User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Study confirms it’s possible to catch COVID-19 twice

Researchers in Hong Kong say they’ve confirmed that a person can be infected with COVID-19 twice.

The new proof comes from a 33-year-old man in Hong Kong who first caught COVID-19 in March. He was tested for the coronavirus after he developed a cough, sore throat, fever, and a headache for 3 days. He stayed in the hospital until he twice tested negative for the virus in mid-April.

On Aug. 15, the man returned to Hong Kong from a recent trip to Spain and the United Kingdom, areas that have recently seen a resurgence of COVID-19 cases. At the airport, he was screened for COVID-19 with a test that checks saliva for the virus. He tested positive, but this time, had no symptoms. He was taken to the hospital for monitoring. His viral load – the amount of virus he had in his body – went down over time, suggesting that his immune system was taking care of the intrusion on its own.

The special thing about his case is that each time he was hospitalized, doctors sequenced the genome of the virus that infected him. It was slightly different from one infection to the next, suggesting that the virus had mutated – or changed – in the 4 months between his infections. It also proves that it’s possible for this coronavirus to infect the same person twice.

Experts with the World Health Organization responded to the case at a news briefing.

“What we are learning about infection is that people do develop an immune response. What is not completely clear yet is how strong that immune response is and for how long that immune response lasts,” said Maria Van Kerkhove, PhD, an infectious disease epidemiologist with the World Health Organization in Geneva, Switzerland.

A study on the man’s case is being prepared for publication in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases. Experts say the finding shouldn’t cause alarm, but it does have important implications for the development of herd immunity and efforts to come up with vaccines and treatments.

“This appears to be pretty clear-cut evidence of reinfection because of sequencing and isolation of two different viruses,” said Gregory Poland, MD, an expert on vaccine development and immunology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. “The big unknown is how often is this happening,” he said. More studies are needed to learn whether this was a rare case or something that is happening often.

Past experience guides present

Until we know more, Dr. Poland said, the possibility of getting COVID-19 twice shouldn’t make anyone worry.

This also happens with other kinds of coronaviruses – the ones that cause common colds. Those coronaviruses change slightly each year as they circle the globe, which allows them to keep spreading and causing their more run-of-the-mill kind of misery.

It also happens with seasonal flu. It is the reason people have to get vaccinated against the flu year after year, and why the flu vaccine has to change slightly each year in an effort to keep up with the ever-evolving influenza virus.

“We’ve been making flu vaccines for 80 years, and there are clinical trials happening as we speak to find new and better influenza vaccines,” Dr. Poland said.

There has been other evidence the virus that causes COVID-19 can change this way, too. Researchers at Howard Hughes Medical Center, at Rockefeller University in New York, recently used a key piece of the SARS-CoV-2 virus – the genetic instructions for its spike protein – to repeatedly infect human cells. Scientists watched as each new generation of the virus went on to infect a new batch of cells. Over time, as it copied itself, some of the copies changed their genes to allow them to survive after scientists attacked them with neutralizing antibodies. Those antibodies are among the main weapons used by the immune system to recognize and disable a virus.

Though that study is still a preprint, which means it hasn’t yet been reviewed by outside experts, the authors wrote that their findings suggest the virus can change in ways that help it evade our immune system. If true, they wrote in mid-July, it means reinfection is possible, especially in people who have a weak immune response to the virus the first time they encounter it.

Good news

That seems to be true in the case of the man from Hong Kong. When doctors tested his blood to look for antibodies to the virus, they didn’t find any. That could mean that he either had a weak immune response to the virus the first time around, or that the antibodies he made during his first infection diminished over time. But during his second infection, he quickly developed more antibodies, suggesting that the second infection acted a little bit like a booster to fire up his immune system. That’s probably the reason he didn’t have any symptoms the second time, too.

That’s good news, Dr. Poland said. It means our bodies can get better at fighting off the COVID-19 virus and that catching it once means the second time might not be so bad.

But the fact that the virus can change quickly this way does have some impact on the effort to come up with a vaccine that works well.

“I think a potential implication of this is that we will have to give booster doses. The question is how frequently,” Dr. Poland said. That will depend on how fast the virus is changing, and how often reinfection is happening in the real world.

“I’m a little surprised at 4½ months,” Dr. Poland said, referencing the time between the Hong Kong man’s infections. “I’m not surprised by, you know, I got infected last winter and I got infected again this winter,” he said.

It also suggests that immune-based therapies such as convalescent plasma and monoclonal antibodies may be of limited help over time, since the virus might be changing in ways that help it outsmart those treatments.

Convalescent plasma is essentially a concentrated dose of antibodies from people who have recovered from a COVID-19 infection. As the virus changes, the antibodies in that plasma may not work as well for future infections.

Drug companies have learned to harness the power of monoclonal antibodies as powerful treatments against cancer and other diseases. Monoclonal antibodies, which are mass-produced in a lab, mimic the body’s natural defenses against a pathogen. Just like the virus can become resistant to natural immunity, it can change in ways that help it outsmart lab-created treatments. Some drug companies that are developing monoclonal antibodies to fight COVID-19 have already prepared for that possibility by making antibody cocktails that are designed to disable the virus by locking onto it in different places, which may help prevent it from developing resistance to those therapies.

“We have a lot to learn,” Dr. Poland said. “Now that the proof of principle has been established, and I would say it has with this man, and with our knowledge of seasonal coronaviruses, we need to look more aggressively to define how often this occurs.”

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

Researchers in Hong Kong say they’ve confirmed that a person can be infected with COVID-19 twice.

The new proof comes from a 33-year-old man in Hong Kong who first caught COVID-19 in March. He was tested for the coronavirus after he developed a cough, sore throat, fever, and a headache for 3 days. He stayed in the hospital until he twice tested negative for the virus in mid-April.

On Aug. 15, the man returned to Hong Kong from a recent trip to Spain and the United Kingdom, areas that have recently seen a resurgence of COVID-19 cases. At the airport, he was screened for COVID-19 with a test that checks saliva for the virus. He tested positive, but this time, had no symptoms. He was taken to the hospital for monitoring. His viral load – the amount of virus he had in his body – went down over time, suggesting that his immune system was taking care of the intrusion on its own.

The special thing about his case is that each time he was hospitalized, doctors sequenced the genome of the virus that infected him. It was slightly different from one infection to the next, suggesting that the virus had mutated – or changed – in the 4 months between his infections. It also proves that it’s possible for this coronavirus to infect the same person twice.

Experts with the World Health Organization responded to the case at a news briefing.

“What we are learning about infection is that people do develop an immune response. What is not completely clear yet is how strong that immune response is and for how long that immune response lasts,” said Maria Van Kerkhove, PhD, an infectious disease epidemiologist with the World Health Organization in Geneva, Switzerland.

A study on the man’s case is being prepared for publication in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases. Experts say the finding shouldn’t cause alarm, but it does have important implications for the development of herd immunity and efforts to come up with vaccines and treatments.

“This appears to be pretty clear-cut evidence of reinfection because of sequencing and isolation of two different viruses,” said Gregory Poland, MD, an expert on vaccine development and immunology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. “The big unknown is how often is this happening,” he said. More studies are needed to learn whether this was a rare case or something that is happening often.

Past experience guides present

Until we know more, Dr. Poland said, the possibility of getting COVID-19 twice shouldn’t make anyone worry.

This also happens with other kinds of coronaviruses – the ones that cause common colds. Those coronaviruses change slightly each year as they circle the globe, which allows them to keep spreading and causing their more run-of-the-mill kind of misery.

It also happens with seasonal flu. It is the reason people have to get vaccinated against the flu year after year, and why the flu vaccine has to change slightly each year in an effort to keep up with the ever-evolving influenza virus.

“We’ve been making flu vaccines for 80 years, and there are clinical trials happening as we speak to find new and better influenza vaccines,” Dr. Poland said.

There has been other evidence the virus that causes COVID-19 can change this way, too. Researchers at Howard Hughes Medical Center, at Rockefeller University in New York, recently used a key piece of the SARS-CoV-2 virus – the genetic instructions for its spike protein – to repeatedly infect human cells. Scientists watched as each new generation of the virus went on to infect a new batch of cells. Over time, as it copied itself, some of the copies changed their genes to allow them to survive after scientists attacked them with neutralizing antibodies. Those antibodies are among the main weapons used by the immune system to recognize and disable a virus.

Though that study is still a preprint, which means it hasn’t yet been reviewed by outside experts, the authors wrote that their findings suggest the virus can change in ways that help it evade our immune system. If true, they wrote in mid-July, it means reinfection is possible, especially in people who have a weak immune response to the virus the first time they encounter it.

Good news

That seems to be true in the case of the man from Hong Kong. When doctors tested his blood to look for antibodies to the virus, they didn’t find any. That could mean that he either had a weak immune response to the virus the first time around, or that the antibodies he made during his first infection diminished over time. But during his second infection, he quickly developed more antibodies, suggesting that the second infection acted a little bit like a booster to fire up his immune system. That’s probably the reason he didn’t have any symptoms the second time, too.

That’s good news, Dr. Poland said. It means our bodies can get better at fighting off the COVID-19 virus and that catching it once means the second time might not be so bad.

But the fact that the virus can change quickly this way does have some impact on the effort to come up with a vaccine that works well.

“I think a potential implication of this is that we will have to give booster doses. The question is how frequently,” Dr. Poland said. That will depend on how fast the virus is changing, and how often reinfection is happening in the real world.

“I’m a little surprised at 4½ months,” Dr. Poland said, referencing the time between the Hong Kong man’s infections. “I’m not surprised by, you know, I got infected last winter and I got infected again this winter,” he said.

It also suggests that immune-based therapies such as convalescent plasma and monoclonal antibodies may be of limited help over time, since the virus might be changing in ways that help it outsmart those treatments.

Convalescent plasma is essentially a concentrated dose of antibodies from people who have recovered from a COVID-19 infection. As the virus changes, the antibodies in that plasma may not work as well for future infections.

