User login

Team applies single-cell genomics to malaria

Credit: Peter H. Seeberger

Researchers have devised a way to perform genome sequencing on individual cells infected with malaria parasites.

The team found this single-cell approach could generate parasite genome sequences directly from the blood of patients infected with Plasmodium vivax or Plasmodium falciparum.

It provided new insight into the biology of the parasites, revealing their virulence and capacity for drug resistance.

The team described this work in Genome Research.

They noted that malaria infections commonly contain complex mixtures of Plasmodium parasites. These multiple-genotype infections (MGIs) can alter the impact of the infection and drive the spread of drug resistance. MGIs are extremely common in regions with high levels of malaria infection, but their biology is poorly understood.

“Up to 70% of infections in sub-Saharan Africa are MGIs, and we currently don’t know how many genotypes are present and whether parasites come from a single mosquito bite or multiple mosquito bites,” said study author Shalini Nair, of Texas Biomedical Research Institute in San Antonio.

“Current sequencing techniques really limit our understanding of malaria parasite biology,” added study author Ian Cheeseman, PhD, also of Texas Biomed.

“It’s like trying to understand human genetics by taking DNA from everyone in a village at once. The data is all jumbled up, but what we really want is information from individuals.”

To achieve a better understanding of MGIs and malaria parasites in general, the researchers developed a method for isolating an individual parasite cell and sequencing its genome. Although single-cell genomics approaches are already used in cancer research, it has been difficult to adapt the approach to other organisms.

“One of the real challenges was learning how to cope with the tiny amounts of DNA involved,” Nair said. “In a single cell, we have a thousand-million-millionth of a gram of DNA. It took a lot of effort before we developed a method where we simply didn’t lose this.”

But the researchers eventually found they could use methods of single-cell sorting and whole-genome amplification to separate out individual cells and amplify their DNA for sequencing. The team sequenced the DNA from red blood cells infected with P falciparum or P vivax.

They discovered this technique can reveal the composition of MGIs and provide information on the strength of an infection and the development of drug resistance.

“One of the major surprises we found when we started looking at individual parasites instead of whole infections was the level of variation in drug-resistance genes,” Nair said. “The patterns we saw suggested that different parasites within a single malaria infection would react very differently to drug treatment.”

Unfortunately, this technology is currently too expensive and demanding for routine use in the clinic. But the potential applications are significant, according to the researchers.

“We’re now able to look at malaria infections with incredible detail,” Dr Cheeseman said. “This will help us understand how to best design drugs and vaccines to tackle this major global killer.” ![]()

Credit: Peter H. Seeberger

Researchers have devised a way to perform genome sequencing on individual cells infected with malaria parasites.

The team found this single-cell approach could generate parasite genome sequences directly from the blood of patients infected with Plasmodium vivax or Plasmodium falciparum.

It provided new insight into the biology of the parasites, revealing their virulence and capacity for drug resistance.

The team described this work in Genome Research.

They noted that malaria infections commonly contain complex mixtures of Plasmodium parasites. These multiple-genotype infections (MGIs) can alter the impact of the infection and drive the spread of drug resistance. MGIs are extremely common in regions with high levels of malaria infection, but their biology is poorly understood.

“Up to 70% of infections in sub-Saharan Africa are MGIs, and we currently don’t know how many genotypes are present and whether parasites come from a single mosquito bite or multiple mosquito bites,” said study author Shalini Nair, of Texas Biomedical Research Institute in San Antonio.

“Current sequencing techniques really limit our understanding of malaria parasite biology,” added study author Ian Cheeseman, PhD, also of Texas Biomed.

“It’s like trying to understand human genetics by taking DNA from everyone in a village at once. The data is all jumbled up, but what we really want is information from individuals.”

To achieve a better understanding of MGIs and malaria parasites in general, the researchers developed a method for isolating an individual parasite cell and sequencing its genome. Although single-cell genomics approaches are already used in cancer research, it has been difficult to adapt the approach to other organisms.

“One of the real challenges was learning how to cope with the tiny amounts of DNA involved,” Nair said. “In a single cell, we have a thousand-million-millionth of a gram of DNA. It took a lot of effort before we developed a method where we simply didn’t lose this.”

But the researchers eventually found they could use methods of single-cell sorting and whole-genome amplification to separate out individual cells and amplify their DNA for sequencing. The team sequenced the DNA from red blood cells infected with P falciparum or P vivax.

They discovered this technique can reveal the composition of MGIs and provide information on the strength of an infection and the development of drug resistance.

“One of the major surprises we found when we started looking at individual parasites instead of whole infections was the level of variation in drug-resistance genes,” Nair said. “The patterns we saw suggested that different parasites within a single malaria infection would react very differently to drug treatment.”

Unfortunately, this technology is currently too expensive and demanding for routine use in the clinic. But the potential applications are significant, according to the researchers.

“We’re now able to look at malaria infections with incredible detail,” Dr Cheeseman said. “This will help us understand how to best design drugs and vaccines to tackle this major global killer.” ![]()

Credit: Peter H. Seeberger

Researchers have devised a way to perform genome sequencing on individual cells infected with malaria parasites.

The team found this single-cell approach could generate parasite genome sequences directly from the blood of patients infected with Plasmodium vivax or Plasmodium falciparum.

It provided new insight into the biology of the parasites, revealing their virulence and capacity for drug resistance.

The team described this work in Genome Research.

They noted that malaria infections commonly contain complex mixtures of Plasmodium parasites. These multiple-genotype infections (MGIs) can alter the impact of the infection and drive the spread of drug resistance. MGIs are extremely common in regions with high levels of malaria infection, but their biology is poorly understood.

“Up to 70% of infections in sub-Saharan Africa are MGIs, and we currently don’t know how many genotypes are present and whether parasites come from a single mosquito bite or multiple mosquito bites,” said study author Shalini Nair, of Texas Biomedical Research Institute in San Antonio.

“Current sequencing techniques really limit our understanding of malaria parasite biology,” added study author Ian Cheeseman, PhD, also of Texas Biomed.

“It’s like trying to understand human genetics by taking DNA from everyone in a village at once. The data is all jumbled up, but what we really want is information from individuals.”

To achieve a better understanding of MGIs and malaria parasites in general, the researchers developed a method for isolating an individual parasite cell and sequencing its genome. Although single-cell genomics approaches are already used in cancer research, it has been difficult to adapt the approach to other organisms.

“One of the real challenges was learning how to cope with the tiny amounts of DNA involved,” Nair said. “In a single cell, we have a thousand-million-millionth of a gram of DNA. It took a lot of effort before we developed a method where we simply didn’t lose this.”

But the researchers eventually found they could use methods of single-cell sorting and whole-genome amplification to separate out individual cells and amplify their DNA for sequencing. The team sequenced the DNA from red blood cells infected with P falciparum or P vivax.

They discovered this technique can reveal the composition of MGIs and provide information on the strength of an infection and the development of drug resistance.

“One of the major surprises we found when we started looking at individual parasites instead of whole infections was the level of variation in drug-resistance genes,” Nair said. “The patterns we saw suggested that different parasites within a single malaria infection would react very differently to drug treatment.”

Unfortunately, this technology is currently too expensive and demanding for routine use in the clinic. But the potential applications are significant, according to the researchers.

“We’re now able to look at malaria infections with incredible detail,” Dr Cheeseman said. “This will help us understand how to best design drugs and vaccines to tackle this major global killer.” ![]()

Antiviral agent may prevent CMV infection

An antiviral agent can reduce the incidence of cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection in patients receiving an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell

transplant, according to a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The agent, letermovir, proved more effective than placebo in preventing CMV, and the highest dose tested, 240 mg/day, was most effective.

The most common adverse events were gastrointestinal disorders and infections.

However, the incidence of events was similar among treated patients and those in the placebo arm.

Roy F. Chemaly, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, and his colleagues conducted this randomized, double-blind, phase 2 trial. It was funded by AiCuris, the company that was developing letermovir before Merck purchased worldwide rights to develop and commercialize the drug in 2012.

