User login

Knowing when enough is enough

“On which side of the bed did you get up this morning?” Obviously, your inquisitor assumes that to avoid clumsily crawling over your sleeping partner you always get up on the side with the table stacked with unread books.

You know as well as I do that you have just received a totally undisguised comment on your recent behavior that has been several shades less than cheery. You may have already sensed your own grumpiness. Do you have an explanation? Did the commute leave you with a case of unresolved road rage? Did you wake up feeling unrested? How often does that happen? Do you think you are getting enough sleep?

A few weeks ago I wrote a Letters From Maine column in which I shared a study suggesting that the regularity of an individual’s sleep pattern may, in many cases, be more important than his or her total number of hours slept. In that same column I wrote that sleep scientists don’t as yet have a good definition of sleep irregularity, nor can they give us any more than a broad range for the total number of hours a person needs to maintain wellness.

How do you determine whether you are getting enough sleep? Do you keep a chart of how many times you were asked which side of the bed you got up on in a week? Or is it how you feel in the morning? Is it when you instantly doze off any time you sit down in a quiet place?

Although many adults are clueless (or in denial) that they are sleep deprived, generally if you ask them and take a brief history they will tell you. On the other hand, determining when a child, particularly one who is preverbal, is sleep deprived is a bit more difficult. Asking the patient isn’t going to give you the answer. You must rely on parental observations. And, to some extent, this can be difficult because parents are, by definition, learning on the job. They may not realize the symptoms and behaviors they are seeing in their child are the result of sleep deficiency.

Over the last half century of observing children, I have developed a very low threshold for diagnosing sleep deprivation. Basically, any child who is cranky and not obviously sick is overtired until proven otherwise. For example, colic does not appear on my frequently used, or in fact ever used, list of diagnoses. Colicky is an adjective that I may use to describe some episodic pain or behavior, but colic as a working diagnosis? Never.

When presented with a child who has already been diagnosed with “colic” by its aunt or the lady next door, this is when the astute pediatrician must be at his or her best. If a thorough history, including sleep pattern, yields no obvious evidence of illness, the next step should be some sleep coaching. However, this is where the “until proven otherwise” thing becomes important, because not providing close follow-up and continuing to keep an open mind for the less likely coexisting conditions can be dangerous and certainly not in the patient’s best interest.

For the older child crankiness, temper tantrums, mood disorders and signs and symptoms often (some might say too often) associated with attention-deficit disorder should trigger an immediate investigation of sleep habits and appropriate advice. Less well-known conditions associated with sleep deprivation are migraine and nocturnal leg pains, often mislabeled as growing pains.

The physicians planning on using sleep as a therapeutic modality is going to quickly run into several challenges. First is convincing the parents, the patient, and the family that the condition is to a greater or lesser degree the result of sleep deprivation. Because sleep is still underappreciated as a component of wellness, this is often not an easy sell.

Second, everyone must accept that altering sleep patterns regardless of age is often not easy and will not be achieved in 1 night or 2. Keeping up the drumbeat of encouragement with close follow-up is critical. Parents must be continually reminded that sleep is being used as a medicine and the dose is not measured in hours. The improvement in symptoms will tell us when enough is enough.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

“On which side of the bed did you get up this morning?” Obviously, your inquisitor assumes that to avoid clumsily crawling over your sleeping partner you always get up on the side with the table stacked with unread books.

You know as well as I do that you have just received a totally undisguised comment on your recent behavior that has been several shades less than cheery. You may have already sensed your own grumpiness. Do you have an explanation? Did the commute leave you with a case of unresolved road rage? Did you wake up feeling unrested? How often does that happen? Do you think you are getting enough sleep?

A few weeks ago I wrote a Letters From Maine column in which I shared a study suggesting that the regularity of an individual’s sleep pattern may, in many cases, be more important than his or her total number of hours slept. In that same column I wrote that sleep scientists don’t as yet have a good definition of sleep irregularity, nor can they give us any more than a broad range for the total number of hours a person needs to maintain wellness.

How do you determine whether you are getting enough sleep? Do you keep a chart of how many times you were asked which side of the bed you got up on in a week? Or is it how you feel in the morning? Is it when you instantly doze off any time you sit down in a quiet place?

Although many adults are clueless (or in denial) that they are sleep deprived, generally if you ask them and take a brief history they will tell you. On the other hand, determining when a child, particularly one who is preverbal, is sleep deprived is a bit more difficult. Asking the patient isn’t going to give you the answer. You must rely on parental observations. And, to some extent, this can be difficult because parents are, by definition, learning on the job. They may not realize the symptoms and behaviors they are seeing in their child are the result of sleep deficiency.

Over the last half century of observing children, I have developed a very low threshold for diagnosing sleep deprivation. Basically, any child who is cranky and not obviously sick is overtired until proven otherwise. For example, colic does not appear on my frequently used, or in fact ever used, list of diagnoses. Colicky is an adjective that I may use to describe some episodic pain or behavior, but colic as a working diagnosis? Never.

When presented with a child who has already been diagnosed with “colic” by its aunt or the lady next door, this is when the astute pediatrician must be at his or her best. If a thorough history, including sleep pattern, yields no obvious evidence of illness, the next step should be some sleep coaching. However, this is where the “until proven otherwise” thing becomes important, because not providing close follow-up and continuing to keep an open mind for the less likely coexisting conditions can be dangerous and certainly not in the patient’s best interest.

For the older child crankiness, temper tantrums, mood disorders and signs and symptoms often (some might say too often) associated with attention-deficit disorder should trigger an immediate investigation of sleep habits and appropriate advice. Less well-known conditions associated with sleep deprivation are migraine and nocturnal leg pains, often mislabeled as growing pains.

The physicians planning on using sleep as a therapeutic modality is going to quickly run into several challenges. First is convincing the parents, the patient, and the family that the condition is to a greater or lesser degree the result of sleep deprivation. Because sleep is still underappreciated as a component of wellness, this is often not an easy sell.

Second, everyone must accept that altering sleep patterns regardless of age is often not easy and will not be achieved in 1 night or 2. Keeping up the drumbeat of encouragement with close follow-up is critical. Parents must be continually reminded that sleep is being used as a medicine and the dose is not measured in hours. The improvement in symptoms will tell us when enough is enough.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

“On which side of the bed did you get up this morning?” Obviously, your inquisitor assumes that to avoid clumsily crawling over your sleeping partner you always get up on the side with the table stacked with unread books.

You know as well as I do that you have just received a totally undisguised comment on your recent behavior that has been several shades less than cheery. You may have already sensed your own grumpiness. Do you have an explanation? Did the commute leave you with a case of unresolved road rage? Did you wake up feeling unrested? How often does that happen? Do you think you are getting enough sleep?

A few weeks ago I wrote a Letters From Maine column in which I shared a study suggesting that the regularity of an individual’s sleep pattern may, in many cases, be more important than his or her total number of hours slept. In that same column I wrote that sleep scientists don’t as yet have a good definition of sleep irregularity, nor can they give us any more than a broad range for the total number of hours a person needs to maintain wellness.

How do you determine whether you are getting enough sleep? Do you keep a chart of how many times you were asked which side of the bed you got up on in a week? Or is it how you feel in the morning? Is it when you instantly doze off any time you sit down in a quiet place?

Although many adults are clueless (or in denial) that they are sleep deprived, generally if you ask them and take a brief history they will tell you. On the other hand, determining when a child, particularly one who is preverbal, is sleep deprived is a bit more difficult. Asking the patient isn’t going to give you the answer. You must rely on parental observations. And, to some extent, this can be difficult because parents are, by definition, learning on the job. They may not realize the symptoms and behaviors they are seeing in their child are the result of sleep deficiency.

