User login

Keeping Pain A Priority

Before pain was introduced as the “fifth vital sign” and the Joint Commission issued its standards, more than a decade’s worth of international research indicated that pain was largely ignored, untreated, or undertreated. The best tools available to treat pain (opioids) were reserved for patients on their deathbed. The horrific results of the SUPPORT study at the nation’s leading hospitals revealed that most patients had severe, uncontrolled pain up until their final days of life.1 Unfortunately, research suggests we are still reserving opioids for the last days or weeks of life.2

In 1992 and 1994, the Department of Health and Human Services issued clinical practice guidelines highlighting the huge gap between the availability of evidence-based pain control methods and the lack of pain assessment and treatment in practice.3 When these guidelines failed to change practice, the Joint Commission added “attending to pain” to its standards—the first effort to require that evidence-based practices be utilized. Twenty years later, the National Academy of Science issued a report stating that, despite transient improvements, the current state is inadequate since pain is the leading reason people seek health care. Patients with pain report an inability to get help, which is “viewed worldwide as poor medicine, unethical practice, and an abrogation of a fundamental human right.”4 Since I started working as an NP in 1983, I have never seen as many patients with pain stigmatized, ignored, labeled, and denied access to treatment as I have in the past year.

Pain afflicts more than 100 million Americans and is the leading cause of disability worldwide.5 Acute pain that is not effectively treated progresses to chronic pain in 51% of cases.6 An estimated 23 million Americans report frequent intense pain, 25 million endure daily chronic pain, and 40 million adults have high-impact, disabling, chronic pain that degrades health and requires health care intervention.6,7 The most notable damage is to the structure and function of the central nervous system.8 Brain remodeling and loss of gray matter occurs, producing changes in the brain similar to those observed with 10 to 20 years of aging; this explains why some of the learning, memory, and emotional difficulties endured by many with ongoing pain can be partially reversed with effective treatment.9 Left untreated, pain can result in significant biopsychosocial problems, frailty, financial ruin, and premature death.10-14

Prescription drug misuse and addiction also affect millions and have been a largely ignored public health problem for decades. Trying to fix the pain problem without attending equally to the problems of nonmedical drug use, addiction, and overdose deaths has contributed to the escalation of health problems to “epidemic” and “crisis” proportions. Although most patients who are prescribed medically indicated opioids for pain do not misuse their medications or become addicted, the failure to subsequently identify and properly treat an emergent substance use disorder is a problem in our current system.15 Unfortunately, making prescription opioids inaccessible to patients forces some to abuse alcohol or seek drugs from illicit sources, which only exacerbates the situation.16 A national study performed over a five-year period revealed that only 10% of patients admitted for prescription opioid treatment were referred from their health care providers.17 So, health care providers may have been part of the problem but have not been fully engaged in the solution.

Although opioids are neither the firstline, nor only, treatment option in our current evidence-based treatment toolbox, their prudent use does not cause addiction. Only 1% of patients who receive postoperative opioids go on to develop chronic opioid use, and adolescents treated with medically necessary opioids have no greater risk for future addiction than unexposed children. It is the nonmedical use of opioids, rather than proper medical use, that predisposes people to addiction.18,19 Discharging or not treating patients suspected of “drug-seeking” exacerbates the problem. Rates of opioid prescription have declined, while overdoses of illicitly manufactured fentanyl increased by 79% in 27 states from 2013 to 2014.20 In Massachusetts, only 8% of people who fatally overdosed had a prescription, while illicit fentanyl accounted for 54% of overdose deaths in 2015 and more than 74% in the third quarter of 2016.21 We need to screen for nonmedical use, drug misuse, and addiction before, during, and after we treat with this particular tool.

Unfortunately, the prevalence of pain and addiction are both increasing, especially for women and minorities—but there are safe, effective medications and non-drug approaches available to combat this.22-24 These problems will not go away on their own, and every health care professional must choose to be part of the solution rather than perpetuate the problem. A good place to start is to become familiar with the Surgeon General’s Report and the National Pain Strategy. Educate your patients, colleagues, and policy makers about the true nature of these problems. Take a public health approach to primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention by recognizing and treating these conditions in an expedient and effective matter. When problems persist, expand the treatment team to include specialists who can develop a patient-centered, multimodal treatment plan that treats co-occurring conditions. If we continue to ignore these problems, or focus on one at the expense of the other, both problems will worsen and our patients will suffer serious consequences.

Paul Arnstein, PhD, NP-C, FAAN, FNP-C

Boston, MA

1. Lynn J, Teno JM, Phillips RS, et al; SUPPORT Investigators. Perceptions by family members of the dying experience of older and seriously ill patients. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(2):97-106.

2. Ziegler L, Mulvey M, Blenkinsopp A, et al. Opioid prescribing for patients with cancer in the last year of life: a longitudinal population cohort study. Pain. 2016;157(11):2445-2451.

3. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research [AHCPR]. Acute Pain Management: Operative or Medical Procedures and Trauma. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 1992.

4. Institute of Medicine (IOM). Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2011.

5. GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016; 388(10053):1545-1602.

6. Macfarlane GJ. The epidemiology of chronic pain. Pain. 2016;157(10):2158-2159.

7. Nahin RL. Estimates of pain prevalence and severity in adults: United States, 2012. J Pain. 2015;16(8):769-780.

8. Pozek JP, Beausang D, Baratta JL, Viscusi ER. The acute to chronic pain transition: can chronic pain be prevented? Med Clin North Am. 2016;100(1):17-30.

9. Seminowicz DA, Wideman TH, Naso L, et al. Effective treatment of chronic low back pain in humans reverses abnormal brain anatomy and function. J Neurosci. 2011; 31(20):7540-7550.

10. Wade KF, Lee DM, McBeth J, et al. Chronic widespread pain is associated with worsening frailty in European men. Age Ageing. 2016;45(2):268-274.

11. Torrance N, Elliott A, Lee AJ, Smith BH. Severe chronic pain is associated with increased 10 year mortality. A cohort record linkage study. Eur J Pain. 2010;14(4):380-386.

12. Tang NK, Beckwith P, Ashworth P. Mental defeat is associated with suicide intent in patients with chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2016;32(5):411-419.

13. Schaefer C, Sadosky A, Mann R, et al. Pain severity and the economic burden of neuropathic pain in the United States: BEAT Neuropathic Pain Observational Study. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2014;6:483-496.

14. Schofield D, Kelly S, Shrestha R, et al. The impact of back problems on retirement wealth. Pain. 2012;153(1):203-210.

15. Chou R, Deyo R, Devine B, et al. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid treatment of chronic pain. AHRQ Report No. 218. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; September 2014. www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/557/1988/chronic-pain-opioid-treat ment-executive-141022.pdf. Accessed December 2, 2016.

16. Alford DP, German JS, Samet JH, et al. Primary care patients with drug use report chronic pain and self-medicate with alcohol and other drugs. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(5):486-491.

17. St. Marie BJ, Sahker E, Arndt S. Referrals and treatment completion for prescription opioid admissions: five years of national data. J Subst Abus Treat. 2015;59:109-114.

18. Sun EC, Darnall B, Baker LC, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for chronic opioid use among opioid-naive patients in the postoperative period. JAMA Intern Med. 2016; 176(9):1286-1293.

19. McCabe SE, Veliz P, Schulenberg JE. Adolescent context of exposure to prescription opioids and substance use disorder (SUD) symptoms at age 35: a national longitudinal study. Pain. 2016;157(10):2171-2178.

20. Gladden RM, Martinez P, Seth P. Fentanyl law enforcement submissions and increases in synthetic opioid-involved overdose deaths—27 states, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(33):837-843.

21. Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Data Brief: Opioid-related Overdose Deaths Among Massachusetts Residents. www.mass.gov/eohhs/docs/dph/quality/drugcontrol/county-level-pmp/data-brief-overdose-deaths-may-2016.pdf. Accessed December 2, 2016.

22. Barbour KE, Boring M, Helmick CG, et al. Prevalence of severe joint pain among adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis—United States, 2002–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(39):1052-1056.

23. US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of the Surgeon General. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health, Executive Summary. Washington, DC: HHS; 2016. https://addiction.surgeongeneral.gov/executive-summary.pdf. Accessed December 2, 2016.

24. Herndon CM, Arnstein P, Darnall B, et al. Principles of Analgesic Use. 7th ed. Chicago, IL: American Pain Society Press; 2016.

