User login

Vagus nerve stimulator used for epilepsy also improves symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis

An implanted vagus nerve stimulator like that used for epilepsy treatment reduced inflammatory markers and significantly improved symptoms and function in a small cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

After 42 days, almost 30% of patients had achieved disease remission, Frieda A. Koopman, MD, and her colleagues reported in the July issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605635113). The improvements disappeared rapidly when the devices were turned off, but were quickly reestablished after stimulation resumed.

“This first-in-class study supports a conceptual framework for further studies of electronic medical devices in diseases currently treated with drugs, an approach termed ‘bioelectronic medicine,’” wrote Dr. Koopman of the University of Amsterdam, and her coauthors.

The team built on evidence of what they termed a “reflex neural circuit” in the vagus that strongly influences the production of inflammatory cytokines. Animal studies showed that electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve encouraged choline acetyltransferase–positive T cells to secrete acetylcholine in the spleen and other tissues. Acetylcholine binds to a class of nicotinic receptors on monocytes, macrophages, and stromal cells, and inhibits their inflammatory response.

“Inflammatory reflex signaling, which is enhanced by electrically stimulating the vagus nerve, significantly reduces cytokine production and attenuates disease severity in experimental models of endotoxemia, sepsis, colitis, and other preclinical animal models of inflammatory syndromes,” the team noted.

The group reported on two human studies, totaling 25 patients. The first comprised seven patients with epilepsy who received the implanted vagus nerve stimulator for medically refractory seizures. None of these patients had a history of RA or any other inflammatory disease. The second group was all patients with active RA.

Each epilepsy patient contributed peripheral blood for study, which was collected before, during and after the implantation surgery. The team studied inflammatory markers by adding endotoxin to the samples. Those collected after the patient had been exposed to a single 30-second stimulation at 20 Hertz showed significantly inhibited production of TNF-alpha, compared with that seen in unexposed blood. Interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-1beta was also inhibited significantly by vagus nerve stimulation.

The next study involved 17 patients who had active RA, but not epilepsy. Of these, seven had failed methotrexate but were naïve to biologics; the rest had failed methotrexate and at least two biologics from different classes. Their average disease duration was 11 years.

The 86-day study gradually titrated the stimulation dose, but even at its highest, stimulation was far less than what is typically employed in epilepsy, “in which current is delivered at 60-second intervals, followed by an off interval of 5-180 minutes, repeated continuously,” the investigators wrote. “Thus, epilepsy patients may receive electrical current delivery for up to 240 minutes daily. Preclinical studies have established that stimulation of the inflammatory reflex for as little as 60 seconds confers significant inhibition of cytokine production for up to 24 hours.”

There was a 14-day post-implantation washout period with no stimulation, followed by 28 days of treatment titration. During that time, stimulation was ramped up from single 60-second stimulation with electric pulses of 250-microseconds duration at 10 Hertz and an output current between 0.25-2.0 milliamps, to the highest amperage tolerated (up to 2.0 milliamps).

That dose was the treatment target, and delivered once daily for 60 seconds in 250-microsecond pulse widths at 10 Hertz. At day 28, patients who had not had good clinical response according to EULAR response criteria, had their stimulation increased to four times daily.

In the group of seven methotrexate-resistant patients, two received electric current pulses four times daily. In the group of 10 methotrexate- and biologic-resistant patients, 6 received the four-dose stimulation.

On day 42, TNF-alpha levels in cultured peripheral blood were significantly reduced from baseline.

At that time, the vagus nerve stimulator was turned off for 14 days. By the end of the silent period, TNF-alpha levels had risen significantly from the day 42 levels. The stimulator was restarted on day 56. By day 84, after 28 more days of stimulation, TNF-alpha levels had again decreased significantly.

Symptoms and function as measured by the Disease Activity Score 28 followed a similar trajectory, improving during the initial treatment, worsening during the period of no stimulation, and improving again when stimulation was restarted. Symptom and function scores correlated positively with change in TNF levels.

The investigators also assessed the response rates according to American College of Rheumatology criteria. At day 42, 71% of those in the methotrexate-resistant group had achieved a 20% response; 57% a 50% response; and 28.6% a 70% response. Response was not as dramatic in the group resistant to both drug classes: rates were 70%, 30%, and 0%.

By day 42, nearly 30% of patients overall achieved remission, which was defined as a DAS28 score of less than 2.6. This constituted improvement in all the score components, including tender joint count, swollen joint count, patient’s assessment of pain, patient’s global assessment, physician’s global assessment, and C-reactive protein.

Finally, the investigators noted decreased levels of most serum cytokines. Most, including serum TNF, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-13, IL-1alpha, IL-1beta, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, and TNF-a-beta, were below 1 pg/ml.

Adverse events were common (16 patients) but reported as mild-moderate. The included hoarseness (5), hypoesthesia (4), parasthesia (2), dyspnea (2), and bradycardia (1), among others. There were no implantation-related infections. One patient reported postimplantation pain.

SetPoint Medical, of Valencia, Calif., makes the device and conducted the study. Dr. Koopman made no financial disclosures. However, several of the other authors are employees of Set Point, and of GlaxoSmithKline, which holds equity interest in the company.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

The many different functions and brain regions associated with the vagus nerve have led researchers to test its usefulness in treating several illnesses, including epilepsy, treatment-resistant depression, anxiety disorders, Alzheimer’s disease, migraines, fibromyalgia, obesity, and tinnitus.

The Food and Drug Administration’s approval of a vagus nerve stimulator (VNS) subsequent to a 1997 neurological devices panel meeting has remained controversial. In the only randomized, controlled trial of severe depression, VNS failed to perform any better when turned on than in otherwise similarly implanted patients whose device was not turned on, according to the agency’s summary of the data.

|

| Dr. Maurizio Cutolo |

However, the discovery in 2007 by Kevin J. Tracey that vagus nerve stimulation inhibits inflammation by suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokine production (inflammatory reflex) has led to significant interest in the potential to use this approach for treating inflammatory diseases ranging from arthritis to colitis, ischemia, myocardial infarction, and heart failure (J Clin Invest. 2007;117[2]:289-96).

At present, the study by Dr. Koopman and her colleagues showed that vagus nerve stimulation (up to four times daily) by the implantable VNS in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients significantly inhibited tumor necrosis factor (TNF) production for up to 84 days. RA disease severity apparently improved significantly. The results of this investigation seem to confirm the crucial role played by the neuroendocrine immune system network in RA (Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7[9]:500-2).

However, the question now is: Are there issues and limitations about this possible new approach to RA treatment based on previous experiences? An obvious issue is the limited number of adverse events reported by the authors.

In contrast, adverse events have been signaled in all previous studies for VNS use as expected: cardiac arrhythmia during implantation, intermittent decrease in respiratory flow during sleep, posttreatment increase of apnea hypopnea index, and the development of posttreatment mild obstructive sleep apnea in up to one-third of patients, a minority of whom develop severe obstructive sleep apnea clearly related to VNS therapy. Another study has shown alteration of voice in 66%, coughing in 45%, pharyngitis in 35%, and throat pain in 28% (Pediatr Neurol. 2008;38[2]:99-103). Other reports of VNS device adverse events range from hoarseness (very common) to frank laryngeal muscle spasm and upper airway obstruction (rare). Other nonspecific symptoms include headache, nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, dyspnea, and paresthesia.

At present, the approach of VNS therapy in RA needs further strict investigations, especially regarding the large number of potential adverse events expected. In addition, the target of reducing TNF levels in RA patients is already obtainable with several other noninvasive and established treatments.

Maurizio Cutolo, MD, is professor of rheumatology and internal medicine and director of the research laboratories and academic division of clinical rheumatology in the department of internal medicine at the University of Genova (Italy). He has no relevant disclosures.

The many different functions and brain regions associated with the vagus nerve have led researchers to test its usefulness in treating several illnesses, including epilepsy, treatment-resistant depression, anxiety disorders, Alzheimer’s disease, migraines, fibromyalgia, obesity, and tinnitus.

