User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Epidiolex plus THC lowers seizures in pediatric epilepsy

the component of cannabis that makes people high in larger quantities, researchers reported.

“THC can contribute to seizure control and mitigation some of the side effects of CBD,” said study coauthor and Austin, Tex., child neurologist Karen Keough, MD, in an interview. Dr. Keough and colleagues presented their findings at the 50th annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society.

In a landmark move, the Food and Drug Administration approved Epidiolex in 2018 for the treatment of seizures in two rare forms of epilepsy, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome. The agency had never before approved a drug with a purified ingredient derived from marijuana.

CBD, the active ingredient in Epidiolex, is nonpsychoactive. The use in medicine of THC, the main driver of marijuana’s ability to make people stoned, is much more controversial.

Dr. Keough said she had treated 60-70 children with CBD, at the same strength as in Epidiolex (100 mg), and 5 mg of THC before the drug was approved. “I was seeing some very impressive results, and some became seizure free who’d always been refractory,” she said.

When the Epidiolex became available, she said, some patients transitioned to it and stopped taking THC. According to her, some patients fared well. But others immediately experienced worse seizures, she said, and some developed side effects to Epidiolex in the absence of THC, such as agitation and appetite suppression.

Combination therapy

For the new study, a retrospective, unblinded cohort analysis, Dr. Keough and colleagues tracked patients who received various doses of CBD, in some cases as Epidiolex, and various doses of THC prescribed by the Texas Original Compassionate Cultivation dispensary, where she serves as chief medical officer.

The initial number of patients was 212; 135 consented to review and 10 were excluded for various reasons leaving a total of 74 subjects in the study. The subjects, whose median age at the start of the study was 12 years (range, 2-25 years), were tracked from 2018 to2021. Just over half (55%) were male, and they remained on the regimen for a median of 805 days (range, 400-1,141).

Of the 74 subjects, 45.9% had a reduction of seizures of more than 75%, and 20.3% had a reduction of 50%-75%. Only 4.1% saw their seizures worsen.

The THC doses varied from none to more than 12 mg/day; CBD doses varied from none to more than 26 mg/kg per day. O the 74 patients, 18 saw their greatest seizure reduction from baseline when they received no THC; 12 saw their greatest seizure reduction from baseline when they received 0-2 mg/kg per day of CBD.

Still controversial

Did the patients get high? In some cases they did, Dr. Keough said. However, “a lot of these patients are either too young or too cognitively limited to describe whether they’re feeling intoxicated. That’s one of the many reasons why this is so controversial. You have to go into this with eyes wide open. We’re working in an environment with limited information as to what an intoxicating dose is for a small kid.”

However, she said, it seems clear that “THC can enhance the effect of CBD in children with epilepsy” and reduce CBD side effects. It’s not surprising that the substances work differently since they interact with brain cells in different ways, she said.

For neurologists, she said, “the challenge is to find a reliable source of THC that you can count on and verify so you aren’t overdosing the patients.”

University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, child neurologist and cannabinoid researcher Richard Huntsman, MD, who’s familiar with the study findings, said in an interview that they “provide another strong signal that the addition of THC provides benefit, at least in some patients.”

But it’s still unclear “why some children respond best in regards to seizure reduction and side effect profile with combination CBD:THC therapy, and others seemed to do better with CBD alone,” he said. Also unknown: “the ideal THC:CBD ratio that allows optimal seizure control while preventing the potential harmful effects of THC.”

As for the future, he said, “as we are just scratching the surface of our knowledge about the use of cannabis-based therapies in children with neurological disorders, I suspect that the use of these therapies will expand over time.”

No study funding is reported. Dr. Keough disclosed serving as chief medical officer of Texas Original Compassionate Cultivation. Dr. Huntsman disclosed serving as lead investigator of the Cannabidiol in Children with Refractory Epileptic Encephalopathy study and serving on the boards of the Cannabinoid Research Initiative of Saskatchewan (University of Saskatchewan) and Canadian Childhood Cannabinoid Clinical Trials Consortium. He is also cochair of Health Canada’s Scientific Advisory Committee on Cannabinoids for Health Purposes.

the component of cannabis that makes people high in larger quantities, researchers reported.

“THC can contribute to seizure control and mitigation some of the side effects of CBD,” said study coauthor and Austin, Tex., child neurologist Karen Keough, MD, in an interview. Dr. Keough and colleagues presented their findings at the 50th annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society.

In a landmark move, the Food and Drug Administration approved Epidiolex in 2018 for the treatment of seizures in two rare forms of epilepsy, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome. The agency had never before approved a drug with a purified ingredient derived from marijuana.

CBD, the active ingredient in Epidiolex, is nonpsychoactive. The use in medicine of THC, the main driver of marijuana’s ability to make people stoned, is much more controversial.

Dr. Keough said she had treated 60-70 children with CBD, at the same strength as in Epidiolex (100 mg), and 5 mg of THC before the drug was approved. “I was seeing some very impressive results, and some became seizure free who’d always been refractory,” she said.

When the Epidiolex became available, she said, some patients transitioned to it and stopped taking THC. According to her, some patients fared well. But others immediately experienced worse seizures, she said, and some developed side effects to Epidiolex in the absence of THC, such as agitation and appetite suppression.

Combination therapy

For the new study, a retrospective, unblinded cohort analysis, Dr. Keough and colleagues tracked patients who received various doses of CBD, in some cases as Epidiolex, and various doses of THC prescribed by the Texas Original Compassionate Cultivation dispensary, where she serves as chief medical officer.

The initial number of patients was 212; 135 consented to review and 10 were excluded for various reasons leaving a total of 74 subjects in the study. The subjects, whose median age at the start of the study was 12 years (range, 2-25 years), were tracked from 2018 to2021. Just over half (55%) were male, and they remained on the regimen for a median of 805 days (range, 400-1,141).

Of the 74 subjects, 45.9% had a reduction of seizures of more than 75%, and 20.3% had a reduction of 50%-75%. Only 4.1% saw their seizures worsen.

The THC doses varied from none to more than 12 mg/day; CBD doses varied from none to more than 26 mg/kg per day. O the 74 patients, 18 saw their greatest seizure reduction from baseline when they received no THC; 12 saw their greatest seizure reduction from baseline when they received 0-2 mg/kg per day of CBD.

Still controversial

Did the patients get high? In some cases they did, Dr. Keough said. However, “a lot of these patients are either too young or too cognitively limited to describe whether they’re feeling intoxicated. That’s one of the many reasons why this is so controversial. You have to go into this with eyes wide open. We’re working in an environment with limited information as to what an intoxicating dose is for a small kid.”

However, she said, it seems clear that “THC can enhance the effect of CBD in children with epilepsy” and reduce CBD side effects. It’s not surprising that the substances work differently since they interact with brain cells in different ways, she said.

For neurologists, she said, “the challenge is to find a reliable source of THC that you can count on and verify so you aren’t overdosing the patients.”

University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, child neurologist and cannabinoid researcher Richard Huntsman, MD, who’s familiar with the study findings, said in an interview that they “provide another strong signal that the addition of THC provides benefit, at least in some patients.”

But it’s still unclear “why some children respond best in regards to seizure reduction and side effect profile with combination CBD:THC therapy, and others seemed to do better with CBD alone,” he said. Also unknown: “the ideal THC:CBD ratio that allows optimal seizure control while preventing the potential harmful effects of THC.”

As for the future, he said, “as we are just scratching the surface of our knowledge about the use of cannabis-based therapies in children with neurological disorders, I suspect that the use of these therapies will expand over time.”

No study funding is reported. Dr. Keough disclosed serving as chief medical officer of Texas Original Compassionate Cultivation. Dr. Huntsman disclosed serving as lead investigator of the Cannabidiol in Children with Refractory Epileptic Encephalopathy study and serving on the boards of the Cannabinoid Research Initiative of Saskatchewan (University of Saskatchewan) and Canadian Childhood Cannabinoid Clinical Trials Consortium. He is also cochair of Health Canada’s Scientific Advisory Committee on Cannabinoids for Health Purposes.

the component of cannabis that makes people high in larger quantities, researchers reported.

“THC can contribute to seizure control and mitigation some of the side effects of CBD,” said study coauthor and Austin, Tex., child neurologist Karen Keough, MD, in an interview. Dr. Keough and colleagues presented their findings at the 50th annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society.

In a landmark move, the Food and Drug Administration approved Epidiolex in 2018 for the treatment of seizures in two rare forms of epilepsy, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome. The agency had never before approved a drug with a purified ingredient derived from marijuana.

CBD, the active ingredient in Epidiolex, is nonpsychoactive. The use in medicine of THC, the main driver of marijuana’s ability to make people stoned, is much more controversial.

Dr. Keough said she had treated 60-70 children with CBD, at the same strength as in Epidiolex (100 mg), and 5 mg of THC before the drug was approved. “I was seeing some very impressive results, and some became seizure free who’d always been refractory,” she said.

When the Epidiolex became available, she said, some patients transitioned to it and stopped taking THC. According to her, some patients fared well. But others immediately experienced worse seizures, she said, and some developed side effects to Epidiolex in the absence of THC, such as agitation and appetite suppression.

