User login

Developing a Pediatric Epilepsy Self-Management Protocol

Pediatric patients with epilepsy would benefit from a comprehensive self-management system that includes several modifiable targets such as adherence, self-sufficiency, attitudes about the disorder, and family variables, according to a review published in Epilepsia.

- To reach that conclusion, investigators studied English-based literature from 1985 to 2014, concentrating on countries with a very high human development index.

- They identified 25 studies related to self-management of epilepsy and found that individual and family-focused factors were most often analyzed for their ability to predict successful self-management.

- Psychosocial care needs and self-efficiency were identified as key factors linked to pediatric epilepsy self-management.

- Researchers identified adherence, self-efficacy for seizure management, attitudes toward epilepsy, and family variables as skills to concentrate on when developing a self-management model.

Smith G, Modi AC, Johnson EK, et al. Measurement in pediatric epilepsy self-management: a critical review. Epilepsia. 2018;59(3):509-522.

Pediatric patients with epilepsy would benefit from a comprehensive self-management system that includes several modifiable targets such as adherence, self-sufficiency, attitudes about the disorder, and family variables, according to a review published in Epilepsia.

- To reach that conclusion, investigators studied English-based literature from 1985 to 2014, concentrating on countries with a very high human development index.

- They identified 25 studies related to self-management of epilepsy and found that individual and family-focused factors were most often analyzed for their ability to predict successful self-management.

- Psychosocial care needs and self-efficiency were identified as key factors linked to pediatric epilepsy self-management.

- Researchers identified adherence, self-efficacy for seizure management, attitudes toward epilepsy, and family variables as skills to concentrate on when developing a self-management model.

Smith G, Modi AC, Johnson EK, et al. Measurement in pediatric epilepsy self-management: a critical review. Epilepsia. 2018;59(3):509-522.

Pediatric patients with epilepsy would benefit from a comprehensive self-management system that includes several modifiable targets such as adherence, self-sufficiency, attitudes about the disorder, and family variables, according to a review published in Epilepsia.

- To reach that conclusion, investigators studied English-based literature from 1985 to 2014, concentrating on countries with a very high human development index.

- They identified 25 studies related to self-management of epilepsy and found that individual and family-focused factors were most often analyzed for their ability to predict successful self-management.

- Psychosocial care needs and self-efficiency were identified as key factors linked to pediatric epilepsy self-management.

- Researchers identified adherence, self-efficacy for seizure management, attitudes toward epilepsy, and family variables as skills to concentrate on when developing a self-management model.

Smith G, Modi AC, Johnson EK, et al. Measurement in pediatric epilepsy self-management: a critical review. Epilepsia. 2018;59(3):509-522.

Linking EEG Oscillations to Epileptic Spasms

The occurrence rate of high-frequency oscillations is higher in children with drug-resistant multilobar epilepsy who experience epileptic spasms, when compared with those who do not, according to a study published in Epilepsia.

- Researchers found that the number of electrodes with high-rate fast ripple (FR) amplitude and the modulation index of coupling between slow and fast oscillations in all electrodes were significantly higher in children with epileptic spasms.

- The investigation involved 24 pediatric patients with drug-resistant multilobar onset epilepsy who had intracranial video EEGs done before multilobar resection.

- The modulation index was highest in 5 frequency bands among both epileptic spasm and nonepileptic spasm prone children.

- Researchers concluded that the greater number of high-rate FR electrodes provided evidence that there was more widespread epileptogenicity in the spasming patients, compared to those without spasms.

- Children with epileptic spasms who were free of seizures after surgery had strong coupling between slow oscillations and FRs.

Iimura Y, Jones K, Takada L, et al. Strong coupling between slow oscillations and wide fast ripples in children with epileptic spasms: Investigation of modulation index and occurrence rate. Epilepsia. 2018;59(3):544-554.

The occurrence rate of high-frequency oscillations is higher in children with drug-resistant multilobar epilepsy who experience epileptic spasms, when compared with those who do not, according to a study published in Epilepsia.

- Researchers found that the number of electrodes with high-rate fast ripple (FR) amplitude and the modulation index of coupling between slow and fast oscillations in all electrodes were significantly higher in children with epileptic spasms.

- The investigation involved 24 pediatric patients with drug-resistant multilobar onset epilepsy who had intracranial video EEGs done before multilobar resection.

- The modulation index was highest in 5 frequency bands among both epileptic spasm and nonepileptic spasm prone children.

- Researchers concluded that the greater number of high-rate FR electrodes provided evidence that there was more widespread epileptogenicity in the spasming patients, compared to those without spasms.

- Children with epileptic spasms who were free of seizures after surgery had strong coupling between slow oscillations and FRs.

Iimura Y, Jones K, Takada L, et al. Strong coupling between slow oscillations and wide fast ripples in children with epileptic spasms: Investigation of modulation index and occurrence rate. Epilepsia. 2018;59(3):544-554.

The occurrence rate of high-frequency oscillations is higher in children with drug-resistant multilobar epilepsy who experience epileptic spasms, when compared with those who do not, according to a study published in Epilepsia.

- Researchers found that the number of electrodes with high-rate fast ripple (FR) amplitude and the modulation index of coupling between slow and fast oscillations in all electrodes were significantly higher in children with epileptic spasms.

- The investigation involved 24 pediatric patients with drug-resistant multilobar onset epilepsy who had intracranial video EEGs done before multilobar resection.

- The modulation index was highest in 5 frequency bands among both epileptic spasm and nonepileptic spasm prone children.

- Researchers concluded that the greater number of high-rate FR electrodes provided evidence that there was more widespread epileptogenicity in the spasming patients, compared to those without spasms.

- Children with epileptic spasms who were free of seizures after surgery had strong coupling between slow oscillations and FRs.

Iimura Y, Jones K, Takada L, et al. Strong coupling between slow oscillations and wide fast ripples in children with epileptic spasms: Investigation of modulation index and occurrence rate. Epilepsia. 2018;59(3):544-554.

Angelman Syndrome Accompanied by Nonepileptic Myoclonus

Angelman syndrome, a neurogenetic disorder brought on by loss of the Ube3a gene, is often accompanied by nonepileptic myoclonus according to a study of 200 patients reported by the Massachusetts General Hospital and the Lurie Center for Autism.

- Myoclonus seizures were reported in 14% of patients with Angelman syndrome, with the first episode beginning before 8 years of age.

- The seizures were usually brief, unless the patient was experiencing myoclonic status, and EEGs showed interictal generalized spike and wave activity.

- 40% of patients older than 10 years had nonepileptic myoclonus.

- Nonepileptic myoclonus typically started during puberty or later.

- The nonepileptic myoclonus lasted from seconds to hours and always began in patients’ hands and, in some cases, spread to face and all extremities.

Pollack SF, Grocott OR, Parkin KA, et al. Myoclonus in Angelman syndrome [Published online ahead of print March 17, 2018]. Epilepsy Behav. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.02.006.

Angelman syndrome, a neurogenetic disorder brought on by loss of the Ube3a gene, is often accompanied by nonepileptic myoclonus according to a study of 200 patients reported by the Massachusetts General Hospital and the Lurie Center for Autism.

- Myoclonus seizures were reported in 14% of patients with Angelman syndrome, with the first episode beginning before 8 years of age.

- The seizures were usually brief, unless the patient was experiencing myoclonic status, and EEGs showed interictal generalized spike and wave activity.

- 40% of patients older than 10 years had nonepileptic myoclonus.

- Nonepileptic myoclonus typically started during puberty or later.

- The nonepileptic myoclonus lasted from seconds to hours and always began in patients’ hands and, in some cases, spread to face and all extremities.

Pollack SF, Grocott OR, Parkin KA, et al. Myoclonus in Angelman syndrome [Published online ahead of print March 17, 2018]. Epilepsy Behav. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.02.006.

Angelman syndrome, a neurogenetic disorder brought on by loss of the Ube3a gene, is often accompanied by nonepileptic myoclonus according to a study of 200 patients reported by the Massachusetts General Hospital and the Lurie Center for Autism.

- Myoclonus seizures were reported in 14% of patients with Angelman syndrome, with the first episode beginning before 8 years of age.

- The seizures were usually brief, unless the patient was experiencing myoclonic status, and EEGs showed interictal generalized spike and wave activity.

- 40% of patients older than 10 years had nonepileptic myoclonus.

- Nonepileptic myoclonus typically started during puberty or later.