Over the last half century of observing children, I have developed a very low threshold for diagnosing sleep deprivation. Basically, any child who is cranky and not obviously sick is overtired until proven otherwise. For example, colic does not appear on my frequently used, or in fact ever used, list of diagnoses. Colicky is an adjective that I may use to describe some episodic pain or behavior, but colic as a working diagnosis? Never.

When presented with a child who has already been diagnosed with “colic” by its aunt or the lady next door, this is when the astute pediatrician must be at his or her best. If a thorough history, including sleep pattern, yields no obvious evidence of illness, the next step should be some sleep coaching. However, this is where the “until proven otherwise” thing becomes important, because not providing close follow-up and continuing to keep an open mind for the less likely coexisting conditions can be dangerous and certainly not in the patient’s best interest.

For the older child crankiness, temper tantrums, mood disorders and signs and symptoms often (some might say too often) associated with attention-deficit disorder should trigger an immediate investigation of sleep habits and appropriate advice. Less well-known conditions associated with sleep deprivation are migraine and nocturnal leg pains, often mislabeled as growing pains.

The physicians planning on using sleep as a therapeutic modality is going to quickly run into several challenges. First is convincing the parents, the patient, and the family that the condition is to a greater or lesser degree the result of sleep deprivation. Because sleep is still underappreciated as a component of wellness, this is often not an easy sell.

Second, everyone must accept that altering sleep patterns regardless of age is often not easy and will not be achieved in 1 night or 2. Keeping up the drumbeat of encouragement with close follow-up is critical. Parents must be continually reminded that sleep is being used as a medicine and the dose is not measured in hours. The improvement in symptoms will tell us when enough is enough.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Marijuana use dramatically increases risk of heart problems, stroke

Regularly using marijuana can significantly increase a person’s risk of heart attack, heart failure, and stroke, according to a pair of new studies that will be presented at a major upcoming medical conference.

People who use marijuana daily have a 34% increased risk of heart failure, compared with people who don’t use the drug, according to one of the new studies.

The new findings leverage health data from 157,000 people in the National Institutes of Health “All of Us” research program. Researchers analyzed whether marijuana users were more likely to experience heart failure than nonusers over the course of nearly 4 years. The results indicated that coronary artery disease was behind marijuana users’ increased risk. (Coronary artery disease is the buildup of plaque on the walls of the arteries that supply blood to the heart.)

The research was conducted by a team at Medstar Health, a large Maryland health care system that operates 10 hospitals plus hundreds of clinics. The findings will be presented at the American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2023 in Philadelphia.

“Our results should encourage more researchers to study the use of marijuana to better understand its health implications, especially on cardiovascular risk,” said researcher Yakubu Bene-Alhasan, MD, MPH, a doctor at Medstar Health in Baltimore. “We want to provide the population with high-quality information on marijuana use and to help inform policy decisions at the state level, to educate patients, and to guide health care professionals.”

About one in five people in the United States use marijuana, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The majority of U.S. states allow marijuana to be used legally for medical purposes, and more than 20 states have legalized recreational marijuana, a tracker from the National Conference of State Legislatures shows.

A second study that will be presented at the conference shows that older people with any combination of type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol who use marijuana have an increased risk for a major heart or brain event, compared with people who never used the drug.

The researchers analyzed data for more than 28,000 people age 65 and older who had health conditions that put them at risk for heart problems and whose medical records showed they were marijuana users but not tobacco users. The results showed at least a 20% increased risk of heart attack, stroke, cardiac arrest, or arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat).

The findings are significant because medical professionals have long said that research on the long-term health effects of using marijuana are limited.

“The latest research about cannabis use indicates that smoking and inhaling cannabis increases concentrations of blood carboxyhemoglobin (carbon monoxide, a poisonous gas), tar (partly burned combustible matter) similar to the effects of inhaling a tobacco cigarette, both of which have been linked to heart muscle disease, chest pain, heart rhythm disturbances, heart attacks and other serious conditions,” said Robert L. Page II, PharmD, MSPH, chair of the volunteer writing group for the 2020 American Heart Association Scientific Statement: Medical Marijuana, Recreational Cannabis, and Cardiovascular Health, in a statement. “Together with the results of these two research studies, the cardiovascular risks of cannabis use are becoming clearer and should be carefully considered and monitored by health care professionals and the public.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Regularly using marijuana can significantly increase a person’s risk of heart attack, heart failure, and stroke, according to a pair of new studies that will be presented at a major upcoming medical conference.

People who use marijuana daily have a 34% increased risk of heart failure, compared with people who don’t use the drug, according to one of the new studies.

The new findings leverage health data from 157,000 people in the National Institutes of Health “All of Us” research program. Researchers analyzed whether marijuana users were more likely to experience heart failure than nonusers over the course of nearly 4 years. The results indicated that coronary artery disease was behind marijuana users’ increased risk. (Coronary artery disease is the buildup of plaque on the walls of the arteries that supply blood to the heart.)

The research was conducted by a team at Medstar Health, a large Maryland health care system that operates 10 hospitals plus hundreds of clinics. The findings will be presented at the American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2023 in Philadelphia.

“Our results should encourage more researchers to study the use of marijuana to better understand its health implications, especially on cardiovascular risk,” said researcher Yakubu Bene-Alhasan, MD, MPH, a doctor at Medstar Health in Baltimore. “We want to provide the population with high-quality information on marijuana use and to help inform policy decisions at the state level, to educate patients, and to guide health care professionals.”

About one in five people in the United States use marijuana, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The majority of U.S. states allow marijuana to be used legally for medical purposes, and more than 20 states have legalized recreational marijuana, a tracker from the National Conference of State Legislatures shows.

A second study that will be presented at the conference shows that older people with any combination of type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol who use marijuana have an increased risk for a major heart or brain event, compared with people who never used the drug.

The researchers analyzed data for more than 28,000 people age 65 and older who had health conditions that put them at risk for heart problems and whose medical records showed they were marijuana users but not tobacco users. The results showed at least a 20% increased risk of heart attack, stroke, cardiac arrest, or arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat).

The findings are significant because medical professionals have long said that research on the long-term health effects of using marijuana are limited.

“The latest research about cannabis use indicates that smoking and inhaling cannabis increases concentrations of blood carboxyhemoglobin (carbon monoxide, a poisonous gas), tar (partly burned combustible matter) similar to the effects of inhaling a tobacco cigarette, both of which have been linked to heart muscle disease, chest pain, heart rhythm disturbances, heart attacks and other serious conditions,” said Robert L. Page II, PharmD, MSPH, chair of the volunteer writing group for the 2020 American Heart Association Scientific Statement: Medical Marijuana, Recreational Cannabis, and Cardiovascular Health, in a statement. “Together with the results of these two research studies, the cardiovascular risks of cannabis use are becoming clearer and should be carefully considered and monitored by health care professionals and the public.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Regularly using marijuana can significantly increase a person’s risk of heart attack, heart failure, and stroke, according to a pair of new studies that will be presented at a major upcoming medical conference.

People who use marijuana daily have a 34% increased risk of heart failure, compared with people who don’t use the drug, according to one of the new studies.

The new findings leverage health data from 157,000 people in the National Institutes of Health “All of Us” research program. Researchers analyzed whether marijuana users were more likely to experience heart failure than nonusers over the course of nearly 4 years. The results indicated that coronary artery disease was behind marijuana users’ increased risk. (Coronary artery disease is the buildup of plaque on the walls of the arteries that supply blood to the heart.)

