User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

History of depression, stress tied to Alzheimer’s, MCI risk

TOPLINE:

compared with those without either condition, a new study found.

METHODOLOGY:

- Longitudinal cohort study of 1,362,548 people with records in the Region Stockholm administrative health care database with a diagnosis of stress-induced exhaustion disorder (SED), depression, or both between 2012 and 2013.

- Cohort followed for diagnosis of MCI or AD between 2014 and 2022.

TAKEAWAY:

- SED diagnosed in 0.3%, depression in 2.9% and both SED and depression in 0.1%

- Compared with people without SED or depression, AD risk was more than double in patients with SED (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.45; 99% confidence interval [CI], 1.22-4.91) or depression (aOR, 2.32; 99% CI, 1.85-2.90) and four times higher in patients with both SED and depression (aOR, 4.00; 99% CI, 1.67-9.58)

- Risk for MCI was also higher in people with SED (aOR, 1.87; 99% CI,1.20-2.91), depression (aOR, 2.85; 99% CI, 2.53-3.22) or both SED and depression (aOR, 3.87; 99% CI, 2.39-6.27) vs patients with no history of SED or depression.

- Only patients with depression had a higher risk for another dementia type (aOR, 2.39; 99% CI, 1.92-2.96).

IN PRACTICE:

“Future studies should examine the possibility that symptoms of depression and/or chronic stress could be prodromal symptoms of dementia rather than risk factors,” study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Johanna Wallensten, doctoral student, department of clinical sciences, Danderyd Hospital, Stockholm, and colleagues and funded by the Karolinska Institute. It was published online in Alzheimer’s Research and Therapy.

LIMITATIONS:

Use of a health care registry could have led to over- or underestimation of depression, MCI and AD. The study probably captures most people with depression but not most people with depressive symptoms.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors reported no relevant conflicts.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

compared with those without either condition, a new study found.

METHODOLOGY:

- Longitudinal cohort study of 1,362,548 people with records in the Region Stockholm administrative health care database with a diagnosis of stress-induced exhaustion disorder (SED), depression, or both between 2012 and 2013.

- Cohort followed for diagnosis of MCI or AD between 2014 and 2022.

TAKEAWAY:

- SED diagnosed in 0.3%, depression in 2.9% and both SED and depression in 0.1%

- Compared with people without SED or depression, AD risk was more than double in patients with SED (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.45; 99% confidence interval [CI], 1.22-4.91) or depression (aOR, 2.32; 99% CI, 1.85-2.90) and four times higher in patients with both SED and depression (aOR, 4.00; 99% CI, 1.67-9.58)

- Risk for MCI was also higher in people with SED (aOR, 1.87; 99% CI,1.20-2.91), depression (aOR, 2.85; 99% CI, 2.53-3.22) or both SED and depression (aOR, 3.87; 99% CI, 2.39-6.27) vs patients with no history of SED or depression.

- Only patients with depression had a higher risk for another dementia type (aOR, 2.39; 99% CI, 1.92-2.96).

IN PRACTICE:

“Future studies should examine the possibility that symptoms of depression and/or chronic stress could be prodromal symptoms of dementia rather than risk factors,” study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Johanna Wallensten, doctoral student, department of clinical sciences, Danderyd Hospital, Stockholm, and colleagues and funded by the Karolinska Institute. It was published online in Alzheimer’s Research and Therapy.

LIMITATIONS:

Use of a health care registry could have led to over- or underestimation of depression, MCI and AD. The study probably captures most people with depression but not most people with depressive symptoms.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors reported no relevant conflicts.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

compared with those without either condition, a new study found.

METHODOLOGY:

- Longitudinal cohort study of 1,362,548 people with records in the Region Stockholm administrative health care database with a diagnosis of stress-induced exhaustion disorder (SED), depression, or both between 2012 and 2013.

- Cohort followed for diagnosis of MCI or AD between 2014 and 2022.

TAKEAWAY:

- SED diagnosed in 0.3%, depression in 2.9% and both SED and depression in 0.1%

- Compared with people without SED or depression, AD risk was more than double in patients with SED (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.45; 99% confidence interval [CI], 1.22-4.91) or depression (aOR, 2.32; 99% CI, 1.85-2.90) and four times higher in patients with both SED and depression (aOR, 4.00; 99% CI, 1.67-9.58)

- Risk for MCI was also higher in people with SED (aOR, 1.87; 99% CI,1.20-2.91), depression (aOR, 2.85; 99% CI, 2.53-3.22) or both SED and depression (aOR, 3.87; 99% CI, 2.39-6.27) vs patients with no history of SED or depression.

- Only patients with depression had a higher risk for another dementia type (aOR, 2.39; 99% CI, 1.92-2.96).

IN PRACTICE:

“Future studies should examine the possibility that symptoms of depression and/or chronic stress could be prodromal symptoms of dementia rather than risk factors,” study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Johanna Wallensten, doctoral student, department of clinical sciences, Danderyd Hospital, Stockholm, and colleagues and funded by the Karolinska Institute. It was published online in Alzheimer’s Research and Therapy.

LIMITATIONS:

Use of a health care registry could have led to over- or underestimation of depression, MCI and AD. The study probably captures most people with depression but not most people with depressive symptoms.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors reported no relevant conflicts.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Do new Alzheimer’s drugs get us closer to solving the Alzheimer’s disease riddle?

Two antiamyloid drugs were recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating early-stage Alzheimer’s disease (AD). In trials of both lecanemab (Leqembi) and donanemab, a long-held neuropharmacologic dream was realized: Most amyloid plaques – the primary pathologic marker for AD – were eliminated from the brains of patients with late pre-AD or early AD.

Implications for the amyloid hypothesis

The reduction of amyloid plaques has been argued by many scientists and clinical authorities to be the likely pharmacologic solution for AD. These trials are appropriately viewed as a test of the hypothesis that amyloid bodies are a primary cause of the neurobehavioral symptoms we call AD.

In parallel with that striking reduction in amyloid bodies, drug-treated patients had an initially slower progression of neurobehavioral decline than did placebo-treated control patients. That slowing in symptom progression was accompanied by a modest but statistically significant difference in neurobehavioral ability. After several months in treatment, the rate of decline again paralleled that recorded in the control group. The sustained difference of about a half point on cognitive assessment scores separating treatment and control participants was well short of the 1.5-point difference typically considered clinically significant.

A small number of unexpected and unexplained deaths occurred in the treatment groups. Brain swelling and/or micro-hemorrhages were seen in 20%-30% of treated individuals. Significant brain shrinkage was recorded. These adverse findings are indicative of drug-induced trauma in the target organ for these drugs (i.e., the brain) and were the basis for a boxed warning label for drug usage. Antiamyloid drug treatment was not effective in patients who had higher initial numbers of amyloid plaques, indicating that these drugs would not measurably help the majority of AD patients, who are at more advanced disease stages.

These drugs do not appear to be an “answer” for AD. A modest delay in progression does not mean that we’re on a path to a “cure.” Treatment cost estimates are high – more than $80,000 per year. With requisite PET exams and high copays, patient accessibility issues will be daunting.

Of note, To the contrary, they add strong support for the counterargument that the emergence of amyloid plaques is an effect and not a fundamental cause of that progressive loss of neurologic function that we ultimately define as “Alzheimer’s disease.”

Time to switch gears

The more obvious path to winning the battle against this human scourge is prevention. A recent analysis published in The Lancet argued that about 40% of AD and other dementias are potentially preventable. I disagree. I believe that 80%-90% of prospective cases can be substantially delayed or prevented. Studies have shown that progression to AD or other dementias is driven primarily by the progressive deterioration of organic brain health, expressed by the loss of what psychologists have termed “cognitive reserve.” Cognitive reserve is resilience arising from active brain usage, akin to physical resilience attributable to a physically active life. Scientific studies have shown us that an individual’s cognitive resilience (reserve) is a greater predictor of risk for dementia than are amyloid plaques – indeed, greater than any combination of pathologic markers in dementia patients.

