User login

Behavioral Therapy for Migraine and Tension-Type Headache

Steven M. Baskin, PhD, a clinical psychologist at the New England Institute for Neurology and Headache in Stamford, Connecticut, recently answered the Migraine Resource Center’s questions about the benefits of behavioral therapy in the treatment of migraine and tension-type headache.

Alan M. Rapoport, MD: Could you please give a brief description of the 5 best modalities of behavioral therapy for migraine and tension-type headache?

Steven M. Baskin, PhD: The most researched modalities that have a good evidence base for both migraine and tension-type headache (TTHA) are relaxation therapies that often combine abdominal breathing with some form of progressive relaxation, electromyography (EMG) biofeedback therapy where headache patients learn to decrease scalp and neck muscle tension utilizing muscular biofeedback, thermal biofeedback where migraine sufferers learn a way to warm their hands which often creates a low arousal state that may reduce brain hyperexcitability, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques to learn stress management. The combination of behavioral medicine techniques plus preventive pharmacological treatment has been showed to be more efficacious than either treatment alone. (Holroyd KA, et al. Effect of preventive (β blocker) treatment, behavioural migraine management, or their combination on outcomes of optimised acute treatment in frequent migraine: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;1-12)

CBT to treat insomnia has also been shown to reverse many chronic migraine sufferers back to episodic migraine. (Smitherman TA, et al. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia to Reduce Chronic Migraine: A Sequential Bayesian Analysis. Headache 2018;58:1052-1059)

Dr. Rapoport: How do you identify a patient who may benefit from behavioral therapy over acute medication, and what is the first step that you suggest?

Dr. Baskin: Behavioral therapies for migraine management are typically preventive therapies that can and should be combined with medications to control acute attacks. There are behavioral principles that can maximize adherence to abortive agents in order to optimize acute care.

Dr. Rapoport: Which tends to work the best for migraine?

Dr. Baskin: What works best is to first do a good behavioral assessment of the frequency, duration, intensity, and disability level of their headaches as well as current stress levels, history, and adherence to drug and nondrug therapies, and psychiatric comorbidities. A program should then be developed that includes some combination of pharmacological and behavioral interventions to address these issues. It is important to increase self-efficacy: patients’ belief in the ability to control the headache, belief in the ability to manage emotional reactivity to pain, and belief that they can achieve functionality in the presence of a significant headache disorder.

Dr. Rapoport: Who should not have biofeedback therapy?

Dr. Baskin: Biofeedback has shown to be effective in treating migraine and TTHA. It has not been shown to be effective in treating trigeminal autonomic cephalgias (TACs) such as cluster headache. Like pharmacological therapies, it is less effective in chronic migraine that is daily and constant. A patient with severe psychiatric disorder should be treated for their psychiatric disorder before beginning biofeedback therapy.

Dr. Rapoport: Some doctors see patients twice per week for several months. What is your typical routine for behavioral therapy?

Dr. Baskin: We have a variety of programs. For complicated patients, we tend to see them weekly and have a very systematic program of biofeedback and CBT for approximately 12 to 15 sessions. This may include treating psychiatric comorbidities. We see many other patients for 1 or 2 sessions of biofeedback to try to effect physiological learning and for 1 or 2 sessions of CBT to help them manage stressors and learn coping skills that they can use to help manage migraines and life stress.

Dr. Rapoport: Does behavioral medicine work best in conjunction with preventive medications, or on its own?

Dr. Baskin: Many patients do well with a behavioral treatment as a preventive therapy and a pharmacologic agent to optimize acute care. I believe that many patients with higher frequency migraine with psychological issues or ongoing stressors do best with a combination of preventive pharmacologic therapy and behavior therapy. Any migraine patient with sleep issues should learn CBT for insomnia.

Dr. Rapoport: Is there evidence that suggests behavioral therapy can help patients at various ages manage their migraines?

Dr. Baskin: There is both adult and child data on behavioral therapy for migraine. An excellent study was done in children and adolescents by Powers et al. It showed that adding 10 sessions of CBT to preventive amitriptyline therapy, compared to adding headache education, significantly reduced the number of headache days, level of disability, and kids with a better than 50% decrease in days of headache compared to amitriptyline, plus headache education control in chronic migraine patients. (Powers SW et al. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Plus Amitriptyline for Chronic Migraine in Children and Adolescents: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2013;310(24):2622-2630)

Dr. Rapoport: A recent MedPage Today article noted that “anxiety may complicate migraine more than depression with greater long-term persistence, greater headache-related disability, and reduced satisfaction with acute therapies.” Could you please elaborate on why this may be the case?

Dr. Baskin: Anxiety disorders are often based on feeling threat. They are always associated with avoidance behaviors. Headache sufferers with significant anxiety tend to overestimate the probability of danger (migraine) and perceive it as more unmanageable and threatening than objective reality. They are often very sensitive to medication side effects and benign somatic sensations. They sometimes take medications pre-emptively, because of their fear of getting a migraine, which may lead to medication misuse or overuse. The lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in migraineurs (ranging from 51-58%) is almost twice that of major depression.

Please write to us at Neurology Reviews Migraine Resource Center ([email protected]) with your opinions.

Alan M. Rapoport, M.D.

Editor-in-Chief

Migraine Resource Center

Clinical Professor of Neurology

The David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA

Los Angeles, California

Steven M. Baskin, PhD, a clinical psychologist at the New England Institute for Neurology and Headache in Stamford, Connecticut, recently answered the Migraine Resource Center’s questions about the benefits of behavioral therapy in the treatment of migraine and tension-type headache.

Alan M. Rapoport, MD: Could you please give a brief description of the 5 best modalities of behavioral therapy for migraine and tension-type headache?

Steven M. Baskin, PhD: The most researched modalities that have a good evidence base for both migraine and tension-type headache (TTHA) are relaxation therapies that often combine abdominal breathing with some form of progressive relaxation, electromyography (EMG) biofeedback therapy where headache patients learn to decrease scalp and neck muscle tension utilizing muscular biofeedback, thermal biofeedback where migraine sufferers learn a way to warm their hands which often creates a low arousal state that may reduce brain hyperexcitability, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques to learn stress management. The combination of behavioral medicine techniques plus preventive pharmacological treatment has been showed to be more efficacious than either treatment alone. (Holroyd KA, et al. Effect of preventive (β blocker) treatment, behavioural migraine management, or their combination on outcomes of optimised acute treatment in frequent migraine: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;1-12)

CBT to treat insomnia has also been shown to reverse many chronic migraine sufferers back to episodic migraine. (Smitherman TA, et al. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia to Reduce Chronic Migraine: A Sequential Bayesian Analysis. Headache 2018;58:1052-1059)

Dr. Rapoport: How do you identify a patient who may benefit from behavioral therapy over acute medication, and what is the first step that you suggest?

Dr. Baskin: Behavioral therapies for migraine management are typically preventive therapies that can and should be combined with medications to control acute attacks. There are behavioral principles that can maximize adherence to abortive agents in order to optimize acute care.

Dr. Rapoport: Which tends to work the best for migraine?

Dr. Baskin: What works best is to first do a good behavioral assessment of the frequency, duration, intensity, and disability level of their headaches as well as current stress levels, history, and adherence to drug and nondrug therapies, and psychiatric comorbidities. A program should then be developed that includes some combination of pharmacological and behavioral interventions to address these issues. It is important to increase self-efficacy: patients’ belief in the ability to control the headache, belief in the ability to manage emotional reactivity to pain, and belief that they can achieve functionality in the presence of a significant headache disorder.

Dr. Rapoport: Who should not have biofeedback therapy?

Dr. Baskin: Biofeedback has shown to be effective in treating migraine and TTHA. It has not been shown to be effective in treating trigeminal autonomic cephalgias (TACs) such as cluster headache. Like pharmacological therapies, it is less effective in chronic migraine that is daily and constant. A patient with severe psychiatric disorder should be treated for their psychiatric disorder before beginning biofeedback therapy.

Dr. Rapoport: Some doctors see patients twice per week for several months. What is your typical routine for behavioral therapy?

Dr. Baskin: We have a variety of programs. For complicated patients, we tend to see them weekly and have a very systematic program of biofeedback and CBT for approximately 12 to 15 sessions. This may include treating psychiatric comorbidities. We see many other patients for 1 or 2 sessions of biofeedback to try to effect physiological learning and for 1 or 2 sessions of CBT to help them manage stressors and learn coping skills that they can use to help manage migraines and life stress.

