User login

Interhospital Transfer Handoff Practice Variance at U.S. Tertiary Care Centers

Clinical question: How do interhospital handoff practices differ among U.S. tertiary care centers, and what challenges and innovations have providers encountered?

Background: Little has been studied regarding interhospital transfers. Many centers differ in the processes they follow, and well-delineated national guidelines are lacking. Adverse events occur in up to 30% of transfers. Standardization of these handoffs has been shown to reduce preventable errors and near misses.

Study design: Survey of convenience sample of institutions.

Setting: Transfer center directors from 32 tertiary care centers in the U.S.

Synopsis: The authors surveyed directors of 32 transfer centers between 2013 and 2015. Hospitals were selected from a nationally ranked list as well as those comparable to the authors’ own institutions. The median number of patients transferred per month was 700.

Only 23% of hospitals surveyed identified significant EHR interoperability. Almost all required three-way recorded discussion between transfer center staff and referring and accepting physicians. Only 29% had available objective clinical information to share. Only 23% recorded a three-way nursing handoff, and only 32% used their EHR to document the transfer process and share clinical information among providers.

Innovations included electronic transfer notes, a standardized system of feedback to referring hospitals, automatic internal review for adverse events and delayed transfers, and use of a scorecard with key measures shared with stakeholders.

Barriers noted included complexity, acuity, and lack of continuity. Increased use of EHRs, checklists, and common processes were identified as best practices.

Limitations of the study included reliance on verbal qualitative data, a single investigator doing most of the discussions, and possible sampling bias.

Bottom line: Interhospital transfer practices at academic tertiary care centers vary widely, and optimizing and aligning practices between sending and receiving hospitals may improve efficiency and patient outcomes.

References: Herrigel DJ, Carroll M, Fanning C, Steinberg MB, Parikh A, Usher M. Interhospital transfer handoff practices among US tertiary care centers: a descriptive survey. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(6):413-417.

Clinical question: How do interhospital handoff practices differ among U.S. tertiary care centers, and what challenges and innovations have providers encountered?

Background: Little has been studied regarding interhospital transfers. Many centers differ in the processes they follow, and well-delineated national guidelines are lacking. Adverse events occur in up to 30% of transfers. Standardization of these handoffs has been shown to reduce preventable errors and near misses.

Study design: Survey of convenience sample of institutions.

Setting: Transfer center directors from 32 tertiary care centers in the U.S.

Synopsis: The authors surveyed directors of 32 transfer centers between 2013 and 2015. Hospitals were selected from a nationally ranked list as well as those comparable to the authors’ own institutions. The median number of patients transferred per month was 700.

Only 23% of hospitals surveyed identified significant EHR interoperability. Almost all required three-way recorded discussion between transfer center staff and referring and accepting physicians. Only 29% had available objective clinical information to share. Only 23% recorded a three-way nursing handoff, and only 32% used their EHR to document the transfer process and share clinical information among providers.

Innovations included electronic transfer notes, a standardized system of feedback to referring hospitals, automatic internal review for adverse events and delayed transfers, and use of a scorecard with key measures shared with stakeholders.

Barriers noted included complexity, acuity, and lack of continuity. Increased use of EHRs, checklists, and common processes were identified as best practices.

Limitations of the study included reliance on verbal qualitative data, a single investigator doing most of the discussions, and possible sampling bias.

Bottom line: Interhospital transfer practices at academic tertiary care centers vary widely, and optimizing and aligning practices between sending and receiving hospitals may improve efficiency and patient outcomes.

References: Herrigel DJ, Carroll M, Fanning C, Steinberg MB, Parikh A, Usher M. Interhospital transfer handoff practices among US tertiary care centers: a descriptive survey. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(6):413-417.

Clinical question: How do interhospital handoff practices differ among U.S. tertiary care centers, and what challenges and innovations have providers encountered?

Background: Little has been studied regarding interhospital transfers. Many centers differ in the processes they follow, and well-delineated national guidelines are lacking. Adverse events occur in up to 30% of transfers. Standardization of these handoffs has been shown to reduce preventable errors and near misses.

Study design: Survey of convenience sample of institutions.

Setting: Transfer center directors from 32 tertiary care centers in the U.S.

Synopsis: The authors surveyed directors of 32 transfer centers between 2013 and 2015. Hospitals were selected from a nationally ranked list as well as those comparable to the authors’ own institutions. The median number of patients transferred per month was 700.

Only 23% of hospitals surveyed identified significant EHR interoperability. Almost all required three-way recorded discussion between transfer center staff and referring and accepting physicians. Only 29% had available objective clinical information to share. Only 23% recorded a three-way nursing handoff, and only 32% used their EHR to document the transfer process and share clinical information among providers.

Innovations included electronic transfer notes, a standardized system of feedback to referring hospitals, automatic internal review for adverse events and delayed transfers, and use of a scorecard with key measures shared with stakeholders.

Barriers noted included complexity, acuity, and lack of continuity. Increased use of EHRs, checklists, and common processes were identified as best practices.

Limitations of the study included reliance on verbal qualitative data, a single investigator doing most of the discussions, and possible sampling bias.

Bottom line: Interhospital transfer practices at academic tertiary care centers vary widely, and optimizing and aligning practices between sending and receiving hospitals may improve efficiency and patient outcomes.

References: Herrigel DJ, Carroll M, Fanning C, Steinberg MB, Parikh A, Usher M. Interhospital transfer handoff practices among US tertiary care centers: a descriptive survey. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(6):413-417.

Oral Steroids as Good as NSAIDs for Acute Gout

Clinical question: Are oral steroids as effective as NSAIDs in treating acute gout?

Background: Two small trials have suggested that oral steroids are as effective as NSAIDs in treating acute gout. Wider acceptance of steroids as first-line agents for acute gout may require more robust evidence supporting their safety and efficacy.

Study design: Multicenter, double-blind, randomized equivalence trial.

Setting: Four EDs in Hong Kong.

Synopsis: The study included 416 patients presenting to the ED with clinically suspected acute gout who were randomized to treatment with either oral indomethacin or oral prednisolone for five days. A research investigator assessed response to therapy in the ED at 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes after administration of the initial dose of medication. Patients then kept pain-assessment diaries for 14 days after discharge from the ED.

Pain scores were assessed using a visual analog scale of 0 mm (no pain) to 100 mm (worst pain the patient had experienced). Clinically significant changes in pain scores were defined as decreases of >13 mm on the visual analog scale.

The number of patients with clinically significant decreases in pain scores did not differ statistically between groups. Both groups had similar reductions in mean pain scores over the course of the study. Patients in the indomethacin group had a statistically significant increase in minor adverse events. No patients in either group had major adverse events.

Bottom line: Oral prednisolone appears to be a safe and effective first-line agent for the treatment of acute gout.

Citation: Rainer TH, Chen CH, Janssens HJEM, et al. Oral prednisolone in the treatment of acute gout. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(7):464-471.

Short Take

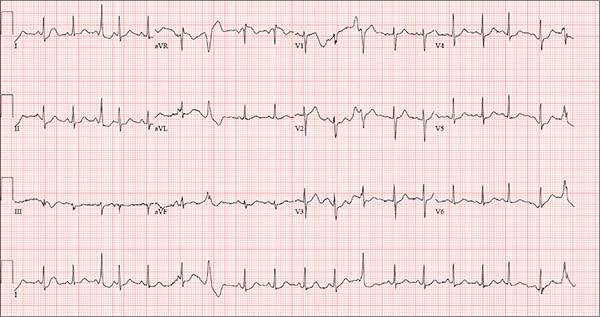

Rate Control as Effective as Rhythm Control in Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation

This study randomized patients with postoperative atrial fibrillation to rhythm control (using amiodarone and/or direct current cardioversion) or rate control and found neither treatment strategy has a clinical benefit over the other.

Citation: Gillinov AM, Bagiella E, Moskowitz AJ, et al. Rate control versus rhythm control for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(20):1911-1921.

Clinical question: Are oral steroids as effective as NSAIDs in treating acute gout?

Background: Two small trials have suggested that oral steroids are as effective as NSAIDs in treating acute gout. Wider acceptance of steroids as first-line agents for acute gout may require more robust evidence supporting their safety and efficacy.

Study design: Multicenter, double-blind, randomized equivalence trial.

Setting: Four EDs in Hong Kong.

Synopsis: The study included 416 patients presenting to the ED with clinically suspected acute gout who were randomized to treatment with either oral indomethacin or oral prednisolone for five days. A research investigator assessed response to therapy in the ED at 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes after administration of the initial dose of medication. Patients then kept pain-assessment diaries for 14 days after discharge from the ED.

Pain scores were assessed using a visual analog scale of 0 mm (no pain) to 100 mm (worst pain the patient had experienced). Clinically significant changes in pain scores were defined as decreases of >13 mm on the visual analog scale.

The number of patients with clinically significant decreases in pain scores did not differ statistically between groups. Both groups had similar reductions in mean pain scores over the course of the study. Patients in the indomethacin group had a statistically significant increase in minor adverse events. No patients in either group had major adverse events.

Bottom line: Oral prednisolone appears to be a safe and effective first-line agent for the treatment of acute gout.

