User login

Delaying RT for higher-risk prostate cancer found safe

A study of more than 60,000 prostate cancer patients suggests it is safe to delay radiation therapy (RT) for at least 6 months for localized higher-risk disease being treated with androgen deprivation therapy.

These findings are relevant to oncology care in the COVID-19 era, as the pandemic has complicated delivery of radiation therapy (RT) in several ways, the study authors wrote in JAMA Oncology.

“Daily hospital trips for RT create many possible points of COVID-19 transmission, and patients with cancer are at high risk of COVID-19 mortality,” Edward Christopher Dee, a research fellow at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and colleagues wrote.

To assess the safety of delaying RT, the investigators analyzed National Cancer Database data for 63,858 men with localized but unfavorable intermediate-risk, high-risk, or very-high-risk prostate cancer diagnosed during 2004-2014 and managed with external beam RT and androgen deprivation therapy (ADT).

Only 5.6% of patients (n = 3,572) initiated their RT 0-60 days before starting ADT. Another 36.3% (n = 23,207) initiated RT 1-60 days after starting ADT, 47.4% (n = 30,285) initiated RT 61-120 days after starting ADT, and 10.6% (n = 6,794) initiated RT 121-180 days after starting ADT.

The investigators found that 10-year overall survival rates were similar regardless of when patients started RT.

Multivariate analysis in the unfavorable intermediate-risk group showed that, relative to peers who started RT before ADT, men initiating RT later did not have significantly poorer overall survival, regardless of whether RT was initiated 1-60 days after starting ADT (hazard ratio for death, 1.03; P = .64), 61-120 days after (HR, 0.95; P = .42), or 121-180 days after (HR, 0.99; P = .90).

Findings were similar in the combined high-risk and very-high-risk group, with no significant elevation of mortality risk for patients initiating RT 1-60 days after starting ADT (HR, 1.07; P = .12), 61-120 days after (HR, 1.04; P = .36), or 121-180 days after (HR, 1.07; P = .17).

“These results validate the findings of two prior randomized trials and possibly justify the delay of prostate RT for patients currently receiving ADT until COVID-19 infection rates in the community and hospitals are lower,” the authors wrote.

Despite the fairly short follow-up period and other study limitations, “if COVID-19 outbreaks continue to occur sporadically during the coming months to years, these data could allow future flexibility about the timing of RT initiation,” the authors concluded.

Experts weigh in

“Overall, this study is asking a good question given the COVID situation and the fact that many providers are delaying RT due to COVID concerns of patients and providers,” Colleen A. Lawton, MD, of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, commented in an interview.

At the same time, Dr. Lawton cautioned about oversimplifying the issue, noting that results of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 9413 trial suggest important interactions between the anatomic extent of RT and the timing of ADT on outcomes (Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007 Nov 1;69[3]:646-55).

“I have certainly delayed some of my own patients with ADT during the COVID pandemic,” she reported. “No one knows what the maximum acceptable delay should be. A few months is likely not a problem, and a year is probably too much, but scientifically, we just don’t know.”

The interplay of volume irradiated and ADT timing is relevant here, agreed Mack Roach III, MD, of University of California, San Francisco.

In addition, the study did not address why ADT was given when it was, the duration of this therapy, and endpoints other than overall survival (such as prostate-specific antigen failure rate) that may better reflect the effectiveness of cancer treatment.

“Yes, delays are safe for patients on ADT, but not for the reasons stated. A more appropriate source of data is RTOG 9910, which compared 28 versus 8 weeks of ADT prior to RT for mostly intermediate-risk prostate cancer patients with comparable results,” Dr. Roach noted (J Clin Oncol. 2015 Feb 1;33[4]:332-9).

“Delay duration should be based on the risk of disease, but 6 months is probably safe, especially if on ADT,” he said.

Michael J. Zelefsky, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, said he agreed with the investigators’ main conclusions. “Once ADT suppression is achieved, maintaining patients on this regimen for 6 months would not likely lead to the development of a castrate-resistant state where radiotherapy would be less effective,” he elaborated.

However, limitations of the database used preclude conclusions about the safety of longer delays or the impact on other outcomes, he cautioned.

“This study provides further support to the accepted notion that delays of up to 6 months prior to initiation of planned prostate radiation would be safe and appropriate, especially where concerns of COVID outbreaks may present significant logistic challenges and concerns for the patient, who needs to commit to a course of daily radiation treatments, which could span for 5-8 weeks,” Dr. Zelefsky said.

“We have, in fact, adopted this approach in our clinics during the COVID outbreaks in New York,” he reported. “Most of our patients with unfavorable intermediate- or high-risk disease were initiated on ADT planned for at least 4-6 months before the radiotherapy was initiated. In addition, for these reasons, our preference has been to also offer such patients, if feasible, an ultrahypofractionated treatment course where the radiotherapy course is completed in five fractions over 1-2 weeks.”

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors disclosed various grants and personal fees outside the submitted work. Dr. Lawton disclosed that she was a coauthor on RTOG 9413. Dr. Roach and Dr. Zelefsky disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Dee EC et al. JAMA Oncol. 2020 Aug 13. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.3545.

A study of more than 60,000 prostate cancer patients suggests it is safe to delay radiation therapy (RT) for at least 6 months for localized higher-risk disease being treated with androgen deprivation therapy.

These findings are relevant to oncology care in the COVID-19 era, as the pandemic has complicated delivery of radiation therapy (RT) in several ways, the study authors wrote in JAMA Oncology.

“Daily hospital trips for RT create many possible points of COVID-19 transmission, and patients with cancer are at high risk of COVID-19 mortality,” Edward Christopher Dee, a research fellow at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and colleagues wrote.

To assess the safety of delaying RT, the investigators analyzed National Cancer Database data for 63,858 men with localized but unfavorable intermediate-risk, high-risk, or very-high-risk prostate cancer diagnosed during 2004-2014 and managed with external beam RT and androgen deprivation therapy (ADT).

Only 5.6% of patients (n = 3,572) initiated their RT 0-60 days before starting ADT. Another 36.3% (n = 23,207) initiated RT 1-60 days after starting ADT, 47.4% (n = 30,285) initiated RT 61-120 days after starting ADT, and 10.6% (n = 6,794) initiated RT 121-180 days after starting ADT.

The investigators found that 10-year overall survival rates were similar regardless of when patients started RT.

Multivariate analysis in the unfavorable intermediate-risk group showed that, relative to peers who started RT before ADT, men initiating RT later did not have significantly poorer overall survival, regardless of whether RT was initiated 1-60 days after starting ADT (hazard ratio for death, 1.03; P = .64), 61-120 days after (HR, 0.95; P = .42), or 121-180 days after (HR, 0.99; P = .90).

Findings were similar in the combined high-risk and very-high-risk group, with no significant elevation of mortality risk for patients initiating RT 1-60 days after starting ADT (HR, 1.07; P = .12), 61-120 days after (HR, 1.04; P = .36), or 121-180 days after (HR, 1.07; P = .17).

“These results validate the findings of two prior randomized trials and possibly justify the delay of prostate RT for patients currently receiving ADT until COVID-19 infection rates in the community and hospitals are lower,” the authors wrote.

Despite the fairly short follow-up period and other study limitations, “if COVID-19 outbreaks continue to occur sporadically during the coming months to years, these data could allow future flexibility about the timing of RT initiation,” the authors concluded.

Experts weigh in

“Overall, this study is asking a good question given the COVID situation and the fact that many providers are delaying RT due to COVID concerns of patients and providers,” Colleen A. Lawton, MD, of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, commented in an interview.

At the same time, Dr. Lawton cautioned about oversimplifying the issue, noting that results of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 9413 trial suggest important interactions between the anatomic extent of RT and the timing of ADT on outcomes (Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007 Nov 1;69[3]:646-55).

“I have certainly delayed some of my own patients with ADT during the COVID pandemic,” she reported. “No one knows what the maximum acceptable delay should be. A few months is likely not a problem, and a year is probably too much, but scientifically, we just don’t know.”

