User login

In Case You Missed It: COVID

Vaccinating homebound patients is an uphill battle

There are about 2 million to 4 million homebound patients in the United States, according to a webinar from The Trust for America’s Health, which was broadcast in March. But many of these individuals have not been vaccinated yet because of logistical challenges.

Some homebound COVID-19 immunization programs are administering Moderna and Pfizer vaccines to their patients, but many state, city, and local programs administered the Johnson & Johnson vaccine after it was cleared for use by the Food and Drug Administration in February 2021. The efficacy of the one-shot vaccine, as well as it being easier to store and ship than the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines, makes getting it to homebound patients less challenging.

“With Pfizer and Moderna, transportation is a challenge because the temperature demands and the fragility of [messenger] RNA–based vaccines,” Brent Feorene, executive director of the American Academy of Home Care Medicine, said in an interview. That’s why [the Johnson & Johnson] vaccine held such promise – it’s less fragile, [can be stored in] higher temperatures, and was a one shot.”

Other hurdles to getting homebound patients vaccinated had already been in place prior to the 10-day-pause on using the J&J vaccine that occurred for federal agencies to consider possible serious side effects linked to it.

Many roadblocks to vaccination

Although many homebound patients can’t readily go out into the community and be exposed to the COVID-19 virus themselves, they are dependent on caregivers and family members who do go out into the community.

