User login

Drug gets orphan designation for chronic ITP

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to the SYK inhibitor fostamatinib as a treatment for patients

with chronic immune thrombocytopenia (ITP).

Fostamatinib (also known as R935788 or R788) has been shown to increase platelet counts in patients with chronic ITP.

The drug, which comes in tablet form, is thought to prevent macrophages from destroying platelets by inhibiting SYK activation.

Fostamatinib previously produced promising results in a phase 2 trial of ITP patients and is now under investigation in a pair of phase 3 trials (NCT02076412 and NCT02076399).

Results from these trials are expected in mid-2016, according to Rigel Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing fostamatinib.

Phase 2 trial

The trial included 16 adults with chronic ITP. Fostamatinib doses began at 75 mg and were increased until a patient experienced a persistent response, toxicity occurred, or the patient reached the maximum dose—175 mg twice daily.

Eight patients achieved persistent responses. They maintained platelet counts above 50,000/mm3 on a median of 95% of study visits and were able to avoid receiving other treatments.

Four other patients experienced transient responses. They had an increase in platelet count from a median minimum of 17,000/mm3 at baseline to a median maximum of 177,000/mm3.

In all 12 responders, the median platelet count increased from 16,000/mm3 at baseline to a median peak of 105,000/mm3 while on fostamatinib.

Adverse events considered probably related to fostamatinib were diarrhea (n=6), an increase in systolic blood pressure of more than 10 mm Hg (n=5), nausea (n=4), headache (n=4), weight gain of more than 5 kg (n=3), vomiting (n=3), abdominal pain (n=3), constipation (n=2), and alanine aminotransferase levels greater than 2 times the upper limit of normal (n=2).

Three patients stopped treatment due to adverse events. One patient developed a urinary tract infection and deep vein thrombosis (both considered unrelated to treatment).

The second patient withdrew consent due to gastrointestinal toxicity. And the last patient withdrew consent due to preexisting elevated transaminase levels that worsened on fostamatinib and prevented increases in the dose.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to drugs that are intended to treat diseases or conditions affecting fewer than 200,000 patients in the US.

Orphan designation provides the sponsor of a drug with various development incentives, including opportunities to apply for research-related tax credits and

grant funding, assistance in designing clinical trials, and 7 years of US marketing exclusivity if the drug is approved. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to the SYK inhibitor fostamatinib as a treatment for patients

with chronic immune thrombocytopenia (ITP).

Fostamatinib (also known as R935788 or R788) has been shown to increase platelet counts in patients with chronic ITP.

The drug, which comes in tablet form, is thought to prevent macrophages from destroying platelets by inhibiting SYK activation.

Fostamatinib previously produced promising results in a phase 2 trial of ITP patients and is now under investigation in a pair of phase 3 trials (NCT02076412 and NCT02076399).

Results from these trials are expected in mid-2016, according to Rigel Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing fostamatinib.

Phase 2 trial

The trial included 16 adults with chronic ITP. Fostamatinib doses began at 75 mg and were increased until a patient experienced a persistent response, toxicity occurred, or the patient reached the maximum dose—175 mg twice daily.

Eight patients achieved persistent responses. They maintained platelet counts above 50,000/mm3 on a median of 95% of study visits and were able to avoid receiving other treatments.

Four other patients experienced transient responses. They had an increase in platelet count from a median minimum of 17,000/mm3 at baseline to a median maximum of 177,000/mm3.

In all 12 responders, the median platelet count increased from 16,000/mm3 at baseline to a median peak of 105,000/mm3 while on fostamatinib.

Adverse events considered probably related to fostamatinib were diarrhea (n=6), an increase in systolic blood pressure of more than 10 mm Hg (n=5), nausea (n=4), headache (n=4), weight gain of more than 5 kg (n=3), vomiting (n=3), abdominal pain (n=3), constipation (n=2), and alanine aminotransferase levels greater than 2 times the upper limit of normal (n=2).

Three patients stopped treatment due to adverse events. One patient developed a urinary tract infection and deep vein thrombosis (both considered unrelated to treatment).

The second patient withdrew consent due to gastrointestinal toxicity. And the last patient withdrew consent due to preexisting elevated transaminase levels that worsened on fostamatinib and prevented increases in the dose.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to drugs that are intended to treat diseases or conditions affecting fewer than 200,000 patients in the US.

Orphan designation provides the sponsor of a drug with various development incentives, including opportunities to apply for research-related tax credits and

grant funding, assistance in designing clinical trials, and 7 years of US marketing exclusivity if the drug is approved. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to the SYK inhibitor fostamatinib as a treatment for patients

with chronic immune thrombocytopenia (ITP).

Fostamatinib (also known as R935788 or R788) has been shown to increase platelet counts in patients with chronic ITP.

The drug, which comes in tablet form, is thought to prevent macrophages from destroying platelets by inhibiting SYK activation.

Fostamatinib previously produced promising results in a phase 2 trial of ITP patients and is now under investigation in a pair of phase 3 trials (NCT02076412 and NCT02076399).

Results from these trials are expected in mid-2016, according to Rigel Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing fostamatinib.

Phase 2 trial

The trial included 16 adults with chronic ITP. Fostamatinib doses began at 75 mg and were increased until a patient experienced a persistent response, toxicity occurred, or the patient reached the maximum dose—175 mg twice daily.

Eight patients achieved persistent responses. They maintained platelet counts above 50,000/mm3 on a median of 95% of study visits and were able to avoid receiving other treatments.

Four other patients experienced transient responses. They had an increase in platelet count from a median minimum of 17,000/mm3 at baseline to a median maximum of 177,000/mm3.

In all 12 responders, the median platelet count increased from 16,000/mm3 at baseline to a median peak of 105,000/mm3 while on fostamatinib.

Adverse events considered probably related to fostamatinib were diarrhea (n=6), an increase in systolic blood pressure of more than 10 mm Hg (n=5), nausea (n=4), headache (n=4), weight gain of more than 5 kg (n=3), vomiting (n=3), abdominal pain (n=3), constipation (n=2), and alanine aminotransferase levels greater than 2 times the upper limit of normal (n=2).

Three patients stopped treatment due to adverse events. One patient developed a urinary tract infection and deep vein thrombosis (both considered unrelated to treatment).

The second patient withdrew consent due to gastrointestinal toxicity. And the last patient withdrew consent due to preexisting elevated transaminase levels that worsened on fostamatinib and prevented increases in the dose.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to drugs that are intended to treat diseases or conditions affecting fewer than 200,000 patients in the US.

Orphan designation provides the sponsor of a drug with various development incentives, including opportunities to apply for research-related tax credits and

grant funding, assistance in designing clinical trials, and 7 years of US marketing exclusivity if the drug is approved. ![]()

Extensive Skin Necrosis From Suspected Levamisole-Contaminated Cocaine

To the Editor:

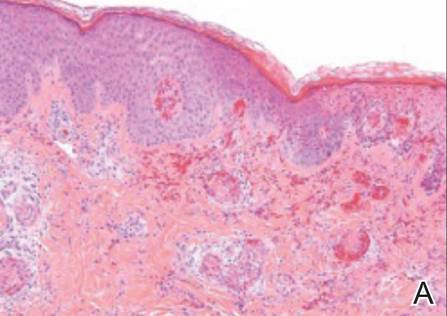

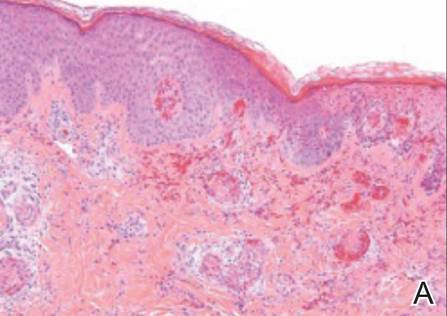

A 52-year-old man presented to the emergency department with skin pain. Although he felt well overall, he reported that he had developed skin sores 3 weeks prior to presentation that were progressively causing skin pain and sleep loss. He acknowledged smoking cigarettes and snorting cocaine but denied intravenous use of cocaine or using any other drugs. His usual medications were lisinopril and tramadol, and he had no known drug allergies. His history was remarkable for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) septic arthritis of the shoulder and MRSA prepatellar bursitis within the last 2 years. During examination in the emergency department he was alert, afebrile, nontoxic, generally healthy, and in no acute distress. Extensive necrotic skin lesions were present on the trunk, extremities, and both ears. The lesions were large necrotic patches with irregular, sharply angulated borders with thin or ulcerated epidermis surrounded by a bright halo of erythema (Figure 1). Ulcers were noted on the tongue (Figure 2).

|

| Figure 1. Extensive skin necrosis on the leg from levamisole-contaminated cocaine (A). Necrotic skin lesions also were present on the trunk, arm (B), and ear (C). |

The clinical diagnosis was probable thrombosis of skin vessels with skin necrosis due to cocaine that was likely contaminated with levamisole. Pertinent laboratory results included the following: mild anemia and mild leukopenia; values within reference range for liver function, serum protein electrophoresis, hepatitis profile, human immunodeficiency virus 1 and 2, rapid plasma reagin, and antinuclear antibody; normal thrombotic studies for antithrombin III, protein C, protein S, factor V Leiden, prothrombin mutation G20210A, anticardiolipin IgG, IgM, and IgA; erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 26 mm/h (reference range, 0–15 mm/h); perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody greater than 1:320 (reference range, <1:20) with normal proteinase 3 and myeloperoxidase antibodies; urine positive for cocaine but blood negative for cocaine; normal chest radiograph; and normal electrocardiogram.

