User login

Understanding the human papillomavirus

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most prevalent sexually transmitted disease globally. It is causally related to the development of several malignancies, including cervical, anal, and oropharyngeal ones, because of its integration and dysregulation of the genome of infected cells. Fortunately, vaccination is available to prevent development of HPV-related diseases. Understanding this virus, its carcinogenic role, and the importance of prevention through vaccination are critically important for ob.gyns. This column reviews the fundamentals of HPV biology, epidemiology, and carcinogenesis.

Viral anatomy

HPV are members of the A genus of the family Papovaviridae. They contain between 7,800 and 7,900 base pairs. They are nonenveloped, double-stranded DNA viruses with a circular structure. The viral DNA is contained within an icosahedral capsid that measures 45 nm-55 nm. The HPV genome has three critical regions: the long control region, otherwise known as the upstream regulatory region; the early region; and the late region.1

Capsid proteins are similar between groups. Therefore, HPV are categorized into “types” and “subtypes” based on the extent of DNA similarity. There are more than 100 types of HPV in humans.2 The type of HPV is determined by the gene sequences of E6/E7 and L1 and must show more than 10% difference between types. The gene sequences between different subtypes differ by 2%-5%.

Epidemiology of HPV infection

HPV are widely distributed among mammalian species but are species specific. Their tissue affinity varies by type. HPV types 1, 2, and 4 cause common or plantar warts. HPV types 6 and 11 cause condyloma acuminata (genital warts) and low grade dysplasia. HPV types 16 and 18 – in addition to 31 and 52 – are of particular interest to oncologists because they are associated with lower genital tract high grade dysplasia and invasive carcinoma. Infection with HPV 16 is present in about half of invasive cervical cancers, with HPV type 18 present in 20% of cervical cancers. Adenocarcinomas of the cervix are more commonly associated with HPV 18. Anal cancer and oropharyngeal cancer are more commonly associated with HPV 16.3

HPV infections are acquired through cutaneous touching (including hand to genital) and HPV positivity is most commonly present within the first 10 years after sexual debut.4 However, most individuals who acquire HPV do so as a transient infection, which is cleared without sequelae. Those who fail to rapidly clear HPV infection, and in whom it becomes chronic, face an increasing risk of development of dysplasia and invasive carcinoma. The incidence of HPV infection increases again at menopause, but, for these older women, the new finding of HPV detection may be related to reactivation of an earlier infection rather than exclusively new exposure to the virus.5

Diagnosis and testing

HPV infection can be detected through DNA testing, RNA testing, and cellular markers.6

HPV DNA testing was the original form of testing offered. It improved the sensitivity over cytology alone in the detection of precursors to malignancy but had relatively poor specificity, resulting in a high false positive rate and unnecessary referral to colposcopy. The various tests approved by the Food and Drug Administration – Hybrid Capture 2 (HC2), Cervista, and Cobas 4800 – differ in the number and nature of HPV types that they detect.

HPV RNA testing has developed and involves measuring the expression of E6 and E7 RNA. This testing is FDA approved and has the potential to improve upon the specificity of DNA testing procedures by decreasing false positives.

Measurement of cellular markers is currently considered experimental/exploratory and is not yet FDA approved for diagnostic purposes in screening or confirmation of HPV infection or coexisting dysplasia. It involves measuring the downstream cellular targets (such as p16) of E6 or E7 activity.

The mechanism of carcinogenesis

The early region of the HPV genome is downstream from the upstream regulatory region. It codes for proteins involved in viral infection and replication. The two most important genes in the early region are E6 and E7. When integrated into the human genome of the lower genital tract cell, the viral genes E6 and E7 negatively interfere with cell cycle control and mechanisms to halt dysregulation.7

E6 and E7 are considered oncogenes because they cause loss of function of the critical tumor suppressor proteins p53 and the retinoblastoma protein. The p53 protein is typically responsible for controlling cell cycling through the G0/G1 to S phases. It involves stalling cellular mitosis in order to facilitate DNA repair mechanisms in the case of damaged cells, thereby preventing replication of DNA aberrations. The retinoblastoma protein also functions to inhibit cells that have acquired DNA damage from cycling and induces apoptosis in DNA damaged cells. When protein products of E6 and E7 negatively interact with these two tumor suppressor proteins they overcome the cell’s safeguard arrest response.

In the presence of other carcinogens, such as products of tobacco exposure, the increased DNA damage sustained by the genital tract cell is allowed to go relatively unchecked by the HPV coinfection, which has disabled tumor suppressor function. This facilitates immortality of the damaged cell, amplification of additional DNA mutations, and unchecked cellular growth and dysplastic transformation. E6 and E7 are strongly expressed in invasive genital tract lesions to support its important role in carcinogenesis.

HIV coinfection is another factor that promotes carcinogenesis following HPV infection because it inhibits clearance of the virus through T-cell mediated immunosuppression and directly enhances expression of E6 and E7 proteins in the HIV and HPV coinfected cell.8 For these reasons, HIV-positive women are less likely to clear HPV infection and more likely to develop high grade dysplasia or invasive carcinomas.

Prevention and vaccination

HPV vaccinations utilize virus-like particles (VLPs). These VLPs are capsid particles generated from the L1 region of the HPV DNA. The capsid proteins coded for by L1 are highly immunogenic. VLPs are recombinant proteins created in benign biologic systems (such as yeast) and contain no inner DNA core (effectively empty viral capsids) and therefore are not infectious. The L1 gene is incorporated into a plasmid, which is inserted into the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell. Transcription and translation of the L1 gene takes place, creating capsid proteins that self-assemble into VLPs. These VLPs are retrieved and inoculated into candidate patients to illicit an immune response.

Quadrivalent, nine-valent, and bivalent vaccines are available worldwide. However, only the nine-valent vaccine – protective against types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58 – is available in the United States. This theoretically provides more comprehensive coverage against cervical cancer–causing HPV types, as 70% of cervical cancer is attributable to HPV 16 and 18, but an additional 20% is attributable to HPV 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58. This vaccine also provides protection against the HPV strains that cause genital warts and low-grade dysplastic changes.9

HPV, in most instances, is a transient virus with no sequelae. However, if not cleared from the cells of the lower genital tract, anus, or oropharynx it can result in the breakdown of cellular correction strategies and culminate in invasive carcinoma. Fortunately, highly effective and safe vaccinations are available and should be broadly prescribed.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1995 Jun;4(4):415-28.

2. Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Apr;121(1):32-42.

3. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008 Jul;17(7):1611-22.

4. JAMA. 2007 Feb 28;297(8):813-9.

5. J Infect Dis. 2013; 207(2): 272-80.

6. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011 Mar 2;103(5):368-83.

7. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000 May 3;92(9):690-8.

8. Lancet. 2002 Jan 12;359(9301):108-13.

9. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:e173–8.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most prevalent sexually transmitted disease globally. It is causally related to the development of several malignancies, including cervical, anal, and oropharyngeal ones, because of its integration and dysregulation of the genome of infected cells. Fortunately, vaccination is available to prevent development of HPV-related diseases. Understanding this virus, its carcinogenic role, and the importance of prevention through vaccination are critically important for ob.gyns. This column reviews the fundamentals of HPV biology, epidemiology, and carcinogenesis.

Viral anatomy

HPV are members of the A genus of the family Papovaviridae. They contain between 7,800 and 7,900 base pairs. They are nonenveloped, double-stranded DNA viruses with a circular structure. The viral DNA is contained within an icosahedral capsid that measures 45 nm-55 nm. The HPV genome has three critical regions: the long control region, otherwise known as the upstream regulatory region; the early region; and the late region.1

Capsid proteins are similar between groups. Therefore, HPV are categorized into “types” and “subtypes” based on the extent of DNA similarity. There are more than 100 types of HPV in humans.2 The type of HPV is determined by the gene sequences of E6/E7 and L1 and must show more than 10% difference between types. The gene sequences between different subtypes differ by 2%-5%.

Epidemiology of HPV infection

HPV are widely distributed among mammalian species but are species specific. Their tissue affinity varies by type. HPV types 1, 2, and 4 cause common or plantar warts. HPV types 6 and 11 cause condyloma acuminata (genital warts) and low grade dysplasia. HPV types 16 and 18 – in addition to 31 and 52 – are of particular interest to oncologists because they are associated with lower genital tract high grade dysplasia and invasive carcinoma. Infection with HPV 16 is present in about half of invasive cervical cancers, with HPV type 18 present in 20% of cervical cancers. Adenocarcinomas of the cervix are more commonly associated with HPV 18. Anal cancer and oropharyngeal cancer are more commonly associated with HPV 16.3

HPV infections are acquired through cutaneous touching (including hand to genital) and HPV positivity is most commonly present within the first 10 years after sexual debut.4 However, most individuals who acquire HPV do so as a transient infection, which is cleared without sequelae. Those who fail to rapidly clear HPV infection, and in whom it becomes chronic, face an increasing risk of development of dysplasia and invasive carcinoma. The incidence of HPV infection increases again at menopause, but, for these older women, the new finding of HPV detection may be related to reactivation of an earlier infection rather than exclusively new exposure to the virus.5

Diagnosis and testing

HPV infection can be detected through DNA testing, RNA testing, and cellular markers.6

HPV DNA testing was the original form of testing offered. It improved the sensitivity over cytology alone in the detection of precursors to malignancy but had relatively poor specificity, resulting in a high false positive rate and unnecessary referral to colposcopy. The various tests approved by the Food and Drug Administration – Hybrid Capture 2 (HC2), Cervista, and Cobas 4800 – differ in the number and nature of HPV types that they detect.

