User login

AAD guidelines’ conflict-of-interest policies discussed in pro-con debate

SAN DIEGO – The American Academy of Dermatology’s policies that regulate conflicts of interest among members of its guidelines panels are “pretty good, but could be improved,” Lionel G. Bercovitch, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy Dermatology.

One positive step might be to tighten the current American Academy of Dermatology requirement that more than half of the members in clinical guideline work groups be free of any financial conflicts and the minimum be raised to a higher percentage, such as more than 70%, suggested Dr. Bercovitch, a professor of dermatology at Brown University, Providence, R.I.

But his concern over the adequacy of existing conflict barriers during the writing of clinical guidelines wasn’t shared by Clifford Perlis, MD, who countered that “there are reasons not to waste too much time wringing our hands over conflicts of interest.”

He offered four reasons to support his statement:

- Conflicts of interest are ubiquitous and thus impossible to eliminate.

- Excluding working group members with conflicts can deprive the guidelines of valuable expertise.

- Checks and balances that are already in place in guideline development prevent inappropriate influence from conflicts of interest.

- No evidence has shown that conflicts of interest have inappropriately influenced development of treatment guidelines.

Conflicts of interest may not be as well managed as AAD policies suggest, Dr. Bercovitch noted. He cited a report published in late 2017 that tallied the actual conflicts of 49 people who served as the authors of three AAD guidelines published during 2013-2016. To objectively double check each author’s conflicts the researchers used the Open Payments database run by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (JAMA Dermatol. 2017 Dec;153[12]:1229-35).

The analysis showed that 40 of the 49 authors (82%) had received some amount of industry payment, 63% had received more than $1,000, and 51% had received more than $10,000. The median amount received from industry was just over $33,000. The analysis also showed that 22 of the 40 authors who received an industry payment had disclosure statements for the guideline they participated in that did not agree with the information in the Open Payments database.

“The AAD relies on information obtained through its self-reported online member disclosure system. This internal system collects updates to disclosed relationships on a real-time, ongoing basis, allowing the AAD to regularly assess any changes,” wrote Dr. Lim and his coauthors. “This provides information in a more meaningful and time-sensitive way” than the Open Payments database. In addition, the Open Payments database “is known to be inaccurate,” while the AAD “relies on information obtained through its self-reported online member disclosure system.” This includes an assessment of the relevancy of the conflict to the guideline involved. “This critical evaluation of relevancy was not addressed in the authors’ analysis,” they added.

They reported an adjusted analysis of the percentage of authors with relevant conflicts for each of the guidelines examined in the initial study. The percentages shrank to zero, 40%, and 43% of the authors with relevant conflicts, percentages that fell within the AAD’s ceiling for an acceptable percentage of work group members with conflicts.

The discussion on this topic was presented during a forum on dermatoethics at the meeting, structured as a debate in which presenters are assigned an ethical argument or point-of-view to discuss and defend. The position taken by the speaker need not (and often does not) correspond to the speaker’s personal views.

SAN DIEGO – The American Academy of Dermatology’s policies that regulate conflicts of interest among members of its guidelines panels are “pretty good, but could be improved,” Lionel G. Bercovitch, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy Dermatology.

One positive step might be to tighten the current American Academy of Dermatology requirement that more than half of the members in clinical guideline work groups be free of any financial conflicts and the minimum be raised to a higher percentage, such as more than 70%, suggested Dr. Bercovitch, a professor of dermatology at Brown University, Providence, R.I.

But his concern over the adequacy of existing conflict barriers during the writing of clinical guidelines wasn’t shared by Clifford Perlis, MD, who countered that “there are reasons not to waste too much time wringing our hands over conflicts of interest.”

He offered four reasons to support his statement:

- Conflicts of interest are ubiquitous and thus impossible to eliminate.

- Excluding working group members with conflicts can deprive the guidelines of valuable expertise.

- Checks and balances that are already in place in guideline development prevent inappropriate influence from conflicts of interest.

- No evidence has shown that conflicts of interest have inappropriately influenced development of treatment guidelines.

Conflicts of interest may not be as well managed as AAD policies suggest, Dr. Bercovitch noted. He cited a report published in late 2017 that tallied the actual conflicts of 49 people who served as the authors of three AAD guidelines published during 2013-2016. To objectively double check each author’s conflicts the researchers used the Open Payments database run by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (JAMA Dermatol. 2017 Dec;153[12]:1229-35).

The analysis showed that 40 of the 49 authors (82%) had received some amount of industry payment, 63% had received more than $1,000, and 51% had received more than $10,000. The median amount received from industry was just over $33,000. The analysis also showed that 22 of the 40 authors who received an industry payment had disclosure statements for the guideline they participated in that did not agree with the information in the Open Payments database.

“The AAD relies on information obtained through its self-reported online member disclosure system. This internal system collects updates to disclosed relationships on a real-time, ongoing basis, allowing the AAD to regularly assess any changes,” wrote Dr. Lim and his coauthors. “This provides information in a more meaningful and time-sensitive way” than the Open Payments database. In addition, the Open Payments database “is known to be inaccurate,” while the AAD “relies on information obtained through its self-reported online member disclosure system.” This includes an assessment of the relevancy of the conflict to the guideline involved. “This critical evaluation of relevancy was not addressed in the authors’ analysis,” they added.

They reported an adjusted analysis of the percentage of authors with relevant conflicts for each of the guidelines examined in the initial study. The percentages shrank to zero, 40%, and 43% of the authors with relevant conflicts, percentages that fell within the AAD’s ceiling for an acceptable percentage of work group members with conflicts.

The discussion on this topic was presented during a forum on dermatoethics at the meeting, structured as a debate in which presenters are assigned an ethical argument or point-of-view to discuss and defend. The position taken by the speaker need not (and often does not) correspond to the speaker’s personal views.

SAN DIEGO – The American Academy of Dermatology’s policies that regulate conflicts of interest among members of its guidelines panels are “pretty good, but could be improved,” Lionel G. Bercovitch, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy Dermatology.

One positive step might be to tighten the current American Academy of Dermatology requirement that more than half of the members in clinical guideline work groups be free of any financial conflicts and the minimum be raised to a higher percentage, such as more than 70%, suggested Dr. Bercovitch, a professor of dermatology at Brown University, Providence, R.I.

But his concern over the adequacy of existing conflict barriers during the writing of clinical guidelines wasn’t shared by Clifford Perlis, MD, who countered that “there are reasons not to waste too much time wringing our hands over conflicts of interest.”

He offered four reasons to support his statement:

- Conflicts of interest are ubiquitous and thus impossible to eliminate.

- Excluding working group members with conflicts can deprive the guidelines of valuable expertise.

- Checks and balances that are already in place in guideline development prevent inappropriate influence from conflicts of interest.

- No evidence has shown that conflicts of interest have inappropriately influenced development of treatment guidelines.

Conflicts of interest may not be as well managed as AAD policies suggest, Dr. Bercovitch noted. He cited a report published in late 2017 that tallied the actual conflicts of 49 people who served as the authors of three AAD guidelines published during 2013-2016. To objectively double check each author’s conflicts the researchers used the Open Payments database run by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (JAMA Dermatol. 2017 Dec;153[12]:1229-35).

The analysis showed that 40 of the 49 authors (82%) had received some amount of industry payment, 63% had received more than $1,000, and 51% had received more than $10,000. The median amount received from industry was just over $33,000. The analysis also showed that 22 of the 40 authors who received an industry payment had disclosure statements for the guideline they participated in that did not agree with the information in the Open Payments database.

