User login

Noise and Light Pollution in the Hospital: A Call for Action

“Unnecessary noise is the most cruel abuse of care which can be inflicted on either the sick or the well.”

–Florence Nightingale1

Motivated by the “unsustainable” rise in noise pollution and its “direct, as well as cumulative, adverse health effects,” an expert World Health Organization (WHO) task force composed the Guidelines for Community Noise, outlining specific noise recommendations for public settings, including hospitals.2 In ward settings, these guidelines mandate that background noise (which is defined as unwanted sound) levels average <35 decibels (dB; ie, a typical library) during the day, average <30 dB at night, and peak no higher than 40 dB (ie, a normal conversation), a level sufficient to awaken someone from sleep.

Since the publication of these guidelines in 1999, substantial new research has added to our understanding of hospital noise levels. Recent research has demonstrated that few, if any, hospitals comply with WHO noise recommendations.3 Moreover, since 1960, hospital sound levels have risen ~4 dB per decade; based on the logarithmic decibel scale, if this trend continues, this translates to a 528% increase in loudness by 2020.3

The overwhelming majority of research on hospital noise has focused on the intensive care unit (ICU), where beeping machines and busy staff often push peak nighttime noise levels over 80 dB (ie, a kitchen blender).4 When evaluated during sleep, noise in the ICU causes frequent arousals and awakenings. When noise is combined with other factors, such as bright light and patient care interactions, poor sleep quality invariably results.4

While it has been known for years that critically ill patients experience markedly fragmented and nonrestorative sleep,5 poor sleep has recently gained attention due to its potential role as a modifiable risk factor for delirium and its associated consequences, including prolonged length of stay and long-lasting neuropsychological and physical impairments.6 Due to this interest, numerous interventions have been attempted,7 including multicomponent bundles to promote sleep,8 which have been shown to reduce delirium in the ICU.9-12 Therefore, efforts to promote sleep in the ICU, including interventions to minimize nighttime noise, are recommended in Society of Critical Care Medicine clinical practice guidelines13 and are listed as a top 5 research priority by an expert panel of ICU delirium researchers.14

In contrast to the ICU, there has been little attention paid to noise in other patient care areas. Existing studies in non-ICU ward settings suggest that excessive noise is common,3 similar to the ICU, and that patients experience poor sleep, with noise being a significant disruptor of sleep.5,15,16 Such poor sleep is thought to contribute to uncontrolled pain, labile blood pressure, and dissatisfaction with care.16,17

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Jaiswal and colleagues18 report on an important study evaluating sound and light levels in both non-ICU and ICU settings within a busy tertiary-care hospital. In 8 general ward, 8 telemetry, and 8 ICU patient rooms, the investigators used meters to record sound and light levels for 24 to 72 hours. In each of these locations, they detected average hourly sound levels ranging from 45 to 54 dB, 47 to 55 dB, and 56 to 60 dB, respectively, with ICUs consistently registering the highest hourly sound levels. Notably, all locations exceeded WHO noise limits at all hours of the day. As a novel measure, the investigators evaluated sound level changes (SLCs), or the difference between peak and background sound levels, based on research suggesting that dramatic SLCs (≥17.5 dB) are more disruptive than constant loud noise.19 The authors observed that SLCs ≥17.5 dB occur predominantly during daytime hours and, interestingly, at a similar rate in the wards versus the ICU.

Importantly, the authors do not link their findings with patient sleep or other patient outcomes but instead focus on employing rigorous methods to gather continuous recordings. By measuring light levels, the authors bring attention to an issue often considered less disruptive to sleep than noise.6,10,20 Similar to prior research,21 Jaiswal and colleagues demonstrate low levels of light at night, with no substantial difference between non-ICU and ICU settings. As a key finding, the authors bring attention to low levels of light during daytime hours, particularly in the morning, when levels range from 22 to 101 lux in the wards and 16 to 39 lux in the ICU. While the optimal timing and brightness of light exposure remains unknown, it is well established that ambient light is the most potent cue for circadian rhythms, with levels >100 lux necessary to suppress melatonin, the key hormone involved in circadian entrainment. Hence, the levels of morning light observed in this study were likely insufficient to maintain healthy circadian rhythms. When exposed to abnormal light levels and factors such as noise, stress, and medications, hospitalized patients are at risk for circadian rhythm misalignment, which can disrupt sleep and trigger a complex molecular cascade, leading to end-organ dysfunction including depressed immunity, glucose dysregulation, arrhythmias, and delirium.22-24

What are the major takeaway messages from this study? First, it confirms that sound levels are not only high in the ICU but also in non-ICU wards. As hospital ratings and reimbursements now rely on favorable patient ratings, future noise-reduction efforts will surely expand more vigorously across patient care areas.25 Second, SLCs and daytime recordings must be included in efforts to understand and improve sleep and circadian rhythms in hospitalized patients. Finally, this study provides a sobering reminder of the challenge of meeting WHO guidelines and facilitating an optimal healing environment for patients. Sadly, hospital sound levels continue to rise, and quiet-time interventions consistently fail to lower noise to levels anywhere near WHO limits.26 Hence, to make any progress, hospitals of the future must entertain novel design modifications (eg, sound-absorbing walls and alternative room layouts), fix common sources of noise pollution (eg, ventilation systems and alarms), and critically evaluate and update interventions aimed at improving sleep and aligning circadian rhythms for hospitalized patients.27

Acknowledgments

B.B.K. is currently supported by a grant through the University of California, Los Angeles Clinical Translational Research Institute and the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000124).

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Nightingale F. Notes on Nursing: What It Is, and What It Is Not. Harrison; 1860. PubMed

2. Berglund B, Lindvall T, Schwela DH. Guidelines for Community Noise. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1999. http://www.who.int/docstore/peh/noise/guidelines2.html. Accessed on June 23, 2017.

3. Busch-Vishniac IJ, West JE, Barnhill C, Hunter T, Orellana D, Chivukula R. Noise levels in Johns Hopkins Hospital. J Acoust Soc Am. 2005;118(6):3629-3645. PubMed

4. Kamdar BB, Needham DM, Collop NA. Sleep deprivation in critical illness: its role in physical and psychological recovery. J Intensive Care Med. 2012;27(2):97-111. PubMed

5. Knauert MP, Malik V, Kamdar BB. Sleep and sleep disordered breathing in hospitalized patients. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;35(5):582-592. PubMed

6. Kamdar BB, Knauert MP, Jones SF, et al. Perceptions and practices regarding sleep in the intensive care unit. A survey of 1,223 critical care providers. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(8):1370-1377. PubMed

7. DuBose JR, Hadi K. Improving inpatient environments to support patient sleep. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(5):540-553. PubMed

8. Kamdar BB, Kamdar BB, Needham DM. Bundling sleep promotion with delirium prevention: ready for prime time? Anaesthesia. 2014;69(6):527-531. PubMed

9. Patel J, Baldwin J, Bunting P, Laha S. The effect of a multicomponent multidisciplinary bundle of interventions on sleep and delirium in medical and surgical intensive care patients. Anaesthesia. 2014;69(6):540-549. PubMed

10. Kamdar BB, King LM, Collop NA, et al. The effect of a quality improvement intervention on perceived sleep quality and cognition in a medical ICU. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(3):800-809. PubMed

11. van de Pol I, van Iterson M, Maaskant J. Effect of nocturnal sound reduction on the incidence of delirium in intensive care unit patients: An interrupted time series analysis. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2017;41:18-25. PubMed

12. Flannery AH, Oyler DR, Weinhouse GL. The impact of interventions to improve sleep on delirium in the ICU: a systematic review and research framework. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(12):2231-2240. PubMed

13. Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(1):263-306. PubMed

14. Pandharipande PP, Ely EW, Arora RC, et al. The intensive care delirium research agenda: a multinational, interprofessional perspective [published online ahead of print June 13, 2017]. Intensive Care Med. PubMed

15. Topf M, Thompson S. Interactive relationships between hospital patients’ noise-induced stress and other stress with sleep. Heart Lung. 2001;30(4):237-243. PubMed

16. Tamrat R, Huynh-Le MP, Goyal M. Non-pharmacologic interventions to improve the sleep of hospitalized patients: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(5):788-795. PubMed

17. Fillary J, Chaplin H, Jones G, Thompson A, Holme A, Wilson P. Noise at night in hospital general wards: a mapping of the literature. Br J Nurs. 2015;24(10):536-540. PubMed

18. Jaiswal SJ, Garcia S, Owens RL. Sound and light levels are similarly disruptive in ICU and non-ICU wards. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(10):798-804. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2826.

