User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Adding salt to food linked to higher risk of premature death

in a new study.

In the study of more than 500,000 people, compared with those who never or rarely added salt, those who always added salt to their food had a 28% increased risk of dying prematurely (defined as death before the age of 75 years).

Results also showed that adding salt to food was linked to a lower life expectancy. At the age of 50 years, life expectancy was reduced by 1.5 years in women and by 2.28 years in men who always added salt to their food, compared with those who never or rarely did.

However, these increased risks appeared to be attenuated with increasing intakes of high-potassium foods (vegetables and fruits).

The study was published online in the European Heart Journal.

“As far as we are aware, this is the first study to analyze adding salt to meals as a unique measurement for dietary sodium intake. Such a measure is less likely affected by other dietary components, especially potassium intake,” senior author Lu Qi, MD, Tulane University, New Orleans, told this news organization.

“Our study provides supportive evidence from a novel perspective to show the adverse effects of high sodium intake on human health, which is still a controversial topic. Our findings support the advice that reduction of salt intake by reducing the salt added to meals may benefit health and improve life expectancy. Our results also suggest that high intakes of fruits and vegetables are beneficial regarding lowering the adverse effects of salt,” he added.

Link between dietary salt and health is subject of longstanding debate

The researchers explained that the relationship between dietary salt intake and health remains a subject of longstanding debate, with previous studies on the association between sodium intake and mortality having shown conflicting results.

They attributed the inconsistent results to the low accuracy of sodium measurement, noting that sodium intake varies widely from day to day, but the majority of previous studies have largely relied on a single day’s urine collection or dietary survey for estimating the sodium intake, which is inadequate to assess an individual’s usual consumption levels.

They also pointed out that it is difficult to separate the contributions of intakes of sodium and potassium to health based on current methods for measuring dietary sodium and potassium, and this may confound the association between sodium intake and health outcomes.

They noted that the hypothesis that a high-potassium intake may attenuate the adverse association of high-sodium intake with health outcomes has been proposed for many years, but studies assessing the interaction between sodium intake and potassium intake on the risk of mortality are scarce.

Adding salt to food at the table is a common eating behavior directly related to an individual’s long-term preference for salty tasting foods and habitual salt intake, the authors said, adding that commonly used table salt contains 97%-99% sodium chloride, minimizing the potential confounding effects of other dietary factors including potassium. “Therefore, adding salt to foods provides a unique assessment to evaluate the association between habitual sodium intake and mortality.”

UK Biobank study

For the current study Dr. Qi and colleagues analyzed data from 501,379 people taking part in the UK Biobank study. When joining the study between 2006 and 2010, the participants were asked whether they added salt to their foods never/rarely, sometimes, usually or always. Participants were then followed for a median of 9 years.

After adjustment for sex, age, race, smoking, moderate drinking, body mass index, physical activity, Townsend deprivation index, high cholesterol, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer, results showed an increasing risk of all-cause premature mortality rose with increasing frequency of adding salt to foods.

The adjusted hazard ratios, compared with those who never or rarely added salt, were 1.02 (95% CI, 0.99-1.06) for those who added salt sometimes, 1.07 (95% CI, 1.02-1.11) for those who usually added salt, and 1.28 (95% CI, 1.20-1.35) for those who always added salt.

The researchers also estimated the lower survival time caused by the high frequency of adding salt to foods. At age 50, women who always added salt to foods had an average 1.50 fewer years of life expectancy, and men who always added salt had an average 2.28 fewer years of life expectancy, as compared with their counterparts who never/rarely added salt to foods.

For cause-specific premature mortality, results showed that higher frequency of adding salt to foods was significantly associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular mortality and cancer mortality, but not for dementia mortality or respiratory mortality. For the subtypes of cardiovascular mortality, adding salt to foods was significantly associated with higher risk of stroke mortality but not coronary heart disease mortality.

Other analyses suggested that the association of adding salt to foods with an increased risk of premature mortality appeared to be attenuated with increasing intake of food high in potassium (fruits and vegetables).

The authors point out that the amounts of discretionary sodium intake (the salt used at the table or in home cooking) have been largely overlooked in previous studies, even though adding salt to foods accounts for a considerable proportion of total sodium intake (6%-20%) in Western diets.

“Our findings also support the notion that even a modest reduction in sodium intake is likely to result in substantial health benefits, especially when it is achieved in the general population,” they conclude.

Conflicting information from different studies

But the current findings seem to directly contradict those from another recent study by Messerli and colleagues showing higher sodium intake correlates with improved life expectancy.

Addressing these contradictory results, Dr. Qi commented: “The study of Messerli et al. is based on an ecological design, in which the analysis is performed on country average sodium intake, rather than at the individual level. This type of ecological study has several major limitations, such as the lack of individuals’ sodium intake, uncontrolled confounding, and the cross-sectional nature. Typically, ecological studies are not considered useful for testing hypothesis in epidemiological studies.”

Dr. Qi noted that, in contrast, his current study analyzes individuals’ exposure, and has a prospective design. “Our findings are supported by previous large-scale observational studies and clinical trials which show the high intake of sodium may adversely affect chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease and hypertension.” =

Lead author of the ecological study, Franz Messerli, MD, Bern (Switzerland) University Hospital, however, was not convinced by the findings from Dr. Qi’s study.

“The difference in 24-hour sodium intake between those who never/rarely added salt and those who always did is a minuscule 0.17 g. It is highly unlikely that such negligible quantity has any impact on blood pressure, not to mention cardiovascular mortality or life expectancy,” he commented in an interview.

He also pointed out that, in Dr. Qi’s study, people who added salt more frequently also consumed more red meat and processed meat, as well as less fish and less fruit and vegetables. “I would suggest that the bad habit of adding salt at the table is simply a powerful marker for an unhealthy diet.”

“There is no question that an excessive salt intake is harmful in hypertensive patients and increases the risk of stroke. But 0.17 g is not going to make any difference,” Dr. Messerli added.

What is the optimum level?

In an editorial accompanying the study by Dr. Qi and colleagues in the European Heart Journal, Annika Rosengren, MD, PhD, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden, noted that guidelines recommend a salt intake below 5 g, or about a teaspoon, per day. But few individuals meet this recommendation.

Because several recent studies show a U- or J-shaped association between salt and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, reducing salt intake across the whole population may not be universally beneficial, Dr. Rosengren said.

“So far, what the collective evidence about salt seems to indicate is that healthy people consuming what constitutes normal levels of ordinary salt need not worry too much about their salt intake,” she wrote.

Instead, she advised a diet rich in fruit and vegetables should be a priority to counterbalance potentially harmful effects of salt, and for many other reasons.

And she added that people at high risk, such as those with hypertension who have a high salt intake, are probably well advised to cut down, and not adding extra salt to already prepared foods is one way of achieving this. However, at the individual level, the optimal salt consumption range, or the “sweet spot” remains to be determined.

“Not adding extra salt to food is unlikely to be harmful and could contribute to strategies to lower population blood pressure levels,” Dr. Rosengren concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

in a new study.

In the study of more than 500,000 people, compared with those who never or rarely added salt, those who always added salt to their food had a 28% increased risk of dying prematurely (defined as death before the age of 75 years).

Results also showed that adding salt to food was linked to a lower life expectancy. At the age of 50 years, life expectancy was reduced by 1.5 years in women and by 2.28 years in men who always added salt to their food, compared with those who never or rarely did.

However, these increased risks appeared to be attenuated with increasing intakes of high-potassium foods (vegetables and fruits).

The study was published online in the European Heart Journal.

