User login

The Ads Say ‘Get Your Flu Shot Today,’ But It May Be Wiser To Wait

The pharmacy chain pitches started in August: Come in and get your flu shot.

Convenience is touted. So are incentives: CVS offers a 20-percent-off shopping pass for everyone who gets a shot, while Walgreens donates toward international vaccination efforts.

The start of flu season is still weeks — if not months — away. Yet marketing of the vaccine has become an almost year-round effort, beginning when the shots become available in August and hyped as long as the supply lasts, often into April or May.

Not that long ago, most flu-shot campaigns started as the leaves began to turn in October. But the rise of retail medical clinics inside drug stores over the past decade — and state laws allowing pharmacists to give vaccinations — has stretched the flu-shot season.

The stores have figured out how “to deliver medical services in an on-demand way” which appeals to customers, particularly millennials, said Tom Charland, founder and CEO of Merchant Medicine, which tracks the walk-in clinic industry. “It’s a way to get people into the store to buy other things.”

But some experts say the marketing may be overtaking medical wisdom since it’s unclear how long the immunity imparted by the vaccine lasts, particularly in older people.

Federal health officials say it’s better to get the shot whenever you can. An early flu shot is better than no flu shot at all. But the science is mixed when it comes to how long a flu shot promoted and given during the waning days of summer will provide optimal protection, especially because flu season generally peaks in mid-winter or beyond. Experts are divided on how patients should respond to such offers.

“If you’re over 65, don’t get the flu vaccine in September. Or August. It’s a marketing scheme,” said Laura Haynes, an immunologist at the University of Connecticut Center on Aging.

That’s because a combination of factors makes it more difficult for the immune systems of people older than age 65 to respond to the vaccination in the first place. And its protective effects may wear off faster for this age group than it does for young people.

When is the best time to vaccinate? It’s a question even doctors have.

“Should I wait until October or November to vaccinate my elderly or medically frail patients?” That’s one of the queries on the website of the board that advises the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on immunizations. The answer is that it is safe to make the shots available to all age groups when the vaccine becomes available, although it does include a caution.

The board says antibodies created by the vaccine decline in the months following vaccination “primarily affecting persons age 65 and older,” citing a study done during the 2011-2012 flu season. Still, while “delaying vaccination might permit greater immunity later in the season,” the CDC notes that “deferral could result in missed opportunities to vaccinate.”

How long will the immunity last?

“The data are very mixed,” said. John J. Treanor, a vaccine expert at the University of Rochester medical school. Some studies suggest vaccines lose some protectiveness during the course of a single flu season. Flu activity generally starts in the fall, but peaks in January or February and can run into the spring.

“So some might worry that if [they] got vaccinated very early and flu didn’t show up until very late, it might not work as well,” he said.

But other studies “show you still have protection from the shot you got last year if it’s a year when the strains didn’t change, Treanor said.

In any given flu season, vaccine effectiveness varies. One factor is how well the vaccines match the virus that is actually prevalent. Other factors influencing effectiveness include the age and general health of the recipient. In the overall population, the CDC says studies show vaccines can reduce the risk of flu by about 50 to 60 percent when the vaccines are well matched.

Health officials say it’s especially important to vaccinate children because they often spread the disease, are better able to develop antibodies from the vaccines and, if they don’t get sick, they won’t expose grandma and grandpa. While most people who get the flu recover, it is a serious disease responsible for many deaths each year, particularly among older adults and young children. Influenza’s intensity varies annually, with the CDC saying deaths associated with the flu have ranged from about 3,300 a year to 49,000 during the past 31 seasons.

To develop vaccines, manufacturers and scientists study what’s circulating in the Southern Hemisphere during its winter, which is our summer. Then — based on that evidence — forecast what flu strains might circulate here to make vaccines that are generally delivered in late July.

For the upcoming season, the vaccines will include three or four strains, including two A strains, an H1N1 and an H3N2, as well as one or two B strains, according to the CDC. It recommends that everyone older than 6 months get vaccinated, unless they have health conditions that would prevent it.

The vaccines can’t give a person the flu because the virus is killed before it’s included in the shot. This year, the nasal vaccine is not recommended for use, as studies showed it was not effective during several of the past flu seasons.

But when to go?

“The ideal time is between Halloween and Thanksgiving,” said Haynes at UConn. “If you can’t wait and the only chance is to get it in September, then go ahead and get it. It’s best to get it early rather than not at all.”

This Kaiser Health News story also ran on NPR.

The pharmacy chain pitches started in August: Come in and get your flu shot.

Convenience is touted. So are incentives: CVS offers a 20-percent-off shopping pass for everyone who gets a shot, while Walgreens donates toward international vaccination efforts.

The start of flu season is still weeks — if not months — away. Yet marketing of the vaccine has become an almost year-round effort, beginning when the shots become available in August and hyped as long as the supply lasts, often into April or May.

Not that long ago, most flu-shot campaigns started as the leaves began to turn in October. But the rise of retail medical clinics inside drug stores over the past decade — and state laws allowing pharmacists to give vaccinations — has stretched the flu-shot season.

The stores have figured out how “to deliver medical services in an on-demand way” which appeals to customers, particularly millennials, said Tom Charland, founder and CEO of Merchant Medicine, which tracks the walk-in clinic industry. “It’s a way to get people into the store to buy other things.”

But some experts say the marketing may be overtaking medical wisdom since it’s unclear how long the immunity imparted by the vaccine lasts, particularly in older people.

Federal health officials say it’s better to get the shot whenever you can. An early flu shot is better than no flu shot at all. But the science is mixed when it comes to how long a flu shot promoted and given during the waning days of summer will provide optimal protection, especially because flu season generally peaks in mid-winter or beyond. Experts are divided on how patients should respond to such offers.

“If you’re over 65, don’t get the flu vaccine in September. Or August. It’s a marketing scheme,” said Laura Haynes, an immunologist at the University of Connecticut Center on Aging.

That’s because a combination of factors makes it more difficult for the immune systems of people older than age 65 to respond to the vaccination in the first place. And its protective effects may wear off faster for this age group than it does for young people.

When is the best time to vaccinate? It’s a question even doctors have.

“Should I wait until October or November to vaccinate my elderly or medically frail patients?” That’s one of the queries on the website of the board that advises the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on immunizations. The answer is that it is safe to make the shots available to all age groups when the vaccine becomes available, although it does include a caution.

The board says antibodies created by the vaccine decline in the months following vaccination “primarily affecting persons age 65 and older,” citing a study done during the 2011-2012 flu season. Still, while “delaying vaccination might permit greater immunity later in the season,” the CDC notes that “deferral could result in missed opportunities to vaccinate.”

How long will the immunity last?

“The data are very mixed,” said. John J. Treanor, a vaccine expert at the University of Rochester medical school. Some studies suggest vaccines lose some protectiveness during the course of a single flu season. Flu activity generally starts in the fall, but peaks in January or February and can run into the spring.

“So some might worry that if [they] got vaccinated very early and flu didn’t show up until very late, it might not work as well,” he said.

But other studies “show you still have protection from the shot you got last year if it’s a year when the strains didn’t change, Treanor said.

In any given flu season, vaccine effectiveness varies. One factor is how well the vaccines match the virus that is actually prevalent. Other factors influencing effectiveness include the age and general health of the recipient. In the overall population, the CDC says studies show vaccines can reduce the risk of flu by about 50 to 60 percent when the vaccines are well matched.

Health officials say it’s especially important to vaccinate children because they often spread the disease, are better able to develop antibodies from the vaccines and, if they don’t get sick, they won’t expose grandma and grandpa. While most people who get the flu recover, it is a serious disease responsible for many deaths each year, particularly among older adults and young children. Influenza’s intensity varies annually, with the CDC saying deaths associated with the flu have ranged from about 3,300 a year to 49,000 during the past 31 seasons.

To develop vaccines, manufacturers and scientists study what’s circulating in the Southern Hemisphere during its winter, which is our summer. Then — based on that evidence — forecast what flu strains might circulate here to make vaccines that are generally delivered in late July.

For the upcoming season, the vaccines will include three or four strains, including two A strains, an H1N1 and an H3N2, as well as one or two B strains, according to the CDC. It recommends that everyone older than 6 months get vaccinated, unless they have health conditions that would prevent it.

The vaccines can’t give a person the flu because the virus is killed before it’s included in the shot. This year, the nasal vaccine is not recommended for use, as studies showed it was not effective during several of the past flu seasons.

But when to go?

“The ideal time is between Halloween and Thanksgiving,” said Haynes at UConn. “If you can’t wait and the only chance is to get it in September, then go ahead and get it. It’s best to get it early rather than not at all.”

This Kaiser Health News story also ran on NPR.

The pharmacy chain pitches started in August: Come in and get your flu shot.

Convenience is touted. So are incentives: CVS offers a 20-percent-off shopping pass for everyone who gets a shot, while Walgreens donates toward international vaccination efforts.

The start of flu season is still weeks — if not months — away. Yet marketing of the vaccine has become an almost year-round effort, beginning when the shots become available in August and hyped as long as the supply lasts, often into April or May.

Not that long ago, most flu-shot campaigns started as the leaves began to turn in October. But the rise of retail medical clinics inside drug stores over the past decade — and state laws allowing pharmacists to give vaccinations — has stretched the flu-shot season.

The stores have figured out how “to deliver medical services in an on-demand way” which appeals to customers, particularly millennials, said Tom Charland, founder and CEO of Merchant Medicine, which tracks the walk-in clinic industry. “It’s a way to get people into the store to buy other things.”

But some experts say the marketing may be overtaking medical wisdom since it’s unclear how long the immunity imparted by the vaccine lasts, particularly in older people.

Federal health officials say it’s better to get the shot whenever you can. An early flu shot is better than no flu shot at all. But the science is mixed when it comes to how long a flu shot promoted and given during the waning days of summer will provide optimal protection, especially because flu season generally peaks in mid-winter or beyond. Experts are divided on how patients should respond to such offers.

“If you’re over 65, don’t get the flu vaccine in September. Or August. It’s a marketing scheme,” said Laura Haynes, an immunologist at the University of Connecticut Center on Aging.

That’s because a combination of factors makes it more difficult for the immune systems of people older than age 65 to respond to the vaccination in the first place. And its protective effects may wear off faster for this age group than it does for young people.

When is the best time to vaccinate? It’s a question even doctors have.

“Should I wait until October or November to vaccinate my elderly or medically frail patients?” That’s one of the queries on the website of the board that advises the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on immunizations. The answer is that it is safe to make the shots available to all age groups when the vaccine becomes available, although it does include a caution.

The board says antibodies created by the vaccine decline in the months following vaccination “primarily affecting persons age 65 and older,” citing a study done during the 2011-2012 flu season. Still, while “delaying vaccination might permit greater immunity later in the season,” the CDC notes that “deferral could result in missed opportunities to vaccinate.”

How long will the immunity last?

“The data are very mixed,” said. John J. Treanor, a vaccine expert at the University of Rochester medical school. Some studies suggest vaccines lose some protectiveness during the course of a single flu season. Flu activity generally starts in the fall, but peaks in January or February and can run into the spring.

“So some might worry that if [they] got vaccinated very early and flu didn’t show up until very late, it might not work as well,” he said.

But other studies “show you still have protection from the shot you got last year if it’s a year when the strains didn’t change, Treanor said.

In any given flu season, vaccine effectiveness varies. One factor is how well the vaccines match the virus that is actually prevalent. Other factors influencing effectiveness include the age and general health of the recipient. In the overall population, the CDC says studies show vaccines can reduce the risk of flu by about 50 to 60 percent when the vaccines are well matched.

Health officials say it’s especially important to vaccinate children because they often spread the disease, are better able to develop antibodies from the vaccines and, if they don’t get sick, they won’t expose grandma and grandpa. While most people who get the flu recover, it is a serious disease responsible for many deaths each year, particularly among older adults and young children. Influenza’s intensity varies annually, with the CDC saying deaths associated with the flu have ranged from about 3,300 a year to 49,000 during the past 31 seasons.

To develop vaccines, manufacturers and scientists study what’s circulating in the Southern Hemisphere during its winter, which is our summer. Then — based on that evidence — forecast what flu strains might circulate here to make vaccines that are generally delivered in late July.

For the upcoming season, the vaccines will include three or four strains, including two A strains, an H1N1 and an H3N2, as well as one or two B strains, according to the CDC. It recommends that everyone older than 6 months get vaccinated, unless they have health conditions that would prevent it.

The vaccines can’t give a person the flu because the virus is killed before it’s included in the shot. This year, the nasal vaccine is not recommended for use, as studies showed it was not effective during several of the past flu seasons.

But when to go?

“The ideal time is between Halloween and Thanksgiving,” said Haynes at UConn. “If you can’t wait and the only chance is to get it in September, then go ahead and get it. It’s best to get it early rather than not at all.”

This Kaiser Health News story also ran on NPR.

Novel De Novo Heterozygous Frameshift Mutation of the ADAR1 Gene in Heavy Dyschromatosis Symmetrica Hereditaria

To the Editor:

Dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria (DSH)(Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man 127400), also called reticulate acropigmentation of Dohi, is a pigmentary genodermatosis characterized by a mixture of hyperpigmented and hypopigmented macules of various sizes on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet. Linkage analysis has revealed that the DSH gene locus resides on chromosome 1q11-q21,1 and the adenosine deaminase RNA specific gene, ADAR1 (also called DSRAD), in this region has been identified as being responsible for the development of DSH.2 We report a sporadic case of severe DSH with the ADAR1 gene detected in a mutation analysis.