The research was conducted by a team at Medstar Health, a large Maryland health care system that operates 10 hospitals plus hundreds of clinics. The findings will be presented at the American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2023 in Philadelphia.

“Our results should encourage more researchers to study the use of marijuana to better understand its health implications, especially on cardiovascular risk,” said researcher Yakubu Bene-Alhasan, MD, MPH, a doctor at Medstar Health in Baltimore. “We want to provide the population with high-quality information on marijuana use and to help inform policy decisions at the state level, to educate patients, and to guide health care professionals.”

About one in five people in the United States use marijuana, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The majority of U.S. states allow marijuana to be used legally for medical purposes, and more than 20 states have legalized recreational marijuana, a tracker from the National Conference of State Legislatures shows.

A second study that will be presented at the conference shows that older people with any combination of type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol who use marijuana have an increased risk for a major heart or brain event, compared with people who never used the drug.

The researchers analyzed data for more than 28,000 people age 65 and older who had health conditions that put them at risk for heart problems and whose medical records showed they were marijuana users but not tobacco users. The results showed at least a 20% increased risk of heart attack, stroke, cardiac arrest, or arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat).

The findings are significant because medical professionals have long said that research on the long-term health effects of using marijuana are limited.

“The latest research about cannabis use indicates that smoking and inhaling cannabis increases concentrations of blood carboxyhemoglobin (carbon monoxide, a poisonous gas), tar (partly burned combustible matter) similar to the effects of inhaling a tobacco cigarette, both of which have been linked to heart muscle disease, chest pain, heart rhythm disturbances, heart attacks and other serious conditions,” said Robert L. Page II, PharmD, MSPH, chair of the volunteer writing group for the 2020 American Heart Association Scientific Statement: Medical Marijuana, Recreational Cannabis, and Cardiovascular Health, in a statement. “Together with the results of these two research studies, the cardiovascular risks of cannabis use are becoming clearer and should be carefully considered and monitored by health care professionals and the public.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM AHA 2023

Body dysmorphic disorder diagnosis guidelines completed in Europe

BERLIN – were outlined in a late-breaker presentation at the annual Congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

The development of guidelines for BDD, a disorder familiar to many clinical dermatologists, is intended as a practical tool, according to Maria-Angeliki Gkini, MD, who has appointments at both Bart’s Health NHS Trust in London and the 401 General Army Hospital in Athens.

“BDD is a relatively common disorder in which the patients are preoccupied with a perceived defect or defects,” Dr. Gkini explained. “This affects them so intensely that it affects their mental health and their quality of life.”

In the DSM-5, published by the American Psychiatric Association, BDD is specifically defined as a preoccupation with “one or more perceived defects or flaws in physical appearance that are not observable or appear slight to others.” But Dr. Gkini said that BDD can also develop as a comorbidity of dermatological disorders that are visible.

These patients are challenging because they are difficult to please, added Dr. Gkini, who said they commonly become involved in doctor shopping, leaving negative reviews on social media for the clinicians they have cycled through. The problem is that the defects they seek to resolve typically stem from distorted perceptions.

BDD is related to obsessive-compulsive disorder by the frequency with which patients pursue repetitive behaviors related to their preoccupation, such as intensive grooming, frequent trips to the mirror, or difficulty in focusing on topics other than their own appearance.

The process to develop the soon-to-be-published guidelines began with a literature search. Of the approximately 3,200 articles identified on BDD, only 10 involved randomized controlled trials. Moreover, even the quality of these trials was considered “low to very low” by the experts who reviewed them, Dr. Gkini said.

One explanation is that psychodermatology has only recently started to attract more research interest, and better studies are now underway, she noted.

However, because of the dearth of high quality evidence now available, the guideline development relied on a Delphi method to reach consensus based on expert opinion in discussion of the available data.

Consensus reached by 17 experts

Specifically, 17 experts, all of whom were members of the European Society for Dermatology and Psychiatry proceeded to systematically address a series of clinical questions and recommendations. Consensus was defined as at least 75% of the participants strongly agreeing or agreeing. Several rounds of discussion were often required.

Among the conclusions, the guidelines support uniform screening for BDD in all patients prior to cosmetic procedures. In identifying depression, anxiety, and distorted perceptions, simple tools, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire might be adequate for an initial evaluation, but Dr. Gkini also recommended routinely inquiring about suicidal ideation, which has been reported in up to 80% of individuals with BDD.

Other instruments for screening that can be considered include DSM-5 criteria for BDD and the Body Dysmorphic Disorder Questionnaire–Dermatology Version, which might be particularly useful and appropriate for dermatologists.

One of the reasons to screen for BDD is that these patients often convince themselves that some specific procedure is needed to resolve the source of their obsession. The goal of screening is to verify that it is the dermatologic concern, not an underlying psychiatric disorder that is driving their search for relief. The risk of dermatologic interventions is not only that expectations are not met, but the patient’s perception of a failed intervention “sometimes makes these worse,” Dr. Gkini explained.

Collaboration with psychiatrists recommended

The guidelines include suggestions for treatment of BDD. Of these, SSRIs are recommended at high relative doses, according to Dr. Gkini. Consistent with the consensus recommendation of collaborating with mental health specialists, she said that the recommendations acknowledge evidence of greater benefits when SSRIs are combined with psychotherapy.

Katharine A. Phillips, MD, professor of psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, has been conducting BDD research for several years and has written numerous books and articles about this topic, including a review in the journal Focus. She cautioned that, because of a normal concern for appearance, BDD is easily missed by dermatologists.

“For BDD to be diagnosed, the preoccupation with a nonexistent or slight defect in appearance must cause clinically significant distress or impairment in functioning,” she said in an interview. “This is necessary to differentiate BDD from more normal and common appearance concerns that do not qualify for the diagnosis”

She specified that patients should be considered for cognitive-behavioral therapy rather than psychotherapy, a generic term that covers many forms of treatment. She said that most other types of psychotherapy “are probably not effective” for BDD.

Dr. Phillips highly endorsed the development of BDD guidelines for dermatologists because of the frequency with which physicians in this specialty encounter BDD – and believes that more attention to this diagnosis is needed.

“I recommend that dermatologists who have a patient with BDD collaborate with a psychiatrist in delivering care with an SSRI,” she said. “High doses of these medications are often needed to effectively treat BDD.”

Dr. Gkini reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Almirall, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, LEO, Novartis, Sanofi, and Regenlab. Dr. Phillips reported no relevant financial relationships.

BERLIN – were outlined in a late-breaker presentation at the annual Congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

The development of guidelines for BDD, a disorder familiar to many clinical dermatologists, is intended as a practical tool, according to Maria-Angeliki Gkini, MD, who has appointments at both Bart’s Health NHS Trust in London and the 401 General Army Hospital in Athens.

“BDD is a relatively common disorder in which the patients are preoccupied with a perceived defect or defects,” Dr. Gkini explained. “This affects them so intensely that it affects their mental health and their quality of life.”

In the DSM-5, published by the American Psychiatric Association, BDD is specifically defined as a preoccupation with “one or more perceived defects or flaws in physical appearance that are not observable or appear slight to others.” But Dr. Gkini said that BDD can also develop as a comorbidity of dermatological disorders that are visible.

These patients are challenging because they are difficult to please, added Dr. Gkini, who said they commonly become involved in doctor shopping, leaving negative reviews on social media for the clinicians they have cycled through. The problem is that the defects they seek to resolve typically stem from distorted perceptions.

BDD is related to obsessive-compulsive disorder by the frequency with which patients pursue repetitive behaviors related to their preoccupation, such as intensive grooming, frequent trips to the mirror, or difficulty in focusing on topics other than their own appearance.

