User login

Managing irritable bowel syndrome: The low-FODMAP diet

The role of diet in controlling symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) has gained much traction over the years,1 but until recently, diet therapy for IBS has been hindered by a lack of quality evidence, in part because of the challenges of conducting dietary clinical trials.

Several clinical trials have now been done that support a diet low in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs) for managing IBS. Although restrictive and difficult to follow, the low-FODMAP diet is gaining popularity.

This article provides an overview of dietary interventions used to manage IBS, focusing on the low-FODMAP diet. We discuss mechanisms of malabsorption of FODMAPs and the role of FODMAPS in symptom induction; highlight clinical trials that provide evidence of benefits of the diet for IBS; and discuss the steps to implement it. We also address the nutritional adequacy of the diet and its potential effects on the gut microbiome.

IBS IS A COMMON FUNCTIONAL DISORDER

IBS is one of the most commonly diagnosed gastrointestinal disorders, and it has a significant impact on quality of life.2 It is a functional disorder characterized by chronic abdominal pain and altered bowel habits in the absence of a structural or organic cause.

The Rome IV diagnostic criteria define IBS by the following:

- Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort at least 1 day a week in the last 3 months, associated with two or more of the following:

- Symptoms improved by defecation

- Onset associated with a change in frequency of stool

- Onset associated with a change in form or appearance of stool.

IBS mainly arises during young adulthood but can be diagnosed at any age.3

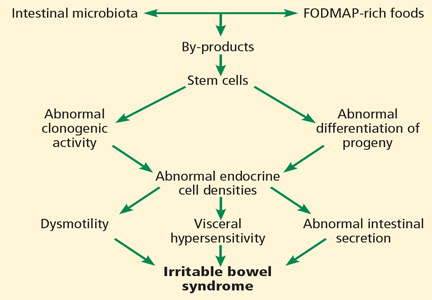

The pathophysiology of IBS involves mechanisms such as bowel distention, altered bowel motility, visceral hypersensitivity, and disruption of mucosal permeability.4 Several therapeutic modalities targeting these mechanisms have been implemented in IBS management, including antispasmodics, laxatives, antidepressants, antibiotics, and behavioral therapy. Diet is only one line of treatment and is most effective when part of a multipronged approach.

TRADITIONAL DIETARY MANAGEMENT

Diet is important in inducing the symptoms of IBS—and in controlling them. Patients identify eating as a common precipitator of symptoms, but the complex diet-symptom interaction is not fully understood and varies widely among patients. Traditional dietary advice for IBS includes adhering to a regular meal pattern, avoiding large meals, and reducing intake of fat, insoluble fibers, caffeine, spicy and gas-producing foods, and carbonated beverages.5,6

Increase soluble fiber

Fiber and fiber supplements, particularly soluble fibers such as psyllium, calcium polycarbophil, and ispaghula husk are often recommended. A meta-analysis7 found that soluble fiber but not insoluble fiber (eg, wheat bran) is associated with an improvement in IBS symptoms (relative risk [RR] 0.84, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.73–0.94). By improving stool consistency and accelerating transit, soluble fiber is especially useful in constipation-predominant IBS while posing a low risk for adverse outcomes.7 Fiber should be started at a low dose and gradually increased over several weeks to as much as 20 to 30 g/day.

Avoid wheat

Only about 4% of patients with IBS also have celiac disease, but estimating the prevalence of nonceliac gluten sensitivity is confounded by overlapping symptoms. There is some evidence implicating gluten in IBS: celiac disease and IBS overlap in their symptoms, and symptoms are often precipitated by gluten-containing foods in patients with IBS.8 The pathogenesis of gluten-induced (or wheat-induced) symptoms in IBS is unclear, and studies have had conflicting results as to the benefits of gluten restriction in IBS.9

In a study of patients with IBS whose symptoms improved when they started a gluten-free and low-FODMAP diet, symptoms did not return when gluten was reintroduced, suggesting that it is the fructan (a FODMAP) component of wheat rather than gluten that contributes to symptoms in IBS.10

Probiotics

Probiotics are increasingly being recommended as dietary supplements for people with IBS, as awareness increases of the importance of the gut microbiota. In addition to their effects on the gut microbiota, probiotics in IBS have been shown to have anti-inflammatory effects, to alter gut motility, to modulate visceral hypersensitivity, and to restore epithelial integrity.

In a meta-analysis, Ford et al11 found that probiotics improved global IBS symptoms more than placebo (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.70–0.89) and also reduced abdominal pain, bloating, and flatulence scores.

Which species and strains are most beneficial and the optimal dosing and duration of treatment are still unclear. Data from studies of prebiotics (nutrients that encourage the growth of probiotic bacteria) and synbiotics (combinations of prebiotics and probiotics) are limited and insufficient to draw conclusions.

FODMAPS ARE SHORT-CHAIN CARBOHYDRATES

The term FODMAPs was initially coined by researchers at Monash University in Australia to describe a collection of poorly absorbed short-chain fermentable carbohydrates that are natural components of many foods:

- Oligosaccharides, including fructans (which include inulins) and galacto-oligosaccharides

- Disaccharides, including lactose and sucrose

- Monosaccharides, including fructose

- Polyols, including sorbitol and mannitol.12

Intake of FODMAPs, especially fructose, has increased in Western diets over the past several decades from increased consumption of fruits and concentrated fruit juices, as well as from the widespread use of high-fructose corn syrup in processed foods and beverages.13

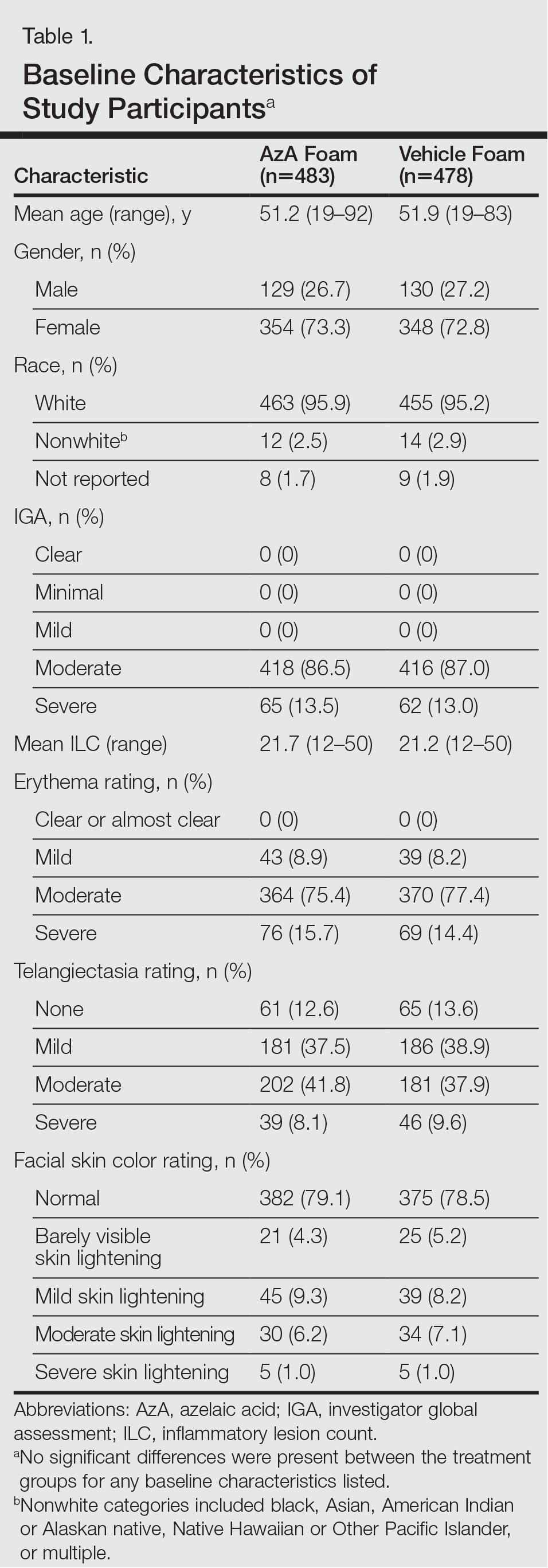

FODMAPs ARE POORLY ABSORBED

Different FODMAPs can be poorly absorbed for different reasons (Table 1). The poor absorption is related either to reduced or absent digestive enzymes (ie, hydrolases) or to slow transport across the intestinal mucosa. Excess FODMAPs in the distal small intestine and proximal colon exert osmotic pressure, drawing more water into the lumen. FODMAPs are also rapidly fermented by colonic bacteria, producing gas, bowel distention, and altered motility, all of which induce IBS symptoms.14

Fructans are fructose polymers that are not absorbed in human intestines. They have no intestinal hydrolases and no mechanisms for direct transport across the epithelium. However, a negligible amount may be absorbed after being degraded by microbes in the gut.15 Most dietary fructans are obtained from wheat and onion, which are actually low in fructans but tend to be consumed in large quantities.16

