User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Pathways to new therapeutic agents for human coronaviruses

No specific treatment is currently available for human coronaviruses to date, but numerous antiviral agents are being identified through a variety of approaches, according to Thanigaimalai Pillaiyar, PhD, and colleagues in a review published in Drug Discovery Today.

Using the six previously discovered human coronaviruses – human CoV 229E (HCoV-229E), OC43 (HCoV-OC43), NL63 (HCoV-NL63), HKU1 (HCoV-HKU1); severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) CoV; and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) CoV – the investigators examined progress in the use and development of therapeutic drugs, focusing on the potential roles of virus inhibitors.

“Research has mainly been focused on SARS- and MERS-CoV infections, because they were responsible for severe illness when compared with other CoVs,” Dr. Pillaiyar, of the department of pharmaceutical and medicinal chemistry at the University of Bonn (Germany), and colleagues wrote.

2019-nCov has been linked genomically as most closely related to SARS, and the Coronavirus Study Group of the International Committee on Virus Taxonomy, which has the responsibility for naming viruses, has designated the new virus SARS-CoV-2.

Examining extant drugs

The first approach to identifying possible antiviral agents reevaluates known, broadly acting antiviral drugs that have been used for other viral infections or other indications. The initial research into coronavirus therapeutics, in particular, has examined current antiviral therapeutics for their effectiveness against both SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, but with mixed results.

For example, in a search of potential antiviral agents against CoVs, researchers identified four drugs – chloroquine, chlorpromazine, loperamide, and lopinavir – by screening drug libraries approved by the Food and Drug Administration. They were all able to inhibit the replication of MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, and HCoV-229E in the low-micromolar range, which suggested that they could be used for broad-spectrum antiviral activity, according to Dr. Pillaiyar and colleagues.

Other research groups have also reported the discovery of antiviral drugs using this drug-repurposing approach, which included a number of broad-spectrum inhibitors of HCoVs (lycorine, emetine, monensin sodium, mycophenolate mofetil, mycophenolic acid, phenazopyridine, and pyrvinium pamoate) that showed strong inhibition of replication by four CoVs in vitro at low-micromolar concentrations and suppressed the replication of all CoVs in a dose-dependent manner. Findings from in vivo studies showed lycorine protected mice against lethal HCoV-OC43 infection.

Along with the aforementioned drugs, a number of others have also shown potential usefulness, but, as yet, none has been validated for use in humans.

Developing new antivirals

The second approach for anti-CoV drug discovery involves the development of new therapeutics based on the genomic and biophysical understanding of the individual CoV in order to interfere with the virus itself or to disrupt its direct metabolic requirements. This can take several approaches.

MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV PL protease inhibitors

Of particular interest are antiviral therapies that attack papain-like protease, which is an important target because it is a multifunctional protein involved in proteolytic deubiquitination and viral evasion of the innate immune response. One such potential therapeutic that takes advantage of this target is disulfiram, an FDA-approved drug for use in alcohol-aversion therapy. Disulfiram has been reported as an allosteric inhibitor of MERS-CoV papain-like protease. Numerous other drug categories are being examined, with promising results in targeting the papain-like protease enzymes of both SARS and MERS.

Replicase inhibitors

Helicase (nsP13) protein is a crucial component required for virus replication in host cells and could serve as a feasible target for anti-MERS and anti-SARS chemical therapies, the review authors wrote, citing as an example, the recent development of a small 1,2,4-triazole derivative that inhibited the viral NTPase/helicase of SARS- and MERS-CoVs and demonstrated high antiviral activity and low cytotoxicity.

Membrane-bound viral RNA synthesis inhibitors

Antiviral agents that target membrane-bound coronaviral RNA synthesis represent a novel and attractive approach, according to Dr. Pillaiyar and colleagues. And recently, an inhibitor was developed that targets membrane-bound coronaviral RNA synthesis and “showed potent antiviral activity of MERS-CoV infection with remarkable efficacy.”

Host-based, anti-CoV treatment options

An alternate therapeutic tactic is to bolster host defenses or to modify host susceptibilities to prevent virus infection or replication. The innate interferon response of the host is crucial for the control of viral replication after infection, and the addition of exogenous recombinant interferon or use of drugs to stimulate the normal host interferon response are both potential therapeutic avenues. For example, nitazoxanide is a potent type I interferon inducer that has been used in humans for parasitic infections, and a synthetic nitrothiazolyl-salicylamide derivative was found to exhibit broad-spectrum antiviral activities against RNA and DNA viruses, including some coronaviruses.

Numerous other host pathways are being investigated as potential areas to enhance defense against infection and replication, for example, using inhibitors to block nucleic acid synthesis has been shown to provide broad-spectrum activity against SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV.

One particular example is remdesivir, a novel nucleotide analog antiviral drug, that was developed as a therapy for Ebola virus disease and Marburg virus infections. It was later shown to provide “reasonable antiviral activity against more distantly related viruses, such as respiratory syncytial virus, Junin virus, Lassa fever virus, and MERS-CoV,” the authors wrote.

Also of interest regarding remdesivir’s potential broad-spectrum use is that it has shown potent in vitro “antiviral activity against Malaysian and Bangladesh genotypes of Nipah virus (an RNA virus, although not a coronavirus, that infects both humans and animals) and reduced replication of Malaysian Nipah virus in primary human lung microvascular endothelial cells by more than four orders of magnitude,” Dr. Pillaiyar and colleagues added. Of particular note, all remdesivir-treated, Nipah virus–infected animals “survived the lethal challenge, indicating that remdesivir represents a promising antiviral treatment.”

In a press briefing earlier this month, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, reported that a randomized, controlled, phase 3 trial of the antiviral drug remdesivir is currently underway in China to establish whether the drug would be an effective and safe treatment for adults patients with mild or moderate 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) disease.

“Our increasing understanding of novel emerging coronaviruses will be accompanied by increasing opportunities for the reasonable design of therapeutics. Importantly, understanding this basic information about CoV protease targets will not only aid the public health against SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV but also help in advance to target new coronaviruses that might emerge in the future,” the authors concluded.

Dr. Pillaiyar and colleagues reported that they had no financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Pillaiyar T et al. Drug Discov Today. 2020 Jan 30. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2020.01.015.

No specific treatment is currently available for human coronaviruses to date, but numerous antiviral agents are being identified through a variety of approaches, according to Thanigaimalai Pillaiyar, PhD, and colleagues in a review published in Drug Discovery Today.

Using the six previously discovered human coronaviruses – human CoV 229E (HCoV-229E), OC43 (HCoV-OC43), NL63 (HCoV-NL63), HKU1 (HCoV-HKU1); severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) CoV; and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) CoV – the investigators examined progress in the use and development of therapeutic drugs, focusing on the potential roles of virus inhibitors.

“Research has mainly been focused on SARS- and MERS-CoV infections, because they were responsible for severe illness when compared with other CoVs,” Dr. Pillaiyar, of the department of pharmaceutical and medicinal chemistry at the University of Bonn (Germany), and colleagues wrote.

2019-nCov has been linked genomically as most closely related to SARS, and the Coronavirus Study Group of the International Committee on Virus Taxonomy, which has the responsibility for naming viruses, has designated the new virus SARS-CoV-2.

Examining extant drugs

The first approach to identifying possible antiviral agents reevaluates known, broadly acting antiviral drugs that have been used for other viral infections or other indications. The initial research into coronavirus therapeutics, in particular, has examined current antiviral therapeutics for their effectiveness against both SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, but with mixed results.

For example, in a search of potential antiviral agents against CoVs, researchers identified four drugs – chloroquine, chlorpromazine, loperamide, and lopinavir – by screening drug libraries approved by the Food and Drug Administration. They were all able to inhibit the replication of MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, and HCoV-229E in the low-micromolar range, which suggested that they could be used for broad-spectrum antiviral activity, according to Dr. Pillaiyar and colleagues.

