User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Triage, L&D, postpartum care during the COVID-19 pandemic

The meteoric rise in the number of test-positive and clinical cases of COVID-19 because of infection with the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in states and cities across the United States has added urgency to the efforts to develop protocols for hospital triage, admission, labor and delivery management, and other aspects of obstetrical care.

Emerging data suggest that, while SARS-CoV-2 is less lethal overall than the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) proved to be, it is significantly more contagious. Although a severe disease, the limited worldwide data so far available (as of early May) do not indicate that pregnant women are at greater risk of severe disease, compared with the general population. However, there remains a critical need for data on maternal and perinatal outcomes in women infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Multiple physiological changes in pregnancy, from reduced cell-based immune competence to changes in respiratory tract and pulmonary function – e.g., edema of the respiratory tract, increases in secretions and oxygen consumption, elevation of the diaphragm, and decrease in functional residual capacity – have historically contributed to worse obstetric outcomes in pregnant women who have had viral pneumonias. Furthermore, limited published experience with COVID-19 in China suggests worse perinatal outcomes in some affected pregnancies, including prematurity and perinatal death.

With evolution of the pandemic and accumulation of experience, it is expected that data-driven guidelines on assessment and management of infected pregnant women will contribute to improved maternal and perinatal outcomes. What is clear now, however, is that,

Here are my recommendations, based on a currently limited body of literature on COVID-19 and other communicable viral respiratory disorders, as well my experience in the greater Detroit area, a COVID-19 hot spot.

Preparing for hospital evaluation and admission

The obstetric triage or labor and delivery (L&D) unit should be notified prior to the arrival of a patient suspected of or known to be infected with the virus. This will minimize staff exposure and allow sufficient time to prepare appropriate accommodations, equipment, and supplies for the patient’s care. Hospital infection control should be promptly notified by L&D of the expected arrival of such a patient. Placement ideally should be in a negative-pressure room, which allows outside air to flow into the room but prevents contaminated air from escaping. In the absence of a negative-pressure room, an infection isolation area should be utilized.

The patient and one accompanying support individual should wear either medical-grade masks brought from home or supplied upon entry to the hospital or homemade masks or bandanas. This will reduce the risk of viral transmission to hospital workers and other individuals encountered in the hospital prior to arriving in L&D. An ideal setup is to have separate entry areas, access corridors, and elevators for patients known or suspected to have COVID-19 infection. The patient and visitor should be expeditiously escorted to the prepared area for evaluation. Patients who are not known or suspected to be infected ideally should be tested.

Screening of patients & support individuals

Proper screening of patients and support individuals is critical to protecting both patients and staff in the L&D unit. This should include an expanded questionnaire that asks about disturbances of smell and taste and GI symptoms like loss of appetite – not only the more commonly queried symptoms of fever, shortness of breath, coughing, and exposure to someone who may have been ill.

Recent studies regarding presenting symptoms cast significant doubt, in fact, on the validity of patients with “asymptomatic COVID-19.” Over 15% of patients with confirmed infection in one published case series had solely GI symptoms and almost all had some digestive symptoms, for example, and almost 90% in another study had absent or reduced sense of smell and/or taste.1,2 In fact, the use of the term “paucisymptomatic” rather than “asymptomatic” may be most appropriate.

Support individuals also should undergo temperature screening, ideally with laser noncontact thermometers on entry to the hospital or triage.

Visitor policy

The number of visitors/support individuals should be kept to a minimum to reduce transmission risk. The actual number will be determined by hospital or state policy, but up to one visitor in the labor room appears reasonable. Very strong individual justification should be required to exceed this threshold! The visitor should not only be screened for an expanded list of symptoms, but they also should be queried for underlying illnesses (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular disease, significant lung disease, undergoing cancer therapy) as well as for age over 65 years, each of which increase the chances of severe COVID-19 disease should infection occur. The visitor should be informed of such risks and, especially when accompanying a patient with known or suspected COVID-19, provided the option of voluntarily revoking their visitor status. A visitor with known or suspected COVID-19 infection based on testing or screening should not be allowed into the L&D unit.

In addition, institutions may be considered to have obligations to the visitor/support person beyond screening. These include instructions in proper mask usage, hand washing, and limiting the touching of surfaces to lower infection risk.

“Visitor relays” where one visitor replaces another should be strongly discouraged. Visitors should similarly not be allowed to wander around the hospital (to use phones, for instance); transiting back and forth to obtain food and coffee should be kept to a strict minimum. For visitors accompanying COVID-19–-infected women, “visitor’s plates” provided by the hospital at reasonable cost is a much-preferred arrangement for obtaining meals during the course of the hospital stay. In addition, visitors should be sent out of the room during the performance of aerosolizing procedures.

Labor and delivery management

The successful management of patients with COVID-19 requires a rigorous infection control protocol informed by guidelines from national entities, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and by state health departments when available.

Strict limits on the number of obstetricians and other health care workers (HCWs) entering the patient’s room should be enforced and documented to minimize risk to the HCWs attending to patients who have a positive diagnosis or who are under investigation. Only in cases of demonstrable clinical benefit should repeat visits by the same or additional HCWs be permitted. Conventional and electronic tablets present an excellent opportunity for patient follow-up visits without room entry. In our institution, this has been successfully piloted in nonpregnant patients. Obstetricians and others caring for obstetrical patients – especially those who are infected or under investigation for infection – should always wear a properly fitted N95 mask.

Because patients with COVID-19 may have or go on to develop a constellation of organ abnormalities (e.g., cardiovascular, renal, pulmonary), it is vital that a standardized panel of baseline laboratory studies be developed for pregnant patients. This will minimize the need for repeated blood draws and other testing which may increase HCW exposure.

A negative screen based on nonreport of symptoms, lack of temperature elevation, and reported nonexposure to individuals with COVID-19 symptoms still has limitations in terms of disease detection. A recent report from a tertiary care hospital in New York City found that close to one-third of pregnant patients with confirmed COVID-19 admitted over a 2-week period had no viral symptoms or instructive history on initial admission.3 This is consistent with our clinical experience. Most importantly, therefore, routine quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction testing should be performed on all patients admitted to the L&D unit.

Given the reported variability in the accuracy of polymerase chain reaction testing induced by variable effectiveness of sampling techniques, stage of infection, and inherent test accuracy issues, symptomatic patients with a negative test should first obtain clearance from infectious disease specialists before isolation precautions are discontinued. Repeat testing in 24 hours, including testing of multiple sites, may subsequently yield a positive result in persistently symptomatic patients.

Intrapartum management

As much as possible, standard obstetric indications should guide the timing and route of delivery. In the case of a COVID-19–positive patient or a patient under investigation, nonobstetric factors may bear heavily on decision making, and management flexibility is of great value. For example, in cases of severe or critical disease status, evidence suggests that early delivery regardless of gestational age can improve maternal oxygenation; this supports the liberal use of C-sections in these circumstances. In addition, shortening labor length as well as duration of hospitalization may be expected to reduce the risk of transmission to HCWs, other staff, and other patients.

High rates of cesarean delivery unsurprisingly have been reported thus far: One review of 108 case reports and series of test-positive COVID-19 pregnancies found a 92% C-section rate, and another review and meta-analysis of studies of SARS, MERS, and COVID-19 during pregnancy similarly found that the majority of patients – 84% across all coronavirus infections and 91% in COVID-19 pregnancies – were delivered by C-section.4,5 Given these high rates of cesarean deliveries, the early placement of neuraxial anesthesia while the patient is stable appears to be prudent and obviates the need for intubation, the latter of which is associated with increased aerosol generation and increased virus transmission risk.

Strict protocols for the optimal protection of staff should be observed, including proper personal protective equipment (PPE) protection. Protocols have been detailed in various guidelines and publications; they include the wearing of shoe covers, gowns, N95 masks, goggles, face shields, and two layers of gloves.

