User login

Minimally invasive screening for Barrett’s esophagus offers cost-effective alternative

The high costs of endoscopy make screening patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) for Barrett’s esophagus a costly endeavor. But using a minimally invasive test followed by endoscopy only if results are positive could cut costs by up to 41%, according to investigators.

The report is in the September issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.02.017).

The findings mirror those from a prior study (Gastroenterology. 2013 Jan;144[1]:62-73.e60) of the new cytosponge device, which tests surface esophageal tissue for trefoil factor 3, a biomarker for Barrett’s esophagus, said Curtis R. Heberle, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and his associates. In addition, two separate models found the cytosponge strategy cost effective compared with no screening (incremental cost-effectiveness ratios [ICERs], about $26,000-$33,000). However, using the cytosponge instead of screening all GERD patients with endoscopy would reduce quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) by about 1.8-5.5 years for every 1,000 patients.

Rates of esophageal adenocarcinoma have climbed more than sixfold in the United States in 4 decades, and 5-year survival rates remain below 20%. Nonetheless, the high cost of endoscopy and 10%-20% prevalence of GERD makes screening all patients for Barrett’s esophagus infeasible. To evaluate the cytosponge strategy, the researchers fit data from the multicenter BEST2 study (PLoS Med. 2015 Jan; 12[1]: e1001780) into two validated models calibrated to high-quality Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data on esophageal cancer. Both models compared no screening with a one-time screen by either endoscopy alone or cytosponge with follow-up endoscopy in the event of a positive test. The models assumed patients were male, were 60 years old, and had GERD but not esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Without screening, there were about 14-16 cancer cases and about 15,077 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) for every 1,000 patients. The cytosponge strategy was associated with about 8-13 cancer cases and about 15,105 QALYs. Endoscopic screening produced the most benefit overall – only about 7-12 cancer cases, with more than 15,100 QALYs. “However, greater benefits were accompanied by higher total costs,” the researchers said. For every 1,000 patients, no screening cost about $704,000 to $762,000, the cytosponge strategy cost about $1.5 to $1.6 million, and population-wide endoscopy cost about $2.1 to $2.2 million. Thus, the cytosponge method would lower the cost of screening by 37%-41% compared with endoscopically screening all men with GERD. The cytosponge was also cost effective in a model of 60-year-old women with GERD.

Using only endoscopic screening was not cost effective in either model, exceeding a $100,000 threshold of willingness to pay by anywhere from $107,000 to $330,000. The cytosponge is not yet available commercially, but the investigators assumed it cost $182 based on information from the manufacturer (Medtronic) and Medicare payments for similar devices. Although the findings withstood variations in indirect costs and age at initial screening, they were “somewhat sensitive” to variations in costs of the cytosponge and its presumed sensitivity and specificity in clinical settings. However, endoscopic screening only became cost effective when the cytosponge test cost at least $225.

The models assumed perfect adherence to screening, which probably exaggerated the effectiveness of the cytosponge and endoscopic screening, the investigators said. They noted that cytosponge screening can be performed without sedation during a short outpatient visit.

The National Institutes of Health provided funding. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

The high costs of endoscopy make screening patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) for Barrett’s esophagus a costly endeavor. But using a minimally invasive test followed by endoscopy only if results are positive could cut costs by up to 41%, according to investigators.

The report is in the September issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.02.017).

The findings mirror those from a prior study (Gastroenterology. 2013 Jan;144[1]:62-73.e60) of the new cytosponge device, which tests surface esophageal tissue for trefoil factor 3, a biomarker for Barrett’s esophagus, said Curtis R. Heberle, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and his associates. In addition, two separate models found the cytosponge strategy cost effective compared with no screening (incremental cost-effectiveness ratios [ICERs], about $26,000-$33,000). However, using the cytosponge instead of screening all GERD patients with endoscopy would reduce quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) by about 1.8-5.5 years for every 1,000 patients.

Rates of esophageal adenocarcinoma have climbed more than sixfold in the United States in 4 decades, and 5-year survival rates remain below 20%. Nonetheless, the high cost of endoscopy and 10%-20% prevalence of GERD makes screening all patients for Barrett’s esophagus infeasible. To evaluate the cytosponge strategy, the researchers fit data from the multicenter BEST2 study (PLoS Med. 2015 Jan; 12[1]: e1001780) into two validated models calibrated to high-quality Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data on esophageal cancer. Both models compared no screening with a one-time screen by either endoscopy alone or cytosponge with follow-up endoscopy in the event of a positive test. The models assumed patients were male, were 60 years old, and had GERD but not esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Without screening, there were about 14-16 cancer cases and about 15,077 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) for every 1,000 patients. The cytosponge strategy was associated with about 8-13 cancer cases and about 15,105 QALYs. Endoscopic screening produced the most benefit overall – only about 7-12 cancer cases, with more than 15,100 QALYs. “However, greater benefits were accompanied by higher total costs,” the researchers said. For every 1,000 patients, no screening cost about $704,000 to $762,000, the cytosponge strategy cost about $1.5 to $1.6 million, and population-wide endoscopy cost about $2.1 to $2.2 million. Thus, the cytosponge method would lower the cost of screening by 37%-41% compared with endoscopically screening all men with GERD. The cytosponge was also cost effective in a model of 60-year-old women with GERD.

Using only endoscopic screening was not cost effective in either model, exceeding a $100,000 threshold of willingness to pay by anywhere from $107,000 to $330,000. The cytosponge is not yet available commercially, but the investigators assumed it cost $182 based on information from the manufacturer (Medtronic) and Medicare payments for similar devices. Although the findings withstood variations in indirect costs and age at initial screening, they were “somewhat sensitive” to variations in costs of the cytosponge and its presumed sensitivity and specificity in clinical settings. However, endoscopic screening only became cost effective when the cytosponge test cost at least $225.

The models assumed perfect adherence to screening, which probably exaggerated the effectiveness of the cytosponge and endoscopic screening, the investigators said. They noted that cytosponge screening can be performed without sedation during a short outpatient visit.

The National Institutes of Health provided funding. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

The high costs of endoscopy make screening patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) for Barrett’s esophagus a costly endeavor. But using a minimally invasive test followed by endoscopy only if results are positive could cut costs by up to 41%, according to investigators.

The report is in the September issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.02.017).

The findings mirror those from a prior study (Gastroenterology. 2013 Jan;144[1]:62-73.e60) of the new cytosponge device, which tests surface esophageal tissue for trefoil factor 3, a biomarker for Barrett’s esophagus, said Curtis R. Heberle, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and his associates. In addition, two separate models found the cytosponge strategy cost effective compared with no screening (incremental cost-effectiveness ratios [ICERs], about $26,000-$33,000). However, using the cytosponge instead of screening all GERD patients with endoscopy would reduce quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) by about 1.8-5.5 years for every 1,000 patients.

Rates of esophageal adenocarcinoma have climbed more than sixfold in the United States in 4 decades, and 5-year survival rates remain below 20%. Nonetheless, the high cost of endoscopy and 10%-20% prevalence of GERD makes screening all patients for Barrett’s esophagus infeasible. To evaluate the cytosponge strategy, the researchers fit data from the multicenter BEST2 study (PLoS Med. 2015 Jan; 12[1]: e1001780) into two validated models calibrated to high-quality Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data on esophageal cancer. Both models compared no screening with a one-time screen by either endoscopy alone or cytosponge with follow-up endoscopy in the event of a positive test. The models assumed patients were male, were 60 years old, and had GERD but not esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Without screening, there were about 14-16 cancer cases and about 15,077 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) for every 1,000 patients. The cytosponge strategy was associated with about 8-13 cancer cases and about 15,105 QALYs. Endoscopic screening produced the most benefit overall – only about 7-12 cancer cases, with more than 15,100 QALYs. “However, greater benefits were accompanied by higher total costs,” the researchers said. For every 1,000 patients, no screening cost about $704,000 to $762,000, the cytosponge strategy cost about $1.5 to $1.6 million, and population-wide endoscopy cost about $2.1 to $2.2 million. Thus, the cytosponge method would lower the cost of screening by 37%-41% compared with endoscopically screening all men with GERD. The cytosponge was also cost effective in a model of 60-year-old women with GERD.

Using only endoscopic screening was not cost effective in either model, exceeding a $100,000 threshold of willingness to pay by anywhere from $107,000 to $330,000. The cytosponge is not yet available commercially, but the investigators assumed it cost $182 based on information from the manufacturer (Medtronic) and Medicare payments for similar devices. Although the findings withstood variations in indirect costs and age at initial screening, they were “somewhat sensitive” to variations in costs of the cytosponge and its presumed sensitivity and specificity in clinical settings. However, endoscopic screening only became cost effective when the cytosponge test cost at least $225.

