User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Laurence Wellikson, MD, MHM, announces retirement as CEO of Society of Hospital Medicine

Society recognizes Dr. Wellikson’s leadership, retains Spencer Stuart for successor search

Philadelphia – After serving as the first and only chief executive officer of the Society of Hospital Medicine since January of 2000, Laurence Wellikson, MD, MHM, has announced his retirement effective on Dec. 31, 2020. In parallel, the SHM Board of Directors have commenced a search for his successor.

“When I began as CEO 20 years ago, SHM – then known as the National Association of Inpatient Physicians – was a young national organization with approximately 500 members, and there was minimal understanding as to the value that hospitalists could add to their health communities,” Dr. Wellikson said. “I am proud to say that, nearly 20 years later, SHM boasts a growing membership of more than 17,000, and hospitalists are on the front line of innovation as a driving force in improving patient care.”

SHM has not only grown its membership but also its diverse portfolio of offerings for hospital medicine professionals under Dr. Wellikson’s leadership. Its first annual conference welcomed approximately 300 attendees; the most recent conference, Hospital Medicine 2019, saw that number increase more than tenfold to nearly 4,000. Its conferences, publications, online education, chapter program, advocacy efforts, quality improvement programs, and more have evolved significantly to ensure hospitalists at all stages of their careers – and those who support them – have access to resources to keep them up to date and demonstrate their value in America’s health care system.

During Dr. Wellikson’s tenure, SHM launched its peer-reviewed Journal of Hospital Medicine, the premier, ISI-indexed publication for the specialty, successfully advocated for a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine certification option and C6 hospitalist specialty code, and earned the John M. Eisenberg Patient Safety and Quality Award for its quality improvement programs. These are just a few of the noteworthy accomplishments that have elevated SHM as a key partner for hospitalists and their institutions.

To assist with the search for SHM’s next CEO, the society has retained Spencer Stuart, a leading global executive and leadership advisory firm. The search process is being overseen by a diverse search committee led by the president-elect of SHM’s Board of Directors, Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM.

“On behalf of the society and its members, I want to extend a sincere thank you to Larry for his years of dedication and service to SHM, its staff, and the hospital medicine professionals we serve,” said Christopher Frost, MD, SFHM, president of SHM’s Board of Directors. “His legacy will allow SHM to continue its growth trajectory through key programs and services supporting members’ needs for years to come. Larry has taken the specialty of hospital medicine and created a movement in SHM, where the entire hospital medicine team can come for education, community, and betterment of the care we provide to our patients. We are indebted to him beyond words.”

Those who are interested in leading SHM into the future as its next CEO are encouraged to contact either Jennifer P. Heenan ([email protected]) or Mark Furman, MD ([email protected]).

Society recognizes Dr. Wellikson’s leadership, retains Spencer Stuart for successor search

Society recognizes Dr. Wellikson’s leadership, retains Spencer Stuart for successor search

Philadelphia – After serving as the first and only chief executive officer of the Society of Hospital Medicine since January of 2000, Laurence Wellikson, MD, MHM, has announced his retirement effective on Dec. 31, 2020. In parallel, the SHM Board of Directors have commenced a search for his successor.

“When I began as CEO 20 years ago, SHM – then known as the National Association of Inpatient Physicians – was a young national organization with approximately 500 members, and there was minimal understanding as to the value that hospitalists could add to their health communities,” Dr. Wellikson said. “I am proud to say that, nearly 20 years later, SHM boasts a growing membership of more than 17,000, and hospitalists are on the front line of innovation as a driving force in improving patient care.”

SHM has not only grown its membership but also its diverse portfolio of offerings for hospital medicine professionals under Dr. Wellikson’s leadership. Its first annual conference welcomed approximately 300 attendees; the most recent conference, Hospital Medicine 2019, saw that number increase more than tenfold to nearly 4,000. Its conferences, publications, online education, chapter program, advocacy efforts, quality improvement programs, and more have evolved significantly to ensure hospitalists at all stages of their careers – and those who support them – have access to resources to keep them up to date and demonstrate their value in America’s health care system.

During Dr. Wellikson’s tenure, SHM launched its peer-reviewed Journal of Hospital Medicine, the premier, ISI-indexed publication for the specialty, successfully advocated for a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine certification option and C6 hospitalist specialty code, and earned the John M. Eisenberg Patient Safety and Quality Award for its quality improvement programs. These are just a few of the noteworthy accomplishments that have elevated SHM as a key partner for hospitalists and their institutions.

To assist with the search for SHM’s next CEO, the society has retained Spencer Stuart, a leading global executive and leadership advisory firm. The search process is being overseen by a diverse search committee led by the president-elect of SHM’s Board of Directors, Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM.

“On behalf of the society and its members, I want to extend a sincere thank you to Larry for his years of dedication and service to SHM, its staff, and the hospital medicine professionals we serve,” said Christopher Frost, MD, SFHM, president of SHM’s Board of Directors. “His legacy will allow SHM to continue its growth trajectory through key programs and services supporting members’ needs for years to come. Larry has taken the specialty of hospital medicine and created a movement in SHM, where the entire hospital medicine team can come for education, community, and betterment of the care we provide to our patients. We are indebted to him beyond words.”

Those who are interested in leading SHM into the future as its next CEO are encouraged to contact either Jennifer P. Heenan ([email protected]) or Mark Furman, MD ([email protected]).

Philadelphia – After serving as the first and only chief executive officer of the Society of Hospital Medicine since January of 2000, Laurence Wellikson, MD, MHM, has announced his retirement effective on Dec. 31, 2020. In parallel, the SHM Board of Directors have commenced a search for his successor.

“When I began as CEO 20 years ago, SHM – then known as the National Association of Inpatient Physicians – was a young national organization with approximately 500 members, and there was minimal understanding as to the value that hospitalists could add to their health communities,” Dr. Wellikson said. “I am proud to say that, nearly 20 years later, SHM boasts a growing membership of more than 17,000, and hospitalists are on the front line of innovation as a driving force in improving patient care.”

SHM has not only grown its membership but also its diverse portfolio of offerings for hospital medicine professionals under Dr. Wellikson’s leadership. Its first annual conference welcomed approximately 300 attendees; the most recent conference, Hospital Medicine 2019, saw that number increase more than tenfold to nearly 4,000. Its conferences, publications, online education, chapter program, advocacy efforts, quality improvement programs, and more have evolved significantly to ensure hospitalists at all stages of their careers – and those who support them – have access to resources to keep them up to date and demonstrate their value in America’s health care system.

During Dr. Wellikson’s tenure, SHM launched its peer-reviewed Journal of Hospital Medicine, the premier, ISI-indexed publication for the specialty, successfully advocated for a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine certification option and C6 hospitalist specialty code, and earned the John M. Eisenberg Patient Safety and Quality Award for its quality improvement programs. These are just a few of the noteworthy accomplishments that have elevated SHM as a key partner for hospitalists and their institutions.

To assist with the search for SHM’s next CEO, the society has retained Spencer Stuart, a leading global executive and leadership advisory firm. The search process is being overseen by a diverse search committee led by the president-elect of SHM’s Board of Directors, Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM.

“On behalf of the society and its members, I want to extend a sincere thank you to Larry for his years of dedication and service to SHM, its staff, and the hospital medicine professionals we serve,” said Christopher Frost, MD, SFHM, president of SHM’s Board of Directors. “His legacy will allow SHM to continue its growth trajectory through key programs and services supporting members’ needs for years to come. Larry has taken the specialty of hospital medicine and created a movement in SHM, where the entire hospital medicine team can come for education, community, and betterment of the care we provide to our patients. We are indebted to him beyond words.”

Those who are interested in leading SHM into the future as its next CEO are encouraged to contact either Jennifer P. Heenan ([email protected]) or Mark Furman, MD ([email protected]).

In newborns, concentrated urine helps rule out UTI

SEATTLE – according to investigators at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston.

The researchers found that urine testing negative for nitrites with a specific gravity above 1.015 in children up to 2 months old had a sensitivity of 53% for ruling out UTIs, but that urine with a specific gravity below that mark had a sensitivity of just 14%. The finding “should be taken into account when interpreting nitrite results ... in this high-risk population,” they concluded.

Bacteria in the bladder convert nitrates to nitrites, so positive results are pretty much pathognomonic for UTIs, with a specificity of nearly 100%, according to the researchers.

Negative results, however, don’t reliably rule out infection, and are even less reliable in infants because they urinate frequently, which means they usually flush out bacteria before they have enough time to make the conversion, which takes several hours, they said.

The lead investigator Raymond Parlar-Chun, MD, an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Texas McGovern Medical School in Houston, said he had a hunch that negative results might be more reliable when newborns urinate less frequently and have more concentrated urine.

He and his team reviewed data collected on 413 infants up to 2 months old who were admitted for fever workup and treated for UTIs both in the hospital and after discharge. Nitrite results were stratified by urine concentration. A specific gravity of 1.015 was used as the cutoff between concentrated and dilute urine, which was “midway between the parameters reported” in every urinalysis, Dr. Parlar-Chun said.

Although the sensitivity of concentrated urine was only 53%, “it’s a stark difference from” the 14% in dilute urine, he said.“You should take a look at specific gravity to interpret nitrites. If urine is concentrated, you have [more confidence] that you don’t have a UTI if you’re negative. It’s better than taking [nitrites] at face value.”

The subjects were 31 days old, on average, and 62% were boys; 112 had a specific gravity above 1.015, and 301 below.

There was no external funding, and Dr. Parlar-Chun didn’t have any disclosures.

SEATTLE – according to investigators at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston.

The researchers found that urine testing negative for nitrites with a specific gravity above 1.015 in children up to 2 months old had a sensitivity of 53% for ruling out UTIs, but that urine with a specific gravity below that mark had a sensitivity of just 14%. The finding “should be taken into account when interpreting nitrite results ... in this high-risk population,” they concluded.

Bacteria in the bladder convert nitrates to nitrites, so positive results are pretty much pathognomonic for UTIs, with a specificity of nearly 100%, according to the researchers.

Negative results, however, don’t reliably rule out infection, and are even less reliable in infants because they urinate frequently, which means they usually flush out bacteria before they have enough time to make the conversion, which takes several hours, they said.

The lead investigator Raymond Parlar-Chun, MD, an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Texas McGovern Medical School in Houston, said he had a hunch that negative results might be more reliable when newborns urinate less frequently and have more concentrated urine.

