User login

The future of ketamine in psychiatry

Ketamine, a high-affinity, noncompetitive N-methyl-

How ketamine works

Water- and lipid-soluble, ketamine is available in oral, topical, IM, and IV forms. Plasma concentrations reach maximum levels minutes after IV infusion; 5 to 15 minutes after IM administration; and 30 minutes after oral ingestion.1 The duration of action is as long as 2 hours after IM injection, and 4 to 6 hours orally. Metabolites are eliminated in urine.

Ketamine, co-prescribed with stimulants and some antidepressant drugs, can induce unwanted effects, such as increased blood pressure. Auditory and visual hallucinations are reported occasionally, especially in patients receiving a high dosage or in those with alcohol dependence.1 Hypertension, tachycardia, cardiac arrhythmia, and pain at injection site are the most common adverse effects.

Some advantages over ECT in treating depression

The efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in alleviating depression depends on seizure duration. Compared with methohexital, an anesthetic used for ECT, ketamine offers some advantages:

- increased ictal time

- augmented mid-ictal slow-wave amplitude

- shortened post-treatment re-orientation time

- less cognitive dysfunction.2

Uses for ketamine

Treatment-resistant depression. The glutamatergic system is implicated in depression.2,3 Ketamine works in patients with treatment-resistant depression by blocking glutamate NMDA receptors and increasing the activity of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors, resulting in a rapid, sustained antidepressant effect. Response to ketamine occurs within 2 hours and lasts approximately 1 week.

Bipolar and unipolar depression. Ketamine has rapid antidepressant properties in unipolar and bipolar depression. It is most beneficial in people with a family history of alcohol dependence, because similar glutamatergic system alterations might be involved in the pathophysiology of both disorders.3,4 An antidepressant effect has been reported as soon as 40 minutes after ketamine infusions.3

Suicide prevention. A single sub-anesthetic IV dose of ketamine rapidly diminishes acute suicidal ideation.1 This effect can be maintained through repeated ketamine infusions, episodically on a clinically derived basis. The exact duration and period between ketamine readministrations are not fully established. A variety of clinical-, patient-, and circumstance-related factors, history, response, and physician preferences alter such patterns, in an individualized way. This is also a promising means to reduce hospitalizations and at least mitigate the severity of depressive patient presentations.

Anesthesia and analgesia. Because ketamine induces anesthesia with minimal effect on respiratory function, it could be used in patients with pulmonary conditions.5 Ketamine can provide analgesia during brief operative and diagnostic procedures; because of its hypertensive actions, it is useful in trauma patients with hypotension.A low dose of ketamine effectively diminishes the discomfort of complex regional pain and other pain syndromes.

Abuse potential

There is documented risk of ketamine abuse. It may create psychedelic effects that some people find pleasurable, such as sedation, disinhibition, and altered perceptions.6 There also may be a component of physiological dependence.6

Conclusion

Ketamine’s rapid antidepressant effect results could be beneficial when used in severely depressed and suicidal patients. Given the potential risks of ketamine, safety considerations will determine whether this drug is successful as a therapy for people with a mood disorder.

Further research about ketamine usage including pain management and affective disorders is anticipated.7 Investigations substantiating relative safety and clinical trials are still on-going.8

Related Resources

• Nichols SD, Bishop J. Is the evidence compelling for using ketamine to treat resistant depression? Current Psychiatry. 2015;15(5):48-51.

• National Institute of Mental Health. Highlight: ketamine: a new (and faster) path to treating depression. www.nimh.nih.gov/about/strategic-planning-reports/highlights/highlight-ketamine-a-new-and-faster-path-to-treatingdepression.shtml.

1. Sinner B, Graf BM. Ketamine. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008;(128):313-333.

2. Krystal AD, Dean MD, Weiner RD, et al. ECT stimulus intensity: are present ECT devices too limited? Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):963-967.

3. Phelps LE, Brutsche N, Moral JR, et al. Family history of alcohol dependence and initial antidepressant response to an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:181-184.

4. Nery FG, Stanley JA, Chen HH, et al. Bipolar disorder comorbid with alcoholism: a 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. J Psychiatry Res. 2010;44(5):278-285.

5. Meller, ST. Ketamine: relief from chronic pain through actions at the NMDA receptor. Pain. 1996;68(2-3):435-436.

6. Sassano-Higgins S, Baron D, Juarez G, et al. A review of ketamine abuse and diversion. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(8):718-727.

7. Jafarinia M, Afarideh M, Tafakhori A, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral ketamine versus diclofenac to alleviate mild to moderate depression in chronic pain patients: A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2016;204:1-8.

8. Wan LB, Levitch CF, Perez AM, et al. Ketamine safety and tolerability in clinical trials for treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):247-252.

Ketamine, a high-affinity, noncompetitive N-methyl-

How ketamine works

Water- and lipid-soluble, ketamine is available in oral, topical, IM, and IV forms. Plasma concentrations reach maximum levels minutes after IV infusion; 5 to 15 minutes after IM administration; and 30 minutes after oral ingestion.1 The duration of action is as long as 2 hours after IM injection, and 4 to 6 hours orally. Metabolites are eliminated in urine.

Ketamine, co-prescribed with stimulants and some antidepressant drugs, can induce unwanted effects, such as increased blood pressure. Auditory and visual hallucinations are reported occasionally, especially in patients receiving a high dosage or in those with alcohol dependence.1 Hypertension, tachycardia, cardiac arrhythmia, and pain at injection site are the most common adverse effects.

Some advantages over ECT in treating depression

The efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in alleviating depression depends on seizure duration. Compared with methohexital, an anesthetic used for ECT, ketamine offers some advantages:

- increased ictal time

- augmented mid-ictal slow-wave amplitude

- shortened post-treatment re-orientation time

- less cognitive dysfunction.2

Uses for ketamine

Treatment-resistant depression. The glutamatergic system is implicated in depression.2,3 Ketamine works in patients with treatment-resistant depression by blocking glutamate NMDA receptors and increasing the activity of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors, resulting in a rapid, sustained antidepressant effect. Response to ketamine occurs within 2 hours and lasts approximately 1 week.

Bipolar and unipolar depression. Ketamine has rapid antidepressant properties in unipolar and bipolar depression. It is most beneficial in people with a family history of alcohol dependence, because similar glutamatergic system alterations might be involved in the pathophysiology of both disorders.3,4 An antidepressant effect has been reported as soon as 40 minutes after ketamine infusions.3

Suicide prevention. A single sub-anesthetic IV dose of ketamine rapidly diminishes acute suicidal ideation.1 This effect can be maintained through repeated ketamine infusions, episodically on a clinically derived basis. The exact duration and period between ketamine readministrations are not fully established. A variety of clinical-, patient-, and circumstance-related factors, history, response, and physician preferences alter such patterns, in an individualized way. This is also a promising means to reduce hospitalizations and at least mitigate the severity of depressive patient presentations.

Anesthesia and analgesia. Because ketamine induces anesthesia with minimal effect on respiratory function, it could be used in patients with pulmonary conditions.5 Ketamine can provide analgesia during brief operative and diagnostic procedures; because of its hypertensive actions, it is useful in trauma patients with hypotension.A low dose of ketamine effectively diminishes the discomfort of complex regional pain and other pain syndromes.

Abuse potential

There is documented risk of ketamine abuse. It may create psychedelic effects that some people find pleasurable, such as sedation, disinhibition, and altered perceptions.6 There also may be a component of physiological dependence.6

Conclusion

Ketamine’s rapid antidepressant effect results could be beneficial when used in severely depressed and suicidal patients. Given the potential risks of ketamine, safety considerations will determine whether this drug is successful as a therapy for people with a mood disorder.

Further research about ketamine usage including pain management and affective disorders is anticipated.7 Investigations substantiating relative safety and clinical trials are still on-going.8

Related Resources

• Nichols SD, Bishop J. Is the evidence compelling for using ketamine to treat resistant depression? Current Psychiatry. 2015;15(5):48-51.

• National Institute of Mental Health. Highlight: ketamine: a new (and faster) path to treating depression. www.nimh.nih.gov/about/strategic-planning-reports/highlights/highlight-ketamine-a-new-and-faster-path-to-treatingdepression.shtml.