“The AAD relies on information obtained through its self-reported online member disclosure system. This internal system collects updates to disclosed relationships on a real-time, ongoing basis, allowing the AAD to regularly assess any changes,” wrote Dr. Lim and his coauthors. “This provides information in a more meaningful and time-sensitive way” than the Open Payments database. In addition, the Open Payments database “is known to be inaccurate,” while the AAD “relies on information obtained through its self-reported online member disclosure system.” This includes an assessment of the relevancy of the conflict to the guideline involved. “This critical evaluation of relevancy was not addressed in the authors’ analysis,” they added.

They reported an adjusted analysis of the percentage of authors with relevant conflicts for each of the guidelines examined in the initial study. The percentages shrank to zero, 40%, and 43% of the authors with relevant conflicts, percentages that fell within the AAD’s ceiling for an acceptable percentage of work group members with conflicts.

The discussion on this topic was presented during a forum on dermatoethics at the meeting, structured as a debate in which presenters are assigned an ethical argument or point-of-view to discuss and defend. The position taken by the speaker need not (and often does not) correspond to the speaker’s personal views.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAD 18

Updated CLL guidelines incorporate a decade of advances

include new and revised recommendations based on major advances in genomics, targeted therapies, and biomarkers that have occurred since the last iteration in 2008.

The guidelines are an update from a consensus document issued a decade ago by the International Workshop on CLL, focusing on the conduct of clinical trials in patients with CLL. The new guidelines are published in Blood.

Major changes or additions include:

Molecular genetics: The updated guidelines recognize the clinical importance of specific genomic alterations/mutations on response to standard chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy, including the 17p deletion and mutations in TP53.

“Therefore, the assessment of both del(17p) and TP53 mutation has prognostic and predictive value and should guide therapeutic decisions in routine practice. For clinical trials, it is recommended that molecular genetics be performed prior to treating a patient on protocol,” the guidelines state.

IGHV mutational status: The mutational status of immunoglobulin variable heavy chain (IGHV) genes has been demonstrated to offer important prognostic information, according to the guidelines authors led by Michael Hallek, MD of the University of Cologne, Germany.

Specifically, leukemia with IGHV genes without somatic mutations are associated with worse clinical outcomes, compared with leukemia with IGHV mutations. Patients with mutated IGHV and other prognostic factors such as favorable cytogenetics or minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity generally have excellent outcomes with a chemoimmunotherapy regimen consisting of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab, the authors noted.

Biomarkers: The guidelines call for standardization and use in prospective clinical trials of assays for serum markers such as soluble CD23, thymidine kinase, and beta-2-microglobulin. These markers have been shown in several studies to be associated with overall survival or progression-free survival, and of these markers, beta-2-microglobulin “has retained independent prognostic value in several multiparameter scores,” the guidelines state.

The authors also tip their hats to recently developed or improved prognostic scores, especially the CLL International Prognostic Index (CLL-IPI), which incorporates clinical stage, age, IGHV mutational status, beta-2-microglobulin, and del(17p) and/or TP53 mutations.

Organ function assessment: Not new, but improved in the current version of the guidelines, are recommendations for evaluation of splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, and lymphadenopathy in response assessment. These recommendations were harmonized with the relevant sections of the updated lymphoma response guidelines.

Continuous therapy: The guidelines panel recommends assessment of response duration during continuous therapy with oral agents and after the end of therapy, especially after chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy.

“Study protocols should provide detailed specifications of the planned time points for the assessment of the treatment response under continuous therapy. Response durations of less than six months are not considered clinically relevant,” the panel cautioned.

Response assessments for treatments with a maintenance phase should be performed at a minimum of 2 months after patients achieve their best responses.

MRD: The guidelines call for minimal residual disease (MRD) assessment in clinical trials aimed at maximizing remission depth, with emphasis on reporting the sensitivity of the MRD evaluation method used, and the type of tissue assessed.

Antiviral prophylaxis: The guidelines caution that because patients treated with anti-CD20 antibodies, such as rituximab or obinutuzumab, could have reactivation of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections, patients should be tested for HBV serological status before starting on an anti-CD20 agent.

“Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy has been reported in a few CLL patients treated with anti-CD20 antibodies; therefore, infections with John Cunningham (JC) virus should be ruled out in situations of unclear neurological symptoms,” the panel recommended.

They note that patients younger than 65 treated with fludarabine-based therapy in the first line do not require routine monitoring or infection prophylaxis, due to the low reported incidence of infections in this group.

The authors reported having no financial disclosures related to the guidelines.

include new and revised recommendations based on major advances in genomics, targeted therapies, and biomarkers that have occurred since the last iteration in 2008.

The guidelines are an update from a consensus document issued a decade ago by the International Workshop on CLL, focusing on the conduct of clinical trials in patients with CLL. The new guidelines are published in Blood.

Major changes or additions include:

Molecular genetics: The updated guidelines recognize the clinical importance of specific genomic alterations/mutations on response to standard chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy, including the 17p deletion and mutations in TP53.

“Therefore, the assessment of both del(17p) and TP53 mutation has prognostic and predictive value and should guide therapeutic decisions in routine practice. For clinical trials, it is recommended that molecular genetics be performed prior to treating a patient on protocol,” the guidelines state.

IGHV mutational status: The mutational status of immunoglobulin variable heavy chain (IGHV) genes has been demonstrated to offer important prognostic information, according to the guidelines authors led by Michael Hallek, MD of the University of Cologne, Germany.

Specifically, leukemia with IGHV genes without somatic mutations are associated with worse clinical outcomes, compared with leukemia with IGHV mutations. Patients with mutated IGHV and other prognostic factors such as favorable cytogenetics or minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity generally have excellent outcomes with a chemoimmunotherapy regimen consisting of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab, the authors noted.

Biomarkers: The guidelines call for standardization and use in prospective clinical trials of assays for serum markers such as soluble CD23, thymidine kinase, and beta-2-microglobulin. These markers have been shown in several studies to be associated with overall survival or progression-free survival, and of these markers, beta-2-microglobulin “has retained independent prognostic value in several multiparameter scores,” the guidelines state.

The authors also tip their hats to recently developed or improved prognostic scores, especially the CLL International Prognostic Index (CLL-IPI), which incorporates clinical stage, age, IGHV mutational status, beta-2-microglobulin, and del(17p) and/or TP53 mutations.

Organ function assessment: Not new, but improved in the current version of the guidelines, are recommendations for evaluation of splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, and lymphadenopathy in response assessment. These recommendations were harmonized with the relevant sections of the updated lymphoma response guidelines.

Continuous therapy: The guidelines panel recommends assessment of response duration during continuous therapy with oral agents and after the end of therapy, especially after chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy.

“Study protocols should provide detailed specifications of the planned time points for the assessment of the treatment response under continuous therapy. Response durations of less than six months are not considered clinically relevant,” the panel cautioned.

Response assessments for treatments with a maintenance phase should be performed at a minimum of 2 months after patients achieve their best responses.

MRD: The guidelines call for minimal residual disease (MRD) assessment in clinical trials aimed at maximizing remission depth, with emphasis on reporting the sensitivity of the MRD evaluation method used, and the type of tissue assessed.

Antiviral prophylaxis: The guidelines caution that because patients treated with anti-CD20 antibodies, such as rituximab or obinutuzumab, could have reactivation of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections, patients should be tested for HBV serological status before starting on an anti-CD20 agent.

“Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy has been reported in a few CLL patients treated with anti-CD20 antibodies; therefore, infections with John Cunningham (JC) virus should be ruled out in situations of unclear neurological symptoms,” the panel recommended.

They note that patients younger than 65 treated with fludarabine-based therapy in the first line do not require routine monitoring or infection prophylaxis, due to the low reported incidence of infections in this group.

