User login

FDA places CAR-T cell trial on hold following patient deaths

The Food and Drug Administration placed Juno Therapeutics’ phase II ROCKET trial, involving CAR-T cell therapy, on clinical hold following two treatment-related patient deaths caused by excess fluid accumulation in the brain.

The ROCKET trial is a single-arm, multicenter phase II study treating adult patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia with an infusion of the patient’s own T cells that have been genetically modified to express a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) that will bind to CD19-expressing leukemia cells. This treatment is referred to as JCAR015, and the ROCKET trial is only one of three current clinical trials testing its safety and efficacy.

Just before the ROCKET trial commenced, researchers added the chemotherapy drug fludarabine, which was successful in improving the performance of other immunotherapies, to the JCAR015 infusion. Researchers involved in the trial reported that the addition of this drug was likely the cause of the patient deaths.

Juno Therapeuticswill submit a revised trial protocol and patient consent form to the FDA before the hold is lifted, Juno reported in a written statement. The other trials led by Juno Therapeutics involving CAR-T cell product candidates are not affected.

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

The Food and Drug Administration placed Juno Therapeutics’ phase II ROCKET trial, involving CAR-T cell therapy, on clinical hold following two treatment-related patient deaths caused by excess fluid accumulation in the brain.

The ROCKET trial is a single-arm, multicenter phase II study treating adult patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia with an infusion of the patient’s own T cells that have been genetically modified to express a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) that will bind to CD19-expressing leukemia cells. This treatment is referred to as JCAR015, and the ROCKET trial is only one of three current clinical trials testing its safety and efficacy.

Just before the ROCKET trial commenced, researchers added the chemotherapy drug fludarabine, which was successful in improving the performance of other immunotherapies, to the JCAR015 infusion. Researchers involved in the trial reported that the addition of this drug was likely the cause of the patient deaths.

Juno Therapeuticswill submit a revised trial protocol and patient consent form to the FDA before the hold is lifted, Juno reported in a written statement. The other trials led by Juno Therapeutics involving CAR-T cell product candidates are not affected.

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

The Food and Drug Administration placed Juno Therapeutics’ phase II ROCKET trial, involving CAR-T cell therapy, on clinical hold following two treatment-related patient deaths caused by excess fluid accumulation in the brain.

The ROCKET trial is a single-arm, multicenter phase II study treating adult patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia with an infusion of the patient’s own T cells that have been genetically modified to express a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) that will bind to CD19-expressing leukemia cells. This treatment is referred to as JCAR015, and the ROCKET trial is only one of three current clinical trials testing its safety and efficacy.

Just before the ROCKET trial commenced, researchers added the chemotherapy drug fludarabine, which was successful in improving the performance of other immunotherapies, to the JCAR015 infusion. Researchers involved in the trial reported that the addition of this drug was likely the cause of the patient deaths.

Juno Therapeuticswill submit a revised trial protocol and patient consent form to the FDA before the hold is lifted, Juno reported in a written statement. The other trials led by Juno Therapeutics involving CAR-T cell product candidates are not affected.

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

Most interventional cardiologists don’t fully grasp radiation risks

PARIS – What most interventional cardiologists and electrophysiologists do not know about their health risks due to occupational radiation exposure and how best to protect themselves could fill a book – or better still, make for an illuminating 2-hour expert panel discussion at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

“There’s a problem of lack of awareness on the part of interventional cardiologists, and also of institutional insensitivity to the problem,” declared Emanuela Piccaluga, MD, an investigator in the eye-opening Healthy Cath Lab study. This Italian national study showed that cardiac catheterization laboratory staff had radiation exposure duration–dependent increased risks of cataracts, cancers, and skin lesions, as well as other radiogenic noncancer effects: anxiety and depression, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.

Cardiologists at some European hospitals have to pay for their own lead aprons and other protective gear. And even if the hospital does pick up the bill, administrators often balk at authorizing replacement of a lead apron that has developed microfractures and cracks. They view these imperfections as cosmetic defects, unaware that the damage renders the apron less protective, according to Dr. Piccaluga of Niguarda Ca’ Granda Hospital in Milan.

Ariel Roguin, MD, head of interventional cardiology at Rambam Medical Center in Haifa, Israel, said every cardiologist working with radiation should understand the three principles of radiation reduction, which he refers to in shorthand as “TDS,” for Time, Distance, and Shielding. Radiation is here to stay in cardiology, he said, but interventionalists can maximize their safety by keeping the fluoroscopy time and number of acquired images down, standing as far away as possible from both the radiation source and patient while still getting the job done well, and using appropriate shielding routinely.

Dr. Roguin gained notoriety with his report that 26 of 30 interventional cardiologists with glioblastoma multiforme or other brain malignancies had left-hemisphere cancers and 1 had a midline malignancy; only 3 were right-sided (Eur Heart J. 2014 Mar;35[10]:599-600). That distribution is highly unlikely to be due to play of chance, given that an interventional cardiologist’s left side is the side that’s usually exposed to more radiation.

“We should form a wall against radiation. Apart from the leaded aprons, for every procedure we all should also use lead skirts going from the table to the floor to block backscatter, ceiling-mounted overhead radiation shields, special glasses to protect against cataracts, and thyroid collars. And it’s very important to wear a dosimeter with sound; it helps increase awareness of our exposure,” he said.

Dr. Roguin has been a pioneer in the use of a thin, 0.5-mm lead shield draped across the patient’s abdomen from the umbilicus down during radial-access angiography. In a 322-patient randomized trial, he and his coinvestigators showed that this practice results in a threefold reduction in radiation to the operator, albeit at the cost of doubling the patient’s radiation exposure (Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015 Jun;85[7]:1164-70).

“We now routinely do our radials with the lead apron across the patient’s abdomen. We’ve reached the conclusion that we work with radiation in the cath lab every day for many years and the patient is there only once or twice in a lifetime, hopefully,” the cardiologist explained.

With the growing popularity of radial-access interventions, audience members wanted to know if there is an advantage in terms of radiation exposure to left versus right radial artery access. The answer is no, according to Dr. Roguin.

“There are several studies showing no difference in radiation exposure. Left radial artery access is faster, but you’re leaning on the patient and getting more radiation as a result, while with right radial access you have to do more catheter manipulation, which takes longer. Both approaches involve more radiation to the operator than the transfemoral approach,” he said.

Dr. Piccaluga presented highlights from the Healthy Cath Lab study, sponsored by the Italian Society of Invasive Cardiology and the Italian National Research Council’s Institute of Clinical Physiology. The study involved detailed self-administered questionnaires completed by 218 interventional cardiologists and electrophysiologists, 191 nurses, and 57 technicians regularly exposed to ionizing radiation in the cardiac cath lab for a median of 10 years, along with 280 unexposed controls.

A variety of health problems were more frequent in the cath lab personnel regularly exposed to radiation. Rates were consistently highest in the cardiologists, followed next by the cath lab nurses, and then the radiation technicians.

Rates of health problems were highest in the 227 individuals with at least 13 years of cath lab radiation exposure. For example, their adjusted risks of cataracts, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and cancers were respectively 9-, 1.7-, 2.9-, and 4.5-fold fold greater than in unexposed controls, as detailed in a recent report (Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016 April. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.115.003273).

Dr. Piccaluga also shared data from several other pertinent recent studies in which she was a coinvestigator. In one, 83 cardiologists and nurses working in cardiac catheterization laboratories and 83 matched radiation-nonexposed controls completed a neuropsychological test battery. The radiation-exposed group scored significantly lower on measures of delayed recall, visual short-term memory, and verbal fluency, all of which are skills located in left hemisphere structures of the brain – the side with more exposure to ionizing radiation during interventional procedures (J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2015 Oct;21[9]:670-6).

In another study, Dr. Piccaluga and her coinvestigators had participants perform an odor-sniffing test. Olfactory discrimination in the cardiac cath lab staffers was significantly diminished in a pattern that has been identified in other studies as an early signal of impending clinical onset of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases (Int J Cardiol. 2014 Feb 15;171[3]:461-3).

