User login

Meet the new members of the CHEST Physician® Editorial Board

We’re happy to introduce these new board members whose primary responsibility is the active review each month of potential articles for publication that could have an impact on or be of interest to our health-care professional readership.

Carolyn M. D’Ambrosio, MD, FCCP, is the Program Director for the Harvard-Brigham and Women’s Hospital Fellowship in Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine and is Associate Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. Most recently, she was awarded the Pillar Award for Educational Program Leadership, the top award for program directors throughout the Mass General Brigham institutions. In addition to teaching and clinical work, Dr. D’Ambrosio has conducted research on sleep and menopause, sleep and breathing in infants, and participated as the sleep medicine expert in two systemic reviews on home sleep apnea testing and fixed vs auto-titrating CPAP. She continues her work in Medical Ethics as a Senior Ethics Consultant at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Jonathan (Jona) Ludmir, MD, FCCP

After completing internal medicine/pediatrics, cardiology, and critical care training, Dr. Ludmir joined the Massachusetts General Hospital staff as a cardiac intensivist and noninvasive cardiologist. His clinical focus is in the heart center ICU, the echocardiography lab, as well as in outpatient cardiology. Additionally, he is the lead physician for the Family-Centered Care Initiative, where he focuses on incorporating evidence-based guidelines and leads in the science of family-centered cardiovascular care delivery. Dr. Ludmir’s research focuses on identifying and addressing psychological symptoms in the ICU, optimizing ICU communication, and enhancing delivery of family-centered care.

Abbie Begnaud, MD, FCCP

Dr. Begnaud hails from south Louisiana and reveals that she attended her first CHEST Annual Meeting in 2011 in Hawaii, and she was “instantly hooked.” Clinically, she practices general pulmonology, critical care, and interventional pulmonology and focuses her research on lung cancer screening and health disparities. She has been on faculty at the University of Minnesota since 2013 and is passionate about lung cancer, health equity, and mentoring.

Shyam Subramanian, MD , FCCP

Dr. Subramanian is currently the Section Chief for Specialty Clinics and the Division Chief for Pulmonary/Critical Care and Sleep Medicine at Sutter Gould Medical Foundation, Tracy, California.

He previously was Systems Director at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston and Section Chief at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. Dr. Subramanian currently serves as Chair for the CHEST Clinical Pulmonary NetWork and has previously served as Chair of the Practice Operations NetWork. He is a member of the Executive Committee of the Council of NetWorks and the Scientific Program Committee for the CHEST Annual Meeting.

Mary Jo S. Farmer, MD, PhD, FCCP

Dr. Farmer is a pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine physician at Baystate Medical Center (Springfield, MA); Assistant Professor of Medicine University at Massachusetts Medical School – Baystate; and adjunct faculty Tufts University School of Medicine. Dr. Farmer serves as director of pulmonary hypertension services for the Pulmonary & Critical Care Division. Pulmonary vascular disease, interprofessional education, clinical trials research, endobronchial ultrasound, and medical student, resident, and fellow education are her major interests. She is a member of the CHEST Interprofessional NetWork and Clinical Pulmonary NetWork.

We’re happy to introduce these new board members whose primary responsibility is the active review each month of potential articles for publication that could have an impact on or be of interest to our health-care professional readership.

Carolyn M. D’Ambrosio, MD, FCCP, is the Program Director for the Harvard-Brigham and Women’s Hospital Fellowship in Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine and is Associate Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. Most recently, she was awarded the Pillar Award for Educational Program Leadership, the top award for program directors throughout the Mass General Brigham institutions. In addition to teaching and clinical work, Dr. D’Ambrosio has conducted research on sleep and menopause, sleep and breathing in infants, and participated as the sleep medicine expert in two systemic reviews on home sleep apnea testing and fixed vs auto-titrating CPAP. She continues her work in Medical Ethics as a Senior Ethics Consultant at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Jonathan (Jona) Ludmir, MD, FCCP

After completing internal medicine/pediatrics, cardiology, and critical care training, Dr. Ludmir joined the Massachusetts General Hospital staff as a cardiac intensivist and noninvasive cardiologist. His clinical focus is in the heart center ICU, the echocardiography lab, as well as in outpatient cardiology. Additionally, he is the lead physician for the Family-Centered Care Initiative, where he focuses on incorporating evidence-based guidelines and leads in the science of family-centered cardiovascular care delivery. Dr. Ludmir’s research focuses on identifying and addressing psychological symptoms in the ICU, optimizing ICU communication, and enhancing delivery of family-centered care.

Abbie Begnaud, MD, FCCP

Dr. Begnaud hails from south Louisiana and reveals that she attended her first CHEST Annual Meeting in 2011 in Hawaii, and she was “instantly hooked.” Clinically, she practices general pulmonology, critical care, and interventional pulmonology and focuses her research on lung cancer screening and health disparities. She has been on faculty at the University of Minnesota since 2013 and is passionate about lung cancer, health equity, and mentoring.

Shyam Subramanian, MD , FCCP

Dr. Subramanian is currently the Section Chief for Specialty Clinics and the Division Chief for Pulmonary/Critical Care and Sleep Medicine at Sutter Gould Medical Foundation, Tracy, California.

He previously was Systems Director at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston and Section Chief at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. Dr. Subramanian currently serves as Chair for the CHEST Clinical Pulmonary NetWork and has previously served as Chair of the Practice Operations NetWork. He is a member of the Executive Committee of the Council of NetWorks and the Scientific Program Committee for the CHEST Annual Meeting.

Mary Jo S. Farmer, MD, PhD, FCCP

Dr. Farmer is a pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine physician at Baystate Medical Center (Springfield, MA); Assistant Professor of Medicine University at Massachusetts Medical School – Baystate; and adjunct faculty Tufts University School of Medicine. Dr. Farmer serves as director of pulmonary hypertension services for the Pulmonary & Critical Care Division. Pulmonary vascular disease, interprofessional education, clinical trials research, endobronchial ultrasound, and medical student, resident, and fellow education are her major interests. She is a member of the CHEST Interprofessional NetWork and Clinical Pulmonary NetWork.

We’re happy to introduce these new board members whose primary responsibility is the active review each month of potential articles for publication that could have an impact on or be of interest to our health-care professional readership.

Carolyn M. D’Ambrosio, MD, FCCP, is the Program Director for the Harvard-Brigham and Women’s Hospital Fellowship in Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine and is Associate Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. Most recently, she was awarded the Pillar Award for Educational Program Leadership, the top award for program directors throughout the Mass General Brigham institutions. In addition to teaching and clinical work, Dr. D’Ambrosio has conducted research on sleep and menopause, sleep and breathing in infants, and participated as the sleep medicine expert in two systemic reviews on home sleep apnea testing and fixed vs auto-titrating CPAP. She continues her work in Medical Ethics as a Senior Ethics Consultant at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Jonathan (Jona) Ludmir, MD, FCCP

After completing internal medicine/pediatrics, cardiology, and critical care training, Dr. Ludmir joined the Massachusetts General Hospital staff as a cardiac intensivist and noninvasive cardiologist. His clinical focus is in the heart center ICU, the echocardiography lab, as well as in outpatient cardiology. Additionally, he is the lead physician for the Family-Centered Care Initiative, where he focuses on incorporating evidence-based guidelines and leads in the science of family-centered cardiovascular care delivery. Dr. Ludmir’s research focuses on identifying and addressing psychological symptoms in the ICU, optimizing ICU communication, and enhancing delivery of family-centered care.

Abbie Begnaud, MD, FCCP

Dr. Begnaud hails from south Louisiana and reveals that she attended her first CHEST Annual Meeting in 2011 in Hawaii, and she was “instantly hooked.” Clinically, she practices general pulmonology, critical care, and interventional pulmonology and focuses her research on lung cancer screening and health disparities. She has been on faculty at the University of Minnesota since 2013 and is passionate about lung cancer, health equity, and mentoring.

Shyam Subramanian, MD , FCCP

Dr. Subramanian is currently the Section Chief for Specialty Clinics and the Division Chief for Pulmonary/Critical Care and Sleep Medicine at Sutter Gould Medical Foundation, Tracy, California.

He previously was Systems Director at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston and Section Chief at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. Dr. Subramanian currently serves as Chair for the CHEST Clinical Pulmonary NetWork and has previously served as Chair of the Practice Operations NetWork. He is a member of the Executive Committee of the Council of NetWorks and the Scientific Program Committee for the CHEST Annual Meeting.