Combination therapy

For the new study, a retrospective, unblinded cohort analysis, Dr. Keough and colleagues tracked patients who received various doses of CBD, in some cases as Epidiolex, and various doses of THC prescribed by the Texas Original Compassionate Cultivation dispensary, where she serves as chief medical officer.

The initial number of patients was 212; 135 consented to review and 10 were excluded for various reasons leaving a total of 74 subjects in the study. The subjects, whose median age at the start of the study was 12 years (range, 2-25 years), were tracked from 2018 to2021. Just over half (55%) were male, and they remained on the regimen for a median of 805 days (range, 400-1,141).

Of the 74 subjects, 45.9% had a reduction of seizures of more than 75%, and 20.3% had a reduction of 50%-75%. Only 4.1% saw their seizures worsen.

The THC doses varied from none to more than 12 mg/day; CBD doses varied from none to more than 26 mg/kg per day. O the 74 patients, 18 saw their greatest seizure reduction from baseline when they received no THC; 12 saw their greatest seizure reduction from baseline when they received 0-2 mg/kg per day of CBD.

Still controversial

Did the patients get high? In some cases they did, Dr. Keough said. However, “a lot of these patients are either too young or too cognitively limited to describe whether they’re feeling intoxicated. That’s one of the many reasons why this is so controversial. You have to go into this with eyes wide open. We’re working in an environment with limited information as to what an intoxicating dose is for a small kid.”

However, she said, it seems clear that “THC can enhance the effect of CBD in children with epilepsy” and reduce CBD side effects. It’s not surprising that the substances work differently since they interact with brain cells in different ways, she said.

For neurologists, she said, “the challenge is to find a reliable source of THC that you can count on and verify so you aren’t overdosing the patients.”

University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, child neurologist and cannabinoid researcher Richard Huntsman, MD, who’s familiar with the study findings, said in an interview that they “provide another strong signal that the addition of THC provides benefit, at least in some patients.”

But it’s still unclear “why some children respond best in regards to seizure reduction and side effect profile with combination CBD:THC therapy, and others seemed to do better with CBD alone,” he said. Also unknown: “the ideal THC:CBD ratio that allows optimal seizure control while preventing the potential harmful effects of THC.”

As for the future, he said, “as we are just scratching the surface of our knowledge about the use of cannabis-based therapies in children with neurological disorders, I suspect that the use of these therapies will expand over time.”

No study funding is reported. Dr. Keough disclosed serving as chief medical officer of Texas Original Compassionate Cultivation. Dr. Huntsman disclosed serving as lead investigator of the Cannabidiol in Children with Refractory Epileptic Encephalopathy study and serving on the boards of the Cannabinoid Research Initiative of Saskatchewan (University of Saskatchewan) and Canadian Childhood Cannabinoid Clinical Trials Consortium. He is also cochair of Health Canada’s Scientific Advisory Committee on Cannabinoids for Health Purposes.

FROM CNS 2021

Double antiglutamatergic therapy is ‘promising’ for super-refractory status epilepticus

(SRSE), new research suggests.

In a retrospective cohort study of survivors of cardiac arrest with postanoxic sustained SRSE, resolution of the condition was achieved by 81% of those who received intensive treatment of ketamine plus perampanel, versus 41% of those who received standard care.

The novelty of the new treatment approach is the duration of therapy as well as the dual antiglutamate drugs, researchers note.

“So the logic is to continue treatment until resolution of refractory status epilepticus under continuous EEG [electroencephalographic] monitoring,” reported lead investigator Simone Beretta, MD, San Gerardo University Hospital, Monza, Italy.

Therapy was guided by data on brainstem reflexes, N20 cortical responses, neuronal serum enolase levels, and neuroimaging.

If all or most of these indicators are favorable, “we continue to treat without any time limit,” Dr. Beretta said. However, if the indicators become unfavorable, clinicians should consider lowering the intensity of care, he added.

The findings were presented at the 2021 World Congress of Neurology (WCN).

SUPER-CAT trial

In SRSE, epileptic seizures occur one after another without patients recovering consciousness in between. Standard aggressive therapy for the condition does not include antiglutamatergic drugs, the researchers noted.

In the Super-Refractory Status Epilepticus After Cardiac Arrest: Aggressive Treatment Guided by Multimodal Prognostic Indicators (SUPER-CAT) study, researchers assessed the combination of two such medications.

The first was the anti-NMDA receptor drug ketamine, which was given by intravenous bolus and then continuous infusion for 3 days guided by continuous EEG to reach a ketamine EEG pattern, as evidenced by alpha and beta waves. It was combined with the anti-AMPA receptor antiepileptic perampanel via nasogastric tube for 5 days, followed by slow tapering.

Dr. Beretta noted that in the ongoing TELSTAR trial, which involved a similar patient population, a different drug combination is being used. A major difference between the two trials is that in the TELSTAR trial, aggressive therapy continues for only 2 days if there is no response.

“In the SUPER-CAT study, we continue far beyond 2 days in the majority of patients,” he said. In addition, ketamine and perampanel were not assessed in TELSTAR.

In SUPER-CAT, 489 survivors of cardiac arrest were recruited over 10 years. Of these, 101 had refractory status epilepticus. After excluding those with more than two indicators of poor prognosis (n = 31) or whose status epilepticus resolved (n = 14), 56 patients were determined to have SRSE. All had experienced relapse after undergoing one cycle of anesthetic.

The 56 participants received one of three treatment regimens: double antiglutamate (DAG) therapy of ketamine and perampanel (n = 26), single antiglutamate therapy with either agent (n = 8), or aggressive nonantiglutamate (NAG) therapy with antiepilepsy drugs and anesthetics other than ketamine or perampanel (n = 22).

The single-antiglutamate group was not included in the analysis of patient outcomes.

The DAG and NAG groups were well balanced at baseline. There were no significant differences in median age (60 years vs. 66 years), gender, low cerebral blood flow, presence of bilateral pupillary or corneal reflexes, neuron-specific enolase levels, cortical N20 somatosenory evoked potentials, moderate to severe postanoxic brain injury, and hypothermia/targeted temperature management.

Primary outcome met

More patients in the DAG group (42%) had moderate to severe postanoxic brain injury than in the NAG group (28%). However, the difference was not statistically significant (P = .08), possibly because of the small sample sizes. The number of antiepileptic drugs and the number of cycles of anesthetics did not differ between the groups.

Results showed that efficacy and safety outcomes favored DAG therapy.

The primary efficacy outcome was resolution of status epilepticus within 3 days after initiation of treatments. Status epilepticus resolved for 21 of 26 patients in the DAG group (81%), versus 9 of 22 patients in the NAG group (41%; odds ratio, 6.06; 95% confidence interval, 1.66-22.12; P = .005).

For secondary efficacy outcomes, there was a trend in favor of DAG, but differences from the NAG group were not statistically significant. In the groups, 46% versus 32% awakened and responded to commands before discharge from the intensive care unit, and 32% versus 23% showed good neurologic outcome at 6 months.

The primary safety outcome of all-cause mortality risk in the ICU was 90% lower for patients treated with DAG than for those treated with NAG (15% vs. 64%; OR, 0.1; 95% CI, 0.02-0.41; P < .01). Dr. Beretta explained that the high mortality rate in the NAG group was presumably a result of unresolved status epilepticus.

The secondary safety outcome of a transitory rise of gamma-glutamyl transferase greater than three times the upper limit of normal in the DAG group was expected with high-dose perampanel, the investigators noted. This outcome occurred in 77% of the DAG group versus 27% of the NAG group (OR, 9.88; 95% CI, 2.4-32.9; P < .001).

There was no statistically significant difference in incidence of recurrent cardiac arrest during therapy. This occurred in one member of the DAG group and in none in the NAG group.

Dr. Beretta reported that their investigations are still in a retrospective phase, but the researchers plan to move the work into a prospective phase and possibly a randomized trial soon.

Fascinating, promising

Commenting on the findings, Jaysingh Singh, MD, co-director of the Epilepsy Surgery Center at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, said the study provides “fascinating, very helpful data” about a condition that has responded well to current treatment options.

He added that his center has used “the innovative treatments” discussed in the study for a few patients.

“More concrete evidence will push us to use it more uniformly across all our patient population [that] has refractory status. So I’m very optimistic, and the data were very promising,” said Dr. Singh, who was not involved with the research.

He cautioned that the study was retrospective, not randomized or controlled, and that it involved a small number of patients but said that the data were “heading in the right direction.”

Although resolution of status epilepticus was better among patients in the DAG group than in the NAG group, the awakenings and neurologic outcomes were “pretty much same as standard medical therapy, which we commonly give to our patients,” said Dr. Singh. “We see this phenomenon all the time in our patients.”

He noted that other factors can determine how patients respond, such as conditions of the heart or kidneys, the presence of sepsis, and multiorgan dysfunction. These factors were not controlled for in the study.

