User login

Mental health services can be successfully integrated in primary care

CHICAGO – , and follow-up compared with traditional external referrals. When done right, a pediatric practice also can make a profit.

“It’s convenient, it’s your office, and your patients know how to get there. It could increase compliance, and there is better follow-up for sure,” Jay Rabinowitz, MD, MPH, said. “It also reduces the stigma associated with mental health care.”

The kinds of mental health disorders you want to manage in your practice, how you plan to schedule the longer appointments, and what kind of providers you foresee hiring are among the initial considerations. You also need to figure out how to pay a psychologist, social worker, or certified counselor.

Define the diagnoses you wish to see ahead of time, said Dr. Rabinowitz, who is in private practice at Parker Pediatrics near Denver and a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. In his office, he and his colleagues typically refer internally for evaluation or management of ADHD, depression, anxiety, behavioral problems, adjustment disorders, drug counseling, and behavioral addictions. In contrast, they tend to refer out education testing because “it takes a lot of time, and you cannot bill insurance for it anyway”; patients with autism because there are specialty centers nearby; and difficult divorce cases because they consume a lot of time and resources. In general, any behavioral health issues that appear likely to require 20 or more visits to address also are referred to specialists outside the practice.

When first integrating behavioral health services, scheduling the typical 50-minute visits can be a challenge for staff accustomed to the 20-minute clinical time slots. Schedulers also need to confirm that all patients at the practice have a physical examination first and complete the different consent and privacy forms. In addition, mental health counseling sessions get canceled a lot, he said, so his practice maintains a “move up” list and a late cancellation/no-show policy. “These are expensive 50-minute visits.”

The practice has a dedicated waiting room for mental health appointments. Also, “initially we used exam rooms; that was fine for a while. But eventually we remodeled and have some nice consult rooms that are carpeted with comfortable chairs,” Dr. Rabinowitz said. “I like using the rooms sometimes when [patients] are not there for consults.”

Choosing and paying your colleagues

Decide what kind of work arrangement makes the most sense for your practice, Dr. Rabinowitz said. Options include hiring providers as employees of the practice, as independent contractors, or based on a space-sharing agreement where they rent space in the office.

Some primary care practices contract with psychiatrists, psychiatric nurse practitioners, social workers, and/or licensed counselors. Parker Pediatrics employs two PhD child psychologists. In response to an attendee question about how the practice pays the psychologists, Dr. Rabinowitz said, “Initially it was hourly. But we now have a formula that if you bill this amount, you make this, so it’s performance-based.” He added, “They do pretty well. I think we pay them better than they could make on their own.”

“Our [pediatricians] love this. It is so much easier than the old system where they had to refer out and try to follow up. There is better communication and, of course, better follow-up for the children, too.” Dr. Rabinowitz added, “You meet the needs of families and patients – that’s obviously very important. Plus it attracts new patients. There could be some income involved, too – that always is an advantage.”

In response to another attendee question about profitability, Dr. Rabinowitz said, “We make a decent profit on them, although the goal isn’t to make a gigantic profit.”

Better reimbursement needed

A concierge-type mental health service, where patients pay out of pocket, is not an economic option for Medicaid and many other patients, Dr. Rabinowitz said. In addition, “mental health networks are great, but there is poor reimbursement for those.” He recommended pediatricians search for grants – his practice initially had a grant to see Medicaid patients – and to check state and local regulations about reimbursement for mental health services. In most cases, a practice cannot bill on the same day for a medical and mental health visit, with the exception of a flu shot, he said.

“Then there is financial integration, which is what we do. We can bill incident to our psychologists as long as we’ve done an initial physical exam, which we do.” The pediatric practice does all the billing, collection, and other financial services for the psychologists they employ; this allows the psychologists to bill under the physician’s name and receive a higher rate of reimbursement.

Negotiate contracts with insurance companies to include integrated mental health services and remember to get malpractice insurance that includes the additional providers, he added.

Unanswered question

“Hopefully there are better outcomes [with integrated mental health services]. We think there are, but some of that has not been proven,” Dr. Rabinowitz said, and it’s a potential target for future research. “Our mental health costs for emergency visits are way down compared to everyone else – we think this is the reason why, but we can’t prove that,” he added.

Dr. Rabinowitz reported having no financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – , and follow-up compared with traditional external referrals. When done right, a pediatric practice also can make a profit.

“It’s convenient, it’s your office, and your patients know how to get there. It could increase compliance, and there is better follow-up for sure,” Jay Rabinowitz, MD, MPH, said. “It also reduces the stigma associated with mental health care.”

The kinds of mental health disorders you want to manage in your practice, how you plan to schedule the longer appointments, and what kind of providers you foresee hiring are among the initial considerations. You also need to figure out how to pay a psychologist, social worker, or certified counselor.

Define the diagnoses you wish to see ahead of time, said Dr. Rabinowitz, who is in private practice at Parker Pediatrics near Denver and a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. In his office, he and his colleagues typically refer internally for evaluation or management of ADHD, depression, anxiety, behavioral problems, adjustment disorders, drug counseling, and behavioral addictions. In contrast, they tend to refer out education testing because “it takes a lot of time, and you cannot bill insurance for it anyway”; patients with autism because there are specialty centers nearby; and difficult divorce cases because they consume a lot of time and resources. In general, any behavioral health issues that appear likely to require 20 or more visits to address also are referred to specialists outside the practice.

When first integrating behavioral health services, scheduling the typical 50-minute visits can be a challenge for staff accustomed to the 20-minute clinical time slots. Schedulers also need to confirm that all patients at the practice have a physical examination first and complete the different consent and privacy forms. In addition, mental health counseling sessions get canceled a lot, he said, so his practice maintains a “move up” list and a late cancellation/no-show policy. “These are expensive 50-minute visits.”

The practice has a dedicated waiting room for mental health appointments. Also, “initially we used exam rooms; that was fine for a while. But eventually we remodeled and have some nice consult rooms that are carpeted with comfortable chairs,” Dr. Rabinowitz said. “I like using the rooms sometimes when [patients] are not there for consults.”

Choosing and paying your colleagues

Decide what kind of work arrangement makes the most sense for your practice, Dr. Rabinowitz said. Options include hiring providers as employees of the practice, as independent contractors, or based on a space-sharing agreement where they rent space in the office.

Some primary care practices contract with psychiatrists, psychiatric nurse practitioners, social workers, and/or licensed counselors. Parker Pediatrics employs two PhD child psychologists. In response to an attendee question about how the practice pays the psychologists, Dr. Rabinowitz said, “Initially it was hourly. But we now have a formula that if you bill this amount, you make this, so it’s performance-based.” He added, “They do pretty well. I think we pay them better than they could make on their own.”

“Our [pediatricians] love this. It is so much easier than the old system where they had to refer out and try to follow up. There is better communication and, of course, better follow-up for the children, too.” Dr. Rabinowitz added, “You meet the needs of families and patients – that’s obviously very important. Plus it attracts new patients. There could be some income involved, too – that always is an advantage.”

In response to another attendee question about profitability, Dr. Rabinowitz said, “We make a decent profit on them, although the goal isn’t to make a gigantic profit.”

Better reimbursement needed

A concierge-type mental health service, where patients pay out of pocket, is not an economic option for Medicaid and many other patients, Dr. Rabinowitz said. In addition, “mental health networks are great, but there is poor reimbursement for those.” He recommended pediatricians search for grants – his practice initially had a grant to see Medicaid patients – and to check state and local regulations about reimbursement for mental health services. In most cases, a practice cannot bill on the same day for a medical and mental health visit, with the exception of a flu shot, he said.

“Then there is financial integration, which is what we do. We can bill incident to our psychologists as long as we’ve done an initial physical exam, which we do.” The pediatric practice does all the billing, collection, and other financial services for the psychologists they employ; this allows the psychologists to bill under the physician’s name and receive a higher rate of reimbursement.

Negotiate contracts with insurance companies to include integrated mental health services and remember to get malpractice insurance that includes the additional providers, he added.

