User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

What is the microbiology of liver abscess?

Case

A 29-year-old woman with chronic urticaria, previously on omalizumab, presented with 2 weeks of abdominal pain and fever. She had traveled to Nicaragua within the past 10 months. CT showed a 6 x 5 cm liver abscess. Entamoeba histolytica was detected by stool polymerase chain reaction, and E. histolytica antibody was positive. The abscess was drained, and she completed a 10-day course of metronidazole followed by a 7-day course of paromomycin.

Brief overview

Bacterial, parasitic, and fungal organisms can cause liver abscess. Worldwide, bacteria are the most common cause of liver abscess. Infection is usually polymicrobial, though Klebsiella and the Streptococcus milleri group are the most common organisms identified.

Entamoeba histolytica is the most frequent cause of amoebic liver abscess and should be strongly considered in a returning traveler, visitor from another country, or those on monoclonal antibody therapy directed against IgE such as omalizumab. Candida species are the most common fungal etiology; an example being hepatosplenic candidiasis in hematologic malignancies.

Overview of the data

Pyogenic liver abscess. A variety of bacteria have been isolated from pyogenic liver abscesses (PLA) because of differences in mechanism of infection (such as biliary tract interventions, postoperative complications, and hematogenous spread), immunocompromised states, and geographical variation. The literature is not robust for pyogenic liver abscesses, and the microbiology isolated via epidemiologic studies are confounded by the mechanism of infection and thus difficult to generalize.

Initially, the Enterobacteriaceae including Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli were the most common cause of PLA in the United States. The emergence of improved culturing techniques, which has improved the yield of facultative anaerobes such as the Streptococcus milleri (also known as Streptococcus anginosus) group, has led to an increased incidence and wider assortment of bacteria, with a more recent study of 38 patients in the Cleveland Clinic system showing that about half of the PLA were polymicrobial with the predominant organism when monomicrobial being of the Strep milleri group in 9/22 patients (Chemaly et al.).

Biliary tract disease, whether from choledocholithiasis, stricture, or malignant obstruction is the most common etiology of PLA. Much of the PLA-focused literature is from Asia, where Klebsiella is more commonly a cause of liver abscess. In a study of 248 Taiwanese patients with PLA, Klebsiella was responsible for 69% of PLA (Yang et al.). In a study of 79 patients hospitalized in New York, Klebsiella was the most common bacteria isolated, although more than half of the patients studied were Asian, and Klebsiella was more common among Asian patients than the other groups studied. An 8-year analysis of patients admitted to a University Hospital in Taiwan with cryptogenic PLA showed that the etiology was Klebsiella in 46/52 patients (Chen et al.). Most patients with Klebsiella liver abscess have documented bacteremia.

The second most common mechanism is bacterial translocation through the portal venous system. E. coli is commonly isolated and is frequently spread from intra-abdominal infections such as appendicitis leading to pylephlebitis. As the diagnosis and management of appendicitis has improved, the incidence of appendicitis causing a PLA has decreased.

PLA should be cultured to guide therapy and catheter drainage may be required. However, common organisms causing liver abscess should also be considered when selecting initial antibiotic therapy as cultures are frequently affected by previous antibiotic exposure or imprecise culturing techniques. Blood cultures should be obtained, and empiric therapy with a beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor or third-generation cephalosporin plus metronidazole should be started thereafter.

Entamoeba histolytica. E. histolytica, an anaerobic parasite that can lead to amoebic dysentery and liver abscess, affects upwards of 50 million people worldwide, predominantly in India and sub-Saharan Africa. Travel to an endemic area for longer than 1 month carries a high risk of transmission, though cases have been described with less than a week of exposure.

Infection occurs following consumption of affected food or water and can lead to dysentery within 3 weeks. Fever and right upper quadrant pain develop later, anywhere from 3 months to years following initial exposure. To diagnose, both serologic and stool testing for E. histolytica are recommended owing to the high sensitivity and low specificity of the serologic antibody test and the low sensitivity and high specificity of the stool antigen test. Imaging may reveal a single cyst with surrounding edema, which is characteristic.

Effective treatment is a two-step process. Metronidazole targets trophozoites that cause liver abscesses followed by paromomycin or diloxanide furoate to eradicate luminal oocysts and prevent reinfection. Aspiration and catheter drainage is necessary if the microbiology or etiology of the liver abscess remains uncertain, patients are not responding to antibiotics, or there is concern for impending rupture with cyst size greater than 6 cm (Jun et al.).

Hydatid cysts. Serologic testing via enzyme-linked immunoassay and radiographic characteristics are used to diagnose cysts caused by Echinococcus, of which there are many species. Imaging typically shows a well-defined cyst with calcifications and budding daughter cysts. Aspiration of an echinococcal cyst carries a risk of anaphylaxis and spread of infection and should only be undertaken if there is serologic and radiographic uncertainty.

Fungal abscesses. Fungal abscesses are most commonly caused by Candida species. The typical patient presentation includes high fever and elevated alkaline phosphatase, usually during the count recovery phase of patients with hematologic malignancies undergoing chemotherapy.

Fungal abscesses are frequently too small to aspirate. Fortunately, serum and radiographic results, as well as the clinical setting, make diagnosis more straightforward. Serum fungal markers can be checked and empiric treatment with amphotericin B or an echinocandin is recommended, followed by narrowing to oral fluconazole. Treatment should continue until abscesses resolve.

Interestingly, if patients become neutropenic during their antifungal course, the microabscesses may disappear on CT or MRI, only to reappear once neutrophils return. Once patients have a stable neutrophil count and imaging shows no abscesses, antifungal treatment can be discontinued, but must be restarted if patients are to undergo additional chemotherapy with expected neutropenia.

Back to the case

While impossible to state with certainty, infection with E. histolytica while in Nicaragua was thought most likely in this case. This patient was on omalizumab for chronic urticaria immediately prior to acquiring the infection and this anti-IgE monoclonal antibody likely predisposed her to a parasitic infection. Knowing this epidemiology, she may not have required catheter drainage, however, the cyst was causing pain and drainage provided decompression. She was treated with antibiotics followed by paromomycin.

Bottom line

Entamoeba histolytica is the most common cause of liver abscess worldwide, but identifying risk factors and mechanism of infection can lead to the most likely infecting organism.

Dr. Mehra is assistant professor of medicine in the Section of Hospital Medicine at the University of Virginia Medical Center and School of Medicine, Charlottesville. Dr. Parsons is also assistant professor of medicine in the Section of Hospital Medicine at the University of Virginia Medical Center and School of Medicine.

References

Chemaly RF. Microbiology of liver abscesses and the predictive value of abscess gram stain and associated blood cultures. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;46(4):245-8.

Yang CC. Comparison of pyogenic liver abscess caused by non-Klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2004;37(3):176.

Chen SC. Comparison of pyogenic liver abscesses of biliary and cryptogenic origin. An eight-year analysis in a University Hospital. Swiss Med Wkly. 2005;135(23-24):344-51.

Yang CC. Pyogenic liver abscess in Taiwan: emphasis on gas-forming liver abscess in diabetics. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1911-15.

Jun CH. Risk factors and clinical outcomes for spontaneous rupture of pyogenic liver abscess. J Dig Dis. 2015;16(1):31-6.

Smego RA Jr. Treatment options for hepatic cystic echinococcosis. Int J Infect Dis. 2005;9(2):69-76.

Additional reading

Huang CJ et al. Pyogenic hepatic abscess. Changing trends over 42 years. Ann Surg. 1996;223(5):600-7.

Meddings L et al. A population-based study of pyogenic liver abscesses in the United States: incidence, mortality, and temporal trends. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(1):117-24..

Petri WA, Singh U. Diagnosis and management of amoebiasis. Clin Infect Dis. 1999 Nov;29(5):1117-25.

