User login

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease: How to Recognize and Treat Revised

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Diagnostic tests

- Complications of PID

- CDC treatment regimens

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is an ascending polymicrobial infection of the female upper reproductive tract that primarily affects sexually active women ages 15 to 29. Around 5% of sexually active women in the United States were treated for PID from 2011-2013.1 The rates and severity of PID have declined in North America and Western Europe due to overall decrease in sexually transmitted infection (STI) rates, improved screening initiatives for Chlamydia trachomatis, better treatment compliance secondary to increased access to antibiotics, and diagnostic tests with higher sensitivity.2 Despite this rate reduction, PID remains a major public health concern given the significant long-term complications, which include infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and chronic pelvic pain.3

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

PID is caused by sexually transmitted bacteria or enteric organisms that have spread to internal reproductive organs. Historically, the two most common pathogens identified in cases of PID have been Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae; however, the decline in rates of gonorrhea has led to a diminished role for N gonorrhoeae (though it continues to be associated with more severe cases).4,5

More recent studies have suggested a shift in the causative organisms; less than half of women diagnosed with acute PID test positive for either N gonorrhoeae or C trachomatis.6 Emerging infectious agents associated with PID include Mycoplasma genitalium, Gardnerella vaginalis, and bacterial vaginosis–associated bacteria.5,7,8-10

RISK FACTORS

Women ages 15 to 25 are at an increased risk for PID. The high prevalence in this age group may be attributable to high-risk behaviors, including a high number of sexual partners, high frequency of new sexual partners, and engagement in sexual intercourse without condoms.11

Taking an accurate sexual history is imperative. Clinicians should maintain a high level of suspicion for PID in women with a history of the disease, as 25% will experience recurrence.12

Clinicians should not be deterred from screening for STIs and cervical cancer in women who report having sex with other women. In addition, transgender patients should be assessed for STIs and HIV-related risks based on current anatomy sexual practices.13

PHYSICAL EXAM

While some cases of PID are asymptomatic, the typical presentation includes bilateral abdominal pain and/or pelvic pain, with onset during or shortly after menses. The pain often worsens with movement and coitus. Associated signs and symptoms include abnormal uterine bleeding or vaginal discharge; dysuria; fever and chills; frequent urination; lower back pain; and nausea and/or vomiting.14,15

All females suspected of having PID should undergo both a bimanual exam and a speculum exam. On bimanual examination, adnexal tenderness has the highest sensitivity (93% to 95.5%) for ruling out acute PID, whereas on speculum exam, purulent endocervical discharge has the highest specificity (93%).16,17 Bimanual exam findings suggestive of PID include cervical motion tenderness, uterine tenderness, and/or adnexal tenderness. Suggestive speculum exam findings include abnormal discoloration or texture of the cervix and/or endocervical mucopurulent discharge.5,16,17

One cardinal rule that should not be overlooked is that all females of reproductive age who present with abdominal pain and/or pelvic pain should take a pregnancy test to rule out ectopic pregnancy and any other pregnancy-related complications.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of PID relies on clinical judgement and a high index of suspicion.5,18 The CDC’s diagnostic criteria for acute PID include

- Sexually active female AND

- Pelvic or lower abdominal pain AND

- Cervical motion tenderness OR uterine tenderness OR adnexal tenderness.5

Additional findings that support the diagnosis include

- Abnormal cervical mucopurulent discharge or cervical friability

- Abundant white blood cells (WBCs) on saline microscopy of vaginal fluid

- Elevated C-reactive protein

- Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- Laboratory documentation of infection with C trachomatis or N gonorrhea

- Oral temperature > 101°F.5,18

The CDC notes that the first two findings (mucopurulent discharge and evidence of WBCs on microscopy) occur in most women with PID; in their absence, the diagnosis is unlikely and other sources of pain should be considered.5 The differential for PID includes acute appendicitis; adhesions; carcinoid tumor; cholecystitis; ectopic pregnancy; endometriosis; inflammatory bowel disease; and ovarian cyst.19