The researchers evaluated the effect of letermovir on the incidence and time-to-onset of CMV prophylaxis failure in CMV-seropositive, matched transplant recipients.

The study included 131 patients. For 12 weeks after engraftment, they received placebo (n=33) or letermovir at 60 mg/day (n=33), 120 mg/day (n=31), or 240 mg/day (n=34).

Efficacy analysis

The primary endpoint was all-cause prophylaxis failure, which was defined as discontinuation of the study drug due to CMV antigen or CMV DNA detection, end-organ disease, or any other causes unrelated to CMV.

The primary efficacy analysis population was a modified intention-to-treat population, which included all patients who received at least 1 dose of the study drug and had at least 1 measurement of the CMV viral load during the study.

The incidence of all-cause prophylaxis failure was significantly lower in the groups that received letermovir at doses of 120 mg/day or 240 mg/day, when compared with the placebo group—32% and 29% vs 64%; P=0.01 and P=0.007, respectively.

The time to the onset of prophylaxis failure was significantly shorter in the 240-mg group (range, 1 to 8 days) than in the placebo group (range, 1 to 21 days; P=0.002).

However, comparisons with the placebo group were not significant for the 60-mg group (range, 1 to 42 days; P=0.15) or the 120-mg group (range, 1 to 15 days; P=0.13).

The incidence of virologic failure was lower in the 240-mg group (6%) than in the 120-mg group (19%), the 60-mg group (21%), or the placebo group (36%).

Virologic failure was defined as either detectable CMV antigen or DNA in the blood at 2 consecutive time points (with at least 1 instance confirmed by the central lab), leading to discontinuation of the study drug and the administration of rescue medication or the development of CMV end-organ disease.

Safety analysis

Nearly all of the patients had at least 1 adverse event during treatment—94% in the 60-mg and 120-mg groups and 100% in the 240-mg and placebo groups. Most events were mild or moderate.

However, 24% of letermovir-treated patients and 30% of those who received placebo experienced severe adverse events during treatment. Investigators, who were blinded to treatment, considered 17% of the severe events in the letermovir group to be drug-related and 33% of severe events in the placebo group to be drug-related.

Most adverse events were gastrointestinal disorders—diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting—which occurred in 66% of letermovir-treated patients and 61% of patients in the placebo group. Infections—mostly CMV—were also common, occurring in 59% of letermovir-treated patients and 76% of patients in the placebo group.

Five patients died during the trial. None of the deaths were thought to be related to treatment or to CMV. ![]()

An antiviral agent can reduce the incidence of cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection in patients receiving an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell

transplant, according to a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The agent, letermovir, proved more effective than placebo in preventing CMV, and the highest dose tested, 240 mg/day, was most effective.

The most common adverse events were gastrointestinal disorders and infections.

However, the incidence of events was similar among treated patients and those in the placebo arm.

Roy F. Chemaly, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, and his colleagues conducted this randomized, double-blind, phase 2 trial. It was funded by AiCuris, the company that was developing letermovir before Merck purchased worldwide rights to develop and commercialize the drug in 2012.

The researchers evaluated the effect of letermovir on the incidence and time-to-onset of CMV prophylaxis failure in CMV-seropositive, matched transplant recipients.

The study included 131 patients. For 12 weeks after engraftment, they received placebo (n=33) or letermovir at 60 mg/day (n=33), 120 mg/day (n=31), or 240 mg/day (n=34).

Efficacy analysis

The primary endpoint was all-cause prophylaxis failure, which was defined as discontinuation of the study drug due to CMV antigen or CMV DNA detection, end-organ disease, or any other causes unrelated to CMV.

The primary efficacy analysis population was a modified intention-to-treat population, which included all patients who received at least 1 dose of the study drug and had at least 1 measurement of the CMV viral load during the study.

The incidence of all-cause prophylaxis failure was significantly lower in the groups that received letermovir at doses of 120 mg/day or 240 mg/day, when compared with the placebo group—32% and 29% vs 64%; P=0.01 and P=0.007, respectively.

The time to the onset of prophylaxis failure was significantly shorter in the 240-mg group (range, 1 to 8 days) than in the placebo group (range, 1 to 21 days; P=0.002).

However, comparisons with the placebo group were not significant for the 60-mg group (range, 1 to 42 days; P=0.15) or the 120-mg group (range, 1 to 15 days; P=0.13).

The incidence of virologic failure was lower in the 240-mg group (6%) than in the 120-mg group (19%), the 60-mg group (21%), or the placebo group (36%).

Virologic failure was defined as either detectable CMV antigen or DNA in the blood at 2 consecutive time points (with at least 1 instance confirmed by the central lab), leading to discontinuation of the study drug and the administration of rescue medication or the development of CMV end-organ disease.

Safety analysis

Nearly all of the patients had at least 1 adverse event during treatment—94% in the 60-mg and 120-mg groups and 100% in the 240-mg and placebo groups. Most events were mild or moderate.

However, 24% of letermovir-treated patients and 30% of those who received placebo experienced severe adverse events during treatment. Investigators, who were blinded to treatment, considered 17% of the severe events in the letermovir group to be drug-related and 33% of severe events in the placebo group to be drug-related.

Most adverse events were gastrointestinal disorders—diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting—which occurred in 66% of letermovir-treated patients and 61% of patients in the placebo group. Infections—mostly CMV—were also common, occurring in 59% of letermovir-treated patients and 76% of patients in the placebo group.

Five patients died during the trial. None of the deaths were thought to be related to treatment or to CMV. ![]()

An antiviral agent can reduce the incidence of cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection in patients receiving an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell

transplant, according to a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The agent, letermovir, proved more effective than placebo in preventing CMV, and the highest dose tested, 240 mg/day, was most effective.

The most common adverse events were gastrointestinal disorders and infections.

However, the incidence of events was similar among treated patients and those in the placebo arm.

Roy F. Chemaly, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, and his colleagues conducted this randomized, double-blind, phase 2 trial. It was funded by AiCuris, the company that was developing letermovir before Merck purchased worldwide rights to develop and commercialize the drug in 2012.

The researchers evaluated the effect of letermovir on the incidence and time-to-onset of CMV prophylaxis failure in CMV-seropositive, matched transplant recipients.

The study included 131 patients. For 12 weeks after engraftment, they received placebo (n=33) or letermovir at 60 mg/day (n=33), 120 mg/day (n=31), or 240 mg/day (n=34).

Efficacy analysis

The primary endpoint was all-cause prophylaxis failure, which was defined as discontinuation of the study drug due to CMV antigen or CMV DNA detection, end-organ disease, or any other causes unrelated to CMV.

The primary efficacy analysis population was a modified intention-to-treat population, which included all patients who received at least 1 dose of the study drug and had at least 1 measurement of the CMV viral load during the study.

The incidence of all-cause prophylaxis failure was significantly lower in the groups that received letermovir at doses of 120 mg/day or 240 mg/day, when compared with the placebo group—32% and 29% vs 64%; P=0.01 and P=0.007, respectively.

The time to the onset of prophylaxis failure was significantly shorter in the 240-mg group (range, 1 to 8 days) than in the placebo group (range, 1 to 21 days; P=0.002).

However, comparisons with the placebo group were not significant for the 60-mg group (range, 1 to 42 days; P=0.15) or the 120-mg group (range, 1 to 15 days; P=0.13).

The incidence of virologic failure was lower in the 240-mg group (6%) than in the 120-mg group (19%), the 60-mg group (21%), or the placebo group (36%).

Virologic failure was defined as either detectable CMV antigen or DNA in the blood at 2 consecutive time points (with at least 1 instance confirmed by the central lab), leading to discontinuation of the study drug and the administration of rescue medication or the development of CMV end-organ disease.

Safety analysis

Nearly all of the patients had at least 1 adverse event during treatment—94% in the 60-mg and 120-mg groups and 100% in the 240-mg and placebo groups. Most events were mild or moderate.

