User login

Systematic Review of Novel Synovial Fluid Markers and Polymerase Chain Reaction in the Diagnosis of Prosthetic Joint Infection

Take-Home Points

- Novel synovial markers and PCR have the potential to improve the detection of PJIs.

- 10Difficult-to-detect infections of prosthetic joints pose a diagnostic problem to surgeons and can lead to suboptimal outcomes.

- AD is a highly sensitive and specific synovial fluid marker for detecting PJIs.

- AD has shown promising results in detecting low virulence organisms.

- Studies are needed to determine how to best incorporate novel synovial markers and PCR to current diagnostic criteria in order to improve diagnostic accuracy.

Approximately 7 million Americans are living with a hip or knee replacement.1 According to projections, primary hip arthroplasties will increase by 174% and knee arthroplasties by 673% by 2030. Revision arthroplasties are projected to increase by 137% for hips and 601% for knees during the same time period.2 Infection and aseptic loosening are the most common causes of implant failure.3 The literature shows that infection is the most common cause of failure within 2 years after surgery and that aseptic loosening is the most common cause for late revision.3

Recent studies suggest that prosthetic joint infection (PJI) may be underreported because of difficulty making a diagnosis and that cases of aseptic loosening may in fact be attributable to infections with low-virulence organisms.2,3 These findings have led to new efforts to develop uniform criteria for diagnosing PJIs. In 2011, the Musculoskeletal Infection Society (MSIS) offered a new definition for PJI diagnosis, based on clinical and laboratory criteria, to increase the accuracy of PJI diagnosis.4 The MSIS committee acknowledged that PJI may be present even if these criteria are not met, particularly in the case of low-virulence organisms, as patients may not present with clinical signs of infection and may have normal inflammatory markers and joint aspirates. Reports of PJI cases misdiagnosed as aseptic loosening suggest that current screening and diagnostic tools are not sensitive enough to detect all infections and that PJI is likely underdiagnosed.

According to MSIS criteria, the diagnosis of PJI can be made when there is a sinus tract communicating with the prosthesis, when a pathogen is isolated by culture from 2 or more separate tissue or fluid samples obtained from the affected prosthetic joint, or when 4 of 6 criteria are met. The 6 criteria are (1) elevated serum erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (>30 mm/hour) and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) level (>10 mg/L); (2) elevated synovial white blood cell (WBC) count (1100-4000 cells/μL); (3) elevated synovial polymorphonuclear leukocytes (>64%); (4) purulence in affected joint; (5) isolation of a microorganism in a culture of periprosthetic tissue or fluid; and (6) more than 5 neutrophils per high-power field in 5 high-power fields observed.

In this review article, we discuss recently developed novel synovial biomarkers and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technologies that may help increase the sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic guidelines for PJI.

Methods

Using PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses), we performed a systematic review of specific synovial fluid markers and PCR used in PJI diagnosis. In May 2016, we searched the PubMed database for these criteria: ((((((PCR[Text Word]) OR IL-6[Text Word]) OR leukocyte esterase[Text Word]) OR alpha defensin[Text Word]) AND ((“infection/diagnosis”[MeSH Terms] OR “infection/surgery”[MeSH Terms])))) AND (prosthetic joint infection[MeSH Terms] OR periprosthetic joint infection[MeSH Terms]).

We included patients who had undergone total hip, knee, or shoulder arthroplasty (THA, TKA, TSA). Index tests were PCR and the synovial fluid markers α-defensin (AD), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and leukocyte esterase (LE). Reference tests included joint fluid/serum analysis or tissue analysis (ESR/CRP level, cell count, culture, frozen section), which defined the MSIS criteria for PJI. Primary outcomes of interest were sensitivity and specificity, and secondary outcomes of interest included positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), positive likelihood ratio (+LR), and negative likelihood ratio (–LR). Randomized controlled trials and controlled cohort studies in humans published within the past 10 years were included.

Results

Our full-text review yielded 15 papers that met our study inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

α-Defensin

One of the novel synovial biomarkers that has shown significant promise in diagnosing PJIs, even with difficult-to-detect organisms, is AD.

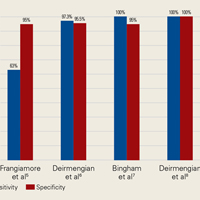

AD has shown even more impressive results as a biomarker for PJI in the hip and knee, where infection with low virulence organism is less common. In 2014, Deirmengian and colleagues6 conducted a prospective clinical study of 149 patients who underwent revision THA or TKA for aseptic loosening (n = 112) or PJI (n = 37) as defined by MSIS criteria. Aseptic loosening was diagnosed when there was no identifiable reason for pain, and MSIS criteria were not met. Synovial fluid aspirates were collected before or during surgery. AD correctly identified 143 of the 149 patients with confirmed infection with sensitivity of 97.3% (95% confidence interval [CI], 85.8%-99.6%) and specificity of 95.5% (95% CI, 89.9%-98.5%). Similarly, Bingham and colleagues7 conducted a retrospective clinical study of 61 assays done on 57 patients who underwent revision arthroplasty for PJI as defined by MSIS criteria. Synovial fluid aspirates were collected before or during surgery. AD correctly identified all 19 PJIs with sensitivity of 100% (95% CI, 79%-100%) and specificity of 95% (95% CI, 83%-99%). Sensitivity and specificity of the AD assay more accurately predicted infection than synovial cell count or serum ESR/CRP level did.

These results are supported by another prospective study by Deirmengian and colleagues8 differentiating aseptic failures and PJIs in THA or TKA. The sensitivity and specificity of AD in diagnosing PJI were 100% (95% CI, 85.05%-100%).

In a prospective study of 102 patients who underwent revision THA or TKA secondary to aseptic loosening or PJI, Frangiamore and colleagues9 also demonstrated the value of AD as a diagnostic for PJI in primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty.

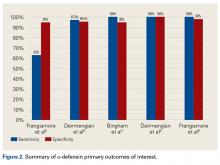

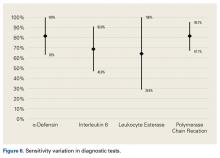

Table 1 and Figure 2 provide a concise review of the findings of each study.

Interleukin 6

Another synovial fluid biomarker that has shown promise in PJI diagnosis is IL-6. In 2015, Frangiamore and colleagues10 conducted a prospective clinical study of 32 patients who underwent revision TSA. Synovial fluid aspiration was obtained before or during surgery. MSIS criteria were used to establish the diagnosis of PJI. IL-6 had sensitivity of 87% and specificity of 90%, with +LR of 8.45 and –LR of 0.15 in predicting PJI. Synovial fluid IL-6 had strong associations with frozen section histology and growth of P acnes. Frangiamore and colleagues10 recommended an ideal IL-6 cutoff of 359.1 pg/mL and reported that, though not as accurate as AD, synovial fluid IL-6 levels can help predict positive cultures in patients who undergo revision TSA.

Lenski and Scherer11 conducted another retrospective clinical study of the diagnostic value of IL-6 in PJI.

Randau and colleagues12 conducted a prospective clinical study of 120 patients who presented with painful THA or TKA and underwent revision for PJI, aseptic failure, or aseptic revision without signs of infection or loosening. Synovial fluid aspirate was collected before or during surgery.

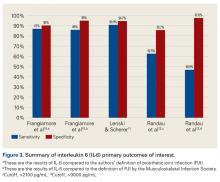

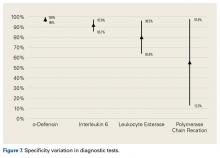

Table 2 and Figure 3 provide a concise review of the findings of each study.

Leukocyte Esterase

LE strips are an inexpensive screening tool for PJI, according to some studies. In a prospective clinical study of 364 endoprosthetic joint (hip, knee, shoulder) interventions, Guenther and colleagues13 collected synovial fluid before surgery. Samples were tested with graded LE strips using PJI criteria set by the authors. Results were correlated with preoperative synovial fluid aspirations, serum CRP level, serum WBC count, and intraoperative histopathologic and microbiological findings. Whereas 293 (93.31%) of the 314 aseptic cases had negative test strip readings, 100% of the 50 infected cases were positive. LE had sensitivity of 100%, specificity of 96.5%, PPV of 82%, and NPV of 100%.

Wetters et al14 performed a prospective clinical study on 223 patients who underwent TKAs and THAs for suspected PJI based on having criteria defined by the authors of the study. Synovial fluid samples were collected either preoperatively or intraoperatively.

Other authors have reported different findings that LE is an unreliable marker in PJI diagnosis. In one prospective clinical study of 85 patients who underwent primary or revision TSA, synovial fluid was collected during surgery.15 According to MSIS criteria, only 5 positive LE results predicted PJI among 21 primary and revision patients with positive cultures. Of the 7 revision patients who met the MSIS criteria for PJI, only 2 had a positive LE test. LE had sensitivity of 28.6%, specificity of 63.6%, PPV of 28.6%, and NPV of 87.5%. Six of the 7 revision patients grew P acnes. These results showed that LE was unreliable in detecting shoulder PJI.15

In another prospective clinical study, Tischler and colleagues16 enrolled 189 patients who underwent revision TKA or THA for aseptic failure or PJI as defined by the MSIS criteria. Synovial fluid was collected intraoperatively.