Citation: Rainer TH, Chen CH, Janssens HJEM, et al. Oral prednisolone in the treatment of acute gout. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(7):464-471.

Short Take

Rate Control as Effective as Rhythm Control in Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation

This study randomized patients with postoperative atrial fibrillation to rhythm control (using amiodarone and/or direct current cardioversion) or rate control and found neither treatment strategy has a clinical benefit over the other.

Citation: Gillinov AM, Bagiella E, Moskowitz AJ, et al. Rate control versus rhythm control for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(20):1911-1921.

Clinical question: Are oral steroids as effective as NSAIDs in treating acute gout?

Background: Two small trials have suggested that oral steroids are as effective as NSAIDs in treating acute gout. Wider acceptance of steroids as first-line agents for acute gout may require more robust evidence supporting their safety and efficacy.

Study design: Multicenter, double-blind, randomized equivalence trial.

Setting: Four EDs in Hong Kong.

Synopsis: The study included 416 patients presenting to the ED with clinically suspected acute gout who were randomized to treatment with either oral indomethacin or oral prednisolone for five days. A research investigator assessed response to therapy in the ED at 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes after administration of the initial dose of medication. Patients then kept pain-assessment diaries for 14 days after discharge from the ED.

Pain scores were assessed using a visual analog scale of 0 mm (no pain) to 100 mm (worst pain the patient had experienced). Clinically significant changes in pain scores were defined as decreases of >13 mm on the visual analog scale.

The number of patients with clinically significant decreases in pain scores did not differ statistically between groups. Both groups had similar reductions in mean pain scores over the course of the study. Patients in the indomethacin group had a statistically significant increase in minor adverse events. No patients in either group had major adverse events.

Bottom line: Oral prednisolone appears to be a safe and effective first-line agent for the treatment of acute gout.

Citation: Rainer TH, Chen CH, Janssens HJEM, et al. Oral prednisolone in the treatment of acute gout. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(7):464-471.

Short Take

Rate Control as Effective as Rhythm Control in Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation

This study randomized patients with postoperative atrial fibrillation to rhythm control (using amiodarone and/or direct current cardioversion) or rate control and found neither treatment strategy has a clinical benefit over the other.

Citation: Gillinov AM, Bagiella E, Moskowitz AJ, et al. Rate control versus rhythm control for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(20):1911-1921.

Drug enables transfusion independence in lower-risk MDS

COPENHAGEN—Results from a pair of phase 2 trials suggest luspatercept can produce erythroid responses and enable transfusion independence in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

In a 3-month base study, 51% of patients treated with luspatercept had an erythroid response, and 35% achieved transfusion independence.

In an ongoing extension study, 81% of luspatercept-treated patients have had an erythroid response, and 50% have achieved transfusion independence.

The majority of adverse events in both trials were grade 1 and 2.

Uwe Platzbecker, MD, of the University Hospital in Dresden, Germany, presented these results at the 21st Congress of the European Hematology Association (abstract S131*). The studies were sponsored by Acceleron Pharma, Inc.

Luspatercept (formerly ACE-536) is a modified activin receptor type IIB fusion protein that increases red blood cell (RBC) levels by targeting molecules in the TGF-β superfamily. Acceleron and Celgene are developing luspatercept to treat anemia in patients with rare blood disorders.

The phase 2 base study was a dose-escalation trial in which MDS patients received luspatercept for 3 months. In the ongoing extension study, patients from the base study are receiving luspatercept for an additional 24 months.

In both studies, patients with high transfusion burden (≥4 RBC units/8 weeks) and those with low transfusion burden (<4 RBC units/8 weeks) received luspatercept once every 3 weeks.

Base study

This study included 58 patients with a median age of 71.5 (range, 27-90). Their median time since diagnosis was 2.4 years (range, 0-14). Seventeen percent of patients had prior lenalidomide treatment, and 66% had previously received erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs).

In patients with low transfusion burden (n=19), the median hemoglobin at baseline was 8.7 g/dL (range, 6.4-10.1). In patients with high transfusion burden (n=39), the median number of RBC units transfused per 8 weeks was 6 (range, 4-18).

Patients received luspatercept subcutaneously every 3 weeks for up to 5 doses. The study included 7 dose-escalation cohorts (n=27, 0.125 to 1.75 mg/kg) and an expansion cohort (n=31, 1.0 to 1.75 mg/kg).

The primary outcome measure was the proportion of patients who had an erythroid response. In non-transfusion-dependent patients, an erythroid response was defined as a hemoglobin increase of at least 1.5 g/dL from baseline for at least 14 days.

In transfusion-dependent patients, an erythroid response was defined as a reduction of at least 4 RBC units transfused or a reduction of at least 50% of RBC units transfused compared to pretreatment.

Fifty-one percent (25/49) of patients treated at the higher dose levels had an erythroid response. And 35% (14/40) of transfused patients treated at the higher dose levels were transfusion independent for at least 8 weeks.

Extension study

This study includes 32 patients with a median age of 71.5 (range, 29-90). Their median time since diagnosis was 2.9 years (range, 0-14). Nineteen percent of patients had prior lenalidomide treatment, and 59% had previously received ESAs.

In patients with low transfusion burden (n=13), the median hemoglobin at baseline was 8.5 g/dL (range, 6.4-10.1). In patients with high transfusion burden (n=19), the median number of RBC units transfused per 8 weeks was 6 (range, 4-14).

In this ongoing study, patients are receiving luspatercept (1.0 to 1.75 mg/kg) subcutaneously every 3 weeks for an additional 24 months.

At last follow-up (March 4, 2016), 81% (26/32) of patients had an erythroid response. And 50% (11/22) of patients who were transfused prior to study initiation achieved transfusion independence for at least 8 weeks (range, 9-80+ weeks).

Dr Platzbecker noted that, in both studies, erythroid responses were observed whether or not patients previously received ESAs and regardless of patients’ baseline erythropoietin levels.

Safety

There were three grade 3 adverse events that were possibly or probably related to luspatercept—an increase in blast cell count, myalgia, and worsening of general condition.

Adverse events that were possibly or probably related to luspatercept and occurred in at least 2 patients were fatigue (7%, n=4), bone pain (5%, n=3), diarrhea (5%, n=3), myalgia (5%, n=3), headache (3%, n=2), hypertension (3%, n=2), and injection site erythema (3%, n=2).

Dr Platzbecker said luspatercept was generally safe and well-tolerated in these studies. And the results of these trials supported the initiation of a phase 3 study (MEDALIST, NCT02631070) in patients with lower-risk MDS. ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ from data presented at the meeting.

COPENHAGEN—Results from a pair of phase 2 trials suggest luspatercept can produce erythroid responses and enable transfusion independence in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

In a 3-month base study, 51% of patients treated with luspatercept had an erythroid response, and 35% achieved transfusion independence.

In an ongoing extension study, 81% of luspatercept-treated patients have had an erythroid response, and 50% have achieved transfusion independence.

The majority of adverse events in both trials were grade 1 and 2.

Uwe Platzbecker, MD, of the University Hospital in Dresden, Germany, presented these results at the 21st Congress of the European Hematology Association (abstract S131*). The studies were sponsored by Acceleron Pharma, Inc.

Luspatercept (formerly ACE-536) is a modified activin receptor type IIB fusion protein that increases red blood cell (RBC) levels by targeting molecules in the TGF-β superfamily. Acceleron and Celgene are developing luspatercept to treat anemia in patients with rare blood disorders.

The phase 2 base study was a dose-escalation trial in which MDS patients received luspatercept for 3 months. In the ongoing extension study, patients from the base study are receiving luspatercept for an additional 24 months.

In both studies, patients with high transfusion burden (≥4 RBC units/8 weeks) and those with low transfusion burden (<4 RBC units/8 weeks) received luspatercept once every 3 weeks.

Base study

This study included 58 patients with a median age of 71.5 (range, 27-90). Their median time since diagnosis was 2.4 years (range, 0-14). Seventeen percent of patients had prior lenalidomide treatment, and 66% had previously received erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs).

In patients with low transfusion burden (n=19), the median hemoglobin at baseline was 8.7 g/dL (range, 6.4-10.1). In patients with high transfusion burden (n=39), the median number of RBC units transfused per 8 weeks was 6 (range, 4-18).

Patients received luspatercept subcutaneously every 3 weeks for up to 5 doses. The study included 7 dose-escalation cohorts (n=27, 0.125 to 1.75 mg/kg) and an expansion cohort (n=31, 1.0 to 1.75 mg/kg).

The primary outcome measure was the proportion of patients who had an erythroid response. In non-transfusion-dependent patients, an erythroid response was defined as a hemoglobin increase of at least 1.5 g/dL from baseline for at least 14 days.

In transfusion-dependent patients, an erythroid response was defined as a reduction of at least 4 RBC units transfused or a reduction of at least 50% of RBC units transfused compared to pretreatment.

Fifty-one percent (25/49) of patients treated at the higher dose levels had an erythroid response. And 35% (14/40) of transfused patients treated at the higher dose levels were transfusion independent for at least 8 weeks.