Dr. Rapoport: Does behavioral medicine work best in conjunction with preventive medications, or on its own?

Dr. Baskin: Many patients do well with a behavioral treatment as a preventive therapy and a pharmacologic agent to optimize acute care. I believe that many patients with higher frequency migraine with psychological issues or ongoing stressors do best with a combination of preventive pharmacologic therapy and behavior therapy. Any migraine patient with sleep issues should learn CBT for insomnia.

Dr. Rapoport: Is there evidence that suggests behavioral therapy can help patients at various ages manage their migraines?

Dr. Baskin: There is both adult and child data on behavioral therapy for migraine. An excellent study was done in children and adolescents by Powers et al. It showed that adding 10 sessions of CBT to preventive amitriptyline therapy, compared to adding headache education, significantly reduced the number of headache days, level of disability, and kids with a better than 50% decrease in days of headache compared to amitriptyline, plus headache education control in chronic migraine patients. (Powers SW et al. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Plus Amitriptyline for Chronic Migraine in Children and Adolescents: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2013;310(24):2622-2630)

Dr. Rapoport: A recent MedPage Today article noted that “anxiety may complicate migraine more than depression with greater long-term persistence, greater headache-related disability, and reduced satisfaction with acute therapies.” Could you please elaborate on why this may be the case?

Dr. Baskin: Anxiety disorders are often based on feeling threat. They are always associated with avoidance behaviors. Headache sufferers with significant anxiety tend to overestimate the probability of danger (migraine) and perceive it as more unmanageable and threatening than objective reality. They are often very sensitive to medication side effects and benign somatic sensations. They sometimes take medications pre-emptively, because of their fear of getting a migraine, which may lead to medication misuse or overuse. The lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in migraineurs (ranging from 51-58%) is almost twice that of major depression.

Please write to us at Neurology Reviews Migraine Resource Center ([email protected]) with your opinions.

Alan M. Rapoport, M.D.

Editor-in-Chief

Migraine Resource Center

Clinical Professor of Neurology

The David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA

Los Angeles, California

Steven M. Baskin, PhD, a clinical psychologist at the New England Institute for Neurology and Headache in Stamford, Connecticut, recently answered the Migraine Resource Center’s questions about the benefits of behavioral therapy in the treatment of migraine and tension-type headache.

Alan M. Rapoport, MD: Could you please give a brief description of the 5 best modalities of behavioral therapy for migraine and tension-type headache?

Steven M. Baskin, PhD: The most researched modalities that have a good evidence base for both migraine and tension-type headache (TTHA) are relaxation therapies that often combine abdominal breathing with some form of progressive relaxation, electromyography (EMG) biofeedback therapy where headache patients learn to decrease scalp and neck muscle tension utilizing muscular biofeedback, thermal biofeedback where migraine sufferers learn a way to warm their hands which often creates a low arousal state that may reduce brain hyperexcitability, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques to learn stress management. The combination of behavioral medicine techniques plus preventive pharmacological treatment has been showed to be more efficacious than either treatment alone. (Holroyd KA, et al. Effect of preventive (β blocker) treatment, behavioural migraine management, or their combination on outcomes of optimised acute treatment in frequent migraine: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;1-12)

CBT to treat insomnia has also been shown to reverse many chronic migraine sufferers back to episodic migraine. (Smitherman TA, et al. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia to Reduce Chronic Migraine: A Sequential Bayesian Analysis. Headache 2018;58:1052-1059)

Dr. Rapoport: How do you identify a patient who may benefit from behavioral therapy over acute medication, and what is the first step that you suggest?

Dr. Baskin: Behavioral therapies for migraine management are typically preventive therapies that can and should be combined with medications to control acute attacks. There are behavioral principles that can maximize adherence to abortive agents in order to optimize acute care.

Dr. Rapoport: Which tends to work the best for migraine?

Dr. Baskin: What works best is to first do a good behavioral assessment of the frequency, duration, intensity, and disability level of their headaches as well as current stress levels, history, and adherence to drug and nondrug therapies, and psychiatric comorbidities. A program should then be developed that includes some combination of pharmacological and behavioral interventions to address these issues. It is important to increase self-efficacy: patients’ belief in the ability to control the headache, belief in the ability to manage emotional reactivity to pain, and belief that they can achieve functionality in the presence of a significant headache disorder.

Dr. Rapoport: Who should not have biofeedback therapy?

Dr. Baskin: Biofeedback has shown to be effective in treating migraine and TTHA. It has not been shown to be effective in treating trigeminal autonomic cephalgias (TACs) such as cluster headache. Like pharmacological therapies, it is less effective in chronic migraine that is daily and constant. A patient with severe psychiatric disorder should be treated for their psychiatric disorder before beginning biofeedback therapy.

Dr. Rapoport: Some doctors see patients twice per week for several months. What is your typical routine for behavioral therapy?

Dr. Baskin: We have a variety of programs. For complicated patients, we tend to see them weekly and have a very systematic program of biofeedback and CBT for approximately 12 to 15 sessions. This may include treating psychiatric comorbidities. We see many other patients for 1 or 2 sessions of biofeedback to try to effect physiological learning and for 1 or 2 sessions of CBT to help them manage stressors and learn coping skills that they can use to help manage migraines and life stress.

Dr. Rapoport: Does behavioral medicine work best in conjunction with preventive medications, or on its own?

Dr. Baskin: Many patients do well with a behavioral treatment as a preventive therapy and a pharmacologic agent to optimize acute care. I believe that many patients with higher frequency migraine with psychological issues or ongoing stressors do best with a combination of preventive pharmacologic therapy and behavior therapy. Any migraine patient with sleep issues should learn CBT for insomnia.

Dr. Rapoport: Is there evidence that suggests behavioral therapy can help patients at various ages manage their migraines?

Dr. Baskin: There is both adult and child data on behavioral therapy for migraine. An excellent study was done in children and adolescents by Powers et al. It showed that adding 10 sessions of CBT to preventive amitriptyline therapy, compared to adding headache education, significantly reduced the number of headache days, level of disability, and kids with a better than 50% decrease in days of headache compared to amitriptyline, plus headache education control in chronic migraine patients. (Powers SW et al. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Plus Amitriptyline for Chronic Migraine in Children and Adolescents: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2013;310(24):2622-2630)

Dr. Rapoport: A recent MedPage Today article noted that “anxiety may complicate migraine more than depression with greater long-term persistence, greater headache-related disability, and reduced satisfaction with acute therapies.” Could you please elaborate on why this may be the case?

Dr. Baskin: Anxiety disorders are often based on feeling threat. They are always associated with avoidance behaviors. Headache sufferers with significant anxiety tend to overestimate the probability of danger (migraine) and perceive it as more unmanageable and threatening than objective reality. They are often very sensitive to medication side effects and benign somatic sensations. They sometimes take medications pre-emptively, because of their fear of getting a migraine, which may lead to medication misuse or overuse. The lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in migraineurs (ranging from 51-58%) is almost twice that of major depression.

Please write to us at Neurology Reviews Migraine Resource Center ([email protected]) with your opinions.

Alan M. Rapoport, M.D.

Editor-in-Chief

Migraine Resource Center

Clinical Professor of Neurology

The David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA

Los Angeles, California

Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: A primary care guide

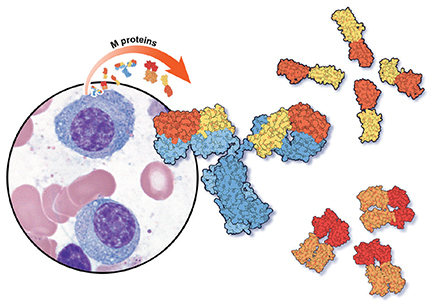

MGUS is present in 3% to 4% of the population over age 50 and is more common in older men, African Americans, and Africans.1–6

The overall risk of progression to myeloma and related disorders is less than or equal to 1% per year depending on the subtype of the M protein (higher risk with IgM than non-IgM and light-chain MGUS).7,8 While the risk of malignant transformation is low, multiple myeloma is almost always preceded by the presence of an asymptomatic and often unrecognized monoclonal protein.

WHEN SHOULD WE LOOK FOR AN M PROTEIN?