Mary Jo S. Farmer, MD, PhD, FCCP

Dr. Farmer is a pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine physician at Baystate Medical Center (Springfield, MA); Assistant Professor of Medicine University at Massachusetts Medical School – Baystate; and adjunct faculty Tufts University School of Medicine. Dr. Farmer serves as director of pulmonary hypertension services for the Pulmonary & Critical Care Division. Pulmonary vascular disease, interprofessional education, clinical trials research, endobronchial ultrasound, and medical student, resident, and fellow education are her major interests. She is a member of the CHEST Interprofessional NetWork and Clinical Pulmonary NetWork.

How the Foundation’s virtual listening tour aims to help patients like James

Constance Baker was juggling the dual stresses of mothering a newborn and raising a teenager when she noticed a skin patch on her father looked discolored. His breathing soon became labored, and the skin on his hands turned calloused. Then he passed out. Initially, doctors thought his problems were cardiovascular.

Since James didn’t have a primary doctor, Constance repeatedly took him to the emergency room to receive care. His frequent visits attracted the attention of a medical intern who ordered tests and asked James to see a specialist. More than half a year later, Constance and James met pulmonologist Dr. Demondes Haynes and learned the cause of James’ troubled breathing. James has a rare disease called scleroderma, which hardens patches of skin and created scarring of his lung tissue. He also had pulmonary hypertension. James needed rapid intervention with a complicated regimen of medication.

At first, James didn’t want to go along with the program, but Dr. Haynes’ attentive and gentle nature changed his mind. “Dr. Haynes always made us comfortable, taking the time to listen and show us his concern. He even explained that we wouldn’t have to worry about paying for anything, which was a huge relief.”

Before Dr. Haynes, James and Constance had never met a doctor who didn’t treat them like a case file. “He actually acknowledged our circumstances, which meant he acknowledged us.”

As a native Mississippian, Dr. Haynes knows the plight of many of his patients. “Not everyone with lung disease can access a pulmonologist, like me, and not everyone can afford appropriate treatment. You have to recognize these disparities in order to build a relationship of trust with your patients.”

James was ready to start treatment with Dr. Haynes’ guidance, but since he couldn’t read, he couldn’t understand how to put the medication together. That’s when Constance had to step up. They worked together to change and clean the tubing to the port by his heart and make his medication. “We leaned on each other a lot during that time, and you know what? We made it through.”

Even though James’ disease can be debilitating at times, and his care can seem completely overwhelming, Constance wouldn’t have it any other way. “It’s always been my father and I, just us two. He’s always taken care of me, and now it’s my turn to take care of him.”

Unfortunately, Constance and James’ story is not unique. So many patients don’t have access to doctors, specialists, and caregivers, and many aren’t empowered enough to take

their medications. These stories don’t get posted on Instagram and they don’t make the evening news. Underprivileged and underserved patients have been left behind – left without a voice.

That’s why the foundation launched its virtual listening tours across America in September. Our tours give patients, caregivers, and physicians the opportunity to raise issues that they believe are impacting health care in their communities.

How can physicians work to understand their patients better? How can patients learn to trust their providers? These are all the questions we aim to answer.

James is doing as well as he is because of his relationship with Dr. Haynes. What can we do with that information? We can listen, we can learn, and we can spread the word.

Read more about the work of the CHEST Foundation in its 2020 Impact Report at chestfoundation.org.

Constance Baker was juggling the dual stresses of mothering a newborn and raising a teenager when she noticed a skin patch on her father looked discolored. His breathing soon became labored, and the skin on his hands turned calloused. Then he passed out. Initially, doctors thought his problems were cardiovascular.

Since James didn’t have a primary doctor, Constance repeatedly took him to the emergency room to receive care. His frequent visits attracted the attention of a medical intern who ordered tests and asked James to see a specialist. More than half a year later, Constance and James met pulmonologist Dr. Demondes Haynes and learned the cause of James’ troubled breathing. James has a rare disease called scleroderma, which hardens patches of skin and created scarring of his lung tissue. He also had pulmonary hypertension. James needed rapid intervention with a complicated regimen of medication.

At first, James didn’t want to go along with the program, but Dr. Haynes’ attentive and gentle nature changed his mind. “Dr. Haynes always made us comfortable, taking the time to listen and show us his concern. He even explained that we wouldn’t have to worry about paying for anything, which was a huge relief.”

Before Dr. Haynes, James and Constance had never met a doctor who didn’t treat them like a case file. “He actually acknowledged our circumstances, which meant he acknowledged us.”

As a native Mississippian, Dr. Haynes knows the plight of many of his patients. “Not everyone with lung disease can access a pulmonologist, like me, and not everyone can afford appropriate treatment. You have to recognize these disparities in order to build a relationship of trust with your patients.”

James was ready to start treatment with Dr. Haynes’ guidance, but since he couldn’t read, he couldn’t understand how to put the medication together. That’s when Constance had to step up. They worked together to change and clean the tubing to the port by his heart and make his medication. “We leaned on each other a lot during that time, and you know what? We made it through.”

Even though James’ disease can be debilitating at times, and his care can seem completely overwhelming, Constance wouldn’t have it any other way. “It’s always been my father and I, just us two. He’s always taken care of me, and now it’s my turn to take care of him.”

Unfortunately, Constance and James’ story is not unique. So many patients don’t have access to doctors, specialists, and caregivers, and many aren’t empowered enough to take

their medications. These stories don’t get posted on Instagram and they don’t make the evening news. Underprivileged and underserved patients have been left behind – left without a voice.

That’s why the foundation launched its virtual listening tours across America in September. Our tours give patients, caregivers, and physicians the opportunity to raise issues that they believe are impacting health care in their communities.

How can physicians work to understand their patients better? How can patients learn to trust their providers? These are all the questions we aim to answer.

James is doing as well as he is because of his relationship with Dr. Haynes. What can we do with that information? We can listen, we can learn, and we can spread the word.

Read more about the work of the CHEST Foundation in its 2020 Impact Report at chestfoundation.org.

Constance Baker was juggling the dual stresses of mothering a newborn and raising a teenager when she noticed a skin patch on her father looked discolored. His breathing soon became labored, and the skin on his hands turned calloused. Then he passed out. Initially, doctors thought his problems were cardiovascular.

Since James didn’t have a primary doctor, Constance repeatedly took him to the emergency room to receive care. His frequent visits attracted the attention of a medical intern who ordered tests and asked James to see a specialist. More than half a year later, Constance and James met pulmonologist Dr. Demondes Haynes and learned the cause of James’ troubled breathing. James has a rare disease called scleroderma, which hardens patches of skin and created scarring of his lung tissue. He also had pulmonary hypertension. James needed rapid intervention with a complicated regimen of medication.

At first, James didn’t want to go along with the program, but Dr. Haynes’ attentive and gentle nature changed his mind. “Dr. Haynes always made us comfortable, taking the time to listen and show us his concern. He even explained that we wouldn’t have to worry about paying for anything, which was a huge relief.”

Before Dr. Haynes, James and Constance had never met a doctor who didn’t treat them like a case file. “He actually acknowledged our circumstances, which meant he acknowledged us.”

As a native Mississippian, Dr. Haynes knows the plight of many of his patients. “Not everyone with lung disease can access a pulmonologist, like me, and not everyone can afford appropriate treatment. You have to recognize these disparities in order to build a relationship of trust with your patients.”

James was ready to start treatment with Dr. Haynes’ guidance, but since he couldn’t read, he couldn’t understand how to put the medication together. That’s when Constance had to step up. They worked together to change and clean the tubing to the port by his heart and make his medication. “We leaned on each other a lot during that time, and you know what? We made it through.”

Even though James’ disease can be debilitating at times, and his care can seem completely overwhelming, Constance wouldn’t have it any other way. “It’s always been my father and I, just us two. He’s always taken care of me, and now it’s my turn to take care of him.”

Unfortunately, Constance and James’ story is not unique. So many patients don’t have access to doctors, specialists, and caregivers, and many aren’t empowered enough to take

their medications. These stories don’t get posted on Instagram and they don’t make the evening news. Underprivileged and underserved patients have been left behind – left without a voice.

That’s why the foundation launched its virtual listening tours across America in September. Our tours give patients, caregivers, and physicians the opportunity to raise issues that they believe are impacting health care in their communities.

How can physicians work to understand their patients better? How can patients learn to trust their providers? These are all the questions we aim to answer.