Ketamine, a high-affinity, noncompetitive N-methyl-

How ketamine works

Water- and lipid-soluble, ketamine is available in oral, topical, IM, and IV forms. Plasma concentrations reach maximum levels minutes after IV infusion; 5 to 15 minutes after IM administration; and 30 minutes after oral ingestion.1 The duration of action is as long as 2 hours after IM injection, and 4 to 6 hours orally. Metabolites are eliminated in urine.

Ketamine, co-prescribed with stimulants and some antidepressant drugs, can induce unwanted effects, such as increased blood pressure. Auditory and visual hallucinations are reported occasionally, especially in patients receiving a high dosage or in those with alcohol dependence.1 Hypertension, tachycardia, cardiac arrhythmia, and pain at injection site are the most common adverse effects.

Some advantages over ECT in treating depression

The efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in alleviating depression depends on seizure duration. Compared with methohexital, an anesthetic used for ECT, ketamine offers some advantages:

- increased ictal time

- augmented mid-ictal slow-wave amplitude

- shortened post-treatment re-orientation time

- less cognitive dysfunction.2

Uses for ketamine

Treatment-resistant depression. The glutamatergic system is implicated in depression.2,3 Ketamine works in patients with treatment-resistant depression by blocking glutamate NMDA receptors and increasing the activity of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors, resulting in a rapid, sustained antidepressant effect. Response to ketamine occurs within 2 hours and lasts approximately 1 week.

Bipolar and unipolar depression. Ketamine has rapid antidepressant properties in unipolar and bipolar depression. It is most beneficial in people with a family history of alcohol dependence, because similar glutamatergic system alterations might be involved in the pathophysiology of both disorders.3,4 An antidepressant effect has been reported as soon as 40 minutes after ketamine infusions.3

Suicide prevention. A single sub-anesthetic IV dose of ketamine rapidly diminishes acute suicidal ideation.1 This effect can be maintained through repeated ketamine infusions, episodically on a clinically derived basis. The exact duration and period between ketamine readministrations are not fully established. A variety of clinical-, patient-, and circumstance-related factors, history, response, and physician preferences alter such patterns, in an individualized way. This is also a promising means to reduce hospitalizations and at least mitigate the severity of depressive patient presentations.

Anesthesia and analgesia. Because ketamine induces anesthesia with minimal effect on respiratory function, it could be used in patients with pulmonary conditions.5 Ketamine can provide analgesia during brief operative and diagnostic procedures; because of its hypertensive actions, it is useful in trauma patients with hypotension.A low dose of ketamine effectively diminishes the discomfort of complex regional pain and other pain syndromes.

Abuse potential

There is documented risk of ketamine abuse. It may create psychedelic effects that some people find pleasurable, such as sedation, disinhibition, and altered perceptions.6 There also may be a component of physiological dependence.6

Conclusion

Ketamine’s rapid antidepressant effect results could be beneficial when used in severely depressed and suicidal patients. Given the potential risks of ketamine, safety considerations will determine whether this drug is successful as a therapy for people with a mood disorder.

Further research about ketamine usage including pain management and affective disorders is anticipated.7 Investigations substantiating relative safety and clinical trials are still on-going.8

Related Resources

• Nichols SD, Bishop J. Is the evidence compelling for using ketamine to treat resistant depression? Current Psychiatry. 2015;15(5):48-51.

• National Institute of Mental Health. Highlight: ketamine: a new (and faster) path to treating depression. www.nimh.nih.gov/about/strategic-planning-reports/highlights/highlight-ketamine-a-new-and-faster-path-to-treatingdepression.shtml.

1. Sinner B, Graf BM. Ketamine. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008;(128):313-333.

2. Krystal AD, Dean MD, Weiner RD, et al. ECT stimulus intensity: are present ECT devices too limited? Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):963-967.

3. Phelps LE, Brutsche N, Moral JR, et al. Family history of alcohol dependence and initial antidepressant response to an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:181-184.

4. Nery FG, Stanley JA, Chen HH, et al. Bipolar disorder comorbid with alcoholism: a 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. J Psychiatry Res. 2010;44(5):278-285.

5. Meller, ST. Ketamine: relief from chronic pain through actions at the NMDA receptor. Pain. 1996;68(2-3):435-436.

6. Sassano-Higgins S, Baron D, Juarez G, et al. A review of ketamine abuse and diversion. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(8):718-727.

7. Jafarinia M, Afarideh M, Tafakhori A, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral ketamine versus diclofenac to alleviate mild to moderate depression in chronic pain patients: A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2016;204:1-8.

8. Wan LB, Levitch CF, Perez AM, et al. Ketamine safety and tolerability in clinical trials for treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):247-252.

1. Sinner B, Graf BM. Ketamine. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008;(128):313-333.

2. Krystal AD, Dean MD, Weiner RD, et al. ECT stimulus intensity: are present ECT devices too limited? Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):963-967.

3. Phelps LE, Brutsche N, Moral JR, et al. Family history of alcohol dependence and initial antidepressant response to an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:181-184.

4. Nery FG, Stanley JA, Chen HH, et al. Bipolar disorder comorbid with alcoholism: a 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. J Psychiatry Res. 2010;44(5):278-285.

5. Meller, ST. Ketamine: relief from chronic pain through actions at the NMDA receptor. Pain. 1996;68(2-3):435-436.

6. Sassano-Higgins S, Baron D, Juarez G, et al. A review of ketamine abuse and diversion. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(8):718-727.

7. Jafarinia M, Afarideh M, Tafakhori A, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral ketamine versus diclofenac to alleviate mild to moderate depression in chronic pain patients: A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2016;204:1-8.

8. Wan LB, Levitch CF, Perez AM, et al. Ketamine safety and tolerability in clinical trials for treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):247-252.

Scaling Up Efforts to Bring Weight Down: An Update on Recommendations, Techniques, and Pharmacotherapies for Adult Weight Management

|

Obesity meets 3 standard defining criteria of a disease: it is associated with impairment of normal bodily function, has characteristic signs and symptoms, and results in bodily harm.1 Accordingly, authoritative organizations, including the American Medical Association, formally recognize obesity as a disease—more specifically, a chronic, relapsing, neurobehavioral disease.1-6

Click here to read the activity.

Click here to complete the posttest and evaluation.

|

Obesity meets 3 standard defining criteria of a disease: it is associated with impairment of normal bodily function, has characteristic signs and symptoms, and results in bodily harm.1 Accordingly, authoritative organizations, including the American Medical Association, formally recognize obesity as a disease—more specifically, a chronic, relapsing, neurobehavioral disease.1-6

Click here to read the activity.

Click here to complete the posttest and evaluation.

|

Obesity meets 3 standard defining criteria of a disease: it is associated with impairment of normal bodily function, has characteristic signs and symptoms, and results in bodily harm.1 Accordingly, authoritative organizations, including the American Medical Association, formally recognize obesity as a disease—more specifically, a chronic, relapsing, neurobehavioral disease.1-6

Click here to read the activity.

Click here to complete the posttest and evaluation.

Biosimilar version of etanercept gains FDA approval

A biosimilar of etanercept received clearance for marketing from the Food and Drug Administration on Aug. 30 for all of the inflammatory disease indications held by the reference originator etanercept product, Enbrel, according to an announcement from the agency.

Approval for all of Enbrel’s indications – rheumatoid arthritis, plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis – was initially met with skepticism by members of the agency’s Arthritis Advisory Committee at a meeting in July because the biosimilar was compared against Enbrel in patients with plaque psoriasis only, but eventually all panel members voted to recommend approval.

The approval allows the biosimilar etanercept, called etanercept-szzs, to be marketed as a biosimilar only, not as an interchangeable product. The FDA has not yet developed guidance for manufacturers to follow to get approval for interchangeability, which means that a biosimilar “may be substituted for the reference product by a pharmacist without the intervention of the health care provider who prescribed the reference product,” according to the agency.

“We carefully evaluate the structural and functional characteristics of these complex molecules. Patients and providers can have confidence that there are no clinically meaningful differences in safety and efficacy from the reference product,” Janet Woodcock, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the agency’s announcement.