For institutions that currently do not offer routine COVID-19 testing to pregnant patients – especially those in areas of outbreaks – N95 masks and eye protection should still be provided to all HCWs involved in the intrapartum management of untested asymptomatic patients, particularly those in the active phase of labor. This protection is justified given the limitations of symptom- and history-based screening and the not-uncommon experience of the patient with a negative screen who subsequently develops the clinical syndrome.

Obstetric management of labor requires close patient contact that potentially elevates the risk of contamination and infection. During the active stage of labor, patient shouting, rapid mouth breathing, and other behaviors inherent to labor all increase the risk of aerosolization of oronasal secretions. In addition, nasal-prong oxygen administration is believed to independently increase the risk of aerosolization of secretions. The casual practice of nasal oxygen application should thus be discontinued and, where felt to be absolutely necessary, a mask should be worn on top of the prongs.

Regarding operative delivery, each participating obstetric surgeon should observe guidelines and recommendations of governing national organizations and professional groups – including the American College of Surgeons – regarding the safe conduct of operations on patients with COVID-19. Written guidelines should be tailored as needed to the performance of C-sections and readily available in L&D. Drills and simulations are generally valuable, and expertise and support should always be available in the labor room to assist with donning and doffing of PPE.

Postpartum care

Expeditious separation of the COVID-19–positive mother from her infant is recommended, including avoidance of delayed cord clamping because of insufficient evidence of benefit to the infant. Insufficient evidence exists to support vertical transmission, but the possibility of maternal-infant transmission is clinically accepted based on small case reports of infection in a neonate at 30 hours of life and in infants of mothers with suspected or confirmed COVID-19.6,7 Accordingly, it is recommended that the benefit of early infant separation should be discussed with the mother. If approved, the infant should be kept in a separate isolation area and observed.

There is no evidence of breast milk transmission of the virus. For those electing to breastfeed, the patient should be provided with a breast pump to express and store the milk for subsequent bottle feeding. For mothers who elect to room in with the infant, a separation distance of 6 feet is recommended with an intervening barrier curtain. For COVID-19–positive mothers who elect breastfeeding, meticulous hand and face washing, continuous wearing of a mask, and cleansing of the breast prior to feeding needs to be maintained.

Restrictive visiting policies of no more than one visitor should be maintained. For severely or critically ill patients with COVID-19, it has been suggested that no visitors be allowed. As with other hospitalizations of COVID-19 patients, the HCW contact should be kept at a justifiable minimum to reduce the risk of transmission.

Protecting the obstetrician and other HCWs

Protecting the health of obstetricians and other HCWs is central to any successful strategy to fight the COVID-19 epidemic. For the individual obstetrician, careful attention to national and local hospital guidelines is required as these are rapidly evolving.

Physicians and their leadership must maintain an ongoing dialogue with hospital leadership to continually upgrade and optimize infection prevention and control measures, and to uphold best practices. The experience in Wuhan, China, illustrates the effectiveness of the proper use of PPE along with population control measures to reduce infections in HCWs. Prior to understanding the mechanism of virus transmission and using protective equipment, infection rates of 3%-29% were reported among HCWs. With the meticulous utilization of mitigation strategies and population control measures – including consistent use of PPE – the rate of infection of HCWs reportedly fell to zero.

In outpatient offices, all staff and HCWs should wear masks at all times and engage in social distancing and in frequent hand sanitization. Patients should be strongly encouraged to wear masks during office visits and on all other occasions when they will be in physical proximity to other individuals outside of the home.

Reports from epidemic areas describe transmission from household sources as a significant cause of HCW infection. The information emphasizes the need for ongoing vigilance and attention to sanitization measures even when at home with one’s family. An additional benefit is reduced risk of transmission from HCWs to family members.

Dr. Bahado-Singh is professor and chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Oakland University, Rochester, Mich., and health system chair for obstetrics and gynecology at Beaumont Health System.

References

1. Luo S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Mar 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.03.043.

2. Lechien JR et al. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020 Apr 6. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-05965-1.

3. Breslin N et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020 Apr 9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100118.

4. Zaigham M, Andersson O. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020 Apr 7. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13867.

5. Di Mascio D et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020 Mar 25. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100107.

6. Ital J. Pediatr 2020;46(1) doi: 10.1186/s13052-020-0820-x.

7. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020;149(2):130-6.

*This article was updated 5/6/2020.

The meteoric rise in the number of test-positive and clinical cases of COVID-19 because of infection with the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in states and cities across the United States has added urgency to the efforts to develop protocols for hospital triage, admission, labor and delivery management, and other aspects of obstetrical care.

Emerging data suggest that, while SARS-CoV-2 is less lethal overall than the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) proved to be, it is significantly more contagious. Although a severe disease, the limited worldwide data so far available (as of early May) do not indicate that pregnant women are at greater risk of severe disease, compared with the general population. However, there remains a critical need for data on maternal and perinatal outcomes in women infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Multiple physiological changes in pregnancy, from reduced cell-based immune competence to changes in respiratory tract and pulmonary function – e.g., edema of the respiratory tract, increases in secretions and oxygen consumption, elevation of the diaphragm, and decrease in functional residual capacity – have historically contributed to worse obstetric outcomes in pregnant women who have had viral pneumonias. Furthermore, limited published experience with COVID-19 in China suggests worse perinatal outcomes in some affected pregnancies, including prematurity and perinatal death.

With evolution of the pandemic and accumulation of experience, it is expected that data-driven guidelines on assessment and management of infected pregnant women will contribute to improved maternal and perinatal outcomes. What is clear now, however, is that,

Here are my recommendations, based on a currently limited body of literature on COVID-19 and other communicable viral respiratory disorders, as well my experience in the greater Detroit area, a COVID-19 hot spot.

Preparing for hospital evaluation and admission

The obstetric triage or labor and delivery (L&D) unit should be notified prior to the arrival of a patient suspected of or known to be infected with the virus. This will minimize staff exposure and allow sufficient time to prepare appropriate accommodations, equipment, and supplies for the patient’s care. Hospital infection control should be promptly notified by L&D of the expected arrival of such a patient. Placement ideally should be in a negative-pressure room, which allows outside air to flow into the room but prevents contaminated air from escaping. In the absence of a negative-pressure room, an infection isolation area should be utilized.

The patient and one accompanying support individual should wear either medical-grade masks brought from home or supplied upon entry to the hospital or homemade masks or bandanas. This will reduce the risk of viral transmission to hospital workers and other individuals encountered in the hospital prior to arriving in L&D. An ideal setup is to have separate entry areas, access corridors, and elevators for patients known or suspected to have COVID-19 infection. The patient and visitor should be expeditiously escorted to the prepared area for evaluation. Patients who are not known or suspected to be infected ideally should be tested.

Screening of patients & support individuals

Proper screening of patients and support individuals is critical to protecting both patients and staff in the L&D unit. This should include an expanded questionnaire that asks about disturbances of smell and taste and GI symptoms like loss of appetite – not only the more commonly queried symptoms of fever, shortness of breath, coughing, and exposure to someone who may have been ill.

Recent studies regarding presenting symptoms cast significant doubt, in fact, on the validity of patients with “asymptomatic COVID-19.” Over 15% of patients with confirmed infection in one published case series had solely GI symptoms and almost all had some digestive symptoms, for example, and almost 90% in another study had absent or reduced sense of smell and/or taste.1,2 In fact, the use of the term “paucisymptomatic” rather than “asymptomatic” may be most appropriate.

Support individuals also should undergo temperature screening, ideally with laser noncontact thermometers on entry to the hospital or triage.

