User login

An Update on Neurotoxin Products and Administration Methods

The first botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was onabotulinumtoxinA in 1989 for the treatment of strabismus and blepharospasm. It was not until 1992, however, that the aesthetic benefits of BoNT were first reported in the medical literature by Carruthers and Carruthers,1 and a cosmetic indication was not approved by the FDA until 2002. Since that time, the popularity of BoNT products has grown rapidly with a nearly 6500% increase in popularity from 1997 to 2015 in addition to the introduction of a variety of new BoNT formulations to the market.2 It is estimated by the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery that there were at least 4,000,000 BoNT injections performed in 2015 alone, making it the most popular nonsurgical aesthetic procedure available.2 As the demand for minimally invasive cosmetic procedures continues to increase, we will continue to see the introduction of additional formulations of BoNT products as well as novel administration techniques and delivery devices. In this article, we provide an update on current and upcoming BoNT products and also review the literature on novel administration methods based on studies published from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2015.

Current Products

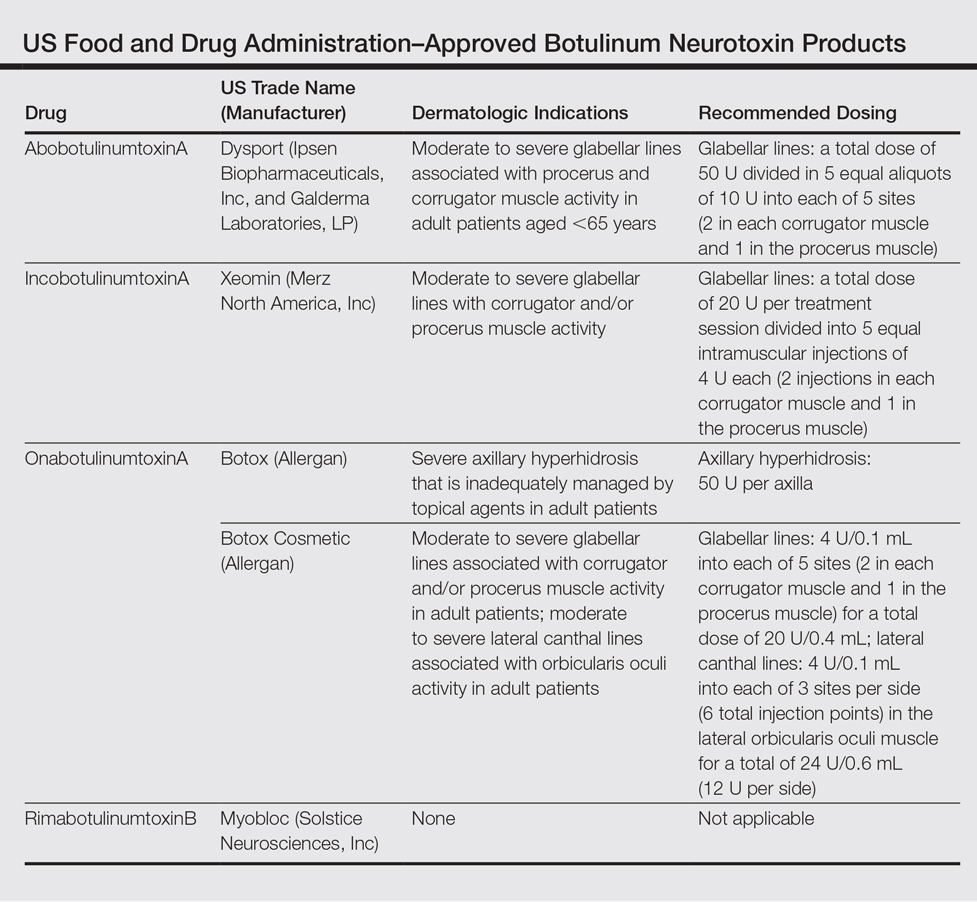

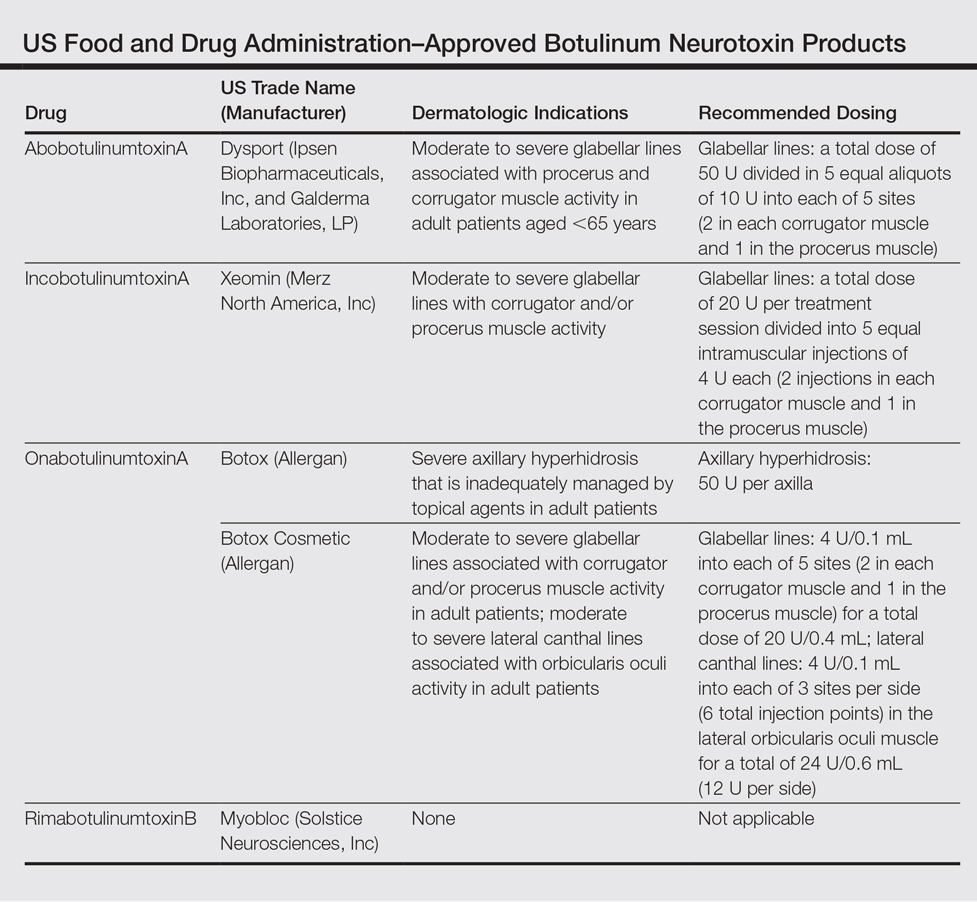

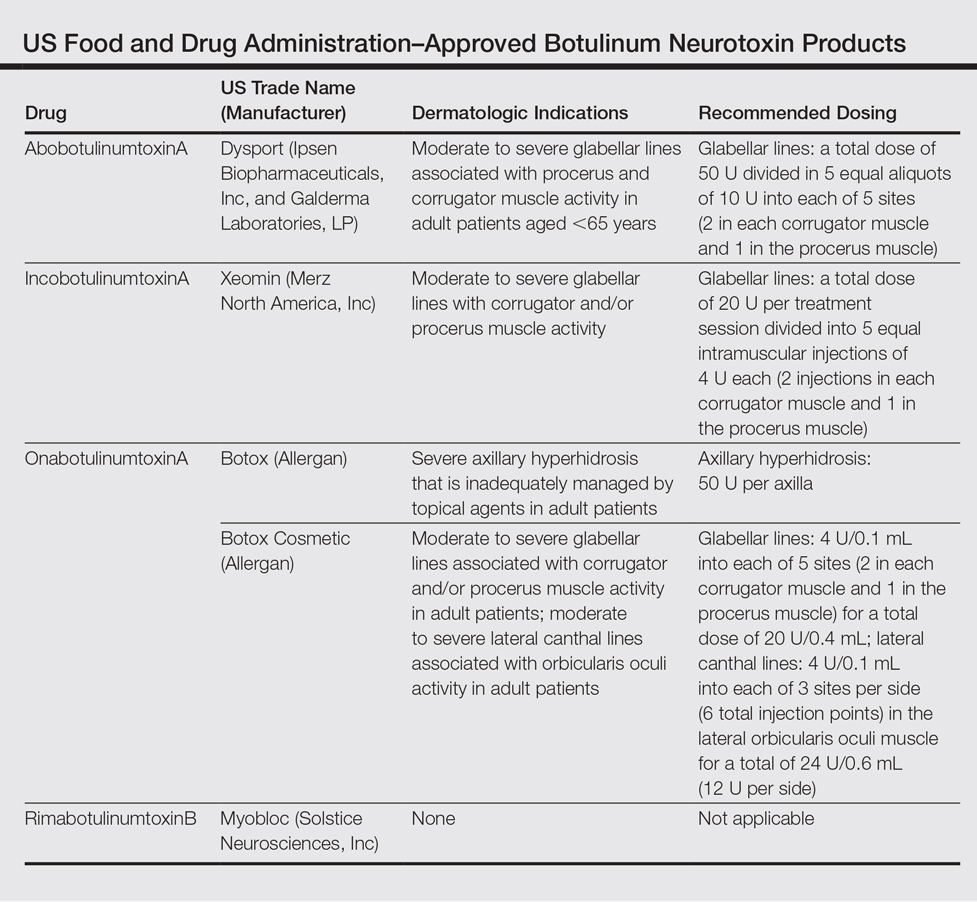

To date, there are only 4 FDA-approved formulations of BoNT available for clinical use (eg, cervical dystonia, strabismus, blepharospasm, headache, urinary incontinence) in the United States: abobotulinumtoxinA, incobotulinumtoxinA, onabotulinumtoxinA, and rimabotulinumtoxinB.The FDA-approved dermatologic indications (eg, moderate to severe glabellar or canthal lines, severe axillary hyperhidrosis) for these products are provided in the Table. On a global scale, there are several other commonly utilized formulations of BoNT, including a Korean serotype resembling onabotulinumtoxinA and a Chinese botulinum toxin type A.3 Although there is some evidence to demonstrate comparable efficacy and safety of these latter products, the literature is relatively lacking in comparison to the FDA-approved products.4,5

