7 group required platelet transfusions during cycle 1 (62% vs 77%) and the cycle 1 rates of neutropenic fever and red cell transfusion requirements were similar in the two treatment groups, Dr. Bazinet said.

Study participants were 82 adults from seven centers in France who received the 7+7 regimen, and 166 adults from MD Anderson who received standard therapy with a hypomethylating agent plus venetoclax doublets given for 21-28 days during induction. Preliminary data on the 7+7 regimen in patients from the French centers were reported previously and “suggested preserved efficacy with potentially less toxicity,” he noted.

“A hypomethylating agent plus venetoclax doublets are standard-of-care in patients with AML who are older or ineligible for chemotherapy due to comorbidities,” Dr. Bazinet explained, adding that although the venetoclax label calls for 28 days of drug per cycle, shorter courses of 14 to 21 days are commonly used.

These findings are limited by the retrospective study design and by small patient numbers in many subgroups, he said.

“In addition, the cohorts were heterogeneous, consisting of patients treated with a variety of different regimens and across multiple centers and countries. The distribution of FLT3-ITD and NRAS/KRAS mutations differed significantly between cohorts,” he explained, also noting that prophylactic azole use differed across the cohort. “Furthermore, analysis of the toxicity results was also limited by likely differing transfusion polices in different centers.”

Overall, however, the findings suggest that reducing the duration of venetoclax is safe and results in similar CRc rates, although responses may be faster with standard dosing, he said, adding that “7+7 is potentially less toxic and is attractive in patients who are more frail or at risk for complications.”

“Our data support further study of shorter venetoclax duration, within emerging triplet regimens in patients with intermediate or low predictive benefit to mitigate toxicity,” he concluded.

Dr. Bazinet reported having no disclosures.

FROM ASCO 2024

FDA Proposes that Interchangeability Status for Biosimilars Doesn’t Need Switching Studies

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued new draft guidance that does not require additional switching studies for biosimilars seeking interchangeability. These studies were previously recommended to demonstrate that switching between the biosimilar and its reference product showed no greater risk than using the reference product alone.

“The recommendations in today’s draft guidance, when finalized, will provide clarity and transparency about the FDA’s thinking and align the review and approval process with existing and emerging science,” said Sarah Yim, MD, director of the FDA’s Office of Therapeutic Biologics and Biosimilars in a statement on June 20. “We have gained valuable experience reviewing both biosimilar and interchangeable biosimilar medications over the past 10 years. Both biosimilars and interchangeable biosimilars meet the same high standard of biosimilarity for FDA approval and both are as safe and effective as the reference product.”

An interchangeable status allows a biosimilar product to be swapped with the reference product without involvement from the prescribing provider, depending on state law.

While switching studies were not required under previous FDA guidance, the 2019 document did state that the agency “expects that applications generally will include data from a switching study or studies in one or more appropriate conditions of use.”

However, of the 13 biosimilars that received interchangeability status, 9 did not include switching study data.

“Experience has shown that, for the products approved as biosimilars to date, the risk in terms of safety or diminished efficacy is insignificant following single or multiple switches between a reference product and a biosimilar product,” the FDA stated. The agency’s investigators also conducted a systematic review of switching studies, which found no differences in risk for death, serious adverse events, and treatment discontinuations in participants switched between biosimilars and reference products and those that remained on reference products.

“Additionally, today’s analytical tools can accurately evaluate the structure and effects [of] biologic products, both in the lab (in vitro) and in living organisms (in vivo) with more precision and sensitivity than switching studies,” the agency noted.

The FDA is now calling for commentary on these draft recommendations to be submitted by Aug. 20, 2024.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued new draft guidance that does not require additional switching studies for biosimilars seeking interchangeability. These studies were previously recommended to demonstrate that switching between the biosimilar and its reference product showed no greater risk than using the reference product alone.

“The recommendations in today’s draft guidance, when finalized, will provide clarity and transparency about the FDA’s thinking and align the review and approval process with existing and emerging science,” said Sarah Yim, MD, director of the FDA’s Office of Therapeutic Biologics and Biosimilars in a statement on June 20. “We have gained valuable experience reviewing both biosimilar and interchangeable biosimilar medications over the past 10 years. Both biosimilars and interchangeable biosimilars meet the same high standard of biosimilarity for FDA approval and both are as safe and effective as the reference product.”

An interchangeable status allows a biosimilar product to be swapped with the reference product without involvement from the prescribing provider, depending on state law.

