User login

Drug receives priority review for HCL

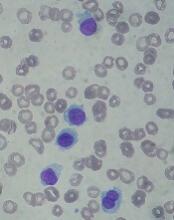

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has accepted for priority review the biologics license application (BLA) for moxetumomab pasudotox, an investigational anti-CD22 recombinant immunotoxin.

With this BLA, AstraZeneca is seeking approval for moxetumomab pasudotox for the treatment of adults with hairy cell leukemia (HCL) who have received at least 2 prior lines of therapy.

The FDA expects to make a decision on the BLA in the third quarter of this year.

The FDA aims to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10 months.

The agency grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

About moxetumomab pasudotox

Moxetumomab pasudotox (formerly CAT-8015 or HA22) is composed of a binding portion of an anti-CD22 antibody fused to a toxin. After binding to CD22, the molecule is internalized, processed, and releases its modified protein toxin, which inhibits protein translation and leads to apoptosis.

In addition to priority review, moxetumomab pasudotox has received orphan drug designation from the FDA.

Moxetumomab pasudotox has been tested in a phase 1 trial. Initial results from this trial were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2012. Long-term follow-up was presented at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting.

The ASH data included 49 patients with relapsed/refractory HCL. Their median age was 57 (range, 40-77), most (n=41) were male, and they had a median of 35 (range, 1-60,444) circulating HCL cells/mm3 at baseline (in 48 evaluable patients).

Twenty-eight patients received moxetumomab pasudotox in the dose-escalation portion of the study—at 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, or 50 µg/kg—and 21 received the drug at 50 µg/kg for the extension portion of the study.

Among the 33 patients who received moxetumomab pasudotox at 50 µg/kg, the overall response rate was 88%, and the complete response (CR) rate was 64% (n=21). The median time to CR was 3.6 months, and the median duration of CR was 70.3 months.

The median follow-up was 75 months for the entire study population. At 72 months, the progression-free survival (PFS) rate was 77%.

The researchers found that minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity (via immunohistochemistry) was associated with extended response duration and prolonged PFS.

The MRD evaluation included 19 MRD+ patients and 18 MRD- patients. Forty-seven percent of the MRD+ patients (n=9) and 94% of the MRD- patients (n=17) had a CR as their best response.

The median duration of CR was 13.1 months among the MRD+ patients and was not reached among the MRD- patients (P=0.0002). The median PFS was 82.1 months among the MRD+ patients and not reached among the MRD- patients (P=0.0031).

Moxetumomab pasudotox did not undergo phase 2 testing but proceeded to a phase 3 trial. In this single-arm study, researchers evaluated the drug in HCL patients who had received at least 2 prior therapies.

According to AstraZeneca, the study’s primary endpoint—durable CR—was met. The company said the phase 3 results will be presented at an upcoming medical meeting.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has accepted for priority review the biologics license application (BLA) for moxetumomab pasudotox, an investigational anti-CD22 recombinant immunotoxin.

With this BLA, AstraZeneca is seeking approval for moxetumomab pasudotox for the treatment of adults with hairy cell leukemia (HCL) who have received at least 2 prior lines of therapy.

The FDA expects to make a decision on the BLA in the third quarter of this year.

The FDA aims to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10 months.

The agency grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

About moxetumomab pasudotox

Moxetumomab pasudotox (formerly CAT-8015 or HA22) is composed of a binding portion of an anti-CD22 antibody fused to a toxin. After binding to CD22, the molecule is internalized, processed, and releases its modified protein toxin, which inhibits protein translation and leads to apoptosis.

In addition to priority review, moxetumomab pasudotox has received orphan drug designation from the FDA.

Moxetumomab pasudotox has been tested in a phase 1 trial. Initial results from this trial were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2012. Long-term follow-up was presented at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting.

The ASH data included 49 patients with relapsed/refractory HCL. Their median age was 57 (range, 40-77), most (n=41) were male, and they had a median of 35 (range, 1-60,444) circulating HCL cells/mm3 at baseline (in 48 evaluable patients).

Twenty-eight patients received moxetumomab pasudotox in the dose-escalation portion of the study—at 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, or 50 µg/kg—and 21 received the drug at 50 µg/kg for the extension portion of the study.

Among the 33 patients who received moxetumomab pasudotox at 50 µg/kg, the overall response rate was 88%, and the complete response (CR) rate was 64% (n=21). The median time to CR was 3.6 months, and the median duration of CR was 70.3 months.

The median follow-up was 75 months for the entire study population. At 72 months, the progression-free survival (PFS) rate was 77%.

The researchers found that minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity (via immunohistochemistry) was associated with extended response duration and prolonged PFS.

The MRD evaluation included 19 MRD+ patients and 18 MRD- patients. Forty-seven percent of the MRD+ patients (n=9) and 94% of the MRD- patients (n=17) had a CR as their best response.

The median duration of CR was 13.1 months among the MRD+ patients and was not reached among the MRD- patients (P=0.0002). The median PFS was 82.1 months among the MRD+ patients and not reached among the MRD- patients (P=0.0031).

Moxetumomab pasudotox did not undergo phase 2 testing but proceeded to a phase 3 trial. In this single-arm study, researchers evaluated the drug in HCL patients who had received at least 2 prior therapies.

According to AstraZeneca, the study’s primary endpoint—durable CR—was met. The company said the phase 3 results will be presented at an upcoming medical meeting.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has accepted for priority review the biologics license application (BLA) for moxetumomab pasudotox, an investigational anti-CD22 recombinant immunotoxin.

With this BLA, AstraZeneca is seeking approval for moxetumomab pasudotox for the treatment of adults with hairy cell leukemia (HCL) who have received at least 2 prior lines of therapy.

The FDA expects to make a decision on the BLA in the third quarter of this year.

The FDA aims to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10 months.

The agency grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

About moxetumomab pasudotox

Moxetumomab pasudotox (formerly CAT-8015 or HA22) is composed of a binding portion of an anti-CD22 antibody fused to a toxin. After binding to CD22, the molecule is internalized, processed, and releases its modified protein toxin, which inhibits protein translation and leads to apoptosis.

In addition to priority review, moxetumomab pasudotox has received orphan drug designation from the FDA.

Moxetumomab pasudotox has been tested in a phase 1 trial. Initial results from this trial were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2012. Long-term follow-up was presented at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting.

The ASH data included 49 patients with relapsed/refractory HCL. Their median age was 57 (range, 40-77), most (n=41) were male, and they had a median of 35 (range, 1-60,444) circulating HCL cells/mm3 at baseline (in 48 evaluable patients).

Twenty-eight patients received moxetumomab pasudotox in the dose-escalation portion of the study—at 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, or 50 µg/kg—and 21 received the drug at 50 µg/kg for the extension portion of the study.

Among the 33 patients who received moxetumomab pasudotox at 50 µg/kg, the overall response rate was 88%, and the complete response (CR) rate was 64% (n=21). The median time to CR was 3.6 months, and the median duration of CR was 70.3 months.

The median follow-up was 75 months for the entire study population. At 72 months, the progression-free survival (PFS) rate was 77%.

The researchers found that minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity (via immunohistochemistry) was associated with extended response duration and prolonged PFS.

The MRD evaluation included 19 MRD+ patients and 18 MRD- patients. Forty-seven percent of the MRD+ patients (n=9) and 94% of the MRD- patients (n=17) had a CR as their best response.

The median duration of CR was 13.1 months among the MRD+ patients and was not reached among the MRD- patients (P=0.0002). The median PFS was 82.1 months among the MRD+ patients and not reached among the MRD- patients (P=0.0031).

Moxetumomab pasudotox did not undergo phase 2 testing but proceeded to a phase 3 trial. In this single-arm study, researchers evaluated the drug in HCL patients who had received at least 2 prior therapies.

According to AstraZeneca, the study’s primary endpoint—durable CR—was met. The company said the phase 3 results will be presented at an upcoming medical meeting.

