User login

Stranger than Fiction

A 65‐year‐old man suffered a myocardial infarction (MI) while traveling in Thailand. After 7 days of recovery, the patient departed for his home in the United States. He developed substernal, nonexertional, inspiratory chest pain and shortness of breath during his return flight and presented directly to an emergency room after arrival.

Initially, the evaluation should focus on life‐threatening diagnoses and not be distracted by the travel history. The immediate diagnostic concerns are active cardiac ischemia, complications of MI, and pulmonary embolus. Other cardiac causes of dyspnea include ischemic mitral regurgitation, postinfarction pericarditis with or without pericardial effusion, and heart failure. Mechanical complications of infarction, such as left ventricular free wall rupture or rupture of the interventricular septum, can occur in this time frame and are associated with significant morbidity. Pneumothorax may be precipitated by air travel, especially in patients with underlying lung disease. The immobilization associated with long airline flights is a risk factor for thromboembolic disease, which is classically associated with pleuritic chest pain. Inspiratory chest pain is also associated with inflammatory processes involving the pericardium or pleura. If pneumonia, pericarditis, or pleural effusion is present, details of his travel history will become more important in his evaluation.

The patient elaborated that he spent 10 days in Thailand. On the third day of his trip he developed severe chest pain while hiking toward a waterfall in a rural northern district. He was transferred to a large private hospital, where he received a stent in the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery 4 hours after symptom onset. At discharge he was prescribed ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily and daily doses of losartan 50 mg, furosemide 20 mg, spironolactone 12.5 mg, aspirin 81 mg, ivabradine 2.5 mg, and pravastatin 40 mg. He had also been taking doxycycline for malaria prophylaxis since departing the United States.

His past medical history was notable for hypertension and hyperlipidemia. The patient was a lifelong nonsmoker, did not use illicit substances, and consumed no more than 2 alcoholic beverages per day. He denied cough, fevers, chills, diaphoresis, weight loss, recent upper respiratory infection, abdominal pain, hematuria, and nausea. However, he reported exertional dyspnea following his MI and nonbloody diarrhea that occurred a few days prior to his return flight and resolved without intervention.

The remainder of his past medical history confirms that he received appropriate post‐MI care, but does not substantially alter the high priority concerns in his differential diagnosis. Diarrhea may occur in up to 50% of international travelers, and is especially common when returning from Southeast Asia or the Indian subcontinent. Disease processes that may explain diarrhea and subsequent dyspnea include intestinal infections that spread to the lung (eg, ascariasis and Loeffler syndrome), infection that precipitates neuromuscular weakness (eg, Campylobacter and Guillain‐Barr syndrome), or infection that precipitates heart failure (eg, coxsackievirus, myocarditis).

On admission, his temperature was 36.2C, heart rate 91 beats per minute, blood pressure 135/81 mm Hg, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. Cardiac exam revealed a regular rhythm without rubs, murmurs, or diastolic gallops. He had no jugular venous distention, and no lower extremity edema. His distal pulses were equal and palpable throughout. Pulmonary exam was notable for decreased breath sounds at both bases without wheezing, rhonchi, or crackles noted. He had no rashes, joint effusions, or jaundice. Abdominal and neurologic examinations were unremarkable.

Diminished breath sounds may suggest atelectasis or pleural effusion; the latter could account for the patient's inspiratory chest pain. A chest radiograph is essential to evaluate this finding further. The physical examination is not suggestive of decompensated heart failure; measurement of serum brain natriuretic peptide level would further exclude that diagnosis.

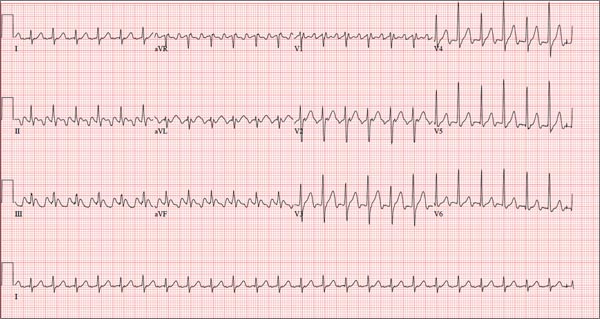

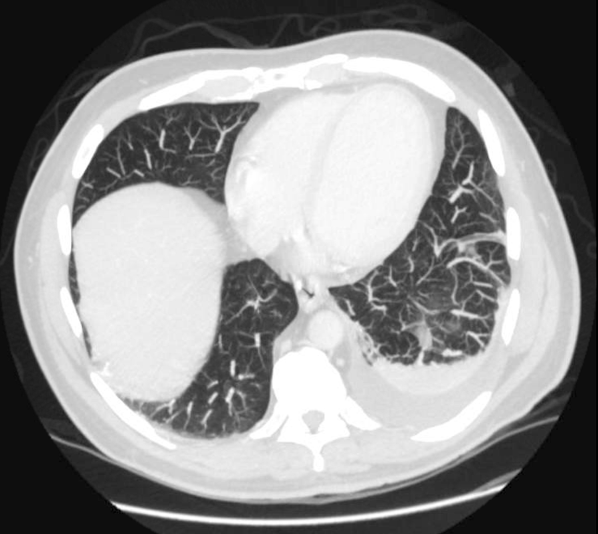

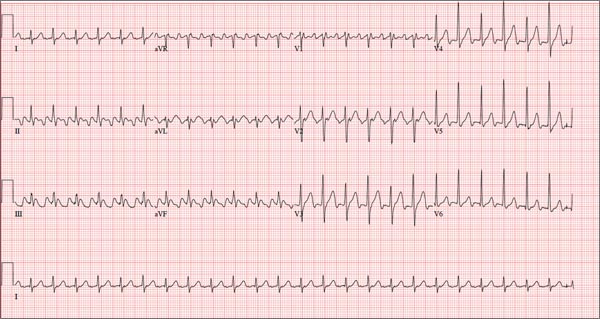

Laboratory evaluation revealed a leukocytosis of 16,000/L, with 76% polymorphonuclear cells and 12% lymphocytes without eosinophils or band forms; a hematocrit of 38%; and a platelet count of 363,000/L. The patient had a creatinine of 1.6 mg/dL, potassium of 2.7 mEq/L, and a troponin‐I of 1.0 ng/mL (normal 0.40 ng/mL), with the remainder of the routine serum chemistries within normal limits. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed QS complexes in the anteroseptal leads, and a chest radiograph showed bibasilar consolidations and a left pleural effusion. A ventilation‐perfusion scan of the chest was performed to evaluate for pulmonary embolism, and was interpreted as low probability. Transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction with anterior wall akinesis, and an aneurysmal left ventricle with an apical thrombus. No significant valvular pathology or other structural defects were noted.

The ECG and echocardiogram confirm the history of a large anteroseptal infarction with severe left ventricular dysfunction. Serial troponin testing would be reasonable. However, the absence of any acute ischemic ECG changes, typical angina symptoms, and a relatively normal troponin level all suggest his chest pain does not represent active ischemia. His low abnormal troponin‐I is consistent with slow resolution after a large ischemic event in the recent past, and his anterior wall akinesis is consistent with prior infarction in the territory of his culprit left anterior descending coronary artery.

Although acute cardiac conditions appear less likely, the brisk leukocytosis in a returned traveler prompts consideration of infection. His lung consolidations could represent either new or resolving pneumonia. The complete absence of cough and fever is unusual for pneumonia, yet clinical findings are not as sensitive as chest radiograph for this diagnosis. At this point, typical organisms as well as uncommon pathogens associated with diarrhea or his travel history should be included in the differential.

After 24 hours, the patient was discharged on warfarin to treat the apical thrombus and moxifloxacin for a presumed community‐acquired pneumonia. Eight days after discharge, the patient visited his primary care physician with improving, but not resolved, shortness of breath and pleuritic pain despite completing the 7‐day course of moxifloxacin. A chest radiograph showed a large posterior left basal pleural fluid collection, increased from previous.

In the setting of a recent infection, the symptoms and radiographic findings suggest a complicated parapneumonic effusion or empyema. Failure to drain a previously seeded fluid collection leaves bacterial pathogens susceptible to moxifloxacin on the differential, including Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Legionella species, and other enterobacteriaciae (eg, Klebsiella pneumoniae).

The indolent course should also prompt consideration of more unusual pathogens, including roundworms (such as Ascaris) or lung flukes (Paragonimus), either of which can cause a lung infection without traditional pneumonia symptoms. Tuberculosis tends to present months (or years) after exposure. Older adults may manifest primary pulmonary tuberculosis with lower lobe infiltrates, consistent with this presentation. However, moxifloxacin is quite active against tuberculosis, and although single drug therapy would not be expected to cure the patient, it would be surprising for him to progress this quickly on moxifloxacin.

