User login

Little Less Talk and a Lot More Action

No matter where one looks for the statistics, no matter what words one chooses to describe it, this country has a child and adolescent mental health crisis. Almost 20% of young people in the 3-17 age bracket have a mental, emotional, developmental, or behavioral disorder. COVID-19 has certainly exacerbated the problem, but the downward trend in the mental health of this nation has been going on for decades.

The voices calling for more services to address the problem are getting more numerous and louder. But, what exactly should those services look like and who should be delivering them?

When considered together, two recent research papers suggest that we should be venturing well beyond the usual mental health strategies if we are going to be successful in addressing the current crisis.

The first paper is an analysis by two psychologists who contend that our efforts to raise the awareness of mental issues may be contributing to the increase in reported mental health problems. The authors agree that more attention paid to mental health conditions can result in “more accurate reporting of previous under-recognized symptoms” and would seem to be a positive. However, the investigators also observe that when exposed to this flood of information, some individuals who are only experiencing minor distress may report their symptoms as mental problems. The authors of the paper have coined the term for this phenomenon as “prevalence inflation.” Their preliminary investigation suggests it may be much more common than once believed and they present numerous situations in which prevalence inflation seems to have occurred.

A New York Times article about this hypothesis reports on a British study in which nearly 30,000 teenagers were instructed by their teachers to “direct their attentions to the present moment” and utilize other mindfulness strategies. The educators had hoped that after 8 years of this indoctrination, the students’ mental health would have improved. The bottom line was that this mindfulness-based program was of no help and may have actually made things worse for a subgroup of students who were at greatest risk for mental health challenges.

Dr. Jack Andrews, one of the authors, feels that mindfulness training may encourage what he calls “co-rumination,” which he describes as “the kind of long, unresolved group discussion that churns up problems without finding solutions.” One has to wonder if “prevalence inflation” and “co-rumination,” if they do exist, may be playing a role in the hotly debated phenomenon some have termed “late-onset gender dysphoria.”

Never having been a fan of mindfulness training as an effective strategy, I am relieved to learn that serious investigators are finding evidence that supports my gut reaction.

If raising awareness, “education,” and group discussion aren’t working, and in some cases are actually contributing to the crisis, or at least making the data difficult to interpret, what should we be doing to turn this foundering ship around?

A second paper, coming from Taiwan, may provide an answer. Huey-Ling Chiang and fellow investigators have reported on a study of nearly two million children and adolescents in which they found improved performance in a variety of physical fitness challenges “was linked with a lower risk of mental health disorder.” The dose-dependent effect resulted in less anxiety and depressive disorders as well as less attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder when cardio-respiratory, muscle endurance, and power indices improved.

There have been other observers who have suggested a link between physical fitness and improved mental health, but this Taiwanese study is by far one of the largest. And, the discovery of a dose-dependent effect makes it particularly convincing.

As I reviewed these two papers, I became increasingly frustrated because this is another example in which one of the answers is staring us in the face and we continue to do nothing more than talk about it.

We already know that physically active people are healthier both physically and mentally, but we do little more than talk. It may be helpful for some people to become a bit more self-aware. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that you can’t talk yourself into being mentally healthy without a concurrent effort to actually do the things that can improve your overall health, such as being physically active and adopting healthy sleep habits. A political advisor once said, “It’s the economy, stupid.” As a community interested in the health of our children and the adults they will become, we need to remind ourselves again, “It’s the old Mind-Body Thing, Stupid.” Our children need a little less talk and a lot more action.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

No matter where one looks for the statistics, no matter what words one chooses to describe it, this country has a child and adolescent mental health crisis. Almost 20% of young people in the 3-17 age bracket have a mental, emotional, developmental, or behavioral disorder. COVID-19 has certainly exacerbated the problem, but the downward trend in the mental health of this nation has been going on for decades.

The voices calling for more services to address the problem are getting more numerous and louder. But, what exactly should those services look like and who should be delivering them?

When considered together, two recent research papers suggest that we should be venturing well beyond the usual mental health strategies if we are going to be successful in addressing the current crisis.

The first paper is an analysis by two psychologists who contend that our efforts to raise the awareness of mental issues may be contributing to the increase in reported mental health problems. The authors agree that more attention paid to mental health conditions can result in “more accurate reporting of previous under-recognized symptoms” and would seem to be a positive. However, the investigators also observe that when exposed to this flood of information, some individuals who are only experiencing minor distress may report their symptoms as mental problems. The authors of the paper have coined the term for this phenomenon as “prevalence inflation.” Their preliminary investigation suggests it may be much more common than once believed and they present numerous situations in which prevalence inflation seems to have occurred.

A New York Times article about this hypothesis reports on a British study in which nearly 30,000 teenagers were instructed by their teachers to “direct their attentions to the present moment” and utilize other mindfulness strategies. The educators had hoped that after 8 years of this indoctrination, the students’ mental health would have improved. The bottom line was that this mindfulness-based program was of no help and may have actually made things worse for a subgroup of students who were at greatest risk for mental health challenges.

Dr. Jack Andrews, one of the authors, feels that mindfulness training may encourage what he calls “co-rumination,” which he describes as “the kind of long, unresolved group discussion that churns up problems without finding solutions.” One has to wonder if “prevalence inflation” and “co-rumination,” if they do exist, may be playing a role in the hotly debated phenomenon some have termed “late-onset gender dysphoria.”

Never having been a fan of mindfulness training as an effective strategy, I am relieved to learn that serious investigators are finding evidence that supports my gut reaction.

If raising awareness, “education,” and group discussion aren’t working, and in some cases are actually contributing to the crisis, or at least making the data difficult to interpret, what should we be doing to turn this foundering ship around?

A second paper, coming from Taiwan, may provide an answer. Huey-Ling Chiang and fellow investigators have reported on a study of nearly two million children and adolescents in which they found improved performance in a variety of physical fitness challenges “was linked with a lower risk of mental health disorder.” The dose-dependent effect resulted in less anxiety and depressive disorders as well as less attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder when cardio-respiratory, muscle endurance, and power indices improved.

There have been other observers who have suggested a link between physical fitness and improved mental health, but this Taiwanese study is by far one of the largest. And, the discovery of a dose-dependent effect makes it particularly convincing.

As I reviewed these two papers, I became increasingly frustrated because this is another example in which one of the answers is staring us in the face and we continue to do nothing more than talk about it.

We already know that physically active people are healthier both physically and mentally, but we do little more than talk. It may be helpful for some people to become a bit more self-aware. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that you can’t talk yourself into being mentally healthy without a concurrent effort to actually do the things that can improve your overall health, such as being physically active and adopting healthy sleep habits. A political advisor once said, “It’s the economy, stupid.” As a community interested in the health of our children and the adults they will become, we need to remind ourselves again, “It’s the old Mind-Body Thing, Stupid.” Our children need a little less talk and a lot more action.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

No matter where one looks for the statistics, no matter what words one chooses to describe it, this country has a child and adolescent mental health crisis. Almost 20% of young people in the 3-17 age bracket have a mental, emotional, developmental, or behavioral disorder. COVID-19 has certainly exacerbated the problem, but the downward trend in the mental health of this nation has been going on for decades.

The voices calling for more services to address the problem are getting more numerous and louder. But, what exactly should those services look like and who should be delivering them?

When considered together, two recent research papers suggest that we should be venturing well beyond the usual mental health strategies if we are going to be successful in addressing the current crisis.

The first paper is an analysis by two psychologists who contend that our efforts to raise the awareness of mental issues may be contributing to the increase in reported mental health problems. The authors agree that more attention paid to mental health conditions can result in “more accurate reporting of previous under-recognized symptoms” and would seem to be a positive. However, the investigators also observe that when exposed to this flood of information, some individuals who are only experiencing minor distress may report their symptoms as mental problems. The authors of the paper have coined the term for this phenomenon as “prevalence inflation.” Their preliminary investigation suggests it may be much more common than once believed and they present numerous situations in which prevalence inflation seems to have occurred.

A New York Times article about this hypothesis reports on a British study in which nearly 30,000 teenagers were instructed by their teachers to “direct their attentions to the present moment” and utilize other mindfulness strategies. The educators had hoped that after 8 years of this indoctrination, the students’ mental health would have improved. The bottom line was that this mindfulness-based program was of no help and may have actually made things worse for a subgroup of students who were at greatest risk for mental health challenges.

Dr. Jack Andrews, one of the authors, feels that mindfulness training may encourage what he calls “co-rumination,” which he describes as “the kind of long, unresolved group discussion that churns up problems without finding solutions.” One has to wonder if “prevalence inflation” and “co-rumination,” if they do exist, may be playing a role in the hotly debated phenomenon some have termed “late-onset gender dysphoria.”

Never having been a fan of mindfulness training as an effective strategy, I am relieved to learn that serious investigators are finding evidence that supports my gut reaction.

If raising awareness, “education,” and group discussion aren’t working, and in some cases are actually contributing to the crisis, or at least making the data difficult to interpret, what should we be doing to turn this foundering ship around?

A second paper, coming from Taiwan, may provide an answer. Huey-Ling Chiang and fellow investigators have reported on a study of nearly two million children and adolescents in which they found improved performance in a variety of physical fitness challenges “was linked with a lower risk of mental health disorder.” The dose-dependent effect resulted in less anxiety and depressive disorders as well as less attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder when cardio-respiratory, muscle endurance, and power indices improved.

There have been other observers who have suggested a link between physical fitness and improved mental health, but this Taiwanese study is by far one of the largest. And, the discovery of a dose-dependent effect makes it particularly convincing.

As I reviewed these two papers, I became increasingly frustrated because this is another example in which one of the answers is staring us in the face and we continue to do nothing more than talk about it.

We already know that physically active people are healthier both physically and mentally, but we do little more than talk. It may be helpful for some people to become a bit more self-aware. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that you can’t talk yourself into being mentally healthy without a concurrent effort to actually do the things that can improve your overall health, such as being physically active and adopting healthy sleep habits. A political advisor once said, “It’s the economy, stupid.” As a community interested in the health of our children and the adults they will become, we need to remind ourselves again, “It’s the old Mind-Body Thing, Stupid.” Our children need a little less talk and a lot more action.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Hypopigmented Cutaneous Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis in a Hispanic Infant

To the Editor:

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare inflammatory neoplasia caused by accumulation of clonal Langerhans cells in 1 or more organs. The clinical spectrum is diverse, ranging from mild, single-organ involvement that may resolve spontaneously to severe progressive multisystem disease that can be fatal. It is most prevalent in children, affecting an estimated 4 to 5 children for every 1 million annually, with male predominance.1 The pathogenesis is driven by activating mutations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, with the BRAF V600E mutation detected in most LCH patients, resulting in proliferation of pathologic Langerhans cells and dysregulated expression of inflammatory cytokines in LCH lesions.2 A biopsy of lesional tissue is required for definitive diagnosis. Histopathology reveals a mixed inflammatory infiltrate and characteristic mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei that are positive for CD1a and CD207 proteins on immunohistochemical staining.3

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is categorized by the extent of organ involvement. It commonly affects the bones, skin, pituitary gland, liver, lungs, bone marrow, and lymph nodes.4 Single-system LCH involves a single organ with unifocal or multifocal lesions; multisystem LCH involves 2 or more organs and has a worse prognosis if risk organs (eg, liver, spleen, bone marrow) are involved.4

Skin lesions are reported in more than half of LCH cases and are the most common initial manifestation in patients younger than 2 years.4 Cutaneous findings are highly variable, which poses a diagnostic challenge. Common morphologies include erythematous papules, pustules, papulovesicles, scaly plaques, erosions, and petechiae. Lesions can be solitary or widespread and favor the trunk, head, and face.4 We describe an atypical case of hypopigmented cutaneous LCH and review the literature on this morphology in patients with skin of color.