However, 24% of letermovir-treated patients and 30% of those who received placebo experienced severe adverse events during treatment. Investigators, who were blinded to treatment, considered 17% of the severe events in the letermovir group to be drug-related and 33% of severe events in the placebo group to be drug-related.

Most adverse events were gastrointestinal disorders—diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting—which occurred in 66% of letermovir-treated patients and 61% of patients in the placebo group. Infections—mostly CMV—were also common, occurring in 59% of letermovir-treated patients and 76% of patients in the placebo group.

Five patients died during the trial. None of the deaths were thought to be related to treatment or to CMV. ![]()

How IL-27 promotes tumor growth

Credit: Kathryn T. Iacono

Research in mice has revealed a potential approach to cancer treatment—a way to inhibit the recruitment of regulatory T cells (Tregs) to tumors.

The study showed that dendritic-cell-derived interleukin-27 (IL-27) promotes Treg recruitment in models of lymphoma, melanoma, and fibrosarcoma.

This suggests that if cancer therapies can inhibit IL-27’s immunosuppressive function, they could more effectively activate other T cells to attack and destroy tumors.

Researchers described this discovery in the Journal of Leukocyte Biology.

“Our study not only provides a new insight into the effects of interleukin-27 in regulatory T-cell biology but also greatly improves our understanding of the physiological functions of interleukin-27, especially in tumor immunology,” said study author Siyuan Xia, of Nankai University in Tianjin, China.

“We hope our study could shed new light on developing novel interventional therapies by targeting regulatory T cells in cancer patients.”

The researchers made their discovery by using mice deficient in a specific subunit of IL-27 called p28. They compared tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes between IL-27p28 knockout mice and wild-type mice.

This revealed that Tregs were significantly decreased in knockout mice transplanted with EL-4 lymphoma, B16 melanoma, and MCA-induced fibrosarcoma.

The team also found that IL-27 promotes the expression of CCL22, which is known to mediate Treg recruitment to tumors. And tumor-associated dendritic cells were the major source of CCL22.

When the researchers restored CCL22 or IL-27 in the knockout mice, they observed significant restoration of the tumor-infiltrating Tregs.

Furthermore, tumor-infiltrating CD4 T cells produced much more IFN-γ in the IL-27p28 knockout mice than in wild-type mice. According to the researchers, this reinforces the physiological importance of Tregs in suppressing an antitumor immune response.

“Suppressive and regulatory pathways in the immune system are incredibly important for normal health and preventing autoimmunity,” said John Wherry, PhD, Deputy Editor of the Journal of Leukocyte Biology.

“However, these pathways also get exploited by cancer to prevent immune responses leading to cancer progression. The current studies point to an important regulatory network centered on interleukin-27 that could be targeted to improve immunity to cancer in humans.” ![]()

Credit: Kathryn T. Iacono

Research in mice has revealed a potential approach to cancer treatment—a way to inhibit the recruitment of regulatory T cells (Tregs) to tumors.

The study showed that dendritic-cell-derived interleukin-27 (IL-27) promotes Treg recruitment in models of lymphoma, melanoma, and fibrosarcoma.

This suggests that if cancer therapies can inhibit IL-27’s immunosuppressive function, they could more effectively activate other T cells to attack and destroy tumors.

Researchers described this discovery in the Journal of Leukocyte Biology.

“Our study not only provides a new insight into the effects of interleukin-27 in regulatory T-cell biology but also greatly improves our understanding of the physiological functions of interleukin-27, especially in tumor immunology,” said study author Siyuan Xia, of Nankai University in Tianjin, China.

“We hope our study could shed new light on developing novel interventional therapies by targeting regulatory T cells in cancer patients.”

The researchers made their discovery by using mice deficient in a specific subunit of IL-27 called p28. They compared tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes between IL-27p28 knockout mice and wild-type mice.

This revealed that Tregs were significantly decreased in knockout mice transplanted with EL-4 lymphoma, B16 melanoma, and MCA-induced fibrosarcoma.

The team also found that IL-27 promotes the expression of CCL22, which is known to mediate Treg recruitment to tumors. And tumor-associated dendritic cells were the major source of CCL22.

When the researchers restored CCL22 or IL-27 in the knockout mice, they observed significant restoration of the tumor-infiltrating Tregs.

Furthermore, tumor-infiltrating CD4 T cells produced much more IFN-γ in the IL-27p28 knockout mice than in wild-type mice. According to the researchers, this reinforces the physiological importance of Tregs in suppressing an antitumor immune response.

“Suppressive and regulatory pathways in the immune system are incredibly important for normal health and preventing autoimmunity,” said John Wherry, PhD, Deputy Editor of the Journal of Leukocyte Biology.

“However, these pathways also get exploited by cancer to prevent immune responses leading to cancer progression. The current studies point to an important regulatory network centered on interleukin-27 that could be targeted to improve immunity to cancer in humans.” ![]()

Credit: Kathryn T. Iacono

Research in mice has revealed a potential approach to cancer treatment—a way to inhibit the recruitment of regulatory T cells (Tregs) to tumors.

The study showed that dendritic-cell-derived interleukin-27 (IL-27) promotes Treg recruitment in models of lymphoma, melanoma, and fibrosarcoma.

This suggests that if cancer therapies can inhibit IL-27’s immunosuppressive function, they could more effectively activate other T cells to attack and destroy tumors.

Researchers described this discovery in the Journal of Leukocyte Biology.

“Our study not only provides a new insight into the effects of interleukin-27 in regulatory T-cell biology but also greatly improves our understanding of the physiological functions of interleukin-27, especially in tumor immunology,” said study author Siyuan Xia, of Nankai University in Tianjin, China.

“We hope our study could shed new light on developing novel interventional therapies by targeting regulatory T cells in cancer patients.”

The researchers made their discovery by using mice deficient in a specific subunit of IL-27 called p28. They compared tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes between IL-27p28 knockout mice and wild-type mice.

This revealed that Tregs were significantly decreased in knockout mice transplanted with EL-4 lymphoma, B16 melanoma, and MCA-induced fibrosarcoma.

The team also found that IL-27 promotes the expression of CCL22, which is known to mediate Treg recruitment to tumors. And tumor-associated dendritic cells were the major source of CCL22.

When the researchers restored CCL22 or IL-27 in the knockout mice, they observed significant restoration of the tumor-infiltrating Tregs.

Furthermore, tumor-infiltrating CD4 T cells produced much more IFN-γ in the IL-27p28 knockout mice than in wild-type mice. According to the researchers, this reinforces the physiological importance of Tregs in suppressing an antitumor immune response.

“Suppressive and regulatory pathways in the immune system are incredibly important for normal health and preventing autoimmunity,” said John Wherry, PhD, Deputy Editor of the Journal of Leukocyte Biology.

“However, these pathways also get exploited by cancer to prevent immune responses leading to cancer progression. The current studies point to an important regulatory network centered on interleukin-27 that could be targeted to improve immunity to cancer in humans.” ![]()

Hepcidin levels vary according to cause of anemia

showing anemia

Measuring levels of the hormone hepcidin can help us distinguish anemia caused by iron deficiency from anemia caused by other conditions, a new study suggests.

Investigators say the findings, published in Science Translational Medicine, could help public officials make more informed decisions about distributing iron supplements.

Giving iron supplements to individuals who don’t need them can promote or exacerbate malaria and other infections.

With this research, the investigators linked low levels of hepcidin to iron-deficiency anemia in preschool children living in Africa.

Sant-Rayn Pasricha, PhD, of the University of Oxford in the UK, and his colleagues tested hepcidin levels in 1313 samples taken in 2001 and 2008 from children in The Gambia and Tanzania, respectively.

The team also looked at retrospective data from 25 Gambian children with either postmalarial or nonmalarial anemia.

The mean hepcidin level was significantly lower in children with iron-deficiency anemia than in children with anemia due to inflammation/infection (1.8 ng/mL and 21.7 ng/mL, respectively; P<0.0001).

To expand upon this finding, the investigators modeled the potential impact of screening children for iron supplementation needs based on hepcidin levels rather than anemia status.