In northern Thailand, Burkholderia pseudomallei is a common cause of bacteremic pneumonia. The organism often has high‐level resistance to fluoroquinolones, and may present in a more insidious fashion than other causes of community‐acquired pneumonia. Although infection with B pseudomallei (melioidosis) can occasionally mimic apical pulmonary tuberculosis and may present after a prolonged latent period, it most commonly manifests as an acute pneumonia.

The patient was prescribed 10 days of amoxicillin‐clavulanic acid and clindamycin, and decubitus films were ordered to assess the effusion. These films, obtained 5 days later, showed a persistent pleural effusion. Subsequent ultrasound demonstrated loculated fluid, but a thoracentesis was not performed at that time due to the patient's therapeutic international normalized ratio and dual antiplatelet therapy.

The loculation further suggests a complicated parapneumonic effusion or empyema. Clindamycin adds very little to amoxicillin‐clavulanate as far as coverage of oral anaerobes or common pneumonia pathogens and may add to the risk of antibiotic side effects. A susceptible organism might not clear because of failure to drain this collection; if undertreated bacterial infection is suspected, tube thoracentesis is the established standard of care. However, the protracted course of illness makes untreated pyogenic bacterial infections unlikely.

At this point, the top 2 diagnostic considerations are Paragonimus westermani and B pseudomallei. P westermani is initially ingested, usually from an undercooked freshwater crustacean. Infected patients may experience a brief diarrheal illness, as this patient reported. However, infected patients typically have a brisk peripheral eosinophilia.

Melioidosis is thus the leading concern. Amoxicillin‐clavulanate is active against many strains of B pseudomallei, so the failure of the patient to worsen could be seen as a partial treatment and supports this diagnosis. However, as prolonged therapy is necessary for complete eradication of B pseudomallei, a definitive, culture‐based diagnosis should be established before committing the patient to months of antibiotics.

After completing 10 days of clindamycin and amoxicillin‐clavulanate, the patient reported improvement of his pleuritic pain, and repeat physical exam suggested interval decrease in the size of the effusion. Two days later, the patient began experiencing dysuria that persisted despite 3 days of nitrofurantoin.

Melioidosis can also involve the genitourinary tract. Hematogenous spread of B pseudomallei can seed a number of visceral organs including the bladder, joints, and bones. Men with suspected urinary infection should be evaluated for the possibility of prostatitis, an infection with considerable morbidity that requires extended therapy. This gentleman should have a prostate exam, and blood and urine cultures should be collected if prostatitis is suspected. Empiric antibiotics are not recommended without culture in a patient with complicated urinary tract infection.

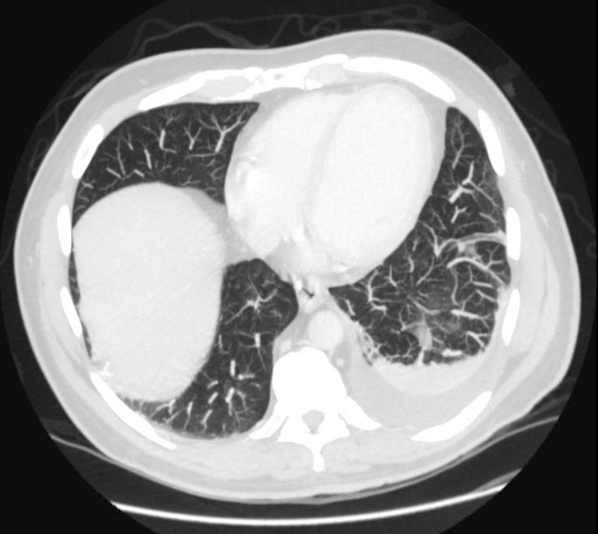

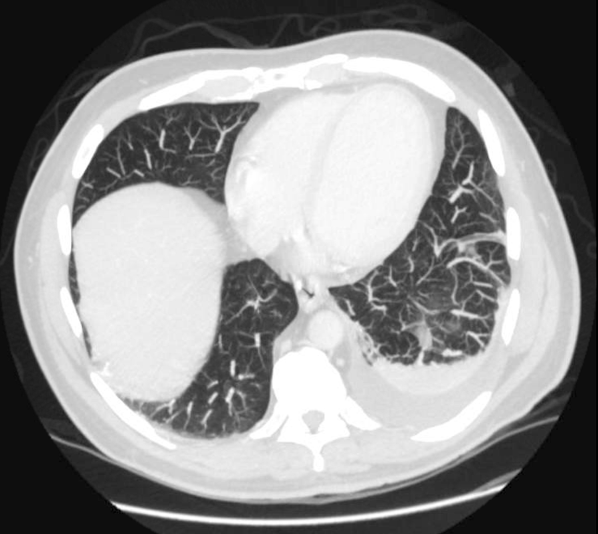

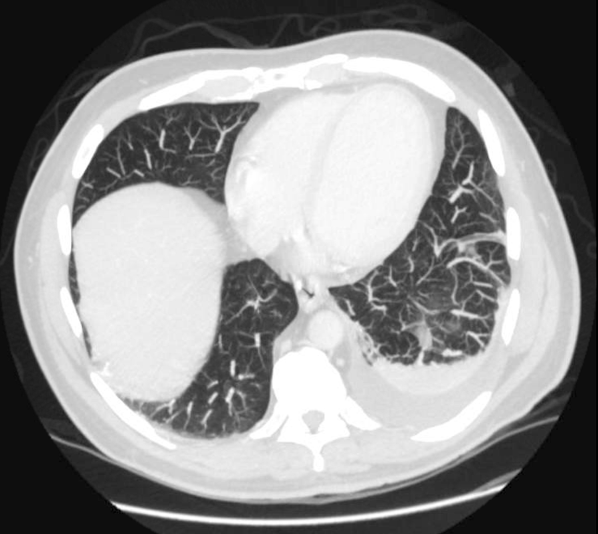

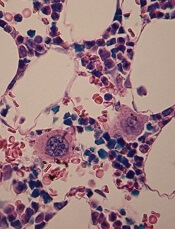

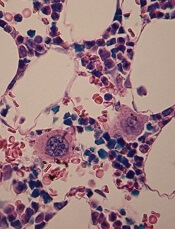

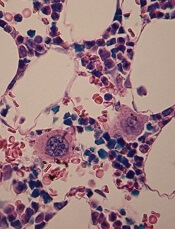

Prostate exam was unremarkable. A urine culture grew a gram‐negative rod identified as B pseudomallei. Because B pseudomallei can cause fulminant sepsis, the infectious disease consultant requested that he return for admission, further evaluation, and initiation of intravenous antibiotics. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed multiple pulmonary nodules, a persistent left pleural effusion, and a rim‐enhancing hypodensity in the prostate consistent with abscess (Figure 1). Blood and pleural fluid cultures were negative.

Initial treatment for a patient with severe or metastatic B pseudomallei infection requires high‐dose intravenous antibiotic therapy. Ceftazidime, imipenem, and meropenem are the best studied agents for this purpose. Surgical drainage should be considered for the abscess. Following the completion of intensive intravenous therapy, relapse rates are high unless a longer‐term, consolidation therapy is pursued. Trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole is the recommended agent.

The patient was treated with high‐dose ceftazidime for 2 weeks, followed by 6 months of high‐dose oral trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole. His symptoms resolved, and 7 months after presentation, he continued to feel well.

DISCUSSION

Melioidosis refers to any infection caused by B pseudomallei, a gram‐negative bacillus found in soil and water, most commonly in Southeast Asia and Australia.[1] It is an important cause of pneumonia in endemic regions; in Thailand, the incidence is as high as 12 cases per 100,000 people, and it is the third leading infectious cause of death, following human immunodeficiency virus and tuberculosis.[2] However, it occurs only as an imported infection in the United States and remains an unfamiliar infection for many US medical practitioners. Melioidosis should be considered in patients returning from endemic regions presenting with sepsis, pneumonia, urinary symptoms, or abscesses.