Drug companies have learned to harness the power of monoclonal antibodies as powerful treatments against cancer and other diseases. Monoclonal antibodies, which are mass-produced in a lab, mimic the body’s natural defenses against a pathogen. Just like the virus can become resistant to natural immunity, it can change in ways that help it outsmart lab-created treatments. Some drug companies that are developing monoclonal antibodies to fight COVID-19 have already prepared for that possibility by making antibody cocktails that are designed to disable the virus by locking onto it in different places, which may help prevent it from developing resistance to those therapies.

“We have a lot to learn,” Dr. Poland said. “Now that the proof of principle has been established, and I would say it has with this man, and with our knowledge of seasonal coronaviruses, we need to look more aggressively to define how often this occurs.”

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

Researchers in Hong Kong say they’ve confirmed that a person can be infected with COVID-19 twice.

The new proof comes from a 33-year-old man in Hong Kong who first caught COVID-19 in March. He was tested for the coronavirus after he developed a cough, sore throat, fever, and a headache for 3 days. He stayed in the hospital until he twice tested negative for the virus in mid-April.

On Aug. 15, the man returned to Hong Kong from a recent trip to Spain and the United Kingdom, areas that have recently seen a resurgence of COVID-19 cases. At the airport, he was screened for COVID-19 with a test that checks saliva for the virus. He tested positive, but this time, had no symptoms. He was taken to the hospital for monitoring. His viral load – the amount of virus he had in his body – went down over time, suggesting that his immune system was taking care of the intrusion on its own.

The special thing about his case is that each time he was hospitalized, doctors sequenced the genome of the virus that infected him. It was slightly different from one infection to the next, suggesting that the virus had mutated – or changed – in the 4 months between his infections. It also proves that it’s possible for this coronavirus to infect the same person twice.

Experts with the World Health Organization responded to the case at a news briefing.

“What we are learning about infection is that people do develop an immune response. What is not completely clear yet is how strong that immune response is and for how long that immune response lasts,” said Maria Van Kerkhove, PhD, an infectious disease epidemiologist with the World Health Organization in Geneva, Switzerland.

A study on the man’s case is being prepared for publication in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases. Experts say the finding shouldn’t cause alarm, but it does have important implications for the development of herd immunity and efforts to come up with vaccines and treatments.

“This appears to be pretty clear-cut evidence of reinfection because of sequencing and isolation of two different viruses,” said Gregory Poland, MD, an expert on vaccine development and immunology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. “The big unknown is how often is this happening,” he said. More studies are needed to learn whether this was a rare case or something that is happening often.

Past experience guides present

Until we know more, Dr. Poland said, the possibility of getting COVID-19 twice shouldn’t make anyone worry.

This also happens with other kinds of coronaviruses – the ones that cause common colds. Those coronaviruses change slightly each year as they circle the globe, which allows them to keep spreading and causing their more run-of-the-mill kind of misery.

It also happens with seasonal flu. It is the reason people have to get vaccinated against the flu year after year, and why the flu vaccine has to change slightly each year in an effort to keep up with the ever-evolving influenza virus.

“We’ve been making flu vaccines for 80 years, and there are clinical trials happening as we speak to find new and better influenza vaccines,” Dr. Poland said.

There has been other evidence the virus that causes COVID-19 can change this way, too. Researchers at Howard Hughes Medical Center, at Rockefeller University in New York, recently used a key piece of the SARS-CoV-2 virus – the genetic instructions for its spike protein – to repeatedly infect human cells. Scientists watched as each new generation of the virus went on to infect a new batch of cells. Over time, as it copied itself, some of the copies changed their genes to allow them to survive after scientists attacked them with neutralizing antibodies. Those antibodies are among the main weapons used by the immune system to recognize and disable a virus.

Though that study is still a preprint, which means it hasn’t yet been reviewed by outside experts, the authors wrote that their findings suggest the virus can change in ways that help it evade our immune system. If true, they wrote in mid-July, it means reinfection is possible, especially in people who have a weak immune response to the virus the first time they encounter it.

Good news

That seems to be true in the case of the man from Hong Kong. When doctors tested his blood to look for antibodies to the virus, they didn’t find any. That could mean that he either had a weak immune response to the virus the first time around, or that the antibodies he made during his first infection diminished over time. But during his second infection, he quickly developed more antibodies, suggesting that the second infection acted a little bit like a booster to fire up his immune system. That’s probably the reason he didn’t have any symptoms the second time, too.

That’s good news, Dr. Poland said. It means our bodies can get better at fighting off the COVID-19 virus and that catching it once means the second time might not be so bad.

But the fact that the virus can change quickly this way does have some impact on the effort to come up with a vaccine that works well.

“I think a potential implication of this is that we will have to give booster doses. The question is how frequently,” Dr. Poland said. That will depend on how fast the virus is changing, and how often reinfection is happening in the real world.

“I’m a little surprised at 4½ months,” Dr. Poland said, referencing the time between the Hong Kong man’s infections. “I’m not surprised by, you know, I got infected last winter and I got infected again this winter,” he said.

It also suggests that immune-based therapies such as convalescent plasma and monoclonal antibodies may be of limited help over time, since the virus might be changing in ways that help it outsmart those treatments.

Convalescent plasma is essentially a concentrated dose of antibodies from people who have recovered from a COVID-19 infection. As the virus changes, the antibodies in that plasma may not work as well for future infections.

Drug companies have learned to harness the power of monoclonal antibodies as powerful treatments against cancer and other diseases. Monoclonal antibodies, which are mass-produced in a lab, mimic the body’s natural defenses against a pathogen. Just like the virus can become resistant to natural immunity, it can change in ways that help it outsmart lab-created treatments. Some drug companies that are developing monoclonal antibodies to fight COVID-19 have already prepared for that possibility by making antibody cocktails that are designed to disable the virus by locking onto it in different places, which may help prevent it from developing resistance to those therapies.

“We have a lot to learn,” Dr. Poland said. “Now that the proof of principle has been established, and I would say it has with this man, and with our knowledge of seasonal coronaviruses, we need to look more aggressively to define how often this occurs.”

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

Research examines links between ‘long COVID’ and ME/CFS

Some patients who had COVID-19 continue to have symptoms weeks to months later, even after they no longer test positive for the virus. In two recent reports – one published in JAMA in July and another published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report in August – chronic fatigue was listed as the top symptom among individuals still feeling unwell beyond 2 weeks after COVID-19 onset.

Although some of the reported persistent symptoms appear specific to SARS-CoV-2 – such as cough, chest pain, and dyspnea – others overlap with the diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS, which is defined by substantial, profound fatigue for at least 6 months, postexertional malaise, unrefreshing sleep, and one or both of orthostatic intolerance and/or cognitive impairment. Although the etiology of ME/CFS is unclear, the condition commonly arises following a viral illness.

At the virtual meeting of the International Association for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis August 21, the opening session was devoted to research documenting the extent to which COVID-19 survivors subsequently meet ME/CFS criteria, and to exploring underlying mechanisms.

“It offers a lot of opportunities for us to study potentially early ME/CFS and how it develops, but in addition, a lot of the research that has been done on ME/CFS may also provide answers for COVID-19,” IACFS/ME vice president Lily Chu, MD, said in an interview.

A hint from the SARS outbreak

This isn’t the first time researchers have seen a possible link between a coronavirus and ME/CFS, Harvey Moldofsky, MD, told attendees. To illustrate that point, Dr. Moldofsky, of the department of psychiatry (emeritus) at the University of Toronto, reviewed data from a previously published case-controlled study, which included 22 health care workers who had been infected in 2003 with SARS-CoV-1 and continued to report chronic fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, and disturbed and unrefreshing sleep with EEG-documented sleep disturbances 1-3 years following the illness. None had been able to return to work by 1 year.

“We’re looking at similar symptoms now” among survivors of COVID-19, Dr. Moldofsky said. “[T]he key issue is that we have no idea of its prevalence. … We need epidemiologic studies.”

Distinguishing ME/CFS from other post–COVID-19 symptoms

Not everyone who has persistent symptoms after COVID-19 will develop ME/CFS, and distinguishing between cases may be important.

Clinically, Dr. Chu said, one way to assess whether a patient with persistent COVID-19 symptoms might be progressing to ME/CFS is to ask him or her specifically about the level of fatigue following physical exertion and the timing of any fatigue. With ME/CFS, postexertional malaise often involves a dramatic exacerbation of symptoms such as fatigue, pain, and cognitive impairment a day or 2 after exertion rather than immediately following it. In contrast, shortness of breath during exertion isn’t typical of ME/CFS.

Objective measures of ME/CFS include low natural killer cell function (the test can be ordered from commercial labs but requires rapid transport of the blood sample), and autonomic dysfunction assessed by a tilt-table test.

While there is currently no cure for ME/CFS, diagnosing it allows for the patient to be taught “pacing” in which the person conserves his or her energy by balancing activity with rest. “That type of behavioral technique is valuable for everyone who suffers from a chronic disease with fatigue. It can help them be more functional,” Dr. Chu said.

If a patient appears to be exhibiting signs of ME/CFS, “don’t wait until they hit the 6-month mark to start helping them manage their symptoms,” she said. “Teaching pacing to COVID-19 patients who have a lot of fatigue isn’t going to harm them. As they get better they’re going to just naturally do more. But if they do have ME/CFS, [pacing] stresses their system less, since the data seem to be pointing to deficiencies in producing energy.”

Will COVID-19 unleash a new wave of ME/CFS patients?

Much of the session at the virtual meeting was devoted to ongoing studies. For example, Leonard Jason, PhD, of the Center for Community Research at DePaul University, Chicago, described a prospective study launched in 2014 that looked at risk factors for developing ME/CFS in college students who contracted infectious mononucleosis as a result of Epstein-Barr virus. Now, his team is also following students from the same cohort who develop COVID-19.

Because the study included collection of baseline biological samples, the results could help reveal predisposing factors associated with long-term illness from either virus.

Another project, funded by the Open Medicine Foundation, will follow patients who are discharged from the ICU following severe COVID-19 illness. Blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid will be collected from those with persistent symptoms at 6 months, along with questionnaire data. At 18-24 months, those who continue to report symptoms will undergo more intensive evaluation using genomics, metabolomics, and proteomics.