And in yet another study, Dr. Piccaluga and her coworkers found that left and right carotid intima-media thickness as measured by ultrasound in cardiac cath lab personnel having high lifetime radiation exposure was significantly greater than in those with low exposure and in nonexposed controls. In the left carotid artery, but not the right, intimal-medial thickness was significantly correlated with a total occupational radiologic risk score.

Moreover, the Italian investigators found a significant reduction in leukocyte telomere length – a biomarker for accelerated vascular aging – in cardiac cath lab staff regularly exposed to ionizing radiation, compared with controls (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015 Apr 20;8[4]:616-27).

All of these findings, she stressed, make a persuasive case for interventional cardiologists doing everything they can to protect themselves from unnecessary radiation exposure at all times.

How to best go about accomplishing this was the territory covered by Alaide Chieffo, MD, of San Raffaele Scientific Institute in Milan.

The patient-related factors germane to radiation dose – procedure complexity and body thickness – are outside physician control. But there are plenty of operator-dependent factors, including, for starters, procedural experience. In one classic study, Dr. Chieffo noted, Greek investigators showed that interventional cardiologists’ radiation exposure dose was 60% greater in their first year of practice than in their second year.

Distance from the patient is crucial, she observed, since the patient is the greatest source of radiation to the operator. If the operator is 35 cm from the patient, the radiation exposure is fourfold greater than at a distance of 70 cm. At a distance of 17.5 cm, the exposure intensity is 16-fold greater than at a 70-cm distance. And at 8.8 cm of distance, it’s 64 times greater.

Image acquisition is another key variable within the interventionalist’s control. Cine images entail 12- to 20-times greater radiation doses than those of fluoroscopy, so don’t resort to cine when fluoroscopy will do. Also, reducing the fluoroscopy frame rate from 15 to 7.5 frames per second significantly decreases the amount of radiation released while providing images of adequate quality for many procedures. Tight collimation, the use of manually inserted wedge filters, and thoughtful selection of tube angulations result in less radiation for both patient and physician. It has been shown that tube angulations that expose a patient to intense radiation levels increase the operator’s radiation exposure exponentially. The least-irradiating tube angulations are caudal posteroanterior 0°/30°– angulation for the left coronary main stem, cranial posteroanterior 0°/30°+ for the left anterior descending coronary artery bifurcation, and right anterior oblique views of 40° or more. Left anterior oblique projections are the most radiation intensive, according to a comprehensive study (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004 Oct 6;44[7]:1420-8), Dr. Chieffo continued.

Panelist Ghada Mikhail, MD, of Imperial College London, said there is some relatively new operator protective gear available. She cited lightweight protective caps, for example, but an audience show of hands indicated almost no one uses them.

“Protectors for the breasts and gonads are available. You can wear them underneath the lead. The extra time to put them on is worthwhile,” she said.

“I think the risk of radiation is completely underestimated,” Dr. Mikhail added. “We have a responsibility to young trainees to teach them about radiation protection, which a lot of institutions and supervisors don’t do. That’s partly because a lot of them don’t know the details.”

All of the speakers indicated they had no financial conflicts regarding their presentations.

PARIS – What most interventional cardiologists and electrophysiologists do not know about their health risks due to occupational radiation exposure and how best to protect themselves could fill a book – or better still, make for an illuminating 2-hour expert panel discussion at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

“There’s a problem of lack of awareness on the part of interventional cardiologists, and also of institutional insensitivity to the problem,” declared Emanuela Piccaluga, MD, an investigator in the eye-opening Healthy Cath Lab study. This Italian national study showed that cardiac catheterization laboratory staff had radiation exposure duration–dependent increased risks of cataracts, cancers, and skin lesions, as well as other radiogenic noncancer effects: anxiety and depression, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.

Cardiologists at some European hospitals have to pay for their own lead aprons and other protective gear. And even if the hospital does pick up the bill, administrators often balk at authorizing replacement of a lead apron that has developed microfractures and cracks. They view these imperfections as cosmetic defects, unaware that the damage renders the apron less protective, according to Dr. Piccaluga of Niguarda Ca’ Granda Hospital in Milan.

Ariel Roguin, MD, head of interventional cardiology at Rambam Medical Center in Haifa, Israel, said every cardiologist working with radiation should understand the three principles of radiation reduction, which he refers to in shorthand as “TDS,” for Time, Distance, and Shielding. Radiation is here to stay in cardiology, he said, but interventionalists can maximize their safety by keeping the fluoroscopy time and number of acquired images down, standing as far away as possible from both the radiation source and patient while still getting the job done well, and using appropriate shielding routinely.

Dr. Roguin gained notoriety with his report that 26 of 30 interventional cardiologists with glioblastoma multiforme or other brain malignancies had left-hemisphere cancers and 1 had a midline malignancy; only 3 were right-sided (Eur Heart J. 2014 Mar;35[10]:599-600). That distribution is highly unlikely to be due to play of chance, given that an interventional cardiologist’s left side is the side that’s usually exposed to more radiation.

“We should form a wall against radiation. Apart from the leaded aprons, for every procedure we all should also use lead skirts going from the table to the floor to block backscatter, ceiling-mounted overhead radiation shields, special glasses to protect against cataracts, and thyroid collars. And it’s very important to wear a dosimeter with sound; it helps increase awareness of our exposure,” he said.

Dr. Roguin has been a pioneer in the use of a thin, 0.5-mm lead shield draped across the patient’s abdomen from the umbilicus down during radial-access angiography. In a 322-patient randomized trial, he and his coinvestigators showed that this practice results in a threefold reduction in radiation to the operator, albeit at the cost of doubling the patient’s radiation exposure (Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015 Jun;85[7]:1164-70).

“We now routinely do our radials with the lead apron across the patient’s abdomen. We’ve reached the conclusion that we work with radiation in the cath lab every day for many years and the patient is there only once or twice in a lifetime, hopefully,” the cardiologist explained.

With the growing popularity of radial-access interventions, audience members wanted to know if there is an advantage in terms of radiation exposure to left versus right radial artery access. The answer is no, according to Dr. Roguin.

“There are several studies showing no difference in radiation exposure. Left radial artery access is faster, but you’re leaning on the patient and getting more radiation as a result, while with right radial access you have to do more catheter manipulation, which takes longer. Both approaches involve more radiation to the operator than the transfemoral approach,” he said.

Dr. Piccaluga presented highlights from the Healthy Cath Lab study, sponsored by the Italian Society of Invasive Cardiology and the Italian National Research Council’s Institute of Clinical Physiology. The study involved detailed self-administered questionnaires completed by 218 interventional cardiologists and electrophysiologists, 191 nurses, and 57 technicians regularly exposed to ionizing radiation in the cardiac cath lab for a median of 10 years, along with 280 unexposed controls.

A variety of health problems were more frequent in the cath lab personnel regularly exposed to radiation. Rates were consistently highest in the cardiologists, followed next by the cath lab nurses, and then the radiation technicians.

Rates of health problems were highest in the 227 individuals with at least 13 years of cath lab radiation exposure. For example, their adjusted risks of cataracts, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and cancers were respectively 9-, 1.7-, 2.9-, and 4.5-fold fold greater than in unexposed controls, as detailed in a recent report (Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016 April. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.115.003273).

Dr. Piccaluga also shared data from several other pertinent recent studies in which she was a coinvestigator. In one, 83 cardiologists and nurses working in cardiac catheterization laboratories and 83 matched radiation-nonexposed controls completed a neuropsychological test battery. The radiation-exposed group scored significantly lower on measures of delayed recall, visual short-term memory, and verbal fluency, all of which are skills located in left hemisphere structures of the brain – the side with more exposure to ionizing radiation during interventional procedures (J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2015 Oct;21[9]:670-6).

In another study, Dr. Piccaluga and her coinvestigators had participants perform an odor-sniffing test. Olfactory discrimination in the cardiac cath lab staffers was significantly diminished in a pattern that has been identified in other studies as an early signal of impending clinical onset of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases (Int J Cardiol. 2014 Feb 15;171[3]:461-3).

And in yet another study, Dr. Piccaluga and her coworkers found that left and right carotid intima-media thickness as measured by ultrasound in cardiac cath lab personnel having high lifetime radiation exposure was significantly greater than in those with low exposure and in nonexposed controls. In the left carotid artery, but not the right, intimal-medial thickness was significantly correlated with a total occupational radiologic risk score.