19. Stanchina ML, Abu-Hijleh M, Chaudhry BK, Carlisle CC, Millman RP. The influence of white noise on sleep in subjects exposed to ICU noise. Sleep Med. 2005;6(5):423-428. PubMed

20. Freedman NS, Kotzer N, Schwab RJ. Patient perception of sleep quality and etiology of sleep disruption in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(4, Pt 1):1155-1162. PubMed

21. Meyer TJ, Eveloff SE, Bauer MS, Schwartz WA, Hill NS, Millman RP. Adverse environmental conditions in the respiratory and medical ICU settings. Chest. 1994;105(4):1211-1216. PubMed

22. Castro R, Angus DC, Rosengart MR. The effect of light on critical illness. Crit Care. 2011;15(2):218. PubMed

23. Brainard J, Gobel M, Scott B, Koeppen M, Eckle T. Health implications of disrupted circadian rhythms and the potential for daylight as therapy. Anesthesiology. 2015;122(5):1170-1175. PubMed

24. Fitzgerald JM, Adamis D, Trzepacz PT, et al. Delirium: a disturbance of circadian integrity? Med Hypotheses. 2013;81(4):568-576. PubMed

25. Stafford A, Haverland A, Bridges E. Noise in the ICU. Am J Nurs. 2014;114(5):57-63. PubMed

26. Tainter CR, Levine AR, Quraishi SA, et al. Noise levels in surgical ICUs are consistently above recommended standards. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(1):147-152. PubMed

27. Ulrich RS, Zimring C, Zhu X, et al. A review of the research literature on evidence-based healthcare design. HERD. 2008;1(3):61-125. PubMed

“Unnecessary noise is the most cruel abuse of care which can be inflicted on either the sick or the well.”

–Florence Nightingale1

Motivated by the “unsustainable” rise in noise pollution and its “direct, as well as cumulative, adverse health effects,” an expert World Health Organization (WHO) task force composed the Guidelines for Community Noise, outlining specific noise recommendations for public settings, including hospitals.2 In ward settings, these guidelines mandate that background noise (which is defined as unwanted sound) levels average <35 decibels (dB; ie, a typical library) during the day, average <30 dB at night, and peak no higher than 40 dB (ie, a normal conversation), a level sufficient to awaken someone from sleep.

Since the publication of these guidelines in 1999, substantial new research has added to our understanding of hospital noise levels. Recent research has demonstrated that few, if any, hospitals comply with WHO noise recommendations.3 Moreover, since 1960, hospital sound levels have risen ~4 dB per decade; based on the logarithmic decibel scale, if this trend continues, this translates to a 528% increase in loudness by 2020.3

The overwhelming majority of research on hospital noise has focused on the intensive care unit (ICU), where beeping machines and busy staff often push peak nighttime noise levels over 80 dB (ie, a kitchen blender).4 When evaluated during sleep, noise in the ICU causes frequent arousals and awakenings. When noise is combined with other factors, such as bright light and patient care interactions, poor sleep quality invariably results.4

While it has been known for years that critically ill patients experience markedly fragmented and nonrestorative sleep,5 poor sleep has recently gained attention due to its potential role as a modifiable risk factor for delirium and its associated consequences, including prolonged length of stay and long-lasting neuropsychological and physical impairments.6 Due to this interest, numerous interventions have been attempted,7 including multicomponent bundles to promote sleep,8 which have been shown to reduce delirium in the ICU.9-12 Therefore, efforts to promote sleep in the ICU, including interventions to minimize nighttime noise, are recommended in Society of Critical Care Medicine clinical practice guidelines13 and are listed as a top 5 research priority by an expert panel of ICU delirium researchers.14

In contrast to the ICU, there has been little attention paid to noise in other patient care areas. Existing studies in non-ICU ward settings suggest that excessive noise is common,3 similar to the ICU, and that patients experience poor sleep, with noise being a significant disruptor of sleep.5,15,16 Such poor sleep is thought to contribute to uncontrolled pain, labile blood pressure, and dissatisfaction with care.16,17

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Jaiswal and colleagues18 report on an important study evaluating sound and light levels in both non-ICU and ICU settings within a busy tertiary-care hospital. In 8 general ward, 8 telemetry, and 8 ICU patient rooms, the investigators used meters to record sound and light levels for 24 to 72 hours. In each of these locations, they detected average hourly sound levels ranging from 45 to 54 dB, 47 to 55 dB, and 56 to 60 dB, respectively, with ICUs consistently registering the highest hourly sound levels. Notably, all locations exceeded WHO noise limits at all hours of the day. As a novel measure, the investigators evaluated sound level changes (SLCs), or the difference between peak and background sound levels, based on research suggesting that dramatic SLCs (≥17.5 dB) are more disruptive than constant loud noise.19 The authors observed that SLCs ≥17.5 dB occur predominantly during daytime hours and, interestingly, at a similar rate in the wards versus the ICU.

Importantly, the authors do not link their findings with patient sleep or other patient outcomes but instead focus on employing rigorous methods to gather continuous recordings. By measuring light levels, the authors bring attention to an issue often considered less disruptive to sleep than noise.6,10,20 Similar to prior research,21 Jaiswal and colleagues demonstrate low levels of light at night, with no substantial difference between non-ICU and ICU settings. As a key finding, the authors bring attention to low levels of light during daytime hours, particularly in the morning, when levels range from 22 to 101 lux in the wards and 16 to 39 lux in the ICU. While the optimal timing and brightness of light exposure remains unknown, it is well established that ambient light is the most potent cue for circadian rhythms, with levels >100 lux necessary to suppress melatonin, the key hormone involved in circadian entrainment. Hence, the levels of morning light observed in this study were likely insufficient to maintain healthy circadian rhythms. When exposed to abnormal light levels and factors such as noise, stress, and medications, hospitalized patients are at risk for circadian rhythm misalignment, which can disrupt sleep and trigger a complex molecular cascade, leading to end-organ dysfunction including depressed immunity, glucose dysregulation, arrhythmias, and delirium.22-24

What are the major takeaway messages from this study? First, it confirms that sound levels are not only high in the ICU but also in non-ICU wards. As hospital ratings and reimbursements now rely on favorable patient ratings, future noise-reduction efforts will surely expand more vigorously across patient care areas.25 Second, SLCs and daytime recordings must be included in efforts to understand and improve sleep and circadian rhythms in hospitalized patients. Finally, this study provides a sobering reminder of the challenge of meeting WHO guidelines and facilitating an optimal healing environment for patients. Sadly, hospital sound levels continue to rise, and quiet-time interventions consistently fail to lower noise to levels anywhere near WHO limits.26 Hence, to make any progress, hospitals of the future must entertain novel design modifications (eg, sound-absorbing walls and alternative room layouts), fix common sources of noise pollution (eg, ventilation systems and alarms), and critically evaluate and update interventions aimed at improving sleep and aligning circadian rhythms for hospitalized patients.27

Acknowledgments

B.B.K. is currently supported by a grant through the University of California, Los Angeles Clinical Translational Research Institute and the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000124).

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

“Unnecessary noise is the most cruel abuse of care which can be inflicted on either the sick or the well.”

–Florence Nightingale1

Motivated by the “unsustainable” rise in noise pollution and its “direct, as well as cumulative, adverse health effects,” an expert World Health Organization (WHO) task force composed the Guidelines for Community Noise, outlining specific noise recommendations for public settings, including hospitals.2 In ward settings, these guidelines mandate that background noise (which is defined as unwanted sound) levels average <35 decibels (dB; ie, a typical library) during the day, average <30 dB at night, and peak no higher than 40 dB (ie, a normal conversation), a level sufficient to awaken someone from sleep.