Nonetheless, he said the study achieved its primary endpoint of better resolution of status epilepticus “because that’s the first thing you want to see: whether the treatment is taking care of that.”

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Beretta and Dr. Singh have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

(SRSE), new research suggests.

In a retrospective cohort study of survivors of cardiac arrest with postanoxic sustained SRSE, resolution of the condition was achieved by 81% of those who received intensive treatment of ketamine plus perampanel, versus 41% of those who received standard care.

The novelty of the new treatment approach is the duration of therapy as well as the dual antiglutamate drugs, researchers note.

“So the logic is to continue treatment until resolution of refractory status epilepticus under continuous EEG [electroencephalographic] monitoring,” reported lead investigator Simone Beretta, MD, San Gerardo University Hospital, Monza, Italy.

Therapy was guided by data on brainstem reflexes, N20 cortical responses, neuronal serum enolase levels, and neuroimaging.

If all or most of these indicators are favorable, “we continue to treat without any time limit,” Dr. Beretta said. However, if the indicators become unfavorable, clinicians should consider lowering the intensity of care, he added.

The findings were presented at the 2021 World Congress of Neurology (WCN).

SUPER-CAT trial

In SRSE, epileptic seizures occur one after another without patients recovering consciousness in between. Standard aggressive therapy for the condition does not include antiglutamatergic drugs, the researchers noted.

In the Super-Refractory Status Epilepticus After Cardiac Arrest: Aggressive Treatment Guided by Multimodal Prognostic Indicators (SUPER-CAT) study, researchers assessed the combination of two such medications.

The first was the anti-NMDA receptor drug ketamine, which was given by intravenous bolus and then continuous infusion for 3 days guided by continuous EEG to reach a ketamine EEG pattern, as evidenced by alpha and beta waves. It was combined with the anti-AMPA receptor antiepileptic perampanel via nasogastric tube for 5 days, followed by slow tapering.

Dr. Beretta noted that in the ongoing TELSTAR trial, which involved a similar patient population, a different drug combination is being used. A major difference between the two trials is that in the TELSTAR trial, aggressive therapy continues for only 2 days if there is no response.

“In the SUPER-CAT study, we continue far beyond 2 days in the majority of patients,” he said. In addition, ketamine and perampanel were not assessed in TELSTAR.

In SUPER-CAT, 489 survivors of cardiac arrest were recruited over 10 years. Of these, 101 had refractory status epilepticus. After excluding those with more than two indicators of poor prognosis (n = 31) or whose status epilepticus resolved (n = 14), 56 patients were determined to have SRSE. All had experienced relapse after undergoing one cycle of anesthetic.

The 56 participants received one of three treatment regimens: double antiglutamate (DAG) therapy of ketamine and perampanel (n = 26), single antiglutamate therapy with either agent (n = 8), or aggressive nonantiglutamate (NAG) therapy with antiepilepsy drugs and anesthetics other than ketamine or perampanel (n = 22).

The single-antiglutamate group was not included in the analysis of patient outcomes.

The DAG and NAG groups were well balanced at baseline. There were no significant differences in median age (60 years vs. 66 years), gender, low cerebral blood flow, presence of bilateral pupillary or corneal reflexes, neuron-specific enolase levels, cortical N20 somatosenory evoked potentials, moderate to severe postanoxic brain injury, and hypothermia/targeted temperature management.

Primary outcome met

More patients in the DAG group (42%) had moderate to severe postanoxic brain injury than in the NAG group (28%). However, the difference was not statistically significant (P = .08), possibly because of the small sample sizes. The number of antiepileptic drugs and the number of cycles of anesthetics did not differ between the groups.

Results showed that efficacy and safety outcomes favored DAG therapy.

The primary efficacy outcome was resolution of status epilepticus within 3 days after initiation of treatments. Status epilepticus resolved for 21 of 26 patients in the DAG group (81%), versus 9 of 22 patients in the NAG group (41%; odds ratio, 6.06; 95% confidence interval, 1.66-22.12; P = .005).

For secondary efficacy outcomes, there was a trend in favor of DAG, but differences from the NAG group were not statistically significant. In the groups, 46% versus 32% awakened and responded to commands before discharge from the intensive care unit, and 32% versus 23% showed good neurologic outcome at 6 months.

The primary safety outcome of all-cause mortality risk in the ICU was 90% lower for patients treated with DAG than for those treated with NAG (15% vs. 64%; OR, 0.1; 95% CI, 0.02-0.41; P < .01). Dr. Beretta explained that the high mortality rate in the NAG group was presumably a result of unresolved status epilepticus.

The secondary safety outcome of a transitory rise of gamma-glutamyl transferase greater than three times the upper limit of normal in the DAG group was expected with high-dose perampanel, the investigators noted. This outcome occurred in 77% of the DAG group versus 27% of the NAG group (OR, 9.88; 95% CI, 2.4-32.9; P < .001).

There was no statistically significant difference in incidence of recurrent cardiac arrest during therapy. This occurred in one member of the DAG group and in none in the NAG group.

Dr. Beretta reported that their investigations are still in a retrospective phase, but the researchers plan to move the work into a prospective phase and possibly a randomized trial soon.

Fascinating, promising

Commenting on the findings, Jaysingh Singh, MD, co-director of the Epilepsy Surgery Center at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, said the study provides “fascinating, very helpful data” about a condition that has responded well to current treatment options.

He added that his center has used “the innovative treatments” discussed in the study for a few patients.

“More concrete evidence will push us to use it more uniformly across all our patient population [that] has refractory status. So I’m very optimistic, and the data were very promising,” said Dr. Singh, who was not involved with the research.

He cautioned that the study was retrospective, not randomized or controlled, and that it involved a small number of patients but said that the data were “heading in the right direction.”

Although resolution of status epilepticus was better among patients in the DAG group than in the NAG group, the awakenings and neurologic outcomes were “pretty much same as standard medical therapy, which we commonly give to our patients,” said Dr. Singh. “We see this phenomenon all the time in our patients.”

He noted that other factors can determine how patients respond, such as conditions of the heart or kidneys, the presence of sepsis, and multiorgan dysfunction. These factors were not controlled for in the study.

Nonetheless, he said the study achieved its primary endpoint of better resolution of status epilepticus “because that’s the first thing you want to see: whether the treatment is taking care of that.”

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Beretta and Dr. Singh have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

(SRSE), new research suggests.

In a retrospective cohort study of survivors of cardiac arrest with postanoxic sustained SRSE, resolution of the condition was achieved by 81% of those who received intensive treatment of ketamine plus perampanel, versus 41% of those who received standard care.

The novelty of the new treatment approach is the duration of therapy as well as the dual antiglutamate drugs, researchers note.

“So the logic is to continue treatment until resolution of refractory status epilepticus under continuous EEG [electroencephalographic] monitoring,” reported lead investigator Simone Beretta, MD, San Gerardo University Hospital, Monza, Italy.

Therapy was guided by data on brainstem reflexes, N20 cortical responses, neuronal serum enolase levels, and neuroimaging.

If all or most of these indicators are favorable, “we continue to treat without any time limit,” Dr. Beretta said. However, if the indicators become unfavorable, clinicians should consider lowering the intensity of care, he added.

The findings were presented at the 2021 World Congress of Neurology (WCN).

SUPER-CAT trial

In SRSE, epileptic seizures occur one after another without patients recovering consciousness in between. Standard aggressive therapy for the condition does not include antiglutamatergic drugs, the researchers noted.

In the Super-Refractory Status Epilepticus After Cardiac Arrest: Aggressive Treatment Guided by Multimodal Prognostic Indicators (SUPER-CAT) study, researchers assessed the combination of two such medications.

The first was the anti-NMDA receptor drug ketamine, which was given by intravenous bolus and then continuous infusion for 3 days guided by continuous EEG to reach a ketamine EEG pattern, as evidenced by alpha and beta waves. It was combined with the anti-AMPA receptor antiepileptic perampanel via nasogastric tube for 5 days, followed by slow tapering.

Dr. Beretta noted that in the ongoing TELSTAR trial, which involved a similar patient population, a different drug combination is being used. A major difference between the two trials is that in the TELSTAR trial, aggressive therapy continues for only 2 days if there is no response.

“In the SUPER-CAT study, we continue far beyond 2 days in the majority of patients,” he said. In addition, ketamine and perampanel were not assessed in TELSTAR.

In SUPER-CAT, 489 survivors of cardiac arrest were recruited over 10 years. Of these, 101 had refractory status epilepticus. After excluding those with more than two indicators of poor prognosis (n = 31) or whose status epilepticus resolved (n = 14), 56 patients were determined to have SRSE. All had experienced relapse after undergoing one cycle of anesthetic.

The 56 participants received one of three treatment regimens: double antiglutamate (DAG) therapy of ketamine and perampanel (n = 26), single antiglutamate therapy with either agent (n = 8), or aggressive nonantiglutamate (NAG) therapy with antiepilepsy drugs and anesthetics other than ketamine or perampanel (n = 22).

The single-antiglutamate group was not included in the analysis of patient outcomes.