The interplay of volume irradiated and ADT timing is relevant here, agreed Mack Roach III, MD, of University of California, San Francisco.

In addition, the study did not address why ADT was given when it was, the duration of this therapy, and endpoints other than overall survival (such as prostate-specific antigen failure rate) that may better reflect the effectiveness of cancer treatment.

“Yes, delays are safe for patients on ADT, but not for the reasons stated. A more appropriate source of data is RTOG 9910, which compared 28 versus 8 weeks of ADT prior to RT for mostly intermediate-risk prostate cancer patients with comparable results,” Dr. Roach noted (J Clin Oncol. 2015 Feb 1;33[4]:332-9).

“Delay duration should be based on the risk of disease, but 6 months is probably safe, especially if on ADT,” he said.

Michael J. Zelefsky, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, said he agreed with the investigators’ main conclusions. “Once ADT suppression is achieved, maintaining patients on this regimen for 6 months would not likely lead to the development of a castrate-resistant state where radiotherapy would be less effective,” he elaborated.

However, limitations of the database used preclude conclusions about the safety of longer delays or the impact on other outcomes, he cautioned.

“This study provides further support to the accepted notion that delays of up to 6 months prior to initiation of planned prostate radiation would be safe and appropriate, especially where concerns of COVID outbreaks may present significant logistic challenges and concerns for the patient, who needs to commit to a course of daily radiation treatments, which could span for 5-8 weeks,” Dr. Zelefsky said.

“We have, in fact, adopted this approach in our clinics during the COVID outbreaks in New York,” he reported. “Most of our patients with unfavorable intermediate- or high-risk disease were initiated on ADT planned for at least 4-6 months before the radiotherapy was initiated. In addition, for these reasons, our preference has been to also offer such patients, if feasible, an ultrahypofractionated treatment course where the radiotherapy course is completed in five fractions over 1-2 weeks.”

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors disclosed various grants and personal fees outside the submitted work. Dr. Lawton disclosed that she was a coauthor on RTOG 9413. Dr. Roach and Dr. Zelefsky disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Dee EC et al. JAMA Oncol. 2020 Aug 13. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.3545.

A study of more than 60,000 prostate cancer patients suggests it is safe to delay radiation therapy (RT) for at least 6 months for localized higher-risk disease being treated with androgen deprivation therapy.

These findings are relevant to oncology care in the COVID-19 era, as the pandemic has complicated delivery of radiation therapy (RT) in several ways, the study authors wrote in JAMA Oncology.

“Daily hospital trips for RT create many possible points of COVID-19 transmission, and patients with cancer are at high risk of COVID-19 mortality,” Edward Christopher Dee, a research fellow at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and colleagues wrote.

To assess the safety of delaying RT, the investigators analyzed National Cancer Database data for 63,858 men with localized but unfavorable intermediate-risk, high-risk, or very-high-risk prostate cancer diagnosed during 2004-2014 and managed with external beam RT and androgen deprivation therapy (ADT).

Only 5.6% of patients (n = 3,572) initiated their RT 0-60 days before starting ADT. Another 36.3% (n = 23,207) initiated RT 1-60 days after starting ADT, 47.4% (n = 30,285) initiated RT 61-120 days after starting ADT, and 10.6% (n = 6,794) initiated RT 121-180 days after starting ADT.

The investigators found that 10-year overall survival rates were similar regardless of when patients started RT.

Multivariate analysis in the unfavorable intermediate-risk group showed that, relative to peers who started RT before ADT, men initiating RT later did not have significantly poorer overall survival, regardless of whether RT was initiated 1-60 days after starting ADT (hazard ratio for death, 1.03; P = .64), 61-120 days after (HR, 0.95; P = .42), or 121-180 days after (HR, 0.99; P = .90).

Findings were similar in the combined high-risk and very-high-risk group, with no significant elevation of mortality risk for patients initiating RT 1-60 days after starting ADT (HR, 1.07; P = .12), 61-120 days after (HR, 1.04; P = .36), or 121-180 days after (HR, 1.07; P = .17).

“These results validate the findings of two prior randomized trials and possibly justify the delay of prostate RT for patients currently receiving ADT until COVID-19 infection rates in the community and hospitals are lower,” the authors wrote.

Despite the fairly short follow-up period and other study limitations, “if COVID-19 outbreaks continue to occur sporadically during the coming months to years, these data could allow future flexibility about the timing of RT initiation,” the authors concluded.

Experts weigh in

“Overall, this study is asking a good question given the COVID situation and the fact that many providers are delaying RT due to COVID concerns of patients and providers,” Colleen A. Lawton, MD, of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, commented in an interview.

At the same time, Dr. Lawton cautioned about oversimplifying the issue, noting that results of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 9413 trial suggest important interactions between the anatomic extent of RT and the timing of ADT on outcomes (Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007 Nov 1;69[3]:646-55).

“I have certainly delayed some of my own patients with ADT during the COVID pandemic,” she reported. “No one knows what the maximum acceptable delay should be. A few months is likely not a problem, and a year is probably too much, but scientifically, we just don’t know.”

The interplay of volume irradiated and ADT timing is relevant here, agreed Mack Roach III, MD, of University of California, San Francisco.

In addition, the study did not address why ADT was given when it was, the duration of this therapy, and endpoints other than overall survival (such as prostate-specific antigen failure rate) that may better reflect the effectiveness of cancer treatment.

“Yes, delays are safe for patients on ADT, but not for the reasons stated. A more appropriate source of data is RTOG 9910, which compared 28 versus 8 weeks of ADT prior to RT for mostly intermediate-risk prostate cancer patients with comparable results,” Dr. Roach noted (J Clin Oncol. 2015 Feb 1;33[4]:332-9).

“Delay duration should be based on the risk of disease, but 6 months is probably safe, especially if on ADT,” he said.

Michael J. Zelefsky, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, said he agreed with the investigators’ main conclusions. “Once ADT suppression is achieved, maintaining patients on this regimen for 6 months would not likely lead to the development of a castrate-resistant state where radiotherapy would be less effective,” he elaborated.

However, limitations of the database used preclude conclusions about the safety of longer delays or the impact on other outcomes, he cautioned.

“This study provides further support to the accepted notion that delays of up to 6 months prior to initiation of planned prostate radiation would be safe and appropriate, especially where concerns of COVID outbreaks may present significant logistic challenges and concerns for the patient, who needs to commit to a course of daily radiation treatments, which could span for 5-8 weeks,” Dr. Zelefsky said.

“We have, in fact, adopted this approach in our clinics during the COVID outbreaks in New York,” he reported. “Most of our patients with unfavorable intermediate- or high-risk disease were initiated on ADT planned for at least 4-6 months before the radiotherapy was initiated. In addition, for these reasons, our preference has been to also offer such patients, if feasible, an ultrahypofractionated treatment course where the radiotherapy course is completed in five fractions over 1-2 weeks.”

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors disclosed various grants and personal fees outside the submitted work. Dr. Lawton disclosed that she was a coauthor on RTOG 9413. Dr. Roach and Dr. Zelefsky disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Dee EC et al. JAMA Oncol. 2020 Aug 13. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.3545.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Fecal transplant shows promise in reducing alcohol craving

Fecal microbiota transplantation results in a short-term reduction in alcohol craving in patients with alcohol-induced cirrhosis who can’t stop drinking, results from a new study show.

And that reduction could lead to a better psychosocial quality of life for patients with cirrhosis and alcohol use disorder, said investigator Jasmohan Bajaj, MD, from Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond.

“This is the most common addiction disorder worldwide, but we have nothing to treat these patients with,” he said.

Cirrhosis is associated with an altered gut-brain axis. It leads to organ damage in several parts of the body, including the brain, gut, pancreas, and liver. This makes changing the gut microbes “an attractive target,” Dr. Bajaj said at the Digital International Liver Congress 2020.

For their phase 1, double-blind study, he and his colleagues assessed 20 men from a Virginia veteran’s hospital with untreatable alcohol use disorder who were not eligible for liver transplantation.