The models assumed perfect adherence to screening, which probably exaggerated the effectiveness of the cytosponge and endoscopic screening, the investigators said. They noted that cytosponge screening can be performed without sedation during a short outpatient visit.

The National Institutes of Health provided funding. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Using a minimally invasive screen for Barrett’s esophagus and following up with endoscopy if results are positive is a cost-effective alternative to endoscopy alone in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Major finding: The two-step screening strategy cut screening costs by 37%-41% but was associated with 1.8-5.5 fewer quality-adjusted life years for every 1,000 patients with GERD.

Data source: Two validated models based on Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data, and data from the multicenter BEST2 trial.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health provided funding. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

Ex Vivo Confocal Microscopy: A Diagnostic Tool for Skin Malignancies

Skin cancer is diagnosed in approximately 5.4 million individuals annually in the United States, more than the total number of breast, lung, colon, and prostate cancers diagnosed per year.1 It is estimated that 1 in 5 Americans will develop skin cancer during their lifetime.2 The 2 most common forms of skin cancer are basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), accounting for 4 million and 1 million cases diagnosed each year, respectively.3 With the increasing incidence of these skin cancers, the use of noninvasive imaging tools for detection and diagnosis has grown.

Ex vivo confocal microscopy is a diagnostic imaging tool that can be used in real-time at the bedside to assess freshly excised tissue for malignancies. It images tissue samples with cellular resolution and within minutes of biopsy or excision. Ex vivo confocal microscopy is a versatile tool that can assist in the diagnosis and management of skin malignancies such as melanoma, BCC, and SCC.

Reflectance vs Fluorescence Mode

Excised lesions can be examined in reflectance or fluorescence mode in great detail but with slightly varying nuclear-to-dermis contrasts depending on the chromophore that is targeted. In reflectance mode (reflectance confocal microscopy [RCM]), melanin and keratin act as endogenous chromophores because of their high refractive index relative to water,4,5 which allows for the visualization of cellular structures of the skin at low power, as well as microscopic substructures such as melanosomes, cytoplasmic granules, and other cellular organelles at high power. Although an exogenous contrast agent is not required, acetic acid has the capability to highlight nuclei, enhancing the tumor cell-to-dermis contrast in RCM.6 Acetic acid is clinically used as a predictor for certain skin and mucosal membrane neoplasms that blanch when exposed to the solution. In the case of RCM, acetic acid increases the visibility of nuclei by inducing the compaction of chromatin. For the acetowhitening to be effective, the sample must be soaked in the solution for a specific amount of time, depending on the concentration.7 A concentration between 1% and 10% can be used, but the less concentrated the solution, the longer the time of soaking that is required to achieve sufficiently bright nuclei.6

The contrast with acetic acid, however, is quite weak when the tissue is imaged en face, or along the horizontal surface of the sample, due to the collagen in the dermal layer, which has a high reflectance index. This issue is rectified when using the confocal microscope in the fluorescence mode with an exogenous fluorescent dye as a nuclear stain. Fluorescence confocal microscopy (FCM), results in a stronger nuclear-to-dermal contrast because of the role of contrast agents.8 The 1000-fold increase in contrast between nuclei and dermis is the result of dye agents that preferentially bind to nuclear DNA, of which acridine orange is the most commonly used.5,8 Basal cell carcinoma and SCC tumor cells can be visualized with FCM because they appear hyperfluorescent when stained with acridine orange.9 The acridine orange–stained cells display bright nuclei, while the cytoplasm and collagen remains dark. A positive feature of acridine orange is that it does not alter the tissue sample during freezing or formalin fixation and thus has no effect on subsequent histopathology that may need to be performed on the sample.10

High-Resolution Images Aid in Diagnosis

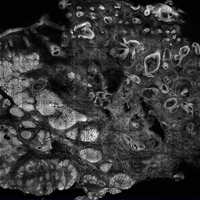

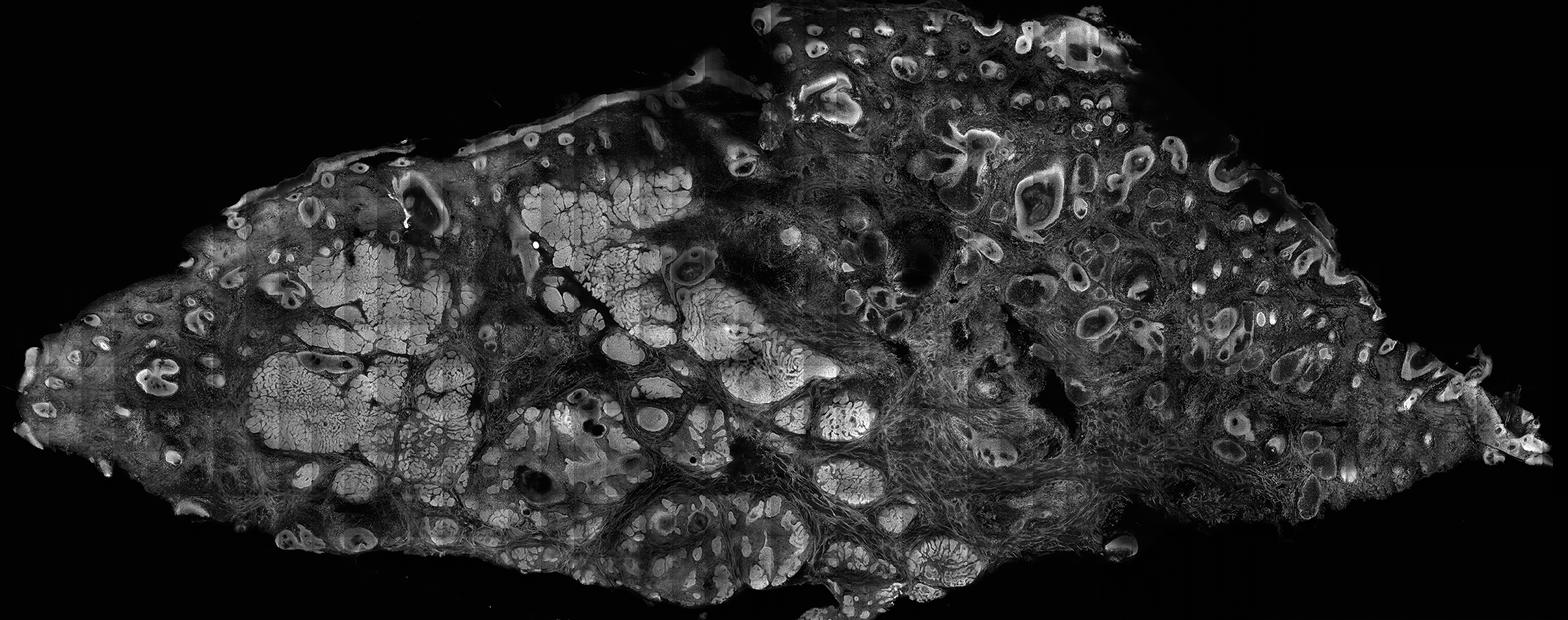

After it is harvested, the tissue sample is soaked in a contrast agent or dye, if needed, depending on the confocal mode to be used. The confocal microscope is then used to take a series of high-resolution individual en face images that are then stitched together to create a final mosaic image that can be up to 12×12 mm.6,11 With a 200-µm depth visibility, confocal microscopy can capture the cellular structures in the epidermis, dermis, and (if compressed enough) subcutaneous fat in just under 3 minutes.12

The images produced through confocal microscopy have an excellent correlation to frozen histological sections and can aid in the diagnosis of many epidermal and dermal malignancies including melanoma, BCC, and SCC. New criteria have been established to aid in the interpretation of the confocal images and identify some of the more common skin cancers.5,12,13 Basal cell carcinoma samples imaged through fluorescence and reflectance in low-power mode display the distinct nodular patterns with well-demarcated edges, as seen on classical histopathology. In the case of FCM, the cells that make up the tumor display hyperfluorescent areas consistent with nucleated cells that are stained with acridine orange. The main features that identify BCC on FCM images include nuclear pleomorphism and crowding, peripheral palisading, clefting of the basaloid islands, increased nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio, and the presence of a modified dermis surrounding the mass known as the tumoral stroma5,12 (Figure).