Visitor policy

The number of visitors/support individuals should be kept to a minimum to reduce transmission risk. The actual number will be determined by hospital or state policy, but up to one visitor in the labor room appears reasonable. Very strong individual justification should be required to exceed this threshold! The visitor should not only be screened for an expanded list of symptoms, but they also should be queried for underlying illnesses (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular disease, significant lung disease, undergoing cancer therapy) as well as for age over 65 years, each of which increase the chances of severe COVID-19 disease should infection occur. The visitor should be informed of such risks and, especially when accompanying a patient with known or suspected COVID-19, provided the option of voluntarily revoking their visitor status. A visitor with known or suspected COVID-19 infection based on testing or screening should not be allowed into the L&D unit.

In addition, institutions may be considered to have obligations to the visitor/support person beyond screening. These include instructions in proper mask usage, hand washing, and limiting the touching of surfaces to lower infection risk.

“Visitor relays” where one visitor replaces another should be strongly discouraged. Visitors should similarly not be allowed to wander around the hospital (to use phones, for instance); transiting back and forth to obtain food and coffee should be kept to a strict minimum. For visitors accompanying COVID-19–-infected women, “visitor’s plates” provided by the hospital at reasonable cost is a much-preferred arrangement for obtaining meals during the course of the hospital stay. In addition, visitors should be sent out of the room during the performance of aerosolizing procedures.

Labor and delivery management

The successful management of patients with COVID-19 requires a rigorous infection control protocol informed by guidelines from national entities, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and by state health departments when available.

Strict limits on the number of obstetricians and other health care workers (HCWs) entering the patient’s room should be enforced and documented to minimize risk to the HCWs attending to patients who have a positive diagnosis or who are under investigation. Only in cases of demonstrable clinical benefit should repeat visits by the same or additional HCWs be permitted. Conventional and electronic tablets present an excellent opportunity for patient follow-up visits without room entry. In our institution, this has been successfully piloted in nonpregnant patients. Obstetricians and others caring for obstetrical patients – especially those who are infected or under investigation for infection – should always wear a properly fitted N95 mask.

Because patients with COVID-19 may have or go on to develop a constellation of organ abnormalities (e.g., cardiovascular, renal, pulmonary), it is vital that a standardized panel of baseline laboratory studies be developed for pregnant patients. This will minimize the need for repeated blood draws and other testing which may increase HCW exposure.

A negative screen based on nonreport of symptoms, lack of temperature elevation, and reported nonexposure to individuals with COVID-19 symptoms still has limitations in terms of disease detection. A recent report from a tertiary care hospital in New York City found that close to one-third of pregnant patients with confirmed COVID-19 admitted over a 2-week period had no viral symptoms or instructive history on initial admission.3 This is consistent with our clinical experience. Most importantly, therefore, routine quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction testing should be performed on all patients admitted to the L&D unit.

Given the reported variability in the accuracy of polymerase chain reaction testing induced by variable effectiveness of sampling techniques, stage of infection, and inherent test accuracy issues, symptomatic patients with a negative test should first obtain clearance from infectious disease specialists before isolation precautions are discontinued. Repeat testing in 24 hours, including testing of multiple sites, may subsequently yield a positive result in persistently symptomatic patients.

Intrapartum management

As much as possible, standard obstetric indications should guide the timing and route of delivery. In the case of a COVID-19–positive patient or a patient under investigation, nonobstetric factors may bear heavily on decision making, and management flexibility is of great value. For example, in cases of severe or critical disease status, evidence suggests that early delivery regardless of gestational age can improve maternal oxygenation; this supports the liberal use of C-sections in these circumstances. In addition, shortening labor length as well as duration of hospitalization may be expected to reduce the risk of transmission to HCWs, other staff, and other patients.

High rates of cesarean delivery unsurprisingly have been reported thus far: One review of 108 case reports and series of test-positive COVID-19 pregnancies found a 92% C-section rate, and another review and meta-analysis of studies of SARS, MERS, and COVID-19 during pregnancy similarly found that the majority of patients – 84% across all coronavirus infections and 91% in COVID-19 pregnancies – were delivered by C-section.4,5 Given these high rates of cesarean deliveries, the early placement of neuraxial anesthesia while the patient is stable appears to be prudent and obviates the need for intubation, the latter of which is associated with increased aerosol generation and increased virus transmission risk.

Strict protocols for the optimal protection of staff should be observed, including proper personal protective equipment (PPE) protection. Protocols have been detailed in various guidelines and publications; they include the wearing of shoe covers, gowns, N95 masks, goggles, face shields, and two layers of gloves.

For institutions that currently do not offer routine COVID-19 testing to pregnant patients – especially those in areas of outbreaks – N95 masks and eye protection should still be provided to all HCWs involved in the intrapartum management of untested asymptomatic patients, particularly those in the active phase of labor. This protection is justified given the limitations of symptom- and history-based screening and the not-uncommon experience of the patient with a negative screen who subsequently develops the clinical syndrome.

Obstetric management of labor requires close patient contact that potentially elevates the risk of contamination and infection. During the active stage of labor, patient shouting, rapid mouth breathing, and other behaviors inherent to labor all increase the risk of aerosolization of oronasal secretions. In addition, nasal-prong oxygen administration is believed to independently increase the risk of aerosolization of secretions. The casual practice of nasal oxygen application should thus be discontinued and, where felt to be absolutely necessary, a mask should be worn on top of the prongs.

Regarding operative delivery, each participating obstetric surgeon should observe guidelines and recommendations of governing national organizations and professional groups – including the American College of Surgeons – regarding the safe conduct of operations on patients with COVID-19. Written guidelines should be tailored as needed to the performance of C-sections and readily available in L&D. Drills and simulations are generally valuable, and expertise and support should always be available in the labor room to assist with donning and doffing of PPE.

Postpartum care

Expeditious separation of the COVID-19–positive mother from her infant is recommended, including avoidance of delayed cord clamping because of insufficient evidence of benefit to the infant. Insufficient evidence exists to support vertical transmission, but the possibility of maternal-infant transmission is clinically accepted based on small case reports of infection in a neonate at 30 hours of life and in infants of mothers with suspected or confirmed COVID-19.6,7 Accordingly, it is recommended that the benefit of early infant separation should be discussed with the mother. If approved, the infant should be kept in a separate isolation area and observed.

There is no evidence of breast milk transmission of the virus. For those electing to breastfeed, the patient should be provided with a breast pump to express and store the milk for subsequent bottle feeding. For mothers who elect to room in with the infant, a separation distance of 6 feet is recommended with an intervening barrier curtain. For COVID-19–positive mothers who elect breastfeeding, meticulous hand and face washing, continuous wearing of a mask, and cleansing of the breast prior to feeding needs to be maintained.

Restrictive visiting policies of no more than one visitor should be maintained. For severely or critically ill patients with COVID-19, it has been suggested that no visitors be allowed. As with other hospitalizations of COVID-19 patients, the HCW contact should be kept at a justifiable minimum to reduce the risk of transmission.

Protecting the obstetrician and other HCWs

Protecting the health of obstetricians and other HCWs is central to any successful strategy to fight the COVID-19 epidemic. For the individual obstetrician, careful attention to national and local hospital guidelines is required as these are rapidly evolving.

Physicians and their leadership must maintain an ongoing dialogue with hospital leadership to continually upgrade and optimize infection prevention and control measures, and to uphold best practices. The experience in Wuhan, China, illustrates the effectiveness of the proper use of PPE along with population control measures to reduce infections in HCWs. Prior to understanding the mechanism of virus transmission and using protective equipment, infection rates of 3%-29% were reported among HCWs. With the meticulous utilization of mitigation strategies and population control measures – including consistent use of PPE – the rate of infection of HCWs reportedly fell to zero.

In outpatient offices, all staff and HCWs should wear masks at all times and engage in social distancing and in frequent hand sanitization. Patients should be strongly encouraged to wear masks during office visits and on all other occasions when they will be in physical proximity to other individuals outside of the home.