“We’re taking advantage of this horrible situation, hoping to understand how a serious viral infection might lead to ME/CFS,” said lead investigator Ronald Tompkins, MD, ScD, chief medical officer at the Open Medicine Foundation and a faculty member at Harvard Medical School, Boston. The results, he said, “might give us insight into potential drug targets or biomarkers useful for prevention and treatment strategies.”

Meanwhile, Sadie Whittaker, PhD, head of the Solve ME/CFS initiative, described her organization’s new plan to use their registry to prospectively track the impact of COVID-19 on people with ME/CFS.

She noted that they’ve also teamed up with “long-COVID” communities including Body Politic. “Our goal is to form a coalition to study together or at least harmonize data … and understand what’s going on through the power of bigger sample sizes,” Dr. Whittaker said.

None of the speakers disclosed relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Some patients who had COVID-19 continue to have symptoms weeks to months later, even after they no longer test positive for the virus. In two recent reports – one published in JAMA in July and another published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report in August – chronic fatigue was listed as the top symptom among individuals still feeling unwell beyond 2 weeks after COVID-19 onset.

Although some of the reported persistent symptoms appear specific to SARS-CoV-2 – such as cough, chest pain, and dyspnea – others overlap with the diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS, which is defined by substantial, profound fatigue for at least 6 months, postexertional malaise, unrefreshing sleep, and one or both of orthostatic intolerance and/or cognitive impairment. Although the etiology of ME/CFS is unclear, the condition commonly arises following a viral illness.

At the virtual meeting of the International Association for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis August 21, the opening session was devoted to research documenting the extent to which COVID-19 survivors subsequently meet ME/CFS criteria, and to exploring underlying mechanisms.

“It offers a lot of opportunities for us to study potentially early ME/CFS and how it develops, but in addition, a lot of the research that has been done on ME/CFS may also provide answers for COVID-19,” IACFS/ME vice president Lily Chu, MD, said in an interview.

A hint from the SARS outbreak

This isn’t the first time researchers have seen a possible link between a coronavirus and ME/CFS, Harvey Moldofsky, MD, told attendees. To illustrate that point, Dr. Moldofsky, of the department of psychiatry (emeritus) at the University of Toronto, reviewed data from a previously published case-controlled study, which included 22 health care workers who had been infected in 2003 with SARS-CoV-1 and continued to report chronic fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, and disturbed and unrefreshing sleep with EEG-documented sleep disturbances 1-3 years following the illness. None had been able to return to work by 1 year.

“We’re looking at similar symptoms now” among survivors of COVID-19, Dr. Moldofsky said. “[T]he key issue is that we have no idea of its prevalence. … We need epidemiologic studies.”

Distinguishing ME/CFS from other post–COVID-19 symptoms

Not everyone who has persistent symptoms after COVID-19 will develop ME/CFS, and distinguishing between cases may be important.

Clinically, Dr. Chu said, one way to assess whether a patient with persistent COVID-19 symptoms might be progressing to ME/CFS is to ask him or her specifically about the level of fatigue following physical exertion and the timing of any fatigue. With ME/CFS, postexertional malaise often involves a dramatic exacerbation of symptoms such as fatigue, pain, and cognitive impairment a day or 2 after exertion rather than immediately following it. In contrast, shortness of breath during exertion isn’t typical of ME/CFS.

Objective measures of ME/CFS include low natural killer cell function (the test can be ordered from commercial labs but requires rapid transport of the blood sample), and autonomic dysfunction assessed by a tilt-table test.

While there is currently no cure for ME/CFS, diagnosing it allows for the patient to be taught “pacing” in which the person conserves his or her energy by balancing activity with rest. “That type of behavioral technique is valuable for everyone who suffers from a chronic disease with fatigue. It can help them be more functional,” Dr. Chu said.

If a patient appears to be exhibiting signs of ME/CFS, “don’t wait until they hit the 6-month mark to start helping them manage their symptoms,” she said. “Teaching pacing to COVID-19 patients who have a lot of fatigue isn’t going to harm them. As they get better they’re going to just naturally do more. But if they do have ME/CFS, [pacing] stresses their system less, since the data seem to be pointing to deficiencies in producing energy.”

Will COVID-19 unleash a new wave of ME/CFS patients?

Much of the session at the virtual meeting was devoted to ongoing studies. For example, Leonard Jason, PhD, of the Center for Community Research at DePaul University, Chicago, described a prospective study launched in 2014 that looked at risk factors for developing ME/CFS in college students who contracted infectious mononucleosis as a result of Epstein-Barr virus. Now, his team is also following students from the same cohort who develop COVID-19.

Because the study included collection of baseline biological samples, the results could help reveal predisposing factors associated with long-term illness from either virus.

Another project, funded by the Open Medicine Foundation, will follow patients who are discharged from the ICU following severe COVID-19 illness. Blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid will be collected from those with persistent symptoms at 6 months, along with questionnaire data. At 18-24 months, those who continue to report symptoms will undergo more intensive evaluation using genomics, metabolomics, and proteomics.

“We’re taking advantage of this horrible situation, hoping to understand how a serious viral infection might lead to ME/CFS,” said lead investigator Ronald Tompkins, MD, ScD, chief medical officer at the Open Medicine Foundation and a faculty member at Harvard Medical School, Boston. The results, he said, “might give us insight into potential drug targets or biomarkers useful for prevention and treatment strategies.”

Meanwhile, Sadie Whittaker, PhD, head of the Solve ME/CFS initiative, described her organization’s new plan to use their registry to prospectively track the impact of COVID-19 on people with ME/CFS.

She noted that they’ve also teamed up with “long-COVID” communities including Body Politic. “Our goal is to form a coalition to study together or at least harmonize data … and understand what’s going on through the power of bigger sample sizes,” Dr. Whittaker said.

None of the speakers disclosed relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Some patients who had COVID-19 continue to have symptoms weeks to months later, even after they no longer test positive for the virus. In two recent reports – one published in JAMA in July and another published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report in August – chronic fatigue was listed as the top symptom among individuals still feeling unwell beyond 2 weeks after COVID-19 onset.

Although some of the reported persistent symptoms appear specific to SARS-CoV-2 – such as cough, chest pain, and dyspnea – others overlap with the diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS, which is defined by substantial, profound fatigue for at least 6 months, postexertional malaise, unrefreshing sleep, and one or both of orthostatic intolerance and/or cognitive impairment. Although the etiology of ME/CFS is unclear, the condition commonly arises following a viral illness.

At the virtual meeting of the International Association for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis August 21, the opening session was devoted to research documenting the extent to which COVID-19 survivors subsequently meet ME/CFS criteria, and to exploring underlying mechanisms.

“It offers a lot of opportunities for us to study potentially early ME/CFS and how it develops, but in addition, a lot of the research that has been done on ME/CFS may also provide answers for COVID-19,” IACFS/ME vice president Lily Chu, MD, said in an interview.

A hint from the SARS outbreak

This isn’t the first time researchers have seen a possible link between a coronavirus and ME/CFS, Harvey Moldofsky, MD, told attendees. To illustrate that point, Dr. Moldofsky, of the department of psychiatry (emeritus) at the University of Toronto, reviewed data from a previously published case-controlled study, which included 22 health care workers who had been infected in 2003 with SARS-CoV-1 and continued to report chronic fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, and disturbed and unrefreshing sleep with EEG-documented sleep disturbances 1-3 years following the illness. None had been able to return to work by 1 year.

“We’re looking at similar symptoms now” among survivors of COVID-19, Dr. Moldofsky said. “[T]he key issue is that we have no idea of its prevalence. … We need epidemiologic studies.”

Distinguishing ME/CFS from other post–COVID-19 symptoms

Not everyone who has persistent symptoms after COVID-19 will develop ME/CFS, and distinguishing between cases may be important.

Clinically, Dr. Chu said, one way to assess whether a patient with persistent COVID-19 symptoms might be progressing to ME/CFS is to ask him or her specifically about the level of fatigue following physical exertion and the timing of any fatigue. With ME/CFS, postexertional malaise often involves a dramatic exacerbation of symptoms such as fatigue, pain, and cognitive impairment a day or 2 after exertion rather than immediately following it. In contrast, shortness of breath during exertion isn’t typical of ME/CFS.

Objective measures of ME/CFS include low natural killer cell function (the test can be ordered from commercial labs but requires rapid transport of the blood sample), and autonomic dysfunction assessed by a tilt-table test.

While there is currently no cure for ME/CFS, diagnosing it allows for the patient to be taught “pacing” in which the person conserves his or her energy by balancing activity with rest. “That type of behavioral technique is valuable for everyone who suffers from a chronic disease with fatigue. It can help them be more functional,” Dr. Chu said.

If a patient appears to be exhibiting signs of ME/CFS, “don’t wait until they hit the 6-month mark to start helping them manage their symptoms,” she said. “Teaching pacing to COVID-19 patients who have a lot of fatigue isn’t going to harm them. As they get better they’re going to just naturally do more. But if they do have ME/CFS, [pacing] stresses their system less, since the data seem to be pointing to deficiencies in producing energy.”

Will COVID-19 unleash a new wave of ME/CFS patients?

Much of the session at the virtual meeting was devoted to ongoing studies. For example, Leonard Jason, PhD, of the Center for Community Research at DePaul University, Chicago, described a prospective study launched in 2014 that looked at risk factors for developing ME/CFS in college students who contracted infectious mononucleosis as a result of Epstein-Barr virus. Now, his team is also following students from the same cohort who develop COVID-19.

Because the study included collection of baseline biological samples, the results could help reveal predisposing factors associated with long-term illness from either virus.

Another project, funded by the Open Medicine Foundation, will follow patients who are discharged from the ICU following severe COVID-19 illness. Blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid will be collected from those with persistent symptoms at 6 months, along with questionnaire data. At 18-24 months, those who continue to report symptoms will undergo more intensive evaluation using genomics, metabolomics, and proteomics.