Building up cognitive reserve

It’s increasingly clear to this observer that cognitive reserve is synonymous with organic brain health. The primary factors that underlie cognitive reserve are processing speed in the brain, executive control, response withholding, memory acquisition, reasoning, and attention abilities. Faster, more accurate brains are necessarily more physically optimized. They necessarily sustain brain system connectivity. They are necessarily healthier. Such brains bear a relatively low risk of developing AD or other dementias, just as physically healthier bodies bear a lower risk of being prematurely banished to semi-permanent residence in an easy chair or a bed.

Brain health can be sustained by deploying inexpensive, self-administered, app-based assessments of neurologic performance limits, which inform patients and their medical teams about general brain health status. These assessments can help doctors guide their patients to adopt more intelligent brain-healthy lifestyles, or direct them to the “brain gym” to progressively exercise their brains in ways that contribute to rapid, potentially large-scale, rejuvenating improvements in physical and functional brain health.

Randomized controlled trials incorporating different combinations of physical exercise, diet, and cognitive training have recorded significant improvements in physical and functional neurologic status, indicating substantially advanced brain health. Consistent moderate-to-intense physical exercise, brain- and heart-healthy eating habits, and, particularly, computerized brain training have repeatedly been shown to improve cognitive function and physically rejuvenate the brain. With cognitive training in the right forms, improvements in processing speed and other measures manifest improving brain health and greater safety.

In the National Institutes of Health–funded ACTIVE study with more than 2,800 older adults, just 10-18 hours of a specific speed of processing training (now part of BrainHQ, a program that I was involved in developing) reduced the probability of a progression to dementia over the following 10 years by 29%, and by 48% in those who did the most training.

This approach is several orders of magnitude less expensive than the pricey new AD drugs. It presents less serious issues of accessibility and has no side effects. It delivers far more powerful therapeutic benefits in older normal and at-risk populations.

Sustained wellness supporting prevention is the far more sensible medical way forward to save people from AD and other dementias – at a far lower medical and societal cost.

Dr. Merzenich is professor emeritus, department of neuroscience, University of California, San Francisco. He reported conflicts of interest with Posit Science, Stronger Brains, and the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two antiamyloid drugs were recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating early-stage Alzheimer’s disease (AD). In trials of both lecanemab (Leqembi) and donanemab, a long-held neuropharmacologic dream was realized: Most amyloid plaques – the primary pathologic marker for AD – were eliminated from the brains of patients with late pre-AD or early AD.

Implications for the amyloid hypothesis

The reduction of amyloid plaques has been argued by many scientists and clinical authorities to be the likely pharmacologic solution for AD. These trials are appropriately viewed as a test of the hypothesis that amyloid bodies are a primary cause of the neurobehavioral symptoms we call AD.

In parallel with that striking reduction in amyloid bodies, drug-treated patients had an initially slower progression of neurobehavioral decline than did placebo-treated control patients. That slowing in symptom progression was accompanied by a modest but statistically significant difference in neurobehavioral ability. After several months in treatment, the rate of decline again paralleled that recorded in the control group. The sustained difference of about a half point on cognitive assessment scores separating treatment and control participants was well short of the 1.5-point difference typically considered clinically significant.

A small number of unexpected and unexplained deaths occurred in the treatment groups. Brain swelling and/or micro-hemorrhages were seen in 20%-30% of treated individuals. Significant brain shrinkage was recorded. These adverse findings are indicative of drug-induced trauma in the target organ for these drugs (i.e., the brain) and were the basis for a boxed warning label for drug usage. Antiamyloid drug treatment was not effective in patients who had higher initial numbers of amyloid plaques, indicating that these drugs would not measurably help the majority of AD patients, who are at more advanced disease stages.

These drugs do not appear to be an “answer” for AD. A modest delay in progression does not mean that we’re on a path to a “cure.” Treatment cost estimates are high – more than $80,000 per year. With requisite PET exams and high copays, patient accessibility issues will be daunting.

Of note, To the contrary, they add strong support for the counterargument that the emergence of amyloid plaques is an effect and not a fundamental cause of that progressive loss of neurologic function that we ultimately define as “Alzheimer’s disease.”

Time to switch gears

The more obvious path to winning the battle against this human scourge is prevention. A recent analysis published in The Lancet argued that about 40% of AD and other dementias are potentially preventable. I disagree. I believe that 80%-90% of prospective cases can be substantially delayed or prevented. Studies have shown that progression to AD or other dementias is driven primarily by the progressive deterioration of organic brain health, expressed by the loss of what psychologists have termed “cognitive reserve.” Cognitive reserve is resilience arising from active brain usage, akin to physical resilience attributable to a physically active life. Scientific studies have shown us that an individual’s cognitive resilience (reserve) is a greater predictor of risk for dementia than are amyloid plaques – indeed, greater than any combination of pathologic markers in dementia patients.

Building up cognitive reserve

It’s increasingly clear to this observer that cognitive reserve is synonymous with organic brain health. The primary factors that underlie cognitive reserve are processing speed in the brain, executive control, response withholding, memory acquisition, reasoning, and attention abilities. Faster, more accurate brains are necessarily more physically optimized. They necessarily sustain brain system connectivity. They are necessarily healthier. Such brains bear a relatively low risk of developing AD or other dementias, just as physically healthier bodies bear a lower risk of being prematurely banished to semi-permanent residence in an easy chair or a bed.

Brain health can be sustained by deploying inexpensive, self-administered, app-based assessments of neurologic performance limits, which inform patients and their medical teams about general brain health status. These assessments can help doctors guide their patients to adopt more intelligent brain-healthy lifestyles, or direct them to the “brain gym” to progressively exercise their brains in ways that contribute to rapid, potentially large-scale, rejuvenating improvements in physical and functional brain health.

Randomized controlled trials incorporating different combinations of physical exercise, diet, and cognitive training have recorded significant improvements in physical and functional neurologic status, indicating substantially advanced brain health. Consistent moderate-to-intense physical exercise, brain- and heart-healthy eating habits, and, particularly, computerized brain training have repeatedly been shown to improve cognitive function and physically rejuvenate the brain. With cognitive training in the right forms, improvements in processing speed and other measures manifest improving brain health and greater safety.

In the National Institutes of Health–funded ACTIVE study with more than 2,800 older adults, just 10-18 hours of a specific speed of processing training (now part of BrainHQ, a program that I was involved in developing) reduced the probability of a progression to dementia over the following 10 years by 29%, and by 48% in those who did the most training.

This approach is several orders of magnitude less expensive than the pricey new AD drugs. It presents less serious issues of accessibility and has no side effects. It delivers far more powerful therapeutic benefits in older normal and at-risk populations.

Sustained wellness supporting prevention is the far more sensible medical way forward to save people from AD and other dementias – at a far lower medical and societal cost.

Dr. Merzenich is professor emeritus, department of neuroscience, University of California, San Francisco. He reported conflicts of interest with Posit Science, Stronger Brains, and the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two antiamyloid drugs were recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating early-stage Alzheimer’s disease (AD). In trials of both lecanemab (Leqembi) and donanemab, a long-held neuropharmacologic dream was realized: Most amyloid plaques – the primary pathologic marker for AD – were eliminated from the brains of patients with late pre-AD or early AD.

Implications for the amyloid hypothesis

The reduction of amyloid plaques has been argued by many scientists and clinical authorities to be the likely pharmacologic solution for AD. These trials are appropriately viewed as a test of the hypothesis that amyloid bodies are a primary cause of the neurobehavioral symptoms we call AD.

In parallel with that striking reduction in amyloid bodies, drug-treated patients had an initially slower progression of neurobehavioral decline than did placebo-treated control patients. That slowing in symptom progression was accompanied by a modest but statistically significant difference in neurobehavioral ability. After several months in treatment, the rate of decline again paralleled that recorded in the control group. The sustained difference of about a half point on cognitive assessment scores separating treatment and control participants was well short of the 1.5-point difference typically considered clinically significant.