All had failed behavioral or pharmacologic therapy and were unwilling to try again. “That’s what made them good candidates to try something new,” Dr. Bajaj said during a press briefing.

Mean age in the study cohort was 65 years, mean Model for End-Stage Liver disease score was 8.9, and demographic characteristics were similar between the 10 men randomly assigned to fecal transplantation and the 10 assigned to placebo. One man in each group dropped out of the study.

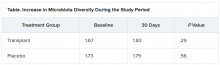

The investigators evaluated cravings, microbiota, and quality of life during the 30-day study period.

At day 15, significantly more men in the transplant group than in the placebo group experienced a reduction in alcohol cravings (90% vs. 30%).

At 30 days, levels of creatinine, serum interleukin-6, and lipopolysaccharide-binding protein were lower in the transplant group than in the placebo group. In addition, levels of butyrate and isobutyrate increased, as did cognition and quality of life scores.

There was also a decrease in urinary ethyl glucuronide in the transplant group, which “is the objective criteria for alcohol intake,” Dr. Bajaj reported, noting that there was no change in ethyl glucuronide in the placebo group.

The increase in microbiota diversity was significant in the transplant group but not in the placebo group. Alistipes, Odoribacter, and Roseburia were more abundant in the transplant group than in the placebo group.

During the 30-day study period, two men in the placebo group required medical attention, one for hyponatremia and the other for atrial fibrillation. However, no adverse events were seen in any men in the transplant group. “This was the No. 1 result,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Liver disease and the microbiome

“Understanding of interactions between the human and microbiome genome [metagenome] in health and disease has represented one of the major areas of progress in the last few years,” said Luca Valenti, MD, from the University of Milan, who is a member of the scientific committee of the European Association the Study of the Liver, which organized the congress.

“These studies lay the groundwork for the exploitation of this new knowledge for the treatment of liver disease,” he said.

“We are [now] diagnosing liver disease and the stages of liver disease based on microbiome changes,” said Jonel Trebicka, MD, PhD, from University Hospital Frankfurt (Germany), who chaired a session at the congress on the role of the microbiome in liver disease.

“This and other studies have shown us that the microbiome itself may influence liver disease,” he added.

Dr. Bajaj is considered one of the world’s experts on cirrhosis and the microbiome, Dr. Trebicka explained. Last year, Dr. Bajaj and his team demonstrated that fecal microbiota transplantation can reduce the incidence of recurrent hepatic encephalopathy, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

The current study also “shows clearly that the microbiome plays a role in craving. FMT reduces the desire for alcohol,” said Dr. Trebicka.

“The way to the brain is through the gut,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Dr. Bajaj, Dr. Trebicka, and Dr. Valenti disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fecal microbiota transplantation results in a short-term reduction in alcohol craving in patients with alcohol-induced cirrhosis who can’t stop drinking, results from a new study show.

And that reduction could lead to a better psychosocial quality of life for patients with cirrhosis and alcohol use disorder, said investigator Jasmohan Bajaj, MD, from Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond.

“This is the most common addiction disorder worldwide, but we have nothing to treat these patients with,” he said.

Cirrhosis is associated with an altered gut-brain axis. It leads to organ damage in several parts of the body, including the brain, gut, pancreas, and liver. This makes changing the gut microbes “an attractive target,” Dr. Bajaj said at the Digital International Liver Congress 2020.

For their phase 1, double-blind study, he and his colleagues assessed 20 men from a Virginia veteran’s hospital with untreatable alcohol use disorder who were not eligible for liver transplantation.

All had failed behavioral or pharmacologic therapy and were unwilling to try again. “That’s what made them good candidates to try something new,” Dr. Bajaj said during a press briefing.

Mean age in the study cohort was 65 years, mean Model for End-Stage Liver disease score was 8.9, and demographic characteristics were similar between the 10 men randomly assigned to fecal transplantation and the 10 assigned to placebo. One man in each group dropped out of the study.

The investigators evaluated cravings, microbiota, and quality of life during the 30-day study period.

At day 15, significantly more men in the transplant group than in the placebo group experienced a reduction in alcohol cravings (90% vs. 30%).

At 30 days, levels of creatinine, serum interleukin-6, and lipopolysaccharide-binding protein were lower in the transplant group than in the placebo group. In addition, levels of butyrate and isobutyrate increased, as did cognition and quality of life scores.

There was also a decrease in urinary ethyl glucuronide in the transplant group, which “is the objective criteria for alcohol intake,” Dr. Bajaj reported, noting that there was no change in ethyl glucuronide in the placebo group.

The increase in microbiota diversity was significant in the transplant group but not in the placebo group. Alistipes, Odoribacter, and Roseburia were more abundant in the transplant group than in the placebo group.

During the 30-day study period, two men in the placebo group required medical attention, one for hyponatremia and the other for atrial fibrillation. However, no adverse events were seen in any men in the transplant group. “This was the No. 1 result,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Liver disease and the microbiome

“Understanding of interactions between the human and microbiome genome [metagenome] in health and disease has represented one of the major areas of progress in the last few years,” said Luca Valenti, MD, from the University of Milan, who is a member of the scientific committee of the European Association the Study of the Liver, which organized the congress.

“These studies lay the groundwork for the exploitation of this new knowledge for the treatment of liver disease,” he said.

“We are [now] diagnosing liver disease and the stages of liver disease based on microbiome changes,” said Jonel Trebicka, MD, PhD, from University Hospital Frankfurt (Germany), who chaired a session at the congress on the role of the microbiome in liver disease.

“This and other studies have shown us that the microbiome itself may influence liver disease,” he added.

Dr. Bajaj is considered one of the world’s experts on cirrhosis and the microbiome, Dr. Trebicka explained. Last year, Dr. Bajaj and his team demonstrated that fecal microbiota transplantation can reduce the incidence of recurrent hepatic encephalopathy, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

The current study also “shows clearly that the microbiome plays a role in craving. FMT reduces the desire for alcohol,” said Dr. Trebicka.

“The way to the brain is through the gut,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Dr. Bajaj, Dr. Trebicka, and Dr. Valenti disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fecal microbiota transplantation results in a short-term reduction in alcohol craving in patients with alcohol-induced cirrhosis who can’t stop drinking, results from a new study show.

And that reduction could lead to a better psychosocial quality of life for patients with cirrhosis and alcohol use disorder, said investigator Jasmohan Bajaj, MD, from Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond.

“This is the most common addiction disorder worldwide, but we have nothing to treat these patients with,” he said.

Cirrhosis is associated with an altered gut-brain axis. It leads to organ damage in several parts of the body, including the brain, gut, pancreas, and liver. This makes changing the gut microbes “an attractive target,” Dr. Bajaj said at the Digital International Liver Congress 2020.

For their phase 1, double-blind study, he and his colleagues assessed 20 men from a Virginia veteran’s hospital with untreatable alcohol use disorder who were not eligible for liver transplantation.

All had failed behavioral or pharmacologic therapy and were unwilling to try again. “That’s what made them good candidates to try something new,” Dr. Bajaj said during a press briefing.

Mean age in the study cohort was 65 years, mean Model for End-Stage Liver disease score was 8.9, and demographic characteristics were similar between the 10 men randomly assigned to fecal transplantation and the 10 assigned to placebo. One man in each group dropped out of the study.

The investigators evaluated cravings, microbiota, and quality of life during the 30-day study period.

At day 15, significantly more men in the transplant group than in the placebo group experienced a reduction in alcohol cravings (90% vs. 30%).

At 30 days, levels of creatinine, serum interleukin-6, and lipopolysaccharide-binding protein were lower in the transplant group than in the placebo group. In addition, levels of butyrate and isobutyrate increased, as did cognition and quality of life scores.

There was also a decrease in urinary ethyl glucuronide in the transplant group, which “is the objective criteria for alcohol intake,” Dr. Bajaj reported, noting that there was no change in ethyl glucuronide in the placebo group.