A 7-month-old Hispanic male infant who was otherwise healthy presented with numerous hypopigmented macules and pink papules on the trunk and groin that had progressed since birth. A review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed 1- to 3-mm, discrete, hypopigmented macules intermixed with 1- to 2-mm pearly pink papules scattered on the back, chest, abdomen, and inguinal folds (Figure 1). Some lesions appeared koebnerized; however, the parents denied a history of scratching or trauma.

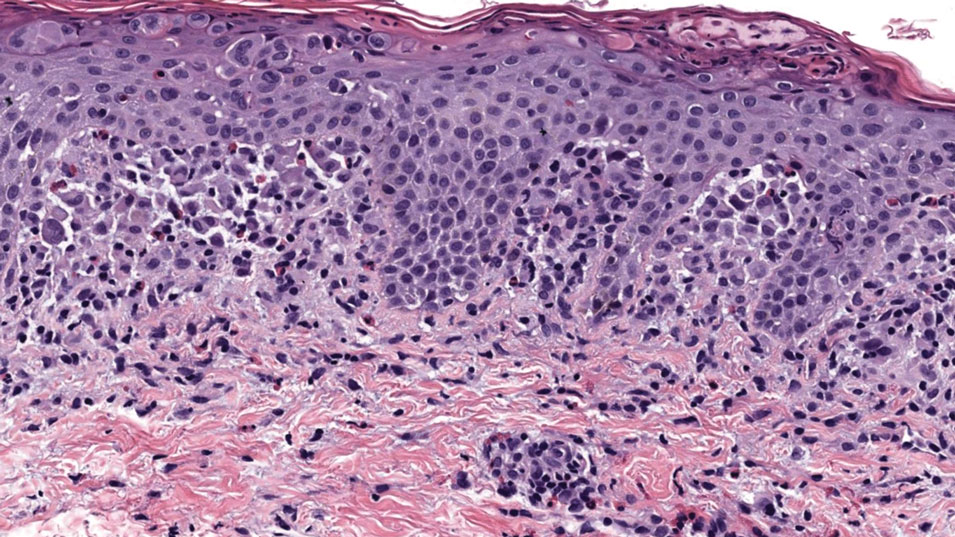

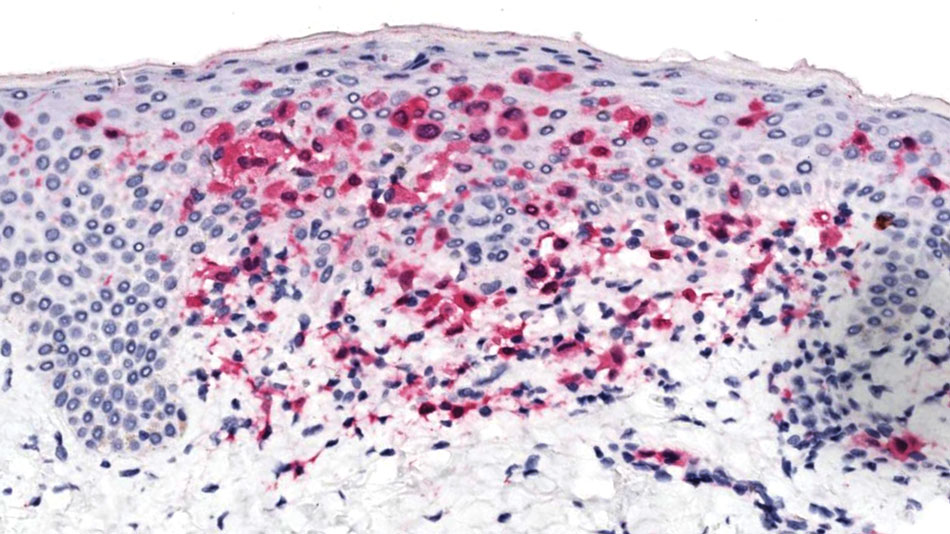

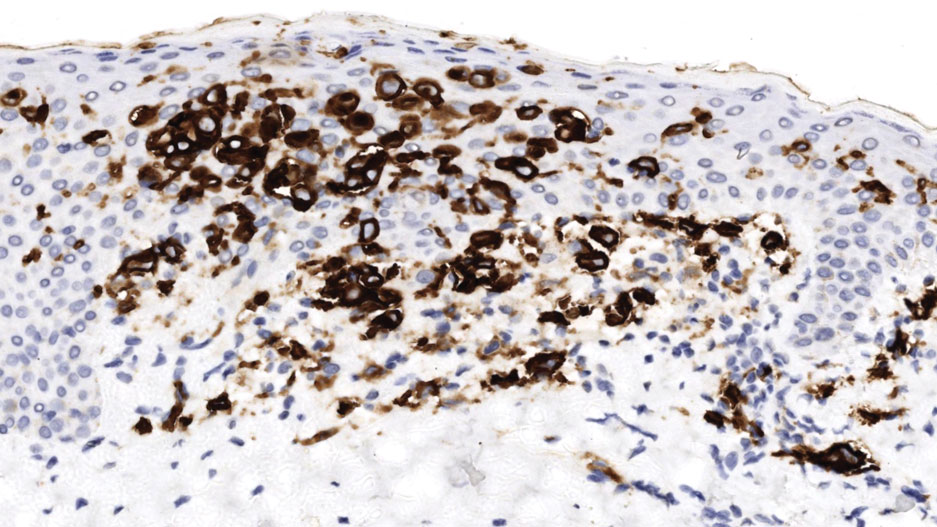

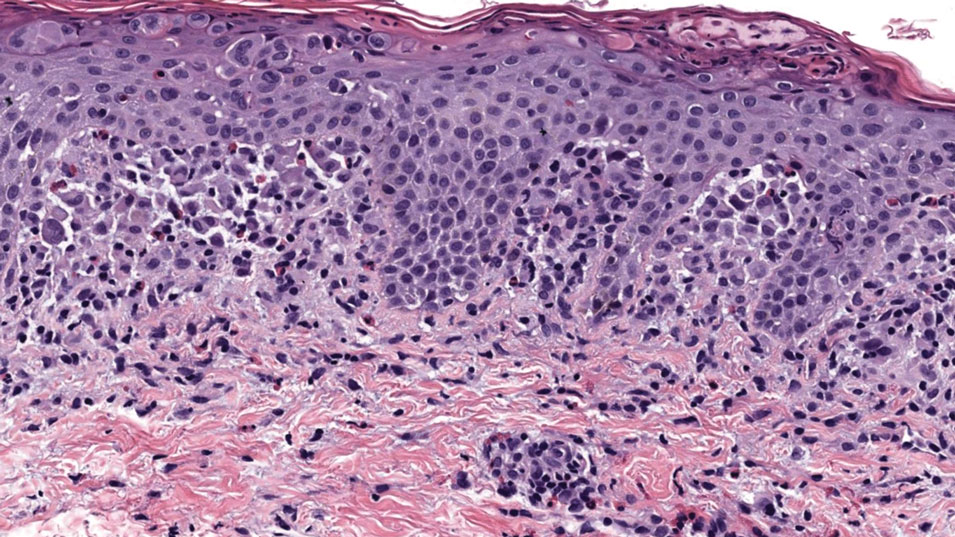

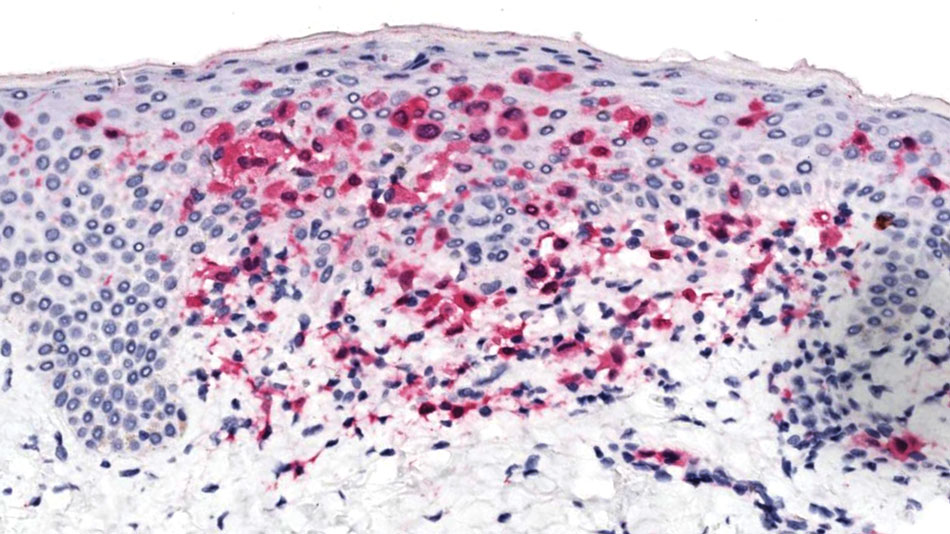

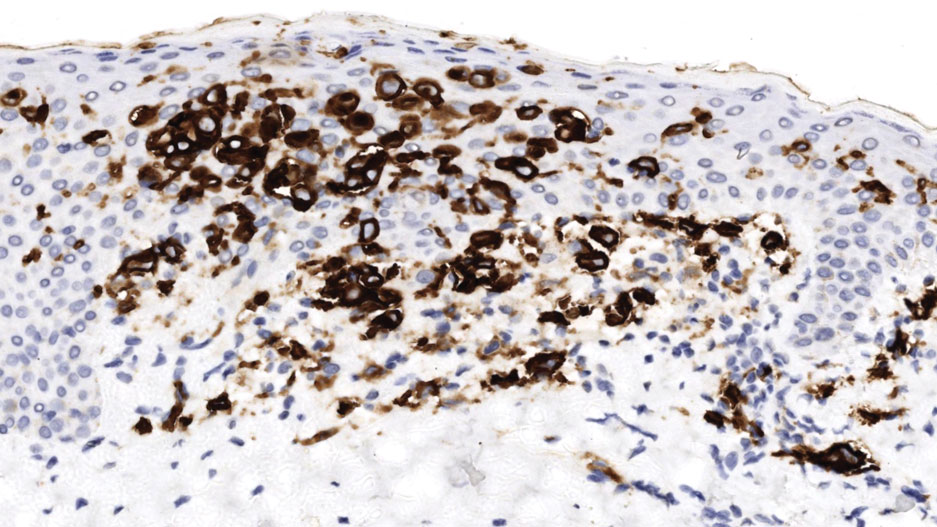

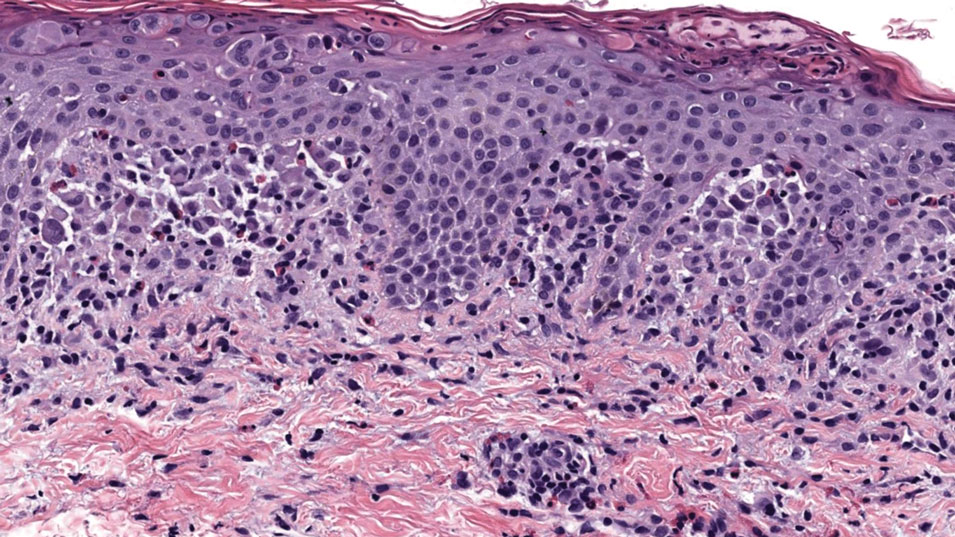

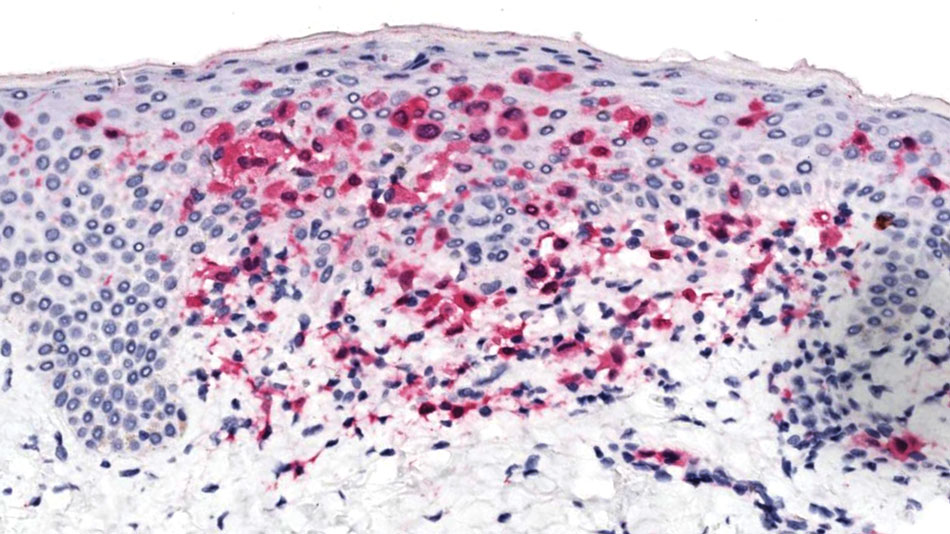

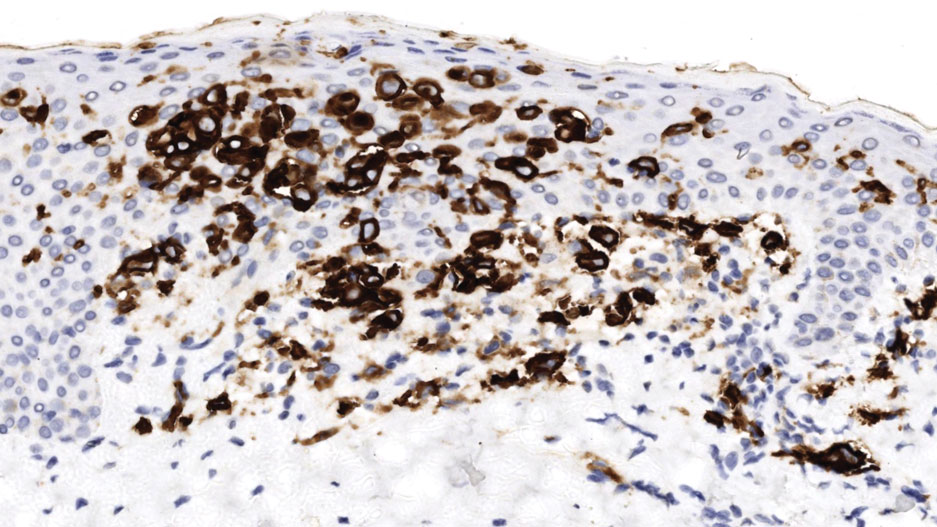

Histopathology of a lesion in the inguinal fold showed aggregates of mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei and abundant amphophilic cytoplasm in the papillary dermis, with focal extension into the epidermis. Scattered eosinophils and multinucleated giant cells were present in the dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD1a (Figure 3) and S-100 protein (Figure 4). Although epidermal Langerhans cell collections also can be seen in allergic contact dermatitis,5 predominant involvement of the papillary dermis and the presence of multinucleated giant cells are characteristic of LCH.4 Given these findings, which were consistent with LCH, the dermatopathology deemed BRAF V600E immunostaining unnecessary for diagnostic purposes.

The patient was referred to the hematology and oncology department to undergo thorough evaluation for extracutaneous involvement. The workup included a complete blood cell count, liver function testing, electrolyte assessment, skeletal survey, chest radiography, and ultrasonography of the liver and spleen. All results were negative, suggesting a diagnosis of single-system cutaneous LCH.

Three months later, the patient presented to dermatology with spontaneous regression of all skin lesions. Continued follow-up—every 6 months for 5 years—was recommended to monitor for disease recurrence or progression to multisystem disease.

Cutaneous LCH is a clinically heterogeneous disease with the potential for multisystem involvement and long-term sequelae; therefore, timely diagnosis is paramount to optimize outcomes. However, delayed diagnosis is common because of the spectrum of skin findings that can mimic common pediatric dermatoses, such as seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and diaper dermatitis.4 In one study, the median time from onset of skin lesions to diagnostic biopsy was longer than 3 months (maximum, 5 years).6 Our patient was referred to dermatology 7 months after onset of hypopigmented macules, a rarely reported cutaneous manifestation of LCH.

