User login

Most cardiologists misstep on aspirin in ACS

SNOWMASS, COLO. – U.S. cardiologists are glaringly out of touch with the guidelines on maintenance aspirin dosing in patients with acute coronary syndrome, American College of Cardiology President Dr. Patrick T. O’Gara said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

The latest AHA/ACC guidelines state that maintenance aspirin therapy at 81 mg/day to be continued indefinitely is preferred over 325 mg/day in patients with ACS, regardless of whether they have received a coronary stent or noninvasive medical management (Circulation 2014 Dec 23;130(25):e344-426).

“This statement has been out there in the guidelines for several years now. Yet the last time we interrogated the NCDR [National Cardiovascular Data Registry], 70% of patients with ACS were discharged on 325 mg/day of aspirin in the U.S.,” said Dr. O’Gara, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of clinical cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

The recommendation in the guidelines is based on several solid studies, including OASIS 7, which in more than 25,000 randomized patients showed no difference in outcomes when aspirin at 75-100 mg/day was compared with 300-325 mg/day, but an increased incidence of bleeding at the higher dose (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:930-42).

“Aspirin at 81 mg/day is not inferior with respect to clinical efficacy and it’s superior with respect to its safety outcome. But here in the United States we are still very much wedded to using 325 mg of aspirin. I’m not exactly sure of the reasons for that. Maybe it’s a catch up phenomenon,” Dr. O’Gara commented.

In the setting of percutaneous coronary intervention with a bare metal or drug-eluting stent for patients with either non–ST-elevation ACS or ST-elevation MI, the AHA/ACC guidelines give a class I recommendation for at least 12 months of dual-antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor. Either ticagrelor (Brilinta) at 90 mg twice daily or prasugrel (Effient) once daily at 10 mg is recommended over clopidogrel at 75 mg/day in patients who can take those medications safely; this guidance is based on ticagrelor’s superior efficacy compared with clopidogrel as shown in TRITON TIMI-38 (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:2001-15) and prasugrel’s superiority in the PLATO trial (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:1045-57).

The AHA/ACC guidelines give a relatively tepid level IIb recommendation that continuation of DAPT beyond 12 months may be considered in stent recipients. Many observers expect a stronger endorsement in the next iteration of the guidelines on the strength of the recent DAPT study, which showed that 30 months of DAPT was better than 12 in terms of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:2155-66).

“Interestingly enough, the mechanism of benefit had less to do with prevention of stent thrombosis than it did with prevention of recurrent MI and stroke. This renders into much sharper focus the question of whether we’re treating the patient or we’re treating the stent. This result would imply that we’re treating the patient,” Dr. O’Gara observed.

The guidelines also include a bail-out option which states that if the risk of bleeding outweighs the anticipated benefit, it’s reasonable to discontinue DAPT before 12 months.

“I don’t know a single practitioner who’s not had to withdraw one or both elements of DAPT because of bleeding or because of the need for unanticipated noncardiac surgery. It’s a fact of life, and sometimes you have to just hope for the best,” the cardiologist said.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – U.S. cardiologists are glaringly out of touch with the guidelines on maintenance aspirin dosing in patients with acute coronary syndrome, American College of Cardiology President Dr. Patrick T. O’Gara said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

The latest AHA/ACC guidelines state that maintenance aspirin therapy at 81 mg/day to be continued indefinitely is preferred over 325 mg/day in patients with ACS, regardless of whether they have received a coronary stent or noninvasive medical management (Circulation 2014 Dec 23;130(25):e344-426).

“This statement has been out there in the guidelines for several years now. Yet the last time we interrogated the NCDR [National Cardiovascular Data Registry], 70% of patients with ACS were discharged on 325 mg/day of aspirin in the U.S.,” said Dr. O’Gara, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of clinical cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

The recommendation in the guidelines is based on several solid studies, including OASIS 7, which in more than 25,000 randomized patients showed no difference in outcomes when aspirin at 75-100 mg/day was compared with 300-325 mg/day, but an increased incidence of bleeding at the higher dose (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:930-42).

“Aspirin at 81 mg/day is not inferior with respect to clinical efficacy and it’s superior with respect to its safety outcome. But here in the United States we are still very much wedded to using 325 mg of aspirin. I’m not exactly sure of the reasons for that. Maybe it’s a catch up phenomenon,” Dr. O’Gara commented.

In the setting of percutaneous coronary intervention with a bare metal or drug-eluting stent for patients with either non–ST-elevation ACS or ST-elevation MI, the AHA/ACC guidelines give a class I recommendation for at least 12 months of dual-antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor. Either ticagrelor (Brilinta) at 90 mg twice daily or prasugrel (Effient) once daily at 10 mg is recommended over clopidogrel at 75 mg/day in patients who can take those medications safely; this guidance is based on ticagrelor’s superior efficacy compared with clopidogrel as shown in TRITON TIMI-38 (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:2001-15) and prasugrel’s superiority in the PLATO trial (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:1045-57).

The AHA/ACC guidelines give a relatively tepid level IIb recommendation that continuation of DAPT beyond 12 months may be considered in stent recipients. Many observers expect a stronger endorsement in the next iteration of the guidelines on the strength of the recent DAPT study, which showed that 30 months of DAPT was better than 12 in terms of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:2155-66).

“Interestingly enough, the mechanism of benefit had less to do with prevention of stent thrombosis than it did with prevention of recurrent MI and stroke. This renders into much sharper focus the question of whether we’re treating the patient or we’re treating the stent. This result would imply that we’re treating the patient,” Dr. O’Gara observed.

The guidelines also include a bail-out option which states that if the risk of bleeding outweighs the anticipated benefit, it’s reasonable to discontinue DAPT before 12 months.

“I don’t know a single practitioner who’s not had to withdraw one or both elements of DAPT because of bleeding or because of the need for unanticipated noncardiac surgery. It’s a fact of life, and sometimes you have to just hope for the best,” the cardiologist said.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – U.S. cardiologists are glaringly out of touch with the guidelines on maintenance aspirin dosing in patients with acute coronary syndrome, American College of Cardiology President Dr. Patrick T. O’Gara said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

The latest AHA/ACC guidelines state that maintenance aspirin therapy at 81 mg/day to be continued indefinitely is preferred over 325 mg/day in patients with ACS, regardless of whether they have received a coronary stent or noninvasive medical management (Circulation 2014 Dec 23;130(25):e344-426).

“This statement has been out there in the guidelines for several years now. Yet the last time we interrogated the NCDR [National Cardiovascular Data Registry], 70% of patients with ACS were discharged on 325 mg/day of aspirin in the U.S.,” said Dr. O’Gara, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of clinical cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

The recommendation in the guidelines is based on several solid studies, including OASIS 7, which in more than 25,000 randomized patients showed no difference in outcomes when aspirin at 75-100 mg/day was compared with 300-325 mg/day, but an increased incidence of bleeding at the higher dose (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:930-42).

“Aspirin at 81 mg/day is not inferior with respect to clinical efficacy and it’s superior with respect to its safety outcome. But here in the United States we are still very much wedded to using 325 mg of aspirin. I’m not exactly sure of the reasons for that. Maybe it’s a catch up phenomenon,” Dr. O’Gara commented.

In the setting of percutaneous coronary intervention with a bare metal or drug-eluting stent for patients with either non–ST-elevation ACS or ST-elevation MI, the AHA/ACC guidelines give a class I recommendation for at least 12 months of dual-antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor. Either ticagrelor (Brilinta) at 90 mg twice daily or prasugrel (Effient) once daily at 10 mg is recommended over clopidogrel at 75 mg/day in patients who can take those medications safely; this guidance is based on ticagrelor’s superior efficacy compared with clopidogrel as shown in TRITON TIMI-38 (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:2001-15) and prasugrel’s superiority in the PLATO trial (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:1045-57).

