User login

ID Practitioner is an independent news source that provides infectious disease specialists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on the infectious disease specialist’s practice. Specialty focus topics include antimicrobial resistance, emerging infections, global ID, hepatitis, HIV, hospital-acquired infections, immunizations and vaccines, influenza, mycoses, pediatric infections, and STIs. Infectious Diseases News is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

sofosbuvir

ritonavir with dasabuvir

discount

support path

program

ritonavir

greedy

ledipasvir

assistance

viekira pak

vpak

advocacy

needy

protest

abbvie

paritaprevir

ombitasvir

direct-acting antivirals

dasabuvir

gilead

fake-ovir

support

v pak

oasis

harvoni

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-medstat-latest-articles-articles-section')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-idp')]

Treatment paradigm for chronic HBV in flux

These days deciding when to stop targeted treatment for chronic hepatitis B is a bigger challenge than knowing when to start, Norah A. Terrault, MD, MPH, observed at the Gastroenterology Updates, IBD, Liver Disease Conference.

That’s because the treatment paradigm is in flux. The strategy is shifting from achieving hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA suppression through indefinite use of nucleoside analogues to striving for functional cure, which means eliminating hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and sustained inactive chronic hepatitis B off therapy. It’s a goal that recognizes that, while suppression is worthwhile because it reduces a patient’s risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, HBsAg clearance is better because it’s associated with an even lower risk of the malignancy, explained Dr. Terrault, professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology and liver diseases at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

The current strategy in patients who are hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positive at the outset is to treat with a nucleoside analogue until seroconversion, followed by a further year or more of consolidation therapy then treatment withdrawal. It’s a rational approach whose primary benefit is it allows identification of the roughly 50% of patients who can remain off treatment with inactive chronic hepatitis B. The other 50% – those who experience clinical relapse – will need retreatment.

Factors predictive of increased likelihood of a sustained off-treatment response include age younger than 40 years at the time of seroconversion, more than 1 year of consolidation therapy, and undetectable HBV DNA at cessation of treatment.

“In my own practice now, I actually extend the consolidation period for 2 years before I consider stopping, and I really favor doing a trial of stopping treatment in those who are younger,” Dr. Terrault said.

The biggest change in thinking involves the duration of therapy in patients who are HBeAg negative. The strategy has been to treat indefinitely unless there is a compelling reason to stop, such as toxicity, cost, or patient preference. However, it has now been demonstrated in at least nine published studies that withdrawal of therapy has a favorable immunologic effect in noncirrhotic patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B who have been HBV DNA negative on nucleoside analogues for at least 3 years. This trial off therapy can bring major benefits because roughly 50% of patients will have sustained inactive chronic hepatitis B off-treatment and 20% of patients will become HbsAg negative with functional cure at 3-5 years of follow-up.

“This is what’s impressive: that 20% of patients have lost surface antigen, because if you continue HbeAg-negative patients on nucleoside analogue therapy, essentially none of them lose surface antigen. This is an impressive number, and you’re also able to identify about 50% of patients who didn’t need to be on treatment because they now have immune control and can remain inactive carriers off treatment,” the gastroenterologist commented.

Treatment withdrawal in HBeAg-negative patients usually is followed by disease flares 8-12 weeks later because of host immune clearance, and therein lies a problem.

“The challenge with the withdrawal strategy is these flares that appear to be necessary and important, can be good or bad, and we’re really not very good at predicting what the flare is going to look like and how severe it’s going to be,” according to Dr. Terrault, first author of the current American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guidance on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B.

The good flares are accompanied by a reductions in HBV DNA and viral proteins, loss of HbsAg, and preserved liver function. The bad flares entail excessive host immune clearance leading to liver dysfunction or failure, with no reduction in viral proteins. The search is on for predictors of response to treatment withdrawal in HbeAg-negative patients. Potential differences in outcomes with the three available nucleoside analogues are being looked at, as are duration of viral suppression on treatment and differences in patient characteristics. A low quantitative HbsAg level at the time of drug withdrawal may also be important as a predictor of a higher likelihood of HBsAg loss over time off treatment.

“The studies that have been done are basically withdrawing everyone and then seeing what happens. I think we want to have a more refined approach,” she said.

This is an unfolding story. The encouraging news is that the drug development pipeline is rich with agents with a variety of mechanisms aimed at achieving HbsAg loss with finite therapy. Some of the studies are now in phase 2 and 3.

“We should be extremely excited,” Dr. Terrault said. “I think in the future we’re very likely to have curative therapies in a much greater proportion of our patients.”

When to start nucleoside analogues

Three antiviral oral nucleoside analogues are available as preferred therapies for chronic HBV: entecavir (Baraclude), tenofovir alafenamide (Vemlidy), and tenofovir disoproxil (Viread). All three provide high antiviral efficacy and low risk for resistance. The treatment goal is to prevent disease progression and HBV complications, including hepatocellular carcinoma, in individuals with active chronic hepatitis B.

The major liver disease medical societies differ only slightly on the criteria for starting treatment. Broadly, they recommend starting therapy in all patients with cirrhosis, as well as in patients without cirrhosis who have both a serum ALT level more than twice the upper limit of normal and elevated HBV DNA levels. The treatment threshold for HBV DNA levels is higher in patients who are HBeAg positive than it is for patients who are HBeAg negative; for example, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases recommends that an HbeAg-positive patient should have a HBV DNA titer greater than 20,000 IU/mL, which is a level 10 times higher than the group’s treatment threshold in HBeAg-negative patients. However, these thresholds are intended as guidance, not absolute rules, Dr. Terrault emphasized. Nearly 40% of patients don’t meet the dual ALT and HBV DNA thresholds, and serial monitoring of such patients for 6-12 months is recommended because they may be in transition.

The choice of nucleoside analogue is largely based on comorbidities. Any of the three preferred antivirals can be used when there are none. Tenofovir disoproxil is preferred in pregnancy because of its safety profile in that setting. In patients who are aged over 60 years or have bone disease or renal impairment, tenofovir alafenamide and entecavir are preferred. Entecavir should be avoided in favor of either form of tenofovir in patients who are HIV positive or have prior exposure to lamivudine.

Regarding treatment with these drugs, the recommendations target those whose liver disease is being driven by active HBV rather than fatty liver disease or some other cause. That’s the reason for the reserving treatment for patients with both high HBV DNA and high serum ALT.

“There’s definitely a camp that feels these are safe drugs, easy to use, and we should treat more people. I have to say I’m not hanging out in that camp. I still feel we should do targeted treatment, especially since there are many new drugs coming where we’re going to be able to offer cure to more people. So I feel like putting everybody on suppressive therapy isn’t the answer,” she said.

Dr. Terrault receives research grants from and/or serves as a consultant to numerous pharmaceutical companies.

These days deciding when to stop targeted treatment for chronic hepatitis B is a bigger challenge than knowing when to start, Norah A. Terrault, MD, MPH, observed at the Gastroenterology Updates, IBD, Liver Disease Conference.

That’s because the treatment paradigm is in flux. The strategy is shifting from achieving hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA suppression through indefinite use of nucleoside analogues to striving for functional cure, which means eliminating hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and sustained inactive chronic hepatitis B off therapy. It’s a goal that recognizes that, while suppression is worthwhile because it reduces a patient’s risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, HBsAg clearance is better because it’s associated with an even lower risk of the malignancy, explained Dr. Terrault, professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology and liver diseases at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

The current strategy in patients who are hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positive at the outset is to treat with a nucleoside analogue until seroconversion, followed by a further year or more of consolidation therapy then treatment withdrawal. It’s a rational approach whose primary benefit is it allows identification of the roughly 50% of patients who can remain off treatment with inactive chronic hepatitis B. The other 50% – those who experience clinical relapse – will need retreatment.

Factors predictive of increased likelihood of a sustained off-treatment response include age younger than 40 years at the time of seroconversion, more than 1 year of consolidation therapy, and undetectable HBV DNA at cessation of treatment.

“In my own practice now, I actually extend the consolidation period for 2 years before I consider stopping, and I really favor doing a trial of stopping treatment in those who are younger,” Dr. Terrault said.