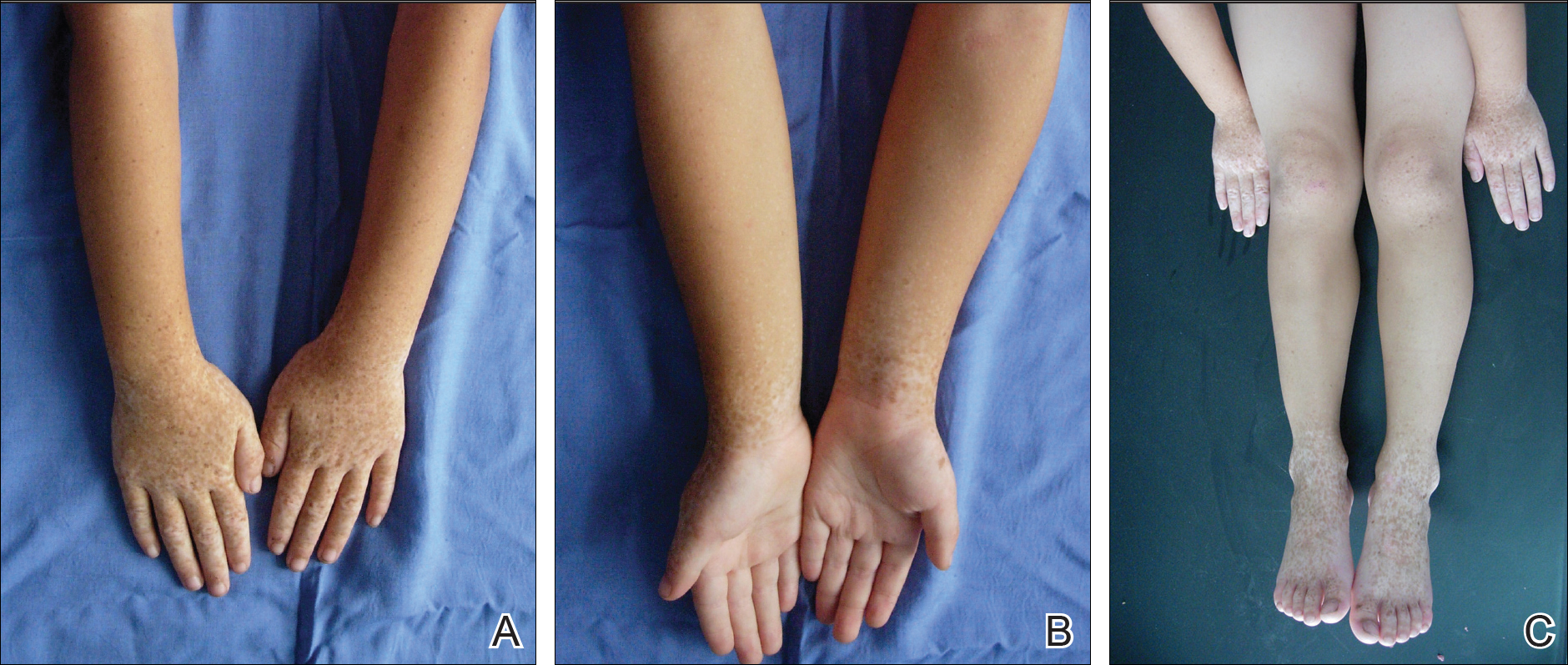

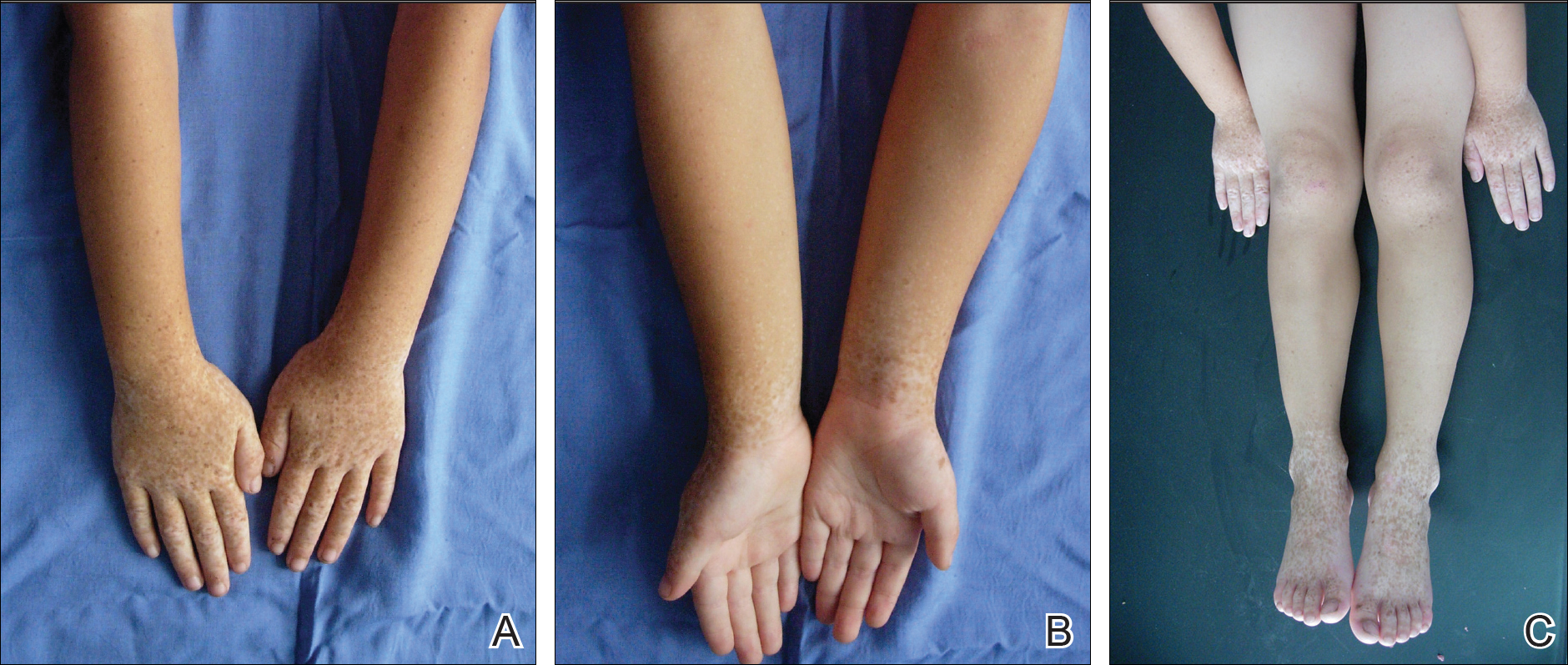

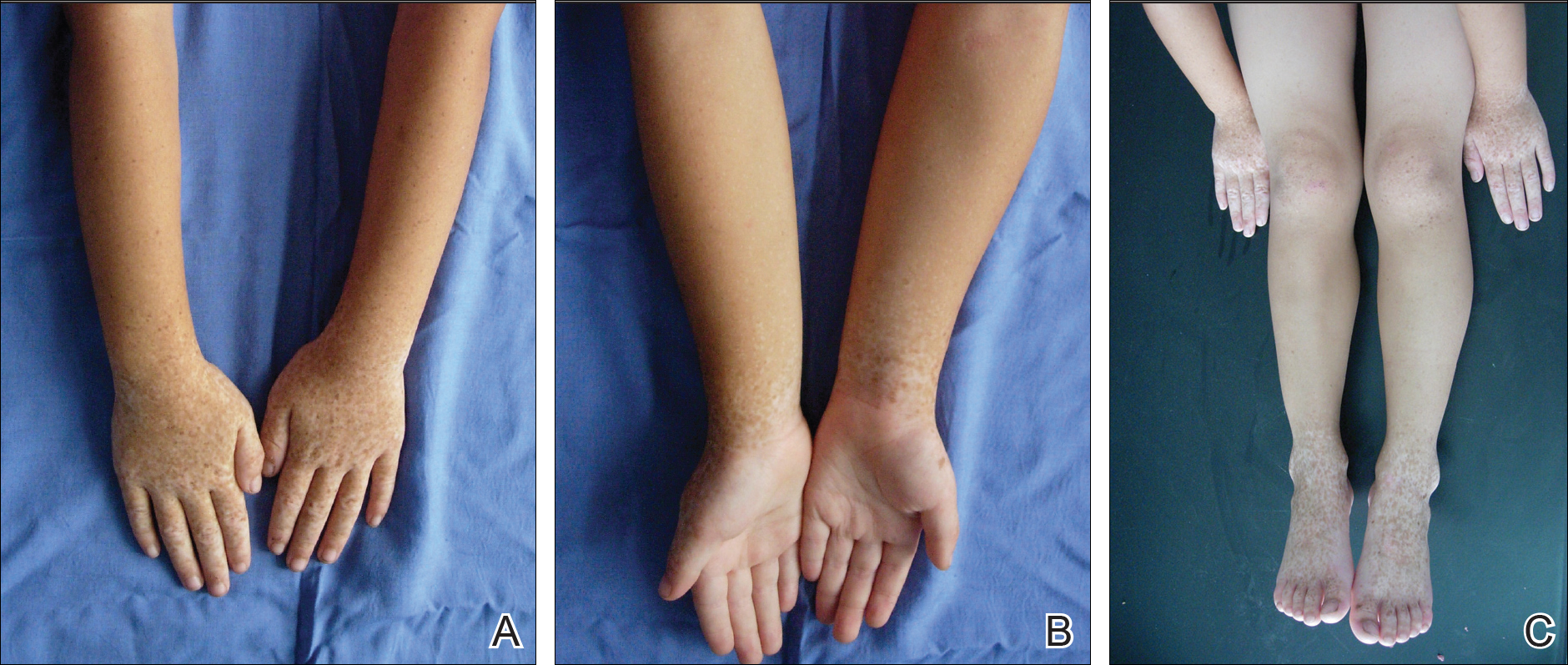

A 6-year-old girl presented with a mixture of hyperpigmented and hypopigmented macules on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet and the curved side of the wrists, heels, and knees, as well as scattered frecklelike and depigmented spots on the face, ears, neck, arms, and upper back (Figure 1). Her parents noted that hyperpigmented and hypopigmented macules on the dorsal aspects of the hands developed at 5 months of age. Exacerbation after exposure to sunlight resulted in the eruption becoming remarkable in summer and fainter in winter. The skin lesions gradually became more progressive. Physical examination revealed that the patient generally was healthy.