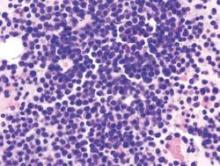

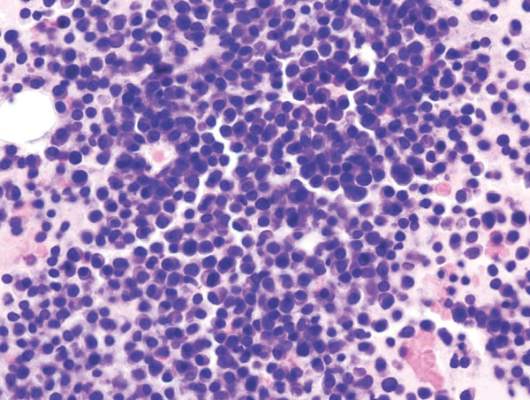

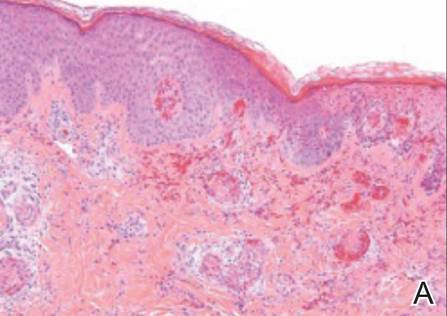

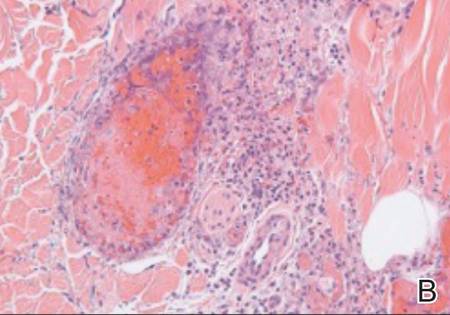

The patient was stable with good family support and was discharged from the emergency department to be followed in our dermatology office. The following day his skin biopsies were interpreted as neutrophilic vasculitis with extensive intravascular early and organizing thrombi involving all small- and medium-sized blood vessels consistent with levamisole-induced necrosis or septic vasculitis (Figure 3). With his history of MRSA septic arthritis and bursitis, he was hospitalized for treatment with intravenous vancomycin pending further studies. Skin biopsy for direct immunofluorescence revealed granular deposits of IgM and linear deposits of C3 at the dermoepidermal junction and in blood vessel walls. Two tissue cultures for bacteria and fungi were negative and 2 blood cultures were negative. An echocardiogram was normal and without evidence of emboli. The patient remained stable and antibiotics were discontinued. He was released from the hospital and his skin lesions healed satisfactorily with showering and mupirocin ointment.

|

| Figure 3. Thrombotic occlusion of blood vessels was seen on histopathology (A and B)(H&E, original magnifications ×100 and ×400).

|

Cocaine is a white powder that is primarily derived from the leaves of the coca plant in South America. It is ingested orally; injected intravenously; snorted intranasally; chewed; eaten; used as a suppository; or dissolved in water and baking soda then heated to crystallization for smoking, which is the most addictive method and known as freebasing. When smoked, crack cocaine produces a crackling sound. Cocaine stimulates the central nervous system similar to amphetamine but may harm any body organ through vasoconstriction/vasospasm and cause skin necrosis without any additive. Perhaps less known is its ability to produce smooth muscle hyperplasia of small vessels and premature atherosclerosis.1

Levamisole has been used to treat worms, cancer, and stimulation of the immune system but currently is used only by veterinarians because of agranulocytosis and vasculitis in humans. As of July 2009, the Drug Enforcement Agency reported that 69% of seized cocaine lots coming into the United States contained levamisole.2 By January 2010, 73.2% of seized cocaine exhibits contained levamisole according to the California Poison Control System, with reports of contamination rates from across the country ranging from 40% to 90%.3 Levamisole is an inexpensive additive to cocaine and may increase the release of brain dopamine.4 It is difficult to detect levamisole in urine due to its short half-life of 5.6 hours and only 2% to 5% of the parent compound being found in the urine.5

Skin necrosis due to cocaine-contaminated levamisole usually occurs in younger individuals who have characteristic skin lesions and a history of cocaine use. Skin lesions usually are multiple, purpuric or necrotic with irregular angulated edges and a halo of erythema. Ear involvement is common but not invariable.6 Descriptive adjectives include branched, netlike, retiform, and stellate, all revealing the compromised underlying dermal and subcutaneous vascular anatomy. Supportive evidence includes a decreased white blood cell count (neutropenia in up to 50%),5 positive antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies,5,7 and/or positive drug screen. Skin biopsy may reveal thrombosis,4 fibrin thrombi without vasculitis,8 or leukocytoclastic vasculitis,4,5 or may suggest septic vasculitis.9 Direct immunofluorescence may suggest an immune complex-mediated vasculitis.5

The differential diagnosis for a patient with purpuric/necrotic skin lesions should be broad and include vasculitis (eg, inflammatory, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody positive, septic), hypercoagulopathy (eg, antiphospholipid syndrome, antithrombin III, prothrombin mutation G20210A, factor V Leiden, protein C, protein S), drugs (eg, heparin, warfarin, cocaine with or without levamisole, intravenous drug use, hydroxyurea, ergotamine, propylthiouracil10), calciphylaxis, cold-induced thrombosis, emboli (eg, atheroma, cholesterol, endocarditis, myxoma, aortic angiosarcoma, marantic), febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease, infection especially if immunosuppressed (eg, disseminated Acanthamoeba/Candida/histoplasmosis/strongyloides/varicella-zoster virus, S aureus, streptococcus, ecthyma gangrenosum, gas gangrene, hemorrhagic smallpox, lues maligna with human immunodeficiency virus, Meleney ulcer, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Vibrio vulnificus), idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, thrombocythemia, Waldenström hyperglobulinemic purpura, pyoderma gangrenosum, cancer (eg, paraneoplastic arterial thrombi), oxalosis, paraproteinemia (eg, multiple myeloma), and lupus with generalized coagulopathy. Less likely diagnoses might include Degos disease, factitial dermatitis, foreign bodies, multiple spider bites, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, sickle cell anemia, Buruli ulcer, or thromboangiitis obliterans. Branched, angulated, retiform lesions are an important finding, and some of these diagnostic possibilities are not classically retiform. However, clinical findings are not always classical, and astute physicians want to be circumspect. Had more ominous findings been present in our patient (eg, fever, hemodynamic instability, progressive skin lesions, systemic organ involvement), prompt hospitalization and additional considerations would have been necessary, such as septicemia (eg, meningococcemia, bubonic plague [Black Death], necrotizing fasciitis, purpura fulminans), catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome, or disseminated intra- vascular coagulation.

The prognosis for skin necrosis caused by levamisole-contaminated cocaine generally is good without long-term sequelae.5 Autoantibody serologies normalize within weeks to months after stopping levamisole.5,8 Our patient recovered with conservative measures.

1. Dhawan SS, Wang BW. Four-extremity gangrene associated with crack cocaine abuse [published online ahead of print October 23, 2006]. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:186-189.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Agranulocytosis associated with cocaine use—four states, March 2008–November 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:1381-1385.

3. Buchanan J; California Poison Control System. Levamisole-contaminated cocaine. Call Us… December 3, 2014. http://www.calpoison.org/hcp/2014/ callusvol12no3.htm. Accessed September 1, 2015.

4. Mouzakis J, Somboonwit C, Lakshmi S, et al. Levamisole induced necrosis of the skin and neutropenia following intranasal cocaine use: a newly recognized syndrome. J Drugs Dermatology. 2011;10:1204-1207.

5. Chung C, Tumeh PC, Birnbaum R, et al. Characteristic purpura of the ears, vasculitis, and neutropenia—a potential public health epidemic associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine [published online ahead of print June 11, 2011]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:722-725.

6. Farhat EK, Muirhead TT, Chaffins ML, et al. Levamisole-induced cutaneous necrosis mimicking coagulopathy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;46:1320-1321.