Moreover, the Italian investigators found a significant reduction in leukocyte telomere length – a biomarker for accelerated vascular aging – in cardiac cath lab staff regularly exposed to ionizing radiation, compared with controls (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015 Apr 20;8[4]:616-27).

All of these findings, she stressed, make a persuasive case for interventional cardiologists doing everything they can to protect themselves from unnecessary radiation exposure at all times.

How to best go about accomplishing this was the territory covered by Alaide Chieffo, MD, of San Raffaele Scientific Institute in Milan.

The patient-related factors germane to radiation dose – procedure complexity and body thickness – are outside physician control. But there are plenty of operator-dependent factors, including, for starters, procedural experience. In one classic study, Dr. Chieffo noted, Greek investigators showed that interventional cardiologists’ radiation exposure dose was 60% greater in their first year of practice than in their second year.

Distance from the patient is crucial, she observed, since the patient is the greatest source of radiation to the operator. If the operator is 35 cm from the patient, the radiation exposure is fourfold greater than at a distance of 70 cm. At a distance of 17.5 cm, the exposure intensity is 16-fold greater than at a 70-cm distance. And at 8.8 cm of distance, it’s 64 times greater.

Image acquisition is another key variable within the interventionalist’s control. Cine images entail 12- to 20-times greater radiation doses than those of fluoroscopy, so don’t resort to cine when fluoroscopy will do. Also, reducing the fluoroscopy frame rate from 15 to 7.5 frames per second significantly decreases the amount of radiation released while providing images of adequate quality for many procedures. Tight collimation, the use of manually inserted wedge filters, and thoughtful selection of tube angulations result in less radiation for both patient and physician. It has been shown that tube angulations that expose a patient to intense radiation levels increase the operator’s radiation exposure exponentially. The least-irradiating tube angulations are caudal posteroanterior 0°/30°– angulation for the left coronary main stem, cranial posteroanterior 0°/30°+ for the left anterior descending coronary artery bifurcation, and right anterior oblique views of 40° or more. Left anterior oblique projections are the most radiation intensive, according to a comprehensive study (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004 Oct 6;44[7]:1420-8), Dr. Chieffo continued.

Panelist Ghada Mikhail, MD, of Imperial College London, said there is some relatively new operator protective gear available. She cited lightweight protective caps, for example, but an audience show of hands indicated almost no one uses them.

“Protectors for the breasts and gonads are available. You can wear them underneath the lead. The extra time to put them on is worthwhile,” she said.

“I think the risk of radiation is completely underestimated,” Dr. Mikhail added. “We have a responsibility to young trainees to teach them about radiation protection, which a lot of institutions and supervisors don’t do. That’s partly because a lot of them don’t know the details.”

All of the speakers indicated they had no financial conflicts regarding their presentations.

PARIS – What most interventional cardiologists and electrophysiologists do not know about their health risks due to occupational radiation exposure and how best to protect themselves could fill a book – or better still, make for an illuminating 2-hour expert panel discussion at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

“There’s a problem of lack of awareness on the part of interventional cardiologists, and also of institutional insensitivity to the problem,” declared Emanuela Piccaluga, MD, an investigator in the eye-opening Healthy Cath Lab study. This Italian national study showed that cardiac catheterization laboratory staff had radiation exposure duration–dependent increased risks of cataracts, cancers, and skin lesions, as well as other radiogenic noncancer effects: anxiety and depression, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.

Cardiologists at some European hospitals have to pay for their own lead aprons and other protective gear. And even if the hospital does pick up the bill, administrators often balk at authorizing replacement of a lead apron that has developed microfractures and cracks. They view these imperfections as cosmetic defects, unaware that the damage renders the apron less protective, according to Dr. Piccaluga of Niguarda Ca’ Granda Hospital in Milan.

Ariel Roguin, MD, head of interventional cardiology at Rambam Medical Center in Haifa, Israel, said every cardiologist working with radiation should understand the three principles of radiation reduction, which he refers to in shorthand as “TDS,” for Time, Distance, and Shielding. Radiation is here to stay in cardiology, he said, but interventionalists can maximize their safety by keeping the fluoroscopy time and number of acquired images down, standing as far away as possible from both the radiation source and patient while still getting the job done well, and using appropriate shielding routinely.

Dr. Roguin gained notoriety with his report that 26 of 30 interventional cardiologists with glioblastoma multiforme or other brain malignancies had left-hemisphere cancers and 1 had a midline malignancy; only 3 were right-sided (Eur Heart J. 2014 Mar;35[10]:599-600). That distribution is highly unlikely to be due to play of chance, given that an interventional cardiologist’s left side is the side that’s usually exposed to more radiation.

“We should form a wall against radiation. Apart from the leaded aprons, for every procedure we all should also use lead skirts going from the table to the floor to block backscatter, ceiling-mounted overhead radiation shields, special glasses to protect against cataracts, and thyroid collars. And it’s very important to wear a dosimeter with sound; it helps increase awareness of our exposure,” he said.

Dr. Roguin has been a pioneer in the use of a thin, 0.5-mm lead shield draped across the patient’s abdomen from the umbilicus down during radial-access angiography. In a 322-patient randomized trial, he and his coinvestigators showed that this practice results in a threefold reduction in radiation to the operator, albeit at the cost of doubling the patient’s radiation exposure (Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015 Jun;85[7]:1164-70).

“We now routinely do our radials with the lead apron across the patient’s abdomen. We’ve reached the conclusion that we work with radiation in the cath lab every day for many years and the patient is there only once or twice in a lifetime, hopefully,” the cardiologist explained.

With the growing popularity of radial-access interventions, audience members wanted to know if there is an advantage in terms of radiation exposure to left versus right radial artery access. The answer is no, according to Dr. Roguin.

“There are several studies showing no difference in radiation exposure. Left radial artery access is faster, but you’re leaning on the patient and getting more radiation as a result, while with right radial access you have to do more catheter manipulation, which takes longer. Both approaches involve more radiation to the operator than the transfemoral approach,” he said.

Dr. Piccaluga presented highlights from the Healthy Cath Lab study, sponsored by the Italian Society of Invasive Cardiology and the Italian National Research Council’s Institute of Clinical Physiology. The study involved detailed self-administered questionnaires completed by 218 interventional cardiologists and electrophysiologists, 191 nurses, and 57 technicians regularly exposed to ionizing radiation in the cardiac cath lab for a median of 10 years, along with 280 unexposed controls.

A variety of health problems were more frequent in the cath lab personnel regularly exposed to radiation. Rates were consistently highest in the cardiologists, followed next by the cath lab nurses, and then the radiation technicians.

Rates of health problems were highest in the 227 individuals with at least 13 years of cath lab radiation exposure. For example, their adjusted risks of cataracts, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and cancers were respectively 9-, 1.7-, 2.9-, and 4.5-fold fold greater than in unexposed controls, as detailed in a recent report (Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016 April. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.115.003273).

Dr. Piccaluga also shared data from several other pertinent recent studies in which she was a coinvestigator. In one, 83 cardiologists and nurses working in cardiac catheterization laboratories and 83 matched radiation-nonexposed controls completed a neuropsychological test battery. The radiation-exposed group scored significantly lower on measures of delayed recall, visual short-term memory, and verbal fluency, all of which are skills located in left hemisphere structures of the brain – the side with more exposure to ionizing radiation during interventional procedures (J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2015 Oct;21[9]:670-6).

In another study, Dr. Piccaluga and her coinvestigators had participants perform an odor-sniffing test. Olfactory discrimination in the cardiac cath lab staffers was significantly diminished in a pattern that has been identified in other studies as an early signal of impending clinical onset of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases (Int J Cardiol. 2014 Feb 15;171[3]:461-3).

And in yet another study, Dr. Piccaluga and her coworkers found that left and right carotid intima-media thickness as measured by ultrasound in cardiac cath lab personnel having high lifetime radiation exposure was significantly greater than in those with low exposure and in nonexposed controls. In the left carotid artery, but not the right, intimal-medial thickness was significantly correlated with a total occupational radiologic risk score.