The authors reported having no financial disclosures related to the guidelines.

include new and revised recommendations based on major advances in genomics, targeted therapies, and biomarkers that have occurred since the last iteration in 2008.

The guidelines are an update from a consensus document issued a decade ago by the International Workshop on CLL, focusing on the conduct of clinical trials in patients with CLL. The new guidelines are published in Blood.

Major changes or additions include:

Molecular genetics: The updated guidelines recognize the clinical importance of specific genomic alterations/mutations on response to standard chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy, including the 17p deletion and mutations in TP53.

“Therefore, the assessment of both del(17p) and TP53 mutation has prognostic and predictive value and should guide therapeutic decisions in routine practice. For clinical trials, it is recommended that molecular genetics be performed prior to treating a patient on protocol,” the guidelines state.

IGHV mutational status: The mutational status of immunoglobulin variable heavy chain (IGHV) genes has been demonstrated to offer important prognostic information, according to the guidelines authors led by Michael Hallek, MD of the University of Cologne, Germany.

Specifically, leukemia with IGHV genes without somatic mutations are associated with worse clinical outcomes, compared with leukemia with IGHV mutations. Patients with mutated IGHV and other prognostic factors such as favorable cytogenetics or minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity generally have excellent outcomes with a chemoimmunotherapy regimen consisting of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab, the authors noted.

Biomarkers: The guidelines call for standardization and use in prospective clinical trials of assays for serum markers such as soluble CD23, thymidine kinase, and beta-2-microglobulin. These markers have been shown in several studies to be associated with overall survival or progression-free survival, and of these markers, beta-2-microglobulin “has retained independent prognostic value in several multiparameter scores,” the guidelines state.

The authors also tip their hats to recently developed or improved prognostic scores, especially the CLL International Prognostic Index (CLL-IPI), which incorporates clinical stage, age, IGHV mutational status, beta-2-microglobulin, and del(17p) and/or TP53 mutations.

Organ function assessment: Not new, but improved in the current version of the guidelines, are recommendations for evaluation of splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, and lymphadenopathy in response assessment. These recommendations were harmonized with the relevant sections of the updated lymphoma response guidelines.

Continuous therapy: The guidelines panel recommends assessment of response duration during continuous therapy with oral agents and after the end of therapy, especially after chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy.

“Study protocols should provide detailed specifications of the planned time points for the assessment of the treatment response under continuous therapy. Response durations of less than six months are not considered clinically relevant,” the panel cautioned.

Response assessments for treatments with a maintenance phase should be performed at a minimum of 2 months after patients achieve their best responses.

MRD: The guidelines call for minimal residual disease (MRD) assessment in clinical trials aimed at maximizing remission depth, with emphasis on reporting the sensitivity of the MRD evaluation method used, and the type of tissue assessed.

Antiviral prophylaxis: The guidelines caution that because patients treated with anti-CD20 antibodies, such as rituximab or obinutuzumab, could have reactivation of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections, patients should be tested for HBV serological status before starting on an anti-CD20 agent.

“Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy has been reported in a few CLL patients treated with anti-CD20 antibodies; therefore, infections with John Cunningham (JC) virus should be ruled out in situations of unclear neurological symptoms,” the panel recommended.

They note that patients younger than 65 treated with fludarabine-based therapy in the first line do not require routine monitoring or infection prophylaxis, due to the low reported incidence of infections in this group.

The authors reported having no financial disclosures related to the guidelines.

FROM BLOOD

MDedge Daily News: Antibiotic resistance leads to ‘nightmare’ bacteria

PPIs aren’t responsible for cognitive decline. Levothyroxine comes with risks for older patients. And Medicare formulary changes could be on the way.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

PPIs aren’t responsible for cognitive decline. Levothyroxine comes with risks for older patients. And Medicare formulary changes could be on the way.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

PPIs aren’t responsible for cognitive decline. Levothyroxine comes with risks for older patients. And Medicare formulary changes could be on the way.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

HSV-2 Has Little to No Effect on HIV Progression

Patients with HIV often also have herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) infection in part because lesions act as entry portals to susceptible HIV target cells. Some research also has suggested that HSV-2 accelerates HIV progression by upregulating HIV replication and increasing HIV viral load, but data are inconclusive, say researchers from the Iranian Research Center for HIV/AIDS, Pasteur Institute of Iran, Iranian Society for Support of Patients With Infectious Disease, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, and Zanjan University of Medical Sciences in Iran. They conducted a study to investigate HSV-2 seroprevalence in patients with and without HIV and to find out whether HSV-2 serostatus changed as CD4 counts and HIV viral load changed after 1 year.

The researchers compared 116 HIV patients who were not on HAART with 85 healthy controls. The prevalence and incidence of HSV-2 infection were low in the HIV cases and “negligible” in the control group: 18% of naïve HIV patients had HSV-2 IgG, and none of the control patients did.

Few data exist about HSV-2 seroconversion in HIV patients, the researchers say. In this study, HSV-2 seroconversion was found in 2.43% of HIV patients after 1 year.

Co-infection with HSV-2 had no association with CD4 count and HIV RNA viral load changes in the study participants at baseline or over time, the researchers say. CD4 counts after 1 year were 550 cells/mm3 in the HSV-2 seropositive patients and 563 cells/mm3 in the control group. The viral load in the seropositive group was 3.97 log copies/mL, and 3.49 log copies/mL in the seronegative group.

The researchers conclude that HIV-HSV-2 co-infection does not seem to play a role in HIV infection progression.

Patients with HIV often also have herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) infection in part because lesions act as entry portals to susceptible HIV target cells. Some research also has suggested that HSV-2 accelerates HIV progression by upregulating HIV replication and increasing HIV viral load, but data are inconclusive, say researchers from the Iranian Research Center for HIV/AIDS, Pasteur Institute of Iran, Iranian Society for Support of Patients With Infectious Disease, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, and Zanjan University of Medical Sciences in Iran. They conducted a study to investigate HSV-2 seroprevalence in patients with and without HIV and to find out whether HSV-2 serostatus changed as CD4 counts and HIV viral load changed after 1 year.

The researchers compared 116 HIV patients who were not on HAART with 85 healthy controls. The prevalence and incidence of HSV-2 infection were low in the HIV cases and “negligible” in the control group: 18% of naïve HIV patients had HSV-2 IgG, and none of the control patients did.

Few data exist about HSV-2 seroconversion in HIV patients, the researchers say. In this study, HSV-2 seroconversion was found in 2.43% of HIV patients after 1 year.

Co-infection with HSV-2 had no association with CD4 count and HIV RNA viral load changes in the study participants at baseline or over time, the researchers say. CD4 counts after 1 year were 550 cells/mm3 in the HSV-2 seropositive patients and 563 cells/mm3 in the control group. The viral load in the seropositive group was 3.97 log copies/mL, and 3.49 log copies/mL in the seronegative group.

The researchers conclude that HIV-HSV-2 co-infection does not seem to play a role in HIV infection progression.

Patients with HIV often also have herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) infection in part because lesions act as entry portals to susceptible HIV target cells. Some research also has suggested that HSV-2 accelerates HIV progression by upregulating HIV replication and increasing HIV viral load, but data are inconclusive, say researchers from the Iranian Research Center for HIV/AIDS, Pasteur Institute of Iran, Iranian Society for Support of Patients With Infectious Disease, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, and Zanjan University of Medical Sciences in Iran. They conducted a study to investigate HSV-2 seroprevalence in patients with and without HIV and to find out whether HSV-2 serostatus changed as CD4 counts and HIV viral load changed after 1 year.