7. Geller L, Whang TB, Mercer SE. Retiform purpura: a new stigmata of illicit drug use? Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:7.

8. Waller JM, Feramisco JD, Alberta-Wszolek L, et al. Cocaine-associated retiform purpura and neutropenia: is levamisole the culprit [published online ahead of print March 20, 2010]? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:530-535.

9. Reutemann P, Grenier N, Telang GH. Occlusive vasculopathy with vascular and skin necrosis secondary to smoking crack cocaine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1004-1006.

10. Mahmood T, Delacerda A, Fiala K. Painful purpura on bilateral helices. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:551-552.

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old man presented to the emergency department with skin pain. Although he felt well overall, he reported that he had developed skin sores 3 weeks prior to presentation that were progressively causing skin pain and sleep loss. He acknowledged smoking cigarettes and snorting cocaine but denied intravenous use of cocaine or using any other drugs. His usual medications were lisinopril and tramadol, and he had no known drug allergies. His history was remarkable for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) septic arthritis of the shoulder and MRSA prepatellar bursitis within the last 2 years. During examination in the emergency department he was alert, afebrile, nontoxic, generally healthy, and in no acute distress. Extensive necrotic skin lesions were present on the trunk, extremities, and both ears. The lesions were large necrotic patches with irregular, sharply angulated borders with thin or ulcerated epidermis surrounded by a bright halo of erythema (Figure 1). Ulcers were noted on the tongue (Figure 2).

|

| Figure 1. Extensive skin necrosis on the leg from levamisole-contaminated cocaine (A). Necrotic skin lesions also were present on the trunk, arm (B), and ear (C). |

The clinical diagnosis was probable thrombosis of skin vessels with skin necrosis due to cocaine that was likely contaminated with levamisole. Pertinent laboratory results included the following: mild anemia and mild leukopenia; values within reference range for liver function, serum protein electrophoresis, hepatitis profile, human immunodeficiency virus 1 and 2, rapid plasma reagin, and antinuclear antibody; normal thrombotic studies for antithrombin III, protein C, protein S, factor V Leiden, prothrombin mutation G20210A, anticardiolipin IgG, IgM, and IgA; erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 26 mm/h (reference range, 0–15 mm/h); perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody greater than 1:320 (reference range, <1:20) with normal proteinase 3 and myeloperoxidase antibodies; urine positive for cocaine but blood negative for cocaine; normal chest radiograph; and normal electrocardiogram.

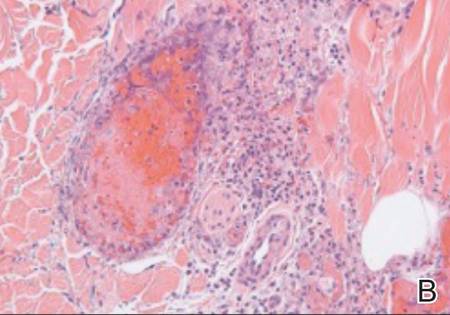

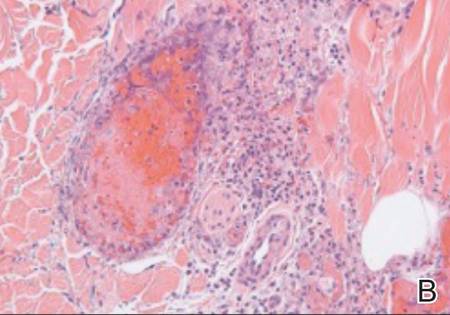

The patient was stable with good family support and was discharged from the emergency department to be followed in our dermatology office. The following day his skin biopsies were interpreted as neutrophilic vasculitis with extensive intravascular early and organizing thrombi involving all small- and medium-sized blood vessels consistent with levamisole-induced necrosis or septic vasculitis (Figure 3). With his history of MRSA septic arthritis and bursitis, he was hospitalized for treatment with intravenous vancomycin pending further studies. Skin biopsy for direct immunofluorescence revealed granular deposits of IgM and linear deposits of C3 at the dermoepidermal junction and in blood vessel walls. Two tissue cultures for bacteria and fungi were negative and 2 blood cultures were negative. An echocardiogram was normal and without evidence of emboli. The patient remained stable and antibiotics were discontinued. He was released from the hospital and his skin lesions healed satisfactorily with showering and mupirocin ointment.

|

| Figure 3. Thrombotic occlusion of blood vessels was seen on histopathology (A and B)(H&E, original magnifications ×100 and ×400).

|

Cocaine is a white powder that is primarily derived from the leaves of the coca plant in South America. It is ingested orally; injected intravenously; snorted intranasally; chewed; eaten; used as a suppository; or dissolved in water and baking soda then heated to crystallization for smoking, which is the most addictive method and known as freebasing. When smoked, crack cocaine produces a crackling sound. Cocaine stimulates the central nervous system similar to amphetamine but may harm any body organ through vasoconstriction/vasospasm and cause skin necrosis without any additive. Perhaps less known is its ability to produce smooth muscle hyperplasia of small vessels and premature atherosclerosis.1

Levamisole has been used to treat worms, cancer, and stimulation of the immune system but currently is used only by veterinarians because of agranulocytosis and vasculitis in humans. As of July 2009, the Drug Enforcement Agency reported that 69% of seized cocaine lots coming into the United States contained levamisole.2 By January 2010, 73.2% of seized cocaine exhibits contained levamisole according to the California Poison Control System, with reports of contamination rates from across the country ranging from 40% to 90%.3 Levamisole is an inexpensive additive to cocaine and may increase the release of brain dopamine.4 It is difficult to detect levamisole in urine due to its short half-life of 5.6 hours and only 2% to 5% of the parent compound being found in the urine.5

Skin necrosis due to cocaine-contaminated levamisole usually occurs in younger individuals who have characteristic skin lesions and a history of cocaine use. Skin lesions usually are multiple, purpuric or necrotic with irregular angulated edges and a halo of erythema. Ear involvement is common but not invariable.6 Descriptive adjectives include branched, netlike, retiform, and stellate, all revealing the compromised underlying dermal and subcutaneous vascular anatomy. Supportive evidence includes a decreased white blood cell count (neutropenia in up to 50%),5 positive antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies,5,7 and/or positive drug screen. Skin biopsy may reveal thrombosis,4 fibrin thrombi without vasculitis,8 or leukocytoclastic vasculitis,4,5 or may suggest septic vasculitis.9 Direct immunofluorescence may suggest an immune complex-mediated vasculitis.5

The differential diagnosis for a patient with purpuric/necrotic skin lesions should be broad and include vasculitis (eg, inflammatory, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody positive, septic), hypercoagulopathy (eg, antiphospholipid syndrome, antithrombin III, prothrombin mutation G20210A, factor V Leiden, protein C, protein S), drugs (eg, heparin, warfarin, cocaine with or without levamisole, intravenous drug use, hydroxyurea, ergotamine, propylthiouracil10), calciphylaxis, cold-induced thrombosis, emboli (eg, atheroma, cholesterol, endocarditis, myxoma, aortic angiosarcoma, marantic), febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease, infection especially if immunosuppressed (eg, disseminated Acanthamoeba/Candida/histoplasmosis/strongyloides/varicella-zoster virus, S aureus, streptococcus, ecthyma gangrenosum, gas gangrene, hemorrhagic smallpox, lues maligna with human immunodeficiency virus, Meleney ulcer, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Vibrio vulnificus), idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, thrombocythemia, Waldenström hyperglobulinemic purpura, pyoderma gangrenosum, cancer (eg, paraneoplastic arterial thrombi), oxalosis, paraproteinemia (eg, multiple myeloma), and lupus with generalized coagulopathy. Less likely diagnoses might include Degos disease, factitial dermatitis, foreign bodies, multiple spider bites, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, sickle cell anemia, Buruli ulcer, or thromboangiitis obliterans. Branched, angulated, retiform lesions are an important finding, and some of these diagnostic possibilities are not classically retiform. However, clinical findings are not always classical, and astute physicians want to be circumspect. Had more ominous findings been present in our patient (eg, fever, hemodynamic instability, progressive skin lesions, systemic organ involvement), prompt hospitalization and additional considerations would have been necessary, such as septicemia (eg, meningococcemia, bubonic plague [Black Death], necrotizing fasciitis, purpura fulminans), catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome, or disseminated intra- vascular coagulation.

The prognosis for skin necrosis caused by levamisole-contaminated cocaine generally is good without long-term sequelae.5 Autoantibody serologies normalize within weeks to months after stopping levamisole.5,8 Our patient recovered with conservative measures.