In addition to fluorescence and a well-defined tumor silhouette, SCC under FCM displays keratin pearls composed of keratinized squames, nuclear pleomorphism, and fluorescent scales in the stratum corneum that are a result of keratin formation.5,13 The extent of differentiation of the SCC lesion also can be determined by assessing if the silhouette is well defined. A well-defined tumor silhouette is consistent with the diagnosis of a well-differentiated SCC, and vice versa.13 Ex vivo RCM also has been shown to be useful in diagnosing malignant melanomas, with melanin acting as an endogenous chromophore. Some of the features seen on imaging include a disarranged epithelium, hyperreflective roundish and dendritic pagetoid cells, and large hyperreflective polymorphic cells in the superficial chorion.14

Comparison to Conventional Histopathology

Ex vivo confocal microscopy in both the reflectance and fluorescence mode has been shown to perform well compared to conventional histopathology in the diagnosis of biopsy specimens. Ex vivo FCM has been shown to have an overall sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 99% in detecting residual BCC at the margins of excised tissue samples and in the fraction of the time it takes to attain similar results with frozen histopathology.9 Ex vivo RCM has been shown to have a higher prognostic capability, with 100% sensitivity and specificity in identifying BCC when scanning the tissue samples en face.15

Qualitatively, the images produced by RCM and FCM are similar to histopathology in overall architecture. Both techniques enhance the contrast between the epithelium and stroma and create images that can be examined in low as well as high resolution. A substantial difference between confocal microscopy and conventional hematoxylin and eosin–stained histopathology is that the confocal microscope produces images in gray scale. One way to alter the black-and-white images to resemble hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides is through the use of digital staining,16 which could boost clinical acceptance by physicians who are accustomed to the classical pink-purple appearance of pathology slides and could potentially limit the learning curve needed to read the confocal images.

Application in Mohs Micrographic Surgery

An important clinical application of ex vivo FCM imaging that has emerged is the detection of malignant cells at the excision margins during Mohs micrographic surgery. The use of confocal microscopy has the potential to save time by eliminating the need for tissue fixation while still providing good diagnostic accuracy. Implementing FCM as an imaging tool to guide surgical excisions could provide rapid diagnosis of the tissue, expediting excisions and reconstruction or the Mohs procedure while eliminating patient wait time and the need for frozen histopathology. Ex vivo RCM also has been used to establish laser parameters for CO2 laser ablation of superficial and early nodular BCC lesions.17 Other potential uses for ex vivo RCM/FCM could include rapid evaluation of tissue during operating room procedures where rapid frozen sections are currently utilized.

Combining In Vivo and Ex Vivo Confocal Microscopy

Many of the diagnostic guidelines created with the use of ex vivo confocal microscopy have been applied to in vivo use, and therefore the use of both modalities is appealing. In vivo confocal microscopy is a noninvasive technique that has been used to map margins of skin tumors such as BCC and lentigo maligna at the bedside.5 It also has been shown to help plan both surgical and nonsurgical treatment modalities and reconstruction before the tumor is excised.18 This technique also can help the patient understand the extent of the excision and any subsequent reconstruction that may be needed.

Limitations

Ex vivo confocal microscopy used as a diagnostic tool does have some limitations. Its novelty may require surgeons and pathologists to be trained to interpret the images properly and correlate them to conventional diagnostic guidelines. The imaging also is limited to a depth of approximately 200 µm; however, the sample may be flipped so that the underside can be imaged as well, which increases the depth to approximately 400 µm. The tissue being imaged must be fixed flat, which may alter its shape. Complex tissue samples may be difficult to flatten out completely and therefore may be difficult to image. A special mount may be required for the sample to be fixed in a proper position for imaging.6

Final Thoughts

Despite some of these limitations, the need for rapid bedside tissue diagnosis makes ex vivo confocal microscopy an attractive device that can be used as an additional diagnostic tool to histopathology and also has been tested in other disciplines, such as breast cancer pathology. In the future, both in vivo and ex vivo confocal microscopy may be utilized to diagnose cutaneous malignancies, guide surgical excisions, and detect lesion progression, and it may become a basis for rapid diagnosis and detection.19

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016 [published online January 7, 2016]. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7-30.

- Robinson JK. Sun exposure, sun protection, and vitamin D. JAMA. 2005;294:1541-1543.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Welzel J, Kästle R, Sattler EC. Fluorescence (multiwave) confocal microscopy. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:527-533.

- Longo C, Ragazzi M, Rajadhyaksha M, et al. In vivo and ex vivo confocal microscopy for dermatologic and Mohs surgeons. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:497-504.

- Patel YG, Nehal KS, Aranda I, et al. Confocal reflectance mosaicing of basal cell carcinomas in Mohs surgical skin excisions. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12:034027.

- Rajadhyaksha M, Gonzalez S, Zavislan JM. Detectability of contrast agents for confocal reflectance imaging of skin and microcirculation. J Biomed Opt. 2004;9:323-331.

- Karen JK, Gareau DS, Dusza SW, et al. Detection of basal cell carcinomas in Mohs excisions with fluorescence confocal mosaicing microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:1242-1250.

- Bennàssar A, Vilata A, Puig S, et al. Ex vivo fluorescence confocal microscopy for fast evaluation of tumour margins during Mohs surgery. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:360-365.

- Gareau DS, Li Y, Huang B, et al. Confocal mosaicing microscopy in Mohs skin excisions: feasibility of rapid surgical pathology. J Biomed Opt. 2008;13:054001.

- Bini J, Spain J, Nehal K, et al. Confocal mosaicing microscopy of human skin ex vivo: spectral analysis for digital staining to simulate histology-like appearance. J Biomed Opt. 2011;16:076008.

- Bennàssar A, Carrera C, Puig S, et al. Fast evaluation of 69 basal cell carcinomas with ex vivo fluorescence confocal microscopy: criteria description, histopathological correlation, and interobserver agreement. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:839-847.

- Longo C, Ragazzi M, Gardini S, et al. Ex vivo fluorescence confocal microscopy in conjunction with Mohs micrographic surgery for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:321-322.

- Cinotti E, Haouas M, Grivet D, et al. In vivo and ex vivo confocal microscopy for the management of a melanoma of the eyelid margin. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:1437-1440.

- , , , ‘En face’ ex vivo reflectance confocal microscopy to help the surgery of basal cell carcinoma of the eyelid [published online December 19, 2016]. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. doi:10.1111/ceo.12904.

- Gareau DS, Jeon H, Nehal KS, et al. Rapid screening of cancer margins in tissue with multimodal confocal microscopy. J Surg Res. 2012;178:533-538.

- Sierra H, Damanpour S, Hibler B, et al. Confocal imaging of carbon dioxide laser-ablated basal cell carcinomas: an ex-vivo study on the uptake of contrast agent and ablation parameters [published online September 22, 2015]. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:133-139.

- Hibler BP, Yélamos O, Cordova M, et al. Handheld reflectance confocal microscopy to aid in the management of complex facial lentigo maligna. Cutis. 2017;99:346-352.

- Rajadhyaksha M, Marghoob A, Rossi A, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy of skin in vivo: from bench to bedside. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:7-19.

Skin cancer is diagnosed in approximately 5.4 million individuals annually in the United States, more than the total number of breast, lung, colon, and prostate cancers diagnosed per year.1 It is estimated that 1 in 5 Americans will develop skin cancer during their lifetime.2 The 2 most common forms of skin cancer are basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), accounting for 4 million and 1 million cases diagnosed each year, respectively.3 With the increasing incidence of these skin cancers, the use of noninvasive imaging tools for detection and diagnosis has grown.

Ex vivo confocal microscopy is a diagnostic imaging tool that can be used in real-time at the bedside to assess freshly excised tissue for malignancies. It images tissue samples with cellular resolution and within minutes of biopsy or excision. Ex vivo confocal microscopy is a versatile tool that can assist in the diagnosis and management of skin malignancies such as melanoma, BCC, and SCC.

