User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Final ‘Vision’ report addresses MOC woes

Whatever you do, change the name.

That was key among the final recommendations the Vision Initiative Commission submitted to the American Board of Medical Specialties on how to improve the maintenance of certification process.

“A new term that communicates the concept, intent, and expectations of continuing certification programs should be adopted by the ABMS in order to reengage disaffected diplomates and assure the public and other stakeholders that the certificate has enduring meaning and value,” according to the final report. A new term was not suggested.

The commission recommended a continuing certification system with four aims:

- Become a meaningful, contemporary, and relevant professional development activity for diplomates that ensures they remain up-to-date in their specialty.

- Demonstrate a commitment to professional self-regulation to both diplomates and the public.

- Align with international and national standards for certification programs.

- Provide a specialty-based credential that would be of value to diplomates and to multiple stakeholders, including patients, families, the public, and health care institutions.

Testing methods and situations must be simplified and updated, according to the report, which was submitted to ABMS on Feb. 12. Continuing certification “must change to incorporate longitudinal and other innovative formative assessment strategies that support learning, identify knowledge and skills gaps, and help diplomates stay current. The ABMS Boards must offer an alternative to burdensome highly secure, point-in-time examinations of knowledge.” In addition, the boards “must no longer use a single point-in-time examination or a series of single point-in-time assessments as the sole method to determine certification status.”

Instead, the commission recommends that ABMS “move quickly to formative assessment formats that are not characterized by high-stakes summative outcomes (pass/fail), specified time frames for high-stakes assessment, or require burdensome testing formats (such as testing centers or remote proctoring) that are inconsistent with the desired goals for continuing certification – support learning; identify knowledge and skills gaps; and help diplomates stay current.”

The commission also defined how the certification process should be used by other stakeholders.

“ABMS must demonstrate and communicate that continuing certification has value, meaning, and purpose in the health care environment,” the report states. “Hospitals, health systems, payers, and other health care organizations can independently decide what factors are used in credentialing and privileging decisions. ABMS must inform these organizations that continuing certification should not be the only criterion used in these decisions, and these organizations should use a wide portfolio of criteria in these decisions. ABMS must encourage hospitals, health systems, payers, and other health care organizations to not deny credentialing or privileging to a physician solely on the basis of certification status.”

Additionally, the commission report states that “ABMS and the ABMS Boards should collaborate with specialty societies, the [continuing medical education/continuing professional development] community, and other expert stakeholders to develop the infrastructure to support learning activities that produce data-driven advances in clinical practice. The ABMS Boards must ensure that their continuing certification programs recognize and document participation in a wide range of quality assessment activities in which diplomates already engage.”

The report adds that the boards “should readily accept existing activities that diplomates are doing to advance their clinical practice and to provide credit for performing low-resource, high-impact activities as part of their daily practice routine.”

The commission’s final report incorporates a number of changes that physicians offered based on a draft version of the report.

The American College of Physicians commented that it “objects to the use of data regarding quality measures for individual diplomate certification status, because physician-level measures of quality are flawed, and because physician-level data inevitably leads to physician-level documentation burden. Flawed performance measures also often inadequately adjust for patient comorbidities and socioeconomic status, which leads to assessments that do not reflect the actual quality of care.”

Similarly, the American Society of Hematology noted in a statement that it “disagrees with the commission’s recommendation to retain the reporting of practice improvement activities as part of continuous certification due to direct and indirect costs needed to fulfill this requirement on top of requirements for engagement in quality improvement mandated by insurers, institutions, and health systems.”

While the draft report recommended that specialty boards provide aggregated feedback to medical societies, a more individualized dissemination on the gaps in knowledge would be more helpful, according to Doug Henley, MD, CEO of the American Academy of Family Physicians, who said that a more individualized approach would help his organization better provide CME to its members to help fill in the knowledge gaps.

“If we can identify these and use other processes and then target at the individual level to seek improvement, I think that will be a better outcome rather than just x learners don’t do well in diabetic care,” he said in an interview. “That doesn’t really help me in terms of who needs the real education in diabetic care versus who needs it for heart failure.”

The final recommendation notes that ABMS member boards “must collaborate with professional and/or CME/CPD organizations to share data and information to guide and support diplomate engagement in continuing certification.”

The document further clarifies that the boards should examine “the aggregated results from assessments to identify knowledge, skills, and other competency gaps,” and the aggregated data should be shared with specialty societies, CME/CPD providers, quality improvement professionals, and other health care organizations.

One weakness in the draft noted by Dr. Henley was the lack of a more forceful tone within the recommendations. Even though AMBS is not bound by its recommendations, he said that he would like to see stronger language throughout the document.

“We would certainly hope that the ABMS and the member boards will follow the direction of the Vision Commission very directly and succinctly,” he said. “That is why we suggested that some of the recommendations from the Vision Commission should use words like ‘should’ and ‘must’ and not just ‘encourage’ and words like that.”

That recommendation was taken and implemented in the final document.

Societies differed in how often participation in the certification process should occur.

The American College of Rheumatology in its comments challenged a recommendation that certification should be structured to expect participation on an annual basis.

“The ACR supports the importance of ongoing learning,” it stated. “However, no discussion is provided as to how and why the recommendation for annual participation by diplomates was conceived. For some ABMS Boards, an annual requirement will increase physician burden unless continuing certification is modified to a formative pathway. If this recommendation is to be retained, the commission would be encouraged to emphasize that inclusion of annual participation should be part of an overall program structure plan that supports a formative approach to assessment. In addition, the ACR requests that ABMS Boards allow exceptions without penalty to be made to this annual requirement to all for live events.”

The American College of Cardiology took a different point of view with regard to this recommendation.

In its comments, ACC stated that it “concurs with this recommendation. Annual participation is a feature of the ACC’s proposed maintenance of certification solution. The ACC believes that ABMS boards should recognize, and make allowances for, physicians who may, for valid reasons (illness, sabbatical, medical or family issue) may not participate in MOC for a period of a year.” ACC generally concurred with the recommendations in the draft.

The final document presented the commission’s view that the ABMS member boards “need to engage with diplomates on an ongoing basis instead of every 2, 5, or 10 years. The ABMS Boards should develop a diplomate engagement strategy and support the idea that diplomates are committed to learning and continually improving their practice, skills, and competencies. The ABMS Boards should expect that diplomates would engage in some learning, assessment, or advancing practice work annually.”

The American Gastroenterological Association, in its comment letter on the draft, said it was “greatly concerned” about the inclusion of practice improvement data, noting it is “debatable whether it is even within the appropriate domain of the boards to assume responsibility for clinical practice performance and quality assurance.”

The final report states that ABMS “must ensure that their continuing certification programs recognize and document participation in a wide range of quality assessment activities in which diplomates already engage,” and added that “when appropriate, taking advantage of other organizations’ quality improvement and reporting activities should be maximized to avoid additional burdens on diplomates.”

ABMS and its board are not bound to follow any of the recommendations contained within the report, but the commission states that it “expects that the ABMS and the ABMS Boards, in collaboration with professional organizations and other stakeholders, will prioritize these recommendations and develop the necessary strategies and infrastructure to implement them.”

Whatever you do, change the name.

That was key among the final recommendations the Vision Initiative Commission submitted to the American Board of Medical Specialties on how to improve the maintenance of certification process.

“A new term that communicates the concept, intent, and expectations of continuing certification programs should be adopted by the ABMS in order to reengage disaffected diplomates and assure the public and other stakeholders that the certificate has enduring meaning and value,” according to the final report. A new term was not suggested.

The commission recommended a continuing certification system with four aims:

- Become a meaningful, contemporary, and relevant professional development activity for diplomates that ensures they remain up-to-date in their specialty.