B pseudomallei can be transmitted to humans through exposure to contaminated soil or water via ingestion, inhalation, or percutaneous inoculation.[1] Outbreaks typically occur during the rainy season and after typhoons.[1, 3] Presumably, this patient's exposure to B pseudomallei occurred while hiking and wading in freshwater lakes and waterfalls. Although hospital‐acquired melioidosis has not been reported, and isolation precautions are not necessary, rare cases of disease acquired via laboratory exposure have been reported among US healthcare workers. Clinicians suspecting melioidosis should alert the receiving laboratory.[4]

The treatment course for melioidosis is lengthy and should involve consultation with an infectious disease specialist. B pseudomallei is known to be resistant to penicillin, first‐ and second‐generation cephalosporins, and moxifloxacin. The standard treatment includes 10 to 14 days of intravenous ceftazidime, meropenem, or imipenem, and then trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole for 3 to 6 months.[1] Treatment should be guided by culture susceptibility data when available. There are reports of B pseudomallei having different resistance patterns within the same host; clinicians should culture all drained fluid collections and tailor antibiotics to the most resistant strain recovered.[5, 6] Although melioidosis is a life‐threatening infection, previously healthy patients have an excellent prognosis assuming prompt diagnosis and treatment are provided.[3]

After excluding common causes of chest pain, the discussant identified the need to definitively establish a microbiologic diagnosis by obtaining pleural fluid. Although common clinical scenarios can often be treated with guideline‐supported empiric antibiotics, the use of serial courses of empiric antibiotics should be carefully questioned and is generally discouraged. Specific data to prove or disprove the presence of infection should be obtained before exposing a patient to the risks of multiple drugs or prolonged antibiotic therapy, as well as the risks of delayed (or missed) diagnosis. Unfortunately, a complete evaluation was delayed by clinical contraindications to diagnostic thoracentesis, and a definitive diagnosis was reached only after development of more widespread symptoms.

This patient's protean presentation is not surprising given his ultimate diagnosis. B pseudomallei has been termed the great mimicker, as disease presentation and organ involvement can vary from an indolent localized infection to acute severe sepsis.[7] Pneumonia and genitourinary infections are the most common manifestations, although skin infections, bacteremia, septic arthritis, and neurologic disease are also possible.[1, 3] In addition, melioidosis may develop after a lengthy incubation. In a case series, confirmed incubation periods ranged from 1 to 21 days (mean, 9 days); however, cases of chronic (>2 months) infection, mimicking tuberculosis, are estimated to occur in about 12% of cases.[4] B pseudomallei is also capable of causing reactivation disease, similar to tuberculosis. It was referred to as the Vietnamese time bomb when US Vietnam War veterans, exposed to the disease when helicopters aerosolized the bacteria in the soil, developed the disease only after their return to the United States.[8] Fortunately, only a tiny fraction of the quarter‐million soldiers with serologically confirmed exposure to the bacteria ultimately developed disease.

In The Adventure of the Dying Detective, Sherlock Holmes fakes a serious illness characterized by shortness of breath and weakness to trick an adversary into confessing to murder. The abrupt, crippling infection mimicked by Holmes is thought by some to be melioidosis.[9, 10] Conan Doyle's story was published in 1913, a year after melioidosis was first reported in the medical literature, and the exotic, protean infection may well have sparked Doyle's imagination. However, this patient's case of melioidosis proved stranger than fiction in its untimely concomitant development with an MI. Cracking our case required imagination and nimble thinking to avoid a number of cognitive pitfalls. The patient's recent MI anchored reasoning at his initial presentation, and the initial diagnosis of community‐acquired pneumonia raised the danger of premature closure. Reaching the correct diagnosis required an open mind, a detailed travel history, and firm microbiologic evidence. Hospitalists need not be expert in the health risks of travel to specific foreign destinations, but investigating those risks can hasten proper diagnosis and treatment.

TEACHING POINTS

- Melioidosis should be considered in patients returning from endemic regions who present with sepsis, pneumonia, urinary symptoms, or an abscess.

- For patients with a loculated parapneumonic effusion, tube thoracentesis for culture and drainage is the standard of care for diagnosis and treatment.

- Culture identification and antibiotic sensitivities are critical for management of B pseudomallei, because prolonged antibiotic treatment is needed.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , . Melioidosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(11):1035–1044.

- , , , et al. Increasing incidence of human melioidosis in Northeast Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82(6):1113–1117.

- , , . The epidemiology and clinical spectrum of melioidosis: 540 cases from the 20 year Darwin prospective study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(11):e900.

- , , , et al. Management of accidental laboratory exposure to Burkholderia pseudomallei and B. mallei. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(7):e2.

- , , . Variations in ceftazidime and amoxicillin‐clavulanate susceptibilities within a clonal infection of Burkholderia pseudomallei. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(5):1556–1558.

- , , , et al. Within‐host evolution of Burkholderia pseudomallei in four cases of acute melioidosis. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(1):e1000725.

- , , , , . Melioidosis: insights into the pathogenicity of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4(4):272–282.

- , . Melioidosis. In: Dembeck ZF, ed. Medical Aspects of Biological Warfare. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Office of the Surgeon General; 2007:146–166.

- . Sherlock Holmes and a biological weapon. J R Soc Med. 2002;95(2):101–103.

- . Sherlock Holmes and tropical medicine: a centennial appraisal. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;50:99–101.

A 65‐year‐old man suffered a myocardial infarction (MI) while traveling in Thailand. After 7 days of recovery, the patient departed for his home in the United States. He developed substernal, nonexertional, inspiratory chest pain and shortness of breath during his return flight and presented directly to an emergency room after arrival.

Initially, the evaluation should focus on life‐threatening diagnoses and not be distracted by the travel history. The immediate diagnostic concerns are active cardiac ischemia, complications of MI, and pulmonary embolus. Other cardiac causes of dyspnea include ischemic mitral regurgitation, postinfarction pericarditis with or without pericardial effusion, and heart failure. Mechanical complications of infarction, such as left ventricular free wall rupture or rupture of the interventricular septum, can occur in this time frame and are associated with significant morbidity. Pneumothorax may be precipitated by air travel, especially in patients with underlying lung disease. The immobilization associated with long airline flights is a risk factor for thromboembolic disease, which is classically associated with pleuritic chest pain. Inspiratory chest pain is also associated with inflammatory processes involving the pericardium or pleura. If pneumonia, pericarditis, or pleural effusion is present, details of his travel history will become more important in his evaluation.

The patient elaborated that he spent 10 days in Thailand. On the third day of his trip he developed severe chest pain while hiking toward a waterfall in a rural northern district. He was transferred to a large private hospital, where he received a stent in the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery 4 hours after symptom onset. At discharge he was prescribed ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily and daily doses of losartan 50 mg, furosemide 20 mg, spironolactone 12.5 mg, aspirin 81 mg, ivabradine 2.5 mg, and pravastatin 40 mg. He had also been taking doxycycline for malaria prophylaxis since departing the United States.

His past medical history was notable for hypertension and hyperlipidemia. The patient was a lifelong nonsmoker, did not use illicit substances, and consumed no more than 2 alcoholic beverages per day. He denied cough, fevers, chills, diaphoresis, weight loss, recent upper respiratory infection, abdominal pain, hematuria, and nausea. However, he reported exertional dyspnea following his MI and nonbloody diarrhea that occurred a few days prior to his return flight and resolved without intervention.

The remainder of his past medical history confirms that he received appropriate post‐MI care, but does not substantially alter the high priority concerns in his differential diagnosis. Diarrhea may occur in up to 50% of international travelers, and is especially common when returning from Southeast Asia or the Indian subcontinent. Disease processes that may explain diarrhea and subsequent dyspnea include intestinal infections that spread to the lung (eg, ascariasis and Loeffler syndrome), infection that precipitates neuromuscular weakness (eg, Campylobacter and Guillain‐Barr syndrome), or infection that precipitates heart failure (eg, coxsackievirus, myocarditis).

On admission, his temperature was 36.2C, heart rate 91 beats per minute, blood pressure 135/81 mm Hg, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. Cardiac exam revealed a regular rhythm without rubs, murmurs, or diastolic gallops. He had no jugular venous distention, and no lower extremity edema. His distal pulses were equal and palpable throughout. Pulmonary exam was notable for decreased breath sounds at both bases without wheezing, rhonchi, or crackles noted. He had no rashes, joint effusions, or jaundice. Abdominal and neurologic examinations were unremarkable.

Diminished breath sounds may suggest atelectasis or pleural effusion; the latter could account for the patient's inspiratory chest pain. A chest radiograph is essential to evaluate this finding further. The physical examination is not suggestive of decompensated heart failure; measurement of serum brain natriuretic peptide level would further exclude that diagnosis.

Laboratory evaluation revealed a leukocytosis of 16,000/L, with 76% polymorphonuclear cells and 12% lymphocytes without eosinophils or band forms; a hematocrit of 38%; and a platelet count of 363,000/L. The patient had a creatinine of 1.6 mg/dL, potassium of 2.7 mEq/L, and a troponin‐I of 1.0 ng/mL (normal 0.40 ng/mL), with the remainder of the routine serum chemistries within normal limits. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed QS complexes in the anteroseptal leads, and a chest radiograph showed bibasilar consolidations and a left pleural effusion. A ventilation‐perfusion scan of the chest was performed to evaluate for pulmonary embolism, and was interpreted as low probability. Transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction with anterior wall akinesis, and an aneurysmal left ventricle with an apical thrombus. No significant valvular pathology or other structural defects were noted.

