User login

How much is enough?

How much do I make compared with other doctors?

I see questions like that on surveys I get, asking me to fill something out on the Internet, then I’ll get back a list of how well other docs in my field/city/state/blood type are doing.

Nah. I’ll pass.

Realistically, why? So I can feel I’m superior or inferior to others? Isn’t keeping up with the Joneses the purpose of the doctors’ parking lot at the hospital? (Actually, the number of pricey cars there has dropped off over time).

I really don’t want to know how much others make. It’s probably more than what I make, but that’s the trade-off I accepted when I went with a small solo practice instead of a large group 20 years ago.

We become so obsessed with the question of “how much money should I be making?” and comparing it with the salaries of others that we lose track of the real question: “How much money do I need?”

That should be the real number to look at. How much money do I really need to pay for a comfortable home, support my family, pay for my kids’ education, fund my retirement?

Enough should be as good as a feast.

Yet, even when content we get caught in the trap of comparing ourselves with others. This is human nature. We’re programmed to be competitive to survive. Whether that means anything when we don’t have to be hunters and gatherers is irrelevant. It is who we are.

But we’re also intelligent enough to realize that. I for one, don’t want to know, or care, how much money the neurologist down the street is earning.

To quote Sheryl Crow, “it’s not having what you want, it’s wanting what you’ve got.”

So I’ll skip the comparisons and focus on the only people that really matter to me.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

How much do I make compared with other doctors?

I see questions like that on surveys I get, asking me to fill something out on the Internet, then I’ll get back a list of how well other docs in my field/city/state/blood type are doing.

Nah. I’ll pass.

Realistically, why? So I can feel I’m superior or inferior to others? Isn’t keeping up with the Joneses the purpose of the doctors’ parking lot at the hospital? (Actually, the number of pricey cars there has dropped off over time).

I really don’t want to know how much others make. It’s probably more than what I make, but that’s the trade-off I accepted when I went with a small solo practice instead of a large group 20 years ago.

We become so obsessed with the question of “how much money should I be making?” and comparing it with the salaries of others that we lose track of the real question: “How much money do I need?”

That should be the real number to look at. How much money do I really need to pay for a comfortable home, support my family, pay for my kids’ education, fund my retirement?

Enough should be as good as a feast.

Yet, even when content we get caught in the trap of comparing ourselves with others. This is human nature. We’re programmed to be competitive to survive. Whether that means anything when we don’t have to be hunters and gatherers is irrelevant. It is who we are.

But we’re also intelligent enough to realize that. I for one, don’t want to know, or care, how much money the neurologist down the street is earning.

To quote Sheryl Crow, “it’s not having what you want, it’s wanting what you’ve got.”

So I’ll skip the comparisons and focus on the only people that really matter to me.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

How much do I make compared with other doctors?

I see questions like that on surveys I get, asking me to fill something out on the Internet, then I’ll get back a list of how well other docs in my field/city/state/blood type are doing.

Nah. I’ll pass.

Realistically, why? So I can feel I’m superior or inferior to others? Isn’t keeping up with the Joneses the purpose of the doctors’ parking lot at the hospital? (Actually, the number of pricey cars there has dropped off over time).

I really don’t want to know how much others make. It’s probably more than what I make, but that’s the trade-off I accepted when I went with a small solo practice instead of a large group 20 years ago.

We become so obsessed with the question of “how much money should I be making?” and comparing it with the salaries of others that we lose track of the real question: “How much money do I need?”

That should be the real number to look at. How much money do I really need to pay for a comfortable home, support my family, pay for my kids’ education, fund my retirement?

Enough should be as good as a feast.

Yet, even when content we get caught in the trap of comparing ourselves with others. This is human nature. We’re programmed to be competitive to survive. Whether that means anything when we don’t have to be hunters and gatherers is irrelevant. It is who we are.

But we’re also intelligent enough to realize that. I for one, don’t want to know, or care, how much money the neurologist down the street is earning.

To quote Sheryl Crow, “it’s not having what you want, it’s wanting what you’ve got.”

So I’ll skip the comparisons and focus on the only people that really matter to me.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Cutaneous Insulin-Derived Amyloidosis Presenting as Hyperkeratotic Nodules

Amyloidosis consists of approximately 30 protein-folding disorders sharing the common feature of abnormal extracellular amyloid deposition. In each condition, a specific soluble precursor protein aggregates to form the insoluble fibrils of amyloid, characterized by the beta-pleated sheet structure.1 Amyloidosis occurs as either a systemic or localized process. Insulin-derived (AIns) amyloidosis, a localized process occurring at insulin injection sites, was first reported in 1983.2 There were fewer than 20 reported cases until 2014, when 57 additional cases were reported by just 2 institutions,3,4 indicating that AIns amyloidosis may be more common than previously thought.3,5

Despite the increasing prevalence of diabetes mellitus and insulin use, there is a paucity of published cases of AIns amyloidosis. The lack of awareness of this condition among both dermatologists and general practitioners may be in part due to its variable clinical manifestations. We describe 2 patients with unique presentations of localized amyloidosis at repeated insulin injection sites.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 39-year-old man with a history of type 1 diabetes mellitus presented with 4 asymptomatic nodules on the lateral thighs in areas of previous insulin injection. He first noticed the lesions 9 months prior to presentation and subsequently switched the injection site to the abdomen without development of new nodules. Despite being compliant with his insulin regimen, he had a long history of irregular glucose control, including frequent hypoglycemic episodes. The patient was using regular and neutral protamine hagedorn insulin.