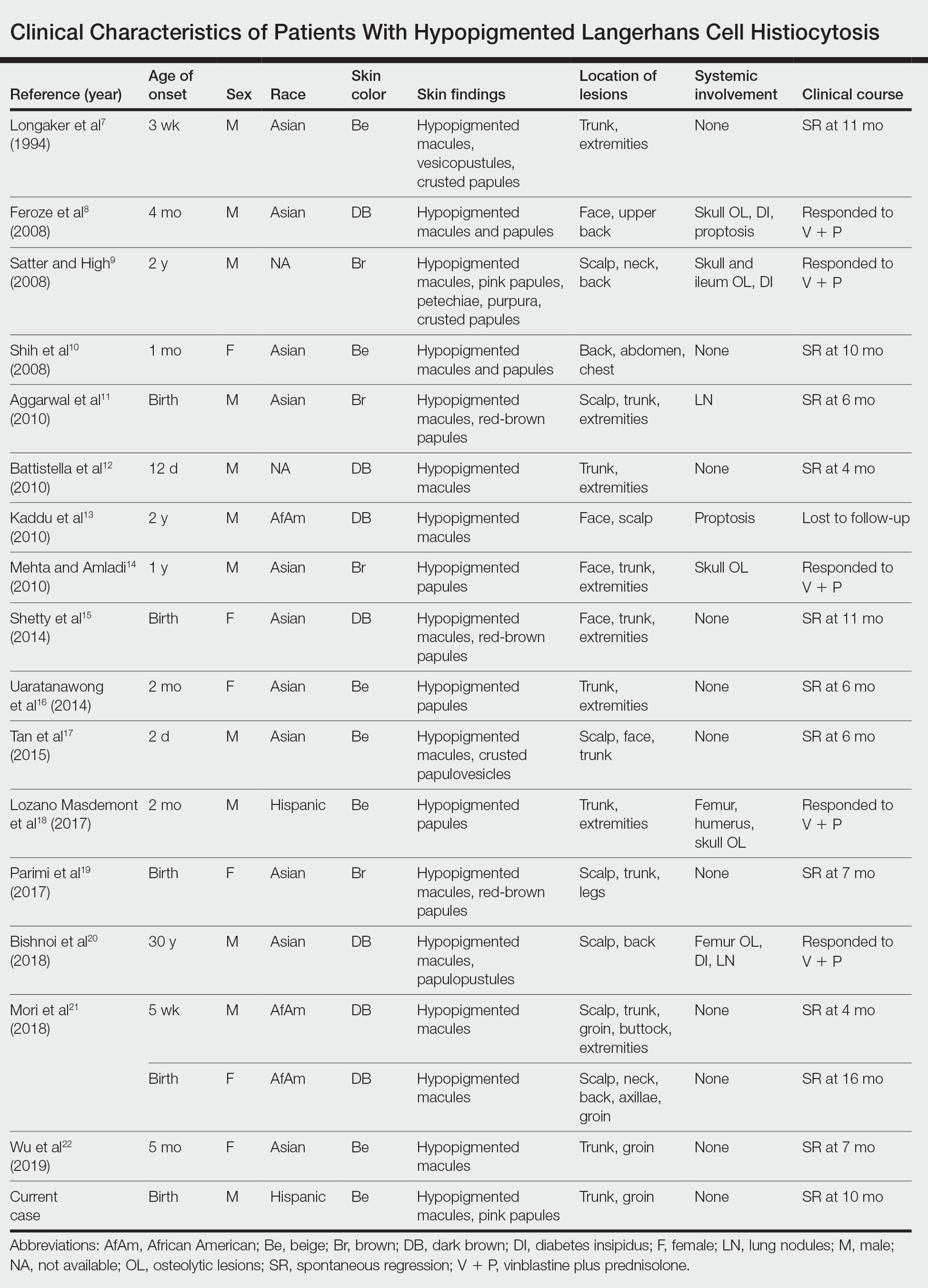

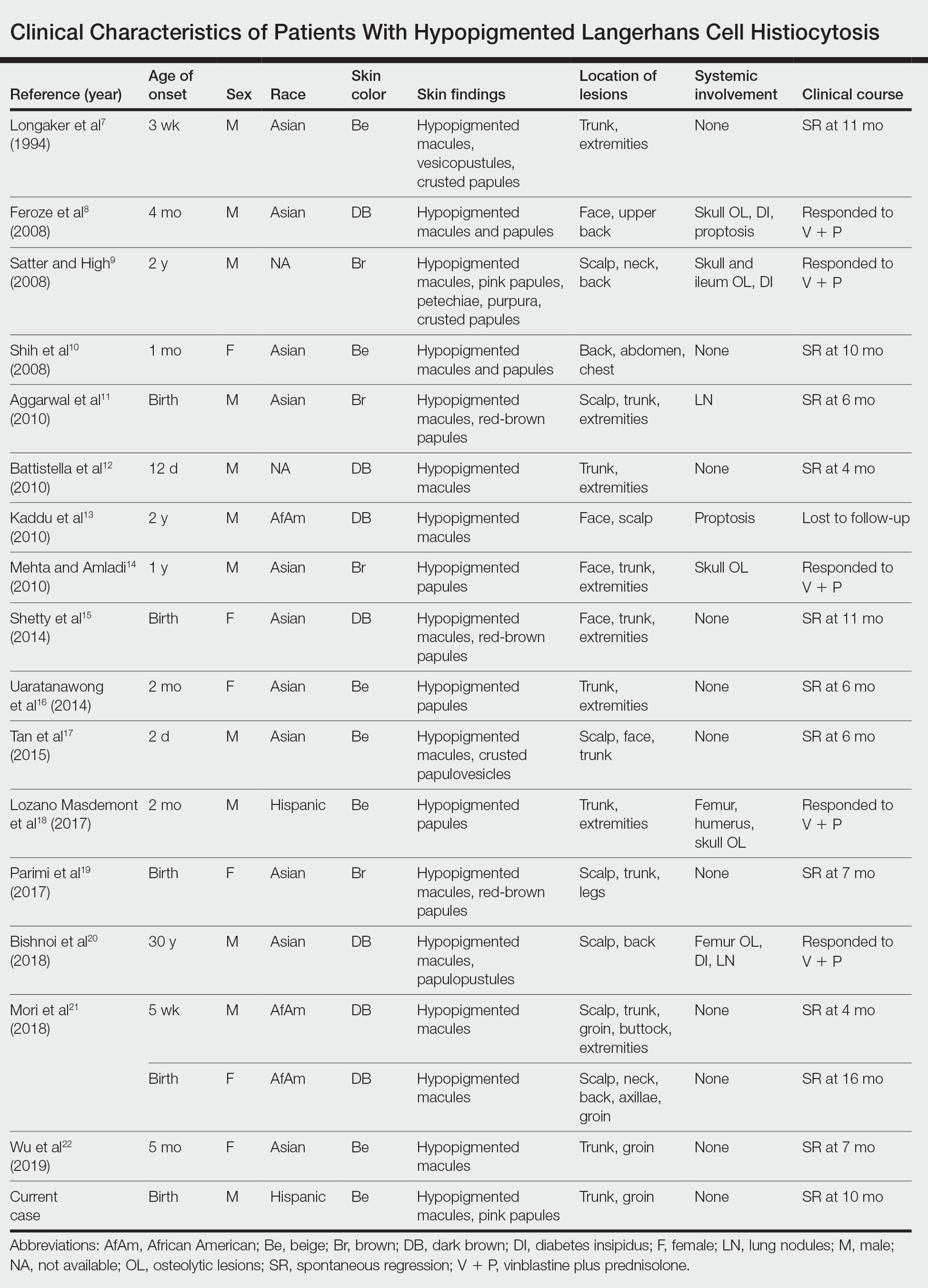

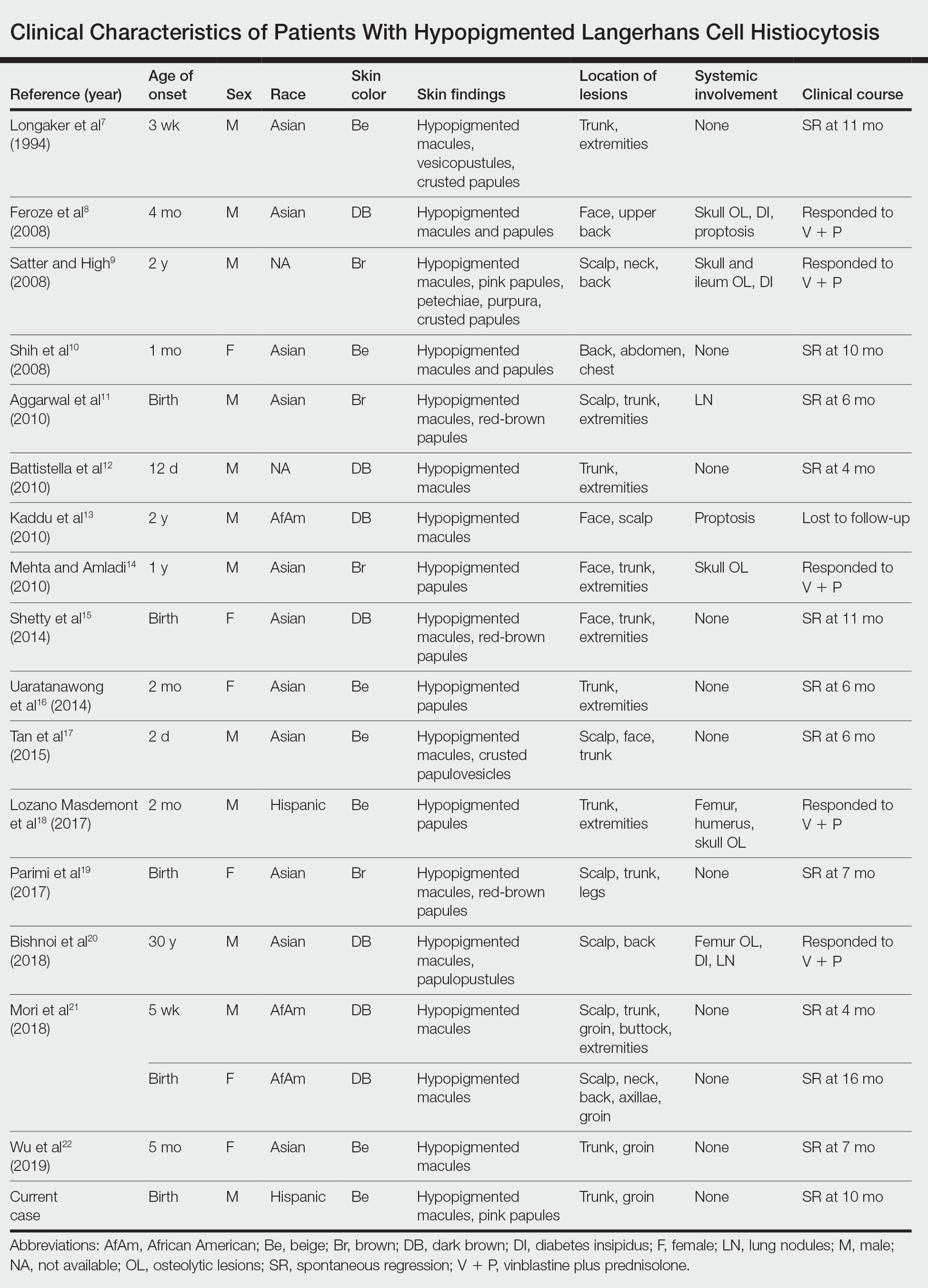

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE from 1994 to 2019 using the terms Langerhans cell histiocytotis and hypopigmented yielded 17 cases of LCH presenting as hypopigmented skin lesions (Table).7-22 All cases occurred in patients with skin of color (ie, patients of Asian, Hispanic, or African descent). Hypopigmented macules were the only cutaneous manifestation in 10 (59%) cases. Lesions most commonly were distributed on the trunk (16/17 [94%]) and extremities (8/17 [47%]). The median age of onset was 1 month; 76% (13/17) of patients developed skin lesions before 1 year of age, indicating that this morphology may be more common in newborns. In most patients, the diagnosis was single-system cutaneous LCH; they exhibited spontaneous regression by 8 months of age on average, suggesting that this variant may be associated with a better prognosis. Mori and colleagues21 hypothesized that hypopigmented lesions may represent the resolving stage of active LCH based on histopathologic findings of dermal pallor and fibrosis in a hypopigmented LCH lesion. However, systemic involvement was reported in 7 cases of hypopigmented LCH, highlighting the importance of assessing for multisystem disease regardless of cutaneous morphology.21Langerhans cell histiocytosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating hypopigmented skin eruptions in infants with darker skin types. Prompt diagnosis of this atypical variant requires a higher index of suspicion because of its rarity and the polymorphic nature of cutaneous LCH. This morphology may go undiagnosed in the setting of mild or spontaneously resolving disease; notwithstanding, accurate diagnosis and longitudinal surveillance are necessary given the potential for progressive systemic involvement.

1. Guyot-Goubin A, Donadieu J, Barkaoui M, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of childhood Langerhans cell histiocytosis in France, 2000–2004. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:71-75. doi:10.1002/pbc.21498

2. Badalian-Very G, Vergilio J-A, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:1919-1923. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-04-279083

3. Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al; Euro Histio Network. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work‐up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184. doi:10.1002/pbc.24367

4. Krooks J, Minkov M, Weatherall AG. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: history, classification, pathobiology, clinical manifestations, and prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1035-1044. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.059

5. Rosa G, Fernandez AP, Vij A, et al. Langerhans cell collections, but not eosinophils, are clues to a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in appropriate skin biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:498-504. doi:10.1111/cup.12707

6. Simko SJ, Garmezy B, Abhyankar H, et al. Differentiating skin-limited and multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2014;165:990-996. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.07.063

7. Longaker MA, Frieden IJ, LeBoit PE, et al. Congenital “self-healing” Langerhans cell histiocytosis: the need for long-term follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(5, pt 2):910-916. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70258-6

8. Feroze K, Unni M, Jayasree MG, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting with hypopigmented macules. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:670-672. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.45128

9. Satter EK, High WA. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a case report and summary of the current recommendations of the Histiocyte Society. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:3.