Reflectance vs Fluorescence Mode

Excised lesions can be examined in reflectance or fluorescence mode in great detail but with slightly varying nuclear-to-dermis contrasts depending on the chromophore that is targeted. In reflectance mode (reflectance confocal microscopy [RCM]), melanin and keratin act as endogenous chromophores because of their high refractive index relative to water,4,5 which allows for the visualization of cellular structures of the skin at low power, as well as microscopic substructures such as melanosomes, cytoplasmic granules, and other cellular organelles at high power. Although an exogenous contrast agent is not required, acetic acid has the capability to highlight nuclei, enhancing the tumor cell-to-dermis contrast in RCM.6 Acetic acid is clinically used as a predictor for certain skin and mucosal membrane neoplasms that blanch when exposed to the solution. In the case of RCM, acetic acid increases the visibility of nuclei by inducing the compaction of chromatin. For the acetowhitening to be effective, the sample must be soaked in the solution for a specific amount of time, depending on the concentration.7 A concentration between 1% and 10% can be used, but the less concentrated the solution, the longer the time of soaking that is required to achieve sufficiently bright nuclei.6

The contrast with acetic acid, however, is quite weak when the tissue is imaged en face, or along the horizontal surface of the sample, due to the collagen in the dermal layer, which has a high reflectance index. This issue is rectified when using the confocal microscope in the fluorescence mode with an exogenous fluorescent dye as a nuclear stain. Fluorescence confocal microscopy (FCM), results in a stronger nuclear-to-dermal contrast because of the role of contrast agents.8 The 1000-fold increase in contrast between nuclei and dermis is the result of dye agents that preferentially bind to nuclear DNA, of which acridine orange is the most commonly used.5,8 Basal cell carcinoma and SCC tumor cells can be visualized with FCM because they appear hyperfluorescent when stained with acridine orange.9 The acridine orange–stained cells display bright nuclei, while the cytoplasm and collagen remains dark. A positive feature of acridine orange is that it does not alter the tissue sample during freezing or formalin fixation and thus has no effect on subsequent histopathology that may need to be performed on the sample.10

High-Resolution Images Aid in Diagnosis

After it is harvested, the tissue sample is soaked in a contrast agent or dye, if needed, depending on the confocal mode to be used. The confocal microscope is then used to take a series of high-resolution individual en face images that are then stitched together to create a final mosaic image that can be up to 12×12 mm.6,11 With a 200-µm depth visibility, confocal microscopy can capture the cellular structures in the epidermis, dermis, and (if compressed enough) subcutaneous fat in just under 3 minutes.12

The images produced through confocal microscopy have an excellent correlation to frozen histological sections and can aid in the diagnosis of many epidermal and dermal malignancies including melanoma, BCC, and SCC. New criteria have been established to aid in the interpretation of the confocal images and identify some of the more common skin cancers.5,12,13 Basal cell carcinoma samples imaged through fluorescence and reflectance in low-power mode display the distinct nodular patterns with well-demarcated edges, as seen on classical histopathology. In the case of FCM, the cells that make up the tumor display hyperfluorescent areas consistent with nucleated cells that are stained with acridine orange. The main features that identify BCC on FCM images include nuclear pleomorphism and crowding, peripheral palisading, clefting of the basaloid islands, increased nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio, and the presence of a modified dermis surrounding the mass known as the tumoral stroma5,12 (Figure).

In addition to fluorescence and a well-defined tumor silhouette, SCC under FCM displays keratin pearls composed of keratinized squames, nuclear pleomorphism, and fluorescent scales in the stratum corneum that are a result of keratin formation.5,13 The extent of differentiation of the SCC lesion also can be determined by assessing if the silhouette is well defined. A well-defined tumor silhouette is consistent with the diagnosis of a well-differentiated SCC, and vice versa.13 Ex vivo RCM also has been shown to be useful in diagnosing malignant melanomas, with melanin acting as an endogenous chromophore. Some of the features seen on imaging include a disarranged epithelium, hyperreflective roundish and dendritic pagetoid cells, and large hyperreflective polymorphic cells in the superficial chorion.14

Comparison to Conventional Histopathology

Ex vivo confocal microscopy in both the reflectance and fluorescence mode has been shown to perform well compared to conventional histopathology in the diagnosis of biopsy specimens. Ex vivo FCM has been shown to have an overall sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 99% in detecting residual BCC at the margins of excised tissue samples and in the fraction of the time it takes to attain similar results with frozen histopathology.9 Ex vivo RCM has been shown to have a higher prognostic capability, with 100% sensitivity and specificity in identifying BCC when scanning the tissue samples en face.15

Qualitatively, the images produced by RCM and FCM are similar to histopathology in overall architecture. Both techniques enhance the contrast between the epithelium and stroma and create images that can be examined in low as well as high resolution. A substantial difference between confocal microscopy and conventional hematoxylin and eosin–stained histopathology is that the confocal microscope produces images in gray scale. One way to alter the black-and-white images to resemble hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides is through the use of digital staining,16 which could boost clinical acceptance by physicians who are accustomed to the classical pink-purple appearance of pathology slides and could potentially limit the learning curve needed to read the confocal images.

Application in Mohs Micrographic Surgery

An important clinical application of ex vivo FCM imaging that has emerged is the detection of malignant cells at the excision margins during Mohs micrographic surgery. The use of confocal microscopy has the potential to save time by eliminating the need for tissue fixation while still providing good diagnostic accuracy. Implementing FCM as an imaging tool to guide surgical excisions could provide rapid diagnosis of the tissue, expediting excisions and reconstruction or the Mohs procedure while eliminating patient wait time and the need for frozen histopathology. Ex vivo RCM also has been used to establish laser parameters for CO2 laser ablation of superficial and early nodular BCC lesions.17 Other potential uses for ex vivo RCM/FCM could include rapid evaluation of tissue during operating room procedures where rapid frozen sections are currently utilized.

Combining In Vivo and Ex Vivo Confocal Microscopy

Many of the diagnostic guidelines created with the use of ex vivo confocal microscopy have been applied to in vivo use, and therefore the use of both modalities is appealing. In vivo confocal microscopy is a noninvasive technique that has been used to map margins of skin tumors such as BCC and lentigo maligna at the bedside.5 It also has been shown to help plan both surgical and nonsurgical treatment modalities and reconstruction before the tumor is excised.18 This technique also can help the patient understand the extent of the excision and any subsequent reconstruction that may be needed.

Limitations

Ex vivo confocal microscopy used as a diagnostic tool does have some limitations. Its novelty may require surgeons and pathologists to be trained to interpret the images properly and correlate them to conventional diagnostic guidelines. The imaging also is limited to a depth of approximately 200 µm; however, the sample may be flipped so that the underside can be imaged as well, which increases the depth to approximately 400 µm. The tissue being imaged must be fixed flat, which may alter its shape. Complex tissue samples may be difficult to flatten out completely and therefore may be difficult to image. A special mount may be required for the sample to be fixed in a proper position for imaging.6

Final Thoughts

Despite some of these limitations, the need for rapid bedside tissue diagnosis makes ex vivo confocal microscopy an attractive device that can be used as an additional diagnostic tool to histopathology and also has been tested in other disciplines, such as breast cancer pathology. In the future, both in vivo and ex vivo confocal microscopy may be utilized to diagnose cutaneous malignancies, guide surgical excisions, and detect lesion progression, and it may become a basis for rapid diagnosis and detection.19

Skin cancer is diagnosed in approximately 5.4 million individuals annually in the United States, more than the total number of breast, lung, colon, and prostate cancers diagnosed per year.1 It is estimated that 1 in 5 Americans will develop skin cancer during their lifetime.2 The 2 most common forms of skin cancer are basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), accounting for 4 million and 1 million cases diagnosed each year, respectively.3 With the increasing incidence of these skin cancers, the use of noninvasive imaging tools for detection and diagnosis has grown.

Ex vivo confocal microscopy is a diagnostic imaging tool that can be used in real-time at the bedside to assess freshly excised tissue for malignancies. It images tissue samples with cellular resolution and within minutes of biopsy or excision. Ex vivo confocal microscopy is a versatile tool that can assist in the diagnosis and management of skin malignancies such as melanoma, BCC, and SCC.

Reflectance vs Fluorescence Mode

Excised lesions can be examined in reflectance or fluorescence mode in great detail but with slightly varying nuclear-to-dermis contrasts depending on the chromophore that is targeted. In reflectance mode (reflectance confocal microscopy [RCM]), melanin and keratin act as endogenous chromophores because of their high refractive index relative to water,4,5 which allows for the visualization of cellular structures of the skin at low power, as well as microscopic substructures such as melanosomes, cytoplasmic granules, and other cellular organelles at high power. Although an exogenous contrast agent is not required, acetic acid has the capability to highlight nuclei, enhancing the tumor cell-to-dermis contrast in RCM.6 Acetic acid is clinically used as a predictor for certain skin and mucosal membrane neoplasms that blanch when exposed to the solution. In the case of RCM, acetic acid increases the visibility of nuclei by inducing the compaction of chromatin. For the acetowhitening to be effective, the sample must be soaked in the solution for a specific amount of time, depending on the concentration.7 A concentration between 1% and 10% can be used, but the less concentrated the solution, the longer the time of soaking that is required to achieve sufficiently bright nuclei.6