Etanercept-szzs will be marketed by Sandoz as Erelzi. Erelzi’s prescribing information can be found here. The biosimilar is currently undergoing review with the European Medicines Agency.

A biosimilar of etanercept received clearance for marketing from the Food and Drug Administration on Aug. 30 for all of the inflammatory disease indications held by the reference originator etanercept product, Enbrel, according to an announcement from the agency.

Approval for all of Enbrel’s indications – rheumatoid arthritis, plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis – was initially met with skepticism by members of the agency’s Arthritis Advisory Committee at a meeting in July because the biosimilar was compared against Enbrel in patients with plaque psoriasis only, but eventually all panel members voted to recommend approval.

The approval allows the biosimilar etanercept, called etanercept-szzs, to be marketed as a biosimilar only, not as an interchangeable product. The FDA has not yet developed guidance for manufacturers to follow to get approval for interchangeability, which means that a biosimilar “may be substituted for the reference product by a pharmacist without the intervention of the health care provider who prescribed the reference product,” according to the agency.

“We carefully evaluate the structural and functional characteristics of these complex molecules. Patients and providers can have confidence that there are no clinically meaningful differences in safety and efficacy from the reference product,” Janet Woodcock, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the agency’s announcement.

Etanercept-szzs will be marketed by Sandoz as Erelzi. Erelzi’s prescribing information can be found here. The biosimilar is currently undergoing review with the European Medicines Agency.

A biosimilar of etanercept received clearance for marketing from the Food and Drug Administration on Aug. 30 for all of the inflammatory disease indications held by the reference originator etanercept product, Enbrel, according to an announcement from the agency.

Approval for all of Enbrel’s indications – rheumatoid arthritis, plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis – was initially met with skepticism by members of the agency’s Arthritis Advisory Committee at a meeting in July because the biosimilar was compared against Enbrel in patients with plaque psoriasis only, but eventually all panel members voted to recommend approval.

The approval allows the biosimilar etanercept, called etanercept-szzs, to be marketed as a biosimilar only, not as an interchangeable product. The FDA has not yet developed guidance for manufacturers to follow to get approval for interchangeability, which means that a biosimilar “may be substituted for the reference product by a pharmacist without the intervention of the health care provider who prescribed the reference product,” according to the agency.

“We carefully evaluate the structural and functional characteristics of these complex molecules. Patients and providers can have confidence that there are no clinically meaningful differences in safety and efficacy from the reference product,” Janet Woodcock, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the agency’s announcement.

Etanercept-szzs will be marketed by Sandoz as Erelzi. Erelzi’s prescribing information can be found here. The biosimilar is currently undergoing review with the European Medicines Agency.

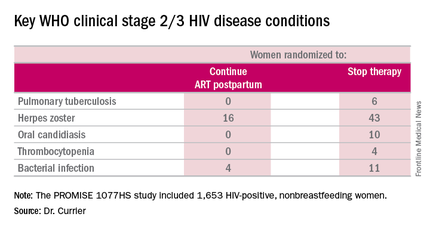

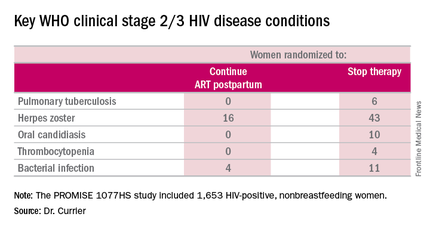

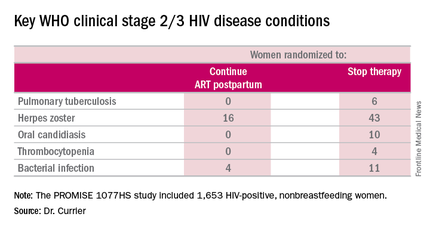

Postpartum HIV treatment reduces key maternal illnesses

DURBAN, SOUTH AFRICA – HIV-infected women who remained on antiretroviral therapy throughout the postpartum period reduced their risk of clinical stage 2 or 3 HIV disease events by 53%, compared with those who stopped treatment postpartum in the PROMISE 1077HS trial, Judith Currier, MD, reported at the 21st International AIDS Conference.

PROMISE (Promoting Maternal and Infant Survival Everywhere) is an ongoing multinational, multicomponent series of clinical trials. PROMISE 1077HS was designed to assess the risks and benefits of continued antiretroviral therapy (ART), compared with stopping therapy among nonbreastfeeding women postpartum, explained Dr. Currier, professor of medicine and chief of infectious diseases at the University of California, Los Angeles.

PROMISE 1077HS included 1,653 HIV-positive women in the United States and seven low- or middle-income countries. All participants were relatively healthy as evidenced by their median CD4+ count of 550 cells/mm3 prior to starting ART in pregnancy. None were planning to breastfeed. Upon delivery, the women were randomized to continue ART – the chief regimen was ritonavir-boosted lopinavir (Kaletra) plus tenofovir/emtricitabine (Truvada) – or stop therapy, restarting only when their CD4+ count fell below 350 cells/mm3.

Participants were prospectively followed for a median of 2.3 years post delivery. At that point, in summer 2015, the results of the landmark START trial were released (N Engl J Med. 2015 Aug 27;373[9]:795-807), paving the way for the current global strategy of ART for life in HIV-infected patients regardless of their CD4+ cell count.

The primary efficacy endpoint in PROMISE 1077HS was a composite of an AIDS event, death, or a serious cardiovascular, renal, or hepatic event. In this relatively healthy population, too few of these events occurred to allow the researchers to draw conclusions (four in the continued-ART group and six in the controls who stopped ART post partum).

But the secondary endpoint of time to World Health Organization (WHO) clinical stage 2 or 3 HIV disease events was a different story. A total of 39 of these events occurred in the continued-ART group, for a rate of 2.02% per year, compared with 80 events and a rate of 4.36% per year in controls. That difference translated into a 53% relative risk reduction. Some key WHO clinical stage 2 and 3 HIV disease events include pulmonary tuberculosis, herpes zoster, oral candidiasis, thrombocytopenia, and bacterial infection.

Fully 23% of patients in the continued-ART group had laboratory-confirmed virologic failure as defined by a viral load of HIV RNA in excess of 1,000 copies/mL after at least 24 weeks of postpartum ART. Additionally, resistance testing indicated two-thirds of affected patients showed no evidence of resistance at the time of virologic failure, meaning their viremia was due to nonadherence to ART.

“This virologic failure rate highlights the importance of the challenge of adherence in this population,” Dr. Currier said. “Interventions to improve adherence as well as studies to examine newer regimens with a high genetic barrier to resistance are needed to ensure maximal long-term benefit from this strategy of continued ART postpartum.”

The PROMISE studies are funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Currier reported having no financial disclosures.

DURBAN, SOUTH AFRICA – HIV-infected women who remained on antiretroviral therapy throughout the postpartum period reduced their risk of clinical stage 2 or 3 HIV disease events by 53%, compared with those who stopped treatment postpartum in the PROMISE 1077HS trial, Judith Currier, MD, reported at the 21st International AIDS Conference.

PROMISE (Promoting Maternal and Infant Survival Everywhere) is an ongoing multinational, multicomponent series of clinical trials. PROMISE 1077HS was designed to assess the risks and benefits of continued antiretroviral therapy (ART), compared with stopping therapy among nonbreastfeeding women postpartum, explained Dr. Currier, professor of medicine and chief of infectious diseases at the University of California, Los Angeles.

PROMISE 1077HS included 1,653 HIV-positive women in the United States and seven low- or middle-income countries. All participants were relatively healthy as evidenced by their median CD4+ count of 550 cells/mm3 prior to starting ART in pregnancy. None were planning to breastfeed. Upon delivery, the women were randomized to continue ART – the chief regimen was ritonavir-boosted lopinavir (Kaletra) plus tenofovir/emtricitabine (Truvada) – or stop therapy, restarting only when their CD4+ count fell below 350 cells/mm3.

Participants were prospectively followed for a median of 2.3 years post delivery. At that point, in summer 2015, the results of the landmark START trial were released (N Engl J Med. 2015 Aug 27;373[9]:795-807), paving the way for the current global strategy of ART for life in HIV-infected patients regardless of their CD4+ cell count.

