User login

Team says antioxidant has no effect on cancer risk, overall health

Contrary to previous findings, a new study suggests the antioxidant resveratrol is not associated with improvements in health, including reducing the risk of cancer.

Researchers found that Italians who consumed a diet rich in resveratrol—a compound in red wine, dark chocolate, and berries—lived no longer than and were just as likely to develop cardiovascular disease or cancer as Italians who consumed smaller amounts of the antioxidant.

However, the investigators said unknown compounds in these foods and drinks may still confer health benefits.

“The story of resveratrol turns out to be another case where you get a lot of hype about health benefits that doesn’t stand the test of time,” said study author Richard D. Semba, MD, MPH, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

“The thinking was that certain foods are good for you because they contain resveratrol. We didn’t find that at all.”

Dr Semba and his colleagues recounted their findings in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Their study included 783 subjects, all of whom were older than 65 years of age. Participants were part of the Aging in the Chianti Region study, conducted from 1998 to 2009 in 2 Italian villages where supplement use is uncommon and the consumption of red wine is the norm. The subjects were not on any prescribed diet.

The researchers wanted to determine if diet-related resveratrol levels were associated with inflammation, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and death. So they collected urine samples from study participants and used advanced mass spectrometry to analyze the samples for metabolites of resveratrol.

After accounting for such factors as age and gender, the investigators found that subjects with the highest concentration of resveratrol metabolites were no less likely to have died of any cause than subjects with the lowest levels of resveratrol in their urine.

Likewise, the concentration of resveratrol was not associated with inflammatory markers (serum CRP, IL-6, IL-1β,TNF), cardiovascular disease, or cancer rates.

During 9 years of follow-up, 268 participants (34.3%) died. From the lowest to the highest quartile of baseline total urinary resveratrol metabolites, the proportion of subjects who died from all causes was 34.4%, 31.6%, 33.5%, and 37.4%, respectively (P=0.67).

Of the 734 participants who were free of cancer at enrollment, 34 (4.6%) developed cancer during follow-up. The proportions of subjects with incident cancer from the lowest to the highest quartiles of resveratrol were 4.4%, 4.9%, 5.0%, and 4.3%, respectively (P=0.98).

Of the 639 subjects who were free of cardiovascular disease at enrollment, 174 (27.2%) developed cardiovascular disease during follow-up. The proportions of participants with incident cardiovascular disease from the lowest to the highest quartiles of resveratrol were 22.3%, 29.6%, 28.4%, and 28.0%, respectively (P=0.44).

Despite these negative results, Dr Semba noted that studies have shown the consumption of red wine, dark chocolate, and berries does reduce inflammation in some people and still appears to protect the heart.

“It’s just that the benefits, if they are there, must come from other polyphenols or substances found in those foodstuffs,” he said. “These are complex foods, and all we really know from our study is that the benefits are probably not due to resveratrol.” ![]()

Contrary to previous findings, a new study suggests the antioxidant resveratrol is not associated with improvements in health, including reducing the risk of cancer.

Researchers found that Italians who consumed a diet rich in resveratrol—a compound in red wine, dark chocolate, and berries—lived no longer than and were just as likely to develop cardiovascular disease or cancer as Italians who consumed smaller amounts of the antioxidant.

However, the investigators said unknown compounds in these foods and drinks may still confer health benefits.

“The story of resveratrol turns out to be another case where you get a lot of hype about health benefits that doesn’t stand the test of time,” said study author Richard D. Semba, MD, MPH, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

“The thinking was that certain foods are good for you because they contain resveratrol. We didn’t find that at all.”

Dr Semba and his colleagues recounted their findings in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Their study included 783 subjects, all of whom were older than 65 years of age. Participants were part of the Aging in the Chianti Region study, conducted from 1998 to 2009 in 2 Italian villages where supplement use is uncommon and the consumption of red wine is the norm. The subjects were not on any prescribed diet.

The researchers wanted to determine if diet-related resveratrol levels were associated with inflammation, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and death. So they collected urine samples from study participants and used advanced mass spectrometry to analyze the samples for metabolites of resveratrol.

After accounting for such factors as age and gender, the investigators found that subjects with the highest concentration of resveratrol metabolites were no less likely to have died of any cause than subjects with the lowest levels of resveratrol in their urine.

Likewise, the concentration of resveratrol was not associated with inflammatory markers (serum CRP, IL-6, IL-1β,TNF), cardiovascular disease, or cancer rates.

During 9 years of follow-up, 268 participants (34.3%) died. From the lowest to the highest quartile of baseline total urinary resveratrol metabolites, the proportion of subjects who died from all causes was 34.4%, 31.6%, 33.5%, and 37.4%, respectively (P=0.67).

Of the 734 participants who were free of cancer at enrollment, 34 (4.6%) developed cancer during follow-up. The proportions of subjects with incident cancer from the lowest to the highest quartiles of resveratrol were 4.4%, 4.9%, 5.0%, and 4.3%, respectively (P=0.98).

Of the 639 subjects who were free of cardiovascular disease at enrollment, 174 (27.2%) developed cardiovascular disease during follow-up. The proportions of participants with incident cardiovascular disease from the lowest to the highest quartiles of resveratrol were 22.3%, 29.6%, 28.4%, and 28.0%, respectively (P=0.44).

Despite these negative results, Dr Semba noted that studies have shown the consumption of red wine, dark chocolate, and berries does reduce inflammation in some people and still appears to protect the heart.

“It’s just that the benefits, if they are there, must come from other polyphenols or substances found in those foodstuffs,” he said. “These are complex foods, and all we really know from our study is that the benefits are probably not due to resveratrol.” ![]()

Contrary to previous findings, a new study suggests the antioxidant resveratrol is not associated with improvements in health, including reducing the risk of cancer.

Researchers found that Italians who consumed a diet rich in resveratrol—a compound in red wine, dark chocolate, and berries—lived no longer than and were just as likely to develop cardiovascular disease or cancer as Italians who consumed smaller amounts of the antioxidant.

However, the investigators said unknown compounds in these foods and drinks may still confer health benefits.

“The story of resveratrol turns out to be another case where you get a lot of hype about health benefits that doesn’t stand the test of time,” said study author Richard D. Semba, MD, MPH, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

“The thinking was that certain foods are good for you because they contain resveratrol. We didn’t find that at all.”

Dr Semba and his colleagues recounted their findings in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Their study included 783 subjects, all of whom were older than 65 years of age. Participants were part of the Aging in the Chianti Region study, conducted from 1998 to 2009 in 2 Italian villages where supplement use is uncommon and the consumption of red wine is the norm. The subjects were not on any prescribed diet.

The researchers wanted to determine if diet-related resveratrol levels were associated with inflammation, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and death. So they collected urine samples from study participants and used advanced mass spectrometry to analyze the samples for metabolites of resveratrol.

After accounting for such factors as age and gender, the investigators found that subjects with the highest concentration of resveratrol metabolites were no less likely to have died of any cause than subjects with the lowest levels of resveratrol in their urine.

Likewise, the concentration of resveratrol was not associated with inflammatory markers (serum CRP, IL-6, IL-1β,TNF), cardiovascular disease, or cancer rates.

During 9 years of follow-up, 268 participants (34.3%) died. From the lowest to the highest quartile of baseline total urinary resveratrol metabolites, the proportion of subjects who died from all causes was 34.4%, 31.6%, 33.5%, and 37.4%, respectively (P=0.67).