- The nonepileptic myoclonus lasted from seconds to hours and always began in patients’ hands and, in some cases, spread to face and all extremities.

Pollack SF, Grocott OR, Parkin KA, et al. Myoclonus in Angelman syndrome [Published online ahead of print March 17, 2018]. Epilepsy Behav. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.02.006.

Evaluating fever in the first 90 days of life

Fever in the youngest of infants creates a challenge for the pediatric clinician. Fever is a common presentation for serious bacterial infection (SBI) although most fevers are due to viral infection. However, the clinical presentation does not necessarily differ, and the risk for a poor outcome in this age group is substantial.

In the early stages of my pediatric career, most febrile infants less than 90 days of age were evaluated for sepsis, admitted, and treated with antibiotics pending culture results. Group B streptococcal sepsis or Escherichia coli sepsis were common in the first month of life, and Haemophilus influenza type B or Streptococcus pneumoniae in the second and third months of life. The approach to fever in the first 90 days has changed following both the introduction of haemophilus and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, the experience with risk stratification criteria for identifying infants at low risk for SBI, and the recognition of urinary tract infection (UTI) as a common source of infection in this age group as well as development of criteria for diagnosis.

A further nuance was subsequently added with the introduction of rapid diagnostics for viral infection. Byington et al. found that the majority of febrile infants less than 90 days of age had viral infection with enterovirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza or rotavirus.1 Using the Rochester risk stratification and the presence or absence of viral infection, she demonstrated that the risk of SBI was reduced in both high- and low-risk infants in the presence of viral infection; in low risk infants with viral infection, SBI was identified in 1.8%, compared with 3.1% in those without viral infection, and in high-risk infants. 5.5% has SBI when viral infection was found, compared to 16.7% in the absence of viral infection. She also proposed risk features to identify those infected with herpes simplex virus; age less than 42 days, vesicular rash, elevated alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), CSF pleocytosis, and seizure or twitching.

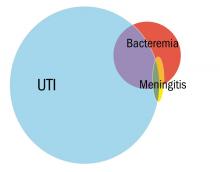

Greenhow et al. reported on the experience with “serious” bacterial infection in infants less than 90 days of age receiving care at Northern California Kaiser Permanente during the period 2005-2011.2 As pictured, the majority of children have UTI, and smaller numbers have bacteremia or meningitis. A small group of children with UTI have urosepsis as well; those with urosepsis can be differentiated from those with only UTI by age (less than 21 days), clinical exam (ill appearing), and elevated C reactive protein (greater than 20 mg/L) or elevated procalcitonin (greater than 0.5 ng/mL).3 Further evaluation of procalcitonin by other groups appears to validate its role in identifying children at low risk of SBI (procalcitonin less than 0.3 ng/mL).4

Currently, studies of febrile infants less than 90 days of age demonstrate that E. coli dominates in bacteremia, UTI, and meningitis, with Group B streptococcus as the next most frequent pathogen identified.2 Increasingly ampicillin resistance has been reported among E. coli isolates from both early- and late-onset disease as well as rare isolates that are resistant to third generation cephalosporins or gentamicin. Surveillance to identify changes in antimicrobial susceptibility will need to be ongoing to ensure that current approaches for initial therapy in high-risk infants aligns with current susceptibility patterns.

Dr. Pelton is chief of the section of pediatric infectious diseases and coordinator of the maternal-child HIV program at Boston Medical Center. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatrics. 2004 Jun;113(6):1662-6.

2. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014 Jun;33(6):595-9.

3. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015 Jan;34(1):17-21.

4. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(1):17-18.

5. “AAP Proposes Update to Evaluating, Managing Febrile Infants Guideline,” The Hospitalist, 2016.

Fever in the youngest of infants creates a challenge for the pediatric clinician. Fever is a common presentation for serious bacterial infection (SBI) although most fevers are due to viral infection. However, the clinical presentation does not necessarily differ, and the risk for a poor outcome in this age group is substantial.

In the early stages of my pediatric career, most febrile infants less than 90 days of age were evaluated for sepsis, admitted, and treated with antibiotics pending culture results. Group B streptococcal sepsis or Escherichia coli sepsis were common in the first month of life, and Haemophilus influenza type B or Streptococcus pneumoniae in the second and third months of life. The approach to fever in the first 90 days has changed following both the introduction of haemophilus and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, the experience with risk stratification criteria for identifying infants at low risk for SBI, and the recognition of urinary tract infection (UTI) as a common source of infection in this age group as well as development of criteria for diagnosis.

A further nuance was subsequently added with the introduction of rapid diagnostics for viral infection. Byington et al. found that the majority of febrile infants less than 90 days of age had viral infection with enterovirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza or rotavirus.1 Using the Rochester risk stratification and the presence or absence of viral infection, she demonstrated that the risk of SBI was reduced in both high- and low-risk infants in the presence of viral infection; in low risk infants with viral infection, SBI was identified in 1.8%, compared with 3.1% in those without viral infection, and in high-risk infants. 5.5% has SBI when viral infection was found, compared to 16.7% in the absence of viral infection. She also proposed risk features to identify those infected with herpes simplex virus; age less than 42 days, vesicular rash, elevated alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), CSF pleocytosis, and seizure or twitching.

Greenhow et al. reported on the experience with “serious” bacterial infection in infants less than 90 days of age receiving care at Northern California Kaiser Permanente during the period 2005-2011.2 As pictured, the majority of children have UTI, and smaller numbers have bacteremia or meningitis. A small group of children with UTI have urosepsis as well; those with urosepsis can be differentiated from those with only UTI by age (less than 21 days), clinical exam (ill appearing), and elevated C reactive protein (greater than 20 mg/L) or elevated procalcitonin (greater than 0.5 ng/mL).3 Further evaluation of procalcitonin by other groups appears to validate its role in identifying children at low risk of SBI (procalcitonin less than 0.3 ng/mL).4

Currently, studies of febrile infants less than 90 days of age demonstrate that E. coli dominates in bacteremia, UTI, and meningitis, with Group B streptococcus as the next most frequent pathogen identified.2 Increasingly ampicillin resistance has been reported among E. coli isolates from both early- and late-onset disease as well as rare isolates that are resistant to third generation cephalosporins or gentamicin. Surveillance to identify changes in antimicrobial susceptibility will need to be ongoing to ensure that current approaches for initial therapy in high-risk infants aligns with current susceptibility patterns.

Dr. Pelton is chief of the section of pediatric infectious diseases and coordinator of the maternal-child HIV program at Boston Medical Center. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatrics. 2004 Jun;113(6):1662-6.

2. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014 Jun;33(6):595-9.

3. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015 Jan;34(1):17-21.

4. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(1):17-18.

5. “AAP Proposes Update to Evaluating, Managing Febrile Infants Guideline,” The Hospitalist, 2016.

Fever in the youngest of infants creates a challenge for the pediatric clinician. Fever is a common presentation for serious bacterial infection (SBI) although most fevers are due to viral infection. However, the clinical presentation does not necessarily differ, and the risk for a poor outcome in this age group is substantial.

In the early stages of my pediatric career, most febrile infants less than 90 days of age were evaluated for sepsis, admitted, and treated with antibiotics pending culture results. Group B streptococcal sepsis or Escherichia coli sepsis were common in the first month of life, and Haemophilus influenza type B or Streptococcus pneumoniae in the second and third months of life. The approach to fever in the first 90 days has changed following both the introduction of haemophilus and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, the experience with risk stratification criteria for identifying infants at low risk for SBI, and the recognition of urinary tract infection (UTI) as a common source of infection in this age group as well as development of criteria for diagnosis.

A further nuance was subsequently added with the introduction of rapid diagnostics for viral infection. Byington et al. found that the majority of febrile infants less than 90 days of age had viral infection with enterovirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza or rotavirus.1 Using the Rochester risk stratification and the presence or absence of viral infection, she demonstrated that the risk of SBI was reduced in both high- and low-risk infants in the presence of viral infection; in low risk infants with viral infection, SBI was identified in 1.8%, compared with 3.1% in those without viral infection, and in high-risk infants. 5.5% has SBI when viral infection was found, compared to 16.7% in the absence of viral infection. She also proposed risk features to identify those infected with herpes simplex virus; age less than 42 days, vesicular rash, elevated alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), CSF pleocytosis, and seizure or twitching.