He and his team reviewed data collected on 413 infants up to 2 months old who were admitted for fever workup and treated for UTIs both in the hospital and after discharge. Nitrite results were stratified by urine concentration. A specific gravity of 1.015 was used as the cutoff between concentrated and dilute urine, which was “midway between the parameters reported” in every urinalysis, Dr. Parlar-Chun said.

Although the sensitivity of concentrated urine was only 53%, “it’s a stark difference from” the 14% in dilute urine, he said.“You should take a look at specific gravity to interpret nitrites. If urine is concentrated, you have [more confidence] that you don’t have a UTI if you’re negative. It’s better than taking [nitrites] at face value.”

The subjects were 31 days old, on average, and 62% were boys; 112 had a specific gravity above 1.015, and 301 below.

There was no external funding, and Dr. Parlar-Chun didn’t have any disclosures.

SEATTLE – according to investigators at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston.

The researchers found that urine testing negative for nitrites with a specific gravity above 1.015 in children up to 2 months old had a sensitivity of 53% for ruling out UTIs, but that urine with a specific gravity below that mark had a sensitivity of just 14%. The finding “should be taken into account when interpreting nitrite results ... in this high-risk population,” they concluded.

Bacteria in the bladder convert nitrates to nitrites, so positive results are pretty much pathognomonic for UTIs, with a specificity of nearly 100%, according to the researchers.

Negative results, however, don’t reliably rule out infection, and are even less reliable in infants because they urinate frequently, which means they usually flush out bacteria before they have enough time to make the conversion, which takes several hours, they said.

The lead investigator Raymond Parlar-Chun, MD, an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Texas McGovern Medical School in Houston, said he had a hunch that negative results might be more reliable when newborns urinate less frequently and have more concentrated urine.

He and his team reviewed data collected on 413 infants up to 2 months old who were admitted for fever workup and treated for UTIs both in the hospital and after discharge. Nitrite results were stratified by urine concentration. A specific gravity of 1.015 was used as the cutoff between concentrated and dilute urine, which was “midway between the parameters reported” in every urinalysis, Dr. Parlar-Chun said.

Although the sensitivity of concentrated urine was only 53%, “it’s a stark difference from” the 14% in dilute urine, he said.“You should take a look at specific gravity to interpret nitrites. If urine is concentrated, you have [more confidence] that you don’t have a UTI if you’re negative. It’s better than taking [nitrites] at face value.”

The subjects were 31 days old, on average, and 62% were boys; 112 had a specific gravity above 1.015, and 301 below.

There was no external funding, and Dr. Parlar-Chun didn’t have any disclosures.

REPORTING FROM PHM 2019

Sepsis survivors’ persistent immunosuppression raises mortality risk

readmission after discharge, and mortality, according to a study published in JAMA Network Open.

“Individuals with persistent biomarkers of inflammation and immunosuppression had a higher risk of readmission and death due to cardiovascular disease and cancer compared with those with normal circulating biomarkers,” Sachin Yende, MD, of the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System and the University of Pittsburgh and colleagues wrote in their study. “Our findings suggest that long-term immunomodulation strategies should be explored in patients hospitalized with sepsis.”

Dr. Yende and colleagues performed a multicenter, prospective cohort study of 483 patients who were hospitalized for sepsis at 12 different sites between January 2012 and May 2017. They measured inflammation using interleukin-6, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), and soluble programmed death-ligand 1 (sPD-L1); hemostasis using plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 and D-dimer; and endothelial dysfunction using intercellular adhesion molecule 1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, and E-selectin. The patients included were mean age 60.5 years, 54.9% were male, the mean Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score was 4.2, and a total of 376 patients (77.8%) had one or more chronic diseases.

Overall, there were 485 readmissions in 205 patients (42.5%). The mortality rate was 43 patients (8.9%) at 3 months, 56 patients (11.6%) at 6 months, and 85 patients (17.6%) at 12 months. At 3 months, 23 patients (25.8%) had elevated hs-CRP levels, which increased to 26 patients (30.2%) at 6 months and 40 patients (44.9%) at 12 months. sPD-L1 levels were elevated in 45 patients (46.4%) at 3 months, but the number of patients with elevated sPD-L1 did not appear to significantly increase at 6 months (40 patients; 44.9%) or 12 months (44 patients; 49.4%).

From these results, researchers developed a phenotype of hyperinflammation and immunosuppression that consisted of 326 of 477 (68.3%) patients with high hs-CRP and elevated sPD-L1 levels. Patients with this phenotype of hyperinflammation and immunosuppression had more than eight times the risk of 1-year mortality (odds ratio, 8.26; 95% confidence interval, 3.45-21.69; P less than .001) and more than five times the risk of readmission or mortality at 6 months related to cardiovascular disease (hazard ratio, 5.07; 95% CI, 1.18-21.84; P = .02) or cancer (hazard ratio, 5.15; 95% CI, 1.25-21.18; P = .02), compared with patients who had normal hs-CRP and sPD-L1 levels. This hyperinflammation and immunosuppression phenotype also was associated with greater risk of 6-month all-cause readmission or mortality (HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.10-2.13; P = .01), compared with patients who had the normal phenotype.

“The persistence of hyperinflammation in a large number of sepsis survivors and the increased risk of cardiovascular events among these patients may explain the association between infection and cardiovascular disease in a prior study,” the authors said. “Although prior trials tested immunomodulation strategies during only the early phase of hospitalization for sepsis, immunomodulation may be needed after hospital discharge,” and suggest points of future study for patients who survive sepsis and develop long-term sequelae.

This study was funded by grants from National Institutes of Health and resources from the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System. The authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of personal fees, grants, and patents for Alung Technologies, Atox Bio, Bayer AG, Beckman Coulter, BristolMyers Squibb, Ferring, NIH, Roche, Selepressin, and the University of Pittsburgh.

SOURCE: Yende S et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Aug 7. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8686.

readmission after discharge, and mortality, according to a study published in JAMA Network Open.

“Individuals with persistent biomarkers of inflammation and immunosuppression had a higher risk of readmission and death due to cardiovascular disease and cancer compared with those with normal circulating biomarkers,” Sachin Yende, MD, of the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System and the University of Pittsburgh and colleagues wrote in their study. “Our findings suggest that long-term immunomodulation strategies should be explored in patients hospitalized with sepsis.”

Dr. Yende and colleagues performed a multicenter, prospective cohort study of 483 patients who were hospitalized for sepsis at 12 different sites between January 2012 and May 2017. They measured inflammation using interleukin-6, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), and soluble programmed death-ligand 1 (sPD-L1); hemostasis using plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 and D-dimer; and endothelial dysfunction using intercellular adhesion molecule 1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, and E-selectin. The patients included were mean age 60.5 years, 54.9% were male, the mean Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score was 4.2, and a total of 376 patients (77.8%) had one or more chronic diseases.

Overall, there were 485 readmissions in 205 patients (42.5%). The mortality rate was 43 patients (8.9%) at 3 months, 56 patients (11.6%) at 6 months, and 85 patients (17.6%) at 12 months. At 3 months, 23 patients (25.8%) had elevated hs-CRP levels, which increased to 26 patients (30.2%) at 6 months and 40 patients (44.9%) at 12 months. sPD-L1 levels were elevated in 45 patients (46.4%) at 3 months, but the number of patients with elevated sPD-L1 did not appear to significantly increase at 6 months (40 patients; 44.9%) or 12 months (44 patients; 49.4%).

From these results, researchers developed a phenotype of hyperinflammation and immunosuppression that consisted of 326 of 477 (68.3%) patients with high hs-CRP and elevated sPD-L1 levels. Patients with this phenotype of hyperinflammation and immunosuppression had more than eight times the risk of 1-year mortality (odds ratio, 8.26; 95% confidence interval, 3.45-21.69; P less than .001) and more than five times the risk of readmission or mortality at 6 months related to cardiovascular disease (hazard ratio, 5.07; 95% CI, 1.18-21.84; P = .02) or cancer (hazard ratio, 5.15; 95% CI, 1.25-21.18; P = .02), compared with patients who had normal hs-CRP and sPD-L1 levels. This hyperinflammation and immunosuppression phenotype also was associated with greater risk of 6-month all-cause readmission or mortality (HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.10-2.13; P = .01), compared with patients who had the normal phenotype.

“The persistence of hyperinflammation in a large number of sepsis survivors and the increased risk of cardiovascular events among these patients may explain the association between infection and cardiovascular disease in a prior study,” the authors said. “Although prior trials tested immunomodulation strategies during only the early phase of hospitalization for sepsis, immunomodulation may be needed after hospital discharge,” and suggest points of future study for patients who survive sepsis and develop long-term sequelae.

This study was funded by grants from National Institutes of Health and resources from the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System. The authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of personal fees, grants, and patents for Alung Technologies, Atox Bio, Bayer AG, Beckman Coulter, BristolMyers Squibb, Ferring, NIH, Roche, Selepressin, and the University of Pittsburgh.

SOURCE: Yende S et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Aug 7. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8686.

readmission after discharge, and mortality, according to a study published in JAMA Network Open.

“Individuals with persistent biomarkers of inflammation and immunosuppression had a higher risk of readmission and death due to cardiovascular disease and cancer compared with those with normal circulating biomarkers,” Sachin Yende, MD, of the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System and the University of Pittsburgh and colleagues wrote in their study. “Our findings suggest that long-term immunomodulation strategies should be explored in patients hospitalized with sepsis.”

Dr. Yende and colleagues performed a multicenter, prospective cohort study of 483 patients who were hospitalized for sepsis at 12 different sites between January 2012 and May 2017. They measured inflammation using interleukin-6, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), and soluble programmed death-ligand 1 (sPD-L1); hemostasis using plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 and D-dimer; and endothelial dysfunction using intercellular adhesion molecule 1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, and E-selectin. The patients included were mean age 60.5 years, 54.9% were male, the mean Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score was 4.2, and a total of 376 patients (77.8%) had one or more chronic diseases.

Overall, there were 485 readmissions in 205 patients (42.5%). The mortality rate was 43 patients (8.9%) at 3 months, 56 patients (11.6%) at 6 months, and 85 patients (17.6%) at 12 months. At 3 months, 23 patients (25.8%) had elevated hs-CRP levels, which increased to 26 patients (30.2%) at 6 months and 40 patients (44.9%) at 12 months. sPD-L1 levels were elevated in 45 patients (46.4%) at 3 months, but the number of patients with elevated sPD-L1 did not appear to significantly increase at 6 months (40 patients; 44.9%) or 12 months (44 patients; 49.4%).