Of the 734 participants who were free of cancer at enrollment, 34 (4.6%) developed cancer during follow-up. The proportions of subjects with incident cancer from the lowest to the highest quartiles of resveratrol were 4.4%, 4.9%, 5.0%, and 4.3%, respectively (P=0.98).

Of the 639 subjects who were free of cardiovascular disease at enrollment, 174 (27.2%) developed cardiovascular disease during follow-up. The proportions of participants with incident cardiovascular disease from the lowest to the highest quartiles of resveratrol were 22.3%, 29.6%, 28.4%, and 28.0%, respectively (P=0.44).

Despite these negative results, Dr Semba noted that studies have shown the consumption of red wine, dark chocolate, and berries does reduce inflammation in some people and still appears to protect the heart.

“It’s just that the benefits, if they are there, must come from other polyphenols or substances found in those foodstuffs,” he said. “These are complex foods, and all we really know from our study is that the benefits are probably not due to resveratrol.” ![]()

90 US healthcare professionals charged with fraud

Credit: NIH

As a result of Medicare Fraud Strike Force operations in 6 US cities, 90 healthcare professionals have been charged with fraud.

These individuals—doctors, nurses, healthcare company owners, and others—are accused of participating in Medicare fraud schemes involving approximately $260 million in false billings.

They have been charged with various crimes, including conspiracy to commit healthcare fraud, violations of the anti-kickback statutes, and money laundering.

According to court documents, the defendants allegedly participated in schemes to submit claims to Medicare for treatments that were medically unnecessary and often never provided.

In many cases, court documents allege that patient recruiters, Medicare beneficiaries, and other co-conspirators were paid cash kickbacks in return for supplying beneficiary information to providers so the providers could then submit fraudulent bills to Medicare for services that were medically unnecessary or never performed.

“[T]he crimes charged represent the face of healthcare fraud today—doctors billing for services that were never rendered, supply companies providing motorized wheelchairs that were never needed, recruiters paying kickbacks to get Medicare billing numbers of patients,” said Acting Assistant Attorney General David O’Neil.

Case details

In Miami, Florida, 50 defendants were charged for their alleged participation in various fraud schemes involving approximately $65.5 million in false billings for home healthcare and mental health services, as well as pharmacy fraud.

Two of these defendants were charged in connection with a $23 million pharmacy kickback and laundering scheme. Court documents allege that the defendants solicited kickbacks from a pharmacy owner for Medicare beneficiary information, which was used to bill for drugs that were never dispensed.

The kickbacks were concealed as bi-weekly payments under a sham services contract and were laundered through shell entities owned by the defendants.

Eleven individuals were charged by the Medicare Strike Force in Houston, Texas. Five Houston-area physicians were charged with conspiring to bill Medicare for medically unnecessary home health services. According to court documents, the defendant doctors were paid by 2 co-conspirators to sign off on home healthcare services that were not necessary and often never provided.

Eight defendants were charged in Los Angeles, California, for their roles in schemes to defraud Medicare of approximately $32 million.

One doctor was charged for causing almost $24 million in losses to Medicare through his own fraudulent billing and referrals for durable medical equipment, including more than 1000 expensive power wheelchairs, and home health services that were not medically necessary and frequently not provided.

In Detroit, Michigan, 7 defendants were charged for their roles in fraud schemes involving approximately $30 million in false claims for medically unnecessary services, including home health services, psychotherapy, and infusion therapy.

Four of these individuals were charged in a $28 million fraud scheme, where a physician billed for expensive tests, physical therapy, and injections that were not necessary and not provided.

Court documents allege that when the physician’s billings raised red flags, he was put on payment review by Medicare. He was allegedly able to continue his scheme and evade detection by continuing to bill using the billing information of other Medicare providers, sometimes without their knowledge.

In Tampa, Florida, 7 individuals were charged in a variety of schemes, ranging from fraudulent physical therapy billings to a scheme involving millions of dollars in physician services and tests that never occurred.

Five of these individuals were charged for their alleged roles in a $12 million healthcare fraud and money laundering scheme that involved billing Medicare using names of beneficiaries from Miami-Dade County for services purportedly provided in Tampa-area clinics, 280 miles away. The defendants then allegedly laundered the proceeds through a number of transactions involving several shell entities.

In Brooklyn, New York, the Strike Force announced an indictment against Syed Imran Ahmed, MD, in connection with his alleged $85 million scheme involving billings for surgeries that never occurred. Dr Ahmed had been arrested last month and charged by complaint. He is now charged with healthcare fraud and making false statements.

The Brooklyn Strike Force also charged 6 other individuals, including a physician and 2 billers who allegedly concocted a $14.4 million scheme in which they recruited elderly Medicare beneficiaries and billed Medicare for medically unnecessary vitamin infusions, diagnostic tests, and physical and occupational therapy supposedly provided to these patients.

The cases are being prosecuted and investigated by Medicare Fraud Strike Force teams comprised of attorneys from the Fraud Section of the Justice Department’s Criminal Division and from the US Attorney’s Offices for the Southern District of Florida, the Eastern District of Michigan, the Eastern District of New York, the Southern District of Texas, the Central District of California, the Middle District of Louisiana, the Northern District of Illinois and the Middle District of Florida; and agents from the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)-Office of Inspector General (OIG), and state Medicaid Fraud Control Units.

About the Medicare Fraud Strike Force

This is the seventh national Medicare fraud takedown in Medicare Fraud Strike Force history. The Strike Force’s operations are part of the Health Care Fraud Prevention & Enforcement Action Team (HEAT), a joint initiative announced in May 2009 between the Department of Justice and the HHS to focus their efforts to prevent and deter fraud and enforce current anti-fraud laws around the country.

Since their inception in March 2007, Strike Force operations in 9 locations have charged almost 1900 defendants who collectively have falsely billed the Medicare program for almost $6 billion.

In addition, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, working in conjunction with HHS-OIG, has suspended enrollments of high-risk providers in 5 Strike Force locations and has removed more than 17,000 providers from the Medicare program since 2011.

The joint Department of Justice and HHS Medicare Fraud Strike Force is a multi-agency team of federal, state, and local investigators designed to combat Medicare fraud through the use of Medicare data analysis techniques and an increased focus on community policing.

To learn more, visit www.stopmedicarefraud.gov. ![]()

Credit: NIH

As a result of Medicare Fraud Strike Force operations in 6 US cities, 90 healthcare professionals have been charged with fraud.

These individuals—doctors, nurses, healthcare company owners, and others—are accused of participating in Medicare fraud schemes involving approximately $260 million in false billings.

They have been charged with various crimes, including conspiracy to commit healthcare fraud, violations of the anti-kickback statutes, and money laundering.

According to court documents, the defendants allegedly participated in schemes to submit claims to Medicare for treatments that were medically unnecessary and often never provided.

In many cases, court documents allege that patient recruiters, Medicare beneficiaries, and other co-conspirators were paid cash kickbacks in return for supplying beneficiary information to providers so the providers could then submit fraudulent bills to Medicare for services that were medically unnecessary or never performed.

“[T]he crimes charged represent the face of healthcare fraud today—doctors billing for services that were never rendered, supply companies providing motorized wheelchairs that were never needed, recruiters paying kickbacks to get Medicare billing numbers of patients,” said Acting Assistant Attorney General David O’Neil.

Case details

In Miami, Florida, 50 defendants were charged for their alleged participation in various fraud schemes involving approximately $65.5 million in false billings for home healthcare and mental health services, as well as pharmacy fraud.

Two of these defendants were charged in connection with a $23 million pharmacy kickback and laundering scheme. Court documents allege that the defendants solicited kickbacks from a pharmacy owner for Medicare beneficiary information, which was used to bill for drugs that were never dispensed.