Upcoming Products

Currently, there are several new BoNT formulations being studied for clinical use. RT 002 (Revance Therapeutics, Inc) is a novel injectable formulation of onabotulinumtoxinA that consists of the purified neurotoxin in combination with patented TransMTS peptides that have been shown to provide high-binding avidity for the neurotoxin, and thus the product is designed to reduce diffusion to adjacent muscles and diminish unwanted effects. With a reduced level of neurotoxin dissemination, it is theorized that a higher administration of targeted doses can be injected, which may lead to a longer duration of desired effects.6 A clinical pilot study done to establish the safety and efficacy of RT 002 for treatment of moderate to severe glabellar lines evaluated 4 equally sized cohorts of 12 participants, each receiving single-dose administration of RT 002 ranging in potency equivalent to 25 U, 50 U, 75 U, and 100 U of abobotulinumtoxinA as determined by the gelatin phosphate method.6 It was concluded that RT 002 is both safe and efficacious with an extended duration of action, with a median duration of effect of 7 months observed in the highest dose group (dose equivalent to 100 U of abobotulinumtoxinA). Notably, 80% of all 48 participants maintained a minimum 1-point improvement in investigator-determined glabellar line severity scores at the 6-month time point and 60% achieved wrinkle scores of none or mild at 6 months posttreatment.6

DWP 450 (Daewoong Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd) is derived from the wild-type Clostridium botulinum and is reported to be of higher purity than standard onabotulinumtoxinA. An initial 16-week pilot study demonstrated that 20 U of DWP 450 is noninferior and of comparable efficacy and safety to 20 U of onabotulinumtoxinA in the treatment of glabellar lines.7

NTC (Botulax [Hugel, Inc]) is the name of the toxin derived from the C botulinum strain CBFC26, which has already been approved in many Asian, European, and Latin American countries for the treatment of blepharospasm. This formulation has demonstrated noninferiority to onabotulinumtoxinA at equivalent 20-U doses for the treatment of moderate to severe glabellar lines in a double-blind, randomized, multicenter, phase 3 trial of 272 participants with a 16-week follow-up.8

MT 10109L (Medytox Inc) is a unique product in that it is distributed as a liquid type A botulinum toxin rather than the standard freeze-dried formulation; thus, a major advantage of this product is its convenience, as it does not need reconstitution or dilution prior to administration. In a double-blind, randomized, active drug–controlled, phase 3 study of 168 participants, it was determined that MT 10109L (20 U) is comparable in efficacy to onabotulinumtoxinA (20 U) for the treatment of moderate to severe glabellar lines. No significant difference was seen between the 2 treatment groups when glabellar lines were assessed at rest at 4 and 16 weeks after treatment, but a significantly greater improvement in glabellar lines was seen at maximum frown in the MT 10109L group at the 16-week follow-up (P=.0064).9

Administration Techniques

With regard to safe and effective BoNT product administration techniques, a variety of studies have provided insight into optimal practice methods. A 2015 expert consensus statement formed by an American Society for Dermatologic Surgery task force reviewed data from 42 papers and unanimously determined that for all current type A BoNT products available in the United States, a vial of BoNT reconstituted appropriately for the purpose of facial injections can be reconstituted at least 4 weeks prior to administration without contamination risk or decrease in efficacy and that multiple patients can be treated with the same vial.Although the statement was not explicit on whether or not preserved or unpreserved saline is to be used, it is considered routine practice to use preservative-containing saline to reconstitute BoNT, as it has been shown to reduce patient discomfort and is not associated with adverse effects.10

Pain Minimization

With respect to minimizing the pain associated with BoNT injections, several studies have assessed administration techniques to minimize patient discomfort. A split-face, double-blind study of 20 participants demonstrated that the use of a 32-gauge needle has a significantly greater chance of reducing clinically significant levels of pain as compared to a 30-gauge needle when performing facial injections (P=.04). Overall, however, injections of the face and arms were on average only nominally and not significantly more painful with 30-gauge needles compared to 32-gauge needles.11

Another technique that has been found to reduce patient discomfort is the application of cold packs prior to injection. A study of patients with chronic facial palsy observed a significant reduction in pain with the administration of a cold (3°C–5°C) gel pack for 1 minute compared to a room temperature (20°C) gel pack prior to the administration of onabotulinumtoxinA into the platysma (P<.001).12 In the matter of injection with rimabotulinumtoxinB, which has been shown to be considerably more painful to receive than its more popularly administered counterpart onabotulinumtoxinA, a split-face pilot study examined the effect of increasing the pH of rimabotulinumtoxinB to 7.5 with sodium bicarbonate from the usual pH of 5.6.13,14 Pain was reported to be considerably less in the higher pH group and no reduction of efficacy was seen over the 10-week follow-up period.14

Delivery Methods

Several preliminary studies also have examined novel delivery techniques to identify minimally painful yet effective methods for administering BoNT. It has been reported that standard BoNT formulations are not effective as topical agents in a comparison study in which onabotulinumtoxinA injection was compared to topically applied onabotulinumtoxinA.15 However, a follow-up prospective study by the same authors has demonstrated efficacy of topical onabotulinumtoxinA following pretreatment with a fractional ablative CO2 laser for treatment of crow’s-feet. In this randomized, split-face, controlled trial (N=10), participants were first pretreated with topical lidocaine 30% before receiving a single pass of fractional ablative CO2 laser with no overlap and a pulse energy of 100 mJ. Within 60 seconds of laser treatment, participants then received either 100 U of abobotulinumtoxinA diluted in 0.1 mL of saline or simple normal saline applied topically. A clinically significant improvement in periorbital wrinkles was seen both at 1-week and 1-month posttreatment in the laser and onabotulinumtoxinA–treated group compared to the laser and topical saline–treated group (P<.02).15

Another unique administration method studied, albeit with less successful results, involves the use of iontophoresis to deliver BoNT painlessly in a transdermal fashion with the assistance of an electrical current.16 This prospective, randomized, assessor-blinded, split-axilla, controlled trial of 11 participants compared the effectiveness of administering onabotulinumtoxinA via iontophoresis to traditional injection with onabotulinumtoxinA (250 U). Iontophoresis was accomplished with a single electrode pad soaked with 250 U of onabotulinumtoxinA applied directly to the axilla and a second electrode pad soaked in 0.9% saline applied to the hand to complete the circuit. An alternating electrical current was slowly increased for 30 minutes to a maximum current of 15 mA with a voltage of 12 V. Among the 11 participants recruited, the side treated with traditional injection showed a significantly greater percentage reduction in baseline sweating at the 1-week, 1-month, and 6-month posttreatment evaluations compared to iontophoresis (84%, 76%, and 50%, respectively vs 73%, 22%, and 32%, respectively)(P<.05). Despite being less efficacious than standard injection therapy, participants reported that iontophoresis delivery was significantly less painful (P<.05).16

A high-pressure oxygen delivery device, which utilizes a powerful jet of microdroplets containing water, the drug, air, and oxygen to deliver medication onto the skin surface, also has been studied as a means of delivery of BoNT in a minimally painful manner. In this study, the device was used to assess the efficacy of transdermal delivery of BoNT via jet nebulization in the treatment of primary palmar, plantar, and axillary hyperhidrosis.17 The 20 participants included in the study were randomized to receive either a combination of lidocaine and onabotulinumtoxinA (50 U) administered through the device or lidocaine delivered through the device followed by multiple transcutaneous injections of onabotulinumtoxinA (100 U). Both treatments significantly reduced sweating compared to baseline as measured by a visual analogue scale at 3-month follow-up (P<.001), but the combination delivery of lidocaine and onabotulinumtoxinA via the device resulted in significantly less procedure-related pain and sweating (P<.001) as well as significantly greater patient satisfaction (P<.001).17