Moreover, the Italian investigators found a significant reduction in leukocyte telomere length – a biomarker for accelerated vascular aging – in cardiac cath lab staff regularly exposed to ionizing radiation, compared with controls (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015 Apr 20;8[4]:616-27).

All of these findings, she stressed, make a persuasive case for interventional cardiologists doing everything they can to protect themselves from unnecessary radiation exposure at all times.

How to best go about accomplishing this was the territory covered by Alaide Chieffo, MD, of San Raffaele Scientific Institute in Milan.

The patient-related factors germane to radiation dose – procedure complexity and body thickness – are outside physician control. But there are plenty of operator-dependent factors, including, for starters, procedural experience. In one classic study, Dr. Chieffo noted, Greek investigators showed that interventional cardiologists’ radiation exposure dose was 60% greater in their first year of practice than in their second year.

Distance from the patient is crucial, she observed, since the patient is the greatest source of radiation to the operator. If the operator is 35 cm from the patient, the radiation exposure is fourfold greater than at a distance of 70 cm. At a distance of 17.5 cm, the exposure intensity is 16-fold greater than at a 70-cm distance. And at 8.8 cm of distance, it’s 64 times greater.

Image acquisition is another key variable within the interventionalist’s control. Cine images entail 12- to 20-times greater radiation doses than those of fluoroscopy, so don’t resort to cine when fluoroscopy will do. Also, reducing the fluoroscopy frame rate from 15 to 7.5 frames per second significantly decreases the amount of radiation released while providing images of adequate quality for many procedures. Tight collimation, the use of manually inserted wedge filters, and thoughtful selection of tube angulations result in less radiation for both patient and physician. It has been shown that tube angulations that expose a patient to intense radiation levels increase the operator’s radiation exposure exponentially. The least-irradiating tube angulations are caudal posteroanterior 0°/30°– angulation for the left coronary main stem, cranial posteroanterior 0°/30°+ for the left anterior descending coronary artery bifurcation, and right anterior oblique views of 40° or more. Left anterior oblique projections are the most radiation intensive, according to a comprehensive study (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004 Oct 6;44[7]:1420-8), Dr. Chieffo continued.

Panelist Ghada Mikhail, MD, of Imperial College London, said there is some relatively new operator protective gear available. She cited lightweight protective caps, for example, but an audience show of hands indicated almost no one uses them.

“Protectors for the breasts and gonads are available. You can wear them underneath the lead. The extra time to put them on is worthwhile,” she said.

“I think the risk of radiation is completely underestimated,” Dr. Mikhail added. “We have a responsibility to young trainees to teach them about radiation protection, which a lot of institutions and supervisors don’t do. That’s partly because a lot of them don’t know the details.”

All of the speakers indicated they had no financial conflicts regarding their presentations.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM EUROPCR 2016

Bendamustine-based chemotherapy induces high CR rate in relapsed HL

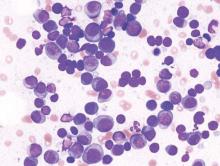

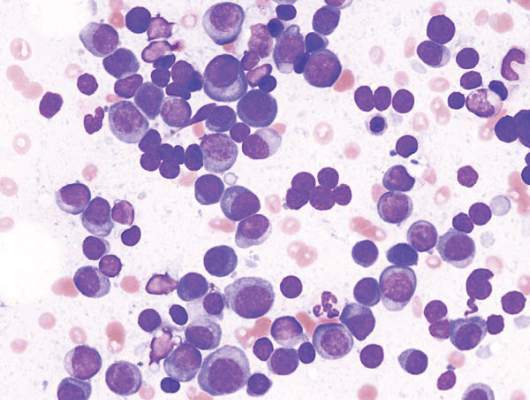

Combination chemotherapy with bendamustine, gemcitabine, and vinorelbine can induce high complete response rates among patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) who are candidates for autologous stem cell transplantation, final results of a phase II study show.

Among 59 patients enrolled in the multicenter study, 49 (83%) had responses, including 43 (73%) who achieved a complete response (CR), and 6 (10%) who had a partial response after 4 cycles of chemotherapy with bendamustine (Treanda), gemcitabine (Gemzar), and vinorelbine (BeGEV).

Of the 49 patients with responses, 43 went on to autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), reported Armando Santoro, MD, from the Humanitas Cancer Center in Rozzano, Italy.

“These findings provide a strong rationale for further development of the BeGEV regimen,” the investigators wrote in a study published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology (2016 Jul 5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.4466).

The investigators had previously shown that a regimen of ifosfamide, gemcitabine, and vinorelbine (IEGV) as salvage chemotherapy prior to ASCT was associated with an 81% overall response rate (ORR) 54% CR rate.

Because bendamustine has shown good activity as monotherapy against relapsed/refractory HL, they conducted a phase II study with an IEGV-like regimen in which bendamustine would be substituted for ifosfamide, to determine whether the substitution could improve response rates.

They enrolled 59 consecutive patients aged 18 years and older with HL that had relapsed or was refractory to one previous line of chemotherapy. Patients were treated with gemcitabine 800 mg/m2 on days 1 and 4, vinorelbine 20 mg/m2 on day 1, and bendamustine 90 mg/m2 on days 2 and 3. Patients also received prednisolone 100 mg/day for days 1 to 4. The patients were treated for four 21-day cycles.

Patients who achieved either a complete or partial response after completion of the four planned cycles then underwent myeloablative therapy with carmustine or fotemustine plus etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan, followed by reinfusion of mobilized CD34-positive circulating stem cells.

Grade 3 or 4 hematologic toxicities included thrombocytopenia and neutropenia, which occurred in eight patients each. Fifty-five of 57 total evaluable patients had successful mobilization and harvesting of CD34-positive cells, and, as noted before, 43 went on to ASCT.

After a median follow-up of 29 months, the 2-year progression-free survival (PFS) rate for the total population was 62%, and the overall survival rates was nearly 78%. For patients who went on to ASCT, the 2-year PFS rate was 81%, and the 2-year survival rate was 89%.

The authors noted that BeGV was associated with higher CR rates than IEGV, and with “excellent” stem cell mobilization activity and engraftment. Additionally, BeGV has a favorable toxicity profile, because of the absence of ifosfamide which is known to significantly increase risk for hemorrhagic cystitis.

“Because the number of novel agents that may be added in the pretransplantation therapy setting is growing, direct comparisons of combinations incorporating novel agents with BeGEV and other regimens will be necessary to identify the best salvage strategy for relapsed and refractory HL,” the authors wrote.

The study was supported in part by a grant from Mundipharma Pharmaceuticals. Two coauthors disclosed consulting/advisory roles and travel accommodations and expenses from the company.

Combination chemotherapy with bendamustine, gemcitabine, and vinorelbine can induce high complete response rates among patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) who are candidates for autologous stem cell transplantation, final results of a phase II study show.

Among 59 patients enrolled in the multicenter study, 49 (83%) had responses, including 43 (73%) who achieved a complete response (CR), and 6 (10%) who had a partial response after 4 cycles of chemotherapy with bendamustine (Treanda), gemcitabine (Gemzar), and vinorelbine (BeGEV).

Of the 49 patients with responses, 43 went on to autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), reported Armando Santoro, MD, from the Humanitas Cancer Center in Rozzano, Italy.

“These findings provide a strong rationale for further development of the BeGEV regimen,” the investigators wrote in a study published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology (2016 Jul 5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.4466).

The investigators had previously shown that a regimen of ifosfamide, gemcitabine, and vinorelbine (IEGV) as salvage chemotherapy prior to ASCT was associated with an 81% overall response rate (ORR) 54% CR rate.

Because bendamustine has shown good activity as monotherapy against relapsed/refractory HL, they conducted a phase II study with an IEGV-like regimen in which bendamustine would be substituted for ifosfamide, to determine whether the substitution could improve response rates.

They enrolled 59 consecutive patients aged 18 years and older with HL that had relapsed or was refractory to one previous line of chemotherapy. Patients were treated with gemcitabine 800 mg/m2 on days 1 and 4, vinorelbine 20 mg/m2 on day 1, and bendamustine 90 mg/m2 on days 2 and 3. Patients also received prednisolone 100 mg/day for days 1 to 4. The patients were treated for four 21-day cycles.