The Food and Drug Administration’s approval of a vagus nerve stimulator (VNS) subsequent to a 1997 neurological devices panel meeting has remained controversial. In the only randomized, controlled trial of severe depression, VNS failed to perform any better when turned on than in otherwise similarly implanted patients whose device was not turned on, according to the agency’s summary of the data.

|

| Dr. Maurizio Cutolo |

However, the discovery in 2007 by Kevin J. Tracey that vagus nerve stimulation inhibits inflammation by suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokine production (inflammatory reflex) has led to significant interest in the potential to use this approach for treating inflammatory diseases ranging from arthritis to colitis, ischemia, myocardial infarction, and heart failure (J Clin Invest. 2007;117[2]:289-96).

At present, the study by Dr. Koopman and her colleagues showed that vagus nerve stimulation (up to four times daily) by the implantable VNS in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients significantly inhibited tumor necrosis factor (TNF) production for up to 84 days. RA disease severity apparently improved significantly. The results of this investigation seem to confirm the crucial role played by the neuroendocrine immune system network in RA (Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7[9]:500-2).

However, the question now is: Are there issues and limitations about this possible new approach to RA treatment based on previous experiences? An obvious issue is the limited number of adverse events reported by the authors.

In contrast, adverse events have been signaled in all previous studies for VNS use as expected: cardiac arrhythmia during implantation, intermittent decrease in respiratory flow during sleep, posttreatment increase of apnea hypopnea index, and the development of posttreatment mild obstructive sleep apnea in up to one-third of patients, a minority of whom develop severe obstructive sleep apnea clearly related to VNS therapy. Another study has shown alteration of voice in 66%, coughing in 45%, pharyngitis in 35%, and throat pain in 28% (Pediatr Neurol. 2008;38[2]:99-103). Other reports of VNS device adverse events range from hoarseness (very common) to frank laryngeal muscle spasm and upper airway obstruction (rare). Other nonspecific symptoms include headache, nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, dyspnea, and paresthesia.

At present, the approach of VNS therapy in RA needs further strict investigations, especially regarding the large number of potential adverse events expected. In addition, the target of reducing TNF levels in RA patients is already obtainable with several other noninvasive and established treatments.

Maurizio Cutolo, MD, is professor of rheumatology and internal medicine and director of the research laboratories and academic division of clinical rheumatology in the department of internal medicine at the University of Genova (Italy). He has no relevant disclosures.

The many different functions and brain regions associated with the vagus nerve have led researchers to test its usefulness in treating several illnesses, including epilepsy, treatment-resistant depression, anxiety disorders, Alzheimer’s disease, migraines, fibromyalgia, obesity, and tinnitus.

The Food and Drug Administration’s approval of a vagus nerve stimulator (VNS) subsequent to a 1997 neurological devices panel meeting has remained controversial. In the only randomized, controlled trial of severe depression, VNS failed to perform any better when turned on than in otherwise similarly implanted patients whose device was not turned on, according to the agency’s summary of the data.

|

| Dr. Maurizio Cutolo |

However, the discovery in 2007 by Kevin J. Tracey that vagus nerve stimulation inhibits inflammation by suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokine production (inflammatory reflex) has led to significant interest in the potential to use this approach for treating inflammatory diseases ranging from arthritis to colitis, ischemia, myocardial infarction, and heart failure (J Clin Invest. 2007;117[2]:289-96).

At present, the study by Dr. Koopman and her colleagues showed that vagus nerve stimulation (up to four times daily) by the implantable VNS in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients significantly inhibited tumor necrosis factor (TNF) production for up to 84 days. RA disease severity apparently improved significantly. The results of this investigation seem to confirm the crucial role played by the neuroendocrine immune system network in RA (Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7[9]:500-2).

However, the question now is: Are there issues and limitations about this possible new approach to RA treatment based on previous experiences? An obvious issue is the limited number of adverse events reported by the authors.

In contrast, adverse events have been signaled in all previous studies for VNS use as expected: cardiac arrhythmia during implantation, intermittent decrease in respiratory flow during sleep, posttreatment increase of apnea hypopnea index, and the development of posttreatment mild obstructive sleep apnea in up to one-third of patients, a minority of whom develop severe obstructive sleep apnea clearly related to VNS therapy. Another study has shown alteration of voice in 66%, coughing in 45%, pharyngitis in 35%, and throat pain in 28% (Pediatr Neurol. 2008;38[2]:99-103). Other reports of VNS device adverse events range from hoarseness (very common) to frank laryngeal muscle spasm and upper airway obstruction (rare). Other nonspecific symptoms include headache, nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, dyspnea, and paresthesia.

At present, the approach of VNS therapy in RA needs further strict investigations, especially regarding the large number of potential adverse events expected. In addition, the target of reducing TNF levels in RA patients is already obtainable with several other noninvasive and established treatments.

Maurizio Cutolo, MD, is professor of rheumatology and internal medicine and director of the research laboratories and academic division of clinical rheumatology in the department of internal medicine at the University of Genova (Italy). He has no relevant disclosures.

An implanted vagus nerve stimulator like that used for epilepsy treatment reduced inflammatory markers and significantly improved symptoms and function in a small cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

After 42 days, almost 30% of patients had achieved disease remission, Frieda A. Koopman, MD, and her colleagues reported in the July issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605635113). The improvements disappeared rapidly when the devices were turned off, but were quickly reestablished after stimulation resumed.

“This first-in-class study supports a conceptual framework for further studies of electronic medical devices in diseases currently treated with drugs, an approach termed ‘bioelectronic medicine,’” wrote Dr. Koopman of the University of Amsterdam, and her coauthors.

The team built on evidence of what they termed a “reflex neural circuit” in the vagus that strongly influences the production of inflammatory cytokines. Animal studies showed that electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve encouraged choline acetyltransferase–positive T cells to secrete acetylcholine in the spleen and other tissues. Acetylcholine binds to a class of nicotinic receptors on monocytes, macrophages, and stromal cells, and inhibits their inflammatory response.

“Inflammatory reflex signaling, which is enhanced by electrically stimulating the vagus nerve, significantly reduces cytokine production and attenuates disease severity in experimental models of endotoxemia, sepsis, colitis, and other preclinical animal models of inflammatory syndromes,” the team noted.

The group reported on two human studies, totaling 25 patients. The first comprised seven patients with epilepsy who received the implanted vagus nerve stimulator for medically refractory seizures. None of these patients had a history of RA or any other inflammatory disease. The second group was all patients with active RA.

Each epilepsy patient contributed peripheral blood for study, which was collected before, during and after the implantation surgery. The team studied inflammatory markers by adding endotoxin to the samples. Those collected after the patient had been exposed to a single 30-second stimulation at 20 Hertz showed significantly inhibited production of TNF-alpha, compared with that seen in unexposed blood. Interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-1beta was also inhibited significantly by vagus nerve stimulation.

The next study involved 17 patients who had active RA, but not epilepsy. Of these, seven had failed methotrexate but were naïve to biologics; the rest had failed methotrexate and at least two biologics from different classes. Their average disease duration was 11 years.

The 86-day study gradually titrated the stimulation dose, but even at its highest, stimulation was far less than what is typically employed in epilepsy, “in which current is delivered at 60-second intervals, followed by an off interval of 5-180 minutes, repeated continuously,” the investigators wrote. “Thus, epilepsy patients may receive electrical current delivery for up to 240 minutes daily. Preclinical studies have established that stimulation of the inflammatory reflex for as little as 60 seconds confers significant inhibition of cytokine production for up to 24 hours.”

There was a 14-day post-implantation washout period with no stimulation, followed by 28 days of treatment titration. During that time, stimulation was ramped up from single 60-second stimulation with electric pulses of 250-microseconds duration at 10 Hertz and an output current between 0.25-2.0 milliamps, to the highest amperage tolerated (up to 2.0 milliamps).