10. Chang SL, Shih IH, Kuo TT, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis presenting as hypopigmented macules and papules in a neonate. Dermatologica Sinica 2008;26:80-84.

11. Aggarwal V, Seth A, Jain M, et al. Congenital Langerhans cell histiocytosis with skin and lung involvement: spontaneous regression. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:811-812.

12. Battistella M, Fraitag S, Teillac DH, et al. Neonatal and early infantile cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis: comparison of self-regressive and non-self-regressive forms. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:149-156. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.360

13. Kaddu S, Mulyowa G, Kovarik C. Hypopigmented scaly, scalp and facial lesions and disfiguring exopthalmus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;3:E52-E53. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03336.x

14. Mehta B, Amladi S. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as hypopigmented papules. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:215-217. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01104.x

15. Shetty S, Monappa V, Pai K, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: a case report. Our Dermatol Online. 2014;5:264-266.

16. Uaratanawong R, Kootiratrakarn T, Sudtikoonaseth P, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis presented with multiple hypopigmented flat-topped papules: a case report and review of literatures. J Med Assoc Thai. 2014;97:993-997.

17. Tan Q, Gan LQ, Wang H. Congenital self-healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis in a male neonate. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:75-77. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.148587

18. Lozano Masdemont B, Gómez‐Recuero Muñoz L, Villanueva Álvarez‐Santullano A, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis mimicking lichen nitidus with bone involvement. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:231-233. doi:10.1111/ajd.12467

19. Parimi LR, You J, Hong L, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with spontaneous regression. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:553-555. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175432

20. Bishnoi A, De D, Khullar G, et al. Hypopigmented and acneiform lesions: an unusual initial presentation of adult-onset multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84:621-626. doi:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_639_17

21. Mori S, Adar T, Kazlouskaya V, et al. Cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting with hypopigmented lesions: report of two cases and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:502-506. doi:10.1111/pde.13509

22. Wu X, Huang J, Jiang L, et al. Congenital self‐healing reticulohistiocytosis with BRAF V600E mutation in an infant. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:647-650. doi:10.1111/ced.13880

To the Editor:

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare inflammatory neoplasia caused by accumulation of clonal Langerhans cells in 1 or more organs. The clinical spectrum is diverse, ranging from mild, single-organ involvement that may resolve spontaneously to severe progressive multisystem disease that can be fatal. It is most prevalent in children, affecting an estimated 4 to 5 children for every 1 million annually, with male predominance.1 The pathogenesis is driven by activating mutations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, with the BRAF V600E mutation detected in most LCH patients, resulting in proliferation of pathologic Langerhans cells and dysregulated expression of inflammatory cytokines in LCH lesions.2 A biopsy of lesional tissue is required for definitive diagnosis. Histopathology reveals a mixed inflammatory infiltrate and characteristic mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei that are positive for CD1a and CD207 proteins on immunohistochemical staining.3

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is categorized by the extent of organ involvement. It commonly affects the bones, skin, pituitary gland, liver, lungs, bone marrow, and lymph nodes.4 Single-system LCH involves a single organ with unifocal or multifocal lesions; multisystem LCH involves 2 or more organs and has a worse prognosis if risk organs (eg, liver, spleen, bone marrow) are involved.4

Skin lesions are reported in more than half of LCH cases and are the most common initial manifestation in patients younger than 2 years.4 Cutaneous findings are highly variable, which poses a diagnostic challenge. Common morphologies include erythematous papules, pustules, papulovesicles, scaly plaques, erosions, and petechiae. Lesions can be solitary or widespread and favor the trunk, head, and face.4 We describe an atypical case of hypopigmented cutaneous LCH and review the literature on this morphology in patients with skin of color.

A 7-month-old Hispanic male infant who was otherwise healthy presented with numerous hypopigmented macules and pink papules on the trunk and groin that had progressed since birth. A review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed 1- to 3-mm, discrete, hypopigmented macules intermixed with 1- to 2-mm pearly pink papules scattered on the back, chest, abdomen, and inguinal folds (Figure 1). Some lesions appeared koebnerized; however, the parents denied a history of scratching or trauma.

Histopathology of a lesion in the inguinal fold showed aggregates of mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei and abundant amphophilic cytoplasm in the papillary dermis, with focal extension into the epidermis. Scattered eosinophils and multinucleated giant cells were present in the dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD1a (Figure 3) and S-100 protein (Figure 4). Although epidermal Langerhans cell collections also can be seen in allergic contact dermatitis,5 predominant involvement of the papillary dermis and the presence of multinucleated giant cells are characteristic of LCH.4 Given these findings, which were consistent with LCH, the dermatopathology deemed BRAF V600E immunostaining unnecessary for diagnostic purposes.

The patient was referred to the hematology and oncology department to undergo thorough evaluation for extracutaneous involvement. The workup included a complete blood cell count, liver function testing, electrolyte assessment, skeletal survey, chest radiography, and ultrasonography of the liver and spleen. All results were negative, suggesting a diagnosis of single-system cutaneous LCH.

Three months later, the patient presented to dermatology with spontaneous regression of all skin lesions. Continued follow-up—every 6 months for 5 years—was recommended to monitor for disease recurrence or progression to multisystem disease.

Cutaneous LCH is a clinically heterogeneous disease with the potential for multisystem involvement and long-term sequelae; therefore, timely diagnosis is paramount to optimize outcomes. However, delayed diagnosis is common because of the spectrum of skin findings that can mimic common pediatric dermatoses, such as seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and diaper dermatitis.4 In one study, the median time from onset of skin lesions to diagnostic biopsy was longer than 3 months (maximum, 5 years).6 Our patient was referred to dermatology 7 months after onset of hypopigmented macules, a rarely reported cutaneous manifestation of LCH.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE from 1994 to 2019 using the terms Langerhans cell histiocytotis and hypopigmented yielded 17 cases of LCH presenting as hypopigmented skin lesions (Table).7-22 All cases occurred in patients with skin of color (ie, patients of Asian, Hispanic, or African descent). Hypopigmented macules were the only cutaneous manifestation in 10 (59%) cases. Lesions most commonly were distributed on the trunk (16/17 [94%]) and extremities (8/17 [47%]). The median age of onset was 1 month; 76% (13/17) of patients developed skin lesions before 1 year of age, indicating that this morphology may be more common in newborns. In most patients, the diagnosis was single-system cutaneous LCH; they exhibited spontaneous regression by 8 months of age on average, suggesting that this variant may be associated with a better prognosis. Mori and colleagues21 hypothesized that hypopigmented lesions may represent the resolving stage of active LCH based on histopathologic findings of dermal pallor and fibrosis in a hypopigmented LCH lesion. However, systemic involvement was reported in 7 cases of hypopigmented LCH, highlighting the importance of assessing for multisystem disease regardless of cutaneous morphology.21Langerhans cell histiocytosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating hypopigmented skin eruptions in infants with darker skin types. Prompt diagnosis of this atypical variant requires a higher index of suspicion because of its rarity and the polymorphic nature of cutaneous LCH. This morphology may go undiagnosed in the setting of mild or spontaneously resolving disease; notwithstanding, accurate diagnosis and longitudinal surveillance are necessary given the potential for progressive systemic involvement.

To the Editor:

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare inflammatory neoplasia caused by accumulation of clonal Langerhans cells in 1 or more organs. The clinical spectrum is diverse, ranging from mild, single-organ involvement that may resolve spontaneously to severe progressive multisystem disease that can be fatal. It is most prevalent in children, affecting an estimated 4 to 5 children for every 1 million annually, with male predominance.1 The pathogenesis is driven by activating mutations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, with the BRAF V600E mutation detected in most LCH patients, resulting in proliferation of pathologic Langerhans cells and dysregulated expression of inflammatory cytokines in LCH lesions.2 A biopsy of lesional tissue is required for definitive diagnosis. Histopathology reveals a mixed inflammatory infiltrate and characteristic mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei that are positive for CD1a and CD207 proteins on immunohistochemical staining.3

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is categorized by the extent of organ involvement. It commonly affects the bones, skin, pituitary gland, liver, lungs, bone marrow, and lymph nodes.4 Single-system LCH involves a single organ with unifocal or multifocal lesions; multisystem LCH involves 2 or more organs and has a worse prognosis if risk organs (eg, liver, spleen, bone marrow) are involved.4

Skin lesions are reported in more than half of LCH cases and are the most common initial manifestation in patients younger than 2 years.4 Cutaneous findings are highly variable, which poses a diagnostic challenge. Common morphologies include erythematous papules, pustules, papulovesicles, scaly plaques, erosions, and petechiae. Lesions can be solitary or widespread and favor the trunk, head, and face.4 We describe an atypical case of hypopigmented cutaneous LCH and review the literature on this morphology in patients with skin of color.

A 7-month-old Hispanic male infant who was otherwise healthy presented with numerous hypopigmented macules and pink papules on the trunk and groin that had progressed since birth. A review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed 1- to 3-mm, discrete, hypopigmented macules intermixed with 1- to 2-mm pearly pink papules scattered on the back, chest, abdomen, and inguinal folds (Figure 1). Some lesions appeared koebnerized; however, the parents denied a history of scratching or trauma.

Histopathology of a lesion in the inguinal fold showed aggregates of mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei and abundant amphophilic cytoplasm in the papillary dermis, with focal extension into the epidermis. Scattered eosinophils and multinucleated giant cells were present in the dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD1a (Figure 3) and S-100 protein (Figure 4). Although epidermal Langerhans cell collections also can be seen in allergic contact dermatitis,5 predominant involvement of the papillary dermis and the presence of multinucleated giant cells are characteristic of LCH.4 Given these findings, which were consistent with LCH, the dermatopathology deemed BRAF V600E immunostaining unnecessary for diagnostic purposes.

The patient was referred to the hematology and oncology department to undergo thorough evaluation for extracutaneous involvement. The workup included a complete blood cell count, liver function testing, electrolyte assessment, skeletal survey, chest radiography, and ultrasonography of the liver and spleen. All results were negative, suggesting a diagnosis of single-system cutaneous LCH.

Three months later, the patient presented to dermatology with spontaneous regression of all skin lesions. Continued follow-up—every 6 months for 5 years—was recommended to monitor for disease recurrence or progression to multisystem disease.