The biggest change in thinking involves the duration of therapy in patients who are HBeAg negative. The strategy has been to treat indefinitely unless there is a compelling reason to stop, such as toxicity, cost, or patient preference. However, it has now been demonstrated in at least nine published studies that withdrawal of therapy has a favorable immunologic effect in noncirrhotic patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B who have been HBV DNA negative on nucleoside analogues for at least 3 years. This trial off therapy can bring major benefits because roughly 50% of patients will have sustained inactive chronic hepatitis B off-treatment and 20% of patients will become HbsAg negative with functional cure at 3-5 years of follow-up.

“This is what’s impressive: that 20% of patients have lost surface antigen, because if you continue HbeAg-negative patients on nucleoside analogue therapy, essentially none of them lose surface antigen. This is an impressive number, and you’re also able to identify about 50% of patients who didn’t need to be on treatment because they now have immune control and can remain inactive carriers off treatment,” the gastroenterologist commented.

Treatment withdrawal in HBeAg-negative patients usually is followed by disease flares 8-12 weeks later because of host immune clearance, and therein lies a problem.

“The challenge with the withdrawal strategy is these flares that appear to be necessary and important, can be good or bad, and we’re really not very good at predicting what the flare is going to look like and how severe it’s going to be,” according to Dr. Terrault, first author of the current American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guidance on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B.

The good flares are accompanied by a reductions in HBV DNA and viral proteins, loss of HbsAg, and preserved liver function. The bad flares entail excessive host immune clearance leading to liver dysfunction or failure, with no reduction in viral proteins. The search is on for predictors of response to treatment withdrawal in HbeAg-negative patients. Potential differences in outcomes with the three available nucleoside analogues are being looked at, as are duration of viral suppression on treatment and differences in patient characteristics. A low quantitative HbsAg level at the time of drug withdrawal may also be important as a predictor of a higher likelihood of HBsAg loss over time off treatment.

“The studies that have been done are basically withdrawing everyone and then seeing what happens. I think we want to have a more refined approach,” she said.

This is an unfolding story. The encouraging news is that the drug development pipeline is rich with agents with a variety of mechanisms aimed at achieving HbsAg loss with finite therapy. Some of the studies are now in phase 2 and 3.

“We should be extremely excited,” Dr. Terrault said. “I think in the future we’re very likely to have curative therapies in a much greater proportion of our patients.”

When to start nucleoside analogues

Three antiviral oral nucleoside analogues are available as preferred therapies for chronic HBV: entecavir (Baraclude), tenofovir alafenamide (Vemlidy), and tenofovir disoproxil (Viread). All three provide high antiviral efficacy and low risk for resistance. The treatment goal is to prevent disease progression and HBV complications, including hepatocellular carcinoma, in individuals with active chronic hepatitis B.

The major liver disease medical societies differ only slightly on the criteria for starting treatment. Broadly, they recommend starting therapy in all patients with cirrhosis, as well as in patients without cirrhosis who have both a serum ALT level more than twice the upper limit of normal and elevated HBV DNA levels. The treatment threshold for HBV DNA levels is higher in patients who are HBeAg positive than it is for patients who are HBeAg negative; for example, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases recommends that an HbeAg-positive patient should have a HBV DNA titer greater than 20,000 IU/mL, which is a level 10 times higher than the group’s treatment threshold in HBeAg-negative patients. However, these thresholds are intended as guidance, not absolute rules, Dr. Terrault emphasized. Nearly 40% of patients don’t meet the dual ALT and HBV DNA thresholds, and serial monitoring of such patients for 6-12 months is recommended because they may be in transition.

The choice of nucleoside analogue is largely based on comorbidities. Any of the three preferred antivirals can be used when there are none. Tenofovir disoproxil is preferred in pregnancy because of its safety profile in that setting. In patients who are aged over 60 years or have bone disease or renal impairment, tenofovir alafenamide and entecavir are preferred. Entecavir should be avoided in favor of either form of tenofovir in patients who are HIV positive or have prior exposure to lamivudine.

Regarding treatment with these drugs, the recommendations target those whose liver disease is being driven by active HBV rather than fatty liver disease or some other cause. That’s the reason for the reserving treatment for patients with both high HBV DNA and high serum ALT.

“There’s definitely a camp that feels these are safe drugs, easy to use, and we should treat more people. I have to say I’m not hanging out in that camp. I still feel we should do targeted treatment, especially since there are many new drugs coming where we’re going to be able to offer cure to more people. So I feel like putting everybody on suppressive therapy isn’t the answer,” she said.

Dr. Terrault receives research grants from and/or serves as a consultant to numerous pharmaceutical companies.

These days deciding when to stop targeted treatment for chronic hepatitis B is a bigger challenge than knowing when to start, Norah A. Terrault, MD, MPH, observed at the Gastroenterology Updates, IBD, Liver Disease Conference.

That’s because the treatment paradigm is in flux. The strategy is shifting from achieving hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA suppression through indefinite use of nucleoside analogues to striving for functional cure, which means eliminating hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and sustained inactive chronic hepatitis B off therapy. It’s a goal that recognizes that, while suppression is worthwhile because it reduces a patient’s risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, HBsAg clearance is better because it’s associated with an even lower risk of the malignancy, explained Dr. Terrault, professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology and liver diseases at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

The current strategy in patients who are hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positive at the outset is to treat with a nucleoside analogue until seroconversion, followed by a further year or more of consolidation therapy then treatment withdrawal. It’s a rational approach whose primary benefit is it allows identification of the roughly 50% of patients who can remain off treatment with inactive chronic hepatitis B. The other 50% – those who experience clinical relapse – will need retreatment.

Factors predictive of increased likelihood of a sustained off-treatment response include age younger than 40 years at the time of seroconversion, more than 1 year of consolidation therapy, and undetectable HBV DNA at cessation of treatment.

“In my own practice now, I actually extend the consolidation period for 2 years before I consider stopping, and I really favor doing a trial of stopping treatment in those who are younger,” Dr. Terrault said.

The biggest change in thinking involves the duration of therapy in patients who are HBeAg negative. The strategy has been to treat indefinitely unless there is a compelling reason to stop, such as toxicity, cost, or patient preference. However, it has now been demonstrated in at least nine published studies that withdrawal of therapy has a favorable immunologic effect in noncirrhotic patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B who have been HBV DNA negative on nucleoside analogues for at least 3 years. This trial off therapy can bring major benefits because roughly 50% of patients will have sustained inactive chronic hepatitis B off-treatment and 20% of patients will become HbsAg negative with functional cure at 3-5 years of follow-up.

“This is what’s impressive: that 20% of patients have lost surface antigen, because if you continue HbeAg-negative patients on nucleoside analogue therapy, essentially none of them lose surface antigen. This is an impressive number, and you’re also able to identify about 50% of patients who didn’t need to be on treatment because they now have immune control and can remain inactive carriers off treatment,” the gastroenterologist commented.

Treatment withdrawal in HBeAg-negative patients usually is followed by disease flares 8-12 weeks later because of host immune clearance, and therein lies a problem.

“The challenge with the withdrawal strategy is these flares that appear to be necessary and important, can be good or bad, and we’re really not very good at predicting what the flare is going to look like and how severe it’s going to be,” according to Dr. Terrault, first author of the current American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guidance on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B.

The good flares are accompanied by a reductions in HBV DNA and viral proteins, loss of HbsAg, and preserved liver function. The bad flares entail excessive host immune clearance leading to liver dysfunction or failure, with no reduction in viral proteins. The search is on for predictors of response to treatment withdrawal in HbeAg-negative patients. Potential differences in outcomes with the three available nucleoside analogues are being looked at, as are duration of viral suppression on treatment and differences in patient characteristics. A low quantitative HbsAg level at the time of drug withdrawal may also be important as a predictor of a higher likelihood of HBsAg loss over time off treatment.

“The studies that have been done are basically withdrawing everyone and then seeing what happens. I think we want to have a more refined approach,” she said.