The primary efficacy endpoint in PROMISE 1077HS was a composite of an AIDS event, death, or a serious cardiovascular, renal, or hepatic event. In this relatively healthy population, too few of these events occurred to allow the researchers to draw conclusions (four in the continued-ART group and six in the controls who stopped ART post partum).

But the secondary endpoint of time to World Health Organization (WHO) clinical stage 2 or 3 HIV disease events was a different story. A total of 39 of these events occurred in the continued-ART group, for a rate of 2.02% per year, compared with 80 events and a rate of 4.36% per year in controls. That difference translated into a 53% relative risk reduction. Some key WHO clinical stage 2 and 3 HIV disease events include pulmonary tuberculosis, herpes zoster, oral candidiasis, thrombocytopenia, and bacterial infection.

Fully 23% of patients in the continued-ART group had laboratory-confirmed virologic failure as defined by a viral load of HIV RNA in excess of 1,000 copies/mL after at least 24 weeks of postpartum ART. Additionally, resistance testing indicated two-thirds of affected patients showed no evidence of resistance at the time of virologic failure, meaning their viremia was due to nonadherence to ART.

“This virologic failure rate highlights the importance of the challenge of adherence in this population,” Dr. Currier said. “Interventions to improve adherence as well as studies to examine newer regimens with a high genetic barrier to resistance are needed to ensure maximal long-term benefit from this strategy of continued ART postpartum.”

The PROMISE studies are funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Currier reported having no financial disclosures.

DURBAN, SOUTH AFRICA – HIV-infected women who remained on antiretroviral therapy throughout the postpartum period reduced their risk of clinical stage 2 or 3 HIV disease events by 53%, compared with those who stopped treatment postpartum in the PROMISE 1077HS trial, Judith Currier, MD, reported at the 21st International AIDS Conference.

PROMISE (Promoting Maternal and Infant Survival Everywhere) is an ongoing multinational, multicomponent series of clinical trials. PROMISE 1077HS was designed to assess the risks and benefits of continued antiretroviral therapy (ART), compared with stopping therapy among nonbreastfeeding women postpartum, explained Dr. Currier, professor of medicine and chief of infectious diseases at the University of California, Los Angeles.

PROMISE 1077HS included 1,653 HIV-positive women in the United States and seven low- or middle-income countries. All participants were relatively healthy as evidenced by their median CD4+ count of 550 cells/mm3 prior to starting ART in pregnancy. None were planning to breastfeed. Upon delivery, the women were randomized to continue ART – the chief regimen was ritonavir-boosted lopinavir (Kaletra) plus tenofovir/emtricitabine (Truvada) – or stop therapy, restarting only when their CD4+ count fell below 350 cells/mm3.

Participants were prospectively followed for a median of 2.3 years post delivery. At that point, in summer 2015, the results of the landmark START trial were released (N Engl J Med. 2015 Aug 27;373[9]:795-807), paving the way for the current global strategy of ART for life in HIV-infected patients regardless of their CD4+ cell count.

The primary efficacy endpoint in PROMISE 1077HS was a composite of an AIDS event, death, or a serious cardiovascular, renal, or hepatic event. In this relatively healthy population, too few of these events occurred to allow the researchers to draw conclusions (four in the continued-ART group and six in the controls who stopped ART post partum).

But the secondary endpoint of time to World Health Organization (WHO) clinical stage 2 or 3 HIV disease events was a different story. A total of 39 of these events occurred in the continued-ART group, for a rate of 2.02% per year, compared with 80 events and a rate of 4.36% per year in controls. That difference translated into a 53% relative risk reduction. Some key WHO clinical stage 2 and 3 HIV disease events include pulmonary tuberculosis, herpes zoster, oral candidiasis, thrombocytopenia, and bacterial infection.

Fully 23% of patients in the continued-ART group had laboratory-confirmed virologic failure as defined by a viral load of HIV RNA in excess of 1,000 copies/mL after at least 24 weeks of postpartum ART. Additionally, resistance testing indicated two-thirds of affected patients showed no evidence of resistance at the time of virologic failure, meaning their viremia was due to nonadherence to ART.

“This virologic failure rate highlights the importance of the challenge of adherence in this population,” Dr. Currier said. “Interventions to improve adherence as well as studies to examine newer regimens with a high genetic barrier to resistance are needed to ensure maximal long-term benefit from this strategy of continued ART postpartum.”

The PROMISE studies are funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Currier reported having no financial disclosures.

AT AIDS 2016

Key clinical point: Women with HIV should continue antiretroviral therapy post partum.

Major finding: HIV-infected women who continued antiretroviral therapy post partum experienced 53% fewer WHO clinical stage 2 or 3 HIV disease events than women assigned to stop therapy after delivery.

Data source: The PROMISE 1077HS study included 1,653 HIV-positive, nonbreastfeeding women randomized to either continue or stop antiretroviral therapy post partum.

Disclosures: The PROMISE studies are funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Currier reported having no financial disclosures.

QUIZ: Which Pain Medication to Use for Patients with ESRD on HD?

[WpProQuiz 13] [WpProQuiz_toplist 13]

[WpProQuiz 13] [WpProQuiz_toplist 13]

[WpProQuiz 13] [WpProQuiz_toplist 13]

Single dose bacterial vaginosis treatment performs well in phase III trial

ANNAPOLIS, MD. – Women with bacterial vaginosis could soon have an effective oral, single-dose treatment option, if results of a phase III study result in approval by the Food and Drug Administration.

In a modified intention-to-treat study of 189 women with bacterial vaginosis (BV) randomly assigned 2:1 to treatment or placebo, a single, granulated oral dose of secnidazole 2g was found to be statistically superior to placebo on all clinical endpoints.

Secnidazole (SYM-1219) has a longer half-life, compared with metronidazole, the current treatment standard, according to Jane R. Schwebke, MD, the study investigator and a professor of medicine in the infectious disease department of the University of Alabama, Birmingham. Dr. Schwebke credits the study drug’s high bioavailablility and rapid absorption for its efficacy.

“You get a very high peak with SYM-1219 initially, and I think that might be the reason for the single-dose therapy’s efficacy. It’s due to the pharmacokinetics of the drug itself,” she reported at the annual scientific meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society for Obstetrics and Gynecology.

If the drug is approved, it would likely mean better adherence when compared with current standards of treatment, according to Sharon Hillier, PhD, director of reproductive infectious disease research at the Magee-Women’s Hospital of the University of Pittsburgh.

“It will absolutely improve compliance,” Dr. Hillier said in an interview. “Obviously, it’s much easier than taking [metronidazole] twice a day for 7 days.”

Treatment with metronidazole also requires a week of abstinence from alcohol, compared with what Dr. Hillier anticipates would be 2 or 3 days of alcohol abstinence with secnidazole.

The initial study enrollment was 189 women who were randomized 2:1 to secnidazole or placebo and treated at 21 sites nationally. After assessment for common sexually transmitted diseases, Nugent scores of 4 or greater, and all Amsel criteria (including a vaginal pH of 4.7 or greater, clue cells at or greater than 20%, and a positive KOH whiff test), 164 women remained in the modified intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis. A quarter of all women across the modified ITT group were recurrent BV sufferers, having had at least four episodes of BV in the previous year, and 87% had Nugent scores of 7 or greater.

“These were true BV cases; none were in the intermediate or mild zone,” Dr. Schwebke said.

Responders were women who, between days 21 and 30, had “normal” discharge, less than 20% clue cells, and a negative KOH whiff test. In the study arm, 53.3% of women had “normal” discharge and less than 20% clue cells at their 21-30 day visit, compared with 19.3% in the placebo group (P less than .001). The secondary endpoint – Nugent scores of 3 or less at days 7-14 – was achieved by 43.9% in the study group, compared with 5.3% of controls (P less than .001).

Just over a third of women in the study arm experienced one or more adverse events, compared with 21.9% of controls. Yeast infections were the most common adverse event. Less than 5% of the study group experienced nausea, headache, or diarrhea, compared with up to 3% of controls.