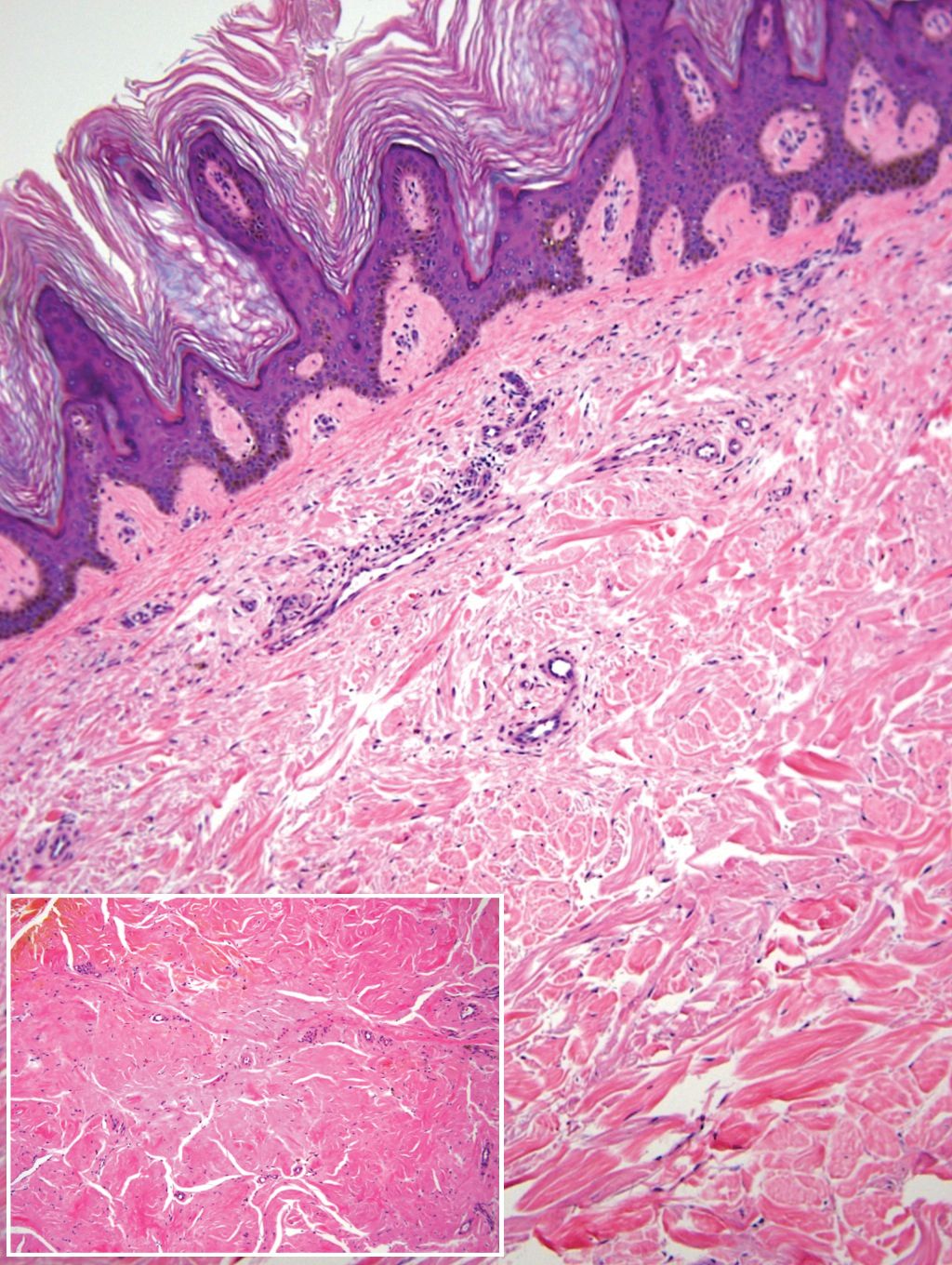

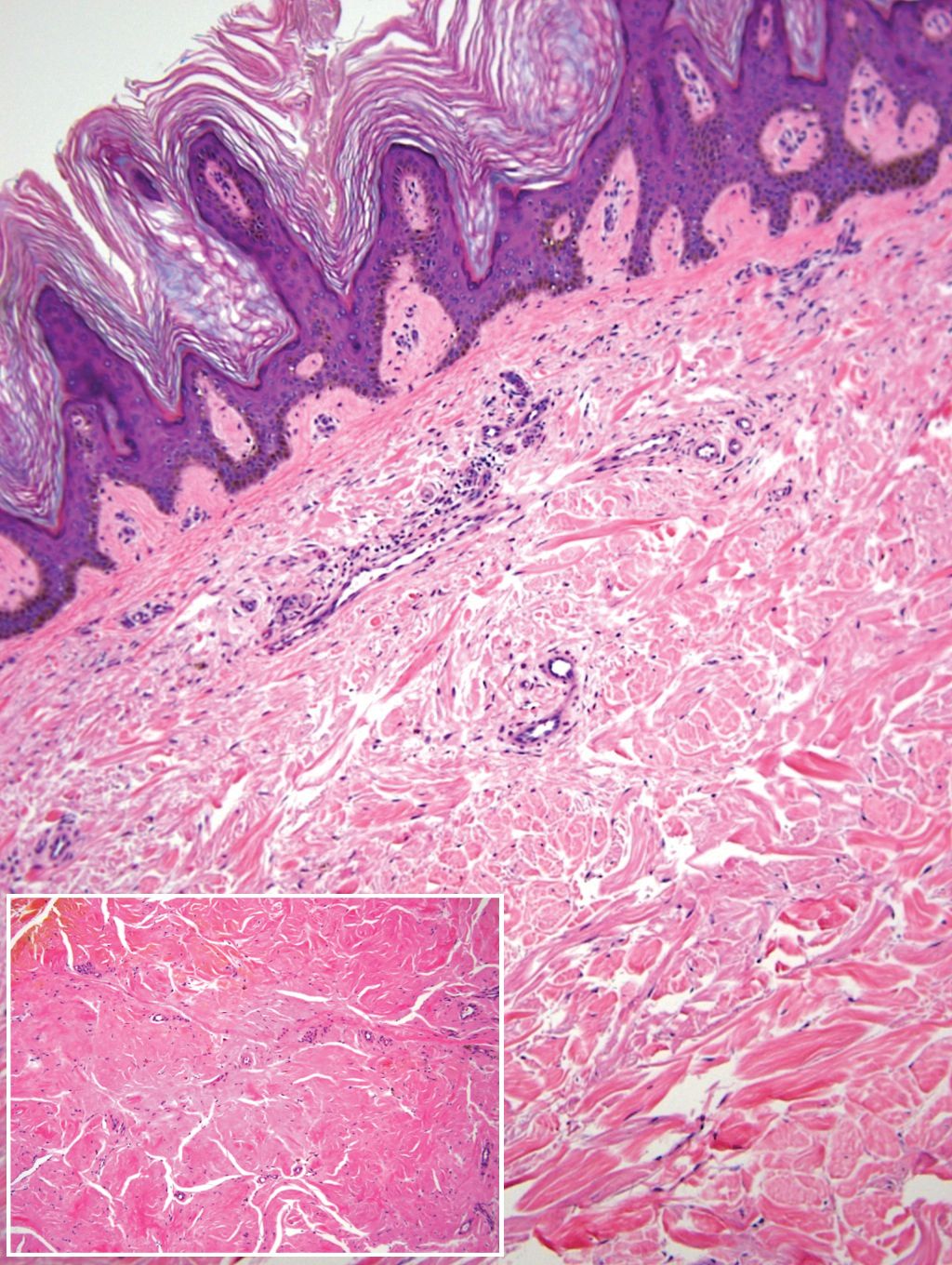

On physical examination, 2 soft, nontender, exophytic nodules were noted on each upper thigh with surrounding hyperpigmented and hyperkeratotic collarettes (Figure 1). The nodules ranged in size from 2 to 3.5 cm in diameter.