This is an unfolding story. The encouraging news is that the drug development pipeline is rich with agents with a variety of mechanisms aimed at achieving HbsAg loss with finite therapy. Some of the studies are now in phase 2 and 3.

“We should be extremely excited,” Dr. Terrault said. “I think in the future we’re very likely to have curative therapies in a much greater proportion of our patients.”

When to start nucleoside analogues

Three antiviral oral nucleoside analogues are available as preferred therapies for chronic HBV: entecavir (Baraclude), tenofovir alafenamide (Vemlidy), and tenofovir disoproxil (Viread). All three provide high antiviral efficacy and low risk for resistance. The treatment goal is to prevent disease progression and HBV complications, including hepatocellular carcinoma, in individuals with active chronic hepatitis B.

The major liver disease medical societies differ only slightly on the criteria for starting treatment. Broadly, they recommend starting therapy in all patients with cirrhosis, as well as in patients without cirrhosis who have both a serum ALT level more than twice the upper limit of normal and elevated HBV DNA levels. The treatment threshold for HBV DNA levels is higher in patients who are HBeAg positive than it is for patients who are HBeAg negative; for example, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases recommends that an HbeAg-positive patient should have a HBV DNA titer greater than 20,000 IU/mL, which is a level 10 times higher than the group’s treatment threshold in HBeAg-negative patients. However, these thresholds are intended as guidance, not absolute rules, Dr. Terrault emphasized. Nearly 40% of patients don’t meet the dual ALT and HBV DNA thresholds, and serial monitoring of such patients for 6-12 months is recommended because they may be in transition.

The choice of nucleoside analogue is largely based on comorbidities. Any of the three preferred antivirals can be used when there are none. Tenofovir disoproxil is preferred in pregnancy because of its safety profile in that setting. In patients who are aged over 60 years or have bone disease or renal impairment, tenofovir alafenamide and entecavir are preferred. Entecavir should be avoided in favor of either form of tenofovir in patients who are HIV positive or have prior exposure to lamivudine.

Regarding treatment with these drugs, the recommendations target those whose liver disease is being driven by active HBV rather than fatty liver disease or some other cause. That’s the reason for the reserving treatment for patients with both high HBV DNA and high serum ALT.

“There’s definitely a camp that feels these are safe drugs, easy to use, and we should treat more people. I have to say I’m not hanging out in that camp. I still feel we should do targeted treatment, especially since there are many new drugs coming where we’re going to be able to offer cure to more people. So I feel like putting everybody on suppressive therapy isn’t the answer,” she said.

Dr. Terrault receives research grants from and/or serves as a consultant to numerous pharmaceutical companies.

FROM GUILD 2021

Vaccine mismatch: What to do after dose 1 when plans change

Ideally, Americans receiving their Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna COVID-19 vaccines will get both doses from the same manufacturer, said Gregory Poland, MD, a vaccinologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

After all, that’s how they were tested for efficacy and safety, and it was results from those studies that led to emergency use authorization (EUA) being granted by the Food and Drug Administration.

But states and countries have struggled to keep up with the demand for vaccine, and more flexible vaccination schedules could help.

So researchers are exploring whether it is safe and effective to get the first and second doses from different manufacturers. And they are even wondering whether mixing doses from different manufacturers could increase effectiveness, particularly in light of emerging variants.

It’s called the “interchangeability issue,” said Dr. Poland, who has gotten a steady stream of questions about it.

For example, a patient recently asked about options for his father, who had gotten his first dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine in Ecuador, but had since moved to the United States, where that product has not been approved for use.

Dr. Poland said in an interview that he prefaces each answer with: “I’ve got no science for what I’m about to tell you.”

In this particular case, he recommended that the man’s father talk with his doctor about his level of COVID-19 risk and consider whether he should gamble on the AstraZeneca vaccine getting approved in the United States soon, or whether he should ask for a second dose from one of the three vaccines currently approved.

On March 22, 2021, AstraZeneca released positive results from its phase 3 trial, which will likely speed its path toward use in the United States.

Although clinical trials have started to test combinations and boosters, there’s currently no definitive evidence from human trials on mixing COVID vaccines, Dr. Poland pointed out.

But a study of a mixed-vaccine regimen is currently underway in the United Kingdom.

Participants in that 13-month trial will be given the Oxford/AstraZeneca and Pfizer/BioNTech vaccines in different combinations and at different intervals. The first results from that trial are expected this summer.

And interim results from a trial combining Russia’s Sputnik V and the AstraZeneca vaccines are expected in 2 months, according to a Reuters report.

Mix only in ‘exceptional situations’

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been hesitant to open the door to mixing Pfizer and Moderna vaccinations, noting that the two “are not interchangeable.” But CDC guidance has changed slightly. Now, instead of saying the two vaccines should not be mixed, CDC guidance says they can be mixed in “exceptional situations,” and that the second dose can be administered up to 6 weeks after the first dose.

It is reasonable to assume that mixing COVID-19 vaccines that use the same platform – such as the mRNA platform used by both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines – will be acceptable, Dr. Poland said, although human trials have not proven that.

However, it is unclear whether vaccines that use different platforms can be mixed. Can the first dose of an mRNA vaccine be followed by an adenovirus-based vaccine, like the Johnson & Johnson product or Novavax, if that vaccine is granted an EUA?

Ross Kedl, PhD, a vaccine researcher and professor of immunology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, said matching vaccine platforms might not be the preferred vaccination strategy.

He disagreed that there’s a lack of science surrounding the issue, and said all signs point to mixing as not only a good option, but probably a better one.

Researcher says science backs mixing

A mix of two different vaccine platforms likely enhances immunity, Dr. Kedl said. The heterologous prime-boost strategy has been used in animal studies for decades, “and it is well known that this promotes a much better immune response than when immunizing with the same vaccine twice.

“If you think about it in a Venn diagram sort of way, it makes sense,” he said in an interview. “Each vaccine has a number of components in it that influence immunity in various ways, but between the two of them, they only have one component that is similar. In the case of the coronavirus vaccines, the one thing both have in common is the spike protein from SARS-CoV-2. In essence, this gives you two shots at generating immunity against the one thing in each vaccine you care most about, but only one shot for the other vaccine components in each platform, resulting in an amplified response against the common target.”

In fact, the heterologous prime-boost vaccination strategy has proven to be effective in humans in early studies.

For example, an Ebola regimen that consisted of an adenovirus vector, similar to the AstraZeneca COVID vaccine, and a modified vaccinia virus vector showed promise in a phase 1 study. And an HIV regimen that consisted of the combination of a DNA vaccine, similar to the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines, and another viral vector showed encouraging results in a proof-of-concept study.

In both these cases, the heterologous prime-boost strategy was far better than single-vaccine prime-boost regimens, Dr. Kedl pointed out. And neither study reported any safety issues with the combinations.

For now, it’s best to stick with the same manufacturer for both shots, as the CDC guidance suggests, he said, agreeing with Dr. Poland.

But “I would be very surprised if we didn’t move to a mixing of vaccine platforms for the population,” Dr. Kedl said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ideally, Americans receiving their Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna COVID-19 vaccines will get both doses from the same manufacturer, said Gregory Poland, MD, a vaccinologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

After all, that’s how they were tested for efficacy and safety, and it was results from those studies that led to emergency use authorization (EUA) being granted by the Food and Drug Administration.

But states and countries have struggled to keep up with the demand for vaccine, and more flexible vaccination schedules could help.

So researchers are exploring whether it is safe and effective to get the first and second doses from different manufacturers. And they are even wondering whether mixing doses from different manufacturers could increase effectiveness, particularly in light of emerging variants.

It’s called the “interchangeability issue,” said Dr. Poland, who has gotten a steady stream of questions about it.

For example, a patient recently asked about options for his father, who had gotten his first dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine in Ecuador, but had since moved to the United States, where that product has not been approved for use.

Dr. Poland said in an interview that he prefaces each answer with: “I’ve got no science for what I’m about to tell you.”

In this particular case, he recommended that the man’s father talk with his doctor about his level of COVID-19 risk and consider whether he should gamble on the AstraZeneca vaccine getting approved in the United States soon, or whether he should ask for a second dose from one of the three vaccines currently approved.