A small number of unexpected and unexplained deaths occurred in the treatment groups. Brain swelling and/or micro-hemorrhages were seen in 20%-30% of treated individuals. Significant brain shrinkage was recorded. These adverse findings are indicative of drug-induced trauma in the target organ for these drugs (i.e., the brain) and were the basis for a boxed warning label for drug usage. Antiamyloid drug treatment was not effective in patients who had higher initial numbers of amyloid plaques, indicating that these drugs would not measurably help the majority of AD patients, who are at more advanced disease stages.

These drugs do not appear to be an “answer” for AD. A modest delay in progression does not mean that we’re on a path to a “cure.” Treatment cost estimates are high – more than $80,000 per year. With requisite PET exams and high copays, patient accessibility issues will be daunting.

Of note, To the contrary, they add strong support for the counterargument that the emergence of amyloid plaques is an effect and not a fundamental cause of that progressive loss of neurologic function that we ultimately define as “Alzheimer’s disease.”

Time to switch gears

The more obvious path to winning the battle against this human scourge is prevention. A recent analysis published in The Lancet argued that about 40% of AD and other dementias are potentially preventable. I disagree. I believe that 80%-90% of prospective cases can be substantially delayed or prevented. Studies have shown that progression to AD or other dementias is driven primarily by the progressive deterioration of organic brain health, expressed by the loss of what psychologists have termed “cognitive reserve.” Cognitive reserve is resilience arising from active brain usage, akin to physical resilience attributable to a physically active life. Scientific studies have shown us that an individual’s cognitive resilience (reserve) is a greater predictor of risk for dementia than are amyloid plaques – indeed, greater than any combination of pathologic markers in dementia patients.

Building up cognitive reserve

It’s increasingly clear to this observer that cognitive reserve is synonymous with organic brain health. The primary factors that underlie cognitive reserve are processing speed in the brain, executive control, response withholding, memory acquisition, reasoning, and attention abilities. Faster, more accurate brains are necessarily more physically optimized. They necessarily sustain brain system connectivity. They are necessarily healthier. Such brains bear a relatively low risk of developing AD or other dementias, just as physically healthier bodies bear a lower risk of being prematurely banished to semi-permanent residence in an easy chair or a bed.

Brain health can be sustained by deploying inexpensive, self-administered, app-based assessments of neurologic performance limits, which inform patients and their medical teams about general brain health status. These assessments can help doctors guide their patients to adopt more intelligent brain-healthy lifestyles, or direct them to the “brain gym” to progressively exercise their brains in ways that contribute to rapid, potentially large-scale, rejuvenating improvements in physical and functional brain health.

Randomized controlled trials incorporating different combinations of physical exercise, diet, and cognitive training have recorded significant improvements in physical and functional neurologic status, indicating substantially advanced brain health. Consistent moderate-to-intense physical exercise, brain- and heart-healthy eating habits, and, particularly, computerized brain training have repeatedly been shown to improve cognitive function and physically rejuvenate the brain. With cognitive training in the right forms, improvements in processing speed and other measures manifest improving brain health and greater safety.

In the National Institutes of Health–funded ACTIVE study with more than 2,800 older adults, just 10-18 hours of a specific speed of processing training (now part of BrainHQ, a program that I was involved in developing) reduced the probability of a progression to dementia over the following 10 years by 29%, and by 48% in those who did the most training.

This approach is several orders of magnitude less expensive than the pricey new AD drugs. It presents less serious issues of accessibility and has no side effects. It delivers far more powerful therapeutic benefits in older normal and at-risk populations.

Sustained wellness supporting prevention is the far more sensible medical way forward to save people from AD and other dementias – at a far lower medical and societal cost.

Dr. Merzenich is professor emeritus, department of neuroscience, University of California, San Francisco. He reported conflicts of interest with Posit Science, Stronger Brains, and the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for traumatic brain injury: Promising or wishful thinking?

A recent review by Hadanny and colleagues recommends hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) for acute moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) and selected patients with prolonged postconcussive syndrome.

This article piqued my curiosity because I trained in HBOT more than 20 years ago. As a passionate scuba diver, my motivation was to master treatment for air embolism and decompression illness. Thankfully, these diving accidents are rare. However, I used HBOT for nonhealing wounds, and its efficacy was sometimes remarkable.

Paradoxical results with oxygen therapy

Although it may seem self-evident that “more oxygen is better” for medical illness, this is not necessarily true. I recently interviewed Ola Didrik Saugstad, MD, who demonstrated that the traditional practice of resuscitating newborns with 100% oxygen was more toxic than resuscitation with air (which contains 21% oxygen). His counterintuitive discovery led to a lifesaving change in the international newborn resuscitation guidelines.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved HBOT for a wide variety of conditions, but some practitioners enthusiastically promote it for off-label indications. These include antiaging, autism, multiple sclerosis, and the aforementioned TBI.

More than 50 years ago, HBOT was proposed for stroke, another disorder where the brain has been deprived of oxygen. Despite obvious logic, clinical trials have been unconvincing. The FDA has not approved HBOT for stroke.

HBOT in practice

During HBOT, the patient breathes 100% oxygen while the whole body is pressurized within a hyperbaric chamber. The chamber’s construction allows pressures above normal sea level of 1.0 atmosphere absolute (ATA). For example, The U.S. Navy Treatment Table for decompression sickness recommends 100% oxygen at 2.8 ATA. Chambers may hold one or more patients at a time.

The frequency of therapy varies but often consists of 20-60 sessions lasting 90-120 minutes. For off-label use like TBI, patients usually pay out of pocket. Given the multiple treatments, costs can add up.

Inconsistent evidence and sham controls

The unwieldy 33-page evidence review by Hadanny and colleagues cites multiple studies supporting HBOT for TBI. However, many, if not all, suffer from methodological flaws. These include vague inclusion criteria, lack of a control group, small patient numbers, treatment at different times since injury, poorly defined or varying HBOT protocols, varying outcome measures, and superficial results analysis.

A sham or control arm is essential for HBOT research trials, given the potential placebo effect of placing a human being inside a large, high-tech, sealed tube for an hour or more. In some sham-controlled studies, which consisted of low-pressure oxygen (that is, 1.3 ATA as sham vs. 2.4 ATA as treatment), all groups experienced symptom improvement. The review authors argue that the low-dose HBOT sham arms were biologically active and that the improvements seen mean that both high- and low-dose HBOT is therapeutic. The alternative explanation is that the placebo effect accounted for improvement in both groups.

The late Michael Bennett, a world authority on hyperbaric and underwater medicine, doubted that conventional HBOT sham controls could genuinely have a therapeutic effect, and I agree. The upcoming HOT-POCS trial (discussed below) should answer the question more definitively.

Mechanisms of action and safety

Mechanisms of benefit for HBOT include increased oxygen availability and angiogenesis. Animal research suggests that it may reduce secondary cell death from TBI, through stabilization of the blood-brain barrier and inflammation reduction.

HBOT is generally safe and well tolerated. A retrospective analysis of 1.5 million outpatient hyperbaric treatments revealed that less than 1% were associated with adverse events. The most common were ear and sinus barotrauma. Because HBOT uses increased air pressure, patients must equalize their ears and sinuses. Those who cannot because of altered consciousness, anatomical defects, or congestion must undergo myringotomy or terminate therapy. Claustrophobia was the second most common adverse effect. Convulsions and tension pneumocephalus were rare.

Perhaps the most concerning risk of HBOT for patients with TBI is the potential waste of human and financial resources.

Desperate physicians and patients

As a neurologist who regularly treats patients with TBI, I share the review authors’ frustration regarding the limited efficacy of available treatments. However, the suboptimal efficacy of currently available therapy is insufficient justification to recommend HBOT.

With respect to chronic TBI, it is difficult to imagine how HBOT could reverse brain injury that has been present for months or years. No other therapy exists that reliably encourages neuronal regeneration or prevents the development of posttraumatic epilepsy.

Frank Conidi, MD, a board-certified sports neurologist and headache specialist, shared his thoughts via email. He agrees that HBOT may have a role in TBI, but after reviewing Hadanny and colleagues’ paper, he concluded that there is insufficient evidence for the use of HBOT in all forms of TBI. He would like to see large multicenter, well-designed studies with standardized pressures and duration and a standard definition of the various types of head injury.