An M protein is typically an incidental finding when a patient is being assessed for any of a number of presenting symptoms or conditions. A large retrospective study9 found that screening for MGUS was mostly performed by internal medicine physicians. The indications for testing were anemia, bone-related issues, elevated creatinine, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and neuropathy.

A low anion gap is not a major indicator of an M protein unless in a high concentration, in which case other manifestations would be present, such as renal failure, which would guide the diagnosis. Polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia as a cause of low anion gap is far more common than MGUS.

HOW SHOULD WE SCREEN FOR AN M PROTEIN?

Serum protein electrophoresis is an initial test used to identify an M protein and has a key role in quantifying it (Figure 2). An M protein appears as a narrow spike on the agarose gel and should be distinguished from the broad band seen in polyclonal gammopathies associated with cirrhosis and chronic infectious and inflammatory conditions, among others.12 A major disadvantage of serum protein electrophoresis is that it cannot detect an M protein in very low concentrations or determine its identity.

Serum immunofixation is more sensitive than serum protein electrophoresis and should always be ordered in conjunction with it, mostly to ensure detecting tiny amounts of M protein and to identify the type of its heavy chain and light-chain components.13

The serum free light-chain assay is also considered an essential part of the screening process to detect light-chain MGUS and light-chain myeloma. As many as 16% of myeloma patients secrete only light chains, which may not be identified on serum immunofixation.3,6,7,10,14,15 In general, a low kappa-lambda ratio (< 0.26) indicates the overproduction of lambda light chains, and a high ratio (> 1.65) indicates the overproduction of kappa light chains.

The serum free light-chain assay helps detect abnormal secretion of monoclonal light chains before they appear in the urine once the kidney tubules become saturated and unable to reabsorb them.

Of note, the free light-chain ratio can be abnormal (< 0.26 or > 1.65) in chronic kidney disease. Thus, it may be challenging to discern whether an abnormal light-chain ratio is related to impaired light-chain clearance by the kidneys or to MGUS. In general, kappa light chains are more elevated than lambda light chains in chronic kidney disease, but the ratio should not be considerably skewed. A kappa-lambda ratio below 0.37 or above 3 is rarely seen in chronic kidney disease and should prompt workup for MGUS.16

Tests in combination. The sensitivity of screening for M proteins ranges from 82% with serum protein electrophoresis alone to 93% with the addition of serum immunofixation and to 98% with the serum free light-chain assay.15 The latter can replace urine protein electrophoresis and immunofixation when screening for M protein, given its higher sensitivity.15,17 An important caveat is that urine dipstick testing does not detect urine light chains.

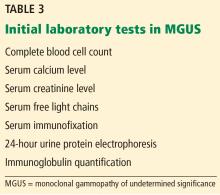

Table 3 lists the initial laboratory tests required in patients with MGUS.

WHAT IS THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF MONOCLONAL GAMMOPATHIES?

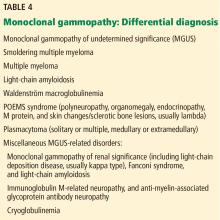

that feature an M protein and would otherwise require treatment (Table 4). The differential diagnosis includes smoldering multiple myeloma, symptomatic multiple myeloma, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, light-chain amyloidosis, low-grade B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders, a variety of monoclonal protein-related kidney disorders, and plasmacytomas.10,14

MGUS

Based on the International Myeloma Working Group consensus, a formal diagnosis of MGUS is established when a serum M protein is detected and measured at a concentration less than 3 g/dL on serum protein electrophoresis along with less than 10% clonal plasma cells in the bone marrow.1–6,14,18,19 Nevertheless, bone marrow biopsy can be omitted in certain patients as discussed below. The absence of myeloma-related organ damage—particularly osteolytic bone lesions, anemia, otherwise unexplained renal failure, and hypercalcemia—is fundamental and necessary for a diagnosis of MGUS.

Smoldering multiple myeloma

Compared with patients with MGUS, patients with smoldering multiple myeloma have higher M protein concentrations (≥ 3 g/dL) or 10% or more clonal plasma cells in the marrow or both, and are at higher risk of progression to symptomatic multiple myeloma. Nevertheless, like patients with MGUS, they have no myeloma symptoms or evidence of end-organ damage.

Symptomatic multiple myeloma

By definition, patients with multiple myeloma develop organ damage related to their malignancy and need therapy to halt disease progression. Multiple myeloma causes clinical manifestations through cellular infiltration of the bone and bone marrow (anemia, osteolysis, and hypercalcemia) and light chain-induced toxicity (renal tubular damage and cast nephropathy).

In 2014, the definition of multiple myeloma was updated to include 3 new myeloma-defining events that herald a significantly higher risk of progression from smoldering to symptomatic multiple myeloma, and now constitute an integral part of the diagnosis of symptomatic multiple myeloma. These are:

- Focal lesions (> 1 lesion larger than 5 mm) visible on magnetic resonance imaging

- ≥ 60% clonal plasma cells on bone marrow biopsy

- Ratio of involved to uninvolved serum free light chains ≥ 100 (the involved light chain is the one detected on serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation).14

Bone pain, symptoms of anemia, and decreased urine output may suggest myeloma, but are not diagnostic. Although the “CRAB” criteria (elevated calcium, renal failure, anemia, and bone lesions) define multiple myeloma, the presence of anemia, hypercalcemia, or renal dysfunction do not by themselves mark transformation from MGUS to multiple myeloma. Thus, other causes need to be considered, since the risk of transformation is so low. Importantly, hyperparathyroidism must be ruled out if hypercalcemia is present in a patient with MGUS.10

Waldenström macroglobulinemia

Waldenström macroglobulinemia, also called lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, is an indolent non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma that can invade the marrow, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes, leading to anemia and organomegaly. It features a monoclonal IgM protein that can be associated with increased blood viscosity, cold agglutinin disease, peripheral neuropathy, and cryoglobulinemia.

Waldenström macroglobulinemia should be suspected in any patient with IgM type M protein and symptoms related to hyperviscosity (headache, blurry vision, lightheadedness, shortness of breath, unexplained epistaxis, gum bleeding); systemic symptoms (fever, weight loss, and night sweats); and abdominal pain (due to organomegaly).23

Monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance

Monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance (MGRS) is a newly recognized entity defined by kidney dysfunction associated with an M protein without evidence of myeloma or other lymphoid disorders.24 Multiple disorders have been included in this category with different underlying mechanisms of kidney injury. This entity is beyond the scope of this discussion.

Light-chain amyloidosis

Misfolded light-chain deposition leading to organ dysfunction is the hallmark of light-chain amyloidosis, which constitutes a subset of MGRS. An abnormal light-chain ratio, especially if skewed toward lambda should trigger an investigation for light-chain amyloidosis.10

Abnormal light chains may infiltrate any organ or tissue, but of greatest concern is infiltration of the myocardium with ensuing heart failure manifestations. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) is a sensitive marker for cardiac amyloidosis in the presence of suggestive features on transthoracic echocardiography (eg, left ventricular hypertrophy) but is not specific as it can be elevated in heart failure regardless of the underlying cause.10

Glomerular injury with nephrotic syndrome may also point toward renal involvement by light-chain amyloidosis and establishes a key distinctive factor from myeloma in which tubular injury is the main mechanism of kidney dysfunction.

Clinical clues for light-chain amyloidosis include heart failure symptoms, neuropathy, and macroglossia. If any of these symptoms and signs is present, we recommend electrocardiography (look for low voltage in limb leads), transthoracic echocardiography, measuring the NT-proBNP level, and urinalysis to look for albuminuria. Notably, carpal tunnel syndrome may be a very early clinical manifestation of amyloidosis, but by itself it is nonspecific. Light-chain amyloidosis is a common cause of macroglossia in adults.10,25

Neuropathy associated with M proteins is a clinical entity related to a multitude of disorders that may necessitate treating the underlying cellular clone responsible for the secretion of the toxic M protein. These disorders include light-chain amyloidosis, POEMS (polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, M protein, and skin changes or sclerotic bone lesions) syndrome, and IgM-related neuropathies with anti-myelin-associated glycoprotein antibodies.3,10,11,14

Notably, weight loss and fatigue in a patient with MGUS may be the first signs of light-chain amyloidosis or Waldenström macroglobulinemia and should prompt further evaluation.25

HOW ARE PATIENTS WITH MGUS RISK-STRATIFIED AND FOLLOWED?