Enlarging dark patch on back

The FP recognized this to be a Becker's nevus, also known as a Becker nevus.

This nevus, which tends to occur in adolescent males, presents as a brown patch (often with hair) that is located on the shoulder, back, or submammary area. The lesion may enlarge to cover an entire shoulder or upper arm. While the nevus in this case did not have hair, it did have increased acne within the area—another feature of Becker nevus.

Although it is called a nevus, it does not actually have nevus cells and has no malignant potential. It is a type of hamartoma—an abnormal mixture of cells and tissues normally found in the area of the body where the growth occurs. Becker nevi do not become melanoma because they lack melanocytes. Therefore, there is no reason to excise them. Generally, these lesions are large and the risks of excision for cosmetic reasons outweigh the benefits.

In this case, the patient and his mother were reassured that no treatment was needed and they opted to leave it alone.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized this to be a Becker's nevus, also known as a Becker nevus.

This nevus, which tends to occur in adolescent males, presents as a brown patch (often with hair) that is located on the shoulder, back, or submammary area. The lesion may enlarge to cover an entire shoulder or upper arm. While the nevus in this case did not have hair, it did have increased acne within the area—another feature of Becker nevus.

Although it is called a nevus, it does not actually have nevus cells and has no malignant potential. It is a type of hamartoma—an abnormal mixture of cells and tissues normally found in the area of the body where the growth occurs. Becker nevi do not become melanoma because they lack melanocytes. Therefore, there is no reason to excise them. Generally, these lesions are large and the risks of excision for cosmetic reasons outweigh the benefits.

In this case, the patient and his mother were reassured that no treatment was needed and they opted to leave it alone.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized this to be a Becker's nevus, also known as a Becker nevus.

This nevus, which tends to occur in adolescent males, presents as a brown patch (often with hair) that is located on the shoulder, back, or submammary area. The lesion may enlarge to cover an entire shoulder or upper arm. While the nevus in this case did not have hair, it did have increased acne within the area—another feature of Becker nevus.

Although it is called a nevus, it does not actually have nevus cells and has no malignant potential. It is a type of hamartoma—an abnormal mixture of cells and tissues normally found in the area of the body where the growth occurs. Becker nevi do not become melanoma because they lack melanocytes. Therefore, there is no reason to excise them. Generally, these lesions are large and the risks of excision for cosmetic reasons outweigh the benefits.

In this case, the patient and his mother were reassured that no treatment was needed and they opted to leave it alone.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Outpatient talc administration improves malignant effusion outcomes

Patients with malignant pleural effusion treated with an indwelling pleural catheter have an improved chance of a positive outcome when talc administration is part of their procedure, suggest the results of a randomized, placebo-controlled study.

Malignant pleural effusion, which is usually caused by the spread of metastatic cancer, is typically treated by inducement of pleurodesis. Talc is probably the most effective agent for achieving this result, but there are drawbacks to using talc to induce pleurodesis. Patients who receive this treatment often need to stay in the hospital for 4-7 days, according to Rahul Bhatnagar, PhD, and the coauthors of a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine). Indwelling pleural catheters provide an “ambulatory alternative” for fluid management, they noted. In a noncomparative series of 22 patients, administering talc through such a catheter produced high rates of pleurodesis, they added.

In the new study, Dr. Bhatnagar of the Academic Respiratory Unit, University of Bristol, England, and his coauthors evaluated the use of an indwelling catheter, with or without talc, in patients with malignant pleural effusion recruited at 18 centers in the United Kingdom over 4 years.

“Our primary-outcome results, which were backed up by robust sensitivity analyses, strongly suggest that the administration of talc through an indwelling pleural catheter was significantly more efficacious than the use of an indwelling pleural catheter alone among patients without substantial lung entrapment,” the authors wrote.

A total of 154 patients underwent randomization to the talc or placebo group, and 139 had sufficient data to evaluate the primary outcome of successful pleurodesis at 35 days after randomization. The researchers excluded patients with evidence of lung entrapment, or nonexpandable lung, according to the study report.

In the talc group, pleurodesis was successful at day 35 in 30 of 69 patients (43%) versus 16 of 70 patients (23%) in the placebo group (P = .008).

At day 70, the success rate was 51% for the talc group vs. 27% for the placebo group, respectively.

The rate of pleurodesis was significantly higher when talc was administered through an indwelling pleural catheter, Dr. Bhatnagar and his colleagues noted.

“Success rates at day 70 suggested that pleurodesis was maintained to a point that is clinically relevant for patients with short median survival,” they added.

No excess of side effects or catheter blockages were associated with talc vs. placebo administration through a catheter. Additionally, no differences were seen between the talc and placebo groups in the number of adverse events, number of inpatient days, mortality, or other outcomes tracked by the researchers.

Dr. Bhatnagar reported he had no disclosures related to the study. Study coauthors reported disclosures related to Becton Dickinson – CareFusion, Rosetrees Trust, GE Medical, and Rocket Medical. Becton Dickinson supported the trial with an unrestricted research grant and supplied catheters and drainage bottles for the study’s participants.

SOURCE: Bhatnagar R et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1313-22.

Patients with malignant pleural effusion treated with an indwelling pleural catheter have an improved chance of a positive outcome when talc administration is part of their procedure, suggest the results of a randomized, placebo-controlled study.

Malignant pleural effusion, which is usually caused by the spread of metastatic cancer, is typically treated by inducement of pleurodesis. Talc is probably the most effective agent for achieving this result, but there are drawbacks to using talc to induce pleurodesis. Patients who receive this treatment often need to stay in the hospital for 4-7 days, according to Rahul Bhatnagar, PhD, and the coauthors of a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine). Indwelling pleural catheters provide an “ambulatory alternative” for fluid management, they noted. In a noncomparative series of 22 patients, administering talc through such a catheter produced high rates of pleurodesis, they added.

In the new study, Dr. Bhatnagar of the Academic Respiratory Unit, University of Bristol, England, and his coauthors evaluated the use of an indwelling catheter, with or without talc, in patients with malignant pleural effusion recruited at 18 centers in the United Kingdom over 4 years.

“Our primary-outcome results, which were backed up by robust sensitivity analyses, strongly suggest that the administration of talc through an indwelling pleural catheter was significantly more efficacious than the use of an indwelling pleural catheter alone among patients without substantial lung entrapment,” the authors wrote.

A total of 154 patients underwent randomization to the talc or placebo group, and 139 had sufficient data to evaluate the primary outcome of successful pleurodesis at 35 days after randomization. The researchers excluded patients with evidence of lung entrapment, or nonexpandable lung, according to the study report.

In the talc group, pleurodesis was successful at day 35 in 30 of 69 patients (43%) versus 16 of 70 patients (23%) in the placebo group (P = .008).

At day 70, the success rate was 51% for the talc group vs. 27% for the placebo group, respectively.

The rate of pleurodesis was significantly higher when talc was administered through an indwelling pleural catheter, Dr. Bhatnagar and his colleagues noted.

“Success rates at day 70 suggested that pleurodesis was maintained to a point that is clinically relevant for patients with short median survival,” they added.

No excess of side effects or catheter blockages were associated with talc vs. placebo administration through a catheter. Additionally, no differences were seen between the talc and placebo groups in the number of adverse events, number of inpatient days, mortality, or other outcomes tracked by the researchers.

Dr. Bhatnagar reported he had no disclosures related to the study. Study coauthors reported disclosures related to Becton Dickinson – CareFusion, Rosetrees Trust, GE Medical, and Rocket Medical. Becton Dickinson supported the trial with an unrestricted research grant and supplied catheters and drainage bottles for the study’s participants.

SOURCE: Bhatnagar R et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1313-22.

Patients with malignant pleural effusion treated with an indwelling pleural catheter have an improved chance of a positive outcome when talc administration is part of their procedure, suggest the results of a randomized, placebo-controlled study.