Reports from epidemic areas describe transmission from household sources as a significant cause of HCW infection. The information emphasizes the need for ongoing vigilance and attention to sanitization measures even when at home with one’s family. An additional benefit is reduced risk of transmission from HCWs to family members.

Dr. Bahado-Singh is professor and chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Oakland University, Rochester, Mich., and health system chair for obstetrics and gynecology at Beaumont Health System.

References

1. Luo S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Mar 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.03.043.

2. Lechien JR et al. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020 Apr 6. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-05965-1.

3. Breslin N et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020 Apr 9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100118.

4. Zaigham M, Andersson O. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020 Apr 7. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13867.

5. Di Mascio D et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020 Mar 25. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100107.

6. Ital J. Pediatr 2020;46(1) doi: 10.1186/s13052-020-0820-x.

7. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020;149(2):130-6.

*This article was updated 5/6/2020.

The meteoric rise in the number of test-positive and clinical cases of COVID-19 because of infection with the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in states and cities across the United States has added urgency to the efforts to develop protocols for hospital triage, admission, labor and delivery management, and other aspects of obstetrical care.

Emerging data suggest that, while SARS-CoV-2 is less lethal overall than the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) proved to be, it is significantly more contagious. Although a severe disease, the limited worldwide data so far available (as of early May) do not indicate that pregnant women are at greater risk of severe disease, compared with the general population. However, there remains a critical need for data on maternal and perinatal outcomes in women infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Multiple physiological changes in pregnancy, from reduced cell-based immune competence to changes in respiratory tract and pulmonary function – e.g., edema of the respiratory tract, increases in secretions and oxygen consumption, elevation of the diaphragm, and decrease in functional residual capacity – have historically contributed to worse obstetric outcomes in pregnant women who have had viral pneumonias. Furthermore, limited published experience with COVID-19 in China suggests worse perinatal outcomes in some affected pregnancies, including prematurity and perinatal death.

With evolution of the pandemic and accumulation of experience, it is expected that data-driven guidelines on assessment and management of infected pregnant women will contribute to improved maternal and perinatal outcomes. What is clear now, however, is that,

Here are my recommendations, based on a currently limited body of literature on COVID-19 and other communicable viral respiratory disorders, as well my experience in the greater Detroit area, a COVID-19 hot spot.

Preparing for hospital evaluation and admission

The obstetric triage or labor and delivery (L&D) unit should be notified prior to the arrival of a patient suspected of or known to be infected with the virus. This will minimize staff exposure and allow sufficient time to prepare appropriate accommodations, equipment, and supplies for the patient’s care. Hospital infection control should be promptly notified by L&D of the expected arrival of such a patient. Placement ideally should be in a negative-pressure room, which allows outside air to flow into the room but prevents contaminated air from escaping. In the absence of a negative-pressure room, an infection isolation area should be utilized.

The patient and one accompanying support individual should wear either medical-grade masks brought from home or supplied upon entry to the hospital or homemade masks or bandanas. This will reduce the risk of viral transmission to hospital workers and other individuals encountered in the hospital prior to arriving in L&D. An ideal setup is to have separate entry areas, access corridors, and elevators for patients known or suspected to have COVID-19 infection. The patient and visitor should be expeditiously escorted to the prepared area for evaluation. Patients who are not known or suspected to be infected ideally should be tested.

Screening of patients & support individuals

Proper screening of patients and support individuals is critical to protecting both patients and staff in the L&D unit. This should include an expanded questionnaire that asks about disturbances of smell and taste and GI symptoms like loss of appetite – not only the more commonly queried symptoms of fever, shortness of breath, coughing, and exposure to someone who may have been ill.

Recent studies regarding presenting symptoms cast significant doubt, in fact, on the validity of patients with “asymptomatic COVID-19.” Over 15% of patients with confirmed infection in one published case series had solely GI symptoms and almost all had some digestive symptoms, for example, and almost 90% in another study had absent or reduced sense of smell and/or taste.1,2 In fact, the use of the term “paucisymptomatic” rather than “asymptomatic” may be most appropriate.

Support individuals also should undergo temperature screening, ideally with laser noncontact thermometers on entry to the hospital or triage.

Visitor policy

The number of visitors/support individuals should be kept to a minimum to reduce transmission risk. The actual number will be determined by hospital or state policy, but up to one visitor in the labor room appears reasonable. Very strong individual justification should be required to exceed this threshold! The visitor should not only be screened for an expanded list of symptoms, but they also should be queried for underlying illnesses (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular disease, significant lung disease, undergoing cancer therapy) as well as for age over 65 years, each of which increase the chances of severe COVID-19 disease should infection occur. The visitor should be informed of such risks and, especially when accompanying a patient with known or suspected COVID-19, provided the option of voluntarily revoking their visitor status. A visitor with known or suspected COVID-19 infection based on testing or screening should not be allowed into the L&D unit.

In addition, institutions may be considered to have obligations to the visitor/support person beyond screening. These include instructions in proper mask usage, hand washing, and limiting the touching of surfaces to lower infection risk.

“Visitor relays” where one visitor replaces another should be strongly discouraged. Visitors should similarly not be allowed to wander around the hospital (to use phones, for instance); transiting back and forth to obtain food and coffee should be kept to a strict minimum. For visitors accompanying COVID-19–-infected women, “visitor’s plates” provided by the hospital at reasonable cost is a much-preferred arrangement for obtaining meals during the course of the hospital stay. In addition, visitors should be sent out of the room during the performance of aerosolizing procedures.

Labor and delivery management

The successful management of patients with COVID-19 requires a rigorous infection control protocol informed by guidelines from national entities, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and by state health departments when available.

Strict limits on the number of obstetricians and other health care workers (HCWs) entering the patient’s room should be enforced and documented to minimize risk to the HCWs attending to patients who have a positive diagnosis or who are under investigation. Only in cases of demonstrable clinical benefit should repeat visits by the same or additional HCWs be permitted. Conventional and electronic tablets present an excellent opportunity for patient follow-up visits without room entry. In our institution, this has been successfully piloted in nonpregnant patients. Obstetricians and others caring for obstetrical patients – especially those who are infected or under investigation for infection – should always wear a properly fitted N95 mask.

Because patients with COVID-19 may have or go on to develop a constellation of organ abnormalities (e.g., cardiovascular, renal, pulmonary), it is vital that a standardized panel of baseline laboratory studies be developed for pregnant patients. This will minimize the need for repeated blood draws and other testing which may increase HCW exposure.

A negative screen based on nonreport of symptoms, lack of temperature elevation, and reported nonexposure to individuals with COVID-19 symptoms still has limitations in terms of disease detection. A recent report from a tertiary care hospital in New York City found that close to one-third of pregnant patients with confirmed COVID-19 admitted over a 2-week period had no viral symptoms or instructive history on initial admission.3 This is consistent with our clinical experience. Most importantly, therefore, routine quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction testing should be performed on all patients admitted to the L&D unit.

Given the reported variability in the accuracy of polymerase chain reaction testing induced by variable effectiveness of sampling techniques, stage of infection, and inherent test accuracy issues, symptomatic patients with a negative test should first obtain clearance from infectious disease specialists before isolation precautions are discontinued. Repeat testing in 24 hours, including testing of multiple sites, may subsequently yield a positive result in persistently symptomatic patients.

Intrapartum management

As much as possible, standard obstetric indications should guide the timing and route of delivery. In the case of a COVID-19–positive patient or a patient under investigation, nonobstetric factors may bear heavily on decision making, and management flexibility is of great value. For example, in cases of severe or critical disease status, evidence suggests that early delivery regardless of gestational age can improve maternal oxygenation; this supports the liberal use of C-sections in these circumstances. In addition, shortening labor length as well as duration of hospitalization may be expected to reduce the risk of transmission to HCWs, other staff, and other patients.