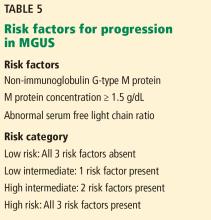

Research has helped to refine the diagnostic workup and recognize subsets of patients with MGUS at different risks of progression to myeloma and related disorders. Factors predicting progression are 1,6,7,26,27:

- The amount of the M protein

- The type of M protein (IgG vs non-IgG)

- An abnormal free light-chain ratio.

Half of patients with MGUS fall into the low-risk category, which is defined by IgG-type serum M protein in a concentration less than 1.5 g/dL and a normal serum free light-chain ratio (kappa-lambda 0.26–1.65).5,27 The absolute risk of progression at 20 years is only 5% for patients with low-risk MGUS, compared with 58% in patients with high-risk MGUS (positive for all 3 risk factors).5

The presence of less than 10% plasma cells in the bone marrow is required to satisfy the definition of MGUS, but bone marrow biopsy can be omitted for patients with low-risk MGUS, given the slim chance of finding a significant percentage of clonal plasma cells in the marrow and the inherently low risk of progression.5,10 Skeletal surveys are often deferred for low-risk MGUS, but we obtain them in all our patients to ensure the absence of plasmacytomas, which need to be treated (typically with radiotherapy). Importantly, patients with unexplained bone pain (mostly in long bones, ribs, and spine, whereas joints are not typically involved) and a normal skeletal survey should undergo advanced imaging (whole-body magnetic resonance imaging or whole-body positron emission tomography and computed tomography) to detect bone lesions otherwise missed on plain radiography.28,29

Most of the recommendations regarding follow-up are based on expert opinion, given the lack of randomized data. Most experts agree that all patients should be reevaluated 6 months after an M protein is detected, with laboratory surveillance tests (complete blood cell count, serum creatinine, serum calcium level, serum protein electrophoresis, and serum free light chains). Low-risk patients with a stable M protein level can be followed every 2 to 3 years.

Suspect malignant progression if the serum M protein level increases by 50% or more (with an absolute increase of ≥ 0.5 g/dL); the serum M protein level is 3 g/dL or higher; the serum free light-chain ratio is more than 100; or the patient has unexplained anemia, elevated creatinine, bone pain, fracture, or hypercalcemia.

Patients at intermediate or high risk should be followed annually after the initial 6-month visit.5,7,10

A recent study highlighted the importance of risk stratification in reducing the costs associated with an overzealous diagnostic workup of patients with low-risk MGUS.30 These savings are in addition to a reduction in patient anticipation and anxiety that universally occur before invasive procedures.

THE ROLE OF THE PRIMARY CARE PROVIDER AND THE HEMATOLOGIST

Once an M protein is identified, a comprehensive history, physical examination, and laboratory tests (serum protein electrophoresis to quantify the protein, serum immunofixation, serum free light chains, complete blood cell count, calcium, and creatinine) should be done, taking into consideration the differential diagnosis of monoclonal gammopathies discussed above. After MGUS is confirmed, the patient should be risk-stratified to determine the need for bone marrow biopsy and to predict the risk of progression to more serious conditions.

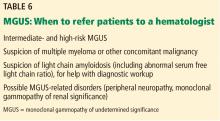

Referral to a hematologist is warranted for patients with intermediate- and high-risk MGUS, patients with abnormal serum free light-chain ratios, and those who show evidence of malignant progression. Patients with intermediate- and high-risk MGUS could be referred for bone marrow biopsy before assessment by a hematologist. The primary care provider may continue to follow patients with low-risk MGUS who do not display clinical or laboratory evidence of myeloma or related disorders.

The importance of educating patients to report any new worrisome symptom (eg, fatigue, neuropathy, weight loss, night sweats, bone pain) cannot be overemphasized, as some patients may progress to myeloma or other disorders between follow-up visits.

- van de Donk NW, Palumbo A, Johnsen HE, et al; European Myeloma Network. The clinical relevance and management of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and related disorders: recommendations from the European Myeloma Network. Haematologica 2014; 99(6):984–996. doi:10.3324/haematol.2013.100552

- International Myeloma Working Group. Criteria for the classification of monoclonal gammopathies, multiple myeloma and related disorders: a report of the International Myeloma Working Group. Br J Haematol 2003; 121(5):749–757. pmid:12780789

- Rajan AM, Rajkumar SV. Diagnostic evaluation of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Eur J Haematol 2013; 91(6):561–562. doi:10.1111/ejh.12198

- Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Br J Haematol 2006; 134(6):573–589. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06235.x

- Kyle RA, Durie BG, Rajkumar SV, et al; International Myeloma Working Group. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma: IMWG consensus perspectives risk factors for progression and guidelines for monitoring and management. Leukemia 2010; 24(6):1121–1127. doi:10.1038/leu.2010.60

- Bird J, Behrens J, Westin J, et al; Haemato-oncology Task Force of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology, UK Myeloma Forum and Nordic Myeloma Study Group. UK Myeloma Forum (UKMF) and Nordic Myeloma Study Group (NMSG): guidelines for the investigation of newly detected M-proteins and the management of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS). Br J Haematol 2009; 147(1):22–42. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07807.x

- Rajkumar SV, Kyle RA, Buadi FK. Advances in the diagnosis, classification, risk stratification, and management of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: implications for recategorizing disease entities in the presence of evolving scientific evidence. Mayo Clin Proc 2010; 85(10):945–948. doi:10.4065/mcp.2010.0520

- Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Rajkumar SV, et al. A long-term study of prognosis in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med 2002; 346(8):564–569. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa01133202

- Doyle LM, Gundrum JD, Farnen JP, Wright LJ, Kranig JAI, Go RS. Determining why and which clinicians order serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP), subsequent diagnoses based on indications, and clinical significance of routine follow-up: a study of patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS). Blood 2009; 114(22):Abstr 4883. www.bloodjournal.org/content/114/22/4883. Accessed December 4, 2018.

- Merlini G, Palladini G. Differential diagnosis of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2012; 2012:595–603. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2012.1.595

- Glavey SV, Leung N. Monoclonal gammopathy: the good, the bad and the ugly. Blood Rev 2016; 30(3):223–231. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2015.12.001

- Dispenzieri A, Gertz MA, Therneau TM, Kyle RA. Retrospective cohort study of 148 patients with polyclonal gammopathy. Mayo Clin Proc 2001; 76(5):476–487. doi:10.4065/76.5.476

- Merlini G, Stone MJ. Dangerous small B-cell clones. Blood 2006; 108(8):2520–2530. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-03-001164

- Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15(12):e538–e548. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70442-5

- Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Witzig TE, et al. Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc 2003; 78(1):21–33. doi:10.4065/78.1.21

- Hutchison CA, Harding S, Hewins P, et al. Quantitative assessment of serum and urinary polyclonal free light chains in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 3(6):1684–1690. doi:10.2215/CJN.02290508

- Katzmann JA, Dispenzieri A, Kyle RA, et al. Elimination of the need for urine studies in the screening algorithm for monoclonal gammopathies by using serum immunofixation and free light chain assays. Mayo Clin Proc 2006; 81(12):1575–1578. doi:10.4065/81.12.1575

- Berenson JR, Anderson KC, Audell RA, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: a consensus statement. Br J Haematol 2010; 150(1):28–38. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08207.x

- Mangiacavalli S, Cocito F, Pochintesta L, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: a new proposal of workup. Eur J Haematol 2013; 91(4):356–360. doi:10.1111/ejh.12172

- Bianchi G, Kyle RA, Colby CL, et al. Impact of optimal follow-up of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance on early diagnosis and prevention of myeloma-related complications. Blood 2010;116:2019–2025. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-04-277566

- Rosiñol L, Cibeira MT, Montoto S, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: predictors of malignant transformation and recognition of an evolving type characterized by a progressive increase in M protein size. Mayo Clin Proc 2007; 82(4):428–434. doi:10.4065/82.4.428

- Vanderschueren S, Mylle M, Dierickx D, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: significant beyond hematology. Mayo Clin Proc 2009; 84(9):842–845. doi:10.4065/84.9.842

- Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and smouldering multiple myeloma: emphasis on risk factors for progression. Br J Haematol 2007; 139(5):730–743. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06873.x