Malignant pleural effusion, which is usually caused by the spread of metastatic cancer, is typically treated by inducement of pleurodesis. Talc is probably the most effective agent for achieving this result, but there are drawbacks to using talc to induce pleurodesis. Patients who receive this treatment often need to stay in the hospital for 4-7 days, according to Rahul Bhatnagar, PhD, and the coauthors of a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine). Indwelling pleural catheters provide an “ambulatory alternative” for fluid management, they noted. In a noncomparative series of 22 patients, administering talc through such a catheter produced high rates of pleurodesis, they added.

In the new study, Dr. Bhatnagar of the Academic Respiratory Unit, University of Bristol, England, and his coauthors evaluated the use of an indwelling catheter, with or without talc, in patients with malignant pleural effusion recruited at 18 centers in the United Kingdom over 4 years.

“Our primary-outcome results, which were backed up by robust sensitivity analyses, strongly suggest that the administration of talc through an indwelling pleural catheter was significantly more efficacious than the use of an indwelling pleural catheter alone among patients without substantial lung entrapment,” the authors wrote.

A total of 154 patients underwent randomization to the talc or placebo group, and 139 had sufficient data to evaluate the primary outcome of successful pleurodesis at 35 days after randomization. The researchers excluded patients with evidence of lung entrapment, or nonexpandable lung, according to the study report.

In the talc group, pleurodesis was successful at day 35 in 30 of 69 patients (43%) versus 16 of 70 patients (23%) in the placebo group (P = .008).

At day 70, the success rate was 51% for the talc group vs. 27% for the placebo group, respectively.

The rate of pleurodesis was significantly higher when talc was administered through an indwelling pleural catheter, Dr. Bhatnagar and his colleagues noted.

“Success rates at day 70 suggested that pleurodesis was maintained to a point that is clinically relevant for patients with short median survival,” they added.

No excess of side effects or catheter blockages were associated with talc vs. placebo administration through a catheter. Additionally, no differences were seen between the talc and placebo groups in the number of adverse events, number of inpatient days, mortality, or other outcomes tracked by the researchers.

Dr. Bhatnagar reported he had no disclosures related to the study. Study coauthors reported disclosures related to Becton Dickinson – CareFusion, Rosetrees Trust, GE Medical, and Rocket Medical. Becton Dickinson supported the trial with an unrestricted research grant and supplied catheters and drainage bottles for the study’s participants.

SOURCE: Bhatnagar R et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1313-22.

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: with no deleterious effects.

Major finding: At 35 days post randomization, pleurodesis was successful in 30 of 69 patients (43%) in the talc group versus 16 of 70 patients (23%) in the placebo group (P = .008).

Study details: A randomized, placebo-controlled, single-blind, parallel-group trial including 154 patients with malignant pleural effusion recruited at 18 U.K. centers over a period of 4 years.

Disclosures: Becton Dickinson supported the trial with an unrestricted research grant and supplied catheters and drainage bottles for participants. Study authors reported disclosures related to Becton Dickinson – CareFusion, Rosetrees Trust, GE Medical, and Rocket Medical.

Source: Bhatnagar R et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1313-22.

Being overweight as a child increases the risk of developing diabetes

a time marked by decreased insulin sensitivity, or by early adulthood, according to data from a study of Danish men.

“This large-scale longitudinal study showed that men who had remission of overweight between 7 and 13 years of age and had subsequently maintained a normal weight in early adulthood had a risk of type 2 diabetes similar to that among men with normal weights at all of these ages,” Lise G. Bjerregaard, PhD, of the Center for Clinical Research and Prevention in Copenhagen and her colleagues wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Studies in adults have shown that lowering body weights and body mass indexes delayed the onset of type 2 diabetes. While correcting body mass index seems to benefit adults, little is known about how being overweight or obese as children and young adults can affect the risk for type 2 diabetes. This is a particularly pressing issue because almost a quarter of children in developed countries are either overweight or obese.

The investigators looked at the heights and weights of 62,565 Danish men during childhood, measured at 7 and 13 years of age, and during early adulthood between 17 and 26 years of age. The height and weight data were obtained from two national health databases. The Copenhagen School Health Record Register (CSHRR) contains information on most of the children in Copenhagen who attended school during 1930-1989. The researchers then corroborated the information from this database and connected it with data from the Danish Conscription Database, which included heights and weights of men born during 1939-1959 that was taken at conscription examinations. In addition, diagnoses of type 2 diabetes were obtained from the Danish National Patient Register.

A little more than 10% (6,710) of the 62,565 men in the study were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes during the course of the 2 million person-years of follow-up. The prevalence of being overweight increased from 5.4% to 8.2% from age 7 years of age to early adulthood.

The risk of developing type 2 diabetes was heavily dependent on how old patients were when they were overweight and at what age they reduced their bodyweight. Being overweight at any age corresponded to an increased risk of type 2 diabetes. Men who were overweight during early adulthood had the highest incidence of type 2 diabetes. An encouraging finding was that men who had been overweight at age 7 years but had reduced their bodyweight by age 13 years and maintained a stable bodyweight as young men had a risk of being diagnosed similar to men who had never been overweight (hazard ratio, 0.96; 95% confidence interval, 0.75-1.21). Similarly, men who had been overweight only at age 13 years or between ages 7 and 13 years had a lower risks of developing type 2 diabetes than did men who had been persistently overweight, but the risks were still higher than in men who had never been overweight (overweight only at 7 and 13 years of age vs. never overweight: HR , 1.47; 95% CI, 1.10-1.9; persistently overweight vs. never overweight: HR, 4.14; 95% CI, 3.57-4.79). Men who had been overweight later in life had a higher risk of type 2 diabetes, compared with men who were only overweight as young adults, but the risk was similar to men who had been overweight at all ages.

The findings from this study are supported by the large sample size and the length of follow-up. Unfortunately, the researchers analyzed exclusively men and no information was available for early-life explanatory factors like pubertal timing and parental socioeconomic class or later-life body mass index.

The findings for this study were reason to be positive, according to, Elvira Isganaitis, MD, an assistant investigator and staff pediatric endocrinologist at the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston.

“What I found really interesting about this study is that the authors were able to define certain periods over the life course where one’s bodyweight – being obese versus lean – seems to predict the long term risk of type 2 diabetes. And, so, it turned out that certain time periods were potentially more important than others, which is important for public health considerations and prevention. Individuals who were only overweight or obese at age 7 but had a healthy weight by age 13 and older, the risk of developing type 2 diabetes normalized. But, for those individuals in whom the overweight persisted beyond childhood, the risk was a lot stronger,” she said.

“As a pediatric endocrinologist who is really interested in obesity treatment and prevention, it is a really heartening message that our efforts to achieve healthy weight balance in early childhood has the potential to pay dividends over decades,” she added.

The results of the study offer greater insight regarding how being overweight at younger ages can influence the development of type 2 diabetes. When asked how these results from a population with broad access to health care may translate to the U.S. population, Dr. Bjerregaard stated, “The organization of the health care system and access to treatment of type 2 diabetes is not relevant if type 2 diabetes is successfully prevented by early normalization of weight. However, access to health care for the overweight pediatric population may be an important factor determining the likelihood of remission of overweight in contemporary populations who are exposed to more obesogenic environments.”

Dr. Bjerregaard and another researcher both received grants from the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation program. All other researchers had no financial conflicts to report. The study was supported by funding from the European Commission Horizon 2020 program as part of the DynaHEALTH project and by the European Research Council.

SOURCE: Bjerregaard L et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Apr 04. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713231.

a time marked by decreased insulin sensitivity, or by early adulthood, according to data from a study of Danish men.