Extension study

This study includes 32 patients with a median age of 71.5 (range, 29-90). Their median time since diagnosis was 2.9 years (range, 0-14). Nineteen percent of patients had prior lenalidomide treatment, and 59% had previously received ESAs.

In patients with low transfusion burden (n=13), the median hemoglobin at baseline was 8.5 g/dL (range, 6.4-10.1). In patients with high transfusion burden (n=19), the median number of RBC units transfused per 8 weeks was 6 (range, 4-14).

In this ongoing study, patients are receiving luspatercept (1.0 to 1.75 mg/kg) subcutaneously every 3 weeks for an additional 24 months.

At last follow-up (March 4, 2016), 81% (26/32) of patients had an erythroid response. And 50% (11/22) of patients who were transfused prior to study initiation achieved transfusion independence for at least 8 weeks (range, 9-80+ weeks).

Dr Platzbecker noted that, in both studies, erythroid responses were observed whether or not patients previously received ESAs and regardless of patients’ baseline erythropoietin levels.

Safety

There were three grade 3 adverse events that were possibly or probably related to luspatercept—an increase in blast cell count, myalgia, and worsening of general condition.

Adverse events that were possibly or probably related to luspatercept and occurred in at least 2 patients were fatigue (7%, n=4), bone pain (5%, n=3), diarrhea (5%, n=3), myalgia (5%, n=3), headache (3%, n=2), hypertension (3%, n=2), and injection site erythema (3%, n=2).

Dr Platzbecker said luspatercept was generally safe and well-tolerated in these studies. And the results of these trials supported the initiation of a phase 3 study (MEDALIST, NCT02631070) in patients with lower-risk MDS. ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ from data presented at the meeting.

COPENHAGEN—Results from a pair of phase 2 trials suggest luspatercept can produce erythroid responses and enable transfusion independence in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

In a 3-month base study, 51% of patients treated with luspatercept had an erythroid response, and 35% achieved transfusion independence.

In an ongoing extension study, 81% of luspatercept-treated patients have had an erythroid response, and 50% have achieved transfusion independence.

The majority of adverse events in both trials were grade 1 and 2.

Uwe Platzbecker, MD, of the University Hospital in Dresden, Germany, presented these results at the 21st Congress of the European Hematology Association (abstract S131*). The studies were sponsored by Acceleron Pharma, Inc.

Luspatercept (formerly ACE-536) is a modified activin receptor type IIB fusion protein that increases red blood cell (RBC) levels by targeting molecules in the TGF-β superfamily. Acceleron and Celgene are developing luspatercept to treat anemia in patients with rare blood disorders.

The phase 2 base study was a dose-escalation trial in which MDS patients received luspatercept for 3 months. In the ongoing extension study, patients from the base study are receiving luspatercept for an additional 24 months.

In both studies, patients with high transfusion burden (≥4 RBC units/8 weeks) and those with low transfusion burden (<4 RBC units/8 weeks) received luspatercept once every 3 weeks.

Base study

This study included 58 patients with a median age of 71.5 (range, 27-90). Their median time since diagnosis was 2.4 years (range, 0-14). Seventeen percent of patients had prior lenalidomide treatment, and 66% had previously received erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs).

In patients with low transfusion burden (n=19), the median hemoglobin at baseline was 8.7 g/dL (range, 6.4-10.1). In patients with high transfusion burden (n=39), the median number of RBC units transfused per 8 weeks was 6 (range, 4-18).

Patients received luspatercept subcutaneously every 3 weeks for up to 5 doses. The study included 7 dose-escalation cohorts (n=27, 0.125 to 1.75 mg/kg) and an expansion cohort (n=31, 1.0 to 1.75 mg/kg).

The primary outcome measure was the proportion of patients who had an erythroid response. In non-transfusion-dependent patients, an erythroid response was defined as a hemoglobin increase of at least 1.5 g/dL from baseline for at least 14 days.

In transfusion-dependent patients, an erythroid response was defined as a reduction of at least 4 RBC units transfused or a reduction of at least 50% of RBC units transfused compared to pretreatment.

Fifty-one percent (25/49) of patients treated at the higher dose levels had an erythroid response. And 35% (14/40) of transfused patients treated at the higher dose levels were transfusion independent for at least 8 weeks.

Extension study

This study includes 32 patients with a median age of 71.5 (range, 29-90). Their median time since diagnosis was 2.9 years (range, 0-14). Nineteen percent of patients had prior lenalidomide treatment, and 59% had previously received ESAs.

In patients with low transfusion burden (n=13), the median hemoglobin at baseline was 8.5 g/dL (range, 6.4-10.1). In patients with high transfusion burden (n=19), the median number of RBC units transfused per 8 weeks was 6 (range, 4-14).

In this ongoing study, patients are receiving luspatercept (1.0 to 1.75 mg/kg) subcutaneously every 3 weeks for an additional 24 months.

At last follow-up (March 4, 2016), 81% (26/32) of patients had an erythroid response. And 50% (11/22) of patients who were transfused prior to study initiation achieved transfusion independence for at least 8 weeks (range, 9-80+ weeks).

Dr Platzbecker noted that, in both studies, erythroid responses were observed whether or not patients previously received ESAs and regardless of patients’ baseline erythropoietin levels.

Safety

There were three grade 3 adverse events that were possibly or probably related to luspatercept—an increase in blast cell count, myalgia, and worsening of general condition.

Adverse events that were possibly or probably related to luspatercept and occurred in at least 2 patients were fatigue (7%, n=4), bone pain (5%, n=3), diarrhea (5%, n=3), myalgia (5%, n=3), headache (3%, n=2), hypertension (3%, n=2), and injection site erythema (3%, n=2).

Dr Platzbecker said luspatercept was generally safe and well-tolerated in these studies. And the results of these trials supported the initiation of a phase 3 study (MEDALIST, NCT02631070) in patients with lower-risk MDS. ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ from data presented at the meeting.

Team describes method of targeting LSCs in BC-CML

Photo courtesy of

UC San Diego Health

New research has revealed a method of targeting leukemia stem cells (LSCs) in blast crisis chronic myeloid leukemia (BC-CML).

For this study, investigators used human cells and mouse models to define the role of ADAR1, an RNA editing enzyme, in BC-CML.

The team discovered how ADAR1 promotes LSC generation and identified a small molecule that can disrupt this process to fight BC-CML.

Catriona Jamieson, MD, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, and her colleagues described this work in Cell Stem Cell.

“In this study, we showed that cancer stem cells co-opt an RNA editing system to clone themselves,” Dr Jamieson said. “What’s more, we found a method to dial it down.”

The investigators knew that ADAR1 can edit the sequence of microRNAs. By swapping out just one microRNA building block for another, ADAR1 alters the carefully orchestrated system cells use to control which genes are turned on or off at which times.

ADAR1 is also known to promote cancer progression and resistance to therapy. But Dr Jamieson’s team wanted to determine ADAR1’s role in governing LSCs.

The investigators conducted experiments with human BC-CML cells and mouse models of BC-CML. And they found that increased JAK2 signaling and BCR-ABL1 amplification activate ADAR1 in BC-CML cells. Then, hyper-ADAR1 editing slows down microRNAs known as let-7.

Ultimately, this activity increases cellular regeneration, turning white blood cell precursors into LSCs. And LSCs promote BC-CML.

After learning how the ADAR1 system works, Dr Jamieson and her colleagues looked for a way to stop it.

By inhibiting ADAR1 with a small-molecule compound known as 8-Aza, the investigators were able to counter ADAR1’s effect on LSC self-renewal and restore let-7.

Treatment with 8-Aza reduced self-renewal of BC-CML cells by approximately 40%, when compared to untreated cells.

“Based on this research, we believe that detecting ADAR1 activity will be important for predicting cancer progression,” Dr Jamieson said.

“In addition, inhibiting this enzyme represents a unique therapeutic vulnerability in cancer stem cells with active inflammatory signaling that may respond to pharmacologic inhibitors of inflammation sensitivity or selective ADAR1 inhibitors that are currently being developed.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of

UC San Diego Health

New research has revealed a method of targeting leukemia stem cells (LSCs) in blast crisis chronic myeloid leukemia (BC-CML).

For this study, investigators used human cells and mouse models to define the role of ADAR1, an RNA editing enzyme, in BC-CML.

The team discovered how ADAR1 promotes LSC generation and identified a small molecule that can disrupt this process to fight BC-CML.

Catriona Jamieson, MD, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, and her colleagues described this work in Cell Stem Cell.

“In this study, we showed that cancer stem cells co-opt an RNA editing system to clone themselves,” Dr Jamieson said. “What’s more, we found a method to dial it down.”

The investigators knew that ADAR1 can edit the sequence of microRNAs. By swapping out just one microRNA building block for another, ADAR1 alters the carefully orchestrated system cells use to control which genes are turned on or off at which times.

ADAR1 is also known to promote cancer progression and resistance to therapy. But Dr Jamieson’s team wanted to determine ADAR1’s role in governing LSCs.

The investigators conducted experiments with human BC-CML cells and mouse models of BC-CML. And they found that increased JAK2 signaling and BCR-ABL1 amplification activate ADAR1 in BC-CML cells. Then, hyper-ADAR1 editing slows down microRNAs known as let-7.

