User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Hospital safety program curbs surgical site infections

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) designed the program to reduce surgical site infections (SSIs), which are harmful to patients and expensive for the health care system, wrote Della M. Lin, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and the department of surgery at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu, and her colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons, the researchers reviewed data from a statewide intervention conducted at 15 hospitals in Hawaii from January 2013 to June 2015. The intervention included the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program and individualized interventions for each hospital to help reduce SSIs. The primary outcome was the number of colorectal SSIs. A secondary outcome of hospital safety culture was assessed using the AHRQ Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture. The participating hospitals ranged from a 25-bed critical-access hospital to a 533-bed academic medical center.

Overall, the colorectal SSI rate decreased significantly (from 12% to 5%) from the first quarter of 2013 to the second quarter of 2015, with a significant linear decrease over the study period. The rate of superficial SSIs decreased significantly, falling from 8% to 3%. However, the rate of deep SSIs was not significantly different before and after the intervention program (2% vs. 0%), nor was the organ space SSI rate (3% vs. 2%). The standardized infection ratio decreased from 1.83 to 0.92.

The culture of safety in the hospitals improved, but more modestly, in 10 of 12 areas that were measured over the study period.

The overall perception of patient safety improved from 49% to 53%, teamwork across different units improved from 49% to 54%, management and support for patient safety improved from 53% to 60%, and nonpunitive response to errors improved from 36% to 40%.

In addition, communication and openness improved from 50% to 53%, frequency of reported events improved from 51% to 60%, feedback and communication about errors improved from 52% to 59%, organizational learning and continuous improvement increased from 59% to 70%, teamwork within units improved from 68% to 75%, and expectations and actions by supervisors and managers to promote safety improved from 58% to 64%. Staff responses reflect agreement on improvement in the areas of issues of communication, feedback mechanisms, and teamwork, but the change in culture was not on the order of the SSI change.

The most common interventions to reduce SSIs were the use of reliable chlorhexidine wash or wipe before surgery/surgical prep; appropriate use of antibiotics with respect to selection, dosage, and timing; standardized postsurgical debriefing; and differentiating clean/dirty/clean in the use of anastomosis trays and closing trays.

One bundle component, the implementation of the standard operating room debrief, was found to be of particular value to participants. The investigators noted that debrief questions such as “What went well?” and “What needs to be improved?” had “encouraged new processes of thinking beyond first-order problem solving. The debrief challenge embraced by the teams emphasized that ‘bundles’ did not consist of only technical interventions [e.g. clean/dirty trays, chlorhexidine gluconate wipes in preop], but embedded culture interventions—new processes for problem solving.”

The study findings were limited by several factors, such as the use of public SSI data that were not audited for accuracy and the inability to monitor the reliability of the implementation of the various interventions, the researchers said. In addition, “In this current study, there was a change in SSI rates and a change in safety culture, but correlations between the two were negligible or weak for most domains of safety culture,” they noted. The question of sustainability of the SSI improvement without the concomitant staff support of culture change was not addressed by the investigators.

However, the results suggest that a 62% decrease is robust, and that for some hospitals with a low volume of colorectal cases, “teams could attend to iteratively reduce surgical harm beyond SSI,” the researchers wrote.

The study was supported in part by the AHRQ. Dr. Lin disclosed serving as a board member and as a paid independent contractor to the Hawaii Medical Service Association. Her coauthors had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Lin DM et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2018 May 18. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.04.031.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) designed the program to reduce surgical site infections (SSIs), which are harmful to patients and expensive for the health care system, wrote Della M. Lin, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and the department of surgery at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu, and her colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons, the researchers reviewed data from a statewide intervention conducted at 15 hospitals in Hawaii from January 2013 to June 2015. The intervention included the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program and individualized interventions for each hospital to help reduce SSIs. The primary outcome was the number of colorectal SSIs. A secondary outcome of hospital safety culture was assessed using the AHRQ Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture. The participating hospitals ranged from a 25-bed critical-access hospital to a 533-bed academic medical center.

Overall, the colorectal SSI rate decreased significantly (from 12% to 5%) from the first quarter of 2013 to the second quarter of 2015, with a significant linear decrease over the study period. The rate of superficial SSIs decreased significantly, falling from 8% to 3%. However, the rate of deep SSIs was not significantly different before and after the intervention program (2% vs. 0%), nor was the organ space SSI rate (3% vs. 2%). The standardized infection ratio decreased from 1.83 to 0.92.

The culture of safety in the hospitals improved, but more modestly, in 10 of 12 areas that were measured over the study period.

The overall perception of patient safety improved from 49% to 53%, teamwork across different units improved from 49% to 54%, management and support for patient safety improved from 53% to 60%, and nonpunitive response to errors improved from 36% to 40%.

In addition, communication and openness improved from 50% to 53%, frequency of reported events improved from 51% to 60%, feedback and communication about errors improved from 52% to 59%, organizational learning and continuous improvement increased from 59% to 70%, teamwork within units improved from 68% to 75%, and expectations and actions by supervisors and managers to promote safety improved from 58% to 64%. Staff responses reflect agreement on improvement in the areas of issues of communication, feedback mechanisms, and teamwork, but the change in culture was not on the order of the SSI change.

The most common interventions to reduce SSIs were the use of reliable chlorhexidine wash or wipe before surgery/surgical prep; appropriate use of antibiotics with respect to selection, dosage, and timing; standardized postsurgical debriefing; and differentiating clean/dirty/clean in the use of anastomosis trays and closing trays.

One bundle component, the implementation of the standard operating room debrief, was found to be of particular value to participants. The investigators noted that debrief questions such as “What went well?” and “What needs to be improved?” had “encouraged new processes of thinking beyond first-order problem solving. The debrief challenge embraced by the teams emphasized that ‘bundles’ did not consist of only technical interventions [e.g. clean/dirty trays, chlorhexidine gluconate wipes in preop], but embedded culture interventions—new processes for problem solving.”

The study findings were limited by several factors, such as the use of public SSI data that were not audited for accuracy and the inability to monitor the reliability of the implementation of the various interventions, the researchers said. In addition, “In this current study, there was a change in SSI rates and a change in safety culture, but correlations between the two were negligible or weak for most domains of safety culture,” they noted. The question of sustainability of the SSI improvement without the concomitant staff support of culture change was not addressed by the investigators.

However, the results suggest that a 62% decrease is robust, and that for some hospitals with a low volume of colorectal cases, “teams could attend to iteratively reduce surgical harm beyond SSI,” the researchers wrote.

The study was supported in part by the AHRQ. Dr. Lin disclosed serving as a board member and as a paid independent contractor to the Hawaii Medical Service Association. Her coauthors had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Lin DM et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2018 May 18. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.04.031.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) designed the program to reduce surgical site infections (SSIs), which are harmful to patients and expensive for the health care system, wrote Della M. Lin, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and the department of surgery at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu, and her colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons, the researchers reviewed data from a statewide intervention conducted at 15 hospitals in Hawaii from January 2013 to June 2015. The intervention included the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program and individualized interventions for each hospital to help reduce SSIs. The primary outcome was the number of colorectal SSIs. A secondary outcome of hospital safety culture was assessed using the AHRQ Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture. The participating hospitals ranged from a 25-bed critical-access hospital to a 533-bed academic medical center.

Overall, the colorectal SSI rate decreased significantly (from 12% to 5%) from the first quarter of 2013 to the second quarter of 2015, with a significant linear decrease over the study period. The rate of superficial SSIs decreased significantly, falling from 8% to 3%. However, the rate of deep SSIs was not significantly different before and after the intervention program (2% vs. 0%), nor was the organ space SSI rate (3% vs. 2%). The standardized infection ratio decreased from 1.83 to 0.92.

The culture of safety in the hospitals improved, but more modestly, in 10 of 12 areas that were measured over the study period.

The overall perception of patient safety improved from 49% to 53%, teamwork across different units improved from 49% to 54%, management and support for patient safety improved from 53% to 60%, and nonpunitive response to errors improved from 36% to 40%.