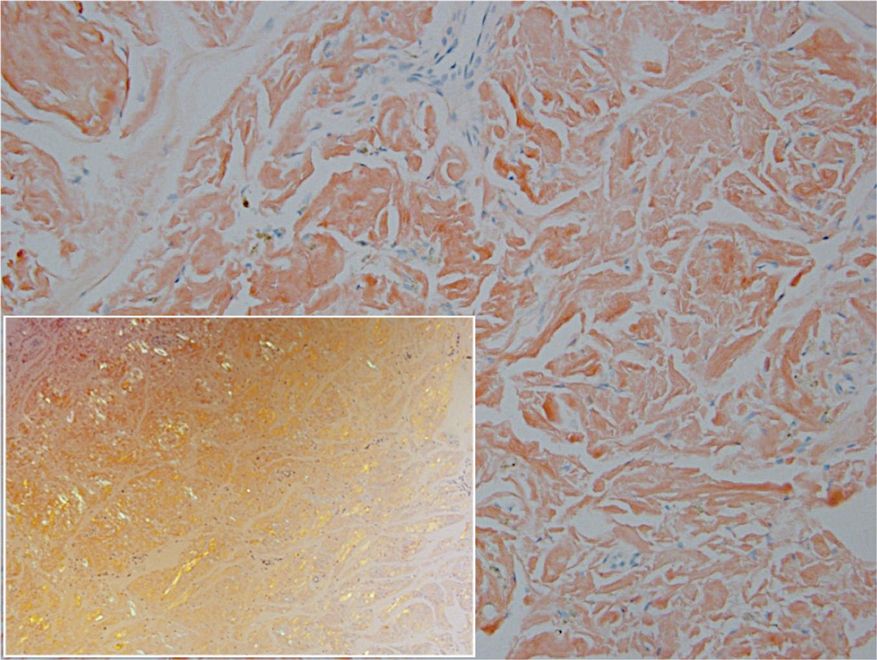

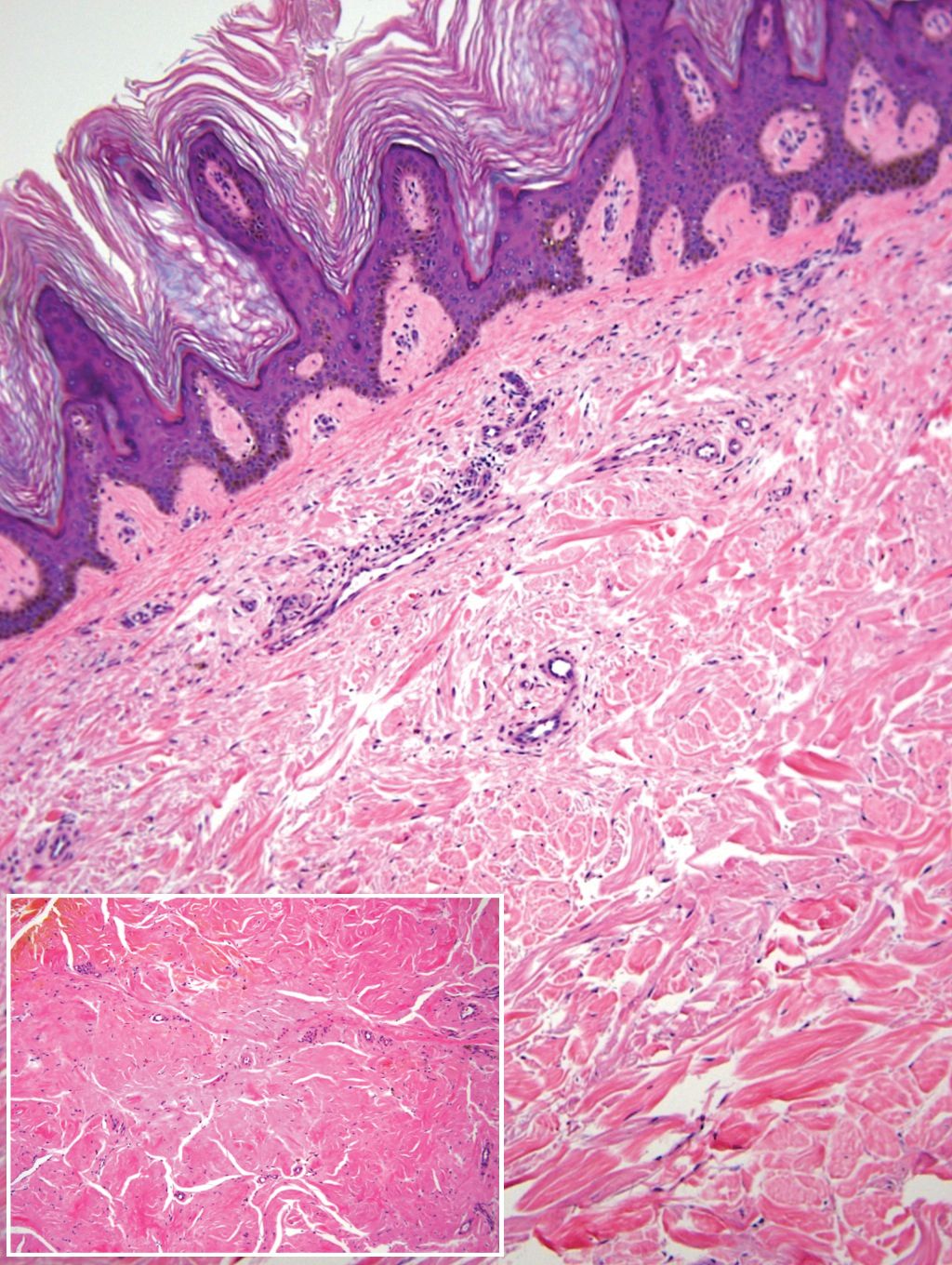

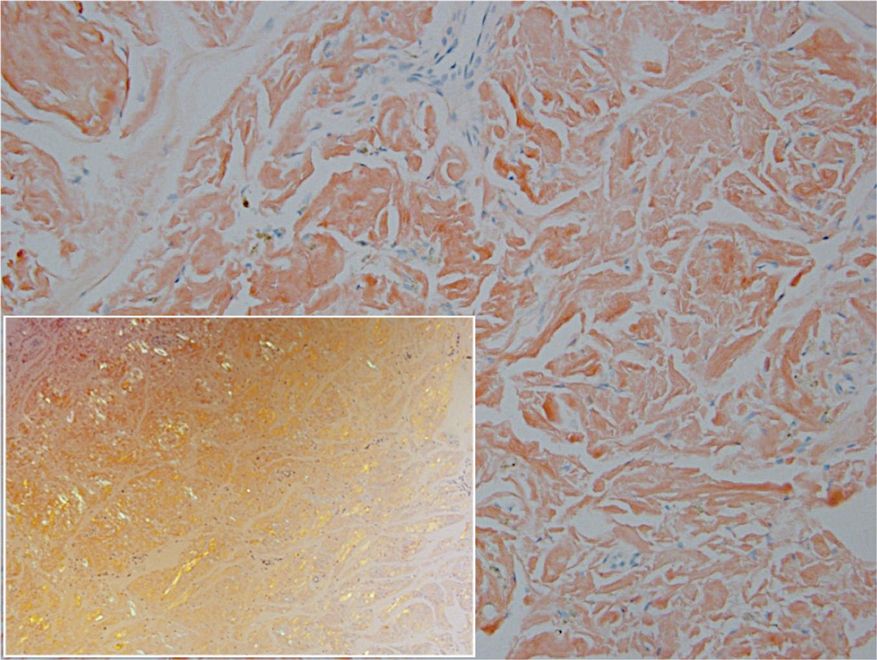

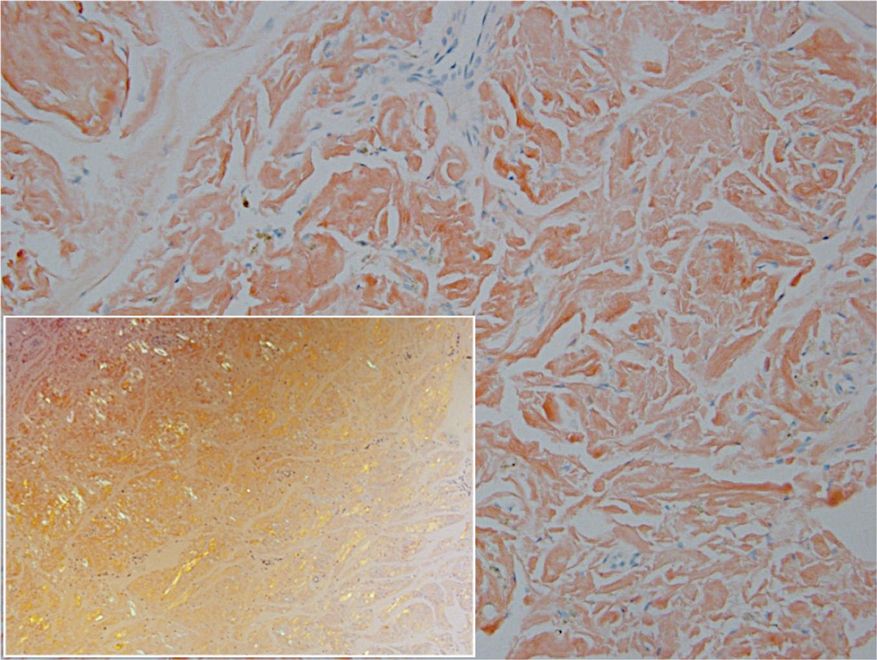

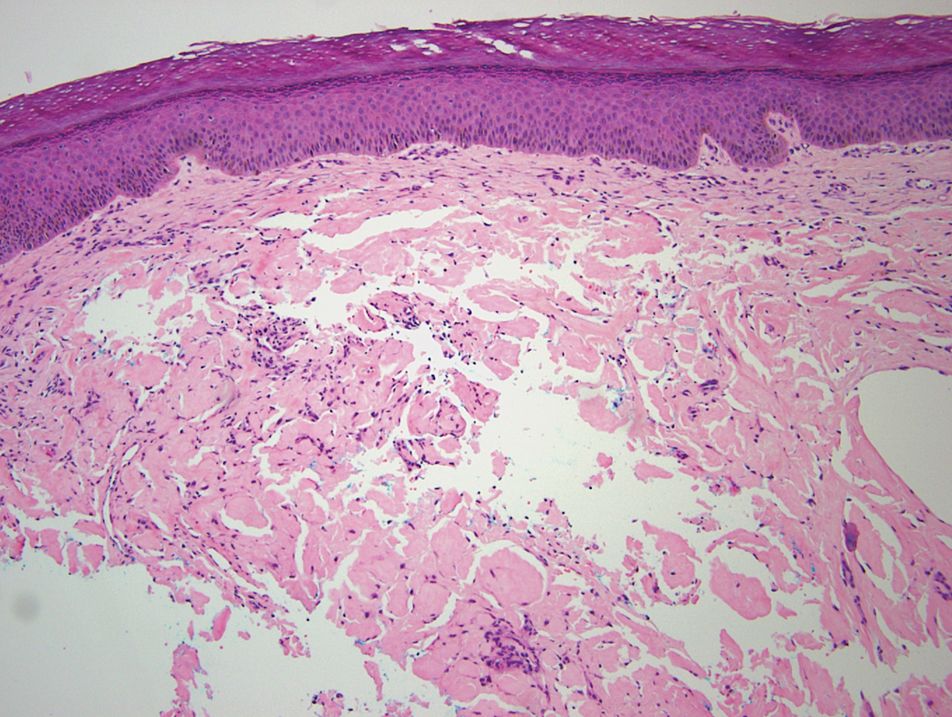

Remarkable laboratory data included a fasting glucose level of 207 mg/dL (reference range, 70–110 mg/dL) and a glycohemoglobin of 8.8% (reference range, <5.7%). Serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation were normal. Histopathology of the lesions demonstrated diffuse deposition of pink amorphous material associated with prominent papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and acanthosis (Figure 2). Congo red staining was positive with green birefringence under polarized light, indicative of amyloid deposits (Figure 3). Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry of the specimens was consistent with deposition of AIns amyloidosis.

Due to the size and persistent nature of the lesions, the nodules were removed by tangential excision. In addition, the patient was advised to continue rotating injection sites frequently. His blood glucose levels are now well controlled, and he has not developed any new nodules.

Patient 2

A 53-year-old woman with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with painful subcutaneous nodules on the lower abdomen at sites of previous insulin injections. The nodules developed approximately 1 month after she started treatment with neutral protamine hagedorn insulin and had been slowly enlarging over the past year. She tried switching injection sites after noticing the lesions, but the nodules persisted. The patient had a long history of poor glucose control with chronically elevated glycohemoglobin and blood glucose levels.

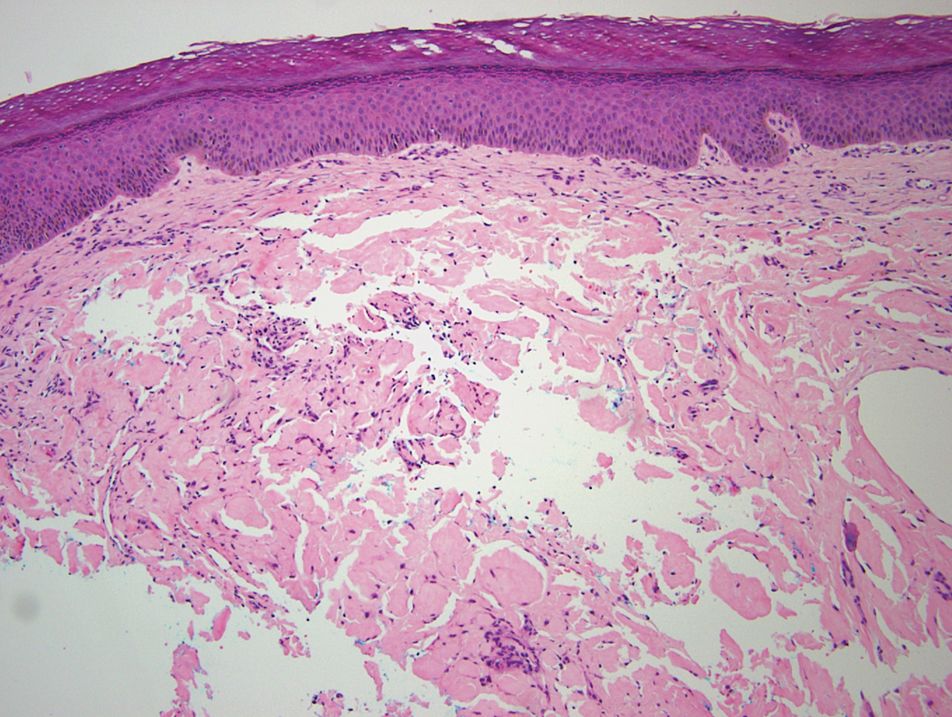

On physical examination, 2 hyperpigmented, exophytic, smooth nodules were noted on the right and left lower abdomen, ranging in size from 2.5 to 5.5 cm in diameter (Figure 4).

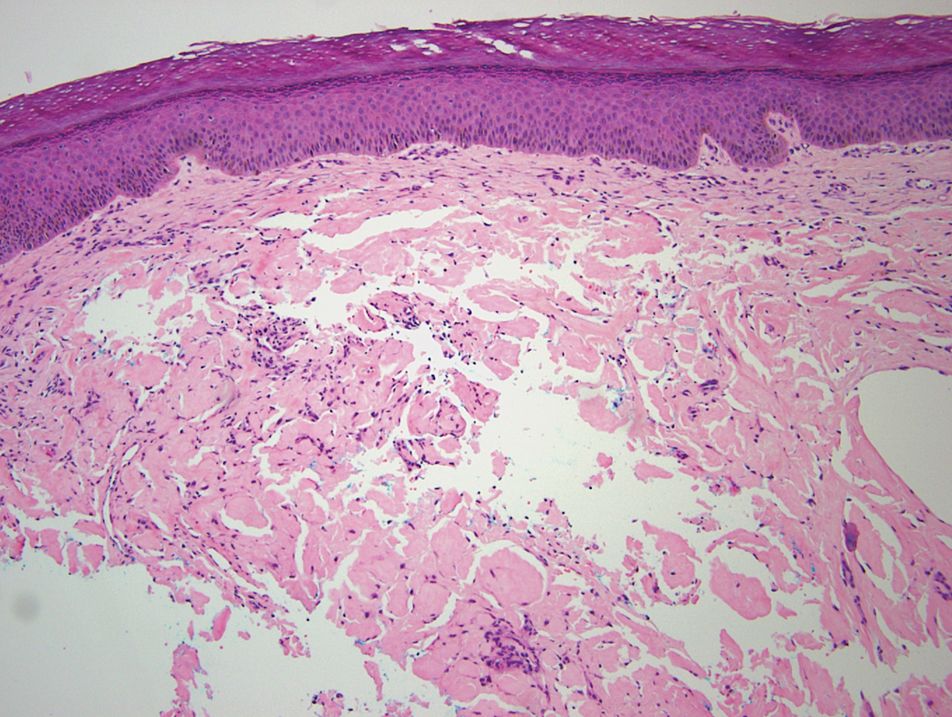

Relevant laboratory data included a fasting glucose level of 197 mg/dL and a glycohemoglobin of 9.3%. A biopsy of the lesion on the left lower abdomen revealed eosinophilic amorphous deposits with fissuring in the dermis (Figure 5). Congo red stain was positive with green birefringence under polarized light. Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry of the specimen showed deposition of AIns amyloid. The patient began injecting away from the amyloid nodules without development of any new lesions. The original nodules have persisted, and surgical excision is planned.

Comment

Insulin is the suspected precursor protein in AIns amyloidosis, but the exact pathogenesis is unknown. The protein that is derived from insulin in these tumors is now identified as AIns amyloidosis.5,6 It is hypothesized that insulin accumulates locally and is converted to amyloid by an unknown mechanism.7 Other potential contributory factors include chronic inflammation and foreign body reactions developing around amyloid deposits, as well as repeated trauma from injections into a single site.4,5 It appears that lesions may derive from a wide range of insulin types and occur after variable time periods.

A majority of cases of iatrogenic amyloid have been described as single, firm, subcutaneous masses at an injection site that commonly are misdiagnosed as lipomas or lipohypertrophy.7-11 To our knowledge, none of the reported cases resembled the multiple, discrete, exophytic nodules seen in our patients.3,4 The surrounding hyperkeratosis noted in patient 1 is another uncommon feature of AIns amyloidosis (Figures 1 and 2). Only 3 AIns amyloidosis cases described lesions with acanthosis nigricans–like changes, only 1 of which provided a clinical image.6,7,12The mechanism for the acanthosis nigricans–like changes may have been due to the high levels of insulin at the injection site. It has been suggested that the activation of insulinlike growth factor receptor by insulin leads to the proliferation of keratinocytes and fibroblasts.6 Histologic examination of AIns amyloidosis lesions generally demonstrates deposition of homogenous eosinophilic material consistent with amyloid, as well as positive Congo red staining with green birefringence by polarization. Immunohistologic staining with insulin antibody with or without proteomic analysis of the amyloid deposits can confirm the diagnosis. In both of our patients’ specimens, liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry was performed for proteomic analysis, and results were consistent with AIns amyloidosis.