Greenhow et al. reported on the experience with “serious” bacterial infection in infants less than 90 days of age receiving care at Northern California Kaiser Permanente during the period 2005-2011.2 As pictured, the majority of children have UTI, and smaller numbers have bacteremia or meningitis. A small group of children with UTI have urosepsis as well; those with urosepsis can be differentiated from those with only UTI by age (less than 21 days), clinical exam (ill appearing), and elevated C reactive protein (greater than 20 mg/L) or elevated procalcitonin (greater than 0.5 ng/mL).3 Further evaluation of procalcitonin by other groups appears to validate its role in identifying children at low risk of SBI (procalcitonin less than 0.3 ng/mL).4

Currently, studies of febrile infants less than 90 days of age demonstrate that E. coli dominates in bacteremia, UTI, and meningitis, with Group B streptococcus as the next most frequent pathogen identified.2 Increasingly ampicillin resistance has been reported among E. coli isolates from both early- and late-onset disease as well as rare isolates that are resistant to third generation cephalosporins or gentamicin. Surveillance to identify changes in antimicrobial susceptibility will need to be ongoing to ensure that current approaches for initial therapy in high-risk infants aligns with current susceptibility patterns.

Dr. Pelton is chief of the section of pediatric infectious diseases and coordinator of the maternal-child HIV program at Boston Medical Center. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatrics. 2004 Jun;113(6):1662-6.

2. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014 Jun;33(6):595-9.

3. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015 Jan;34(1):17-21.

4. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(1):17-18.

5. “AAP Proposes Update to Evaluating, Managing Febrile Infants Guideline,” The Hospitalist, 2016.

What Are the Therapeutic Considerations of Antiseizure Drugs in the Elderly?

WASHINGTON, DC—When initiating antiseizure therapy for elderly patients with epilepsy, drug interactions and side effects, especially impaired cognition and falls, are important treatment considerations, according to an overview given at the 71st Annual Meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

In addition, neurologists should take into account comorbidities and concomitant medications that could be relevant in the future—similar to considering the possibility of pregnancy when treating a patient of childbearing potential, said Ilo Leppik, MD, Professor of Neurology and Pharmacy at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. An elderly patient with poststroke seizures, for instance, may not be on warfarin at an initial visit. “But they might be … the next time you see them,” he said. “In the next six months, what could this person have in terms of comorbidities?”

Interactions and Side Effects

“In general, most antiseizure drugs are effective for epilepsy encountered in the elderly,” Dr. Leppik said. “Drug interactions and cognitive and behavioral side effects are key.”

Research indicates that a drug’s side effect profile, rather than its efficacy, determines how long patients stay on a medication. Dr. Leppik tries to see elderly patients about a month after starting treatment and asks family members to report cognitive or behavioral changes.

“My preferred approach is not to use drugs that are strong enzyme inducers because of the issues with drug–drug interactions,” Dr. Leppik said. Blood levels of simvastatin, for example, are markedly lower in patients who receive carbamazepine and are likely to be so with other inducing antiseizure drugs.

Hyponatremia may be a concern. Xiaoming Dong, MD, Dr. Leppik, and colleagues found that oxcarbazepine is a significant cause of hyponatremia in people over age 40, and the risk is greater in people over age 65, he said.

In addition, many older patients have cognitive issues, and antiseizure drugs (eg, topiramate, zonisamide, valproic acid, phenobarbital, and phenytoin) may cause cognitive side effects. One clinical question that neurologists may encounter is whether to treat a patient with end-stage Alzheimer’s disease who has a single convulsion. Families may want to initiate antiseizure treatment. “But my experience is that if you start them on any of our antiseizure medications, [these patients] are much more sensitive to side effects,” Dr. Leppik said. “I have seen them deteriorate cognitively once they are started on an antiseizure medication.”

The risk of falls increases with age, and studies have found that higher levels of antiseizure drugs are associated with falls and fractures. Falls may be related to the adverse effects of antiseizure drugs, such as dizziness or ataxia. Prescribing an antiseizure drug with a long half-life once daily at bedtime may help to avoid daytime imbalance, Dr. Leppik said.

Therapeutic Drug Monitoring

Monitoring serum concentrations of antiseizure drugs may help guide patient management. When a therapeutic response has been reached, measuring the drug level can provide a target benchmark. When treatment is not working, in most cases it is because blood levels are not at the target level, Dr. Leppik added. Monitoring also may be useful when a drug is added or removed, or when there are concerns about toxicity or compliance.

“Most breakthrough seizures are d

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Dong X, Leppik IE, White J, Rarick J. Hyponatremia from oxcarbazepine and carbamazepine. Neurology. 2005;65(12):1976-1978.

Leppik IE, Birnbaum AK. Epilepsy in the elderly. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1184:208-224.

Leppik IE, Walczak TS, Birnbaum AK. Challenges ofepilepsy in elderly people. Lancet. 2012;380(9848):1128-1130.

Patsalos PN, Berry DJ, Bourgeois BF, et al. Antiepileptic drugs--best practice guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring: a position paper by the subcommission on therapeutic drug monitoring, ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia. 2008;49(7):1239-1276.

WASHINGTON, DC—When initiating antiseizure therapy for elderly patients with epilepsy, drug interactions and side effects, especially impaired cognition and falls, are important treatment considerations, according to an overview given at the 71st Annual Meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

In addition, neurologists should take into account comorbidities and concomitant medications that could be relevant in the future—similar to considering the possibility of pregnancy when treating a patient of childbearing potential, said Ilo Leppik, MD, Professor of Neurology and Pharmacy at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. An elderly patient with poststroke seizures, for instance, may not be on warfarin at an initial visit. “But they might be … the next time you see them,” he said. “In the next six months, what could this person have in terms of comorbidities?”

Interactions and Side Effects

“In general, most antiseizure drugs are effective for epilepsy encountered in the elderly,” Dr. Leppik said. “Drug interactions and cognitive and behavioral side effects are key.”

Research indicates that a drug’s side effect profile, rather than its efficacy, determines how long patients stay on a medication. Dr. Leppik tries to see elderly patients about a month after starting treatment and asks family members to report cognitive or behavioral changes.

“My preferred approach is not to use drugs that are strong enzyme inducers because of the issues with drug–drug interactions,” Dr. Leppik said. Blood levels of simvastatin, for example, are markedly lower in patients who receive carbamazepine and are likely to be so with other inducing antiseizure drugs.

Hyponatremia may be a concern. Xiaoming Dong, MD, Dr. Leppik, and colleagues found that oxcarbazepine is a significant cause of hyponatremia in people over age 40, and the risk is greater in people over age 65, he said.

In addition, many older patients have cognitive issues, and antiseizure drugs (eg, topiramate, zonisamide, valproic acid, phenobarbital, and phenytoin) may cause cognitive side effects. One clinical question that neurologists may encounter is whether to treat a patient with end-stage Alzheimer’s disease who has a single convulsion. Families may want to initiate antiseizure treatment. “But my experience is that if you start them on any of our antiseizure medications, [these patients] are much more sensitive to side effects,” Dr. Leppik said. “I have seen them deteriorate cognitively once they are started on an antiseizure medication.”

The risk of falls increases with age, and studies have found that higher levels of antiseizure drugs are associated with falls and fractures. Falls may be related to the adverse effects of antiseizure drugs, such as dizziness or ataxia. Prescribing an antiseizure drug with a long half-life once daily at bedtime may help to avoid daytime imbalance, Dr. Leppik said.

Therapeutic Drug Monitoring

Monitoring serum concentrations of antiseizure drugs may help guide patient management. When a therapeutic response has been reached, measuring the drug level can provide a target benchmark. When treatment is not working, in most cases it is because blood levels are not at the target level, Dr. Leppik added. Monitoring also may be useful when a drug is added or removed, or when there are concerns about toxicity or compliance.

“Most breakthrough seizures are d

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Dong X, Leppik IE, White J, Rarick J. Hyponatremia from oxcarbazepine and carbamazepine. Neurology. 2005;65(12):1976-1978.

Leppik IE, Birnbaum AK. Epilepsy in the elderly. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1184:208-224.

Leppik IE, Walczak TS, Birnbaum AK. Challenges ofepilepsy in elderly people. Lancet. 2012;380(9848):1128-1130.

Patsalos PN, Berry DJ, Bourgeois BF, et al. Antiepileptic drugs--best practice guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring: a position paper by the subcommission on therapeutic drug monitoring, ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia. 2008;49(7):1239-1276.