The kickbacks were concealed as bi-weekly payments under a sham services contract and were laundered through shell entities owned by the defendants.

Eleven individuals were charged by the Medicare Strike Force in Houston, Texas. Five Houston-area physicians were charged with conspiring to bill Medicare for medically unnecessary home health services. According to court documents, the defendant doctors were paid by 2 co-conspirators to sign off on home healthcare services that were not necessary and often never provided.

Eight defendants were charged in Los Angeles, California, for their roles in schemes to defraud Medicare of approximately $32 million.

One doctor was charged for causing almost $24 million in losses to Medicare through his own fraudulent billing and referrals for durable medical equipment, including more than 1000 expensive power wheelchairs, and home health services that were not medically necessary and frequently not provided.

In Detroit, Michigan, 7 defendants were charged for their roles in fraud schemes involving approximately $30 million in false claims for medically unnecessary services, including home health services, psychotherapy, and infusion therapy.

Four of these individuals were charged in a $28 million fraud scheme, where a physician billed for expensive tests, physical therapy, and injections that were not necessary and not provided.

Court documents allege that when the physician’s billings raised red flags, he was put on payment review by Medicare. He was allegedly able to continue his scheme and evade detection by continuing to bill using the billing information of other Medicare providers, sometimes without their knowledge.

In Tampa, Florida, 7 individuals were charged in a variety of schemes, ranging from fraudulent physical therapy billings to a scheme involving millions of dollars in physician services and tests that never occurred.

Five of these individuals were charged for their alleged roles in a $12 million healthcare fraud and money laundering scheme that involved billing Medicare using names of beneficiaries from Miami-Dade County for services purportedly provided in Tampa-area clinics, 280 miles away. The defendants then allegedly laundered the proceeds through a number of transactions involving several shell entities.

In Brooklyn, New York, the Strike Force announced an indictment against Syed Imran Ahmed, MD, in connection with his alleged $85 million scheme involving billings for surgeries that never occurred. Dr Ahmed had been arrested last month and charged by complaint. He is now charged with healthcare fraud and making false statements.

The Brooklyn Strike Force also charged 6 other individuals, including a physician and 2 billers who allegedly concocted a $14.4 million scheme in which they recruited elderly Medicare beneficiaries and billed Medicare for medically unnecessary vitamin infusions, diagnostic tests, and physical and occupational therapy supposedly provided to these patients.

The cases are being prosecuted and investigated by Medicare Fraud Strike Force teams comprised of attorneys from the Fraud Section of the Justice Department’s Criminal Division and from the US Attorney’s Offices for the Southern District of Florida, the Eastern District of Michigan, the Eastern District of New York, the Southern District of Texas, the Central District of California, the Middle District of Louisiana, the Northern District of Illinois and the Middle District of Florida; and agents from the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)-Office of Inspector General (OIG), and state Medicaid Fraud Control Units.

About the Medicare Fraud Strike Force

This is the seventh national Medicare fraud takedown in Medicare Fraud Strike Force history. The Strike Force’s operations are part of the Health Care Fraud Prevention & Enforcement Action Team (HEAT), a joint initiative announced in May 2009 between the Department of Justice and the HHS to focus their efforts to prevent and deter fraud and enforce current anti-fraud laws around the country.

Since their inception in March 2007, Strike Force operations in 9 locations have charged almost 1900 defendants who collectively have falsely billed the Medicare program for almost $6 billion.

In addition, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, working in conjunction with HHS-OIG, has suspended enrollments of high-risk providers in 5 Strike Force locations and has removed more than 17,000 providers from the Medicare program since 2011.

The joint Department of Justice and HHS Medicare Fraud Strike Force is a multi-agency team of federal, state, and local investigators designed to combat Medicare fraud through the use of Medicare data analysis techniques and an increased focus on community policing.

To learn more, visit www.stopmedicarefraud.gov. ![]()

Credit: NIH

As a result of Medicare Fraud Strike Force operations in 6 US cities, 90 healthcare professionals have been charged with fraud.

These individuals—doctors, nurses, healthcare company owners, and others—are accused of participating in Medicare fraud schemes involving approximately $260 million in false billings.

They have been charged with various crimes, including conspiracy to commit healthcare fraud, violations of the anti-kickback statutes, and money laundering.

According to court documents, the defendants allegedly participated in schemes to submit claims to Medicare for treatments that were medically unnecessary and often never provided.

In many cases, court documents allege that patient recruiters, Medicare beneficiaries, and other co-conspirators were paid cash kickbacks in return for supplying beneficiary information to providers so the providers could then submit fraudulent bills to Medicare for services that were medically unnecessary or never performed.

“[T]he crimes charged represent the face of healthcare fraud today—doctors billing for services that were never rendered, supply companies providing motorized wheelchairs that were never needed, recruiters paying kickbacks to get Medicare billing numbers of patients,” said Acting Assistant Attorney General David O’Neil.

Case details

In Miami, Florida, 50 defendants were charged for their alleged participation in various fraud schemes involving approximately $65.5 million in false billings for home healthcare and mental health services, as well as pharmacy fraud.

Two of these defendants were charged in connection with a $23 million pharmacy kickback and laundering scheme. Court documents allege that the defendants solicited kickbacks from a pharmacy owner for Medicare beneficiary information, which was used to bill for drugs that were never dispensed.

The kickbacks were concealed as bi-weekly payments under a sham services contract and were laundered through shell entities owned by the defendants.

Eleven individuals were charged by the Medicare Strike Force in Houston, Texas. Five Houston-area physicians were charged with conspiring to bill Medicare for medically unnecessary home health services. According to court documents, the defendant doctors were paid by 2 co-conspirators to sign off on home healthcare services that were not necessary and often never provided.

Eight defendants were charged in Los Angeles, California, for their roles in schemes to defraud Medicare of approximately $32 million.

One doctor was charged for causing almost $24 million in losses to Medicare through his own fraudulent billing and referrals for durable medical equipment, including more than 1000 expensive power wheelchairs, and home health services that were not medically necessary and frequently not provided.

In Detroit, Michigan, 7 defendants were charged for their roles in fraud schemes involving approximately $30 million in false claims for medically unnecessary services, including home health services, psychotherapy, and infusion therapy.

Four of these individuals were charged in a $28 million fraud scheme, where a physician billed for expensive tests, physical therapy, and injections that were not necessary and not provided.

Court documents allege that when the physician’s billings raised red flags, he was put on payment review by Medicare. He was allegedly able to continue his scheme and evade detection by continuing to bill using the billing information of other Medicare providers, sometimes without their knowledge.

In Tampa, Florida, 7 individuals were charged in a variety of schemes, ranging from fraudulent physical therapy billings to a scheme involving millions of dollars in physician services and tests that never occurred.

Five of these individuals were charged for their alleged roles in a $12 million healthcare fraud and money laundering scheme that involved billing Medicare using names of beneficiaries from Miami-Dade County for services purportedly provided in Tampa-area clinics, 280 miles away. The defendants then allegedly laundered the proceeds through a number of transactions involving several shell entities.

In Brooklyn, New York, the Strike Force announced an indictment against Syed Imran Ahmed, MD, in connection with his alleged $85 million scheme involving billings for surgeries that never occurred. Dr Ahmed had been arrested last month and charged by complaint. He is now charged with healthcare fraud and making false statements.

The Brooklyn Strike Force also charged 6 other individuals, including a physician and 2 billers who allegedly concocted a $14.4 million scheme in which they recruited elderly Medicare beneficiaries and billed Medicare for medically unnecessary vitamin infusions, diagnostic tests, and physical and occupational therapy supposedly provided to these patients.