James is doing as well as he is because of his relationship with Dr. Haynes. What can we do with that information? We can listen, we can learn, and we can spread the word.

Read more about the work of the CHEST Foundation in its 2020 Impact Report at chestfoundation.org.

This month in CHEST

Editor’s picks

Original Research

A behaviour change intervention aimed at increasing physical activity improves clinical control in adults with asthma: a randomised controlled trial. By Dr. C. Carvalho, et al.

Critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New Orleans and care with an evidence-based protocol. By Dr. D. Janz, et al.

Mortality trends of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the United States from 2004 to 2017.By Dr. N. Jeganathan, et al.

United States Pulmonary Hypertension Scientific Registry (USPHSR): Baseline characteristics. By Dr. J. Badlam, et al.

CHEST Review

Pulmonary exacerbations in adults with cystic fibrosis: A grown-up issue in a changing CF landscape. By Dr. G. Stanford, et al.

Computed tomography imaging and comorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Beyond lung cancer screening. By Dr. J. Bon, et al.

How I Do It

The PERT concept: A step-by-step approach to managing PE. By Dr. B. Rivera-Lebron, et al.

Special Feature

A brief overview of the national outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury (EVALI) and the primary causes. By Dr. E. Kiernan, et al.

Editor’s picks

Editor’s picks

Original Research

A behaviour change intervention aimed at increasing physical activity improves clinical control in adults with asthma: a randomised controlled trial. By Dr. C. Carvalho, et al.

Critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New Orleans and care with an evidence-based protocol. By Dr. D. Janz, et al.

Mortality trends of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the United States from 2004 to 2017.By Dr. N. Jeganathan, et al.

United States Pulmonary Hypertension Scientific Registry (USPHSR): Baseline characteristics. By Dr. J. Badlam, et al.

CHEST Review

Pulmonary exacerbations in adults with cystic fibrosis: A grown-up issue in a changing CF landscape. By Dr. G. Stanford, et al.

Computed tomography imaging and comorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Beyond lung cancer screening. By Dr. J. Bon, et al.

How I Do It

The PERT concept: A step-by-step approach to managing PE. By Dr. B. Rivera-Lebron, et al.

Special Feature

A brief overview of the national outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury (EVALI) and the primary causes. By Dr. E. Kiernan, et al.

Original Research

A behaviour change intervention aimed at increasing physical activity improves clinical control in adults with asthma: a randomised controlled trial. By Dr. C. Carvalho, et al.

Critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New Orleans and care with an evidence-based protocol. By Dr. D. Janz, et al.

Mortality trends of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the United States from 2004 to 2017.By Dr. N. Jeganathan, et al.

United States Pulmonary Hypertension Scientific Registry (USPHSR): Baseline characteristics. By Dr. J. Badlam, et al.

CHEST Review

Pulmonary exacerbations in adults with cystic fibrosis: A grown-up issue in a changing CF landscape. By Dr. G. Stanford, et al.

Computed tomography imaging and comorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Beyond lung cancer screening. By Dr. J. Bon, et al.

How I Do It

The PERT concept: A step-by-step approach to managing PE. By Dr. B. Rivera-Lebron, et al.

Special Feature

A brief overview of the national outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury (EVALI) and the primary causes. By Dr. E. Kiernan, et al.

Cardiovascular Medicine and Surgery

Cardiovascular Medicine and Surgery

Use of hepatitis C donors in thoracic organ transplantation: Reportedly associated with increased risk of rejection

Mark Jay Zucker, MD, JD, FCCP

Vice-Chair

Transplanting organs from hepatitis C (HCV) antibody and/or antigen-positive donors is associated with a greater than 8%-90% likelihood that the recipient will acquire the infection. Several studies reported that if HCV conversion happened, the outcomes in both heart and lung recipients were worse, even if treated with interferon/ribavirin (Haji SA, et al J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004;23:277; Wang BY, et al. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010 May;89[5]:1645; Carreno MC, et al. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2001;20(2):224). Thus, despite the shortage of thoracic organ donors and high wait-list mortality, the practice was strongly discouraged.

In 2016, the successful use of a direct-acting antiviral (DAA) for 12 weeks to eliminate HCV in a lung transplant recipient of a seropositive organ was published (Khan B, et al. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:1129). Two years later, the outcomes of seronegative heart (n=8) or lung (n=36) transplant recipients receiving organs from seropositive donors were presented (Woolley AE, et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1606). Forty-two of the patients had viremia within days of the operation. All patients were treated with 4 weeks of a DAA and, of the 35 patients available for 6-month analysis, viral load was undetectable in all. Of concern, however—more cellular rejection requiring treatment was seen in the lung recipients of HCV+ donors compared with recipients of HCV- donors. The difference was not statistically significant.

The largest analysis of the safety of HCV+ donors in HCV- thoracic organ transplant recipients involved 343 heart transplant recipients (Kilic A, et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(2):e014495). No differences were noted in outcomes, strokes, need for dialysis, or incidence of treated rejection during the first year. However, the observation regarding rejection was not subsequently confirmed by the NYU team (Gidea CG, et al. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39:1199). Of 22 HCV- recipients of an HCV donor with viremia, the rate of rejection was 64% vs 18% in 28 patients receiving a donor without viremia (through day 180 (P=.001)).

In summary, the ability of DAAs to render 97%-99% of immunosuppressed transplant recipients HCV seronegative has transformed the landscape and HCV viremia in the donor (or recipient) and is no longer an absolute contraindication to transplantation. However, more information is needed as to whether there is an increased incidence of rejection.

Cardiovascular Medicine and Surgery

Use of hepatitis C donors in thoracic organ transplantation: Reportedly associated with increased risk of rejection

Mark Jay Zucker, MD, JD, FCCP

Vice-Chair

Transplanting organs from hepatitis C (HCV) antibody and/or antigen-positive donors is associated with a greater than 8%-90% likelihood that the recipient will acquire the infection. Several studies reported that if HCV conversion happened, the outcomes in both heart and lung recipients were worse, even if treated with interferon/ribavirin (Haji SA, et al J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004;23:277; Wang BY, et al. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010 May;89[5]:1645; Carreno MC, et al. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2001;20(2):224). Thus, despite the shortage of thoracic organ donors and high wait-list mortality, the practice was strongly discouraged.

In 2016, the successful use of a direct-acting antiviral (DAA) for 12 weeks to eliminate HCV in a lung transplant recipient of a seropositive organ was published (Khan B, et al. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:1129). Two years later, the outcomes of seronegative heart (n=8) or lung (n=36) transplant recipients receiving organs from seropositive donors were presented (Woolley AE, et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1606). Forty-two of the patients had viremia within days of the operation. All patients were treated with 4 weeks of a DAA and, of the 35 patients available for 6-month analysis, viral load was undetectable in all. Of concern, however—more cellular rejection requiring treatment was seen in the lung recipients of HCV+ donors compared with recipients of HCV- donors. The difference was not statistically significant.

The largest analysis of the safety of HCV+ donors in HCV- thoracic organ transplant recipients involved 343 heart transplant recipients (Kilic A, et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(2):e014495). No differences were noted in outcomes, strokes, need for dialysis, or incidence of treated rejection during the first year. However, the observation regarding rejection was not subsequently confirmed by the NYU team (Gidea CG, et al. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39:1199). Of 22 HCV- recipients of an HCV donor with viremia, the rate of rejection was 64% vs 18% in 28 patients receiving a donor without viremia (through day 180 (P=.001)).

In summary, the ability of DAAs to render 97%-99% of immunosuppressed transplant recipients HCV seronegative has transformed the landscape and HCV viremia in the donor (or recipient) and is no longer an absolute contraindication to transplantation. However, more information is needed as to whether there is an increased incidence of rejection.

Cardiovascular Medicine and Surgery

Use of hepatitis C donors in thoracic organ transplantation: Reportedly associated with increased risk of rejection

Mark Jay Zucker, MD, JD, FCCP

Vice-Chair

Transplanting organs from hepatitis C (HCV) antibody and/or antigen-positive donors is associated with a greater than 8%-90% likelihood that the recipient will acquire the infection. Several studies reported that if HCV conversion happened, the outcomes in both heart and lung recipients were worse, even if treated with interferon/ribavirin (Haji SA, et al J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004;23:277; Wang BY, et al. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010 May;89[5]:1645; Carreno MC, et al. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2001;20(2):224). Thus, despite the shortage of thoracic organ donors and high wait-list mortality, the practice was strongly discouraged.