On March 22, 2021, AstraZeneca released positive results from its phase 3 trial, which will likely speed its path toward use in the United States.

Although clinical trials have started to test combinations and boosters, there’s currently no definitive evidence from human trials on mixing COVID vaccines, Dr. Poland pointed out.

But a study of a mixed-vaccine regimen is currently underway in the United Kingdom.

Participants in that 13-month trial will be given the Oxford/AstraZeneca and Pfizer/BioNTech vaccines in different combinations and at different intervals. The first results from that trial are expected this summer.

And interim results from a trial combining Russia’s Sputnik V and the AstraZeneca vaccines are expected in 2 months, according to a Reuters report.

Mix only in ‘exceptional situations’

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been hesitant to open the door to mixing Pfizer and Moderna vaccinations, noting that the two “are not interchangeable.” But CDC guidance has changed slightly. Now, instead of saying the two vaccines should not be mixed, CDC guidance says they can be mixed in “exceptional situations,” and that the second dose can be administered up to 6 weeks after the first dose.

It is reasonable to assume that mixing COVID-19 vaccines that use the same platform – such as the mRNA platform used by both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines – will be acceptable, Dr. Poland said, although human trials have not proven that.

However, it is unclear whether vaccines that use different platforms can be mixed. Can the first dose of an mRNA vaccine be followed by an adenovirus-based vaccine, like the Johnson & Johnson product or Novavax, if that vaccine is granted an EUA?

Ross Kedl, PhD, a vaccine researcher and professor of immunology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, said matching vaccine platforms might not be the preferred vaccination strategy.

He disagreed that there’s a lack of science surrounding the issue, and said all signs point to mixing as not only a good option, but probably a better one.

Researcher says science backs mixing

A mix of two different vaccine platforms likely enhances immunity, Dr. Kedl said. The heterologous prime-boost strategy has been used in animal studies for decades, “and it is well known that this promotes a much better immune response than when immunizing with the same vaccine twice.

“If you think about it in a Venn diagram sort of way, it makes sense,” he said in an interview. “Each vaccine has a number of components in it that influence immunity in various ways, but between the two of them, they only have one component that is similar. In the case of the coronavirus vaccines, the one thing both have in common is the spike protein from SARS-CoV-2. In essence, this gives you two shots at generating immunity against the one thing in each vaccine you care most about, but only one shot for the other vaccine components in each platform, resulting in an amplified response against the common target.”

In fact, the heterologous prime-boost vaccination strategy has proven to be effective in humans in early studies.

For example, an Ebola regimen that consisted of an adenovirus vector, similar to the AstraZeneca COVID vaccine, and a modified vaccinia virus vector showed promise in a phase 1 study. And an HIV regimen that consisted of the combination of a DNA vaccine, similar to the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines, and another viral vector showed encouraging results in a proof-of-concept study.

In both these cases, the heterologous prime-boost strategy was far better than single-vaccine prime-boost regimens, Dr. Kedl pointed out. And neither study reported any safety issues with the combinations.

For now, it’s best to stick with the same manufacturer for both shots, as the CDC guidance suggests, he said, agreeing with Dr. Poland.

But “I would be very surprised if we didn’t move to a mixing of vaccine platforms for the population,” Dr. Kedl said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ideally, Americans receiving their Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna COVID-19 vaccines will get both doses from the same manufacturer, said Gregory Poland, MD, a vaccinologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

After all, that’s how they were tested for efficacy and safety, and it was results from those studies that led to emergency use authorization (EUA) being granted by the Food and Drug Administration.

But states and countries have struggled to keep up with the demand for vaccine, and more flexible vaccination schedules could help.

So researchers are exploring whether it is safe and effective to get the first and second doses from different manufacturers. And they are even wondering whether mixing doses from different manufacturers could increase effectiveness, particularly in light of emerging variants.

It’s called the “interchangeability issue,” said Dr. Poland, who has gotten a steady stream of questions about it.

For example, a patient recently asked about options for his father, who had gotten his first dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine in Ecuador, but had since moved to the United States, where that product has not been approved for use.

Dr. Poland said in an interview that he prefaces each answer with: “I’ve got no science for what I’m about to tell you.”

In this particular case, he recommended that the man’s father talk with his doctor about his level of COVID-19 risk and consider whether he should gamble on the AstraZeneca vaccine getting approved in the United States soon, or whether he should ask for a second dose from one of the three vaccines currently approved.

On March 22, 2021, AstraZeneca released positive results from its phase 3 trial, which will likely speed its path toward use in the United States.

Although clinical trials have started to test combinations and boosters, there’s currently no definitive evidence from human trials on mixing COVID vaccines, Dr. Poland pointed out.

But a study of a mixed-vaccine regimen is currently underway in the United Kingdom.

Participants in that 13-month trial will be given the Oxford/AstraZeneca and Pfizer/BioNTech vaccines in different combinations and at different intervals. The first results from that trial are expected this summer.

And interim results from a trial combining Russia’s Sputnik V and the AstraZeneca vaccines are expected in 2 months, according to a Reuters report.

Mix only in ‘exceptional situations’

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been hesitant to open the door to mixing Pfizer and Moderna vaccinations, noting that the two “are not interchangeable.” But CDC guidance has changed slightly. Now, instead of saying the two vaccines should not be mixed, CDC guidance says they can be mixed in “exceptional situations,” and that the second dose can be administered up to 6 weeks after the first dose.

It is reasonable to assume that mixing COVID-19 vaccines that use the same platform – such as the mRNA platform used by both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines – will be acceptable, Dr. Poland said, although human trials have not proven that.

However, it is unclear whether vaccines that use different platforms can be mixed. Can the first dose of an mRNA vaccine be followed by an adenovirus-based vaccine, like the Johnson & Johnson product or Novavax, if that vaccine is granted an EUA?

Ross Kedl, PhD, a vaccine researcher and professor of immunology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, said matching vaccine platforms might not be the preferred vaccination strategy.

He disagreed that there’s a lack of science surrounding the issue, and said all signs point to mixing as not only a good option, but probably a better one.

Researcher says science backs mixing

A mix of two different vaccine platforms likely enhances immunity, Dr. Kedl said. The heterologous prime-boost strategy has been used in animal studies for decades, “and it is well known that this promotes a much better immune response than when immunizing with the same vaccine twice.

“If you think about it in a Venn diagram sort of way, it makes sense,” he said in an interview. “Each vaccine has a number of components in it that influence immunity in various ways, but between the two of them, they only have one component that is similar. In the case of the coronavirus vaccines, the one thing both have in common is the spike protein from SARS-CoV-2. In essence, this gives you two shots at generating immunity against the one thing in each vaccine you care most about, but only one shot for the other vaccine components in each platform, resulting in an amplified response against the common target.”

In fact, the heterologous prime-boost vaccination strategy has proven to be effective in humans in early studies.

For example, an Ebola regimen that consisted of an adenovirus vector, similar to the AstraZeneca COVID vaccine, and a modified vaccinia virus vector showed promise in a phase 1 study. And an HIV regimen that consisted of the combination of a DNA vaccine, similar to the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines, and another viral vector showed encouraging results in a proof-of-concept study.

In both these cases, the heterologous prime-boost strategy was far better than single-vaccine prime-boost regimens, Dr. Kedl pointed out. And neither study reported any safety issues with the combinations.

For now, it’s best to stick with the same manufacturer for both shots, as the CDC guidance suggests, he said, agreeing with Dr. Poland.

But “I would be very surprised if we didn’t move to a mixing of vaccine platforms for the population,” Dr. Kedl said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID vaccines could lose their punch within a year, experts say

In a survey of 77 epidemiologists from 28 countries by the People’s Vaccine Alliance, 66.2% predicted that the world has a year or less before variants make current vaccines ineffective. The People’s Vaccine Alliance is a coalition of more than 50 organizations, including the African Alliance, Oxfam, Public Citizen, and UNAIDS (the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS).

Almost a third (32.5%) of those surveyed said ineffectiveness would happen in 9 months or less; 18.2% said 6 months or less.