Before pain was introduced as the “fifth vital sign” and the Joint Commission issued its standards, more than a decade’s worth of international research indicated that pain was largely ignored, untreated, or undertreated. The best tools available to treat pain (opioids) were reserved for patients on their deathbed. The horrific results of the SUPPORT study at the nation’s leading hospitals revealed that most patients had severe, uncontrolled pain up until their final days of life.1 Unfortunately, research suggests we are still reserving opioids for the last days or weeks of life.2

In 1992 and 1994, the Department of Health and Human Services issued clinical practice guidelines highlighting the huge gap between the availability of evidence-based pain control methods and the lack of pain assessment and treatment in practice.3 When these guidelines failed to change practice, the Joint Commission added “attending to pain” to its standards—the first effort to require that evidence-based practices be utilized. Twenty years later, the National Academy of Science issued a report stating that, despite transient improvements, the current state is inadequate since pain is the leading reason people seek health care. Patients with pain report an inability to get help, which is “viewed worldwide as poor medicine, unethical practice, and an abrogation of a fundamental human right.”4 Since I started working as an NP in 1983, I have never seen as many patients with pain stigmatized, ignored, labeled, and denied access to treatment as I have in the past year.

Pain afflicts more than 100 million Americans and is the leading cause of disability worldwide.5 Acute pain that is not effectively treated progresses to chronic pain in 51% of cases.6 An estimated 23 million Americans report frequent intense pain, 25 million endure daily chronic pain, and 40 million adults have high-impact, disabling, chronic pain that degrades health and requires health care intervention.6,7 The most notable damage is to the structure and function of the central nervous system.8 Brain remodeling and loss of gray matter occurs, producing changes in the brain similar to those observed with 10 to 20 years of aging; this explains why some of the learning, memory, and emotional difficulties endured by many with ongoing pain can be partially reversed with effective treatment.9 Left untreated, pain can result in significant biopsychosocial problems, frailty, financial ruin, and premature death.10-14

Prescription drug misuse and addiction also affect millions and have been a largely ignored public health problem for decades. Trying to fix the pain problem without attending equally to the problems of nonmedical drug use, addiction, and overdose deaths has contributed to the escalation of health problems to “epidemic” and “crisis” proportions. Although most patients who are prescribed medically indicated opioids for pain do not misuse their medications or become addicted, the failure to subsequently identify and properly treat an emergent substance use disorder is a problem in our current system.15 Unfortunately, making prescription opioids inaccessible to patients forces some to abuse alcohol or seek drugs from illicit sources, which only exacerbates the situation.16 A national study performed over a five-year period revealed that only 10% of patients admitted for prescription opioid treatment were referred from their health care providers.17 So, health care providers may have been part of the problem but have not been fully engaged in the solution.

Although opioids are neither the firstline, nor only, treatment option in our current evidence-based treatment toolbox, their prudent use does not cause addiction. Only 1% of patients who receive postoperative opioids go on to develop chronic opioid use, and adolescents treated with medically necessary opioids have no greater risk for future addiction than unexposed children. It is the nonmedical use of opioids, rather than proper medical use, that predisposes people to addiction.18,19 Discharging or not treating patients suspected of “drug-seeking” exacerbates the problem. Rates of opioid prescription have declined, while overdoses of illicitly manufactured fentanyl increased by 79% in 27 states from 2013 to 2014.20 In Massachusetts, only 8% of people who fatally overdosed had a prescription, while illicit fentanyl accounted for 54% of overdose deaths in 2015 and more than 74% in the third quarter of 2016.21 We need to screen for nonmedical use, drug misuse, and addiction before, during, and after we treat with this particular tool.

Unfortunately, the prevalence of pain and addiction are both increasing, especially for women and minorities—but there are safe, effective medications and non-drug approaches available to combat this.22-24 These problems will not go away on their own, and every health care professional must choose to be part of the solution rather than perpetuate the problem. A good place to start is to become familiar with the Surgeon General’s Report and the National Pain Strategy. Educate your patients, colleagues, and policy makers about the true nature of these problems. Take a public health approach to primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention by recognizing and treating these conditions in an expedient and effective matter. When problems persist, expand the treatment team to include specialists who can develop a patient-centered, multimodal treatment plan that treats co-occurring conditions. If we continue to ignore these problems, or focus on one at the expense of the other, both problems will worsen and our patients will suffer serious consequences.

Paul Arnstein, PhD, NP-C, FAAN, FNP-C

Boston, MA

Before pain was introduced as the “fifth vital sign” and the Joint Commission issued its standards, more than a decade’s worth of international research indicated that pain was largely ignored, untreated, or undertreated. The best tools available to treat pain (opioids) were reserved for patients on their deathbed. The horrific results of the SUPPORT study at the nation’s leading hospitals revealed that most patients had severe, uncontrolled pain up until their final days of life.1 Unfortunately, research suggests we are still reserving opioids for the last days or weeks of life.2

In 1992 and 1994, the Department of Health and Human Services issued clinical practice guidelines highlighting the huge gap between the availability of evidence-based pain control methods and the lack of pain assessment and treatment in practice.3 When these guidelines failed to change practice, the Joint Commission added “attending to pain” to its standards—the first effort to require that evidence-based practices be utilized. Twenty years later, the National Academy of Science issued a report stating that, despite transient improvements, the current state is inadequate since pain is the leading reason people seek health care. Patients with pain report an inability to get help, which is “viewed worldwide as poor medicine, unethical practice, and an abrogation of a fundamental human right.”4 Since I started working as an NP in 1983, I have never seen as many patients with pain stigmatized, ignored, labeled, and denied access to treatment as I have in the past year.

Pain afflicts more than 100 million Americans and is the leading cause of disability worldwide.5 Acute pain that is not effectively treated progresses to chronic pain in 51% of cases.6 An estimated 23 million Americans report frequent intense pain, 25 million endure daily chronic pain, and 40 million adults have high-impact, disabling, chronic pain that degrades health and requires health care intervention.6,7 The most notable damage is to the structure and function of the central nervous system.8 Brain remodeling and loss of gray matter occurs, producing changes in the brain similar to those observed with 10 to 20 years of aging; this explains why some of the learning, memory, and emotional difficulties endured by many with ongoing pain can be partially reversed with effective treatment.9 Left untreated, pain can result in significant biopsychosocial problems, frailty, financial ruin, and premature death.10-14

Prescription drug misuse and addiction also affect millions and have been a largely ignored public health problem for decades. Trying to fix the pain problem without attending equally to the problems of nonmedical drug use, addiction, and overdose deaths has contributed to the escalation of health problems to “epidemic” and “crisis” proportions. Although most patients who are prescribed medically indicated opioids for pain do not misuse their medications or become addicted, the failure to subsequently identify and properly treat an emergent substance use disorder is a problem in our current system.15 Unfortunately, making prescription opioids inaccessible to patients forces some to abuse alcohol or seek drugs from illicit sources, which only exacerbates the situation.16 A national study performed over a five-year period revealed that only 10% of patients admitted for prescription opioid treatment were referred from their health care providers.17 So, health care providers may have been part of the problem but have not been fully engaged in the solution.

Although opioids are neither the firstline, nor only, treatment option in our current evidence-based treatment toolbox, their prudent use does not cause addiction. Only 1% of patients who receive postoperative opioids go on to develop chronic opioid use, and adolescents treated with medically necessary opioids have no greater risk for future addiction than unexposed children. It is the nonmedical use of opioids, rather than proper medical use, that predisposes people to addiction.18,19 Discharging or not treating patients suspected of “drug-seeking” exacerbates the problem. Rates of opioid prescription have declined, while overdoses of illicitly manufactured fentanyl increased by 79% in 27 states from 2013 to 2014.20 In Massachusetts, only 8% of people who fatally overdosed had a prescription, while illicit fentanyl accounted for 54% of overdose deaths in 2015 and more than 74% in the third quarter of 2016.21 We need to screen for nonmedical use, drug misuse, and addiction before, during, and after we treat with this particular tool.

Unfortunately, the prevalence of pain and addiction are both increasing, especially for women and minorities—but there are safe, effective medications and non-drug approaches available to combat this.22-24 These problems will not go away on their own, and every health care professional must choose to be part of the solution rather than perpetuate the problem. A good place to start is to become familiar with the Surgeon General’s Report and the National Pain Strategy. Educate your patients, colleagues, and policy makers about the true nature of these problems. Take a public health approach to primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention by recognizing and treating these conditions in an expedient and effective matter. When problems persist, expand the treatment team to include specialists who can develop a patient-centered, multimodal treatment plan that treats co-occurring conditions. If we continue to ignore these problems, or focus on one at the expense of the other, both problems will worsen and our patients will suffer serious consequences.

Paul Arnstein, PhD, NP-C, FAAN, FNP-C

Boston, MA

1. Lynn J, Teno JM, Phillips RS, et al; SUPPORT Investigators. Perceptions by family members of the dying experience of older and seriously ill patients. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(2):97-106.

2. Ziegler L, Mulvey M, Blenkinsopp A, et al. Opioid prescribing for patients with cancer in the last year of life: a longitudinal population cohort study. Pain. 2016;157(11):2445-2451.

3. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research [AHCPR]. Acute Pain Management: Operative or Medical Procedures and Trauma. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 1992.