HPV RNA testing has developed and involves measuring the expression of E6 and E7 RNA. This testing is FDA approved and has the potential to improve upon the specificity of DNA testing procedures by decreasing false positives.

Measurement of cellular markers is currently considered experimental/exploratory and is not yet FDA approved for diagnostic purposes in screening or confirmation of HPV infection or coexisting dysplasia. It involves measuring the downstream cellular targets (such as p16) of E6 or E7 activity.

The mechanism of carcinogenesis

The early region of the HPV genome is downstream from the upstream regulatory region. It codes for proteins involved in viral infection and replication. The two most important genes in the early region are E6 and E7. When integrated into the human genome of the lower genital tract cell, the viral genes E6 and E7 negatively interfere with cell cycle control and mechanisms to halt dysregulation.7

E6 and E7 are considered oncogenes because they cause loss of function of the critical tumor suppressor proteins p53 and the retinoblastoma protein. The p53 protein is typically responsible for controlling cell cycling through the G0/G1 to S phases. It involves stalling cellular mitosis in order to facilitate DNA repair mechanisms in the case of damaged cells, thereby preventing replication of DNA aberrations. The retinoblastoma protein also functions to inhibit cells that have acquired DNA damage from cycling and induces apoptosis in DNA damaged cells. When protein products of E6 and E7 negatively interact with these two tumor suppressor proteins they overcome the cell’s safeguard arrest response.

In the presence of other carcinogens, such as products of tobacco exposure, the increased DNA damage sustained by the genital tract cell is allowed to go relatively unchecked by the HPV coinfection, which has disabled tumor suppressor function. This facilitates immortality of the damaged cell, amplification of additional DNA mutations, and unchecked cellular growth and dysplastic transformation. E6 and E7 are strongly expressed in invasive genital tract lesions to support its important role in carcinogenesis.

HIV coinfection is another factor that promotes carcinogenesis following HPV infection because it inhibits clearance of the virus through T-cell mediated immunosuppression and directly enhances expression of E6 and E7 proteins in the HIV and HPV coinfected cell.8 For these reasons, HIV-positive women are less likely to clear HPV infection and more likely to develop high grade dysplasia or invasive carcinomas.

Prevention and vaccination

HPV vaccinations utilize virus-like particles (VLPs). These VLPs are capsid particles generated from the L1 region of the HPV DNA. The capsid proteins coded for by L1 are highly immunogenic. VLPs are recombinant proteins created in benign biologic systems (such as yeast) and contain no inner DNA core (effectively empty viral capsids) and therefore are not infectious. The L1 gene is incorporated into a plasmid, which is inserted into the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell. Transcription and translation of the L1 gene takes place, creating capsid proteins that self-assemble into VLPs. These VLPs are retrieved and inoculated into candidate patients to illicit an immune response.

Quadrivalent, nine-valent, and bivalent vaccines are available worldwide. However, only the nine-valent vaccine – protective against types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58 – is available in the United States. This theoretically provides more comprehensive coverage against cervical cancer–causing HPV types, as 70% of cervical cancer is attributable to HPV 16 and 18, but an additional 20% is attributable to HPV 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58. This vaccine also provides protection against the HPV strains that cause genital warts and low-grade dysplastic changes.9

HPV, in most instances, is a transient virus with no sequelae. However, if not cleared from the cells of the lower genital tract, anus, or oropharynx it can result in the breakdown of cellular correction strategies and culminate in invasive carcinoma. Fortunately, highly effective and safe vaccinations are available and should be broadly prescribed.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1995 Jun;4(4):415-28.

2. Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Apr;121(1):32-42.

3. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008 Jul;17(7):1611-22.

4. JAMA. 2007 Feb 28;297(8):813-9.

5. J Infect Dis. 2013; 207(2): 272-80.

6. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011 Mar 2;103(5):368-83.

7. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000 May 3;92(9):690-8.

8. Lancet. 2002 Jan 12;359(9301):108-13.

9. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:e173–8.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most prevalent sexually transmitted disease globally. It is causally related to the development of several malignancies, including cervical, anal, and oropharyngeal ones, because of its integration and dysregulation of the genome of infected cells. Fortunately, vaccination is available to prevent development of HPV-related diseases. Understanding this virus, its carcinogenic role, and the importance of prevention through vaccination are critically important for ob.gyns. This column reviews the fundamentals of HPV biology, epidemiology, and carcinogenesis.

Viral anatomy

HPV are members of the A genus of the family Papovaviridae. They contain between 7,800 and 7,900 base pairs. They are nonenveloped, double-stranded DNA viruses with a circular structure. The viral DNA is contained within an icosahedral capsid that measures 45 nm-55 nm. The HPV genome has three critical regions: the long control region, otherwise known as the upstream regulatory region; the early region; and the late region.1

Capsid proteins are similar between groups. Therefore, HPV are categorized into “types” and “subtypes” based on the extent of DNA similarity. There are more than 100 types of HPV in humans.2 The type of HPV is determined by the gene sequences of E6/E7 and L1 and must show more than 10% difference between types. The gene sequences between different subtypes differ by 2%-5%.

Epidemiology of HPV infection

HPV are widely distributed among mammalian species but are species specific. Their tissue affinity varies by type. HPV types 1, 2, and 4 cause common or plantar warts. HPV types 6 and 11 cause condyloma acuminata (genital warts) and low grade dysplasia. HPV types 16 and 18 – in addition to 31 and 52 – are of particular interest to oncologists because they are associated with lower genital tract high grade dysplasia and invasive carcinoma. Infection with HPV 16 is present in about half of invasive cervical cancers, with HPV type 18 present in 20% of cervical cancers. Adenocarcinomas of the cervix are more commonly associated with HPV 18. Anal cancer and oropharyngeal cancer are more commonly associated with HPV 16.3

HPV infections are acquired through cutaneous touching (including hand to genital) and HPV positivity is most commonly present within the first 10 years after sexual debut.4 However, most individuals who acquire HPV do so as a transient infection, which is cleared without sequelae. Those who fail to rapidly clear HPV infection, and in whom it becomes chronic, face an increasing risk of development of dysplasia and invasive carcinoma. The incidence of HPV infection increases again at menopause, but, for these older women, the new finding of HPV detection may be related to reactivation of an earlier infection rather than exclusively new exposure to the virus.5

Diagnosis and testing

HPV infection can be detected through DNA testing, RNA testing, and cellular markers.6

HPV DNA testing was the original form of testing offered. It improved the sensitivity over cytology alone in the detection of precursors to malignancy but had relatively poor specificity, resulting in a high false positive rate and unnecessary referral to colposcopy. The various tests approved by the Food and Drug Administration – Hybrid Capture 2 (HC2), Cervista, and Cobas 4800 – differ in the number and nature of HPV types that they detect.

HPV RNA testing has developed and involves measuring the expression of E6 and E7 RNA. This testing is FDA approved and has the potential to improve upon the specificity of DNA testing procedures by decreasing false positives.

Measurement of cellular markers is currently considered experimental/exploratory and is not yet FDA approved for diagnostic purposes in screening or confirmation of HPV infection or coexisting dysplasia. It involves measuring the downstream cellular targets (such as p16) of E6 or E7 activity.

The mechanism of carcinogenesis

The early region of the HPV genome is downstream from the upstream regulatory region. It codes for proteins involved in viral infection and replication. The two most important genes in the early region are E6 and E7. When integrated into the human genome of the lower genital tract cell, the viral genes E6 and E7 negatively interfere with cell cycle control and mechanisms to halt dysregulation.7

E6 and E7 are considered oncogenes because they cause loss of function of the critical tumor suppressor proteins p53 and the retinoblastoma protein. The p53 protein is typically responsible for controlling cell cycling through the G0/G1 to S phases. It involves stalling cellular mitosis in order to facilitate DNA repair mechanisms in the case of damaged cells, thereby preventing replication of DNA aberrations. The retinoblastoma protein also functions to inhibit cells that have acquired DNA damage from cycling and induces apoptosis in DNA damaged cells. When protein products of E6 and E7 negatively interact with these two tumor suppressor proteins they overcome the cell’s safeguard arrest response.

In the presence of other carcinogens, such as products of tobacco exposure, the increased DNA damage sustained by the genital tract cell is allowed to go relatively unchecked by the HPV coinfection, which has disabled tumor suppressor function. This facilitates immortality of the damaged cell, amplification of additional DNA mutations, and unchecked cellular growth and dysplastic transformation. E6 and E7 are strongly expressed in invasive genital tract lesions to support its important role in carcinogenesis.