- Demonstrate a commitment to professional self-regulation to both diplomates and the public.

- Align with international and national standards for certification programs.

- Provide a specialty-based credential that would be of value to diplomates and to multiple stakeholders, including patients, families, the public, and health care institutions.

Testing methods and situations must be simplified and updated, according to the report, which was submitted to ABMS on Feb. 12. Continuing certification “must change to incorporate longitudinal and other innovative formative assessment strategies that support learning, identify knowledge and skills gaps, and help diplomates stay current. The ABMS Boards must offer an alternative to burdensome highly secure, point-in-time examinations of knowledge.” In addition, the boards “must no longer use a single point-in-time examination or a series of single point-in-time assessments as the sole method to determine certification status.”

Instead, the commission recommends that ABMS “move quickly to formative assessment formats that are not characterized by high-stakes summative outcomes (pass/fail), specified time frames for high-stakes assessment, or require burdensome testing formats (such as testing centers or remote proctoring) that are inconsistent with the desired goals for continuing certification – support learning; identify knowledge and skills gaps; and help diplomates stay current.”

The commission also defined how the certification process should be used by other stakeholders.

“ABMS must demonstrate and communicate that continuing certification has value, meaning, and purpose in the health care environment,” the report states. “Hospitals, health systems, payers, and other health care organizations can independently decide what factors are used in credentialing and privileging decisions. ABMS must inform these organizations that continuing certification should not be the only criterion used in these decisions, and these organizations should use a wide portfolio of criteria in these decisions. ABMS must encourage hospitals, health systems, payers, and other health care organizations to not deny credentialing or privileging to a physician solely on the basis of certification status.”

Additionally, the commission report states that “ABMS and the ABMS Boards should collaborate with specialty societies, the [continuing medical education/continuing professional development] community, and other expert stakeholders to develop the infrastructure to support learning activities that produce data-driven advances in clinical practice. The ABMS Boards must ensure that their continuing certification programs recognize and document participation in a wide range of quality assessment activities in which diplomates already engage.”

The report adds that the boards “should readily accept existing activities that diplomates are doing to advance their clinical practice and to provide credit for performing low-resource, high-impact activities as part of their daily practice routine.”

The commission’s final report incorporates a number of changes that physicians offered based on a draft version of the report.

The American College of Physicians commented that it “objects to the use of data regarding quality measures for individual diplomate certification status, because physician-level measures of quality are flawed, and because physician-level data inevitably leads to physician-level documentation burden. Flawed performance measures also often inadequately adjust for patient comorbidities and socioeconomic status, which leads to assessments that do not reflect the actual quality of care.”

Similarly, the American Society of Hematology noted in a statement that it “disagrees with the commission’s recommendation to retain the reporting of practice improvement activities as part of continuous certification due to direct and indirect costs needed to fulfill this requirement on top of requirements for engagement in quality improvement mandated by insurers, institutions, and health systems.”

While the draft report recommended that specialty boards provide aggregated feedback to medical societies, a more individualized dissemination on the gaps in knowledge would be more helpful, according to Doug Henley, MD, CEO of the American Academy of Family Physicians, who said that a more individualized approach would help his organization better provide CME to its members to help fill in the knowledge gaps.

“If we can identify these and use other processes and then target at the individual level to seek improvement, I think that will be a better outcome rather than just x learners don’t do well in diabetic care,” he said in an interview. “That doesn’t really help me in terms of who needs the real education in diabetic care versus who needs it for heart failure.”

The final recommendation notes that ABMS member boards “must collaborate with professional and/or CME/CPD organizations to share data and information to guide and support diplomate engagement in continuing certification.”

The document further clarifies that the boards should examine “the aggregated results from assessments to identify knowledge, skills, and other competency gaps,” and the aggregated data should be shared with specialty societies, CME/CPD providers, quality improvement professionals, and other health care organizations.

One weakness in the draft noted by Dr. Henley was the lack of a more forceful tone within the recommendations. Even though AMBS is not bound by its recommendations, he said that he would like to see stronger language throughout the document.

“We would certainly hope that the ABMS and the member boards will follow the direction of the Vision Commission very directly and succinctly,” he said. “That is why we suggested that some of the recommendations from the Vision Commission should use words like ‘should’ and ‘must’ and not just ‘encourage’ and words like that.”

That recommendation was taken and implemented in the final document.

Societies differed in how often participation in the certification process should occur.

The American College of Rheumatology in its comments challenged a recommendation that certification should be structured to expect participation on an annual basis.

“The ACR supports the importance of ongoing learning,” it stated. “However, no discussion is provided as to how and why the recommendation for annual participation by diplomates was conceived. For some ABMS Boards, an annual requirement will increase physician burden unless continuing certification is modified to a formative pathway. If this recommendation is to be retained, the commission would be encouraged to emphasize that inclusion of annual participation should be part of an overall program structure plan that supports a formative approach to assessment. In addition, the ACR requests that ABMS Boards allow exceptions without penalty to be made to this annual requirement to all for live events.”

The American College of Cardiology took a different point of view with regard to this recommendation.

In its comments, ACC stated that it “concurs with this recommendation. Annual participation is a feature of the ACC’s proposed maintenance of certification solution. The ACC believes that ABMS boards should recognize, and make allowances for, physicians who may, for valid reasons (illness, sabbatical, medical or family issue) may not participate in MOC for a period of a year.” ACC generally concurred with the recommendations in the draft.

The final document presented the commission’s view that the ABMS member boards “need to engage with diplomates on an ongoing basis instead of every 2, 5, or 10 years. The ABMS Boards should develop a diplomate engagement strategy and support the idea that diplomates are committed to learning and continually improving their practice, skills, and competencies. The ABMS Boards should expect that diplomates would engage in some learning, assessment, or advancing practice work annually.”

The American Gastroenterological Association, in its comment letter on the draft, said it was “greatly concerned” about the inclusion of practice improvement data, noting it is “debatable whether it is even within the appropriate domain of the boards to assume responsibility for clinical practice performance and quality assurance.”

The final report states that ABMS “must ensure that their continuing certification programs recognize and document participation in a wide range of quality assessment activities in which diplomates already engage,” and added that “when appropriate, taking advantage of other organizations’ quality improvement and reporting activities should be maximized to avoid additional burdens on diplomates.”

ABMS and its board are not bound to follow any of the recommendations contained within the report, but the commission states that it “expects that the ABMS and the ABMS Boards, in collaboration with professional organizations and other stakeholders, will prioritize these recommendations and develop the necessary strategies and infrastructure to implement them.”

Whatever you do, change the name.

That was key among the final recommendations the Vision Initiative Commission submitted to the American Board of Medical Specialties on how to improve the maintenance of certification process.

“A new term that communicates the concept, intent, and expectations of continuing certification programs should be adopted by the ABMS in order to reengage disaffected diplomates and assure the public and other stakeholders that the certificate has enduring meaning and value,” according to the final report. A new term was not suggested.

The commission recommended a continuing certification system with four aims:

- Become a meaningful, contemporary, and relevant professional development activity for diplomates that ensures they remain up-to-date in their specialty.

- Demonstrate a commitment to professional self-regulation to both diplomates and the public.

- Align with international and national standards for certification programs.

- Provide a specialty-based credential that would be of value to diplomates and to multiple stakeholders, including patients, families, the public, and health care institutions.

Testing methods and situations must be simplified and updated, according to the report, which was submitted to ABMS on Feb. 12. Continuing certification “must change to incorporate longitudinal and other innovative formative assessment strategies that support learning, identify knowledge and skills gaps, and help diplomates stay current. The ABMS Boards must offer an alternative to burdensome highly secure, point-in-time examinations of knowledge.” In addition, the boards “must no longer use a single point-in-time examination or a series of single point-in-time assessments as the sole method to determine certification status.”