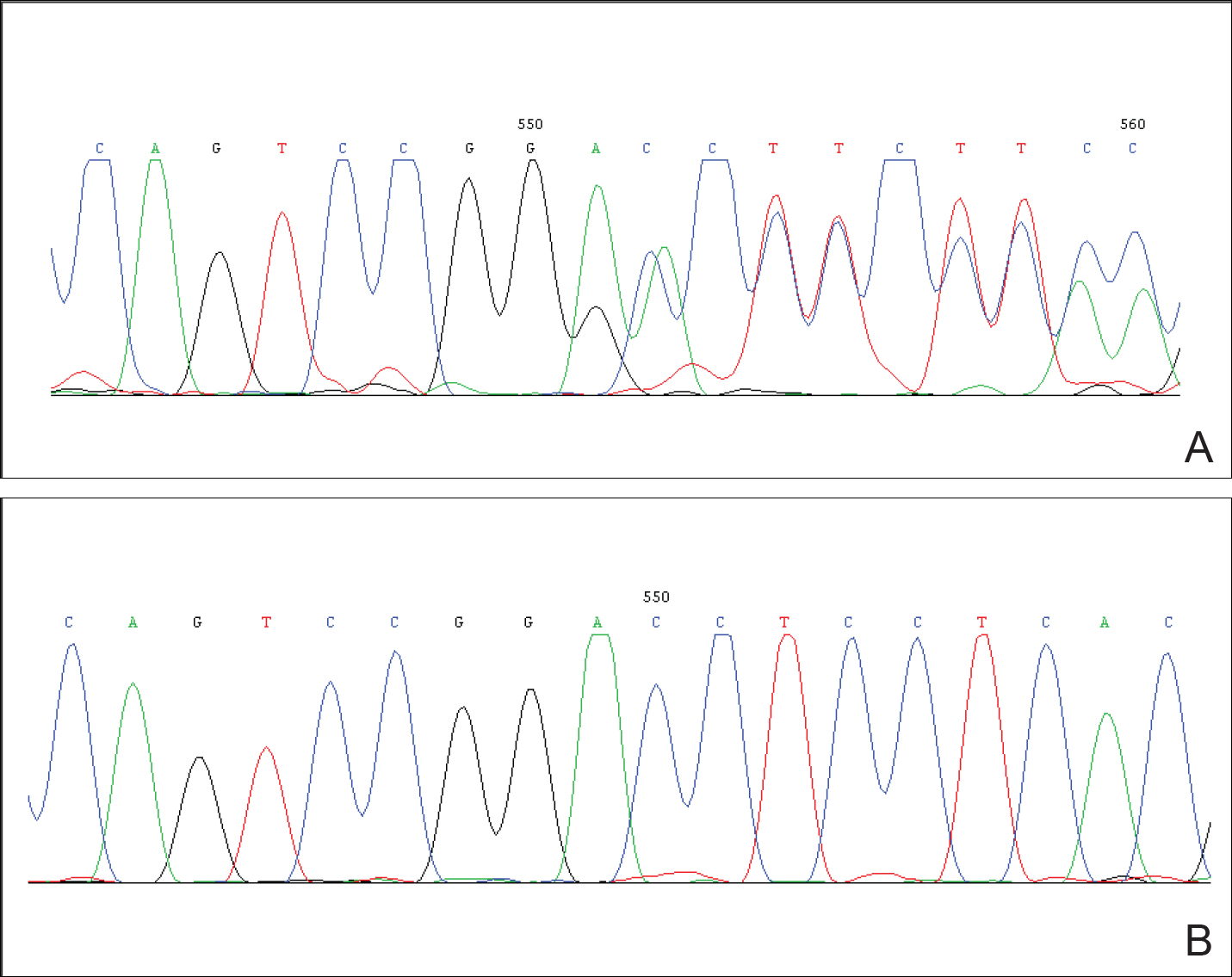

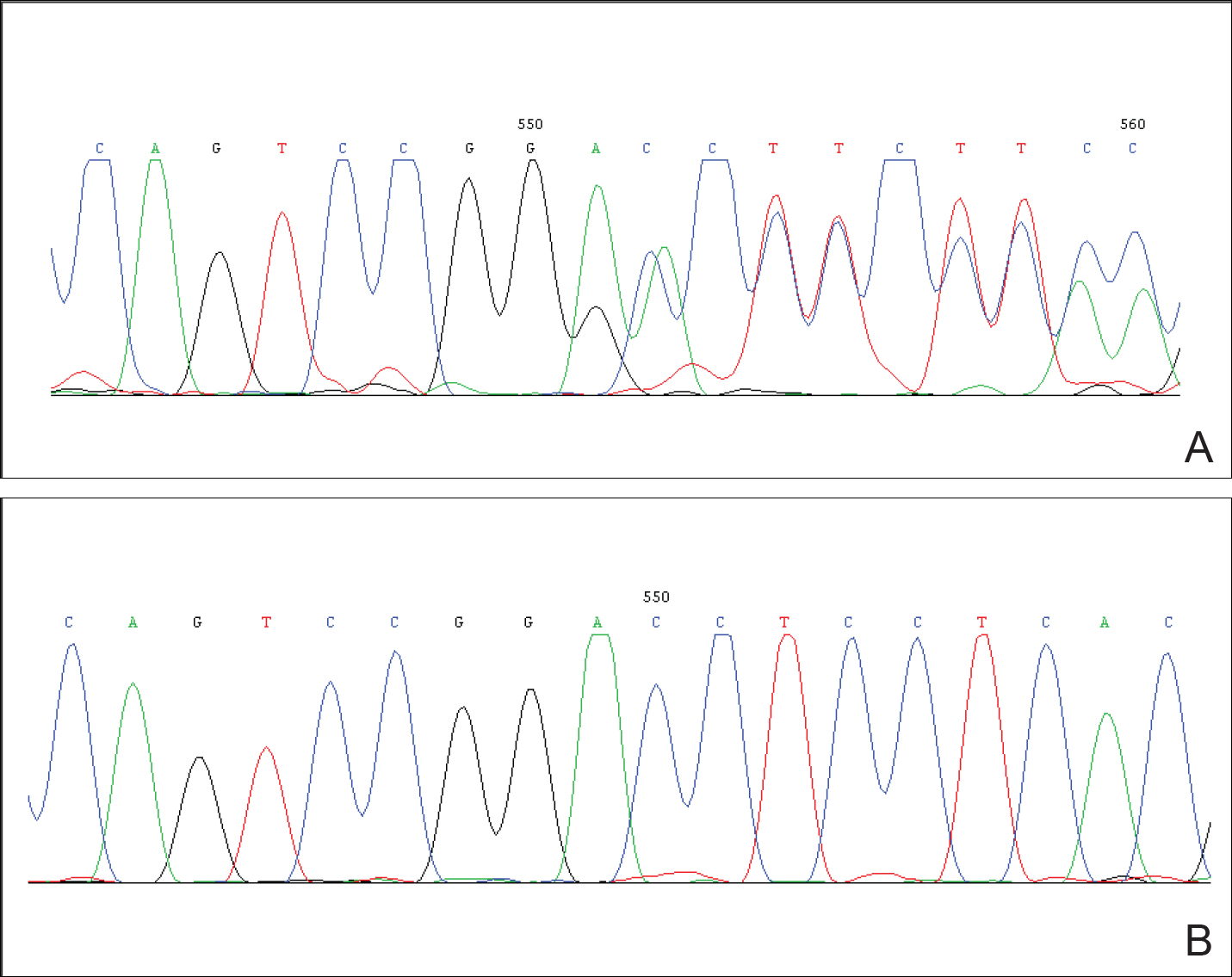

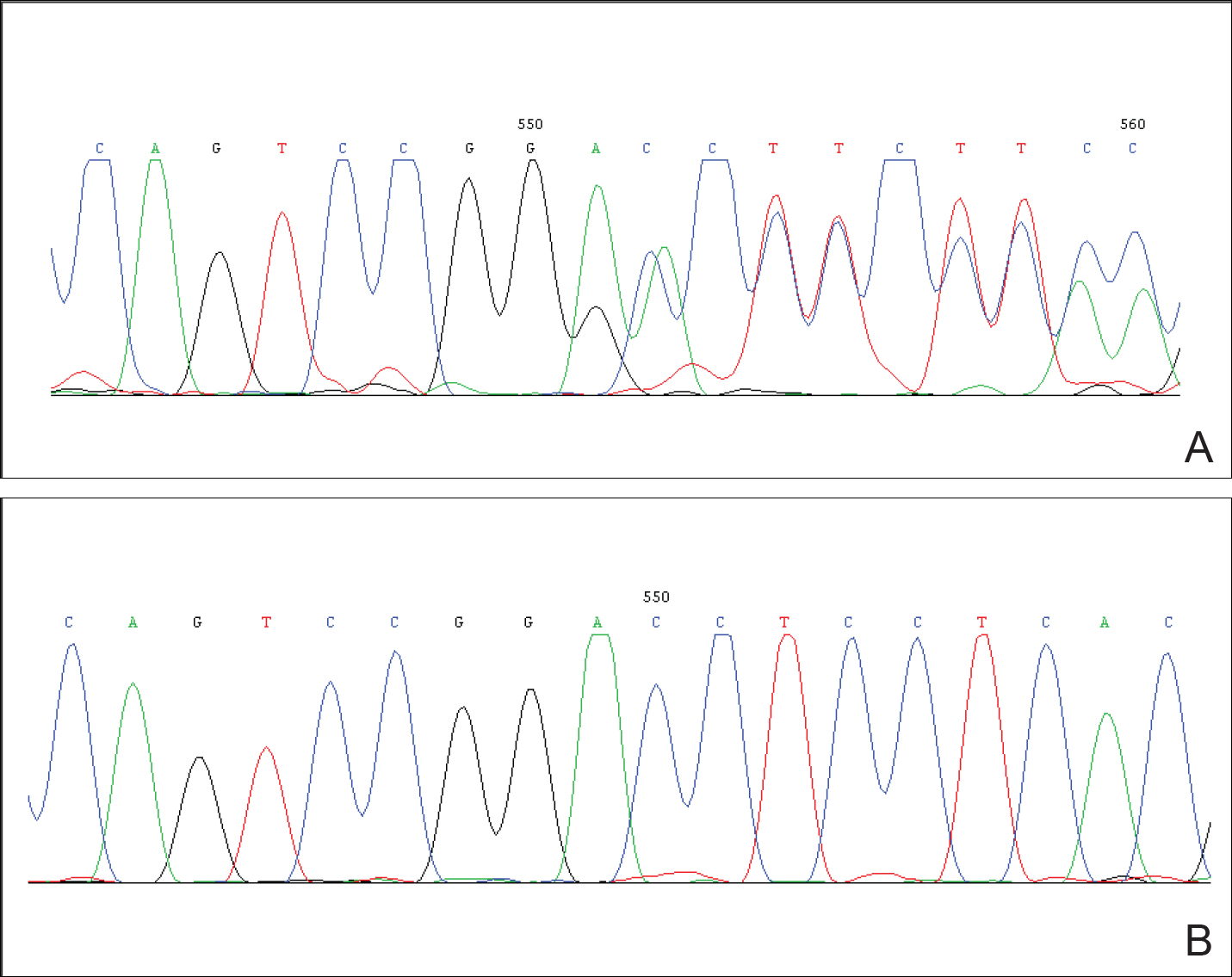

After obtaining informed consent, we performed a mutation analysis of the ADAR1 gene in our patient and her parents. We used a kit to extract genomic DNA from peripheral blood, which was then used to amplify the exons of the ADAR1 gene with intronic flanking sequences by polymerase chain reaction with the primer.3 After amplification, polymerase chain reaction products were purified. We sequenced the ADAR1 gene. Sequence comparisons and analysis found that the patient (proband) carried a heterozygous insertional mutation c.2253insG in exon 6 of the ADAR1 gene. This mutation was not detected in the proband’s healthy parents and 100 normal individuals (Figure 2).

Dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria is acquired by autosomal-dominant inheritance and is mainly reported in Asians, especially in Japan and China. Oyama et al4 reviewed 185 cases of DSH in Japan and found the onset of this disease usually was during infancy or childhood; 73% of patients developed the skin lesions before 6 years of age. Suzuki et al5 reported 10 unrelated Japanese patients and found the onset of disease ranged from 1 year of age to childhood. Zhang et al1,6 investigated 78 Chinese patients with DSH including 8 multigenerational families and 2 sporadic patients and found the age of disease onset ranged from 6 months to 15 years of age. The age of onset in our patient (5 months) was younger than these prior reports.

Patients with DSH have a characteristic appearance including a mixture of hyperpigmented and hypopigmented macules of various sizes on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet. Few patients have similar lesions on the knees and elbows. Many patients have frecklelike macules on the face and arms.1-6 One patient has been described with scattered depigmented spots on the face and chest.1 Our patient had a characteristic appearance as well as some special manifestations including skin lesions on the curved side of the wrist, ears, neck, and upper back.

The human ADAR1 gene spans 30 kilobase and contains 15 exons. It encodes RNA-specific adenosine deaminase composed of 1226 amino acid residues. This enzyme is important for various functions such as site-specific RNA editing and nuclear translation. This enzyme has 2 Z-alpha domains, 3 double-stranded RNA–binding domains, and the putative deaminase domain corresponding to exon 2, exons 2 to 7, and exons 9 to 14 of ADAR1, respectively.6

Mutation analysis of the ADAR1 gene in this case showed heterozygous insertion mutation c.2253insG in exon 6 of the ADAR1 gene, which changed the reading frame, and 475 amino acid residues in C-terminus are replaced by 90 amino acid residues (TSSRAQVRLPSKSWGSLVPSRLRTQQEA RQAGSSRCGSPCLDWGEREGRTHGFHRG NPSDRGQSQKNYAPPLKVPRSTAKT DTPSHWQHLP). This mutation was not detected in the proband’s healthy parents and the 100 control individuals, which indicated that it was a de novo mutation and the pathogenic mutation of DSH rather than a common polymorphism.

In conclusion, we report a novel mutation of the ADAR1 gene with a heavy clinical phenotype in DSH. This study expands the spectrum of clinical manifestations and demonstrates the ADAR1 mutation in DSH.

Acknowledgments

We are most grateful to the patient and her family for taking part in our study.

- Zhang XJ, Gao M, Li M, et al. Identification of a locus for dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria at chromosome 1q11-1q21. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:776-780.

- Miyamura Y, Suzuki T, Kono M, et al. Mutations of the RNA-specific adenosine deaminase gene (DSRAD) are involved in dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria [published online August 11, 2003]. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:693-699.

- Li M, Li C, Hua H, et al. Identification of two novel mutations in Chinese patients with dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria [published online October 8, 2005]. Arch Dermatol Res. 2005;297:196-200.

- Oyama M, Shimizu H, Ohata Y, et al. Dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria (reticulate acropigmentation of Dohi): report of a Japanese family with the condition and a literature review of 185 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:491-496.

- Suzuki N, Suzuki T, Inagaki K, et al. Ten novel mutations of the ADAR1 gene in Japanese patients with dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria [published online August 17, 2006]. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:309-311.

- Zhang XJ, He PP, Li M, et al. Seven novel mutations of the ADAR gene in Chinese families and sporadic patients with dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria (DSH). Hum Mutat. 2004;23:629-630.

To the Editor:

Dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria (DSH)(Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man 127400), also called reticulate acropigmentation of Dohi, is a pigmentary genodermatosis characterized by a mixture of hyperpigmented and hypopigmented macules of various sizes on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet. Linkage analysis has revealed that the DSH gene locus resides on chromosome 1q11-q21,1 and the adenosine deaminase RNA specific gene, ADAR1 (also called DSRAD), in this region has been identified as being responsible for the development of DSH.2 We report a sporadic case of severe DSH with the ADAR1 gene detected in a mutation analysis.

A 6-year-old girl presented with a mixture of hyperpigmented and hypopigmented macules on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet and the curved side of the wrists, heels, and knees, as well as scattered frecklelike and depigmented spots on the face, ears, neck, arms, and upper back (Figure 1). Her parents noted that hyperpigmented and hypopigmented macules on the dorsal aspects of the hands developed at 5 months of age. Exacerbation after exposure to sunlight resulted in the eruption becoming remarkable in summer and fainter in winter. The skin lesions gradually became more progressive. Physical examination revealed that the patient generally was healthy.

After obtaining informed consent, we performed a mutation analysis of the ADAR1 gene in our patient and her parents. We used a kit to extract genomic DNA from peripheral blood, which was then used to amplify the exons of the ADAR1 gene with intronic flanking sequences by polymerase chain reaction with the primer.3 After amplification, polymerase chain reaction products were purified. We sequenced the ADAR1 gene. Sequence comparisons and analysis found that the patient (proband) carried a heterozygous insertional mutation c.2253insG in exon 6 of the ADAR1 gene. This mutation was not detected in the proband’s healthy parents and 100 normal individuals (Figure 2).

Dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria is acquired by autosomal-dominant inheritance and is mainly reported in Asians, especially in Japan and China. Oyama et al4 reviewed 185 cases of DSH in Japan and found the onset of this disease usually was during infancy or childhood; 73% of patients developed the skin lesions before 6 years of age. Suzuki et al5 reported 10 unrelated Japanese patients and found the onset of disease ranged from 1 year of age to childhood. Zhang et al1,6 investigated 78 Chinese patients with DSH including 8 multigenerational families and 2 sporadic patients and found the age of disease onset ranged from 6 months to 15 years of age. The age of onset in our patient (5 months) was younger than these prior reports.

Patients with DSH have a characteristic appearance including a mixture of hyperpigmented and hypopigmented macules of various sizes on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet. Few patients have similar lesions on the knees and elbows. Many patients have frecklelike macules on the face and arms.1-6 One patient has been described with scattered depigmented spots on the face and chest.1 Our patient had a characteristic appearance as well as some special manifestations including skin lesions on the curved side of the wrist, ears, neck, and upper back.