- Leung N, Bridoux F, Hutchison CA, et al; International Kidney and Monoclonal Gammopathy Research Group. Monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance: when MGUS is no longer undetermined or insignificant. Blood. 2012; 120(22):4292–4295. doi:10.1182/blood-2012-07-445304

- Merlini G, Wechalekar AD, Palladini G. Systemic light chain amyloidosis: an update for treating physicians. Blood 2013; 121(26):5124–5130. doi:10.1182/blood-2013-01-453001

- Dispenzieri A, Katzmann JA, Kyle RA, et al. Prevalence and risk of progression of light-chain monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: a retrospective population-based cohort study. Lancet 2010; 375(9727):1721–1728. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60482-5

- Rajkumar SV, Kyle RA, Therneau TM, et al. Serum free light chain ratio is an independent risk factor for progression in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Blood 2005; 106(3):812–817. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-03-1038

- Dimopoulos MA, Hillengass J, Usmani S, et al. Role of magnetic resonance imaging in the management of patients with multiple myeloma: a consensus statement. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33(6):657–664. doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.57.9961

- Dimopoulos M, Kyle R, Fermand JP, et al. Consensus recommendations for standard investigative workup: report of the International Myeloma Workshop Consensus Panel 3. Blood 2011; 117(18):4701–4705. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-10-299529

- Pompa T, Maddox M, Woodard A, et al. Cost effectiveness in low risk MGUS patients. Blood 2016; 128:2360. http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/128/22/2360. Accessed December 4, 2018.

MGUS is present in 3% to 4% of the population over age 50 and is more common in older men, African Americans, and Africans.1–6

The overall risk of progression to myeloma and related disorders is less than or equal to 1% per year depending on the subtype of the M protein (higher risk with IgM than non-IgM and light-chain MGUS).7,8 While the risk of malignant transformation is low, multiple myeloma is almost always preceded by the presence of an asymptomatic and often unrecognized monoclonal protein.

WHEN SHOULD WE LOOK FOR AN M PROTEIN?

An M protein is typically an incidental finding when a patient is being assessed for any of a number of presenting symptoms or conditions. A large retrospective study9 found that screening for MGUS was mostly performed by internal medicine physicians. The indications for testing were anemia, bone-related issues, elevated creatinine, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and neuropathy.

A low anion gap is not a major indicator of an M protein unless in a high concentration, in which case other manifestations would be present, such as renal failure, which would guide the diagnosis. Polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia as a cause of low anion gap is far more common than MGUS.

HOW SHOULD WE SCREEN FOR AN M PROTEIN?

Serum protein electrophoresis is an initial test used to identify an M protein and has a key role in quantifying it (Figure 2). An M protein appears as a narrow spike on the agarose gel and should be distinguished from the broad band seen in polyclonal gammopathies associated with cirrhosis and chronic infectious and inflammatory conditions, among others.12 A major disadvantage of serum protein electrophoresis is that it cannot detect an M protein in very low concentrations or determine its identity.

Serum immunofixation is more sensitive than serum protein electrophoresis and should always be ordered in conjunction with it, mostly to ensure detecting tiny amounts of M protein and to identify the type of its heavy chain and light-chain components.13

The serum free light-chain assay is also considered an essential part of the screening process to detect light-chain MGUS and light-chain myeloma. As many as 16% of myeloma patients secrete only light chains, which may not be identified on serum immunofixation.3,6,7,10,14,15 In general, a low kappa-lambda ratio (< 0.26) indicates the overproduction of lambda light chains, and a high ratio (> 1.65) indicates the overproduction of kappa light chains.

The serum free light-chain assay helps detect abnormal secretion of monoclonal light chains before they appear in the urine once the kidney tubules become saturated and unable to reabsorb them.

Of note, the free light-chain ratio can be abnormal (< 0.26 or > 1.65) in chronic kidney disease. Thus, it may be challenging to discern whether an abnormal light-chain ratio is related to impaired light-chain clearance by the kidneys or to MGUS. In general, kappa light chains are more elevated than lambda light chains in chronic kidney disease, but the ratio should not be considerably skewed. A kappa-lambda ratio below 0.37 or above 3 is rarely seen in chronic kidney disease and should prompt workup for MGUS.16

Tests in combination. The sensitivity of screening for M proteins ranges from 82% with serum protein electrophoresis alone to 93% with the addition of serum immunofixation and to 98% with the serum free light-chain assay.15 The latter can replace urine protein electrophoresis and immunofixation when screening for M protein, given its higher sensitivity.15,17 An important caveat is that urine dipstick testing does not detect urine light chains.

Table 3 lists the initial laboratory tests required in patients with MGUS.

WHAT IS THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF MONOCLONAL GAMMOPATHIES?

that feature an M protein and would otherwise require treatment (Table 4). The differential diagnosis includes smoldering multiple myeloma, symptomatic multiple myeloma, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, light-chain amyloidosis, low-grade B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders, a variety of monoclonal protein-related kidney disorders, and plasmacytomas.10,14

MGUS

Based on the International Myeloma Working Group consensus, a formal diagnosis of MGUS is established when a serum M protein is detected and measured at a concentration less than 3 g/dL on serum protein electrophoresis along with less than 10% clonal plasma cells in the bone marrow.1–6,14,18,19 Nevertheless, bone marrow biopsy can be omitted in certain patients as discussed below. The absence of myeloma-related organ damage—particularly osteolytic bone lesions, anemia, otherwise unexplained renal failure, and hypercalcemia—is fundamental and necessary for a diagnosis of MGUS.

Smoldering multiple myeloma

Compared with patients with MGUS, patients with smoldering multiple myeloma have higher M protein concentrations (≥ 3 g/dL) or 10% or more clonal plasma cells in the marrow or both, and are at higher risk of progression to symptomatic multiple myeloma. Nevertheless, like patients with MGUS, they have no myeloma symptoms or evidence of end-organ damage.

Symptomatic multiple myeloma

By definition, patients with multiple myeloma develop organ damage related to their malignancy and need therapy to halt disease progression. Multiple myeloma causes clinical manifestations through cellular infiltration of the bone and bone marrow (anemia, osteolysis, and hypercalcemia) and light chain-induced toxicity (renal tubular damage and cast nephropathy).

In 2014, the definition of multiple myeloma was updated to include 3 new myeloma-defining events that herald a significantly higher risk of progression from smoldering to symptomatic multiple myeloma, and now constitute an integral part of the diagnosis of symptomatic multiple myeloma. These are:

- Focal lesions (> 1 lesion larger than 5 mm) visible on magnetic resonance imaging

- ≥ 60% clonal plasma cells on bone marrow biopsy

- Ratio of involved to uninvolved serum free light chains ≥ 100 (the involved light chain is the one detected on serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation).14

Bone pain, symptoms of anemia, and decreased urine output may suggest myeloma, but are not diagnostic. Although the “CRAB” criteria (elevated calcium, renal failure, anemia, and bone lesions) define multiple myeloma, the presence of anemia, hypercalcemia, or renal dysfunction do not by themselves mark transformation from MGUS to multiple myeloma. Thus, other causes need to be considered, since the risk of transformation is so low. Importantly, hyperparathyroidism must be ruled out if hypercalcemia is present in a patient with MGUS.10

Waldenström macroglobulinemia

Waldenström macroglobulinemia, also called lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, is an indolent non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma that can invade the marrow, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes, leading to anemia and organomegaly. It features a monoclonal IgM protein that can be associated with increased blood viscosity, cold agglutinin disease, peripheral neuropathy, and cryoglobulinemia.

Waldenström macroglobulinemia should be suspected in any patient with IgM type M protein and symptoms related to hyperviscosity (headache, blurry vision, lightheadedness, shortness of breath, unexplained epistaxis, gum bleeding); systemic symptoms (fever, weight loss, and night sweats); and abdominal pain (due to organomegaly).23

Monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance

Monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance (MGRS) is a newly recognized entity defined by kidney dysfunction associated with an M protein without evidence of myeloma or other lymphoid disorders.24 Multiple disorders have been included in this category with different underlying mechanisms of kidney injury. This entity is beyond the scope of this discussion.

