User login

Atopic Dermatitis Treatments Moving Forward: Report From the AAD Meeting

Although psoriasis was once at the forefront of therapeutic advancements in dermatology, atopic dermatitis (AD) is now taking center stage with several new treatments in the pipeline. Dr. Emma Guttman-Yassky provides an overview of the future of AD treatment, which includes new topical and systemic agents that currently are moving forward in advanced clinical trials or are close to registration. She also discusses strategies for improving disease management in AD patients, noting that prevention and education of both patients and their caregivers are key to effective treatment.

Although psoriasis was once at the forefront of therapeutic advancements in dermatology, atopic dermatitis (AD) is now taking center stage with several new treatments in the pipeline. Dr. Emma Guttman-Yassky provides an overview of the future of AD treatment, which includes new topical and systemic agents that currently are moving forward in advanced clinical trials or are close to registration. She also discusses strategies for improving disease management in AD patients, noting that prevention and education of both patients and their caregivers are key to effective treatment.

Although psoriasis was once at the forefront of therapeutic advancements in dermatology, atopic dermatitis (AD) is now taking center stage with several new treatments in the pipeline. Dr. Emma Guttman-Yassky provides an overview of the future of AD treatment, which includes new topical and systemic agents that currently are moving forward in advanced clinical trials or are close to registration. She also discusses strategies for improving disease management in AD patients, noting that prevention and education of both patients and their caregivers are key to effective treatment.

Tool May Help Predict Persistent Postconcussion Symptoms

A clinical risk score may help identify which children and adolescents with recent head injury are at risk for persistent postconcussion symptoms, according to an investigation published March 8 in JAMA.

Approximately one-third of pediatric patients with concussion have ongoing somatic, cognitive, psychological, or behavioral symptoms at 28 days. At present, neurologists have no tools to help predict which patients will be affected in this way. The 5P (Preventing Postconcussive Problems in Pediatrics) study was performed to develop and validate a clinical risk score for this purpose, said Roger Zemek, MD, a scientist at Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute in Ottawa, Canada, and his associates.

This prospective cohort study involved patients between ages 5 and 17 (median age, 12) who presented to one of nine Canadian pediatric emergency departments within 48 hours of sustaining a concussion.

In the derivation cohort, 510 of 1,701 participants (30%) met the criteria for persistent postconcussion symptoms. The investigators assessed 47 possible predictive variables for their usefulness in predicting persistent postconcussion symptoms in this cohort. The variables were collected from demographic data, patient history, injury characteristics, physical examination, results on the Acute Concussion Evaluation Inventory and the Postconcussion Symptom Inventory, and patient and parent responses to weekly follow-up surveys during the month after the injury.

The investigators devised a clinical risk score using the following nine predictors that they found to be most accurate: age, gender, presence or absence of prior concussion, migraine history, presence or absence of current headache, sensitivity to noise, fatigue, slow responses to questions, and an abnormal tandem stance. They then selected three cutoff points to stratify the risk of persistent postconcussion symptoms: 0–3 points indicated low risk, 4–8 points indicated intermediate risk, and 9 or more points indicated high risk. Treating physicians also were asked to predict the likelihood of persistent postconcussion symptoms.

In the validation cohort, 291 of 883 participants (33%) met the criteria for persistent postconcussion symptoms. For low-risk patients, the sensitivity of the clinical risk score was 94%, the specificity was 18%, the negative predictive value was 85%, and the positive predictive value was 36%. For high-risk patients, the sensitivity of the clinical risk score was 20%, the specificity was 94%, the negative predictive value was 70%, and the positive predictive value was 60%.

In both sets of patients, the clinical risk score was significantly better than physician judgment in predicting persistent postconcussion symptoms. The clinical risk score has modest accuracy, however, at distinguishing between who will and who will not have persistent symptoms. This tool could be refined further, perhaps, by adding information regarding biomarkers, genetic susceptibility, or advanced neuroimaging, said Dr. Zemek and his associates.

—Mary Ann Moon

Suggested Reading

Zemek R, Barrowman N, Freedman SB, et al. Clinical risk score for persistent postconcussion symptoms among children with acute concussion in the ED. JAMA. 2016;315(10):1014-1025.

A clinical risk score may help identify which children and adolescents with recent head injury are at risk for persistent postconcussion symptoms, according to an investigation published March 8 in JAMA.

Approximately one-third of pediatric patients with concussion have ongoing somatic, cognitive, psychological, or behavioral symptoms at 28 days. At present, neurologists have no tools to help predict which patients will be affected in this way. The 5P (Preventing Postconcussive Problems in Pediatrics) study was performed to develop and validate a clinical risk score for this purpose, said Roger Zemek, MD, a scientist at Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute in Ottawa, Canada, and his associates.

This prospective cohort study involved patients between ages 5 and 17 (median age, 12) who presented to one of nine Canadian pediatric emergency departments within 48 hours of sustaining a concussion.

In the derivation cohort, 510 of 1,701 participants (30%) met the criteria for persistent postconcussion symptoms. The investigators assessed 47 possible predictive variables for their usefulness in predicting persistent postconcussion symptoms in this cohort. The variables were collected from demographic data, patient history, injury characteristics, physical examination, results on the Acute Concussion Evaluation Inventory and the Postconcussion Symptom Inventory, and patient and parent responses to weekly follow-up surveys during the month after the injury.

The investigators devised a clinical risk score using the following nine predictors that they found to be most accurate: age, gender, presence or absence of prior concussion, migraine history, presence or absence of current headache, sensitivity to noise, fatigue, slow responses to questions, and an abnormal tandem stance. They then selected three cutoff points to stratify the risk of persistent postconcussion symptoms: 0–3 points indicated low risk, 4–8 points indicated intermediate risk, and 9 or more points indicated high risk. Treating physicians also were asked to predict the likelihood of persistent postconcussion symptoms.

In the validation cohort, 291 of 883 participants (33%) met the criteria for persistent postconcussion symptoms. For low-risk patients, the sensitivity of the clinical risk score was 94%, the specificity was 18%, the negative predictive value was 85%, and the positive predictive value was 36%. For high-risk patients, the sensitivity of the clinical risk score was 20%, the specificity was 94%, the negative predictive value was 70%, and the positive predictive value was 60%.

In both sets of patients, the clinical risk score was significantly better than physician judgment in predicting persistent postconcussion symptoms. The clinical risk score has modest accuracy, however, at distinguishing between who will and who will not have persistent symptoms. This tool could be refined further, perhaps, by adding information regarding biomarkers, genetic susceptibility, or advanced neuroimaging, said Dr. Zemek and his associates.

—Mary Ann Moon

A clinical risk score may help identify which children and adolescents with recent head injury are at risk for persistent postconcussion symptoms, according to an investigation published March 8 in JAMA.

Approximately one-third of pediatric patients with concussion have ongoing somatic, cognitive, psychological, or behavioral symptoms at 28 days. At present, neurologists have no tools to help predict which patients will be affected in this way. The 5P (Preventing Postconcussive Problems in Pediatrics) study was performed to develop and validate a clinical risk score for this purpose, said Roger Zemek, MD, a scientist at Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute in Ottawa, Canada, and his associates.

This prospective cohort study involved patients between ages 5 and 17 (median age, 12) who presented to one of nine Canadian pediatric emergency departments within 48 hours of sustaining a concussion.

In the derivation cohort, 510 of 1,701 participants (30%) met the criteria for persistent postconcussion symptoms. The investigators assessed 47 possible predictive variables for their usefulness in predicting persistent postconcussion symptoms in this cohort. The variables were collected from demographic data, patient history, injury characteristics, physical examination, results on the Acute Concussion Evaluation Inventory and the Postconcussion Symptom Inventory, and patient and parent responses to weekly follow-up surveys during the month after the injury.