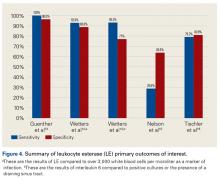

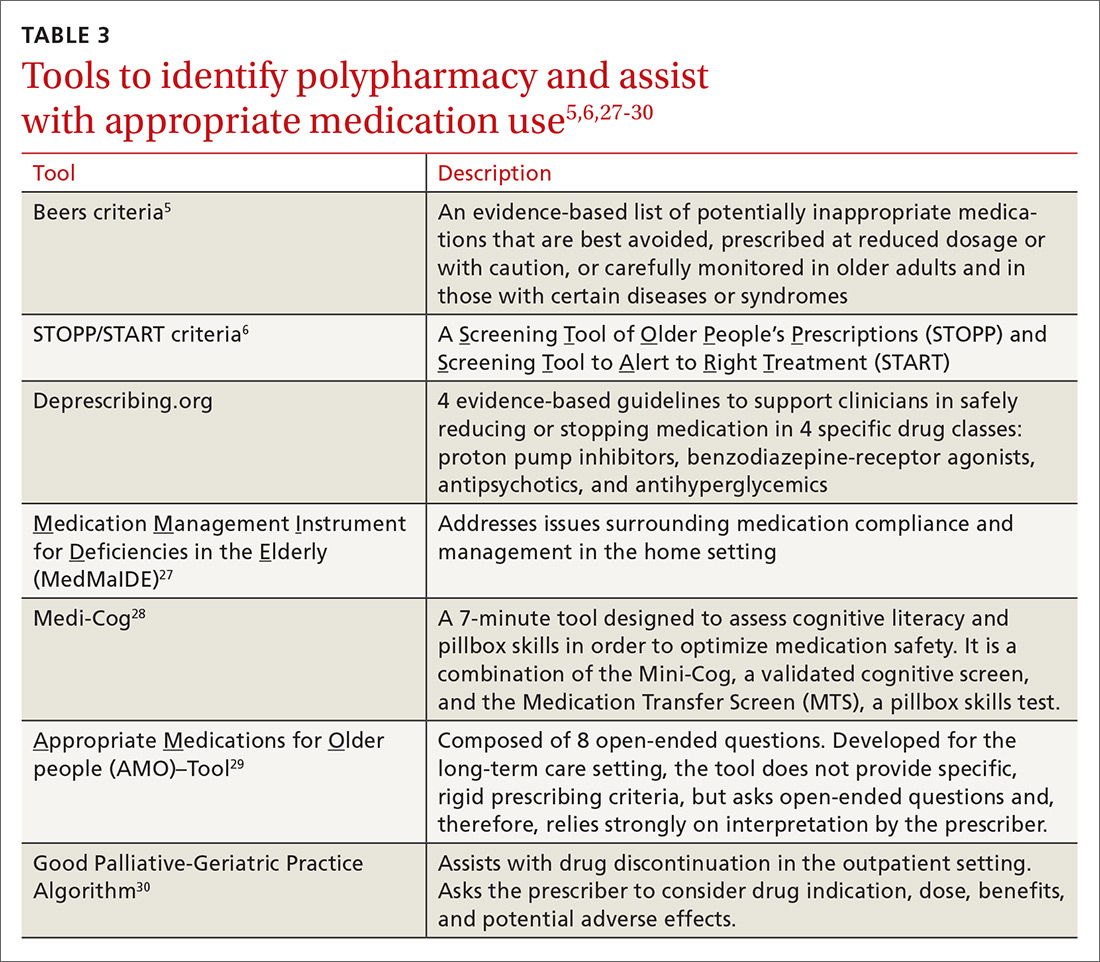

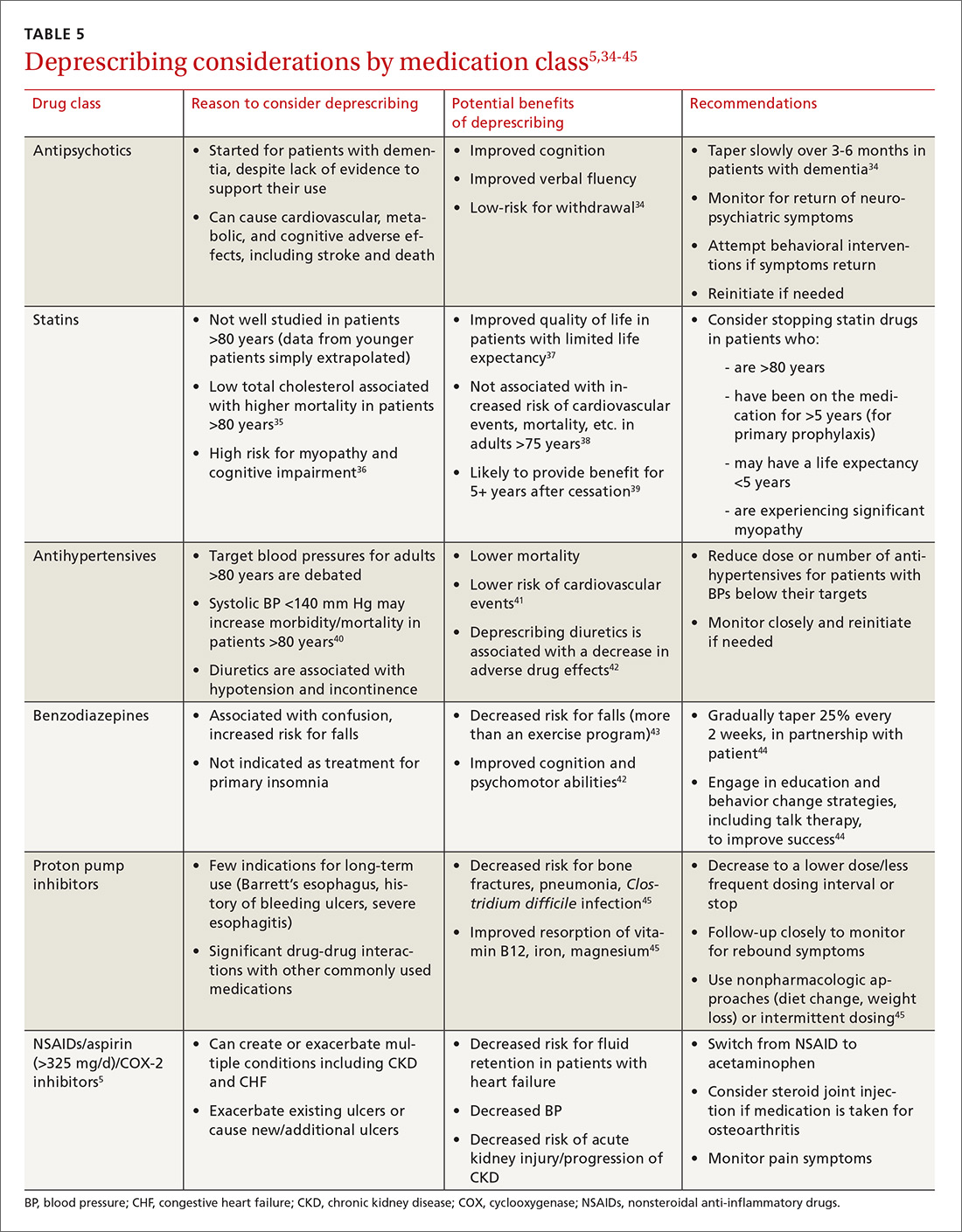

Table 3 and Figure 4 provide a concise review of the findings of each study.

Polymerase Chain Reaction

Studies have found that PCR analysis of synovial fluid is effective in detecting bacteria on the surface of implants removed during revision arthroplasties. Comparison of the 16S rRNA gene sequences of bacterial genomes showed a diverse range of bacterial species within biofilms on the surface of clinical and subclinical infections.17 These findings, along with those of other studies, suggest that PCR analysis of synovial fluid is useful in diagnosing PJI and identifying organisms and their sensitivities to antibiotics.

Gallo and colleagues18 performed a prospective clinical study on 115 patients who underwent revision TKAs or THAs. Synovial fluid was collected intraoperatively. PCR assays targeting the 16S rDNA were carried out on 101 patients. PJIs were classified based on criteria of the authors of this study, of which there were 42. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, +LR, and -LR for PCR were 71.4% (95% CI, 61.5%-75.5%), 97% (95% CI, 91.7%-99.1%), 92.6% (95% CI, 79.8%-97.9%), 86.5% (95% CI, 81.8%-88.4%), 23.6 (95% CI, 5.9%-93.8%), and 0.29 (95% CI, 0.17%-0.49%), respectively. Of note the most common organism detected in 42 PJIs was coagulase-negative Staphylococcus.

Marin and colleagues19 conducted a prospective study of 122 patients who underwent arthroplasty for suspected infection or aseptic loosening as defined by the authors’ clinicohistopathologic criteria. Synovial fluid and biopsy specimens were collected during surgery, and 40 patients met the infection criteria. The authors concluded that 16S PCR is more specific and has better PPV than culture does as one positive 16S PCR resulted in a specificity and PPV of PJI of 96.3% and 91.7%, respectively. However, they noted that culture was more sensitive in diagnosing PJI.

Jacovides and colleagues20 conducted a prospective study on 82 patients undergoing primary TKA, revision TKA, and revision THA.

The low PCR sensitivities reported in the literature were explained in a review by Hartley and Harris.21 They wrote that BR 16S rDNA and sequencing of PJI samples inherently have low sensitivity because of the contamination that can occur from the PCR reagents themselves or from sample mishandling. Techniques that address contaminant (extraneous DNA) removal, such as ultraviolet irradiation and DNase treatment, reduce Taq DNA polymerase activity, which reduces PCR sensitivity.

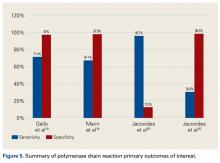

Table 4 and Figure 5 provide a concise review of the findings of each study.

Discussion

Although there is no gold standard for the diagnosis of PJIs, several clinical and laboratory criteria guidelines are currently used to help clinicians diagnose infections of prosthetic joints. However, despite standardization of diagnostic criteria, PJI continue to be a diagnostic challenge.

AD is a highly sensitive and specific synovial fluid biomarker in detecting common PJIs.