4. Institute of Medicine (IOM). Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2011.

5. GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016; 388(10053):1545-1602.

6. Macfarlane GJ. The epidemiology of chronic pain. Pain. 2016;157(10):2158-2159.

7. Nahin RL. Estimates of pain prevalence and severity in adults: United States, 2012. J Pain. 2015;16(8):769-780.

8. Pozek JP, Beausang D, Baratta JL, Viscusi ER. The acute to chronic pain transition: can chronic pain be prevented? Med Clin North Am. 2016;100(1):17-30.

9. Seminowicz DA, Wideman TH, Naso L, et al. Effective treatment of chronic low back pain in humans reverses abnormal brain anatomy and function. J Neurosci. 2011; 31(20):7540-7550.

10. Wade KF, Lee DM, McBeth J, et al. Chronic widespread pain is associated with worsening frailty in European men. Age Ageing. 2016;45(2):268-274.

11. Torrance N, Elliott A, Lee AJ, Smith BH. Severe chronic pain is associated with increased 10 year mortality. A cohort record linkage study. Eur J Pain. 2010;14(4):380-386.

12. Tang NK, Beckwith P, Ashworth P. Mental defeat is associated with suicide intent in patients with chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2016;32(5):411-419.

13. Schaefer C, Sadosky A, Mann R, et al. Pain severity and the economic burden of neuropathic pain in the United States: BEAT Neuropathic Pain Observational Study. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2014;6:483-496.

14. Schofield D, Kelly S, Shrestha R, et al. The impact of back problems on retirement wealth. Pain. 2012;153(1):203-210.

15. Chou R, Deyo R, Devine B, et al. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid treatment of chronic pain. AHRQ Report No. 218. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; September 2014. www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/557/1988/chronic-pain-opioid-treat ment-executive-141022.pdf. Accessed December 2, 2016.

16. Alford DP, German JS, Samet JH, et al. Primary care patients with drug use report chronic pain and self-medicate with alcohol and other drugs. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(5):486-491.

17. St. Marie BJ, Sahker E, Arndt S. Referrals and treatment completion for prescription opioid admissions: five years of national data. J Subst Abus Treat. 2015;59:109-114.

18. Sun EC, Darnall B, Baker LC, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for chronic opioid use among opioid-naive patients in the postoperative period. JAMA Intern Med. 2016; 176(9):1286-1293.

19. McCabe SE, Veliz P, Schulenberg JE. Adolescent context of exposure to prescription opioids and substance use disorder (SUD) symptoms at age 35: a national longitudinal study. Pain. 2016;157(10):2171-2178.

20. Gladden RM, Martinez P, Seth P. Fentanyl law enforcement submissions and increases in synthetic opioid-involved overdose deaths—27 states, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(33):837-843.

21. Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Data Brief: Opioid-related Overdose Deaths Among Massachusetts Residents. www.mass.gov/eohhs/docs/dph/quality/drugcontrol/county-level-pmp/data-brief-overdose-deaths-may-2016.pdf. Accessed December 2, 2016.

22. Barbour KE, Boring M, Helmick CG, et al. Prevalence of severe joint pain among adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis—United States, 2002–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(39):1052-1056.

23. US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of the Surgeon General. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health, Executive Summary. Washington, DC: HHS; 2016. https://addiction.surgeongeneral.gov/executive-summary.pdf. Accessed December 2, 2016.

24. Herndon CM, Arnstein P, Darnall B, et al. Principles of Analgesic Use. 7th ed. Chicago, IL: American Pain Society Press; 2016.

1. Lynn J, Teno JM, Phillips RS, et al; SUPPORT Investigators. Perceptions by family members of the dying experience of older and seriously ill patients. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(2):97-106.

2. Ziegler L, Mulvey M, Blenkinsopp A, et al. Opioid prescribing for patients with cancer in the last year of life: a longitudinal population cohort study. Pain. 2016;157(11):2445-2451.

3. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research [AHCPR]. Acute Pain Management: Operative or Medical Procedures and Trauma. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 1992.

4. Institute of Medicine (IOM). Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2011.

5. GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016; 388(10053):1545-1602.

6. Macfarlane GJ. The epidemiology of chronic pain. Pain. 2016;157(10):2158-2159.

7. Nahin RL. Estimates of pain prevalence and severity in adults: United States, 2012. J Pain. 2015;16(8):769-780.

8. Pozek JP, Beausang D, Baratta JL, Viscusi ER. The acute to chronic pain transition: can chronic pain be prevented? Med Clin North Am. 2016;100(1):17-30.

9. Seminowicz DA, Wideman TH, Naso L, et al. Effective treatment of chronic low back pain in humans reverses abnormal brain anatomy and function. J Neurosci. 2011; 31(20):7540-7550.

10. Wade KF, Lee DM, McBeth J, et al. Chronic widespread pain is associated with worsening frailty in European men. Age Ageing. 2016;45(2):268-274.

11. Torrance N, Elliott A, Lee AJ, Smith BH. Severe chronic pain is associated with increased 10 year mortality. A cohort record linkage study. Eur J Pain. 2010;14(4):380-386.

12. Tang NK, Beckwith P, Ashworth P. Mental defeat is associated with suicide intent in patients with chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2016;32(5):411-419.

13. Schaefer C, Sadosky A, Mann R, et al. Pain severity and the economic burden of neuropathic pain in the United States: BEAT Neuropathic Pain Observational Study. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2014;6:483-496.

14. Schofield D, Kelly S, Shrestha R, et al. The impact of back problems on retirement wealth. Pain. 2012;153(1):203-210.

15. Chou R, Deyo R, Devine B, et al. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid treatment of chronic pain. AHRQ Report No. 218. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; September 2014. www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/557/1988/chronic-pain-opioid-treat ment-executive-141022.pdf. Accessed December 2, 2016.

16. Alford DP, German JS, Samet JH, et al. Primary care patients with drug use report chronic pain and self-medicate with alcohol and other drugs. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(5):486-491.

17. St. Marie BJ, Sahker E, Arndt S. Referrals and treatment completion for prescription opioid admissions: five years of national data. J Subst Abus Treat. 2015;59:109-114.

18. Sun EC, Darnall B, Baker LC, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for chronic opioid use among opioid-naive patients in the postoperative period. JAMA Intern Med. 2016; 176(9):1286-1293.

19. McCabe SE, Veliz P, Schulenberg JE. Adolescent context of exposure to prescription opioids and substance use disorder (SUD) symptoms at age 35: a national longitudinal study. Pain. 2016;157(10):2171-2178.

20. Gladden RM, Martinez P, Seth P. Fentanyl law enforcement submissions and increases in synthetic opioid-involved overdose deaths—27 states, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(33):837-843.

21. Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Data Brief: Opioid-related Overdose Deaths Among Massachusetts Residents. www.mass.gov/eohhs/docs/dph/quality/drugcontrol/county-level-pmp/data-brief-overdose-deaths-may-2016.pdf. Accessed December 2, 2016.

22. Barbour KE, Boring M, Helmick CG, et al. Prevalence of severe joint pain among adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis—United States, 2002–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(39):1052-1056.

23. US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of the Surgeon General. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health, Executive Summary. Washington, DC: HHS; 2016. https://addiction.surgeongeneral.gov/executive-summary.pdf. Accessed December 2, 2016.

24. Herndon CM, Arnstein P, Darnall B, et al. Principles of Analgesic Use. 7th ed. Chicago, IL: American Pain Society Press; 2016.

Gene, risk signatures could predict PARP inhibitor response in breast cancer

SAN ANTONIO – PARPi 7, BRCAness, and MammaPrint high1/(ultra)high2 signatures could help predict response to combination therapy with the poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors veliparib and carboplatin among high-risk breast cancer patients and thereby improve patient care, according to findings from the I-SPY 2 clinical trial.

“I-SPY 2 is a phase II adaptively randomized neoadjuvant clinical trial with a shared control arm where patients receive standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and up to 4 simultaneous investigational arms. The primary endpoint of the trial is pathologic complete response, or pCR. The goal is to match therapies with the most responsive breast cancer subtypes,” Denise M. Wolf, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco, explained at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

The current analysis of I-Spy 2 data focuses on veliparib/carboplatin (VC), and the subtypes Dr. Wolf mentioned are defined by hormone receptor (HR) and HER2 expression, and by MammaPrint high1 or (ultra)high2 risk status, which, “roughly speaking, is a further stratification of the poor prognosis group into high- and extra-high-risk groups,” she said.

“This arm was open to HER2-negative patients, and graduated successfully in the triple-negative subset,” she noted, explaining that “agents or combinations graduate for efficacy if they reach 85% predicted probability of success in a subsequent phase III trial in the most responsive patient subset.”

The biomarker component of the trial aimed to evaluate biomarkers associated with the mechanisms of action of each investigational agent along with the predefined subsets.