Since the publication of these guidelines in 1999, substantial new research has added to our understanding of hospital noise levels. Recent research has demonstrated that few, if any, hospitals comply with WHO noise recommendations.3 Moreover, since 1960, hospital sound levels have risen ~4 dB per decade; based on the logarithmic decibel scale, if this trend continues, this translates to a 528% increase in loudness by 2020.3

The overwhelming majority of research on hospital noise has focused on the intensive care unit (ICU), where beeping machines and busy staff often push peak nighttime noise levels over 80 dB (ie, a kitchen blender).4 When evaluated during sleep, noise in the ICU causes frequent arousals and awakenings. When noise is combined with other factors, such as bright light and patient care interactions, poor sleep quality invariably results.4

While it has been known for years that critically ill patients experience markedly fragmented and nonrestorative sleep,5 poor sleep has recently gained attention due to its potential role as a modifiable risk factor for delirium and its associated consequences, including prolonged length of stay and long-lasting neuropsychological and physical impairments.6 Due to this interest, numerous interventions have been attempted,7 including multicomponent bundles to promote sleep,8 which have been shown to reduce delirium in the ICU.9-12 Therefore, efforts to promote sleep in the ICU, including interventions to minimize nighttime noise, are recommended in Society of Critical Care Medicine clinical practice guidelines13 and are listed as a top 5 research priority by an expert panel of ICU delirium researchers.14

In contrast to the ICU, there has been little attention paid to noise in other patient care areas. Existing studies in non-ICU ward settings suggest that excessive noise is common,3 similar to the ICU, and that patients experience poor sleep, with noise being a significant disruptor of sleep.5,15,16 Such poor sleep is thought to contribute to uncontrolled pain, labile blood pressure, and dissatisfaction with care.16,17

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Jaiswal and colleagues18 report on an important study evaluating sound and light levels in both non-ICU and ICU settings within a busy tertiary-care hospital. In 8 general ward, 8 telemetry, and 8 ICU patient rooms, the investigators used meters to record sound and light levels for 24 to 72 hours. In each of these locations, they detected average hourly sound levels ranging from 45 to 54 dB, 47 to 55 dB, and 56 to 60 dB, respectively, with ICUs consistently registering the highest hourly sound levels. Notably, all locations exceeded WHO noise limits at all hours of the day. As a novel measure, the investigators evaluated sound level changes (SLCs), or the difference between peak and background sound levels, based on research suggesting that dramatic SLCs (≥17.5 dB) are more disruptive than constant loud noise.19 The authors observed that SLCs ≥17.5 dB occur predominantly during daytime hours and, interestingly, at a similar rate in the wards versus the ICU.

Importantly, the authors do not link their findings with patient sleep or other patient outcomes but instead focus on employing rigorous methods to gather continuous recordings. By measuring light levels, the authors bring attention to an issue often considered less disruptive to sleep than noise.6,10,20 Similar to prior research,21 Jaiswal and colleagues demonstrate low levels of light at night, with no substantial difference between non-ICU and ICU settings. As a key finding, the authors bring attention to low levels of light during daytime hours, particularly in the morning, when levels range from 22 to 101 lux in the wards and 16 to 39 lux in the ICU. While the optimal timing and brightness of light exposure remains unknown, it is well established that ambient light is the most potent cue for circadian rhythms, with levels >100 lux necessary to suppress melatonin, the key hormone involved in circadian entrainment. Hence, the levels of morning light observed in this study were likely insufficient to maintain healthy circadian rhythms. When exposed to abnormal light levels and factors such as noise, stress, and medications, hospitalized patients are at risk for circadian rhythm misalignment, which can disrupt sleep and trigger a complex molecular cascade, leading to end-organ dysfunction including depressed immunity, glucose dysregulation, arrhythmias, and delirium.22-24

What are the major takeaway messages from this study? First, it confirms that sound levels are not only high in the ICU but also in non-ICU wards. As hospital ratings and reimbursements now rely on favorable patient ratings, future noise-reduction efforts will surely expand more vigorously across patient care areas.25 Second, SLCs and daytime recordings must be included in efforts to understand and improve sleep and circadian rhythms in hospitalized patients. Finally, this study provides a sobering reminder of the challenge of meeting WHO guidelines and facilitating an optimal healing environment for patients. Sadly, hospital sound levels continue to rise, and quiet-time interventions consistently fail to lower noise to levels anywhere near WHO limits.26 Hence, to make any progress, hospitals of the future must entertain novel design modifications (eg, sound-absorbing walls and alternative room layouts), fix common sources of noise pollution (eg, ventilation systems and alarms), and critically evaluate and update interventions aimed at improving sleep and aligning circadian rhythms for hospitalized patients.27

Acknowledgments

B.B.K. is currently supported by a grant through the University of California, Los Angeles Clinical Translational Research Institute and the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000124).

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Nightingale F. Notes on Nursing: What It Is, and What It Is Not. Harrison; 1860. PubMed

2. Berglund B, Lindvall T, Schwela DH. Guidelines for Community Noise. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1999. http://www.who.int/docstore/peh/noise/guidelines2.html. Accessed on June 23, 2017.

3. Busch-Vishniac IJ, West JE, Barnhill C, Hunter T, Orellana D, Chivukula R. Noise levels in Johns Hopkins Hospital. J Acoust Soc Am. 2005;118(6):3629-3645. PubMed

4. Kamdar BB, Needham DM, Collop NA. Sleep deprivation in critical illness: its role in physical and psychological recovery. J Intensive Care Med. 2012;27(2):97-111. PubMed

5. Knauert MP, Malik V, Kamdar BB. Sleep and sleep disordered breathing in hospitalized patients. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;35(5):582-592. PubMed

6. Kamdar BB, Knauert MP, Jones SF, et al. Perceptions and practices regarding sleep in the intensive care unit. A survey of 1,223 critical care providers. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(8):1370-1377. PubMed

7. DuBose JR, Hadi K. Improving inpatient environments to support patient sleep. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(5):540-553. PubMed

8. Kamdar BB, Kamdar BB, Needham DM. Bundling sleep promotion with delirium prevention: ready for prime time? Anaesthesia. 2014;69(6):527-531. PubMed

9. Patel J, Baldwin J, Bunting P, Laha S. The effect of a multicomponent multidisciplinary bundle of interventions on sleep and delirium in medical and surgical intensive care patients. Anaesthesia. 2014;69(6):540-549. PubMed

10. Kamdar BB, King LM, Collop NA, et al. The effect of a quality improvement intervention on perceived sleep quality and cognition in a medical ICU. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(3):800-809. PubMed

11. van de Pol I, van Iterson M, Maaskant J. Effect of nocturnal sound reduction on the incidence of delirium in intensive care unit patients: An interrupted time series analysis. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2017;41:18-25. PubMed

12. Flannery AH, Oyler DR, Weinhouse GL. The impact of interventions to improve sleep on delirium in the ICU: a systematic review and research framework. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(12):2231-2240. PubMed

13. Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(1):263-306. PubMed

14. Pandharipande PP, Ely EW, Arora RC, et al. The intensive care delirium research agenda: a multinational, interprofessional perspective [published online ahead of print June 13, 2017]. Intensive Care Med. PubMed

15. Topf M, Thompson S. Interactive relationships between hospital patients’ noise-induced stress and other stress with sleep. Heart Lung. 2001;30(4):237-243. PubMed

16. Tamrat R, Huynh-Le MP, Goyal M. Non-pharmacologic interventions to improve the sleep of hospitalized patients: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(5):788-795. PubMed

17. Fillary J, Chaplin H, Jones G, Thompson A, Holme A, Wilson P. Noise at night in hospital general wards: a mapping of the literature. Br J Nurs. 2015;24(10):536-540. PubMed

18. Jaiswal SJ, Garcia S, Owens RL. Sound and light levels are similarly disruptive in ICU and non-ICU wards. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(10):798-804. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2826.

19. Stanchina ML, Abu-Hijleh M, Chaudhry BK, Carlisle CC, Millman RP. The influence of white noise on sleep in subjects exposed to ICU noise. Sleep Med. 2005;6(5):423-428. PubMed

20. Freedman NS, Kotzer N, Schwab RJ. Patient perception of sleep quality and etiology of sleep disruption in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(4, Pt 1):1155-1162. PubMed

21. Meyer TJ, Eveloff SE, Bauer MS, Schwartz WA, Hill NS, Millman RP. Adverse environmental conditions in the respiratory and medical ICU settings. Chest. 1994;105(4):1211-1216. PubMed

22. Castro R, Angus DC, Rosengart MR. The effect of light on critical illness. Crit Care. 2011;15(2):218. PubMed

23. Brainard J, Gobel M, Scott B, Koeppen M, Eckle T. Health implications of disrupted circadian rhythms and the potential for daylight as therapy. Anesthesiology. 2015;122(5):1170-1175. PubMed

24. Fitzgerald JM, Adamis D, Trzepacz PT, et al. Delirium: a disturbance of circadian integrity? Med Hypotheses. 2013;81(4):568-576. PubMed

25. Stafford A, Haverland A, Bridges E. Noise in the ICU. Am J Nurs. 2014;114(5):57-63. PubMed

26. Tainter CR, Levine AR, Quraishi SA, et al. Noise levels in surgical ICUs are consistently above recommended standards. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(1):147-152. PubMed

27. Ulrich RS, Zimring C, Zhu X, et al. A review of the research literature on evidence-based healthcare design. HERD. 2008;1(3):61-125. PubMed

1. Nightingale F. Notes on Nursing: What It Is, and What It Is Not. Harrison; 1860. PubMed

2. Berglund B, Lindvall T, Schwela DH. Guidelines for Community Noise. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1999. http://www.who.int/docstore/peh/noise/guidelines2.html. Accessed on June 23, 2017.