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old man presented to the emergency department with skin pain. Although he felt well overall, he reported that he had developed skin sores 3 weeks prior to presentation that were progressively causing skin pain and sleep loss. He acknowledged smoking cigarettes and snorting cocaine but denied intravenous use of cocaine or using any other drugs. His usual medications were lisinopril and tramadol, and he had no known drug allergies. His history was remarkable for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) septic arthritis of the shoulder and MRSA prepatellar bursitis within the last 2 years. During examination in the emergency department he was alert, afebrile, nontoxic, generally healthy, and in no acute distress. Extensive necrotic skin lesions were present on the trunk, extremities, and both ears. The lesions were large necrotic patches with irregular, sharply angulated borders with thin or ulcerated epidermis surrounded by a bright halo of erythema (Figure 1). Ulcers were noted on the tongue (Figure 2).

|

| Figure 1. Extensive skin necrosis on the leg from levamisole-contaminated cocaine (A). Necrotic skin lesions also were present on the trunk, arm (B), and ear (C). |

The clinical diagnosis was probable thrombosis of skin vessels with skin necrosis due to cocaine that was likely contaminated with levamisole. Pertinent laboratory results included the following: mild anemia and mild leukopenia; values within reference range for liver function, serum protein electrophoresis, hepatitis profile, human immunodeficiency virus 1 and 2, rapid plasma reagin, and antinuclear antibody; normal thrombotic studies for antithrombin III, protein C, protein S, factor V Leiden, prothrombin mutation G20210A, anticardiolipin IgG, IgM, and IgA; erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 26 mm/h (reference range, 0–15 mm/h); perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody greater than 1:320 (reference range, <1:20) with normal proteinase 3 and myeloperoxidase antibodies; urine positive for cocaine but blood negative for cocaine; normal chest radiograph; and normal electrocardiogram.

The patient was stable with good family support and was discharged from the emergency department to be followed in our dermatology office. The following day his skin biopsies were interpreted as neutrophilic vasculitis with extensive intravascular early and organizing thrombi involving all small- and medium-sized blood vessels consistent with levamisole-induced necrosis or septic vasculitis (Figure 3). With his history of MRSA septic arthritis and bursitis, he was hospitalized for treatment with intravenous vancomycin pending further studies. Skin biopsy for direct immunofluorescence revealed granular deposits of IgM and linear deposits of C3 at the dermoepidermal junction and in blood vessel walls. Two tissue cultures for bacteria and fungi were negative and 2 blood cultures were negative. An echocardiogram was normal and without evidence of emboli. The patient remained stable and antibiotics were discontinued. He was released from the hospital and his skin lesions healed satisfactorily with showering and mupirocin ointment.

|

| Figure 3. Thrombotic occlusion of blood vessels was seen on histopathology (A and B)(H&E, original magnifications ×100 and ×400).

|

Cocaine is a white powder that is primarily derived from the leaves of the coca plant in South America. It is ingested orally; injected intravenously; snorted intranasally; chewed; eaten; used as a suppository; or dissolved in water and baking soda then heated to crystallization for smoking, which is the most addictive method and known as freebasing. When smoked, crack cocaine produces a crackling sound. Cocaine stimulates the central nervous system similar to amphetamine but may harm any body organ through vasoconstriction/vasospasm and cause skin necrosis without any additive. Perhaps less known is its ability to produce smooth muscle hyperplasia of small vessels and premature atherosclerosis.1

Levamisole has been used to treat worms, cancer, and stimulation of the immune system but currently is used only by veterinarians because of agranulocytosis and vasculitis in humans. As of July 2009, the Drug Enforcement Agency reported that 69% of seized cocaine lots coming into the United States contained levamisole.2 By January 2010, 73.2% of seized cocaine exhibits contained levamisole according to the California Poison Control System, with reports of contamination rates from across the country ranging from 40% to 90%.3 Levamisole is an inexpensive additive to cocaine and may increase the release of brain dopamine.4 It is difficult to detect levamisole in urine due to its short half-life of 5.6 hours and only 2% to 5% of the parent compound being found in the urine.5

Skin necrosis due to cocaine-contaminated levamisole usually occurs in younger individuals who have characteristic skin lesions and a history of cocaine use. Skin lesions usually are multiple, purpuric or necrotic with irregular angulated edges and a halo of erythema. Ear involvement is common but not invariable.6 Descriptive adjectives include branched, netlike, retiform, and stellate, all revealing the compromised underlying dermal and subcutaneous vascular anatomy. Supportive evidence includes a decreased white blood cell count (neutropenia in up to 50%),5 positive antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies,5,7 and/or positive drug screen. Skin biopsy may reveal thrombosis,4 fibrin thrombi without vasculitis,8 or leukocytoclastic vasculitis,4,5 or may suggest septic vasculitis.9 Direct immunofluorescence may suggest an immune complex-mediated vasculitis.5

The differential diagnosis for a patient with purpuric/necrotic skin lesions should be broad and include vasculitis (eg, inflammatory, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody positive, septic), hypercoagulopathy (eg, antiphospholipid syndrome, antithrombin III, prothrombin mutation G20210A, factor V Leiden, protein C, protein S), drugs (eg, heparin, warfarin, cocaine with or without levamisole, intravenous drug use, hydroxyurea, ergotamine, propylthiouracil10), calciphylaxis, cold-induced thrombosis, emboli (eg, atheroma, cholesterol, endocarditis, myxoma, aortic angiosarcoma, marantic), febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease, infection especially if immunosuppressed (eg, disseminated Acanthamoeba/Candida/histoplasmosis/strongyloides/varicella-zoster virus, S aureus, streptococcus, ecthyma gangrenosum, gas gangrene, hemorrhagic smallpox, lues maligna with human immunodeficiency virus, Meleney ulcer, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Vibrio vulnificus), idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, thrombocythemia, Waldenström hyperglobulinemic purpura, pyoderma gangrenosum, cancer (eg, paraneoplastic arterial thrombi), oxalosis, paraproteinemia (eg, multiple myeloma), and lupus with generalized coagulopathy. Less likely diagnoses might include Degos disease, factitial dermatitis, foreign bodies, multiple spider bites, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, sickle cell anemia, Buruli ulcer, or thromboangiitis obliterans. Branched, angulated, retiform lesions are an important finding, and some of these diagnostic possibilities are not classically retiform. However, clinical findings are not always classical, and astute physicians want to be circumspect. Had more ominous findings been present in our patient (eg, fever, hemodynamic instability, progressive skin lesions, systemic organ involvement), prompt hospitalization and additional considerations would have been necessary, such as septicemia (eg, meningococcemia, bubonic plague [Black Death], necrotizing fasciitis, purpura fulminans), catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome, or disseminated intra- vascular coagulation.

The prognosis for skin necrosis caused by levamisole-contaminated cocaine generally is good without long-term sequelae.5 Autoantibody serologies normalize within weeks to months after stopping levamisole.5,8 Our patient recovered with conservative measures.

1. Dhawan SS, Wang BW. Four-extremity gangrene associated with crack cocaine abuse [published online ahead of print October 23, 2006]. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:186-189.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Agranulocytosis associated with cocaine use—four states, March 2008–November 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:1381-1385.

3. Buchanan J; California Poison Control System. Levamisole-contaminated cocaine. Call Us… December 3, 2014. http://www.calpoison.org/hcp/2014/ callusvol12no3.htm. Accessed September 1, 2015.

4. Mouzakis J, Somboonwit C, Lakshmi S, et al. Levamisole induced necrosis of the skin and neutropenia following intranasal cocaine use: a newly recognized syndrome. J Drugs Dermatology. 2011;10:1204-1207.

5. Chung C, Tumeh PC, Birnbaum R, et al. Characteristic purpura of the ears, vasculitis, and neutropenia—a potential public health epidemic associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine [published online ahead of print June 11, 2011]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:722-725.

6. Farhat EK, Muirhead TT, Chaffins ML, et al. Levamisole-induced cutaneous necrosis mimicking coagulopathy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;46:1320-1321.

7. Geller L, Whang TB, Mercer SE. Retiform purpura: a new stigmata of illicit drug use? Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:7.

8. Waller JM, Feramisco JD, Alberta-Wszolek L, et al. Cocaine-associated retiform purpura and neutropenia: is levamisole the culprit [published online ahead of print March 20, 2010]? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:530-535.

9. Reutemann P, Grenier N, Telang GH. Occlusive vasculopathy with vascular and skin necrosis secondary to smoking crack cocaine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1004-1006.

10. Mahmood T, Delacerda A, Fiala K. Painful purpura on bilateral helices. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:551-552.

1. Dhawan SS, Wang BW. Four-extremity gangrene associated with crack cocaine abuse [published online ahead of print October 23, 2006]. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:186-189.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Agranulocytosis associated with cocaine use—four states, March 2008–November 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:1381-1385.

3. Buchanan J; California Poison Control System. Levamisole-contaminated cocaine. Call Us… December 3, 2014. http://www.calpoison.org/hcp/2014/ callusvol12no3.htm. Accessed September 1, 2015.

