User login

Obesity: Don’t separate mental health from physical health

“The patient is ready,” the medical assistant informs you while handing you the chart. The chart reads: “Chief complaint: Weight gain/Discuss weight loss options.” You note the normal vital signs other than an increased BMI to 34 from 4 months ago. You knock on the exam room door with your plan half-formulated.

“Come in,” the patient says, almost too softly for you to hear. Shock overtakes you as you enter the room and see something you never imagined. The patient is holding their disconnected head in their lap as they say, “Nice to see you, Doc. I want to do something about my weight.”

You’re baffled at how they are speaking with a disconnected head. Of course, this outlandish patient scenario isn’t real. Or is it?

Patients with mental health concerns don’t literally present with their head disconnected from their bodies. Too often, mental health is treated as separate from physical health, especially regarding weight management and obesity. However, studies have shown an association between mental health and obesity. In this pivotal time of pharmacologic innovation in obesity care, we must also ensure that we effectively address the mental health of our patients with obesity.

Screening

Mental health conditions can look different for everyone. It can be hard to diagnose a mental health condition without validated screening. For example, depression is one of the most common mental health disorders. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends depression screening in all adults.

The Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) is one screening tool that can alert doctors and clinicians to potential depression. Patients with obesity have higher rates of depression and other mental health conditions. It’s even more critical to screen for depression and other mental health disorders when prescribing these new medications, given recent reports of suicidal ideation with certain antiobesity medications.

Stigma

Mental health–related stigma can trigger shame and prevent patients from seeking psychological help. Furthermore, compounded stigma in patients with larger bodies (weight bias) and from marginalized communities such as the Black community (racial discrimination) add more barriers to seeking mental health care. When patients seek care for mental health conditions, they may feel more comfortable seeing a primary care physician or other clinician than a mental health professional. Therefore, all physicians and clinicians are integral in normalizing mental health care. Instead of treating mental health as separate from physical health, discussing the bidirectional relationship between mental health conditions and physiologic diseases can help patients understand that having a mental health condition isn’t a choice and facilitate openness to multiple treatment options to improve their quality of life.

Support

Addressing mental health effectively often requires multiple layers of patient support. Support can come from loved ones or community groups. But for severe stress and other mental health conditions, treatment with psychotherapy or psychiatric medications is essential. Unfortunately, even if a patient is willing to see a mental health professional, availability or access may be a challenge. Therefore, other clinicians may have to step in and serve as a bridge to mental health care. It’s also essential to ensure that patients are aware of crisis support lines and online resources for mental health care.

Stress

Having a high level of stress can be harmful physically and can also worsen mental health conditions. Additionally, it can contribute to a higher risk for obesity and can trigger emotional eating. Chronic stress has become so common in society that patients often underestimate how much stress they are under. Assessments like the Holmes-Rahe Stress Inventory can help patients identify and quantify potential stressors. While some stressors are uncontrollable, such as social determinants of health (SDOH), addressing controllable stressors and improving coping mechanisms is possible. For instance, mindfulness and breathwork are easy to follow and relatively accessible for most patients.

Social determinants of health

For a treatment plan to be maximally impactful, we must incorporate SDOH in clinical care. SDOH includes financial instability, safe neighborhoods, and more, and can significantly influence an ideal treatment plan. Furthermore, a high SDOH burden can negatively affect mental health and obesity rates. It’s helpful to incorporate patients’ SDOH burden into treatment planning. Learn how to take action on SDOH.

Empowerment

Patients who address their mental health have taken a courageous step toward health and healing. As mentioned, they may experience gaps in care while awaiting connection to the next steps of their journey, such as starting care with a mental health professional or waiting for a medication to take effect. All clinicians can empower patients about their weight by informing them that:

Food may affect their mood. Studies show that certain foods and eating patterns are associated with high levels of depression and anxiety. Limiting processed foods and increasing fruits, vegetables, and foods high in vitamin D, C, and other nutrients is helpful. Everyone is different, so encourage patients to pay attention to how food uniquely affects their mood by keeping a food/feeling log for 1-3 days.

Move more. Increased physical activity can improve mental health.

Get outdoors. Time in nature is associated with better mental health. Spending as little as 10 minutes outside can be beneficial. It’s important to be aware that SDOH factors such as unsafe environments or limited outdoor access may make this difficult for some patients.

Positive stress-relieving activities. Each person has their own way of reducing stress. It is helpful to remind patients of unhealthy stress relievers such as overeating, drinking alcohol, and smoking, and encourage them to replace those with positive stress relievers.

Spiritual well-being. Spirituality is often overlooked in health care. But studies have shown that incorporating a person’s spirituality may have positive health benefits.

It’s time to stop disconnecting mental health from physical health. Each clinician plays a vital role in treating the whole person. Just as you wouldn’t let a patient with a disconnected head leave the office without addressing it, let’s not leave mental health out when addressing our patients’ weight concerns.

Dr. Gonsahn-Bollie is an integrative obesity specialist focused on individualized solutions for emotional and biological overeating. Connect with her at www.embraceyouweightloss.com or on Instagram @embraceyoumd. Her bestselling book, “Embrace You: Your Guide to Transforming Weight Loss Misconceptions Into Lifelong Wellness,” (Baltimore: Purposely Created Publishing Group, 2019) was Healthline.com’s Best Overall Weight Loss Book of 2022 and one of Livestrong.com’s 8 Best Weight-Loss Books to Read in 2022.

Dr. Gonsahn-Bollie is CEO and Lead Physician, Embrace You Weight and Wellness, Telehealth & Virtual Counseling. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“The patient is ready,” the medical assistant informs you while handing you the chart. The chart reads: “Chief complaint: Weight gain/Discuss weight loss options.” You note the normal vital signs other than an increased BMI to 34 from 4 months ago. You knock on the exam room door with your plan half-formulated.

“Come in,” the patient says, almost too softly for you to hear. Shock overtakes you as you enter the room and see something you never imagined. The patient is holding their disconnected head in their lap as they say, “Nice to see you, Doc. I want to do something about my weight.”

You’re baffled at how they are speaking with a disconnected head. Of course, this outlandish patient scenario isn’t real. Or is it?

Patients with mental health concerns don’t literally present with their head disconnected from their bodies. Too often, mental health is treated as separate from physical health, especially regarding weight management and obesity. However, studies have shown an association between mental health and obesity. In this pivotal time of pharmacologic innovation in obesity care, we must also ensure that we effectively address the mental health of our patients with obesity.

Screening

Mental health conditions can look different for everyone. It can be hard to diagnose a mental health condition without validated screening. For example, depression is one of the most common mental health disorders. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends depression screening in all adults.

The Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) is one screening tool that can alert doctors and clinicians to potential depression. Patients with obesity have higher rates of depression and other mental health conditions. It’s even more critical to screen for depression and other mental health disorders when prescribing these new medications, given recent reports of suicidal ideation with certain antiobesity medications.

Stigma

Mental health–related stigma can trigger shame and prevent patients from seeking psychological help. Furthermore, compounded stigma in patients with larger bodies (weight bias) and from marginalized communities such as the Black community (racial discrimination) add more barriers to seeking mental health care. When patients seek care for mental health conditions, they may feel more comfortable seeing a primary care physician or other clinician than a mental health professional. Therefore, all physicians and clinicians are integral in normalizing mental health care. Instead of treating mental health as separate from physical health, discussing the bidirectional relationship between mental health conditions and physiologic diseases can help patients understand that having a mental health condition isn’t a choice and facilitate openness to multiple treatment options to improve their quality of life.

Support

Addressing mental health effectively often requires multiple layers of patient support. Support can come from loved ones or community groups. But for severe stress and other mental health conditions, treatment with psychotherapy or psychiatric medications is essential. Unfortunately, even if a patient is willing to see a mental health professional, availability or access may be a challenge. Therefore, other clinicians may have to step in and serve as a bridge to mental health care. It’s also essential to ensure that patients are aware of crisis support lines and online resources for mental health care.