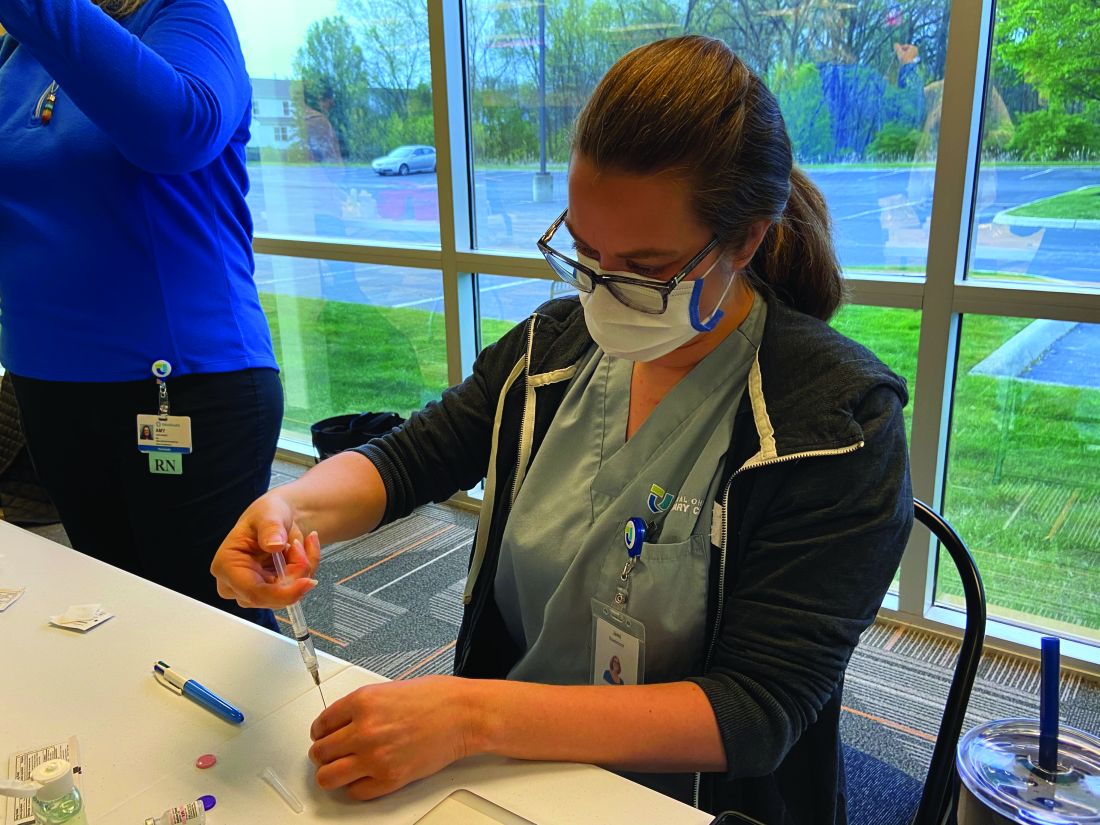

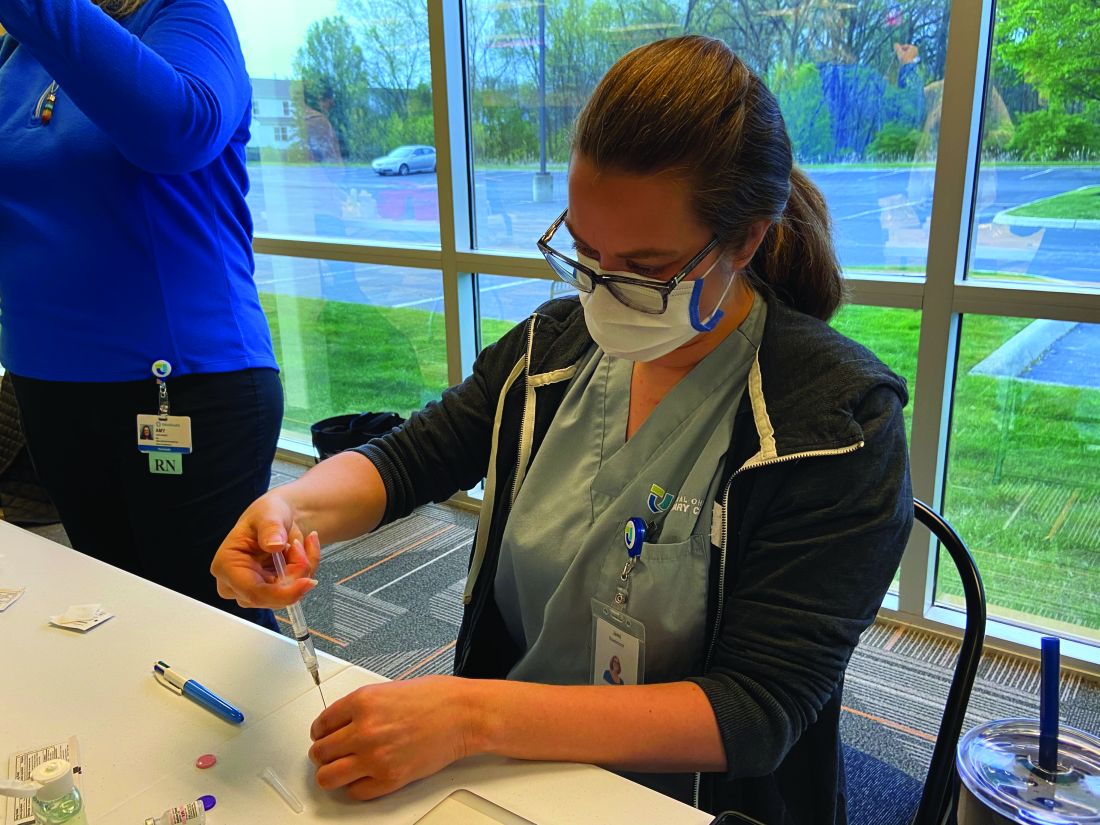

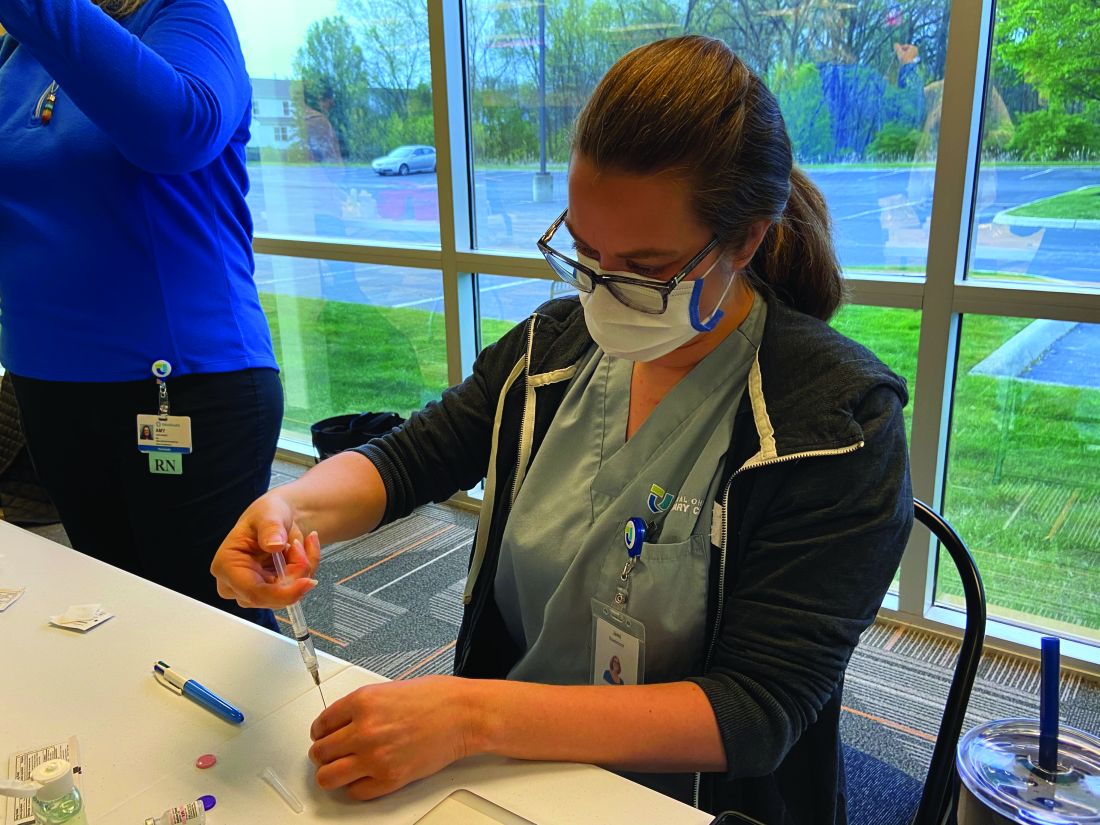

“Their friends, family, neighbors, home health aides, and other kinds of health care workers come into the home,” said Shawn Amer, clinical program director at Central Ohio Primary Care in Columbus.

Nurses from Ms. Amer’s practice vaccinated approximately ten homebound patients with the J&J vaccine through a pilot program in March. Then on April 24, nurses from Central Ohio Primary Care vaccinated just under 40 homebound patients and about a handful of their caregivers who were not able to get their vaccines elsewhere, according to Ms. Amer. This time they used the Pfizer vaccine and will be returning to these patients’ homes on May 15 to administer the second dose.

“Any time you are getting in the car and adding miles, it adds complexity,” Ms. Amer said.

“We called patients 24 to 36 hours before coming to their homes to make sure they were ready, but we learned that just because the healthcare power of attorney agrees to a patient getting vaccinated does not mean that patient will be willing to get the vaccine when the nurse shows up," she noted.

Ms. Amer elaborated that three patients with dementia refused the vaccine when nurses arrived at their home on April 24.

“We had to pivot and find other people,” Ms. Amer. Her practice ended up having to waste one shot.

Expenses are greater

The higher costs of getting homebound patients vaccinated is an additional hurdle to getting these vulnerable individuals protected by COVID-19 shots.

Vaccinating patients in their homes “doesn’t require a lot of technology, but it does require a lot of time” and the staffing expense becomes part of the challenge, Ms. Amer noted.

For each of the two days that Central Ohio Primary Care provides the Pfizer vaccine to homebound patients, the practice needs to pay seven nurses to administer the vaccine, Ms. Amer explained.

There have also been reports of organizations that administer the vaccines – which are free for patients because the federal government is paying for them – not being paid enough by Medicare to cover staff time and efforts to vaccinate patients in their homes, Kaiser Health News reported. According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, they pay $40 for the administration of a single-dose COVID-19 vaccine and, for COVID-19 vaccines requiring multiple doses, Medicare pays approximately $40 for each dose in the series. These rates were implemented after March 15. Before that date, the rates were even lower, with the Medicare reimbursement rates for initial doses of COVID-19 vaccines being $16.94 and final doses being $28.39.

William Dombi, president of the National Association for Home Care & Hospice, told Kaiser Health News that the actual cost of these homebound visits are closer to $150 or $160.

“The reimbursement for the injection is pretty minimal,” Mr. Feorene said. “So unless you’re a larger organization and able to have staff to deploy some of your smaller practices, just couldn’t afford to do it.”

Many homebound patients have also been unable to get the lifesaving shots because of logistical roadblocks and many practices not being able to do home visits.

“I think that initially when the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] came out with vaccine guidance for medical providers, they offered no guidance for in-home medical providers and we had to go back and ask for that, which they did produce,” Mr. Feorene said. “And we’re grateful for that. But I think just this general understanding that there is a population of folks that are [limited to their home], that they do receive medical care and other care in the home, and that we have to remember that the medical providers who provide care in the home are also primary care providers.”

Furthermore, trying to navigate or find programs delivering vaccines to the homebound can be difficult depending on where a patient lives.

While some programs have been launched on the country or city level – the New York Fire Department launched a pilot program to bring the Johnson & Johnson vaccine to homebound seniors – other programs have been spearheaded by hospital networks like Northwell and Mount Sinai. However, many of these hospital networks only reach out to people who already have a relationship with the hospital.

Ms Amer said identifying homebound patients and reaching out to them can be tough and can contribute to the logistics and time involved in setting patients up for the vaccine.

“Reaching some of these patients is difficult,” Ms. Amer noted. “Sometimes the best way to reach them or get a hold of them is through their caregiver. And so do you have the right phone number? Do you have the right name?”

Overcoming the challenges

With the absence of a national plan targeting homebound patients, many local initiatives were launched to help these individuals get vaccinated. Local fire department paramedics have gone door to door to administer the COVID-19 vaccine in cities like Chicago, New York, and Miami. The suspension of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine resulted in the suspension of in-home vaccinations for some people in New York City. However, the program resumed after the FDA and CDC lifted the pause on April 24.

Health systems like Mount Sinai vaccinated approximately 530 people through the Mount Sinai Visiting Doctors Program, including patients and their caregivers, according to Peter Gliatto, MD, associate director of the Mount Sinai Visiting Doctors Program.

“In different cities, townships, and jurisdictions, different health departments and different provider groups are approaching [the distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine] slightly differently,” Ms. Amer said. So a lot of the decisions surrounding the distribution of shots are local or dependent on local resourcing.

People who live in rural areas present a unique challenge, but Mr. Feorene said reaching out to local emergency medical services or the local health departments can provide some insight on what their town is doing to vaccinate homebound patients.

“I think understanding what a [public health department] is doing would be the very first place to start,” Mr. Feorene said in an interview.

If a patient is bedridden and is mobile enough to sit in a car, Mr. Feorene also recommends finding out if there are vaccine fairs “within a reasonable driving distance.”

Ms. Amer said continuing this mission of getting homebound patients vaccinated is necessary for public health.

“Even if it’s going to take longer to vaccinate these homebound patients, we still have to make an effort. So much of the country’s vaccine efforts have been focused on getting as many shots in as many arms as quickly as possible. And that is definitely super important,” she said.

Ms. Amer is working with her practice’s primary care physicians to try to identify all of those patients who are functionally debilitated or unable to leave their home to get vaccinated and that Central Ohio Primary Care will vaccinate more homebound patients, she added.

The experts interviewed in this article have no conflicts.

Katie Lennon contributed to this report.

This article was updated 4/29/21.

There are about 2 million to 4 million homebound patients in the United States, according to a webinar from The Trust for America’s Health, which was broadcast in March. But many of these individuals have not been vaccinated yet because of logistical challenges.

Some homebound COVID-19 immunization programs are administering Moderna and Pfizer vaccines to their patients, but many state, city, and local programs administered the Johnson & Johnson vaccine after it was cleared for use by the Food and Drug Administration in February 2021. The efficacy of the one-shot vaccine, as well as it being easier to store and ship than the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines, makes getting it to homebound patients less challenging.

“With Pfizer and Moderna, transportation is a challenge because the temperature demands and the fragility of [messenger] RNA–based vaccines,” Brent Feorene, executive director of the American Academy of Home Care Medicine, said in an interview. That’s why [the Johnson & Johnson] vaccine held such promise – it’s less fragile, [can be stored in] higher temperatures, and was a one shot.”

Other hurdles to getting homebound patients vaccinated had already been in place prior to the 10-day-pause on using the J&J vaccine that occurred for federal agencies to consider possible serious side effects linked to it.

Many roadblocks to vaccination

Although many homebound patients can’t readily go out into the community and be exposed to the COVID-19 virus themselves, they are dependent on caregivers and family members who do go out into the community.

“Their friends, family, neighbors, home health aides, and other kinds of health care workers come into the home,” said Shawn Amer, clinical program director at Central Ohio Primary Care in Columbus.