Instead, the commission recommends that ABMS “move quickly to formative assessment formats that are not characterized by high-stakes summative outcomes (pass/fail), specified time frames for high-stakes assessment, or require burdensome testing formats (such as testing centers or remote proctoring) that are inconsistent with the desired goals for continuing certification – support learning; identify knowledge and skills gaps; and help diplomates stay current.”

The commission also defined how the certification process should be used by other stakeholders.

“ABMS must demonstrate and communicate that continuing certification has value, meaning, and purpose in the health care environment,” the report states. “Hospitals, health systems, payers, and other health care organizations can independently decide what factors are used in credentialing and privileging decisions. ABMS must inform these organizations that continuing certification should not be the only criterion used in these decisions, and these organizations should use a wide portfolio of criteria in these decisions. ABMS must encourage hospitals, health systems, payers, and other health care organizations to not deny credentialing or privileging to a physician solely on the basis of certification status.”

Additionally, the commission report states that “ABMS and the ABMS Boards should collaborate with specialty societies, the [continuing medical education/continuing professional development] community, and other expert stakeholders to develop the infrastructure to support learning activities that produce data-driven advances in clinical practice. The ABMS Boards must ensure that their continuing certification programs recognize and document participation in a wide range of quality assessment activities in which diplomates already engage.”

The report adds that the boards “should readily accept existing activities that diplomates are doing to advance their clinical practice and to provide credit for performing low-resource, high-impact activities as part of their daily practice routine.”

The commission’s final report incorporates a number of changes that physicians offered based on a draft version of the report.

The American College of Physicians commented that it “objects to the use of data regarding quality measures for individual diplomate certification status, because physician-level measures of quality are flawed, and because physician-level data inevitably leads to physician-level documentation burden. Flawed performance measures also often inadequately adjust for patient comorbidities and socioeconomic status, which leads to assessments that do not reflect the actual quality of care.”

Similarly, the American Society of Hematology noted in a statement that it “disagrees with the commission’s recommendation to retain the reporting of practice improvement activities as part of continuous certification due to direct and indirect costs needed to fulfill this requirement on top of requirements for engagement in quality improvement mandated by insurers, institutions, and health systems.”

While the draft report recommended that specialty boards provide aggregated feedback to medical societies, a more individualized dissemination on the gaps in knowledge would be more helpful, according to Doug Henley, MD, CEO of the American Academy of Family Physicians, who said that a more individualized approach would help his organization better provide CME to its members to help fill in the knowledge gaps.

“If we can identify these and use other processes and then target at the individual level to seek improvement, I think that will be a better outcome rather than just x learners don’t do well in diabetic care,” he said in an interview. “That doesn’t really help me in terms of who needs the real education in diabetic care versus who needs it for heart failure.”

The final recommendation notes that ABMS member boards “must collaborate with professional and/or CME/CPD organizations to share data and information to guide and support diplomate engagement in continuing certification.”

The document further clarifies that the boards should examine “the aggregated results from assessments to identify knowledge, skills, and other competency gaps,” and the aggregated data should be shared with specialty societies, CME/CPD providers, quality improvement professionals, and other health care organizations.

One weakness in the draft noted by Dr. Henley was the lack of a more forceful tone within the recommendations. Even though AMBS is not bound by its recommendations, he said that he would like to see stronger language throughout the document.

“We would certainly hope that the ABMS and the member boards will follow the direction of the Vision Commission very directly and succinctly,” he said. “That is why we suggested that some of the recommendations from the Vision Commission should use words like ‘should’ and ‘must’ and not just ‘encourage’ and words like that.”

That recommendation was taken and implemented in the final document.

Societies differed in how often participation in the certification process should occur.

The American College of Rheumatology in its comments challenged a recommendation that certification should be structured to expect participation on an annual basis.

“The ACR supports the importance of ongoing learning,” it stated. “However, no discussion is provided as to how and why the recommendation for annual participation by diplomates was conceived. For some ABMS Boards, an annual requirement will increase physician burden unless continuing certification is modified to a formative pathway. If this recommendation is to be retained, the commission would be encouraged to emphasize that inclusion of annual participation should be part of an overall program structure plan that supports a formative approach to assessment. In addition, the ACR requests that ABMS Boards allow exceptions without penalty to be made to this annual requirement to all for live events.”

The American College of Cardiology took a different point of view with regard to this recommendation.

In its comments, ACC stated that it “concurs with this recommendation. Annual participation is a feature of the ACC’s proposed maintenance of certification solution. The ACC believes that ABMS boards should recognize, and make allowances for, physicians who may, for valid reasons (illness, sabbatical, medical or family issue) may not participate in MOC for a period of a year.” ACC generally concurred with the recommendations in the draft.

The final document presented the commission’s view that the ABMS member boards “need to engage with diplomates on an ongoing basis instead of every 2, 5, or 10 years. The ABMS Boards should develop a diplomate engagement strategy and support the idea that diplomates are committed to learning and continually improving their practice, skills, and competencies. The ABMS Boards should expect that diplomates would engage in some learning, assessment, or advancing practice work annually.”

The American Gastroenterological Association, in its comment letter on the draft, said it was “greatly concerned” about the inclusion of practice improvement data, noting it is “debatable whether it is even within the appropriate domain of the boards to assume responsibility for clinical practice performance and quality assurance.”

The final report states that ABMS “must ensure that their continuing certification programs recognize and document participation in a wide range of quality assessment activities in which diplomates already engage,” and added that “when appropriate, taking advantage of other organizations’ quality improvement and reporting activities should be maximized to avoid additional burdens on diplomates.”

ABMS and its board are not bound to follow any of the recommendations contained within the report, but the commission states that it “expects that the ABMS and the ABMS Boards, in collaboration with professional organizations and other stakeholders, will prioritize these recommendations and develop the necessary strategies and infrastructure to implement them.”

Palliative care has improved for critically ill children, but challenges remain

SAN DIEGO – and is more common among older children, female children, and those with government insurance or at a high risk of mortality. The findings come from a retrospective analysis of data from 52 hospitals, which included ICU admissions (except neonatal ICU) during 2007-2018.

The good news is that palliative care consultations have increased, with consultations in less than 1% of cases at the start of the study and rising quickly to more than 7% in 2018.

“In the adult world, palliative care has expanded in recent decades, and I think now that it’s coming to the pediatric world, it’ll just continue to go up,” said Siobhan O’Keefe, MD, in an interview. Dr. O’Keefe is with Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora. She presented the study at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

More work needs to be done, she said. “We are not uniformly using palliative care for critically ill children in the U.S., and it varies across institutions. That’s probably not the ideal situation,” said Dr. O’Keefe. The study did not track palliative care versus the presence of board-certified palliative care physicians or palliative care fellowships, but she suspects they would correlate.

Dr. O’Keefe called for physicians to think beyond the patient, to family members and caregivers. “We need to focus on family outcomes, how they are taking care of children with moderate disability, and incorporate that into our outcomes,” she said. Previous research has shown family members to be at risk of anxiety, depression, unemployment, and financial distress.

The researchers analyzed data from 740,890 patients with 1,024,666 hospitalizations (82% had one hospitalization). They divided subjects into three cohorts, one of which was a category of patients with criteria for palliative care based on previous research (PC-ICU). The PC-ICU cohort included patients with an expected length of stay more than 2 weeks, patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), severe brain injuries, acute respiratory failure with serious comorbidity, hematologic or oncologic disease, metabolic disease, renal failure that required continuous renal replacement therapy, hepatic failure, or serious chromosomal abnormality. A second cohort included chronic complex conditions not found in the PC-ICU cohort (additional criteria), and a third cohort had no criteria for palliative care.