If a screen was based on the presence of anemia (hemoglobin <11 g/dL), 77% of iron-deficient children would have received iron supplements, but so would 73% of children with Plasmodium falciparum parasitemia and all of the children with anemia due to inflammation.

On the other hand, if a screen was based on a hepcidin cutoff of <5.5 ng/mL, iron supplements would be given to 77% of children with iron deficiency, 80% of children with iron-deficiency anemia, 20% of children with P falciparum infection, and 14% of children with anemia due to inflammation.

The investigators noted that a lower hepcidin cutoff would have reduced the proportion of individuals with infection and/or inflammation receiving iron, but it would have increased the risk that more children with iron-deficiency anemia would not receive iron. And of course, the reverse is true of a higher hepcidin cutoff.

Nevertheless, the team believes these results are promising. They are now conducting clinical trials to test whether hepcidin levels can be used as a marker to guide iron supplementation decisions. ![]()

showing anemia

Measuring levels of the hormone hepcidin can help us distinguish anemia caused by iron deficiency from anemia caused by other conditions, a new study suggests.

Investigators say the findings, published in Science Translational Medicine, could help public officials make more informed decisions about distributing iron supplements.

Giving iron supplements to individuals who don’t need them can promote or exacerbate malaria and other infections.

With this research, the investigators linked low levels of hepcidin to iron-deficiency anemia in preschool children living in Africa.

Sant-Rayn Pasricha, PhD, of the University of Oxford in the UK, and his colleagues tested hepcidin levels in 1313 samples taken in 2001 and 2008 from children in The Gambia and Tanzania, respectively.

The team also looked at retrospective data from 25 Gambian children with either postmalarial or nonmalarial anemia.

The mean hepcidin level was significantly lower in children with iron-deficiency anemia than in children with anemia due to inflammation/infection (1.8 ng/mL and 21.7 ng/mL, respectively; P<0.0001).

To expand upon this finding, the investigators modeled the potential impact of screening children for iron supplementation needs based on hepcidin levels rather than anemia status.

If a screen was based on the presence of anemia (hemoglobin <11 g/dL), 77% of iron-deficient children would have received iron supplements, but so would 73% of children with Plasmodium falciparum parasitemia and all of the children with anemia due to inflammation.

On the other hand, if a screen was based on a hepcidin cutoff of <5.5 ng/mL, iron supplements would be given to 77% of children with iron deficiency, 80% of children with iron-deficiency anemia, 20% of children with P falciparum infection, and 14% of children with anemia due to inflammation.

The investigators noted that a lower hepcidin cutoff would have reduced the proportion of individuals with infection and/or inflammation receiving iron, but it would have increased the risk that more children with iron-deficiency anemia would not receive iron. And of course, the reverse is true of a higher hepcidin cutoff.

Nevertheless, the team believes these results are promising. They are now conducting clinical trials to test whether hepcidin levels can be used as a marker to guide iron supplementation decisions. ![]()

showing anemia

Measuring levels of the hormone hepcidin can help us distinguish anemia caused by iron deficiency from anemia caused by other conditions, a new study suggests.

Investigators say the findings, published in Science Translational Medicine, could help public officials make more informed decisions about distributing iron supplements.

Giving iron supplements to individuals who don’t need them can promote or exacerbate malaria and other infections.

With this research, the investigators linked low levels of hepcidin to iron-deficiency anemia in preschool children living in Africa.

Sant-Rayn Pasricha, PhD, of the University of Oxford in the UK, and his colleagues tested hepcidin levels in 1313 samples taken in 2001 and 2008 from children in The Gambia and Tanzania, respectively.

The team also looked at retrospective data from 25 Gambian children with either postmalarial or nonmalarial anemia.

The mean hepcidin level was significantly lower in children with iron-deficiency anemia than in children with anemia due to inflammation/infection (1.8 ng/mL and 21.7 ng/mL, respectively; P<0.0001).

To expand upon this finding, the investigators modeled the potential impact of screening children for iron supplementation needs based on hepcidin levels rather than anemia status.

If a screen was based on the presence of anemia (hemoglobin <11 g/dL), 77% of iron-deficient children would have received iron supplements, but so would 73% of children with Plasmodium falciparum parasitemia and all of the children with anemia due to inflammation.

On the other hand, if a screen was based on a hepcidin cutoff of <5.5 ng/mL, iron supplements would be given to 77% of children with iron deficiency, 80% of children with iron-deficiency anemia, 20% of children with P falciparum infection, and 14% of children with anemia due to inflammation.

The investigators noted that a lower hepcidin cutoff would have reduced the proportion of individuals with infection and/or inflammation receiving iron, but it would have increased the risk that more children with iron-deficiency anemia would not receive iron. And of course, the reverse is true of a higher hepcidin cutoff.

Nevertheless, the team believes these results are promising. They are now conducting clinical trials to test whether hepcidin levels can be used as a marker to guide iron supplementation decisions. ![]()

FDA declines to approve IV antiplatelet drug cangrelor

The Food and Drug Administration has rejected the approval of the intravenous antiplatelet drug cangrelor, suggesting that the company provide more data, according to the drug’s manufacturer.

The Medicines Company applied for approval of cangrelor for two indications: the reduction of death, MI, stent thrombosis, and ischemic-driven revascularization in patients who have not been recently treated with a thienopyridine and who are undergoing PCI; and for patients with stents who are at an increased risk for thrombotic events, such as stent thrombosis, when oral P2Y12 therapy is interrupted for surgery.

At a meeting earlier this year, the FDA’s Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee voted 7-2 against approval of the first indication, and unanimously voted against approval of the second indication, citing numerous issues with clinical trials.

The company’s April 30 statement announcing the FDA decision said that the agency had suggested that the company conduct "a series of data analyses" from the CHAMPION PHOENIX study that was the basis of the PCI indication (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:1303-13).

The FDA also concluded that a prospective controlled study to evaluate the risk-benefit of cangrelor for the second bridging indication with outcomes that included bleeding was needed, the statement said. For this indication, the company had submitted only a small pharmacodynamic study, which showed that a cangrelor infusion could maintain platelet inhibition similar to that achieved with clopidogrel.

In the statement Dr. Clive A. Meanwell, the company’s chairman and chief executive officer, said that "the next steps of review will focus on additional analyses in response to the FDA."

Cangrelor is a platelet P2Y12 inhibitor administered intravenously; with a half-life of 3-6 minutes, platelet function returns to normal within 1 hour of stopping the infusion of cangrelor, according to the company. The oral P2Y12 inhibitor clopidogrel has a more delayed action, with activity that lasts for days after is stopped.

The Food and Drug Administration has rejected the approval of the intravenous antiplatelet drug cangrelor, suggesting that the company provide more data, according to the drug’s manufacturer.

The Medicines Company applied for approval of cangrelor for two indications: the reduction of death, MI, stent thrombosis, and ischemic-driven revascularization in patients who have not been recently treated with a thienopyridine and who are undergoing PCI; and for patients with stents who are at an increased risk for thrombotic events, such as stent thrombosis, when oral P2Y12 therapy is interrupted for surgery.

At a meeting earlier this year, the FDA’s Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee voted 7-2 against approval of the first indication, and unanimously voted against approval of the second indication, citing numerous issues with clinical trials.

The company’s April 30 statement announcing the FDA decision said that the agency had suggested that the company conduct "a series of data analyses" from the CHAMPION PHOENIX study that was the basis of the PCI indication (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:1303-13).

The FDA also concluded that a prospective controlled study to evaluate the risk-benefit of cangrelor for the second bridging indication with outcomes that included bleeding was needed, the statement said. For this indication, the company had submitted only a small pharmacodynamic study, which showed that a cangrelor infusion could maintain platelet inhibition similar to that achieved with clopidogrel.

In the statement Dr. Clive A. Meanwell, the company’s chairman and chief executive officer, said that "the next steps of review will focus on additional analyses in response to the FDA."

Cangrelor is a platelet P2Y12 inhibitor administered intravenously; with a half-life of 3-6 minutes, platelet function returns to normal within 1 hour of stopping the infusion of cangrelor, according to the company. The oral P2Y12 inhibitor clopidogrel has a more delayed action, with activity that lasts for days after is stopped.