Nurses from Ms. Amer’s practice vaccinated approximately ten homebound patients with the J&J vaccine through a pilot program in March. Then on April 24, nurses from Central Ohio Primary Care vaccinated just under 40 homebound patients and about a handful of their caregivers who were not able to get their vaccines elsewhere, according to Ms. Amer. This time they used the Pfizer vaccine and will be returning to these patients’ homes on May 15 to administer the second dose.

“Any time you are getting in the car and adding miles, it adds complexity,” Ms. Amer said.

“We called patients 24 to 36 hours before coming to their homes to make sure they were ready, but we learned that just because the healthcare power of attorney agrees to a patient getting vaccinated does not mean that patient will be willing to get the vaccine when the nurse shows up," she noted.

Ms. Amer elaborated that three patients with dementia refused the vaccine when nurses arrived at their home on April 24.

“We had to pivot and find other people,” Ms. Amer. Her practice ended up having to waste one shot.

Expenses are greater

The higher costs of getting homebound patients vaccinated is an additional hurdle to getting these vulnerable individuals protected by COVID-19 shots.

Vaccinating patients in their homes “doesn’t require a lot of technology, but it does require a lot of time” and the staffing expense becomes part of the challenge, Ms. Amer noted.

For each of the two days that Central Ohio Primary Care provides the Pfizer vaccine to homebound patients, the practice needs to pay seven nurses to administer the vaccine, Ms. Amer explained.

There have also been reports of organizations that administer the vaccines – which are free for patients because the federal government is paying for them – not being paid enough by Medicare to cover staff time and efforts to vaccinate patients in their homes, Kaiser Health News reported. According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, they pay $40 for the administration of a single-dose COVID-19 vaccine and, for COVID-19 vaccines requiring multiple doses, Medicare pays approximately $40 for each dose in the series. These rates were implemented after March 15. Before that date, the rates were even lower, with the Medicare reimbursement rates for initial doses of COVID-19 vaccines being $16.94 and final doses being $28.39.

William Dombi, president of the National Association for Home Care & Hospice, told Kaiser Health News that the actual cost of these homebound visits are closer to $150 or $160.

“The reimbursement for the injection is pretty minimal,” Mr. Feorene said. “So unless you’re a larger organization and able to have staff to deploy some of your smaller practices, just couldn’t afford to do it.”

Many homebound patients have also been unable to get the lifesaving shots because of logistical roadblocks and many practices not being able to do home visits.

“I think that initially when the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] came out with vaccine guidance for medical providers, they offered no guidance for in-home medical providers and we had to go back and ask for that, which they did produce,” Mr. Feorene said. “And we’re grateful for that. But I think just this general understanding that there is a population of folks that are [limited to their home], that they do receive medical care and other care in the home, and that we have to remember that the medical providers who provide care in the home are also primary care providers.”

Furthermore, trying to navigate or find programs delivering vaccines to the homebound can be difficult depending on where a patient lives.

While some programs have been launched on the country or city level – the New York Fire Department launched a pilot program to bring the Johnson & Johnson vaccine to homebound seniors – other programs have been spearheaded by hospital networks like Northwell and Mount Sinai. However, many of these hospital networks only reach out to people who already have a relationship with the hospital.

Ms Amer said identifying homebound patients and reaching out to them can be tough and can contribute to the logistics and time involved in setting patients up for the vaccine.

“Reaching some of these patients is difficult,” Ms. Amer noted. “Sometimes the best way to reach them or get a hold of them is through their caregiver. And so do you have the right phone number? Do you have the right name?”

Overcoming the challenges

With the absence of a national plan targeting homebound patients, many local initiatives were launched to help these individuals get vaccinated. Local fire department paramedics have gone door to door to administer the COVID-19 vaccine in cities like Chicago, New York, and Miami. The suspension of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine resulted in the suspension of in-home vaccinations for some people in New York City. However, the program resumed after the FDA and CDC lifted the pause on April 24.

Health systems like Mount Sinai vaccinated approximately 530 people through the Mount Sinai Visiting Doctors Program, including patients and their caregivers, according to Peter Gliatto, MD, associate director of the Mount Sinai Visiting Doctors Program.

“In different cities, townships, and jurisdictions, different health departments and different provider groups are approaching [the distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine] slightly differently,” Ms. Amer said. So a lot of the decisions surrounding the distribution of shots are local or dependent on local resourcing.

People who live in rural areas present a unique challenge, but Mr. Feorene said reaching out to local emergency medical services or the local health departments can provide some insight on what their town is doing to vaccinate homebound patients.

“I think understanding what a [public health department] is doing would be the very first place to start,” Mr. Feorene said in an interview.

If a patient is bedridden and is mobile enough to sit in a car, Mr. Feorene also recommends finding out if there are vaccine fairs “within a reasonable driving distance.”

Ms. Amer said continuing this mission of getting homebound patients vaccinated is necessary for public health.

“Even if it’s going to take longer to vaccinate these homebound patients, we still have to make an effort. So much of the country’s vaccine efforts have been focused on getting as many shots in as many arms as quickly as possible. And that is definitely super important,” she said.

Ms. Amer is working with her practice’s primary care physicians to try to identify all of those patients who are functionally debilitated or unable to leave their home to get vaccinated and that Central Ohio Primary Care will vaccinate more homebound patients, she added.

The experts interviewed in this article have no conflicts.

Katie Lennon contributed to this report.

This article was updated 4/29/21.

There are about 2 million to 4 million homebound patients in the United States, according to a webinar from The Trust for America’s Health, which was broadcast in March. But many of these individuals have not been vaccinated yet because of logistical challenges.

Some homebound COVID-19 immunization programs are administering Moderna and Pfizer vaccines to their patients, but many state, city, and local programs administered the Johnson & Johnson vaccine after it was cleared for use by the Food and Drug Administration in February 2021. The efficacy of the one-shot vaccine, as well as it being easier to store and ship than the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines, makes getting it to homebound patients less challenging.

“With Pfizer and Moderna, transportation is a challenge because the temperature demands and the fragility of [messenger] RNA–based vaccines,” Brent Feorene, executive director of the American Academy of Home Care Medicine, said in an interview. That’s why [the Johnson & Johnson] vaccine held such promise – it’s less fragile, [can be stored in] higher temperatures, and was a one shot.”

Other hurdles to getting homebound patients vaccinated had already been in place prior to the 10-day-pause on using the J&J vaccine that occurred for federal agencies to consider possible serious side effects linked to it.

Many roadblocks to vaccination

Although many homebound patients can’t readily go out into the community and be exposed to the COVID-19 virus themselves, they are dependent on caregivers and family members who do go out into the community.

“Their friends, family, neighbors, home health aides, and other kinds of health care workers come into the home,” said Shawn Amer, clinical program director at Central Ohio Primary Care in Columbus.

Nurses from Ms. Amer’s practice vaccinated approximately ten homebound patients with the J&J vaccine through a pilot program in March. Then on April 24, nurses from Central Ohio Primary Care vaccinated just under 40 homebound patients and about a handful of their caregivers who were not able to get their vaccines elsewhere, according to Ms. Amer. This time they used the Pfizer vaccine and will be returning to these patients’ homes on May 15 to administer the second dose.

“Any time you are getting in the car and adding miles, it adds complexity,” Ms. Amer said.

“We called patients 24 to 36 hours before coming to their homes to make sure they were ready, but we learned that just because the healthcare power of attorney agrees to a patient getting vaccinated does not mean that patient will be willing to get the vaccine when the nurse shows up," she noted.

Ms. Amer elaborated that three patients with dementia refused the vaccine when nurses arrived at their home on April 24.

“We had to pivot and find other people,” Ms. Amer. Her practice ended up having to waste one shot.

Expenses are greater

The higher costs of getting homebound patients vaccinated is an additional hurdle to getting these vulnerable individuals protected by COVID-19 shots.

Vaccinating patients in their homes “doesn’t require a lot of technology, but it does require a lot of time” and the staffing expense becomes part of the challenge, Ms. Amer noted.

For each of the two days that Central Ohio Primary Care provides the Pfizer vaccine to homebound patients, the practice needs to pay seven nurses to administer the vaccine, Ms. Amer explained.

There have also been reports of organizations that administer the vaccines – which are free for patients because the federal government is paying for them – not being paid enough by Medicare to cover staff time and efforts to vaccinate patients in their homes, Kaiser Health News reported. According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, they pay $40 for the administration of a single-dose COVID-19 vaccine and, for COVID-19 vaccines requiring multiple doses, Medicare pays approximately $40 for each dose in the series. These rates were implemented after March 15. Before that date, the rates were even lower, with the Medicare reimbursement rates for initial doses of COVID-19 vaccines being $16.94 and final doses being $28.39.

William Dombi, president of the National Association for Home Care & Hospice, told Kaiser Health News that the actual cost of these homebound visits are closer to $150 or $160.