That dose was the treatment target, and delivered once daily for 60 seconds in 250-microsecond pulse widths at 10 Hertz. At day 28, patients who had not had good clinical response according to EULAR response criteria, had their stimulation increased to four times daily.

In the group of seven methotrexate-resistant patients, two received electric current pulses four times daily. In the group of 10 methotrexate- and biologic-resistant patients, 6 received the four-dose stimulation.

On day 42, TNF-alpha levels in cultured peripheral blood were significantly reduced from baseline.

At that time, the vagus nerve stimulator was turned off for 14 days. By the end of the silent period, TNF-alpha levels had risen significantly from the day 42 levels. The stimulator was restarted on day 56. By day 84, after 28 more days of stimulation, TNF-alpha levels had again decreased significantly.

Symptoms and function as measured by the Disease Activity Score 28 followed a similar trajectory, improving during the initial treatment, worsening during the period of no stimulation, and improving again when stimulation was restarted. Symptom and function scores correlated positively with change in TNF levels.

The investigators also assessed the response rates according to American College of Rheumatology criteria. At day 42, 71% of those in the methotrexate-resistant group had achieved a 20% response; 57% a 50% response; and 28.6% a 70% response. Response was not as dramatic in the group resistant to both drug classes: rates were 70%, 30%, and 0%.

By day 42, nearly 30% of patients overall achieved remission, which was defined as a DAS28 score of less than 2.6. This constituted improvement in all the score components, including tender joint count, swollen joint count, patient’s assessment of pain, patient’s global assessment, physician’s global assessment, and C-reactive protein.

Finally, the investigators noted decreased levels of most serum cytokines. Most, including serum TNF, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-13, IL-1alpha, IL-1beta, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, and TNF-a-beta, were below 1 pg/ml.

Adverse events were common (16 patients) but reported as mild-moderate. The included hoarseness (5), hypoesthesia (4), parasthesia (2), dyspnea (2), and bradycardia (1), among others. There were no implantation-related infections. One patient reported postimplantation pain.

SetPoint Medical, of Valencia, Calif., makes the device and conducted the study. Dr. Koopman made no financial disclosures. However, several of the other authors are employees of Set Point, and of GlaxoSmithKline, which holds equity interest in the company.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

An implanted vagus nerve stimulator like that used for epilepsy treatment reduced inflammatory markers and significantly improved symptoms and function in a small cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

After 42 days, almost 30% of patients had achieved disease remission, Frieda A. Koopman, MD, and her colleagues reported in the July issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605635113). The improvements disappeared rapidly when the devices were turned off, but were quickly reestablished after stimulation resumed.

“This first-in-class study supports a conceptual framework for further studies of electronic medical devices in diseases currently treated with drugs, an approach termed ‘bioelectronic medicine,’” wrote Dr. Koopman of the University of Amsterdam, and her coauthors.

The team built on evidence of what they termed a “reflex neural circuit” in the vagus that strongly influences the production of inflammatory cytokines. Animal studies showed that electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve encouraged choline acetyltransferase–positive T cells to secrete acetylcholine in the spleen and other tissues. Acetylcholine binds to a class of nicotinic receptors on monocytes, macrophages, and stromal cells, and inhibits their inflammatory response.

“Inflammatory reflex signaling, which is enhanced by electrically stimulating the vagus nerve, significantly reduces cytokine production and attenuates disease severity in experimental models of endotoxemia, sepsis, colitis, and other preclinical animal models of inflammatory syndromes,” the team noted.

The group reported on two human studies, totaling 25 patients. The first comprised seven patients with epilepsy who received the implanted vagus nerve stimulator for medically refractory seizures. None of these patients had a history of RA or any other inflammatory disease. The second group was all patients with active RA.

Each epilepsy patient contributed peripheral blood for study, which was collected before, during and after the implantation surgery. The team studied inflammatory markers by adding endotoxin to the samples. Those collected after the patient had been exposed to a single 30-second stimulation at 20 Hertz showed significantly inhibited production of TNF-alpha, compared with that seen in unexposed blood. Interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-1beta was also inhibited significantly by vagus nerve stimulation.

The next study involved 17 patients who had active RA, but not epilepsy. Of these, seven had failed methotrexate but were naïve to biologics; the rest had failed methotrexate and at least two biologics from different classes. Their average disease duration was 11 years.

The 86-day study gradually titrated the stimulation dose, but even at its highest, stimulation was far less than what is typically employed in epilepsy, “in which current is delivered at 60-second intervals, followed by an off interval of 5-180 minutes, repeated continuously,” the investigators wrote. “Thus, epilepsy patients may receive electrical current delivery for up to 240 minutes daily. Preclinical studies have established that stimulation of the inflammatory reflex for as little as 60 seconds confers significant inhibition of cytokine production for up to 24 hours.”

There was a 14-day post-implantation washout period with no stimulation, followed by 28 days of treatment titration. During that time, stimulation was ramped up from single 60-second stimulation with electric pulses of 250-microseconds duration at 10 Hertz and an output current between 0.25-2.0 milliamps, to the highest amperage tolerated (up to 2.0 milliamps).

That dose was the treatment target, and delivered once daily for 60 seconds in 250-microsecond pulse widths at 10 Hertz. At day 28, patients who had not had good clinical response according to EULAR response criteria, had their stimulation increased to four times daily.

In the group of seven methotrexate-resistant patients, two received electric current pulses four times daily. In the group of 10 methotrexate- and biologic-resistant patients, 6 received the four-dose stimulation.

On day 42, TNF-alpha levels in cultured peripheral blood were significantly reduced from baseline.

At that time, the vagus nerve stimulator was turned off for 14 days. By the end of the silent period, TNF-alpha levels had risen significantly from the day 42 levels. The stimulator was restarted on day 56. By day 84, after 28 more days of stimulation, TNF-alpha levels had again decreased significantly.

Symptoms and function as measured by the Disease Activity Score 28 followed a similar trajectory, improving during the initial treatment, worsening during the period of no stimulation, and improving again when stimulation was restarted. Symptom and function scores correlated positively with change in TNF levels.

The investigators also assessed the response rates according to American College of Rheumatology criteria. At day 42, 71% of those in the methotrexate-resistant group had achieved a 20% response; 57% a 50% response; and 28.6% a 70% response. Response was not as dramatic in the group resistant to both drug classes: rates were 70%, 30%, and 0%.

By day 42, nearly 30% of patients overall achieved remission, which was defined as a DAS28 score of less than 2.6. This constituted improvement in all the score components, including tender joint count, swollen joint count, patient’s assessment of pain, patient’s global assessment, physician’s global assessment, and C-reactive protein.

Finally, the investigators noted decreased levels of most serum cytokines. Most, including serum TNF, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-13, IL-1alpha, IL-1beta, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, and TNF-a-beta, were below 1 pg/ml.

Adverse events were common (16 patients) but reported as mild-moderate. The included hoarseness (5), hypoesthesia (4), parasthesia (2), dyspnea (2), and bradycardia (1), among others. There were no implantation-related infections. One patient reported postimplantation pain.

SetPoint Medical, of Valencia, Calif., makes the device and conducted the study. Dr. Koopman made no financial disclosures. However, several of the other authors are employees of Set Point, and of GlaxoSmithKline, which holds equity interest in the company.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

FROM PNAS

Key clinical point: A vagus nerve stimulator reduced inflammatory markers and improved symptoms in patients with medication-refractory RA.

Major finding: About 30% of patients experienced clinical disease remission by day 42.

Data source: The open-label, prospective study comprised 17 patients with RA.

Disclosures: SetPoint Medical, of Valencia, Calif., makes the device and conducted the study. Dr. Koopman made no financial disclosures. However, several of the other authors are employees of SetPoint, and of GlaxoSmithKline, which holds equity interest in the company.