In summary, 5 AD studies5-9 had sensitivity ranging from 63% to 100% and specificity ranging from 95% to 100%; 3 IL-6 studies10-12 had sensitivity ranging from 46.8% to 90.9% and specificity ranging from 85.7% to 97.6%; 4 LE studies13-16 had sensitivity ranging from 28.6% to 100% and specificity ranging from 63.6% to 96.5%; and 3 PCR studies18-20 had sensitivity ranging from 67.1% to 95.7% and specificity ranging from 12.3% to 97.8%. Sensitivity and specificity were consistently higher for AD than for IL-6, LE, and PCR, though there was significant overlap, heterogeneity, and variation across all the included studies.

Although the overall incidence of PJI is low, infected revisions remain a substantial financial burden to hospitals, as annual costs of infected revisions is estimated to exceed $1.62 billion by 2020.25 The usefulness of novel biomarkers and PCR in diagnosing PJI can be found in their ability to diagnose infections and facilitate appropriate early treatment. Several of these tests are readily available commercially and have the potential to be cost-effective diagnostic tools. The price to perform an AD test from Synovasure TM (Zimmer Biomet) ranges from $93 to $143. LE also provides an economic option for diagnosing PJI, as LE strips are commercially available for the cost of about 25 cents. PCR has also become an economic option, as costs can average $15.50 per sample extraction or PCR assay and $42.50 per amplicon sequence as reported in a study by Vandercam and colleagues.26 Future studies are needed to determine a diagnostic algorithm which incorporates these novel synovial markers to improve diagnostic accuracy of PJI in the most cost effective manner.

The current literature supports that AD can potentially be used to screen for PJI. Our findings suggest novel synovial fluid biomarkers may become of significant diagnostic use when combined with current laboratory and clinical diagnostic criteria. We recommend use of AD in cases in which pain, stiffness, and poor TJA outcome cannot be explained by errors in surgical technique, and infection is suspected despite MSIS criteria not being met.

The studies reviewed in this manuscript were limited in that none presented level I evidence (12 had level II evidence, and 3 had level III evidence), and there was significant heterogeneity (some studies used their own diagnostic standard, and others used the MSIS criteria). Larger scale prospective studies comparing serum ESR/CRP level and synovial fluid analysis to novel synovial markers are needed.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(4):190-198. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Maradit Kremers H, Larson DR, Crowson CS, et al. Prevalence of total hip and knee replacement in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(17):1386-1397.

2. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780-785.

3. Sharkey PF, Lichstein PM, Shen C, Tokarski AT, Parvizi J. Why are total knee arthroplasties failing today—has anything changed after 10 years? J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(9):1774-1778.

4. Butler-Wu SM, Burns EM, Pottinger PS, et al. Optimization of periprosthetic culture for diagnosis of Propionibacterium acnes prosthetic joint infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(7):2490-2495.

5. Frangiamore SJ, Saleh A, Grosso MJ, et al. α-Defensin as a predictor of periprosthetic shoulder infection. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(7):1021-1027.

6. Deirmengian C, Kardos K, Kilmartin P, Cameron A, Schiller K, Parvizi J. Combined measurement of synovial fluid α-defensin and C-reactive protein levels: highly accurate for diagnosing periprosthetic joint infection. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(17):1439-1445.

7. Bingham J, Clarke H, Spangehl M, Schwartz A, Beauchamp C, Goldberg B. The alpha defensin-1 biomarker assay can be used to evaluate the potentially infected total joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(12):4006-4009.

8. Deirmengian C, Kardos K, Kilmartin P, et al. The alpha-defensin test for periprosthetic joint infection outperforms the leukocyte esterase test strip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(1):198-203.

9. Frangiamore SJ, Gajewski ND, Saleh A, Farias-Kovac M, Barsoum WK, Higuera CA. α-Defensin accuracy to diagnose periprosthetic joint infection—best available test? J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(2):456-460.

10. Frangiamore SJ, Saleh A, Kovac MF, et al. Synovial fluid interleukin-6 as a predictor of periprosthetic shoulder infection. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(1):63-70.

11. Lenski M, Scherer MA. Synovial IL-6 as inflammatory marker in periprosthetic joint infections. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(6):1105-1109.

12. Randau TM, Friedrich MJ, Wimmer MD, et al. Interleukin-6 in serum and in synovial fluid enhances the differentiation between periprosthetic joint infection and aseptic loosening. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e89045.

13. Guenther D, Kokenge T, Jacobs O, et al. Excluding infections in arthroplasty using leucocyte esterase test. Int Orthop. 2014;38(11):2385-2390.

14. Wetters NG, Berend KR, Lombardi AV, Morris MJ, Tucker TL, Della Valle CJ. Leukocyte esterase reagent strips for the rapid diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(8 suppl):8-11.

15. Nelson GN, Paxton ES, Narzikul A, Williams G, Lazarus MD, Abboud JA. Leukocyte esterase in the diagnosis of shoulder periprosthetic joint infection. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(9):1421-1426.

16. Tischler EH, Cavanaugh PK, Parvizi J. Leukocyte esterase strip test: matched for Musculoskeletal Infection Society criteria. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(22):1917-1920.

17. Dempsey KE, Riggio MP, Lennon A, et al. Identification of bacteria on the surface of clinically infected and non-infected prosthetic hip joints removed during revision arthroplasties by 16S rRNA gene sequencing and by microbiological culture. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(3):R46.

18. Gallo J, Kolar M, Dendis M, et al. Culture and PCR analysis of joint fluid in the diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. New Microbiol. 2008;31(1):97-104.

19. Marin M, Garcia-Lechuz JM, Alonso P, et al. Role of universal 16S rRNA gene PCR and sequencing in diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(3):583-589.

20. Jacovides CL, Kreft R, Adeli B, Hozack B, Ehrlich GD, Parvizi J. Successful identification of pathogens by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based electron spray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (ESI-TOF-MS) in culture-negative periprosthetic joint infection. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(24):2247-2254.

21. Hartley JC, Harris KA. Molecular techniques for diagnosing prosthetic joint infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(suppl 1):i21-i24.

22. Zappe B, Graf S, Ochsner PE, Zimmerli W, Sendi P. Propionibacterium spp. in prosthetic joint infections: a diagnostic challenge. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128(10):1039-1046.

23. Rasouli MR, Harandi AA, Adeli B, Purtill JJ, Parvizi J. Revision total knee arthroplasty: infection should be ruled out in all cases. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(6):1239-1243.e1-e2.

24. Hunt RW, Bond MJ, Pater GD. Psychological responses to cancer: a case for cancer support groups. Community Health Stud. 1990;14(1):35-38.

25. Kurtz SM, Lau E, Schmier J, Ong KL, Zhao K, Parvizi J. Infection burden for hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(7):984-991.

26. Vandercam B, Jeumont S, Cornu O, et al. Amplification-based DNA analysis in the diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. J Mol Diagn. 2008;10(6):537-543.

Take-Home Points

- Novel synovial markers and PCR have the potential to improve the detection of PJIs.

- 10Difficult-to-detect infections of prosthetic joints pose a diagnostic problem to surgeons and can lead to suboptimal outcomes.

- AD is a highly sensitive and specific synovial fluid marker for detecting PJIs.

- AD has shown promising results in detecting low virulence organisms.

- Studies are needed to determine how to best incorporate novel synovial markers and PCR to current diagnostic criteria in order to improve diagnostic accuracy.

Approximately 7 million Americans are living with a hip or knee replacement.1 According to projections, primary hip arthroplasties will increase by 174% and knee arthroplasties by 673% by 2030. Revision arthroplasties are projected to increase by 137% for hips and 601% for knees during the same time period.2 Infection and aseptic loosening are the most common causes of implant failure.3 The literature shows that infection is the most common cause of failure within 2 years after surgery and that aseptic loosening is the most common cause for late revision.3

Recent studies suggest that prosthetic joint infection (PJI) may be underreported because of difficulty making a diagnosis and that cases of aseptic loosening may in fact be attributable to infections with low-virulence organisms.2,3 These findings have led to new efforts to develop uniform criteria for diagnosing PJIs. In 2011, the Musculoskeletal Infection Society (MSIS) offered a new definition for PJI diagnosis, based on clinical and laboratory criteria, to increase the accuracy of PJI diagnosis.4 The MSIS committee acknowledged that PJI may be present even if these criteria are not met, particularly in the case of low-virulence organisms, as patients may not present with clinical signs of infection and may have normal inflammatory markers and joint aspirates. Reports of PJI cases misdiagnosed as aseptic loosening suggest that current screening and diagnostic tools are not sensitive enough to detect all infections and that PJI is likely underdiagnosed.

According to MSIS criteria, the diagnosis of PJI can be made when there is a sinus tract communicating with the prosthesis, when a pathogen is isolated by culture from 2 or more separate tissue or fluid samples obtained from the affected prosthetic joint, or when 4 of 6 criteria are met. The 6 criteria are (1) elevated serum erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (>30 mm/hour) and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) level (>10 mg/L); (2) elevated synovial white blood cell (WBC) count (1100-4000 cells/μL); (3) elevated synovial polymorphonuclear leukocytes (>64%); (4) purulence in affected joint; (5) isolation of a microorganism in a culture of periprosthetic tissue or fluid; and (6) more than 5 neutrophils per high-power field in 5 high-power fields observed.

In this review article, we discuss recently developed novel synovial biomarkers and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technologies that may help increase the sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic guidelines for PJI.

Methods

Using PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses), we performed a systematic review of specific synovial fluid markers and PCR used in PJI diagnosis. In May 2016, we searched the PubMed database for these criteria: ((((((PCR[Text Word]) OR IL-6[Text Word]) OR leukocyte esterase[Text Word]) OR alpha defensin[Text Word]) AND ((“infection/diagnosis”[MeSH Terms] OR “infection/surgery”[MeSH Terms])))) AND (prosthetic joint infection[MeSH Terms] OR periprosthetic joint infection[MeSH Terms]).