“What’s exciting about this new product is that it will be a single dose oral [that women] can take with a meal and with none of the adverse effects, and it relieves symptoms as well as other treatments,” Dr. Hillier said.

How treatment efficacy should be defined was a matter of debate during the presentation’s question and answer period. The FDA did not issue BV treatment guidance until 1998, despite prior approval of BV treatments clindamycin and metronidazole. The rigorous definition of clinical cure rate put forward in the FDA guidance document caused the cure rates that had been generally accepted by physicians to drop from as high as 80% to around 40%, according to Dr. Hilliard.

“I personally would like to see some head-to-head comparisons of the various treatments we have to know whether some are better than others,” Dr. Hillier said in the interview.

The ideal BV treatment should also provoke a microbiological cure, according to Dr. Schwebke. “What I would do is combine a drug like this with a biofilm inhibitor. Right now, this is great, because it’s single dose oral, and it’s as good as anything out there, but, I don’t think we’re taking the next step necessarily with efficacy.”

The study was supported by Symbiomix. Dr. Schwebke is a consultant for Symbiomix and receives funding from Alfa Wassermann and Starpharma, among others. Dr. Hillier is coprincipal investigator of the Microbicide Trials Network, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ANNAPOLIS, MD. – Women with bacterial vaginosis could soon have an effective oral, single-dose treatment option, if results of a phase III study result in approval by the Food and Drug Administration.

In a modified intention-to-treat study of 189 women with bacterial vaginosis (BV) randomly assigned 2:1 to treatment or placebo, a single, granulated oral dose of secnidazole 2g was found to be statistically superior to placebo on all clinical endpoints.

Secnidazole (SYM-1219) has a longer half-life, compared with metronidazole, the current treatment standard, according to Jane R. Schwebke, MD, the study investigator and a professor of medicine in the infectious disease department of the University of Alabama, Birmingham. Dr. Schwebke credits the study drug’s high bioavailablility and rapid absorption for its efficacy.

“You get a very high peak with SYM-1219 initially, and I think that might be the reason for the single-dose therapy’s efficacy. It’s due to the pharmacokinetics of the drug itself,” she reported at the annual scientific meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society for Obstetrics and Gynecology.

If the drug is approved, it would likely mean better adherence when compared with current standards of treatment, according to Sharon Hillier, PhD, director of reproductive infectious disease research at the Magee-Women’s Hospital of the University of Pittsburgh.

“It will absolutely improve compliance,” Dr. Hillier said in an interview. “Obviously, it’s much easier than taking [metronidazole] twice a day for 7 days.”

Treatment with metronidazole also requires a week of abstinence from alcohol, compared with what Dr. Hillier anticipates would be 2 or 3 days of alcohol abstinence with secnidazole.

The initial study enrollment was 189 women who were randomized 2:1 to secnidazole or placebo and treated at 21 sites nationally. After assessment for common sexually transmitted diseases, Nugent scores of 4 or greater, and all Amsel criteria (including a vaginal pH of 4.7 or greater, clue cells at or greater than 20%, and a positive KOH whiff test), 164 women remained in the modified intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis. A quarter of all women across the modified ITT group were recurrent BV sufferers, having had at least four episodes of BV in the previous year, and 87% had Nugent scores of 7 or greater.

“These were true BV cases; none were in the intermediate or mild zone,” Dr. Schwebke said.

Responders were women who, between days 21 and 30, had “normal” discharge, less than 20% clue cells, and a negative KOH whiff test. In the study arm, 53.3% of women had “normal” discharge and less than 20% clue cells at their 21-30 day visit, compared with 19.3% in the placebo group (P less than .001). The secondary endpoint – Nugent scores of 3 or less at days 7-14 – was achieved by 43.9% in the study group, compared with 5.3% of controls (P less than .001).

Just over a third of women in the study arm experienced one or more adverse events, compared with 21.9% of controls. Yeast infections were the most common adverse event. Less than 5% of the study group experienced nausea, headache, or diarrhea, compared with up to 3% of controls.

“What’s exciting about this new product is that it will be a single dose oral [that women] can take with a meal and with none of the adverse effects, and it relieves symptoms as well as other treatments,” Dr. Hillier said.

How treatment efficacy should be defined was a matter of debate during the presentation’s question and answer period. The FDA did not issue BV treatment guidance until 1998, despite prior approval of BV treatments clindamycin and metronidazole. The rigorous definition of clinical cure rate put forward in the FDA guidance document caused the cure rates that had been generally accepted by physicians to drop from as high as 80% to around 40%, according to Dr. Hilliard.

“I personally would like to see some head-to-head comparisons of the various treatments we have to know whether some are better than others,” Dr. Hillier said in the interview.

The ideal BV treatment should also provoke a microbiological cure, according to Dr. Schwebke. “What I would do is combine a drug like this with a biofilm inhibitor. Right now, this is great, because it’s single dose oral, and it’s as good as anything out there, but, I don’t think we’re taking the next step necessarily with efficacy.”

The study was supported by Symbiomix. Dr. Schwebke is a consultant for Symbiomix and receives funding from Alfa Wassermann and Starpharma, among others. Dr. Hillier is coprincipal investigator of the Microbicide Trials Network, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ANNAPOLIS, MD. – Women with bacterial vaginosis could soon have an effective oral, single-dose treatment option, if results of a phase III study result in approval by the Food and Drug Administration.

In a modified intention-to-treat study of 189 women with bacterial vaginosis (BV) randomly assigned 2:1 to treatment or placebo, a single, granulated oral dose of secnidazole 2g was found to be statistically superior to placebo on all clinical endpoints.

Secnidazole (SYM-1219) has a longer half-life, compared with metronidazole, the current treatment standard, according to Jane R. Schwebke, MD, the study investigator and a professor of medicine in the infectious disease department of the University of Alabama, Birmingham. Dr. Schwebke credits the study drug’s high bioavailablility and rapid absorption for its efficacy.

“You get a very high peak with SYM-1219 initially, and I think that might be the reason for the single-dose therapy’s efficacy. It’s due to the pharmacokinetics of the drug itself,” she reported at the annual scientific meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society for Obstetrics and Gynecology.

If the drug is approved, it would likely mean better adherence when compared with current standards of treatment, according to Sharon Hillier, PhD, director of reproductive infectious disease research at the Magee-Women’s Hospital of the University of Pittsburgh.

“It will absolutely improve compliance,” Dr. Hillier said in an interview. “Obviously, it’s much easier than taking [metronidazole] twice a day for 7 days.”

Treatment with metronidazole also requires a week of abstinence from alcohol, compared with what Dr. Hillier anticipates would be 2 or 3 days of alcohol abstinence with secnidazole.

The initial study enrollment was 189 women who were randomized 2:1 to secnidazole or placebo and treated at 21 sites nationally. After assessment for common sexually transmitted diseases, Nugent scores of 4 or greater, and all Amsel criteria (including a vaginal pH of 4.7 or greater, clue cells at or greater than 20%, and a positive KOH whiff test), 164 women remained in the modified intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis. A quarter of all women across the modified ITT group were recurrent BV sufferers, having had at least four episodes of BV in the previous year, and 87% had Nugent scores of 7 or greater.

“These were true BV cases; none were in the intermediate or mild zone,” Dr. Schwebke said.

Responders were women who, between days 21 and 30, had “normal” discharge, less than 20% clue cells, and a negative KOH whiff test. In the study arm, 53.3% of women had “normal” discharge and less than 20% clue cells at their 21-30 day visit, compared with 19.3% in the placebo group (P less than .001). The secondary endpoint – Nugent scores of 3 or less at days 7-14 – was achieved by 43.9% in the study group, compared with 5.3% of controls (P less than .001).

Just over a third of women in the study arm experienced one or more adverse events, compared with 21.9% of controls. Yeast infections were the most common adverse event. Less than 5% of the study group experienced nausea, headache, or diarrhea, compared with up to 3% of controls.

“What’s exciting about this new product is that it will be a single dose oral [that women] can take with a meal and with none of the adverse effects, and it relieves symptoms as well as other treatments,” Dr. Hillier said.