The researchers compared 116 HIV patients who were not on HAART with 85 healthy controls. The prevalence and incidence of HSV-2 infection were low in the HIV cases and “negligible” in the control group: 18% of naïve HIV patients had HSV-2 IgG, and none of the control patients did.

Few data exist about HSV-2 seroconversion in HIV patients, the researchers say. In this study, HSV-2 seroconversion was found in 2.43% of HIV patients after 1 year.

Co-infection with HSV-2 had no association with CD4 count and HIV RNA viral load changes in the study participants at baseline or over time, the researchers say. CD4 counts after 1 year were 550 cells/mm3 in the HSV-2 seropositive patients and 563 cells/mm3 in the control group. The viral load in the seropositive group was 3.97 log copies/mL, and 3.49 log copies/mL in the seronegative group.

The researchers conclude that HIV-HSV-2 co-infection does not seem to play a role in HIV infection progression.

Stopping the Suicide “Contagion” Among Native Americans

American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/AN) have a disproportionately high rate of suicide—more than 3.5 times those of racial/ethnic groups with the lowest rates, according to a CDC study. And the rate has been steadily rising since 2003.

Those at highest risk are young people aged 10 to 24 years: More than one-third of suicides have occurred in that group compared with 11% of whites in the same age group.

In the CDC study, about 70% of AI/AN decedents lived in nonmetropolitan areas, including rural areas, which underscores the importance of implementing suicide prevention strategies in rural AI/AN communities, the researchers say. Rural areas often have fewer mental health services due to provider shortages and social barriers, among other factors. The researchers point out that in their study AI/AN had lower odds than did white decedents of having received a mental health diagnosis or mental health treatment.

The researchers also found suggestions of “suicide contagion”; AI/AN decedents were more than twice as likely to have a friend’s or family member’s suicide contribute to their death. Community-level programs that focus on “postvention,” such as survivor support groups, should be considered, the researchers say. They also advise that media should focus on “safe reporting of suicides,” for example, by not using sensationalized headlines.

Nearly 28% of the people who died had reported alcohol abuse problems, and 49% had used alcohol in the hours before their death. The researchers caution that differences in the prevalence of alcohol use among AI/AN might be a symptom of “disproportionate exposure to poverty, historical trauma, and other contexts of inequity and should not be viewed as inherent to AI/AN culture.”

American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/AN) have a disproportionately high rate of suicide—more than 3.5 times those of racial/ethnic groups with the lowest rates, according to a CDC study. And the rate has been steadily rising since 2003.

Those at highest risk are young people aged 10 to 24 years: More than one-third of suicides have occurred in that group compared with 11% of whites in the same age group.

In the CDC study, about 70% of AI/AN decedents lived in nonmetropolitan areas, including rural areas, which underscores the importance of implementing suicide prevention strategies in rural AI/AN communities, the researchers say. Rural areas often have fewer mental health services due to provider shortages and social barriers, among other factors. The researchers point out that in their study AI/AN had lower odds than did white decedents of having received a mental health diagnosis or mental health treatment.

The researchers also found suggestions of “suicide contagion”; AI/AN decedents were more than twice as likely to have a friend’s or family member’s suicide contribute to their death. Community-level programs that focus on “postvention,” such as survivor support groups, should be considered, the researchers say. They also advise that media should focus on “safe reporting of suicides,” for example, by not using sensationalized headlines.

Nearly 28% of the people who died had reported alcohol abuse problems, and 49% had used alcohol in the hours before their death. The researchers caution that differences in the prevalence of alcohol use among AI/AN might be a symptom of “disproportionate exposure to poverty, historical trauma, and other contexts of inequity and should not be viewed as inherent to AI/AN culture.”

American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/AN) have a disproportionately high rate of suicide—more than 3.5 times those of racial/ethnic groups with the lowest rates, according to a CDC study. And the rate has been steadily rising since 2003.

Those at highest risk are young people aged 10 to 24 years: More than one-third of suicides have occurred in that group compared with 11% of whites in the same age group.

In the CDC study, about 70% of AI/AN decedents lived in nonmetropolitan areas, including rural areas, which underscores the importance of implementing suicide prevention strategies in rural AI/AN communities, the researchers say. Rural areas often have fewer mental health services due to provider shortages and social barriers, among other factors. The researchers point out that in their study AI/AN had lower odds than did white decedents of having received a mental health diagnosis or mental health treatment.

The researchers also found suggestions of “suicide contagion”; AI/AN decedents were more than twice as likely to have a friend’s or family member’s suicide contribute to their death. Community-level programs that focus on “postvention,” such as survivor support groups, should be considered, the researchers say. They also advise that media should focus on “safe reporting of suicides,” for example, by not using sensationalized headlines.

Nearly 28% of the people who died had reported alcohol abuse problems, and 49% had used alcohol in the hours before their death. The researchers caution that differences in the prevalence of alcohol use among AI/AN might be a symptom of “disproportionate exposure to poverty, historical trauma, and other contexts of inequity and should not be viewed as inherent to AI/AN culture.”

Project provides ‘unprecedented understanding’ of cancers

Through extensive analyses of data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), researchers have produced a new resource known as the Pan-Cancer Atlas.

Multiple research groups analyzed data on more than 10,000 tumors spanning 33 types of cancer, including acute myeloid leukemia and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

The work revealed new insights regarding cells of origin, oncogenic processes, and signaling pathways.

These insights make up the Pan-Cancer Atlas and are described in 27 papers published in Cell Press journals. The entire collection of papers is available through a portal on cell.com.

The Pan-Cancer Atlas is the final output of TCGA, a joint effort of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) to “collect, select, and analyze human tissues for genomic alterations on a very large scale.”

“This project is the culmination of more than a decade of ground-breaking work,” said Francis S. Collins, MD, PhD, director of the National Institutes of Health.

“This analysis provides cancer researchers with unprecedented understanding of how, where, and why tumors arise in humans, enabling better informed clinical trials and future treatments.”

The project focused on genome sequencing as well as other analyses, such as investigating gene and protein expression profiles and associating them with clinical and imaging data.

“The Pan-Cancer Atlas effort complements the over 30 tumor-specific papers that have been published by TCGA in the last decade and expands upon earlier pan-cancer work that was published in 2013,” said Jean Claude Zenklusen, PhD, director of the TCGA Program Office at NCI.

The Pan-Cancer Atlas is divided into 3 main categories—cell of origin, oncogenic processes, and signaling pathways—each anchored by a summary paper that recaps the core findings for the topic. Companion papers report in-depth explorations of individual topics within these categories.

Cell of origin

In the first Pan-Cancer Atlas summary paper, the authors review the findings from analyses using a technique called molecular clustering, which groups tumors by parameters such as genes being expressed, abnormality of chromosome numbers in tumor cells, and DNA modifications.

The analyses suggest that tumor types cluster by their possible cells of origin, a finding that has implications for the classification and treatment of various cancers.

“Rather than the organ of origin, we can now use molecular features to identify the cancer’s cell of origin,” said Li Ding, PhD, of Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri.

“We are looking at what genes are turned on in the tumor, and that brings us to a particular cell type. For example, squamous cell cancers can arise in the lung, bladder, cervix, and some tumors of the head and neck. We traditionally have treated cancers in these areas as completely different diseases, but, [by] studying their molecular features, we now know such cancers are closely related.”

“This new molecular-based classification system should greatly help in the clinic, where it is already explaining some of the similar clinical behavior of what we thought were different tumor types,” said Charles Perou, PhD, of UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

“These findings also provide many new therapeutic opportunities, which can and will be tested in the next phase of human clinical trials.”