The increase in microbiota diversity was significant in the transplant group but not in the placebo group. Alistipes, Odoribacter, and Roseburia were more abundant in the transplant group than in the placebo group.

During the 30-day study period, two men in the placebo group required medical attention, one for hyponatremia and the other for atrial fibrillation. However, no adverse events were seen in any men in the transplant group. “This was the No. 1 result,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Liver disease and the microbiome

“Understanding of interactions between the human and microbiome genome [metagenome] in health and disease has represented one of the major areas of progress in the last few years,” said Luca Valenti, MD, from the University of Milan, who is a member of the scientific committee of the European Association the Study of the Liver, which organized the congress.

“These studies lay the groundwork for the exploitation of this new knowledge for the treatment of liver disease,” he said.

“We are [now] diagnosing liver disease and the stages of liver disease based on microbiome changes,” said Jonel Trebicka, MD, PhD, from University Hospital Frankfurt (Germany), who chaired a session at the congress on the role of the microbiome in liver disease.

“This and other studies have shown us that the microbiome itself may influence liver disease,” he added.

Dr. Bajaj is considered one of the world’s experts on cirrhosis and the microbiome, Dr. Trebicka explained. Last year, Dr. Bajaj and his team demonstrated that fecal microbiota transplantation can reduce the incidence of recurrent hepatic encephalopathy, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

The current study also “shows clearly that the microbiome plays a role in craving. FMT reduces the desire for alcohol,” said Dr. Trebicka.

“The way to the brain is through the gut,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Dr. Bajaj, Dr. Trebicka, and Dr. Valenti disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Psoriasis, PsA, and pregnancy: Tailoring treatment with increasing data

With an average age of diagnosis of 28 years, and one of two incidence peaks occurring at 15-30 years, psoriasis affects many women in the midst of their reproductive years. The prospect of pregnancy – or the reality of a surprise pregnancy – drives questions about heritability of the disease in offspring, the impact of the disease on pregnancy outcomes and breastfeeding, and how to best balance risks of treatments with risks of uncontrolled psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

While answers to these questions are not always clear, discussions about pregnancy and psoriasis management “shouldn’t be scary,” said Jenny E. Murase, MD, a dermatologist who speaks and writes widely about her research and experience with psoriasis and pregnancy. “We have access to information and data and educational resources to [work with] and reassure our patients – we just need to use it. Right now, there’s unnecessary suffering [with some patients unnecessarily stopping all treatment].”

Much has been learned in the past 2 decades about the course of psoriasis in pregnancy, and pregnancy outcomes data on the safety of biologics during pregnancy are increasingly emerging – particularly for tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha inhibitors.

Ideally, since half of all pregnancies are unplanned, the implications of therapeutic options should be discussed with all women with psoriasis who are of reproductive age, whether they are sexually active or not. “The onus is on us to make sure that we’re considering the possibility [that our patient] could become pregnant without consulting us first,” said Dr. Murase, associate professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, and director of medical consultative dermatology for the Palo Alto Foundation Medical Group in Mountain View, Calif.

Lisa R. Sammaritano, MD, associate professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine and a rheumatologist at the Hospital for Special Surgery, both in New York, urges similar attention for PsA. “Pregnancy is best planned while patients have quiescent disease on pregnancy-compatible medications,” she said. “We encourage [more] rheumatologists to be actively involved in pregnancy planning [in order] to guide therapy.”

The impact of estrogen

Dr. Murase was inspired to study psoriasis and pregnancy in part by a patient she met as a medical student. “She had severe psoriasis covering her body, and she said that the only times her psoriasis cleared was during her three pregnancies,” Dr. Murase recalled. “I wondered: What about the pregnancies resulted in such a substantial reduction of her psoriasis?”

She subsequently led a study, published in 2005, of 47 pregnant and 27 nonpregnant patients with psoriasis. More than half of the patients – 55% – reported improvements in their psoriasis during pregnancy, 21% reported no change, and 23% reported worsening. Among the 16 patients who had 10% or greater psoriatic body surface area (BSA) involvement and reported improvements, lesions decreased by 84%.

In the postpartum period, only 9% reported improvement, 26% reported no change, and 65% reported worsening. The increased BSA values observed 6 weeks postpartum did not exceed those of the first trimester, suggesting a return to the patients’ baseline status.

Earlier and smaller retrospective studies had also shown that approximately half of patients improve during pregnancy, and it was believed that progesterone was most likely responsible for this improvement. Dr. Murase’s study moved the needle in that it examined BSA in pregnancy and the postpartum period. It also turned the spotlight on estrogen: Patients who had higher levels of improvement also had higher levels of estradiol, estrone, and the ratio of estrogen to progesterone. However, there was no correlation between psoriatic change and levels of progesterone.

To promote fetal survival, pregnancy triggers a shift from Th1 cell–mediated immunity – and Th17 immunity – to Th2 immunity. While there’s no proof of a causative effect, increased estrogen appears to play a role in this shift and in the reduced production of Th1 and Th17 cytokines. Psoriasis is believed to be primarily a Th17-mediated disease, with some Th1 involvement, so this down-regulation can result in improved disease status, Dr. Murase said. (A host of other autoimmune diseases categorized as Th1 mediated similarly tend to improve during pregnancy, she added.)

Information on the effect of pregnancy on PsA is “conflicting,” Dr. Sammaritano said. “Some [of a limited number of studies] suggest a beneficial effect as is generally seen for rheumatoid arthritis. Others, however, have found an increased risk of disease activity during pregnancy ... It may be that psoriatic arthritis can be quite variable from patient to patient in its clinical presentation.”

At least one study, Dr. Sammaritano added, “has shown that the arthritis in pregnancy patients with PsA did not improve, compared to control nonpregnant patients, while the psoriasis rash did improve.”

The mixed findings don’t surprise Dr. Murase. “It harder to quantify joint disease in general,” she said. “And during pregnancy, physiologic changes relating to the pregnancy itself can cause discomfort – your joints ache. The numbers [of improved] cases aren’t as high with PsA, but it’s a more complex question.”

In the postpartum period, however, research findings “all suggest an increased risk of flare” of PsA, Dr. Sammaritano said, just as with psoriasis.

Assessing risk of treatment

Understanding the immunologic effects of pregnancy on psoriasis and PsA – and appreciating the concept of a hormonal component – is an important part of treatment decision making. So is understanding pregnancy outcomes data.

Researchers have looked at a host of pregnancy outcomes – including congenital malformations, preterm birth, spontaneous abortion, low birth weight, macrosomia, and gestational diabetes and hypertension – in women with psoriasis or psoriasis/PsA, compared with control groups. Some studies have suggested a link between disease activity and pregnancy complications or adverse pregnancy outcomes, “just as a result of having moderate to severe disease,” while others have found no evidence of increased risk, Dr. Murase said.

“It’s a bit unclear and a difficult question to answer; it depends on what study you look at and what data you believe. It would be nice to have some clarity, but basically the jury is still out,” said Dr. Murase, who, with coauthors Alice B. Gottlieb, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and Caitriona Ryan, MD, of the Blackrock Clinic and Charles Institute of Dermatology, University College Dublin, discussed the pregnancy outcomes data in a recently published review of psoriasis in women.

“In my opinion, because we have therapies that are so low risk and well tolerated, it’s better to make sure that the inflammatory cascade and inflammation created by psoriasis is under control,” she said. “So whether or not the pregnancy itself causes the patient to go into remission, or whether you have to use therapy to help the patient stay in remission, it’s important to control the inflammation.”

Contraindicated in pregnancy are oral psoralen, methotrexate, and acitretin, the latter of which should be avoided for several years before pregnancy and “therefore shouldn’t be used in a woman of childbearing age,” said Dr. Murase. Methotrexate, said Dr. Sammaritano, should generally be stopped 1-3 months prior to conception.

For psoriasis, the therapy that’s “classically considered the safest in pregnancy is UVB light therapy, specifically the 300-nm wavelength of light, which works really well as an anti-inflammatory,” Dr. Murase said. Because of the potential for maternal folate degradation with phototherapy and the long-known association of folate deficiency with neural tube defects, women of childbearing age who are receiving light therapy should take daily folic acid supplementation. (She prescribes a daily prenatal vitamin containing at least 1 mg of folic acid for women who are utilizing light therapy.)