The cases are being prosecuted and investigated by Medicare Fraud Strike Force teams comprised of attorneys from the Fraud Section of the Justice Department’s Criminal Division and from the US Attorney’s Offices for the Southern District of Florida, the Eastern District of Michigan, the Eastern District of New York, the Southern District of Texas, the Central District of California, the Middle District of Louisiana, the Northern District of Illinois and the Middle District of Florida; and agents from the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)-Office of Inspector General (OIG), and state Medicaid Fraud Control Units.

About the Medicare Fraud Strike Force

This is the seventh national Medicare fraud takedown in Medicare Fraud Strike Force history. The Strike Force’s operations are part of the Health Care Fraud Prevention & Enforcement Action Team (HEAT), a joint initiative announced in May 2009 between the Department of Justice and the HHS to focus their efforts to prevent and deter fraud and enforce current anti-fraud laws around the country.

Since their inception in March 2007, Strike Force operations in 9 locations have charged almost 1900 defendants who collectively have falsely billed the Medicare program for almost $6 billion.

In addition, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, working in conjunction with HHS-OIG, has suspended enrollments of high-risk providers in 5 Strike Force locations and has removed more than 17,000 providers from the Medicare program since 2011.

The joint Department of Justice and HHS Medicare Fraud Strike Force is a multi-agency team of federal, state, and local investigators designed to combat Medicare fraud through the use of Medicare data analysis techniques and an increased focus on community policing.

To learn more, visit www.stopmedicarefraud.gov. ![]()

Cell phone records aid fight against malaria

Credit: James Gathany

Data that tracks cell phone activity can help us more accurately target antimalaria interventions, according to a paper published in Malaria Journal.

Researchers used anonymized cell phone records to measure population movements within Namibia, Africa, over a year.

By combining this data with information about malaria cases, topography, and climate, the group was able to identify geographical “hotspots” of the disease and design targeted plans for its elimination.

“If we are to eliminate this disease, we need to deploy the right measures in the right place, but figures on human movement patterns in endemic regions are hard to come by and often restricted to local travel surveys and census-based migration data,” said study author Andrew Tatem, PhD, of the University of Southampton in the UK.

“Our study demonstrates that the rapid global proliferation of mobile phones now provides us with an opportunity to study the movement of people, using sample sizes running in to millions. This data, combined with disease-case-based mapping, can help us plan where and how to intervene.”

Dr Tatem and his colleagues looked at anonymized Call Data Records from 2010 to 2011, provided by Mobile Telecommunications Limited. The data represented 9 billion communications from 1.19 million unique subscribers, around 52% of the population of Namibia.

The researchers analyzed aggregated movements of phone users between urban areas and urban and rural areas, in conjunction with data based on rapid diagnostic testing of malaria and information on the climate, environment, and topography of the country.

In this way, the team identified communities that were strongly connected by relatively higher levels of population movement. They quantified the net export and import of travelers and mapped malaria infection risks by region.

The researchers said these malaria risk maps can aid the design of targeted interventions to reduce the number of malaria cases exported to other regions and help manage the risk of infection in places that import the disease.

In fact, the maps have already helped the Namibia National Vector-borne Diseases Control Programme improve their targeting of malaria interventions to communities most at risk.

Specifically, the maps prompted the organization to target insecticide-treated bed net distribution in the Omusati, Kavango, and Zambezi regions in 2013.

“The importation of malaria from outside a country will always be a crucial focus of disease control programs, but movement of the disease within countries is also of huge significance,” Dr Tatem said. “Understanding the human element of this movement should be a critical component when designing elimination strategies—to help target resources most efficiently.”

“The use of mobile phone data is one example of how new technologies are overcoming past problems of quantifying and gaining a better understanding of human movement patterns in relation to disease control.” ![]()

Credit: James Gathany

Data that tracks cell phone activity can help us more accurately target antimalaria interventions, according to a paper published in Malaria Journal.

Researchers used anonymized cell phone records to measure population movements within Namibia, Africa, over a year.

By combining this data with information about malaria cases, topography, and climate, the group was able to identify geographical “hotspots” of the disease and design targeted plans for its elimination.

“If we are to eliminate this disease, we need to deploy the right measures in the right place, but figures on human movement patterns in endemic regions are hard to come by and often restricted to local travel surveys and census-based migration data,” said study author Andrew Tatem, PhD, of the University of Southampton in the UK.

“Our study demonstrates that the rapid global proliferation of mobile phones now provides us with an opportunity to study the movement of people, using sample sizes running in to millions. This data, combined with disease-case-based mapping, can help us plan where and how to intervene.”

Dr Tatem and his colleagues looked at anonymized Call Data Records from 2010 to 2011, provided by Mobile Telecommunications Limited. The data represented 9 billion communications from 1.19 million unique subscribers, around 52% of the population of Namibia.

The researchers analyzed aggregated movements of phone users between urban areas and urban and rural areas, in conjunction with data based on rapid diagnostic testing of malaria and information on the climate, environment, and topography of the country.

In this way, the team identified communities that were strongly connected by relatively higher levels of population movement. They quantified the net export and import of travelers and mapped malaria infection risks by region.

The researchers said these malaria risk maps can aid the design of targeted interventions to reduce the number of malaria cases exported to other regions and help manage the risk of infection in places that import the disease.

In fact, the maps have already helped the Namibia National Vector-borne Diseases Control Programme improve their targeting of malaria interventions to communities most at risk.

Specifically, the maps prompted the organization to target insecticide-treated bed net distribution in the Omusati, Kavango, and Zambezi regions in 2013.

“The importation of malaria from outside a country will always be a crucial focus of disease control programs, but movement of the disease within countries is also of huge significance,” Dr Tatem said. “Understanding the human element of this movement should be a critical component when designing elimination strategies—to help target resources most efficiently.”

“The use of mobile phone data is one example of how new technologies are overcoming past problems of quantifying and gaining a better understanding of human movement patterns in relation to disease control.” ![]()

Credit: James Gathany

Data that tracks cell phone activity can help us more accurately target antimalaria interventions, according to a paper published in Malaria Journal.

Researchers used anonymized cell phone records to measure population movements within Namibia, Africa, over a year.

By combining this data with information about malaria cases, topography, and climate, the group was able to identify geographical “hotspots” of the disease and design targeted plans for its elimination.

“If we are to eliminate this disease, we need to deploy the right measures in the right place, but figures on human movement patterns in endemic regions are hard to come by and often restricted to local travel surveys and census-based migration data,” said study author Andrew Tatem, PhD, of the University of Southampton in the UK.

“Our study demonstrates that the rapid global proliferation of mobile phones now provides us with an opportunity to study the movement of people, using sample sizes running in to millions. This data, combined with disease-case-based mapping, can help us plan where and how to intervene.”

Dr Tatem and his colleagues looked at anonymized Call Data Records from 2010 to 2011, provided by Mobile Telecommunications Limited. The data represented 9 billion communications from 1.19 million unique subscribers, around 52% of the population of Namibia.

The researchers analyzed aggregated movements of phone users between urban areas and urban and rural areas, in conjunction with data based on rapid diagnostic testing of malaria and information on the climate, environment, and topography of the country.

In this way, the team identified communities that were strongly connected by relatively higher levels of population movement. They quantified the net export and import of travelers and mapped malaria infection risks by region.

The researchers said these malaria risk maps can aid the design of targeted interventions to reduce the number of malaria cases exported to other regions and help manage the risk of infection in places that import the disease.

