User login

Bezafibrate eased pruritus in patients with fibrosing cholangiopathies

Once-daily treatment with the lipid-lowering agent bezafibrate significantly reduced moderate to severe pruritis among patients with cholestasis, according to the findings of a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study (Fibrates for Itch, or FITCH).

Two weeks after completing treatment, 45% of bezafibrate recipients met the primary endpoint, reporting at least a 50% decrease in itch on a 10-point visual analog scale (VAS), compared with 11% of patients in the placebo group (P = .003). There was also a statistically significant decrease in serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels from baseline (35% vs. 6%, respectively; P = .03) that corresponded with improved pruritus, and bezafibrate significantly improved both morning and evening pruritus. Bezafibrate was not associated with myalgia, rhabdomyolysis, or serum alanine transaminase elevations but did lead to a 3% increase in serum creatinine that “was not different from the placebo group,” wrote Elsemieke de Vries, MD, PhD, of the department of gastroenterology & hepatology at Tytgat Institute for Liver and Intestinal Research, Amsterdam, and of department of gastroenterology & metabolism at Amsterdam University Medical Centers, and associates. Their report is in Gastroenterology.

Up to 70% of patients with cholangitis experience pruritus. Current guidelines recommend management with cholestyramine, rifampin, naltrexone, or sertraline, but efficacy and tolerability are subpar, the investigators wrote. In a recent study, a selective inhibitor of an ileal bile acid transporter (GSK2330672) reduced pruritus in primary biliary cholangitis but frequently was associated with diarrhea. In another recent study of patients with primary biliary cholangitis who had responded inadequately to ursodeoxycholic acid (BEZURSO), bezafibrate induced biochemical responses that correlated with improvements in pruritis (a secondary endpoint).

Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) has been implicated in cholangiopathy-associated pruritus but is not found in bile. However, biliary drainage rapidly improves severe itch in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Therefore, Dr. de Vries and associates hypothesized that an as-yet unknown factor in bile contributes to pruritus in fibrosing cholangiopathies and that bezafibrate reduces itch by “alleviating hepatobiliary cholestasis and injury and, thereby, reducing formation and biliary secretion of this biliary factor X.”

The FITCH study, which was conducted at seven academic hospitals in the Netherlands and one in Spain, enrolled 74 patients 18 years and older with primary biliary cholangitis or primary or secondary sclerosing cholangitis who reported having pruritus with an intensity of at least 5 on the 10-point VAS at baseline (with 10 indicating “worst itch possible”; median, 7; interquartile range, 7-8). Patients with hepatocellular cholestasis caused by medications or pregnancy were excluded. Ages among most participants ranged from 30s to 50s, and approximately two-thirds were female. None had received another pruritus treatment within 10 days of enrollment, and prior treatment with bezafibrate was not allowed. Patients received once-daily bezafibrate (400 mg) or placebo tablets for 21 days, with visits to the outpatient clinic on days 0, 21, and 35.

There were no serious adverse events or new safety signals. One event of oral pain was considered possibly related to bezafibrate, and itch and jaundice worsened in two patients after completing treatment. As in the 24-month BEZURSO study, increases in serum creatinine were modest and similar between groups (3% with bezafibrate and 5% with placebo). Myalgia and increases in serum alanine transaminase were observed in BEZURSO but not in FITCH. However, the short treatment duration provides “no judgment on long-term safety [of bezafibrate] in complex diseases such as primary sclerosing cholangitis or primary biliary cholangitis,” the investigators wrote.

Four patients discontinued treatment – three stopped placebo because of “unbearable pruritus,” and one stopped bezafibrate after developing acute bacterial cholangitis that required emergency treatment. Although FITCH excluded patients whose estimated glomerular filtration rate was less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, one such patient was accidentally enrolled. Her serum creatinine, measured in mmol/L, rose from 121 at baseline to 148 on day 21, and then dropped to 134 after 2 weeks off treatment.

The trial was supported by patient donations, the Netherlands Society of Gastroenterology, and Instituto de Salud Carlos III. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: de Vries E et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Oct 5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.10.001.

Itch really matters to patients with cholestatic liver diseases, and effective treatment can make a significant difference to life quality. Although therapies exist for cholestatic itch (such as cholestyramine, rifampin, and naltrexone) recent data from the United Kingdom and United States suggest that therapy in practice is poor. It is likely that this results, at least in part, from the limitations of the existing treatments which can be unpleasant to take (cholestyramine) or difficult to use because of monitoring needs and side-effects (rifampin and naltrexone). Itch has therefore been identified as an area of real unmet need in cholestatic disease and there are a number of trials in progress or in set-up. This is extremely positive for patients.

The FITCH trial is one of the first of these “new generation” cholestatic itch trials to report and explore the efficacy of the PPAR-agonist bezafibrate in a mixed cholestatic population. Clear benefit was seen with around 50% of all disease groups meeting the primary endpoint and good drug tolerance. Is bezafibrate therefore the answer to cholestatic itch? The cautious answer is ... possibly, but more experience is needed. The trial duration was only 21 days, which means that long-term safety and efficacy remain to be explored. Bezafibrate is now being used in practice to treat cholestatic itch with effects similar to those reported in the trial. It is therefore clearly an important new option. Where it ultimately ends up in the treatment pathway only time and experience will tell.

David Jones, BM, BCh, PhD, is a professor of liver immunology at Newcastle University, Newcastle Upon Tyne, England. He reported having no disclosures relevant to this commentary.

Itch really matters to patients with cholestatic liver diseases, and effective treatment can make a significant difference to life quality. Although therapies exist for cholestatic itch (such as cholestyramine, rifampin, and naltrexone) recent data from the United Kingdom and United States suggest that therapy in practice is poor. It is likely that this results, at least in part, from the limitations of the existing treatments which can be unpleasant to take (cholestyramine) or difficult to use because of monitoring needs and side-effects (rifampin and naltrexone). Itch has therefore been identified as an area of real unmet need in cholestatic disease and there are a number of trials in progress or in set-up. This is extremely positive for patients.

The FITCH trial is one of the first of these “new generation” cholestatic itch trials to report and explore the efficacy of the PPAR-agonist bezafibrate in a mixed cholestatic population. Clear benefit was seen with around 50% of all disease groups meeting the primary endpoint and good drug tolerance. Is bezafibrate therefore the answer to cholestatic itch? The cautious answer is ... possibly, but more experience is needed. The trial duration was only 21 days, which means that long-term safety and efficacy remain to be explored. Bezafibrate is now being used in practice to treat cholestatic itch with effects similar to those reported in the trial. It is therefore clearly an important new option. Where it ultimately ends up in the treatment pathway only time and experience will tell.

David Jones, BM, BCh, PhD, is a professor of liver immunology at Newcastle University, Newcastle Upon Tyne, England. He reported having no disclosures relevant to this commentary.

Itch really matters to patients with cholestatic liver diseases, and effective treatment can make a significant difference to life quality. Although therapies exist for cholestatic itch (such as cholestyramine, rifampin, and naltrexone) recent data from the United Kingdom and United States suggest that therapy in practice is poor. It is likely that this results, at least in part, from the limitations of the existing treatments which can be unpleasant to take (cholestyramine) or difficult to use because of monitoring needs and side-effects (rifampin and naltrexone). Itch has therefore been identified as an area of real unmet need in cholestatic disease and there are a number of trials in progress or in set-up. This is extremely positive for patients.

The FITCH trial is one of the first of these “new generation” cholestatic itch trials to report and explore the efficacy of the PPAR-agonist bezafibrate in a mixed cholestatic population. Clear benefit was seen with around 50% of all disease groups meeting the primary endpoint and good drug tolerance. Is bezafibrate therefore the answer to cholestatic itch? The cautious answer is ... possibly, but more experience is needed. The trial duration was only 21 days, which means that long-term safety and efficacy remain to be explored. Bezafibrate is now being used in practice to treat cholestatic itch with effects similar to those reported in the trial. It is therefore clearly an important new option. Where it ultimately ends up in the treatment pathway only time and experience will tell.