WASHINGTON, DC—When initiating antiseizure therapy for elderly patients with epilepsy, drug interactions and side effects, especially impaired cognition and falls, are important treatment considerations, according to an overview given at the 71st Annual Meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

In addition, neurologists should take into account comorbidities and concomitant medications that could be relevant in the future—similar to considering the possibility of pregnancy when treating a patient of childbearing potential, said Ilo Leppik, MD, Professor of Neurology and Pharmacy at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. An elderly patient with poststroke seizures, for instance, may not be on warfarin at an initial visit. “But they might be … the next time you see them,” he said. “In the next six months, what could this person have in terms of comorbidities?”

Interactions and Side Effects

“In general, most antiseizure drugs are effective for epilepsy encountered in the elderly,” Dr. Leppik said. “Drug interactions and cognitive and behavioral side effects are key.”

Research indicates that a drug’s side effect profile, rather than its efficacy, determines how long patients stay on a medication. Dr. Leppik tries to see elderly patients about a month after starting treatment and asks family members to report cognitive or behavioral changes.

“My preferred approach is not to use drugs that are strong enzyme inducers because of the issues with drug–drug interactions,” Dr. Leppik said. Blood levels of simvastatin, for example, are markedly lower in patients who receive carbamazepine and are likely to be so with other inducing antiseizure drugs.

Hyponatremia may be a concern. Xiaoming Dong, MD, Dr. Leppik, and colleagues found that oxcarbazepine is a significant cause of hyponatremia in people over age 40, and the risk is greater in people over age 65, he said.

In addition, many older patients have cognitive issues, and antiseizure drugs (eg, topiramate, zonisamide, valproic acid, phenobarbital, and phenytoin) may cause cognitive side effects. One clinical question that neurologists may encounter is whether to treat a patient with end-stage Alzheimer’s disease who has a single convulsion. Families may want to initiate antiseizure treatment. “But my experience is that if you start them on any of our antiseizure medications, [these patients] are much more sensitive to side effects,” Dr. Leppik said. “I have seen them deteriorate cognitively once they are started on an antiseizure medication.”

The risk of falls increases with age, and studies have found that higher levels of antiseizure drugs are associated with falls and fractures. Falls may be related to the adverse effects of antiseizure drugs, such as dizziness or ataxia. Prescribing an antiseizure drug with a long half-life once daily at bedtime may help to avoid daytime imbalance, Dr. Leppik said.

Therapeutic Drug Monitoring

Monitoring serum concentrations of antiseizure drugs may help guide patient management. When a therapeutic response has been reached, measuring the drug level can provide a target benchmark. When treatment is not working, in most cases it is because blood levels are not at the target level, Dr. Leppik added. Monitoring also may be useful when a drug is added or removed, or when there are concerns about toxicity or compliance.

“Most breakthrough seizures are d

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Dong X, Leppik IE, White J, Rarick J. Hyponatremia from oxcarbazepine and carbamazepine. Neurology. 2005;65(12):1976-1978.

Leppik IE, Birnbaum AK. Epilepsy in the elderly. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1184:208-224.

Leppik IE, Walczak TS, Birnbaum AK. Challenges ofepilepsy in elderly people. Lancet. 2012;380(9848):1128-1130.

Patsalos PN, Berry DJ, Bourgeois BF, et al. Antiepileptic drugs--best practice guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring: a position paper by the subcommission on therapeutic drug monitoring, ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia. 2008;49(7):1239-1276.

Causes, Mimics, and Pitfalls of Epilepsy in the Elderly

WASHINGTON, DC—The diagnosis of epilepsy in elderly patients may be challenging due to the disease’s many mimics, a patient’s cognitive impairment, unwitnessed events, and the potential for false positives on imaging or EEG, according to a lecture delivered at the 71st Annual Meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

“The onus is on us to rigorously explore the histories of these patients,” said Colin Josephson, MD, Assistant Professor of Neurology and Community Health Sciences at the University of Calgary in Alberta. “Ninety percent of our diagnosis is in the history.”

The Differential Diagnosis

Preictal premonitory symptoms, ictal semiology, and postictal symptoms may be key to distinguishing between epilepsy and its mimics, which include cardiac arrhythmia, hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, syncope, transient ischemic attack, stroke, transient global amnesia, delirium, sleep disorders, and psychogenic nonepileptic attacks. Abrupt loss of consciousness, for example, may suggest a diagnosis of cardiac arrhythmia. In cases involving impaired awareness, neurologists should have a high level of suspicion for hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia. “Delirium in and of itself can mimic nonconvulsive status epilepticus,” Dr. Josephson said.

Medications may cause glucose or electrolyte abnormalities that trigger seizures or similar events. One study found that about 40% of patients older than 65 were taking five to nine medications, and 18% were taking 10 or more medications. A 2011 study by Budnitz et al found that, based on a sample of 58 hospitals, adverse drug events may result in about 1.5% of emergency hospitalizations among older adults. In particular, endocrine, cardiovascular, neurologic, and anti-infectious agents can cause provoked acute seizures and seizure mimics, Dr. Josephson said.

Causes of Epilepsy in the Elderly

The etiology of epilepsy in the elderly may influence the disease’s comorbidities, psychosocial impact, functional status, and treatment. The largest group of cases—about 30% to 50% of the total—has cerebrovascular etiology. Neurodegenerative conditions may be the etiology in 10% to 20% of cases, and other conditions (eg, tumor, trauma, or autoimmune epilepsy) may cause 5% to 15% of cases. The cause may be unknown in 30% to 50% of cases.

After ischemic stroke, the incidence of epilepsy ranges from about 2.5% to 15% up to one year, and from 7% to 10% up to five years. After hemorrhagic stroke, the incidence of epilepsy ranges from 10% to 20%. A recent systematic review found that the likelihood of developing a seizure or seizure disorder is about 1.4- to 1.5-fold greater after a hemorrhagic stroke, compared with after an ischemic stroke. A review by Ferlazzo et al identified three main risk factors for poststroke epilepsy: cerebral hemorrhage, early-onset seizures, and cortical involvement.

About 5% of patients with dementia develop epilepsy. “It can be hard to distinguish [epilepsy] in this population due to the fact that a lot of seizures would involve altered levels of awareness or confusion, which is a feature of dementias, as well,” Dr. Josephson said.

Research suggests that elderly-onset epilepsy may be a unique disease entity with etiologies, seizure characteristics, and comorbidities that differ from those of younger-onset epilepsy. Using a prospective cohort database, Dr. Josephson and colleagues examined differences in patients according to age of epilepsy onset and identified 14 clinical variables that predict whether a patient will have elderly-onset epilepsy or young-onset epilepsy. “We may be able to develop targeted therapy or precision medicine for this population,” he said.

The new operational definition of epilepsy allows neurologists to diagnose epilepsy based on one unprovoked seizure when the 10-year risk of having a second seizure is at least 60%. Many elderly patients have focal lesional epilepsy, which suggests that many patients’ 10-year risk of a second seizure is greater than 50%. “This is a paradigm shift that we continue to take into account when evaluating this patient population,” Dr. Josephson said. Further research is needed to determine “whether the vast majority of these patients, if they are 65 or older, actually have a diagnosis of epilepsy.”

Nonspecific Findings

Neurologists should be aware of potential pitfalls when investigating suspected epilepsy in the elderly. Incidental imaging findings are common and more likely with age. “Video-EEG telemetry may be just as useful for this population as it is for younger adults or children,” however, Dr. Josephson said.

A systematic review by Morris et al found that among patients ages 70 to 89 with no neurologic symptoms who were evaluated for screening purposes with MRI, between 15% and 25% had nonspecific white matter hyperintensities. Likewise, non-neoplastic incidental brain findings occurred in as much as 10% of patients. “Silent infarcts were relatively common in 2% to 3% of patients, as well,” Dr. Josephson said. “You do run the risk, if you start a scattershot approach for these patients, of running down the black hole of finding nonspecific findings and then trying to explain them or going to further investigations … when they may in fact be red herrings. In this population, we have to be careful about what we order, why we order it, and how we interpret it.”

Elderly patients may have high rates of nonspecific EEG findings, as well. Generalized slowing was reported in about 31% of elderly patients examined by Widdess-Walsh et al. Focal slowing, especially within the temporal lobes, was seen in about 10% of patients, and about 5% of these patients had epileptiform discharges.