Cutaneous LCH is a clinically heterogeneous disease with the potential for multisystem involvement and long-term sequelae; therefore, timely diagnosis is paramount to optimize outcomes. However, delayed diagnosis is common because of the spectrum of skin findings that can mimic common pediatric dermatoses, such as seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and diaper dermatitis.4 In one study, the median time from onset of skin lesions to diagnostic biopsy was longer than 3 months (maximum, 5 years).6 Our patient was referred to dermatology 7 months after onset of hypopigmented macules, a rarely reported cutaneous manifestation of LCH.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE from 1994 to 2019 using the terms Langerhans cell histiocytotis and hypopigmented yielded 17 cases of LCH presenting as hypopigmented skin lesions (Table).7-22 All cases occurred in patients with skin of color (ie, patients of Asian, Hispanic, or African descent). Hypopigmented macules were the only cutaneous manifestation in 10 (59%) cases. Lesions most commonly were distributed on the trunk (16/17 [94%]) and extremities (8/17 [47%]). The median age of onset was 1 month; 76% (13/17) of patients developed skin lesions before 1 year of age, indicating that this morphology may be more common in newborns. In most patients, the diagnosis was single-system cutaneous LCH; they exhibited spontaneous regression by 8 months of age on average, suggesting that this variant may be associated with a better prognosis. Mori and colleagues21 hypothesized that hypopigmented lesions may represent the resolving stage of active LCH based on histopathologic findings of dermal pallor and fibrosis in a hypopigmented LCH lesion. However, systemic involvement was reported in 7 cases of hypopigmented LCH, highlighting the importance of assessing for multisystem disease regardless of cutaneous morphology.21Langerhans cell histiocytosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating hypopigmented skin eruptions in infants with darker skin types. Prompt diagnosis of this atypical variant requires a higher index of suspicion because of its rarity and the polymorphic nature of cutaneous LCH. This morphology may go undiagnosed in the setting of mild or spontaneously resolving disease; notwithstanding, accurate diagnosis and longitudinal surveillance are necessary given the potential for progressive systemic involvement.

1. Guyot-Goubin A, Donadieu J, Barkaoui M, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of childhood Langerhans cell histiocytosis in France, 2000–2004. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:71-75. doi:10.1002/pbc.21498

2. Badalian-Very G, Vergilio J-A, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:1919-1923. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-04-279083

3. Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al; Euro Histio Network. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work‐up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184. doi:10.1002/pbc.24367

4. Krooks J, Minkov M, Weatherall AG. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: history, classification, pathobiology, clinical manifestations, and prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1035-1044. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.059

5. Rosa G, Fernandez AP, Vij A, et al. Langerhans cell collections, but not eosinophils, are clues to a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in appropriate skin biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:498-504. doi:10.1111/cup.12707

6. Simko SJ, Garmezy B, Abhyankar H, et al. Differentiating skin-limited and multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2014;165:990-996. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.07.063

7. Longaker MA, Frieden IJ, LeBoit PE, et al. Congenital “self-healing” Langerhans cell histiocytosis: the need for long-term follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(5, pt 2):910-916. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70258-6

8. Feroze K, Unni M, Jayasree MG, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting with hypopigmented macules. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:670-672. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.45128

9. Satter EK, High WA. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a case report and summary of the current recommendations of the Histiocyte Society. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:3.

10. Chang SL, Shih IH, Kuo TT, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis presenting as hypopigmented macules and papules in a neonate. Dermatologica Sinica 2008;26:80-84.

11. Aggarwal V, Seth A, Jain M, et al. Congenital Langerhans cell histiocytosis with skin and lung involvement: spontaneous regression. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:811-812.

12. Battistella M, Fraitag S, Teillac DH, et al. Neonatal and early infantile cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis: comparison of self-regressive and non-self-regressive forms. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:149-156. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.360

13. Kaddu S, Mulyowa G, Kovarik C. Hypopigmented scaly, scalp and facial lesions and disfiguring exopthalmus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;3:E52-E53. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03336.x

14. Mehta B, Amladi S. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as hypopigmented papules. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:215-217. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01104.x

15. Shetty S, Monappa V, Pai K, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: a case report. Our Dermatol Online. 2014;5:264-266.

16. Uaratanawong R, Kootiratrakarn T, Sudtikoonaseth P, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis presented with multiple hypopigmented flat-topped papules: a case report and review of literatures. J Med Assoc Thai. 2014;97:993-997.

17. Tan Q, Gan LQ, Wang H. Congenital self-healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis in a male neonate. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:75-77. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.148587

18. Lozano Masdemont B, Gómez‐Recuero Muñoz L, Villanueva Álvarez‐Santullano A, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis mimicking lichen nitidus with bone involvement. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:231-233. doi:10.1111/ajd.12467

19. Parimi LR, You J, Hong L, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with spontaneous regression. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:553-555. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175432

20. Bishnoi A, De D, Khullar G, et al. Hypopigmented and acneiform lesions: an unusual initial presentation of adult-onset multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84:621-626. doi:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_639_17

21. Mori S, Adar T, Kazlouskaya V, et al. Cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting with hypopigmented lesions: report of two cases and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:502-506. doi:10.1111/pde.13509

22. Wu X, Huang J, Jiang L, et al. Congenital self‐healing reticulohistiocytosis with BRAF V600E mutation in an infant. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:647-650. doi:10.1111/ced.13880

1. Guyot-Goubin A, Donadieu J, Barkaoui M, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of childhood Langerhans cell histiocytosis in France, 2000–2004. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:71-75. doi:10.1002/pbc.21498

2. Badalian-Very G, Vergilio J-A, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:1919-1923. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-04-279083

3. Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al; Euro Histio Network. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work‐up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184. doi:10.1002/pbc.24367

4. Krooks J, Minkov M, Weatherall AG. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: history, classification, pathobiology, clinical manifestations, and prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1035-1044. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.059

5. Rosa G, Fernandez AP, Vij A, et al. Langerhans cell collections, but not eosinophils, are clues to a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in appropriate skin biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:498-504. doi:10.1111/cup.12707

6. Simko SJ, Garmezy B, Abhyankar H, et al. Differentiating skin-limited and multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2014;165:990-996. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.07.063

7. Longaker MA, Frieden IJ, LeBoit PE, et al. Congenital “self-healing” Langerhans cell histiocytosis: the need for long-term follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(5, pt 2):910-916. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70258-6

8. Feroze K, Unni M, Jayasree MG, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting with hypopigmented macules. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:670-672. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.45128

9. Satter EK, High WA. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a case report and summary of the current recommendations of the Histiocyte Society. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:3.

10. Chang SL, Shih IH, Kuo TT, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis presenting as hypopigmented macules and papules in a neonate. Dermatologica Sinica 2008;26:80-84.

11. Aggarwal V, Seth A, Jain M, et al. Congenital Langerhans cell histiocytosis with skin and lung involvement: spontaneous regression. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:811-812.

12. Battistella M, Fraitag S, Teillac DH, et al. Neonatal and early infantile cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis: comparison of self-regressive and non-self-regressive forms. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:149-156. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.360

13. Kaddu S, Mulyowa G, Kovarik C. Hypopigmented scaly, scalp and facial lesions and disfiguring exopthalmus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;3:E52-E53. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03336.x

14. Mehta B, Amladi S. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as hypopigmented papules. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:215-217. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01104.x

15. Shetty S, Monappa V, Pai K, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: a case report. Our Dermatol Online. 2014;5:264-266.

16. Uaratanawong R, Kootiratrakarn T, Sudtikoonaseth P, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis presented with multiple hypopigmented flat-topped papules: a case report and review of literatures. J Med Assoc Thai. 2014;97:993-997.

17. Tan Q, Gan LQ, Wang H. Congenital self-healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis in a male neonate. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:75-77. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.148587

18. Lozano Masdemont B, Gómez‐Recuero Muñoz L, Villanueva Álvarez‐Santullano A, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis mimicking lichen nitidus with bone involvement. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:231-233. doi:10.1111/ajd.12467

19. Parimi LR, You J, Hong L, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with spontaneous regression. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:553-555. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175432

20. Bishnoi A, De D, Khullar G, et al. Hypopigmented and acneiform lesions: an unusual initial presentation of adult-onset multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84:621-626. doi:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_639_17

21. Mori S, Adar T, Kazlouskaya V, et al. Cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting with hypopigmented lesions: report of two cases and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:502-506. doi:10.1111/pde.13509

22. Wu X, Huang J, Jiang L, et al. Congenital self‐healing reticulohistiocytosis with BRAF V600E mutation in an infant. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:647-650. doi:10.1111/ced.13880

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should be aware of the hypopigmented variant of cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), which has been reported exclusively in patients with skin of color.

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of hypopigmented macules, which may be the only cutaneous manifestation or may coincide with typical lesions of LCH.

- Hypopigmented cutaneous LCH may be more common in newborns and associated with a better prognosis.

Arthroscopy Doesn’t Delay Total Knee Replacement in Knee Osteoarthritis

TOPLINE:

Adding arthroscopic surgery to nonoperative management neither delays nor accelerates the timing of total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA).

METHODOLOGY:

- Some case series show that arthroscopic surgery for knee OA may delay more invasive procedures, such as TKA or osteotomy, while longitudinal cohort studies often contradict this. Current OA guidelines are yet to address this issue.

- This secondary analysis of a randomized trial compared the long-term incidence of TKA in 178 patients (mean age, 59 years; 64.3% women) with knee OA who were referred for potential arthroscopic surgery at a tertiary care center in Canada.

- The patients received nonoperative care with or without additional arthroscopic surgery.

- Patients in the arthroscopic surgery group had specific knee procedures (resection of degenerative knee tissues) along with nonoperative management (physical therapy plus medications as required), while the control group received nonoperative management alone.

- The primary outcome was TKA on the knee being studied, and the secondary outcome was TKA or osteotomy on either knee.

TAKEAWAY:

- During a median follow-up of 13.8 years, 37.6% of patients underwent TKA, with comparable proportions of patients in the arthroscopic surgery and control groups undergoing TKA (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.85; 95% CI, 0.52-1.40).

- The rates of TKA or osteotomy on either knee were similar in both groups (aHR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.59-1.41).

- A time-stratified analysis done for 0-5 years, 5-10 years, and beyond 10 years of follow-up also showed a consistent interpretation.

- When patients with crossover to arthroscopic surgery during the follow-up were included, the results remained similar for both the primary (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.53-1.44) and secondary (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.69-1.68) outcomes.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our study findings do not support the use of arthroscopic surgery for OA of the knee.” “Arthroscopic surgery does not provide additional benefit to nonoperative management for improving pain, stiffness, and function and is likely not cost-effective at 2 years of follow-up,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Trevor B. Birmingham, PhD, Fowler Kennedy Sport Medicine Clinic, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada. It was published online in JAMA Network Open

LIMITATIONS:

The study was designed to assess differences in 2-year patient-reported outcomes rather than long-term TKA incidence. Factors influencing decisions to undergo TKA or osteotomy were not considered. Moreover, the effects observed in this study should be evaluated considering the estimated confidence intervals.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by the ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Long-Term Care. Some authors declared consulting, performing contracted services, or receiving grant funding, royalties, and nonfinancial support from various sources.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Adding arthroscopic surgery to nonoperative management neither delays nor accelerates the timing of total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA).