4. Mouzakis J, Somboonwit C, Lakshmi S, et al. Levamisole induced necrosis of the skin and neutropenia following intranasal cocaine use: a newly recognized syndrome. J Drugs Dermatology. 2011;10:1204-1207.

5. Chung C, Tumeh PC, Birnbaum R, et al. Characteristic purpura of the ears, vasculitis, and neutropenia—a potential public health epidemic associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine [published online ahead of print June 11, 2011]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:722-725.

6. Farhat EK, Muirhead TT, Chaffins ML, et al. Levamisole-induced cutaneous necrosis mimicking coagulopathy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;46:1320-1321.

7. Geller L, Whang TB, Mercer SE. Retiform purpura: a new stigmata of illicit drug use? Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:7.

8. Waller JM, Feramisco JD, Alberta-Wszolek L, et al. Cocaine-associated retiform purpura and neutropenia: is levamisole the culprit [published online ahead of print March 20, 2010]? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:530-535.

9. Reutemann P, Grenier N, Telang GH. Occlusive vasculopathy with vascular and skin necrosis secondary to smoking crack cocaine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1004-1006.

10. Mahmood T, Delacerda A, Fiala K. Painful purpura on bilateral helices. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:551-552.

Agent blocks STAT3 protein and might prevent AML relapse

The discovery of a new therapeutic target site on the STAT3 oncoprotein – a protein that interferes with chemotherapy by halting deaths of cancerous cells – could cut down on acute myeloid leukemia (AML) relapse in chemoresistant patients, according to research published in Angewandte Chemie.

The STAT3 protein – which stands for “signal transducer and activator of transcription 3” – is a suspected factor in the relapse of nearly 40% of children with AML. A team of researchers from Rice University, working with colleagues at Baylor College of Medicine and the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, all in Houston, developed a proximity-driven rhodium (II) catalyst known as MM-206, which blocks STAT3 function by identifying the STAT3 coiled-coil domain as a novel ligand-binding site and delivering a naphthalene sulfonamide inhibitor, thus halting the disease promoting effects of STAT3.

The effects were replicated in tumor growth models and testing in a leukemia mouse model suggest this approach can be used to shut down STAT3 activity in AML patients, according to coauthor Dr. Zachary Ball of the department of chemistry at Rice.

Read the full article here: Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015 Sep 7. doi: 10.1002/anie.201506889.

The discovery of a new therapeutic target site on the STAT3 oncoprotein – a protein that interferes with chemotherapy by halting deaths of cancerous cells – could cut down on acute myeloid leukemia (AML) relapse in chemoresistant patients, according to research published in Angewandte Chemie.

The STAT3 protein – which stands for “signal transducer and activator of transcription 3” – is a suspected factor in the relapse of nearly 40% of children with AML. A team of researchers from Rice University, working with colleagues at Baylor College of Medicine and the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, all in Houston, developed a proximity-driven rhodium (II) catalyst known as MM-206, which blocks STAT3 function by identifying the STAT3 coiled-coil domain as a novel ligand-binding site and delivering a naphthalene sulfonamide inhibitor, thus halting the disease promoting effects of STAT3.

The effects were replicated in tumor growth models and testing in a leukemia mouse model suggest this approach can be used to shut down STAT3 activity in AML patients, according to coauthor Dr. Zachary Ball of the department of chemistry at Rice.

Read the full article here: Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015 Sep 7. doi: 10.1002/anie.201506889.

The discovery of a new therapeutic target site on the STAT3 oncoprotein – a protein that interferes with chemotherapy by halting deaths of cancerous cells – could cut down on acute myeloid leukemia (AML) relapse in chemoresistant patients, according to research published in Angewandte Chemie.

The STAT3 protein – which stands for “signal transducer and activator of transcription 3” – is a suspected factor in the relapse of nearly 40% of children with AML. A team of researchers from Rice University, working with colleagues at Baylor College of Medicine and the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, all in Houston, developed a proximity-driven rhodium (II) catalyst known as MM-206, which blocks STAT3 function by identifying the STAT3 coiled-coil domain as a novel ligand-binding site and delivering a naphthalene sulfonamide inhibitor, thus halting the disease promoting effects of STAT3.

The effects were replicated in tumor growth models and testing in a leukemia mouse model suggest this approach can be used to shut down STAT3 activity in AML patients, according to coauthor Dr. Zachary Ball of the department of chemistry at Rice.

Read the full article here: Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015 Sep 7. doi: 10.1002/anie.201506889.

FROM ANGEWANDTE CHEMIE

ESC: Too much TV boosts PE risk

LONDON – Middle-aged adults who watch TV for an average of 5 or more hours per night face an adjusted 6.5-fold increased risk of fatal pulmonary embolism, compared with those who watch less than 2.5 hours per night, Toru Shirakawa reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

This was the key lesson gleaned from an analysis from the Japan Collaborative Cohort Study, the first large-scale prospective investigation of the relationship between prolonged television watching and pulmonary embolism (PE). The study included 86,024 Japanese participants aged 40-79 years prospectively followed for a median of 18.4 years, explained Mr. Shirakawa, a medical student at Osaka (Japan) University.

And while many busy medical professionals might presume 5 hours–plus of TV watching per night constitutes extreme behavior, that’s hardly the case. Indeed, according to the Nielsen survey, American adults watch an average of 4.85 hours of TV nightly.

During the study period there were 59 confirmed deaths from PE. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for sex and baseline age, cardiovascular risk factors, and physical activity level, a strong dose-response relationship was evident between hours of TV viewing and fatal PE.

This association was most pronounced in the 40- to 59-year-olds. Using as a reference group subjects who watched less than 2.5 hours per day, those who watched 2.5-4.9 hours had an adjusted 3.14-fold increased risk of fatal PE. Individuals who watched 5 hours or more – less than the average length of two American football games – were at 6.49-fold increased risk.

The same dose-response association was evident in the full study population spanning ages 40 through 79 years at entry. However, the magnitude of risk attributable to prolonged television watching in the overall group wasn’t as great, since 60- to 79-year-olds face multiple age-related competing mortality risks. Still, 40- to 79-year-olds who watched at least 5 hours of TV daily had an adjusted 2.36-fold greater risk of fatal PE, compared with those who watched for less than 2.5 hours.

Mr. Shirakawa observed that the mechanism of injury is presumably the same as previously reported in studies of “shelter death” during the bombing of London during World War II, as well as “economy-class syndrome,” first described in conjunction with long-distance airplane flights in 1954. Basically, prolonged leg immobility leads to inadequate circulation and resultant venous clot formation. But prolonged TV watching is a much more common risk factor than is economy-class syndrome, he noted.

“The take-home message is this: Public awareness of the risk of pulmonary embolism from lengthy leg immobility is essential. To prevent the occurrence of pulmonary embolism, we recommend the same preventive behavior used against economy-class syndrome. That is, take a break, stand up, and walk around during the television viewing. And drink water to prevent dehydration; that is also important,” Mr. Shirakawa said.

Session cochair Dr. José Ramón González Juanatey observed that the true burden of PE triggered by prolonged TV watching is far greater than documented in the Japanese study because the analysis focused exclusively on fatal cases.

“Only about 10% of cases of pulmonary embolism are immediately fatal events,” commented Dr. González Juanatey of the University of Santiago de Compostela and president of the Spanish Society of Cardiology.

“The absolute risk may be fairly small, but it’s a devastating thing to have happen to you,” added cochair Dr. Ian Graham, professor of cardiovascular medicine at Trinity College, Dublin.

The Japan Collaborative Cohort Study has been funded by scientific grants from various Japanese health and education ministries. Mr. Shirakawa reported having no financial conflicts.

LONDON – Middle-aged adults who watch TV for an average of 5 or more hours per night face an adjusted 6.5-fold increased risk of fatal pulmonary embolism, compared with those who watch less than 2.5 hours per night, Toru Shirakawa reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

This was the key lesson gleaned from an analysis from the Japan Collaborative Cohort Study, the first large-scale prospective investigation of the relationship between prolonged television watching and pulmonary embolism (PE). The study included 86,024 Japanese participants aged 40-79 years prospectively followed for a median of 18.4 years, explained Mr. Shirakawa, a medical student at Osaka (Japan) University.

And while many busy medical professionals might presume 5 hours–plus of TV watching per night constitutes extreme behavior, that’s hardly the case. Indeed, according to the Nielsen survey, American adults watch an average of 4.85 hours of TV nightly.

During the study period there were 59 confirmed deaths from PE. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for sex and baseline age, cardiovascular risk factors, and physical activity level, a strong dose-response relationship was evident between hours of TV viewing and fatal PE.