Thirty percent of hospitalizations met the PC-ICU cohort criteria, 40% met the additional cohort criteria, and 30% fell in the no criteria cohort. The PC-ICU group had the highest mortality, at 8.03%, compared with 1.08% in the additional criteria group and 0.34% in the no criteria group (P less than .00001).

Palliative care consultations occurred more frequently in 5-12 year olds (odds ratio 1.06; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.13) and in those aged 13 years or older (OR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.3-1.46), in females (OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.06-1.15), and in patients with government insurance (OR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.17-1.29). Compared with those in the no criteria cohort, PC-ICU patients were more likely to receive a palliative care consult (OR, 75.5; 95% CI, 60.4-94.3), as were those in the additional criteria group (OR, 19.1; 95% CI, 15.3-23.9).

Cross-institutional palliative care frequency varied widely among patients in the PC-ICU group, ranging from 0% to 44%. The frequency ranged from 0% to 12% across institutions for patients in the additional criteria group.

SOURCE: O’Keefe S et al. Critical Care Congress 2019, Abstract 418.

SAN DIEGO – and is more common among older children, female children, and those with government insurance or at a high risk of mortality. The findings come from a retrospective analysis of data from 52 hospitals, which included ICU admissions (except neonatal ICU) during 2007-2018.

The good news is that palliative care consultations have increased, with consultations in less than 1% of cases at the start of the study and rising quickly to more than 7% in 2018.

“In the adult world, palliative care has expanded in recent decades, and I think now that it’s coming to the pediatric world, it’ll just continue to go up,” said Siobhan O’Keefe, MD, in an interview. Dr. O’Keefe is with Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora. She presented the study at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

More work needs to be done, she said. “We are not uniformly using palliative care for critically ill children in the U.S., and it varies across institutions. That’s probably not the ideal situation,” said Dr. O’Keefe. The study did not track palliative care versus the presence of board-certified palliative care physicians or palliative care fellowships, but she suspects they would correlate.

Dr. O’Keefe called for physicians to think beyond the patient, to family members and caregivers. “We need to focus on family outcomes, how they are taking care of children with moderate disability, and incorporate that into our outcomes,” she said. Previous research has shown family members to be at risk of anxiety, depression, unemployment, and financial distress.

The researchers analyzed data from 740,890 patients with 1,024,666 hospitalizations (82% had one hospitalization). They divided subjects into three cohorts, one of which was a category of patients with criteria for palliative care based on previous research (PC-ICU). The PC-ICU cohort included patients with an expected length of stay more than 2 weeks, patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), severe brain injuries, acute respiratory failure with serious comorbidity, hematologic or oncologic disease, metabolic disease, renal failure that required continuous renal replacement therapy, hepatic failure, or serious chromosomal abnormality. A second cohort included chronic complex conditions not found in the PC-ICU cohort (additional criteria), and a third cohort had no criteria for palliative care.

Thirty percent of hospitalizations met the PC-ICU cohort criteria, 40% met the additional cohort criteria, and 30% fell in the no criteria cohort. The PC-ICU group had the highest mortality, at 8.03%, compared with 1.08% in the additional criteria group and 0.34% in the no criteria group (P less than .00001).

Palliative care consultations occurred more frequently in 5-12 year olds (odds ratio 1.06; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.13) and in those aged 13 years or older (OR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.3-1.46), in females (OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.06-1.15), and in patients with government insurance (OR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.17-1.29). Compared with those in the no criteria cohort, PC-ICU patients were more likely to receive a palliative care consult (OR, 75.5; 95% CI, 60.4-94.3), as were those in the additional criteria group (OR, 19.1; 95% CI, 15.3-23.9).

Cross-institutional palliative care frequency varied widely among patients in the PC-ICU group, ranging from 0% to 44%. The frequency ranged from 0% to 12% across institutions for patients in the additional criteria group.

SOURCE: O’Keefe S et al. Critical Care Congress 2019, Abstract 418.

SAN DIEGO – and is more common among older children, female children, and those with government insurance or at a high risk of mortality. The findings come from a retrospective analysis of data from 52 hospitals, which included ICU admissions (except neonatal ICU) during 2007-2018.

The good news is that palliative care consultations have increased, with consultations in less than 1% of cases at the start of the study and rising quickly to more than 7% in 2018.

“In the adult world, palliative care has expanded in recent decades, and I think now that it’s coming to the pediatric world, it’ll just continue to go up,” said Siobhan O’Keefe, MD, in an interview. Dr. O’Keefe is with Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora. She presented the study at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

More work needs to be done, she said. “We are not uniformly using palliative care for critically ill children in the U.S., and it varies across institutions. That’s probably not the ideal situation,” said Dr. O’Keefe. The study did not track palliative care versus the presence of board-certified palliative care physicians or palliative care fellowships, but she suspects they would correlate.

Dr. O’Keefe called for physicians to think beyond the patient, to family members and caregivers. “We need to focus on family outcomes, how they are taking care of children with moderate disability, and incorporate that into our outcomes,” she said. Previous research has shown family members to be at risk of anxiety, depression, unemployment, and financial distress.

The researchers analyzed data from 740,890 patients with 1,024,666 hospitalizations (82% had one hospitalization). They divided subjects into three cohorts, one of which was a category of patients with criteria for palliative care based on previous research (PC-ICU). The PC-ICU cohort included patients with an expected length of stay more than 2 weeks, patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), severe brain injuries, acute respiratory failure with serious comorbidity, hematologic or oncologic disease, metabolic disease, renal failure that required continuous renal replacement therapy, hepatic failure, or serious chromosomal abnormality. A second cohort included chronic complex conditions not found in the PC-ICU cohort (additional criteria), and a third cohort had no criteria for palliative care.

Thirty percent of hospitalizations met the PC-ICU cohort criteria, 40% met the additional cohort criteria, and 30% fell in the no criteria cohort. The PC-ICU group had the highest mortality, at 8.03%, compared with 1.08% in the additional criteria group and 0.34% in the no criteria group (P less than .00001).

Palliative care consultations occurred more frequently in 5-12 year olds (odds ratio 1.06; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.13) and in those aged 13 years or older (OR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.3-1.46), in females (OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.06-1.15), and in patients with government insurance (OR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.17-1.29). Compared with those in the no criteria cohort, PC-ICU patients were more likely to receive a palliative care consult (OR, 75.5; 95% CI, 60.4-94.3), as were those in the additional criteria group (OR, 19.1; 95% CI, 15.3-23.9).

Cross-institutional palliative care frequency varied widely among patients in the PC-ICU group, ranging from 0% to 44%. The frequency ranged from 0% to 12% across institutions for patients in the additional criteria group.

SOURCE: O’Keefe S et al. Critical Care Congress 2019, Abstract 418.