We included patients who had undergone total hip, knee, or shoulder arthroplasty (THA, TKA, TSA). Index tests were PCR and the synovial fluid markers α-defensin (AD), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and leukocyte esterase (LE). Reference tests included joint fluid/serum analysis or tissue analysis (ESR/CRP level, cell count, culture, frozen section), which defined the MSIS criteria for PJI. Primary outcomes of interest were sensitivity and specificity, and secondary outcomes of interest included positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), positive likelihood ratio (+LR), and negative likelihood ratio (–LR). Randomized controlled trials and controlled cohort studies in humans published within the past 10 years were included.

Results

Our full-text review yielded 15 papers that met our study inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

α-Defensin

One of the novel synovial biomarkers that has shown significant promise in diagnosing PJIs, even with difficult-to-detect organisms, is AD.

AD has shown even more impressive results as a biomarker for PJI in the hip and knee, where infection with low virulence organism is less common. In 2014, Deirmengian and colleagues6 conducted a prospective clinical study of 149 patients who underwent revision THA or TKA for aseptic loosening (n = 112) or PJI (n = 37) as defined by MSIS criteria. Aseptic loosening was diagnosed when there was no identifiable reason for pain, and MSIS criteria were not met. Synovial fluid aspirates were collected before or during surgery. AD correctly identified 143 of the 149 patients with confirmed infection with sensitivity of 97.3% (95% confidence interval [CI], 85.8%-99.6%) and specificity of 95.5% (95% CI, 89.9%-98.5%). Similarly, Bingham and colleagues7 conducted a retrospective clinical study of 61 assays done on 57 patients who underwent revision arthroplasty for PJI as defined by MSIS criteria. Synovial fluid aspirates were collected before or during surgery. AD correctly identified all 19 PJIs with sensitivity of 100% (95% CI, 79%-100%) and specificity of 95% (95% CI, 83%-99%). Sensitivity and specificity of the AD assay more accurately predicted infection than synovial cell count or serum ESR/CRP level did.

These results are supported by another prospective study by Deirmengian and colleagues8 differentiating aseptic failures and PJIs in THA or TKA. The sensitivity and specificity of AD in diagnosing PJI were 100% (95% CI, 85.05%-100%).

In a prospective study of 102 patients who underwent revision THA or TKA secondary to aseptic loosening or PJI, Frangiamore and colleagues9 also demonstrated the value of AD as a diagnostic for PJI in primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty.

Table 1 and Figure 2 provide a concise review of the findings of each study.

Interleukin 6

Another synovial fluid biomarker that has shown promise in PJI diagnosis is IL-6. In 2015, Frangiamore and colleagues10 conducted a prospective clinical study of 32 patients who underwent revision TSA. Synovial fluid aspiration was obtained before or during surgery. MSIS criteria were used to establish the diagnosis of PJI. IL-6 had sensitivity of 87% and specificity of 90%, with +LR of 8.45 and –LR of 0.15 in predicting PJI. Synovial fluid IL-6 had strong associations with frozen section histology and growth of P acnes. Frangiamore and colleagues10 recommended an ideal IL-6 cutoff of 359.1 pg/mL and reported that, though not as accurate as AD, synovial fluid IL-6 levels can help predict positive cultures in patients who undergo revision TSA.

Lenski and Scherer11 conducted another retrospective clinical study of the diagnostic value of IL-6 in PJI.

Randau and colleagues12 conducted a prospective clinical study of 120 patients who presented with painful THA or TKA and underwent revision for PJI, aseptic failure, or aseptic revision without signs of infection or loosening. Synovial fluid aspirate was collected before or during surgery.

Table 2 and Figure 3 provide a concise review of the findings of each study.

Leukocyte Esterase

LE strips are an inexpensive screening tool for PJI, according to some studies. In a prospective clinical study of 364 endoprosthetic joint (hip, knee, shoulder) interventions, Guenther and colleagues13 collected synovial fluid before surgery. Samples were tested with graded LE strips using PJI criteria set by the authors. Results were correlated with preoperative synovial fluid aspirations, serum CRP level, serum WBC count, and intraoperative histopathologic and microbiological findings. Whereas 293 (93.31%) of the 314 aseptic cases had negative test strip readings, 100% of the 50 infected cases were positive. LE had sensitivity of 100%, specificity of 96.5%, PPV of 82%, and NPV of 100%.

Wetters et al14 performed a prospective clinical study on 223 patients who underwent TKAs and THAs for suspected PJI based on having criteria defined by the authors of the study. Synovial fluid samples were collected either preoperatively or intraoperatively.

Other authors have reported different findings that LE is an unreliable marker in PJI diagnosis. In one prospective clinical study of 85 patients who underwent primary or revision TSA, synovial fluid was collected during surgery.15 According to MSIS criteria, only 5 positive LE results predicted PJI among 21 primary and revision patients with positive cultures. Of the 7 revision patients who met the MSIS criteria for PJI, only 2 had a positive LE test. LE had sensitivity of 28.6%, specificity of 63.6%, PPV of 28.6%, and NPV of 87.5%. Six of the 7 revision patients grew P acnes. These results showed that LE was unreliable in detecting shoulder PJI.15

In another prospective clinical study, Tischler and colleagues16 enrolled 189 patients who underwent revision TKA or THA for aseptic failure or PJI as defined by the MSIS criteria. Synovial fluid was collected intraoperatively.

Table 3 and Figure 4 provide a concise review of the findings of each study.

Polymerase Chain Reaction

Studies have found that PCR analysis of synovial fluid is effective in detecting bacteria on the surface of implants removed during revision arthroplasties. Comparison of the 16S rRNA gene sequences of bacterial genomes showed a diverse range of bacterial species within biofilms on the surface of clinical and subclinical infections.17 These findings, along with those of other studies, suggest that PCR analysis of synovial fluid is useful in diagnosing PJI and identifying organisms and their sensitivities to antibiotics.

Gallo and colleagues18 performed a prospective clinical study on 115 patients who underwent revision TKAs or THAs. Synovial fluid was collected intraoperatively. PCR assays targeting the 16S rDNA were carried out on 101 patients. PJIs were classified based on criteria of the authors of this study, of which there were 42. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, +LR, and -LR for PCR were 71.4% (95% CI, 61.5%-75.5%), 97% (95% CI, 91.7%-99.1%), 92.6% (95% CI, 79.8%-97.9%), 86.5% (95% CI, 81.8%-88.4%), 23.6 (95% CI, 5.9%-93.8%), and 0.29 (95% CI, 0.17%-0.49%), respectively. Of note the most common organism detected in 42 PJIs was coagulase-negative Staphylococcus.

Marin and colleagues19 conducted a prospective study of 122 patients who underwent arthroplasty for suspected infection or aseptic loosening as defined by the authors’ clinicohistopathologic criteria. Synovial fluid and biopsy specimens were collected during surgery, and 40 patients met the infection criteria. The authors concluded that 16S PCR is more specific and has better PPV than culture does as one positive 16S PCR resulted in a specificity and PPV of PJI of 96.3% and 91.7%, respectively. However, they noted that culture was more sensitive in diagnosing PJI.

Jacovides and colleagues20 conducted a prospective study on 82 patients undergoing primary TKA, revision TKA, and revision THA.

The low PCR sensitivities reported in the literature were explained in a review by Hartley and Harris.21 They wrote that BR 16S rDNA and sequencing of PJI samples inherently have low sensitivity because of the contamination that can occur from the PCR reagents themselves or from sample mishandling. Techniques that address contaminant (extraneous DNA) removal, such as ultraviolet irradiation and DNase treatment, reduce Taq DNA polymerase activity, which reduces PCR sensitivity.

Table 4 and Figure 5 provide a concise review of the findings of each study.

Discussion

Although there is no gold standard for the diagnosis of PJIs, several clinical and laboratory criteria guidelines are currently used to help clinicians diagnose infections of prosthetic joints. However, despite standardization of diagnostic criteria, PJI continue to be a diagnostic challenge.

AD is a highly sensitive and specific synovial fluid biomarker in detecting common PJIs.

In summary, 5 AD studies5-9 had sensitivity ranging from 63% to 100% and specificity ranging from 95% to 100%; 3 IL-6 studies10-12 had sensitivity ranging from 46.8% to 90.9% and specificity ranging from 85.7% to 97.6%; 4 LE studies13-16 had sensitivity ranging from 28.6% to 100% and specificity ranging from 63.6% to 96.5%; and 3 PCR studies18-20 had sensitivity ranging from 67.1% to 95.7% and specificity ranging from 12.3% to 97.8%. Sensitivity and specificity were consistently higher for AD than for IL-6, LE, and PCR, though there was significant overlap, heterogeneity, and variation across all the included studies.

Although the overall incidence of PJI is low, infected revisions remain a substantial financial burden to hospitals, as annual costs of infected revisions is estimated to exceed $1.62 billion by 2020.25 The usefulness of novel biomarkers and PCR in diagnosing PJI can be found in their ability to diagnose infections and facilitate appropriate early treatment. Several of these tests are readily available commercially and have the potential to be cost-effective diagnostic tools. The price to perform an AD test from Synovasure TM (Zimmer Biomet) ranges from $93 to $143. LE also provides an economic option for diagnosing PJI, as LE strips are commercially available for the cost of about 25 cents. PCR has also become an economic option, as costs can average $15.50 per sample extraction or PCR assay and $42.50 per amplicon sequence as reported in a study by Vandercam and colleagues.26 Future studies are needed to determine a diagnostic algorithm which incorporates these novel synovial markers to improve diagnostic accuracy of PJI in the most cost effective manner.