Stress

Having a high level of stress can be harmful physically and can also worsen mental health conditions. Additionally, it can contribute to a higher risk for obesity and can trigger emotional eating. Chronic stress has become so common in society that patients often underestimate how much stress they are under. Assessments like the Holmes-Rahe Stress Inventory can help patients identify and quantify potential stressors. While some stressors are uncontrollable, such as social determinants of health (SDOH), addressing controllable stressors and improving coping mechanisms is possible. For instance, mindfulness and breathwork are easy to follow and relatively accessible for most patients.

Social determinants of health

For a treatment plan to be maximally impactful, we must incorporate SDOH in clinical care. SDOH includes financial instability, safe neighborhoods, and more, and can significantly influence an ideal treatment plan. Furthermore, a high SDOH burden can negatively affect mental health and obesity rates. It’s helpful to incorporate patients’ SDOH burden into treatment planning. Learn how to take action on SDOH.

Empowerment

Patients who address their mental health have taken a courageous step toward health and healing. As mentioned, they may experience gaps in care while awaiting connection to the next steps of their journey, such as starting care with a mental health professional or waiting for a medication to take effect. All clinicians can empower patients about their weight by informing them that:

Food may affect their mood. Studies show that certain foods and eating patterns are associated with high levels of depression and anxiety. Limiting processed foods and increasing fruits, vegetables, and foods high in vitamin D, C, and other nutrients is helpful. Everyone is different, so encourage patients to pay attention to how food uniquely affects their mood by keeping a food/feeling log for 1-3 days.

Move more. Increased physical activity can improve mental health.

Get outdoors. Time in nature is associated with better mental health. Spending as little as 10 minutes outside can be beneficial. It’s important to be aware that SDOH factors such as unsafe environments or limited outdoor access may make this difficult for some patients.

Positive stress-relieving activities. Each person has their own way of reducing stress. It is helpful to remind patients of unhealthy stress relievers such as overeating, drinking alcohol, and smoking, and encourage them to replace those with positive stress relievers.

Spiritual well-being. Spirituality is often overlooked in health care. But studies have shown that incorporating a person’s spirituality may have positive health benefits.

It’s time to stop disconnecting mental health from physical health. Each clinician plays a vital role in treating the whole person. Just as you wouldn’t let a patient with a disconnected head leave the office without addressing it, let’s not leave mental health out when addressing our patients’ weight concerns.

Dr. Gonsahn-Bollie is an integrative obesity specialist focused on individualized solutions for emotional and biological overeating. Connect with her at www.embraceyouweightloss.com or on Instagram @embraceyoumd. Her bestselling book, “Embrace You: Your Guide to Transforming Weight Loss Misconceptions Into Lifelong Wellness,” (Baltimore: Purposely Created Publishing Group, 2019) was Healthline.com’s Best Overall Weight Loss Book of 2022 and one of Livestrong.com’s 8 Best Weight-Loss Books to Read in 2022.

Dr. Gonsahn-Bollie is CEO and Lead Physician, Embrace You Weight and Wellness, Telehealth & Virtual Counseling. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“The patient is ready,” the medical assistant informs you while handing you the chart. The chart reads: “Chief complaint: Weight gain/Discuss weight loss options.” You note the normal vital signs other than an increased BMI to 34 from 4 months ago. You knock on the exam room door with your plan half-formulated.

“Come in,” the patient says, almost too softly for you to hear. Shock overtakes you as you enter the room and see something you never imagined. The patient is holding their disconnected head in their lap as they say, “Nice to see you, Doc. I want to do something about my weight.”

You’re baffled at how they are speaking with a disconnected head. Of course, this outlandish patient scenario isn’t real. Or is it?

Patients with mental health concerns don’t literally present with their head disconnected from their bodies. Too often, mental health is treated as separate from physical health, especially regarding weight management and obesity. However, studies have shown an association between mental health and obesity. In this pivotal time of pharmacologic innovation in obesity care, we must also ensure that we effectively address the mental health of our patients with obesity.

Screening

Mental health conditions can look different for everyone. It can be hard to diagnose a mental health condition without validated screening. For example, depression is one of the most common mental health disorders. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends depression screening in all adults.

The Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) is one screening tool that can alert doctors and clinicians to potential depression. Patients with obesity have higher rates of depression and other mental health conditions. It’s even more critical to screen for depression and other mental health disorders when prescribing these new medications, given recent reports of suicidal ideation with certain antiobesity medications.

Stigma

Mental health–related stigma can trigger shame and prevent patients from seeking psychological help. Furthermore, compounded stigma in patients with larger bodies (weight bias) and from marginalized communities such as the Black community (racial discrimination) add more barriers to seeking mental health care. When patients seek care for mental health conditions, they may feel more comfortable seeing a primary care physician or other clinician than a mental health professional. Therefore, all physicians and clinicians are integral in normalizing mental health care. Instead of treating mental health as separate from physical health, discussing the bidirectional relationship between mental health conditions and physiologic diseases can help patients understand that having a mental health condition isn’t a choice and facilitate openness to multiple treatment options to improve their quality of life.

Support

Addressing mental health effectively often requires multiple layers of patient support. Support can come from loved ones or community groups. But for severe stress and other mental health conditions, treatment with psychotherapy or psychiatric medications is essential. Unfortunately, even if a patient is willing to see a mental health professional, availability or access may be a challenge. Therefore, other clinicians may have to step in and serve as a bridge to mental health care. It’s also essential to ensure that patients are aware of crisis support lines and online resources for mental health care.

Stress

Having a high level of stress can be harmful physically and can also worsen mental health conditions. Additionally, it can contribute to a higher risk for obesity and can trigger emotional eating. Chronic stress has become so common in society that patients often underestimate how much stress they are under. Assessments like the Holmes-Rahe Stress Inventory can help patients identify and quantify potential stressors. While some stressors are uncontrollable, such as social determinants of health (SDOH), addressing controllable stressors and improving coping mechanisms is possible. For instance, mindfulness and breathwork are easy to follow and relatively accessible for most patients.

Social determinants of health

For a treatment plan to be maximally impactful, we must incorporate SDOH in clinical care. SDOH includes financial instability, safe neighborhoods, and more, and can significantly influence an ideal treatment plan. Furthermore, a high SDOH burden can negatively affect mental health and obesity rates. It’s helpful to incorporate patients’ SDOH burden into treatment planning. Learn how to take action on SDOH.

Empowerment

Patients who address their mental health have taken a courageous step toward health and healing. As mentioned, they may experience gaps in care while awaiting connection to the next steps of their journey, such as starting care with a mental health professional or waiting for a medication to take effect. All clinicians can empower patients about their weight by informing them that:

Food may affect their mood. Studies show that certain foods and eating patterns are associated with high levels of depression and anxiety. Limiting processed foods and increasing fruits, vegetables, and foods high in vitamin D, C, and other nutrients is helpful. Everyone is different, so encourage patients to pay attention to how food uniquely affects their mood by keeping a food/feeling log for 1-3 days.

Move more. Increased physical activity can improve mental health.

Get outdoors. Time in nature is associated with better mental health. Spending as little as 10 minutes outside can be beneficial. It’s important to be aware that SDOH factors such as unsafe environments or limited outdoor access may make this difficult for some patients.

Positive stress-relieving activities. Each person has their own way of reducing stress. It is helpful to remind patients of unhealthy stress relievers such as overeating, drinking alcohol, and smoking, and encourage them to replace those with positive stress relievers.

Spiritual well-being. Spirituality is often overlooked in health care. But studies have shown that incorporating a person’s spirituality may have positive health benefits.