HIV coinfection is another factor that promotes carcinogenesis following HPV infection because it inhibits clearance of the virus through T-cell mediated immunosuppression and directly enhances expression of E6 and E7 proteins in the HIV and HPV coinfected cell.8 For these reasons, HIV-positive women are less likely to clear HPV infection and more likely to develop high grade dysplasia or invasive carcinomas.

Prevention and vaccination

HPV vaccinations utilize virus-like particles (VLPs). These VLPs are capsid particles generated from the L1 region of the HPV DNA. The capsid proteins coded for by L1 are highly immunogenic. VLPs are recombinant proteins created in benign biologic systems (such as yeast) and contain no inner DNA core (effectively empty viral capsids) and therefore are not infectious. The L1 gene is incorporated into a plasmid, which is inserted into the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell. Transcription and translation of the L1 gene takes place, creating capsid proteins that self-assemble into VLPs. These VLPs are retrieved and inoculated into candidate patients to illicit an immune response.

Quadrivalent, nine-valent, and bivalent vaccines are available worldwide. However, only the nine-valent vaccine – protective against types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58 – is available in the United States. This theoretically provides more comprehensive coverage against cervical cancer–causing HPV types, as 70% of cervical cancer is attributable to HPV 16 and 18, but an additional 20% is attributable to HPV 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58. This vaccine also provides protection against the HPV strains that cause genital warts and low-grade dysplastic changes.9

HPV, in most instances, is a transient virus with no sequelae. However, if not cleared from the cells of the lower genital tract, anus, or oropharynx it can result in the breakdown of cellular correction strategies and culminate in invasive carcinoma. Fortunately, highly effective and safe vaccinations are available and should be broadly prescribed.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1995 Jun;4(4):415-28.

2. Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Apr;121(1):32-42.

3. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008 Jul;17(7):1611-22.

4. JAMA. 2007 Feb 28;297(8):813-9.

5. J Infect Dis. 2013; 207(2): 272-80.

6. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011 Mar 2;103(5):368-83.

7. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000 May 3;92(9):690-8.

8. Lancet. 2002 Jan 12;359(9301):108-13.

9. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:e173–8.

FDA clears use of reagents to detect hematopoietic neoplasia

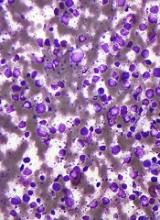

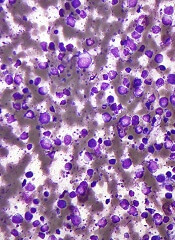

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has allowed marketing of the ClearLLab Reagent Panel, a combination of conjugated antibody cocktails designed to aid the detection of hematopoietic neoplasia.

This includes chronic and acute leukemias, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, myeloma, myelodysplastic syndromes, and myeloproliferative neoplasms.

The ClearLLab reagents are intended for in vitro diagnostic use to identify various cell populations by immunophenotyping on an FC 500 flow cytometer.

The reagents are directed against B, T, and myeloid lineage antigens and intended to identify relevant leukocyte surface molecules.

ClearLLab provides 2 T-cell tubes, 2 B-cell tubes, and a myeloid tube, each consisting of pre-mixed 4- to 5-color cocktails. Together, this totals 18 markers as directly conjugated antibodies.

The reagents can be used with peripheral whole blood, bone marrow, and lymph node specimens.

The results obtained via testing with the ClearLLab reagents should be interpreted along with additional clinical and laboratory findings, according to Beckman Coulter, Inc., the company that will be marketing the reagents.

The FDA reviewed data for the ClearLLab reagents through the de novo premarket review pathway, a regulatory pathway for novel, low-to-moderate-risk devices that are not substantially equivalent to an already legally marketed device.

The FDA’s clearance of the ClearLLab reagents was supported by a study designed to demonstrate the reagents’ performance, which was conducted on 279 samples at 4 independent clinical sites.

Results with the ClearLLab reagents were compared to results with alternative detection methods used at the sites.

The ClearLLab results aligned with the study sites’ final diagnosis 93.4% of the time and correctly detected abnormalities 84.2% of the time.

Along with its clearance of the ClearLLab reagents, the FDA is establishing criteria, called special controls, which clarify the agency’s expectations in assuring the reagents’ accuracy, reliability, and clinical relevance.

These special controls, when met along with general controls, provide reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness for the ClearLLab reagents and similar tools.

The special controls also describe the least burdensome regulatory pathway for future developers of similar diagnostic tests. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has allowed marketing of the ClearLLab Reagent Panel, a combination of conjugated antibody cocktails designed to aid the detection of hematopoietic neoplasia.

This includes chronic and acute leukemias, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, myeloma, myelodysplastic syndromes, and myeloproliferative neoplasms.

The ClearLLab reagents are intended for in vitro diagnostic use to identify various cell populations by immunophenotyping on an FC 500 flow cytometer.

The reagents are directed against B, T, and myeloid lineage antigens and intended to identify relevant leukocyte surface molecules.

ClearLLab provides 2 T-cell tubes, 2 B-cell tubes, and a myeloid tube, each consisting of pre-mixed 4- to 5-color cocktails. Together, this totals 18 markers as directly conjugated antibodies.

The reagents can be used with peripheral whole blood, bone marrow, and lymph node specimens.

The results obtained via testing with the ClearLLab reagents should be interpreted along with additional clinical and laboratory findings, according to Beckman Coulter, Inc., the company that will be marketing the reagents.

The FDA reviewed data for the ClearLLab reagents through the de novo premarket review pathway, a regulatory pathway for novel, low-to-moderate-risk devices that are not substantially equivalent to an already legally marketed device.

The FDA’s clearance of the ClearLLab reagents was supported by a study designed to demonstrate the reagents’ performance, which was conducted on 279 samples at 4 independent clinical sites.

Results with the ClearLLab reagents were compared to results with alternative detection methods used at the sites.

The ClearLLab results aligned with the study sites’ final diagnosis 93.4% of the time and correctly detected abnormalities 84.2% of the time.

Along with its clearance of the ClearLLab reagents, the FDA is establishing criteria, called special controls, which clarify the agency’s expectations in assuring the reagents’ accuracy, reliability, and clinical relevance.

These special controls, when met along with general controls, provide reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness for the ClearLLab reagents and similar tools.

The special controls also describe the least burdensome regulatory pathway for future developers of similar diagnostic tests. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has allowed marketing of the ClearLLab Reagent Panel, a combination of conjugated antibody cocktails designed to aid the detection of hematopoietic neoplasia.

This includes chronic and acute leukemias, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, myeloma, myelodysplastic syndromes, and myeloproliferative neoplasms.

The ClearLLab reagents are intended for in vitro diagnostic use to identify various cell populations by immunophenotyping on an FC 500 flow cytometer.

The reagents are directed against B, T, and myeloid lineage antigens and intended to identify relevant leukocyte surface molecules.

ClearLLab provides 2 T-cell tubes, 2 B-cell tubes, and a myeloid tube, each consisting of pre-mixed 4- to 5-color cocktails. Together, this totals 18 markers as directly conjugated antibodies.

The reagents can be used with peripheral whole blood, bone marrow, and lymph node specimens.

The results obtained via testing with the ClearLLab reagents should be interpreted along with additional clinical and laboratory findings, according to Beckman Coulter, Inc., the company that will be marketing the reagents.

The FDA reviewed data for the ClearLLab reagents through the de novo premarket review pathway, a regulatory pathway for novel, low-to-moderate-risk devices that are not substantially equivalent to an already legally marketed device.

The FDA’s clearance of the ClearLLab reagents was supported by a study designed to demonstrate the reagents’ performance, which was conducted on 279 samples at 4 independent clinical sites.

Results with the ClearLLab reagents were compared to results with alternative detection methods used at the sites.

The ClearLLab results aligned with the study sites’ final diagnosis 93.4% of the time and correctly detected abnormalities 84.2% of the time.

Along with its clearance of the ClearLLab reagents, the FDA is establishing criteria, called special controls, which clarify the agency’s expectations in assuring the reagents’ accuracy, reliability, and clinical relevance.

These special controls, when met along with general controls, provide reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness for the ClearLLab reagents and similar tools.

The special controls also describe the least burdensome regulatory pathway for future developers of similar diagnostic tests. ![]()

Study indicates parent-reported penicillin allergy in question

, according to David Vyles, DO, and his associates at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

Because there is no process to safely and rapidly diagnose true penicillin allergy in a critical care setting, pediatric providers are reluctant to prescribe penicillin to children with a reported allergy. In this study, a three-tier penicillin testing process was used to evaluate the accuracy of a parent-reported penicillin allergy questionnaire in identifying children likely to be at low risk for penicillin allergy in an ED setting.

“Our results in the current study highlight that the high percentage of patients reporting a penicillin allergy to medical providers are likely inconsistent with true allergy,” concluded Dr. Vyles and his associates.

Read more at Pediatrics (2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0471).

, according to David Vyles, DO, and his associates at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

Because there is no process to safely and rapidly diagnose true penicillin allergy in a critical care setting, pediatric providers are reluctant to prescribe penicillin to children with a reported allergy. In this study, a three-tier penicillin testing process was used to evaluate the accuracy of a parent-reported penicillin allergy questionnaire in identifying children likely to be at low risk for penicillin allergy in an ED setting.