The investigators devised a clinical risk score using the following nine predictors that they found to be most accurate: age, gender, presence or absence of prior concussion, migraine history, presence or absence of current headache, sensitivity to noise, fatigue, slow responses to questions, and an abnormal tandem stance. They then selected three cutoff points to stratify the risk of persistent postconcussion symptoms: 0–3 points indicated low risk, 4–8 points indicated intermediate risk, and 9 or more points indicated high risk. Treating physicians also were asked to predict the likelihood of persistent postconcussion symptoms.

In the validation cohort, 291 of 883 participants (33%) met the criteria for persistent postconcussion symptoms. For low-risk patients, the sensitivity of the clinical risk score was 94%, the specificity was 18%, the negative predictive value was 85%, and the positive predictive value was 36%. For high-risk patients, the sensitivity of the clinical risk score was 20%, the specificity was 94%, the negative predictive value was 70%, and the positive predictive value was 60%.

In both sets of patients, the clinical risk score was significantly better than physician judgment in predicting persistent postconcussion symptoms. The clinical risk score has modest accuracy, however, at distinguishing between who will and who will not have persistent symptoms. This tool could be refined further, perhaps, by adding information regarding biomarkers, genetic susceptibility, or advanced neuroimaging, said Dr. Zemek and his associates.

—Mary Ann Moon

Suggested Reading

Zemek R, Barrowman N, Freedman SB, et al. Clinical risk score for persistent postconcussion symptoms among children with acute concussion in the ED. JAMA. 2016;315(10):1014-1025.

Suggested Reading

Zemek R, Barrowman N, Freedman SB, et al. Clinical risk score for persistent postconcussion symptoms among children with acute concussion in the ED. JAMA. 2016;315(10):1014-1025.

Bone sarcomas are not just for kids

The treatment of bone sarcomas in adults is guided as much by experience as it is by medical evidence, say sarcoma experts who should know.

“[L]arge prospective clinical trials in adults with bone sarcomas are lacking. Although translation of findings in pediatric studies to adults is possible, it is not clear if findings from pediatric studies truly apply to adults,” Dr. Michael J. Wagner and his colleagues from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston said.

In a review article in the Journal of Oncology Practice, the investigators outline how they have melded lessons learned from pediatric clinical trials with clinical experience treating adults with bone sarcomas.

Adult osteosarcomas

Although the peak incidence of osteosarcoma occurs in adolescents and young adults, some studies of various chemotherapy regimens have included middle-aged adults and even some patients in their 90s, although many have excluded patients older than 30, the authors noted.

In adults, and in children and adolescents and young adults, chemotherapy and definitive surgical resection are the mainstays of treatment, with the exception of osteosarcomas of the jaw, which are generally treated with resection alone. For the past three decades, adults with high-grade osteosarcomas have been treated with chemotherapy containing doxorubicin, cisplatin, high-dose methotrexate, and ifosfamide.

“However, important differences to consider in the treatment of older patients include, but are not limited to, the increased incidence of histologic variants of osteosarcoma (including secondary osteosarcomas) and medical comorbidities that may limit tolerance of older adults to dose-intense chemotherapy,” wrote Dr. Wagner and his colleagues (J Oncol Pract. 2016 Mar. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.009944).

High-grade localized osteosarcoma is treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, followed by limb-sparing surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy.

A poor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, defined as tumor necrosis of less than 90% at resection, is a marker for poor prognosis.

The authors previously reported that for patients with a poor response following a regimen of doxorubicin intravenous infusion at 90 mg/m2 over 96 hours plus cisplatin infused intra-arterially at 120-160 mg/m2 over 2 to 24 hours, the addition of high-dose methotrexate and ifosfamide resulted in significant improvement in continuous relapse-free survival.

At MD Anderson, adults with osteosarcoma receive preoperative chemotherapy with doxorubicin and cisplatin for three to four cycles and then undergo surgical resection. Those who have a good response go on to receive adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin 75 mg/m2 and ifosfamide 10g/m2 for four cycles. Patients who have a poor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy receive alternating courses of ifosfamide 14 g/m2, high-dose methotrexate 10 to 12 g/m2, and doxorubicin 75 mg/m2 and ifosfamide 10 g/m2 for up to 12 cycles or until intolerable adverse events.

Patients with metastatic relapsed/refractory osteosarcoma have 5-year overall survival rates ranging from 15% to 20%, the authors noted, adding that chemotherapy has “limited efficacy” in this setting.

Targeted agents, including the tyrosine kinase inhibitor sorafenib (Nexavar) and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor everolimus (Afinitor) have been evaluated in phase II trials.

Ewing sarcoma

Evidence from clinical trials of chemotherapy regimens in Ewing sarcoma show that patients 18 and older tend to have less favorable outcomes than younger patients when treated with dose-dense regimens, the authors noted.

Their practice is to treat adults with Ewing sarcoma with upfront vincristine 2 mg on day 1, doxorubicin 75 to 90 mg/m2 in a continuous 72-hour infusion, and ifosfamide 2.5 g/m2 given over 3 hours daily for four doses, followed by surgery, and adjuvant chemotherapy with an ifosfamide-based regimen.

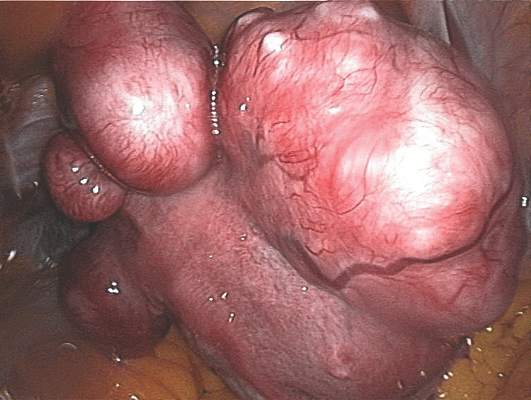

Giant cell tumors of bone

These rare osteolytic tumors are treated with surgery as the primary therapy if they are resectable. Patients with metastases (which paradoxically, are usually histologically benign) as well as those who have tumors in areas where surgery may cause unacceptable morbidities may be treated with serial embolization, denosumab (Xgeva), interferon, or pegylated interferon.

Chondrosarcoma

The so-called “conventional” sub-type of chondrosarcomas are not generally responsive to cytotoxic chemotherapy and best managed with surgery alone, the authors say. However, patients with mesenchymal chondrosarcoma are treated similarly to patients with Ewing sarcoma, and those with the dedifferentiated subtype are treated with an osteosarcoma regimens.

The authors noted that point mutations in IDH1 and IDH2 have recently been discovered in chondrosarcomas, making them potential targets for an experimental IDH-1 inhibitor.

Dr. Wagner and coauthor Dr. J. Andrew Livingston reported no relevant disclosures. Coauthors Dr. Shreyaskumar R. Patel and Dr. Robert S. Benjamin reported consulting, advisory roles, research funding, or ownership interests in various pharmaceutical companies.

The treatment of bone sarcomas in adults is guided as much by experience as it is by medical evidence, say sarcoma experts who should know.

“[L]arge prospective clinical trials in adults with bone sarcomas are lacking. Although translation of findings in pediatric studies to adults is possible, it is not clear if findings from pediatric studies truly apply to adults,” Dr. Michael J. Wagner and his colleagues from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston said.

In a review article in the Journal of Oncology Practice, the investigators outline how they have melded lessons learned from pediatric clinical trials with clinical experience treating adults with bone sarcomas.

Adult osteosarcomas

Although the peak incidence of osteosarcoma occurs in adolescents and young adults, some studies of various chemotherapy regimens have included middle-aged adults and even some patients in their 90s, although many have excluded patients older than 30, the authors noted.

In adults, and in children and adolescents and young adults, chemotherapy and definitive surgical resection are the mainstays of treatment, with the exception of osteosarcomas of the jaw, which are generally treated with resection alone. For the past three decades, adults with high-grade osteosarcomas have been treated with chemotherapy containing doxorubicin, cisplatin, high-dose methotrexate, and ifosfamide.