High rates of cesarean delivery unsurprisingly have been reported thus far: One review of 108 case reports and series of test-positive COVID-19 pregnancies found a 92% C-section rate, and another review and meta-analysis of studies of SARS, MERS, and COVID-19 during pregnancy similarly found that the majority of patients – 84% across all coronavirus infections and 91% in COVID-19 pregnancies – were delivered by C-section.4,5 Given these high rates of cesarean deliveries, the early placement of neuraxial anesthesia while the patient is stable appears to be prudent and obviates the need for intubation, the latter of which is associated with increased aerosol generation and increased virus transmission risk.

Strict protocols for the optimal protection of staff should be observed, including proper personal protective equipment (PPE) protection. Protocols have been detailed in various guidelines and publications; they include the wearing of shoe covers, gowns, N95 masks, goggles, face shields, and two layers of gloves.

For institutions that currently do not offer routine COVID-19 testing to pregnant patients – especially those in areas of outbreaks – N95 masks and eye protection should still be provided to all HCWs involved in the intrapartum management of untested asymptomatic patients, particularly those in the active phase of labor. This protection is justified given the limitations of symptom- and history-based screening and the not-uncommon experience of the patient with a negative screen who subsequently develops the clinical syndrome.

Obstetric management of labor requires close patient contact that potentially elevates the risk of contamination and infection. During the active stage of labor, patient shouting, rapid mouth breathing, and other behaviors inherent to labor all increase the risk of aerosolization of oronasal secretions. In addition, nasal-prong oxygen administration is believed to independently increase the risk of aerosolization of secretions. The casual practice of nasal oxygen application should thus be discontinued and, where felt to be absolutely necessary, a mask should be worn on top of the prongs.

Regarding operative delivery, each participating obstetric surgeon should observe guidelines and recommendations of governing national organizations and professional groups – including the American College of Surgeons – regarding the safe conduct of operations on patients with COVID-19. Written guidelines should be tailored as needed to the performance of C-sections and readily available in L&D. Drills and simulations are generally valuable, and expertise and support should always be available in the labor room to assist with donning and doffing of PPE.

Postpartum care

Expeditious separation of the COVID-19–positive mother from her infant is recommended, including avoidance of delayed cord clamping because of insufficient evidence of benefit to the infant. Insufficient evidence exists to support vertical transmission, but the possibility of maternal-infant transmission is clinically accepted based on small case reports of infection in a neonate at 30 hours of life and in infants of mothers with suspected or confirmed COVID-19.6,7 Accordingly, it is recommended that the benefit of early infant separation should be discussed with the mother. If approved, the infant should be kept in a separate isolation area and observed.

There is no evidence of breast milk transmission of the virus. For those electing to breastfeed, the patient should be provided with a breast pump to express and store the milk for subsequent bottle feeding. For mothers who elect to room in with the infant, a separation distance of 6 feet is recommended with an intervening barrier curtain. For COVID-19–positive mothers who elect breastfeeding, meticulous hand and face washing, continuous wearing of a mask, and cleansing of the breast prior to feeding needs to be maintained.

Restrictive visiting policies of no more than one visitor should be maintained. For severely or critically ill patients with COVID-19, it has been suggested that no visitors be allowed. As with other hospitalizations of COVID-19 patients, the HCW contact should be kept at a justifiable minimum to reduce the risk of transmission.

Protecting the obstetrician and other HCWs

Protecting the health of obstetricians and other HCWs is central to any successful strategy to fight the COVID-19 epidemic. For the individual obstetrician, careful attention to national and local hospital guidelines is required as these are rapidly evolving.

Physicians and their leadership must maintain an ongoing dialogue with hospital leadership to continually upgrade and optimize infection prevention and control measures, and to uphold best practices. The experience in Wuhan, China, illustrates the effectiveness of the proper use of PPE along with population control measures to reduce infections in HCWs. Prior to understanding the mechanism of virus transmission and using protective equipment, infection rates of 3%-29% were reported among HCWs. With the meticulous utilization of mitigation strategies and population control measures – including consistent use of PPE – the rate of infection of HCWs reportedly fell to zero.

In outpatient offices, all staff and HCWs should wear masks at all times and engage in social distancing and in frequent hand sanitization. Patients should be strongly encouraged to wear masks during office visits and on all other occasions when they will be in physical proximity to other individuals outside of the home.

Reports from epidemic areas describe transmission from household sources as a significant cause of HCW infection. The information emphasizes the need for ongoing vigilance and attention to sanitization measures even when at home with one’s family. An additional benefit is reduced risk of transmission from HCWs to family members.

Dr. Bahado-Singh is professor and chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Oakland University, Rochester, Mich., and health system chair for obstetrics and gynecology at Beaumont Health System.

References

1. Luo S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Mar 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.03.043.

2. Lechien JR et al. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020 Apr 6. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-05965-1.

3. Breslin N et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020 Apr 9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100118.

4. Zaigham M, Andersson O. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020 Apr 7. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13867.

5. Di Mascio D et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020 Mar 25. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100107.

6. Ital J. Pediatr 2020;46(1) doi: 10.1186/s13052-020-0820-x.

7. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020;149(2):130-6.

*This article was updated 5/6/2020.

Obstetrics during the COVID-19 pandemic

The identification of the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) and emergence of the associated infectious respiratory disease, COVID-19, in late 2019 catapulted the citizens of the world, especially those in the health care professions, into an era of considerable uncertainty. At this moment in human history, calm reassurance – founded in fact and evidence – seems its greatest need. Much of the focus within the biomedical community has been on containment, prevention, and treatment of this highly contagious and, for some, extremely virulent disease.

However, for ob.gyns on the front lines of the COVID-19 fight, there is the additional challenge of caring for at least two patients simultaneously: the mother and her unborn baby. Studies in mother-baby dyads, while being published at an incredible pace, are still quite scarce. In addition, published reports are limited by the small sample size of the patient population (many are single-case reports), lack of uniformity in the timing and types of clinical samples collected, testing delays, and varying isolation protocols in cases where the mother has confirmed SARS-CoV-2.

Five months into a pandemic that has swept the world, we still know very little about COVID-19 infection in the general population, let alone the obstetric one. We do not know if having and resolving COVID-19 infection provides any long-term protection against future disease. We do not know if vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 occurs. We do not know if maternal infection confers any immunologic benefit to the neonate. The list goes on.

What we do know is that taking extra precautions works. Use of personal protective equipment saves health care practitioner and patient lives. Prohibiting or restricting visitors to only one person in hospitals reduces risk of transmission to vulnerable patients.

Additionally, we know that leading with compassion is vital to easing patient – and practitioner – anxiety and stress. Most importantly, we know that people are extraordinarily resilient, especially when it comes to safeguarding the health of their families.

To address some of the major concerns that many ob.gyns. have regarding their risk of coronavirus exposure when caring for patients, we have invited Ray Bahado-Singh, MD, professor and chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Oakland University, Rochester, Mich., and health system chair for obstetrics and gynecology at Beaumont Health System, who works in a suburb of Detroit, one of our nation’s COVID-19 hot spots.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland School of Medicine as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

The identification of the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) and emergence of the associated infectious respiratory disease, COVID-19, in late 2019 catapulted the citizens of the world, especially those in the health care professions, into an era of considerable uncertainty. At this moment in human history, calm reassurance – founded in fact and evidence – seems its greatest need. Much of the focus within the biomedical community has been on containment, prevention, and treatment of this highly contagious and, for some, extremely virulent disease.

However, for ob.gyns on the front lines of the COVID-19 fight, there is the additional challenge of caring for at least two patients simultaneously: the mother and her unborn baby. Studies in mother-baby dyads, while being published at an incredible pace, are still quite scarce. In addition, published reports are limited by the small sample size of the patient population (many are single-case reports), lack of uniformity in the timing and types of clinical samples collected, testing delays, and varying isolation protocols in cases where the mother has confirmed SARS-CoV-2.