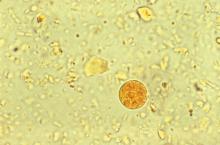

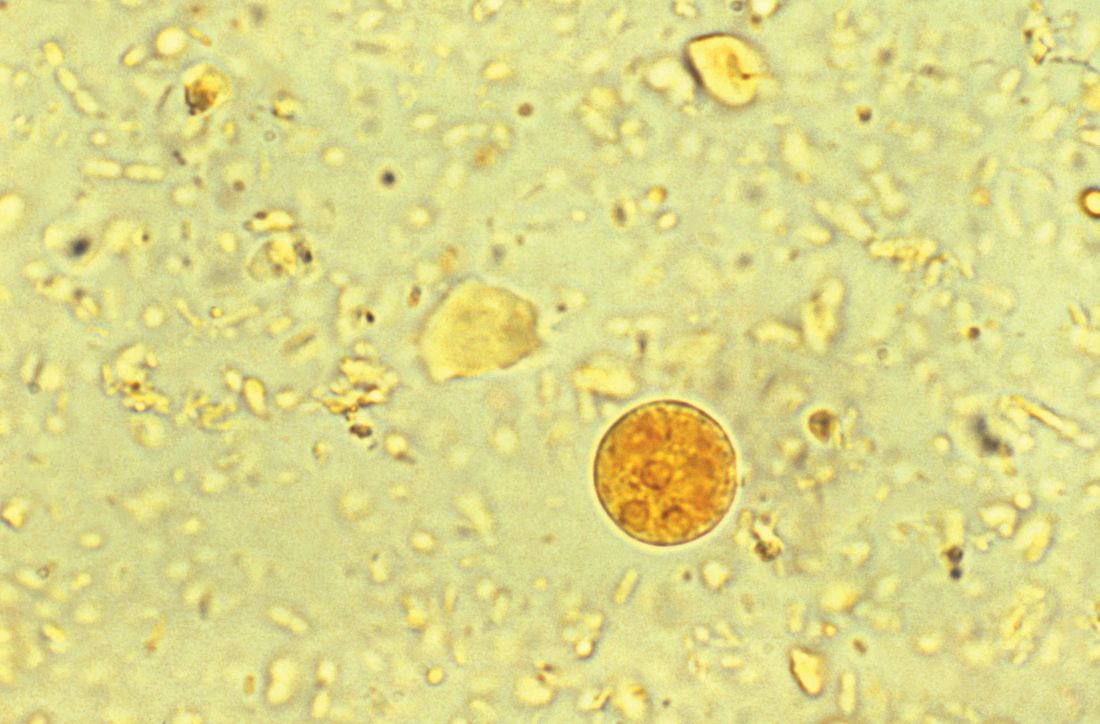

Accompanying Photo caption: CT scan showing E. histolytica liver abscess. RELATED PHOTO IS PHOTOMICROGRAPH, NOT CT SCAN. G

Quiz

Microbiology of liver abscesses

Bacterial, parasitic, and fungal organisms can all cause liver abscesses. History, including travel history, is very important in deciphering which organisms are present.

Question 1: What is the most common cause of an amoebic liver abscess worldwide?

A. Echinococcus

B. Klebsiella pneumoniae

C. Entamoeba histolytica

D. Escherichia coli

The best answer is choice C. E. histolytica causes amoebic dysentery and liver abscess. This anaerobic parasite affects 50 million people worldwide, with the highest prevalence in India, sub-Saharan Africa, Mexico, and parts of Central and South America. Travelers spending a month or more in endemic areas are at highest risk, but cases have been reported with less than one week of exposure.

Question 2: Which type of parasitic cyst should not be aspirated?

A. Echinococcus

B. Entamoeba histolytica

C. Schistosomiasis

D. Paramoeba

The best answer is choice A. Aspiration of an echinococcal cyst carries a risk of anaphylaxis and spread of infection and should only be done if there is serologic and radiographic uncertainty. Imaging typically shows a well-defined cyst with calcifications and budding daughter cysts.

Key Points

- Risk factors and mechanism of action will suggest the most likely organisms and guide antibiotic choice.

- Entamoeba histolytica is the most common cause of liver abscess worldwide.

- Stool PCR and antibody testing for E. histolytica should both be ordered in the work-up of a liver abscess.

- Calcifications and daughter cysts budding off the main cyst can distinguish echinococcal cyst from E. histolytica abscess radiographically.

Case

A 29-year-old woman with chronic urticaria, previously on omalizumab, presented with 2 weeks of abdominal pain and fever. She had traveled to Nicaragua within the past 10 months. CT showed a 6 x 5 cm liver abscess. Entamoeba histolytica was detected by stool polymerase chain reaction, and E. histolytica antibody was positive. The abscess was drained, and she completed a 10-day course of metronidazole followed by a 7-day course of paromomycin.

Brief overview

Bacterial, parasitic, and fungal organisms can cause liver abscess. Worldwide, bacteria are the most common cause of liver abscess. Infection is usually polymicrobial, though Klebsiella and the Streptococcus milleri group are the most common organisms identified.

Entamoeba histolytica is the most frequent cause of amoebic liver abscess and should be strongly considered in a returning traveler, visitor from another country, or those on monoclonal antibody therapy directed against IgE such as omalizumab. Candida species are the most common fungal etiology; an example being hepatosplenic candidiasis in hematologic malignancies.

Overview of the data

Pyogenic liver abscess. A variety of bacteria have been isolated from pyogenic liver abscesses (PLA) because of differences in mechanism of infection (such as biliary tract interventions, postoperative complications, and hematogenous spread), immunocompromised states, and geographical variation. The literature is not robust for pyogenic liver abscesses, and the microbiology isolated via epidemiologic studies are confounded by the mechanism of infection and thus difficult to generalize.

Initially, the Enterobacteriaceae including Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli were the most common cause of PLA in the United States. The emergence of improved culturing techniques, which has improved the yield of facultative anaerobes such as the Streptococcus milleri (also known as Streptococcus anginosus) group, has led to an increased incidence and wider assortment of bacteria, with a more recent study of 38 patients in the Cleveland Clinic system showing that about half of the PLA were polymicrobial with the predominant organism when monomicrobial being of the Strep milleri group in 9/22 patients (Chemaly et al.).

Biliary tract disease, whether from choledocholithiasis, stricture, or malignant obstruction is the most common etiology of PLA. Much of the PLA-focused literature is from Asia, where Klebsiella is more commonly a cause of liver abscess. In a study of 248 Taiwanese patients with PLA, Klebsiella was responsible for 69% of PLA (Yang et al.). In a study of 79 patients hospitalized in New York, Klebsiella was the most common bacteria isolated, although more than half of the patients studied were Asian, and Klebsiella was more common among Asian patients than the other groups studied. An 8-year analysis of patients admitted to a University Hospital in Taiwan with cryptogenic PLA showed that the etiology was Klebsiella in 46/52 patients (Chen et al.). Most patients with Klebsiella liver abscess have documented bacteremia.

The second most common mechanism is bacterial translocation through the portal venous system. E. coli is commonly isolated and is frequently spread from intra-abdominal infections such as appendicitis leading to pylephlebitis. As the diagnosis and management of appendicitis has improved, the incidence of appendicitis causing a PLA has decreased.

PLA should be cultured to guide therapy and catheter drainage may be required. However, common organisms causing liver abscess should also be considered when selecting initial antibiotic therapy as cultures are frequently affected by previous antibiotic exposure or imprecise culturing techniques. Blood cultures should be obtained, and empiric therapy with a beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor or third-generation cephalosporin plus metronidazole should be started thereafter.

Entamoeba histolytica. E. histolytica, an anaerobic parasite that can lead to amoebic dysentery and liver abscess, affects upwards of 50 million people worldwide, predominantly in India and sub-Saharan Africa. Travel to an endemic area for longer than 1 month carries a high risk of transmission, though cases have been described with less than a week of exposure.

Infection occurs following consumption of affected food or water and can lead to dysentery within 3 weeks. Fever and right upper quadrant pain develop later, anywhere from 3 months to years following initial exposure. To diagnose, both serologic and stool testing for E. histolytica are recommended owing to the high sensitivity and low specificity of the serologic antibody test and the low sensitivity and high specificity of the stool antigen test. Imaging may reveal a single cyst with surrounding edema, which is characteristic.

Effective treatment is a two-step process. Metronidazole targets trophozoites that cause liver abscesses followed by paromomycin or diloxanide furoate to eradicate luminal oocysts and prevent reinfection. Aspiration and catheter drainage is necessary if the microbiology or etiology of the liver abscess remains uncertain, patients are not responding to antibiotics, or there is concern for impending rupture with cyst size greater than 6 cm (Jun et al.).

Hydatid cysts. Serologic testing via enzyme-linked immunoassay and radiographic characteristics are used to diagnose cysts caused by Echinococcus, of which there are many species. Imaging typically shows a well-defined cyst with calcifications and budding daughter cysts. Aspiration of an echinococcal cyst carries a risk of anaphylaxis and spread of infection and should only be undertaken if there is serologic and radiographic uncertainty.