“However, important differences to consider in the treatment of older patients include, but are not limited to, the increased incidence of histologic variants of osteosarcoma (including secondary osteosarcomas) and medical comorbidities that may limit tolerance of older adults to dose-intense chemotherapy,” wrote Dr. Wagner and his colleagues (J Oncol Pract. 2016 Mar. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.009944).

High-grade localized osteosarcoma is treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, followed by limb-sparing surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy.

A poor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, defined as tumor necrosis of less than 90% at resection, is a marker for poor prognosis.

The authors previously reported that for patients with a poor response following a regimen of doxorubicin intravenous infusion at 90 mg/m2 over 96 hours plus cisplatin infused intra-arterially at 120-160 mg/m2 over 2 to 24 hours, the addition of high-dose methotrexate and ifosfamide resulted in significant improvement in continuous relapse-free survival.

At MD Anderson, adults with osteosarcoma receive preoperative chemotherapy with doxorubicin and cisplatin for three to four cycles and then undergo surgical resection. Those who have a good response go on to receive adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin 75 mg/m2 and ifosfamide 10g/m2 for four cycles. Patients who have a poor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy receive alternating courses of ifosfamide 14 g/m2, high-dose methotrexate 10 to 12 g/m2, and doxorubicin 75 mg/m2 and ifosfamide 10 g/m2 for up to 12 cycles or until intolerable adverse events.

Patients with metastatic relapsed/refractory osteosarcoma have 5-year overall survival rates ranging from 15% to 20%, the authors noted, adding that chemotherapy has “limited efficacy” in this setting.

Targeted agents, including the tyrosine kinase inhibitor sorafenib (Nexavar) and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor everolimus (Afinitor) have been evaluated in phase II trials.

Ewing sarcoma

Evidence from clinical trials of chemotherapy regimens in Ewing sarcoma show that patients 18 and older tend to have less favorable outcomes than younger patients when treated with dose-dense regimens, the authors noted.

Their practice is to treat adults with Ewing sarcoma with upfront vincristine 2 mg on day 1, doxorubicin 75 to 90 mg/m2 in a continuous 72-hour infusion, and ifosfamide 2.5 g/m2 given over 3 hours daily for four doses, followed by surgery, and adjuvant chemotherapy with an ifosfamide-based regimen.

Giant cell tumors of bone

These rare osteolytic tumors are treated with surgery as the primary therapy if they are resectable. Patients with metastases (which paradoxically, are usually histologically benign) as well as those who have tumors in areas where surgery may cause unacceptable morbidities may be treated with serial embolization, denosumab (Xgeva), interferon, or pegylated interferon.

Chondrosarcoma

The so-called “conventional” sub-type of chondrosarcomas are not generally responsive to cytotoxic chemotherapy and best managed with surgery alone, the authors say. However, patients with mesenchymal chondrosarcoma are treated similarly to patients with Ewing sarcoma, and those with the dedifferentiated subtype are treated with an osteosarcoma regimens.

The authors noted that point mutations in IDH1 and IDH2 have recently been discovered in chondrosarcomas, making them potential targets for an experimental IDH-1 inhibitor.

Dr. Wagner and coauthor Dr. J. Andrew Livingston reported no relevant disclosures. Coauthors Dr. Shreyaskumar R. Patel and Dr. Robert S. Benjamin reported consulting, advisory roles, research funding, or ownership interests in various pharmaceutical companies.

The treatment of bone sarcomas in adults is guided as much by experience as it is by medical evidence, say sarcoma experts who should know.

“[L]arge prospective clinical trials in adults with bone sarcomas are lacking. Although translation of findings in pediatric studies to adults is possible, it is not clear if findings from pediatric studies truly apply to adults,” Dr. Michael J. Wagner and his colleagues from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston said.

In a review article in the Journal of Oncology Practice, the investigators outline how they have melded lessons learned from pediatric clinical trials with clinical experience treating adults with bone sarcomas.

Adult osteosarcomas

Although the peak incidence of osteosarcoma occurs in adolescents and young adults, some studies of various chemotherapy regimens have included middle-aged adults and even some patients in their 90s, although many have excluded patients older than 30, the authors noted.

In adults, and in children and adolescents and young adults, chemotherapy and definitive surgical resection are the mainstays of treatment, with the exception of osteosarcomas of the jaw, which are generally treated with resection alone. For the past three decades, adults with high-grade osteosarcomas have been treated with chemotherapy containing doxorubicin, cisplatin, high-dose methotrexate, and ifosfamide.

“However, important differences to consider in the treatment of older patients include, but are not limited to, the increased incidence of histologic variants of osteosarcoma (including secondary osteosarcomas) and medical comorbidities that may limit tolerance of older adults to dose-intense chemotherapy,” wrote Dr. Wagner and his colleagues (J Oncol Pract. 2016 Mar. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.009944).

High-grade localized osteosarcoma is treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, followed by limb-sparing surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy.

A poor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, defined as tumor necrosis of less than 90% at resection, is a marker for poor prognosis.

The authors previously reported that for patients with a poor response following a regimen of doxorubicin intravenous infusion at 90 mg/m2 over 96 hours plus cisplatin infused intra-arterially at 120-160 mg/m2 over 2 to 24 hours, the addition of high-dose methotrexate and ifosfamide resulted in significant improvement in continuous relapse-free survival.

At MD Anderson, adults with osteosarcoma receive preoperative chemotherapy with doxorubicin and cisplatin for three to four cycles and then undergo surgical resection. Those who have a good response go on to receive adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin 75 mg/m2 and ifosfamide 10g/m2 for four cycles. Patients who have a poor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy receive alternating courses of ifosfamide 14 g/m2, high-dose methotrexate 10 to 12 g/m2, and doxorubicin 75 mg/m2 and ifosfamide 10 g/m2 for up to 12 cycles or until intolerable adverse events.

Patients with metastatic relapsed/refractory osteosarcoma have 5-year overall survival rates ranging from 15% to 20%, the authors noted, adding that chemotherapy has “limited efficacy” in this setting.

Targeted agents, including the tyrosine kinase inhibitor sorafenib (Nexavar) and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor everolimus (Afinitor) have been evaluated in phase II trials.

Ewing sarcoma

Evidence from clinical trials of chemotherapy regimens in Ewing sarcoma show that patients 18 and older tend to have less favorable outcomes than younger patients when treated with dose-dense regimens, the authors noted.

Their practice is to treat adults with Ewing sarcoma with upfront vincristine 2 mg on day 1, doxorubicin 75 to 90 mg/m2 in a continuous 72-hour infusion, and ifosfamide 2.5 g/m2 given over 3 hours daily for four doses, followed by surgery, and adjuvant chemotherapy with an ifosfamide-based regimen.

Giant cell tumors of bone

These rare osteolytic tumors are treated with surgery as the primary therapy if they are resectable. Patients with metastases (which paradoxically, are usually histologically benign) as well as those who have tumors in areas where surgery may cause unacceptable morbidities may be treated with serial embolization, denosumab (Xgeva), interferon, or pegylated interferon.

Chondrosarcoma

The so-called “conventional” sub-type of chondrosarcomas are not generally responsive to cytotoxic chemotherapy and best managed with surgery alone, the authors say. However, patients with mesenchymal chondrosarcoma are treated similarly to patients with Ewing sarcoma, and those with the dedifferentiated subtype are treated with an osteosarcoma regimens.

The authors noted that point mutations in IDH1 and IDH2 have recently been discovered in chondrosarcomas, making them potential targets for an experimental IDH-1 inhibitor.

Dr. Wagner and coauthor Dr. J. Andrew Livingston reported no relevant disclosures. Coauthors Dr. Shreyaskumar R. Patel and Dr. Robert S. Benjamin reported consulting, advisory roles, research funding, or ownership interests in various pharmaceutical companies.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY PRACTICE

Key clinical point: Sarcomas of bone have their peak incidence in children and adolescents, but are also seen in adults.

Major finding: Findings from clinical trials in pediatric bone sarcomas may not be applicable to treatment of adults with the same malignancies.