“This large-scale longitudinal study showed that men who had remission of overweight between 7 and 13 years of age and had subsequently maintained a normal weight in early adulthood had a risk of type 2 diabetes similar to that among men with normal weights at all of these ages,” Lise G. Bjerregaard, PhD, of the Center for Clinical Research and Prevention in Copenhagen and her colleagues wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Studies in adults have shown that lowering body weights and body mass indexes delayed the onset of type 2 diabetes. While correcting body mass index seems to benefit adults, little is known about how being overweight or obese as children and young adults can affect the risk for type 2 diabetes. This is a particularly pressing issue because almost a quarter of children in developed countries are either overweight or obese.

The investigators looked at the heights and weights of 62,565 Danish men during childhood, measured at 7 and 13 years of age, and during early adulthood between 17 and 26 years of age. The height and weight data were obtained from two national health databases. The Copenhagen School Health Record Register (CSHRR) contains information on most of the children in Copenhagen who attended school during 1930-1989. The researchers then corroborated the information from this database and connected it with data from the Danish Conscription Database, which included heights and weights of men born during 1939-1959 that was taken at conscription examinations. In addition, diagnoses of type 2 diabetes were obtained from the Danish National Patient Register.

A little more than 10% (6,710) of the 62,565 men in the study were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes during the course of the 2 million person-years of follow-up. The prevalence of being overweight increased from 5.4% to 8.2% from age 7 years of age to early adulthood.

The risk of developing type 2 diabetes was heavily dependent on how old patients were when they were overweight and at what age they reduced their bodyweight. Being overweight at any age corresponded to an increased risk of type 2 diabetes. Men who were overweight during early adulthood had the highest incidence of type 2 diabetes. An encouraging finding was that men who had been overweight at age 7 years but had reduced their bodyweight by age 13 years and maintained a stable bodyweight as young men had a risk of being diagnosed similar to men who had never been overweight (hazard ratio, 0.96; 95% confidence interval, 0.75-1.21). Similarly, men who had been overweight only at age 13 years or between ages 7 and 13 years had a lower risks of developing type 2 diabetes than did men who had been persistently overweight, but the risks were still higher than in men who had never been overweight (overweight only at 7 and 13 years of age vs. never overweight: HR , 1.47; 95% CI, 1.10-1.9; persistently overweight vs. never overweight: HR, 4.14; 95% CI, 3.57-4.79). Men who had been overweight later in life had a higher risk of type 2 diabetes, compared with men who were only overweight as young adults, but the risk was similar to men who had been overweight at all ages.

The findings from this study are supported by the large sample size and the length of follow-up. Unfortunately, the researchers analyzed exclusively men and no information was available for early-life explanatory factors like pubertal timing and parental socioeconomic class or later-life body mass index.

The findings for this study were reason to be positive, according to, Elvira Isganaitis, MD, an assistant investigator and staff pediatric endocrinologist at the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston.

“What I found really interesting about this study is that the authors were able to define certain periods over the life course where one’s bodyweight – being obese versus lean – seems to predict the long term risk of type 2 diabetes. And, so, it turned out that certain time periods were potentially more important than others, which is important for public health considerations and prevention. Individuals who were only overweight or obese at age 7 but had a healthy weight by age 13 and older, the risk of developing type 2 diabetes normalized. But, for those individuals in whom the overweight persisted beyond childhood, the risk was a lot stronger,” she said.

“As a pediatric endocrinologist who is really interested in obesity treatment and prevention, it is a really heartening message that our efforts to achieve healthy weight balance in early childhood has the potential to pay dividends over decades,” she added.

The results of the study offer greater insight regarding how being overweight at younger ages can influence the development of type 2 diabetes. When asked how these results from a population with broad access to health care may translate to the U.S. population, Dr. Bjerregaard stated, “The organization of the health care system and access to treatment of type 2 diabetes is not relevant if type 2 diabetes is successfully prevented by early normalization of weight. However, access to health care for the overweight pediatric population may be an important factor determining the likelihood of remission of overweight in contemporary populations who are exposed to more obesogenic environments.”

Dr. Bjerregaard and another researcher both received grants from the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation program. All other researchers had no financial conflicts to report. The study was supported by funding from the European Commission Horizon 2020 program as part of the DynaHEALTH project and by the European Research Council.

SOURCE: Bjerregaard L et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Apr 04. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713231.

a time marked by decreased insulin sensitivity, or by early adulthood, according to data from a study of Danish men.

“This large-scale longitudinal study showed that men who had remission of overweight between 7 and 13 years of age and had subsequently maintained a normal weight in early adulthood had a risk of type 2 diabetes similar to that among men with normal weights at all of these ages,” Lise G. Bjerregaard, PhD, of the Center for Clinical Research and Prevention in Copenhagen and her colleagues wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Studies in adults have shown that lowering body weights and body mass indexes delayed the onset of type 2 diabetes. While correcting body mass index seems to benefit adults, little is known about how being overweight or obese as children and young adults can affect the risk for type 2 diabetes. This is a particularly pressing issue because almost a quarter of children in developed countries are either overweight or obese.

The investigators looked at the heights and weights of 62,565 Danish men during childhood, measured at 7 and 13 years of age, and during early adulthood between 17 and 26 years of age. The height and weight data were obtained from two national health databases. The Copenhagen School Health Record Register (CSHRR) contains information on most of the children in Copenhagen who attended school during 1930-1989. The researchers then corroborated the information from this database and connected it with data from the Danish Conscription Database, which included heights and weights of men born during 1939-1959 that was taken at conscription examinations. In addition, diagnoses of type 2 diabetes were obtained from the Danish National Patient Register.

A little more than 10% (6,710) of the 62,565 men in the study were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes during the course of the 2 million person-years of follow-up. The prevalence of being overweight increased from 5.4% to 8.2% from age 7 years of age to early adulthood.

The risk of developing type 2 diabetes was heavily dependent on how old patients were when they were overweight and at what age they reduced their bodyweight. Being overweight at any age corresponded to an increased risk of type 2 diabetes. Men who were overweight during early adulthood had the highest incidence of type 2 diabetes. An encouraging finding was that men who had been overweight at age 7 years but had reduced their bodyweight by age 13 years and maintained a stable bodyweight as young men had a risk of being diagnosed similar to men who had never been overweight (hazard ratio, 0.96; 95% confidence interval, 0.75-1.21). Similarly, men who had been overweight only at age 13 years or between ages 7 and 13 years had a lower risks of developing type 2 diabetes than did men who had been persistently overweight, but the risks were still higher than in men who had never been overweight (overweight only at 7 and 13 years of age vs. never overweight: HR , 1.47; 95% CI, 1.10-1.9; persistently overweight vs. never overweight: HR, 4.14; 95% CI, 3.57-4.79). Men who had been overweight later in life had a higher risk of type 2 diabetes, compared with men who were only overweight as young adults, but the risk was similar to men who had been overweight at all ages.

The findings from this study are supported by the large sample size and the length of follow-up. Unfortunately, the researchers analyzed exclusively men and no information was available for early-life explanatory factors like pubertal timing and parental socioeconomic class or later-life body mass index.

The findings for this study were reason to be positive, according to, Elvira Isganaitis, MD, an assistant investigator and staff pediatric endocrinologist at the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston.

“What I found really interesting about this study is that the authors were able to define certain periods over the life course where one’s bodyweight – being obese versus lean – seems to predict the long term risk of type 2 diabetes. And, so, it turned out that certain time periods were potentially more important than others, which is important for public health considerations and prevention. Individuals who were only overweight or obese at age 7 but had a healthy weight by age 13 and older, the risk of developing type 2 diabetes normalized. But, for those individuals in whom the overweight persisted beyond childhood, the risk was a lot stronger,” she said.

“As a pediatric endocrinologist who is really interested in obesity treatment and prevention, it is a really heartening message that our efforts to achieve healthy weight balance in early childhood has the potential to pay dividends over decades,” she added.

The results of the study offer greater insight regarding how being overweight at younger ages can influence the development of type 2 diabetes. When asked how these results from a population with broad access to health care may translate to the U.S. population, Dr. Bjerregaard stated, “The organization of the health care system and access to treatment of type 2 diabetes is not relevant if type 2 diabetes is successfully prevented by early normalization of weight. However, access to health care for the overweight pediatric population may be an important factor determining the likelihood of remission of overweight in contemporary populations who are exposed to more obesogenic environments.”