In fact, the maps have already helped the Namibia National Vector-borne Diseases Control Programme improve their targeting of malaria interventions to communities most at risk.

Specifically, the maps prompted the organization to target insecticide-treated bed net distribution in the Omusati, Kavango, and Zambezi regions in 2013.

“The importation of malaria from outside a country will always be a crucial focus of disease control programs, but movement of the disease within countries is also of huge significance,” Dr Tatem said. “Understanding the human element of this movement should be a critical component when designing elimination strategies—to help target resources most efficiently.”

“The use of mobile phone data is one example of how new technologies are overcoming past problems of quantifying and gaining a better understanding of human movement patterns in relation to disease control.” ![]()

COMMENTARY: How and why to perform research as a trainee

"Why do I need to do research if I'm going into private practice anyway?"

I have heard this question multiple times throughout my career as a resident, fellow, and attending thoracic surgeon. The truth is, there are multiple reasons, any of which is sufficient to justify your participation in clinical research during training. First, and perhaps most importantly, it teaches you to critically appraise the literature.

This is a skill that will serve you well throughout your career, guiding your clinical decision making, regardless if you choose private practice or academic surgery.

Another reason is that performing clinical research allows you to become a content expert on a specific topic early in your career. This knowledge base is something that will serve as a foundation for ongoing learning and may help in designing future studies.

Once your project is complete, it will be your ticket to attend and present at regional, national, or international meetings. There is no better forum to gain public recognition for your investigative efforts and network with potential future partners than societal meetings.

Formal and informal interviews routinely occur at these gatherings and you do not want to be left out because you chose not to participate in research as a trainee. Finally, it is your responsibility to the patients that you have sworn to treat.

There are many ways to care for patients, and pushing back the frontiers of medical knowledge is as important as the day-to-day tasks that you perform on the ward or in the operating room.

So, now that you have decided that you want to participate in a research project as a trainee, how do you make it happen? Before you begin a project, you will have to choose a mentor; a topic; a clear, novel question; and the appropriate study design.

Chances are that at some point, a mentor helped guide you toward a career in cardiovascular surgery. A research mentor is just as important as a clinical mentor for a young surgeon. The most important trait that you should seek out in a research mentor is the ability to delineate important questions. All too often, residents and fellows are approached by attending surgeons with good intentions, but bad research ideas. Trainees then feel obligated to take them up on the project (in order to not appear like a slacker) and for various reasons, it does not result in an abstract, presentation, or publication. In fact, all it results in is frustration, a distaste for investigation, and wasted time.

The bottom line is that only you can protect your time, and as a surgical trainee, you must guard it ferociously. Look for a mentor that is an expert in your field of interest and who has a track record of publications.

He or she must be a logical thinker who can help you delineate a clear, novel question, choose the appropriate study design, guide your writing of the manuscript, and direct your submission to the appropriate meetings and journals.

Finally, your mentor must be dedicated to your success. We are all busy, but if your mentor cannot find the time to routinely meet with you at every step of your project, you need to find a new mentor.

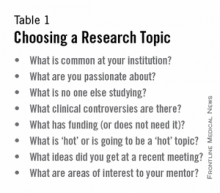

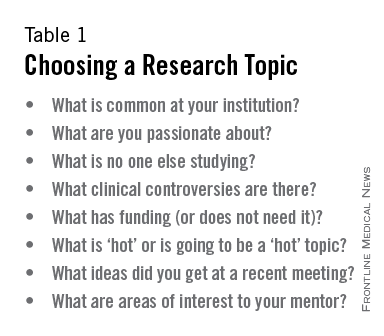

Choosing a clear, novel clinical question starts with choosing an appropriate topic (Table 1). With the right topic and question, the hypothesis is obvious, it is easy to define your endpoints, and your study design will fall into place. But with the wrong question, your study will lack focus, it will be difficult to explain the relevance of your study, and you will not want to present your data on the podium. An example of a good question is: "Do patients with a given disease treated with operation X live longer than those treated with operation Y?"

Stay away from the lure of "Let's review our experience of operation X…" or "Why don't I see how many of operation Y we've done over the past 10 years…" These topics are vague and do not ask a specific question. There must be a clear hypothesis for any study that is expected to produce meaningful results.

Once you have chosen an appropriate question, you must decide on a study design. Although case reports are marginally publishable, they will not answer your clinical questions. For many reasons, randomized, controlled trials, the gold standard of research, are difficult to design, carry out, and complete in your short time as a trainee.

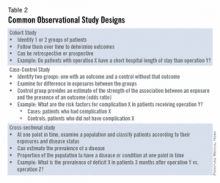

The good news is that well-designed and sufficiently powered observational studies often give similar results as randomized, controlled studies. Examples of common observational study designs include cohort studies, case control studies, and cross-sectional studies (Table 2).

Each study design is different and your mentor should be able to help you decide which is the best to answer the question you want to ask.

In the design of a study, one of the most important principles is defining a priori end points.

Every study will have one primary end point that reflects the hypothesis. Secondary endpoints are interesting and potentially helpful, but are not the main message. It will be important to meet with a statistician before you start data collection. Understanding the statistics to be used will allow you to collect your data in the correct way (categorical vs. continuous, etc.). Reviewing charts is very time consuming and you have to do everything in your power to ensure you do it only once.

The next step is to create a research proposal. To do this, you will need to go to the literature and see what published data relate to your study. Perhaps, there are previous studies examining your question with conflicting results?

Or if your question has not been previously investigated, what supporting literature suggests that yours is the next logical study? Your proposal should include a background section (1-2 paragraphs), hypothesis (1 sentence), the specific aims of the study (1-3 sentences), methods (2-4 paragraphs), anticipated results (1 paragraph), proposed timeline, and anticipated meeting to which it will be submitted. Your mentor will revise and critique the proposal and eventually give you a signature of approval. This proposal serves many purposes. It will allow you to fully understand the study before you begin, some form of it is usually required for the Institutional Review Board application, it will serve as the outline for your eventual manuscript, and it sets a timeline for completion of the project. Without an agreed-upon deadline, too many good studies are left in various states of completion when the trainee moves on, and are never finished. The deadline should be based on the meeting that you and your mentor agree is appropriate for reporting your results.

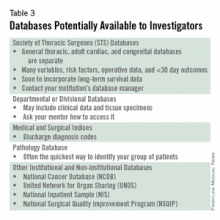

Most would agree that data collection is the most painful part of doing clinical research. However, there are a few tricks to ease your pain. First, there are many databases available that you may be able to harvest data from to minimize your chart work (Table 3). Before you hit the charts, it is essential to think through every step of the project. Anticipate problems (where in the chart will you locate each data point), do not collect unnecessary data points (postoperative data #3 serum [Na+] when looking at survival of thoracoscopic vs. open lobectomy), meet with your statistician beforehand to collect data for the correct analysis, collect the raw data (creatinine and weight, not presence of renal failure and obesity).

Finally, be sure that your data are backed up in multiple places. Some prefer to collect data on paper then enter it later into a spreadsheet. This ensures a hard copy of the data exists regardless if the electronic version is lost.

After the data are collected and the statistics are done, you will be faced with interpreting your results and composing an abstract and manuscript. If your study is focused and hypothesis driven, this step should be fairly straightforward. Schedule time with your mentor and discuss the results to ensure your interpretation of the data is correct.

Next using your proposal as an outline, put together a rough draft of a manuscript. Remember that manuscripts are the currency of academia. If you do not present and publish your work, you have not fully capitalized on the hard work you have put in to your study.