Although the findings require verification in a larger trial, Dr. Wolf and her colleagues found that three biomarkers – the PARPi 7 gene signature, the 77-gene BRCAness signature (which both relate to DNA damage repair deficiency), and the MammaPrint high1 and (ultra)high2 risk categories – were each moderately correlated with treatment response in 72 patients receiving veliparib/carboplatin (VC), but not in 44 controls, and that the treatment-biomarker interactions retained statistical significance after adjusting for hormone receptor status.

“And so we asked the question, ‘Are these signatures identifying the same patients – and if not, might there be a way to combine them to identify a subset of patients who are especially likely to respond to VC?’” she said.

Further analysis showed that even though each of the biomarkers was a predictor of response, the biomarkers did not appear to identify exactly the same patients, therefore combining them might be of benefit.

“We did this using a simple voting scheme to combine pairs of biomarkers,” she said, adding that if the two paired biomarkers predicted resistance, the biomarker also predicted resistance. If only 1 predicted resistance, the combination predicted resistance, and only if both biomarkers predicted sensitivity did the combination predict sensitivity.

In the graduated triple-negative subset, for example, the 40% of patients who were PARPi 7–high and MammaPrint high2 (the two biomarkers most predictive of response) a dramatic separation was seen in the pCR probability curves, with an estimated pCR of 79% with VC treatment vs. 23% in the control arm.

“In contrast, triple-negative patients who were negative for one or more of the sensitivity markers had nearly overlapping probability response curves, from which we conclude that nearly all of the specific sensitivity to VC seen in the triple-negative patients is found in that subset who are positive for both sensitivity markers,” she said.

Additionally, although only 9% of HR-positive/HER2-negative patients were PARPi 7-high and MammaPrint high2, those patients also appeared to be more responsive to VC vs. the control arm (49% vs. 15%).

The results also demonstrate the value of an exploratory voting method for combining multiple biomarkers for the same treatment, Dr. Wolf noted.

However, the findings are limited by the small sample size and need to be evaluated in larger trials, and the biomarkers also need to be evaluated in carboplatin-only arms in order to “tease out whether the biomarkers are really specific to a PARP inhibitor with carboplatin or whether they might also apply to carboplatin alone.

“Our ongoing and future work is to develop predictive biomarkers for other I-Spy 2 agents,” she said.

Dr. Wolf reported having no disclosures.

SAN ANTONIO – PARPi 7, BRCAness, and MammaPrint high1/(ultra)high2 signatures could help predict response to combination therapy with the poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors veliparib and carboplatin among high-risk breast cancer patients and thereby improve patient care, according to findings from the I-SPY 2 clinical trial.

“I-SPY 2 is a phase II adaptively randomized neoadjuvant clinical trial with a shared control arm where patients receive standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and up to 4 simultaneous investigational arms. The primary endpoint of the trial is pathologic complete response, or pCR. The goal is to match therapies with the most responsive breast cancer subtypes,” Denise M. Wolf, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco, explained at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

The current analysis of I-Spy 2 data focuses on veliparib/carboplatin (VC), and the subtypes Dr. Wolf mentioned are defined by hormone receptor (HR) and HER2 expression, and by MammaPrint high1 or (ultra)high2 risk status, which, “roughly speaking, is a further stratification of the poor prognosis group into high- and extra-high-risk groups,” she said.

“This arm was open to HER2-negative patients, and graduated successfully in the triple-negative subset,” she noted, explaining that “agents or combinations graduate for efficacy if they reach 85% predicted probability of success in a subsequent phase III trial in the most responsive patient subset.”

The biomarker component of the trial aimed to evaluate biomarkers associated with the mechanisms of action of each investigational agent along with the predefined subsets.

Although the findings require verification in a larger trial, Dr. Wolf and her colleagues found that three biomarkers – the PARPi 7 gene signature, the 77-gene BRCAness signature (which both relate to DNA damage repair deficiency), and the MammaPrint high1 and (ultra)high2 risk categories – were each moderately correlated with treatment response in 72 patients receiving veliparib/carboplatin (VC), but not in 44 controls, and that the treatment-biomarker interactions retained statistical significance after adjusting for hormone receptor status.

“And so we asked the question, ‘Are these signatures identifying the same patients – and if not, might there be a way to combine them to identify a subset of patients who are especially likely to respond to VC?’” she said.

Further analysis showed that even though each of the biomarkers was a predictor of response, the biomarkers did not appear to identify exactly the same patients, therefore combining them might be of benefit.

“We did this using a simple voting scheme to combine pairs of biomarkers,” she said, adding that if the two paired biomarkers predicted resistance, the biomarker also predicted resistance. If only 1 predicted resistance, the combination predicted resistance, and only if both biomarkers predicted sensitivity did the combination predict sensitivity.

In the graduated triple-negative subset, for example, the 40% of patients who were PARPi 7–high and MammaPrint high2 (the two biomarkers most predictive of response) a dramatic separation was seen in the pCR probability curves, with an estimated pCR of 79% with VC treatment vs. 23% in the control arm.

“In contrast, triple-negative patients who were negative for one or more of the sensitivity markers had nearly overlapping probability response curves, from which we conclude that nearly all of the specific sensitivity to VC seen in the triple-negative patients is found in that subset who are positive for both sensitivity markers,” she said.

Additionally, although only 9% of HR-positive/HER2-negative patients were PARPi 7-high and MammaPrint high2, those patients also appeared to be more responsive to VC vs. the control arm (49% vs. 15%).

The results also demonstrate the value of an exploratory voting method for combining multiple biomarkers for the same treatment, Dr. Wolf noted.

However, the findings are limited by the small sample size and need to be evaluated in larger trials, and the biomarkers also need to be evaluated in carboplatin-only arms in order to “tease out whether the biomarkers are really specific to a PARP inhibitor with carboplatin or whether they might also apply to carboplatin alone.

“Our ongoing and future work is to develop predictive biomarkers for other I-Spy 2 agents,” she said.

Dr. Wolf reported having no disclosures.

SAN ANTONIO – PARPi 7, BRCAness, and MammaPrint high1/(ultra)high2 signatures could help predict response to combination therapy with the poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors veliparib and carboplatin among high-risk breast cancer patients and thereby improve patient care, according to findings from the I-SPY 2 clinical trial.

“I-SPY 2 is a phase II adaptively randomized neoadjuvant clinical trial with a shared control arm where patients receive standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and up to 4 simultaneous investigational arms. The primary endpoint of the trial is pathologic complete response, or pCR. The goal is to match therapies with the most responsive breast cancer subtypes,” Denise M. Wolf, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco, explained at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

The current analysis of I-Spy 2 data focuses on veliparib/carboplatin (VC), and the subtypes Dr. Wolf mentioned are defined by hormone receptor (HR) and HER2 expression, and by MammaPrint high1 or (ultra)high2 risk status, which, “roughly speaking, is a further stratification of the poor prognosis group into high- and extra-high-risk groups,” she said.

“This arm was open to HER2-negative patients, and graduated successfully in the triple-negative subset,” she noted, explaining that “agents or combinations graduate for efficacy if they reach 85% predicted probability of success in a subsequent phase III trial in the most responsive patient subset.”

The biomarker component of the trial aimed to evaluate biomarkers associated with the mechanisms of action of each investigational agent along with the predefined subsets.

Although the findings require verification in a larger trial, Dr. Wolf and her colleagues found that three biomarkers – the PARPi 7 gene signature, the 77-gene BRCAness signature (which both relate to DNA damage repair deficiency), and the MammaPrint high1 and (ultra)high2 risk categories – were each moderately correlated with treatment response in 72 patients receiving veliparib/carboplatin (VC), but not in 44 controls, and that the treatment-biomarker interactions retained statistical significance after adjusting for hormone receptor status.

“And so we asked the question, ‘Are these signatures identifying the same patients – and if not, might there be a way to combine them to identify a subset of patients who are especially likely to respond to VC?’” she said.

Further analysis showed that even though each of the biomarkers was a predictor of response, the biomarkers did not appear to identify exactly the same patients, therefore combining them might be of benefit.

“We did this using a simple voting scheme to combine pairs of biomarkers,” she said, adding that if the two paired biomarkers predicted resistance, the biomarker also predicted resistance. If only 1 predicted resistance, the combination predicted resistance, and only if both biomarkers predicted sensitivity did the combination predict sensitivity.

In the graduated triple-negative subset, for example, the 40% of patients who were PARPi 7–high and MammaPrint high2 (the two biomarkers most predictive of response) a dramatic separation was seen in the pCR probability curves, with an estimated pCR of 79% with VC treatment vs. 23% in the control arm.

“In contrast, triple-negative patients who were negative for one or more of the sensitivity markers had nearly overlapping probability response curves, from which we conclude that nearly all of the specific sensitivity to VC seen in the triple-negative patients is found in that subset who are positive for both sensitivity markers,” she said.