David Jones, BM, BCh, PhD, is a professor of liver immunology at Newcastle University, Newcastle Upon Tyne, England. He reported having no disclosures relevant to this commentary.

Once-daily treatment with the lipid-lowering agent bezafibrate significantly reduced moderate to severe pruritis among patients with cholestasis, according to the findings of a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study (Fibrates for Itch, or FITCH).

Two weeks after completing treatment, 45% of bezafibrate recipients met the primary endpoint, reporting at least a 50% decrease in itch on a 10-point visual analog scale (VAS), compared with 11% of patients in the placebo group (P = .003). There was also a statistically significant decrease in serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels from baseline (35% vs. 6%, respectively; P = .03) that corresponded with improved pruritus, and bezafibrate significantly improved both morning and evening pruritus. Bezafibrate was not associated with myalgia, rhabdomyolysis, or serum alanine transaminase elevations but did lead to a 3% increase in serum creatinine that “was not different from the placebo group,” wrote Elsemieke de Vries, MD, PhD, of the department of gastroenterology & hepatology at Tytgat Institute for Liver and Intestinal Research, Amsterdam, and of department of gastroenterology & metabolism at Amsterdam University Medical Centers, and associates. Their report is in Gastroenterology.

Up to 70% of patients with cholangitis experience pruritus. Current guidelines recommend management with cholestyramine, rifampin, naltrexone, or sertraline, but efficacy and tolerability are subpar, the investigators wrote. In a recent study, a selective inhibitor of an ileal bile acid transporter (GSK2330672) reduced pruritus in primary biliary cholangitis but frequently was associated with diarrhea. In another recent study of patients with primary biliary cholangitis who had responded inadequately to ursodeoxycholic acid (BEZURSO), bezafibrate induced biochemical responses that correlated with improvements in pruritis (a secondary endpoint).

Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) has been implicated in cholangiopathy-associated pruritus but is not found in bile. However, biliary drainage rapidly improves severe itch in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Therefore, Dr. de Vries and associates hypothesized that an as-yet unknown factor in bile contributes to pruritus in fibrosing cholangiopathies and that bezafibrate reduces itch by “alleviating hepatobiliary cholestasis and injury and, thereby, reducing formation and biliary secretion of this biliary factor X.”

The FITCH study, which was conducted at seven academic hospitals in the Netherlands and one in Spain, enrolled 74 patients 18 years and older with primary biliary cholangitis or primary or secondary sclerosing cholangitis who reported having pruritus with an intensity of at least 5 on the 10-point VAS at baseline (with 10 indicating “worst itch possible”; median, 7; interquartile range, 7-8). Patients with hepatocellular cholestasis caused by medications or pregnancy were excluded. Ages among most participants ranged from 30s to 50s, and approximately two-thirds were female. None had received another pruritus treatment within 10 days of enrollment, and prior treatment with bezafibrate was not allowed. Patients received once-daily bezafibrate (400 mg) or placebo tablets for 21 days, with visits to the outpatient clinic on days 0, 21, and 35.

There were no serious adverse events or new safety signals. One event of oral pain was considered possibly related to bezafibrate, and itch and jaundice worsened in two patients after completing treatment. As in the 24-month BEZURSO study, increases in serum creatinine were modest and similar between groups (3% with bezafibrate and 5% with placebo). Myalgia and increases in serum alanine transaminase were observed in BEZURSO but not in FITCH. However, the short treatment duration provides “no judgment on long-term safety [of bezafibrate] in complex diseases such as primary sclerosing cholangitis or primary biliary cholangitis,” the investigators wrote.

Four patients discontinued treatment – three stopped placebo because of “unbearable pruritus,” and one stopped bezafibrate after developing acute bacterial cholangitis that required emergency treatment. Although FITCH excluded patients whose estimated glomerular filtration rate was less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, one such patient was accidentally enrolled. Her serum creatinine, measured in mmol/L, rose from 121 at baseline to 148 on day 21, and then dropped to 134 after 2 weeks off treatment.

The trial was supported by patient donations, the Netherlands Society of Gastroenterology, and Instituto de Salud Carlos III. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: de Vries E et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Oct 5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.10.001.

Once-daily treatment with the lipid-lowering agent bezafibrate significantly reduced moderate to severe pruritis among patients with cholestasis, according to the findings of a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study (Fibrates for Itch, or FITCH).

Two weeks after completing treatment, 45% of bezafibrate recipients met the primary endpoint, reporting at least a 50% decrease in itch on a 10-point visual analog scale (VAS), compared with 11% of patients in the placebo group (P = .003). There was also a statistically significant decrease in serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels from baseline (35% vs. 6%, respectively; P = .03) that corresponded with improved pruritus, and bezafibrate significantly improved both morning and evening pruritus. Bezafibrate was not associated with myalgia, rhabdomyolysis, or serum alanine transaminase elevations but did lead to a 3% increase in serum creatinine that “was not different from the placebo group,” wrote Elsemieke de Vries, MD, PhD, of the department of gastroenterology & hepatology at Tytgat Institute for Liver and Intestinal Research, Amsterdam, and of department of gastroenterology & metabolism at Amsterdam University Medical Centers, and associates. Their report is in Gastroenterology.

Up to 70% of patients with cholangitis experience pruritus. Current guidelines recommend management with cholestyramine, rifampin, naltrexone, or sertraline, but efficacy and tolerability are subpar, the investigators wrote. In a recent study, a selective inhibitor of an ileal bile acid transporter (GSK2330672) reduced pruritus in primary biliary cholangitis but frequently was associated with diarrhea. In another recent study of patients with primary biliary cholangitis who had responded inadequately to ursodeoxycholic acid (BEZURSO), bezafibrate induced biochemical responses that correlated with improvements in pruritis (a secondary endpoint).

Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) has been implicated in cholangiopathy-associated pruritus but is not found in bile. However, biliary drainage rapidly improves severe itch in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Therefore, Dr. de Vries and associates hypothesized that an as-yet unknown factor in bile contributes to pruritus in fibrosing cholangiopathies and that bezafibrate reduces itch by “alleviating hepatobiliary cholestasis and injury and, thereby, reducing formation and biliary secretion of this biliary factor X.”

The FITCH study, which was conducted at seven academic hospitals in the Netherlands and one in Spain, enrolled 74 patients 18 years and older with primary biliary cholangitis or primary or secondary sclerosing cholangitis who reported having pruritus with an intensity of at least 5 on the 10-point VAS at baseline (with 10 indicating “worst itch possible”; median, 7; interquartile range, 7-8). Patients with hepatocellular cholestasis caused by medications or pregnancy were excluded. Ages among most participants ranged from 30s to 50s, and approximately two-thirds were female. None had received another pruritus treatment within 10 days of enrollment, and prior treatment with bezafibrate was not allowed. Patients received once-daily bezafibrate (400 mg) or placebo tablets for 21 days, with visits to the outpatient clinic on days 0, 21, and 35.

There were no serious adverse events or new safety signals. One event of oral pain was considered possibly related to bezafibrate, and itch and jaundice worsened in two patients after completing treatment. As in the 24-month BEZURSO study, increases in serum creatinine were modest and similar between groups (3% with bezafibrate and 5% with placebo). Myalgia and increases in serum alanine transaminase were observed in BEZURSO but not in FITCH. However, the short treatment duration provides “no judgment on long-term safety [of bezafibrate] in complex diseases such as primary sclerosing cholangitis or primary biliary cholangitis,” the investigators wrote.