Your mentor will need to revise your manuscript repeatedly; use it as a learning experience for critiquing the literature and writing future manuscripts. He or she likely knows what editors and readers will be looking for in your finished product. Remember, you will need multiple revisions of the abstract and manuscript, so plan adequate time prior to your deadline for writing.

Most institutions have medical illustrators available for hire; consider including a drawing or photograph if it legitimately adds content to your manuscript.

The final step in the process is presenting your work in front of experts who likely know more about cardiothoracic surgery than you. Just remember, no one knows more about your data than you.

Prepare relentlessly for your talk, take a deep breath before you walk on stage, speak with confidence, and if you don't know the answer to a given question from the audience, admit it. Soon enough you will be the expert in the audience asking the tough questions. Then spend as much time as possible after the session speaking with audience members about you and your study.

You will meet lifelong colleagues, and maybe even your future partner. For many, research is a rewarding lifelong endeavor. For others, it is a means of learning to critically appraise the literature and landing a job. Either way, you cannot afford not to do research as a trainee.

Acknowledgment: I would like to thank my friend and colleague, Dr. Stephen H. McKellar (University of Utah), for his advice on performing research as a cardiothoracic trainee.

Dr. Seder is in the department of cardiovascular and thoracic surgery at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago.

"Why do I need to do research if I'm going into private practice anyway?"

I have heard this question multiple times throughout my career as a resident, fellow, and attending thoracic surgeon. The truth is, there are multiple reasons, any of which is sufficient to justify your participation in clinical research during training. First, and perhaps most importantly, it teaches you to critically appraise the literature.

This is a skill that will serve you well throughout your career, guiding your clinical decision making, regardless if you choose private practice or academic surgery.

Another reason is that performing clinical research allows you to become a content expert on a specific topic early in your career. This knowledge base is something that will serve as a foundation for ongoing learning and may help in designing future studies.

Once your project is complete, it will be your ticket to attend and present at regional, national, or international meetings. There is no better forum to gain public recognition for your investigative efforts and network with potential future partners than societal meetings.

Formal and informal interviews routinely occur at these gatherings and you do not want to be left out because you chose not to participate in research as a trainee. Finally, it is your responsibility to the patients that you have sworn to treat.

There are many ways to care for patients, and pushing back the frontiers of medical knowledge is as important as the day-to-day tasks that you perform on the ward or in the operating room.

So, now that you have decided that you want to participate in a research project as a trainee, how do you make it happen? Before you begin a project, you will have to choose a mentor; a topic; a clear, novel question; and the appropriate study design.

Chances are that at some point, a mentor helped guide you toward a career in cardiovascular surgery. A research mentor is just as important as a clinical mentor for a young surgeon. The most important trait that you should seek out in a research mentor is the ability to delineate important questions. All too often, residents and fellows are approached by attending surgeons with good intentions, but bad research ideas. Trainees then feel obligated to take them up on the project (in order to not appear like a slacker) and for various reasons, it does not result in an abstract, presentation, or publication. In fact, all it results in is frustration, a distaste for investigation, and wasted time.

The bottom line is that only you can protect your time, and as a surgical trainee, you must guard it ferociously. Look for a mentor that is an expert in your field of interest and who has a track record of publications.

He or she must be a logical thinker who can help you delineate a clear, novel question, choose the appropriate study design, guide your writing of the manuscript, and direct your submission to the appropriate meetings and journals.

Finally, your mentor must be dedicated to your success. We are all busy, but if your mentor cannot find the time to routinely meet with you at every step of your project, you need to find a new mentor.

Choosing a clear, novel clinical question starts with choosing an appropriate topic (Table 1). With the right topic and question, the hypothesis is obvious, it is easy to define your endpoints, and your study design will fall into place. But with the wrong question, your study will lack focus, it will be difficult to explain the relevance of your study, and you will not want to present your data on the podium. An example of a good question is: "Do patients with a given disease treated with operation X live longer than those treated with operation Y?"

Stay away from the lure of "Let's review our experience of operation X…" or "Why don't I see how many of operation Y we've done over the past 10 years…" These topics are vague and do not ask a specific question. There must be a clear hypothesis for any study that is expected to produce meaningful results.

Once you have chosen an appropriate question, you must decide on a study design. Although case reports are marginally publishable, they will not answer your clinical questions. For many reasons, randomized, controlled trials, the gold standard of research, are difficult to design, carry out, and complete in your short time as a trainee.

The good news is that well-designed and sufficiently powered observational studies often give similar results as randomized, controlled studies. Examples of common observational study designs include cohort studies, case control studies, and cross-sectional studies (Table 2).

Each study design is different and your mentor should be able to help you decide which is the best to answer the question you want to ask.

In the design of a study, one of the most important principles is defining a priori end points.

Every study will have one primary end point that reflects the hypothesis. Secondary endpoints are interesting and potentially helpful, but are not the main message. It will be important to meet with a statistician before you start data collection. Understanding the statistics to be used will allow you to collect your data in the correct way (categorical vs. continuous, etc.). Reviewing charts is very time consuming and you have to do everything in your power to ensure you do it only once.

The next step is to create a research proposal. To do this, you will need to go to the literature and see what published data relate to your study. Perhaps, there are previous studies examining your question with conflicting results?

Or if your question has not been previously investigated, what supporting literature suggests that yours is the next logical study? Your proposal should include a background section (1-2 paragraphs), hypothesis (1 sentence), the specific aims of the study (1-3 sentences), methods (2-4 paragraphs), anticipated results (1 paragraph), proposed timeline, and anticipated meeting to which it will be submitted. Your mentor will revise and critique the proposal and eventually give you a signature of approval. This proposal serves many purposes. It will allow you to fully understand the study before you begin, some form of it is usually required for the Institutional Review Board application, it will serve as the outline for your eventual manuscript, and it sets a timeline for completion of the project. Without an agreed-upon deadline, too many good studies are left in various states of completion when the trainee moves on, and are never finished. The deadline should be based on the meeting that you and your mentor agree is appropriate for reporting your results.

Most would agree that data collection is the most painful part of doing clinical research. However, there are a few tricks to ease your pain. First, there are many databases available that you may be able to harvest data from to minimize your chart work (Table 3). Before you hit the charts, it is essential to think through every step of the project. Anticipate problems (where in the chart will you locate each data point), do not collect unnecessary data points (postoperative data #3 serum [Na+] when looking at survival of thoracoscopic vs. open lobectomy), meet with your statistician beforehand to collect data for the correct analysis, collect the raw data (creatinine and weight, not presence of renal failure and obesity).

Finally, be sure that your data are backed up in multiple places. Some prefer to collect data on paper then enter it later into a spreadsheet. This ensures a hard copy of the data exists regardless if the electronic version is lost.

After the data are collected and the statistics are done, you will be faced with interpreting your results and composing an abstract and manuscript. If your study is focused and hypothesis driven, this step should be fairly straightforward. Schedule time with your mentor and discuss the results to ensure your interpretation of the data is correct.

Next using your proposal as an outline, put together a rough draft of a manuscript. Remember that manuscripts are the currency of academia. If you do not present and publish your work, you have not fully capitalized on the hard work you have put in to your study.

Your mentor will need to revise your manuscript repeatedly; use it as a learning experience for critiquing the literature and writing future manuscripts. He or she likely knows what editors and readers will be looking for in your finished product. Remember, you will need multiple revisions of the abstract and manuscript, so plan adequate time prior to your deadline for writing.

Most institutions have medical illustrators available for hire; consider including a drawing or photograph if it legitimately adds content to your manuscript.