Additionally, although only 9% of HR-positive/HER2-negative patients were PARPi 7-high and MammaPrint high2, those patients also appeared to be more responsive to VC vs. the control arm (49% vs. 15%).

The results also demonstrate the value of an exploratory voting method for combining multiple biomarkers for the same treatment, Dr. Wolf noted.

However, the findings are limited by the small sample size and need to be evaluated in larger trials, and the biomarkers also need to be evaluated in carboplatin-only arms in order to “tease out whether the biomarkers are really specific to a PARP inhibitor with carboplatin or whether they might also apply to carboplatin alone.

“Our ongoing and future work is to develop predictive biomarkers for other I-Spy 2 agents,” she said.

Dr. Wolf reported having no disclosures.

AT SABCS 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Estimated pCR in PARPi 7–high and MammaPrint 2 triple-negative patients was 79% vs. 23% for the VC arm vs. control arm.

Data source: The phase II adaptively randomized I-Spy 2 clinical trial of 116 subjects.

Disclosures: Dr. Wolf reported having no disclosures.

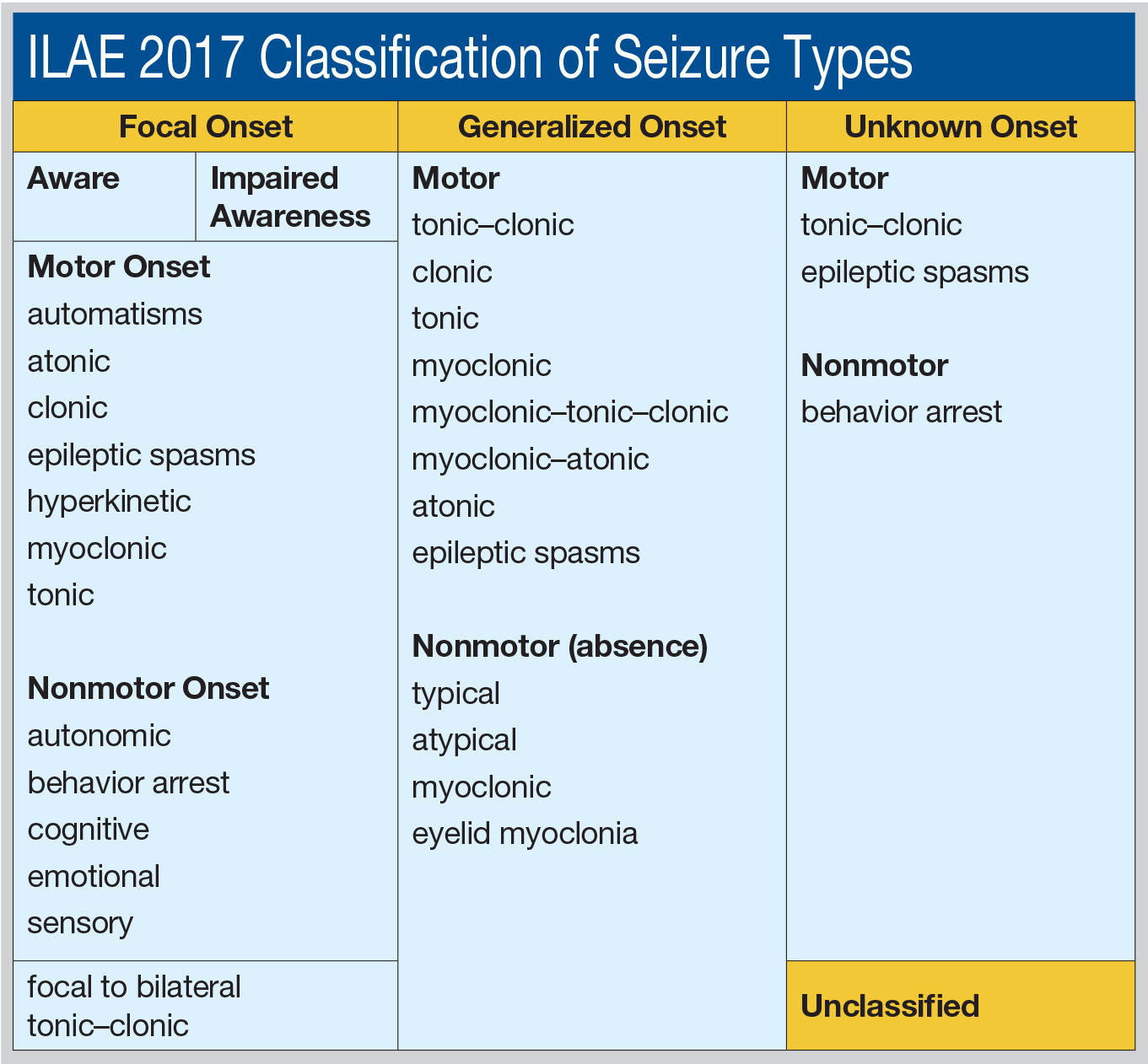

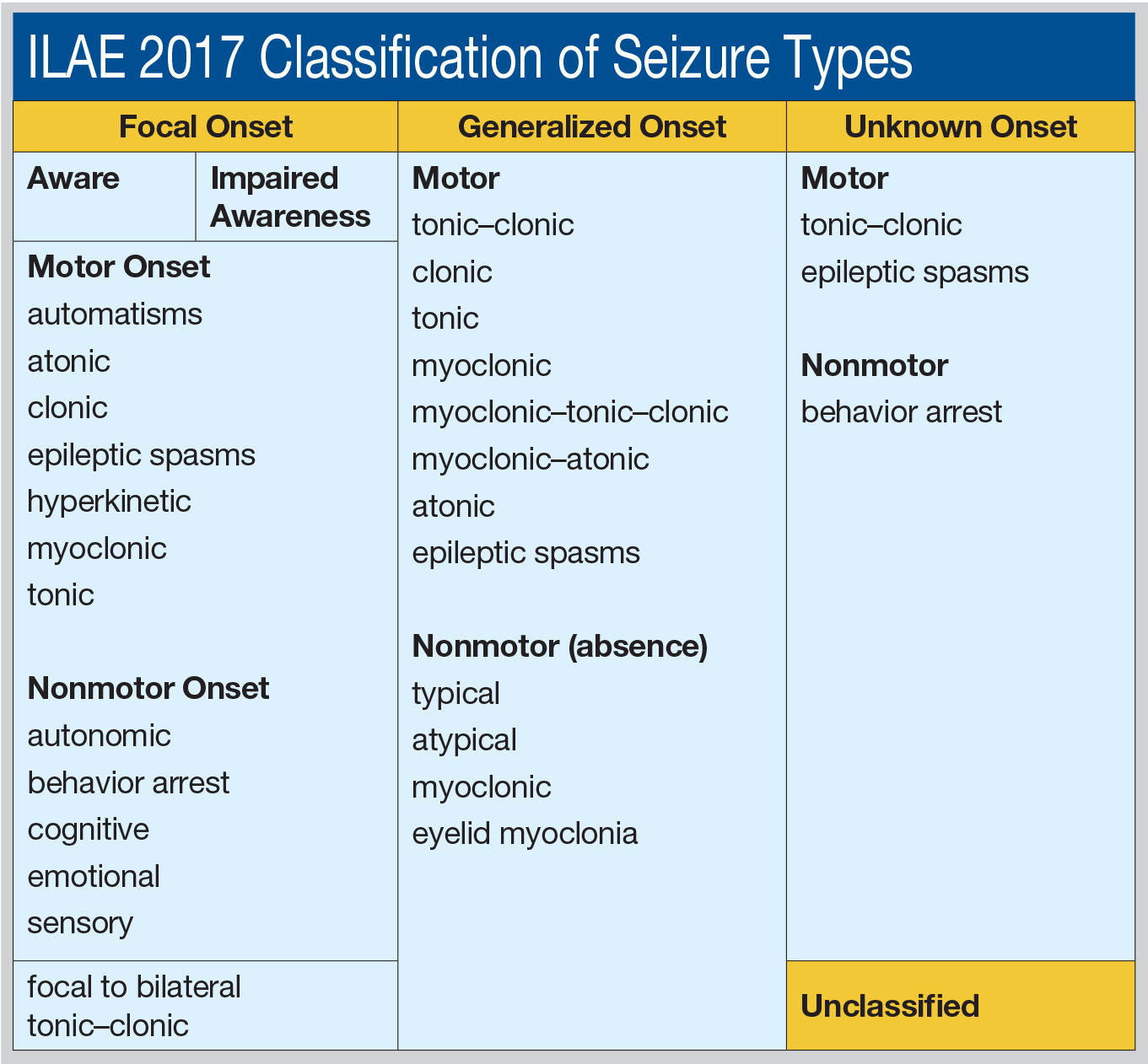

Study eyes fracture risk in pediatric patients taking antiepileptic drugs

HOUSTON – The incidence of fractures in pediatric patients taking antiepileptic medication stands at an estimated 1.1%, according to results from a 4-year period at a children’s hospital.