Safety of sentinel node dissection alone holds up a decade out

CHICAGO – Women with clinical early-stage breast cancer and a positive sentinel lymph node who receive breast-conserving therapy can safely skip an axillary lymph node dissection (ALND), and therefore avoid its associated morbidity, confirms long-term follow-up of the Z0011 trial conducted by the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group and the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology.

The phase III trial enrolled 891 women with clinical T1-2,N0,M0 disease who underwent lumpectomy and were found to have sentinel node involvement. They were randomized to ALND or no further surgery, followed by whole-breast radiation therapy and, in most cases, systemic adjuvant therapy.

The trial was closed early because of low rates of accrual and events. Results at 6.3 years of follow-up showed that compared with peers who had an ALND, the women who skipped this surgery did not have inferior 5-year rates of locoregional recurrence or overall survival (JAMA. 2011;305:569-75).

“The study, however, like most breast cancer studies, contained mostly postmenopausal women with hormone receptor–positive tumors who are known to have late recurrences, and it was criticized for short follow-up,” commented first author Armando E. Giuliano, MD, executive vice chair of surgical oncology in the department of surgery, and associate director of surgical oncology in the Samuel Oschin Comprehensive Cancer Institute, Los Angeles.

In an update of the findings, now with a median follow-up of 9.3 years, the groups were statistically indistinguishable with respect to 10-year rates of the same outcomes, he reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“This study... shows that sentinel node biopsy alone provides excellent 10-year locoregional control and survival comparable to completion axillary lymph node dissection for these patients, even with long-term follow-up,” he maintained. “Routine use of axillary lymph node dissection should be abandoned.”

“This was designed as a noninferiority trial, and I would suggest that based on the data we have seen, even if they had hit their target accrual, the outcomes would not be different,” said invited discussant Elizabeth A. Mittendorf, MD, PhD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. “Clearly, even before today’s presentation, Z0011 has been identified as a practice-changing trial, as evidenced by the NCCN guidelines.”

In fact, a study last year showed that among patients in the general U.S. population meeting the trial’s enrollment criteria, the use of sentinel lymph node dissection alone has increased significantly since the Z0011 results were first reported (J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:71-81).

“However, I would highlight that we have also seen an increase in omission of axillary lymph node dissection for patients who do not meet the Z0011 criteria to include those not planned for radiotherapy, those receiving APBI [accelerated partial breast irradiation], and those undergoing mastectomy,” she added. “I highlight these examples specifically because it’s been suggested that one of the reasons the patients on the trial have outstanding regional control is because of the radiation administered as part of their breast-conserving therapy.”

“We will obtain additional data on the locoregional management of these early-stage patients with clinically node-negative breast cancer,” Dr. Mittendorf predicted, pointing to the similar POSNOC trial (which is comparing systemic therapy with versus without axillary treatment) and SOUND trial (which is comparing sentinel node dissection versus no axillary surgery).

In Z0011, all women had tumor in sentinel nodes detected with hematoxylin and eosin staining. Those with sentinel node tumor detected only by immunohistochemistry were excluded, as were those who had matted nodes, three or more involved sentinel nodes, or planned third-field (nodal) irradiation.

Overall, 27.4% of the patients in the ALND group had additional positive nodes removed beyond their sentinel nodes. “There is no reason to suspect that women with sentinel node biopsy [only] had fewer involved nodes than the women treated with axillary lymph node dissection,” Dr. Giuliano commented; thus, a similar share of the former group likely had residual axillary disease that went unresected.

The updated findings showed that the women received ALND and the women who did not were statistically indistinguishable with respect to the 10-year rate of locoregional recurrence (6.2% and 5.3%). Of note, only a single regional recurrence was seen after the initial 5 years of follow-up, and it occurred in the group that did not have ALND.

The groups treated with and without ALND were also statistically indistinguishable with respect to 10-year rates of disease-free survival (78.2% and 80.2%), locoregional recurrence–free survival (81.2% and 83.0%), and overall survival (83.6% and 86.3%).

In multivariate analysis, omission of ALND did not significantly predict locoregional recurrence or overall survival, reported Dr. Giuliano. Additionally, stratified analysis showed that the lack of difference in overall survival between study groups was the same whether tumors had hormone receptors or not.

In a related analysis of radiation protocol deviations in a subset of women from the trial, 11% did not receive any radiation therapy, while 18.9% received third-field radiation, with equal distribution of the latter between study groups (J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3600-6). Omission of radiation was associated with an increased risk of local recurrence and death, but it did not affect nodal recurrences. Receipt of third-field radiation did not influence survival.

CHICAGO – Women with clinical early-stage breast cancer and a positive sentinel lymph node who receive breast-conserving therapy can safely skip an axillary lymph node dissection (ALND), and therefore avoid its associated morbidity, confirms long-term follow-up of the Z0011 trial conducted by the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group and the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology.

The phase III trial enrolled 891 women with clinical T1-2,N0,M0 disease who underwent lumpectomy and were found to have sentinel node involvement. They were randomized to ALND or no further surgery, followed by whole-breast radiation therapy and, in most cases, systemic adjuvant therapy.

The trial was closed early because of low rates of accrual and events. Results at 6.3 years of follow-up showed that compared with peers who had an ALND, the women who skipped this surgery did not have inferior 5-year rates of locoregional recurrence or overall survival (JAMA. 2011;305:569-75).

“The study, however, like most breast cancer studies, contained mostly postmenopausal women with hormone receptor–positive tumors who are known to have late recurrences, and it was criticized for short follow-up,” commented first author Armando E. Giuliano, MD, executive vice chair of surgical oncology in the department of surgery, and associate director of surgical oncology in the Samuel Oschin Comprehensive Cancer Institute, Los Angeles.

In an update of the findings, now with a median follow-up of 9.3 years, the groups were statistically indistinguishable with respect to 10-year rates of the same outcomes, he reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“This study... shows that sentinel node biopsy alone provides excellent 10-year locoregional control and survival comparable to completion axillary lymph node dissection for these patients, even with long-term follow-up,” he maintained. “Routine use of axillary lymph node dissection should be abandoned.”

“This was designed as a noninferiority trial, and I would suggest that based on the data we have seen, even if they had hit their target accrual, the outcomes would not be different,” said invited discussant Elizabeth A. Mittendorf, MD, PhD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. “Clearly, even before today’s presentation, Z0011 has been identified as a practice-changing trial, as evidenced by the NCCN guidelines.”

In fact, a study last year showed that among patients in the general U.S. population meeting the trial’s enrollment criteria, the use of sentinel lymph node dissection alone has increased significantly since the Z0011 results were first reported (J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:71-81).

“However, I would highlight that we have also seen an increase in omission of axillary lymph node dissection for patients who do not meet the Z0011 criteria to include those not planned for radiotherapy, those receiving APBI [accelerated partial breast irradiation], and those undergoing mastectomy,” she added. “I highlight these examples specifically because it’s been suggested that one of the reasons the patients on the trial have outstanding regional control is because of the radiation administered as part of their breast-conserving therapy.”

“We will obtain additional data on the locoregional management of these early-stage patients with clinically node-negative breast cancer,” Dr. Mittendorf predicted, pointing to the similar POSNOC trial (which is comparing systemic therapy with versus without axillary treatment) and SOUND trial (which is comparing sentinel node dissection versus no axillary surgery).

In Z0011, all women had tumor in sentinel nodes detected with hematoxylin and eosin staining. Those with sentinel node tumor detected only by immunohistochemistry were excluded, as were those who had matted nodes, three or more involved sentinel nodes, or planned third-field (nodal) irradiation.

Overall, 27.4% of the patients in the ALND group had additional positive nodes removed beyond their sentinel nodes. “There is no reason to suspect that women with sentinel node biopsy [only] had fewer involved nodes than the women treated with axillary lymph node dissection,” Dr. Giuliano commented; thus, a similar share of the former group likely had residual axillary disease that went unresected.