Paul A. Offit, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said in an interview that, while it’s hard to say whether vaccines could become ineffective in that time frame, “It’s perfectly reasonable to think it could happen.”

The good news, said Dr. Offit, who was not involved with the survey, is that SARS-CoV-2 mutates slowly, compared with other viruses such as influenza.

“To date,” he said, “the mutations that have occurred are not far enough away from the immunity induced by your natural infection or immunization such that one isn’t protected at least against severe and critical disease.”

That’s the goal of vaccines, he noted: “to keep people from suffering mightily.”

A line may be crossed

“And so far that’s happening, even with the variants,” Dr. Offit said. “That line has not been crossed. But I think we should assume that it might be.”

Dr. Offit said it will be critical to monitor anyone who gets hospitalized who is known to have been infected or fully vaccinated. Then countries need to get really good at sequencing those viruses.

The great majority of those surveyed (88%) said that persistently low vaccine coverage in many countries would make it more likely that vaccine-resistant mutations will appear.

Coverage comparisons between countries are stark.

Many countries haven’t given a single vaccine dose

While rich countries are giving COVID-19 vaccinations at the rate of a person a second, many of the poorest countries have given hardly any vaccines, the People’s Vaccine Alliance says.

Additionally, according to researchers at the Global Health Innovation Center at Duke University, Durham, N.C., high- and upper-middle–income countries, which represent one-fifth of the world’s population, have bought about 6 billion doses. But low- and lower-middle–income countries, which make up four-fifths of the population, have bought only about 2.6 billion, an article in Nature reports.

“You’re only as strong as your weakest country,” Dr. Offit said. “If we haven’t learned that what happens in other countries can [affect the global population], we haven’t been paying attention.”

Gregg Gonsalves, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., one of the academic centers surveyed, didn’t specify a timeline for when vaccines would become ineffective, but said in a press release that the urgency for widespread global vaccination is real.

“Unless we vaccinate the world,” he said, “we leave the playing field open to more and more mutations, which could churn out variants that could evade our current vaccines and require booster shots to deal with them.”

“Dire, but not surprising”

Panagis Galiatsatos, MD, MHS, a pulmonologist at John Hopkins University, Baltimore, whose research focuses on health care disparities, said the survey findings were “dire, but not surprising.”

Johns Hopkins was another of the centers surveyed, but Dr. Galiatsatos wasn’t personally involved with the survey.

COVID-19, Dr. Galiatsatos pointed out, has laid bare disparities, both in who gets the vaccine and who’s involved in trials to develop the vaccines.

“It’s morally concerning and an ethical reckoning,” he said in an interview.

Recognition of the borderless swath of destruction the virus is exacting is critical, he said.

The United States “has to realize this can’t be a U.S.-centric issue,” he said. “We’re going to be back to the beginning if we don’t make sure that every country is doing well. We haven’t seen that level of uniform approach.”

He noted that scientists have always known that viruses mutate, but now the race is on to find the parts of SARS-CoV-2 that don’t mutate as much.

“My suspicion is we’ll probably need boosters instead of a whole different vaccine,” Dr. Galiatsatos said.

Among the strategies sought by the People’s Vaccine Alliance is for all pharmaceutical companies working on COVID-19 vaccines to openly share technology and intellectual property through the World Health Organization COVID-19 Technology Access Pool, to speed production and rollout of vaccines to all countries.

In the survey, 74% said that open sharing of technology and intellectual property could boost global vaccine coverage; 23% said maybe and 3% said it wouldn’t help.

The survey was carried out between Feb. 17 and March 25, 2021. Respondents included epidemiologists, virologists, and infection disease specialists from the following countries: Algeria, Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Bolivia, Canada, Denmark, Ethiopia, France, Guatemala, India, Italy, Kenya, Lebanon, Norway, Philippines, Senegal, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan, Spain, United Arab Emirates, Uganda, United Kingdom, United States, Vietnam, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

Dr. Offit and Dr. Galiatsatos reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a survey of 77 epidemiologists from 28 countries by the People’s Vaccine Alliance, 66.2% predicted that the world has a year or less before variants make current vaccines ineffective. The People’s Vaccine Alliance is a coalition of more than 50 organizations, including the African Alliance, Oxfam, Public Citizen, and UNAIDS (the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS).

Almost a third (32.5%) of those surveyed said ineffectiveness would happen in 9 months or less; 18.2% said 6 months or less.

Paul A. Offit, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said in an interview that, while it’s hard to say whether vaccines could become ineffective in that time frame, “It’s perfectly reasonable to think it could happen.”

The good news, said Dr. Offit, who was not involved with the survey, is that SARS-CoV-2 mutates slowly, compared with other viruses such as influenza.

“To date,” he said, “the mutations that have occurred are not far enough away from the immunity induced by your natural infection or immunization such that one isn’t protected at least against severe and critical disease.”

That’s the goal of vaccines, he noted: “to keep people from suffering mightily.”

A line may be crossed

“And so far that’s happening, even with the variants,” Dr. Offit said. “That line has not been crossed. But I think we should assume that it might be.”

Dr. Offit said it will be critical to monitor anyone who gets hospitalized who is known to have been infected or fully vaccinated. Then countries need to get really good at sequencing those viruses.

The great majority of those surveyed (88%) said that persistently low vaccine coverage in many countries would make it more likely that vaccine-resistant mutations will appear.

Coverage comparisons between countries are stark.

Many countries haven’t given a single vaccine dose

While rich countries are giving COVID-19 vaccinations at the rate of a person a second, many of the poorest countries have given hardly any vaccines, the People’s Vaccine Alliance says.

Additionally, according to researchers at the Global Health Innovation Center at Duke University, Durham, N.C., high- and upper-middle–income countries, which represent one-fifth of the world’s population, have bought about 6 billion doses. But low- and lower-middle–income countries, which make up four-fifths of the population, have bought only about 2.6 billion, an article in Nature reports.

“You’re only as strong as your weakest country,” Dr. Offit said. “If we haven’t learned that what happens in other countries can [affect the global population], we haven’t been paying attention.”

Gregg Gonsalves, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., one of the academic centers surveyed, didn’t specify a timeline for when vaccines would become ineffective, but said in a press release that the urgency for widespread global vaccination is real.

“Unless we vaccinate the world,” he said, “we leave the playing field open to more and more mutations, which could churn out variants that could evade our current vaccines and require booster shots to deal with them.”

“Dire, but not surprising”

Panagis Galiatsatos, MD, MHS, a pulmonologist at John Hopkins University, Baltimore, whose research focuses on health care disparities, said the survey findings were “dire, but not surprising.”

Johns Hopkins was another of the centers surveyed, but Dr. Galiatsatos wasn’t personally involved with the survey.

COVID-19, Dr. Galiatsatos pointed out, has laid bare disparities, both in who gets the vaccine and who’s involved in trials to develop the vaccines.

“It’s morally concerning and an ethical reckoning,” he said in an interview.

Recognition of the borderless swath of destruction the virus is exacting is critical, he said.

The United States “has to realize this can’t be a U.S.-centric issue,” he said. “We’re going to be back to the beginning if we don’t make sure that every country is doing well. We haven’t seen that level of uniform approach.”

He noted that scientists have always known that viruses mutate, but now the race is on to find the parts of SARS-CoV-2 that don’t mutate as much.

“My suspicion is we’ll probably need boosters instead of a whole different vaccine,” Dr. Galiatsatos said.

Among the strategies sought by the People’s Vaccine Alliance is for all pharmaceutical companies working on COVID-19 vaccines to openly share technology and intellectual property through the World Health Organization COVID-19 Technology Access Pool, to speed production and rollout of vaccines to all countries.

In the survey, 74% said that open sharing of technology and intellectual property could boost global vaccine coverage; 23% said maybe and 3% said it wouldn’t help.