The Food and Drug Administration has rejected the approval of the intravenous antiplatelet drug cangrelor, suggesting that the company provide more data, according to the drug’s manufacturer.

The Medicines Company applied for approval of cangrelor for two indications: the reduction of death, MI, stent thrombosis, and ischemic-driven revascularization in patients who have not been recently treated with a thienopyridine and who are undergoing PCI; and for patients with stents who are at an increased risk for thrombotic events, such as stent thrombosis, when oral P2Y12 therapy is interrupted for surgery.

At a meeting earlier this year, the FDA’s Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee voted 7-2 against approval of the first indication, and unanimously voted against approval of the second indication, citing numerous issues with clinical trials.

The company’s April 30 statement announcing the FDA decision said that the agency had suggested that the company conduct "a series of data analyses" from the CHAMPION PHOENIX study that was the basis of the PCI indication (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:1303-13).

The FDA also concluded that a prospective controlled study to evaluate the risk-benefit of cangrelor for the second bridging indication with outcomes that included bleeding was needed, the statement said. For this indication, the company had submitted only a small pharmacodynamic study, which showed that a cangrelor infusion could maintain platelet inhibition similar to that achieved with clopidogrel.

In the statement Dr. Clive A. Meanwell, the company’s chairman and chief executive officer, said that "the next steps of review will focus on additional analyses in response to the FDA."

Cangrelor is a platelet P2Y12 inhibitor administered intravenously; with a half-life of 3-6 minutes, platelet function returns to normal within 1 hour of stopping the infusion of cangrelor, according to the company. The oral P2Y12 inhibitor clopidogrel has a more delayed action, with activity that lasts for days after is stopped.

Potpourri of travel medicine tips and updates

School’s out for the summer soon! Many of your patients may have plans to travel to areas where they may be exposed to infectious diseases and other health risks not routinely encountered in the United States. They will join the 29 million Americans, including almost 3 million children, who traveled to overseas destinations in 2013. The potential for exposures to these risks is dependent on several factors, including the traveler’s age, health and immunization status, destination, accommodations, and duration of travel. Leisure travel, including visiting friends and relatives, accounts for approximately 90% of overseas travel. Some adolescents are traveling to resource-limited areas for adventure travel, educational experiences, and volunteerism. Many times they will reside with host families as part of this experience. There are also children who will have prolonged stays as a result of parental job relocation.

Unfortunately, health precautions often are not considered as many make their travel arrangements. International trips on average are planned at least 105 days in advance; however, many patients wait until the last minute to seek medical advice, if at all. Of 10,032 ill persons who sought post-travel evaluations at participating surveillance facilities (U.S. GeoSentinel sites) between 1997 and 2011, less than half (44%) reported seeking pretravel advice (MMWR 2013;62(SS03):1-15).

Here are some tips that should be useful and easy to implement in your practice for your internationally traveling patients.

• Make sure routine immunizations are up-to-date for age. The exception to this rule is for measles. All children at least 12 months age should receive two doses of MMR prior to departure regardless of their international destination. The second dose of MMR can be administered as early as 4 weeks after the first. Children between 6 and 11 months of age should receive a single dose of MMR prior to departure. If the initial dose is administered at less than 12 months of age, two additional doses will need to be administered to complete the series beginning at 12 months of age.

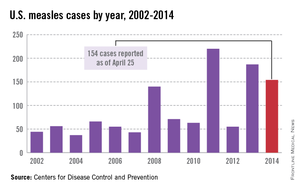

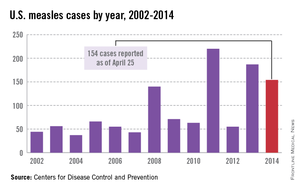

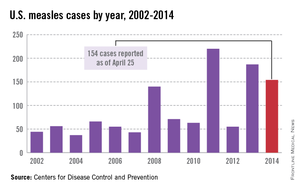

While measles is no longer endemic in the United States, as of April 25, 2014, there have been 154 cases reported from 14 states. (See measles graphic.) The majority of cases were imported by unvaccinated travelers who became ill after returning home and exposed susceptible individuals. In the last few years, most of the U.S. cases were imported from Western Europe. Currently, there are several countries experiencing record numbers of cases, including Vietnam (3,700) and the Philippines (26,000). This is not to imply that ongoing international outbreaks are limited to these two countries. For additional information, go to cdc.gov/measles.

• Identify someone in your area as a local resource for travel-related information and referrals. Make sure they are willing to see children. Develop a system to send out reminders to families to seek pretravel advice, ideally at least 1 month prior to departure. For children with chronic diseases or compromised immune systems, destination selection may need to be adjusted depending on their medical needs, availability of comparable health care at the overseas destination, and ability to receive pretravel vaccine interventions. Involvement prior to booking the trip would be advisable. Many offices successfully send out reminders for well visits and influenza vaccine. Consider incorporating one for overseas travel.

• The timing of initiation of antimalarial prophylaxis is dependent on the medication. Weekly medications such as chloroquine and mefloquine should begin at least 2 weeks prior to exposure. Atovaquone/proguanil and doxycycline are two drugs that are administered daily, and travelers can begin as late as 2 days prior to entry into a malaria-endemic area. This is a great option for the last-minute traveler.

However, there are contraindications for the use of each drug. Some are age dependent, while others are directly related to the presence of a specific medical condition. Areas where chloroquine-sensitive malaria is present are limited. It is always important to prescribe a prophylactic antimalarial agent, but even more prudent to prescribe the appropriate drug and dosage.

Not sure which drug is most appropriate for your patient? Refer to your local travel medicine expert, or visit cdc.gov/malaria.

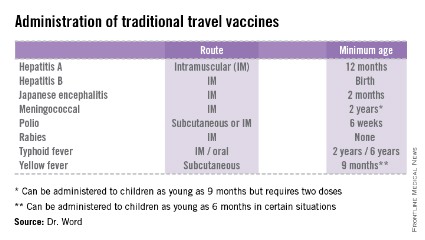

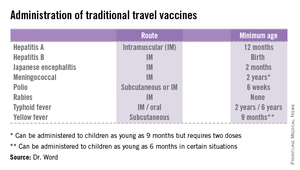

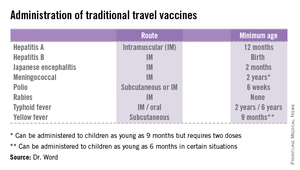

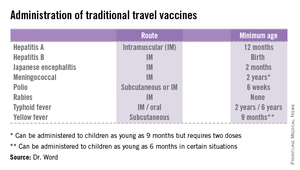

• The accompanying table lists vaccines that are traditionally considered to be travel vaccines, but pediatricians and family physicians might not consider all to belong in that group. Most are not required for entry into a specific country, but are recommended based on the risk for potential exposure and disease acquisition. In contrast, yellow fever and meningococcal vaccines are required for entry into certain countries. Yellow fever vaccine can be administered only at authorized sites and should be received at least 10 days prior to arrival at the destination. As with routinely administered vaccines, occasionally there are shortages of travel-related vaccines. Most recently, a shortage of yellow fever vaccine has been resolved.

The majority of vaccines should be administered at least 2 weeks prior to departure, while others, such as rabies and Japanese encephalitis, take at least 28 days to complete the series. These are a few additional reasons it behooves your patients to seek advice early.

Travel updates

Chikungunya virus (CHIK V). Local transmission in the Americas was first reported from St. Martin in December 2013. As of May 5, 2014, a total of 12 Caribbean countries have reported locally acquired cases. The disease is transmitted by Aedes species, which are the same species that transmit dengue fever. Disease is characterized by sudden onset of high fever with severe polyarthralgia. Additional symptoms can include headache, myalgias, rash, nausea, and vomiting. Epidemics have historically occurred in Africa, Asia, and islands in the Indian Ocean. Outbreaks also have occurred in Italy and France.