It’s time to stop disconnecting mental health from physical health. Each clinician plays a vital role in treating the whole person. Just as you wouldn’t let a patient with a disconnected head leave the office without addressing it, let’s not leave mental health out when addressing our patients’ weight concerns.

Dr. Gonsahn-Bollie is an integrative obesity specialist focused on individualized solutions for emotional and biological overeating. Connect with her at www.embraceyouweightloss.com or on Instagram @embraceyoumd. Her bestselling book, “Embrace You: Your Guide to Transforming Weight Loss Misconceptions Into Lifelong Wellness,” (Baltimore: Purposely Created Publishing Group, 2019) was Healthline.com’s Best Overall Weight Loss Book of 2022 and one of Livestrong.com’s 8 Best Weight-Loss Books to Read in 2022.

Dr. Gonsahn-Bollie is CEO and Lead Physician, Embrace You Weight and Wellness, Telehealth & Virtual Counseling. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Prescribing lifestyle changes: When medicine isn’t enough

In psychiatry, patients come to us with their list of symptoms, often a diagnosis they’ve made themselves, and the expectation that they will be given medication to fix their problem. Their diagnoses are often right on target – people often know if they are depressed or anxious, and Doctor Google may provide useful information.

Sometimes they want a specific medication, one they saw in a TV ad, or one that helped them in the past or has helped someone they know. As psychiatrists have focused more on their strengths as psychopharmacologists and less on psychotherapy, it gets easy for both the patient and the doctor to look to medication, cocktails, and titration as the only thing we do.

“My medicine stopped working,” is a line I commonly hear. Often the patient is on a complicated regimen that has been serving them well, and it seems unlikely that the five psychotropic medications they are taking have suddenly “stopped working.” An obvious exception is the SSRI “poop out” that can occur 6-12 months or more after beginning treatment. In addition, it’s important to make sure patients are taking their medications as prescribed, and that the generic formulations have not changed.

But as rates of mental illness increase, some of it spurred on by difficult times,

This is not to devalue our medications, but to help the patient see symptoms as having multiple factors and give them some means to intervene, in addition to medications. At the beginning of therapy, it is important to “prescribe” lifestyle changes that will facilitate the best possible outcomes.

Nonpharmaceutical prescriptions

Early in my career, people with alcohol use problems were told they needed to be substance free before they were candidates for antidepressants. While we no longer do that, it is still important to emphasize abstinence from addictive substances, and to recommend specific treatment when necessary.

Patients are often reluctant to see their use of alcohol, marijuana (it’s medical! It’s part of wellness!), or their pain medications as part of the problem, and this can be difficult. There have been times, after multiple medications have failed to help their symptoms, when I have said, “If you don’t get treatment for this problem, I am not going to be able to help you feel better” and that has been motivating for the patient.

There are other “prescriptions” to write. Regular sleep is essential for people with mood disorders, and this can be difficult for many patients, especially those who do shift work, or who have regular disruptions to their sleep from noise, pets, and children. Exercise is wonderful for the cardiovascular system, calms anxiety, and maintains strength, endurance, mobility, and quality of life as people age. But it can be a hard sell to people in a mental health crisis.

Nature is healing, and sunshine helps with maintaining circadian rhythms. For those who don’t exercise, I often “prescribe” 20 to 30 minutes a day of walking, preferably outside, during daylight hours, in a park or natural setting. For people with anxiety, it is important to check their caffeine consumption and to suggest ways to moderate it – moving to decaffeinated beverages or titrating down by mixing decaf with caffeinated.

Meditation is something that many people find helpful. For anxious people, it can be very difficult, and I will prescribe a specific instructional video course that I like on the well-being app InsightTimer – Sarah Blondin’s Learn How to Meditate in Seven Days. The sessions are approximately 10 minutes long, and that seems like the right amount of time for a beginner.

When people are very ill and don’t want to go into the hospital, I talk with them about things that happen in the hospital that are helpful, things they can try to mimic at home. In the hospital, patients don’t go to work, they don’t spend hours a day on the computer, and they are given a pass from dealing with the routine stresses of daily life.

I ask them to take time off work, to avoid as much stress as possible, to spend time with loved ones who give them comfort, and to avoid the people who leave them feeling drained or distressed. I ask them to engage in activities they find healing, to eat well, exercise, and avoid social media. In the hospital, I emphasize, they wake patients up in the morning, ask them to get out of bed and engage in therapeutic activities. They are fed and kept from intoxicants.

When it comes to nutrition, we know so little about how food affects mental health. I feel like it can’t hurt to ask people to avoid fast foods, soft drinks, and processed foods, and so I do.

And what about compliance? Of course, not everyone complies; not everyone is interested in making changes and these can be hard changes. I’ve recently started to recommend the book Atomic Habits by James Clear. Sometimes a bit of motivational interviewing can also be helpful in getting people to look at slowly moving toward making changes.

In prescribing lifestyle changes, it is important to offer most of these changes as suggestions, not as things we insist on, or that will leave the patient feeling ashamed if he doesn’t follow through. They should be discussed early in treatment so that patients don’t feel blamed for their illness or relapses. As with all the things we prescribe, some of these behavior changes help some of the people some of the time. Suggesting them, however, makes the strong statement that treating psychiatric disorders can be about more than passively swallowing a pill.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. She disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

In psychiatry, patients come to us with their list of symptoms, often a diagnosis they’ve made themselves, and the expectation that they will be given medication to fix their problem. Their diagnoses are often right on target – people often know if they are depressed or anxious, and Doctor Google may provide useful information.

Sometimes they want a specific medication, one they saw in a TV ad, or one that helped them in the past or has helped someone they know. As psychiatrists have focused more on their strengths as psychopharmacologists and less on psychotherapy, it gets easy for both the patient and the doctor to look to medication, cocktails, and titration as the only thing we do.

“My medicine stopped working,” is a line I commonly hear. Often the patient is on a complicated regimen that has been serving them well, and it seems unlikely that the five psychotropic medications they are taking have suddenly “stopped working.” An obvious exception is the SSRI “poop out” that can occur 6-12 months or more after beginning treatment. In addition, it’s important to make sure patients are taking their medications as prescribed, and that the generic formulations have not changed.

But as rates of mental illness increase, some of it spurred on by difficult times,

This is not to devalue our medications, but to help the patient see symptoms as having multiple factors and give them some means to intervene, in addition to medications. At the beginning of therapy, it is important to “prescribe” lifestyle changes that will facilitate the best possible outcomes.

Nonpharmaceutical prescriptions

Early in my career, people with alcohol use problems were told they needed to be substance free before they were candidates for antidepressants. While we no longer do that, it is still important to emphasize abstinence from addictive substances, and to recommend specific treatment when necessary.

Patients are often reluctant to see their use of alcohol, marijuana (it’s medical! It’s part of wellness!), or their pain medications as part of the problem, and this can be difficult. There have been times, after multiple medications have failed to help their symptoms, when I have said, “If you don’t get treatment for this problem, I am not going to be able to help you feel better” and that has been motivating for the patient.

There are other “prescriptions” to write. Regular sleep is essential for people with mood disorders, and this can be difficult for many patients, especially those who do shift work, or who have regular disruptions to their sleep from noise, pets, and children. Exercise is wonderful for the cardiovascular system, calms anxiety, and maintains strength, endurance, mobility, and quality of life as people age. But it can be a hard sell to people in a mental health crisis.

Nature is healing, and sunshine helps with maintaining circadian rhythms. For those who don’t exercise, I often “prescribe” 20 to 30 minutes a day of walking, preferably outside, during daylight hours, in a park or natural setting. For people with anxiety, it is important to check their caffeine consumption and to suggest ways to moderate it – moving to decaffeinated beverages or titrating down by mixing decaf with caffeinated.