The ECG and echocardiogram confirm the history of a large anteroseptal infarction with severe left ventricular dysfunction. Serial troponin testing would be reasonable. However, the absence of any acute ischemic ECG changes, typical angina symptoms, and a relatively normal troponin level all suggest his chest pain does not represent active ischemia. His low abnormal troponin‐I is consistent with slow resolution after a large ischemic event in the recent past, and his anterior wall akinesis is consistent with prior infarction in the territory of his culprit left anterior descending coronary artery.

Although acute cardiac conditions appear less likely, the brisk leukocytosis in a returned traveler prompts consideration of infection. His lung consolidations could represent either new or resolving pneumonia. The complete absence of cough and fever is unusual for pneumonia, yet clinical findings are not as sensitive as chest radiograph for this diagnosis. At this point, typical organisms as well as uncommon pathogens associated with diarrhea or his travel history should be included in the differential.

After 24 hours, the patient was discharged on warfarin to treat the apical thrombus and moxifloxacin for a presumed community‐acquired pneumonia. Eight days after discharge, the patient visited his primary care physician with improving, but not resolved, shortness of breath and pleuritic pain despite completing the 7‐day course of moxifloxacin. A chest radiograph showed a large posterior left basal pleural fluid collection, increased from previous.

In the setting of a recent infection, the symptoms and radiographic findings suggest a complicated parapneumonic effusion or empyema. Failure to drain a previously seeded fluid collection leaves bacterial pathogens susceptible to moxifloxacin on the differential, including Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Legionella species, and other enterobacteriaciae (eg, Klebsiella pneumoniae).

The indolent course should also prompt consideration of more unusual pathogens, including roundworms (such as Ascaris) or lung flukes (Paragonimus), either of which can cause a lung infection without traditional pneumonia symptoms. Tuberculosis tends to present months (or years) after exposure. Older adults may manifest primary pulmonary tuberculosis with lower lobe infiltrates, consistent with this presentation. However, moxifloxacin is quite active against tuberculosis, and although single drug therapy would not be expected to cure the patient, it would be surprising for him to progress this quickly on moxifloxacin.

In northern Thailand, Burkholderia pseudomallei is a common cause of bacteremic pneumonia. The organism often has high‐level resistance to fluoroquinolones, and may present in a more insidious fashion than other causes of community‐acquired pneumonia. Although infection with B pseudomallei (melioidosis) can occasionally mimic apical pulmonary tuberculosis and may present after a prolonged latent period, it most commonly manifests as an acute pneumonia.

The patient was prescribed 10 days of amoxicillin‐clavulanic acid and clindamycin, and decubitus films were ordered to assess the effusion. These films, obtained 5 days later, showed a persistent pleural effusion. Subsequent ultrasound demonstrated loculated fluid, but a thoracentesis was not performed at that time due to the patient's therapeutic international normalized ratio and dual antiplatelet therapy.

The loculation further suggests a complicated parapneumonic effusion or empyema. Clindamycin adds very little to amoxicillin‐clavulanate as far as coverage of oral anaerobes or common pneumonia pathogens and may add to the risk of antibiotic side effects. A susceptible organism might not clear because of failure to drain this collection; if undertreated bacterial infection is suspected, tube thoracentesis is the established standard of care. However, the protracted course of illness makes untreated pyogenic bacterial infections unlikely.

At this point, the top 2 diagnostic considerations are Paragonimus westermani and B pseudomallei. P westermani is initially ingested, usually from an undercooked freshwater crustacean. Infected patients may experience a brief diarrheal illness, as this patient reported. However, infected patients typically have a brisk peripheral eosinophilia.

Melioidosis is thus the leading concern. Amoxicillin‐clavulanate is active against many strains of B pseudomallei, so the failure of the patient to worsen could be seen as a partial treatment and supports this diagnosis. However, as prolonged therapy is necessary for complete eradication of B pseudomallei, a definitive, culture‐based diagnosis should be established before committing the patient to months of antibiotics.

After completing 10 days of clindamycin and amoxicillin‐clavulanate, the patient reported improvement of his pleuritic pain, and repeat physical exam suggested interval decrease in the size of the effusion. Two days later, the patient began experiencing dysuria that persisted despite 3 days of nitrofurantoin.

Melioidosis can also involve the genitourinary tract. Hematogenous spread of B pseudomallei can seed a number of visceral organs including the bladder, joints, and bones. Men with suspected urinary infection should be evaluated for the possibility of prostatitis, an infection with considerable morbidity that requires extended therapy. This gentleman should have a prostate exam, and blood and urine cultures should be collected if prostatitis is suspected. Empiric antibiotics are not recommended without culture in a patient with complicated urinary tract infection.

Prostate exam was unremarkable. A urine culture grew a gram‐negative rod identified as B pseudomallei. Because B pseudomallei can cause fulminant sepsis, the infectious disease consultant requested that he return for admission, further evaluation, and initiation of intravenous antibiotics. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed multiple pulmonary nodules, a persistent left pleural effusion, and a rim‐enhancing hypodensity in the prostate consistent with abscess (Figure 1). Blood and pleural fluid cultures were negative.

Initial treatment for a patient with severe or metastatic B pseudomallei infection requires high‐dose intravenous antibiotic therapy. Ceftazidime, imipenem, and meropenem are the best studied agents for this purpose. Surgical drainage should be considered for the abscess. Following the completion of intensive intravenous therapy, relapse rates are high unless a longer‐term, consolidation therapy is pursued. Trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole is the recommended agent.

The patient was treated with high‐dose ceftazidime for 2 weeks, followed by 6 months of high‐dose oral trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole. His symptoms resolved, and 7 months after presentation, he continued to feel well.

DISCUSSION

Melioidosis refers to any infection caused by B pseudomallei, a gram‐negative bacillus found in soil and water, most commonly in Southeast Asia and Australia.[1] It is an important cause of pneumonia in endemic regions; in Thailand, the incidence is as high as 12 cases per 100,000 people, and it is the third leading infectious cause of death, following human immunodeficiency virus and tuberculosis.[2] However, it occurs only as an imported infection in the United States and remains an unfamiliar infection for many US medical practitioners. Melioidosis should be considered in patients returning from endemic regions presenting with sepsis, pneumonia, urinary symptoms, or abscesses.

B pseudomallei can be transmitted to humans through exposure to contaminated soil or water via ingestion, inhalation, or percutaneous inoculation.[1] Outbreaks typically occur during the rainy season and after typhoons.[1, 3] Presumably, this patient's exposure to B pseudomallei occurred while hiking and wading in freshwater lakes and waterfalls. Although hospital‐acquired melioidosis has not been reported, and isolation precautions are not necessary, rare cases of disease acquired via laboratory exposure have been reported among US healthcare workers. Clinicians suspecting melioidosis should alert the receiving laboratory.[4]

The treatment course for melioidosis is lengthy and should involve consultation with an infectious disease specialist. B pseudomallei is known to be resistant to penicillin, first‐ and second‐generation cephalosporins, and moxifloxacin. The standard treatment includes 10 to 14 days of intravenous ceftazidime, meropenem, or imipenem, and then trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole for 3 to 6 months.[1] Treatment should be guided by culture susceptibility data when available. There are reports of B pseudomallei having different resistance patterns within the same host; clinicians should culture all drained fluid collections and tailor antibiotics to the most resistant strain recovered.[5, 6] Although melioidosis is a life‐threatening infection, previously healthy patients have an excellent prognosis assuming prompt diagnosis and treatment are provided.[3]

After excluding common causes of chest pain, the discussant identified the need to definitively establish a microbiologic diagnosis by obtaining pleural fluid. Although common clinical scenarios can often be treated with guideline‐supported empiric antibiotics, the use of serial courses of empiric antibiotics should be carefully questioned and is generally discouraged. Specific data to prove or disprove the presence of infection should be obtained before exposing a patient to the risks of multiple drugs or prolonged antibiotic therapy, as well as the risks of delayed (or missed) diagnosis. Unfortunately, a complete evaluation was delayed by clinical contraindications to diagnostic thoracentesis, and a definitive diagnosis was reached only after development of more widespread symptoms.

This patient's protean presentation is not surprising given his ultimate diagnosis. B pseudomallei has been termed the great mimicker, as disease presentation and organ involvement can vary from an indolent localized infection to acute severe sepsis.[7] Pneumonia and genitourinary infections are the most common manifestations, although skin infections, bacteremia, septic arthritis, and neurologic disease are also possible.[1, 3] In addition, melioidosis may develop after a lengthy incubation. In a case series, confirmed incubation periods ranged from 1 to 21 days (mean, 9 days); however, cases of chronic (>2 months) infection, mimicking tuberculosis, are estimated to occur in about 12% of cases.[4] B pseudomallei is also capable of causing reactivation disease, similar to tuberculosis. It was referred to as the Vietnamese time bomb when US Vietnam War veterans, exposed to the disease when helicopters aerosolized the bacteria in the soil, developed the disease only after their return to the United States.[8] Fortunately, only a tiny fraction of the quarter‐million soldiers with serologically confirmed exposure to the bacteria ultimately developed disease.