From these results, researchers developed a phenotype of hyperinflammation and immunosuppression that consisted of 326 of 477 (68.3%) patients with high hs-CRP and elevated sPD-L1 levels. Patients with this phenotype of hyperinflammation and immunosuppression had more than eight times the risk of 1-year mortality (odds ratio, 8.26; 95% confidence interval, 3.45-21.69; P less than .001) and more than five times the risk of readmission or mortality at 6 months related to cardiovascular disease (hazard ratio, 5.07; 95% CI, 1.18-21.84; P = .02) or cancer (hazard ratio, 5.15; 95% CI, 1.25-21.18; P = .02), compared with patients who had normal hs-CRP and sPD-L1 levels. This hyperinflammation and immunosuppression phenotype also was associated with greater risk of 6-month all-cause readmission or mortality (HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.10-2.13; P = .01), compared with patients who had the normal phenotype.

“The persistence of hyperinflammation in a large number of sepsis survivors and the increased risk of cardiovascular events among these patients may explain the association between infection and cardiovascular disease in a prior study,” the authors said. “Although prior trials tested immunomodulation strategies during only the early phase of hospitalization for sepsis, immunomodulation may be needed after hospital discharge,” and suggest points of future study for patients who survive sepsis and develop long-term sequelae.

This study was funded by grants from National Institutes of Health and resources from the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System. The authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of personal fees, grants, and patents for Alung Technologies, Atox Bio, Bayer AG, Beckman Coulter, BristolMyers Squibb, Ferring, NIH, Roche, Selepressin, and the University of Pittsburgh.

SOURCE: Yende S et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Aug 7. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8686.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Key clinical point: Markers of inflammation and immunosuppression persist in over two-thirds of patients hospitalized for sepsis, which could explain worsened outcomes and mortality up to 1 year after hospitalization.

Major finding: Patients with signs of hyperinflammation and immunosuppression had significantly increased mortality after 1 year and were significantly more likely to be readmitted or die because of cardiovascular disease or cancer.

Study details: A prospective cohort study of 483 patients who were hospitalized because of sepsis at 12 different centers between January 2012 and May 2017.

Disclosures: This study was funded by grants from National Institutes of Health and resources from the Veterans Affairs Pittsburgh Healthcare System. The authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of personal fees, grants, and patents for Alung Technologies, Atox Bio, Bayer AG, Beckman Coulter, BristolMyers Squibb, Ferring, NIH, Roche, Selepressin, and the University of Pittsburgh.

Source: Yende S et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Aug 7. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8686.

Hospital slashes S. aureus vancomycin resistance

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – , Johannes Huebner, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

He presented a retrospective analysis of S. aureus isolates obtained from 540 patients at the Dr. von Hauner Children’s Hospital, Munich, from 2002 to 2017. All were either newly identified methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) or specimens from bacteremic children with invasive MRSA or methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA). The strains were tested for vancomycin resistance and minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). The results from the 200 isolates obtained from 2002 to 2009 were then compared to the 340 specimens from 2010 to 2017, when antibiotic stewardship programs rose to the fore at the pediatric hospital.

All samples proved to be vancomycin sensitive. The further good news was there was absolutely no evidence of the worrisome vancomycin MIC creep that has been described at some centers. On the contrary, the MIC was significantly lower in the later samples, at 0.99 mcg/mL, compared with 1.11 mcg/mL in the earlier period. Moreover, the prevalence of heterogeneous glycopeptide-intermediate S. aureus (hGISA) – a phenotype that has been associated with increased rates of treatment failure – improved from 25% in the earlier period to 6% during the later period, reported Dr. Huebner, head of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at the children’s hospital, part of the University of Munich.

Vancomycin MICs weren’t significantly different between the MRSA and MSSA samples.

Based upon this favorable institutional experience, vancomycin remains the first-line treatment for suspected severe gram-positive cocci infections as well as proven infections involving MRSA at Dr. von Hauner Children’s Hospital.

These vancomycin MIC and hGISA data underscore the importance of periodically monitoring local S. aureus antimicrobial susceptibilities, which, as in this case, can differ from the broader global trends. The vancomycin MIC creep issue hadn’t been studied previously in German hospitals, according to Dr. Huebner.

He and his coworkers have published details of the elements of pediatric antibiotic stewardship programs they have found to be most effective (Infection. 2017 Aug;45[4]:493-504) as well as a systematic review of studies on the favorable economic impact of such programs (J Hosp Infect. 2019 Aug;102[4]:369-376).

Dr. Huebner reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – , Johannes Huebner, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

He presented a retrospective analysis of S. aureus isolates obtained from 540 patients at the Dr. von Hauner Children’s Hospital, Munich, from 2002 to 2017. All were either newly identified methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) or specimens from bacteremic children with invasive MRSA or methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA). The strains were tested for vancomycin resistance and minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). The results from the 200 isolates obtained from 2002 to 2009 were then compared to the 340 specimens from 2010 to 2017, when antibiotic stewardship programs rose to the fore at the pediatric hospital.

All samples proved to be vancomycin sensitive. The further good news was there was absolutely no evidence of the worrisome vancomycin MIC creep that has been described at some centers. On the contrary, the MIC was significantly lower in the later samples, at 0.99 mcg/mL, compared with 1.11 mcg/mL in the earlier period. Moreover, the prevalence of heterogeneous glycopeptide-intermediate S. aureus (hGISA) – a phenotype that has been associated with increased rates of treatment failure – improved from 25% in the earlier period to 6% during the later period, reported Dr. Huebner, head of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at the children’s hospital, part of the University of Munich.

Vancomycin MICs weren’t significantly different between the MRSA and MSSA samples.

Based upon this favorable institutional experience, vancomycin remains the first-line treatment for suspected severe gram-positive cocci infections as well as proven infections involving MRSA at Dr. von Hauner Children’s Hospital.

These vancomycin MIC and hGISA data underscore the importance of periodically monitoring local S. aureus antimicrobial susceptibilities, which, as in this case, can differ from the broader global trends. The vancomycin MIC creep issue hadn’t been studied previously in German hospitals, according to Dr. Huebner.

He and his coworkers have published details of the elements of pediatric antibiotic stewardship programs they have found to be most effective (Infection. 2017 Aug;45[4]:493-504) as well as a systematic review of studies on the favorable economic impact of such programs (J Hosp Infect. 2019 Aug;102[4]:369-376).

Dr. Huebner reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – , Johannes Huebner, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

He presented a retrospective analysis of S. aureus isolates obtained from 540 patients at the Dr. von Hauner Children’s Hospital, Munich, from 2002 to 2017. All were either newly identified methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) or specimens from bacteremic children with invasive MRSA or methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA). The strains were tested for vancomycin resistance and minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). The results from the 200 isolates obtained from 2002 to 2009 were then compared to the 340 specimens from 2010 to 2017, when antibiotic stewardship programs rose to the fore at the pediatric hospital.

All samples proved to be vancomycin sensitive. The further good news was there was absolutely no evidence of the worrisome vancomycin MIC creep that has been described at some centers. On the contrary, the MIC was significantly lower in the later samples, at 0.99 mcg/mL, compared with 1.11 mcg/mL in the earlier period. Moreover, the prevalence of heterogeneous glycopeptide-intermediate S. aureus (hGISA) – a phenotype that has been associated with increased rates of treatment failure – improved from 25% in the earlier period to 6% during the later period, reported Dr. Huebner, head of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at the children’s hospital, part of the University of Munich.

Vancomycin MICs weren’t significantly different between the MRSA and MSSA samples.

Based upon this favorable institutional experience, vancomycin remains the first-line treatment for suspected severe gram-positive cocci infections as well as proven infections involving MRSA at Dr. von Hauner Children’s Hospital.

These vancomycin MIC and hGISA data underscore the importance of periodically monitoring local S. aureus antimicrobial susceptibilities, which, as in this case, can differ from the broader global trends. The vancomycin MIC creep issue hadn’t been studied previously in German hospitals, according to Dr. Huebner.

He and his coworkers have published details of the elements of pediatric antibiotic stewardship programs they have found to be most effective (Infection. 2017 Aug;45[4]:493-504) as well as a systematic review of studies on the favorable economic impact of such programs (J Hosp Infect. 2019 Aug;102[4]:369-376).

Dr. Huebner reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

REPORTING FROM ESPID 2019

Key clinical point: Staphylococcus aureus vancomycin MIC creep is reversible through dedicated antimicrobial stewardship.

Major finding: The prevalence of hGISA in MRSA and MSSA specimens improved from 25% during 2002-2009 to 6% during 2010-2017 at one German tertiary children’s hospital.

Study details: This was a retrospective single-center analysis of vancomycin resistance trends over time in 540 S. aureus specimens gathered in 2002-2017.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

Maximize your leadership in academic hospital medicine

AHA Level 2 course now available

Over the past 2 decades, hospital medicine has grown from a nascent collection of hospitalists to one of the fastest growing specialties, with more than 60,000 active practitioners today.

Ten years ago, the need for mentoring and growth of a new generation of young academic faculty led to the development of the first Academic Hospitalist Academy (AHA) through the coordinated efforts of the Society of Hospital Medicine, the Society of General Internal Medicine, and the Association of Clinical Leaders of General Internal Medicine.

As modern medicine moves at an increasing pace, the intersection of patient care, research, and education has opened further opportunities for fostering the expertise of hospital medicine practitioners. The next level of training is now available with the advent of AHA’s Level 2 course.

Ever wonder why the new clinical service you’ve designed to improve physician and patient efficiency isn’t functioning like it did in the beginning? Patients are staying longer in the hospital, and physicians are working harder. The principles of change management, personal leadership styles, and adult learning will be covered in the AHA Level 2 course. How do I get my project funded and then what do I do with the results? Keys to negotiating for time and resources as well as the skills to write and disseminate your work are integrated into the curriculum.

Participants will be engaged in an interactive course designed around the challenges of practicing and leading in an academic environment. AHA Level 2 aims to help attendees – regardless of their areas of interest – identify and acquire the skills necessary to advance their career, describe the business and cultural landscape of academic health systems, and learn how to leverage that knowledge; to list resources and techniques to continue to further build their skills, and identify and pursue their unique scholarly niche.

Based on the success of AHA’s Level 1 course and the feedback from the almost 1,000 participants who have attended, AHA Level 2 is a 2.5-day course that will allow for the exchange of ideas and skills from nationally regarded faculty and fellow attendees. Through plenary sessions, workshops, small groups, and networking opportunities, attendees will be immersed in the realm of modern academic hospital medicine. The new course is offered in parallel with AHA Level 1 at the Inverness Resort, outside of Denver, on Sept. 10-12, 2019.

