User login

ECHO-CT: An Interdisciplinary Videoconference Model for Identifying Potential Postdischarge Transition-of-Care Events

As the population of the United States continues to age, hospitals are seeing an increasing number of older patients with significant medical and social complexity. Medicare data have shown that an increasing number require post–acute care after a hospitalization.1 Discharges to post–acute care settings are often longer and more costly compared with discharges to other settings, which suggests that targeting quality improvement efforts at this transition period may improve the value of care.2

The transition from the hospital setting to a post–acute care facility can be dangerous and complicated due to lapses in communication, medication errors, and the complexity of medical treatment plans. Suboptimal transitions in care can result in adverse events for the patient, as well as confusion in medication regimens or incomplete plans for follow-up care.3

The Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) model was first developed and launched by Sanjeev Arora, MD, in New Mexico in 2003 to expand access to subspecialist care using videoconferencing.4 We first applied this model in 2013 to evaluate the impact of this interdisciplinary videoconferencing tool on the care of patients discharged to post–acute settings.5 We found that patients participating in the Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes–Care Transitions (ECHO-CT) model experienced decreased risk of rehospitalization, decreased skilled nursing facility (SNF) length of stay, and reduced 30-day healthcare costs, compared with those patients not enrolled in this program; these outcomes were likely due to identification and correction of medication-related errors, improved care coordination, improved disease management, and clarification of goals of care.6 Though these investigations did identify some issues arising during the care transition process, they did not fully describe the types of problems uncovered. We sought to better characterize the clinical and operational issues identified through the ECHO-CT conference, hereafter known as transition-of-care events (TCEs). These issues may include new or evolving medical concerns, an adverse event, or a “near miss.” Identification and classification of TCEs that may contribute to unsafe or fractured care transitions are critical in developing systematic solutions to improve transitions of care, which can ultimately improve patient safety and potentially avoid preventable errors.

METHODS

ECHO-CT Multidisciplinary Video Conference

We conducted ECHO-CT at a large, tertiary care academic medical center. The project design for the ECHO-CT program has been previously described.5 In brief, the program is a weekly, multidisciplinary videoconference between a hospital-based team and post–acute care providers to discuss patients discharged from inpatient services to post–acute care sites, including SNFs and long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs), during the preceding week. All patients discharged from the tertiary care inpatient site to one of the eight participating SNFs or LTACHs, from either a medical or surgical service, are eligible to be discussed at this weekly interdisciplinary conference. Long-term care facilities were not included in this study. The ECHO-CT program used HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act)-compliant videoconferencing technology to connect hospital and post–acute care providers.

During the videoconferences, each patient’s hospital course and discharge documentation are reviewed by a hospitalist, and a pharmacist performs a medication reconciliation of each patient’s admission, discharge, and post–acute care medication list. The discharging attending, primary care providers, residents, other trainees, and subspecialist providers are invited to attend. Typically, the interdisciplinary team at the post–acute care sites includes physicians, nurse practitioners, physical therapists, social workers, and case managers. Between 10 and 20 patients are discussed in a case-based format, which includes a summary of the patient’s hospital course, an update from the post–acute care team on the patient’s care, and an opportunity for a discussion regarding any concerns or questions raised by the post–acute care or inpatient care teams. The content and duration of discussion typically lasts approximately 3 to 10 minutes, depending on the needs of the patient and the care team. Each of the eight post–acute care sites participating in the project are assigned a 10- to 15-minute block. A copy of the ECHO-CT session process document is included in the Appendix.

Data Collection

At each interdisciplinary patient review, TCEs were identified and recorded. These events were categorized in real time by the ECHO-CT data collection team into the following categories: medication related, medical, discharge communication/coordination, or other, and recorded in a secured, deidentified database. For individuals whose TCEs could represent more than one category, authors reviewed the available information about the TCEs and determined the most appropriate category; if more than one category was felt to be applicable to a patient’s situation, the events were reclassified into all applicable categories. Data about individual patients, including gender, age at the time of discharge, and other demographic information, were obtained from hospital databases. Number of diagnoses included any diagnosis billed during the patient’s hospital stay, and these data were obtained from a hospital billing database. Average number of medications at discharge was obtained from a hospital pharmacy database.