Four patients discontinued treatment – three stopped placebo because of “unbearable pruritus,” and one stopped bezafibrate after developing acute bacterial cholangitis that required emergency treatment. Although FITCH excluded patients whose estimated glomerular filtration rate was less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, one such patient was accidentally enrolled. Her serum creatinine, measured in mmol/L, rose from 121 at baseline to 148 on day 21, and then dropped to 134 after 2 weeks off treatment.

The trial was supported by patient donations, the Netherlands Society of Gastroenterology, and Instituto de Salud Carlos III. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: de Vries E et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Oct 5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.10.001.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Examining the Interfacility Variation of Social Determinants of Health in the Veterans Health Administration

Social determinants of health (SDoH) are social, economic, environmental, and occupational factors that are known to influence an individual’s health care utilization and clinical outcomes.1,2 Because the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is charged to address both the medical and nonmedical needs of the veteran population, it is increasingly interested in the impact SDoH have on veteran care.3,4 To combat the adverse impact of such factors, the VHA has implemented several large-scale programs across the US that focus on prevalent SDoH, such as homelessness, substance abuse, and alcohol use disorders.5,6 While such risk factors are generally universal in their distribution, variation across regions, between urban and rural spaces, and even within cities has been shown to exist in private settings.7 Understanding such variability potentially could be helpful to US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) policymakers and leaders to better allocate funding and resources to address such issues.

Although previous work has highlighted regional and neighborhood-level variability of SDoH, no study has examined the facility-level variability of commonly encountered social risk factors within the VHA.4,8 The aim of this study was to describe the interfacility variation of 5 common SDoH known to influence health and health outcomes among a national cohort of veterans hospitalized for common medical issues by using administrative data.

Methods

We used a national cohort of veterans aged ≥ 65 years who were hospitalized at a VHA acute care facility with a primary discharge diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure (HF), or pneumonia in 2012. These conditions were chosen because they are publicly reported and frequently used for interfacility comparison.

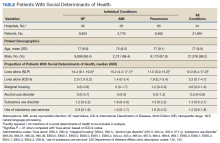

Using the International Classification of Diseases–9th Revision (ICD-9) and VHA clinical stop codes, we calculated the median documented proportion of patients with any of the following 5 SDoH: lived alone, marginal housing, alcohol use disorder, substance use disorder, and use of substance use services for patients presenting with HF, MI, and pneumonia (Table). These SDoH were chosen because they are intervenable risk factors for which the VHA has several programs (eg, homeless outreach, substance abuse, and tobacco cessation). To examine the variability of these SDoH across VHA facilities, we determined the number of hospitals that had a sufficient number of admissions (≥ 50) to be included in the analyses. We then examined the administratively documented, facility-level variation in the proportion of individuals with any of the 5 SDoH administrative codes and examined the distribution of their use across all qualifying facilities.

Because variability may be due to regional coding differences, we examined the difference in the estimated prevalence of the risk factor lives alone by using a previously developed natural language processing (NLP) program.9 The NLP program is a rule-based system designed to automatically extract information that requires inferencing from clinical notes (eg, discharge summaries and nursing, social work, emergency department physician, primary care, and hospital admission notes). For instance, the program identifies whether there was direct or indirect evidence that the patient did or did not live alone. In addition to extracting data on lives alone, the NLP program has the capacity to extract information on lack of social support and living alone—2 characteristics without VHA interventions, which were not examined here. The NLP program was developed and evaluated using at least 1 year of notes prior to index hospitalization. Because this program was developed and validated on a 2012 data set, we were limited to using a cohort from this year as well.

All analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.4. The San Francisco VA Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Results

In total, 21,991 patients with either HF (9,853), pneumonia (9,362), or AMI (2,776) were identified across 91 VHA facilities. The majority were male (98%) and had a median (SD) age of 77.0 (9.0) years. The median facility-level proportion of veterans who had any of the SDoH risk factors extracted through administrative codes was low across all conditions, ranging from 0.5 to 2.2%. The most prevalent factors among patients admitted for HF, AMI, and pneumonia were lives alone (2.0% [Interquartile range (IQR), 1.0-5.2], 1.4% [IQR, 0-3.4], and 1.9% [IQR, 0.7-5.4]), substance use disorder (1.2% [IQR, 0-2.2], 1.6% [IQR: 0-3.0], and 1.3% [IQR, 0-2.2] and use of substance use services (0.9% [IQR, 0-1.6%], 1.0% [IQR, 0-1.7%], and 1.6% [IQR, 0-2.2%], respectively [Table]).

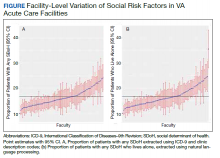

When utilizing the NLP algorithm, the documented prevalence of lives alone in the free text of the medical record was higher than administrative coding across all conditions (12.3% vs. 2.2%; P < .01). Among each of the 3 assessed conditions, HF (14.4% vs 2.0%, P < .01) had higher levels of lives alone compared with pneumonia (11% vs 1.9%, P < .01), and AMI (10.2% vs 1.4%, P < .01) when using the NLP algorithm. When we examined the documented facility-level variation in the proportion of individuals with any of the 5 SDoH administrative codes or NLP, we found large variability across all facilities—regardless of extraction method (Figure).

Discussion

While SDoH are known to impact health outcomes, the presence of these risk factors in administrative data among individuals hospitalized for common medical issues is low and variable across VHA facilities. Understanding the documented, facility-level variability of these measures may assist the VHA in determining how it invests time and resources—as different facilities may disproportionately serve a higher number of vulnerable individuals. Beyond the VHA, these findings have generalizable lessons for the US health care system, which has come to recognize how these risk factors impact patients’ health.10

Although the proportion of individuals with any of the assessed SDoH identified by administrative data was low, our findings are in line with recent studies that showed other risk factors such as social isolation (0.65%), housing issues (0.19%), and financial strain (0.07%) had similarly low prevalence.8,11 Although the exact prevalence of such factors remains unclear, these findings highlight that SDoH do not appear to be well documented in administrative data. Low coding rates are likely due to the fact that SDoH administrative codes are not tied to financial reimbursement—thus not incentivizing their use by clinicians or hospital systems.

In 2014, an Institute of Medicine report suggested that collection of SDoH in electronic health data as a means to better empower clinicians and health care systems to address social disparities and further support research in SDoH.12 Since then, data collection using SDoH screening tools has become more common across settings, but is not consistently translated to standardized data due to lack of industry consensus and technical barriers.13 To improve this process, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services created “z-codes” for the ICD-10 classification system—a subset of codes that are meant to better capture patients’ underlying social risk.14 It remains to be seen if such administrative codes have improved the documentation of SDoH.

As health care systems have grown to understand the impact of SDoH on health outcomes,other means of collecting these data have evolved.1,10 For example, NLP-based extraction methods and electronic screening tools have been proposed and utilized as alternative for obtaining this information. Our findings suggest that some of these measures (eg, lives alone) often may be documented as part of routine care in the electronic health record, thus highlighting NLP as a tool to obtain such data. However, other studies using NLP technology to extract SDoH have shown this technology is often complicated by quality issues (ie, missing data), complex methods, and poor integration with current information technology infrastructures—thus limiting its use in health care delivery.15-18

While variance among SDoH across a national health care system is natural, it remains an important systems-level characteristic that health care leaders and policymakers should appreciate. As health care systems disperse financial resources and initiate quality improvement initiatives to address SDoH, knowing that not all facilities are equally affected by SDoH should impact allocation of such resources and energies. Although previous work has highlighted regional and neighborhood levels of variation within the VHA and other health care systems, to our knowledge, this is the first study to examine variability at the facility-level within the VHA.2,4,13,19

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, though our findings are in line with previous data in other health care systems, generalizability beyond the VA, which primarily cares for older, male patients, may be limited.8 Though, as the nation’s largest health care system, lessons from the VHA can still be useful for other health care systems as they consider SDoH variation. Second, among the many SDoH previously identified to impact health, our analysis only focused on 5 such variables. Administrative and medical record documentation of other SDoH may be more common and less variable across institutions. Third, while our data suggests facility-level variation in these measures, this may be in part related to variation in coding across facilities. However, the single SDoH variable extracted using NLP also varied at the facility-level, suggesting that coding may not entirely drive the variation observed.