“Our results in the current study highlight that the high percentage of patients reporting a penicillin allergy to medical providers are likely inconsistent with true allergy,” concluded Dr. Vyles and his associates.

Read more at Pediatrics (2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0471).

, according to David Vyles, DO, and his associates at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

Because there is no process to safely and rapidly diagnose true penicillin allergy in a critical care setting, pediatric providers are reluctant to prescribe penicillin to children with a reported allergy. In this study, a three-tier penicillin testing process was used to evaluate the accuracy of a parent-reported penicillin allergy questionnaire in identifying children likely to be at low risk for penicillin allergy in an ED setting.

“Our results in the current study highlight that the high percentage of patients reporting a penicillin allergy to medical providers are likely inconsistent with true allergy,” concluded Dr. Vyles and his associates.

Read more at Pediatrics (2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0471).

FROM PEDIATRICS

Daily probiotics have no effect on infections causing child care absences

Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled study do not support use of probiotics to prevent upper respiratory and gastrointestinal infections in children aged 8-14 months at enrollment, as the probiotics did not reduce infection-related child care absences.

In the study of 290 Danish infants randomly allocated to receive a placebo or a combination of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp lactis (BB-12) and Lactobacillus rhamnosus (LGG) in a dose of 109 colony-forming units of each daily for a 6-month intervention period, there were no differences in absences from child care between the two groups (1.14 days; 95% confidence interval, −0.55 to 2.82), reported Rikke Pilmann Laursen, MSc, and her associates at the University of Copenhagen (Pediatrics. 2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0735).

Infants were a mean 10 months old at baseline, and 47% were still breastfeeding. The mean age at breastfeeding discontinuation was 12 months.

In terms of the number of children with one or more episodes of an upper respiratory tract infection, the LGG and BB-12 vs. placebo odds ratio was 1.22 (95% CI, 0.74-2.00; P = .43). The number of children with one or more episodes of diarrhea in the LGG and BB-12 vs. placebo odds ratio was 1.42 (95% CI, 0.88-2.32; P = .15).

The effect of probiotics in preventing infections in preschool-aged children has been explored in several studies and recent reviews, suggesting an effect specifically on upper respiratory tract and GI infections in small children. This study diverges in that it examined the effect of a combination of probiotics on absences from child care related to those infections in infants aged 8-14 months at the time of enrollment, whereas previous studies focused on children older than 1 year.

This study was funded by Innovation Fund Denmark, the University of Copenhagen, and Chr Hansen A/S. Dr. Kim Fleischer Michaelsen and Dr. Christian Mølgaard received a grant from Chr Hansen for the current study. None of the other investigators had any relevant financial disclosures.

Any intervention that can prevent child care–associated illnesses can have economic and educational implications, as well as public health ones. However, in the Laursen et al. study, almost 47% of the infants enrolled were breastfed, as opposed to previous studies in which the children participating generally were over 1 year old.

Given the positive effects of breastfeeding in preventing infections and the high percentage of infants who were breastfed in this study, it may be harder to distinguish the effects of the probiotic supplement in the Laursen et al. study. Indirectly, this study suggests additional information on the relative value of a probiotic intervention, compared with breastfeeding and diet, is warranted, and perhaps there is another reason to encourage breastfeeding as long as possible.

Michael D. Cabana, MD, MPH, is a professor of pediatrics, epidemiology and biostatistics and a member of the faculty at the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies at the University of California, San Francisco. Daniel J. Merenstein, MD, is an associate professor of family medicine at Georgetown University, Washington. Pharmavite, Bayer, and Sanofi have provided Georgetown University with consulting funding. Both physicians, who commented in an editorial accompanying the article by Laursen et al. (Pediatrics. 2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1729), disclosed no financial relationships relevant to this article. Dr. Merenstein has been an expert witness for Proctor & Gamble while Dr. Cabana has served as a consultant for BioGaia, Nestle, Mead Johnson, and Wyeth.

Any intervention that can prevent child care–associated illnesses can have economic and educational implications, as well as public health ones. However, in the Laursen et al. study, almost 47% of the infants enrolled were breastfed, as opposed to previous studies in which the children participating generally were over 1 year old.

Given the positive effects of breastfeeding in preventing infections and the high percentage of infants who were breastfed in this study, it may be harder to distinguish the effects of the probiotic supplement in the Laursen et al. study. Indirectly, this study suggests additional information on the relative value of a probiotic intervention, compared with breastfeeding and diet, is warranted, and perhaps there is another reason to encourage breastfeeding as long as possible.

Michael D. Cabana, MD, MPH, is a professor of pediatrics, epidemiology and biostatistics and a member of the faculty at the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies at the University of California, San Francisco. Daniel J. Merenstein, MD, is an associate professor of family medicine at Georgetown University, Washington. Pharmavite, Bayer, and Sanofi have provided Georgetown University with consulting funding. Both physicians, who commented in an editorial accompanying the article by Laursen et al. (Pediatrics. 2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1729), disclosed no financial relationships relevant to this article. Dr. Merenstein has been an expert witness for Proctor & Gamble while Dr. Cabana has served as a consultant for BioGaia, Nestle, Mead Johnson, and Wyeth.

Any intervention that can prevent child care–associated illnesses can have economic and educational implications, as well as public health ones. However, in the Laursen et al. study, almost 47% of the infants enrolled were breastfed, as opposed to previous studies in which the children participating generally were over 1 year old.

Given the positive effects of breastfeeding in preventing infections and the high percentage of infants who were breastfed in this study, it may be harder to distinguish the effects of the probiotic supplement in the Laursen et al. study. Indirectly, this study suggests additional information on the relative value of a probiotic intervention, compared with breastfeeding and diet, is warranted, and perhaps there is another reason to encourage breastfeeding as long as possible.

Michael D. Cabana, MD, MPH, is a professor of pediatrics, epidemiology and biostatistics and a member of the faculty at the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies at the University of California, San Francisco. Daniel J. Merenstein, MD, is an associate professor of family medicine at Georgetown University, Washington. Pharmavite, Bayer, and Sanofi have provided Georgetown University with consulting funding. Both physicians, who commented in an editorial accompanying the article by Laursen et al. (Pediatrics. 2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1729), disclosed no financial relationships relevant to this article. Dr. Merenstein has been an expert witness for Proctor & Gamble while Dr. Cabana has served as a consultant for BioGaia, Nestle, Mead Johnson, and Wyeth.

Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled study do not support use of probiotics to prevent upper respiratory and gastrointestinal infections in children aged 8-14 months at enrollment, as the probiotics did not reduce infection-related child care absences.

In the study of 290 Danish infants randomly allocated to receive a placebo or a combination of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp lactis (BB-12) and Lactobacillus rhamnosus (LGG) in a dose of 109 colony-forming units of each daily for a 6-month intervention period, there were no differences in absences from child care between the two groups (1.14 days; 95% confidence interval, −0.55 to 2.82), reported Rikke Pilmann Laursen, MSc, and her associates at the University of Copenhagen (Pediatrics. 2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0735).

Infants were a mean 10 months old at baseline, and 47% were still breastfeeding. The mean age at breastfeeding discontinuation was 12 months.

In terms of the number of children with one or more episodes of an upper respiratory tract infection, the LGG and BB-12 vs. placebo odds ratio was 1.22 (95% CI, 0.74-2.00; P = .43). The number of children with one or more episodes of diarrhea in the LGG and BB-12 vs. placebo odds ratio was 1.42 (95% CI, 0.88-2.32; P = .15).

The effect of probiotics in preventing infections in preschool-aged children has been explored in several studies and recent reviews, suggesting an effect specifically on upper respiratory tract and GI infections in small children. This study diverges in that it examined the effect of a combination of probiotics on absences from child care related to those infections in infants aged 8-14 months at the time of enrollment, whereas previous studies focused on children older than 1 year.

This study was funded by Innovation Fund Denmark, the University of Copenhagen, and Chr Hansen A/S. Dr. Kim Fleischer Michaelsen and Dr. Christian Mølgaard received a grant from Chr Hansen for the current study. None of the other investigators had any relevant financial disclosures.

Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled study do not support use of probiotics to prevent upper respiratory and gastrointestinal infections in children aged 8-14 months at enrollment, as the probiotics did not reduce infection-related child care absences.

In the study of 290 Danish infants randomly allocated to receive a placebo or a combination of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp lactis (BB-12) and Lactobacillus rhamnosus (LGG) in a dose of 109 colony-forming units of each daily for a 6-month intervention period, there were no differences in absences from child care between the two groups (1.14 days; 95% confidence interval, −0.55 to 2.82), reported Rikke Pilmann Laursen, MSc, and her associates at the University of Copenhagen (Pediatrics. 2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0735).

Infants were a mean 10 months old at baseline, and 47% were still breastfeeding. The mean age at breastfeeding discontinuation was 12 months.

In terms of the number of children with one or more episodes of an upper respiratory tract infection, the LGG and BB-12 vs. placebo odds ratio was 1.22 (95% CI, 0.74-2.00; P = .43). The number of children with one or more episodes of diarrhea in the LGG and BB-12 vs. placebo odds ratio was 1.42 (95% CI, 0.88-2.32; P = .15).