The human ADAR1 gene spans 30 kilobase and contains 15 exons. It encodes RNA-specific adenosine deaminase composed of 1226 amino acid residues. This enzyme is important for various functions such as site-specific RNA editing and nuclear translation. This enzyme has 2 Z-alpha domains, 3 double-stranded RNA–binding domains, and the putative deaminase domain corresponding to exon 2, exons 2 to 7, and exons 9 to 14 of ADAR1, respectively.6

Mutation analysis of the ADAR1 gene in this case showed heterozygous insertion mutation c.2253insG in exon 6 of the ADAR1 gene, which changed the reading frame, and 475 amino acid residues in C-terminus are replaced by 90 amino acid residues (TSSRAQVRLPSKSWGSLVPSRLRTQQEA RQAGSSRCGSPCLDWGEREGRTHGFHRG NPSDRGQSQKNYAPPLKVPRSTAKT DTPSHWQHLP). This mutation was not detected in the proband’s healthy parents and the 100 control individuals, which indicated that it was a de novo mutation and the pathogenic mutation of DSH rather than a common polymorphism.

In conclusion, we report a novel mutation of the ADAR1 gene with a heavy clinical phenotype in DSH. This study expands the spectrum of clinical manifestations and demonstrates the ADAR1 mutation in DSH.

Acknowledgments

We are most grateful to the patient and her family for taking part in our study.

To the Editor:

Dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria (DSH)(Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man 127400), also called reticulate acropigmentation of Dohi, is a pigmentary genodermatosis characterized by a mixture of hyperpigmented and hypopigmented macules of various sizes on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet. Linkage analysis has revealed that the DSH gene locus resides on chromosome 1q11-q21,1 and the adenosine deaminase RNA specific gene, ADAR1 (also called DSRAD), in this region has been identified as being responsible for the development of DSH.2 We report a sporadic case of severe DSH with the ADAR1 gene detected in a mutation analysis.

A 6-year-old girl presented with a mixture of hyperpigmented and hypopigmented macules on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet and the curved side of the wrists, heels, and knees, as well as scattered frecklelike and depigmented spots on the face, ears, neck, arms, and upper back (Figure 1). Her parents noted that hyperpigmented and hypopigmented macules on the dorsal aspects of the hands developed at 5 months of age. Exacerbation after exposure to sunlight resulted in the eruption becoming remarkable in summer and fainter in winter. The skin lesions gradually became more progressive. Physical examination revealed that the patient generally was healthy.

After obtaining informed consent, we performed a mutation analysis of the ADAR1 gene in our patient and her parents. We used a kit to extract genomic DNA from peripheral blood, which was then used to amplify the exons of the ADAR1 gene with intronic flanking sequences by polymerase chain reaction with the primer.3 After amplification, polymerase chain reaction products were purified. We sequenced the ADAR1 gene. Sequence comparisons and analysis found that the patient (proband) carried a heterozygous insertional mutation c.2253insG in exon 6 of the ADAR1 gene. This mutation was not detected in the proband’s healthy parents and 100 normal individuals (Figure 2).

Dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria is acquired by autosomal-dominant inheritance and is mainly reported in Asians, especially in Japan and China. Oyama et al4 reviewed 185 cases of DSH in Japan and found the onset of this disease usually was during infancy or childhood; 73% of patients developed the skin lesions before 6 years of age. Suzuki et al5 reported 10 unrelated Japanese patients and found the onset of disease ranged from 1 year of age to childhood. Zhang et al1,6 investigated 78 Chinese patients with DSH including 8 multigenerational families and 2 sporadic patients and found the age of disease onset ranged from 6 months to 15 years of age. The age of onset in our patient (5 months) was younger than these prior reports.

Patients with DSH have a characteristic appearance including a mixture of hyperpigmented and hypopigmented macules of various sizes on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet. Few patients have similar lesions on the knees and elbows. Many patients have frecklelike macules on the face and arms.1-6 One patient has been described with scattered depigmented spots on the face and chest.1 Our patient had a characteristic appearance as well as some special manifestations including skin lesions on the curved side of the wrist, ears, neck, and upper back.

The human ADAR1 gene spans 30 kilobase and contains 15 exons. It encodes RNA-specific adenosine deaminase composed of 1226 amino acid residues. This enzyme is important for various functions such as site-specific RNA editing and nuclear translation. This enzyme has 2 Z-alpha domains, 3 double-stranded RNA–binding domains, and the putative deaminase domain corresponding to exon 2, exons 2 to 7, and exons 9 to 14 of ADAR1, respectively.6

Mutation analysis of the ADAR1 gene in this case showed heterozygous insertion mutation c.2253insG in exon 6 of the ADAR1 gene, which changed the reading frame, and 475 amino acid residues in C-terminus are replaced by 90 amino acid residues (TSSRAQVRLPSKSWGSLVPSRLRTQQEA RQAGSSRCGSPCLDWGEREGRTHGFHRG NPSDRGQSQKNYAPPLKVPRSTAKT DTPSHWQHLP). This mutation was not detected in the proband’s healthy parents and the 100 control individuals, which indicated that it was a de novo mutation and the pathogenic mutation of DSH rather than a common polymorphism.

In conclusion, we report a novel mutation of the ADAR1 gene with a heavy clinical phenotype in DSH. This study expands the spectrum of clinical manifestations and demonstrates the ADAR1 mutation in DSH.

Acknowledgments

We are most grateful to the patient and her family for taking part in our study.

- Zhang XJ, Gao M, Li M, et al. Identification of a locus for dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria at chromosome 1q11-1q21. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:776-780.

- Miyamura Y, Suzuki T, Kono M, et al. Mutations of the RNA-specific adenosine deaminase gene (DSRAD) are involved in dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria [published online August 11, 2003]. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:693-699.

- Li M, Li C, Hua H, et al. Identification of two novel mutations in Chinese patients with dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria [published online October 8, 2005]. Arch Dermatol Res. 2005;297:196-200.

- Oyama M, Shimizu H, Ohata Y, et al. Dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria (reticulate acropigmentation of Dohi): report of a Japanese family with the condition and a literature review of 185 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:491-496.

- Suzuki N, Suzuki T, Inagaki K, et al. Ten novel mutations of the ADAR1 gene in Japanese patients with dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria [published online August 17, 2006]. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:309-311.

- Zhang XJ, He PP, Li M, et al. Seven novel mutations of the ADAR gene in Chinese families and sporadic patients with dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria (DSH). Hum Mutat. 2004;23:629-630.

- Zhang XJ, Gao M, Li M, et al. Identification of a locus for dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria at chromosome 1q11-1q21. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:776-780.

- Miyamura Y, Suzuki T, Kono M, et al. Mutations of the RNA-specific adenosine deaminase gene (DSRAD) are involved in dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria [published online August 11, 2003]. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:693-699.

- Li M, Li C, Hua H, et al. Identification of two novel mutations in Chinese patients with dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria [published online October 8, 2005]. Arch Dermatol Res. 2005;297:196-200.

- Oyama M, Shimizu H, Ohata Y, et al. Dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria (reticulate acropigmentation of Dohi): report of a Japanese family with the condition and a literature review of 185 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:491-496.

- Suzuki N, Suzuki T, Inagaki K, et al. Ten novel mutations of the ADAR1 gene in Japanese patients with dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria [published online August 17, 2006]. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:309-311.

- Zhang XJ, He PP, Li M, et al. Seven novel mutations of the ADAR gene in Chinese families and sporadic patients with dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria (DSH). Hum Mutat. 2004;23:629-630.

Practice Points

- The adenosine deaminase RNA specific gene, ADAR1, has been identified as being responsible for the development of dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria (DSH).

- The characteristic appearance of DSH is a mixture of hyperpigmented and hypopigmented macules of various sizes on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet.

Should I throw out my expired medications?

A 55-year-old patient requests new prescriptions at a routine appointment. She will be traveling internationally next month and wants to replace her emergency medication kit, as the medications in it (ciprofloxacin, loperamide, and oxycodone) have all expired.

What do you do?

A) Replace the prescription for ciprofloxacin.

B) Replace all three medications.

C) Tell the patient that all the meds should still be fine.

This is a common concern brought up by patients. Many patients discard medications when they pass the expiration date on the package. Is this necessary? Is there a health risk to taking expired medications, and is it okay from a therapeutic standpoint to use medications past their expiration date?

The expiration date is not a date that the drug stops being effective or potentially becomes toxic. It is a date, required by law, that the manufacturer can guarantee greater than 90% original potency of the medication. There really isn’t incentive for pharmaceutical companies to extend the expiration dates, as it is profitable for patients to throw away expired medications and replace them with new prescriptions.

The U.S. military purchases a large stockpile of drugs and has the potential for having a great deal of expired medications. To help reduce this problem, the Food and Drug Administration administers the shelf-life extension program (SLEP) for the U.S. military as a testing and evaluation program designed to justify an extension of the shelf life of stockpiled drug products.1

Robbe Lyon, MD, and colleagues reported data from the SLEP.2 A total of 122 drugs were studied representing 3,005 lots, with 88% of these extended at least 1 year past the expiration date, with an average extension of more than 5 years. Several antibiotics were studied, including ciprofloxacin (mean extension, 55 months), amoxicillin (mean extension, 23 months), and doxycycline (mean extension, 50 months).

Lee Cantrell, PharmD, and coinvestigators looked at sealed drugs from a retail pharmacy that were 28-40 years past their expiration date.3 Amazingly, 12 of the 14 compounds tested were in concentrations that were at least 90% of the labeled amount. Among the drugs that were tested that maintained greater than 90% of the labeled amount were acetaminophen, codeine, hydrocodone, and barbiturates. Aspirin and amphetamine were the two drugs that did not have greater than 90% of the labeled amount. The aspirin amounts were very low, about 1% of the listed amount on the package.

The major myth surrounding expired medications is that taking an expired medication could be toxic.

There is one case report of toxicity from the use of expired tetracycline.4 This was a case series of three patients who developed reversible Fanconi syndrome linked to using an expired tetracycline preparation. That preparation of tetracycline is no longer available.

There are no other reports of toxicity due to use of expired medications.5,6 There appears to be no direct risk of toxicity to the patient by using medication past the expiration date.

The risk that isn’t answered is the risk of using medications that may not be effective if potency isn’t guaranteed beyond the expiration date. It appears that most drugs are effective for years past the expiration date.

This isn’t an issue for medications for treatment of chronic conditions, as patients take the medications every day, and the medications will be used up long before they expire. For medications that are used infrequently – analgesics, antihistamines, and medications for traveler’s diarrhea – they appear to be stable for years past expiration, and there is little risk to the patient if the medications are not fully effective.

I think aspirin should not be used past expiration, given the data showing that it breaks down more so than other medications. For the case at the start of this article, I think having the patient use the expired medications should be fine.

References

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

A 55-year-old patient requests new prescriptions at a routine appointment. She will be traveling internationally next month and wants to replace her emergency medication kit, as the medications in it (ciprofloxacin, loperamide, and oxycodone) have all expired.

What do you do?

A) Replace the prescription for ciprofloxacin.

B) Replace all three medications.

C) Tell the patient that all the meds should still be fine.

This is a common concern brought up by patients. Many patients discard medications when they pass the expiration date on the package. Is this necessary? Is there a health risk to taking expired medications, and is it okay from a therapeutic standpoint to use medications past their expiration date?

The expiration date is not a date that the drug stops being effective or potentially becomes toxic. It is a date, required by law, that the manufacturer can guarantee greater than 90% original potency of the medication. There really isn’t incentive for pharmaceutical companies to extend the expiration dates, as it is profitable for patients to throw away expired medications and replace them with new prescriptions.

The U.S. military purchases a large stockpile of drugs and has the potential for having a great deal of expired medications. To help reduce this problem, the Food and Drug Administration administers the shelf-life extension program (SLEP) for the U.S. military as a testing and evaluation program designed to justify an extension of the shelf life of stockpiled drug products.1

Robbe Lyon, MD, and colleagues reported data from the SLEP.2 A total of 122 drugs were studied representing 3,005 lots, with 88% of these extended at least 1 year past the expiration date, with an average extension of more than 5 years. Several antibiotics were studied, including ciprofloxacin (mean extension, 55 months), amoxicillin (mean extension, 23 months), and doxycycline (mean extension, 50 months).

Lee Cantrell, PharmD, and coinvestigators looked at sealed drugs from a retail pharmacy that were 28-40 years past their expiration date.3 Amazingly, 12 of the 14 compounds tested were in concentrations that were at least 90% of the labeled amount. Among the drugs that were tested that maintained greater than 90% of the labeled amount were acetaminophen, codeine, hydrocodone, and barbiturates. Aspirin and amphetamine were the two drugs that did not have greater than 90% of the labeled amount. The aspirin amounts were very low, about 1% of the listed amount on the package.

The major myth surrounding expired medications is that taking an expired medication could be toxic.

There is one case report of toxicity from the use of expired tetracycline.4 This was a case series of three patients who developed reversible Fanconi syndrome linked to using an expired tetracycline preparation. That preparation of tetracycline is no longer available.

There are no other reports of toxicity due to use of expired medications.5,6 There appears to be no direct risk of toxicity to the patient by using medication past the expiration date.

The risk that isn’t answered is the risk of using medications that may not be effective if potency isn’t guaranteed beyond the expiration date. It appears that most drugs are effective for years past the expiration date.

This isn’t an issue for medications for treatment of chronic conditions, as patients take the medications every day, and the medications will be used up long before they expire. For medications that are used infrequently – analgesics, antihistamines, and medications for traveler’s diarrhea – they appear to be stable for years past expiration, and there is little risk to the patient if the medications are not fully effective.

I think aspirin should not be used past expiration, given the data showing that it breaks down more so than other medications. For the case at the start of this article, I think having the patient use the expired medications should be fine.