In addition, communication and openness improved from 50% to 53%, frequency of reported events improved from 51% to 60%, feedback and communication about errors improved from 52% to 59%, organizational learning and continuous improvement increased from 59% to 70%, teamwork within units improved from 68% to 75%, and expectations and actions by supervisors and managers to promote safety improved from 58% to 64%. Staff responses reflect agreement on improvement in the areas of issues of communication, feedback mechanisms, and teamwork, but the change in culture was not on the order of the SSI change.

The most common interventions to reduce SSIs were the use of reliable chlorhexidine wash or wipe before surgery/surgical prep; appropriate use of antibiotics with respect to selection, dosage, and timing; standardized postsurgical debriefing; and differentiating clean/dirty/clean in the use of anastomosis trays and closing trays.

One bundle component, the implementation of the standard operating room debrief, was found to be of particular value to participants. The investigators noted that debrief questions such as “What went well?” and “What needs to be improved?” had “encouraged new processes of thinking beyond first-order problem solving. The debrief challenge embraced by the teams emphasized that ‘bundles’ did not consist of only technical interventions [e.g. clean/dirty trays, chlorhexidine gluconate wipes in preop], but embedded culture interventions—new processes for problem solving.”

The study findings were limited by several factors, such as the use of public SSI data that were not audited for accuracy and the inability to monitor the reliability of the implementation of the various interventions, the researchers said. In addition, “In this current study, there was a change in SSI rates and a change in safety culture, but correlations between the two were negligible or weak for most domains of safety culture,” they noted. The question of sustainability of the SSI improvement without the concomitant staff support of culture change was not addressed by the investigators.

However, the results suggest that a 62% decrease is robust, and that for some hospitals with a low volume of colorectal cases, “teams could attend to iteratively reduce surgical harm beyond SSI,” the researchers wrote.

The study was supported in part by the AHRQ. Dr. Lin disclosed serving as a board member and as a paid independent contractor to the Hawaii Medical Service Association. Her coauthors had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Lin DM et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2018 May 18. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.04.031.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF SURGEONS

Key clinical point: Hospital participation in an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality safety program improved safety culture and reduced surgical site infections.

Major finding: Surgical site infections among colorectal surgery patients decreased by 61.7% after the intervention.

Study details: The data come from a cohort study of 15 hospitals in Hawaii from January 2013 to June 2015.

Disclosures: The study was supported in part by the AHRQ. Dr. Lin disclosed serving as a board member and as a paid independent contractor to the Hawaii Medical Service Association. Her coauthors had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Lin DM et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2018 May 18. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.04.031.

Clinician denial of some patient requests decrease patient satisfaction

Background: Literature regarding patient satisfaction often focuses on nonspecific recommendations to improve patient-centered communication. There is lack of guidance on concrete advice for clinicians, particularly with regard to how a provider’s responses to different patient requests are received.

Study design: Cross-sectional study.

Setting: An outpatient family medicine clinic.

Synopsis: Patient requests from 1,141 patients visiting the University of California, Davis, Family Medicine Clinic were sampled. The study examined clinician’s approval or denial of patients’ requests for referrals, pain medications, other new medicines, laboratory testing, radiology testing, or other testing and the patients’ reported satisfaction of the clinician.

Clinician denial of particular requests was associated with decreased patient satisfaction. Specifically, a 19.75% drop for referral, 10.72% drop for pain medication, 20.36% drop for other new medications, and 9.19% drop for laboratory test. This study did not examine other potential reasons for decreased satisfaction.

Bottom line: Clinicians can better understand how to communicate in a patient-centered manner by understanding that not all patient requests are perceived as equal.

Citation: Jerant A et al. Association of clinical denial of patient requests with patient satisfaction. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jan 1;178(1):85-91.

Dr. Shaffie is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Background: Literature regarding patient satisfaction often focuses on nonspecific recommendations to improve patient-centered communication. There is lack of guidance on concrete advice for clinicians, particularly with regard to how a provider’s responses to different patient requests are received.

Study design: Cross-sectional study.

Setting: An outpatient family medicine clinic.

Synopsis: Patient requests from 1,141 patients visiting the University of California, Davis, Family Medicine Clinic were sampled. The study examined clinician’s approval or denial of patients’ requests for referrals, pain medications, other new medicines, laboratory testing, radiology testing, or other testing and the patients’ reported satisfaction of the clinician.

Clinician denial of particular requests was associated with decreased patient satisfaction. Specifically, a 19.75% drop for referral, 10.72% drop for pain medication, 20.36% drop for other new medications, and 9.19% drop for laboratory test. This study did not examine other potential reasons for decreased satisfaction.

Bottom line: Clinicians can better understand how to communicate in a patient-centered manner by understanding that not all patient requests are perceived as equal.

Citation: Jerant A et al. Association of clinical denial of patient requests with patient satisfaction. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jan 1;178(1):85-91.

Dr. Shaffie is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Background: Literature regarding patient satisfaction often focuses on nonspecific recommendations to improve patient-centered communication. There is lack of guidance on concrete advice for clinicians, particularly with regard to how a provider’s responses to different patient requests are received.

Study design: Cross-sectional study.

Setting: An outpatient family medicine clinic.

Synopsis: Patient requests from 1,141 patients visiting the University of California, Davis, Family Medicine Clinic were sampled. The study examined clinician’s approval or denial of patients’ requests for referrals, pain medications, other new medicines, laboratory testing, radiology testing, or other testing and the patients’ reported satisfaction of the clinician.

Clinician denial of particular requests was associated with decreased patient satisfaction. Specifically, a 19.75% drop for referral, 10.72% drop for pain medication, 20.36% drop for other new medications, and 9.19% drop for laboratory test. This study did not examine other potential reasons for decreased satisfaction.

Bottom line: Clinicians can better understand how to communicate in a patient-centered manner by understanding that not all patient requests are perceived as equal.

Citation: Jerant A et al. Association of clinical denial of patient requests with patient satisfaction. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jan 1;178(1):85-91.

Dr. Shaffie is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Postop delirium management proposed as hospital performance measure

A study suggests that outcome measures, and assessment of hospital performance.

Lead author Julia R. Berian, MD, of the University of Chicago Medical Center and her colleagues wrote, “Postoperative delirium has been associated with mortality, morbidity, prolonged length of stay, and increased costs of care. Furthermore, postoperative delirium may be associated with long-term cognitive and functional decline. However, postoperative delirium has not been incorporated as an outcome measure into major surgical quality registries. Approximately one-third of hospitalized delirium is believed to be preventable, making postoperative delirium an ideal target for surgical quality improvement efforts,” Dr. Berian and her colleagues reported in the Annals of Surgery.

The Geriatric Surgery Pilot data abstractors were instructed to assign postoperative delirium if the medical record words indicating an acute confusional stat such a mental status change, confusion, disorientation, agitation, delirium, and inappropriate behavior. Data were collected from the period 2 hours after surgery to exclude effects of the pharmacologic agents of anesthesia. Delirium status was ascertained as a binary outcome (Yes/No).

Postoperative delirium was observed in 2,427 patients for an average, unadjusted rate of 12.0%. Investigators identified 20 risk factors markedly associated with delirium. The strongest predictors included preoperative cognitive impairment, preoperative use of mobility aid, surrogate consent form, ASA class 4 or greater, age 80 years and older, preoperative sepsis, and fall history within 1 year. Patients with delirium generally were older than patients without delirium were and accounted for a greater proportion of emergency cases. Postoperative hospital length of stay was about 4 days longer on average for patients with delirium, compared with those without delirium.

By specialty, the highest rates of postoperative delirium occurred following cardiothoracic (13.7%), orthopedic (13.0%), and general surgeries (13.0%). Study authors found varied associated risk for postoperative delirium within each surgical specialty. For example, in general surgery, the risk for postoperative delirium with partial mastectomy was low, compared with a mid-level risk in the repair of a recurrent, incarcerated, or strangulated inguinal hernia and a high-level risk in Whipple operations.

The model developed to measure delirium management success in 30 hospitals found that adjusted delirium rates ranged from 3.2% to 27.5%, with eight poor- and five excellent-performing outliers. Authors noted that their model demonstrated good calibration and discrimination. Examination of changes in the Bayesian Information Criteria indicates that as few as 10-12 variables may suffice in building a parsimonious model with “an excellent fit.”