Other research groups have also reported the discovery of antiviral drugs using this drug-repurposing approach, which included a number of broad-spectrum inhibitors of HCoVs (lycorine, emetine, monensin sodium, mycophenolate mofetil, mycophenolic acid, phenazopyridine, and pyrvinium pamoate) that showed strong inhibition of replication by four CoVs in vitro at low-micromolar concentrations and suppressed the replication of all CoVs in a dose-dependent manner. Findings from in vivo studies showed lycorine protected mice against lethal HCoV-OC43 infection.

Along with the aforementioned drugs, a number of others have also shown potential usefulness, but, as yet, none has been validated for use in humans.

Developing new antivirals

The second approach for anti-CoV drug discovery involves the development of new therapeutics based on the genomic and biophysical understanding of the individual CoV in order to interfere with the virus itself or to disrupt its direct metabolic requirements. This can take several approaches.

MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV PL protease inhibitors

Of particular interest are antiviral therapies that attack papain-like protease, which is an important target because it is a multifunctional protein involved in proteolytic deubiquitination and viral evasion of the innate immune response. One such potential therapeutic that takes advantage of this target is disulfiram, an FDA-approved drug for use in alcohol-aversion therapy. Disulfiram has been reported as an allosteric inhibitor of MERS-CoV papain-like protease. Numerous other drug categories are being examined, with promising results in targeting the papain-like protease enzymes of both SARS and MERS.

Replicase inhibitors

Helicase (nsP13) protein is a crucial component required for virus replication in host cells and could serve as a feasible target for anti-MERS and anti-SARS chemical therapies, the review authors wrote, citing as an example, the recent development of a small 1,2,4-triazole derivative that inhibited the viral NTPase/helicase of SARS- and MERS-CoVs and demonstrated high antiviral activity and low cytotoxicity.

Membrane-bound viral RNA synthesis inhibitors

Antiviral agents that target membrane-bound coronaviral RNA synthesis represent a novel and attractive approach, according to Dr. Pillaiyar and colleagues. And recently, an inhibitor was developed that targets membrane-bound coronaviral RNA synthesis and “showed potent antiviral activity of MERS-CoV infection with remarkable efficacy.”

Host-based, anti-CoV treatment options

An alternate therapeutic tactic is to bolster host defenses or to modify host susceptibilities to prevent virus infection or replication. The innate interferon response of the host is crucial for the control of viral replication after infection, and the addition of exogenous recombinant interferon or use of drugs to stimulate the normal host interferon response are both potential therapeutic avenues. For example, nitazoxanide is a potent type I interferon inducer that has been used in humans for parasitic infections, and a synthetic nitrothiazolyl-salicylamide derivative was found to exhibit broad-spectrum antiviral activities against RNA and DNA viruses, including some coronaviruses.

Numerous other host pathways are being investigated as potential areas to enhance defense against infection and replication, for example, using inhibitors to block nucleic acid synthesis has been shown to provide broad-spectrum activity against SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV.

One particular example is remdesivir, a novel nucleotide analog antiviral drug, that was developed as a therapy for Ebola virus disease and Marburg virus infections. It was later shown to provide “reasonable antiviral activity against more distantly related viruses, such as respiratory syncytial virus, Junin virus, Lassa fever virus, and MERS-CoV,” the authors wrote.

Also of interest regarding remdesivir’s potential broad-spectrum use is that it has shown potent in vitro “antiviral activity against Malaysian and Bangladesh genotypes of Nipah virus (an RNA virus, although not a coronavirus, that infects both humans and animals) and reduced replication of Malaysian Nipah virus in primary human lung microvascular endothelial cells by more than four orders of magnitude,” Dr. Pillaiyar and colleagues added. Of particular note, all remdesivir-treated, Nipah virus–infected animals “survived the lethal challenge, indicating that remdesivir represents a promising antiviral treatment.”

In a press briefing earlier this month, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, reported that a randomized, controlled, phase 3 trial of the antiviral drug remdesivir is currently underway in China to establish whether the drug would be an effective and safe treatment for adults patients with mild or moderate 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) disease.

“Our increasing understanding of novel emerging coronaviruses will be accompanied by increasing opportunities for the reasonable design of therapeutics. Importantly, understanding this basic information about CoV protease targets will not only aid the public health against SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV but also help in advance to target new coronaviruses that might emerge in the future,” the authors concluded.

Dr. Pillaiyar and colleagues reported that they had no financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Pillaiyar T et al. Drug Discov Today. 2020 Jan 30. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2020.01.015.

No specific treatment is currently available for human coronaviruses to date, but numerous antiviral agents are being identified through a variety of approaches, according to Thanigaimalai Pillaiyar, PhD, and colleagues in a review published in Drug Discovery Today.

Using the six previously discovered human coronaviruses – human CoV 229E (HCoV-229E), OC43 (HCoV-OC43), NL63 (HCoV-NL63), HKU1 (HCoV-HKU1); severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) CoV; and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) CoV – the investigators examined progress in the use and development of therapeutic drugs, focusing on the potential roles of virus inhibitors.

“Research has mainly been focused on SARS- and MERS-CoV infections, because they were responsible for severe illness when compared with other CoVs,” Dr. Pillaiyar, of the department of pharmaceutical and medicinal chemistry at the University of Bonn (Germany), and colleagues wrote.

2019-nCov has been linked genomically as most closely related to SARS, and the Coronavirus Study Group of the International Committee on Virus Taxonomy, which has the responsibility for naming viruses, has designated the new virus SARS-CoV-2.

Examining extant drugs

The first approach to identifying possible antiviral agents reevaluates known, broadly acting antiviral drugs that have been used for other viral infections or other indications. The initial research into coronavirus therapeutics, in particular, has examined current antiviral therapeutics for their effectiveness against both SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, but with mixed results.

For example, in a search of potential antiviral agents against CoVs, researchers identified four drugs – chloroquine, chlorpromazine, loperamide, and lopinavir – by screening drug libraries approved by the Food and Drug Administration. They were all able to inhibit the replication of MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, and HCoV-229E in the low-micromolar range, which suggested that they could be used for broad-spectrum antiviral activity, according to Dr. Pillaiyar and colleagues.

Other research groups have also reported the discovery of antiviral drugs using this drug-repurposing approach, which included a number of broad-spectrum inhibitors of HCoVs (lycorine, emetine, monensin sodium, mycophenolate mofetil, mycophenolic acid, phenazopyridine, and pyrvinium pamoate) that showed strong inhibition of replication by four CoVs in vitro at low-micromolar concentrations and suppressed the replication of all CoVs in a dose-dependent manner. Findings from in vivo studies showed lycorine protected mice against lethal HCoV-OC43 infection.

Along with the aforementioned drugs, a number of others have also shown potential usefulness, but, as yet, none has been validated for use in humans.

Developing new antivirals

The second approach for anti-CoV drug discovery involves the development of new therapeutics based on the genomic and biophysical understanding of the individual CoV in order to interfere with the virus itself or to disrupt its direct metabolic requirements. This can take several approaches.

MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV PL protease inhibitors

Of particular interest are antiviral therapies that attack papain-like protease, which is an important target because it is a multifunctional protein involved in proteolytic deubiquitination and viral evasion of the innate immune response. One such potential therapeutic that takes advantage of this target is disulfiram, an FDA-approved drug for use in alcohol-aversion therapy. Disulfiram has been reported as an allosteric inhibitor of MERS-CoV papain-like protease. Numerous other drug categories are being examined, with promising results in targeting the papain-like protease enzymes of both SARS and MERS.

Replicase inhibitors

Helicase (nsP13) protein is a crucial component required for virus replication in host cells and could serve as a feasible target for anti-MERS and anti-SARS chemical therapies, the review authors wrote, citing as an example, the recent development of a small 1,2,4-triazole derivative that inhibited the viral NTPase/helicase of SARS- and MERS-CoVs and demonstrated high antiviral activity and low cytotoxicity.