The current literature supports that AD can potentially be used to screen for PJI. Our findings suggest novel synovial fluid biomarkers may become of significant diagnostic use when combined with current laboratory and clinical diagnostic criteria. We recommend use of AD in cases in which pain, stiffness, and poor TJA outcome cannot be explained by errors in surgical technique, and infection is suspected despite MSIS criteria not being met.

The studies reviewed in this manuscript were limited in that none presented level I evidence (12 had level II evidence, and 3 had level III evidence), and there was significant heterogeneity (some studies used their own diagnostic standard, and others used the MSIS criteria). Larger scale prospective studies comparing serum ESR/CRP level and synovial fluid analysis to novel synovial markers are needed.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(4):190-198. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

Take-Home Points

- Novel synovial markers and PCR have the potential to improve the detection of PJIs.

- 10Difficult-to-detect infections of prosthetic joints pose a diagnostic problem to surgeons and can lead to suboptimal outcomes.

- AD is a highly sensitive and specific synovial fluid marker for detecting PJIs.

- AD has shown promising results in detecting low virulence organisms.

- Studies are needed to determine how to best incorporate novel synovial markers and PCR to current diagnostic criteria in order to improve diagnostic accuracy.

Approximately 7 million Americans are living with a hip or knee replacement.1 According to projections, primary hip arthroplasties will increase by 174% and knee arthroplasties by 673% by 2030. Revision arthroplasties are projected to increase by 137% for hips and 601% for knees during the same time period.2 Infection and aseptic loosening are the most common causes of implant failure.3 The literature shows that infection is the most common cause of failure within 2 years after surgery and that aseptic loosening is the most common cause for late revision.3

Recent studies suggest that prosthetic joint infection (PJI) may be underreported because of difficulty making a diagnosis and that cases of aseptic loosening may in fact be attributable to infections with low-virulence organisms.2,3 These findings have led to new efforts to develop uniform criteria for diagnosing PJIs. In 2011, the Musculoskeletal Infection Society (MSIS) offered a new definition for PJI diagnosis, based on clinical and laboratory criteria, to increase the accuracy of PJI diagnosis.4 The MSIS committee acknowledged that PJI may be present even if these criteria are not met, particularly in the case of low-virulence organisms, as patients may not present with clinical signs of infection and may have normal inflammatory markers and joint aspirates. Reports of PJI cases misdiagnosed as aseptic loosening suggest that current screening and diagnostic tools are not sensitive enough to detect all infections and that PJI is likely underdiagnosed.

According to MSIS criteria, the diagnosis of PJI can be made when there is a sinus tract communicating with the prosthesis, when a pathogen is isolated by culture from 2 or more separate tissue or fluid samples obtained from the affected prosthetic joint, or when 4 of 6 criteria are met. The 6 criteria are (1) elevated serum erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (>30 mm/hour) and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) level (>10 mg/L); (2) elevated synovial white blood cell (WBC) count (1100-4000 cells/μL); (3) elevated synovial polymorphonuclear leukocytes (>64%); (4) purulence in affected joint; (5) isolation of a microorganism in a culture of periprosthetic tissue or fluid; and (6) more than 5 neutrophils per high-power field in 5 high-power fields observed.

In this review article, we discuss recently developed novel synovial biomarkers and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technologies that may help increase the sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic guidelines for PJI.

Methods

Using PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses), we performed a systematic review of specific synovial fluid markers and PCR used in PJI diagnosis. In May 2016, we searched the PubMed database for these criteria: ((((((PCR[Text Word]) OR IL-6[Text Word]) OR leukocyte esterase[Text Word]) OR alpha defensin[Text Word]) AND ((“infection/diagnosis”[MeSH Terms] OR “infection/surgery”[MeSH Terms])))) AND (prosthetic joint infection[MeSH Terms] OR periprosthetic joint infection[MeSH Terms]).

We included patients who had undergone total hip, knee, or shoulder arthroplasty (THA, TKA, TSA). Index tests were PCR and the synovial fluid markers α-defensin (AD), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and leukocyte esterase (LE). Reference tests included joint fluid/serum analysis or tissue analysis (ESR/CRP level, cell count, culture, frozen section), which defined the MSIS criteria for PJI. Primary outcomes of interest were sensitivity and specificity, and secondary outcomes of interest included positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), positive likelihood ratio (+LR), and negative likelihood ratio (–LR). Randomized controlled trials and controlled cohort studies in humans published within the past 10 years were included.

Results

Our full-text review yielded 15 papers that met our study inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

α-Defensin

One of the novel synovial biomarkers that has shown significant promise in diagnosing PJIs, even with difficult-to-detect organisms, is AD.

AD has shown even more impressive results as a biomarker for PJI in the hip and knee, where infection with low virulence organism is less common. In 2014, Deirmengian and colleagues6 conducted a prospective clinical study of 149 patients who underwent revision THA or TKA for aseptic loosening (n = 112) or PJI (n = 37) as defined by MSIS criteria. Aseptic loosening was diagnosed when there was no identifiable reason for pain, and MSIS criteria were not met. Synovial fluid aspirates were collected before or during surgery. AD correctly identified 143 of the 149 patients with confirmed infection with sensitivity of 97.3% (95% confidence interval [CI], 85.8%-99.6%) and specificity of 95.5% (95% CI, 89.9%-98.5%). Similarly, Bingham and colleagues7 conducted a retrospective clinical study of 61 assays done on 57 patients who underwent revision arthroplasty for PJI as defined by MSIS criteria. Synovial fluid aspirates were collected before or during surgery. AD correctly identified all 19 PJIs with sensitivity of 100% (95% CI, 79%-100%) and specificity of 95% (95% CI, 83%-99%). Sensitivity and specificity of the AD assay more accurately predicted infection than synovial cell count or serum ESR/CRP level did.

These results are supported by another prospective study by Deirmengian and colleagues8 differentiating aseptic failures and PJIs in THA or TKA. The sensitivity and specificity of AD in diagnosing PJI were 100% (95% CI, 85.05%-100%).

In a prospective study of 102 patients who underwent revision THA or TKA secondary to aseptic loosening or PJI, Frangiamore and colleagues9 also demonstrated the value of AD as a diagnostic for PJI in primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty.

Table 1 and Figure 2 provide a concise review of the findings of each study.

Interleukin 6

Another synovial fluid biomarker that has shown promise in PJI diagnosis is IL-6. In 2015, Frangiamore and colleagues10 conducted a prospective clinical study of 32 patients who underwent revision TSA. Synovial fluid aspiration was obtained before or during surgery. MSIS criteria were used to establish the diagnosis of PJI. IL-6 had sensitivity of 87% and specificity of 90%, with +LR of 8.45 and –LR of 0.15 in predicting PJI. Synovial fluid IL-6 had strong associations with frozen section histology and growth of P acnes. Frangiamore and colleagues10 recommended an ideal IL-6 cutoff of 359.1 pg/mL and reported that, though not as accurate as AD, synovial fluid IL-6 levels can help predict positive cultures in patients who undergo revision TSA.

Lenski and Scherer11 conducted another retrospective clinical study of the diagnostic value of IL-6 in PJI.

Randau and colleagues12 conducted a prospective clinical study of 120 patients who presented with painful THA or TKA and underwent revision for PJI, aseptic failure, or aseptic revision without signs of infection or loosening. Synovial fluid aspirate was collected before or during surgery.

Table 2 and Figure 3 provide a concise review of the findings of each study.

Leukocyte Esterase

LE strips are an inexpensive screening tool for PJI, according to some studies. In a prospective clinical study of 364 endoprosthetic joint (hip, knee, shoulder) interventions, Guenther and colleagues13 collected synovial fluid before surgery. Samples were tested with graded LE strips using PJI criteria set by the authors. Results were correlated with preoperative synovial fluid aspirations, serum CRP level, serum WBC count, and intraoperative histopathologic and microbiological findings. Whereas 293 (93.31%) of the 314 aseptic cases had negative test strip readings, 100% of the 50 infected cases were positive. LE had sensitivity of 100%, specificity of 96.5%, PPV of 82%, and NPV of 100%.

Wetters et al14 performed a prospective clinical study on 223 patients who underwent TKAs and THAs for suspected PJI based on having criteria defined by the authors of the study. Synovial fluid samples were collected either preoperatively or intraoperatively.

Other authors have reported different findings that LE is an unreliable marker in PJI diagnosis. In one prospective clinical study of 85 patients who underwent primary or revision TSA, synovial fluid was collected during surgery.15 According to MSIS criteria, only 5 positive LE results predicted PJI among 21 primary and revision patients with positive cultures. Of the 7 revision patients who met the MSIS criteria for PJI, only 2 had a positive LE test. LE had sensitivity of 28.6%, specificity of 63.6%, PPV of 28.6%, and NPV of 87.5%. Six of the 7 revision patients grew P acnes. These results showed that LE was unreliable in detecting shoulder PJI.15

In another prospective clinical study, Tischler and colleagues16 enrolled 189 patients who underwent revision TKA or THA for aseptic failure or PJI as defined by the MSIS criteria. Synovial fluid was collected intraoperatively.

Table 3 and Figure 4 provide a concise review of the findings of each study.

Polymerase Chain Reaction

Studies have found that PCR analysis of synovial fluid is effective in detecting bacteria on the surface of implants removed during revision arthroplasties. Comparison of the 16S rRNA gene sequences of bacterial genomes showed a diverse range of bacterial species within biofilms on the surface of clinical and subclinical infections.17 These findings, along with those of other studies, suggest that PCR analysis of synovial fluid is useful in diagnosing PJI and identifying organisms and their sensitivities to antibiotics.