References

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

A 55-year-old patient requests new prescriptions at a routine appointment. She will be traveling internationally next month and wants to replace her emergency medication kit, as the medications in it (ciprofloxacin, loperamide, and oxycodone) have all expired.

What do you do?

A) Replace the prescription for ciprofloxacin.

B) Replace all three medications.

C) Tell the patient that all the meds should still be fine.

This is a common concern brought up by patients. Many patients discard medications when they pass the expiration date on the package. Is this necessary? Is there a health risk to taking expired medications, and is it okay from a therapeutic standpoint to use medications past their expiration date?

The expiration date is not a date that the drug stops being effective or potentially becomes toxic. It is a date, required by law, that the manufacturer can guarantee greater than 90% original potency of the medication. There really isn’t incentive for pharmaceutical companies to extend the expiration dates, as it is profitable for patients to throw away expired medications and replace them with new prescriptions.

The U.S. military purchases a large stockpile of drugs and has the potential for having a great deal of expired medications. To help reduce this problem, the Food and Drug Administration administers the shelf-life extension program (SLEP) for the U.S. military as a testing and evaluation program designed to justify an extension of the shelf life of stockpiled drug products.1

Robbe Lyon, MD, and colleagues reported data from the SLEP.2 A total of 122 drugs were studied representing 3,005 lots, with 88% of these extended at least 1 year past the expiration date, with an average extension of more than 5 years. Several antibiotics were studied, including ciprofloxacin (mean extension, 55 months), amoxicillin (mean extension, 23 months), and doxycycline (mean extension, 50 months).

Lee Cantrell, PharmD, and coinvestigators looked at sealed drugs from a retail pharmacy that were 28-40 years past their expiration date.3 Amazingly, 12 of the 14 compounds tested were in concentrations that were at least 90% of the labeled amount. Among the drugs that were tested that maintained greater than 90% of the labeled amount were acetaminophen, codeine, hydrocodone, and barbiturates. Aspirin and amphetamine were the two drugs that did not have greater than 90% of the labeled amount. The aspirin amounts were very low, about 1% of the listed amount on the package.

The major myth surrounding expired medications is that taking an expired medication could be toxic.

There is one case report of toxicity from the use of expired tetracycline.4 This was a case series of three patients who developed reversible Fanconi syndrome linked to using an expired tetracycline preparation. That preparation of tetracycline is no longer available.

There are no other reports of toxicity due to use of expired medications.5,6 There appears to be no direct risk of toxicity to the patient by using medication past the expiration date.

The risk that isn’t answered is the risk of using medications that may not be effective if potency isn’t guaranteed beyond the expiration date. It appears that most drugs are effective for years past the expiration date.

This isn’t an issue for medications for treatment of chronic conditions, as patients take the medications every day, and the medications will be used up long before they expire. For medications that are used infrequently – analgesics, antihistamines, and medications for traveler’s diarrhea – they appear to be stable for years past expiration, and there is little risk to the patient if the medications are not fully effective.

I think aspirin should not be used past expiration, given the data showing that it breaks down more so than other medications. For the case at the start of this article, I think having the patient use the expired medications should be fine.

References

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

Metastatic Crohn Disease Clinically Reminiscent of Erythema Nodosum on the Right Leg

Metastatic Crohn disease (MCD) is defined by the presence of cutaneous noncaseating granulomatous lesions that are noncontiguous with the gastrointestinal (GI) tract or fistulae.1 The clinical presentation of MCD is so variable that its diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion.1,2 In particular, the presence of erythematous tender nodules on the legs is easily mistaken for erythema nodosum (EN). Skin biopsy has an important role in confirming the diagnosis, as histopathological examination would reveal a noncaseating granuloma similar to those in the involved GI tract.2 Herein, we report a case of MCD on the right leg that was clinically reminiscent of unilateral EN.

Case Report

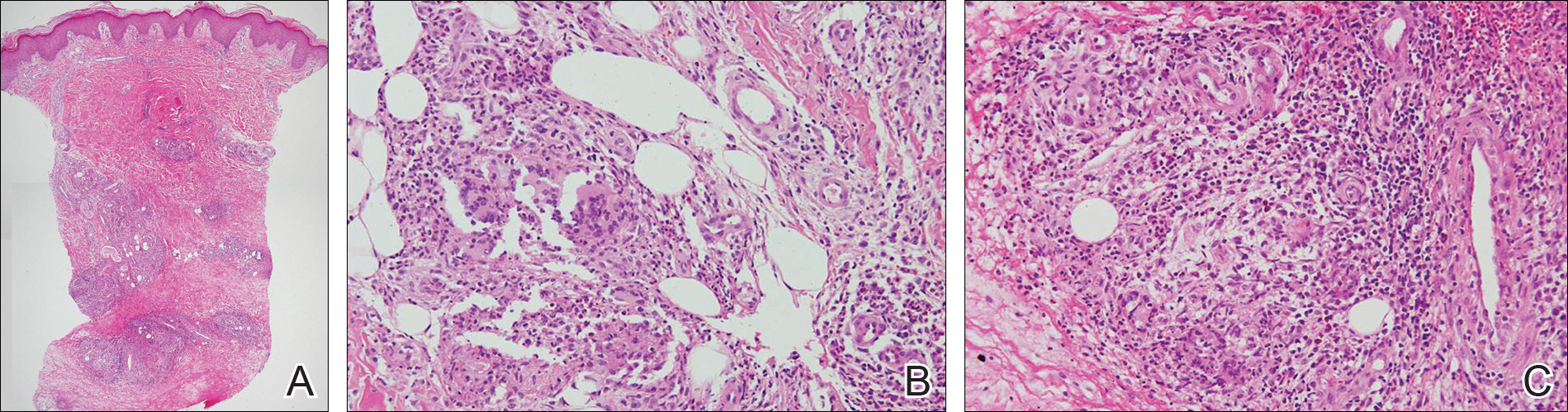

A 21-year-old woman presented to the dermatology department with 2 painful erythematous nodules on the lower right leg of 2 weeks’ duration. She also reported abdominal pain, diarrhea, and bloody stool. She had been diagnosed with Crohn disease (CD) 6 years prior that had been well controlled with systemic low-dose steroids (5–15 mg/d), metronidazole (750 mg/d), and intermittent mesalamine and antidiarrheal drugs. However, she had not taken her medication for several weeks on her own authority. Subsequently, the patient developed skin lesions, which were characterized by ill-defined erythematous nodules with tenderness on the right lower leg along with GI symptoms (Figure 1). Laboratory studies revealed anemia (hemoglobin, 9.9 g/dL [reference range, 12.0–16.0 g/dL]) and an elevated C-reactive protein level (4.3 mg/dL [reference range, 0–0.3 mg/dL]). Other routine laboratory findings were normal.

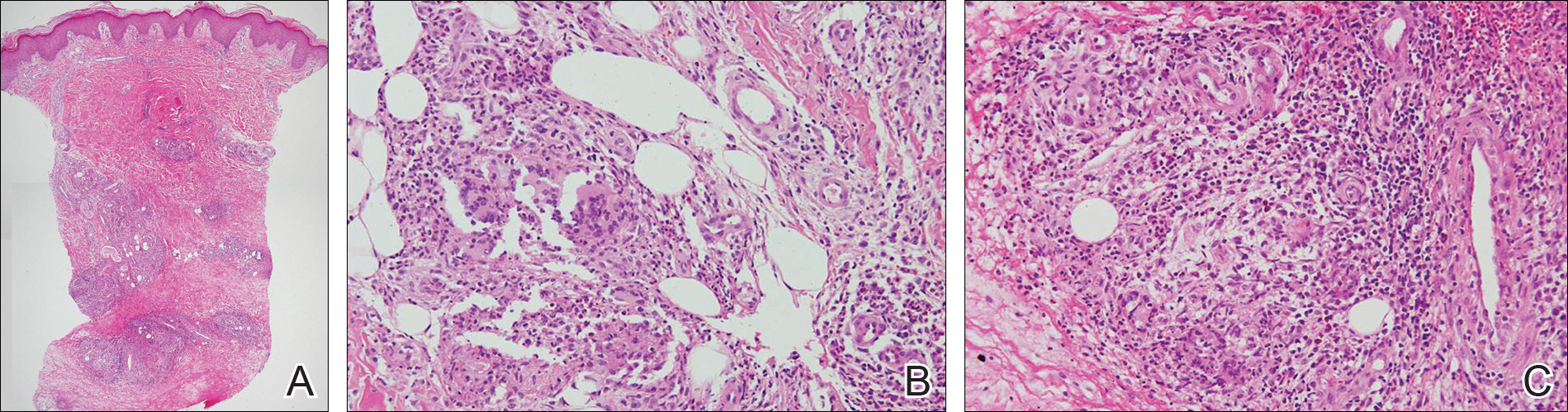

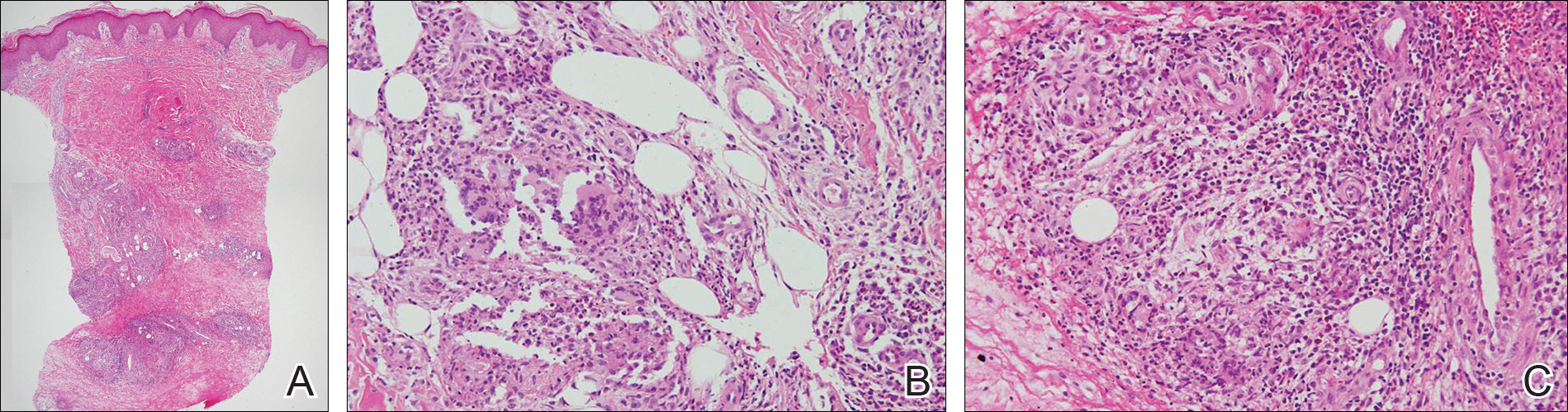

Histopathologically, a skin biopsy from the right ankle showed vague, ill-defined, noncaseating granulomas scattered in the deep dermis and lobules of the subcutis (Figure 2). The granulomas were composed of epithelioid cells and Langerhans-type giant cells. Lymphocytes and neutrophils also were present, but eosinophils were absent. Immunohistochemical staining revealed that the infiltrating cells were mostly CD4+ helper/inducer T cells intermixed with CD8+ suppressor/cytotoxic T cells. The CD4:CD8 ratio was approximately 2:1. Counts of CD20+ B cells were low. Epithelioid cells and giant cells were positive for CD68.

×20). The skin biopsy showed granulomas composed of epithelioid cells and multinucleated giant cells in the deep dermis and in the lobules of the subcutis (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). Histopathologic features such as small vessel vasculitis characterized by a fibrin deposit in the small blood vessels and swelling of the endothelial cells as well as granulomatous perivasculitis with perivascular infiltration of the epithelioid cells were present (C)(H&E, original magnification ×200).