McBride et al studied 94 patients ages 60 and older who were admitted to a seizure monitoring unit. About 26% of patients with nonepileptic events nevertheless had epileptiform discharges. Of the patients with epileptic events, 76% had interictal epileptiform discharges. “Overreliance on the EEG when making a diagnosis in this population is a major mistake,” and neurologists should not solely rely on the interictal EEG, Dr. Josephson said. “The sensitivity and the specificity are not high enough…. You want to capture events.”

In McBride’s eight-year study, about 42% of the patients had epilepsy. “But interestingly, about 14% had nonepileptic attacks.... This is not necessarily a rare consideration in these patients,” said Dr. Josephson.

About 30% of the patients did not have an event during their admissions to the unit, but for about 60%, neurologists were able to establish a diagnosis of epilepsy or epilepsy mimic. Video-EEG monitoring may be useful “in those patients in which there are diagnostic conundrums,” Dr. Josephson said. Establishing the correct diagnosis is important because even appropriate therapy entails additional risk in elderly patients.

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Brodie MJ, Kwan P. Epilepsy in elderly people. BMJ. 2005;331(7528):1317-1322.

Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC, Shehab N, Richards CL. Emergency hospitalizations for adverse drug events in older Americans. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(21):2002-2012.

Ferlazzo E, Gasparini S, Beghi E, et al. Epilepsy in cerebrovascular diseases: Review of experimental and clinical data with meta-analysis of risk factors. Epilepsia. 2016;57(8):1205-1214.

Josephson CB, Engbers JD, Sajobi TT, et al. Towards a clinically informed, data-driven definition of elderly onset epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2016;57(2):298-305.

McBride AE, Shih TT, Hirsch LJ. Video-EEG monitoring in the elderly: a review of 94 patients. Epilepsia. 2002; 43(2):165-169.

Morris Z, Whiteley WN, Longstreth WT Jr, et al. Incidental findings on brain magnetic resonanceimaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009; 339:b3016.

Subota A, Pham T, Jetté N, et al. The association between dementia and epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epilepsia. 2017;58(6):962-972.

Widdess-Walsh P, Sweeney BJ, Galvin R, McNamara B. Utilization and yield of EEG in the elderly population. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;22(4):253-255.

WASHINGTON, DC—The diagnosis of epilepsy in elderly patients may be challenging due to the disease’s many mimics, a patient’s cognitive impairment, unwitnessed events, and the potential for false positives on imaging or EEG, according to a lecture delivered at the 71st Annual Meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

“The onus is on us to rigorously explore the histories of these patients,” said Colin Josephson, MD, Assistant Professor of Neurology and Community Health Sciences at the University of Calgary in Alberta. “Ninety percent of our diagnosis is in the history.”

The Differential Diagnosis

Preictal premonitory symptoms, ictal semiology, and postictal symptoms may be key to distinguishing between epilepsy and its mimics, which include cardiac arrhythmia, hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, syncope, transient ischemic attack, stroke, transient global amnesia, delirium, sleep disorders, and psychogenic nonepileptic attacks. Abrupt loss of consciousness, for example, may suggest a diagnosis of cardiac arrhythmia. In cases involving impaired awareness, neurologists should have a high level of suspicion for hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia. “Delirium in and of itself can mimic nonconvulsive status epilepticus,” Dr. Josephson said.

Medications may cause glucose or electrolyte abnormalities that trigger seizures or similar events. One study found that about 40% of patients older than 65 were taking five to nine medications, and 18% were taking 10 or more medications. A 2011 study by Budnitz et al found that, based on a sample of 58 hospitals, adverse drug events may result in about 1.5% of emergency hospitalizations among older adults. In particular, endocrine, cardiovascular, neurologic, and anti-infectious agents can cause provoked acute seizures and seizure mimics, Dr. Josephson said.

Causes of Epilepsy in the Elderly

The etiology of epilepsy in the elderly may influence the disease’s comorbidities, psychosocial impact, functional status, and treatment. The largest group of cases—about 30% to 50% of the total—has cerebrovascular etiology. Neurodegenerative conditions may be the etiology in 10% to 20% of cases, and other conditions (eg, tumor, trauma, or autoimmune epilepsy) may cause 5% to 15% of cases. The cause may be unknown in 30% to 50% of cases.

After ischemic stroke, the incidence of epilepsy ranges from about 2.5% to 15% up to one year, and from 7% to 10% up to five years. After hemorrhagic stroke, the incidence of epilepsy ranges from 10% to 20%. A recent systematic review found that the likelihood of developing a seizure or seizure disorder is about 1.4- to 1.5-fold greater after a hemorrhagic stroke, compared with after an ischemic stroke. A review by Ferlazzo et al identified three main risk factors for poststroke epilepsy: cerebral hemorrhage, early-onset seizures, and cortical involvement.

About 5% of patients with dementia develop epilepsy. “It can be hard to distinguish [epilepsy] in this population due to the fact that a lot of seizures would involve altered levels of awareness or confusion, which is a feature of dementias, as well,” Dr. Josephson said.

Research suggests that elderly-onset epilepsy may be a unique disease entity with etiologies, seizure characteristics, and comorbidities that differ from those of younger-onset epilepsy. Using a prospective cohort database, Dr. Josephson and colleagues examined differences in patients according to age of epilepsy onset and identified 14 clinical variables that predict whether a patient will have elderly-onset epilepsy or young-onset epilepsy. “We may be able to develop targeted therapy or precision medicine for this population,” he said.

The new operational definition of epilepsy allows neurologists to diagnose epilepsy based on one unprovoked seizure when the 10-year risk of having a second seizure is at least 60%. Many elderly patients have focal lesional epilepsy, which suggests that many patients’ 10-year risk of a second seizure is greater than 50%. “This is a paradigm shift that we continue to take into account when evaluating this patient population,” Dr. Josephson said. Further research is needed to determine “whether the vast majority of these patients, if they are 65 or older, actually have a diagnosis of epilepsy.”

Nonspecific Findings

Neurologists should be aware of potential pitfalls when investigating suspected epilepsy in the elderly. Incidental imaging findings are common and more likely with age. “Video-EEG telemetry may be just as useful for this population as it is for younger adults or children,” however, Dr. Josephson said.

A systematic review by Morris et al found that among patients ages 70 to 89 with no neurologic symptoms who were evaluated for screening purposes with MRI, between 15% and 25% had nonspecific white matter hyperintensities. Likewise, non-neoplastic incidental brain findings occurred in as much as 10% of patients. “Silent infarcts were relatively common in 2% to 3% of patients, as well,” Dr. Josephson said. “You do run the risk, if you start a scattershot approach for these patients, of running down the black hole of finding nonspecific findings and then trying to explain them or going to further investigations … when they may in fact be red herrings. In this population, we have to be careful about what we order, why we order it, and how we interpret it.”

Elderly patients may have high rates of nonspecific EEG findings, as well. Generalized slowing was reported in about 31% of elderly patients examined by Widdess-Walsh et al. Focal slowing, especially within the temporal lobes, was seen in about 10% of patients, and about 5% of these patients had epileptiform discharges.

McBride et al studied 94 patients ages 60 and older who were admitted to a seizure monitoring unit. About 26% of patients with nonepileptic events nevertheless had epileptiform discharges. Of the patients with epileptic events, 76% had interictal epileptiform discharges. “Overreliance on the EEG when making a diagnosis in this population is a major mistake,” and neurologists should not solely rely on the interictal EEG, Dr. Josephson said. “The sensitivity and the specificity are not high enough…. You want to capture events.”

In McBride’s eight-year study, about 42% of the patients had epilepsy. “But interestingly, about 14% had nonepileptic attacks.... This is not necessarily a rare consideration in these patients,” said Dr. Josephson.

About 30% of the patients did not have an event during their admissions to the unit, but for about 60%, neurologists were able to establish a diagnosis of epilepsy or epilepsy mimic. Video-EEG monitoring may be useful “in those patients in which there are diagnostic conundrums,” Dr. Josephson said. Establishing the correct diagnosis is important because even appropriate therapy entails additional risk in elderly patients.

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Brodie MJ, Kwan P. Epilepsy in elderly people. BMJ. 2005;331(7528):1317-1322.

Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC, Shehab N, Richards CL. Emergency hospitalizations for adverse drug events in older Americans. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(21):2002-2012.

Ferlazzo E, Gasparini S, Beghi E, et al. Epilepsy in cerebrovascular diseases: Review of experimental and clinical data with meta-analysis of risk factors. Epilepsia. 2016;57(8):1205-1214.