The survey was carried out between Feb. 17 and March 25, 2021. Respondents included epidemiologists, virologists, and infection disease specialists from the following countries: Algeria, Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Bolivia, Canada, Denmark, Ethiopia, France, Guatemala, India, Italy, Kenya, Lebanon, Norway, Philippines, Senegal, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan, Spain, United Arab Emirates, Uganda, United Kingdom, United States, Vietnam, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

Dr. Offit and Dr. Galiatsatos reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a survey of 77 epidemiologists from 28 countries by the People’s Vaccine Alliance, 66.2% predicted that the world has a year or less before variants make current vaccines ineffective. The People’s Vaccine Alliance is a coalition of more than 50 organizations, including the African Alliance, Oxfam, Public Citizen, and UNAIDS (the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS).

Almost a third (32.5%) of those surveyed said ineffectiveness would happen in 9 months or less; 18.2% said 6 months or less.

Paul A. Offit, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said in an interview that, while it’s hard to say whether vaccines could become ineffective in that time frame, “It’s perfectly reasonable to think it could happen.”

The good news, said Dr. Offit, who was not involved with the survey, is that SARS-CoV-2 mutates slowly, compared with other viruses such as influenza.

“To date,” he said, “the mutations that have occurred are not far enough away from the immunity induced by your natural infection or immunization such that one isn’t protected at least against severe and critical disease.”

That’s the goal of vaccines, he noted: “to keep people from suffering mightily.”

A line may be crossed

“And so far that’s happening, even with the variants,” Dr. Offit said. “That line has not been crossed. But I think we should assume that it might be.”

Dr. Offit said it will be critical to monitor anyone who gets hospitalized who is known to have been infected or fully vaccinated. Then countries need to get really good at sequencing those viruses.

The great majority of those surveyed (88%) said that persistently low vaccine coverage in many countries would make it more likely that vaccine-resistant mutations will appear.

Coverage comparisons between countries are stark.

Many countries haven’t given a single vaccine dose

While rich countries are giving COVID-19 vaccinations at the rate of a person a second, many of the poorest countries have given hardly any vaccines, the People’s Vaccine Alliance says.

Additionally, according to researchers at the Global Health Innovation Center at Duke University, Durham, N.C., high- and upper-middle–income countries, which represent one-fifth of the world’s population, have bought about 6 billion doses. But low- and lower-middle–income countries, which make up four-fifths of the population, have bought only about 2.6 billion, an article in Nature reports.

“You’re only as strong as your weakest country,” Dr. Offit said. “If we haven’t learned that what happens in other countries can [affect the global population], we haven’t been paying attention.”

Gregg Gonsalves, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., one of the academic centers surveyed, didn’t specify a timeline for when vaccines would become ineffective, but said in a press release that the urgency for widespread global vaccination is real.

“Unless we vaccinate the world,” he said, “we leave the playing field open to more and more mutations, which could churn out variants that could evade our current vaccines and require booster shots to deal with them.”

“Dire, but not surprising”

Panagis Galiatsatos, MD, MHS, a pulmonologist at John Hopkins University, Baltimore, whose research focuses on health care disparities, said the survey findings were “dire, but not surprising.”

Johns Hopkins was another of the centers surveyed, but Dr. Galiatsatos wasn’t personally involved with the survey.

COVID-19, Dr. Galiatsatos pointed out, has laid bare disparities, both in who gets the vaccine and who’s involved in trials to develop the vaccines.

“It’s morally concerning and an ethical reckoning,” he said in an interview.

Recognition of the borderless swath of destruction the virus is exacting is critical, he said.

The United States “has to realize this can’t be a U.S.-centric issue,” he said. “We’re going to be back to the beginning if we don’t make sure that every country is doing well. We haven’t seen that level of uniform approach.”

He noted that scientists have always known that viruses mutate, but now the race is on to find the parts of SARS-CoV-2 that don’t mutate as much.

“My suspicion is we’ll probably need boosters instead of a whole different vaccine,” Dr. Galiatsatos said.

Among the strategies sought by the People’s Vaccine Alliance is for all pharmaceutical companies working on COVID-19 vaccines to openly share technology and intellectual property through the World Health Organization COVID-19 Technology Access Pool, to speed production and rollout of vaccines to all countries.

In the survey, 74% said that open sharing of technology and intellectual property could boost global vaccine coverage; 23% said maybe and 3% said it wouldn’t help.

The survey was carried out between Feb. 17 and March 25, 2021. Respondents included epidemiologists, virologists, and infection disease specialists from the following countries: Algeria, Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Bolivia, Canada, Denmark, Ethiopia, France, Guatemala, India, Italy, Kenya, Lebanon, Norway, Philippines, Senegal, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan, Spain, United Arab Emirates, Uganda, United Kingdom, United States, Vietnam, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

Dr. Offit and Dr. Galiatsatos reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

National Psoriasis Foundation recommends some stop methotrexate for 2 weeks after J&J vaccine

The , Joel M. Gelfand, MD, said at Innovations in Dermatology: Virtual Spring Conference 2021.

The new guidance states: “Patients 60 or older who have at least one comorbidity associated with an increased risk for poor COVID-19 outcomes, and who are taking methotrexate with well-controlled psoriatic disease, may, in consultation with their prescriber, consider holding it for 2 weeks after receiving the Ad26.COV2.S [Johnson & Johnson] vaccine in order to potentially improve vaccine response.”

The key word here is “potentially.” There is no hard evidence that a 2-week hold on methotrexate after receiving the killed adenovirus vaccine will actually provide a clinically meaningful benefit. But it’s a hypothetical possibility. The rationale stems from a small randomized trial conducted in South Korea several years ago in which patients with rheumatoid arthritis were assigned to hold or continue their methotrexate for the first 2 weeks after receiving an inactivated-virus influenza vaccine. The antibody response to the vaccine was better in those who temporarily halted their methotrexate, explained Dr. Gelfand, cochair of the NPF COVID-19 Task Force and professor of dermatology and of epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“If you have a patient on methotrexate who’s 60 or older and whose psoriasis is completely controlled and quiescent and the patient is concerned about how well the vaccine is going to work, this is a reasonable thing to consider in someone who’s at higher risk for poor outcomes if they get infected,” he said.

If the informed patient wants to continue on methotrexate without interruption, that’s fine, too, in light of the lack of compelling evidence on this issue, the dermatologist added at the conference, sponsored by MedscapeLIVE! and the producers of the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar and Caribbean Dermatology Symposium.

The NPF task force does not extend the recommendation to consider holding methotrexate in recipients of the mRNA-based Moderna and Pfizer vaccines because of their very different mechanisms of action. Nor is it recommended to hold biologic agents after receiving any of the available COVID-19 vaccines. Studies have shown no altered immunologic response to influenza or pneumococcal vaccines in patients who continued on tumor necrosis factor inhibitors or interleukin-17 inhibitors. The interleukin-23 inhibitors haven’t been studied in this regard.

The task force recommends that most psoriasis patients should continue on treatment throughout the pandemic, and newly diagnosed patients should commence appropriate therapy as if there was no pandemic.

“We’ve learned that many patients who stopped their treatment for psoriatic disease early in the pandemic came to regret that decision because their psoriasis flared and got worse and required reinstitution of therapy,” Dr. Gelfand said. “The current data is largely reassuring that if there is an effect of our therapies on the risk of COVID, it must be rather small and therefore unlikely to be clinically meaningful for our patients.”

Dr. Gelfand reported serving as a consultant to and recipient of institutional research grants from Pfizer and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

MedscapeLIVE and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

The , Joel M. Gelfand, MD, said at Innovations in Dermatology: Virtual Spring Conference 2021.

The new guidance states: “Patients 60 or older who have at least one comorbidity associated with an increased risk for poor COVID-19 outcomes, and who are taking methotrexate with well-controlled psoriatic disease, may, in consultation with their prescriber, consider holding it for 2 weeks after receiving the Ad26.COV2.S [Johnson & Johnson] vaccine in order to potentially improve vaccine response.”