In The Adventure of the Dying Detective, Sherlock Holmes fakes a serious illness characterized by shortness of breath and weakness to trick an adversary into confessing to murder. The abrupt, crippling infection mimicked by Holmes is thought by some to be melioidosis.[9, 10] Conan Doyle's story was published in 1913, a year after melioidosis was first reported in the medical literature, and the exotic, protean infection may well have sparked Doyle's imagination. However, this patient's case of melioidosis proved stranger than fiction in its untimely concomitant development with an MI. Cracking our case required imagination and nimble thinking to avoid a number of cognitive pitfalls. The patient's recent MI anchored reasoning at his initial presentation, and the initial diagnosis of community‐acquired pneumonia raised the danger of premature closure. Reaching the correct diagnosis required an open mind, a detailed travel history, and firm microbiologic evidence. Hospitalists need not be expert in the health risks of travel to specific foreign destinations, but investigating those risks can hasten proper diagnosis and treatment.

TEACHING POINTS

- Melioidosis should be considered in patients returning from endemic regions who present with sepsis, pneumonia, urinary symptoms, or an abscess.

- For patients with a loculated parapneumonic effusion, tube thoracentesis for culture and drainage is the standard of care for diagnosis and treatment.

- Culture identification and antibiotic sensitivities are critical for management of B pseudomallei, because prolonged antibiotic treatment is needed.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

A 65‐year‐old man suffered a myocardial infarction (MI) while traveling in Thailand. After 7 days of recovery, the patient departed for his home in the United States. He developed substernal, nonexertional, inspiratory chest pain and shortness of breath during his return flight and presented directly to an emergency room after arrival.

Initially, the evaluation should focus on life‐threatening diagnoses and not be distracted by the travel history. The immediate diagnostic concerns are active cardiac ischemia, complications of MI, and pulmonary embolus. Other cardiac causes of dyspnea include ischemic mitral regurgitation, postinfarction pericarditis with or without pericardial effusion, and heart failure. Mechanical complications of infarction, such as left ventricular free wall rupture or rupture of the interventricular septum, can occur in this time frame and are associated with significant morbidity. Pneumothorax may be precipitated by air travel, especially in patients with underlying lung disease. The immobilization associated with long airline flights is a risk factor for thromboembolic disease, which is classically associated with pleuritic chest pain. Inspiratory chest pain is also associated with inflammatory processes involving the pericardium or pleura. If pneumonia, pericarditis, or pleural effusion is present, details of his travel history will become more important in his evaluation.

The patient elaborated that he spent 10 days in Thailand. On the third day of his trip he developed severe chest pain while hiking toward a waterfall in a rural northern district. He was transferred to a large private hospital, where he received a stent in the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery 4 hours after symptom onset. At discharge he was prescribed ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily and daily doses of losartan 50 mg, furosemide 20 mg, spironolactone 12.5 mg, aspirin 81 mg, ivabradine 2.5 mg, and pravastatin 40 mg. He had also been taking doxycycline for malaria prophylaxis since departing the United States.

His past medical history was notable for hypertension and hyperlipidemia. The patient was a lifelong nonsmoker, did not use illicit substances, and consumed no more than 2 alcoholic beverages per day. He denied cough, fevers, chills, diaphoresis, weight loss, recent upper respiratory infection, abdominal pain, hematuria, and nausea. However, he reported exertional dyspnea following his MI and nonbloody diarrhea that occurred a few days prior to his return flight and resolved without intervention.

The remainder of his past medical history confirms that he received appropriate post‐MI care, but does not substantially alter the high priority concerns in his differential diagnosis. Diarrhea may occur in up to 50% of international travelers, and is especially common when returning from Southeast Asia or the Indian subcontinent. Disease processes that may explain diarrhea and subsequent dyspnea include intestinal infections that spread to the lung (eg, ascariasis and Loeffler syndrome), infection that precipitates neuromuscular weakness (eg, Campylobacter and Guillain‐Barr syndrome), or infection that precipitates heart failure (eg, coxsackievirus, myocarditis).

On admission, his temperature was 36.2C, heart rate 91 beats per minute, blood pressure 135/81 mm Hg, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. Cardiac exam revealed a regular rhythm without rubs, murmurs, or diastolic gallops. He had no jugular venous distention, and no lower extremity edema. His distal pulses were equal and palpable throughout. Pulmonary exam was notable for decreased breath sounds at both bases without wheezing, rhonchi, or crackles noted. He had no rashes, joint effusions, or jaundice. Abdominal and neurologic examinations were unremarkable.

Diminished breath sounds may suggest atelectasis or pleural effusion; the latter could account for the patient's inspiratory chest pain. A chest radiograph is essential to evaluate this finding further. The physical examination is not suggestive of decompensated heart failure; measurement of serum brain natriuretic peptide level would further exclude that diagnosis.

Laboratory evaluation revealed a leukocytosis of 16,000/L, with 76% polymorphonuclear cells and 12% lymphocytes without eosinophils or band forms; a hematocrit of 38%; and a platelet count of 363,000/L. The patient had a creatinine of 1.6 mg/dL, potassium of 2.7 mEq/L, and a troponin‐I of 1.0 ng/mL (normal 0.40 ng/mL), with the remainder of the routine serum chemistries within normal limits. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed QS complexes in the anteroseptal leads, and a chest radiograph showed bibasilar consolidations and a left pleural effusion. A ventilation‐perfusion scan of the chest was performed to evaluate for pulmonary embolism, and was interpreted as low probability. Transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction with anterior wall akinesis, and an aneurysmal left ventricle with an apical thrombus. No significant valvular pathology or other structural defects were noted.

The ECG and echocardiogram confirm the history of a large anteroseptal infarction with severe left ventricular dysfunction. Serial troponin testing would be reasonable. However, the absence of any acute ischemic ECG changes, typical angina symptoms, and a relatively normal troponin level all suggest his chest pain does not represent active ischemia. His low abnormal troponin‐I is consistent with slow resolution after a large ischemic event in the recent past, and his anterior wall akinesis is consistent with prior infarction in the territory of his culprit left anterior descending coronary artery.

Although acute cardiac conditions appear less likely, the brisk leukocytosis in a returned traveler prompts consideration of infection. His lung consolidations could represent either new or resolving pneumonia. The complete absence of cough and fever is unusual for pneumonia, yet clinical findings are not as sensitive as chest radiograph for this diagnosis. At this point, typical organisms as well as uncommon pathogens associated with diarrhea or his travel history should be included in the differential.

After 24 hours, the patient was discharged on warfarin to treat the apical thrombus and moxifloxacin for a presumed community‐acquired pneumonia. Eight days after discharge, the patient visited his primary care physician with improving, but not resolved, shortness of breath and pleuritic pain despite completing the 7‐day course of moxifloxacin. A chest radiograph showed a large posterior left basal pleural fluid collection, increased from previous.

In the setting of a recent infection, the symptoms and radiographic findings suggest a complicated parapneumonic effusion or empyema. Failure to drain a previously seeded fluid collection leaves bacterial pathogens susceptible to moxifloxacin on the differential, including Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Legionella species, and other enterobacteriaciae (eg, Klebsiella pneumoniae).

The indolent course should also prompt consideration of more unusual pathogens, including roundworms (such as Ascaris) or lung flukes (Paragonimus), either of which can cause a lung infection without traditional pneumonia symptoms. Tuberculosis tends to present months (or years) after exposure. Older adults may manifest primary pulmonary tuberculosis with lower lobe infiltrates, consistent with this presentation. However, moxifloxacin is quite active against tuberculosis, and although single drug therapy would not be expected to cure the patient, it would be surprising for him to progress this quickly on moxifloxacin.

In northern Thailand, Burkholderia pseudomallei is a common cause of bacteremic pneumonia. The organism often has high‐level resistance to fluoroquinolones, and may present in a more insidious fashion than other causes of community‐acquired pneumonia. Although infection with B pseudomallei (melioidosis) can occasionally mimic apical pulmonary tuberculosis and may present after a prolonged latent period, it most commonly manifests as an acute pneumonia.

The patient was prescribed 10 days of amoxicillin‐clavulanic acid and clindamycin, and decubitus films were ordered to assess the effusion. These films, obtained 5 days later, showed a persistent pleural effusion. Subsequent ultrasound demonstrated loculated fluid, but a thoracentesis was not performed at that time due to the patient's therapeutic international normalized ratio and dual antiplatelet therapy.