“The reimbursement for the injection is pretty minimal,” Mr. Feorene said. “So unless you’re a larger organization and able to have staff to deploy some of your smaller practices, just couldn’t afford to do it.”

Many homebound patients have also been unable to get the lifesaving shots because of logistical roadblocks and many practices not being able to do home visits.

“I think that initially when the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] came out with vaccine guidance for medical providers, they offered no guidance for in-home medical providers and we had to go back and ask for that, which they did produce,” Mr. Feorene said. “And we’re grateful for that. But I think just this general understanding that there is a population of folks that are [limited to their home], that they do receive medical care and other care in the home, and that we have to remember that the medical providers who provide care in the home are also primary care providers.”

Furthermore, trying to navigate or find programs delivering vaccines to the homebound can be difficult depending on where a patient lives.

While some programs have been launched on the country or city level – the New York Fire Department launched a pilot program to bring the Johnson & Johnson vaccine to homebound seniors – other programs have been spearheaded by hospital networks like Northwell and Mount Sinai. However, many of these hospital networks only reach out to people who already have a relationship with the hospital.

Ms Amer said identifying homebound patients and reaching out to them can be tough and can contribute to the logistics and time involved in setting patients up for the vaccine.

“Reaching some of these patients is difficult,” Ms. Amer noted. “Sometimes the best way to reach them or get a hold of them is through their caregiver. And so do you have the right phone number? Do you have the right name?”

Overcoming the challenges

With the absence of a national plan targeting homebound patients, many local initiatives were launched to help these individuals get vaccinated. Local fire department paramedics have gone door to door to administer the COVID-19 vaccine in cities like Chicago, New York, and Miami. The suspension of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine resulted in the suspension of in-home vaccinations for some people in New York City. However, the program resumed after the FDA and CDC lifted the pause on April 24.

Health systems like Mount Sinai vaccinated approximately 530 people through the Mount Sinai Visiting Doctors Program, including patients and their caregivers, according to Peter Gliatto, MD, associate director of the Mount Sinai Visiting Doctors Program.

“In different cities, townships, and jurisdictions, different health departments and different provider groups are approaching [the distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine] slightly differently,” Ms. Amer said. So a lot of the decisions surrounding the distribution of shots are local or dependent on local resourcing.

People who live in rural areas present a unique challenge, but Mr. Feorene said reaching out to local emergency medical services or the local health departments can provide some insight on what their town is doing to vaccinate homebound patients.

“I think understanding what a [public health department] is doing would be the very first place to start,” Mr. Feorene said in an interview.

If a patient is bedridden and is mobile enough to sit in a car, Mr. Feorene also recommends finding out if there are vaccine fairs “within a reasonable driving distance.”

Ms. Amer said continuing this mission of getting homebound patients vaccinated is necessary for public health.

“Even if it’s going to take longer to vaccinate these homebound patients, we still have to make an effort. So much of the country’s vaccine efforts have been focused on getting as many shots in as many arms as quickly as possible. And that is definitely super important,” she said.

Ms. Amer is working with her practice’s primary care physicians to try to identify all of those patients who are functionally debilitated or unable to leave their home to get vaccinated and that Central Ohio Primary Care will vaccinate more homebound patients, she added.

The experts interviewed in this article have no conflicts.

Katie Lennon contributed to this report.

This article was updated 4/29/21.

COVID plus MI confers poor prognosis; 1 in 3 die in hospital

COVID-19 patients with ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) represent a population with unique demographic and clinical features resulting in a high risk for mortality, according to initial findings from the North American Cardiovascular COVID-19 Myocardial Infarction (NACMI) Registry.

“This is the largest registry of COVID-positive patients presenting with STEMI [and] the results clearly illustrate the challenges and uniqueness of this patient population that deserves prompt and special attention,” study cochair Timothy Henry, MD, president-elect of the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions, said in a news release.

The NACMI registry is a collaborative effort between the SCAI, the American College of Cardiology Interventional Council, and the Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology.

“The rapid development of this ongoing, critically important prospective registry reflects the strong and unique collaboration of all three societies. It was gratifying to be part of this process and hopefully the results will improve the care of our patients and stimulate further research,” Dr. Henry said in the news release.

The registry has enrolled 1,185 patients presenting with STEMI at 64 sites across the United States and Canada. Participants include 230 COVID-positive STEMI patients; 495 STEMI patients suspected but ultimately confirmed not to have COVID-19; and 460 age-and sex-matched control STEMI patients treated prior to the pandemic who are part of the Midwest STEMI Consortium.

The initial findings from the registry were published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Atypical symptoms may explain high death rate

The primary outcome – a composite of in-hospital death, stroke, recurrent MI, or repeat unplanned revascularization – occurred in 36% of COVID-positive patients, compared with 13% of COVID-negative patients and 5% of control patients (P < .001 relative to controls).

This difference was driven largely by a “very high” in-hospital death rate in COVID-positive patients, lead author Santiago Garcia, MD, Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation, said in an interview.

The in-hospital death rate was 33% in COVID-positive patients, compared with 11% in COVID-negative patients and 4% in controls. Stroke also occurred more often in COVID-positive patients at 3% versus 2% in COVID-negative and 0% in controls.

These initial findings suggest that the combination of STEMI and COVID-19 infection “confers a poor prognosis, with one in three patients succumbing to the disease, even among patients selected for invasive angiography (28% mortality),” the investigators wrote.

The data also show that STEMI in COVID-positive patients disproportionately affects ethnic minorities (23% Hispanic and 24% Black) with diabetes, which was present in 46% of COVID-positive patients.

COVID-positive patients with STEMI are more likely to present with atypical symptoms such as dyspnea (54%), pulmonary infiltrates on chest x-ray (46%), and high-risk conditions such as cardiogenic shock (18%), “which may explain the high fatality rate,” Dr. Garcia said.

Despite these high-risk features, COVID-positive patients are less apt to undergo invasive angiography when compared with COVID-negative and control STEMI patients (78% vs. 96% vs. 100%).

The majority of patients (71%) who did under angiography received primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) with very small treatment delays (at 15 minutes) during the pandemic.

Another notable finding is that “many patients (23%) have ‘no culprit’ vessel and may represent different etiologies of ST-segment elevation including microemboli, myocarditis, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy,” Dr. Garcia said in an interview.

“In line with current guidelines, patients with suspected STEMI should be managed with PPCI, without delay while the safety of health care providers is ensured,” Ran Kornowski, MD, and Katia Orvin, MD, both with Rabin Medical Center, Petah Tikva, Israel, and Tel Aviv University, wrote in a linked editorial.

“In this case, PPCI should be performed routinely, even if the patient is presumed to have COVID-19, because PPCI should not be postponed. Confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection should not delay urgent decision management concerning reperfusion strategy,” they advised.

Looking ahead, Garcia said plans for the registry include determining predictors of in-hospital mortality and studying demographic and treatment trends as the pandemic continues with more virulent strains of the virus.

Various subgroup analyses are also planned as well as an independent angiographic and electrocardiographic core lab analysis. A comparative analysis of data from the US and Canada is also planned.

This work was supported by an ACC Accreditation Grant, Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation, and grants from Medtronic and Abbott Vascular to SCAI. Dr. Garcia has received institutional research grants from Edwards Lifesciences, BSCI, Medtronic, and Abbott Vascular; has served as a consultant for Medtronic and BSCI; and has served as a proctor for Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Kornowski and Dr. Orvin disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 patients with ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) represent a population with unique demographic and clinical features resulting in a high risk for mortality, according to initial findings from the North American Cardiovascular COVID-19 Myocardial Infarction (NACMI) Registry.

“This is the largest registry of COVID-positive patients presenting with STEMI [and] the results clearly illustrate the challenges and uniqueness of this patient population that deserves prompt and special attention,” study cochair Timothy Henry, MD, president-elect of the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions, said in a news release.

The NACMI registry is a collaborative effort between the SCAI, the American College of Cardiology Interventional Council, and the Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology.

“The rapid development of this ongoing, critically important prospective registry reflects the strong and unique collaboration of all three societies. It was gratifying to be part of this process and hopefully the results will improve the care of our patients and stimulate further research,” Dr. Henry said in the news release.

The registry has enrolled 1,185 patients presenting with STEMI at 64 sites across the United States and Canada. Participants include 230 COVID-positive STEMI patients; 495 STEMI patients suspected but ultimately confirmed not to have COVID-19; and 460 age-and sex-matched control STEMI patients treated prior to the pandemic who are part of the Midwest STEMI Consortium.

The initial findings from the registry were published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Atypical symptoms may explain high death rate

The primary outcome – a composite of in-hospital death, stroke, recurrent MI, or repeat unplanned revascularization – occurred in 36% of COVID-positive patients, compared with 13% of COVID-negative patients and 5% of control patients (P < .001 relative to controls).