Study authors noted that screening for postoperative delirium in older adults is likely in the best interests of patients. However, they also mentioned that such screening may identify cases of postoperative delirium that were previously unrecognized, resulting in higher rates. In addition, the inclusion of only ACS NSQIP hospitals and the voluntary participation may mean a biased dataset. No one delirium prevention intervention was implemented across the hospitals and so the study doesn’t indicate why some hospitals are more successful than are others. Chart-based identification of patients who have delirium needs further study to assess validity.

Authors concluded that one solution may be to “standardize and consistently employ delirium screening in high-risk patients across hospitals, as has been advocated by a coalition of interdisciplinary experts in geriatric care.”

This project is funded in part by a grant from the John A. Hartford Foundation. The authors declare no conflict of interests.

SOURCE: Berlan JR et al. Ann Surg. 2017 July 24. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002436

A study suggests that outcome measures, and assessment of hospital performance.

Lead author Julia R. Berian, MD, of the University of Chicago Medical Center and her colleagues wrote, “Postoperative delirium has been associated with mortality, morbidity, prolonged length of stay, and increased costs of care. Furthermore, postoperative delirium may be associated with long-term cognitive and functional decline. However, postoperative delirium has not been incorporated as an outcome measure into major surgical quality registries. Approximately one-third of hospitalized delirium is believed to be preventable, making postoperative delirium an ideal target for surgical quality improvement efforts,” Dr. Berian and her colleagues reported in the Annals of Surgery.

The Geriatric Surgery Pilot data abstractors were instructed to assign postoperative delirium if the medical record words indicating an acute confusional stat such a mental status change, confusion, disorientation, agitation, delirium, and inappropriate behavior. Data were collected from the period 2 hours after surgery to exclude effects of the pharmacologic agents of anesthesia. Delirium status was ascertained as a binary outcome (Yes/No).

Postoperative delirium was observed in 2,427 patients for an average, unadjusted rate of 12.0%. Investigators identified 20 risk factors markedly associated with delirium. The strongest predictors included preoperative cognitive impairment, preoperative use of mobility aid, surrogate consent form, ASA class 4 or greater, age 80 years and older, preoperative sepsis, and fall history within 1 year. Patients with delirium generally were older than patients without delirium were and accounted for a greater proportion of emergency cases. Postoperative hospital length of stay was about 4 days longer on average for patients with delirium, compared with those without delirium.

By specialty, the highest rates of postoperative delirium occurred following cardiothoracic (13.7%), orthopedic (13.0%), and general surgeries (13.0%). Study authors found varied associated risk for postoperative delirium within each surgical specialty. For example, in general surgery, the risk for postoperative delirium with partial mastectomy was low, compared with a mid-level risk in the repair of a recurrent, incarcerated, or strangulated inguinal hernia and a high-level risk in Whipple operations.

The model developed to measure delirium management success in 30 hospitals found that adjusted delirium rates ranged from 3.2% to 27.5%, with eight poor- and five excellent-performing outliers. Authors noted that their model demonstrated good calibration and discrimination. Examination of changes in the Bayesian Information Criteria indicates that as few as 10-12 variables may suffice in building a parsimonious model with “an excellent fit.”

Study authors noted that screening for postoperative delirium in older adults is likely in the best interests of patients. However, they also mentioned that such screening may identify cases of postoperative delirium that were previously unrecognized, resulting in higher rates. In addition, the inclusion of only ACS NSQIP hospitals and the voluntary participation may mean a biased dataset. No one delirium prevention intervention was implemented across the hospitals and so the study doesn’t indicate why some hospitals are more successful than are others. Chart-based identification of patients who have delirium needs further study to assess validity.

Authors concluded that one solution may be to “standardize and consistently employ delirium screening in high-risk patients across hospitals, as has been advocated by a coalition of interdisciplinary experts in geriatric care.”

This project is funded in part by a grant from the John A. Hartford Foundation. The authors declare no conflict of interests.

SOURCE: Berlan JR et al. Ann Surg. 2017 July 24. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002436

A study suggests that outcome measures, and assessment of hospital performance.

Lead author Julia R. Berian, MD, of the University of Chicago Medical Center and her colleagues wrote, “Postoperative delirium has been associated with mortality, morbidity, prolonged length of stay, and increased costs of care. Furthermore, postoperative delirium may be associated with long-term cognitive and functional decline. However, postoperative delirium has not been incorporated as an outcome measure into major surgical quality registries. Approximately one-third of hospitalized delirium is believed to be preventable, making postoperative delirium an ideal target for surgical quality improvement efforts,” Dr. Berian and her colleagues reported in the Annals of Surgery.

The Geriatric Surgery Pilot data abstractors were instructed to assign postoperative delirium if the medical record words indicating an acute confusional stat such a mental status change, confusion, disorientation, agitation, delirium, and inappropriate behavior. Data were collected from the period 2 hours after surgery to exclude effects of the pharmacologic agents of anesthesia. Delirium status was ascertained as a binary outcome (Yes/No).

Postoperative delirium was observed in 2,427 patients for an average, unadjusted rate of 12.0%. Investigators identified 20 risk factors markedly associated with delirium. The strongest predictors included preoperative cognitive impairment, preoperative use of mobility aid, surrogate consent form, ASA class 4 or greater, age 80 years and older, preoperative sepsis, and fall history within 1 year. Patients with delirium generally were older than patients without delirium were and accounted for a greater proportion of emergency cases. Postoperative hospital length of stay was about 4 days longer on average for patients with delirium, compared with those without delirium.

By specialty, the highest rates of postoperative delirium occurred following cardiothoracic (13.7%), orthopedic (13.0%), and general surgeries (13.0%). Study authors found varied associated risk for postoperative delirium within each surgical specialty. For example, in general surgery, the risk for postoperative delirium with partial mastectomy was low, compared with a mid-level risk in the repair of a recurrent, incarcerated, or strangulated inguinal hernia and a high-level risk in Whipple operations.

The model developed to measure delirium management success in 30 hospitals found that adjusted delirium rates ranged from 3.2% to 27.5%, with eight poor- and five excellent-performing outliers. Authors noted that their model demonstrated good calibration and discrimination. Examination of changes in the Bayesian Information Criteria indicates that as few as 10-12 variables may suffice in building a parsimonious model with “an excellent fit.”

Study authors noted that screening for postoperative delirium in older adults is likely in the best interests of patients. However, they also mentioned that such screening may identify cases of postoperative delirium that were previously unrecognized, resulting in higher rates. In addition, the inclusion of only ACS NSQIP hospitals and the voluntary participation may mean a biased dataset. No one delirium prevention intervention was implemented across the hospitals and so the study doesn’t indicate why some hospitals are more successful than are others. Chart-based identification of patients who have delirium needs further study to assess validity.

Authors concluded that one solution may be to “standardize and consistently employ delirium screening in high-risk patients across hospitals, as has been advocated by a coalition of interdisciplinary experts in geriatric care.”

This project is funded in part by a grant from the John A. Hartford Foundation. The authors declare no conflict of interests.

SOURCE: Berlan JR et al. Ann Surg. 2017 July 24. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002436

FROM ANNALS OF SURGERY

Key clinical point: Through predictive modeling, the study identified 20 risk factors markedly associated with delirium that can be used to identify high-risk patients.

Major finding: Among the 2,427 patients who experienced delirium, 35% had preoperative cognitive impairment, 30 % had a surrogate sign the consent form, and 32% experienced serious postoperative complications or death.

Study details: An analysis of 2,427 elderly patients at 30 hospitals through data from the ACS NSQIP Geriatric Surgery Pilot Project.

Disclosures: This project is funded in part by a grant from the John A. Hartford Foundation. The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Source: Berian JR et al. Ann Surg. 2017Jul 24. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002436

MDR Candida auris is on the move

MADRID – The anticipated global emergence of multidrug resistant Candida auris is now an established fact, but a case study presented at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress demonstrates just how devastating an outbreak can be to a medical facility and its surgical ICU patients.

The dangerous invasive infection is spreading through Asia, Europe, and the Americas, causing potentially fatal candidemias and proving devilishly difficult to eradicate in health care facilities once it becomes established.