The loculation further suggests a complicated parapneumonic effusion or empyema. Clindamycin adds very little to amoxicillin‐clavulanate as far as coverage of oral anaerobes or common pneumonia pathogens and may add to the risk of antibiotic side effects. A susceptible organism might not clear because of failure to drain this collection; if undertreated bacterial infection is suspected, tube thoracentesis is the established standard of care. However, the protracted course of illness makes untreated pyogenic bacterial infections unlikely.

At this point, the top 2 diagnostic considerations are Paragonimus westermani and B pseudomallei. P westermani is initially ingested, usually from an undercooked freshwater crustacean. Infected patients may experience a brief diarrheal illness, as this patient reported. However, infected patients typically have a brisk peripheral eosinophilia.

Melioidosis is thus the leading concern. Amoxicillin‐clavulanate is active against many strains of B pseudomallei, so the failure of the patient to worsen could be seen as a partial treatment and supports this diagnosis. However, as prolonged therapy is necessary for complete eradication of B pseudomallei, a definitive, culture‐based diagnosis should be established before committing the patient to months of antibiotics.

After completing 10 days of clindamycin and amoxicillin‐clavulanate, the patient reported improvement of his pleuritic pain, and repeat physical exam suggested interval decrease in the size of the effusion. Two days later, the patient began experiencing dysuria that persisted despite 3 days of nitrofurantoin.

Melioidosis can also involve the genitourinary tract. Hematogenous spread of B pseudomallei can seed a number of visceral organs including the bladder, joints, and bones. Men with suspected urinary infection should be evaluated for the possibility of prostatitis, an infection with considerable morbidity that requires extended therapy. This gentleman should have a prostate exam, and blood and urine cultures should be collected if prostatitis is suspected. Empiric antibiotics are not recommended without culture in a patient with complicated urinary tract infection.

Prostate exam was unremarkable. A urine culture grew a gram‐negative rod identified as B pseudomallei. Because B pseudomallei can cause fulminant sepsis, the infectious disease consultant requested that he return for admission, further evaluation, and initiation of intravenous antibiotics. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed multiple pulmonary nodules, a persistent left pleural effusion, and a rim‐enhancing hypodensity in the prostate consistent with abscess (Figure 1). Blood and pleural fluid cultures were negative.

Initial treatment for a patient with severe or metastatic B pseudomallei infection requires high‐dose intravenous antibiotic therapy. Ceftazidime, imipenem, and meropenem are the best studied agents for this purpose. Surgical drainage should be considered for the abscess. Following the completion of intensive intravenous therapy, relapse rates are high unless a longer‐term, consolidation therapy is pursued. Trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole is the recommended agent.

The patient was treated with high‐dose ceftazidime for 2 weeks, followed by 6 months of high‐dose oral trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole. His symptoms resolved, and 7 months after presentation, he continued to feel well.

DISCUSSION

Melioidosis refers to any infection caused by B pseudomallei, a gram‐negative bacillus found in soil and water, most commonly in Southeast Asia and Australia.[1] It is an important cause of pneumonia in endemic regions; in Thailand, the incidence is as high as 12 cases per 100,000 people, and it is the third leading infectious cause of death, following human immunodeficiency virus and tuberculosis.[2] However, it occurs only as an imported infection in the United States and remains an unfamiliar infection for many US medical practitioners. Melioidosis should be considered in patients returning from endemic regions presenting with sepsis, pneumonia, urinary symptoms, or abscesses.

B pseudomallei can be transmitted to humans through exposure to contaminated soil or water via ingestion, inhalation, or percutaneous inoculation.[1] Outbreaks typically occur during the rainy season and after typhoons.[1, 3] Presumably, this patient's exposure to B pseudomallei occurred while hiking and wading in freshwater lakes and waterfalls. Although hospital‐acquired melioidosis has not been reported, and isolation precautions are not necessary, rare cases of disease acquired via laboratory exposure have been reported among US healthcare workers. Clinicians suspecting melioidosis should alert the receiving laboratory.[4]

The treatment course for melioidosis is lengthy and should involve consultation with an infectious disease specialist. B pseudomallei is known to be resistant to penicillin, first‐ and second‐generation cephalosporins, and moxifloxacin. The standard treatment includes 10 to 14 days of intravenous ceftazidime, meropenem, or imipenem, and then trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole for 3 to 6 months.[1] Treatment should be guided by culture susceptibility data when available. There are reports of B pseudomallei having different resistance patterns within the same host; clinicians should culture all drained fluid collections and tailor antibiotics to the most resistant strain recovered.[5, 6] Although melioidosis is a life‐threatening infection, previously healthy patients have an excellent prognosis assuming prompt diagnosis and treatment are provided.[3]

After excluding common causes of chest pain, the discussant identified the need to definitively establish a microbiologic diagnosis by obtaining pleural fluid. Although common clinical scenarios can often be treated with guideline‐supported empiric antibiotics, the use of serial courses of empiric antibiotics should be carefully questioned and is generally discouraged. Specific data to prove or disprove the presence of infection should be obtained before exposing a patient to the risks of multiple drugs or prolonged antibiotic therapy, as well as the risks of delayed (or missed) diagnosis. Unfortunately, a complete evaluation was delayed by clinical contraindications to diagnostic thoracentesis, and a definitive diagnosis was reached only after development of more widespread symptoms.

This patient's protean presentation is not surprising given his ultimate diagnosis. B pseudomallei has been termed the great mimicker, as disease presentation and organ involvement can vary from an indolent localized infection to acute severe sepsis.[7] Pneumonia and genitourinary infections are the most common manifestations, although skin infections, bacteremia, septic arthritis, and neurologic disease are also possible.[1, 3] In addition, melioidosis may develop after a lengthy incubation. In a case series, confirmed incubation periods ranged from 1 to 21 days (mean, 9 days); however, cases of chronic (>2 months) infection, mimicking tuberculosis, are estimated to occur in about 12% of cases.[4] B pseudomallei is also capable of causing reactivation disease, similar to tuberculosis. It was referred to as the Vietnamese time bomb when US Vietnam War veterans, exposed to the disease when helicopters aerosolized the bacteria in the soil, developed the disease only after their return to the United States.[8] Fortunately, only a tiny fraction of the quarter‐million soldiers with serologically confirmed exposure to the bacteria ultimately developed disease.

In The Adventure of the Dying Detective, Sherlock Holmes fakes a serious illness characterized by shortness of breath and weakness to trick an adversary into confessing to murder. The abrupt, crippling infection mimicked by Holmes is thought by some to be melioidosis.[9, 10] Conan Doyle's story was published in 1913, a year after melioidosis was first reported in the medical literature, and the exotic, protean infection may well have sparked Doyle's imagination. However, this patient's case of melioidosis proved stranger than fiction in its untimely concomitant development with an MI. Cracking our case required imagination and nimble thinking to avoid a number of cognitive pitfalls. The patient's recent MI anchored reasoning at his initial presentation, and the initial diagnosis of community‐acquired pneumonia raised the danger of premature closure. Reaching the correct diagnosis required an open mind, a detailed travel history, and firm microbiologic evidence. Hospitalists need not be expert in the health risks of travel to specific foreign destinations, but investigating those risks can hasten proper diagnosis and treatment.

TEACHING POINTS

- Melioidosis should be considered in patients returning from endemic regions who present with sepsis, pneumonia, urinary symptoms, or an abscess.

- For patients with a loculated parapneumonic effusion, tube thoracentesis for culture and drainage is the standard of care for diagnosis and treatment.

- Culture identification and antibiotic sensitivities are critical for management of B pseudomallei, because prolonged antibiotic treatment is needed.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , . Melioidosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(11):1035–1044.

- , , , et al. Increasing incidence of human melioidosis in Northeast Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82(6):1113–1117.

- , , . The epidemiology and clinical spectrum of melioidosis: 540 cases from the 20 year Darwin prospective study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(11):e900.

- , , , et al. Management of accidental laboratory exposure to Burkholderia pseudomallei and B. mallei. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(7):e2.

- , , . Variations in ceftazidime and amoxicillin‐clavulanate susceptibilities within a clonal infection of Burkholderia pseudomallei. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(5):1556–1558.

- , , , et al. Within‐host evolution of Burkholderia pseudomallei in four cases of acute melioidosis. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(1):e1000725.

- , , , , . Melioidosis: insights into the pathogenicity of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4(4):272–282.

- , . Melioidosis. In: Dembeck ZF, ed. Medical Aspects of Biological Warfare. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Office of the Surgeon General; 2007:146–166.

- . Sherlock Holmes and a biological weapon. J R Soc Med. 2002;95(2):101–103.

- . Sherlock Holmes and tropical medicine: a centennial appraisal. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;50:99–101.

- , , . Melioidosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(11):1035–1044.

- , , , et al. Increasing incidence of human melioidosis in Northeast Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82(6):1113–1117.

- , , . The epidemiology and clinical spectrum of melioidosis: 540 cases from the 20 year Darwin prospective study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(11):e900.