The DAG and NAG groups were well balanced at baseline. There were no significant differences in median age (60 years vs. 66 years), gender, low cerebral blood flow, presence of bilateral pupillary or corneal reflexes, neuron-specific enolase levels, cortical N20 somatosenory evoked potentials, moderate to severe postanoxic brain injury, and hypothermia/targeted temperature management.

Primary outcome met

More patients in the DAG group (42%) had moderate to severe postanoxic brain injury than in the NAG group (28%). However, the difference was not statistically significant (P = .08), possibly because of the small sample sizes. The number of antiepileptic drugs and the number of cycles of anesthetics did not differ between the groups.

Results showed that efficacy and safety outcomes favored DAG therapy.

The primary efficacy outcome was resolution of status epilepticus within 3 days after initiation of treatments. Status epilepticus resolved for 21 of 26 patients in the DAG group (81%), versus 9 of 22 patients in the NAG group (41%; odds ratio, 6.06; 95% confidence interval, 1.66-22.12; P = .005).

For secondary efficacy outcomes, there was a trend in favor of DAG, but differences from the NAG group were not statistically significant. In the groups, 46% versus 32% awakened and responded to commands before discharge from the intensive care unit, and 32% versus 23% showed good neurologic outcome at 6 months.

The primary safety outcome of all-cause mortality risk in the ICU was 90% lower for patients treated with DAG than for those treated with NAG (15% vs. 64%; OR, 0.1; 95% CI, 0.02-0.41; P < .01). Dr. Beretta explained that the high mortality rate in the NAG group was presumably a result of unresolved status epilepticus.

The secondary safety outcome of a transitory rise of gamma-glutamyl transferase greater than three times the upper limit of normal in the DAG group was expected with high-dose perampanel, the investigators noted. This outcome occurred in 77% of the DAG group versus 27% of the NAG group (OR, 9.88; 95% CI, 2.4-32.9; P < .001).

There was no statistically significant difference in incidence of recurrent cardiac arrest during therapy. This occurred in one member of the DAG group and in none in the NAG group.

Dr. Beretta reported that their investigations are still in a retrospective phase, but the researchers plan to move the work into a prospective phase and possibly a randomized trial soon.

Fascinating, promising

Commenting on the findings, Jaysingh Singh, MD, co-director of the Epilepsy Surgery Center at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, said the study provides “fascinating, very helpful data” about a condition that has responded well to current treatment options.

He added that his center has used “the innovative treatments” discussed in the study for a few patients.

“More concrete evidence will push us to use it more uniformly across all our patient population [that] has refractory status. So I’m very optimistic, and the data were very promising,” said Dr. Singh, who was not involved with the research.

He cautioned that the study was retrospective, not randomized or controlled, and that it involved a small number of patients but said that the data were “heading in the right direction.”

Although resolution of status epilepticus was better among patients in the DAG group than in the NAG group, the awakenings and neurologic outcomes were “pretty much same as standard medical therapy, which we commonly give to our patients,” said Dr. Singh. “We see this phenomenon all the time in our patients.”

He noted that other factors can determine how patients respond, such as conditions of the heart or kidneys, the presence of sepsis, and multiorgan dysfunction. These factors were not controlled for in the study.

Nonetheless, he said the study achieved its primary endpoint of better resolution of status epilepticus “because that’s the first thing you want to see: whether the treatment is taking care of that.”

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Beretta and Dr. Singh have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

From WCN 2021

Is genetic testing valuable in the clinical management of epilepsy?

, new research shows.

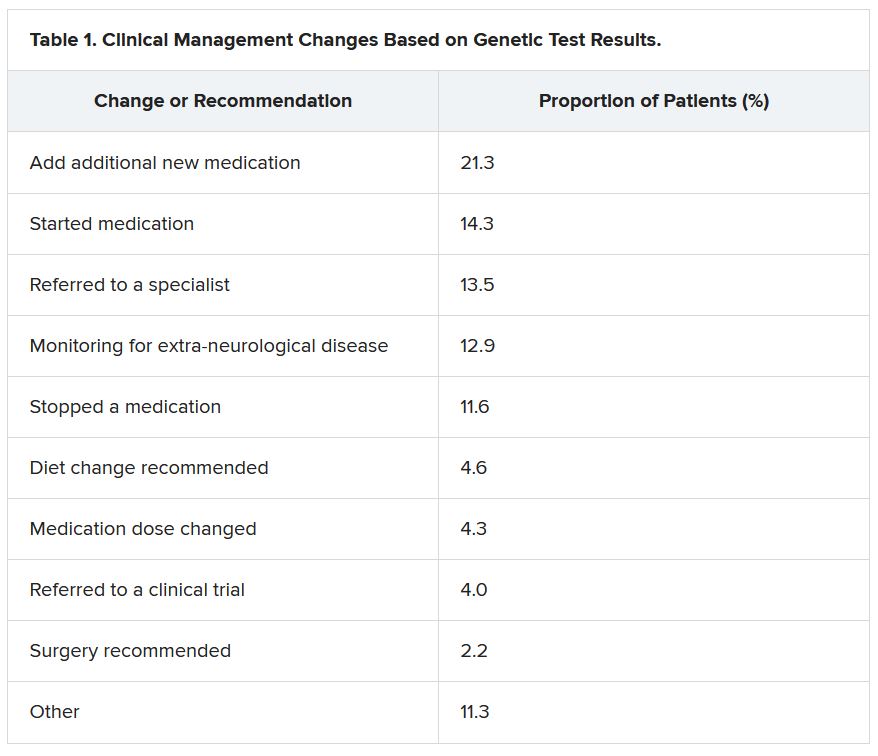

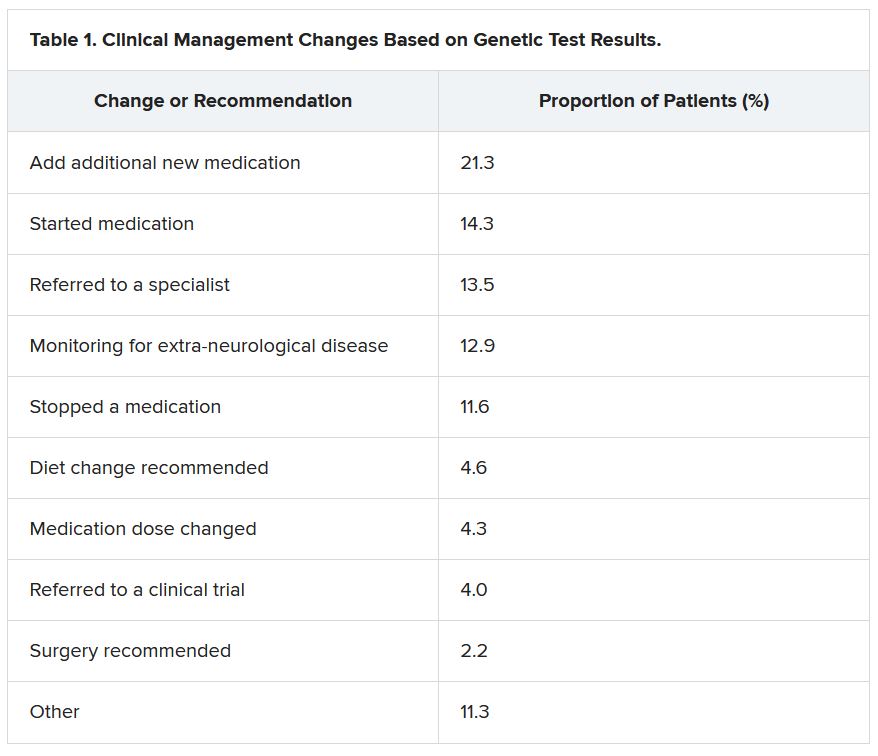

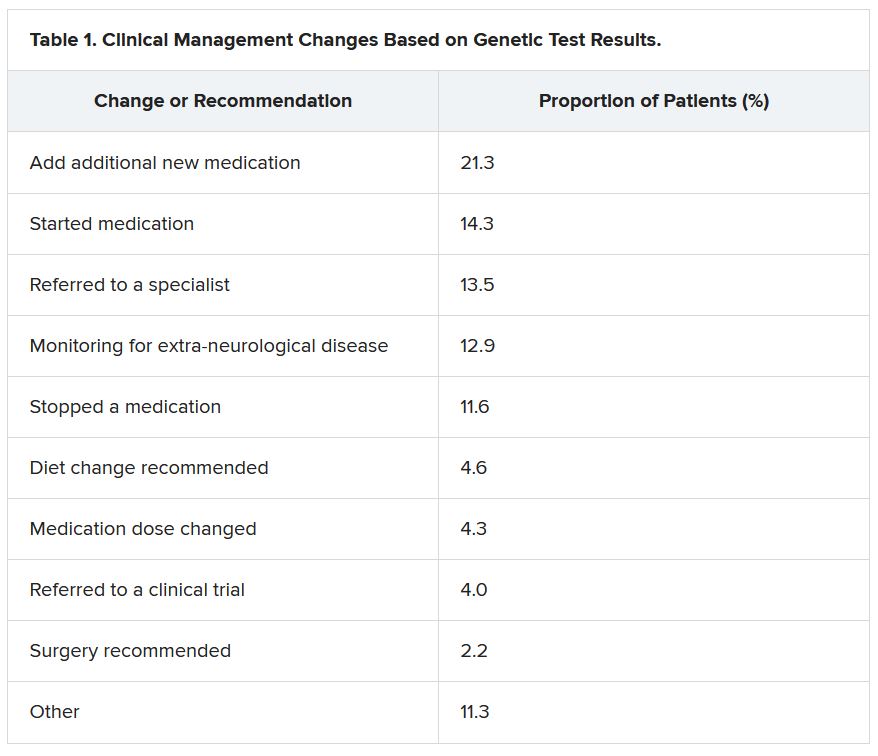

Results of a survey that included more than 400 patients showed that positive findings from genetic testing helped guide clinical management in 50% of cases and improved patient outcomes in 75%. In addition, the findings were applicable to both children and adults.