The updated findings showed that the women received ALND and the women who did not were statistically indistinguishable with respect to the 10-year rate of locoregional recurrence (6.2% and 5.3%). Of note, only a single regional recurrence was seen after the initial 5 years of follow-up, and it occurred in the group that did not have ALND.

The groups treated with and without ALND were also statistically indistinguishable with respect to 10-year rates of disease-free survival (78.2% and 80.2%), locoregional recurrence–free survival (81.2% and 83.0%), and overall survival (83.6% and 86.3%).

In multivariate analysis, omission of ALND did not significantly predict locoregional recurrence or overall survival, reported Dr. Giuliano. Additionally, stratified analysis showed that the lack of difference in overall survival between study groups was the same whether tumors had hormone receptors or not.

In a related analysis of radiation protocol deviations in a subset of women from the trial, 11% did not receive any radiation therapy, while 18.9% received third-field radiation, with equal distribution of the latter between study groups (J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3600-6). Omission of radiation was associated with an increased risk of local recurrence and death, but it did not affect nodal recurrences. Receipt of third-field radiation did not influence survival.

CHICAGO – Women with clinical early-stage breast cancer and a positive sentinel lymph node who receive breast-conserving therapy can safely skip an axillary lymph node dissection (ALND), and therefore avoid its associated morbidity, confirms long-term follow-up of the Z0011 trial conducted by the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group and the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology.

The phase III trial enrolled 891 women with clinical T1-2,N0,M0 disease who underwent lumpectomy and were found to have sentinel node involvement. They were randomized to ALND or no further surgery, followed by whole-breast radiation therapy and, in most cases, systemic adjuvant therapy.

The trial was closed early because of low rates of accrual and events. Results at 6.3 years of follow-up showed that compared with peers who had an ALND, the women who skipped this surgery did not have inferior 5-year rates of locoregional recurrence or overall survival (JAMA. 2011;305:569-75).

“The study, however, like most breast cancer studies, contained mostly postmenopausal women with hormone receptor–positive tumors who are known to have late recurrences, and it was criticized for short follow-up,” commented first author Armando E. Giuliano, MD, executive vice chair of surgical oncology in the department of surgery, and associate director of surgical oncology in the Samuel Oschin Comprehensive Cancer Institute, Los Angeles.

In an update of the findings, now with a median follow-up of 9.3 years, the groups were statistically indistinguishable with respect to 10-year rates of the same outcomes, he reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“This study... shows that sentinel node biopsy alone provides excellent 10-year locoregional control and survival comparable to completion axillary lymph node dissection for these patients, even with long-term follow-up,” he maintained. “Routine use of axillary lymph node dissection should be abandoned.”

“This was designed as a noninferiority trial, and I would suggest that based on the data we have seen, even if they had hit their target accrual, the outcomes would not be different,” said invited discussant Elizabeth A. Mittendorf, MD, PhD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. “Clearly, even before today’s presentation, Z0011 has been identified as a practice-changing trial, as evidenced by the NCCN guidelines.”

In fact, a study last year showed that among patients in the general U.S. population meeting the trial’s enrollment criteria, the use of sentinel lymph node dissection alone has increased significantly since the Z0011 results were first reported (J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:71-81).

“However, I would highlight that we have also seen an increase in omission of axillary lymph node dissection for patients who do not meet the Z0011 criteria to include those not planned for radiotherapy, those receiving APBI [accelerated partial breast irradiation], and those undergoing mastectomy,” she added. “I highlight these examples specifically because it’s been suggested that one of the reasons the patients on the trial have outstanding regional control is because of the radiation administered as part of their breast-conserving therapy.”

“We will obtain additional data on the locoregional management of these early-stage patients with clinically node-negative breast cancer,” Dr. Mittendorf predicted, pointing to the similar POSNOC trial (which is comparing systemic therapy with versus without axillary treatment) and SOUND trial (which is comparing sentinel node dissection versus no axillary surgery).

In Z0011, all women had tumor in sentinel nodes detected with hematoxylin and eosin staining. Those with sentinel node tumor detected only by immunohistochemistry were excluded, as were those who had matted nodes, three or more involved sentinel nodes, or planned third-field (nodal) irradiation.

Overall, 27.4% of the patients in the ALND group had additional positive nodes removed beyond their sentinel nodes. “There is no reason to suspect that women with sentinel node biopsy [only] had fewer involved nodes than the women treated with axillary lymph node dissection,” Dr. Giuliano commented; thus, a similar share of the former group likely had residual axillary disease that went unresected.

The updated findings showed that the women received ALND and the women who did not were statistically indistinguishable with respect to the 10-year rate of locoregional recurrence (6.2% and 5.3%). Of note, only a single regional recurrence was seen after the initial 5 years of follow-up, and it occurred in the group that did not have ALND.

The groups treated with and without ALND were also statistically indistinguishable with respect to 10-year rates of disease-free survival (78.2% and 80.2%), locoregional recurrence–free survival (81.2% and 83.0%), and overall survival (83.6% and 86.3%).

In multivariate analysis, omission of ALND did not significantly predict locoregional recurrence or overall survival, reported Dr. Giuliano. Additionally, stratified analysis showed that the lack of difference in overall survival between study groups was the same whether tumors had hormone receptors or not.

In a related analysis of radiation protocol deviations in a subset of women from the trial, 11% did not receive any radiation therapy, while 18.9% received third-field radiation, with equal distribution of the latter between study groups (J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3600-6). Omission of radiation was associated with an increased risk of local recurrence and death, but it did not affect nodal recurrences. Receipt of third-field radiation did not influence survival.

AT THE 2016 ASCO ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: In women with clinical early-stage breast cancer who have a positive sentinel node and undergo breast-conserving therapy, skipping ALND does not compromise outcomes.

Major finding: Women treated with and without ALND were statistically indistinguishable with respect to 10-year rates of locoregional recurrence (6.2% and 5.3%), disease-free survival (78.2% and 80.2%), and overall survival (83.6% and 86.3%).

Data source: A randomized phase III trial among 891 women with clinical T1-2,N0,M0 breast cancer and positive sentinel nodes treated with breast-conserving therapy and usually adjuvant systemic therapy (ACOSOG Z0011).

Disclosures: Dr. Giuliano disclosed that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Drug’s benefits outweigh risks, PRAC says

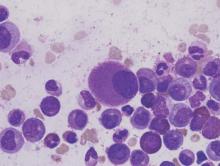

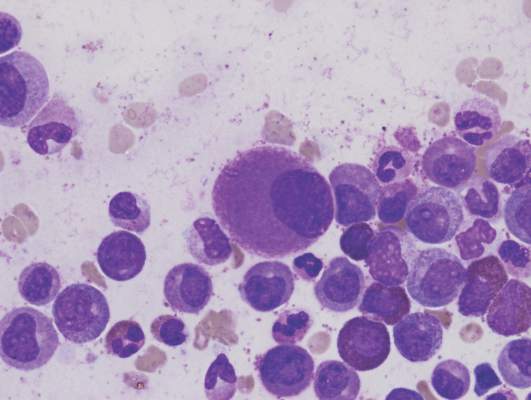

Photo courtesy of

Gilead Sciences, Inc.

The European Medicines Agency’s Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) has completed its review of the PI3Kδ inhibitor idelalisib (Zyedelig) and concluded that the drug’s benefits outweigh its risks in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and follicular lymphoma.

However, the PRAC also confirmed that the drug increases the risk of serious infections, including Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia.

And the committee updated its previous recommendations to manage this risk.

The PRAC’s recommendations will now be sent to the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use, which will adopt the EMA’s final opinion. The final stage of the review procedure is the adoption by the European Commission of a legally binding decision applicable in all member states of the European Union (EU).

About idelalisib

In the EU, idelalisib is approved for use in combination with rituximab to treat adults with CLL who have received at least 1 prior therapy or as first-line treatment in the presence of 17p deletion or TP53 mutation in CLL patients unsuitable for chemo-immunotherapy.