“As far as we are aware, this is the first study to analyze adding salt to meals as a unique measurement for dietary sodium intake. Such a measure is less likely affected by other dietary components, especially potassium intake,” senior author Lu Qi, MD, Tulane University, New Orleans, told this news organization.

“Our study provides supportive evidence from a novel perspective to show the adverse effects of high sodium intake on human health, which is still a controversial topic. Our findings support the advice that reduction of salt intake by reducing the salt added to meals may benefit health and improve life expectancy. Our results also suggest that high intakes of fruits and vegetables are beneficial regarding lowering the adverse effects of salt,” he added.

Link between dietary salt and health is subject of longstanding debate

The researchers explained that the relationship between dietary salt intake and health remains a subject of longstanding debate, with previous studies on the association between sodium intake and mortality having shown conflicting results.

They attributed the inconsistent results to the low accuracy of sodium measurement, noting that sodium intake varies widely from day to day, but the majority of previous studies have largely relied on a single day’s urine collection or dietary survey for estimating the sodium intake, which is inadequate to assess an individual’s usual consumption levels.

They also pointed out that it is difficult to separate the contributions of intakes of sodium and potassium to health based on current methods for measuring dietary sodium and potassium, and this may confound the association between sodium intake and health outcomes.

They noted that the hypothesis that a high-potassium intake may attenuate the adverse association of high-sodium intake with health outcomes has been proposed for many years, but studies assessing the interaction between sodium intake and potassium intake on the risk of mortality are scarce.

Adding salt to food at the table is a common eating behavior directly related to an individual’s long-term preference for salty tasting foods and habitual salt intake, the authors said, adding that commonly used table salt contains 97%-99% sodium chloride, minimizing the potential confounding effects of other dietary factors including potassium. “Therefore, adding salt to foods provides a unique assessment to evaluate the association between habitual sodium intake and mortality.”

UK Biobank study

For the current study Dr. Qi and colleagues analyzed data from 501,379 people taking part in the UK Biobank study. When joining the study between 2006 and 2010, the participants were asked whether they added salt to their foods never/rarely, sometimes, usually or always. Participants were then followed for a median of 9 years.

After adjustment for sex, age, race, smoking, moderate drinking, body mass index, physical activity, Townsend deprivation index, high cholesterol, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer, results showed an increasing risk of all-cause premature mortality rose with increasing frequency of adding salt to foods.

The adjusted hazard ratios, compared with those who never or rarely added salt, were 1.02 (95% CI, 0.99-1.06) for those who added salt sometimes, 1.07 (95% CI, 1.02-1.11) for those who usually added salt, and 1.28 (95% CI, 1.20-1.35) for those who always added salt.

The researchers also estimated the lower survival time caused by the high frequency of adding salt to foods. At age 50, women who always added salt to foods had an average 1.50 fewer years of life expectancy, and men who always added salt had an average 2.28 fewer years of life expectancy, as compared with their counterparts who never/rarely added salt to foods.

For cause-specific premature mortality, results showed that higher frequency of adding salt to foods was significantly associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular mortality and cancer mortality, but not for dementia mortality or respiratory mortality. For the subtypes of cardiovascular mortality, adding salt to foods was significantly associated with higher risk of stroke mortality but not coronary heart disease mortality.

Other analyses suggested that the association of adding salt to foods with an increased risk of premature mortality appeared to be attenuated with increasing intake of food high in potassium (fruits and vegetables).

The authors point out that the amounts of discretionary sodium intake (the salt used at the table or in home cooking) have been largely overlooked in previous studies, even though adding salt to foods accounts for a considerable proportion of total sodium intake (6%-20%) in Western diets.

“Our findings also support the notion that even a modest reduction in sodium intake is likely to result in substantial health benefits, especially when it is achieved in the general population,” they conclude.

Conflicting information from different studies

But the current findings seem to directly contradict those from another recent study by Messerli and colleagues showing higher sodium intake correlates with improved life expectancy.

Addressing these contradictory results, Dr. Qi commented: “The study of Messerli et al. is based on an ecological design, in which the analysis is performed on country average sodium intake, rather than at the individual level. This type of ecological study has several major limitations, such as the lack of individuals’ sodium intake, uncontrolled confounding, and the cross-sectional nature. Typically, ecological studies are not considered useful for testing hypothesis in epidemiological studies.”

Dr. Qi noted that, in contrast, his current study analyzes individuals’ exposure, and has a prospective design. “Our findings are supported by previous large-scale observational studies and clinical trials which show the high intake of sodium may adversely affect chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease and hypertension.” =

Lead author of the ecological study, Franz Messerli, MD, Bern (Switzerland) University Hospital, however, was not convinced by the findings from Dr. Qi’s study.

“The difference in 24-hour sodium intake between those who never/rarely added salt and those who always did is a minuscule 0.17 g. It is highly unlikely that such negligible quantity has any impact on blood pressure, not to mention cardiovascular mortality or life expectancy,” he commented in an interview.

He also pointed out that, in Dr. Qi’s study, people who added salt more frequently also consumed more red meat and processed meat, as well as less fish and less fruit and vegetables. “I would suggest that the bad habit of adding salt at the table is simply a powerful marker for an unhealthy diet.”

“There is no question that an excessive salt intake is harmful in hypertensive patients and increases the risk of stroke. But 0.17 g is not going to make any difference,” Dr. Messerli added.

What is the optimum level?

In an editorial accompanying the study by Dr. Qi and colleagues in the European Heart Journal, Annika Rosengren, MD, PhD, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden, noted that guidelines recommend a salt intake below 5 g, or about a teaspoon, per day. But few individuals meet this recommendation.

Because several recent studies show a U- or J-shaped association between salt and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, reducing salt intake across the whole population may not be universally beneficial, Dr. Rosengren said.

“So far, what the collective evidence about salt seems to indicate is that healthy people consuming what constitutes normal levels of ordinary salt need not worry too much about their salt intake,” she wrote.

Instead, she advised a diet rich in fruit and vegetables should be a priority to counterbalance potentially harmful effects of salt, and for many other reasons.

And she added that people at high risk, such as those with hypertension who have a high salt intake, are probably well advised to cut down, and not adding extra salt to already prepared foods is one way of achieving this. However, at the individual level, the optimal salt consumption range, or the “sweet spot” remains to be determined.

“Not adding extra salt to food is unlikely to be harmful and could contribute to strategies to lower population blood pressure levels,” Dr. Rosengren concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

in a new study.

In the study of more than 500,000 people, compared with those who never or rarely added salt, those who always added salt to their food had a 28% increased risk of dying prematurely (defined as death before the age of 75 years).

Results also showed that adding salt to food was linked to a lower life expectancy. At the age of 50 years, life expectancy was reduced by 1.5 years in women and by 2.28 years in men who always added salt to their food, compared with those who never or rarely did.

However, these increased risks appeared to be attenuated with increasing intakes of high-potassium foods (vegetables and fruits).

The study was published online in the European Heart Journal.

“As far as we are aware, this is the first study to analyze adding salt to meals as a unique measurement for dietary sodium intake. Such a measure is less likely affected by other dietary components, especially potassium intake,” senior author Lu Qi, MD, Tulane University, New Orleans, told this news organization.

“Our study provides supportive evidence from a novel perspective to show the adverse effects of high sodium intake on human health, which is still a controversial topic. Our findings support the advice that reduction of salt intake by reducing the salt added to meals may benefit health and improve life expectancy. Our results also suggest that high intakes of fruits and vegetables are beneficial regarding lowering the adverse effects of salt,” he added.