Reports in the literature have suggested that the deposition of amyloid at insulin injection sites has the potential to interfere with insulin absorption, leading to poor glucose control.4,11,13 Hence, injection site rotation is a crucial aspect of treatment and prevention of AIns amyloidosis. In their study of 4 patients, Nagase et al4 compared serum insulin levels after insulin injection into amyloid nodules vs insulin levels after injection into normal skin. Insulin absorption at the amyloid sites was 34% of that at normal sites. Given these results, patients should be instructed to inject away from the amyloid deposit once it is identified.6 Glucose levels should be monitored closely when patients first inject away from the amyloid mass, as injection of the same dosage to an area of normal skin can lead to increased insulin absorption and hypoglycemia.4,6 It is possible that the frequent hypoglycemic episodes noted in patient 1 were due to increased insulin sensitivity after switching to injection sites away from amyloid lesions.

Conclusion

Our patients demonstrate unique presentations of localized cutaneous amyloidosis at repeated insulin injection sites. We report these cases to complement the current data of iatrogenic amyloidosis and provide insight into this likely underreported phenomenon.

- Hazenberg BPC. Amyloidosis: a clinical overview. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2013;39:323-345.

- Storkel S, Schneider HM, Muntefering H, et al. Iatrogenic, insulin-dependent, local amyloidosis. Lab Invest. 1983;48:108-111.

- D’souza A, Theis JD, Vrana JA, et al. Pharmaceutical amyloidosis associated with subcutaneous insulin and enfuvirtide administration. Amyloid. 2014;21:71-75.

- Nagase T, Iwaya K, Iwaki Y, et al. Insulin-derived amyloidosis and poor glycemic control: a case series. Am J Med. 2014;127:450-454.

- Gupta Y, Singla G, Singla R. Insulin-derived amyloidosis. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19:174-177.

- Kudo-Watanuki S, Kurihara E, Yamamoto K, et al. Coexistence of insulin-derived amyloidosis and an overlying acanthosis nigricans-like lesion at the site of insulin injection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:25-29.

- Yumlu S, Barany R, Eriksson M, et al. Localized insulin-derived amyloidosis in patients with diabetes mellitus: a case report. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:1655-1660.

- Okamura S, Hayashino Y, Kore-Eda S, et al. Localized amyloidosis at the site of repeated insulin injection in a patient with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:E200.

- Dische FE, Wernstedt C, Westermark GT, et al. Insulin as an amyloid-fibril protein at sites of repeated insulin injections in a diabetic patient. Diabetologia. 1988;31:158-161.

- Swift B, Hawkins PN, Richards C, et al. Examination of insulin injection sites: an unexpected finding of localized amyloidosis. Diabetic Med. 2002;19:881-882.

- Albert SG, Obadiah J, Parseghian SA, et al. Severe insulin resistance associated with subcutaneous amyloid deposition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;75:374-376.

- Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T, Shubha B. Cutaneous amyloidosis and insulin with coexistence of acanthosis nigricans. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2014;57:127-129.

- Endo JO, Rocken C, Lamb S, et al. Nodular amyloidosis in a diabetic patient with frequent hypoglycemia: sequelae of repeatedly injecting insulin without site rotation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:E113-E114.

Amyloidosis consists of approximately 30 protein-folding disorders sharing the common feature of abnormal extracellular amyloid deposition. In each condition, a specific soluble precursor protein aggregates to form the insoluble fibrils of amyloid, characterized by the beta-pleated sheet structure.1 Amyloidosis occurs as either a systemic or localized process. Insulin-derived (AIns) amyloidosis, a localized process occurring at insulin injection sites, was first reported in 1983.2 There were fewer than 20 reported cases until 2014, when 57 additional cases were reported by just 2 institutions,3,4 indicating that AIns amyloidosis may be more common than previously thought.3,5

Despite the increasing prevalence of diabetes mellitus and insulin use, there is a paucity of published cases of AIns amyloidosis. The lack of awareness of this condition among both dermatologists and general practitioners may be in part due to its variable clinical manifestations. We describe 2 patients with unique presentations of localized amyloidosis at repeated insulin injection sites.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 39-year-old man with a history of type 1 diabetes mellitus presented with 4 asymptomatic nodules on the lateral thighs in areas of previous insulin injection. He first noticed the lesions 9 months prior to presentation and subsequently switched the injection site to the abdomen without development of new nodules. Despite being compliant with his insulin regimen, he had a long history of irregular glucose control, including frequent hypoglycemic episodes. The patient was using regular and neutral protamine hagedorn insulin.

On physical examination, 2 soft, nontender, exophytic nodules were noted on each upper thigh with surrounding hyperpigmented and hyperkeratotic collarettes (Figure 1). The nodules ranged in size from 2 to 3.5 cm in diameter.

Remarkable laboratory data included a fasting glucose level of 207 mg/dL (reference range, 70–110 mg/dL) and a glycohemoglobin of 8.8% (reference range, <5.7%). Serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation were normal. Histopathology of the lesions demonstrated diffuse deposition of pink amorphous material associated with prominent papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and acanthosis (Figure 2). Congo red staining was positive with green birefringence under polarized light, indicative of amyloid deposits (Figure 3). Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry of the specimens was consistent with deposition of AIns amyloidosis.

Due to the size and persistent nature of the lesions, the nodules were removed by tangential excision. In addition, the patient was advised to continue rotating injection sites frequently. His blood glucose levels are now well controlled, and he has not developed any new nodules.

Patient 2

A 53-year-old woman with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with painful subcutaneous nodules on the lower abdomen at sites of previous insulin injections. The nodules developed approximately 1 month after she started treatment with neutral protamine hagedorn insulin and had been slowly enlarging over the past year. She tried switching injection sites after noticing the lesions, but the nodules persisted. The patient had a long history of poor glucose control with chronically elevated glycohemoglobin and blood glucose levels.

On physical examination, 2 hyperpigmented, exophytic, smooth nodules were noted on the right and left lower abdomen, ranging in size from 2.5 to 5.5 cm in diameter (Figure 4).

Relevant laboratory data included a fasting glucose level of 197 mg/dL and a glycohemoglobin of 9.3%. A biopsy of the lesion on the left lower abdomen revealed eosinophilic amorphous deposits with fissuring in the dermis (Figure 5). Congo red stain was positive with green birefringence under polarized light. Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry of the specimen showed deposition of AIns amyloid. The patient began injecting away from the amyloid nodules without development of any new lesions. The original nodules have persisted, and surgical excision is planned.

Comment

Insulin is the suspected precursor protein in AIns amyloidosis, but the exact pathogenesis is unknown. The protein that is derived from insulin in these tumors is now identified as AIns amyloidosis.5,6 It is hypothesized that insulin accumulates locally and is converted to amyloid by an unknown mechanism.7 Other potential contributory factors include chronic inflammation and foreign body reactions developing around amyloid deposits, as well as repeated trauma from injections into a single site.4,5 It appears that lesions may derive from a wide range of insulin types and occur after variable time periods.

A majority of cases of iatrogenic amyloid have been described as single, firm, subcutaneous masses at an injection site that commonly are misdiagnosed as lipomas or lipohypertrophy.7-11 To our knowledge, none of the reported cases resembled the multiple, discrete, exophytic nodules seen in our patients.3,4 The surrounding hyperkeratosis noted in patient 1 is another uncommon feature of AIns amyloidosis (Figures 1 and 2). Only 3 AIns amyloidosis cases described lesions with acanthosis nigricans–like changes, only 1 of which provided a clinical image.6,7,12The mechanism for the acanthosis nigricans–like changes may have been due to the high levels of insulin at the injection site. It has been suggested that the activation of insulinlike growth factor receptor by insulin leads to the proliferation of keratinocytes and fibroblasts.6 Histologic examination of AIns amyloidosis lesions generally demonstrates deposition of homogenous eosinophilic material consistent with amyloid, as well as positive Congo red staining with green birefringence by polarization. Immunohistologic staining with insulin antibody with or without proteomic analysis of the amyloid deposits can confirm the diagnosis. In both of our patients’ specimens, liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry was performed for proteomic analysis, and results were consistent with AIns amyloidosis.

Reports in the literature have suggested that the deposition of amyloid at insulin injection sites has the potential to interfere with insulin absorption, leading to poor glucose control.4,11,13 Hence, injection site rotation is a crucial aspect of treatment and prevention of AIns amyloidosis. In their study of 4 patients, Nagase et al4 compared serum insulin levels after insulin injection into amyloid nodules vs insulin levels after injection into normal skin. Insulin absorption at the amyloid sites was 34% of that at normal sites. Given these results, patients should be instructed to inject away from the amyloid deposit once it is identified.6 Glucose levels should be monitored closely when patients first inject away from the amyloid mass, as injection of the same dosage to an area of normal skin can lead to increased insulin absorption and hypoglycemia.4,6 It is possible that the frequent hypoglycemic episodes noted in patient 1 were due to increased insulin sensitivity after switching to injection sites away from amyloid lesions.

Conclusion

Our patients demonstrate unique presentations of localized cutaneous amyloidosis at repeated insulin injection sites. We report these cases to complement the current data of iatrogenic amyloidosis and provide insight into this likely underreported phenomenon.

Amyloidosis consists of approximately 30 protein-folding disorders sharing the common feature of abnormal extracellular amyloid deposition. In each condition, a specific soluble precursor protein aggregates to form the insoluble fibrils of amyloid, characterized by the beta-pleated sheet structure.1 Amyloidosis occurs as either a systemic or localized process. Insulin-derived (AIns) amyloidosis, a localized process occurring at insulin injection sites, was first reported in 1983.2 There were fewer than 20 reported cases until 2014, when 57 additional cases were reported by just 2 institutions,3,4 indicating that AIns amyloidosis may be more common than previously thought.3,5

Despite the increasing prevalence of diabetes mellitus and insulin use, there is a paucity of published cases of AIns amyloidosis. The lack of awareness of this condition among both dermatologists and general practitioners may be in part due to its variable clinical manifestations. We describe 2 patients with unique presentations of localized amyloidosis at repeated insulin injection sites.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 39-year-old man with a history of type 1 diabetes mellitus presented with 4 asymptomatic nodules on the lateral thighs in areas of previous insulin injection. He first noticed the lesions 9 months prior to presentation and subsequently switched the injection site to the abdomen without development of new nodules. Despite being compliant with his insulin regimen, he had a long history of irregular glucose control, including frequent hypoglycemic episodes. The patient was using regular and neutral protamine hagedorn insulin.