Idelalisib is also approved as monotherapy for adults with follicular lymphoma that is refractory to 2 prior lines of treatment.

About the review

The PRAC’s review of idelalisib began after a higher rate of serious adverse events, including deaths, was seen in 3 clinical trials evaluating the addition of idelalisib to standard therapy in first-line CLL and relapsed indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

Most of the deaths were related to infections such as Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia and cytomegalovirus infection. Other excess deaths were related mainly to respiratory events.

The NHL studies (NCT01732926 and NCT01732913) included patients with disease characteristics different from those covered by the currently approved indications for idelalisib and investigated combinations of drugs that are not currently approved in the EU—idelalisib plus rituximab for NHL and idelalisib plus bendamustine and rituximab for NHL.

The CLL trial (NCT01980888) involved patients who had not received previous treatment, some of whom had the 17p deletion or TP53 mutation. However, the trial also investigated a combination of drugs not currently approved in the EU—idelalisib plus bendamustine and rituximab.

PRAC’s recommendations

The PRAC noted that, although the aforementioned trials did not all use idelalisib as currently authorized, the risk of serious infection is considered relevant to the authorized use.

Therefore, the PRAC recommends that all patients treated with idelalisib receive antibiotics to prevent Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia during treatment and for up to 2 to 6 months after treatment has stopped.

Patients should also be monitored for infection and have regular blood tests for white cell counts because low counts can increase their risk of infection.

Furthermore, idelalisib should not be started in patients with a generalized infection.

At the beginning of its review, the PRAC had said idelalisib should not be started in patients with previously untreated CLL and 17p deletion or TP53 mutation.

Now, the PRAC has concluded that idelalisib can be initiated in these patients, provided they cannot take any alternative treatment and that the recommended measures to prevent infection are followed. ![]()

Photo courtesy of

Gilead Sciences, Inc.

The European Medicines Agency’s Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) has completed its review of the PI3Kδ inhibitor idelalisib (Zyedelig) and concluded that the drug’s benefits outweigh its risks in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and follicular lymphoma.

However, the PRAC also confirmed that the drug increases the risk of serious infections, including Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia.

And the committee updated its previous recommendations to manage this risk.

The PRAC’s recommendations will now be sent to the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use, which will adopt the EMA’s final opinion. The final stage of the review procedure is the adoption by the European Commission of a legally binding decision applicable in all member states of the European Union (EU).

About idelalisib

In the EU, idelalisib is approved for use in combination with rituximab to treat adults with CLL who have received at least 1 prior therapy or as first-line treatment in the presence of 17p deletion or TP53 mutation in CLL patients unsuitable for chemo-immunotherapy.

Idelalisib is also approved as monotherapy for adults with follicular lymphoma that is refractory to 2 prior lines of treatment.

About the review

The PRAC’s review of idelalisib began after a higher rate of serious adverse events, including deaths, was seen in 3 clinical trials evaluating the addition of idelalisib to standard therapy in first-line CLL and relapsed indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

Most of the deaths were related to infections such as Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia and cytomegalovirus infection. Other excess deaths were related mainly to respiratory events.

The NHL studies (NCT01732926 and NCT01732913) included patients with disease characteristics different from those covered by the currently approved indications for idelalisib and investigated combinations of drugs that are not currently approved in the EU—idelalisib plus rituximab for NHL and idelalisib plus bendamustine and rituximab for NHL.

The CLL trial (NCT01980888) involved patients who had not received previous treatment, some of whom had the 17p deletion or TP53 mutation. However, the trial also investigated a combination of drugs not currently approved in the EU—idelalisib plus bendamustine and rituximab.

PRAC’s recommendations

The PRAC noted that, although the aforementioned trials did not all use idelalisib as currently authorized, the risk of serious infection is considered relevant to the authorized use.

Therefore, the PRAC recommends that all patients treated with idelalisib receive antibiotics to prevent Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia during treatment and for up to 2 to 6 months after treatment has stopped.

Patients should also be monitored for infection and have regular blood tests for white cell counts because low counts can increase their risk of infection.

Furthermore, idelalisib should not be started in patients with a generalized infection.

At the beginning of its review, the PRAC had said idelalisib should not be started in patients with previously untreated CLL and 17p deletion or TP53 mutation.

Now, the PRAC has concluded that idelalisib can be initiated in these patients, provided they cannot take any alternative treatment and that the recommended measures to prevent infection are followed. ![]()

Photo courtesy of

Gilead Sciences, Inc.

The European Medicines Agency’s Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) has completed its review of the PI3Kδ inhibitor idelalisib (Zyedelig) and concluded that the drug’s benefits outweigh its risks in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and follicular lymphoma.

However, the PRAC also confirmed that the drug increases the risk of serious infections, including Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia.

And the committee updated its previous recommendations to manage this risk.

The PRAC’s recommendations will now be sent to the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use, which will adopt the EMA’s final opinion. The final stage of the review procedure is the adoption by the European Commission of a legally binding decision applicable in all member states of the European Union (EU).

About idelalisib

In the EU, idelalisib is approved for use in combination with rituximab to treat adults with CLL who have received at least 1 prior therapy or as first-line treatment in the presence of 17p deletion or TP53 mutation in CLL patients unsuitable for chemo-immunotherapy.

Idelalisib is also approved as monotherapy for adults with follicular lymphoma that is refractory to 2 prior lines of treatment.

About the review

The PRAC’s review of idelalisib began after a higher rate of serious adverse events, including deaths, was seen in 3 clinical trials evaluating the addition of idelalisib to standard therapy in first-line CLL and relapsed indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

Most of the deaths were related to infections such as Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia and cytomegalovirus infection. Other excess deaths were related mainly to respiratory events.

The NHL studies (NCT01732926 and NCT01732913) included patients with disease characteristics different from those covered by the currently approved indications for idelalisib and investigated combinations of drugs that are not currently approved in the EU—idelalisib plus rituximab for NHL and idelalisib plus bendamustine and rituximab for NHL.

The CLL trial (NCT01980888) involved patients who had not received previous treatment, some of whom had the 17p deletion or TP53 mutation. However, the trial also investigated a combination of drugs not currently approved in the EU—idelalisib plus bendamustine and rituximab.

PRAC’s recommendations

The PRAC noted that, although the aforementioned trials did not all use idelalisib as currently authorized, the risk of serious infection is considered relevant to the authorized use.

Therefore, the PRAC recommends that all patients treated with idelalisib receive antibiotics to prevent Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia during treatment and for up to 2 to 6 months after treatment has stopped.

Patients should also be monitored for infection and have regular blood tests for white cell counts because low counts can increase their risk of infection.

Furthermore, idelalisib should not be started in patients with a generalized infection.

At the beginning of its review, the PRAC had said idelalisib should not be started in patients with previously untreated CLL and 17p deletion or TP53 mutation.

Now, the PRAC has concluded that idelalisib can be initiated in these patients, provided they cannot take any alternative treatment and that the recommended measures to prevent infection are followed. ![]()

Bioabsorbable percutaneous device fully closes large femoral arteriotomies

PARIS – A new bioabsorbable sutureless device provides operators with a safe, simple, and dependable option for fully percutaneous closure of the large, 12-24 French femoral arteriotomies created for transcatheter aortic valve replacement or endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, Arne Schwindt, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

He presented the 12-month follow-up results of the FRONTIER II study of the Vivasure PerQseal device. The device recently received European marketing approval on the strength of FRONTIER II but remains investigational in the United States.

The PerQseal device is deployed in less than 1 minute at the end of the primary procedure and achieves immediate hemostasis. It’s a simple three-step deployment process with essentially no learning curve, as evidenced by the fact that in FRONTIER II, the technical success rate starting from no experience was 97%, explained Dr. Schwindt of St. Franziskus Hospital in Muenster, Germany.