Ultimately, this activity increases cellular regeneration, turning white blood cell precursors into LSCs. And LSCs promote BC-CML.

After learning how the ADAR1 system works, Dr Jamieson and her colleagues looked for a way to stop it.

By inhibiting ADAR1 with a small-molecule compound known as 8-Aza, the investigators were able to counter ADAR1’s effect on LSC self-renewal and restore let-7.

Treatment with 8-Aza reduced self-renewal of BC-CML cells by approximately 40%, when compared to untreated cells.

“Based on this research, we believe that detecting ADAR1 activity will be important for predicting cancer progression,” Dr Jamieson said.

“In addition, inhibiting this enzyme represents a unique therapeutic vulnerability in cancer stem cells with active inflammatory signaling that may respond to pharmacologic inhibitors of inflammation sensitivity or selective ADAR1 inhibitors that are currently being developed.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of

UC San Diego Health

New research has revealed a method of targeting leukemia stem cells (LSCs) in blast crisis chronic myeloid leukemia (BC-CML).

For this study, investigators used human cells and mouse models to define the role of ADAR1, an RNA editing enzyme, in BC-CML.

The team discovered how ADAR1 promotes LSC generation and identified a small molecule that can disrupt this process to fight BC-CML.

Catriona Jamieson, MD, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, and her colleagues described this work in Cell Stem Cell.

“In this study, we showed that cancer stem cells co-opt an RNA editing system to clone themselves,” Dr Jamieson said. “What’s more, we found a method to dial it down.”

The investigators knew that ADAR1 can edit the sequence of microRNAs. By swapping out just one microRNA building block for another, ADAR1 alters the carefully orchestrated system cells use to control which genes are turned on or off at which times.

ADAR1 is also known to promote cancer progression and resistance to therapy. But Dr Jamieson’s team wanted to determine ADAR1’s role in governing LSCs.

The investigators conducted experiments with human BC-CML cells and mouse models of BC-CML. And they found that increased JAK2 signaling and BCR-ABL1 amplification activate ADAR1 in BC-CML cells. Then, hyper-ADAR1 editing slows down microRNAs known as let-7.

Ultimately, this activity increases cellular regeneration, turning white blood cell precursors into LSCs. And LSCs promote BC-CML.

After learning how the ADAR1 system works, Dr Jamieson and her colleagues looked for a way to stop it.

By inhibiting ADAR1 with a small-molecule compound known as 8-Aza, the investigators were able to counter ADAR1’s effect on LSC self-renewal and restore let-7.

Treatment with 8-Aza reduced self-renewal of BC-CML cells by approximately 40%, when compared to untreated cells.

“Based on this research, we believe that detecting ADAR1 activity will be important for predicting cancer progression,” Dr Jamieson said.

“In addition, inhibiting this enzyme represents a unique therapeutic vulnerability in cancer stem cells with active inflammatory signaling that may respond to pharmacologic inhibitors of inflammation sensitivity or selective ADAR1 inhibitors that are currently being developed.” ![]()

FDA grants drug breakthrough designation to treat GVHD

Photo from Business Wire

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted breakthrough therapy designation for ruxolitinib (Jakafi) for the treatment of patients with acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

Ruxolitinib is a JAK1/2 inhibitor that is already FDA-approved to treat patients with polycythemia vera who have had an inadequate response to or are intolerant of hydroxyurea.

The drug is also approved to treat patients with intermediate or high-risk myelofibrosis (MF), including primary MF, post-polycythemia vera MF, and post-essential thrombocythemia MF.

Ruxolitinib is marketed as Jakafi by Incyte in the US and as Jakavi by Novartis outside the US.

“Receiving breakthrough therapy designation from the FDA recognizes the severe nature of acute GVHD, the clear unmet medical need of these patients, and the potential, based on clinical evidence to date, for ruxolitinib to address the urgent needs of patients with this life-threatening disease,” said Steven Stein, MD, Incyte’s chief medical officer.

The FDA’s breakthrough therapy designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new therapies for serious or life-threatening conditions.

To earn the designation, a treatment must show encouraging early clinical results demonstrating substantial improvement over available therapies with regard to a clinically significant endpoint, or it must fulfill an unmet need. ![]()

Photo from Business Wire

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted breakthrough therapy designation for ruxolitinib (Jakafi) for the treatment of patients with acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

Ruxolitinib is a JAK1/2 inhibitor that is already FDA-approved to treat patients with polycythemia vera who have had an inadequate response to or are intolerant of hydroxyurea.

The drug is also approved to treat patients with intermediate or high-risk myelofibrosis (MF), including primary MF, post-polycythemia vera MF, and post-essential thrombocythemia MF.

Ruxolitinib is marketed as Jakafi by Incyte in the US and as Jakavi by Novartis outside the US.

“Receiving breakthrough therapy designation from the FDA recognizes the severe nature of acute GVHD, the clear unmet medical need of these patients, and the potential, based on clinical evidence to date, for ruxolitinib to address the urgent needs of patients with this life-threatening disease,” said Steven Stein, MD, Incyte’s chief medical officer.

The FDA’s breakthrough therapy designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new therapies for serious or life-threatening conditions.

To earn the designation, a treatment must show encouraging early clinical results demonstrating substantial improvement over available therapies with regard to a clinically significant endpoint, or it must fulfill an unmet need. ![]()

Photo from Business Wire

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted breakthrough therapy designation for ruxolitinib (Jakafi) for the treatment of patients with acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

Ruxolitinib is a JAK1/2 inhibitor that is already FDA-approved to treat patients with polycythemia vera who have had an inadequate response to or are intolerant of hydroxyurea.

The drug is also approved to treat patients with intermediate or high-risk myelofibrosis (MF), including primary MF, post-polycythemia vera MF, and post-essential thrombocythemia MF.

Ruxolitinib is marketed as Jakafi by Incyte in the US and as Jakavi by Novartis outside the US.

“Receiving breakthrough therapy designation from the FDA recognizes the severe nature of acute GVHD, the clear unmet medical need of these patients, and the potential, based on clinical evidence to date, for ruxolitinib to address the urgent needs of patients with this life-threatening disease,” said Steven Stein, MD, Incyte’s chief medical officer.

The FDA’s breakthrough therapy designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new therapies for serious or life-threatening conditions.

To earn the designation, a treatment must show encouraging early clinical results demonstrating substantial improvement over available therapies with regard to a clinically significant endpoint, or it must fulfill an unmet need. ![]()

Company recalls blood collection system

Photo by Charles Haymond

Haemonetics Corporation is recalling all lots of the Leukotrap RC System with RC2D Filter (re-order numbers 129-62 and 129-63) distributed since April 14, 2016.

The company says using these lots of the blood collection system may result in a higher-than-expected level of leukocytes in transfused blood.

Earlier this month, Haemonetics recalled 3 lots of the Leukotrap RC System with RC2D Filter due to reports of higher-than-expected residual white blood cells.

Since then, the company has received additional reports related to other lots.

Blood products that have been processed with the lots distributed since April 14, 2016, should not be re-filtered and should be labeled as non-leukoreduced, unless individual units have been tested and found suitable to be labeled as leukoreduced.

Continued use of these lots will require customers to verify that each unit labeled as leukoreduced was tested and meets standards for residual white blood cells acceptable to the US Food and Drug Administration.

Customers who want to return unused product to Haemonetics should contact their local customer service representative. ![]()

Photo by Charles Haymond

Haemonetics Corporation is recalling all lots of the Leukotrap RC System with RC2D Filter (re-order numbers 129-62 and 129-63) distributed since April 14, 2016.

The company says using these lots of the blood collection system may result in a higher-than-expected level of leukocytes in transfused blood.

Earlier this month, Haemonetics recalled 3 lots of the Leukotrap RC System with RC2D Filter due to reports of higher-than-expected residual white blood cells.

Since then, the company has received additional reports related to other lots.

Blood products that have been processed with the lots distributed since April 14, 2016, should not be re-filtered and should be labeled as non-leukoreduced, unless individual units have been tested and found suitable to be labeled as leukoreduced.

Continued use of these lots will require customers to verify that each unit labeled as leukoreduced was tested and meets standards for residual white blood cells acceptable to the US Food and Drug Administration.

Customers who want to return unused product to Haemonetics should contact their local customer service representative. ![]()

Photo by Charles Haymond

Haemonetics Corporation is recalling all lots of the Leukotrap RC System with RC2D Filter (re-order numbers 129-62 and 129-63) distributed since April 14, 2016.

The company says using these lots of the blood collection system may result in a higher-than-expected level of leukocytes in transfused blood.

Earlier this month, Haemonetics recalled 3 lots of the Leukotrap RC System with RC2D Filter due to reports of higher-than-expected residual white blood cells.

Since then, the company has received additional reports related to other lots.

Blood products that have been processed with the lots distributed since April 14, 2016, should not be re-filtered and should be labeled as non-leukoreduced, unless individual units have been tested and found suitable to be labeled as leukoreduced.