Galacto-oligosaccharides are available for colonic fermentation after ingestion due to lack of a human alpha-galactosidase. Common sources of galacto-oligosaccharides include legumes, nuts, seeds, some grains, dairy products, human milk, and some commercially produced forms added to infant formula.17,18

Lactose is poorly absorbed in people with lactase deficiency. It is mainly present in dairy products but is also added to commercial foods, including breads, cakes, and some diet products.19

Fructose is the most abundant FODMAP in the Western diet. It is either present as a free sugar or generated from the digestive breakdown of sucrose. In the intestine, it is absorbed via a direct low-capacity glucose transporter (GLUT)-5 and through GLUT-2, which is more efficient but requires the coexistence of glucose. Because of this requirement, fructose is more likely to be malabsorbed when present in excess of glucose, as in people with diminished sucrase activity. The main sources of fructose in the Western diet are fruits and fruit products, honey, and foods with added high-fructose sweeteners.13

Polyols such as sorbitol and mannitol are absorbed by slow passive diffusion because they have no active intestinal transport system. They are found in fruits and vegetables. Sugar-free chewing gum is a particularly rich source of sorbitol.20

QUANTIFYING FODMAP CONTENT

As interest in the low-FODMAP diet grew, studies were conducted to quantify FODMAPs in foods. One study used high-performance liquid chromatography to analyze FODMAP content in foods,21 and another evaluated fructan levels in a variety of fruits and vegetables using enzymatic hydrolysis.22 The Monash University low-FODMAP diet smartphone application provides patients and healthcare providers easy access to updated and detailed food analyses.23

Table 2 lists foods high in FODMAPs along with low-FODMAP alternatives. Total FODMAP intake is important, as the effects are additive.24 Readers and patients can be directed to the following websites for more information on the low-FODMAP diet: www.med.monash.edu/cecs/gastro/fodmap or www.ibsfree.net/what-is-fodmap-diet.

LOW-FODMAP DIET REDUCES SYMPTOMS

The low-FODMAP diet was inspired by the results of several studies that evaluated the role of dietary carbohydrates in inducing IBS symptoms and found improvement with their restriction.25,26

One study found that 74% of patients with IBS had less bloating, nausea, abdominal pain, and diarrhea when they restricted their intake of fructose and fructans.27

A prospective trial randomized 41 patients with IBS to 4 weeks of either a low-FODMAP diet or their habitual diet.28 The low-FODMAP diet resulted in greater improvement in overall IBS symptoms (P < .05) and stool frequency (P = .008). This study was limited by different habitual diets between patients and by lack of standardization of the low-FODMAP diet.

Halmos et al,29 in a randomized crossover trial, compared gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS patients over 3 weeks on a low-FODMAP diet vs a moderate-FODMAP (ie, regular) diet, as well as in healthy controls. Food was provided by the study and was matched for all nutrients. Up to 70% of the IBS patients had significantly lower overall symptom scores while on a low-FODMAP diet vs IBS patients on a regular diet (P < .001); bloating, abdominal pain, and flatulence were reduced. Symptoms were minimal and unaffected by either diet in the healthy controls.

A double-blind trial30 randomly assigned 25 patients with IBS who initially responded to a low-FODMAP diet to be challenged by a graduated dose of fructose alone, fructans alone, a combination of both, or glucose. The severity of overall and individual symptoms was markedly more reduced with glucose consumption than with the other carbohydrates: 70% of patients receiving fructose, 77% of those receiving fructans, and 79% of those receiving a mixture of both reported that their symptoms were not adequately controlled, compared with 14% of patients receiving glucose (P ≤ .002).30

Murray et al31 evaluated the gastrointestinal tract after a carbohydrate challenge consisting of 0.5 L of water containing 40 g of glucose, fructose, or inulin or a combination of 40 g of glucose and 40 g of fructose in 16 healthy volunteers. Magnetic resonance imaging was performed hourly for 5 hours to assess the volume of gastric contents, small-bowel water content, and colonic gas. Breath hydrogen was also measured, and symptoms were recorded after each imaging session.

Fructose significantly increased small-bowel water content compared with glucose (mean difference 28 L/min, P < .001), but combined glucose and fructose lessened the effect. Inulin had no significant effect on small-bowel water content (mean difference with glucose 2 L/min, P > .7) but led to the greatest production of colonic gas compared with glucose alone (mean difference 15 L/min, P < .05) and combined glucose and fructose (mean difference 12 L/min, P < .05). Inulin also produced the most breath hydrogen: 81% of participants had a rise after drinking inulin compared with 50% after drinking fructose. Glucose did not affect breath hydrogen concentrations, and combined glucose and fructose significantly reduced the concentration measured vs fructose alone. In patients who reported “gas” symptoms, a correlation was observed between the volume of gas in the colon and gas symptoms (r = 0.59, P < .0001).31

The authors concluded31 that long-chain carbohydrates such as inulin have a greater effect on colonic gas production and little effect on small-bowel water content, whereas small-chain FODMAPs such as fructose are likely to cause luminal distention in both the small and large intestines. The study also showed that combining equal amounts of glucose and fructose reduces malabsorption of fructose in the small bowel and reduces the effect of fructose on small-bowel water content and breath hydrogen concentration.31

PROBIOTICS HELP

A Danish study32 randomized 123 patients with IBS to one of three treatments: a low-FODMAP diet, a normal diet with probiotics containing the strain Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (two capsules daily), or no special intervention. Symptoms were recorded weekly. IBS severity scores at week 6 were lower in patients on either the low-FODMAP diet or probiotics compared with the control group (P < .01). Subgroup analysis determined that patients with primarily diarrheal symptoms were more likely to have improved quality of life with the low-FODMAP diet.

A LOW-FODMAP DIET MAY ALSO HELP IN INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

The low-FODMAP diet has also been studied in patients with inflammatory bowel disease with functional gut symptoms. In a retrospective pilot study,33 overall symptoms improved in about half of such patients on a low-FODMAP diet. A controlled dietary intervention trial is needed to confirm these findings and define the role of the low-FODMAP approach for patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

Marsh et al34 performed a meta-analysis of six randomized clinical trials and 16 nonrandomized interventions of a low-FODMAP diet on improving functional gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with either IBS or inflammatory bowel disease. They found significant improvements in:

- IBS Symptoms Severity Scores in the randomized trials (odds ratio [OR] 0.44, 95% CI 0.25–0.76)

- IBS Symptoms Severity Scores in the nonrandomized interventions (OR 0.03, 95% CI 0.01–0.2)

- IBS Quality of Life scores in the randomized trials (OR 1.84, 95% CI 1.12–3.03)

- IBS Quality of Life scores in the nonrandomized interventions (OR 3.18, 95% CI 1.6–6.31)

- Overall symptom severity in the randomized trials (OR 1.81, 95% CI 1.11–2.95).

DIETARY COUNSELING IS RECOMMENDED

Adherence is a major factor in the success of the low-FODMAP diet in IBS management and is strongly correlated with improved symptoms.35 Patients should be counseled on the role of food in inducing their symptoms. Haphazard dietary advice can be detrimental to outcomes, as many diets restrict food groups, impairing the consumption of essential nutrients.36 The involvement of a knowledgeable dietitian is helpful, as physicians may lack sufficient training in dietary skills and knowledge of food composition.

Access to and cost of dietary counseling can be prohibitive for some patients. Group consultation, which can decrease costs to each patient, has been found to be as effective as one-on-one sessions when administering the low-FODMAP diet in functional bowel disorders.37

ELIMINATION, THEN REINTRODUCTION

Before embarking on the low-FODMAP diet, the patient’s interest in making dietary changes should be explored, a dietary history taken, and unusual food choices or dietary behaviors assessed. The patient’s ability to adopt a restricted diet should also be gauged.

The diet should be implemented in two phases. The initial phase involves strict elimination of foods high in FODMAPs, usually over 6 to 8 weeks.38 Symptom control should be assessed: failure to control symptoms requires assessment of adherence.

If symptoms are successfully controlled, then the second phase should begin with the aim of following a less-restricted version of the diet as tolerated. Foods should gradually be phased back in and symptoms monitored. This approach minimizes unnecessary dietary restriction and ensures that a maximum variety in the diet is achieved while maintaining adequate symptom control.39

LOW-FODMAP DIET ALTERS THE GUT MICROBIOTA

Multiple putative benefits of certain bacterial species for colonic health have been reported, including the production of short-chain fatty acids. Colonic luminal concentrations of short-chain fatty acids may be important to gut health, given their role in intestinal secretion, absorption, motility, and epithelial cell structure. Because short-chain fatty acids are products of bacterial fermentation, a change in the delivery of fermentable substrates to the colon would be expected to alter the concentrations and output of fecal short-chain fatty acids.18

Several studies evaluated the effect of the low-FODMAP diet on intestinal microbiota, finding a change in the bacterial profile in the stool of patients who adopt this diet. Staudacher et al28 found a marked reduction in luminal bifidobacteria concentration after 4 weeks of a low-FODMAP diet in patients with IBS.