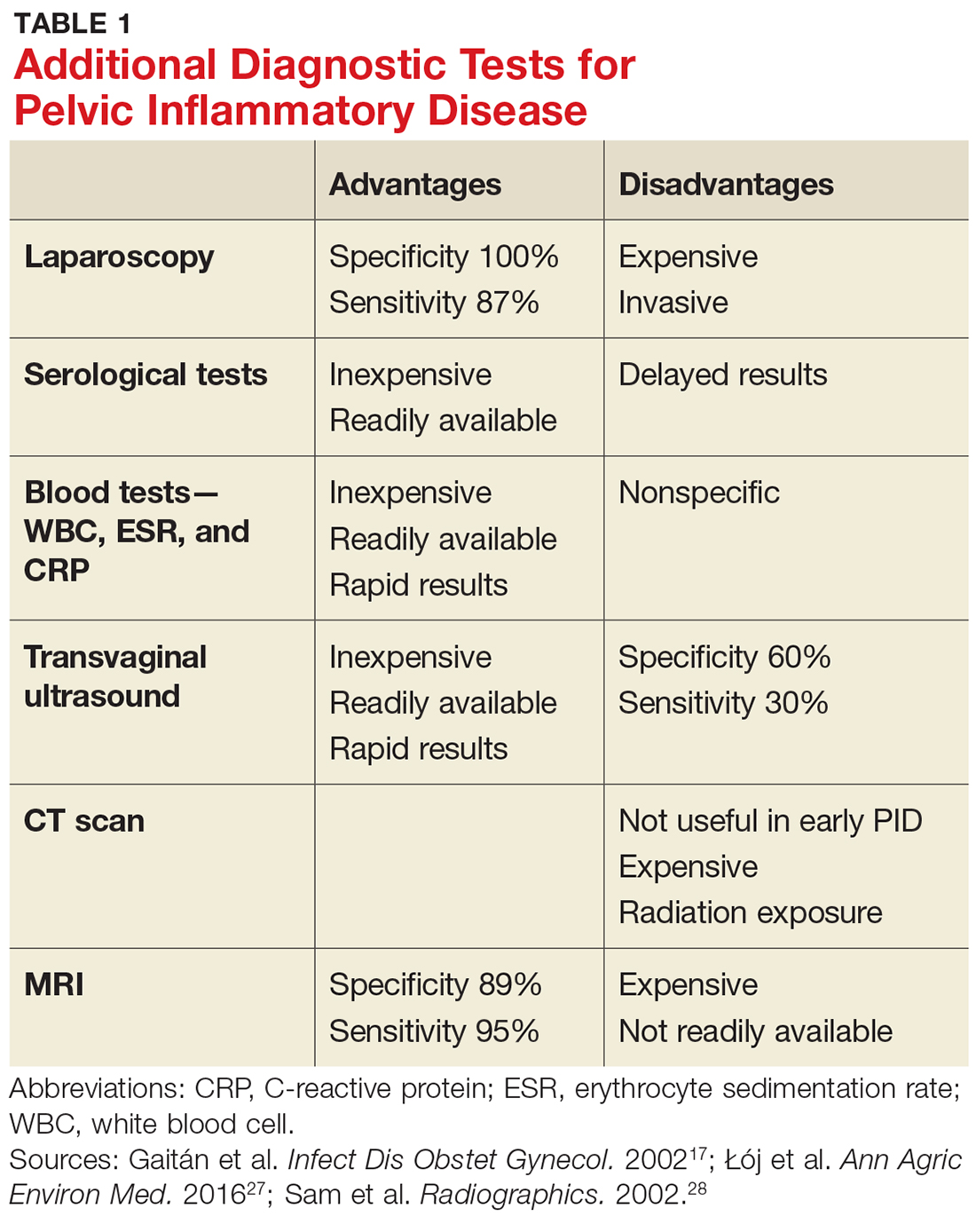

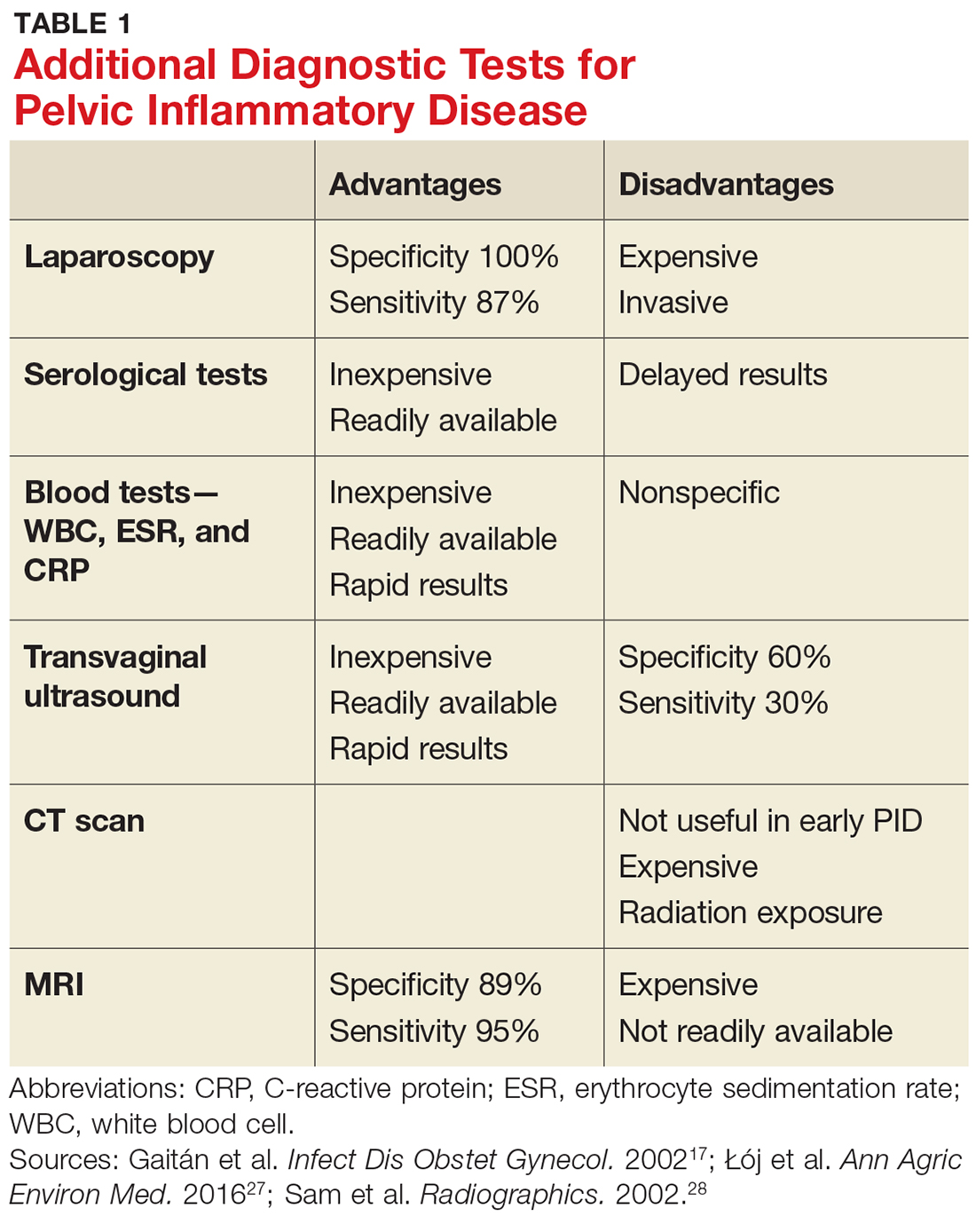

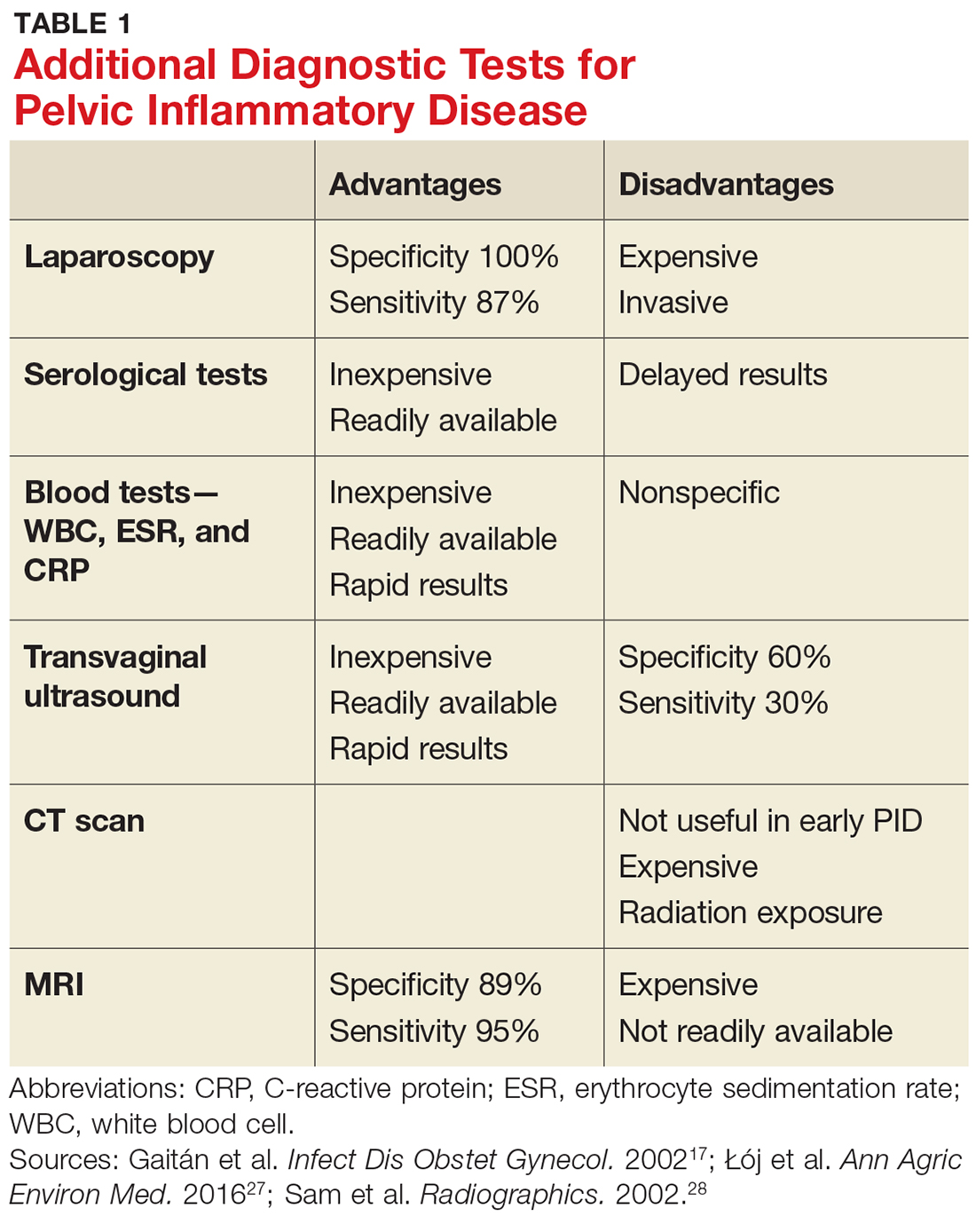

Given the variability in presentation, clinicians may find it useful to perform further diagnostic testing. There are additional laboratory tests that may be ordered for patients with a suspected diagnosis of PID (see Table 1).

TREATMENT

According to the CDC’s 2015 treatment guidelines for PID, a negative endocervical exam and negative microbial screening do not rule out an upper reproductive tract infection. Therefore, all sexually active women who present with lower abdominal pain and/or pelvic pain and have evidence of cervical motion, uterine, or adnexal tenderness on bimanual exam should be treated immediately.5