Fungal abscesses. Fungal abscesses are most commonly caused by Candida species. The typical patient presentation includes high fever and elevated alkaline phosphatase, usually during the count recovery phase of patients with hematologic malignancies undergoing chemotherapy.

Fungal abscesses are frequently too small to aspirate. Fortunately, serum and radiographic results, as well as the clinical setting, make diagnosis more straightforward. Serum fungal markers can be checked and empiric treatment with amphotericin B or an echinocandin is recommended, followed by narrowing to oral fluconazole. Treatment should continue until abscesses resolve.

Interestingly, if patients become neutropenic during their antifungal course, the microabscesses may disappear on CT or MRI, only to reappear once neutrophils return. Once patients have a stable neutrophil count and imaging shows no abscesses, antifungal treatment can be discontinued, but must be restarted if patients are to undergo additional chemotherapy with expected neutropenia.

Back to the case

While impossible to state with certainty, infection with E. histolytica while in Nicaragua was thought most likely in this case. This patient was on omalizumab for chronic urticaria immediately prior to acquiring the infection and this anti-IgE monoclonal antibody likely predisposed her to a parasitic infection. Knowing this epidemiology, she may not have required catheter drainage, however, the cyst was causing pain and drainage provided decompression. She was treated with antibiotics followed by paromomycin.

Bottom line

Entamoeba histolytica is the most common cause of liver abscess worldwide, but identifying risk factors and mechanism of infection can lead to the most likely infecting organism.

Dr. Mehra is assistant professor of medicine in the Section of Hospital Medicine at the University of Virginia Medical Center and School of Medicine, Charlottesville. Dr. Parsons is also assistant professor of medicine in the Section of Hospital Medicine at the University of Virginia Medical Center and School of Medicine.

References

Chemaly RF. Microbiology of liver abscesses and the predictive value of abscess gram stain and associated blood cultures. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;46(4):245-8.

Yang CC. Comparison of pyogenic liver abscess caused by non-Klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2004;37(3):176.

Chen SC. Comparison of pyogenic liver abscesses of biliary and cryptogenic origin. An eight-year analysis in a University Hospital. Swiss Med Wkly. 2005;135(23-24):344-51.

Yang CC. Pyogenic liver abscess in Taiwan: emphasis on gas-forming liver abscess in diabetics. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1911-15.

Jun CH. Risk factors and clinical outcomes for spontaneous rupture of pyogenic liver abscess. J Dig Dis. 2015;16(1):31-6.

Smego RA Jr. Treatment options for hepatic cystic echinococcosis. Int J Infect Dis. 2005;9(2):69-76.

Additional reading

Huang CJ et al. Pyogenic hepatic abscess. Changing trends over 42 years. Ann Surg. 1996;223(5):600-7.

Meddings L et al. A population-based study of pyogenic liver abscesses in the United States: incidence, mortality, and temporal trends. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(1):117-24..

Petri WA, Singh U. Diagnosis and management of amoebiasis. Clin Infect Dis. 1999 Nov;29(5):1117-25.

Accompanying Photo caption: CT scan showing E. histolytica liver abscess. RELATED PHOTO IS PHOTOMICROGRAPH, NOT CT SCAN. G

Quiz

Microbiology of liver abscesses

Bacterial, parasitic, and fungal organisms can all cause liver abscesses. History, including travel history, is very important in deciphering which organisms are present.

Question 1: What is the most common cause of an amoebic liver abscess worldwide?

A. Echinococcus

B. Klebsiella pneumoniae

C. Entamoeba histolytica

D. Escherichia coli

The best answer is choice C. E. histolytica causes amoebic dysentery and liver abscess. This anaerobic parasite affects 50 million people worldwide, with the highest prevalence in India, sub-Saharan Africa, Mexico, and parts of Central and South America. Travelers spending a month or more in endemic areas are at highest risk, but cases have been reported with less than one week of exposure.

Question 2: Which type of parasitic cyst should not be aspirated?

A. Echinococcus

B. Entamoeba histolytica

C. Schistosomiasis

D. Paramoeba

The best answer is choice A. Aspiration of an echinococcal cyst carries a risk of anaphylaxis and spread of infection and should only be done if there is serologic and radiographic uncertainty. Imaging typically shows a well-defined cyst with calcifications and budding daughter cysts.

Key Points

- Risk factors and mechanism of action will suggest the most likely organisms and guide antibiotic choice.

- Entamoeba histolytica is the most common cause of liver abscess worldwide.

- Stool PCR and antibody testing for E. histolytica should both be ordered in the work-up of a liver abscess.

- Calcifications and daughter cysts budding off the main cyst can distinguish echinococcal cyst from E. histolytica abscess radiographically.

Case

A 29-year-old woman with chronic urticaria, previously on omalizumab, presented with 2 weeks of abdominal pain and fever. She had traveled to Nicaragua within the past 10 months. CT showed a 6 x 5 cm liver abscess. Entamoeba histolytica was detected by stool polymerase chain reaction, and E. histolytica antibody was positive. The abscess was drained, and she completed a 10-day course of metronidazole followed by a 7-day course of paromomycin.

Brief overview

Bacterial, parasitic, and fungal organisms can cause liver abscess. Worldwide, bacteria are the most common cause of liver abscess. Infection is usually polymicrobial, though Klebsiella and the Streptococcus milleri group are the most common organisms identified.

Entamoeba histolytica is the most frequent cause of amoebic liver abscess and should be strongly considered in a returning traveler, visitor from another country, or those on monoclonal antibody therapy directed against IgE such as omalizumab. Candida species are the most common fungal etiology; an example being hepatosplenic candidiasis in hematologic malignancies.

Overview of the data

Pyogenic liver abscess. A variety of bacteria have been isolated from pyogenic liver abscesses (PLA) because of differences in mechanism of infection (such as biliary tract interventions, postoperative complications, and hematogenous spread), immunocompromised states, and geographical variation. The literature is not robust for pyogenic liver abscesses, and the microbiology isolated via epidemiologic studies are confounded by the mechanism of infection and thus difficult to generalize.

Initially, the Enterobacteriaceae including Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli were the most common cause of PLA in the United States. The emergence of improved culturing techniques, which has improved the yield of facultative anaerobes such as the Streptococcus milleri (also known as Streptococcus anginosus) group, has led to an increased incidence and wider assortment of bacteria, with a more recent study of 38 patients in the Cleveland Clinic system showing that about half of the PLA were polymicrobial with the predominant organism when monomicrobial being of the Strep milleri group in 9/22 patients (Chemaly et al.).

Biliary tract disease, whether from choledocholithiasis, stricture, or malignant obstruction is the most common etiology of PLA. Much of the PLA-focused literature is from Asia, where Klebsiella is more commonly a cause of liver abscess. In a study of 248 Taiwanese patients with PLA, Klebsiella was responsible for 69% of PLA (Yang et al.). In a study of 79 patients hospitalized in New York, Klebsiella was the most common bacteria isolated, although more than half of the patients studied were Asian, and Klebsiella was more common among Asian patients than the other groups studied. An 8-year analysis of patients admitted to a University Hospital in Taiwan with cryptogenic PLA showed that the etiology was Klebsiella in 46/52 patients (Chen et al.). Most patients with Klebsiella liver abscess have documented bacteremia.

The second most common mechanism is bacterial translocation through the portal venous system. E. coli is commonly isolated and is frequently spread from intra-abdominal infections such as appendicitis leading to pylephlebitis. As the diagnosis and management of appendicitis has improved, the incidence of appendicitis causing a PLA has decreased.

PLA should be cultured to guide therapy and catheter drainage may be required. However, common organisms causing liver abscess should also be considered when selecting initial antibiotic therapy as cultures are frequently affected by previous antibiotic exposure or imprecise culturing techniques. Blood cultures should be obtained, and empiric therapy with a beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor or third-generation cephalosporin plus metronidazole should be started thereafter.

Entamoeba histolytica. E. histolytica, an anaerobic parasite that can lead to amoebic dysentery and liver abscess, affects upwards of 50 million people worldwide, predominantly in India and sub-Saharan Africa. Travel to an endemic area for longer than 1 month carries a high risk of transmission, though cases have been described with less than a week of exposure.

Infection occurs following consumption of affected food or water and can lead to dysentery within 3 weeks. Fever and right upper quadrant pain develop later, anywhere from 3 months to years following initial exposure. To diagnose, both serologic and stool testing for E. histolytica are recommended owing to the high sensitivity and low specificity of the serologic antibody test and the low sensitivity and high specificity of the stool antigen test. Imaging may reveal a single cyst with surrounding edema, which is characteristic.