The course will leave attendees with an individualized career plan and enhance their area of expertise. The lessons learned and shared will allow participants to return to their institutions and continue to lead in the areas of patient care, financial resourcefulness, and the education of current and future generations of hospital medicine specialists.

Dr. O’Dorisio is a Med-Peds hospitalist at the Ohio State University, Columbus.

AHA Level 2 course now available

AHA Level 2 course now available

Over the past 2 decades, hospital medicine has grown from a nascent collection of hospitalists to one of the fastest growing specialties, with more than 60,000 active practitioners today.

Ten years ago, the need for mentoring and growth of a new generation of young academic faculty led to the development of the first Academic Hospitalist Academy (AHA) through the coordinated efforts of the Society of Hospital Medicine, the Society of General Internal Medicine, and the Association of Clinical Leaders of General Internal Medicine.

As modern medicine moves at an increasing pace, the intersection of patient care, research, and education has opened further opportunities for fostering the expertise of hospital medicine practitioners. The next level of training is now available with the advent of AHA’s Level 2 course.

Ever wonder why the new clinical service you’ve designed to improve physician and patient efficiency isn’t functioning like it did in the beginning? Patients are staying longer in the hospital, and physicians are working harder. The principles of change management, personal leadership styles, and adult learning will be covered in the AHA Level 2 course. How do I get my project funded and then what do I do with the results? Keys to negotiating for time and resources as well as the skills to write and disseminate your work are integrated into the curriculum.

Participants will be engaged in an interactive course designed around the challenges of practicing and leading in an academic environment. AHA Level 2 aims to help attendees – regardless of their areas of interest – identify and acquire the skills necessary to advance their career, describe the business and cultural landscape of academic health systems, and learn how to leverage that knowledge; to list resources and techniques to continue to further build their skills, and identify and pursue their unique scholarly niche.

Based on the success of AHA’s Level 1 course and the feedback from the almost 1,000 participants who have attended, AHA Level 2 is a 2.5-day course that will allow for the exchange of ideas and skills from nationally regarded faculty and fellow attendees. Through plenary sessions, workshops, small groups, and networking opportunities, attendees will be immersed in the realm of modern academic hospital medicine. The new course is offered in parallel with AHA Level 1 at the Inverness Resort, outside of Denver, on Sept. 10-12, 2019.

The course will leave attendees with an individualized career plan and enhance their area of expertise. The lessons learned and shared will allow participants to return to their institutions and continue to lead in the areas of patient care, financial resourcefulness, and the education of current and future generations of hospital medicine specialists.

Dr. O’Dorisio is a Med-Peds hospitalist at the Ohio State University, Columbus.

Over the past 2 decades, hospital medicine has grown from a nascent collection of hospitalists to one of the fastest growing specialties, with more than 60,000 active practitioners today.

Ten years ago, the need for mentoring and growth of a new generation of young academic faculty led to the development of the first Academic Hospitalist Academy (AHA) through the coordinated efforts of the Society of Hospital Medicine, the Society of General Internal Medicine, and the Association of Clinical Leaders of General Internal Medicine.

As modern medicine moves at an increasing pace, the intersection of patient care, research, and education has opened further opportunities for fostering the expertise of hospital medicine practitioners. The next level of training is now available with the advent of AHA’s Level 2 course.

Ever wonder why the new clinical service you’ve designed to improve physician and patient efficiency isn’t functioning like it did in the beginning? Patients are staying longer in the hospital, and physicians are working harder. The principles of change management, personal leadership styles, and adult learning will be covered in the AHA Level 2 course. How do I get my project funded and then what do I do with the results? Keys to negotiating for time and resources as well as the skills to write and disseminate your work are integrated into the curriculum.

Participants will be engaged in an interactive course designed around the challenges of practicing and leading in an academic environment. AHA Level 2 aims to help attendees – regardless of their areas of interest – identify and acquire the skills necessary to advance their career, describe the business and cultural landscape of academic health systems, and learn how to leverage that knowledge; to list resources and techniques to continue to further build their skills, and identify and pursue their unique scholarly niche.

Based on the success of AHA’s Level 1 course and the feedback from the almost 1,000 participants who have attended, AHA Level 2 is a 2.5-day course that will allow for the exchange of ideas and skills from nationally regarded faculty and fellow attendees. Through plenary sessions, workshops, small groups, and networking opportunities, attendees will be immersed in the realm of modern academic hospital medicine. The new course is offered in parallel with AHA Level 1 at the Inverness Resort, outside of Denver, on Sept. 10-12, 2019.

The course will leave attendees with an individualized career plan and enhance their area of expertise. The lessons learned and shared will allow participants to return to their institutions and continue to lead in the areas of patient care, financial resourcefulness, and the education of current and future generations of hospital medicine specialists.

Dr. O’Dorisio is a Med-Peds hospitalist at the Ohio State University, Columbus.