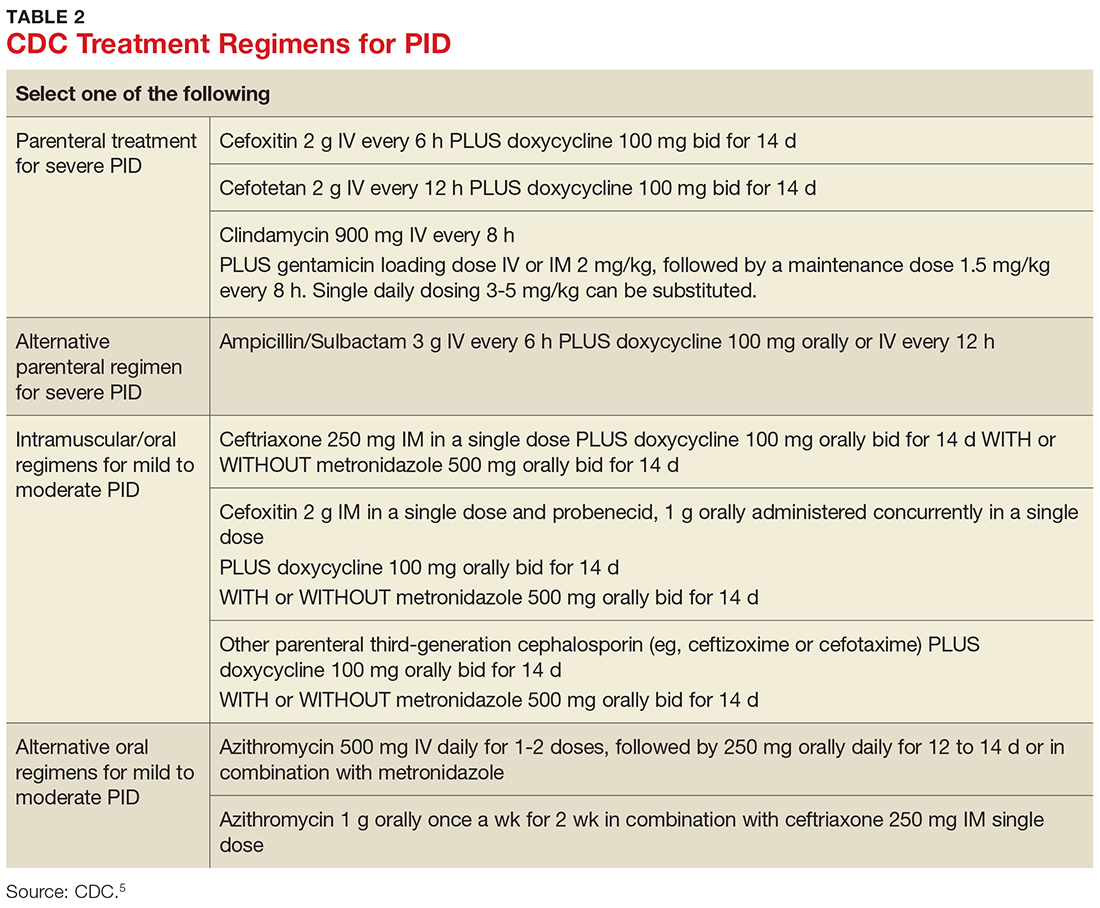

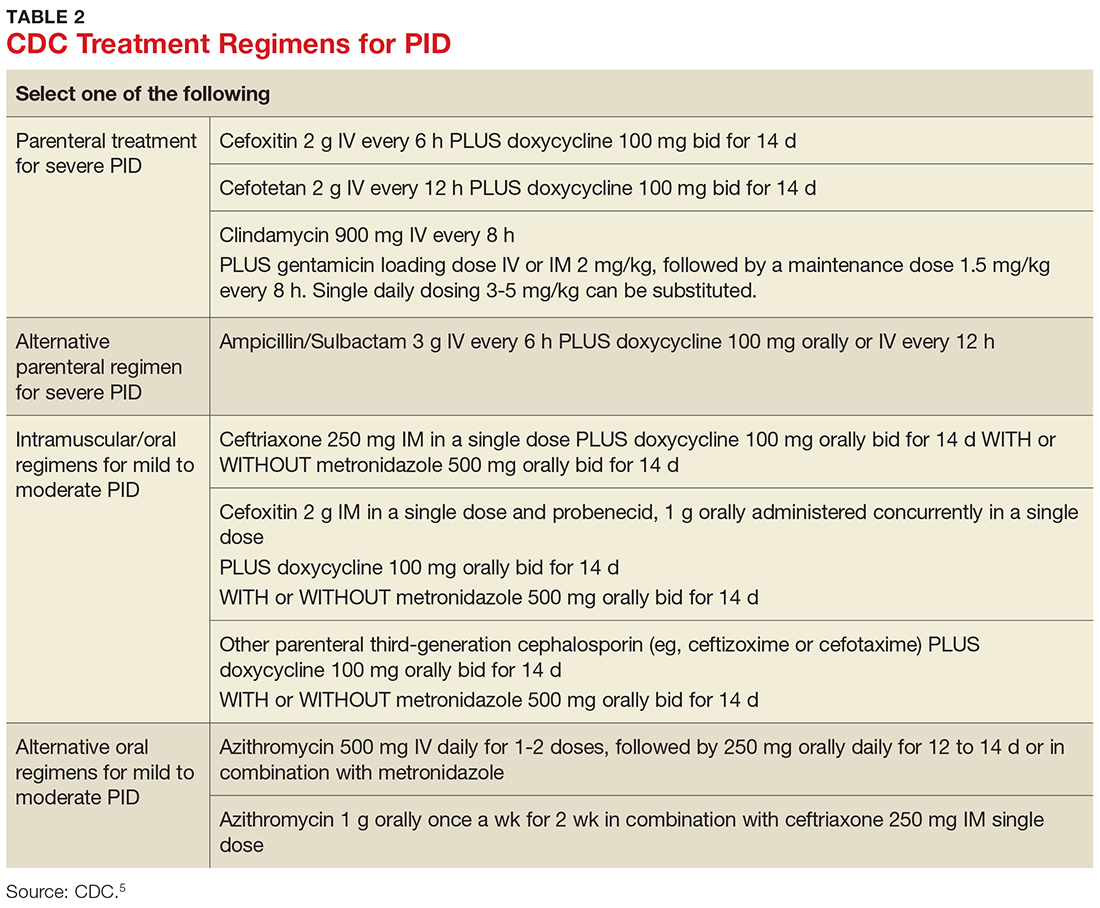

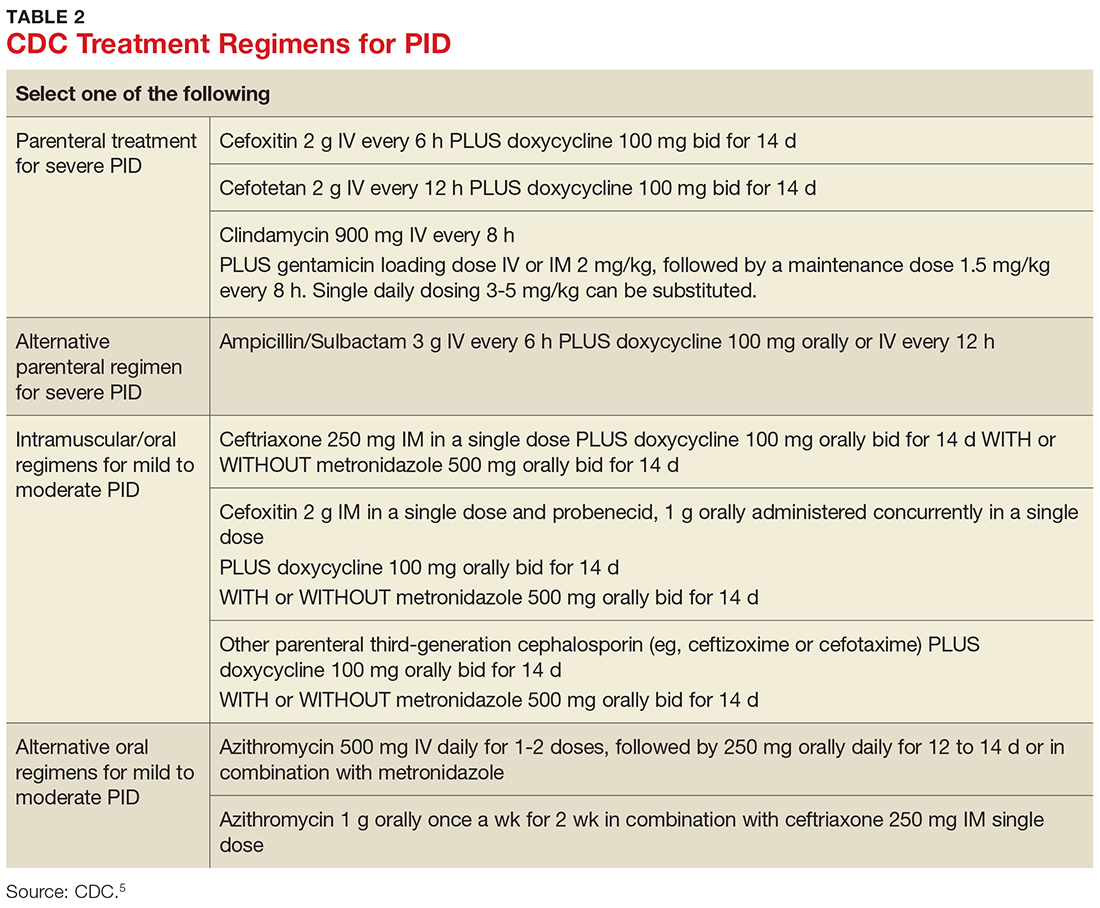

Treatment guidelines are outlined in Table 2. The polymicrobial nature of PID requires gram-negative antibiotic coverage, such as doxycycline plus a second/third-generation cephalosporin.5 Clinicians should note that cefoxitin, a second-generation cephalosporin, is recommended as firstline therapy for inpatients, as it has better anaerobic coverage than ceftriaxone.19 A targeted change in antibiotic coverage—such as inclusion of a macrolide and/or metronidazole—might be necessary if a causative organism is identified by culture.7

Treatment is indicated for all patients with a presumptive diagnosis of PID regardless of symptoms or exam findings, as PID may be asymptomatic and long-term sequelae (eg, infertility, ectopic pregnancy) are often irreversible. At-risk patients include sexually active adolescents, women with multiple sexual partners, women with a history of STI, those whose sexual partner has an STI, and women living in communities with a high prevalence of disease.20,21

Women being treated for PID should be advised to abstain from sexual intercourse until symptoms have resolved, treatment is completed, and any sexual partners have been treated as well. It is essential to emphasize to patients (and their partners) the importance of compliance to treatment regimens and the risk for PID co-infection and reinfection, as recurrence leads to an increase in long-term complications.5

Treatment of sexual partners. The CDC instructs that a woman’s most recent partner should be treated if she had sexual intercourse within 60 days of onset of symptoms or diagnosis. Furthermore, men who have had sexual contact with a woman who has PID in the 60 days prior to onset of her symptoms should be evaluated, tested, and treated for chlamydia and gonorrhea, regardless of the etiology of PID or the pathogens isolated from the woman.5

Admission criteria. Hospitalization should be based on provider judgment despite patient age. The suggested admission criteria include surgical emergency (eg, appendicitis), tubo-ovarian abscess, pregnancy, severe illness, nausea and vomiting, high fever, inability to follow or tolerate an outpatient oral regimen, and lack of clinical response to oral antimicrobial therapy.5

Follow-up care. Clinical improvement (ie, reduction in abdominal, uterine, adnexal, and cervical motion tenderness) should occur within 72 hours of antimicrobial therapy initiation. If it does not, hospital admission or adjustment in antimicrobial regimen should be considered, as well as additional diagnostic testing (eg, laparoscopy). In addition, all women with chlamydial- or gonococcal-related PID should return in three months for surveillance testing.22

COMPLICATIONS

Long-term complications—including infertility, chronic pelvic pain, and ectopic pregnancy—may occur, even when there has been a clinical response to adequate treatment. Data from the PID Evaluation and Clinical Health (PEACH) study were analyzed to assess long-term sequelae at seven years postdiagnosis and treatment. The researchers found that about 21% of women experienced recurrent PID, 19% developed infertility, and 42% reported chronic pelvic pain.3 Other research has also shown that repeat episodes of PID and delayed treatment increase the risk for long-term complications.23,24

SCREENING AND PREVENTION

Ten percent of women with an untreated STI will go on to develop PID.4 It is imperative to educate patients on the dangers and consequences of STIs when they become sexually active. Adolescents benefit the most from preventive education; this group is twice as likely as any other age group to be diagnosed with PID due to their inclination toward risky sexual behavior. Additionally, younger women tend to have a more friable cervix, increasing their risk for infection.25,26 Providers should promote safe sexual practices, such as condom use and less frequent partner exchange, in order to reduce STI exposure.

In 2015, the rate of reported cases of C trachomatis was 645.5 per 100,000 females, and of N gonorrheae, 107.2 per 100,000 females.23 The United States Preventive Services Task Force and the CDC recommend annual screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea in all sexually active women younger than 25, as well as sexually active women ages 25 and older who are considered at increased risk.5

CONCLUSION

PID is often difficult to diagnose, since patients may be asymptomatic or present with vague symptoms. Clinicians should maintain a high level of suspicion for PID in adolescent females due to the high incidence of STI exposure in this population. The best way to prevent long-term complications of PID is to prevent the first episode of PID and/or first exposure to STIs. Therefore, clinicians should be proactive in offering STI screenings to all sexually active patients younger than 25 who request care, regardless of their chief complaint, and educating patients on the potential long-term effects of PID and STIs.

1. Leichliter JS, Chandra A, Aral SO. Correlates of self-reported pelvic inflammatory disease treatment in sexually experienced reproductive-aged women in the United States, 1995 and 2006-2010. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(5):413-418.

2. Owusu-Edusei K Jr, Bohm MK, Chesson HW, Kent CK. Chlamydia screening and pelvic inflammatory disease: insights from exploratory time-series analyses. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(6):652-657.

3. Trent M, Bass D, Ness RB, Haggerty C. Recurrent PID, subsequent STI, and reproductive health outcomes: findings from the PID evaluation and clinical health (PEACH) study. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(9):879-881.

4. Mitchell C, Prabhu M. Pelvic inflammatory disease: current concepts in pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2013;27(4):793-809.

5. CDC. Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/pid.htm. Accessed July 13, 2017.

6. Burnett AM, Anderson CP, Zwank MD. Laboratory-confirmed gonorrhea and/or chlamydia rates in clinically diagnosed pelvic inflammatory disease and cervicitis. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:1114–1117.

7. Bjartling C, Osser S, Persson K. The association between Mycoplasma genitalium and pelvic inflammatory disease after termination of pregnancy. BJOG. 2010;117(3):361-364.

8. Ness RB, Kip KE, Hillier SL, et al. A cluster analysis of bacterial vaginosis-associated microflora and pelvic inflammatory disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(6):585-590.

9. Ness RB, Hillier SL, Kip KE, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and risk of pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(4):761-769.

10. Cherpes TL, Wiesenfeld HC, Melan MA, et al. The associations between pelvic inflammatory disease, Trichomonas vaginalis infection, and positive herpes simplex virus type 2 serology. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(12):747-752.

11. Simms I, Stephenson JM, Mallinson H, et al. Risk factors associated with pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(6):452-457.

12. Schindlbeck C, Dziura D, Mylonas I. Diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID): intra-operative findings and comparison of vaginal and intra-abdominal cultures. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289(6):1263-1269.

13. CDC. 2015 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm. Accessed September 6, 2017.

14. Korn AP, Hessol NA, Padian NS, et al. Risk factors for plasma cell endometritis among women with cervical Neisseria gonorrhoeae, cervical Chlamydia trachomatis, or bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178(5):987-990.

15. Wiesenfeld HC, Sweet RL, Ness RB, et al. Comparison of acute and subclinical pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32(7):400-405.

16. Peipert JF, Ness RB, Blume J, et al. Clinical predictors of endometritis in women with symptoms and signs of pelvic inflammatory disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(5):856-864.

17. Gaitán H, Angel E, Diaz R, et al. Accuracy of five different diagnostic techniques in mild-to-moderate pelvic inflammatory disease. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2002;10(4):171-180.