“We’re taking advantage of this horrible situation, hoping to understand how a serious viral infection might lead to ME/CFS,” said lead investigator Ronald Tompkins, MD, ScD, chief medical officer at the Open Medicine Foundation and a faculty member at Harvard Medical School, Boston. The results, he said, “might give us insight into potential drug targets or biomarkers useful for prevention and treatment strategies.”

Meanwhile, Sadie Whittaker, PhD, head of the Solve ME/CFS initiative, described her organization’s new plan to use their registry to prospectively track the impact of COVID-19 on people with ME/CFS.

She noted that they’ve also teamed up with “long-COVID” communities including Body Politic. “Our goal is to form a coalition to study together or at least harmonize data … and understand what’s going on through the power of bigger sample sizes,” Dr. Whittaker said.

None of the speakers disclosed relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA authorizes convalescent plasma for COVID-19

Convalescent plasma contains antibodies from the blood of recovered COVID-19 patients, which can be used to treat people with severe infections. Convalescent plasma has been used to treat patients for other infectious diseases. The authorization allows the plasma to be distributed in the United States and administered by health care providers.

“COVID-19 convalescent plasma is safe and shows promising efficacy,” Stephen Hahn, MD, commissioner of the FDA, said during a press briefing with President Donald Trump.

In April, the FDA approved a program to test convalescent plasma in COVID-19 patients at the Mayo Clinic, followed by other institutions. More than 90,000 patients have enrolled in the program, and 70,000 have received the treatment, Dr. Hahn said.

The data indicate that the plasma can reduce mortality in patients by 35%, particularly if patients are treated within 3 days of being diagnosed. Those who have benefited the most were under age 80 and not on artificial respiration, Alex Azar, the secretary for the Department of Health & Human Services, said during the briefing.

“We dream, in drug development, of something like a 35% mortality reduction,” he said.

But top scientists pushed back against the announcement.

Eric Topol, MD, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute, professor of molecular medicine, and executive vice president of Scripps Research, said the data the FDA are relying on did not come from the rigorous randomized, double-blind placebo trials that best determine if a treatment is successful.

Still, convalescent plasma is “one more tool added to the arsenal” of combating COVID-19, Mr. Azar said. The FDA will continue to study convalescent plasma as a COVID-19 treatment, Dr. Hahn added.

“We’re waiting for more data. We’re going to continue to gather data,” Dr. Hahn said during the briefing, but the current results meet FDA criteria for issuing an emergency use authorization.

Convalescent plasma “may be effective in lessening the severity or shortening the length of COVID-19 illness in some hospitalized patients,” according to the FDA announcement. Potential side effects include allergic reactions, transfusion-transmitted infections, and transfusion-associated lung injury.

“We’ve seen a great deal of demand for this from doctors around the country,” Dr. Hahn said during the briefing. “The EUA … allows us to continue that and meet that demand.”

Dr. Topol, however, said it appears Trump and the FDA are playing politics with science.

“There’s no evidence to support any survival benefit,” Dr. Topol said on Twitter. “Two days ago [the] FDA’s website stated there was no evidence for an EUA.”

The American Red Cross and other blood centers put out a national call for blood donors in July, especially for patients who have recovered from COVID-19. Mr. Azar and Dr. Hahn emphasized the need for blood donors during the press briefing.

“If you donate plasma, you could save a life,” Mr. Azar said.

The study has not been peer reviewed and did not include a placebo group for comparison, STAT reported.

Last week several health officials warned that the scientific data were too weak to warrant an emergency authorization, the New York Times reported.

A version of this originally appeared on WebMD.com.

Convalescent plasma contains antibodies from the blood of recovered COVID-19 patients, which can be used to treat people with severe infections. Convalescent plasma has been used to treat patients for other infectious diseases. The authorization allows the plasma to be distributed in the United States and administered by health care providers.

“COVID-19 convalescent plasma is safe and shows promising efficacy,” Stephen Hahn, MD, commissioner of the FDA, said during a press briefing with President Donald Trump.

In April, the FDA approved a program to test convalescent plasma in COVID-19 patients at the Mayo Clinic, followed by other institutions. More than 90,000 patients have enrolled in the program, and 70,000 have received the treatment, Dr. Hahn said.

The data indicate that the plasma can reduce mortality in patients by 35%, particularly if patients are treated within 3 days of being diagnosed. Those who have benefited the most were under age 80 and not on artificial respiration, Alex Azar, the secretary for the Department of Health & Human Services, said during the briefing.

“We dream, in drug development, of something like a 35% mortality reduction,” he said.

But top scientists pushed back against the announcement.

Eric Topol, MD, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute, professor of molecular medicine, and executive vice president of Scripps Research, said the data the FDA are relying on did not come from the rigorous randomized, double-blind placebo trials that best determine if a treatment is successful.

Still, convalescent plasma is “one more tool added to the arsenal” of combating COVID-19, Mr. Azar said. The FDA will continue to study convalescent plasma as a COVID-19 treatment, Dr. Hahn added.

“We’re waiting for more data. We’re going to continue to gather data,” Dr. Hahn said during the briefing, but the current results meet FDA criteria for issuing an emergency use authorization.

Convalescent plasma “may be effective in lessening the severity or shortening the length of COVID-19 illness in some hospitalized patients,” according to the FDA announcement. Potential side effects include allergic reactions, transfusion-transmitted infections, and transfusion-associated lung injury.

“We’ve seen a great deal of demand for this from doctors around the country,” Dr. Hahn said during the briefing. “The EUA … allows us to continue that and meet that demand.”

Dr. Topol, however, said it appears Trump and the FDA are playing politics with science.

“There’s no evidence to support any survival benefit,” Dr. Topol said on Twitter. “Two days ago [the] FDA’s website stated there was no evidence for an EUA.”

The American Red Cross and other blood centers put out a national call for blood donors in July, especially for patients who have recovered from COVID-19. Mr. Azar and Dr. Hahn emphasized the need for blood donors during the press briefing.

“If you donate plasma, you could save a life,” Mr. Azar said.

The study has not been peer reviewed and did not include a placebo group for comparison, STAT reported.

Last week several health officials warned that the scientific data were too weak to warrant an emergency authorization, the New York Times reported.

A version of this originally appeared on WebMD.com.

Convalescent plasma contains antibodies from the blood of recovered COVID-19 patients, which can be used to treat people with severe infections. Convalescent plasma has been used to treat patients for other infectious diseases. The authorization allows the plasma to be distributed in the United States and administered by health care providers.

“COVID-19 convalescent plasma is safe and shows promising efficacy,” Stephen Hahn, MD, commissioner of the FDA, said during a press briefing with President Donald Trump.

In April, the FDA approved a program to test convalescent plasma in COVID-19 patients at the Mayo Clinic, followed by other institutions. More than 90,000 patients have enrolled in the program, and 70,000 have received the treatment, Dr. Hahn said.

The data indicate that the plasma can reduce mortality in patients by 35%, particularly if patients are treated within 3 days of being diagnosed. Those who have benefited the most were under age 80 and not on artificial respiration, Alex Azar, the secretary for the Department of Health & Human Services, said during the briefing.

“We dream, in drug development, of something like a 35% mortality reduction,” he said.

But top scientists pushed back against the announcement.

Eric Topol, MD, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute, professor of molecular medicine, and executive vice president of Scripps Research, said the data the FDA are relying on did not come from the rigorous randomized, double-blind placebo trials that best determine if a treatment is successful.

Still, convalescent plasma is “one more tool added to the arsenal” of combating COVID-19, Mr. Azar said. The FDA will continue to study convalescent plasma as a COVID-19 treatment, Dr. Hahn added.

“We’re waiting for more data. We’re going to continue to gather data,” Dr. Hahn said during the briefing, but the current results meet FDA criteria for issuing an emergency use authorization.

Convalescent plasma “may be effective in lessening the severity or shortening the length of COVID-19 illness in some hospitalized patients,” according to the FDA announcement. Potential side effects include allergic reactions, transfusion-transmitted infections, and transfusion-associated lung injury.

“We’ve seen a great deal of demand for this from doctors around the country,” Dr. Hahn said during the briefing. “The EUA … allows us to continue that and meet that demand.”

Dr. Topol, however, said it appears Trump and the FDA are playing politics with science.

“There’s no evidence to support any survival benefit,” Dr. Topol said on Twitter. “Two days ago [the] FDA’s website stated there was no evidence for an EUA.”

The American Red Cross and other blood centers put out a national call for blood donors in July, especially for patients who have recovered from COVID-19. Mr. Azar and Dr. Hahn emphasized the need for blood donors during the press briefing.

“If you donate plasma, you could save a life,” Mr. Azar said.

The study has not been peer reviewed and did not include a placebo group for comparison, STAT reported.

Last week several health officials warned that the scientific data were too weak to warrant an emergency authorization, the New York Times reported.

A version of this originally appeared on WebMD.com.

Serum cortisol testing for suspected adrenal insufficiency

Evaluating the hospitalized adult patient

Case

A 45-year-old female with moderate persistent asthma is admitted for right lower extremity cellulitis. She has hyponatremia with a sodium of 129 mEq/L and reports a history of longstanding fatigue and lightheadedness on standing. An early morning serum cortisol was 10 mcg/dL, normal per the reference range for the laboratory. Has adrenal insufficiency been excluded in this patient?