How treatment efficacy should be defined was a matter of debate during the presentation’s question and answer period. The FDA did not issue BV treatment guidance until 1998, despite prior approval of BV treatments clindamycin and metronidazole. The rigorous definition of clinical cure rate put forward in the FDA guidance document caused the cure rates that had been generally accepted by physicians to drop from as high as 80% to around 40%, according to Dr. Hilliard.

“I personally would like to see some head-to-head comparisons of the various treatments we have to know whether some are better than others,” Dr. Hillier said in the interview.

The ideal BV treatment should also provoke a microbiological cure, according to Dr. Schwebke. “What I would do is combine a drug like this with a biofilm inhibitor. Right now, this is great, because it’s single dose oral, and it’s as good as anything out there, but, I don’t think we’re taking the next step necessarily with efficacy.”

The study was supported by Symbiomix. Dr. Schwebke is a consultant for Symbiomix and receives funding from Alfa Wassermann and Starpharma, among others. Dr. Hillier is coprincipal investigator of the Microbicide Trials Network, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT IDSOG

Key clinical point: Granulated, single-dose oral secnidazole was statistically superior to placebo in treating bacterial vaginosis.

Major finding: In the study arm, 53.3% of women had “normal” discharge and less than 20% clue cells at their 21-30 day visit, compared with 19.3% in the placebo group (P less than .001).

Data source: A randomized, controlled phase III study of 189 women with bacterial vaginosis.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Symbiomix. Dr. Schwebke is a consultant for Symbiomix and receives funding from Alfa Wassermann and Starpharma, among others. Dr. Hillier is coprincipal investigator of the Microbicide Trials Network, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health.

FDG-PET gives early indication of response to therapy for Ewing sarcoma

Among patients with Ewing sarcoma, functional imaging with 18fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)–PET was a better predictor of response 9 days after the start of therapy than anatomic imaging modalities were at 6 weeks, results of a retrospective analysis suggest.

A study comparing the predictive ability of functional imaging modalities such as FDG-PET with that of anatomic imaging modalities such as CT or MRI showed that an early signal with FDG-PET was superior to anatomic imaging, and that newly defined tumor volume criteria were better at predicting response and clinical benefit than either World Health Organization (WHO) criteria or Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), reported Vadim S. Koshkin, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic and colleagues.

“The time needed to assess tumors volumetrically is slightly greater than to do so unidimensionally or bidimensionally, but the process is now automated. The analysis presented here suggests that assessment of tumor volume is superior to predict response in clinical trials, compared with the currently widely used RECIST and WHO criteria. This requires additional validation with prospective clinical trials,” they wrote (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Aug 29. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.1858].

To get a better idea of the relative benefits of FDG-PET and anatomic imaging for assessing clinical outcomes, the investigators took a retrospective look at patients with Ewing sarcoma who were enrolled in the SARC 011 trial, a single-arm, multicenter, multicohort phase II study of patients with recurrent Ewing sarcoma treated with the investigational insulinlike growth factor–1 receptor antibody R1507.

Of the 115 patients enrolled, 76 had available anatomic imaging at baseline and at 6 weeks after the start of treatment. The imaging studies were assessed by the treating oncologist according to WHO criteria and by a central, external group of radiologists blinded to clinical outcomes of individual patients. FDG-PET studies were performed at baseline and on day 9 and were assessed by central reviewers using PET Response Criteria in Solid Tumors (PERCIST).

The authors compared PERCIST 1.0 criteria for functional imaging with FDG-PET, and for anatomic imaging, WHO and RECIST criteria were assessed independently, and newly defined volumetric criteria were based on measurements done by the central radiology group using semi-automated solid tumor segmentation software.

As noted before, the investigators found results of day 9 FDG-PET scans were associated with reduced overall survival (OS) in patients with disease progression, compared with those without progression (P = .001), and with improved OS among patients with responses to the antibody, compared with those without responses.

“There was no significance in median survival between patients who responded to treatment and patients with stable disease for any of the imaging criteria. However, for all of the criteria, there was a trend toward longer survival for patients in the response group, compared with the stable disease group,” the authors wrote.

They found that the anatomic imaging criteria (WHO local and centralized assessments, RECIST, and volume) identified fewer patients in the response group than PERCIST (FDG-PET) criteria did.

When they looked at the subgroup of 66 patients who had both interpretable functional and anatomic imaging, they found that PERCIST identified 43.9% of patients as responders, and 90.9% as nonprogressors.

The authors acknowledged that their study was hampered by the retrospective design, small sample size relative to the trial population, and lack of FDG-PET standardization to common criteria across the treatment centers.

Among patients with Ewing sarcoma, functional imaging with 18fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)–PET was a better predictor of response 9 days after the start of therapy than anatomic imaging modalities were at 6 weeks, results of a retrospective analysis suggest.

A study comparing the predictive ability of functional imaging modalities such as FDG-PET with that of anatomic imaging modalities such as CT or MRI showed that an early signal with FDG-PET was superior to anatomic imaging, and that newly defined tumor volume criteria were better at predicting response and clinical benefit than either World Health Organization (WHO) criteria or Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), reported Vadim S. Koshkin, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic and colleagues.

“The time needed to assess tumors volumetrically is slightly greater than to do so unidimensionally or bidimensionally, but the process is now automated. The analysis presented here suggests that assessment of tumor volume is superior to predict response in clinical trials, compared with the currently widely used RECIST and WHO criteria. This requires additional validation with prospective clinical trials,” they wrote (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Aug 29. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.1858].

To get a better idea of the relative benefits of FDG-PET and anatomic imaging for assessing clinical outcomes, the investigators took a retrospective look at patients with Ewing sarcoma who were enrolled in the SARC 011 trial, a single-arm, multicenter, multicohort phase II study of patients with recurrent Ewing sarcoma treated with the investigational insulinlike growth factor–1 receptor antibody R1507.

Of the 115 patients enrolled, 76 had available anatomic imaging at baseline and at 6 weeks after the start of treatment. The imaging studies were assessed by the treating oncologist according to WHO criteria and by a central, external group of radiologists blinded to clinical outcomes of individual patients. FDG-PET studies were performed at baseline and on day 9 and were assessed by central reviewers using PET Response Criteria in Solid Tumors (PERCIST).

The authors compared PERCIST 1.0 criteria for functional imaging with FDG-PET, and for anatomic imaging, WHO and RECIST criteria were assessed independently, and newly defined volumetric criteria were based on measurements done by the central radiology group using semi-automated solid tumor segmentation software.

As noted before, the investigators found results of day 9 FDG-PET scans were associated with reduced overall survival (OS) in patients with disease progression, compared with those without progression (P = .001), and with improved OS among patients with responses to the antibody, compared with those without responses.

“There was no significance in median survival between patients who responded to treatment and patients with stable disease for any of the imaging criteria. However, for all of the criteria, there was a trend toward longer survival for patients in the response group, compared with the stable disease group,” the authors wrote.

They found that the anatomic imaging criteria (WHO local and centralized assessments, RECIST, and volume) identified fewer patients in the response group than PERCIST (FDG-PET) criteria did.

When they looked at the subgroup of 66 patients who had both interpretable functional and anatomic imaging, they found that PERCIST identified 43.9% of patients as responders, and 90.9% as nonprogressors.

The authors acknowledged that their study was hampered by the retrospective design, small sample size relative to the trial population, and lack of FDG-PET standardization to common criteria across the treatment centers.

Among patients with Ewing sarcoma, functional imaging with 18fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)–PET was a better predictor of response 9 days after the start of therapy than anatomic imaging modalities were at 6 weeks, results of a retrospective analysis suggest.

A study comparing the predictive ability of functional imaging modalities such as FDG-PET with that of anatomic imaging modalities such as CT or MRI showed that an early signal with FDG-PET was superior to anatomic imaging, and that newly defined tumor volume criteria were better at predicting response and clinical benefit than either World Health Organization (WHO) criteria or Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), reported Vadim S. Koshkin, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic and colleagues.

“The time needed to assess tumors volumetrically is slightly greater than to do so unidimensionally or bidimensionally, but the process is now automated. The analysis presented here suggests that assessment of tumor volume is superior to predict response in clinical trials, compared with the currently widely used RECIST and WHO criteria. This requires additional validation with prospective clinical trials,” they wrote (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Aug 29. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.1858].