There is no preventive vaccine or drug available. Treatment is symptomatic care. The disease is best prevented by taking adequate mosquito precautions, especially during the daytime. Application of DEET (N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide) and picaridin-containing agents to the skin or treating clothes with a permethrin-containing agent are just two ways to avoid sustaining a mosquito bite.

While no cases Chikungunya virus have been acquired in the United States, there is a potential risk that the virus will be introduced by an infected traveler or mosquito. The Aedes species that transmits the virus is present in several areas of the United States. For additional information, go to cdc.gov/chikungunya.

Polio. While polio has been eliminated in the United States since 1979, it has never been eradicated in Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Pakistan. For a country to be certified as polio free, there cannot be evidence of circulation of wild polio virus for 3 consecutive years. In spite of a massive global initiative to eliminate this disease, in the last 3 months there have been cases confirmed in the following countries: Cameroon, Ethiopia, Equatorial Guinea, Iraq, Kenya, Somalia, and Syria. While no cases of flaccid paralysis have been confirmed in Israel, wild polio virus has been detected in sewage and isolated from stool of asymptomatic individuals.

Completion of the polio series is recommended for those persons inadequately immunized, and a one-time booster dose is recommended for all adults with travel plans to these countries. This should not be an issue for most pediatric patients, except those who may have deferred immunizations. Booster doses are no longer recommended for travel to countries that border countries with active circulation

African tick bite fever. Frequently overshadowed by the appropriate concern for prevention and acquisition of malaria is a rickettsial disease caused by Rickettsia africae, one of the spotted fever group of rickettsial infections. Its geographic distribution is limited to sub-Saharan Africa, and as its name implies, it is transmitted by a tick. It is the most commonly diagnosed rickettsial disease acquired by travelers (Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009;15:1791-8). Of 280 individuals diagnosed with rickettsiosis, 231 (82.5%) had spotted fever; almost 87% of the spotted fever rickettsiosis cases were acquired in sub-Saharan Africa, and 69% of these patients reported leisure travel to South Africa. In another review, it was the second-leading cause of systemic febrile illnesses acquired in travelers to sub-Saharan Africa. It was surpassed only by malaria (N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:119-30). All age groups are at risk.

Transmission occurs most frequently during the spring and summer months, coinciding with increased tick activity and greater outdoor activities. It is commonly acquired by tourists between November and April in South Africa during a safari or game hunting vacation. Because the incubation period is 5 to 14 days, most travelers may not become symptomatic until after their return. This disease should be suspected in any traveler who presents with fever, headache, and myalgias; has an eschar; and indicates they have recently returned from South Africa. Diagnosis is based on clinical history and serology. Therapy with doxycycline is initiated pending laboratory results.

Disease is controlled by prevention of transmission of the organism by the vector to humans. Use of repellents that contain 20%-30% DEET on exposed skin and wearing clothes treated with permethrin are recommended. Pretreated clothing is also available. Travelers should be encouraged to always check their body after exposure and remove ticks if discovered. Many advocate a bath or shower after coming indoors to facilitate finding any ticks.

Parents should check their children thoroughly for ticks under the arms, in and around the ears, inside the belly button, behind the knees, between the legs, around the waist, and especially in their hair.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Write to Dr. Word at [email protected].

School’s out for the summer soon! Many of your patients may have plans to travel to areas where they may be exposed to infectious diseases and other health risks not routinely encountered in the United States. They will join the 29 million Americans, including almost 3 million children, who traveled to overseas destinations in 2013. The potential for exposures to these risks is dependent on several factors, including the traveler’s age, health and immunization status, destination, accommodations, and duration of travel. Leisure travel, including visiting friends and relatives, accounts for approximately 90% of overseas travel. Some adolescents are traveling to resource-limited areas for adventure travel, educational experiences, and volunteerism. Many times they will reside with host families as part of this experience. There are also children who will have prolonged stays as a result of parental job relocation.

Unfortunately, health precautions often are not considered as many make their travel arrangements. International trips on average are planned at least 105 days in advance; however, many patients wait until the last minute to seek medical advice, if at all. Of 10,032 ill persons who sought post-travel evaluations at participating surveillance facilities (U.S. GeoSentinel sites) between 1997 and 2011, less than half (44%) reported seeking pretravel advice (MMWR 2013;62(SS03):1-15).

Here are some tips that should be useful and easy to implement in your practice for your internationally traveling patients.

• Make sure routine immunizations are up-to-date for age. The exception to this rule is for measles. All children at least 12 months age should receive two doses of MMR prior to departure regardless of their international destination. The second dose of MMR can be administered as early as 4 weeks after the first. Children between 6 and 11 months of age should receive a single dose of MMR prior to departure. If the initial dose is administered at less than 12 months of age, two additional doses will need to be administered to complete the series beginning at 12 months of age.

While measles is no longer endemic in the United States, as of April 25, 2014, there have been 154 cases reported from 14 states. (See measles graphic.) The majority of cases were imported by unvaccinated travelers who became ill after returning home and exposed susceptible individuals. In the last few years, most of the U.S. cases were imported from Western Europe. Currently, there are several countries experiencing record numbers of cases, including Vietnam (3,700) and the Philippines (26,000). This is not to imply that ongoing international outbreaks are limited to these two countries. For additional information, go to cdc.gov/measles.

• Identify someone in your area as a local resource for travel-related information and referrals. Make sure they are willing to see children. Develop a system to send out reminders to families to seek pretravel advice, ideally at least 1 month prior to departure. For children with chronic diseases or compromised immune systems, destination selection may need to be adjusted depending on their medical needs, availability of comparable health care at the overseas destination, and ability to receive pretravel vaccine interventions. Involvement prior to booking the trip would be advisable. Many offices successfully send out reminders for well visits and influenza vaccine. Consider incorporating one for overseas travel.

• The timing of initiation of antimalarial prophylaxis is dependent on the medication. Weekly medications such as chloroquine and mefloquine should begin at least 2 weeks prior to exposure. Atovaquone/proguanil and doxycycline are two drugs that are administered daily, and travelers can begin as late as 2 days prior to entry into a malaria-endemic area. This is a great option for the last-minute traveler.

However, there are contraindications for the use of each drug. Some are age dependent, while others are directly related to the presence of a specific medical condition. Areas where chloroquine-sensitive malaria is present are limited. It is always important to prescribe a prophylactic antimalarial agent, but even more prudent to prescribe the appropriate drug and dosage.

Not sure which drug is most appropriate for your patient? Refer to your local travel medicine expert, or visit cdc.gov/malaria.

• The accompanying table lists vaccines that are traditionally considered to be travel vaccines, but pediatricians and family physicians might not consider all to belong in that group. Most are not required for entry into a specific country, but are recommended based on the risk for potential exposure and disease acquisition. In contrast, yellow fever and meningococcal vaccines are required for entry into certain countries. Yellow fever vaccine can be administered only at authorized sites and should be received at least 10 days prior to arrival at the destination. As with routinely administered vaccines, occasionally there are shortages of travel-related vaccines. Most recently, a shortage of yellow fever vaccine has been resolved.

The majority of vaccines should be administered at least 2 weeks prior to departure, while others, such as rabies and Japanese encephalitis, take at least 28 days to complete the series. These are a few additional reasons it behooves your patients to seek advice early.

Travel updates

Chikungunya virus (CHIK V). Local transmission in the Americas was first reported from St. Martin in December 2013. As of May 5, 2014, a total of 12 Caribbean countries have reported locally acquired cases. The disease is transmitted by Aedes species, which are the same species that transmit dengue fever. Disease is characterized by sudden onset of high fever with severe polyarthralgia. Additional symptoms can include headache, myalgias, rash, nausea, and vomiting. Epidemics have historically occurred in Africa, Asia, and islands in the Indian Ocean. Outbreaks also have occurred in Italy and France.

There is no preventive vaccine or drug available. Treatment is symptomatic care. The disease is best prevented by taking adequate mosquito precautions, especially during the daytime. Application of DEET (N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide) and picaridin-containing agents to the skin or treating clothes with a permethrin-containing agent are just two ways to avoid sustaining a mosquito bite.