Patients who achieved either a complete or partial response after completion of the four planned cycles then underwent myeloablative therapy with carmustine or fotemustine plus etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan, followed by reinfusion of mobilized CD34-positive circulating stem cells.

Grade 3 or 4 hematologic toxicities included thrombocytopenia and neutropenia, which occurred in eight patients each. Fifty-five of 57 total evaluable patients had successful mobilization and harvesting of CD34-positive cells, and, as noted before, 43 went on to ASCT.

After a median follow-up of 29 months, the 2-year progression-free survival (PFS) rate for the total population was 62%, and the overall survival rates was nearly 78%. For patients who went on to ASCT, the 2-year PFS rate was 81%, and the 2-year survival rate was 89%.

The authors noted that BeGV was associated with higher CR rates than IEGV, and with “excellent” stem cell mobilization activity and engraftment. Additionally, BeGV has a favorable toxicity profile, because of the absence of ifosfamide which is known to significantly increase risk for hemorrhagic cystitis.

“Because the number of novel agents that may be added in the pretransplantation therapy setting is growing, direct comparisons of combinations incorporating novel agents with BeGEV and other regimens will be necessary to identify the best salvage strategy for relapsed and refractory HL,” the authors wrote.

The study was supported in part by a grant from Mundipharma Pharmaceuticals. Two coauthors disclosed consulting/advisory roles and travel accommodations and expenses from the company.

Combination chemotherapy with bendamustine, gemcitabine, and vinorelbine can induce high complete response rates among patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) who are candidates for autologous stem cell transplantation, final results of a phase II study show.

Among 59 patients enrolled in the multicenter study, 49 (83%) had responses, including 43 (73%) who achieved a complete response (CR), and 6 (10%) who had a partial response after 4 cycles of chemotherapy with bendamustine (Treanda), gemcitabine (Gemzar), and vinorelbine (BeGEV).

Of the 49 patients with responses, 43 went on to autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), reported Armando Santoro, MD, from the Humanitas Cancer Center in Rozzano, Italy.

“These findings provide a strong rationale for further development of the BeGEV regimen,” the investigators wrote in a study published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology (2016 Jul 5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.4466).

The investigators had previously shown that a regimen of ifosfamide, gemcitabine, and vinorelbine (IEGV) as salvage chemotherapy prior to ASCT was associated with an 81% overall response rate (ORR) 54% CR rate.

Because bendamustine has shown good activity as monotherapy against relapsed/refractory HL, they conducted a phase II study with an IEGV-like regimen in which bendamustine would be substituted for ifosfamide, to determine whether the substitution could improve response rates.

They enrolled 59 consecutive patients aged 18 years and older with HL that had relapsed or was refractory to one previous line of chemotherapy. Patients were treated with gemcitabine 800 mg/m2 on days 1 and 4, vinorelbine 20 mg/m2 on day 1, and bendamustine 90 mg/m2 on days 2 and 3. Patients also received prednisolone 100 mg/day for days 1 to 4. The patients were treated for four 21-day cycles.

Patients who achieved either a complete or partial response after completion of the four planned cycles then underwent myeloablative therapy with carmustine or fotemustine plus etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan, followed by reinfusion of mobilized CD34-positive circulating stem cells.

Grade 3 or 4 hematologic toxicities included thrombocytopenia and neutropenia, which occurred in eight patients each. Fifty-five of 57 total evaluable patients had successful mobilization and harvesting of CD34-positive cells, and, as noted before, 43 went on to ASCT.

After a median follow-up of 29 months, the 2-year progression-free survival (PFS) rate for the total population was 62%, and the overall survival rates was nearly 78%. For patients who went on to ASCT, the 2-year PFS rate was 81%, and the 2-year survival rate was 89%.

The authors noted that BeGV was associated with higher CR rates than IEGV, and with “excellent” stem cell mobilization activity and engraftment. Additionally, BeGV has a favorable toxicity profile, because of the absence of ifosfamide which is known to significantly increase risk for hemorrhagic cystitis.

“Because the number of novel agents that may be added in the pretransplantation therapy setting is growing, direct comparisons of combinations incorporating novel agents with BeGEV and other regimens will be necessary to identify the best salvage strategy for relapsed and refractory HL,” the authors wrote.

The study was supported in part by a grant from Mundipharma Pharmaceuticals. Two coauthors disclosed consulting/advisory roles and travel accommodations and expenses from the company.

FROM JCO

Key clinical point: Bendamustine in combination chemotherapy produces high response rates in relapsed refractory Hodgkin lymphoma (HL).

Major finding: The complete response rate with bendamustine, gemcitabine, and vinorelbine was 83%.

Data source: Multicenter phase II study of the BeGV salvage chemotherapy regimen in 59 patients with relapsed/refractory HL.

Disclosures: The study was supported in part by a grant from Mundipharma Pharmaceuticals. Two coauthors disclosed consulting/advisory roles and travel accommodations and expenses from the company.

CAC Progression No Better Than Most Recent CAC Score: Study

NEW YORK - Progression of the coronary artery calcification (CAC) score over time predicts the risk of cardiovascular disease, but it performs no better than the most recent CAC score, according to findings from the Cooper Center Longitudinal Study (CCLS).

"I must admit that I expected to find that the change in CAC was going to provide a lot of information about cardiovascular events, and was quite surprised when it didn't add much," Dr. Benjamin D. Levine from Cooper Clinic and University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas told Reuters Health by email. "I was then also surprised when Dr. Andre Paixao, one of our cardiology fellows at the time (now at Emory), suggested that we look at the last CAC score as the best measure for risk attributable to CAC, and he turned out to be right!"

CAC correlates with overall atherosclerotic plaque and predicts incident coronary heart disease (CHD) events, CHD mortality, and total mortality, but only a few studies have evaluated the implications of CAC progression.

Dr. Levine and colleagues used CCLS data from 5,933 participants free of cardiovascular disease (CVD) at baseline to evaluate the relative contributions of baseline CAC score, follow-up CAC score, and CAC progression rates to the risk of incident CVD events.

At baseline, 2,870 (48%) individuals had CAC. These individuals were older, more likely to be on statin therapy, and had higher systolic blood pressure and lower cardiorespiratory fitness, according to the June 29th JACC Cardiovascular Imaging online report.

Individuals with detectable CAC at baseline had significantly higher total CVD event rates than those without detectable CAC (7.70 vs 1.44 per 1,000 person-years, respectively), as well as hard CVD event rates, i.e., CVD death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal atherosclerotic stroke (2.68 vs 1.14 per 1,000 person-years, respectively).

Rates of total CVD and CHD events increased across quartiles of CAC progression, but there was no independent association between CAC progression and CVD outcomes after adjustment for the follow-up CAC score.

"These findings greatly simplify the interpretation of CAC scores over time," Dr. Levine said. "Because it is so difficult to quantify 'change' (a score that goes from 1 to 2 is 100% change, but from 101 to 102 is 1% change), it has been hard for clinicians to wrap their minds around the additional risk information that is contained in follow up scores. Since it is not the calcium we are worried about anyway (calcified plaque generally doesn't rupture - it is the company it keeps that is important), what matters is the overall atherosclerotic burden, as reflected by the absolute CAC score. How fast it changes doesn't matter at all!"

"Don't worry about complicated formulas for quantifying change in CAC," Dr. Levine said. "Just use the latest score to calculate the risk associated with CAC. Now that new calculators are available (and some new ones coming from our work in this space), only the latest CAC score is needed to assess risk."

In an editorial, Dr. Prediman K. Shah from Cedars Sinai Hart Institute in Los Angeles writes, "So change in CAC score may be bad, indifferent, or possibly even good depending on what causes the change: progression of underlying atherosclerosis (potentially bad) versus increased density of calcification indicating a plaque stabilizing response (potentially good)."

Dr. Shah continues. "How to distinguish potential contributors to change in CAC score remains an important and at this time an unanswered question."