Membrane-bound viral RNA synthesis inhibitors

Antiviral agents that target membrane-bound coronaviral RNA synthesis represent a novel and attractive approach, according to Dr. Pillaiyar and colleagues. And recently, an inhibitor was developed that targets membrane-bound coronaviral RNA synthesis and “showed potent antiviral activity of MERS-CoV infection with remarkable efficacy.”

Host-based, anti-CoV treatment options

An alternate therapeutic tactic is to bolster host defenses or to modify host susceptibilities to prevent virus infection or replication. The innate interferon response of the host is crucial for the control of viral replication after infection, and the addition of exogenous recombinant interferon or use of drugs to stimulate the normal host interferon response are both potential therapeutic avenues. For example, nitazoxanide is a potent type I interferon inducer that has been used in humans for parasitic infections, and a synthetic nitrothiazolyl-salicylamide derivative was found to exhibit broad-spectrum antiviral activities against RNA and DNA viruses, including some coronaviruses.

Numerous other host pathways are being investigated as potential areas to enhance defense against infection and replication, for example, using inhibitors to block nucleic acid synthesis has been shown to provide broad-spectrum activity against SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV.

One particular example is remdesivir, a novel nucleotide analog antiviral drug, that was developed as a therapy for Ebola virus disease and Marburg virus infections. It was later shown to provide “reasonable antiviral activity against more distantly related viruses, such as respiratory syncytial virus, Junin virus, Lassa fever virus, and MERS-CoV,” the authors wrote.

Also of interest regarding remdesivir’s potential broad-spectrum use is that it has shown potent in vitro “antiviral activity against Malaysian and Bangladesh genotypes of Nipah virus (an RNA virus, although not a coronavirus, that infects both humans and animals) and reduced replication of Malaysian Nipah virus in primary human lung microvascular endothelial cells by more than four orders of magnitude,” Dr. Pillaiyar and colleagues added. Of particular note, all remdesivir-treated, Nipah virus–infected animals “survived the lethal challenge, indicating that remdesivir represents a promising antiviral treatment.”

In a press briefing earlier this month, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, reported that a randomized, controlled, phase 3 trial of the antiviral drug remdesivir is currently underway in China to establish whether the drug would be an effective and safe treatment for adults patients with mild or moderate 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) disease.

“Our increasing understanding of novel emerging coronaviruses will be accompanied by increasing opportunities for the reasonable design of therapeutics. Importantly, understanding this basic information about CoV protease targets will not only aid the public health against SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV but also help in advance to target new coronaviruses that might emerge in the future,” the authors concluded.

Dr. Pillaiyar and colleagues reported that they had no financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Pillaiyar T et al. Drug Discov Today. 2020 Jan 30. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2020.01.015.

FROM DRUG DISCOVERY TODAY

Newborn transfer may not reflect true rate of complications

Neonatal transfer was the factor most often associated with unexpected, severe complications at birth, particularly at hospitals that had the highest rates of complications, according to a cross-sectional study published online in JAMA Network Open (2020;3[2]:e1919498).

Mark A. Clapp, MD, MPH, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and colleagues wrote. “Thus, if this metric is to be used in its current form, it would appear that accreditors, regulatory bodies, and payers should consider adjusting for or stratifying by a hospital’s level of neonatal care to avoid disincentivizing against appropriate transfers.”

The Joint Commission recently included unexpected complications in term newborns as a marker of quality of obstetric care, but it does not currently recommend any risk adjustment for the metric. The authors aimed to learn which factors regarding patients and hospitals were associated with such complications. Severe, unexpected newborn complications include death, seizure, use of assisted ventilation for at least 6 hours, transfer to another facility, or a 5-minute Apgar score of 3 or less.

“This measure has been proposed to serve as a balancing measure to maternal metrics, such as the rate of nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex-presenting cesarean deliveries,” the authors explained.

This study was supported by a Health Policy Award from the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

This story first appeared on Medscape.

Neonatal transfer was the factor most often associated with unexpected, severe complications at birth, particularly at hospitals that had the highest rates of complications, according to a cross-sectional study published online in JAMA Network Open (2020;3[2]:e1919498).

Mark A. Clapp, MD, MPH, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and colleagues wrote. “Thus, if this metric is to be used in its current form, it would appear that accreditors, regulatory bodies, and payers should consider adjusting for or stratifying by a hospital’s level of neonatal care to avoid disincentivizing against appropriate transfers.”

The Joint Commission recently included unexpected complications in term newborns as a marker of quality of obstetric care, but it does not currently recommend any risk adjustment for the metric. The authors aimed to learn which factors regarding patients and hospitals were associated with such complications. Severe, unexpected newborn complications include death, seizure, use of assisted ventilation for at least 6 hours, transfer to another facility, or a 5-minute Apgar score of 3 or less.

“This measure has been proposed to serve as a balancing measure to maternal metrics, such as the rate of nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex-presenting cesarean deliveries,” the authors explained.

This study was supported by a Health Policy Award from the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

This story first appeared on Medscape.

Neonatal transfer was the factor most often associated with unexpected, severe complications at birth, particularly at hospitals that had the highest rates of complications, according to a cross-sectional study published online in JAMA Network Open (2020;3[2]:e1919498).

Mark A. Clapp, MD, MPH, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and colleagues wrote. “Thus, if this metric is to be used in its current form, it would appear that accreditors, regulatory bodies, and payers should consider adjusting for or stratifying by a hospital’s level of neonatal care to avoid disincentivizing against appropriate transfers.”

The Joint Commission recently included unexpected complications in term newborns as a marker of quality of obstetric care, but it does not currently recommend any risk adjustment for the metric. The authors aimed to learn which factors regarding patients and hospitals were associated with such complications. Severe, unexpected newborn complications include death, seizure, use of assisted ventilation for at least 6 hours, transfer to another facility, or a 5-minute Apgar score of 3 or less.

“This measure has been proposed to serve as a balancing measure to maternal metrics, such as the rate of nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex-presenting cesarean deliveries,” the authors explained.

This study was supported by a Health Policy Award from the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

This story first appeared on Medscape.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Tools for preventing heart failure

SNOWMASS, COLO. – If ever there was a major chronic disease that’s teed up and ready to be stamped into submission through diligent application of preventive medicine, it’s the epidemic of heart failure.

“The best way to treat heart failure is to prevent it in the first place. There will be more than 1 million new cases of heart failure this year, and the vast majority of them could have been prevented,” Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, asserted at the annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass sponsored by the American College of Cardiology.

Using firmly evidence-based, guideline-directed therapies, it’s often possible to prevent patients at high risk for developing heart failure (HF) from actually doing so. Or, in the terminology of the ACC/American Heart Association heart failure guidelines coauthored by Dr. Fonarow, the goal is to keep patients who are stage A – that is, pre-HF but at high risk because of hypertension, coronary artery disease, diabetes, family history of cardiomyopathy, or other reasons – from progressing to stage B, marked by asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction, a prior MI, or asymptomatic valvular disease; and blocking those who are stage B from then moving on to stage C, the classic symptomatic form of HF; and thence to end-stage stage D disease.

Heart failure is an enormous public health problem, and one of the most expensive of all diseases. The prognostic impact of newly diagnosed HF is profound, with 10-15 years of life lost, compared with the general population. Even today, roughly one in five newly diagnosed patients won’t survive for a year, and the 5-year mortality is about 50%, said Dr. Fonarow, who is professor of cardiovascular medicine and chief of the division of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of the Ahmanson-UCLA Cardiomyopathy Center, also in Los Angeles.

Symptomatic stage C is “the tip of the iceberg,” the cardiologist stressed. Vastly more patients are in stages A and B. In order to keep them from progressing to stage C, it’s first necessary to identify them. That’s why the 2013 guidelines give a class IC recommendation for periodic evaluation for signs and symptoms of HF in patients who are at high risk, and for a noninvasive assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction in those with a strong family history of cardiomyopathy or who are on cardiotoxic drugs (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Oct 15;62[16]:e147-239).