Overview

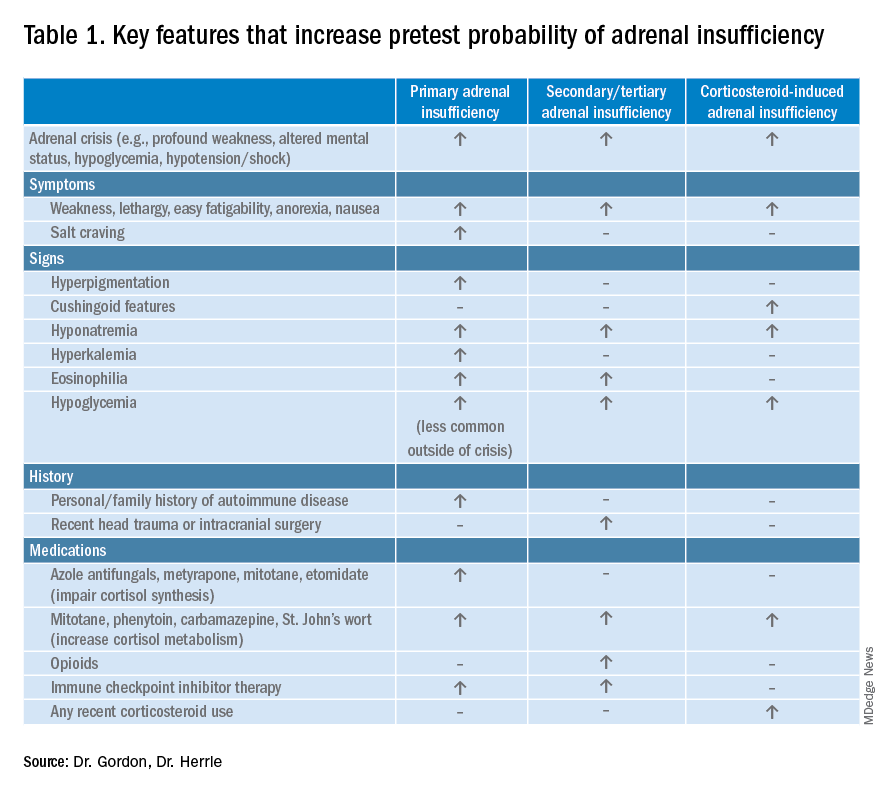

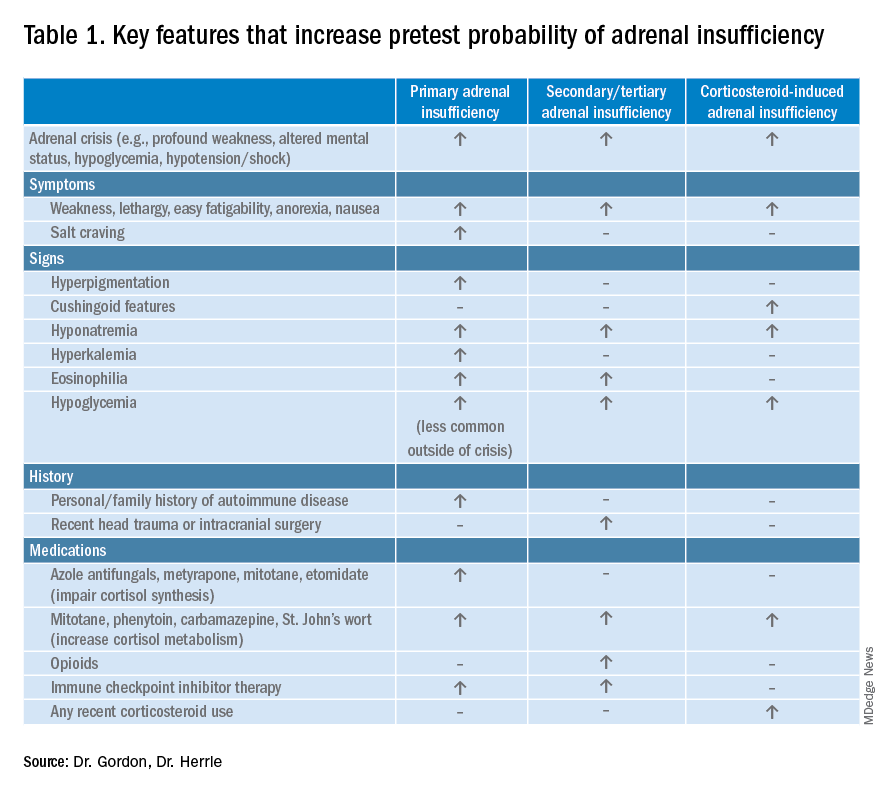

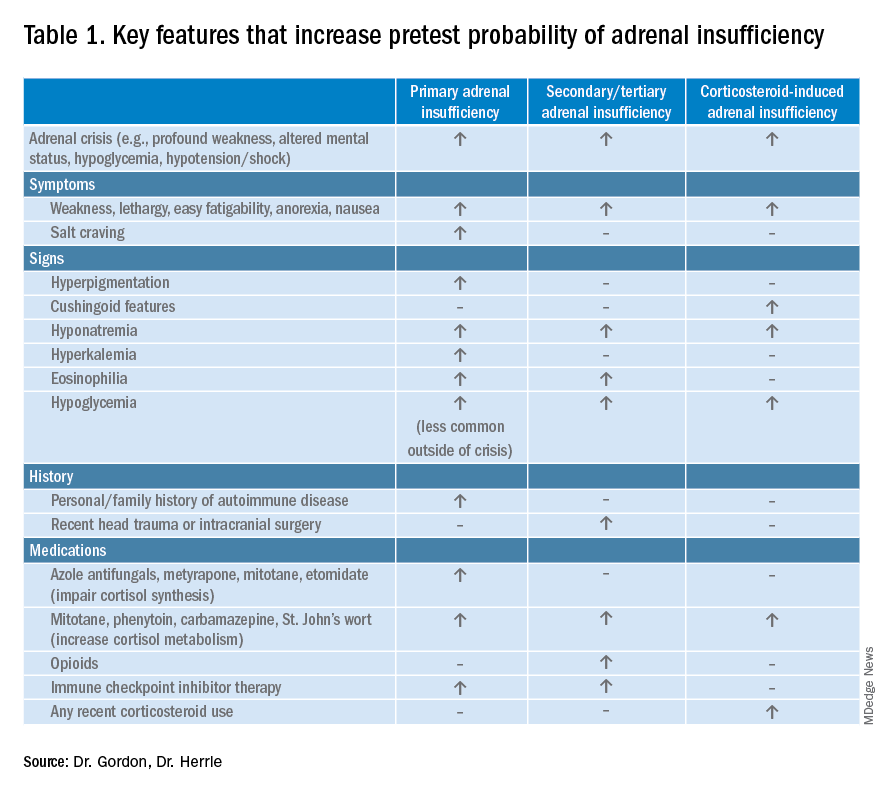

Adrenal insufficiency (AI) is a clinical syndrome characterized by a deficiency of cortisol. Presentation may range from nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, weight loss, and gastrointestinal concerns to a fulminant adrenal crisis with severe weakness and hypotension (Table 1). The diagnosis of AI is commonly delayed, negatively impacting patients’ quality of life and risking dangerous complications.1,2

AI can occur due to diseases of the adrenal glands themselves (primary) or impairment of adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) secretion from the pituitary (secondary) or corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) secretion from the hypothalamus (tertiary). In the hospital setting, causes of primary AI may include autoimmune disease, infection, metastatic disease, hemorrhage, and adverse medication effects. Secondary and tertiary AI would be of particular concern for patients with traumatic brain injuries or pituitary surgery, but also are seen commonly as a result of adverse medication effects in the hospitalized patient, notably opioids and corticosteroids through suppression the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and immune checkpoint inhibitors via autoimmune hypophysitis.

Testing for AI in the hospitalized patient presents a host of challenges. Among these are the variability in presentation of different types of AI, high rates of exogenous corticosteroid use, the impact of critical illness on the HPA axis, medical illness altering protein binding of serum cortisol, interfering medications, the variation in assays used by laboratories, and the logistical challenges of obtaining appropriately timed phlebotomy.2,3

Cortisol testing

An intact HPA axis results in ACTH-dependent cortisol release from the adrenal glands. Cortisol secretion exhibits circadian rhythm, with the highest levels in the early morning (6 a.m. to 8 a.m.) and the lowest at night (12 a.m.). It also is pulsatile, which may explain the range of “normal” morning serum cortisol observed in a study of healthy volunteers.3 Note that serum cortisol is equivalent to plasma cortisol in current immunoassays, and will henceforth be called “cortisol” in this paper.3

There are instances when morning cortisol may strongly suggest a diagnosis of AI on its own. A meta-analysis found that morning cortisol of < 5 mcg/dL predicts AI and morning cortisol of > 13 mcg/dL ruled out AI.4 The Endocrine Society of America favors dynamic assessment of adrenal function for most patients.2

Historically, the gold standard for assessing dynamic adrenal function has been the insulin tolerance test (ITT), whereby cortisol is measured after inducing hypoglycemia to a blood glucose < 35 mg/dL. ITT is logistically difficult and poses some risk to the patient. The corticotropin (or cosyntropin) stimulation test (CST), in which a supraphysiologic dose of a synthetic ACTH analog is administered parenterally to a patient and resultant cortisol levels are measured, has been validated against the ITT and is generally preferred.5 CST is used to diagnose primary AI as well as chronic secondary and tertiary AI, given that longstanding lack of ACTH stimulation causes atrophy of the adrenal glands. The sensitivity for secondary and tertiary AI is likely lower than primary AI especially in acute onset of disease.6,7