The AHA/ACC guidelines give a relatively tepid level IIb recommendation that continuation of DAPT beyond 12 months may be considered in stent recipients. Many observers expect a stronger endorsement in the next iteration of the guidelines on the strength of the recent DAPT study, which showed that 30 months of DAPT was better than 12 in terms of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:2155-66).

“Interestingly enough, the mechanism of benefit had less to do with prevention of stent thrombosis than it did with prevention of recurrent MI and stroke. This renders into much sharper focus the question of whether we’re treating the patient or we’re treating the stent. This result would imply that we’re treating the patient,” Dr. O’Gara observed.

The guidelines also include a bail-out option which states that if the risk of bleeding outweighs the anticipated benefit, it’s reasonable to discontinue DAPT before 12 months.

“I don’t know a single practitioner who’s not had to withdraw one or both elements of DAPT because of bleeding or because of the need for unanticipated noncardiac surgery. It’s a fact of life, and sometimes you have to just hope for the best,” the cardiologist said.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

Your practice moves but your address on the Internet doesn’t

I moved offices in April 2014, for the first time in my career. Overall, it went quite smoothly.

But one problem persists, thanks to the Internet age.

The majority of search engines and rate-a-doc sites haven’t updated my address. I’ve e-mailed them about it, but get either no response or (even better) a response saying “We’ve reviewed your note and found our information is correct.” Apparently, I don’t know my correct address, in spite of driving there every day.

But what’s even more frustrating is when my patients follow these instructions. My secretary is quite conscientious about giving patients, new and old, the correct location when they make the appointment. My practice website even has a map.

Despite this, we still have a roughly 20% rate of people going to my old office across the street, then calling to see where we went. Worse, this even happens with patients who were never even seen at that office, yet have been to my new one several times.

Then they come in and yell at my staff for giving them the wrong address. They claim my website has the wrong address. It doesn’t, but I can’t control other sites.

The problem is that most don’t trust other people as much as they trust their phones. Rather than writing down my address when talking to my secretary, it’s easier to just tell Siri, “find Dr. Allan Block’s office.” Siri checks the Internet, where the majority of incorrect listings drown out my dinky little practice site. So people follow the phone’s instructions without questioning them. Even those who’ve previously been to this office, or think, “that doesn’t sound right,” will often follow the directions without question. After all, the Internet knows best.

I’m not knocking the rise of the smartphone. They’re awesome. I rely on Siri myself a great deal. But the phone is only as good as the data supplied, and isn’t capable of questioning it. If most sites list an incorrect address, then who am I to argue? I’m just the guy who’s actually renting the place.

The problem is that information itself is often unhelpful and misleading, and the Internet isn’t always right.

When I dictate an EEG report, I often end it with “clinical correlation is advised.” We need to keep that in mind for everyday life, too.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I moved offices in April 2014, for the first time in my career. Overall, it went quite smoothly.

But one problem persists, thanks to the Internet age.

The majority of search engines and rate-a-doc sites haven’t updated my address. I’ve e-mailed them about it, but get either no response or (even better) a response saying “We’ve reviewed your note and found our information is correct.” Apparently, I don’t know my correct address, in spite of driving there every day.

But what’s even more frustrating is when my patients follow these instructions. My secretary is quite conscientious about giving patients, new and old, the correct location when they make the appointment. My practice website even has a map.

Despite this, we still have a roughly 20% rate of people going to my old office across the street, then calling to see where we went. Worse, this even happens with patients who were never even seen at that office, yet have been to my new one several times.

Then they come in and yell at my staff for giving them the wrong address. They claim my website has the wrong address. It doesn’t, but I can’t control other sites.

The problem is that most don’t trust other people as much as they trust their phones. Rather than writing down my address when talking to my secretary, it’s easier to just tell Siri, “find Dr. Allan Block’s office.” Siri checks the Internet, where the majority of incorrect listings drown out my dinky little practice site. So people follow the phone’s instructions without questioning them. Even those who’ve previously been to this office, or think, “that doesn’t sound right,” will often follow the directions without question. After all, the Internet knows best.

I’m not knocking the rise of the smartphone. They’re awesome. I rely on Siri myself a great deal. But the phone is only as good as the data supplied, and isn’t capable of questioning it. If most sites list an incorrect address, then who am I to argue? I’m just the guy who’s actually renting the place.

The problem is that information itself is often unhelpful and misleading, and the Internet isn’t always right.

When I dictate an EEG report, I often end it with “clinical correlation is advised.” We need to keep that in mind for everyday life, too.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I moved offices in April 2014, for the first time in my career. Overall, it went quite smoothly.

But one problem persists, thanks to the Internet age.

The majority of search engines and rate-a-doc sites haven’t updated my address. I’ve e-mailed them about it, but get either no response or (even better) a response saying “We’ve reviewed your note and found our information is correct.” Apparently, I don’t know my correct address, in spite of driving there every day.

But what’s even more frustrating is when my patients follow these instructions. My secretary is quite conscientious about giving patients, new and old, the correct location when they make the appointment. My practice website even has a map.

Despite this, we still have a roughly 20% rate of people going to my old office across the street, then calling to see where we went. Worse, this even happens with patients who were never even seen at that office, yet have been to my new one several times.

Then they come in and yell at my staff for giving them the wrong address. They claim my website has the wrong address. It doesn’t, but I can’t control other sites.

The problem is that most don’t trust other people as much as they trust their phones. Rather than writing down my address when talking to my secretary, it’s easier to just tell Siri, “find Dr. Allan Block’s office.” Siri checks the Internet, where the majority of incorrect listings drown out my dinky little practice site. So people follow the phone’s instructions without questioning them. Even those who’ve previously been to this office, or think, “that doesn’t sound right,” will often follow the directions without question. After all, the Internet knows best.

I’m not knocking the rise of the smartphone. They’re awesome. I rely on Siri myself a great deal. But the phone is only as good as the data supplied, and isn’t capable of questioning it. If most sites list an incorrect address, then who am I to argue? I’m just the guy who’s actually renting the place.

The problem is that information itself is often unhelpful and misleading, and the Internet isn’t always right.

When I dictate an EEG report, I often end it with “clinical correlation is advised.” We need to keep that in mind for everyday life, too.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Early initiation of postpartum contraception decreases rapid repeat pregnancy in teens

In an effort to determine how to curb rapid repeat adolescent pregnancy, researchers at MedStar Washington Hospital Center in Washington, DC, conducted a retrospective cohort study with first-time adolescent mothers, aged 19 years or younger. The repeat pregnancy rate at 2 years was 35% (n = 340). The average (SD) time from delivery to the second pregnancy was 9.9 (6.4) months.

Damle and colleagues found that leaving the hospital after giving birth without initiating any contraception was associated with more than double the risk of repeat pregnancy (odds ratio [OR], 2.447; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.326–4.515). Follow-up in clinic within an 8-week postpartum period significantly reduced the chance of repeat pregnancy (OR, 0.322; 95% CI, 0.172–0.603). And placement of a long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), including intrauterine device or etonogestrel subdermal implant, by 8 weeks’ postpartum decreased the chance of rapid repeat pregnancy (OR, 0.118; 95% CI, 0.035-0.397).

Researchers Damle and colleagues concluded that adolescent mothers who begin to use a LARC within 8 weeks’ postpartum are less likely to have a repeat pregnancy within 2 years than those who chose another method or no contraception at all.

“First time adolescent mothers should be counseled about this advantage of using LARC,” wrote the authors.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Reference

1. Damle LF, Gohari AC, McEvoy AK, Desale SY, Gomez-Lobo V. Early initiation of postpartum contraception: does it decrease rapid repeat pregnancy in adolescents? J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2015;28(1):57–62.

In an effort to determine how to curb rapid repeat adolescent pregnancy, researchers at MedStar Washington Hospital Center in Washington, DC, conducted a retrospective cohort study with first-time adolescent mothers, aged 19 years or younger. The repeat pregnancy rate at 2 years was 35% (n = 340). The average (SD) time from delivery to the second pregnancy was 9.9 (6.4) months.