On physical examination, 2 soft, nontender, exophytic nodules were noted on each upper thigh with surrounding hyperpigmented and hyperkeratotic collarettes (Figure 1). The nodules ranged in size from 2 to 3.5 cm in diameter.

Remarkable laboratory data included a fasting glucose level of 207 mg/dL (reference range, 70–110 mg/dL) and a glycohemoglobin of 8.8% (reference range, <5.7%). Serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation were normal. Histopathology of the lesions demonstrated diffuse deposition of pink amorphous material associated with prominent papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and acanthosis (Figure 2). Congo red staining was positive with green birefringence under polarized light, indicative of amyloid deposits (Figure 3). Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry of the specimens was consistent with deposition of AIns amyloidosis.

Due to the size and persistent nature of the lesions, the nodules were removed by tangential excision. In addition, the patient was advised to continue rotating injection sites frequently. His blood glucose levels are now well controlled, and he has not developed any new nodules.

Patient 2

A 53-year-old woman with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with painful subcutaneous nodules on the lower abdomen at sites of previous insulin injections. The nodules developed approximately 1 month after she started treatment with neutral protamine hagedorn insulin and had been slowly enlarging over the past year. She tried switching injection sites after noticing the lesions, but the nodules persisted. The patient had a long history of poor glucose control with chronically elevated glycohemoglobin and blood glucose levels.

On physical examination, 2 hyperpigmented, exophytic, smooth nodules were noted on the right and left lower abdomen, ranging in size from 2.5 to 5.5 cm in diameter (Figure 4).

Relevant laboratory data included a fasting glucose level of 197 mg/dL and a glycohemoglobin of 9.3%. A biopsy of the lesion on the left lower abdomen revealed eosinophilic amorphous deposits with fissuring in the dermis (Figure 5). Congo red stain was positive with green birefringence under polarized light. Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry of the specimen showed deposition of AIns amyloid. The patient began injecting away from the amyloid nodules without development of any new lesions. The original nodules have persisted, and surgical excision is planned.

Comment

Insulin is the suspected precursor protein in AIns amyloidosis, but the exact pathogenesis is unknown. The protein that is derived from insulin in these tumors is now identified as AIns amyloidosis.5,6 It is hypothesized that insulin accumulates locally and is converted to amyloid by an unknown mechanism.7 Other potential contributory factors include chronic inflammation and foreign body reactions developing around amyloid deposits, as well as repeated trauma from injections into a single site.4,5 It appears that lesions may derive from a wide range of insulin types and occur after variable time periods.

A majority of cases of iatrogenic amyloid have been described as single, firm, subcutaneous masses at an injection site that commonly are misdiagnosed as lipomas or lipohypertrophy.7-11 To our knowledge, none of the reported cases resembled the multiple, discrete, exophytic nodules seen in our patients.3,4 The surrounding hyperkeratosis noted in patient 1 is another uncommon feature of AIns amyloidosis (Figures 1 and 2). Only 3 AIns amyloidosis cases described lesions with acanthosis nigricans–like changes, only 1 of which provided a clinical image.6,7,12The mechanism for the acanthosis nigricans–like changes may have been due to the high levels of insulin at the injection site. It has been suggested that the activation of insulinlike growth factor receptor by insulin leads to the proliferation of keratinocytes and fibroblasts.6 Histologic examination of AIns amyloidosis lesions generally demonstrates deposition of homogenous eosinophilic material consistent with amyloid, as well as positive Congo red staining with green birefringence by polarization. Immunohistologic staining with insulin antibody with or without proteomic analysis of the amyloid deposits can confirm the diagnosis. In both of our patients’ specimens, liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry was performed for proteomic analysis, and results were consistent with AIns amyloidosis.

Reports in the literature have suggested that the deposition of amyloid at insulin injection sites has the potential to interfere with insulin absorption, leading to poor glucose control.4,11,13 Hence, injection site rotation is a crucial aspect of treatment and prevention of AIns amyloidosis. In their study of 4 patients, Nagase et al4 compared serum insulin levels after insulin injection into amyloid nodules vs insulin levels after injection into normal skin. Insulin absorption at the amyloid sites was 34% of that at normal sites. Given these results, patients should be instructed to inject away from the amyloid deposit once it is identified.6 Glucose levels should be monitored closely when patients first inject away from the amyloid mass, as injection of the same dosage to an area of normal skin can lead to increased insulin absorption and hypoglycemia.4,6 It is possible that the frequent hypoglycemic episodes noted in patient 1 were due to increased insulin sensitivity after switching to injection sites away from amyloid lesions.

Conclusion

Our patients demonstrate unique presentations of localized cutaneous amyloidosis at repeated insulin injection sites. We report these cases to complement the current data of iatrogenic amyloidosis and provide insight into this likely underreported phenomenon.

- Hazenberg BPC. Amyloidosis: a clinical overview. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2013;39:323-345.

- Storkel S, Schneider HM, Muntefering H, et al. Iatrogenic, insulin-dependent, local amyloidosis. Lab Invest. 1983;48:108-111.

- D’souza A, Theis JD, Vrana JA, et al. Pharmaceutical amyloidosis associated with subcutaneous insulin and enfuvirtide administration. Amyloid. 2014;21:71-75.

- Nagase T, Iwaya K, Iwaki Y, et al. Insulin-derived amyloidosis and poor glycemic control: a case series. Am J Med. 2014;127:450-454.

- Gupta Y, Singla G, Singla R. Insulin-derived amyloidosis. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19:174-177.

- Kudo-Watanuki S, Kurihara E, Yamamoto K, et al. Coexistence of insulin-derived amyloidosis and an overlying acanthosis nigricans-like lesion at the site of insulin injection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:25-29.

- Yumlu S, Barany R, Eriksson M, et al. Localized insulin-derived amyloidosis in patients with diabetes mellitus: a case report. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:1655-1660.

- Okamura S, Hayashino Y, Kore-Eda S, et al. Localized amyloidosis at the site of repeated insulin injection in a patient with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:E200.

- Dische FE, Wernstedt C, Westermark GT, et al. Insulin as an amyloid-fibril protein at sites of repeated insulin injections in a diabetic patient. Diabetologia. 1988;31:158-161.

- Swift B, Hawkins PN, Richards C, et al. Examination of insulin injection sites: an unexpected finding of localized amyloidosis. Diabetic Med. 2002;19:881-882.

- Albert SG, Obadiah J, Parseghian SA, et al. Severe insulin resistance associated with subcutaneous amyloid deposition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;75:374-376.

- Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T, Shubha B. Cutaneous amyloidosis and insulin with coexistence of acanthosis nigricans. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2014;57:127-129.

- Endo JO, Rocken C, Lamb S, et al. Nodular amyloidosis in a diabetic patient with frequent hypoglycemia: sequelae of repeatedly injecting insulin without site rotation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:E113-E114.

- Hazenberg BPC. Amyloidosis: a clinical overview. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2013;39:323-345.

- Storkel S, Schneider HM, Muntefering H, et al. Iatrogenic, insulin-dependent, local amyloidosis. Lab Invest. 1983;48:108-111.

- D’souza A, Theis JD, Vrana JA, et al. Pharmaceutical amyloidosis associated with subcutaneous insulin and enfuvirtide administration. Amyloid. 2014;21:71-75.

- Nagase T, Iwaya K, Iwaki Y, et al. Insulin-derived amyloidosis and poor glycemic control: a case series. Am J Med. 2014;127:450-454.

- Gupta Y, Singla G, Singla R. Insulin-derived amyloidosis. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19:174-177.

- Kudo-Watanuki S, Kurihara E, Yamamoto K, et al. Coexistence of insulin-derived amyloidosis and an overlying acanthosis nigricans-like lesion at the site of insulin injection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:25-29.

- Yumlu S, Barany R, Eriksson M, et al. Localized insulin-derived amyloidosis in patients with diabetes mellitus: a case report. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:1655-1660.

- Okamura S, Hayashino Y, Kore-Eda S, et al. Localized amyloidosis at the site of repeated insulin injection in a patient with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:E200.

- Dische FE, Wernstedt C, Westermark GT, et al. Insulin as an amyloid-fibril protein at sites of repeated insulin injections in a diabetic patient. Diabetologia. 1988;31:158-161.

- Swift B, Hawkins PN, Richards C, et al. Examination of insulin injection sites: an unexpected finding of localized amyloidosis. Diabetic Med. 2002;19:881-882.

- Albert SG, Obadiah J, Parseghian SA, et al. Severe insulin resistance associated with subcutaneous amyloid deposition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;75:374-376.

- Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T, Shubha B. Cutaneous amyloidosis and insulin with coexistence of acanthosis nigricans. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2014;57:127-129.

- Endo JO, Rocken C, Lamb S, et al. Nodular amyloidosis in a diabetic patient with frequent hypoglycemia: sequelae of repeatedly injecting insulin without site rotation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:E113-E114.

Practice Points

- Deposition of amyloid at insulin injection sites has the potential to interfere with insulin absorption, leading to poor glucose control.

- Patients with insulin-derived (AIns) amyloidosis may initially present after noticing nodular deposits.

- Insulin injection site rotation is a crucial aspect of treatment and prevention of AIns amyloidosis.

Boost dose reduces recurrence in high-risk DCIS

Giving a tumor bed boost (TBB) reduced the risk of local recurrence and overall disease recurrence, but there were no significant differences in recurrence rates between conventional WBI and hypofractionated WBI.

Boon Hui Chua, MD, of the University of New South Wales, Sydney, presented these results at the 2020 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Dr. Chua and colleagues studied 1,608 women with DCIS resected by conservative surgery. Patients were either younger than 50 years or age 50 and older with at least one of the following risk factors: symptomatic presentation, palpable tumor, multifocal disease, tumor size 1.5 cm or larger, intermediate or high nuclear grade, central necrosis, comedo histology, and/or surgical margins less than 10 mm.

The patients were randomized to treatment in three categories. In randomization A (n = 503), patients were randomized to one of the following treatments:

- WBI at 50 Gy in 25 fractions

- WBI at 42.5 Gy in 16 fractions

- WBI at 50 Gy in 25 fractions plus TBB at 16 Gy in 8 fractions

- WBI at 42.5 Gy in 16 fractions plus TBB at 16 Gy in 8 fractions.

In randomization B (n = 581), patients received WBI at 50 Gy in 25 fractions, with or without TBB at 16 Gy in 8 fractions. In randomization C (n = 524), patients received WBI at 42.5 Gy in 16 fractions, with or without TBB at 16 Gy in 8 fractions.

All patients underwent CT-based radiation planning. WBI was delivered with tangential MV photon beams, and TBB was performed with CT contouring of protocol-defined tumor bed target volumes, with electron or photon energy. The median follow-up was 6.6 years.

Giving a boost to better outcomes

The 5-year rate of freedom from local recurrence was 97% for patients who received TBB and 93% for patients who did not (hazard ratio, 0.47; P < .001). The benefit of TBB was consistent across subgroups.