18. Tukeva TA, Aronen HJ, Karjalainen PT, et al. MR imaging in pelvic inflammatory disease: comparison with laparoscopy and US. Radiology. 1999;210(1):209-216.

19. Morino M, Pellegrino L, Castagna E, et al. Acute nonspecific abdominal pain. Ann Surg. 2006;244(6):881-888.

20. Woods JL, Scurlock AM, Hensel DJ. Pelvic inflammatory disease in the adolescent: understanding diagnosis and treatment as a health care provider. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2013;29(6):720-725.

21. LeFevre ML; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(12):902-910.

22. Hosenfeld CB, Workowski KA, Berman S, et al. Repeat infection with Chlamydia and gonorrhea among females: a systematic review of the literature. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(8):478-489.

23. CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance. www.cdc.gov/std/stats15/STD-Surveillance-2015-print.pdf. Accessed July 13, 2017.

24. Hillis SD, Joesoef R, Marchbanks PA, et al. Delayed care of pelvic inflammatory disease as a risk factor for impaired fertility. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168(5):1503-1509.

25. Goyal M, Hersh A, Luan X, et al. National trends in pelvic inflammatory disease among adolescents in the emergency department. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(2):249-252.

26. Gray-Swain MR, Peipert JF. Pelvic inflammatory disease in adolescents. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;18(5):503-510.

27. Łój B, Brodowska A, Ciecwiez S, et al. The role of serological testing for Chlamydia trachomatis in differential diagnosis of pelvic pain. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2016;23(3):506-510.

28. Sam JW, Jacobs JE, Birnbaum BA. Spectrum of CT findings in acute pyogenic pelvic inflammatory disease. Radiographics. 2002;22(6):1327-1 334.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Diagnostic tests

- Complications of PID

- CDC treatment regimens

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is an ascending polymicrobial infection of the female upper reproductive tract that primarily affects sexually active women ages 15 to 29. Around 5% of sexually active women in the United States were treated for PID from 2011-2013.1 The rates and severity of PID have declined in North America and Western Europe due to overall decrease in sexually transmitted infection (STI) rates, improved screening initiatives for Chlamydia trachomatis, better treatment compliance secondary to increased access to antibiotics, and diagnostic tests with higher sensitivity.2 Despite this rate reduction, PID remains a major public health concern given the significant long-term complications, which include infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and chronic pelvic pain.3

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

PID is caused by sexually transmitted bacteria or enteric organisms that have spread to internal reproductive organs. Historically, the two most common pathogens identified in cases of PID have been Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae; however, the decline in rates of gonorrhea has led to a diminished role for N gonorrhoeae (though it continues to be associated with more severe cases).4,5

More recent studies have suggested a shift in the causative organisms; less than half of women diagnosed with acute PID test positive for either N gonorrhoeae or C trachomatis.6 Emerging infectious agents associated with PID include Mycoplasma genitalium, Gardnerella vaginalis, and bacterial vaginosis–associated bacteria.5,7,8-10

RISK FACTORS

Women ages 15 to 25 are at an increased risk for PID. The high prevalence in this age group may be attributable to high-risk behaviors, including a high number of sexual partners, high frequency of new sexual partners, and engagement in sexual intercourse without condoms.11

Taking an accurate sexual history is imperative. Clinicians should maintain a high level of suspicion for PID in women with a history of the disease, as 25% will experience recurrence.12

Clinicians should not be deterred from screening for STIs and cervical cancer in women who report having sex with other women. In addition, transgender patients should be assessed for STIs and HIV-related risks based on current anatomy sexual practices.13

PHYSICAL EXAM

While some cases of PID are asymptomatic, the typical presentation includes bilateral abdominal pain and/or pelvic pain, with onset during or shortly after menses. The pain often worsens with movement and coitus. Associated signs and symptoms include abnormal uterine bleeding or vaginal discharge; dysuria; fever and chills; frequent urination; lower back pain; and nausea and/or vomiting.14,15

All females suspected of having PID should undergo both a bimanual exam and a speculum exam. On bimanual examination, adnexal tenderness has the highest sensitivity (93% to 95.5%) for ruling out acute PID, whereas on speculum exam, purulent endocervical discharge has the highest specificity (93%).16,17 Bimanual exam findings suggestive of PID include cervical motion tenderness, uterine tenderness, and/or adnexal tenderness. Suggestive speculum exam findings include abnormal discoloration or texture of the cervix and/or endocervical mucopurulent discharge.5,16,17

One cardinal rule that should not be overlooked is that all females of reproductive age who present with abdominal pain and/or pelvic pain should take a pregnancy test to rule out ectopic pregnancy and any other pregnancy-related complications.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of PID relies on clinical judgement and a high index of suspicion.5,18 The CDC’s diagnostic criteria for acute PID include

- Sexually active female AND

- Pelvic or lower abdominal pain AND

- Cervical motion tenderness OR uterine tenderness OR adnexal tenderness.5

Additional findings that support the diagnosis include

- Abnormal cervical mucopurulent discharge or cervical friability

- Abundant white blood cells (WBCs) on saline microscopy of vaginal fluid

- Elevated C-reactive protein

- Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- Laboratory documentation of infection with C trachomatis or N gonorrhea

- Oral temperature > 101°F.5,18

The CDC notes that the first two findings (mucopurulent discharge and evidence of WBCs on microscopy) occur in most women with PID; in their absence, the diagnosis is unlikely and other sources of pain should be considered.5 The differential for PID includes acute appendicitis; adhesions; carcinoid tumor; cholecystitis; ectopic pregnancy; endometriosis; inflammatory bowel disease; and ovarian cyst.19

Given the variability in presentation, clinicians may find it useful to perform further diagnostic testing. There are additional laboratory tests that may be ordered for patients with a suspected diagnosis of PID (see Table 1).

TREATMENT

According to the CDC’s 2015 treatment guidelines for PID, a negative endocervical exam and negative microbial screening do not rule out an upper reproductive tract infection. Therefore, all sexually active women who present with lower abdominal pain and/or pelvic pain and have evidence of cervical motion, uterine, or adnexal tenderness on bimanual exam should be treated immediately.5

Treatment guidelines are outlined in Table 2. The polymicrobial nature of PID requires gram-negative antibiotic coverage, such as doxycycline plus a second/third-generation cephalosporin.5 Clinicians should note that cefoxitin, a second-generation cephalosporin, is recommended as firstline therapy for inpatients, as it has better anaerobic coverage than ceftriaxone.19 A targeted change in antibiotic coverage—such as inclusion of a macrolide and/or metronidazole—might be necessary if a causative organism is identified by culture.7

Treatment is indicated for all patients with a presumptive diagnosis of PID regardless of symptoms or exam findings, as PID may be asymptomatic and long-term sequelae (eg, infertility, ectopic pregnancy) are often irreversible. At-risk patients include sexually active adolescents, women with multiple sexual partners, women with a history of STI, those whose sexual partner has an STI, and women living in communities with a high prevalence of disease.20,21

Women being treated for PID should be advised to abstain from sexual intercourse until symptoms have resolved, treatment is completed, and any sexual partners have been treated as well. It is essential to emphasize to patients (and their partners) the importance of compliance to treatment regimens and the risk for PID co-infection and reinfection, as recurrence leads to an increase in long-term complications.5

Treatment of sexual partners. The CDC instructs that a woman’s most recent partner should be treated if she had sexual intercourse within 60 days of onset of symptoms or diagnosis. Furthermore, men who have had sexual contact with a woman who has PID in the 60 days prior to onset of her symptoms should be evaluated, tested, and treated for chlamydia and gonorrhea, regardless of the etiology of PID or the pathogens isolated from the woman.5

Admission criteria. Hospitalization should be based on provider judgment despite patient age. The suggested admission criteria include surgical emergency (eg, appendicitis), tubo-ovarian abscess, pregnancy, severe illness, nausea and vomiting, high fever, inability to follow or tolerate an outpatient oral regimen, and lack of clinical response to oral antimicrobial therapy.5

Follow-up care. Clinical improvement (ie, reduction in abdominal, uterine, adnexal, and cervical motion tenderness) should occur within 72 hours of antimicrobial therapy initiation. If it does not, hospital admission or adjustment in antimicrobial regimen should be considered, as well as additional diagnostic testing (eg, laparoscopy). In addition, all women with chlamydial- or gonococcal-related PID should return in three months for surveillance testing.22

COMPLICATIONS

Long-term complications—including infertility, chronic pelvic pain, and ectopic pregnancy—may occur, even when there has been a clinical response to adequate treatment. Data from the PID Evaluation and Clinical Health (PEACH) study were analyzed to assess long-term sequelae at seven years postdiagnosis and treatment. The researchers found that about 21% of women experienced recurrent PID, 19% developed infertility, and 42% reported chronic pelvic pain.3 Other research has also shown that repeat episodes of PID and delayed treatment increase the risk for long-term complications.23,24

SCREENING AND PREVENTION

Ten percent of women with an untreated STI will go on to develop PID.4 It is imperative to educate patients on the dangers and consequences of STIs when they become sexually active. Adolescents benefit the most from preventive education; this group is twice as likely as any other age group to be diagnosed with PID due to their inclination toward risky sexual behavior. Additionally, younger women tend to have a more friable cervix, increasing their risk for infection.25,26 Providers should promote safe sexual practices, such as condom use and less frequent partner exchange, in order to reduce STI exposure.