The process to develop the soon-to-be-published guidelines began with a literature search. Of the approximately 3,200 articles identified on BDD, only 10 involved randomized controlled trials. Moreover, even the quality of these trials was considered “low to very low” by the experts who reviewed them, Dr. Gkini said.

One explanation is that psychodermatology has only recently started to attract more research interest, and better studies are now underway, she noted.

However, because of the dearth of high quality evidence now available, the guideline development relied on a Delphi method to reach consensus based on expert opinion in discussion of the available data.

Consensus reached by 17 experts

Specifically, 17 experts, all of whom were members of the European Society for Dermatology and Psychiatry proceeded to systematically address a series of clinical questions and recommendations. Consensus was defined as at least 75% of the participants strongly agreeing or agreeing. Several rounds of discussion were often required.

Among the conclusions, the guidelines support uniform screening for BDD in all patients prior to cosmetic procedures. In identifying depression, anxiety, and distorted perceptions, simple tools, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire might be adequate for an initial evaluation, but Dr. Gkini also recommended routinely inquiring about suicidal ideation, which has been reported in up to 80% of individuals with BDD.

Other instruments for screening that can be considered include DSM-5 criteria for BDD and the Body Dysmorphic Disorder Questionnaire–Dermatology Version, which might be particularly useful and appropriate for dermatologists.

One of the reasons to screen for BDD is that these patients often convince themselves that some specific procedure is needed to resolve the source of their obsession. The goal of screening is to verify that it is the dermatologic concern, not an underlying psychiatric disorder that is driving their search for relief. The risk of dermatologic interventions is not only that expectations are not met, but the patient’s perception of a failed intervention “sometimes makes these worse,” Dr. Gkini explained.

Collaboration with psychiatrists recommended

The guidelines include suggestions for treatment of BDD. Of these, SSRIs are recommended at high relative doses, according to Dr. Gkini. Consistent with the consensus recommendation of collaborating with mental health specialists, she said that the recommendations acknowledge evidence of greater benefits when SSRIs are combined with psychotherapy.

Katharine A. Phillips, MD, professor of psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, has been conducting BDD research for several years and has written numerous books and articles about this topic, including a review in the journal Focus. She cautioned that, because of a normal concern for appearance, BDD is easily missed by dermatologists.

“For BDD to be diagnosed, the preoccupation with a nonexistent or slight defect in appearance must cause clinically significant distress or impairment in functioning,” she said in an interview. “This is necessary to differentiate BDD from more normal and common appearance concerns that do not qualify for the diagnosis”

She specified that patients should be considered for cognitive-behavioral therapy rather than psychotherapy, a generic term that covers many forms of treatment. She said that most other types of psychotherapy “are probably not effective” for BDD.

Dr. Phillips highly endorsed the development of BDD guidelines for dermatologists because of the frequency with which physicians in this specialty encounter BDD – and believes that more attention to this diagnosis is needed.

“I recommend that dermatologists who have a patient with BDD collaborate with a psychiatrist in delivering care with an SSRI,” she said. “High doses of these medications are often needed to effectively treat BDD.”

Dr. Gkini reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Almirall, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, LEO, Novartis, Sanofi, and Regenlab. Dr. Phillips reported no relevant financial relationships.

BERLIN – were outlined in a late-breaker presentation at the annual Congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

The development of guidelines for BDD, a disorder familiar to many clinical dermatologists, is intended as a practical tool, according to Maria-Angeliki Gkini, MD, who has appointments at both Bart’s Health NHS Trust in London and the 401 General Army Hospital in Athens.

“BDD is a relatively common disorder in which the patients are preoccupied with a perceived defect or defects,” Dr. Gkini explained. “This affects them so intensely that it affects their mental health and their quality of life.”

In the DSM-5, published by the American Psychiatric Association, BDD is specifically defined as a preoccupation with “one or more perceived defects or flaws in physical appearance that are not observable or appear slight to others.” But Dr. Gkini said that BDD can also develop as a comorbidity of dermatological disorders that are visible.

These patients are challenging because they are difficult to please, added Dr. Gkini, who said they commonly become involved in doctor shopping, leaving negative reviews on social media for the clinicians they have cycled through. The problem is that the defects they seek to resolve typically stem from distorted perceptions.

BDD is related to obsessive-compulsive disorder by the frequency with which patients pursue repetitive behaviors related to their preoccupation, such as intensive grooming, frequent trips to the mirror, or difficulty in focusing on topics other than their own appearance.

The process to develop the soon-to-be-published guidelines began with a literature search. Of the approximately 3,200 articles identified on BDD, only 10 involved randomized controlled trials. Moreover, even the quality of these trials was considered “low to very low” by the experts who reviewed them, Dr. Gkini said.

One explanation is that psychodermatology has only recently started to attract more research interest, and better studies are now underway, she noted.

However, because of the dearth of high quality evidence now available, the guideline development relied on a Delphi method to reach consensus based on expert opinion in discussion of the available data.

Consensus reached by 17 experts

Specifically, 17 experts, all of whom were members of the European Society for Dermatology and Psychiatry proceeded to systematically address a series of clinical questions and recommendations. Consensus was defined as at least 75% of the participants strongly agreeing or agreeing. Several rounds of discussion were often required.

Among the conclusions, the guidelines support uniform screening for BDD in all patients prior to cosmetic procedures. In identifying depression, anxiety, and distorted perceptions, simple tools, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire might be adequate for an initial evaluation, but Dr. Gkini also recommended routinely inquiring about suicidal ideation, which has been reported in up to 80% of individuals with BDD.

Other instruments for screening that can be considered include DSM-5 criteria for BDD and the Body Dysmorphic Disorder Questionnaire–Dermatology Version, which might be particularly useful and appropriate for dermatologists.

One of the reasons to screen for BDD is that these patients often convince themselves that some specific procedure is needed to resolve the source of their obsession. The goal of screening is to verify that it is the dermatologic concern, not an underlying psychiatric disorder that is driving their search for relief. The risk of dermatologic interventions is not only that expectations are not met, but the patient’s perception of a failed intervention “sometimes makes these worse,” Dr. Gkini explained.

Collaboration with psychiatrists recommended

The guidelines include suggestions for treatment of BDD. Of these, SSRIs are recommended at high relative doses, according to Dr. Gkini. Consistent with the consensus recommendation of collaborating with mental health specialists, she said that the recommendations acknowledge evidence of greater benefits when SSRIs are combined with psychotherapy.

Katharine A. Phillips, MD, professor of psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, has been conducting BDD research for several years and has written numerous books and articles about this topic, including a review in the journal Focus. She cautioned that, because of a normal concern for appearance, BDD is easily missed by dermatologists.

“For BDD to be diagnosed, the preoccupation with a nonexistent or slight defect in appearance must cause clinically significant distress or impairment in functioning,” she said in an interview. “This is necessary to differentiate BDD from more normal and common appearance concerns that do not qualify for the diagnosis”

She specified that patients should be considered for cognitive-behavioral therapy rather than psychotherapy, a generic term that covers many forms of treatment. She said that most other types of psychotherapy “are probably not effective” for BDD.

Dr. Phillips highly endorsed the development of BDD guidelines for dermatologists because of the frequency with which physicians in this specialty encounter BDD – and believes that more attention to this diagnosis is needed.

“I recommend that dermatologists who have a patient with BDD collaborate with a psychiatrist in delivering care with an SSRI,” she said. “High doses of these medications are often needed to effectively treat BDD.”