The final step in the process is presenting your work in front of experts who likely know more about cardiothoracic surgery than you. Just remember, no one knows more about your data than you.

Prepare relentlessly for your talk, take a deep breath before you walk on stage, speak with confidence, and if you don't know the answer to a given question from the audience, admit it. Soon enough you will be the expert in the audience asking the tough questions. Then spend as much time as possible after the session speaking with audience members about you and your study.

You will meet lifelong colleagues, and maybe even your future partner. For many, research is a rewarding lifelong endeavor. For others, it is a means of learning to critically appraise the literature and landing a job. Either way, you cannot afford not to do research as a trainee.

Acknowledgment: I would like to thank my friend and colleague, Dr. Stephen H. McKellar (University of Utah), for his advice on performing research as a cardiothoracic trainee.

Dr. Seder is in the department of cardiovascular and thoracic surgery at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago.

"Why do I need to do research if I'm going into private practice anyway?"

I have heard this question multiple times throughout my career as a resident, fellow, and attending thoracic surgeon. The truth is, there are multiple reasons, any of which is sufficient to justify your participation in clinical research during training. First, and perhaps most importantly, it teaches you to critically appraise the literature.

This is a skill that will serve you well throughout your career, guiding your clinical decision making, regardless if you choose private practice or academic surgery.

Another reason is that performing clinical research allows you to become a content expert on a specific topic early in your career. This knowledge base is something that will serve as a foundation for ongoing learning and may help in designing future studies.

Once your project is complete, it will be your ticket to attend and present at regional, national, or international meetings. There is no better forum to gain public recognition for your investigative efforts and network with potential future partners than societal meetings.

Formal and informal interviews routinely occur at these gatherings and you do not want to be left out because you chose not to participate in research as a trainee. Finally, it is your responsibility to the patients that you have sworn to treat.

There are many ways to care for patients, and pushing back the frontiers of medical knowledge is as important as the day-to-day tasks that you perform on the ward or in the operating room.

So, now that you have decided that you want to participate in a research project as a trainee, how do you make it happen? Before you begin a project, you will have to choose a mentor; a topic; a clear, novel question; and the appropriate study design.

Chances are that at some point, a mentor helped guide you toward a career in cardiovascular surgery. A research mentor is just as important as a clinical mentor for a young surgeon. The most important trait that you should seek out in a research mentor is the ability to delineate important questions. All too often, residents and fellows are approached by attending surgeons with good intentions, but bad research ideas. Trainees then feel obligated to take them up on the project (in order to not appear like a slacker) and for various reasons, it does not result in an abstract, presentation, or publication. In fact, all it results in is frustration, a distaste for investigation, and wasted time.

The bottom line is that only you can protect your time, and as a surgical trainee, you must guard it ferociously. Look for a mentor that is an expert in your field of interest and who has a track record of publications.

He or she must be a logical thinker who can help you delineate a clear, novel question, choose the appropriate study design, guide your writing of the manuscript, and direct your submission to the appropriate meetings and journals.

Finally, your mentor must be dedicated to your success. We are all busy, but if your mentor cannot find the time to routinely meet with you at every step of your project, you need to find a new mentor.

Choosing a clear, novel clinical question starts with choosing an appropriate topic (Table 1). With the right topic and question, the hypothesis is obvious, it is easy to define your endpoints, and your study design will fall into place. But with the wrong question, your study will lack focus, it will be difficult to explain the relevance of your study, and you will not want to present your data on the podium. An example of a good question is: "Do patients with a given disease treated with operation X live longer than those treated with operation Y?"

Stay away from the lure of "Let's review our experience of operation X…" or "Why don't I see how many of operation Y we've done over the past 10 years…" These topics are vague and do not ask a specific question. There must be a clear hypothesis for any study that is expected to produce meaningful results.

Once you have chosen an appropriate question, you must decide on a study design. Although case reports are marginally publishable, they will not answer your clinical questions. For many reasons, randomized, controlled trials, the gold standard of research, are difficult to design, carry out, and complete in your short time as a trainee.

The good news is that well-designed and sufficiently powered observational studies often give similar results as randomized, controlled studies. Examples of common observational study designs include cohort studies, case control studies, and cross-sectional studies (Table 2).

Each study design is different and your mentor should be able to help you decide which is the best to answer the question you want to ask.

In the design of a study, one of the most important principles is defining a priori end points.

Every study will have one primary end point that reflects the hypothesis. Secondary endpoints are interesting and potentially helpful, but are not the main message. It will be important to meet with a statistician before you start data collection. Understanding the statistics to be used will allow you to collect your data in the correct way (categorical vs. continuous, etc.). Reviewing charts is very time consuming and you have to do everything in your power to ensure you do it only once.

The next step is to create a research proposal. To do this, you will need to go to the literature and see what published data relate to your study. Perhaps, there are previous studies examining your question with conflicting results?

Or if your question has not been previously investigated, what supporting literature suggests that yours is the next logical study? Your proposal should include a background section (1-2 paragraphs), hypothesis (1 sentence), the specific aims of the study (1-3 sentences), methods (2-4 paragraphs), anticipated results (1 paragraph), proposed timeline, and anticipated meeting to which it will be submitted. Your mentor will revise and critique the proposal and eventually give you a signature of approval. This proposal serves many purposes. It will allow you to fully understand the study before you begin, some form of it is usually required for the Institutional Review Board application, it will serve as the outline for your eventual manuscript, and it sets a timeline for completion of the project. Without an agreed-upon deadline, too many good studies are left in various states of completion when the trainee moves on, and are never finished. The deadline should be based on the meeting that you and your mentor agree is appropriate for reporting your results.

Most would agree that data collection is the most painful part of doing clinical research. However, there are a few tricks to ease your pain. First, there are many databases available that you may be able to harvest data from to minimize your chart work (Table 3). Before you hit the charts, it is essential to think through every step of the project. Anticipate problems (where in the chart will you locate each data point), do not collect unnecessary data points (postoperative data #3 serum [Na+] when looking at survival of thoracoscopic vs. open lobectomy), meet with your statistician beforehand to collect data for the correct analysis, collect the raw data (creatinine and weight, not presence of renal failure and obesity).

Finally, be sure that your data are backed up in multiple places. Some prefer to collect data on paper then enter it later into a spreadsheet. This ensures a hard copy of the data exists regardless if the electronic version is lost.

After the data are collected and the statistics are done, you will be faced with interpreting your results and composing an abstract and manuscript. If your study is focused and hypothesis driven, this step should be fairly straightforward. Schedule time with your mentor and discuss the results to ensure your interpretation of the data is correct.

Next using your proposal as an outline, put together a rough draft of a manuscript. Remember that manuscripts are the currency of academia. If you do not present and publish your work, you have not fully capitalized on the hard work you have put in to your study.

Your mentor will need to revise your manuscript repeatedly; use it as a learning experience for critiquing the literature and writing future manuscripts. He or she likely knows what editors and readers will be looking for in your finished product. Remember, you will need multiple revisions of the abstract and manuscript, so plan adequate time prior to your deadline for writing.

Most institutions have medical illustrators available for hire; consider including a drawing or photograph if it legitimately adds content to your manuscript.

The final step in the process is presenting your work in front of experts who likely know more about cardiothoracic surgery than you. Just remember, no one knows more about your data than you.

Prepare relentlessly for your talk, take a deep breath before you walk on stage, speak with confidence, and if you don't know the answer to a given question from the audience, admit it. Soon enough you will be the expert in the audience asking the tough questions. Then spend as much time as possible after the session speaking with audience members about you and your study.