While switching studies were not required under previous FDA guidance, the 2019 document did state that the agency “expects that applications generally will include data from a switching study or studies in one or more appropriate conditions of use.”

However, of the 13 biosimilars that received interchangeability status, 9 did not include switching study data.

“Experience has shown that, for the products approved as biosimilars to date, the risk in terms of safety or diminished efficacy is insignificant following single or multiple switches between a reference product and a biosimilar product,” the FDA stated. The agency’s investigators also conducted a systematic review of switching studies, which found no differences in risk for death, serious adverse events, and treatment discontinuations in participants switched between biosimilars and reference products and those that remained on reference products.

“Additionally, today’s analytical tools can accurately evaluate the structure and effects [of] biologic products, both in the lab (in vitro) and in living organisms (in vivo) with more precision and sensitivity than switching studies,” the agency noted.

The FDA is now calling for commentary on these draft recommendations to be submitted by Aug. 20, 2024.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued new draft guidance that does not require additional switching studies for biosimilars seeking interchangeability. These studies were previously recommended to demonstrate that switching between the biosimilar and its reference product showed no greater risk than using the reference product alone.

“The recommendations in today’s draft guidance, when finalized, will provide clarity and transparency about the FDA’s thinking and align the review and approval process with existing and emerging science,” said Sarah Yim, MD, director of the FDA’s Office of Therapeutic Biologics and Biosimilars in a statement on June 20. “We have gained valuable experience reviewing both biosimilar and interchangeable biosimilar medications over the past 10 years. Both biosimilars and interchangeable biosimilars meet the same high standard of biosimilarity for FDA approval and both are as safe and effective as the reference product.”

An interchangeable status allows a biosimilar product to be swapped with the reference product without involvement from the prescribing provider, depending on state law.

While switching studies were not required under previous FDA guidance, the 2019 document did state that the agency “expects that applications generally will include data from a switching study or studies in one or more appropriate conditions of use.”

However, of the 13 biosimilars that received interchangeability status, 9 did not include switching study data.

“Experience has shown that, for the products approved as biosimilars to date, the risk in terms of safety or diminished efficacy is insignificant following single or multiple switches between a reference product and a biosimilar product,” the FDA stated. The agency’s investigators also conducted a systematic review of switching studies, which found no differences in risk for death, serious adverse events, and treatment discontinuations in participants switched between biosimilars and reference products and those that remained on reference products.

“Additionally, today’s analytical tools can accurately evaluate the structure and effects [of] biologic products, both in the lab (in vitro) and in living organisms (in vivo) with more precision and sensitivity than switching studies,” the agency noted.

The FDA is now calling for commentary on these draft recommendations to be submitted by Aug. 20, 2024.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

B-ALL: New Findings Confirm Efficacy of CAR T Product

These findings also highlight the favorable impact of CAR T persistence on treatment outcomes, and suggest that consolidative stem cell transplant (SCT) in R/R B-ALL patients treated with obe-cel does not improve outcomes, Elias Jabbour, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, reported at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual meeting.

The overall complete remission or complete remission with incomplete count recovery rate was 78% among 127 patients enrolled in the open-label, single-arm study and infused with obe-cel. Among the 99 patients who responded, 18 proceeded to consolidative SCT while in remission, Dr. Jabbour said, noting that all 18 who received SCT were in minimal residual disease (MRD)–negative remission at the time of transplant.

Of those 18 patients, 10 had ongoing CAR T persistence prior to transplant, he said.

At median follow-up of 21.5 months, 40% of responders were in ongoing remission without the need for subsequent consolidation with SCT or other therapy, whereas SCT did not appear to improve outcomes.

The median event-free survival (EFS) after censoring for transplant was 11.9 months, and the 12-month EFS rate was 49.5%. Without censoring for transplant, the EFS and 12-month EFS rate were 9.0 months and 44%, respectively.

“I would like to highlight that the time to transplant was 100 days, and of those 18 patients, all in MRD-negative status ... 80% relapsed or died from transplant-related complications,” Dr. Jabbour said.

Median overall survival (OS) without censoring for transplant was 15.6 months, and the 12-month OS rate was 61.1%. After censoring for transplant, the median OS and 12-month OS rate 23.8 months 63.7%, respectively. The survival curves were fully overlapping, indicating that transplant did not improve OS outcomes.

“Furthermore, when you look at the EFS and [OS], both show a potential plateau for a long-term outcome, and this trend is similar to what was reported in a phase 1 trial with 2 years of follow up and more,” Dr. Jabbour said.