The key word here is “potentially.” There is no hard evidence that a 2-week hold on methotrexate after receiving the killed adenovirus vaccine will actually provide a clinically meaningful benefit. But it’s a hypothetical possibility. The rationale stems from a small randomized trial conducted in South Korea several years ago in which patients with rheumatoid arthritis were assigned to hold or continue their methotrexate for the first 2 weeks after receiving an inactivated-virus influenza vaccine. The antibody response to the vaccine was better in those who temporarily halted their methotrexate, explained Dr. Gelfand, cochair of the NPF COVID-19 Task Force and professor of dermatology and of epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“If you have a patient on methotrexate who’s 60 or older and whose psoriasis is completely controlled and quiescent and the patient is concerned about how well the vaccine is going to work, this is a reasonable thing to consider in someone who’s at higher risk for poor outcomes if they get infected,” he said.

If the informed patient wants to continue on methotrexate without interruption, that’s fine, too, in light of the lack of compelling evidence on this issue, the dermatologist added at the conference, sponsored by MedscapeLIVE! and the producers of the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar and Caribbean Dermatology Symposium.

The NPF task force does not extend the recommendation to consider holding methotrexate in recipients of the mRNA-based Moderna and Pfizer vaccines because of their very different mechanisms of action. Nor is it recommended to hold biologic agents after receiving any of the available COVID-19 vaccines. Studies have shown no altered immunologic response to influenza or pneumococcal vaccines in patients who continued on tumor necrosis factor inhibitors or interleukin-17 inhibitors. The interleukin-23 inhibitors haven’t been studied in this regard.

The task force recommends that most psoriasis patients should continue on treatment throughout the pandemic, and newly diagnosed patients should commence appropriate therapy as if there was no pandemic.

“We’ve learned that many patients who stopped their treatment for psoriatic disease early in the pandemic came to regret that decision because their psoriasis flared and got worse and required reinstitution of therapy,” Dr. Gelfand said. “The current data is largely reassuring that if there is an effect of our therapies on the risk of COVID, it must be rather small and therefore unlikely to be clinically meaningful for our patients.”

Dr. Gelfand reported serving as a consultant to and recipient of institutional research grants from Pfizer and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

MedscapeLIVE and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

The , Joel M. Gelfand, MD, said at Innovations in Dermatology: Virtual Spring Conference 2021.

The new guidance states: “Patients 60 or older who have at least one comorbidity associated with an increased risk for poor COVID-19 outcomes, and who are taking methotrexate with well-controlled psoriatic disease, may, in consultation with their prescriber, consider holding it for 2 weeks after receiving the Ad26.COV2.S [Johnson & Johnson] vaccine in order to potentially improve vaccine response.”

The key word here is “potentially.” There is no hard evidence that a 2-week hold on methotrexate after receiving the killed adenovirus vaccine will actually provide a clinically meaningful benefit. But it’s a hypothetical possibility. The rationale stems from a small randomized trial conducted in South Korea several years ago in which patients with rheumatoid arthritis were assigned to hold or continue their methotrexate for the first 2 weeks after receiving an inactivated-virus influenza vaccine. The antibody response to the vaccine was better in those who temporarily halted their methotrexate, explained Dr. Gelfand, cochair of the NPF COVID-19 Task Force and professor of dermatology and of epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“If you have a patient on methotrexate who’s 60 or older and whose psoriasis is completely controlled and quiescent and the patient is concerned about how well the vaccine is going to work, this is a reasonable thing to consider in someone who’s at higher risk for poor outcomes if they get infected,” he said.

If the informed patient wants to continue on methotrexate without interruption, that’s fine, too, in light of the lack of compelling evidence on this issue, the dermatologist added at the conference, sponsored by MedscapeLIVE! and the producers of the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar and Caribbean Dermatology Symposium.

The NPF task force does not extend the recommendation to consider holding methotrexate in recipients of the mRNA-based Moderna and Pfizer vaccines because of their very different mechanisms of action. Nor is it recommended to hold biologic agents after receiving any of the available COVID-19 vaccines. Studies have shown no altered immunologic response to influenza or pneumococcal vaccines in patients who continued on tumor necrosis factor inhibitors or interleukin-17 inhibitors. The interleukin-23 inhibitors haven’t been studied in this regard.

The task force recommends that most psoriasis patients should continue on treatment throughout the pandemic, and newly diagnosed patients should commence appropriate therapy as if there was no pandemic.

“We’ve learned that many patients who stopped their treatment for psoriatic disease early in the pandemic came to regret that decision because their psoriasis flared and got worse and required reinstitution of therapy,” Dr. Gelfand said. “The current data is largely reassuring that if there is an effect of our therapies on the risk of COVID, it must be rather small and therefore unlikely to be clinically meaningful for our patients.”

Dr. Gelfand reported serving as a consultant to and recipient of institutional research grants from Pfizer and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

MedscapeLIVE and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

FROM INNOVATIONS IN DERMATOLOGY

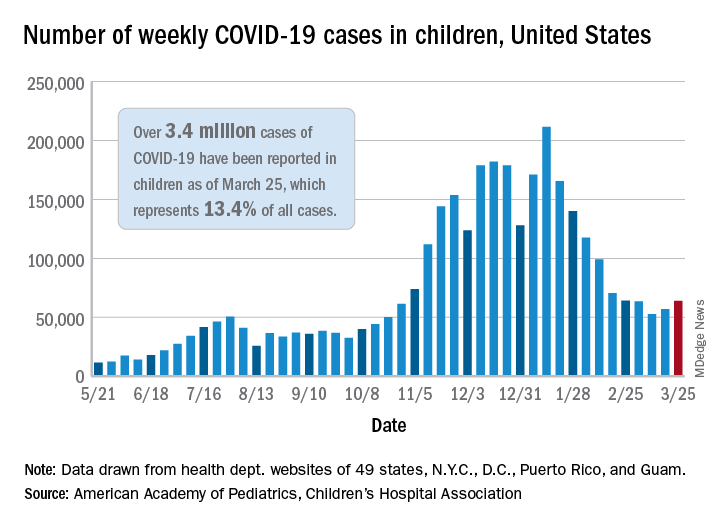

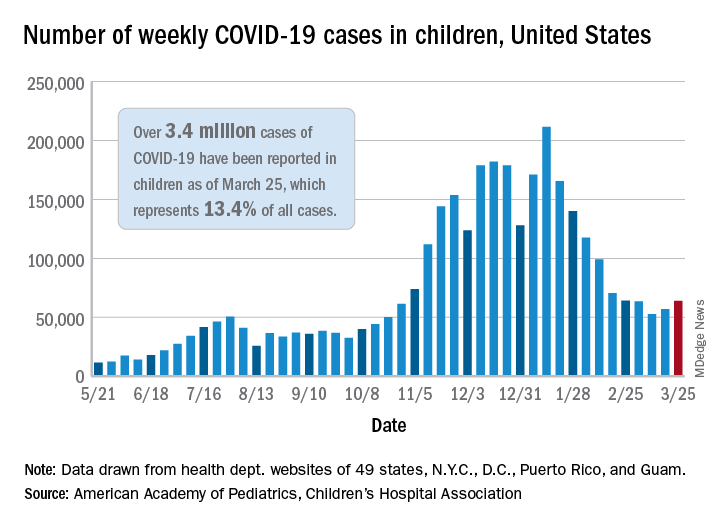

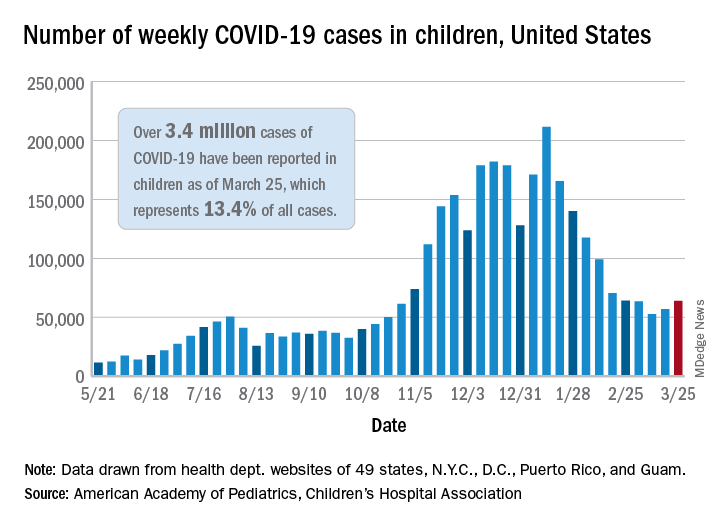

New COVID-19 cases rise again in children

The number of new COVID-19 cases in children increased for the second consecutive week in the United States, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That brings the number of children infected with the coronavirus to over 3.4 million since the beginning of the pandemic, or 13.4% of all reported cases, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

For just the week of March 19-25, however, the proportion of all cases occurring in children was quite a bit higher, 19.1%. That’s higher than at any other point during the pandemic, passing the previous high of 18.7% set just a week earlier, based on the data collected by AAP/CHA from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The national infection rate was 4,525 cases per 100,000 children for the week of March 19-25, compared with 4,440 per 100,000 the previous week. States falling the farthest from that national mark were Hawaii at 1,101 per 100,000 and North Dakota at 8,848, the AAP and CHA said.