The effect of probiotics in preventing infections in preschool-aged children has been explored in several studies and recent reviews, suggesting an effect specifically on upper respiratory tract and GI infections in small children. This study diverges in that it examined the effect of a combination of probiotics on absences from child care related to those infections in infants aged 8-14 months at the time of enrollment, whereas previous studies focused on children older than 1 year.

This study was funded by Innovation Fund Denmark, the University of Copenhagen, and Chr Hansen A/S. Dr. Kim Fleischer Michaelsen and Dr. Christian Mølgaard received a grant from Chr Hansen for the current study. None of the other investigators had any relevant financial disclosures.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Intention-to-treat analysis showed no difference between the probiotics and placebo study groups.

Data source: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 290 infants aged 8-14 months at enrollment.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Innovation Fund Denmark, the University of Copenhagen, and Chr Hansen A/S. Dr. Kim Fleischer Michaelsen and Dr. Christian Mølgaard received a grant from Chr Hansen for the current study. None of the other investigators had any relevant financial disclosures.

How Low Should You Go? Optimizing BP in CKD

Q) I hear providers quote different numbers for target blood pressure in kidney patients. Which are correct?

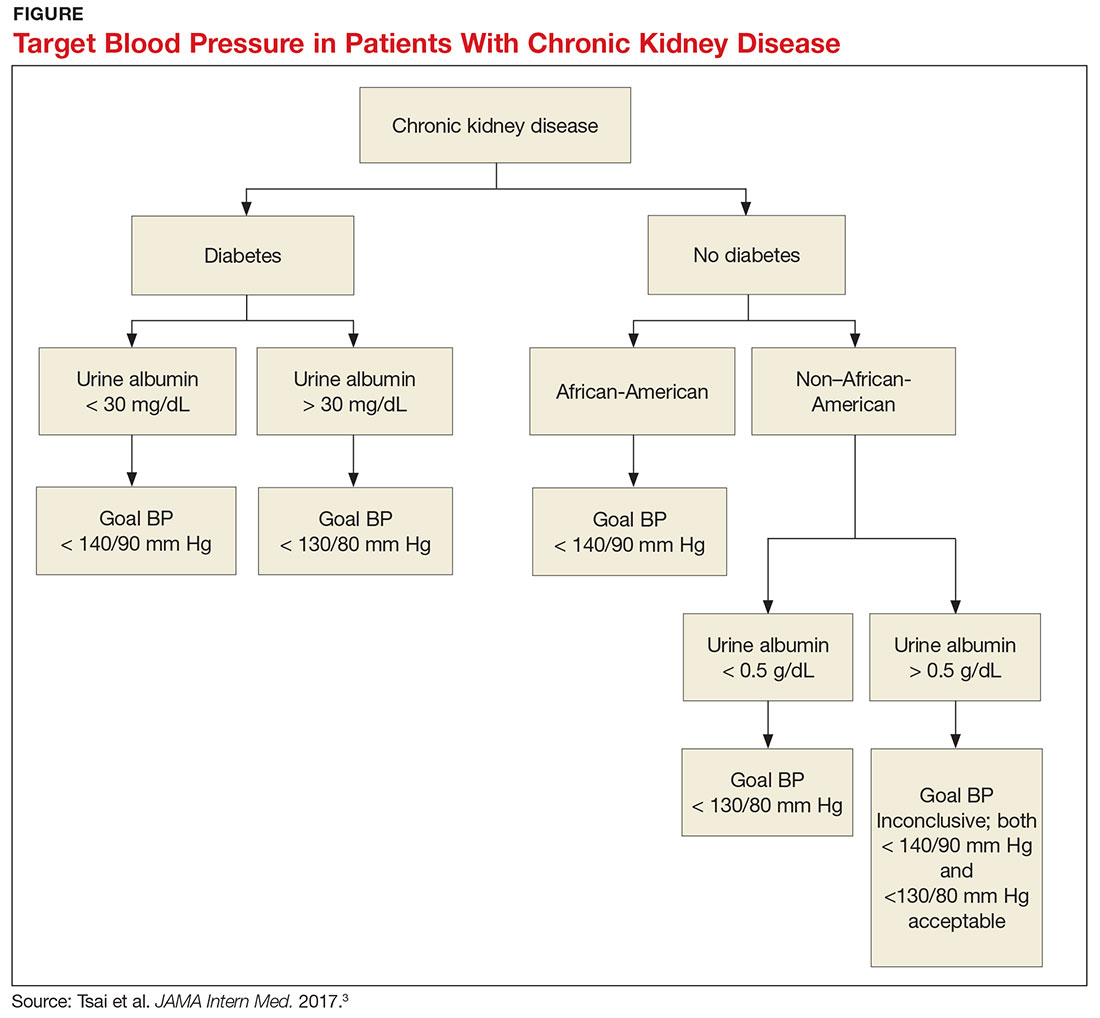

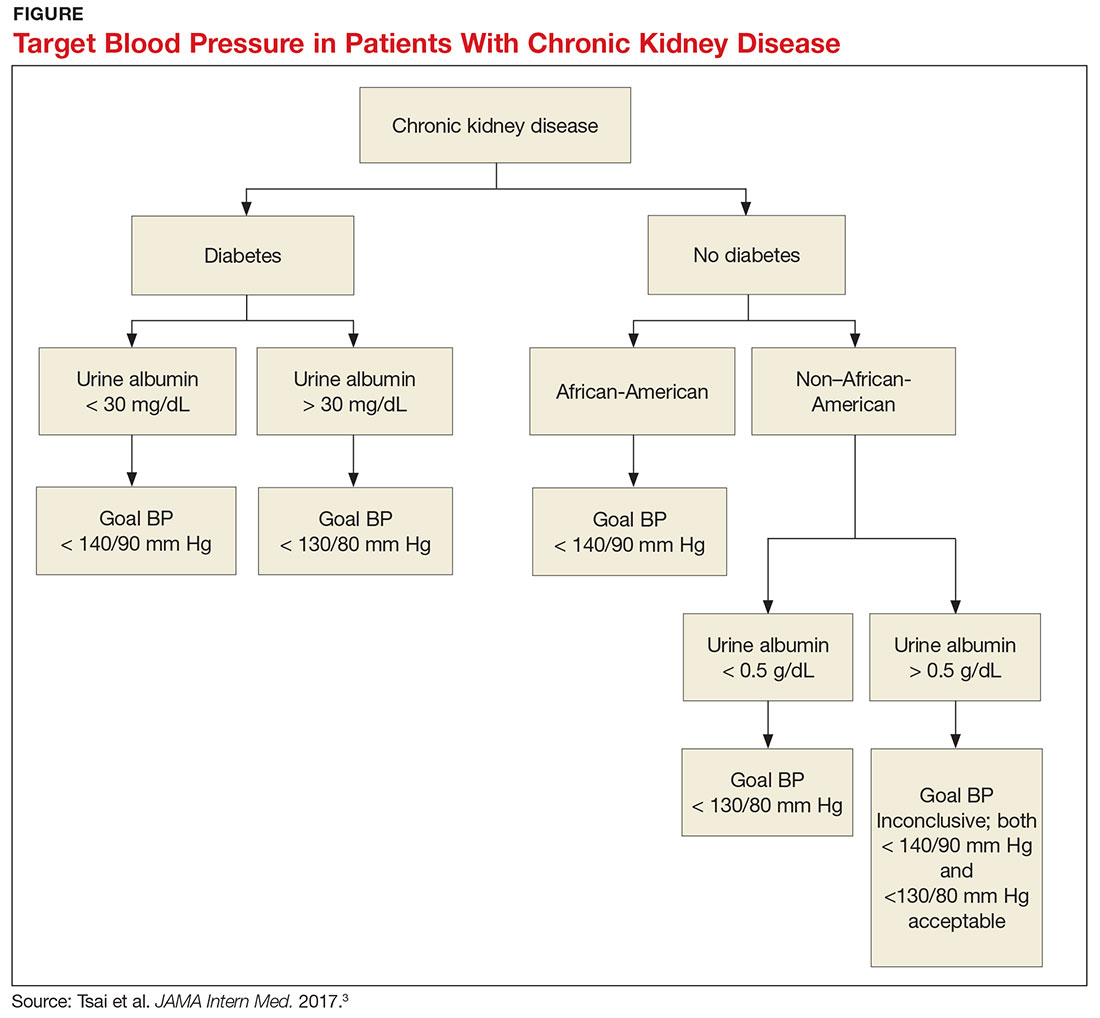

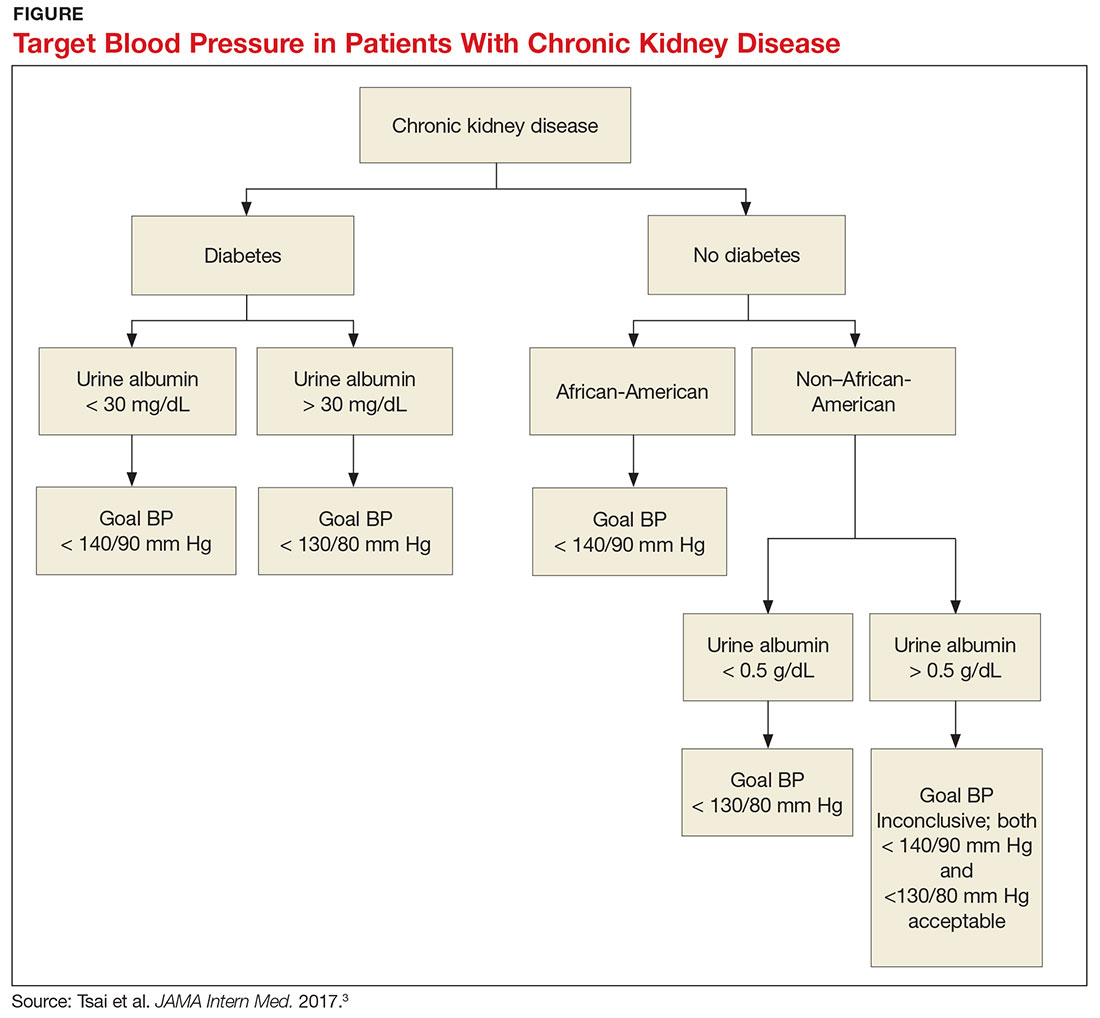

The answer to this question starts with the word “meta-analysis”—but don’t stop reading! We’ll get down to the basics quickly. Determining the goal blood pressure (BP) for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) comes down to three questions.

1. Does the patient have diabetes? The National Kidney Foundation states that the goal BP for a patient with type 2 diabetes, CKD, and urine albumin > 30 mg/dL is < 140/90 mm Hg.1 This is in line with the JNC-8 recommendations for patients with hypertension and CKD, which do not take urine albumin level into consideration.2 It is important to recognize that while many patients with CKD do not have diabetes, those who do have a worse prognosis.3

2. Is the patient African-American? A meta-analysis of nine randomized clinical trials found that lowering BP to < 130/80 mm Hg was linked to a slower decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in non-African-American patients.3 But this BP was not beneficial for African-American patients; in fact, it actually caused a faster decline in GFR.3 Therefore, target BP for African-American patients should be < 140/90 mm Hg.

3. Does the patient have significant albuminuria? An additional subgroup analysis for patients with high levels of proteinuria (defined as > 1 g/d) yielded inconclusive results.3 Patients with proteinuria > 1 g/d tended to have a slower decline in GFR with intensive BP control.3 Proteinuria > 0.5 g/d was correlated with a slowed progression to end-stage renal disease with intensive BP control.3 Again, these were trends and not statistically significant. So, for patients with high levels of proteinuria, it will not hurt to achieve a BP < 130/80 mm Hg, but there is no statistically significant difference between BP < 130/80 mm Hg and BP < 140/90 mm Hg.

What, then, are the recommendations for an African-American patient with significant proteinuria? While not addressed directly in the analysis, the study results suggest that the goal should still be < 140/90 mm Hg, since the link between race and changes in GFR is statistically significant and the effects of proteinuria are not. Although the recommendations from this review are many, the main points are summarized in the Figure.—RC

Rebecca Clawson, MAT, PA-C

Instructor, PA Program, LSU Health Shreveport, Louisiana

1. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD work group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Inter Suppl. 2013;3(1):1-150.

2. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520.

3. Tsai WC, Wu HY, Peng YS, et al. Association of intensive blood pressure control and kidney disease progression in nondiabetic patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:792-799.

Q) I hear providers quote different numbers for target blood pressure in kidney patients. Which are correct?

The answer to this question starts with the word “meta-analysis”—but don’t stop reading! We’ll get down to the basics quickly. Determining the goal blood pressure (BP) for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) comes down to three questions.