Data source: Review of the medical literature and of clinical experience at the authors’ center.

Disclosures: Dr. Wagner and coauthor Dr. J. Andrew Livingston reported no relevant disclosures. Coauthors Dr. Shreyaskumar R. Patel and Dr. Robert S. Benjamin reported consulting, advisory roles, research funding, or ownership interests in various pharmaceutical companies.

High Coffee Consumption May Decrease Risk for MS

High coffee consumption decreases the odds of developing multiple sclerosis (MS), according to two case–control studies published online ahead of print March 3 in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. Anna K. Hedström, MD, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, and her associates conducted the studies.

The investigators analyzed coffee consumption among 1,620 adults with MS and 2,788 healthy controls in the Swedish Epidemiological Investigation of Multiple Sclerosis (EIMS). They also examined coffee consumption in 1,159 adults with MS and 1,172 healthy controls in the Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Plan, Northern California Region (KPNC).

In EIMS, the adjusted odds ratio (OR) for developing MS was 0.70 among participants who drank more than six cups of coffee (ie, greater than 900 mL) daily at the index year, which was defined as the year of the initial appearance of symptoms indicative of MS. The corresponding ORs for those who reported high coffee consumption at five or 10 years before the study were 0.72 and 0.71, respectively, but these results were not statistically significant.

In KPNC, those who consumed four or more cups of coffee (ie, more than 948 mL) daily were significantly less likely to develop MS than were those who never drank coffee (OR, 0.69). In addition, people who drank four or more cups of coffee daily at least five years prior to the index year had significantly reduced odds of MS (OR, 0.64).

A meta-analysis of the combined results of the two studies indicated a significant 29% reduction in the likelihood of developing MS among the people with the greatest coffee consumption (ie, greater than 900 mL daily in EIMS and greater than 948 mL in KPNC). The investigators adjusted all the analyses for many demographic and environmental risk factors for MS, including age, gender, residential area, ancestry, smoking habits, exposure to passive smoking, sun exposure habits, and BMI at age 20.

No evidence indicated any associations between increased amounts of tea or soda intake and MS.

“Further studies are required to establish if it is in fact caffeine, or if there is another molecule in coffee underlying the findings, to longitudinally assess the association between consumption of coffee and disease activity in MS, and to evaluate the mechanisms by which coffee may be acting, which could thus lead to new therapeutic targets,” the researchers concluded.

—Lori Laubach

Suggested Reading

Hedström AK, Mowry EM, Gianfrancesco MA, et al. High consumption of coffee is associated with decreased multiple sclerosis risk; results from two independent studies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016 March 3 [Epub ahead of print].

High coffee consumption decreases the odds of developing multiple sclerosis (MS), according to two case–control studies published online ahead of print March 3 in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. Anna K. Hedström, MD, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, and her associates conducted the studies.

The investigators analyzed coffee consumption among 1,620 adults with MS and 2,788 healthy controls in the Swedish Epidemiological Investigation of Multiple Sclerosis (EIMS). They also examined coffee consumption in 1,159 adults with MS and 1,172 healthy controls in the Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Plan, Northern California Region (KPNC).

In EIMS, the adjusted odds ratio (OR) for developing MS was 0.70 among participants who drank more than six cups of coffee (ie, greater than 900 mL) daily at the index year, which was defined as the year of the initial appearance of symptoms indicative of MS. The corresponding ORs for those who reported high coffee consumption at five or 10 years before the study were 0.72 and 0.71, respectively, but these results were not statistically significant.

In KPNC, those who consumed four or more cups of coffee (ie, more than 948 mL) daily were significantly less likely to develop MS than were those who never drank coffee (OR, 0.69). In addition, people who drank four or more cups of coffee daily at least five years prior to the index year had significantly reduced odds of MS (OR, 0.64).

A meta-analysis of the combined results of the two studies indicated a significant 29% reduction in the likelihood of developing MS among the people with the greatest coffee consumption (ie, greater than 900 mL daily in EIMS and greater than 948 mL in KPNC). The investigators adjusted all the analyses for many demographic and environmental risk factors for MS, including age, gender, residential area, ancestry, smoking habits, exposure to passive smoking, sun exposure habits, and BMI at age 20.

No evidence indicated any associations between increased amounts of tea or soda intake and MS.

“Further studies are required to establish if it is in fact caffeine, or if there is another molecule in coffee underlying the findings, to longitudinally assess the association between consumption of coffee and disease activity in MS, and to evaluate the mechanisms by which coffee may be acting, which could thus lead to new therapeutic targets,” the researchers concluded.

—Lori Laubach

High coffee consumption decreases the odds of developing multiple sclerosis (MS), according to two case–control studies published online ahead of print March 3 in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. Anna K. Hedström, MD, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, and her associates conducted the studies.

The investigators analyzed coffee consumption among 1,620 adults with MS and 2,788 healthy controls in the Swedish Epidemiological Investigation of Multiple Sclerosis (EIMS). They also examined coffee consumption in 1,159 adults with MS and 1,172 healthy controls in the Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Plan, Northern California Region (KPNC).

In EIMS, the adjusted odds ratio (OR) for developing MS was 0.70 among participants who drank more than six cups of coffee (ie, greater than 900 mL) daily at the index year, which was defined as the year of the initial appearance of symptoms indicative of MS. The corresponding ORs for those who reported high coffee consumption at five or 10 years before the study were 0.72 and 0.71, respectively, but these results were not statistically significant.

In KPNC, those who consumed four or more cups of coffee (ie, more than 948 mL) daily were significantly less likely to develop MS than were those who never drank coffee (OR, 0.69). In addition, people who drank four or more cups of coffee daily at least five years prior to the index year had significantly reduced odds of MS (OR, 0.64).

A meta-analysis of the combined results of the two studies indicated a significant 29% reduction in the likelihood of developing MS among the people with the greatest coffee consumption (ie, greater than 900 mL daily in EIMS and greater than 948 mL in KPNC). The investigators adjusted all the analyses for many demographic and environmental risk factors for MS, including age, gender, residential area, ancestry, smoking habits, exposure to passive smoking, sun exposure habits, and BMI at age 20.

No evidence indicated any associations between increased amounts of tea or soda intake and MS.

“Further studies are required to establish if it is in fact caffeine, or if there is another molecule in coffee underlying the findings, to longitudinally assess the association between consumption of coffee and disease activity in MS, and to evaluate the mechanisms by which coffee may be acting, which could thus lead to new therapeutic targets,” the researchers concluded.

—Lori Laubach

Suggested Reading

Hedström AK, Mowry EM, Gianfrancesco MA, et al. High consumption of coffee is associated with decreased multiple sclerosis risk; results from two independent studies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016 March 3 [Epub ahead of print].

Suggested Reading

Hedström AK, Mowry EM, Gianfrancesco MA, et al. High consumption of coffee is associated with decreased multiple sclerosis risk; results from two independent studies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016 March 3 [Epub ahead of print].

Home infusion policies called out in ACR position statement

Proper administration of intravenous biologics should take place under the close supervision of a physician in a physician’s office, infusion center, or hospital rather than in a patient’s home in order to address potential infusion reactions that can range from mild to life threatening, according to a position statement issued by the American College of Rheumatology’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care.

The “Patient Safety and Site of Service for Infusible Biologics” statement, issued in late February, comes in opposition to “policies that require home infusion” that appear to seek potential cost savings with home infusions rather than meet the standard of care with on-site physician supervision.

“One observation made by some but not all payers is that infusible biologics are about twice as expensive when infused in a hospital-based infusion center as compared to other locations, such as a clinic-based infusion center or the patient’s home. Thus, some payers are rolling out policies designed to shift patients from hospital-based infusion centers to less expensive sites. The ACR is opposed to policies that would force patients, solely for the purpose of cost containment, to receive infusible biologics in an improperly supervised setting. The purpose of the position statement is to outline that stance,” Dr. Douglas W. White, chair of the ACR’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care, said in an interview.