There was double-digit increase, 11, in the number of child deaths, as the total went from 268 to 279 despite Virginia’s revising its mortality data downward. The mortality rate for children remains 0.01%, and children represent only 0.06% of all COVID-19–related deaths in the 43 states, along with New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, that are reporting deaths by age, the report shows.

The state/local-level data show that Texas has the highest number of child deaths (48), followed by Arizona (26), New York City (22), California (16), and Illinois (16), while nine states and the District of Columbia have not yet reported a death, the AAP and CHA said.

The number of new COVID-19 cases in children increased for the second consecutive week in the United States, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That brings the number of children infected with the coronavirus to over 3.4 million since the beginning of the pandemic, or 13.4% of all reported cases, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

For just the week of March 19-25, however, the proportion of all cases occurring in children was quite a bit higher, 19.1%. That’s higher than at any other point during the pandemic, passing the previous high of 18.7% set just a week earlier, based on the data collected by AAP/CHA from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The national infection rate was 4,525 cases per 100,000 children for the week of March 19-25, compared with 4,440 per 100,000 the previous week. States falling the farthest from that national mark were Hawaii at 1,101 per 100,000 and North Dakota at 8,848, the AAP and CHA said.

There was double-digit increase, 11, in the number of child deaths, as the total went from 268 to 279 despite Virginia’s revising its mortality data downward. The mortality rate for children remains 0.01%, and children represent only 0.06% of all COVID-19–related deaths in the 43 states, along with New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, that are reporting deaths by age, the report shows.

The state/local-level data show that Texas has the highest number of child deaths (48), followed by Arizona (26), New York City (22), California (16), and Illinois (16), while nine states and the District of Columbia have not yet reported a death, the AAP and CHA said.

The number of new COVID-19 cases in children increased for the second consecutive week in the United States, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That brings the number of children infected with the coronavirus to over 3.4 million since the beginning of the pandemic, or 13.4% of all reported cases, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

For just the week of March 19-25, however, the proportion of all cases occurring in children was quite a bit higher, 19.1%. That’s higher than at any other point during the pandemic, passing the previous high of 18.7% set just a week earlier, based on the data collected by AAP/CHA from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The national infection rate was 4,525 cases per 100,000 children for the week of March 19-25, compared with 4,440 per 100,000 the previous week. States falling the farthest from that national mark were Hawaii at 1,101 per 100,000 and North Dakota at 8,848, the AAP and CHA said.

There was double-digit increase, 11, in the number of child deaths, as the total went from 268 to 279 despite Virginia’s revising its mortality data downward. The mortality rate for children remains 0.01%, and children represent only 0.06% of all COVID-19–related deaths in the 43 states, along with New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, that are reporting deaths by age, the report shows.

The state/local-level data show that Texas has the highest number of child deaths (48), followed by Arizona (26), New York City (22), California (16), and Illinois (16), while nine states and the District of Columbia have not yet reported a death, the AAP and CHA said.

COVID-19 ‘long-haul’ symptoms overlap with ME/CFS

People experiencing long-term symptoms following acute COVID-19 infection are increasingly meeting criteria for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), a phenomenon that highlights the need for unified research and clinical approaches, speakers said at a press briefing March 25 held by the advocacy group MEAction.

“Post-COVID lingering illness was predictable. Similar lingering fatigue syndromes have been reported in the scientific literature for nearly 100 years, following a variety of well-documented infections with viruses, bacteria, fungi, and even protozoa,” said Anthony Komaroff, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Core criteria for ME/CFS established by the Institute of Medicine in 2015 include substantial decrement in functioning for at least 6 months, postexertional malaise (PEM), or a worsening of symptoms following even minor exertion (often described as “crashes”), unrefreshing sleep, and cognitive impairment and/or orthostatic intolerance.

Patients with ME/CFS also commonly experience painful headaches, muscle or joint aches, and allergies/other sensitivities. Although many patients can trace their symptoms to an initiating infection, “the cause is often unclear because the diagnosis is often delayed for months or years after symptom onset,” said Lucinda Bateman, MD, founder of the Bateman Horne Center, Salt Lake City, who leads a clinician coalition that aims to improve ME/CFS management.

In an international survey of 3762 COVID-19 “long-haulers” published in a preprint in December of 2020, the most frequent symptoms reported at least 6 months after illness onset were fatigue in 78%, PEM in 72%, and cognitive dysfunction (“brain fog”) in 55%. At the time of the survey, 45% reported requiring reduced work schedules because of their illness, and 22% reported being unable to work at all.

Dr. Bateman said those findings align with her experience so far with 12 COVID-19 “long haulers” who self-referred to her ME/CFS and fibromyalgia specialty clinic. Nine of the 12 met criteria for postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) based on the 10-minute NASA Lean Test, she said, and half also met the 2016 American College of Rheumatology criteria for fibromyalgia.

“Some were severely impaired. We suspect a small fiber polyneuropathy in about half, and mast cell activation syndrome in more than half. We look forward to doing more testing,” Dr. Bateman said.

To be sure, Dr. Komaroff noted, there are some differences. “Long COVID” patients will often experience breathlessness and ongoing anosmia (loss of taste and smell), which aren’t typical of ME/CFS.

But, he said, “many of the symptoms are quite similar ... My guess is that ME/CFS is an illness with a final common pathway that can be triggered by different things,” said Dr. Komaroff, a senior physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and editor-in-chief of the Harvard Health Letter.

Based on previous data about CFS suggesting a 10% rate of symptoms persisting at least a year following a variety of infectious agents and the predicted 200 million COVID-19 cases globally by the end of 2021, Dr. Komaroff estimated that about 20 million cases of “long COVID” would be expected in the next year.

‘A huge investment’

On the research side, the National Institutes of Health recently appropriated $1.15 billion dollars over the next 4 years to investigate “the heterogeneity in the recovery process after COVID and to develop treatments for those suffering from [postacute COVID-19 syndrome]” according to a Feb. 5, 2021, blog from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS).

That same day, another NINDS blog announced “new resources for large-scale ME/CFS research” and emphasized the tie-in with long–COVID-19 syndrome.

“That’s a huge investment. In my opinion, there will be several lingering illnesses following COVID,” Dr. Komaroff said, adding, “It’s my bet that long COVID will prove to be caused by certain kinds of abnormalities in the brain, some of the same abnormalities already identified in ME/CFS. Research will determine whether that’s right or wrong.”

In 2017, NINDS had announced a large increase in funding for ME/CFS research, including the creation of four dedicated research centers. In April 2019, NINDS held a 2-day conference highlighting that ongoing work, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

During the briefing, NINDS clinical director Avindra Nath, MD, described a comprehensive ongoing ME/CFS intramural study he’s been leading since 2016.

He’s now also overseeing two long–COVID-19 studies, one of which has a protocol similar to that of the ME/CFS study and will include individuals who are still experiencing long-term symptoms following confirmed cases of COVID-19. The aim is to screen about 1,300 patients. Several task forces are now examining all of these data together.

“Each aspect is now being analyzed … What we learn from one applies to the other,” Dr. Nath said.

Advice for clinicians

In interviews, Dr. Bateman and Dr. Nath offered clinical advice for managing patients who meet ME/CFS criteria, whether they had confirmed or suspected COVID-19, a different infection, or unknown trigger(s).