RESULTS

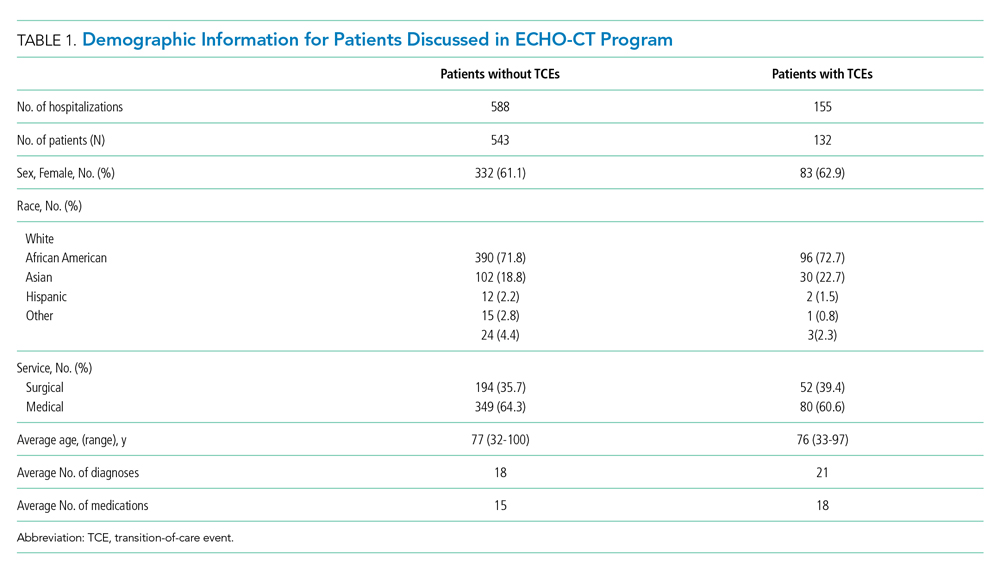

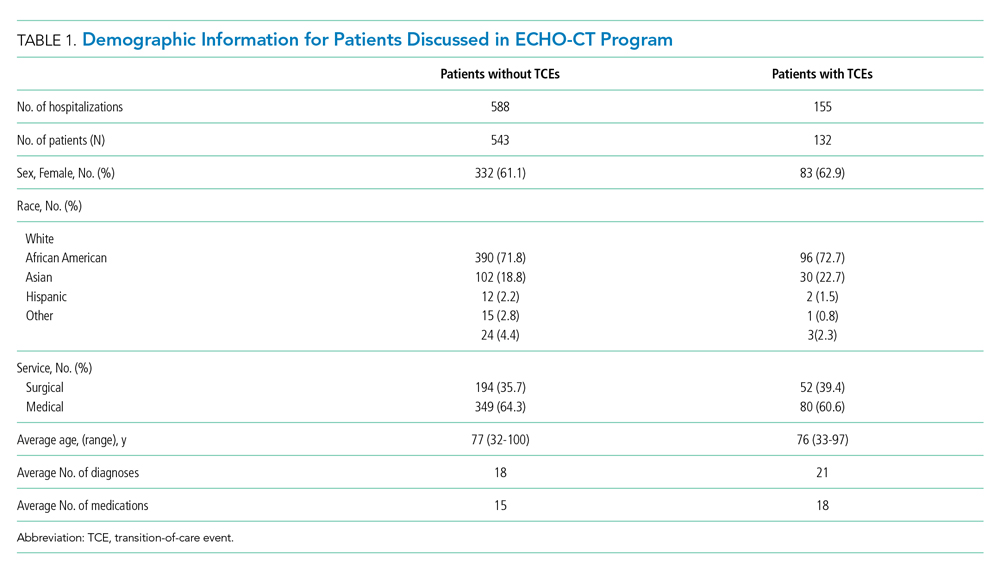

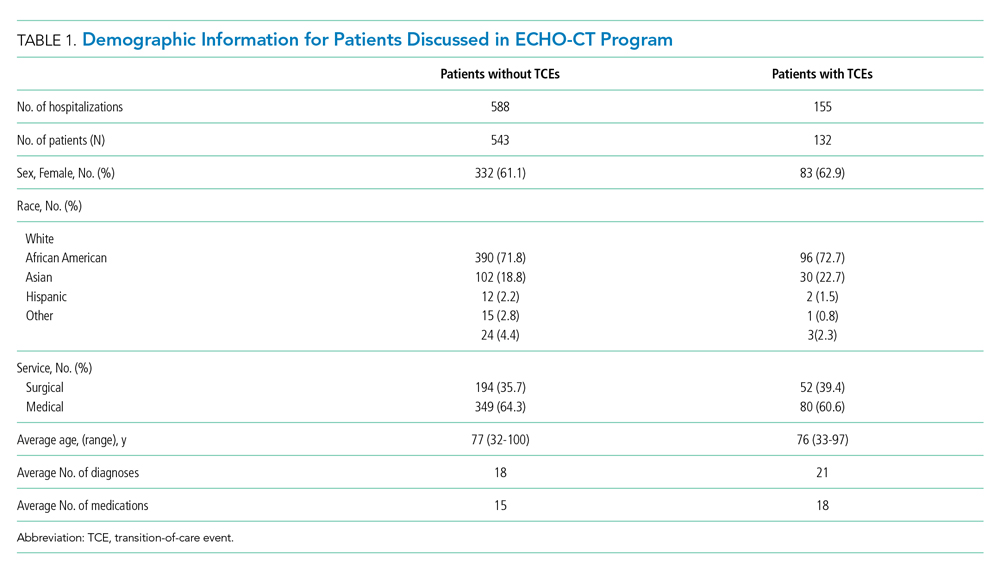

A total of 675 patients (experiencing 743 hospitalizations) were discharged from a medical or surgical service to one of the participating post–acute care sites from January 2016 to October 2018, and were discussed at the interdisciplinary conference. During that time, 139 TCEs were recorded for review, involving 132 patients (Table 1). Patients who experienced TCEs were noted to have a slightly higher average number of diagnoses than did those in the non-TCE group (21 vs 18, respectively) and number of medications (18 vs 15).

Representative examples of TCEs are provided in Table 2. Fifty-eight issues were identified as discharge communication or coordination issues (eg, discharge summary was late or missing at time of discharge to facility, transitional issues were unclear, follow-up appointments were not appropriately scheduled or documented). An additional 52 TCEs were identified as pharmacy or medication issues (eg, medications were inadvertently omitted from discharge medication list, prehospital medication list was incorrect). Medical issues accounted for an additional 27 concerns (eg, patient was hypoglycemic on arrival, inadequate pain control, discovery of new acute medical issues or medical diagnoses that were not clearly documented or communicated by the inpatient team). “Other” issues (two) included unaddressed social concerns, such as insurance issues.

DISCUSSION

The ECHO-CT model unites hospital and post–acute care providers to improve transitions of care and is unique in its focus on the transition from hospital to post–acute care rather than to home care. In 2 years of data collection, we identified several TCEs encompassing a range of concerns. Of the 675 patients discussed, 132 (20%) were noted to have a TCE. When these percentages are applied to the 140 million Medicare hospital discharges that took place during 2000 to 2015, we would estimate nearly 5.5 million TCEs, or 375,000 TCEs per year, that may have affected this population.

The majority of TCEs were communication and coordination errors. Missing or incomplete discharge paperwork, inadequate documentation of inpatient care, and confusion about medical devices or postoperative needs (eg, slings, braces, wound care, drains) were commonly reported. Follow-up appointments with specialists were often not appropriately scheduled or communicated. This may have resulted from unstandardized discharge documentation and a lower priority given to documentation in the setting of multiple clinical demands (eg, direct patient care, complex care coordination, and clinical paperwork and charting). Studies have demonstrated that fewer than one-third of discharge summaries are received by outpatient providers before postdischarge follow-up, and additionally that nearly 40% of patients did not undergo recommended workups for medical issues identified during their hospital stay.7,8 All of this is problematic because appropriate documentation in discharge summaries is associated with a decreased risk of hospital readmission.9

Pharmacy issues were the second most common TCE identified. One member of the post–acute care team noted that “omissions, additions, and replacements” relating to medications were common occurrences. Additionally, it was noted that medications were inadvertently continued for longer than planned or not adjusted appropriately with changing clinical parameters, such as renal function. The results of our analysis are consistent with current literature, which suggests that up to 60% of all medication errors occur during the period surrounding transitions of care.10

There were several limitations to this investigation. Though recording of identified TCEs occurred in real time, analysis of these identified events occurred retrospectively; therefore, investigators had limited ability to retroactively review or recategorize recorded issues, which potentially could have resulted in misclassification or misinterpretation. Additionally, the data were intended to be descriptive; therefore, outcomes such as hospital readmission and patient harm could not be linked to specific TCEs. Furthermore, it is possible that events were not detected by either the postdischarge team or the hospital-based team and, therefore, not captured in this analysis. Further work would be helpful to determine the root causes underlying the identified issues in care transitions, with the goal of improving patient safety and avoiding preventable errors during transitions of care. Although there is comprehensive literature related to errors and medication-related adverse events,11 there is not a consensus of how to classify and report, in a standardized fashion, events arising during the transition period. A validated structure for systematically identifying, monitoring, recording, and reporting issues arising during care transitions will be critical in preventing errors and ensuring patient safety during this high-risk period.

CONCLUSION

Our model is a unique intervention that uses the expertise and engagement of an interdisciplinary team and seeks to identify and remedy issues arising during transitions of care—in real time—to prevent direct harm to vulnerable patients. We have already implemented interventions to improve care based on our experiences with this videoconference-based program. For example, direct feedback was given to discharging teams to improve the discharge summary and associated documentation, and changes to the medication-ordering system were implemented to address specific medication errors discovered. The TCEs identified in this investigation highlight specific areas for improvement with the goal of providing high-quality care for patients and seamless transitions to post–acute care. As health systems and hospitals face new challenges in communication and care coordination, especially due to the recent COVID-19 pandemic, the technology and communication methods used in the ECHO-CT model may become even more relevant for promoting clear communication and patient safety during transitions of care.

Acknowledgment

The ECHO CT team thanks Sabrina Carretie for her contributions in data collection and analysis.

1. Werner RM, Konetzka RT. Trends in post-acute care use among medicare beneficiaries: 2000 to 2015. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1616–1617. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.2408

2. Tian W. An All-Payer View of Hospital Discharge to Postacute Care, 2013. Statistical Brief #205. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; May 2016. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb205-Hospital-Discharge-Postacute-Care.pdf

3. Kessler C, Williams MC, Moustoukas JN, Pappas C. Transitions of care for the geriatric patient in the emergency department. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29(1):49-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2012.10.005

4. Arora S, Thornton K, Jenkusky SM, Parish B, Scaletti JV. Project ECHO: linking university specialists with rural and prison-based clinicians to improve care for people with chronic hepatitis C in New Mexico. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(Suppl 2):74-77. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549071220s214

5. Farris G, Sircar M, Bortinger J, et al. Extension for community healthcare outcomes–care transitions: enhancing geriatric care transitions through a multidisciplinary videoconference. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(3):598-602. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14690

6. Moore AB, Krupp JE, Dufour AB, et al. Improving transitions to postacute care for elderly patients using a novel video-conferencing program: ECHO-Care transitions. Am J Med. 2017;130(10):1199-1204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.04.041

7. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–841. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.8.831

8. Moore C, McGinn T, Halm E. Tying up loose ends: discharging patients with unresolved medical issues. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(12):1305-1311. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.12.1305

9. van Walraven C, Seth R, Austin PC, Laupacis A. Effect of discharge summary availability during post-discharge visits on hospital readmission. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(3):186-192. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10741.x

10. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-167. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007

11. Claeys C, Nève J, Tulkens PM, Spinewine A. Content validity and inter-rater reliability of an instrument to characterize unintentional medication discrepancies. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(7):577-591. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03262275