Continued use of these lots will require customers to verify that each unit labeled as leukoreduced was tested and meets standards for residual white blood cells acceptable to the US Food and Drug Administration.

Customers who want to return unused product to Haemonetics should contact their local customer service representative. ![]()

Unnerving

A 73‐year‐old African American man presented to his primary care physician's office concerned about several years of muscle cramps throughout his body as if his nerves were jumping and 1 month of bilateral arm weakness.

For the past 10 years, he had experienced intermittent cramping in his calves and thighs, described as a slow tightening of the muscles associated with mild pain. Initially, the cramps lasted less than 5 minutes, occurred every few days at various times of the day, and might awaken him from sleep. They happened more often following periods of inactivity and on occasion would resolve after playing golf. In recent weeks, the sensations became more frequent, more diffuse, and lasted up to several hours. He described them as a shivering. They began to affect his biceps, pectorals, deltoids, forearms, back, and calves, and would occur unrelated to activity or inactivity. He denied sensory disturbances, facial twitching or facial weakness, diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia, dyspnea, changes in bowel or bladder function, unexplained lapses of consciousness, fevers, or weight loss.

Long‐standing cramping is nonspecific and may reflect transient electrolyte derangements or muscle overuse. However, the more recent change in frequency, duration, and quality of these sensations, along with the reported weakness, raises concern for a process involving the peripheral nervous system. It will be important to differentiate cramping from other abnormal movements such as fasciculations, tremor, or myoclonus, and to determine whether there is objective weakness on the neurological examination.

His past medical history was significant for coronary artery disease with an ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction several years prior, which was treated with a drug‐eluting stent. He was also diagnosed with essential thrombocythemia at the time of his myocardial infarction and tested positive for the JAK2 mutation. He was treated for several years with hydroxyurea following his diagnosis of essential thrombocythemia. Hydroxyurea had been discontinued 6 months prior due to cytopenias. The remainder of his history was significant for hypertension, chronic kidney disease stage 3, and prediabetes.

Medications were clopidogrel, atorvastatin, metoprolol, lisinopril, and hydrochlorothiazide. He did not use tobacco nor consume alcohol or illicit drugs, and he drank caffeine only occasionally. He had no family history of neurologic disorders.

Apart from his use of statins, which often affect muscles (and less commonly the nerves), the past medical history provides minimal additional insights into the cause of his symptoms. If weakness is detected on physical exam, the next step would be to distinguish upper (central) from a lower motor neuron (peripheral) localization. A diffuse problem involving all 4 limbs is generally more likely to arise from a disorder of a lower motor neuron (LMN) structure (anterior horn cell, nerve, neuromuscular junction, or muscle). To explain bilateral symptoms of the upper and lower limbs, an upper motor neuron (UMN) disease would have to affect the bilateral brain or cervical cord, a somewhat less likely possibility given the cramps described. It would also be quite unusual to have weakness of central nervous system origin without sensory deficits.

On physical examination, the patient was well‐appearing and in no apparent distress. Temperature was 98.1, blood pressure 134/84, pulse 110 beats per minute, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation was 100% while breathing ambient air. There was no lymphadenopathy. Lung, heart, abdominal, and skin exams were unremarkable. He was alert and oriented. His speech was without dysarthria. Examinations of the cranial nerves were intact. No tongue atrophy or fasciculations were noted. No pooling of secretions was appreciated in the oropharynx. Examination of the musculature revealed normal tone, strength, and bulk. However, there were diffuse fasciculations present, most prominent in the bilateral biceps, pectorals, deltoids, forearms, upper back, and calves. Sensation to light touch, temperature, and vibration were intact. Babinski's sign was absent, and deep tendon reflexes were normal, except at the ankles where they were reduced. Coordination and gait were normal.

The exam is notable for diffuse fasciculations, defined as spontaneous local involuntary muscle contraction and relaxation, which is often visible. Benign fasciculations are extremely common, with up to 70% of otherwise healthy adults experiencing them, and may be brought on by physical exertion. Men experience these benign fasciculations more frequently than women, and they can occur at any age and persist throughout life. Fasciculations may point to LMN disease, usually localizing to the anterior horn cell (for instance in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [ALS]), muscle, or nerve disorders (including diffuse polyneuropathy). The presence of fasciculations in patients without other complaints and an otherwise normal physical examination supports benign fasciculations. The presence of neurologic deficits, however, such as weakness or reflex loss, is worrisome for another etiology. The absence of sensory changes makes anterior horn cell disease or myopathy most likely, as pure motor neuropathies are uncommon.

The fasciculations in this patient are most prominent in the proximal muscles, which may indicate a primary muscle disorder. Myopathies are typically characterized by diffuse symmetric weakness that is more proximal than distal, with no changes in sensation or deep tendon reflexes. One muscle disease characterized by fasciculations and cramping is periodic paralysis, which is often associated with potassium abnormalities or thyroid dysfunction caused by specific channelopathies. However, patients with this disorder typically present with episodic crises in contrast to the constant symptoms in this case.

Given the accelerated tempo of this patient's symptoms, further diagnostic evaluation should include basic laboratory testing including electrolytes, creatinine kinase, and thyrotropin. If these initial tests fail to reveal an etiology, the next study of choice would be an electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction study (NCS), which can definitively localize the disorder to and within the peripheral nervous system. Unlike in UMN disease, in which neuroimaging is crucial, imaging is unlikely to be informative in patients with an LMN disorder.