A single-blind randomized crossover trial40 investigated the effects of a low-FODMAP diet vs a carefully matched typical Australian diet in 27 patients with IBS and 6 healthy controls. Marked differences in absolute and relative bacterial abundance and diversity were found between the diets, but not in short-chain fatty acids or gut transit time. Compared with fecal microbiota on the typical diet, low FODMAP intake was associated with reduced absolute abundance of bacteria, and the typical FODMAP diet had evidence of stimulation of the growth of bacterial groups with putative health benefits.

The authors concluded40 that the functional significance and health implications of such changes are reasons for caution when reducing FODMAP intake in the long term and recommended liberalizing FODMAP restriction to the level of adequate symptom control in IBS patients. The study also recommended that people without symptoms not go on the low-FODMAP diet.40

Molecular approaches to characterize the gut microbiota are also being explored in an effort to identify its association with diet.

The sustainability of changes in gut microbiota and the potential long-term impact on health of following a low-FODMAP diet require further evaluation. In the meantime, patients following this diet should have FODMAP foods reintroduced based on tolerance and should consider taking probiotic supplements.41

DIETARY ADEQUACY OF THE LOW-FODMAP DIET

Continual dietary counseling should minimize nutritional inadequacies and ensure that FODMAPS are restricted only enough to control symptoms. Because no single food group is completely eliminated in this diet, patients are unlikely to experience inadequate nutrition.

Ledochowski et al26 found that in the initial, strict phase of the diet, total intake of carbohydrates (eg, starches, sugars) was reduced but intake of total energy, protein, fat, and nonstarch polysaccharides was not affected. Calcium intake was reduced in those following a low-FODMAP diet for 4 weeks.

The diet can also reduce total fiber intake and subsequently worsen constipation-predominant IBS. For those patients, lightly fermented high-fiber alternatives like oat and rice bran can be used.

ACCUMULATING EVIDENCE

The low-FODMAP diet is accumulating quality evidence for its effectiveness in controlling the functional gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with IBS. It can be difficult to adhere to over the long term due to its restrictiveness, and it is important to gradually liberalize the diet while tailoring it to the individual patient and monitoring symptoms. Further clinical trials are needed to evaluate this diet in different IBS subtypes and other gastrointestinal disorders, while defining its nutritional adequacy and effects on the intestinal microbiota profile.

- Hayes P, Corish C, O’Mahony E, Quigley EM. A dietary survey of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet 2014; 27(suppl 2):36–47.

- Pare P, Gray J, Lam S, et al. Health-related quality of life, work productivity, and health care resource utilization of subjects with irritable bowel syndrome: baseline results from LOGIC (Longitudinal Outcomes Study of Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Canada), a naturalistic study. Clin Ther 2006; 28:1726–1735; discussion 1710–1711.

- Lacey BE, Mearin F, Chang L, et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2016; 150:1393–1407.

- Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Whitehead WE. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2002; 123:2108–2131.

- Floch MH, Narayan R. Diet in the irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol 2002; 35(suppl 1):S45–S52.

- Reding KW, Cain KC, Jarrett ME, Eugenio MD, Heitkemper MM. Relationship between patterns of alcohol consumption and gastrointestinal symptoms among patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108:270–276.

- Moayyedi P, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, et al. The effect of fiber supplementation on irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109:1367–1374.

- Vazquez Roque MI, Camilleri M, Smyrk T, et al. A controlled trial of gluten-free diet in patients with irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea: effects on bowel frequency and intestinal function. Gastroenterology 2013; 144:903–911.

- Biesiekierski JR, Newnham ED, Irving PM, et al. Gluten causes gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects without celiac disease: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106:508–515.

- Biesiekierski JR, Peters SL, Newnham ED, Rosella O, Muir JG, Gibson PR. No effects of gluten in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity after dietary reduction of fermentable, poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates. Gastroenterology 2013; 145:320–328.

- Ford AC, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, et al. Efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics in irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2013; 145:320–328.e1–e3.

- Central Clinical School, Monash University and The Alfred Hospital. The Monash University Low FODMAP Diet. 4th ed. Melbourne, Australia: Monash University; 2012.

- Parker K, Salas M, Nwosu VC. High fructose corn syrup: production, uses and public health concerns. Biotechnol Mol Biol Rev 2010; 5:71–78.

- Clausen MR, Jorgensen J, Mortensen PB. Comparison of diarrhea induced by ingestion of fructooligosaccharide idolax and disaccharide lactulose: role of osmolarity versus fermentation of malabsorbed carbohydrate. Dig Dis Sci 1998; 43:2696–2707.

- Barrett JS, Gearry RB, Muir JG, et al. Dietary poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates increase delivery of water and fermentable substrates to the proximal colon. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010; 31:874–882.

- Whelan K, Abrahmsohn O, David GJ, et al. Fructan content of commonly consumed wheat, rye and gluten-free breads. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2011; 62:498–503.

- Sangwan V, Tomar SK, Singh RR, Singh AK, Ali B. Galactooligosaccharides: novel components of designer foods. J Food Sci 2011; 76:R103–R111.

- Russell DA, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF, Stanton C. Metabolic activities and probiotic potential of bifidobacteria. Int J Food Microbiol 2011; 149:88–105.

- Lomer MC, Parkes GC, Sanderson JD. Review article: lactose intolerance in clinical practice—myths and realities. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008; 27:93–103.

- Langkilde AM, Andersson H, Schweizer TF, Würsch P. Digestion and absorption of sorbitol, maltitol and isomalt from the small bowel. A study in ileostomy subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr 1994; 48:768–775.

- Muir JG, Rose R, Rosella O, et al. Measurement of short-chain carbohydrates in common Australian vegetables and fruits by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). J Agric Food Chem 2009; 57:554–565.

- Muir JG, Shepherd SJ, Rosella O, Rose R, Barrett JS, Gibson PR. Fructan and free fructose content of common Australian vegetables and fruit. J Agric Food Chem 2007; 55:6619–6627.

- Monash University. Monash launches Low FODMAP Diet smartphone app. http://med.monash.edu.au/news/2012/fodmap-app.html. Accessed July 13, 2016.

- Fedewa A, Rao SS. Dietary fructose intolerance, fructan intolerance and FODMAPs. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2014; 16:370.

- Born P, Vierling T, Barina W. Fructose malabsorption and the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 1991; 101:1454.

- Ledochowski M, Widner B, Bair H, Probst T, Fuchs D. Fructose- and sorbitol-reduced diet improves mood and gastrointestinal disturbances in fructose malabsorbers. Scand J Gastroenterol 2000; 35:1048–1052.

- Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR. Fructose malabsorption and symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome: guidelines for effective dietary management. J Am Diet Assoc 2006; 106:1631–1639.

- Staudacher HM, Lomer MC, Anderson JL, et al. Fermentable carbohydrate restriction reduces luminal bifidobacteria and gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Nutr 2012; 142:1510–1518.

- Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2014; 146:67–75.e5.

- Shepherd SJ, Parker FC, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Dietary triggers of abdominal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: randomized placebo-controlled evidence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 6:765–771.

- Murray K, Wilkinson-Smith V, Hoad C, et al. Differential effects of FODMAPs (fermentable oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides and polyols) on small and large intestinal contents in healthy subjects shown by MRI. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109:110–119.

- Pedersen N, Andersen NN, Vegh Z, et al. Ehealth: low FODMAP diet vs Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20:16215–16226.

- Gearry RB, Irving PM, Barrett JS, Nathan DM, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR. Reduction of dietary poorly absorbed short-chain carbohydrates (FODMAPs) improves abdominal symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease-a pilot study. J Crohns Colitis 2009; 3:8–14.

- Marsh A, Eslick EM, Eslick GD. Does a diet low in FODMAPs reduce symptoms associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders? A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Nutr 2015 May 17. Epub ahead of print.

- de Roest RH, Dobbs BR, Chapman BA, et al. The low FODMAP diet improves gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective study. Int J Clin Pract 2013; 67:895–903.

- Gibson PR, Barrett JS, Muir JG. Functional bowel symptoms and diet. Intern Med J 2013; 43:1067–1074.

- Whigham L, Joyce T, Harper G, et al. Clinical effectiveness and economic costs of group versus one-to-one education for short-chain fermentable carbohydrate restriction (low FODMAP diet) in the management of irritable bowel syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet 2015; 28:687–696.

- Shepherd SJ, Lomer MC, Gibson PR. Short-chain carbohydrates and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108:707–717.