Gallo and colleagues18 performed a prospective clinical study on 115 patients who underwent revision TKAs or THAs. Synovial fluid was collected intraoperatively. PCR assays targeting the 16S rDNA were carried out on 101 patients. PJIs were classified based on criteria of the authors of this study, of which there were 42. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, +LR, and -LR for PCR were 71.4% (95% CI, 61.5%-75.5%), 97% (95% CI, 91.7%-99.1%), 92.6% (95% CI, 79.8%-97.9%), 86.5% (95% CI, 81.8%-88.4%), 23.6 (95% CI, 5.9%-93.8%), and 0.29 (95% CI, 0.17%-0.49%), respectively. Of note the most common organism detected in 42 PJIs was coagulase-negative Staphylococcus.

Marin and colleagues19 conducted a prospective study of 122 patients who underwent arthroplasty for suspected infection or aseptic loosening as defined by the authors’ clinicohistopathologic criteria. Synovial fluid and biopsy specimens were collected during surgery, and 40 patients met the infection criteria. The authors concluded that 16S PCR is more specific and has better PPV than culture does as one positive 16S PCR resulted in a specificity and PPV of PJI of 96.3% and 91.7%, respectively. However, they noted that culture was more sensitive in diagnosing PJI.

Jacovides and colleagues20 conducted a prospective study on 82 patients undergoing primary TKA, revision TKA, and revision THA.

The low PCR sensitivities reported in the literature were explained in a review by Hartley and Harris.21 They wrote that BR 16S rDNA and sequencing of PJI samples inherently have low sensitivity because of the contamination that can occur from the PCR reagents themselves or from sample mishandling. Techniques that address contaminant (extraneous DNA) removal, such as ultraviolet irradiation and DNase treatment, reduce Taq DNA polymerase activity, which reduces PCR sensitivity.

Table 4 and Figure 5 provide a concise review of the findings of each study.

Discussion

Although there is no gold standard for the diagnosis of PJIs, several clinical and laboratory criteria guidelines are currently used to help clinicians diagnose infections of prosthetic joints. However, despite standardization of diagnostic criteria, PJI continue to be a diagnostic challenge.

AD is a highly sensitive and specific synovial fluid biomarker in detecting common PJIs.

In summary, 5 AD studies5-9 had sensitivity ranging from 63% to 100% and specificity ranging from 95% to 100%; 3 IL-6 studies10-12 had sensitivity ranging from 46.8% to 90.9% and specificity ranging from 85.7% to 97.6%; 4 LE studies13-16 had sensitivity ranging from 28.6% to 100% and specificity ranging from 63.6% to 96.5%; and 3 PCR studies18-20 had sensitivity ranging from 67.1% to 95.7% and specificity ranging from 12.3% to 97.8%. Sensitivity and specificity were consistently higher for AD than for IL-6, LE, and PCR, though there was significant overlap, heterogeneity, and variation across all the included studies.

Although the overall incidence of PJI is low, infected revisions remain a substantial financial burden to hospitals, as annual costs of infected revisions is estimated to exceed $1.62 billion by 2020.25 The usefulness of novel biomarkers and PCR in diagnosing PJI can be found in their ability to diagnose infections and facilitate appropriate early treatment. Several of these tests are readily available commercially and have the potential to be cost-effective diagnostic tools. The price to perform an AD test from Synovasure TM (Zimmer Biomet) ranges from $93 to $143. LE also provides an economic option for diagnosing PJI, as LE strips are commercially available for the cost of about 25 cents. PCR has also become an economic option, as costs can average $15.50 per sample extraction or PCR assay and $42.50 per amplicon sequence as reported in a study by Vandercam and colleagues.26 Future studies are needed to determine a diagnostic algorithm which incorporates these novel synovial markers to improve diagnostic accuracy of PJI in the most cost effective manner.

The current literature supports that AD can potentially be used to screen for PJI. Our findings suggest novel synovial fluid biomarkers may become of significant diagnostic use when combined with current laboratory and clinical diagnostic criteria. We recommend use of AD in cases in which pain, stiffness, and poor TJA outcome cannot be explained by errors in surgical technique, and infection is suspected despite MSIS criteria not being met.

The studies reviewed in this manuscript were limited in that none presented level I evidence (12 had level II evidence, and 3 had level III evidence), and there was significant heterogeneity (some studies used their own diagnostic standard, and others used the MSIS criteria). Larger scale prospective studies comparing serum ESR/CRP level and synovial fluid analysis to novel synovial markers are needed.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(4):190-198. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Maradit Kremers H, Larson DR, Crowson CS, et al. Prevalence of total hip and knee replacement in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(17):1386-1397.

2. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780-785.

3. Sharkey PF, Lichstein PM, Shen C, Tokarski AT, Parvizi J. Why are total knee arthroplasties failing today—has anything changed after 10 years? J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(9):1774-1778.

4. Butler-Wu SM, Burns EM, Pottinger PS, et al. Optimization of periprosthetic culture for diagnosis of Propionibacterium acnes prosthetic joint infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(7):2490-2495.

5. Frangiamore SJ, Saleh A, Grosso MJ, et al. α-Defensin as a predictor of periprosthetic shoulder infection. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(7):1021-1027.

6. Deirmengian C, Kardos K, Kilmartin P, Cameron A, Schiller K, Parvizi J. Combined measurement of synovial fluid α-defensin and C-reactive protein levels: highly accurate for diagnosing periprosthetic joint infection. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(17):1439-1445.

7. Bingham J, Clarke H, Spangehl M, Schwartz A, Beauchamp C, Goldberg B. The alpha defensin-1 biomarker assay can be used to evaluate the potentially infected total joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(12):4006-4009.

8. Deirmengian C, Kardos K, Kilmartin P, et al. The alpha-defensin test for periprosthetic joint infection outperforms the leukocyte esterase test strip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(1):198-203.

9. Frangiamore SJ, Gajewski ND, Saleh A, Farias-Kovac M, Barsoum WK, Higuera CA. α-Defensin accuracy to diagnose periprosthetic joint infection—best available test? J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(2):456-460.

10. Frangiamore SJ, Saleh A, Kovac MF, et al. Synovial fluid interleukin-6 as a predictor of periprosthetic shoulder infection. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(1):63-70.

11. Lenski M, Scherer MA. Synovial IL-6 as inflammatory marker in periprosthetic joint infections. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(6):1105-1109.

12. Randau TM, Friedrich MJ, Wimmer MD, et al. Interleukin-6 in serum and in synovial fluid enhances the differentiation between periprosthetic joint infection and aseptic loosening. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e89045.

13. Guenther D, Kokenge T, Jacobs O, et al. Excluding infections in arthroplasty using leucocyte esterase test. Int Orthop. 2014;38(11):2385-2390.

14. Wetters NG, Berend KR, Lombardi AV, Morris MJ, Tucker TL, Della Valle CJ. Leukocyte esterase reagent strips for the rapid diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(8 suppl):8-11.

15. Nelson GN, Paxton ES, Narzikul A, Williams G, Lazarus MD, Abboud JA. Leukocyte esterase in the diagnosis of shoulder periprosthetic joint infection. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(9):1421-1426.

16. Tischler EH, Cavanaugh PK, Parvizi J. Leukocyte esterase strip test: matched for Musculoskeletal Infection Society criteria. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(22):1917-1920.

17. Dempsey KE, Riggio MP, Lennon A, et al. Identification of bacteria on the surface of clinically infected and non-infected prosthetic hip joints removed during revision arthroplasties by 16S rRNA gene sequencing and by microbiological culture. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(3):R46.

18. Gallo J, Kolar M, Dendis M, et al. Culture and PCR analysis of joint fluid in the diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. New Microbiol. 2008;31(1):97-104.

19. Marin M, Garcia-Lechuz JM, Alonso P, et al. Role of universal 16S rRNA gene PCR and sequencing in diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(3):583-589.

20. Jacovides CL, Kreft R, Adeli B, Hozack B, Ehrlich GD, Parvizi J. Successful identification of pathogens by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based electron spray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (ESI-TOF-MS) in culture-negative periprosthetic joint infection. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(24):2247-2254.

21. Hartley JC, Harris KA. Molecular techniques for diagnosing prosthetic joint infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(suppl 1):i21-i24.

22. Zappe B, Graf S, Ochsner PE, Zimmerli W, Sendi P. Propionibacterium spp. in prosthetic joint infections: a diagnostic challenge. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128(10):1039-1046.

23. Rasouli MR, Harandi AA, Adeli B, Purtill JJ, Parvizi J. Revision total knee arthroplasty: infection should be ruled out in all cases. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(6):1239-1243.e1-e2.

24. Hunt RW, Bond MJ, Pater GD. Psychological responses to cancer: a case for cancer support groups. Community Health Stud. 1990;14(1):35-38.

25. Kurtz SM, Lau E, Schmier J, Ong KL, Zhao K, Parvizi J. Infection burden for hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(7):984-991.

26. Vandercam B, Jeumont S, Cornu O, et al. Amplification-based DNA analysis in the diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. J Mol Diagn. 2008;10(6):537-543.

1. Maradit Kremers H, Larson DR, Crowson CS, et al. Prevalence of total hip and knee replacement in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(17):1386-1397.

2. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780-785.

3. Sharkey PF, Lichstein PM, Shen C, Tokarski AT, Parvizi J. Why are total knee arthroplasties failing today—has anything changed after 10 years? J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(9):1774-1778.

4. Butler-Wu SM, Burns EM, Pottinger PS, et al. Optimization of periprosthetic culture for diagnosis of Propionibacterium acnes prosthetic joint infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(7):2490-2495.

5. Frangiamore SJ, Saleh A, Grosso MJ, et al. α-Defensin as a predictor of periprosthetic shoulder infection. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(7):1021-1027.

6. Deirmengian C, Kardos K, Kilmartin P, Cameron A, Schiller K, Parvizi J. Combined measurement of synovial fluid α-defensin and C-reactive protein levels: highly accurate for diagnosing periprosthetic joint infection. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(17):1439-1445.