Several multidrug resistant (MDR) C. auris outbreaks were reported at the ECCMID meeting. Most troubling: a continuing outbreak in a hospital in Valencia, Spain, in which 17 patients have died – a 41% fatality rate among those who developed a fulminant C. auris candidemia, Javier Pemán, MD, said at the meeting. The strain appeared to be a clonal population not previously identified in published reports.

“C. auris is hard to remove from the hospital environment,” once it becomes established, said Dr. Pemán of La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital, Valencia. “When an outbreak lasts for months, as ours has, it is difficult, but necessary, to maintain control measures, identify it early in the lab, and isolate and treat patients early with combination therapy.”

He and his team have relied primarily on a combination of amphotericin B and echinocandin (AMB+ECN), although, he added, the optimal dosing and treatment time aren’t known, and many C. auris isolates are echinocandin resistant.

MDR C. auris first appearedin Tokyo in 2009. It then spread to South Korea around 2011, and then appeared across Asia and Western Europe. Its first appearance in Spain was the 2016 Le Fe outbreak.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, single cases have appeared in Austria, Belgium, Malaysia, Norway, and the United Arab Emirates. Canada, Colombia, France, Germany, India, Israel, Japan, Kenya, Kuwait, Oman, Pakistan, Panama, South Korea, South Africa, Spain, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and Venezuela have experienced multiple outbreaks.

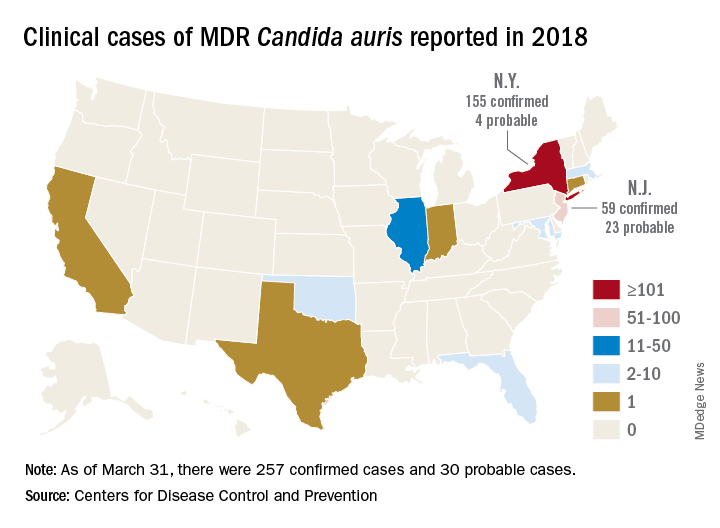

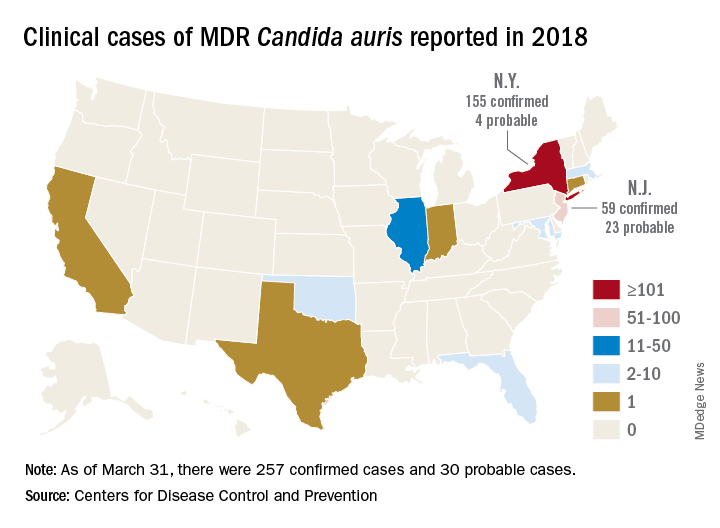

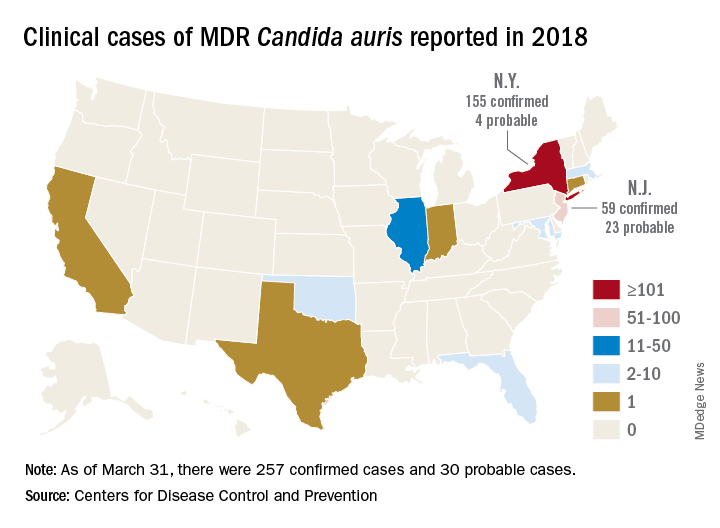

The CDC has recorded 257 confirmed and 30 probable cases of MDR C. auris in the United States as of March 31, 2018. Most of these occurred in New York City and New Jersey; a number of patients had recent stays in hospitals in India, Pakistan, South Africa, the UAE, and Venezuela.

Jacques Meis, MD, of the department of medical microbiology and infectious diseases at Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, set the stage for an extended discussion of C. auris at the meeting.

“This is a multidrug resistant yeast that has emerged in the last decade. Some rare isolates are resistant to all three major antifungal classes. Unlike other Candida species, it seems to persist for prolonged periods in health care environments and to colonize patients’ skin. It behaves rather like resistant bacteria.”

Once established in a health care setting – often an intensive care ward – C. auris poses major infection controls challenges and can be very hard to identify and eradicate, said Dr. Meis.

The identification problem is well known. The 2016 CDC alert noted that “commercially available biochemical-based tests, including API strips and VITEK-2, used in many U.S. laboratories to identify fungi, cannot differentiate C. auris from related species. Because of these challenges, clinical laboratories have misidentified the organism as C. haemulonii and Saccharomyces cerevisiae.”

“It’s often misidentified as other Candida species or as Saccharomyces when we investigate with biochemical methods. C. auris is best identified using Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF),” said Dr. Meis.

Among the presentations at ECCMID were a report of a U.K. outbreak that affected 70 patients in a neuroscience ICU. It was traced to axillary skin-surface temperature probes, and eradicated only after those probes were removed. More than 90% of the isolates were resistant to fluconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole; 18% were amphotericin resistant.

A poster described the microbiological characteristics of 50 C. auris isolates taken from 11 hospitals in Korea.

Dr. Pemán described the outbreak in Valencia, which began in April 2016; the report was simultaneously published in the online journal Mycoses (2018 Apr 14. doi: 10.1111/myc.12781).

The index case was a 66-year-old man with hepatocellular carcinoma who underwent a liver resection at Hospital Le Fe in April 2016. During his stay in the surgical ICU (SICU), he developed a fungal infection from an unknown, highly fluconazole-resistant yeast. The pathogen was twice misidentified, first as C. haemulonii and then as S. cerevisiae.

Three weeks later, the patient in the adjacent bed developed a similar infection. Sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer confirmed both as a Candida isolate – an organism previously unknown in Spain.

The SICU setup was apparently very conducive to the C. auris life cycle, Dr. Pemán said. It’s a relatively open ward divided into three rooms with 12 beds in each. There are no isolation beds, and dozens of workers have access to the ward every day, including clinical and cleaning staff.

After identifying the second isolate, Dr. Pemán said, infection control staff went into action. They instituted contact precautions in the SICU, and took regular cultures from newly admitted patients and cultures of every SICU patient every 7 days.

“We also started an intense search for more cases throughout the hospital and in 101 SICU workers. Of 305 samples from hands and ears, we found nothing.” They reviewed all the prior fluconazole-resistant Candida isolates; C. auris was not present in the hospital before the index case.

Three weeks after case 2, six new SICU patients tested positive for C. auris (two blood cultures, one vascular line, one respiratory specimen, two rectal swabs, and one urinary tract sample).

“We reinforced contact precautions in colonized and infected patients and started a twice-daily environmental cleaning practice with quaternary ammonium around them,” said Dr. Pemán. They instituted a proactive hospital-wide hand hygiene campaign and spread the word about the outbreak.