The two biggest risk factors for the development of symptomatic stage C HF are hypertension and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Close to 80% of patients presenting with heart failure have prevalent hypertension, and a history of ischemic heart disease is nearly as common.

Other major modifiable risk factors are diabetes, overweight and obesity, metabolic syndrome, dyslipidemia, smoking, valvular heart disease, and chronic kidney disease.

Hypertension

Most patients with high blood pressure believe they’re on antihypertensive medication to prevent MI and stroke, but in reality the largest benefit is what Dr. Fonarow termed the “phenomenal” reduction in the risk of developing HF, which amounted to a 52% relative risk reduction in one meta-analysis of older randomized trials. In the contemporary era, the landmark SPRINT trial of close to 10,000 randomized hypertensive patients showed that more-intensive blood pressure lowering to a target systolic BP of less than 120 mm Hg resulted in a 38% reduction in the risk of new-onset HF, compared with standard treatment to a target of less than 140 mm Hg. That’s why the 2017 focused update of the HF guidelines gives a strong class IB recommendation for a target blood pressure of less than 130/80 mm Hg in hypertensive patients with stage A HF (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Aug 8;70[6]:776-803).

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

Within 6 years after diagnosis of an MI, 22% of men and 46% of women will develop symptomatic heart failure. Intensive statin therapy gets a strong recommendation post MI in the guidelines, not only because in a meta-analysis of four major randomized trials it resulted in a further 64% reduction in the risk of coronary death or recurrent MI, compared with moderate statin therapy, but also because of the 27% relative risk reduction in new-onset HF. ACE inhibitors get a class IA recommendation for prevention of symptomatic HF in patients who are stage A with a history of atherosclerotic disease, diabetes, or hypertension. Angiotensin receptor blockers get a class IC recommendation.

Diabetes

Diabetes markedly increases the risk of developing HF: by two to four times overall and by four to eight times in younger diabetes patients. The two chronic diseases are highly comorbid, with roughly 45% of patients with HF also having diabetes. Moreover, diabetes in HF patients is associated with a substantially worse prognosis, even when standard HF therapies are applied.

Choices regarding glycemic management can markedly affect HF risk and outcomes. Randomized trials show that the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists double the risk of HF. The glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists are absolutely neutral with regard to HF outcomes. Similarly, the dipeptidyl peptidase–4 inhibitors have no impact on the risks of major adverse cardiovascular events or HF. Intensive glycemic control has no impact on the risk of new-onset HF. Insulin therapy, too, is neutral on this score.

“Depressingly, even lifestyle modification with weight loss, once you have type 2 diabetes, does not lower the risk,” Dr. Fonarow continued.

In contrast, the sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors have impressive cardiovascular and renal protective benefits in patients with type 2 diabetes, as demonstrated in a meta-analysis of more than 34,000 participants in the randomized trials of empagliflozin (Jardiance) in EMPA-REG OUTCOME, canagliflozin (Invokana) in CANVAS/CANVAS-R, and dapagliflozin (Farxiga) in DECLARE-TIMI 58. The SGLT2 inhibitors collectively reduced the risk of HF hospitalization by 21% in participants with no baseline history of the disease and by 29% in those with a history of HF. Moreover, the risk of progression of renal disease was reduced by 45% (Lancet. 2019 Jan 5;393[10166]:31-9).

More recently, the landmark DAPA-HF trial established SGLT2 inhibitor therapy as part of standard-of-care, guideline-directed medical therapy for patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction regardless of whether they have comorbid type 2 diabetes (N Engl J Med. 2019 Nov 21;381[21]:1995-2008).

These are remarkable medications, generally very well tolerated, and it’s critical that cardiologists get on board in prescribing them, Dr. Fonarow emphasized. He alerted his colleagues to what he called an “incredibly helpful” review article that provides practical guidance for cardiologists in how to start using the SGLT2 inhibitors (JACC Heart Fail. 2019 Feb;7[2]:169-72).

“It’s pretty straightforward,” according to Dr. Fonarow. “If you’re comfortable enough in using ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and beta-blockers, I think you’ll find these medications fit similarly when you actually get experience in utilizing them.”

He reported serving as a consultant to 10 pharmaceutical or medical device companies.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – If ever there was a major chronic disease that’s teed up and ready to be stamped into submission through diligent application of preventive medicine, it’s the epidemic of heart failure.

“The best way to treat heart failure is to prevent it in the first place. There will be more than 1 million new cases of heart failure this year, and the vast majority of them could have been prevented,” Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, asserted at the annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass sponsored by the American College of Cardiology.

Using firmly evidence-based, guideline-directed therapies, it’s often possible to prevent patients at high risk for developing heart failure (HF) from actually doing so. Or, in the terminology of the ACC/American Heart Association heart failure guidelines coauthored by Dr. Fonarow, the goal is to keep patients who are stage A – that is, pre-HF but at high risk because of hypertension, coronary artery disease, diabetes, family history of cardiomyopathy, or other reasons – from progressing to stage B, marked by asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction, a prior MI, or asymptomatic valvular disease; and blocking those who are stage B from then moving on to stage C, the classic symptomatic form of HF; and thence to end-stage stage D disease.

Heart failure is an enormous public health problem, and one of the most expensive of all diseases. The prognostic impact of newly diagnosed HF is profound, with 10-15 years of life lost, compared with the general population. Even today, roughly one in five newly diagnosed patients won’t survive for a year, and the 5-year mortality is about 50%, said Dr. Fonarow, who is professor of cardiovascular medicine and chief of the division of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of the Ahmanson-UCLA Cardiomyopathy Center, also in Los Angeles.

Symptomatic stage C is “the tip of the iceberg,” the cardiologist stressed. Vastly more patients are in stages A and B. In order to keep them from progressing to stage C, it’s first necessary to identify them. That’s why the 2013 guidelines give a class IC recommendation for periodic evaluation for signs and symptoms of HF in patients who are at high risk, and for a noninvasive assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction in those with a strong family history of cardiomyopathy or who are on cardiotoxic drugs (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Oct 15;62[16]:e147-239).

The two biggest risk factors for the development of symptomatic stage C HF are hypertension and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Close to 80% of patients presenting with heart failure have prevalent hypertension, and a history of ischemic heart disease is nearly as common.

Other major modifiable risk factors are diabetes, overweight and obesity, metabolic syndrome, dyslipidemia, smoking, valvular heart disease, and chronic kidney disease.

Hypertension

Most patients with high blood pressure believe they’re on antihypertensive medication to prevent MI and stroke, but in reality the largest benefit is what Dr. Fonarow termed the “phenomenal” reduction in the risk of developing HF, which amounted to a 52% relative risk reduction in one meta-analysis of older randomized trials. In the contemporary era, the landmark SPRINT trial of close to 10,000 randomized hypertensive patients showed that more-intensive blood pressure lowering to a target systolic BP of less than 120 mm Hg resulted in a 38% reduction in the risk of new-onset HF, compared with standard treatment to a target of less than 140 mm Hg. That’s why the 2017 focused update of the HF guidelines gives a strong class IB recommendation for a target blood pressure of less than 130/80 mm Hg in hypertensive patients with stage A HF (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Aug 8;70[6]:776-803).

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

Within 6 years after diagnosis of an MI, 22% of men and 46% of women will develop symptomatic heart failure. Intensive statin therapy gets a strong recommendation post MI in the guidelines, not only because in a meta-analysis of four major randomized trials it resulted in a further 64% reduction in the risk of coronary death or recurrent MI, compared with moderate statin therapy, but also because of the 27% relative risk reduction in new-onset HF. ACE inhibitors get a class IA recommendation for prevention of symptomatic HF in patients who are stage A with a history of atherosclerotic disease, diabetes, or hypertension. Angiotensin receptor blockers get a class IC recommendation.