REPORTING FROM CCC48

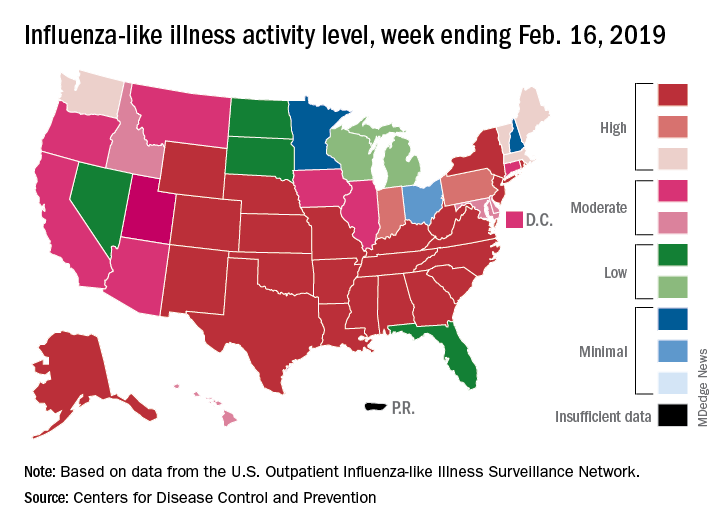

Influenza activity continues to increase

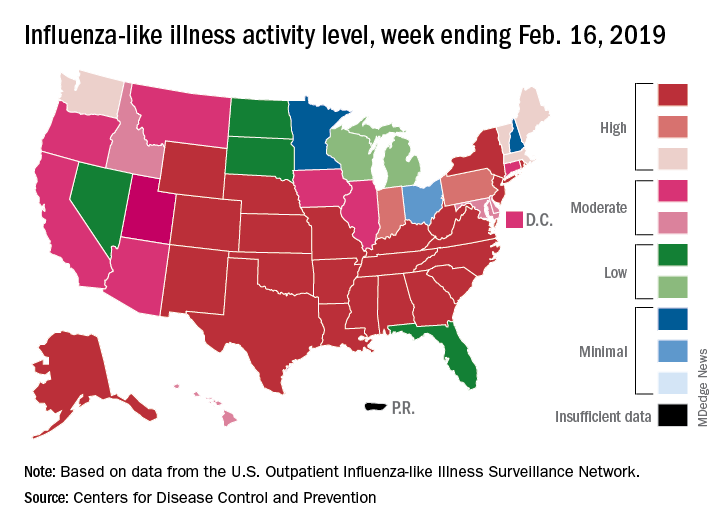

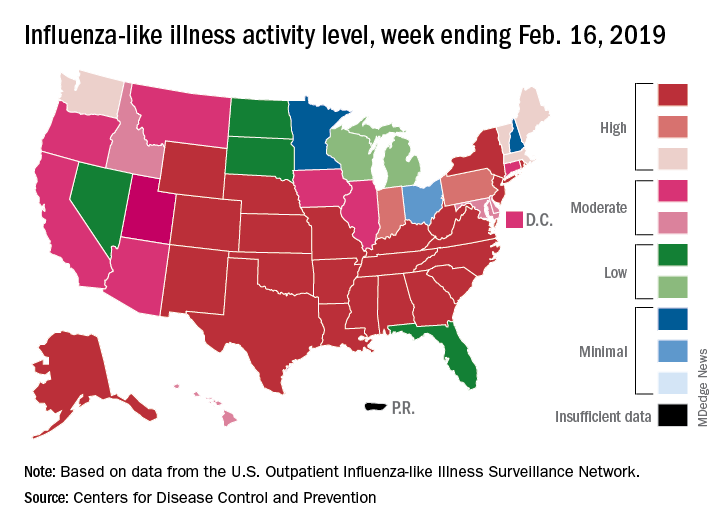

The 2018-2019 flu season is showing no signs of decline as activity measures continued to increase into mid-February, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Eight of the last 10 flu seasons had already reached their peak before mid-February, but another rise brought the proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) to 5.1% for the week ending Feb. 16, compared with 4.8% the week before, the CDC’s influenza division reported Feb. 22. ILI is defined as fever (temperature of 100°F [37.8°C] or greater) and cough and/or sore throat.

The week also brought more ILI to more states, as the number reporting an activity level of 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale rose from 21 to 24 and the number in the high range of 8-10 increased from 26 to 30. Another seven states – including California, which was at level 5 the previous week – and the District of Columbia were at level 7 for the current reporting week, the CDC said.

Two flu-related pediatric deaths occurred during the week ending Feb. 16 and another five were reported from previous weeks, which brings the total to 41 for the 2018-2019 season. Data for influenza deaths at all ages, which are reported a week later, show that 205 occurred in the week ending Feb. 9, with reporting 75% complete. There were 236 total deaths for the week ending Feb. 2 (94% reporting) and 218 deaths during the week ending Jan. 26 (99% reporting), the CDC said.

The 2018-2019 flu season is showing no signs of decline as activity measures continued to increase into mid-February, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Eight of the last 10 flu seasons had already reached their peak before mid-February, but another rise brought the proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) to 5.1% for the week ending Feb. 16, compared with 4.8% the week before, the CDC’s influenza division reported Feb. 22. ILI is defined as fever (temperature of 100°F [37.8°C] or greater) and cough and/or sore throat.

The week also brought more ILI to more states, as the number reporting an activity level of 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale rose from 21 to 24 and the number in the high range of 8-10 increased from 26 to 30. Another seven states – including California, which was at level 5 the previous week – and the District of Columbia were at level 7 for the current reporting week, the CDC said.

Two flu-related pediatric deaths occurred during the week ending Feb. 16 and another five were reported from previous weeks, which brings the total to 41 for the 2018-2019 season. Data for influenza deaths at all ages, which are reported a week later, show that 205 occurred in the week ending Feb. 9, with reporting 75% complete. There were 236 total deaths for the week ending Feb. 2 (94% reporting) and 218 deaths during the week ending Jan. 26 (99% reporting), the CDC said.

The 2018-2019 flu season is showing no signs of decline as activity measures continued to increase into mid-February, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Eight of the last 10 flu seasons had already reached their peak before mid-February, but another rise brought the proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) to 5.1% for the week ending Feb. 16, compared with 4.8% the week before, the CDC’s influenza division reported Feb. 22. ILI is defined as fever (temperature of 100°F [37.8°C] or greater) and cough and/or sore throat.

The week also brought more ILI to more states, as the number reporting an activity level of 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale rose from 21 to 24 and the number in the high range of 8-10 increased from 26 to 30. Another seven states – including California, which was at level 5 the previous week – and the District of Columbia were at level 7 for the current reporting week, the CDC said.

Two flu-related pediatric deaths occurred during the week ending Feb. 16 and another five were reported from previous weeks, which brings the total to 41 for the 2018-2019 season. Data for influenza deaths at all ages, which are reported a week later, show that 205 occurred in the week ending Feb. 9, with reporting 75% complete. There were 236 total deaths for the week ending Feb. 2 (94% reporting) and 218 deaths during the week ending Jan. 26 (99% reporting), the CDC said.

Medicare’s two-midnight rule

What hospitalists must know

Most hospitalists’ training likely included caring for patients in the ambulatory clinic, urgent care, and ED settings. One of the most important aspects of medical training is deciding which of the patients seen in these settings need to “be admitted” to a hospital because of risk, severity of illness, and/or need for certain medical services. In this context, “admit” is a synonym for “hospitalize.”

However, in today’s health care system, in which hospitalization costs are usually borne by a third-party payer, “admit” can have a very different meaning. For most payers, “admit” means “hospitalize as inpatient.” This is distinct from “hospitalize as an outpatient.” (“Observation” or “obs” is the most common example of a hospitalization as an outpatient.) In the medical payer world, inpatient and outpatient are often referred to as “statuses.” The distinction between inpatient versus outpatient status can affect payment and is based on rules that a hospital and payer have agreed upon. (Inpatient hospital care is generally paid at a higher rate than outpatient hospital care.) It is important for hospitalists to have a basic understanding of these rules because it can affect hospital billing, the hospitalist’s professional fees, beneficiary liability, and payer denials of inpatient care.

For years, Medicare’s definition of an inpatient hospitalization was primarily based on an expectation of a hospitalization of at least 24 hours and a physician’s judgment of the beneficiary’s need for inpatient hospital services. This judgment was to be based on the physician’s assessment of the patient’s severity of illness, the risk of an adverse outcome, and the hospital services required. (The exact definition by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is much longer and can be found in the Medicare Benefits Policy Manual.1) Under Medicare, defining a hospitalization as inpatient versus outpatient is especially important because they are billed to different Medicare programs (Part A for inpatient, Part B for outpatient), and both hospital reimbursement and the patient liability can vary significantly.