You will meet lifelong colleagues, and maybe even your future partner. For many, research is a rewarding lifelong endeavor. For others, it is a means of learning to critically appraise the literature and landing a job. Either way, you cannot afford not to do research as a trainee.

Acknowledgment: I would like to thank my friend and colleague, Dr. Stephen H. McKellar (University of Utah), for his advice on performing research as a cardiothoracic trainee.

Dr. Seder is in the department of cardiovascular and thoracic surgery at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago.

Is an MI following CEA or CAS just as clinically important as stroke?

The answer is yes!

I was not involved in the design of CREST, but I do have a responsibility to interpret the results and incorporate them into my clinical approach. When MI occurred after carotid endarterectomy (CEA) or carotid artery stenting (CAS) in CREST, the 1-year mortality was 14.2% versus 2.2% among those who did not have an MI (Blackshear et al. Circulation 2011;123:2571). This is consistent with the vascular literature, which is chock-full of strongly compelling data showing that we should take cardiac risk into account when planning our therapy.

It is not a mystery as to who is at risk for an MI. The significant independent risk factors for MI in CREST were known coronary artery disease or previous coronary revascularization. Since this is well known to us prior to treatment, shouldn’t this information be part of our therapeutic plan?

Suppose I said that perioperative MI is not important after abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, fem-pop bypass, or distal bypass?

A large part of the growth of endovascular approaches in recent years has been motivated by our best efforts to avoid MI. Think of the early days of endovascular aneurysm repair, prior to establishment of this as standard of care for most patients, and how many patients were treated with stent-grafts in an attempt to avoid cardiac risk. How could we now claim that it is unimportant?

There were two independent risk factors for mortality during CREST that increased the hazard ratio more than two times: stroke and MI (FDA panel presentation, Jan. 26, 2011).

The reason to revascularize the carotid is to prevent stroke, and this is a worthwhile endeavor. However, if the patient is harmed in some other way, especially in a manner associated with dramatically increased mortality, shouldn’t we understand that?

At some point, with further technological development, mesh-covered carotid stents, customized protection devices, and more informed patient selection, the stroke risk of CAS is likely to decrease. At that point, our relative concern about the risk of MI and the importance of MI as an endpoint is likely to increase, not decrease.

There is no doubt that we all fear stroke. Unfortunately, when something bad happens to a patient, they don’t get to select which complication they are going to have. We owe it to our patients to do what we can to diminish all the risks they face. I cannot envision an honest and useful future carotid trial design in which MI is not considered an endpoint.

Dr. Peter A. Schneider is chief of the division of vascular surgery, Hawaii Permanente Medical Group and Kaiser Foundation Hospital, Honolulu.

The answer is no!

Being given a choice between MI and stroke is like asking someone if they would rather be rich and healthy or poor and sick. The best option is to have neither an MI nor a stroke following carotid intervention. However, when given this unpleasant choice, the participants in CREST clearly stated that MI was preferable to either major or minor stroke. How often have we heard our patients state, "Doc, I’m not afraid to die, but I don’t want to live disabled from a stroke"?

A quality-of-life assessment was carried out in CREST patients using an SF-36.

This questionnaire looked at both the physical and the emotional effect of the complications of stroke and MI compared with those who were complication free.

One year after a complication, the patients stated that the worst thing that happened was a major stroke. The next worse thing was a minor stroke.

Myocardial infarction, 1 year later, from the patient’s perspective, was a nonevent. The argument that has been used regarding the importance of MI is that it has an adverse effect on life expectancy.

This is true, and it has been confirmed in several trials including CREST. The surprise finding is that stroke, including so-called minor strokes, also reduced life expectancy.

In CREST, 4 years following an adjudicated MI, the mortality rate was 19.1% versus 6.7% for those not suffering an MI.

However, the 4-year mortality rate among patients having suffered a stroke was 20%.

Therefore, compromised survival occurred equally among those patients following either stroke or MI.

However, not only did patients suffering a stroke have an equally high mortality, the group was further compromised by neurologic disability among the survivors, whereas the survivors following MI returned to their precomplication status.

Therefore, from the patients’ subjective status as well as objective clinical considerations, stroke is clearly more deleterious than MI.

Dr. Wesley S. Moore is a vascular and endovascular surgeon, and professor and chief, emeritus, of the division of vascular surgery, University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center.

The answer is yes!

I was not involved in the design of CREST, but I do have a responsibility to interpret the results and incorporate them into my clinical approach. When MI occurred after carotid endarterectomy (CEA) or carotid artery stenting (CAS) in CREST, the 1-year mortality was 14.2% versus 2.2% among those who did not have an MI (Blackshear et al. Circulation 2011;123:2571). This is consistent with the vascular literature, which is chock-full of strongly compelling data showing that we should take cardiac risk into account when planning our therapy.

It is not a mystery as to who is at risk for an MI. The significant independent risk factors for MI in CREST were known coronary artery disease or previous coronary revascularization. Since this is well known to us prior to treatment, shouldn’t this information be part of our therapeutic plan?

Suppose I said that perioperative MI is not important after abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, fem-pop bypass, or distal bypass?

A large part of the growth of endovascular approaches in recent years has been motivated by our best efforts to avoid MI. Think of the early days of endovascular aneurysm repair, prior to establishment of this as standard of care for most patients, and how many patients were treated with stent-grafts in an attempt to avoid cardiac risk. How could we now claim that it is unimportant?

There were two independent risk factors for mortality during CREST that increased the hazard ratio more than two times: stroke and MI (FDA panel presentation, Jan. 26, 2011).

The reason to revascularize the carotid is to prevent stroke, and this is a worthwhile endeavor. However, if the patient is harmed in some other way, especially in a manner associated with dramatically increased mortality, shouldn’t we understand that?

At some point, with further technological development, mesh-covered carotid stents, customized protection devices, and more informed patient selection, the stroke risk of CAS is likely to decrease. At that point, our relative concern about the risk of MI and the importance of MI as an endpoint is likely to increase, not decrease.

There is no doubt that we all fear stroke. Unfortunately, when something bad happens to a patient, they don’t get to select which complication they are going to have. We owe it to our patients to do what we can to diminish all the risks they face. I cannot envision an honest and useful future carotid trial design in which MI is not considered an endpoint.

Dr. Peter A. Schneider is chief of the division of vascular surgery, Hawaii Permanente Medical Group and Kaiser Foundation Hospital, Honolulu.

The answer is no!

Being given a choice between MI and stroke is like asking someone if they would rather be rich and healthy or poor and sick. The best option is to have neither an MI nor a stroke following carotid intervention. However, when given this unpleasant choice, the participants in CREST clearly stated that MI was preferable to either major or minor stroke. How often have we heard our patients state, "Doc, I’m not afraid to die, but I don’t want to live disabled from a stroke"?

A quality-of-life assessment was carried out in CREST patients using an SF-36.

This questionnaire looked at both the physical and the emotional effect of the complications of stroke and MI compared with those who were complication free.

One year after a complication, the patients stated that the worst thing that happened was a major stroke. The next worse thing was a minor stroke.

Myocardial infarction, 1 year later, from the patient’s perspective, was a nonevent. The argument that has been used regarding the importance of MI is that it has an adverse effect on life expectancy.

This is true, and it has been confirmed in several trials including CREST. The surprise finding is that stroke, including so-called minor strokes, also reduced life expectancy.

In CREST, 4 years following an adjudicated MI, the mortality rate was 19.1% versus 6.7% for those not suffering an MI.

However, the 4-year mortality rate among patients having suffered a stroke was 20%.