Conclusions

As US health care systems continue to address SDoH, our findings highlight the various challenges in obtaining accurate data on a patient’s social risk. Moreover, these findings highlight the large variability that exists among institutions in a national integrated health care system. Future work should explore the prevalence and variance of other SDoH as a means to help guide resource allocation and prioritize spending to better address SDoH where it is most needed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NHLBI R01 RO1 HL116522-01A1. Support for VA/CMS data is provided by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development, VA Information Resource Center (Project Numbers SDR 02-237 and 98-004).

1. Social determinants of health (SDOH). https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.17.0312. Published December 1, 2017. Accessed December 8, 2020.

2. Hatef E, Searle KM, Predmore Z, et al. The Impact of Social Determinants of Health on hospitalization in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(6):811-818. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.12.012

3. Lushniak BD, Alley DE, Ulin B, Graffunder C. The National Prevention Strategy: leveraging multiple sectors to improve population health. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):229-231. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302257

4. Nelson K, Schwartz G, Hernandez S, Simonetti J, Curtis I, Fihn SD. The association between neighborhood environment and mortality: results from a national study of veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(4):416-422. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3905-x

5. Gundlapalli AV, Redd A, Bolton D, et al. Patient-aligned care team engagement to connect veterans experiencing homelessness with appropriate health care. Med Care. 2017;55 Suppl 9 Suppl 2:S104-S110. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000770

6. Rash CJ, DePhilippis D. Considerations for implementing contingency management in substance abuse treatment clinics: the Veterans Affairs initiative as a model. Perspect Behav Sci. 2019;42(3):479-499. doi:10.1007/s40614-019-00204-3.

7. Ompad DC, Galea S, Caiaffa WT, Vlahov D. Social determinants of the health of urban populations: methodologic considerations. J Urban Health. 2007;84(3 Suppl):i42-i53. doi:10.1007/s11524-007-9168-4

8. Hatef E, Rouhizadeh M, Tia I, et al. Assessing the availability of data on social and behavioral determinants in structured and unstructured electronic health records: a retrospective analysis of a multilevel health care system. JMIR Med Inform. 2019;7(3):e13802. doi:10.2196/13802

9. Conway M, Keyhani S, Christensen L, et al. Moonstone: a novel natural language processing system for inferring social risk from clinical narratives. J Biomed Semantics. 2019;10(1):6. doi:10.1186/s13326-019-0198-0

10. Adler NE, Cutler DM, Fielding JE, et al. Addressing social determinants of health and health disparities: a vital direction for health and health care. Discussion Paper. NAM Perspectives. National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. doi:10.31478/201609t

11. Cottrell EK, Dambrun K, Cowburn S, et al. Variation in electronic health record documentation of social determinants of health across a national network of community health centers. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(6):S65-S73. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.014

12. Committee on the Recommended Social and Behavioral Domains and Measures for Electronic Health Records, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, Institute of Medicine. Capturing Social and Behavioral Domains and Measures in Electronic Health Records: Phase 2. National Academies Press (US); 2015.

13. Gottlieb L, Tobey R, Cantor J, Hessler D, Adler NE. Integrating Social And Medical Data To Improve Population Health: Opportunities And Barriers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(11):2116-2123. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0723

14. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Service, Office of Minority Health. Z codes utilization among medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries in 2017. Published January 2020. Accessed December 8, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/cms-omh-january2020-zcode-data-highlightpdf.pdf

15. Kharrazi H, Wang C, Scharfstein D. Prospective EHR-based clinical trials: the challenge of missing data. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):976-978. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-2883-0

16. Weiskopf NG, Weng C. Methods and dimensions of electronic health record data quality assessment: enabling reuse for clinical research. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(1):144-151. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000681

17. Anzaldi LJ, Davison A, Boyd CM, Leff B, Kharrazi H. Comparing clinician descriptions of frailty and geriatric syndromes using electronic health records: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):248. doi:10.1186/s12877-017-0645-7

18. Chen T, Dredze M, Weiner JP, Kharrazi H. Identifying vulnerable older adult populations by contextualizing geriatric syndrome information in clinical notes of electronic health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019;26(8-9):787-795. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocz093

19. Raphael E, Gaynes R, Hamad R. Cross-sectional analysis of place-based and racial disparities in hospitalisation rates by disease category in California in 2001 and 2011. BMJ Open. 2019;9(10):e031556. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031556

Social determinants of health (SDoH) are social, economic, environmental, and occupational factors that are known to influence an individual’s health care utilization and clinical outcomes.1,2 Because the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is charged to address both the medical and nonmedical needs of the veteran population, it is increasingly interested in the impact SDoH have on veteran care.3,4 To combat the adverse impact of such factors, the VHA has implemented several large-scale programs across the US that focus on prevalent SDoH, such as homelessness, substance abuse, and alcohol use disorders.5,6 While such risk factors are generally universal in their distribution, variation across regions, between urban and rural spaces, and even within cities has been shown to exist in private settings.7 Understanding such variability potentially could be helpful to US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) policymakers and leaders to better allocate funding and resources to address such issues.

Although previous work has highlighted regional and neighborhood-level variability of SDoH, no study has examined the facility-level variability of commonly encountered social risk factors within the VHA.4,8 The aim of this study was to describe the interfacility variation of 5 common SDoH known to influence health and health outcomes among a national cohort of veterans hospitalized for common medical issues by using administrative data.

Methods

We used a national cohort of veterans aged ≥ 65 years who were hospitalized at a VHA acute care facility with a primary discharge diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure (HF), or pneumonia in 2012. These conditions were chosen because they are publicly reported and frequently used for interfacility comparison.

Using the International Classification of Diseases–9th Revision (ICD-9) and VHA clinical stop codes, we calculated the median documented proportion of patients with any of the following 5 SDoH: lived alone, marginal housing, alcohol use disorder, substance use disorder, and use of substance use services for patients presenting with HF, MI, and pneumonia (Table). These SDoH were chosen because they are intervenable risk factors for which the VHA has several programs (eg, homeless outreach, substance abuse, and tobacco cessation). To examine the variability of these SDoH across VHA facilities, we determined the number of hospitals that had a sufficient number of admissions (≥ 50) to be included in the analyses. We then examined the administratively documented, facility-level variation in the proportion of individuals with any of the 5 SDoH administrative codes and examined the distribution of their use across all qualifying facilities.

Because variability may be due to regional coding differences, we examined the difference in the estimated prevalence of the risk factor lives alone by using a previously developed natural language processing (NLP) program.9 The NLP program is a rule-based system designed to automatically extract information that requires inferencing from clinical notes (eg, discharge summaries and nursing, social work, emergency department physician, primary care, and hospital admission notes). For instance, the program identifies whether there was direct or indirect evidence that the patient did or did not live alone. In addition to extracting data on lives alone, the NLP program has the capacity to extract information on lack of social support and living alone—2 characteristics without VHA interventions, which were not examined here. The NLP program was developed and evaluated using at least 1 year of notes prior to index hospitalization. Because this program was developed and validated on a 2012 data set, we were limited to using a cohort from this year as well.

All analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.4. The San Francisco VA Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Results

In total, 21,991 patients with either HF (9,853), pneumonia (9,362), or AMI (2,776) were identified across 91 VHA facilities. The majority were male (98%) and had a median (SD) age of 77.0 (9.0) years. The median facility-level proportion of veterans who had any of the SDoH risk factors extracted through administrative codes was low across all conditions, ranging from 0.5 to 2.2%. The most prevalent factors among patients admitted for HF, AMI, and pneumonia were lives alone (2.0% [Interquartile range (IQR), 1.0-5.2], 1.4% [IQR, 0-3.4], and 1.9% [IQR, 0.7-5.4]), substance use disorder (1.2% [IQR, 0-2.2], 1.6% [IQR: 0-3.0], and 1.3% [IQR, 0-2.2] and use of substance use services (0.9% [IQR, 0-1.6%], 1.0% [IQR, 0-1.7%], and 1.6% [IQR, 0-2.2%], respectively [Table]).

When utilizing the NLP algorithm, the documented prevalence of lives alone in the free text of the medical record was higher than administrative coding across all conditions (12.3% vs. 2.2%; P < .01). Among each of the 3 assessed conditions, HF (14.4% vs 2.0%, P < .01) had higher levels of lives alone compared with pneumonia (11% vs 1.9%, P < .01), and AMI (10.2% vs 1.4%, P < .01) when using the NLP algorithm. When we examined the documented facility-level variation in the proportion of individuals with any of the 5 SDoH administrative codes or NLP, we found large variability across all facilities—regardless of extraction method (Figure).

Discussion

While SDoH are known to impact health outcomes, the presence of these risk factors in administrative data among individuals hospitalized for common medical issues is low and variable across VHA facilities. Understanding the documented, facility-level variability of these measures may assist the VHA in determining how it invests time and resources—as different facilities may disproportionately serve a higher number of vulnerable individuals. Beyond the VHA, these findings have generalizable lessons for the US health care system, which has come to recognize how these risk factors impact patients’ health.10

Although the proportion of individuals with any of the assessed SDoH identified by administrative data was low, our findings are in line with recent studies that showed other risk factors such as social isolation (0.65%), housing issues (0.19%), and financial strain (0.07%) had similarly low prevalence.8,11 Although the exact prevalence of such factors remains unclear, these findings highlight that SDoH do not appear to be well documented in administrative data. Low coding rates are likely due to the fact that SDoH administrative codes are not tied to financial reimbursement—thus not incentivizing their use by clinicians or hospital systems.

In 2014, an Institute of Medicine report suggested that collection of SDoH in electronic health data as a means to better empower clinicians and health care systems to address social disparities and further support research in SDoH.12 Since then, data collection using SDoH screening tools has become more common across settings, but is not consistently translated to standardized data due to lack of industry consensus and technical barriers.13 To improve this process, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services created “z-codes” for the ICD-10 classification system—a subset of codes that are meant to better capture patients’ underlying social risk.14 It remains to be seen if such administrative codes have improved the documentation of SDoH.

As health care systems have grown to understand the impact of SDoH on health outcomes,other means of collecting these data have evolved.1,10 For example, NLP-based extraction methods and electronic screening tools have been proposed and utilized as alternative for obtaining this information. Our findings suggest that some of these measures (eg, lives alone) often may be documented as part of routine care in the electronic health record, thus highlighting NLP as a tool to obtain such data. However, other studies using NLP technology to extract SDoH have shown this technology is often complicated by quality issues (ie, missing data), complex methods, and poor integration with current information technology infrastructures—thus limiting its use in health care delivery.15-18

While variance among SDoH across a national health care system is natural, it remains an important systems-level characteristic that health care leaders and policymakers should appreciate. As health care systems disperse financial resources and initiate quality improvement initiatives to address SDoH, knowing that not all facilities are equally affected by SDoH should impact allocation of such resources and energies. Although previous work has highlighted regional and neighborhood levels of variation within the VHA and other health care systems, to our knowledge, this is the first study to examine variability at the facility-level within the VHA.2,4,13,19

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, though our findings are in line with previous data in other health care systems, generalizability beyond the VA, which primarily cares for older, male patients, may be limited.8 Though, as the nation’s largest health care system, lessons from the VHA can still be useful for other health care systems as they consider SDoH variation. Second, among the many SDoH previously identified to impact health, our analysis only focused on 5 such variables. Administrative and medical record documentation of other SDoH may be more common and less variable across institutions. Third, while our data suggests facility-level variation in these measures, this may be in part related to variation in coding across facilities. However, the single SDoH variable extracted using NLP also varied at the facility-level, suggesting that coding may not entirely drive the variation observed.

Conclusions

As US health care systems continue to address SDoH, our findings highlight the various challenges in obtaining accurate data on a patient’s social risk. Moreover, these findings highlight the large variability that exists among institutions in a national integrated health care system. Future work should explore the prevalence and variance of other SDoH as a means to help guide resource allocation and prioritize spending to better address SDoH where it is most needed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NHLBI R01 RO1 HL116522-01A1. Support for VA/CMS data is provided by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development, VA Information Resource Center (Project Numbers SDR 02-237 and 98-004).

Social determinants of health (SDoH) are social, economic, environmental, and occupational factors that are known to influence an individual’s health care utilization and clinical outcomes.1,2 Because the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is charged to address both the medical and nonmedical needs of the veteran population, it is increasingly interested in the impact SDoH have on veteran care.3,4 To combat the adverse impact of such factors, the VHA has implemented several large-scale programs across the US that focus on prevalent SDoH, such as homelessness, substance abuse, and alcohol use disorders.5,6 While such risk factors are generally universal in their distribution, variation across regions, between urban and rural spaces, and even within cities has been shown to exist in private settings.7 Understanding such variability potentially could be helpful to US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) policymakers and leaders to better allocate funding and resources to address such issues.

Although previous work has highlighted regional and neighborhood-level variability of SDoH, no study has examined the facility-level variability of commonly encountered social risk factors within the VHA.4,8 The aim of this study was to describe the interfacility variation of 5 common SDoH known to influence health and health outcomes among a national cohort of veterans hospitalized for common medical issues by using administrative data.

Methods

We used a national cohort of veterans aged ≥ 65 years who were hospitalized at a VHA acute care facility with a primary discharge diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure (HF), or pneumonia in 2012. These conditions were chosen because they are publicly reported and frequently used for interfacility comparison.

Using the International Classification of Diseases–9th Revision (ICD-9) and VHA clinical stop codes, we calculated the median documented proportion of patients with any of the following 5 SDoH: lived alone, marginal housing, alcohol use disorder, substance use disorder, and use of substance use services for patients presenting with HF, MI, and pneumonia (Table). These SDoH were chosen because they are intervenable risk factors for which the VHA has several programs (eg, homeless outreach, substance abuse, and tobacco cessation). To examine the variability of these SDoH across VHA facilities, we determined the number of hospitals that had a sufficient number of admissions (≥ 50) to be included in the analyses. We then examined the administratively documented, facility-level variation in the proportion of individuals with any of the 5 SDoH administrative codes and examined the distribution of their use across all qualifying facilities.

Because variability may be due to regional coding differences, we examined the difference in the estimated prevalence of the risk factor lives alone by using a previously developed natural language processing (NLP) program.9 The NLP program is a rule-based system designed to automatically extract information that requires inferencing from clinical notes (eg, discharge summaries and nursing, social work, emergency department physician, primary care, and hospital admission notes). For instance, the program identifies whether there was direct or indirect evidence that the patient did or did not live alone. In addition to extracting data on lives alone, the NLP program has the capacity to extract information on lack of social support and living alone—2 characteristics without VHA interventions, which were not examined here. The NLP program was developed and evaluated using at least 1 year of notes prior to index hospitalization. Because this program was developed and validated on a 2012 data set, we were limited to using a cohort from this year as well.

All analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.4. The San Francisco VA Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Results

In total, 21,991 patients with either HF (9,853), pneumonia (9,362), or AMI (2,776) were identified across 91 VHA facilities. The majority were male (98%) and had a median (SD) age of 77.0 (9.0) years. The median facility-level proportion of veterans who had any of the SDoH risk factors extracted through administrative codes was low across all conditions, ranging from 0.5 to 2.2%. The most prevalent factors among patients admitted for HF, AMI, and pneumonia were lives alone (2.0% [Interquartile range (IQR), 1.0-5.2], 1.4% [IQR, 0-3.4], and 1.9% [IQR, 0.7-5.4]), substance use disorder (1.2% [IQR, 0-2.2], 1.6% [IQR: 0-3.0], and 1.3% [IQR, 0-2.2] and use of substance use services (0.9% [IQR, 0-1.6%], 1.0% [IQR, 0-1.7%], and 1.6% [IQR, 0-2.2%], respectively [Table]).

When utilizing the NLP algorithm, the documented prevalence of lives alone in the free text of the medical record was higher than administrative coding across all conditions (12.3% vs. 2.2%; P < .01). Among each of the 3 assessed conditions, HF (14.4% vs 2.0%, P < .01) had higher levels of lives alone compared with pneumonia (11% vs 1.9%, P < .01), and AMI (10.2% vs 1.4%, P < .01) when using the NLP algorithm. When we examined the documented facility-level variation in the proportion of individuals with any of the 5 SDoH administrative codes or NLP, we found large variability across all facilities—regardless of extraction method (Figure).

Discussion

While SDoH are known to impact health outcomes, the presence of these risk factors in administrative data among individuals hospitalized for common medical issues is low and variable across VHA facilities. Understanding the documented, facility-level variability of these measures may assist the VHA in determining how it invests time and resources—as different facilities may disproportionately serve a higher number of vulnerable individuals. Beyond the VHA, these findings have generalizable lessons for the US health care system, which has come to recognize how these risk factors impact patients’ health.10

Although the proportion of individuals with any of the assessed SDoH identified by administrative data was low, our findings are in line with recent studies that showed other risk factors such as social isolation (0.65%), housing issues (0.19%), and financial strain (0.07%) had similarly low prevalence.8,11 Although the exact prevalence of such factors remains unclear, these findings highlight that SDoH do not appear to be well documented in administrative data. Low coding rates are likely due to the fact that SDoH administrative codes are not tied to financial reimbursement—thus not incentivizing their use by clinicians or hospital systems.

In 2014, an Institute of Medicine report suggested that collection of SDoH in electronic health data as a means to better empower clinicians and health care systems to address social disparities and further support research in SDoH.12 Since then, data collection using SDoH screening tools has become more common across settings, but is not consistently translated to standardized data due to lack of industry consensus and technical barriers.13 To improve this process, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services created “z-codes” for the ICD-10 classification system—a subset of codes that are meant to better capture patients’ underlying social risk.14 It remains to be seen if such administrative codes have improved the documentation of SDoH.

As health care systems have grown to understand the impact of SDoH on health outcomes,other means of collecting these data have evolved.1,10 For example, NLP-based extraction methods and electronic screening tools have been proposed and utilized as alternative for obtaining this information. Our findings suggest that some of these measures (eg, lives alone) often may be documented as part of routine care in the electronic health record, thus highlighting NLP as a tool to obtain such data. However, other studies using NLP technology to extract SDoH have shown this technology is often complicated by quality issues (ie, missing data), complex methods, and poor integration with current information technology infrastructures—thus limiting its use in health care delivery.15-18

While variance among SDoH across a national health care system is natural, it remains an important systems-level characteristic that health care leaders and policymakers should appreciate. As health care systems disperse financial resources and initiate quality improvement initiatives to address SDoH, knowing that not all facilities are equally affected by SDoH should impact allocation of such resources and energies. Although previous work has highlighted regional and neighborhood levels of variation within the VHA and other health care systems, to our knowledge, this is the first study to examine variability at the facility-level within the VHA.2,4,13,19

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, though our findings are in line with previous data in other health care systems, generalizability beyond the VA, which primarily cares for older, male patients, may be limited.8 Though, as the nation’s largest health care system, lessons from the VHA can still be useful for other health care systems as they consider SDoH variation. Second, among the many SDoH previously identified to impact health, our analysis only focused on 5 such variables. Administrative and medical record documentation of other SDoH may be more common and less variable across institutions. Third, while our data suggests facility-level variation in these measures, this may be in part related to variation in coding across facilities. However, the single SDoH variable extracted using NLP also varied at the facility-level, suggesting that coding may not entirely drive the variation observed.

Conclusions

As US health care systems continue to address SDoH, our findings highlight the various challenges in obtaining accurate data on a patient’s social risk. Moreover, these findings highlight the large variability that exists among institutions in a national integrated health care system. Future work should explore the prevalence and variance of other SDoH as a means to help guide resource allocation and prioritize spending to better address SDoH where it is most needed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NHLBI R01 RO1 HL116522-01A1. Support for VA/CMS data is provided by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development, VA Information Resource Center (Project Numbers SDR 02-237 and 98-004).

1. Social determinants of health (SDOH). https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.17.0312. Published December 1, 2017. Accessed December 8, 2020.

2. Hatef E, Searle KM, Predmore Z, et al. The Impact of Social Determinants of Health on hospitalization in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(6):811-818. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.12.012

3. Lushniak BD, Alley DE, Ulin B, Graffunder C. The National Prevention Strategy: leveraging multiple sectors to improve population health. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):229-231. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302257

4. Nelson K, Schwartz G, Hernandez S, Simonetti J, Curtis I, Fihn SD. The association between neighborhood environment and mortality: results from a national study of veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(4):416-422. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3905-x

5. Gundlapalli AV, Redd A, Bolton D, et al. Patient-aligned care team engagement to connect veterans experiencing homelessness with appropriate health care. Med Care. 2017;55 Suppl 9 Suppl 2:S104-S110. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000770

6. Rash CJ, DePhilippis D. Considerations for implementing contingency management in substance abuse treatment clinics: the Veterans Affairs initiative as a model. Perspect Behav Sci. 2019;42(3):479-499. doi:10.1007/s40614-019-00204-3.

7. Ompad DC, Galea S, Caiaffa WT, Vlahov D. Social determinants of the health of urban populations: methodologic considerations. J Urban Health. 2007;84(3 Suppl):i42-i53. doi:10.1007/s11524-007-9168-4

8. Hatef E, Rouhizadeh M, Tia I, et al. Assessing the availability of data on social and behavioral determinants in structured and unstructured electronic health records: a retrospective analysis of a multilevel health care system. JMIR Med Inform. 2019;7(3):e13802. doi:10.2196/13802

9. Conway M, Keyhani S, Christensen L, et al. Moonstone: a novel natural language processing system for inferring social risk from clinical narratives. J Biomed Semantics. 2019;10(1):6. doi:10.1186/s13326-019-0198-0

10. Adler NE, Cutler DM, Fielding JE, et al. Addressing social determinants of health and health disparities: a vital direction for health and health care. Discussion Paper. NAM Perspectives. National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. doi:10.31478/201609t

11. Cottrell EK, Dambrun K, Cowburn S, et al. Variation in electronic health record documentation of social determinants of health across a national network of community health centers. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(6):S65-S73. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.014

12. Committee on the Recommended Social and Behavioral Domains and Measures for Electronic Health Records, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, Institute of Medicine. Capturing Social and Behavioral Domains and Measures in Electronic Health Records: Phase 2. National Academies Press (US); 2015.