This difference was driven largely by a “very high” in-hospital death rate in COVID-positive patients, lead author Santiago Garcia, MD, Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation, said in an interview.

The in-hospital death rate was 33% in COVID-positive patients, compared with 11% in COVID-negative patients and 4% in controls. Stroke also occurred more often in COVID-positive patients at 3% versus 2% in COVID-negative and 0% in controls.

These initial findings suggest that the combination of STEMI and COVID-19 infection “confers a poor prognosis, with one in three patients succumbing to the disease, even among patients selected for invasive angiography (28% mortality),” the investigators wrote.

The data also show that STEMI in COVID-positive patients disproportionately affects ethnic minorities (23% Hispanic and 24% Black) with diabetes, which was present in 46% of COVID-positive patients.

COVID-positive patients with STEMI are more likely to present with atypical symptoms such as dyspnea (54%), pulmonary infiltrates on chest x-ray (46%), and high-risk conditions such as cardiogenic shock (18%), “which may explain the high fatality rate,” Dr. Garcia said.

Despite these high-risk features, COVID-positive patients are less apt to undergo invasive angiography when compared with COVID-negative and control STEMI patients (78% vs. 96% vs. 100%).

The majority of patients (71%) who did under angiography received primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) with very small treatment delays (at 15 minutes) during the pandemic.

Another notable finding is that “many patients (23%) have ‘no culprit’ vessel and may represent different etiologies of ST-segment elevation including microemboli, myocarditis, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy,” Dr. Garcia said in an interview.

“In line with current guidelines, patients with suspected STEMI should be managed with PPCI, without delay while the safety of health care providers is ensured,” Ran Kornowski, MD, and Katia Orvin, MD, both with Rabin Medical Center, Petah Tikva, Israel, and Tel Aviv University, wrote in a linked editorial.

“In this case, PPCI should be performed routinely, even if the patient is presumed to have COVID-19, because PPCI should not be postponed. Confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection should not delay urgent decision management concerning reperfusion strategy,” they advised.

Looking ahead, Garcia said plans for the registry include determining predictors of in-hospital mortality and studying demographic and treatment trends as the pandemic continues with more virulent strains of the virus.

Various subgroup analyses are also planned as well as an independent angiographic and electrocardiographic core lab analysis. A comparative analysis of data from the US and Canada is also planned.

This work was supported by an ACC Accreditation Grant, Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation, and grants from Medtronic and Abbott Vascular to SCAI. Dr. Garcia has received institutional research grants from Edwards Lifesciences, BSCI, Medtronic, and Abbott Vascular; has served as a consultant for Medtronic and BSCI; and has served as a proctor for Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Kornowski and Dr. Orvin disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 patients with ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) represent a population with unique demographic and clinical features resulting in a high risk for mortality, according to initial findings from the North American Cardiovascular COVID-19 Myocardial Infarction (NACMI) Registry.

“This is the largest registry of COVID-positive patients presenting with STEMI [and] the results clearly illustrate the challenges and uniqueness of this patient population that deserves prompt and special attention,” study cochair Timothy Henry, MD, president-elect of the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions, said in a news release.

The NACMI registry is a collaborative effort between the SCAI, the American College of Cardiology Interventional Council, and the Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology.

“The rapid development of this ongoing, critically important prospective registry reflects the strong and unique collaboration of all three societies. It was gratifying to be part of this process and hopefully the results will improve the care of our patients and stimulate further research,” Dr. Henry said in the news release.

The registry has enrolled 1,185 patients presenting with STEMI at 64 sites across the United States and Canada. Participants include 230 COVID-positive STEMI patients; 495 STEMI patients suspected but ultimately confirmed not to have COVID-19; and 460 age-and sex-matched control STEMI patients treated prior to the pandemic who are part of the Midwest STEMI Consortium.

The initial findings from the registry were published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Atypical symptoms may explain high death rate

The primary outcome – a composite of in-hospital death, stroke, recurrent MI, or repeat unplanned revascularization – occurred in 36% of COVID-positive patients, compared with 13% of COVID-negative patients and 5% of control patients (P < .001 relative to controls).

This difference was driven largely by a “very high” in-hospital death rate in COVID-positive patients, lead author Santiago Garcia, MD, Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation, said in an interview.

The in-hospital death rate was 33% in COVID-positive patients, compared with 11% in COVID-negative patients and 4% in controls. Stroke also occurred more often in COVID-positive patients at 3% versus 2% in COVID-negative and 0% in controls.

These initial findings suggest that the combination of STEMI and COVID-19 infection “confers a poor prognosis, with one in three patients succumbing to the disease, even among patients selected for invasive angiography (28% mortality),” the investigators wrote.

The data also show that STEMI in COVID-positive patients disproportionately affects ethnic minorities (23% Hispanic and 24% Black) with diabetes, which was present in 46% of COVID-positive patients.

COVID-positive patients with STEMI are more likely to present with atypical symptoms such as dyspnea (54%), pulmonary infiltrates on chest x-ray (46%), and high-risk conditions such as cardiogenic shock (18%), “which may explain the high fatality rate,” Dr. Garcia said.

Despite these high-risk features, COVID-positive patients are less apt to undergo invasive angiography when compared with COVID-negative and control STEMI patients (78% vs. 96% vs. 100%).

The majority of patients (71%) who did under angiography received primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) with very small treatment delays (at 15 minutes) during the pandemic.

Another notable finding is that “many patients (23%) have ‘no culprit’ vessel and may represent different etiologies of ST-segment elevation including microemboli, myocarditis, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy,” Dr. Garcia said in an interview.

“In line with current guidelines, patients with suspected STEMI should be managed with PPCI, without delay while the safety of health care providers is ensured,” Ran Kornowski, MD, and Katia Orvin, MD, both with Rabin Medical Center, Petah Tikva, Israel, and Tel Aviv University, wrote in a linked editorial.

“In this case, PPCI should be performed routinely, even if the patient is presumed to have COVID-19, because PPCI should not be postponed. Confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection should not delay urgent decision management concerning reperfusion strategy,” they advised.

Looking ahead, Garcia said plans for the registry include determining predictors of in-hospital mortality and studying demographic and treatment trends as the pandemic continues with more virulent strains of the virus.

Various subgroup analyses are also planned as well as an independent angiographic and electrocardiographic core lab analysis. A comparative analysis of data from the US and Canada is also planned.

This work was supported by an ACC Accreditation Grant, Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation, and grants from Medtronic and Abbott Vascular to SCAI. Dr. Garcia has received institutional research grants from Edwards Lifesciences, BSCI, Medtronic, and Abbott Vascular; has served as a consultant for Medtronic and BSCI; and has served as a proctor for Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Kornowski and Dr. Orvin disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More signs COVID shots are safe for pregnant women

As the U.S. races to vaccinate millions of people against the coronavirus, pregnant women face the extra challenge of not knowing whether the vaccines are safe for them or their unborn babies.

None of the recent COVID-19 vaccine trials, including those for Pfizer, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson, enrolled pregnant or breastfeeding women because they consider them a high-risk group.

That was despite the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists asking that pregnant and breastfeeding women be included in trials. The Food and Drug Administration even included pregnant women in the COVID-19 vaccine emergency use authorization (EUA) because of their higher risk of having a more severe disease.

Despite that lack of clinical trial data, more and more smaller studies are suggesting that the vaccines are safe for both mother and child.

Pfizer is now studying its two-dose vaccine in 4,000 pregnant and breastfeeding women to see how safe, tolerated, and robust their immune response is. Researchers will also look at how safe the vaccine is for infants and whether mothers pass along antibodies to children. But the preliminary results won’t be available until the end of the year, a Pfizer spokesperson says.

Without that information, pregnant women are less likely to get vaccinated, according to a large international survey. Less than 45% of pregnant women in the United States said they intended to get vaccinated even when they were told the vaccine was safe and 90% effective. That figure rises to 52% of pregnant women in 16 countries, including the United States, compared with 74% of nonpregnant women willing to be vaccinated. The findings were published online March 1, 2021, in the European Journal of Epidemiology.

The vaccine-hesitant pregnant women in the international study were most concerned that the COVID-19 vaccine could harm their developing fetuses, a worry related to the lack of clinical evidence in pregnant women, said lead researcher Julia Wu, ScD, an epidemiologist at the Harvard School of Public Health’s Human Immunomics Initiative in Boston.

The information vacuum also increases the chances that “people will fall victim to misinformation campaigns like the one on social media that claims that the COVID-19 vaccine causes infertility,” Dr. Wu said. This unfounded claim has deterred some women of childbearing age from getting the vaccine.