“Fifty percent of the time the physicians reported that, yes, receiving the genetic diagnosis did change how they managed the patients,” reported co-investigator Dianalee McKnight, PhD, director of medical affairs at Invitae, a medical genetic testing company headquartered in San Francisco. In 81.3% of cases, providers reported they changed clinical management within 3 months of receiving the genetic results, she added.

The findings were presented at the 2021 World Congress of Neurology (WCN).

Test results can be practice-changing

Nearly 50% of positive genetic test results in epilepsy patients can help guide clinical management, Dr. McKnight noted. However, information on how physicians use genetic information in decision-making has been limited, prompting her conduct the survey.

A total of 1,567 physicians with 3,572 patients who had a definitive diagnosis of epilepsy were contacted. A total of 170 (10.8%) clinicians provided completed and eligible surveys on 429 patients with epilepsy.

The patient cohort comprised mostly children, with nearly 50 adults, which Dr. McKnight said is typical of the population receiving genetic testing in clinical practice.

She reported that genetic testing results prompted clinicians to make medication changes about 50% of the time. Other changes included specialist referral or to a clinical trial, monitoring for other neurological disease, and recommendations for dietary change or for surgery.

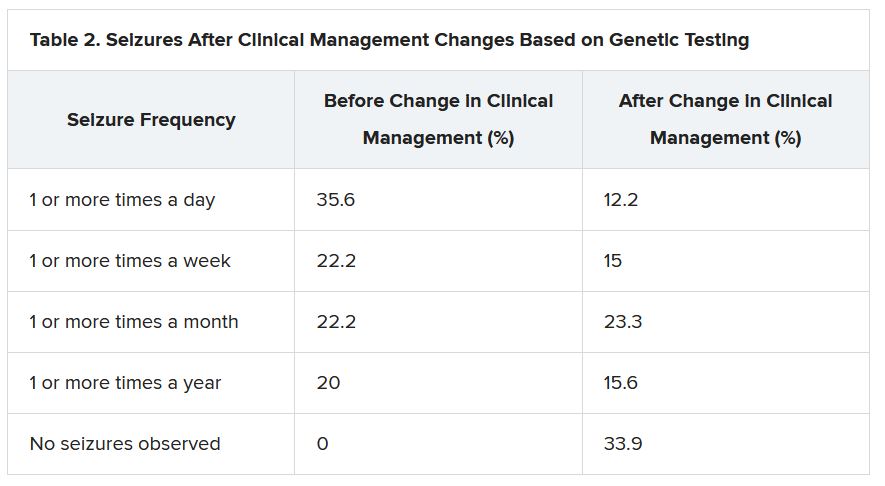

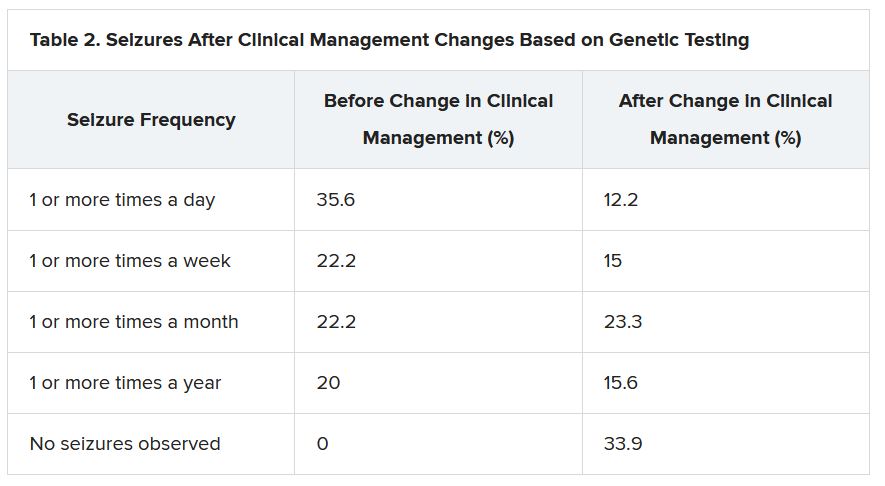

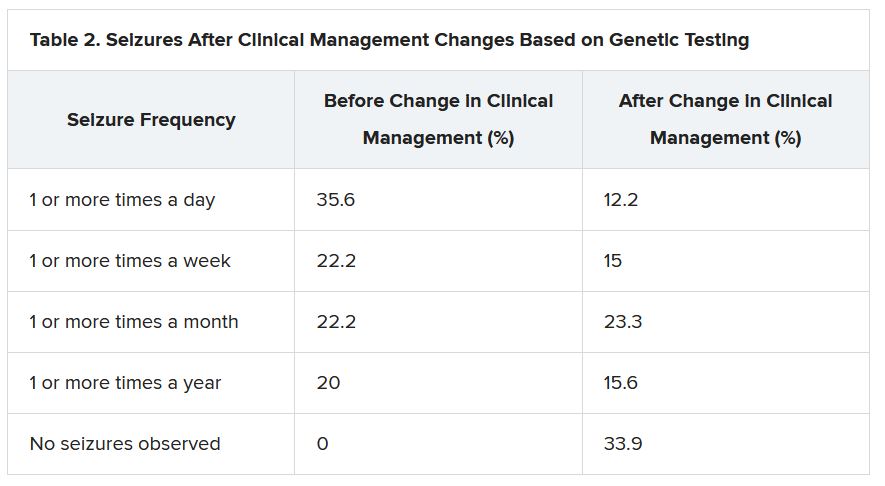

“Of the physicians who changed treatment, 75% reported there were positive outcomes for the patients,” Dr. McKnight told meeting attendees. “Most common was a reduction or a complete elimination of seizures, and that was reported in 65% of the cases.”

In many cases, the changes resulted in clinical improvements.

“There were 64 individuals who were having daily seizures before the genetic testing,” Dr. McKnight reported via email. “After receiving the genetic diagnosis and modifying their treatment, their physicians reported that 26% of individuals had complete seizure control and 46% of individuals had reduced seizure frequency to either weekly (20%), monthly (20%) or annually (6%).”

The best seizure control after modifying disease management occurred among children. Although the changes were not as dramatic for adults, they trended toward lower seizure frequency.

“It is still pretty significant that adults can receive genetic testing later in life and still have benefit in controlling their seizures,” Dr. McKnight said.

Twenty-three percent of patients showed improvement in behavior, development, academics, or movement issues, while 6% experienced reduced medication side effects.

Dr. McKnight also explored reasons for physicians not making changes to clinical management of patients based on the genetic results. The most common reason was that management was already consistent with the results (47.3%), followed by the results not being informative (26.1%), the results possibly being useful for future treatments in development (19.0%), or other or unknown reasons (7.6%).

Besides direct health and quality of life benefits from better seizure control, Dr. McKnight cited previous economic studies showing lower health care costs.

“It looked like an individual who has good seizure control will incur about 14,000 U.S. dollars a year compared with an individual with pretty poor seizure control, where it can be closer to 23,000 U.S. dollars a year,” Dr. McKnight said. This is mainly attributed to reduced hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

Dr. McKnight noted that currently there is no cost of genetic testing to the patient, the hospital, or insurers. Pharmaceutical companies, she said, sponsor the testing to potentially gather patients for clinical drug trials in development. However, patients remain completely anonymous.

Physicians who wish to have patient samples tested agree that the companies may contact them to ask if any of their patients with positive genetic test results would like to participate in a trial.

Dr. McKnight noted that genetic testing can be considered actionable in the clinic, helping to guide clinical decision-making and potentially leading to better outcomes. Going forward, she suggested performing large case-controlled studies “of individuals with the same genetic etiology ... to really find a true causation or correlation.”

Growing influence of genetic testing

Commenting on the findings, Jaysingh Singh, MD, co-director of the Epilepsy Surgery Center at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, noted that the study highlights the value of gene testing in improving outcomes in patients with epilepsy, particularly the pediatric population.

He said the findings make him optimistic about the potential of genetic testing in adult patients – with at least one caveat.

“The limitation is that if we do find some mutation, we don’t know what to do with that. That’s definitely one challenge. And we see that more often in the adult patient population,” said Dr. Singh, who was not involved with the research.