To get a better idea of the relative benefits of FDG-PET and anatomic imaging for assessing clinical outcomes, the investigators took a retrospective look at patients with Ewing sarcoma who were enrolled in the SARC 011 trial, a single-arm, multicenter, multicohort phase II study of patients with recurrent Ewing sarcoma treated with the investigational insulinlike growth factor–1 receptor antibody R1507.

Of the 115 patients enrolled, 76 had available anatomic imaging at baseline and at 6 weeks after the start of treatment. The imaging studies were assessed by the treating oncologist according to WHO criteria and by a central, external group of radiologists blinded to clinical outcomes of individual patients. FDG-PET studies were performed at baseline and on day 9 and were assessed by central reviewers using PET Response Criteria in Solid Tumors (PERCIST).

The authors compared PERCIST 1.0 criteria for functional imaging with FDG-PET, and for anatomic imaging, WHO and RECIST criteria were assessed independently, and newly defined volumetric criteria were based on measurements done by the central radiology group using semi-automated solid tumor segmentation software.

As noted before, the investigators found results of day 9 FDG-PET scans were associated with reduced overall survival (OS) in patients with disease progression, compared with those without progression (P = .001), and with improved OS among patients with responses to the antibody, compared with those without responses.

“There was no significance in median survival between patients who responded to treatment and patients with stable disease for any of the imaging criteria. However, for all of the criteria, there was a trend toward longer survival for patients in the response group, compared with the stable disease group,” the authors wrote.

They found that the anatomic imaging criteria (WHO local and centralized assessments, RECIST, and volume) identified fewer patients in the response group than PERCIST (FDG-PET) criteria did.

When they looked at the subgroup of 66 patients who had both interpretable functional and anatomic imaging, they found that PERCIST identified 43.9% of patients as responders, and 90.9% as nonprogressors.

The authors acknowledged that their study was hampered by the retrospective design, small sample size relative to the trial population, and lack of FDG-PET standardization to common criteria across the treatment centers.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: FDG-PET predicted response to Ewing sarcoma therapy significantly earlier than MRI or CT.

Major finding: Day 9 FDG-PET scans were associated with reduced overall survival (OS) in patients with disease progression, compared with those without progression (P = .001).

Data source: Retrospective analysis of data on 76 patients enrolled in the SARC 011 trial.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Radiological Society of North America; Quantitative Imaging Biomarker Alliance; the Sarcoma Alliance for Research Through Collaboration (SARC), and the National Institutes of Health. Vadim S. Koshkin and three coauthors reported no conflicts of interest. Seven coauthors reported financial relationships with various drug and/or device companies.

Vascular surgeons assisting nonvascular colleagues require depth/breadth of experience

Vascular surgeons called upon to provide intraoperative assistance should be prepared to undertake a wide range of repairs.

Nonvascular surgery patients who required any vascular repair had a higher incidence of the primary endpoint of death, myocardial infarction, or unplanned return to the operating room within 30 days post surgery. In addition, such cases accounted for almost 7% of the operative volume of the hospital’s vascular surgery service, according to the results of a retrospective record review of all 533 patients who underwent nonvascular surgery requiring intraoperative assistance by a vascular surgeon at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago, between January 2010 and June 2014.

After excluding 28 trauma patients and 226 who required placement of an inferior vena cava filter only, the remaining cohort of 299 patients were assessed. This cohort represented 6.9% of the entire operative output of the vascular surgery service at the hospital during the period assessed. The cohort comprised 49.5% men and a had mean patient age of 56.4 years, according to Tadaki M. Tomita, MD, and his colleagues at Northwestern University, Chicago.

Intraoperative assistance was requested by 12 different surgical subspecialties during the period studied, with the most common being neurosurgery (33.8%), orthopedic surgery (26.4%), urology (15.7%), and surgical oncology (6.7%). The major vascular surgeon participation by indications were spine exposure (52%), vascular reconstruction (19%), vascular control without hemorrhage (14.4%), and control of hemorrhage (14.4%), according to a report published online in JAMA Surgery (2016 Aug 3. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.2247).

For the entire cohort, 110 patients (36.8%) required vascular repairs, with 13 bypasses (4.4%), 18 patch angioplasties (6.0%), and 79 primary repairs (26.4%) performed; 64 cases were venous (21.4%) and 43 arterial (14.7%). The anatomic distribution in patients requiring vascular repair was 72.7% truncal and 27.4% peripheral.

Patients who required any vascular repair had a significantly higher incidence of the primary endpoint than did patients who did not require vascular repair (17.4% vs. 7.9%; P = .01), with five deaths, 16 MIs, and 20 unplanned returns to the OR.

“Vascular surgeons are often called on by nonvascular surgeons for assistance in the OR in a variety of clinical situations and anatomic locations,” the researchers stated. The vascular surgeon in all cases performed an open surgical exposure and open repair was performed in all cases that required vascular repair.

“While most consultations occurred preoperatively, a high proportion of emergent cases that are more likely to require vascular repair demonstrates the importance of having vascular surgeons immediately available at the hospital. To continue providing this valuable service, vascular trainees will need to continue to learn the full breadth of anatomic exposures and open vascular reconstructions,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no disclosures.

Vascular surgeons called upon to provide intraoperative assistance should be prepared to undertake a wide range of repairs.

Nonvascular surgery patients who required any vascular repair had a higher incidence of the primary endpoint of death, myocardial infarction, or unplanned return to the operating room within 30 days post surgery. In addition, such cases accounted for almost 7% of the operative volume of the hospital’s vascular surgery service, according to the results of a retrospective record review of all 533 patients who underwent nonvascular surgery requiring intraoperative assistance by a vascular surgeon at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago, between January 2010 and June 2014.

After excluding 28 trauma patients and 226 who required placement of an inferior vena cava filter only, the remaining cohort of 299 patients were assessed. This cohort represented 6.9% of the entire operative output of the vascular surgery service at the hospital during the period assessed. The cohort comprised 49.5% men and a had mean patient age of 56.4 years, according to Tadaki M. Tomita, MD, and his colleagues at Northwestern University, Chicago.

Intraoperative assistance was requested by 12 different surgical subspecialties during the period studied, with the most common being neurosurgery (33.8%), orthopedic surgery (26.4%), urology (15.7%), and surgical oncology (6.7%). The major vascular surgeon participation by indications were spine exposure (52%), vascular reconstruction (19%), vascular control without hemorrhage (14.4%), and control of hemorrhage (14.4%), according to a report published online in JAMA Surgery (2016 Aug 3. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.2247).

For the entire cohort, 110 patients (36.8%) required vascular repairs, with 13 bypasses (4.4%), 18 patch angioplasties (6.0%), and 79 primary repairs (26.4%) performed; 64 cases were venous (21.4%) and 43 arterial (14.7%). The anatomic distribution in patients requiring vascular repair was 72.7% truncal and 27.4% peripheral.

Patients who required any vascular repair had a significantly higher incidence of the primary endpoint than did patients who did not require vascular repair (17.4% vs. 7.9%; P = .01), with five deaths, 16 MIs, and 20 unplanned returns to the OR.

“Vascular surgeons are often called on by nonvascular surgeons for assistance in the OR in a variety of clinical situations and anatomic locations,” the researchers stated. The vascular surgeon in all cases performed an open surgical exposure and open repair was performed in all cases that required vascular repair.

“While most consultations occurred preoperatively, a high proportion of emergent cases that are more likely to require vascular repair demonstrates the importance of having vascular surgeons immediately available at the hospital. To continue providing this valuable service, vascular trainees will need to continue to learn the full breadth of anatomic exposures and open vascular reconstructions,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no disclosures.

Vascular surgeons called upon to provide intraoperative assistance should be prepared to undertake a wide range of repairs.

Nonvascular surgery patients who required any vascular repair had a higher incidence of the primary endpoint of death, myocardial infarction, or unplanned return to the operating room within 30 days post surgery. In addition, such cases accounted for almost 7% of the operative volume of the hospital’s vascular surgery service, according to the results of a retrospective record review of all 533 patients who underwent nonvascular surgery requiring intraoperative assistance by a vascular surgeon at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago, between January 2010 and June 2014.