Diabetes

Diabetes markedly increases the risk of developing HF: by two to four times overall and by four to eight times in younger diabetes patients. The two chronic diseases are highly comorbid, with roughly 45% of patients with HF also having diabetes. Moreover, diabetes in HF patients is associated with a substantially worse prognosis, even when standard HF therapies are applied.

Choices regarding glycemic management can markedly affect HF risk and outcomes. Randomized trials show that the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists double the risk of HF. The glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists are absolutely neutral with regard to HF outcomes. Similarly, the dipeptidyl peptidase–4 inhibitors have no impact on the risks of major adverse cardiovascular events or HF. Intensive glycemic control has no impact on the risk of new-onset HF. Insulin therapy, too, is neutral on this score.

“Depressingly, even lifestyle modification with weight loss, once you have type 2 diabetes, does not lower the risk,” Dr. Fonarow continued.

In contrast, the sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors have impressive cardiovascular and renal protective benefits in patients with type 2 diabetes, as demonstrated in a meta-analysis of more than 34,000 participants in the randomized trials of empagliflozin (Jardiance) in EMPA-REG OUTCOME, canagliflozin (Invokana) in CANVAS/CANVAS-R, and dapagliflozin (Farxiga) in DECLARE-TIMI 58. The SGLT2 inhibitors collectively reduced the risk of HF hospitalization by 21% in participants with no baseline history of the disease and by 29% in those with a history of HF. Moreover, the risk of progression of renal disease was reduced by 45% (Lancet. 2019 Jan 5;393[10166]:31-9).

More recently, the landmark DAPA-HF trial established SGLT2 inhibitor therapy as part of standard-of-care, guideline-directed medical therapy for patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction regardless of whether they have comorbid type 2 diabetes (N Engl J Med. 2019 Nov 21;381[21]:1995-2008).

These are remarkable medications, generally very well tolerated, and it’s critical that cardiologists get on board in prescribing them, Dr. Fonarow emphasized. He alerted his colleagues to what he called an “incredibly helpful” review article that provides practical guidance for cardiologists in how to start using the SGLT2 inhibitors (JACC Heart Fail. 2019 Feb;7[2]:169-72).

“It’s pretty straightforward,” according to Dr. Fonarow. “If you’re comfortable enough in using ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and beta-blockers, I think you’ll find these medications fit similarly when you actually get experience in utilizing them.”

He reported serving as a consultant to 10 pharmaceutical or medical device companies.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – If ever there was a major chronic disease that’s teed up and ready to be stamped into submission through diligent application of preventive medicine, it’s the epidemic of heart failure.

“The best way to treat heart failure is to prevent it in the first place. There will be more than 1 million new cases of heart failure this year, and the vast majority of them could have been prevented,” Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, asserted at the annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass sponsored by the American College of Cardiology.

Using firmly evidence-based, guideline-directed therapies, it’s often possible to prevent patients at high risk for developing heart failure (HF) from actually doing so. Or, in the terminology of the ACC/American Heart Association heart failure guidelines coauthored by Dr. Fonarow, the goal is to keep patients who are stage A – that is, pre-HF but at high risk because of hypertension, coronary artery disease, diabetes, family history of cardiomyopathy, or other reasons – from progressing to stage B, marked by asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction, a prior MI, or asymptomatic valvular disease; and blocking those who are stage B from then moving on to stage C, the classic symptomatic form of HF; and thence to end-stage stage D disease.

Heart failure is an enormous public health problem, and one of the most expensive of all diseases. The prognostic impact of newly diagnosed HF is profound, with 10-15 years of life lost, compared with the general population. Even today, roughly one in five newly diagnosed patients won’t survive for a year, and the 5-year mortality is about 50%, said Dr. Fonarow, who is professor of cardiovascular medicine and chief of the division of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of the Ahmanson-UCLA Cardiomyopathy Center, also in Los Angeles.

Symptomatic stage C is “the tip of the iceberg,” the cardiologist stressed. Vastly more patients are in stages A and B. In order to keep them from progressing to stage C, it’s first necessary to identify them. That’s why the 2013 guidelines give a class IC recommendation for periodic evaluation for signs and symptoms of HF in patients who are at high risk, and for a noninvasive assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction in those with a strong family history of cardiomyopathy or who are on cardiotoxic drugs (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Oct 15;62[16]:e147-239).

The two biggest risk factors for the development of symptomatic stage C HF are hypertension and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Close to 80% of patients presenting with heart failure have prevalent hypertension, and a history of ischemic heart disease is nearly as common.

Other major modifiable risk factors are diabetes, overweight and obesity, metabolic syndrome, dyslipidemia, smoking, valvular heart disease, and chronic kidney disease.

Hypertension

Most patients with high blood pressure believe they’re on antihypertensive medication to prevent MI and stroke, but in reality the largest benefit is what Dr. Fonarow termed the “phenomenal” reduction in the risk of developing HF, which amounted to a 52% relative risk reduction in one meta-analysis of older randomized trials. In the contemporary era, the landmark SPRINT trial of close to 10,000 randomized hypertensive patients showed that more-intensive blood pressure lowering to a target systolic BP of less than 120 mm Hg resulted in a 38% reduction in the risk of new-onset HF, compared with standard treatment to a target of less than 140 mm Hg. That’s why the 2017 focused update of the HF guidelines gives a strong class IB recommendation for a target blood pressure of less than 130/80 mm Hg in hypertensive patients with stage A HF (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Aug 8;70[6]:776-803).

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

Within 6 years after diagnosis of an MI, 22% of men and 46% of women will develop symptomatic heart failure. Intensive statin therapy gets a strong recommendation post MI in the guidelines, not only because in a meta-analysis of four major randomized trials it resulted in a further 64% reduction in the risk of coronary death or recurrent MI, compared with moderate statin therapy, but also because of the 27% relative risk reduction in new-onset HF. ACE inhibitors get a class IA recommendation for prevention of symptomatic HF in patients who are stage A with a history of atherosclerotic disease, diabetes, or hypertension. Angiotensin receptor blockers get a class IC recommendation.

Diabetes

Diabetes markedly increases the risk of developing HF: by two to four times overall and by four to eight times in younger diabetes patients. The two chronic diseases are highly comorbid, with roughly 45% of patients with HF also having diabetes. Moreover, diabetes in HF patients is associated with a substantially worse prognosis, even when standard HF therapies are applied.

Choices regarding glycemic management can markedly affect HF risk and outcomes. Randomized trials show that the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists double the risk of HF. The glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists are absolutely neutral with regard to HF outcomes. Similarly, the dipeptidyl peptidase–4 inhibitors have no impact on the risks of major adverse cardiovascular events or HF. Intensive glycemic control has no impact on the risk of new-onset HF. Insulin therapy, too, is neutral on this score.

“Depressingly, even lifestyle modification with weight loss, once you have type 2 diabetes, does not lower the risk,” Dr. Fonarow continued.

In contrast, the sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors have impressive cardiovascular and renal protective benefits in patients with type 2 diabetes, as demonstrated in a meta-analysis of more than 34,000 participants in the randomized trials of empagliflozin (Jardiance) in EMPA-REG OUTCOME, canagliflozin (Invokana) in CANVAS/CANVAS-R, and dapagliflozin (Farxiga) in DECLARE-TIMI 58. The SGLT2 inhibitors collectively reduced the risk of HF hospitalization by 21% in participants with no baseline history of the disease and by 29% in those with a history of HF. Moreover, the risk of progression of renal disease was reduced by 45% (Lancet. 2019 Jan 5;393[10166]:31-9).