3. Busch-Vishniac IJ, West JE, Barnhill C, Hunter T, Orellana D, Chivukula R. Noise levels in Johns Hopkins Hospital. J Acoust Soc Am. 2005;118(6):3629-3645. PubMed

4. Kamdar BB, Needham DM, Collop NA. Sleep deprivation in critical illness: its role in physical and psychological recovery. J Intensive Care Med. 2012;27(2):97-111. PubMed

5. Knauert MP, Malik V, Kamdar BB. Sleep and sleep disordered breathing in hospitalized patients. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;35(5):582-592. PubMed

6. Kamdar BB, Knauert MP, Jones SF, et al. Perceptions and practices regarding sleep in the intensive care unit. A survey of 1,223 critical care providers. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(8):1370-1377. PubMed

7. DuBose JR, Hadi K. Improving inpatient environments to support patient sleep. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(5):540-553. PubMed

8. Kamdar BB, Kamdar BB, Needham DM. Bundling sleep promotion with delirium prevention: ready for prime time? Anaesthesia. 2014;69(6):527-531. PubMed

9. Patel J, Baldwin J, Bunting P, Laha S. The effect of a multicomponent multidisciplinary bundle of interventions on sleep and delirium in medical and surgical intensive care patients. Anaesthesia. 2014;69(6):540-549. PubMed

10. Kamdar BB, King LM, Collop NA, et al. The effect of a quality improvement intervention on perceived sleep quality and cognition in a medical ICU. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(3):800-809. PubMed

11. van de Pol I, van Iterson M, Maaskant J. Effect of nocturnal sound reduction on the incidence of delirium in intensive care unit patients: An interrupted time series analysis. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2017;41:18-25. PubMed

12. Flannery AH, Oyler DR, Weinhouse GL. The impact of interventions to improve sleep on delirium in the ICU: a systematic review and research framework. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(12):2231-2240. PubMed

13. Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(1):263-306. PubMed

14. Pandharipande PP, Ely EW, Arora RC, et al. The intensive care delirium research agenda: a multinational, interprofessional perspective [published online ahead of print June 13, 2017]. Intensive Care Med. PubMed

15. Topf M, Thompson S. Interactive relationships between hospital patients’ noise-induced stress and other stress with sleep. Heart Lung. 2001;30(4):237-243. PubMed

16. Tamrat R, Huynh-Le MP, Goyal M. Non-pharmacologic interventions to improve the sleep of hospitalized patients: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(5):788-795. PubMed

17. Fillary J, Chaplin H, Jones G, Thompson A, Holme A, Wilson P. Noise at night in hospital general wards: a mapping of the literature. Br J Nurs. 2015;24(10):536-540. PubMed

18. Jaiswal SJ, Garcia S, Owens RL. Sound and light levels are similarly disruptive in ICU and non-ICU wards. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(10):798-804. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2826.

19. Stanchina ML, Abu-Hijleh M, Chaudhry BK, Carlisle CC, Millman RP. The influence of white noise on sleep in subjects exposed to ICU noise. Sleep Med. 2005;6(5):423-428. PubMed

20. Freedman NS, Kotzer N, Schwab RJ. Patient perception of sleep quality and etiology of sleep disruption in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(4, Pt 1):1155-1162. PubMed

21. Meyer TJ, Eveloff SE, Bauer MS, Schwartz WA, Hill NS, Millman RP. Adverse environmental conditions in the respiratory and medical ICU settings. Chest. 1994;105(4):1211-1216. PubMed

22. Castro R, Angus DC, Rosengart MR. The effect of light on critical illness. Crit Care. 2011;15(2):218. PubMed

23. Brainard J, Gobel M, Scott B, Koeppen M, Eckle T. Health implications of disrupted circadian rhythms and the potential for daylight as therapy. Anesthesiology. 2015;122(5):1170-1175. PubMed

24. Fitzgerald JM, Adamis D, Trzepacz PT, et al. Delirium: a disturbance of circadian integrity? Med Hypotheses. 2013;81(4):568-576. PubMed

25. Stafford A, Haverland A, Bridges E. Noise in the ICU. Am J Nurs. 2014;114(5):57-63. PubMed

26. Tainter CR, Levine AR, Quraishi SA, et al. Noise levels in surgical ICUs are consistently above recommended standards. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(1):147-152. PubMed

27. Ulrich RS, Zimring C, Zhu X, et al. A review of the research literature on evidence-based healthcare design. HERD. 2008;1(3):61-125. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

A Search for Tools to Support Decision-Making for PIVC Use

Peripheral intravenous catheters (PIVCs) are the most frequently used vascular access devices (VADs) in all patient populations and practice settings. Because of its invasive nature and the fact that PIVCs are placed and medications are administered directly into the bloodstream, vascular access is risky. There are multiple factors to consider when placing a PIVC, the least of which is determining the most appropriate device for the patient based on the prescribed therapy.

VAD planning and assessment needs to occur at the first patient encounter so that the most appropriate device is selected and it aligns with the duration of the treatment, minimizes the number of unnecessary VADs placed, and preserves veins for any future needs. The level of the clinician’s expertise, coupled with challenging environments of care, add to the complexity of what most perceive to be a “simple” procedure—placing a PIVC. For these reasons, it’s imperative that clinicians are competent in the use and placement of VADs to ensure safe patient care.

Carr and colleagues1 performed a notable scoping review to determine the existence of tools, clinical prediction rules, and algorithms (TRAs) that would support decision-making for the use of PIVCs and promote first-time insertion success (FTIS). They refined their search strategy to studies that described the use or development of any TRA regarding PIVC insertion in hospitalized adult patients.

The team identified 36 references for screening and based on their inclusion and exclusion criteria, were left with 13 studies in the final review. Inclusion criteria included TRAs for PIVC insertion in hospitalized adult patients using a traditional insertion approach, which was defined as “an assessment and/or insertion with touch and feel, therefore, without vessel locating technology such as ultrasound and/or near infrared technology.” 1 Of note is that some of the exclusion criteria included pediatric studies, TRAs focused on postinsertion assessment, studies that examined VADs other than PIVCs, and studies in which vascular visualization techniques were used.

In general, the authors were unable to find reported evidence that the study recommendations were adopted in clinical practice or to what degree any TRA had on the success of a PIVC insertion. As a result, they were unable to determine what, if any, clinical value the TRAs had.

The review of the studies, however, identified 3 variables that had an impact on PIVC insertion success: patient, clinician, and product characteristics. Vein characteristics, such as the number, size, and location of veins, and patients’ clinical conditions, such as diabetes, sickle cell anemia, and intravenous drug abuse, were noted as predictors of PIVC insertion success. In 7 papers, the primary focus was on patients with a history of difficult intravenous access (DIVA). The definition of DIVA varied from time to insertion of the PIVC to the number of failed attempts, ranging from 1 to 3 or more attempts.

Clinician variables, such as specialty nurse certification, years of experience, and self-reporting skill level, were associated with successful insertions, and clinicians who predicted FTIS were likely to have FTIS. Product variables included PIVC gauge size and the number of vein options and the relationship with successful first attempts.

Limitations noted by the researchers were a lack of sufficient published evidence for TRAs for PIVC insertion and standardized definitions for DIVA and expert inserters. The number of variables and the dearth of standardized terms may also influence the ability to adopt any TRAs.

While the purpose of the research was to identify TRAs that could guide clinical practice for the use of PIVCs and successful insertions, the authors make an important point that dwell time was not considered. While a TRA may lead to a successful insertion, it may not transcend the intended life of the PIVC or the duration of the therapy. Therefore, TRAs should embed steps that ensure the appropriate device is selected at the start of the patient’s treatment.

The authors identified a need for undertaking and providing research in a critical area of patient care and safety. This article increases awareness of issues related to PIVCs and the impact they have on patient care. FTIS rates vary and the implications of their use are many. Patient satisfaction, no delay in treatment, vein preservation, a decreased risk of complications, and the cost of labor and products are factors to consider. Tools to improve patient outcomes related to device insertion, care, and management need to be developed and validated. The authors also note that future TRAs should integrate the use of ultrasound and vascular visualization technologies.