The contrast with acetic acid, however, is quite weak when the tissue is imaged en face, or along the horizontal surface of the sample, due to the collagen in the dermal layer, which has a high reflectance index. This issue is rectified when using the confocal microscope in the fluorescence mode with an exogenous fluorescent dye as a nuclear stain. Fluorescence confocal microscopy (FCM), results in a stronger nuclear-to-dermal contrast because of the role of contrast agents.8 The 1000-fold increase in contrast between nuclei and dermis is the result of dye agents that preferentially bind to nuclear DNA, of which acridine orange is the most commonly used.5,8 Basal cell carcinoma and SCC tumor cells can be visualized with FCM because they appear hyperfluorescent when stained with acridine orange.9 The acridine orange–stained cells display bright nuclei, while the cytoplasm and collagen remains dark. A positive feature of acridine orange is that it does not alter the tissue sample during freezing or formalin fixation and thus has no effect on subsequent histopathology that may need to be performed on the sample.10

High-Resolution Images Aid in Diagnosis

After it is harvested, the tissue sample is soaked in a contrast agent or dye, if needed, depending on the confocal mode to be used. The confocal microscope is then used to take a series of high-resolution individual en face images that are then stitched together to create a final mosaic image that can be up to 12×12 mm.6,11 With a 200-µm depth visibility, confocal microscopy can capture the cellular structures in the epidermis, dermis, and (if compressed enough) subcutaneous fat in just under 3 minutes.12

The images produced through confocal microscopy have an excellent correlation to frozen histological sections and can aid in the diagnosis of many epidermal and dermal malignancies including melanoma, BCC, and SCC. New criteria have been established to aid in the interpretation of the confocal images and identify some of the more common skin cancers.5,12,13 Basal cell carcinoma samples imaged through fluorescence and reflectance in low-power mode display the distinct nodular patterns with well-demarcated edges, as seen on classical histopathology. In the case of FCM, the cells that make up the tumor display hyperfluorescent areas consistent with nucleated cells that are stained with acridine orange. The main features that identify BCC on FCM images include nuclear pleomorphism and crowding, peripheral palisading, clefting of the basaloid islands, increased nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio, and the presence of a modified dermis surrounding the mass known as the tumoral stroma5,12 (Figure).

In addition to fluorescence and a well-defined tumor silhouette, SCC under FCM displays keratin pearls composed of keratinized squames, nuclear pleomorphism, and fluorescent scales in the stratum corneum that are a result of keratin formation.5,13 The extent of differentiation of the SCC lesion also can be determined by assessing if the silhouette is well defined. A well-defined tumor silhouette is consistent with the diagnosis of a well-differentiated SCC, and vice versa.13 Ex vivo RCM also has been shown to be useful in diagnosing malignant melanomas, with melanin acting as an endogenous chromophore. Some of the features seen on imaging include a disarranged epithelium, hyperreflective roundish and dendritic pagetoid cells, and large hyperreflective polymorphic cells in the superficial chorion.14

Comparison to Conventional Histopathology

Ex vivo confocal microscopy in both the reflectance and fluorescence mode has been shown to perform well compared to conventional histopathology in the diagnosis of biopsy specimens. Ex vivo FCM has been shown to have an overall sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 99% in detecting residual BCC at the margins of excised tissue samples and in the fraction of the time it takes to attain similar results with frozen histopathology.9 Ex vivo RCM has been shown to have a higher prognostic capability, with 100% sensitivity and specificity in identifying BCC when scanning the tissue samples en face.15

Qualitatively, the images produced by RCM and FCM are similar to histopathology in overall architecture. Both techniques enhance the contrast between the epithelium and stroma and create images that can be examined in low as well as high resolution. A substantial difference between confocal microscopy and conventional hematoxylin and eosin–stained histopathology is that the confocal microscope produces images in gray scale. One way to alter the black-and-white images to resemble hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides is through the use of digital staining,16 which could boost clinical acceptance by physicians who are accustomed to the classical pink-purple appearance of pathology slides and could potentially limit the learning curve needed to read the confocal images.

Application in Mohs Micrographic Surgery

An important clinical application of ex vivo FCM imaging that has emerged is the detection of malignant cells at the excision margins during Mohs micrographic surgery. The use of confocal microscopy has the potential to save time by eliminating the need for tissue fixation while still providing good diagnostic accuracy. Implementing FCM as an imaging tool to guide surgical excisions could provide rapid diagnosis of the tissue, expediting excisions and reconstruction or the Mohs procedure while eliminating patient wait time and the need for frozen histopathology. Ex vivo RCM also has been used to establish laser parameters for CO2 laser ablation of superficial and early nodular BCC lesions.17 Other potential uses for ex vivo RCM/FCM could include rapid evaluation of tissue during operating room procedures where rapid frozen sections are currently utilized.

Combining In Vivo and Ex Vivo Confocal Microscopy

Many of the diagnostic guidelines created with the use of ex vivo confocal microscopy have been applied to in vivo use, and therefore the use of both modalities is appealing. In vivo confocal microscopy is a noninvasive technique that has been used to map margins of skin tumors such as BCC and lentigo maligna at the bedside.5 It also has been shown to help plan both surgical and nonsurgical treatment modalities and reconstruction before the tumor is excised.18 This technique also can help the patient understand the extent of the excision and any subsequent reconstruction that may be needed.

Limitations

Ex vivo confocal microscopy used as a diagnostic tool does have some limitations. Its novelty may require surgeons and pathologists to be trained to interpret the images properly and correlate them to conventional diagnostic guidelines. The imaging also is limited to a depth of approximately 200 µm; however, the sample may be flipped so that the underside can be imaged as well, which increases the depth to approximately 400 µm. The tissue being imaged must be fixed flat, which may alter its shape. Complex tissue samples may be difficult to flatten out completely and therefore may be difficult to image. A special mount may be required for the sample to be fixed in a proper position for imaging.6

Final Thoughts

Despite some of these limitations, the need for rapid bedside tissue diagnosis makes ex vivo confocal microscopy an attractive device that can be used as an additional diagnostic tool to histopathology and also has been tested in other disciplines, such as breast cancer pathology. In the future, both in vivo and ex vivo confocal microscopy may be utilized to diagnose cutaneous malignancies, guide surgical excisions, and detect lesion progression, and it may become a basis for rapid diagnosis and detection.19

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016 [published online January 7, 2016]. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7-30.

- Robinson JK. Sun exposure, sun protection, and vitamin D. JAMA. 2005;294:1541-1543.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Welzel J, Kästle R, Sattler EC. Fluorescence (multiwave) confocal microscopy. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:527-533.

- Longo C, Ragazzi M, Rajadhyaksha M, et al. In vivo and ex vivo confocal microscopy for dermatologic and Mohs surgeons. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:497-504.

- Patel YG, Nehal KS, Aranda I, et al. Confocal reflectance mosaicing of basal cell carcinomas in Mohs surgical skin excisions. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12:034027.

- Rajadhyaksha M, Gonzalez S, Zavislan JM. Detectability of contrast agents for confocal reflectance imaging of skin and microcirculation. J Biomed Opt. 2004;9:323-331.

- Karen JK, Gareau DS, Dusza SW, et al. Detection of basal cell carcinomas in Mohs excisions with fluorescence confocal mosaicing microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:1242-1250.

- Bennàssar A, Vilata A, Puig S, et al. Ex vivo fluorescence confocal microscopy for fast evaluation of tumour margins during Mohs surgery. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:360-365.

- Gareau DS, Li Y, Huang B, et al. Confocal mosaicing microscopy in Mohs skin excisions: feasibility of rapid surgical pathology. J Biomed Opt. 2008;13:054001.

- Bini J, Spain J, Nehal K, et al. Confocal mosaicing microscopy of human skin ex vivo: spectral analysis for digital staining to simulate histology-like appearance. J Biomed Opt. 2011;16:076008.

- Bennàssar A, Carrera C, Puig S, et al. Fast evaluation of 69 basal cell carcinomas with ex vivo fluorescence confocal microscopy: criteria description, histopathological correlation, and interobserver agreement. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:839-847.

- Longo C, Ragazzi M, Gardini S, et al. Ex vivo fluorescence confocal microscopy in conjunction with Mohs micrographic surgery for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:321-322.

- Cinotti E, Haouas M, Grivet D, et al. In vivo and ex vivo confocal microscopy for the management of a melanoma of the eyelid margin. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:1437-1440.

- , , , ‘En face’ ex vivo reflectance confocal microscopy to help the surgery of basal cell carcinoma of the eyelid [published online December 19, 2016]. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. doi:10.1111/ceo.12904.

- Gareau DS, Jeon H, Nehal KS, et al. Rapid screening of cancer margins in tissue with multimodal confocal microscopy. J Surg Res. 2012;178:533-538.

- Sierra H, Damanpour S, Hibler B, et al. Confocal imaging of carbon dioxide laser-ablated basal cell carcinomas: an ex-vivo study on the uptake of contrast agent and ablation parameters [published online September 22, 2015]. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:133-139.