By July, there were 11 new colonized patients, 3 of whom developed candidemia. These patients were grouped in the same SICU ward and underwent daily skin treatments with 4% aqueous chlorhexidine wipes.

The environmental inspection found C. auris on beds, tables, walls, and the floor all around infected patients. The pathogen also was living on IV pumps, computer keyboards, and bedside tables. Blood pressure cuffs were a favorite haunt: 19 of 36 samples in the adjacent ICU were positive. These data were separately reported at ECCMID.

Despite all of these efforts at eradication, infections continued to rise. By November, there were 24 newly colonized patients and nine new candidemia episodes in SICU and regular ICU patients. In December, a new infection control bundle began: A surveillance nurse in the C. auris SICU ward was in charge of compliance; any patient with any yeast growth in culture was isolated, and staff used 2% alcohol chlorhexidine wipes before and after IV catheter handling. Staff also washed down all surfaces three times daily with a disinfectant.

Patients could leave isolation after three consecutive C. auris–negative cultures. After discharge, an ultraviolet light decontamination procedure disinfected each patient room.

The pathogen was almost unbelievably resilient, Dr. Pemán noted in the Mycoses article. “In some cases, C. auris was recovered from walls after cleaning with cationic surface–active products ... it was not known until very recently that these products, as well as quaternary ammonium disinfectants, cannot effectively remove C. auris from surfaces.”

As a result of the previous measures, the outbreak slowed down during December 2016, with two new candidemia cases, but by February, the outbreak resumed with 50 new cases and 18 candidemias detected. Cases continued to emerge throughout 2017.

By September 2017, 250 patients had been colonized; 116 of these were included in the Mycoses report. There were 30 episodes of candidemia (26%); of these, 17 died by 30 days (41.4%). Spondylodiscitis and endocarditis each developed in two patients and one developed ventriculitis.

A separate poster by Dr. Pemán and his colleagues gave more details:

• A 52-year-old woman with C. auris–induced endocarditis died after 4 weeks of treatment with AMB+ECN and flucytosine. She had undergone a prosthetic heart valve placement for Ebstein’s anomaly.

• A 71-year-old man with hydrocephalus developed a C. auris–induced infection of his ventriculoperitoneal shunt; he also had undergone cardiovascular surgery and had an ischemic cardiomyopathy. He died despite shunt removal and 8 weeks of AMB+ECN.

• A 71-year-old man who underwent cardiovascular surgery and received a prosthetic heart valve developed endocarditis. He is alive and at last report, on week 26 of AMB+ECN, flucytosine, and isavuconazole.

• A 68-year-old man who underwent abdominal surgery for hepatocellular carcinoma developed spondylodiscitis and is alive after 24 weeks of AMB+ECN.

• A 48-year old female multiple trauma patient developed spondylodiscitis and is alive after 48 weeks of treatment with AMB+ECN.

A multivariate analysis determined that antibacterial treatment increased the risk of candidemia by almost 30 times (odds ratio, 29.59). The next highest risk was neutropenia (OR, 20.7) and then simply being a hospital and SICU patient. Dr. Pemán’s poster said, “In the 16 months before the index case, La Fe recorded 89 candidemias, none caused by C. auris. In the 16 months afterward, there were 154 candidemias, largely C. auris. Before April 2016, C. parapsilosis accounted for the largest portion of candidemias (46%) followed by C. albicans. After the index case, C. auris accounted for 42%, followed by C. parapsilosis (21%) and C. albicans (18%).”

Because of its fluconazole resistance, patients with C. auris received a combined antifungal treatment of liposomal amphotericin B 3 mg/kg per day for 5 days, and a standard dose of echinocandin for 3 weeks. Many C. auris strains are echinocandin resistant, Dr. Pemán noted. This particular strain was clonal, different from any other previously reported, he said.

“Our results confirm those previously reported by other authors, that C. auris is grouped in different independent clusters according to its geographical origin. Although all Spanish isolates were genotypically distinct from Indian, Omani, U.K., and Venezuelan isolates, there seems to be some connection with South African isolates.”

Hospital Le Fe continues to struggle with C. auris. As of March, 335 patients have tested positive for the pathogen, and 80 have developed candidemias.

“We feel we may be approaching the end of this episode, but it’s really not possible to be sure,” he said.

Dr. Pemán had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: ECCMID 2018 Peman et al. S0067.

MADRID – The anticipated global emergence of multidrug resistant Candida auris is now an established fact, but a case study presented at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress demonstrates just how devastating an outbreak can be to a medical facility and its surgical ICU patients.

The dangerous invasive infection is spreading through Asia, Europe, and the Americas, causing potentially fatal candidemias and proving devilishly difficult to eradicate in health care facilities once it becomes established.

Several multidrug resistant (MDR) C. auris outbreaks were reported at the ECCMID meeting. Most troubling: a continuing outbreak in a hospital in Valencia, Spain, in which 17 patients have died – a 41% fatality rate among those who developed a fulminant C. auris candidemia, Javier Pemán, MD, said at the meeting. The strain appeared to be a clonal population not previously identified in published reports.

“C. auris is hard to remove from the hospital environment,” once it becomes established, said Dr. Pemán of La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital, Valencia. “When an outbreak lasts for months, as ours has, it is difficult, but necessary, to maintain control measures, identify it early in the lab, and isolate and treat patients early with combination therapy.”

He and his team have relied primarily on a combination of amphotericin B and echinocandin (AMB+ECN), although, he added, the optimal dosing and treatment time aren’t known, and many C. auris isolates are echinocandin resistant.

MDR C. auris first appearedin Tokyo in 2009. It then spread to South Korea around 2011, and then appeared across Asia and Western Europe. Its first appearance in Spain was the 2016 Le Fe outbreak.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, single cases have appeared in Austria, Belgium, Malaysia, Norway, and the United Arab Emirates. Canada, Colombia, France, Germany, India, Israel, Japan, Kenya, Kuwait, Oman, Pakistan, Panama, South Korea, South Africa, Spain, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and Venezuela have experienced multiple outbreaks.

The CDC has recorded 257 confirmed and 30 probable cases of MDR C. auris in the United States as of March 31, 2018. Most of these occurred in New York City and New Jersey; a number of patients had recent stays in hospitals in India, Pakistan, South Africa, the UAE, and Venezuela.

Jacques Meis, MD, of the department of medical microbiology and infectious diseases at Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, set the stage for an extended discussion of C. auris at the meeting.

“This is a multidrug resistant yeast that has emerged in the last decade. Some rare isolates are resistant to all three major antifungal classes. Unlike other Candida species, it seems to persist for prolonged periods in health care environments and to colonize patients’ skin. It behaves rather like resistant bacteria.”

Once established in a health care setting – often an intensive care ward – C. auris poses major infection controls challenges and can be very hard to identify and eradicate, said Dr. Meis.

The identification problem is well known. The 2016 CDC alert noted that “commercially available biochemical-based tests, including API strips and VITEK-2, used in many U.S. laboratories to identify fungi, cannot differentiate C. auris from related species. Because of these challenges, clinical laboratories have misidentified the organism as C. haemulonii and Saccharomyces cerevisiae.”

“It’s often misidentified as other Candida species or as Saccharomyces when we investigate with biochemical methods. C. auris is best identified using Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF),” said Dr. Meis.

Among the presentations at ECCMID were a report of a U.K. outbreak that affected 70 patients in a neuroscience ICU. It was traced to axillary skin-surface temperature probes, and eradicated only after those probes were removed. More than 90% of the isolates were resistant to fluconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole; 18% were amphotericin resistant.

A poster described the microbiological characteristics of 50 C. auris isolates taken from 11 hospitals in Korea.

Dr. Pemán described the outbreak in Valencia, which began in April 2016; the report was simultaneously published in the online journal Mycoses (2018 Apr 14. doi: 10.1111/myc.12781).

The index case was a 66-year-old man with hepatocellular carcinoma who underwent a liver resection at Hospital Le Fe in April 2016. During his stay in the surgical ICU (SICU), he developed a fungal infection from an unknown, highly fluconazole-resistant yeast. The pathogen was twice misidentified, first as C. haemulonii and then as S. cerevisiae.