1. Does the patient have diabetes? The National Kidney Foundation states that the goal BP for a patient with type 2 diabetes, CKD, and urine albumin > 30 mg/dL is < 140/90 mm Hg.1 This is in line with the JNC-8 recommendations for patients with hypertension and CKD, which do not take urine albumin level into consideration.2 It is important to recognize that while many patients with CKD do not have diabetes, those who do have a worse prognosis.3

2. Is the patient African-American? A meta-analysis of nine randomized clinical trials found that lowering BP to < 130/80 mm Hg was linked to a slower decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in non-African-American patients.3 But this BP was not beneficial for African-American patients; in fact, it actually caused a faster decline in GFR.3 Therefore, target BP for African-American patients should be < 140/90 mm Hg.

3. Does the patient have significant albuminuria? An additional subgroup analysis for patients with high levels of proteinuria (defined as > 1 g/d) yielded inconclusive results.3 Patients with proteinuria > 1 g/d tended to have a slower decline in GFR with intensive BP control.3 Proteinuria > 0.5 g/d was correlated with a slowed progression to end-stage renal disease with intensive BP control.3 Again, these were trends and not statistically significant. So, for patients with high levels of proteinuria, it will not hurt to achieve a BP < 130/80 mm Hg, but there is no statistically significant difference between BP < 130/80 mm Hg and BP < 140/90 mm Hg.

What, then, are the recommendations for an African-American patient with significant proteinuria? While not addressed directly in the analysis, the study results suggest that the goal should still be < 140/90 mm Hg, since the link between race and changes in GFR is statistically significant and the effects of proteinuria are not. Although the recommendations from this review are many, the main points are summarized in the Figure.—RC

Rebecca Clawson, MAT, PA-C

Instructor, PA Program, LSU Health Shreveport, Louisiana

Q) I hear providers quote different numbers for target blood pressure in kidney patients. Which are correct?

The answer to this question starts with the word “meta-analysis”—but don’t stop reading! We’ll get down to the basics quickly. Determining the goal blood pressure (BP) for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) comes down to three questions.

1. Does the patient have diabetes? The National Kidney Foundation states that the goal BP for a patient with type 2 diabetes, CKD, and urine albumin > 30 mg/dL is < 140/90 mm Hg.1 This is in line with the JNC-8 recommendations for patients with hypertension and CKD, which do not take urine albumin level into consideration.2 It is important to recognize that while many patients with CKD do not have diabetes, those who do have a worse prognosis.3

2. Is the patient African-American? A meta-analysis of nine randomized clinical trials found that lowering BP to < 130/80 mm Hg was linked to a slower decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in non-African-American patients.3 But this BP was not beneficial for African-American patients; in fact, it actually caused a faster decline in GFR.3 Therefore, target BP for African-American patients should be < 140/90 mm Hg.

3. Does the patient have significant albuminuria? An additional subgroup analysis for patients with high levels of proteinuria (defined as > 1 g/d) yielded inconclusive results.3 Patients with proteinuria > 1 g/d tended to have a slower decline in GFR with intensive BP control.3 Proteinuria > 0.5 g/d was correlated with a slowed progression to end-stage renal disease with intensive BP control.3 Again, these were trends and not statistically significant. So, for patients with high levels of proteinuria, it will not hurt to achieve a BP < 130/80 mm Hg, but there is no statistically significant difference between BP < 130/80 mm Hg and BP < 140/90 mm Hg.

What, then, are the recommendations for an African-American patient with significant proteinuria? While not addressed directly in the analysis, the study results suggest that the goal should still be < 140/90 mm Hg, since the link between race and changes in GFR is statistically significant and the effects of proteinuria are not. Although the recommendations from this review are many, the main points are summarized in the Figure.—RC

Rebecca Clawson, MAT, PA-C

Instructor, PA Program, LSU Health Shreveport, Louisiana

1. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD work group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Inter Suppl. 2013;3(1):1-150.

2. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520.

3. Tsai WC, Wu HY, Peng YS, et al. Association of intensive blood pressure control and kidney disease progression in nondiabetic patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:792-799.

1. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD work group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Inter Suppl. 2013;3(1):1-150.

2. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520.

3. Tsai WC, Wu HY, Peng YS, et al. Association of intensive blood pressure control and kidney disease progression in nondiabetic patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:792-799.

AHRQ identifies interventions, drugs that best target diabetic neuropathy

Contextual influences of trainee characteristics and daily workload on trainee learning preferences

We previously identified key domains of attending attributes for successful rounds1 and adapted them to represent the trainees’ perspective: Teaching Process (eg, sharing decision-making process, physical exam skills), Learning Environment (eg, being approachable, respectful), Role Modeling (eg, teaching by example, bedside manner), and Team Management (eg, efficiency, providing autonomy). Though all domains are necessary, the relative importance may change in response to external pressures. Inpatient service demands and time constraints fluctuate daily due to patient admissions and discharges, educational conference schedules, and concurrent outpatient clinic responsibilities.2–4 Furthermore, the 2011 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) duty hour rules placed greater time pressure on inpatient ward attending rounds.5 It is plausible that these pressures affect trainees’ needs and priorities during rounds.

Therefore, we sought to refine our understanding of the learners’ needs during ward rounds. Because we were interested in the contextual influences of trainee characteristics and workload on their preferences, we used the principles of ecological momentary assessment (EMA) to design a novel system to assess daily changes in trainee priorities and associated workload.

METHODS

Design, Participants, and Setting

In a prospective observational study, we assessed trainee priorities during inpatient rounds. Participants included third- and fourth-year medical students in the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) School of Medicine (Birmingham campus) and residents in the Tinsley Harrison Internal Medicine Residency Training Program assigned to inpatient general medicine ward services from September 2010 to February 2011 (except from December 20, 2010, to January 3, 2011). Three training sites were included in this study: UAB Hospital (>1000-bed, university-based hospital), Birmingham Veterans Affairs Medical Center (300-bed), and Cooper Green Hospital (40-bed county hospital). Each site housed 4 or 5 general medicine ward teams, composed of 1–3 medical students (third or fourth year), 2 first-year residents, 1 upper level resident (postgraduate year 2–4), and 1 attending physician.

Trainees were recruited to participate via e-mail and verbal announcements during program conferences. Participation was voluntary and responses were confidential. As an incentive, the team submitting the highest number of cards per site each month received 1 free lunch. Institutional review boards of all 3 participating hospitals approved this study.

Assessment

Our original domains of attending rounds were derived from groupings and ratings of specific teaching characteristics by attending physicians, residents, and students.1 However, because our goal was to understand the learners’ perspective of successful ward rounds, we revised these domains by limiting the algorithm to data on groupings and ratings by residents and students only. This process resulted in the domains used in this study (Appendix).

We used EMA principles to create a novel system to assess daily variation in trainees’ prioritization of these domains and workload.6,7 EMA-derived assessment tools collect data frequently (several times per week, up to multiple times per day) to identify time-sensitive fluctuations. We designed a pocket-sized daily assessment card for trainees to complete each day after rounds (Figure 1). Trainees were asked to indicate the most important domain for successful ward rounds to them that day and provide individual characteristics (ie, sex and training level) and data on factors we hypothesized were related to perceived work load (ie, patient census, day of call cycle, and number of team members absent on rounds that day). We anticipated the Expectations domain would not be responsive to daily changes in workload because expectations are usually set once on the first day of the rotation, and thus we did not include this domain in our final assessment tool. Assessment cards and locked receptacles were kept in team workrooms for ease of accessibility; cards were collected twice monthly. All data were anonymous.

Analysis

Our unit of analysis was the EMA card. We examined associations between daily domain priority with respondent demographics and workload information using Pearson’s chi-squared analyses, adjusted for clustering effects by team. α was set at 0.05. All analyses were performed by using Stata 13.0 (Stata Statistical Software: Release 13; College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Sex and training level were associated with prioritization of teaching domains. Male trainees were more likely to choose Team Management (P = 0.01) or Teaching Process (P = 0.04) as their preferred domain. Medical students valued Teaching Process 42% of the time, compared with 23% for interns and 21% for upper level residents (P = 0.005). The opposite trend emerged for Team Management: as training level increased, the importance of Team Management increased (P < 0.001). There were no significant trends by training level for the Role Modeling and Learning Environment domains.

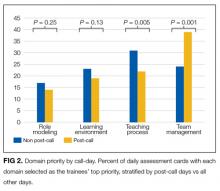

Domain priority was also associated with workload characteristics. On post-call days, Team Management (P < 0.001) was more likely to be selected as the most important domain, but on other days, Teaching Process (P = 0.005) was more often selected (Figure 2). Trainees also selected Team Management as the most important domain with an increasing number of team members absent (P = 0.001), and as the teams’ overall patient census increased (P < 0.001). The Learning Environment and Role Modeling domains’ importance did not vary by call-day or patient census.

DISCUSSION

We used a novel approach to assess contextual factors affecting trainee prioritization of 4 domains that contribute to successful inpatient internal medicine attending rounds. We found training level and workload demands were associated with prioritization of teaching domains. Prioritization of Teaching Process, exemplified by setting aside time to teach, demonstrating physical exam skills, and clear delineation of the attending’s thought process, was inversely associated with training level. On the days with highest workload, Team Management was most likely to be prioritized. Our findings suggest that attending physicians should consider adapting rounding style based on team members’ training levels and workload.

Prior work has described teaching and rounding styles, influences, and priorities in response to workload from the attending physician’s perspective,8–11 and our study extends these reports by providing the complementary perspective of trainees. On days with high workload, trainees prefer the Team Management domain, characterized by organized and efficient rounds, agreement on a clear and consistent plan of care, and being allowed independence and time during rounds to meet other responsibilities.1 These findings support an “empowerment style,” defined by Goldszmidt et al. as using integrated teaching and oversight strategies to support trainees’ progressive independence.9 Though some attending physicians report shifting to a more direct patient care style on days with a high patient census,9 our results suggest that learners instead prefer more independence, being empowered to perform more direct care. While there is an increasing pressure to heighten attending supervision due to concerns about patient safety, restricted work hours, and litigation,12 trainees value being part of the care process and being included as integral members of the care team, which may actually mitigate patient safety risks.8

Our results are consistent with prior studies, reporting that learners at different levels of training have different instructional needs: medical students seek more teaching, and senior residents sought an efficient leader.13,14 Taken together, these studies suggest that attending physicians should tailor rounds to the level of the trainee. For example, it may be beneficial for the attending physician to spend time outside of rounds with students to teach medical knowledge. During rounds, the entire group benefits most from modeling clinical reasoning, discussing new medical evidence, and demonstrating communication skills and leadership.

Our study has limitations. Though our study was performed before the 2011 ACGME duty hour restrictions,5 our results are likely of greater importance and relevance, as our findings ultimately highlight the competing demands of time vs duty. Also, while our study was performed at a single institution, potentially limiting generalizability, we included 3 types of training hospitals, a university, veterans and a county hospital, and found no differences between sites. Additionally, we collected over 1,000 cards over the course of 6 months, assessing rounds of over 50 different attending physicians, suggesting broader applicability. Our overall response rate was low, a typical signal for respondent bias, but because we collected daily assessments, standard interpretation of response rates referring to a one-time survey do not apply.15 We believe we achieved an adequate sample, as the majority of teams participated, the respondent demographics were proportional to the base population eligible to participate, and we received a similar number of cards on all months. Finally, although we were unable to account for clustering effects by individual respondents because response cards were anonymous, we adjusted for clustering effects by team.

Attending physicians may use our findings to adapt teaching techniques to appeal to specific training levels and to external pressures during teaching rounds. Focusing and investing time in teaching medical knowledge and clinical reasoning tailored to each level of learner is paramount on most days. However, days with a high workload may require emphasis on delegating clear, rational treatment plans, when learners are less receptive to traditional didactic methods.