Unanswered question

“Hopefully there are better outcomes [with integrated mental health services]. We think there are, but some of that has not been proven,” Dr. Rabinowitz said, and it’s a potential target for future research. “Our mental health costs for emergency visits are way down compared to everyone else – we think this is the reason why, but we can’t prove that,” he added.

Dr. Rabinowitz reported having no financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – , and follow-up compared with traditional external referrals. When done right, a pediatric practice also can make a profit.

“It’s convenient, it’s your office, and your patients know how to get there. It could increase compliance, and there is better follow-up for sure,” Jay Rabinowitz, MD, MPH, said. “It also reduces the stigma associated with mental health care.”

The kinds of mental health disorders you want to manage in your practice, how you plan to schedule the longer appointments, and what kind of providers you foresee hiring are among the initial considerations. You also need to figure out how to pay a psychologist, social worker, or certified counselor.

Define the diagnoses you wish to see ahead of time, said Dr. Rabinowitz, who is in private practice at Parker Pediatrics near Denver and a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. In his office, he and his colleagues typically refer internally for evaluation or management of ADHD, depression, anxiety, behavioral problems, adjustment disorders, drug counseling, and behavioral addictions. In contrast, they tend to refer out education testing because “it takes a lot of time, and you cannot bill insurance for it anyway”; patients with autism because there are specialty centers nearby; and difficult divorce cases because they consume a lot of time and resources. In general, any behavioral health issues that appear likely to require 20 or more visits to address also are referred to specialists outside the practice.

When first integrating behavioral health services, scheduling the typical 50-minute visits can be a challenge for staff accustomed to the 20-minute clinical time slots. Schedulers also need to confirm that all patients at the practice have a physical examination first and complete the different consent and privacy forms. In addition, mental health counseling sessions get canceled a lot, he said, so his practice maintains a “move up” list and a late cancellation/no-show policy. “These are expensive 50-minute visits.”

The practice has a dedicated waiting room for mental health appointments. Also, “initially we used exam rooms; that was fine for a while. But eventually we remodeled and have some nice consult rooms that are carpeted with comfortable chairs,” Dr. Rabinowitz said. “I like using the rooms sometimes when [patients] are not there for consults.”

Choosing and paying your colleagues

Decide what kind of work arrangement makes the most sense for your practice, Dr. Rabinowitz said. Options include hiring providers as employees of the practice, as independent contractors, or based on a space-sharing agreement where they rent space in the office.

Some primary care practices contract with psychiatrists, psychiatric nurse practitioners, social workers, and/or licensed counselors. Parker Pediatrics employs two PhD child psychologists. In response to an attendee question about how the practice pays the psychologists, Dr. Rabinowitz said, “Initially it was hourly. But we now have a formula that if you bill this amount, you make this, so it’s performance-based.” He added, “They do pretty well. I think we pay them better than they could make on their own.”

“Our [pediatricians] love this. It is so much easier than the old system where they had to refer out and try to follow up. There is better communication and, of course, better follow-up for the children, too.” Dr. Rabinowitz added, “You meet the needs of families and patients – that’s obviously very important. Plus it attracts new patients. There could be some income involved, too – that always is an advantage.”

In response to another attendee question about profitability, Dr. Rabinowitz said, “We make a decent profit on them, although the goal isn’t to make a gigantic profit.”

Better reimbursement needed

A concierge-type mental health service, where patients pay out of pocket, is not an economic option for Medicaid and many other patients, Dr. Rabinowitz said. In addition, “mental health networks are great, but there is poor reimbursement for those.” He recommended pediatricians search for grants – his practice initially had a grant to see Medicaid patients – and to check state and local regulations about reimbursement for mental health services. In most cases, a practice cannot bill on the same day for a medical and mental health visit, with the exception of a flu shot, he said.

“Then there is financial integration, which is what we do. We can bill incident to our psychologists as long as we’ve done an initial physical exam, which we do.” The pediatric practice does all the billing, collection, and other financial services for the psychologists they employ; this allows the psychologists to bill under the physician’s name and receive a higher rate of reimbursement.

Negotiate contracts with insurance companies to include integrated mental health services and remember to get malpractice insurance that includes the additional providers, he added.

Unanswered question

“Hopefully there are better outcomes [with integrated mental health services]. We think there are, but some of that has not been proven,” Dr. Rabinowitz said, and it’s a potential target for future research. “Our mental health costs for emergency visits are way down compared to everyone else – we think this is the reason why, but we can’t prove that,” he added.

Dr. Rabinowitz reported having no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 2017

Gene therapy for cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy shows promise

Gene therapy using autologous hematopoietic stem cells appears safe and effective as a treatment for early-stage cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy, according to an interim analysis of results from the STARBEAM study.

X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy is characterized by a defect in the ABCD1 gene, leading to progressive demyelination that most commonly presents as learning and behavioral changes in boys aged 3-15 years. The only effective treatment to date has been allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants, but these come with considerable risks, including graft-versus-host disease and graft failure.

The study enrolled 17 boys, all with early-stage cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy and gadolinium enhancement on MRI, and treated them with a single infusion of the autologous cells, then followed them for a median of 29.4 months (N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700554).

The interim analysis found 14 of the 17 patients (88%) were alive, without any major functional disability and with minimal clinical symptoms. There was no incidence of graft-versus-host disease and no treatment-related deaths.

Lesion progression stabilized in 12 of the 17 patients, and gadolinium enhancement resolved by month 6 in the 16 patients who could be evaluated. It did enhance again in six patients by month 12 but then resolved again later.

One patient in the study experienced a seizure, which led to an increase in the neurologic function score. The remaining two patients had disease progression. One was withdrawn from the study and later died from complications associated with an allogeneic transplant, while the other showed rapid deterioration following treatment and later died from a viral infection complicated by rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney and liver failure.

The latter patient “had a rapid increase in both the Loes score and the score on the neurologic function scale as early as 2 weeks after treatment, findings that suggested that he may have had marked disease progression before treatment,” wrote Florian Eichler, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his coauthors. “Similar to allogeneic transplantation, hematopoietic stem-cell gene therapy is not expected to have an effect on the phenotypes of adrenomyeloneuropathy or adrenal insufficiency.”

The study found no evidence of integration of the altered ABCD1 gene near sites previously associated with serious adverse events with gene therapy, such as MDS1, EVI1, and LMO2.

The lentiviral vector used in the study also appeared to avoid mutagenesis associated with viral integration, which has been seen in patients treated with gamma-retroviral vector gene therapy, although the authors noted that longer follow-up and larger sample sizes were needed to confirm this.

Neither hematopoietic stem cell transplantation nor gene therapy appeared to prevent the progression of white matter lesions in the first 12-18 months after treatment, the authors wrote.

“Microglial cell death appears to play an important role in the pathophysiology of cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy, and therefore early disease progression may occur during the time before the replacement of microglial cells,” they wrote. “Our data, and the results of studies of allogeneic transplantation, show that some disease progression on MRI during the first year after transplantation is common, and therefore reinforce the urgency in identifying cerebral disease early and treating it swiftly.”

Bluebird Bio, the National Institutes of Health, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, the Great Ormond Street Hospital, and the University College London Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health Biomedical Research Centre supported the study. Nine authors declared financial ties to Bluebird Bio, and four authors were employees of Bluebird Bio. One author declared personal fees from a pharmaceutical company involved with lentiviral vectors and a patent related to enhanced lentiviral vector expression, and another two authors declared fees and funding from other pharmaceutical companies unrelated to the study.

These results suggest that transplantation with autologous hematopoietic stem cells transfected with Lenti-D is at least as effective as conventional allogeneic transplantation for the treatment of cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy, and it is possibly safer. Lenti-D therapy certainly has potential but some concerns remain. Careful surveillance to assess long-term outcomes is therefore essential.

For many years, gene therapy has shown great promise, but clinical applications have always seemed just beyond the horizon. Today, Lenti-D therapy appears to be poised as a real treatment option for cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy, and it might even become the first gene therapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

Marc Engelen, MD, PhD, is at the Academic Medical Center – Emma Children’s Hospital, Amsterdam. His comments are taken from an editorial (N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1709253). Dr. Engelen declared grant support from Minoryx Therapeutics and personal fees from Vertex Pharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work.