Link between dietary salt and health is subject of longstanding debate

The researchers explained that the relationship between dietary salt intake and health remains a subject of longstanding debate, with previous studies on the association between sodium intake and mortality having shown conflicting results.

They attributed the inconsistent results to the low accuracy of sodium measurement, noting that sodium intake varies widely from day to day, but the majority of previous studies have largely relied on a single day’s urine collection or dietary survey for estimating the sodium intake, which is inadequate to assess an individual’s usual consumption levels.

They also pointed out that it is difficult to separate the contributions of intakes of sodium and potassium to health based on current methods for measuring dietary sodium and potassium, and this may confound the association between sodium intake and health outcomes.

They noted that the hypothesis that a high-potassium intake may attenuate the adverse association of high-sodium intake with health outcomes has been proposed for many years, but studies assessing the interaction between sodium intake and potassium intake on the risk of mortality are scarce.

Adding salt to food at the table is a common eating behavior directly related to an individual’s long-term preference for salty tasting foods and habitual salt intake, the authors said, adding that commonly used table salt contains 97%-99% sodium chloride, minimizing the potential confounding effects of other dietary factors including potassium. “Therefore, adding salt to foods provides a unique assessment to evaluate the association between habitual sodium intake and mortality.”

UK Biobank study

For the current study Dr. Qi and colleagues analyzed data from 501,379 people taking part in the UK Biobank study. When joining the study between 2006 and 2010, the participants were asked whether they added salt to their foods never/rarely, sometimes, usually or always. Participants were then followed for a median of 9 years.

After adjustment for sex, age, race, smoking, moderate drinking, body mass index, physical activity, Townsend deprivation index, high cholesterol, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer, results showed an increasing risk of all-cause premature mortality rose with increasing frequency of adding salt to foods.

The adjusted hazard ratios, compared with those who never or rarely added salt, were 1.02 (95% CI, 0.99-1.06) for those who added salt sometimes, 1.07 (95% CI, 1.02-1.11) for those who usually added salt, and 1.28 (95% CI, 1.20-1.35) for those who always added salt.

The researchers also estimated the lower survival time caused by the high frequency of adding salt to foods. At age 50, women who always added salt to foods had an average 1.50 fewer years of life expectancy, and men who always added salt had an average 2.28 fewer years of life expectancy, as compared with their counterparts who never/rarely added salt to foods.

For cause-specific premature mortality, results showed that higher frequency of adding salt to foods was significantly associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular mortality and cancer mortality, but not for dementia mortality or respiratory mortality. For the subtypes of cardiovascular mortality, adding salt to foods was significantly associated with higher risk of stroke mortality but not coronary heart disease mortality.

Other analyses suggested that the association of adding salt to foods with an increased risk of premature mortality appeared to be attenuated with increasing intake of food high in potassium (fruits and vegetables).

The authors point out that the amounts of discretionary sodium intake (the salt used at the table or in home cooking) have been largely overlooked in previous studies, even though adding salt to foods accounts for a considerable proportion of total sodium intake (6%-20%) in Western diets.

“Our findings also support the notion that even a modest reduction in sodium intake is likely to result in substantial health benefits, especially when it is achieved in the general population,” they conclude.

Conflicting information from different studies

But the current findings seem to directly contradict those from another recent study by Messerli and colleagues showing higher sodium intake correlates with improved life expectancy.

Addressing these contradictory results, Dr. Qi commented: “The study of Messerli et al. is based on an ecological design, in which the analysis is performed on country average sodium intake, rather than at the individual level. This type of ecological study has several major limitations, such as the lack of individuals’ sodium intake, uncontrolled confounding, and the cross-sectional nature. Typically, ecological studies are not considered useful for testing hypothesis in epidemiological studies.”

Dr. Qi noted that, in contrast, his current study analyzes individuals’ exposure, and has a prospective design. “Our findings are supported by previous large-scale observational studies and clinical trials which show the high intake of sodium may adversely affect chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease and hypertension.” =

Lead author of the ecological study, Franz Messerli, MD, Bern (Switzerland) University Hospital, however, was not convinced by the findings from Dr. Qi’s study.

“The difference in 24-hour sodium intake between those who never/rarely added salt and those who always did is a minuscule 0.17 g. It is highly unlikely that such negligible quantity has any impact on blood pressure, not to mention cardiovascular mortality or life expectancy,” he commented in an interview.

He also pointed out that, in Dr. Qi’s study, people who added salt more frequently also consumed more red meat and processed meat, as well as less fish and less fruit and vegetables. “I would suggest that the bad habit of adding salt at the table is simply a powerful marker for an unhealthy diet.”

“There is no question that an excessive salt intake is harmful in hypertensive patients and increases the risk of stroke. But 0.17 g is not going to make any difference,” Dr. Messerli added.

What is the optimum level?

In an editorial accompanying the study by Dr. Qi and colleagues in the European Heart Journal, Annika Rosengren, MD, PhD, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden, noted that guidelines recommend a salt intake below 5 g, or about a teaspoon, per day. But few individuals meet this recommendation.

Because several recent studies show a U- or J-shaped association between salt and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, reducing salt intake across the whole population may not be universally beneficial, Dr. Rosengren said.

“So far, what the collective evidence about salt seems to indicate is that healthy people consuming what constitutes normal levels of ordinary salt need not worry too much about their salt intake,” she wrote.

Instead, she advised a diet rich in fruit and vegetables should be a priority to counterbalance potentially harmful effects of salt, and for many other reasons.

And she added that people at high risk, such as those with hypertension who have a high salt intake, are probably well advised to cut down, and not adding extra salt to already prepared foods is one way of achieving this. However, at the individual level, the optimal salt consumption range, or the “sweet spot” remains to be determined.

“Not adding extra salt to food is unlikely to be harmful and could contribute to strategies to lower population blood pressure levels,” Dr. Rosengren concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE EUROPEAN HEART JOURNAL

Sleep-deprived physicians less empathetic to patient pain?

new research suggests.

In the first of two studies, resident physicians were presented with two hypothetical scenarios involving a patient who complains of pain. They were asked about their likelihood of prescribing pain medication. The test was given to one group of residents who were just starting their day and to another group who were at the end of their night shift after being on call for 26 hours.

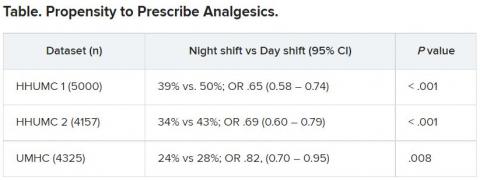

Results showed that the night shift residents were less likely than their daytime counterparts to say they would prescribe pain medication to the patients.

In further analysis of discharge notes from more than 13,000 electronic records of patients presenting with pain complaints at hospitals in Israel and the United States, the likelihood of an analgesic being prescribed during the night shift was 11% lower in Israel and 9% lower in the United States, compared with the day shift.

“Pain management is a major challenge, and a doctor’s perception of a patient’s subjective pain is susceptible to bias,” coinvestigator David Gozal, MD, the Marie M. and Harry L. Smith Endowed Chair of Child Health, University of Missouri–Columbia, said in a press release.

“This study demonstrated that night shift work is an important and previously unrecognized source of bias in pain management, likely stemming from impaired perception of pain,” Dr. Gozal added.

The findings were published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

‘Directional’ differences

Senior investigator Alex Gileles-Hillel, MD, senior pediatric pulmonologist and sleep researcher at Hadassah University Medical Center, Jerusalem, said in an interview that physicians must make “complex assessments of patients’ subjective pain experience” – and the “subjective nature of pain management decisions can give rise to various biases.”