- , , , et al. Management of accidental laboratory exposure to Burkholderia pseudomallei and B. mallei. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(7):e2.

- , , . Variations in ceftazidime and amoxicillin‐clavulanate susceptibilities within a clonal infection of Burkholderia pseudomallei. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(5):1556–1558.

- , , , et al. Within‐host evolution of Burkholderia pseudomallei in four cases of acute melioidosis. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(1):e1000725.

- , , , , . Melioidosis: insights into the pathogenicity of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4(4):272–282.

- , . Melioidosis. In: Dembeck ZF, ed. Medical Aspects of Biological Warfare. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Office of the Surgeon General; 2007:146–166.

- . Sherlock Holmes and a biological weapon. J R Soc Med. 2002;95(2):101–103.

- . Sherlock Holmes and tropical medicine: a centennial appraisal. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;50:99–101.

Patient safety and tort reform

Question: Developments in medical tort reform include:

A. Continued constitutional challenges to caps on damages.

B. An emphasis on patient safety.

C. Hillary Clinton’s Senate bill.

D. Linking medical tort reform to error reduction.

E. All of the above.

Answer: E. Recent years have witnessed a stabilizing environment for medical liability, although insurance premiums continue to vary greatly by specialty and geographic location.

Recent statistics from the American Medical Association show that 2014 ob.gyn. insurance rates range from less than $50,000 in some areas of California to a high of $215,000 in Nassau and Suffolk counties in New York. The highest average expense in 2013, around a quarter of a million dollars, was for those claims that resulted in plaintiff verdicts, while defendant verdicts were substantially lower and averaged $140,000.

As in the past, most claims were dropped, dismissed, or withdrawn. About one-quarter of claims were settled, with only 2% decided by an alternative dispute resolution. Less than 8% were decided by trial verdict, with the vast majority won by the defendant.

The plaintiff bar continues to mount constitutional challenges to caps on damages. The California Supreme Court had previously ruled that reforms under California’s historic Medical Injury Compensation Reform Act (MICRA)1, which limits noneconomic recovery to $250,000, are constitutional, because they are rationally related to the legitimate legislative goal of reducing medical costs.

However, the statute has again come under challenge, only to be reaffirmed by a California state appeals court. In November 2014, California voters rejected Proposition 46, which sought to increase the cap from $250,000 to $1.1 million.

Texas, another pro-reform state, sides with California, and Mississippi also ruled that its damage cap is constitutional. However, Florida and Oklahoma recently joined jurisdictions such as Georgia, Illinois, and Missouri in ruling that damage caps are unconstitutional.

Asserting that the current health care liability system has been an inefficient and sometimes ineffective mechanism for initiating or resolving claims of medical error, medical negligence, or malpractice, then-U.S. senators Hillary Clinton (D-N.Y.) and Barack Obama (D-Ill.) in 2005 jointly sponsored legislation (S. 1784) to establish a National Medical Error Disclosure and Compensation Program (National MEDiC Act). Although the bill was killed in Senate committee, its key provisions were subsequently published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2006;354:2205-8).

The senators noted that the liability system has failed to the extent that only one medical malpractice claim is filed for every eight medical injuries, that it takes 4-8 years to resolve a claim, and that “solutions to the patient safety, litigation, and medical liability insurance problems have been elusive.”

Accordingly, the bill’s purpose was to promote the confidential disclosure to patients of medical errors in an effort to improve patient-safety systems. At the time of disclosure, there would be negotiations for compensation and proposals to prevent a recurrence of the problem that led to the patient’s injury. However, the patient would retain the right to counsel during negotiations, as well as access to the courts if no agreement were reached. The bill was entirely silent on traditional tort reform measures.

Nearly 4 decades earlier, a no-fault proposal by Professor Jeffrey O’Connell made some of these points, but with sharper focus and specificity, especially regarding damages.2

In marked contrast to the Clinton-Obama bill, his proposal gave the medical provider the exclusive option to tender payment, which would completely foreclose future tort action by the victim. Compensation benefits included net economic loss such as 100% of lost wages, replacement service loss, medical treatment expenses, and reasonable attorney’s fees. But noneconomic losses, such as pain and suffering, were not reimbursable, and payment was net of any benefits from collateral sources.

This proposal elegantly combined efficiency and fairness, and would have ameliorated the financial and emotional toll that comes with litigating injuries arising out of health care. Legislation in the House of Representatives, the Alternative Medical Liability Act (H.R. 5400), incorporated many of these features, and came before the 98th U.S. Congress in 1984. It, too, died in committee.

There may be something to the current trend toward pairing tort reform with error reduction. Thoughtful observers point to “disclosure and offer” programs such as the one at the Lexington (Ky.) Veterans Affairs Medical Center, which boasts average settlements of approximately $15,000 per claim – compared with more than $98,000 at other VA institutions. Its policy has also decreased the average duration of cases, previously 2-4 years, to 2-4 months, as well as reduced costs for legal defense.

Likewise, the program at the University of Michigan Health System has reduced both the frequency and severity of claims, duration of cases, and litigation costs. Aware of these developments, some private insurers, such as the COPIC Insurance Company in Colorado, are adopting a similar approach.

In its updated 2014 tort reform position paper, the American College of Physicians continues to endorse caps on noneconomic and punitive damages, as well as other tort reform measures.

However, it now acknowledges that “improving patient safety and preventing errors must be at the fore of the medical liability reform discussion.” The ACP correctly asserts that “emphasizing patient safety, promoting a culture of quality improvement and coordinated care, and training physicians in best practices to avoid errors and reduce risk will prevent harm and reduce the waste associated with defensive medicine.”

This hybrid approach combining traditional tort reforms with a renewed attention to patient safety through medical error reduction may yet yield additional practical benefits.

Here, the experience in anesthesiology bears recounting: Its dramatic progress in risk management has cut patient death rate from 1 in 5,000 to 1 in 200,000 to 300,000 in the space of 20 years, and this has been associated with a concurrent 37% fall in insurance premiums.

References

1. Medical Injury Compensation Reform Act of 1975, Cal. Civ. Proc. Code § 3333.2 (West 1982).

2. O’Connell, J. No-Fault Insurance for Injuries Arising from Medical Treatment: A Proposal for Elective Coverage. Emory L. J. 1975;24:21.

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. Currently, he directs the St. Francis International Center for Healthcare Ethics in Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the articles in this series are adapted from the author’s 2006 book, “Medical Malpractice: Understanding the Law, Managing the Risk,” and his 2012 Halsbury treatise, “Medical Negligence and Professional Misconduct.” For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Question: Developments in medical tort reform include:

A. Continued constitutional challenges to caps on damages.

B. An emphasis on patient safety.

C. Hillary Clinton’s Senate bill.

D. Linking medical tort reform to error reduction.

E. All of the above.

Answer: E. Recent years have witnessed a stabilizing environment for medical liability, although insurance premiums continue to vary greatly by specialty and geographic location.

Recent statistics from the American Medical Association show that 2014 ob.gyn. insurance rates range from less than $50,000 in some areas of California to a high of $215,000 in Nassau and Suffolk counties in New York. The highest average expense in 2013, around a quarter of a million dollars, was for those claims that resulted in plaintiff verdicts, while defendant verdicts were substantially lower and averaged $140,000.

As in the past, most claims were dropped, dismissed, or withdrawn. About one-quarter of claims were settled, with only 2% decided by an alternative dispute resolution. Less than 8% were decided by trial verdict, with the vast majority won by the defendant.

The plaintiff bar continues to mount constitutional challenges to caps on damages. The California Supreme Court had previously ruled that reforms under California’s historic Medical Injury Compensation Reform Act (MICRA)1, which limits noneconomic recovery to $250,000, are constitutional, because they are rationally related to the legitimate legislative goal of reducing medical costs.

However, the statute has again come under challenge, only to be reaffirmed by a California state appeals court. In November 2014, California voters rejected Proposition 46, which sought to increase the cap from $250,000 to $1.1 million.

Texas, another pro-reform state, sides with California, and Mississippi also ruled that its damage cap is constitutional. However, Florida and Oklahoma recently joined jurisdictions such as Georgia, Illinois, and Missouri in ruling that damage caps are unconstitutional.

Asserting that the current health care liability system has been an inefficient and sometimes ineffective mechanism for initiating or resolving claims of medical error, medical negligence, or malpractice, then-U.S. senators Hillary Clinton (D-N.Y.) and Barack Obama (D-Ill.) in 2005 jointly sponsored legislation (S. 1784) to establish a National Medical Error Disclosure and Compensation Program (National MEDiC Act). Although the bill was killed in Senate committee, its key provisions were subsequently published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2006;354:2205-8).