These results suggest that transplantation with autologous hematopoietic stem cells transfected with Lenti-D is at least as effective as conventional allogeneic transplantation for the treatment of cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy, and it is possibly safer. Lenti-D therapy certainly has potential but some concerns remain. Careful surveillance to assess long-term outcomes is therefore essential.

For many years, gene therapy has shown great promise, but clinical applications have always seemed just beyond the horizon. Today, Lenti-D therapy appears to be poised as a real treatment option for cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy, and it might even become the first gene therapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

Marc Engelen, MD, PhD, is at the Academic Medical Center – Emma Children’s Hospital, Amsterdam. His comments are taken from an editorial (N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1709253). Dr. Engelen declared grant support from Minoryx Therapeutics and personal fees from Vertex Pharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work.

These results suggest that transplantation with autologous hematopoietic stem cells transfected with Lenti-D is at least as effective as conventional allogeneic transplantation for the treatment of cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy, and it is possibly safer. Lenti-D therapy certainly has potential but some concerns remain. Careful surveillance to assess long-term outcomes is therefore essential.

For many years, gene therapy has shown great promise, but clinical applications have always seemed just beyond the horizon. Today, Lenti-D therapy appears to be poised as a real treatment option for cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy, and it might even become the first gene therapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

Marc Engelen, MD, PhD, is at the Academic Medical Center – Emma Children’s Hospital, Amsterdam. His comments are taken from an editorial (N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1709253). Dr. Engelen declared grant support from Minoryx Therapeutics and personal fees from Vertex Pharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work.

Gene therapy using autologous hematopoietic stem cells appears safe and effective as a treatment for early-stage cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy, according to an interim analysis of results from the STARBEAM study.

X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy is characterized by a defect in the ABCD1 gene, leading to progressive demyelination that most commonly presents as learning and behavioral changes in boys aged 3-15 years. The only effective treatment to date has been allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants, but these come with considerable risks, including graft-versus-host disease and graft failure.

The study enrolled 17 boys, all with early-stage cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy and gadolinium enhancement on MRI, and treated them with a single infusion of the autologous cells, then followed them for a median of 29.4 months (N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700554).

The interim analysis found 14 of the 17 patients (88%) were alive, without any major functional disability and with minimal clinical symptoms. There was no incidence of graft-versus-host disease and no treatment-related deaths.

Lesion progression stabilized in 12 of the 17 patients, and gadolinium enhancement resolved by month 6 in the 16 patients who could be evaluated. It did enhance again in six patients by month 12 but then resolved again later.

One patient in the study experienced a seizure, which led to an increase in the neurologic function score. The remaining two patients had disease progression. One was withdrawn from the study and later died from complications associated with an allogeneic transplant, while the other showed rapid deterioration following treatment and later died from a viral infection complicated by rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney and liver failure.

The latter patient “had a rapid increase in both the Loes score and the score on the neurologic function scale as early as 2 weeks after treatment, findings that suggested that he may have had marked disease progression before treatment,” wrote Florian Eichler, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his coauthors. “Similar to allogeneic transplantation, hematopoietic stem-cell gene therapy is not expected to have an effect on the phenotypes of adrenomyeloneuropathy or adrenal insufficiency.”

The study found no evidence of integration of the altered ABCD1 gene near sites previously associated with serious adverse events with gene therapy, such as MDS1, EVI1, and LMO2.

The lentiviral vector used in the study also appeared to avoid mutagenesis associated with viral integration, which has been seen in patients treated with gamma-retroviral vector gene therapy, although the authors noted that longer follow-up and larger sample sizes were needed to confirm this.

Neither hematopoietic stem cell transplantation nor gene therapy appeared to prevent the progression of white matter lesions in the first 12-18 months after treatment, the authors wrote.

“Microglial cell death appears to play an important role in the pathophysiology of cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy, and therefore early disease progression may occur during the time before the replacement of microglial cells,” they wrote. “Our data, and the results of studies of allogeneic transplantation, show that some disease progression on MRI during the first year after transplantation is common, and therefore reinforce the urgency in identifying cerebral disease early and treating it swiftly.”

Bluebird Bio, the National Institutes of Health, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, the Great Ormond Street Hospital, and the University College London Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health Biomedical Research Centre supported the study. Nine authors declared financial ties to Bluebird Bio, and four authors were employees of Bluebird Bio. One author declared personal fees from a pharmaceutical company involved with lentiviral vectors and a patent related to enhanced lentiviral vector expression, and another two authors declared fees and funding from other pharmaceutical companies unrelated to the study.

Gene therapy using autologous hematopoietic stem cells appears safe and effective as a treatment for early-stage cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy, according to an interim analysis of results from the STARBEAM study.

X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy is characterized by a defect in the ABCD1 gene, leading to progressive demyelination that most commonly presents as learning and behavioral changes in boys aged 3-15 years. The only effective treatment to date has been allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants, but these come with considerable risks, including graft-versus-host disease and graft failure.

The study enrolled 17 boys, all with early-stage cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy and gadolinium enhancement on MRI, and treated them with a single infusion of the autologous cells, then followed them for a median of 29.4 months (N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700554).

The interim analysis found 14 of the 17 patients (88%) were alive, without any major functional disability and with minimal clinical symptoms. There was no incidence of graft-versus-host disease and no treatment-related deaths.

Lesion progression stabilized in 12 of the 17 patients, and gadolinium enhancement resolved by month 6 in the 16 patients who could be evaluated. It did enhance again in six patients by month 12 but then resolved again later.

One patient in the study experienced a seizure, which led to an increase in the neurologic function score. The remaining two patients had disease progression. One was withdrawn from the study and later died from complications associated with an allogeneic transplant, while the other showed rapid deterioration following treatment and later died from a viral infection complicated by rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney and liver failure.

The latter patient “had a rapid increase in both the Loes score and the score on the neurologic function scale as early as 2 weeks after treatment, findings that suggested that he may have had marked disease progression before treatment,” wrote Florian Eichler, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his coauthors. “Similar to allogeneic transplantation, hematopoietic stem-cell gene therapy is not expected to have an effect on the phenotypes of adrenomyeloneuropathy or adrenal insufficiency.”

The study found no evidence of integration of the altered ABCD1 gene near sites previously associated with serious adverse events with gene therapy, such as MDS1, EVI1, and LMO2.

The lentiviral vector used in the study also appeared to avoid mutagenesis associated with viral integration, which has been seen in patients treated with gamma-retroviral vector gene therapy, although the authors noted that longer follow-up and larger sample sizes were needed to confirm this.

Neither hematopoietic stem cell transplantation nor gene therapy appeared to prevent the progression of white matter lesions in the first 12-18 months after treatment, the authors wrote.

“Microglial cell death appears to play an important role in the pathophysiology of cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy, and therefore early disease progression may occur during the time before the replacement of microglial cells,” they wrote. “Our data, and the results of studies of allogeneic transplantation, show that some disease progression on MRI during the first year after transplantation is common, and therefore reinforce the urgency in identifying cerebral disease early and treating it swiftly.”

Bluebird Bio, the National Institutes of Health, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, the Great Ormond Street Hospital, and the University College London Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health Biomedical Research Centre supported the study. Nine authors declared financial ties to Bluebird Bio, and four authors were employees of Bluebird Bio. One author declared personal fees from a pharmaceutical company involved with lentiviral vectors and a patent related to enhanced lentiviral vector expression, and another two authors declared fees and funding from other pharmaceutical companies unrelated to the study.

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Gene therapy involving transduced autologous hematopoietic stem cell transfers is associated with stabilization of lesion progression and no major functional disability in a majority of patients with cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy.

Data source: Open-label, phase 2-3, STARBEAM trial in 17 patients with early-stage cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy.