As the population of the United States continues to age, hospitals are seeing an increasing number of older patients with significant medical and social complexity. Medicare data have shown that an increasing number require post–acute care after a hospitalization.1 Discharges to post–acute care settings are often longer and more costly compared with discharges to other settings, which suggests that targeting quality improvement efforts at this transition period may improve the value of care.2

The transition from the hospital setting to a post–acute care facility can be dangerous and complicated due to lapses in communication, medication errors, and the complexity of medical treatment plans. Suboptimal transitions in care can result in adverse events for the patient, as well as confusion in medication regimens or incomplete plans for follow-up care.3

The Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) model was first developed and launched by Sanjeev Arora, MD, in New Mexico in 2003 to expand access to subspecialist care using videoconferencing.4 We first applied this model in 2013 to evaluate the impact of this interdisciplinary videoconferencing tool on the care of patients discharged to post–acute settings.5 We found that patients participating in the Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes–Care Transitions (ECHO-CT) model experienced decreased risk of rehospitalization, decreased skilled nursing facility (SNF) length of stay, and reduced 30-day healthcare costs, compared with those patients not enrolled in this program; these outcomes were likely due to identification and correction of medication-related errors, improved care coordination, improved disease management, and clarification of goals of care.6 Though these investigations did identify some issues arising during the care transition process, they did not fully describe the types of problems uncovered. We sought to better characterize the clinical and operational issues identified through the ECHO-CT conference, hereafter known as transition-of-care events (TCEs). These issues may include new or evolving medical concerns, an adverse event, or a “near miss.” Identification and classification of TCEs that may contribute to unsafe or fractured care transitions are critical in developing systematic solutions to improve transitions of care, which can ultimately improve patient safety and potentially avoid preventable errors.

METHODS

ECHO-CT Multidisciplinary Video Conference

We conducted ECHO-CT at a large, tertiary care academic medical center. The project design for the ECHO-CT program has been previously described.5 In brief, the program is a weekly, multidisciplinary videoconference between a hospital-based team and post–acute care providers to discuss patients discharged from inpatient services to post–acute care sites, including SNFs and long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs), during the preceding week. All patients discharged from the tertiary care inpatient site to one of the eight participating SNFs or LTACHs, from either a medical or surgical service, are eligible to be discussed at this weekly interdisciplinary conference. Long-term care facilities were not included in this study. The ECHO-CT program used HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act)-compliant videoconferencing technology to connect hospital and post–acute care providers.

During the videoconferences, each patient’s hospital course and discharge documentation are reviewed by a hospitalist, and a pharmacist performs a medication reconciliation of each patient’s admission, discharge, and post–acute care medication list. The discharging attending, primary care providers, residents, other trainees, and subspecialist providers are invited to attend. Typically, the interdisciplinary team at the post–acute care sites includes physicians, nurse practitioners, physical therapists, social workers, and case managers. Between 10 and 20 patients are discussed in a case-based format, which includes a summary of the patient’s hospital course, an update from the post–acute care team on the patient’s care, and an opportunity for a discussion regarding any concerns or questions raised by the post–acute care or inpatient care teams. The content and duration of discussion typically lasts approximately 3 to 10 minutes, depending on the needs of the patient and the care team. Each of the eight post–acute care sites participating in the project are assigned a 10- to 15-minute block. A copy of the ECHO-CT session process document is included in the Appendix.

Data Collection

At each interdisciplinary patient review, TCEs were identified and recorded. These events were categorized in real time by the ECHO-CT data collection team into the following categories: medication related, medical, discharge communication/coordination, or other, and recorded in a secured, deidentified database. For individuals whose TCEs could represent more than one category, authors reviewed the available information about the TCEs and determined the most appropriate category; if more than one category was felt to be applicable to a patient’s situation, the events were reclassified into all applicable categories. Data about individual patients, including gender, age at the time of discharge, and other demographic information, were obtained from hospital databases. Number of diagnoses included any diagnosis billed during the patient’s hospital stay, and these data were obtained from a hospital billing database. Average number of medications at discharge was obtained from a hospital pharmacy database.

RESULTS

A total of 675 patients (experiencing 743 hospitalizations) were discharged from a medical or surgical service to one of the participating post–acute care sites from January 2016 to October 2018, and were discussed at the interdisciplinary conference. During that time, 139 TCEs were recorded for review, involving 132 patients (Table 1). Patients who experienced TCEs were noted to have a slightly higher average number of diagnoses than did those in the non-TCE group (21 vs 18, respectively) and number of medications (18 vs 15).

Representative examples of TCEs are provided in Table 2. Fifty-eight issues were identified as discharge communication or coordination issues (eg, discharge summary was late or missing at time of discharge to facility, transitional issues were unclear, follow-up appointments were not appropriately scheduled or documented). An additional 52 TCEs were identified as pharmacy or medication issues (eg, medications were inadvertently omitted from discharge medication list, prehospital medication list was incorrect). Medical issues accounted for an additional 27 concerns (eg, patient was hypoglycemic on arrival, inadequate pain control, discovery of new acute medical issues or medical diagnoses that were not clearly documented or communicated by the inpatient team). “Other” issues (two) included unaddressed social concerns, such as insurance issues.

DISCUSSION

The ECHO-CT model unites hospital and post–acute care providers to improve transitions of care and is unique in its focus on the transition from hospital to post–acute care rather than to home care. In 2 years of data collection, we identified several TCEs encompassing a range of concerns. Of the 675 patients discussed, 132 (20%) were noted to have a TCE. When these percentages are applied to the 140 million Medicare hospital discharges that took place during 2000 to 2015, we would estimate nearly 5.5 million TCEs, or 375,000 TCEs per year, that may have affected this population.

The majority of TCEs were communication and coordination errors. Missing or incomplete discharge paperwork, inadequate documentation of inpatient care, and confusion about medical devices or postoperative needs (eg, slings, braces, wound care, drains) were commonly reported. Follow-up appointments with specialists were often not appropriately scheduled or communicated. This may have resulted from unstandardized discharge documentation and a lower priority given to documentation in the setting of multiple clinical demands (eg, direct patient care, complex care coordination, and clinical paperwork and charting). Studies have demonstrated that fewer than one-third of discharge summaries are received by outpatient providers before postdischarge follow-up, and additionally that nearly 40% of patients did not undergo recommended workups for medical issues identified during their hospital stay.7,8 All of this is problematic because appropriate documentation in discharge summaries is associated with a decreased risk of hospital readmission.9

Pharmacy issues were the second most common TCE identified. One member of the post–acute care team noted that “omissions, additions, and replacements” relating to medications were common occurrences. Additionally, it was noted that medications were inadvertently continued for longer than planned or not adjusted appropriately with changing clinical parameters, such as renal function. The results of our analysis are consistent with current literature, which suggests that up to 60% of all medication errors occur during the period surrounding transitions of care.10

There were several limitations to this investigation. Though recording of identified TCEs occurred in real time, analysis of these identified events occurred retrospectively; therefore, investigators had limited ability to retroactively review or recategorize recorded issues, which potentially could have resulted in misclassification or misinterpretation. Additionally, the data were intended to be descriptive; therefore, outcomes such as hospital readmission and patient harm could not be linked to specific TCEs. Furthermore, it is possible that events were not detected by either the postdischarge team or the hospital-based team and, therefore, not captured in this analysis. Further work would be helpful to determine the root causes underlying the identified issues in care transitions, with the goal of improving patient safety and avoiding preventable errors during transitions of care. Although there is comprehensive literature related to errors and medication-related adverse events,11 there is not a consensus of how to classify and report, in a standardized fashion, events arising during the transition period. A validated structure for systematically identifying, monitoring, recording, and reporting issues arising during care transitions will be critical in preventing errors and ensuring patient safety during this high-risk period.