In 2015, the rate of reported cases of C trachomatis was 645.5 per 100,000 females, and of N gonorrheae, 107.2 per 100,000 females.23 The United States Preventive Services Task Force and the CDC recommend annual screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea in all sexually active women younger than 25, as well as sexually active women ages 25 and older who are considered at increased risk.5

CONCLUSION

PID is often difficult to diagnose, since patients may be asymptomatic or present with vague symptoms. Clinicians should maintain a high level of suspicion for PID in adolescent females due to the high incidence of STI exposure in this population. The best way to prevent long-term complications of PID is to prevent the first episode of PID and/or first exposure to STIs. Therefore, clinicians should be proactive in offering STI screenings to all sexually active patients younger than 25 who request care, regardless of their chief complaint, and educating patients on the potential long-term effects of PID and STIs.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Diagnostic tests

- Complications of PID

- CDC treatment regimens

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is an ascending polymicrobial infection of the female upper reproductive tract that primarily affects sexually active women ages 15 to 29. Around 5% of sexually active women in the United States were treated for PID from 2011-2013.1 The rates and severity of PID have declined in North America and Western Europe due to overall decrease in sexually transmitted infection (STI) rates, improved screening initiatives for Chlamydia trachomatis, better treatment compliance secondary to increased access to antibiotics, and diagnostic tests with higher sensitivity.2 Despite this rate reduction, PID remains a major public health concern given the significant long-term complications, which include infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and chronic pelvic pain.3

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

PID is caused by sexually transmitted bacteria or enteric organisms that have spread to internal reproductive organs. Historically, the two most common pathogens identified in cases of PID have been Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae; however, the decline in rates of gonorrhea has led to a diminished role for N gonorrhoeae (though it continues to be associated with more severe cases).4,5

More recent studies have suggested a shift in the causative organisms; less than half of women diagnosed with acute PID test positive for either N gonorrhoeae or C trachomatis.6 Emerging infectious agents associated with PID include Mycoplasma genitalium, Gardnerella vaginalis, and bacterial vaginosis–associated bacteria.5,7,8-10

RISK FACTORS

Women ages 15 to 25 are at an increased risk for PID. The high prevalence in this age group may be attributable to high-risk behaviors, including a high number of sexual partners, high frequency of new sexual partners, and engagement in sexual intercourse without condoms.11

Taking an accurate sexual history is imperative. Clinicians should maintain a high level of suspicion for PID in women with a history of the disease, as 25% will experience recurrence.12

Clinicians should not be deterred from screening for STIs and cervical cancer in women who report having sex with other women. In addition, transgender patients should be assessed for STIs and HIV-related risks based on current anatomy sexual practices.13

PHYSICAL EXAM

While some cases of PID are asymptomatic, the typical presentation includes bilateral abdominal pain and/or pelvic pain, with onset during or shortly after menses. The pain often worsens with movement and coitus. Associated signs and symptoms include abnormal uterine bleeding or vaginal discharge; dysuria; fever and chills; frequent urination; lower back pain; and nausea and/or vomiting.14,15

All females suspected of having PID should undergo both a bimanual exam and a speculum exam. On bimanual examination, adnexal tenderness has the highest sensitivity (93% to 95.5%) for ruling out acute PID, whereas on speculum exam, purulent endocervical discharge has the highest specificity (93%).16,17 Bimanual exam findings suggestive of PID include cervical motion tenderness, uterine tenderness, and/or adnexal tenderness. Suggestive speculum exam findings include abnormal discoloration or texture of the cervix and/or endocervical mucopurulent discharge.5,16,17

One cardinal rule that should not be overlooked is that all females of reproductive age who present with abdominal pain and/or pelvic pain should take a pregnancy test to rule out ectopic pregnancy and any other pregnancy-related complications.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of PID relies on clinical judgement and a high index of suspicion.5,18 The CDC’s diagnostic criteria for acute PID include

- Sexually active female AND

- Pelvic or lower abdominal pain AND

- Cervical motion tenderness OR uterine tenderness OR adnexal tenderness.5

Additional findings that support the diagnosis include

- Abnormal cervical mucopurulent discharge or cervical friability

- Abundant white blood cells (WBCs) on saline microscopy of vaginal fluid

- Elevated C-reactive protein

- Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- Laboratory documentation of infection with C trachomatis or N gonorrhea

- Oral temperature > 101°F.5,18

The CDC notes that the first two findings (mucopurulent discharge and evidence of WBCs on microscopy) occur in most women with PID; in their absence, the diagnosis is unlikely and other sources of pain should be considered.5 The differential for PID includes acute appendicitis; adhesions; carcinoid tumor; cholecystitis; ectopic pregnancy; endometriosis; inflammatory bowel disease; and ovarian cyst.19

Given the variability in presentation, clinicians may find it useful to perform further diagnostic testing. There are additional laboratory tests that may be ordered for patients with a suspected diagnosis of PID (see Table 1).

TREATMENT

According to the CDC’s 2015 treatment guidelines for PID, a negative endocervical exam and negative microbial screening do not rule out an upper reproductive tract infection. Therefore, all sexually active women who present with lower abdominal pain and/or pelvic pain and have evidence of cervical motion, uterine, or adnexal tenderness on bimanual exam should be treated immediately.5

Treatment guidelines are outlined in Table 2. The polymicrobial nature of PID requires gram-negative antibiotic coverage, such as doxycycline plus a second/third-generation cephalosporin.5 Clinicians should note that cefoxitin, a second-generation cephalosporin, is recommended as firstline therapy for inpatients, as it has better anaerobic coverage than ceftriaxone.19 A targeted change in antibiotic coverage—such as inclusion of a macrolide and/or metronidazole—might be necessary if a causative organism is identified by culture.7

Treatment is indicated for all patients with a presumptive diagnosis of PID regardless of symptoms or exam findings, as PID may be asymptomatic and long-term sequelae (eg, infertility, ectopic pregnancy) are often irreversible. At-risk patients include sexually active adolescents, women with multiple sexual partners, women with a history of STI, those whose sexual partner has an STI, and women living in communities with a high prevalence of disease.20,21

Women being treated for PID should be advised to abstain from sexual intercourse until symptoms have resolved, treatment is completed, and any sexual partners have been treated as well. It is essential to emphasize to patients (and their partners) the importance of compliance to treatment regimens and the risk for PID co-infection and reinfection, as recurrence leads to an increase in long-term complications.5

Treatment of sexual partners. The CDC instructs that a woman’s most recent partner should be treated if she had sexual intercourse within 60 days of onset of symptoms or diagnosis. Furthermore, men who have had sexual contact with a woman who has PID in the 60 days prior to onset of her symptoms should be evaluated, tested, and treated for chlamydia and gonorrhea, regardless of the etiology of PID or the pathogens isolated from the woman.5

Admission criteria. Hospitalization should be based on provider judgment despite patient age. The suggested admission criteria include surgical emergency (eg, appendicitis), tubo-ovarian abscess, pregnancy, severe illness, nausea and vomiting, high fever, inability to follow or tolerate an outpatient oral regimen, and lack of clinical response to oral antimicrobial therapy.5

Follow-up care. Clinical improvement (ie, reduction in abdominal, uterine, adnexal, and cervical motion tenderness) should occur within 72 hours of antimicrobial therapy initiation. If it does not, hospital admission or adjustment in antimicrobial regimen should be considered, as well as additional diagnostic testing (eg, laparoscopy). In addition, all women with chlamydial- or gonococcal-related PID should return in three months for surveillance testing.22

COMPLICATIONS

Long-term complications—including infertility, chronic pelvic pain, and ectopic pregnancy—may occur, even when there has been a clinical response to adequate treatment. Data from the PID Evaluation and Clinical Health (PEACH) study were analyzed to assess long-term sequelae at seven years postdiagnosis and treatment. The researchers found that about 21% of women experienced recurrent PID, 19% developed infertility, and 42% reported chronic pelvic pain.3 Other research has also shown that repeat episodes of PID and delayed treatment increase the risk for long-term complications.23,24

SCREENING AND PREVENTION

Ten percent of women with an untreated STI will go on to develop PID.4 It is imperative to educate patients on the dangers and consequences of STIs when they become sexually active. Adolescents benefit the most from preventive education; this group is twice as likely as any other age group to be diagnosed with PID due to their inclination toward risky sexual behavior. Additionally, younger women tend to have a more friable cervix, increasing their risk for infection.25,26 Providers should promote safe sexual practices, such as condom use and less frequent partner exchange, in order to reduce STI exposure.

In 2015, the rate of reported cases of C trachomatis was 645.5 per 100,000 females, and of N gonorrheae, 107.2 per 100,000 females.23 The United States Preventive Services Task Force and the CDC recommend annual screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea in all sexually active women younger than 25, as well as sexually active women ages 25 and older who are considered at increased risk.5

CONCLUSION

PID is often difficult to diagnose, since patients may be asymptomatic or present with vague symptoms. Clinicians should maintain a high level of suspicion for PID in adolescent females due to the high incidence of STI exposure in this population. The best way to prevent long-term complications of PID is to prevent the first episode of PID and/or first exposure to STIs. Therefore, clinicians should be proactive in offering STI screenings to all sexually active patients younger than 25 who request care, regardless of their chief complaint, and educating patients on the potential long-term effects of PID and STIs.

1. Leichliter JS, Chandra A, Aral SO. Correlates of self-reported pelvic inflammatory disease treatment in sexually experienced reproductive-aged women in the United States, 1995 and 2006-2010. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(5):413-418.

2. Owusu-Edusei K Jr, Bohm MK, Chesson HW, Kent CK. Chlamydia screening and pelvic inflammatory disease: insights from exploratory time-series analyses. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(6):652-657.

3. Trent M, Bass D, Ness RB, Haggerty C. Recurrent PID, subsequent STI, and reproductive health outcomes: findings from the PID evaluation and clinical health (PEACH) study. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(9):879-881.

4. Mitchell C, Prabhu M. Pelvic inflammatory disease: current concepts in pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2013;27(4):793-809.

5. CDC. Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/pid.htm. Accessed July 13, 2017.

6. Burnett AM, Anderson CP, Zwank MD. Laboratory-confirmed gonorrhea and/or chlamydia rates in clinically diagnosed pelvic inflammatory disease and cervicitis. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:1114–1117.

7. Bjartling C, Osser S, Persson K. The association between Mycoplasma genitalium and pelvic inflammatory disease after termination of pregnancy. BJOG. 2010;117(3):361-364.

8. Ness RB, Kip KE, Hillier SL, et al. A cluster analysis of bacterial vaginosis-associated microflora and pelvic inflammatory disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(6):585-590.

9. Ness RB, Hillier SL, Kip KE, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and risk of pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(4):761-769.

10. Cherpes TL, Wiesenfeld HC, Melan MA, et al. The associations between pelvic inflammatory disease, Trichomonas vaginalis infection, and positive herpes simplex virus type 2 serology. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(12):747-752.

11. Simms I, Stephenson JM, Mallinson H, et al. Risk factors associated with pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(6):452-457.

12. Schindlbeck C, Dziura D, Mylonas I. Diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID): intra-operative findings and comparison of vaginal and intra-abdominal cultures. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289(6):1263-1269.

13. CDC. 2015 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm. Accessed September 6, 2017.

14. Korn AP, Hessol NA, Padian NS, et al. Risk factors for plasma cell endometritis among women with cervical Neisseria gonorrhoeae, cervical Chlamydia trachomatis, or bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178(5):987-990.

15. Wiesenfeld HC, Sweet RL, Ness RB, et al. Comparison of acute and subclinical pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32(7):400-405.

16. Peipert JF, Ness RB, Blume J, et al. Clinical predictors of endometritis in women with symptoms and signs of pelvic inflammatory disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(5):856-864.

17. Gaitán H, Angel E, Diaz R, et al. Accuracy of five different diagnostic techniques in mild-to-moderate pelvic inflammatory disease. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2002;10(4):171-180.

18. Tukeva TA, Aronen HJ, Karjalainen PT, et al. MR imaging in pelvic inflammatory disease: comparison with laparoscopy and US. Radiology. 1999;210(1):209-216.