Many topical agents can be used during pregnancy, Dr. Murase said. Topical corticosteroids, she noted, have the most safety-affirming data of any topical medication.

Regarding oral therapies, Dr. Murase recommends against the use of apremilast (Otezla) for her patients. “It’s not contraindicated, but the animal studies don’t look promising, so I don’t use that one in women of childbearing age just in case. There’s just very little data to support the safety of this medication [in pregnancy].”

There are no therapeutic guidelines in the United States for guiding the management of psoriasis in women who are considering pregnancy. In 2012, the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation published a review of treatment options for psoriasis in pregnant or lactating women, the “closest thing to guidelines that we’ve had,” said Dr. Murase. (Now almost a decade old, the review addresses TNF inhibitors but does not cover the anti-interleukin agents more recently approved for moderate to severe psoriasis and PsA.)

For treating PsA, rheumatologists now have the American College of Rheumatology’s first guideline for the management of reproductive health in rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases to reference. The 2020 guideline does not address PsA specifically, but its section on pregnancy and lactation includes recommendations on biologic and other therapies used to treat the disease.

Guidelines aside, physician-patient discussions over drug safety have the potential to be much more meaningful now that drug labels offer clinical summaries, data, and risk summaries regarding potential use in pregnancy. The labels have “more of a narrative, which is a more useful way to counsel patients and make risk-benefit decisions” than the former system of five-letter categories, said Dr. Murase. (The changes were made per the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule of 2015.)

MothertoBaby, a service of the nonprofit Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, also provides good evidence-based information to physicians and mothers, Dr. Sammaritano noted.

The use of biologic therapies

In a 2017 review of biologic safety for patients with psoriasis during pregnancy, Alexa B. Kimball, MD, MPH, professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston; Martina L. Porter, MD, currently with the department of dermatology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston; and Stephen J. Lockwood, MD, MPH, of the department of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, concluded that an increasing body of literature suggests that biologic agents can be used during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Anti-TNF agents “should be considered over IL-12/23 and IL-17 inhibitors due to the increased availability of long-term data,” they wrote.

“In general,” said Dr. Murase, “there’s more and more data coming out from gastroenterology and rheumatology to reassure patients and prescribing physicians that the TNF-blocker class is likely safe to use in pregnancy,” particularly during the first trimester and early second trimester, when the transport of maternal antibodies across the placenta is “essentially nonexistent.” In the third trimester, the active transport of IgG antibodies increases rapidly.

If possible, said Dr. Sammaritano, who served as lead author of the ACR’s reproductive health guideline, TNF inhibitors “will be stopped prior to the third trimester to avoid [the possibility of] high drug levels in the infant at birth, which raises concern for immunosuppression in the newborn. If disease is very active, however, they can be continued throughout the pregnancy.”

The TNF inhibitor certolizumab pegol (Cimzia) has the advantage of being transported only minimally across the placenta, if at all, she and Dr. Murase both explained. “To be actively carried across, antibodies need what’s called an Fc region for the placenta to grab onto,” Dr. Murase said. Certolizumab – a pegylated anti–binding fragment antibody – lacks this Fc region.

Two recent studies – CRIB and a UCB Pharma safety database analysis – showed “essentially no medication crossing – there were barely detectable levels,” Dr. Murase said. Certolizumab’s label contains this information and other clinical trial data as well as findings from safety database analyses/surveillance registries.

“Before we had much data for the biologics, I’d advise transitioning patients to light therapy from their biologics and a lot of times their psoriasis would improve, but it was more of a dance,” she said. “Now we tend to look at [certolizumab] when they’re of childbearing age and keep them on the treatment. I know that the baby is not being immunosuppressed.”

Consideration of the use of certolizumab when treatment with biologic agents is required throughout the pregnancy is a recommendation included in Dr. Kimball’s 2017 review.

As newer anti-interleukin agents – the IL-12/23 and IL-17 inhibitors – play a growing role in the treatment of psoriasis and PsA, questions loom about their safety profile. Dr. Murase and Dr. Sammaritano are waiting for more data. “In general,” Dr. Sammaritano said, “we recommend stopping them at the time pregnancy is detected, based on a lack of data at this time.”

Small-molecule drugs are also less well studied, she noted. “Because of their low molecular weight, we anticipate they will easily cross the placenta, so we recommend avoiding use during pregnancy until more information is available.”

Postpartum care

The good news, both experts say, is that the vast majority of medications, including biologics, are safe to use during breastfeeding. Methotrexate should be avoided, Dr. Sammaritano pointed out, and the impact of novel small-molecule therapies on breast milk has not been studied.

In her 2019 review of psoriasis in women, Dr. Murase and coauthors wrote that too many dermatologists believe that breastfeeding women should either not be on biologics or are uncertain about biologic use during breastfeeding. However, “biologics are considered compatible for use while breastfeeding due to their large molecular size and the proteolytic environment in the neonatal gastrointestinal tract,” they added.

Counseling and support for breastfeeding is especially important for women with psoriasis, Dr. Murase emphasized. “Breastfeeding is very traumatizing to the skin, and psoriasis can form in skin that’s injured. I have my patients set up an office visit very soon after the pregnancy to make sure they’re doing alright with their breastfeeding and that they’re coating their nipple area with some type of moisturizer and keeping the health of their nipples in good shape.”

Timely reviews of therapy and adjustments are also a priority, she said. “We need to prepare for 6 weeks post partum” when psoriasis will often flare without treatment.

Dr. Murase disclosed that she is a consultant for Dermira, UCB Pharma, Sanofi, Ferndale, and Regeneron. She is also coeditor in chief of the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology. Dr. Sammaritano reported that she has no disclosures relating to the treatment of PsA.

With an average age of diagnosis of 28 years, and one of two incidence peaks occurring at 15-30 years, psoriasis affects many women in the midst of their reproductive years. The prospect of pregnancy – or the reality of a surprise pregnancy – drives questions about heritability of the disease in offspring, the impact of the disease on pregnancy outcomes and breastfeeding, and how to best balance risks of treatments with risks of uncontrolled psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

While answers to these questions are not always clear, discussions about pregnancy and psoriasis management “shouldn’t be scary,” said Jenny E. Murase, MD, a dermatologist who speaks and writes widely about her research and experience with psoriasis and pregnancy. “We have access to information and data and educational resources to [work with] and reassure our patients – we just need to use it. Right now, there’s unnecessary suffering [with some patients unnecessarily stopping all treatment].”

Much has been learned in the past 2 decades about the course of psoriasis in pregnancy, and pregnancy outcomes data on the safety of biologics during pregnancy are increasingly emerging – particularly for tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha inhibitors.

Ideally, since half of all pregnancies are unplanned, the implications of therapeutic options should be discussed with all women with psoriasis who are of reproductive age, whether they are sexually active or not. “The onus is on us to make sure that we’re considering the possibility [that our patient] could become pregnant without consulting us first,” said Dr. Murase, associate professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, and director of medical consultative dermatology for the Palo Alto Foundation Medical Group in Mountain View, Calif.

Lisa R. Sammaritano, MD, associate professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine and a rheumatologist at the Hospital for Special Surgery, both in New York, urges similar attention for PsA. “Pregnancy is best planned while patients have quiescent disease on pregnancy-compatible medications,” she said. “We encourage [more] rheumatologists to be actively involved in pregnancy planning [in order] to guide therapy.”

The impact of estrogen

Dr. Murase was inspired to study psoriasis and pregnancy in part by a patient she met as a medical student. “She had severe psoriasis covering her body, and she said that the only times her psoriasis cleared was during her three pregnancies,” Dr. Murase recalled. “I wondered: What about the pregnancies resulted in such a substantial reduction of her psoriasis?”