Ongoing research

There are at least five ongoing trials on HBOT for TBI or postconcussive syndrome, including the well-designed placebo-controlled HOT-POCS study. The latter has a novel placebo gas system that addresses Hadanny and colleagues’ contention that even low-dose HBOT might be effective.

The placebo arm in HOT-POCS mimics the HBO environment but provides only 0.21 ATA of oxygen, the same as room air. The active arm provides 100% oxygen at 2.0 ATA. If patients in both arms improve, the benefit will be caused by a placebo response, not HBOT.

Conflict of interest

Another concern with the review is that all three authors are affiliated with Aviv Scientific. This company has an exclusive partnership with the world’s largest hyperbaric medicine and research facility, the Sagol Center at Shamir Medical Center in Be’er Ya’akov, Israel.

This conflict of interest does not a priori invalidate their conclusions. However, official HBOT guidelines from a leading organization like the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine Society or the American Academy of Neurology would be preferable.

Conclusion

There is an urgent unmet need for more effective treatments for postconcussive syndrome and chronic TBI.

The review authors’ recommendations for HBOT seem premature. They are arguably a disservice to the many desperate patients and their families who will be tempted to expend valuable resources of time and money for an appealing but unproven therapy. Appropriately designed placebo-controlled studies such as HOT-POCS will help separate fact from wishful thinking.

Dr. Wilner is associate professor of neurology at University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis. He reported a conflict of interest with Accordant Health Services.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A recent review by Hadanny and colleagues recommends hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) for acute moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) and selected patients with prolonged postconcussive syndrome.

This article piqued my curiosity because I trained in HBOT more than 20 years ago. As a passionate scuba diver, my motivation was to master treatment for air embolism and decompression illness. Thankfully, these diving accidents are rare. However, I used HBOT for nonhealing wounds, and its efficacy was sometimes remarkable.

Paradoxical results with oxygen therapy

Although it may seem self-evident that “more oxygen is better” for medical illness, this is not necessarily true. I recently interviewed Ola Didrik Saugstad, MD, who demonstrated that the traditional practice of resuscitating newborns with 100% oxygen was more toxic than resuscitation with air (which contains 21% oxygen). His counterintuitive discovery led to a lifesaving change in the international newborn resuscitation guidelines.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved HBOT for a wide variety of conditions, but some practitioners enthusiastically promote it for off-label indications. These include antiaging, autism, multiple sclerosis, and the aforementioned TBI.

More than 50 years ago, HBOT was proposed for stroke, another disorder where the brain has been deprived of oxygen. Despite obvious logic, clinical trials have been unconvincing. The FDA has not approved HBOT for stroke.

HBOT in practice

During HBOT, the patient breathes 100% oxygen while the whole body is pressurized within a hyperbaric chamber. The chamber’s construction allows pressures above normal sea level of 1.0 atmosphere absolute (ATA). For example, The U.S. Navy Treatment Table for decompression sickness recommends 100% oxygen at 2.8 ATA. Chambers may hold one or more patients at a time.

The frequency of therapy varies but often consists of 20-60 sessions lasting 90-120 minutes. For off-label use like TBI, patients usually pay out of pocket. Given the multiple treatments, costs can add up.

Inconsistent evidence and sham controls

The unwieldy 33-page evidence review by Hadanny and colleagues cites multiple studies supporting HBOT for TBI. However, many, if not all, suffer from methodological flaws. These include vague inclusion criteria, lack of a control group, small patient numbers, treatment at different times since injury, poorly defined or varying HBOT protocols, varying outcome measures, and superficial results analysis.

A sham or control arm is essential for HBOT research trials, given the potential placebo effect of placing a human being inside a large, high-tech, sealed tube for an hour or more. In some sham-controlled studies, which consisted of low-pressure oxygen (that is, 1.3 ATA as sham vs. 2.4 ATA as treatment), all groups experienced symptom improvement. The review authors argue that the low-dose HBOT sham arms were biologically active and that the improvements seen mean that both high- and low-dose HBOT is therapeutic. The alternative explanation is that the placebo effect accounted for improvement in both groups.

The late Michael Bennett, a world authority on hyperbaric and underwater medicine, doubted that conventional HBOT sham controls could genuinely have a therapeutic effect, and I agree. The upcoming HOT-POCS trial (discussed below) should answer the question more definitively.

Mechanisms of action and safety

Mechanisms of benefit for HBOT include increased oxygen availability and angiogenesis. Animal research suggests that it may reduce secondary cell death from TBI, through stabilization of the blood-brain barrier and inflammation reduction.

HBOT is generally safe and well tolerated. A retrospective analysis of 1.5 million outpatient hyperbaric treatments revealed that less than 1% were associated with adverse events. The most common were ear and sinus barotrauma. Because HBOT uses increased air pressure, patients must equalize their ears and sinuses. Those who cannot because of altered consciousness, anatomical defects, or congestion must undergo myringotomy or terminate therapy. Claustrophobia was the second most common adverse effect. Convulsions and tension pneumocephalus were rare.

Perhaps the most concerning risk of HBOT for patients with TBI is the potential waste of human and financial resources.

Desperate physicians and patients

As a neurologist who regularly treats patients with TBI, I share the review authors’ frustration regarding the limited efficacy of available treatments. However, the suboptimal efficacy of currently available therapy is insufficient justification to recommend HBOT.

With respect to chronic TBI, it is difficult to imagine how HBOT could reverse brain injury that has been present for months or years. No other therapy exists that reliably encourages neuronal regeneration or prevents the development of posttraumatic epilepsy.

Frank Conidi, MD, a board-certified sports neurologist and headache specialist, shared his thoughts via email. He agrees that HBOT may have a role in TBI, but after reviewing Hadanny and colleagues’ paper, he concluded that there is insufficient evidence for the use of HBOT in all forms of TBI. He would like to see large multicenter, well-designed studies with standardized pressures and duration and a standard definition of the various types of head injury.

Ongoing research

There are at least five ongoing trials on HBOT for TBI or postconcussive syndrome, including the well-designed placebo-controlled HOT-POCS study. The latter has a novel placebo gas system that addresses Hadanny and colleagues’ contention that even low-dose HBOT might be effective.

The placebo arm in HOT-POCS mimics the HBO environment but provides only 0.21 ATA of oxygen, the same as room air. The active arm provides 100% oxygen at 2.0 ATA. If patients in both arms improve, the benefit will be caused by a placebo response, not HBOT.

Conflict of interest

Another concern with the review is that all three authors are affiliated with Aviv Scientific. This company has an exclusive partnership with the world’s largest hyperbaric medicine and research facility, the Sagol Center at Shamir Medical Center in Be’er Ya’akov, Israel.

This conflict of interest does not a priori invalidate their conclusions. However, official HBOT guidelines from a leading organization like the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine Society or the American Academy of Neurology would be preferable.

Conclusion

There is an urgent unmet need for more effective treatments for postconcussive syndrome and chronic TBI.

The review authors’ recommendations for HBOT seem premature. They are arguably a disservice to the many desperate patients and their families who will be tempted to expend valuable resources of time and money for an appealing but unproven therapy. Appropriately designed placebo-controlled studies such as HOT-POCS will help separate fact from wishful thinking.

Dr. Wilner is associate professor of neurology at University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis. He reported a conflict of interest with Accordant Health Services.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A recent review by Hadanny and colleagues recommends hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) for acute moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) and selected patients with prolonged postconcussive syndrome.

This article piqued my curiosity because I trained in HBOT more than 20 years ago. As a passionate scuba diver, my motivation was to master treatment for air embolism and decompression illness. Thankfully, these diving accidents are rare. However, I used HBOT for nonhealing wounds, and its efficacy was sometimes remarkable.

Paradoxical results with oxygen therapy

Although it may seem self-evident that “more oxygen is better” for medical illness, this is not necessarily true. I recently interviewed Ola Didrik Saugstad, MD, who demonstrated that the traditional practice of resuscitating newborns with 100% oxygen was more toxic than resuscitation with air (which contains 21% oxygen). His counterintuitive discovery led to a lifesaving change in the international newborn resuscitation guidelines.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved HBOT for a wide variety of conditions, but some practitioners enthusiastically promote it for off-label indications. These include antiaging, autism, multiple sclerosis, and the aforementioned TBI.