Meditation is something that many people find helpful. For anxious people, it can be very difficult, and I will prescribe a specific instructional video course that I like on the well-being app InsightTimer – Sarah Blondin’s Learn How to Meditate in Seven Days. The sessions are approximately 10 minutes long, and that seems like the right amount of time for a beginner.

When people are very ill and don’t want to go into the hospital, I talk with them about things that happen in the hospital that are helpful, things they can try to mimic at home. In the hospital, patients don’t go to work, they don’t spend hours a day on the computer, and they are given a pass from dealing with the routine stresses of daily life.

I ask them to take time off work, to avoid as much stress as possible, to spend time with loved ones who give them comfort, and to avoid the people who leave them feeling drained or distressed. I ask them to engage in activities they find healing, to eat well, exercise, and avoid social media. In the hospital, I emphasize, they wake patients up in the morning, ask them to get out of bed and engage in therapeutic activities. They are fed and kept from intoxicants.

When it comes to nutrition, we know so little about how food affects mental health. I feel like it can’t hurt to ask people to avoid fast foods, soft drinks, and processed foods, and so I do.

And what about compliance? Of course, not everyone complies; not everyone is interested in making changes and these can be hard changes. I’ve recently started to recommend the book Atomic Habits by James Clear. Sometimes a bit of motivational interviewing can also be helpful in getting people to look at slowly moving toward making changes.

In prescribing lifestyle changes, it is important to offer most of these changes as suggestions, not as things we insist on, or that will leave the patient feeling ashamed if he doesn’t follow through. They should be discussed early in treatment so that patients don’t feel blamed for their illness or relapses. As with all the things we prescribe, some of these behavior changes help some of the people some of the time. Suggesting them, however, makes the strong statement that treating psychiatric disorders can be about more than passively swallowing a pill.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. She disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

In psychiatry, patients come to us with their list of symptoms, often a diagnosis they’ve made themselves, and the expectation that they will be given medication to fix their problem. Their diagnoses are often right on target – people often know if they are depressed or anxious, and Doctor Google may provide useful information.

Sometimes they want a specific medication, one they saw in a TV ad, or one that helped them in the past or has helped someone they know. As psychiatrists have focused more on their strengths as psychopharmacologists and less on psychotherapy, it gets easy for both the patient and the doctor to look to medication, cocktails, and titration as the only thing we do.

“My medicine stopped working,” is a line I commonly hear. Often the patient is on a complicated regimen that has been serving them well, and it seems unlikely that the five psychotropic medications they are taking have suddenly “stopped working.” An obvious exception is the SSRI “poop out” that can occur 6-12 months or more after beginning treatment. In addition, it’s important to make sure patients are taking their medications as prescribed, and that the generic formulations have not changed.

But as rates of mental illness increase, some of it spurred on by difficult times,

This is not to devalue our medications, but to help the patient see symptoms as having multiple factors and give them some means to intervene, in addition to medications. At the beginning of therapy, it is important to “prescribe” lifestyle changes that will facilitate the best possible outcomes.

Nonpharmaceutical prescriptions

Early in my career, people with alcohol use problems were told they needed to be substance free before they were candidates for antidepressants. While we no longer do that, it is still important to emphasize abstinence from addictive substances, and to recommend specific treatment when necessary.

Patients are often reluctant to see their use of alcohol, marijuana (it’s medical! It’s part of wellness!), or their pain medications as part of the problem, and this can be difficult. There have been times, after multiple medications have failed to help their symptoms, when I have said, “If you don’t get treatment for this problem, I am not going to be able to help you feel better” and that has been motivating for the patient.

There are other “prescriptions” to write. Regular sleep is essential for people with mood disorders, and this can be difficult for many patients, especially those who do shift work, or who have regular disruptions to their sleep from noise, pets, and children. Exercise is wonderful for the cardiovascular system, calms anxiety, and maintains strength, endurance, mobility, and quality of life as people age. But it can be a hard sell to people in a mental health crisis.

Nature is healing, and sunshine helps with maintaining circadian rhythms. For those who don’t exercise, I often “prescribe” 20 to 30 minutes a day of walking, preferably outside, during daylight hours, in a park or natural setting. For people with anxiety, it is important to check their caffeine consumption and to suggest ways to moderate it – moving to decaffeinated beverages or titrating down by mixing decaf with caffeinated.

Meditation is something that many people find helpful. For anxious people, it can be very difficult, and I will prescribe a specific instructional video course that I like on the well-being app InsightTimer – Sarah Blondin’s Learn How to Meditate in Seven Days. The sessions are approximately 10 minutes long, and that seems like the right amount of time for a beginner.

When people are very ill and don’t want to go into the hospital, I talk with them about things that happen in the hospital that are helpful, things they can try to mimic at home. In the hospital, patients don’t go to work, they don’t spend hours a day on the computer, and they are given a pass from dealing with the routine stresses of daily life.

I ask them to take time off work, to avoid as much stress as possible, to spend time with loved ones who give them comfort, and to avoid the people who leave them feeling drained or distressed. I ask them to engage in activities they find healing, to eat well, exercise, and avoid social media. In the hospital, I emphasize, they wake patients up in the morning, ask them to get out of bed and engage in therapeutic activities. They are fed and kept from intoxicants.

When it comes to nutrition, we know so little about how food affects mental health. I feel like it can’t hurt to ask people to avoid fast foods, soft drinks, and processed foods, and so I do.

And what about compliance? Of course, not everyone complies; not everyone is interested in making changes and these can be hard changes. I’ve recently started to recommend the book Atomic Habits by James Clear. Sometimes a bit of motivational interviewing can also be helpful in getting people to look at slowly moving toward making changes.

In prescribing lifestyle changes, it is important to offer most of these changes as suggestions, not as things we insist on, or that will leave the patient feeling ashamed if he doesn’t follow through. They should be discussed early in treatment so that patients don’t feel blamed for their illness or relapses. As with all the things we prescribe, some of these behavior changes help some of the people some of the time. Suggesting them, however, makes the strong statement that treating psychiatric disorders can be about more than passively swallowing a pill.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. She disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

Family physicians get lowest net return for HPV vaccine

Family physicians receive less private insurer reimbursement for the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine than do pediatricians, according to a new analysis in Family Medicine.

HPV is the most expensive of all routine pediatric vaccines and the reimbursement by third-party payers varies widely. The concerns about HPV reimbursement often appear on clinician surveys.

This study, led by Yenan Zhu, PhD, who was with the department of public health sciences, college of medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, at the time of the research, found that, on average, pediatricians received higher reimbursement ($216.07) for HPV vaccine cost when compared with family physicians ($211.33), internists ($212.97), nurse practitioners ($212.91), and “other” clinicians who administer the vaccine ($213.29) (P values for all comparisons were < .001).

The final sample for this study included 34,247 clinicians.

The net return from vaccine cost reimbursements was lowest for family physicians ($0.34 per HPV vaccine dose administered) and highest for pediatricians ($5.08 per HPV vaccine dose administered).

“Adequate cost reimbursement by third-party payers is a critical enabling factor for clinicians to continue offering vaccines,” the authors wrote.

The authors concluded that “reimbursement for HPV vaccine costs by private payers is adequate; however, return margins are small for nonpediatric specialties.”

CDC, AAP differ in recommendations

In the United States, private insurers use the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention vaccine list price as a benchmark.

Overall in this study, HPV vaccine cost reimbursement by private payers was at or above the CDC list price of $210.99 but below the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations ($263.74).

The study found that every $1 increment in return was associated with an increase in HPV vaccine doses administered. That was highest for family physicians at 0.08% per dollar.