Dr. Bjerregaard and another researcher both received grants from the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation program. All other researchers had no financial conflicts to report. The study was supported by funding from the European Commission Horizon 2020 program as part of the DynaHEALTH project and by the European Research Council.

SOURCE: Bjerregaard L et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Apr 04. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713231.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Being overweight in childhood was associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes in adulthood unless weight is normalized before puberty.

Major finding: Men who had been overweight age 7 years but had reduced their body weight by age 13 years and maintained a stable body weight as young men had a risk of being diagnosed with diabetes similar to that among men who had never been overweight (hazard ratio, 0.96; 95% confidence interval, 0.75-1.21).

Study details: Using information from several databases, researchers looked at the heights and weights of 62,565 Danish men from childhood and young adulthood.

Disclosures: Dr. Bjerregaard and another researcher both received grants from the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation program. All other researchers had no financial conflicts to report.

Source: Bjerregaard L et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Apr 04. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713231.

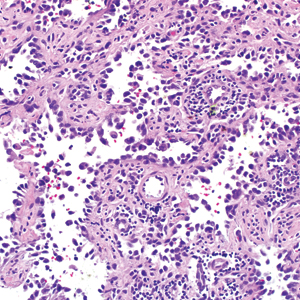

Gone Fishing: A Unique Histologic Pattern in Cutaneous Angiosarcoma

Cutaneous angiosarcoma is a rare malignant tumor of vascular endothelial cells that has the propensity to arise in various clinical settings. This tumor predominantly occurs in the head and neck region in elderly patients, but it also has been reported to develop postradiotherapy or in the setting of chronic lymphedema in the extremities.1-3 In all settings, the diagnosis carries a very poor prognosis with a high likelihood of local recurrence and rapid dissemination. The mortality rate typically is 80% or higher.2,4-6

Making the correct clinical diagnosis of cutaneous angiosarcoma may be difficult given the variety of patient symptoms and clinical appearances that can be demonstrated on presentation. Lesions can appear as bluish or violaceous plaques, macules, or nodules, and ulceration may be present in some advanced cases.5,7 Clinical misdiagnosis is common, as cutaneous angiosarcomas may be mistaken for infectious processes, benign vascular malformations, and other cutaneous malignancies.1 Biopsy often is delayed given the initial benign appearance of the lesions, and this frequently results in aggressive and extensive disease at the time of diagnosis, which is unfortunate given that small tumor size has been shown to be one of the only favorable prognostic indicators in cutaneous angiosarcoma.1,2,6,8

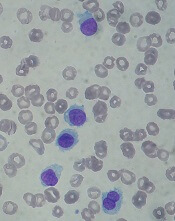

Microscopically, diagnosis of cutaneous angiosarcoma can present a challenge, as the histology varies between a well-differentiated vascular neoplasm and a considerably anaplastic and poorly differentiated malignancy. On low power, some areas may appear as benign hemangiomas with other areas showing frank sarcomatous features.9 As a result, these tumors can be mistaken for a variety of other diseases including melanomas, carcinomas, or other vascular tumors.6,8,9 Previously, electron microscopy has been utilized on undifferentiated tumors to help distinguish cutaneous angiosarcomas from other potential diagnoses. The atypical tumor cells of cutaneous angiosarcoma display common features of endothelial cells (eg, pinocytotic vesicles, tubulated bodies).7 Historically, it has been noted that the histologic findings and tumor grade provide little evidence regarding the aggressiveness of the tumor, and all cutaneous angiosarcoma diagnoses receive a poor prognosis.6,8

Classically, the histologic findings of cutaneous angiosarcoma include a highly infiltrative neoplasm forming irregular vascular channels that penetrate through the cutaneous soft tissues and frequently extend into the subcutaneous fat. The vascular spaces are lined by hyperchromatic endothelial cells with varying degrees of atypia.1,2,4,6,7,10 Occasionally, prominent endothelial cells lining a papillary structure within the lumen of the neoformed vessel may also be observed. Currently, immunohistochemical staining for MYC, Ki-67, D2-40, and various other markers complement the histologic findings to aid in the diagnosis of cutaneous angiosarcoma.11,12 An additional diagnostic clue that has been described in cases of postirradiation cutaneous angiosarcoma shows free-floating or tufted pleomorphic spindle cells within the vascular lumen (Figure). This finding has been described as “fish in the creek.”11 In this study, we aimed to determine the frequency and subsequent diagnostic utility of the fish-in-the-creek finding in cases of cutaneous angiosarcoma.

Methods

A natural language search of our institutional archives over a 20-year period (1997–2017) using the term angiosarcoma was performed. Fifteen cases of cutaneous angiosarcoma were identified. Fifteen additional benign and malignant vascular tumors with cutaneous angiosarco

Results

The histologic pattern of fish in the creek was identified in all 15 cases of cutaneous angiosarcoma and was absent in the other 15 malignancies examined in this study. This finding shows the potential for the fish-in-the-creek pattern to be used as an additional diagnostic tool for dermatopathologists.

Comment

Cutaneous angiosarcoma is a rare but aggressive malignancy that proves difficult to diagnose both clinically and histologically as well as to treat effectively.1,5-8 Our results indicate that fish in the creek may be a useful and salient histologic feature in cutaneous angiosarcoma. It is important to recognize, however, that this finding should not be the sole feature upon which a diagnosis of cutaneous angiosarcoma is made, as it requires corroboration with positivity of MYC and D2-40 as well as a high Ki-67 proliferation index (>20%).11,12 Finding a fish-in-the-creek pattern should prompt dermatopathologists to consider a diagnosis of cutaneous angiosarcoma in the appropriate clinical and histologic settings.

The chief limitation of this study was the small sample size, with only 15 cases of cutaneous angiosarcoma available in the last 20 years at our institution. The limited sample size did not allow us to make claims on sensitivity and specificity regarding this histologic feature; however, with a larger sample size, the true diagnostic potential could be elucidated. Although the pathologists were blinded to the original diagnoses as they examined it for fish in the creek, it is possible they were able to make the correct diagnosis based on other histopathologic clues and therefore were biased.

Although the fish-in-the-creek pattern is present in cutaneous angiosarcoma, there may be other mimickers to consider. Intraluminal papillary projections lined by endothelial cells may be sectioned in a manner imitating this finding.3 In such a case, these endothelial cells must be differentiated from the free-floating or tufted spindle cells in order to have a positive finding for fish in the creek. There can be confusion if the biopsy cuts through a section of spindled cells, resulting in difficulty differentiating cutaneous angiosarcoma from other spindle tumors such as spindle cell melanoma or spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma.6 In such cases, immunohistochemistry may be helpful, as spindle cell melanoma would stain positive for S100 and SOX10 and spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma would stain positive for p63 and cytokeratin.

Various treatment strategies for cutaneous angiosarcoma have been employed, with the majority still resulting in poor outcomes.2,4-6 The recommended treatment is radical surgical excision of the primary tumor with lymph node clearance if possible. Following excision, the patient should undergo high-dose, wide-field radiotherapy to the region.5,8 Cutaneous angiosarcomas also have the ability to spread extensively through the dermis and can result in subclinical or clinically obvious widespread disease with multifocal or satellite lesions present. Distant metastases occur most frequently in the cervical lymph nodes and lungs.7 In cases where the disease is too extensive for surgery, palliative radiation monotherapy can be used.5,6

As atypical vascular lesions are considered to be a precursor to cutaneous angiosarcoma, it is important to note that the fish-in-the-creek feature was absent in all 6 of the atypical vascular lesions observed in the study. The differentiation generally is made based on MYC, which is present in cutaneous angiosarcomas and absent in atypical vascular lesions.10 The feature of fish in the creek may now be an additional clue for dermatopathologists to differentiate between angiosarcomas and other similar-appearing tumors.