This association was most pronounced in the 40- to 59-year-olds. Using as a reference group subjects who watched less than 2.5 hours per day, those who watched 2.5-4.9 hours had an adjusted 3.14-fold increased risk of fatal PE. Individuals who watched 5 hours or more – less than the average length of two American football games – were at 6.49-fold increased risk.

The same dose-response association was evident in the full study population spanning ages 40 through 79 years at entry. However, the magnitude of risk attributable to prolonged television watching in the overall group wasn’t as great, since 60- to 79-year-olds face multiple age-related competing mortality risks. Still, 40- to 79-year-olds who watched at least 5 hours of TV daily had an adjusted 2.36-fold greater risk of fatal PE, compared with those who watched for less than 2.5 hours.

Mr. Shirakawa observed that the mechanism of injury is presumably the same as previously reported in studies of “shelter death” during the bombing of London during World War II, as well as “economy-class syndrome,” first described in conjunction with long-distance airplane flights in 1954. Basically, prolonged leg immobility leads to inadequate circulation and resultant venous clot formation. But prolonged TV watching is a much more common risk factor than is economy-class syndrome, he noted.

“The take-home message is this: Public awareness of the risk of pulmonary embolism from lengthy leg immobility is essential. To prevent the occurrence of pulmonary embolism, we recommend the same preventive behavior used against economy-class syndrome. That is, take a break, stand up, and walk around during the television viewing. And drink water to prevent dehydration; that is also important,” Mr. Shirakawa said.

Session cochair Dr. José Ramón González Juanatey observed that the true burden of PE triggered by prolonged TV watching is far greater than documented in the Japanese study because the analysis focused exclusively on fatal cases.

“Only about 10% of cases of pulmonary embolism are immediately fatal events,” commented Dr. González Juanatey of the University of Santiago de Compostela and president of the Spanish Society of Cardiology.

“The absolute risk may be fairly small, but it’s a devastating thing to have happen to you,” added cochair Dr. Ian Graham, professor of cardiovascular medicine at Trinity College, Dublin.

The Japan Collaborative Cohort Study has been funded by scientific grants from various Japanese health and education ministries. Mr. Shirakawa reported having no financial conflicts.

LONDON – Middle-aged adults who watch TV for an average of 5 or more hours per night face an adjusted 6.5-fold increased risk of fatal pulmonary embolism, compared with those who watch less than 2.5 hours per night, Toru Shirakawa reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

This was the key lesson gleaned from an analysis from the Japan Collaborative Cohort Study, the first large-scale prospective investigation of the relationship between prolonged television watching and pulmonary embolism (PE). The study included 86,024 Japanese participants aged 40-79 years prospectively followed for a median of 18.4 years, explained Mr. Shirakawa, a medical student at Osaka (Japan) University.

And while many busy medical professionals might presume 5 hours–plus of TV watching per night constitutes extreme behavior, that’s hardly the case. Indeed, according to the Nielsen survey, American adults watch an average of 4.85 hours of TV nightly.

During the study period there were 59 confirmed deaths from PE. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for sex and baseline age, cardiovascular risk factors, and physical activity level, a strong dose-response relationship was evident between hours of TV viewing and fatal PE.

This association was most pronounced in the 40- to 59-year-olds. Using as a reference group subjects who watched less than 2.5 hours per day, those who watched 2.5-4.9 hours had an adjusted 3.14-fold increased risk of fatal PE. Individuals who watched 5 hours or more – less than the average length of two American football games – were at 6.49-fold increased risk.

The same dose-response association was evident in the full study population spanning ages 40 through 79 years at entry. However, the magnitude of risk attributable to prolonged television watching in the overall group wasn’t as great, since 60- to 79-year-olds face multiple age-related competing mortality risks. Still, 40- to 79-year-olds who watched at least 5 hours of TV daily had an adjusted 2.36-fold greater risk of fatal PE, compared with those who watched for less than 2.5 hours.

Mr. Shirakawa observed that the mechanism of injury is presumably the same as previously reported in studies of “shelter death” during the bombing of London during World War II, as well as “economy-class syndrome,” first described in conjunction with long-distance airplane flights in 1954. Basically, prolonged leg immobility leads to inadequate circulation and resultant venous clot formation. But prolonged TV watching is a much more common risk factor than is economy-class syndrome, he noted.

“The take-home message is this: Public awareness of the risk of pulmonary embolism from lengthy leg immobility is essential. To prevent the occurrence of pulmonary embolism, we recommend the same preventive behavior used against economy-class syndrome. That is, take a break, stand up, and walk around during the television viewing. And drink water to prevent dehydration; that is also important,” Mr. Shirakawa said.

Session cochair Dr. José Ramón González Juanatey observed that the true burden of PE triggered by prolonged TV watching is far greater than documented in the Japanese study because the analysis focused exclusively on fatal cases.

“Only about 10% of cases of pulmonary embolism are immediately fatal events,” commented Dr. González Juanatey of the University of Santiago de Compostela and president of the Spanish Society of Cardiology.

“The absolute risk may be fairly small, but it’s a devastating thing to have happen to you,” added cochair Dr. Ian Graham, professor of cardiovascular medicine at Trinity College, Dublin.

The Japan Collaborative Cohort Study has been funded by scientific grants from various Japanese health and education ministries. Mr. Shirakawa reported having no financial conflicts.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2015

Key clinical point: Tuning in to the television for an average of 5 hours or more per day is independently associated with a sharply increased pulmonary embolism risk.

Major finding: Middle-aged Japanese adults who spent 5 or more hours per day watching television were at an adjusted 6.5-fold greater risk of fatal pulmonary embolism than were those who averaged less than 2.5 hours of viewing.

Data source: This prospective Japanese national study included 86,024 participants aged 40-79 years who were followed for a median of 18.4 years.

Disclosures: The Japan Collaborative Cohort Study has been funded by scientific grants from various Japanese health and education ministries. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

ESC: Rivaroxaban safety highlighted in real-world setting

LONDON – The factor Xa inhibitor rivaroxaban was associated with low rates of bleeding and stroke in two observational studies that included more than 45,000 people with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.

The XANTUS (Xarelto for Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation) study involved 6,784 individuals treated at centers in Europe, Canada, and Israel. The incidence of major bleeding was 2.1% per year and the risk of stroke was 0.7% per year. Rates of fatal, critical organ, and intracranial bleeding were also low at 0.2%, 0.7%, and 0.4% per year, respectively.

“The rates of stroke and systemic embolism, all strokes and gastrointestinal bleeding were markedly lower in XANTUS in comparison to ROCKET-AF,” noted Dr. John Camm who presented the XANTUS study findings at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. “Major bleeding was also largely reduced in XANTUS, however the death rate and intracranial hemorrhage rate was similar,” he added.

Dr. Camm, who is professor of clinical cardiology at St George’s Hospital in London, noted that the patient populations and the design of the XANTUS study and phase III ROCKET-AF trial (N Engl J Med. 2011;365:883-91) were slightly different. Patients in the single-arm, prospective, observational XANTUS study were recruited from routine primary care practices and had an overall lower risk of stroke than those enrolled in the randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial who were at more moderate to high risk respective CHADS2 scores of 2.0 and 3.5. The incidence of major bleeding was also slightly higher in the ROCKET-AF, at 3.6% per year, which was similar to that seen with warfarin (3.4%; P = .58), the active comparator used.

Nevertheless, the findings of the XANTUS study, which were published online simultaneously with their presentation at the conference (Eur Heart J. Sep 1. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv466), highlight the “real-world” safety of rivaroxaban, Dr. Camm said.

Results from the separate PMSS (Post-Marketing Safety Surveillance) study reported in a poster at the meeting were similar. The PMSS study is being conducted in the United States and is an ongoing, retrospective, 5-year, observational study of more than 39,000 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. At 2 years follow-up, the incidence of major bleeding was 2.89% per year and the incidence of fatal bleeding was 0.1% per year (Eur Heart J. 2015;36:687.P4066).

“Real-world research is an essential complement to clinical trials and helps inform treatment decisions,” PMSS study investigator Dr. Frank Peacock said in a press release issued by Janssen. Dr. Peacock, who is professor of emergency medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, added, “These studies confirm the safety profile of rivaroxaban in real-world settings around the globe.”

The XANTUS and PMSS studies are part of a large postlicensing program and were respectively designed to meet European Medicines Agency and U.S. Food and Drug Administration requirements on the long-term monitoring of medicines. There are also similar programs running in other world regions, such as XANTUS-EL and XANAP.

Other real-world data gleaned from electronic medical records (EMRs) comparing the potential bleeding risks of the factor Xa inhibitor apixaban (Eliquis) versus other available non–vitamin K antagonists (NOACs) including rivaroxaban and the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran (Pradaxa) were reported in several posters supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer and in an oral presentation given by Dr. Gregory Lip of the University of Birmingham, England.