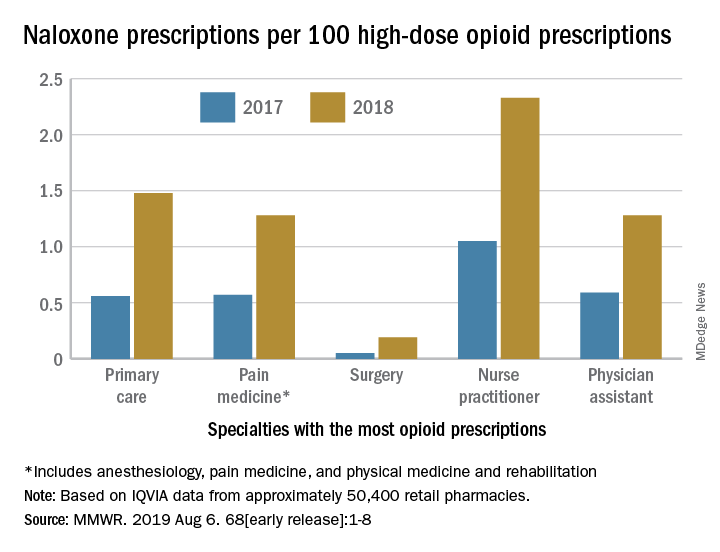

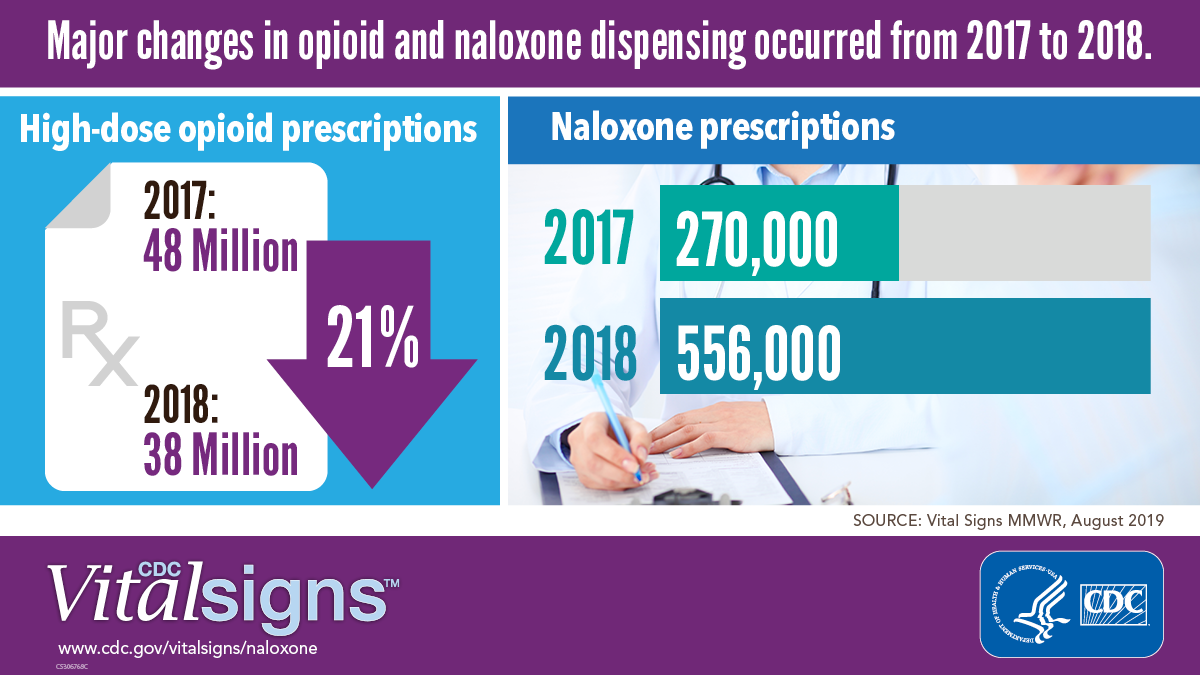

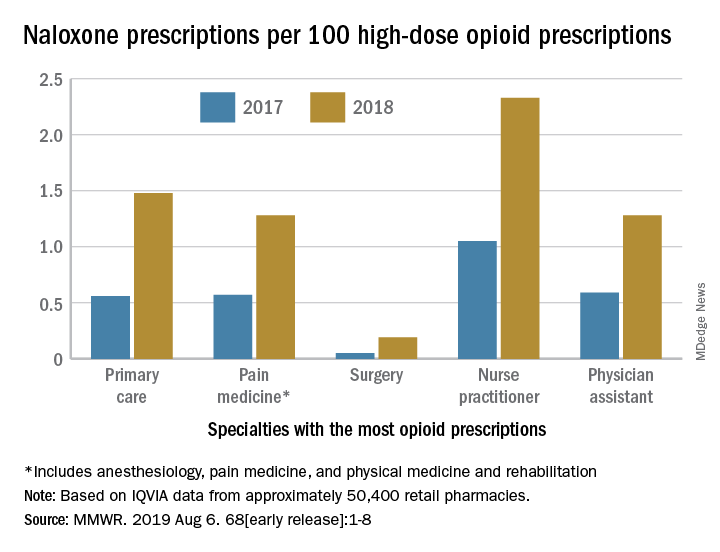

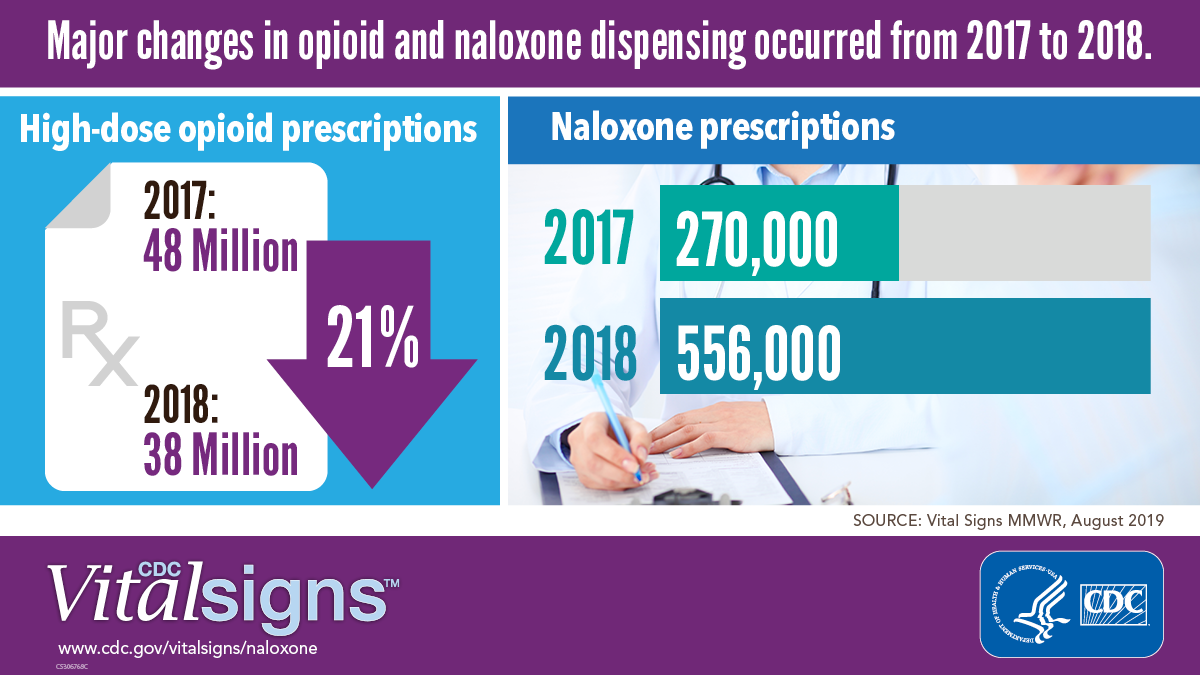

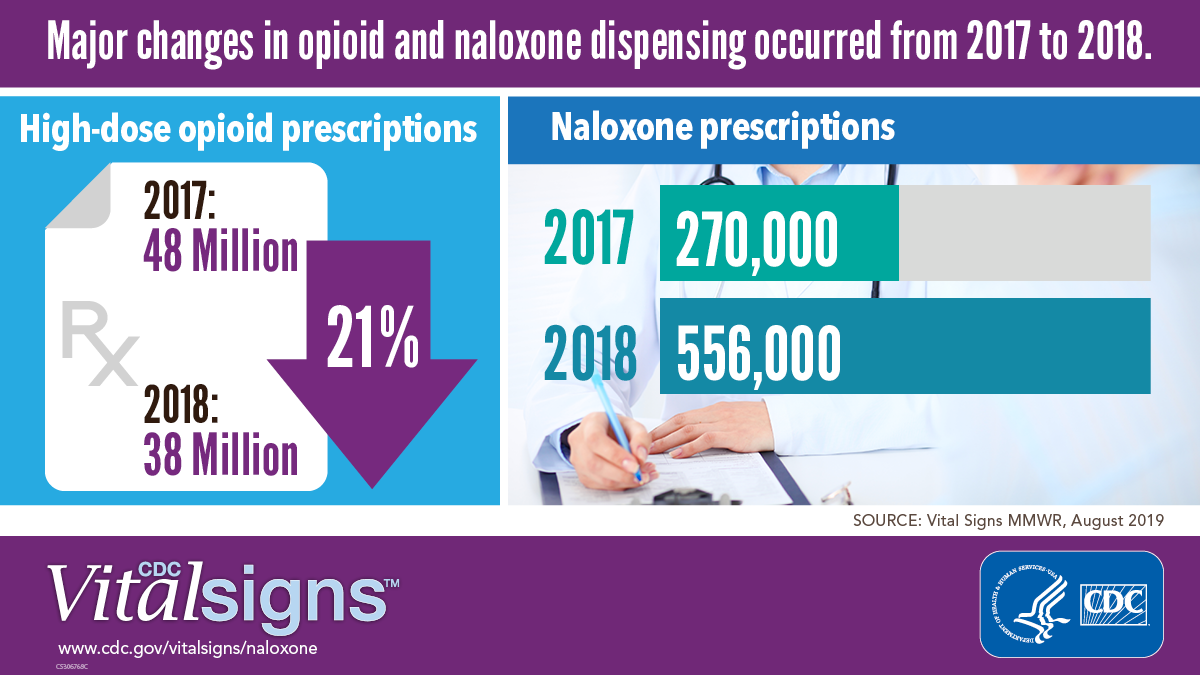

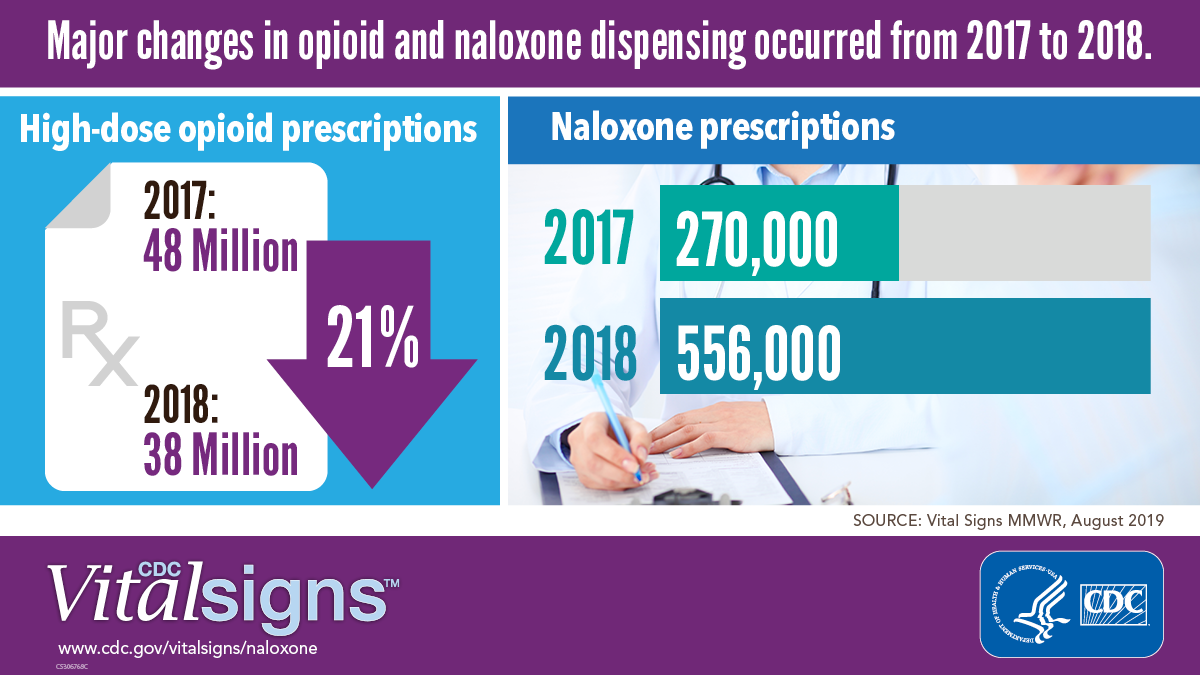

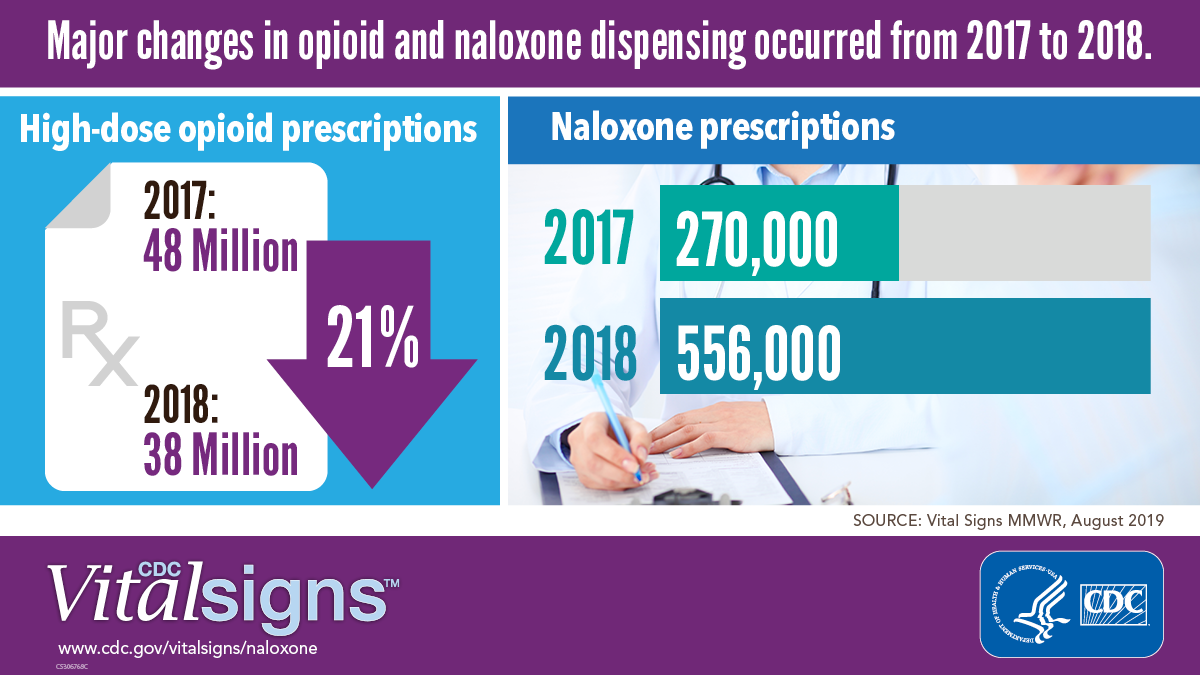

CDC finds that too little naloxone is dispensed

Although the CDC recommends that clinicians consider prescribing naloxone, which can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose, to patients who receive high-dose opioid prescriptions, one naloxone prescription was dispensed in 2018 for every 69 such patients, according to a Vital Signs investigation published Aug. 6 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Approximately 9 million more naloxone prescriptions could have been dispensed in 2018 if every patient with a high-dose opioid prescription were offered the drug, according to the agency. In addition, the rate at which naloxone is dispensed varies significantly according to region.