METHODOLOGY:

- Some case series show that arthroscopic surgery for knee OA may delay more invasive procedures, such as TKA or osteotomy, while longitudinal cohort studies often contradict this. Current OA guidelines are yet to address this issue.

- This secondary analysis of a randomized trial compared the long-term incidence of TKA in 178 patients (mean age, 59 years; 64.3% women) with knee OA who were referred for potential arthroscopic surgery at a tertiary care center in Canada.

- The patients received nonoperative care with or without additional arthroscopic surgery.

- Patients in the arthroscopic surgery group had specific knee procedures (resection of degenerative knee tissues) along with nonoperative management (physical therapy plus medications as required), while the control group received nonoperative management alone.

- The primary outcome was TKA on the knee being studied, and the secondary outcome was TKA or osteotomy on either knee.

TAKEAWAY:

- During a median follow-up of 13.8 years, 37.6% of patients underwent TKA, with comparable proportions of patients in the arthroscopic surgery and control groups undergoing TKA (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.85; 95% CI, 0.52-1.40).

- The rates of TKA or osteotomy on either knee were similar in both groups (aHR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.59-1.41).

- A time-stratified analysis done for 0-5 years, 5-10 years, and beyond 10 years of follow-up also showed a consistent interpretation.

- When patients with crossover to arthroscopic surgery during the follow-up were included, the results remained similar for both the primary (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.53-1.44) and secondary (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.69-1.68) outcomes.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our study findings do not support the use of arthroscopic surgery for OA of the knee.” “Arthroscopic surgery does not provide additional benefit to nonoperative management for improving pain, stiffness, and function and is likely not cost-effective at 2 years of follow-up,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Trevor B. Birmingham, PhD, Fowler Kennedy Sport Medicine Clinic, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada. It was published online in JAMA Network Open

LIMITATIONS:

The study was designed to assess differences in 2-year patient-reported outcomes rather than long-term TKA incidence. Factors influencing decisions to undergo TKA or osteotomy were not considered. Moreover, the effects observed in this study should be evaluated considering the estimated confidence intervals.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by the ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Long-Term Care. Some authors declared consulting, performing contracted services, or receiving grant funding, royalties, and nonfinancial support from various sources.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Adding arthroscopic surgery to nonoperative management neither delays nor accelerates the timing of total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA).

METHODOLOGY:

- Some case series show that arthroscopic surgery for knee OA may delay more invasive procedures, such as TKA or osteotomy, while longitudinal cohort studies often contradict this. Current OA guidelines are yet to address this issue.

- This secondary analysis of a randomized trial compared the long-term incidence of TKA in 178 patients (mean age, 59 years; 64.3% women) with knee OA who were referred for potential arthroscopic surgery at a tertiary care center in Canada.

- The patients received nonoperative care with or without additional arthroscopic surgery.

- Patients in the arthroscopic surgery group had specific knee procedures (resection of degenerative knee tissues) along with nonoperative management (physical therapy plus medications as required), while the control group received nonoperative management alone.

- The primary outcome was TKA on the knee being studied, and the secondary outcome was TKA or osteotomy on either knee.

TAKEAWAY:

- During a median follow-up of 13.8 years, 37.6% of patients underwent TKA, with comparable proportions of patients in the arthroscopic surgery and control groups undergoing TKA (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.85; 95% CI, 0.52-1.40).

- The rates of TKA or osteotomy on either knee were similar in both groups (aHR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.59-1.41).

- A time-stratified analysis done for 0-5 years, 5-10 years, and beyond 10 years of follow-up also showed a consistent interpretation.

- When patients with crossover to arthroscopic surgery during the follow-up were included, the results remained similar for both the primary (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.53-1.44) and secondary (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.69-1.68) outcomes.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our study findings do not support the use of arthroscopic surgery for OA of the knee.” “Arthroscopic surgery does not provide additional benefit to nonoperative management for improving pain, stiffness, and function and is likely not cost-effective at 2 years of follow-up,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Trevor B. Birmingham, PhD, Fowler Kennedy Sport Medicine Clinic, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada. It was published online in JAMA Network Open

LIMITATIONS:

The study was designed to assess differences in 2-year patient-reported outcomes rather than long-term TKA incidence. Factors influencing decisions to undergo TKA or osteotomy were not considered. Moreover, the effects observed in this study should be evaluated considering the estimated confidence intervals.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by the ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Long-Term Care. Some authors declared consulting, performing contracted services, or receiving grant funding, royalties, and nonfinancial support from various sources.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Vigilance Needed in Gout Treatment to Reduce CVD Risks

NEW YORK — Urate, the culprit of gout, affects the vasculature in multiple ways that can raise cardiovascular risk (CV) in an individual with gout, and following guidelines for gout treatment, including the use of colchicine, can be the key to reducing those risks.

“Guideline-concordant gout treatment, which is essentially an anti-inflammatory urate-lowering strategy, at least improves arterial physiology and likely reduces cardiovascular risk,” Michael H. Pillinger, MD, told attendees at the 4th Annual Cardiometabolic Risk in Inflammatory Conditions conference. Dr. Pillinger is professor of medicine and biochemistry and molecular pharmacology at New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York City, who has published multiple studies on gout.

He cited evidence that has shown soluble urate stimulates the production of C-reactive protein (CRP), which is a predictor of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Another study, in which Dr. Pillinger participated, demonstrated that gout patients have impaired vascular endothelial function associated with a chronic, low-level inflammatory state, he said.

“There’s good evidence that urate itself affects the vasculature in multiple ways, and I suspect this may be a model for other metabolic effects on vasculature,” Dr. Pillinger said. “Patients with gout have abnormal endothelium in ways that really convey vascular risk.”

Gout, Inflammation, and CVD

However, for rheumatologists to study the association between gout-related inflammation and CVD is “very, very hard,” Dr. Pillinger added. “But I do think that the mechanisms by which gout induces biological changes in the vasculature may provide insights into cardiovascular disease in general.”

One way to evaluate the effects of gout on the endothelium in the clinic is to measure flow-mediated dilation. This technique involves placing an ultrasound probe over the brachial artery and measuring the baseline artery diameter. Then, with the blood pressure cuff over the forearm, inflate it to reduce flow, then release the cuff and measure the brachial artery diameter after the endothelium releases vasodilators.

Dr. Pillinger and colleagues evaluated this technique in 34 patients with gout and 64 controls and found that patients with gout had an almost 50% decrease in flow-mediated dilation, he said. “Interestingly, the higher the urate, the worse the flow; the more the inflammation, the worse the flow, so seemingly corresponding with the severity of the gout,” he said. That raised an obvious question, Dr. Pillinger continued: “If you can treat the gout, can you improve the flow-mediated dilation?”

His group answered that question with a study in 38 previously untreated patients with gout, giving them colchicine 0.6 mg twice daily for a month plus a urate-lowering xanthine oxidase inhibitor (allopurinol or febuxostat) to treat them to a target urate level of < 6 mg/dL. “We saw an increase in endothelial function, and it normalized,” Dr. Pillinger said.

However, some study participants didn’t respond. “They were people with well-established other cardiovascular comorbidities — hypertension, hyperlipidemia,” he said. “I think some people just have vessels that are too damaged to get at them just by fixing their gout problem or their inflammation.”

That means patients with gout need to be treated with colchicine early on to avoid CV problems, Dr. Pillinger added. “We ought to get to them before they have the other problems,” he said.

Managing gout, and the concomitant CV problems, requires vigilance both during and in between flares, Dr. Pillinger said after his presentation.

“We have always taught that patients between flares basically look like people with no gout, but we do know now that patients with gout between flares tend to have what you might call ‘subclinical’ inflammation: CRPs and ESRs [erythrocyte sedimentation rates] that are higher than those of the general population, though not so excessive that they might grab attention,” he said. “We also know that many, if not all, patients between flares have urate deposited in or around their joints, but how these two relate is not fully established.”

Better treatment within 3 months of an acute gout flare may reduce the risk for CV events, he said, but that’s based on speculation more so than clinical data.

Potential Benefits of Targeting Inflammation

“More chronically, we know from the cardiologists’ studies that anti-inflammatory therapy should reduce risk in the high-risk general population,” Dr. Pillinger said. “There are no prospective studies confirming that this approach will work among gout patients, but there is no reason why it shouldn’t work — except perhaps that gout patients may have higher inflammation than the general population and also have more comorbidities, so they could perhaps be more resistant.”

Dr. Pillinger said that his group’s studies and another led by Daniel Solomon, MD, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, have indicated that anti-inflammatory strategies in gout will lower CV risk.

“And interestingly,” he added, “our data suggest that colchicine use may lower risk not only in high-risk gout patients but also in gout patients who start with no CAD [coronary artery disease] but who seem to have less incident CAD on colchicine. I see this as identifying that gout patients are intrinsically at high risk for CAD, even if they don’t actually have any, so they represent a population for whom lowering chronic inflammation may help prevent incident disease.”

Dr. Pillinger provided more evidence that the understanding of the relationship between gout, gout flares, and CV risk is evolving, said Michael S. Garshick, MD, who attended the conference and is head of the Cardio-Rheumatology Program at NYU Langone, New York City.

“There’s epidemiologic evidence supporting the association,” Dr. Garshick told this news organization after the conference. “We think that most conditions with immune system activation do tend to have an increased risk of some form of cardiovascular disease, but I think the relationship with gout has been highly underpublicized.”

Many patients with gout tend to have a higher prevalence of traditional cardiometabolic issues, which may compound the relationship, Dr. Garshick added. “However, I would argue that with this patient subset that it doesn’t matter because gout patients have a higher risk of traditional risk factors, and you have to [treat-to-target] those traditional risk factors.”

While the clinical evidence of a link between gout and atherosclerosis may not be conclusive, enough circumstantial evidence exists to believe that treating gout will reduce CV risks, he said. “Some of the imaging techniques do suggest that gouty crystals [are] in the atherosclerotic plaque of gout patients,” Dr. Garshick added. Dr. Pillinger’s work, he said, “is showing us that there are different pathways to develop atherosclerosis.”

Dr. Pillinger disclosed relationships with Federation Bio, Fortress Biotech, Amgen, Scilex, Hikma Pharmaceuticals, LG Chem, and Olatec Therapeutics. Dr. Garshick disclosed relationships with Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals, Agepha Pharma, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Horizon Therapeutics.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

NEW YORK — Urate, the culprit of gout, affects the vasculature in multiple ways that can raise cardiovascular risk (CV) in an individual with gout, and following guidelines for gout treatment, including the use of colchicine, can be the key to reducing those risks.