- Shepherd SJ, Halmos E, Glance S. The role of FODMAPs in irritable bowel syndrome. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2014; 17:605–609.

- Halmos EP, Christophersen CT, Bird AR, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. Diets that differ in their FODMAP content alter the colonic luminal microenvironment. Gut 2015; 64:93–100.

- Staudacher HM, Irving PM, Lomer MC, Whelan K. Mechanisms and efficacy of dietary FODMAP restriction in IBS. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 11:256–266.

The role of diet in controlling symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) has gained much traction over the years,1 but until recently, diet therapy for IBS has been hindered by a lack of quality evidence, in part because of the challenges of conducting dietary clinical trials.

Several clinical trials have now been done that support a diet low in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs) for managing IBS. Although restrictive and difficult to follow, the low-FODMAP diet is gaining popularity.

This article provides an overview of dietary interventions used to manage IBS, focusing on the low-FODMAP diet. We discuss mechanisms of malabsorption of FODMAPs and the role of FODMAPS in symptom induction; highlight clinical trials that provide evidence of benefits of the diet for IBS; and discuss the steps to implement it. We also address the nutritional adequacy of the diet and its potential effects on the gut microbiome.

IBS IS A COMMON FUNCTIONAL DISORDER

IBS is one of the most commonly diagnosed gastrointestinal disorders, and it has a significant impact on quality of life.2 It is a functional disorder characterized by chronic abdominal pain and altered bowel habits in the absence of a structural or organic cause.

The Rome IV diagnostic criteria define IBS by the following:

- Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort at least 1 day a week in the last 3 months, associated with two or more of the following:

- Symptoms improved by defecation

- Onset associated with a change in frequency of stool

- Onset associated with a change in form or appearance of stool.

IBS mainly arises during young adulthood but can be diagnosed at any age.3

The pathophysiology of IBS involves mechanisms such as bowel distention, altered bowel motility, visceral hypersensitivity, and disruption of mucosal permeability.4 Several therapeutic modalities targeting these mechanisms have been implemented in IBS management, including antispasmodics, laxatives, antidepressants, antibiotics, and behavioral therapy. Diet is only one line of treatment and is most effective when part of a multipronged approach.

TRADITIONAL DIETARY MANAGEMENT

Diet is important in inducing the symptoms of IBS—and in controlling them. Patients identify eating as a common precipitator of symptoms, but the complex diet-symptom interaction is not fully understood and varies widely among patients. Traditional dietary advice for IBS includes adhering to a regular meal pattern, avoiding large meals, and reducing intake of fat, insoluble fibers, caffeine, spicy and gas-producing foods, and carbonated beverages.5,6

Increase soluble fiber

Fiber and fiber supplements, particularly soluble fibers such as psyllium, calcium polycarbophil, and ispaghula husk are often recommended. A meta-analysis7 found that soluble fiber but not insoluble fiber (eg, wheat bran) is associated with an improvement in IBS symptoms (relative risk [RR] 0.84, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.73–0.94). By improving stool consistency and accelerating transit, soluble fiber is especially useful in constipation-predominant IBS while posing a low risk for adverse outcomes.7 Fiber should be started at a low dose and gradually increased over several weeks to as much as 20 to 30 g/day.

Avoid wheat

Only about 4% of patients with IBS also have celiac disease, but estimating the prevalence of nonceliac gluten sensitivity is confounded by overlapping symptoms. There is some evidence implicating gluten in IBS: celiac disease and IBS overlap in their symptoms, and symptoms are often precipitated by gluten-containing foods in patients with IBS.8 The pathogenesis of gluten-induced (or wheat-induced) symptoms in IBS is unclear, and studies have had conflicting results as to the benefits of gluten restriction in IBS.9

In a study of patients with IBS whose symptoms improved when they started a gluten-free and low-FODMAP diet, symptoms did not return when gluten was reintroduced, suggesting that it is the fructan (a FODMAP) component of wheat rather than gluten that contributes to symptoms in IBS.10

Probiotics

Probiotics are increasingly being recommended as dietary supplements for people with IBS, as awareness increases of the importance of the gut microbiota. In addition to their effects on the gut microbiota, probiotics in IBS have been shown to have anti-inflammatory effects, to alter gut motility, to modulate visceral hypersensitivity, and to restore epithelial integrity.

In a meta-analysis, Ford et al11 found that probiotics improved global IBS symptoms more than placebo (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.70–0.89) and also reduced abdominal pain, bloating, and flatulence scores.

Which species and strains are most beneficial and the optimal dosing and duration of treatment are still unclear. Data from studies of prebiotics (nutrients that encourage the growth of probiotic bacteria) and synbiotics (combinations of prebiotics and probiotics) are limited and insufficient to draw conclusions.

FODMAPS ARE SHORT-CHAIN CARBOHYDRATES

The term FODMAPs was initially coined by researchers at Monash University in Australia to describe a collection of poorly absorbed short-chain fermentable carbohydrates that are natural components of many foods:

- Oligosaccharides, including fructans (which include inulins) and galacto-oligosaccharides

- Disaccharides, including lactose and sucrose

- Monosaccharides, including fructose

- Polyols, including sorbitol and mannitol.12

Intake of FODMAPs, especially fructose, has increased in Western diets over the past several decades from increased consumption of fruits and concentrated fruit juices, as well as from the widespread use of high-fructose corn syrup in processed foods and beverages.13

FODMAPs ARE POORLY ABSORBED

Different FODMAPs can be poorly absorbed for different reasons (Table 1). The poor absorption is related either to reduced or absent digestive enzymes (ie, hydrolases) or to slow transport across the intestinal mucosa. Excess FODMAPs in the distal small intestine and proximal colon exert osmotic pressure, drawing more water into the lumen. FODMAPs are also rapidly fermented by colonic bacteria, producing gas, bowel distention, and altered motility, all of which induce IBS symptoms.14

Fructans are fructose polymers that are not absorbed in human intestines. They have no intestinal hydrolases and no mechanisms for direct transport across the epithelium. However, a negligible amount may be absorbed after being degraded by microbes in the gut.15 Most dietary fructans are obtained from wheat and onion, which are actually low in fructans but tend to be consumed in large quantities.16

Galacto-oligosaccharides are available for colonic fermentation after ingestion due to lack of a human alpha-galactosidase. Common sources of galacto-oligosaccharides include legumes, nuts, seeds, some grains, dairy products, human milk, and some commercially produced forms added to infant formula.17,18

Lactose is poorly absorbed in people with lactase deficiency. It is mainly present in dairy products but is also added to commercial foods, including breads, cakes, and some diet products.19

Fructose is the most abundant FODMAP in the Western diet. It is either present as a free sugar or generated from the digestive breakdown of sucrose. In the intestine, it is absorbed via a direct low-capacity glucose transporter (GLUT)-5 and through GLUT-2, which is more efficient but requires the coexistence of glucose. Because of this requirement, fructose is more likely to be malabsorbed when present in excess of glucose, as in people with diminished sucrase activity. The main sources of fructose in the Western diet are fruits and fruit products, honey, and foods with added high-fructose sweeteners.13

Polyols such as sorbitol and mannitol are absorbed by slow passive diffusion because they have no active intestinal transport system. They are found in fruits and vegetables. Sugar-free chewing gum is a particularly rich source of sorbitol.20

QUANTIFYING FODMAP CONTENT

As interest in the low-FODMAP diet grew, studies were conducted to quantify FODMAPs in foods. One study used high-performance liquid chromatography to analyze FODMAP content in foods,21 and another evaluated fructan levels in a variety of fruits and vegetables using enzymatic hydrolysis.22 The Monash University low-FODMAP diet smartphone application provides patients and healthcare providers easy access to updated and detailed food analyses.23

Table 2 lists foods high in FODMAPs along with low-FODMAP alternatives. Total FODMAP intake is important, as the effects are additive.24 Readers and patients can be directed to the following websites for more information on the low-FODMAP diet: www.med.monash.edu/cecs/gastro/fodmap or www.ibsfree.net/what-is-fodmap-diet.

LOW-FODMAP DIET REDUCES SYMPTOMS

The low-FODMAP diet was inspired by the results of several studies that evaluated the role of dietary carbohydrates in inducing IBS symptoms and found improvement with their restriction.25,26

One study found that 74% of patients with IBS had less bloating, nausea, abdominal pain, and diarrhea when they restricted their intake of fructose and fructans.27

A prospective trial randomized 41 patients with IBS to 4 weeks of either a low-FODMAP diet or their habitual diet.28 The low-FODMAP diet resulted in greater improvement in overall IBS symptoms (P < .05) and stool frequency (P = .008). This study was limited by different habitual diets between patients and by lack of standardization of the low-FODMAP diet.