Effective treatment is a two-step process. Metronidazole targets trophozoites that cause liver abscesses followed by paromomycin or diloxanide furoate to eradicate luminal oocysts and prevent reinfection. Aspiration and catheter drainage is necessary if the microbiology or etiology of the liver abscess remains uncertain, patients are not responding to antibiotics, or there is concern for impending rupture with cyst size greater than 6 cm (Jun et al.).

Hydatid cysts. Serologic testing via enzyme-linked immunoassay and radiographic characteristics are used to diagnose cysts caused by Echinococcus, of which there are many species. Imaging typically shows a well-defined cyst with calcifications and budding daughter cysts. Aspiration of an echinococcal cyst carries a risk of anaphylaxis and spread of infection and should only be undertaken if there is serologic and radiographic uncertainty.

Fungal abscesses. Fungal abscesses are most commonly caused by Candida species. The typical patient presentation includes high fever and elevated alkaline phosphatase, usually during the count recovery phase of patients with hematologic malignancies undergoing chemotherapy.

Fungal abscesses are frequently too small to aspirate. Fortunately, serum and radiographic results, as well as the clinical setting, make diagnosis more straightforward. Serum fungal markers can be checked and empiric treatment with amphotericin B or an echinocandin is recommended, followed by narrowing to oral fluconazole. Treatment should continue until abscesses resolve.

Interestingly, if patients become neutropenic during their antifungal course, the microabscesses may disappear on CT or MRI, only to reappear once neutrophils return. Once patients have a stable neutrophil count and imaging shows no abscesses, antifungal treatment can be discontinued, but must be restarted if patients are to undergo additional chemotherapy with expected neutropenia.

Back to the case

While impossible to state with certainty, infection with E. histolytica while in Nicaragua was thought most likely in this case. This patient was on omalizumab for chronic urticaria immediately prior to acquiring the infection and this anti-IgE monoclonal antibody likely predisposed her to a parasitic infection. Knowing this epidemiology, she may not have required catheter drainage, however, the cyst was causing pain and drainage provided decompression. She was treated with antibiotics followed by paromomycin.

Bottom line

Entamoeba histolytica is the most common cause of liver abscess worldwide, but identifying risk factors and mechanism of infection can lead to the most likely infecting organism.

Dr. Mehra is assistant professor of medicine in the Section of Hospital Medicine at the University of Virginia Medical Center and School of Medicine, Charlottesville. Dr. Parsons is also assistant professor of medicine in the Section of Hospital Medicine at the University of Virginia Medical Center and School of Medicine.

References

Chemaly RF. Microbiology of liver abscesses and the predictive value of abscess gram stain and associated blood cultures. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;46(4):245-8.

Yang CC. Comparison of pyogenic liver abscess caused by non-Klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2004;37(3):176.

Chen SC. Comparison of pyogenic liver abscesses of biliary and cryptogenic origin. An eight-year analysis in a University Hospital. Swiss Med Wkly. 2005;135(23-24):344-51.

Yang CC. Pyogenic liver abscess in Taiwan: emphasis on gas-forming liver abscess in diabetics. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1911-15.

Jun CH. Risk factors and clinical outcomes for spontaneous rupture of pyogenic liver abscess. J Dig Dis. 2015;16(1):31-6.

Smego RA Jr. Treatment options for hepatic cystic echinococcosis. Int J Infect Dis. 2005;9(2):69-76.

Additional reading

Huang CJ et al. Pyogenic hepatic abscess. Changing trends over 42 years. Ann Surg. 1996;223(5):600-7.

Meddings L et al. A population-based study of pyogenic liver abscesses in the United States: incidence, mortality, and temporal trends. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(1):117-24..

Petri WA, Singh U. Diagnosis and management of amoebiasis. Clin Infect Dis. 1999 Nov;29(5):1117-25.

Accompanying Photo caption: CT scan showing E. histolytica liver abscess. RELATED PHOTO IS PHOTOMICROGRAPH, NOT CT SCAN. G

Quiz

Microbiology of liver abscesses

Bacterial, parasitic, and fungal organisms can all cause liver abscesses. History, including travel history, is very important in deciphering which organisms are present.

Question 1: What is the most common cause of an amoebic liver abscess worldwide?

A. Echinococcus

B. Klebsiella pneumoniae

C. Entamoeba histolytica

D. Escherichia coli

The best answer is choice C. E. histolytica causes amoebic dysentery and liver abscess. This anaerobic parasite affects 50 million people worldwide, with the highest prevalence in India, sub-Saharan Africa, Mexico, and parts of Central and South America. Travelers spending a month or more in endemic areas are at highest risk, but cases have been reported with less than one week of exposure.

Question 2: Which type of parasitic cyst should not be aspirated?

A. Echinococcus

B. Entamoeba histolytica

C. Schistosomiasis

D. Paramoeba

The best answer is choice A. Aspiration of an echinococcal cyst carries a risk of anaphylaxis and spread of infection and should only be done if there is serologic and radiographic uncertainty. Imaging typically shows a well-defined cyst with calcifications and budding daughter cysts.

Key Points

- Risk factors and mechanism of action will suggest the most likely organisms and guide antibiotic choice.

- Entamoeba histolytica is the most common cause of liver abscess worldwide.

- Stool PCR and antibody testing for E. histolytica should both be ordered in the work-up of a liver abscess.

- Calcifications and daughter cysts budding off the main cyst can distinguish echinococcal cyst from E. histolytica abscess radiographically.

Design limitations may have compromised DVT intervention trial

WASHINGTON – On the basis of a large randomized trial called ATTRACT, many clinicians have concluded that pharmacomechanical intervention is ineffective for preventing postthrombotic syndrome (PTS) in patients with deep venous thrombosis (DVT). But weaknesses in the study design challenge this conclusion, according to several experts in a DVT symposium at the 2018 Cardiovascular Research Technologies (CRT) meeting.

“The diagnosis and evaluation of DVT must be performed with IVUS [intravascular ultrasound], not with venography,” said Peter A. Soukas, MD, director of vascular medicine at Miriam Hospital in Providence, R.I. “You cannot know whether you successfully treated the clot if you cannot see it.”

“There were lots of limitations to that study. Here are some,” said Dr. Soukas, who then listed on a list of several considerations, including the fact that venograms – rather than IVUS, which Dr. Soukas labeled the “current gold standard” – were taken to evaluate procedure success. Another was that only half of patients had a moderate to severe DVT based on a Villalta score.

“If you look at the subgroup with a Villalta score of 10 or greater, the benefit [of pharmacomechanical intervention] was statistically significant,” he said.

In addition, the study enrolled a substantial number of patients with femoral-popliteal DVTs even though iliofemoral DVTs pose the greatest risk of postthrombotic syndrome. Dr. Soukas suggested these would have been a more appropriate focus of a study exploring the benefits of an intervention.

The limitations of the ATTRACT trial, which was conceived more than 5 years ago, have arisen primarily from advances in the field rather than problems with the design, Dr. Soukas explained. IVUS was not the preferred method for deep vein thrombosis evaluation then as it is now, and there have been several advances in current models of pharmacomechanical devices, which involve catheter-directed delivery of fibrinolytic therapy into the thrombus along with mechanical destruction of the clot.

Although further steps beyond clot lysis, such as stenting, were encouraged in ATTRACT to maintain venous patency, Dr. Soukas questioned whether these were employed sufficiently. For example, the rate of stenting in the experimental arm was 28%, a rate that “is not what we currently do” for patients at high risk of PTS, Dr. Soukas said.

In ATTRACT, major bleeding events were significantly higher in the experimental group (1.7% vs. 0.3%; P = .049). The authors cited this finding when they concluded that the experimental intervention was ineffective. Dr. Soukas acknowledged that bleeding risk is an important factor to consider, but he also emphasized the serious risks for failing to treat patients at high risk for PTS.

“PTS is devastating for patients, both functionally and economically,” Dr. Soukas said. He called the morbidity of deep vein thrombosis “staggering,” with in-hospital mortality in some series exceeding 10% and a risk of late development of postthrombotic syndrome persisting for up to 5 years. For those with proximal iliofemoral DVT, the PTS rate can reach 90%, about 15% of which can develop claudication with ulcerations, according to Dr. Soukas.

A large trial that was published in a prominent journal, ATTRACT has the potential to dissuade clinicians from considering pharmacomechanical intervention in high-risk patients who could benefit, Dr. Soukas said. Others speaking during the same symposium about advances in this field, such as John Fritz Angle, MD, director of the division of vascular and interventional radiology at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, agreed with this assessment. Although other studies underway will reexamine this issue, there was consensus from several speakers at the CRT symposium that the results of ATTRACT should not preclude intervention in patients at high risk of PTS.