Damle and colleagues found that leaving the hospital after giving birth without initiating any contraception was associated with more than double the risk of repeat pregnancy (odds ratio [OR], 2.447; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.326–4.515). Follow-up in clinic within an 8-week postpartum period significantly reduced the chance of repeat pregnancy (OR, 0.322; 95% CI, 0.172–0.603). And placement of a long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), including intrauterine device or etonogestrel subdermal implant, by 8 weeks’ postpartum decreased the chance of rapid repeat pregnancy (OR, 0.118; 95% CI, 0.035-0.397).

Researchers Damle and colleagues concluded that adolescent mothers who begin to use a LARC within 8 weeks’ postpartum are less likely to have a repeat pregnancy within 2 years than those who chose another method or no contraception at all.

“First time adolescent mothers should be counseled about this advantage of using LARC,” wrote the authors.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

In an effort to determine how to curb rapid repeat adolescent pregnancy, researchers at MedStar Washington Hospital Center in Washington, DC, conducted a retrospective cohort study with first-time adolescent mothers, aged 19 years or younger. The repeat pregnancy rate at 2 years was 35% (n = 340). The average (SD) time from delivery to the second pregnancy was 9.9 (6.4) months.

Damle and colleagues found that leaving the hospital after giving birth without initiating any contraception was associated with more than double the risk of repeat pregnancy (odds ratio [OR], 2.447; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.326–4.515). Follow-up in clinic within an 8-week postpartum period significantly reduced the chance of repeat pregnancy (OR, 0.322; 95% CI, 0.172–0.603). And placement of a long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), including intrauterine device or etonogestrel subdermal implant, by 8 weeks’ postpartum decreased the chance of rapid repeat pregnancy (OR, 0.118; 95% CI, 0.035-0.397).

Researchers Damle and colleagues concluded that adolescent mothers who begin to use a LARC within 8 weeks’ postpartum are less likely to have a repeat pregnancy within 2 years than those who chose another method or no contraception at all.

“First time adolescent mothers should be counseled about this advantage of using LARC,” wrote the authors.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Reference

1. Damle LF, Gohari AC, McEvoy AK, Desale SY, Gomez-Lobo V. Early initiation of postpartum contraception: does it decrease rapid repeat pregnancy in adolescents? J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2015;28(1):57–62.

Reference

1. Damle LF, Gohari AC, McEvoy AK, Desale SY, Gomez-Lobo V. Early initiation of postpartum contraception: does it decrease rapid repeat pregnancy in adolescents? J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2015;28(1):57–62.

FDA approves ibrutinib for WM

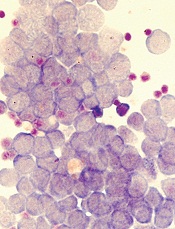

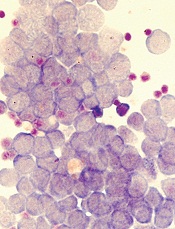

Credit: CDC

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted approval for ibrutinib (Imbruvica) as the first and only treatment for patients with Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia (WM).

The drug is now approved as a single agent for use in all lines of therapy.

This is the fourth indication for ibrutinib, which is also FDA-approved to treat patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who have received at least one prior therapy, CLL patients with del 17p, and patients with mantle cell lymphoma.

Ibrutinib is being jointly developed and commercialized by Pharmacyclics and Janssen Biotech, Inc.

The latest FDA approval is based on results from a multicenter, phase 2 study in which researchers evaluated the efficacy and tolerability of ibrutinib in 63 patients with previously treated WM.

The response rate, according to an independent review committee, was 62%. Eleven percent of patients had a very good partial response rate, and 51% had a partial response rate.

The median duration of response has not been reached, with a range of 2.8 to 18.8 months.

The most commonly occurring adverse events (>20%) were neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, diarrhea, rash, nausea, muscle spasms, and fatigue.

Six percent of patients discontinued treatment due to adverse events. Events leading to dose reduction occurred in 11% of patients.

For more details, see the full prescribing information. ![]()

Credit: CDC

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted approval for ibrutinib (Imbruvica) as the first and only treatment for patients with Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia (WM).

The drug is now approved as a single agent for use in all lines of therapy.

This is the fourth indication for ibrutinib, which is also FDA-approved to treat patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who have received at least one prior therapy, CLL patients with del 17p, and patients with mantle cell lymphoma.

Ibrutinib is being jointly developed and commercialized by Pharmacyclics and Janssen Biotech, Inc.

The latest FDA approval is based on results from a multicenter, phase 2 study in which researchers evaluated the efficacy and tolerability of ibrutinib in 63 patients with previously treated WM.

The response rate, according to an independent review committee, was 62%. Eleven percent of patients had a very good partial response rate, and 51% had a partial response rate.

The median duration of response has not been reached, with a range of 2.8 to 18.8 months.

The most commonly occurring adverse events (>20%) were neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, diarrhea, rash, nausea, muscle spasms, and fatigue.

Six percent of patients discontinued treatment due to adverse events. Events leading to dose reduction occurred in 11% of patients.

For more details, see the full prescribing information. ![]()

Credit: CDC

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted approval for ibrutinib (Imbruvica) as the first and only treatment for patients with Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia (WM).

The drug is now approved as a single agent for use in all lines of therapy.

This is the fourth indication for ibrutinib, which is also FDA-approved to treat patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who have received at least one prior therapy, CLL patients with del 17p, and patients with mantle cell lymphoma.

Ibrutinib is being jointly developed and commercialized by Pharmacyclics and Janssen Biotech, Inc.

The latest FDA approval is based on results from a multicenter, phase 2 study in which researchers evaluated the efficacy and tolerability of ibrutinib in 63 patients with previously treated WM.

The response rate, according to an independent review committee, was 62%. Eleven percent of patients had a very good partial response rate, and 51% had a partial response rate.

The median duration of response has not been reached, with a range of 2.8 to 18.8 months.

The most commonly occurring adverse events (>20%) were neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, diarrhea, rash, nausea, muscle spasms, and fatigue.

Six percent of patients discontinued treatment due to adverse events. Events leading to dose reduction occurred in 11% of patients.

For more details, see the full prescribing information. ![]()

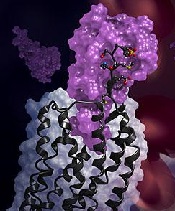

Kinase plays key role in leukemia

Credit: Robert Paulson

Inhibiting the cell-cycle kinase CDK6 may prevent leukemic relapse, according to research published in Blood.

Investigators found that CDK6 regulates the activation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and leukemic stem cells (LSCs), which it does by inhibiting the transcription factor Egr1.

When CDK6 is lost, Egr1 becomes active and prevents stem cells from dividing.

However, the mechanism operates only when HSCs are stressed—such as in leukemia—and not in the normal physiological situation.

“CDK6 is absolutely necessary for leukemic stem cells to induce disease but plays no part in normal hematopoiesis,” said study author Ruth Scheicher, of the University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna.

“We thus have a novel opportunity to target leukemia at its origin. Inhibiting CDK6 should attack leukemic stem cells while leaving healthy HSCs unaffected.”

Specifically, Scheicher and her colleagues found that Cdk6−/− HSCs did not efficiently repopulate when transplanted into mice. And Cdk6−/− mice could tolerate fewer cycles of treatment with 5-fluorouracil than wild-type mice.

Mice that received BCR-ABLp210+–infected bone marrow harvested from Cdk6−/− mice did not develop leukemia. However, the recipient mice did harbor LSCs.

And knocking down Egr1 in Cdk6−/− BCR-ABLp210+ LSCs enhanced the cells’ ability to form colonies.