- Hibler BP, Yélamos O, Cordova M, et al. Handheld reflectance confocal microscopy to aid in the management of complex facial lentigo maligna. Cutis. 2017;99:346-352.

- Rajadhyaksha M, Marghoob A, Rossi A, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy of skin in vivo: from bench to bedside. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:7-19.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016 [published online January 7, 2016]. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7-30.

- Robinson JK. Sun exposure, sun protection, and vitamin D. JAMA. 2005;294:1541-1543.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Welzel J, Kästle R, Sattler EC. Fluorescence (multiwave) confocal microscopy. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:527-533.

- Longo C, Ragazzi M, Rajadhyaksha M, et al. In vivo and ex vivo confocal microscopy for dermatologic and Mohs surgeons. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:497-504.

- Patel YG, Nehal KS, Aranda I, et al. Confocal reflectance mosaicing of basal cell carcinomas in Mohs surgical skin excisions. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12:034027.

- Rajadhyaksha M, Gonzalez S, Zavislan JM. Detectability of contrast agents for confocal reflectance imaging of skin and microcirculation. J Biomed Opt. 2004;9:323-331.

- Karen JK, Gareau DS, Dusza SW, et al. Detection of basal cell carcinomas in Mohs excisions with fluorescence confocal mosaicing microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:1242-1250.

- Bennàssar A, Vilata A, Puig S, et al. Ex vivo fluorescence confocal microscopy for fast evaluation of tumour margins during Mohs surgery. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:360-365.

- Gareau DS, Li Y, Huang B, et al. Confocal mosaicing microscopy in Mohs skin excisions: feasibility of rapid surgical pathology. J Biomed Opt. 2008;13:054001.

- Bini J, Spain J, Nehal K, et al. Confocal mosaicing microscopy of human skin ex vivo: spectral analysis for digital staining to simulate histology-like appearance. J Biomed Opt. 2011;16:076008.

- Bennàssar A, Carrera C, Puig S, et al. Fast evaluation of 69 basal cell carcinomas with ex vivo fluorescence confocal microscopy: criteria description, histopathological correlation, and interobserver agreement. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:839-847.

- Longo C, Ragazzi M, Gardini S, et al. Ex vivo fluorescence confocal microscopy in conjunction with Mohs micrographic surgery for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:321-322.

- Cinotti E, Haouas M, Grivet D, et al. In vivo and ex vivo confocal microscopy for the management of a melanoma of the eyelid margin. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:1437-1440.

- , , , ‘En face’ ex vivo reflectance confocal microscopy to help the surgery of basal cell carcinoma of the eyelid [published online December 19, 2016]. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. doi:10.1111/ceo.12904.

- Gareau DS, Jeon H, Nehal KS, et al. Rapid screening of cancer margins in tissue with multimodal confocal microscopy. J Surg Res. 2012;178:533-538.

- Sierra H, Damanpour S, Hibler B, et al. Confocal imaging of carbon dioxide laser-ablated basal cell carcinomas: an ex-vivo study on the uptake of contrast agent and ablation parameters [published online September 22, 2015]. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:133-139.

- Hibler BP, Yélamos O, Cordova M, et al. Handheld reflectance confocal microscopy to aid in the management of complex facial lentigo maligna. Cutis. 2017;99:346-352.

- Rajadhyaksha M, Marghoob A, Rossi A, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy of skin in vivo: from bench to bedside. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:7-19.

Practice Points

- Confocal microscopy is an imaging tool that can be used both in vivo and ex vivo to aid in the diagnosis and management of cutaneous neoplasms, including melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma, as well as inflammatory dermatoses.

- Ex vivo confocal microscopy can be used in both reflectance and fluorescent modes to render diagnosis in excised tissue or check surgical margins.

- Both in vivo and ex vivo confocal microscopy produces images with cellular resolution with a main limitation being depth of imaging.

Surveillance Colonoscopy After Screening Polypectomy Reduces Colorectal Cancer Incidence in Intermediate-Risk Patients

Study Overview

Objective. To examine the heterogeneity in colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence in intermediate-risk patients and the effect of surveillance on CRC incidence.

Design. Retrospective, multicenter cohort study.

Setting and participants. Study patients underwent colonoscopy between 1 January 1990 and 21 December 2010 at 17 hospitals in the United Kingdom. Patients were eligible for the study if they had a baseline colonoscopy with a newly diagnosed intermediate-risk adenoma. Intermediate-risk adenomas (as defined by the UK guidelines) included 1 to 2 large adenomas ≥ 10 mm or 3 to 4 small adenomas < 10 mm in size. Patients with a history of prior resections, colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease or a family history of CRC were excluded from the study. Patient, procedural, and polyp characteristics were assessed at baseline.

Main outcome measures. The primary outcome was inci-dence of CRC. Additional factors assessed included age at first polyp detection, sex, completeness of colonoscopy, preparation quality, number of adenomas, size of largest adenoma, histology, and location. Proximal polyps were defined as those proximal to the descending colon. Information regarding social history (eg, smoking status) was not available.

Results. The authors identified 253,798 patients who underwent colonoscopy between 1 January 1990 and 21 December 2010. Of those, 223,539 were excluded based on not meeting the pre-specified inclusion criteria, resulting in 30,259 eligible patients for analysis. Review of histological data confirmed intermediate-risk adenomas in 11,995 (40%) of the patients. The median age in this study was 66 years and 55% were men. Fifty-eight percent attended 1 or more follow-up surveillance visits while 42% had no follow-up surveillance colonoscopy. Those who attended more than 1 follow-up surveillance visits were younger, had a greater proportion of large adenomas (> 20 mm), or had an adenoma with high-grade dysplasia. Both groups had similar rates of villous histology (9% vs. 10%).

After a median follow-up of 7.9 years, 210 CRCs were diagnosed and 32% of patients died. In the group with no follow-up surveillance, 46% died and 2% were diagnosed with cancer. In the group who had 1 or more follow-up colonoscopies, 21% died and 1% were diagnosed with cancer. One or 2 surveillance visits were associated with a significant reduction in CRC incidence (HR 0.57 [95% confidence interval {CI} 0.4–0.8) and 0.51 [95% CI 0.31–0.84], respectively). Three or more surveillance exams were also associated with a similar reduction in CRC incidence (HR 0.54; CI 0.29–0.99). Characteristics associated with increased CRC incidence were older age, adenomas > 20 mm, high-grade dysplasia, proximal polyps, and colonoscopies that were either incomplete or with poor preparation. The number of adenomas was not independently associated with CRC incidence.

The authors divided the cohort into higher-risk (74%) and lower-risk (26%) subgroups based on polyp and procedural characteristics. The higher-risk group included patients with baseline adenomas ≥ 20 mm, high-grade dysplasia, proximal polyps, or suboptimal evaluation. The lower-risk group included all others. CRC incidence was higher in the “higher-risk” subgroup (247 CRC per 100,000 vs. 93 CRC per 100,000). In the higher-risk group, risk of CRC decreased with more surveillance visits, a finding that was not observed in the lower-risk group. The 10-year incidence of CRC in the cohort overall was 2.7%, in the higher-risk group was 3.3% and in the lower risk group was 1.1%. CRC incidence was significantly higher in the higher-risk subgroup compared with the general population.

Conclusion. Colonoscopy surveillance significantly reducedthe incidence of CRC in intermediate-risk patients (1 to 3 large adenomas ≥ 10 mm or 3 to 4 small adenomas < 10 mm in size) who were offered surveillance at 3-year intervals. Moreover, the benefit of surveillance was particularly noted in a sub-group of patients who had large adenomas (≥ 20 mm), high-grade dysplasia, proximal polyps or poor endoscopic evaluation at the time of initial screening.

Commentary

Screening colonoscopy with removal of adenomatous polyps prevents many CRCs and has been shown to reduce mortality [1]. The results of this retrospective study suggest that patients with intermediate-risk adenomas who underwent at least 1 surveillance colonoscopy at 3-year intervals had a significant reduction in the incidence of CRC. The authors have identified a subgroup of patients at higher risk for CRC, which included those who had a suboptimal initial colonoscopy including poor bowel preparation, adenomas ≥ 20 mm, adenomas with high-grade dysplasia, or proximal adenomas. In particular, ongoing surveillance in this high-risk cohort was associated with significant reductions in CRC incidence. Conversely, those in the lower-risk group had a CRC incidence lower than that of the general population, raising some questions as to whether this group benefits from ongoing surveillance. However, definitive conclusions are difficult to make given the relatively low incidence of CRC in this group.