Light-chain amyloidosis

Misfolded light-chain deposition leading to organ dysfunction is the hallmark of light-chain amyloidosis, which constitutes a subset of MGRS. An abnormal light-chain ratio, especially if skewed toward lambda should trigger an investigation for light-chain amyloidosis.10

Abnormal light chains may infiltrate any organ or tissue, but of greatest concern is infiltration of the myocardium with ensuing heart failure manifestations. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) is a sensitive marker for cardiac amyloidosis in the presence of suggestive features on transthoracic echocardiography (eg, left ventricular hypertrophy) but is not specific as it can be elevated in heart failure regardless of the underlying cause.10

Glomerular injury with nephrotic syndrome may also point toward renal involvement by light-chain amyloidosis and establishes a key distinctive factor from myeloma in which tubular injury is the main mechanism of kidney dysfunction.

Clinical clues for light-chain amyloidosis include heart failure symptoms, neuropathy, and macroglossia. If any of these symptoms and signs is present, we recommend electrocardiography (look for low voltage in limb leads), transthoracic echocardiography, measuring the NT-proBNP level, and urinalysis to look for albuminuria. Notably, carpal tunnel syndrome may be a very early clinical manifestation of amyloidosis, but by itself it is nonspecific. Light-chain amyloidosis is a common cause of macroglossia in adults.10,25

Neuropathy associated with M proteins is a clinical entity related to a multitude of disorders that may necessitate treating the underlying cellular clone responsible for the secretion of the toxic M protein. These disorders include light-chain amyloidosis, POEMS (polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, M protein, and skin changes or sclerotic bone lesions) syndrome, and IgM-related neuropathies with anti-myelin-associated glycoprotein antibodies.3,10,11,14

Notably, weight loss and fatigue in a patient with MGUS may be the first signs of light-chain amyloidosis or Waldenström macroglobulinemia and should prompt further evaluation.25

HOW ARE PATIENTS WITH MGUS RISK-STRATIFIED AND FOLLOWED?

Research has helped to refine the diagnostic workup and recognize subsets of patients with MGUS at different risks of progression to myeloma and related disorders. Factors predicting progression are 1,6,7,26,27:

- The amount of the M protein

- The type of M protein (IgG vs non-IgG)

- An abnormal free light-chain ratio.

Half of patients with MGUS fall into the low-risk category, which is defined by IgG-type serum M protein in a concentration less than 1.5 g/dL and a normal serum free light-chain ratio (kappa-lambda 0.26–1.65).5,27 The absolute risk of progression at 20 years is only 5% for patients with low-risk MGUS, compared with 58% in patients with high-risk MGUS (positive for all 3 risk factors).5

The presence of less than 10% plasma cells in the bone marrow is required to satisfy the definition of MGUS, but bone marrow biopsy can be omitted for patients with low-risk MGUS, given the slim chance of finding a significant percentage of clonal plasma cells in the marrow and the inherently low risk of progression.5,10 Skeletal surveys are often deferred for low-risk MGUS, but we obtain them in all our patients to ensure the absence of plasmacytomas, which need to be treated (typically with radiotherapy). Importantly, patients with unexplained bone pain (mostly in long bones, ribs, and spine, whereas joints are not typically involved) and a normal skeletal survey should undergo advanced imaging (whole-body magnetic resonance imaging or whole-body positron emission tomography and computed tomography) to detect bone lesions otherwise missed on plain radiography.28,29

Most of the recommendations regarding follow-up are based on expert opinion, given the lack of randomized data. Most experts agree that all patients should be reevaluated 6 months after an M protein is detected, with laboratory surveillance tests (complete blood cell count, serum creatinine, serum calcium level, serum protein electrophoresis, and serum free light chains). Low-risk patients with a stable M protein level can be followed every 2 to 3 years.

Suspect malignant progression if the serum M protein level increases by 50% or more (with an absolute increase of ≥ 0.5 g/dL); the serum M protein level is 3 g/dL or higher; the serum free light-chain ratio is more than 100; or the patient has unexplained anemia, elevated creatinine, bone pain, fracture, or hypercalcemia.

Patients at intermediate or high risk should be followed annually after the initial 6-month visit.5,7,10

A recent study highlighted the importance of risk stratification in reducing the costs associated with an overzealous diagnostic workup of patients with low-risk MGUS.30 These savings are in addition to a reduction in patient anticipation and anxiety that universally occur before invasive procedures.

THE ROLE OF THE PRIMARY CARE PROVIDER AND THE HEMATOLOGIST

Once an M protein is identified, a comprehensive history, physical examination, and laboratory tests (serum protein electrophoresis to quantify the protein, serum immunofixation, serum free light chains, complete blood cell count, calcium, and creatinine) should be done, taking into consideration the differential diagnosis of monoclonal gammopathies discussed above. After MGUS is confirmed, the patient should be risk-stratified to determine the need for bone marrow biopsy and to predict the risk of progression to more serious conditions.

Referral to a hematologist is warranted for patients with intermediate- and high-risk MGUS, patients with abnormal serum free light-chain ratios, and those who show evidence of malignant progression. Patients with intermediate- and high-risk MGUS could be referred for bone marrow biopsy before assessment by a hematologist. The primary care provider may continue to follow patients with low-risk MGUS who do not display clinical or laboratory evidence of myeloma or related disorders.

The importance of educating patients to report any new worrisome symptom (eg, fatigue, neuropathy, weight loss, night sweats, bone pain) cannot be overemphasized, as some patients may progress to myeloma or other disorders between follow-up visits.

MGUS is present in 3% to 4% of the population over age 50 and is more common in older men, African Americans, and Africans.1–6

The overall risk of progression to myeloma and related disorders is less than or equal to 1% per year depending on the subtype of the M protein (higher risk with IgM than non-IgM and light-chain MGUS).7,8 While the risk of malignant transformation is low, multiple myeloma is almost always preceded by the presence of an asymptomatic and often unrecognized monoclonal protein.

WHEN SHOULD WE LOOK FOR AN M PROTEIN?

An M protein is typically an incidental finding when a patient is being assessed for any of a number of presenting symptoms or conditions. A large retrospective study9 found that screening for MGUS was mostly performed by internal medicine physicians. The indications for testing were anemia, bone-related issues, elevated creatinine, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and neuropathy.

A low anion gap is not a major indicator of an M protein unless in a high concentration, in which case other manifestations would be present, such as renal failure, which would guide the diagnosis. Polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia as a cause of low anion gap is far more common than MGUS.

HOW SHOULD WE SCREEN FOR AN M PROTEIN?

Serum protein electrophoresis is an initial test used to identify an M protein and has a key role in quantifying it (Figure 2). An M protein appears as a narrow spike on the agarose gel and should be distinguished from the broad band seen in polyclonal gammopathies associated with cirrhosis and chronic infectious and inflammatory conditions, among others.12 A major disadvantage of serum protein electrophoresis is that it cannot detect an M protein in very low concentrations or determine its identity.

Serum immunofixation is more sensitive than serum protein electrophoresis and should always be ordered in conjunction with it, mostly to ensure detecting tiny amounts of M protein and to identify the type of its heavy chain and light-chain components.13

The serum free light-chain assay is also considered an essential part of the screening process to detect light-chain MGUS and light-chain myeloma. As many as 16% of myeloma patients secrete only light chains, which may not be identified on serum immunofixation.3,6,7,10,14,15 In general, a low kappa-lambda ratio (< 0.26) indicates the overproduction of lambda light chains, and a high ratio (> 1.65) indicates the overproduction of kappa light chains.

The serum free light-chain assay helps detect abnormal secretion of monoclonal light chains before they appear in the urine once the kidney tubules become saturated and unable to reabsorb them.

Of note, the free light-chain ratio can be abnormal (< 0.26 or > 1.65) in chronic kidney disease. Thus, it may be challenging to discern whether an abnormal light-chain ratio is related to impaired light-chain clearance by the kidneys or to MGUS. In general, kappa light chains are more elevated than lambda light chains in chronic kidney disease, but the ratio should not be considerably skewed. A kappa-lambda ratio below 0.37 or above 3 is rarely seen in chronic kidney disease and should prompt workup for MGUS.16

Tests in combination. The sensitivity of screening for M proteins ranges from 82% with serum protein electrophoresis alone to 93% with the addition of serum immunofixation and to 98% with the serum free light-chain assay.15 The latter can replace urine protein electrophoresis and immunofixation when screening for M protein, given its higher sensitivity.15,17 An important caveat is that urine dipstick testing does not detect urine light chains.

Table 3 lists the initial laboratory tests required in patients with MGUS.