The researchers said these results suggest CDK6 is “an important regulator of stem cell activation and an essential component of a transcriptional complex that suppresses Egr1 in HSCs and LSCs.” ![]()

Credit: Robert Paulson

Inhibiting the cell-cycle kinase CDK6 may prevent leukemic relapse, according to research published in Blood.

Investigators found that CDK6 regulates the activation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and leukemic stem cells (LSCs), which it does by inhibiting the transcription factor Egr1.

When CDK6 is lost, Egr1 becomes active and prevents stem cells from dividing.

However, the mechanism operates only when HSCs are stressed—such as in leukemia—and not in the normal physiological situation.

“CDK6 is absolutely necessary for leukemic stem cells to induce disease but plays no part in normal hematopoiesis,” said study author Ruth Scheicher, of the University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna.

“We thus have a novel opportunity to target leukemia at its origin. Inhibiting CDK6 should attack leukemic stem cells while leaving healthy HSCs unaffected.”

Specifically, Scheicher and her colleagues found that Cdk6−/− HSCs did not efficiently repopulate when transplanted into mice. And Cdk6−/− mice could tolerate fewer cycles of treatment with 5-fluorouracil than wild-type mice.

Mice that received BCR-ABLp210+–infected bone marrow harvested from Cdk6−/− mice did not develop leukemia. However, the recipient mice did harbor LSCs.

And knocking down Egr1 in Cdk6−/− BCR-ABLp210+ LSCs enhanced the cells’ ability to form colonies.

The researchers said these results suggest CDK6 is “an important regulator of stem cell activation and an essential component of a transcriptional complex that suppresses Egr1 in HSCs and LSCs.” ![]()

Credit: Robert Paulson

Inhibiting the cell-cycle kinase CDK6 may prevent leukemic relapse, according to research published in Blood.

Investigators found that CDK6 regulates the activation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and leukemic stem cells (LSCs), which it does by inhibiting the transcription factor Egr1.

When CDK6 is lost, Egr1 becomes active and prevents stem cells from dividing.

However, the mechanism operates only when HSCs are stressed—such as in leukemia—and not in the normal physiological situation.

“CDK6 is absolutely necessary for leukemic stem cells to induce disease but plays no part in normal hematopoiesis,” said study author Ruth Scheicher, of the University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna.

“We thus have a novel opportunity to target leukemia at its origin. Inhibiting CDK6 should attack leukemic stem cells while leaving healthy HSCs unaffected.”

Specifically, Scheicher and her colleagues found that Cdk6−/− HSCs did not efficiently repopulate when transplanted into mice. And Cdk6−/− mice could tolerate fewer cycles of treatment with 5-fluorouracil than wild-type mice.

Mice that received BCR-ABLp210+–infected bone marrow harvested from Cdk6−/− mice did not develop leukemia. However, the recipient mice did harbor LSCs.

And knocking down Egr1 in Cdk6−/− BCR-ABLp210+ LSCs enhanced the cells’ ability to form colonies.

The researchers said these results suggest CDK6 is “an important regulator of stem cell activation and an essential component of a transcriptional complex that suppresses Egr1 in HSCs and LSCs.” ![]()

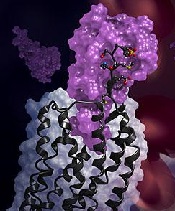

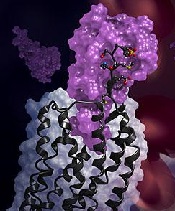

Group uncovers structure of receptor-chemokine complex

in complex with a chemokine

(purple surface)

Credit: Katya Kadyshevskaya

Researchers have reported the first crystal structure of the cellular receptor CXCR4 bound to the viral chemokine antagonist vMIP-II.

The structure, published in Science, answers longstanding questions about a molecular interaction that plays an important role in human development, immune responses, cancer spread, and HIV infections.

“This new information could ultimately aid the development of better small molecular inhibitors of CXCR4-chemokine interactions—inhibitors that have the potential to block cancer metastasis or viral infections,” said study author Tracy M. Handel, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego.

Dr Handel and her colleagues knew that CXCR4 binds chemokines to transmit messages to the inside of the cell. This signal relay helps cells migrate normally during development and inflammation.

But CXCR4 signaling can also play a role in abnormal cell migration, such as when cancer cells metastasize. And CXCR4 is infamous for another reason: HIV uses it to bind and infect human immune cells.

Despite its far-reaching consequences, researchers have long lacked data to show how exactly the CXCR4-chemokine interaction occurs, or even how many CXCR4 receptors a single chemokine molecule might simultaneously engage.

This is because membrane receptors like CXCR4 are exceptionally challenging structural targets. And the difficulty dramatically increases when studying such receptors in complexes with the proteins they bind.

To overcome these experimental challenges, Dr Handel’s team used a novel approach. They combined computational modeling and a technique known as disulfide trapping to stabilize the complex.

Once it was stabilized, the researchers were able to use X-ray crystallography to determine the CXCR4-chemokine complex’s 3D atomic structure.

This is the first time a receptor like CXCR4 has been crystallized with a protein binding partner, and the results revealed several new insights. First, the new crystal structure shows that one chemokine binds to just one receptor.

Additionally, the structure reveals that the contacts between the receptor and its binding partner are more extensive than previously thought. It is one very large, contiguous surface of interaction rather than two separate binding sites.

“The plasticity of the CXCR4 receptor—its ability to bind many unrelated small molecules, peptides, and proteins—is remarkable,” said Irina Kufareva, PhD, also of UC San Diego.

“Our understanding of this plasticity may impact the design of therapeutics with better inhibition and safety profiles.”

“With more than 800 members, 7-transmembrane receptors like CXCR4 are the largest protein family in the human genome,” added Raymond Stevens, PhD, of the Bridge Institute at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. “Each new structure opens up so many doors to understanding different aspects of human biology, and this time it is about chemokine signaling.” ![]()

in complex with a chemokine

(purple surface)

Credit: Katya Kadyshevskaya

Researchers have reported the first crystal structure of the cellular receptor CXCR4 bound to the viral chemokine antagonist vMIP-II.

The structure, published in Science, answers longstanding questions about a molecular interaction that plays an important role in human development, immune responses, cancer spread, and HIV infections.

“This new information could ultimately aid the development of better small molecular inhibitors of CXCR4-chemokine interactions—inhibitors that have the potential to block cancer metastasis or viral infections,” said study author Tracy M. Handel, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego.

Dr Handel and her colleagues knew that CXCR4 binds chemokines to transmit messages to the inside of the cell. This signal relay helps cells migrate normally during development and inflammation.

But CXCR4 signaling can also play a role in abnormal cell migration, such as when cancer cells metastasize. And CXCR4 is infamous for another reason: HIV uses it to bind and infect human immune cells.

Despite its far-reaching consequences, researchers have long lacked data to show how exactly the CXCR4-chemokine interaction occurs, or even how many CXCR4 receptors a single chemokine molecule might simultaneously engage.

This is because membrane receptors like CXCR4 are exceptionally challenging structural targets. And the difficulty dramatically increases when studying such receptors in complexes with the proteins they bind.

To overcome these experimental challenges, Dr Handel’s team used a novel approach. They combined computational modeling and a technique known as disulfide trapping to stabilize the complex.

Once it was stabilized, the researchers were able to use X-ray crystallography to determine the CXCR4-chemokine complex’s 3D atomic structure.

This is the first time a receptor like CXCR4 has been crystallized with a protein binding partner, and the results revealed several new insights. First, the new crystal structure shows that one chemokine binds to just one receptor.

Additionally, the structure reveals that the contacts between the receptor and its binding partner are more extensive than previously thought. It is one very large, contiguous surface of interaction rather than two separate binding sites.

“The plasticity of the CXCR4 receptor—its ability to bind many unrelated small molecules, peptides, and proteins—is remarkable,” said Irina Kufareva, PhD, also of UC San Diego.

“Our understanding of this plasticity may impact the design of therapeutics with better inhibition and safety profiles.”