CONCLUSION

Our model is a unique intervention that uses the expertise and engagement of an interdisciplinary team and seeks to identify and remedy issues arising during transitions of care—in real time—to prevent direct harm to vulnerable patients. We have already implemented interventions to improve care based on our experiences with this videoconference-based program. For example, direct feedback was given to discharging teams to improve the discharge summary and associated documentation, and changes to the medication-ordering system were implemented to address specific medication errors discovered. The TCEs identified in this investigation highlight specific areas for improvement with the goal of providing high-quality care for patients and seamless transitions to post–acute care. As health systems and hospitals face new challenges in communication and care coordination, especially due to the recent COVID-19 pandemic, the technology and communication methods used in the ECHO-CT model may become even more relevant for promoting clear communication and patient safety during transitions of care.

Acknowledgment

The ECHO CT team thanks Sabrina Carretie for her contributions in data collection and analysis.

As the population of the United States continues to age, hospitals are seeing an increasing number of older patients with significant medical and social complexity. Medicare data have shown that an increasing number require post–acute care after a hospitalization.1 Discharges to post–acute care settings are often longer and more costly compared with discharges to other settings, which suggests that targeting quality improvement efforts at this transition period may improve the value of care.2

The transition from the hospital setting to a post–acute care facility can be dangerous and complicated due to lapses in communication, medication errors, and the complexity of medical treatment plans. Suboptimal transitions in care can result in adverse events for the patient, as well as confusion in medication regimens or incomplete plans for follow-up care.3

The Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) model was first developed and launched by Sanjeev Arora, MD, in New Mexico in 2003 to expand access to subspecialist care using videoconferencing.4 We first applied this model in 2013 to evaluate the impact of this interdisciplinary videoconferencing tool on the care of patients discharged to post–acute settings.5 We found that patients participating in the Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes–Care Transitions (ECHO-CT) model experienced decreased risk of rehospitalization, decreased skilled nursing facility (SNF) length of stay, and reduced 30-day healthcare costs, compared with those patients not enrolled in this program; these outcomes were likely due to identification and correction of medication-related errors, improved care coordination, improved disease management, and clarification of goals of care.6 Though these investigations did identify some issues arising during the care transition process, they did not fully describe the types of problems uncovered. We sought to better characterize the clinical and operational issues identified through the ECHO-CT conference, hereafter known as transition-of-care events (TCEs). These issues may include new or evolving medical concerns, an adverse event, or a “near miss.” Identification and classification of TCEs that may contribute to unsafe or fractured care transitions are critical in developing systematic solutions to improve transitions of care, which can ultimately improve patient safety and potentially avoid preventable errors.

METHODS

ECHO-CT Multidisciplinary Video Conference

We conducted ECHO-CT at a large, tertiary care academic medical center. The project design for the ECHO-CT program has been previously described.5 In brief, the program is a weekly, multidisciplinary videoconference between a hospital-based team and post–acute care providers to discuss patients discharged from inpatient services to post–acute care sites, including SNFs and long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs), during the preceding week. All patients discharged from the tertiary care inpatient site to one of the eight participating SNFs or LTACHs, from either a medical or surgical service, are eligible to be discussed at this weekly interdisciplinary conference. Long-term care facilities were not included in this study. The ECHO-CT program used HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act)-compliant videoconferencing technology to connect hospital and post–acute care providers.

During the videoconferences, each patient’s hospital course and discharge documentation are reviewed by a hospitalist, and a pharmacist performs a medication reconciliation of each patient’s admission, discharge, and post–acute care medication list. The discharging attending, primary care providers, residents, other trainees, and subspecialist providers are invited to attend. Typically, the interdisciplinary team at the post–acute care sites includes physicians, nurse practitioners, physical therapists, social workers, and case managers. Between 10 and 20 patients are discussed in a case-based format, which includes a summary of the patient’s hospital course, an update from the post–acute care team on the patient’s care, and an opportunity for a discussion regarding any concerns or questions raised by the post–acute care or inpatient care teams. The content and duration of discussion typically lasts approximately 3 to 10 minutes, depending on the needs of the patient and the care team. Each of the eight post–acute care sites participating in the project are assigned a 10- to 15-minute block. A copy of the ECHO-CT session process document is included in the Appendix.

Data Collection

At each interdisciplinary patient review, TCEs were identified and recorded. These events were categorized in real time by the ECHO-CT data collection team into the following categories: medication related, medical, discharge communication/coordination, or other, and recorded in a secured, deidentified database. For individuals whose TCEs could represent more than one category, authors reviewed the available information about the TCEs and determined the most appropriate category; if more than one category was felt to be applicable to a patient’s situation, the events were reclassified into all applicable categories. Data about individual patients, including gender, age at the time of discharge, and other demographic information, were obtained from hospital databases. Number of diagnoses included any diagnosis billed during the patient’s hospital stay, and these data were obtained from a hospital billing database. Average number of medications at discharge was obtained from a hospital pharmacy database.

RESULTS

A total of 675 patients (experiencing 743 hospitalizations) were discharged from a medical or surgical service to one of the participating post–acute care sites from January 2016 to October 2018, and were discussed at the interdisciplinary conference. During that time, 139 TCEs were recorded for review, involving 132 patients (Table 1). Patients who experienced TCEs were noted to have a slightly higher average number of diagnoses than did those in the non-TCE group (21 vs 18, respectively) and number of medications (18 vs 15).

Representative examples of TCEs are provided in Table 2. Fifty-eight issues were identified as discharge communication or coordination issues (eg, discharge summary was late or missing at time of discharge to facility, transitional issues were unclear, follow-up appointments were not appropriately scheduled or documented). An additional 52 TCEs were identified as pharmacy or medication issues (eg, medications were inadvertently omitted from discharge medication list, prehospital medication list was incorrect). Medical issues accounted for an additional 27 concerns (eg, patient was hypoglycemic on arrival, inadequate pain control, discovery of new acute medical issues or medical diagnoses that were not clearly documented or communicated by the inpatient team). “Other” issues (two) included unaddressed social concerns, such as insurance issues.

DISCUSSION

The ECHO-CT model unites hospital and post–acute care providers to improve transitions of care and is unique in its focus on the transition from hospital to post–acute care rather than to home care. In 2 years of data collection, we identified several TCEs encompassing a range of concerns. Of the 675 patients discussed, 132 (20%) were noted to have a TCE. When these percentages are applied to the 140 million Medicare hospital discharges that took place during 2000 to 2015, we would estimate nearly 5.5 million TCEs, or 375,000 TCEs per year, that may have affected this population.

The majority of TCEs were communication and coordination errors. Missing or incomplete discharge paperwork, inadequate documentation of inpatient care, and confusion about medical devices or postoperative needs (eg, slings, braces, wound care, drains) were commonly reported. Follow-up appointments with specialists were often not appropriately scheduled or communicated. This may have resulted from unstandardized discharge documentation and a lower priority given to documentation in the setting of multiple clinical demands (eg, direct patient care, complex care coordination, and clinical paperwork and charting). Studies have demonstrated that fewer than one-third of discharge summaries are received by outpatient providers before postdischarge follow-up, and additionally that nearly 40% of patients did not undergo recommended workups for medical issues identified during their hospital stay.7,8 All of this is problematic because appropriate documentation in discharge summaries is associated with a decreased risk of hospital readmission.9

Pharmacy issues were the second most common TCE identified. One member of the post–acute care team noted that “omissions, additions, and replacements” relating to medications were common occurrences. Additionally, it was noted that medications were inadvertently continued for longer than planned or not adjusted appropriately with changing clinical parameters, such as renal function. The results of our analysis are consistent with current literature, which suggests that up to 60% of all medication errors occur during the period surrounding transitions of care.10

There were several limitations to this investigation. Though recording of identified TCEs occurred in real time, analysis of these identified events occurred retrospectively; therefore, investigators had limited ability to retroactively review or recategorize recorded issues, which potentially could have resulted in misclassification or misinterpretation. Additionally, the data were intended to be descriptive; therefore, outcomes such as hospital readmission and patient harm could not be linked to specific TCEs. Furthermore, it is possible that events were not detected by either the postdischarge team or the hospital-based team and, therefore, not captured in this analysis. Further work would be helpful to determine the root causes underlying the identified issues in care transitions, with the goal of improving patient safety and avoiding preventable errors during transitions of care. Although there is comprehensive literature related to errors and medication-related adverse events,11 there is not a consensus of how to classify and report, in a standardized fashion, events arising during the transition period. A validated structure for systematically identifying, monitoring, recording, and reporting issues arising during care transitions will be critical in preventing errors and ensuring patient safety during this high-risk period.