The modeling showed that changing the HPV vaccine reimbursement to the AAP-recommended level could translate to “an estimated 18,643 additional HPV vaccine doses administrated by pediatricians, 4,041 additional doses by family physicians, and 433 doses by ‘other’ specialties in 2017-2018.”

The authors noted that U.S. vaccination coverage has improved in recent years but initiation and completion rates are lower among privately insured adolescents (4.6% lower for initiation and 2.0% points lower for completion in 2021), compared with adolescents covered under public insurance.

Why the difference among specialties?

Variation in reimbursements might be tied to the ability to negotiate reimbursements for adolescent vaccines, the authors said.

“For instance, pediatricians may be able to negotiate higher cost reimbursement, compared with nonpediatric specialties, given that adolescents constitute a large fraction of their patient volume,” they wrote.

Dr. Zhu and colleagues wrote that it should be noted that HPV vaccine cost reimbursement to family practitioners was considerably less than other specialties and they are barely breaking even though they have the second-highest volume of HPV vaccinations (after pediatricians).

The authors acknowledged that it may not be possible to raise reimbursement to the AAP level, but added that “a reasonable increase that can cover direct and indirect expenses (acquisition cost, storage cost, personnel cost for monitoring inventory, insurance, waste, and lost opportunity costs) will reduce the financial strain on nonpediatric clinicians.” That may encourage clinicians to stock and offer the vaccine.

Limitations

The researchers acknowledged several limitations. The models did not account for factors such as vaccination bundling, physicians’ recommendation style or differences in knowledge of the vaccination schedule.

The models were also not able to adjust for whether a clinic had reminder prompts in the electronic health records, the overhead costs of vaccines, or vaccine knowledge or hesitancy on the part of the adolescents’ parents.

Additionally, they used data from one private payer, which limits generalizability.

Researchers identified a sample of adolescents eligible for the HPV vaccine (9-14 years old) enrolled in a large private health insurance plan during 2017-2018. Data from states with universal or universal select vaccine purchasing were excluded. These states included Alaska, Hawaii, Idaho, Maine, Massachusetts, South Dakota, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

One coauthor reported receiving a consulting fee from Merck on unrelated projects. Another coauthor has provided consultancy to Value Analytics Labs on unrelated projects. All other authors declared no competing interests.

Family physicians receive less private insurer reimbursement for the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine than do pediatricians, according to a new analysis in Family Medicine.

HPV is the most expensive of all routine pediatric vaccines and the reimbursement by third-party payers varies widely. The concerns about HPV reimbursement often appear on clinician surveys.

This study, led by Yenan Zhu, PhD, who was with the department of public health sciences, college of medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, at the time of the research, found that, on average, pediatricians received higher reimbursement ($216.07) for HPV vaccine cost when compared with family physicians ($211.33), internists ($212.97), nurse practitioners ($212.91), and “other” clinicians who administer the vaccine ($213.29) (P values for all comparisons were < .001).

The final sample for this study included 34,247 clinicians.

The net return from vaccine cost reimbursements was lowest for family physicians ($0.34 per HPV vaccine dose administered) and highest for pediatricians ($5.08 per HPV vaccine dose administered).

“Adequate cost reimbursement by third-party payers is a critical enabling factor for clinicians to continue offering vaccines,” the authors wrote.

The authors concluded that “reimbursement for HPV vaccine costs by private payers is adequate; however, return margins are small for nonpediatric specialties.”

CDC, AAP differ in recommendations

In the United States, private insurers use the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention vaccine list price as a benchmark.

Overall in this study, HPV vaccine cost reimbursement by private payers was at or above the CDC list price of $210.99 but below the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations ($263.74).

The study found that every $1 increment in return was associated with an increase in HPV vaccine doses administered. That was highest for family physicians at 0.08% per dollar.

The modeling showed that changing the HPV vaccine reimbursement to the AAP-recommended level could translate to “an estimated 18,643 additional HPV vaccine doses administrated by pediatricians, 4,041 additional doses by family physicians, and 433 doses by ‘other’ specialties in 2017-2018.”

The authors noted that U.S. vaccination coverage has improved in recent years but initiation and completion rates are lower among privately insured adolescents (4.6% lower for initiation and 2.0% points lower for completion in 2021), compared with adolescents covered under public insurance.

Why the difference among specialties?

Variation in reimbursements might be tied to the ability to negotiate reimbursements for adolescent vaccines, the authors said.

“For instance, pediatricians may be able to negotiate higher cost reimbursement, compared with nonpediatric specialties, given that adolescents constitute a large fraction of their patient volume,” they wrote.

Dr. Zhu and colleagues wrote that it should be noted that HPV vaccine cost reimbursement to family practitioners was considerably less than other specialties and they are barely breaking even though they have the second-highest volume of HPV vaccinations (after pediatricians).

The authors acknowledged that it may not be possible to raise reimbursement to the AAP level, but added that “a reasonable increase that can cover direct and indirect expenses (acquisition cost, storage cost, personnel cost for monitoring inventory, insurance, waste, and lost opportunity costs) will reduce the financial strain on nonpediatric clinicians.” That may encourage clinicians to stock and offer the vaccine.

Limitations

The researchers acknowledged several limitations. The models did not account for factors such as vaccination bundling, physicians’ recommendation style or differences in knowledge of the vaccination schedule.

The models were also not able to adjust for whether a clinic had reminder prompts in the electronic health records, the overhead costs of vaccines, or vaccine knowledge or hesitancy on the part of the adolescents’ parents.

Additionally, they used data from one private payer, which limits generalizability.

Researchers identified a sample of adolescents eligible for the HPV vaccine (9-14 years old) enrolled in a large private health insurance plan during 2017-2018. Data from states with universal or universal select vaccine purchasing were excluded. These states included Alaska, Hawaii, Idaho, Maine, Massachusetts, South Dakota, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

One coauthor reported receiving a consulting fee from Merck on unrelated projects. Another coauthor has provided consultancy to Value Analytics Labs on unrelated projects. All other authors declared no competing interests.

Family physicians receive less private insurer reimbursement for the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine than do pediatricians, according to a new analysis in Family Medicine.

HPV is the most expensive of all routine pediatric vaccines and the reimbursement by third-party payers varies widely. The concerns about HPV reimbursement often appear on clinician surveys.

This study, led by Yenan Zhu, PhD, who was with the department of public health sciences, college of medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, at the time of the research, found that, on average, pediatricians received higher reimbursement ($216.07) for HPV vaccine cost when compared with family physicians ($211.33), internists ($212.97), nurse practitioners ($212.91), and “other” clinicians who administer the vaccine ($213.29) (P values for all comparisons were < .001).

The final sample for this study included 34,247 clinicians.

The net return from vaccine cost reimbursements was lowest for family physicians ($0.34 per HPV vaccine dose administered) and highest for pediatricians ($5.08 per HPV vaccine dose administered).

“Adequate cost reimbursement by third-party payers is a critical enabling factor for clinicians to continue offering vaccines,” the authors wrote.

The authors concluded that “reimbursement for HPV vaccine costs by private payers is adequate; however, return margins are small for nonpediatric specialties.”

CDC, AAP differ in recommendations

In the United States, private insurers use the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention vaccine list price as a benchmark.

Overall in this study, HPV vaccine cost reimbursement by private payers was at or above the CDC list price of $210.99 but below the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations ($263.74).

The study found that every $1 increment in return was associated with an increase in HPV vaccine doses administered. That was highest for family physicians at 0.08% per dollar.

The modeling showed that changing the HPV vaccine reimbursement to the AAP-recommended level could translate to “an estimated 18,643 additional HPV vaccine doses administrated by pediatricians, 4,041 additional doses by family physicians, and 433 doses by ‘other’ specialties in 2017-2018.”