19. Morino M, Pellegrino L, Castagna E, et al. Acute nonspecific abdominal pain. Ann Surg. 2006;244(6):881-888.

20. Woods JL, Scurlock AM, Hensel DJ. Pelvic inflammatory disease in the adolescent: understanding diagnosis and treatment as a health care provider. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2013;29(6):720-725.

21. LeFevre ML; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(12):902-910.

22. Hosenfeld CB, Workowski KA, Berman S, et al. Repeat infection with Chlamydia and gonorrhea among females: a systematic review of the literature. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(8):478-489.

23. CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance. www.cdc.gov/std/stats15/STD-Surveillance-2015-print.pdf. Accessed July 13, 2017.

24. Hillis SD, Joesoef R, Marchbanks PA, et al. Delayed care of pelvic inflammatory disease as a risk factor for impaired fertility. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168(5):1503-1509.

25. Goyal M, Hersh A, Luan X, et al. National trends in pelvic inflammatory disease among adolescents in the emergency department. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(2):249-252.

26. Gray-Swain MR, Peipert JF. Pelvic inflammatory disease in adolescents. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;18(5):503-510.

27. Łój B, Brodowska A, Ciecwiez S, et al. The role of serological testing for Chlamydia trachomatis in differential diagnosis of pelvic pain. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2016;23(3):506-510.

28. Sam JW, Jacobs JE, Birnbaum BA. Spectrum of CT findings in acute pyogenic pelvic inflammatory disease. Radiographics. 2002;22(6):1327-1 334.

1. Leichliter JS, Chandra A, Aral SO. Correlates of self-reported pelvic inflammatory disease treatment in sexually experienced reproductive-aged women in the United States, 1995 and 2006-2010. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(5):413-418.

2. Owusu-Edusei K Jr, Bohm MK, Chesson HW, Kent CK. Chlamydia screening and pelvic inflammatory disease: insights from exploratory time-series analyses. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(6):652-657.

3. Trent M, Bass D, Ness RB, Haggerty C. Recurrent PID, subsequent STI, and reproductive health outcomes: findings from the PID evaluation and clinical health (PEACH) study. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(9):879-881.

4. Mitchell C, Prabhu M. Pelvic inflammatory disease: current concepts in pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2013;27(4):793-809.

5. CDC. Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/pid.htm. Accessed July 13, 2017.

6. Burnett AM, Anderson CP, Zwank MD. Laboratory-confirmed gonorrhea and/or chlamydia rates in clinically diagnosed pelvic inflammatory disease and cervicitis. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:1114–1117.

7. Bjartling C, Osser S, Persson K. The association between Mycoplasma genitalium and pelvic inflammatory disease after termination of pregnancy. BJOG. 2010;117(3):361-364.

8. Ness RB, Kip KE, Hillier SL, et al. A cluster analysis of bacterial vaginosis-associated microflora and pelvic inflammatory disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(6):585-590.

9. Ness RB, Hillier SL, Kip KE, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and risk of pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(4):761-769.

10. Cherpes TL, Wiesenfeld HC, Melan MA, et al. The associations between pelvic inflammatory disease, Trichomonas vaginalis infection, and positive herpes simplex virus type 2 serology. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(12):747-752.

11. Simms I, Stephenson JM, Mallinson H, et al. Risk factors associated with pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(6):452-457.

12. Schindlbeck C, Dziura D, Mylonas I. Diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID): intra-operative findings and comparison of vaginal and intra-abdominal cultures. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289(6):1263-1269.

13. CDC. 2015 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm. Accessed September 6, 2017.

14. Korn AP, Hessol NA, Padian NS, et al. Risk factors for plasma cell endometritis among women with cervical Neisseria gonorrhoeae, cervical Chlamydia trachomatis, or bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178(5):987-990.

15. Wiesenfeld HC, Sweet RL, Ness RB, et al. Comparison of acute and subclinical pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32(7):400-405.

16. Peipert JF, Ness RB, Blume J, et al. Clinical predictors of endometritis in women with symptoms and signs of pelvic inflammatory disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(5):856-864.

17. Gaitán H, Angel E, Diaz R, et al. Accuracy of five different diagnostic techniques in mild-to-moderate pelvic inflammatory disease. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2002;10(4):171-180.

18. Tukeva TA, Aronen HJ, Karjalainen PT, et al. MR imaging in pelvic inflammatory disease: comparison with laparoscopy and US. Radiology. 1999;210(1):209-216.

19. Morino M, Pellegrino L, Castagna E, et al. Acute nonspecific abdominal pain. Ann Surg. 2006;244(6):881-888.

20. Woods JL, Scurlock AM, Hensel DJ. Pelvic inflammatory disease in the adolescent: understanding diagnosis and treatment as a health care provider. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2013;29(6):720-725.

21. LeFevre ML; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(12):902-910.

22. Hosenfeld CB, Workowski KA, Berman S, et al. Repeat infection with Chlamydia and gonorrhea among females: a systematic review of the literature. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(8):478-489.

23. CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance. www.cdc.gov/std/stats15/STD-Surveillance-2015-print.pdf. Accessed July 13, 2017.

24. Hillis SD, Joesoef R, Marchbanks PA, et al. Delayed care of pelvic inflammatory disease as a risk factor for impaired fertility. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168(5):1503-1509.

25. Goyal M, Hersh A, Luan X, et al. National trends in pelvic inflammatory disease among adolescents in the emergency department. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(2):249-252.

26. Gray-Swain MR, Peipert JF. Pelvic inflammatory disease in adolescents. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;18(5):503-510.

27. Łój B, Brodowska A, Ciecwiez S, et al. The role of serological testing for Chlamydia trachomatis in differential diagnosis of pelvic pain. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2016;23(3):506-510.

28. Sam JW, Jacobs JE, Birnbaum BA. Spectrum of CT findings in acute pyogenic pelvic inflammatory disease. Radiographics. 2002;22(6):1327-1 334.

Can we stop worrying about the age of blood?

Blood transfusions are common in critically ill patients; two in five adults admitted to an ICU receive at least one transfusion during their hospitalization (Corwin HL, et al. Crit Care Med. 2004;32[1]:39). Recently, there has been growing concern about the potential dangers involved with prolonged blood storage. Several provocative observational and retrospective studies found that prolonged storage time (ie, the age of the blood being transfused) negatively affects clinical outcomes (Wang D, et al. Transfusion. 2012;52[6]:1184). But now, some newly published trials on blood transfusion practice, including one published in late September 2017 (Cooper DJ, et al. N Engl J Med. Published online, September 27, 2017) seem to debunk much of this literature. Was all of the concern about age of blood overblown?

The appeal of “fresh” blood is intuitive. As consumers, we’re conditioned that the fresher the better. Fresh food tastes best. Carbonated beverages go “flat” over time. The newest iPhone® device is superior to your old one. So, of course, it follows that fresh blood is also better for your health than older blood.

But, in order to have a viable transfusion service, blood has to be stored. Blood is a scarce resource, and blood banks need to keep an adequate supply on hand for expected clinical necessities, as well as for emergencies. Donors can’t be on standby, waiting in the hospital to provide immediate whole blood transfusion. Also, blood needs to be tested for infections and for potential interactions with the patient, and whole blood must be broken down into individual components for transfusion. All of this requires time and storage.

In a randomized study of 100 critically ill adults supported by mechanical ventilation, 50 were randomized to receive “fresh” blood (median storage age 4 days, interquartile range 3-5 days) and 50 were randomized to receive “standard” blood (median storage age 26.5 days, interquartile range 21-36 days) (Kor DJ, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185[8]:842). The primary outcome was gas exchange, as prolonged storage of red blood cells could potentially lead to an increased inflammatory response in patients. However, the authors found no difference in gas exchange between the two groups, and there were no differences in immunologic function or coagulation status.

The ABLE (Age of Blood Evaluation) trial was a randomized, blinded trial of transfusion practices in critically ill patients (Lacroix J, et al. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1410). In 64 centers in Canada and Europe, 2,430 critically ill adults were randomized to receive either “fresh” blood (mean storage age 6.1 ± 4.9 days) or “standard” blood (mean storage age 22.0 ± 8.4 days). The primary outcome was 90-day mortality, with a power of 90% to detect a 5% change in mortality between the two groups. The investigators found no statistically significant difference in 90-day mortality between the “fresh” and “standard” groups (37% vs 35.3%; hazard ratio 1.1; 95% CI 0.9 – 1.2). Additionally, there were no differences in secondary outcomes, including multiorgan system dysfunction, duration of supportive care, or development of nosocomial infections.

The INFORM (Informing Fresh versus Old Red Cell Management) trial was a randomized study of patients hospitalized in six centers in Canada, Australia, Israel, and the United States (Heddle NM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;375[2]:1937). A total of 24,736 patients received transfusions with either “fresh” blood (median storage age 11 days) or “standard” blood (median storage age 23 days). The primary outcome was in-hospital death, with a 90% power to detect a 15% lower relative risk. When comparing the 8,215 patients who received “fresh” blood and the 16,521 patients who received “standard” blood, the authors found no difference in mortality between the two groups (9.1% vs 8.8%; odds ratio 1.04; 95% CI 0.95 to 1.14). Furthermore, there were no differences in outcomes in the high-risk subgroups that included patients with cancer, patients in the ICU, and patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery.

A meta-analysis examined 12 trials of patients who received “fresh” blood compared with those who received “older” or “standard” blood (Alexander PE, et al. Blood. 2016;127[4]:400); 5,229 patients were included in these trials, in which “fresh” blood was defined as blood stored for 3 to 10 days and “older” blood was stored for longer durations. There was no difference in mortality between the two groups (relative risk 1.04; 95% CI 0.94 - 1.14), and no difference in adverse events (relative risk 1.02; 95% CI 0.91 - 1.14). However, perhaps surprisingly, “fresh” blood was associated with an increased risk of nosocomial infections (relative risk 1.09; 95% CI 1.00 - 1.18).

So, can we stop worrying about the age of the blood that we are about to transfuse? Probably. Taken together, these studies suggest that differences in the duration of red blood cell storage allowed within current US FDA standards aren’t clinically relevant, even in critically ill patients. At least, for now, the current practices for age of blood and duration of storage appear unrelated to adverse clinical outcomes.

Dr. Carroll is Professor of Pediatrics, University of Connecticut, Division of Critical Care, Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford, Connecticut.

Blood transfusions are common in critically ill patients; two in five adults admitted to an ICU receive at least one transfusion during their hospitalization (Corwin HL, et al. Crit Care Med. 2004;32[1]:39). Recently, there has been growing concern about the potential dangers involved with prolonged blood storage. Several provocative observational and retrospective studies found that prolonged storage time (ie, the age of the blood being transfused) negatively affects clinical outcomes (Wang D, et al. Transfusion. 2012;52[6]:1184). But now, some newly published trials on blood transfusion practice, including one published in late September 2017 (Cooper DJ, et al. N Engl J Med. Published online, September 27, 2017) seem to debunk much of this literature. Was all of the concern about age of blood overblown?