The investigators also assessed the impact of loss of CAR T-cell persistence and loss of B-cell aplasia and found that “both ongoing CAR T-cell persistence and ongoing B-cell aplasia, were correlated with better event-free survival,” he noted, explaining that the risk of relapse was 2.7 times greater in those who lost versus maintained CAR T-cell persistence, and 1.7 times greater in those who lost versus maintained B-cell aplasia.

Among those with ongoing remission at 6 months, median EFS was 15.1 months in those who lost CAR T-cell persistence, whereas the median EFS was not reached in those who maintained CAR T-cell persistence.

Obe-cel is an autologous CAR T-cell product with a fast off-rate CD19 binder designed to mitigate immunotoxicity and improve CAR T-cell expansion and persistence, Dr. Jabbour said, noting that pooled efficacy and safety results from the FELIX phase 1b and 2 trials of heavily pretreated patients have previously been reported.

The findings support the use of obe-cel as a standard treatment in this patient population, and demonstrate that ongoing CAR T-cell persistence and B-cell aplasia are associated with improved EFS — without further consolidation therapy after treatment, he concluded.

This study was funded by Autolus Therapeutics. Dr. Jabbour disclosed ties with Abbvie, Ascentage Pharma, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Amgen, Astellas Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Incyte, Pfizer, and Takeda.

These findings also highlight the favorable impact of CAR T persistence on treatment outcomes, and suggest that consolidative stem cell transplant (SCT) in R/R B-ALL patients treated with obe-cel does not improve outcomes, Elias Jabbour, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, reported at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual meeting.

The overall complete remission or complete remission with incomplete count recovery rate was 78% among 127 patients enrolled in the open-label, single-arm study and infused with obe-cel. Among the 99 patients who responded, 18 proceeded to consolidative SCT while in remission, Dr. Jabbour said, noting that all 18 who received SCT were in minimal residual disease (MRD)–negative remission at the time of transplant.

Of those 18 patients, 10 had ongoing CAR T persistence prior to transplant, he said.

At median follow-up of 21.5 months, 40% of responders were in ongoing remission without the need for subsequent consolidation with SCT or other therapy, whereas SCT did not appear to improve outcomes.

The median event-free survival (EFS) after censoring for transplant was 11.9 months, and the 12-month EFS rate was 49.5%. Without censoring for transplant, the EFS and 12-month EFS rate were 9.0 months and 44%, respectively.

“I would like to highlight that the time to transplant was 100 days, and of those 18 patients, all in MRD-negative status ... 80% relapsed or died from transplant-related complications,” Dr. Jabbour said.

Median overall survival (OS) without censoring for transplant was 15.6 months, and the 12-month OS rate was 61.1%. After censoring for transplant, the median OS and 12-month OS rate 23.8 months 63.7%, respectively. The survival curves were fully overlapping, indicating that transplant did not improve OS outcomes.

“Furthermore, when you look at the EFS and [OS], both show a potential plateau for a long-term outcome, and this trend is similar to what was reported in a phase 1 trial with 2 years of follow up and more,” Dr. Jabbour said.

The investigators also assessed the impact of loss of CAR T-cell persistence and loss of B-cell aplasia and found that “both ongoing CAR T-cell persistence and ongoing B-cell aplasia, were correlated with better event-free survival,” he noted, explaining that the risk of relapse was 2.7 times greater in those who lost versus maintained CAR T-cell persistence, and 1.7 times greater in those who lost versus maintained B-cell aplasia.

Among those with ongoing remission at 6 months, median EFS was 15.1 months in those who lost CAR T-cell persistence, whereas the median EFS was not reached in those who maintained CAR T-cell persistence.

Obe-cel is an autologous CAR T-cell product with a fast off-rate CD19 binder designed to mitigate immunotoxicity and improve CAR T-cell expansion and persistence, Dr. Jabbour said, noting that pooled efficacy and safety results from the FELIX phase 1b and 2 trials of heavily pretreated patients have previously been reported.

The findings support the use of obe-cel as a standard treatment in this patient population, and demonstrate that ongoing CAR T-cell persistence and B-cell aplasia are associated with improved EFS — without further consolidation therapy after treatment, he concluded.

This study was funded by Autolus Therapeutics. Dr. Jabbour disclosed ties with Abbvie, Ascentage Pharma, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Amgen, Astellas Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Incyte, Pfizer, and Takeda.

These findings also highlight the favorable impact of CAR T persistence on treatment outcomes, and suggest that consolidative stem cell transplant (SCT) in R/R B-ALL patients treated with obe-cel does not improve outcomes, Elias Jabbour, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, reported at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual meeting.