In 2016, the successful use of a direct-acting antiviral (DAA) for 12 weeks to eliminate HCV in a lung transplant recipient of a seropositive organ was published (Khan B, et al. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:1129). Two years later, the outcomes of seronegative heart (n=8) or lung (n=36) transplant recipients receiving organs from seropositive donors were presented (Woolley AE, et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1606). Forty-two of the patients had viremia within days of the operation. All patients were treated with 4 weeks of a DAA and, of the 35 patients available for 6-month analysis, viral load was undetectable in all. Of concern, however—more cellular rejection requiring treatment was seen in the lung recipients of HCV+ donors compared with recipients of HCV- donors. The difference was not statistically significant.

The largest analysis of the safety of HCV+ donors in HCV- thoracic organ transplant recipients involved 343 heart transplant recipients (Kilic A, et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(2):e014495). No differences were noted in outcomes, strokes, need for dialysis, or incidence of treated rejection during the first year. However, the observation regarding rejection was not subsequently confirmed by the NYU team (Gidea CG, et al. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39:1199). Of 22 HCV- recipients of an HCV donor with viremia, the rate of rejection was 64% vs 18% in 28 patients receiving a donor without viremia (through day 180 (P=.001)).

In summary, the ability of DAAs to render 97%-99% of immunosuppressed transplant recipients HCV seronegative has transformed the landscape and HCV viremia in the donor (or recipient) and is no longer an absolute contraindication to transplantation. However, more information is needed as to whether there is an increased incidence of rejection.

Finding meaning in ‘Lean’?

Using systems improvement strategies to support the Quadruple Aim

General background on well-being and burnout

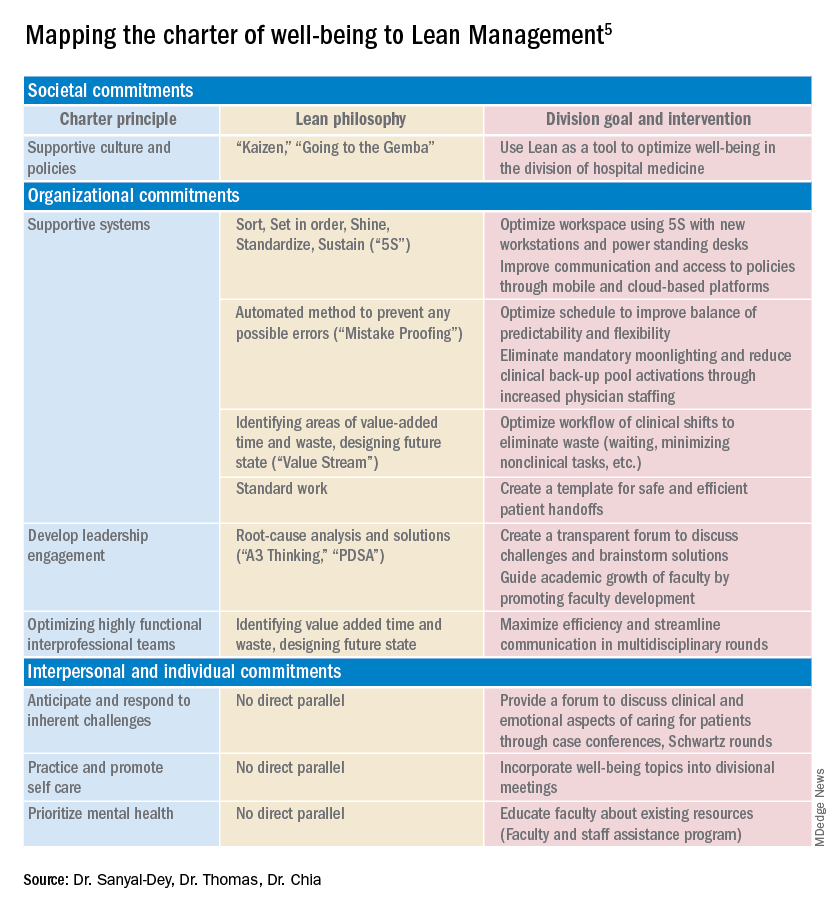

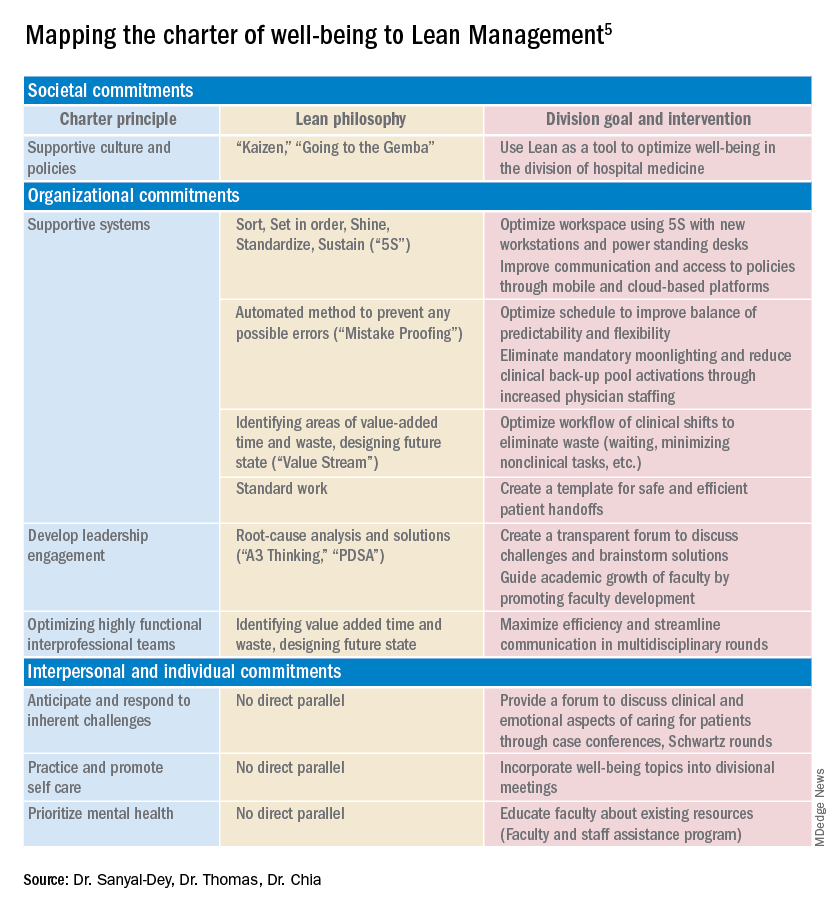

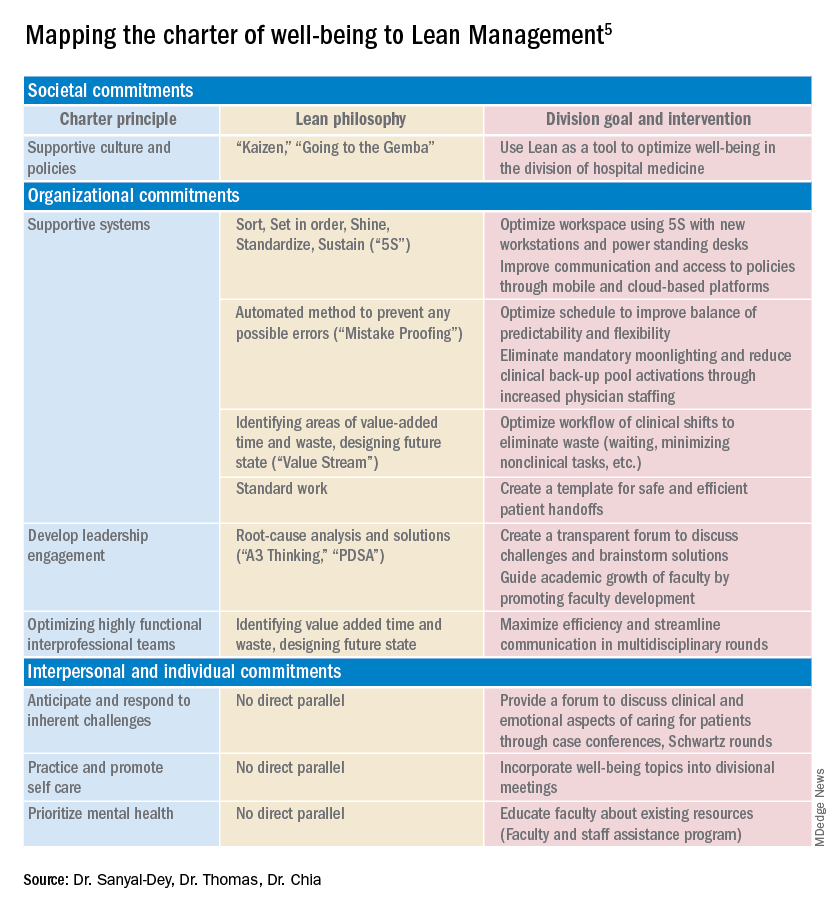

With burnout increasingly recognized as a shared responsibility that requires addressing organizational drivers while supporting individuals to be well,1-4 practical strategies and examples of successful implementation of systems interventions to address burnout will be helpful for service directors to support their staff. The Charter on Physician Well-being, recently developed through collaborative input from multiple organizations, defines guiding principles and key commitments at the societal, organizational, interpersonal, and individual levels and may be a useful framework for organizations that are developing well-being initiatives.5