“I believe there is a role for DVT intervention for symptomatic patients with an extensive [proximal iliofemoral] clot provided they have a low bleeding risk,” Dr. Soukas said.

Dr. Soukas reported no potential conflicts of interest.

WASHINGTON – On the basis of a large randomized trial called ATTRACT, many clinicians have concluded that pharmacomechanical intervention is ineffective for preventing postthrombotic syndrome (PTS) in patients with deep venous thrombosis (DVT). But weaknesses in the study design challenge this conclusion, according to several experts in a DVT symposium at the 2018 Cardiovascular Research Technologies (CRT) meeting.

“The diagnosis and evaluation of DVT must be performed with IVUS [intravascular ultrasound], not with venography,” said Peter A. Soukas, MD, director of vascular medicine at Miriam Hospital in Providence, R.I. “You cannot know whether you successfully treated the clot if you cannot see it.”

“There were lots of limitations to that study. Here are some,” said Dr. Soukas, who then listed on a list of several considerations, including the fact that venograms – rather than IVUS, which Dr. Soukas labeled the “current gold standard” – were taken to evaluate procedure success. Another was that only half of patients had a moderate to severe DVT based on a Villalta score.

“If you look at the subgroup with a Villalta score of 10 or greater, the benefit [of pharmacomechanical intervention] was statistically significant,” he said.

In addition, the study enrolled a substantial number of patients with femoral-popliteal DVTs even though iliofemoral DVTs pose the greatest risk of postthrombotic syndrome. Dr. Soukas suggested these would have been a more appropriate focus of a study exploring the benefits of an intervention.

The limitations of the ATTRACT trial, which was conceived more than 5 years ago, have arisen primarily from advances in the field rather than problems with the design, Dr. Soukas explained. IVUS was not the preferred method for deep vein thrombosis evaluation then as it is now, and there have been several advances in current models of pharmacomechanical devices, which involve catheter-directed delivery of fibrinolytic therapy into the thrombus along with mechanical destruction of the clot.

Although further steps beyond clot lysis, such as stenting, were encouraged in ATTRACT to maintain venous patency, Dr. Soukas questioned whether these were employed sufficiently. For example, the rate of stenting in the experimental arm was 28%, a rate that “is not what we currently do” for patients at high risk of PTS, Dr. Soukas said.

In ATTRACT, major bleeding events were significantly higher in the experimental group (1.7% vs. 0.3%; P = .049). The authors cited this finding when they concluded that the experimental intervention was ineffective. Dr. Soukas acknowledged that bleeding risk is an important factor to consider, but he also emphasized the serious risks for failing to treat patients at high risk for PTS.

“PTS is devastating for patients, both functionally and economically,” Dr. Soukas said. He called the morbidity of deep vein thrombosis “staggering,” with in-hospital mortality in some series exceeding 10% and a risk of late development of postthrombotic syndrome persisting for up to 5 years. For those with proximal iliofemoral DVT, the PTS rate can reach 90%, about 15% of which can develop claudication with ulcerations, according to Dr. Soukas.

A large trial that was published in a prominent journal, ATTRACT has the potential to dissuade clinicians from considering pharmacomechanical intervention in high-risk patients who could benefit, Dr. Soukas said. Others speaking during the same symposium about advances in this field, such as John Fritz Angle, MD, director of the division of vascular and interventional radiology at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, agreed with this assessment. Although other studies underway will reexamine this issue, there was consensus from several speakers at the CRT symposium that the results of ATTRACT should not preclude intervention in patients at high risk of PTS.

“I believe there is a role for DVT intervention for symptomatic patients with an extensive [proximal iliofemoral] clot provided they have a low bleeding risk,” Dr. Soukas said.

Dr. Soukas reported no potential conflicts of interest.

WASHINGTON – On the basis of a large randomized trial called ATTRACT, many clinicians have concluded that pharmacomechanical intervention is ineffective for preventing postthrombotic syndrome (PTS) in patients with deep venous thrombosis (DVT). But weaknesses in the study design challenge this conclusion, according to several experts in a DVT symposium at the 2018 Cardiovascular Research Technologies (CRT) meeting.

“The diagnosis and evaluation of DVT must be performed with IVUS [intravascular ultrasound], not with venography,” said Peter A. Soukas, MD, director of vascular medicine at Miriam Hospital in Providence, R.I. “You cannot know whether you successfully treated the clot if you cannot see it.”

“There were lots of limitations to that study. Here are some,” said Dr. Soukas, who then listed on a list of several considerations, including the fact that venograms – rather than IVUS, which Dr. Soukas labeled the “current gold standard” – were taken to evaluate procedure success. Another was that only half of patients had a moderate to severe DVT based on a Villalta score.

“If you look at the subgroup with a Villalta score of 10 or greater, the benefit [of pharmacomechanical intervention] was statistically significant,” he said.

In addition, the study enrolled a substantial number of patients with femoral-popliteal DVTs even though iliofemoral DVTs pose the greatest risk of postthrombotic syndrome. Dr. Soukas suggested these would have been a more appropriate focus of a study exploring the benefits of an intervention.

The limitations of the ATTRACT trial, which was conceived more than 5 years ago, have arisen primarily from advances in the field rather than problems with the design, Dr. Soukas explained. IVUS was not the preferred method for deep vein thrombosis evaluation then as it is now, and there have been several advances in current models of pharmacomechanical devices, which involve catheter-directed delivery of fibrinolytic therapy into the thrombus along with mechanical destruction of the clot.

Although further steps beyond clot lysis, such as stenting, were encouraged in ATTRACT to maintain venous patency, Dr. Soukas questioned whether these were employed sufficiently. For example, the rate of stenting in the experimental arm was 28%, a rate that “is not what we currently do” for patients at high risk of PTS, Dr. Soukas said.

In ATTRACT, major bleeding events were significantly higher in the experimental group (1.7% vs. 0.3%; P = .049). The authors cited this finding when they concluded that the experimental intervention was ineffective. Dr. Soukas acknowledged that bleeding risk is an important factor to consider, but he also emphasized the serious risks for failing to treat patients at high risk for PTS.

“PTS is devastating for patients, both functionally and economically,” Dr. Soukas said. He called the morbidity of deep vein thrombosis “staggering,” with in-hospital mortality in some series exceeding 10% and a risk of late development of postthrombotic syndrome persisting for up to 5 years. For those with proximal iliofemoral DVT, the PTS rate can reach 90%, about 15% of which can develop claudication with ulcerations, according to Dr. Soukas.

A large trial that was published in a prominent journal, ATTRACT has the potential to dissuade clinicians from considering pharmacomechanical intervention in high-risk patients who could benefit, Dr. Soukas said. Others speaking during the same symposium about advances in this field, such as John Fritz Angle, MD, director of the division of vascular and interventional radiology at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, agreed with this assessment. Although other studies underway will reexamine this issue, there was consensus from several speakers at the CRT symposium that the results of ATTRACT should not preclude intervention in patients at high risk of PTS.

“I believe there is a role for DVT intervention for symptomatic patients with an extensive [proximal iliofemoral] clot provided they have a low bleeding risk,” Dr. Soukas said.

Dr. Soukas reported no potential conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE 2018 CRT MEETING

ESBL-resistant bacteria spread in hospital despite strict contact precautions

MADRID – even when staff employed an active surveillance screening protocol to identify every carrier at admission.

The failure of precautions may have root in two thorny issues, said Friederike Maechler, MD, who presented the data at the the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress.

“Adherence to strict contact isolation and hand hygiene is never 100% in a real-life scenario,” said Dr. Maechler, of Charite University Hospital, Berlin. Also, she said, contact isolation can only be effective in a ward if all, or at least most, of the ESBL-E carriers are identified. “Even with an extensive surveillance screening program established, many carriers remained unknown to the health care staff.”

The 25-month study, dubbed R-Gnosis, was conducted in 20 Western European hospitals in Madrid, Berlin, Utrecht, and Geneva. It compared 12 months of contact precaution with standard precaution infection control strategies in medical and surgical non-ICUs.

The entire study hinged on a strict protocol to identify as many ESBL-E carriers as possible. This was done by screening upon admission to the unit, screening once per week during the hospital stay, and screening on discharge. Each patient underwent deep rectal swabs that were cultured on agar and screened for resistance.