Conclusion

Our study aimed to highlight an important histologic feature of cutaneous angiosarcomas that can aid in the diagnosis of this deceptive malignancy. Our findings warrant further study of the fish-in-the-creek histologic pattern in a larger sample size to determine its success as a diagnostic tool for cutaneous angiosarcomas. As noted previously, tumor grade does not impact survival outcome, but small tumor size has been one of the only features found to result in a more favorable prognosis.1,6,8 Future studies to identify a correlation between the histologic finding of fish in the creek and disease outcome in cutaneous angiosarcoma may be helpful to determine if these histologic findings provide prognostic significance in cases of cutaneous angiosarcoma.

- Aust MR, Olsen KD, Lewis JE, et al. Angiosarcomas of the head and neck: clinical and pathologic characteristics. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1997;106:943-951.

- Holden CA, Spittle MF, Jones EW. Angiosarcoma of the face and scalp, prognosis and treatment. Cancer. 1987;59:1046-1057.

- Woodward AH, Ivins JC, Soule EH. Lymphangiosarcoma arising in chronic lymphedematous extremities. Cancer. 1972;30:562-572.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, McKee PH, et al. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Morrison WH, Byers RM, Garden AS, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head and neck. a therapeutic dilemma. Cancer. 1995;76:319-327.

- Hodgkinson DJ, Soule EH, Woods JE. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head and neck. Cancer. 1979;44:1106-1113.

- Rosai J, Sumner HW, Kostianovsky M, et al. Angiosarcoma of the skin: a clinicopathologic and fine structural study. Hum Pathol. 1976;7:83-109.

- Pawlik TM, Paulino AF, Mcginn CJ, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp: a multidisciplinary approach. Cancer. 2003;98:1716-1726.

- Haustein UF. Angiosarcoma of the face and scalp. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:851-856.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

- Requena L, Kutzner H. Cutaneous Soft Tissue Tumors. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

- Cuda J, Mirzamani N, Kantipudi R, et al. Diagnostic utility of Fli-1 and D2-40 in distinguishing atypical fibroxanthoma from angiosarcoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:316-318.

Cutaneous angiosarcoma is a rare malignant tumor of vascular endothelial cells that has the propensity to arise in various clinical settings. This tumor predominantly occurs in the head and neck region in elderly patients, but it also has been reported to develop postradiotherapy or in the setting of chronic lymphedema in the extremities.1-3 In all settings, the diagnosis carries a very poor prognosis with a high likelihood of local recurrence and rapid dissemination. The mortality rate typically is 80% or higher.2,4-6

Making the correct clinical diagnosis of cutaneous angiosarcoma may be difficult given the variety of patient symptoms and clinical appearances that can be demonstrated on presentation. Lesions can appear as bluish or violaceous plaques, macules, or nodules, and ulceration may be present in some advanced cases.5,7 Clinical misdiagnosis is common, as cutaneous angiosarcomas may be mistaken for infectious processes, benign vascular malformations, and other cutaneous malignancies.1 Biopsy often is delayed given the initial benign appearance of the lesions, and this frequently results in aggressive and extensive disease at the time of diagnosis, which is unfortunate given that small tumor size has been shown to be one of the only favorable prognostic indicators in cutaneous angiosarcoma.1,2,6,8

Microscopically, diagnosis of cutaneous angiosarcoma can present a challenge, as the histology varies between a well-differentiated vascular neoplasm and a considerably anaplastic and poorly differentiated malignancy. On low power, some areas may appear as benign hemangiomas with other areas showing frank sarcomatous features.9 As a result, these tumors can be mistaken for a variety of other diseases including melanomas, carcinomas, or other vascular tumors.6,8,9 Previously, electron microscopy has been utilized on undifferentiated tumors to help distinguish cutaneous angiosarcomas from other potential diagnoses. The atypical tumor cells of cutaneous angiosarcoma display common features of endothelial cells (eg, pinocytotic vesicles, tubulated bodies).7 Historically, it has been noted that the histologic findings and tumor grade provide little evidence regarding the aggressiveness of the tumor, and all cutaneous angiosarcoma diagnoses receive a poor prognosis.6,8

Classically, the histologic findings of cutaneous angiosarcoma include a highly infiltrative neoplasm forming irregular vascular channels that penetrate through the cutaneous soft tissues and frequently extend into the subcutaneous fat. The vascular spaces are lined by hyperchromatic endothelial cells with varying degrees of atypia.1,2,4,6,7,10 Occasionally, prominent endothelial cells lining a papillary structure within the lumen of the neoformed vessel may also be observed. Currently, immunohistochemical staining for MYC, Ki-67, D2-40, and various other markers complement the histologic findings to aid in the diagnosis of cutaneous angiosarcoma.11,12 An additional diagnostic clue that has been described in cases of postirradiation cutaneous angiosarcoma shows free-floating or tufted pleomorphic spindle cells within the vascular lumen (Figure). This finding has been described as “fish in the creek.”11 In this study, we aimed to determine the frequency and subsequent diagnostic utility of the fish-in-the-creek finding in cases of cutaneous angiosarcoma.

Methods

A natural language search of our institutional archives over a 20-year period (1997–2017) using the term angiosarcoma was performed. Fifteen cases of cutaneous angiosarcoma were identified. Fifteen additional benign and malignant vascular tumors with cutaneous angiosarco

Results

The histologic pattern of fish in the creek was identified in all 15 cases of cutaneous angiosarcoma and was absent in the other 15 malignancies examined in this study. This finding shows the potential for the fish-in-the-creek pattern to be used as an additional diagnostic tool for dermatopathologists.

Comment

Cutaneous angiosarcoma is a rare but aggressive malignancy that proves difficult to diagnose both clinically and histologically as well as to treat effectively.1,5-8 Our results indicate that fish in the creek may be a useful and salient histologic feature in cutaneous angiosarcoma. It is important to recognize, however, that this finding should not be the sole feature upon which a diagnosis of cutaneous angiosarcoma is made, as it requires corroboration with positivity of MYC and D2-40 as well as a high Ki-67 proliferation index (>20%).11,12 Finding a fish-in-the-creek pattern should prompt dermatopathologists to consider a diagnosis of cutaneous angiosarcoma in the appropriate clinical and histologic settings.

The chief limitation of this study was the small sample size, with only 15 cases of cutaneous angiosarcoma available in the last 20 years at our institution. The limited sample size did not allow us to make claims on sensitivity and specificity regarding this histologic feature; however, with a larger sample size, the true diagnostic potential could be elucidated. Although the pathologists were blinded to the original diagnoses as they examined it for fish in the creek, it is possible they were able to make the correct diagnosis based on other histopathologic clues and therefore were biased.

Although the fish-in-the-creek pattern is present in cutaneous angiosarcoma, there may be other mimickers to consider. Intraluminal papillary projections lined by endothelial cells may be sectioned in a manner imitating this finding.3 In such a case, these endothelial cells must be differentiated from the free-floating or tufted spindle cells in order to have a positive finding for fish in the creek. There can be confusion if the biopsy cuts through a section of spindled cells, resulting in difficulty differentiating cutaneous angiosarcoma from other spindle tumors such as spindle cell melanoma or spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma.6 In such cases, immunohistochemistry may be helpful, as spindle cell melanoma would stain positive for S100 and SOX10 and spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma would stain positive for p63 and cytokeratin.