Optimizing Aesthetic Outcomes

A frequent concern of patients receiving BoNT for cosmetic purposes is a desire to avoid a “frozen” or expressionless look. As such, many clinicians have attempted a variety of techniques to achieve more natural aesthetic results. One such method is known as the multipoint and multilevel injection technique, which consists of utilizing multiple injection sites at varying depths (intramuscular, subcutaneous, or intradermal) and doses (2–6 U) depending on the degree of contractility of the targeted muscle. In a preliminary study of 223 participants using this technique with a total dose of 125 U of abobotulinumtoxinA, good and natural results were reported with perseveration of facial emotion in all participants in addition to a mean overall satisfaction rate of 6.4 of 7 on the Facial Line Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire with the maximum satisfaction rating possible reported in 66% of cases.18 It also has been postulated that injection depth of BoNT can affect brow elevation whereupon deeper injection depths can result in inactivation of the brow depressors and allow for increased elevation of the eyebrows. This technique has been applied in attempts to correct brow height asymmetry. However, a prospective, split-face study of 23 women suggested that this method is not effective.19 Participants received 64 U of onabotulinumtoxinA via 16 injection sites in the glabella, forehead, and lateral canthal area with either all deep or all shallow injections depending on the side treated and whether brow-lift was desired. Results at 4 weeks posttreatment showed no significant difference in brow height, and it was concluded that eyebrow depressor muscles cannot be accurately targeted with deep injection into the muscle belly for correction of eyebrow height discrepancies.19 Conversely, a 5-year retrospective, nonrandomized study of 227 patients with 563 treatments utilizing a “microdroplet” technique reported success at selectively targeting the eyebrow depressors while leaving the brow elevators unaffected.20 Here, a total dose of 33 U of onabotulinumtoxinA was administered via microdroplets of 10 to 20 μL, each with more than 60 to 100 injections into the brow, glabella, and crow’s-feet area. This method of injection resulted in a statistically significant improvement of forehead lines and brow ptosis and furrowing at follow-up between 10 and 45 days after treatment (P<.0001). Additionally, average brow height was significantly increased from 24.6 mm to 25 mm after treatment (P=.02).20

Conclusion

The use of BoNT products for both on- and off-label cosmetic and medical indications has rapidly grown over the past 2 decades. As demonstrated in this review, a variety of promising new products and delivery techniques are being developed. Given the rise in popularity of BoNT products among both physicians and consumers, clinicians should be aware of the current data and ongoing research.

- Carruthers JD, Carruthers JA. Treatment of glabellar frown lines with C. botulinum-A exotoxin. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:17-21.

- American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank statistics. American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery website. http://www.surgery.org/sites/default/files/ASAPS-Stats2015.pdf. Accessed June 12, 2016.

- Walker TJ, Dayan SH. Comparison and overview of currently available neurotoxins. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:31-39.

- Feng Z, Sun Q, He L, et al. Optimal dosage of botulinum toxin type A for treatment of glabellar frown lines: efficacy and safety in a clinical trial. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 1):S56-S63.

- Jiang HY, Chen S, Zhou J, et al. Diffusion of two botulinum toxins type A on the forehead: double-blinded, randomized, controlled study. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:184-192.

- Garcia-Murray E, Velasco Villasenor ML, Acevedo B, et al. Safety and efficacy of RT002, an injectable botulinum toxin type A, for treating glabellar lines: results of a phase 1/2, open-label, sequential dose-escalation study. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 1):S47-S55.

- Won CH, Kim HK, Kim BJ, et al. Comparative trial of a novel botulinum neurotoxin type A versus onabotulinumtoxinA in the treatment of glabellar lines: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, active-controlled study. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:227-234.

- Kim BJ, Kwon HH, Park SY, et al. Double-blind, randomized non-inferiority trial of a novel botulinum toxin A processed from the strain CBFC26, compared with onabotulinumtoxin A in the treatment of glabellar lines. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1761-1767.

- Kim JE, Song EJ, Choi GS, et al. The efficacy and safety of liquid-type botulinum toxin type A for the management of moderate to severe glabellar frown lines. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135:732-741.

- Alam M, Bolotin D, Carruthers J, et al. Consensus statement regarding storage and reuse of previously reconstituted neuromodulators. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:321-326.

- Alam M, Geisler A, Sadhwani D, et al. Effect of needle size on pain perception in patients treated with botulinum toxin type A injections: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1194-1199.

- Pucks N, Thomas A, Hallam MJ, et al. Cutaneous cooling to manage botulinum toxin injection-associated pain in patients with facial palsy: a randomised controlled trial. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015;68:1701-1705.

- Kranz G, Sycha T, Voller B, et al. Pain sensation during intradermal injections of three different botulinum toxin preparations in different doses and dilutions. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:886-890.

- Lowe PL, Lowe NJ. Botulinum toxin type B: pH change reduces injection pain, retains efficacy. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1328-1333.

- Mahmoud BH, Burnett C, Ozog D. Prospective randomized controlled study to determine the effect of topical application of botulinum toxin A for crow’s feet after treatment with ablative fractional CO2 laser. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 1):S75-S81.

- Montaser-Kouhsari L, Zartab H, Fanian F, et al. Comparison of intradermal injection with iontophoresis of abo-botulinum toxin A for the treatment of primary axillary hyperhidrosis: a randomized, controlled trial. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014;25:337-341.

- Iannitti T, Palmieri B, Aspiro A, et al. A preliminary study of painless and effective transdermal botulinum toxin A delivery by jet nebulization for treatment of primary hyperhidrosis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:931-935.

- Iozzo I, Tengattini V, Antonucci VA. Multipoint and multilevel injection technique of botulinum toxin A in facial aesthetics. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2014;13:135-142.

- Sneath J, Humphrey S, Carruthers A, et al. Injecting botulinum toxin at different depths is not effective for the correction of eyebrow asymmetry. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 1):S82-S87.

- Steinsapir KD, Rootman D, Wulc A, et al. Cosmetic microdroplet botulinum toxin A forehead lift: a new treatment paradigm. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;31:263-268.

The first botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was onabotulinumtoxinA in 1989 for the treatment of strabismus and blepharospasm. It was not until 1992, however, that the aesthetic benefits of BoNT were first reported in the medical literature by Carruthers and Carruthers,1 and a cosmetic indication was not approved by the FDA until 2002. Since that time, the popularity of BoNT products has grown rapidly with a nearly 6500% increase in popularity from 1997 to 2015 in addition to the introduction of a variety of new BoNT formulations to the market.2 It is estimated by the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery that there were at least 4,000,000 BoNT injections performed in 2015 alone, making it the most popular nonsurgical aesthetic procedure available.2 As the demand for minimally invasive cosmetic procedures continues to increase, we will continue to see the introduction of additional formulations of BoNT products as well as novel administration techniques and delivery devices. In this article, we provide an update on current and upcoming BoNT products and also review the literature on novel administration methods based on studies published from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2015.

Current Products

To date, there are only 4 FDA-approved formulations of BoNT available for clinical use (eg, cervical dystonia, strabismus, blepharospasm, headache, urinary incontinence) in the United States: abobotulinumtoxinA, incobotulinumtoxinA, onabotulinumtoxinA, and rimabotulinumtoxinB.The FDA-approved dermatologic indications (eg, moderate to severe glabellar or canthal lines, severe axillary hyperhidrosis) for these products are provided in the Table. On a global scale, there are several other commonly utilized formulations of BoNT, including a Korean serotype resembling onabotulinumtoxinA and a Chinese botulinum toxin type A.3 Although there is some evidence to demonstrate comparable efficacy and safety of these latter products, the literature is relatively lacking in comparison to the FDA-approved products.4,5

Upcoming Products

Currently, there are several new BoNT formulations being studied for clinical use. RT 002 (Revance Therapeutics, Inc) is a novel injectable formulation of onabotulinumtoxinA that consists of the purified neurotoxin in combination with patented TransMTS peptides that have been shown to provide high-binding avidity for the neurotoxin, and thus the product is designed to reduce diffusion to adjacent muscles and diminish unwanted effects. With a reduced level of neurotoxin dissemination, it is theorized that a higher administration of targeted doses can be injected, which may lead to a longer duration of desired effects.6 A clinical pilot study done to establish the safety and efficacy of RT 002 for treatment of moderate to severe glabellar lines evaluated 4 equally sized cohorts of 12 participants, each receiving single-dose administration of RT 002 ranging in potency equivalent to 25 U, 50 U, 75 U, and 100 U of abobotulinumtoxinA as determined by the gelatin phosphate method.6 It was concluded that RT 002 is both safe and efficacious with an extended duration of action, with a median duration of effect of 7 months observed in the highest dose group (dose equivalent to 100 U of abobotulinumtoxinA). Notably, 80% of all 48 participants maintained a minimum 1-point improvement in investigator-determined glabellar line severity scores at the 6-month time point and 60% achieved wrinkle scores of none or mild at 6 months posttreatment.6

DWP 450 (Daewoong Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd) is derived from the wild-type Clostridium botulinum and is reported to be of higher purity than standard onabotulinumtoxinA. An initial 16-week pilot study demonstrated that 20 U of DWP 450 is noninferior and of comparable efficacy and safety to 20 U of onabotulinumtoxinA in the treatment of glabellar lines.7

NTC (Botulax [Hugel, Inc]) is the name of the toxin derived from the C botulinum strain CBFC26, which has already been approved in many Asian, European, and Latin American countries for the treatment of blepharospasm. This formulation has demonstrated noninferiority to onabotulinumtoxinA at equivalent 20-U doses for the treatment of moderate to severe glabellar lines in a double-blind, randomized, multicenter, phase 3 trial of 272 participants with a 16-week follow-up.8