The large femoral arteriotomies created for TAVR or endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair have typically required surgical cut down and sutured repair with a 3- to 5-cm incision. Vascular complications have been common. Indeed, the literature shows this method entails on average a 14.7% rate of major vascular complications up to 3 months post procedure, so that was the bar set in FRONTIER II: In order for the PerQseal to be deemed noninferior to surgical cut down and sutured repair, the rate of major complications directly related to the novel device at 3 months follow-up could be no greater than 14.7%. The current Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC) 2 definition of major complications was used.

In fact, the vascular complication rate proved to be zero. Moreover, at 12 months of follow-up, no cases of groin fibrosis or scarring had been observed, Dr. Schwindt reported.

FRONTIER II was a single-arm, prospective, multicenter European study of 58 patients who received the PerQseal device for 66 closures. They were evaluated at discharge and 1, 3, and 12 months post procedure by Doppler ultrasound, with uniformly unremarkable findings.

PerQseal features a synthetic low-profile implant with over-the-wire delivery. The implant is loaded into a sheath, released by pulling back on the sheath, then pulled up against the arteriotomy from the inside. Blood pressure molds the device to the arterial wall and seals it. The device is fully absorbed in 180 days.

Session co-chair Dr. Ted E. Feldman was favorably impressed.

“This is really terrific. It’s very nice to see we’re finally making progress with large-bore closure devices,” commented Dr. Feldman, professor of medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago.

Dr. Schwindt reported receiving a research grant from Vivasure, which sponsored the FRONTIER II study. In addition, he serves as a consultant to a half dozen medical device companies.

PARIS – A new bioabsorbable sutureless device provides operators with a safe, simple, and dependable option for fully percutaneous closure of the large, 12-24 French femoral arteriotomies created for transcatheter aortic valve replacement or endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, Arne Schwindt, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

He presented the 12-month follow-up results of the FRONTIER II study of the Vivasure PerQseal device. The device recently received European marketing approval on the strength of FRONTIER II but remains investigational in the United States.

The PerQseal device is deployed in less than 1 minute at the end of the primary procedure and achieves immediate hemostasis. It’s a simple three-step deployment process with essentially no learning curve, as evidenced by the fact that in FRONTIER II, the technical success rate starting from no experience was 97%, explained Dr. Schwindt of St. Franziskus Hospital in Muenster, Germany.

The large femoral arteriotomies created for TAVR or endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair have typically required surgical cut down and sutured repair with a 3- to 5-cm incision. Vascular complications have been common. Indeed, the literature shows this method entails on average a 14.7% rate of major vascular complications up to 3 months post procedure, so that was the bar set in FRONTIER II: In order for the PerQseal to be deemed noninferior to surgical cut down and sutured repair, the rate of major complications directly related to the novel device at 3 months follow-up could be no greater than 14.7%. The current Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC) 2 definition of major complications was used.

In fact, the vascular complication rate proved to be zero. Moreover, at 12 months of follow-up, no cases of groin fibrosis or scarring had been observed, Dr. Schwindt reported.

FRONTIER II was a single-arm, prospective, multicenter European study of 58 patients who received the PerQseal device for 66 closures. They were evaluated at discharge and 1, 3, and 12 months post procedure by Doppler ultrasound, with uniformly unremarkable findings.

PerQseal features a synthetic low-profile implant with over-the-wire delivery. The implant is loaded into a sheath, released by pulling back on the sheath, then pulled up against the arteriotomy from the inside. Blood pressure molds the device to the arterial wall and seals it. The device is fully absorbed in 180 days.

Session co-chair Dr. Ted E. Feldman was favorably impressed.

“This is really terrific. It’s very nice to see we’re finally making progress with large-bore closure devices,” commented Dr. Feldman, professor of medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago.

Dr. Schwindt reported receiving a research grant from Vivasure, which sponsored the FRONTIER II study. In addition, he serves as a consultant to a half dozen medical device companies.

PARIS – A new bioabsorbable sutureless device provides operators with a safe, simple, and dependable option for fully percutaneous closure of the large, 12-24 French femoral arteriotomies created for transcatheter aortic valve replacement or endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, Arne Schwindt, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

He presented the 12-month follow-up results of the FRONTIER II study of the Vivasure PerQseal device. The device recently received European marketing approval on the strength of FRONTIER II but remains investigational in the United States.

The PerQseal device is deployed in less than 1 minute at the end of the primary procedure and achieves immediate hemostasis. It’s a simple three-step deployment process with essentially no learning curve, as evidenced by the fact that in FRONTIER II, the technical success rate starting from no experience was 97%, explained Dr. Schwindt of St. Franziskus Hospital in Muenster, Germany.

The large femoral arteriotomies created for TAVR or endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair have typically required surgical cut down and sutured repair with a 3- to 5-cm incision. Vascular complications have been common. Indeed, the literature shows this method entails on average a 14.7% rate of major vascular complications up to 3 months post procedure, so that was the bar set in FRONTIER II: In order for the PerQseal to be deemed noninferior to surgical cut down and sutured repair, the rate of major complications directly related to the novel device at 3 months follow-up could be no greater than 14.7%. The current Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC) 2 definition of major complications was used.

In fact, the vascular complication rate proved to be zero. Moreover, at 12 months of follow-up, no cases of groin fibrosis or scarring had been observed, Dr. Schwindt reported.

FRONTIER II was a single-arm, prospective, multicenter European study of 58 patients who received the PerQseal device for 66 closures. They were evaluated at discharge and 1, 3, and 12 months post procedure by Doppler ultrasound, with uniformly unremarkable findings.

PerQseal features a synthetic low-profile implant with over-the-wire delivery. The implant is loaded into a sheath, released by pulling back on the sheath, then pulled up against the arteriotomy from the inside. Blood pressure molds the device to the arterial wall and seals it. The device is fully absorbed in 180 days.

Session co-chair Dr. Ted E. Feldman was favorably impressed.

“This is really terrific. It’s very nice to see we’re finally making progress with large-bore closure devices,” commented Dr. Feldman, professor of medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago.

Dr. Schwindt reported receiving a research grant from Vivasure, which sponsored the FRONTIER II study. In addition, he serves as a consultant to a half dozen medical device companies.

AT EUROPCR 2016

Key clinical point: The PerQseal device provides a simpler alternative to existing closure methods.

Major finding: No major vascular complications were seen during structured follow-up of recipients of the novel bioabsorbable fully percutaneous PerQseal device for closure of large-bore femoral arteriotomies.

Data source: FRONTIER II was a prospective, single-arm, 12-month multicenter study including 58 patients who underwent closure of 66 large femoral arteriotomies using the PerQseal device.

Disclosures: The presenter reported receiving a research grant from Vivasure, which sponsored the FRONTIER II study.

Long-term analysis shows dwindling RT benefit for DLBCL

Long-term follow-up from two randomized trials shows that the treatment advantage initially seen by adding radiotherapy to the CHOP regimen in patients with limited-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma disappeared over time.

After a median follow-up of nearly 18 years, there were no significant differences in either progression-free survival (PFS) or overall survival between patients who had received standard CHOP chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) for 8 cycles (CHOP8), or 3 cycles of CHOP with involved-field radiotherapy (CHOP3RT), reported Deborah M. Stephens, DO, of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, and her colleagues.

The addition of rituximab to CHOP plus involved-field radiotherapy (IFRT) in a separate cohort did not appear to reduce the continued relapse risk, the investigators noted (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jul. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.4582).

The findings suggest that long-term follow-up of patients enrolled in clinical trials may provide clinically important additional information, and that limited-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) may have a biology that is distinctly different from that of advanced stage DLBCL, the investigators wrote.

Initial results from the SWOG (Southwest Oncology Group) Study 8736, published after a median follow-up of 4.4 years, showed that CHOP3RT was associated with significantly better 5-year PFS and OS rates, compared with patients treated with CHOP8.