She subsequently led a study, published in 2005, of 47 pregnant and 27 nonpregnant patients with psoriasis. More than half of the patients – 55% – reported improvements in their psoriasis during pregnancy, 21% reported no change, and 23% reported worsening. Among the 16 patients who had 10% or greater psoriatic body surface area (BSA) involvement and reported improvements, lesions decreased by 84%.

In the postpartum period, only 9% reported improvement, 26% reported no change, and 65% reported worsening. The increased BSA values observed 6 weeks postpartum did not exceed those of the first trimester, suggesting a return to the patients’ baseline status.

Earlier and smaller retrospective studies had also shown that approximately half of patients improve during pregnancy, and it was believed that progesterone was most likely responsible for this improvement. Dr. Murase’s study moved the needle in that it examined BSA in pregnancy and the postpartum period. It also turned the spotlight on estrogen: Patients who had higher levels of improvement also had higher levels of estradiol, estrone, and the ratio of estrogen to progesterone. However, there was no correlation between psoriatic change and levels of progesterone.

To promote fetal survival, pregnancy triggers a shift from Th1 cell–mediated immunity – and Th17 immunity – to Th2 immunity. While there’s no proof of a causative effect, increased estrogen appears to play a role in this shift and in the reduced production of Th1 and Th17 cytokines. Psoriasis is believed to be primarily a Th17-mediated disease, with some Th1 involvement, so this down-regulation can result in improved disease status, Dr. Murase said. (A host of other autoimmune diseases categorized as Th1 mediated similarly tend to improve during pregnancy, she added.)

Information on the effect of pregnancy on PsA is “conflicting,” Dr. Sammaritano said. “Some [of a limited number of studies] suggest a beneficial effect as is generally seen for rheumatoid arthritis. Others, however, have found an increased risk of disease activity during pregnancy ... It may be that psoriatic arthritis can be quite variable from patient to patient in its clinical presentation.”

At least one study, Dr. Sammaritano added, “has shown that the arthritis in pregnancy patients with PsA did not improve, compared to control nonpregnant patients, while the psoriasis rash did improve.”

The mixed findings don’t surprise Dr. Murase. “It harder to quantify joint disease in general,” she said. “And during pregnancy, physiologic changes relating to the pregnancy itself can cause discomfort – your joints ache. The numbers [of improved] cases aren’t as high with PsA, but it’s a more complex question.”

In the postpartum period, however, research findings “all suggest an increased risk of flare” of PsA, Dr. Sammaritano said, just as with psoriasis.

Assessing risk of treatment

Understanding the immunologic effects of pregnancy on psoriasis and PsA – and appreciating the concept of a hormonal component – is an important part of treatment decision making. So is understanding pregnancy outcomes data.

Researchers have looked at a host of pregnancy outcomes – including congenital malformations, preterm birth, spontaneous abortion, low birth weight, macrosomia, and gestational diabetes and hypertension – in women with psoriasis or psoriasis/PsA, compared with control groups. Some studies have suggested a link between disease activity and pregnancy complications or adverse pregnancy outcomes, “just as a result of having moderate to severe disease,” while others have found no evidence of increased risk, Dr. Murase said.

“It’s a bit unclear and a difficult question to answer; it depends on what study you look at and what data you believe. It would be nice to have some clarity, but basically the jury is still out,” said Dr. Murase, who, with coauthors Alice B. Gottlieb, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and Caitriona Ryan, MD, of the Blackrock Clinic and Charles Institute of Dermatology, University College Dublin, discussed the pregnancy outcomes data in a recently published review of psoriasis in women.

“In my opinion, because we have therapies that are so low risk and well tolerated, it’s better to make sure that the inflammatory cascade and inflammation created by psoriasis is under control,” she said. “So whether or not the pregnancy itself causes the patient to go into remission, or whether you have to use therapy to help the patient stay in remission, it’s important to control the inflammation.”

Contraindicated in pregnancy are oral psoralen, methotrexate, and acitretin, the latter of which should be avoided for several years before pregnancy and “therefore shouldn’t be used in a woman of childbearing age,” said Dr. Murase. Methotrexate, said Dr. Sammaritano, should generally be stopped 1-3 months prior to conception.

For psoriasis, the therapy that’s “classically considered the safest in pregnancy is UVB light therapy, specifically the 300-nm wavelength of light, which works really well as an anti-inflammatory,” Dr. Murase said. Because of the potential for maternal folate degradation with phototherapy and the long-known association of folate deficiency with neural tube defects, women of childbearing age who are receiving light therapy should take daily folic acid supplementation. (She prescribes a daily prenatal vitamin containing at least 1 mg of folic acid for women who are utilizing light therapy.)

Many topical agents can be used during pregnancy, Dr. Murase said. Topical corticosteroids, she noted, have the most safety-affirming data of any topical medication.

Regarding oral therapies, Dr. Murase recommends against the use of apremilast (Otezla) for her patients. “It’s not contraindicated, but the animal studies don’t look promising, so I don’t use that one in women of childbearing age just in case. There’s just very little data to support the safety of this medication [in pregnancy].”

There are no therapeutic guidelines in the United States for guiding the management of psoriasis in women who are considering pregnancy. In 2012, the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation published a review of treatment options for psoriasis in pregnant or lactating women, the “closest thing to guidelines that we’ve had,” said Dr. Murase. (Now almost a decade old, the review addresses TNF inhibitors but does not cover the anti-interleukin agents more recently approved for moderate to severe psoriasis and PsA.)

For treating PsA, rheumatologists now have the American College of Rheumatology’s first guideline for the management of reproductive health in rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases to reference. The 2020 guideline does not address PsA specifically, but its section on pregnancy and lactation includes recommendations on biologic and other therapies used to treat the disease.

Guidelines aside, physician-patient discussions over drug safety have the potential to be much more meaningful now that drug labels offer clinical summaries, data, and risk summaries regarding potential use in pregnancy. The labels have “more of a narrative, which is a more useful way to counsel patients and make risk-benefit decisions” than the former system of five-letter categories, said Dr. Murase. (The changes were made per the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule of 2015.)

MothertoBaby, a service of the nonprofit Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, also provides good evidence-based information to physicians and mothers, Dr. Sammaritano noted.

The use of biologic therapies

In a 2017 review of biologic safety for patients with psoriasis during pregnancy, Alexa B. Kimball, MD, MPH, professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston; Martina L. Porter, MD, currently with the department of dermatology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston; and Stephen J. Lockwood, MD, MPH, of the department of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, concluded that an increasing body of literature suggests that biologic agents can be used during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Anti-TNF agents “should be considered over IL-12/23 and IL-17 inhibitors due to the increased availability of long-term data,” they wrote.

“In general,” said Dr. Murase, “there’s more and more data coming out from gastroenterology and rheumatology to reassure patients and prescribing physicians that the TNF-blocker class is likely safe to use in pregnancy,” particularly during the first trimester and early second trimester, when the transport of maternal antibodies across the placenta is “essentially nonexistent.” In the third trimester, the active transport of IgG antibodies increases rapidly.

If possible, said Dr. Sammaritano, who served as lead author of the ACR’s reproductive health guideline, TNF inhibitors “will be stopped prior to the third trimester to avoid [the possibility of] high drug levels in the infant at birth, which raises concern for immunosuppression in the newborn. If disease is very active, however, they can be continued throughout the pregnancy.”

The TNF inhibitor certolizumab pegol (Cimzia) has the advantage of being transported only minimally across the placenta, if at all, she and Dr. Murase both explained. “To be actively carried across, antibodies need what’s called an Fc region for the placenta to grab onto,” Dr. Murase said. Certolizumab – a pegylated anti–binding fragment antibody – lacks this Fc region.

Two recent studies – CRIB and a UCB Pharma safety database analysis – showed “essentially no medication crossing – there were barely detectable levels,” Dr. Murase said. Certolizumab’s label contains this information and other clinical trial data as well as findings from safety database analyses/surveillance registries.