In a complex, challenging healthcare environment, tools and guidance that enhance practice do not only help clinicians; they have a positive impact on patient care. The need for research, so that gaps in knowledge and science can be bridged, is clear. Gaps must be identified, research conducted, and TRAs developed and adopted to enhance patient outcomes.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest.

1. Carr PJ, Higgins NS, Rippey J, Cooke ML, Rickard CM. Tools, clinical prediction rules, and algorithms for the insertion of peripheral intravenous catheters in adult hospitalized patients: a systematic scoping review of literature. J Hosp Med. 2017; 12(10):851-858

Peripheral intravenous catheters (PIVCs) are the most frequently used vascular access devices (VADs) in all patient populations and practice settings. Because of its invasive nature and the fact that PIVCs are placed and medications are administered directly into the bloodstream, vascular access is risky. There are multiple factors to consider when placing a PIVC, the least of which is determining the most appropriate device for the patient based on the prescribed therapy.

VAD planning and assessment needs to occur at the first patient encounter so that the most appropriate device is selected and it aligns with the duration of the treatment, minimizes the number of unnecessary VADs placed, and preserves veins for any future needs. The level of the clinician’s expertise, coupled with challenging environments of care, add to the complexity of what most perceive to be a “simple” procedure—placing a PIVC. For these reasons, it’s imperative that clinicians are competent in the use and placement of VADs to ensure safe patient care.

Carr and colleagues1 performed a notable scoping review to determine the existence of tools, clinical prediction rules, and algorithms (TRAs) that would support decision-making for the use of PIVCs and promote first-time insertion success (FTIS). They refined their search strategy to studies that described the use or development of any TRA regarding PIVC insertion in hospitalized adult patients.

The team identified 36 references for screening and based on their inclusion and exclusion criteria, were left with 13 studies in the final review. Inclusion criteria included TRAs for PIVC insertion in hospitalized adult patients using a traditional insertion approach, which was defined as “an assessment and/or insertion with touch and feel, therefore, without vessel locating technology such as ultrasound and/or near infrared technology.” 1 Of note is that some of the exclusion criteria included pediatric studies, TRAs focused on postinsertion assessment, studies that examined VADs other than PIVCs, and studies in which vascular visualization techniques were used.

In general, the authors were unable to find reported evidence that the study recommendations were adopted in clinical practice or to what degree any TRA had on the success of a PIVC insertion. As a result, they were unable to determine what, if any, clinical value the TRAs had.

The review of the studies, however, identified 3 variables that had an impact on PIVC insertion success: patient, clinician, and product characteristics. Vein characteristics, such as the number, size, and location of veins, and patients’ clinical conditions, such as diabetes, sickle cell anemia, and intravenous drug abuse, were noted as predictors of PIVC insertion success. In 7 papers, the primary focus was on patients with a history of difficult intravenous access (DIVA). The definition of DIVA varied from time to insertion of the PIVC to the number of failed attempts, ranging from 1 to 3 or more attempts.

Clinician variables, such as specialty nurse certification, years of experience, and self-reporting skill level, were associated with successful insertions, and clinicians who predicted FTIS were likely to have FTIS. Product variables included PIVC gauge size and the number of vein options and the relationship with successful first attempts.

Limitations noted by the researchers were a lack of sufficient published evidence for TRAs for PIVC insertion and standardized definitions for DIVA and expert inserters. The number of variables and the dearth of standardized terms may also influence the ability to adopt any TRAs.

While the purpose of the research was to identify TRAs that could guide clinical practice for the use of PIVCs and successful insertions, the authors make an important point that dwell time was not considered. While a TRA may lead to a successful insertion, it may not transcend the intended life of the PIVC or the duration of the therapy. Therefore, TRAs should embed steps that ensure the appropriate device is selected at the start of the patient’s treatment.

The authors identified a need for undertaking and providing research in a critical area of patient care and safety. This article increases awareness of issues related to PIVCs and the impact they have on patient care. FTIS rates vary and the implications of their use are many. Patient satisfaction, no delay in treatment, vein preservation, a decreased risk of complications, and the cost of labor and products are factors to consider. Tools to improve patient outcomes related to device insertion, care, and management need to be developed and validated. The authors also note that future TRAs should integrate the use of ultrasound and vascular visualization technologies.

In a complex, challenging healthcare environment, tools and guidance that enhance practice do not only help clinicians; they have a positive impact on patient care. The need for research, so that gaps in knowledge and science can be bridged, is clear. Gaps must be identified, research conducted, and TRAs developed and adopted to enhance patient outcomes.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest.

Peripheral intravenous catheters (PIVCs) are the most frequently used vascular access devices (VADs) in all patient populations and practice settings. Because of its invasive nature and the fact that PIVCs are placed and medications are administered directly into the bloodstream, vascular access is risky. There are multiple factors to consider when placing a PIVC, the least of which is determining the most appropriate device for the patient based on the prescribed therapy.

VAD planning and assessment needs to occur at the first patient encounter so that the most appropriate device is selected and it aligns with the duration of the treatment, minimizes the number of unnecessary VADs placed, and preserves veins for any future needs. The level of the clinician’s expertise, coupled with challenging environments of care, add to the complexity of what most perceive to be a “simple” procedure—placing a PIVC. For these reasons, it’s imperative that clinicians are competent in the use and placement of VADs to ensure safe patient care.

Carr and colleagues1 performed a notable scoping review to determine the existence of tools, clinical prediction rules, and algorithms (TRAs) that would support decision-making for the use of PIVCs and promote first-time insertion success (FTIS). They refined their search strategy to studies that described the use or development of any TRA regarding PIVC insertion in hospitalized adult patients.

The team identified 36 references for screening and based on their inclusion and exclusion criteria, were left with 13 studies in the final review. Inclusion criteria included TRAs for PIVC insertion in hospitalized adult patients using a traditional insertion approach, which was defined as “an assessment and/or insertion with touch and feel, therefore, without vessel locating technology such as ultrasound and/or near infrared technology.” 1 Of note is that some of the exclusion criteria included pediatric studies, TRAs focused on postinsertion assessment, studies that examined VADs other than PIVCs, and studies in which vascular visualization techniques were used.

In general, the authors were unable to find reported evidence that the study recommendations were adopted in clinical practice or to what degree any TRA had on the success of a PIVC insertion. As a result, they were unable to determine what, if any, clinical value the TRAs had.

The review of the studies, however, identified 3 variables that had an impact on PIVC insertion success: patient, clinician, and product characteristics. Vein characteristics, such as the number, size, and location of veins, and patients’ clinical conditions, such as diabetes, sickle cell anemia, and intravenous drug abuse, were noted as predictors of PIVC insertion success. In 7 papers, the primary focus was on patients with a history of difficult intravenous access (DIVA). The definition of DIVA varied from time to insertion of the PIVC to the number of failed attempts, ranging from 1 to 3 or more attempts.

Clinician variables, such as specialty nurse certification, years of experience, and self-reporting skill level, were associated with successful insertions, and clinicians who predicted FTIS were likely to have FTIS. Product variables included PIVC gauge size and the number of vein options and the relationship with successful first attempts.

Limitations noted by the researchers were a lack of sufficient published evidence for TRAs for PIVC insertion and standardized definitions for DIVA and expert inserters. The number of variables and the dearth of standardized terms may also influence the ability to adopt any TRAs.

While the purpose of the research was to identify TRAs that could guide clinical practice for the use of PIVCs and successful insertions, the authors make an important point that dwell time was not considered. While a TRA may lead to a successful insertion, it may not transcend the intended life of the PIVC or the duration of the therapy. Therefore, TRAs should embed steps that ensure the appropriate device is selected at the start of the patient’s treatment.

The authors identified a need for undertaking and providing research in a critical area of patient care and safety. This article increases awareness of issues related to PIVCs and the impact they have on patient care. FTIS rates vary and the implications of their use are many. Patient satisfaction, no delay in treatment, vein preservation, a decreased risk of complications, and the cost of labor and products are factors to consider. Tools to improve patient outcomes related to device insertion, care, and management need to be developed and validated. The authors also note that future TRAs should integrate the use of ultrasound and vascular visualization technologies.

In a complex, challenging healthcare environment, tools and guidance that enhance practice do not only help clinicians; they have a positive impact on patient care. The need for research, so that gaps in knowledge and science can be bridged, is clear. Gaps must be identified, research conducted, and TRAs developed and adopted to enhance patient outcomes.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest.