Dr. Gkini reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Almirall, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, LEO, Novartis, Sanofi, and Regenlab. Dr. Phillips reported no relevant financial relationships.

AT THE EADV CONGRESS

Discomfort in right breast

Breast cancer is the most common tumor type and second only to lung cancer as a cause of cancer death in women. Nearly 300,000 women (and 2800 men) will receive a new diagnosis of breast cancer in the United States in 2023. Despite improvements in treatment options, breast cancer still will lead to 43,700 deaths among women this year.

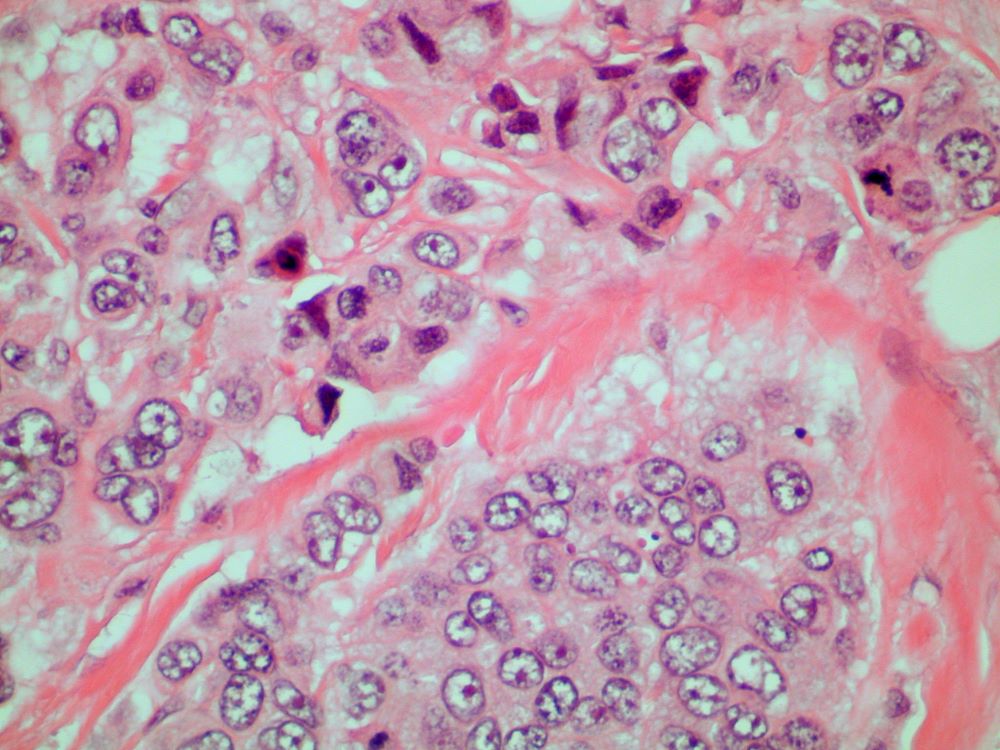

Breast tumors generally are either ductal or lobular in origin. Ductal carcinomas arise in the lining of the milk ducts and are the most commonly found tumor type in breast cancer. Almost 3 in 4 diagnosed breast cancers histologically are invasive ductal carcinomas, which have spread from the source into surrounding structures. It has no specific histologic indicators and is differentiated from ductal carcinoma in situ by its having spread outside the duct. The presence of lymph node involvement in this patient also confirms invasive ductal carcinoma without metastatic spread. Invasive lobular carcinomas occur much less frequently and have a different histologic appearance of smaller cells that appear to be arranged in linear groups.

Mammography involves low-dose radiation and is used in diagnosis and is the most widely used screening technique for breast cancer. As a screening tool, mammography may detect lesions 1-2 years before they become palpable on breast self-examination. While the incidence of breast cancer in women has slowly increased over the past 20 years, mortality has decreased largely as a result of improved awareness and uptake of screening mammography. Current American Cancer Society guidelines recommend continued mammography screenings at least every other year after age 55 and continued for as long as a woman has a life expectancy > 10 years. Screening or diagnosis using MRI is usually reserved for individuals at high risk for breast cancer or a history of breast cancer before age 50.

For all newly diagnosed primary invasive breast cancers, biomarker testing for estrogen and progesterone receptor expression and HER2 expression are part of the standard workup recommended by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) to help guide treatment decisions. Biomarker testing showed that her tumor was ER+ and HER2-negative, the most common finding in breast cancer. The patient's history did not suggest a risk for BRCA or other familial cancer mutations, but molecular testing was done and was negative for BRCA1 and BRCA2. In postmenopausal women, ASCO and NCCN also recommend use of risk assessment tools, such as Oncotype DX, to determine whether chemotherapy will add benefit to systemic endocrine therapy. Postmenopausal patients with ER+/HER2-negative breast cancer, one to three positive nodes, and a score < 26 on the 21-gene Oncotype DX can safely forego cytotoxic chemotherapy and derive maximum survival benefit from hormonal therapy alone.

This patient was diagnosed with a primary tumor of approximately 25 mm, metastasis to two ipsilateral nodes, and no distant metastasis, or stage IIIA. Her risk recurrence score was 20, indicating that she could safely forego the rigors of cytotoxic chemotherapy. She underwent localized breast-conserving surgery and began adjuvant tamoxifen therapy (x 2 years) to be followed with an aromatase inhibitor (x 3 years).

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Breast cancer is the most common tumor type and second only to lung cancer as a cause of cancer death in women. Nearly 300,000 women (and 2800 men) will receive a new diagnosis of breast cancer in the United States in 2023. Despite improvements in treatment options, breast cancer still will lead to 43,700 deaths among women this year.

Breast tumors generally are either ductal or lobular in origin. Ductal carcinomas arise in the lining of the milk ducts and are the most commonly found tumor type in breast cancer. Almost 3 in 4 diagnosed breast cancers histologically are invasive ductal carcinomas, which have spread from the source into surrounding structures. It has no specific histologic indicators and is differentiated from ductal carcinoma in situ by its having spread outside the duct. The presence of lymph node involvement in this patient also confirms invasive ductal carcinoma without metastatic spread. Invasive lobular carcinomas occur much less frequently and have a different histologic appearance of smaller cells that appear to be arranged in linear groups.

Mammography involves low-dose radiation and is used in diagnosis and is the most widely used screening technique for breast cancer. As a screening tool, mammography may detect lesions 1-2 years before they become palpable on breast self-examination. While the incidence of breast cancer in women has slowly increased over the past 20 years, mortality has decreased largely as a result of improved awareness and uptake of screening mammography. Current American Cancer Society guidelines recommend continued mammography screenings at least every other year after age 55 and continued for as long as a woman has a life expectancy > 10 years. Screening or diagnosis using MRI is usually reserved for individuals at high risk for breast cancer or a history of breast cancer before age 50.

For all newly diagnosed primary invasive breast cancers, biomarker testing for estrogen and progesterone receptor expression and HER2 expression are part of the standard workup recommended by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) to help guide treatment decisions. Biomarker testing showed that her tumor was ER+ and HER2-negative, the most common finding in breast cancer. The patient's history did not suggest a risk for BRCA or other familial cancer mutations, but molecular testing was done and was negative for BRCA1 and BRCA2. In postmenopausal women, ASCO and NCCN also recommend use of risk assessment tools, such as Oncotype DX, to determine whether chemotherapy will add benefit to systemic endocrine therapy. Postmenopausal patients with ER+/HER2-negative breast cancer, one to three positive nodes, and a score < 26 on the 21-gene Oncotype DX can safely forego cytotoxic chemotherapy and derive maximum survival benefit from hormonal therapy alone.