"Addition of other variables that incorporate regions of change, change in regional density and other volumetric aspect of CAC change, extracoronary calcification, and epicardial fat volume may improve the value and relevance of change in CAC score," Dr. Shah said. "Further studies are needed to address these issues."

Dr. Joseph Yeboah from Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, who has also researched the association between CAC scores and cardiovascular disease risk, told Reuters Health by email, "This happens to be the first study to show that CAC progression is not informative for CVD risk assessment. At the very best, this study makes the data mixed, which is not surprising given the challenge of using a change in a variable (CAC progression) as a predictor. Some researchers have suggested that CAC density progression instead of CAC score progression may be more appropriate."

"In my opinion, these results will have very little influence on how CAC is used presently for CVD risk assessment," he said. "To my knowledge, there is presently no guideline or recommendation regarding the use of CAC progression for CVD risk assessment. This is because of the inherent challenges in assessing CAC progression and the paucity of data."

"The ACC/AHA guidelines clearly recommend the use of CAC, not CAC progression," Dr. Yeboah concluded. "The take away message here is that physicians should not use CAC progression for CVD risk assessment. More research is needed to fully understand CAC progression."

SOURCE: http://bit.ly/29rOdFM and http://bit.ly/29olMIA

J Am Coll Cardiol Imag 2016.

NEW YORK - Progression of the coronary artery calcification (CAC) score over time predicts the risk of cardiovascular disease, but it performs no better than the most recent CAC score, according to findings from the Cooper Center Longitudinal Study (CCLS).

"I must admit that I expected to find that the change in CAC was going to provide a lot of information about cardiovascular events, and was quite surprised when it didn't add much," Dr. Benjamin D. Levine from Cooper Clinic and University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas told Reuters Health by email. "I was then also surprised when Dr. Andre Paixao, one of our cardiology fellows at the time (now at Emory), suggested that we look at the last CAC score as the best measure for risk attributable to CAC, and he turned out to be right!"

CAC correlates with overall atherosclerotic plaque and predicts incident coronary heart disease (CHD) events, CHD mortality, and total mortality, but only a few studies have evaluated the implications of CAC progression.

Dr. Levine and colleagues used CCLS data from 5,933 participants free of cardiovascular disease (CVD) at baseline to evaluate the relative contributions of baseline CAC score, follow-up CAC score, and CAC progression rates to the risk of incident CVD events.

At baseline, 2,870 (48%) individuals had CAC. These individuals were older, more likely to be on statin therapy, and had higher systolic blood pressure and lower cardiorespiratory fitness, according to the June 29th JACC Cardiovascular Imaging online report.

Individuals with detectable CAC at baseline had significantly higher total CVD event rates than those without detectable CAC (7.70 vs 1.44 per 1,000 person-years, respectively), as well as hard CVD event rates, i.e., CVD death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal atherosclerotic stroke (2.68 vs 1.14 per 1,000 person-years, respectively).

Rates of total CVD and CHD events increased across quartiles of CAC progression, but there was no independent association between CAC progression and CVD outcomes after adjustment for the follow-up CAC score.

"These findings greatly simplify the interpretation of CAC scores over time," Dr. Levine said. "Because it is so difficult to quantify 'change' (a score that goes from 1 to 2 is 100% change, but from 101 to 102 is 1% change), it has been hard for clinicians to wrap their minds around the additional risk information that is contained in follow up scores. Since it is not the calcium we are worried about anyway (calcified plaque generally doesn't rupture - it is the company it keeps that is important), what matters is the overall atherosclerotic burden, as reflected by the absolute CAC score. How fast it changes doesn't matter at all!"

"Don't worry about complicated formulas for quantifying change in CAC," Dr. Levine said. "Just use the latest score to calculate the risk associated with CAC. Now that new calculators are available (and some new ones coming from our work in this space), only the latest CAC score is needed to assess risk."

In an editorial, Dr. Prediman K. Shah from Cedars Sinai Hart Institute in Los Angeles writes, "So change in CAC score may be bad, indifferent, or possibly even good depending on what causes the change: progression of underlying atherosclerosis (potentially bad) versus increased density of calcification indicating a plaque stabilizing response (potentially good)."

Dr. Shah continues. "How to distinguish potential contributors to change in CAC score remains an important and at this time an unanswered question."

"Addition of other variables that incorporate regions of change, change in regional density and other volumetric aspect of CAC change, extracoronary calcification, and epicardial fat volume may improve the value and relevance of change in CAC score," Dr. Shah said. "Further studies are needed to address these issues."

Dr. Joseph Yeboah from Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, who has also researched the association between CAC scores and cardiovascular disease risk, told Reuters Health by email, "This happens to be the first study to show that CAC progression is not informative for CVD risk assessment. At the very best, this study makes the data mixed, which is not surprising given the challenge of using a change in a variable (CAC progression) as a predictor. Some researchers have suggested that CAC density progression instead of CAC score progression may be more appropriate."

"In my opinion, these results will have very little influence on how CAC is used presently for CVD risk assessment," he said. "To my knowledge, there is presently no guideline or recommendation regarding the use of CAC progression for CVD risk assessment. This is because of the inherent challenges in assessing CAC progression and the paucity of data."

"The ACC/AHA guidelines clearly recommend the use of CAC, not CAC progression," Dr. Yeboah concluded. "The take away message here is that physicians should not use CAC progression for CVD risk assessment. More research is needed to fully understand CAC progression."

SOURCE: http://bit.ly/29rOdFM and http://bit.ly/29olMIA

J Am Coll Cardiol Imag 2016.

NEW YORK - Progression of the coronary artery calcification (CAC) score over time predicts the risk of cardiovascular disease, but it performs no better than the most recent CAC score, according to findings from the Cooper Center Longitudinal Study (CCLS).

"I must admit that I expected to find that the change in CAC was going to provide a lot of information about cardiovascular events, and was quite surprised when it didn't add much," Dr. Benjamin D. Levine from Cooper Clinic and University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas told Reuters Health by email. "I was then also surprised when Dr. Andre Paixao, one of our cardiology fellows at the time (now at Emory), suggested that we look at the last CAC score as the best measure for risk attributable to CAC, and he turned out to be right!"

CAC correlates with overall atherosclerotic plaque and predicts incident coronary heart disease (CHD) events, CHD mortality, and total mortality, but only a few studies have evaluated the implications of CAC progression.

Dr. Levine and colleagues used CCLS data from 5,933 participants free of cardiovascular disease (CVD) at baseline to evaluate the relative contributions of baseline CAC score, follow-up CAC score, and CAC progression rates to the risk of incident CVD events.

At baseline, 2,870 (48%) individuals had CAC. These individuals were older, more likely to be on statin therapy, and had higher systolic blood pressure and lower cardiorespiratory fitness, according to the June 29th JACC Cardiovascular Imaging online report.

Individuals with detectable CAC at baseline had significantly higher total CVD event rates than those without detectable CAC (7.70 vs 1.44 per 1,000 person-years, respectively), as well as hard CVD event rates, i.e., CVD death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal atherosclerotic stroke (2.68 vs 1.14 per 1,000 person-years, respectively).

Rates of total CVD and CHD events increased across quartiles of CAC progression, but there was no independent association between CAC progression and CVD outcomes after adjustment for the follow-up CAC score.

"These findings greatly simplify the interpretation of CAC scores over time," Dr. Levine said. "Because it is so difficult to quantify 'change' (a score that goes from 1 to 2 is 100% change, but from 101 to 102 is 1% change), it has been hard for clinicians to wrap their minds around the additional risk information that is contained in follow up scores. Since it is not the calcium we are worried about anyway (calcified plaque generally doesn't rupture - it is the company it keeps that is important), what matters is the overall atherosclerotic burden, as reflected by the absolute CAC score. How fast it changes doesn't matter at all!"

"Don't worry about complicated formulas for quantifying change in CAC," Dr. Levine said. "Just use the latest score to calculate the risk associated with CAC. Now that new calculators are available (and some new ones coming from our work in this space), only the latest CAC score is needed to assess risk."