“Understanding the prevalence of fractures in pediatric patients on an AED [antiepileptic drug] will allow clinicians to weigh the risk versus benefit of therapy,” researchers led by Shannon DiCarlo, MD, wrote in an abstract presented during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “Recognizing a risk of fractures with AEDs will permit clinicians to provide appropriate supportive care and monitoring from the initiation of therapy.”

Dr. DiCarlo of Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, and her associates went on to note that adults with epilepsy have a twofold to sixfold greater risk of experiencing fractures, compared with the general population, and that fractures secondary to seizures “are a major concern in pediatrics.” In fact, one survey of 404 pediatric neurologists found that only 41% of respondents were aware of the association between AEDs and reduced bone mass (Arch Neurol. 2001;58[9]:1369-74).

In an effort to evaluate the prevalence of fractures in pediatric patients on an antiepileptic drug, the researchers conducted a cohort study of 10,153 patients younger than 18 years of age who received an AED at Texas Children’s Hospital from 2011 to 2014. Half of the study population were female, and the most common concomitant disease was epilepsy (52.6%), followed by cerebral palsy (8.3%), epilepsy plus cerebral palsy (6.9%), osteoporosis (0.2%), and osteopenia (0.3%). In all, 113 patients (1.1%) experienced a fracture while on an antiepileptic drug, and the mean time from initiation of an AED to time of fracture was 1.6 years. Patients on enzyme-inducing AEDs were two times more likely to experience a fracture, while those with cerebral palsy and epilepsy were three times more likely to experience a fracture. Proton pump inhibitors and corticosteroids were the most common concomitant drugs. The researchers also found that less than 10% of patients were on calcium or vitamin D supplementation.

“Vigilant monitoring should be employed for at-risk patients,” the researchers concluded. “Regular monitoring of calcium and vitamin D levels may be warranted; further studies are needed to evaluate the roll of prophylactic calcium and vitamin D supplements.”

The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – The incidence of fractures in pediatric patients taking antiepileptic medication stands at an estimated 1.1%, according to results from a 4-year period at a children’s hospital.

“Understanding the prevalence of fractures in pediatric patients on an AED [antiepileptic drug] will allow clinicians to weigh the risk versus benefit of therapy,” researchers led by Shannon DiCarlo, MD, wrote in an abstract presented during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “Recognizing a risk of fractures with AEDs will permit clinicians to provide appropriate supportive care and monitoring from the initiation of therapy.”

Dr. DiCarlo of Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, and her associates went on to note that adults with epilepsy have a twofold to sixfold greater risk of experiencing fractures, compared with the general population, and that fractures secondary to seizures “are a major concern in pediatrics.” In fact, one survey of 404 pediatric neurologists found that only 41% of respondents were aware of the association between AEDs and reduced bone mass (Arch Neurol. 2001;58[9]:1369-74).

In an effort to evaluate the prevalence of fractures in pediatric patients on an antiepileptic drug, the researchers conducted a cohort study of 10,153 patients younger than 18 years of age who received an AED at Texas Children’s Hospital from 2011 to 2014. Half of the study population were female, and the most common concomitant disease was epilepsy (52.6%), followed by cerebral palsy (8.3%), epilepsy plus cerebral palsy (6.9%), osteoporosis (0.2%), and osteopenia (0.3%). In all, 113 patients (1.1%) experienced a fracture while on an antiepileptic drug, and the mean time from initiation of an AED to time of fracture was 1.6 years. Patients on enzyme-inducing AEDs were two times more likely to experience a fracture, while those with cerebral palsy and epilepsy were three times more likely to experience a fracture. Proton pump inhibitors and corticosteroids were the most common concomitant drugs. The researchers also found that less than 10% of patients were on calcium or vitamin D supplementation.

“Vigilant monitoring should be employed for at-risk patients,” the researchers concluded. “Regular monitoring of calcium and vitamin D levels may be warranted; further studies are needed to evaluate the roll of prophylactic calcium and vitamin D supplements.”

The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – The incidence of fractures in pediatric patients taking antiepileptic medication stands at an estimated 1.1%, according to results from a 4-year period at a children’s hospital.

“Understanding the prevalence of fractures in pediatric patients on an AED [antiepileptic drug] will allow clinicians to weigh the risk versus benefit of therapy,” researchers led by Shannon DiCarlo, MD, wrote in an abstract presented during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “Recognizing a risk of fractures with AEDs will permit clinicians to provide appropriate supportive care and monitoring from the initiation of therapy.”

Dr. DiCarlo of Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, and her associates went on to note that adults with epilepsy have a twofold to sixfold greater risk of experiencing fractures, compared with the general population, and that fractures secondary to seizures “are a major concern in pediatrics.” In fact, one survey of 404 pediatric neurologists found that only 41% of respondents were aware of the association between AEDs and reduced bone mass (Arch Neurol. 2001;58[9]:1369-74).

In an effort to evaluate the prevalence of fractures in pediatric patients on an antiepileptic drug, the researchers conducted a cohort study of 10,153 patients younger than 18 years of age who received an AED at Texas Children’s Hospital from 2011 to 2014. Half of the study population were female, and the most common concomitant disease was epilepsy (52.6%), followed by cerebral palsy (8.3%), epilepsy plus cerebral palsy (6.9%), osteoporosis (0.2%), and osteopenia (0.3%). In all, 113 patients (1.1%) experienced a fracture while on an antiepileptic drug, and the mean time from initiation of an AED to time of fracture was 1.6 years. Patients on enzyme-inducing AEDs were two times more likely to experience a fracture, while those with cerebral palsy and epilepsy were three times more likely to experience a fracture. Proton pump inhibitors and corticosteroids were the most common concomitant drugs. The researchers also found that less than 10% of patients were on calcium or vitamin D supplementation.

“Vigilant monitoring should be employed for at-risk patients,” the researchers concluded. “Regular monitoring of calcium and vitamin D levels may be warranted; further studies are needed to evaluate the roll of prophylactic calcium and vitamin D supplements.”

The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In all, 113 patients (1.1%) experienced a fracture while on an antiepileptic drug, and the mean time from initiation of AED to time of fracture was 1.6 years.

Data source: A cohort study of 10,153 patients younger than 18 years of age who received an AED at Texas Children’s Hospital from 2011 to 2014.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Which maternal beta-blockers boost SGA risk?

NEW ORLEANS – The use of labetalol or atenolol in pregnancy is associated with significantly increased risk of having a small-for-gestational-age (SGA) baby; metoprolol and propranolol are not.

And none of these four beta-blockers are associated with increased risk of congenital cardiac anomalies, Angie Ng, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Overall, the average birth weight for babies whose mothers were on a beta-blocker was 2,996 g, significantly less than the 3,353 g in 374,391 controls who weren’t exposed to beta-blockers during pregnancy. But beta-blockers are not a monolithic class of drugs; their pharmacokinetics and physical properties differ. And so did their associated incidence of SGA, according to Dr. Ng of Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles.

The rate of SGA below the 10th percentile was 17.6% in the 3,357 women on labetalol during pregnancy and the same in the 638 women on atenolol. In contrast, the SGA rates in women on metoprolol or propranolol – 10.8% and 10.3%, respectively – weren’t significantly different from the 8.7% incidence in controls.

To deal with the possibility of confounding by indication, Dr. Ng and her coinvestigators performed a multivariate analysis adjusted for maternal age, white race, body mass index, gestational age, diabetes, hypertension, arrhythmias, dyslipidemia, and renal insufficiency. The resultant adjusted risk of having an SGA baby was 2.9-fold greater in women on labetalol and 2.4-fold greater in those on atenolol than in controls. Women on the other two beta-blockers faced no increased risk.

The incidence of congenital cardiac anomalies was 5.1% in women exposed to beta-blockers in pregnancy and 1.9% in controls who weren’t. The most commonly diagnosed anomalies – patent ductus arteriosus, atrial septal defect, and ventricular septal defect – were two- to threefold more frequent in the setting of maternal beta-blocker exposure. However, in a multivariate analysis the use of any beta-blocker was no longer associated with significantly elevated risk of congenital cardiac anomalies.

“This suggests that the initial association we see in the unadjusted analysis is likely due to confounders and not due to the beta-blocker exposure,” Dr. Ng said.

Labetalol and atenolol were prescribed during pregnancy most often for hypertension, while metoprolol and propranolol were typically prescribed to control arrhythmias.

Previous reports by other investigators have yielded conflicting results as to whether maternal beta-blocker therapy is associated with increased risk of SGA. A major limitation of those studies was that they examined beta-blockers as a class rather than assessing the impact of specific agents, according to Dr. Ng.

She reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

NEW ORLEANS – The use of labetalol or atenolol in pregnancy is associated with significantly increased risk of having a small-for-gestational-age (SGA) baby; metoprolol and propranolol are not.

And none of these four beta-blockers are associated with increased risk of congenital cardiac anomalies, Angie Ng, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Overall, the average birth weight for babies whose mothers were on a beta-blocker was 2,996 g, significantly less than the 3,353 g in 374,391 controls who weren’t exposed to beta-blockers during pregnancy. But beta-blockers are not a monolithic class of drugs; their pharmacokinetics and physical properties differ. And so did their associated incidence of SGA, according to Dr. Ng of Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles.

The rate of SGA below the 10th percentile was 17.6% in the 3,357 women on labetalol during pregnancy and the same in the 638 women on atenolol. In contrast, the SGA rates in women on metoprolol or propranolol – 10.8% and 10.3%, respectively – weren’t significantly different from the 8.7% incidence in controls.

To deal with the possibility of confounding by indication, Dr. Ng and her coinvestigators performed a multivariate analysis adjusted for maternal age, white race, body mass index, gestational age, diabetes, hypertension, arrhythmias, dyslipidemia, and renal insufficiency. The resultant adjusted risk of having an SGA baby was 2.9-fold greater in women on labetalol and 2.4-fold greater in those on atenolol than in controls. Women on the other two beta-blockers faced no increased risk.

The incidence of congenital cardiac anomalies was 5.1% in women exposed to beta-blockers in pregnancy and 1.9% in controls who weren’t. The most commonly diagnosed anomalies – patent ductus arteriosus, atrial septal defect, and ventricular septal defect – were two- to threefold more frequent in the setting of maternal beta-blocker exposure. However, in a multivariate analysis the use of any beta-blocker was no longer associated with significantly elevated risk of congenital cardiac anomalies.

“This suggests that the initial association we see in the unadjusted analysis is likely due to confounders and not due to the beta-blocker exposure,” Dr. Ng said.

Labetalol and atenolol were prescribed during pregnancy most often for hypertension, while metoprolol and propranolol were typically prescribed to control arrhythmias.

Previous reports by other investigators have yielded conflicting results as to whether maternal beta-blocker therapy is associated with increased risk of SGA. A major limitation of those studies was that they examined beta-blockers as a class rather than assessing the impact of specific agents, according to Dr. Ng.

She reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

NEW ORLEANS – The use of labetalol or atenolol in pregnancy is associated with significantly increased risk of having a small-for-gestational-age (SGA) baby; metoprolol and propranolol are not.

And none of these four beta-blockers are associated with increased risk of congenital cardiac anomalies, Angie Ng, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Overall, the average birth weight for babies whose mothers were on a beta-blocker was 2,996 g, significantly less than the 3,353 g in 374,391 controls who weren’t exposed to beta-blockers during pregnancy. But beta-blockers are not a monolithic class of drugs; their pharmacokinetics and physical properties differ. And so did their associated incidence of SGA, according to Dr. Ng of Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles.

The rate of SGA below the 10th percentile was 17.6% in the 3,357 women on labetalol during pregnancy and the same in the 638 women on atenolol. In contrast, the SGA rates in women on metoprolol or propranolol – 10.8% and 10.3%, respectively – weren’t significantly different from the 8.7% incidence in controls.

To deal with the possibility of confounding by indication, Dr. Ng and her coinvestigators performed a multivariate analysis adjusted for maternal age, white race, body mass index, gestational age, diabetes, hypertension, arrhythmias, dyslipidemia, and renal insufficiency. The resultant adjusted risk of having an SGA baby was 2.9-fold greater in women on labetalol and 2.4-fold greater in those on atenolol than in controls. Women on the other two beta-blockers faced no increased risk.

The incidence of congenital cardiac anomalies was 5.1% in women exposed to beta-blockers in pregnancy and 1.9% in controls who weren’t. The most commonly diagnosed anomalies – patent ductus arteriosus, atrial septal defect, and ventricular septal defect – were two- to threefold more frequent in the setting of maternal beta-blocker exposure. However, in a multivariate analysis the use of any beta-blocker was no longer associated with significantly elevated risk of congenital cardiac anomalies.

“This suggests that the initial association we see in the unadjusted analysis is likely due to confounders and not due to the beta-blocker exposure,” Dr. Ng said.

Labetalol and atenolol were prescribed during pregnancy most often for hypertension, while metoprolol and propranolol were typically prescribed to control arrhythmias.

Previous reports by other investigators have yielded conflicting results as to whether maternal beta-blocker therapy is associated with increased risk of SGA. A major limitation of those studies was that they examined beta-blockers as a class rather than assessing the impact of specific agents, according to Dr. Ng.

She reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Women on labetalol or atenolol during pregnancy had a 17.6% incidence of small-for-gestational-age babies, a rate more than twice that in women not exposed to a beta-blocker during pregnancy.

Data source: This was a retrospective study of fetal outcomes in nearly 380,000 pregnant women, 4,847 of whom were on beta-blocker therapy during their pregnancy.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

Infantile spasms diagnosis, treatment too often delayed

HOUSTON – The appropriate evaluation and treatment of infantile spasms often comes after significant delays that are largely attributable to lack of recognition of the condition, according to recent survey results.

“Parental suspicions that ‘something was wrong’ were often discounted by health care providers, and survey respondents frequently reported that health care providers (including neurologists) were unfamiliar with infantile spasms [IS],” wrote Johnson Lay and his collaborators, in presenting results of the recently-completed Assessment of Symptoms and Specialists in Infantile Spasms (ASSIST) study at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. It’s critically important not to discount parental concerns, senior author Shaun Hussain, MD, said in an interview about the study, which surveyed parents of children with IS: “Sometimes we get in the habit of reassuring patients too much.”

On average, a pediatrician will see two cases of infantile spasms in a career of caring for children, Dr. Hussain said. These characteristically brief episodes last just a second or so, and frequently come in clusters, during or after which crying is common. Though the classic presentation of IS is a brief drop of the head with accompanying elevation of the shoulders – and perhaps a lifting of the arms – there’s wide variation in presentation. “Infantile spasms can present in a lot of different ways; babies haven’t read the neurology textbooks,” Dr. Hussain said. A curated collection of videos showing the variety of infantile spasms is available on the Infantile Spasms Project website.

Mr. Lay and his collaborators surveyed the parents of 100 children with IS in order to understand and describe their experiences in having their child receive the correct diagnosis and treatment. Also, they sought to determine whether socioeconomic factors affected prompt access to care. Dr. Lay completed the study with Dr. Hussain and other coauthors after graduating from UCLA in 2015.

The study, presented during a poster session at the meeting, measured the time between the parents’ first identification of IS and their contact with an “effective provider.” A provider was deemed effective if he or she correctly diagnosed IS and prescribed a first-line therapy: adrenocorticotropin-releasing hormone (ACTH), corticosteroids, or vigabatrin (Sabril).

Of the 100 children whose families were surveyed, 29% were seen by an effective provider within a week of the onset of IS. The median time from the onset of IS to the patient’s being seen by an effective provider was 24.5 days, with a wide range seen in the population surveyed (interquartile range, 0-110.5 days). This exceeds the 7 days that has been identified as the goal cumulative latency to treatment, Mr. Lay and his coauthors said.

The median age of onset of IS was 6.6 months in the study population, 45% of whom were female.

A total of 64 patients were first seen for IS concerns by a provider who was not a neurologist. Of those, the cumulative latency to seeing the first effective provider was over 100 days, with some patients’ wait time stretching to over 200 days.

The survey asked about socioeconomic factors, including income, health insurance status, proximity to specialty care, ethnicity, and parental language preference. Of these, only a non-English parental language preference was associated with increased time to seeing an effective provider (hazard ratio, 0.37; 95% confidence interval, 0.20-0.68; P = .002).

“These results suggest that a simple lack of awareness of infantile spasms among health care providers may be responsible for potentially catastrophic delays in IS care,” wrote Mr. Lay and his coauthors. Dr. Hussain concurred: “The clear driver of treatment delay is the failure of health care providers to recognize the appearance, importance, and urgency of infantile spasms. Delay in diagnosis and treatment of infantile spasms is common, costly – to both patients and the health care system – and almost entirely preventable.”

The Elsie and Isaac Fogelman Endowment, the Hughes Family Foundation, and the UCLA Children’s Discovery and Innovation Institute funded the study. Dr. Hussain has received research support from and been on the advisory boards of several pharmaceutical companies. Mr. Lay reported no disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – The appropriate evaluation and treatment of infantile spasms often comes after significant delays that are largely attributable to lack of recognition of the condition, according to recent survey results.