A second trial, SWOG Study 0014, looked at the addition of rituximab (Rituxan) to CHOP plus IFRT in patients with high-risk DLBCL with at least one adverse feature of the stage-modified International Prognostic Index. In this trial, after a median follow-up of 5.3 years, 4-year PFS was 88%, and 4-year OS was 92%.

5 years not enough

Results of both trials were published around the 5-year follow-up mark. However, an analysis of 10-year follow-up data from the S8736 trial, published only as an abstract (Blood. 98:724a-725a, 2001; abstr 3024), showed that “the survival curves for CHOP8 and CHOP3RT, surprisingly, began to overlap,” Dr. Stephens and her colleagues wrote.

“Additionally, for both S8736 and S0014, no plateau had been reached in the PFS curves. These data contrasted the expected cure rates for advanced-stage DLBCL, leading to the hypothesis that limited-stage DLBCL may have a unique biology from its advanced-stage counterpart,” they added.

Although more than half of patients with advanced-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) can be cured with anthracycline-based chemotherapy, cure rates are markedly lower among patients with limited-stage disease, defined as Ann Arbor stage I or II, confined to a single irradiation field. Limited-stage disease accounts for approximately one-third DLBCL cases.

To see whether the trends observed at 10 years continued, the investigators conducted a survival analysis from S8736 and compared the data from similar patients in the S0014 study.

They found that after a median follow-up of 17.7 years in S8736, median PFS was 12.0 years for patients treated with CHOP8, and 11.1 years for patients treated with CHOP3RT, a difference that was not statistically significant.

Median OS was 13.0 and 13.7 years, respectively, and was also not significant.

In S0014, after a median follow-up of 12 years, the 5-year OS rate was 82%, and 10-year rate was 67%. In this trial, the investigators observed “a persistent pattern of relapse despite the addition of rituximab.”

“The populations were not entirely identical; however, even the addition of rituximab as per S0014 to combined-modality therapy did not seem to mitigate the continued relapse risk, underscoring the value of prolonged observation of clinical trial patients and possible unique biology of limited-stage DLBCL,” Dr. Stephens and her associates wrote.

The study was sponsored by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Stephens reported having no financial disclosures. Several coauthors disclosed research funding, consulting, speakers’ bureau participation or travel expenses from various oncology drug makers.

Long-term follow-up from two randomized trials shows that the treatment advantage initially seen by adding radiotherapy to the CHOP regimen in patients with limited-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma disappeared over time.

After a median follow-up of nearly 18 years, there were no significant differences in either progression-free survival (PFS) or overall survival between patients who had received standard CHOP chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) for 8 cycles (CHOP8), or 3 cycles of CHOP with involved-field radiotherapy (CHOP3RT), reported Deborah M. Stephens, DO, of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, and her colleagues.

The addition of rituximab to CHOP plus involved-field radiotherapy (IFRT) in a separate cohort did not appear to reduce the continued relapse risk, the investigators noted (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jul. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.4582).

The findings suggest that long-term follow-up of patients enrolled in clinical trials may provide clinically important additional information, and that limited-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) may have a biology that is distinctly different from that of advanced stage DLBCL, the investigators wrote.

Initial results from the SWOG (Southwest Oncology Group) Study 8736, published after a median follow-up of 4.4 years, showed that CHOP3RT was associated with significantly better 5-year PFS and OS rates, compared with patients treated with CHOP8.

A second trial, SWOG Study 0014, looked at the addition of rituximab (Rituxan) to CHOP plus IFRT in patients with high-risk DLBCL with at least one adverse feature of the stage-modified International Prognostic Index. In this trial, after a median follow-up of 5.3 years, 4-year PFS was 88%, and 4-year OS was 92%.

5 years not enough

Results of both trials were published around the 5-year follow-up mark. However, an analysis of 10-year follow-up data from the S8736 trial, published only as an abstract (Blood. 98:724a-725a, 2001; abstr 3024), showed that “the survival curves for CHOP8 and CHOP3RT, surprisingly, began to overlap,” Dr. Stephens and her colleagues wrote.

“Additionally, for both S8736 and S0014, no plateau had been reached in the PFS curves. These data contrasted the expected cure rates for advanced-stage DLBCL, leading to the hypothesis that limited-stage DLBCL may have a unique biology from its advanced-stage counterpart,” they added.

Although more than half of patients with advanced-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) can be cured with anthracycline-based chemotherapy, cure rates are markedly lower among patients with limited-stage disease, defined as Ann Arbor stage I or II, confined to a single irradiation field. Limited-stage disease accounts for approximately one-third DLBCL cases.

To see whether the trends observed at 10 years continued, the investigators conducted a survival analysis from S8736 and compared the data from similar patients in the S0014 study.

They found that after a median follow-up of 17.7 years in S8736, median PFS was 12.0 years for patients treated with CHOP8, and 11.1 years for patients treated with CHOP3RT, a difference that was not statistically significant.

Median OS was 13.0 and 13.7 years, respectively, and was also not significant.

In S0014, after a median follow-up of 12 years, the 5-year OS rate was 82%, and 10-year rate was 67%. In this trial, the investigators observed “a persistent pattern of relapse despite the addition of rituximab.”

“The populations were not entirely identical; however, even the addition of rituximab as per S0014 to combined-modality therapy did not seem to mitigate the continued relapse risk, underscoring the value of prolonged observation of clinical trial patients and possible unique biology of limited-stage DLBCL,” Dr. Stephens and her associates wrote.

The study was sponsored by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Stephens reported having no financial disclosures. Several coauthors disclosed research funding, consulting, speakers’ bureau participation or travel expenses from various oncology drug makers.

Long-term follow-up from two randomized trials shows that the treatment advantage initially seen by adding radiotherapy to the CHOP regimen in patients with limited-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma disappeared over time.

After a median follow-up of nearly 18 years, there were no significant differences in either progression-free survival (PFS) or overall survival between patients who had received standard CHOP chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) for 8 cycles (CHOP8), or 3 cycles of CHOP with involved-field radiotherapy (CHOP3RT), reported Deborah M. Stephens, DO, of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, and her colleagues.

The addition of rituximab to CHOP plus involved-field radiotherapy (IFRT) in a separate cohort did not appear to reduce the continued relapse risk, the investigators noted (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jul. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.4582).

The findings suggest that long-term follow-up of patients enrolled in clinical trials may provide clinically important additional information, and that limited-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) may have a biology that is distinctly different from that of advanced stage DLBCL, the investigators wrote.

Initial results from the SWOG (Southwest Oncology Group) Study 8736, published after a median follow-up of 4.4 years, showed that CHOP3RT was associated with significantly better 5-year PFS and OS rates, compared with patients treated with CHOP8.

A second trial, SWOG Study 0014, looked at the addition of rituximab (Rituxan) to CHOP plus IFRT in patients with high-risk DLBCL with at least one adverse feature of the stage-modified International Prognostic Index. In this trial, after a median follow-up of 5.3 years, 4-year PFS was 88%, and 4-year OS was 92%.

5 years not enough

Results of both trials were published around the 5-year follow-up mark. However, an analysis of 10-year follow-up data from the S8736 trial, published only as an abstract (Blood. 98:724a-725a, 2001; abstr 3024), showed that “the survival curves for CHOP8 and CHOP3RT, surprisingly, began to overlap,” Dr. Stephens and her colleagues wrote.

“Additionally, for both S8736 and S0014, no plateau had been reached in the PFS curves. These data contrasted the expected cure rates for advanced-stage DLBCL, leading to the hypothesis that limited-stage DLBCL may have a unique biology from its advanced-stage counterpart,” they added.

Although more than half of patients with advanced-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) can be cured with anthracycline-based chemotherapy, cure rates are markedly lower among patients with limited-stage disease, defined as Ann Arbor stage I or II, confined to a single irradiation field. Limited-stage disease accounts for approximately one-third DLBCL cases.

To see whether the trends observed at 10 years continued, the investigators conducted a survival analysis from S8736 and compared the data from similar patients in the S0014 study.