After excluding 28 trauma patients and 226 who required placement of an inferior vena cava filter only, the remaining cohort of 299 patients were assessed. This cohort represented 6.9% of the entire operative output of the vascular surgery service at the hospital during the period assessed. The cohort comprised 49.5% men and a had mean patient age of 56.4 years, according to Tadaki M. Tomita, MD, and his colleagues at Northwestern University, Chicago.

Intraoperative assistance was requested by 12 different surgical subspecialties during the period studied, with the most common being neurosurgery (33.8%), orthopedic surgery (26.4%), urology (15.7%), and surgical oncology (6.7%). The major vascular surgeon participation by indications were spine exposure (52%), vascular reconstruction (19%), vascular control without hemorrhage (14.4%), and control of hemorrhage (14.4%), according to a report published online in JAMA Surgery (2016 Aug 3. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.2247).

For the entire cohort, 110 patients (36.8%) required vascular repairs, with 13 bypasses (4.4%), 18 patch angioplasties (6.0%), and 79 primary repairs (26.4%) performed; 64 cases were venous (21.4%) and 43 arterial (14.7%). The anatomic distribution in patients requiring vascular repair was 72.7% truncal and 27.4% peripheral.

Patients who required any vascular repair had a significantly higher incidence of the primary endpoint than did patients who did not require vascular repair (17.4% vs. 7.9%; P = .01), with five deaths, 16 MIs, and 20 unplanned returns to the OR.

“Vascular surgeons are often called on by nonvascular surgeons for assistance in the OR in a variety of clinical situations and anatomic locations,” the researchers stated. The vascular surgeon in all cases performed an open surgical exposure and open repair was performed in all cases that required vascular repair.

“While most consultations occurred preoperatively, a high proportion of emergent cases that are more likely to require vascular repair demonstrates the importance of having vascular surgeons immediately available at the hospital. To continue providing this valuable service, vascular trainees will need to continue to learn the full breadth of anatomic exposures and open vascular reconstructions,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no disclosures.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Key clinical point: Intraoperative assistance of vascular surgeons in nonvascular procedures accounted for nearly 7% of vascular work at a single institution and uniformly required open repair.

Major finding: Patients who required any intraoperative vascular repair had a higher incidence of the primary endpoint of death, myocardial infarction, or unplanned return to the operating room within 30 days post surgery.

Data source: The study was a retrospective review of all 299 patients undergoing nonvascular surgery who required intraoperative vascular surgery assistance at a single institution between January 2010 and June 2014.

Disclosures: The authors reported that they had no disclosures.

Serious infections in second trimester increase epilepsy risk

ANNAPOLIS, MD. – Febrile infections occurring in the second trimester appear to pose the greatest risk to the neurodevelopment of the fetus, a population based cohort study has shown.

In a review of 8,618,171 California births between January 1991 and December 2008, Ms. Hilary Haber, a third-year medical student at the University of California, Davis, and her coinvestigators found that maternal infections requiring hospitalizations during the second trimester were associated with a relative risk of 2.5 of having a child with epilepsy, a relative risk of 2.3 of having a child with an intellectual disability, and a relative risk of 1.2 of having a child with autism.

Significant associations were observed between subcategories of infection and intellectual disability and epilepsy, particularly those of a bacterial cause and from respiratory and genitourinary sites. Overall, any maternal infection during pregnancy was associated with a 43% increased risk of epilepsy, a 33% increased risk of intellectual disability, and an 8% increased risk of autism.

The exact mechanism of action between the maternal infection and adverse fetal neurodevelopmental outcomes is still unclear, Ms. Haber said at the annual scientific meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society for Obstetrics and Gynecology.

“Next, we are considering which specific [maternal] infections we should look at,” Ms. Haber said in an interview. “There is something about febrile infections, so we want to narrow that down and better characterize the outcomes from mild, moderate, severe infections.”

Ms. Haber reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ANNAPOLIS, MD. – Febrile infections occurring in the second trimester appear to pose the greatest risk to the neurodevelopment of the fetus, a population based cohort study has shown.

In a review of 8,618,171 California births between January 1991 and December 2008, Ms. Hilary Haber, a third-year medical student at the University of California, Davis, and her coinvestigators found that maternal infections requiring hospitalizations during the second trimester were associated with a relative risk of 2.5 of having a child with epilepsy, a relative risk of 2.3 of having a child with an intellectual disability, and a relative risk of 1.2 of having a child with autism.

Significant associations were observed between subcategories of infection and intellectual disability and epilepsy, particularly those of a bacterial cause and from respiratory and genitourinary sites. Overall, any maternal infection during pregnancy was associated with a 43% increased risk of epilepsy, a 33% increased risk of intellectual disability, and an 8% increased risk of autism.

The exact mechanism of action between the maternal infection and adverse fetal neurodevelopmental outcomes is still unclear, Ms. Haber said at the annual scientific meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society for Obstetrics and Gynecology.

“Next, we are considering which specific [maternal] infections we should look at,” Ms. Haber said in an interview. “There is something about febrile infections, so we want to narrow that down and better characterize the outcomes from mild, moderate, severe infections.”

Ms. Haber reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ANNAPOLIS, MD. – Febrile infections occurring in the second trimester appear to pose the greatest risk to the neurodevelopment of the fetus, a population based cohort study has shown.

In a review of 8,618,171 California births between January 1991 and December 2008, Ms. Hilary Haber, a third-year medical student at the University of California, Davis, and her coinvestigators found that maternal infections requiring hospitalizations during the second trimester were associated with a relative risk of 2.5 of having a child with epilepsy, a relative risk of 2.3 of having a child with an intellectual disability, and a relative risk of 1.2 of having a child with autism.

Significant associations were observed between subcategories of infection and intellectual disability and epilepsy, particularly those of a bacterial cause and from respiratory and genitourinary sites. Overall, any maternal infection during pregnancy was associated with a 43% increased risk of epilepsy, a 33% increased risk of intellectual disability, and an 8% increased risk of autism.

The exact mechanism of action between the maternal infection and adverse fetal neurodevelopmental outcomes is still unclear, Ms. Haber said at the annual scientific meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society for Obstetrics and Gynecology.

“Next, we are considering which specific [maternal] infections we should look at,” Ms. Haber said in an interview. “There is something about febrile infections, so we want to narrow that down and better characterize the outcomes from mild, moderate, severe infections.”

Ms. Haber reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT IDSOG

Key clinical point: Serious maternal infections in the second trimester pose an increased risk of having a child with epilepsy or intellectual disability.

Major finding: Maternal infections in the second trimester were associated with a relative risk of 2.5 of having a child with epilepsy.

Data source: Retrospective, population-based cohort study of more than 8 million births between 1991 and 2008.

Disclosures: Ms. Haber reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Medication List Discrepancies and Therapeutic Duplications Among Dual Use Veterans

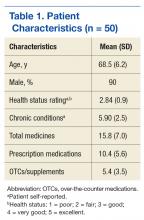

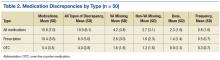

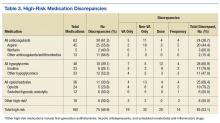

In the U.S., 4.5 million ambulatory care visits occur annually due to adverse drug reactions (ADRs) of prescription medications.1 Many ADRs are severe, and they result in more than 100,000 death per year.2 A significant number of these ADRs are preventable and are a result of inappropriate prescribing.3 It is well-documented that inappropriate prescribing is exacerbated by the number of patients who see multiple prescribers and use many different prescription medications.4 This situation results in many versions of a patient’s medication list and in discrepancies across data sources.5

Medication list discrepancies have been researched in the context of care transitions between the hospital and home.6,7 However, less attention has been given to community-dwelling adults who use multiple outpatient prescribers, a practice common among older adults with chronic conditions who see a primary care provider and several specialists.4 Also, veterans are a growing patient population who use providers from multiple health care systems.8 Up to 70% of veterans enrolled in VA health care use both VA and non-VA providers. These patients are referred to as dual users.9,10