Disclosures: Bluebird Bio, the National Institutes of Health, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, the Great Ormond Street Hospital, and the University College London Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health Biomedical Research Centre supported the study. Nine authors declared financial ties to Bluebird Bio, and four authors were employees of Bluebird Bio. One author declared personal fees from a pharmaceutical company involved with lentiviral vectors and a patent related to enhanced lentiviral vector expression, and another two authors declared fees and funding from other pharmaceutical companies unrelated to the study.

ALL therapies grow, so do the complexities of choosing the order of treatments

SAN FRANCISCO – A growing number of immunotherapy options for adults with acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) – rituximab, inotuzumab ozogamicin, blinatumomab and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy – have improved remission rates, but their collective effects on patient outcomes remain to be seen, David Maloney, MD, PhD, said at the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Annual Congress: Hematologic Malignancies.

The main challenge for the field is deciding when and how to use a variety of therapies, he said. “How are we going to put these together? What’s the order?” he asked. “Are we going to be able to decrease the need for allogeneic stem cell transplant? And, obviously, that’s the goal.”

About 30%-50% of adults with ALL exhibit CD20-positive cells, making them potentially treatable with rituximab. Data show a better event-free survival rate and a reduced relapse rate when rituximab is added to standard chemotherapy as compared with standard chemotherapy alone, Dr. Maloney of the clinical research division at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, noted (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 15;375[11]:1044-53). But the improvement was only “modest,” he said.

The anti-CD22 antibody inotuzumab ozogamicin has produced complete remission in 81% of relapsed or refractory ALL patients, compared with those getting standard therapy (N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug 25;375:740-53). Dr. Maloney said it seems well tolerated, but there is concern about an increase in veno-occlusive disease in patients who have undergone or will undergo an allogeneic stem cell transplant.

Blinatumomab produces moderate response rates and minimal residual disease–negative remissions, but delivery of the drug is “cumbersome,” requiring a 4-week continuous infusion, he said. The drug seems to be more effective in those with a lower burden of disease, he noted.

CAR T-cell therapy has produced MRD-negative complete responses in 94% of patients, based on results from a clinical trial at Fred Hutchinson. And using the chemotherapy drug fludarabine in combination with this therapy “dramatically” boosts the peak number of the CAR T cells and how long they persist, Dr. Maloney said. Still, CAR T-cell therapy is a work-intensive treatment requiring cells harvested from the patient, and the procedure often brings on cytokine-release syndrome and neurotoxicity, though both adverse events are typically reversible, he said.

It may be that using fewer CAR T cells can reduce toxicity without compromising treatment response, he said.

Questions remain over whether to transplant patients who are in remission after CAR T-cell therapy. “This is a hot debate,” he said. The decision will likely depend on their prior therapy, whether they’ve had a prior transplant, and the how robust the CAR T-cell expansion has been, he said.

Dr. Maloney reports financial relationships with Celgene, Gilead Sciences, Kite Pharma, and Roche.

SAN FRANCISCO – A growing number of immunotherapy options for adults with acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) – rituximab, inotuzumab ozogamicin, blinatumomab and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy – have improved remission rates, but their collective effects on patient outcomes remain to be seen, David Maloney, MD, PhD, said at the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Annual Congress: Hematologic Malignancies.

The main challenge for the field is deciding when and how to use a variety of therapies, he said. “How are we going to put these together? What’s the order?” he asked. “Are we going to be able to decrease the need for allogeneic stem cell transplant? And, obviously, that’s the goal.”

About 30%-50% of adults with ALL exhibit CD20-positive cells, making them potentially treatable with rituximab. Data show a better event-free survival rate and a reduced relapse rate when rituximab is added to standard chemotherapy as compared with standard chemotherapy alone, Dr. Maloney of the clinical research division at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, noted (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 15;375[11]:1044-53). But the improvement was only “modest,” he said.

The anti-CD22 antibody inotuzumab ozogamicin has produced complete remission in 81% of relapsed or refractory ALL patients, compared with those getting standard therapy (N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug 25;375:740-53). Dr. Maloney said it seems well tolerated, but there is concern about an increase in veno-occlusive disease in patients who have undergone or will undergo an allogeneic stem cell transplant.

Blinatumomab produces moderate response rates and minimal residual disease–negative remissions, but delivery of the drug is “cumbersome,” requiring a 4-week continuous infusion, he said. The drug seems to be more effective in those with a lower burden of disease, he noted.

CAR T-cell therapy has produced MRD-negative complete responses in 94% of patients, based on results from a clinical trial at Fred Hutchinson. And using the chemotherapy drug fludarabine in combination with this therapy “dramatically” boosts the peak number of the CAR T cells and how long they persist, Dr. Maloney said. Still, CAR T-cell therapy is a work-intensive treatment requiring cells harvested from the patient, and the procedure often brings on cytokine-release syndrome and neurotoxicity, though both adverse events are typically reversible, he said.

It may be that using fewer CAR T cells can reduce toxicity without compromising treatment response, he said.

Questions remain over whether to transplant patients who are in remission after CAR T-cell therapy. “This is a hot debate,” he said. The decision will likely depend on their prior therapy, whether they’ve had a prior transplant, and the how robust the CAR T-cell expansion has been, he said.

Dr. Maloney reports financial relationships with Celgene, Gilead Sciences, Kite Pharma, and Roche.

SAN FRANCISCO – A growing number of immunotherapy options for adults with acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) – rituximab, inotuzumab ozogamicin, blinatumomab and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy – have improved remission rates, but their collective effects on patient outcomes remain to be seen, David Maloney, MD, PhD, said at the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Annual Congress: Hematologic Malignancies.

The main challenge for the field is deciding when and how to use a variety of therapies, he said. “How are we going to put these together? What’s the order?” he asked. “Are we going to be able to decrease the need for allogeneic stem cell transplant? And, obviously, that’s the goal.”

About 30%-50% of adults with ALL exhibit CD20-positive cells, making them potentially treatable with rituximab. Data show a better event-free survival rate and a reduced relapse rate when rituximab is added to standard chemotherapy as compared with standard chemotherapy alone, Dr. Maloney of the clinical research division at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, noted (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 15;375[11]:1044-53). But the improvement was only “modest,” he said.

The anti-CD22 antibody inotuzumab ozogamicin has produced complete remission in 81% of relapsed or refractory ALL patients, compared with those getting standard therapy (N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug 25;375:740-53). Dr. Maloney said it seems well tolerated, but there is concern about an increase in veno-occlusive disease in patients who have undergone or will undergo an allogeneic stem cell transplant.

Blinatumomab produces moderate response rates and minimal residual disease–negative remissions, but delivery of the drug is “cumbersome,” requiring a 4-week continuous infusion, he said. The drug seems to be more effective in those with a lower burden of disease, he noted.

CAR T-cell therapy has produced MRD-negative complete responses in 94% of patients, based on results from a clinical trial at Fred Hutchinson. And using the chemotherapy drug fludarabine in combination with this therapy “dramatically” boosts the peak number of the CAR T cells and how long they persist, Dr. Maloney said. Still, CAR T-cell therapy is a work-intensive treatment requiring cells harvested from the patient, and the procedure often brings on cytokine-release syndrome and neurotoxicity, though both adverse events are typically reversible, he said.

It may be that using fewer CAR T cells can reduce toxicity without compromising treatment response, he said.

Questions remain over whether to transplant patients who are in remission after CAR T-cell therapy. “This is a hot debate,” he said. The decision will likely depend on their prior therapy, whether they’ve had a prior transplant, and the how robust the CAR T-cell expansion has been, he said.