Oncogenic processes

The second Pan-Cancer Atlas summary paper presents a broad view of the TCGA findings on the processes that lead to cancer development and progression.

The research revealed insights into 3 critical oncogenic processes—germline and somatic mutations, the influence of the tumor’s underlying genome and epigenome on gene and protein expression, and the interplay of tumor and immune cells.

“For the 10,000 tumors we analyzed, we now know—in detail—the inherited mutations driving cancer and the genetic errors that accumulate as people age, increasing the risk of cancer,” Dr Ding said. “This is the first definitive summary of the genetics behind 33 major types of cancer.”

“TCGA has created a catalogue of alterations that occur in a variety of cancer types,” said Katherine Hoadley, PhD, of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“Having this catalogue of alterations is really important for us to look, in future studies, at why these alterations are there and to predict outcomes for patients.”

Signaling pathways

The final Pan-Cancer Atlas summary paper details TCGA research on the genomic alterations in the signaling pathways that control cell-cycle progression, cell death, and cell growth. The work highlights the similarities and differences in these processes across a range of cancers.

The researchers believe these studies have revealed new patterns of potential vulnerabilities that might aid the development of targeted and combination therapies.

Through extensive analyses of data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), researchers have produced a new resource known as the Pan-Cancer Atlas.

Multiple research groups analyzed data on more than 10,000 tumors spanning 33 types of cancer, including acute myeloid leukemia and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

The work revealed new insights regarding cells of origin, oncogenic processes, and signaling pathways.

These insights make up the Pan-Cancer Atlas and are described in 27 papers published in Cell Press journals. The entire collection of papers is available through a portal on cell.com.

The Pan-Cancer Atlas is the final output of TCGA, a joint effort of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) to “collect, select, and analyze human tissues for genomic alterations on a very large scale.”

“This project is the culmination of more than a decade of ground-breaking work,” said Francis S. Collins, MD, PhD, director of the National Institutes of Health.

“This analysis provides cancer researchers with unprecedented understanding of how, where, and why tumors arise in humans, enabling better informed clinical trials and future treatments.”

The project focused on genome sequencing as well as other analyses, such as investigating gene and protein expression profiles and associating them with clinical and imaging data.

“The Pan-Cancer Atlas effort complements the over 30 tumor-specific papers that have been published by TCGA in the last decade and expands upon earlier pan-cancer work that was published in 2013,” said Jean Claude Zenklusen, PhD, director of the TCGA Program Office at NCI.

The Pan-Cancer Atlas is divided into 3 main categories—cell of origin, oncogenic processes, and signaling pathways—each anchored by a summary paper that recaps the core findings for the topic. Companion papers report in-depth explorations of individual topics within these categories.

Cell of origin

In the first Pan-Cancer Atlas summary paper, the authors review the findings from analyses using a technique called molecular clustering, which groups tumors by parameters such as genes being expressed, abnormality of chromosome numbers in tumor cells, and DNA modifications.

The analyses suggest that tumor types cluster by their possible cells of origin, a finding that has implications for the classification and treatment of various cancers.

“Rather than the organ of origin, we can now use molecular features to identify the cancer’s cell of origin,” said Li Ding, PhD, of Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri.

“We are looking at what genes are turned on in the tumor, and that brings us to a particular cell type. For example, squamous cell cancers can arise in the lung, bladder, cervix, and some tumors of the head and neck. We traditionally have treated cancers in these areas as completely different diseases, but, [by] studying their molecular features, we now know such cancers are closely related.”

“This new molecular-based classification system should greatly help in the clinic, where it is already explaining some of the similar clinical behavior of what we thought were different tumor types,” said Charles Perou, PhD, of UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

“These findings also provide many new therapeutic opportunities, which can and will be tested in the next phase of human clinical trials.”

Oncogenic processes

The second Pan-Cancer Atlas summary paper presents a broad view of the TCGA findings on the processes that lead to cancer development and progression.

The research revealed insights into 3 critical oncogenic processes—germline and somatic mutations, the influence of the tumor’s underlying genome and epigenome on gene and protein expression, and the interplay of tumor and immune cells.

“For the 10,000 tumors we analyzed, we now know—in detail—the inherited mutations driving cancer and the genetic errors that accumulate as people age, increasing the risk of cancer,” Dr Ding said. “This is the first definitive summary of the genetics behind 33 major types of cancer.”

“TCGA has created a catalogue of alterations that occur in a variety of cancer types,” said Katherine Hoadley, PhD, of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“Having this catalogue of alterations is really important for us to look, in future studies, at why these alterations are there and to predict outcomes for patients.”

Signaling pathways

The final Pan-Cancer Atlas summary paper details TCGA research on the genomic alterations in the signaling pathways that control cell-cycle progression, cell death, and cell growth. The work highlights the similarities and differences in these processes across a range of cancers.

The researchers believe these studies have revealed new patterns of potential vulnerabilities that might aid the development of targeted and combination therapies.

Through extensive analyses of data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), researchers have produced a new resource known as the Pan-Cancer Atlas.

Multiple research groups analyzed data on more than 10,000 tumors spanning 33 types of cancer, including acute myeloid leukemia and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

The work revealed new insights regarding cells of origin, oncogenic processes, and signaling pathways.

These insights make up the Pan-Cancer Atlas and are described in 27 papers published in Cell Press journals. The entire collection of papers is available through a portal on cell.com.

The Pan-Cancer Atlas is the final output of TCGA, a joint effort of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) to “collect, select, and analyze human tissues for genomic alterations on a very large scale.”

“This project is the culmination of more than a decade of ground-breaking work,” said Francis S. Collins, MD, PhD, director of the National Institutes of Health.

“This analysis provides cancer researchers with unprecedented understanding of how, where, and why tumors arise in humans, enabling better informed clinical trials and future treatments.”

The project focused on genome sequencing as well as other analyses, such as investigating gene and protein expression profiles and associating them with clinical and imaging data.

“The Pan-Cancer Atlas effort complements the over 30 tumor-specific papers that have been published by TCGA in the last decade and expands upon earlier pan-cancer work that was published in 2013,” said Jean Claude Zenklusen, PhD, director of the TCGA Program Office at NCI.

The Pan-Cancer Atlas is divided into 3 main categories—cell of origin, oncogenic processes, and signaling pathways—each anchored by a summary paper that recaps the core findings for the topic. Companion papers report in-depth explorations of individual topics within these categories.

Cell of origin

In the first Pan-Cancer Atlas summary paper, the authors review the findings from analyses using a technique called molecular clustering, which groups tumors by parameters such as genes being expressed, abnormality of chromosome numbers in tumor cells, and DNA modifications.

The analyses suggest that tumor types cluster by their possible cells of origin, a finding that has implications for the classification and treatment of various cancers.

“Rather than the organ of origin, we can now use molecular features to identify the cancer’s cell of origin,” said Li Ding, PhD, of Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri.

“We are looking at what genes are turned on in the tumor, and that brings us to a particular cell type. For example, squamous cell cancers can arise in the lung, bladder, cervix, and some tumors of the head and neck. We traditionally have treated cancers in these areas as completely different diseases, but, [by] studying their molecular features, we now know such cancers are closely related.”

“This new molecular-based classification system should greatly help in the clinic, where it is already explaining some of the similar clinical behavior of what we thought were different tumor types,” said Charles Perou, PhD, of UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

“These findings also provide many new therapeutic opportunities, which can and will be tested in the next phase of human clinical trials.”

Oncogenic processes

The second Pan-Cancer Atlas summary paper presents a broad view of the TCGA findings on the processes that lead to cancer development and progression.