Deciding to get vaccinated

Frontline health care professionals were in the first group eligible to receive the vaccine in December 2020. “All of us who were pregnant ... had to decide whether to wait for the data, because we don’t know what the risks are, or go ahead and get it [the vaccine]. We had been dealing with the pandemic for months and were afraid of being exposed to the virus and infecting family members,” said Jacqueline Parchem, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston.

Given the lack of safety data, the CDC guidance to pregnant women has been to consult with their doctors and that it’s a personal choice. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest vaccine guidance said that “there is no evidence that antibodies formed from COVID-19 vaccination cause any problem with pregnancy, including the development of the placenta.”

The CDC is monitoring vaccinated people through its v-safe program and reported on April 12 that more than 86,000 v-safe participants said they were pregnant when they were vaccinated.

Health care workers who were nursing their infants when they were eligible for the vaccine faced a similar dilemma as pregnant women – they lacked the data on them to make a truly informed decision.

“I was nervous about the vaccine side effects for myself and whether my son Bennett, who was about a year old, would experience any of these himself,” said Christa Carrig, a labor and delivery nurse at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, who was breastfeeding at the time.

She and Dr. Parchem know that pregnant women with COVID-19 are more likely to have severe illness and complications such as high blood pressure and preterm delivery. “Pregnancy takes a toll on the body. When a woman gets COVID-19 and that insult is added, women who were otherwise young and healthy get much sicker than you would expect,” said Ms. Carrig.

“As a high-risk pregnancy specialist, I know that, with COVID, that babies don’t do well when moms are sick,” said Dr. Parchem.

Pregnant women accounted for more than 84,629 cases of COVID-19 and 95 deaths in the United States between Jan. 22 last year and April 12 this year, according to the CDC COVID data tracker.

Dr. Parchem and Ms. Carrig decided to get vaccinated because of their high risk of exposure to COVID-19 at work. After the second dose, Ms. Carrig reported chills but Bennett had no side effects from breastfeeding. Dr. Parchem, who delivered a healthy baby boy in February, reported no side effects other than a sore arm.

“There’s also a psychological benefit to returning to some sense of normalcy,” said Dr. Parchem. “My mother was finally able to visit us to see the new baby after we were all vaccinated. This was the first visit in more than a year.”

New study results

Ms. Carrig was one of 131 vaccinated hospital workers in the Boston area who took part in the first study to profile the immune response in pregnant and breastfeeding women and compare it with both nonpregnant and pregnant women who had COVID-19.

The study was not designed to evaluate the safety of the vaccines or whether they prevent COVID-19 illness and hospitalizations. That is the role of the large vaccine trials, the authors said.

The participants were aged 18-45 years and received both doses of either Pfizer or Moderna vaccines during one of their trimesters. They provided blood and/or breast milk samples after each vaccine dose, 2-6 weeks after the last dose, and at delivery for the 10 who gave birth during the study.

The vaccines produced a similar strong antibody response among the pregnant/breastfeeding women and nonpregnant women. Their antibody levels were much higher than those found in the pregnant women who had COVID-19, the researchers reported on March 25, 2021, in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

“This is important because a lot of people tend to think once they’ve had COVID-19, they are protected from the virus. This finding suggests that the vaccines produce a stronger antibody response than the infection itself, and this might be important for long-lasting protection against COVID-19,” said Dr. Parchem.

The study also addressed whether newborns benefit from the antibodies produced by their mothers. “In the 10 women who delivered, we detected antibodies in their umbilical cords and breast milk,” says Andrea Edlow, MD, lead researcher and a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Newborns are particularly vulnerable to respiratory infections because they have small airways and their immune systems are underdeveloped. These infections can be lethal early in life.

“The public health strategy is to vaccinate mothers against respiratory viruses, bacteria, and parasites that neonates up to 6 months are exposed to. Influenza and pertussis (whooping cough) are two examples of vaccines that we give mothers that we know transfer [antibodies] across the umbilical cord,” said Dr. Edlow.

But this “passive transfer immunity” is different from active immunity, when the body produces its own antibody immune response, she explains.

A different study, also published in March, confirmed that antibodies were transferred from 27 vaccinated pregnant mothers to their infants when they delivered. A new finding was that the women who were vaccinated with both doses and earlier in their third semester passed on more antibodies than the women who were vaccinated later or with only one dose.

Impact of the studies

The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine updated its guidance on counseling pregnant and lactating patients about the COVID-19 vaccines to include Dr. Edlow’s study.

“We were struck by how much pregnant and breastfeeding women want to participate in research and to help others in the same situation make decisions. I hope this will be an example to drug companies doing research on new vaccines in the future – that they should not be left behind and can make decisions themselves whether to participate after weighing the risks and benefits,” said Dr. Edlow.

She continues to enroll more vaccinated women in her study in the Boston area, including non–health care workers who have asked to take part.

“It was worth getting vaccinated and participating in the study. I know that I have antibodies and it worked and that I passed them on to Bennett. Also, I know that all the information is available for other women who are questioning whether to get vaccinated or not,” said Ms. Carrig.

Dr. Parchem is also taking part in the CDC’s v-safe pregnancy registry, which is collecting health and safety data on vaccinated pregnant women.

Before she was vaccinated, Dr. Parchem said, “my advice was very measured because we lacked data either saying that it definitely works or showing that it was unsafe. Now that we have this data supporting the benefits, I feel more confident in recommending the vaccines.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As the U.S. races to vaccinate millions of people against the coronavirus, pregnant women face the extra challenge of not knowing whether the vaccines are safe for them or their unborn babies.

None of the recent COVID-19 vaccine trials, including those for Pfizer, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson, enrolled pregnant or breastfeeding women because they consider them a high-risk group.

That was despite the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists asking that pregnant and breastfeeding women be included in trials. The Food and Drug Administration even included pregnant women in the COVID-19 vaccine emergency use authorization (EUA) because of their higher risk of having a more severe disease.

Despite that lack of clinical trial data, more and more smaller studies are suggesting that the vaccines are safe for both mother and child.

Pfizer is now studying its two-dose vaccine in 4,000 pregnant and breastfeeding women to see how safe, tolerated, and robust their immune response is. Researchers will also look at how safe the vaccine is for infants and whether mothers pass along antibodies to children. But the preliminary results won’t be available until the end of the year, a Pfizer spokesperson says.

Without that information, pregnant women are less likely to get vaccinated, according to a large international survey. Less than 45% of pregnant women in the United States said they intended to get vaccinated even when they were told the vaccine was safe and 90% effective. That figure rises to 52% of pregnant women in 16 countries, including the United States, compared with 74% of nonpregnant women willing to be vaccinated. The findings were published online March 1, 2021, in the European Journal of Epidemiology.

The vaccine-hesitant pregnant women in the international study were most concerned that the COVID-19 vaccine could harm their developing fetuses, a worry related to the lack of clinical evidence in pregnant women, said lead researcher Julia Wu, ScD, an epidemiologist at the Harvard School of Public Health’s Human Immunomics Initiative in Boston.

The information vacuum also increases the chances that “people will fall victim to misinformation campaigns like the one on social media that claims that the COVID-19 vaccine causes infertility,” Dr. Wu said. This unfounded claim has deterred some women of childbearing age from getting the vaccine.

Deciding to get vaccinated

Frontline health care professionals were in the first group eligible to receive the vaccine in December 2020. “All of us who were pregnant ... had to decide whether to wait for the data, because we don’t know what the risks are, or go ahead and get it [the vaccine]. We had been dealing with the pandemic for months and were afraid of being exposed to the virus and infecting family members,” said Jacqueline Parchem, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston.

Given the lack of safety data, the CDC guidance to pregnant women has been to consult with their doctors and that it’s a personal choice. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest vaccine guidance said that “there is no evidence that antibodies formed from COVID-19 vaccination cause any problem with pregnancy, including the development of the placenta.”

The CDC is monitoring vaccinated people through its v-safe program and reported on April 12 that more than 86,000 v-safe participants said they were pregnant when they were vaccinated.

Health care workers who were nursing their infants when they were eligible for the vaccine faced a similar dilemma as pregnant women – they lacked the data on them to make a truly informed decision.

“I was nervous about the vaccine side effects for myself and whether my son Bennett, who was about a year old, would experience any of these himself,” said Christa Carrig, a labor and delivery nurse at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, who was breastfeeding at the time.

She and Dr. Parchem know that pregnant women with COVID-19 are more likely to have severe illness and complications such as high blood pressure and preterm delivery. “Pregnancy takes a toll on the body. When a woman gets COVID-19 and that insult is added, women who were otherwise young and healthy get much sicker than you would expect,” said Ms. Carrig.