This patient was diagnosed with a primary tumor of approximately 25 mm, metastasis to two ipsilateral nodes, and no distant metastasis, or stage IIIA. Her risk recurrence score was 20, indicating that she could safely forego the rigors of cytotoxic chemotherapy. She underwent localized breast-conserving surgery and began adjuvant tamoxifen therapy (x 2 years) to be followed with an aromatase inhibitor (x 3 years).

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Breast cancer is the most common tumor type and second only to lung cancer as a cause of cancer death in women. Nearly 300,000 women (and 2800 men) will receive a new diagnosis of breast cancer in the United States in 2023. Despite improvements in treatment options, breast cancer still will lead to 43,700 deaths among women this year.

Breast tumors generally are either ductal or lobular in origin. Ductal carcinomas arise in the lining of the milk ducts and are the most commonly found tumor type in breast cancer. Almost 3 in 4 diagnosed breast cancers histologically are invasive ductal carcinomas, which have spread from the source into surrounding structures. It has no specific histologic indicators and is differentiated from ductal carcinoma in situ by its having spread outside the duct. The presence of lymph node involvement in this patient also confirms invasive ductal carcinoma without metastatic spread. Invasive lobular carcinomas occur much less frequently and have a different histologic appearance of smaller cells that appear to be arranged in linear groups.

Mammography involves low-dose radiation and is used in diagnosis and is the most widely used screening technique for breast cancer. As a screening tool, mammography may detect lesions 1-2 years before they become palpable on breast self-examination. While the incidence of breast cancer in women has slowly increased over the past 20 years, mortality has decreased largely as a result of improved awareness and uptake of screening mammography. Current American Cancer Society guidelines recommend continued mammography screenings at least every other year after age 55 and continued for as long as a woman has a life expectancy > 10 years. Screening or diagnosis using MRI is usually reserved for individuals at high risk for breast cancer or a history of breast cancer before age 50.

For all newly diagnosed primary invasive breast cancers, biomarker testing for estrogen and progesterone receptor expression and HER2 expression are part of the standard workup recommended by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) to help guide treatment decisions. Biomarker testing showed that her tumor was ER+ and HER2-negative, the most common finding in breast cancer. The patient's history did not suggest a risk for BRCA or other familial cancer mutations, but molecular testing was done and was negative for BRCA1 and BRCA2. In postmenopausal women, ASCO and NCCN also recommend use of risk assessment tools, such as Oncotype DX, to determine whether chemotherapy will add benefit to systemic endocrine therapy. Postmenopausal patients with ER+/HER2-negative breast cancer, one to three positive nodes, and a score < 26 on the 21-gene Oncotype DX can safely forego cytotoxic chemotherapy and derive maximum survival benefit from hormonal therapy alone.

This patient was diagnosed with a primary tumor of approximately 25 mm, metastasis to two ipsilateral nodes, and no distant metastasis, or stage IIIA. Her risk recurrence score was 20, indicating that she could safely forego the rigors of cytotoxic chemotherapy. She underwent localized breast-conserving surgery and began adjuvant tamoxifen therapy (x 2 years) to be followed with an aromatase inhibitor (x 3 years).

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 70-year-old woman presents for an annual exam and reports development of a firm lump in her right breast. She remarks that she has had discomfort in the same area for "at least a year," but the lump has become noticeable with even a cursory self-exam over the past 2 months. She has no previous history of breast cancer, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, or other cardiometabolic disease. She had no previous abnormal findings on mammograms through age 65 but has not had one since. Her family history includes a grandmother who died of breast cancer at age 64 and her father who lived with prostate cancer for 20 years after diagnosis at age 60. The physical exam reveals a firm, palpable lump in the upper right quadrant of her right breast. The exam is otherwise normal for the patient's age, with minor osteoarthritis that she remarks has worsened over the past year. Mammography, image-guided biopsy, and biomarker and molecular testing are ordered. Lymph node testing reveals two involved nodes, and histology reveals the following (see image).

Second infection hikes long COVID risk: Expert Q&A

Those are two of the most striking findings of a comprehensive new research study of 138,000 veterans.

Lead researcher Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, chief of research at Veterans Affairs St. Louis Health Care and clinical epidemiologist at Washington University in St. Louis, spoke with this news organization about his team’s findings, what we know – and don’t – about long COVID, and what it means for physicians treating patients with the condition.

Excerpts of the interview follow.

Your research concluded that for those infected early in the pandemic, some long COVID symptoms declined over 2 years, but some did not. You have also concluded that long COVID is a chronic disease. Why?

We’ve been in this journey a little bit more than three and a half years. Some patients do experience some recovery. But that’s not the norm. Most people do not really fully recover. The health trajectory for people with long COVID is really very heterogeneous. There is no one-size-fits-all. There’s really no one line that I could give you that could cover all your patients. But it is very, very, very clear that a bunch of them experienced long COVID for sure; that’s really happening.

It happened in the pre-Delta era and in the Delta era, and with Omicron subvariants, even now. There are people who think, “This is a nothing-burger anymore,” or “It’s not an issue anymore.” It’s still happening with the current variants. Vaccines do reduce risk for long COVID, but do not completely eliminate the risk for long COVID.

You work with patients with long COVID in the clinic and also analyze data from thousands more. If long COVID does not go away, what should doctors look for in everyday practice that will help them recognize and help patients with long COVID?

Long COVID is not uncommon. We see it in the clinic in large numbers. Whatever clinic you’re running – if you’re running a cardiology clinic, or a nephrology clinic, or diabetes, or primary care – probably some of your people have it. You may not know about it. They may not tell you about it. You may not recognize it.

Not all long COVID is the same, and that’s really what makes it complex and makes it really hard to deal with in the clinic. But that’s the reality that we’re all dealing with. And it’s multisystemic; it’s not like it affects the heart only, the brain only, or the autonomic nervous system only. It does not behave in the same way in different individuals – they may have different manifestations, various health trajectories, and different outcomes. It’s important for doctors to get up to speed on long COVID as a multisystem illness.

Management at this point is really managing the symptoms. We don’t have a treatment for it; we don’t have a cure for it.

Some patients experience what you’ve described as partial recovery. What does that look like?

Some individuals do experience some recovery over time, but for most individuals, the recovery is long and arduous. Long COVID can last with them for many years. Some people may come back to the clinic and say, “I’m doing better,” but if you really flesh it out and dig deeper, they didn’t do better; they adjusted to a new baseline. They used to walk the dog three to four blocks, and now they walk the dog only half a block. They used to do an activity with their partner every Saturday or Sunday, and now they do half of that.

If you’re a physician, a primary care provider, or any other provider who is dealing with a patient with long COVID, know that this is really happening. It can happen even in vaccinated individuals. The presentation is heterogeneous. Some people may present to you with and say. “Well, before I had COVID I was mentally sharp and now having I’m having difficulty with memory, etc.” It can sometimes present as fatigue or postexertional malaise.

In some instances, it can present as sleep problems. It can present as what we call postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS). Those people get a significant increase in heart rate with postural changes.

What the most important thing we can we learn from the emergence of long COVID?

This whole thing taught us that infections can cause chronic disease. That’s really the No. 1 lesson that I take from this pandemic – that infections can cause chronic disease.

Looking at only acute illness from COVID is really only looking at the tip of the iceberg. Beneath that tip of the iceberg lies this hidden toll of disease that we don’t really talk about that much.

This pandemic shone a very, very good light on the idea that there is really an intimate connection between infections and chronic disease. It was really hardwired into our medical training as doctors that most infections, when people get over the hump of the acute phase of the disease, it’s all behind them. I think long COVID has humbled us in many, many ways, but chief among those is the realization – the stark realization – that infections can cause chronic disease.