Dr. Gileles-Hillel has previously researched the cognitive toll of night shift work on physicians.

“It’s pretty established, for example, not to drive when sleep deprived because cognition is impaired,” he said. The current study explored whether sleep deprivation could affect areas other than cognition, including emotions and empathy.

The researchers used “two complementary approaches.” First, they administered tests to measure empathy and pain management decisions in 67 resident physicians at Hadassah Medical Centers either following a 26-hour night shift that began at 8:00 a.m. the day before (n = 36) or immediately before starting the workday (n = 31).

There were no significant differences in demographic, sleep, or burnout measures between the two groups, except that night shift physicians had slept less than those in the daytime group (2.93 vs. 5.96 hours).

Participants completed two tasks. In the empathy-for-pain task, they rated their emotional reactions to pictures of individuals in pain. In the empathy accuracy task, they were asked to assess the feelings of videotaped individuals telling emotional stories.

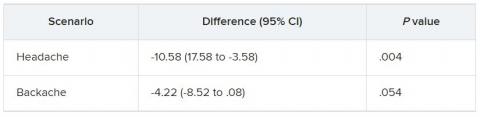

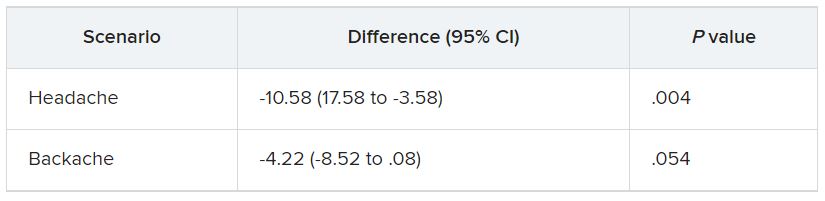

They were then presented with two clinical scenarios: a female patient with a headache and a male patient with a backache. Following that, they were asked to assess the magnitude of the patients’ pain and how likely they would be to prescribe pain medication.

In the empathy-for-pain task, physicians’ empathy scores were significantly lower in the night shift group than in the day group (difference, –0.83; 95% CI, –1.55 to –0.10; P = .026). There were no significant differences between the groups in the empathy accuracy task.

In both scenarios, physicians in the night shift group assessed the patient’s pain as weaker in comparison with physicians in the day group. There was a statistically significant difference in the headache scenario but not the backache scenario.

In the headache scenario, the propensity of the physicians to prescribe analgesics was “directionally lower” but did not reach statistical significance. In the backache scenario, there was no significant difference between the groups’ prescribing propensities.

In both scenarios, pain assessment was positively correlated with the propensity to prescribe analgesics.

Despite the lack of statistical significance, the findings “documented a negative effect of night shift work on physician empathy for pain and a positive association between physician assessment of patient pain and the propensity to prescribe analgesics,” the investigators wrote.

Need for naps?

The researchers then analyzed analgesic prescription patterns drawn from three datasets of discharge notes of patients presenting to the emergency department with pain complaints (n = 13,482) at two branches of Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center and the University of Missouri Health Center.

The researchers collected data, including discharge time, medications patients were prescribed upon discharge, and patients’ subjective pain rating on a scale of 0-10 on a visual analogue scale (VAS).

Although patients’ VAS scores did not differ with respect to time or shift, patients were discharged with significantly less prescribed analgesics during the night shift in comparison with the day shift.

No similar differences in prescriptions between night shifts and day shifts were found for nonanalgesic medications, such as for diabetes or blood pressure. This suggests “the effect was specific to pain,” Dr. Gileles-Hillel said.

The pattern remained significant after controlling for potential confounders, including patient and physician variables and emergency department characteristics.

In addition, patients seen during night shifts received fewer analgesics, particularly opioids, than recommended by the World Health Organization for pain management.

“The first study enabled us to measure empathy for pain directly and examine our hypothesis in a controlled environment, while the second enabled us to test the implications by examining real-life pain management decisions,” Dr. Gileles-Hillel said.

“Physicians need to be aware of this,” he noted. “I try to be aware when I’m taking calls [at night] that I’m less empathetic to others and I might be more brief or angry with others.”

On a “house management level, perhaps institutions should try to schedule naps either before or during overnight call. A nap might give a boost and reboot not only to cognitive but also to emotional resources,” Dr. Gileles-Hillel added.

Compromised safety

In a comment, Eti Ben Simon, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Human Sleep Science, University of California, Berkeley, called the study “an important contribution to a growing list of studies that reveal how long night shifts reduce overall safety” for both patients and clinicians.

“It’s time to abandon the notion that the human brain can function as normal after being deprived of sleep for 24 hours,” said Dr. Ben Simon, who was not involved with the research.

“This is especially true in medicine, where we trust others to take care of us and feel our pain. These functions are simply not possible without adequate sleep,” she added.

Also commenting, Kannan Ramar, MD, president of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, suggested that being cognizant of these findings “may help providers to mitigate this bias” of underprescribing pain medications when treating their patients.

Dr. Ramar, who is also a critical care specialist, pulmonologist, and sleep medicine specialist at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., was not involved with the research.

He noted that “further studies that systematically evaluate this further in a prospective and blinded way will be important.”

The research was supported in part by grants from the Israel Science Foundation, Joy Ventures, the Recanati Fund at the Jerusalem School of Business at the Hebrew University, and a fellowship from the Azrieli Foundation and received grant support to various investigators from the NIH, the Leda J. Sears Foundation, and the University of Missouri. The investigators, Ramar, and Ben Simon have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

In the first of two studies, resident physicians were presented with two hypothetical scenarios involving a patient who complains of pain. They were asked about their likelihood of prescribing pain medication. The test was given to one group of residents who were just starting their day and to another group who were at the end of their night shift after being on call for 26 hours.

Results showed that the night shift residents were less likely than their daytime counterparts to say they would prescribe pain medication to the patients.

In further analysis of discharge notes from more than 13,000 electronic records of patients presenting with pain complaints at hospitals in Israel and the United States, the likelihood of an analgesic being prescribed during the night shift was 11% lower in Israel and 9% lower in the United States, compared with the day shift.

“Pain management is a major challenge, and a doctor’s perception of a patient’s subjective pain is susceptible to bias,” coinvestigator David Gozal, MD, the Marie M. and Harry L. Smith Endowed Chair of Child Health, University of Missouri–Columbia, said in a press release.

“This study demonstrated that night shift work is an important and previously unrecognized source of bias in pain management, likely stemming from impaired perception of pain,” Dr. Gozal added.

The findings were published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

‘Directional’ differences

Senior investigator Alex Gileles-Hillel, MD, senior pediatric pulmonologist and sleep researcher at Hadassah University Medical Center, Jerusalem, said in an interview that physicians must make “complex assessments of patients’ subjective pain experience” – and the “subjective nature of pain management decisions can give rise to various biases.”

Dr. Gileles-Hillel has previously researched the cognitive toll of night shift work on physicians.

“It’s pretty established, for example, not to drive when sleep deprived because cognition is impaired,” he said. The current study explored whether sleep deprivation could affect areas other than cognition, including emotions and empathy.

The researchers used “two complementary approaches.” First, they administered tests to measure empathy and pain management decisions in 67 resident physicians at Hadassah Medical Centers either following a 26-hour night shift that began at 8:00 a.m. the day before (n = 36) or immediately before starting the workday (n = 31).

There were no significant differences in demographic, sleep, or burnout measures between the two groups, except that night shift physicians had slept less than those in the daytime group (2.93 vs. 5.96 hours).