“Before we had much data for the biologics, I’d advise transitioning patients to light therapy from their biologics and a lot of times their psoriasis would improve, but it was more of a dance,” she said. “Now we tend to look at [certolizumab] when they’re of childbearing age and keep them on the treatment. I know that the baby is not being immunosuppressed.”

Consideration of the use of certolizumab when treatment with biologic agents is required throughout the pregnancy is a recommendation included in Dr. Kimball’s 2017 review.

As newer anti-interleukin agents – the IL-12/23 and IL-17 inhibitors – play a growing role in the treatment of psoriasis and PsA, questions loom about their safety profile. Dr. Murase and Dr. Sammaritano are waiting for more data. “In general,” Dr. Sammaritano said, “we recommend stopping them at the time pregnancy is detected, based on a lack of data at this time.”

Small-molecule drugs are also less well studied, she noted. “Because of their low molecular weight, we anticipate they will easily cross the placenta, so we recommend avoiding use during pregnancy until more information is available.”

Postpartum care

The good news, both experts say, is that the vast majority of medications, including biologics, are safe to use during breastfeeding. Methotrexate should be avoided, Dr. Sammaritano pointed out, and the impact of novel small-molecule therapies on breast milk has not been studied.

In her 2019 review of psoriasis in women, Dr. Murase and coauthors wrote that too many dermatologists believe that breastfeeding women should either not be on biologics or are uncertain about biologic use during breastfeeding. However, “biologics are considered compatible for use while breastfeeding due to their large molecular size and the proteolytic environment in the neonatal gastrointestinal tract,” they added.

Counseling and support for breastfeeding is especially important for women with psoriasis, Dr. Murase emphasized. “Breastfeeding is very traumatizing to the skin, and psoriasis can form in skin that’s injured. I have my patients set up an office visit very soon after the pregnancy to make sure they’re doing alright with their breastfeeding and that they’re coating their nipple area with some type of moisturizer and keeping the health of their nipples in good shape.”

Timely reviews of therapy and adjustments are also a priority, she said. “We need to prepare for 6 weeks post partum” when psoriasis will often flare without treatment.

Dr. Murase disclosed that she is a consultant for Dermira, UCB Pharma, Sanofi, Ferndale, and Regeneron. She is also coeditor in chief of the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology. Dr. Sammaritano reported that she has no disclosures relating to the treatment of PsA.

With an average age of diagnosis of 28 years, and one of two incidence peaks occurring at 15-30 years, psoriasis affects many women in the midst of their reproductive years. The prospect of pregnancy – or the reality of a surprise pregnancy – drives questions about heritability of the disease in offspring, the impact of the disease on pregnancy outcomes and breastfeeding, and how to best balance risks of treatments with risks of uncontrolled psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

While answers to these questions are not always clear, discussions about pregnancy and psoriasis management “shouldn’t be scary,” said Jenny E. Murase, MD, a dermatologist who speaks and writes widely about her research and experience with psoriasis and pregnancy. “We have access to information and data and educational resources to [work with] and reassure our patients – we just need to use it. Right now, there’s unnecessary suffering [with some patients unnecessarily stopping all treatment].”

Much has been learned in the past 2 decades about the course of psoriasis in pregnancy, and pregnancy outcomes data on the safety of biologics during pregnancy are increasingly emerging – particularly for tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha inhibitors.

Ideally, since half of all pregnancies are unplanned, the implications of therapeutic options should be discussed with all women with psoriasis who are of reproductive age, whether they are sexually active or not. “The onus is on us to make sure that we’re considering the possibility [that our patient] could become pregnant without consulting us first,” said Dr. Murase, associate professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, and director of medical consultative dermatology for the Palo Alto Foundation Medical Group in Mountain View, Calif.

Lisa R. Sammaritano, MD, associate professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine and a rheumatologist at the Hospital for Special Surgery, both in New York, urges similar attention for PsA. “Pregnancy is best planned while patients have quiescent disease on pregnancy-compatible medications,” she said. “We encourage [more] rheumatologists to be actively involved in pregnancy planning [in order] to guide therapy.”

The impact of estrogen

Dr. Murase was inspired to study psoriasis and pregnancy in part by a patient she met as a medical student. “She had severe psoriasis covering her body, and she said that the only times her psoriasis cleared was during her three pregnancies,” Dr. Murase recalled. “I wondered: What about the pregnancies resulted in such a substantial reduction of her psoriasis?”

She subsequently led a study, published in 2005, of 47 pregnant and 27 nonpregnant patients with psoriasis. More than half of the patients – 55% – reported improvements in their psoriasis during pregnancy, 21% reported no change, and 23% reported worsening. Among the 16 patients who had 10% or greater psoriatic body surface area (BSA) involvement and reported improvements, lesions decreased by 84%.

In the postpartum period, only 9% reported improvement, 26% reported no change, and 65% reported worsening. The increased BSA values observed 6 weeks postpartum did not exceed those of the first trimester, suggesting a return to the patients’ baseline status.

Earlier and smaller retrospective studies had also shown that approximately half of patients improve during pregnancy, and it was believed that progesterone was most likely responsible for this improvement. Dr. Murase’s study moved the needle in that it examined BSA in pregnancy and the postpartum period. It also turned the spotlight on estrogen: Patients who had higher levels of improvement also had higher levels of estradiol, estrone, and the ratio of estrogen to progesterone. However, there was no correlation between psoriatic change and levels of progesterone.

To promote fetal survival, pregnancy triggers a shift from Th1 cell–mediated immunity – and Th17 immunity – to Th2 immunity. While there’s no proof of a causative effect, increased estrogen appears to play a role in this shift and in the reduced production of Th1 and Th17 cytokines. Psoriasis is believed to be primarily a Th17-mediated disease, with some Th1 involvement, so this down-regulation can result in improved disease status, Dr. Murase said. (A host of other autoimmune diseases categorized as Th1 mediated similarly tend to improve during pregnancy, she added.)

Information on the effect of pregnancy on PsA is “conflicting,” Dr. Sammaritano said. “Some [of a limited number of studies] suggest a beneficial effect as is generally seen for rheumatoid arthritis. Others, however, have found an increased risk of disease activity during pregnancy ... It may be that psoriatic arthritis can be quite variable from patient to patient in its clinical presentation.”

At least one study, Dr. Sammaritano added, “has shown that the arthritis in pregnancy patients with PsA did not improve, compared to control nonpregnant patients, while the psoriasis rash did improve.”

The mixed findings don’t surprise Dr. Murase. “It harder to quantify joint disease in general,” she said. “And during pregnancy, physiologic changes relating to the pregnancy itself can cause discomfort – your joints ache. The numbers [of improved] cases aren’t as high with PsA, but it’s a more complex question.”

In the postpartum period, however, research findings “all suggest an increased risk of flare” of PsA, Dr. Sammaritano said, just as with psoriasis.

Assessing risk of treatment

Understanding the immunologic effects of pregnancy on psoriasis and PsA – and appreciating the concept of a hormonal component – is an important part of treatment decision making. So is understanding pregnancy outcomes data.

Researchers have looked at a host of pregnancy outcomes – including congenital malformations, preterm birth, spontaneous abortion, low birth weight, macrosomia, and gestational diabetes and hypertension – in women with psoriasis or psoriasis/PsA, compared with control groups. Some studies have suggested a link between disease activity and pregnancy complications or adverse pregnancy outcomes, “just as a result of having moderate to severe disease,” while others have found no evidence of increased risk, Dr. Murase said.

“It’s a bit unclear and a difficult question to answer; it depends on what study you look at and what data you believe. It would be nice to have some clarity, but basically the jury is still out,” said Dr. Murase, who, with coauthors Alice B. Gottlieb, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and Caitriona Ryan, MD, of the Blackrock Clinic and Charles Institute of Dermatology, University College Dublin, discussed the pregnancy outcomes data in a recently published review of psoriasis in women.

“In my opinion, because we have therapies that are so low risk and well tolerated, it’s better to make sure that the inflammatory cascade and inflammation created by psoriasis is under control,” she said. “So whether or not the pregnancy itself causes the patient to go into remission, or whether you have to use therapy to help the patient stay in remission, it’s important to control the inflammation.”