That’s really going back to your [first] question: What does it mean that some people are not recovering? They actually have chronic illness. I’m hoping that we will find a treatment, that we’ll start finding things that would help them get back to baseline. But at this point in time, what we’re dealing with is people with chronic illness or chronic disease that may continue to affect them for many years to come in the absence of a treatment or a cure.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Those are two of the most striking findings of a comprehensive new research study of 138,000 veterans.

Lead researcher Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, chief of research at Veterans Affairs St. Louis Health Care and clinical epidemiologist at Washington University in St. Louis, spoke with this news organization about his team’s findings, what we know – and don’t – about long COVID, and what it means for physicians treating patients with the condition.

Excerpts of the interview follow.

Your research concluded that for those infected early in the pandemic, some long COVID symptoms declined over 2 years, but some did not. You have also concluded that long COVID is a chronic disease. Why?

We’ve been in this journey a little bit more than three and a half years. Some patients do experience some recovery. But that’s not the norm. Most people do not really fully recover. The health trajectory for people with long COVID is really very heterogeneous. There is no one-size-fits-all. There’s really no one line that I could give you that could cover all your patients. But it is very, very, very clear that a bunch of them experienced long COVID for sure; that’s really happening.

It happened in the pre-Delta era and in the Delta era, and with Omicron subvariants, even now. There are people who think, “This is a nothing-burger anymore,” or “It’s not an issue anymore.” It’s still happening with the current variants. Vaccines do reduce risk for long COVID, but do not completely eliminate the risk for long COVID.

You work with patients with long COVID in the clinic and also analyze data from thousands more. If long COVID does not go away, what should doctors look for in everyday practice that will help them recognize and help patients with long COVID?

Long COVID is not uncommon. We see it in the clinic in large numbers. Whatever clinic you’re running – if you’re running a cardiology clinic, or a nephrology clinic, or diabetes, or primary care – probably some of your people have it. You may not know about it. They may not tell you about it. You may not recognize it.

Not all long COVID is the same, and that’s really what makes it complex and makes it really hard to deal with in the clinic. But that’s the reality that we’re all dealing with. And it’s multisystemic; it’s not like it affects the heart only, the brain only, or the autonomic nervous system only. It does not behave in the same way in different individuals – they may have different manifestations, various health trajectories, and different outcomes. It’s important for doctors to get up to speed on long COVID as a multisystem illness.

Management at this point is really managing the symptoms. We don’t have a treatment for it; we don’t have a cure for it.

Some patients experience what you’ve described as partial recovery. What does that look like?

Some individuals do experience some recovery over time, but for most individuals, the recovery is long and arduous. Long COVID can last with them for many years. Some people may come back to the clinic and say, “I’m doing better,” but if you really flesh it out and dig deeper, they didn’t do better; they adjusted to a new baseline. They used to walk the dog three to four blocks, and now they walk the dog only half a block. They used to do an activity with their partner every Saturday or Sunday, and now they do half of that.

If you’re a physician, a primary care provider, or any other provider who is dealing with a patient with long COVID, know that this is really happening. It can happen even in vaccinated individuals. The presentation is heterogeneous. Some people may present to you with and say. “Well, before I had COVID I was mentally sharp and now having I’m having difficulty with memory, etc.” It can sometimes present as fatigue or postexertional malaise.

In some instances, it can present as sleep problems. It can present as what we call postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS). Those people get a significant increase in heart rate with postural changes.

What the most important thing we can we learn from the emergence of long COVID?

This whole thing taught us that infections can cause chronic disease. That’s really the No. 1 lesson that I take from this pandemic – that infections can cause chronic disease.

Looking at only acute illness from COVID is really only looking at the tip of the iceberg. Beneath that tip of the iceberg lies this hidden toll of disease that we don’t really talk about that much.

This pandemic shone a very, very good light on the idea that there is really an intimate connection between infections and chronic disease. It was really hardwired into our medical training as doctors that most infections, when people get over the hump of the acute phase of the disease, it’s all behind them. I think long COVID has humbled us in many, many ways, but chief among those is the realization – the stark realization – that infections can cause chronic disease.

That’s really going back to your [first] question: What does it mean that some people are not recovering? They actually have chronic illness. I’m hoping that we will find a treatment, that we’ll start finding things that would help them get back to baseline. But at this point in time, what we’re dealing with is people with chronic illness or chronic disease that may continue to affect them for many years to come in the absence of a treatment or a cure.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Those are two of the most striking findings of a comprehensive new research study of 138,000 veterans.

Lead researcher Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, chief of research at Veterans Affairs St. Louis Health Care and clinical epidemiologist at Washington University in St. Louis, spoke with this news organization about his team’s findings, what we know – and don’t – about long COVID, and what it means for physicians treating patients with the condition.

Excerpts of the interview follow.

Your research concluded that for those infected early in the pandemic, some long COVID symptoms declined over 2 years, but some did not. You have also concluded that long COVID is a chronic disease. Why?

We’ve been in this journey a little bit more than three and a half years. Some patients do experience some recovery. But that’s not the norm. Most people do not really fully recover. The health trajectory for people with long COVID is really very heterogeneous. There is no one-size-fits-all. There’s really no one line that I could give you that could cover all your patients. But it is very, very, very clear that a bunch of them experienced long COVID for sure; that’s really happening.

It happened in the pre-Delta era and in the Delta era, and with Omicron subvariants, even now. There are people who think, “This is a nothing-burger anymore,” or “It’s not an issue anymore.” It’s still happening with the current variants. Vaccines do reduce risk for long COVID, but do not completely eliminate the risk for long COVID.

You work with patients with long COVID in the clinic and also analyze data from thousands more. If long COVID does not go away, what should doctors look for in everyday practice that will help them recognize and help patients with long COVID?

Long COVID is not uncommon. We see it in the clinic in large numbers. Whatever clinic you’re running – if you’re running a cardiology clinic, or a nephrology clinic, or diabetes, or primary care – probably some of your people have it. You may not know about it. They may not tell you about it. You may not recognize it.

Not all long COVID is the same, and that’s really what makes it complex and makes it really hard to deal with in the clinic. But that’s the reality that we’re all dealing with. And it’s multisystemic; it’s not like it affects the heart only, the brain only, or the autonomic nervous system only. It does not behave in the same way in different individuals – they may have different manifestations, various health trajectories, and different outcomes. It’s important for doctors to get up to speed on long COVID as a multisystem illness.

Management at this point is really managing the symptoms. We don’t have a treatment for it; we don’t have a cure for it.

Some patients experience what you’ve described as partial recovery. What does that look like?

Some individuals do experience some recovery over time, but for most individuals, the recovery is long and arduous. Long COVID can last with them for many years. Some people may come back to the clinic and say, “I’m doing better,” but if you really flesh it out and dig deeper, they didn’t do better; they adjusted to a new baseline. They used to walk the dog three to four blocks, and now they walk the dog only half a block. They used to do an activity with their partner every Saturday or Sunday, and now they do half of that.

If you’re a physician, a primary care provider, or any other provider who is dealing with a patient with long COVID, know that this is really happening. It can happen even in vaccinated individuals. The presentation is heterogeneous. Some people may present to you with and say. “Well, before I had COVID I was mentally sharp and now having I’m having difficulty with memory, etc.” It can sometimes present as fatigue or postexertional malaise.

In some instances, it can present as sleep problems. It can present as what we call postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS). Those people get a significant increase in heart rate with postural changes.

What the most important thing we can we learn from the emergence of long COVID?