Josephson CB, Engbers JD, Sajobi TT, et al. Towards a clinically informed, data-driven definition of elderly onset epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2016;57(2):298-305.

McBride AE, Shih TT, Hirsch LJ. Video-EEG monitoring in the elderly: a review of 94 patients. Epilepsia. 2002; 43(2):165-169.

Morris Z, Whiteley WN, Longstreth WT Jr, et al. Incidental findings on brain magnetic resonanceimaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009; 339:b3016.

Subota A, Pham T, Jetté N, et al. The association between dementia and epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epilepsia. 2017;58(6):962-972.

Widdess-Walsh P, Sweeney BJ, Galvin R, McNamara B. Utilization and yield of EEG in the elderly population. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;22(4):253-255.

WASHINGTON, DC—The diagnosis of epilepsy in elderly patients may be challenging due to the disease’s many mimics, a patient’s cognitive impairment, unwitnessed events, and the potential for false positives on imaging or EEG, according to a lecture delivered at the 71st Annual Meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

“The onus is on us to rigorously explore the histories of these patients,” said Colin Josephson, MD, Assistant Professor of Neurology and Community Health Sciences at the University of Calgary in Alberta. “Ninety percent of our diagnosis is in the history.”

The Differential Diagnosis

Preictal premonitory symptoms, ictal semiology, and postictal symptoms may be key to distinguishing between epilepsy and its mimics, which include cardiac arrhythmia, hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, syncope, transient ischemic attack, stroke, transient global amnesia, delirium, sleep disorders, and psychogenic nonepileptic attacks. Abrupt loss of consciousness, for example, may suggest a diagnosis of cardiac arrhythmia. In cases involving impaired awareness, neurologists should have a high level of suspicion for hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia. “Delirium in and of itself can mimic nonconvulsive status epilepticus,” Dr. Josephson said.

Medications may cause glucose or electrolyte abnormalities that trigger seizures or similar events. One study found that about 40% of patients older than 65 were taking five to nine medications, and 18% were taking 10 or more medications. A 2011 study by Budnitz et al found that, based on a sample of 58 hospitals, adverse drug events may result in about 1.5% of emergency hospitalizations among older adults. In particular, endocrine, cardiovascular, neurologic, and anti-infectious agents can cause provoked acute seizures and seizure mimics, Dr. Josephson said.

Causes of Epilepsy in the Elderly

The etiology of epilepsy in the elderly may influence the disease’s comorbidities, psychosocial impact, functional status, and treatment. The largest group of cases—about 30% to 50% of the total—has cerebrovascular etiology. Neurodegenerative conditions may be the etiology in 10% to 20% of cases, and other conditions (eg, tumor, trauma, or autoimmune epilepsy) may cause 5% to 15% of cases. The cause may be unknown in 30% to 50% of cases.

After ischemic stroke, the incidence of epilepsy ranges from about 2.5% to 15% up to one year, and from 7% to 10% up to five years. After hemorrhagic stroke, the incidence of epilepsy ranges from 10% to 20%. A recent systematic review found that the likelihood of developing a seizure or seizure disorder is about 1.4- to 1.5-fold greater after a hemorrhagic stroke, compared with after an ischemic stroke. A review by Ferlazzo et al identified three main risk factors for poststroke epilepsy: cerebral hemorrhage, early-onset seizures, and cortical involvement.

About 5% of patients with dementia develop epilepsy. “It can be hard to distinguish [epilepsy] in this population due to the fact that a lot of seizures would involve altered levels of awareness or confusion, which is a feature of dementias, as well,” Dr. Josephson said.

Research suggests that elderly-onset epilepsy may be a unique disease entity with etiologies, seizure characteristics, and comorbidities that differ from those of younger-onset epilepsy. Using a prospective cohort database, Dr. Josephson and colleagues examined differences in patients according to age of epilepsy onset and identified 14 clinical variables that predict whether a patient will have elderly-onset epilepsy or young-onset epilepsy. “We may be able to develop targeted therapy or precision medicine for this population,” he said.

The new operational definition of epilepsy allows neurologists to diagnose epilepsy based on one unprovoked seizure when the 10-year risk of having a second seizure is at least 60%. Many elderly patients have focal lesional epilepsy, which suggests that many patients’ 10-year risk of a second seizure is greater than 50%. “This is a paradigm shift that we continue to take into account when evaluating this patient population,” Dr. Josephson said. Further research is needed to determine “whether the vast majority of these patients, if they are 65 or older, actually have a diagnosis of epilepsy.”

Nonspecific Findings

Neurologists should be aware of potential pitfalls when investigating suspected epilepsy in the elderly. Incidental imaging findings are common and more likely with age. “Video-EEG telemetry may be just as useful for this population as it is for younger adults or children,” however, Dr. Josephson said.

A systematic review by Morris et al found that among patients ages 70 to 89 with no neurologic symptoms who were evaluated for screening purposes with MRI, between 15% and 25% had nonspecific white matter hyperintensities. Likewise, non-neoplastic incidental brain findings occurred in as much as 10% of patients. “Silent infarcts were relatively common in 2% to 3% of patients, as well,” Dr. Josephson said. “You do run the risk, if you start a scattershot approach for these patients, of running down the black hole of finding nonspecific findings and then trying to explain them or going to further investigations … when they may in fact be red herrings. In this population, we have to be careful about what we order, why we order it, and how we interpret it.”

Elderly patients may have high rates of nonspecific EEG findings, as well. Generalized slowing was reported in about 31% of elderly patients examined by Widdess-Walsh et al. Focal slowing, especially within the temporal lobes, was seen in about 10% of patients, and about 5% of these patients had epileptiform discharges.

McBride et al studied 94 patients ages 60 and older who were admitted to a seizure monitoring unit. About 26% of patients with nonepileptic events nevertheless had epileptiform discharges. Of the patients with epileptic events, 76% had interictal epileptiform discharges. “Overreliance on the EEG when making a diagnosis in this population is a major mistake,” and neurologists should not solely rely on the interictal EEG, Dr. Josephson said. “The sensitivity and the specificity are not high enough…. You want to capture events.”

In McBride’s eight-year study, about 42% of the patients had epilepsy. “But interestingly, about 14% had nonepileptic attacks.... This is not necessarily a rare consideration in these patients,” said Dr. Josephson.

About 30% of the patients did not have an event during their admissions to the unit, but for about 60%, neurologists were able to establish a diagnosis of epilepsy or epilepsy mimic. Video-EEG monitoring may be useful “in those patients in which there are diagnostic conundrums,” Dr. Josephson said. Establishing the correct diagnosis is important because even appropriate therapy entails additional risk in elderly patients.

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Brodie MJ, Kwan P. Epilepsy in elderly people. BMJ. 2005;331(7528):1317-1322.

Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC, Shehab N, Richards CL. Emergency hospitalizations for adverse drug events in older Americans. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(21):2002-2012.

Ferlazzo E, Gasparini S, Beghi E, et al. Epilepsy in cerebrovascular diseases: Review of experimental and clinical data with meta-analysis of risk factors. Epilepsia. 2016;57(8):1205-1214.

Josephson CB, Engbers JD, Sajobi TT, et al. Towards a clinically informed, data-driven definition of elderly onset epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2016;57(2):298-305.

McBride AE, Shih TT, Hirsch LJ. Video-EEG monitoring in the elderly: a review of 94 patients. Epilepsia. 2002; 43(2):165-169.

Morris Z, Whiteley WN, Longstreth WT Jr, et al. Incidental findings on brain magnetic resonanceimaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009; 339:b3016.

Subota A, Pham T, Jetté N, et al. The association between dementia and epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epilepsia. 2017;58(6):962-972.

Widdess-Walsh P, Sweeney BJ, Galvin R, McNamara B. Utilization and yield of EEG in the elderly population. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;22(4):253-255.

Recent Studies Elucidate the Advantages of the Newest AEDs

NAPLES, FL—The new antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) perampanel, eslicarbazepine, and brivaracetam have been the subjects of much research in recent years. Investigators have shed light on areas such as drug interactions, tolerability, and drug response in different patient populations, according to Bassel W. Abou-Khalil, MD, Professor of Neurology and Director of the Epilepsy Center at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville.