Three weeks later, the patient in the adjacent bed developed a similar infection. Sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer confirmed both as a Candida isolate – an organism previously unknown in Spain.

The SICU setup was apparently very conducive to the C. auris life cycle, Dr. Pemán said. It’s a relatively open ward divided into three rooms with 12 beds in each. There are no isolation beds, and dozens of workers have access to the ward every day, including clinical and cleaning staff.

After identifying the second isolate, Dr. Pemán said, infection control staff went into action. They instituted contact precautions in the SICU, and took regular cultures from newly admitted patients and cultures of every SICU patient every 7 days.

“We also started an intense search for more cases throughout the hospital and in 101 SICU workers. Of 305 samples from hands and ears, we found nothing.” They reviewed all the prior fluconazole-resistant Candida isolates; C. auris was not present in the hospital before the index case.

Three weeks after case 2, six new SICU patients tested positive for C. auris (two blood cultures, one vascular line, one respiratory specimen, two rectal swabs, and one urinary tract sample).

“We reinforced contact precautions in colonized and infected patients and started a twice-daily environmental cleaning practice with quaternary ammonium around them,” said Dr. Pemán. They instituted a proactive hospital-wide hand hygiene campaign and spread the word about the outbreak.

By July, there were 11 new colonized patients, 3 of whom developed candidemia. These patients were grouped in the same SICU ward and underwent daily skin treatments with 4% aqueous chlorhexidine wipes.

The environmental inspection found C. auris on beds, tables, walls, and the floor all around infected patients. The pathogen also was living on IV pumps, computer keyboards, and bedside tables. Blood pressure cuffs were a favorite haunt: 19 of 36 samples in the adjacent ICU were positive. These data were separately reported at ECCMID.

Despite all of these efforts at eradication, infections continued to rise. By November, there were 24 newly colonized patients and nine new candidemia episodes in SICU and regular ICU patients. In December, a new infection control bundle began: A surveillance nurse in the C. auris SICU ward was in charge of compliance; any patient with any yeast growth in culture was isolated, and staff used 2% alcohol chlorhexidine wipes before and after IV catheter handling. Staff also washed down all surfaces three times daily with a disinfectant.

Patients could leave isolation after three consecutive C. auris–negative cultures. After discharge, an ultraviolet light decontamination procedure disinfected each patient room.

The pathogen was almost unbelievably resilient, Dr. Pemán noted in the Mycoses article. “In some cases, C. auris was recovered from walls after cleaning with cationic surface–active products ... it was not known until very recently that these products, as well as quaternary ammonium disinfectants, cannot effectively remove C. auris from surfaces.”

As a result of the previous measures, the outbreak slowed down during December 2016, with two new candidemia cases, but by February, the outbreak resumed with 50 new cases and 18 candidemias detected. Cases continued to emerge throughout 2017.

By September 2017, 250 patients had been colonized; 116 of these were included in the Mycoses report. There were 30 episodes of candidemia (26%); of these, 17 died by 30 days (41.4%). Spondylodiscitis and endocarditis each developed in two patients and one developed ventriculitis.

A separate poster by Dr. Pemán and his colleagues gave more details:

• A 52-year-old woman with C. auris–induced endocarditis died after 4 weeks of treatment with AMB+ECN and flucytosine. She had undergone a prosthetic heart valve placement for Ebstein’s anomaly.

• A 71-year-old man with hydrocephalus developed a C. auris–induced infection of his ventriculoperitoneal shunt; he also had undergone cardiovascular surgery and had an ischemic cardiomyopathy. He died despite shunt removal and 8 weeks of AMB+ECN.

• A 71-year-old man who underwent cardiovascular surgery and received a prosthetic heart valve developed endocarditis. He is alive and at last report, on week 26 of AMB+ECN, flucytosine, and isavuconazole.

• A 68-year-old man who underwent abdominal surgery for hepatocellular carcinoma developed spondylodiscitis and is alive after 24 weeks of AMB+ECN.

• A 48-year old female multiple trauma patient developed spondylodiscitis and is alive after 48 weeks of treatment with AMB+ECN.

A multivariate analysis determined that antibacterial treatment increased the risk of candidemia by almost 30 times (odds ratio, 29.59). The next highest risk was neutropenia (OR, 20.7) and then simply being a hospital and SICU patient. Dr. Pemán’s poster said, “In the 16 months before the index case, La Fe recorded 89 candidemias, none caused by C. auris. In the 16 months afterward, there were 154 candidemias, largely C. auris. Before April 2016, C. parapsilosis accounted for the largest portion of candidemias (46%) followed by C. albicans. After the index case, C. auris accounted for 42%, followed by C. parapsilosis (21%) and C. albicans (18%).”

Because of its fluconazole resistance, patients with C. auris received a combined antifungal treatment of liposomal amphotericin B 3 mg/kg per day for 5 days, and a standard dose of echinocandin for 3 weeks. Many C. auris strains are echinocandin resistant, Dr. Pemán noted. This particular strain was clonal, different from any other previously reported, he said.

“Our results confirm those previously reported by other authors, that C. auris is grouped in different independent clusters according to its geographical origin. Although all Spanish isolates were genotypically distinct from Indian, Omani, U.K., and Venezuelan isolates, there seems to be some connection with South African isolates.”

Hospital Le Fe continues to struggle with C. auris. As of March, 335 patients have tested positive for the pathogen, and 80 have developed candidemias.

“We feel we may be approaching the end of this episode, but it’s really not possible to be sure,” he said.

Dr. Pemán had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: ECCMID 2018 Peman et al. S0067.

MADRID – The anticipated global emergence of multidrug resistant Candida auris is now an established fact, but a case study presented at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress demonstrates just how devastating an outbreak can be to a medical facility and its surgical ICU patients.

The dangerous invasive infection is spreading through Asia, Europe, and the Americas, causing potentially fatal candidemias and proving devilishly difficult to eradicate in health care facilities once it becomes established.

Several multidrug resistant (MDR) C. auris outbreaks were reported at the ECCMID meeting. Most troubling: a continuing outbreak in a hospital in Valencia, Spain, in which 17 patients have died – a 41% fatality rate among those who developed a fulminant C. auris candidemia, Javier Pemán, MD, said at the meeting. The strain appeared to be a clonal population not previously identified in published reports.

“C. auris is hard to remove from the hospital environment,” once it becomes established, said Dr. Pemán of La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital, Valencia. “When an outbreak lasts for months, as ours has, it is difficult, but necessary, to maintain control measures, identify it early in the lab, and isolate and treat patients early with combination therapy.”

He and his team have relied primarily on a combination of amphotericin B and echinocandin (AMB+ECN), although, he added, the optimal dosing and treatment time aren’t known, and many C. auris isolates are echinocandin resistant.

MDR C. auris first appearedin Tokyo in 2009. It then spread to South Korea around 2011, and then appeared across Asia and Western Europe. Its first appearance in Spain was the 2016 Le Fe outbreak.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, single cases have appeared in Austria, Belgium, Malaysia, Norway, and the United Arab Emirates. Canada, Colombia, France, Germany, India, Israel, Japan, Kenya, Kuwait, Oman, Pakistan, Panama, South Korea, South Africa, Spain, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and Venezuela have experienced multiple outbreaks.

The CDC has recorded 257 confirmed and 30 probable cases of MDR C. auris in the United States as of March 31, 2018. Most of these occurred in New York City and New Jersey; a number of patients had recent stays in hospitals in India, Pakistan, South Africa, the UAE, and Venezuela.

Jacques Meis, MD, of the department of medical microbiology and infectious diseases at Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, set the stage for an extended discussion of C. auris at the meeting.

“This is a multidrug resistant yeast that has emerged in the last decade. Some rare isolates are resistant to all three major antifungal classes. Unlike other Candida species, it seems to persist for prolonged periods in health care environments and to colonize patients’ skin. It behaves rather like resistant bacteria.”

Once established in a health care setting – often an intensive care ward – C. auris poses major infection controls challenges and can be very hard to identify and eradicate, said Dr. Meis.

The identification problem is well known. The 2016 CDC alert noted that “commercially available biochemical-based tests, including API strips and VITEK-2, used in many U.S. laboratories to identify fungi, cannot differentiate C. auris from related species. Because of these challenges, clinical laboratories have misidentified the organism as C. haemulonii and Saccharomyces cerevisiae.”