The crossover design trial randomized each unit to either contact precautions or standard precautions for 12 months, followed by a 1-month washout period, after which they began the other protocol.

In all, 50,870 patients were entered into the study. By the end, Dr. Maechler had data on 11,367 patients with full screening and follow-up.

Standard precautions did not require a private bedroom, with gloves, gowns, and apron needed for direct contact to body fluids or wounds only, and consistent hand hygiene. Contact precautions required a private bedroom and strict hand hygiene, with gloves, gowns, and aprons used for any patient contact. Study staff monitored compliance with these procedures monthly.

The primary outcome was the ESBL-E acquisition rate per 1,000 patient days. This was defined as a new ESBL-E detection after the patient had a prior negative screen. Dr. Maechler noted that by epidemiological definition, acquisition does not necessarily imply cross-transmission from other patients.

Adherence to the study protocols was good, she said. Adherence to both contact and standard precautions was about 85%, while adherence to hand hygiene was less at around 62%.

Admission ESBL-E screenings revealed that about 12% of the study population was colonized with the strain at admission. The proportion was nearly identical in the contact and standard precaution groups (11.6%, 12.2%).

The incidence density of ward-acquired ESBL-E per 1,000 patient-days at risk was 4.6 in both intervention periods, regardless of the type of precaution taken. Contact precautions appeared to be slightly less effective for Escherichia coli (3.6 per 1,000 patient-days in contact precautions vs. 3.5 in standard), compared with Klebsiella pneumoniae (1.8 vs. 2.2).

A multivariate analysis controlled for screening compliance, colonization pressure, and length of stay, study site, and season of year. It showed that strict contact precautions did not reduce the risk of ward-acquired ESBL-E carriage.

Dr. Maechler had no financial disclosures. The R-Gnosis study was funded by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme.

SOURCE: Maechler F et al. ECCMID 2018, Oral Abstract O1130.

MADRID – even when staff employed an active surveillance screening protocol to identify every carrier at admission.

The failure of precautions may have root in two thorny issues, said Friederike Maechler, MD, who presented the data at the the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress.

“Adherence to strict contact isolation and hand hygiene is never 100% in a real-life scenario,” said Dr. Maechler, of Charite University Hospital, Berlin. Also, she said, contact isolation can only be effective in a ward if all, or at least most, of the ESBL-E carriers are identified. “Even with an extensive surveillance screening program established, many carriers remained unknown to the health care staff.”

The 25-month study, dubbed R-Gnosis, was conducted in 20 Western European hospitals in Madrid, Berlin, Utrecht, and Geneva. It compared 12 months of contact precaution with standard precaution infection control strategies in medical and surgical non-ICUs.

The entire study hinged on a strict protocol to identify as many ESBL-E carriers as possible. This was done by screening upon admission to the unit, screening once per week during the hospital stay, and screening on discharge. Each patient underwent deep rectal swabs that were cultured on agar and screened for resistance.

The crossover design trial randomized each unit to either contact precautions or standard precautions for 12 months, followed by a 1-month washout period, after which they began the other protocol.

In all, 50,870 patients were entered into the study. By the end, Dr. Maechler had data on 11,367 patients with full screening and follow-up.

Standard precautions did not require a private bedroom, with gloves, gowns, and apron needed for direct contact to body fluids or wounds only, and consistent hand hygiene. Contact precautions required a private bedroom and strict hand hygiene, with gloves, gowns, and aprons used for any patient contact. Study staff monitored compliance with these procedures monthly.

The primary outcome was the ESBL-E acquisition rate per 1,000 patient days. This was defined as a new ESBL-E detection after the patient had a prior negative screen. Dr. Maechler noted that by epidemiological definition, acquisition does not necessarily imply cross-transmission from other patients.

Adherence to the study protocols was good, she said. Adherence to both contact and standard precautions was about 85%, while adherence to hand hygiene was less at around 62%.

Admission ESBL-E screenings revealed that about 12% of the study population was colonized with the strain at admission. The proportion was nearly identical in the contact and standard precaution groups (11.6%, 12.2%).

The incidence density of ward-acquired ESBL-E per 1,000 patient-days at risk was 4.6 in both intervention periods, regardless of the type of precaution taken. Contact precautions appeared to be slightly less effective for Escherichia coli (3.6 per 1,000 patient-days in contact precautions vs. 3.5 in standard), compared with Klebsiella pneumoniae (1.8 vs. 2.2).

A multivariate analysis controlled for screening compliance, colonization pressure, and length of stay, study site, and season of year. It showed that strict contact precautions did not reduce the risk of ward-acquired ESBL-E carriage.

Dr. Maechler had no financial disclosures. The R-Gnosis study was funded by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme.

SOURCE: Maechler F et al. ECCMID 2018, Oral Abstract O1130.

MADRID – even when staff employed an active surveillance screening protocol to identify every carrier at admission.

The failure of precautions may have root in two thorny issues, said Friederike Maechler, MD, who presented the data at the the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress.

“Adherence to strict contact isolation and hand hygiene is never 100% in a real-life scenario,” said Dr. Maechler, of Charite University Hospital, Berlin. Also, she said, contact isolation can only be effective in a ward if all, or at least most, of the ESBL-E carriers are identified. “Even with an extensive surveillance screening program established, many carriers remained unknown to the health care staff.”

The 25-month study, dubbed R-Gnosis, was conducted in 20 Western European hospitals in Madrid, Berlin, Utrecht, and Geneva. It compared 12 months of contact precaution with standard precaution infection control strategies in medical and surgical non-ICUs.

The entire study hinged on a strict protocol to identify as many ESBL-E carriers as possible. This was done by screening upon admission to the unit, screening once per week during the hospital stay, and screening on discharge. Each patient underwent deep rectal swabs that were cultured on agar and screened for resistance.

The crossover design trial randomized each unit to either contact precautions or standard precautions for 12 months, followed by a 1-month washout period, after which they began the other protocol.

In all, 50,870 patients were entered into the study. By the end, Dr. Maechler had data on 11,367 patients with full screening and follow-up.

Standard precautions did not require a private bedroom, with gloves, gowns, and apron needed for direct contact to body fluids or wounds only, and consistent hand hygiene. Contact precautions required a private bedroom and strict hand hygiene, with gloves, gowns, and aprons used for any patient contact. Study staff monitored compliance with these procedures monthly.

The primary outcome was the ESBL-E acquisition rate per 1,000 patient days. This was defined as a new ESBL-E detection after the patient had a prior negative screen. Dr. Maechler noted that by epidemiological definition, acquisition does not necessarily imply cross-transmission from other patients.

Adherence to the study protocols was good, she said. Adherence to both contact and standard precautions was about 85%, while adherence to hand hygiene was less at around 62%.

Admission ESBL-E screenings revealed that about 12% of the study population was colonized with the strain at admission. The proportion was nearly identical in the contact and standard precaution groups (11.6%, 12.2%).

The incidence density of ward-acquired ESBL-E per 1,000 patient-days at risk was 4.6 in both intervention periods, regardless of the type of precaution taken. Contact precautions appeared to be slightly less effective for Escherichia coli (3.6 per 1,000 patient-days in contact precautions vs. 3.5 in standard), compared with Klebsiella pneumoniae (1.8 vs. 2.2).

A multivariate analysis controlled for screening compliance, colonization pressure, and length of stay, study site, and season of year. It showed that strict contact precautions did not reduce the risk of ward-acquired ESBL-E carriage.

Dr. Maechler had no financial disclosures. The R-Gnosis study was funded by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme.

SOURCE: Maechler F et al. ECCMID 2018, Oral Abstract O1130.

REPORTING FROM ECCMID 2018

Key clinical point: A protocol of strict contact precautions and hand hygiene was no better than standard contact precautions at preventing the spread of extended-spectrum, beta-lactamase–resistant Enterobacteriaceae.

Major finding: The incidence density of ward-acquired ESBL-E per 1,000 patient-days at risk was 4.6, regardless of precaution.

Study details: The 25-month crossover trial comprised more than 11,000 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Maechler had no financial disclosures. The R-Gnosis study was funded by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme.

Source: Maechler F et al. ECCMID 2018, Oral Abstract O1130.

Multiple analgesia options for kids with acute pain

TORONTO – according to Naveen Poonai, MD, FRCPC.

“Too many times, nonpharmacologic therapies are relegated to the very last paragraph of recommendations or to the very bottom of a URL,” he said at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting. “Nonpharmacologic therapies are things that our grandparents told us to do: common sense things that can be done at triage. They don’t require memorization of dosing, and most importantly, they don’t have side effects.”