Five months into a pandemic that has swept the world, we still know very little about COVID-19 infection in the general population, let alone the obstetric one. We do not know if having and resolving COVID-19 infection provides any long-term protection against future disease. We do not know if vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 occurs. We do not know if maternal infection confers any immunologic benefit to the neonate. The list goes on.

What we do know is that taking extra precautions works. Use of personal protective equipment saves health care practitioner and patient lives. Prohibiting or restricting visitors to only one person in hospitals reduces risk of transmission to vulnerable patients.

Additionally, we know that leading with compassion is vital to easing patient – and practitioner – anxiety and stress. Most importantly, we know that people are extraordinarily resilient, especially when it comes to safeguarding the health of their families.

To address some of the major concerns that many ob.gyns. have regarding their risk of coronavirus exposure when caring for patients, we have invited Ray Bahado-Singh, MD, professor and chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Oakland University, Rochester, Mich., and health system chair for obstetrics and gynecology at Beaumont Health System, who works in a suburb of Detroit, one of our nation’s COVID-19 hot spots.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland School of Medicine as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

The identification of the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) and emergence of the associated infectious respiratory disease, COVID-19, in late 2019 catapulted the citizens of the world, especially those in the health care professions, into an era of considerable uncertainty. At this moment in human history, calm reassurance – founded in fact and evidence – seems its greatest need. Much of the focus within the biomedical community has been on containment, prevention, and treatment of this highly contagious and, for some, extremely virulent disease.

However, for ob.gyns on the front lines of the COVID-19 fight, there is the additional challenge of caring for at least two patients simultaneously: the mother and her unborn baby. Studies in mother-baby dyads, while being published at an incredible pace, are still quite scarce. In addition, published reports are limited by the small sample size of the patient population (many are single-case reports), lack of uniformity in the timing and types of clinical samples collected, testing delays, and varying isolation protocols in cases where the mother has confirmed SARS-CoV-2.

Five months into a pandemic that has swept the world, we still know very little about COVID-19 infection in the general population, let alone the obstetric one. We do not know if having and resolving COVID-19 infection provides any long-term protection against future disease. We do not know if vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 occurs. We do not know if maternal infection confers any immunologic benefit to the neonate. The list goes on.

What we do know is that taking extra precautions works. Use of personal protective equipment saves health care practitioner and patient lives. Prohibiting or restricting visitors to only one person in hospitals reduces risk of transmission to vulnerable patients.

Additionally, we know that leading with compassion is vital to easing patient – and practitioner – anxiety and stress. Most importantly, we know that people are extraordinarily resilient, especially when it comes to safeguarding the health of their families.

To address some of the major concerns that many ob.gyns. have regarding their risk of coronavirus exposure when caring for patients, we have invited Ray Bahado-Singh, MD, professor and chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Oakland University, Rochester, Mich., and health system chair for obstetrics and gynecology at Beaumont Health System, who works in a suburb of Detroit, one of our nation’s COVID-19 hot spots.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland School of Medicine as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

Researchers identify a cause of L-DOPA–induced dyskinesia in Parkinson’s disease

The conclusion is based on animal studies that were published May 1 in Science Advances. “These studies show that, if we can downregulate RasGRP1 signaling before dopamine replacement, we have an opportunity to greatly improve [patients’] quality of life,” said Srinivasa Subramaniam, PhD, of the department of neuroscience at Scripps Research in Jupiter, Fla., in a press release. Dr. Subramaniam is one of the investigators.

Parkinson’s disease results from the loss of substantia nigral projections neurons, which causes decreased levels of dopamine in the dorsal striatum. Treatment with L-DOPA reduces the disease’s motor symptoms effectively, but ultimately leads to the onset of LID. Previous data suggest that LID results from the abnormal activation of dopamine-1 (D1)–dependent cyclic adenosine 3´,5´-monophosphate (cAMP)/protein kinase A (PKA), extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK), and mammalian target of rapamycin kinase complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling in the dorsal striatum.

Animal and biochemical data

Based on earlier animal studies, Dr. Subramaniam and colleagues hypothesized that RasGRP1 might regulate LID. To test this theory, the investigators created lesions in wild-type and RasGRP1 knockout mice to create models of Parkinson’s disease. The investigators saw similar Parkinsonian symptoms in both groups of mice on the drag, rotarod, turning, and open-field tests. After all mice received daily treatment with L-DOPA, RasGRP1 knockout mice had significantly fewer abnormal involuntary movements, compared with the wild-type mice. All aspects of dyskinesia appeared to be equally dampened in the knockout mice.

To analyze whether RasGRP1 deletion affected the efficacy of L-DOPA, the investigators subjected the treated mice to motor tests. Parkinsonian symptoms were decreased among wild-type and knockout mice on the drag and turning tests. “RasGRP1 promoted the adverse effects of L-DOPA but did not interfere with its therapeutic motor effects,” the investigators wrote. Compared with the wild-type mice, the knockout mice had no changes in basal motor behavior or coordination or amphetamine-induced motor activity.

In addition, Dr. Subramaniam and colleagues observed that RasGRP1 levels were increased in the striatum after L-DOPA injection, but not after injection of vehicle control. This and other biochemical findings indicated that striatal RasGRP1 is upregulated in an L-DOPA–dependent manner and is causally linked to the development of LID, according to the investigators.

Other observations indicated that RasGRP1 physiologically activates mTORC1 signaling, which contributes to LID. Using liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry, Dr. Subramaniam and colleagues saw that RasGRP1 acts upstream in response to L-DOPA and regulates a specific and diverse group of proteins to promote LID. When they examined a nonhuman primate model of Parkinson’s disease, they noted similar findings.

New therapeutic targets

“There is an immediate need for new therapeutic targets to stop LID ... in Parkinson’s disease,” said Dr. Subramaniam in a press release. “The treatments now available work poorly and have many additional unwanted side effects. We believe this [study] represents an important step toward better options for people with Parkinson’s disease.”

Future research should attempt to identify the best method of selectively reducing expression of RasGRP1 in the striatum without affecting its expression in other areas of the body, according to Dr. Subramaniam. “The good news is that in mice a total lack of RasGRP1 is not lethal, so we think that blocking RasGRP1 with drugs, or even with gene therapy, may have very few or no major side effects.”

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Eshraghi M et al. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eaaz7001.

The conclusion is based on animal studies that were published May 1 in Science Advances. “These studies show that, if we can downregulate RasGRP1 signaling before dopamine replacement, we have an opportunity to greatly improve [patients’] quality of life,” said Srinivasa Subramaniam, PhD, of the department of neuroscience at Scripps Research in Jupiter, Fla., in a press release. Dr. Subramaniam is one of the investigators.

Parkinson’s disease results from the loss of substantia nigral projections neurons, which causes decreased levels of dopamine in the dorsal striatum. Treatment with L-DOPA reduces the disease’s motor symptoms effectively, but ultimately leads to the onset of LID. Previous data suggest that LID results from the abnormal activation of dopamine-1 (D1)–dependent cyclic adenosine 3´,5´-monophosphate (cAMP)/protein kinase A (PKA), extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK), and mammalian target of rapamycin kinase complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling in the dorsal striatum.

Animal and biochemical data

Based on earlier animal studies, Dr. Subramaniam and colleagues hypothesized that RasGRP1 might regulate LID. To test this theory, the investigators created lesions in wild-type and RasGRP1 knockout mice to create models of Parkinson’s disease. The investigators saw similar Parkinsonian symptoms in both groups of mice on the drag, rotarod, turning, and open-field tests. After all mice received daily treatment with L-DOPA, RasGRP1 knockout mice had significantly fewer abnormal involuntary movements, compared with the wild-type mice. All aspects of dyskinesia appeared to be equally dampened in the knockout mice.