More than 50 years ago, HBOT was proposed for stroke, another disorder where the brain has been deprived of oxygen. Despite obvious logic, clinical trials have been unconvincing. The FDA has not approved HBOT for stroke.

HBOT in practice

During HBOT, the patient breathes 100% oxygen while the whole body is pressurized within a hyperbaric chamber. The chamber’s construction allows pressures above normal sea level of 1.0 atmosphere absolute (ATA). For example, The U.S. Navy Treatment Table for decompression sickness recommends 100% oxygen at 2.8 ATA. Chambers may hold one or more patients at a time.

The frequency of therapy varies but often consists of 20-60 sessions lasting 90-120 minutes. For off-label use like TBI, patients usually pay out of pocket. Given the multiple treatments, costs can add up.

Inconsistent evidence and sham controls

The unwieldy 33-page evidence review by Hadanny and colleagues cites multiple studies supporting HBOT for TBI. However, many, if not all, suffer from methodological flaws. These include vague inclusion criteria, lack of a control group, small patient numbers, treatment at different times since injury, poorly defined or varying HBOT protocols, varying outcome measures, and superficial results analysis.

A sham or control arm is essential for HBOT research trials, given the potential placebo effect of placing a human being inside a large, high-tech, sealed tube for an hour or more. In some sham-controlled studies, which consisted of low-pressure oxygen (that is, 1.3 ATA as sham vs. 2.4 ATA as treatment), all groups experienced symptom improvement. The review authors argue that the low-dose HBOT sham arms were biologically active and that the improvements seen mean that both high- and low-dose HBOT is therapeutic. The alternative explanation is that the placebo effect accounted for improvement in both groups.

The late Michael Bennett, a world authority on hyperbaric and underwater medicine, doubted that conventional HBOT sham controls could genuinely have a therapeutic effect, and I agree. The upcoming HOT-POCS trial (discussed below) should answer the question more definitively.

Mechanisms of action and safety

Mechanisms of benefit for HBOT include increased oxygen availability and angiogenesis. Animal research suggests that it may reduce secondary cell death from TBI, through stabilization of the blood-brain barrier and inflammation reduction.

HBOT is generally safe and well tolerated. A retrospective analysis of 1.5 million outpatient hyperbaric treatments revealed that less than 1% were associated with adverse events. The most common were ear and sinus barotrauma. Because HBOT uses increased air pressure, patients must equalize their ears and sinuses. Those who cannot because of altered consciousness, anatomical defects, or congestion must undergo myringotomy or terminate therapy. Claustrophobia was the second most common adverse effect. Convulsions and tension pneumocephalus were rare.

Perhaps the most concerning risk of HBOT for patients with TBI is the potential waste of human and financial resources.

Desperate physicians and patients

As a neurologist who regularly treats patients with TBI, I share the review authors’ frustration regarding the limited efficacy of available treatments. However, the suboptimal efficacy of currently available therapy is insufficient justification to recommend HBOT.

With respect to chronic TBI, it is difficult to imagine how HBOT could reverse brain injury that has been present for months or years. No other therapy exists that reliably encourages neuronal regeneration or prevents the development of posttraumatic epilepsy.

Frank Conidi, MD, a board-certified sports neurologist and headache specialist, shared his thoughts via email. He agrees that HBOT may have a role in TBI, but after reviewing Hadanny and colleagues’ paper, he concluded that there is insufficient evidence for the use of HBOT in all forms of TBI. He would like to see large multicenter, well-designed studies with standardized pressures and duration and a standard definition of the various types of head injury.

Ongoing research

There are at least five ongoing trials on HBOT for TBI or postconcussive syndrome, including the well-designed placebo-controlled HOT-POCS study. The latter has a novel placebo gas system that addresses Hadanny and colleagues’ contention that even low-dose HBOT might be effective.

The placebo arm in HOT-POCS mimics the HBO environment but provides only 0.21 ATA of oxygen, the same as room air. The active arm provides 100% oxygen at 2.0 ATA. If patients in both arms improve, the benefit will be caused by a placebo response, not HBOT.

Conflict of interest

Another concern with the review is that all three authors are affiliated with Aviv Scientific. This company has an exclusive partnership with the world’s largest hyperbaric medicine and research facility, the Sagol Center at Shamir Medical Center in Be’er Ya’akov, Israel.

This conflict of interest does not a priori invalidate their conclusions. However, official HBOT guidelines from a leading organization like the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine Society or the American Academy of Neurology would be preferable.

Conclusion

There is an urgent unmet need for more effective treatments for postconcussive syndrome and chronic TBI.

The review authors’ recommendations for HBOT seem premature. They are arguably a disservice to the many desperate patients and their families who will be tempted to expend valuable resources of time and money for an appealing but unproven therapy. Appropriately designed placebo-controlled studies such as HOT-POCS will help separate fact from wishful thinking.

Dr. Wilner is associate professor of neurology at University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis. He reported a conflict of interest with Accordant Health Services.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Loneliness tied to increased risk for Parkinson’s disease

TOPLINE:

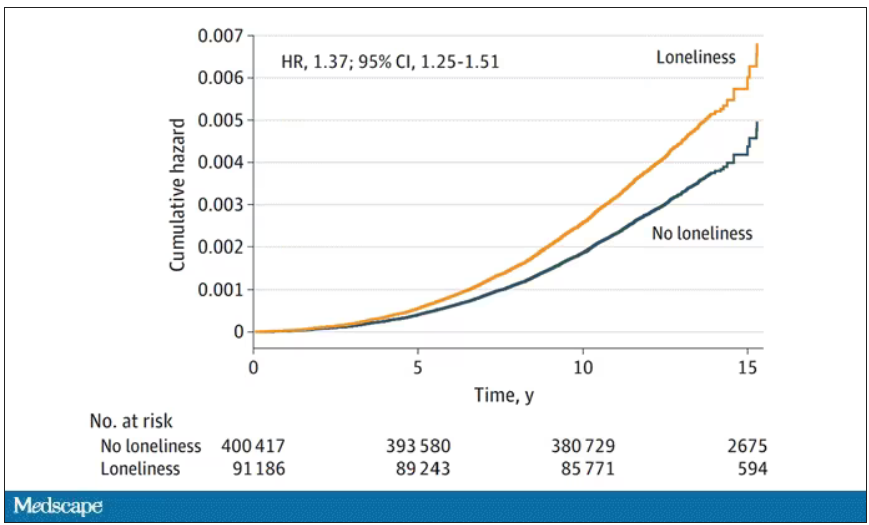

Loneliness is associated with a higher risk of developing Parkinson’s disease (PD) across demographic groups and independent of other risk factors, data from nearly 500,000 U.K. adults suggest.

METHODOLOGY:

- Loneliness is associated with illness and death, including higher risk of neurodegenerative diseases, but no study has examined whether the association between loneliness and detrimental outcomes extends to PD.

- The current analysis included 491,603 U.K. Biobank participants (mean age, 56; 54% women) without a diagnosis of PD at baseline.

- Loneliness was assessed by a single question at baseline and incident PD was ascertained via health records over 15 years.

- Researchers assessed whether the association between loneliness and PD was moderated by age, sex, or genetic risk and whether the association was accounted for by sociodemographic factors; behavioral, mental, physical, or social factors; or genetic risk.

TAKEAWAY:

- Roughly 19% of the cohort reported being lonely. Compared with those who were not lonely, those who did report being lonely were slightly younger and were more likely to be women. They also had fewer resources, more health risk behaviors (current smoker and physically inactive), and worse physical and mental health.

- Over 15+ years of follow-up, 2,822 participants developed PD (incidence rate: 47 per 100,000 person-years). Compared with those who did not develop PD, those who did were older and more likely to be male, former smokers, have higher BMI and PD polygenetic risk score, and to have diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction or stroke, anxiety, or depression.