MT 10109L (Medytox Inc) is a unique product in that it is distributed as a liquid type A botulinum toxin rather than the standard freeze-dried formulation; thus, a major advantage of this product is its convenience, as it does not need reconstitution or dilution prior to administration. In a double-blind, randomized, active drug–controlled, phase 3 study of 168 participants, it was determined that MT 10109L (20 U) is comparable in efficacy to onabotulinumtoxinA (20 U) for the treatment of moderate to severe glabellar lines. No significant difference was seen between the 2 treatment groups when glabellar lines were assessed at rest at 4 and 16 weeks after treatment, but a significantly greater improvement in glabellar lines was seen at maximum frown in the MT 10109L group at the 16-week follow-up (P=.0064).9

Administration Techniques

With regard to safe and effective BoNT product administration techniques, a variety of studies have provided insight into optimal practice methods. A 2015 expert consensus statement formed by an American Society for Dermatologic Surgery task force reviewed data from 42 papers and unanimously determined that for all current type A BoNT products available in the United States, a vial of BoNT reconstituted appropriately for the purpose of facial injections can be reconstituted at least 4 weeks prior to administration without contamination risk or decrease in efficacy and that multiple patients can be treated with the same vial.Although the statement was not explicit on whether or not preserved or unpreserved saline is to be used, it is considered routine practice to use preservative-containing saline to reconstitute BoNT, as it has been shown to reduce patient discomfort and is not associated with adverse effects.10

Pain Minimization

With respect to minimizing the pain associated with BoNT injections, several studies have assessed administration techniques to minimize patient discomfort. A split-face, double-blind study of 20 participants demonstrated that the use of a 32-gauge needle has a significantly greater chance of reducing clinically significant levels of pain as compared to a 30-gauge needle when performing facial injections (P=.04). Overall, however, injections of the face and arms were on average only nominally and not significantly more painful with 30-gauge needles compared to 32-gauge needles.11

Another technique that has been found to reduce patient discomfort is the application of cold packs prior to injection. A study of patients with chronic facial palsy observed a significant reduction in pain with the administration of a cold (3°C–5°C) gel pack for 1 minute compared to a room temperature (20°C) gel pack prior to the administration of onabotulinumtoxinA into the platysma (P<.001).12 In the matter of injection with rimabotulinumtoxinB, which has been shown to be considerably more painful to receive than its more popularly administered counterpart onabotulinumtoxinA, a split-face pilot study examined the effect of increasing the pH of rimabotulinumtoxinB to 7.5 with sodium bicarbonate from the usual pH of 5.6.13,14 Pain was reported to be considerably less in the higher pH group and no reduction of efficacy was seen over the 10-week follow-up period.14

Delivery Methods

Several preliminary studies also have examined novel delivery techniques to identify minimally painful yet effective methods for administering BoNT. It has been reported that standard BoNT formulations are not effective as topical agents in a comparison study in which onabotulinumtoxinA injection was compared to topically applied onabotulinumtoxinA.15 However, a follow-up prospective study by the same authors has demonstrated efficacy of topical onabotulinumtoxinA following pretreatment with a fractional ablative CO2 laser for treatment of crow’s-feet. In this randomized, split-face, controlled trial (N=10), participants were first pretreated with topical lidocaine 30% before receiving a single pass of fractional ablative CO2 laser with no overlap and a pulse energy of 100 mJ. Within 60 seconds of laser treatment, participants then received either 100 U of abobotulinumtoxinA diluted in 0.1 mL of saline or simple normal saline applied topically. A clinically significant improvement in periorbital wrinkles was seen both at 1-week and 1-month posttreatment in the laser and onabotulinumtoxinA–treated group compared to the laser and topical saline–treated group (P<.02).15

Another unique administration method studied, albeit with less successful results, involves the use of iontophoresis to deliver BoNT painlessly in a transdermal fashion with the assistance of an electrical current.16 This prospective, randomized, assessor-blinded, split-axilla, controlled trial of 11 participants compared the effectiveness of administering onabotulinumtoxinA via iontophoresis to traditional injection with onabotulinumtoxinA (250 U). Iontophoresis was accomplished with a single electrode pad soaked with 250 U of onabotulinumtoxinA applied directly to the axilla and a second electrode pad soaked in 0.9% saline applied to the hand to complete the circuit. An alternating electrical current was slowly increased for 30 minutes to a maximum current of 15 mA with a voltage of 12 V. Among the 11 participants recruited, the side treated with traditional injection showed a significantly greater percentage reduction in baseline sweating at the 1-week, 1-month, and 6-month posttreatment evaluations compared to iontophoresis (84%, 76%, and 50%, respectively vs 73%, 22%, and 32%, respectively)(P<.05). Despite being less efficacious than standard injection therapy, participants reported that iontophoresis delivery was significantly less painful (P<.05).16

A high-pressure oxygen delivery device, which utilizes a powerful jet of microdroplets containing water, the drug, air, and oxygen to deliver medication onto the skin surface, also has been studied as a means of delivery of BoNT in a minimally painful manner. In this study, the device was used to assess the efficacy of transdermal delivery of BoNT via jet nebulization in the treatment of primary palmar, plantar, and axillary hyperhidrosis.17 The 20 participants included in the study were randomized to receive either a combination of lidocaine and onabotulinumtoxinA (50 U) administered through the device or lidocaine delivered through the device followed by multiple transcutaneous injections of onabotulinumtoxinA (100 U). Both treatments significantly reduced sweating compared to baseline as measured by a visual analogue scale at 3-month follow-up (P<.001), but the combination delivery of lidocaine and onabotulinumtoxinA via the device resulted in significantly less procedure-related pain and sweating (P<.001) as well as significantly greater patient satisfaction (P<.001).17

Optimizing Aesthetic Outcomes

A frequent concern of patients receiving BoNT for cosmetic purposes is a desire to avoid a “frozen” or expressionless look. As such, many clinicians have attempted a variety of techniques to achieve more natural aesthetic results. One such method is known as the multipoint and multilevel injection technique, which consists of utilizing multiple injection sites at varying depths (intramuscular, subcutaneous, or intradermal) and doses (2–6 U) depending on the degree of contractility of the targeted muscle. In a preliminary study of 223 participants using this technique with a total dose of 125 U of abobotulinumtoxinA, good and natural results were reported with perseveration of facial emotion in all participants in addition to a mean overall satisfaction rate of 6.4 of 7 on the Facial Line Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire with the maximum satisfaction rating possible reported in 66% of cases.18 It also has been postulated that injection depth of BoNT can affect brow elevation whereupon deeper injection depths can result in inactivation of the brow depressors and allow for increased elevation of the eyebrows. This technique has been applied in attempts to correct brow height asymmetry. However, a prospective, split-face study of 23 women suggested that this method is not effective.19 Participants received 64 U of onabotulinumtoxinA via 16 injection sites in the glabella, forehead, and lateral canthal area with either all deep or all shallow injections depending on the side treated and whether brow-lift was desired. Results at 4 weeks posttreatment showed no significant difference in brow height, and it was concluded that eyebrow depressor muscles cannot be accurately targeted with deep injection into the muscle belly for correction of eyebrow height discrepancies.19 Conversely, a 5-year retrospective, nonrandomized study of 227 patients with 563 treatments utilizing a “microdroplet” technique reported success at selectively targeting the eyebrow depressors while leaving the brow elevators unaffected.20 Here, a total dose of 33 U of onabotulinumtoxinA was administered via microdroplets of 10 to 20 μL, each with more than 60 to 100 injections into the brow, glabella, and crow’s-feet area. This method of injection resulted in a statistically significant improvement of forehead lines and brow ptosis and furrowing at follow-up between 10 and 45 days after treatment (P<.0001). Additionally, average brow height was significantly increased from 24.6 mm to 25 mm after treatment (P=.02).20

Conclusion

The use of BoNT products for both on- and off-label cosmetic and medical indications has rapidly grown over the past 2 decades. As demonstrated in this review, a variety of promising new products and delivery techniques are being developed. Given the rise in popularity of BoNT products among both physicians and consumers, clinicians should be aware of the current data and ongoing research.

The first botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was onabotulinumtoxinA in 1989 for the treatment of strabismus and blepharospasm. It was not until 1992, however, that the aesthetic benefits of BoNT were first reported in the medical literature by Carruthers and Carruthers,1 and a cosmetic indication was not approved by the FDA until 2002. Since that time, the popularity of BoNT products has grown rapidly with a nearly 6500% increase in popularity from 1997 to 2015 in addition to the introduction of a variety of new BoNT formulations to the market.2 It is estimated by the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery that there were at least 4,000,000 BoNT injections performed in 2015 alone, making it the most popular nonsurgical aesthetic procedure available.2 As the demand for minimally invasive cosmetic procedures continues to increase, we will continue to see the introduction of additional formulations of BoNT products as well as novel administration techniques and delivery devices. In this article, we provide an update on current and upcoming BoNT products and also review the literature on novel administration methods based on studies published from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2015.