The appeal of “fresh” blood is intuitive. As consumers, we’re conditioned that the fresher the better. Fresh food tastes best. Carbonated beverages go “flat” over time. The newest iPhone® device is superior to your old one. So, of course, it follows that fresh blood is also better for your health than older blood.

But, in order to have a viable transfusion service, blood has to be stored. Blood is a scarce resource, and blood banks need to keep an adequate supply on hand for expected clinical necessities, as well as for emergencies. Donors can’t be on standby, waiting in the hospital to provide immediate whole blood transfusion. Also, blood needs to be tested for infections and for potential interactions with the patient, and whole blood must be broken down into individual components for transfusion. All of this requires time and storage.

In a randomized study of 100 critically ill adults supported by mechanical ventilation, 50 were randomized to receive “fresh” blood (median storage age 4 days, interquartile range 3-5 days) and 50 were randomized to receive “standard” blood (median storage age 26.5 days, interquartile range 21-36 days) (Kor DJ, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185[8]:842). The primary outcome was gas exchange, as prolonged storage of red blood cells could potentially lead to an increased inflammatory response in patients. However, the authors found no difference in gas exchange between the two groups, and there were no differences in immunologic function or coagulation status.

The ABLE (Age of Blood Evaluation) trial was a randomized, blinded trial of transfusion practices in critically ill patients (Lacroix J, et al. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1410). In 64 centers in Canada and Europe, 2,430 critically ill adults were randomized to receive either “fresh” blood (mean storage age 6.1 ± 4.9 days) or “standard” blood (mean storage age 22.0 ± 8.4 days). The primary outcome was 90-day mortality, with a power of 90% to detect a 5% change in mortality between the two groups. The investigators found no statistically significant difference in 90-day mortality between the “fresh” and “standard” groups (37% vs 35.3%; hazard ratio 1.1; 95% CI 0.9 – 1.2). Additionally, there were no differences in secondary outcomes, including multiorgan system dysfunction, duration of supportive care, or development of nosocomial infections.

The INFORM (Informing Fresh versus Old Red Cell Management) trial was a randomized study of patients hospitalized in six centers in Canada, Australia, Israel, and the United States (Heddle NM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;375[2]:1937). A total of 24,736 patients received transfusions with either “fresh” blood (median storage age 11 days) or “standard” blood (median storage age 23 days). The primary outcome was in-hospital death, with a 90% power to detect a 15% lower relative risk. When comparing the 8,215 patients who received “fresh” blood and the 16,521 patients who received “standard” blood, the authors found no difference in mortality between the two groups (9.1% vs 8.8%; odds ratio 1.04; 95% CI 0.95 to 1.14). Furthermore, there were no differences in outcomes in the high-risk subgroups that included patients with cancer, patients in the ICU, and patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery.

A meta-analysis examined 12 trials of patients who received “fresh” blood compared with those who received “older” or “standard” blood (Alexander PE, et al. Blood. 2016;127[4]:400); 5,229 patients were included in these trials, in which “fresh” blood was defined as blood stored for 3 to 10 days and “older” blood was stored for longer durations. There was no difference in mortality between the two groups (relative risk 1.04; 95% CI 0.94 - 1.14), and no difference in adverse events (relative risk 1.02; 95% CI 0.91 - 1.14). However, perhaps surprisingly, “fresh” blood was associated with an increased risk of nosocomial infections (relative risk 1.09; 95% CI 1.00 - 1.18).

So, can we stop worrying about the age of the blood that we are about to transfuse? Probably. Taken together, these studies suggest that differences in the duration of red blood cell storage allowed within current US FDA standards aren’t clinically relevant, even in critically ill patients. At least, for now, the current practices for age of blood and duration of storage appear unrelated to adverse clinical outcomes.

Dr. Carroll is Professor of Pediatrics, University of Connecticut, Division of Critical Care, Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford, Connecticut.

Blood transfusions are common in critically ill patients; two in five adults admitted to an ICU receive at least one transfusion during their hospitalization (Corwin HL, et al. Crit Care Med. 2004;32[1]:39). Recently, there has been growing concern about the potential dangers involved with prolonged blood storage. Several provocative observational and retrospective studies found that prolonged storage time (ie, the age of the blood being transfused) negatively affects clinical outcomes (Wang D, et al. Transfusion. 2012;52[6]:1184). But now, some newly published trials on blood transfusion practice, including one published in late September 2017 (Cooper DJ, et al. N Engl J Med. Published online, September 27, 2017) seem to debunk much of this literature. Was all of the concern about age of blood overblown?

The appeal of “fresh” blood is intuitive. As consumers, we’re conditioned that the fresher the better. Fresh food tastes best. Carbonated beverages go “flat” over time. The newest iPhone® device is superior to your old one. So, of course, it follows that fresh blood is also better for your health than older blood.

But, in order to have a viable transfusion service, blood has to be stored. Blood is a scarce resource, and blood banks need to keep an adequate supply on hand for expected clinical necessities, as well as for emergencies. Donors can’t be on standby, waiting in the hospital to provide immediate whole blood transfusion. Also, blood needs to be tested for infections and for potential interactions with the patient, and whole blood must be broken down into individual components for transfusion. All of this requires time and storage.

In a randomized study of 100 critically ill adults supported by mechanical ventilation, 50 were randomized to receive “fresh” blood (median storage age 4 days, interquartile range 3-5 days) and 50 were randomized to receive “standard” blood (median storage age 26.5 days, interquartile range 21-36 days) (Kor DJ, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185[8]:842). The primary outcome was gas exchange, as prolonged storage of red blood cells could potentially lead to an increased inflammatory response in patients. However, the authors found no difference in gas exchange between the two groups, and there were no differences in immunologic function or coagulation status.

The ABLE (Age of Blood Evaluation) trial was a randomized, blinded trial of transfusion practices in critically ill patients (Lacroix J, et al. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1410). In 64 centers in Canada and Europe, 2,430 critically ill adults were randomized to receive either “fresh” blood (mean storage age 6.1 ± 4.9 days) or “standard” blood (mean storage age 22.0 ± 8.4 days). The primary outcome was 90-day mortality, with a power of 90% to detect a 5% change in mortality between the two groups. The investigators found no statistically significant difference in 90-day mortality between the “fresh” and “standard” groups (37% vs 35.3%; hazard ratio 1.1; 95% CI 0.9 – 1.2). Additionally, there were no differences in secondary outcomes, including multiorgan system dysfunction, duration of supportive care, or development of nosocomial infections.

The INFORM (Informing Fresh versus Old Red Cell Management) trial was a randomized study of patients hospitalized in six centers in Canada, Australia, Israel, and the United States (Heddle NM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;375[2]:1937). A total of 24,736 patients received transfusions with either “fresh” blood (median storage age 11 days) or “standard” blood (median storage age 23 days). The primary outcome was in-hospital death, with a 90% power to detect a 15% lower relative risk. When comparing the 8,215 patients who received “fresh” blood and the 16,521 patients who received “standard” blood, the authors found no difference in mortality between the two groups (9.1% vs 8.8%; odds ratio 1.04; 95% CI 0.95 to 1.14). Furthermore, there were no differences in outcomes in the high-risk subgroups that included patients with cancer, patients in the ICU, and patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery.

A meta-analysis examined 12 trials of patients who received “fresh” blood compared with those who received “older” or “standard” blood (Alexander PE, et al. Blood. 2016;127[4]:400); 5,229 patients were included in these trials, in which “fresh” blood was defined as blood stored for 3 to 10 days and “older” blood was stored for longer durations. There was no difference in mortality between the two groups (relative risk 1.04; 95% CI 0.94 - 1.14), and no difference in adverse events (relative risk 1.02; 95% CI 0.91 - 1.14). However, perhaps surprisingly, “fresh” blood was associated with an increased risk of nosocomial infections (relative risk 1.09; 95% CI 1.00 - 1.18).

So, can we stop worrying about the age of the blood that we are about to transfuse? Probably. Taken together, these studies suggest that differences in the duration of red blood cell storage allowed within current US FDA standards aren’t clinically relevant, even in critically ill patients. At least, for now, the current practices for age of blood and duration of storage appear unrelated to adverse clinical outcomes.

Dr. Carroll is Professor of Pediatrics, University of Connecticut, Division of Critical Care, Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford, Connecticut.

Ribaxamase reduced new CDI infection by 71%

SAN DIEGO – , results from a phase 2b study showed.

At an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases, lead investigator John F. Kokai-Kun, PhD, said that the finding represents a paradigm shift in the use of intravenous beta-lactam antibiotics to prevent opportunistic infections. “We currently treat Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) with antibiotics, which attack the vegetative cells,” said Dr. Kokai-Kun, vice president of nonclinical affairs for Rockville, Md.–based Synthetic Biologics, which is developing ribaxamase. “Since C. diff. is primarily a toxin-mediated disease, certain products seem to neutralize the toxin. There’s also been work with probiotics and prebiotics to try to strengthen and repair the dysbiotic colon. Fecal replacement therapy has been shown to be fairly effective for treatment of recurrent C. diff. infection. What if we could simply block the initial insult that leads to this cascade? That’s the damage caused to the gut microbiome by the antibiotic that’s excreted to the intestine.”

That’s where ribaxamase comes in, he said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. Ribaxamase is an orally administered beta-lactamase designed to degrade penicillin and cephalosporins in the intestinal lumen. It’s formulated for release in the proximal small intestine and is expected to be given during or a short time after administration of IV beta-lactam antibiotics such as ceftriaxone. “This is expected to degrade the excess antibiotics that are excreted into the small intestine via the bile,” Dr. Kokai-Kun explained. “It’s designed to prevent disruption of the gut microbiome and thus protect from opportunistic GI infections like CDI.” Early-stage clinical studies demonstrated that ribaxamase was well tolerated and that it is not systemically absorbed, while phase 2 studies showed that ribaxamase degrades ceftriaxone in the intestine to below the level of detection while not affecting the pharmacokinetics of ceftriaxone in the plasma.

For the current study, 412 patients were enrolled at 84 multinational clinical sites. These patients were admitted to the hospital for treatment of a lower respiratory tract infection and were randomized 1:1 to receive ceftriaxone plus 150 mg ribaxamase or ceftriaxone plus placebo. Patients in both groups could also receive an oral macrolide at the discretion of the clinical investigator. The researchers also obtained fecal samples at screening, 72 hours post antibiotic treatment, and at the end of a 4-week follow-up visit, to determine colonization by opportunistic pathogens and to examine changes in the gut microbiome. Patients were monitored for 6 weeks for diarrhea and CDI. Diarrhea was defined as three or more loose or watery stools in a 24-hour period. “If that occurred, then we collected a sample, which was sent to the local lab to determine the presence of C. difficile toxins,” Dr. Kokai-Kun said.