There were no significant differences in 5-year rates of freedom from local recurrence by WBI fractionation, either in randomization A (P = .837) or among all randomized patients (P = .887).

The tests for interactions between TBB and WBI fractionation on local recurrence were not significant in randomization A (P = .89) or in all randomized patients (P = .89).

The risk of overall disease recurrence was lower among patients who had received TBB, with an HR of 0.63 (P = .004). The 5-year rate of freedom from disease recurrence was 97% with TBB and 91% with no boost (P = .002).

There were no significant differences in freedom from disease recurrence rates by WBI fractionation either in randomization A (P = .443) or among all randomized patients (P = .605).

Acute radiation dermatitis occurred in significantly more patients who received TBB (P = .006), as did late breast pain (P = .003), induration or fibrosis (P < .0001), and telangiectasia (P = .02). There were no significant differences by boost status for acute or late fatigue, pneumonitis, cardiac complications, or second malignancies.

Reduce the boost dose?

A radiation oncologist who was not involved in this study said that, while the results confirm a benefit of boost dose for patients with non–low-risk DCIS, the doses used in the BIG-3-07 study may be higher than needed to achieve a protective effect.

“Here in America, we usually give 10 Gy in five fractions, and, in many countries, actually, it’s 10 Gy in five fractions, although a few European centers give 16 Gy in eight fractions,” said Alphose Taghian, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

“I personally only give 10 Gy in five fractions. I am not under the impression that 16 Gy in eight fractions will give better results. The local failure rate is so low, it’s likely that 10 Gy will do the job,” Dr. Taghian said in an interview.

Dr. Taghian noted that raising the dose to 16 Gy increases the risk of fibrosis, as seen in the BIG-3-07 trial.

Nonetheless, the trial demonstrates the benefit of radiation boost dose in patients with high-risk DCIS, he said, adding that the local recurrence-free benefit curves may separate further with longer follow-up.

The study was sponsored by the Trans Tasman Radiation Oncology Group. Dr. Chua and Dr. Taghian reported no conflicts of interest.

Giving a tumor bed boost (TBB) reduced the risk of local recurrence and overall disease recurrence, but there were no significant differences in recurrence rates between conventional WBI and hypofractionated WBI.

Boon Hui Chua, MD, of the University of New South Wales, Sydney, presented these results at the 2020 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Dr. Chua and colleagues studied 1,608 women with DCIS resected by conservative surgery. Patients were either younger than 50 years or age 50 and older with at least one of the following risk factors: symptomatic presentation, palpable tumor, multifocal disease, tumor size 1.5 cm or larger, intermediate or high nuclear grade, central necrosis, comedo histology, and/or surgical margins less than 10 mm.

The patients were randomized to treatment in three categories. In randomization A (n = 503), patients were randomized to one of the following treatments:

- WBI at 50 Gy in 25 fractions

- WBI at 42.5 Gy in 16 fractions

- WBI at 50 Gy in 25 fractions plus TBB at 16 Gy in 8 fractions

- WBI at 42.5 Gy in 16 fractions plus TBB at 16 Gy in 8 fractions.

In randomization B (n = 581), patients received WBI at 50 Gy in 25 fractions, with or without TBB at 16 Gy in 8 fractions. In randomization C (n = 524), patients received WBI at 42.5 Gy in 16 fractions, with or without TBB at 16 Gy in 8 fractions.

All patients underwent CT-based radiation planning. WBI was delivered with tangential MV photon beams, and TBB was performed with CT contouring of protocol-defined tumor bed target volumes, with electron or photon energy. The median follow-up was 6.6 years.

Giving a boost to better outcomes

The 5-year rate of freedom from local recurrence was 97% for patients who received TBB and 93% for patients who did not (hazard ratio, 0.47; P < .001). The benefit of TBB was consistent across subgroups.

There were no significant differences in 5-year rates of freedom from local recurrence by WBI fractionation, either in randomization A (P = .837) or among all randomized patients (P = .887).

The tests for interactions between TBB and WBI fractionation on local recurrence were not significant in randomization A (P = .89) or in all randomized patients (P = .89).

The risk of overall disease recurrence was lower among patients who had received TBB, with an HR of 0.63 (P = .004). The 5-year rate of freedom from disease recurrence was 97% with TBB and 91% with no boost (P = .002).

There were no significant differences in freedom from disease recurrence rates by WBI fractionation either in randomization A (P = .443) or among all randomized patients (P = .605).

Acute radiation dermatitis occurred in significantly more patients who received TBB (P = .006), as did late breast pain (P = .003), induration or fibrosis (P < .0001), and telangiectasia (P = .02). There were no significant differences by boost status for acute or late fatigue, pneumonitis, cardiac complications, or second malignancies.

Reduce the boost dose?

A radiation oncologist who was not involved in this study said that, while the results confirm a benefit of boost dose for patients with non–low-risk DCIS, the doses used in the BIG-3-07 study may be higher than needed to achieve a protective effect.

“Here in America, we usually give 10 Gy in five fractions, and, in many countries, actually, it’s 10 Gy in five fractions, although a few European centers give 16 Gy in eight fractions,” said Alphose Taghian, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

“I personally only give 10 Gy in five fractions. I am not under the impression that 16 Gy in eight fractions will give better results. The local failure rate is so low, it’s likely that 10 Gy will do the job,” Dr. Taghian said in an interview.

Dr. Taghian noted that raising the dose to 16 Gy increases the risk of fibrosis, as seen in the BIG-3-07 trial.

Nonetheless, the trial demonstrates the benefit of radiation boost dose in patients with high-risk DCIS, he said, adding that the local recurrence-free benefit curves may separate further with longer follow-up.

The study was sponsored by the Trans Tasman Radiation Oncology Group. Dr. Chua and Dr. Taghian reported no conflicts of interest.

Giving a tumor bed boost (TBB) reduced the risk of local recurrence and overall disease recurrence, but there were no significant differences in recurrence rates between conventional WBI and hypofractionated WBI.

Boon Hui Chua, MD, of the University of New South Wales, Sydney, presented these results at the 2020 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Dr. Chua and colleagues studied 1,608 women with DCIS resected by conservative surgery. Patients were either younger than 50 years or age 50 and older with at least one of the following risk factors: symptomatic presentation, palpable tumor, multifocal disease, tumor size 1.5 cm or larger, intermediate or high nuclear grade, central necrosis, comedo histology, and/or surgical margins less than 10 mm.

The patients were randomized to treatment in three categories. In randomization A (n = 503), patients were randomized to one of the following treatments:

- WBI at 50 Gy in 25 fractions

- WBI at 42.5 Gy in 16 fractions

- WBI at 50 Gy in 25 fractions plus TBB at 16 Gy in 8 fractions

- WBI at 42.5 Gy in 16 fractions plus TBB at 16 Gy in 8 fractions.

In randomization B (n = 581), patients received WBI at 50 Gy in 25 fractions, with or without TBB at 16 Gy in 8 fractions. In randomization C (n = 524), patients received WBI at 42.5 Gy in 16 fractions, with or without TBB at 16 Gy in 8 fractions.

All patients underwent CT-based radiation planning. WBI was delivered with tangential MV photon beams, and TBB was performed with CT contouring of protocol-defined tumor bed target volumes, with electron or photon energy. The median follow-up was 6.6 years.

Giving a boost to better outcomes

The 5-year rate of freedom from local recurrence was 97% for patients who received TBB and 93% for patients who did not (hazard ratio, 0.47; P < .001). The benefit of TBB was consistent across subgroups.

There were no significant differences in 5-year rates of freedom from local recurrence by WBI fractionation, either in randomization A (P = .837) or among all randomized patients (P = .887).

The tests for interactions between TBB and WBI fractionation on local recurrence were not significant in randomization A (P = .89) or in all randomized patients (P = .89).

The risk of overall disease recurrence was lower among patients who had received TBB, with an HR of 0.63 (P = .004). The 5-year rate of freedom from disease recurrence was 97% with TBB and 91% with no boost (P = .002).

There were no significant differences in freedom from disease recurrence rates by WBI fractionation either in randomization A (P = .443) or among all randomized patients (P = .605).

Acute radiation dermatitis occurred in significantly more patients who received TBB (P = .006), as did late breast pain (P = .003), induration or fibrosis (P < .0001), and telangiectasia (P = .02). There were no significant differences by boost status for acute or late fatigue, pneumonitis, cardiac complications, or second malignancies.

Reduce the boost dose?

A radiation oncologist who was not involved in this study said that, while the results confirm a benefit of boost dose for patients with non–low-risk DCIS, the doses used in the BIG-3-07 study may be higher than needed to achieve a protective effect.

“Here in America, we usually give 10 Gy in five fractions, and, in many countries, actually, it’s 10 Gy in five fractions, although a few European centers give 16 Gy in eight fractions,” said Alphose Taghian, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

“I personally only give 10 Gy in five fractions. I am not under the impression that 16 Gy in eight fractions will give better results. The local failure rate is so low, it’s likely that 10 Gy will do the job,” Dr. Taghian said in an interview.

Dr. Taghian noted that raising the dose to 16 Gy increases the risk of fibrosis, as seen in the BIG-3-07 trial.

Nonetheless, the trial demonstrates the benefit of radiation boost dose in patients with high-risk DCIS, he said, adding that the local recurrence-free benefit curves may separate further with longer follow-up.

The study was sponsored by the Trans Tasman Radiation Oncology Group. Dr. Chua and Dr. Taghian reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM SABCS 2020

Immunotherapy response linked to low TMB in recurrent glioblastoma

In contrast to what has been seen in other tumor types, recurrent glioblastoma (rGBM) may respond better to immunotherapy when tumor mutational burden (TMB) is low, new research suggests.

There’s an “unexpected correlation between TMB, tumor-intrinsic inflammation, and survival after immunotherapy” in this patient population, researchers noted in a Nature Communications report.

Cases of rGBM in which TMB is low are more likely to respond to immunotherapy than cases in which TMB is higher, the investigators concluded from an analysis of tumor tissue from more than 100 patients.

“We need to do a prospective study and establish a threshold in a particular assay format,” senior author David Ashley, MBBS, PhD, a neurosurgery professor at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said in an interview.

Andrew Sloan, MD, a neurosurgery professor at the Seidman Cancer Center, Cleveland, said in a comment that “many have given up on immunotherapy for GBM because these tumors tend to have lower TMB than tumors that typically respond to immunotherapy, including checkpoint inhibitors.” (Examples include melanoma and lung cancer.)

“If the findings are confirmed, it would be very useful clinically to select” patients for immunotherapy, Dr. Sloan commented.

Correlation seen with rGBM, not primary tumor

Recurrence of GBM is almost inevitable, even when aggressive standard-of-care therapy is given initially, according to Dr. Ashley and colleagues. Studies have indicated that, in 10%-20% of patients with rGBM, disease responds to subsequent immunotherapy, and patients live beyond the predicted median survival of about 12 months. It’s been unclear, however, what distinguishes these survivors from the other patients.