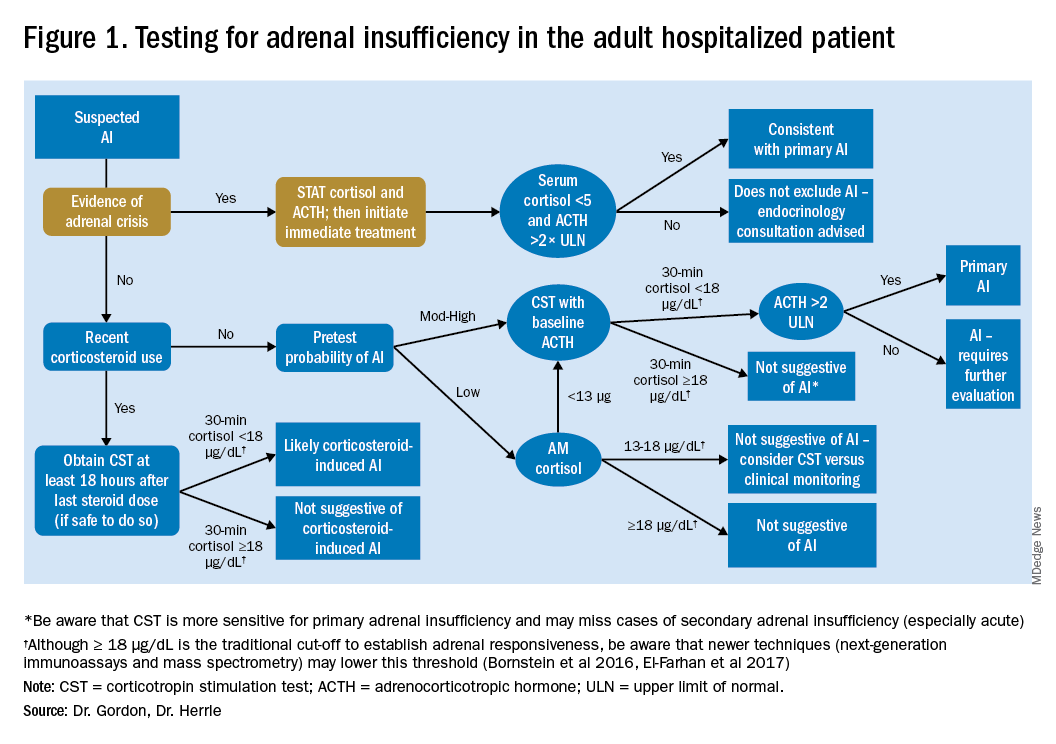

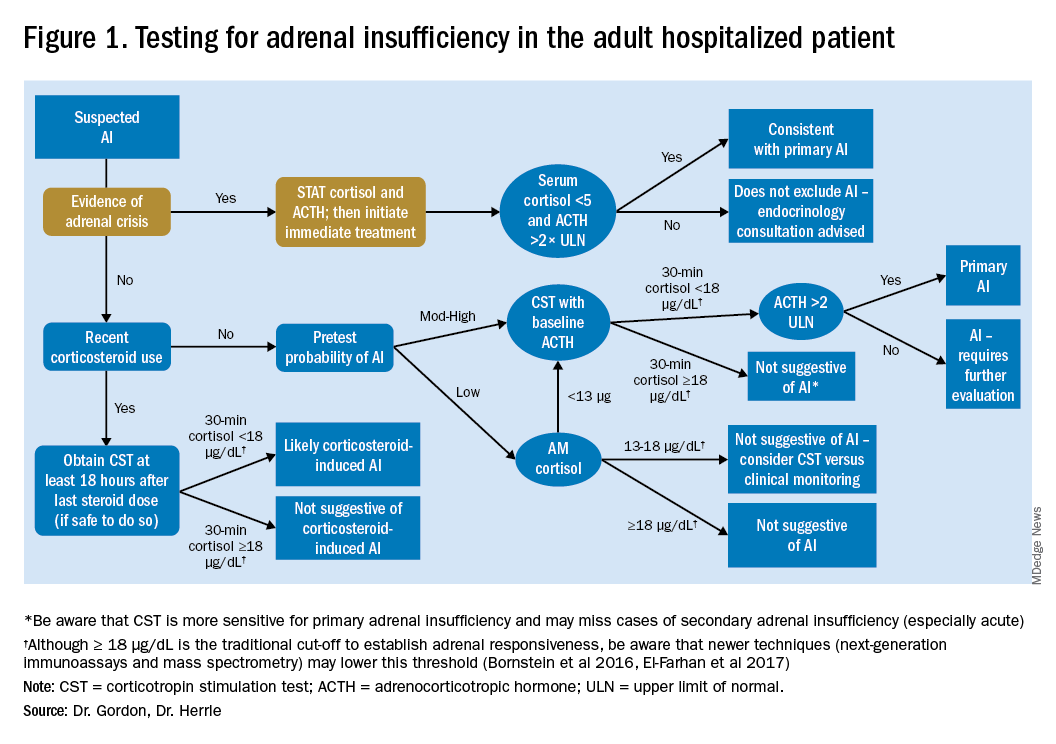

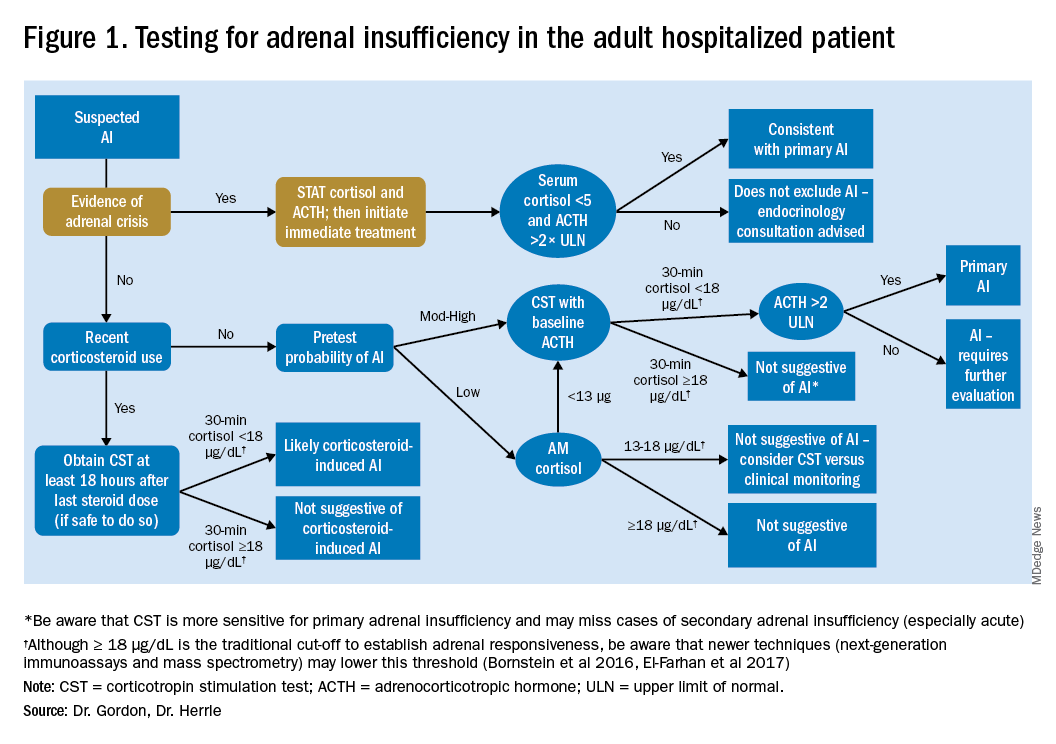

In performance of the CST a baseline cortisol and ACTH are obtained, with subsequent cortisol testing at 30 and/or 60 minutes after administration of the ACTH analog (Figure 1). Currently, there is no consensus for which time point is preferred, but the 30-minute test is more sensitive for AI and the 60-minute test is more specific.2,7,8

CST is typically performed using a “standard high dose” of 250 mcg of the ACTH analog. There has been interest in the use of a “low-dose” 1 mcg test, which is closer to normal physiologic stimulation of the adrenal glands and may have better sensitivity for early secondary or partial AI. However, the 250-mcg dose is easier to prepare and has fewer technical pitfalls in administration as well as a lower risk for false positive testing. At this point the data do not compellingly favor the use of low-dose CST testing in general practice.2,3,7

Clinical decision making

Diagnostic evaluation should be guided by the likelihood of the disease (i.e., the pretest probability) (Figure 1). Begin with a review of the patient’s signs and symptoms, medical and family history, and medications with special consideration for opioids, exogenous steroids, and immune checkpoint inhibitors (Table 1).

For patients with low pretest probability for AI, morning cortisol and ACTH is a reasonable first test (Figure 1). A cortisol value of 18 mcg/dL or greater does not support AI and no further testing is needed.2 Patients with morning cortisol of 13-18 mcg/dL could be followed clinically or could undergo further testing in the inpatient environment with CST, depending upon the clinical scenario.4 Patients with serum cortisol of <13 mcg/dL warrant CST.

For patients with moderate to high pretest probability for AI, we recommend initial testing with CST. While the results of high-dose CST are not necessarily impacted by time of day, if an a.m. cortisol has not yet been obtained and it is logistically feasible to do so, performing CST in the morning will provide the most useful data for clinical interpretation.

For patients presenting with possible adrenal crisis, it is essential not to delay treatment. In these patients, obtain a cortisol paired with ACTH and initiate treatment immediately. Further testing can be deferred until the time the patient is stable.2