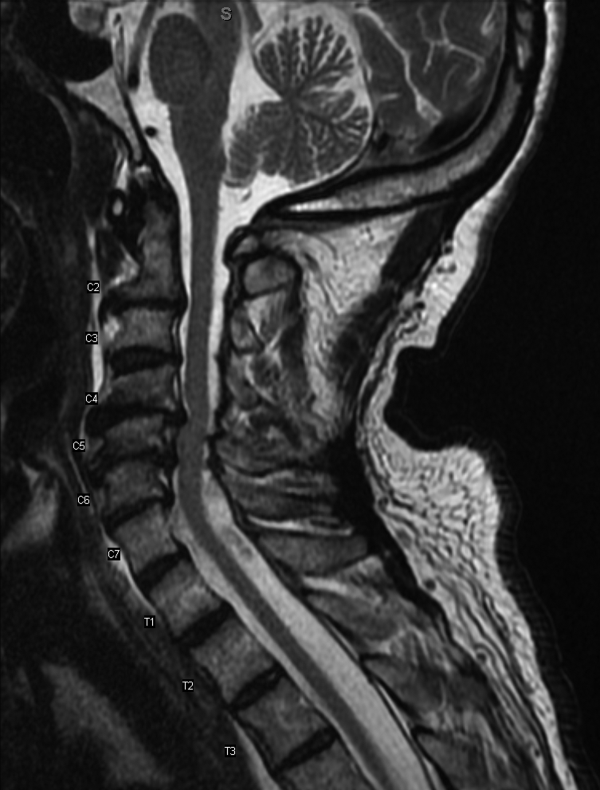

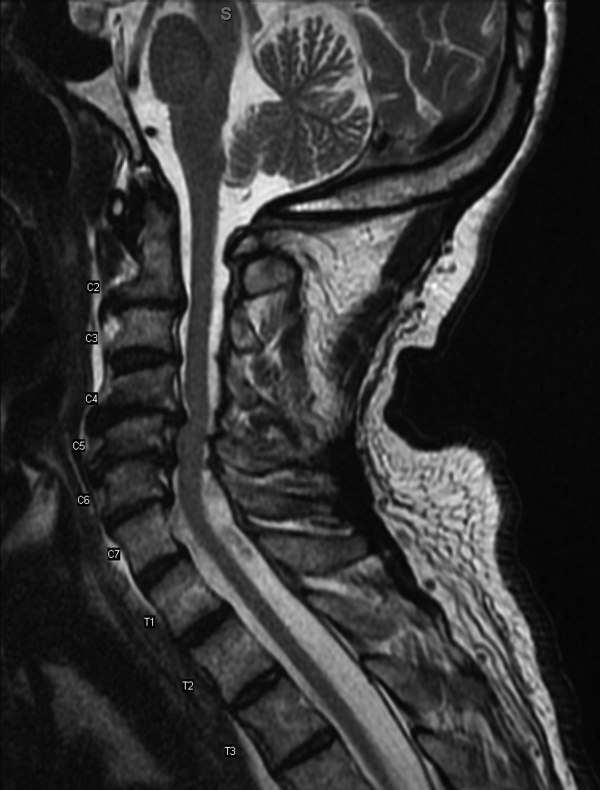

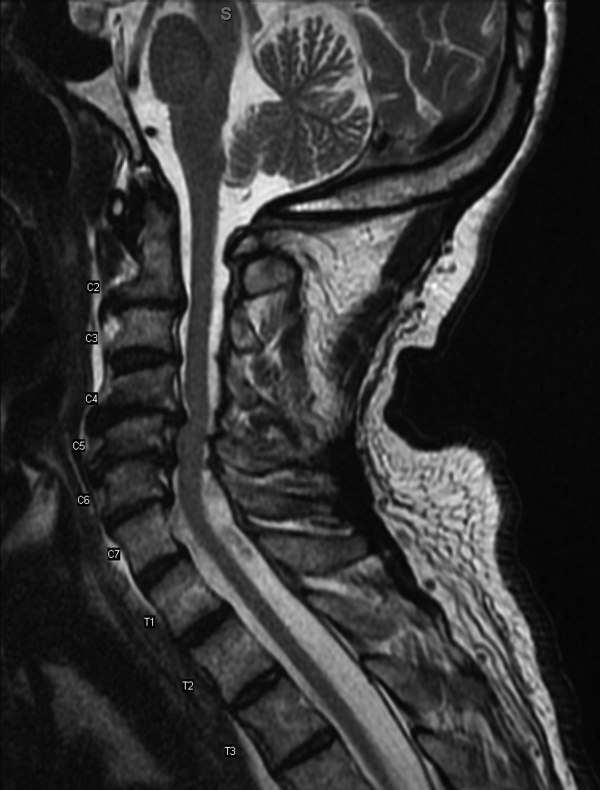

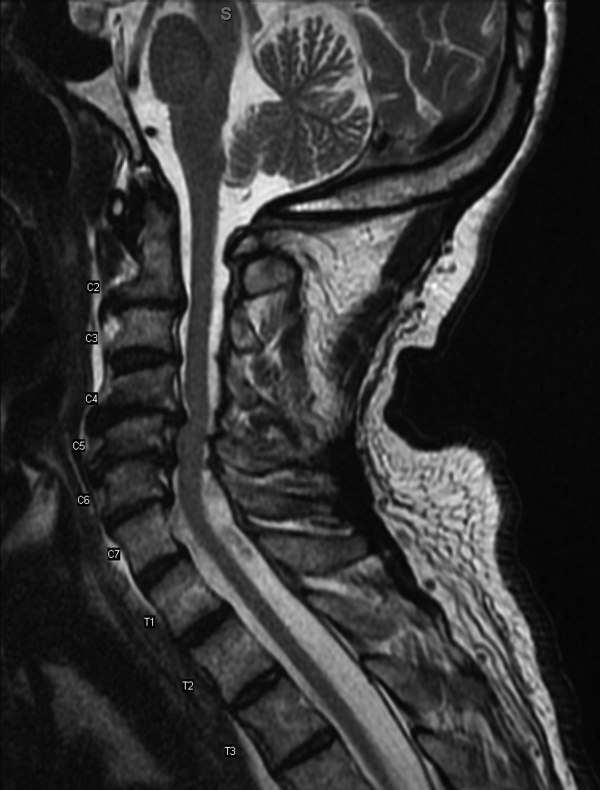

Results of a complete blood count demonstrated a platelet count of 590,000/L (normal 140400 K/L), but was otherwise normal. Sodium, potassium, magnesium, and calcium levels were normal as were alanine aminotransferase, thyrotropin, and urinalysis. The hemoglobin A1c was 6.4%. Serum creatinine kinase was 157 U/L (normal170 U/L), and the serum creatinine was 1.7mg/dL, similar to previous results. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 58mm/h (normal 020mm/h). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figure 1) of the cervical spine demonstrated diffuse disc desiccation, and multilevel spondylosis most prominent at C4C5 and C5C6, with severe central canal stenosis and neural foraminal narrowing.

The routine laboratory tests do not point to an obvious cause of this man's symptoms. As expected, the MRI findings do not explain diffuse fascinations in all limbs with no sensory disturbance. Further evaluation should include EMG and NCS.

NCS of the median and ulnar nerves demonstrated minimally reduced conduction velocities and markedly prolonged latencies. Sensory responses were absent. No conduction block was detected. EMG demonstrated fasciculations of the right extensor digitorum and first dorsal interossei, as well as decreased amplitude and decreased recruitment of motor units.

Abnormalities on the EMG testing can reflect either a primary muscle disorder or muscle derangement resulting from disease of the nerves. NCSs are important to differentiate these 2 possibilities. This patient's NCS indicates that the primary process is a diffuse motor and sensory neuropathy, not myopathy. The lack of sensory findings on physical examination emphasizes the ability of electrodiagnostic testing to extend the clinical neurologic examination in some cases. Markedly prolonged latencies and more modest reduction in amplitude support a motor and sensory neuropathy mostly due to demyelination, rather than axonal loss, and that it is more severe in the lower limbs.

Among the demyelinating neuropathies, acute inflammatory demyelinating neuropathy (Guillain‐Barr syndrome), is the most commonly recognized. The prolonged time course of this patient's illness excludes this possibility. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy is also very unlikely in the absence of conduction block on NCS. Demyelinating neuropathies may also result from antibody‐mediated nerve injury. The serum paraprotein most commonly involved is immunoglobulin M (IgM), as is detected in neuropathy due to antibodies to myelin‐associated glycoprotein (anti‐MAG) neuropathy. Another variant is the ganglioside monosialic acid antibody (anti‐GM1) associated with a rare disease called multifocal motor neuropathy (MMN), an important condition to recognize because symptoms of this illness may mimic the presentation of ALS, often with fasciculations and weakness. Unlike ALS, MMN is very responsive to treatment. Other antibody‐mediated neuropathies are much rarer. In this patient, MMN is unlikely because sensory nerves are affected in addition to motor nerves.

Because NCSs also indicate some axonal loss, it would be reasonable to screen for vitamin deficiencies, human immunodeficiency virus, and viral hepatitis. The pattern here is more symmetric and confluent than would be expected if he had mononeuritic multiplex from vasculitis.

Vitamin E level was normal. Vitamin B12 level was 323 pg/mL (normal>200 pg/mL), methylmalonate 0.3mol/L (normal 00.3mol/L). Antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus and surface antibody and antigen to hepatitis B were not detected. Cryoglobulins, anti‐nuclear antibody, and antibodies to myeloperoxidase and proteinase 3 were not detected. Serum antibodies to tissue transglutaminase and Borrelia burgdorferi were not detectable. Serum protein electrophoresis demonstrated 2 small spikes in the gamma region. Quantitative serum immunoglobulin levels were normal except for IgM, which was elevated at 1.7g/dL (normal0.19g/dL). Serum free light chains showed a kappa component of 43.7mg/L (normal 319mg/L), a lambda component of 13.8mg/L (normal 526mg/L), and a kappa/lambda ratio of 3.17mg/L (normal 0.261.65mg/L).

The differential for a symmetric demyelinating neuropathy is quite narrow, and tests for vasculitis, celiac disease, and Lyme disease are not necessary. To pursue the cause of the elevated IgM, specific serum testing should be obtained for anti‐MAG antibodies. Many cases of anti‐MAG neuropathy are associated with an underlying lymphoproliferative disorder. As such, additional imaging to identify occult lymphoma is warranted.

Anti‐GM1 and asialoganglioside were not detectable. The anti‐MAG IgM titer was >102,400 (normal1:1600). Abdominal ultrasound showed normal sized kidneys with normal cortical echogenicity and no splenomegaly. Computed tomography with contrast was not performed due to chronic kidney disease.

Treatment for anti‐MAG neuropathy is evolving rapidly as our understanding of the entity improves. Cyclophosphamide, intravenous immune globulin, and plasmapheresis have been the traditional treatments, but in the past decade, favorable experiences with rituximab have led some to try this medication earlier in the course. Prognosis can be favorable in many patients.

Over the next 2 months he continued to have fasciculations. He developed progressive generalized weakness, an unsteady gait, required a walker for mobility, and began to have trouble with his activities of daily living. His cognition remained intact. There was no pooling of secretions. Serial neurologic examinations demonstrated persistent fasciculations, progressive atrophy, most notably in the intrinsic hand muscles and legs, and progressive weakness of all limbs, worse in the distal muscle groups. Deep tendon reflexes remained preserved, except at the ankles where they were absent. Sensory exam showed stocking diminution to temperature up to his knees and elbows. Romberg sign was present, and he could not walk without support. He was started on rituximab, and after 4 weeks his condition continued to deteriorate.

The response to rituximab may be delayed. Alternatively, his disease may have an underlying cause such as occult lymphoma not yet identified, which would require treatment to control the neuropathy. Because of the potential association between lymphoma in some patients with anti‐MAG neuropathy, and because he is not responding to immunotherapy, whole body imaging with positron emission tomography and bone marrow biopsy should be performed.

CD19 levels indicated an appropriate B cell response to rituximab, but the anti‐MAG titer remained elevated at >102,400. He received additional doses of rituximab, but continued to decline. A bone marrow biopsy was considered, but the patient opted to forgo the procedure. After several months of rituximab, he developed mild dysarthria and dysphagia and was hospitalized for plasma exchange. After 5 sessions of plasma exchange, he showed no improvement and was discharged to a rehabilitation facility. Over the ensuing months, he became restricted to wheel chair or bed and eventually opted for comfort measures. He died after an aspiration pneumonia 15 months after his initial visit to his physician. Permission for an autopsy was not granted.