Contraindicated in pregnancy are oral psoralen, methotrexate, and acitretin, the latter of which should be avoided for several years before pregnancy and “therefore shouldn’t be used in a woman of childbearing age,” said Dr. Murase. Methotrexate, said Dr. Sammaritano, should generally be stopped 1-3 months prior to conception.

For psoriasis, the therapy that’s “classically considered the safest in pregnancy is UVB light therapy, specifically the 300-nm wavelength of light, which works really well as an anti-inflammatory,” Dr. Murase said. Because of the potential for maternal folate degradation with phototherapy and the long-known association of folate deficiency with neural tube defects, women of childbearing age who are receiving light therapy should take daily folic acid supplementation. (She prescribes a daily prenatal vitamin containing at least 1 mg of folic acid for women who are utilizing light therapy.)

Many topical agents can be used during pregnancy, Dr. Murase said. Topical corticosteroids, she noted, have the most safety-affirming data of any topical medication.

Regarding oral therapies, Dr. Murase recommends against the use of apremilast (Otezla) for her patients. “It’s not contraindicated, but the animal studies don’t look promising, so I don’t use that one in women of childbearing age just in case. There’s just very little data to support the safety of this medication [in pregnancy].”

There are no therapeutic guidelines in the United States for guiding the management of psoriasis in women who are considering pregnancy. In 2012, the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation published a review of treatment options for psoriasis in pregnant or lactating women, the “closest thing to guidelines that we’ve had,” said Dr. Murase. (Now almost a decade old, the review addresses TNF inhibitors but does not cover the anti-interleukin agents more recently approved for moderate to severe psoriasis and PsA.)

For treating PsA, rheumatologists now have the American College of Rheumatology’s first guideline for the management of reproductive health in rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases to reference. The 2020 guideline does not address PsA specifically, but its section on pregnancy and lactation includes recommendations on biologic and other therapies used to treat the disease.

Guidelines aside, physician-patient discussions over drug safety have the potential to be much more meaningful now that drug labels offer clinical summaries, data, and risk summaries regarding potential use in pregnancy. The labels have “more of a narrative, which is a more useful way to counsel patients and make risk-benefit decisions” than the former system of five-letter categories, said Dr. Murase. (The changes were made per the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule of 2015.)

MothertoBaby, a service of the nonprofit Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, also provides good evidence-based information to physicians and mothers, Dr. Sammaritano noted.

The use of biologic therapies

In a 2017 review of biologic safety for patients with psoriasis during pregnancy, Alexa B. Kimball, MD, MPH, professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston; Martina L. Porter, MD, currently with the department of dermatology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston; and Stephen J. Lockwood, MD, MPH, of the department of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, concluded that an increasing body of literature suggests that biologic agents can be used during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Anti-TNF agents “should be considered over IL-12/23 and IL-17 inhibitors due to the increased availability of long-term data,” they wrote.

“In general,” said Dr. Murase, “there’s more and more data coming out from gastroenterology and rheumatology to reassure patients and prescribing physicians that the TNF-blocker class is likely safe to use in pregnancy,” particularly during the first trimester and early second trimester, when the transport of maternal antibodies across the placenta is “essentially nonexistent.” In the third trimester, the active transport of IgG antibodies increases rapidly.

If possible, said Dr. Sammaritano, who served as lead author of the ACR’s reproductive health guideline, TNF inhibitors “will be stopped prior to the third trimester to avoid [the possibility of] high drug levels in the infant at birth, which raises concern for immunosuppression in the newborn. If disease is very active, however, they can be continued throughout the pregnancy.”

The TNF inhibitor certolizumab pegol (Cimzia) has the advantage of being transported only minimally across the placenta, if at all, she and Dr. Murase both explained. “To be actively carried across, antibodies need what’s called an Fc region for the placenta to grab onto,” Dr. Murase said. Certolizumab – a pegylated anti–binding fragment antibody – lacks this Fc region.

Two recent studies – CRIB and a UCB Pharma safety database analysis – showed “essentially no medication crossing – there were barely detectable levels,” Dr. Murase said. Certolizumab’s label contains this information and other clinical trial data as well as findings from safety database analyses/surveillance registries.

“Before we had much data for the biologics, I’d advise transitioning patients to light therapy from their biologics and a lot of times their psoriasis would improve, but it was more of a dance,” she said. “Now we tend to look at [certolizumab] when they’re of childbearing age and keep them on the treatment. I know that the baby is not being immunosuppressed.”

Consideration of the use of certolizumab when treatment with biologic agents is required throughout the pregnancy is a recommendation included in Dr. Kimball’s 2017 review.

As newer anti-interleukin agents – the IL-12/23 and IL-17 inhibitors – play a growing role in the treatment of psoriasis and PsA, questions loom about their safety profile. Dr. Murase and Dr. Sammaritano are waiting for more data. “In general,” Dr. Sammaritano said, “we recommend stopping them at the time pregnancy is detected, based on a lack of data at this time.”

Small-molecule drugs are also less well studied, she noted. “Because of their low molecular weight, we anticipate they will easily cross the placenta, so we recommend avoiding use during pregnancy until more information is available.”

Postpartum care

The good news, both experts say, is that the vast majority of medications, including biologics, are safe to use during breastfeeding. Methotrexate should be avoided, Dr. Sammaritano pointed out, and the impact of novel small-molecule therapies on breast milk has not been studied.

In her 2019 review of psoriasis in women, Dr. Murase and coauthors wrote that too many dermatologists believe that breastfeeding women should either not be on biologics or are uncertain about biologic use during breastfeeding. However, “biologics are considered compatible for use while breastfeeding due to their large molecular size and the proteolytic environment in the neonatal gastrointestinal tract,” they added.

Counseling and support for breastfeeding is especially important for women with psoriasis, Dr. Murase emphasized. “Breastfeeding is very traumatizing to the skin, and psoriasis can form in skin that’s injured. I have my patients set up an office visit very soon after the pregnancy to make sure they’re doing alright with their breastfeeding and that they’re coating their nipple area with some type of moisturizer and keeping the health of their nipples in good shape.”

Timely reviews of therapy and adjustments are also a priority, she said. “We need to prepare for 6 weeks post partum” when psoriasis will often flare without treatment.

Dr. Murase disclosed that she is a consultant for Dermira, UCB Pharma, Sanofi, Ferndale, and Regeneron. She is also coeditor in chief of the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology. Dr. Sammaritano reported that she has no disclosures relating to the treatment of PsA.

Interstitial lung abnormalities linked to COPD exacerbations

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who also had certain interstitial lung abnormalities experienced more exacerbations and reduced lung function than those without such abnormalities, findings from a retrospective study has shown.

Interstitial lung abnormalities (ILA) are considered precursor lesions of interstitial lung disease and previous studies suggested an association with poor outcomes among chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients, but data on long-term clinical relevance are limited, wrote Tae Seung Lee, MD, of Seoul (South Korea) National University Hospital, and colleagues.

In a study published in Chest, the researchers reviewed data from 363 COPD patients including 44 with equivocal ILA and 103 with definite ILA. Overall, the ILA patients were older and had poorer lung function than non-ILA patients. Patients received chest CT scan and longitudinal pulmonary function tests between January 2013 and December 2018.

Over an average follow-up period of 5.4 years, patients with ILA experienced significantly more acute COPD exacerbations than did those without ILA (adjusted odds ratio, 2.03). The percentages of frequent exacerbators among patients with no ILA, equivocal ILA, and definite ILA were 8.3%, 15.9%, and 20.4%, respectively.

“Acute exacerbation is an important event during the clinical course of COPD, because it is associated with temporary or persistent reductions in lung function, lower quality of life, hospitalization, and mortality,” the researchers noted.

In a multivariate analysis, the annual decline in lung function (FEV1) was –35.7 in patients with equivocal ILA, compared with –28.0 in patients with no ILA and –15.9 in those with definite ILA.