- In the primary analysis, individuals who reported being lonely had a higher risk for PD (hazard ratio, 1.37) – an association that remained after accounting for demographic and socioeconomic status, social isolation, PD polygenetic risk score, smoking, physical activity, BMI, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, depression, and having ever seen a psychiatrist (fully adjusted HR, 1.25).

- The association between loneliness and incident PD was not moderated by sex, age, or polygenetic risk score.

- Contrary to expectations for a prodromal syndrome, loneliness was not associated with incident PD in the first 5 years after baseline but was associated with PD risk in the subsequent 10 years of follow-up (HR, 1.32).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings complement other evidence that loneliness is a psychosocial determinant of health associated with increased risk of morbidity and mortality [and] supports recent calls for the protective and healing effects of personally meaningful social connection,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Antonio Terracciano, PhD, of Florida State University College of Medicine, Tallahassee, was published online in JAMA Neurology.

LIMITATIONS:

This observational study could not determine causality or whether reverse causality could explain the association. Loneliness was assessed by a single yes/no question. PD diagnosis relied on hospital admission and death records and may have missed early PD diagnoses.

DISCLOSURES:

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Health and National Institute on Aging. The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

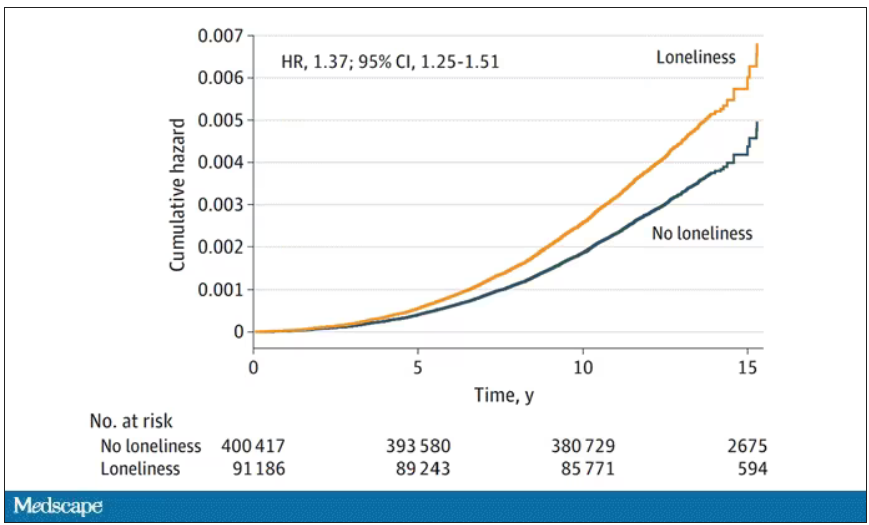

TOPLINE:

Loneliness is associated with a higher risk of developing Parkinson’s disease (PD) across demographic groups and independent of other risk factors, data from nearly 500,000 U.K. adults suggest.

METHODOLOGY:

- Loneliness is associated with illness and death, including higher risk of neurodegenerative diseases, but no study has examined whether the association between loneliness and detrimental outcomes extends to PD.

- The current analysis included 491,603 U.K. Biobank participants (mean age, 56; 54% women) without a diagnosis of PD at baseline.

- Loneliness was assessed by a single question at baseline and incident PD was ascertained via health records over 15 years.

- Researchers assessed whether the association between loneliness and PD was moderated by age, sex, or genetic risk and whether the association was accounted for by sociodemographic factors; behavioral, mental, physical, or social factors; or genetic risk.

TAKEAWAY:

- Roughly 19% of the cohort reported being lonely. Compared with those who were not lonely, those who did report being lonely were slightly younger and were more likely to be women. They also had fewer resources, more health risk behaviors (current smoker and physically inactive), and worse physical and mental health.

- Over 15+ years of follow-up, 2,822 participants developed PD (incidence rate: 47 per 100,000 person-years). Compared with those who did not develop PD, those who did were older and more likely to be male, former smokers, have higher BMI and PD polygenetic risk score, and to have diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction or stroke, anxiety, or depression.

- In the primary analysis, individuals who reported being lonely had a higher risk for PD (hazard ratio, 1.37) – an association that remained after accounting for demographic and socioeconomic status, social isolation, PD polygenetic risk score, smoking, physical activity, BMI, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, depression, and having ever seen a psychiatrist (fully adjusted HR, 1.25).

- The association between loneliness and incident PD was not moderated by sex, age, or polygenetic risk score.

- Contrary to expectations for a prodromal syndrome, loneliness was not associated with incident PD in the first 5 years after baseline but was associated with PD risk in the subsequent 10 years of follow-up (HR, 1.32).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings complement other evidence that loneliness is a psychosocial determinant of health associated with increased risk of morbidity and mortality [and] supports recent calls for the protective and healing effects of personally meaningful social connection,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Antonio Terracciano, PhD, of Florida State University College of Medicine, Tallahassee, was published online in JAMA Neurology.

LIMITATIONS:

This observational study could not determine causality or whether reverse causality could explain the association. Loneliness was assessed by a single yes/no question. PD diagnosis relied on hospital admission and death records and may have missed early PD diagnoses.

DISCLOSURES:

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Health and National Institute on Aging. The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

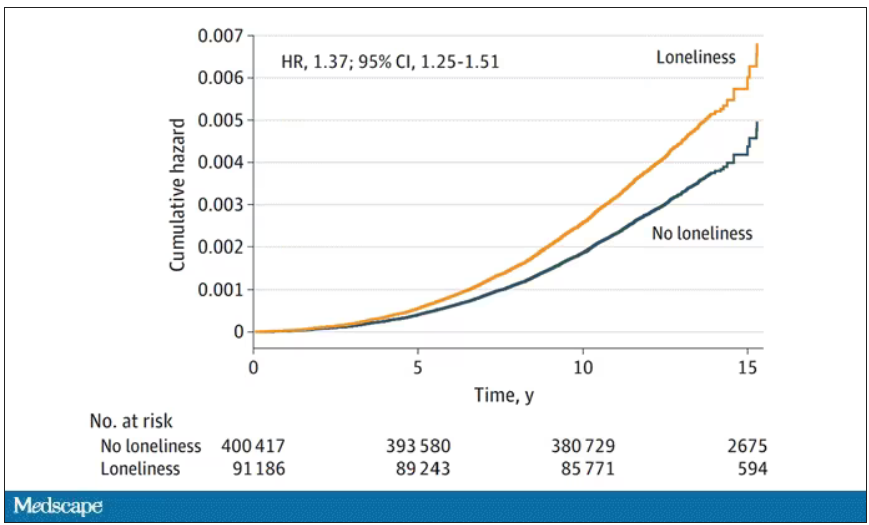

TOPLINE:

Loneliness is associated with a higher risk of developing Parkinson’s disease (PD) across demographic groups and independent of other risk factors, data from nearly 500,000 U.K. adults suggest.

METHODOLOGY:

- Loneliness is associated with illness and death, including higher risk of neurodegenerative diseases, but no study has examined whether the association between loneliness and detrimental outcomes extends to PD.

- The current analysis included 491,603 U.K. Biobank participants (mean age, 56; 54% women) without a diagnosis of PD at baseline.

- Loneliness was assessed by a single question at baseline and incident PD was ascertained via health records over 15 years.

- Researchers assessed whether the association between loneliness and PD was moderated by age, sex, or genetic risk and whether the association was accounted for by sociodemographic factors; behavioral, mental, physical, or social factors; or genetic risk.

TAKEAWAY:

- Roughly 19% of the cohort reported being lonely. Compared with those who were not lonely, those who did report being lonely were slightly younger and were more likely to be women. They also had fewer resources, more health risk behaviors (current smoker and physically inactive), and worse physical and mental health.

- Over 15+ years of follow-up, 2,822 participants developed PD (incidence rate: 47 per 100,000 person-years). Compared with those who did not develop PD, those who did were older and more likely to be male, former smokers, have higher BMI and PD polygenetic risk score, and to have diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction or stroke, anxiety, or depression.

- In the primary analysis, individuals who reported being lonely had a higher risk for PD (hazard ratio, 1.37) – an association that remained after accounting for demographic and socioeconomic status, social isolation, PD polygenetic risk score, smoking, physical activity, BMI, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, depression, and having ever seen a psychiatrist (fully adjusted HR, 1.25).