7. Bingham J, Clarke H, Spangehl M, Schwartz A, Beauchamp C, Goldberg B. The alpha defensin-1 biomarker assay can be used to evaluate the potentially infected total joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(12):4006-4009.

8. Deirmengian C, Kardos K, Kilmartin P, et al. The alpha-defensin test for periprosthetic joint infection outperforms the leukocyte esterase test strip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(1):198-203.

9. Frangiamore SJ, Gajewski ND, Saleh A, Farias-Kovac M, Barsoum WK, Higuera CA. α-Defensin accuracy to diagnose periprosthetic joint infection—best available test? J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(2):456-460.

10. Frangiamore SJ, Saleh A, Kovac MF, et al. Synovial fluid interleukin-6 as a predictor of periprosthetic shoulder infection. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(1):63-70.

11. Lenski M, Scherer MA. Synovial IL-6 as inflammatory marker in periprosthetic joint infections. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(6):1105-1109.

12. Randau TM, Friedrich MJ, Wimmer MD, et al. Interleukin-6 in serum and in synovial fluid enhances the differentiation between periprosthetic joint infection and aseptic loosening. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e89045.

13. Guenther D, Kokenge T, Jacobs O, et al. Excluding infections in arthroplasty using leucocyte esterase test. Int Orthop. 2014;38(11):2385-2390.

14. Wetters NG, Berend KR, Lombardi AV, Morris MJ, Tucker TL, Della Valle CJ. Leukocyte esterase reagent strips for the rapid diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(8 suppl):8-11.

15. Nelson GN, Paxton ES, Narzikul A, Williams G, Lazarus MD, Abboud JA. Leukocyte esterase in the diagnosis of shoulder periprosthetic joint infection. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(9):1421-1426.

16. Tischler EH, Cavanaugh PK, Parvizi J. Leukocyte esterase strip test: matched for Musculoskeletal Infection Society criteria. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(22):1917-1920.

17. Dempsey KE, Riggio MP, Lennon A, et al. Identification of bacteria on the surface of clinically infected and non-infected prosthetic hip joints removed during revision arthroplasties by 16S rRNA gene sequencing and by microbiological culture. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(3):R46.

18. Gallo J, Kolar M, Dendis M, et al. Culture and PCR analysis of joint fluid in the diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. New Microbiol. 2008;31(1):97-104.

19. Marin M, Garcia-Lechuz JM, Alonso P, et al. Role of universal 16S rRNA gene PCR and sequencing in diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(3):583-589.

20. Jacovides CL, Kreft R, Adeli B, Hozack B, Ehrlich GD, Parvizi J. Successful identification of pathogens by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based electron spray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (ESI-TOF-MS) in culture-negative periprosthetic joint infection. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(24):2247-2254.

21. Hartley JC, Harris KA. Molecular techniques for diagnosing prosthetic joint infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(suppl 1):i21-i24.

22. Zappe B, Graf S, Ochsner PE, Zimmerli W, Sendi P. Propionibacterium spp. in prosthetic joint infections: a diagnostic challenge. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128(10):1039-1046.

23. Rasouli MR, Harandi AA, Adeli B, Purtill JJ, Parvizi J. Revision total knee arthroplasty: infection should be ruled out in all cases. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(6):1239-1243.e1-e2.

24. Hunt RW, Bond MJ, Pater GD. Psychological responses to cancer: a case for cancer support groups. Community Health Stud. 1990;14(1):35-38.

25. Kurtz SM, Lau E, Schmier J, Ong KL, Zhao K, Parvizi J. Infection burden for hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(7):984-991.

26. Vandercam B, Jeumont S, Cornu O, et al. Amplification-based DNA analysis in the diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. J Mol Diagn. 2008;10(6):537-543.

Traumatic Anterior Shoulder Instability: The US Military Experience

Take-Home Points

- Arthroscopic stabilization performed early results in better outcomes in patients with Bankart lesions.

- A subcritical level of bone loss of 13.5% has been shown to have a significant effect on outcomes, in addition to the established “critical amount”.

- Bone loss is a bipolar issue. Both sides must be considered in order to properly address shoulder instability.

- Off-track measurement has been shown to be even more positively predictive of outcomes than glenoid bone loss assessment.

- There are several bone loss management options including, the most common coracoid transfer, as well as distal tibial allograft and distal clavicular autograft.

Given its relatively young age, high activity level, and centralized medical care system, the US military population is ideal for studying traumatic anterior shoulder instability. There is a long history of military surgeons who have made significant contributions that have advanced our understanding of this pathology and its treatment and results. In this article, we describe the scope, treatment, and results of this pathology in the US military population.

Incidence and Pathology

At the United States Military Academy (USMA), Owens and colleagues1 studied the incidence of shoulder instability, including dislocation and subluxation, and found anterior instability events were far more common than in civilian populations. The incidence of shoulder instability was 0.08 per 1000 person-years in the general US population vs 1.69 per 1000 person-years in US military personnel. The factors associated with increased risk of shoulder instability injury in the military population were male sex, white race, junior enlisted rank, and age under 30 years. Owens and colleagues2 noted that subluxation accounted for almost 85% of the total anterior instability events. Owens and colleagues3 found the pathology in subluxation events was similar to that in full dislocations, with a soft-tissue anterior Bankart lesion and a Hill-Sachs lesion detected on magnetic resonance imaging in more than 90% of patients. In another study at the USMA, DeBerardino and colleagues4 noted that 97% of arthroscopically assessed shoulders in first-time dislocators involved complete detachment of the capsuloligamentous complex from the anterior glenoid rim and neck—a so-called Bankart lesion. Thus, in a military population, anterior instability resulting from subluxation or dislocation is a common finding that is often represented by a soft-tissue Bankart lesion and a Hill-Sachs defect.

Natural History of Traumatic Anterior Shoulder Instability in the Military

Several studies have evaluated the outcomes of nonoperative and operative treatment of shoulder instability. Although most have found better outcomes with operative intervention, Aronen and Regan5 reported good results (25% recurrence at nearly 3-year follow-up) with nonoperative treatment and adherence to a strict rehabilitation program. Most other comparative studies in this population have published contrary results. Wheeler and colleagues6 studied the natural history of anterior shoulder dislocations in a USMA cadet cohort and found recurrent instability after shoulder dislocation in 92% of cadets who had nonoperative treatment. Similarly, DeBerardino and colleagues4 found that, in the USMA, 90% of first-time traumatic anterior shoulder dislocations managed nonoperatively experienced recurrent instability. In a series of Army soldiers with shoulder instability, Bottoni and colleagues7 reported that 75% of nonoperatively managed patients had recurrent instability, and, of these, 67% progressed to surgical intervention. Nonoperative treatment for a first-time dislocation is still reasonable if a cadet or soldier needs to quickly return to functional duties. Athletes who develop shoulder instability during their playing season have been studied in a military population as well. In a multicenter study of service academy athletes with anterior instability, Dickens and colleagues8 found that, with conservative management and accelerated rehabilitation of in-season shoulder instability, 73% of athletes returned to sport by a mean of 5 days. However, the durability of this treatment should be questioned, as 64% later experienced recurrence.

Arthroscopic Stabilization of Acute Anterior Shoulder Dislocations

In an early series of cases of traumatic anterior shoulder instability in USMA cadets, Wheeler and colleagues6 found that, at 14 months, 78% of arthroscopically stabilized cases and 92% of nonoperatively treated cases were successful. Then, in the 1990s, DeBerardino and colleagues4 studied a series of young, active patients in the USMA and noted significantly better results with arthroscopic treatment, vs nonoperative treatment, at 2- to 5-year follow-up. Of the arthroscopically treated shoulders, 88% remained stable during the study and returned to preinjury activity levels, and 12% experienced recurrent instability (risk factors included 2+ sulcus sign, poor capsular labral tissue, and history of bilateral shoulder instability). In a long-term follow-up (mean, 11.7 years; range, 9.1-13.9 years) of the same cohort, Owens and colleagues9 found that 14% of patients available for follow-up had undergone revision stabilization surgery, and, of these, 21% reported experiencing subluxation events. The authors concluded that, in first-time dislocators in this active military population, acute arthroscopic Bankart repair resulted in excellent return to athletics and subjective function, and had acceptable recurrence and reoperation rates. Bottoni and colleagues,7 in a prospective, randomized evaluation of arthroscopic stabilization of acute, traumatic, first-time shoulder dislocations in the Army, noted an 89% success rate for arthroscopic treatment at an average follow-up of 36 months, with no recurrent instability. DeBerardino and colleagues10 compared West Point patients treated nonoperatively with those arthroscopically treated with staples, transglenoid sutures, or bioabsorbable anchors. Recurrence rates were 85% for nonoperative treatment, 22% for staples, 14% for transglenoid sutures, and 10% for bioabsorbable anchors.

Arthroscopic Versus Open Stabilization of Anterior Shoulder Instability

In a prospective, randomized clinical trial comparing open and arthroscopic shoulder stabilization for recurrent anterior instability in active-duty Army personnel, Bottoni and colleagues11 found comparable clinical outcomes. Stabilization surgery failed clinically in only 3 cases, 2 open and 1 arthroscopic. The authors concluded that arthroscopic stabilization can be safely performed for recurrent shoulder instability and that arthroscopic outcomes are similar to open outcomes. In a series of anterior shoulder subluxations in young athletes with Bankart lesions, Owens and colleagues12 found that open and arthroscopic stabilization performed early resulted in better outcomes, regardless of technique used. Recurrent subluxation occurred at a mean of 17 months in 3 of the 10 patients in the open group and 3 of the 9 patients in the arthroscopic group, for an overall recurrence rate of 31%. The authors concluded that, in this patient population with Bankart lesions caused by anterior subluxation events, surgery should be performed early.