This whole thing taught us that infections can cause chronic disease. That’s really the No. 1 lesson that I take from this pandemic – that infections can cause chronic disease.

Looking at only acute illness from COVID is really only looking at the tip of the iceberg. Beneath that tip of the iceberg lies this hidden toll of disease that we don’t really talk about that much.

This pandemic shone a very, very good light on the idea that there is really an intimate connection between infections and chronic disease. It was really hardwired into our medical training as doctors that most infections, when people get over the hump of the acute phase of the disease, it’s all behind them. I think long COVID has humbled us in many, many ways, but chief among those is the realization – the stark realization – that infections can cause chronic disease.

That’s really going back to your [first] question: What does it mean that some people are not recovering? They actually have chronic illness. I’m hoping that we will find a treatment, that we’ll start finding things that would help them get back to baseline. But at this point in time, what we’re dealing with is people with chronic illness or chronic disease that may continue to affect them for many years to come in the absence of a treatment or a cure.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

EMR prompt boosts albuminuria measurement in T2D

PHILADELPHIA – An electronic medical record alert to primary care physicians that their adult patients with type 2 diabetes were due for an albuminuria and renal-function check boosted screening for chronic kidney disease (CKD) by roughly half compared with the preintervention rate in a single U.S. academic health system.

“Screening rates for CKD more rapidly improved after implementation” of the EMR alert, said Maggy M. Spolnik, MD, at Kidney Week 2023, organized by the American Society of Nephrology.

“There was an immediate and ongoing effect over a year,” said Dr. Spolnik, a nephrologist at Indiana University in Indianapolis.

However, CKD screening rates in the primary care setting remain a challenge. In the study, the EMR alert produced a urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) screening rate of about 26% of patient encounters, she reported. While this was significantly above the roughly 17% rate that had persisted for months before the intervention, it still fell short of the universal annual screening for adults with type 2 diabetes not previously diagnosed with CKD recommended by medical groups such as the American Diabetes Association and the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes organization. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force’s assessment in 2012 concluded inadequate information existed at that time to make recommendations about CKD screening, but the group is now revisiting the issue.

‘Albuminuria is an earlier marker’ than eGFR

“Primary care physicians need to regularly monitor albuminuria in adults with type 2 diabetes,” commented Karen A. Griffin, MD, a nephrologist and professor at Loyola University in Maywood, Ill. “By the time you diagnose CKD based on reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), a patient has already lost more than half their renal function. Albuminuria is an earlier marker of a problem,” Dr. Griffin said in an interview.

Primary care physicians have been slow to adopt at least annual checks on both eGFR and the urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) in their adult patients with type 2 diabetes. Dr. Spolnik cited reasons such as the brief 15-minute consultation that primary care physicians have when seeing a patient, and an often confusing ordering menu that gives a UACR test various other names such as tests for microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria.

To simplify ordering, the EMR prompt assessed in Dr. Spolnik’s study called the test “kidney screening” that automatically bundled an order for both eGFR calculation with UACR measurement. Another limitation is that UACR measurement requires a urine sample, which patients often find inconvenient to provide at the time of their examination.

The study run by Dr. Spolnik involved 10,744 adults with type 2 diabetes without an existing diagnosis of CKD seen in an outpatient, primary care visit to the UVA Health system centered in Charlottesville, Va. during April 2021–April 2022. A total of 23,419 encounters served as usual-care controls. The intervention period with active EMR alerts for kidney screening included 10,204 similar patients seen during April 2022–April 2023 in a total of 20,358 encounters. The patients averaged about 61-62 years old, and about 45% were men.

Bundling alerts into a single pop-up

The primary care clinicians who received the prompts were generally receptive to them, but they asked the researchers to bundle the UACR and eGFR measurement prompts along with any other alerts they received in the EMR into a single on-screen pop-up.

Dr. Spolnik acknowledged the need for further research and refinement to the prompt. For example, she wants to assess prompts for patients identified as having CKD that would promote best-practice management, including lifestyle and medical interventions. She also envisions expanding the prompts to also include other, related disorders such as hypertension.

But she and her colleagues were convinced enough by the results that they have not only continued the program at UVA Health but they also expanded it, starting in October 2023, to the academic primary care practice at Indiana University.

If the Indiana University trial confirms the efficacy seen in Virginia, the next step might be inclusion by Epic of the CKD screening alert as a routine option in the EMR software it distributes to its U.S. clients, Dr. Spolnik said in an interview.

Dr. Spolnik and Dr. Griffin had no disclosures.

PHILADELPHIA – An electronic medical record alert to primary care physicians that their adult patients with type 2 diabetes were due for an albuminuria and renal-function check boosted screening for chronic kidney disease (CKD) by roughly half compared with the preintervention rate in a single U.S. academic health system.

“Screening rates for CKD more rapidly improved after implementation” of the EMR alert, said Maggy M. Spolnik, MD, at Kidney Week 2023, organized by the American Society of Nephrology.

“There was an immediate and ongoing effect over a year,” said Dr. Spolnik, a nephrologist at Indiana University in Indianapolis.

However, CKD screening rates in the primary care setting remain a challenge. In the study, the EMR alert produced a urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) screening rate of about 26% of patient encounters, she reported. While this was significantly above the roughly 17% rate that had persisted for months before the intervention, it still fell short of the universal annual screening for adults with type 2 diabetes not previously diagnosed with CKD recommended by medical groups such as the American Diabetes Association and the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes organization. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force’s assessment in 2012 concluded inadequate information existed at that time to make recommendations about CKD screening, but the group is now revisiting the issue.

‘Albuminuria is an earlier marker’ than eGFR

“Primary care physicians need to regularly monitor albuminuria in adults with type 2 diabetes,” commented Karen A. Griffin, MD, a nephrologist and professor at Loyola University in Maywood, Ill. “By the time you diagnose CKD based on reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), a patient has already lost more than half their renal function. Albuminuria is an earlier marker of a problem,” Dr. Griffin said in an interview.

Primary care physicians have been slow to adopt at least annual checks on both eGFR and the urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) in their adult patients with type 2 diabetes. Dr. Spolnik cited reasons such as the brief 15-minute consultation that primary care physicians have when seeing a patient, and an often confusing ordering menu that gives a UACR test various other names such as tests for microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria.

To simplify ordering, the EMR prompt assessed in Dr. Spolnik’s study called the test “kidney screening” that automatically bundled an order for both eGFR calculation with UACR measurement. Another limitation is that UACR measurement requires a urine sample, which patients often find inconvenient to provide at the time of their examination.

The study run by Dr. Spolnik involved 10,744 adults with type 2 diabetes without an existing diagnosis of CKD seen in an outpatient, primary care visit to the UVA Health system centered in Charlottesville, Va. during April 2021–April 2022. A total of 23,419 encounters served as usual-care controls. The intervention period with active EMR alerts for kidney screening included 10,204 similar patients seen during April 2022–April 2023 in a total of 20,358 encounters. The patients averaged about 61-62 years old, and about 45% were men.

Bundling alerts into a single pop-up

The primary care clinicians who received the prompts were generally receptive to them, but they asked the researchers to bundle the UACR and eGFR measurement prompts along with any other alerts they received in the EMR into a single on-screen pop-up.

Dr. Spolnik acknowledged the need for further research and refinement to the prompt. For example, she wants to assess prompts for patients identified as having CKD that would promote best-practice management, including lifestyle and medical interventions. She also envisions expanding the prompts to also include other, related disorders such as hypertension.

But she and her colleagues were convinced enough by the results that they have not only continued the program at UVA Health but they also expanded it, starting in October 2023, to the academic primary care practice at Indiana University.