He noted that he’s “been in on conversations with two payers who are implementing policies to move patients away from hospital-based infusions, but we are aware that others are in various stages of implementing such policies, too. It’s not so much an issue of critical mass for us, rather we’re just trying to keep ahead of the trends, and we think this will be a big trend.”

The potential for adverse reactions is not uncommon during intravenous administration of biologics, the committee wrote, noting, for example, that 10% of patients given infliximab have acute infusion reactions. On-site physicians such as rheumatologists who have experience with the “tremendous heterogeneity of patients with autoimmune disease and the diversity of conditions treated with biologics” can determine the severity of infusion reactions and decide whether or not it is safe to continue a particular biologic agent, in addition to providing reassurance to patients during acute and potentially severe reactions, according to the ACR statement.

Infusion reactions can range in severity from a mild rash to life-threatening anaphylaxis that can involve multiple organ systems leading to respiratory and cardiovascular collapse and requiring immediate treatment with medications such as epinephrine or intravenous glucocorticoids.

The position statement recognizes unusual situations in which home infusion is necessary for a patient to receive treatment because of transportation problems to a medical facility or comorbid conditions in which the risk of no treatment may outweigh the risk of home infusion. In these circumstances, the ACR “encourages providers in such unusual and difficult situations to make the best medical decision based on the individual needs of the patient. Routine home infusion of biologics is considered an unnecessary and dangerous risk to patients and violates our current clinical standards of practice.”

Requirements for using home infusion also threaten “to reduce access to” intravenous biologics, the ACR contends, because “specially trained physicians are less likely to prescribe treatments that are not properly administered in the safest clinical setting [and] patient fear of biologic therapy may lead to noncompliance and inadequate control of disease.”

The ACR noted that home administration of subcutaneous biologics is medically appropriate and the injection site reactions that can occur with their use are often easily managed.

Proper administration of intravenous biologics should take place under the close supervision of a physician in a physician’s office, infusion center, or hospital rather than in a patient’s home in order to address potential infusion reactions that can range from mild to life threatening, according to a position statement issued by the American College of Rheumatology’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care.

The “Patient Safety and Site of Service for Infusible Biologics” statement, issued in late February, comes in opposition to “policies that require home infusion” that appear to seek potential cost savings with home infusions rather than meet the standard of care with on-site physician supervision.

“One observation made by some but not all payers is that infusible biologics are about twice as expensive when infused in a hospital-based infusion center as compared to other locations, such as a clinic-based infusion center or the patient’s home. Thus, some payers are rolling out policies designed to shift patients from hospital-based infusion centers to less expensive sites. The ACR is opposed to policies that would force patients, solely for the purpose of cost containment, to receive infusible biologics in an improperly supervised setting. The purpose of the position statement is to outline that stance,” Dr. Douglas W. White, chair of the ACR’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care, said in an interview.

He noted that he’s “been in on conversations with two payers who are implementing policies to move patients away from hospital-based infusions, but we are aware that others are in various stages of implementing such policies, too. It’s not so much an issue of critical mass for us, rather we’re just trying to keep ahead of the trends, and we think this will be a big trend.”

The potential for adverse reactions is not uncommon during intravenous administration of biologics, the committee wrote, noting, for example, that 10% of patients given infliximab have acute infusion reactions. On-site physicians such as rheumatologists who have experience with the “tremendous heterogeneity of patients with autoimmune disease and the diversity of conditions treated with biologics” can determine the severity of infusion reactions and decide whether or not it is safe to continue a particular biologic agent, in addition to providing reassurance to patients during acute and potentially severe reactions, according to the ACR statement.

Infusion reactions can range in severity from a mild rash to life-threatening anaphylaxis that can involve multiple organ systems leading to respiratory and cardiovascular collapse and requiring immediate treatment with medications such as epinephrine or intravenous glucocorticoids.

The position statement recognizes unusual situations in which home infusion is necessary for a patient to receive treatment because of transportation problems to a medical facility or comorbid conditions in which the risk of no treatment may outweigh the risk of home infusion. In these circumstances, the ACR “encourages providers in such unusual and difficult situations to make the best medical decision based on the individual needs of the patient. Routine home infusion of biologics is considered an unnecessary and dangerous risk to patients and violates our current clinical standards of practice.”

Requirements for using home infusion also threaten “to reduce access to” intravenous biologics, the ACR contends, because “specially trained physicians are less likely to prescribe treatments that are not properly administered in the safest clinical setting [and] patient fear of biologic therapy may lead to noncompliance and inadequate control of disease.”

The ACR noted that home administration of subcutaneous biologics is medically appropriate and the injection site reactions that can occur with their use are often easily managed.

Proper administration of intravenous biologics should take place under the close supervision of a physician in a physician’s office, infusion center, or hospital rather than in a patient’s home in order to address potential infusion reactions that can range from mild to life threatening, according to a position statement issued by the American College of Rheumatology’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care.

The “Patient Safety and Site of Service for Infusible Biologics” statement, issued in late February, comes in opposition to “policies that require home infusion” that appear to seek potential cost savings with home infusions rather than meet the standard of care with on-site physician supervision.

“One observation made by some but not all payers is that infusible biologics are about twice as expensive when infused in a hospital-based infusion center as compared to other locations, such as a clinic-based infusion center or the patient’s home. Thus, some payers are rolling out policies designed to shift patients from hospital-based infusion centers to less expensive sites. The ACR is opposed to policies that would force patients, solely for the purpose of cost containment, to receive infusible biologics in an improperly supervised setting. The purpose of the position statement is to outline that stance,” Dr. Douglas W. White, chair of the ACR’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care, said in an interview.

He noted that he’s “been in on conversations with two payers who are implementing policies to move patients away from hospital-based infusions, but we are aware that others are in various stages of implementing such policies, too. It’s not so much an issue of critical mass for us, rather we’re just trying to keep ahead of the trends, and we think this will be a big trend.”

The potential for adverse reactions is not uncommon during intravenous administration of biologics, the committee wrote, noting, for example, that 10% of patients given infliximab have acute infusion reactions. On-site physicians such as rheumatologists who have experience with the “tremendous heterogeneity of patients with autoimmune disease and the diversity of conditions treated with biologics” can determine the severity of infusion reactions and decide whether or not it is safe to continue a particular biologic agent, in addition to providing reassurance to patients during acute and potentially severe reactions, according to the ACR statement.

Infusion reactions can range in severity from a mild rash to life-threatening anaphylaxis that can involve multiple organ systems leading to respiratory and cardiovascular collapse and requiring immediate treatment with medications such as epinephrine or intravenous glucocorticoids.

The position statement recognizes unusual situations in which home infusion is necessary for a patient to receive treatment because of transportation problems to a medical facility or comorbid conditions in which the risk of no treatment may outweigh the risk of home infusion. In these circumstances, the ACR “encourages providers in such unusual and difficult situations to make the best medical decision based on the individual needs of the patient. Routine home infusion of biologics is considered an unnecessary and dangerous risk to patients and violates our current clinical standards of practice.”

Requirements for using home infusion also threaten “to reduce access to” intravenous biologics, the ACR contends, because “specially trained physicians are less likely to prescribe treatments that are not properly administered in the safest clinical setting [and] patient fear of biologic therapy may lead to noncompliance and inadequate control of disease.”

The ACR noted that home administration of subcutaneous biologics is medically appropriate and the injection site reactions that can occur with their use are often easily managed.

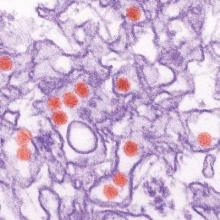

Zika virus: More questions than answers?

With spring break in full swing and summer vacations right around the corner, pediatricians are increasingly fielding questions from families about Zika virus.

“There are a lot of resources available online, but they’re constantly being updated, and it’s difficult to stay current,” a friend and fellow pediatrician confided. “It seems like there’s new information every day, but still as many questions as answers.”