The authors noted that U.S. vaccination coverage has improved in recent years but initiation and completion rates are lower among privately insured adolescents (4.6% lower for initiation and 2.0% points lower for completion in 2021), compared with adolescents covered under public insurance.

Why the difference among specialties?

Variation in reimbursements might be tied to the ability to negotiate reimbursements for adolescent vaccines, the authors said.

“For instance, pediatricians may be able to negotiate higher cost reimbursement, compared with nonpediatric specialties, given that adolescents constitute a large fraction of their patient volume,” they wrote.

Dr. Zhu and colleagues wrote that it should be noted that HPV vaccine cost reimbursement to family practitioners was considerably less than other specialties and they are barely breaking even though they have the second-highest volume of HPV vaccinations (after pediatricians).

The authors acknowledged that it may not be possible to raise reimbursement to the AAP level, but added that “a reasonable increase that can cover direct and indirect expenses (acquisition cost, storage cost, personnel cost for monitoring inventory, insurance, waste, and lost opportunity costs) will reduce the financial strain on nonpediatric clinicians.” That may encourage clinicians to stock and offer the vaccine.

Limitations

The researchers acknowledged several limitations. The models did not account for factors such as vaccination bundling, physicians’ recommendation style or differences in knowledge of the vaccination schedule.

The models were also not able to adjust for whether a clinic had reminder prompts in the electronic health records, the overhead costs of vaccines, or vaccine knowledge or hesitancy on the part of the adolescents’ parents.

Additionally, they used data from one private payer, which limits generalizability.

Researchers identified a sample of adolescents eligible for the HPV vaccine (9-14 years old) enrolled in a large private health insurance plan during 2017-2018. Data from states with universal or universal select vaccine purchasing were excluded. These states included Alaska, Hawaii, Idaho, Maine, Massachusetts, South Dakota, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

One coauthor reported receiving a consulting fee from Merck on unrelated projects. Another coauthor has provided consultancy to Value Analytics Labs on unrelated projects. All other authors declared no competing interests.

FROM FAMILY MEDICINE

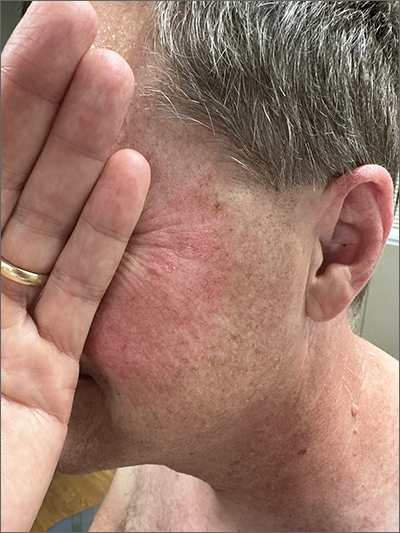

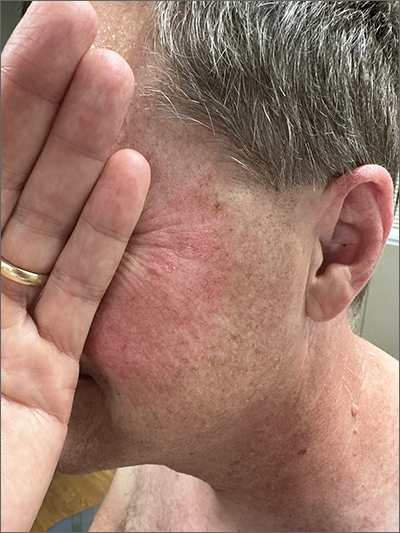

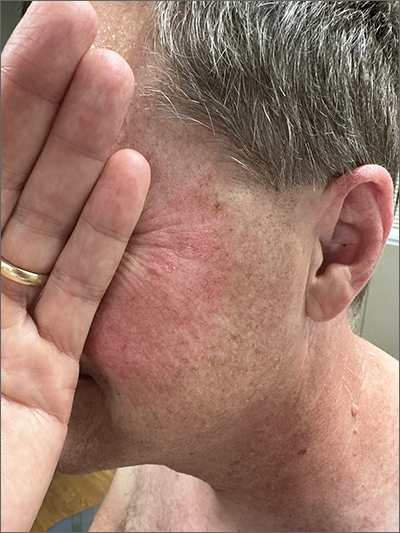

Rosacea look-alike

Although it’s easy to jump to the conclusion that facial erythema is rosacea, there are multiple other conditions that can lead to reddening of the face. In this case, excessive sun exposure had resulted in a diffuse actinic change of the malar and lateral aspects of this patient’s face. The palpably rough lesions were actinic keratoses.

Actinic keratoses are caused by exposure to ultraviolet radiation. These lesions are premalignant and common. Areas of the body at greatest risk include those not typically covered by clothing (eg, face, hands, arms, ears, forehead, and top of the scalp—especially in individuals with hair loss). There is a range of estimates regarding the percentage of actinic keratoses that will progress to squamous cell carcinoma in situ, and then invasive squamous cell carcinoma. One study determined that 10% of actinic keratoses progress to squamous cell carcinoma over the course of 2 years.1

In patients with broad areas of multiple clinically palpable lesions with rough sandpapery texture or visible white scale, there are likely preclinical lesions in the same areas. With so many lesions, field therapy of the entire region is often performed instead of treating the lesions 1 at a time.

There are multiple topical agents for field therapy, including 5-fluorouracil, diclofenac gel, and imiquimod gel.2 Since significant erythema and inflammation usually follow application of the topical agent, clinicians may want to have patients treat in segments to make the process more tolerable.

5-fluorouracil has a complete clearance rate (CCR) of 75% to 90% and is usually applied twice daily for 2 weeks, although there are multiple different protocols. Diclofenac has a CCR of 58% over a 60- to 90-day course, and imiquimod has a CCR of 54% after a 120-day course. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has the advantage of a single treatment but a CCR of 38%. PDT may be advantageous for a patient who has difficulty applying topical medication over a period of weeks.

Niacinamide has been shown to help with skin repair and reduce the risk of additional nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSC) by 23% and additional actinic keratoses by about 15% in individuals with a history of actinic keratoses or NMSC.3 In contrast to niacin, niacinamide does not cause flushing. Niacinamide is used long term; if discontinued, it no longer confers benefit in helping the skin repair itself.

The patient in this case was prescribed topical 5% fluorouracil cream to be applied twice daily to the malar regions bilaterally for 2 weeks and, if not inflamed by 2 weeks, to extend the treatment until there is robust inflammation (but not to exceed 3 weeks). He was scheduled to follow up in 3 months for reexamination. He was also advised to start taking niacinamide 500 mg twice daily to reduce his risk of additional precancerous and cancerous skin lesions and counseled on the importance of sunscreen, hats, and sun-protective clothing.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

- Fuchs A, Marmur E. The kinetics of skin cancer: progression of actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1099-1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33224.x

- Jansen MHE, Kessels JPHM, Nelemans PJ, et al. Randomized trial of four treatment approaches for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:935-946. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1811850

- Starr P. Oral nicotinamide prevents common skin cancers in high-risk patients, reduces costs. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8(spec issue):13-14.

Although it’s easy to jump to the conclusion that facial erythema is rosacea, there are multiple other conditions that can lead to reddening of the face. In this case, excessive sun exposure had resulted in a diffuse actinic change of the malar and lateral aspects of this patient’s face. The palpably rough lesions were actinic keratoses.

Actinic keratoses are caused by exposure to ultraviolet radiation. These lesions are premalignant and common. Areas of the body at greatest risk include those not typically covered by clothing (eg, face, hands, arms, ears, forehead, and top of the scalp—especially in individuals with hair loss). There is a range of estimates regarding the percentage of actinic keratoses that will progress to squamous cell carcinoma in situ, and then invasive squamous cell carcinoma. One study determined that 10% of actinic keratoses progress to squamous cell carcinoma over the course of 2 years.1

In patients with broad areas of multiple clinically palpable lesions with rough sandpapery texture or visible white scale, there are likely preclinical lesions in the same areas. With so many lesions, field therapy of the entire region is often performed instead of treating the lesions 1 at a time.