Not surprisingly, CMS found that how physicians were making status decisions for medically similar hospitalized patients varied greatly. CMS noted two major concerns: an overuse of inpatient for patients hospitalized overnight leading to increased charges to CMS and multiday observation hospitalizations for lower-acuity patients leading to excessive liability for Medicare beneficiaries. (Observation stays are billed under Part B, under which the beneficiary generally has a 20% copay.)

To address these concerns, in October 2013, CMS adjusted the definition of inpatient to include “the two-midnight rule.” Basically, CMS said that, in order to qualify for inpatient, the admitting physician should expect the beneficiary to require hospital care spanning at least two midnights, rather than the previous 24-hour benchmark, regardless of the severity of illness or risk of adverse outcome. (There are exceptions and exemptions to the two-midnight rule, which are discussed later in this article.)

The idea of the two-midnight rule was to address the two concerns noted above. Under this rule, most expected overnight hospitalizations should be outpatients, even if they are more than 24 hours in length, and any medically necessary outpatient hospitalization should be “converted” to inpatient if and when it is clear that a second midnight of hospitalization is medically necessary.

In January 2016, CMS amended the two-midnight rule to recognize, as it had done prior to October 2013, that some hospitalizations, based on physician judgment, would be appropriate for inpatient without an expectation of a hospitalization that spans at least two midnights. Unfortunately, CMS has not been forthcoming with guidance of examples of which hospitalizations would fall into this new category, other than to say they expect the use of this new provision would generally not be appropriate for a hospital stay of less than 24 hours.

As of today, physicians should order inpatient services under the following three situations:

- The physician expects the beneficiary to require hospital care spanning at least two midnights.

- The physician provides a service on Medicare’s inpatient-only list.

- The physician expects the beneficiary to require hospital care for less than two midnights but feels that inpatient services are nevertheless appropriate.

This most recently updated version of the two-midnight rule can be found in Section 42 CFR §412.3 of the Code of Federal Regulations.2 Each of these three situations warrants additional discussion.

Care expected to span two midnights

The first situation is the one most applicable to hospitalists. In this circumstance there are three key points to remember.

The first point is that the two-midnight rule is based on a reasonable expectation of a need for hospitalization for at least two nights, not the actual length of hospitalization. Auditors, based on long-standing guidance from the CMS, should consider only the information known (or that should have been known) to the provider at the time the inpatient decision is made.

For example, if the expectation of the need for hospitalization of at least 2 midnights is well documented in the admission note, but the beneficiary improves more rapidly than expected and can be discharged before the second midnight, billing Medicare under Part A for inpatient admission remains appropriate. Auditors may look for provider documentation describing the unexpected improvement, and while such documentation is not an absolute requirement, its presence can be helpful in defending inpatient billing.

Other situations in which there can be an expectation of hospitalization of at least two midnights, but the actual length of stay does not meet this benchmark, are death, patients leaving against medical advice, or transfer to another hospital. For example, if a patient is hospitalized as an inpatient for bacterial endocarditis, and the documented plan of care includes at least 2 days of IV antibiotics and monitoring of cultures, inpatient remains appropriate even if the patient signs out against medical advice the following day.

The second key point to understand is that a night must be “medically necessary” to count toward the two-midnight benchmark. Hospital time spent receiving custodial care, because of excessive delays, or incurred because of the convenience of the beneficiary or provider does not count toward the two-midnight benchmark. For example, imagine a patient hospitalized with chest pain on Saturday evening and the attending physician determines that the patient requires serial cardiac isoenzymes and ECGs followed, most likely, by a noninvasive stress test. The attending physician, knowing that the hospital does not offer stress testing on Sunday, expects the patient to remain hospitalized at least until Monday, thus two midnights. However, in this situation, the second midnight (Sunday night) was not medically necessary and does not count toward the two midnight expectation.

The third key point to know is that the clock for calculating the two-midnight rule begins when the beneficiary starts receiving hospital care, not when the inpatient order is placed. Further, care that starts in the ED or at another hospital counts, too. In contrast, care at an outpatient clinic, an urgent care facility, or waiting-room time in an ED does not count.

When CMS implemented the two-midnight rule in 2013, they said that they would be open to exceptions. The first and only exception to date to the two-midnight rule is newly initiated and unanticipated mechanical ventilation. (This excludes anticipated intubations related to other care, such as procedures.) For example, inpatient is appropriate for a patient who requires hospitalization for an anaphylactic reaction or a drug overdose and needs intubation and mechanical ventilation, even if discharge is expected before a second midnight of hospital care.

CMS’s inpatient-only list

Each year, CMS publishes a list of procedures that CMS will pay only under Part A (that is, as inpatient). This list is updated quarterly (Addendum E) and can be found on the CMS website.3 Hospitalizations associated with the procedures on this list should always be inpatient, regardless of the expected length of stay.

It is important to note that the inpatient-only list is dynamic; it is revised annually, and procedures can come on or off the list. Notably, in January 2018, elective total knee replacements and laparoscopic radical prostatectomies came off the inpatient-only list. Most surgeons and proceduralists know whether the procedure they are performing is on this list, and they should advise hospitalists accordingly if the hospitalist is to be the attending of record and will be writing the admission order.

Inpatient services are nevertheless appropriate

The third situation, in which an inpatient admission is appropriate even when the admitting provider does not expect a two-midnight stay, was added to the two-midnight rule in January 2016. CMS states that the factors used in making this determination can be based on physician judgment and documented in the medical record.

At first reading, one might think that CMS is, in effect, returning to the definition of an inpatient prior to the two-midnight rule’s implementation in 2013. However, CMS has not offered clear guidance for its use, and they did not remove any of the previous two-midnight rule guidance. In the absence of clear guidance, hospitalists may be best served by not using this latest change to the two-midnight rule in determining which Medicare beneficiary hospitalizations are appropriate for inpatient designation.

A final, and critical, point about the two-midnight rule is that it only applies to traditional Medicare, and it does not apply to other payers, including commercial insurance and Medicaid. Medicare Advantage plans may or may not follow the two-midnight rule, depending on their contract with the hospital. Which patients are appropriate for inpatient designations are usually determined by the individual contract that the hospital has signed with that payer.

A better understanding of the two-midnight rule including to whom it applies, when it applies, and how to apply it will help you accurately determine which hospitalizations are appropriate for inpatient payment. With this understanding you will quickly become the hero of your hospital’s case managers and billing department.

Dr. Locke is senior physician advisor at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore and president-elect of the American College of Physician Advisors. Dr. Hu is executive director of physician advisor services at the University of North Carolina Health Care System, Chapel Hill, and president of the American College of Physician Advisors.

References

1. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual. Chapter 1 - Inpatient Hospital Services Covered Under Part A. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/bp102c01.pdf.

2. Code of Federal Regulations. https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=958ee67a826285698204a34e1e5d6406&node=42:2.0.1.2.12.1.47.3&rgn=div8.

3. Current Procedural Terminology, Fourth Edition. https://www.cms.gov/apps/ama/license.asp?file=/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/HospitalOutpatientPPS/Downloads/CMS-1695-FC-2019-OPPS-FR-Addenda.zip.

What hospitalists must know

What hospitalists must know

Most hospitalists’ training likely included caring for patients in the ambulatory clinic, urgent care, and ED settings. One of the most important aspects of medical training is deciding which of the patients seen in these settings need to “be admitted” to a hospital because of risk, severity of illness, and/or need for certain medical services. In this context, “admit” is a synonym for “hospitalize.”