Dr. Maloney reports financial relationships with Celgene, Gilead Sciences, Kite Pharma, and Roche.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE NCCN ANNUAL CONGRESS: HEMATOLOGIC MALIGNANCIES

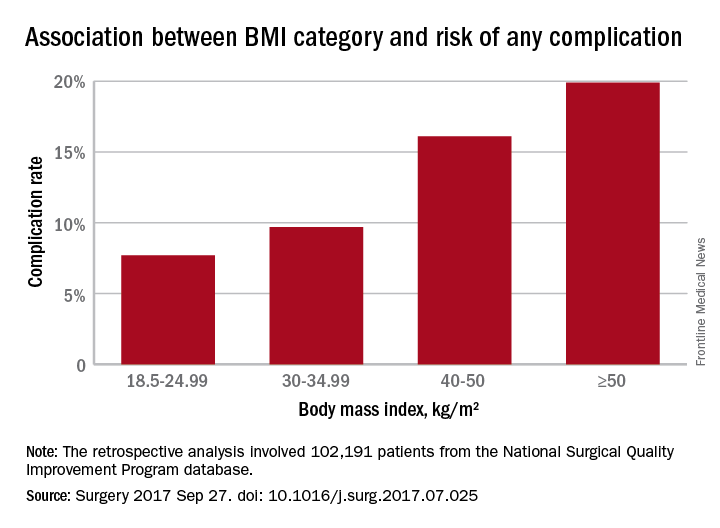

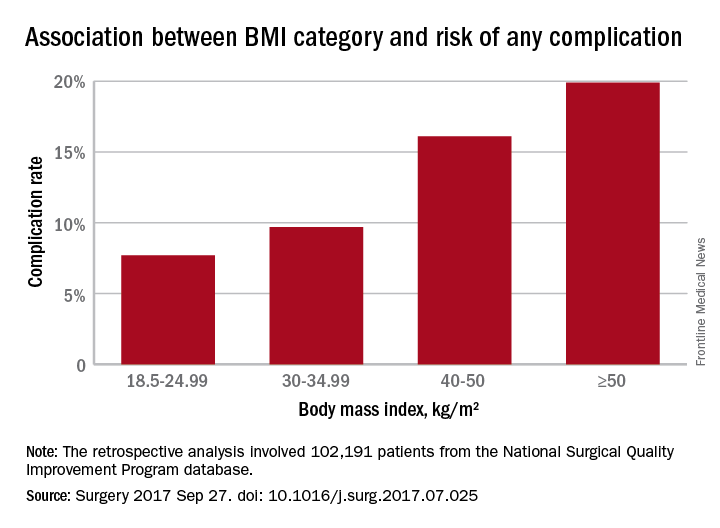

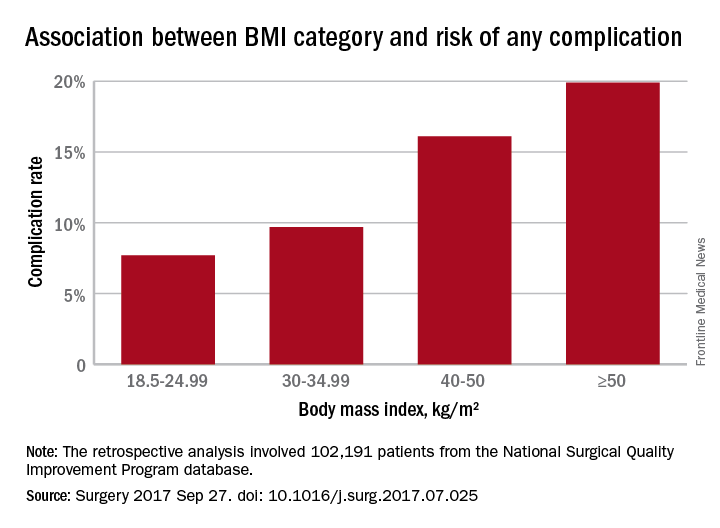

Obesity increases risk of complications with hernia repair

Both obese and underweight patients undergoing ventral hernia repair have a significantly greater risk of complications, particularly if they have strangulated/reducible hernias, according to data published online in Surgery.

In a retrospective analysis, researchers examined data from 102,191 patients – 58.5% of whom were obese – who underwent ventral hernia repair, and found a J-shaped curve in the association between complication rates and body mass index.

Underweight patients with a BMI less than 18.5kg/m2 had a 10% risk of complications, while those of normal BMI (18.5-24.99) had the lowest complication risk: 7.7%. Complication rates then increased steadily with increasing BMI; 8.2% for overweight patients, 9.7% for the obese, 12.2% for the severely obese, 16.1% for the morbidly obese, and 19.9% for the super obese (Surgery 2017, Sep 27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2017.07.025).

Analysis by individual medical complications showed that postoperative pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, acute renal failure, and urinary tract infection were all statistically significantly more common with increasing BMI. The risk of myocardial infarction did not differ significantly with BMI.

The researchers also examined the effects of different hernia types. The 70.3% of patients who had reducible hernias had lower complication rates overall, as well as lower rates of complications in each category of operative, medical, and respiratory, compared with the 29.7% of patients with strangulated/incarcerated hernias.

Nearly one-quarter of the patients in the study were undergoing recurrent ventral hernia repair, and these patients were more likely to have a higher BMI.

After taking into account variables such as age, smoking comorbidities, type of hernia, and type of repair, the authors concluded that the odds of having any complication increased significantly above a BMI of 30 kg/m2, using normal weight BMI as a reference. The odds were 22% higher in those with BMIs in the 30-34.99 range, 54% higher for those in the 35-39.99 range, twofold higher for those with a BMI between 40 and 50, and 2.6-fold higher above 50 kg/m2.

“Surgeons are presented with increasing numbers of obese patients, and the best way to manage ventral hernias in this population remains unclear,” the authors wrote, although they raised the possibility that laparoscopic procedures reduce the risk of some complications.

“Although the majority of VHRs performed utilize an open technique, studies have found decreased duration of stay, morbidity, and, in selected studies, even decreased recurrence using the laparoscopic approach.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

Both obese and underweight patients undergoing ventral hernia repair have a significantly greater risk of complications, particularly if they have strangulated/reducible hernias, according to data published online in Surgery.

In a retrospective analysis, researchers examined data from 102,191 patients – 58.5% of whom were obese – who underwent ventral hernia repair, and found a J-shaped curve in the association between complication rates and body mass index.

Underweight patients with a BMI less than 18.5kg/m2 had a 10% risk of complications, while those of normal BMI (18.5-24.99) had the lowest complication risk: 7.7%. Complication rates then increased steadily with increasing BMI; 8.2% for overweight patients, 9.7% for the obese, 12.2% for the severely obese, 16.1% for the morbidly obese, and 19.9% for the super obese (Surgery 2017, Sep 27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2017.07.025).

Analysis by individual medical complications showed that postoperative pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, acute renal failure, and urinary tract infection were all statistically significantly more common with increasing BMI. The risk of myocardial infarction did not differ significantly with BMI.

The researchers also examined the effects of different hernia types. The 70.3% of patients who had reducible hernias had lower complication rates overall, as well as lower rates of complications in each category of operative, medical, and respiratory, compared with the 29.7% of patients with strangulated/incarcerated hernias.

Nearly one-quarter of the patients in the study were undergoing recurrent ventral hernia repair, and these patients were more likely to have a higher BMI.

After taking into account variables such as age, smoking comorbidities, type of hernia, and type of repair, the authors concluded that the odds of having any complication increased significantly above a BMI of 30 kg/m2, using normal weight BMI as a reference. The odds were 22% higher in those with BMIs in the 30-34.99 range, 54% higher for those in the 35-39.99 range, twofold higher for those with a BMI between 40 and 50, and 2.6-fold higher above 50 kg/m2.

“Surgeons are presented with increasing numbers of obese patients, and the best way to manage ventral hernias in this population remains unclear,” the authors wrote, although they raised the possibility that laparoscopic procedures reduce the risk of some complications.

“Although the majority of VHRs performed utilize an open technique, studies have found decreased duration of stay, morbidity, and, in selected studies, even decreased recurrence using the laparoscopic approach.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

Both obese and underweight patients undergoing ventral hernia repair have a significantly greater risk of complications, particularly if they have strangulated/reducible hernias, according to data published online in Surgery.

In a retrospective analysis, researchers examined data from 102,191 patients – 58.5% of whom were obese – who underwent ventral hernia repair, and found a J-shaped curve in the association between complication rates and body mass index.