The charter advocates including physician well-being as a quality improvement metric for health systems, aligned with the concept of the Quadruple Aim of optimizing patient care by enhancing provider experience, promoting high-value care, and improving population health.6 Identifying areas of alignment between the charter’s recommendations and systems improvement strategies that seek to optimize efficiency and reduce waste, such as Lean Management, may help physician leaders to contextualize well-being initiatives more easily within ongoing systems improvement efforts. In this perspective, we provide one division’s experience using the Charter to assess successes and identify additional areas of improvement for well-being initiatives developed using Lean Management methodology.

Past and current state of affairs

In 2011, the division of hospital medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital was established and has seen continual expansion in terms of direct patient care, medical education, and hospital leadership.

In 2015, the division of hospital medicine experienced leadership transitions, faculty attrition, and insufficient recruitment resulting in staffing shortages, service line closure, schedule instability, and ultimately, low morale. A baseline survey conducted using the 2-Item Maslach Burnout Inventory. This survey, which uses one item in the domain of emotional exhaustion and one item in the domain of depersonalization, has shown good correlation with the full Maslach Burnout Inventory.7 At baseline, approximately one-third of the division’s physicians experienced burnout.

In response, a subsequent retreat focused on the three greatest areas of concern identified by the survey: scheduling, faculty development, and well-being.

Like many health systems, the hospital has adopted Lean as its preferred systems-improvement framework. The retreat was structured around the principles of Lean philosophy, and was designed to emulate that of a consolidated Kaizen workshop.

“Kaizen” in Japanese means “change for the better.” A typical Kaizen workshop revolves around rapid problem-solving over the course of 3-5 days, in which a team of people come together to identify and implement significant improvements for a selected process. To this end, the retreat was divided into subgroups for each area of concern. In turn, each subgroup mapped out existing workflows (“value stream”), identified areas of waste and non–value added time, and generated ideas of what an idealized process would be. Next, a root-cause analysis was performed and subsequent interventions (“countermeasures”) developed to address each problem. At the conclusion of the retreat, each subgroup shared a summary of their findings with the larger group.

Moving forward, this information served as a guiding framework for service and division leadership to run small tests of change. We enacted a series of countermeasures over the course of several years, and multiple cycles of improvement work addressed the three areas of concern. We developed an A3 report (a Lean project management tool that incorporates the plan-do-study-act cycle, organizes strategic efforts, and tracks progress on a single page) to summarize and present these initiatives to the Performance Improvement and Patient Safety Committee of the hospital executive leadership team. This structure illustrated alignment with the hospital’s core values (“true north”) of “developing people” and “care experience.”

In 2018, interval surveys demonstrated a gradual reduction of burnout to approximately one-fifth of division physicians as measured by the 2-item Maslach Burnout Inventory.

Initiatives in faculty well-being

The Charter of Physician Well-being outlines a framework to promote well-being among doctors by maximizing a sense of fulfillment and minimizing the harms of burnout. It shares this responsibility among societal, organizational, and interpersonal and individual commitments.5

As illustrated above, we used principles of Lean Management to prospectively create initiatives to improve well-being in our division. Lean in health care is designed to optimize primarily the patient experience; its implementation has subsequently demonstrated mixed provider and staff experiences,8,9 and many providers are skeptical of Lean’s potential to improve their own well-being. If, however, Lean is aligned with best practice frameworks for well-being such as those outline in the charter, it may also help to meet the Quadruple Aim of optimizing both provider well-being and patient experience. To further test this hypothesis, we retrospectively categorized our Lean-based interventions into the commitments described by the charter to identify areas of alignment and gaps that were not initially addressed using Lean Management (Table).

Organizational commitments5Supportive systems

We optimized scheduling and enhanced physician staffing by budgeting for a physician staffing buffer each academic year in order to minimize mandatory moonlighting and jeopardy pool activations that result from operating on a thin staffing margin when expected personal leave and reductions in clinical effort occur. Furthermore, we revised scheduling principles to balance patient continuity and individual time off requests while setting limits on the maximum duration of clinical stretches and instituting mandatory minimum time off between them.

Leadership engagement

We initiated monthly operations meetings as a forum to discuss challenges, brainstorm solutions, and message new initiatives with group input. For example, as a result of these meetings, we designed and implemented an additional service line to address the high census, revised the distribution of new patient admissions to level-load clinical shifts, and established a maximum number of weekends worked per month and year. This approach aligns with recommendations to use participatory leadership strategies to enhance physician well-being.10 Engaging both executive level and service level management to focus on burnout and other related well-being metrics is necessary for sustaining such work.

Interprofessional teamwork

We revised multidisciplinary rounds with social work, utilization management, and physical therapy to maximize efficiency and streamline communication by developing standard approaches for each patient presentation.

Interpersonal and individual commitments5Address emotional challenges of physician work

Although these commitments did not have a direct corollary with Lean philosophy, some of these needs were identified by our physician group at our annual retreats. As a result, we initiated a monthly faculty-led noon conference series focused on the clinical challenges of caring for vulnerable populations, a particular source of distress in our practice setting, and revised the division schedule to encourage attendance at the hospital’s Schwartz rounds.

Mental health and self-care

We organized focus groups and faculty development sessions on provider well-being and burnout and dealing with challenging patients and invited the Faculty and Staff Assistance Program, our institution’s mental health service provider, to our weekly division meeting.

Future directions

After using Lean Management as an approach to prospectively improve physician well-being, we were able to use the Charter on Physician Well-being retrospectively as a “checklist” to identify additional gaps for targeted intervention to ensure all commitments are sufficiently addressed.

Overall, we found that, not surprisingly, Lean Management aligned best with the organizational commitments in the charter. Reviewing the organizational commitments, we found our biggest remaining challenges are in building supportive systems, namely ensuring sustainable workloads, offloading and delegating nonphysician tasks, and minimizing the burden of documentation and administration.

Reviewing the societal commitments helped us to identify opportunities for future directions that we may not have otherwise considered. As a safety-net institution, we benefit from a strong sense of mission and shared values within our hospital and division. However, we recognize the need to continue to be vigilant to ensure that our physicians perceive that their own values are aligned with the division’s stated mission. Devoting a Kaizen-style retreat to well-being likely helped, and allocating divisional resources to a well-being committee indirectly helped, to foster a culture of well-being; however, we could more deliberately identify local policies that may benefit from advocacy or revision. Although our faculty identified interventions to improve interpersonal and individual drivers of well-being, these charter commitments did not have direct parallels in Lean philosophy, and organizations may need to deliberately seek to address these commitments outside of a Lean approach. Specifically, by reviewing the charter, we identified opportunities to provide additional resources for peer support and protected time for mental health care and self-care.

Conclusion

Lean Management can be an effective strategy to address many of the organizational commitments outlined in the Charter on Physician Well-being. This approach may be particularly effective for solving local challenges with systems and workflows. Those who use Lean as a primary method to approach systems improvement in support of the Quadruple Aim may need to use additional strategies to address societal and interpersonal and individual commitments outlined in the charter.

Dr. Sanyal-Dey is visiting associate clinical professor of medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and director of client services, LeanTaaS. Dr. Thomas is associate clinical professor of medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. Dr. Chia is associate professor of clinical medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital.

References

1. West CP et al. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-81.

2. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129-46.