The risk of neoplasia in patients with colorectal ade-nomas has been evaluated in multiple studies. A pooled analysis by Martinez and colleagues examined over 9000 patients and noted advanced adenomas were found during follow up in 11.2% of the population, with 0.6% of the population developing invasive CRC [2]. Compared with adenomas < 5 mm, those with baseline adenomas 10–19 mm had a higher risk of advanced neoplasia (15.9% vs 7.7%; OR 2.2). Moreover, those with a baseline polyp ≥ 20 mm had a risk of advanced neoplasia at follow-up of 19.3% (OR 2.99). The results of the current investigation also suggest an increased risk of neoplasia with increased polyp size. Interestingly, the polyp size that conferred a higher risk in this study was ≥ 20 mm. The authors of this study suggest that polyps ≥ 20 mm along with the previously mentioned high-risk features may identify a subgroup within the intermediate-risk population who may benefit from close surveillance. One particularly interesting finding in this study was the identification of proximal colon polyps as a risk factor. While less well defined, previous investigations have noted a similar finding suggesting a risk of advanced neoplasia of up to 80% in patients with proximal polyps [3]. Given such, intensive surveillance may not be appropriate for all intermediate-risk patients and a more refined risk-adapted approach may be preferred.

There are some important limitations of the current study that warrant discussion. First, it should be emphasized that this study is observational in nature and therefore, definitive conclusions cannot be made despite the significant effect of surveillance colonoscopy in patients with high-risk features. In addition, the median follow-up in this study was 7.9 years and one could argue that longer-follow up is needed in order to validate the findings of this study, particularly in patients in the lower-risk cohort. Nevertheless, this study does suggest that there may be a population of patients that harbor higher-risk features and close surveillance limited to this group may be more appropriate. Furthermore, the duration of surveillance remains an important clinical question that requires further research.

Applications for Clinical Practice

In 2012, the United States Multi-Society Task Force (MSTF) on CRC issued updated guidelines defining adenoma risk and postpolypectomy surveillance. Low-risk adenomas (1 to 2 tubular adenomas ≤ 10 mm at baseline) should have repeat surveillance colonoscopy in 5 to 10 years. Advanced adenomas (≥ 10 mm, villous histology, or high-grade dysplasia) or those with 3 to 10 adenomas at baseline should undergo first surveillance in 3 years [4]. The authors of the current study suggest that surveillance colonoscopy at 3-year intervals for patients with particularly high-risk features including those with poor bowel preparation, adenomas ≥ 20 mm, adenomas with high-grade dysplasia or proximal adenomas benefit the greatest from at least 1 surveillance colonoscopy. Those with lower- risk features may not require such rigorous follow-up; however, further work to define which high-risk cohorts should undergo close surveillance is warranted. It is vital that the primary care provider understand such guidelines in order to facilitate the appropriate follow-up.

—Daniel Isaac, DO, MS, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI

1. Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O’Brien MJ, et al. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal cancer deaths. N Engl J Med 2012;366:687–96.

2. Martinez ME, Baron JA, Lieberman DA, et al. A pooled analysis of advanced colorectal neoplasia diagnosis after colonoscopic polypectomy. Gastroenterology 2009;136:832–41.

3. Pinsky PF, Schoen RE, Weissfeld JL, et al. The yield of surveillance colonoscopy by adenoma history and time to examination. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:86–92.

4. Lieberman DA, Rex DK, Winawer SJ, et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: A consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2012;143:844–57.

Study Overview

Objective. To examine the heterogeneity in colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence in intermediate-risk patients and the effect of surveillance on CRC incidence.

Design. Retrospective, multicenter cohort study.

Setting and participants. Study patients underwent colonoscopy between 1 January 1990 and 21 December 2010 at 17 hospitals in the United Kingdom. Patients were eligible for the study if they had a baseline colonoscopy with a newly diagnosed intermediate-risk adenoma. Intermediate-risk adenomas (as defined by the UK guidelines) included 1 to 2 large adenomas ≥ 10 mm or 3 to 4 small adenomas < 10 mm in size. Patients with a history of prior resections, colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease or a family history of CRC were excluded from the study. Patient, procedural, and polyp characteristics were assessed at baseline.

Main outcome measures. The primary outcome was inci-dence of CRC. Additional factors assessed included age at first polyp detection, sex, completeness of colonoscopy, preparation quality, number of adenomas, size of largest adenoma, histology, and location. Proximal polyps were defined as those proximal to the descending colon. Information regarding social history (eg, smoking status) was not available.

Results. The authors identified 253,798 patients who underwent colonoscopy between 1 January 1990 and 21 December 2010. Of those, 223,539 were excluded based on not meeting the pre-specified inclusion criteria, resulting in 30,259 eligible patients for analysis. Review of histological data confirmed intermediate-risk adenomas in 11,995 (40%) of the patients. The median age in this study was 66 years and 55% were men. Fifty-eight percent attended 1 or more follow-up surveillance visits while 42% had no follow-up surveillance colonoscopy. Those who attended more than 1 follow-up surveillance visits were younger, had a greater proportion of large adenomas (> 20 mm), or had an adenoma with high-grade dysplasia. Both groups had similar rates of villous histology (9% vs. 10%).

After a median follow-up of 7.9 years, 210 CRCs were diagnosed and 32% of patients died. In the group with no follow-up surveillance, 46% died and 2% were diagnosed with cancer. In the group who had 1 or more follow-up colonoscopies, 21% died and 1% were diagnosed with cancer. One or 2 surveillance visits were associated with a significant reduction in CRC incidence (HR 0.57 [95% confidence interval {CI} 0.4–0.8) and 0.51 [95% CI 0.31–0.84], respectively). Three or more surveillance exams were also associated with a similar reduction in CRC incidence (HR 0.54; CI 0.29–0.99). Characteristics associated with increased CRC incidence were older age, adenomas > 20 mm, high-grade dysplasia, proximal polyps, and colonoscopies that were either incomplete or with poor preparation. The number of adenomas was not independently associated with CRC incidence.

The authors divided the cohort into higher-risk (74%) and lower-risk (26%) subgroups based on polyp and procedural characteristics. The higher-risk group included patients with baseline adenomas ≥ 20 mm, high-grade dysplasia, proximal polyps, or suboptimal evaluation. The lower-risk group included all others. CRC incidence was higher in the “higher-risk” subgroup (247 CRC per 100,000 vs. 93 CRC per 100,000). In the higher-risk group, risk of CRC decreased with more surveillance visits, a finding that was not observed in the lower-risk group. The 10-year incidence of CRC in the cohort overall was 2.7%, in the higher-risk group was 3.3% and in the lower risk group was 1.1%. CRC incidence was significantly higher in the higher-risk subgroup compared with the general population.

Conclusion. Colonoscopy surveillance significantly reducedthe incidence of CRC in intermediate-risk patients (1 to 3 large adenomas ≥ 10 mm or 3 to 4 small adenomas < 10 mm in size) who were offered surveillance at 3-year intervals. Moreover, the benefit of surveillance was particularly noted in a sub-group of patients who had large adenomas (≥ 20 mm), high-grade dysplasia, proximal polyps or poor endoscopic evaluation at the time of initial screening.

Commentary

Screening colonoscopy with removal of adenomatous polyps prevents many CRCs and has been shown to reduce mortality [1]. The results of this retrospective study suggest that patients with intermediate-risk adenomas who underwent at least 1 surveillance colonoscopy at 3-year intervals had a significant reduction in the incidence of CRC. The authors have identified a subgroup of patients at higher risk for CRC, which included those who had a suboptimal initial colonoscopy including poor bowel preparation, adenomas ≥ 20 mm, adenomas with high-grade dysplasia, or proximal adenomas. In particular, ongoing surveillance in this high-risk cohort was associated with significant reductions in CRC incidence. Conversely, those in the lower-risk group had a CRC incidence lower than that of the general population, raising some questions as to whether this group benefits from ongoing surveillance. However, definitive conclusions are difficult to make given the relatively low incidence of CRC in this group.

The risk of neoplasia in patients with colorectal ade-nomas has been evaluated in multiple studies. A pooled analysis by Martinez and colleagues examined over 9000 patients and noted advanced adenomas were found during follow up in 11.2% of the population, with 0.6% of the population developing invasive CRC [2]. Compared with adenomas < 5 mm, those with baseline adenomas 10–19 mm had a higher risk of advanced neoplasia (15.9% vs 7.7%; OR 2.2). Moreover, those with a baseline polyp ≥ 20 mm had a risk of advanced neoplasia at follow-up of 19.3% (OR 2.99). The results of the current investigation also suggest an increased risk of neoplasia with increased polyp size. Interestingly, the polyp size that conferred a higher risk in this study was ≥ 20 mm. The authors of this study suggest that polyps ≥ 20 mm along with the previously mentioned high-risk features may identify a subgroup within the intermediate-risk population who may benefit from close surveillance. One particularly interesting finding in this study was the identification of proximal colon polyps as a risk factor. While less well defined, previous investigations have noted a similar finding suggesting a risk of advanced neoplasia of up to 80% in patients with proximal polyps [3]. Given such, intensive surveillance may not be appropriate for all intermediate-risk patients and a more refined risk-adapted approach may be preferred.