1. Carr PJ, Higgins NS, Rippey J, Cooke ML, Rickard CM. Tools, clinical prediction rules, and algorithms for the insertion of peripheral intravenous catheters in adult hospitalized patients: a systematic scoping review of literature. J Hosp Med. 2017; 12(10):851-858

1. Carr PJ, Higgins NS, Rippey J, Cooke ML, Rickard CM. Tools, clinical prediction rules, and algorithms for the insertion of peripheral intravenous catheters in adult hospitalized patients: a systematic scoping review of literature. J Hosp Med. 2017; 12(10):851-858

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Tools, Clinical Prediction Rules, and Algorithms for the Insertion of Peripheral Intravenous Catheters in Adult Hospitalized Patients: A Systematic Scoping Review of Literature

Up to a billion peripheral intravenous catheters (PIVCs) are inserted annually; therefore, the importance of this invasive device in modern medicine cannot be argued.1 The insertion of a PIVC is a clinical procedure undertaken by a range of clinical staff and in a variety of patient populations and settings. In many clinical environments (for example, the emergency department [ED]), PIVCs are the predominant first-choice vascular access device (VAD).2,3 Researchers in one study estimated over 25 million PIVCs are used in French EDs each year,3 and intravenous therapy is the leading ED treatment in the United States.4

The purpose of this systematic scoping review was to investigate what PIVC decision-making approaches exist to facilitate FTIS of PIVCs in adult hospitalized patients. Our intention was to systematically synthesize the research on TRAs, to review significant associations identified with these TRAs, and to critique TRA validity and reliability.

METHODS

Scoping Review

We selected a scoping review method that, by definition, maps the evidence to identify gaps,13,14 set research agendas, and identify implications for decision making. This allowed a targeted approach to answering our 3 research questions:

- What published clinical TRAs exist to facilitate PIVC insertion in adults?

- What clinical, patient and/or product variables have been identified using TRAs as having significant associations with FTIS for PIVCs in adult patients?

- What is the reported reliability, validity, responsiveness, clinical feasibility, and utility of existing TRAs for PIVC insertion in adults?

Our aim was to identify the amount, variety and essential qualities of TRA literature rather than to critically appraise and evaluate the effectiveness of TRAs, a process reserved for systematic review and meta-analysis of interventional studies.13,14 We followed scoping review guidelines published by members and collaborators of the Joanna Briggs Institute, an internationally recognized leader in research synthesis, evidence use, and implementation. The guidance is based on 5 steps: (i) scoping review objective and question, (ii) background of the topic to support scoping review, (iii) study selection, (iv) charting the results, and (v) collating and summarizing results.15 Clinicometric assessment of a TRA or any clinical prediction rule requires 4 specific phases: (i) development (identification of predictors from data), (ii) validation (testing the rule in a separate population for reliability), (iii) impact analysis or responsiveness (How clinically useful is the rule in the clinical setting? Is it resource heavy or light? Is it cost effective?), and (iv) implementation and adoption (uptake into clinical practice).16

Search Strategy

We included studies that described the use or development of any TRA regarding PIVC insertion in the adult hospitalized population.

Inclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they were published in the English Language, included TRAs for PIVC insertion in adult hospital patients, and prospectively assessed a clinical category of patient for PIVC insertion using a traditional approach. We defined a traditional PIVC insertion approach as an assessment and/or insertion with touch and feel, therefore, without vessel-locating technology such as ultrasound and/or near infrared technology.

Exclusion Criteria

Exclusion criteria included pediatric studies, authors’ personal (nonresearch) experience of tools, TRAs focused on postinsertion assessment of the cannula (such as phlebitis, infiltration, and/or dressing failure), and papers with a focus on VADs other than PIVCs. We excluded studies using PIVC ultrasound and/or near infrared technology because these are not standard in all insertions and greatly change the information available for pre-insertion assessment as well as the likelihood of insertion success.

In June 2016, a systematic search of the Cochrane library, Ovid Medline® In-process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1946 to Present>, EBSCO CINAHL databases, and Google Scholar with specific keywords to identify publications that identified or defined TRAs was undertaken. Medical subject headings were created with assistance from a research librarian using tailored functions within individual databases. With key search terms, we limited studies to those related to our inclusion criteria. See Appendix 1 for our search strategy for Medline and CINAHL.

We used Covidence, a web-based application specifically designed for systematic reviews to screen and evaluate eligible publications.17 Two authors (PJC and NSH) screened the initial retrieved searches based upon the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data Extraction

A paper template was developed and used by 2 reviewers (P.J.C. and N.S.H.). Data included the following: study sample, aim(s), design, setting and country in which the study took place, clinical and patient variables, and how the TRAs were developed and tested. Studies were categorized by TRA type. We also sought to identify if clinical trial registration (where appropriate) was evidenced, in addition to evidence of protocol publication and what standardized reporting guidelines were used (such as those outlined by the EQUATOR Network).18

Data Synthesis

Formal meta-analysis was beyond the scope and intention of this review. However, we provide the FTIS rate and the ranges of odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for certain independent predictors.

RESULTS

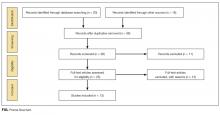

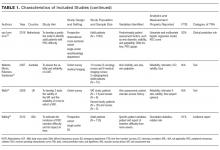

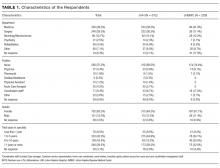

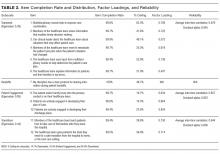

Thirty-six references were imported for screening against title and abstract content, with 11 studies excluded and 25 studies assessed for full-text eligibility (see Figure, PRISMA Flowchart). We then excluded a further 12 studies (6 did not meet inclusion criteria, 2 were focused on the prehospital setting, 2 were personal correspondence and focused on another type of VAD, 1 was a protocol to establish a TRA, and 1 was a framework for all device types), leaving 13 studies included in the final review (see Figure). These studies presented data on 4 tools,19-22 4 predictive models3,23-25 (of which 3 present receiver operating characteristic/area under the curve scores),3,23,24 2 framed as risk factor studies,26,27 and 1 of each of the following: a scale,28 a score,29 and an estimation of the incidence report rate (Table 1).30 Seven studies had “difficult” or “difficulty” in their title as a term to use to describe insertion failure.3,19,24-27,30 One study was titled exclusively for the nursing profession,20 5 studies were reported in medical journals,3,24,26,29,30 and 6 were reported in nursing journals,19-22,25,27 with the remainder published in a vascular access journal.23,28

General Characteristics of Included Studies

One TRA which was registered as a clinical trial24 involved a standardized reporting tool as is recommended by the EQUATOR Network.18

Nine of the 13 papers reported that TRA components were chosen based on identified predictors of successful insertion from observational data3,19,23-28,30, with 5 papers using multivariate logistic regression to identify independent predictors.3,23,24,26,2 At least 4330 insertion attempts on patients were reported. Seven papers reported FTIS, which ranged from 61%-90%.3,23-27,30

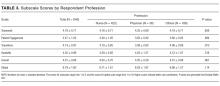

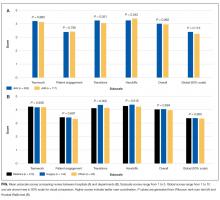

Two clinical settings accounted for 10 of the 13 included studies. We identified 5 papers from the ED setting3,23,26,29,30 and 5 studies specific to cancer settings.19-22,28 Two ED papers identified clinical predictors of insertion difficulty, with 1 identifying an existing medical diagnosis (such as sickle cell disease, diabetes, or intravenous drug abuse) and the other reporting a pragmatic patient self-report of difficulty.26,30 Three studies focused on patient-exclusive variables (such as vein characteristics)19,21,28 and some with a combined clinician and patient focus.3,23-25,27,30Relatively few studies reported interobserver measurements to describe the reliability of clinical assessments made.3,19,21,28 Webster et al. in Australia assessed interrater reliability of a vein assessment tool (VAT) and found high agreement (kappa 0.83 for medical imaging nurses and 0.93 for oncology nurses).21 Wells compared reliability with Altman’s K scores obtained from a different VAT when compared with the Deciding on Intravenous Access tool and found good agreement.22 Vein deterioration was proposed as a variable for inclusion when developing an assessment tool within an oncological context.31 In Spain, de la Torre and colleagues28 demonstrated good interrater agreement (with kappa, 0.77) for the Venous International Assessment (VIA) tool. The VIA offers a grading system scale to predict the patient’s declining vessel size while undergoing chemotherapy via peripheral veins with PIVCs. Grade I suggests little or no insertion failure, whereas a Grade V should predict insertion failure.