CONCLUSION

Our model is a unique intervention that uses the expertise and engagement of an interdisciplinary team and seeks to identify and remedy issues arising during transitions of care—in real time—to prevent direct harm to vulnerable patients. We have already implemented interventions to improve care based on our experiences with this videoconference-based program. For example, direct feedback was given to discharging teams to improve the discharge summary and associated documentation, and changes to the medication-ordering system were implemented to address specific medication errors discovered. The TCEs identified in this investigation highlight specific areas for improvement with the goal of providing high-quality care for patients and seamless transitions to post–acute care. As health systems and hospitals face new challenges in communication and care coordination, especially due to the recent COVID-19 pandemic, the technology and communication methods used in the ECHO-CT model may become even more relevant for promoting clear communication and patient safety during transitions of care.

Acknowledgment

The ECHO CT team thanks Sabrina Carretie for her contributions in data collection and analysis.

1. Werner RM, Konetzka RT. Trends in post-acute care use among medicare beneficiaries: 2000 to 2015. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1616–1617. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.2408

2. Tian W. An All-Payer View of Hospital Discharge to Postacute Care, 2013. Statistical Brief #205. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; May 2016. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb205-Hospital-Discharge-Postacute-Care.pdf

3. Kessler C, Williams MC, Moustoukas JN, Pappas C. Transitions of care for the geriatric patient in the emergency department. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29(1):49-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2012.10.005

4. Arora S, Thornton K, Jenkusky SM, Parish B, Scaletti JV. Project ECHO: linking university specialists with rural and prison-based clinicians to improve care for people with chronic hepatitis C in New Mexico. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(Suppl 2):74-77. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549071220s214

5. Farris G, Sircar M, Bortinger J, et al. Extension for community healthcare outcomes–care transitions: enhancing geriatric care transitions through a multidisciplinary videoconference. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(3):598-602. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14690

6. Moore AB, Krupp JE, Dufour AB, et al. Improving transitions to postacute care for elderly patients using a novel video-conferencing program: ECHO-Care transitions. Am J Med. 2017;130(10):1199-1204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.04.041

7. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–841. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.8.831

8. Moore C, McGinn T, Halm E. Tying up loose ends: discharging patients with unresolved medical issues. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(12):1305-1311. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.12.1305

9. van Walraven C, Seth R, Austin PC, Laupacis A. Effect of discharge summary availability during post-discharge visits on hospital readmission. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(3):186-192. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10741.x

10. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-167. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007

11. Claeys C, Nève J, Tulkens PM, Spinewine A. Content validity and inter-rater reliability of an instrument to characterize unintentional medication discrepancies. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(7):577-591. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03262275

1. Werner RM, Konetzka RT. Trends in post-acute care use among medicare beneficiaries: 2000 to 2015. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1616–1617. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.2408

2. Tian W. An All-Payer View of Hospital Discharge to Postacute Care, 2013. Statistical Brief #205. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; May 2016. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb205-Hospital-Discharge-Postacute-Care.pdf

3. Kessler C, Williams MC, Moustoukas JN, Pappas C. Transitions of care for the geriatric patient in the emergency department. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29(1):49-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2012.10.005

4. Arora S, Thornton K, Jenkusky SM, Parish B, Scaletti JV. Project ECHO: linking university specialists with rural and prison-based clinicians to improve care for people with chronic hepatitis C in New Mexico. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(Suppl 2):74-77. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549071220s214

5. Farris G, Sircar M, Bortinger J, et al. Extension for community healthcare outcomes–care transitions: enhancing geriatric care transitions through a multidisciplinary videoconference. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(3):598-602. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14690

6. Moore AB, Krupp JE, Dufour AB, et al. Improving transitions to postacute care for elderly patients using a novel video-conferencing program: ECHO-Care transitions. Am J Med. 2017;130(10):1199-1204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.04.041

7. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–841. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.8.831

8. Moore C, McGinn T, Halm E. Tying up loose ends: discharging patients with unresolved medical issues. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(12):1305-1311. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.12.1305

9. van Walraven C, Seth R, Austin PC, Laupacis A. Effect of discharge summary availability during post-discharge visits on hospital readmission. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(3):186-192. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10741.x

10. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-167. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007

11. Claeys C, Nève J, Tulkens PM, Spinewine A. Content validity and inter-rater reliability of an instrument to characterize unintentional medication discrepancies. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(7):577-591. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03262275

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist: Anaphylaxis Management in Adults and Children

Anaphylaxis, an acute, life-threatening allergic response, affects multiple organ systems and manifests variably. Anaphylaxis is likely taking place if one or more of the following occurs: (a) sudden- onset skin and mucosal tissue swelling, (b) skin and mucosal abnormalities or respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms after exposure to an allergen, or (c) reduced blood pressure after exposure to an allergen. With an estimated lifetime prevalence of up to 5.1%, it is a significant cause of morbidity in adults and children.1 The 2020 anaphylaxis practice parameter update provides recommendations on treatment, prevention, and assessment of biphasic symptom risk in patients experiencing anaphylaxis.2 The guideline provides five key recommendations and four good-practice statements, which we have consolidated into five recommendations for this update.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE HOSPITALIST

Recommendation 1. All patients with suspected or confirmed anaphylaxis should be treated with epinephrine. (Good-practice statement)

Self-injectable epinephrine is the first-line treatment for anaphylaxis, with weight-based dosing of 0.15 mg/kg for children weighing less than 30 kg and 0.30 mg/kg for children weighing more than 30 kg and adults. Delayed administration of epinephrine can increase anaphylaxis-associated morbidity and mortality. After epinephrine administration, patients should be observed in a healthcare setting for symptom resolution.

Recommendation 2. For all patients, clinicians should assess the risk for developing biphasic anaphylaxis. (Conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

Biphasic anaphylaxis is defined as the return of anaphylaxis symptoms after an asymptomatic period of at least 1 hour, all during a single instance of anaphylaxis. Biphasic anaphylaxis occurs in up to 20% of patients.3 Biphasic anaphylaxis is more likely among patients receiving repeated doses of epinephrine (odds ratio [OR], 4.82; 95% CI, 2.70-8.58), delayed epinephrine administration greater than 60 minutes (OR, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.09-4.79), or a severe initial presentation (OR, 4.82; 95% CI, 1.23-3.61).2 The presence of any of these risk factors raises the risk for developing biphasic anaphylaxis by 17%.4 Severe anaphylaxis is characterized by life-threatening symptoms, including loss of consciousness, syncope or dizziness, hypotension, cardiovascular system collapse, or neurologic dysfunction from hypoperfusion or hypoxia after exposure to an allergen.5

Other risk factors for biphasic anaphylaxis in all ages include a widened pulse pressure, unknown anaphylaxis trigger, and cutaneous signs and symptoms. Drug triggers are also a risk factor in pediatric patients.2

Recommendation 3. All patients with anaphylaxis and risk factors for biphasic anaphylaxis should undergo extended clinical observation in a setting capable of managing anaphylaxis. (Conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

All patients should be monitored for resolution of symptoms prior to discharge, regardless of age or severity at onset. Patients with all three of the following can be discharged 1 hour after symptom resolution because these three factors together have a 95% negative predictive value for biphasic anaphylaxis: nonsevere anaphylaxis, prompt response to epinephrine, and access to medical care.5 In contrast, extended observation of at least 6 hours should be offered to patients with increased risk of biphasic reactions. Patients who have potentially fatal underlying illnesses (eg, severe respiratory or cardiac disease), poor access to emergency medical services, poor self-management skills, or inability to access epinephrine should also be considered for extended observation or hospitalization. Evidence is lacking to define the optimal observation time because extended biphasic reactions can occur from 1 to 78 hours after initial anaphylaxis symptoms.6

Given the lack of specific evidence around length of observation, there is an opportunity for shared decision-making. Every patient should receive education regarding trigger avoidance, reasons to seek care or activate emergency medical services, and warning signs of biphasic anaphylaxis. Additionally, self-injectable epinephrine and an action plan detailing how and when to administer the epinephrine should be provided. Patients with anaphylaxis should follow up with an allergist.