The average age of study participants was 70 years, and about one-third in each arm received oral macrolides. The number of adverse events and serious adverse events were similar between active and placebo arms, and there was no trend associated with ribaxamase use. The lower respiratory tract infection cure rate to the ceftriaxone treatment was about 99% in both arms at 72 hours post treatment and at 2 weeks post treatment.

To analyze changes in the gut microbiome, the researchers conducted 16S rRNA sequencing of DNA extracted from fecal samples. In all, 652 samples were sequenced from 229 patients. Results from that analysis suggests that ribaxamase “appears to protect the gut microbiome from the onslaught of the ceftriaxone,” he said.

Ribaxamase reduced the incidence of new-onset CDI by 71%, compared with placebo (P = .045). “It apparently did this by protecting the integrity of the gut microbiome,” Dr. Kokai-Kun said. “There was also a significant reduction of new colonization by vancomycin-resistant enterococci at 72 hours and 4 weeks (P = .0001 and P = .0002, respectively) which is an opportunistic pathogen that is known to be able to inhabit gut microbiome when there is dysbiosis.”

The study was sponsored by Synthetic Biologics. Dr. Kokai-Kun is an employee of the company.

SAN DIEGO – , results from a phase 2b study showed.

At an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases, lead investigator John F. Kokai-Kun, PhD, said that the finding represents a paradigm shift in the use of intravenous beta-lactam antibiotics to prevent opportunistic infections. “We currently treat Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) with antibiotics, which attack the vegetative cells,” said Dr. Kokai-Kun, vice president of nonclinical affairs for Rockville, Md.–based Synthetic Biologics, which is developing ribaxamase. “Since C. diff. is primarily a toxin-mediated disease, certain products seem to neutralize the toxin. There’s also been work with probiotics and prebiotics to try to strengthen and repair the dysbiotic colon. Fecal replacement therapy has been shown to be fairly effective for treatment of recurrent C. diff. infection. What if we could simply block the initial insult that leads to this cascade? That’s the damage caused to the gut microbiome by the antibiotic that’s excreted to the intestine.”

That’s where ribaxamase comes in, he said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. Ribaxamase is an orally administered beta-lactamase designed to degrade penicillin and cephalosporins in the intestinal lumen. It’s formulated for release in the proximal small intestine and is expected to be given during or a short time after administration of IV beta-lactam antibiotics such as ceftriaxone. “This is expected to degrade the excess antibiotics that are excreted into the small intestine via the bile,” Dr. Kokai-Kun explained. “It’s designed to prevent disruption of the gut microbiome and thus protect from opportunistic GI infections like CDI.” Early-stage clinical studies demonstrated that ribaxamase was well tolerated and that it is not systemically absorbed, while phase 2 studies showed that ribaxamase degrades ceftriaxone in the intestine to below the level of detection while not affecting the pharmacokinetics of ceftriaxone in the plasma.

For the current study, 412 patients were enrolled at 84 multinational clinical sites. These patients were admitted to the hospital for treatment of a lower respiratory tract infection and were randomized 1:1 to receive ceftriaxone plus 150 mg ribaxamase or ceftriaxone plus placebo. Patients in both groups could also receive an oral macrolide at the discretion of the clinical investigator. The researchers also obtained fecal samples at screening, 72 hours post antibiotic treatment, and at the end of a 4-week follow-up visit, to determine colonization by opportunistic pathogens and to examine changes in the gut microbiome. Patients were monitored for 6 weeks for diarrhea and CDI. Diarrhea was defined as three or more loose or watery stools in a 24-hour period. “If that occurred, then we collected a sample, which was sent to the local lab to determine the presence of C. difficile toxins,” Dr. Kokai-Kun said.

The average age of study participants was 70 years, and about one-third in each arm received oral macrolides. The number of adverse events and serious adverse events were similar between active and placebo arms, and there was no trend associated with ribaxamase use. The lower respiratory tract infection cure rate to the ceftriaxone treatment was about 99% in both arms at 72 hours post treatment and at 2 weeks post treatment.

To analyze changes in the gut microbiome, the researchers conducted 16S rRNA sequencing of DNA extracted from fecal samples. In all, 652 samples were sequenced from 229 patients. Results from that analysis suggests that ribaxamase “appears to protect the gut microbiome from the onslaught of the ceftriaxone,” he said.

Ribaxamase reduced the incidence of new-onset CDI by 71%, compared with placebo (P = .045). “It apparently did this by protecting the integrity of the gut microbiome,” Dr. Kokai-Kun said. “There was also a significant reduction of new colonization by vancomycin-resistant enterococci at 72 hours and 4 weeks (P = .0001 and P = .0002, respectively) which is an opportunistic pathogen that is known to be able to inhabit gut microbiome when there is dysbiosis.”

The study was sponsored by Synthetic Biologics. Dr. Kokai-Kun is an employee of the company.

SAN DIEGO – , results from a phase 2b study showed.

At an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases, lead investigator John F. Kokai-Kun, PhD, said that the finding represents a paradigm shift in the use of intravenous beta-lactam antibiotics to prevent opportunistic infections. “We currently treat Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) with antibiotics, which attack the vegetative cells,” said Dr. Kokai-Kun, vice president of nonclinical affairs for Rockville, Md.–based Synthetic Biologics, which is developing ribaxamase. “Since C. diff. is primarily a toxin-mediated disease, certain products seem to neutralize the toxin. There’s also been work with probiotics and prebiotics to try to strengthen and repair the dysbiotic colon. Fecal replacement therapy has been shown to be fairly effective for treatment of recurrent C. diff. infection. What if we could simply block the initial insult that leads to this cascade? That’s the damage caused to the gut microbiome by the antibiotic that’s excreted to the intestine.”

That’s where ribaxamase comes in, he said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. Ribaxamase is an orally administered beta-lactamase designed to degrade penicillin and cephalosporins in the intestinal lumen. It’s formulated for release in the proximal small intestine and is expected to be given during or a short time after administration of IV beta-lactam antibiotics such as ceftriaxone. “This is expected to degrade the excess antibiotics that are excreted into the small intestine via the bile,” Dr. Kokai-Kun explained. “It’s designed to prevent disruption of the gut microbiome and thus protect from opportunistic GI infections like CDI.” Early-stage clinical studies demonstrated that ribaxamase was well tolerated and that it is not systemically absorbed, while phase 2 studies showed that ribaxamase degrades ceftriaxone in the intestine to below the level of detection while not affecting the pharmacokinetics of ceftriaxone in the plasma.

For the current study, 412 patients were enrolled at 84 multinational clinical sites. These patients were admitted to the hospital for treatment of a lower respiratory tract infection and were randomized 1:1 to receive ceftriaxone plus 150 mg ribaxamase or ceftriaxone plus placebo. Patients in both groups could also receive an oral macrolide at the discretion of the clinical investigator. The researchers also obtained fecal samples at screening, 72 hours post antibiotic treatment, and at the end of a 4-week follow-up visit, to determine colonization by opportunistic pathogens and to examine changes in the gut microbiome. Patients were monitored for 6 weeks for diarrhea and CDI. Diarrhea was defined as three or more loose or watery stools in a 24-hour period. “If that occurred, then we collected a sample, which was sent to the local lab to determine the presence of C. difficile toxins,” Dr. Kokai-Kun said.

The average age of study participants was 70 years, and about one-third in each arm received oral macrolides. The number of adverse events and serious adverse events were similar between active and placebo arms, and there was no trend associated with ribaxamase use. The lower respiratory tract infection cure rate to the ceftriaxone treatment was about 99% in both arms at 72 hours post treatment and at 2 weeks post treatment.

To analyze changes in the gut microbiome, the researchers conducted 16S rRNA sequencing of DNA extracted from fecal samples. In all, 652 samples were sequenced from 229 patients. Results from that analysis suggests that ribaxamase “appears to protect the gut microbiome from the onslaught of the ceftriaxone,” he said.

Ribaxamase reduced the incidence of new-onset CDI by 71%, compared with placebo (P = .045). “It apparently did this by protecting the integrity of the gut microbiome,” Dr. Kokai-Kun said. “There was also a significant reduction of new colonization by vancomycin-resistant enterococci at 72 hours and 4 weeks (P = .0001 and P = .0002, respectively) which is an opportunistic pathogen that is known to be able to inhabit gut microbiome when there is dysbiosis.”

The study was sponsored by Synthetic Biologics. Dr. Kokai-Kun is an employee of the company.

REPORTING FROM ID WEEK 2017

Key clinical point: Ribaxamase reduced new colonization with C. diff. and vancomycin-resistant enterococci.

Major finding: Ribaxamase reduced the incidence of new onset CDI by 71%, compared with placebo (P = 0.045).

Study details: A trial of 412 patients admitted to the hospital for treatment of a lower respiratory tract infection who were randomized to receive ceftriaxone plus 150 mg ribaxamase or ceftriaxone plus placebo.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Synthetic Biologics. Dr. Kokai-Kun is an employee of the company.

New App Aims to Bring Personalized Headache Medicine One Step Closer

STANFORD, CA—Headache specialists have created a new app intended to support patients with headache pain. Developed by board-certified headache specialists in collaboration with a machine learning and artificial intelligence professional, the BonTriage Headache Compass may help patients with headache better manage and improve their condition. When used consistently over time, this app is intended to help patients reduce the frequency, severity, and duration of headaches, as well as the disability they cause.

“The BonTriage Headache Compass provides a diagnostic clinical impression and monitoring, which patients can take to their doctor or just use to gain insight into their condition,” said Robert Cowan, MD, Professor of Neurology and Chief of the Division of Headache Medicine at Stanford University and a co-creator of the new app.

Personalized Data

The BonTriage Headache Compass app is the second product developed by BonTriage. The first is a detailed web-based questionnaire, available at www.bontriage.com, that creates a detailed report about a patient’s headache. The questionnaire has been validated and its accuracy is greater than 90%. Once completed, the questionnaire can be printed and shared with the patient’s physician.

The app works together with the questionnaire, but can be used independently. “When you first download the app, it asks the questions that are necessary to make the diagnostic clinical impression,” Dr. Cowan said. After asking basic demographic questions, the app poses specific questions about the characteristics of typical and current headaches and other related conditions. This information, which takes about 10 minutes to enter, will populate the app and generate a clinical impression similar to one formed at an initial clinical presentation.

The BonTriage Headache Compass then prompts users daily for data on headaches, medications, triggers, and lifestyle factors. Based on these data, the app can predict headache frequency; report the effect of treatment strategies on headache frequency, severity, and duration in real time; and answer questions based on personalized data. Users can thus see potential connections between their headaches, triggers, and behaviors. Data entry requires a minute or two each day.

Individualized Advice