Patient Variables

Vein characteristics were significant independent factors associated with insertion success in a number of studies.3,19,23,24,27,28 These included the number of veins, descriptive quality (eg, small, medium, large), size, location, visible veins, and palpable veins. Other factors appear to be patient specific (such as chronic conditions), including diabetes (OR, 2.1 [adjusted to identify demographic risk factors]; 95% CI, 1.3-3.4), sickle cell disease (OR, 3.5; 95% CI, 1.4-4.8), and intravenous drug abuse (OR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.1-5.3).26 It is unclear if a consistent relationship between weight classification and insertion outcomes exists. Despite a finding that BMI was not independently associated with insertion difficulty,26 one study reports that BMI was independently associated with insertion failure (BMI <18.5 [OR, 2.24; 95% CI, 1.07-4.67], BMI >30 [OR, 1.98; 95% CI, 1.9-3.60])3 and another reports emaciated patients were associated with greater failure when compared to normal weight patients (OR, 0.07; 95% CI, 0.02-0.34).23 Consequently, extremes of BMI appear to be associated with insertion outcomes despite 1 study reporting no significant association with BMI as an independent factor of insertion failure.26 A history of difficult intravenous access (DIVA) was reported in 1 study and independently associated with insertion failure (OR, 3.86; 95% CI, 2.39-6.25; see Table 2). DIVA appears to be the motivating factor in the title of 7 studies. When defined, the definitions of DIVA are heterogeneous and varied and include the following: >1 minute to insert a PIVC and requiring >1 attempt27; 2 failed attempts30; 3 or more PIVC attempts.26 In the remaining 4 studies, variables associated with difficulty are identified and, therefore, TRAs to target those in future with predicted difficulty prior to any attempts are proposed.3,19,24,25

Clinician Variables

Specialist nurse certification, years of experience, and self-report skill level (P < 0.001) appear to be significantly associated with successful insertions.25 This is in part validated in another study reporting greater procedural inserting PIVCs as an independent predictor of success (OR, 4.404; 95% CI, 1.61-12-06; see Table 2).23 Two studies involved simple pragmatic percentage cut offs for PIVCs: likelihood of use29 and likelihood of insertion success.23 One paper using a cross-sectional design that surveyed ED clinicians suggested if the clinician’s predicted likelihood of the patient needing a PIVC was >80%, this was a reasonable trigger for PIVC insertion.29 The other, in a self-report cohort study, reported that a clinician’s likelihood estimation of PIVC FTIS prior to insertion is independently associated with FTIS (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.04-1.07).23

Product Variables

In this review, higher failure rates were identified in smaller sizes (22-24 g).26 One study revealed gauge size was significantly associated with a failed first attempt in a univariate analysis (OR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.34-0.58), but this was not retained in a multivariate model.24 Matching the PIVC size with vein assessment is considered in the VIA tool.28 It suggests a large PIVC (18 g) can be considered in patients with at least 6 vein options; smaller PIVCs of 22 to 24 g are recommended when 3 or fewer veins are found.28 One paper describes a greater proportion of success between PIVC brands.25

DISCUSSION

The published evidence for TRAs for PIVCs is limited, with few studies using 2 or more reliability, validity, responsiveness, clinical feasibility, or utility measurements in their development. There is a clear need to assess the clinical utility and clinical feasibility of these approaches so they can be externally validated prior to clinical adoption.16 For this reason, a validated TRA is likely required but must be appropriate for the capability of the healthcare services to use it. We suggest the consistent absence of all of these phases is owing to the variety of healthcare practitioners who are responsible for the insertion, the care and surveillance of peripheral cannulae, and the fragmentation of clinical approaches that exist.32

Previously, a comprehensive systematic review on the subject of PIVCs found that the presence of a visible and/or palpable vein is usually associated with FTIS.33 This current review found evidence of simple scores or cutoff percentage estimates in 2 TRA reports to predict either appropriate PIVC insertion or FTIS.23,29 If such methods are supported by future experimental trials, then such simple approaches could initiate huge clinical return, particularly given that idle or unused PIVCs are of substantial clinical concern.34-36 PIVCs transcend a variety of clinical environments with excessive use identified in the ED, where it may be performed for blood sampling alone and, hence, are labeled as “just in case” PIVCs and contribute to the term “idle PIVC.”23,34 Therefore, a clinical indication to perform PIVC insertion in the first instance must be embedded into any TRA; for example, clinical deterioration is likely and the risks are outweighed by benefit, intravenous fluids and/or medicines are required, and/or diagnostic or clinical procedures are requested (such as contrast scans or procedural sedation).

In the majority of papers reviewed, researchers described how to categorize patients into levels of anticipated and predicted difficulty, but none offered corresponding detailed recommendations for strategies to increase insertion success, such as insertion with ultrasound or vascular access expert. Hypothetically, adopting a TRA may assist with the early identification of difficult to cannulate patients who may require a more expert vascular access clinician. However, in this review, we identify that a uniform definition for DIVA is lacking. Both Webster et al.21 and Wells22 suggest that an expert inserter is required if difficult access is identified by their tools, but there is no clear description of the qualities of an expert inserter in the literature.37 Recently, consensus recommendations for the definition of vascular access specialist add to discussions about defining vascular access as an interdisciplinary specialist role.38 This is supported by other publications that highlight the association between PIVC procedural experience and increased insertion success.6,23,39-41With regards to products, PIVC gauge size may or may not be significantly associated with insertion success. For identifying a relationship of PIVC gauge with vein quality, both the vein diameter and description will help with the clinical interpretation of results. For example, it may be the case that bigger veins are easier to insert a PIVC and, thus, larger PIVCs are inserted. The opposite can occur when the veins are small and poorly visualized; hence, one may select a small gauge catheter. This argument is supported by Prottengeier et al.42 in a prehospital study that excluded PIVC size in a multivariate analysis because of confounding. However, gauge size is very likely to influence postinsertion complications. Prospective studies are contradictory and suggest 16 to 18 g PIVCs are more likely to contribute to superficial thrombus,43 phlebitis, and, thus, device failure, in contrast to others reporting more frequent dislodgement with smaller 22 g PIVCs.6,44Finally, the studies included did not assess survival times of the inserted PIVCs, given postinsertion failure in the hospitalized patient is prevalent45 and, importantly, modifiable.46 A TRA may yield initial insertion success, but if postinsertion the PIVC fails because of a modifiable reason that the TRA has not acknowledged, then it may be of negligible overall benefit. Therefore, TRAs for PIVC insertion need calibration, further development, and ongoing refinement prior to external validation testing.24 Future research should also examine the role of TRAs in settings where ultrasound or other insertion technology is routinely used.

CONCLUSION

This review identifies a clinically significant gap in vascular access science. The findings of this review support recent work on vessel health and preservation47-49 and appropriate device insertion.50 It also points to the need for further research on the development and testing of an appropriate clinical TRA to improve vascular access outcomes in clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Kylie Black and Mr. Simon Lewis, who are medical research librarians at The University of Western Australia.

Disclosure

Mr. Carr has received “speakers bureau” payment form CareFusion in 2013 and Becton Dickinson (BD) in 2014 for lectures on the subject of vascular access. He received a grant from CareFusion (facilitated by his institution at the time) to attend a scientific meeting on vascular access in the USA in 2012. Griffith University has received unrestricted investigator initiated research or educational grants on Marie Cooke’s behalf from product manufacturers: Baxter; Becton, Dickinson and Company; Centurion Medical Products and Entrotech Lifesciences. Griffith University has received unrestricted investigator initiated research or educational grants on Claire M. Rickard’s behalf from product manufacturers: 3M; Adhezion Biomedical, AngioDynamics; Bard, Baxter; B.Braun; Becton, Dickinson and Company; Centurion Medical Products; Cook Medical; Entrotech, Flomedical; ICU Medical; Medtronic; Smiths Medical, Teleflex. Griffith University has received consultancy payments on Claire M. Rickard’s behalf from product manufacturers: 3M, Bard; BBraun, BD, ResQDevices, Smiths Medical. Dr. Higgins and Dr. Rippey have nothing to disclose. All of the aforementioned have not biased or influenced this review.

All authors have made substantial contributions with this review. Each author has contributed to drafting and editing the manuscript and approves the final version for publishing.