Participants completed two tasks. In the empathy-for-pain task, they rated their emotional reactions to pictures of individuals in pain. In the empathy accuracy task, they were asked to assess the feelings of videotaped individuals telling emotional stories.

They were then presented with two clinical scenarios: a female patient with a headache and a male patient with a backache. Following that, they were asked to assess the magnitude of the patients’ pain and how likely they would be to prescribe pain medication.

In the empathy-for-pain task, physicians’ empathy scores were significantly lower in the night shift group than in the day group (difference, –0.83; 95% CI, –1.55 to –0.10; P = .026). There were no significant differences between the groups in the empathy accuracy task.

In both scenarios, physicians in the night shift group assessed the patient’s pain as weaker in comparison with physicians in the day group. There was a statistically significant difference in the headache scenario but not the backache scenario.

In the headache scenario, the propensity of the physicians to prescribe analgesics was “directionally lower” but did not reach statistical significance. In the backache scenario, there was no significant difference between the groups’ prescribing propensities.

In both scenarios, pain assessment was positively correlated with the propensity to prescribe analgesics.

Despite the lack of statistical significance, the findings “documented a negative effect of night shift work on physician empathy for pain and a positive association between physician assessment of patient pain and the propensity to prescribe analgesics,” the investigators wrote.

Need for naps?

The researchers then analyzed analgesic prescription patterns drawn from three datasets of discharge notes of patients presenting to the emergency department with pain complaints (n = 13,482) at two branches of Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center and the University of Missouri Health Center.

The researchers collected data, including discharge time, medications patients were prescribed upon discharge, and patients’ subjective pain rating on a scale of 0-10 on a visual analogue scale (VAS).

Although patients’ VAS scores did not differ with respect to time or shift, patients were discharged with significantly less prescribed analgesics during the night shift in comparison with the day shift.

No similar differences in prescriptions between night shifts and day shifts were found for nonanalgesic medications, such as for diabetes or blood pressure. This suggests “the effect was specific to pain,” Dr. Gileles-Hillel said.

The pattern remained significant after controlling for potential confounders, including patient and physician variables and emergency department characteristics.

In addition, patients seen during night shifts received fewer analgesics, particularly opioids, than recommended by the World Health Organization for pain management.

“The first study enabled us to measure empathy for pain directly and examine our hypothesis in a controlled environment, while the second enabled us to test the implications by examining real-life pain management decisions,” Dr. Gileles-Hillel said.

“Physicians need to be aware of this,” he noted. “I try to be aware when I’m taking calls [at night] that I’m less empathetic to others and I might be more brief or angry with others.”

On a “house management level, perhaps institutions should try to schedule naps either before or during overnight call. A nap might give a boost and reboot not only to cognitive but also to emotional resources,” Dr. Gileles-Hillel added.

Compromised safety

In a comment, Eti Ben Simon, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Human Sleep Science, University of California, Berkeley, called the study “an important contribution to a growing list of studies that reveal how long night shifts reduce overall safety” for both patients and clinicians.

“It’s time to abandon the notion that the human brain can function as normal after being deprived of sleep for 24 hours,” said Dr. Ben Simon, who was not involved with the research.

“This is especially true in medicine, where we trust others to take care of us and feel our pain. These functions are simply not possible without adequate sleep,” she added.

Also commenting, Kannan Ramar, MD, president of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, suggested that being cognizant of these findings “may help providers to mitigate this bias” of underprescribing pain medications when treating their patients.

Dr. Ramar, who is also a critical care specialist, pulmonologist, and sleep medicine specialist at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., was not involved with the research.

He noted that “further studies that systematically evaluate this further in a prospective and blinded way will be important.”

The research was supported in part by grants from the Israel Science Foundation, Joy Ventures, the Recanati Fund at the Jerusalem School of Business at the Hebrew University, and a fellowship from the Azrieli Foundation and received grant support to various investigators from the NIH, the Leda J. Sears Foundation, and the University of Missouri. The investigators, Ramar, and Ben Simon have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

In the first of two studies, resident physicians were presented with two hypothetical scenarios involving a patient who complains of pain. They were asked about their likelihood of prescribing pain medication. The test was given to one group of residents who were just starting their day and to another group who were at the end of their night shift after being on call for 26 hours.

Results showed that the night shift residents were less likely than their daytime counterparts to say they would prescribe pain medication to the patients.

In further analysis of discharge notes from more than 13,000 electronic records of patients presenting with pain complaints at hospitals in Israel and the United States, the likelihood of an analgesic being prescribed during the night shift was 11% lower in Israel and 9% lower in the United States, compared with the day shift.

“Pain management is a major challenge, and a doctor’s perception of a patient’s subjective pain is susceptible to bias,” coinvestigator David Gozal, MD, the Marie M. and Harry L. Smith Endowed Chair of Child Health, University of Missouri–Columbia, said in a press release.

“This study demonstrated that night shift work is an important and previously unrecognized source of bias in pain management, likely stemming from impaired perception of pain,” Dr. Gozal added.

The findings were published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

‘Directional’ differences

Senior investigator Alex Gileles-Hillel, MD, senior pediatric pulmonologist and sleep researcher at Hadassah University Medical Center, Jerusalem, said in an interview that physicians must make “complex assessments of patients’ subjective pain experience” – and the “subjective nature of pain management decisions can give rise to various biases.”

Dr. Gileles-Hillel has previously researched the cognitive toll of night shift work on physicians.

“It’s pretty established, for example, not to drive when sleep deprived because cognition is impaired,” he said. The current study explored whether sleep deprivation could affect areas other than cognition, including emotions and empathy.

The researchers used “two complementary approaches.” First, they administered tests to measure empathy and pain management decisions in 67 resident physicians at Hadassah Medical Centers either following a 26-hour night shift that began at 8:00 a.m. the day before (n = 36) or immediately before starting the workday (n = 31).

There were no significant differences in demographic, sleep, or burnout measures between the two groups, except that night shift physicians had slept less than those in the daytime group (2.93 vs. 5.96 hours).

Participants completed two tasks. In the empathy-for-pain task, they rated their emotional reactions to pictures of individuals in pain. In the empathy accuracy task, they were asked to assess the feelings of videotaped individuals telling emotional stories.

They were then presented with two clinical scenarios: a female patient with a headache and a male patient with a backache. Following that, they were asked to assess the magnitude of the patients’ pain and how likely they would be to prescribe pain medication.

In the empathy-for-pain task, physicians’ empathy scores were significantly lower in the night shift group than in the day group (difference, –0.83; 95% CI, –1.55 to –0.10; P = .026). There were no significant differences between the groups in the empathy accuracy task.

In both scenarios, physicians in the night shift group assessed the patient’s pain as weaker in comparison with physicians in the day group. There was a statistically significant difference in the headache scenario but not the backache scenario.

In the headache scenario, the propensity of the physicians to prescribe analgesics was “directionally lower” but did not reach statistical significance. In the backache scenario, there was no significant difference between the groups’ prescribing propensities.

In both scenarios, pain assessment was positively correlated with the propensity to prescribe analgesics.

Despite the lack of statistical significance, the findings “documented a negative effect of night shift work on physician empathy for pain and a positive association between physician assessment of patient pain and the propensity to prescribe analgesics,” the investigators wrote.

Need for naps?

The researchers then analyzed analgesic prescription patterns drawn from three datasets of discharge notes of patients presenting to the emergency department with pain complaints (n = 13,482) at two branches of Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center and the University of Missouri Health Center.

The researchers collected data, including discharge time, medications patients were prescribed upon discharge, and patients’ subjective pain rating on a scale of 0-10 on a visual analogue scale (VAS).