He noted that there is a small group of genetic mutations when, found in adults, may dramatically alter treatment.

For example, he noted that if there is a gene mutation related to mTOR pathways, that could provide a future target because there are already medications that target this pathway.

Genetic testing may also be useful in cases where patients have normal brain imaging and poor response to standard treatment or in cases where patients have congenital abnormalities such as intellectual impairment or facial dysmorphic features and a co-morbid seizure disorder, he said.

Dr. Singh noted that he has often found genetic testing impractical because “if I order DNA testing right now, it will take 4 months for me to get the results. I cannot wait 4 months for the results to come back” to adjust treatment.

Dr. McKnight is an employee of and a shareholder in Invitae, which funded the study. Dr. Singh has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows.

Results of a survey that included more than 400 patients showed that positive findings from genetic testing helped guide clinical management in 50% of cases and improved patient outcomes in 75%. In addition, the findings were applicable to both children and adults.

“Fifty percent of the time the physicians reported that, yes, receiving the genetic diagnosis did change how they managed the patients,” reported co-investigator Dianalee McKnight, PhD, director of medical affairs at Invitae, a medical genetic testing company headquartered in San Francisco. In 81.3% of cases, providers reported they changed clinical management within 3 months of receiving the genetic results, she added.

The findings were presented at the 2021 World Congress of Neurology (WCN).

Test results can be practice-changing

Nearly 50% of positive genetic test results in epilepsy patients can help guide clinical management, Dr. McKnight noted. However, information on how physicians use genetic information in decision-making has been limited, prompting her conduct the survey.

A total of 1,567 physicians with 3,572 patients who had a definitive diagnosis of epilepsy were contacted. A total of 170 (10.8%) clinicians provided completed and eligible surveys on 429 patients with epilepsy.

The patient cohort comprised mostly children, with nearly 50 adults, which Dr. McKnight said is typical of the population receiving genetic testing in clinical practice.

She reported that genetic testing results prompted clinicians to make medication changes about 50% of the time. Other changes included specialist referral or to a clinical trial, monitoring for other neurological disease, and recommendations for dietary change or for surgery.

“Of the physicians who changed treatment, 75% reported there were positive outcomes for the patients,” Dr. McKnight told meeting attendees. “Most common was a reduction or a complete elimination of seizures, and that was reported in 65% of the cases.”

In many cases, the changes resulted in clinical improvements.

“There were 64 individuals who were having daily seizures before the genetic testing,” Dr. McKnight reported via email. “After receiving the genetic diagnosis and modifying their treatment, their physicians reported that 26% of individuals had complete seizure control and 46% of individuals had reduced seizure frequency to either weekly (20%), monthly (20%) or annually (6%).”

The best seizure control after modifying disease management occurred among children. Although the changes were not as dramatic for adults, they trended toward lower seizure frequency.

“It is still pretty significant that adults can receive genetic testing later in life and still have benefit in controlling their seizures,” Dr. McKnight said.

Twenty-three percent of patients showed improvement in behavior, development, academics, or movement issues, while 6% experienced reduced medication side effects.

Dr. McKnight also explored reasons for physicians not making changes to clinical management of patients based on the genetic results. The most common reason was that management was already consistent with the results (47.3%), followed by the results not being informative (26.1%), the results possibly being useful for future treatments in development (19.0%), or other or unknown reasons (7.6%).

Besides direct health and quality of life benefits from better seizure control, Dr. McKnight cited previous economic studies showing lower health care costs.

“It looked like an individual who has good seizure control will incur about 14,000 U.S. dollars a year compared with an individual with pretty poor seizure control, where it can be closer to 23,000 U.S. dollars a year,” Dr. McKnight said. This is mainly attributed to reduced hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

Dr. McKnight noted that currently there is no cost of genetic testing to the patient, the hospital, or insurers. Pharmaceutical companies, she said, sponsor the testing to potentially gather patients for clinical drug trials in development. However, patients remain completely anonymous.

Physicians who wish to have patient samples tested agree that the companies may contact them to ask if any of their patients with positive genetic test results would like to participate in a trial.

Dr. McKnight noted that genetic testing can be considered actionable in the clinic, helping to guide clinical decision-making and potentially leading to better outcomes. Going forward, she suggested performing large case-controlled studies “of individuals with the same genetic etiology ... to really find a true causation or correlation.”

Growing influence of genetic testing

Commenting on the findings, Jaysingh Singh, MD, co-director of the Epilepsy Surgery Center at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, noted that the study highlights the value of gene testing in improving outcomes in patients with epilepsy, particularly the pediatric population.

He said the findings make him optimistic about the potential of genetic testing in adult patients – with at least one caveat.

“The limitation is that if we do find some mutation, we don’t know what to do with that. That’s definitely one challenge. And we see that more often in the adult patient population,” said Dr. Singh, who was not involved with the research.

He noted that there is a small group of genetic mutations when, found in adults, may dramatically alter treatment.

For example, he noted that if there is a gene mutation related to mTOR pathways, that could provide a future target because there are already medications that target this pathway.

Genetic testing may also be useful in cases where patients have normal brain imaging and poor response to standard treatment or in cases where patients have congenital abnormalities such as intellectual impairment or facial dysmorphic features and a co-morbid seizure disorder, he said.

Dr. Singh noted that he has often found genetic testing impractical because “if I order DNA testing right now, it will take 4 months for me to get the results. I cannot wait 4 months for the results to come back” to adjust treatment.

Dr. McKnight is an employee of and a shareholder in Invitae, which funded the study. Dr. Singh has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows.

Results of a survey that included more than 400 patients showed that positive findings from genetic testing helped guide clinical management in 50% of cases and improved patient outcomes in 75%. In addition, the findings were applicable to both children and adults.

“Fifty percent of the time the physicians reported that, yes, receiving the genetic diagnosis did change how they managed the patients,” reported co-investigator Dianalee McKnight, PhD, director of medical affairs at Invitae, a medical genetic testing company headquartered in San Francisco. In 81.3% of cases, providers reported they changed clinical management within 3 months of receiving the genetic results, she added.

The findings were presented at the 2021 World Congress of Neurology (WCN).

Test results can be practice-changing

Nearly 50% of positive genetic test results in epilepsy patients can help guide clinical management, Dr. McKnight noted. However, information on how physicians use genetic information in decision-making has been limited, prompting her conduct the survey.

A total of 1,567 physicians with 3,572 patients who had a definitive diagnosis of epilepsy were contacted. A total of 170 (10.8%) clinicians provided completed and eligible surveys on 429 patients with epilepsy.

The patient cohort comprised mostly children, with nearly 50 adults, which Dr. McKnight said is typical of the population receiving genetic testing in clinical practice.

She reported that genetic testing results prompted clinicians to make medication changes about 50% of the time. Other changes included specialist referral or to a clinical trial, monitoring for other neurological disease, and recommendations for dietary change or for surgery.

“Of the physicians who changed treatment, 75% reported there were positive outcomes for the patients,” Dr. McKnight told meeting attendees. “Most common was a reduction or a complete elimination of seizures, and that was reported in 65% of the cases.”

In many cases, the changes resulted in clinical improvements.

“There were 64 individuals who were having daily seizures before the genetic testing,” Dr. McKnight reported via email. “After receiving the genetic diagnosis and modifying their treatment, their physicians reported that 26% of individuals had complete seizure control and 46% of individuals had reduced seizure frequency to either weekly (20%), monthly (20%) or annually (6%).”

The best seizure control after modifying disease management occurred among children. Although the changes were not as dramatic for adults, they trended toward lower seizure frequency.

“It is still pretty significant that adults can receive genetic testing later in life and still have benefit in controlling their seizures,” Dr. McKnight said.

Twenty-three percent of patients showed improvement in behavior, development, academics, or movement issues, while 6% experienced reduced medication side effects.

Dr. McKnight also explored reasons for physicians not making changes to clinical management of patients based on the genetic results. The most common reason was that management was already consistent with the results (47.3%), followed by the results not being informative (26.1%), the results possibly being useful for future treatments in development (19.0%), or other or unknown reasons (7.6%).

Besides direct health and quality of life benefits from better seizure control, Dr. McKnight cited previous economic studies showing lower health care costs.

“It looked like an individual who has good seizure control will incur about 14,000 U.S. dollars a year compared with an individual with pretty poor seizure control, where it can be closer to 23,000 U.S. dollars a year,” Dr. McKnight said. This is mainly attributed to reduced hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

Dr. McKnight noted that currently there is no cost of genetic testing to the patient, the hospital, or insurers. Pharmaceutical companies, she said, sponsor the testing to potentially gather patients for clinical drug trials in development. However, patients remain completely anonymous.

Physicians who wish to have patient samples tested agree that the companies may contact them to ask if any of their patients with positive genetic test results would like to participate in a trial.

Dr. McKnight noted that genetic testing can be considered actionable in the clinic, helping to guide clinical decision-making and potentially leading to better outcomes. Going forward, she suggested performing large case-controlled studies “of individuals with the same genetic etiology ... to really find a true causation or correlation.”