Perampanel

Perampanel is a noncompetitive AMPA glutamate receptor antagonist that was originally approved in 2012 as adjunctive therapy for patients with partial-onset seizures, said Dr. Abou-Khalil at the 45th Annual Meeting of the Southern Clinical Neurological Society. The drug was approved as adjunctive treatment for primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures in 2015. In 2017, the FDA extrapolated from the drug’s efficacy and safety as adjunctive therapy and granted it additional approval as monotherapy for partial-onset seizures, making it the first AED to be approved via this regulatory pathway.

Although perampanel does not appear to have significant interactions with other new AEDs, it has been shown that the 12-mg dose, but not the 8-mg dose, reduces levels of the oral contraceptive levonorgestrel by approximately 40%. Enzyme inducers such as phenytoin, carbamazepine, and phenobarbital decrease perampanel levels, Dr. Abou-Khalil said. Perampanel has a black box warning about aggression and hostility, particularly in patients taking the 12-mg dose. “Research suggests that severe psychiatric adverse effects are rare and appear to be more common in patients with intellectual disability,” Dr. Abou-Khalil said.

Two case reports have documented significant responses to adjunctive perampanel in patients with Lafora disease, a fatal autosomal-recessive genetic disorder. These patients had significantly reduced or remitted myoclonus and seizures and regained the ability to ambulate, Dr. Abou-Khalil said. Similarly, in a small study involving 10 patients with Lafora disease taking adjunctive perampanel, four had a 74% or greater reduction in seizures from baseline, and seven had major improvements in myoclonus. “In this study, there were no significant improvements in the progressive disability and cognitive decline that Lafora disease patients experience. However, it still is an exceptional drug for this very difficult type of epilepsy,” Dr. Abou-Khalil said.

In another study, perampanel also had significantly beneficial effects on myoclonus and conferred seizure freedom in 12 patients with Unverricht-Lundborg disease, a rare, inherited form of epilepsy that can interfere with walking and performance of everyday activities.

Eslicarbazepine Acetate

“Eslicarbazepine acetate, which has the same mechanism of action as oxcarbazepine, blocks sodium channels and stabilizes the inactive state of the voltage-gated sodium channel,” Dr. Abou-Khalil said. Oxcarbazepine is metabolized to both S-licarbazepine and the inactive R-licarbazepine and is detectible in serum as the parent compound, while eslicarbazepine acetate is rapidly converted primarily to S-licarbazepine and is generally undetectable in serum as the parent compound. “With eslicarbazepine, we are giving the patient more of the active metabolite of oxcarbazepine, while avoiding the adverse effects of the parent drug and the inactive element,” said Dr. Abou-Khalil.

Eslicarbazepine acetate was first approved in 2013 as add-on therapy, then in 2015 as monotherapy to treat partial-onset seizures in adults. In 2017, eslicarbazepine’s indication was expanded to include treatment of partial-onset seizures in children and adolescents age 4 and older.

Risk of common adverse effects, which include dizziness, somnolence, vomiting, blurred vision, and vertigo, are increased with concomitant use of other sodium-channel blockers, particularly carbamazepine. “However, the way the drug is titrated seems to be more important than the final dose,” Dr. Abou-Khalil said. One study demonstrated that the incidence of adverse events was lower in patients who initiated eslicarbazepine at 400 mg/day versus 800 mg/day. As much as 3% of patients taking 1,200 mg/day may develop rash.

Furthermore, research shows that elderly patients have a higher incidence of adverse effects than younger patients. “This suggests that eslicarbazepine acetate may not be an ideal drug in the older age group.”

Eslicarbazepine acetate also may have beneficial effects on lipid levels. In a retrospective cohort study of 36 adults with epilepsy taking eslicarbazepine acetate as add-on treatment, total and LDL cholesterol values were significantly decreased after at least six months of treatment, compared with the period before treatment (191.3 mg/dL vs 179.7 mg/dL, and 114.58 mg/dL vs 103.11mg/dL, respectively). HDL values were significantly increased (57.5 mg/dL vs 63.9 mg/dL before treatment).

Brivaracetam

Brivaracetam, approved in 2016 as adjunctive treatment for partial-onset seizures and in 2017 as monotherapy, binds to synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A with a 20-fold higher affinity than levetiracetam and higher brain permeability. “As far as drug interactions are concerned, enzyme inducers will reduce brivaracetam levels. In turn, brivaracetam may increase 10,11-carbamazepine epoxide and phenytoin concentrations,” Dr. Abou-Khalil explained.

Clinical studies have demonstrated that adjunctive brivaracetam at doses of 100 mg and 200 mg is more effective than placebo for all outcome measures, with 50% responder rates of 38.9% and 37.8%, respectively. “Yet there does not appear to be a clear dose–response effect,” Dr. Abou-Khalil said. “In addition, the efficacy of the 20-mg and 50-mg doses is inconsistent across studies, although in a pooled analysis, the 50-mg dose was more effective than placebo.”

Generally, brivaracetam does not appear to be effective when taken concomitantly with levetiracetam. In addition, brivaracetam’s efficacy is greater in levetiracetam-naïve patients than in patients who have failed levetiracetam, but that could be because the latter patients have greater drug resistance, he added.

“Switching to brivaracetam may be a consideration for patients who have seizure control with levetiracetam, but cannot tolerate it due to adverse effects,” Dr. Abou-Khalil said. In one study, patients who switched overnight from levetiracetam 1–3 g/day to brivaracetam 200 mg/day had clinically meaningful reductions in nonpsychotic behavioral adverse events. Health-related quality of life scores were improved, as well.

In an analysis of data from three phase III trials, adjunctive brivaracetam effectively reduced the frequency of generalized tonic-clonic seizures in 409 patients, with around one-third achieving seizure freedom at 100 mg and 200 mg per day. Another study showed that brivaracetam may be more effective in patients age 65 and older than in the general population of epilepsy patients, Dr. Abou-Khalil said. In that study, the median reduction from baseline in focal seizure frequency was 14.0% for placebo versus 25.5%, 49.6%, and 74.9% for brivaracetam 50 mg/day, 100 mg/day, and 200 mg/day, respectively.

—Adriene Marshall

NAPLES, FL—The new antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) perampanel, eslicarbazepine, and brivaracetam have been the subjects of much research in recent years. Investigators have shed light on areas such as drug interactions, tolerability, and drug response in different patient populations, according to Bassel W. Abou-Khalil, MD, Professor of Neurology and Director of the Epilepsy Center at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville.

Perampanel

Perampanel is a noncompetitive AMPA glutamate receptor antagonist that was originally approved in 2012 as adjunctive therapy for patients with partial-onset seizures, said Dr. Abou-Khalil at the 45th Annual Meeting of the Southern Clinical Neurological Society. The drug was approved as adjunctive treatment for primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures in 2015. In 2017, the FDA extrapolated from the drug’s efficacy and safety as adjunctive therapy and granted it additional approval as monotherapy for partial-onset seizures, making it the first AED to be approved via this regulatory pathway.

Although perampanel does not appear to have significant interactions with other new AEDs, it has been shown that the 12-mg dose, but not the 8-mg dose, reduces levels of the oral contraceptive levonorgestrel by approximately 40%. Enzyme inducers such as phenytoin, carbamazepine, and phenobarbital decrease perampanel levels, Dr. Abou-Khalil said. Perampanel has a black box warning about aggression and hostility, particularly in patients taking the 12-mg dose. “Research suggests that severe psychiatric adverse effects are rare and appear to be more common in patients with intellectual disability,” Dr. Abou-Khalil said.

Two case reports have documented significant responses to adjunctive perampanel in patients with Lafora disease, a fatal autosomal-recessive genetic disorder. These patients had significantly reduced or remitted myoclonus and seizures and regained the ability to ambulate, Dr. Abou-Khalil said. Similarly, in a small study involving 10 patients with Lafora disease taking adjunctive perampanel, four had a 74% or greater reduction in seizures from baseline, and seven had major improvements in myoclonus. “In this study, there were no significant improvements in the progressive disability and cognitive decline that Lafora disease patients experience. However, it still is an exceptional drug for this very difficult type of epilepsy,” Dr. Abou-Khalil said.

In another study, perampanel also had significantly beneficial effects on myoclonus and conferred seizure freedom in 12 patients with Unverricht-Lundborg disease, a rare, inherited form of epilepsy that can interfere with walking and performance of everyday activities.