Halmos et al,29 in a randomized crossover trial, compared gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS patients over 3 weeks on a low-FODMAP diet vs a moderate-FODMAP (ie, regular) diet, as well as in healthy controls. Food was provided by the study and was matched for all nutrients. Up to 70% of the IBS patients had significantly lower overall symptom scores while on a low-FODMAP diet vs IBS patients on a regular diet (P < .001); bloating, abdominal pain, and flatulence were reduced. Symptoms were minimal and unaffected by either diet in the healthy controls.

A double-blind trial30 randomly assigned 25 patients with IBS who initially responded to a low-FODMAP diet to be challenged by a graduated dose of fructose alone, fructans alone, a combination of both, or glucose. The severity of overall and individual symptoms was markedly more reduced with glucose consumption than with the other carbohydrates: 70% of patients receiving fructose, 77% of those receiving fructans, and 79% of those receiving a mixture of both reported that their symptoms were not adequately controlled, compared with 14% of patients receiving glucose (P ≤ .002).30

Murray et al31 evaluated the gastrointestinal tract after a carbohydrate challenge consisting of 0.5 L of water containing 40 g of glucose, fructose, or inulin or a combination of 40 g of glucose and 40 g of fructose in 16 healthy volunteers. Magnetic resonance imaging was performed hourly for 5 hours to assess the volume of gastric contents, small-bowel water content, and colonic gas. Breath hydrogen was also measured, and symptoms were recorded after each imaging session.

Fructose significantly increased small-bowel water content compared with glucose (mean difference 28 L/min, P < .001), but combined glucose and fructose lessened the effect. Inulin had no significant effect on small-bowel water content (mean difference with glucose 2 L/min, P > .7) but led to the greatest production of colonic gas compared with glucose alone (mean difference 15 L/min, P < .05) and combined glucose and fructose (mean difference 12 L/min, P < .05). Inulin also produced the most breath hydrogen: 81% of participants had a rise after drinking inulin compared with 50% after drinking fructose. Glucose did not affect breath hydrogen concentrations, and combined glucose and fructose significantly reduced the concentration measured vs fructose alone. In patients who reported “gas” symptoms, a correlation was observed between the volume of gas in the colon and gas symptoms (r = 0.59, P < .0001).31

The authors concluded31 that long-chain carbohydrates such as inulin have a greater effect on colonic gas production and little effect on small-bowel water content, whereas small-chain FODMAPs such as fructose are likely to cause luminal distention in both the small and large intestines. The study also showed that combining equal amounts of glucose and fructose reduces malabsorption of fructose in the small bowel and reduces the effect of fructose on small-bowel water content and breath hydrogen concentration.31

PROBIOTICS HELP

A Danish study32 randomized 123 patients with IBS to one of three treatments: a low-FODMAP diet, a normal diet with probiotics containing the strain Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (two capsules daily), or no special intervention. Symptoms were recorded weekly. IBS severity scores at week 6 were lower in patients on either the low-FODMAP diet or probiotics compared with the control group (P < .01). Subgroup analysis determined that patients with primarily diarrheal symptoms were more likely to have improved quality of life with the low-FODMAP diet.

A LOW-FODMAP DIET MAY ALSO HELP IN INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

The low-FODMAP diet has also been studied in patients with inflammatory bowel disease with functional gut symptoms. In a retrospective pilot study,33 overall symptoms improved in about half of such patients on a low-FODMAP diet. A controlled dietary intervention trial is needed to confirm these findings and define the role of the low-FODMAP approach for patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

Marsh et al34 performed a meta-analysis of six randomized clinical trials and 16 nonrandomized interventions of a low-FODMAP diet on improving functional gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with either IBS or inflammatory bowel disease. They found significant improvements in:

- IBS Symptoms Severity Scores in the randomized trials (odds ratio [OR] 0.44, 95% CI 0.25–0.76)

- IBS Symptoms Severity Scores in the nonrandomized interventions (OR 0.03, 95% CI 0.01–0.2)

- IBS Quality of Life scores in the randomized trials (OR 1.84, 95% CI 1.12–3.03)

- IBS Quality of Life scores in the nonrandomized interventions (OR 3.18, 95% CI 1.6–6.31)

- Overall symptom severity in the randomized trials (OR 1.81, 95% CI 1.11–2.95).

DIETARY COUNSELING IS RECOMMENDED

Adherence is a major factor in the success of the low-FODMAP diet in IBS management and is strongly correlated with improved symptoms.35 Patients should be counseled on the role of food in inducing their symptoms. Haphazard dietary advice can be detrimental to outcomes, as many diets restrict food groups, impairing the consumption of essential nutrients.36 The involvement of a knowledgeable dietitian is helpful, as physicians may lack sufficient training in dietary skills and knowledge of food composition.

Access to and cost of dietary counseling can be prohibitive for some patients. Group consultation, which can decrease costs to each patient, has been found to be as effective as one-on-one sessions when administering the low-FODMAP diet in functional bowel disorders.37

ELIMINATION, THEN REINTRODUCTION

Before embarking on the low-FODMAP diet, the patient’s interest in making dietary changes should be explored, a dietary history taken, and unusual food choices or dietary behaviors assessed. The patient’s ability to adopt a restricted diet should also be gauged.

The diet should be implemented in two phases. The initial phase involves strict elimination of foods high in FODMAPs, usually over 6 to 8 weeks.38 Symptom control should be assessed: failure to control symptoms requires assessment of adherence.

If symptoms are successfully controlled, then the second phase should begin with the aim of following a less-restricted version of the diet as tolerated. Foods should gradually be phased back in and symptoms monitored. This approach minimizes unnecessary dietary restriction and ensures that a maximum variety in the diet is achieved while maintaining adequate symptom control.39

LOW-FODMAP DIET ALTERS THE GUT MICROBIOTA

Multiple putative benefits of certain bacterial species for colonic health have been reported, including the production of short-chain fatty acids. Colonic luminal concentrations of short-chain fatty acids may be important to gut health, given their role in intestinal secretion, absorption, motility, and epithelial cell structure. Because short-chain fatty acids are products of bacterial fermentation, a change in the delivery of fermentable substrates to the colon would be expected to alter the concentrations and output of fecal short-chain fatty acids.18

Several studies evaluated the effect of the low-FODMAP diet on intestinal microbiota, finding a change in the bacterial profile in the stool of patients who adopt this diet. Staudacher et al28 found a marked reduction in luminal bifidobacteria concentration after 4 weeks of a low-FODMAP diet in patients with IBS.

A single-blind randomized crossover trial40 investigated the effects of a low-FODMAP diet vs a carefully matched typical Australian diet in 27 patients with IBS and 6 healthy controls. Marked differences in absolute and relative bacterial abundance and diversity were found between the diets, but not in short-chain fatty acids or gut transit time. Compared with fecal microbiota on the typical diet, low FODMAP intake was associated with reduced absolute abundance of bacteria, and the typical FODMAP diet had evidence of stimulation of the growth of bacterial groups with putative health benefits.

The authors concluded40 that the functional significance and health implications of such changes are reasons for caution when reducing FODMAP intake in the long term and recommended liberalizing FODMAP restriction to the level of adequate symptom control in IBS patients. The study also recommended that people without symptoms not go on the low-FODMAP diet.40

Molecular approaches to characterize the gut microbiota are also being explored in an effort to identify its association with diet.

The sustainability of changes in gut microbiota and the potential long-term impact on health of following a low-FODMAP diet require further evaluation. In the meantime, patients following this diet should have FODMAP foods reintroduced based on tolerance and should consider taking probiotic supplements.41

DIETARY ADEQUACY OF THE LOW-FODMAP DIET

Continual dietary counseling should minimize nutritional inadequacies and ensure that FODMAPS are restricted only enough to control symptoms. Because no single food group is completely eliminated in this diet, patients are unlikely to experience inadequate nutrition.

Ledochowski et al26 found that in the initial, strict phase of the diet, total intake of carbohydrates (eg, starches, sugars) was reduced but intake of total energy, protein, fat, and nonstarch polysaccharides was not affected. Calcium intake was reduced in those following a low-FODMAP diet for 4 weeks.

The diet can also reduce total fiber intake and subsequently worsen constipation-predominant IBS. For those patients, lightly fermented high-fiber alternatives like oat and rice bran can be used.

ACCUMULATING EVIDENCE

The low-FODMAP diet is accumulating quality evidence for its effectiveness in controlling the functional gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with IBS. It can be difficult to adhere to over the long term due to its restrictiveness, and it is important to gradually liberalize the diet while tailoring it to the individual patient and monitoring symptoms. Further clinical trials are needed to evaluate this diet in different IBS subtypes and other gastrointestinal disorders, while defining its nutritional adequacy and effects on the intestinal microbiota profile.

The role of diet in controlling symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) has gained much traction over the years,1 but until recently, diet therapy for IBS has been hindered by a lack of quality evidence, in part because of the challenges of conducting dietary clinical trials.