More recently, the landmark DAPA-HF trial established SGLT2 inhibitor therapy as part of standard-of-care, guideline-directed medical therapy for patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction regardless of whether they have comorbid type 2 diabetes (N Engl J Med. 2019 Nov 21;381[21]:1995-2008).

These are remarkable medications, generally very well tolerated, and it’s critical that cardiologists get on board in prescribing them, Dr. Fonarow emphasized. He alerted his colleagues to what he called an “incredibly helpful” review article that provides practical guidance for cardiologists in how to start using the SGLT2 inhibitors (JACC Heart Fail. 2019 Feb;7[2]:169-72).

“It’s pretty straightforward,” according to Dr. Fonarow. “If you’re comfortable enough in using ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and beta-blockers, I think you’ll find these medications fit similarly when you actually get experience in utilizing them.”

He reported serving as a consultant to 10 pharmaceutical or medical device companies.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ACC SNOWMASS 2020

Work the program for NP/PAs, and the program will work

A ‘knowledge gap’ in best practices exists

Hospital medicine has been the fastest growing medical specialty since the term “hospitalist” was coined by Bob Wachter, MD, in the famous 1996 New England Journal of Medicine article (doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608153350713). The growth and change within this specialty is also reflected in the changing and migrating target of hospitals and hospital systems as they continue to effectively and safely move from fee-for-service to a payer model that rewards value and improvement in the health of a population – both in and outside of hospital walls.

In a short time, nurse practitioners and physician assistants have become a growing population in the hospital medicine workforce. The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report notes a 42% increase in 4 years, and about 75% of hospital medicine groups across the country currently incorporate NP/PAs within a hospital medicine practice. This evolution has occurred in the setting of a looming and well-documented physician shortage, a variety of cost pressures on hospitals that reflect the need for an efficient and cost-effective care delivery model, an increasing NP/PA workforce (the Department of Labor notes increases of 35% and 36% respectively by 2036), and data that indicates similar outcomes, for example, HCAHPS (the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems), readmission, and morbidity and mortality in NP/PA-driven care.

This evolution, however, reveals a true knowledge gap in best practices related to integration of these providers. This is impacted by wide variability in the preparation of NPs – they may enter hospitalist practice from a variety of clinical exposures and training, for example, adult gerontology acute care, adult, or even, in some states, family NPs. For PAs, this is reflected in the variety of clinical rotations and pregraduate clinical exposure.

This variability is compounded, too, by the lack of standardization of hospital medicine practices, both with site size and patient acuity, a variety of challenges that drive the need for integration of NP/PA providers, and by-laws that define advanced practice clinical models and function.

In that perspective, it is important to define what constitutes a leading and successful advanced practice provider (APP) integration program. I would suggest:

- A structured and formalized transition-to-practice program for all new graduates and those new to hospital medicine. This program should consist of clinical volume progression, formalized didactic congruent with the Society of Hospital Medicine Core Competencies, and a process for evaluating knowledge and decision making throughout the program and upon completion.

- Development of physician competencies related to APP integration. Physicians are not prepared in their medical school training or residency to understand the differences and similarities of NP/PA providers. These competencies should be required and can best be developed through steady leadership, formalized instruction and accountability for professional teamwork.

- Allowance for NP/PA providers to work at the top of their skills and license. This means utilizing NP/PAs as providers who care for patients – not as scribes or clerical workers. The evolution of the acuity of patients provided for may evolve with the skill set and experience of NP/PAs, but it will evolve – especially if steps 1 and 2 are in place.

- Productivity expectations that reach near physician level of volume. In 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report data, yearly billable encounters for NP/PAs were within 10% of that of physicians. I think 15% is a reasonable goal.

- Implementation and support of APP administrative leadership structure at the system/site level. This can be as simple as having APPs on the same leadership committees as physician team members, being involved in hiring and training newer physicians and NP/PAs or as broad as having all NP/PAs report to an APP leader. Having an intentional leadership structure that demonstrates and reflects inclusivity and belonging is crucial.

Consistent application of these frameworks will provide a strong infrastructure for successful NP/PA practice.

Ms. Cardin is currently the vice president of advanced practice providers at Sound Physicians and serves on SHM’s board of directors as its secretary. This article appeared initially at the Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

A ‘knowledge gap’ in best practices exists

A ‘knowledge gap’ in best practices exists

Hospital medicine has been the fastest growing medical specialty since the term “hospitalist” was coined by Bob Wachter, MD, in the famous 1996 New England Journal of Medicine article (doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608153350713). The growth and change within this specialty is also reflected in the changing and migrating target of hospitals and hospital systems as they continue to effectively and safely move from fee-for-service to a payer model that rewards value and improvement in the health of a population – both in and outside of hospital walls.

In a short time, nurse practitioners and physician assistants have become a growing population in the hospital medicine workforce. The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report notes a 42% increase in 4 years, and about 75% of hospital medicine groups across the country currently incorporate NP/PAs within a hospital medicine practice. This evolution has occurred in the setting of a looming and well-documented physician shortage, a variety of cost pressures on hospitals that reflect the need for an efficient and cost-effective care delivery model, an increasing NP/PA workforce (the Department of Labor notes increases of 35% and 36% respectively by 2036), and data that indicates similar outcomes, for example, HCAHPS (the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems), readmission, and morbidity and mortality in NP/PA-driven care.

This evolution, however, reveals a true knowledge gap in best practices related to integration of these providers. This is impacted by wide variability in the preparation of NPs – they may enter hospitalist practice from a variety of clinical exposures and training, for example, adult gerontology acute care, adult, or even, in some states, family NPs. For PAs, this is reflected in the variety of clinical rotations and pregraduate clinical exposure.

This variability is compounded, too, by the lack of standardization of hospital medicine practices, both with site size and patient acuity, a variety of challenges that drive the need for integration of NP/PA providers, and by-laws that define advanced practice clinical models and function.

In that perspective, it is important to define what constitutes a leading and successful advanced practice provider (APP) integration program. I would suggest:

- A structured and formalized transition-to-practice program for all new graduates and those new to hospital medicine. This program should consist of clinical volume progression, formalized didactic congruent with the Society of Hospital Medicine Core Competencies, and a process for evaluating knowledge and decision making throughout the program and upon completion.

- Development of physician competencies related to APP integration. Physicians are not prepared in their medical school training or residency to understand the differences and similarities of NP/PA providers. These competencies should be required and can best be developed through steady leadership, formalized instruction and accountability for professional teamwork.

- Allowance for NP/PA providers to work at the top of their skills and license. This means utilizing NP/PAs as providers who care for patients – not as scribes or clerical workers. The evolution of the acuity of patients provided for may evolve with the skill set and experience of NP/PAs, but it will evolve – especially if steps 1 and 2 are in place.

- Productivity expectations that reach near physician level of volume. In 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report data, yearly billable encounters for NP/PAs were within 10% of that of physicians. I think 15% is a reasonable goal.

- Implementation and support of APP administrative leadership structure at the system/site level. This can be as simple as having APPs on the same leadership committees as physician team members, being involved in hiring and training newer physicians and NP/PAs or as broad as having all NP/PAs report to an APP leader. Having an intentional leadership structure that demonstrates and reflects inclusivity and belonging is crucial.

Consistent application of these frameworks will provide a strong infrastructure for successful NP/PA practice.

Ms. Cardin is currently the vice president of advanced practice providers at Sound Physicians and serves on SHM’s board of directors as its secretary. This article appeared initially at the Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

Hospital medicine has been the fastest growing medical specialty since the term “hospitalist” was coined by Bob Wachter, MD, in the famous 1996 New England Journal of Medicine article (doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608153350713). The growth and change within this specialty is also reflected in the changing and migrating target of hospitals and hospital systems as they continue to effectively and safely move from fee-for-service to a payer model that rewards value and improvement in the health of a population – both in and outside of hospital walls.