1. Alexandrou E, Ray-Barruel G, Carr PJ, et al. International prevalence of the use of peripheral intravenous catheters. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):530-533. PubMed

2. Tiwari MM, Hermsen ED, Charlton ME, Anderson JR, Rupp ME. Inappropriate intravascular device use: a prospective study. J Hosp Infect. 2011;78(2):128-132. PubMed

3. Sebbane M, Claret PG, Lefebvre S, et al. Predicting peripheral venous access difficulty in the emergency department using body mass index and a clinical evaluation of venous accessibility. J Emerg Med. 2013;44(2):299-305. PubMed

4. Niska R, Bhuiya F, Xu J. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2007 emergency department summary. Natl Health Stat Report. 2010;(26):1-31. PubMed

5. Aulagnier J, Hoc C, Mathieu E, Dreyfus JF, Fischler M, Le Guen M. Efficacy of AccuVein to Facilitate Peripheral Intravenous Placement in Adults Presenting to an Emergency Department: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(8):858-863. PubMed

6. Carr PJ, Glynn RW, Dineen B, Kropmans TJ. A pilot intravenous cannulation team: an Irish perspective. Br J Nurs. 2010;19(10):S19-S27. PubMed

7. Conaghan PG. Predicting outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30(Suppl 1):S41-S47. PubMed

8. Hendriksen JM, Geersing GJ, Moons KG, de Groot JA. Diagnostic and prognostic prediction models. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(Suppl 1):129-141. PubMed

9. Hodgson C, Needham D, Haines K, et al. Feasibility and inter-rater reliability of the ICU Mobility Scale. Heart Lung. 2014;43(1):19-24. PubMed

10. Pace NL, Eberhart LHJ, Kranke PR. Quantifying prognosis with risk predictions. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2012;29(1):7-16. PubMed

11. Yen K, Riegert A, Gorelick MH. Derivation of the DIVA score: A clinical prediction rule for the identification of children with difficult intravenous access. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24(3):143-147. PubMed

12. Manuel DG, Rosella LC, Hennessy D, Sanmartin C, Wilson K. Predictive risk algorithms in a population setting: An overview. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(10):859-865. PubMed

13. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16:15. PubMed

14. Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(4):371-385. PubMed

15. Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141-146. PubMed

16. Adams ST, Leveson SH. Clinical prediction rules. BMJ. 2012;344:d8312 PubMed

17. Babineau J. Product Review: Covidence (Systematic Review Software). J Can Health Libr Assoc. 2014;35(2):68-71.

18. Morris C. The EQUATOR network: Promoting the transparent and accurate reporting of research. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50(10):723. PubMed

19. Pagnutti L, Bin A, Donato R, et al. Difficult intravenous access tool in patients receiving peripheral chemotherapy: A pilot-validation study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2016;20:58-63. PubMed

20. Ung L, Cook S, Edwards B, Hocking L, Osmond F, Buttergieg H. Peripheral intravenous cannulation in nursing: performance predictors. J Infus Nurs. 2002;25(3):189-195. PubMed

21. Webster J, Morris H-L, Robinson K, Sanderson U. Development and validation of a Vein Assessment Tool (VAT). Aust J Adv Nurs. 2007;24(4):5-7. PubMed

22. Wells S. Venous access in oncology and haematology patients: Part two. Nurs Stand. 2008;23(1):35–42. PubMed

23. Carr PJ, Rippey JA, Budgeon CA, Cooke ML, Higgins NS, Rickard Claire M. Insertion of peripheral intravenous cannulae in the Emergency Department: factors associated with first-time insertion success. J Vasc Access. 2016;17(2):182-190. PubMed

24. Loon FHJ van, Puijn LAPM, Houterman S, Bouwman ARA. Development of the A-DIVA Scale: A Clinical Predictive Scale to Identify Difficult Intravenous Access in Adult Patients Based on Clinical Observations. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(16):e3428. PubMed

25. Jacobson AF, Winslow EH. Variables influencing intravenous catheter insertion difficulty and failure: an analysis of 339 intravenous catheter insertions. Heart Lung. 2005;34(5):345-359. PubMed

26. Fields MJ, Piela NE, Au AK, Ku BS. Risk factors associated with difficult venous access in adult ED patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(10):1179-1182 PubMed

27. Piredda M, Biagioli V, Barrella B, et al. Factors Affecting Difficult Peripheral Intravenous Cannulation in Adults: A Prospective Observational Study. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(7-8):1074-1084 PubMed

28. de la Torre-Montero J-C, Montealegre-Sanz M, Faraldo-Cabana A, et al. Venous International Assessment, VIA scale, validated classification procedure for the peripheral venous system. J Vasc Access. 2014;15(1):45-50. PubMed

29. Kelly AM, Egerton-Warburton D. When is peripheral intravenous catheter insertion indicated in the emergency department? Emerg Med Australas. 2014;26(5):515–516. PubMed

30. Witting MD. IV access difficulty: Incidence and delays in an urban emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2012;42(4):483-487. PubMed

31. McGowan D, Wood S. Developing a venous assessment tool in IV chemotherapy administration. Br J Nurs. 2008;17(3):158-164. PubMed

32. Castro-Sánchez E, Charani E, Drumright LN, Sevdalis N, Shah N, Holmes AH. Fragmentation of Care Threatens Patient Safety in Peripheral Vascular Catheter Management in Acute Care–A Qualitative Study. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e86167. PubMed

33. Sabri A, Szalas J, Holmes KS, Labib L, Mussivand T. Failed attempts and improvement strategies in peripheral intravenous catheterization. Biomed Mater Eng. 2013;23(1-2):93-108. PubMed

34. Limm EI, Fang X, Dendle C, Stuart RL, Egerton Warburton D. Half of All Peripheral Intravenous Lines in an Australian Tertiary Emergency Department Are Unused: Pain With No Gain? Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(5):521-525 PubMed

35. Egerton-Warburton D, Ieraci S. First do no harm: In fact, first do nothing, at least not a cannula. Emerg Med Australas. 2013;25(4):289-290.

36. Becerra MB, Shirley D, Safdar N. Prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes of idle intravenous catheters: An integrative review. Am J Infect Control. 2016;44(10):e167-e172. PubMed

37. Carr PJ, Higgins NS, Cooke ML, Mihala G, Rickard CM. Vascular access specialist teams for device insertion and prevention of failure. Cochrane Library. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2014.

38. Davis L, Owens AK, Thompson J. Defining the Specialty of Vascular Access through Consensus: Shaping the Future of Vascular Access. J Assoc Vasc Access. 2016;21(3):125-130.

39. Da Silva GA, Priebe S, Dias FN. Benefits of establishing an intravenous team and the standardization of peripheral intravenous catheters. J Infus Nurs. 2010;33(3):156-160. PubMed

40. Soifer NE, Borzak S, Edlin BR, Weinstein RA. Prevention of peripheral venous catheter complications with an intravenous therapy team: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(5):473-477. PubMed

41. Cuper NJ, de Graaff JC, van Dijk AT, Verdaasdonk RM, van der Werff DB, Kalkman CJ. Predictive factors for difficult intravenous cannulation in pediatric patients at a tertiary pediatric hospital. Paediatr Anaesth. 2012;22(3):223-229. PubMed

42. Prottengeier J, Albermann M, Heinrich S, Birkholz T, Gall C, Schmidt J. The prehospital intravenous access assessment: a prospective study on intravenous access failure and access delay in prehospital emergency medicine. Eur J Emerg Med. 2016; 23(6)442-447. PubMed

43. Cicolini G, Bonghi AP, Di Labio L, Di Mascio R. Position of peripheral venous cannulae and the incidence of thrombophlebitis: an observational study. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(6):1268-1273. PubMed

44. Wallis MC, McGrail M, Webster J, et al. Risk factors for peripheral intravenous catheter failure: a multivariate analysis of data from a randomized controlled trial. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(1):63-68. PubMed

45. Carr PJ, Rippey J, Moore T, et al. Reasons for Removal of Emergency Department-Inserted Peripheral Intravenous Cannulae in Admitted Patients: A Retrospective Medical Chart Audit in Australia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(7):874-876. PubMed

46. Bugden S, Shean K, Scott M, et al. Skin Glue Reduces the Failure Rate of Emergency Department-Inserted Peripheral Intravenous Catheters: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(2):196-201. PubMed

47. Moureau N, Trick N, Nifong T, Perry C, Kelley C, Carrico R, et al. Vessel health and preservation (Part 1): a new evidence-based approach to vascular access selection and management. J Vasc Access. 2012;13(3):351-356. PubMed

48. Jackson T, Hallam C, Corner T, Hill S. Right line, right patient, right time: Every choice matters. Br J Nurs. 2013;22(8):S24-S28. PubMed