WHAT IS THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF MONOCLONAL GAMMOPATHIES?

that feature an M protein and would otherwise require treatment (Table 4). The differential diagnosis includes smoldering multiple myeloma, symptomatic multiple myeloma, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, light-chain amyloidosis, low-grade B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders, a variety of monoclonal protein-related kidney disorders, and plasmacytomas.10,14

MGUS

Based on the International Myeloma Working Group consensus, a formal diagnosis of MGUS is established when a serum M protein is detected and measured at a concentration less than 3 g/dL on serum protein electrophoresis along with less than 10% clonal plasma cells in the bone marrow.1–6,14,18,19 Nevertheless, bone marrow biopsy can be omitted in certain patients as discussed below. The absence of myeloma-related organ damage—particularly osteolytic bone lesions, anemia, otherwise unexplained renal failure, and hypercalcemia—is fundamental and necessary for a diagnosis of MGUS.

Smoldering multiple myeloma

Compared with patients with MGUS, patients with smoldering multiple myeloma have higher M protein concentrations (≥ 3 g/dL) or 10% or more clonal plasma cells in the marrow or both, and are at higher risk of progression to symptomatic multiple myeloma. Nevertheless, like patients with MGUS, they have no myeloma symptoms or evidence of end-organ damage.

Symptomatic multiple myeloma

By definition, patients with multiple myeloma develop organ damage related to their malignancy and need therapy to halt disease progression. Multiple myeloma causes clinical manifestations through cellular infiltration of the bone and bone marrow (anemia, osteolysis, and hypercalcemia) and light chain-induced toxicity (renal tubular damage and cast nephropathy).

In 2014, the definition of multiple myeloma was updated to include 3 new myeloma-defining events that herald a significantly higher risk of progression from smoldering to symptomatic multiple myeloma, and now constitute an integral part of the diagnosis of symptomatic multiple myeloma. These are:

- Focal lesions (> 1 lesion larger than 5 mm) visible on magnetic resonance imaging

- ≥ 60% clonal plasma cells on bone marrow biopsy

- Ratio of involved to uninvolved serum free light chains ≥ 100 (the involved light chain is the one detected on serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation).14

Bone pain, symptoms of anemia, and decreased urine output may suggest myeloma, but are not diagnostic. Although the “CRAB” criteria (elevated calcium, renal failure, anemia, and bone lesions) define multiple myeloma, the presence of anemia, hypercalcemia, or renal dysfunction do not by themselves mark transformation from MGUS to multiple myeloma. Thus, other causes need to be considered, since the risk of transformation is so low. Importantly, hyperparathyroidism must be ruled out if hypercalcemia is present in a patient with MGUS.10

Waldenström macroglobulinemia

Waldenström macroglobulinemia, also called lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, is an indolent non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma that can invade the marrow, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes, leading to anemia and organomegaly. It features a monoclonal IgM protein that can be associated with increased blood viscosity, cold agglutinin disease, peripheral neuropathy, and cryoglobulinemia.

Waldenström macroglobulinemia should be suspected in any patient with IgM type M protein and symptoms related to hyperviscosity (headache, blurry vision, lightheadedness, shortness of breath, unexplained epistaxis, gum bleeding); systemic symptoms (fever, weight loss, and night sweats); and abdominal pain (due to organomegaly).23

Monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance

Monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance (MGRS) is a newly recognized entity defined by kidney dysfunction associated with an M protein without evidence of myeloma or other lymphoid disorders.24 Multiple disorders have been included in this category with different underlying mechanisms of kidney injury. This entity is beyond the scope of this discussion.

Light-chain amyloidosis

Misfolded light-chain deposition leading to organ dysfunction is the hallmark of light-chain amyloidosis, which constitutes a subset of MGRS. An abnormal light-chain ratio, especially if skewed toward lambda should trigger an investigation for light-chain amyloidosis.10

Abnormal light chains may infiltrate any organ or tissue, but of greatest concern is infiltration of the myocardium with ensuing heart failure manifestations. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) is a sensitive marker for cardiac amyloidosis in the presence of suggestive features on transthoracic echocardiography (eg, left ventricular hypertrophy) but is not specific as it can be elevated in heart failure regardless of the underlying cause.10

Glomerular injury with nephrotic syndrome may also point toward renal involvement by light-chain amyloidosis and establishes a key distinctive factor from myeloma in which tubular injury is the main mechanism of kidney dysfunction.

Clinical clues for light-chain amyloidosis include heart failure symptoms, neuropathy, and macroglossia. If any of these symptoms and signs is present, we recommend electrocardiography (look for low voltage in limb leads), transthoracic echocardiography, measuring the NT-proBNP level, and urinalysis to look for albuminuria. Notably, carpal tunnel syndrome may be a very early clinical manifestation of amyloidosis, but by itself it is nonspecific. Light-chain amyloidosis is a common cause of macroglossia in adults.10,25

Neuropathy associated with M proteins is a clinical entity related to a multitude of disorders that may necessitate treating the underlying cellular clone responsible for the secretion of the toxic M protein. These disorders include light-chain amyloidosis, POEMS (polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, M protein, and skin changes or sclerotic bone lesions) syndrome, and IgM-related neuropathies with anti-myelin-associated glycoprotein antibodies.3,10,11,14

Notably, weight loss and fatigue in a patient with MGUS may be the first signs of light-chain amyloidosis or Waldenström macroglobulinemia and should prompt further evaluation.25

HOW ARE PATIENTS WITH MGUS RISK-STRATIFIED AND FOLLOWED?

Research has helped to refine the diagnostic workup and recognize subsets of patients with MGUS at different risks of progression to myeloma and related disorders. Factors predicting progression are 1,6,7,26,27:

- The amount of the M protein

- The type of M protein (IgG vs non-IgG)

- An abnormal free light-chain ratio.

Half of patients with MGUS fall into the low-risk category, which is defined by IgG-type serum M protein in a concentration less than 1.5 g/dL and a normal serum free light-chain ratio (kappa-lambda 0.26–1.65).5,27 The absolute risk of progression at 20 years is only 5% for patients with low-risk MGUS, compared with 58% in patients with high-risk MGUS (positive for all 3 risk factors).5

The presence of less than 10% plasma cells in the bone marrow is required to satisfy the definition of MGUS, but bone marrow biopsy can be omitted for patients with low-risk MGUS, given the slim chance of finding a significant percentage of clonal plasma cells in the marrow and the inherently low risk of progression.5,10 Skeletal surveys are often deferred for low-risk MGUS, but we obtain them in all our patients to ensure the absence of plasmacytomas, which need to be treated (typically with radiotherapy). Importantly, patients with unexplained bone pain (mostly in long bones, ribs, and spine, whereas joints are not typically involved) and a normal skeletal survey should undergo advanced imaging (whole-body magnetic resonance imaging or whole-body positron emission tomography and computed tomography) to detect bone lesions otherwise missed on plain radiography.28,29

Most of the recommendations regarding follow-up are based on expert opinion, given the lack of randomized data. Most experts agree that all patients should be reevaluated 6 months after an M protein is detected, with laboratory surveillance tests (complete blood cell count, serum creatinine, serum calcium level, serum protein electrophoresis, and serum free light chains). Low-risk patients with a stable M protein level can be followed every 2 to 3 years.

Suspect malignant progression if the serum M protein level increases by 50% or more (with an absolute increase of ≥ 0.5 g/dL); the serum M protein level is 3 g/dL or higher; the serum free light-chain ratio is more than 100; or the patient has unexplained anemia, elevated creatinine, bone pain, fracture, or hypercalcemia.

Patients at intermediate or high risk should be followed annually after the initial 6-month visit.5,7,10

A recent study highlighted the importance of risk stratification in reducing the costs associated with an overzealous diagnostic workup of patients with low-risk MGUS.30 These savings are in addition to a reduction in patient anticipation and anxiety that universally occur before invasive procedures.

THE ROLE OF THE PRIMARY CARE PROVIDER AND THE HEMATOLOGIST

Once an M protein is identified, a comprehensive history, physical examination, and laboratory tests (serum protein electrophoresis to quantify the protein, serum immunofixation, serum free light chains, complete blood cell count, calcium, and creatinine) should be done, taking into consideration the differential diagnosis of monoclonal gammopathies discussed above. After MGUS is confirmed, the patient should be risk-stratified to determine the need for bone marrow biopsy and to predict the risk of progression to more serious conditions.