“With more than 800 members, 7-transmembrane receptors like CXCR4 are the largest protein family in the human genome,” added Raymond Stevens, PhD, of the Bridge Institute at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. “Each new structure opens up so many doors to understanding different aspects of human biology, and this time it is about chemokine signaling.” ![]()

in complex with a chemokine

(purple surface)

Credit: Katya Kadyshevskaya

Researchers have reported the first crystal structure of the cellular receptor CXCR4 bound to the viral chemokine antagonist vMIP-II.

The structure, published in Science, answers longstanding questions about a molecular interaction that plays an important role in human development, immune responses, cancer spread, and HIV infections.

“This new information could ultimately aid the development of better small molecular inhibitors of CXCR4-chemokine interactions—inhibitors that have the potential to block cancer metastasis or viral infections,” said study author Tracy M. Handel, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego.

Dr Handel and her colleagues knew that CXCR4 binds chemokines to transmit messages to the inside of the cell. This signal relay helps cells migrate normally during development and inflammation.

But CXCR4 signaling can also play a role in abnormal cell migration, such as when cancer cells metastasize. And CXCR4 is infamous for another reason: HIV uses it to bind and infect human immune cells.

Despite its far-reaching consequences, researchers have long lacked data to show how exactly the CXCR4-chemokine interaction occurs, or even how many CXCR4 receptors a single chemokine molecule might simultaneously engage.

This is because membrane receptors like CXCR4 are exceptionally challenging structural targets. And the difficulty dramatically increases when studying such receptors in complexes with the proteins they bind.

To overcome these experimental challenges, Dr Handel’s team used a novel approach. They combined computational modeling and a technique known as disulfide trapping to stabilize the complex.

Once it was stabilized, the researchers were able to use X-ray crystallography to determine the CXCR4-chemokine complex’s 3D atomic structure.

This is the first time a receptor like CXCR4 has been crystallized with a protein binding partner, and the results revealed several new insights. First, the new crystal structure shows that one chemokine binds to just one receptor.

Additionally, the structure reveals that the contacts between the receptor and its binding partner are more extensive than previously thought. It is one very large, contiguous surface of interaction rather than two separate binding sites.

“The plasticity of the CXCR4 receptor—its ability to bind many unrelated small molecules, peptides, and proteins—is remarkable,” said Irina Kufareva, PhD, also of UC San Diego.

“Our understanding of this plasticity may impact the design of therapeutics with better inhibition and safety profiles.”

“With more than 800 members, 7-transmembrane receptors like CXCR4 are the largest protein family in the human genome,” added Raymond Stevens, PhD, of the Bridge Institute at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. “Each new structure opens up so many doors to understanding different aspects of human biology, and this time it is about chemokine signaling.” ![]()

Five touch points for mobile patient education

All current health care initiatives, whether overseen by providers, insurers, Pharma, or other industries, are focused on patient engagement. This overused but important term implies the active participation of patients in their own care. It implies that patients have the best means and educational resources available to them. Traditionally, patient education is achieve via face-to-face discussions with the physician or nurse or via third-party, preprinted written materials. Even now, 70% of patients report getting their medical information from physicians or nurses, according to a survey by the Pew Internet Research Project.

That said, more and more patients are seeking health information online – 60% of U.S. adults reported doing so within the past year, the Pew survey found.

Patients and caregivers are now becoming mobile. Baby boomers are becoming “seniors” at the rate of 8,000 per day. Mobile health digital tools can take the form of apps, multimedia offerings of videos, printable patient instructions, disease state education, and follow-up appointment reminders. These can be done with proprietary third-party platforms, or SAAS (software as a service), or practice developed and available via a portal on a website. The reason for this lies in its relevancy and the critical need for education at that corner the patient and caregiver are turning. I will discuss five touch points that are important to the patient and optimal for delivering digital health tools.

• Office encounter for a new medical problem. When a patient is seen for a new clinical problem, there is a seemingly overwhelming amount of new information transmitted. This involves the definition and description of the diagnosis; the level of severity; implications for life expectancy, occupation, and lifestyle; and the impact on others. Often patients focus on the latter issues and not the medical aspects including treatment purpose, options, and impact. Much of what was discussed with them at the encounter is forgotten. After all, how much can patients learn in a 15-minute visit? The ability to furnish patients with a digital replay of their encounter, along with educational materials pertinent to a diagnosis or recommended testing/procedure, is appealing. A company with the technology to do that is Liberate Health. (Ed. note: This publication’s parent company has a relationship with Liberate Health. Dr. Scher leads Liberate’s Digital Clinician Advisory group.) Of course, not all patients learn the same way. Guidelines on how to choose the most effective patient education material have been updated by the National Institutes of Health.

• Seeing a new health care provider. Walking into a new physician’s office is always intimidating. The encounter includes exploring personalities while discussing the clinical aspects of the visit. Compatibility with regards to treatment philosophy should be of paramount concern to the patient. Discussion surrounding how the physician communicates with and supports the patient experience goes a long way in creating a good physician-patient relationship. The mention of digital tools to recommend (apps, links to reliable website) conveys empathy, which is critical to patient engagement.

• Recommendation for new therapy, test, or procedure. While a patient’s head is swimming thinking about what will be found and recommended after a test or procedure is discussed, specifics about the test itself can be lost. Support provided via easy-to-understand digital explanation and visuals, viewed at a patient’s convenience and shared with a caregiver, seem like a no-brainer.

• Hospital discharge. The hospital discharge process is a whirlwind of explanations, instructions, and hopefully, follow-up appointments. It is usually crammed into a few minutes. In one study, only 42% of patients being discharged were able to state their diagnosis or diagnoses and even fewer (37%) were able to identify the purpose of all the medications they were going home on (Mayo Clin. Proc. 2005;80:991-4). Another larger study describes the mismatch between thoroughness of written instructions and patient understanding (JAMA Intern. Med. 2013;173:1715-22). Again, digital instructions reviewed at a convenient time and place would facilitate understanding.

• Becoming a caregiver. No one teaches a family member how to become a caregiver. It’s even harder than becoming a parent which is often facilitated by observation while growing up. Caregiving is often thrust upon someone with an untimely diagnosis of a loved one. There is upheaval on emotional, physical, and logistical levels. Caregivers are critical in the adoption of mobile health technologies. They need to be included in the delivery of these tools for a couple of reasons: They will likely be more digital savvy than the elderly patient is, and they need to have accurate information to be a better caregiver. They are the “silent majority” of health care stakeholders and probably the most critical.

It is not difficult to see how digital technology tools can help the physician-patient relationship by making the patient a better partner in care. While adoption of these tools will not happen overnight, it will happen.

Dr. Scher is an electrophysiologist with the Heart Group of Lancaster (Pa.) General Health. He is also director of DLS Healthcare Consulting, Harrisburg, Pa., and clinical associate professor of medicine at the Pennsylvania State University, Hershey.

All current health care initiatives, whether overseen by providers, insurers, Pharma, or other industries, are focused on patient engagement. This overused but important term implies the active participation of patients in their own care. It implies that patients have the best means and educational resources available to them. Traditionally, patient education is achieve via face-to-face discussions with the physician or nurse or via third-party, preprinted written materials. Even now, 70% of patients report getting their medical information from physicians or nurses, according to a survey by the Pew Internet Research Project.

That said, more and more patients are seeking health information online – 60% of U.S. adults reported doing so within the past year, the Pew survey found.

Patients and caregivers are now becoming mobile. Baby boomers are becoming “seniors” at the rate of 8,000 per day. Mobile health digital tools can take the form of apps, multimedia offerings of videos, printable patient instructions, disease state education, and follow-up appointment reminders. These can be done with proprietary third-party platforms, or SAAS (software as a service), or practice developed and available via a portal on a website. The reason for this lies in its relevancy and the critical need for education at that corner the patient and caregiver are turning. I will discuss five touch points that are important to the patient and optimal for delivering digital health tools.