Underweight patients with a BMI less than 18.5kg/m2 had a 10% risk of complications, while those of normal BMI (18.5-24.99) had the lowest complication risk: 7.7%. Complication rates then increased steadily with increasing BMI; 8.2% for overweight patients, 9.7% for the obese, 12.2% for the severely obese, 16.1% for the morbidly obese, and 19.9% for the super obese (Surgery 2017, Sep 27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2017.07.025).

Analysis by individual medical complications showed that postoperative pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, acute renal failure, and urinary tract infection were all statistically significantly more common with increasing BMI. The risk of myocardial infarction did not differ significantly with BMI.

The researchers also examined the effects of different hernia types. The 70.3% of patients who had reducible hernias had lower complication rates overall, as well as lower rates of complications in each category of operative, medical, and respiratory, compared with the 29.7% of patients with strangulated/incarcerated hernias.

Nearly one-quarter of the patients in the study were undergoing recurrent ventral hernia repair, and these patients were more likely to have a higher BMI.

After taking into account variables such as age, smoking comorbidities, type of hernia, and type of repair, the authors concluded that the odds of having any complication increased significantly above a BMI of 30 kg/m2, using normal weight BMI as a reference. The odds were 22% higher in those with BMIs in the 30-34.99 range, 54% higher for those in the 35-39.99 range, twofold higher for those with a BMI between 40 and 50, and 2.6-fold higher above 50 kg/m2.

“Surgeons are presented with increasing numbers of obese patients, and the best way to manage ventral hernias in this population remains unclear,” the authors wrote, although they raised the possibility that laparoscopic procedures reduce the risk of some complications.

“Although the majority of VHRs performed utilize an open technique, studies have found decreased duration of stay, morbidity, and, in selected studies, even decreased recurrence using the laparoscopic approach.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM SURGERY

Key clinical point: Obesity, as well as underweight, are associated with significantly higher rates of complications with ventral repair.

Major finding: Complication rates increased with increasing BMI; 8.2% for overweight patients, 9.7% for the obese, 12.2% for the severely obese, 16.1% for the morbidly obese, and 19.9% for the super obese.

Data source: Retrospective analysis of 102,191 patients who underwent ventral hernia repair.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were declared.

To boost HCV testing in baby boomers, offer the option

Rates of hepatitis C testing increased among New York adults born between 1945 and 1965 after the state passed a law mandating that health care providers offer HCV testing to people of that age, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2013, the year before the new law became effective on Jan. 1, 2014, the total of specimens collected for HCV testing from the 106 clinics that reported data for both 2013 and 2014 was 538,229. In the following year after the law became effective, 813,492 samples were collected from the same clinics, an increase of 51.1% over 2013. The rate of increase for New York Medicaid recipients was similar at 52%.

“This report highlights the potential for state laws to promote HCV testing and the utility of HCV surveillance and Medicaid claims data to monitor the quality of HCV testing and linkage to care for HCV-infected persons,” the CDC investigators concluded.

Find the full report in the MMWR (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6638a3).

Rates of hepatitis C testing increased among New York adults born between 1945 and 1965 after the state passed a law mandating that health care providers offer HCV testing to people of that age, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2013, the year before the new law became effective on Jan. 1, 2014, the total of specimens collected for HCV testing from the 106 clinics that reported data for both 2013 and 2014 was 538,229. In the following year after the law became effective, 813,492 samples were collected from the same clinics, an increase of 51.1% over 2013. The rate of increase for New York Medicaid recipients was similar at 52%.

“This report highlights the potential for state laws to promote HCV testing and the utility of HCV surveillance and Medicaid claims data to monitor the quality of HCV testing and linkage to care for HCV-infected persons,” the CDC investigators concluded.

Find the full report in the MMWR (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6638a3).

Rates of hepatitis C testing increased among New York adults born between 1945 and 1965 after the state passed a law mandating that health care providers offer HCV testing to people of that age, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2013, the year before the new law became effective on Jan. 1, 2014, the total of specimens collected for HCV testing from the 106 clinics that reported data for both 2013 and 2014 was 538,229. In the following year after the law became effective, 813,492 samples were collected from the same clinics, an increase of 51.1% over 2013. The rate of increase for New York Medicaid recipients was similar at 52%.

“This report highlights the potential for state laws to promote HCV testing and the utility of HCV surveillance and Medicaid claims data to monitor the quality of HCV testing and linkage to care for HCV-infected persons,” the CDC investigators concluded.

Find the full report in the MMWR (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6638a3).

FROM THE MMWR

Clinical trial: Mesh weights compared for ventral hernia repair

A clinical trial comparing heavy- and medium-weight surgical mesh for ventral hernia repairs is recruiting patients.

The Long-term Results of Heavy Weight Versus Medium Weight Mesh in Ventral Hernia Repair trial will determine if mesh weight has an impact on postoperative pain, ventral hernia recurrence, incidence of deep wound infection, and overall quality of life following ventral hernia repair with mesh.

Patients will be included if they have a ventral hernia, are 18 years of age or older, have a defect classified as CDC wound class 1, are able to achieve midline fascial closure, have a hernia defect width less than or equal to 20 cm, can tolerate general anesthesia, and can give informed consent. Patients will be excluded if they have undergone emergent ventral hernia repair, undergone laparoscopic or robotic ventral hernia repair, undergone staged repair of their ventral hernia, or are pregnant at the time of the surgery.

The primary outcome of this trial is pain that will be measured via the NIH Promis 3A Pain instrument in 1 year postoperatively. Other outcomes include hernia recurrence, to be determined via the Ventral Hernia Recurrence Inventory; the occurrence of a deep wound infection, to be determined by physical examination and/or computed tomography scanning; and quality of life measured by the HerQLes questionnaire.

Find more information at clinicaltrials.gov.

A clinical trial comparing heavy- and medium-weight surgical mesh for ventral hernia repairs is recruiting patients.

The Long-term Results of Heavy Weight Versus Medium Weight Mesh in Ventral Hernia Repair trial will determine if mesh weight has an impact on postoperative pain, ventral hernia recurrence, incidence of deep wound infection, and overall quality of life following ventral hernia repair with mesh.

Patients will be included if they have a ventral hernia, are 18 years of age or older, have a defect classified as CDC wound class 1, are able to achieve midline fascial closure, have a hernia defect width less than or equal to 20 cm, can tolerate general anesthesia, and can give informed consent. Patients will be excluded if they have undergone emergent ventral hernia repair, undergone laparoscopic or robotic ventral hernia repair, undergone staged repair of their ventral hernia, or are pregnant at the time of the surgery.

The primary outcome of this trial is pain that will be measured via the NIH Promis 3A Pain instrument in 1 year postoperatively. Other outcomes include hernia recurrence, to be determined via the Ventral Hernia Recurrence Inventory; the occurrence of a deep wound infection, to be determined by physical examination and/or computed tomography scanning; and quality of life measured by the HerQLes questionnaire.

Find more information at clinicaltrials.gov.

A clinical trial comparing heavy- and medium-weight surgical mesh for ventral hernia repairs is recruiting patients.

The Long-term Results of Heavy Weight Versus Medium Weight Mesh in Ventral Hernia Repair trial will determine if mesh weight has an impact on postoperative pain, ventral hernia recurrence, incidence of deep wound infection, and overall quality of life following ventral hernia repair with mesh.

Patients will be included if they have a ventral hernia, are 18 years of age or older, have a defect classified as CDC wound class 1, are able to achieve midline fascial closure, have a hernia defect width less than or equal to 20 cm, can tolerate general anesthesia, and can give informed consent. Patients will be excluded if they have undergone emergent ventral hernia repair, undergone laparoscopic or robotic ventral hernia repair, undergone staged repair of their ventral hernia, or are pregnant at the time of the surgery.

The primary outcome of this trial is pain that will be measured via the NIH Promis 3A Pain instrument in 1 year postoperatively. Other outcomes include hernia recurrence, to be determined via the Ventral Hernia Recurrence Inventory; the occurrence of a deep wound infection, to be determined by physical examination and/or computed tomography scanning; and quality of life measured by the HerQLes questionnaire.

Find more information at clinicaltrials.gov.