Bone Lesions

Burkhart and De Beer13 first noted that bone loss has emerged as one of the most important considerations in the setting of shoulder instability in active patients. Other authors have found this to be true in military populations.14,15

The diagnosis of bone loss may include historical findings, such as increased number and ease of dislocations, as well as dislocation in lower positions of abduction. Physical examination findings may include apprehension in the midrange of motion. Advanced imaging, such as magnetic resonance arthrography, has since been validated as equivalent to 3-dimensional computed tomography (3-D CT) in determining glenoid bone loss.16 In 2007, Mologne and colleagues15 studied the amount of glenoid bone loss and the presence of fragmented bone or attritional bone loss and its effect on outcomes. They evaluated 21 patients who had arthroscopic treatment for anterior instability with anteroinferior glenoid bone loss between 20% and 30%. Average follow-up was 34 months. All patients received 3 or 4 anterior anchors. No patient with a bone fragment incorporated into the repair experienced recurrence or subluxation, whereas 30% of patients with attritional bone loss had recurrent instability.15

Classifying Bone Loss and Recognizing Its Effects

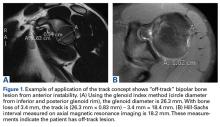

Burkhart and De Beer13 helped define the role and significance of bone loss in the setting of shoulder instability. They defined significant bone loss as an engaging Hill-Sachs lesion of the humerus in an abducted and externally rotated position or an “inverted pear” lesion of the glenoid. Overall analysis revealed recurrence in 4% of cases without significant bone loss and 65% of cases with significant bone loss. In a subanalysis of contact-sport athletes in the setting of bone loss, the failure rate increased to 89%, from 6.5%. Aiding in the quantitative assessment of glenoid bone loss, Itoi and colleagues17 showed that 21% glenoid bone loss resulted in instability that would not be corrected by a soft-tissue procedure alone. Bone loss of 20% to 25% has since been considered a “critical amount,” above which an arthroscopic Bankart has been questioned. More recently, several authors have shown that even less bone loss can have a significant effect on outcomes. Shaha and colleagues18 established that a subcritical level of bone loss (13.5%) on the anteroinferior glenoid resulted in clinical failure (as determined with the Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index) even in cases in which frank recurrence or subluxation was avoided. It is thought that, in recurrent instability, glenoid bone loss incident rate is as high as 90%, and the corresponding percentage of patients with Hill-Sachs lesions is almost 100%.19,20 Thus, it is increasingly understood that bone loss is a bipolar issue and that both sides must be considered in order to properly address shoulder instability in this setting. In 2007, Yamamoto and colleagues21 introduced the glenoid track, a method for predicting whether a Hill-Sachs lesion will engage. Di Giacomo and colleagues22 refined the track concept to quantitatively determine which lesions will engage in the setting of both glenoid and humeral bone loss. Metzger and colleagues,23 confirming the track concept arthroscopically, found that manipulation with anesthesia and arthroscopic visualization was well predicted by preoperative track measurements, and thus these measurements can be a good guide for surgical management (Figures 1A, 1B).

Strategies for Addressing Bone Loss in Anterior Shoulder Instability

Several approaches for managing bone loss in shoulder instability have been described—the most common being coracoid transfer (Latarjet procedure). Waterman and colleagues25 recently studied the effects of coracoid transfer, distal tibial allograft, and iliac crest augmentation on anterior shoulder instability in US military patients treated between 2006 and 2012. Of 64 patients who underwent a bone block procedure, 16 (25%) had a complication during short-term follow-up. Complications included neurologic injury, pain, infection, hardware failure, and recurrent instability.

Conclusion

Traumatic anterior shoulder instability is a common pathology that continues to significantly challenge the readiness of the US military. Military surgeon-researchers have a long history of investigating approaches to the treatment of this pathology—applying good science to a large controlled population, using a single medical record, and demonstrating a commitment to return service members to the ready defense of the nation.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(4):184-189. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Owens BD, Dawson L, Burks R, Cameron KL. Incidence of shoulder dislocation in the United States military: demographic considerations from a high-risk population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(4):791-796.

2. Owens BD, Duffey ML, Nelson BJ, DeBerardino TM, Taylor DC, Mountcastle SB. The incidence and characteristics of shoulder instability at the United States Military Academy. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(7):1168-1173.

3. Owens BD, Nelson BJ, Duffey ML, et al. Pathoanatomy of first-time, traumatic, anterior glenohumeral subluxation events. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(7):1605-1611.

4. DeBerardino TM, Arciero RA, Taylor DC, Uhorchak JM. Prospective evaluation of arthroscopic stabilization of acute, initial anterior shoulder dislocations in young athletes. Two- to five-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(5):586-592.

5. Aronen JG, Regan K. Decreasing the incidence of recurrence of first time anterior shoulder dislocations with rehabilitation. Am J Sports Med. 1984;12(4):283-291.

6. Wheeler JH, Ryan JB, Arciero RA, Molinari RN. Arthroscopic versus nonoperative treatment of acute shoulder dislocations in young athletes. Arthroscopy. 1989;5(3):213-217.

7. Bottoni CR, Wilckens JH, DeBerardino TM, et al. A prospective, randomized evaluation of arthroscopic stabilization versus nonoperative treatment in patients with acute, traumatic, first-time shoulder dislocations. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(4):576-580.

8. Dickens JF, Owens BD, Cameron KL, et al. Return to play and recurrent instability after in-season anterior shoulder instability: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(12):2842-2850.

9. Owens BD, DeBerardino TM, Nelson BJ, et al. Long-term follow-up of acute arthroscopic Bankart repair for initial anterior shoulder dislocations in young athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(4):669-673.

10. DeBerardino TM, Arciero RA, Taylor DC. Arthroscopic stabilization of acute initial anterior shoulder dislocation: the West Point experience. J South Orthop Assoc. 1996;5(4):263-271.

11. Bottoni CR, Smith EL, Berkowitz MJ, Towle RB, Moore JH. Arthroscopic versus open shoulder stabilization for recurrent anterior instability: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(11):1730-1737.

12. Owens BD, Cameron KL, Peck KY, et al. Arthroscopic versus open stabilization for anterior shoulder subluxations. Orthop J Sports Med. 2015;3(1):2325967115571084.

13. Burkhart SS, De Beer JF. Traumatic glenohumeral bone defects and their relationship to failure of arthroscopic Bankart repairs: significance of the inverted-pear glenoid and the humeral engaging Hill-Sachs lesion. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(7):677-694.14. Shaha JS, Cook JB, Rowles DJ, Bottoni CR, Shaha SH, Tokish JM. Clinical validation of the glenoid track concept in anterior glenohumeral instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(22):1918-1923.

15. Mologne TS, Provencher MT, Menzel KA, Vachon TA, Dewing CB. Arthroscopic stabilization in patients with an inverted pear glenoid: results in patients with bone loss of the anterior glenoid. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(8):1276-1283.

16. Markenstein JE, Jaspars KC, van der Hulst VP, Willems WJ. The quantification of glenoid bone loss in anterior shoulder instability; MR-arthro compared to 3D-CT. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43(4):475-483.

17. Itoi E, Lee SB, Berglund LJ, Berge LL, An KN. The effect of a glenoid defect on anteroinferior stability of the shoulder after Bankart repair: a cadaveric study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(1):35-46.

18. Shaha JS, Cook JB, Song DJ, et al. Redefining “critical” bone loss in shoulder instability: functional outcomes worsen with “subcritical” bone loss. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(7):1719-1725.

19. Piasecki DP, Verma NN, Romeo AA, Levine WN, Bach BR Jr, Provencher MT. Glenoid bone deficiency in recurrent anterior shoulder instability: diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17(8):482-493.

20. Provencher MT, Frank RM, Leclere LE, et al. The Hill-Sachs lesion: diagnosis, classification, and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(4):242-252.

21. Yamamoto N, Itoi E, Abe H, et al. Contact between the glenoid and the humeral head in abduction, external rotation, and horizontal extension: a new concept of glenoid track. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(5):649-656.

22. Di Giacomo G, Itoi E, Burkhart SS. Evolving concept of bipolar bone loss and the Hill-Sachs lesion: from “engaging/non-engaging” lesion to “on-track/off-track” lesion. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(1):90-98.

23. Metzger PD, Barlow B, Leonardelli D, Peace W, Solomon DJ, Provencher MT. Clinical application of the “glenoid track” concept for defining humeral head engagement in anterior shoulder instability: a preliminary report. Orthop J Sports Med. 2013;1(2):2325967113496213.

24. Arciero RA, Parrino A, Bernhardson AS, et al. The effect of a combined glenoid and Hill-Sachs defect on glenohumeral stability: a biomechanical cadaveric study using 3-dimensional modeling of 142 patients. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(6):1422-1429.

25. Waterman BR, Chandler PJ, Teague E, Provencher MT, Tokish JM, Pallis MP. Short-term outcomes of glenoid bone block augmentation for complex anterior shoulder instability in a high-risk population. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(9):1784-1790.

26. Schroder DT, Provencher MT, Mologne TS, Muldoon MP, Cox JS. The modified Bristow procedure for anterior shoulder instability: 26-year outcomes in Naval Academy midshipmen. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(5):778-786.

27. Provencher MT, Frank RM, Golijanin P, et al. Distal tibia allograft glenoid reconstruction in recurrent anterior shoulder instability: clinical and radiographic outcomes. Arthroscopy. 2017;33(5):891-897.

28. Tokish JM, Fitzpatrick K, Cook JB, Mallon WJ. Arthroscopic distal clavicular autograft for treating shoulder instability with glenoid bone loss. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3(4):e475-e481.

Take-Home Points

- Arthroscopic stabilization performed early results in better outcomes in patients with Bankart lesions.

- A subcritical level of bone loss of 13.5% has been shown to have a significant effect on outcomes, in addition to the established “critical amount”.