13. Gottlieb L, Tobey R, Cantor J, Hessler D, Adler NE. Integrating Social And Medical Data To Improve Population Health: Opportunities And Barriers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(11):2116-2123. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0723

14. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Service, Office of Minority Health. Z codes utilization among medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries in 2017. Published January 2020. Accessed December 8, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/cms-omh-january2020-zcode-data-highlightpdf.pdf

15. Kharrazi H, Wang C, Scharfstein D. Prospective EHR-based clinical trials: the challenge of missing data. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):976-978. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-2883-0

16. Weiskopf NG, Weng C. Methods and dimensions of electronic health record data quality assessment: enabling reuse for clinical research. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(1):144-151. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000681

17. Anzaldi LJ, Davison A, Boyd CM, Leff B, Kharrazi H. Comparing clinician descriptions of frailty and geriatric syndromes using electronic health records: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):248. doi:10.1186/s12877-017-0645-7

18. Chen T, Dredze M, Weiner JP, Kharrazi H. Identifying vulnerable older adult populations by contextualizing geriatric syndrome information in clinical notes of electronic health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019;26(8-9):787-795. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocz093

19. Raphael E, Gaynes R, Hamad R. Cross-sectional analysis of place-based and racial disparities in hospitalisation rates by disease category in California in 2001 and 2011. BMJ Open. 2019;9(10):e031556. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031556

1. Social determinants of health (SDOH). https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.17.0312. Published December 1, 2017. Accessed December 8, 2020.

2. Hatef E, Searle KM, Predmore Z, et al. The Impact of Social Determinants of Health on hospitalization in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(6):811-818. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.12.012

3. Lushniak BD, Alley DE, Ulin B, Graffunder C. The National Prevention Strategy: leveraging multiple sectors to improve population health. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):229-231. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302257

4. Nelson K, Schwartz G, Hernandez S, Simonetti J, Curtis I, Fihn SD. The association between neighborhood environment and mortality: results from a national study of veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(4):416-422. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3905-x

5. Gundlapalli AV, Redd A, Bolton D, et al. Patient-aligned care team engagement to connect veterans experiencing homelessness with appropriate health care. Med Care. 2017;55 Suppl 9 Suppl 2:S104-S110. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000770

6. Rash CJ, DePhilippis D. Considerations for implementing contingency management in substance abuse treatment clinics: the Veterans Affairs initiative as a model. Perspect Behav Sci. 2019;42(3):479-499. doi:10.1007/s40614-019-00204-3.

7. Ompad DC, Galea S, Caiaffa WT, Vlahov D. Social determinants of the health of urban populations: methodologic considerations. J Urban Health. 2007;84(3 Suppl):i42-i53. doi:10.1007/s11524-007-9168-4

8. Hatef E, Rouhizadeh M, Tia I, et al. Assessing the availability of data on social and behavioral determinants in structured and unstructured electronic health records: a retrospective analysis of a multilevel health care system. JMIR Med Inform. 2019;7(3):e13802. doi:10.2196/13802

9. Conway M, Keyhani S, Christensen L, et al. Moonstone: a novel natural language processing system for inferring social risk from clinical narratives. J Biomed Semantics. 2019;10(1):6. doi:10.1186/s13326-019-0198-0

10. Adler NE, Cutler DM, Fielding JE, et al. Addressing social determinants of health and health disparities: a vital direction for health and health care. Discussion Paper. NAM Perspectives. National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. doi:10.31478/201609t

11. Cottrell EK, Dambrun K, Cowburn S, et al. Variation in electronic health record documentation of social determinants of health across a national network of community health centers. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(6):S65-S73. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.014

12. Committee on the Recommended Social and Behavioral Domains and Measures for Electronic Health Records, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, Institute of Medicine. Capturing Social and Behavioral Domains and Measures in Electronic Health Records: Phase 2. National Academies Press (US); 2015.

13. Gottlieb L, Tobey R, Cantor J, Hessler D, Adler NE. Integrating Social And Medical Data To Improve Population Health: Opportunities And Barriers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(11):2116-2123. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0723

14. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Service, Office of Minority Health. Z codes utilization among medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries in 2017. Published January 2020. Accessed December 8, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/cms-omh-january2020-zcode-data-highlightpdf.pdf

15. Kharrazi H, Wang C, Scharfstein D. Prospective EHR-based clinical trials: the challenge of missing data. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):976-978. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-2883-0

16. Weiskopf NG, Weng C. Methods and dimensions of electronic health record data quality assessment: enabling reuse for clinical research. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(1):144-151. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000681

17. Anzaldi LJ, Davison A, Boyd CM, Leff B, Kharrazi H. Comparing clinician descriptions of frailty and geriatric syndromes using electronic health records: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):248. doi:10.1186/s12877-017-0645-7

18. Chen T, Dredze M, Weiner JP, Kharrazi H. Identifying vulnerable older adult populations by contextualizing geriatric syndrome information in clinical notes of electronic health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019;26(8-9):787-795. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocz093

19. Raphael E, Gaynes R, Hamad R. Cross-sectional analysis of place-based and racial disparities in hospitalisation rates by disease category in California in 2001 and 2011. BMJ Open. 2019;9(10):e031556. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031556

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder-Associated Cognitive Deficits on the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status in a Veteran Population

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) affects about 10 to 25% of veterans in the US and is associated with reductions in quality of life and poor occupational functioning.1,2 PTSD is often associated with multiple cognitive deficits that play a role in a number of clinical symptoms and impair cognition beyond what can be solely attributed to the effects of physical or psychological trauma.3-5 Although the literature on the pattern and magnitude of cognitive deficits associated with PTSD is mixed, dysfunction in attention, verbal memory, speed of information processing, working memory, and executive functioning are the most consistent findings.6-11Verbal memory and attention seem to be particularly negatively impacted by PTSD and especially so in combat-exposed war veterans.7,12 Verbal memory difficulties in returning war veterans also may mediate quality of life and be particularly disruptive to everyday functioning.13 Further, evidence exists that a diagnosis of PTSD is associated with increased risk for dementia and deficits in episodic memory in older adults.14,15

The PTSD-associated cognitive deficits are routinely assessed through neuropsychological measures within the US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA). The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) is a commonly used cognitive screening measure in medical settings, and prior research has reinforced its clinical utility across a variety of populations, including Alzheimer disease, schizophrenia, Parkinson disease, Huntington disease, stroke, and traumatic brain injury (TBI).16-24

McKay and colleagues previously examined the use of the RBANS within a sample of individuals who had a history of moderate-to-severe TBIs, with findings suggesting the RBANS is a valid and reliable screening measure in this population.25However, McKay and colleagues used a carefully defined sample in a cognitive neurorehabilitation setting, many of whom experienced a TBI significant enough to require ongoing medical monitoring, attendant care, or substantial support services.

The influence of PTSD-associated cognitive deficits on the RBANS performance is unclear, and which subtests of the measure, if any, are differentially impacted in individuals with and those without a diagnosis of PTSD is uncertain. Further, less is known about the influence of PTSD in outpatient clinical settings when PTSD and TBI are not necessarily the primary presenting problem. The purpose of the current study was to determine the influence of a PTSD diagnosis on performance on the RBANS in an outpatient VA setting.

Methods

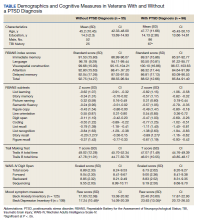

Participants included 153 veterans who were 90% male with a mean (SD) age of 46.8 (11.3) years and a mean (SD) education of 14.2 (2.3) years from a catchment area ranging from Montana south through western Texas, and all states west of that line, sequentially evaluated as part of a clinic workup at the California War Related Illness and Injury Study Center (WRIISC-CA). WRIISC-CA is a second-level evaluation clinic under patient primary care in the VA system dedicated to providing comprehensive medical evaluations on postdeployment veterans with complex medical concerns, including possible TBI and PTSD. Participants included 23 Vietnam-era, 72 Operation Desert Storm/Desert Shield-era, and 58 Operation Iraqi Freedom/Enduring Freedom-era veterans. We have previously published a more thorough analysis of medical characteristics for a WRIISC-CA sample.26

A Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM IV) diagnosis of current PTSD was determined by the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS-IV), as administered or supervised by a licensed clinical psychologist during the course of the larger medical evaluation.27 Given the co-occurring nature of TBI and PTSD and their complicated relationship with regard to cognitive functioning, all veterans also underwent a comprehensive examination by a board-certified neurologist to assess for a possible history of TBI, based on the presence of at least 1 past event according to the guidelines recommended by the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine.28,29Veterans were categorized as having a history of no TBI, mild TBI, or moderate TBI. No veterans met criteria for history of severe TBI.Veterans were excluded from the analysis if unable to complete the mental health, neurological, or cognitive evaluations. Informed consent was obtained consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki and institutional guidelines established by the VA Palo Alto Human Subjects Review Committee. The study was approved by the VA Palo Alto and Stanford School of Medicine institutional review boards.