Recommendation 4. Administration of glucocorticoids or antihistamines for prevention of biphasic anaphylaxis is not recommended. (Conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

This guideline discourages glucocorticoids and antihistamines as a primary treatment as it may delay epinephrine administration. Despite treating the cutaneous manifestations of anaphylaxis, antihistamines fail to treat the life-threatening cardiovascular and respiratory symptoms. No clear evidence exists on whether antihistamines or glucocorticoids prevent biphasic anaphylaxis.

Recommendation 5. In adult patients receiving chemotherapy, premedication with antihistamine and/or glucocorticoid should be used to prevent anaphylaxis or infusion-related reactions for some chemotherapeutic agents in patients with no previous reaction to the drug. (Conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

Premedication with antihistamines and/or glucocorticoids was associated with 51% reduced odds for anaphylaxis and infusion-related reactions to certain chemotherapy agents (pegaspargase, docetaxel, carboplatin, oxaliplatin, and rituximab) in adults who had not previously experienced a reaction to the drug (OR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.37-0.66).2 However, this same benefit was not found with other chemotherapy agents for patients without a prior allergic reaction to the agent, which allows clinicians to defer premedication. The benefit of premedication with antihistamines and/or glucocorticoids to patients with prior anaphylactic reactions to chemotherapy agents was not evaluated in this guideline, nor was the role premedication plays in desensitization to chemotherapy.

CRITIQUE

This guideline was created by a panel of allergists, clinical immunologists, and methodologists using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) approach to draft recommendations. Conflicts of interest (COI) were disclosed by all panel members according to the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (AAAAI) guidelines. The inclusion of many observational studies and meta-analyses improves the generalizability of the guideline. The authors highlighted the low certainty of evidence due to the lack of randomized controlled trials and significant heterogeneity of the included studies.

Some recommendations in the guideline have implications for costs of care. A recent economic analysis looked at cost-effectiveness for extended observation for anaphylaxis and found it was cost-effective only when patients were at increased risk for biphasic anaphylaxis.7 Although Recommendation 4 advises against the use of glucocorticoids for prevention of biphasic anaphylaxis, one retrospective cohort study demonstrated that glucocorticoid use was associated with decreased length of stay in children admitted with anaphylaxis.8 Therefore, the recommendation to avoid glucocorticoids for prevention of biphasic anaphylaxis could possibly increase hospital length of stay for children. The usefulness of dexamethasone to prevent biphasic anaphylaxis in children 3 to 14 months old is being evaluated in a randomized trial (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03523221).

AREAS OF FUTURE STUDY

Future research should better characterize risk factors for biphasic reactions to aid in clinical triage and diagnosis. Additional studies are needed to determine the optimal observation duration for patients experiencing anaphylactic reactions or requiring multiple doses of epinephrine. The role of premedication in patients receiving chemotherapy is poorly described, with few studies evaluating the benefit of premedication in patients with previous anaphylactic reactions.

1. Wood RA, Camargo CA Jr, Lieberman P, et al. Anaphylaxis in America: the prevalence and characteristics of anaphylaxis in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(2):461-467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2013.08.016

2. Shaker MS, Wallace DV, Golden DBK, et al. Anaphylaxis-a 2020 practice parameter update, systematic review, and Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(4):1082-1123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2020.01.017

3. Lieberman P, Camargo CA Jr, Bohlke K, et al. Epidemiology of anaphylaxis: findings of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Epidemiology of Anaphylaxis Working Group. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(5):596-602. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1081-1206(10)61086-1

4. Kim TH, Yoon SH, Hong H, Kang HR, Cho SH, Lee SY. Duration of observation for detecting a biphasic reaction in anaphylaxis: a meta-analysis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2019;179(1):31-36. https://doi.org/10.1159/000496092

5. Brown AF, Mckinnon D, Chu K. Emergency department anaphylaxis: a review of 142 patients in a single year. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108(5):861-866. https://doi.org/10.1067/mai.2001.119028

6. Pourmand A, Robinson C, Syed W, Mazer-Amirshahi M. Biphasic anaphylaxis: a review of the literature and implications for emergency management. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(8):1480-1485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2018.05.009

7. Shaker M, Wallace D, Golden DBK, Oppenheimer J, Greenhawt M. Simulation of health and economic benefits of extended observation of resolved anaphylaxis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1913951. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13951

8. Michelson KA, Monuteaux MC, Neuman MI. Glucocorticoids and hospital length of stay for children with anaphylaxis: a retrospective study. J Pediatr. 2015;167(3):719-724.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.05.033

Anaphylaxis, an acute, life-threatening allergic response, affects multiple organ systems and manifests variably. Anaphylaxis is likely taking place if one or more of the following occurs: (a) sudden- onset skin and mucosal tissue swelling, (b) skin and mucosal abnormalities or respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms after exposure to an allergen, or (c) reduced blood pressure after exposure to an allergen. With an estimated lifetime prevalence of up to 5.1%, it is a significant cause of morbidity in adults and children.1 The 2020 anaphylaxis practice parameter update provides recommendations on treatment, prevention, and assessment of biphasic symptom risk in patients experiencing anaphylaxis.2 The guideline provides five key recommendations and four good-practice statements, which we have consolidated into five recommendations for this update.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE HOSPITALIST

Recommendation 1. All patients with suspected or confirmed anaphylaxis should be treated with epinephrine. (Good-practice statement)

Self-injectable epinephrine is the first-line treatment for anaphylaxis, with weight-based dosing of 0.15 mg/kg for children weighing less than 30 kg and 0.30 mg/kg for children weighing more than 30 kg and adults. Delayed administration of epinephrine can increase anaphylaxis-associated morbidity and mortality. After epinephrine administration, patients should be observed in a healthcare setting for symptom resolution.

Recommendation 2. For all patients, clinicians should assess the risk for developing biphasic anaphylaxis. (Conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

Biphasic anaphylaxis is defined as the return of anaphylaxis symptoms after an asymptomatic period of at least 1 hour, all during a single instance of anaphylaxis. Biphasic anaphylaxis occurs in up to 20% of patients.3 Biphasic anaphylaxis is more likely among patients receiving repeated doses of epinephrine (odds ratio [OR], 4.82; 95% CI, 2.70-8.58), delayed epinephrine administration greater than 60 minutes (OR, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.09-4.79), or a severe initial presentation (OR, 4.82; 95% CI, 1.23-3.61).2 The presence of any of these risk factors raises the risk for developing biphasic anaphylaxis by 17%.4 Severe anaphylaxis is characterized by life-threatening symptoms, including loss of consciousness, syncope or dizziness, hypotension, cardiovascular system collapse, or neurologic dysfunction from hypoperfusion or hypoxia after exposure to an allergen.5

Other risk factors for biphasic anaphylaxis in all ages include a widened pulse pressure, unknown anaphylaxis trigger, and cutaneous signs and symptoms. Drug triggers are also a risk factor in pediatric patients.2

Recommendation 3. All patients with anaphylaxis and risk factors for biphasic anaphylaxis should undergo extended clinical observation in a setting capable of managing anaphylaxis. (Conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

All patients should be monitored for resolution of symptoms prior to discharge, regardless of age or severity at onset. Patients with all three of the following can be discharged 1 hour after symptom resolution because these three factors together have a 95% negative predictive value for biphasic anaphylaxis: nonsevere anaphylaxis, prompt response to epinephrine, and access to medical care.5 In contrast, extended observation of at least 6 hours should be offered to patients with increased risk of biphasic reactions. Patients who have potentially fatal underlying illnesses (eg, severe respiratory or cardiac disease), poor access to emergency medical services, poor self-management skills, or inability to access epinephrine should also be considered for extended observation or hospitalization. Evidence is lacking to define the optimal observation time because extended biphasic reactions can occur from 1 to 78 hours after initial anaphylaxis symptoms.6

Given the lack of specific evidence around length of observation, there is an opportunity for shared decision-making. Every patient should receive education regarding trigger avoidance, reasons to seek care or activate emergency medical services, and warning signs of biphasic anaphylaxis. Additionally, self-injectable epinephrine and an action plan detailing how and when to administer the epinephrine should be provided. Patients with anaphylaxis should follow up with an allergist.