Although patients’ VAS scores did not differ with respect to time or shift, patients were discharged with significantly less prescribed analgesics during the night shift in comparison with the day shift.

No similar differences in prescriptions between night shifts and day shifts were found for nonanalgesic medications, such as for diabetes or blood pressure. This suggests “the effect was specific to pain,” Dr. Gileles-Hillel said.

The pattern remained significant after controlling for potential confounders, including patient and physician variables and emergency department characteristics.

In addition, patients seen during night shifts received fewer analgesics, particularly opioids, than recommended by the World Health Organization for pain management.

“The first study enabled us to measure empathy for pain directly and examine our hypothesis in a controlled environment, while the second enabled us to test the implications by examining real-life pain management decisions,” Dr. Gileles-Hillel said.

“Physicians need to be aware of this,” he noted. “I try to be aware when I’m taking calls [at night] that I’m less empathetic to others and I might be more brief or angry with others.”

On a “house management level, perhaps institutions should try to schedule naps either before or during overnight call. A nap might give a boost and reboot not only to cognitive but also to emotional resources,” Dr. Gileles-Hillel added.

Compromised safety

In a comment, Eti Ben Simon, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Human Sleep Science, University of California, Berkeley, called the study “an important contribution to a growing list of studies that reveal how long night shifts reduce overall safety” for both patients and clinicians.

“It’s time to abandon the notion that the human brain can function as normal after being deprived of sleep for 24 hours,” said Dr. Ben Simon, who was not involved with the research.

“This is especially true in medicine, where we trust others to take care of us and feel our pain. These functions are simply not possible without adequate sleep,” she added.

Also commenting, Kannan Ramar, MD, president of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, suggested that being cognizant of these findings “may help providers to mitigate this bias” of underprescribing pain medications when treating their patients.

Dr. Ramar, who is also a critical care specialist, pulmonologist, and sleep medicine specialist at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., was not involved with the research.

He noted that “further studies that systematically evaluate this further in a prospective and blinded way will be important.”

The research was supported in part by grants from the Israel Science Foundation, Joy Ventures, the Recanati Fund at the Jerusalem School of Business at the Hebrew University, and a fellowship from the Azrieli Foundation and received grant support to various investigators from the NIH, the Leda J. Sears Foundation, and the University of Missouri. The investigators, Ramar, and Ben Simon have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES

Algorithm method versus spidey sense

One to two times a week I go through my junk mail folder. Usually it’s a collection of, well, junk: ads for CME, office software, car warranties, gift cards, dating sites, eyeglass or razor sellers, etc.

But there are usually a few items I’m glad I found, ones that I’m not sure how they ended up there. Bank notifications, package-tracking updates, a few other things. By the same token, every day a few pieces of junk land in my inbox.

This is, however, what we do for a living in this job.

Some patients are straightforward. The story is clear, the plan obvious.

Some require a bit more thinking.

And some are all over the place. Histories that wander everywhere, a million symptoms and clues. Most are likely red herrings, but which ones isn’t immediately obvious. And it’s up to the doctor to work this out.

With my junk folder, though, it’s usually immediately obvious what the useless things are compared with those of value. In medicine it’s often not so simple. You have to be careful what you discard, and you always need to be ready to change your mind and backtrack.

Artificial intelligence gets better every year but still makes plenty of mistakes. In sorting email my computer has to work out the signal-to-noise ratio of incoming items and decide which ones mean something. If my junk folder is any indication, it still has a ways to go.

This isn’t to say I’m infallible. I’m not. Unlike the algorithms my email program uses, there are no definite rules in medical cases. Picking through the clues is something that comes with training, experience, and a bit of luck. When I realize I’m going in the wrong direction I have to step back and rethink it all.

A lot of chart systems try to incorporate algorithms into medical decision-making. Sometimes they’re helpful, such as pointing out a drug interaction I wasn’t aware of. At other times they’re not, telling me I shouldn’t be ordering a test because such-and-such criteria haven’t been met. The trouble is these algorithms are written to apply to all cases, even though every patient is different. Sometimes the best we can go on is what I call “spidey sense” – realizing that there’s more than meets the eye here. In 24 years it’s served me well, far better than any computer algorithm has.

People talk about a natural fear of being replaced by computers. I agree that there are some things they’re very good at, and they keep getting better. But medicine isn’t a one-size-fits-all field. And the consequences are a lot higher than those from my bank statement being overlooked for a few days.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

One to two times a week I go through my junk mail folder. Usually it’s a collection of, well, junk: ads for CME, office software, car warranties, gift cards, dating sites, eyeglass or razor sellers, etc.

But there are usually a few items I’m glad I found, ones that I’m not sure how they ended up there. Bank notifications, package-tracking updates, a few other things. By the same token, every day a few pieces of junk land in my inbox.

This is, however, what we do for a living in this job.

Some patients are straightforward. The story is clear, the plan obvious.

Some require a bit more thinking.

And some are all over the place. Histories that wander everywhere, a million symptoms and clues. Most are likely red herrings, but which ones isn’t immediately obvious. And it’s up to the doctor to work this out.

With my junk folder, though, it’s usually immediately obvious what the useless things are compared with those of value. In medicine it’s often not so simple. You have to be careful what you discard, and you always need to be ready to change your mind and backtrack.

Artificial intelligence gets better every year but still makes plenty of mistakes. In sorting email my computer has to work out the signal-to-noise ratio of incoming items and decide which ones mean something. If my junk folder is any indication, it still has a ways to go.

This isn’t to say I’m infallible. I’m not. Unlike the algorithms my email program uses, there are no definite rules in medical cases. Picking through the clues is something that comes with training, experience, and a bit of luck. When I realize I’m going in the wrong direction I have to step back and rethink it all.

A lot of chart systems try to incorporate algorithms into medical decision-making. Sometimes they’re helpful, such as pointing out a drug interaction I wasn’t aware of. At other times they’re not, telling me I shouldn’t be ordering a test because such-and-such criteria haven’t been met. The trouble is these algorithms are written to apply to all cases, even though every patient is different. Sometimes the best we can go on is what I call “spidey sense” – realizing that there’s more than meets the eye here. In 24 years it’s served me well, far better than any computer algorithm has.

People talk about a natural fear of being replaced by computers. I agree that there are some things they’re very good at, and they keep getting better. But medicine isn’t a one-size-fits-all field. And the consequences are a lot higher than those from my bank statement being overlooked for a few days.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

One to two times a week I go through my junk mail folder. Usually it’s a collection of, well, junk: ads for CME, office software, car warranties, gift cards, dating sites, eyeglass or razor sellers, etc.

But there are usually a few items I’m glad I found, ones that I’m not sure how they ended up there. Bank notifications, package-tracking updates, a few other things. By the same token, every day a few pieces of junk land in my inbox.

This is, however, what we do for a living in this job.

Some patients are straightforward. The story is clear, the plan obvious.

Some require a bit more thinking.

And some are all over the place. Histories that wander everywhere, a million symptoms and clues. Most are likely red herrings, but which ones isn’t immediately obvious. And it’s up to the doctor to work this out.

With my junk folder, though, it’s usually immediately obvious what the useless things are compared with those of value. In medicine it’s often not so simple. You have to be careful what you discard, and you always need to be ready to change your mind and backtrack.

Artificial intelligence gets better every year but still makes plenty of mistakes. In sorting email my computer has to work out the signal-to-noise ratio of incoming items and decide which ones mean something. If my junk folder is any indication, it still has a ways to go.