Several clinical trials have now been done that support a diet low in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs) for managing IBS. Although restrictive and difficult to follow, the low-FODMAP diet is gaining popularity.

This article provides an overview of dietary interventions used to manage IBS, focusing on the low-FODMAP diet. We discuss mechanisms of malabsorption of FODMAPs and the role of FODMAPS in symptom induction; highlight clinical trials that provide evidence of benefits of the diet for IBS; and discuss the steps to implement it. We also address the nutritional adequacy of the diet and its potential effects on the gut microbiome.

IBS IS A COMMON FUNCTIONAL DISORDER

IBS is one of the most commonly diagnosed gastrointestinal disorders, and it has a significant impact on quality of life.2 It is a functional disorder characterized by chronic abdominal pain and altered bowel habits in the absence of a structural or organic cause.

The Rome IV diagnostic criteria define IBS by the following:

- Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort at least 1 day a week in the last 3 months, associated with two or more of the following:

- Symptoms improved by defecation

- Onset associated with a change in frequency of stool

- Onset associated with a change in form or appearance of stool.

IBS mainly arises during young adulthood but can be diagnosed at any age.3

The pathophysiology of IBS involves mechanisms such as bowel distention, altered bowel motility, visceral hypersensitivity, and disruption of mucosal permeability.4 Several therapeutic modalities targeting these mechanisms have been implemented in IBS management, including antispasmodics, laxatives, antidepressants, antibiotics, and behavioral therapy. Diet is only one line of treatment and is most effective when part of a multipronged approach.

TRADITIONAL DIETARY MANAGEMENT

Diet is important in inducing the symptoms of IBS—and in controlling them. Patients identify eating as a common precipitator of symptoms, but the complex diet-symptom interaction is not fully understood and varies widely among patients. Traditional dietary advice for IBS includes adhering to a regular meal pattern, avoiding large meals, and reducing intake of fat, insoluble fibers, caffeine, spicy and gas-producing foods, and carbonated beverages.5,6

Increase soluble fiber

Fiber and fiber supplements, particularly soluble fibers such as psyllium, calcium polycarbophil, and ispaghula husk are often recommended. A meta-analysis7 found that soluble fiber but not insoluble fiber (eg, wheat bran) is associated with an improvement in IBS symptoms (relative risk [RR] 0.84, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.73–0.94). By improving stool consistency and accelerating transit, soluble fiber is especially useful in constipation-predominant IBS while posing a low risk for adverse outcomes.7 Fiber should be started at a low dose and gradually increased over several weeks to as much as 20 to 30 g/day.

Avoid wheat

Only about 4% of patients with IBS also have celiac disease, but estimating the prevalence of nonceliac gluten sensitivity is confounded by overlapping symptoms. There is some evidence implicating gluten in IBS: celiac disease and IBS overlap in their symptoms, and symptoms are often precipitated by gluten-containing foods in patients with IBS.8 The pathogenesis of gluten-induced (or wheat-induced) symptoms in IBS is unclear, and studies have had conflicting results as to the benefits of gluten restriction in IBS.9

In a study of patients with IBS whose symptoms improved when they started a gluten-free and low-FODMAP diet, symptoms did not return when gluten was reintroduced, suggesting that it is the fructan (a FODMAP) component of wheat rather than gluten that contributes to symptoms in IBS.10

Probiotics

Probiotics are increasingly being recommended as dietary supplements for people with IBS, as awareness increases of the importance of the gut microbiota. In addition to their effects on the gut microbiota, probiotics in IBS have been shown to have anti-inflammatory effects, to alter gut motility, to modulate visceral hypersensitivity, and to restore epithelial integrity.

In a meta-analysis, Ford et al11 found that probiotics improved global IBS symptoms more than placebo (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.70–0.89) and also reduced abdominal pain, bloating, and flatulence scores.

Which species and strains are most beneficial and the optimal dosing and duration of treatment are still unclear. Data from studies of prebiotics (nutrients that encourage the growth of probiotic bacteria) and synbiotics (combinations of prebiotics and probiotics) are limited and insufficient to draw conclusions.

FODMAPS ARE SHORT-CHAIN CARBOHYDRATES

The term FODMAPs was initially coined by researchers at Monash University in Australia to describe a collection of poorly absorbed short-chain fermentable carbohydrates that are natural components of many foods:

- Oligosaccharides, including fructans (which include inulins) and galacto-oligosaccharides

- Disaccharides, including lactose and sucrose

- Monosaccharides, including fructose

- Polyols, including sorbitol and mannitol.12

Intake of FODMAPs, especially fructose, has increased in Western diets over the past several decades from increased consumption of fruits and concentrated fruit juices, as well as from the widespread use of high-fructose corn syrup in processed foods and beverages.13

FODMAPs ARE POORLY ABSORBED

Different FODMAPs can be poorly absorbed for different reasons (Table 1). The poor absorption is related either to reduced or absent digestive enzymes (ie, hydrolases) or to slow transport across the intestinal mucosa. Excess FODMAPs in the distal small intestine and proximal colon exert osmotic pressure, drawing more water into the lumen. FODMAPs are also rapidly fermented by colonic bacteria, producing gas, bowel distention, and altered motility, all of which induce IBS symptoms.14

Fructans are fructose polymers that are not absorbed in human intestines. They have no intestinal hydrolases and no mechanisms for direct transport across the epithelium. However, a negligible amount may be absorbed after being degraded by microbes in the gut.15 Most dietary fructans are obtained from wheat and onion, which are actually low in fructans but tend to be consumed in large quantities.16

Galacto-oligosaccharides are available for colonic fermentation after ingestion due to lack of a human alpha-galactosidase. Common sources of galacto-oligosaccharides include legumes, nuts, seeds, some grains, dairy products, human milk, and some commercially produced forms added to infant formula.17,18

Lactose is poorly absorbed in people with lactase deficiency. It is mainly present in dairy products but is also added to commercial foods, including breads, cakes, and some diet products.19

Fructose is the most abundant FODMAP in the Western diet. It is either present as a free sugar or generated from the digestive breakdown of sucrose. In the intestine, it is absorbed via a direct low-capacity glucose transporter (GLUT)-5 and through GLUT-2, which is more efficient but requires the coexistence of glucose. Because of this requirement, fructose is more likely to be malabsorbed when present in excess of glucose, as in people with diminished sucrase activity. The main sources of fructose in the Western diet are fruits and fruit products, honey, and foods with added high-fructose sweeteners.13

Polyols such as sorbitol and mannitol are absorbed by slow passive diffusion because they have no active intestinal transport system. They are found in fruits and vegetables. Sugar-free chewing gum is a particularly rich source of sorbitol.20

QUANTIFYING FODMAP CONTENT

As interest in the low-FODMAP diet grew, studies were conducted to quantify FODMAPs in foods. One study used high-performance liquid chromatography to analyze FODMAP content in foods,21 and another evaluated fructan levels in a variety of fruits and vegetables using enzymatic hydrolysis.22 The Monash University low-FODMAP diet smartphone application provides patients and healthcare providers easy access to updated and detailed food analyses.23

Table 2 lists foods high in FODMAPs along with low-FODMAP alternatives. Total FODMAP intake is important, as the effects are additive.24 Readers and patients can be directed to the following websites for more information on the low-FODMAP diet: www.med.monash.edu/cecs/gastro/fodmap or www.ibsfree.net/what-is-fodmap-diet.

LOW-FODMAP DIET REDUCES SYMPTOMS

The low-FODMAP diet was inspired by the results of several studies that evaluated the role of dietary carbohydrates in inducing IBS symptoms and found improvement with their restriction.25,26

One study found that 74% of patients with IBS had less bloating, nausea, abdominal pain, and diarrhea when they restricted their intake of fructose and fructans.27

A prospective trial randomized 41 patients with IBS to 4 weeks of either a low-FODMAP diet or their habitual diet.28 The low-FODMAP diet resulted in greater improvement in overall IBS symptoms (P < .05) and stool frequency (P = .008). This study was limited by different habitual diets between patients and by lack of standardization of the low-FODMAP diet.

Halmos et al,29 in a randomized crossover trial, compared gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS patients over 3 weeks on a low-FODMAP diet vs a moderate-FODMAP (ie, regular) diet, as well as in healthy controls. Food was provided by the study and was matched for all nutrients. Up to 70% of the IBS patients had significantly lower overall symptom scores while on a low-FODMAP diet vs IBS patients on a regular diet (P < .001); bloating, abdominal pain, and flatulence were reduced. Symptoms were minimal and unaffected by either diet in the healthy controls.