Current Products

To date, there are only 4 FDA-approved formulations of BoNT available for clinical use (eg, cervical dystonia, strabismus, blepharospasm, headache, urinary incontinence) in the United States: abobotulinumtoxinA, incobotulinumtoxinA, onabotulinumtoxinA, and rimabotulinumtoxinB.The FDA-approved dermatologic indications (eg, moderate to severe glabellar or canthal lines, severe axillary hyperhidrosis) for these products are provided in the Table. On a global scale, there are several other commonly utilized formulations of BoNT, including a Korean serotype resembling onabotulinumtoxinA and a Chinese botulinum toxin type A.3 Although there is some evidence to demonstrate comparable efficacy and safety of these latter products, the literature is relatively lacking in comparison to the FDA-approved products.4,5

Upcoming Products

Currently, there are several new BoNT formulations being studied for clinical use. RT 002 (Revance Therapeutics, Inc) is a novel injectable formulation of onabotulinumtoxinA that consists of the purified neurotoxin in combination with patented TransMTS peptides that have been shown to provide high-binding avidity for the neurotoxin, and thus the product is designed to reduce diffusion to adjacent muscles and diminish unwanted effects. With a reduced level of neurotoxin dissemination, it is theorized that a higher administration of targeted doses can be injected, which may lead to a longer duration of desired effects.6 A clinical pilot study done to establish the safety and efficacy of RT 002 for treatment of moderate to severe glabellar lines evaluated 4 equally sized cohorts of 12 participants, each receiving single-dose administration of RT 002 ranging in potency equivalent to 25 U, 50 U, 75 U, and 100 U of abobotulinumtoxinA as determined by the gelatin phosphate method.6 It was concluded that RT 002 is both safe and efficacious with an extended duration of action, with a median duration of effect of 7 months observed in the highest dose group (dose equivalent to 100 U of abobotulinumtoxinA). Notably, 80% of all 48 participants maintained a minimum 1-point improvement in investigator-determined glabellar line severity scores at the 6-month time point and 60% achieved wrinkle scores of none or mild at 6 months posttreatment.6

DWP 450 (Daewoong Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd) is derived from the wild-type Clostridium botulinum and is reported to be of higher purity than standard onabotulinumtoxinA. An initial 16-week pilot study demonstrated that 20 U of DWP 450 is noninferior and of comparable efficacy and safety to 20 U of onabotulinumtoxinA in the treatment of glabellar lines.7

NTC (Botulax [Hugel, Inc]) is the name of the toxin derived from the C botulinum strain CBFC26, which has already been approved in many Asian, European, and Latin American countries for the treatment of blepharospasm. This formulation has demonstrated noninferiority to onabotulinumtoxinA at equivalent 20-U doses for the treatment of moderate to severe glabellar lines in a double-blind, randomized, multicenter, phase 3 trial of 272 participants with a 16-week follow-up.8

MT 10109L (Medytox Inc) is a unique product in that it is distributed as a liquid type A botulinum toxin rather than the standard freeze-dried formulation; thus, a major advantage of this product is its convenience, as it does not need reconstitution or dilution prior to administration. In a double-blind, randomized, active drug–controlled, phase 3 study of 168 participants, it was determined that MT 10109L (20 U) is comparable in efficacy to onabotulinumtoxinA (20 U) for the treatment of moderate to severe glabellar lines. No significant difference was seen between the 2 treatment groups when glabellar lines were assessed at rest at 4 and 16 weeks after treatment, but a significantly greater improvement in glabellar lines was seen at maximum frown in the MT 10109L group at the 16-week follow-up (P=.0064).9

Administration Techniques

With regard to safe and effective BoNT product administration techniques, a variety of studies have provided insight into optimal practice methods. A 2015 expert consensus statement formed by an American Society for Dermatologic Surgery task force reviewed data from 42 papers and unanimously determined that for all current type A BoNT products available in the United States, a vial of BoNT reconstituted appropriately for the purpose of facial injections can be reconstituted at least 4 weeks prior to administration without contamination risk or decrease in efficacy and that multiple patients can be treated with the same vial.Although the statement was not explicit on whether or not preserved or unpreserved saline is to be used, it is considered routine practice to use preservative-containing saline to reconstitute BoNT, as it has been shown to reduce patient discomfort and is not associated with adverse effects.10

Pain Minimization

With respect to minimizing the pain associated with BoNT injections, several studies have assessed administration techniques to minimize patient discomfort. A split-face, double-blind study of 20 participants demonstrated that the use of a 32-gauge needle has a significantly greater chance of reducing clinically significant levels of pain as compared to a 30-gauge needle when performing facial injections (P=.04). Overall, however, injections of the face and arms were on average only nominally and not significantly more painful with 30-gauge needles compared to 32-gauge needles.11

Another technique that has been found to reduce patient discomfort is the application of cold packs prior to injection. A study of patients with chronic facial palsy observed a significant reduction in pain with the administration of a cold (3°C–5°C) gel pack for 1 minute compared to a room temperature (20°C) gel pack prior to the administration of onabotulinumtoxinA into the platysma (P<.001).12 In the matter of injection with rimabotulinumtoxinB, which has been shown to be considerably more painful to receive than its more popularly administered counterpart onabotulinumtoxinA, a split-face pilot study examined the effect of increasing the pH of rimabotulinumtoxinB to 7.5 with sodium bicarbonate from the usual pH of 5.6.13,14 Pain was reported to be considerably less in the higher pH group and no reduction of efficacy was seen over the 10-week follow-up period.14

Delivery Methods

Several preliminary studies also have examined novel delivery techniques to identify minimally painful yet effective methods for administering BoNT. It has been reported that standard BoNT formulations are not effective as topical agents in a comparison study in which onabotulinumtoxinA injection was compared to topically applied onabotulinumtoxinA.15 However, a follow-up prospective study by the same authors has demonstrated efficacy of topical onabotulinumtoxinA following pretreatment with a fractional ablative CO2 laser for treatment of crow’s-feet. In this randomized, split-face, controlled trial (N=10), participants were first pretreated with topical lidocaine 30% before receiving a single pass of fractional ablative CO2 laser with no overlap and a pulse energy of 100 mJ. Within 60 seconds of laser treatment, participants then received either 100 U of abobotulinumtoxinA diluted in 0.1 mL of saline or simple normal saline applied topically. A clinically significant improvement in periorbital wrinkles was seen both at 1-week and 1-month posttreatment in the laser and onabotulinumtoxinA–treated group compared to the laser and topical saline–treated group (P<.02).15

Another unique administration method studied, albeit with less successful results, involves the use of iontophoresis to deliver BoNT painlessly in a transdermal fashion with the assistance of an electrical current.16 This prospective, randomized, assessor-blinded, split-axilla, controlled trial of 11 participants compared the effectiveness of administering onabotulinumtoxinA via iontophoresis to traditional injection with onabotulinumtoxinA (250 U). Iontophoresis was accomplished with a single electrode pad soaked with 250 U of onabotulinumtoxinA applied directly to the axilla and a second electrode pad soaked in 0.9% saline applied to the hand to complete the circuit. An alternating electrical current was slowly increased for 30 minutes to a maximum current of 15 mA with a voltage of 12 V. Among the 11 participants recruited, the side treated with traditional injection showed a significantly greater percentage reduction in baseline sweating at the 1-week, 1-month, and 6-month posttreatment evaluations compared to iontophoresis (84%, 76%, and 50%, respectively vs 73%, 22%, and 32%, respectively)(P<.05). Despite being less efficacious than standard injection therapy, participants reported that iontophoresis delivery was significantly less painful (P<.05).16

A high-pressure oxygen delivery device, which utilizes a powerful jet of microdroplets containing water, the drug, air, and oxygen to deliver medication onto the skin surface, also has been studied as a means of delivery of BoNT in a minimally painful manner. In this study, the device was used to assess the efficacy of transdermal delivery of BoNT via jet nebulization in the treatment of primary palmar, plantar, and axillary hyperhidrosis.17 The 20 participants included in the study were randomized to receive either a combination of lidocaine and onabotulinumtoxinA (50 U) administered through the device or lidocaine delivered through the device followed by multiple transcutaneous injections of onabotulinumtoxinA (100 U). Both treatments significantly reduced sweating compared to baseline as measured by a visual analogue scale at 3-month follow-up (P<.001), but the combination delivery of lidocaine and onabotulinumtoxinA via the device resulted in significantly less procedure-related pain and sweating (P<.001) as well as significantly greater patient satisfaction (P<.001).17