“It’s often misidentified as other Candida species or as Saccharomyces when we investigate with biochemical methods. C. auris is best identified using Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF),” said Dr. Meis.

Among the presentations at ECCMID were a report of a U.K. outbreak that affected 70 patients in a neuroscience ICU. It was traced to axillary skin-surface temperature probes, and eradicated only after those probes were removed. More than 90% of the isolates were resistant to fluconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole; 18% were amphotericin resistant.

A poster described the microbiological characteristics of 50 C. auris isolates taken from 11 hospitals in Korea.

Dr. Pemán described the outbreak in Valencia, which began in April 2016; the report was simultaneously published in the online journal Mycoses (2018 Apr 14. doi: 10.1111/myc.12781).

The index case was a 66-year-old man with hepatocellular carcinoma who underwent a liver resection at Hospital Le Fe in April 2016. During his stay in the surgical ICU (SICU), he developed a fungal infection from an unknown, highly fluconazole-resistant yeast. The pathogen was twice misidentified, first as C. haemulonii and then as S. cerevisiae.

Three weeks later, the patient in the adjacent bed developed a similar infection. Sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer confirmed both as a Candida isolate – an organism previously unknown in Spain.

The SICU setup was apparently very conducive to the C. auris life cycle, Dr. Pemán said. It’s a relatively open ward divided into three rooms with 12 beds in each. There are no isolation beds, and dozens of workers have access to the ward every day, including clinical and cleaning staff.

After identifying the second isolate, Dr. Pemán said, infection control staff went into action. They instituted contact precautions in the SICU, and took regular cultures from newly admitted patients and cultures of every SICU patient every 7 days.

“We also started an intense search for more cases throughout the hospital and in 101 SICU workers. Of 305 samples from hands and ears, we found nothing.” They reviewed all the prior fluconazole-resistant Candida isolates; C. auris was not present in the hospital before the index case.

Three weeks after case 2, six new SICU patients tested positive for C. auris (two blood cultures, one vascular line, one respiratory specimen, two rectal swabs, and one urinary tract sample).

“We reinforced contact precautions in colonized and infected patients and started a twice-daily environmental cleaning practice with quaternary ammonium around them,” said Dr. Pemán. They instituted a proactive hospital-wide hand hygiene campaign and spread the word about the outbreak.

By July, there were 11 new colonized patients, 3 of whom developed candidemia. These patients were grouped in the same SICU ward and underwent daily skin treatments with 4% aqueous chlorhexidine wipes.

The environmental inspection found C. auris on beds, tables, walls, and the floor all around infected patients. The pathogen also was living on IV pumps, computer keyboards, and bedside tables. Blood pressure cuffs were a favorite haunt: 19 of 36 samples in the adjacent ICU were positive. These data were separately reported at ECCMID.

Despite all of these efforts at eradication, infections continued to rise. By November, there were 24 newly colonized patients and nine new candidemia episodes in SICU and regular ICU patients. In December, a new infection control bundle began: A surveillance nurse in the C. auris SICU ward was in charge of compliance; any patient with any yeast growth in culture was isolated, and staff used 2% alcohol chlorhexidine wipes before and after IV catheter handling. Staff also washed down all surfaces three times daily with a disinfectant.

Patients could leave isolation after three consecutive C. auris–negative cultures. After discharge, an ultraviolet light decontamination procedure disinfected each patient room.

The pathogen was almost unbelievably resilient, Dr. Pemán noted in the Mycoses article. “In some cases, C. auris was recovered from walls after cleaning with cationic surface–active products ... it was not known until very recently that these products, as well as quaternary ammonium disinfectants, cannot effectively remove C. auris from surfaces.”

As a result of the previous measures, the outbreak slowed down during December 2016, with two new candidemia cases, but by February, the outbreak resumed with 50 new cases and 18 candidemias detected. Cases continued to emerge throughout 2017.

By September 2017, 250 patients had been colonized; 116 of these were included in the Mycoses report. There were 30 episodes of candidemia (26%); of these, 17 died by 30 days (41.4%). Spondylodiscitis and endocarditis each developed in two patients and one developed ventriculitis.

A separate poster by Dr. Pemán and his colleagues gave more details:

• A 52-year-old woman with C. auris–induced endocarditis died after 4 weeks of treatment with AMB+ECN and flucytosine. She had undergone a prosthetic heart valve placement for Ebstein’s anomaly.

• A 71-year-old man with hydrocephalus developed a C. auris–induced infection of his ventriculoperitoneal shunt; he also had undergone cardiovascular surgery and had an ischemic cardiomyopathy. He died despite shunt removal and 8 weeks of AMB+ECN.

• A 71-year-old man who underwent cardiovascular surgery and received a prosthetic heart valve developed endocarditis. He is alive and at last report, on week 26 of AMB+ECN, flucytosine, and isavuconazole.

• A 68-year-old man who underwent abdominal surgery for hepatocellular carcinoma developed spondylodiscitis and is alive after 24 weeks of AMB+ECN.

• A 48-year old female multiple trauma patient developed spondylodiscitis and is alive after 48 weeks of treatment with AMB+ECN.

A multivariate analysis determined that antibacterial treatment increased the risk of candidemia by almost 30 times (odds ratio, 29.59). The next highest risk was neutropenia (OR, 20.7) and then simply being a hospital and SICU patient. Dr. Pemán’s poster said, “In the 16 months before the index case, La Fe recorded 89 candidemias, none caused by C. auris. In the 16 months afterward, there were 154 candidemias, largely C. auris. Before April 2016, C. parapsilosis accounted for the largest portion of candidemias (46%) followed by C. albicans. After the index case, C. auris accounted for 42%, followed by C. parapsilosis (21%) and C. albicans (18%).”

Because of its fluconazole resistance, patients with C. auris received a combined antifungal treatment of liposomal amphotericin B 3 mg/kg per day for 5 days, and a standard dose of echinocandin for 3 weeks. Many C. auris strains are echinocandin resistant, Dr. Pemán noted. This particular strain was clonal, different from any other previously reported, he said.

“Our results confirm those previously reported by other authors, that C. auris is grouped in different independent clusters according to its geographical origin. Although all Spanish isolates were genotypically distinct from Indian, Omani, U.K., and Venezuelan isolates, there seems to be some connection with South African isolates.”

Hospital Le Fe continues to struggle with C. auris. As of March, 335 patients have tested positive for the pathogen, and 80 have developed candidemias.

“We feel we may be approaching the end of this episode, but it’s really not possible to be sure,” he said.

Dr. Pemán had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: ECCMID 2018 Peman et al. S0067.

REPORTING FROM ECCMID 2018

LAAC in nonvalvular AF provides stroke protection comparable to warfarin

Background: Because thrombi typically form in the left atrial appendage, LAAC may be an alternative to chronic oral anticoagulation in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Two prior randomized controlled trials compared outcomes in patients treated with LAAC with outcomes with warfarin. PROTECT AF trial showed noninferiority of LAAC to warfarin but noted high procedural complication rates. Subsequently, PREVAIL trial failed to demonstrate noninferiority, although complication rates were low overall and similar in both groups. However, longer-term follow-up data were lacking.

Study design: Patient-level meta-analysis of two prospective randomized trials.

Setting: Fifty-nine centers in the United States and Europe (PROTECT AF trial) and 41 centers in the United States (PREVAIL trial).

Synopsis: Meta-analysis of 5-year follow-up data from 1,114 adult patients with atrial fibrillation, most with CHADS2 score greater than or equal to 2 , randomized to receive LAAC or warfarin showed similar frequency of the composite endpoint of stroke, systemic embolism, or cardiovascular/unexplained death (hazard ratio, 0.820; P = .27). Subgroup analysis showed no significant difference in outcomes by patient subset, including CHADS2 or HAS-BLED scores. While the rate of ischemic stroke was similar between groups, the rates of hemorrhagic and disabling/fatal stroke were significantly lower with LAAC (HR, 0.20; P = .0022 and HR, 0.45; P = .034, respectively). All-cause and cardiovascular mortality also were significantly lower with LAAC (HR, 0.73; P = .035 and HR, 0.59; P = .027, respectively), likely because of lower incidence of hemorrhagic stroke.