There are some important limitations of the current study that warrant discussion. First, it should be emphasized that this study is observational in nature and therefore, definitive conclusions cannot be made despite the significant effect of surveillance colonoscopy in patients with high-risk features. In addition, the median follow-up in this study was 7.9 years and one could argue that longer-follow up is needed in order to validate the findings of this study, particularly in patients in the lower-risk cohort. Nevertheless, this study does suggest that there may be a population of patients that harbor higher-risk features and close surveillance limited to this group may be more appropriate. Furthermore, the duration of surveillance remains an important clinical question that requires further research.

Applications for Clinical Practice

In 2012, the United States Multi-Society Task Force (MSTF) on CRC issued updated guidelines defining adenoma risk and postpolypectomy surveillance. Low-risk adenomas (1 to 2 tubular adenomas ≤ 10 mm at baseline) should have repeat surveillance colonoscopy in 5 to 10 years. Advanced adenomas (≥ 10 mm, villous histology, or high-grade dysplasia) or those with 3 to 10 adenomas at baseline should undergo first surveillance in 3 years [4]. The authors of the current study suggest that surveillance colonoscopy at 3-year intervals for patients with particularly high-risk features including those with poor bowel preparation, adenomas ≥ 20 mm, adenomas with high-grade dysplasia or proximal adenomas benefit the greatest from at least 1 surveillance colonoscopy. Those with lower- risk features may not require such rigorous follow-up; however, further work to define which high-risk cohorts should undergo close surveillance is warranted. It is vital that the primary care provider understand such guidelines in order to facilitate the appropriate follow-up.

—Daniel Isaac, DO, MS, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI

Study Overview

Objective. To examine the heterogeneity in colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence in intermediate-risk patients and the effect of surveillance on CRC incidence.

Design. Retrospective, multicenter cohort study.

Setting and participants. Study patients underwent colonoscopy between 1 January 1990 and 21 December 2010 at 17 hospitals in the United Kingdom. Patients were eligible for the study if they had a baseline colonoscopy with a newly diagnosed intermediate-risk adenoma. Intermediate-risk adenomas (as defined by the UK guidelines) included 1 to 2 large adenomas ≥ 10 mm or 3 to 4 small adenomas < 10 mm in size. Patients with a history of prior resections, colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease or a family history of CRC were excluded from the study. Patient, procedural, and polyp characteristics were assessed at baseline.

Main outcome measures. The primary outcome was inci-dence of CRC. Additional factors assessed included age at first polyp detection, sex, completeness of colonoscopy, preparation quality, number of adenomas, size of largest adenoma, histology, and location. Proximal polyps were defined as those proximal to the descending colon. Information regarding social history (eg, smoking status) was not available.

Results. The authors identified 253,798 patients who underwent colonoscopy between 1 January 1990 and 21 December 2010. Of those, 223,539 were excluded based on not meeting the pre-specified inclusion criteria, resulting in 30,259 eligible patients for analysis. Review of histological data confirmed intermediate-risk adenomas in 11,995 (40%) of the patients. The median age in this study was 66 years and 55% were men. Fifty-eight percent attended 1 or more follow-up surveillance visits while 42% had no follow-up surveillance colonoscopy. Those who attended more than 1 follow-up surveillance visits were younger, had a greater proportion of large adenomas (> 20 mm), or had an adenoma with high-grade dysplasia. Both groups had similar rates of villous histology (9% vs. 10%).

After a median follow-up of 7.9 years, 210 CRCs were diagnosed and 32% of patients died. In the group with no follow-up surveillance, 46% died and 2% were diagnosed with cancer. In the group who had 1 or more follow-up colonoscopies, 21% died and 1% were diagnosed with cancer. One or 2 surveillance visits were associated with a significant reduction in CRC incidence (HR 0.57 [95% confidence interval {CI} 0.4–0.8) and 0.51 [95% CI 0.31–0.84], respectively). Three or more surveillance exams were also associated with a similar reduction in CRC incidence (HR 0.54; CI 0.29–0.99). Characteristics associated with increased CRC incidence were older age, adenomas > 20 mm, high-grade dysplasia, proximal polyps, and colonoscopies that were either incomplete or with poor preparation. The number of adenomas was not independently associated with CRC incidence.

The authors divided the cohort into higher-risk (74%) and lower-risk (26%) subgroups based on polyp and procedural characteristics. The higher-risk group included patients with baseline adenomas ≥ 20 mm, high-grade dysplasia, proximal polyps, or suboptimal evaluation. The lower-risk group included all others. CRC incidence was higher in the “higher-risk” subgroup (247 CRC per 100,000 vs. 93 CRC per 100,000). In the higher-risk group, risk of CRC decreased with more surveillance visits, a finding that was not observed in the lower-risk group. The 10-year incidence of CRC in the cohort overall was 2.7%, in the higher-risk group was 3.3% and in the lower risk group was 1.1%. CRC incidence was significantly higher in the higher-risk subgroup compared with the general population.

Conclusion. Colonoscopy surveillance significantly reducedthe incidence of CRC in intermediate-risk patients (1 to 3 large adenomas ≥ 10 mm or 3 to 4 small adenomas < 10 mm in size) who were offered surveillance at 3-year intervals. Moreover, the benefit of surveillance was particularly noted in a sub-group of patients who had large adenomas (≥ 20 mm), high-grade dysplasia, proximal polyps or poor endoscopic evaluation at the time of initial screening.

Commentary

Screening colonoscopy with removal of adenomatous polyps prevents many CRCs and has been shown to reduce mortality [1]. The results of this retrospective study suggest that patients with intermediate-risk adenomas who underwent at least 1 surveillance colonoscopy at 3-year intervals had a significant reduction in the incidence of CRC. The authors have identified a subgroup of patients at higher risk for CRC, which included those who had a suboptimal initial colonoscopy including poor bowel preparation, adenomas ≥ 20 mm, adenomas with high-grade dysplasia, or proximal adenomas. In particular, ongoing surveillance in this high-risk cohort was associated with significant reductions in CRC incidence. Conversely, those in the lower-risk group had a CRC incidence lower than that of the general population, raising some questions as to whether this group benefits from ongoing surveillance. However, definitive conclusions are difficult to make given the relatively low incidence of CRC in this group.

The risk of neoplasia in patients with colorectal ade-nomas has been evaluated in multiple studies. A pooled analysis by Martinez and colleagues examined over 9000 patients and noted advanced adenomas were found during follow up in 11.2% of the population, with 0.6% of the population developing invasive CRC [2]. Compared with adenomas < 5 mm, those with baseline adenomas 10–19 mm had a higher risk of advanced neoplasia (15.9% vs 7.7%; OR 2.2). Moreover, those with a baseline polyp ≥ 20 mm had a risk of advanced neoplasia at follow-up of 19.3% (OR 2.99). The results of the current investigation also suggest an increased risk of neoplasia with increased polyp size. Interestingly, the polyp size that conferred a higher risk in this study was ≥ 20 mm. The authors of this study suggest that polyps ≥ 20 mm along with the previously mentioned high-risk features may identify a subgroup within the intermediate-risk population who may benefit from close surveillance. One particularly interesting finding in this study was the identification of proximal colon polyps as a risk factor. While less well defined, previous investigations have noted a similar finding suggesting a risk of advanced neoplasia of up to 80% in patients with proximal polyps [3]. Given such, intensive surveillance may not be appropriate for all intermediate-risk patients and a more refined risk-adapted approach may be preferred.

There are some important limitations of the current study that warrant discussion. First, it should be emphasized that this study is observational in nature and therefore, definitive conclusions cannot be made despite the significant effect of surveillance colonoscopy in patients with high-risk features. In addition, the median follow-up in this study was 7.9 years and one could argue that longer-follow up is needed in order to validate the findings of this study, particularly in patients in the lower-risk cohort. Nevertheless, this study does suggest that there may be a population of patients that harbor higher-risk features and close surveillance limited to this group may be more appropriate. Furthermore, the duration of surveillance remains an important clinical question that requires further research.

Applications for Clinical Practice