There are multiple topical agents for field therapy, including 5-fluorouracil, diclofenac gel, and imiquimod gel.2 Since significant erythema and inflammation usually follow application of the topical agent, clinicians may want to have patients treat in segments to make the process more tolerable.

5-fluorouracil has a complete clearance rate (CCR) of 75% to 90% and is usually applied twice daily for 2 weeks, although there are multiple different protocols. Diclofenac has a CCR of 58% over a 60- to 90-day course, and imiquimod has a CCR of 54% after a 120-day course. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has the advantage of a single treatment but a CCR of 38%. PDT may be advantageous for a patient who has difficulty applying topical medication over a period of weeks.

Niacinamide has been shown to help with skin repair and reduce the risk of additional nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSC) by 23% and additional actinic keratoses by about 15% in individuals with a history of actinic keratoses or NMSC.3 In contrast to niacin, niacinamide does not cause flushing. Niacinamide is used long term; if discontinued, it no longer confers benefit in helping the skin repair itself.

The patient in this case was prescribed topical 5% fluorouracil cream to be applied twice daily to the malar regions bilaterally for 2 weeks and, if not inflamed by 2 weeks, to extend the treatment until there is robust inflammation (but not to exceed 3 weeks). He was scheduled to follow up in 3 months for reexamination. He was also advised to start taking niacinamide 500 mg twice daily to reduce his risk of additional precancerous and cancerous skin lesions and counseled on the importance of sunscreen, hats, and sun-protective clothing.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

Although it’s easy to jump to the conclusion that facial erythema is rosacea, there are multiple other conditions that can lead to reddening of the face. In this case, excessive sun exposure had resulted in a diffuse actinic change of the malar and lateral aspects of this patient’s face. The palpably rough lesions were actinic keratoses.

Actinic keratoses are caused by exposure to ultraviolet radiation. These lesions are premalignant and common. Areas of the body at greatest risk include those not typically covered by clothing (eg, face, hands, arms, ears, forehead, and top of the scalp—especially in individuals with hair loss). There is a range of estimates regarding the percentage of actinic keratoses that will progress to squamous cell carcinoma in situ, and then invasive squamous cell carcinoma. One study determined that 10% of actinic keratoses progress to squamous cell carcinoma over the course of 2 years.1

In patients with broad areas of multiple clinically palpable lesions with rough sandpapery texture or visible white scale, there are likely preclinical lesions in the same areas. With so many lesions, field therapy of the entire region is often performed instead of treating the lesions 1 at a time.

There are multiple topical agents for field therapy, including 5-fluorouracil, diclofenac gel, and imiquimod gel.2 Since significant erythema and inflammation usually follow application of the topical agent, clinicians may want to have patients treat in segments to make the process more tolerable.

5-fluorouracil has a complete clearance rate (CCR) of 75% to 90% and is usually applied twice daily for 2 weeks, although there are multiple different protocols. Diclofenac has a CCR of 58% over a 60- to 90-day course, and imiquimod has a CCR of 54% after a 120-day course. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has the advantage of a single treatment but a CCR of 38%. PDT may be advantageous for a patient who has difficulty applying topical medication over a period of weeks.

Niacinamide has been shown to help with skin repair and reduce the risk of additional nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSC) by 23% and additional actinic keratoses by about 15% in individuals with a history of actinic keratoses or NMSC.3 In contrast to niacin, niacinamide does not cause flushing. Niacinamide is used long term; if discontinued, it no longer confers benefit in helping the skin repair itself.

The patient in this case was prescribed topical 5% fluorouracil cream to be applied twice daily to the malar regions bilaterally for 2 weeks and, if not inflamed by 2 weeks, to extend the treatment until there is robust inflammation (but not to exceed 3 weeks). He was scheduled to follow up in 3 months for reexamination. He was also advised to start taking niacinamide 500 mg twice daily to reduce his risk of additional precancerous and cancerous skin lesions and counseled on the importance of sunscreen, hats, and sun-protective clothing.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

- Fuchs A, Marmur E. The kinetics of skin cancer: progression of actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1099-1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33224.x

- Jansen MHE, Kessels JPHM, Nelemans PJ, et al. Randomized trial of four treatment approaches for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:935-946. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1811850

- Starr P. Oral nicotinamide prevents common skin cancers in high-risk patients, reduces costs. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8(spec issue):13-14.

- Fuchs A, Marmur E. The kinetics of skin cancer: progression of actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1099-1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33224.x

- Jansen MHE, Kessels JPHM, Nelemans PJ, et al. Randomized trial of four treatment approaches for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:935-946. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1811850

- Starr P. Oral nicotinamide prevents common skin cancers in high-risk patients, reduces costs. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8(spec issue):13-14.

Two-pronged approach needed in alcohol-associated hepatitis

(AUD), concludes a review discussing care for patients recently hospitalized.

“Probably the biggest thing I would want providers to take away from the review is to remember that these patients are likely to carry a dual diagnosis,” said lead author Akshay Shetty, MD, Pfleger Liver Institute, UCLA Medical Center.

“It is important to address the liver disease, because it probably carries the biggest mortality and morbidity risk in the short term, but we have to remember to treat their alcohol use disorder simultaneously,” Dr. Shetty said.

The guidance by Dr. Shetty and coauthors was published online in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology.

More alcohol misuse means more liver disease

AH is a “unique, severe form of alcohol-associated steatohepatitis that is seen in the background of recent heavy alcohol use,” the team writes. Patients with severe AH have faced mortality rates as high as 20%-50%. A recent study reported a drop in 30-day mortality rates to 17%, which the authors credit to improved supportive medical management.

Alcohol misuse has surged over the past two decades, which experts believe will lead to a rise in alcohol-related liver disease, including AH hospitalization, the authors note. Rates of high-risk drinking in the United States (four or more drinks daily for women, five or more for men) increased by almost 30% between 2002 and 2012, particularly among women and ethnic minorities.

At the same time, rates of AUD rose 25% among young adults. In 2019, a U.S. survey found 14.5 million people aged 12 years and older in the United States carried an AUD diagnosis.

Meanwhile, the U.S. National Inpatient Sample revealed a 28.3% rise in AH-related hospitalizations between 2007 and 2014.

“AH patients carry a high short-term mortality [and] require close outpatient monitoring and significant care coordination,” write the authors. Despite the rising rates of severe AH, there is a lack of standardized guidance on post-discharge management, which motivated their clinical care review.

Liver disease shapes short-term outcomes

The management of patients with a recent episode of severe AH requires a two-pronged approach and shared patient management between gastroenterologists/hepatologists and addiction specialists. The multidisciplinary management both improves outcomes and is linked to reduced health care costs, the authors write.

While abstinence from alcohol remains essential to recovery, the authors note, it is the “severity of hepatic decompensation that has been shown to dictate short-term mortality in the initial 6 months” following discharge.

The team created an outpatient algorithm that divides patient care into two main areas: hepatic decompensation and AUD.

For the risk of hepatic decompensation, patients should undergo close monitoring for infections and frequent laboratory tests in the months following discharge.

Moreover, the “majority of patients with severe AH usually have background cirrhosis and are at risk of portal hypertensive decompensations similar to cirrhosis,” the authors write, and so patients should be assessed for hepatic encephalopathy, as well as for ascites and variceal bleeding.

For HE, the authors recommend a low threshold for treatment initiation with lactulose (a colonic acidifier) and the antibiotic rifaximin, but they suggest that ascites management “should be conservative ... with strict adherence to a low-sodium diet as the first-line approach.”