Various treatment strategies for cutaneous angiosarcoma have been employed, with the majority still resulting in poor outcomes.2,4-6 The recommended treatment is radical surgical excision of the primary tumor with lymph node clearance if possible. Following excision, the patient should undergo high-dose, wide-field radiotherapy to the region.5,8 Cutaneous angiosarcomas also have the ability to spread extensively through the dermis and can result in subclinical or clinically obvious widespread disease with multifocal or satellite lesions present. Distant metastases occur most frequently in the cervical lymph nodes and lungs.7 In cases where the disease is too extensive for surgery, palliative radiation monotherapy can be used.5,6

As atypical vascular lesions are considered to be a precursor to cutaneous angiosarcoma, it is important to note that the fish-in-the-creek feature was absent in all 6 of the atypical vascular lesions observed in the study. The differentiation generally is made based on MYC, which is present in cutaneous angiosarcomas and absent in atypical vascular lesions.10 The feature of fish in the creek may now be an additional clue for dermatopathologists to differentiate between angiosarcomas and other similar-appearing tumors.

Conclusion

Our study aimed to highlight an important histologic feature of cutaneous angiosarcomas that can aid in the diagnosis of this deceptive malignancy. Our findings warrant further study of the fish-in-the-creek histologic pattern in a larger sample size to determine its success as a diagnostic tool for cutaneous angiosarcomas. As noted previously, tumor grade does not impact survival outcome, but small tumor size has been one of the only features found to result in a more favorable prognosis.1,6,8 Future studies to identify a correlation between the histologic finding of fish in the creek and disease outcome in cutaneous angiosarcoma may be helpful to determine if these histologic findings provide prognostic significance in cases of cutaneous angiosarcoma.

Cutaneous angiosarcoma is a rare malignant tumor of vascular endothelial cells that has the propensity to arise in various clinical settings. This tumor predominantly occurs in the head and neck region in elderly patients, but it also has been reported to develop postradiotherapy or in the setting of chronic lymphedema in the extremities.1-3 In all settings, the diagnosis carries a very poor prognosis with a high likelihood of local recurrence and rapid dissemination. The mortality rate typically is 80% or higher.2,4-6

Making the correct clinical diagnosis of cutaneous angiosarcoma may be difficult given the variety of patient symptoms and clinical appearances that can be demonstrated on presentation. Lesions can appear as bluish or violaceous plaques, macules, or nodules, and ulceration may be present in some advanced cases.5,7 Clinical misdiagnosis is common, as cutaneous angiosarcomas may be mistaken for infectious processes, benign vascular malformations, and other cutaneous malignancies.1 Biopsy often is delayed given the initial benign appearance of the lesions, and this frequently results in aggressive and extensive disease at the time of diagnosis, which is unfortunate given that small tumor size has been shown to be one of the only favorable prognostic indicators in cutaneous angiosarcoma.1,2,6,8

Microscopically, diagnosis of cutaneous angiosarcoma can present a challenge, as the histology varies between a well-differentiated vascular neoplasm and a considerably anaplastic and poorly differentiated malignancy. On low power, some areas may appear as benign hemangiomas with other areas showing frank sarcomatous features.9 As a result, these tumors can be mistaken for a variety of other diseases including melanomas, carcinomas, or other vascular tumors.6,8,9 Previously, electron microscopy has been utilized on undifferentiated tumors to help distinguish cutaneous angiosarcomas from other potential diagnoses. The atypical tumor cells of cutaneous angiosarcoma display common features of endothelial cells (eg, pinocytotic vesicles, tubulated bodies).7 Historically, it has been noted that the histologic findings and tumor grade provide little evidence regarding the aggressiveness of the tumor, and all cutaneous angiosarcoma diagnoses receive a poor prognosis.6,8

Classically, the histologic findings of cutaneous angiosarcoma include a highly infiltrative neoplasm forming irregular vascular channels that penetrate through the cutaneous soft tissues and frequently extend into the subcutaneous fat. The vascular spaces are lined by hyperchromatic endothelial cells with varying degrees of atypia.1,2,4,6,7,10 Occasionally, prominent endothelial cells lining a papillary structure within the lumen of the neoformed vessel may also be observed. Currently, immunohistochemical staining for MYC, Ki-67, D2-40, and various other markers complement the histologic findings to aid in the diagnosis of cutaneous angiosarcoma.11,12 An additional diagnostic clue that has been described in cases of postirradiation cutaneous angiosarcoma shows free-floating or tufted pleomorphic spindle cells within the vascular lumen (Figure). This finding has been described as “fish in the creek.”11 In this study, we aimed to determine the frequency and subsequent diagnostic utility of the fish-in-the-creek finding in cases of cutaneous angiosarcoma.

Methods

A natural language search of our institutional archives over a 20-year period (1997–2017) using the term angiosarcoma was performed. Fifteen cases of cutaneous angiosarcoma were identified. Fifteen additional benign and malignant vascular tumors with cutaneous angiosarco

Results

The histologic pattern of fish in the creek was identified in all 15 cases of cutaneous angiosarcoma and was absent in the other 15 malignancies examined in this study. This finding shows the potential for the fish-in-the-creek pattern to be used as an additional diagnostic tool for dermatopathologists.

Comment

Cutaneous angiosarcoma is a rare but aggressive malignancy that proves difficult to diagnose both clinically and histologically as well as to treat effectively.1,5-8 Our results indicate that fish in the creek may be a useful and salient histologic feature in cutaneous angiosarcoma. It is important to recognize, however, that this finding should not be the sole feature upon which a diagnosis of cutaneous angiosarcoma is made, as it requires corroboration with positivity of MYC and D2-40 as well as a high Ki-67 proliferation index (>20%).11,12 Finding a fish-in-the-creek pattern should prompt dermatopathologists to consider a diagnosis of cutaneous angiosarcoma in the appropriate clinical and histologic settings.

The chief limitation of this study was the small sample size, with only 15 cases of cutaneous angiosarcoma available in the last 20 years at our institution. The limited sample size did not allow us to make claims on sensitivity and specificity regarding this histologic feature; however, with a larger sample size, the true diagnostic potential could be elucidated. Although the pathologists were blinded to the original diagnoses as they examined it for fish in the creek, it is possible they were able to make the correct diagnosis based on other histopathologic clues and therefore were biased.

Although the fish-in-the-creek pattern is present in cutaneous angiosarcoma, there may be other mimickers to consider. Intraluminal papillary projections lined by endothelial cells may be sectioned in a manner imitating this finding.3 In such a case, these endothelial cells must be differentiated from the free-floating or tufted spindle cells in order to have a positive finding for fish in the creek. There can be confusion if the biopsy cuts through a section of spindled cells, resulting in difficulty differentiating cutaneous angiosarcoma from other spindle tumors such as spindle cell melanoma or spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma.6 In such cases, immunohistochemistry may be helpful, as spindle cell melanoma would stain positive for S100 and SOX10 and spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma would stain positive for p63 and cytokeratin.

Various treatment strategies for cutaneous angiosarcoma have been employed, with the majority still resulting in poor outcomes.2,4-6 The recommended treatment is radical surgical excision of the primary tumor with lymph node clearance if possible. Following excision, the patient should undergo high-dose, wide-field radiotherapy to the region.5,8 Cutaneous angiosarcomas also have the ability to spread extensively through the dermis and can result in subclinical or clinically obvious widespread disease with multifocal or satellite lesions present. Distant metastases occur most frequently in the cervical lymph nodes and lungs.7 In cases where the disease is too extensive for surgery, palliative radiation monotherapy can be used.5,6

As atypical vascular lesions are considered to be a precursor to cutaneous angiosarcoma, it is important to note that the fish-in-the-creek feature was absent in all 6 of the atypical vascular lesions observed in the study. The differentiation generally is made based on MYC, which is present in cutaneous angiosarcomas and absent in atypical vascular lesions.10 The feature of fish in the creek may now be an additional clue for dermatopathologists to differentiate between angiosarcomas and other similar-appearing tumors.

Conclusion

Our study aimed to highlight an important histologic feature of cutaneous angiosarcomas that can aid in the diagnosis of this deceptive malignancy. Our findings warrant further study of the fish-in-the-creek histologic pattern in a larger sample size to determine its success as a diagnostic tool for cutaneous angiosarcomas. As noted previously, tumor grade does not impact survival outcome, but small tumor size has been one of the only features found to result in a more favorable prognosis.1,6,8 Future studies to identify a correlation between the histologic finding of fish in the creek and disease outcome in cutaneous angiosarcoma may be helpful to determine if these histologic findings provide prognostic significance in cases of cutaneous angiosarcoma.