A quick PubMed search validated her concern: More than 200 articles have been published about Zika virus since the beginning of the year. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization post new information to their Zika websites regularly, if not daily, and the WHO has released a Zika app for clinicians. Understanding that the busy pediatrician may not always have time to peruse these authoritative references during the course of a day in the office, I’ve compiled some common questions and answers.

“Is Zika really as serious as the media portrays it?” asked the mother of two children as she contemplated Caribbean vacation plans. In truth, most healthy people infected with Zika virus never develop symptoms. Illness, when it occurs, is most often mild and includes low-grade fever, headache, arthralgia, myalgia, nonpurulent conjunctivitis, and a maculopapular rash. Unlike dengue, another Flavivirus carried by Aedes mosquitoes, Zika does not cause hemorrhagic fever, and death appears to be rare.

An understanding of Zika infection and neurologic complications is a work in progress. A 20-fold increase in the incidence of Guillain-Barré (GBS) cases was noted in French Polynesia during a 2013-2014 outbreak of Zika virus.

In a case-control study involving 42 patients hospitalized with GBS, 98% had anti–Zika virus IgM or IgG, and all had neutralizing antibodies against Zika virus, compared with 56% of 98 control patients (P less than .0001 ) (Lancet. 2016 Feb 29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00562-6).

To date, 10 countries or territories have reported GBS cases with confirmed Zika virus infection. According to the World Health Organization, “Zika virus is highly likely to be a cause of the elevated incidence of GBS in countries and territories in the Western Pacific and Americas,” but further research is needed. Zika has recently been associated with other neurologic disorders, including myelitis, and the full spectrum of disease is likely not yet known.

Most Zika virus infections are transmitted from the bite of an Aedes mosquito. What we know about Zika transmission among humans continues to evolve. Viremia can persist for 14 or more days after the onset of symptoms, during which time blood is a potential source of infection. Two possible cases of transfusion-related viral transmission are under investigation in Brazil, and during the French Polynesia outbreak, 3% of samples from asymptomatic blood donors contained detectable Zika RNA. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has recommended that individuals who have lived in or traveled to an area with active Zika virus transmission defer blood donation for 4 weeks after departure from the area .

Zika virus also has been detected in the urine and saliva of infected individuals, but these fluids have not been linked to transmission. Sexual transmission from infected men to their partners is well documented, but the period of risk remains undefined. The virus can persist in the semen long after viremia clears, and in one individual, Zika virus was detected in the semen 62 days after symptom onset.

Maternal-fetal transmission can occur as early as the first trimester and as late as at the time of delivery. Zika virus has been recovered from both amniotic fluid and placentas. The consequences of maternal-fetal transmission are less certain. Coincident with an epidemic of Zika in Brazil, that country has observed a marked increase in the incidence of microcephaly. Between Oct. 22, 2015, and March 12, 2016, 6,480 cases of microcephaly and/or central nervous system malformation were reported in Brazil, contrasting sharply with the average of 163 cases reported annually from 2001 to 2014. Zika virus has been linked to 863 cases of microcephaly investigated thus far. Proving causality takes time, but the World Health Organization says the link between microcephaly and Zika infection is “strongly suspected.”

Because of the association between Zika virus and birth defects, including abnormal brain development, eye abnormalities, and hearing deficits, the CDC currently recommends that pregnant women not travel to areas with Zika transmission, while men who have lived in or traveled to an area with Zika and who have a pregnant partner should either use condoms or not have sex for the duration of the pregnancy.

The good news for nonpregnant women who contract Zika infection is that the infection is not thought to pose any risk to future pregnancies. Currently, there is no evidence that a fetus conceived after maternal viremia has resolved would be at risk for infection. Still, many unanswered questions remain about Zika infection during pregnancy. For example, it’s currently unknown how often infection is transmitted from an infected mother to her fetus, or if infection is more severe at a particular point in gestation.

Although Zika virus has been isolated from breast milk, no infections have been linked to breastfeeding, and mothers are encouraged to continue to nurse, even in areas with widespread transmission. Infection with Zika at the time of birth or later in childhood has not been linked to microcephaly. Beyond that, the long-term health outcomes of infants and children with Zika virus infection are unknown.

“How far north do you think the virus will spread?” one mom asked me. “Do I need to be worried?”

For public health officials, that’s the sixty-four thousand dollar question. To date, there have been no cases acquired as a result of a mosquito bite in the United States, but the edge of the outbreak continues to creep north. Local transmission of the virus was reported in Cuba on March 14.

As of March 16, 2016, 258 travel-associated Zika virus cases have been diagnosed in the United States, including 18 in pregnant women. Six of these were sexually transmitted. Theoretically, “onward transmission” from one of these cases could occur if the right kind of mosquito bites an infected person during the period of active viremia and then bites someone else, transferring a tiny amount of the virus-contaminated blood.

According to CDC experts, “Texas, Florida, and Hawaii are likely to be the U.S. states with the highest risk of experiencing local transmission of Zika virus by mosquitoes.” Although this estimate is based on prior experience with similar viruses, the principal vector of Zika, Aedes aegypti, has been identified as far west as California and in a number of states across the South, including my home state of Kentucky. Aedes albopictus mosquitoes also have been proven competent vectors for Zika virus transmission and are more widely distributed throughout the continental United States.

In a thoughtful review published in JAMA Pediatrics, “What Pediatricians and Other Clinicians Should Know About Zika Virus,” Dr. Mark W. Kline and Dr. Gordon E. Schutze noted that up to two-thirds of the U.S. population live in an area where Aedes mosquitoes are present at least part of the year (JAMA Pediatr. 2016 Feb 18. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0429). Fortunately, transmission of dengue and chikungunya, two other viruses carried by the same insect, is still very uncommon. Public health experts are urging individuals with Zika virus infection to avoid mosquito bites during the first week of illness, to protect others.

We should start now counseling our patients and families to avoid mosquito bites at home and abroad. Besides Zika virus, mosquitoes transmit several pathogens in the United States each year, including West Nile virus, LaCrosse encephalitis virus, St. Louis encephalitis virus, and dengue.

Any collections of standing water should be eliminated, as these can be mosquito breeding grounds. These include flower pots, buckets, barrels, and discarded tires. The water in bird baths and pet dishes should be changed at least weekly, and children’s wading pools should be drained and stored on their side after use.

To the extent practical, exposed skin should be covered with long-sleeved shirts, long pants, and socks when individuals are in areas with mosquito activity. To enhance protection, clothing can be treated with permethrin, or pretreated clothing can be worn. An FDA-registered insect repellent should be applied to exposed skin, especially during hours of highest mosquito activity. Zika-carrying mosquitoes bite during the day, or dawn to dusk. Effective repellents include DEET, picaridin, IR3535, and oil of lemon eucalyptus, although families should read labels carefully as instructions for use vary, as does the recommended time period of reapplication. Combination sunscreen/insect repellent products are not recommended as repellent usually does not need to be reapplied as often as sunscreen. Parents also should be reminded not to use oil of lemon eucalyptus–containing products on children under 3 years of age.

“We’re going to get a lot more questions as the weather turns warmer,” said a colleague of mine. “I’m just waiting for the first call about a child who develops fever and a rash after a mosquito bite. Parents will wonder if it could be Zika.”

It is going to be an interesting summer. Stay tuned.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Kosair Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She had no relevant financial disclosures.

With spring break in full swing and summer vacations right around the corner, pediatricians are increasingly fielding questions from families about Zika virus.

“There are a lot of resources available online, but they’re constantly being updated, and it’s difficult to stay current,” a friend and fellow pediatrician confided. “It seems like there’s new information every day, but still as many questions as answers.”

A quick PubMed search validated her concern: More than 200 articles have been published about Zika virus since the beginning of the year. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization post new information to their Zika websites regularly, if not daily, and the WHO has released a Zika app for clinicians. Understanding that the busy pediatrician may not always have time to peruse these authoritative references during the course of a day in the office, I’ve compiled some common questions and answers.