However, in today’s health care system, in which hospitalization costs are usually borne by a third-party payer, “admit” can have a very different meaning. For most payers, “admit” means “hospitalize as inpatient.” This is distinct from “hospitalize as an outpatient.” (“Observation” or “obs” is the most common example of a hospitalization as an outpatient.) In the medical payer world, inpatient and outpatient are often referred to as “statuses.” The distinction between inpatient versus outpatient status can affect payment and is based on rules that a hospital and payer have agreed upon. (Inpatient hospital care is generally paid at a higher rate than outpatient hospital care.) It is important for hospitalists to have a basic understanding of these rules because it can affect hospital billing, the hospitalist’s professional fees, beneficiary liability, and payer denials of inpatient care.

For years, Medicare’s definition of an inpatient hospitalization was primarily based on an expectation of a hospitalization of at least 24 hours and a physician’s judgment of the beneficiary’s need for inpatient hospital services. This judgment was to be based on the physician’s assessment of the patient’s severity of illness, the risk of an adverse outcome, and the hospital services required. (The exact definition by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is much longer and can be found in the Medicare Benefits Policy Manual.1) Under Medicare, defining a hospitalization as inpatient versus outpatient is especially important because they are billed to different Medicare programs (Part A for inpatient, Part B for outpatient), and both hospital reimbursement and the patient liability can vary significantly.

Not surprisingly, CMS found that how physicians were making status decisions for medically similar hospitalized patients varied greatly. CMS noted two major concerns: an overuse of inpatient for patients hospitalized overnight leading to increased charges to CMS and multiday observation hospitalizations for lower-acuity patients leading to excessive liability for Medicare beneficiaries. (Observation stays are billed under Part B, under which the beneficiary generally has a 20% copay.)

To address these concerns, in October 2013, CMS adjusted the definition of inpatient to include “the two-midnight rule.” Basically, CMS said that, in order to qualify for inpatient, the admitting physician should expect the beneficiary to require hospital care spanning at least two midnights, rather than the previous 24-hour benchmark, regardless of the severity of illness or risk of adverse outcome. (There are exceptions and exemptions to the two-midnight rule, which are discussed later in this article.)

The idea of the two-midnight rule was to address the two concerns noted above. Under this rule, most expected overnight hospitalizations should be outpatients, even if they are more than 24 hours in length, and any medically necessary outpatient hospitalization should be “converted” to inpatient if and when it is clear that a second midnight of hospitalization is medically necessary.

In January 2016, CMS amended the two-midnight rule to recognize, as it had done prior to October 2013, that some hospitalizations, based on physician judgment, would be appropriate for inpatient without an expectation of a hospitalization that spans at least two midnights. Unfortunately, CMS has not been forthcoming with guidance of examples of which hospitalizations would fall into this new category, other than to say they expect the use of this new provision would generally not be appropriate for a hospital stay of less than 24 hours.

As of today, physicians should order inpatient services under the following three situations:

- The physician expects the beneficiary to require hospital care spanning at least two midnights.

- The physician provides a service on Medicare’s inpatient-only list.

- The physician expects the beneficiary to require hospital care for less than two midnights but feels that inpatient services are nevertheless appropriate.

This most recently updated version of the two-midnight rule can be found in Section 42 CFR §412.3 of the Code of Federal Regulations.2 Each of these three situations warrants additional discussion.

Care expected to span two midnights

The first situation is the one most applicable to hospitalists. In this circumstance there are three key points to remember.

The first point is that the two-midnight rule is based on a reasonable expectation of a need for hospitalization for at least two nights, not the actual length of hospitalization. Auditors, based on long-standing guidance from the CMS, should consider only the information known (or that should have been known) to the provider at the time the inpatient decision is made.

For example, if the expectation of the need for hospitalization of at least 2 midnights is well documented in the admission note, but the beneficiary improves more rapidly than expected and can be discharged before the second midnight, billing Medicare under Part A for inpatient admission remains appropriate. Auditors may look for provider documentation describing the unexpected improvement, and while such documentation is not an absolute requirement, its presence can be helpful in defending inpatient billing.

Other situations in which there can be an expectation of hospitalization of at least two midnights, but the actual length of stay does not meet this benchmark, are death, patients leaving against medical advice, or transfer to another hospital. For example, if a patient is hospitalized as an inpatient for bacterial endocarditis, and the documented plan of care includes at least 2 days of IV antibiotics and monitoring of cultures, inpatient remains appropriate even if the patient signs out against medical advice the following day.

The second key point to understand is that a night must be “medically necessary” to count toward the two-midnight benchmark. Hospital time spent receiving custodial care, because of excessive delays, or incurred because of the convenience of the beneficiary or provider does not count toward the two-midnight benchmark. For example, imagine a patient hospitalized with chest pain on Saturday evening and the attending physician determines that the patient requires serial cardiac isoenzymes and ECGs followed, most likely, by a noninvasive stress test. The attending physician, knowing that the hospital does not offer stress testing on Sunday, expects the patient to remain hospitalized at least until Monday, thus two midnights. However, in this situation, the second midnight (Sunday night) was not medically necessary and does not count toward the two midnight expectation.

The third key point to know is that the clock for calculating the two-midnight rule begins when the beneficiary starts receiving hospital care, not when the inpatient order is placed. Further, care that starts in the ED or at another hospital counts, too. In contrast, care at an outpatient clinic, an urgent care facility, or waiting-room time in an ED does not count.

When CMS implemented the two-midnight rule in 2013, they said that they would be open to exceptions. The first and only exception to date to the two-midnight rule is newly initiated and unanticipated mechanical ventilation. (This excludes anticipated intubations related to other care, such as procedures.) For example, inpatient is appropriate for a patient who requires hospitalization for an anaphylactic reaction or a drug overdose and needs intubation and mechanical ventilation, even if discharge is expected before a second midnight of hospital care.

CMS’s inpatient-only list

Each year, CMS publishes a list of procedures that CMS will pay only under Part A (that is, as inpatient). This list is updated quarterly (Addendum E) and can be found on the CMS website.3 Hospitalizations associated with the procedures on this list should always be inpatient, regardless of the expected length of stay.

It is important to note that the inpatient-only list is dynamic; it is revised annually, and procedures can come on or off the list. Notably, in January 2018, elective total knee replacements and laparoscopic radical prostatectomies came off the inpatient-only list. Most surgeons and proceduralists know whether the procedure they are performing is on this list, and they should advise hospitalists accordingly if the hospitalist is to be the attending of record and will be writing the admission order.

Inpatient services are nevertheless appropriate

The third situation, in which an inpatient admission is appropriate even when the admitting provider does not expect a two-midnight stay, was added to the two-midnight rule in January 2016. CMS states that the factors used in making this determination can be based on physician judgment and documented in the medical record.

At first reading, one might think that CMS is, in effect, returning to the definition of an inpatient prior to the two-midnight rule’s implementation in 2013. However, CMS has not offered clear guidance for its use, and they did not remove any of the previous two-midnight rule guidance. In the absence of clear guidance, hospitalists may be best served by not using this latest change to the two-midnight rule in determining which Medicare beneficiary hospitalizations are appropriate for inpatient designation.

A final, and critical, point about the two-midnight rule is that it only applies to traditional Medicare, and it does not apply to other payers, including commercial insurance and Medicaid. Medicare Advantage plans may or may not follow the two-midnight rule, depending on their contract with the hospital. Which patients are appropriate for inpatient designations are usually determined by the individual contract that the hospital has signed with that payer.

A better understanding of the two-midnight rule including to whom it applies, when it applies, and how to apply it will help you accurately determine which hospitalizations are appropriate for inpatient payment. With this understanding you will quickly become the hero of your hospital’s case managers and billing department.