Recommendation 4. Administration of glucocorticoids or antihistamines for prevention of biphasic anaphylaxis is not recommended. (Conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

This guideline discourages glucocorticoids and antihistamines as a primary treatment as it may delay epinephrine administration. Despite treating the cutaneous manifestations of anaphylaxis, antihistamines fail to treat the life-threatening cardiovascular and respiratory symptoms. No clear evidence exists on whether antihistamines or glucocorticoids prevent biphasic anaphylaxis.

Recommendation 5. In adult patients receiving chemotherapy, premedication with antihistamine and/or glucocorticoid should be used to prevent anaphylaxis or infusion-related reactions for some chemotherapeutic agents in patients with no previous reaction to the drug. (Conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

Premedication with antihistamines and/or glucocorticoids was associated with 51% reduced odds for anaphylaxis and infusion-related reactions to certain chemotherapy agents (pegaspargase, docetaxel, carboplatin, oxaliplatin, and rituximab) in adults who had not previously experienced a reaction to the drug (OR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.37-0.66).2 However, this same benefit was not found with other chemotherapy agents for patients without a prior allergic reaction to the agent, which allows clinicians to defer premedication. The benefit of premedication with antihistamines and/or glucocorticoids to patients with prior anaphylactic reactions to chemotherapy agents was not evaluated in this guideline, nor was the role premedication plays in desensitization to chemotherapy.

CRITIQUE

This guideline was created by a panel of allergists, clinical immunologists, and methodologists using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) approach to draft recommendations. Conflicts of interest (COI) were disclosed by all panel members according to the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (AAAAI) guidelines. The inclusion of many observational studies and meta-analyses improves the generalizability of the guideline. The authors highlighted the low certainty of evidence due to the lack of randomized controlled trials and significant heterogeneity of the included studies.

Some recommendations in the guideline have implications for costs of care. A recent economic analysis looked at cost-effectiveness for extended observation for anaphylaxis and found it was cost-effective only when patients were at increased risk for biphasic anaphylaxis.7 Although Recommendation 4 advises against the use of glucocorticoids for prevention of biphasic anaphylaxis, one retrospective cohort study demonstrated that glucocorticoid use was associated with decreased length of stay in children admitted with anaphylaxis.8 Therefore, the recommendation to avoid glucocorticoids for prevention of biphasic anaphylaxis could possibly increase hospital length of stay for children. The usefulness of dexamethasone to prevent biphasic anaphylaxis in children 3 to 14 months old is being evaluated in a randomized trial (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03523221).

AREAS OF FUTURE STUDY

Future research should better characterize risk factors for biphasic reactions to aid in clinical triage and diagnosis. Additional studies are needed to determine the optimal observation duration for patients experiencing anaphylactic reactions or requiring multiple doses of epinephrine. The role of premedication in patients receiving chemotherapy is poorly described, with few studies evaluating the benefit of premedication in patients with previous anaphylactic reactions.

Anaphylaxis, an acute, life-threatening allergic response, affects multiple organ systems and manifests variably. Anaphylaxis is likely taking place if one or more of the following occurs: (a) sudden- onset skin and mucosal tissue swelling, (b) skin and mucosal abnormalities or respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms after exposure to an allergen, or (c) reduced blood pressure after exposure to an allergen. With an estimated lifetime prevalence of up to 5.1%, it is a significant cause of morbidity in adults and children.1 The 2020 anaphylaxis practice parameter update provides recommendations on treatment, prevention, and assessment of biphasic symptom risk in patients experiencing anaphylaxis.2 The guideline provides five key recommendations and four good-practice statements, which we have consolidated into five recommendations for this update.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE HOSPITALIST

Recommendation 1. All patients with suspected or confirmed anaphylaxis should be treated with epinephrine. (Good-practice statement)

Self-injectable epinephrine is the first-line treatment for anaphylaxis, with weight-based dosing of 0.15 mg/kg for children weighing less than 30 kg and 0.30 mg/kg for children weighing more than 30 kg and adults. Delayed administration of epinephrine can increase anaphylaxis-associated morbidity and mortality. After epinephrine administration, patients should be observed in a healthcare setting for symptom resolution.

Recommendation 2. For all patients, clinicians should assess the risk for developing biphasic anaphylaxis. (Conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

Biphasic anaphylaxis is defined as the return of anaphylaxis symptoms after an asymptomatic period of at least 1 hour, all during a single instance of anaphylaxis. Biphasic anaphylaxis occurs in up to 20% of patients.3 Biphasic anaphylaxis is more likely among patients receiving repeated doses of epinephrine (odds ratio [OR], 4.82; 95% CI, 2.70-8.58), delayed epinephrine administration greater than 60 minutes (OR, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.09-4.79), or a severe initial presentation (OR, 4.82; 95% CI, 1.23-3.61).2 The presence of any of these risk factors raises the risk for developing biphasic anaphylaxis by 17%.4 Severe anaphylaxis is characterized by life-threatening symptoms, including loss of consciousness, syncope or dizziness, hypotension, cardiovascular system collapse, or neurologic dysfunction from hypoperfusion or hypoxia after exposure to an allergen.5

Other risk factors for biphasic anaphylaxis in all ages include a widened pulse pressure, unknown anaphylaxis trigger, and cutaneous signs and symptoms. Drug triggers are also a risk factor in pediatric patients.2

Recommendation 3. All patients with anaphylaxis and risk factors for biphasic anaphylaxis should undergo extended clinical observation in a setting capable of managing anaphylaxis. (Conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

All patients should be monitored for resolution of symptoms prior to discharge, regardless of age or severity at onset. Patients with all three of the following can be discharged 1 hour after symptom resolution because these three factors together have a 95% negative predictive value for biphasic anaphylaxis: nonsevere anaphylaxis, prompt response to epinephrine, and access to medical care.5 In contrast, extended observation of at least 6 hours should be offered to patients with increased risk of biphasic reactions. Patients who have potentially fatal underlying illnesses (eg, severe respiratory or cardiac disease), poor access to emergency medical services, poor self-management skills, or inability to access epinephrine should also be considered for extended observation or hospitalization. Evidence is lacking to define the optimal observation time because extended biphasic reactions can occur from 1 to 78 hours after initial anaphylaxis symptoms.6

Given the lack of specific evidence around length of observation, there is an opportunity for shared decision-making. Every patient should receive education regarding trigger avoidance, reasons to seek care or activate emergency medical services, and warning signs of biphasic anaphylaxis. Additionally, self-injectable epinephrine and an action plan detailing how and when to administer the epinephrine should be provided. Patients with anaphylaxis should follow up with an allergist.

Recommendation 4. Administration of glucocorticoids or antihistamines for prevention of biphasic anaphylaxis is not recommended. (Conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

This guideline discourages glucocorticoids and antihistamines as a primary treatment as it may delay epinephrine administration. Despite treating the cutaneous manifestations of anaphylaxis, antihistamines fail to treat the life-threatening cardiovascular and respiratory symptoms. No clear evidence exists on whether antihistamines or glucocorticoids prevent biphasic anaphylaxis.

Recommendation 5. In adult patients receiving chemotherapy, premedication with antihistamine and/or glucocorticoid should be used to prevent anaphylaxis or infusion-related reactions for some chemotherapeutic agents in patients with no previous reaction to the drug. (Conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

Premedication with antihistamines and/or glucocorticoids was associated with 51% reduced odds for anaphylaxis and infusion-related reactions to certain chemotherapy agents (pegaspargase, docetaxel, carboplatin, oxaliplatin, and rituximab) in adults who had not previously experienced a reaction to the drug (OR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.37-0.66).2 However, this same benefit was not found with other chemotherapy agents for patients without a prior allergic reaction to the agent, which allows clinicians to defer premedication. The benefit of premedication with antihistamines and/or glucocorticoids to patients with prior anaphylactic reactions to chemotherapy agents was not evaluated in this guideline, nor was the role premedication plays in desensitization to chemotherapy.