Optimizing Aesthetic Outcomes

A frequent concern of patients receiving BoNT for cosmetic purposes is a desire to avoid a “frozen” or expressionless look. As such, many clinicians have attempted a variety of techniques to achieve more natural aesthetic results. One such method is known as the multipoint and multilevel injection technique, which consists of utilizing multiple injection sites at varying depths (intramuscular, subcutaneous, or intradermal) and doses (2–6 U) depending on the degree of contractility of the targeted muscle. In a preliminary study of 223 participants using this technique with a total dose of 125 U of abobotulinumtoxinA, good and natural results were reported with perseveration of facial emotion in all participants in addition to a mean overall satisfaction rate of 6.4 of 7 on the Facial Line Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire with the maximum satisfaction rating possible reported in 66% of cases.18 It also has been postulated that injection depth of BoNT can affect brow elevation whereupon deeper injection depths can result in inactivation of the brow depressors and allow for increased elevation of the eyebrows. This technique has been applied in attempts to correct brow height asymmetry. However, a prospective, split-face study of 23 women suggested that this method is not effective.19 Participants received 64 U of onabotulinumtoxinA via 16 injection sites in the glabella, forehead, and lateral canthal area with either all deep or all shallow injections depending on the side treated and whether brow-lift was desired. Results at 4 weeks posttreatment showed no significant difference in brow height, and it was concluded that eyebrow depressor muscles cannot be accurately targeted with deep injection into the muscle belly for correction of eyebrow height discrepancies.19 Conversely, a 5-year retrospective, nonrandomized study of 227 patients with 563 treatments utilizing a “microdroplet” technique reported success at selectively targeting the eyebrow depressors while leaving the brow elevators unaffected.20 Here, a total dose of 33 U of onabotulinumtoxinA was administered via microdroplets of 10 to 20 μL, each with more than 60 to 100 injections into the brow, glabella, and crow’s-feet area. This method of injection resulted in a statistically significant improvement of forehead lines and brow ptosis and furrowing at follow-up between 10 and 45 days after treatment (P<.0001). Additionally, average brow height was significantly increased from 24.6 mm to 25 mm after treatment (P=.02).20

Conclusion

The use of BoNT products for both on- and off-label cosmetic and medical indications has rapidly grown over the past 2 decades. As demonstrated in this review, a variety of promising new products and delivery techniques are being developed. Given the rise in popularity of BoNT products among both physicians and consumers, clinicians should be aware of the current data and ongoing research.

- Carruthers JD, Carruthers JA. Treatment of glabellar frown lines with C. botulinum-A exotoxin. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:17-21.

- American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank statistics. American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery website. http://www.surgery.org/sites/default/files/ASAPS-Stats2015.pdf. Accessed June 12, 2016.

- Walker TJ, Dayan SH. Comparison and overview of currently available neurotoxins. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:31-39.

- Feng Z, Sun Q, He L, et al. Optimal dosage of botulinum toxin type A for treatment of glabellar frown lines: efficacy and safety in a clinical trial. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 1):S56-S63.

- Jiang HY, Chen S, Zhou J, et al. Diffusion of two botulinum toxins type A on the forehead: double-blinded, randomized, controlled study. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:184-192.

- Garcia-Murray E, Velasco Villasenor ML, Acevedo B, et al. Safety and efficacy of RT002, an injectable botulinum toxin type A, for treating glabellar lines: results of a phase 1/2, open-label, sequential dose-escalation study. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 1):S47-S55.

- Won CH, Kim HK, Kim BJ, et al. Comparative trial of a novel botulinum neurotoxin type A versus onabotulinumtoxinA in the treatment of glabellar lines: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, active-controlled study. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:227-234.

- Kim BJ, Kwon HH, Park SY, et al. Double-blind, randomized non-inferiority trial of a novel botulinum toxin A processed from the strain CBFC26, compared with onabotulinumtoxin A in the treatment of glabellar lines. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1761-1767.

- Kim JE, Song EJ, Choi GS, et al. The efficacy and safety of liquid-type botulinum toxin type A for the management of moderate to severe glabellar frown lines. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135:732-741.

- Alam M, Bolotin D, Carruthers J, et al. Consensus statement regarding storage and reuse of previously reconstituted neuromodulators. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:321-326.

- Alam M, Geisler A, Sadhwani D, et al. Effect of needle size on pain perception in patients treated with botulinum toxin type A injections: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1194-1199.

- Pucks N, Thomas A, Hallam MJ, et al. Cutaneous cooling to manage botulinum toxin injection-associated pain in patients with facial palsy: a randomised controlled trial. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015;68:1701-1705.

- Kranz G, Sycha T, Voller B, et al. Pain sensation during intradermal injections of three different botulinum toxin preparations in different doses and dilutions. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:886-890.

- Lowe PL, Lowe NJ. Botulinum toxin type B: pH change reduces injection pain, retains efficacy. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1328-1333.

- Mahmoud BH, Burnett C, Ozog D. Prospective randomized controlled study to determine the effect of topical application of botulinum toxin A for crow’s feet after treatment with ablative fractional CO2 laser. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 1):S75-S81.

- Montaser-Kouhsari L, Zartab H, Fanian F, et al. Comparison of intradermal injection with iontophoresis of abo-botulinum toxin A for the treatment of primary axillary hyperhidrosis: a randomized, controlled trial. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014;25:337-341.

- Iannitti T, Palmieri B, Aspiro A, et al. A preliminary study of painless and effective transdermal botulinum toxin A delivery by jet nebulization for treatment of primary hyperhidrosis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:931-935.

- Iozzo I, Tengattini V, Antonucci VA. Multipoint and multilevel injection technique of botulinum toxin A in facial aesthetics. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2014;13:135-142.

- Sneath J, Humphrey S, Carruthers A, et al. Injecting botulinum toxin at different depths is not effective for the correction of eyebrow asymmetry. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 1):S82-S87.

- Steinsapir KD, Rootman D, Wulc A, et al. Cosmetic microdroplet botulinum toxin A forehead lift: a new treatment paradigm. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;31:263-268.

- Carruthers JD, Carruthers JA. Treatment of glabellar frown lines with C. botulinum-A exotoxin. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:17-21.

- American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank statistics. American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery website. http://www.surgery.org/sites/default/files/ASAPS-Stats2015.pdf. Accessed June 12, 2016.

- Walker TJ, Dayan SH. Comparison and overview of currently available neurotoxins. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:31-39.

- Feng Z, Sun Q, He L, et al. Optimal dosage of botulinum toxin type A for treatment of glabellar frown lines: efficacy and safety in a clinical trial. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 1):S56-S63.

- Jiang HY, Chen S, Zhou J, et al. Diffusion of two botulinum toxins type A on the forehead: double-blinded, randomized, controlled study. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:184-192.

- Garcia-Murray E, Velasco Villasenor ML, Acevedo B, et al. Safety and efficacy of RT002, an injectable botulinum toxin type A, for treating glabellar lines: results of a phase 1/2, open-label, sequential dose-escalation study. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 1):S47-S55.

- Won CH, Kim HK, Kim BJ, et al. Comparative trial of a novel botulinum neurotoxin type A versus onabotulinumtoxinA in the treatment of glabellar lines: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, active-controlled study. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:227-234.

- Kim BJ, Kwon HH, Park SY, et al. Double-blind, randomized non-inferiority trial of a novel botulinum toxin A processed from the strain CBFC26, compared with onabotulinumtoxin A in the treatment of glabellar lines. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1761-1767.

- Kim JE, Song EJ, Choi GS, et al. The efficacy and safety of liquid-type botulinum toxin type A for the management of moderate to severe glabellar frown lines. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135:732-741.

- Alam M, Bolotin D, Carruthers J, et al. Consensus statement regarding storage and reuse of previously reconstituted neuromodulators. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:321-326.

- Alam M, Geisler A, Sadhwani D, et al. Effect of needle size on pain perception in patients treated with botulinum toxin type A injections: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1194-1199.

- Pucks N, Thomas A, Hallam MJ, et al. Cutaneous cooling to manage botulinum toxin injection-associated pain in patients with facial palsy: a randomised controlled trial. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015;68:1701-1705.

- Kranz G, Sycha T, Voller B, et al. Pain sensation during intradermal injections of three different botulinum toxin preparations in different doses and dilutions. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:886-890.

- Lowe PL, Lowe NJ. Botulinum toxin type B: pH change reduces injection pain, retains efficacy. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1328-1333.

- Mahmoud BH, Burnett C, Ozog D. Prospective randomized controlled study to determine the effect of topical application of botulinum toxin A for crow’s feet after treatment with ablative fractional CO2 laser. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 1):S75-S81.

- Montaser-Kouhsari L, Zartab H, Fanian F, et al. Comparison of intradermal injection with iontophoresis of abo-botulinum toxin A for the treatment of primary axillary hyperhidrosis: a randomized, controlled trial. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014;25:337-341.

- Iannitti T, Palmieri B, Aspiro A, et al. A preliminary study of painless and effective transdermal botulinum toxin A delivery by jet nebulization for treatment of primary hyperhidrosis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:931-935.

- Iozzo I, Tengattini V, Antonucci VA. Multipoint and multilevel injection technique of botulinum toxin A in facial aesthetics. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2014;13:135-142.

- Sneath J, Humphrey S, Carruthers A, et al. Injecting botulinum toxin at different depths is not effective for the correction of eyebrow asymmetry. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 1):S82-S87.

- Steinsapir KD, Rootman D, Wulc A, et al. Cosmetic microdroplet botulinum toxin A forehead lift: a new treatment paradigm. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;31:263-268.

Practice Points

- Botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) injection is the most popular nonsurgical aesthetic procedure available of which there are currently 4 products approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

- A variety of new BoNT products with unique properties and formulations are currently being studied, some of which are already available for clinical use in foreign markets.

- Administration technique and novel product delivery methods also can be utilized to minimize pain and maximize aesthetic outcomes.