In a short time, nurse practitioners and physician assistants have become a growing population in the hospital medicine workforce. The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report notes a 42% increase in 4 years, and about 75% of hospital medicine groups across the country currently incorporate NP/PAs within a hospital medicine practice. This evolution has occurred in the setting of a looming and well-documented physician shortage, a variety of cost pressures on hospitals that reflect the need for an efficient and cost-effective care delivery model, an increasing NP/PA workforce (the Department of Labor notes increases of 35% and 36% respectively by 2036), and data that indicates similar outcomes, for example, HCAHPS (the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems), readmission, and morbidity and mortality in NP/PA-driven care.

This evolution, however, reveals a true knowledge gap in best practices related to integration of these providers. This is impacted by wide variability in the preparation of NPs – they may enter hospitalist practice from a variety of clinical exposures and training, for example, adult gerontology acute care, adult, or even, in some states, family NPs. For PAs, this is reflected in the variety of clinical rotations and pregraduate clinical exposure.

This variability is compounded, too, by the lack of standardization of hospital medicine practices, both with site size and patient acuity, a variety of challenges that drive the need for integration of NP/PA providers, and by-laws that define advanced practice clinical models and function.

In that perspective, it is important to define what constitutes a leading and successful advanced practice provider (APP) integration program. I would suggest:

- A structured and formalized transition-to-practice program for all new graduates and those new to hospital medicine. This program should consist of clinical volume progression, formalized didactic congruent with the Society of Hospital Medicine Core Competencies, and a process for evaluating knowledge and decision making throughout the program and upon completion.

- Development of physician competencies related to APP integration. Physicians are not prepared in their medical school training or residency to understand the differences and similarities of NP/PA providers. These competencies should be required and can best be developed through steady leadership, formalized instruction and accountability for professional teamwork.

- Allowance for NP/PA providers to work at the top of their skills and license. This means utilizing NP/PAs as providers who care for patients – not as scribes or clerical workers. The evolution of the acuity of patients provided for may evolve with the skill set and experience of NP/PAs, but it will evolve – especially if steps 1 and 2 are in place.

- Productivity expectations that reach near physician level of volume. In 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report data, yearly billable encounters for NP/PAs were within 10% of that of physicians. I think 15% is a reasonable goal.

- Implementation and support of APP administrative leadership structure at the system/site level. This can be as simple as having APPs on the same leadership committees as physician team members, being involved in hiring and training newer physicians and NP/PAs or as broad as having all NP/PAs report to an APP leader. Having an intentional leadership structure that demonstrates and reflects inclusivity and belonging is crucial.

Consistent application of these frameworks will provide a strong infrastructure for successful NP/PA practice.

Ms. Cardin is currently the vice president of advanced practice providers at Sound Physicians and serves on SHM’s board of directors as its secretary. This article appeared initially at the Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

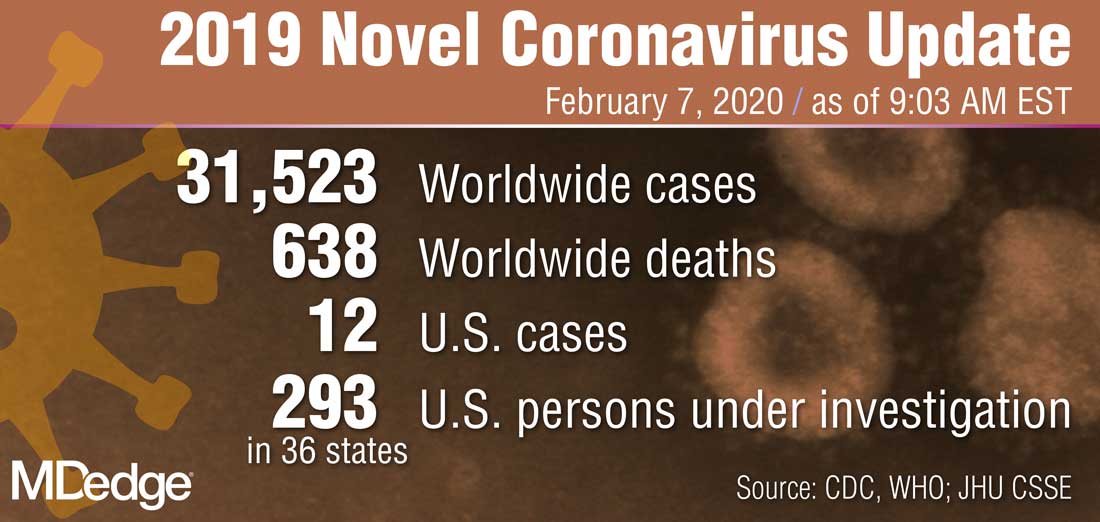

CDC confirms 13th case of coronavirus in U.S.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced the number of confirmed cases of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in the United States has reached 13.

The latest case, announced Feb. 11, 2020, by the CDC, was in a person in California who was previously under federal quarantine because the patient had traveled to Wuhan, China.

The CDC is currently looking into who the patient may have come in contact with to understand the potential for further spread of the coronavirus.

“The contact investigation is ongoing,” CDC principal deputy director Anne Schuchat, MD, said during a Feb. 11 press conference to provide an update on coronavirus containment activities being taken by the CDC.

Dr. Schuchat also addressed issues related to the laboratory test, as the patient in California was initially thought to be negative for the coronavirus.

“With other cases around the country that we are evaluating, we have been doing serial tests to understand whether they are still infectious” and to gather other information about how results change over time, Dr. Schuchat said.

She noted that the CDC does not “have as much information as we would like on the severity of the virus,” noting that there are many cases in China with severe reactions, while the 13 cases in the United States represent a much more mild reaction to the virus so far.

With the latest case in California, she noted that there was “probably a mix-up and the original test wasn’t negative,” although she did not elaborate on what the nature of the mix-up was, stating that was all the information that she had.

In general, Dr. Schuchat touted the actions taken by the CDC and the federal government focused primarily on containing the spread of the virus in the United States, including the implementation of travel advisories, quarantining passengers returning from China, as well as the new test kits that are being distributed by the agency across the nation and around the world. She also mentioned CDC staff are being deployed around the world to monitor the spreading of the disease and highlighted the outreach efforts to keep the public informed.

Dr. Schuchat highlighted the fact that, of the 13 cases in the United States, 11 were with patients that were in Wuhan, and only 2 were because of close contact with a patient, something that she attributed to the actions being taken.

She also noted that cases in the United States have not been as severe as they have been in China, where deaths have been attributed to the coronavirus outbreak. She added that there have been only two deaths outside of mainland China attributed to the coronavirus.

“Some of the steps the CDC has taken have really put us in better shape should widespread transmission occur in the United States,” she said.

Dr. Schuchat also highlighted that the first charter flight of people quarantined after returning from Wuhan have reached the 14-day milestone and should be on their way home beginning today.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced the number of confirmed cases of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in the United States has reached 13.

The latest case, announced Feb. 11, 2020, by the CDC, was in a person in California who was previously under federal quarantine because the patient had traveled to Wuhan, China.

The CDC is currently looking into who the patient may have come in contact with to understand the potential for further spread of the coronavirus.

“The contact investigation is ongoing,” CDC principal deputy director Anne Schuchat, MD, said during a Feb. 11 press conference to provide an update on coronavirus containment activities being taken by the CDC.

Dr. Schuchat also addressed issues related to the laboratory test, as the patient in California was initially thought to be negative for the coronavirus.

“With other cases around the country that we are evaluating, we have been doing serial tests to understand whether they are still infectious” and to gather other information about how results change over time, Dr. Schuchat said.

She noted that the CDC does not “have as much information as we would like on the severity of the virus,” noting that there are many cases in China with severe reactions, while the 13 cases in the United States represent a much more mild reaction to the virus so far.

With the latest case in California, she noted that there was “probably a mix-up and the original test wasn’t negative,” although she did not elaborate on what the nature of the mix-up was, stating that was all the information that she had.