In an editorial, Dr. Prediman K. Shah from Cedars Sinai Hart Institute in Los Angeles writes, "So change in CAC score may be bad, indifferent, or possibly even good depending on what causes the change: progression of underlying atherosclerosis (potentially bad) versus increased density of calcification indicating a plaque stabilizing response (potentially good)."

Dr. Shah continues. "How to distinguish potential contributors to change in CAC score remains an important and at this time an unanswered question."

"Addition of other variables that incorporate regions of change, change in regional density and other volumetric aspect of CAC change, extracoronary calcification, and epicardial fat volume may improve the value and relevance of change in CAC score," Dr. Shah said. "Further studies are needed to address these issues."

Dr. Joseph Yeboah from Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, who has also researched the association between CAC scores and cardiovascular disease risk, told Reuters Health by email, "This happens to be the first study to show that CAC progression is not informative for CVD risk assessment. At the very best, this study makes the data mixed, which is not surprising given the challenge of using a change in a variable (CAC progression) as a predictor. Some researchers have suggested that CAC density progression instead of CAC score progression may be more appropriate."

"In my opinion, these results will have very little influence on how CAC is used presently for CVD risk assessment," he said. "To my knowledge, there is presently no guideline or recommendation regarding the use of CAC progression for CVD risk assessment. This is because of the inherent challenges in assessing CAC progression and the paucity of data."

"The ACC/AHA guidelines clearly recommend the use of CAC, not CAC progression," Dr. Yeboah concluded. "The take away message here is that physicians should not use CAC progression for CVD risk assessment. More research is needed to fully understand CAC progression."

SOURCE: http://bit.ly/29rOdFM and http://bit.ly/29olMIA

J Am Coll Cardiol Imag 2016.

VIDEO: The Maker Movement and Hospital Medicine

The Maker Movement, the 21st century's upgrade of do-it-yourself that includes 3D printers and "the Internet of Things," is showing up in hospitals in interesting ways. Clinical teams confronted with a nagging issue on the wards can work together to design and prototype physical-product solutions. Two Beth Israel Deaconess hospitalists talk about the Maker Movement, and how they've turned it into a team-based, near real-time collaborative process for addressing quality improvement challenges.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The Maker Movement, the 21st century's upgrade of do-it-yourself that includes 3D printers and "the Internet of Things," is showing up in hospitals in interesting ways. Clinical teams confronted with a nagging issue on the wards can work together to design and prototype physical-product solutions. Two Beth Israel Deaconess hospitalists talk about the Maker Movement, and how they've turned it into a team-based, near real-time collaborative process for addressing quality improvement challenges.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The Maker Movement, the 21st century's upgrade of do-it-yourself that includes 3D printers and "the Internet of Things," is showing up in hospitals in interesting ways. Clinical teams confronted with a nagging issue on the wards can work together to design and prototype physical-product solutions. Two Beth Israel Deaconess hospitalists talk about the Maker Movement, and how they've turned it into a team-based, near real-time collaborative process for addressing quality improvement challenges.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Opioid overdose epidemic now felt in the ICU

SAN FRANCISCO – The opioid overdose crisis in the United States is now plainly evident in intensive care units (ICUs), finds a study of hospitals in 44 states conducted between 2009 and 2015.

During the study period, ICU admissions for opioid overdoses increased by almost half, investigators reported in a session and related press briefing an international conference of the American Thoracic Society. Furthermore, ICU deaths from this cause roughly doubled.

“This means the opioid use epidemic has probably reached a new level of crisis,” said lead investigator Jennifer P. Stevens, MD, an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School, and an adult intensive care physician at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, both in Boston. “And this means that in spite of everything that we can do in the ICU – keeping them alive on ventilators, doing life support, doing acute dialysis, doing round-the-clock care, round-the-clock board-certified intensivist care – we are still not able to make a difference in that mortality.”

Dr. Stevens added that any ICU admission for overdose from opioids is a preventable admission. “So if we have an increase in mortality of this population, we have a number of patients who have preventable deaths in our ICU,” she said.

Efforts to track this epidemic on a national level are important, she said, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been investigating opioid overdoses in some cities, including Boston, as they would any epidemic.

The factors driving the observed trends could not be determined from the study data, Dr. Stevens said. But state-specific patterns that show, for example, higher baseline rates and greater increases over time in ICU admissions for opioid overdose in Massachusetts and Indiana may be a starting point for investigation.

Certain practices in the ICU may also be inadvertently contributing. “I imagine that a patient who comes in with an opioid overdose can cause harm to themselves in a number of ways, and the things that we try to do to help them might cause harm in other ways as well,” she said. “So in an effort to try to maintain them in a safe, ventilated state, we might give them a ton of sedation that then prolongs their time on the ventilator. That’s sort of a simple example of how the two could intersect to have a multiplicative effect of harm.”

The idea for the study arose because ICU staff anecdotally noticed an uptick in admissions for opioid use disorder. “Not only were we seeing more people coming in, but we were seeing sicker people coming in, and with the associated tragedy that comes with a lot of young people coming in with opioid use disorder,” Dr. Stevens said. “We wanted to see if this was happening nationally... We asked, is this epidemic now reaching the most technologically advanced parts of our health care system?”

The investigators studied hospitals providing data to Vizient (formerly the University HealthSystem Consortium) between 2009 and 2015. The included hospitals – about 200 for each study year – were predominantly urban and university affiliated, but representation of community hospitals increased during the study period.

Ultimately, analyses were based on a total of 28.2 million hospital discharges of patients aged 18 years or older, which included 4.9 million ICU admissions.

Results reported at the meeting showed that 27,325 patients were admitted to the study hospitals’ ICUs with opioid overdose during the study period, as ascertained from billing codes.

Opioid overdose was seen in 45 patients per 10,000 ICU admissions in 2009 but rose to 65 patients per 10,000 ICU admissions in 2015, a 46% increase.

Furthermore, ICU deaths due to opioid overdose rose by 87% during the same time period, and mortality among patients admitted to the unit with overdose rose at a pace of 0.5% per month.

“This is somewhat unusual because a lot of times, when we are admitting more people to our ICUs or examining [a trend] further, mortality actually goes down. This is partly because maybe we are doing more for them and we are taking care of them in an aggressive way. But it’s also because we are admitting less sick people because we are more aware of the issue,” Dr. Stevens said. “And we saw the opposite of this – we saw that the mortality was going up.”

The use of billing data was a specific means but not a sensitive means of identifying opioid overdoses, she noted. Therefore, the observed values are likely underestimates of these outcomes.

Addressing the opioid overdose epidemic will require a multifaceted approach, according to Dr. Stevens, who disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

“Folks are doing very impressive work in the community trying to make sure EMTs and other first responders have access to the tools that they need in those settings,” she said. “But one thing we haven’t approached before is the care that we provide in the ICU, and maybe that’s a space that we need to think more prospectively about.”

SAN FRANCISCO – The opioid overdose crisis in the United States is now plainly evident in intensive care units (ICUs), finds a study of hospitals in 44 states conducted between 2009 and 2015.

During the study period, ICU admissions for opioid overdoses increased by almost half, investigators reported in a session and related press briefing an international conference of the American Thoracic Society. Furthermore, ICU deaths from this cause roughly doubled.

“This means the opioid use epidemic has probably reached a new level of crisis,” said lead investigator Jennifer P. Stevens, MD, an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School, and an adult intensive care physician at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, both in Boston. “And this means that in spite of everything that we can do in the ICU – keeping them alive on ventilators, doing life support, doing acute dialysis, doing round-the-clock care, round-the-clock board-certified intensivist care – we are still not able to make a difference in that mortality.”

Dr. Stevens added that any ICU admission for overdose from opioids is a preventable admission. “So if we have an increase in mortality of this population, we have a number of patients who have preventable deaths in our ICU,” she said.

Efforts to track this epidemic on a national level are important, she said, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been investigating opioid overdoses in some cities, including Boston, as they would any epidemic.

The factors driving the observed trends could not be determined from the study data, Dr. Stevens said. But state-specific patterns that show, for example, higher baseline rates and greater increases over time in ICU admissions for opioid overdose in Massachusetts and Indiana may be a starting point for investigation.