A double-blind trial30 randomly assigned 25 patients with IBS who initially responded to a low-FODMAP diet to be challenged by a graduated dose of fructose alone, fructans alone, a combination of both, or glucose. The severity of overall and individual symptoms was markedly more reduced with glucose consumption than with the other carbohydrates: 70% of patients receiving fructose, 77% of those receiving fructans, and 79% of those receiving a mixture of both reported that their symptoms were not adequately controlled, compared with 14% of patients receiving glucose (P ≤ .002).30

Murray et al31 evaluated the gastrointestinal tract after a carbohydrate challenge consisting of 0.5 L of water containing 40 g of glucose, fructose, or inulin or a combination of 40 g of glucose and 40 g of fructose in 16 healthy volunteers. Magnetic resonance imaging was performed hourly for 5 hours to assess the volume of gastric contents, small-bowel water content, and colonic gas. Breath hydrogen was also measured, and symptoms were recorded after each imaging session.

Fructose significantly increased small-bowel water content compared with glucose (mean difference 28 L/min, P < .001), but combined glucose and fructose lessened the effect. Inulin had no significant effect on small-bowel water content (mean difference with glucose 2 L/min, P > .7) but led to the greatest production of colonic gas compared with glucose alone (mean difference 15 L/min, P < .05) and combined glucose and fructose (mean difference 12 L/min, P < .05). Inulin also produced the most breath hydrogen: 81% of participants had a rise after drinking inulin compared with 50% after drinking fructose. Glucose did not affect breath hydrogen concentrations, and combined glucose and fructose significantly reduced the concentration measured vs fructose alone. In patients who reported “gas” symptoms, a correlation was observed between the volume of gas in the colon and gas symptoms (r = 0.59, P < .0001).31

The authors concluded31 that long-chain carbohydrates such as inulin have a greater effect on colonic gas production and little effect on small-bowel water content, whereas small-chain FODMAPs such as fructose are likely to cause luminal distention in both the small and large intestines. The study also showed that combining equal amounts of glucose and fructose reduces malabsorption of fructose in the small bowel and reduces the effect of fructose on small-bowel water content and breath hydrogen concentration.31

PROBIOTICS HELP

A Danish study32 randomized 123 patients with IBS to one of three treatments: a low-FODMAP diet, a normal diet with probiotics containing the strain Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (two capsules daily), or no special intervention. Symptoms were recorded weekly. IBS severity scores at week 6 were lower in patients on either the low-FODMAP diet or probiotics compared with the control group (P < .01). Subgroup analysis determined that patients with primarily diarrheal symptoms were more likely to have improved quality of life with the low-FODMAP diet.

A LOW-FODMAP DIET MAY ALSO HELP IN INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

The low-FODMAP diet has also been studied in patients with inflammatory bowel disease with functional gut symptoms. In a retrospective pilot study,33 overall symptoms improved in about half of such patients on a low-FODMAP diet. A controlled dietary intervention trial is needed to confirm these findings and define the role of the low-FODMAP approach for patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

Marsh et al34 performed a meta-analysis of six randomized clinical trials and 16 nonrandomized interventions of a low-FODMAP diet on improving functional gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with either IBS or inflammatory bowel disease. They found significant improvements in:

- IBS Symptoms Severity Scores in the randomized trials (odds ratio [OR] 0.44, 95% CI 0.25–0.76)

- IBS Symptoms Severity Scores in the nonrandomized interventions (OR 0.03, 95% CI 0.01–0.2)

- IBS Quality of Life scores in the randomized trials (OR 1.84, 95% CI 1.12–3.03)

- IBS Quality of Life scores in the nonrandomized interventions (OR 3.18, 95% CI 1.6–6.31)

- Overall symptom severity in the randomized trials (OR 1.81, 95% CI 1.11–2.95).

DIETARY COUNSELING IS RECOMMENDED

Adherence is a major factor in the success of the low-FODMAP diet in IBS management and is strongly correlated with improved symptoms.35 Patients should be counseled on the role of food in inducing their symptoms. Haphazard dietary advice can be detrimental to outcomes, as many diets restrict food groups, impairing the consumption of essential nutrients.36 The involvement of a knowledgeable dietitian is helpful, as physicians may lack sufficient training in dietary skills and knowledge of food composition.

Access to and cost of dietary counseling can be prohibitive for some patients. Group consultation, which can decrease costs to each patient, has been found to be as effective as one-on-one sessions when administering the low-FODMAP diet in functional bowel disorders.37

ELIMINATION, THEN REINTRODUCTION

Before embarking on the low-FODMAP diet, the patient’s interest in making dietary changes should be explored, a dietary history taken, and unusual food choices or dietary behaviors assessed. The patient’s ability to adopt a restricted diet should also be gauged.

The diet should be implemented in two phases. The initial phase involves strict elimination of foods high in FODMAPs, usually over 6 to 8 weeks.38 Symptom control should be assessed: failure to control symptoms requires assessment of adherence.

If symptoms are successfully controlled, then the second phase should begin with the aim of following a less-restricted version of the diet as tolerated. Foods should gradually be phased back in and symptoms monitored. This approach minimizes unnecessary dietary restriction and ensures that a maximum variety in the diet is achieved while maintaining adequate symptom control.39

LOW-FODMAP DIET ALTERS THE GUT MICROBIOTA

Multiple putative benefits of certain bacterial species for colonic health have been reported, including the production of short-chain fatty acids. Colonic luminal concentrations of short-chain fatty acids may be important to gut health, given their role in intestinal secretion, absorption, motility, and epithelial cell structure. Because short-chain fatty acids are products of bacterial fermentation, a change in the delivery of fermentable substrates to the colon would be expected to alter the concentrations and output of fecal short-chain fatty acids.18

Several studies evaluated the effect of the low-FODMAP diet on intestinal microbiota, finding a change in the bacterial profile in the stool of patients who adopt this diet. Staudacher et al28 found a marked reduction in luminal bifidobacteria concentration after 4 weeks of a low-FODMAP diet in patients with IBS.

A single-blind randomized crossover trial40 investigated the effects of a low-FODMAP diet vs a carefully matched typical Australian diet in 27 patients with IBS and 6 healthy controls. Marked differences in absolute and relative bacterial abundance and diversity were found between the diets, but not in short-chain fatty acids or gut transit time. Compared with fecal microbiota on the typical diet, low FODMAP intake was associated with reduced absolute abundance of bacteria, and the typical FODMAP diet had evidence of stimulation of the growth of bacterial groups with putative health benefits.

The authors concluded40 that the functional significance and health implications of such changes are reasons for caution when reducing FODMAP intake in the long term and recommended liberalizing FODMAP restriction to the level of adequate symptom control in IBS patients. The study also recommended that people without symptoms not go on the low-FODMAP diet.40

Molecular approaches to characterize the gut microbiota are also being explored in an effort to identify its association with diet.

The sustainability of changes in gut microbiota and the potential long-term impact on health of following a low-FODMAP diet require further evaluation. In the meantime, patients following this diet should have FODMAP foods reintroduced based on tolerance and should consider taking probiotic supplements.41

DIETARY ADEQUACY OF THE LOW-FODMAP DIET

Continual dietary counseling should minimize nutritional inadequacies and ensure that FODMAPS are restricted only enough to control symptoms. Because no single food group is completely eliminated in this diet, patients are unlikely to experience inadequate nutrition.

Ledochowski et al26 found that in the initial, strict phase of the diet, total intake of carbohydrates (eg, starches, sugars) was reduced but intake of total energy, protein, fat, and nonstarch polysaccharides was not affected. Calcium intake was reduced in those following a low-FODMAP diet for 4 weeks.

The diet can also reduce total fiber intake and subsequently worsen constipation-predominant IBS. For those patients, lightly fermented high-fiber alternatives like oat and rice bran can be used.

ACCUMULATING EVIDENCE

The low-FODMAP diet is accumulating quality evidence for its effectiveness in controlling the functional gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with IBS. It can be difficult to adhere to over the long term due to its restrictiveness, and it is important to gradually liberalize the diet while tailoring it to the individual patient and monitoring symptoms. Further clinical trials are needed to evaluate this diet in different IBS subtypes and other gastrointestinal disorders, while defining its nutritional adequacy and effects on the intestinal microbiota profile.

- Hayes P, Corish C, O’Mahony E, Quigley EM. A dietary survey of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet 2014; 27(suppl 2):36–47.

- Pare P, Gray J, Lam S, et al. Health-related quality of life, work productivity, and health care resource utilization of subjects with irritable bowel syndrome: baseline results from LOGIC (Longitudinal Outcomes Study of Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Canada), a naturalistic study. Clin Ther 2006; 28:1726–1735; discussion 1710–1711.

- Lacey BE, Mearin F, Chang L, et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2016; 150:1393–1407.

- Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Whitehead WE. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2002; 123:2108–2131.

- Floch MH, Narayan R. Diet in the irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol 2002; 35(suppl 1):S45–S52.