The overall complete remission or complete remission with incomplete count recovery rate was 78% among 127 patients enrolled in the open-label, single-arm study and infused with obe-cel. Among the 99 patients who responded, 18 proceeded to consolidative SCT while in remission, Dr. Jabbour said, noting that all 18 who received SCT were in minimal residual disease (MRD)–negative remission at the time of transplant.

Of those 18 patients, 10 had ongoing CAR T persistence prior to transplant, he said.

At median follow-up of 21.5 months, 40% of responders were in ongoing remission without the need for subsequent consolidation with SCT or other therapy, whereas SCT did not appear to improve outcomes.

The median event-free survival (EFS) after censoring for transplant was 11.9 months, and the 12-month EFS rate was 49.5%. Without censoring for transplant, the EFS and 12-month EFS rate were 9.0 months and 44%, respectively.

“I would like to highlight that the time to transplant was 100 days, and of those 18 patients, all in MRD-negative status ... 80% relapsed or died from transplant-related complications,” Dr. Jabbour said.

Median overall survival (OS) without censoring for transplant was 15.6 months, and the 12-month OS rate was 61.1%. After censoring for transplant, the median OS and 12-month OS rate 23.8 months 63.7%, respectively. The survival curves were fully overlapping, indicating that transplant did not improve OS outcomes.

“Furthermore, when you look at the EFS and [OS], both show a potential plateau for a long-term outcome, and this trend is similar to what was reported in a phase 1 trial with 2 years of follow up and more,” Dr. Jabbour said.

The investigators also assessed the impact of loss of CAR T-cell persistence and loss of B-cell aplasia and found that “both ongoing CAR T-cell persistence and ongoing B-cell aplasia, were correlated with better event-free survival,” he noted, explaining that the risk of relapse was 2.7 times greater in those who lost versus maintained CAR T-cell persistence, and 1.7 times greater in those who lost versus maintained B-cell aplasia.

Among those with ongoing remission at 6 months, median EFS was 15.1 months in those who lost CAR T-cell persistence, whereas the median EFS was not reached in those who maintained CAR T-cell persistence.

Obe-cel is an autologous CAR T-cell product with a fast off-rate CD19 binder designed to mitigate immunotoxicity and improve CAR T-cell expansion and persistence, Dr. Jabbour said, noting that pooled efficacy and safety results from the FELIX phase 1b and 2 trials of heavily pretreated patients have previously been reported.

The findings support the use of obe-cel as a standard treatment in this patient population, and demonstrate that ongoing CAR T-cell persistence and B-cell aplasia are associated with improved EFS — without further consolidation therapy after treatment, he concluded.

This study was funded by Autolus Therapeutics. Dr. Jabbour disclosed ties with Abbvie, Ascentage Pharma, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Amgen, Astellas Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Incyte, Pfizer, and Takeda.

FROM ASCO 2024

FDA Approves Epcoritamab for R/R Follicular Lymphoma

This marks the second indication for the bispecific CD20-directed CD3 T-cell engager. The agent was first approved in 2023 for relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in adults.

The current approval was based on the single-arm EPCORE NHL-1 trial in 127 patients with follicular lymphoma who had received at least two lines of systemic therapy.

After a two step-up dosing regimen, the overall response rate was 82%, with 60% of patients achieving a complete response. At a median follow-up of 14.8 months, the median duration of response was not reached. The 12-month duration of response was 68.4%.

Efficacy was similar in the 86 patients who received a three step-up dosing schedule.

Labeling carries a black box warning of cytokine release syndrome and immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome. Adverse events in 20% or more of patients included injection site reactions, cytokine release syndrome, COVID-19 infection, fatigue, upper respiratory tract infection, musculoskeletal pain, rash, diarrhea, pyrexia, cough, and headache.

Decreased lymphocyte count, neutrophil count, white blood cell count, and hemoglobin were the most common grade 3/4 laboratory abnormalities.

Three step-up dosing is the recommended regimen, with epcoritamab administered subcutaneously in 28-day cycles until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Dosing is increased by steps to the full 48 mg in cycle 1.

The price is $16,282.52 for 48 mg/0.8 mL, according to drugs.com.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This marks the second indication for the bispecific CD20-directed CD3 T-cell engager. The agent was first approved in 2023 for relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in adults.

The current approval was based on the single-arm EPCORE NHL-1 trial in 127 patients with follicular lymphoma who had received at least two lines of systemic therapy.