Certain practices in the ICU may also be inadvertently contributing. “I imagine that a patient who comes in with an opioid overdose can cause harm to themselves in a number of ways, and the things that we try to do to help them might cause harm in other ways as well,” she said. “So in an effort to try to maintain them in a safe, ventilated state, we might give them a ton of sedation that then prolongs their time on the ventilator. That’s sort of a simple example of how the two could intersect to have a multiplicative effect of harm.”

The idea for the study arose because ICU staff anecdotally noticed an uptick in admissions for opioid use disorder. “Not only were we seeing more people coming in, but we were seeing sicker people coming in, and with the associated tragedy that comes with a lot of young people coming in with opioid use disorder,” Dr. Stevens said. “We wanted to see if this was happening nationally... We asked, is this epidemic now reaching the most technologically advanced parts of our health care system?”

The investigators studied hospitals providing data to Vizient (formerly the University HealthSystem Consortium) between 2009 and 2015. The included hospitals – about 200 for each study year – were predominantly urban and university affiliated, but representation of community hospitals increased during the study period.

Ultimately, analyses were based on a total of 28.2 million hospital discharges of patients aged 18 years or older, which included 4.9 million ICU admissions.

Results reported at the meeting showed that 27,325 patients were admitted to the study hospitals’ ICUs with opioid overdose during the study period, as ascertained from billing codes.

Opioid overdose was seen in 45 patients per 10,000 ICU admissions in 2009 but rose to 65 patients per 10,000 ICU admissions in 2015, a 46% increase.

Furthermore, ICU deaths due to opioid overdose rose by 87% during the same time period, and mortality among patients admitted to the unit with overdose rose at a pace of 0.5% per month.

“This is somewhat unusual because a lot of times, when we are admitting more people to our ICUs or examining [a trend] further, mortality actually goes down. This is partly because maybe we are doing more for them and we are taking care of them in an aggressive way. But it’s also because we are admitting less sick people because we are more aware of the issue,” Dr. Stevens said. “And we saw the opposite of this – we saw that the mortality was going up.”

The use of billing data was a specific means but not a sensitive means of identifying opioid overdoses, she noted. Therefore, the observed values are likely underestimates of these outcomes.

Addressing the opioid overdose epidemic will require a multifaceted approach, according to Dr. Stevens, who disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

“Folks are doing very impressive work in the community trying to make sure EMTs and other first responders have access to the tools that they need in those settings,” she said. “But one thing we haven’t approached before is the care that we provide in the ICU, and maybe that’s a space that we need to think more prospectively about.”

SAN FRANCISCO – The opioid overdose crisis in the United States is now plainly evident in intensive care units (ICUs), finds a study of hospitals in 44 states conducted between 2009 and 2015.

During the study period, ICU admissions for opioid overdoses increased by almost half, investigators reported in a session and related press briefing an international conference of the American Thoracic Society. Furthermore, ICU deaths from this cause roughly doubled.

“This means the opioid use epidemic has probably reached a new level of crisis,” said lead investigator Jennifer P. Stevens, MD, an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School, and an adult intensive care physician at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, both in Boston. “And this means that in spite of everything that we can do in the ICU – keeping them alive on ventilators, doing life support, doing acute dialysis, doing round-the-clock care, round-the-clock board-certified intensivist care – we are still not able to make a difference in that mortality.”

Dr. Stevens added that any ICU admission for overdose from opioids is a preventable admission. “So if we have an increase in mortality of this population, we have a number of patients who have preventable deaths in our ICU,” she said.

Efforts to track this epidemic on a national level are important, she said, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been investigating opioid overdoses in some cities, including Boston, as they would any epidemic.

The factors driving the observed trends could not be determined from the study data, Dr. Stevens said. But state-specific patterns that show, for example, higher baseline rates and greater increases over time in ICU admissions for opioid overdose in Massachusetts and Indiana may be a starting point for investigation.

Certain practices in the ICU may also be inadvertently contributing. “I imagine that a patient who comes in with an opioid overdose can cause harm to themselves in a number of ways, and the things that we try to do to help them might cause harm in other ways as well,” she said. “So in an effort to try to maintain them in a safe, ventilated state, we might give them a ton of sedation that then prolongs their time on the ventilator. That’s sort of a simple example of how the two could intersect to have a multiplicative effect of harm.”

The idea for the study arose because ICU staff anecdotally noticed an uptick in admissions for opioid use disorder. “Not only were we seeing more people coming in, but we were seeing sicker people coming in, and with the associated tragedy that comes with a lot of young people coming in with opioid use disorder,” Dr. Stevens said. “We wanted to see if this was happening nationally... We asked, is this epidemic now reaching the most technologically advanced parts of our health care system?”

The investigators studied hospitals providing data to Vizient (formerly the University HealthSystem Consortium) between 2009 and 2015. The included hospitals – about 200 for each study year – were predominantly urban and university affiliated, but representation of community hospitals increased during the study period.

Ultimately, analyses were based on a total of 28.2 million hospital discharges of patients aged 18 years or older, which included 4.9 million ICU admissions.

Results reported at the meeting showed that 27,325 patients were admitted to the study hospitals’ ICUs with opioid overdose during the study period, as ascertained from billing codes.

Opioid overdose was seen in 45 patients per 10,000 ICU admissions in 2009 but rose to 65 patients per 10,000 ICU admissions in 2015, a 46% increase.

Furthermore, ICU deaths due to opioid overdose rose by 87% during the same time period, and mortality among patients admitted to the unit with overdose rose at a pace of 0.5% per month.

“This is somewhat unusual because a lot of times, when we are admitting more people to our ICUs or examining [a trend] further, mortality actually goes down. This is partly because maybe we are doing more for them and we are taking care of them in an aggressive way. But it’s also because we are admitting less sick people because we are more aware of the issue,” Dr. Stevens said. “And we saw the opposite of this – we saw that the mortality was going up.”

The use of billing data was a specific means but not a sensitive means of identifying opioid overdoses, she noted. Therefore, the observed values are likely underestimates of these outcomes.

Addressing the opioid overdose epidemic will require a multifaceted approach, according to Dr. Stevens, who disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

“Folks are doing very impressive work in the community trying to make sure EMTs and other first responders have access to the tools that they need in those settings,” she said. “But one thing we haven’t approached before is the care that we provide in the ICU, and maybe that’s a space that we need to think more prospectively about.”

AT ATS 2016

Key clinical point: Opioid-related ICU admissions and mortality have risen sharply in recent years.

Major finding: ICU admissions for opioid overdose increased by 46%, and ICU deaths from this cause increased by 87%.

Data source: A cohort study of 28.2 million U.S. hospital discharges and 4.9 million ICU admissions between 2009 and 2015.

Disclosures: Dr. Stevens disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

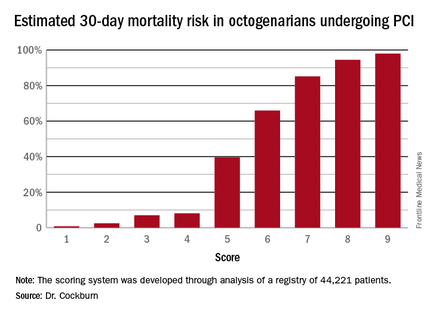

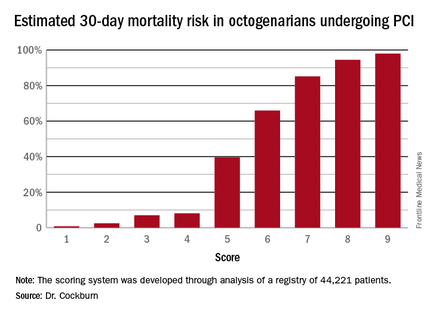

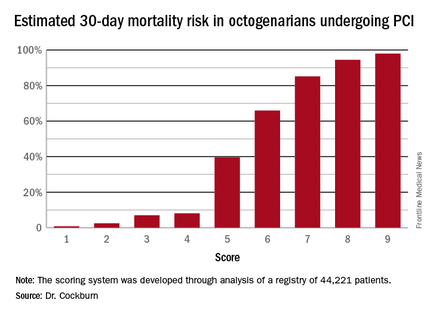

New risk score predicts PCI outcomes in octogenarians