The research revealed insights into 3 critical oncogenic processes—germline and somatic mutations, the influence of the tumor’s underlying genome and epigenome on gene and protein expression, and the interplay of tumor and immune cells.

“For the 10,000 tumors we analyzed, we now know—in detail—the inherited mutations driving cancer and the genetic errors that accumulate as people age, increasing the risk of cancer,” Dr Ding said. “This is the first definitive summary of the genetics behind 33 major types of cancer.”

“TCGA has created a catalogue of alterations that occur in a variety of cancer types,” said Katherine Hoadley, PhD, of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“Having this catalogue of alterations is really important for us to look, in future studies, at why these alterations are there and to predict outcomes for patients.”

Signaling pathways

The final Pan-Cancer Atlas summary paper details TCGA research on the genomic alterations in the signaling pathways that control cell-cycle progression, cell death, and cell growth. The work highlights the similarities and differences in these processes across a range of cancers.

The researchers believe these studies have revealed new patterns of potential vulnerabilities that might aid the development of targeted and combination therapies.

Injectable hydrogels stop bleeding, promote healing

Biomedical engineers have developed hydrogels that can act as an “injectable bandage,” according to preclinical research published in Acta Biomaterialia.

The team engineered injectable hydrogels that were able to promote hemostasis and facilitate wound healing in vitro.

“Injectable hydrogels are promising materials for achieving hemostasis in case of internal injuries and bleeding, as these biomaterials can be introduced into a wound site using minimally invasive approaches,” said study author Akhilesh K. Gaharwar, PhD, of Texas A&M University in College Station, Texas.

“An ideal injectable bandage should solidify after injection in the wound area and promote a natural clotting cascade. In addition, the injectable bandage should initiate wound healing response after achieving hemostasis.”

To create their injectable hydrogels, Dr Gaharwar and his colleagues used a thickening agent known as kappa-carrageenan, which is obtained from seaweed, as well as clay-based nanoparticles known as nanosilicates.

It is the charged characteristics of the nanosilicates that provide the hydrogels with hemostatic ability, according to the researchers.

Specifically, the team said adding nanosilicates to kappa-carrageenan increases protein adsorption on the hydrogels, which enhances cell adhesion and spreading, increases platelet binding, and reduces blood clotting time.

“Interestingly, we also found that these injectable bandages can show a prolonged release of therapeutics that can be used to heal the wound,” said study author Giriraj Lokhande, a graduate student in Dr Gaharwar’s lab.

“The negative surface charge of nanoparticles enabled electrostatic interactions with therapeutics, thus resulting in the slow release of therapeutics.”

The researchers encapsulated vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the hydrogels and observed sustained release of VEGF in experiments. The hydrogels containing VEGF promoted faster wound healing than control hydrogels.

The researchers said a “range of therapeutic biomacromolecules” could be delivered in the same way as the VEGF.

Biomedical engineers have developed hydrogels that can act as an “injectable bandage,” according to preclinical research published in Acta Biomaterialia.

The team engineered injectable hydrogels that were able to promote hemostasis and facilitate wound healing in vitro.

“Injectable hydrogels are promising materials for achieving hemostasis in case of internal injuries and bleeding, as these biomaterials can be introduced into a wound site using minimally invasive approaches,” said study author Akhilesh K. Gaharwar, PhD, of Texas A&M University in College Station, Texas.

“An ideal injectable bandage should solidify after injection in the wound area and promote a natural clotting cascade. In addition, the injectable bandage should initiate wound healing response after achieving hemostasis.”

To create their injectable hydrogels, Dr Gaharwar and his colleagues used a thickening agent known as kappa-carrageenan, which is obtained from seaweed, as well as clay-based nanoparticles known as nanosilicates.

It is the charged characteristics of the nanosilicates that provide the hydrogels with hemostatic ability, according to the researchers.

Specifically, the team said adding nanosilicates to kappa-carrageenan increases protein adsorption on the hydrogels, which enhances cell adhesion and spreading, increases platelet binding, and reduces blood clotting time.

“Interestingly, we also found that these injectable bandages can show a prolonged release of therapeutics that can be used to heal the wound,” said study author Giriraj Lokhande, a graduate student in Dr Gaharwar’s lab.

“The negative surface charge of nanoparticles enabled electrostatic interactions with therapeutics, thus resulting in the slow release of therapeutics.”

The researchers encapsulated vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the hydrogels and observed sustained release of VEGF in experiments. The hydrogels containing VEGF promoted faster wound healing than control hydrogels.

The researchers said a “range of therapeutic biomacromolecules” could be delivered in the same way as the VEGF.

Biomedical engineers have developed hydrogels that can act as an “injectable bandage,” according to preclinical research published in Acta Biomaterialia.

The team engineered injectable hydrogels that were able to promote hemostasis and facilitate wound healing in vitro.

“Injectable hydrogels are promising materials for achieving hemostasis in case of internal injuries and bleeding, as these biomaterials can be introduced into a wound site using minimally invasive approaches,” said study author Akhilesh K. Gaharwar, PhD, of Texas A&M University in College Station, Texas.

“An ideal injectable bandage should solidify after injection in the wound area and promote a natural clotting cascade. In addition, the injectable bandage should initiate wound healing response after achieving hemostasis.”

To create their injectable hydrogels, Dr Gaharwar and his colleagues used a thickening agent known as kappa-carrageenan, which is obtained from seaweed, as well as clay-based nanoparticles known as nanosilicates.

It is the charged characteristics of the nanosilicates that provide the hydrogels with hemostatic ability, according to the researchers.

Specifically, the team said adding nanosilicates to kappa-carrageenan increases protein adsorption on the hydrogels, which enhances cell adhesion and spreading, increases platelet binding, and reduces blood clotting time.

“Interestingly, we also found that these injectable bandages can show a prolonged release of therapeutics that can be used to heal the wound,” said study author Giriraj Lokhande, a graduate student in Dr Gaharwar’s lab.

“The negative surface charge of nanoparticles enabled electrostatic interactions with therapeutics, thus resulting in the slow release of therapeutics.”

The researchers encapsulated vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the hydrogels and observed sustained release of VEGF in experiments. The hydrogels containing VEGF promoted faster wound healing than control hydrogels.

The researchers said a “range of therapeutic biomacromolecules” could be delivered in the same way as the VEGF.

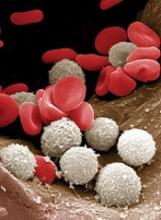

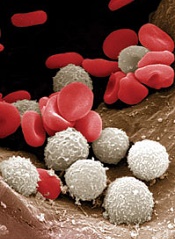

At-home measurement of WBCs

A portable device could be used to monitor patients’ white blood cell (WBC) levels at home, without the need for blood samples, according to researchers.

The team created a prototype that records video of blood cells flowing through capillaries just below the skin surface at the base of the fingernail.

The group is developing a computer algorithm that, in early testing, has been able to analyze the videos and determine if WBC levels are too low.

The researchers believe this type of device could be used to prevent infections among chemotherapy recipients.

“Our vision is that patients will have this portable device that they can take home, and they can monitor daily how they are reacting to the treatment,” said Carlos Castro-Gonzalez, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“If they go below the [safe WBC] threshold, then preventive treatment can be deployed.”

Dr Castro-Gonzalez and his colleagues described their prototype, and the testing of it, in Scientific Reports.

The device consists of a wide-field microscope that emits blue light, which penetrates about 50 to 150 microns below the skin and is reflected back to a video camera.

The researchers decided to image the skin at the base of the nail because the capillaries there are very close to the skin surface. These capillaries are so narrow that WBCs must squeeze through one at a time, making them easier to see.

The researchers tested the device in 11 patients at various points during their chemotherapy treatment.