“Guideline-concordant gout treatment, which is essentially an anti-inflammatory urate-lowering strategy, at least improves arterial physiology and likely reduces cardiovascular risk,” Michael H. Pillinger, MD, told attendees at the 4th Annual Cardiometabolic Risk in Inflammatory Conditions conference. Dr. Pillinger is professor of medicine and biochemistry and molecular pharmacology at New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York City, who has published multiple studies on gout.

He cited evidence that has shown soluble urate stimulates the production of C-reactive protein (CRP), which is a predictor of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Another study, in which Dr. Pillinger participated, demonstrated that gout patients have impaired vascular endothelial function associated with a chronic, low-level inflammatory state, he said.

“There’s good evidence that urate itself affects the vasculature in multiple ways, and I suspect this may be a model for other metabolic effects on vasculature,” Dr. Pillinger said. “Patients with gout have abnormal endothelium in ways that really convey vascular risk.”

Gout, Inflammation, and CVD

However, for rheumatologists to study the association between gout-related inflammation and CVD is “very, very hard,” Dr. Pillinger added. “But I do think that the mechanisms by which gout induces biological changes in the vasculature may provide insights into cardiovascular disease in general.”

One way to evaluate the effects of gout on the endothelium in the clinic is to measure flow-mediated dilation. This technique involves placing an ultrasound probe over the brachial artery and measuring the baseline artery diameter. Then, with the blood pressure cuff over the forearm, inflate it to reduce flow, then release the cuff and measure the brachial artery diameter after the endothelium releases vasodilators.

Dr. Pillinger and colleagues evaluated this technique in 34 patients with gout and 64 controls and found that patients with gout had an almost 50% decrease in flow-mediated dilation, he said. “Interestingly, the higher the urate, the worse the flow; the more the inflammation, the worse the flow, so seemingly corresponding with the severity of the gout,” he said. That raised an obvious question, Dr. Pillinger continued: “If you can treat the gout, can you improve the flow-mediated dilation?”

His group answered that question with a study in 38 previously untreated patients with gout, giving them colchicine 0.6 mg twice daily for a month plus a urate-lowering xanthine oxidase inhibitor (allopurinol or febuxostat) to treat them to a target urate level of < 6 mg/dL. “We saw an increase in endothelial function, and it normalized,” Dr. Pillinger said.

However, some study participants didn’t respond. “They were people with well-established other cardiovascular comorbidities — hypertension, hyperlipidemia,” he said. “I think some people just have vessels that are too damaged to get at them just by fixing their gout problem or their inflammation.”

That means patients with gout need to be treated with colchicine early on to avoid CV problems, Dr. Pillinger added. “We ought to get to them before they have the other problems,” he said.

Managing gout, and the concomitant CV problems, requires vigilance both during and in between flares, Dr. Pillinger said after his presentation.

“We have always taught that patients between flares basically look like people with no gout, but we do know now that patients with gout between flares tend to have what you might call ‘subclinical’ inflammation: CRPs and ESRs [erythrocyte sedimentation rates] that are higher than those of the general population, though not so excessive that they might grab attention,” he said. “We also know that many, if not all, patients between flares have urate deposited in or around their joints, but how these two relate is not fully established.”

Better treatment within 3 months of an acute gout flare may reduce the risk for CV events, he said, but that’s based on speculation more so than clinical data.

Potential Benefits of Targeting Inflammation

“More chronically, we know from the cardiologists’ studies that anti-inflammatory therapy should reduce risk in the high-risk general population,” Dr. Pillinger said. “There are no prospective studies confirming that this approach will work among gout patients, but there is no reason why it shouldn’t work — except perhaps that gout patients may have higher inflammation than the general population and also have more comorbidities, so they could perhaps be more resistant.”

Dr. Pillinger said that his group’s studies and another led by Daniel Solomon, MD, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, have indicated that anti-inflammatory strategies in gout will lower CV risk.

“And interestingly,” he added, “our data suggest that colchicine use may lower risk not only in high-risk gout patients but also in gout patients who start with no CAD [coronary artery disease] but who seem to have less incident CAD on colchicine. I see this as identifying that gout patients are intrinsically at high risk for CAD, even if they don’t actually have any, so they represent a population for whom lowering chronic inflammation may help prevent incident disease.”

Dr. Pillinger provided more evidence that the understanding of the relationship between gout, gout flares, and CV risk is evolving, said Michael S. Garshick, MD, who attended the conference and is head of the Cardio-Rheumatology Program at NYU Langone, New York City.

“There’s epidemiologic evidence supporting the association,” Dr. Garshick told this news organization after the conference. “We think that most conditions with immune system activation do tend to have an increased risk of some form of cardiovascular disease, but I think the relationship with gout has been highly underpublicized.”

Many patients with gout tend to have a higher prevalence of traditional cardiometabolic issues, which may compound the relationship, Dr. Garshick added. “However, I would argue that with this patient subset that it doesn’t matter because gout patients have a higher risk of traditional risk factors, and you have to [treat-to-target] those traditional risk factors.”

While the clinical evidence of a link between gout and atherosclerosis may not be conclusive, enough circumstantial evidence exists to believe that treating gout will reduce CV risks, he said. “Some of the imaging techniques do suggest that gouty crystals [are] in the atherosclerotic plaque of gout patients,” Dr. Garshick added. Dr. Pillinger’s work, he said, “is showing us that there are different pathways to develop atherosclerosis.”

Dr. Pillinger disclosed relationships with Federation Bio, Fortress Biotech, Amgen, Scilex, Hikma Pharmaceuticals, LG Chem, and Olatec Therapeutics. Dr. Garshick disclosed relationships with Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals, Agepha Pharma, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Horizon Therapeutics.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

NEW YORK — Urate, the culprit of gout, affects the vasculature in multiple ways that can raise cardiovascular risk (CV) in an individual with gout, and following guidelines for gout treatment, including the use of colchicine, can be the key to reducing those risks.

“Guideline-concordant gout treatment, which is essentially an anti-inflammatory urate-lowering strategy, at least improves arterial physiology and likely reduces cardiovascular risk,” Michael H. Pillinger, MD, told attendees at the 4th Annual Cardiometabolic Risk in Inflammatory Conditions conference. Dr. Pillinger is professor of medicine and biochemistry and molecular pharmacology at New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York City, who has published multiple studies on gout.

He cited evidence that has shown soluble urate stimulates the production of C-reactive protein (CRP), which is a predictor of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Another study, in which Dr. Pillinger participated, demonstrated that gout patients have impaired vascular endothelial function associated with a chronic, low-level inflammatory state, he said.

“There’s good evidence that urate itself affects the vasculature in multiple ways, and I suspect this may be a model for other metabolic effects on vasculature,” Dr. Pillinger said. “Patients with gout have abnormal endothelium in ways that really convey vascular risk.”

Gout, Inflammation, and CVD

However, for rheumatologists to study the association between gout-related inflammation and CVD is “very, very hard,” Dr. Pillinger added. “But I do think that the mechanisms by which gout induces biological changes in the vasculature may provide insights into cardiovascular disease in general.”

One way to evaluate the effects of gout on the endothelium in the clinic is to measure flow-mediated dilation. This technique involves placing an ultrasound probe over the brachial artery and measuring the baseline artery diameter. Then, with the blood pressure cuff over the forearm, inflate it to reduce flow, then release the cuff and measure the brachial artery diameter after the endothelium releases vasodilators.

Dr. Pillinger and colleagues evaluated this technique in 34 patients with gout and 64 controls and found that patients with gout had an almost 50% decrease in flow-mediated dilation, he said. “Interestingly, the higher the urate, the worse the flow; the more the inflammation, the worse the flow, so seemingly corresponding with the severity of the gout,” he said. That raised an obvious question, Dr. Pillinger continued: “If you can treat the gout, can you improve the flow-mediated dilation?”

His group answered that question with a study in 38 previously untreated patients with gout, giving them colchicine 0.6 mg twice daily for a month plus a urate-lowering xanthine oxidase inhibitor (allopurinol or febuxostat) to treat them to a target urate level of < 6 mg/dL. “We saw an increase in endothelial function, and it normalized,” Dr. Pillinger said.

However, some study participants didn’t respond. “They were people with well-established other cardiovascular comorbidities — hypertension, hyperlipidemia,” he said. “I think some people just have vessels that are too damaged to get at them just by fixing their gout problem or their inflammation.”

That means patients with gout need to be treated with colchicine early on to avoid CV problems, Dr. Pillinger added. “We ought to get to them before they have the other problems,” he said.

Managing gout, and the concomitant CV problems, requires vigilance both during and in between flares, Dr. Pillinger said after his presentation.

“We have always taught that patients between flares basically look like people with no gout, but we do know now that patients with gout between flares tend to have what you might call ‘subclinical’ inflammation: CRPs and ESRs [erythrocyte sedimentation rates] that are higher than those of the general population, though not so excessive that they might grab attention,” he said. “We also know that many, if not all, patients between flares have urate deposited in or around their joints, but how these two relate is not fully established.”

Better treatment within 3 months of an acute gout flare may reduce the risk for CV events, he said, but that’s based on speculation more so than clinical data.

Potential Benefits of Targeting Inflammation

“More chronically, we know from the cardiologists’ studies that anti-inflammatory therapy should reduce risk in the high-risk general population,” Dr. Pillinger said. “There are no prospective studies confirming that this approach will work among gout patients, but there is no reason why it shouldn’t work — except perhaps that gout patients may have higher inflammation than the general population and also have more comorbidities, so they could perhaps be more resistant.”

Dr. Pillinger said that his group’s studies and another led by Daniel Solomon, MD, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, have indicated that anti-inflammatory strategies in gout will lower CV risk.

“And interestingly,” he added, “our data suggest that colchicine use may lower risk not only in high-risk gout patients but also in gout patients who start with no CAD [coronary artery disease] but who seem to have less incident CAD on colchicine. I see this as identifying that gout patients are intrinsically at high risk for CAD, even if they don’t actually have any, so they represent a population for whom lowering chronic inflammation may help prevent incident disease.”

Dr. Pillinger provided more evidence that the understanding of the relationship between gout, gout flares, and CV risk is evolving, said Michael S. Garshick, MD, who attended the conference and is head of the Cardio-Rheumatology Program at NYU Langone, New York City.

“There’s epidemiologic evidence supporting the association,” Dr. Garshick told this news organization after the conference. “We think that most conditions with immune system activation do tend to have an increased risk of some form of cardiovascular disease, but I think the relationship with gout has been highly underpublicized.”

Many patients with gout tend to have a higher prevalence of traditional cardiometabolic issues, which may compound the relationship, Dr. Garshick added. “However, I would argue that with this patient subset that it doesn’t matter because gout patients have a higher risk of traditional risk factors, and you have to [treat-to-target] those traditional risk factors.”