Dr. Ashley and colleagues looked for common genetic factors that distinguish survivors.

The tumor tissue the team analyzed came from three studies. The first was a trial of an intratumoral infusion of a recombinant nonpathogenic poliorhinovirus chimera (PVSRIPO), developed at Duke University, that induces innate inflammation and T-cell attack. Among 61 patients, 21% were alive at 3 years versus 4% of historical control patients.

The second study was a review of 66 patients with GBM who underwent treatment with pembrolizumab or nivolumab. The median survival was 14.3 months among those who experienced a response versus10.1 months for those who did not.

The third study involved more than 1,000 patients with advanced cancer who underwent treatment with checkpoint inhibitors. There was no survival benefit among the 117 patients with glioma who were treated with checkpoint inhibitors.

In the PVSRIPO trial, rGBM tumors from patients who survived longer than 20 months harbored very low TMB, less than 0.6 mutations/Mb. In the two checkpoint inhibitor trials, among 110 patients with rGBM, survival was longer for those whose TMB was at or below the median level.

The differences in survival were not driven by differences in steroid dosing, unfavorable responses among patients with hypermutations, or the presence or absence of IDH1 or PTEN mutations or MGMT promoter methylation, according to Dr. Ashley and colleagues.

“Increased survival of immunotherapy-treated rGBM patients with very low TMB is due to immunotherapy response,” the investigators concluded.

As for the explanation, the team found that rGBM tumors with lower TMB levels had enriched inflammatory gene signatures, compared with tumors with higher TMB levels.

The correlation – and longer survival with low TMB – was not observed in primary GBM tumors, “indicating that a relationship between tumor-intrinsic inflammation and TMB develops upon recurrence. ... We postulate that the baseline inflammatory status of rGBM tumors determines their susceptibility to immunotherapy,” the authors wrote.

Because the correlation between tumor inflammation and TMB was robust in rGBM but not in primary tumors, it might well have been caused by standard-of-care therapy, which affects mutation levels.

“Chemotherapy, which is the standard of care for newly diagnosed glioblastoma, might be altering the inflammatory response in these tumors” and priming an inflammatory process that increases vulnerability to immunotherapy in recurrent tumors, Dr. Ashley said in a press release.

Shorter time to recurrence also correlated with lower TMB and favorable response to PVSRIPO, so shorter duration of standard therapy or shorter time from initial surgery might improve immunotherapy response, he speculated.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and other organizations. Dr. Ashley and other investigators own intellectual property related to PVSRIPO, which has been licensed to Istari Oncology. Several investigators hold equity in and/or are paid consultants for Istari. Dr. Sloan is the Ohio principal investigator for an rGBM PVSRIPO and pembrolizumab study funded by the company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In contrast to what has been seen in other tumor types, recurrent glioblastoma (rGBM) may respond better to immunotherapy when tumor mutational burden (TMB) is low, new research suggests.

There’s an “unexpected correlation between TMB, tumor-intrinsic inflammation, and survival after immunotherapy” in this patient population, researchers noted in a Nature Communications report.

Cases of rGBM in which TMB is low are more likely to respond to immunotherapy than cases in which TMB is higher, the investigators concluded from an analysis of tumor tissue from more than 100 patients.

“We need to do a prospective study and establish a threshold in a particular assay format,” senior author David Ashley, MBBS, PhD, a neurosurgery professor at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said in an interview.

Andrew Sloan, MD, a neurosurgery professor at the Seidman Cancer Center, Cleveland, said in a comment that “many have given up on immunotherapy for GBM because these tumors tend to have lower TMB than tumors that typically respond to immunotherapy, including checkpoint inhibitors.” (Examples include melanoma and lung cancer.)

“If the findings are confirmed, it would be very useful clinically to select” patients for immunotherapy, Dr. Sloan commented.

Correlation seen with rGBM, not primary tumor

Recurrence of GBM is almost inevitable, even when aggressive standard-of-care therapy is given initially, according to Dr. Ashley and colleagues. Studies have indicated that, in 10%-20% of patients with rGBM, disease responds to subsequent immunotherapy, and patients live beyond the predicted median survival of about 12 months. It’s been unclear, however, what distinguishes these survivors from the other patients.

Dr. Ashley and colleagues looked for common genetic factors that distinguish survivors.

The tumor tissue the team analyzed came from three studies. The first was a trial of an intratumoral infusion of a recombinant nonpathogenic poliorhinovirus chimera (PVSRIPO), developed at Duke University, that induces innate inflammation and T-cell attack. Among 61 patients, 21% were alive at 3 years versus 4% of historical control patients.

The second study was a review of 66 patients with GBM who underwent treatment with pembrolizumab or nivolumab. The median survival was 14.3 months among those who experienced a response versus10.1 months for those who did not.

The third study involved more than 1,000 patients with advanced cancer who underwent treatment with checkpoint inhibitors. There was no survival benefit among the 117 patients with glioma who were treated with checkpoint inhibitors.

In the PVSRIPO trial, rGBM tumors from patients who survived longer than 20 months harbored very low TMB, less than 0.6 mutations/Mb. In the two checkpoint inhibitor trials, among 110 patients with rGBM, survival was longer for those whose TMB was at or below the median level.

The differences in survival were not driven by differences in steroid dosing, unfavorable responses among patients with hypermutations, or the presence or absence of IDH1 or PTEN mutations or MGMT promoter methylation, according to Dr. Ashley and colleagues.

“Increased survival of immunotherapy-treated rGBM patients with very low TMB is due to immunotherapy response,” the investigators concluded.

As for the explanation, the team found that rGBM tumors with lower TMB levels had enriched inflammatory gene signatures, compared with tumors with higher TMB levels.

The correlation – and longer survival with low TMB – was not observed in primary GBM tumors, “indicating that a relationship between tumor-intrinsic inflammation and TMB develops upon recurrence. ... We postulate that the baseline inflammatory status of rGBM tumors determines their susceptibility to immunotherapy,” the authors wrote.

Because the correlation between tumor inflammation and TMB was robust in rGBM but not in primary tumors, it might well have been caused by standard-of-care therapy, which affects mutation levels.

“Chemotherapy, which is the standard of care for newly diagnosed glioblastoma, might be altering the inflammatory response in these tumors” and priming an inflammatory process that increases vulnerability to immunotherapy in recurrent tumors, Dr. Ashley said in a press release.

Shorter time to recurrence also correlated with lower TMB and favorable response to PVSRIPO, so shorter duration of standard therapy or shorter time from initial surgery might improve immunotherapy response, he speculated.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and other organizations. Dr. Ashley and other investigators own intellectual property related to PVSRIPO, which has been licensed to Istari Oncology. Several investigators hold equity in and/or are paid consultants for Istari. Dr. Sloan is the Ohio principal investigator for an rGBM PVSRIPO and pembrolizumab study funded by the company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In contrast to what has been seen in other tumor types, recurrent glioblastoma (rGBM) may respond better to immunotherapy when tumor mutational burden (TMB) is low, new research suggests.

There’s an “unexpected correlation between TMB, tumor-intrinsic inflammation, and survival after immunotherapy” in this patient population, researchers noted in a Nature Communications report.

Cases of rGBM in which TMB is low are more likely to respond to immunotherapy than cases in which TMB is higher, the investigators concluded from an analysis of tumor tissue from more than 100 patients.

“We need to do a prospective study and establish a threshold in a particular assay format,” senior author David Ashley, MBBS, PhD, a neurosurgery professor at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said in an interview.

Andrew Sloan, MD, a neurosurgery professor at the Seidman Cancer Center, Cleveland, said in a comment that “many have given up on immunotherapy for GBM because these tumors tend to have lower TMB than tumors that typically respond to immunotherapy, including checkpoint inhibitors.” (Examples include melanoma and lung cancer.)

“If the findings are confirmed, it would be very useful clinically to select” patients for immunotherapy, Dr. Sloan commented.

Correlation seen with rGBM, not primary tumor

Recurrence of GBM is almost inevitable, even when aggressive standard-of-care therapy is given initially, according to Dr. Ashley and colleagues. Studies have indicated that, in 10%-20% of patients with rGBM, disease responds to subsequent immunotherapy, and patients live beyond the predicted median survival of about 12 months. It’s been unclear, however, what distinguishes these survivors from the other patients.

Dr. Ashley and colleagues looked for common genetic factors that distinguish survivors.

The tumor tissue the team analyzed came from three studies. The first was a trial of an intratumoral infusion of a recombinant nonpathogenic poliorhinovirus chimera (PVSRIPO), developed at Duke University, that induces innate inflammation and T-cell attack. Among 61 patients, 21% were alive at 3 years versus 4% of historical control patients.

The second study was a review of 66 patients with GBM who underwent treatment with pembrolizumab or nivolumab. The median survival was 14.3 months among those who experienced a response versus10.1 months for those who did not.

The third study involved more than 1,000 patients with advanced cancer who underwent treatment with checkpoint inhibitors. There was no survival benefit among the 117 patients with glioma who were treated with checkpoint inhibitors.

In the PVSRIPO trial, rGBM tumors from patients who survived longer than 20 months harbored very low TMB, less than 0.6 mutations/Mb. In the two checkpoint inhibitor trials, among 110 patients with rGBM, survival was longer for those whose TMB was at or below the median level.

The differences in survival were not driven by differences in steroid dosing, unfavorable responses among patients with hypermutations, or the presence or absence of IDH1 or PTEN mutations or MGMT promoter methylation, according to Dr. Ashley and colleagues.

“Increased survival of immunotherapy-treated rGBM patients with very low TMB is due to immunotherapy response,” the investigators concluded.

As for the explanation, the team found that rGBM tumors with lower TMB levels had enriched inflammatory gene signatures, compared with tumors with higher TMB levels.

The correlation – and longer survival with low TMB – was not observed in primary GBM tumors, “indicating that a relationship between tumor-intrinsic inflammation and TMB develops upon recurrence. ... We postulate that the baseline inflammatory status of rGBM tumors determines their susceptibility to immunotherapy,” the authors wrote.

Because the correlation between tumor inflammation and TMB was robust in rGBM but not in primary tumors, it might well have been caused by standard-of-care therapy, which affects mutation levels.

“Chemotherapy, which is the standard of care for newly diagnosed glioblastoma, might be altering the inflammatory response in these tumors” and priming an inflammatory process that increases vulnerability to immunotherapy in recurrent tumors, Dr. Ashley said in a press release.