CRITIQUE

This guideline was created by a panel of allergists, clinical immunologists, and methodologists using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) approach to draft recommendations. Conflicts of interest (COI) were disclosed by all panel members according to the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (AAAAI) guidelines. The inclusion of many observational studies and meta-analyses improves the generalizability of the guideline. The authors highlighted the low certainty of evidence due to the lack of randomized controlled trials and significant heterogeneity of the included studies.

Some recommendations in the guideline have implications for costs of care. A recent economic analysis looked at cost-effectiveness for extended observation for anaphylaxis and found it was cost-effective only when patients were at increased risk for biphasic anaphylaxis.7 Although Recommendation 4 advises against the use of glucocorticoids for prevention of biphasic anaphylaxis, one retrospective cohort study demonstrated that glucocorticoid use was associated with decreased length of stay in children admitted with anaphylaxis.8 Therefore, the recommendation to avoid glucocorticoids for prevention of biphasic anaphylaxis could possibly increase hospital length of stay for children. The usefulness of dexamethasone to prevent biphasic anaphylaxis in children 3 to 14 months old is being evaluated in a randomized trial (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03523221).

AREAS OF FUTURE STUDY

Future research should better characterize risk factors for biphasic reactions to aid in clinical triage and diagnosis. Additional studies are needed to determine the optimal observation duration for patients experiencing anaphylactic reactions or requiring multiple doses of epinephrine. The role of premedication in patients receiving chemotherapy is poorly described, with few studies evaluating the benefit of premedication in patients with previous anaphylactic reactions.

1. Wood RA, Camargo CA Jr, Lieberman P, et al. Anaphylaxis in America: the prevalence and characteristics of anaphylaxis in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(2):461-467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2013.08.016

2. Shaker MS, Wallace DV, Golden DBK, et al. Anaphylaxis-a 2020 practice parameter update, systematic review, and Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(4):1082-1123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2020.01.017

3. Lieberman P, Camargo CA Jr, Bohlke K, et al. Epidemiology of anaphylaxis: findings of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Epidemiology of Anaphylaxis Working Group. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(5):596-602. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1081-1206(10)61086-1

4. Kim TH, Yoon SH, Hong H, Kang HR, Cho SH, Lee SY. Duration of observation for detecting a biphasic reaction in anaphylaxis: a meta-analysis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2019;179(1):31-36. https://doi.org/10.1159/000496092

5. Brown AF, Mckinnon D, Chu K. Emergency department anaphylaxis: a review of 142 patients in a single year. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108(5):861-866. https://doi.org/10.1067/mai.2001.119028

6. Pourmand A, Robinson C, Syed W, Mazer-Amirshahi M. Biphasic anaphylaxis: a review of the literature and implications for emergency management. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(8):1480-1485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2018.05.009

7. Shaker M, Wallace D, Golden DBK, Oppenheimer J, Greenhawt M. Simulation of health and economic benefits of extended observation of resolved anaphylaxis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1913951. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13951

8. Michelson KA, Monuteaux MC, Neuman MI. Glucocorticoids and hospital length of stay for children with anaphylaxis: a retrospective study. J Pediatr. 2015;167(3):719-724.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.05.033

1. Wood RA, Camargo CA Jr, Lieberman P, et al. Anaphylaxis in America: the prevalence and characteristics of anaphylaxis in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(2):461-467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2013.08.016

2. Shaker MS, Wallace DV, Golden DBK, et al. Anaphylaxis-a 2020 practice parameter update, systematic review, and Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(4):1082-1123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2020.01.017

3. Lieberman P, Camargo CA Jr, Bohlke K, et al. Epidemiology of anaphylaxis: findings of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Epidemiology of Anaphylaxis Working Group. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(5):596-602. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1081-1206(10)61086-1

4. Kim TH, Yoon SH, Hong H, Kang HR, Cho SH, Lee SY. Duration of observation for detecting a biphasic reaction in anaphylaxis: a meta-analysis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2019;179(1):31-36. https://doi.org/10.1159/000496092

5. Brown AF, Mckinnon D, Chu K. Emergency department anaphylaxis: a review of 142 patients in a single year. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108(5):861-866. https://doi.org/10.1067/mai.2001.119028

6. Pourmand A, Robinson C, Syed W, Mazer-Amirshahi M. Biphasic anaphylaxis: a review of the literature and implications for emergency management. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(8):1480-1485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2018.05.009

7. Shaker M, Wallace D, Golden DBK, Oppenheimer J, Greenhawt M. Simulation of health and economic benefits of extended observation of resolved anaphylaxis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1913951. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13951

8. Michelson KA, Monuteaux MC, Neuman MI. Glucocorticoids and hospital length of stay for children with anaphylaxis: a retrospective study. J Pediatr. 2015;167(3):719-724.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.05.033

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist: Secondary Fracture Prevention for Hospitalized Patients

Osteoporosis is the most prevalent bone disease and a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in older people. According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, from 2005-2010, there were an estimated 10.2 million adults 50 years and older with osteoporosis and 43.4 million more with low bone mass in the United States.1 Osteoporotic fracture is a leading cause of hospitalization in the United States for women 55 years or older, ahead of heart attacks, stroke, and breast cancer.2 Despite elucidation of the pathogenesis of osteoporosis and the advent of effective and widely available therapies, a “treatment gap” separates the many patients who warrant therapy from the few who receive it. Systematic improvement strategies, such as coordinator-based fracture liaison services, have had a positive impact on addressing this treatment gap.3 There is an opportunity for hospitalists to further narrow this treatment gap.

The American Society of Bone and Mineral Research, in conjunction with the Center for Medical Technology Policy, developed consensus clinical recommendations to address secondary fracture prevention for people 65 years or older who have experienced a hip or vertebral fracture.4 We address six of the fundamental and two of the supplemental recommendations as they apply to the practice of hospital medicine.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR HOSPITALISTs

Recommendations 1 and 2

Communicate key information to the patient and their usual healthcare provider. Patients 65 years or older with a hip or vertebral fracture likely have osteoporosis and are at high risk for subsequent fractures, which can lead to a decline in function and an increase in mortality. Patients must be counseled regarding their diagnosis, their risks, and the actions they can take to manage their disease. Primary care providers must be notified of the occurrence of the fracture, the diagnosis of osteoporosis, and the plans for management.

We recommend hospitalists act as leading advocates for at-risk patients to ensure that this communication occurs during hospitalization. We encourage hospitals and institutions to adopt systematic interventions to facilitate postdischarge care for these patients. These may include implementing a fracture liaison service, with multidisciplinary secondary fracture–prevention strategies using physicians, pharmacists, nurses, social workers, and case managers for care coordination and treatment initiation.

Elderly patients with osteoporotic fragility fractures are at risk for further morbidity and mortality. Coordination of care between the inpatient care team and the primary care provider is necessary to reduce this risk. In addition to verbal communication and especially when verbal communication is not feasible, discharge documents provided to patients and outpatient providers should clearly identify the occurrence of a hip or vertebral fracture and a discharge diagnosis of osteoporosis if not previously documented, regardless of bone mineral density (BMD) results or lack of testing.

Recommendation 3

Regularly assess fall risk. Patients 65 years or older with a current or prior hip or vertebral fracture must be regularly assessed for risk of falls. Hospitalists can assess patients’ ongoing risk for falls at time of admission or during hospitalization. Risk factors include prior falls; advanced age; visual, auditory, or cognitive impairment; decreased muscle strength; gait and balance impairment; diabetes mellitus; use of multiple medications, and others.5 Specialist evaluation by a physical therapist or a physiatrist should be considered. Active medications should be reviewed for adverse effects and interactions. The use of diuretics, antipsychotics, antidepressants, benzodiazepines, antiepileptics, and opioids should be minimized.

Recommendations 4, 5, 6, and 11