These data cannot be generalized to patients who have an absolute contraindication to anticoagulation, as these patients were excluded. Further, these trials were conducted before widespread clinical use of novel oral anticoagulants, and LAAC has not yet been compared with these anticoagulants.

Bottom line: In patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, LAAC with the Watchman device provides all-stroke prevention comparable with that of warfarin, and is associated with significantly lower rates of hemorrhagic stroke, disabling or fatal stroke, and mortality.

Citation: Reddy VY et al. 5-year outcomes after left atrial appendage closure: From the PREVAIL and PROTECT AF trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(24):2964-75.

Dr. Indovina is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Background: Because thrombi typically form in the left atrial appendage, LAAC may be an alternative to chronic oral anticoagulation in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Two prior randomized controlled trials compared outcomes in patients treated with LAAC with outcomes with warfarin. PROTECT AF trial showed noninferiority of LAAC to warfarin but noted high procedural complication rates. Subsequently, PREVAIL trial failed to demonstrate noninferiority, although complication rates were low overall and similar in both groups. However, longer-term follow-up data were lacking.

Study design: Patient-level meta-analysis of two prospective randomized trials.

Setting: Fifty-nine centers in the United States and Europe (PROTECT AF trial) and 41 centers in the United States (PREVAIL trial).

Synopsis: Meta-analysis of 5-year follow-up data from 1,114 adult patients with atrial fibrillation, most with CHADS2 score greater than or equal to 2 , randomized to receive LAAC or warfarin showed similar frequency of the composite endpoint of stroke, systemic embolism, or cardiovascular/unexplained death (hazard ratio, 0.820; P = .27). Subgroup analysis showed no significant difference in outcomes by patient subset, including CHADS2 or HAS-BLED scores. While the rate of ischemic stroke was similar between groups, the rates of hemorrhagic and disabling/fatal stroke were significantly lower with LAAC (HR, 0.20; P = .0022 and HR, 0.45; P = .034, respectively). All-cause and cardiovascular mortality also were significantly lower with LAAC (HR, 0.73; P = .035 and HR, 0.59; P = .027, respectively), likely because of lower incidence of hemorrhagic stroke.

These data cannot be generalized to patients who have an absolute contraindication to anticoagulation, as these patients were excluded. Further, these trials were conducted before widespread clinical use of novel oral anticoagulants, and LAAC has not yet been compared with these anticoagulants.

Bottom line: In patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, LAAC with the Watchman device provides all-stroke prevention comparable with that of warfarin, and is associated with significantly lower rates of hemorrhagic stroke, disabling or fatal stroke, and mortality.

Citation: Reddy VY et al. 5-year outcomes after left atrial appendage closure: From the PREVAIL and PROTECT AF trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(24):2964-75.

Dr. Indovina is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Background: Because thrombi typically form in the left atrial appendage, LAAC may be an alternative to chronic oral anticoagulation in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Two prior randomized controlled trials compared outcomes in patients treated with LAAC with outcomes with warfarin. PROTECT AF trial showed noninferiority of LAAC to warfarin but noted high procedural complication rates. Subsequently, PREVAIL trial failed to demonstrate noninferiority, although complication rates were low overall and similar in both groups. However, longer-term follow-up data were lacking.

Study design: Patient-level meta-analysis of two prospective randomized trials.

Setting: Fifty-nine centers in the United States and Europe (PROTECT AF trial) and 41 centers in the United States (PREVAIL trial).

Synopsis: Meta-analysis of 5-year follow-up data from 1,114 adult patients with atrial fibrillation, most with CHADS2 score greater than or equal to 2 , randomized to receive LAAC or warfarin showed similar frequency of the composite endpoint of stroke, systemic embolism, or cardiovascular/unexplained death (hazard ratio, 0.820; P = .27). Subgroup analysis showed no significant difference in outcomes by patient subset, including CHADS2 or HAS-BLED scores. While the rate of ischemic stroke was similar between groups, the rates of hemorrhagic and disabling/fatal stroke were significantly lower with LAAC (HR, 0.20; P = .0022 and HR, 0.45; P = .034, respectively). All-cause and cardiovascular mortality also were significantly lower with LAAC (HR, 0.73; P = .035 and HR, 0.59; P = .027, respectively), likely because of lower incidence of hemorrhagic stroke.

These data cannot be generalized to patients who have an absolute contraindication to anticoagulation, as these patients were excluded. Further, these trials were conducted before widespread clinical use of novel oral anticoagulants, and LAAC has not yet been compared with these anticoagulants.

Bottom line: In patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, LAAC with the Watchman device provides all-stroke prevention comparable with that of warfarin, and is associated with significantly lower rates of hemorrhagic stroke, disabling or fatal stroke, and mortality.

Citation: Reddy VY et al. 5-year outcomes after left atrial appendage closure: From the PREVAIL and PROTECT AF trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(24):2964-75.

Dr. Indovina is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

No clear benefit of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation in the community after hospital discharge

Clinical question: Does pharmacist-led medication reconciliation in the community after hospital discharge reduce health care utilization, readmission rates, ED visits, primary care visits, or primary care workload?

Background: Accurate medication reconciliation is essential to ensure safe transitions of care after hospital discharge. Studies have shown that harm from prescribed or omitted medications is higher after discharge and pharmacist-led medication reconciliation on discharge has been shown to improve clinical outcomes. The effect of medication reconciliation after discharge performed by primary care and community-based pharmacist is unclear.

Study design: A meta-analysis.

Setting: This meta-analysis included five randomized, controlled trials, six cohort studies, two pre- and postintervention studies performed in the United Kingdom and United States as well as one quality improvement project performed in Canada.

Synopsis: The studies included demonstrated that community-based pharmacists were more effective at identifying and resolving discrepancies, compared with usual care, but the clinical relevance was unclear. There was no evidence that this reduced readmission rates. Because of the the heterogeneity of the settings, methods, and data reporting in the included trials, no firm conclusion could be drawn regarding the impact on either ED visits and primary care burden, and no consistent evidence of benefit was found. The benefit in clinical outcomes seen in prior studies may be related to other interventions, including patient education, medication review, and improved communication with primary care physicians. This study aimed to specifically isolate the impact of postdischarge, pharmacist-led medication reconciliation, and further research is still needed to understand the clinical relevance of medication discrepancies and which pharmacist-led interventions are most important.

Bottom line: Community-based pharmacists can identify and resolve discrepancies while performing medication reconciliation after hospital discharge, but there is no conclusive benefit in clinical outcomes, such as readmission rates, health care utilization, and primary care visits.

Citation: McNab D et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation in the community after hospital discharge. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017 Dec 16. pii: bmjqs-2017-007087. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007087.

Dr. Rao is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Clinical question: Does pharmacist-led medication reconciliation in the community after hospital discharge reduce health care utilization, readmission rates, ED visits, primary care visits, or primary care workload?

Background: Accurate medication reconciliation is essential to ensure safe transitions of care after hospital discharge. Studies have shown that harm from prescribed or omitted medications is higher after discharge and pharmacist-led medication reconciliation on discharge has been shown to improve clinical outcomes. The effect of medication reconciliation after discharge performed by primary care and community-based pharmacist is unclear.

Study design: A meta-analysis.

Setting: This meta-analysis included five randomized, controlled trials, six cohort studies, two pre- and postintervention studies performed in the United Kingdom and United States as well as one quality improvement project performed in Canada.

Synopsis: The studies included demonstrated that community-based pharmacists were more effective at identifying and resolving discrepancies, compared with usual care, but the clinical relevance was unclear. There was no evidence that this reduced readmission rates. Because of the the heterogeneity of the settings, methods, and data reporting in the included trials, no firm conclusion could be drawn regarding the impact on either ED visits and primary care burden, and no consistent evidence of benefit was found. The benefit in clinical outcomes seen in prior studies may be related to other interventions, including patient education, medication review, and improved communication with primary care physicians. This study aimed to specifically isolate the impact of postdischarge, pharmacist-led medication reconciliation, and further research is still needed to understand the clinical relevance of medication discrepancies and which pharmacist-led interventions are most important.