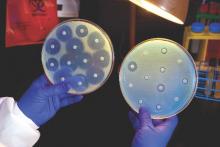

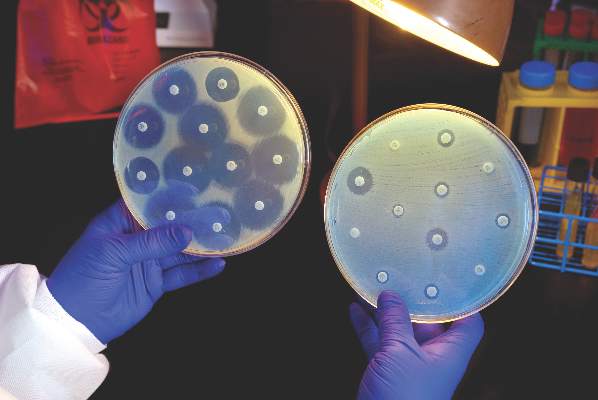

Hospitals increase CRE risk when they share patients

The more hospitals share patients, the more likely they are to have a problem with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), especially if long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs) are in the mix, according to a state-wide investigation from Illinois.

Greater hospital centrality was independently associated with higher rates overall, and sharing four or more patients with a long-term acute care hospital (LTACH) in the 3-month study window doubled the rate of CRE cases.

Although it’s possible that was because of chance (P = 0.11), the link between LTACHs and CRE “is consistent with prior analyses that have shown the central role LTACHs have in” spreading the organism, said the researchers, led by Michael Ray of the Illinois Department of Public Health (Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Aug 2. pii: ciw461).

Patients often spend weeks in LTACH facilities for ongoing, serious health problems. The severity of illness, long stay, and sometimes chronic antibiotic use increase the risk of CRE exposure, and the team found that many LTACH patients are colonized.

“These findings have immediate public health implications. … Early interventions should be focused on the most connected facilities, as well as those with strong connections to LTACHs.” When one hospital has an outbreak, facilities that share its patients need to swing into action screening new admissions and taking other steps to prevent regional spread, the team said.

Meanwhile, “state-wide patient-sharing data, which are now increasingly available through sources like the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, provide an important way to assess hospital risk of CRE exposure based on its position in regional patient-sharing networks,” they noted. “Public health can play a critical role in identifying tightly connected hospitals and educating personnel at such facilities about their risk and need for enhanced infection control interventions.”

The team came to their conclusions after linking Illinois’ drug-resistant organisms registry with admissions data for 185 hospitals. About half reported at least one CRE case over 3 months, with a mean of 3.5 cases per hospital.

There was an average of 64 patient-sharing connections per facility, with a minimum of one connection and a maximum of 145 connections. Each additional patient two hospitals shared corresponded to a 3% increase in the CRE rate in urban facilities and a 6% increase in rural ones. The investigators didn’t explain the discrepancy, except to note that rural areas don’t have LTACHs.

Almost two-thirds of hospitals reporting CRE were in Chicago-area counties; almost half had shared at least one patient with an LTACH, and 21% had shared four or more.

CRE cases were an average of 64 years old, and equally distributed between men and women and black and white patients.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the work. The authors had no disclosures.

The more hospitals share patients, the more likely they are to have a problem with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), especially if long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs) are in the mix, according to a state-wide investigation from Illinois.

Greater hospital centrality was independently associated with higher rates overall, and sharing four or more patients with a long-term acute care hospital (LTACH) in the 3-month study window doubled the rate of CRE cases.

Although it’s possible that was because of chance (P = 0.11), the link between LTACHs and CRE “is consistent with prior analyses that have shown the central role LTACHs have in” spreading the organism, said the researchers, led by Michael Ray of the Illinois Department of Public Health (Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Aug 2. pii: ciw461).

Patients often spend weeks in LTACH facilities for ongoing, serious health problems. The severity of illness, long stay, and sometimes chronic antibiotic use increase the risk of CRE exposure, and the team found that many LTACH patients are colonized.

“These findings have immediate public health implications. … Early interventions should be focused on the most connected facilities, as well as those with strong connections to LTACHs.” When one hospital has an outbreak, facilities that share its patients need to swing into action screening new admissions and taking other steps to prevent regional spread, the team said.

Meanwhile, “state-wide patient-sharing data, which are now increasingly available through sources like the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, provide an important way to assess hospital risk of CRE exposure based on its position in regional patient-sharing networks,” they noted. “Public health can play a critical role in identifying tightly connected hospitals and educating personnel at such facilities about their risk and need for enhanced infection control interventions.”

The team came to their conclusions after linking Illinois’ drug-resistant organisms registry with admissions data for 185 hospitals. About half reported at least one CRE case over 3 months, with a mean of 3.5 cases per hospital.

There was an average of 64 patient-sharing connections per facility, with a minimum of one connection and a maximum of 145 connections. Each additional patient two hospitals shared corresponded to a 3% increase in the CRE rate in urban facilities and a 6% increase in rural ones. The investigators didn’t explain the discrepancy, except to note that rural areas don’t have LTACHs.

Almost two-thirds of hospitals reporting CRE were in Chicago-area counties; almost half had shared at least one patient with an LTACH, and 21% had shared four or more.

CRE cases were an average of 64 years old, and equally distributed between men and women and black and white patients.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the work. The authors had no disclosures.

The more hospitals share patients, the more likely they are to have a problem with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), especially if long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs) are in the mix, according to a state-wide investigation from Illinois.

Greater hospital centrality was independently associated with higher rates overall, and sharing four or more patients with a long-term acute care hospital (LTACH) in the 3-month study window doubled the rate of CRE cases.

Although it’s possible that was because of chance (P = 0.11), the link between LTACHs and CRE “is consistent with prior analyses that have shown the central role LTACHs have in” spreading the organism, said the researchers, led by Michael Ray of the Illinois Department of Public Health (Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Aug 2. pii: ciw461).

Patients often spend weeks in LTACH facilities for ongoing, serious health problems. The severity of illness, long stay, and sometimes chronic antibiotic use increase the risk of CRE exposure, and the team found that many LTACH patients are colonized.

“These findings have immediate public health implications. … Early interventions should be focused on the most connected facilities, as well as those with strong connections to LTACHs.” When one hospital has an outbreak, facilities that share its patients need to swing into action screening new admissions and taking other steps to prevent regional spread, the team said.

Meanwhile, “state-wide patient-sharing data, which are now increasingly available through sources like the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, provide an important way to assess hospital risk of CRE exposure based on its position in regional patient-sharing networks,” they noted. “Public health can play a critical role in identifying tightly connected hospitals and educating personnel at such facilities about their risk and need for enhanced infection control interventions.”

The team came to their conclusions after linking Illinois’ drug-resistant organisms registry with admissions data for 185 hospitals. About half reported at least one CRE case over 3 months, with a mean of 3.5 cases per hospital.

There was an average of 64 patient-sharing connections per facility, with a minimum of one connection and a maximum of 145 connections. Each additional patient two hospitals shared corresponded to a 3% increase in the CRE rate in urban facilities and a 6% increase in rural ones. The investigators didn’t explain the discrepancy, except to note that rural areas don’t have LTACHs.

Almost two-thirds of hospitals reporting CRE were in Chicago-area counties; almost half had shared at least one patient with an LTACH, and 21% had shared four or more.

CRE cases were an average of 64 years old, and equally distributed between men and women and black and white patients.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the work. The authors had no disclosures.

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point: The more hospitals share patients, the more likely they are to have a problem with CRE, especially if long-term acute care hospitals are in the mix.

Major finding: Sharing four or more patients with a long-term acute care hospital in the 3-month study window doubled the rate of CRE cases (P = 0.11).

Data source: 185 Illinois hospitals.

Disclosures: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the work. The authors had no disclosures.

Proper Wound Management: How to Work With Patients

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

A thorough patient history is imperative for proper diagnosis of wounds, thus detailed information on the onset, duration, temporality, modifying factors, symptoms, and attempted treatments should be provided. Associated comorbidities that may influence wound healing, such as diabetes mellitus or connective tissue diseases, must be considered when formulating a treatment regimen. Patients should disclose current medications, as certain medications (eg, vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors) may decrease vascularization or soft tissue matrix regeneration, further complicating the wound healing process. All patients should have a basic understanding of the cause of their wound to have realistic expectations of the prognosis.

What are your go-to treatments?

Treatment ultimately depends on the cause of the wound. In general, proper healing requires a wound bed that is well vascularized and moistened without devitalized tissue or bacterial colonization. Wound dressings should be utilized to reduce dead space, control exudate, prevent bacterial overgrowth, and ensure proper fluid balance. Maintaining good overall health promotes proper healing. Thus, any relevant underlying medical conditions should be properly managed (eg, glycemic control for diabetic patients, management of fluid overload in patients with congestive heart failure).

When treating wounds, it is important to consider several factors. Although all wounds are colonized with microbes, not all wounds are infected. Thus, antibiotic therapy is not necessary for all wounds and should only be used to treat wounds that are clinically infected. Rule out pyoderma gangrenosum prior to wound debridement, as the associated pathergic response will notably worsen the ulcer. Wound dressings have an impact on the speed of wound healing, strength of repaired skin, and cosmetic appearance. Because no single dressing is perfect for all wounds, physicians should use their discretion when determining the type of wound dressing necessary.