3. Shanafelt T et al. The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1826-32.

4. Shanafelt T et al. Building a program on well-being: Key design considerations to meet the unique needs of each organization. Acad Med. 2019 Feb;94(2):156-161.

5. Thomas LR et al. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1541-42.

6. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573-6.

7. West CP et al. Concurrent Validity of Single-Item Measures of Emotional Exhaustion and Depersonalization in Burnout Assessment. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(11):1445-52.

8. Hung DY et al. Experiences of primary care physicians and staff following lean workflow redesign. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018 Apr 10;18(1):274.

9. Zibrowski E et al. Easier and faster is not always better: Grounded theory of the impact of large-scale system transformation on the clinical work of emergency medicine nurses and physicians. JMIR Hum Factors. 2018. doi: 10.2196/11013.

10. Shanafelt TD et al. Impact of organizational leadership on physician burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(4):432-40.

Using systems improvement strategies to support the Quadruple Aim

Using systems improvement strategies to support the Quadruple Aim

General background on well-being and burnout

With burnout increasingly recognized as a shared responsibility that requires addressing organizational drivers while supporting individuals to be well,1-4 practical strategies and examples of successful implementation of systems interventions to address burnout will be helpful for service directors to support their staff. The Charter on Physician Well-being, recently developed through collaborative input from multiple organizations, defines guiding principles and key commitments at the societal, organizational, interpersonal, and individual levels and may be a useful framework for organizations that are developing well-being initiatives.5

The charter advocates including physician well-being as a quality improvement metric for health systems, aligned with the concept of the Quadruple Aim of optimizing patient care by enhancing provider experience, promoting high-value care, and improving population health.6 Identifying areas of alignment between the charter’s recommendations and systems improvement strategies that seek to optimize efficiency and reduce waste, such as Lean Management, may help physician leaders to contextualize well-being initiatives more easily within ongoing systems improvement efforts. In this perspective, we provide one division’s experience using the Charter to assess successes and identify additional areas of improvement for well-being initiatives developed using Lean Management methodology.

Past and current state of affairs

In 2011, the division of hospital medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital was established and has seen continual expansion in terms of direct patient care, medical education, and hospital leadership.

In 2015, the division of hospital medicine experienced leadership transitions, faculty attrition, and insufficient recruitment resulting in staffing shortages, service line closure, schedule instability, and ultimately, low morale. A baseline survey conducted using the 2-Item Maslach Burnout Inventory. This survey, which uses one item in the domain of emotional exhaustion and one item in the domain of depersonalization, has shown good correlation with the full Maslach Burnout Inventory.7 At baseline, approximately one-third of the division’s physicians experienced burnout.

In response, a subsequent retreat focused on the three greatest areas of concern identified by the survey: scheduling, faculty development, and well-being.

Like many health systems, the hospital has adopted Lean as its preferred systems-improvement framework. The retreat was structured around the principles of Lean philosophy, and was designed to emulate that of a consolidated Kaizen workshop.

“Kaizen” in Japanese means “change for the better.” A typical Kaizen workshop revolves around rapid problem-solving over the course of 3-5 days, in which a team of people come together to identify and implement significant improvements for a selected process. To this end, the retreat was divided into subgroups for each area of concern. In turn, each subgroup mapped out existing workflows (“value stream”), identified areas of waste and non–value added time, and generated ideas of what an idealized process would be. Next, a root-cause analysis was performed and subsequent interventions (“countermeasures”) developed to address each problem. At the conclusion of the retreat, each subgroup shared a summary of their findings with the larger group.

Moving forward, this information served as a guiding framework for service and division leadership to run small tests of change. We enacted a series of countermeasures over the course of several years, and multiple cycles of improvement work addressed the three areas of concern. We developed an A3 report (a Lean project management tool that incorporates the plan-do-study-act cycle, organizes strategic efforts, and tracks progress on a single page) to summarize and present these initiatives to the Performance Improvement and Patient Safety Committee of the hospital executive leadership team. This structure illustrated alignment with the hospital’s core values (“true north”) of “developing people” and “care experience.”

In 2018, interval surveys demonstrated a gradual reduction of burnout to approximately one-fifth of division physicians as measured by the 2-item Maslach Burnout Inventory.

Initiatives in faculty well-being

The Charter of Physician Well-being outlines a framework to promote well-being among doctors by maximizing a sense of fulfillment and minimizing the harms of burnout. It shares this responsibility among societal, organizational, and interpersonal and individual commitments.5

As illustrated above, we used principles of Lean Management to prospectively create initiatives to improve well-being in our division. Lean in health care is designed to optimize primarily the patient experience; its implementation has subsequently demonstrated mixed provider and staff experiences,8,9 and many providers are skeptical of Lean’s potential to improve their own well-being. If, however, Lean is aligned with best practice frameworks for well-being such as those outline in the charter, it may also help to meet the Quadruple Aim of optimizing both provider well-being and patient experience. To further test this hypothesis, we retrospectively categorized our Lean-based interventions into the commitments described by the charter to identify areas of alignment and gaps that were not initially addressed using Lean Management (Table).

Organizational commitments5Supportive systems

We optimized scheduling and enhanced physician staffing by budgeting for a physician staffing buffer each academic year in order to minimize mandatory moonlighting and jeopardy pool activations that result from operating on a thin staffing margin when expected personal leave and reductions in clinical effort occur. Furthermore, we revised scheduling principles to balance patient continuity and individual time off requests while setting limits on the maximum duration of clinical stretches and instituting mandatory minimum time off between them.

Leadership engagement

We initiated monthly operations meetings as a forum to discuss challenges, brainstorm solutions, and message new initiatives with group input. For example, as a result of these meetings, we designed and implemented an additional service line to address the high census, revised the distribution of new patient admissions to level-load clinical shifts, and established a maximum number of weekends worked per month and year. This approach aligns with recommendations to use participatory leadership strategies to enhance physician well-being.10 Engaging both executive level and service level management to focus on burnout and other related well-being metrics is necessary for sustaining such work.

Interprofessional teamwork

We revised multidisciplinary rounds with social work, utilization management, and physical therapy to maximize efficiency and streamline communication by developing standard approaches for each patient presentation.

Interpersonal and individual commitments5Address emotional challenges of physician work

Although these commitments did not have a direct corollary with Lean philosophy, some of these needs were identified by our physician group at our annual retreats. As a result, we initiated a monthly faculty-led noon conference series focused on the clinical challenges of caring for vulnerable populations, a particular source of distress in our practice setting, and revised the division schedule to encourage attendance at the hospital’s Schwartz rounds.

Mental health and self-care

We organized focus groups and faculty development sessions on provider well-being and burnout and dealing with challenging patients and invited the Faculty and Staff Assistance Program, our institution’s mental health service provider, to our weekly division meeting.

Future directions

After using Lean Management as an approach to prospectively improve physician well-being, we were able to use the Charter on Physician Well-being retrospectively as a “checklist” to identify additional gaps for targeted intervention to ensure all commitments are sufficiently addressed.

Overall, we found that, not surprisingly, Lean Management aligned best with the organizational commitments in the charter. Reviewing the organizational commitments, we found our biggest remaining challenges are in building supportive systems, namely ensuring sustainable workloads, offloading and delegating nonphysician tasks, and minimizing the burden of documentation and administration.

Reviewing the societal commitments helped us to identify opportunities for future directions that we may not have otherwise considered. As a safety-net institution, we benefit from a strong sense of mission and shared values within our hospital and division. However, we recognize the need to continue to be vigilant to ensure that our physicians perceive that their own values are aligned with the division’s stated mission. Devoting a Kaizen-style retreat to well-being likely helped, and allocating divisional resources to a well-being committee indirectly helped, to foster a culture of well-being; however, we could more deliberately identify local policies that may benefit from advocacy or revision. Although our faculty identified interventions to improve interpersonal and individual drivers of well-being, these charter commitments did not have direct parallels in Lean philosophy, and organizations may need to deliberately seek to address these commitments outside of a Lean approach. Specifically, by reviewing the charter, we identified opportunities to provide additional resources for peer support and protected time for mental health care and self-care.

Conclusion

Lean Management can be an effective strategy to address many of the organizational commitments outlined in the Charter on Physician Well-being. This approach may be particularly effective for solving local challenges with systems and workflows. Those who use Lean as a primary method to approach systems improvement in support of the Quadruple Aim may need to use additional strategies to address societal and interpersonal and individual commitments outlined in the charter.