Dr. Locke is senior physician advisor at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore and president-elect of the American College of Physician Advisors. Dr. Hu is executive director of physician advisor services at the University of North Carolina Health Care System, Chapel Hill, and president of the American College of Physician Advisors.

References

1. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual. Chapter 1 - Inpatient Hospital Services Covered Under Part A. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/bp102c01.pdf.

2. Code of Federal Regulations. https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=958ee67a826285698204a34e1e5d6406&node=42:2.0.1.2.12.1.47.3&rgn=div8.

3. Current Procedural Terminology, Fourth Edition. https://www.cms.gov/apps/ama/license.asp?file=/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/HospitalOutpatientPPS/Downloads/CMS-1695-FC-2019-OPPS-FR-Addenda.zip.

Most hospitalists’ training likely included caring for patients in the ambulatory clinic, urgent care, and ED settings. One of the most important aspects of medical training is deciding which of the patients seen in these settings need to “be admitted” to a hospital because of risk, severity of illness, and/or need for certain medical services. In this context, “admit” is a synonym for “hospitalize.”

However, in today’s health care system, in which hospitalization costs are usually borne by a third-party payer, “admit” can have a very different meaning. For most payers, “admit” means “hospitalize as inpatient.” This is distinct from “hospitalize as an outpatient.” (“Observation” or “obs” is the most common example of a hospitalization as an outpatient.) In the medical payer world, inpatient and outpatient are often referred to as “statuses.” The distinction between inpatient versus outpatient status can affect payment and is based on rules that a hospital and payer have agreed upon. (Inpatient hospital care is generally paid at a higher rate than outpatient hospital care.) It is important for hospitalists to have a basic understanding of these rules because it can affect hospital billing, the hospitalist’s professional fees, beneficiary liability, and payer denials of inpatient care.

For years, Medicare’s definition of an inpatient hospitalization was primarily based on an expectation of a hospitalization of at least 24 hours and a physician’s judgment of the beneficiary’s need for inpatient hospital services. This judgment was to be based on the physician’s assessment of the patient’s severity of illness, the risk of an adverse outcome, and the hospital services required. (The exact definition by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is much longer and can be found in the Medicare Benefits Policy Manual.1) Under Medicare, defining a hospitalization as inpatient versus outpatient is especially important because they are billed to different Medicare programs (Part A for inpatient, Part B for outpatient), and both hospital reimbursement and the patient liability can vary significantly.

Not surprisingly, CMS found that how physicians were making status decisions for medically similar hospitalized patients varied greatly. CMS noted two major concerns: an overuse of inpatient for patients hospitalized overnight leading to increased charges to CMS and multiday observation hospitalizations for lower-acuity patients leading to excessive liability for Medicare beneficiaries. (Observation stays are billed under Part B, under which the beneficiary generally has a 20% copay.)

To address these concerns, in October 2013, CMS adjusted the definition of inpatient to include “the two-midnight rule.” Basically, CMS said that, in order to qualify for inpatient, the admitting physician should expect the beneficiary to require hospital care spanning at least two midnights, rather than the previous 24-hour benchmark, regardless of the severity of illness or risk of adverse outcome. (There are exceptions and exemptions to the two-midnight rule, which are discussed later in this article.)

The idea of the two-midnight rule was to address the two concerns noted above. Under this rule, most expected overnight hospitalizations should be outpatients, even if they are more than 24 hours in length, and any medically necessary outpatient hospitalization should be “converted” to inpatient if and when it is clear that a second midnight of hospitalization is medically necessary.

In January 2016, CMS amended the two-midnight rule to recognize, as it had done prior to October 2013, that some hospitalizations, based on physician judgment, would be appropriate for inpatient without an expectation of a hospitalization that spans at least two midnights. Unfortunately, CMS has not been forthcoming with guidance of examples of which hospitalizations would fall into this new category, other than to say they expect the use of this new provision would generally not be appropriate for a hospital stay of less than 24 hours.

As of today, physicians should order inpatient services under the following three situations:

- The physician expects the beneficiary to require hospital care spanning at least two midnights.

- The physician provides a service on Medicare’s inpatient-only list.

- The physician expects the beneficiary to require hospital care for less than two midnights but feels that inpatient services are nevertheless appropriate.

This most recently updated version of the two-midnight rule can be found in Section 42 CFR §412.3 of the Code of Federal Regulations.2 Each of these three situations warrants additional discussion.

Care expected to span two midnights

The first situation is the one most applicable to hospitalists. In this circumstance there are three key points to remember.

The first point is that the two-midnight rule is based on a reasonable expectation of a need for hospitalization for at least two nights, not the actual length of hospitalization. Auditors, based on long-standing guidance from the CMS, should consider only the information known (or that should have been known) to the provider at the time the inpatient decision is made.

For example, if the expectation of the need for hospitalization of at least 2 midnights is well documented in the admission note, but the beneficiary improves more rapidly than expected and can be discharged before the second midnight, billing Medicare under Part A for inpatient admission remains appropriate. Auditors may look for provider documentation describing the unexpected improvement, and while such documentation is not an absolute requirement, its presence can be helpful in defending inpatient billing.

Other situations in which there can be an expectation of hospitalization of at least two midnights, but the actual length of stay does not meet this benchmark, are death, patients leaving against medical advice, or transfer to another hospital. For example, if a patient is hospitalized as an inpatient for bacterial endocarditis, and the documented plan of care includes at least 2 days of IV antibiotics and monitoring of cultures, inpatient remains appropriate even if the patient signs out against medical advice the following day.

The second key point to understand is that a night must be “medically necessary” to count toward the two-midnight benchmark. Hospital time spent receiving custodial care, because of excessive delays, or incurred because of the convenience of the beneficiary or provider does not count toward the two-midnight benchmark. For example, imagine a patient hospitalized with chest pain on Saturday evening and the attending physician determines that the patient requires serial cardiac isoenzymes and ECGs followed, most likely, by a noninvasive stress test. The attending physician, knowing that the hospital does not offer stress testing on Sunday, expects the patient to remain hospitalized at least until Monday, thus two midnights. However, in this situation, the second midnight (Sunday night) was not medically necessary and does not count toward the two midnight expectation.

The third key point to know is that the clock for calculating the two-midnight rule begins when the beneficiary starts receiving hospital care, not when the inpatient order is placed. Further, care that starts in the ED or at another hospital counts, too. In contrast, care at an outpatient clinic, an urgent care facility, or waiting-room time in an ED does not count.

When CMS implemented the two-midnight rule in 2013, they said that they would be open to exceptions. The first and only exception to date to the two-midnight rule is newly initiated and unanticipated mechanical ventilation. (This excludes anticipated intubations related to other care, such as procedures.) For example, inpatient is appropriate for a patient who requires hospitalization for an anaphylactic reaction or a drug overdose and needs intubation and mechanical ventilation, even if discharge is expected before a second midnight of hospital care.

CMS’s inpatient-only list

Each year, CMS publishes a list of procedures that CMS will pay only under Part A (that is, as inpatient). This list is updated quarterly (Addendum E) and can be found on the CMS website.3 Hospitalizations associated with the procedures on this list should always be inpatient, regardless of the expected length of stay.

It is important to note that the inpatient-only list is dynamic; it is revised annually, and procedures can come on or off the list. Notably, in January 2018, elective total knee replacements and laparoscopic radical prostatectomies came off the inpatient-only list. Most surgeons and proceduralists know whether the procedure they are performing is on this list, and they should advise hospitalists accordingly if the hospitalist is to be the attending of record and will be writing the admission order.

Inpatient services are nevertheless appropriate

The third situation, in which an inpatient admission is appropriate even when the admitting provider does not expect a two-midnight stay, was added to the two-midnight rule in January 2016. CMS states that the factors used in making this determination can be based on physician judgment and documented in the medical record.