Two of the posters reported data from retrospective analyses of different United States EMRs of 29,338 and 35, 757 patients, respectively, with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation newly started on a NOAC or warfarin in 2013 or 2014. Most were started on warfarin (43.3%/69.6%), followed by rivaroxaban (34.3%/17.9%), dabigatran (14.2%/6.8%), and apixaban (8.2%/5.7%).

Results of the first study (Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1085.P6217) showed that patients newly starting treatment with a NOAC had significantly lower rates of major bleeding than those starting treatment with warfarin, which was 4.6% per year versus 2.35% per year for apixiban, 3.38% per year for dabigatran, and 4.57% per year for rivaroxaban in the first study.

In the second study (Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1085.P6215) the respective adjusted hazard ratios for bleeding risk were 1.094, 0.747 and 0.679, comparing rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran against warfarin.

Other data gleaned from separate U.S. EMRs suggested that apixaban was associated with fewer bleeding-related hospital readmissions than either rivaroxaban or dabigatran in hospitalized patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (Eur Heart J. 2015;36: 1085.P6211).

Dr. Lip presented 6-month follow-up data on more than 60,000 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation who were treated with one of the three NOACs that was recorded in a U.S. medical claims database (Eur Heart J. 2015;36:339.1975). Most of the patients were treated with rivaroxaban (50.6%), with 34.8% treated with dabigatran and 14.6% with apixaban. Unadjusted data showed that the rates of major bleeding were 20.2% per year, 13.2% per year, and 14.5% per year, respectively.

Dr. Lip observed that, after adjusting the data, patients taking dabigatran had higher rates of clinically relevant nonmajor gastrointestinal bleeding (HR =1.24), and that those taking rivaroxaban were more likely to have major (HR = 3.6), clinically relevant nonmajor (HR = 1.43), or any bleeding (HR = 1.41) when compared with apixaban users.

“Larger cohort studies and longer follow-up data of general nonvalvular atrial fibrillation populations will be needed to confirm these early observations,” Dr. Lip concluded.

While real-world research of course has its limitations and cannot replace clinical trial findings as a means to accurately compare the clinical efficacy or safety profiles of different medicines, such studies do provide information that can help inform clinical practice.

“With 10 million people in Europe alone affected by atrial fibrillation, a number that is only expected to increase, real-world insights on routine anticoagulation management in everyday clinical practice is increasingly important for physicians and patients,” Dr. Camm noted in a media release on the XANTUS trial issued by the European Society of Cardiology.

Dr. Camm added: “These real-world insights from XANTAS complement and expand on what we already know from clinical trials, and provide physicians with reassurance to prescribe rivaroxaban as an effective and well-tolerated treatment option for the broad range of patients with atrial fibrillation seen in their everyday practice.”

The XANTUS and PMSS studies were supported by Bayer HealthCare and Janssen. The other studies mentioned were supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer. Dr. Camm disclosed acting as a consultant for Bayer Healthcare and other health care companies. Dr. Lip disclosed acting as a consultant for Bayer Healthcare, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Pfizer as well as other health care companies.

LONDON – The factor Xa inhibitor rivaroxaban was associated with low rates of bleeding and stroke in two observational studies that included more than 45,000 people with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.

The XANTUS (Xarelto for Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation) study involved 6,784 individuals treated at centers in Europe, Canada, and Israel. The incidence of major bleeding was 2.1% per year and the risk of stroke was 0.7% per year. Rates of fatal, critical organ, and intracranial bleeding were also low at 0.2%, 0.7%, and 0.4% per year, respectively.

“The rates of stroke and systemic embolism, all strokes and gastrointestinal bleeding were markedly lower in XANTUS in comparison to ROCKET-AF,” noted Dr. John Camm who presented the XANTUS study findings at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. “Major bleeding was also largely reduced in XANTUS, however the death rate and intracranial hemorrhage rate was similar,” he added.

Dr. Camm, who is professor of clinical cardiology at St George’s Hospital in London, noted that the patient populations and the design of the XANTUS study and phase III ROCKET-AF trial (N Engl J Med. 2011;365:883-91) were slightly different. Patients in the single-arm, prospective, observational XANTUS study were recruited from routine primary care practices and had an overall lower risk of stroke than those enrolled in the randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial who were at more moderate to high risk respective CHADS2 scores of 2.0 and 3.5. The incidence of major bleeding was also slightly higher in the ROCKET-AF, at 3.6% per year, which was similar to that seen with warfarin (3.4%; P = .58), the active comparator used.

Nevertheless, the findings of the XANTUS study, which were published online simultaneously with their presentation at the conference (Eur Heart J. Sep 1. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv466), highlight the “real-world” safety of rivaroxaban, Dr. Camm said.

Results from the separate PMSS (Post-Marketing Safety Surveillance) study reported in a poster at the meeting were similar. The PMSS study is being conducted in the United States and is an ongoing, retrospective, 5-year, observational study of more than 39,000 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. At 2 years follow-up, the incidence of major bleeding was 2.89% per year and the incidence of fatal bleeding was 0.1% per year (Eur Heart J. 2015;36:687.P4066).

“Real-world research is an essential complement to clinical trials and helps inform treatment decisions,” PMSS study investigator Dr. Frank Peacock said in a press release issued by Janssen. Dr. Peacock, who is professor of emergency medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, added, “These studies confirm the safety profile of rivaroxaban in real-world settings around the globe.”

The XANTUS and PMSS studies are part of a large postlicensing program and were respectively designed to meet European Medicines Agency and U.S. Food and Drug Administration requirements on the long-term monitoring of medicines. There are also similar programs running in other world regions, such as XANTUS-EL and XANAP.

Other real-world data gleaned from electronic medical records (EMRs) comparing the potential bleeding risks of the factor Xa inhibitor apixaban (Eliquis) versus other available non–vitamin K antagonists (NOACs) including rivaroxaban and the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran (Pradaxa) were reported in several posters supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer and in an oral presentation given by Dr. Gregory Lip of the University of Birmingham, England.

Two of the posters reported data from retrospective analyses of different United States EMRs of 29,338 and 35, 757 patients, respectively, with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation newly started on a NOAC or warfarin in 2013 or 2014. Most were started on warfarin (43.3%/69.6%), followed by rivaroxaban (34.3%/17.9%), dabigatran (14.2%/6.8%), and apixaban (8.2%/5.7%).

Results of the first study (Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1085.P6217) showed that patients newly starting treatment with a NOAC had significantly lower rates of major bleeding than those starting treatment with warfarin, which was 4.6% per year versus 2.35% per year for apixiban, 3.38% per year for dabigatran, and 4.57% per year for rivaroxaban in the first study.

In the second study (Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1085.P6215) the respective adjusted hazard ratios for bleeding risk were 1.094, 0.747 and 0.679, comparing rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran against warfarin.

Other data gleaned from separate U.S. EMRs suggested that apixaban was associated with fewer bleeding-related hospital readmissions than either rivaroxaban or dabigatran in hospitalized patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (Eur Heart J. 2015;36: 1085.P6211).

Dr. Lip presented 6-month follow-up data on more than 60,000 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation who were treated with one of the three NOACs that was recorded in a U.S. medical claims database (Eur Heart J. 2015;36:339.1975). Most of the patients were treated with rivaroxaban (50.6%), with 34.8% treated with dabigatran and 14.6% with apixaban. Unadjusted data showed that the rates of major bleeding were 20.2% per year, 13.2% per year, and 14.5% per year, respectively.

Dr. Lip observed that, after adjusting the data, patients taking dabigatran had higher rates of clinically relevant nonmajor gastrointestinal bleeding (HR =1.24), and that those taking rivaroxaban were more likely to have major (HR = 3.6), clinically relevant nonmajor (HR = 1.43), or any bleeding (HR = 1.41) when compared with apixaban users.

“Larger cohort studies and longer follow-up data of general nonvalvular atrial fibrillation populations will be needed to confirm these early observations,” Dr. Lip concluded.

While real-world research of course has its limitations and cannot replace clinical trial findings as a means to accurately compare the clinical efficacy or safety profiles of different medicines, such studies do provide information that can help inform clinical practice.

“With 10 million people in Europe alone affected by atrial fibrillation, a number that is only expected to increase, real-world insights on routine anticoagulation management in everyday clinical practice is increasingly important for physicians and patients,” Dr. Camm noted in a media release on the XANTUS trial issued by the European Society of Cardiology.

Dr. Camm added: “These real-world insights from XANTAS complement and expand on what we already know from clinical trials, and provide physicians with reassurance to prescribe rivaroxaban as an effective and well-tolerated treatment option for the broad range of patients with atrial fibrillation seen in their everyday practice.”