“Thousands of Americans are alive today thanks to the use of naloxone,” said Alex M. Azar, secretary of Health and Human Services, in a press release. “Giving people a chance to survive an opioid overdose and safely enter recovery is one of the five key pillars of our HHS strategy for ending the overdose epidemic. With help from Congress, the private sector, state, and local governments and communities, targeted access to naloxone has expanded dramatically over the last several years, but today’s CDC report is a reminder that there is much more all of us need to do to save lives.”

Investigators examined retail pharmacy data

In 2017, 47,600 (67.8%) drug overdose deaths in the United States involved opioids. For decades, emergency medical service providers have administered naloxone to patients with suspected drug overdose. A major focus of public health initiatives intended to address the opioid overdose crisis has been to increase access to naloxone through clinician prescribing and pharmacy dispensing. The CDC recommends considering prescribing naloxone to patients with a history of overdose or substance use disorder, those receiving opioid dosages of 50 morphine milligram equivalents per day or greater (that is, high-dose prescriptions), and those who are using benzodiazepines concurrently.

Investigators at the CDC examined retail pharmacy data from IQVIA, a company that maintains information on prescriptions from approximately 50,400 retail pharmacies. They extracted data from 2012 through 2018 to analyze naloxone dispensing by region, urban versus rural status, prescriber specialty, and recipient characteristics (for example, age group, sex, out-of-pocket costs, and method of payment).

Dispensations doubled from 2017 to 2018

Naloxone dispensing from retail pharmacies increased from 0.4 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2012 to 170.2 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2018. From 2017 to 2018 alone, the number of prescriptions dispensed increased by 106%.

Despite consistency among state laws, naloxone dispensation varied by region. The average rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 0.2 in the lowest quartile to 2.9 in the highest quartile. In 2018, the rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 1.5 in metropolitan counties and 1.6 in the Northeast to 1.2 in rural counties and 1.3 in the Midwest. Rural counties were nearly three times more likely to be low-dispensing counties, compared with metropolitan counties.

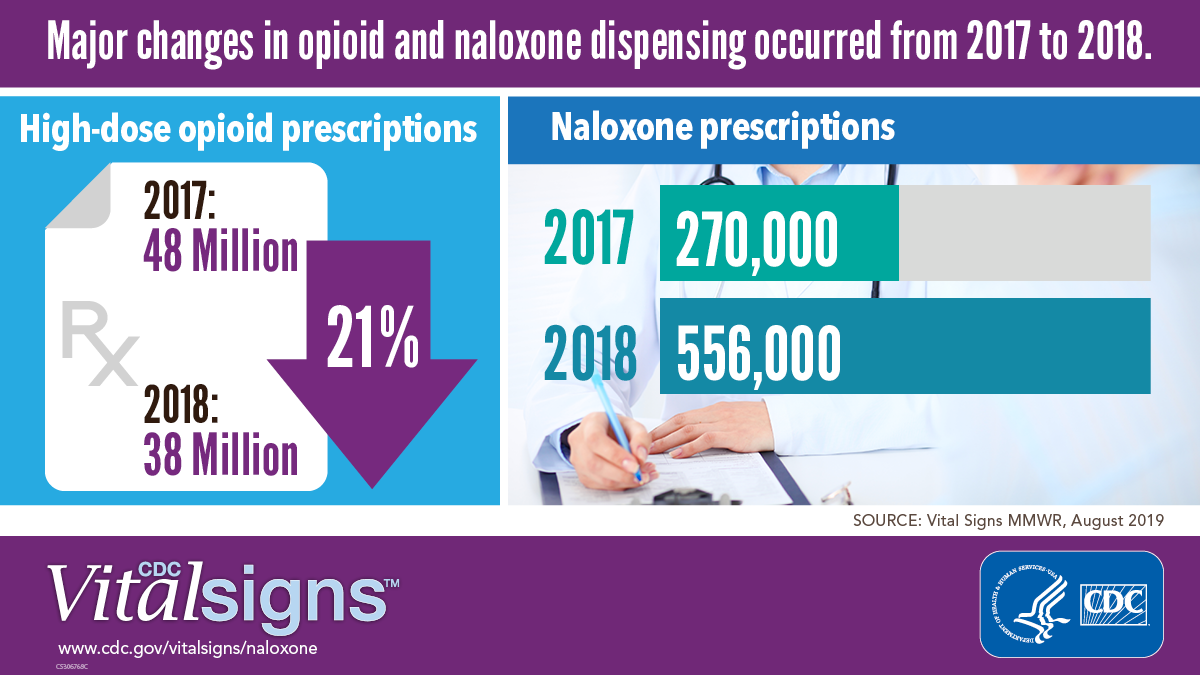

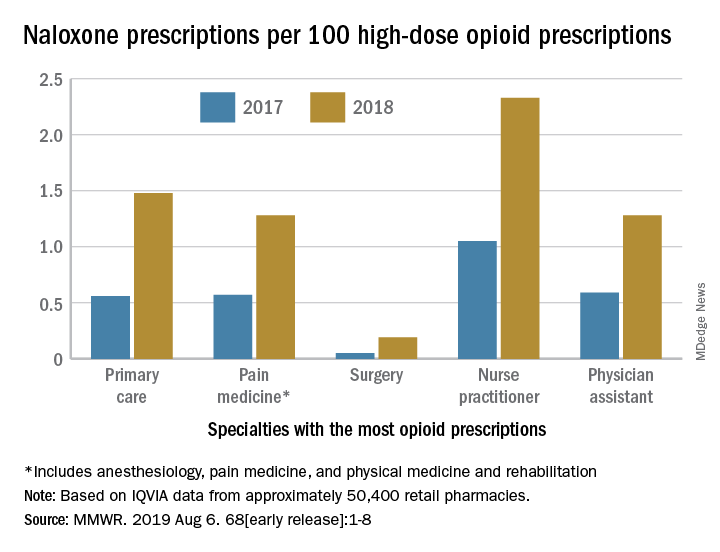

The rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions also varied by provider specialty. This rate was lowest among surgeons (0.2) and highest among psychiatrists (12.9).

Most naloxone prescriptions entailed out-of-pocket costs. About 71% of prescriptions paid for by Medicare entailed out-of-pocket costs, compared with 43.8% of prescriptions paid for by Medicaid, and 41.5% of prescriptions paid for by commercial insurance.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

More can be done

“It is clear from the data that there is still much needed education around the important role naloxone plays in reducing overdose deaths,” said Robert R. Redfield, MD, director of the CDC, in a press release. “The time is now to ensure all individuals who are prescribed high-dose opioids also receive naloxone as a potential life-saving intervention. As we aggressively confront what is the public health crisis of our time, CDC will continue to stress with health care providers the benefit of making this overdose-reversing medicine available to patients.”

“While we’ve seen these important increases [in naloxone prescriptions], we are not as far along as we’d like to be,” said Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, during a press conference. “Cost is one of the issues, but I think awareness is another.” These data should prompt pharmacies to make sure that they stock naloxone and remind clinicians to consider naloxone when they prescribe opioids, she added. Patients and their family members should be aware of naloxone and ask their health care providers about it. “We’d really like to see the increase [in naloxone prescriptions] move much more rapidly,” she concluded.

The investigators disclosed no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Guy GP et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Aug 6.

Although the CDC recommends that clinicians consider prescribing naloxone, which can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose, to patients who receive high-dose opioid prescriptions, one naloxone prescription was dispensed in 2018 for every 69 such patients, according to a Vital Signs investigation published Aug. 6 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Approximately 9 million more naloxone prescriptions could have been dispensed in 2018 if every patient with a high-dose opioid prescription were offered the drug, according to the agency. In addition, the rate at which naloxone is dispensed varies significantly according to region.

“Thousands of Americans are alive today thanks to the use of naloxone,” said Alex M. Azar, secretary of Health and Human Services, in a press release. “Giving people a chance to survive an opioid overdose and safely enter recovery is one of the five key pillars of our HHS strategy for ending the overdose epidemic. With help from Congress, the private sector, state, and local governments and communities, targeted access to naloxone has expanded dramatically over the last several years, but today’s CDC report is a reminder that there is much more all of us need to do to save lives.”

Investigators examined retail pharmacy data

In 2017, 47,600 (67.8%) drug overdose deaths in the United States involved opioids. For decades, emergency medical service providers have administered naloxone to patients with suspected drug overdose. A major focus of public health initiatives intended to address the opioid overdose crisis has been to increase access to naloxone through clinician prescribing and pharmacy dispensing. The CDC recommends considering prescribing naloxone to patients with a history of overdose or substance use disorder, those receiving opioid dosages of 50 morphine milligram equivalents per day or greater (that is, high-dose prescriptions), and those who are using benzodiazepines concurrently.

Investigators at the CDC examined retail pharmacy data from IQVIA, a company that maintains information on prescriptions from approximately 50,400 retail pharmacies. They extracted data from 2012 through 2018 to analyze naloxone dispensing by region, urban versus rural status, prescriber specialty, and recipient characteristics (for example, age group, sex, out-of-pocket costs, and method of payment).

Dispensations doubled from 2017 to 2018

Naloxone dispensing from retail pharmacies increased from 0.4 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2012 to 170.2 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2018. From 2017 to 2018 alone, the number of prescriptions dispensed increased by 106%.

Despite consistency among state laws, naloxone dispensation varied by region. The average rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 0.2 in the lowest quartile to 2.9 in the highest quartile. In 2018, the rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 1.5 in metropolitan counties and 1.6 in the Northeast to 1.2 in rural counties and 1.3 in the Midwest. Rural counties were nearly three times more likely to be low-dispensing counties, compared with metropolitan counties.

The rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions also varied by provider specialty. This rate was lowest among surgeons (0.2) and highest among psychiatrists (12.9).

Most naloxone prescriptions entailed out-of-pocket costs. About 71% of prescriptions paid for by Medicare entailed out-of-pocket costs, compared with 43.8% of prescriptions paid for by Medicaid, and 41.5% of prescriptions paid for by commercial insurance.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

More can be done

“It is clear from the data that there is still much needed education around the important role naloxone plays in reducing overdose deaths,” said Robert R. Redfield, MD, director of the CDC, in a press release. “The time is now to ensure all individuals who are prescribed high-dose opioids also receive naloxone as a potential life-saving intervention. As we aggressively confront what is the public health crisis of our time, CDC will continue to stress with health care providers the benefit of making this overdose-reversing medicine available to patients.”