Dr. Sanyal-Dey is visiting associate clinical professor of medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and director of client services, LeanTaaS. Dr. Thomas is associate clinical professor of medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. Dr. Chia is associate professor of clinical medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital.

References

1. West CP et al. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-81.

2. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129-46.

3. Shanafelt T et al. The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1826-32.

4. Shanafelt T et al. Building a program on well-being: Key design considerations to meet the unique needs of each organization. Acad Med. 2019 Feb;94(2):156-161.

5. Thomas LR et al. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1541-42.

6. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573-6.

7. West CP et al. Concurrent Validity of Single-Item Measures of Emotional Exhaustion and Depersonalization in Burnout Assessment. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(11):1445-52.

8. Hung DY et al. Experiences of primary care physicians and staff following lean workflow redesign. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018 Apr 10;18(1):274.

9. Zibrowski E et al. Easier and faster is not always better: Grounded theory of the impact of large-scale system transformation on the clinical work of emergency medicine nurses and physicians. JMIR Hum Factors. 2018. doi: 10.2196/11013.

10. Shanafelt TD et al. Impact of organizational leadership on physician burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(4):432-40.

General background on well-being and burnout

With burnout increasingly recognized as a shared responsibility that requires addressing organizational drivers while supporting individuals to be well,1-4 practical strategies and examples of successful implementation of systems interventions to address burnout will be helpful for service directors to support their staff. The Charter on Physician Well-being, recently developed through collaborative input from multiple organizations, defines guiding principles and key commitments at the societal, organizational, interpersonal, and individual levels and may be a useful framework for organizations that are developing well-being initiatives.5

The charter advocates including physician well-being as a quality improvement metric for health systems, aligned with the concept of the Quadruple Aim of optimizing patient care by enhancing provider experience, promoting high-value care, and improving population health.6 Identifying areas of alignment between the charter’s recommendations and systems improvement strategies that seek to optimize efficiency and reduce waste, such as Lean Management, may help physician leaders to contextualize well-being initiatives more easily within ongoing systems improvement efforts. In this perspective, we provide one division’s experience using the Charter to assess successes and identify additional areas of improvement for well-being initiatives developed using Lean Management methodology.

Past and current state of affairs

In 2011, the division of hospital medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital was established and has seen continual expansion in terms of direct patient care, medical education, and hospital leadership.

In 2015, the division of hospital medicine experienced leadership transitions, faculty attrition, and insufficient recruitment resulting in staffing shortages, service line closure, schedule instability, and ultimately, low morale. A baseline survey conducted using the 2-Item Maslach Burnout Inventory. This survey, which uses one item in the domain of emotional exhaustion and one item in the domain of depersonalization, has shown good correlation with the full Maslach Burnout Inventory.7 At baseline, approximately one-third of the division’s physicians experienced burnout.

In response, a subsequent retreat focused on the three greatest areas of concern identified by the survey: scheduling, faculty development, and well-being.

Like many health systems, the hospital has adopted Lean as its preferred systems-improvement framework. The retreat was structured around the principles of Lean philosophy, and was designed to emulate that of a consolidated Kaizen workshop.

“Kaizen” in Japanese means “change for the better.” A typical Kaizen workshop revolves around rapid problem-solving over the course of 3-5 days, in which a team of people come together to identify and implement significant improvements for a selected process. To this end, the retreat was divided into subgroups for each area of concern. In turn, each subgroup mapped out existing workflows (“value stream”), identified areas of waste and non–value added time, and generated ideas of what an idealized process would be. Next, a root-cause analysis was performed and subsequent interventions (“countermeasures”) developed to address each problem. At the conclusion of the retreat, each subgroup shared a summary of their findings with the larger group.

Moving forward, this information served as a guiding framework for service and division leadership to run small tests of change. We enacted a series of countermeasures over the course of several years, and multiple cycles of improvement work addressed the three areas of concern. We developed an A3 report (a Lean project management tool that incorporates the plan-do-study-act cycle, organizes strategic efforts, and tracks progress on a single page) to summarize and present these initiatives to the Performance Improvement and Patient Safety Committee of the hospital executive leadership team. This structure illustrated alignment with the hospital’s core values (“true north”) of “developing people” and “care experience.”

In 2018, interval surveys demonstrated a gradual reduction of burnout to approximately one-fifth of division physicians as measured by the 2-item Maslach Burnout Inventory.

Initiatives in faculty well-being

The Charter of Physician Well-being outlines a framework to promote well-being among doctors by maximizing a sense of fulfillment and minimizing the harms of burnout. It shares this responsibility among societal, organizational, and interpersonal and individual commitments.5

As illustrated above, we used principles of Lean Management to prospectively create initiatives to improve well-being in our division. Lean in health care is designed to optimize primarily the patient experience; its implementation has subsequently demonstrated mixed provider and staff experiences,8,9 and many providers are skeptical of Lean’s potential to improve their own well-being. If, however, Lean is aligned with best practice frameworks for well-being such as those outline in the charter, it may also help to meet the Quadruple Aim of optimizing both provider well-being and patient experience. To further test this hypothesis, we retrospectively categorized our Lean-based interventions into the commitments described by the charter to identify areas of alignment and gaps that were not initially addressed using Lean Management (Table).

Organizational commitments5Supportive systems

We optimized scheduling and enhanced physician staffing by budgeting for a physician staffing buffer each academic year in order to minimize mandatory moonlighting and jeopardy pool activations that result from operating on a thin staffing margin when expected personal leave and reductions in clinical effort occur. Furthermore, we revised scheduling principles to balance patient continuity and individual time off requests while setting limits on the maximum duration of clinical stretches and instituting mandatory minimum time off between them.

Leadership engagement

We initiated monthly operations meetings as a forum to discuss challenges, brainstorm solutions, and message new initiatives with group input. For example, as a result of these meetings, we designed and implemented an additional service line to address the high census, revised the distribution of new patient admissions to level-load clinical shifts, and established a maximum number of weekends worked per month and year. This approach aligns with recommendations to use participatory leadership strategies to enhance physician well-being.10 Engaging both executive level and service level management to focus on burnout and other related well-being metrics is necessary for sustaining such work.

Interprofessional teamwork

We revised multidisciplinary rounds with social work, utilization management, and physical therapy to maximize efficiency and streamline communication by developing standard approaches for each patient presentation.

Interpersonal and individual commitments5Address emotional challenges of physician work

Although these commitments did not have a direct corollary with Lean philosophy, some of these needs were identified by our physician group at our annual retreats. As a result, we initiated a monthly faculty-led noon conference series focused on the clinical challenges of caring for vulnerable populations, a particular source of distress in our practice setting, and revised the division schedule to encourage attendance at the hospital’s Schwartz rounds.

Mental health and self-care

We organized focus groups and faculty development sessions on provider well-being and burnout and dealing with challenging patients and invited the Faculty and Staff Assistance Program, our institution’s mental health service provider, to our weekly division meeting.

Future directions

After using Lean Management as an approach to prospectively improve physician well-being, we were able to use the Charter on Physician Well-being retrospectively as a “checklist” to identify additional gaps for targeted intervention to ensure all commitments are sufficiently addressed.

Overall, we found that, not surprisingly, Lean Management aligned best with the organizational commitments in the charter. Reviewing the organizational commitments, we found our biggest remaining challenges are in building supportive systems, namely ensuring sustainable workloads, offloading and delegating nonphysician tasks, and minimizing the burden of documentation and administration.

Reviewing the societal commitments helped us to identify opportunities for future directions that we may not have otherwise considered. As a safety-net institution, we benefit from a strong sense of mission and shared values within our hospital and division. However, we recognize the need to continue to be vigilant to ensure that our physicians perceive that their own values are aligned with the division’s stated mission. Devoting a Kaizen-style retreat to well-being likely helped, and allocating divisional resources to a well-being committee indirectly helped, to foster a culture of well-being; however, we could more deliberately identify local policies that may benefit from advocacy or revision. Although our faculty identified interventions to improve interpersonal and individual drivers of well-being, these charter commitments did not have direct parallels in Lean philosophy, and organizations may need to deliberately seek to address these commitments outside of a Lean approach. Specifically, by reviewing the charter, we identified opportunities to provide additional resources for peer support and protected time for mental health care and self-care.

Conclusion

Lean Management can be an effective strategy to address many of the organizational commitments outlined in the Charter on Physician Well-being. This approach may be particularly effective for solving local challenges with systems and workflows. Those who use Lean as a primary method to approach systems improvement in support of the Quadruple Aim may need to use additional strategies to address societal and interpersonal and individual commitments outlined in the charter.