Disclosure

An abstract based on the current analysis was presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine 34th Annual Meeting, April 2011, Phoenix, AZ. Dr. Brita Roy is supported by grant number K12HS023000 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The authors have no conflicts to disclose. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not reflect the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

1. Roy B, Salanitro AH, Willett L, et al. Using cognitive mapping to identify attributes contributing to successful ward-attending rounds -- a resident and student perspective. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(S3):2. PubMed

2. Ben-Menachem T, Estrada C, Young MJ, et al. Balancing service and education: improving internal medicine residencies in the managed care era. Am J Med. 1996;100(2):224–229. PubMed

3. Drolet BC, Bishop KD. Unintended consequences of duty hours regulation. Acad Med. 2012;87(6):680. PubMed

4. Drolet BC, Spalluto LB, Fischer SA. Residents’ perspectives on ACGME regulation of supervision and duty hours--a national survey. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(23):e34. PubMed

5. Nasca TJ, Day SH, Amis ES, Jr. The new recommendations on duty hours from the ACGME Task Force. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(2):e3. PubMed

6. Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:1–32. PubMed

7. Moskowitz DS, Young SN. Ecological momentary assessment: what it is and why it is a method of the future in clinical psychopharmacology. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2006;31(1):13–20. PubMed

8. Wingo MT, Halvorsen AJ, Beckman TJ, Johnson MG, Reed DA. Associations between attending physician workload, teaching effectiveness, and patient safety. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(3):169–173. PubMed

9. Goldszmidt M, Faden L, Dornan T, van Merriënboer J, Bordage G, Lingard L. Attending physician variability: a model of four supervisory styles. Acad Med. 2015;90(11):1541–1546. PubMed

10. Kennedy TJ, Lingard L, Baker GR, Kitchen L, Regehr G. Clinical oversight: conceptualizing the relationship between supervision and safety. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(8):1080–1085. PubMed

11. Irby DM. How attending physicians make instructional decisions when conducting teaching rounds. Acad Med. 1992;67(10):630–638. PubMed

12. Kennedy TJ, Regehr G, Baker GR, Lingard LA. Progressive independence in clinical training: a tradition worth defending? Acad Med. 2005;80(10):S106–S111. PubMed

13. Tariq M, Motiwala A, Ali SU, Riaz M, Awan S, Akhter J. The learners’ perspective on internal medicine ward rounds: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:53. PubMed

14. Certain LK, Guarino AJ, Greenwald JL. Effective multilevel teaching techniques on attending rounds: a pilot survey and systematic review of the literature. Med Teach. 2011;33(12):e644–e650. PubMed

15. Stone AA, Shiffman S. Capturing momentary, self-report data: A proposal for reporting guidelines. Ann Behav Med. 2002;24(3):236–243. PubMed

We previously identified key domains of attending attributes for successful rounds1 and adapted them to represent the trainees’ perspective: Teaching Process (eg, sharing decision-making process, physical exam skills), Learning Environment (eg, being approachable, respectful), Role Modeling (eg, teaching by example, bedside manner), and Team Management (eg, efficiency, providing autonomy). Though all domains are necessary, the relative importance may change in response to external pressures. Inpatient service demands and time constraints fluctuate daily due to patient admissions and discharges, educational conference schedules, and concurrent outpatient clinic responsibilities.2–4 Furthermore, the 2011 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) duty hour rules placed greater time pressure on inpatient ward attending rounds.5 It is plausible that these pressures affect trainees’ needs and priorities during rounds.

Therefore, we sought to refine our understanding of the learners’ needs during ward rounds. Because we were interested in the contextual influences of trainee characteristics and workload on their preferences, we used the principles of ecological momentary assessment (EMA) to design a novel system to assess daily changes in trainee priorities and associated workload.

METHODS

Design, Participants, and Setting

In a prospective observational study, we assessed trainee priorities during inpatient rounds. Participants included third- and fourth-year medical students in the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) School of Medicine (Birmingham campus) and residents in the Tinsley Harrison Internal Medicine Residency Training Program assigned to inpatient general medicine ward services from September 2010 to February 2011 (except from December 20, 2010, to January 3, 2011). Three training sites were included in this study: UAB Hospital (>1000-bed, university-based hospital), Birmingham Veterans Affairs Medical Center (300-bed), and Cooper Green Hospital (40-bed county hospital). Each site housed 4 or 5 general medicine ward teams, composed of 1–3 medical students (third or fourth year), 2 first-year residents, 1 upper level resident (postgraduate year 2–4), and 1 attending physician.

Trainees were recruited to participate via e-mail and verbal announcements during program conferences. Participation was voluntary and responses were confidential. As an incentive, the team submitting the highest number of cards per site each month received 1 free lunch. Institutional review boards of all 3 participating hospitals approved this study.

Assessment

Our original domains of attending rounds were derived from groupings and ratings of specific teaching characteristics by attending physicians, residents, and students.1 However, because our goal was to understand the learners’ perspective of successful ward rounds, we revised these domains by limiting the algorithm to data on groupings and ratings by residents and students only. This process resulted in the domains used in this study (Appendix).

We used EMA principles to create a novel system to assess daily variation in trainees’ prioritization of these domains and workload.6,7 EMA-derived assessment tools collect data frequently (several times per week, up to multiple times per day) to identify time-sensitive fluctuations. We designed a pocket-sized daily assessment card for trainees to complete each day after rounds (Figure 1). Trainees were asked to indicate the most important domain for successful ward rounds to them that day and provide individual characteristics (ie, sex and training level) and data on factors we hypothesized were related to perceived work load (ie, patient census, day of call cycle, and number of team members absent on rounds that day). We anticipated the Expectations domain would not be responsive to daily changes in workload because expectations are usually set once on the first day of the rotation, and thus we did not include this domain in our final assessment tool. Assessment cards and locked receptacles were kept in team workrooms for ease of accessibility; cards were collected twice monthly. All data were anonymous.

Analysis

Our unit of analysis was the EMA card. We examined associations between daily domain priority with respondent demographics and workload information using Pearson’s chi-squared analyses, adjusted for clustering effects by team. α was set at 0.05. All analyses were performed by using Stata 13.0 (Stata Statistical Software: Release 13; College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Sex and training level were associated with prioritization of teaching domains. Male trainees were more likely to choose Team Management (P = 0.01) or Teaching Process (P = 0.04) as their preferred domain. Medical students valued Teaching Process 42% of the time, compared with 23% for interns and 21% for upper level residents (P = 0.005). The opposite trend emerged for Team Management: as training level increased, the importance of Team Management increased (P < 0.001). There were no significant trends by training level for the Role Modeling and Learning Environment domains.

Domain priority was also associated with workload characteristics. On post-call days, Team Management (P < 0.001) was more likely to be selected as the most important domain, but on other days, Teaching Process (P = 0.005) was more often selected (Figure 2). Trainees also selected Team Management as the most important domain with an increasing number of team members absent (P = 0.001), and as the teams’ overall patient census increased (P < 0.001). The Learning Environment and Role Modeling domains’ importance did not vary by call-day or patient census.

DISCUSSION

We used a novel approach to assess contextual factors affecting trainee prioritization of 4 domains that contribute to successful inpatient internal medicine attending rounds. We found training level and workload demands were associated with prioritization of teaching domains. Prioritization of Teaching Process, exemplified by setting aside time to teach, demonstrating physical exam skills, and clear delineation of the attending’s thought process, was inversely associated with training level. On the days with highest workload, Team Management was most likely to be prioritized. Our findings suggest that attending physicians should consider adapting rounding style based on team members’ training levels and workload.

Prior work has described teaching and rounding styles, influences, and priorities in response to workload from the attending physician’s perspective,8–11 and our study extends these reports by providing the complementary perspective of trainees. On days with high workload, trainees prefer the Team Management domain, characterized by organized and efficient rounds, agreement on a clear and consistent plan of care, and being allowed independence and time during rounds to meet other responsibilities.1 These findings support an “empowerment style,” defined by Goldszmidt et al. as using integrated teaching and oversight strategies to support trainees’ progressive independence.9 Though some attending physicians report shifting to a more direct patient care style on days with a high patient census,9 our results suggest that learners instead prefer more independence, being empowered to perform more direct care. While there is an increasing pressure to heighten attending supervision due to concerns about patient safety, restricted work hours, and litigation,12 trainees value being part of the care process and being included as integral members of the care team, which may actually mitigate patient safety risks.8

Our results are consistent with prior studies, reporting that learners at different levels of training have different instructional needs: medical students seek more teaching, and senior residents sought an efficient leader.13,14 Taken together, these studies suggest that attending physicians should tailor rounds to the level of the trainee. For example, it may be beneficial for the attending physician to spend time outside of rounds with students to teach medical knowledge. During rounds, the entire group benefits most from modeling clinical reasoning, discussing new medical evidence, and demonstrating communication skills and leadership.

Our study has limitations. Though our study was performed before the 2011 ACGME duty hour restrictions,5 our results are likely of greater importance and relevance, as our findings ultimately highlight the competing demands of time vs duty. Also, while our study was performed at a single institution, potentially limiting generalizability, we included 3 types of training hospitals, a university, veterans and a county hospital, and found no differences between sites. Additionally, we collected over 1,000 cards over the course of 6 months, assessing rounds of over 50 different attending physicians, suggesting broader applicability. Our overall response rate was low, a typical signal for respondent bias, but because we collected daily assessments, standard interpretation of response rates referring to a one-time survey do not apply.15 We believe we achieved an adequate sample, as the majority of teams participated, the respondent demographics were proportional to the base population eligible to participate, and we received a similar number of cards on all months. Finally, although we were unable to account for clustering effects by individual respondents because response cards were anonymous, we adjusted for clustering effects by team.

Attending physicians may use our findings to adapt teaching techniques to appeal to specific training levels and to external pressures during teaching rounds. Focusing and investing time in teaching medical knowledge and clinical reasoning tailored to each level of learner is paramount on most days. However, days with a high workload may require emphasis on delegating clear, rational treatment plans, when learners are less receptive to traditional didactic methods.

Disclosure