“While we’ve seen these important increases [in naloxone prescriptions], we are not as far along as we’d like to be,” said Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, during a press conference. “Cost is one of the issues, but I think awareness is another.” These data should prompt pharmacies to make sure that they stock naloxone and remind clinicians to consider naloxone when they prescribe opioids, she added. Patients and their family members should be aware of naloxone and ask their health care providers about it. “We’d really like to see the increase [in naloxone prescriptions] move much more rapidly,” she concluded.

The investigators disclosed no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Guy GP et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Aug 6.

Although the CDC recommends that clinicians consider prescribing naloxone, which can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose, to patients who receive high-dose opioid prescriptions, one naloxone prescription was dispensed in 2018 for every 69 such patients, according to a Vital Signs investigation published Aug. 6 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Approximately 9 million more naloxone prescriptions could have been dispensed in 2018 if every patient with a high-dose opioid prescription were offered the drug, according to the agency. In addition, the rate at which naloxone is dispensed varies significantly according to region.

“Thousands of Americans are alive today thanks to the use of naloxone,” said Alex M. Azar, secretary of Health and Human Services, in a press release. “Giving people a chance to survive an opioid overdose and safely enter recovery is one of the five key pillars of our HHS strategy for ending the overdose epidemic. With help from Congress, the private sector, state, and local governments and communities, targeted access to naloxone has expanded dramatically over the last several years, but today’s CDC report is a reminder that there is much more all of us need to do to save lives.”

Investigators examined retail pharmacy data

In 2017, 47,600 (67.8%) drug overdose deaths in the United States involved opioids. For decades, emergency medical service providers have administered naloxone to patients with suspected drug overdose. A major focus of public health initiatives intended to address the opioid overdose crisis has been to increase access to naloxone through clinician prescribing and pharmacy dispensing. The CDC recommends considering prescribing naloxone to patients with a history of overdose or substance use disorder, those receiving opioid dosages of 50 morphine milligram equivalents per day or greater (that is, high-dose prescriptions), and those who are using benzodiazepines concurrently.

Investigators at the CDC examined retail pharmacy data from IQVIA, a company that maintains information on prescriptions from approximately 50,400 retail pharmacies. They extracted data from 2012 through 2018 to analyze naloxone dispensing by region, urban versus rural status, prescriber specialty, and recipient characteristics (for example, age group, sex, out-of-pocket costs, and method of payment).

Dispensations doubled from 2017 to 2018

Naloxone dispensing from retail pharmacies increased from 0.4 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2012 to 170.2 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2018. From 2017 to 2018 alone, the number of prescriptions dispensed increased by 106%.

Despite consistency among state laws, naloxone dispensation varied by region. The average rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 0.2 in the lowest quartile to 2.9 in the highest quartile. In 2018, the rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 1.5 in metropolitan counties and 1.6 in the Northeast to 1.2 in rural counties and 1.3 in the Midwest. Rural counties were nearly three times more likely to be low-dispensing counties, compared with metropolitan counties.

The rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions also varied by provider specialty. This rate was lowest among surgeons (0.2) and highest among psychiatrists (12.9).

Most naloxone prescriptions entailed out-of-pocket costs. About 71% of prescriptions paid for by Medicare entailed out-of-pocket costs, compared with 43.8% of prescriptions paid for by Medicaid, and 41.5% of prescriptions paid for by commercial insurance.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

More can be done

“It is clear from the data that there is still much needed education around the important role naloxone plays in reducing overdose deaths,” said Robert R. Redfield, MD, director of the CDC, in a press release. “The time is now to ensure all individuals who are prescribed high-dose opioids also receive naloxone as a potential life-saving intervention. As we aggressively confront what is the public health crisis of our time, CDC will continue to stress with health care providers the benefit of making this overdose-reversing medicine available to patients.”

“While we’ve seen these important increases [in naloxone prescriptions], we are not as far along as we’d like to be,” said Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, during a press conference. “Cost is one of the issues, but I think awareness is another.” These data should prompt pharmacies to make sure that they stock naloxone and remind clinicians to consider naloxone when they prescribe opioids, she added. Patients and their family members should be aware of naloxone and ask their health care providers about it. “We’d really like to see the increase [in naloxone prescriptions] move much more rapidly,” she concluded.

The investigators disclosed no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Guy GP et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Aug 6.

FROM MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

IV fluid weaning unnecessary after gastroenteritis rehydration

SEATTLE – Intravenous fluids can simply be stopped after children with acute viral gastroenteritis are rehydrated in the hospital; there’s no need for a slow wean, according to a review at the Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford.

Researchers found that children leave the hospital hours sooner, with no ill effects. “This study suggests that slowly weaning IV fluids may not be necessary,” said lead investigator Danielle Klima, DO, a University of Connecticut pediatrics resident.

The team at Connecticut Children’s noticed that weaning practices after gastroenteritis rehydration varied widely on the pediatric floors, and appeared to be largely provider dependent, with “much subjective decision making.” The team wanted to see if it made a difference one way or the other, Dr. Klima said at Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

During respiratory season, “our pediatric floors are surging. Saving even a couple hours to get these kids out” quicker matters, she said, noting that it’s likely the first time the issue has been studied.

The team reviewed 153 children aged 2 months to 18 years, 95 of whom had IV fluids stopped once physicians deemed they were fluid resuscitated and ready for an oral feeding trial; the other 58 were weaned, with at least two reductions by half before final discontinuation.

There were no significant differences in age, gender, race, or insurance type between the two groups. The mean age was 2.6 years, and there were slightly more boys. The ED triage level was a mean of 3.2 points in both groups on a scale of 1-5, with 1 being the most urgent. Children with serious comorbidities, chronic diarrhea, feeding tubes, severe electrolyte abnormalities, or feeding problems were among those excluded.

Overall length of stay was 36 hours in the stop group versus 40.5 hours in the weaning group (P = .004). Children left the hospital about 6 hours after IV fluids were discontinued, versus 26 hours after weaning was started (P less than .001).

Electrolyte abnormalities on admission were more common in the weaning group (65% versus 57%), but not significantly so (P = .541). Electrolyte abnormalities were also more common at the end of fluid resuscitation in the weaning arm, but again not significantly (65% 42%, P = .077).

Fluid resuscitation needed to be restarted in 15 children in the stop group (16%), versus 11 (19%) in the wean arm (P = .459). One child in the stop group (1%) versus four (7%) who were weaned were readmitted to the hospital within a week for acute viral gastroenteritis (P = .067).

“I expected we were taking a more conservative weaning approach in younger infants,” but age didn’t seem to affect whether patients were weaned or not, Dr. Klima said.

With the results in hand, “our group is taking a closer look at exactly what we are doing,” perhaps with an eye toward standardization or even a randomized trial, she said.

She noted that weaning still makes sense for a fussy toddler who refuses to take anything by mouth.

There was no external funding, and Dr. Klima had no disclosures. The conference was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

SEATTLE – Intravenous fluids can simply be stopped after children with acute viral gastroenteritis are rehydrated in the hospital; there’s no need for a slow wean, according to a review at the Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford.

Researchers found that children leave the hospital hours sooner, with no ill effects. “This study suggests that slowly weaning IV fluids may not be necessary,” said lead investigator Danielle Klima, DO, a University of Connecticut pediatrics resident.

The team at Connecticut Children’s noticed that weaning practices after gastroenteritis rehydration varied widely on the pediatric floors, and appeared to be largely provider dependent, with “much subjective decision making.” The team wanted to see if it made a difference one way or the other, Dr. Klima said at Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

During respiratory season, “our pediatric floors are surging. Saving even a couple hours to get these kids out” quicker matters, she said, noting that it’s likely the first time the issue has been studied.

The team reviewed 153 children aged 2 months to 18 years, 95 of whom had IV fluids stopped once physicians deemed they were fluid resuscitated and ready for an oral feeding trial; the other 58 were weaned, with at least two reductions by half before final discontinuation.

There were no significant differences in age, gender, race, or insurance type between the two groups. The mean age was 2.6 years, and there were slightly more boys. The ED triage level was a mean of 3.2 points in both groups on a scale of 1-5, with 1 being the most urgent. Children with serious comorbidities, chronic diarrhea, feeding tubes, severe electrolyte abnormalities, or feeding problems were among those excluded.

Overall length of stay was 36 hours in the stop group versus 40.5 hours in the weaning group (P = .004). Children left the hospital about 6 hours after IV fluids were discontinued, versus 26 hours after weaning was started (P less than .001).

Electrolyte abnormalities on admission were more common in the weaning group (65% versus 57%), but not significantly so (P = .541). Electrolyte abnormalities were also more common at the end of fluid resuscitation in the weaning arm, but again not significantly (65% 42%, P = .077).

Fluid resuscitation needed to be restarted in 15 children in the stop group (16%), versus 11 (19%) in the wean arm (P = .459). One child in the stop group (1%) versus four (7%) who were weaned were readmitted to the hospital within a week for acute viral gastroenteritis (P = .067).

“I expected we were taking a more conservative weaning approach in younger infants,” but age didn’t seem to affect whether patients were weaned or not, Dr. Klima said.

With the results in hand, “our group is taking a closer look at exactly what we are doing,” perhaps with an eye toward standardization or even a randomized trial, she said.

She noted that weaning still makes sense for a fussy toddler who refuses to take anything by mouth.

There was no external funding, and Dr. Klima had no disclosures. The conference was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

SEATTLE – Intravenous fluids can simply be stopped after children with acute viral gastroenteritis are rehydrated in the hospital; there’s no need for a slow wean, according to a review at the Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford.

Researchers found that children leave the hospital hours sooner, with no ill effects. “This study suggests that slowly weaning IV fluids may not be necessary,” said lead investigator Danielle Klima, DO, a University of Connecticut pediatrics resident.

The team at Connecticut Children’s noticed that weaning practices after gastroenteritis rehydration varied widely on the pediatric floors, and appeared to be largely provider dependent, with “much subjective decision making.” The team wanted to see if it made a difference one way or the other, Dr. Klima said at Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

During respiratory season, “our pediatric floors are surging. Saving even a couple hours to get these kids out” quicker matters, she said, noting that it’s likely the first time the issue has been studied.

The team reviewed 153 children aged 2 months to 18 years, 95 of whom had IV fluids stopped once physicians deemed they were fluid resuscitated and ready for an oral feeding trial; the other 58 were weaned, with at least two reductions by half before final discontinuation.