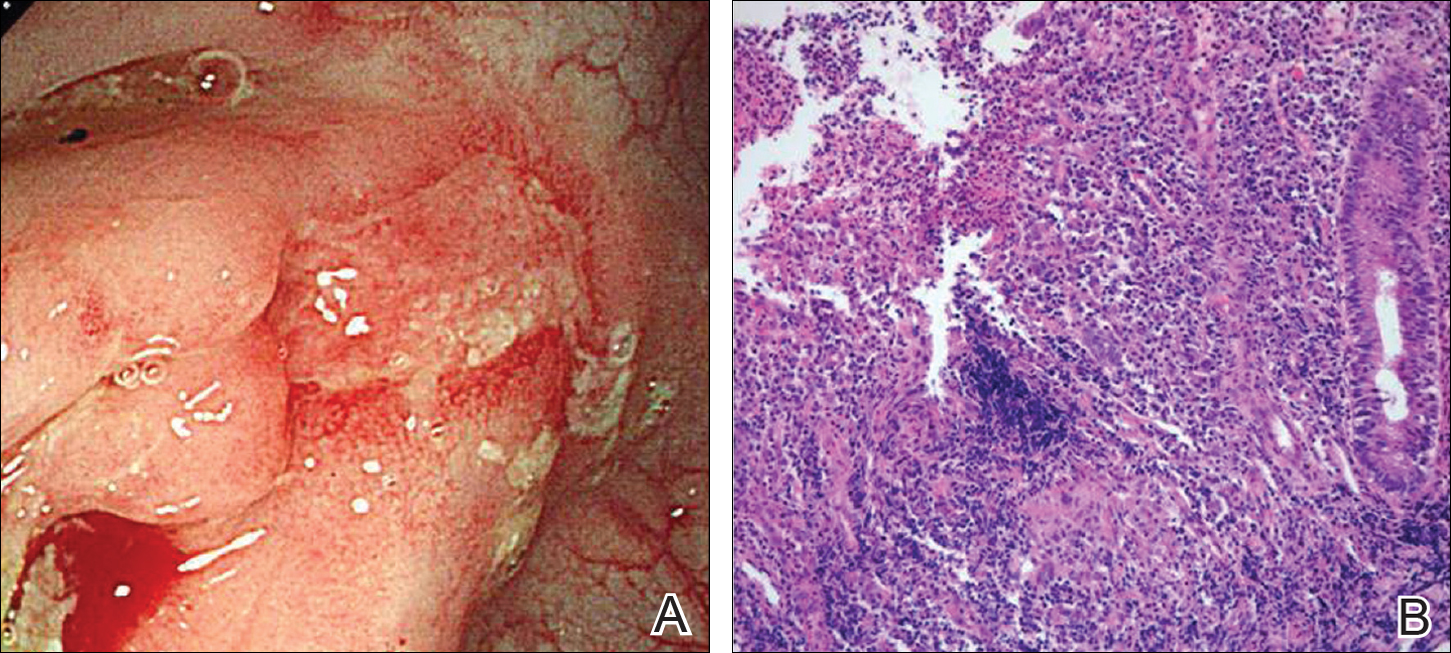

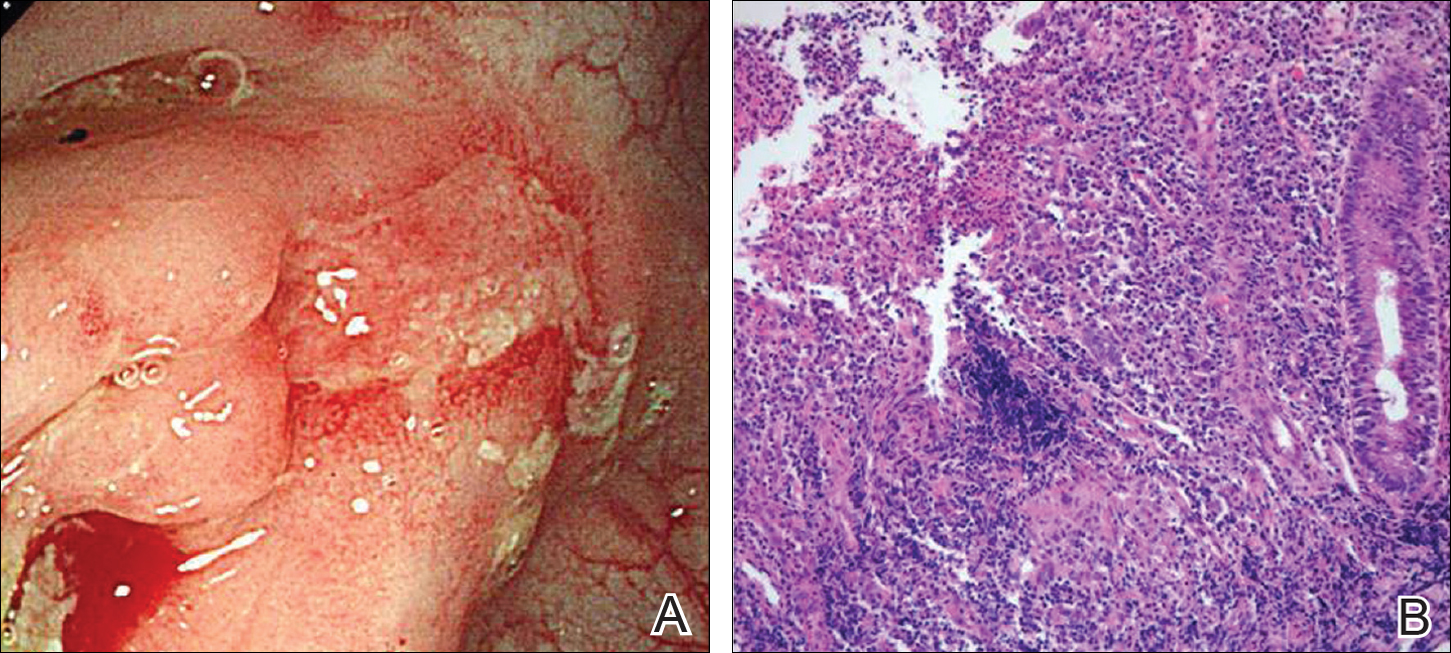

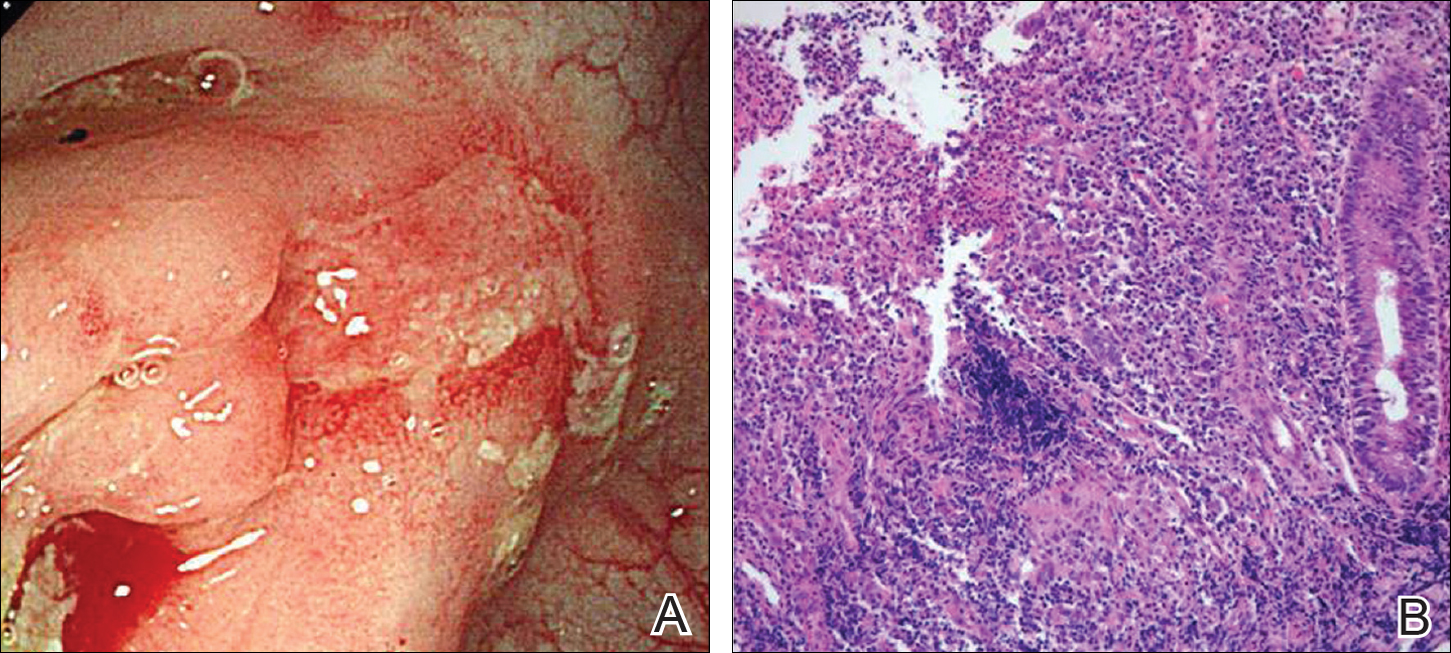

A colonoscopy was performed to evaluate the aggravation of CD. Multiple longitudinal ulcers were observed in the ileocecal valve area and from the transverse colon to the sigmoid colon (Figure 3A). Histopathologic findings from the colon showed mucosal ulceration and noncaseating granulomas with heavy infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells (Figure 3B). Staining for infectious microorganisms (eg, Ziehl-Neelsen, periodic acid–Schiff, Gram) was negative. A polymerase chain reaction performed on sections cut from the paraffin block of the skin biopsy was negative for Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA.

Based on the clinical and histopathologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with MCD that was clinically reminiscent of unilateral EN. Four weeks after the initiation of therapy with systemic corticosteroids (25 mg/d), oral metronidazole (750 mg/d), and mesalamine (1200 mg/d) for CD, the skin lesions were completely resolved and the patient’s GI symptoms improved simultaneously.

Comment

Crohn disease is a chronic inflammatory granulomatous disease of the GI tract that often is associated with reactive cutaneous lesions including EN, pyoderma gangrenosum, necrotizing vasculitis, and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Of these, EN is the most common to appear in CD patients and has been reported to occur in 1% to 15% of patients.3-5 In particular, skin lesions on the leg presenting as tender erythematous nodules and patches are often diagnosed as EN, which is relatively common. In our case, we initially suspected EN due to the rare presentation of MCD and lack of specific clinical features; however, the skin biopsy revealed noncaseating granulomas in the mid to deep dermis and subcutis consistent with MCD.

Metastatic Crohn disease is a rare disease entity and is characterized by the presence of noncaseating granulomas of the skin at sites separated from the GI tract by normal tissue.1 Although its pathogenesis is unclear, it has been suggested that immune complexes deposited in the skin could be responsible for the granulomatous reactions.4 A T lymphocyte–mediated type IV hypersensitivity reaction also could be responsible.6,7 Because antimicrobial therapy can be curative for infection-related MCD, special histologic stains and/or tissue cultures can help to exclude an infectious etiology.8

Clinical presentations of MCD vary greatly, with observations such as single or multiple erythematous swellings, papules, plaques, nodules, abscesses, and ulcers.1,2 The relationship between these clinical presentations and the intestinal activity of CD still is unknown; in some cases, however, the metastatic granulomatous lesions and the bowel disease show comparable severity.2,9,10 In a review of the literature, MCD was generally reported to present in the genital area in children. In adults, lesions most frequently present in the genital area, followed by ulcers on the arms and legs.1,2 These variations in clinical features and location resemble benign or infectious disease and can lead to delays in diagnosis.