Certain wounds require specific treatments. Off-loading and compression dressings/garments are the main components involved in the treatment of pressure ulcers. Protective wound care in conjunction with glycemic control is imperative for diabetic ulcers. Often, the causes of wounds are multifactorial and may complicate treatment. For instance, it is important to confirm that there is no associated arterial insufficiency before treating venous insufficiency with compression. Furthermore, patients with diabetic ulcers in association with venous insufficiency often have minimal response to hyperbaric oxygen treatment.

Several agents have been implicated to improve wound healing. Timolol, a topically applied beta-blocker, may promote keratinocyte migration and epithelialization of chronic refractory wounds. Recombinant human growth factors, most notably becaplermin (a platelet-derived growth factor), have been developed to promote cellular proliferation and angiogenesis, thereby improving healing of chronic wounds. Wounds that have devitalized tissue or contamination require debridement prior to further management.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Because recurrence is a common complication of chronic wounds, it is imperative that patients understand the importance of preventive care and follow-up appointments. Additionally, an open patient-physician dialogue may help address potential lifestyle limitations that may complicate wound care treatment. For instance, home care arrangement may be necessary to assist certain patient populations with wound care management.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

Ultimately, it is hard to enforce treatment if the patient refuses. However, in my experience practicing dermatology, I have found it to be uncommon for patients to refuse treatment without a particular reason. If a patient refuses treatment, try to understand why and then try to alleviate any concerns by clarifying misconceptions and/or recommending alternative therapies.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

Consult the American Academy of Dermatology website (https://www.aad.org/File%20Library/Unassigned/Wound-Dressings_Online-BF-DIR-Summer-2016--FINAL.pdf) for more information.

Additional resources include:

- Diabetic Wound Care (Source: American Podiatric Medical Association)(http://www.apma.org/Learn/FootHealth.cfm?ItemNumber=981)

- Pyoderma Gangrenosum (Source: Wound Care Centers)(http://www.woundcarecenters.org/article/wound-types/pyoderma-gangrenosum)

- Take the Pressure Off: A Patient Guide for Preventing and Treating Pressure Ulcers (Source: Association for the Advancement of Wound Care)(http://aawconline.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Take-the-Pressure-Off.pdf)

- Wound Healing Society (http://woundheal.org/home.aspx)

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

A thorough patient history is imperative for proper diagnosis of wounds, thus detailed information on the onset, duration, temporality, modifying factors, symptoms, and attempted treatments should be provided. Associated comorbidities that may influence wound healing, such as diabetes mellitus or connective tissue diseases, must be considered when formulating a treatment regimen. Patients should disclose current medications, as certain medications (eg, vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors) may decrease vascularization or soft tissue matrix regeneration, further complicating the wound healing process. All patients should have a basic understanding of the cause of their wound to have realistic expectations of the prognosis.

What are your go-to treatments?

Treatment ultimately depends on the cause of the wound. In general, proper healing requires a wound bed that is well vascularized and moistened without devitalized tissue or bacterial colonization. Wound dressings should be utilized to reduce dead space, control exudate, prevent bacterial overgrowth, and ensure proper fluid balance. Maintaining good overall health promotes proper healing. Thus, any relevant underlying medical conditions should be properly managed (eg, glycemic control for diabetic patients, management of fluid overload in patients with congestive heart failure).

When treating wounds, it is important to consider several factors. Although all wounds are colonized with microbes, not all wounds are infected. Thus, antibiotic therapy is not necessary for all wounds and should only be used to treat wounds that are clinically infected. Rule out pyoderma gangrenosum prior to wound debridement, as the associated pathergic response will notably worsen the ulcer. Wound dressings have an impact on the speed of wound healing, strength of repaired skin, and cosmetic appearance. Because no single dressing is perfect for all wounds, physicians should use their discretion when determining the type of wound dressing necessary.

Certain wounds require specific treatments. Off-loading and compression dressings/garments are the main components involved in the treatment of pressure ulcers. Protective wound care in conjunction with glycemic control is imperative for diabetic ulcers. Often, the causes of wounds are multifactorial and may complicate treatment. For instance, it is important to confirm that there is no associated arterial insufficiency before treating venous insufficiency with compression. Furthermore, patients with diabetic ulcers in association with venous insufficiency often have minimal response to hyperbaric oxygen treatment.

Several agents have been implicated to improve wound healing. Timolol, a topically applied beta-blocker, may promote keratinocyte migration and epithelialization of chronic refractory wounds. Recombinant human growth factors, most notably becaplermin (a platelet-derived growth factor), have been developed to promote cellular proliferation and angiogenesis, thereby improving healing of chronic wounds. Wounds that have devitalized tissue or contamination require debridement prior to further management.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Because recurrence is a common complication of chronic wounds, it is imperative that patients understand the importance of preventive care and follow-up appointments. Additionally, an open patient-physician dialogue may help address potential lifestyle limitations that may complicate wound care treatment. For instance, home care arrangement may be necessary to assist certain patient populations with wound care management.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

Ultimately, it is hard to enforce treatment if the patient refuses. However, in my experience practicing dermatology, I have found it to be uncommon for patients to refuse treatment without a particular reason. If a patient refuses treatment, try to understand why and then try to alleviate any concerns by clarifying misconceptions and/or recommending alternative therapies.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

Consult the American Academy of Dermatology website (https://www.aad.org/File%20Library/Unassigned/Wound-Dressings_Online-BF-DIR-Summer-2016--FINAL.pdf) for more information.

Additional resources include:

- Diabetic Wound Care (Source: American Podiatric Medical Association)(http://www.apma.org/Learn/FootHealth.cfm?ItemNumber=981)

- Pyoderma Gangrenosum (Source: Wound Care Centers)(http://www.woundcarecenters.org/article/wound-types/pyoderma-gangrenosum)

- Take the Pressure Off: A Patient Guide for Preventing and Treating Pressure Ulcers (Source: Association for the Advancement of Wound Care)(http://aawconline.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Take-the-Pressure-Off.pdf)

- Wound Healing Society (http://woundheal.org/home.aspx)

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

A thorough patient history is imperative for proper diagnosis of wounds, thus detailed information on the onset, duration, temporality, modifying factors, symptoms, and attempted treatments should be provided. Associated comorbidities that may influence wound healing, such as diabetes mellitus or connective tissue diseases, must be considered when formulating a treatment regimen. Patients should disclose current medications, as certain medications (eg, vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors) may decrease vascularization or soft tissue matrix regeneration, further complicating the wound healing process. All patients should have a basic understanding of the cause of their wound to have realistic expectations of the prognosis.

What are your go-to treatments?

Treatment ultimately depends on the cause of the wound. In general, proper healing requires a wound bed that is well vascularized and moistened without devitalized tissue or bacterial colonization. Wound dressings should be utilized to reduce dead space, control exudate, prevent bacterial overgrowth, and ensure proper fluid balance. Maintaining good overall health promotes proper healing. Thus, any relevant underlying medical conditions should be properly managed (eg, glycemic control for diabetic patients, management of fluid overload in patients with congestive heart failure).

When treating wounds, it is important to consider several factors. Although all wounds are colonized with microbes, not all wounds are infected. Thus, antibiotic therapy is not necessary for all wounds and should only be used to treat wounds that are clinically infected. Rule out pyoderma gangrenosum prior to wound debridement, as the associated pathergic response will notably worsen the ulcer. Wound dressings have an impact on the speed of wound healing, strength of repaired skin, and cosmetic appearance. Because no single dressing is perfect for all wounds, physicians should use their discretion when determining the type of wound dressing necessary.

Certain wounds require specific treatments. Off-loading and compression dressings/garments are the main components involved in the treatment of pressure ulcers. Protective wound care in conjunction with glycemic control is imperative for diabetic ulcers. Often, the causes of wounds are multifactorial and may complicate treatment. For instance, it is important to confirm that there is no associated arterial insufficiency before treating venous insufficiency with compression. Furthermore, patients with diabetic ulcers in association with venous insufficiency often have minimal response to hyperbaric oxygen treatment.

Several agents have been implicated to improve wound healing. Timolol, a topically applied beta-blocker, may promote keratinocyte migration and epithelialization of chronic refractory wounds. Recombinant human growth factors, most notably becaplermin (a platelet-derived growth factor), have been developed to promote cellular proliferation and angiogenesis, thereby improving healing of chronic wounds. Wounds that have devitalized tissue or contamination require debridement prior to further management.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Because recurrence is a common complication of chronic wounds, it is imperative that patients understand the importance of preventive care and follow-up appointments. Additionally, an open patient-physician dialogue may help address potential lifestyle limitations that may complicate wound care treatment. For instance, home care arrangement may be necessary to assist certain patient populations with wound care management.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

Ultimately, it is hard to enforce treatment if the patient refuses. However, in my experience practicing dermatology, I have found it to be uncommon for patients to refuse treatment without a particular reason. If a patient refuses treatment, try to understand why and then try to alleviate any concerns by clarifying misconceptions and/or recommending alternative therapies.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

Consult the American Academy of Dermatology website (https://www.aad.org/File%20Library/Unassigned/Wound-Dressings_Online-BF-DIR-Summer-2016--FINAL.pdf) for more information.

Additional resources include:

- Diabetic Wound Care (Source: American Podiatric Medical Association)(http://www.apma.org/Learn/FootHealth.cfm?ItemNumber=981)