Growing influence of genetic testing

Commenting on the findings, Jaysingh Singh, MD, co-director of the Epilepsy Surgery Center at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, noted that the study highlights the value of gene testing in improving outcomes in patients with epilepsy, particularly the pediatric population.

He said the findings make him optimistic about the potential of genetic testing in adult patients – with at least one caveat.

“The limitation is that if we do find some mutation, we don’t know what to do with that. That’s definitely one challenge. And we see that more often in the adult patient population,” said Dr. Singh, who was not involved with the research.

He noted that there is a small group of genetic mutations when, found in adults, may dramatically alter treatment.

For example, he noted that if there is a gene mutation related to mTOR pathways, that could provide a future target because there are already medications that target this pathway.

Genetic testing may also be useful in cases where patients have normal brain imaging and poor response to standard treatment or in cases where patients have congenital abnormalities such as intellectual impairment or facial dysmorphic features and a co-morbid seizure disorder, he said.

Dr. Singh noted that he has often found genetic testing impractical because “if I order DNA testing right now, it will take 4 months for me to get the results. I cannot wait 4 months for the results to come back” to adjust treatment.

Dr. McKnight is an employee of and a shareholder in Invitae, which funded the study. Dr. Singh has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

From WCN 2021

Merck seeks FDA authorization for antiviral COVID-19 pill

, an experimental antiviral COVID-19 treatment.

If the FDA grants authorization, the drug would be the first oral antiviral treatment for COVID-19. The capsule, made by Merck and Ridgeback Biotherapeutics, is intended to treat mild to moderate COVID-19 in adults who are at risk of having severe COVID-19 or hospitalization.

“The extraordinary impact of this pandemic demands that we move with unprecedented urgency, and that is what our teams have done by submitting this application for molnupiravir to the FDA within 10 days of receiving the data,” Robert Davis, CEO and president of Merck, said in a statement. On Oct. 1, Merck and Ridgeback released interim data from its phase III clinical trial, which showed that molnupiravir reduced the risk of hospitalization or death by about 50%. About 7% of patients who received the drug were hospitalized within 30 days in the study, as compared with 14% of patients who took a placebo, the company said.

No deaths were reported in the group that received the drug, as compared with eight deaths in the group that received the placebo. None of the trial participants had been vaccinated.

“Medicines and vaccines are both essential to our collective efforts,” Mr. Davis said. “We look forward to working with the FDA on its review of our application, and to working with other regulatory agencies as we do everything we can to bring molnupiravir to patients around the world as quickly as possible.”

Merck has been producing molnupiravir in anticipation of the clinical trial results and FDA authorization. The company expects to produce 10 million courses of treatment by the end of the year, with more expected for 2022.

In June, Merck signed an agreement with the United States to supply 1.7 million courses of molnupiravir once the FDA authorizes the drug. The company has agreed to advance purchase agreements with other countries as well.

Earlier in the year, Merck also announced voluntary licensing agreements with several generics manufacturers in India to provide molnupiravir to more than 100 low- and middle-income countries after approval from local regulatory agencies.

Data from the company’s late-stage clinical trial has not yet been peer-reviewed or published.

Last week, Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said the clinical trial results were “very encouraging” but noted that the FDA should closely scrutinize the drug, CNN reported.

“It is very important that this now must go through the usual process of careful examination of the data by the Food and Drug Administration, both for effectiveness but also for safety, because whenever you introduce a new compound, safety is very important,” Dr. Fauci said, adding that vaccines remain “our best tools against COVID-19.”

A version of this article firsts appeared on WebMD.com.

, an experimental antiviral COVID-19 treatment.

If the FDA grants authorization, the drug would be the first oral antiviral treatment for COVID-19. The capsule, made by Merck and Ridgeback Biotherapeutics, is intended to treat mild to moderate COVID-19 in adults who are at risk of having severe COVID-19 or hospitalization.

“The extraordinary impact of this pandemic demands that we move with unprecedented urgency, and that is what our teams have done by submitting this application for molnupiravir to the FDA within 10 days of receiving the data,” Robert Davis, CEO and president of Merck, said in a statement. On Oct. 1, Merck and Ridgeback released interim data from its phase III clinical trial, which showed that molnupiravir reduced the risk of hospitalization or death by about 50%. About 7% of patients who received the drug were hospitalized within 30 days in the study, as compared with 14% of patients who took a placebo, the company said.

No deaths were reported in the group that received the drug, as compared with eight deaths in the group that received the placebo. None of the trial participants had been vaccinated.

“Medicines and vaccines are both essential to our collective efforts,” Mr. Davis said. “We look forward to working with the FDA on its review of our application, and to working with other regulatory agencies as we do everything we can to bring molnupiravir to patients around the world as quickly as possible.”

Merck has been producing molnupiravir in anticipation of the clinical trial results and FDA authorization. The company expects to produce 10 million courses of treatment by the end of the year, with more expected for 2022.

In June, Merck signed an agreement with the United States to supply 1.7 million courses of molnupiravir once the FDA authorizes the drug. The company has agreed to advance purchase agreements with other countries as well.

Earlier in the year, Merck also announced voluntary licensing agreements with several generics manufacturers in India to provide molnupiravir to more than 100 low- and middle-income countries after approval from local regulatory agencies.

Data from the company’s late-stage clinical trial has not yet been peer-reviewed or published.

Last week, Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said the clinical trial results were “very encouraging” but noted that the FDA should closely scrutinize the drug, CNN reported.

“It is very important that this now must go through the usual process of careful examination of the data by the Food and Drug Administration, both for effectiveness but also for safety, because whenever you introduce a new compound, safety is very important,” Dr. Fauci said, adding that vaccines remain “our best tools against COVID-19.”

A version of this article firsts appeared on WebMD.com.

, an experimental antiviral COVID-19 treatment.

If the FDA grants authorization, the drug would be the first oral antiviral treatment for COVID-19. The capsule, made by Merck and Ridgeback Biotherapeutics, is intended to treat mild to moderate COVID-19 in adults who are at risk of having severe COVID-19 or hospitalization.

“The extraordinary impact of this pandemic demands that we move with unprecedented urgency, and that is what our teams have done by submitting this application for molnupiravir to the FDA within 10 days of receiving the data,” Robert Davis, CEO and president of Merck, said in a statement. On Oct. 1, Merck and Ridgeback released interim data from its phase III clinical trial, which showed that molnupiravir reduced the risk of hospitalization or death by about 50%. About 7% of patients who received the drug were hospitalized within 30 days in the study, as compared with 14% of patients who took a placebo, the company said.

No deaths were reported in the group that received the drug, as compared with eight deaths in the group that received the placebo. None of the trial participants had been vaccinated.

“Medicines and vaccines are both essential to our collective efforts,” Mr. Davis said. “We look forward to working with the FDA on its review of our application, and to working with other regulatory agencies as we do everything we can to bring molnupiravir to patients around the world as quickly as possible.”

Merck has been producing molnupiravir in anticipation of the clinical trial results and FDA authorization. The company expects to produce 10 million courses of treatment by the end of the year, with more expected for 2022.

In June, Merck signed an agreement with the United States to supply 1.7 million courses of molnupiravir once the FDA authorizes the drug. The company has agreed to advance purchase agreements with other countries as well.

Earlier in the year, Merck also announced voluntary licensing agreements with several generics manufacturers in India to provide molnupiravir to more than 100 low- and middle-income countries after approval from local regulatory agencies.

Data from the company’s late-stage clinical trial has not yet been peer-reviewed or published.

Last week, Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said the clinical trial results were “very encouraging” but noted that the FDA should closely scrutinize the drug, CNN reported.

“It is very important that this now must go through the usual process of careful examination of the data by the Food and Drug Administration, both for effectiveness but also for safety, because whenever you introduce a new compound, safety is very important,” Dr. Fauci said, adding that vaccines remain “our best tools against COVID-19.”

A version of this article firsts appeared on WebMD.com.

HEPA filters may clean SARS-CoV-2 from the air: Study

, researchers report in the preprint server medRxiv.

The journal Nature reported Oct. 6 that the research, which has not been peer-reviewed, suggests the filters may help reduce the risk of hospital-acquired SARS-CoV-2.

Researchers, led by intensivist Andrew Conway-Morris, MBChB, PhD, with the division of anaesthesia in the school of clinical medicine at University of Cambridge, United Kingdom, write that earlier experiments assessed air filters’ ability to remove inactive particles in carefully controlled environments, but it was unknown how they would work in a real-world setting.

Co-author Vilas Navapurkar, MBChB, an ICU physician at Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, United Kingdom, said that hospitals have used portable air filters when their isolation facilities are full, but evidence was needed as to whether such filters are effective or whether they provide a false sense of security.

The researchers installed the filters in two fully occupied COVID-19 wards — a general ward and an ICU. They chose HEPA filters because they can catch extremely small particles.

The team collected air samples from the wards during a week when the air filters were on and 2 weeks when they were turned off, then compared results.