In general, Dr. Schuchat touted the actions taken by the CDC and the federal government focused primarily on containing the spread of the virus in the United States, including the implementation of travel advisories, quarantining passengers returning from China, as well as the new test kits that are being distributed by the agency across the nation and around the world. She also mentioned CDC staff are being deployed around the world to monitor the spreading of the disease and highlighted the outreach efforts to keep the public informed.

Dr. Schuchat highlighted the fact that, of the 13 cases in the United States, 11 were with patients that were in Wuhan, and only 2 were because of close contact with a patient, something that she attributed to the actions being taken.

She also noted that cases in the United States have not been as severe as they have been in China, where deaths have been attributed to the coronavirus outbreak. She added that there have been only two deaths outside of mainland China attributed to the coronavirus.

“Some of the steps the CDC has taken have really put us in better shape should widespread transmission occur in the United States,” she said.

Dr. Schuchat also highlighted that the first charter flight of people quarantined after returning from Wuhan have reached the 14-day milestone and should be on their way home beginning today.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced the number of confirmed cases of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in the United States has reached 13.

The latest case, announced Feb. 11, 2020, by the CDC, was in a person in California who was previously under federal quarantine because the patient had traveled to Wuhan, China.

The CDC is currently looking into who the patient may have come in contact with to understand the potential for further spread of the coronavirus.

“The contact investigation is ongoing,” CDC principal deputy director Anne Schuchat, MD, said during a Feb. 11 press conference to provide an update on coronavirus containment activities being taken by the CDC.

Dr. Schuchat also addressed issues related to the laboratory test, as the patient in California was initially thought to be negative for the coronavirus.

“With other cases around the country that we are evaluating, we have been doing serial tests to understand whether they are still infectious” and to gather other information about how results change over time, Dr. Schuchat said.

She noted that the CDC does not “have as much information as we would like on the severity of the virus,” noting that there are many cases in China with severe reactions, while the 13 cases in the United States represent a much more mild reaction to the virus so far.

With the latest case in California, she noted that there was “probably a mix-up and the original test wasn’t negative,” although she did not elaborate on what the nature of the mix-up was, stating that was all the information that she had.

In general, Dr. Schuchat touted the actions taken by the CDC and the federal government focused primarily on containing the spread of the virus in the United States, including the implementation of travel advisories, quarantining passengers returning from China, as well as the new test kits that are being distributed by the agency across the nation and around the world. She also mentioned CDC staff are being deployed around the world to monitor the spreading of the disease and highlighted the outreach efforts to keep the public informed.

Dr. Schuchat highlighted the fact that, of the 13 cases in the United States, 11 were with patients that were in Wuhan, and only 2 were because of close contact with a patient, something that she attributed to the actions being taken.

She also noted that cases in the United States have not been as severe as they have been in China, where deaths have been attributed to the coronavirus outbreak. She added that there have been only two deaths outside of mainland China attributed to the coronavirus.

“Some of the steps the CDC has taken have really put us in better shape should widespread transmission occur in the United States,” she said.

Dr. Schuchat also highlighted that the first charter flight of people quarantined after returning from Wuhan have reached the 14-day milestone and should be on their way home beginning today.

Consider PET/CT when infectious source is a puzzler

CHICAGO – Dual positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET/CT) scans changed the treatment course of nearly half of patients whose scans were positive for infection. In a single-center systematic review of 18fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)–PET/CT scans, 55 of the 138 scans (40%) changed clinical management.

Presenting the findings at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America, Benjamin Viglianti, MD, PhD, said that PET/CT had particular utility in cases of bacteremia and endocarditis, in which the scans changed treatment in 46% of those cases.

Dr. Viglianti, a radiologist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, explained that medical student and first author Anitha Menon, himself, and their collaborators deliberately used a broad definition of clinical management change. The management course was considered to change not only if an unknown infection site was discovered or if a new intervention was initiated after the scan, but also if antibiotic choice or duration was changed or an additional specialty was consulted.

Scans were included in the study if an infectious etiology was found in the scan and if the patient received an infectious disease consult. Bacteremia and endocarditis were the most frequent indications for scans and also the indications for which management was most frequently changed. When a vascular cause was the indication for the scan, management changed 41% of the time. For fevers of unknown origin, the scan changed management in 30% of the cases, while for osteomyelitis, management was changed for 28% of patients.

The investigators identified several broad themes from their review that pointed toward when clinicians might consider FDG-PET/CT imaging in infectious disease management.

The first, said Dr. Viglianti, was that “for patients with suspected vascular graft infection, PET/CT using FDG may be a good first-choice imaging modality.” He pointed to an illustrative case of a patient who was 1 month out from open repair of a thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm. The patient had abdominal pain, epigastric tenderness and nausea, as well as an erythematous incision site. A CT scan just revealed an abdominal fluid collection, but the PET/CT scan showed radiotracer uptake at the prior repair site, indicating infection.

For patients with bacteremia, the investigators judged that FDG-PET/CT might be particularly useful in patients who have a graft, prosthetic valve, or cardiac device. Here, Dr. Viglianti and his collaborators highlighted the scan of a woman with DiGeorge syndrome who had received aortic root replacement for truncus arteriosis. She had been found to have persistent enterococcal bacteremia at high levels, but had been symptom free. To take a close look at the suspected infectious nidus, a transesophageal echocardiogram had been obtained, but this study didn’t turn up any clear masses or vegetations. The PET/CT scan, though, revealed avid FDG uptake in the area of the prosthesis.

Management course was not likely to be changed for patients with fever of unknown origin, but the investigators did note that whole-body PET/CT was useful to distinguish infectious etiologies from hematologic and oncologic processes. Their review included a patient who had Crohn’s disease and fever, myalgias, and upper abdominal pain, as well as liver enzyme elevation. The PET/CT showed radiotracer uptake within the spleen, which was enlarged. The scan also showed bone marrow uptake; these findings pointed toward hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis rather than an infectious etiology.

For osteomyelitis, said Dr. Viglianti, FDG-PET may have limited utility; it might be most useful when MRI is contraindicated. Within the study population, the investigators identified a patient who had chills and fever along with focal tenderness over the lumbar spine in the context of recent pyelonephritis of a graft kidney. Here, MRI findings were suspicious for osteomyelitis and diskitis, and the FDG uptake at the L4-L5 vertebral levels confirmed the MRI results.

When a patient with a prosthetic valve is suspected of having endocarditis, “cardiac PET/CT may be of high diagnostic value,” said Dr. Viglianti. For patients with endocarditis of native valves, though, a full-body FDG-PET/CT scan may spot septic emboli. A patient identified in the investigators’ review had been admitted for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. The patient, who had a history of intravenous drug use, received a transesophageal echocardiogram that found severe tricuspid valve regurgitation and vegetations. The whole-body PET/CT scan, though, revealed avid uptake in both buttocks, as well as thigh, ankle and calf muscles – a pattern “suspicious for infectious myositis,” said the researchers.

In discussion during the poster session, Dr. Viglianti said that, although reimbursement for PET/CT scans for infectious etiologies might not be feasible, it can still be a reasonable and even cost-effective choice. At his institution, he said, the requisite radioisotope is made in-house, twice daily, so it’s relatively easy to arrange scans. Since PET/CT scans can be acquired relatively quickly and there’s no delay while waiting for radiotracer uptake, clinical decisions can be made more quickly than when waiting for bone uptake for a technetium-99 scan, he said. This can have the effect of saving a night of hospitalization in many cases.

Dr. Viglianti and Ms. Menon reported that they had no relevant conflicts of interest. No outside sources of funding were reported.

SOURCE: Menon A et al. RSNA 2019, Abstract NM203-SDSUB1.

CHICAGO – Dual positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET/CT) scans changed the treatment course of nearly half of patients whose scans were positive for infection. In a single-center systematic review of 18fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)–PET/CT scans, 55 of the 138 scans (40%) changed clinical management.