“As a high-risk pregnancy specialist, I know that, with COVID, that babies don’t do well when moms are sick,” said Dr. Parchem.

Pregnant women accounted for more than 84,629 cases of COVID-19 and 95 deaths in the United States between Jan. 22 last year and April 12 this year, according to the CDC COVID data tracker.

Dr. Parchem and Ms. Carrig decided to get vaccinated because of their high risk of exposure to COVID-19 at work. After the second dose, Ms. Carrig reported chills but Bennett had no side effects from breastfeeding. Dr. Parchem, who delivered a healthy baby boy in February, reported no side effects other than a sore arm.

“There’s also a psychological benefit to returning to some sense of normalcy,” said Dr. Parchem. “My mother was finally able to visit us to see the new baby after we were all vaccinated. This was the first visit in more than a year.”

New study results

Ms. Carrig was one of 131 vaccinated hospital workers in the Boston area who took part in the first study to profile the immune response in pregnant and breastfeeding women and compare it with both nonpregnant and pregnant women who had COVID-19.

The study was not designed to evaluate the safety of the vaccines or whether they prevent COVID-19 illness and hospitalizations. That is the role of the large vaccine trials, the authors said.

The participants were aged 18-45 years and received both doses of either Pfizer or Moderna vaccines during one of their trimesters. They provided blood and/or breast milk samples after each vaccine dose, 2-6 weeks after the last dose, and at delivery for the 10 who gave birth during the study.

The vaccines produced a similar strong antibody response among the pregnant/breastfeeding women and nonpregnant women. Their antibody levels were much higher than those found in the pregnant women who had COVID-19, the researchers reported on March 25, 2021, in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

“This is important because a lot of people tend to think once they’ve had COVID-19, they are protected from the virus. This finding suggests that the vaccines produce a stronger antibody response than the infection itself, and this might be important for long-lasting protection against COVID-19,” said Dr. Parchem.

The study also addressed whether newborns benefit from the antibodies produced by their mothers. “In the 10 women who delivered, we detected antibodies in their umbilical cords and breast milk,” says Andrea Edlow, MD, lead researcher and a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Newborns are particularly vulnerable to respiratory infections because they have small airways and their immune systems are underdeveloped. These infections can be lethal early in life.

“The public health strategy is to vaccinate mothers against respiratory viruses, bacteria, and parasites that neonates up to 6 months are exposed to. Influenza and pertussis (whooping cough) are two examples of vaccines that we give mothers that we know transfer [antibodies] across the umbilical cord,” said Dr. Edlow.

But this “passive transfer immunity” is different from active immunity, when the body produces its own antibody immune response, she explains.

A different study, also published in March, confirmed that antibodies were transferred from 27 vaccinated pregnant mothers to their infants when they delivered. A new finding was that the women who were vaccinated with both doses and earlier in their third semester passed on more antibodies than the women who were vaccinated later or with only one dose.

Impact of the studies

The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine updated its guidance on counseling pregnant and lactating patients about the COVID-19 vaccines to include Dr. Edlow’s study.

“We were struck by how much pregnant and breastfeeding women want to participate in research and to help others in the same situation make decisions. I hope this will be an example to drug companies doing research on new vaccines in the future – that they should not be left behind and can make decisions themselves whether to participate after weighing the risks and benefits,” said Dr. Edlow.

She continues to enroll more vaccinated women in her study in the Boston area, including non–health care workers who have asked to take part.

“It was worth getting vaccinated and participating in the study. I know that I have antibodies and it worked and that I passed them on to Bennett. Also, I know that all the information is available for other women who are questioning whether to get vaccinated or not,” said Ms. Carrig.

Dr. Parchem is also taking part in the CDC’s v-safe pregnancy registry, which is collecting health and safety data on vaccinated pregnant women.

Before she was vaccinated, Dr. Parchem said, “my advice was very measured because we lacked data either saying that it definitely works or showing that it was unsafe. Now that we have this data supporting the benefits, I feel more confident in recommending the vaccines.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As the U.S. races to vaccinate millions of people against the coronavirus, pregnant women face the extra challenge of not knowing whether the vaccines are safe for them or their unborn babies.

None of the recent COVID-19 vaccine trials, including those for Pfizer, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson, enrolled pregnant or breastfeeding women because they consider them a high-risk group.

That was despite the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists asking that pregnant and breastfeeding women be included in trials. The Food and Drug Administration even included pregnant women in the COVID-19 vaccine emergency use authorization (EUA) because of their higher risk of having a more severe disease.

Despite that lack of clinical trial data, more and more smaller studies are suggesting that the vaccines are safe for both mother and child.

Pfizer is now studying its two-dose vaccine in 4,000 pregnant and breastfeeding women to see how safe, tolerated, and robust their immune response is. Researchers will also look at how safe the vaccine is for infants and whether mothers pass along antibodies to children. But the preliminary results won’t be available until the end of the year, a Pfizer spokesperson says.

Without that information, pregnant women are less likely to get vaccinated, according to a large international survey. Less than 45% of pregnant women in the United States said they intended to get vaccinated even when they were told the vaccine was safe and 90% effective. That figure rises to 52% of pregnant women in 16 countries, including the United States, compared with 74% of nonpregnant women willing to be vaccinated. The findings were published online March 1, 2021, in the European Journal of Epidemiology.

The vaccine-hesitant pregnant women in the international study were most concerned that the COVID-19 vaccine could harm their developing fetuses, a worry related to the lack of clinical evidence in pregnant women, said lead researcher Julia Wu, ScD, an epidemiologist at the Harvard School of Public Health’s Human Immunomics Initiative in Boston.

The information vacuum also increases the chances that “people will fall victim to misinformation campaigns like the one on social media that claims that the COVID-19 vaccine causes infertility,” Dr. Wu said. This unfounded claim has deterred some women of childbearing age from getting the vaccine.

Deciding to get vaccinated

Frontline health care professionals were in the first group eligible to receive the vaccine in December 2020. “All of us who were pregnant ... had to decide whether to wait for the data, because we don’t know what the risks are, or go ahead and get it [the vaccine]. We had been dealing with the pandemic for months and were afraid of being exposed to the virus and infecting family members,” said Jacqueline Parchem, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston.

Given the lack of safety data, the CDC guidance to pregnant women has been to consult with their doctors and that it’s a personal choice. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest vaccine guidance said that “there is no evidence that antibodies formed from COVID-19 vaccination cause any problem with pregnancy, including the development of the placenta.”

The CDC is monitoring vaccinated people through its v-safe program and reported on April 12 that more than 86,000 v-safe participants said they were pregnant when they were vaccinated.

Health care workers who were nursing their infants when they were eligible for the vaccine faced a similar dilemma as pregnant women – they lacked the data on them to make a truly informed decision.

“I was nervous about the vaccine side effects for myself and whether my son Bennett, who was about a year old, would experience any of these himself,” said Christa Carrig, a labor and delivery nurse at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, who was breastfeeding at the time.

She and Dr. Parchem know that pregnant women with COVID-19 are more likely to have severe illness and complications such as high blood pressure and preterm delivery. “Pregnancy takes a toll on the body. When a woman gets COVID-19 and that insult is added, women who were otherwise young and healthy get much sicker than you would expect,” said Ms. Carrig.

“As a high-risk pregnancy specialist, I know that, with COVID, that babies don’t do well when moms are sick,” said Dr. Parchem.

Pregnant women accounted for more than 84,629 cases of COVID-19 and 95 deaths in the United States between Jan. 22 last year and April 12 this year, according to the CDC COVID data tracker.

Dr. Parchem and Ms. Carrig decided to get vaccinated because of their high risk of exposure to COVID-19 at work. After the second dose, Ms. Carrig reported chills but Bennett had no side effects from breastfeeding. Dr. Parchem, who delivered a healthy baby boy in February, reported no side effects other than a sore arm.

“There’s also a psychological benefit to returning to some sense of normalcy,” said Dr. Parchem. “My mother was finally able to visit us to see the new baby after we were all vaccinated. This was the first visit in more than a year.”

New study results

Ms. Carrig was one of 131 vaccinated hospital workers in the Boston area who took part in the first study to profile the immune response in pregnant and breastfeeding women and compare it with both nonpregnant and pregnant women who had COVID-19.

The study was not designed to evaluate the safety of the vaccines or whether they prevent COVID-19 illness and hospitalizations. That is the role of the large vaccine trials, the authors said.

The participants were aged 18-45 years and received both doses of either Pfizer or Moderna vaccines during one of their trimesters. They provided blood and/or breast milk samples after each vaccine dose, 2-6 weeks after the last dose, and at delivery for the 10 who gave birth during the study.