- Reding KW, Cain KC, Jarrett ME, Eugenio MD, Heitkemper MM. Relationship between patterns of alcohol consumption and gastrointestinal symptoms among patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108:270–276.

- Moayyedi P, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, et al. The effect of fiber supplementation on irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109:1367–1374.

- Vazquez Roque MI, Camilleri M, Smyrk T, et al. A controlled trial of gluten-free diet in patients with irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea: effects on bowel frequency and intestinal function. Gastroenterology 2013; 144:903–911.

- Biesiekierski JR, Newnham ED, Irving PM, et al. Gluten causes gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects without celiac disease: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106:508–515.

- Biesiekierski JR, Peters SL, Newnham ED, Rosella O, Muir JG, Gibson PR. No effects of gluten in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity after dietary reduction of fermentable, poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates. Gastroenterology 2013; 145:320–328.

- Ford AC, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, et al. Efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics in irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2013; 145:320–328.e1–e3.

- Central Clinical School, Monash University and The Alfred Hospital. The Monash University Low FODMAP Diet. 4th ed. Melbourne, Australia: Monash University; 2012.

- Parker K, Salas M, Nwosu VC. High fructose corn syrup: production, uses and public health concerns. Biotechnol Mol Biol Rev 2010; 5:71–78.

- Clausen MR, Jorgensen J, Mortensen PB. Comparison of diarrhea induced by ingestion of fructooligosaccharide idolax and disaccharide lactulose: role of osmolarity versus fermentation of malabsorbed carbohydrate. Dig Dis Sci 1998; 43:2696–2707.

- Barrett JS, Gearry RB, Muir JG, et al. Dietary poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates increase delivery of water and fermentable substrates to the proximal colon. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010; 31:874–882.

- Whelan K, Abrahmsohn O, David GJ, et al. Fructan content of commonly consumed wheat, rye and gluten-free breads. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2011; 62:498–503.

- Sangwan V, Tomar SK, Singh RR, Singh AK, Ali B. Galactooligosaccharides: novel components of designer foods. J Food Sci 2011; 76:R103–R111.

- Russell DA, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF, Stanton C. Metabolic activities and probiotic potential of bifidobacteria. Int J Food Microbiol 2011; 149:88–105.

- Lomer MC, Parkes GC, Sanderson JD. Review article: lactose intolerance in clinical practice—myths and realities. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008; 27:93–103.

- Langkilde AM, Andersson H, Schweizer TF, Würsch P. Digestion and absorption of sorbitol, maltitol and isomalt from the small bowel. A study in ileostomy subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr 1994; 48:768–775.

- Muir JG, Rose R, Rosella O, et al. Measurement of short-chain carbohydrates in common Australian vegetables and fruits by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). J Agric Food Chem 2009; 57:554–565.

- Muir JG, Shepherd SJ, Rosella O, Rose R, Barrett JS, Gibson PR. Fructan and free fructose content of common Australian vegetables and fruit. J Agric Food Chem 2007; 55:6619–6627.

- Monash University. Monash launches Low FODMAP Diet smartphone app. http://med.monash.edu.au/news/2012/fodmap-app.html. Accessed July 13, 2016.

- Fedewa A, Rao SS. Dietary fructose intolerance, fructan intolerance and FODMAPs. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2014; 16:370.

- Born P, Vierling T, Barina W. Fructose malabsorption and the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 1991; 101:1454.

- Ledochowski M, Widner B, Bair H, Probst T, Fuchs D. Fructose- and sorbitol-reduced diet improves mood and gastrointestinal disturbances in fructose malabsorbers. Scand J Gastroenterol 2000; 35:1048–1052.

- Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR. Fructose malabsorption and symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome: guidelines for effective dietary management. J Am Diet Assoc 2006; 106:1631–1639.

- Staudacher HM, Lomer MC, Anderson JL, et al. Fermentable carbohydrate restriction reduces luminal bifidobacteria and gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Nutr 2012; 142:1510–1518.

- Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2014; 146:67–75.e5.

- Shepherd SJ, Parker FC, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Dietary triggers of abdominal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: randomized placebo-controlled evidence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 6:765–771.

- Murray K, Wilkinson-Smith V, Hoad C, et al. Differential effects of FODMAPs (fermentable oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides and polyols) on small and large intestinal contents in healthy subjects shown by MRI. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109:110–119.

- Pedersen N, Andersen NN, Vegh Z, et al. Ehealth: low FODMAP diet vs Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20:16215–16226.

- Gearry RB, Irving PM, Barrett JS, Nathan DM, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR. Reduction of dietary poorly absorbed short-chain carbohydrates (FODMAPs) improves abdominal symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease-a pilot study. J Crohns Colitis 2009; 3:8–14.

- Marsh A, Eslick EM, Eslick GD. Does a diet low in FODMAPs reduce symptoms associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders? A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Nutr 2015 May 17. Epub ahead of print.

- de Roest RH, Dobbs BR, Chapman BA, et al. The low FODMAP diet improves gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective study. Int J Clin Pract 2013; 67:895–903.

- Gibson PR, Barrett JS, Muir JG. Functional bowel symptoms and diet. Intern Med J 2013; 43:1067–1074.

- Whigham L, Joyce T, Harper G, et al. Clinical effectiveness and economic costs of group versus one-to-one education for short-chain fermentable carbohydrate restriction (low FODMAP diet) in the management of irritable bowel syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet 2015; 28:687–696.

- Shepherd SJ, Lomer MC, Gibson PR. Short-chain carbohydrates and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108:707–717.

- Shepherd SJ, Halmos E, Glance S. The role of FODMAPs in irritable bowel syndrome. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2014; 17:605–609.

- Halmos EP, Christophersen CT, Bird AR, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. Diets that differ in their FODMAP content alter the colonic luminal microenvironment. Gut 2015; 64:93–100.

- Staudacher HM, Irving PM, Lomer MC, Whelan K. Mechanisms and efficacy of dietary FODMAP restriction in IBS. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 11:256–266.

- Hayes P, Corish C, O’Mahony E, Quigley EM. A dietary survey of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet 2014; 27(suppl 2):36–47.

- Pare P, Gray J, Lam S, et al. Health-related quality of life, work productivity, and health care resource utilization of subjects with irritable bowel syndrome: baseline results from LOGIC (Longitudinal Outcomes Study of Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Canada), a naturalistic study. Clin Ther 2006; 28:1726–1735; discussion 1710–1711.

- Lacey BE, Mearin F, Chang L, et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2016; 150:1393–1407.

- Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Whitehead WE. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2002; 123:2108–2131.

- Floch MH, Narayan R. Diet in the irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol 2002; 35(suppl 1):S45–S52.

- Reding KW, Cain KC, Jarrett ME, Eugenio MD, Heitkemper MM. Relationship between patterns of alcohol consumption and gastrointestinal symptoms among patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108:270–276.

- Moayyedi P, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, et al. The effect of fiber supplementation on irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109:1367–1374.

- Vazquez Roque MI, Camilleri M, Smyrk T, et al. A controlled trial of gluten-free diet in patients with irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea: effects on bowel frequency and intestinal function. Gastroenterology 2013; 144:903–911.

- Biesiekierski JR, Newnham ED, Irving PM, et al. Gluten causes gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects without celiac disease: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106:508–515.

- Biesiekierski JR, Peters SL, Newnham ED, Rosella O, Muir JG, Gibson PR. No effects of gluten in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity after dietary reduction of fermentable, poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates. Gastroenterology 2013; 145:320–328.

- Ford AC, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, et al. Efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics in irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2013; 145:320–328.e1–e3.

- Central Clinical School, Monash University and The Alfred Hospital. The Monash University Low FODMAP Diet. 4th ed. Melbourne, Australia: Monash University; 2012.

- Parker K, Salas M, Nwosu VC. High fructose corn syrup: production, uses and public health concerns. Biotechnol Mol Biol Rev 2010; 5:71–78.

- Clausen MR, Jorgensen J, Mortensen PB. Comparison of diarrhea induced by ingestion of fructooligosaccharide idolax and disaccharide lactulose: role of osmolarity versus fermentation of malabsorbed carbohydrate. Dig Dis Sci 1998; 43:2696–2707.

- Barrett JS, Gearry RB, Muir JG, et al. Dietary poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates increase delivery of water and fermentable substrates to the proximal colon. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010; 31:874–882.

- Whelan K, Abrahmsohn O, David GJ, et al. Fructan content of commonly consumed wheat, rye and gluten-free breads. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2011; 62:498–503.

- Sangwan V, Tomar SK, Singh RR, Singh AK, Ali B. Galactooligosaccharides: novel components of designer foods. J Food Sci 2011; 76:R103–R111.

- Russell DA, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF, Stanton C. Metabolic activities and probiotic potential of bifidobacteria. Int J Food Microbiol 2011; 149:88–105.