This isn’t to say I’m infallible. I’m not. Unlike the algorithms my email program uses, there are no definite rules in medical cases. Picking through the clues is something that comes with training, experience, and a bit of luck. When I realize I’m going in the wrong direction I have to step back and rethink it all.

A lot of chart systems try to incorporate algorithms into medical decision-making. Sometimes they’re helpful, such as pointing out a drug interaction I wasn’t aware of. At other times they’re not, telling me I shouldn’t be ordering a test because such-and-such criteria haven’t been met. The trouble is these algorithms are written to apply to all cases, even though every patient is different. Sometimes the best we can go on is what I call “spidey sense” – realizing that there’s more than meets the eye here. In 24 years it’s served me well, far better than any computer algorithm has.

People talk about a natural fear of being replaced by computers. I agree that there are some things they’re very good at, and they keep getting better. But medicine isn’t a one-size-fits-all field. And the consequences are a lot higher than those from my bank statement being overlooked for a few days.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Cognitive impairment may predict physical disability in MS

, new research suggests. In an analysis of more than 1,600 patients with secondary-progressive MS (SPMS), the likelihood of needing a wheelchair was almost doubled in those who had the worst scores on cognitive testing measures, compared with their counterparts who had the best scores.

“These findings should change our world view of MS,” study investigator Gavin Giovannoni, PhD, professor of neurology, Blizard Institute, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, told attendees at the Congress of the European Academy of Neurology.

On the basis of the results, clinicians should consider testing cognitive processing speed in patients with MS to identify those who are at increased risk for disease progression, Dr. Giovannoni noted. “I urge anybody who runs an MS service to think about putting in place mechanisms in their clinic” to measure cognition of patients over time, he said.

Expand data

Cognitive impairment occurs very early in the course of MS and is part of the disease, although to a greater or lesser degree depending on the patient, Dr. Giovannoni noted. Such impairment has a significant impact on quality of life for patients dealing with this disease, he added.

EXPAND was a phase 3 study of siponimod. Results showed the now-approved oral selective sphingosine 1–phosphate receptor modulator significantly reduced the risk for disability progression in patients with SPMS.

Using the EXPAND clinical trial database, the current researchers assessed 1,628 participants for an association between cognitive processing speed, as measured with the Symbol Digit Modality Test (SDMT), and physical disability progression, as measured with the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). A score of 7 or more on the EDSS indicates wheelchair dependence.

Dr. Giovannoni noted that cognitive processing speed is considered an indirect measure of thalamic network efficiency and functional brain reserve.

Investigators looked at both the core study, in which all patients continued on treatment or placebo for up to 37 months, and the core plus extension part, in which patients received treatment for up to 5 years.

They separated SDMT scores into quartiles: from worst (n = 435) to two intermediate quartiles (n = 808) to the best quartile (n = 385).

Wheelchair dependence

In addition, the researchers examined the predictive value by baseline SDMT, adjusting for treatment, age, gender, baseline EDSS score, baseline SCMT quartile, and treatment-by-baseline SCMT quartile interaction. On-study SDMT change (month 0-24) was also assessed after adjusting for treatment, age, gender, baseline EDS, baseline SCMT, and on-study change in SCMT quartile.

In the core study, those in the worst SDMT quartile at baseline were numerically more likely to reach deterioration to EDSS 7 or greater (wheelchair dependent), compared with patients in the best SDMT quartile (hazard ratio, 1.31; 95% confidence interval, .72-2.38; P = .371).

The short-term predictive value of baseline SDMT for reaching sustained EDSS of at least 7 was more obvious in the placebo arm than in the treatment arm.

Dr. Giovannoni said this is likely due to the treatment effect of siponimod preventing relatively more events in the worse quartile, and so reducing the risk for wheelchair dependency.

In the core plus extension part, there was an almost twofold increased risk for wheelchair dependence in the worse versus best SDMT groups (HR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.17-2.78; P = .007).

Both baseline SDMT (HR, 1.81; P = .007) and on-study change in SDMT (HR, 1.73; P = .046) predicted wheelchair dependence in the long-term.

‘More important than a walking stick’

Measuring cognitive change over time “may be a more important predictor than a walking stick in terms of quality of life and outcomes, and it affects clinical decisionmaking,” said Dr. Giovannoni.

The findings are not novel, as post hoc analyses of other studies showed similar results. However, this new analysis adds more evidence to the importance of cognition in MS, Dr. Giovannoni noted.

“I have patients with EDSS of 0 or 1 who are profoundly disabled because of cognition. You shouldn’t just assume someone is not disabled because they don’t have physical disability,” he said.

However, Dr. Giovannoni noted that the study found an association and does not necessarily indicate a cause.

‘Valuable’ insights

Antonia Lefter, MD, of NeuroHope, Monza Oncologic Hospital, Bucharest, Romania, cochaired the session highlighting the research. Commenting on the study, she called this analysis from the “renowned” EXPAND study “valuable.”

In addition, it “underscores” the importance of assessing cognitive processing speed, as it may predict long-term disability progression in patients with SPMS, Dr. Lefter said.

The study was funded by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. Dr. Giovannoni, a steering committee member of the EXPAND trial, reported receiving consulting fees from AbbVie, Actelion, Atara Bio, Biogen, Celgene, Sanofi-Genzyme, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck-Serono, Novartis, Roche, and Reva. He has also received compensation for research from Biogen, Roche, Merck-Serono, Novartis, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Takeda. Dr. Lefter has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests. In an analysis of more than 1,600 patients with secondary-progressive MS (SPMS), the likelihood of needing a wheelchair was almost doubled in those who had the worst scores on cognitive testing measures, compared with their counterparts who had the best scores.

“These findings should change our world view of MS,” study investigator Gavin Giovannoni, PhD, professor of neurology, Blizard Institute, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, told attendees at the Congress of the European Academy of Neurology.

On the basis of the results, clinicians should consider testing cognitive processing speed in patients with MS to identify those who are at increased risk for disease progression, Dr. Giovannoni noted. “I urge anybody who runs an MS service to think about putting in place mechanisms in their clinic” to measure cognition of patients over time, he said.

Expand data

Cognitive impairment occurs very early in the course of MS and is part of the disease, although to a greater or lesser degree depending on the patient, Dr. Giovannoni noted. Such impairment has a significant impact on quality of life for patients dealing with this disease, he added.

EXPAND was a phase 3 study of siponimod. Results showed the now-approved oral selective sphingosine 1–phosphate receptor modulator significantly reduced the risk for disability progression in patients with SPMS.

Using the EXPAND clinical trial database, the current researchers assessed 1,628 participants for an association between cognitive processing speed, as measured with the Symbol Digit Modality Test (SDMT), and physical disability progression, as measured with the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). A score of 7 or more on the EDSS indicates wheelchair dependence.

Dr. Giovannoni noted that cognitive processing speed is considered an indirect measure of thalamic network efficiency and functional brain reserve.

Investigators looked at both the core study, in which all patients continued on treatment or placebo for up to 37 months, and the core plus extension part, in which patients received treatment for up to 5 years.

They separated SDMT scores into quartiles: from worst (n = 435) to two intermediate quartiles (n = 808) to the best quartile (n = 385).

Wheelchair dependence

In addition, the researchers examined the predictive value by baseline SDMT, adjusting for treatment, age, gender, baseline EDSS score, baseline SCMT quartile, and treatment-by-baseline SCMT quartile interaction. On-study SDMT change (month 0-24) was also assessed after adjusting for treatment, age, gender, baseline EDS, baseline SCMT, and on-study change in SCMT quartile.