• Office encounter for a new medical problem. When a patient is seen for a new clinical problem, there is a seemingly overwhelming amount of new information transmitted. This involves the definition and description of the diagnosis; the level of severity; implications for life expectancy, occupation, and lifestyle; and the impact on others. Often patients focus on the latter issues and not the medical aspects including treatment purpose, options, and impact. Much of what was discussed with them at the encounter is forgotten. After all, how much can patients learn in a 15-minute visit? The ability to furnish patients with a digital replay of their encounter, along with educational materials pertinent to a diagnosis or recommended testing/procedure, is appealing. A company with the technology to do that is Liberate Health. (Ed. note: This publication’s parent company has a relationship with Liberate Health. Dr. Scher leads Liberate’s Digital Clinician Advisory group.) Of course, not all patients learn the same way. Guidelines on how to choose the most effective patient education material have been updated by the National Institutes of Health.

• Seeing a new health care provider. Walking into a new physician’s office is always intimidating. The encounter includes exploring personalities while discussing the clinical aspects of the visit. Compatibility with regards to treatment philosophy should be of paramount concern to the patient. Discussion surrounding how the physician communicates with and supports the patient experience goes a long way in creating a good physician-patient relationship. The mention of digital tools to recommend (apps, links to reliable website) conveys empathy, which is critical to patient engagement.

• Recommendation for new therapy, test, or procedure. While a patient’s head is swimming thinking about what will be found and recommended after a test or procedure is discussed, specifics about the test itself can be lost. Support provided via easy-to-understand digital explanation and visuals, viewed at a patient’s convenience and shared with a caregiver, seem like a no-brainer.

• Hospital discharge. The hospital discharge process is a whirlwind of explanations, instructions, and hopefully, follow-up appointments. It is usually crammed into a few minutes. In one study, only 42% of patients being discharged were able to state their diagnosis or diagnoses and even fewer (37%) were able to identify the purpose of all the medications they were going home on (Mayo Clin. Proc. 2005;80:991-4). Another larger study describes the mismatch between thoroughness of written instructions and patient understanding (JAMA Intern. Med. 2013;173:1715-22). Again, digital instructions reviewed at a convenient time and place would facilitate understanding.

• Becoming a caregiver. No one teaches a family member how to become a caregiver. It’s even harder than becoming a parent which is often facilitated by observation while growing up. Caregiving is often thrust upon someone with an untimely diagnosis of a loved one. There is upheaval on emotional, physical, and logistical levels. Caregivers are critical in the adoption of mobile health technologies. They need to be included in the delivery of these tools for a couple of reasons: They will likely be more digital savvy than the elderly patient is, and they need to have accurate information to be a better caregiver. They are the “silent majority” of health care stakeholders and probably the most critical.

It is not difficult to see how digital technology tools can help the physician-patient relationship by making the patient a better partner in care. While adoption of these tools will not happen overnight, it will happen.

Dr. Scher is an electrophysiologist with the Heart Group of Lancaster (Pa.) General Health. He is also director of DLS Healthcare Consulting, Harrisburg, Pa., and clinical associate professor of medicine at the Pennsylvania State University, Hershey.

All current health care initiatives, whether overseen by providers, insurers, Pharma, or other industries, are focused on patient engagement. This overused but important term implies the active participation of patients in their own care. It implies that patients have the best means and educational resources available to them. Traditionally, patient education is achieve via face-to-face discussions with the physician or nurse or via third-party, preprinted written materials. Even now, 70% of patients report getting their medical information from physicians or nurses, according to a survey by the Pew Internet Research Project.

That said, more and more patients are seeking health information online – 60% of U.S. adults reported doing so within the past year, the Pew survey found.

Patients and caregivers are now becoming mobile. Baby boomers are becoming “seniors” at the rate of 8,000 per day. Mobile health digital tools can take the form of apps, multimedia offerings of videos, printable patient instructions, disease state education, and follow-up appointment reminders. These can be done with proprietary third-party platforms, or SAAS (software as a service), or practice developed and available via a portal on a website. The reason for this lies in its relevancy and the critical need for education at that corner the patient and caregiver are turning. I will discuss five touch points that are important to the patient and optimal for delivering digital health tools.

• Office encounter for a new medical problem. When a patient is seen for a new clinical problem, there is a seemingly overwhelming amount of new information transmitted. This involves the definition and description of the diagnosis; the level of severity; implications for life expectancy, occupation, and lifestyle; and the impact on others. Often patients focus on the latter issues and not the medical aspects including treatment purpose, options, and impact. Much of what was discussed with them at the encounter is forgotten. After all, how much can patients learn in a 15-minute visit? The ability to furnish patients with a digital replay of their encounter, along with educational materials pertinent to a diagnosis or recommended testing/procedure, is appealing. A company with the technology to do that is Liberate Health. (Ed. note: This publication’s parent company has a relationship with Liberate Health. Dr. Scher leads Liberate’s Digital Clinician Advisory group.) Of course, not all patients learn the same way. Guidelines on how to choose the most effective patient education material have been updated by the National Institutes of Health.

• Seeing a new health care provider. Walking into a new physician’s office is always intimidating. The encounter includes exploring personalities while discussing the clinical aspects of the visit. Compatibility with regards to treatment philosophy should be of paramount concern to the patient. Discussion surrounding how the physician communicates with and supports the patient experience goes a long way in creating a good physician-patient relationship. The mention of digital tools to recommend (apps, links to reliable website) conveys empathy, which is critical to patient engagement.

• Recommendation for new therapy, test, or procedure. While a patient’s head is swimming thinking about what will be found and recommended after a test or procedure is discussed, specifics about the test itself can be lost. Support provided via easy-to-understand digital explanation and visuals, viewed at a patient’s convenience and shared with a caregiver, seem like a no-brainer.

• Hospital discharge. The hospital discharge process is a whirlwind of explanations, instructions, and hopefully, follow-up appointments. It is usually crammed into a few minutes. In one study, only 42% of patients being discharged were able to state their diagnosis or diagnoses and even fewer (37%) were able to identify the purpose of all the medications they were going home on (Mayo Clin. Proc. 2005;80:991-4). Another larger study describes the mismatch between thoroughness of written instructions and patient understanding (JAMA Intern. Med. 2013;173:1715-22). Again, digital instructions reviewed at a convenient time and place would facilitate understanding.

• Becoming a caregiver. No one teaches a family member how to become a caregiver. It’s even harder than becoming a parent which is often facilitated by observation while growing up. Caregiving is often thrust upon someone with an untimely diagnosis of a loved one. There is upheaval on emotional, physical, and logistical levels. Caregivers are critical in the adoption of mobile health technologies. They need to be included in the delivery of these tools for a couple of reasons: They will likely be more digital savvy than the elderly patient is, and they need to have accurate information to be a better caregiver. They are the “silent majority” of health care stakeholders and probably the most critical.

It is not difficult to see how digital technology tools can help the physician-patient relationship by making the patient a better partner in care. While adoption of these tools will not happen overnight, it will happen.

Dr. Scher is an electrophysiologist with the Heart Group of Lancaster (Pa.) General Health. He is also director of DLS Healthcare Consulting, Harrisburg, Pa., and clinical associate professor of medicine at the Pennsylvania State University, Hershey.

Sedating antidepressants for insomnia

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Cutaneous Burn Caused by Radiofrequency Ablation Probe During Shoulder Arthroscopy

Cautery and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) devices are commonly used in shoulder arthroscopic surgery for hemostasis and ablation of soft tissue. Although these devices are easily used and applied, complications (eg, extensive release of deltoid muscle,1 nerve damage,2 tendon damage,3 cartilage damage from heat transfer4) can occur during arthroscopic surgery. Radiofrequency devices can elevate fluid temperatures to unsafe levels and directly or indirectly injure surrounding tissue.5,6 Skin complications from using these devices include direct burns to the subcutaneous tissues from the joint to the skin surface7 and skin burns related to overheated arthroscopic fluid.8

In our English-language literature review, however, we found no report of a skin burn secondary to contact between a RFA device and a spinal needle used in identifying structures during an arthroscopic acromioplasty. We report such a case here. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 51-year-old woman injured her left, nondominant shoulder when a descending garage door hit her directly on the superior aspect of the shoulder. She had immediate onset of pain on the top and lateral side of the shoulder and was evaluated by a primary care physician. Radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were normal. The patient was referred to an orthopedic surgeon for further evaluation.