Referral to a hematologist is warranted for patients with intermediate- and high-risk MGUS, patients with abnormal serum free light-chain ratios, and those who show evidence of malignant progression. Patients with intermediate- and high-risk MGUS could be referred for bone marrow biopsy before assessment by a hematologist. The primary care provider may continue to follow patients with low-risk MGUS who do not display clinical or laboratory evidence of myeloma or related disorders.

The importance of educating patients to report any new worrisome symptom (eg, fatigue, neuropathy, weight loss, night sweats, bone pain) cannot be overemphasized, as some patients may progress to myeloma or other disorders between follow-up visits.

- van de Donk NW, Palumbo A, Johnsen HE, et al; European Myeloma Network. The clinical relevance and management of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and related disorders: recommendations from the European Myeloma Network. Haematologica 2014; 99(6):984–996. doi:10.3324/haematol.2013.100552

- International Myeloma Working Group. Criteria for the classification of monoclonal gammopathies, multiple myeloma and related disorders: a report of the International Myeloma Working Group. Br J Haematol 2003; 121(5):749–757. pmid:12780789

- Rajan AM, Rajkumar SV. Diagnostic evaluation of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Eur J Haematol 2013; 91(6):561–562. doi:10.1111/ejh.12198

- Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Br J Haematol 2006; 134(6):573–589. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06235.x

- Kyle RA, Durie BG, Rajkumar SV, et al; International Myeloma Working Group. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma: IMWG consensus perspectives risk factors for progression and guidelines for monitoring and management. Leukemia 2010; 24(6):1121–1127. doi:10.1038/leu.2010.60

- Bird J, Behrens J, Westin J, et al; Haemato-oncology Task Force of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology, UK Myeloma Forum and Nordic Myeloma Study Group. UK Myeloma Forum (UKMF) and Nordic Myeloma Study Group (NMSG): guidelines for the investigation of newly detected M-proteins and the management of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS). Br J Haematol 2009; 147(1):22–42. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07807.x

- Rajkumar SV, Kyle RA, Buadi FK. Advances in the diagnosis, classification, risk stratification, and management of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: implications for recategorizing disease entities in the presence of evolving scientific evidence. Mayo Clin Proc 2010; 85(10):945–948. doi:10.4065/mcp.2010.0520

- Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Rajkumar SV, et al. A long-term study of prognosis in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med 2002; 346(8):564–569. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa01133202

- Doyle LM, Gundrum JD, Farnen JP, Wright LJ, Kranig JAI, Go RS. Determining why and which clinicians order serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP), subsequent diagnoses based on indications, and clinical significance of routine follow-up: a study of patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS). Blood 2009; 114(22):Abstr 4883. www.bloodjournal.org/content/114/22/4883. Accessed December 4, 2018.

- Merlini G, Palladini G. Differential diagnosis of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2012; 2012:595–603. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2012.1.595

- Glavey SV, Leung N. Monoclonal gammopathy: the good, the bad and the ugly. Blood Rev 2016; 30(3):223–231. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2015.12.001

- Dispenzieri A, Gertz MA, Therneau TM, Kyle RA. Retrospective cohort study of 148 patients with polyclonal gammopathy. Mayo Clin Proc 2001; 76(5):476–487. doi:10.4065/76.5.476

- Merlini G, Stone MJ. Dangerous small B-cell clones. Blood 2006; 108(8):2520–2530. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-03-001164

- Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15(12):e538–e548. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70442-5

- Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Witzig TE, et al. Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc 2003; 78(1):21–33. doi:10.4065/78.1.21

- Hutchison CA, Harding S, Hewins P, et al. Quantitative assessment of serum and urinary polyclonal free light chains in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 3(6):1684–1690. doi:10.2215/CJN.02290508

- Katzmann JA, Dispenzieri A, Kyle RA, et al. Elimination of the need for urine studies in the screening algorithm for monoclonal gammopathies by using serum immunofixation and free light chain assays. Mayo Clin Proc 2006; 81(12):1575–1578. doi:10.4065/81.12.1575

- Berenson JR, Anderson KC, Audell RA, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: a consensus statement. Br J Haematol 2010; 150(1):28–38. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08207.x

- Mangiacavalli S, Cocito F, Pochintesta L, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: a new proposal of workup. Eur J Haematol 2013; 91(4):356–360. doi:10.1111/ejh.12172

- Bianchi G, Kyle RA, Colby CL, et al. Impact of optimal follow-up of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance on early diagnosis and prevention of myeloma-related complications. Blood 2010;116:2019–2025. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-04-277566

- Rosiñol L, Cibeira MT, Montoto S, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: predictors of malignant transformation and recognition of an evolving type characterized by a progressive increase in M protein size. Mayo Clin Proc 2007; 82(4):428–434. doi:10.4065/82.4.428

- Vanderschueren S, Mylle M, Dierickx D, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: significant beyond hematology. Mayo Clin Proc 2009; 84(9):842–845. doi:10.4065/84.9.842

- Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and smouldering multiple myeloma: emphasis on risk factors for progression. Br J Haematol 2007; 139(5):730–743. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06873.x

- Leung N, Bridoux F, Hutchison CA, et al; International Kidney and Monoclonal Gammopathy Research Group. Monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance: when MGUS is no longer undetermined or insignificant. Blood. 2012; 120(22):4292–4295. doi:10.1182/blood-2012-07-445304

- Merlini G, Wechalekar AD, Palladini G. Systemic light chain amyloidosis: an update for treating physicians. Blood 2013; 121(26):5124–5130. doi:10.1182/blood-2013-01-453001

- Dispenzieri A, Katzmann JA, Kyle RA, et al. Prevalence and risk of progression of light-chain monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: a retrospective population-based cohort study. Lancet 2010; 375(9727):1721–1728. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60482-5

- Rajkumar SV, Kyle RA, Therneau TM, et al. Serum free light chain ratio is an independent risk factor for progression in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Blood 2005; 106(3):812–817. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-03-1038

- Dimopoulos MA, Hillengass J, Usmani S, et al. Role of magnetic resonance imaging in the management of patients with multiple myeloma: a consensus statement. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33(6):657–664. doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.57.9961

- Dimopoulos M, Kyle R, Fermand JP, et al. Consensus recommendations for standard investigative workup: report of the International Myeloma Workshop Consensus Panel 3. Blood 2011; 117(18):4701–4705. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-10-299529

- Pompa T, Maddox M, Woodard A, et al. Cost effectiveness in low risk MGUS patients. Blood 2016; 128:2360. http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/128/22/2360. Accessed December 4, 2018.

- van de Donk NW, Palumbo A, Johnsen HE, et al; European Myeloma Network. The clinical relevance and management of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and related disorders: recommendations from the European Myeloma Network. Haematologica 2014; 99(6):984–996. doi:10.3324/haematol.2013.100552

- International Myeloma Working Group. Criteria for the classification of monoclonal gammopathies, multiple myeloma and related disorders: a report of the International Myeloma Working Group. Br J Haematol 2003; 121(5):749–757. pmid:12780789

- Rajan AM, Rajkumar SV. Diagnostic evaluation of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Eur J Haematol 2013; 91(6):561–562. doi:10.1111/ejh.12198

- Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Br J Haematol 2006; 134(6):573–589. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06235.x

- Kyle RA, Durie BG, Rajkumar SV, et al; International Myeloma Working Group. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma: IMWG consensus perspectives risk factors for progression and guidelines for monitoring and management. Leukemia 2010; 24(6):1121–1127. doi:10.1038/leu.2010.60

- Bird J, Behrens J, Westin J, et al; Haemato-oncology Task Force of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology, UK Myeloma Forum and Nordic Myeloma Study Group. UK Myeloma Forum (UKMF) and Nordic Myeloma Study Group (NMSG): guidelines for the investigation of newly detected M-proteins and the management of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS). Br J Haematol 2009; 147(1):22–42. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07807.x

- Rajkumar SV, Kyle RA, Buadi FK. Advances in the diagnosis, classification, risk stratification, and management of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: implications for recategorizing disease entities in the presence of evolving scientific evidence. Mayo Clin Proc 2010; 85(10):945–948. doi:10.4065/mcp.2010.0520

- Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Rajkumar SV, et al. A long-term study of prognosis in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med 2002; 346(8):564–569. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa01133202