To analyze whether RasGRP1 deletion affected the efficacy of L-DOPA, the investigators subjected the treated mice to motor tests. Parkinsonian symptoms were decreased among wild-type and knockout mice on the drag and turning tests. “RasGRP1 promoted the adverse effects of L-DOPA but did not interfere with its therapeutic motor effects,” the investigators wrote. Compared with the wild-type mice, the knockout mice had no changes in basal motor behavior or coordination or amphetamine-induced motor activity.

In addition, Dr. Subramaniam and colleagues observed that RasGRP1 levels were increased in the striatum after L-DOPA injection, but not after injection of vehicle control. This and other biochemical findings indicated that striatal RasGRP1 is upregulated in an L-DOPA–dependent manner and is causally linked to the development of LID, according to the investigators.

Other observations indicated that RasGRP1 physiologically activates mTORC1 signaling, which contributes to LID. Using liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry, Dr. Subramaniam and colleagues saw that RasGRP1 acts upstream in response to L-DOPA and regulates a specific and diverse group of proteins to promote LID. When they examined a nonhuman primate model of Parkinson’s disease, they noted similar findings.

New therapeutic targets

“There is an immediate need for new therapeutic targets to stop LID ... in Parkinson’s disease,” said Dr. Subramaniam in a press release. “The treatments now available work poorly and have many additional unwanted side effects. We believe this [study] represents an important step toward better options for people with Parkinson’s disease.”

Future research should attempt to identify the best method of selectively reducing expression of RasGRP1 in the striatum without affecting its expression in other areas of the body, according to Dr. Subramaniam. “The good news is that in mice a total lack of RasGRP1 is not lethal, so we think that blocking RasGRP1 with drugs, or even with gene therapy, may have very few or no major side effects.”

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Eshraghi M et al. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eaaz7001.

The conclusion is based on animal studies that were published May 1 in Science Advances. “These studies show that, if we can downregulate RasGRP1 signaling before dopamine replacement, we have an opportunity to greatly improve [patients’] quality of life,” said Srinivasa Subramaniam, PhD, of the department of neuroscience at Scripps Research in Jupiter, Fla., in a press release. Dr. Subramaniam is one of the investigators.

Parkinson’s disease results from the loss of substantia nigral projections neurons, which causes decreased levels of dopamine in the dorsal striatum. Treatment with L-DOPA reduces the disease’s motor symptoms effectively, but ultimately leads to the onset of LID. Previous data suggest that LID results from the abnormal activation of dopamine-1 (D1)–dependent cyclic adenosine 3´,5´-monophosphate (cAMP)/protein kinase A (PKA), extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK), and mammalian target of rapamycin kinase complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling in the dorsal striatum.

Animal and biochemical data

Based on earlier animal studies, Dr. Subramaniam and colleagues hypothesized that RasGRP1 might regulate LID. To test this theory, the investigators created lesions in wild-type and RasGRP1 knockout mice to create models of Parkinson’s disease. The investigators saw similar Parkinsonian symptoms in both groups of mice on the drag, rotarod, turning, and open-field tests. After all mice received daily treatment with L-DOPA, RasGRP1 knockout mice had significantly fewer abnormal involuntary movements, compared with the wild-type mice. All aspects of dyskinesia appeared to be equally dampened in the knockout mice.

To analyze whether RasGRP1 deletion affected the efficacy of L-DOPA, the investigators subjected the treated mice to motor tests. Parkinsonian symptoms were decreased among wild-type and knockout mice on the drag and turning tests. “RasGRP1 promoted the adverse effects of L-DOPA but did not interfere with its therapeutic motor effects,” the investigators wrote. Compared with the wild-type mice, the knockout mice had no changes in basal motor behavior or coordination or amphetamine-induced motor activity.

In addition, Dr. Subramaniam and colleagues observed that RasGRP1 levels were increased in the striatum after L-DOPA injection, but not after injection of vehicle control. This and other biochemical findings indicated that striatal RasGRP1 is upregulated in an L-DOPA–dependent manner and is causally linked to the development of LID, according to the investigators.

Other observations indicated that RasGRP1 physiologically activates mTORC1 signaling, which contributes to LID. Using liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry, Dr. Subramaniam and colleagues saw that RasGRP1 acts upstream in response to L-DOPA and regulates a specific and diverse group of proteins to promote LID. When they examined a nonhuman primate model of Parkinson’s disease, they noted similar findings.

New therapeutic targets

“There is an immediate need for new therapeutic targets to stop LID ... in Parkinson’s disease,” said Dr. Subramaniam in a press release. “The treatments now available work poorly and have many additional unwanted side effects. We believe this [study] represents an important step toward better options for people with Parkinson’s disease.”

Future research should attempt to identify the best method of selectively reducing expression of RasGRP1 in the striatum without affecting its expression in other areas of the body, according to Dr. Subramaniam. “The good news is that in mice a total lack of RasGRP1 is not lethal, so we think that blocking RasGRP1 with drugs, or even with gene therapy, may have very few or no major side effects.”

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Eshraghi M et al. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eaaz7001.

FROM Science Advances

Pandemic effect: All other health care visits can wait

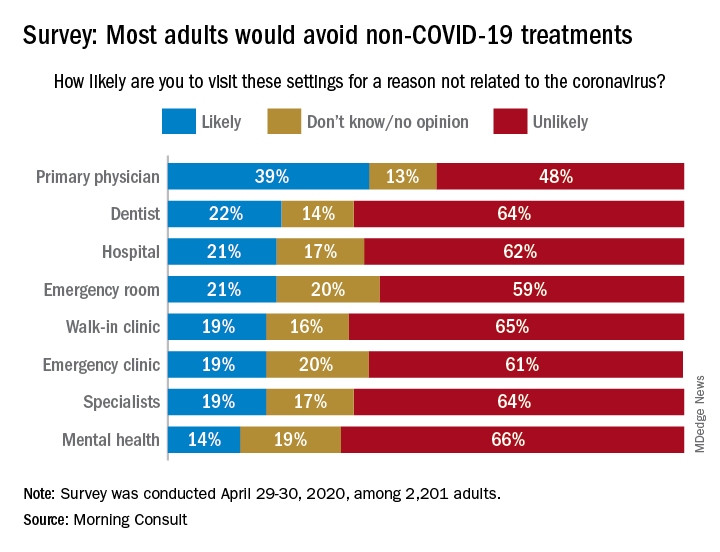

according to survey conducted at the end of April.

When asked how likely they were to visit a variety of health care settings for treatment not related to the coronavirus, 62% of respondents said it was unlikely that they would go to a hospital, 64% wouldn’t go to a specialist, and 65% would avoid walk-in clinics, digital media company Morning Consult reported May 4.

The only setting with less than a majority on the unlikely-to-visit side was primary physicians, who managed to combine a 39% likely vote with a 13% undecided/no-opinion tally, Morning Consult said after surveying 2,201 adults on April 29-30 (margin of error, ±2 percentage points).

As to when they might feel comfortable making such an in-person visit with their primary physician, 24% of respondents said they would willing to go in the next month, 14% said 2 months, 18% said 3 months, 13% said 6 months, and 10% said more than 6 months, the Morning Consult data show.

“Hospitals, despite being overburdened in recent weeks in coronavirus hot spots such as New York City, have reported dips in revenue as a result of potential patients opting against receiving elective surgeries out of fear of contracting COVID-19,” Morning Consult wrote, and these poll results suggest that “health care companies could continue to feel the pinch as long as the coronavirus lingers.”