The orthopedic surgeon found her to be in good health, with no history of diabetes, vascular conditions, or skin disorders. The initial diagnosis after history taking and physical examination was impingement syndrome with subacromial bursitis. The surgeon recommended nonoperative treatment: ice, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and physical therapy. After 3 months, the patient’s examination was unchanged, and there was no improvement in pain. Cortisone injected into the subacromial space helped for a few weeks, but the pain returned. After 2 more cortisone injections over 9 months failed, repeat MRI showed no tears of the rotator cuff or any other salient abnormalities. The treatment options were discussed with the patient, and, because the physical examination findings were consistent with impingement syndrome and nonoperative measures had failed, she consented to arthroscopic evaluation of the shoulder and arthroscopic partial anterior-lateral acromioplasty.

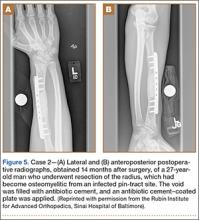

The procedure was performed 8 months after initial injury. With the patient under general anesthesia and in a lateral decubitus position, her arm was placed in an arm holder. Before the partial acromioplasty, two 18-gauge spinal needles were inserted from the skin surface into the subacromial space to help localize the anterolateral acromion and the acromioclavicular joint. The procedure was performed with a pump using saline bags kept at room temperature. A bipolar radiofrequency device (Stryker Energy Radiofrequency Ablation System; Stryker, Mahwah, New Jersey) was used to débride the subacromial bursa and the periosteum of the undersurface of the acromion. While the bursa was being débrided, the radiofrequency device inadvertently touched the anterior lateral needle probe, and a small skin burn formed around the needle on the surface of the shoulder (Figure). The radiofrequency device did not directly contact the skin, and the deltoid fascia was intact. The spinal needle was removed, and the skin around the burn was excised; the muscle beneath the skin was intact and showed no signs of thermal damage. The skin was mobilized and closed with interrupted simple sutures using a 4-0 nylon suture. The procedure was then completed with no other complications.

After surgery, the patient recovered without complications, and the skin lesion healed with no signs of infection and no skin or muscle defects. Some stiffness was treated with medication and physical therapy. Nine months after surgery, the patient reported mild shoulder stiffness and remained dissatisfied with the appearance of the skin in the area of the burn.

Discussion

Our patient’s case is a reminder that contact between a radiofrequency device and metal needles can transfer heat to tissues and cause skin burns. When using a radiofrequency device around metal needles or cannulas, surgeons should be sure to avoid prolonged contact with the metal. Our patient’s case is the first reported case of a thermal skin injury occurring when a spinal needle was heated by an arthroscopic ablater.

Other authors have reported indirect thermal skin injuries caused by radiofrequency devices during arthroscopic surgery, but the causes were postulated to be direct contact between device and skin7 and overheating of the arthroscopy fluid.5,6,8 Huang and colleagues8 reported that full-thickness skin burns occurred when normal saline used during routine knee arthroscopy overheated from use of a radiofrequency device. Burn lesions, noted on their patient’s leg within 1 day after surgery, required subsequent débridement, a muscle flap, and split-skin grafting. Skin burns caused by overheated fluid have occurred irrespective of type of fluid used (eg, 1.5% glycine or lactated Ringer solution).6 There was no evidence that our patient’s burn resulted from extravasated overheated fluid, as the lesion was localized to the area immediately around the needle and was not geographic, as was described by Huang and colleagues.8

Other possible causes of skin burns during arthroscopic surgery have been described, but none applies in our patient’s case. Segami and colleagues7 described a burn resulting from direct transfer of heat from the radiofrequency device to the skin because of their proximity. This mechanism was not the cause in our patient’s case; there was no evidence of a defect or burned deltoid muscle at time of surgery. Lau and Dao9 reported 2 small full-thickness skin burns caused by a fiberoptic-light cable tip placed on a patient’s leg; in addition, the hot (>170°C) cables caused the paper drapes to combust.9 Skin burns secondary to use of skin antiseptics have been reported,10 but such lesions typically are located beneath tourniquets or in areas of friction from surgical drapes. In some cases, lesions described as skin burns may actually have been pressure lesions secondary to moist skin and friction.11

Whether type of radiofrequency device contributes to the occurrence of heat-related lesions during arthroscopic surgery is unknown. Some investigators have suggested there is more potential for harm with bipolar RFA devices than with monopolar devices.12,13 Monopolar devices pass energy between a probe and a grounding plate, whereas bipolar devices pass energy through 2 points on the probe.14 Because the heat for the monopolar probe derives from the frictional resistance of tissues to each other rather than from the probe itself, the bipolar probe theoretically allows for better temperature control. In addition, bipolar probes require less current to achieve the same heating effect. However, recent studies have suggested that, compared with monopolar radiofrequency devices, bipolar radiofrequency devices are associated with larger increases in temperature at equal depths after an equal number of applications.12,13

To our knowledge, no one has specifically investigated the type of bipolar device used in the present case. This case report, the first to describe a thermal skin injury caused by direct contact between a radiofrequency device and a metal needle inserted in the skin, is a reminder that contact between radiofrequency devices and spinal needles or other metal cannulas used in arthroscopic surgery should be avoided.

1. Bonsell S. Detached deltoid during arthroscopic subacromial decompression. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(7):745-748.

2. Mohammed KD, Hayes MG, Saies AD. Unusual complications of shoulder arthroscopy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(4):350-353.

3. Pell RF 4th, Uhl RL. Complications of thermal ablation in wrist arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(suppl 2):84-86.

4. Lu Y, Hayashi K, Hecht P, et al. The effect of monopolar radiofrequency energy on partial-thickness defects of articular cartilage. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(5):527-536.

5. Kouk SN, Zoric B, Stetson WB. Complication of the use of a radiofrequency device in arthroscopic shoulder surgery: second-degree burn of the shoulder girdle. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(1):136-141.

6. Lord MJ, Maltry JA, Shall LM. Thermal injury resulting from arthroscopic lateral retinacular release by electrocautery: report of three cases and a review of the literature. Arthroscopy. 1991;7(1):33-37.

7. Segami N, Yamada T, Nishimura M. Thermal injury during temporomandibular joint arthroscopy: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62(4):508-510.

8. Huang S, Gateley D, Moss ALH. Accidental burn injury during knee arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(12):1363.e1-e3.

9. Lau YJ, Dao Q. Cutaneous burns from a fiberoptic cable tip during arthroscopy of the knee. Knee. 2008;15(4):333-335.

10. Sanders TH, Hawken SM. Chlorhexidine burns after shoulder arthroscopy. Am J Orthop. 2012;41(4):172-174.

11. Keyurapan E, Hu SJ, Redett R, McCarthy EF, McFarland EG. Pressure ulcers of the thorax after shoulder surgery. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(12):1489-1493.

12. Edwards RB 3rd, Lu Y, Rodriguez E, Markel MD. Thermometric determination of cartilage matrix temperatures during thermal chondroplasty: comparison of bipolar and monopolar radiofrequency devices. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(4):339-346.

13. Figueroa D, Calvo R, Vaisman A, et al. Bipolar radiofrequency in the human meniscus. Comparative study between patients younger and older than 40 years of age. Knee. 2007;14(5):357-360.

14. Sahasrabudhe A, McMahon PJ. Thermal probes: what’s available in 2004. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2004;12:206-209.