COMMENTARY

When encountering patients with involuntary muscle movements, hospitalists must recognize potential serious underlying disorders and implement a cost‐effective evaluation strategy. Fasciculations are a common finding that represent involuntary discharges of a motor unit, with a wide array of causes including radiculopathies, neuropathies, metabolic disturbances, and motor neuron diseases.[1, 2] Useful clues might point to a probable cause, such as a statin‐induced myopathy in patients with concomitant myalgias, or hypokalemia in patients on loop diuretics. Confinement of fasciculations to specific anatomic structures may be useful, as in carpal tunnel syndrome, where fasciculations would only be expected distal to median nerve compression. Features such as sensory loss, muscle atrophy, or abnormal reflexes should alert the clinician to a possible neurologic lesion.

Although fasciculations rarely reflect serious underlying pathology, the presence of neurologic deficits, such as muscle weakness, abnormal reflexes, or sensory loss, should prompt further investigation.[3] Because fasciculations typically point to an abnormality of LMN structures, a reasonable approach is to measure serum electrolytes, creatinine kinase, and thyrotropin to evaluate for myopathy. If these tests are unrevealing, the next step would be to perform EMG and NCS to help localize the lesion among the LMN structures. Muscle localization could then be pursued with muscle biopsy. Alternatively, when electrodiagnostic testing indicates peripheral nerve pathology, further evaluation is guided by the type of neuropathy: demyelinating, axonal, or mixed. If electrodiagnostic and clinical findings are unrevealing, the patient is diagnosed with benign fasciculations.

Demyelinating neuropathy, as seen in our patient, is relevant to hospitalists for several reasons. First, the list of diagnostic possibilities is narrow, allowing hospitalists to forgo many unnecessary laboratory tests and brain MRI. Second, unlike many axonal neuropathies, demyelinating neuropathies are potentially reversible if recognized early and promptly treated. Third, demyelinating neuropathy may involve the diaphragm, necessitating vigilance for neuromuscular respiratory failure. Finally, hospitalists need to be aware that some demyelinating neuropathies are associated with underlying malignancy, and identifying and treating the primary cancer may be critical to ameliorating the neuropathy.[4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

IgM paraproteinemia, with or without an underlying malignancy, is 1 type of demyelinating neuropathy that is potentially reversible with early treatment. The typical patient is exemplified by the case presented in this report: an older man who experiences symmetric, gradually worsening sensory disturbances and ataxia over months to years.[9] Motor deficits may progress more rapidly, prompting patients to seek hospital care.[7, 10] The hallmark of NCS in anti‐MAG disease is a demyelinating pattern with a predominance of distal abnormalities including marked prolongation of distal motor latencies and reductions in conduction velocities and sensory action potentials.[9] Findings of areflexia or conduction block should prompt consideration of other etiologies, such as acute or chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy.

For unclear reasons, IgM is more likely than other immunoglobulins to cause neuropathy. Although IgM accounts for only 17% of monoclonal gammopathies, IgM is detected in 50% to 70% of patients who have both monoclonal gammopathy and peripheral neuropathy.[11] Approximately half of the patients with IgM‐associated neuropathy produce antibodies to MAG.[11, 12] Several lines of evidence have firmly established the causative role of anti‐MAG antibodies.[13]

Because the majority of patients with anti‐MAG neuropathy will have no malignant source of IgM paraprotein identified, it is unclear how extensively to search for occult malignancy. A reasonable approach is to perform a bone marrow biopsy to distinguish underlying IgM monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance from Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia.[14] Bone marrow analysis may also detect B‐cell lymphoma, primary amyloidosis, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and hairy cell leukemia, which have been described in cases of anti‐MAG syndrome.[4, 5, 6, 7, 8] There are no reports of anti‐MAG neuropathy linked to either essential thrombocythemia nor hydroxyurea use.

The goals of treatment in anti‐MAG neuropathy are to deplete monoclonal B cells and to reduce antibody levels. Although it is reported that approximately half of patients will improve with some form of immunotherapy, a Cochrane review of randomized controlled trials of treatments for anti‐MAG neuropathy (including plasma exchange, intravenous immunoglobulin [IVIG], rituximab, corticosteroids, and chemotherapy) concluded that evidence is lacking to recommend 1 treatment over another.[15] European guidelines suggest deferring therapy unless progressive or severe neuropathy is present, in which case IVIG, plasma exchange, or rituximab may be tried.[14] In patients with underlying malignancy, treatment of the hematologic disorder may improve the neuropathy.[4, 8]

Although fasciculations and peripheral neuropathy typically present in outpatient settings, they can be harbingers of more dire diagnoses that prompt patients to seek hospitalization. A sequential and cost‐effective approach can allow the astute hospitalist to pinpoint the diagnosis in what might otherwise be an unnerving case.

KEY TEACHING POINTS

- Fasciculations are extremely common and usually benign, but may indicate a more serious neurologic process, especially when accompanied by weakness or other neurologic symptoms.

- Localizing neurologic deficits to upper motor neuron or lower motor neuron structures guides further evaluation.

- Central nervous system imaging is not indicated in demyelinating neuropathies.

- Bone marrow biopsy and cross‐sectional imaging to evaluate for malignancy should be considered in patients with anti‐MAG neuropathy who fail to improve despite therapy.

- , . Fasciculations: what do we know of their significance? J Neurol Sci. 1997;152(suppl 1):S43–S48.

- , . Muscle fasciculations in a healthy population. Arch Neurol. 1963;9:363–367.

- . Muscle pain, fatigue, and fasciculations. Neurol Clin. 1997;15(3):697–709.

- , , , et al. Monocytoid B cell lymphoma associated with antibodies to myelin‐associated glycoprotein and sulphated glucuronyl paragloboside. Acta Haematol. 2001;106(3):130–132.

- . Anti‐myelin‐associated glycoprotein peripheral neuropathy as the only presentation of low grade lymphoma: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2(1):6370–6373.

- , , , et al. Antibodies to myelin‐associated glycoprotein (anti‐Mag) in IgM amyloidosis may influence expression of neuropathy in rare patients. Muscle Nerve. 2008;37(4):490–495.

- , , , et al. Heterogeneity of polyneuropathy associated with anti‐MAG antibodies. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015(3):450391–450399.

- , , , et al. Hairy cell leukaemia complicated by anti‐MAG paraproteinemic demyelinating neuropathy: resolution of neurological syndrome after cladribrine treatment. Leuk Res. 2007;31(6):873–876.

- , , , , , . Neuropathy associated with “benign” anti‐myelin‐associated glycoprotein IgM gammopathy: clinical, immunological, neurophysiological pathological findings and response to treatment in 33 cases. J Neurol. 1996;243(1):34–43.

- , , , et al. IgM MGUS anti‐MAG neuropathy with predominant muscle weakness and extensive muscle atrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2010;42(3):433–435.

- , , , et al. Prevalence of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(13):1362–1369.

- , . Review of peripheral neuropathy in plasma cell disorders. Hematol Oncol. 2008;26(2):55–65.

- , . Effector mechanisms in anti‐MAG antibody‐mediated and other demyelinating neuropathies. J Neurol Sci. 2004;220(1–2):127–129.

- Joint Task Force of the EFNS and the PNS. European Federation of Neurological Societies/Peripheral Nerve Society Guideline on management of paraproteinemic demyelinating neuropathies. Report of a Joint Task Force of the European Federation of Neurological Societies and the Peripheral Nerve Society—first revision. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2010;15(3):185–195.

- , . Immunotherapy for IgM anti‐myelin‐associated glycoprotein paraprotein‐associated peripheral neuropathies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD002827.

A 73‐year‐old African American man presented to his primary care physician's office concerned about several years of muscle cramps throughout his body as if his nerves were jumping and 1 month of bilateral arm weakness.

For the past 10 years, he had experienced intermittent cramping in his calves and thighs, described as a slow tightening of the muscles associated with mild pain. Initially, the cramps lasted less than 5 minutes, occurred every few days at various times of the day, and might awaken him from sleep. They happened more often following periods of inactivity and on occasion would resolve after playing golf. In recent weeks, the sensations became more frequent, more diffuse, and lasted up to several hours. He described them as a shivering. They began to affect his biceps, pectorals, deltoids, forearms, back, and calves, and would occur unrelated to activity or inactivity. He denied sensory disturbances, facial twitching or facial weakness, diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia, dyspnea, changes in bowel or bladder function, unexplained lapses of consciousness, fevers, or weight loss.

Long‐standing cramping is nonspecific and may reflect transient electrolyte derangements or muscle overuse. However, the more recent change in frequency, duration, and quality of these sensations, along with the reported weakness, raises concern for a process involving the peripheral nervous system. It will be important to differentiate cramping from other abnormal movements such as fasciculations, tremor, or myoclonus, and to determine whether there is objective weakness on the neurological examination.

His past medical history was significant for coronary artery disease with an ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction several years prior, which was treated with a drug‐eluting stent. He was also diagnosed with essential thrombocythemia at the time of his myocardial infarction and tested positive for the JAK2 mutation. He was treated for several years with hydroxyurea following his diagnosis of essential thrombocythemia. Hydroxyurea had been discontinued 6 months prior due to cytopenias. The remainder of his history was significant for hypertension, chronic kidney disease stage 3, and prediabetes.