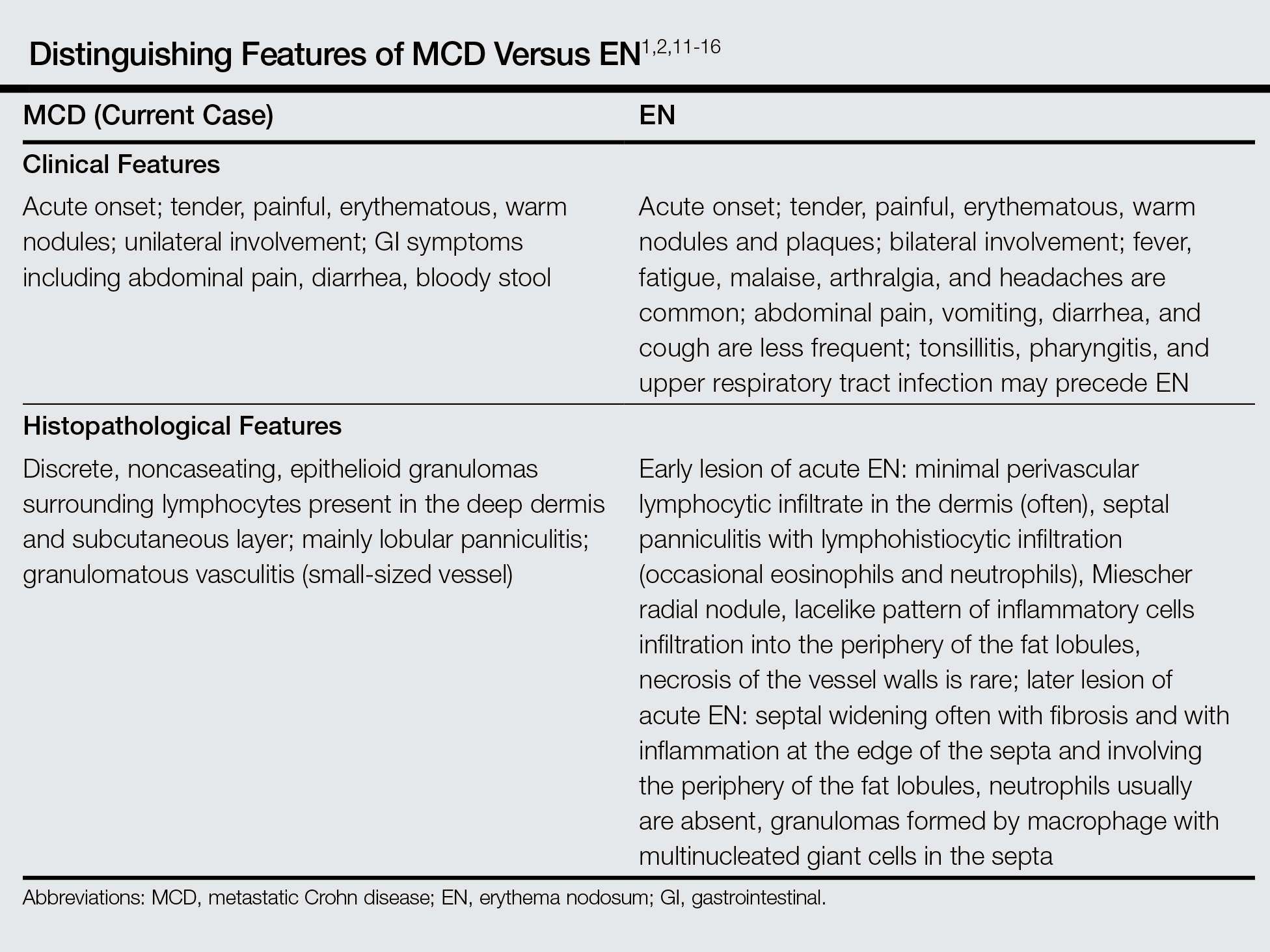

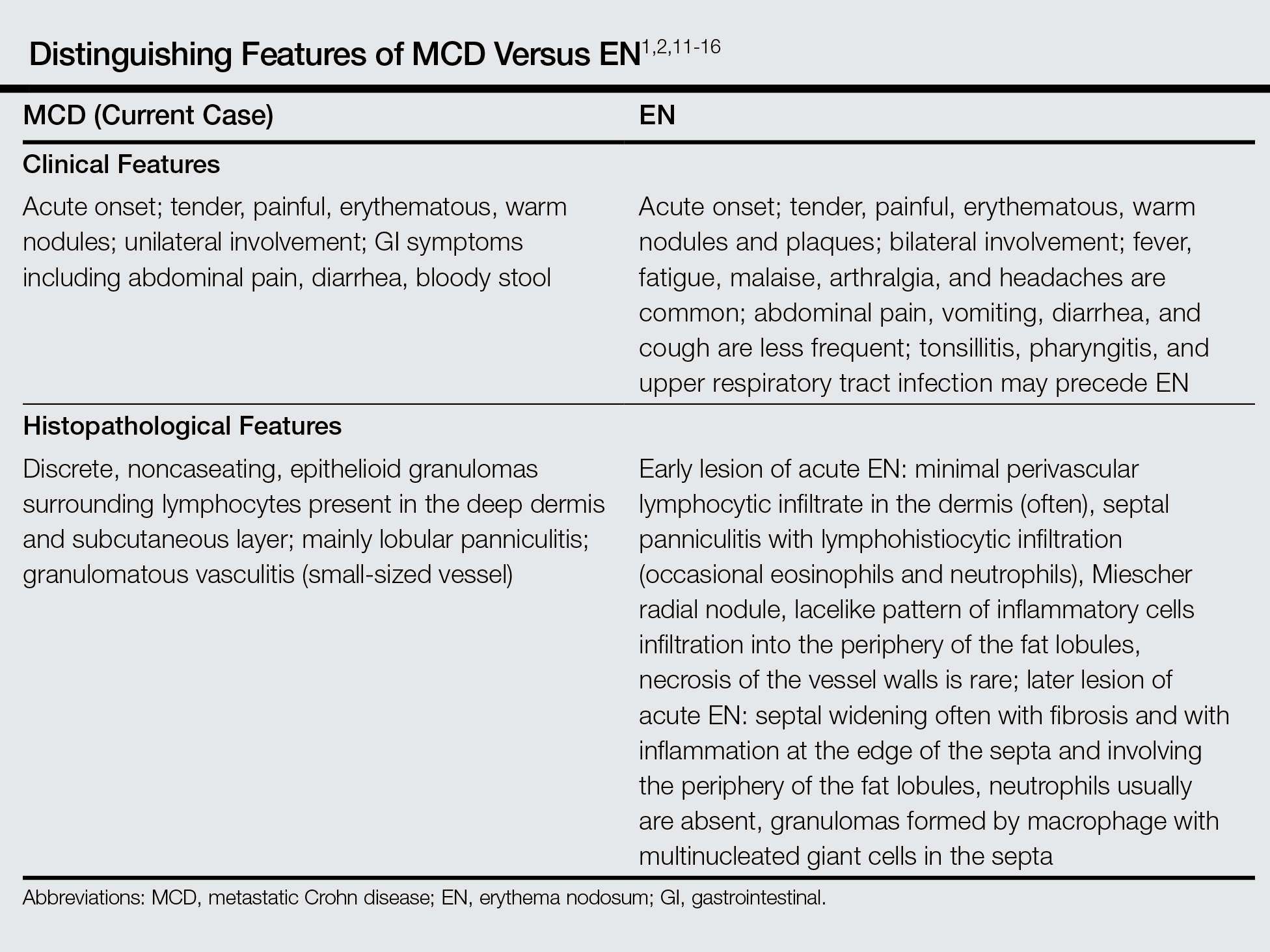

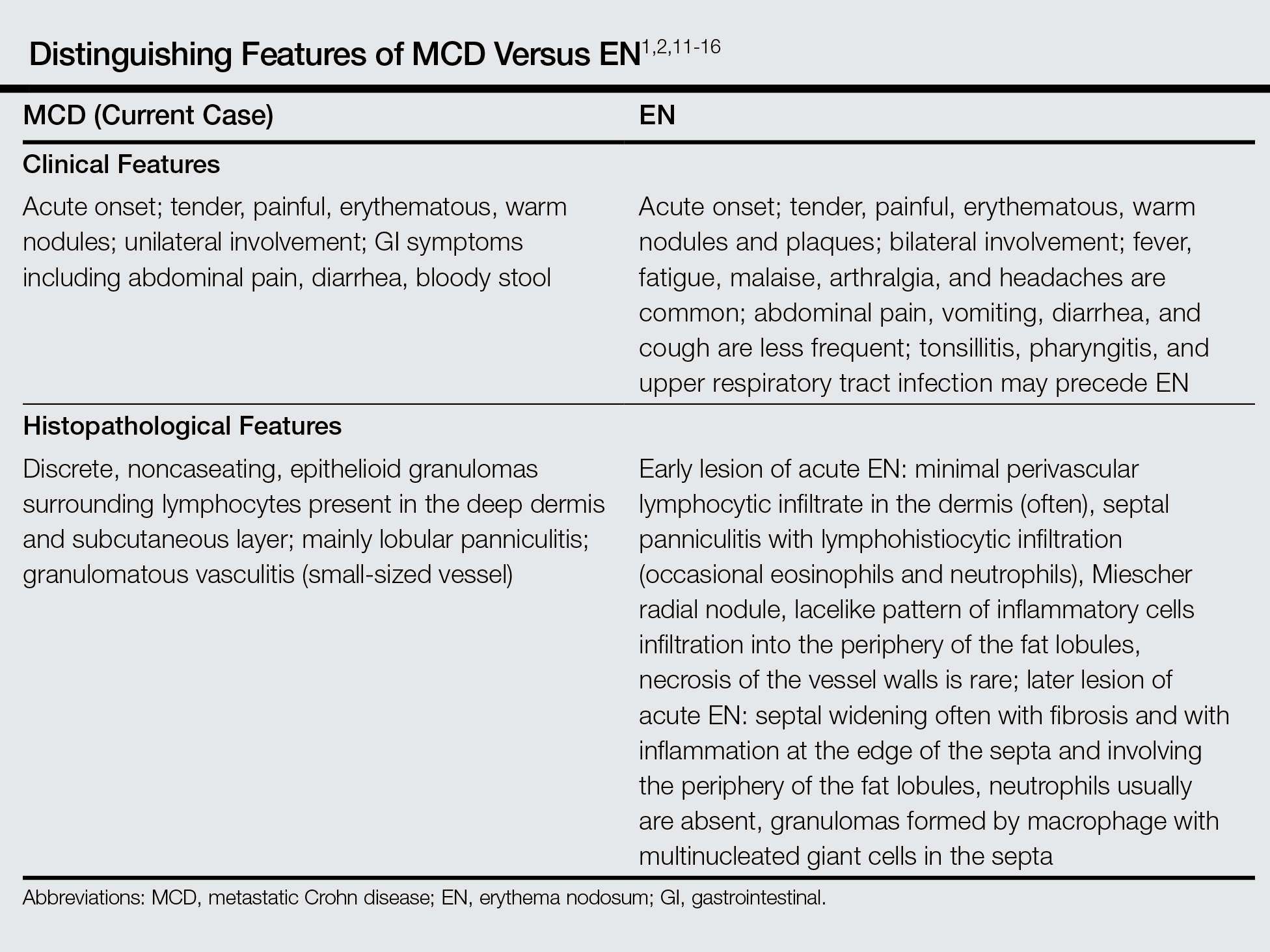

Histopathologically, MCD lesions usually are ill-defined noncaseating granulomas with numerous multinucleated giant cells and lymphomononuclear cells located mostly in the dermis and occasionally extending into the subcutis. The cutaneous granulomata are similar to those present in the affected GI tract. Lymphocytes and plasma cells also are commonly present and eosinophils can be prominent.1,2,11 In some cases of MCD, granulomatous vasculitis of small- to medium-sized vessels can be found and is associated with dermal and subcutaneous granulomatous inflammation.8,11,12 Misago and Narisawa13 suggested that granulomatous vasculitis and panniculitis associated with CD is considered to be a rare subtype of MCD. Few cases of MCD presenting as granulomatous panniculitis have been described in the literature.14-16 Our patient presented with lesions that clinically resembled EN; however, the biopsy was more consistent with MCD. The Table summarizes the distinguishing clinical and histopathological features of MCD in our case and classic EN.

Although some authors believe that MCD is not related to CD activity, others assert that MCD lesions may parallel GI activity.1,2 Our patient was treated with systemic corticosteroids, oral metronidazole, and mesalamine to control the GI symptoms associated with CD. Four weeks after treatment, the GI symptoms and skin lesions improved simultaneously without any additional dermatologic treatment. We believe that MCD has the potential to serve as an early marker of the recurrence of CD and can help with the early diagnosis of CD aggravation, though an association between MCD and CD activity has not been confirmed.

Conclusion

We reported a case of MCD that was clinically reminiscent of unilateral EN and associated with GI disease activity. Physicians should be aware of the possibility of skin manifestations in CD, especially when erythematous nodular lesions are present on the leg.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. Mckee’s Pathology of the Skin: With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2012.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Sonia F, Richard SB. Inflammatory bowel disease. In: Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 16th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005:1776-1789.

- Burgdorf W. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:689-695.

- Crowson AN, Nuovo GJ, Mihm MC Jr, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease, its spectrum, and its pathogenesis: intracellular consensus bacterial 16S rRNA is associated with the gastrointestinal but not the cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1185-1192.

- Tatnall FM, Dodd HJ, Sarkany I. Crohn’s disease with metastatic cutaneous involvement and granulomatous cheilitis. J R Soc Med. 1987;80:49-51.

- Shum DT, Guenther L. Metastatic Crohn’s disease. case report and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:645-648.

- Emanuel PO, Phelps RG. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a histopathologic study of 12 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:457-461.

- Chalvardjian A, Nethercott JR. Cutaneous granulomatous vasculitis associated with Crohn’s disease. Cutis. 1982;30:645-655.

- Lebwohl M, Fleischmajer R, Janowitz H, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:33-38.

- Sabat M, Leulmo J, Saez A. Cutaneous granulomatous vasculitis in metastatic Crohn’s disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:652-653.

- Burns AM, Walsh N, Green PJ. Granulomatous vasculitis in Crohn’s disease: a clinicopathologic correlate of two unusual cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1077-1083.

- Misago N, Narisawa Y. Erythema induratum (nodular vasculitis) associated with Crohn’s disease: a rare type of metastatic Crohn’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:325-329.

- Liebermann TR, Greene JF Jr. Transient subcutaneous granulomatosis of the upper extremities in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1979;72:89-91.

- Levine N, Bangert J. Cutaneous granulomatosis in Crohn’s disease. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:1006-1009.

- Hackzell-Bradley M, Hedblad MA, Stephansson EA. Metastatic Crohn’s disease. report of 3 cases with special reference to histopathologic findings. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:928-932.

Metastatic Crohn disease (MCD) is defined by the presence of cutaneous noncaseating granulomatous lesions that are noncontiguous with the gastrointestinal (GI) tract or fistulae.1 The clinical presentation of MCD is so variable that its diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion.1,2 In particular, the presence of erythematous tender nodules on the legs is easily mistaken for erythema nodosum (EN). Skin biopsy has an important role in confirming the diagnosis, as histopathological examination would reveal a noncaseating granuloma similar to those in the involved GI tract.2 Herein, we report a case of MCD on the right leg that was clinically reminiscent of unilateral EN.

Case Report

A 21-year-old woman presented to the dermatology department with 2 painful erythematous nodules on the lower right leg of 2 weeks’ duration. She also reported abdominal pain, diarrhea, and bloody stool. She had been diagnosed with Crohn disease (CD) 6 years prior that had been well controlled with systemic low-dose steroids (5–15 mg/d), metronidazole (750 mg/d), and intermittent mesalamine and antidiarrheal drugs. However, she had not taken her medication for several weeks on her own authority. Subsequently, the patient developed skin lesions, which were characterized by ill-defined erythematous nodules with tenderness on the right lower leg along with GI symptoms (Figure 1). Laboratory studies revealed anemia (hemoglobin, 9.9 g/dL [reference range, 12.0–16.0 g/dL]) and an elevated C-reactive protein level (4.3 mg/dL [reference range, 0–0.3 mg/dL]). Other routine laboratory findings were normal.

Histopathologically, a skin biopsy from the right ankle showed vague, ill-defined, noncaseating granulomas scattered in the deep dermis and lobules of the subcutis (Figure 2). The granulomas were composed of epithelioid cells and Langerhans-type giant cells. Lymphocytes and neutrophils also were present, but eosinophils were absent. Immunohistochemical staining revealed that the infiltrating cells were mostly CD4+ helper/inducer T cells intermixed with CD8+ suppressor/cytotoxic T cells. The CD4:CD8 ratio was approximately 2:1. Counts of CD20+ B cells were low. Epithelioid cells and giant cells were positive for CD68.

×20). The skin biopsy showed granulomas composed of epithelioid cells and multinucleated giant cells in the deep dermis and in the lobules of the subcutis (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). Histopathologic features such as small vessel vasculitis characterized by a fibrin deposit in the small blood vessels and swelling of the endothelial cells as well as granulomatous perivasculitis with perivascular infiltration of the epithelioid cells were present (C)(H&E, original magnification ×200).

A colonoscopy was performed to evaluate the aggravation of CD. Multiple longitudinal ulcers were observed in the ileocecal valve area and from the transverse colon to the sigmoid colon (Figure 3A). Histopathologic findings from the colon showed mucosal ulceration and noncaseating granulomas with heavy infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells (Figure 3B). Staining for infectious microorganisms (eg, Ziehl-Neelsen, periodic acid–Schiff, Gram) was negative. A polymerase chain reaction performed on sections cut from the paraffin block of the skin biopsy was negative for Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA.

Based on the clinical and histopathologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with MCD that was clinically reminiscent of unilateral EN. Four weeks after the initiation of therapy with systemic corticosteroids (25 mg/d), oral metronidazole (750 mg/d), and mesalamine (1200 mg/d) for CD, the skin lesions were completely resolved and the patient’s GI symptoms improved simultaneously.