FROM CLINICALTRIALS.GOV

Gap in osteoporosis diagnosis and treatment stirs concern

DENVER – A recent study of Medicare recipients who experienced a hip fracture found that just 19% of them had been receiving a bone-active osteoporosis treatment before the fracture occurred. That number reveals an alarming trend of underdiagnosis of osteoporosis.

But that number – from a 2016 study in JAMA Internal Medicine – is just the start. After the fracture, the percentage of women receiving treatment barely changed, rising to just 21% (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Oct 1;176[10]:1531-8).

This trend of under-diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis has occurred in spite of the fact that effective therapy exists to reduce future fractures. In fact, a single dose of zoledronic acid has been shown to reduce clinical fractures by 35%, and mortality by 28% over an average 2-year follow-up (N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1799-1809).

“To me, this is really a shame,” Douglas Bauer, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, said at a session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research that was dedicated to the issue.

It remains unclear why the fracture rate declined despite low levels of diagnosis and treatment. Some researchers, such as Bo Abrahamsen, MD, PhD, suggest there is a population effect. At the ASBMR annual meeting, Dr. Abrahamsen of the University of Southern Denmark, Odense, noted that in the western world, women born in the 1930s appear to be less prone to fractures than other birth cohorts, and it could be that this group contributed to the decline in fracture rates. A Danish study, he said, seems to confirm this idea. As other birth cohorts age, the numbers could well get worse.

And that’s worrying, because a gap in treatment and diagnosis of osteoporosis could lead to an epidemic of new fractures. “We need to address this crisis in health care for a very preventable disease,” Meryl LeBoff, MD, director of the skeletal health and osteoporosis center and bone density unit at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

There are several likely causes of declining treatment and diagnosis rates. In 2003, a report surfaced that osteonecrosis of the jaw occurred in cancer patients taking bisphosphonates to prevent metastasis to bone. Those patients received doses that were far higher than the typical osteoporosis patient, but the reports spooked patients. In 2005, researchers pinned another rare side effect on bisphosphonates – atypical femur fractures.

Other factors contributed. In 2007, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services cut the reimbursement rate for bone densitometry (DXA) testing, which has led to a drop in the number of tests, from a peak of 17.9% of women over age 65 years having been tested in 2009 to 14.8% in 2014. That has complicated efforts to diagnose osteoporosis, and may be affecting patients’ willingness to undergo therapy. A patient may go to the hospital for a hip fracture, but without a bone density test to raise concerns, she may write the fracture off as an accident. A DXA test that returns an abnormal value can change that. “If you have low BMD and a fracture, you have a worse prognosis and a higher risk of the next fracture. It’s much easier to convince patients [to begin therapy],” said John Carey, MD, a rheumatologist at Galway (Ireland) University Hospitals and president of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry.

Others emphasized the need to get DXA reimbursement raised, at least to a point where physicians can break even on the test. “Unfortunately, what’s happening is that as DXA reimbursement goes down, physicians are investing less in the education of their staff according to current guidelines,” Dr. Lewiecki said. He noted that there is draft legislation in Congress to raise DXA reimbursement (H.R. 1898), although it is currently in committee.

The forces that create the treatment and diagnostic gap aren’t simple, and no single strategy is likely to fix the problem. A number have been proposed.

FLS programs seek to quickly identify and provide treatment and monitoring for individuals who are at high risk for additional fractures. The programs identify patients who have suffered a fragility fracture and place them into a coordinated care model. For example, if a radiologist identified a patient of concern, she can be immediately referred to the FLS for quick follow-up, to include bone density scans and other steps to ensure proper diagnosis and treatment. In the absence of an FLS, it could be months before a patient is seen again, if a radiologist refers her at all. “You lose patients. But if they are tied into a coordination of care model, the patient is brought in immediately and they get the attention and awareness. They’re not just lost,” said Debbie Zeldow, executive director of the National Bone Health Alliance (NBHA).

Despite their effectiveness, FLS programs could be a tough sell for the upfront investment they require. To help organizations determine the cost-effectiveness of an FLS, the National Bone Health Alliance has developed a return on investment calculator.

And in fact, FLS programs are gaining traction, according to Ms. Zeldow. NBHA has posted a variety of resources for establishing an FLS on its website, which contains webinars and other resources, including the text of patient flyers produced by Kaiser Permanente translated into many languages. “There’s been a huge jump in interest in implementation. I’m getting calls on a daily basis from sites that want to implement an FLS. People are being pinged for readmission, and they’re looking for ways for their hospital or practice to improve outcomes. It’s definitely a way for hospitals to differentiate themselves around care,” Ms. Zeldow said in an interview.

FLS programs reduce secondary fractures, but the ultimate goal is to catch osteoporosis earlier and prevent even first-time fractures. That will require better communication with primary care providers, who bear the brunt of osteoporosis diagnosis and care.

“We need to do a better job of reducing barriers for primary care doctors, to try to minimize unnecessary treatment complexity, and address the fact that this is one of the many prevention issues that physicians are asked to manage, and all that in an increasingly time-constrained world,” Dr. Bauer said.

With that goal in mind, the American College of Physicians released new guidelines in May (Ann Intern Med. 2017;166[11]:818-39). They were intended to identify first-line therapies and simplify matters for primary care physicians, but they drew the ire of many endocrinologists for being too general. NBHA has formed an ACP guideline working group that aims to refine those guidelines. The committee is drafting a statement and a document for patients to help clarify the guidelines, particularly with respect to high-risk patients. The committee also seeks to avoid any rancor. “We’ve made a concerted effort to include primary care doctors, to make sure there’s not a disconnect between experts and general practitioners. We want to make sure it’s a useful tool and we’re not just bashing the guidelines,” Ms. Zeldow said.

Another way to help overburdened primary care providers is to provide training for physicians, especially in underserved areas. The National Osteoporosis Foundation’s TeleECHO program is a remote training service that can help interested local providers elevate their knowledge so they can become a local osteoporosis expert. “Patients can get better care, at more convenience and at lower cost, rather than having to travel to a specialist center far away,” Dr. Lewiecki said.

Patient concerns about side effects, the changing health care climate, and the challenges facing primary care providers add up to difficult environment for countering the reductions in diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis, but Dr. Lewiecki is hopeful. “Fracture liaison services combined with better education of health care providers through new educational methods I think have great promise. It’s just a matter of getting those things online,” he said.

Dr. Carey has been a speaker for Roche, Pfizer, and AbbVie. Dr. Lewiecki has consulted for Amgen. Dr. Leder has received funding from Lilly and Amgen, and has been a consultant for Lilly, Amgen, and Radius. Dr. Bauer and Ms. Zeldow reported having no financial disclosures.

DENVER – A recent study of Medicare recipients who experienced a hip fracture found that just 19% of them had been receiving a bone-active osteoporosis treatment before the fracture occurred. That number reveals an alarming trend of underdiagnosis of osteoporosis.

But that number – from a 2016 study in JAMA Internal Medicine – is just the start. After the fracture, the percentage of women receiving treatment barely changed, rising to just 21% (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Oct 1;176[10]:1531-8).

This trend of under-diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis has occurred in spite of the fact that effective therapy exists to reduce future fractures. In fact, a single dose of zoledronic acid has been shown to reduce clinical fractures by 35%, and mortality by 28% over an average 2-year follow-up (N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1799-1809).

“To me, this is really a shame,” Douglas Bauer, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, said at a session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research that was dedicated to the issue.

It remains unclear why the fracture rate declined despite low levels of diagnosis and treatment. Some researchers, such as Bo Abrahamsen, MD, PhD, suggest there is a population effect. At the ASBMR annual meeting, Dr. Abrahamsen of the University of Southern Denmark, Odense, noted that in the western world, women born in the 1930s appear to be less prone to fractures than other birth cohorts, and it could be that this group contributed to the decline in fracture rates. A Danish study, he said, seems to confirm this idea. As other birth cohorts age, the numbers could well get worse.