The XANTUS and PMSS studies were supported by Bayer HealthCare and Janssen. The other studies mentioned were supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer. Dr. Camm disclosed acting as a consultant for Bayer Healthcare and other health care companies. Dr. Lip disclosed acting as a consultant for Bayer Healthcare, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Pfizer as well as other health care companies.

LONDON – The factor Xa inhibitor rivaroxaban was associated with low rates of bleeding and stroke in two observational studies that included more than 45,000 people with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.

The XANTUS (Xarelto for Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation) study involved 6,784 individuals treated at centers in Europe, Canada, and Israel. The incidence of major bleeding was 2.1% per year and the risk of stroke was 0.7% per year. Rates of fatal, critical organ, and intracranial bleeding were also low at 0.2%, 0.7%, and 0.4% per year, respectively.

“The rates of stroke and systemic embolism, all strokes and gastrointestinal bleeding were markedly lower in XANTUS in comparison to ROCKET-AF,” noted Dr. John Camm who presented the XANTUS study findings at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. “Major bleeding was also largely reduced in XANTUS, however the death rate and intracranial hemorrhage rate was similar,” he added.

Dr. Camm, who is professor of clinical cardiology at St George’s Hospital in London, noted that the patient populations and the design of the XANTUS study and phase III ROCKET-AF trial (N Engl J Med. 2011;365:883-91) were slightly different. Patients in the single-arm, prospective, observational XANTUS study were recruited from routine primary care practices and had an overall lower risk of stroke than those enrolled in the randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial who were at more moderate to high risk respective CHADS2 scores of 2.0 and 3.5. The incidence of major bleeding was also slightly higher in the ROCKET-AF, at 3.6% per year, which was similar to that seen with warfarin (3.4%; P = .58), the active comparator used.

Nevertheless, the findings of the XANTUS study, which were published online simultaneously with their presentation at the conference (Eur Heart J. Sep 1. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv466), highlight the “real-world” safety of rivaroxaban, Dr. Camm said.

Results from the separate PMSS (Post-Marketing Safety Surveillance) study reported in a poster at the meeting were similar. The PMSS study is being conducted in the United States and is an ongoing, retrospective, 5-year, observational study of more than 39,000 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. At 2 years follow-up, the incidence of major bleeding was 2.89% per year and the incidence of fatal bleeding was 0.1% per year (Eur Heart J. 2015;36:687.P4066).

“Real-world research is an essential complement to clinical trials and helps inform treatment decisions,” PMSS study investigator Dr. Frank Peacock said in a press release issued by Janssen. Dr. Peacock, who is professor of emergency medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, added, “These studies confirm the safety profile of rivaroxaban in real-world settings around the globe.”

The XANTUS and PMSS studies are part of a large postlicensing program and were respectively designed to meet European Medicines Agency and U.S. Food and Drug Administration requirements on the long-term monitoring of medicines. There are also similar programs running in other world regions, such as XANTUS-EL and XANAP.

Other real-world data gleaned from electronic medical records (EMRs) comparing the potential bleeding risks of the factor Xa inhibitor apixaban (Eliquis) versus other available non–vitamin K antagonists (NOACs) including rivaroxaban and the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran (Pradaxa) were reported in several posters supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer and in an oral presentation given by Dr. Gregory Lip of the University of Birmingham, England.

Two of the posters reported data from retrospective analyses of different United States EMRs of 29,338 and 35, 757 patients, respectively, with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation newly started on a NOAC or warfarin in 2013 or 2014. Most were started on warfarin (43.3%/69.6%), followed by rivaroxaban (34.3%/17.9%), dabigatran (14.2%/6.8%), and apixaban (8.2%/5.7%).

Results of the first study (Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1085.P6217) showed that patients newly starting treatment with a NOAC had significantly lower rates of major bleeding than those starting treatment with warfarin, which was 4.6% per year versus 2.35% per year for apixiban, 3.38% per year for dabigatran, and 4.57% per year for rivaroxaban in the first study.

In the second study (Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1085.P6215) the respective adjusted hazard ratios for bleeding risk were 1.094, 0.747 and 0.679, comparing rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran against warfarin.

Other data gleaned from separate U.S. EMRs suggested that apixaban was associated with fewer bleeding-related hospital readmissions than either rivaroxaban or dabigatran in hospitalized patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (Eur Heart J. 2015;36: 1085.P6211).

Dr. Lip presented 6-month follow-up data on more than 60,000 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation who were treated with one of the three NOACs that was recorded in a U.S. medical claims database (Eur Heart J. 2015;36:339.1975). Most of the patients were treated with rivaroxaban (50.6%), with 34.8% treated with dabigatran and 14.6% with apixaban. Unadjusted data showed that the rates of major bleeding were 20.2% per year, 13.2% per year, and 14.5% per year, respectively.

Dr. Lip observed that, after adjusting the data, patients taking dabigatran had higher rates of clinically relevant nonmajor gastrointestinal bleeding (HR =1.24), and that those taking rivaroxaban were more likely to have major (HR = 3.6), clinically relevant nonmajor (HR = 1.43), or any bleeding (HR = 1.41) when compared with apixaban users.

“Larger cohort studies and longer follow-up data of general nonvalvular atrial fibrillation populations will be needed to confirm these early observations,” Dr. Lip concluded.

While real-world research of course has its limitations and cannot replace clinical trial findings as a means to accurately compare the clinical efficacy or safety profiles of different medicines, such studies do provide information that can help inform clinical practice.

“With 10 million people in Europe alone affected by atrial fibrillation, a number that is only expected to increase, real-world insights on routine anticoagulation management in everyday clinical practice is increasingly important for physicians and patients,” Dr. Camm noted in a media release on the XANTUS trial issued by the European Society of Cardiology.

Dr. Camm added: “These real-world insights from XANTAS complement and expand on what we already know from clinical trials, and provide physicians with reassurance to prescribe rivaroxaban as an effective and well-tolerated treatment option for the broad range of patients with atrial fibrillation seen in their everyday practice.”

The XANTUS and PMSS studies were supported by Bayer HealthCare and Janssen. The other studies mentioned were supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer. Dr. Camm disclosed acting as a consultant for Bayer Healthcare and other health care companies. Dr. Lip disclosed acting as a consultant for Bayer Healthcare, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Pfizer as well as other health care companies.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2015

Key clinical point: Data from routine clinical practice studies suggest a low risk of bleeding and stroke with rivaroxaban and other non–vitamin K antagonists.

Major finding: The incidence of major bleeding with rivaroxaban was 2.1% per year and the risk of stroke was 0.7% per year in the XANTUS study.

Data source: More than 45,000 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation treated with rivaroxaban for stroke prevention in two, real-world observational studies and separate electronic medical record analyses of patients treated with apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran.

Disclosures: The XANTUS and PMSS studies were supported by Bayer HealthCare and Janssen. The other studies mentioned were supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer. Dr. Camm disclosed acting as a consultant for Bayer Healthcare and other health care companies. Dr. Lip disclosed acting as a consultant for Bayer Healthcare, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Pfizer as well as other health care companies.

Eculizumab benefited pregnant women with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

Eculizumab therapy led to “acceptable” outcomes among pregnant women with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, investigators reported Sept. 9 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

No woman who received eculizumab died while pregnant or within 6 months of delivery; historic mortality rates for these patients are 8%-20%, said Dr. Richard Kelly at St. James’s University Hospital in Leeds, England, and his associates. Treatment with the monoclonal antibody, “has reduced mortality and morbidity associated with PNH and has allowed patients who were previously severely affected to lead a relatively normal life.”

The fetal death rate was 4%, resembling rates of 4%-9% from the era before eculizumab, the researchers said. The rate of premature births also was high (29%) as a result of preeclampsia, suspected intrauterine growth retardation, maternal thrombocytopenia, and slowed fetal movements, they said.

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria is a rare, chronic stem-cell disease in which complement-mediated intravascular hemolysis causes anemia, fatigue, and venous thromboembolism (Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;735:155-72.). Increased complement activation during pregnancy intensifies the risk of severe hemolytic anemia, fetal morbidity, and fetal mortality for women with PNH. Eculizumab blocks terminal complement activation by binding complement protein C5, and has improved PNH symptoms to the extent that treated women are more likely to consider pregnancy than in the past.

Dr. Kelly and his associates surveyed members of the International PNH Interest Group to study pregnancy outcomes among these women (N Engl J. Med. 2015;373:1032-9). A total of 80% of clinicians responded, reporting data for 75 pregnancies among 61 women, the investigators said. All patients had PNH diagnosed by flow cytometry, and 61% had begun eculizumab therapy before conception. Median age at first pregnancy was 29 years, with a range of 18 to 40 years. The patients received weekly 600-mg IV infusions for 4 weeks, followed by 900 mg every 14 days. Clinicians increased the dose or treatment frequency at their own discretion if patients showed signs of breakthrough intravascular hemolysis.