- The association between loneliness and incident PD was not moderated by sex, age, or polygenetic risk score.

- Contrary to expectations for a prodromal syndrome, loneliness was not associated with incident PD in the first 5 years after baseline but was associated with PD risk in the subsequent 10 years of follow-up (HR, 1.32).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings complement other evidence that loneliness is a psychosocial determinant of health associated with increased risk of morbidity and mortality [and] supports recent calls for the protective and healing effects of personally meaningful social connection,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Antonio Terracciano, PhD, of Florida State University College of Medicine, Tallahassee, was published online in JAMA Neurology.

LIMITATIONS:

This observational study could not determine causality or whether reverse causality could explain the association. Loneliness was assessed by a single yes/no question. PD diagnosis relied on hospital admission and death records and may have missed early PD diagnoses.

DISCLOSURES:

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Health and National Institute on Aging. The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The surprising link between loneliness and Parkinson’s disease

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

On May 3, 2023, Surgeon General Vivek Murthy issued an advisory raising an alarm about what he called an “epidemic of loneliness” in the United States.

Now, I am not saying that Vivek Murthy read my book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t” – released in January and available in bookstores now – where, in chapter 11, I call attention to the problem of loneliness and its relationship to the exponential rise in deaths of despair. But Vivek, if you did, let me know. I could use the publicity.

No, of course the idea that loneliness is a public health issue is not new, but I’m glad to see it finally getting attention. At this point, studies have linked loneliness to heart disease, stroke, dementia, and premature death.

The UK Biobank is really a treasure trove of data for epidemiologists. I must see three to four studies a week coming out of this mega-dataset. This one, appearing in JAMA Neurology, caught my eye for its focus specifically on loneliness as a risk factor – something I’m hoping to see more of in the future.

The study examines data from just under 500,000 individuals in the United Kingdom who answered a survey including the question “Do you often feel lonely?” between 2006 and 2010; 18.4% of people answered yes. Individuals’ electronic health record data were then monitored over time to see who would get a new diagnosis code consistent with Parkinson’s disease. Through 2021, 2822 people did – that’s just over half a percent.

So, now we do the statistics thing. Of the nonlonely folks, 2,273 went on to develop Parkinson’s disease. Of those who said they often feel lonely, 549 people did. The raw numbers here, to be honest, aren’t that compelling. Lonely people had an absolute risk for Parkinson’s disease about 0.03% higher than that of nonlonely people. Put another way, you’d need to take over 3,000 lonely souls and make them not lonely to prevent 1 case of Parkinson’s disease.

Still, the costs of loneliness are not measured exclusively in Parkinson’s disease, and I would argue that the real risks here come from other sources: alcohol abuse, drug abuse, and suicide. Nevertheless, the weak but significant association with Parkinson’s disease reminds us that loneliness is a neurologic phenomenon. There is something about social connection that affects our brain in a way that is not just spiritual; it is actually biological.

Of course, people who say they are often lonely are different in other ways from people who report not being lonely. Lonely people, in this dataset, were younger, more likely to be female, less likely to have a college degree, in worse physical health, and engaged in more high-risk health behaviors like smoking.

The authors adjusted for all of these factors and found that, on the relative scale, lonely people were still about 20%-30% more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease.

So, what do we do about this? There is no pill for loneliness, and God help us if there ever is. Recognizing the problem is a good start. But there are some policy things we can do to reduce loneliness. We can invest in public spaces that bring people together – parks, museums, libraries – and public transportation. We can deal with tech companies that are so optimized at capturing our attention that we cease to engage with other humans. And, individually, we can just reach out a bit more. We’ve spent the past few pandemic years with our attention focused sharply inward. It’s time to look out again.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

On May 3, 2023, Surgeon General Vivek Murthy issued an advisory raising an alarm about what he called an “epidemic of loneliness” in the United States.

Now, I am not saying that Vivek Murthy read my book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t” – released in January and available in bookstores now – where, in chapter 11, I call attention to the problem of loneliness and its relationship to the exponential rise in deaths of despair. But Vivek, if you did, let me know. I could use the publicity.

No, of course the idea that loneliness is a public health issue is not new, but I’m glad to see it finally getting attention. At this point, studies have linked loneliness to heart disease, stroke, dementia, and premature death.

The UK Biobank is really a treasure trove of data for epidemiologists. I must see three to four studies a week coming out of this mega-dataset. This one, appearing in JAMA Neurology, caught my eye for its focus specifically on loneliness as a risk factor – something I’m hoping to see more of in the future.

The study examines data from just under 500,000 individuals in the United Kingdom who answered a survey including the question “Do you often feel lonely?” between 2006 and 2010; 18.4% of people answered yes. Individuals’ electronic health record data were then monitored over time to see who would get a new diagnosis code consistent with Parkinson’s disease. Through 2021, 2822 people did – that’s just over half a percent.

So, now we do the statistics thing. Of the nonlonely folks, 2,273 went on to develop Parkinson’s disease. Of those who said they often feel lonely, 549 people did. The raw numbers here, to be honest, aren’t that compelling. Lonely people had an absolute risk for Parkinson’s disease about 0.03% higher than that of nonlonely people. Put another way, you’d need to take over 3,000 lonely souls and make them not lonely to prevent 1 case of Parkinson’s disease.

Still, the costs of loneliness are not measured exclusively in Parkinson’s disease, and I would argue that the real risks here come from other sources: alcohol abuse, drug abuse, and suicide. Nevertheless, the weak but significant association with Parkinson’s disease reminds us that loneliness is a neurologic phenomenon. There is something about social connection that affects our brain in a way that is not just spiritual; it is actually biological.

Of course, people who say they are often lonely are different in other ways from people who report not being lonely. Lonely people, in this dataset, were younger, more likely to be female, less likely to have a college degree, in worse physical health, and engaged in more high-risk health behaviors like smoking.

The authors adjusted for all of these factors and found that, on the relative scale, lonely people were still about 20%-30% more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease.

So, what do we do about this? There is no pill for loneliness, and God help us if there ever is. Recognizing the problem is a good start. But there are some policy things we can do to reduce loneliness. We can invest in public spaces that bring people together – parks, museums, libraries – and public transportation. We can deal with tech companies that are so optimized at capturing our attention that we cease to engage with other humans. And, individually, we can just reach out a bit more. We’ve spent the past few pandemic years with our attention focused sharply inward. It’s time to look out again.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

On May 3, 2023, Surgeon General Vivek Murthy issued an advisory raising an alarm about what he called an “epidemic of loneliness” in the United States.

Now, I am not saying that Vivek Murthy read my book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t” – released in January and available in bookstores now – where, in chapter 11, I call attention to the problem of loneliness and its relationship to the exponential rise in deaths of despair. But Vivek, if you did, let me know. I could use the publicity.

No, of course the idea that loneliness is a public health issue is not new, but I’m glad to see it finally getting attention. At this point, studies have linked loneliness to heart disease, stroke, dementia, and premature death.

The UK Biobank is really a treasure trove of data for epidemiologists. I must see three to four studies a week coming out of this mega-dataset. This one, appearing in JAMA Neurology, caught my eye for its focus specifically on loneliness as a risk factor – something I’m hoping to see more of in the future.

The study examines data from just under 500,000 individuals in the United Kingdom who answered a survey including the question “Do you often feel lonely?” between 2006 and 2010; 18.4% of people answered yes. Individuals’ electronic health record data were then monitored over time to see who would get a new diagnosis code consistent with Parkinson’s disease. Through 2021, 2822 people did – that’s just over half a percent.

So, now we do the statistics thing. Of the nonlonely folks, 2,273 went on to develop Parkinson’s disease. Of those who said they often feel lonely, 549 people did. The raw numbers here, to be honest, aren’t that compelling. Lonely people had an absolute risk for Parkinson’s disease about 0.03% higher than that of nonlonely people. Put another way, you’d need to take over 3,000 lonely souls and make them not lonely to prevent 1 case of Parkinson’s disease.