“Is Zika really as serious as the media portrays it?” asked the mother of two children as she contemplated Caribbean vacation plans. In truth, most healthy people infected with Zika virus never develop symptoms. Illness, when it occurs, is most often mild and includes low-grade fever, headache, arthralgia, myalgia, nonpurulent conjunctivitis, and a maculopapular rash. Unlike dengue, another Flavivirus carried by Aedes mosquitoes, Zika does not cause hemorrhagic fever, and death appears to be rare.

An understanding of Zika infection and neurologic complications is a work in progress. A 20-fold increase in the incidence of Guillain-Barré (GBS) cases was noted in French Polynesia during a 2013-2014 outbreak of Zika virus.

In a case-control study involving 42 patients hospitalized with GBS, 98% had anti–Zika virus IgM or IgG, and all had neutralizing antibodies against Zika virus, compared with 56% of 98 control patients (P less than .0001 ) (Lancet. 2016 Feb 29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00562-6).

To date, 10 countries or territories have reported GBS cases with confirmed Zika virus infection. According to the World Health Organization, “Zika virus is highly likely to be a cause of the elevated incidence of GBS in countries and territories in the Western Pacific and Americas,” but further research is needed. Zika has recently been associated with other neurologic disorders, including myelitis, and the full spectrum of disease is likely not yet known.

Most Zika virus infections are transmitted from the bite of an Aedes mosquito. What we know about Zika transmission among humans continues to evolve. Viremia can persist for 14 or more days after the onset of symptoms, during which time blood is a potential source of infection. Two possible cases of transfusion-related viral transmission are under investigation in Brazil, and during the French Polynesia outbreak, 3% of samples from asymptomatic blood donors contained detectable Zika RNA. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has recommended that individuals who have lived in or traveled to an area with active Zika virus transmission defer blood donation for 4 weeks after departure from the area .

Zika virus also has been detected in the urine and saliva of infected individuals, but these fluids have not been linked to transmission. Sexual transmission from infected men to their partners is well documented, but the period of risk remains undefined. The virus can persist in the semen long after viremia clears, and in one individual, Zika virus was detected in the semen 62 days after symptom onset.

Maternal-fetal transmission can occur as early as the first trimester and as late as at the time of delivery. Zika virus has been recovered from both amniotic fluid and placentas. The consequences of maternal-fetal transmission are less certain. Coincident with an epidemic of Zika in Brazil, that country has observed a marked increase in the incidence of microcephaly. Between Oct. 22, 2015, and March 12, 2016, 6,480 cases of microcephaly and/or central nervous system malformation were reported in Brazil, contrasting sharply with the average of 163 cases reported annually from 2001 to 2014. Zika virus has been linked to 863 cases of microcephaly investigated thus far. Proving causality takes time, but the World Health Organization says the link between microcephaly and Zika infection is “strongly suspected.”

Because of the association between Zika virus and birth defects, including abnormal brain development, eye abnormalities, and hearing deficits, the CDC currently recommends that pregnant women not travel to areas with Zika transmission, while men who have lived in or traveled to an area with Zika and who have a pregnant partner should either use condoms or not have sex for the duration of the pregnancy.

The good news for nonpregnant women who contract Zika infection is that the infection is not thought to pose any risk to future pregnancies. Currently, there is no evidence that a fetus conceived after maternal viremia has resolved would be at risk for infection. Still, many unanswered questions remain about Zika infection during pregnancy. For example, it’s currently unknown how often infection is transmitted from an infected mother to her fetus, or if infection is more severe at a particular point in gestation.

Although Zika virus has been isolated from breast milk, no infections have been linked to breastfeeding, and mothers are encouraged to continue to nurse, even in areas with widespread transmission. Infection with Zika at the time of birth or later in childhood has not been linked to microcephaly. Beyond that, the long-term health outcomes of infants and children with Zika virus infection are unknown.

“How far north do you think the virus will spread?” one mom asked me. “Do I need to be worried?”

For public health officials, that’s the sixty-four thousand dollar question. To date, there have been no cases acquired as a result of a mosquito bite in the United States, but the edge of the outbreak continues to creep north. Local transmission of the virus was reported in Cuba on March 14.

As of March 16, 2016, 258 travel-associated Zika virus cases have been diagnosed in the United States, including 18 in pregnant women. Six of these were sexually transmitted. Theoretically, “onward transmission” from one of these cases could occur if the right kind of mosquito bites an infected person during the period of active viremia and then bites someone else, transferring a tiny amount of the virus-contaminated blood.

According to CDC experts, “Texas, Florida, and Hawaii are likely to be the U.S. states with the highest risk of experiencing local transmission of Zika virus by mosquitoes.” Although this estimate is based on prior experience with similar viruses, the principal vector of Zika, Aedes aegypti, has been identified as far west as California and in a number of states across the South, including my home state of Kentucky. Aedes albopictus mosquitoes also have been proven competent vectors for Zika virus transmission and are more widely distributed throughout the continental United States.

In a thoughtful review published in JAMA Pediatrics, “What Pediatricians and Other Clinicians Should Know About Zika Virus,” Dr. Mark W. Kline and Dr. Gordon E. Schutze noted that up to two-thirds of the U.S. population live in an area where Aedes mosquitoes are present at least part of the year (JAMA Pediatr. 2016 Feb 18. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0429). Fortunately, transmission of dengue and chikungunya, two other viruses carried by the same insect, is still very uncommon. Public health experts are urging individuals with Zika virus infection to avoid mosquito bites during the first week of illness, to protect others.

We should start now counseling our patients and families to avoid mosquito bites at home and abroad. Besides Zika virus, mosquitoes transmit several pathogens in the United States each year, including West Nile virus, LaCrosse encephalitis virus, St. Louis encephalitis virus, and dengue.

Any collections of standing water should be eliminated, as these can be mosquito breeding grounds. These include flower pots, buckets, barrels, and discarded tires. The water in bird baths and pet dishes should be changed at least weekly, and children’s wading pools should be drained and stored on their side after use.

To the extent practical, exposed skin should be covered with long-sleeved shirts, long pants, and socks when individuals are in areas with mosquito activity. To enhance protection, clothing can be treated with permethrin, or pretreated clothing can be worn. An FDA-registered insect repellent should be applied to exposed skin, especially during hours of highest mosquito activity. Zika-carrying mosquitoes bite during the day, or dawn to dusk. Effective repellents include DEET, picaridin, IR3535, and oil of lemon eucalyptus, although families should read labels carefully as instructions for use vary, as does the recommended time period of reapplication. Combination sunscreen/insect repellent products are not recommended as repellent usually does not need to be reapplied as often as sunscreen. Parents also should be reminded not to use oil of lemon eucalyptus–containing products on children under 3 years of age.

“We’re going to get a lot more questions as the weather turns warmer,” said a colleague of mine. “I’m just waiting for the first call about a child who develops fever and a rash after a mosquito bite. Parents will wonder if it could be Zika.”

It is going to be an interesting summer. Stay tuned.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Kosair Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She had no relevant financial disclosures.

With spring break in full swing and summer vacations right around the corner, pediatricians are increasingly fielding questions from families about Zika virus.

“There are a lot of resources available online, but they’re constantly being updated, and it’s difficult to stay current,” a friend and fellow pediatrician confided. “It seems like there’s new information every day, but still as many questions as answers.”

A quick PubMed search validated her concern: More than 200 articles have been published about Zika virus since the beginning of the year. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization post new information to their Zika websites regularly, if not daily, and the WHO has released a Zika app for clinicians. Understanding that the busy pediatrician may not always have time to peruse these authoritative references during the course of a day in the office, I’ve compiled some common questions and answers.

“Is Zika really as serious as the media portrays it?” asked the mother of two children as she contemplated Caribbean vacation plans. In truth, most healthy people infected with Zika virus never develop symptoms. Illness, when it occurs, is most often mild and includes low-grade fever, headache, arthralgia, myalgia, nonpurulent conjunctivitis, and a maculopapular rash. Unlike dengue, another Flavivirus carried by Aedes mosquitoes, Zika does not cause hemorrhagic fever, and death appears to be rare.