Shorter time to recurrence also correlated with lower TMB and favorable response to PVSRIPO, so shorter duration of standard therapy or shorter time from initial surgery might improve immunotherapy response, he speculated.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and other organizations. Dr. Ashley and other investigators own intellectual property related to PVSRIPO, which has been licensed to Istari Oncology. Several investigators hold equity in and/or are paid consultants for Istari. Dr. Sloan is the Ohio principal investigator for an rGBM PVSRIPO and pembrolizumab study funded by the company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Surprise medical billing may eliminate restrictive networks

Certainly, this has been a tumultuous year for health care, as well as the nation in general. There is so much to cover it is hard to know where to begin.

Against a background of a swelling pandemic, I remain confused about the new evaluation and management coding system, and suspect there will be much more training to be rolled out. It is excellent news that the Paycheck Protection Program has been renewed for a second pass, if you can demonstrate that you suffered at least a 25% drop in income for at least one quarter last year, and have fewer than 300 employees – which covers most dermatology practices. I plan to discuss the impact of price transparency in a future column, but today will discuss one area, where we have had the passage of major health care legislation, that may have been overlooked.

Starting in January 2022, patients are protected from surprise medical bills. For nonemergency services and services outside hospitals and other facilities, a patient can only be billed for the coinsurance/copay that they would have had if the patient had been in network unless you go through a consent process by which you inform the patient that you are out-of-network, inform them of the costs, and inform them of other in-network providers. It also requires that patients’ in-network cost-sharing payments for out-of-network surprise bills are attributed to a patient’s in-network deductible.

In section 103, it further states that, where out-of-network rates are determined, there will be a 30-day open negotiation period for providers and payers to settle out-of-network claims. It also states that if the parties are unable to reach a negotiated agreement, they may access a binding arbitration process – referred to as an independent dispute resolution (IDR) – in which one offer prevails. Providers may batch similar services in one proceeding when claims are from the same payer. The IDR process will be administered by independent, unbiased entities with no affiliation to providers or payers.

The IDR entity is required to consider the market-based median in-network rate, alongside relevant information brought by either party, information requested by the reviewer, as well as factors such as the provider’s training and experience patient acuity, and the complexity of furnishing the item or service, in the case of a provider that is a facility. Other factors include the teaching status, case mix and scope of services of such facility, demonstrations of good faith efforts (or lack of good faith efforts) to enter into a network agreement, prior contracted rates during the previous 4 plan-years, and other items. Billed charges and public payer (Medicare and Medicaid) rates are excluded from consideration. This should result in a payment closer to private insurance rates.

As many of you know, another one of the long-term outrages by insurers has been the closure of their networks and delisting of dermatologists. I have written about this situation before in this column. Insurers have also refused to update their provider lists, effectively denying care by the magical process of not having to pay for medical care, because there aren’t any medical providers.

Inaccurate physician rosters

Obviously, one source of surprise medical bills that is easily correctable are inaccurate insurance company physician rosters. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services implemented new rules with stiff fines instructing Medicare advantage plans to improve the accuracy of physician rosters, after a scathing General Accounting Office report 5 years ago. This process, however, was effectively neutered by the last administration by referring all enforcement action to the states, which did not have the manpower or political will to enforce them. This new surprise billing law directly addresses this issue, requiring insurers to update their provider directories every 90 days and keeping them available to patients on line.

This law also eliminates gag clauses between physicians and patients regarding insurer policies.

In short, this bill solves many problems for dermatologists in their constant struggle with insurers. In particular, accurate provider directories will allow patients and companies buying insurance for their employees, to see what they are getting. I suspect the revelation of the paucity of dermatologists in many of these networks will result in increased demand for your services and perhaps provide you a little negotiating leverage.

Also, if I read this law correctly, and I inform patients of our out-of-network status and give them a reasonable estimate of the cost of their care, network participation will no longer restrict patients who want to see me. I acknowledge that we will have to make good-faith efforts to join their networks (which most of us have repeatedly) and learn how to navigate the arbitration process, but this could be a boon for small-practice dermatologists who have been shut out of participating. In fact, it may be less trouble for insurers to simply invite us in, than going through repeated arbitration.

In the bigger picture, I would remind you of the importance of your legislative participation at the past American Academy of Dermatology Association Washington fly-ins, your support of the American Medical Association, and your support of SkinPac. These issues were always in our top three asks in Washington. All this favorable language was suggested, supported, and aided by your efforts and support of organized medicine.

There is a sign on my desk my wife gave me that reads “Never, Never, Never, Give Up.” I am proud of all of you for never giving up, and think you all deserve a “way to go” and a pat on the back. This law, which is a far walk from abusive air ambulance bills and unexpected anesthesia charges, amply and happily demonstrates that things can be changed for the better, and that access to care for our patients can be improved.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

Certainly, this has been a tumultuous year for health care, as well as the nation in general. There is so much to cover it is hard to know where to begin.

Against a background of a swelling pandemic, I remain confused about the new evaluation and management coding system, and suspect there will be much more training to be rolled out. It is excellent news that the Paycheck Protection Program has been renewed for a second pass, if you can demonstrate that you suffered at least a 25% drop in income for at least one quarter last year, and have fewer than 300 employees – which covers most dermatology practices. I plan to discuss the impact of price transparency in a future column, but today will discuss one area, where we have had the passage of major health care legislation, that may have been overlooked.

Starting in January 2022, patients are protected from surprise medical bills. For nonemergency services and services outside hospitals and other facilities, a patient can only be billed for the coinsurance/copay that they would have had if the patient had been in network unless you go through a consent process by which you inform the patient that you are out-of-network, inform them of the costs, and inform them of other in-network providers. It also requires that patients’ in-network cost-sharing payments for out-of-network surprise bills are attributed to a patient’s in-network deductible.

In section 103, it further states that, where out-of-network rates are determined, there will be a 30-day open negotiation period for providers and payers to settle out-of-network claims. It also states that if the parties are unable to reach a negotiated agreement, they may access a binding arbitration process – referred to as an independent dispute resolution (IDR) – in which one offer prevails. Providers may batch similar services in one proceeding when claims are from the same payer. The IDR process will be administered by independent, unbiased entities with no affiliation to providers or payers.

The IDR entity is required to consider the market-based median in-network rate, alongside relevant information brought by either party, information requested by the reviewer, as well as factors such as the provider’s training and experience patient acuity, and the complexity of furnishing the item or service, in the case of a provider that is a facility. Other factors include the teaching status, case mix and scope of services of such facility, demonstrations of good faith efforts (or lack of good faith efforts) to enter into a network agreement, prior contracted rates during the previous 4 plan-years, and other items. Billed charges and public payer (Medicare and Medicaid) rates are excluded from consideration. This should result in a payment closer to private insurance rates.

As many of you know, another one of the long-term outrages by insurers has been the closure of their networks and delisting of dermatologists. I have written about this situation before in this column. Insurers have also refused to update their provider lists, effectively denying care by the magical process of not having to pay for medical care, because there aren’t any medical providers.

Inaccurate physician rosters

Obviously, one source of surprise medical bills that is easily correctable are inaccurate insurance company physician rosters. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services implemented new rules with stiff fines instructing Medicare advantage plans to improve the accuracy of physician rosters, after a scathing General Accounting Office report 5 years ago. This process, however, was effectively neutered by the last administration by referring all enforcement action to the states, which did not have the manpower or political will to enforce them. This new surprise billing law directly addresses this issue, requiring insurers to update their provider directories every 90 days and keeping them available to patients on line.

This law also eliminates gag clauses between physicians and patients regarding insurer policies.

In short, this bill solves many problems for dermatologists in their constant struggle with insurers. In particular, accurate provider directories will allow patients and companies buying insurance for their employees, to see what they are getting. I suspect the revelation of the paucity of dermatologists in many of these networks will result in increased demand for your services and perhaps provide you a little negotiating leverage.

Also, if I read this law correctly, and I inform patients of our out-of-network status and give them a reasonable estimate of the cost of their care, network participation will no longer restrict patients who want to see me. I acknowledge that we will have to make good-faith efforts to join their networks (which most of us have repeatedly) and learn how to navigate the arbitration process, but this could be a boon for small-practice dermatologists who have been shut out of participating. In fact, it may be less trouble for insurers to simply invite us in, than going through repeated arbitration.

In the bigger picture, I would remind you of the importance of your legislative participation at the past American Academy of Dermatology Association Washington fly-ins, your support of the American Medical Association, and your support of SkinPac. These issues were always in our top three asks in Washington. All this favorable language was suggested, supported, and aided by your efforts and support of organized medicine.

There is a sign on my desk my wife gave me that reads “Never, Never, Never, Give Up.” I am proud of all of you for never giving up, and think you all deserve a “way to go” and a pat on the back. This law, which is a far walk from abusive air ambulance bills and unexpected anesthesia charges, amply and happily demonstrates that things can be changed for the better, and that access to care for our patients can be improved.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

Certainly, this has been a tumultuous year for health care, as well as the nation in general. There is so much to cover it is hard to know where to begin.

Against a background of a swelling pandemic, I remain confused about the new evaluation and management coding system, and suspect there will be much more training to be rolled out. It is excellent news that the Paycheck Protection Program has been renewed for a second pass, if you can demonstrate that you suffered at least a 25% drop in income for at least one quarter last year, and have fewer than 300 employees – which covers most dermatology practices. I plan to discuss the impact of price transparency in a future column, but today will discuss one area, where we have had the passage of major health care legislation, that may have been overlooked.

Starting in January 2022, patients are protected from surprise medical bills. For nonemergency services and services outside hospitals and other facilities, a patient can only be billed for the coinsurance/copay that they would have had if the patient had been in network unless you go through a consent process by which you inform the patient that you are out-of-network, inform them of the costs, and inform them of other in-network providers. It also requires that patients’ in-network cost-sharing payments for out-of-network surprise bills are attributed to a patient’s in-network deductible.

In section 103, it further states that, where out-of-network rates are determined, there will be a 30-day open negotiation period for providers and payers to settle out-of-network claims. It also states that if the parties are unable to reach a negotiated agreement, they may access a binding arbitration process – referred to as an independent dispute resolution (IDR) – in which one offer prevails. Providers may batch similar services in one proceeding when claims are from the same payer. The IDR process will be administered by independent, unbiased entities with no affiliation to providers or payers.

The IDR entity is required to consider the market-based median in-network rate, alongside relevant information brought by either party, information requested by the reviewer, as well as factors such as the provider’s training and experience patient acuity, and the complexity of furnishing the item or service, in the case of a provider that is a facility. Other factors include the teaching status, case mix and scope of services of such facility, demonstrations of good faith efforts (or lack of good faith efforts) to enter into a network agreement, prior contracted rates during the previous 4 plan-years, and other items. Billed charges and public payer (Medicare and Medicaid) rates are excluded from consideration. This should result in a payment closer to private insurance rates.

As many of you know, another one of the long-term outrages by insurers has been the closure of their networks and delisting of dermatologists. I have written about this situation before in this column. Insurers have also refused to update their provider lists, effectively denying care by the magical process of not having to pay for medical care, because there aren’t any medical providers.

Inaccurate physician rosters