Cautery and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) devices are commonly used in shoulder arthroscopic surgery for hemostasis and ablation of soft tissue. Although these devices are easily used and applied, complications (eg, extensive release of deltoid muscle,1 nerve damage,2 tendon damage,3 cartilage damage from heat transfer4) can occur during arthroscopic surgery. Radiofrequency devices can elevate fluid temperatures to unsafe levels and directly or indirectly injure surrounding tissue.5,6 Skin complications from using these devices include direct burns to the subcutaneous tissues from the joint to the skin surface7 and skin burns related to overheated arthroscopic fluid.8

In our English-language literature review, however, we found no report of a skin burn secondary to contact between a RFA device and a spinal needle used in identifying structures during an arthroscopic acromioplasty. We report such a case here. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 51-year-old woman injured her left, nondominant shoulder when a descending garage door hit her directly on the superior aspect of the shoulder. She had immediate onset of pain on the top and lateral side of the shoulder and was evaluated by a primary care physician. Radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were normal. The patient was referred to an orthopedic surgeon for further evaluation.

The orthopedic surgeon found her to be in good health, with no history of diabetes, vascular conditions, or skin disorders. The initial diagnosis after history taking and physical examination was impingement syndrome with subacromial bursitis. The surgeon recommended nonoperative treatment: ice, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and physical therapy. After 3 months, the patient’s examination was unchanged, and there was no improvement in pain. Cortisone injected into the subacromial space helped for a few weeks, but the pain returned. After 2 more cortisone injections over 9 months failed, repeat MRI showed no tears of the rotator cuff or any other salient abnormalities. The treatment options were discussed with the patient, and, because the physical examination findings were consistent with impingement syndrome and nonoperative measures had failed, she consented to arthroscopic evaluation of the shoulder and arthroscopic partial anterior-lateral acromioplasty.

The procedure was performed 8 months after initial injury. With the patient under general anesthesia and in a lateral decubitus position, her arm was placed in an arm holder. Before the partial acromioplasty, two 18-gauge spinal needles were inserted from the skin surface into the subacromial space to help localize the anterolateral acromion and the acromioclavicular joint. The procedure was performed with a pump using saline bags kept at room temperature. A bipolar radiofrequency device (Stryker Energy Radiofrequency Ablation System; Stryker, Mahwah, New Jersey) was used to débride the subacromial bursa and the periosteum of the undersurface of the acromion. While the bursa was being débrided, the radiofrequency device inadvertently touched the anterior lateral needle probe, and a small skin burn formed around the needle on the surface of the shoulder (Figure). The radiofrequency device did not directly contact the skin, and the deltoid fascia was intact. The spinal needle was removed, and the skin around the burn was excised; the muscle beneath the skin was intact and showed no signs of thermal damage. The skin was mobilized and closed with interrupted simple sutures using a 4-0 nylon suture. The procedure was then completed with no other complications.

After surgery, the patient recovered without complications, and the skin lesion healed with no signs of infection and no skin or muscle defects. Some stiffness was treated with medication and physical therapy. Nine months after surgery, the patient reported mild shoulder stiffness and remained dissatisfied with the appearance of the skin in the area of the burn.

Discussion

Our patient’s case is a reminder that contact between a radiofrequency device and metal needles can transfer heat to tissues and cause skin burns. When using a radiofrequency device around metal needles or cannulas, surgeons should be sure to avoid prolonged contact with the metal. Our patient’s case is the first reported case of a thermal skin injury occurring when a spinal needle was heated by an arthroscopic ablater.

Other authors have reported indirect thermal skin injuries caused by radiofrequency devices during arthroscopic surgery, but the causes were postulated to be direct contact between device and skin7 and overheating of the arthroscopy fluid.5,6,8 Huang and colleagues8 reported that full-thickness skin burns occurred when normal saline used during routine knee arthroscopy overheated from use of a radiofrequency device. Burn lesions, noted on their patient’s leg within 1 day after surgery, required subsequent débridement, a muscle flap, and split-skin grafting. Skin burns caused by overheated fluid have occurred irrespective of type of fluid used (eg, 1.5% glycine or lactated Ringer solution).6 There was no evidence that our patient’s burn resulted from extravasated overheated fluid, as the lesion was localized to the area immediately around the needle and was not geographic, as was described by Huang and colleagues.8

Other possible causes of skin burns during arthroscopic surgery have been described, but none applies in our patient’s case. Segami and colleagues7 described a burn resulting from direct transfer of heat from the radiofrequency device to the skin because of their proximity. This mechanism was not the cause in our patient’s case; there was no evidence of a defect or burned deltoid muscle at time of surgery. Lau and Dao9 reported 2 small full-thickness skin burns caused by a fiberoptic-light cable tip placed on a patient’s leg; in addition, the hot (>170°C) cables caused the paper drapes to combust.9 Skin burns secondary to use of skin antiseptics have been reported,10 but such lesions typically are located beneath tourniquets or in areas of friction from surgical drapes. In some cases, lesions described as skin burns may actually have been pressure lesions secondary to moist skin and friction.11

Whether type of radiofrequency device contributes to the occurrence of heat-related lesions during arthroscopic surgery is unknown. Some investigators have suggested there is more potential for harm with bipolar RFA devices than with monopolar devices.12,13 Monopolar devices pass energy between a probe and a grounding plate, whereas bipolar devices pass energy through 2 points on the probe.14 Because the heat for the monopolar probe derives from the frictional resistance of tissues to each other rather than from the probe itself, the bipolar probe theoretically allows for better temperature control. In addition, bipolar probes require less current to achieve the same heating effect. However, recent studies have suggested that, compared with monopolar radiofrequency devices, bipolar radiofrequency devices are associated with larger increases in temperature at equal depths after an equal number of applications.12,13

To our knowledge, no one has specifically investigated the type of bipolar device used in the present case. This case report, the first to describe a thermal skin injury caused by direct contact between a radiofrequency device and a metal needle inserted in the skin, is a reminder that contact between radiofrequency devices and spinal needles or other metal cannulas used in arthroscopic surgery should be avoided.

Cautery and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) devices are commonly used in shoulder arthroscopic surgery for hemostasis and ablation of soft tissue. Although these devices are easily used and applied, complications (eg, extensive release of deltoid muscle,1 nerve damage,2 tendon damage,3 cartilage damage from heat transfer4) can occur during arthroscopic surgery. Radiofrequency devices can elevate fluid temperatures to unsafe levels and directly or indirectly injure surrounding tissue.5,6 Skin complications from using these devices include direct burns to the subcutaneous tissues from the joint to the skin surface7 and skin burns related to overheated arthroscopic fluid.8

In our English-language literature review, however, we found no report of a skin burn secondary to contact between a RFA device and a spinal needle used in identifying structures during an arthroscopic acromioplasty. We report such a case here. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 51-year-old woman injured her left, nondominant shoulder when a descending garage door hit her directly on the superior aspect of the shoulder. She had immediate onset of pain on the top and lateral side of the shoulder and was evaluated by a primary care physician. Radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were normal. The patient was referred to an orthopedic surgeon for further evaluation.

The orthopedic surgeon found her to be in good health, with no history of diabetes, vascular conditions, or skin disorders. The initial diagnosis after history taking and physical examination was impingement syndrome with subacromial bursitis. The surgeon recommended nonoperative treatment: ice, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and physical therapy. After 3 months, the patient’s examination was unchanged, and there was no improvement in pain. Cortisone injected into the subacromial space helped for a few weeks, but the pain returned. After 2 more cortisone injections over 9 months failed, repeat MRI showed no tears of the rotator cuff or any other salient abnormalities. The treatment options were discussed with the patient, and, because the physical examination findings were consistent with impingement syndrome and nonoperative measures had failed, she consented to arthroscopic evaluation of the shoulder and arthroscopic partial anterior-lateral acromioplasty.