When analgesia is indicated, clinicians can choose from a variety of agents in the postcodeine era. Dr. Poonai said that musculoskeletal injuries constitute 10-20% of pediatric emergency department visits, yet fewer than 60% of children receive adequate analgesia. “That’s what’s really important for patient and caregiver satisfaction,” he said.

Mounting evidence supports the use of ibuprofen as a go-to agent for mild to moderate pain in patients with musculoskeletal injuries, including results from a randomized, controlled multicenter trial of 500 youth (Canadian J Emerg Med. 2016:18:S29). “We know that ibuprofen is superior to acetaminophen or codeine and that it’s as good or better than oral opioids and with fewer side effects,” Dr. Poonai said, adding that it provides a 25 mm visual analog score (VAS) reduction in pain at 60 minutes. Another study that compared ibuprofen with codeine for acute pediatric arm fracture pain found that ibuprofen was associated with improved functioning and was at least as effective as acetaminophen plus codeine (Ann Emerg Med. 2009 Oct;54[4]:553-60).

A number of oral opioids have gained favor for use in children who present with acute pain. However, in a randomized trial, Dr. Poonai and his associates found no significant difference in analgesic efficacy between orally administered morphine and ibuprofen for the management of postfracture pain in 134 children (CMAJ. 2014 Dec 9;186[18]:1358-63). Oral morphine was also associated with more side effects. At the same time, tramadol and hydromorphone have not been well studied in children with musculoskeletal pain. “Currently, the use of hydromorphone is limited to children with sickle cell disease, but the use is branching out,” he said. “Oxycodone and oral morphine pose the greatest risk of side effects. The bottom line here is that opioids should be added to ibuprofen and acetaminophen rather than replacing them for mild to moderate pain.”

In 2014, a study from the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews concluded that intranasal fentanyl can be effective for the management of moderate to severe pain in children. A dose of 1.0-1.5 mcg/kg is associated with a 40-mm pain reduction in VAS at 10 minutes. “The benefits are that it is not an invasive approach, it’s been rigorously studied, and it is equivalent to IV morphine for moderate to severe pain,” said Dr. Poonai, who was not part of the Cochrane review. “It lasts about 60 minutes, with minimal side effects.”

A separate analysis found that intranasal fentanyl and ketamine were associated with similar pain reduction in children with moderate to severe pain from limb injury (Ann Emerg Med. 2015 Mar;65[3]:248-54.e1). Ketamine was associated with more minor adverse events. An intranasal dose of 1 mg/kg can cause a 40- to 45-mm reduction in VAS at 30 minutes.

Dr. Poonai went on to discuss treatment options for abdominal pain, noting that fewer than two-thirds of children with suspected appendicitis receive analgesia. “If they are receiving it, it’s often not until after the ultrasound is performed,” he said. “There is a still a reluctance toward providing opioid analgesia for a child with suspected appendicitis for fear of masking a diagnosis or leading to complications.” A systematic review led by Dr. Poonai found that the use of opioids in undifferentiated acute abdominal pain in children is associated with no difference in pain scores and an increased risk of mild side effects (Acad Emerg Med. 2014 21[11]:1183-92). However, there was no increased risk of perforation or abscess. “We found that single-dose IV opioids were actually beneficial,” he said.

Dr. Poonai characterized most of the current evidence on IV morphine for suspected appendicitis as being of low to moderate quality, “but they are generally favorable for the indication,” he said. “It is titratable to effect, and triage-initiated protocols improve timing and consistency of analgesia.” He reported having no financial disclosures.

TORONTO – according to Naveen Poonai, MD, FRCPC.

“Too many times, nonpharmacologic therapies are relegated to the very last paragraph of recommendations or to the very bottom of a URL,” he said at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting. “Nonpharmacologic therapies are things that our grandparents told us to do: common sense things that can be done at triage. They don’t require memorization of dosing, and most importantly, they don’t have side effects.”

When analgesia is indicated, clinicians can choose from a variety of agents in the postcodeine era. Dr. Poonai said that musculoskeletal injuries constitute 10-20% of pediatric emergency department visits, yet fewer than 60% of children receive adequate analgesia. “That’s what’s really important for patient and caregiver satisfaction,” he said.

Mounting evidence supports the use of ibuprofen as a go-to agent for mild to moderate pain in patients with musculoskeletal injuries, including results from a randomized, controlled multicenter trial of 500 youth (Canadian J Emerg Med. 2016:18:S29). “We know that ibuprofen is superior to acetaminophen or codeine and that it’s as good or better than oral opioids and with fewer side effects,” Dr. Poonai said, adding that it provides a 25 mm visual analog score (VAS) reduction in pain at 60 minutes. Another study that compared ibuprofen with codeine for acute pediatric arm fracture pain found that ibuprofen was associated with improved functioning and was at least as effective as acetaminophen plus codeine (Ann Emerg Med. 2009 Oct;54[4]:553-60).

A number of oral opioids have gained favor for use in children who present with acute pain. However, in a randomized trial, Dr. Poonai and his associates found no significant difference in analgesic efficacy between orally administered morphine and ibuprofen for the management of postfracture pain in 134 children (CMAJ. 2014 Dec 9;186[18]:1358-63). Oral morphine was also associated with more side effects. At the same time, tramadol and hydromorphone have not been well studied in children with musculoskeletal pain. “Currently, the use of hydromorphone is limited to children with sickle cell disease, but the use is branching out,” he said. “Oxycodone and oral morphine pose the greatest risk of side effects. The bottom line here is that opioids should be added to ibuprofen and acetaminophen rather than replacing them for mild to moderate pain.”

In 2014, a study from the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews concluded that intranasal fentanyl can be effective for the management of moderate to severe pain in children. A dose of 1.0-1.5 mcg/kg is associated with a 40-mm pain reduction in VAS at 10 minutes. “The benefits are that it is not an invasive approach, it’s been rigorously studied, and it is equivalent to IV morphine for moderate to severe pain,” said Dr. Poonai, who was not part of the Cochrane review. “It lasts about 60 minutes, with minimal side effects.”

A separate analysis found that intranasal fentanyl and ketamine were associated with similar pain reduction in children with moderate to severe pain from limb injury (Ann Emerg Med. 2015 Mar;65[3]:248-54.e1). Ketamine was associated with more minor adverse events. An intranasal dose of 1 mg/kg can cause a 40- to 45-mm reduction in VAS at 30 minutes.

Dr. Poonai went on to discuss treatment options for abdominal pain, noting that fewer than two-thirds of children with suspected appendicitis receive analgesia. “If they are receiving it, it’s often not until after the ultrasound is performed,” he said. “There is a still a reluctance toward providing opioid analgesia for a child with suspected appendicitis for fear of masking a diagnosis or leading to complications.” A systematic review led by Dr. Poonai found that the use of opioids in undifferentiated acute abdominal pain in children is associated with no difference in pain scores and an increased risk of mild side effects (Acad Emerg Med. 2014 21[11]:1183-92). However, there was no increased risk of perforation or abscess. “We found that single-dose IV opioids were actually beneficial,” he said.

Dr. Poonai characterized most of the current evidence on IV morphine for suspected appendicitis as being of low to moderate quality, “but they are generally favorable for the indication,” he said. “It is titratable to effect, and triage-initiated protocols improve timing and consistency of analgesia.” He reported having no financial disclosures.

TORONTO – according to Naveen Poonai, MD, FRCPC.

“Too many times, nonpharmacologic therapies are relegated to the very last paragraph of recommendations or to the very bottom of a URL,” he said at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting. “Nonpharmacologic therapies are things that our grandparents told us to do: common sense things that can be done at triage. They don’t require memorization of dosing, and most importantly, they don’t have side effects.”

When analgesia is indicated, clinicians can choose from a variety of agents in the postcodeine era. Dr. Poonai said that musculoskeletal injuries constitute 10-20% of pediatric emergency department visits, yet fewer than 60% of children receive adequate analgesia. “That’s what’s really important for patient and caregiver satisfaction,” he said.

Mounting evidence supports the use of ibuprofen as a go-to agent for mild to moderate pain in patients with musculoskeletal injuries, including results from a randomized, controlled multicenter trial of 500 youth (Canadian J Emerg Med. 2016:18:S29). “We know that ibuprofen is superior to acetaminophen or codeine and that it’s as good or better than oral opioids and with fewer side effects,” Dr. Poonai said, adding that it provides a 25 mm visual analog score (VAS) reduction in pain at 60 minutes. Another study that compared ibuprofen with codeine for acute pediatric arm fracture pain found that ibuprofen was associated with improved functioning and was at least as effective as acetaminophen plus codeine (Ann Emerg Med. 2009 Oct;54[4]:553-60).