An understanding of Zika infection and neurologic complications is a work in progress. A 20-fold increase in the incidence of Guillain-Barré (GBS) cases was noted in French Polynesia during a 2013-2014 outbreak of Zika virus.

In a case-control study involving 42 patients hospitalized with GBS, 98% had anti–Zika virus IgM or IgG, and all had neutralizing antibodies against Zika virus, compared with 56% of 98 control patients (P less than .0001 ) (Lancet. 2016 Feb 29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00562-6).

To date, 10 countries or territories have reported GBS cases with confirmed Zika virus infection. According to the World Health Organization, “Zika virus is highly likely to be a cause of the elevated incidence of GBS in countries and territories in the Western Pacific and Americas,” but further research is needed. Zika has recently been associated with other neurologic disorders, including myelitis, and the full spectrum of disease is likely not yet known.

Most Zika virus infections are transmitted from the bite of an Aedes mosquito. What we know about Zika transmission among humans continues to evolve. Viremia can persist for 14 or more days after the onset of symptoms, during which time blood is a potential source of infection. Two possible cases of transfusion-related viral transmission are under investigation in Brazil, and during the French Polynesia outbreak, 3% of samples from asymptomatic blood donors contained detectable Zika RNA. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has recommended that individuals who have lived in or traveled to an area with active Zika virus transmission defer blood donation for 4 weeks after departure from the area .

Zika virus also has been detected in the urine and saliva of infected individuals, but these fluids have not been linked to transmission. Sexual transmission from infected men to their partners is well documented, but the period of risk remains undefined. The virus can persist in the semen long after viremia clears, and in one individual, Zika virus was detected in the semen 62 days after symptom onset.

Maternal-fetal transmission can occur as early as the first trimester and as late as at the time of delivery. Zika virus has been recovered from both amniotic fluid and placentas. The consequences of maternal-fetal transmission are less certain. Coincident with an epidemic of Zika in Brazil, that country has observed a marked increase in the incidence of microcephaly. Between Oct. 22, 2015, and March 12, 2016, 6,480 cases of microcephaly and/or central nervous system malformation were reported in Brazil, contrasting sharply with the average of 163 cases reported annually from 2001 to 2014. Zika virus has been linked to 863 cases of microcephaly investigated thus far. Proving causality takes time, but the World Health Organization says the link between microcephaly and Zika infection is “strongly suspected.”

Because of the association between Zika virus and birth defects, including abnormal brain development, eye abnormalities, and hearing deficits, the CDC currently recommends that pregnant women not travel to areas with Zika transmission, while men who have lived in or traveled to an area with Zika and who have a pregnant partner should either use condoms or not have sex for the duration of the pregnancy.

The good news for nonpregnant women who contract Zika infection is that the infection is not thought to pose any risk to future pregnancies. Currently, there is no evidence that a fetus conceived after maternal viremia has resolved would be at risk for infection. Still, many unanswered questions remain about Zika infection during pregnancy. For example, it’s currently unknown how often infection is transmitted from an infected mother to her fetus, or if infection is more severe at a particular point in gestation.

Although Zika virus has been isolated from breast milk, no infections have been linked to breastfeeding, and mothers are encouraged to continue to nurse, even in areas with widespread transmission. Infection with Zika at the time of birth or later in childhood has not been linked to microcephaly. Beyond that, the long-term health outcomes of infants and children with Zika virus infection are unknown.

“How far north do you think the virus will spread?” one mom asked me. “Do I need to be worried?”

For public health officials, that’s the sixty-four thousand dollar question. To date, there have been no cases acquired as a result of a mosquito bite in the United States, but the edge of the outbreak continues to creep north. Local transmission of the virus was reported in Cuba on March 14.

As of March 16, 2016, 258 travel-associated Zika virus cases have been diagnosed in the United States, including 18 in pregnant women. Six of these were sexually transmitted. Theoretically, “onward transmission” from one of these cases could occur if the right kind of mosquito bites an infected person during the period of active viremia and then bites someone else, transferring a tiny amount of the virus-contaminated blood.

According to CDC experts, “Texas, Florida, and Hawaii are likely to be the U.S. states with the highest risk of experiencing local transmission of Zika virus by mosquitoes.” Although this estimate is based on prior experience with similar viruses, the principal vector of Zika, Aedes aegypti, has been identified as far west as California and in a number of states across the South, including my home state of Kentucky. Aedes albopictus mosquitoes also have been proven competent vectors for Zika virus transmission and are more widely distributed throughout the continental United States.

In a thoughtful review published in JAMA Pediatrics, “What Pediatricians and Other Clinicians Should Know About Zika Virus,” Dr. Mark W. Kline and Dr. Gordon E. Schutze noted that up to two-thirds of the U.S. population live in an area where Aedes mosquitoes are present at least part of the year (JAMA Pediatr. 2016 Feb 18. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0429). Fortunately, transmission of dengue and chikungunya, two other viruses carried by the same insect, is still very uncommon. Public health experts are urging individuals with Zika virus infection to avoid mosquito bites during the first week of illness, to protect others.

We should start now counseling our patients and families to avoid mosquito bites at home and abroad. Besides Zika virus, mosquitoes transmit several pathogens in the United States each year, including West Nile virus, LaCrosse encephalitis virus, St. Louis encephalitis virus, and dengue.

Any collections of standing water should be eliminated, as these can be mosquito breeding grounds. These include flower pots, buckets, barrels, and discarded tires. The water in bird baths and pet dishes should be changed at least weekly, and children’s wading pools should be drained and stored on their side after use.

To the extent practical, exposed skin should be covered with long-sleeved shirts, long pants, and socks when individuals are in areas with mosquito activity. To enhance protection, clothing can be treated with permethrin, or pretreated clothing can be worn. An FDA-registered insect repellent should be applied to exposed skin, especially during hours of highest mosquito activity. Zika-carrying mosquitoes bite during the day, or dawn to dusk. Effective repellents include DEET, picaridin, IR3535, and oil of lemon eucalyptus, although families should read labels carefully as instructions for use vary, as does the recommended time period of reapplication. Combination sunscreen/insect repellent products are not recommended as repellent usually does not need to be reapplied as often as sunscreen. Parents also should be reminded not to use oil of lemon eucalyptus–containing products on children under 3 years of age.

“We’re going to get a lot more questions as the weather turns warmer,” said a colleague of mine. “I’m just waiting for the first call about a child who develops fever and a rash after a mosquito bite. Parents will wonder if it could be Zika.”

It is going to be an interesting summer. Stay tuned.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Kosair Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She had no relevant financial disclosures.

Finding the right path for pain control

There has been a lot of publicity surrounding the increasing use of prescription painkillers and subsequent increase in deaths. In 2014, there were close to 19,000 deaths related to opioid painkiller overdose. State and federal governments have reacted with various initiatives, from changing the scheduling of Vicodin, to initiating prescription drug–monitoring programs, to limiting the number of pills dispensed. There are loud voices on either side of this debate, to be sure, but perhaps none so aggravating as the aggravated patient.

I did not start my practice with any prescribing “policy,” as I thought such policies were arbitrary. I am a physician, after all, so why wouldn’t I prescribe a narcotic if necessary? I also trained at a time when pain was considered “the fifth vital sign,” and we were taught to treat it aggressively.

But after a while you learn that trust in patients can be misplaced. You never forget the first nice lady whose urine drug screen comes back negative when you expected it to show the narcotic that you were prescribing her. You never forget the person who calls on a weekend claiming to be a patient of the practice and turns out not to be. And when your colleague gets her DEA number stolen and her signature forged, you finally learn that humanity is imperfect. What’s more, in your transition from young naive doctor to elder statesman, you learn that the push to treat pain so aggressively was achieved, in large part, by lobbying from the pharmaceutical industry.