Cognitive Measures

All veterans completed a targeted cognitive battery that included the following: a reading recognition measure designed to estimate premorbid intellectual functioning (Wechsler Test of Adult Reading [WTAR]); a measure assessing auditory attention and working memory ability (Wechsler Adults Intelligence Scale-IV [WAIS-IV] Digit Span subtest); a measure assessing processing speed, attention, and cognitive flexibility (Trails A and B); and the RBANS.16,30-32The focus of the current study was on the RBANS, a brief cognitive screening measure that contains 12 subtests examining a variety of cognitive functions. Given that all participants were veterans receiving outpatient services, there was no nonpatient control group for comparison. To address this, all raw data were converted to standardized scores based on healthy normative data provided within the test manual. Specifically, the 12 RBANS subtest scores were converted to age-corrected standardized z scores, which in turn created a total summary score and 5 composite summary indexes: immediate memory, visuospatial/constructional, attention, language, and delayed memory. All veterans completed the Form A version of the measure.

Statistical Analyses

Group level differences on selective demographic and cognitive measures between veterans with a diagnosis of PTSD and those without were examined using t tests. Cognitive variables included standardized scores for the RBANS, including age-adjusted total summary score, index scores, and subtest scores.16 Estimated full-scale IQ and standardized summary scores from the WTAR, demographically adjusted standardized scores for the total time to complete Trails A and time to complete Trails B, and age-adjusted standardized scores for the WAIS-IV Digit Span subtest (forward, backward, and sequencing trials, as well as the summary total score) were examined for group differences.30,31,33 To further examine the association between PTSD and RBANS performance, multivariate multiple regressions were conducted using measures of episodic memory and processing speed from the RBANS (ie, story tasks, list learning tasks, and coding subtests). These specific measures were selected ad hoc based on extant literature.6,10The dependent variable for each analysis was the standardized score from the selected subtest; PTSD status, a diagnosis of TBI, a diagnosis of co-occurring TBI and PTSD, gender, and years of education were predictor variables.

Results

Of the 153 study participants, 98 (64%) met DSM-4 criteria for current PTSD, whereas 55 (36%) did not (Table). There was no group statistical difference between veterans with or without a diagnosis of PTSD for age, education, or gender (P < .05). A diagnosis of PTSD tended to be more frequent in participants with a history of head injury (χ2 = 7.72; P < .05). Veterans with a diagnosis of PTSD performed significantly worse on the RBANS Story Recall subtest compared with the results of those without PTSD (t[138] = 3.10; P < .01); performance on other cognitive measures was not significantly different between the PTSD groups. A diagnosis of PTSD was also significantly associated with self-reported depressive symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory-II; t[123] = -2.81; P < .01). Depressive symptoms were not associated with a history of TBI, and group differences were not significant.

Given the high co-occurrence of PTSD and TBI (68%) in our PTSD sample, secondary analyses examined the association of select diagnoses with performance on the RBANS, specifically veterans with a historical diagnosis of TBI (n = 92) from those without a diagnosis of TBI (n = 61), as well as those with co-occurring PTSD and TBI (n = 71) from those without (n = 82). The majority of the sample met criteria for a history of mild TBI (n = 79) when compared with moderate TBI (n = 13); none met criteria for a past history of severe TBI. PTSD status (β = .63, P = .04) and years of education (β = .16, P < .01) were associated with performance on the RBANS Story Recall subtest (R2= .23, F[5,139] = 8.11, P < .01). Education was the only significant predictor for the rest of the multivariate multiple regressions (all P < .05). A diagnosis of TBI or co-occurring PTSD and TBI was not significantly associated with performance on the Story Memory, Story Recall, List Learning, List Recall, or Coding subtests. multivariate analysis of variance tests for the hypothesis of an overall main effect of PTSD (F(5,130) = 1.08, P = .34), TBI (F[5,130] = .91, P = .48), or PTSD+TBI (F[5,130] =.47, P = .80) on the 4 selected tests were not significant.

Discussion

The findings of the present study suggest that veterans with PTSD perform worse on specific RBANS subtests compared with veterans without PTSD. Specifically, worse performance on the Story Recall subtest of the RBANS memory index was a significant predictor of a diagnosis of PTSD within the statistical model. This association with PTSD was not seen in other demographic (excluding education) or cognitive measures, including other memory tasks, such as List Recall and Figure Recall, and attentional measures, such as WAIS-IV Digit Span, and the Trail Making Test. Overall RBANS index scores were not significantly different between groups, though this is not surprising given that recent research suggests the RBANS composite scores have questionable validity and reliability.34

The finding that a measure of episodic memory is most influenced by PTSD status is consistent with prior research.35 However, there are several possible reasons why Story Recall in particular showed the greatest association, even more than other episodic memory measures. A review by Isaac and colleagues found a diagnosis of PTSD correlated with frontal lobe-associated memory deficits.6 As Story Recall provides only 2 rehearsal trials compared with the 4 trials provided in the RBANS List Learning subtest, it is possible that Story Recall relies more on attentional processes than on learning with repetition.

Research has indicated attention and verbal episodic memory dysfunction are associated with a diagnosis of PTSD in combat veterans, and individuals with a diagnosis of PTSD show deficits in executive functioning, including attention difficulties beyond what is seen in trauma-exposed controls.4,7,8,11,35Furthermore, a diagnosis of PTSD has been shown to be associated with impaired performance on the Logical Memory subtest of the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised, a very similar measure to the RBANS Story Recall.36

The present finding that performance on a RBANS subtest was associated with a diagnosis of PTSD but not a history of TBI is not surprising. The majority of the present sample who reported a history of TBI met criteria for a remote head injury of mild severity (86%). Cognitive symptoms related to mild TBI are thought to generally resolve over time, and recent research suggests that PTSD symptoms may account for a substantial portion of reported postconcussive symptoms.37,38Similarly, recent research suggests a diagnosis of mild TBI does not necessarily result in additive cognitive impairment in combat veterans with a diagnosis of PTSD, and that a diagnosis of PTSD is more strongly associated with cognitive symptoms than is mild TBI.5,39,40

The lack of association with RBANS performance and co-occurring PTSD and TBI is less clear. Although both conditions are heterogenous, it may be that individuals with a diagnosis solely of PTSD are quantitively different from those with a concurrent diagnosis of PTSD and TBI (ie, PTSD presumed due to a mild TBI). Specifically, the impact of PTSD on cognition may be related to symptom severity and indexed trauma. A published systematic review on the PTSD-related cognitive impairment showed a medium-to-strong effect size for severity of PTSD symptoms on cognitive performance, with war trauma showing the strongest effect.4In particular, individuals who experience repeated or complex trauma are prone to experience PTSD symptoms with concurrent cognitive deficits, again suggesting the possibility of qualitative differences between outpatient veterans with PTSD and those with mild TBI associated PTSD.41While disentangling PTSD and mild TBI symptoms are notoriously difficult, future research aiming to examine these factors may be beneficial in the ability to draw larger conclusions on the relationship between cognition and PTSD.

Limitations