Still, the costs of loneliness are not measured exclusively in Parkinson’s disease, and I would argue that the real risks here come from other sources: alcohol abuse, drug abuse, and suicide. Nevertheless, the weak but significant association with Parkinson’s disease reminds us that loneliness is a neurologic phenomenon. There is something about social connection that affects our brain in a way that is not just spiritual; it is actually biological.

Of course, people who say they are often lonely are different in other ways from people who report not being lonely. Lonely people, in this dataset, were younger, more likely to be female, less likely to have a college degree, in worse physical health, and engaged in more high-risk health behaviors like smoking.

The authors adjusted for all of these factors and found that, on the relative scale, lonely people were still about 20%-30% more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease.

So, what do we do about this? There is no pill for loneliness, and God help us if there ever is. Recognizing the problem is a good start. But there are some policy things we can do to reduce loneliness. We can invest in public spaces that bring people together – parks, museums, libraries – and public transportation. We can deal with tech companies that are so optimized at capturing our attention that we cease to engage with other humans. And, individually, we can just reach out a bit more. We’ve spent the past few pandemic years with our attention focused sharply inward. It’s time to look out again.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

From scrubs to screens: Growing your patient base with social media

With physicians under increasing pressure to see more patients in shorter office visits, developing a social media presence may offer valuable opportunities to connect with patients, explain procedures, combat misinformation, talk through a published article, and even share a joke or meme.

But there are caveats for doctors posting on social media platforms. This news organization spoke to four doctors who successfully use social media.

Use social media for the right reasons

While you’re under no obligation to build a social media presence, if you’re going to do it, be sure your intentions are solid, said Don S. Dizon, MD, professor of medicine and professor of surgery at Brown University, Providence, R.I. Dr. Dizon, as @DoctorDon, has 44,700 TikTok followers and uses the platform to answer cancer-related questions.

“It should be your altruism that motivates you to post,” said Dr. Dizon, who is also associate director of community outreach and engagement at the Legorreta Cancer Center in Providence, R.I., and director of medical oncology at Rhode Island Hospital. “What we can do for society at large is to provide our input into issues, add informed opinions where there’s controversy, and address misinformation.”

If you don’t know where to start, consider seeking a digital mentor to talk through your options.

“You may never meet this person, but you should choose them if you like their style, their content, their delivery, and their perspective,” Dr. Dizon said. “Find another doctor out there on social media whom you feel you can emulate. Take your time, too. Soon enough, you’ll develop your own style and your own online persona.”

Post clear, accurate information

If you want to be lighthearted on social media, that’s your choice. But Jennifer Trachtenberg, a pediatrician with nearly 7,000 Instagram followers in New York who posts as @askdrjen, prefers to offer vaccine scheduling tips, alert parents about COVID-19 rates, and offer advice on cold and flu prevention.

“Right now, I’m mainly doing this to educate patients and make them aware of topics that I think are important and that I see my patients needing more information on,” she said. “We have to be clear: People take what we say seriously. So, while it’s important to be relatable, it’s even more important to share evidence-based information.”

Many patients get their information on social media

While patients once came to the doctor armed with information sourced via “Doctor Google,” today, just as many patients use social media to learn about their condition or the medications they’re taking.

Unfortunately, a recent Ohio State University, Columbus, study found that the majority of gynecologic cancer advice on TikTok, for example, was either misleading or inaccurate.

“This misinformation should be a motivator for physicians to explore the social media space,” Dr. Dizon said. “Our voices need to be on there.”

Break down barriers – and make connections

Mike Natter, MD, an endocrinologist in New York, has type 1 diabetes. This informs his work – and his life – and he’s passionate about sharing it with his 117,000 followers as @mike.natter on Instagram.

“A lot of type 1s follow me, so there’s an advocacy component to what I do,” he said. “I enjoy being able to raise awareness and keep people up to date on the newest research and treatment.”

But that’s not all: Dr. Natter is also an artist who went to art school before he went to medical school, and his account is rife with his cartoons and illustrations about everything from valvular disease to diabetic ketoacidosis.

“I found that I was drawing a lot of my notes in medical school,” he said. “When I drew my notes, I did quite well, and I think that using art and illustration is a great tool. It breaks down barriers and makes health information all the more accessible to everyone.”

Share your expertise as a doctor – and a person

As a mom and pediatrician, Krupa Playforth, MD, who practices in Vienna, Va., knows that what she posts carries weight. So, whether she’s writing about backpack safety tips, choking hazards, or separation anxiety, her followers can rest assured that she’s posting responsibly.

“Pediatricians often underestimate how smart parents are,” said Dr. Playforth, who has three kids, ages 8, 5, and 2, and has 137,000 followers on @thepediatricianmom, her Instagram account. “Their anxiety comes from an understandable place, which is why I see my role as that of a parent and pediatrician who can translate the knowledge pediatricians have into something parents can understand.”

Dr. Playforth, who jumped on social media during COVID-19 and experienced a positive response in her local community, said being on social media is imperative if you’re a pediatrician.

“This is the future of pediatric medicine in particular,” she said. “A lot of pediatricians don’t want to embrace social media, but I think that’s a mistake. After all, while parents think pediatricians have all the answers, when we think of our own children, most doctors are like other parents – we can’t think objectively about our kids. It’s helpful for me to share that and to help parents feel less alone.”

If you’re not yet using social media to the best of your physician abilities, you might take a shot at becoming widely recognizable. Pick a preferred platform, answer common patient questions, dispel medical myths, provide pertinent information, and let your personality shine.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With physicians under increasing pressure to see more patients in shorter office visits, developing a social media presence may offer valuable opportunities to connect with patients, explain procedures, combat misinformation, talk through a published article, and even share a joke or meme.

But there are caveats for doctors posting on social media platforms. This news organization spoke to four doctors who successfully use social media.

Use social media for the right reasons

While you’re under no obligation to build a social media presence, if you’re going to do it, be sure your intentions are solid, said Don S. Dizon, MD, professor of medicine and professor of surgery at Brown University, Providence, R.I. Dr. Dizon, as @DoctorDon, has 44,700 TikTok followers and uses the platform to answer cancer-related questions.

“It should be your altruism that motivates you to post,” said Dr. Dizon, who is also associate director of community outreach and engagement at the Legorreta Cancer Center in Providence, R.I., and director of medical oncology at Rhode Island Hospital. “What we can do for society at large is to provide our input into issues, add informed opinions where there’s controversy, and address misinformation.”

If you don’t know where to start, consider seeking a digital mentor to talk through your options.

“You may never meet this person, but you should choose them if you like their style, their content, their delivery, and their perspective,” Dr. Dizon said. “Find another doctor out there on social media whom you feel you can emulate. Take your time, too. Soon enough, you’ll develop your own style and your own online persona.”

Post clear, accurate information

If you want to be lighthearted on social media, that’s your choice. But Jennifer Trachtenberg, a pediatrician with nearly 7,000 Instagram followers in New York who posts as @askdrjen, prefers to offer vaccine scheduling tips, alert parents about COVID-19 rates, and offer advice on cold and flu prevention.

“Right now, I’m mainly doing this to educate patients and make them aware of topics that I think are important and that I see my patients needing more information on,” she said. “We have to be clear: People take what we say seriously. So, while it’s important to be relatable, it’s even more important to share evidence-based information.”

Many patients get their information on social media

While patients once came to the doctor armed with information sourced via “Doctor Google,” today, just as many patients use social media to learn about their condition or the medications they’re taking.

Unfortunately, a recent Ohio State University, Columbus, study found that the majority of gynecologic cancer advice on TikTok, for example, was either misleading or inaccurate.

“This misinformation should be a motivator for physicians to explore the social media space,” Dr. Dizon said. “Our voices need to be on there.”

Break down barriers – and make connections

Mike Natter, MD, an endocrinologist in New York, has type 1 diabetes. This informs his work – and his life – and he’s passionate about sharing it with his 117,000 followers as @mike.natter on Instagram.

“A lot of type 1s follow me, so there’s an advocacy component to what I do,” he said. “I enjoy being able to raise awareness and keep people up to date on the newest research and treatment.”