While no cases Chikungunya virus have been acquired in the United States, there is a potential risk that the virus will be introduced by an infected traveler or mosquito. The Aedes species that transmits the virus is present in several areas of the United States. For additional information, go to cdc.gov/chikungunya.

Polio. While polio has been eliminated in the United States since 1979, it has never been eradicated in Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Pakistan. For a country to be certified as polio free, there cannot be evidence of circulation of wild polio virus for 3 consecutive years. In spite of a massive global initiative to eliminate this disease, in the last 3 months there have been cases confirmed in the following countries: Cameroon, Ethiopia, Equatorial Guinea, Iraq, Kenya, Somalia, and Syria. While no cases of flaccid paralysis have been confirmed in Israel, wild polio virus has been detected in sewage and isolated from stool of asymptomatic individuals.

Completion of the polio series is recommended for those persons inadequately immunized, and a one-time booster dose is recommended for all adults with travel plans to these countries. This should not be an issue for most pediatric patients, except those who may have deferred immunizations. Booster doses are no longer recommended for travel to countries that border countries with active circulation

African tick bite fever. Frequently overshadowed by the appropriate concern for prevention and acquisition of malaria is a rickettsial disease caused by Rickettsia africae, one of the spotted fever group of rickettsial infections. Its geographic distribution is limited to sub-Saharan Africa, and as its name implies, it is transmitted by a tick. It is the most commonly diagnosed rickettsial disease acquired by travelers (Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009;15:1791-8). Of 280 individuals diagnosed with rickettsiosis, 231 (82.5%) had spotted fever; almost 87% of the spotted fever rickettsiosis cases were acquired in sub-Saharan Africa, and 69% of these patients reported leisure travel to South Africa. In another review, it was the second-leading cause of systemic febrile illnesses acquired in travelers to sub-Saharan Africa. It was surpassed only by malaria (N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:119-30). All age groups are at risk.

Transmission occurs most frequently during the spring and summer months, coinciding with increased tick activity and greater outdoor activities. It is commonly acquired by tourists between November and April in South Africa during a safari or game hunting vacation. Because the incubation period is 5 to 14 days, most travelers may not become symptomatic until after their return. This disease should be suspected in any traveler who presents with fever, headache, and myalgias; has an eschar; and indicates they have recently returned from South Africa. Diagnosis is based on clinical history and serology. Therapy with doxycycline is initiated pending laboratory results.

Disease is controlled by prevention of transmission of the organism by the vector to humans. Use of repellents that contain 20%-30% DEET on exposed skin and wearing clothes treated with permethrin are recommended. Pretreated clothing is also available. Travelers should be encouraged to always check their body after exposure and remove ticks if discovered. Many advocate a bath or shower after coming indoors to facilitate finding any ticks.

Parents should check their children thoroughly for ticks under the arms, in and around the ears, inside the belly button, behind the knees, between the legs, around the waist, and especially in their hair.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Write to Dr. Word at [email protected].

School’s out for the summer soon! Many of your patients may have plans to travel to areas where they may be exposed to infectious diseases and other health risks not routinely encountered in the United States. They will join the 29 million Americans, including almost 3 million children, who traveled to overseas destinations in 2013. The potential for exposures to these risks is dependent on several factors, including the traveler’s age, health and immunization status, destination, accommodations, and duration of travel. Leisure travel, including visiting friends and relatives, accounts for approximately 90% of overseas travel. Some adolescents are traveling to resource-limited areas for adventure travel, educational experiences, and volunteerism. Many times they will reside with host families as part of this experience. There are also children who will have prolonged stays as a result of parental job relocation.

Unfortunately, health precautions often are not considered as many make their travel arrangements. International trips on average are planned at least 105 days in advance; however, many patients wait until the last minute to seek medical advice, if at all. Of 10,032 ill persons who sought post-travel evaluations at participating surveillance facilities (U.S. GeoSentinel sites) between 1997 and 2011, less than half (44%) reported seeking pretravel advice (MMWR 2013;62(SS03):1-15).

Here are some tips that should be useful and easy to implement in your practice for your internationally traveling patients.

• Make sure routine immunizations are up-to-date for age. The exception to this rule is for measles. All children at least 12 months age should receive two doses of MMR prior to departure regardless of their international destination. The second dose of MMR can be administered as early as 4 weeks after the first. Children between 6 and 11 months of age should receive a single dose of MMR prior to departure. If the initial dose is administered at less than 12 months of age, two additional doses will need to be administered to complete the series beginning at 12 months of age.

While measles is no longer endemic in the United States, as of April 25, 2014, there have been 154 cases reported from 14 states. (See measles graphic.) The majority of cases were imported by unvaccinated travelers who became ill after returning home and exposed susceptible individuals. In the last few years, most of the U.S. cases were imported from Western Europe. Currently, there are several countries experiencing record numbers of cases, including Vietnam (3,700) and the Philippines (26,000). This is not to imply that ongoing international outbreaks are limited to these two countries. For additional information, go to cdc.gov/measles.

• Identify someone in your area as a local resource for travel-related information and referrals. Make sure they are willing to see children. Develop a system to send out reminders to families to seek pretravel advice, ideally at least 1 month prior to departure. For children with chronic diseases or compromised immune systems, destination selection may need to be adjusted depending on their medical needs, availability of comparable health care at the overseas destination, and ability to receive pretravel vaccine interventions. Involvement prior to booking the trip would be advisable. Many offices successfully send out reminders for well visits and influenza vaccine. Consider incorporating one for overseas travel.

• The timing of initiation of antimalarial prophylaxis is dependent on the medication. Weekly medications such as chloroquine and mefloquine should begin at least 2 weeks prior to exposure. Atovaquone/proguanil and doxycycline are two drugs that are administered daily, and travelers can begin as late as 2 days prior to entry into a malaria-endemic area. This is a great option for the last-minute traveler.

However, there are contraindications for the use of each drug. Some are age dependent, while others are directly related to the presence of a specific medical condition. Areas where chloroquine-sensitive malaria is present are limited. It is always important to prescribe a prophylactic antimalarial agent, but even more prudent to prescribe the appropriate drug and dosage.

Not sure which drug is most appropriate for your patient? Refer to your local travel medicine expert, or visit cdc.gov/malaria.

• The accompanying table lists vaccines that are traditionally considered to be travel vaccines, but pediatricians and family physicians might not consider all to belong in that group. Most are not required for entry into a specific country, but are recommended based on the risk for potential exposure and disease acquisition. In contrast, yellow fever and meningococcal vaccines are required for entry into certain countries. Yellow fever vaccine can be administered only at authorized sites and should be received at least 10 days prior to arrival at the destination. As with routinely administered vaccines, occasionally there are shortages of travel-related vaccines. Most recently, a shortage of yellow fever vaccine has been resolved.

The majority of vaccines should be administered at least 2 weeks prior to departure, while others, such as rabies and Japanese encephalitis, take at least 28 days to complete the series. These are a few additional reasons it behooves your patients to seek advice early.

Travel updates

Chikungunya virus (CHIK V). Local transmission in the Americas was first reported from St. Martin in December 2013. As of May 5, 2014, a total of 12 Caribbean countries have reported locally acquired cases. The disease is transmitted by Aedes species, which are the same species that transmit dengue fever. Disease is characterized by sudden onset of high fever with severe polyarthralgia. Additional symptoms can include headache, myalgias, rash, nausea, and vomiting. Epidemics have historically occurred in Africa, Asia, and islands in the Indian Ocean. Outbreaks also have occurred in Italy and France.

There is no preventive vaccine or drug available. Treatment is symptomatic care. The disease is best prevented by taking adequate mosquito precautions, especially during the daytime. Application of DEET (N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide) and picaridin-containing agents to the skin or treating clothes with a permethrin-containing agent are just two ways to avoid sustaining a mosquito bite.

While no cases Chikungunya virus have been acquired in the United States, there is a potential risk that the virus will be introduced by an infected traveler or mosquito. The Aedes species that transmits the virus is present in several areas of the United States. For additional information, go to cdc.gov/chikungunya.