Potential pitfalls

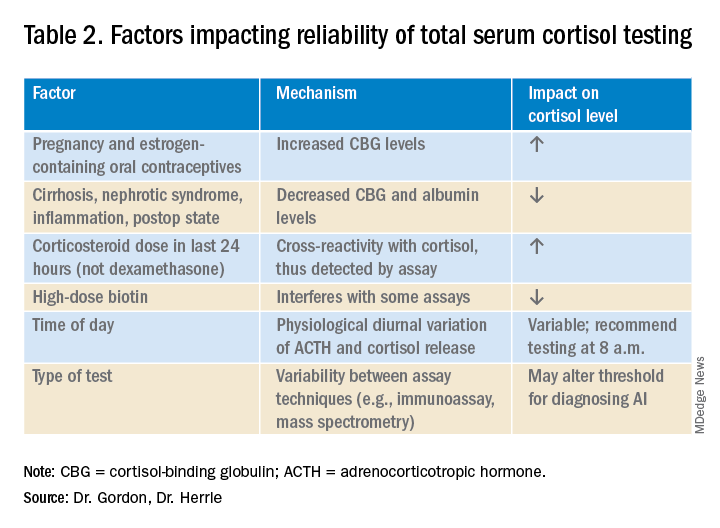

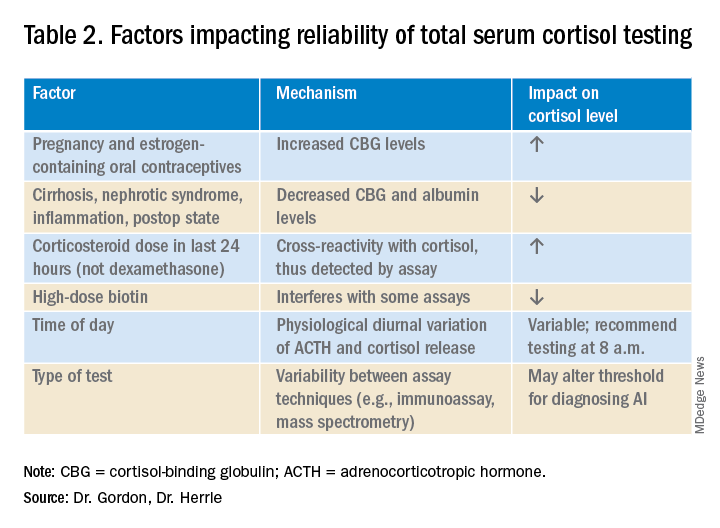

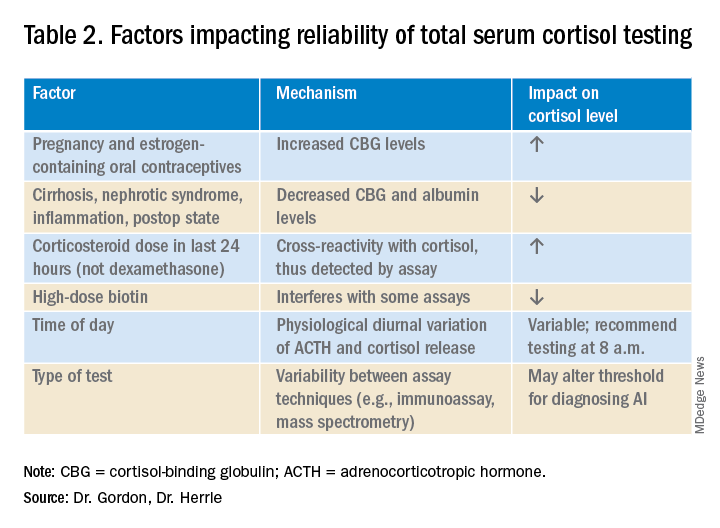

Interpreting cortisol requires awareness of multiple conditions that could directly impact the results.2,3 (Table 2).

Currently available assays measure “total cortisol,” most of which is protein bound (cortisol-binding globulin as well as albumin). Therefore, conditions that lower serum protein (e.g., nephrotic syndrome, liver disease, inflammation) will lower the measured cortisol. Conversely, conditions that increase serum protein (e.g., estrogen excess in pregnancy and oral contraceptive use) will increase the measured cortisol.2,3

It is also important to recognize that existing immunoassay testing techniques informed the established cut-off for exclusion of AI at 18 mcg/dL. With newer immunoassays and emerging liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry, this cut-off may be lowered; thus the assay should be confirmed with the performing laboratory. There is emerging evidence that serum or plasma free cortisol and salivary cortisol testing for AI may be useful in certain cases, but these techniques are not yet widespread or included in clinical practice guidelines.2,3,7

Population focus: Patients on exogenous steroids

Exogenous corticosteroids suppress the HPA axis via negative inhibition of CRH and ACTH release, often resulting in low endogenous cortisol levels which may or may not reflect true loss of adrenal function. In addition, many corticosteroids will be detected by standard serum cortisol tests that rely on immunoassays. For this reason, cortisol measurement and CST should be done at least 18-24 hours after the last dose of exogenous steroids.

Although the focus has been on higher doses and longer courses of steroids (e.g., chronic use of ≥ 5 mg prednisone daily, or ≥ 20 mg prednisone daily for > 3 weeks), there is increasing evidence that lower doses, shorter courses, and alternate routes (e.g., inhaled, intra-articular) can result in biochemical and clinical evidence of AI.9 Thus, a thorough history and exam should be obtained to determine all recent corticosteroid exposure and cushingoid features.

Application of the data to the case

To effectively assess the patient for adrenal insufficiency, we need additional information. First and foremost, is a description of the patient’s current clinical status. If she is demonstrating evidence of adrenal crisis, treatment should not be delayed for additional testing. If she is stable, a thorough history including use of corticosteroids by any route, pregnancy, oral contraceptives, recent surgery, and liver and kidney disease is essential.

Additional evaluation reveals the patient has been using her fluticasone inhaler daily. No other source of hyponatremia or lightheadedness is identified. The patient’s risk factors of corticosteroid use and unexplained hyponatremia with associated lightheadedness increase her pretest probability of AI and a single morning cortisol of 10 mcg/dL is insufficient to exclude adrenal insufficiency. The appropriate follow-up test is a standard high-dose cosyntropin stimulation test at least 18 hours after her last dose of fluticasone. A cortisol level > 18 mcg/dL at 30 minutes in the absence of other conditions that impact cortisol testing would not be suggestive of AI. A serum cortisol level of < 18 mcg/dL at 30 minutes would raise concern for abnormal adrenal reserve due to chronic corticosteroid therapy and would warrant referral to an endocrinologist.

Bottom line

An isolated serum cortisol is often insufficient to exclude adrenal insufficiency. Hospitalists should be aware of the many factors that impact the interpretation of this test.

Dr. Gordon is assistant professor of medicine at Tufts University, Boston, and a hospitalist at Maine Medical Center, Portland. She is the subspecialty education coordinator of inpatient medicine for the Internal Medicine Residency Program. Dr. Herrle is assistant professor of medicine at Tufts University and a hospitalist at Maine Medical Center. She is the associate director of medical student education for the department of internal medicine at MMC and a medical director for clinical informatics at MaineHealth.

References

1. Bleicken B et al. Delayed diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency is common: A cross-sectional study in 216 patients. Am J Med Sci. 2010;339(6):525-31. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181db6b7a.

2. Bornstein SR et al. Diagnosis and treatment of primary adrenal insufficiency: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016 Feb;101(2):364-89.

3. El-Farhan N et al. Measuring cortisol in serum, urine and saliva – Are our assays good enough? Ann Clin Biochem. 2017 May;54(3):308-22. doi: 10.1177/0004563216687335.

4. Kazlauskaite R et al. Corticotropin tests for hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal insufficiency: A metaanalysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4245-53.

5. Wood JB et al. A rapid test of adrenocortical function. Lancet. 1965;191:243-5.

6. Singh Ospina N et al. ACTH stimulation tests for the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(2):427-34.

7. Burgos N et al. Pitfalls in the interpretation of the cosyntropin stimulation test for the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2019;26(3):139-45.

8. Odom DC et al. A Single, post-ACTH cortisol measurement to screen for adrenal insufficiency in the hospitalized patient. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(8):526-30. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2928.

9. Broersen LHA et al. Adrenal insufficiency in corticosteroids use: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(6): 2171-80.

Key points

• In general, random cortisol testing is of limited value and should be avoided.

• Serum cortisol testing in the hospitalized patient is impacted by a variety of patient and disease factors and should be interpreted carefully.

• For patients with low pretest probability of adrenal insufficiency, early morning serum cortisol testing may be sufficient to exclude the diagnosis.

• For patients with moderate to high pretest probability of adrenal insufficiency, standard high-dose (250 mcg) corticotropin stimulation testing is preferred.

Additional reading

Bornstein SR et al. Diagnosis and treatment of primary adrenal insufficiency: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016 Feb;101(2):364-89.

Burgos N et al. Pitfalls in the interpretation of the cosyntropin stimulation test for the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2019;26(3):139-45.

Quiz

An 82 y.o. woman with depression is admitted from her long-term care facility with worsening weakness and mild hypoglycemia. Her supine vital signs are stable, but she exhibits a drop in systolic blood pressure of 21 mm Hg upon standing. There is no evidence of infection by history, exam, or initial workup. She is not on chronic corticosteroids by any route.

What would be your initial workup for adrenal insufficiency?

A) Morning serum cortisol and ACTH

B) Insulin tolerance test

C) Corticotropin stimulation test

D) Would not test at this point

Answer: C. Although her symptom of weakness is nonspecific, her hypoglycemia and orthostatic hypotension are concerning enough that she would qualify as moderate to high pretest probability for AI. In this setting, one would acquire a basal serum total cortisol and ACTH then administer the standard high-dose corticotropin stimulation test (250 mcg) followed by repeat serum total cortisol at 30 or 60 minutes.

Evaluating the hospitalized adult patient

Evaluating the hospitalized adult patient

Case

A 45-year-old female with moderate persistent asthma is admitted for right lower extremity cellulitis. She has hyponatremia with a sodium of 129 mEq/L and reports a history of longstanding fatigue and lightheadedness on standing. An early morning serum cortisol was 10 mcg/dL, normal per the reference range for the laboratory. Has adrenal insufficiency been excluded in this patient?

Overview

Adrenal insufficiency (AI) is a clinical syndrome characterized by a deficiency of cortisol. Presentation may range from nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, weight loss, and gastrointestinal concerns to a fulminant adrenal crisis with severe weakness and hypotension (Table 1). The diagnosis of AI is commonly delayed, negatively impacting patients’ quality of life and risking dangerous complications.1,2

AI can occur due to diseases of the adrenal glands themselves (primary) or impairment of adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) secretion from the pituitary (secondary) or corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) secretion from the hypothalamus (tertiary). In the hospital setting, causes of primary AI may include autoimmune disease, infection, metastatic disease, hemorrhage, and adverse medication effects. Secondary and tertiary AI would be of particular concern for patients with traumatic brain injuries or pituitary surgery, but also are seen commonly as a result of adverse medication effects in the hospitalized patient, notably opioids and corticosteroids through suppression the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and immune checkpoint inhibitors via autoimmune hypophysitis.