And that’s worrying, because a gap in treatment and diagnosis of osteoporosis could lead to an epidemic of new fractures. “We need to address this crisis in health care for a very preventable disease,” Meryl LeBoff, MD, director of the skeletal health and osteoporosis center and bone density unit at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

There are several likely causes of declining treatment and diagnosis rates. In 2003, a report surfaced that osteonecrosis of the jaw occurred in cancer patients taking bisphosphonates to prevent metastasis to bone. Those patients received doses that were far higher than the typical osteoporosis patient, but the reports spooked patients. In 2005, researchers pinned another rare side effect on bisphosphonates – atypical femur fractures.

Other factors contributed. In 2007, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services cut the reimbursement rate for bone densitometry (DXA) testing, which has led to a drop in the number of tests, from a peak of 17.9% of women over age 65 years having been tested in 2009 to 14.8% in 2014. That has complicated efforts to diagnose osteoporosis, and may be affecting patients’ willingness to undergo therapy. A patient may go to the hospital for a hip fracture, but without a bone density test to raise concerns, she may write the fracture off as an accident. A DXA test that returns an abnormal value can change that. “If you have low BMD and a fracture, you have a worse prognosis and a higher risk of the next fracture. It’s much easier to convince patients [to begin therapy],” said John Carey, MD, a rheumatologist at Galway (Ireland) University Hospitals and president of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry.

Others emphasized the need to get DXA reimbursement raised, at least to a point where physicians can break even on the test. “Unfortunately, what’s happening is that as DXA reimbursement goes down, physicians are investing less in the education of their staff according to current guidelines,” Dr. Lewiecki said. He noted that there is draft legislation in Congress to raise DXA reimbursement (H.R. 1898), although it is currently in committee.

The forces that create the treatment and diagnostic gap aren’t simple, and no single strategy is likely to fix the problem. A number have been proposed.

FLS programs seek to quickly identify and provide treatment and monitoring for individuals who are at high risk for additional fractures. The programs identify patients who have suffered a fragility fracture and place them into a coordinated care model. For example, if a radiologist identified a patient of concern, she can be immediately referred to the FLS for quick follow-up, to include bone density scans and other steps to ensure proper diagnosis and treatment. In the absence of an FLS, it could be months before a patient is seen again, if a radiologist refers her at all. “You lose patients. But if they are tied into a coordination of care model, the patient is brought in immediately and they get the attention and awareness. They’re not just lost,” said Debbie Zeldow, executive director of the National Bone Health Alliance (NBHA).

Despite their effectiveness, FLS programs could be a tough sell for the upfront investment they require. To help organizations determine the cost-effectiveness of an FLS, the National Bone Health Alliance has developed a return on investment calculator.

And in fact, FLS programs are gaining traction, according to Ms. Zeldow. NBHA has posted a variety of resources for establishing an FLS on its website, which contains webinars and other resources, including the text of patient flyers produced by Kaiser Permanente translated into many languages. “There’s been a huge jump in interest in implementation. I’m getting calls on a daily basis from sites that want to implement an FLS. People are being pinged for readmission, and they’re looking for ways for their hospital or practice to improve outcomes. It’s definitely a way for hospitals to differentiate themselves around care,” Ms. Zeldow said in an interview.

FLS programs reduce secondary fractures, but the ultimate goal is to catch osteoporosis earlier and prevent even first-time fractures. That will require better communication with primary care providers, who bear the brunt of osteoporosis diagnosis and care.

“We need to do a better job of reducing barriers for primary care doctors, to try to minimize unnecessary treatment complexity, and address the fact that this is one of the many prevention issues that physicians are asked to manage, and all that in an increasingly time-constrained world,” Dr. Bauer said.

With that goal in mind, the American College of Physicians released new guidelines in May (Ann Intern Med. 2017;166[11]:818-39). They were intended to identify first-line therapies and simplify matters for primary care physicians, but they drew the ire of many endocrinologists for being too general. NBHA has formed an ACP guideline working group that aims to refine those guidelines. The committee is drafting a statement and a document for patients to help clarify the guidelines, particularly with respect to high-risk patients. The committee also seeks to avoid any rancor. “We’ve made a concerted effort to include primary care doctors, to make sure there’s not a disconnect between experts and general practitioners. We want to make sure it’s a useful tool and we’re not just bashing the guidelines,” Ms. Zeldow said.

Another way to help overburdened primary care providers is to provide training for physicians, especially in underserved areas. The National Osteoporosis Foundation’s TeleECHO program is a remote training service that can help interested local providers elevate their knowledge so they can become a local osteoporosis expert. “Patients can get better care, at more convenience and at lower cost, rather than having to travel to a specialist center far away,” Dr. Lewiecki said.

Patient concerns about side effects, the changing health care climate, and the challenges facing primary care providers add up to difficult environment for countering the reductions in diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis, but Dr. Lewiecki is hopeful. “Fracture liaison services combined with better education of health care providers through new educational methods I think have great promise. It’s just a matter of getting those things online,” he said.

Dr. Carey has been a speaker for Roche, Pfizer, and AbbVie. Dr. Lewiecki has consulted for Amgen. Dr. Leder has received funding from Lilly and Amgen, and has been a consultant for Lilly, Amgen, and Radius. Dr. Bauer and Ms. Zeldow reported having no financial disclosures.

DENVER – A recent study of Medicare recipients who experienced a hip fracture found that just 19% of them had been receiving a bone-active osteoporosis treatment before the fracture occurred. That number reveals an alarming trend of underdiagnosis of osteoporosis.

But that number – from a 2016 study in JAMA Internal Medicine – is just the start. After the fracture, the percentage of women receiving treatment barely changed, rising to just 21% (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Oct 1;176[10]:1531-8).

This trend of under-diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis has occurred in spite of the fact that effective therapy exists to reduce future fractures. In fact, a single dose of zoledronic acid has been shown to reduce clinical fractures by 35%, and mortality by 28% over an average 2-year follow-up (N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1799-1809).

“To me, this is really a shame,” Douglas Bauer, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, said at a session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research that was dedicated to the issue.

It remains unclear why the fracture rate declined despite low levels of diagnosis and treatment. Some researchers, such as Bo Abrahamsen, MD, PhD, suggest there is a population effect. At the ASBMR annual meeting, Dr. Abrahamsen of the University of Southern Denmark, Odense, noted that in the western world, women born in the 1930s appear to be less prone to fractures than other birth cohorts, and it could be that this group contributed to the decline in fracture rates. A Danish study, he said, seems to confirm this idea. As other birth cohorts age, the numbers could well get worse.

And that’s worrying, because a gap in treatment and diagnosis of osteoporosis could lead to an epidemic of new fractures. “We need to address this crisis in health care for a very preventable disease,” Meryl LeBoff, MD, director of the skeletal health and osteoporosis center and bone density unit at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

There are several likely causes of declining treatment and diagnosis rates. In 2003, a report surfaced that osteonecrosis of the jaw occurred in cancer patients taking bisphosphonates to prevent metastasis to bone. Those patients received doses that were far higher than the typical osteoporosis patient, but the reports spooked patients. In 2005, researchers pinned another rare side effect on bisphosphonates – atypical femur fractures.

Other factors contributed. In 2007, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services cut the reimbursement rate for bone densitometry (DXA) testing, which has led to a drop in the number of tests, from a peak of 17.9% of women over age 65 years having been tested in 2009 to 14.8% in 2014. That has complicated efforts to diagnose osteoporosis, and may be affecting patients’ willingness to undergo therapy. A patient may go to the hospital for a hip fracture, but without a bone density test to raise concerns, she may write the fracture off as an accident. A DXA test that returns an abnormal value can change that. “If you have low BMD and a fracture, you have a worse prognosis and a higher risk of the next fracture. It’s much easier to convince patients [to begin therapy],” said John Carey, MD, a rheumatologist at Galway (Ireland) University Hospitals and president of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry.

Others emphasized the need to get DXA reimbursement raised, at least to a point where physicians can break even on the test. “Unfortunately, what’s happening is that as DXA reimbursement goes down, physicians are investing less in the education of their staff according to current guidelines,” Dr. Lewiecki said. He noted that there is draft legislation in Congress to raise DXA reimbursement (H.R. 1898), although it is currently in committee.