The vaccines produced a similar strong antibody response among the pregnant/breastfeeding women and nonpregnant women. Their antibody levels were much higher than those found in the pregnant women who had COVID-19, the researchers reported on March 25, 2021, in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

“This is important because a lot of people tend to think once they’ve had COVID-19, they are protected from the virus. This finding suggests that the vaccines produce a stronger antibody response than the infection itself, and this might be important for long-lasting protection against COVID-19,” said Dr. Parchem.

The study also addressed whether newborns benefit from the antibodies produced by their mothers. “In the 10 women who delivered, we detected antibodies in their umbilical cords and breast milk,” says Andrea Edlow, MD, lead researcher and a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Newborns are particularly vulnerable to respiratory infections because they have small airways and their immune systems are underdeveloped. These infections can be lethal early in life.

“The public health strategy is to vaccinate mothers against respiratory viruses, bacteria, and parasites that neonates up to 6 months are exposed to. Influenza and pertussis (whooping cough) are two examples of vaccines that we give mothers that we know transfer [antibodies] across the umbilical cord,” said Dr. Edlow.

But this “passive transfer immunity” is different from active immunity, when the body produces its own antibody immune response, she explains.

A different study, also published in March, confirmed that antibodies were transferred from 27 vaccinated pregnant mothers to their infants when they delivered. A new finding was that the women who were vaccinated with both doses and earlier in their third semester passed on more antibodies than the women who were vaccinated later or with only one dose.

Impact of the studies

The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine updated its guidance on counseling pregnant and lactating patients about the COVID-19 vaccines to include Dr. Edlow’s study.

“We were struck by how much pregnant and breastfeeding women want to participate in research and to help others in the same situation make decisions. I hope this will be an example to drug companies doing research on new vaccines in the future – that they should not be left behind and can make decisions themselves whether to participate after weighing the risks and benefits,” said Dr. Edlow.

She continues to enroll more vaccinated women in her study in the Boston area, including non–health care workers who have asked to take part.

“It was worth getting vaccinated and participating in the study. I know that I have antibodies and it worked and that I passed them on to Bennett. Also, I know that all the information is available for other women who are questioning whether to get vaccinated or not,” said Ms. Carrig.

Dr. Parchem is also taking part in the CDC’s v-safe pregnancy registry, which is collecting health and safety data on vaccinated pregnant women.

Before she was vaccinated, Dr. Parchem said, “my advice was very measured because we lacked data either saying that it definitely works or showing that it was unsafe. Now that we have this data supporting the benefits, I feel more confident in recommending the vaccines.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The neurology of long-haul COVID-19

Long-haul neurologic symptoms of COVID-19 seem to be distinct from neurologic conditions found in acute disease. Much work remains to be done to understand the biological mechanisms behind these problems, but inflammation and autoimmune responses may play a role in some cases.

Those were some of the takeaways from a talk by Serena Spudich, MD, who presented her research at the 2021 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. Dr. Spudich is the division chief of neurologic infections and global neurology and codirector of the Center for Neuroepidemiology and Clinical Neurological Research at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

Examining the nervous system’s involvement in COVID-19

Even early on in the pandemic, it became clear that there were lingering complaints of neuromuscular problems, cognitive dysfunction, and mood and psychiatric issues. Breathing and heart rate problems also can arise. “There seems to be a preponderance of syndromes that reflect involvement of the nervous system,” said Dr. Spudich.

To try to understand the etiology of these persistent problems, Dr. Spudich said it’s important to examine the nervous system’s involvement in acute COVID-19. She has been involved in these efforts since early in the pandemic, when she ran an inpatient consult service at Yale dedicated to neurologic effects of acute COVID-19. She witnessed complications including stroke, encephalopathy, and seizures, among others.

Stroke during acute COVID-19 seemed to be associated with inflammation and endothelial activation or endotheliopathy. SARS-CoV-2 has been undetectable in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with acute COVID-19 and neurologic symptoms, but inflammatory cytokines can be present along with increased frequency of B cells. Anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies have also been found in CSF, some of which were auto reactive to brain tissue. The immune response was altered, compared with healthy controls, and in the CNS, compared with in the blood, “raising the question of whether inflammation and autoimmunity may be underlying causes of these syndromes,” said Dr. Spudich.

She also pointed to an MRI study of autopsied brain tissue of patients with COVID-19 and neurologic complications, which showed indications of both hemorrhagic and ischemic microvascular injury. “It’s just a reminder that, during acute COVID-19, there may be inflammation in the brain, there may be autoimmune reactions, and there may be vascular changes that underlie some of the neurologic syndromes that are seen,” said Dr. Spudich.

A panoply of different syndromes

In October, Yale set up a post-COVID neurologic clinic that brought together pulmonary, cardiology, and psychiatric specialists, many of whom saw the same patients, about 60% of whom had cognitive impairment, more than 40% had neuromuscular problems, and over 30% headache. “There’s not a single entity of a post-COVID neurologic syndrome. There’s a panoply of different syndromes that may have similar or distinct etiologies,” said Dr. Spudich.

Most patients were in their 30s, 40s, or 50s. That doesn’t necessarily mean this is the most common age range for these issues, though. There could be some bias if these individuals are seeking specialty care because they expected to recover from COVID-19 quickly. But it could be that there is something biologically unique among this age group that predisposes them to complications. Regardless, two out of three patients were never hospitalized, “suggesting that even mild COVID-19 can lead to some long-term sequelae,” said Dr. Spudich.

One potential explanation for long-term neurologic syndromes is that they are an extension of the inflammation, autoimmunity, and immune perturbation occurring during acute disease. One study looked at 18 cancer patients who had neurologic complications with COVID-19. Two months after onset, they had elevated markers of neuroinflammation and neuronal injury in the cerebral spinal fluid compared to cancer patients with no history of COVID-19.

Looking for biologic markers

An Italian study looked at patients who were evaluated during acute hospitalization and again 3 months later, and found that some markers of inflation in the blood were associated with later cognitive impairment. The patients were more severely ill, so it’s not clear what the findings mean for patients who present with neurologic symptoms after milder illness.

A PET scan study of 35 patients with persistent neurologic symptoms found patterns of reduced fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in some regions of the brain that are believed to be associated with some symptoms. Lower values were associated with greater severity for symptoms like memory dysfunction, and anosmia. “Why there might be hypometabolism in these regions I think needs to be assessed and used as a biomarker to associate hypometabolism with other kinds of processes in blood and spinal fluid,” said Dr. Spudich.

Along with colleagues at Yale, Dr. Spudich is conducting the MIND study, which is using PET and MRI imaging along with blood and CSF biomarkers to track the progress of patients after COVID-19. There are few results to discuss since only 20 patients have been recruited so far, except that brain imaging and blood values are generally normal despite neurologic complaints. Most were not hospitalized for COVID-19. Dr. Spudich highlighted one man in his 30s who developed new-onset psychosis, despite no previous history. Although clinical tests were all negative, a novel autoantibody detection method revealed a previously unknown autoreactive antibody in his spinal fluid. “This may suggest that there is autoantibody production in some individuals with post–COVID-19 psychosis, and potentially other syndromes,” said Dr. Spudich.

The research task ahead

The case illustrates the task ahead for neurology. “There’s a real research mandate to understand the biological substrates of these diverse disorders, not only to address the emergent public health concern and reduce the stigma in our patients, but to develop targeted therapeutic interventions,” said Dr. Spudich.

Anna Cervantes-Arslanian, MD, an associate professor of neurology at Boston University who also treats and studies patients with post-COVID neurologic symptoms, agreed with that assessment. “It’s not like every patient that has muscle aches and fatigue also has brain fog. It’s really hard to parse them out into specific phenotypes that are pretty classic. Some people will have all of those things, some will have very few of them,” said Dr. Cervantes-Arslanian. “We need to be able to identify them sand see if there is clustering of symptoms so we can better look into what the biological underpinnings are. That’s the first step to thinking about a therapeutic target.”

Dr. Spudich and Dr. Cervantes-Arslanian had no relevant financial disclosures.

Long-haul neurologic symptoms of COVID-19 seem to be distinct from neurologic conditions found in acute disease. Much work remains to be done to understand the biological mechanisms behind these problems, but inflammation and autoimmune responses may play a role in some cases.

Those were some of the takeaways from a talk by Serena Spudich, MD, who presented her research at the 2021 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. Dr. Spudich is the division chief of neurologic infections and global neurology and codirector of the Center for Neuroepidemiology and Clinical Neurological Research at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

Examining the nervous system’s involvement in COVID-19

Even early on in the pandemic, it became clear that there were lingering complaints of neuromuscular problems, cognitive dysfunction, and mood and psychiatric issues. Breathing and heart rate problems also can arise. “There seems to be a preponderance of syndromes that reflect involvement of the nervous system,” said Dr. Spudich.