Testing for AI in the hospitalized patient presents a host of challenges. Among these are the variability in presentation of different types of AI, high rates of exogenous corticosteroid use, the impact of critical illness on the HPA axis, medical illness altering protein binding of serum cortisol, interfering medications, the variation in assays used by laboratories, and the logistical challenges of obtaining appropriately timed phlebotomy.2,3

Cortisol testing

An intact HPA axis results in ACTH-dependent cortisol release from the adrenal glands. Cortisol secretion exhibits circadian rhythm, with the highest levels in the early morning (6 a.m. to 8 a.m.) and the lowest at night (12 a.m.). It also is pulsatile, which may explain the range of “normal” morning serum cortisol observed in a study of healthy volunteers.3 Note that serum cortisol is equivalent to plasma cortisol in current immunoassays, and will henceforth be called “cortisol” in this paper.3

There are instances when morning cortisol may strongly suggest a diagnosis of AI on its own. A meta-analysis found that morning cortisol of < 5 mcg/dL predicts AI and morning cortisol of > 13 mcg/dL ruled out AI.4 The Endocrine Society of America favors dynamic assessment of adrenal function for most patients.2

Historically, the gold standard for assessing dynamic adrenal function has been the insulin tolerance test (ITT), whereby cortisol is measured after inducing hypoglycemia to a blood glucose < 35 mg/dL. ITT is logistically difficult and poses some risk to the patient. The corticotropin (or cosyntropin) stimulation test (CST), in which a supraphysiologic dose of a synthetic ACTH analog is administered parenterally to a patient and resultant cortisol levels are measured, has been validated against the ITT and is generally preferred.5 CST is used to diagnose primary AI as well as chronic secondary and tertiary AI, given that longstanding lack of ACTH stimulation causes atrophy of the adrenal glands. The sensitivity for secondary and tertiary AI is likely lower than primary AI especially in acute onset of disease.6,7

In performance of the CST a baseline cortisol and ACTH are obtained, with subsequent cortisol testing at 30 and/or 60 minutes after administration of the ACTH analog (Figure 1). Currently, there is no consensus for which time point is preferred, but the 30-minute test is more sensitive for AI and the 60-minute test is more specific.2,7,8

CST is typically performed using a “standard high dose” of 250 mcg of the ACTH analog. There has been interest in the use of a “low-dose” 1 mcg test, which is closer to normal physiologic stimulation of the adrenal glands and may have better sensitivity for early secondary or partial AI. However, the 250-mcg dose is easier to prepare and has fewer technical pitfalls in administration as well as a lower risk for false positive testing. At this point the data do not compellingly favor the use of low-dose CST testing in general practice.2,3,7

Clinical decision making

Diagnostic evaluation should be guided by the likelihood of the disease (i.e., the pretest probability) (Figure 1). Begin with a review of the patient’s signs and symptoms, medical and family history, and medications with special consideration for opioids, exogenous steroids, and immune checkpoint inhibitors (Table 1).

For patients with low pretest probability for AI, morning cortisol and ACTH is a reasonable first test (Figure 1). A cortisol value of 18 mcg/dL or greater does not support AI and no further testing is needed.2 Patients with morning cortisol of 13-18 mcg/dL could be followed clinically or could undergo further testing in the inpatient environment with CST, depending upon the clinical scenario.4 Patients with serum cortisol of <13 mcg/dL warrant CST.

For patients with moderate to high pretest probability for AI, we recommend initial testing with CST. While the results of high-dose CST are not necessarily impacted by time of day, if an a.m. cortisol has not yet been obtained and it is logistically feasible to do so, performing CST in the morning will provide the most useful data for clinical interpretation.

For patients presenting with possible adrenal crisis, it is essential not to delay treatment. In these patients, obtain a cortisol paired with ACTH and initiate treatment immediately. Further testing can be deferred until the time the patient is stable.2

Potential pitfalls

Interpreting cortisol requires awareness of multiple conditions that could directly impact the results.2,3 (Table 2).

Currently available assays measure “total cortisol,” most of which is protein bound (cortisol-binding globulin as well as albumin). Therefore, conditions that lower serum protein (e.g., nephrotic syndrome, liver disease, inflammation) will lower the measured cortisol. Conversely, conditions that increase serum protein (e.g., estrogen excess in pregnancy and oral contraceptive use) will increase the measured cortisol.2,3

It is also important to recognize that existing immunoassay testing techniques informed the established cut-off for exclusion of AI at 18 mcg/dL. With newer immunoassays and emerging liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry, this cut-off may be lowered; thus the assay should be confirmed with the performing laboratory. There is emerging evidence that serum or plasma free cortisol and salivary cortisol testing for AI may be useful in certain cases, but these techniques are not yet widespread or included in clinical practice guidelines.2,3,7

Population focus: Patients on exogenous steroids

Exogenous corticosteroids suppress the HPA axis via negative inhibition of CRH and ACTH release, often resulting in low endogenous cortisol levels which may or may not reflect true loss of adrenal function. In addition, many corticosteroids will be detected by standard serum cortisol tests that rely on immunoassays. For this reason, cortisol measurement and CST should be done at least 18-24 hours after the last dose of exogenous steroids.

Although the focus has been on higher doses and longer courses of steroids (e.g., chronic use of ≥ 5 mg prednisone daily, or ≥ 20 mg prednisone daily for > 3 weeks), there is increasing evidence that lower doses, shorter courses, and alternate routes (e.g., inhaled, intra-articular) can result in biochemical and clinical evidence of AI.9 Thus, a thorough history and exam should be obtained to determine all recent corticosteroid exposure and cushingoid features.

Application of the data to the case

To effectively assess the patient for adrenal insufficiency, we need additional information. First and foremost, is a description of the patient’s current clinical status. If she is demonstrating evidence of adrenal crisis, treatment should not be delayed for additional testing. If she is stable, a thorough history including use of corticosteroids by any route, pregnancy, oral contraceptives, recent surgery, and liver and kidney disease is essential.

Additional evaluation reveals the patient has been using her fluticasone inhaler daily. No other source of hyponatremia or lightheadedness is identified. The patient’s risk factors of corticosteroid use and unexplained hyponatremia with associated lightheadedness increase her pretest probability of AI and a single morning cortisol of 10 mcg/dL is insufficient to exclude adrenal insufficiency. The appropriate follow-up test is a standard high-dose cosyntropin stimulation test at least 18 hours after her last dose of fluticasone. A cortisol level > 18 mcg/dL at 30 minutes in the absence of other conditions that impact cortisol testing would not be suggestive of AI. A serum cortisol level of < 18 mcg/dL at 30 minutes would raise concern for abnormal adrenal reserve due to chronic corticosteroid therapy and would warrant referral to an endocrinologist.

Bottom line

An isolated serum cortisol is often insufficient to exclude adrenal insufficiency. Hospitalists should be aware of the many factors that impact the interpretation of this test.

Dr. Gordon is assistant professor of medicine at Tufts University, Boston, and a hospitalist at Maine Medical Center, Portland. She is the subspecialty education coordinator of inpatient medicine for the Internal Medicine Residency Program. Dr. Herrle is assistant professor of medicine at Tufts University and a hospitalist at Maine Medical Center. She is the associate director of medical student education for the department of internal medicine at MMC and a medical director for clinical informatics at MaineHealth.

References

1. Bleicken B et al. Delayed diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency is common: A cross-sectional study in 216 patients. Am J Med Sci. 2010;339(6):525-31. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181db6b7a.

2. Bornstein SR et al. Diagnosis and treatment of primary adrenal insufficiency: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016 Feb;101(2):364-89.

3. El-Farhan N et al. Measuring cortisol in serum, urine and saliva – Are our assays good enough? Ann Clin Biochem. 2017 May;54(3):308-22. doi: 10.1177/0004563216687335.

4. Kazlauskaite R et al. Corticotropin tests for hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal insufficiency: A metaanalysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4245-53.

5. Wood JB et al. A rapid test of adrenocortical function. Lancet. 1965;191:243-5.

6. Singh Ospina N et al. ACTH stimulation tests for the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(2):427-34.

7. Burgos N et al. Pitfalls in the interpretation of the cosyntropin stimulation test for the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2019;26(3):139-45.

8. Odom DC et al. A Single, post-ACTH cortisol measurement to screen for adrenal insufficiency in the hospitalized patient. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(8):526-30. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2928.

9. Broersen LHA et al. Adrenal insufficiency in corticosteroids use: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(6): 2171-80.

Key points

• In general, random cortisol testing is of limited value and should be avoided.

• Serum cortisol testing in the hospitalized patient is impacted by a variety of patient and disease factors and should be interpreted carefully.

• For patients with low pretest probability of adrenal insufficiency, early morning serum cortisol testing may be sufficient to exclude the diagnosis.

• For patients with moderate to high pretest probability of adrenal insufficiency, standard high-dose (250 mcg) corticotropin stimulation testing is preferred.

Additional reading

Bornstein SR et al. Diagnosis and treatment of primary adrenal insufficiency: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016 Feb;101(2):364-89.

Burgos N et al. Pitfalls in the interpretation of the cosyntropin stimulation test for the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2019;26(3):139-45.

Quiz

An 82 y.o. woman with depression is admitted from her long-term care facility with worsening weakness and mild hypoglycemia. Her supine vital signs are stable, but she exhibits a drop in systolic blood pressure of 21 mm Hg upon standing. There is no evidence of infection by history, exam, or initial workup. She is not on chronic corticosteroids by any route.

What would be your initial workup for adrenal insufficiency?

A) Morning serum cortisol and ACTH

B) Insulin tolerance test

C) Corticotropin stimulation test

D) Would not test at this point

Answer: C. Although her symptom of weakness is nonspecific, her hypoglycemia and orthostatic hypotension are concerning enough that she would qualify as moderate to high pretest probability for AI. In this setting, one would acquire a basal serum total cortisol and ACTH then administer the standard high-dose corticotropin stimulation test (250 mcg) followed by repeat serum total cortisol at 30 or 60 minutes.

Case

A 45-year-old female with moderate persistent asthma is admitted for right lower extremity cellulitis. She has hyponatremia with a sodium of 129 mEq/L and reports a history of longstanding fatigue and lightheadedness on standing. An early morning serum cortisol was 10 mcg/dL, normal per the reference range for the laboratory. Has adrenal insufficiency been excluded in this patient?

Overview

Adrenal insufficiency (AI) is a clinical syndrome characterized by a deficiency of cortisol. Presentation may range from nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, weight loss, and gastrointestinal concerns to a fulminant adrenal crisis with severe weakness and hypotension (Table 1). The diagnosis of AI is commonly delayed, negatively impacting patients’ quality of life and risking dangerous complications.1,2