A number of oral opioids have gained favor for use in children who present with acute pain. However, in a randomized trial, Dr. Poonai and his associates found no significant difference in analgesic efficacy between orally administered morphine and ibuprofen for the management of postfracture pain in 134 children (CMAJ. 2014 Dec 9;186[18]:1358-63). Oral morphine was also associated with more side effects. At the same time, tramadol and hydromorphone have not been well studied in children with musculoskeletal pain. “Currently, the use of hydromorphone is limited to children with sickle cell disease, but the use is branching out,” he said. “Oxycodone and oral morphine pose the greatest risk of side effects. The bottom line here is that opioids should be added to ibuprofen and acetaminophen rather than replacing them for mild to moderate pain.”

In 2014, a study from the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews concluded that intranasal fentanyl can be effective for the management of moderate to severe pain in children. A dose of 1.0-1.5 mcg/kg is associated with a 40-mm pain reduction in VAS at 10 minutes. “The benefits are that it is not an invasive approach, it’s been rigorously studied, and it is equivalent to IV morphine for moderate to severe pain,” said Dr. Poonai, who was not part of the Cochrane review. “It lasts about 60 minutes, with minimal side effects.”

A separate analysis found that intranasal fentanyl and ketamine were associated with similar pain reduction in children with moderate to severe pain from limb injury (Ann Emerg Med. 2015 Mar;65[3]:248-54.e1). Ketamine was associated with more minor adverse events. An intranasal dose of 1 mg/kg can cause a 40- to 45-mm reduction in VAS at 30 minutes.

Dr. Poonai went on to discuss treatment options for abdominal pain, noting that fewer than two-thirds of children with suspected appendicitis receive analgesia. “If they are receiving it, it’s often not until after the ultrasound is performed,” he said. “There is a still a reluctance toward providing opioid analgesia for a child with suspected appendicitis for fear of masking a diagnosis or leading to complications.” A systematic review led by Dr. Poonai found that the use of opioids in undifferentiated acute abdominal pain in children is associated with no difference in pain scores and an increased risk of mild side effects (Acad Emerg Med. 2014 21[11]:1183-92). However, there was no increased risk of perforation or abscess. “We found that single-dose IV opioids were actually beneficial,” he said.

Dr. Poonai characterized most of the current evidence on IV morphine for suspected appendicitis as being of low to moderate quality, “but they are generally favorable for the indication,” he said. “It is titratable to effect, and triage-initiated protocols improve timing and consistency of analgesia.” He reported having no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM PAS 2018

Keep pushing the envelope

By the time this column is published, we will have wrapped up Hospital Medicine 2018 in Orlando, it will be well into spring, and I will have completed my year as past president as well as my 6-year tenure on the Society of Hospital Medicine board of directors.

I can imagine that will feel like a relief and a milestone, and it also will feel like a loss to no longer be part of something that I have contributed my time, energy, passion, and emotion to for so long. I will retire at the ripe age of 48 – a pretty typical age for ending SHM board tenure, and it’s terribly important for SHM that I do so.

If you attended HM18, I hope you appreciated, as I do every year, the energy, enthusiasm, and youth – if not in years, then in spirit – of the event and of hospitalists. As a society and a profession, we take risks. We have set standards for excellence in hospital medicine programs. We have recognized a unique set of competencies and then not only attempted to expand them with education but also defined a specialty around them. We have welcomed practitioners and administrators as equals into our fold. These and many other accomplishments are the work of a board, committees, chapter leaders, and members who look for opportunity to expand our work into new and necessary domains, and not be limited by precedent.

On the SHM board and committees, we tackle issues of governance and strategy. For most of us, the SHM board is our first exposure to nonprofit oversight. And, to be sure, there is a steep learning curve as new members discover the issues and substance of the work of the society. I recall that I barely spoke the first year on the board, uncertain that I understood items fully, and I also was burned once or twice by making suggestions that reflected my lack of knowledge. While ignorance slowly gave way to experience, we also matured as a group as we found ways to debate and resolve tough, sometimes ambiguous, issues.

I came to appreciate that the strength of the board – and of SHM – is that we join the board naive to much of the past. After 6 years, while I may have come to understand issues with greater depth, I also see that the newer members bring fresher thinking, more creative energy, and even thoughts about how the group could function differently and perhaps better. Over the last few years, I realized that we veterans had developed a cadence and predictability to our work, and every year’s new members disrupt that rhythm. This disruption forces us to challenge each other and to be a better board – and hopefully – represent and advocate for you, our membership, better.

So, it’s time for me to move on. Even though I certainly feel like I still could contribute, it’s time to retire my own way of thinking from the leadership of SHM. The fact that we term-limit out at a (relatively) young age is, I believe, an extraordinary aspect of our organization, which is reflected in the work that our staff, our committees, and our members do.

SHM is an organization that, from the top down, embraces change in ways that few other organizations do. I believe we owe it to you to keep pushing the envelope of creativity – of what our goals are, of what a society can accomplish, of what an annual meeting can consist of. My ask of all of you is that you continue to challenge the leadership of SHM to be disruptive, to push the profession to better places, and to always strive to be more diverse, more inclusive, more communicative, more visible – and to stay young. In spirit and attitude if not in age. Thank you for giving me the opportunity to work on your behalf. It has been the greatest privilege of my career.

Dr. Harte is a past president of SHM and president of Cleveland Clinic Akron General and Southern Region.

By the time this column is published, we will have wrapped up Hospital Medicine 2018 in Orlando, it will be well into spring, and I will have completed my year as past president as well as my 6-year tenure on the Society of Hospital Medicine board of directors.

I can imagine that will feel like a relief and a milestone, and it also will feel like a loss to no longer be part of something that I have contributed my time, energy, passion, and emotion to for so long. I will retire at the ripe age of 48 – a pretty typical age for ending SHM board tenure, and it’s terribly important for SHM that I do so.

If you attended HM18, I hope you appreciated, as I do every year, the energy, enthusiasm, and youth – if not in years, then in spirit – of the event and of hospitalists. As a society and a profession, we take risks. We have set standards for excellence in hospital medicine programs. We have recognized a unique set of competencies and then not only attempted to expand them with education but also defined a specialty around them. We have welcomed practitioners and administrators as equals into our fold. These and many other accomplishments are the work of a board, committees, chapter leaders, and members who look for opportunity to expand our work into new and necessary domains, and not be limited by precedent.

On the SHM board and committees, we tackle issues of governance and strategy. For most of us, the SHM board is our first exposure to nonprofit oversight. And, to be sure, there is a steep learning curve as new members discover the issues and substance of the work of the society. I recall that I barely spoke the first year on the board, uncertain that I understood items fully, and I also was burned once or twice by making suggestions that reflected my lack of knowledge. While ignorance slowly gave way to experience, we also matured as a group as we found ways to debate and resolve tough, sometimes ambiguous, issues.

I came to appreciate that the strength of the board – and of SHM – is that we join the board naive to much of the past. After 6 years, while I may have come to understand issues with greater depth, I also see that the newer members bring fresher thinking, more creative energy, and even thoughts about how the group could function differently and perhaps better. Over the last few years, I realized that we veterans had developed a cadence and predictability to our work, and every year’s new members disrupt that rhythm. This disruption forces us to challenge each other and to be a better board – and hopefully – represent and advocate for you, our membership, better.

So, it’s time for me to move on. Even though I certainly feel like I still could contribute, it’s time to retire my own way of thinking from the leadership of SHM. The fact that we term-limit out at a (relatively) young age is, I believe, an extraordinary aspect of our organization, which is reflected in the work that our staff, our committees, and our members do.

SHM is an organization that, from the top down, embraces change in ways that few other organizations do. I believe we owe it to you to keep pushing the envelope of creativity – of what our goals are, of what a society can accomplish, of what an annual meeting can consist of. My ask of all of you is that you continue to challenge the leadership of SHM to be disruptive, to push the profession to better places, and to always strive to be more diverse, more inclusive, more communicative, more visible – and to stay young. In spirit and attitude if not in age. Thank you for giving me the opportunity to work on your behalf. It has been the greatest privilege of my career.

Dr. Harte is a past president of SHM and president of Cleveland Clinic Akron General and Southern Region.