In the core study, those in the worst SDMT quartile at baseline were numerically more likely to reach deterioration to EDSS 7 or greater (wheelchair dependent), compared with patients in the best SDMT quartile (hazard ratio, 1.31; 95% confidence interval, .72-2.38; P = .371).

The short-term predictive value of baseline SDMT for reaching sustained EDSS of at least 7 was more obvious in the placebo arm than in the treatment arm.

Dr. Giovannoni said this is likely due to the treatment effect of siponimod preventing relatively more events in the worse quartile, and so reducing the risk for wheelchair dependency.

In the core plus extension part, there was an almost twofold increased risk for wheelchair dependence in the worse versus best SDMT groups (HR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.17-2.78; P = .007).

Both baseline SDMT (HR, 1.81; P = .007) and on-study change in SDMT (HR, 1.73; P = .046) predicted wheelchair dependence in the long-term.

‘More important than a walking stick’

Measuring cognitive change over time “may be a more important predictor than a walking stick in terms of quality of life and outcomes, and it affects clinical decisionmaking,” said Dr. Giovannoni.

The findings are not novel, as post hoc analyses of other studies showed similar results. However, this new analysis adds more evidence to the importance of cognition in MS, Dr. Giovannoni noted.

“I have patients with EDSS of 0 or 1 who are profoundly disabled because of cognition. You shouldn’t just assume someone is not disabled because they don’t have physical disability,” he said.

However, Dr. Giovannoni noted that the study found an association and does not necessarily indicate a cause.

‘Valuable’ insights

Antonia Lefter, MD, of NeuroHope, Monza Oncologic Hospital, Bucharest, Romania, cochaired the session highlighting the research. Commenting on the study, she called this analysis from the “renowned” EXPAND study “valuable.”

In addition, it “underscores” the importance of assessing cognitive processing speed, as it may predict long-term disability progression in patients with SPMS, Dr. Lefter said.

The study was funded by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. Dr. Giovannoni, a steering committee member of the EXPAND trial, reported receiving consulting fees from AbbVie, Actelion, Atara Bio, Biogen, Celgene, Sanofi-Genzyme, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck-Serono, Novartis, Roche, and Reva. He has also received compensation for research from Biogen, Roche, Merck-Serono, Novartis, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Takeda. Dr. Lefter has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests. In an analysis of more than 1,600 patients with secondary-progressive MS (SPMS), the likelihood of needing a wheelchair was almost doubled in those who had the worst scores on cognitive testing measures, compared with their counterparts who had the best scores.

“These findings should change our world view of MS,” study investigator Gavin Giovannoni, PhD, professor of neurology, Blizard Institute, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, told attendees at the Congress of the European Academy of Neurology.

On the basis of the results, clinicians should consider testing cognitive processing speed in patients with MS to identify those who are at increased risk for disease progression, Dr. Giovannoni noted. “I urge anybody who runs an MS service to think about putting in place mechanisms in their clinic” to measure cognition of patients over time, he said.

Expand data

Cognitive impairment occurs very early in the course of MS and is part of the disease, although to a greater or lesser degree depending on the patient, Dr. Giovannoni noted. Such impairment has a significant impact on quality of life for patients dealing with this disease, he added.

EXPAND was a phase 3 study of siponimod. Results showed the now-approved oral selective sphingosine 1–phosphate receptor modulator significantly reduced the risk for disability progression in patients with SPMS.

Using the EXPAND clinical trial database, the current researchers assessed 1,628 participants for an association between cognitive processing speed, as measured with the Symbol Digit Modality Test (SDMT), and physical disability progression, as measured with the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). A score of 7 or more on the EDSS indicates wheelchair dependence.

Dr. Giovannoni noted that cognitive processing speed is considered an indirect measure of thalamic network efficiency and functional brain reserve.

Investigators looked at both the core study, in which all patients continued on treatment or placebo for up to 37 months, and the core plus extension part, in which patients received treatment for up to 5 years.

They separated SDMT scores into quartiles: from worst (n = 435) to two intermediate quartiles (n = 808) to the best quartile (n = 385).

Wheelchair dependence

In addition, the researchers examined the predictive value by baseline SDMT, adjusting for treatment, age, gender, baseline EDSS score, baseline SCMT quartile, and treatment-by-baseline SCMT quartile interaction. On-study SDMT change (month 0-24) was also assessed after adjusting for treatment, age, gender, baseline EDS, baseline SCMT, and on-study change in SCMT quartile.

In the core study, those in the worst SDMT quartile at baseline were numerically more likely to reach deterioration to EDSS 7 or greater (wheelchair dependent), compared with patients in the best SDMT quartile (hazard ratio, 1.31; 95% confidence interval, .72-2.38; P = .371).

The short-term predictive value of baseline SDMT for reaching sustained EDSS of at least 7 was more obvious in the placebo arm than in the treatment arm.

Dr. Giovannoni said this is likely due to the treatment effect of siponimod preventing relatively more events in the worse quartile, and so reducing the risk for wheelchair dependency.

In the core plus extension part, there was an almost twofold increased risk for wheelchair dependence in the worse versus best SDMT groups (HR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.17-2.78; P = .007).

Both baseline SDMT (HR, 1.81; P = .007) and on-study change in SDMT (HR, 1.73; P = .046) predicted wheelchair dependence in the long-term.

‘More important than a walking stick’

Measuring cognitive change over time “may be a more important predictor than a walking stick in terms of quality of life and outcomes, and it affects clinical decisionmaking,” said Dr. Giovannoni.

The findings are not novel, as post hoc analyses of other studies showed similar results. However, this new analysis adds more evidence to the importance of cognition in MS, Dr. Giovannoni noted.

“I have patients with EDSS of 0 or 1 who are profoundly disabled because of cognition. You shouldn’t just assume someone is not disabled because they don’t have physical disability,” he said.

However, Dr. Giovannoni noted that the study found an association and does not necessarily indicate a cause.

‘Valuable’ insights

Antonia Lefter, MD, of NeuroHope, Monza Oncologic Hospital, Bucharest, Romania, cochaired the session highlighting the research. Commenting on the study, she called this analysis from the “renowned” EXPAND study “valuable.”

In addition, it “underscores” the importance of assessing cognitive processing speed, as it may predict long-term disability progression in patients with SPMS, Dr. Lefter said.

The study was funded by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. Dr. Giovannoni, a steering committee member of the EXPAND trial, reported receiving consulting fees from AbbVie, Actelion, Atara Bio, Biogen, Celgene, Sanofi-Genzyme, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck-Serono, Novartis, Roche, and Reva. He has also received compensation for research from Biogen, Roche, Merck-Serono, Novartis, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Takeda. Dr. Lefter has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

From EAN 2022

‘Striking’ jump in cost of brand-name epilepsy meds

, a new analysis shows.

After adjustment for inflation, the cost of a 1-year supply of brand-name ASMs grew 277%, while generics became 42% less expensive.

“Our study makes transparent striking trends in brand name prescribing patterns,” the study team wrote.

Since 2010, the costs for brand-name ASMs have “consistently” increased. Costs were particularly boosted by increases in prescriptions for lacosamide (Vimpat), in addition to a “steep increase in the cost per pill, with brand-name drugs costing 10 times more than their generic counterparts,” first author Samuel Waller Terman, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, added in a news release.

The study was published online in Neurology.

Is a 10-fold increase in cost worth it?

To evaluate trends in ASM prescriptions and costs, the researchers used a random sample of 20% of Medicare beneficiaries with coverage from 2008 to 2018. There were 77,000 to 133,000 patients with epilepsy each year.