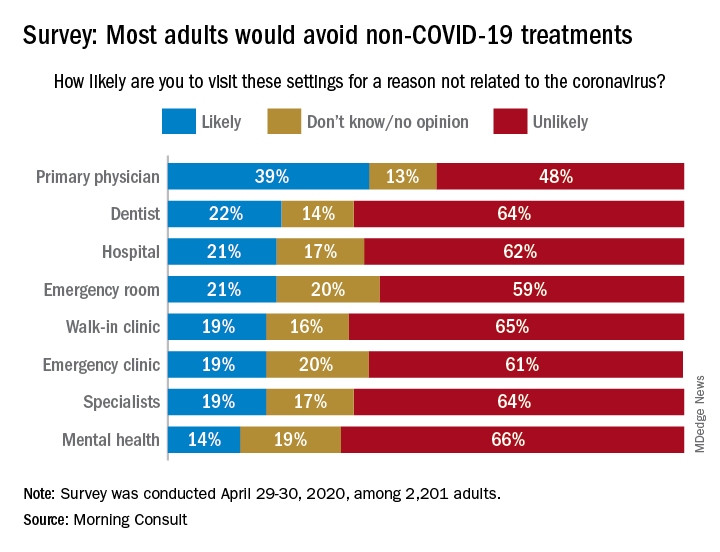

according to survey conducted at the end of April.

When asked how likely they were to visit a variety of health care settings for treatment not related to the coronavirus, 62% of respondents said it was unlikely that they would go to a hospital, 64% wouldn’t go to a specialist, and 65% would avoid walk-in clinics, digital media company Morning Consult reported May 4.

The only setting with less than a majority on the unlikely-to-visit side was primary physicians, who managed to combine a 39% likely vote with a 13% undecided/no-opinion tally, Morning Consult said after surveying 2,201 adults on April 29-30 (margin of error, ±2 percentage points).

As to when they might feel comfortable making such an in-person visit with their primary physician, 24% of respondents said they would willing to go in the next month, 14% said 2 months, 18% said 3 months, 13% said 6 months, and 10% said more than 6 months, the Morning Consult data show.

“Hospitals, despite being overburdened in recent weeks in coronavirus hot spots such as New York City, have reported dips in revenue as a result of potential patients opting against receiving elective surgeries out of fear of contracting COVID-19,” Morning Consult wrote, and these poll results suggest that “health care companies could continue to feel the pinch as long as the coronavirus lingers.”

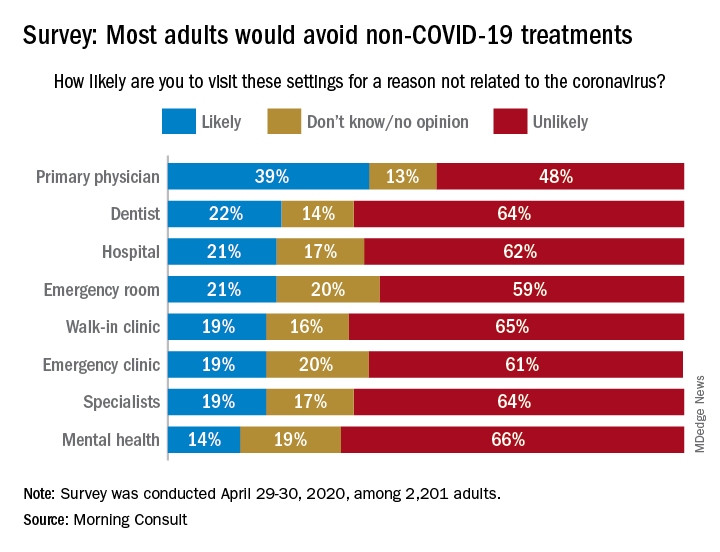

according to survey conducted at the end of April.

When asked how likely they were to visit a variety of health care settings for treatment not related to the coronavirus, 62% of respondents said it was unlikely that they would go to a hospital, 64% wouldn’t go to a specialist, and 65% would avoid walk-in clinics, digital media company Morning Consult reported May 4.

The only setting with less than a majority on the unlikely-to-visit side was primary physicians, who managed to combine a 39% likely vote with a 13% undecided/no-opinion tally, Morning Consult said after surveying 2,201 adults on April 29-30 (margin of error, ±2 percentage points).

As to when they might feel comfortable making such an in-person visit with their primary physician, 24% of respondents said they would willing to go in the next month, 14% said 2 months, 18% said 3 months, 13% said 6 months, and 10% said more than 6 months, the Morning Consult data show.

“Hospitals, despite being overburdened in recent weeks in coronavirus hot spots such as New York City, have reported dips in revenue as a result of potential patients opting against receiving elective surgeries out of fear of contracting COVID-19,” Morning Consult wrote, and these poll results suggest that “health care companies could continue to feel the pinch as long as the coronavirus lingers.”

FDA grants EUA to muscle stimulator to reduce mechanical ventilator usage

The Food and Drug Administration has issued an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for the VentFree Respiratory Muscle Stimulator in order to potentially reduce the number of days adult patients, including those with COVID-19, require mechanical ventilation, according to a press release from Liberate Medical.

In comparison with mechanical ventilation, which is invasive and commonly weakens the breathing muscles, the VentFree system uses noninvasive neuromuscular electrical stimulation to contract the abdominal wall muscles in synchrony with exhalation during mechanical ventilation, according to the press release. This allows patients to begin treatment during the early stages of ventilation while they are sedated and to continue until they are weaned off of ventilation.

A pair of pilot randomized, controlled studies, completed in Europe and Australia, showed that VentFree helped to reduce ventilation duration and ICU length of stay, compared with placebo stimulation. The FDA granted VentFree Breakthrough Device status in 2019.

“We are grateful to the FDA for recognizing the potential of VentFree and feel privileged to have the opportunity to help patients on mechanical ventilation during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Angus McLachlan PhD, cofounder and CEO of Liberate Medical, said in the press release.

VentFree has been authorized for use only for the duration of the current COVID-19 emergency, as it has not yet been approved or cleared for usage by primary care providers.

The Food and Drug Administration has issued an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for the VentFree Respiratory Muscle Stimulator in order to potentially reduce the number of days adult patients, including those with COVID-19, require mechanical ventilation, according to a press release from Liberate Medical.

In comparison with mechanical ventilation, which is invasive and commonly weakens the breathing muscles, the VentFree system uses noninvasive neuromuscular electrical stimulation to contract the abdominal wall muscles in synchrony with exhalation during mechanical ventilation, according to the press release. This allows patients to begin treatment during the early stages of ventilation while they are sedated and to continue until they are weaned off of ventilation.

A pair of pilot randomized, controlled studies, completed in Europe and Australia, showed that VentFree helped to reduce ventilation duration and ICU length of stay, compared with placebo stimulation. The FDA granted VentFree Breakthrough Device status in 2019.

“We are grateful to the FDA for recognizing the potential of VentFree and feel privileged to have the opportunity to help patients on mechanical ventilation during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Angus McLachlan PhD, cofounder and CEO of Liberate Medical, said in the press release.

VentFree has been authorized for use only for the duration of the current COVID-19 emergency, as it has not yet been approved or cleared for usage by primary care providers.

The Food and Drug Administration has issued an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for the VentFree Respiratory Muscle Stimulator in order to potentially reduce the number of days adult patients, including those with COVID-19, require mechanical ventilation, according to a press release from Liberate Medical.

In comparison with mechanical ventilation, which is invasive and commonly weakens the breathing muscles, the VentFree system uses noninvasive neuromuscular electrical stimulation to contract the abdominal wall muscles in synchrony with exhalation during mechanical ventilation, according to the press release. This allows patients to begin treatment during the early stages of ventilation while they are sedated and to continue until they are weaned off of ventilation.

A pair of pilot randomized, controlled studies, completed in Europe and Australia, showed that VentFree helped to reduce ventilation duration and ICU length of stay, compared with placebo stimulation. The FDA granted VentFree Breakthrough Device status in 2019.

“We are grateful to the FDA for recognizing the potential of VentFree and feel privileged to have the opportunity to help patients on mechanical ventilation during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Angus McLachlan PhD, cofounder and CEO of Liberate Medical, said in the press release.

VentFree has been authorized for use only for the duration of the current COVID-19 emergency, as it has not yet been approved or cleared for usage by primary care providers.