After a two step-up dosing regimen, the overall response rate was 82%, with 60% of patients achieving a complete response. At a median follow-up of 14.8 months, the median duration of response was not reached. The 12-month duration of response was 68.4%.

Efficacy was similar in the 86 patients who received a three step-up dosing schedule.

Labeling carries a black box warning of cytokine release syndrome and immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome. Adverse events in 20% or more of patients included injection site reactions, cytokine release syndrome, COVID-19 infection, fatigue, upper respiratory tract infection, musculoskeletal pain, rash, diarrhea, pyrexia, cough, and headache.

Decreased lymphocyte count, neutrophil count, white blood cell count, and hemoglobin were the most common grade 3/4 laboratory abnormalities.

Three step-up dosing is the recommended regimen, with epcoritamab administered subcutaneously in 28-day cycles until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Dosing is increased by steps to the full 48 mg in cycle 1.

The price is $16,282.52 for 48 mg/0.8 mL, according to drugs.com.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This marks the second indication for the bispecific CD20-directed CD3 T-cell engager. The agent was first approved in 2023 for relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in adults.

The current approval was based on the single-arm EPCORE NHL-1 trial in 127 patients with follicular lymphoma who had received at least two lines of systemic therapy.

After a two step-up dosing regimen, the overall response rate was 82%, with 60% of patients achieving a complete response. At a median follow-up of 14.8 months, the median duration of response was not reached. The 12-month duration of response was 68.4%.

Efficacy was similar in the 86 patients who received a three step-up dosing schedule.

Labeling carries a black box warning of cytokine release syndrome and immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome. Adverse events in 20% or more of patients included injection site reactions, cytokine release syndrome, COVID-19 infection, fatigue, upper respiratory tract infection, musculoskeletal pain, rash, diarrhea, pyrexia, cough, and headache.

Decreased lymphocyte count, neutrophil count, white blood cell count, and hemoglobin were the most common grade 3/4 laboratory abnormalities.

Three step-up dosing is the recommended regimen, with epcoritamab administered subcutaneously in 28-day cycles until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Dosing is increased by steps to the full 48 mg in cycle 1.

The price is $16,282.52 for 48 mg/0.8 mL, according to drugs.com.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Hemophilia: Marstacimab Sustains Long-Term Bleeding Reduction

“In the long-term extension study treatment with marstacimab demonstrates sustained or improved efficacy for treated and total annualized bleeding rates (ABR) in adults and adolescents with hemophilia A or hemophilia B in this data set of patients without inhibitors,” first author Shamsah Kazani, MD, of Pfizer, Cambridge, Massachusetts, said in presenting the findings at the 2024 annual meeting of the European Hematology Association (EHA) in Madrid.

“The majority of the patients from the pivotal study chose to transition into the long-term extension, and we are finding that these patients are highly compliant with their weekly marstacimab dose, with more than 98% compliance,” Dr. Kazani said.

Marstacimab targets the tissue factor pathway inhibitor, a natural anticoagulation protein that prevents the formation of blood clots, and is administered as a once-weekly subcutaneous injection.

The therapy has been granted fast-track and orphan drug status in the United States, in addition to orphan drug status in the European Union for the prevention of hemophilia bleeding episodes.

If approved, the therapy would become the first once-weekly subcutaneous therapy for either hemophilia A or B. Emicizumab, which also is administered subcutaneously, is only approved to prevent or reduce bleeding in hemophilia A.

The latest findings are from an interim analysis of a long-term extension study involving 107 of 116 patients who were in the non-inhibitor cohort in the pivotal BASIS trial. Data from that trial, involving patients aged 12-75 previously showed favorable outcomes in the non-inhibitor cohort receiving marstacimab, and a cohort of patients with inhibitors is ongoing.

Participants entering the extension study were continuing on 150-mg subcutaneous doses of marstacimab, which had been administered in the BASIS study for 12 months after a loading dose of 300 mg.

Of the patients, 89 (83%) were adult and 18 (17%) were adolescents. Overall, they had a mean age of 29 years; 83 (76%) patients had hemophilia A, while 24 (22.4%) had hemophilia B.

Prior to switching to marstacimab treatment, 32 patients had been treated with factor replacement therapy on demand, while 75 received the therapy as routine prophylaxis.

With a mean additional duration of follow-up of 12.5 months in the extension study (range, 1-23.1 months), the overall rate of compliance was very high, at 98.9%.

In the pivotal and extension studies combined, 21% of patients had their marstacimab dose increased from 150 mg to 300 mg weekly, which was an option if patients had 2 or more spontaneous bleeds in a major joint while on the 150-mg dose.