“Parental suspicions that ‘something was wrong’ were often discounted by health care providers, and survey respondents frequently reported that health care providers (including neurologists) were unfamiliar with infantile spasms [IS],” wrote Johnson Lay and his collaborators, in presenting results of the recently-completed Assessment of Symptoms and Specialists in Infantile Spasms (ASSIST) study at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. It’s critically important not to discount parental concerns, senior author Shaun Hussain, MD, said in an interview about the study, which surveyed parents of children with IS: “Sometimes we get in the habit of reassuring patients too much.”

On average, a pediatrician will see two cases of infantile spasms in a career of caring for children, Dr. Hussain said. These characteristically brief episodes last just a second or so, and frequently come in clusters, during or after which crying is common. Though the classic presentation of IS is a brief drop of the head with accompanying elevation of the shoulders – and perhaps a lifting of the arms – there’s wide variation in presentation. “Infantile spasms can present in a lot of different ways; babies haven’t read the neurology textbooks,” Dr. Hussain said. A curated collection of videos showing the variety of infantile spasms is available on the Infantile Spasms Project website.

Mr. Lay and his collaborators surveyed the parents of 100 children with IS in order to understand and describe their experiences in having their child receive the correct diagnosis and treatment. Also, they sought to determine whether socioeconomic factors affected prompt access to care. Dr. Lay completed the study with Dr. Hussain and other coauthors after graduating from UCLA in 2015.

The study, presented during a poster session at the meeting, measured the time between the parents’ first identification of IS and their contact with an “effective provider.” A provider was deemed effective if he or she correctly diagnosed IS and prescribed a first-line therapy: adrenocorticotropin-releasing hormone (ACTH), corticosteroids, or vigabatrin (Sabril).

Of the 100 children whose families were surveyed, 29% were seen by an effective provider within a week of the onset of IS. The median time from the onset of IS to the patient’s being seen by an effective provider was 24.5 days, with a wide range seen in the population surveyed (interquartile range, 0-110.5 days). This exceeds the 7 days that has been identified as the goal cumulative latency to treatment, Mr. Lay and his coauthors said.

The median age of onset of IS was 6.6 months in the study population, 45% of whom were female.

A total of 64 patients were first seen for IS concerns by a provider who was not a neurologist. Of those, the cumulative latency to seeing the first effective provider was over 100 days, with some patients’ wait time stretching to over 200 days.

The survey asked about socioeconomic factors, including income, health insurance status, proximity to specialty care, ethnicity, and parental language preference. Of these, only a non-English parental language preference was associated with increased time to seeing an effective provider (hazard ratio, 0.37; 95% confidence interval, 0.20-0.68; P = .002).

“These results suggest that a simple lack of awareness of infantile spasms among health care providers may be responsible for potentially catastrophic delays in IS care,” wrote Mr. Lay and his coauthors. Dr. Hussain concurred: “The clear driver of treatment delay is the failure of health care providers to recognize the appearance, importance, and urgency of infantile spasms. Delay in diagnosis and treatment of infantile spasms is common, costly – to both patients and the health care system – and almost entirely preventable.”

The Elsie and Isaac Fogelman Endowment, the Hughes Family Foundation, and the UCLA Children’s Discovery and Innovation Institute funded the study. Dr. Hussain has received research support from and been on the advisory boards of several pharmaceutical companies. Mr. Lay reported no disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – The appropriate evaluation and treatment of infantile spasms often comes after significant delays that are largely attributable to lack of recognition of the condition, according to recent survey results.

“Parental suspicions that ‘something was wrong’ were often discounted by health care providers, and survey respondents frequently reported that health care providers (including neurologists) were unfamiliar with infantile spasms [IS],” wrote Johnson Lay and his collaborators, in presenting results of the recently-completed Assessment of Symptoms and Specialists in Infantile Spasms (ASSIST) study at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. It’s critically important not to discount parental concerns, senior author Shaun Hussain, MD, said in an interview about the study, which surveyed parents of children with IS: “Sometimes we get in the habit of reassuring patients too much.”

On average, a pediatrician will see two cases of infantile spasms in a career of caring for children, Dr. Hussain said. These characteristically brief episodes last just a second or so, and frequently come in clusters, during or after which crying is common. Though the classic presentation of IS is a brief drop of the head with accompanying elevation of the shoulders – and perhaps a lifting of the arms – there’s wide variation in presentation. “Infantile spasms can present in a lot of different ways; babies haven’t read the neurology textbooks,” Dr. Hussain said. A curated collection of videos showing the variety of infantile spasms is available on the Infantile Spasms Project website.

Mr. Lay and his collaborators surveyed the parents of 100 children with IS in order to understand and describe their experiences in having their child receive the correct diagnosis and treatment. Also, they sought to determine whether socioeconomic factors affected prompt access to care. Dr. Lay completed the study with Dr. Hussain and other coauthors after graduating from UCLA in 2015.

The study, presented during a poster session at the meeting, measured the time between the parents’ first identification of IS and their contact with an “effective provider.” A provider was deemed effective if he or she correctly diagnosed IS and prescribed a first-line therapy: adrenocorticotropin-releasing hormone (ACTH), corticosteroids, or vigabatrin (Sabril).

Of the 100 children whose families were surveyed, 29% were seen by an effective provider within a week of the onset of IS. The median time from the onset of IS to the patient’s being seen by an effective provider was 24.5 days, with a wide range seen in the population surveyed (interquartile range, 0-110.5 days). This exceeds the 7 days that has been identified as the goal cumulative latency to treatment, Mr. Lay and his coauthors said.

The median age of onset of IS was 6.6 months in the study population, 45% of whom were female.

A total of 64 patients were first seen for IS concerns by a provider who was not a neurologist. Of those, the cumulative latency to seeing the first effective provider was over 100 days, with some patients’ wait time stretching to over 200 days.

The survey asked about socioeconomic factors, including income, health insurance status, proximity to specialty care, ethnicity, and parental language preference. Of these, only a non-English parental language preference was associated with increased time to seeing an effective provider (hazard ratio, 0.37; 95% confidence interval, 0.20-0.68; P = .002).

“These results suggest that a simple lack of awareness of infantile spasms among health care providers may be responsible for potentially catastrophic delays in IS care,” wrote Mr. Lay and his coauthors. Dr. Hussain concurred: “The clear driver of treatment delay is the failure of health care providers to recognize the appearance, importance, and urgency of infantile spasms. Delay in diagnosis and treatment of infantile spasms is common, costly – to both patients and the health care system – and almost entirely preventable.”

The Elsie and Isaac Fogelman Endowment, the Hughes Family Foundation, and the UCLA Children’s Discovery and Innovation Institute funded the study. Dr. Hussain has received research support from and been on the advisory boards of several pharmaceutical companies. Mr. Lay reported no disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The cumulative latency to seeing an effective provider was over 100 days for IS patients initially seen by a nonneurologist.

Data source: Survey of parent(s) of 100 children with infantile spasms.

Disclosures: The Elsie and Isaac Fogelman Endowment, the Hughes Family Foundation, and the UCLA Children’s Discovery and Innovation Institute funded the study. Dr. Hussain has received research support from and been on the advisory boards of several pharmaceutical companies. Mr. Lay reported no disclosures.

Intermittent energy restriction

My patients find it extremely difficult to determine the number of calories they consume on a daily basis. This activity can be laborious and time consuming, even when you have the right “app.”

So, when I tell my overweight and obese patients to restrict their caloric consumption to lose weight, the discussion usually begins with, “I know this might be difficult, but …” And it usually ends with me feeling a little less than anemic optimism.

But is it effective for weight loss?

C.S. Davis of Monash University, Melbourne, and colleagues conducted a systematic review of IER for weight loss (Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016 Mar;70[3]:292-9). The authors searched for articles evaluating the IER for weight loss among overweight and obese adults aged 18 years or older. IER was defined as periods of low energy intake (fast) alternating with periods of normal food intake (feed).

Eight studies were included in this review. Included studies defined low energy intake as 25%-50% of daily energy, or 400-1,400 kcal/day. The feed period was defined as either eating ad libitum or no less than 1,400 kcal/day. Studies varied in their approach and ranged from 2-4 consecutive fast days per week, followed by consecutive feed days, to three cycles of 5 weeks of fasting, followed by 5 weeks of ad lib eating.

IER was associated with 0.2-0.8 kg of weight loss per week. IER was associated with weight loss comparable to daily energy restriction (DER; that is, a typical diet). IER was comparable to typical daily energy restriction diets for fat mass, free-fat mass, and waist circumference.

The authors state that the amount of weight loss achieved with IER for a 100-kg individual would be associated with a 5% reduction in weight over a 5-week to 6-month time period. A 5% reduction is associated with a clinically significant reduction in health risk.

However, the authors found that fewer study participants planned to stick with IER beyond 6 months, compared with DER. Perhaps despite the difficulty that may exist in counting calories every day, the habit of doing the counting every day may be easier than doing it on an intermittent basis.

Regardless, IER is an option that may be beneficial to some patients. If other things haven’t worked for your patients, it is definitely worth a try.