Eslicarbazepine Acetate

“Eslicarbazepine acetate, which has the same mechanism of action as oxcarbazepine, blocks sodium channels and stabilizes the inactive state of the voltage-gated sodium channel,” Dr. Abou-Khalil said. Oxcarbazepine is metabolized to both S-licarbazepine and the inactive R-licarbazepine and is detectible in serum as the parent compound, while eslicarbazepine acetate is rapidly converted primarily to S-licarbazepine and is generally undetectable in serum as the parent compound. “With eslicarbazepine, we are giving the patient more of the active metabolite of oxcarbazepine, while avoiding the adverse effects of the parent drug and the inactive element,” said Dr. Abou-Khalil.

Eslicarbazepine acetate was first approved in 2013 as add-on therapy, then in 2015 as monotherapy to treat partial-onset seizures in adults. In 2017, eslicarbazepine’s indication was expanded to include treatment of partial-onset seizures in children and adolescents age 4 and older.

Risk of common adverse effects, which include dizziness, somnolence, vomiting, blurred vision, and vertigo, are increased with concomitant use of other sodium-channel blockers, particularly carbamazepine. “However, the way the drug is titrated seems to be more important than the final dose,” Dr. Abou-Khalil said. One study demonstrated that the incidence of adverse events was lower in patients who initiated eslicarbazepine at 400 mg/day versus 800 mg/day. As much as 3% of patients taking 1,200 mg/day may develop rash.

Furthermore, research shows that elderly patients have a higher incidence of adverse effects than younger patients. “This suggests that eslicarbazepine acetate may not be an ideal drug in the older age group.”

Eslicarbazepine acetate also may have beneficial effects on lipid levels. In a retrospective cohort study of 36 adults with epilepsy taking eslicarbazepine acetate as add-on treatment, total and LDL cholesterol values were significantly decreased after at least six months of treatment, compared with the period before treatment (191.3 mg/dL vs 179.7 mg/dL, and 114.58 mg/dL vs 103.11mg/dL, respectively). HDL values were significantly increased (57.5 mg/dL vs 63.9 mg/dL before treatment).

Brivaracetam

Brivaracetam, approved in 2016 as adjunctive treatment for partial-onset seizures and in 2017 as monotherapy, binds to synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A with a 20-fold higher affinity than levetiracetam and higher brain permeability. “As far as drug interactions are concerned, enzyme inducers will reduce brivaracetam levels. In turn, brivaracetam may increase 10,11-carbamazepine epoxide and phenytoin concentrations,” Dr. Abou-Khalil explained.

Clinical studies have demonstrated that adjunctive brivaracetam at doses of 100 mg and 200 mg is more effective than placebo for all outcome measures, with 50% responder rates of 38.9% and 37.8%, respectively. “Yet there does not appear to be a clear dose–response effect,” Dr. Abou-Khalil said. “In addition, the efficacy of the 20-mg and 50-mg doses is inconsistent across studies, although in a pooled analysis, the 50-mg dose was more effective than placebo.”

Generally, brivaracetam does not appear to be effective when taken concomitantly with levetiracetam. In addition, brivaracetam’s efficacy is greater in levetiracetam-naïve patients than in patients who have failed levetiracetam, but that could be because the latter patients have greater drug resistance, he added.

“Switching to brivaracetam may be a consideration for patients who have seizure control with levetiracetam, but cannot tolerate it due to adverse effects,” Dr. Abou-Khalil said. In one study, patients who switched overnight from levetiracetam 1–3 g/day to brivaracetam 200 mg/day had clinically meaningful reductions in nonpsychotic behavioral adverse events. Health-related quality of life scores were improved, as well.

In an analysis of data from three phase III trials, adjunctive brivaracetam effectively reduced the frequency of generalized tonic-clonic seizures in 409 patients, with around one-third achieving seizure freedom at 100 mg and 200 mg per day. Another study showed that brivaracetam may be more effective in patients age 65 and older than in the general population of epilepsy patients, Dr. Abou-Khalil said. In that study, the median reduction from baseline in focal seizure frequency was 14.0% for placebo versus 25.5%, 49.6%, and 74.9% for brivaracetam 50 mg/day, 100 mg/day, and 200 mg/day, respectively.

—Adriene Marshall

NAPLES, FL—The new antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) perampanel, eslicarbazepine, and brivaracetam have been the subjects of much research in recent years. Investigators have shed light on areas such as drug interactions, tolerability, and drug response in different patient populations, according to Bassel W. Abou-Khalil, MD, Professor of Neurology and Director of the Epilepsy Center at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville.

Perampanel

Perampanel is a noncompetitive AMPA glutamate receptor antagonist that was originally approved in 2012 as adjunctive therapy for patients with partial-onset seizures, said Dr. Abou-Khalil at the 45th Annual Meeting of the Southern Clinical Neurological Society. The drug was approved as adjunctive treatment for primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures in 2015. In 2017, the FDA extrapolated from the drug’s efficacy and safety as adjunctive therapy and granted it additional approval as monotherapy for partial-onset seizures, making it the first AED to be approved via this regulatory pathway.

Although perampanel does not appear to have significant interactions with other new AEDs, it has been shown that the 12-mg dose, but not the 8-mg dose, reduces levels of the oral contraceptive levonorgestrel by approximately 40%. Enzyme inducers such as phenytoin, carbamazepine, and phenobarbital decrease perampanel levels, Dr. Abou-Khalil said. Perampanel has a black box warning about aggression and hostility, particularly in patients taking the 12-mg dose. “Research suggests that severe psychiatric adverse effects are rare and appear to be more common in patients with intellectual disability,” Dr. Abou-Khalil said.

Two case reports have documented significant responses to adjunctive perampanel in patients with Lafora disease, a fatal autosomal-recessive genetic disorder. These patients had significantly reduced or remitted myoclonus and seizures and regained the ability to ambulate, Dr. Abou-Khalil said. Similarly, in a small study involving 10 patients with Lafora disease taking adjunctive perampanel, four had a 74% or greater reduction in seizures from baseline, and seven had major improvements in myoclonus. “In this study, there were no significant improvements in the progressive disability and cognitive decline that Lafora disease patients experience. However, it still is an exceptional drug for this very difficult type of epilepsy,” Dr. Abou-Khalil said.

In another study, perampanel also had significantly beneficial effects on myoclonus and conferred seizure freedom in 12 patients with Unverricht-Lundborg disease, a rare, inherited form of epilepsy that can interfere with walking and performance of everyday activities.

Eslicarbazepine Acetate

“Eslicarbazepine acetate, which has the same mechanism of action as oxcarbazepine, blocks sodium channels and stabilizes the inactive state of the voltage-gated sodium channel,” Dr. Abou-Khalil said. Oxcarbazepine is metabolized to both S-licarbazepine and the inactive R-licarbazepine and is detectible in serum as the parent compound, while eslicarbazepine acetate is rapidly converted primarily to S-licarbazepine and is generally undetectable in serum as the parent compound. “With eslicarbazepine, we are giving the patient more of the active metabolite of oxcarbazepine, while avoiding the adverse effects of the parent drug and the inactive element,” said Dr. Abou-Khalil.

Eslicarbazepine acetate was first approved in 2013 as add-on therapy, then in 2015 as monotherapy to treat partial-onset seizures in adults. In 2017, eslicarbazepine’s indication was expanded to include treatment of partial-onset seizures in children and adolescents age 4 and older.

Risk of common adverse effects, which include dizziness, somnolence, vomiting, blurred vision, and vertigo, are increased with concomitant use of other sodium-channel blockers, particularly carbamazepine. “However, the way the drug is titrated seems to be more important than the final dose,” Dr. Abou-Khalil said. One study demonstrated that the incidence of adverse events was lower in patients who initiated eslicarbazepine at 400 mg/day versus 800 mg/day. As much as 3% of patients taking 1,200 mg/day may develop rash.

Furthermore, research shows that elderly patients have a higher incidence of adverse effects than younger patients. “This suggests that eslicarbazepine acetate may not be an ideal drug in the older age group.”

Eslicarbazepine acetate also may have beneficial effects on lipid levels. In a retrospective cohort study of 36 adults with epilepsy taking eslicarbazepine acetate as add-on treatment, total and LDL cholesterol values were significantly decreased after at least six months of treatment, compared with the period before treatment (191.3 mg/dL vs 179.7 mg/dL, and 114.58 mg/dL vs 103.11mg/dL, respectively). HDL values were significantly increased (57.5 mg/dL vs 63.9 mg/dL before treatment).

Brivaracetam