According to the study, “airborne SARS-CoV-2 was detected in the ward on all five days before activation of air/UV filtration, but on none of the five days when the air/UV filter was operational; SARS-CoV-2 was again detected on four out of five days when the filter was off.”

Airborne SARS-CoV-2 was not frequently detected in the ICU, even when the filters were off.

Cheap and easy

According to the Nature article, the authors suggest several potential explanations for this, “including slower viral replication at later stages of the disease.” Therefore, the authors say, filtering the virus from the air might be more important in general wards than in ICUs.

The filters significantly reduced the other microbial bioaerosols in both the ward (48 pathogens detected before filtration, 2 after, P = .05) and the ICU (45 pathogens detected before filtration, 5 after P = .05).

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) cyclonic aerosol samplers and PCR tests were used to detect airborne SARS-CoV-2 and other microbial bioaerosol.

David Fisman, MD, an epidemiologist at the University of Toronto, who was not involved in the research, said in the Nature article, “This study suggests that HEPA air cleaners, which remain little-used in Canadian hospitals, are a cheap and easy way to reduce risk from airborne pathogens.”This work was supported by a Wellcome senior research fellowship to co-author Stephen Baker. Conway Morris is supported by a Clinician Scientist Fellowship from the Medical Research Council. Dr. Navapurkar is the founder, director, and shareholder of Cambridge Infection Diagnostics Ltd. Dr. Conway-Morris and several co-authors are members of the Scientific Advisory Board of Cambridge Infection Diagnostics Ltd. Co-author Theodore Gouliouris has received a research grant from Shionogi and co-author R. Andres Floto has received research grants and/or consultancy payments from GSK, AstraZeneca, Chiesi, Shionogi, Insmed, and Thirty Technology.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, researchers report in the preprint server medRxiv.

The journal Nature reported Oct. 6 that the research, which has not been peer-reviewed, suggests the filters may help reduce the risk of hospital-acquired SARS-CoV-2.

Researchers, led by intensivist Andrew Conway-Morris, MBChB, PhD, with the division of anaesthesia in the school of clinical medicine at University of Cambridge, United Kingdom, write that earlier experiments assessed air filters’ ability to remove inactive particles in carefully controlled environments, but it was unknown how they would work in a real-world setting.

Co-author Vilas Navapurkar, MBChB, an ICU physician at Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, United Kingdom, said that hospitals have used portable air filters when their isolation facilities are full, but evidence was needed as to whether such filters are effective or whether they provide a false sense of security.

The researchers installed the filters in two fully occupied COVID-19 wards — a general ward and an ICU. They chose HEPA filters because they can catch extremely small particles.

The team collected air samples from the wards during a week when the air filters were on and 2 weeks when they were turned off, then compared results.

According to the study, “airborne SARS-CoV-2 was detected in the ward on all five days before activation of air/UV filtration, but on none of the five days when the air/UV filter was operational; SARS-CoV-2 was again detected on four out of five days when the filter was off.”

Airborne SARS-CoV-2 was not frequently detected in the ICU, even when the filters were off.

Cheap and easy

According to the Nature article, the authors suggest several potential explanations for this, “including slower viral replication at later stages of the disease.” Therefore, the authors say, filtering the virus from the air might be more important in general wards than in ICUs.

The filters significantly reduced the other microbial bioaerosols in both the ward (48 pathogens detected before filtration, 2 after, P = .05) and the ICU (45 pathogens detected before filtration, 5 after P = .05).

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) cyclonic aerosol samplers and PCR tests were used to detect airborne SARS-CoV-2 and other microbial bioaerosol.

David Fisman, MD, an epidemiologist at the University of Toronto, who was not involved in the research, said in the Nature article, “This study suggests that HEPA air cleaners, which remain little-used in Canadian hospitals, are a cheap and easy way to reduce risk from airborne pathogens.”This work was supported by a Wellcome senior research fellowship to co-author Stephen Baker. Conway Morris is supported by a Clinician Scientist Fellowship from the Medical Research Council. Dr. Navapurkar is the founder, director, and shareholder of Cambridge Infection Diagnostics Ltd. Dr. Conway-Morris and several co-authors are members of the Scientific Advisory Board of Cambridge Infection Diagnostics Ltd. Co-author Theodore Gouliouris has received a research grant from Shionogi and co-author R. Andres Floto has received research grants and/or consultancy payments from GSK, AstraZeneca, Chiesi, Shionogi, Insmed, and Thirty Technology.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, researchers report in the preprint server medRxiv.

The journal Nature reported Oct. 6 that the research, which has not been peer-reviewed, suggests the filters may help reduce the risk of hospital-acquired SARS-CoV-2.

Researchers, led by intensivist Andrew Conway-Morris, MBChB, PhD, with the division of anaesthesia in the school of clinical medicine at University of Cambridge, United Kingdom, write that earlier experiments assessed air filters’ ability to remove inactive particles in carefully controlled environments, but it was unknown how they would work in a real-world setting.

Co-author Vilas Navapurkar, MBChB, an ICU physician at Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, United Kingdom, said that hospitals have used portable air filters when their isolation facilities are full, but evidence was needed as to whether such filters are effective or whether they provide a false sense of security.

The researchers installed the filters in two fully occupied COVID-19 wards — a general ward and an ICU. They chose HEPA filters because they can catch extremely small particles.

The team collected air samples from the wards during a week when the air filters were on and 2 weeks when they were turned off, then compared results.

According to the study, “airborne SARS-CoV-2 was detected in the ward on all five days before activation of air/UV filtration, but on none of the five days when the air/UV filter was operational; SARS-CoV-2 was again detected on four out of five days when the filter was off.”

Airborne SARS-CoV-2 was not frequently detected in the ICU, even when the filters were off.

Cheap and easy

According to the Nature article, the authors suggest several potential explanations for this, “including slower viral replication at later stages of the disease.” Therefore, the authors say, filtering the virus from the air might be more important in general wards than in ICUs.

The filters significantly reduced the other microbial bioaerosols in both the ward (48 pathogens detected before filtration, 2 after, P = .05) and the ICU (45 pathogens detected before filtration, 5 after P = .05).

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) cyclonic aerosol samplers and PCR tests were used to detect airborne SARS-CoV-2 and other microbial bioaerosol.

David Fisman, MD, an epidemiologist at the University of Toronto, who was not involved in the research, said in the Nature article, “This study suggests that HEPA air cleaners, which remain little-used in Canadian hospitals, are a cheap and easy way to reduce risk from airborne pathogens.”This work was supported by a Wellcome senior research fellowship to co-author Stephen Baker. Conway Morris is supported by a Clinician Scientist Fellowship from the Medical Research Council. Dr. Navapurkar is the founder, director, and shareholder of Cambridge Infection Diagnostics Ltd. Dr. Conway-Morris and several co-authors are members of the Scientific Advisory Board of Cambridge Infection Diagnostics Ltd. Co-author Theodore Gouliouris has received a research grant from Shionogi and co-author R. Andres Floto has received research grants and/or consultancy payments from GSK, AstraZeneca, Chiesi, Shionogi, Insmed, and Thirty Technology.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adolescents who exercised after a concussion recovered faster in RCT

After a concussion, resuming aerobic exercise relatively early on – at an intensity that does not worsen symptoms – may help young athletes recover sooner, compared with stretching, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) shows.

The study adds to emerging evidence that clinicians should prescribe exercise, rather than strict rest, to facilitate concussion recovery, researchers said.

Tamara McLeod, PhD, ATC, professor and director of athletic training programs at A.T. Still University in Mesa, Ariz., hopes the findings help clinicians see that “this is an approach that should be taken.”

“Too often with concussion, patients are given a laundry list of things they are NOT allowed to do,” including sports, school, and social activities, said Dr. McLeod, who was not involved in the study.

The research, published in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, largely replicates the findings of a prior trial while addressing limitations of the previous study’s design, researchers said.

For the trial, John J. Leddy, MD, with the State University of New York at Buffalo and colleagues recruited 118 male and female adolescent athletes aged 13-18 years who had had a sport-related concussion in the past 10 days. Investigators at three community and hospital-affiliated sports medicine concussion centers in the United States randomly assigned the athletes to individualized subsymptom-threshold aerobic exercise (61 participants) or stretching exercise (57 participants) at least 20 minutes per day for up to 4 weeks. Aerobic exercise included walking, jogging, or stationary cycling at home.

“It is important that the general clinician community appreciates that prolonged rest and avoidance of physical activity until spontaneous symptom resolution is no longer an acceptable approach to caring for adolescents with concussion,” Dr. Leddy and coauthors said.

The investigators improved on the “the scientific rigor of their previous RCT by including intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses, daily symptom reporting, objective exercise adherence measurements, and greater heterogeneity of concussion severity,” said Carolyn A. Emery, PhD, and Jonathan Smirl, PhD, both with the University of Calgary (Alta.), in a related commentary. The new study is the first to show that early targeted heart rate subsymptom-threshold aerobic exercise, relative to stretching, shortened recovery time within 4 weeks after sport-related concussion (hazard ratio, 0.52) when controlling for sex, study site, and average daily exercise time, Dr. Emery and Dr. Smirl said.