The device does not provide precise WBC counts but allowed the team to differentiate cases of severe neutropenia (<500 neutrophils per μL) from non-neutropenic cases (>1500 neutrophils per μL).

To obtain enough data to make these classifications, the researchers recorded 1 minute of video per patient. Three blinded human assistants then watched the videos and noted whenever a WBC passed by.

However, since submitting their paper, the researchers have been developing a computer algorithm to perform the same task automatically.

“Based on the feature-set that our human raters identified, we are now developing an AI and machine-vision algorithm, with preliminary results that indicate the same accuracy as the raters,” said study author Aurélien Bourquard, PhD, of MIT.

The researchers have applied for patents on the technology and launched a company called Leuko, which is working on commercializing the technology with help from MIT.

To move the technology further toward commercialization, the researchers are building a new automated prototype.

“Automating the measurement process is key to making a viable home-use device,” said study author Ian Butterworth, of MIT. “The imaging needs to take place in the right spot on the patient’s finger, and the operation of the device must be straightforward.”

Using this new prototype, the researchers plan to test the device with additional cancer patients. And the team is investigating whether they can get accurate results with shorter lengths of video.

They also plan to adapt the technology so it can generate more precise WBC counts, which would make it useful for monitoring bone marrow transplant recipients or people with certain infectious diseases, Dr Castro-Gonzalez said.

This could also make it possible to determine whether chemotherapy patients can receive their next dose sooner than usual.

“There is a balancing act that oncologists must do,” said study author Alvaro Sanchez-Ferro, MD, of Centro Integral en Neurociencias A.C. HM CINAC in Madrid, Spain.

“Normally, doctors want to make chemotherapy as intensive as possible but without getting people too immunosuppressed. Current 21-day cycles are based on statistics of what most patients can take, but if you are ready early, then they can potentially bring you back early, and that can translate into better survival.”

A portable device could be used to monitor patients’ white blood cell (WBC) levels at home, without the need for blood samples, according to researchers.

The team created a prototype that records video of blood cells flowing through capillaries just below the skin surface at the base of the fingernail.

The group is developing a computer algorithm that, in early testing, has been able to analyze the videos and determine if WBC levels are too low.

The researchers believe this type of device could be used to prevent infections among chemotherapy recipients.

“Our vision is that patients will have this portable device that they can take home, and they can monitor daily how they are reacting to the treatment,” said Carlos Castro-Gonzalez, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“If they go below the [safe WBC] threshold, then preventive treatment can be deployed.”

Dr Castro-Gonzalez and his colleagues described their prototype, and the testing of it, in Scientific Reports.

The device consists of a wide-field microscope that emits blue light, which penetrates about 50 to 150 microns below the skin and is reflected back to a video camera.

The researchers decided to image the skin at the base of the nail because the capillaries there are very close to the skin surface. These capillaries are so narrow that WBCs must squeeze through one at a time, making them easier to see.

The researchers tested the device in 11 patients at various points during their chemotherapy treatment.

The device does not provide precise WBC counts but allowed the team to differentiate cases of severe neutropenia (<500 neutrophils per μL) from non-neutropenic cases (>1500 neutrophils per μL).

To obtain enough data to make these classifications, the researchers recorded 1 minute of video per patient. Three blinded human assistants then watched the videos and noted whenever a WBC passed by.

However, since submitting their paper, the researchers have been developing a computer algorithm to perform the same task automatically.

“Based on the feature-set that our human raters identified, we are now developing an AI and machine-vision algorithm, with preliminary results that indicate the same accuracy as the raters,” said study author Aurélien Bourquard, PhD, of MIT.

The researchers have applied for patents on the technology and launched a company called Leuko, which is working on commercializing the technology with help from MIT.

To move the technology further toward commercialization, the researchers are building a new automated prototype.

“Automating the measurement process is key to making a viable home-use device,” said study author Ian Butterworth, of MIT. “The imaging needs to take place in the right spot on the patient’s finger, and the operation of the device must be straightforward.”

Using this new prototype, the researchers plan to test the device with additional cancer patients. And the team is investigating whether they can get accurate results with shorter lengths of video.

They also plan to adapt the technology so it can generate more precise WBC counts, which would make it useful for monitoring bone marrow transplant recipients or people with certain infectious diseases, Dr Castro-Gonzalez said.

This could also make it possible to determine whether chemotherapy patients can receive their next dose sooner than usual.

“There is a balancing act that oncologists must do,” said study author Alvaro Sanchez-Ferro, MD, of Centro Integral en Neurociencias A.C. HM CINAC in Madrid, Spain.

“Normally, doctors want to make chemotherapy as intensive as possible but without getting people too immunosuppressed. Current 21-day cycles are based on statistics of what most patients can take, but if you are ready early, then they can potentially bring you back early, and that can translate into better survival.”

A portable device could be used to monitor patients’ white blood cell (WBC) levels at home, without the need for blood samples, according to researchers.

The team created a prototype that records video of blood cells flowing through capillaries just below the skin surface at the base of the fingernail.

The group is developing a computer algorithm that, in early testing, has been able to analyze the videos and determine if WBC levels are too low.

The researchers believe this type of device could be used to prevent infections among chemotherapy recipients.

“Our vision is that patients will have this portable device that they can take home, and they can monitor daily how they are reacting to the treatment,” said Carlos Castro-Gonzalez, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“If they go below the [safe WBC] threshold, then preventive treatment can be deployed.”

Dr Castro-Gonzalez and his colleagues described their prototype, and the testing of it, in Scientific Reports.

The device consists of a wide-field microscope that emits blue light, which penetrates about 50 to 150 microns below the skin and is reflected back to a video camera.

The researchers decided to image the skin at the base of the nail because the capillaries there are very close to the skin surface. These capillaries are so narrow that WBCs must squeeze through one at a time, making them easier to see.

The researchers tested the device in 11 patients at various points during their chemotherapy treatment.

The device does not provide precise WBC counts but allowed the team to differentiate cases of severe neutropenia (<500 neutrophils per μL) from non-neutropenic cases (>1500 neutrophils per μL).

To obtain enough data to make these classifications, the researchers recorded 1 minute of video per patient. Three blinded human assistants then watched the videos and noted whenever a WBC passed by.

However, since submitting their paper, the researchers have been developing a computer algorithm to perform the same task automatically.

“Based on the feature-set that our human raters identified, we are now developing an AI and machine-vision algorithm, with preliminary results that indicate the same accuracy as the raters,” said study author Aurélien Bourquard, PhD, of MIT.

The researchers have applied for patents on the technology and launched a company called Leuko, which is working on commercializing the technology with help from MIT.

To move the technology further toward commercialization, the researchers are building a new automated prototype.

“Automating the measurement process is key to making a viable home-use device,” said study author Ian Butterworth, of MIT. “The imaging needs to take place in the right spot on the patient’s finger, and the operation of the device must be straightforward.”

Using this new prototype, the researchers plan to test the device with additional cancer patients. And the team is investigating whether they can get accurate results with shorter lengths of video.

They also plan to adapt the technology so it can generate more precise WBC counts, which would make it useful for monitoring bone marrow transplant recipients or people with certain infectious diseases, Dr Castro-Gonzalez said.

This could also make it possible to determine whether chemotherapy patients can receive their next dose sooner than usual.

“There is a balancing act that oncologists must do,” said study author Alvaro Sanchez-Ferro, MD, of Centro Integral en Neurociencias A.C. HM CINAC in Madrid, Spain.

“Normally, doctors want to make chemotherapy as intensive as possible but without getting people too immunosuppressed. Current 21-day cycles are based on statistics of what most patients can take, but if you are ready early, then they can potentially bring you back early, and that can translate into better survival.”