Comment

Crohn disease is a chronic inflammatory granulomatous disease of the GI tract that often is associated with reactive cutaneous lesions including EN, pyoderma gangrenosum, necrotizing vasculitis, and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Of these, EN is the most common to appear in CD patients and has been reported to occur in 1% to 15% of patients.3-5 In particular, skin lesions on the leg presenting as tender erythematous nodules and patches are often diagnosed as EN, which is relatively common. In our case, we initially suspected EN due to the rare presentation of MCD and lack of specific clinical features; however, the skin biopsy revealed noncaseating granulomas in the mid to deep dermis and subcutis consistent with MCD.

Metastatic Crohn disease is a rare disease entity and is characterized by the presence of noncaseating granulomas of the skin at sites separated from the GI tract by normal tissue.1 Although its pathogenesis is unclear, it has been suggested that immune complexes deposited in the skin could be responsible for the granulomatous reactions.4 A T lymphocyte–mediated type IV hypersensitivity reaction also could be responsible.6,7 Because antimicrobial therapy can be curative for infection-related MCD, special histologic stains and/or tissue cultures can help to exclude an infectious etiology.8

Clinical presentations of MCD vary greatly, with observations such as single or multiple erythematous swellings, papules, plaques, nodules, abscesses, and ulcers.1,2 The relationship between these clinical presentations and the intestinal activity of CD still is unknown; in some cases, however, the metastatic granulomatous lesions and the bowel disease show comparable severity.2,9,10 In a review of the literature, MCD was generally reported to present in the genital area in children. In adults, lesions most frequently present in the genital area, followed by ulcers on the arms and legs.1,2 These variations in clinical features and location resemble benign or infectious disease and can lead to delays in diagnosis.

Histopathologically, MCD lesions usually are ill-defined noncaseating granulomas with numerous multinucleated giant cells and lymphomononuclear cells located mostly in the dermis and occasionally extending into the subcutis. The cutaneous granulomata are similar to those present in the affected GI tract. Lymphocytes and plasma cells also are commonly present and eosinophils can be prominent.1,2,11 In some cases of MCD, granulomatous vasculitis of small- to medium-sized vessels can be found and is associated with dermal and subcutaneous granulomatous inflammation.8,11,12 Misago and Narisawa13 suggested that granulomatous vasculitis and panniculitis associated with CD is considered to be a rare subtype of MCD. Few cases of MCD presenting as granulomatous panniculitis have been described in the literature.14-16 Our patient presented with lesions that clinically resembled EN; however, the biopsy was more consistent with MCD. The Table summarizes the distinguishing clinical and histopathological features of MCD in our case and classic EN.

Although some authors believe that MCD is not related to CD activity, others assert that MCD lesions may parallel GI activity.1,2 Our patient was treated with systemic corticosteroids, oral metronidazole, and mesalamine to control the GI symptoms associated with CD. Four weeks after treatment, the GI symptoms and skin lesions improved simultaneously without any additional dermatologic treatment. We believe that MCD has the potential to serve as an early marker of the recurrence of CD and can help with the early diagnosis of CD aggravation, though an association between MCD and CD activity has not been confirmed.

Conclusion

We reported a case of MCD that was clinically reminiscent of unilateral EN and associated with GI disease activity. Physicians should be aware of the possibility of skin manifestations in CD, especially when erythematous nodular lesions are present on the leg.

Metastatic Crohn disease (MCD) is defined by the presence of cutaneous noncaseating granulomatous lesions that are noncontiguous with the gastrointestinal (GI) tract or fistulae.1 The clinical presentation of MCD is so variable that its diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion.1,2 In particular, the presence of erythematous tender nodules on the legs is easily mistaken for erythema nodosum (EN). Skin biopsy has an important role in confirming the diagnosis, as histopathological examination would reveal a noncaseating granuloma similar to those in the involved GI tract.2 Herein, we report a case of MCD on the right leg that was clinically reminiscent of unilateral EN.

Case Report

A 21-year-old woman presented to the dermatology department with 2 painful erythematous nodules on the lower right leg of 2 weeks’ duration. She also reported abdominal pain, diarrhea, and bloody stool. She had been diagnosed with Crohn disease (CD) 6 years prior that had been well controlled with systemic low-dose steroids (5–15 mg/d), metronidazole (750 mg/d), and intermittent mesalamine and antidiarrheal drugs. However, she had not taken her medication for several weeks on her own authority. Subsequently, the patient developed skin lesions, which were characterized by ill-defined erythematous nodules with tenderness on the right lower leg along with GI symptoms (Figure 1). Laboratory studies revealed anemia (hemoglobin, 9.9 g/dL [reference range, 12.0–16.0 g/dL]) and an elevated C-reactive protein level (4.3 mg/dL [reference range, 0–0.3 mg/dL]). Other routine laboratory findings were normal.

Histopathologically, a skin biopsy from the right ankle showed vague, ill-defined, noncaseating granulomas scattered in the deep dermis and lobules of the subcutis (Figure 2). The granulomas were composed of epithelioid cells and Langerhans-type giant cells. Lymphocytes and neutrophils also were present, but eosinophils were absent. Immunohistochemical staining revealed that the infiltrating cells were mostly CD4+ helper/inducer T cells intermixed with CD8+ suppressor/cytotoxic T cells. The CD4:CD8 ratio was approximately 2:1. Counts of CD20+ B cells were low. Epithelioid cells and giant cells were positive for CD68.

×20). The skin biopsy showed granulomas composed of epithelioid cells and multinucleated giant cells in the deep dermis and in the lobules of the subcutis (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). Histopathologic features such as small vessel vasculitis characterized by a fibrin deposit in the small blood vessels and swelling of the endothelial cells as well as granulomatous perivasculitis with perivascular infiltration of the epithelioid cells were present (C)(H&E, original magnification ×200).

A colonoscopy was performed to evaluate the aggravation of CD. Multiple longitudinal ulcers were observed in the ileocecal valve area and from the transverse colon to the sigmoid colon (Figure 3A). Histopathologic findings from the colon showed mucosal ulceration and noncaseating granulomas with heavy infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells (Figure 3B). Staining for infectious microorganisms (eg, Ziehl-Neelsen, periodic acid–Schiff, Gram) was negative. A polymerase chain reaction performed on sections cut from the paraffin block of the skin biopsy was negative for Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA.

Based on the clinical and histopathologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with MCD that was clinically reminiscent of unilateral EN. Four weeks after the initiation of therapy with systemic corticosteroids (25 mg/d), oral metronidazole (750 mg/d), and mesalamine (1200 mg/d) for CD, the skin lesions were completely resolved and the patient’s GI symptoms improved simultaneously.

Comment

Crohn disease is a chronic inflammatory granulomatous disease of the GI tract that often is associated with reactive cutaneous lesions including EN, pyoderma gangrenosum, necrotizing vasculitis, and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Of these, EN is the most common to appear in CD patients and has been reported to occur in 1% to 15% of patients.3-5 In particular, skin lesions on the leg presenting as tender erythematous nodules and patches are often diagnosed as EN, which is relatively common. In our case, we initially suspected EN due to the rare presentation of MCD and lack of specific clinical features; however, the skin biopsy revealed noncaseating granulomas in the mid to deep dermis and subcutis consistent with MCD.

Metastatic Crohn disease is a rare disease entity and is characterized by the presence of noncaseating granulomas of the skin at sites separated from the GI tract by normal tissue.1 Although its pathogenesis is unclear, it has been suggested that immune complexes deposited in the skin could be responsible for the granulomatous reactions.4 A T lymphocyte–mediated type IV hypersensitivity reaction also could be responsible.6,7 Because antimicrobial therapy can be curative for infection-related MCD, special histologic stains and/or tissue cultures can help to exclude an infectious etiology.8

Clinical presentations of MCD vary greatly, with observations such as single or multiple erythematous swellings, papules, plaques, nodules, abscesses, and ulcers.1,2 The relationship between these clinical presentations and the intestinal activity of CD still is unknown; in some cases, however, the metastatic granulomatous lesions and the bowel disease show comparable severity.2,9,10 In a review of the literature, MCD was generally reported to present in the genital area in children. In adults, lesions most frequently present in the genital area, followed by ulcers on the arms and legs.1,2 These variations in clinical features and location resemble benign or infectious disease and can lead to delays in diagnosis.

Histopathologically, MCD lesions usually are ill-defined noncaseating granulomas with numerous multinucleated giant cells and lymphomononuclear cells located mostly in the dermis and occasionally extending into the subcutis. The cutaneous granulomata are similar to those present in the affected GI tract. Lymphocytes and plasma cells also are commonly present and eosinophils can be prominent.1,2,11 In some cases of MCD, granulomatous vasculitis of small- to medium-sized vessels can be found and is associated with dermal and subcutaneous granulomatous inflammation.8,11,12 Misago and Narisawa13 suggested that granulomatous vasculitis and panniculitis associated with CD is considered to be a rare subtype of MCD. Few cases of MCD presenting as granulomatous panniculitis have been described in the literature.14-16 Our patient presented with lesions that clinically resembled EN; however, the biopsy was more consistent with MCD. The Table summarizes the distinguishing clinical and histopathological features of MCD in our case and classic EN.

Although some authors believe that MCD is not related to CD activity, others assert that MCD lesions may parallel GI activity.1,2 Our patient was treated with systemic corticosteroids, oral metronidazole, and mesalamine to control the GI symptoms associated with CD. Four weeks after treatment, the GI symptoms and skin lesions improved simultaneously without any additional dermatologic treatment. We believe that MCD has the potential to serve as an early marker of the recurrence of CD and can help with the early diagnosis of CD aggravation, though an association between MCD and CD activity has not been confirmed.

Conclusion

We reported a case of MCD that was clinically reminiscent of unilateral EN and associated with GI disease activity. Physicians should be aware of the possibility of skin manifestations in CD, especially when erythematous nodular lesions are present on the leg.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. Mckee’s Pathology of the Skin: With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2012.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Sonia F, Richard SB. Inflammatory bowel disease. In: Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 16th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005:1776-1789.

- Burgdorf W. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:689-695.

- Crowson AN, Nuovo GJ, Mihm MC Jr, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease, its spectrum, and its pathogenesis: intracellular consensus bacterial 16S rRNA is associated with the gastrointestinal but not the cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1185-1192.

- Tatnall FM, Dodd HJ, Sarkany I. Crohn’s disease with metastatic cutaneous involvement and granulomatous cheilitis. J R Soc Med. 1987;80:49-51.

- Shum DT, Guenther L. Metastatic Crohn’s disease. case report and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:645-648.

- Emanuel PO, Phelps RG. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a histopathologic study of 12 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:457-461.

- Chalvardjian A, Nethercott JR. Cutaneous granulomatous vasculitis associated with Crohn’s disease. Cutis. 1982;30:645-655.

- Lebwohl M, Fleischmajer R, Janowitz H, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:33-38.

- Sabat M, Leulmo J, Saez A. Cutaneous granulomatous vasculitis in metastatic Crohn’s disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:652-653.

- Burns AM, Walsh N, Green PJ. Granulomatous vasculitis in Crohn’s disease: a clinicopathologic correlate of two unusual cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1077-1083.

- Misago N, Narisawa Y. Erythema induratum (nodular vasculitis) associated with Crohn’s disease: a rare type of metastatic Crohn’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:325-329.

- Liebermann TR, Greene JF Jr. Transient subcutaneous granulomatosis of the upper extremities in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1979;72:89-91.

- Levine N, Bangert J. Cutaneous granulomatosis in Crohn’s disease. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:1006-1009.

- Hackzell-Bradley M, Hedblad MA, Stephansson EA. Metastatic Crohn’s disease. report of 3 cases with special reference to histopathologic findings. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:928-932.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. Mckee’s Pathology of the Skin: With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2012.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Sonia F, Richard SB. Inflammatory bowel disease. In: Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 16th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005:1776-1789.

- Burgdorf W. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:689-695.

- Crowson AN, Nuovo GJ, Mihm MC Jr, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease, its spectrum, and its pathogenesis: intracellular consensus bacterial 16S rRNA is associated with the gastrointestinal but not the cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1185-1192.

- Tatnall FM, Dodd HJ, Sarkany I. Crohn’s disease with metastatic cutaneous involvement and granulomatous cheilitis. J R Soc Med. 1987;80:49-51.

- Shum DT, Guenther L. Metastatic Crohn’s disease. case report and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:645-648.

- Emanuel PO, Phelps RG. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a histopathologic study of 12 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:457-461.

- Chalvardjian A, Nethercott JR. Cutaneous granulomatous vasculitis associated with Crohn’s disease. Cutis. 1982;30:645-655.

- Lebwohl M, Fleischmajer R, Janowitz H, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:33-38.

- Sabat M, Leulmo J, Saez A. Cutaneous granulomatous vasculitis in metastatic Crohn’s disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:652-653.

- Burns AM, Walsh N, Green PJ. Granulomatous vasculitis in Crohn’s disease: a clinicopathologic correlate of two unusual cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1077-1083.

- Misago N, Narisawa Y. Erythema induratum (nodular vasculitis) associated with Crohn’s disease: a rare type of metastatic Crohn’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:325-329.

- Liebermann TR, Greene JF Jr. Transient subcutaneous granulomatosis of the upper extremities in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1979;72:89-91.

- Levine N, Bangert J. Cutaneous granulomatosis in Crohn’s disease. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:1006-1009.

- Hackzell-Bradley M, Hedblad MA, Stephansson EA. Metastatic Crohn’s disease. report of 3 cases with special reference to histopathologic findings. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:928-932.

Practice Points

- Metastatic Crohn disease (MCD) may be an initial sign indicating the aggravation of intestinal Crohn disease (CD).

- Metastatic Crohn disease on the legs could be clinically reminiscent of erythema nodosum (EN).

- Physicians should be aware of the possibility of MCD when encountering EN-like lesions on the legs in a CD patient.

Should we pursue board certification in Mohs micrographic surgery?