There were no significant differences in age, gender, race, or insurance type between the two groups. The mean age was 2.6 years, and there were slightly more boys. The ED triage level was a mean of 3.2 points in both groups on a scale of 1-5, with 1 being the most urgent. Children with serious comorbidities, chronic diarrhea, feeding tubes, severe electrolyte abnormalities, or feeding problems were among those excluded.

Overall length of stay was 36 hours in the stop group versus 40.5 hours in the weaning group (P = .004). Children left the hospital about 6 hours after IV fluids were discontinued, versus 26 hours after weaning was started (P less than .001).

Electrolyte abnormalities on admission were more common in the weaning group (65% versus 57%), but not significantly so (P = .541). Electrolyte abnormalities were also more common at the end of fluid resuscitation in the weaning arm, but again not significantly (65% 42%, P = .077).

Fluid resuscitation needed to be restarted in 15 children in the stop group (16%), versus 11 (19%) in the wean arm (P = .459). One child in the stop group (1%) versus four (7%) who were weaned were readmitted to the hospital within a week for acute viral gastroenteritis (P = .067).

“I expected we were taking a more conservative weaning approach in younger infants,” but age didn’t seem to affect whether patients were weaned or not, Dr. Klima said.

With the results in hand, “our group is taking a closer look at exactly what we are doing,” perhaps with an eye toward standardization or even a randomized trial, she said.

She noted that weaning still makes sense for a fussy toddler who refuses to take anything by mouth.

There was no external funding, and Dr. Klima had no disclosures. The conference was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

REPORTING FROM PHM 2019

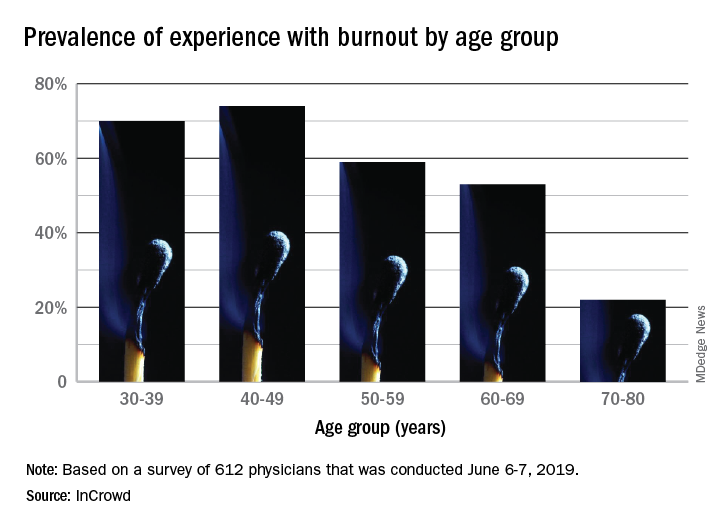

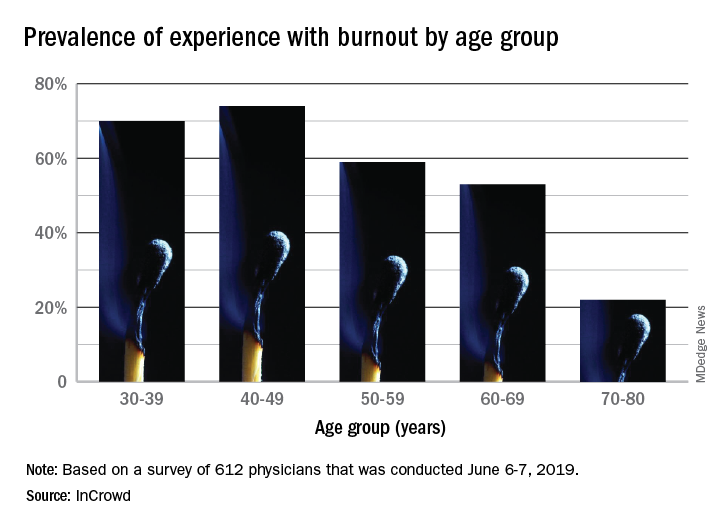

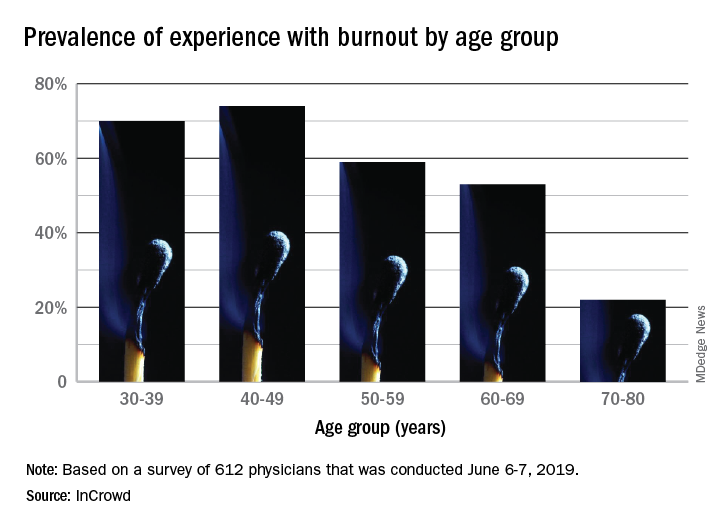

Burnout gets personal for 68% of physicians

by real-time market insights technology firm InCrowd.

The overall prevalence of personal burnout experience was 68% among respondents, and another 28% said that they had not felt burned out but knew other physicians who had, InCrowd reported Aug. 6.

Specialty appeared to play a part given that 79% of primary care physicians reported experiencing burnout versus 57% of specialists. In response to an open-ended question about ability to manage burnout, the most common answer (23%) was that specialty played a large role, with “no role/all specialties affected equally” next at 13%. Equal proportions of respondents, however, said that specialists (24%) and primary care physicians (24%) were the group most affected, InCrowd said.

There was also a disconnect regarding age. When answering another open-ended question about the effects of age, 23% of those surveyed said that older physicians are more affected, compared with 9% who put the greater burden on younger physicians. The self-reporting of burnout, however, showed that younger physicians were much more likely to experience its effects than their older counterparts: 70% of those aged 30-39 years and 74% of those 40-49 versus 22% of those aged 70-80, InCrowd reported.

InCrowd noted that its results fall within the range of other recent surveys involving burnout in physicians that have shown levels that were lower, at 44% (MedScape, 2019) or 43.9% (American Academy of Family Physicians, 2019), and those that were higher, at 77.8% (The Physicians Foundation/Merritt Hawkins, 2018).

“The alarming persistence of physician burnout over the years and across multiple studies unfortunately demonstrates that we have not yet turned the tide on this problematic issue,” Diane Hayes, PhD, president of InCrowd, said in a statement accompanying the survey results. “Since we last looked at this in 2016, there really haven’t been any notable improvements. The healthcare industry would benefit from refining and expanding current initiatives to assure adequate staffing levels needed to deliver the quality care patients deserve.”

The survey was conducted June 6-7, 2019, and involved responses from 612 physicians (51% primary care providers, 49% specialists).

by real-time market insights technology firm InCrowd.

The overall prevalence of personal burnout experience was 68% among respondents, and another 28% said that they had not felt burned out but knew other physicians who had, InCrowd reported Aug. 6.

Specialty appeared to play a part given that 79% of primary care physicians reported experiencing burnout versus 57% of specialists. In response to an open-ended question about ability to manage burnout, the most common answer (23%) was that specialty played a large role, with “no role/all specialties affected equally” next at 13%. Equal proportions of respondents, however, said that specialists (24%) and primary care physicians (24%) were the group most affected, InCrowd said.

There was also a disconnect regarding age. When answering another open-ended question about the effects of age, 23% of those surveyed said that older physicians are more affected, compared with 9% who put the greater burden on younger physicians. The self-reporting of burnout, however, showed that younger physicians were much more likely to experience its effects than their older counterparts: 70% of those aged 30-39 years and 74% of those 40-49 versus 22% of those aged 70-80, InCrowd reported.

InCrowd noted that its results fall within the range of other recent surveys involving burnout in physicians that have shown levels that were lower, at 44% (MedScape, 2019) or 43.9% (American Academy of Family Physicians, 2019), and those that were higher, at 77.8% (The Physicians Foundation/Merritt Hawkins, 2018).

“The alarming persistence of physician burnout over the years and across multiple studies unfortunately demonstrates that we have not yet turned the tide on this problematic issue,” Diane Hayes, PhD, president of InCrowd, said in a statement accompanying the survey results. “Since we last looked at this in 2016, there really haven’t been any notable improvements. The healthcare industry would benefit from refining and expanding current initiatives to assure adequate staffing levels needed to deliver the quality care patients deserve.”

The survey was conducted June 6-7, 2019, and involved responses from 612 physicians (51% primary care providers, 49% specialists).

by real-time market insights technology firm InCrowd.

The overall prevalence of personal burnout experience was 68% among respondents, and another 28% said that they had not felt burned out but knew other physicians who had, InCrowd reported Aug. 6.

Specialty appeared to play a part given that 79% of primary care physicians reported experiencing burnout versus 57% of specialists. In response to an open-ended question about ability to manage burnout, the most common answer (23%) was that specialty played a large role, with “no role/all specialties affected equally” next at 13%. Equal proportions of respondents, however, said that specialists (24%) and primary care physicians (24%) were the group most affected, InCrowd said.

There was also a disconnect regarding age. When answering another open-ended question about the effects of age, 23% of those surveyed said that older physicians are more affected, compared with 9% who put the greater burden on younger physicians. The self-reporting of burnout, however, showed that younger physicians were much more likely to experience its effects than their older counterparts: 70% of those aged 30-39 years and 74% of those 40-49 versus 22% of those aged 70-80, InCrowd reported.

InCrowd noted that its results fall within the range of other recent surveys involving burnout in physicians that have shown levels that were lower, at 44% (MedScape, 2019) or 43.9% (American Academy of Family Physicians, 2019), and those that were higher, at 77.8% (The Physicians Foundation/Merritt Hawkins, 2018).

“The alarming persistence of physician burnout over the years and across multiple studies unfortunately demonstrates that we have not yet turned the tide on this problematic issue,” Diane Hayes, PhD, president of InCrowd, said in a statement accompanying the survey results. “Since we last looked at this in 2016, there really haven’t been any notable improvements. The healthcare industry would benefit from refining and expanding current initiatives to assure adequate staffing levels needed to deliver the quality care patients deserve.”

The survey was conducted June 6-7, 2019, and involved responses from 612 physicians (51% primary care providers, 49% specialists).

Professional coaching keeps doctors in the game