- Aust MR, Olsen KD, Lewis JE, et al. Angiosarcomas of the head and neck: clinical and pathologic characteristics. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1997;106:943-951.

- Holden CA, Spittle MF, Jones EW. Angiosarcoma of the face and scalp, prognosis and treatment. Cancer. 1987;59:1046-1057.

- Woodward AH, Ivins JC, Soule EH. Lymphangiosarcoma arising in chronic lymphedematous extremities. Cancer. 1972;30:562-572.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, McKee PH, et al. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Morrison WH, Byers RM, Garden AS, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head and neck. a therapeutic dilemma. Cancer. 1995;76:319-327.

- Hodgkinson DJ, Soule EH, Woods JE. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head and neck. Cancer. 1979;44:1106-1113.

- Rosai J, Sumner HW, Kostianovsky M, et al. Angiosarcoma of the skin: a clinicopathologic and fine structural study. Hum Pathol. 1976;7:83-109.

- Pawlik TM, Paulino AF, Mcginn CJ, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp: a multidisciplinary approach. Cancer. 2003;98:1716-1726.

- Haustein UF. Angiosarcoma of the face and scalp. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:851-856.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

- Requena L, Kutzner H. Cutaneous Soft Tissue Tumors. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

- Cuda J, Mirzamani N, Kantipudi R, et al. Diagnostic utility of Fli-1 and D2-40 in distinguishing atypical fibroxanthoma from angiosarcoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:316-318.

- Aust MR, Olsen KD, Lewis JE, et al. Angiosarcomas of the head and neck: clinical and pathologic characteristics. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1997;106:943-951.

- Holden CA, Spittle MF, Jones EW. Angiosarcoma of the face and scalp, prognosis and treatment. Cancer. 1987;59:1046-1057.

- Woodward AH, Ivins JC, Soule EH. Lymphangiosarcoma arising in chronic lymphedematous extremities. Cancer. 1972;30:562-572.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, McKee PH, et al. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Morrison WH, Byers RM, Garden AS, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head and neck. a therapeutic dilemma. Cancer. 1995;76:319-327.

- Hodgkinson DJ, Soule EH, Woods JE. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head and neck. Cancer. 1979;44:1106-1113.

- Rosai J, Sumner HW, Kostianovsky M, et al. Angiosarcoma of the skin: a clinicopathologic and fine structural study. Hum Pathol. 1976;7:83-109.

- Pawlik TM, Paulino AF, Mcginn CJ, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp: a multidisciplinary approach. Cancer. 2003;98:1716-1726.

- Haustein UF. Angiosarcoma of the face and scalp. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:851-856.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

- Requena L, Kutzner H. Cutaneous Soft Tissue Tumors. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

- Cuda J, Mirzamani N, Kantipudi R, et al. Diagnostic utility of Fli-1 and D2-40 in distinguishing atypical fibroxanthoma from angiosarcoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:316-318.

Practice Points

- The histologic finding of “fish in the creek” is characterized by free-floating or tufted pleomorphic spindle cells within the vascular lumen.

- Fish in the creek has only been demonstrated in cutaneous angiosarcoma when compared to histologic findings of other similar vascular malignancies.

- The fish-in-the-creek finding may be an additional diagnostic tool in cases of cutaneous angiosarcoma.

Levothyroxine may increase mortality in older patients

CHICAGO – according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

With increased mortality and similar prevalence of atrial fibrillation and femoral fractures between study and control groups, physicians may want to reevaluate giving their elderly patients levothyroxine until more information is available, according to presenter Joseph Meyerovitch, MD, of Schneider Children’s Medical Center, Ramat Hasharon, Israel.

The case-control study included 416 patients 65 years or older with TSH levels of 4.2-10 mIU/L who died between 2012 and 2016, and 1,461 patients with comparable TSH levels who did not die during that time.

Most of the patients in both the control and study group were women. The average age of the patients was 84 years, and most had some form of dementia or senility (86.4%).

Mortality was 19% more likely in the group taking levothyroxine, according to an analysis by Dr. Meyerovitch and his fellow investigators.

When broken down further, presence of certain comorbidities increased mortality dramatically, including dementia (odds ratio, 1.61), heart failure (OR, 2.67), chronic renal failure (OR, 1.89), and cerebrovascular disease (OR, 1.94).

There was no significant difference in prevalence of atrial fibrillation between the test and control groups with thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) testing, nor any difference in femur fracture prevalence.

Patients were given a TSH test three times during follow-up and showed significantly lower TSH levels compared with controls, according to Dr. Meyerovitch.

Dr. Meyerovitch acknowledged that the data he and his team used did not include the reason for a TSH evaluation, nor why patients began levothyroxine treatment. This leaves unanswered questions about the initial baseline mortality risk in patients included in the study.

“This may have resulted in treatment of patients with a higher risk, since we don’t know the reason for the treatment,” he said. “There may have been other reasons that were not included in the database that caused the physician to treat with levothyroxine.”

Details on the cause of death were not included.

Despite these limitations, Dr. Meyerovitch and his team stressed the need for more research before continuing to recommend this treatment to their elderly patients.

Dr. Meyerovitch reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Meyerovitch J et al. ENDO 2018 Abstract OR34-2.

CHICAGO – according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

With increased mortality and similar prevalence of atrial fibrillation and femoral fractures between study and control groups, physicians may want to reevaluate giving their elderly patients levothyroxine until more information is available, according to presenter Joseph Meyerovitch, MD, of Schneider Children’s Medical Center, Ramat Hasharon, Israel.

The case-control study included 416 patients 65 years or older with TSH levels of 4.2-10 mIU/L who died between 2012 and 2016, and 1,461 patients with comparable TSH levels who did not die during that time.

Most of the patients in both the control and study group were women. The average age of the patients was 84 years, and most had some form of dementia or senility (86.4%).

Mortality was 19% more likely in the group taking levothyroxine, according to an analysis by Dr. Meyerovitch and his fellow investigators.

When broken down further, presence of certain comorbidities increased mortality dramatically, including dementia (odds ratio, 1.61), heart failure (OR, 2.67), chronic renal failure (OR, 1.89), and cerebrovascular disease (OR, 1.94).

There was no significant difference in prevalence of atrial fibrillation between the test and control groups with thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) testing, nor any difference in femur fracture prevalence.

Patients were given a TSH test three times during follow-up and showed significantly lower TSH levels compared with controls, according to Dr. Meyerovitch.

Dr. Meyerovitch acknowledged that the data he and his team used did not include the reason for a TSH evaluation, nor why patients began levothyroxine treatment. This leaves unanswered questions about the initial baseline mortality risk in patients included in the study.

“This may have resulted in treatment of patients with a higher risk, since we don’t know the reason for the treatment,” he said. “There may have been other reasons that were not included in the database that caused the physician to treat with levothyroxine.”

Details on the cause of death were not included.

Despite these limitations, Dr. Meyerovitch and his team stressed the need for more research before continuing to recommend this treatment to their elderly patients.

Dr. Meyerovitch reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Meyerovitch J et al. ENDO 2018 Abstract OR34-2.

CHICAGO – according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

With increased mortality and similar prevalence of atrial fibrillation and femoral fractures between study and control groups, physicians may want to reevaluate giving their elderly patients levothyroxine until more information is available, according to presenter Joseph Meyerovitch, MD, of Schneider Children’s Medical Center, Ramat Hasharon, Israel.

The case-control study included 416 patients 65 years or older with TSH levels of 4.2-10 mIU/L who died between 2012 and 2016, and 1,461 patients with comparable TSH levels who did not die during that time.

Most of the patients in both the control and study group were women. The average age of the patients was 84 years, and most had some form of dementia or senility (86.4%).