The senators noted that the liability system has failed to the extent that only one medical malpractice claim is filed for every eight medical injuries, that it takes 4-8 years to resolve a claim, and that “solutions to the patient safety, litigation, and medical liability insurance problems have been elusive.”

Accordingly, the bill’s purpose was to promote the confidential disclosure to patients of medical errors in an effort to improve patient-safety systems. At the time of disclosure, there would be negotiations for compensation and proposals to prevent a recurrence of the problem that led to the patient’s injury. However, the patient would retain the right to counsel during negotiations, as well as access to the courts if no agreement were reached. The bill was entirely silent on traditional tort reform measures.

Nearly 4 decades earlier, a no-fault proposal by Professor Jeffrey O’Connell made some of these points, but with sharper focus and specificity, especially regarding damages.2

In marked contrast to the Clinton-Obama bill, his proposal gave the medical provider the exclusive option to tender payment, which would completely foreclose future tort action by the victim. Compensation benefits included net economic loss such as 100% of lost wages, replacement service loss, medical treatment expenses, and reasonable attorney’s fees. But noneconomic losses, such as pain and suffering, were not reimbursable, and payment was net of any benefits from collateral sources.

This proposal elegantly combined efficiency and fairness, and would have ameliorated the financial and emotional toll that comes with litigating injuries arising out of health care. Legislation in the House of Representatives, the Alternative Medical Liability Act (H.R. 5400), incorporated many of these features, and came before the 98th U.S. Congress in 1984. It, too, died in committee.

There may be something to the current trend toward pairing tort reform with error reduction. Thoughtful observers point to “disclosure and offer” programs such as the one at the Lexington (Ky.) Veterans Affairs Medical Center, which boasts average settlements of approximately $15,000 per claim – compared with more than $98,000 at other VA institutions. Its policy has also decreased the average duration of cases, previously 2-4 years, to 2-4 months, as well as reduced costs for legal defense.

Likewise, the program at the University of Michigan Health System has reduced both the frequency and severity of claims, duration of cases, and litigation costs. Aware of these developments, some private insurers, such as the COPIC Insurance Company in Colorado, are adopting a similar approach.

In its updated 2014 tort reform position paper, the American College of Physicians continues to endorse caps on noneconomic and punitive damages, as well as other tort reform measures.

However, it now acknowledges that “improving patient safety and preventing errors must be at the fore of the medical liability reform discussion.” The ACP correctly asserts that “emphasizing patient safety, promoting a culture of quality improvement and coordinated care, and training physicians in best practices to avoid errors and reduce risk will prevent harm and reduce the waste associated with defensive medicine.”

This hybrid approach combining traditional tort reforms with a renewed attention to patient safety through medical error reduction may yet yield additional practical benefits.

Here, the experience in anesthesiology bears recounting: Its dramatic progress in risk management has cut patient death rate from 1 in 5,000 to 1 in 200,000 to 300,000 in the space of 20 years, and this has been associated with a concurrent 37% fall in insurance premiums.

References

1. Medical Injury Compensation Reform Act of 1975, Cal. Civ. Proc. Code § 3333.2 (West 1982).

2. O’Connell, J. No-Fault Insurance for Injuries Arising from Medical Treatment: A Proposal for Elective Coverage. Emory L. J. 1975;24:21.

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. Currently, he directs the St. Francis International Center for Healthcare Ethics in Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the articles in this series are adapted from the author’s 2006 book, “Medical Malpractice: Understanding the Law, Managing the Risk,” and his 2012 Halsbury treatise, “Medical Negligence and Professional Misconduct.” For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Question: Developments in medical tort reform include:

A. Continued constitutional challenges to caps on damages.

B. An emphasis on patient safety.

C. Hillary Clinton’s Senate bill.

D. Linking medical tort reform to error reduction.

E. All of the above.

Answer: E. Recent years have witnessed a stabilizing environment for medical liability, although insurance premiums continue to vary greatly by specialty and geographic location.

Recent statistics from the American Medical Association show that 2014 ob.gyn. insurance rates range from less than $50,000 in some areas of California to a high of $215,000 in Nassau and Suffolk counties in New York. The highest average expense in 2013, around a quarter of a million dollars, was for those claims that resulted in plaintiff verdicts, while defendant verdicts were substantially lower and averaged $140,000.

As in the past, most claims were dropped, dismissed, or withdrawn. About one-quarter of claims were settled, with only 2% decided by an alternative dispute resolution. Less than 8% were decided by trial verdict, with the vast majority won by the defendant.

The plaintiff bar continues to mount constitutional challenges to caps on damages. The California Supreme Court had previously ruled that reforms under California’s historic Medical Injury Compensation Reform Act (MICRA)1, which limits noneconomic recovery to $250,000, are constitutional, because they are rationally related to the legitimate legislative goal of reducing medical costs.

However, the statute has again come under challenge, only to be reaffirmed by a California state appeals court. In November 2014, California voters rejected Proposition 46, which sought to increase the cap from $250,000 to $1.1 million.

Texas, another pro-reform state, sides with California, and Mississippi also ruled that its damage cap is constitutional. However, Florida and Oklahoma recently joined jurisdictions such as Georgia, Illinois, and Missouri in ruling that damage caps are unconstitutional.

Asserting that the current health care liability system has been an inefficient and sometimes ineffective mechanism for initiating or resolving claims of medical error, medical negligence, or malpractice, then-U.S. senators Hillary Clinton (D-N.Y.) and Barack Obama (D-Ill.) in 2005 jointly sponsored legislation (S. 1784) to establish a National Medical Error Disclosure and Compensation Program (National MEDiC Act). Although the bill was killed in Senate committee, its key provisions were subsequently published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2006;354:2205-8).

The senators noted that the liability system has failed to the extent that only one medical malpractice claim is filed for every eight medical injuries, that it takes 4-8 years to resolve a claim, and that “solutions to the patient safety, litigation, and medical liability insurance problems have been elusive.”

Accordingly, the bill’s purpose was to promote the confidential disclosure to patients of medical errors in an effort to improve patient-safety systems. At the time of disclosure, there would be negotiations for compensation and proposals to prevent a recurrence of the problem that led to the patient’s injury. However, the patient would retain the right to counsel during negotiations, as well as access to the courts if no agreement were reached. The bill was entirely silent on traditional tort reform measures.

Nearly 4 decades earlier, a no-fault proposal by Professor Jeffrey O’Connell made some of these points, but with sharper focus and specificity, especially regarding damages.2

In marked contrast to the Clinton-Obama bill, his proposal gave the medical provider the exclusive option to tender payment, which would completely foreclose future tort action by the victim. Compensation benefits included net economic loss such as 100% of lost wages, replacement service loss, medical treatment expenses, and reasonable attorney’s fees. But noneconomic losses, such as pain and suffering, were not reimbursable, and payment was net of any benefits from collateral sources.

This proposal elegantly combined efficiency and fairness, and would have ameliorated the financial and emotional toll that comes with litigating injuries arising out of health care. Legislation in the House of Representatives, the Alternative Medical Liability Act (H.R. 5400), incorporated many of these features, and came before the 98th U.S. Congress in 1984. It, too, died in committee.

There may be something to the current trend toward pairing tort reform with error reduction. Thoughtful observers point to “disclosure and offer” programs such as the one at the Lexington (Ky.) Veterans Affairs Medical Center, which boasts average settlements of approximately $15,000 per claim – compared with more than $98,000 at other VA institutions. Its policy has also decreased the average duration of cases, previously 2-4 years, to 2-4 months, as well as reduced costs for legal defense.

Likewise, the program at the University of Michigan Health System has reduced both the frequency and severity of claims, duration of cases, and litigation costs. Aware of these developments, some private insurers, such as the COPIC Insurance Company in Colorado, are adopting a similar approach.

In its updated 2014 tort reform position paper, the American College of Physicians continues to endorse caps on noneconomic and punitive damages, as well as other tort reform measures.

However, it now acknowledges that “improving patient safety and preventing errors must be at the fore of the medical liability reform discussion.” The ACP correctly asserts that “emphasizing patient safety, promoting a culture of quality improvement and coordinated care, and training physicians in best practices to avoid errors and reduce risk will prevent harm and reduce the waste associated with defensive medicine.”

This hybrid approach combining traditional tort reforms with a renewed attention to patient safety through medical error reduction may yet yield additional practical benefits.

Here, the experience in anesthesiology bears recounting: Its dramatic progress in risk management has cut patient death rate from 1 in 5,000 to 1 in 200,000 to 300,000 in the space of 20 years, and this has been associated with a concurrent 37% fall in insurance premiums.

References

1. Medical Injury Compensation Reform Act of 1975, Cal. Civ. Proc. Code § 3333.2 (West 1982).

2. O’Connell, J. No-Fault Insurance for Injuries Arising from Medical Treatment: A Proposal for Elective Coverage. Emory L. J. 1975;24:21.