Dr. Sanyal-Dey is visiting associate clinical professor of medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and director of client services, LeanTaaS. Dr. Thomas is associate clinical professor of medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. Dr. Chia is associate professor of clinical medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital.

References

1. West CP et al. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-81.

2. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129-46.

3. Shanafelt T et al. The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1826-32.

4. Shanafelt T et al. Building a program on well-being: Key design considerations to meet the unique needs of each organization. Acad Med. 2019 Feb;94(2):156-161.

5. Thomas LR et al. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1541-42.

6. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573-6.

7. West CP et al. Concurrent Validity of Single-Item Measures of Emotional Exhaustion and Depersonalization in Burnout Assessment. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(11):1445-52.

8. Hung DY et al. Experiences of primary care physicians and staff following lean workflow redesign. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018 Apr 10;18(1):274.

9. Zibrowski E et al. Easier and faster is not always better: Grounded theory of the impact of large-scale system transformation on the clinical work of emergency medicine nurses and physicians. JMIR Hum Factors. 2018. doi: 10.2196/11013.

10. Shanafelt TD et al. Impact of organizational leadership on physician burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(4):432-40.

Case study: Maternal cervical cancer linked to neonate lung cancer

That’s the conclusion of two ground-breaking cases from Japan in which investigators describe lung cancer in two boys that “probably developed” from their respective mothers via vaginal transmission during birth.

“Transmission of maternal cancer to offspring is extremely rare and is estimated to occur in approximately 1 infant per every 500,000 mothers with cancer,” wrote Ayumu Arakawa, MD, of the National Cancer Center Hospital in Japan, and colleagues, in a paper published Jan. 7 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Previous cases, of which only 18 have been recorded, have been presumed to occur via transplacental transmission, they said.

In the two new cases, genetic analyses and other evidence suggest that both boys’ lung cancers developed after aspirating uterine cervical cancer tumor cells into their lungs during passage through the birth canal.

Tragically, both mothers, each of whom was diagnosed with cervical cancer after the births, died while their boys were still infants.

“Most of the maternal-to-infant cases reported have been leukemia or melanoma,” said Mel Greaves, PhD, of the Institute of Cancer Research, London, who was asked for comment. In 2009, Dr. Greaves and colleagues published a case study of maternal-to-infant cancer transmission (presumably via the placenta). “It attracted an enormous amount of publicity and no doubt some alarm,” he said in an interview. He emphasized that the phenomenon is “incredibly rare.”

Dr. Greaves explains why such transmission is so rare. “We suspect that cancer cells do transit from mum to unborn child more often, but the foreign (aka paternal) antigens (HLA) on the tumor cells prompt immunological rejection. The extremely rare cases of successful transmission probably do depend on the fortuitous loss of paternal HLA.”

Advances in genetic technology may allow such cases, which have been recorded since 1950, to be rapidly identified now, he said.

“Where there is an adult-type cancer in an infant or child whose mother carried cancer when pregnant, then whole-genome sequencing should quickly tell if the infant’s tumor was of maternal origin,” Dr. Greaves explained.

“I think we will be seeing more reports like this in the future, now that this phenomenon has been described and next-generation sequencing is more readily available,” added Mae Zakhour, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, when asked for comment.

In the case of the Japanese boys, both cases were discovered incidentally during an analysis of the results of routine next-generation sequencing testing in a prospective gene-profiling trial in cancer patients, known as TOP-GEAR.

How do the investigators know that the spread happened vaginally and not via the placenta?

They explained that, in other cases of mother-to-fetus transmission, the offspring presented with multiple metastases in the brain, bones, liver, lungs, and soft tissues, which were “consistent with presumed hematogenous spread from the placenta.” However, in the two boys, tumors were observed only in the lungs and were localized along the bronchi.

That peribronchial pattern of tumor growth “suggested that the tumors arose from mother-to-infant vaginal transmission through aspiration of tumor-contaminated vaginal fluids during birth.”

In addition, the tumors in both boys lacked the Y chromosome and shared multiple somatic mutations, an HPV genome, and SNP alleles with tumors from the mothers.

“The identical molecular profiles of maternal and pediatric tumors demonstrated by next-generation sequencing, as well as the location of the tumors in the children, provides strong evidence for cancer transmission during delivery,” Dr. Zakhour summarized.

C-section question

The first of the cases reported by the Japanese team was a toddler (23 months) who presented to a local hospital with a 2-week history of a productive cough. Computed tomography revealed multiple masses scattered along the bronchi in both lungs, and a biopsy revealed neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung.

Notably, the mother’s cervical cancer was not diagnosed during her pregnancy. A cervical cytologic test performed in the mother 7 months before the birth was negative. The infant was delivered transvaginally at 39 weeks of gestation.

It was only 3 months after the birth that the 35-year-old mother received a diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. She then underwent radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy, followed by chemotherapy.

Had it been known that she had cervical cancer, she may have been advised to have a cesarean section.

The study authors propose, on the basis of their paper, that all women with cervical cancer should have a cesarean section.

But a U.S. expert questioned this, and said the situation is “a bit nuanced.”

William Grobman, MD, of Northwestern University in Chicago, said the current standard recommendation for many pregnant women known to have cervical cancer is to have a cesarean section and that “the strength of the recommendation is dependent on factors such as stage and size.”

However, in an interview, he added that “it may be premature to make a blanket recommendation for all people based on two reports without any idea of the frequency of this event, and with such uncertainty, it seems that disclosure of all information and shared decision-making would be a key approach.”

In this case report, the authors also noted that the cancer found in the toddler looked similar to the cancer in the mother.

“Histologic similarities between the tumor samples from the mother and child prompted us to compare the results of their next-generation sequencing tests,” they said.

The result? “The comparison of the gene profiles in the samples of tumor and normal tissue confirmed that transmission of maternal tumor to the child had occurred.”

The lung cancer in the toddler progressed despite two chemotherapy regimens, so he was enrolled in a clinical trial of nivolumab therapy. He had a response that continued for 7 months, with no appearance of new lesions. Lobectomy was performed to resect a single remaining nodule. The boy had no evidence of disease recurrence at 12 months after lobectomy.

His mother was also enrolled in a nivolumab trial, but her cervical cancer had spread, and she died 5 months after disease progression.

Second case

In the second reported case, a 6-year-old boy presented to a local hospital with chest pain on the left side. Computed tomography revealed a mass in the left lung, and mucinous adenocarcinoma was eventually diagnosed.

In this case, the mother had a cervical polypoid tumor detected during pregnancy. But, as in the other case, cervical cytologic analysis was negative. Because the tumor was stable without any intervention, the mother delivered the boy vaginally at 38 weeks of gestation.

However, after the delivery, biopsy of the cervical lesion revealed adenocarcinoma. The mother underwent radical hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy 3 months after delivery. She died of the disease 2 years after the surgery.

The boy received chemotherapy and had a partial response, with a reduction in levels of the tumor marker CA19-9 to normal levels. But 3 months later, the disease recurred in the left lung. After more chemotherapy, he underwent total left pneumonectomy and was subsequently free of disease.

The study authors said that they did not suspect maternal transmission of the cancer when her child received a diagnosis at 6 years of age. They explained that metastatic cervical cancer is typically a fast-growing tumor and the slow growth in the child seemed inconsistent with the idea that the cancer had been transmitted to him.

However, the pathology exam showed that the boy had mucinous adenocarcinoma, “which is an unusual morphologic finding for a primary lung tumor, but it was similar to the uterine cervical tumor in the mother,” the authors reported.

Samples of the cervical tumor from the mother and from the lung tumor of the child were submitted for next-generation sequencing tests and, said the authors, indicated mother-to-infant transmission.

The study was supported by grants from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development; the National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund; and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology; and funding from Ono Pharmaceutical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

That’s the conclusion of two ground-breaking cases from Japan in which investigators describe lung cancer in two boys that “probably developed” from their respective mothers via vaginal transmission during birth.

“Transmission of maternal cancer to offspring is extremely rare and is estimated to occur in approximately 1 infant per every 500,000 mothers with cancer,” wrote Ayumu Arakawa, MD, of the National Cancer Center Hospital in Japan, and colleagues, in a paper published Jan. 7 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Previous cases, of which only 18 have been recorded, have been presumed to occur via transplacental transmission, they said.