A key problem among severe AH patients post-discharge is malnutrition, which reaches 100% prevalence and is associated with the severity of liver disease, including decompensation and mortality, they note.

Patients with malnutrition are at risk of entering a catabolic starvation state. The authors recommend avoiding long fasting periods with multiple small meals and late evening snacks.

Long-term, severe AH patients should be assessed for advanced fibrosis, although early diagnosis is often challenging, as the clinical and laboratory results typically mimic findings of liver cirrhosis, the authors write.

Crucially, patients should be considered for early referral for liver transplantation, because early liver transplantation is associated with “excellent transplant outcomes and is noninferior when compared with other etiologies of chronic liver disease,” they write.

Long-term risk rests on preventing alcohol relapse

Turning to AUD, the team notes that long-term outcomes among AH patients depend on the prevention of alcohol relapse, because alcohol use among these patients is directly linked to higher rates of mortality and decompensation.

The authors concede that the “definition of relapse remains a matter of contention, especially in the post-liver transplant population,” but they recommend complete abstinence for patients recovering from AH and define relapse as any use of alcohol.

Dr. Shetty explained that “often, the focus tends to be on the acute threats to a patient’s life, so their liver disease tends to be emphasized, and we often forget why patients present with the liver disease in the first place.”

He continued: “So we do our best to address the liver disease and not a lot gets done for the alcohol-use disorder that the patient may have in the background. The expectation is that, if the doctors help patients with their liver disease, the patients will learn that lesson on their own and stop drinking.”

Instead, Dr. Shetty and his colleagues advise, all patients should be screened for AUD and undergo surveillance with alcohol biomarkers monthly at first. Patients should also be referred to an addiction specialist, where some combination of psychotherapy, mutual support groups, and pharmacotherapy can be tailored to individual patient needs and access.

Multidisciplinary management, comprising hepatology, psychiatry, psychologist, nurse, and social worker consults, has shown “promising results in the management of AUD, improvement in liver disease, and decrease in health care burden,” the authors write, although “multidisciplinary clinics often carry financial and administrative barriers to broad application.”

Moreover, these interventions require a commitment from the patient, at least in the short term, to allow the establishment of a therapeutic relationship between the clinician and the patient and aid compliance over the longer term.

“Patients with AUD remain reluctant to pursue treatment,” the authors write, “and a large-scale effort to improve knowledge gaps in regard to AUD treatment and its success is needed, both from patients’ primary care providers and their consultants.”

Dr. Shetty explained that patient engagement is “probably the most challenging aspect of the disease, especially the alcohol use disorder part.”

This is partly because patients often lack insight, and alcohol addiction carries stigma and shame, as well as self-blame, he said, and so patients will “often delay pursuing any therapy ... even when they are sick.”

Dr. Shetty believes that reducing the stigma around alcohol addiction will require better education of patients and health care providers. To that end, he noted that the scientific literature now avoids the pejorative “alcoholic” and instead describes alcohol use as a disorder rather than having it define the patient.

“But this educational aspect is going to take a long time to really take effect, so from a provider perspective ... it is important to be open-minded when seeing these patients,” he said. This means not focusing on “the medical aspect alone but trying to really see the person who’s come to you for help and understand their motivations for pursing medical care.”

“Despite all these things, some patients may still find it very challenging and awkward. It takes several visits to really establish a rapport with them and get a sense of how to get them to share the challenging aspects of the disease,” Dr. Shetty added.

Multidisciplinary management for optimal outcomes

In a comment, Nancy S. Reau, MD, chair of hepatology, Rush Medical College, Chicago, agreed with the need to address both the risk for hepatic decompensation and AUD, the benefits of multidisciplinary management of patients, and the importance of patient engagement to successful outcomes.

“As hepatologists, we are often best at managing liver disease, but if you don’t also address the alcohol use disorder, the patient will not have the optimal outcome,” she said in an interview. “Most patients with severe AH have cirrhosis, [which] makes longitudinal follow-up imperative.”

“They are at risk for liver complications but also need aggressive nutritional support and management of their addiction,” she said. “As they improve, they can usually continue intensive treatment.”

Akhil Anand, MD, an addiction psychiatrist and co-director of the Multidisciplinary Alcohol Program at the Cleveland Clinic, also noted the increase in cases of alcohol-associated hepatitis from rising alcohol use.

The review “provides a timely, comprehensive, and impartial overview” of how to manage the condition, he said, as well as “how to treat co-occurring alcohol use disorder in this life-threatening situation.”

No funding was declared. The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

(AUD), concludes a review discussing care for patients recently hospitalized.

“Probably the biggest thing I would want providers to take away from the review is to remember that these patients are likely to carry a dual diagnosis,” said lead author Akshay Shetty, MD, Pfleger Liver Institute, UCLA Medical Center.

“It is important to address the liver disease, because it probably carries the biggest mortality and morbidity risk in the short term, but we have to remember to treat their alcohol use disorder simultaneously,” Dr. Shetty said.

The guidance by Dr. Shetty and coauthors was published online in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology.

More alcohol misuse means more liver disease

AH is a “unique, severe form of alcohol-associated steatohepatitis that is seen in the background of recent heavy alcohol use,” the team writes. Patients with severe AH have faced mortality rates as high as 20%-50%. A recent study reported a drop in 30-day mortality rates to 17%, which the authors credit to improved supportive medical management.

Alcohol misuse has surged over the past two decades, which experts believe will lead to a rise in alcohol-related liver disease, including AH hospitalization, the authors note. Rates of high-risk drinking in the United States (four or more drinks daily for women, five or more for men) increased by almost 30% between 2002 and 2012, particularly among women and ethnic minorities.

At the same time, rates of AUD rose 25% among young adults. In 2019, a U.S. survey found 14.5 million people aged 12 years and older in the United States carried an AUD diagnosis.

Meanwhile, the U.S. National Inpatient Sample revealed a 28.3% rise in AH-related hospitalizations between 2007 and 2014.

“AH patients carry a high short-term mortality [and] require close outpatient monitoring and significant care coordination,” write the authors. Despite the rising rates of severe AH, there is a lack of standardized guidance on post-discharge management, which motivated their clinical care review.

Liver disease shapes short-term outcomes

The management of patients with a recent episode of severe AH requires a two-pronged approach and shared patient management between gastroenterologists/hepatologists and addiction specialists. The multidisciplinary management both improves outcomes and is linked to reduced health care costs, the authors write.

While abstinence from alcohol remains essential to recovery, the authors note, it is the “severity of hepatic decompensation that has been shown to dictate short-term mortality in the initial 6 months” following discharge.

The team created an outpatient algorithm that divides patient care into two main areas: hepatic decompensation and AUD.

For the risk of hepatic decompensation, patients should undergo close monitoring for infections and frequent laboratory tests in the months following discharge.

Moreover, the “majority of patients with severe AH usually have background cirrhosis and are at risk of portal hypertensive decompensations similar to cirrhosis,” the authors write, and so patients should be assessed for hepatic encephalopathy, as well as for ascites and variceal bleeding.

For HE, the authors recommend a low threshold for treatment initiation with lactulose (a colonic acidifier) and the antibiotic rifaximin, but they suggest that ascites management “should be conservative ... with strict adherence to a low-sodium diet as the first-line approach.”

A key problem among severe AH patients post-discharge is malnutrition, which reaches 100% prevalence and is associated with the severity of liver disease, including decompensation and mortality, they note.

Patients with malnutrition are at risk of entering a catabolic starvation state. The authors recommend avoiding long fasting periods with multiple small meals and late evening snacks.

Long-term, severe AH patients should be assessed for advanced fibrosis, although early diagnosis is often challenging, as the clinical and laboratory results typically mimic findings of liver cirrhosis, the authors write.