Polio. While polio has been eliminated in the United States since 1979, it has never been eradicated in Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Pakistan. For a country to be certified as polio free, there cannot be evidence of circulation of wild polio virus for 3 consecutive years. In spite of a massive global initiative to eliminate this disease, in the last 3 months there have been cases confirmed in the following countries: Cameroon, Ethiopia, Equatorial Guinea, Iraq, Kenya, Somalia, and Syria. While no cases of flaccid paralysis have been confirmed in Israel, wild polio virus has been detected in sewage and isolated from stool of asymptomatic individuals.

Completion of the polio series is recommended for those persons inadequately immunized, and a one-time booster dose is recommended for all adults with travel plans to these countries. This should not be an issue for most pediatric patients, except those who may have deferred immunizations. Booster doses are no longer recommended for travel to countries that border countries with active circulation

African tick bite fever. Frequently overshadowed by the appropriate concern for prevention and acquisition of malaria is a rickettsial disease caused by Rickettsia africae, one of the spotted fever group of rickettsial infections. Its geographic distribution is limited to sub-Saharan Africa, and as its name implies, it is transmitted by a tick. It is the most commonly diagnosed rickettsial disease acquired by travelers (Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009;15:1791-8). Of 280 individuals diagnosed with rickettsiosis, 231 (82.5%) had spotted fever; almost 87% of the spotted fever rickettsiosis cases were acquired in sub-Saharan Africa, and 69% of these patients reported leisure travel to South Africa. In another review, it was the second-leading cause of systemic febrile illnesses acquired in travelers to sub-Saharan Africa. It was surpassed only by malaria (N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:119-30). All age groups are at risk.

Transmission occurs most frequently during the spring and summer months, coinciding with increased tick activity and greater outdoor activities. It is commonly acquired by tourists between November and April in South Africa during a safari or game hunting vacation. Because the incubation period is 5 to 14 days, most travelers may not become symptomatic until after their return. This disease should be suspected in any traveler who presents with fever, headache, and myalgias; has an eschar; and indicates they have recently returned from South Africa. Diagnosis is based on clinical history and serology. Therapy with doxycycline is initiated pending laboratory results.

Disease is controlled by prevention of transmission of the organism by the vector to humans. Use of repellents that contain 20%-30% DEET on exposed skin and wearing clothes treated with permethrin are recommended. Pretreated clothing is also available. Travelers should be encouraged to always check their body after exposure and remove ticks if discovered. Many advocate a bath or shower after coming indoors to facilitate finding any ticks.

Parents should check their children thoroughly for ticks under the arms, in and around the ears, inside the belly button, behind the knees, between the legs, around the waist, and especially in their hair.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Write to Dr. Word at [email protected].

A more precise method of delivering gene therapy

Jeff Fitlow/Rice University

Researchers have developed an adeno-associated virus (AAV) that releases its payload only in the presence of 2 selected proteases.

Because certain proteases are elevated at tumor sites, the virus can be designed to target and destroy cancer cells.

Junghae Suh, PhD, of Rice University in Houston, Texas, and her colleagues engineered the virus and described their work in ACS Nano.

AAVs have become the object of study as delivery vehicles for gene therapy.

Researchers often try to target AAVs to cellular receptors that may be slightly overexpressed on diseased cells, but Dr Suh’s team took a different approach.

“We were looking for other types of biomarkers beyond cellular receptors present at disease sites,” she said. “In breast cancer, for example, it’s known the tumor cells oversecrete extracellular proteases, but perhaps more important are the infiltrating immune cells that migrate into the tumor microenvironment and start dumping out a whole bunch of proteases as well.”

“So that’s what we’re going after to do targeted delivery. Our basic idea is to create viruses that, in the locked configuration, can’t do anything.”

But when the programmed AAVs encounter the right proteases at sites of disease, they unlock and bind to the cells. The AAVs then deliver payloads that will either kill the cells, in the case of cancer therapy, or deliver genes that can repair the cells.

Dr Suh and her colleagues genetically insert peptides into the self-assembling AAVs to lock the capsids, the hard shells that protect genes contained within. The target proteases recognize the peptides and “chew off the locks,” effectively unlocking the virus and allowing it to bind to the diseased cells.

“If we were just looking for 1 protease, it might be at the cancer site, but it could also be somewhere else in your body where you have inflammation,” Dr Suh said. “This could lead to undesirable side effects.”

“By requiring 2 different proteases—let’s say protease A and protease B—to open the locked virus, we may achieve higher delivery specificity since the chance of having both proteases elevated at a site becomes smaller.”

The ultimate vision of this technology is to design viruses that can carry out a combination of steps for targeting.

“To increase the specificity of virus unlocking, you can imagine creating viruses that require many more keys to open,” Dr Suh said. “For example, you may need both proteases A and B, as well as a cellular receptor, to unlock the virus. The work reported here is a good first step toward this goal.” ![]()

Jeff Fitlow/Rice University

Researchers have developed an adeno-associated virus (AAV) that releases its payload only in the presence of 2 selected proteases.

Because certain proteases are elevated at tumor sites, the virus can be designed to target and destroy cancer cells.

Junghae Suh, PhD, of Rice University in Houston, Texas, and her colleagues engineered the virus and described their work in ACS Nano.

AAVs have become the object of study as delivery vehicles for gene therapy.

Researchers often try to target AAVs to cellular receptors that may be slightly overexpressed on diseased cells, but Dr Suh’s team took a different approach.

“We were looking for other types of biomarkers beyond cellular receptors present at disease sites,” she said. “In breast cancer, for example, it’s known the tumor cells oversecrete extracellular proteases, but perhaps more important are the infiltrating immune cells that migrate into the tumor microenvironment and start dumping out a whole bunch of proteases as well.”

“So that’s what we’re going after to do targeted delivery. Our basic idea is to create viruses that, in the locked configuration, can’t do anything.”

But when the programmed AAVs encounter the right proteases at sites of disease, they unlock and bind to the cells. The AAVs then deliver payloads that will either kill the cells, in the case of cancer therapy, or deliver genes that can repair the cells.

Dr Suh and her colleagues genetically insert peptides into the self-assembling AAVs to lock the capsids, the hard shells that protect genes contained within. The target proteases recognize the peptides and “chew off the locks,” effectively unlocking the virus and allowing it to bind to the diseased cells.

“If we were just looking for 1 protease, it might be at the cancer site, but it could also be somewhere else in your body where you have inflammation,” Dr Suh said. “This could lead to undesirable side effects.”

“By requiring 2 different proteases—let’s say protease A and protease B—to open the locked virus, we may achieve higher delivery specificity since the chance of having both proteases elevated at a site becomes smaller.”

The ultimate vision of this technology is to design viruses that can carry out a combination of steps for targeting.

“To increase the specificity of virus unlocking, you can imagine creating viruses that require many more keys to open,” Dr Suh said. “For example, you may need both proteases A and B, as well as a cellular receptor, to unlock the virus. The work reported here is a good first step toward this goal.” ![]()

Jeff Fitlow/Rice University

Researchers have developed an adeno-associated virus (AAV) that releases its payload only in the presence of 2 selected proteases.

Because certain proteases are elevated at tumor sites, the virus can be designed to target and destroy cancer cells.

Junghae Suh, PhD, of Rice University in Houston, Texas, and her colleagues engineered the virus and described their work in ACS Nano.

AAVs have become the object of study as delivery vehicles for gene therapy.

Researchers often try to target AAVs to cellular receptors that may be slightly overexpressed on diseased cells, but Dr Suh’s team took a different approach.

“We were looking for other types of biomarkers beyond cellular receptors present at disease sites,” she said. “In breast cancer, for example, it’s known the tumor cells oversecrete extracellular proteases, but perhaps more important are the infiltrating immune cells that migrate into the tumor microenvironment and start dumping out a whole bunch of proteases as well.”

“So that’s what we’re going after to do targeted delivery. Our basic idea is to create viruses that, in the locked configuration, can’t do anything.”