Abstract: Collaborative Care for Opioid and Alcohol Use Disorders in Primary Care: The SUMMIT Randomized Clinical Trial

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Watkins, K.E., et al, JAMA Intern Med 177(10):1480, October 1, 2017

BACKGROUND: Collaborative care has been reported to be an effective strategy for the delivery of evidence-based treatments and improving patient outcomes, but its utility for substance abuse treatment in primary care has not been evaluated.

METHODS: The Substance Use Motivation and Medication Integrated Treatment (SUMMIT) study, coordinated at RAND Corporation, included 377 adults (mean age 42 years; 80% male) attending two community health clinics for opioid and alcohol use disorders. The study excluded patients with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or current substance abuse treatment. Study participants were randomized to collaborative care (n=187) or usual care (n=190). Patients were assessed for their use of evidence-based treatments (brief six-session psychotherapy treatment and treatment with buprenorphine/naloxone or naltrexone) and self-reported abstinence from opioids and alcohol at six months.

RESULTS: Only 13% of the patients had received any substance abuse treatment in the previous year. After six months, more patients in the collaborative care group than controls had received psychotherapy or medications (39.0% versus 16.8%; adjusted odds ratio [OR] 3.97, 95% CI 2.32-6.79; p<0.001); the difference was explained by a higher rate of psychotherapy (35.8% versus 10.5%; OR 6.22, 95% CI 3.4-11.5; p<0.001), while rates of medication use in the two groups were similar (13.4% versus 12.6%). Self-reported abstinence at six months was also more frequent with collaborative care (32.8% versus 22.3%; adjusted effect estimate, beta = 0.12; 95% CI 0.01-0.23; p=0.03). Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures of initiation and engagement increased significantly with collaborative care (both, p<0.001).

CONCLUSIONS: A collaborative care intervention increased treatment uptake and six-month abstinence in these primary care patients with opioid and alcohol abuse disorders. 69 references ([email protected] – no reprints)

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Watkins, K.E., et al, JAMA Intern Med 177(10):1480, October 1, 2017

BACKGROUND: Collaborative care has been reported to be an effective strategy for the delivery of evidence-based treatments and improving patient outcomes, but its utility for substance abuse treatment in primary care has not been evaluated.

METHODS: The Substance Use Motivation and Medication Integrated Treatment (SUMMIT) study, coordinated at RAND Corporation, included 377 adults (mean age 42 years; 80% male) attending two community health clinics for opioid and alcohol use disorders. The study excluded patients with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or current substance abuse treatment. Study participants were randomized to collaborative care (n=187) or usual care (n=190). Patients were assessed for their use of evidence-based treatments (brief six-session psychotherapy treatment and treatment with buprenorphine/naloxone or naltrexone) and self-reported abstinence from opioids and alcohol at six months.

RESULTS: Only 13% of the patients had received any substance abuse treatment in the previous year. After six months, more patients in the collaborative care group than controls had received psychotherapy or medications (39.0% versus 16.8%; adjusted odds ratio [OR] 3.97, 95% CI 2.32-6.79; p<0.001); the difference was explained by a higher rate of psychotherapy (35.8% versus 10.5%; OR 6.22, 95% CI 3.4-11.5; p<0.001), while rates of medication use in the two groups were similar (13.4% versus 12.6%). Self-reported abstinence at six months was also more frequent with collaborative care (32.8% versus 22.3%; adjusted effect estimate, beta = 0.12; 95% CI 0.01-0.23; p=0.03). Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures of initiation and engagement increased significantly with collaborative care (both, p<0.001).

CONCLUSIONS: A collaborative care intervention increased treatment uptake and six-month abstinence in these primary care patients with opioid and alcohol abuse disorders. 69 references ([email protected] – no reprints)

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Watkins, K.E., et al, JAMA Intern Med 177(10):1480, October 1, 2017

BACKGROUND: Collaborative care has been reported to be an effective strategy for the delivery of evidence-based treatments and improving patient outcomes, but its utility for substance abuse treatment in primary care has not been evaluated.

METHODS: The Substance Use Motivation and Medication Integrated Treatment (SUMMIT) study, coordinated at RAND Corporation, included 377 adults (mean age 42 years; 80% male) attending two community health clinics for opioid and alcohol use disorders. The study excluded patients with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or current substance abuse treatment. Study participants were randomized to collaborative care (n=187) or usual care (n=190). Patients were assessed for their use of evidence-based treatments (brief six-session psychotherapy treatment and treatment with buprenorphine/naloxone or naltrexone) and self-reported abstinence from opioids and alcohol at six months.

RESULTS: Only 13% of the patients had received any substance abuse treatment in the previous year. After six months, more patients in the collaborative care group than controls had received psychotherapy or medications (39.0% versus 16.8%; adjusted odds ratio [OR] 3.97, 95% CI 2.32-6.79; p<0.001); the difference was explained by a higher rate of psychotherapy (35.8% versus 10.5%; OR 6.22, 95% CI 3.4-11.5; p<0.001), while rates of medication use in the two groups were similar (13.4% versus 12.6%). Self-reported abstinence at six months was also more frequent with collaborative care (32.8% versus 22.3%; adjusted effect estimate, beta = 0.12; 95% CI 0.01-0.23; p=0.03). Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures of initiation and engagement increased significantly with collaborative care (both, p<0.001).

CONCLUSIONS: A collaborative care intervention increased treatment uptake and six-month abstinence in these primary care patients with opioid and alcohol abuse disorders. 69 references ([email protected] – no reprints)

Learn more about the Primary Care Medical Abstracts and podcasts, for which you can earn up to 9 CME credits per month.

Copyright © The Center for Medical Education

Sound and light levels are similarly disruptive in ICU and non-ICU wards

Clinical question: While it is generally thought that ICU wards are not conducive for sleep because of light and noise disruptions, are general wards any better?

Background: Hospitalized patients frequently report poor sleep, partly because of the inpatient environment. Sound level changes (SLCs), rather than the total volumes, are important in disrupting sleep. The World Health Organization recommends that nighttime baseline noise levels do not exceed 30 decibels (dB) and that nighttime noise peaks (i.e., loud noises) do not exceed 40 dB. The circadian rhythm system depends on ambient light to regulate the internal clock. Insufficient and inappropriately timed light exposure can desynchronize the biological clock, thereby negatively affecting sleep quality.

Setting: Tertiary care hospital in La Jolla, Calif.

Synopsis: For approximately 24-72 hours, recordings of sound and light were performed. ICU rooms were louder (hourly averages ranged from 56.1 dB to 60.3 dB) than were non-ICU wards (44.6-55.1 dB). However, SLCs of 17.5 dB or greater were not statistically different (ICU, 203.9 ± 28.8 times; non-ICU, 270.9 ± 39.5; P = .11). In both ICU and non-ICU wards, average daytime light levels were less than 250 lux and generally were brightest in the afternoon. This corresponds to low, office-level lighting, which may not be conducive for maintaining circadian rhythm.

Bottom line: While ICU wards are generally louder than non-ICU wards, sound level changes are equivalent and probably more important concerning sleep disruption. While no significant differences were seen in light levels, the amount and timing of lighting may not be optimal for keeping circadian rhythm.

Citation: Jaiswal SJ et al. Sound and light levels are similarly disruptive in ICU and non-ICU wards. J Hosp Med. 2017 Oct;12(10):798-804.

Dr. Kim is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine, Emory University, Atlanta.

Clinical question: While it is generally thought that ICU wards are not conducive for sleep because of light and noise disruptions, are general wards any better?