Medications were clopidogrel, atorvastatin, metoprolol, lisinopril, and hydrochlorothiazide. He did not use tobacco nor consume alcohol or illicit drugs, and he drank caffeine only occasionally. He had no family history of neurologic disorders.

Apart from his use of statins, which often affect muscles (and less commonly the nerves), the past medical history provides minimal additional insights into the cause of his symptoms. If weakness is detected on physical exam, the next step would be to distinguish upper (central) from a lower motor neuron (peripheral) localization. A diffuse problem involving all 4 limbs is generally more likely to arise from a disorder of a lower motor neuron (LMN) structure (anterior horn cell, nerve, neuromuscular junction, or muscle). To explain bilateral symptoms of the upper and lower limbs, an upper motor neuron (UMN) disease would have to affect the bilateral brain or cervical cord, a somewhat less likely possibility given the cramps described. It would also be quite unusual to have weakness of central nervous system origin without sensory deficits.

On physical examination, the patient was well‐appearing and in no apparent distress. Temperature was 98.1, blood pressure 134/84, pulse 110 beats per minute, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation was 100% while breathing ambient air. There was no lymphadenopathy. Lung, heart, abdominal, and skin exams were unremarkable. He was alert and oriented. His speech was without dysarthria. Examinations of the cranial nerves were intact. No tongue atrophy or fasciculations were noted. No pooling of secretions was appreciated in the oropharynx. Examination of the musculature revealed normal tone, strength, and bulk. However, there were diffuse fasciculations present, most prominent in the bilateral biceps, pectorals, deltoids, forearms, upper back, and calves. Sensation to light touch, temperature, and vibration were intact. Babinski's sign was absent, and deep tendon reflexes were normal, except at the ankles where they were reduced. Coordination and gait were normal.

The exam is notable for diffuse fasciculations, defined as spontaneous local involuntary muscle contraction and relaxation, which is often visible. Benign fasciculations are extremely common, with up to 70% of otherwise healthy adults experiencing them, and may be brought on by physical exertion. Men experience these benign fasciculations more frequently than women, and they can occur at any age and persist throughout life. Fasciculations may point to LMN disease, usually localizing to the anterior horn cell (for instance in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [ALS]), muscle, or nerve disorders (including diffuse polyneuropathy). The presence of fasciculations in patients without other complaints and an otherwise normal physical examination supports benign fasciculations. The presence of neurologic deficits, however, such as weakness or reflex loss, is worrisome for another etiology. The absence of sensory changes makes anterior horn cell disease or myopathy most likely, as pure motor neuropathies are uncommon.

The fasciculations in this patient are most prominent in the proximal muscles, which may indicate a primary muscle disorder. Myopathies are typically characterized by diffuse symmetric weakness that is more proximal than distal, with no changes in sensation or deep tendon reflexes. One muscle disease characterized by fasciculations and cramping is periodic paralysis, which is often associated with potassium abnormalities or thyroid dysfunction caused by specific channelopathies. However, patients with this disorder typically present with episodic crises in contrast to the constant symptoms in this case.

Given the accelerated tempo of this patient's symptoms, further diagnostic evaluation should include basic laboratory testing including electrolytes, creatinine kinase, and thyrotropin. If these initial tests fail to reveal an etiology, the next study of choice would be an electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction study (NCS), which can definitively localize the disorder to and within the peripheral nervous system. Unlike in UMN disease, in which neuroimaging is crucial, imaging is unlikely to be informative in patients with an LMN disorder.

Results of a complete blood count demonstrated a platelet count of 590,000/L (normal 140400 K/L), but was otherwise normal. Sodium, potassium, magnesium, and calcium levels were normal as were alanine aminotransferase, thyrotropin, and urinalysis. The hemoglobin A1c was 6.4%. Serum creatinine kinase was 157 U/L (normal170 U/L), and the serum creatinine was 1.7mg/dL, similar to previous results. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 58mm/h (normal 020mm/h). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figure 1) of the cervical spine demonstrated diffuse disc desiccation, and multilevel spondylosis most prominent at C4C5 and C5C6, with severe central canal stenosis and neural foraminal narrowing.

The routine laboratory tests do not point to an obvious cause of this man's symptoms. As expected, the MRI findings do not explain diffuse fascinations in all limbs with no sensory disturbance. Further evaluation should include EMG and NCS.

NCS of the median and ulnar nerves demonstrated minimally reduced conduction velocities and markedly prolonged latencies. Sensory responses were absent. No conduction block was detected. EMG demonstrated fasciculations of the right extensor digitorum and first dorsal interossei, as well as decreased amplitude and decreased recruitment of motor units.

Abnormalities on the EMG testing can reflect either a primary muscle disorder or muscle derangement resulting from disease of the nerves. NCSs are important to differentiate these 2 possibilities. This patient's NCS indicates that the primary process is a diffuse motor and sensory neuropathy, not myopathy. The lack of sensory findings on physical examination emphasizes the ability of electrodiagnostic testing to extend the clinical neurologic examination in some cases. Markedly prolonged latencies and more modest reduction in amplitude support a motor and sensory neuropathy mostly due to demyelination, rather than axonal loss, and that it is more severe in the lower limbs.

Among the demyelinating neuropathies, acute inflammatory demyelinating neuropathy (Guillain‐Barr syndrome), is the most commonly recognized. The prolonged time course of this patient's illness excludes this possibility. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy is also very unlikely in the absence of conduction block on NCS. Demyelinating neuropathies may also result from antibody‐mediated nerve injury. The serum paraprotein most commonly involved is immunoglobulin M (IgM), as is detected in neuropathy due to antibodies to myelin‐associated glycoprotein (anti‐MAG) neuropathy. Another variant is the ganglioside monosialic acid antibody (anti‐GM1) associated with a rare disease called multifocal motor neuropathy (MMN), an important condition to recognize because symptoms of this illness may mimic the presentation of ALS, often with fasciculations and weakness. Unlike ALS, MMN is very responsive to treatment. Other antibody‐mediated neuropathies are much rarer. In this patient, MMN is unlikely because sensory nerves are affected in addition to motor nerves.

Because NCSs also indicate some axonal loss, it would be reasonable to screen for vitamin deficiencies, human immunodeficiency virus, and viral hepatitis. The pattern here is more symmetric and confluent than would be expected if he had mononeuritic multiplex from vasculitis.

Vitamin E level was normal. Vitamin B12 level was 323 pg/mL (normal>200 pg/mL), methylmalonate 0.3mol/L (normal 00.3mol/L). Antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus and surface antibody and antigen to hepatitis B were not detected. Cryoglobulins, anti‐nuclear antibody, and antibodies to myeloperoxidase and proteinase 3 were not detected. Serum antibodies to tissue transglutaminase and Borrelia burgdorferi were not detectable. Serum protein electrophoresis demonstrated 2 small spikes in the gamma region. Quantitative serum immunoglobulin levels were normal except for IgM, which was elevated at 1.7g/dL (normal0.19g/dL). Serum free light chains showed a kappa component of 43.7mg/L (normal 319mg/L), a lambda component of 13.8mg/L (normal 526mg/L), and a kappa/lambda ratio of 3.17mg/L (normal 0.261.65mg/L).

The differential for a symmetric demyelinating neuropathy is quite narrow, and tests for vasculitis, celiac disease, and Lyme disease are not necessary. To pursue the cause of the elevated IgM, specific serum testing should be obtained for anti‐MAG antibodies. Many cases of anti‐MAG neuropathy are associated with an underlying lymphoproliferative disorder. As such, additional imaging to identify occult lymphoma is warranted.

Anti‐GM1 and asialoganglioside were not detectable. The anti‐MAG IgM titer was >102,400 (normal1:1600). Abdominal ultrasound showed normal sized kidneys with normal cortical echogenicity and no splenomegaly. Computed tomography with contrast was not performed due to chronic kidney disease.

Treatment for anti‐MAG neuropathy is evolving rapidly as our understanding of the entity improves. Cyclophosphamide, intravenous immune globulin, and plasmapheresis have been the traditional treatments, but in the past decade, favorable experiences with rituximab have led some to try this medication earlier in the course. Prognosis can be favorable in many patients.

Over the next 2 months he continued to have fasciculations. He developed progressive generalized weakness, an unsteady gait, required a walker for mobility, and began to have trouble with his activities of daily living. His cognition remained intact. There was no pooling of secretions. Serial neurologic examinations demonstrated persistent fasciculations, progressive atrophy, most notably in the intrinsic hand muscles and legs, and progressive weakness of all limbs, worse in the distal muscle groups. Deep tendon reflexes remained preserved, except at the ankles where they were absent. Sensory exam showed stocking diminution to temperature up to his knees and elbows. Romberg sign was present, and he could not walk without support. He was started on rituximab, and after 4 weeks his condition continued to deteriorate.

The response to rituximab may be delayed. Alternatively, his disease may have an underlying cause such as occult lymphoma not yet identified, which would require treatment to control the neuropathy. Because of the potential association between lymphoma in some patients with anti‐MAG neuropathy, and because he is not responding to immunotherapy, whole body imaging with positron emission tomography and bone marrow biopsy should be performed.